The Science of Paul Scowen

Emeritus Voices

The Journal of the Emeritus College at Arizona State University

Editorial Board

Editor

Richard J. Jacob

Assistant Editor

Joann Tongret

Editorial Assistants

Megan Joyce

Advisory Board

Jean R. Brink (2022)

Aleksandra Gruzinska (2023)

Randel Helms (2022)

Sarah Hudelson (2023)

Leslie Kane (2022)

Shannon Perry (2023)

John Reich (2022)

Stephen Siek (2023)

Ernie Stech (2022)

Harvey Smith, Chair (2022)

JoAnn Tongret (2022)

Emeritus College

Old Main, Room 102 PO Box 873002

Tempe, AZ 85287–3002

emerituscollege@asu.edu

Emeritus College

A place and a purpose.

Emeritus Voices is the literary and scholarly Journal of the Emeritus College at Arizona State University. The Journal is intended for the expression, edification, and enjoyment of members of the Emeritus College and others interested in the content. The Journal provides a vehicle for interdisciplinary interaction and education. Submissions are invited for fiction, non–fiction, memoir, essay, poetry, scholarship, review, photography, graphic arts, etc., exploring all facets of creativity, scholarship and life experience.

Instructions for submissions can be found at: emerituscollege.asu.edu/submission-guidlines

Correspondence should be sent to Editor, Emeritus Voices Arizona State University

P.O. Box 873002, Tempe, AZ 85287-3002, or emerituscollege@asu.edu

Emeritus Voices considers for publication letters from its readers in response to articles published in the journal. Letters will be selected on the basis of interest, thoughtfulness, cogency and reasonableness. Letters may be submitted by email or postal mail. See Submission Guidelines in this issue for details.

Copyright © 2022

Unless indicated otherwise, the copyright for each individual article, poem or illustration in this issue is retained by the author, artist or owner (as indicated in the illustrations credits on p. 182).

Arizona State University

Tempe, AZ 85281

Printed in the United States of America

ISSN 1942-3039

To Catch a Rainbow Richard Jacob

As some of you know, in addition to my day job as a physicist, I was a semi-professional musician; that is to say, I gladly accepted payment for gigs. This often led, in conversational settings with new or casual acquaintances, to my collocutor, not wanting to discuss physics (I never blame them) resorting to the observation that many of their scientific friends, especially from the quantitative sciences, enjoy performing music avocationally, some of them quite well. I would agree; I have observed the same. And then, the new line of discussion apparently bearing fruit, they invariably go on to hypothesize that the reason must be that music—die holde Kunst—can be broken down to mathematical intervals and progressions, it being implied that of course scientists cannot possibly have truly artistic souls. Left brain, right brain and all that. At this point I would suddenly discover that I wanted an hors d’oeuvre from a tray across the room. But occasionally I would spend the time and patience to explain as best I could that it is in fact the other way around, at least for me and most of the musician scientists I know. It is our love of our science, whatever it may be, as an art form; of our work as an artistic endeavor; not its rigor, that expands our attention and efforts beyond that to which we are primarily dedicated. As the most iconic scientist of the Twentieth Century said, “After a certain high level of technical skill is achieved, science and art tend to coalesce in esthetics, plasticity, and form. The greatest scientists are always artists as well.” (A. E.) Of course,

the art of the scientist has always to satisfy the constraints of observation and logic, but this need be no barrier to beauty, imagination or the other aesthetic virtues. Maxwell’s equations governing electricity and magnetism are jaw-droppingly beautiful; Einstein’s Theory of General Relativity, expressed mathematically, is awesome in its efficient simplicity, like a couplet from the world’s best-revered poet; the pictorial reconstruction from data of the collision of two gold atoms at speeds near that of light defies brush and pallet.

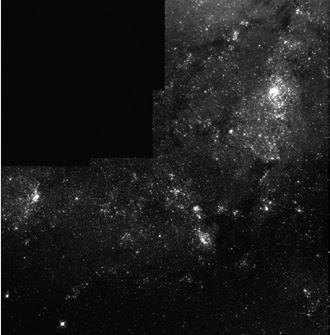

None of this is to assuage my frustration at an old pet peeve, but rather to introduce with pleasure to the faithful Emeritus Voices reader the extension of our usual art pictorial, featuring in each issue one of the Emeritus College’s graphic and performance artists, to the art of our scientist colleagues. Our first scientist cum artist is astronomer Paul Scowen. I hope his amazing photographs from the universe around us inspire you as they do me.

But Scowen is not the only Paul, featured in this issue, to demonstrate the entanglement of the “two cultures.” Geologist Paul Knauth invites us along in his search for ever-clearer skies under which to search the heavens “for purely aesthetic reasons—I’m not doing any science.” And Harvey Smith is persuasive in his portrayal of mathematics as being much more than the cold consideration of numbers and equations. This larger than usual issue of Emeritus Voices (we seem to have emerged from our COVID cocoons) contains thoughtful analyses by Terry Bell on Lincoln’s effective interpretation of texts, in David Berman’s review of Arizona minorities’ battles for voting rights, Gretchen Bataille’s survey of changing patterns in higher education and Dirk Raat’s history of the Mormon pioneers’ interactions with Native Americans. Jeanie Brink reveals an episode in her retirement life, Lee Croft engages with a cold-war spy, Aleksandra Gruzinska recalls her years as a young Polish refugee living on a German farm during World War II and Jane and Paul Jackson describe a scary recent health crisis. Shannon Perry takes her grandson to London! Tally ho! David Kader moves us with his essay of short fragments derived from a consciousness of holocaust horror, and Ernie Stech draws an important lesson from another

culture.

There is poetry to evoke a rainbow of emotions from Shannon, Perry, John Johnson, Babs Gordon and JoAnn Tongret; nostalgia from Tongret’s review of a favorite old movie and a suggestion or two by yours truly for reading the book behind that recent flick (or streaming the film from that book-club read.) Also check out Paul Jackson’s Golden Age of Hollywood impressions. And finally, I hope you like the new look of this, the 30th edition in Emeritus Voice’s fifteen-year existence. Fancy new clothes and accessories, many thanks to VisLab compositor, Megan Joyce.

What is Math About? Harvey

A. SmithI once mentioned to my dentist that I did research in mathematics. Surprised, he asked, "How can you do research in mathematics? Isn't it all known?" Repeating this, which I thought a funny story, I found my non-mathematical friends shared his view.

Teaching a course on the history of modern mathematics to math majors, I would ask them, as their first homework, to interpret the following unrhymed poem by a mathematician:

Paradox

By Clarence R. Wylie, Jr.Not truth, nor certainty. These I foreswore

In my novitiate, as young men called To holy orders must abjure the world

‘If…, then…,’ this only I assert; And my successes are but pretty chains

Linking twin doubts, for it is vain to ask If what I postulate be justified, Or what I prove possess the stamp of fact.

Yet bridges stand, and men no longer crawl In two dimensions. And such triumphs stem

In no small measure from the power of this game, Played with the thrice-attenuated shades Of things, has over their originals. How frail the wand, but how profound the spell!

A few, inspired by literature classes, gave strange, recondite—even religious—interpretations. None of them understood that Wylie was precisely answering the title question of this lecture. Much of my course was devoted to explaining that in great detail. Here, I will give a one-lecture synopsis.

Ancient mathematics developed to meet practical ends: deciding how much to tax the peasants, building temples and pyramids, and settling boundary disputes after floods obliterated established markers. The latter use came to be called "geometry," from the Greek for "earth measurement." Allegedly, Egyptian priests, seeking to resolve disputes, developed a technique for getting the disputants to agree. Starting from a few assertions held in common by the parties, they would then argue logically to arrive at a conclusion which all must accept and so resolve the dispute. Some Greeks—notably Pythagoras—were fascinated by this practice. Pythagoras developed a religious cult devoted to seeking "truth" by this logical method, which he encountered while traveling in Egypt. Geometry flourished in Greek culture; the motto over the door to Plato's Academy in Athens read, "Let no one ignorant of geometry enter here."

Euclid of Alexandria wrote Elements of Geometry in the reign of the first Greek Pharaoh, Ptolemy I, around 300 BCE. It remained the standard approach to plane geometry for over two thousand years. Euclid stated ten assumptions, to which he thought every right-thinking person must agree. Five, like, "Things equal to the same thing are equal to each other," he called "axioms." A second five, such as, "Any two points can be connected by a straight line," he called "postulates" because he considered them less basic. Statements arrived at by arguing logically, assuming only the axioms

and postulates, were called “theorems.” Today, we don’t usually distinguish between "axioms" and “postulates.” The terms “point,” “line,” and “plane”—the idealized “objects” supposedly being studied—were never defined; everyone thought they sort of knew what those terms meant. Many scholars thought one of Euclid's postulates for plane geometry was overly complicated. It said, "For any line, and any point not on that line, there is exactly one line containing that point which has no point in common with the first line." Two lines in the plane that don't intersect are called "parallel," so this is called "the parallel postulate." They felt such a complicated statement should be provable as a theorem, rather than being a separate postulate. For two thousand years, they tried in vain to prove the parallel postulate from the others, rather than assuming it. In 1733, Girollamo Saccheri, a Jesuit priest, convinced himself he had succeeded and published Euclides ab Omni Naevo Vindicatus (Euclid Cleared of Every Blemish). His approach was to assume the falsity of Euclid's parallel postulate and try to establish a contradiction with the others, thereby proving it. Assuming there could be more than one parallel line, Saccheri correctly proved many strange-seeming

theorems, but he never really arrived at a contradiction. Finally, he decided the theorems he proved were so bizarre they contradicted common sense. That, he declared, constituted a contradiction of the other axioms.

Other mathematicians tried a similar, but different, approach. Instead of assuming there was only one parallel line—as Euclid had postulated—or more than one parallel line, as Saccheri had, they assumed there were none. Like Saccheri, they found no contradictions. Soon they realized the theorems they were proving described matters well-known to artists who were drawing scenes in perspective.

Imagine yourself as an artist painting a scene on a flat canvas. Everything along the same line extended from your eye corresponds to a single point on the canvas—the closest point on that line blocks the others from view. Now, think of your eye as being at the center of a sphere, with you looking along a line in a particular direction. To get a familiar picture of this situation, think of the sphere as being a globe of the Earth and the line of sight as being toward the point where the Greenwich meridian (0° longitude) crosses the equator (0° latitude). The north pole is overhead, and the south pole is down. You can see only things in front, between 90° east and 90° west.

Now, imagine that you are at the center of a transparent spherical shell. All points on any particular vertical line you see in space will lie at the same longitude of the sphere, so you see and draw the line as a straight vertical line of longitude; if the original line were extended to infinity at both ends, the line would appear to run from pole to pole. Two different parallel vertical lines at the same longitude are seen as the same line by the artist since one lies behind the other. If they lie at different longitudes, they correspond to different longitudes

on the globe corresponding to circles—which, unlike the original parallel lines—intersect at the poles. The lines representing them on your canvas approach one another as they become more distant from the eye but, since your canvas is finite, you cannot show them intersecting. (Parallel lines that are not vertical behave similarly—just think of the globe being rotated so the plane containing both the circle and the artist’s eye passes through the north and south poles.)

We can think of our canvas as a plane perpendicular to the direction of vision. If the canvas is infinitely large, every visible point corresponds to a point on the canvas but, as the visible points approach the 90° limit of visibility in any direction, the points on the canvas move infinitely far away toward the edges of the canvas and parallel lines emanating from a distant origin at the center of the canvas would diverge as they approach the edge. This is how artists render a scene in strict perspective. For instance, a road of constant width is shown on the finite canvas as diverging as it gets farther away from its distant source near the center of the painting.

Since it is undefined, we can think of the word “line” as meaning a “great circle” on the visible hemisphere (i.e., a circle centered on the artist’s eye, as the longitudes are.) A great circle arc is the shortest distance between two points on the spherical surface. With the exception of the equator, the latitude circles on a globe are not great circles. If we take “line” to mean the portion of a great circle within the visible hemisphere, including its boundary circle, we can say there are no parallel lines.

Today, mathematicians call the visible hemisphere (together with the infinity circle, its diametrically opposite points being thought of as a single point) the projective plane. (Our artist is "projecting" the hemisphere of his vision onto the plane of the canvas.) A "line" in the projective plane, is defined to mean a great circle on that hemisphere. Similarly, it proved possible to construct a more complicated “hyperbolic” surface on which all Saccheri's theorems hold; as with the spherical surface, except for the parallel postulate, all of Euclid's axioms and postulates hold, but there are many parallels through a point, rather than just one. These examples provide two different "non-Euclidean" geometries. In one there are no parallels, and in the other there are infinitely many. Thus, the parallel postulate is not a theorem that can be proved from the other axioms and postulates.

By the mid-nineteenth century, it became apparent to many mathematicians that, rather than describing "reality," mathematics only studied the logical consequences of a set of axioms. This approach led to the development of wholly new fields of mathematics, including spaces with more than three dimensions—even infinitely many—and "curved" spaces. By the second decade of the twentieth century, when Einstein needed a four-dimensional (three space and one time) curved space for his theory of gravity, which is called general relativity, he found the theory of such spaces was already being studied by some Italian mathematicians and they helped him learn how to use their results. Two decades later, physicists found the mathematics they needed for quantum mechanics in a theory of infinite-dimensional spaces. Today mathematics is seen as being simply the process of studying the logical consequences

of a set of axioms about objects that are themselves undefined—just as "line", "point", and “plane” were left undefined by Euclid. If the axioms don't contradict one another, the question of whether they are "true"— in the sense of describing something in the physical universe—doesn't arise. That's a question for physicists and engineers, not mathematicians. Often, when the undefined "objects" (lines, etc.) being discussed in the axioms were given physical interpretations, the results obtained by pursuing the logical consequences of what might seem a bizarre set of axioms proved amazingly useful in unforeseen ways. That is what Wylie's poem is about.

Modern mathematics only says, "Here is a bunch of statements we will call 'axioms’ (The "ifs" of Wylie's poem.) about some undefined objects. We will reason that if they are true, then other statements about those objects, which we will call theorems, must also be true" (the "thens" of the poem.) We make no assertion about the axioms or the theorems themselves being "true" or "certain." Only that if the axioms are assumed to be true then the theorems must logically follow. (Of course, if the axioms contradict one another, some must be discarded, since they can't all be assumed true.)

Let me give a simple example: Suppose there is a (possibly infinite) set of objects which, for convenience, we will sometimes denote by letters. And suppose there is a rule for combining these objects to produce another of the objects. We will denote the combination of the objects a and b (in that order) by a•b. We assume the following axioms:

Axiom 1. For any objects a, b, and c, ((a•b)•c) = (a•(b•c)), where the parentheses denote the order in which the operations are done. That is, if a is combined with b first, (a•b) and the resulting object is combined with c, ((a•b)•c)), it produces the same result as if combine a with (b•c), the result of combining b with c, all in the given order.

Axiom 2. There is a particular object, e, called “the identity,” such that, for any object a, e•a = a•e = a. Combining e with any object, in either order, leaves that object unchanged.

Axiom 3. For any object a, there is an object a-1 (called the inverse of a), such that

A set of objects, with a “combining” operation satisfying 1), 2), and 3) is called a group, and their study is called group theory.

Some easy basic theorems in group theory are:

If e and f are both identities, then e = f. (There is only one identity.)

Proof: f = e•f = e

If c and d are both inverses of a, then c=d. (An object has only one inverse.)

Proof:

One example of a group is all the integers {…,-3,-2,-1,0,1,2,3,…} with • being the usual + operation of addition, e being the number 0, and the inverse of an integer being its negative. Another example is the set of positive rational number with • being the usual operation of multiplication, e being the rational number 1, and the inverse of a positive rational number being its reciprocal: (2/3) • (3/2) = (3/2) • (2/3) = (1/1) = e upon cancellation of the 2’s and the 3’s.

In these examples the operation • also satisfies the rule a•b = b•a. We might conjecture that this is a theorem that could be proved for all groups. That is not true. If we add it as another axiom, we get a special set of groups, called Abelian groups, named after the early 19th century Norwegian mathematician Niels Henrich Abel. Groups in which a•b = b•a doesn’t always hold are called “non-Abelian.” The group of all possible motions of an object in space, with a•b meaning “motion b, followed by motion a,” the identity being not moving, and the inverse of a motion being the reverse motion is an example of a group which is non-Abelian. (To see this, face north and let a be the motion of lying down and b be that of turning to the east. If you turn before lying down, you end up lying on your back, with your legs pointing east.

If you lie down first and then turn east, you end up on your side facing east with your legs pointing north.) You can also try this exercise with a book or a die.

All of the above examples of groups have infinitely many objects. Again, this does not follow from the axioms. A set with only two elements e and a and the operations e•a = a•e = a, a•a = e, (a is its own inverse,) and e•e = e is a group. (Let e represent the set of all even integers and a represent all the odd integers. and • be the usual addition. The operations then just say that the sum of any even and any odd integer is odd, the sum of any two odd integers is even, and the sum of any two even integers is also even.)

There are mathematicians who spend their lives studying the theory of groups. It was a notable achievement when they were able to show how to construct all the finite groups, a project only completed, in 2004, after decades of effort. It took hundreds of pages to establish their results! Group theory is considered a part of "Abstract Algebra," (sometimes called "Modern Algebra" in older texts.")

There are also "Modern Geometries"—even geometries with only finitely many points and lines. They are sometimes named after the mathematician who first studied them. For instance, "Fano's Geometry" and "Young's Geometry" share the following four axioms, but they differ in a fifth, with Fano using the projective plane axiom of no parallels and Young using Euclid's parallel axiom of exactly one parallel:

Axiom 1. There exists at least one line.

Axiom 2. There are exactly three points on every line.

Axiom 3. Not all points are on the same line.

Axiom 4. There is exactly one line on any two points (two points determine a line.)

Axiom 5. (Fano) There is a common point on any two lines (i.e. there are no parallel lines.)

Axiom 5. (Young) For each line L and point P, not on L, there is exactly one line on P having no point in common with L. (i.e. Euclid’s “parallel postulate.”)

You might be interested in proving (or looking up) that Fano's geometry has exactly seven points and seven lines, while Young's geometry has exactly nine points and thirteen lines.

Young children are taught arithmetic without any axioms—often they start by counting their fingers. Does that mean that elementary arithmetic is not part of what we now call mathematics? In 1889, the Italian mathematician Giuseppe Peano introduced five axioms about “natural numbers”.

Axiom 1. Zero is a natural number.

Axiom 2. Every natural number has a “successor”, which is also a natural number.

Axiom 3. Zero is not the successor of any natural number.

Axiom 4. If the successors of natural numbers are the same, those natural numbers are the same.

Axiom 5. If a set contains zero and also contains the successor of every natural number in the set, then the set contains all the natural numbers.

Starting from those axioms, one can define all of simple arithmetic, indeed all of the classical objects of analysis: the negative integers, the rational numbers, the real numbers, and the complex numbers. This was expounded, brilliantly and completely, in the little book Grundla-

gen der Analysis (Foundations of Analysis) that the great number theorist Edmund Landau initially wrote for the education of his daughters°. Published in 1930, it became an international best seller and is still in print and widely available in many languages, including English.

Wylie’s poem tells us that mathematics is not about truth; it’s about logical consistency. There can in fact be a danger in believing that mathematics describes nature. It may lead to overconfidence in making statements about nature based on mathematical assumptions, and a belief the future can be predicted using mathematics. Sometimes it can, and philosophers have wondered why this is so, but mathematical results only reflect what logically follows from the assumptions being made, which may or may not be valid. Many predictions based on mathematical models are highly accurate, but others have proved to be extremely misleading because their underlying assumptions turned out not to be true. The hope is always that in such cases, avé Einstein, a “truer” set of axioms can be found. But it is not guaranteed.

The axioms of plane geometry may be close enough to "truth" for laying out the boundaries of a farmer's field, but for determining the boundaries of a large state or world-wide exploration, the geometry of

a sphere is needed. For even higher accuracy, the fact that the earth is not a sphere, but is flattened at the poles to be (approximately) an "oblate spheroid" may be required. For astronomical distances and powerful gravitational fields, the curved space-time of Einstein's relativity is needed. And to understand the physics involved in the basic workings of a microchip, one needs mathematical spaces of infinite dimension.

The mathematician's patterns, like the painter's or the poet's must be beautiful; the ideas, like the colours or the words must fit together in a harmonious way. Beauty is the first test: there is no permanent place in the world for ugly mathematics.

G. H. HardyIronies and Epiphanies

A Note of Some Importance to a Father

Ernie Stetch

Ernie Stetch

In my years of teaching undergraduates, I was fortunate to have classes of 25-30 students, and we spent much class time in discussion and interaction. Thus, I was able to learn about the learners as individuals. I made it a regular practice, at the end of each semester, to identify several as good human beings. To me, that meant they were open and honest and displayed maturity. If I had been their age, I would have wanted them as friends.

In private, I asked each student for his or her parents’ address and said I would be sending them a note of appreciation of their offspring. I believed that their goodness arose out of parental values and modeling. Of course, the students were pleased and thanked me.

This went on for six or seven years, and I never received a reply from the parents. Neither did I expect one. It was a case of giving without expecting return.

Some years after leaving the full-time academic world, I did get an e-mail from a former colleague. He had met one of our graduates at an art exhibit. She said that her father had died in the previous year, and

she told him about my practice of sending notes to parents. When the family opened the man’s wallet, tucked in between cards, was a folded note. A note from me. Something he clearly prized.

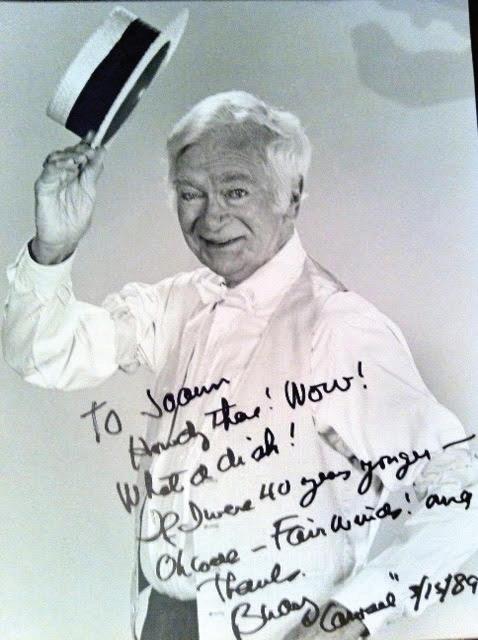

Working with Buddy Ebsen

JoAnn

Yeoman TongretMany years ago, I had the pleasure of working with Buddy Ebsen, well known for his starring roles in the television series The Beverly Hillbillies, Barnaby Jones, and Davy Crockett. I was choreographing a production of Carousel and Buddy was hired in the cameo role of the angel who offers Billy Bigelow a second chance. The musical was produced at Gammage Auditorium by the Musical Theatre of Arizona.

Then in his 80’s, Buddy was as bright and energetic and charming as anyone could imagine. Before film and TV, Buddy had starred in Vaudeville as half of a dancing duo with his sister, Vilma. Vaudeville, for those not familiar with that incredibly popular form of theatre, was a blue-collar, family-friendly, variety revue that appealed to everyone on some level. It was, as is most of the theatre profession, a tight knit and outgoing community; a large family of entertainers ranging from mega stars to performing seals.

Buddy and I became pals during the rehearsal period and, since I knew Phoenix, I was asked to accompany him to the local TV station, where he filmed some commercials for the production. While the crew was setting up the lights he had time to regale the producer, the interviewer, and me with some

stories—including when he had to relinquish his role of the Tin Man in The Wizard of Oz because he was poisoned by the earliest version of the silver emulsion paint in his makeup.

But the best story was yet to come. As vaudevillians toured the country, those who used the local pit orchestra for their number had few, if any, musical rehearsals. They just handed the sheet music to the conductor, sang a phrase for tempo and hoped for the best. As Buddy tells it, the dancers came up with something better. They developed the tradition of the “time step.” As tap dancers pulled into town they added variations of sound and complexity to this combination of percussive information. Then with all the flash of a top-billing act, Buddy got up, shed fifty years and did a single, a double, and a triple time step to illustrate his story. By that time every available employee of the station had slipped into the studio from the booth, the cafeteria, or the editing room to enjoy and applaud.

It was a lesson in time travel, passion, pride, and in the melding of generations, gender, and hierarchy. I’ll bet that everyone who was there still remembers Buddy Ebsen’s visit. I certainly won’t forget it.

A Memorable Student Evaluation of My Teaching Expertise

Shannon E. PerryAs a nursing professor, I taught in the classroom and the clinical area in my specialty of maternity nursing. I was the co-author of the textbook we used. Evaluations in the classroom consisted of multiple-choice tests and sometimes papers. In the clinical area, students were evaluated by observations of the care they provided and by written nursing care plans. Students were required to submit one or more written nursing care plans for evaluation. The textbook contained examples of care plans which students could use as a model.

I had one male student, about 35 years of age, who had emigrated

from Russia. He had some difficulty understanding the requirements for the care plans and toward the end of the semester had not submitted a satisfactory one which was required to pass the course. I informed him that I would give him one last chance to submit a satisfactory care plan. If the plan were not acceptable, he would fail the course. Within a day or two, he submitted a carefully written out care plan. As I read it, I recognized it. He had copied the care plan from the textbook, and it was a care plan that I had written! Needless to say, it was not satisfactory, and I informed him of that fact and that he would not pass the course.

He drew himself up to his full height and with barely concealed fury told me that “I have worked for the KGB; you are WORSE than the KGB!” Needless to say, I did not receive his vote for “Teacher of the Year.”

I learned later that he enrolled in another nursing program and was successful, graduating and obtaining a license to practice nursing so he was able to meet his goal of becoming a nurse.

Faced with the sacredness of life and of the human person, and before the marvels of the universe, wonder is the only appropriate attitude.

Pope John Paul IILincoln’s Deadly Hermeneutics

Terence Ball

My aim here is to extend and further explore the deeper meaning of a phrase that I coined some years ago: “deadly hermeneutics”: roughly, the idea that hermeneutics—the art of textual interpretation—can be, and often is, a deadly business, inasmuch as peoples’ lives, liberties and well-being hang in the balance. (1) By way of introduction and illustration I first consider briefly three modern examples of deadly hermeneutics. I then provide a short account of the hermeneutical-political situation in which Abraham Lincoln found himself in the run-up to the Civil War and subsequently during the war itself. This requires that I sketch an overview of the Southern case for secession and, more particularly, their interpretation of the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution to legitimize that radical move. I then attempt to show how Lincoln invoked and used a counter-interpretation of the Declaration in various of his speeches. I next look at President Lincoln's interpretation of the Constitution in the Emancipation Proclamation (1863), his suspension of Habeas Corpus and, finally, his finest, briefest—and at the time highly controversial—Gettysburg Address.

IIt is a truism that political actors interpret texts to legitimate and justify their actions and policies. For example, consider first how radical Islamists’ interpretation of the Qur’an lends legitimacy (in their eyes, at least) to a particular interpretation of the concepts of jihad (“struggle”) and takfir (the punishment of apostates,) which translates rather quickly into a strategy of terrorism and mass murder. What critics view as rank

rationalization, radical Islamists view as moral justification. Closer to home, radical anti-abortionists cite scripture by way of justifying their bombing of clinics and the killing of abortion providers. Or, if these two examples of deadly hermeneutics seem to be too theological and insufficiently “political,” consider Stalin’s situation in the mid-1930s.

In the course of consolidating his power, Stalin purged potential rivals who were put on trial on trumped-up charges and summarily shot. His fear of and animus toward Trotsky, Bukharin and other political opponents was perhaps understandable; but the execution of others appears, initially at least, to be puzzling, if not inexplicable. Consider the case of David Riazanov, the mild-mannered and deeply learned founder of The Marx-Engels Institute and editor of the MEGA (Marx-Engels Gesamtausgabe, or collected works). Stalin ordered Riazanov shot and publication of the MEGA stopped, and also saw to it that several works by Lenin were omitted from the latter’s Collected Works. (2) At the same time Stalin published his first foray into Marxian theory, Dialectical and Historical Materialism (1938) which reappeared the following year as a chapter in his partisan history of the Russian Revolution and the Communist Party, the History of the CPSU (B), in 1939. (3) All of these events are interconnected. Stalin, who had initially been educated for the priesthood in a Russian Orthodox seminary knew that control over the meaning and interpretation of key texts was itself an important source of political power, authority, and legitimacy. Scholars and theorists who knew much more about Marx and Marxian theory than Stalin did had therefore to be silenced or even eliminated if Stalin's interpretations were to be accepted as authoritative. Hence his—quite literally—deadly hermeneutics.

II

The abrupt transition from Stalin to Lincoln is not quite as strange as it might first appear. Bound by his oath of office to uphold the Constitution, Lincoln lacked the power that Stalin had and exercised so ruthlessly. But he knew what Stalin and all or most major political figures know: that having one’s interpretations of key texts accepted as

authoritative is an important and perhaps indeed indispensable source of power—and political legitimacy. As early as 1838 Lincoln—like Machiavelli, Rousseau and other republican thinkers he had probably never read—advocated a “political religion” as a kind of civic cement to bind citizens to their nation and generations to each other. (4) As with any religion, a political or civil religion must have one or more sacred texts that must be read closely and interpreted carefully and perhaps creatively. For Lincoln the two major texts were the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Of the two, the Declaration was in his view the more basic or fundamental, not only because it was written earlier, but because, Lincoln believed, it made the United States a nation. The Constitution was secondary inasmuch as it promulgated the basic law by which that nation was to organize and govern itself. Moreover, Lincoln used the Declaration as an interpretive lens through which to read, to criticize—and finally to amend—the Constitution. This was no idle intellectual exercise. The 1850s saw constitutional crises of unprecedented scope and severity. Many Southerners spoke openly of secession. In their view secession was tantamount to another American Revolution and could be justified by invoking both the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. For them, the operative part of the Declaration was

. . . whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends [for which government is instituted], it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundations and organizing its powers in such form as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness. . .

If Northern abolitionists and the newly formed Republican Party had their way, white Southerners claimed, slavery would be abolished, their lives endangered, their safety and happiness imperiled, and poverty would replace prosperity. If secession was the only way to stave this off, then so be it. According to the Declaration—as they interpreted

it—they clearly had this right. (5)

But what of the Constitution? It says nothing at all about secession. And that, Southern apologists argued, is precisely the point: if the law is silent about action x, then x is legally permissible. As Hobbes famously said about “the liberty of subjects”: “Lyberties . . . depend on the silence of the law. In cases where the Sovereign has prescribed no rule, there the Subject hath the liberty to do, or forbeare, according to his own discretion.” (6) Since the Constitution says nothing about secession, then surely secession is constitutionally permissible. And when the Constitution does speak, it speaks in favor of the South and slavery though without using the words slave or slavery. For purposes of apportioning representatives in the House, each slave is to count for 3/5 of a person but is to be without the rights of a citizen (Art. I, sec. 2). The Constitution explicitly states that escaped slaves must by law be returned to their masters (Art. IV, sec. 2). It also gives Congress the power to outlaw (after 1808) the importation of slaves—but not the institution of slavery itself (Art. I, sec. 9). (7) And, not least, the concluding clause of the Fifth Amendment—the so-called “takings clause”—stipulates that “private property [shall not] be taken for public use, without just compensation.” It would therefore be unconstitutional to abolish slavery without the federal government (i) bearing the burden of specifying precisely the “public use” to which former slaves would then be put and (ii) compensating slave-owners for the loss of their (human) property. Hence the Constitution, according to the Southern reading, is a pro-slavery document.

Many Northerners regarded this interpretation of the Constitution as unassailable. Even prominent abolitionists such as William Lloyd Garrison and Wendell Phillips agreed that the Constitution was a pro-slavery compact. It was, Garrison said, “a Covenant with Death, an Agreement with Hell,” and to underscore his point he publicly burned a copy in 1844. (8) For Garrison and the abolitionists, the Declaration and the Constitution were dueling documents, the first standing for human liberty and dignity, and the second for slavery and humiliation.

Here then was the hermeneutical situation in which Lincoln found himself in the 1850s. The Declaration's “self-evident” truth that “all men are created equal” was dismissed by many, both South and North, as either a “self-evident lie” (as Senator John Pettit of Indiana asserted), or as applying solely to “all white men” (Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, amongst many others), or as simply a “glittering generality” (Senator Rufus Choate of Maine) that played no part in the Declaration's avowed purpose in declaring American independence from Great Britain (John C. Calhoun). Southern apologists for slavery alternately said that the Declaration—inasmuch as it defended a right of revolution (which in their view was exactly equivalent to secession)—was a vital and living document or, when it suited them, as dead as the proverbial door-nail. And in their view no part of the Declaration was deader than “All men are created equal.” As for the Constitution, it was simply pro-slavery, for the reasons to which I have already alluded.

Lincoln’s task was both hermeneutical and political. He had to dispute and refute the then-influential interpretations just recounted, and do so in a way that would be widely regarded as demonstrably correct and therefore, almost by definition, persuasive. In the political climate of the 1850s this would, he knew, be an uphill struggle—a struggle, above all, to save the Union.

Different as they were, Southern secessionists and radical abolitionists agreed about one thing: Neither regarded the preservation of the Union as being of paramount importance. Preserving the institution of slavery was the primary aim of the former, and abolishing slavery the principal goal of the latter. Many abolitionists believed that the Union established by the Constitution was rotten to the core; if ending slavery meant disunion and civil war, then so be it. Southern secessionists argued that the Union created by the Constitution was an arrangement of convenience; if any state or states were inconvenienced, then they could by right leave the Union at will. The Constitution’s silence secured them that right.

Lincoln strove to save the Union and to make good on the Declara-

tion’s affirmation that all men are created equal. To many contemporaries this dual aspiration was simply a rank contradiction. You can have one or the other, but not both. Just as sailing against the wind requires tacking, so going into the political headwind required that Lincoln pursue a radical agenda while presenting himself as a conservative who sought only to preserve the Union. “What is conservatism?” he asks. “Is it not adherence to the old and tried, against the new and untried?”

(9) On Lincoln's telling, he was the true conservative, and secessionists and abolitionists alike were radicals who would forget—or radically reinterpret—the Declaration and the Constitution, and rend the Union asunder. What follows is a somewhat simplified account and analysis of Lincoln's hermeneutical-political strategy, focusing in particular on his interpretation of the Declaration of Independence.

Lincoln’s stature as a political thinker and his contribution to political thought remains a matter of scholarly controversy. He is certainly no Aristotle or Hobbes or Montesquieu or, for that matter, Thomas Jefferson. (10) But he is closer to Jefferson than one might imagine. For Lincoln is arguably the closest and most careful—and perhaps most creative—reader that Jefferson has ever had. And he interpreted Jefferson’s intentions in drafting the Declaration of Independence to counter the interpretations advanced by others who would reduce the Declaration to a mere pièce d’occasion. Perhaps the most important and influential among the latter was Senator John C. Calhoun of South Carolina.

Calhoun contended that the Declaration had the one-off practical purpose of declaring the American colonies’ independence from Great Britain. Once its work was done it had no further or deeper purpose. Against abolitionists who quoted the opening paragraphs, and particularly the phrase “all men are created equal,” Calhoun countered that “It was inserted into our Declaration of Independence without any necessity. It made no necessary part of our justification in separating from the parent country, and declaring ourselves independent.” (11)

Why then, Lincoln asks, were those paragraphs and that passage

“inserted” by Jefferson and not removed (as were other passages of Jefferson’s draft) by the Congress? In answering, Lincoln constructed a wholly original and innovative interpretation of the Declaration’s meaning. On Lincoln’s reading the Declaration had a dual purpose. The first and most obvious was to declare the American colonies’ independence from Great Britain. The second and less obvious—though no less important—was to issue a warning and a challenge to future generations of Americans. “The assertion that ‘all men are created equal’ was of no practical use in effecting our separation from Great Britain; and it was placed in the Declaration, not for that, but for future use.” (12) This was a theme to which Lincoln returned repeatedly. “The principles of Jefferson,” Lincoln wrote, “are the definitions and axioms of free society . . .. All honor to Jefferson—to the man who, in the concrete pressure of a struggle for national independence . . . had the coolness, forecast, and capacity to introduce into a merely revolutionary document, an abstract truth, applicable to all men and all times, and to embalm it there, that to-day and in coming days, it shall be a rebuke and a stumbling-block to the very harbingers of re-appearing tyranny and oppression.” (13) And in a speech delivered at Independence Hall on the eve of his first inauguration Lincoln said:

I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence. . .. I have often inquired of myself, what great principle or idea it was that kept this Confederacy [i.e., the United States] so long together. It was not the mere matter of the separation of the colonies from the mother land; but something in that Declaration giving liberty, not alone to the people of this country, but hope to the world for all future time. It was that which gave promise that in due time the weights would be lifted from the shoulders of all men, and that all should have an equal chance. This is the sentiment embodied in that Declaration of Independence. (14)

Lincoln insisted time and again that the Declaration’s “all men are created equal” did indeed apply to all men (and women) of all races. His opponents, North and South, contended that this famous phrase refers to all white men. In the North, during the 1858 Lincoln-Douglas debates, Senator Douglas reiterated this point at every opportunity. And in the South, Confederate Vice-President Alexander Stephens not only repudiated Lincoln’s reading of the Declaration but added that “Our new [Confederate] government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its cornerstone rests, upon the great truth

that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery . . . is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first in the history of the world based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth.” (15)

Stephens, Calhoun, and others embraced slavery as a “positive good”; Lincoln believed it a great evil that could be tolerated only if doing so would preserve the Union intact. It was the extension of that institution into the western territories that was intolerable. That, however, is what was afoot in 1854.

The 1854 Kansas-Nebraska Act, sponsored by Senator Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois, repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which forbade the extension of the institution of slavery into the territories acquired through the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, north of parallel 36˚ 30’. Incorporated into the Act was Douglas's doctrine of “popular sovereignty,” according to which white male residents in the territories would decide democratically whether their territory would enter the Union as a free or a slave state. Douglas himself professed to be indifferent as to whether any territory would be admitted into the Union as a free or a slave state. To this Lincoln thundered,

This declared indifference, but as I must think, covert real zeal for the spread of slavery, I cannot but hate. I hate it because of the monstrous injustice of slavery itself. I hate it because it deprives our republican example of its just influence in the world—enables the enemies of free institutions, with plausibility, to taunt us as hypocrites—causes the real friends of freedom to doubt our sincerity, and especially because it forces so many really good men amongst ourselves into an open war with the very fundamental principles of civil liberty—criticizing the Declaration of Independence, and insisting that there is no right principle of action but self-interest. (16)

With the passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act,

Our republican robe is soiled, and trailed in the dust. Let us repurify it. Let us turn and wash it white, in the spirit, if not the blood, of the Revolution. . .. Let us re-adopt the Declaration of Independence, and with it, the practices, and policy, which harmonize with it. . .. If we do this, we shall not only have saved the Union; but we shall have saved it, as to make, and keep it, forever worthy of the saving. (17)

Whilst the Kansas-Nebraska Act was a political disaster, it was in Lincoln’s view a disaster with the legislative remedy of repeal. And if the growing ranks of Republicans had their way, it would be. But then, three years after passage of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, came the even more disastrous Dred Scott decision.

A slave whose master had taken him to the free state of Illinois and the Wisconsin Territory, Dred Scott argued that he was legally free since slavery was not legal in any free state or territory. When his case finally reached the Supreme Court, a majority (seven of nine Justices) ruled that Scott was not and could not be a citizen; therefore, he had no legal “standing” to bring a case; but, clearly contradicting itself, the Court took the case anyway, ruling against Scott. That long and legally tortuous majority opinion, written by Chief Justice Roger B. Taney, is succinctly summarized by Lincoln:

The Constitution of the United States forbids Congress to deprive a man of his property, without due process of law; the right of property in slaves is distinctly and expressly affirmed in that Constitution; therefore, if Congress shall undertake to say that a man’s slave is no longer his slave, when he crosses a certain line into a territory, that is depriving him of his property without due process of law, and is unconstitutional.

(18)

But the loss was not Scott’s alone. The Dred Scott Decision was radical and far-reaching. Indeed, it went much further than the Kansas-Nebraska Act, in that it declared the Missouri Compromise to have been unconstitutional and said that slavery could not be excluded anywhere, including already-existing free states and future states to be carved out of the western territories. Congress, the Court said, had no authority to outlaw slavery anywhere in the United States. (19) In deciding the case the majority felt it necessary to take into account the Declaration of Independence, and in particular the passage which states that “all men are created equal.” “The general words [‘all men are created equal’] would seem to embrace the whole human family,” Taney wrote. “But it is too clear for dispute that the enslaved African race were not intended to be included [in the Declaration of Independence].” The Court also

declared that even free Negroes and mulattos were not intended to be included in the Declaration. The author and signers of “that memorable instrument” believed that blacks are “beings of an inferior order, and altogether unfit to associate with the white race, either in social or political relations, and so far inferior that they had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” (20) Blacks, the Court concluded, never were, are not now, and never can be citizens of the United States.

The Dred Scott decision seemed to deal a death-blow against the Republican Party’s aim of stopping slavery’s spread. Alarmed at the new prospect of slavery’s seemingly inevitable westward extension, Lincoln once again weighed in with a measured but blistering attack on that decision and on Douglas, who had defended it. Lincoln’s critique was at heart a hermeneutical one about the proper way of interpreting the Declaration’s meaning. Taney’s (and Douglas’s) assertion—and it is merely that—that the Declaration of Independence’s promise of equality applies only to whites, not to blacks, says Lincoln, is both erroneous and absurd on its face. Their denial is nothing less than a blatant and willful distortion of the plain words of the Declaration that “all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Happiness.” The words “all men” mean “all men.” Lincoln excoriates Douglas and Taney

for doing this obvious violence to the plain unmistakable language of the Declaration. I think the authors of that noble instrument intended to include all men, but they did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects. They did not mean to say all were equal in color, size, intellect, moral developments, or social capacity. They defined with tolerable distinctness, in what respects they did consider all men created equal in “certain inalienable rights, among which are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” This they said, and this meant. (21)

Clearly the institution of slavery is incompatible with the Declaration, inasmuch as slavery denies the rights to liberty and the pursuit of happiness, and all too often the right to life itself. Once regarded almost as secular scripture, the Declaration is now demeaned and defamed: “to aid in making the bondage of the negro universal and eternal, it is assailed, and sneered at, and construed, and hawked at, and torn, till, if its framers could rise from their graves, they could not at all recognize it.” (22)

To illuminate and illustrate his point, Lincoln quotes Douglas's statement that in declaring all men equal Jefferson and the Congress were referring to “the white race alone” and more specifically still to “British subjects on this continent being equal to British subjects born and residing in Great Britain.” “My good friends,” Lincoln retorts, “read that carefully over some leisure hour, and ponder well upon it—see what a mere wreck—mangled ruin—it makes of our once glorious Declaration…. I had thought the Declaration promised something better than the condition of British subjects; but no, it only meant that we should be equal to them in their own oppressed and unequal condition.” (23) To read the Declaration as Douglas and Taney did, reduces it to inanity and absurdity.

But, Douglas countered, to interpret the Declaration as Lincoln and the Republicans did, would not only eventually destroy the institution of slavery but would allow blacks to associate with whites on equal terms. The utterly unacceptable result will be that blacks will “amalgamate” (i.e., intermarry) with whites. Lincoln’s reply was at once principled, humorous, and acerbic. Douglas and other Democrats are “especially horrified at the thought of the mixing blood by the white and black races: agreed for once—a thousand times agreed. There are white men enough to marry all the white women, and black men enough to marry all the black women; and so, let them be married.” (24) He forthrightly rejected “that counterfeit logic which concludes that, because I do not want a black woman for a slave I must necessarily want her for a wife. I need not have her for either, I can just leave her alone.” And then he added: “In some respects she certainly is not my equal; but in her

natural right to eat the bread she earns with her own hands without asking leave of anyone else, she is my equal, and the equal of all others.”

(25) As for the black man, in the wake of the Dred Scott decision,

All the powers of the earth seem rapidly combining against him. Mammon is after him; ambition follows, and philosophy follows, and the Theology of the day is fast joining the cry. They have him in a prison house; they have searched his person, and left no prying instrument with him. One after another they have closed the heavy iron doors upon him, and now they have him . . . bolted in with a lock of a hundred keys, which can never be unlocked without the concurrence of every key; the keys in the hands of a hundred different men, and they scattered to a hundred different and distant places . . . (26)

American slavery, it seemed, was here to stay.

A year after the Dred Scot decision Lincoln debated Douglas in the U.S. senatorial election in Illinois. The seven Lincoln-Douglas debates were to a remarkable degree hermeneutical contests over the meaning of the Missouri Compromise, its repeal by the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the effective repeal of both by the Supreme Court in its Dred Scott decision—and, not least, the meaning of the Declaration of Independence itself.

Reiterating his defense of the Dred Scott decision, Douglas denied that the Declaration of Independence referred to “all men” regardless of race. He repeated his and Chief Justice Taney’s claim that in writing “all men are created equal,” Jefferson meant all white men. To argue otherwise, as Lincoln had, is a “monstrous heresy.” Douglas asserted that “The signers of the Declaration of Independence never dreamed of the negro when they were writing that document. They referred to white men, to men of European birth and European descent, when they

declared the equality of all men. . .. [T]his government was made by our fathers on the white basis. It was made by white men for the benefit of white men and their posterity forever. . .” (27)

When campaigning in the negrophobic southern part of the state, Lincoln was not above defending himself in terms that were racist, or close to it: “I am not, nor ever have been, in favor of bringing about in any way the social and political equality of the white and black races. I am not nor ever have been in favor of making voters or jurors of negroes, nor of qualifying them to hold office, nor to intermarry with white people.” (28) Even so, Lincoln argued for a rough kind of racial equality, even as he appeared to equivocate. He assuaged his audience by speaking in favor of racial segregation and black inferiority even as he argued for the natural rights of all races:

I have no purpose to introduce political and social equality between the white and the black races. There is a physical difference between the two, which in my judgment will probably forever forbid their living together upon the footing of perfect equality, and inasmuch as it becomes a necessity that there must be a difference, I, as well as Judge Douglas, am in favor of the race to which I belong, having the superior position. I have never said anything to the contrary, but I had that notwithstanding all this, there is no reason in the world why the negro is not entitled to all the natural rights enumerated in the Declaration of Independence, the right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. [Loud cheers.] I hold that he is as much entitled to these as the white man. I agree with [Senator] Douglas he is not my equal in many respects—certainly not in color, perhaps not in moral or intellectual endowment. But in the right to eat the bread, without leave of anybody else, which his own hand earns, he is my equal and the equal of [Senator] Douglas, and the equal of every living man. [Great applause.] (29)

The apparent pander in the first sentence serves a prelude to a ringing reaffirmation (begun midway through the second sentence) of the natural rights of all human beings, regardless of race. In the quicksand that was Illinois politics, this was a daring statement of moral principle, drawn from the Declaration of Independence as interpreted by Lincoln.

VI

When he became president in 1861 Lincoln relied less on the Declaration as he interpreted it and more on the Constitution he had taken an oath to uphold. In his First Inaugural Address, President Lincoln countered the constitutional argument made by Southern secessionists. Just as he had given pride of place to the opening words of the Declaration, Lincoln now focused on the Preamble to the Constitution, which was written and ratified “to form a more perfect Union . . .” Lincoln reasoned that the Union could not be perfected by dismembering it. (30) But southern secessionists were not dissuaded. And the war came.

Once the war was underway Lincoln was determined to see it through—and to see its meaning made clear by being couched in the language of the Declaration of Independence.

Two of President Lincoln’s wartime measures were immediately and immensely controversial. The first was his Emancipation Proclamation, the second his suspension of Habeas Corpus. Lincoln’s hermeneutical strategy was to justify both by interpreting—in a breathtakingly broad way—the vaguely defined powers given by the Constitution to a president in wartime or other times of national emergency. So broadly and liberally did Lincoln interpret the Constitution that some legal scholars have averred that he virtually created his own Constitution— “Lincoln’s Constitution.” (31)

Here is what the Constitution says about the president’s powers as commander-in-chief: “The President shall be Commander in Chief of the Army and Navy of the United States, and of the Militia of the several States, when called into the Actual Service of the United States” (Art. I, sec. 2). That is all. It says nothing about the extent of, or limita-

tions upon, a president’s wartime powers. Lincoln held that his power to emancipate Southern slaves—in apparent violation of the “takings” clause of the Fifth Amendment—and to suspend habeas corpus were implied: if doing these things aided the Union war effort, then he as commander-in-chief has the authority to do them. President Lincoln pushed the doctrine of “implied powers” (derived from the Necessary and Proper Clause in Art. I, sec. 8) up to and perhaps beyond its breaking point.

When President Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, it was greeted with cheers from Frederick Douglass and other abolitionists, and with jeers from Democrats and Southern sympathizers. Contrary to a popular and persistent misunderstanding, the Proclamation did not free all American slaves with a single stroke of the president’s pen. It aimed to free only those slaves residing in the Confederacy; it did not touch slavery in the slave-holding but non-rebellious border states (Maryland, Delaware, Kentucky, Missouri and West Virginia). The Proclamation was made as a matter of “military necessity,” and publicly justified on those grounds alone. Lincoln reasoned, rightly, that the labor of southern slaves was propping up and prolonging the Confederate war effort. If he could induce many of those slaves to escape in hope of finding freedom, he could cripple the South's ability to fight. In his capacity as commander-in-chief Lincoln issued the Proclamation as a businesslike executive order. Richard Hofstadter is correct, if rather unfair, in complaining that “The Emancipation Proclamation had all the moral grandeur of a bill of lading.” (32) The lowkey prose of the Proclamation was intentional. Lincoln sought to free slaves in the rebellious Confederacy without alarming slave owners and sympathizers in the loyal border states.

But there was another, now often overlooked but then-controversial, clause of the Final Emancipation Proclamation. Escaped male slaves, it said, were eligible to enlist as Union soldiers and sailors: “such persons of suitable condition, will be received into the armed service of the United States to garrison forts, positions, stations and other places

(33) This provision of the Proclamation greatly upset and offended

many in the border states and displeased Democrats in the North. In Illinois Peace Democrats drafted resolutions opposing the Emancipation Proclamation, and especially its provision for arming freed blacks. What would come next? they asked. Black emancipation? Enfranchisement? Equality with whites? Intermarriage? The very thought was anathema to them and to many in Illinois and across the North. Union soldiers, they said, had not enlisted to free the slaves but to save the Union; if the aim is now to free the slaves, northern soldiers would and should lay down their arms and cease to fight. (34)

As though the Emancipation Proclamation were not controversial enough, two days after issuing its preliminary version Lincoln made public his Proclamation Suspending Habeas Corpus. (35) Once again, Lincoln's justification turned on his interpretation of the Constitution. He invoked “military necessity” and his constitutional powers as commander-in-chief. Confederate sympathizers in the North and the border states had cut telegraph wires, torn up sections of railroad tracks along which Union troops and supplies were transported, and stirred up anti-war and anti-black feelings (indeed the two were seen by some as interchangeable) among northern laborers. Under Lincoln's suspension of habeas corpus such fifth columnists could be (and indeed were) arrested and imprisoned without trial. When Chief Justice Taney and other critics complained that Lincoln's suspension was unconstitutional, Lincoln quoted the words of the Constitution back at them. “Ours is a clear case of rebellion—. . . in fact, a clear, flagrant, and gigantic case of rebellion; and the provision of the Constitution [Art. I, sec. 9] that ‘the privilege of the writ of habeas corpus shall not be suspended, unless when, in cases of rebellion or invasion, the public safety may require it,’ is the provision which specially applies to our present case.” (36)

But the central constitutional question was concerned with who had the authority to suspend habeas corpus. Since the provision quoted by Lincoln is in Article I—which enumerates the powers of Congress— it appears that Lincoln did indeed overstep his constitutional authority and usurp a power that properly belonged to Congress. This seems a clear-cut case of constitutional misinterpretation—or perhaps creative

interpretation—on Lincoln’s part. And when Chief Justice Taney issued a court order to block Lincoln’s suspension of habeas corpus, he simply ignored it. VII

A turning-point in the war came with the Battle of Gettysburg when Union forces began to turn the tide against the Confederacy. Because losses on both sides were especially horrific, it was decided to turn the battlefield into a national cemetery. Lincoln was invited to the dedication ceremony to—as the invitation said— “make a few appropriate remarks.” Those few remarks became The Gettysburg Address. In his best and briefest address Lincoln effectively recast the meaning of the Civil War by reframing the larger meaning of the war in the words and principles of the Declaration of Independence, as he interpreted it.

“Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” That opening sentence alone was controversial because, among other things, Lincoln radically reinterprets both the date and the meaning of the American Founding. If you do the math, Lincoln dates the American founding back to 1776 and the Declaration of Independence, and not to 1788 and the ratification of the Constitution. The Declaration says that all men are created equal, with certain unalienable rights, including the rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness; the Constitution denies what the Declaration declares and affirms, and condones the institution of slavery. In so doing Lincoln seems to sign onto the abolitionist view that the Declaration, not the Constitution, is the first and truer charter of American liberty, and the Constitution—unless amended to accord with the Declaration by abolishing slavery—is forever freighted and stained with the blood of slaves.

Lincoln then goes on to reframe the reasons for which the Civil War was still being fought. As a matter of historical fact—attested to by Lincoln’s pre-war speeches, along with letters written and speeches delivered early in the war—the war was waged originally to keep the

Union intact, and nothing more. But as a matter of moral meaning, the Civil War was recast by Lincoln as a conflict of an altogether different sort—as a struggle to deliver on the promise of the “real” founding of 1776, which was stated in the form of a "proposition" that all men are created equal. In one brief speech Lincoln reframes the Framing, refounds the Founding, and radically recasts the meaning of the murderous and fratricidal Civil War—no mean feat, surely.

Garry Wills exaggerates only slightly when he says that in delivering the Gettysburg Address Lincoln

performed one of the most daring acts of open-air sleightof-hand ever witnessed by the unsuspecting. Everyone in that vast throng of thousands was having his or her intellectual pocket picked. The crowd departed with a new thing in its ideological luggage, that new constitution Lincoln had substituted for the one they brought there with them. They walked off from those curving graves on the hillside, under a changed sky, into a different America. Lincoln had revolutionized the Revolution, giving [Americans] a new past to live with that would change their future indefinitely. (37)

At least some of Lincoln's contemporaries noticed what he had done, and decried the deed. Democratic editorial writers all across the country said that Lincoln had traduced and misinterpreted the constitution he had sworn to uphold and in so doing had dishonored his office and demeaned the dead. The Constitution, they noted, says nothing at all about equality and it condones slavery. As one Democratic newspaper editorialized, “It was to uphold this constitution, and the Union created by it, that our officers and soldiers gave their lives at Gettysburg. How dare he, then, standing on their graves, misstate the cause for which they died, and libel the statesmen who founded the government? They were men possessing too much self-respect to declare that negroes were their equals, or were entitled to equal privileges.” (38)

Thus, the speech that every American schoolchild now recites al-

most as if it were scripture was quite controversial in its day. It was controversial precisely because Lincoln had at last laid all his cards on the table by publicly interpreting the Constitution and the Founding through the lens of the Declaration of Independence’s “all men are created equal.” And it was Lincoln’s Declaration-based interpretation that was incorporated into the Constitution in the so-called “Reconstruction amendments.” Lincoln worked diligently for but did not live to witness the ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment (1865), which abolished slavery; the Fourteenth (1866), which declared former slaves and their offspring to be full citizens entitled to “the equal protection of the laws”; and the Fifteenth (1869), which gave male citizens of African descent the right to vote.

The Civil War and the Reconstruction that followed it amounted to nothing less than a second American Revolution. (39)

VIII

Lincoln believed with every fiber of his being that in opposing the prefatory principle inscribed in the Declaration of Independence, Senator Douglas, the Taney Court (in the Dred Scott decision), and final-

ly the Confederacy were not only on the wrong side of morality, but on the wrong side of history as well. The opponents of slavery will be remembered, and its defenders forgotten. Every schoolboy, Lincoln wrote, knows that William Wilberforce and Granville Sharp helped to end the English slave trade; but who, he asked, “can now name a single man who labored to retard [that cause]?” Although its opponents “blazed, like tallow-candles for a century, at last they flickered in the socket, died out, stank in the dark for a brief season, and were remembered no more, even by the smell.” (40)

Lincoln, by contrast, is remembered. Throughout his life he thirsted not only for office but for fame. Fame, in the classical republican sense, is as close as humans can come to achieving immortality. Fame belongs to those who speak great words and perform great deeds. And no deed is greater than that of founding a free and long-lived republic. (41) But what of one who re-founds a foundering and divided republic, by preserving it intact while making it more truly free by emancipating its slaves and thereby redeeming the promise of its founding principle that all men are created equal? Therein lies Lincoln’s achievement and his unique claim to fame. And he could hardly have achieved lasting fame, had he not so brilliantly and skillfully practiced his own version of deadly hermeneutics.

References

1. Terence Ball, “Deadly Hermeneutics; or, Sinn and the Social Scientist,” in Ball (ed.), Idioms of Inquiry: Critique and Renewal in Political Science (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987), pp. 95-112.

2. Roy A. Medvedev, Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism, trans. Colleen Taylor (New York: Knopf, 1972), Ch. 14.

3. Stalin’s History was a thinly veiled attempt to refute his archenemy Trotsky’s interpretation of actions and events in his

History of the Russian Revolution (1930).

4. Address to the Young Men’s Lyceum of Springfield, Illinois, 27 January 1838, in Don E. Fehrenbacher (ed.), Lincoln: Speeches and Writings [hereinafter SW], 2 vols. (New York: Library of America, 1989), I, p. 32.

5. My greatly abbreviated summary of the secessionist and proslavery arguments and interpretations of the Declaration and the Constitution is drawn from Thomas R. Dew, Chancellor Harper, and other Southern advocates of slavery and secession, along with Southern states’ subsequent declarations of secession. See, among other works, Cotton is King, and Pro-Slavery Arguments: Comprising the Writings of Hammond, Harper, Christy, Stringfellow, Hodge, Bledsoe, and Cartwright, ed. E.N. Elliott (Augusta, GA: Pritchard, Abbott & Loomis, 1860). See, further, the immediate post-secessionist arguments advanced in various Southern states’ declarations of secession, and most particularly the earliest—that of South Carolina, which became a model or template for those that followed—The South Carolina Declaration of Causes of Secession of December 24, 1860, in H.S. Commager, ed., Documents of American History, 7th ed. (New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1963), vol. I, pp. 372-74.

6. Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, ed. Richard Tuck (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991 [1651]), Bk. II, ch. 21, p. 152.

7. Interestingly, the Constitution of the Confederate States of America (1861) outlawed the importation of slaves. This is hardly surprising, since that prohibition would increase the value of slaves already residing (and reproducing) in the CSA. See further Marshall L. DeRosa, The Confederate Constitution of 1861 (Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1991).

8. Garrison to Rev. Samuel J. May, 17 July 1845, in Walter M. Merrill, ed., The Letters of William Lloyd Garrison (1973), vol. 3, p. 303.

9. Cooper Union Address, 27 February 1860.

10. Several modern scholars have however attempted to recruit Lincoln into the ranks of political philosophers. See, inter alia, Harry V. Jaffa, Crisis of the House Divided: An Interpretation of the Issues in the Lincoln-Douglas Debates, 2nd ed. (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1982); Garry Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg: The Words that Remade America (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1992), esp. ch. 4; Allen C. Guelzo, Lincoln as a Man of Ideas (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2009); Ronald C. White, Jr., Lincoln’s Greatest Speech: The Second Inaugural(New York: Simon and Schuster, 2002); and – most recently and extensively – John Burt, Lincoln’s Tragic Pragmatism: Lincoln, Douglas, and Moral Conflict (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2013)and George Kateb, Lincoln’s Political Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2015).

11. John C. Calhoun, Speech on Oregon Bill, 27 June 1848, in Ross M. Lence (ed.), Union and Liberty: The Political Philosophy of John C. Calhoun (Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, 1992), p. 566.

12. Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, 26 June 1857, SW I, p. 398-99.

13. AL to Henry Pierce and others, 6 April 1859, SW II, p. 19.

14. Speech at Independence Hall, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, SW II, p. 213.

15. Alexander H. Stephens, Cornerstone Speech, 21 March 1861; in S. J. Hammond et al (eds.), Classics of American Political and Constitutional Thought, 2 vols. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2007), I, pp. 1090-93.

16. Speech on the Kansas-Nebraska Act, SW I, p. 315.

17. Speech on the Kansas-Nebraska Act, SW I, pp. 339-40.

18. Speech at Columbus, Ohio, 16 Sept. 1859, in SW II, p. 52.

19. On that decision's doleful impact, see Don E. Fehrenbacher, The Dred Scott Case: Its Significance in American Law and Politics (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978).

20. Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), in Henry Steele Commager, ed., Documents of American History, 7th ed. (New York: AppletonCentury-Crofts, 1963), 2 vols., I, p. 342.

21. Speech on the Dred Scott Decision, 26 June 1857, in SW I, p. 398.

22. Ibid., p. 396.

23. Ibid., p. 399-400.

24. Ibid., p. 400.

25. Ibid., pp. 397-8.

26. Ibid., pp. 396-7.

27. Fifth Lincoln-Douglas Debate, SW I, pp. 697-8.

28. Fourth debate, SW I, p. 636.

29. First Lincoln-Douglas Debate, 21 August 1858, SW I, p. 512.

30. First Inaugural Address, 4 March 1861, SW II, p. 218.

31. Daniel A. Farber, Lincoln’s Constitution (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), contends that Lincoln’s actions, although controversial at the time, nevertheless pass constitutional muster by today’s standards.

32. Richard Hofstadter, The American Political Tradition (New York: Knopf, 1973), p. 159.

33. Final Emancipation Proclamation, 1 January 1863, SW II, p.425.

34. Although doubtless true of some Union soldiers, it was by no means true of all, as Chandra Manning shows in What This Cruel War was Over: Soldiers, Slavery, and the Civil War (New York: Random House, 2007).

35. Proclamation Suspending the Writ of Habeas Corpus, 24 Sept. 1862, SW II, 371.

36. AL to Erastus Corning and others, 12 June 1863, SW II, p. 457.

37. Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg, p. 38.

38. See James M. McPherson, Abraham Lincoln and the Second American Revolution (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1991).

39. “The President at Gettysburg,” Chicago Times, 23 November 1863; quoted in Wills, Lincoln at Gettysburg, pp. 38-39.

40. Fragment on the Struggle Against Slavery, July 1858, SW I, p. 438.