20 minute read

Eric VanSonnenberg

The Evolution of Primary Care Medicine in the United States: From General Practice to Family Medicine

Zach Sitton MD* Eric vanSonnenberg MD*

Advertisement

Introduction

Patients’ lifelines to medical care typically begin with their primary care physician. General Practitioners (GPs) originally served this role in the U.S. Nonetheless, the days of GPs have diminished, to almost obsolescence. However, there has been a positive evolution from General Practice into the medical specialty of Family Medicine. Currently, Family Medicine physicians subsume the bulk of primary medical care in the U.S.

Herein, we present a two-part in depth delve into what ‘was’, i.e.—the General Practice of medicine, and the evolution into currently what ‘is’, the specialty of Family Medicine. The latter is represented by the junior author of the paper (ZS), who is about to embark on his Family Medicine residency. Conversely, the historical foundation for Family Medicine, General Practice, will be highlighted by anecdotes by the senior author (EV) of this paper, who grew up in a “Mom and Pop” shop/home of a semi-rural General Practitioner. Thus, our intent is to provide insights into the origins and current practice of primary care medicine in America.

Part I: The Journey from General Practice to Family Medicine

“To have greatest significance, this close relationship also involves the physician with his patient’s environment and, most particularly, with his family,” declared the AMA in the late 1950s (1). Although the specialty of Family Medicine would not be established until a decade later, it was recognized early on for its role, both to increase access to healthcare during the growing physician shortage, and to help lower healthcare costs (2). Family Medicine physicians strive to provide comprehensive primary healthcare for everyone in an affordable, high quality, and individualized manner (2). In the face of rising healthcare costs today, Family Medicine plays a vital role in healthcare, as studies have shown better health outcomes and lower healthcare costs when populations have access to primary care physicians (3-5). The purpose of this segment of our article is to appreciate the origins of Family Medicine

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir from General Practice, and to discuss the early, current, and future roles of Family Medicine physicians.

Development of Family Medicine

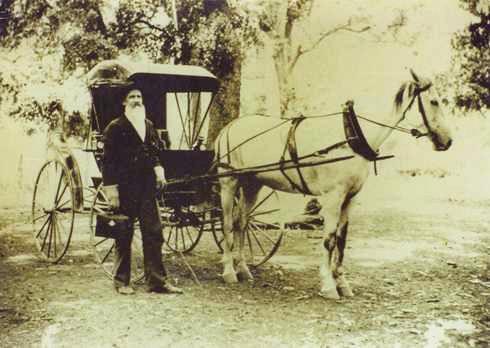

From the origins of the United States until the early 20th century, the medical profession was unorganized and had little regulation (2). During the 1700s and early 1800s, there was no standardized medical education or formal training to certify physicians (6). Only a fraction of physicians had received university-based medical education, from either a European medical school or one of the few US medical schools that was university-based (6). Most physicians during the 18th and early 19th centuries were either self-educated, and/or learned the job as an “apprentice”, training under an older physician for a few years, and later leaving to practice on their own (6). Physicians of this era often traveled to the homes of their patients on horse and buggy, caring for whole families and attempting to treat all medical needs (2).

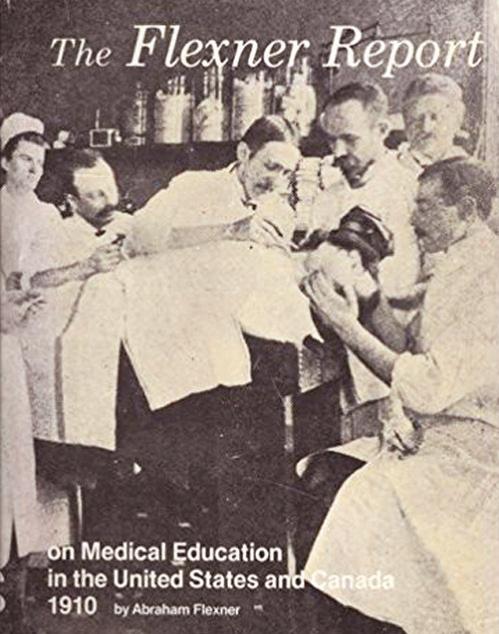

Without formalized medical education, there were no standards of care for physicians, and “quackery” was a growing problem (6). Many proprietary medical schools arose in the second half of the 1800s that were diploma mills, that offered limited, if any, clinical training (7). The formation of the American Medical Association (AMA) in the mid1800s helped shape the profession into the organized system we have today (2). The Flexner report of 1910 was the result of a project funded by the AMA

A 19th century physician making a house call via horse and buggy.

Abraham Flexner

that examined the nation’s medical schools; it led to key changes such as standardized medical curriculum and attaching medical schools to universities (2). Following this pivotal report, 4-year medical schools began to replace the proprietary schools (7).

By the 1920s, most physicians in the US were GPs who had completed medical school, followed by a one-year hospital-based internship (7). These generalists provided most of the medical care for the country during the first half of the 20th century (7). GPs had a broad scope of practice; they often set fractures, performed surgeries, delivered babies, and cared for most of the public’s medical needs (7). These GPs laid the groundwork for what Family Medicine would become (8). Some GPs typically performed house calls, The 1910 Flexner Report. while others treated patients out of their own homes. House calls consisted of traveling and attending to patients in the patient’s home, and comprised 40% of all patient-physician interactions in 1930 (9).

Around the 1920s and 1930s, medical specialization became more formal, and residency training allowed new physicians to become “board certified” in a specific specialty, following completion of the residency (2). This schism of different tracks created tension between the older, aging GPs and the newer, residency-trained specialists, who felt that their additional training made them more fit for hospital privileges and procedural work (1). GPs, meanwhile, maintained that their experience and proven capability meant more than the newly created board requirements (1).

Some GPs, who had been performing surgeries prior to World War II, returned home from the War, and were told they no longer had hospital privileges, nor could they continue to operate (1). A growing feeling also began to arise in the medical community that one year of training following medical school was no longer sufficient to cover the breadth of knowledge required to provide comprehensive healthcare as a generalist (10). GPs began to advocate for a residency of their own, in addition to the one-year internship, that would also allow them to become board certified and maintain hospital priv-

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir ileges (10). Attempting to retain their footing vis-a-vis the increasing number of powerful specialist societies, the American Academy of General Practice was formed in 1947. The Academy would later change its name to the American Academy of Family Physicians in 1971 (11).

The emphasis on specialization and the rapid increase in technology following World War II led to a decreased number of medical students choosing to become GPs (2). Over time, this led to a shortage of GPs that increased the cost, inaccessibility, and depersonalization of healthcare (2). This continued until the 1960s, when both the general public and public health leaders strongly advocated for more physicians that were personal, longitudinal, comprehensive, and focused on prevention (12-14). Eventually this culminated in 1969 when Family Medicine was approved as a new specialty by both the AMA and the American Board of Medical Specialties (11). Growth and Role of Family Medicine

Following the creation of Family Medicine, GPs gradually disappeared. Many became board certified in Family Medicine through continuing medical education and examination (11). While others chose to remain practicing as GPs, medical students largely abandoned pursuing this route, and primary care began to be provided by Internal Medicine, Pediatrics, and Family Medicine physicians (FMPs) (7,11). FMPs have continued to provide a larger portion of primary care, especially as fewer Internal Medicine residents pursue general internal medicine and instead decide to subspecialize (7). From 1961 to 1970, only 10% of Internal Medicine residents subspecialized, while 88% of residents from 2011 to 2015 chose to subspecialize within Internal Medicine, transferring a larger share of primary care to FMPs (7).

FMPs today now see more patients by volume than any other primary care specialty, accounting for approximately 23% of all physician visits in the US annually (2,15). While FMPs today work in an outpatient office rather than making house calls, they often still perform procedures and provide obstetrics, emergency, and hospitalist care (16). This is especially prevalent in rural settings, where FMPs typically provide more comprehensive care and perform more procedures, due to the lack of surrounding specialists (16). In more urban areas, Family Medicine plays a key role in coordinating care when multiple specialists are consulted (16).

Currently, FMPs can subspecialize by completing a fellowship following residency. Available fellowships in Family Medicine include: Adolescent Medicine, Geriatric Medicine, Hospice and Palliative Medicine, Maternal/ Women’s Health, Pain Medicine, Preventive Medicine, Rural Medicine, Sleep Medicine, and Sports Medicine (17).

As of 2020, there were 706 Family Medicine residency programs in the United States, and 4,355 medical students matched into these programs in 2020 (18). While this number of graduates represents the largest to enter the specialty in the history of Family Medicine, it is only 12.6% of all US graduates who matched (18). The proportion of US MD seniors who match into Family Medicine has declined and was 8.6% in 2020, while the proportion of osteopathic (DO) seniors, US international graduates (IMGs), and foreign IMGs who matched into Family Medicine all increased in 2020 compared with the previous year (18). With a predicted primary care physician shortage between 21,400 to 55,200 by the year 2033, the American Academy of Family Physicians initiated a goal in 2018 to increase the proportion of US medical graduates to 25% by the year 2030 (19,20).

Although some roles of Family Medicine have changed since the days of early GPs, the heart of Family Medicine is still the same–treating the whole patient, while developing long-term relationships and providing longitudinal care to the patients and their families (16). The focus of family physicians on wellness and prevention is a major reason why increased spending on primary care is expected to decrease overall healthcare spending on a per patient basis (21). As US healthcare continues to shift towards value-based care, the Family Medicine physician will play an integral role to improve patient and societal outcomes at lower costs (3).

Part II: Growing Up in a Mom and Pop General Practice

General Practice of medicine was the forerunner of today’s Family Medicine. General Practice, other than in rural America nowadays, is emblematic of an era gone by. However, in retrospect, for me (EV), it was a rich and powerful experience growing up in it. Assuredly it has shaped me in infinite ways.

Let’s set the stage—semi-rural, late 1950s-1960s, small, sleepy town of 5000 in New York state (a cat, stuck up in a tree, was called the “town emergency”!), predominantly lower middle-class folks, with no hospital, no movie theater, nor shopping mall. On either side of our house were Italian immigrant families. Across the street was a pickle farm, and next door to the farm was the town’s mayor, also of Italian extraction (although at the time, ethnicity never occurred to me, as we were all ‘just neighbors’). Behind our house was a small stream that my friends and I fished in. Behind the stream were woods that seem to go on for miles, and that we tromped through and picked sarsaparilla plants. Idyllic? Elysian? Paradise? In many ways, it was.

And now where our story is headed, and the protagonists: My Dad was the town doctor, and for much of my youth, the only doctor in the town. In the doctor’s office, Mom was the nurse, the receptionist, the operations man-

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir ager, the radiology technologist, and the chief financial officer. Oh yes, her relevant training for this multiplicity of jobs? None! She graduated college with an elementary school teaching degree.

More of the setting—by today’s standards, our house was undoubtedly modest. My recollection is hearing my parents say that they bought the house for $12,000. The main floor had a living room, dining room, kitchen, 2 bathrooms, and 3 bedrooms. In the northeast, an attic and a basement were typical parts of these houses. The house was set on about 1.5 acres, enough land that my friends and I, when young, converted the backyard into a baseball field. Now to the basement of the house where we find my Dad’s office. It consisted of a treatment room with an examination table, a glass cabinet with all kinds of medical and surgical instruments, a sterilizer, a diathermy machine (never

The side entrance to the doctor’s office in the basement of the house. did know what that was for), a big lamp for reflection of light so my Dad could look into patients’ mouths, eyes, ears, and God knows what else.

Rounding out the office was a waiting room with about 8 chairs, a bath-

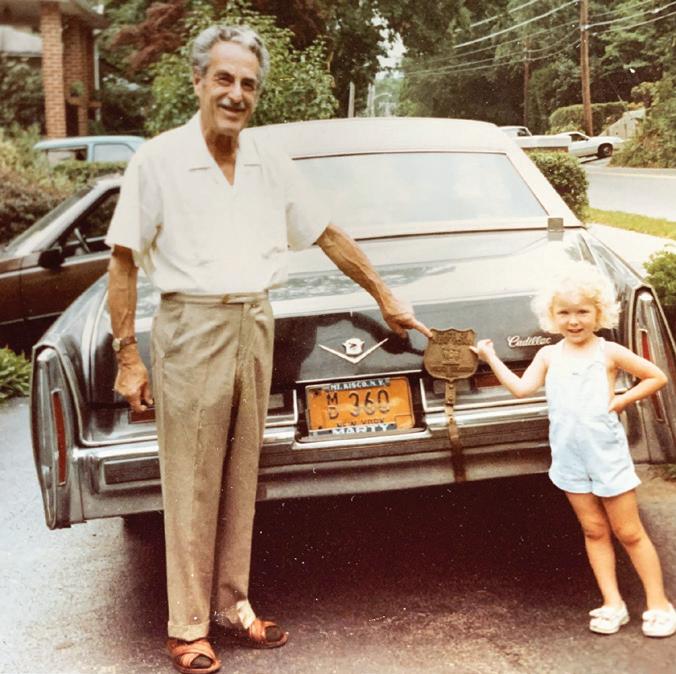

Dad, who went straight from medical school to internship to become a practicing General Practitioner. Mom, who despite no medical training, was the nurse, radiology technologist, operations manager, receptionist, and chief financial officer.

room, and my Dad’s personal office where he had discussions with patients and families. My recollection of the office was the abundance of medical books filling the bookshelves, his many awards from civic groups and the State Police. (He was the “Police Surgeon” for a portion of the State. He even had a police shield that the State Troopers mounted on the license plate on the back of his car that enabled him to rush to acciDad and granddaughter Emily, pointing to the dent scenes.) shield on his car, mounted by the State Troopers. Completing the office was the radiology room with an adjacent dark room with chemicals with which my Mom somehow magically made black x-ray film into real-life radiology images that my Dad “read”, and that he loved to show to his 8-year-old son. As a side note, my Dad had no formal radiology training; rather, after he graduated medical school, he did one year of internship, and then off to General Practice in our small town. So, what was the formal training for my Dad in radiology? None. As a relevant corollary, formal training for my Mom for the radiology machinations that she did—also none. Fast forward to their progeny, who went to medical school, and became—you guessed it…a Radiologist! (Specifically, an Interventional Radiologist.)

Despite the lack of formal training, my Dad, quite careful by nature, apparently well appreciated the hazards of radiation. So, whenever Mom and Dad were taking an x-ray, my Dad rang, no kidding, a cowbell. This signaled to everyone, both upstairs and downstairs, to leave the house immediately, rain, snow, or shine, until the radiation dispersed. Going outside in the summer, albeit briefly, was no big deal. However, doing so during the cold of winter, often with snow on the ground, was much less pleasant. But when that cowbell rang, we all knew very well to drop everything and exit the house immediately.

Let’s now go upstairs and saunter around the main level of the house. Wait, is that a Catholic nun walking around in traditional nun’s garb? Is that not a State Trooper sitting in the living room? What month is it? Oh, it’s February, it’s New York state, and it’s snowing and 25° outside. Let’s check downstairs in the waiting room—oh, all 8 seats are filled with patients waiting to see the doctor. So, it’s the “overflow” of patients waiting to see the doctor who have

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir now migrated upstairs into the living quarters of the house. Why a nun? Well, Mom and Dad’s policy was that all clergy, from any religion, were treated gratis. In the next town from ours was a convent with nuns, hence a steady stream of nuns blessed our house, virtually whenever there were office hours. But why the State Troopers? In a similar vein, all firefighters and police were treated for free as well. As noted previously, Dad was the “Police Surgeon” for a portion of the State, although by training, he was not a surgeon (Nonetheless, GPs like him did perform minor surgery.)

And while he was not an obstetrician, GPs at that time also delivered babies. Reportedly, he delivered a wellknown male, whose good looks and acting eventually made him a “heartthrob” actor of the 1970s. (For HIPAA reasons, he must go unnamed.) Dad also occasionally brought me down to his office (also by ringing the cowbell) at different times to meet several famous baseball players and a very well-known actor, each Restored human bones that Dad kept in his office to help explain maladies to patients. of whom had been brought by the State Troopers for Dad to document that they were violating DUI laws. For me, as a young kid, I was in awe of all of them, although I vaguely remember that they smelled kind of funny and acted a little weird (undoubtedly the excessive alcohol effect!)

During my 17 years in the house, besides Mom and Dad and my younger sister, 2 other women lived with us. First was Ella from South Carolina, and then Priscilla from Honduras. Each was meaningful to my growing up. Ella was like an older sister, Priscilla like a wise aunt. They truly lived with us, in one of the three bedrooms in our relatively small house by today’s standards. Their reasons for being there were largely to care for the office downstairs, although they did some upstairs cleaning and cooking as well. My recollection is that they lived with us for 5 days a week, then were off with family and friends for the other two days. To me as a kid, they seemed part of the family (Ella more so, as I was younger). Anecdotally, Ella once helped me hide from my parents that New Year’s Day, when, at 13 years old, I was recovering from a drunken stupor having partied with my friends the prior evening. That awful alcohol feeling lasted over 10 years, and dissuaded me from drinking alcohol all throughout college, despite influences by my Colgate TKE fraternity brothers to the contrary.

After Dad died, we got a startling revelation from Priscilla. Although our household growing up was largely agnostic with hardly any religious discussion, Priscilla told us that early in the mornings (Dad and Priscilla were early risers), Priscilla, a devout Christian, would read verses from the Bible to Dad almost daily before the rest of us were awake. She even had specifics to relate to us—that Dad’s favorite passages were from John (especially 3:16) and Philippians. We were amazed, as he had never told us about this. I’ve wondered what influence that may have had, as he was so dedicated and unselfish of his time to his patients.

Now some further recollections—my Dad loved taking me on house calls with him when I was a youngster. It was not always at my request, as sometimes I had to wait for him in the car (As a physician myself now, I suppose that was because he was concerned about contagiousness of infection.) As he typically made house calls, I can vividly remember him carrying his medical bag in one hand and an EKG machine in the other hand as he entered patients’ homes. He typically had a wad of one-dollar bills in his back pocket, as apparently that was how patients paid, and probably not very much, given the preponderance of one-dollar bills! Some patients defrayed their bills by barter—for example, an elderly native Italian artisan, whose whole family was cared for by my Dad, built a columnated, concrete fence around our property. Handymen were common in the house, as they and Dad worked out their arrangements.

Another vivid memory I can recall as a 7 to 10-year-old included seeing bodies strewn on the road in a multicar accident on a highway about 15 miles from our house. In emergencies such as these, the State Troopers came to our house and took Dad (and occasionally me) to the scene of the accidents. EMTs, trauma centers, and the specialty of Emergency Medicine came into being later.

After I left my medical and radiology training in Boston, my family and I moved to San Diego, where I worked at the UCSD Medical Center. Mom and Dad came out from New York to California in a motorhome to visit us. (They actually stopped along the way in various states, as he made house calls to several patients across the country who had moved from our small town.) Lo and behold, Dad had a heart attack while in San Diego, and underwent triple cardiac bypass surgery. They stayed with us for three months while Dad recovered. Once people from our small town in New York state found out about Dad, we were bombarded with daily calls, wishing and praying for Dad’s recovery. Testimonials like, “Your Dad took care of my grandma, my husband, my children, and myself”, were so very common. I tell medical stu-

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir dents currently that, “If you want to be loved, appreciated, and esteemed by your patients long-term, it would be hard to beat being a small-town Family Medicine doctor.”

In retrospect, my upbringing was a blessing, although, at the time, I never realized how special it was—it was just our lives—but how fortunate for me. That last concept segues from my upbringing in a Mom and Pop General Practitioner home to today’s Family Medicine doctors. As I am proud of my co-author, Zach, as his mentor, so my Dad and Mom would be proud of him and today’s FMPs to carry on the dedication and exemplary doctor-patient relationship that is no more apparent in medicine than in the specialty of Family Medicine.

*University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix Corresponding Author and Contact Info: Zach Sitton MD Email: zachsitton2@gmail.com Phone: 4806957201 Address: 845 Brent St. Winston-Salem, North Carolina 27103

References

1. American Academy of Family Physicians. Family Practice: creation of a specialty. AAFP. Kansas City, 8 (1980). 2. Gutierrez C, Scheid P. The history of family medicine and its impact in US health care delivery. Leawood, KS: AAFP Foundation, 1-31 (2002).

3. Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q., 83: 457–502(2005). 4. Macinko J, Starfield B, Shi L. Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. Int J Health Serv., 37(1): 111–126 (2007).

5. Chang CH, Stukel TA, Flood AB, Goodman DC. Primary care physician workforce and Medicare beneficiaries’ health outcomes.

Journal of the American Medical Association, 305(20): 2096–2105 (2011).

6. Zervanos, N. J. Why the generalist became a specialist: a history of

General Practice and Family Medicine. https://www.aafpfoundation.org/content/dam/foundation/documents/who-we-are/cfhm/ conductingresearch/Generalist_to_Specialist.pdf. Accessed May 21, (2020).

7. Dalen JE, Ryan KJ, Alpert JS. Where have the generalists gone? They became specialists, then subspecialists. Am J Med., 130: 766–768 (2017).

8. Canfield PR. Family medicine: an historical perspective. J Med Educ. 1976; 51(11): 904–11.

9. Meyer GS, Gibbons RV. House calls to the elderly--a vanishing practice among physicians. N Engl J Med., 337(25): 1815-1820 (1987). 10. Pisacano NJ. “History of the Specialty”. American Board of Family

Medicine, https://www.theabfm.org/about/history.aspx (2001). 11. Phillips WR, Dai M, Frey III J, Peterson LE. General Practitioners in US medical practice compared with Family Physicians. Ann Fam

Med., 18(2): 127-130 (2020).

12. Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education (Millis JS, chairman). The Graduate Education of Physicians. Chicago: American Medical Association, 179 (1966).

13. National Commission on Community Health Services. (Folsom

MB, Chair). Health is a Community affair. Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 26 (1966). 14. Ad Hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice (Willard

Committee). Meeting the Challenge of Family Practice. Chicago:

American Medical Association; 1966; 1.

15. Cherry DK, Woodwell DA, Rechtsteiner EA. National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2005 summary. Adv Data., 387: 1–39 (2007).

16. American Academy of Family Physicians. Family Medicine: Comprehensive Care for the Whole Person. https://www.aafp.org/medical-school-residency/choosing-fm/model.html. Accessed May 22, 2020.

17. Lindbloom, E. Fellowships in Family Medicine: Who? What?

Where? When? Why? American Academy of Family Physicians.

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Sitton and vanSonnenberg | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/events/nc/handouts/ nc17-fellowships-2.pdf. Accessed August 13, 2020. 18. American Academy of Family Physicians. 2019 Match Results for

Family Medicine. https://www.aafp.org/students-residents/residency-program-directors/national-resident-matching-program-results. html. Accessed March 3, 2021.

19. Association of American Medical Colleges. The Complexities of

Physician Supply and Demand: Projections from 2018 to 2033.

June 2020. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/2020-06/stratcomm-aamc-physician-workforce-projections-june-2020.pdf.

Accessed March 3, 2021.

20. Prunuske, J. America Needs More Family Doctors: 25×2030 Collaborative Aims to Get More Medical Students into Family Medicine. Am Fam Physician., 101(2):82-83 (2020). 21. Phillips RL, Bazemore AW. Primary care and why it matters for

U.S. health system reform. Health Aff., 29:806–10 (2010).

The world’s greatest thinkers have often been amateurs; for high thinking is the outcome of fine and independent living, and for that a professional chair offers no special opportunities