22 minute read

Divided We Stood | Doris Marie Provine

Divided We Stood

Doris Marie Provine

Advertisement

This is a narrative about growing up in the 1950s and 1960s, when high racial and gender walls were formidable parts of everyday life. It begins with the nearly all-white, highly gendered context in which I grew up. There were moments of clarity about racism, many of which I owe to my mother, an anti-racist who came from a different mold than most of the parents in my community. Sexism and misogyny challenged me directly after childhood, as I sought an adult relationship with the world. I will unpack some of those experiences. It’s strange and wonderful to be alive in a period when the struggle for equality has gone mainstream with the Me-Too movement and Black Lives Matter. But I think my focus on what came before will demonstrate that both of these movements are built on a foundation that was growing stronger in the 1960s and 1970s, even in the nearly all-white precincts where I lived.

My Jim Crow Youth

I grew up in the 1950s, in the post-war haze of stay-at-home moms and unacknowledged racism. In my neighborhood, middle-class moms stayed home with their kids unless they endured the shame of divorce and had to find a job and live in an apartment. Grade school and high school were segregated by race— – Ohio law provided that if no one from outside your district wanted in, then your school could keep anyone out. The school district borders were carefully drawn to exclude a nearby Black neighborhood within walking distance of my high school. I was the only black-haired child in my acquaintance, which supported my childhood theory that I was part Native American. I spent a lot of time roaming the woods, making moccasins and bows and arrows, collecting acorns with neighborhood boys for imagined wars, swimming in the summers, and impatiently enduring the confinement of school and church.

I have noticed that mothers figure prominently into many of the lives of academics who come from under-represented groups. In the 1970s, white women also definitely fell into that category. My mother was also an important influence, most relevantly here, in her views about race. She married a gentle, loving man stuck in crude southern racism. He grew up poor in a small town in Alabama, in a downwardly mobile family; his father died when he was five years old. His mother took in boarders, and he went to work to help support her before finishing high school. I came to think that he clung

to racism to preserve some vestige of a past in which his family had a secure place in his tiny hometown. His attitude was general, not specific – ironically, he relied with confidence on a Black colleague in the railroad business, a fact my mother reminded him of constantly. He was also a sweet and generous father, and he loved my mother. He helped to put her through the University of Chicago when she was 25. He was an avid reader and student of the economy. Nevertheless, I was convinced that if I came home with a Black friend, he would lock the door against me. My mother’s roots were in working-class Marie Provine and her parents. Toledo. A Democrat, what we would today call a Progressive, she flirted with socialism, and fought my father’s racial bigotry and Republican ideology with evidence and sometimes bitter, ironic humor. These conflicts were never resolved. Their marriage survived for reasons that I didn’t really understand as a kid, probably a shared experience of near poverty growing up in the Depression, a cheerless childhood, love of golf and the outdoors, and joy after seven years of marriage, having a daughter, me.

When I was in fifth grade, my mother began teaching social studies in the Cincinnati city schools, soon landing at an inner-city school where most of her students were Black and all were poor. Going to work with a gainfully employed husband in the house was unusual in my tight-knit suburb. Teaching in an inner-city school was unheard of. My mother loved her work and used her position to push for justice in small ways. She took particular pride in helping her “general” track outshine the higher tracks. She taught students how to figure compound interest rates to help them recognize the exploitation that their families faced from discount furniture stores and other businesses that preyed on the poor.

As a kid, I lived a kind of double life, admiring my mother’s work and visiting her school from time to time, but attending an all-white school. She helped me see white obliviousness to racism. One summer, for example, she informed me, on a pledge of secrecy, that several of her faculty colleagues

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir worked as waiters at the local golf course. They were better educated than most of the golfers, who called them by their first names as they ordered drinks and dinner. She made sure that the Black woman who cleaned our house entered by the front door and I was taught to call her by her full name; back doors and first names were the rule elsewhere in my town. When I was a teenager, my mother took me to hear Reverend Martin Luther King address a virtually all-Black congregation in Cincinnati; that was a big deal for me— – I don’t recall that my father knew about it.

My mom taught me to see racism as a personal failing of whites, my father included. How to address this failing was unclear. Segregation was everywhere, even at my summer job as a carhop at Frisch’s Big Boy. The kitchen staff was almost entirely Black except for a white supervisor. The carhops were all white and female. There was a lot of curiosity on both sides of this racial divide, but I knew to keep my budding race-crossing relationships from work secret from my parents. I left for college in 1964 convinced that I knew of a serious injustice that my white classmates did not recognize, but I had little sense of the tools needed to do much about it or the structural foundations that kept us separate by race.

Intellectual Blind-Spots

The venerable University of Chicago was located in the poorer part of the South Side, a long-standing African American neighborhood. Both the student body and the faculty were virtually all white. The university had an inconsistent and incomplete approach to the racial disadvantage and the segregation that surrounded it. Social scientists studied area neighborhoods as a distinct cultural milieu and debated the merits of gentrification, while university officials sought earnestly to achieve a more middle-class environment. The goal was to be regarded as a safe integrated island in this deteriorated part of the city. The student body confronted an uneasy racial quasi-peace in the neighborhood and avoided going out alone at night. One of my classmates died in a daytime drive-by shooting. Despite all this, racism was treated intellectually, in keeping with the hyper-intellectual traditions of the University.

In my first few weeks at Chicago, I landed a half-time job at the University’s conference center. My boss was a flamboyantly gay Black man named Thurston Moore. We had many adventures exploring the neighborhood in a little conference center cart. We tooled around neighborhoods that my friends considered unsafe, but Thurston seemed to know a lot of the folks we saw, so I was never afraid. Thurston and an array of non-university colleagues at work helped me feel comfortable in my first year away from home. My grades probably suffered from working half-time throughout the academic

year, but the job helped me stay grounded in Chicago’s intellectual milieu.

I received a top-notch education at Chicago. The faculty seemed to enjoy undergraduate teaching. I found a valued mentor in Gilbert White, a world-famous geographer who started a new major in public affairs. There were just four of us in this major, which opened up opportunities to have dinner with famous visitors to the university, including Thurgood Marshall, who was then Solicitor General of the United States. I was shocked to learn from another helpful mentor, law professor Harry Kalven, that the law students had little respect for Marshall, assuming he had gotten his high position through favoritism. This was a moment of clarity for me, having been overwhelmed with Marshall’s brave stories, deep knowledge of our history, and kindness to us students. John Hope Franklin was another influence then because he generously ate dorm food with undergraduate students, in the process teaching us how remembrance and forgiveness can enable a scholar to write about race.

I did my senior thesis on the stark contrast between the pristine and wellstocked Jewell grocery stores in white Chicago neighborhoods and their tawdry, unappetizing counterparts in poorer Black neighborhoods. My advisor, Julian Levi, headed the Southeast Chicago Commission, which concerned itself with protecting the University’s investment in the neighborhood. From the Commission’s perspective, there were no easy answers to the University’s race/class/safety dilemma, but it was striking how disengaged most faculty seemed to be from these concerns.

Educating Women to be…. Mothers and Wives?

The faculty also seemed unconcerned with its stark gender skew toward married white men. Almost every one of the few females on the faculty had forsaken marriage and children. In my third year, I was delighted, finally to find an exception, a biology professor married to a banker, and she had children. By this time, I was in love with a graduate student; we married the summer before my senior year. My parents responded by cutting off my tuition, but University officials, appalled at their decision, somehow bailed me out and I graduated on time in 1968. Marriage finally allowed access to birth control; unmarried female students were usually denied a prescription. I was at a loss as to what to do next, with few available role models and no advice, even from a dean who angrily told me that intellectuals don’t worry about such practical matters. I was devastated that a man I knew and trusted had absolutely no advice for me as I faced an unwelcoming job market for women. I feared going into high-school teaching in the Chicago schools, the one profession my mother had warned me against, despite her own apparent-

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir ly happy experience. Then, like many college grads unsure of their next steps, I thought of law school. I was shocked to learn that I would have trouble getting into most law schools because of my gender. This was a long-deferred wake-up call to address gender discrimination, a subject that had never been raised in any of my social-sciences courses at Chicago.

I was admitted to the University of Michigan Law School, thanks to affirmative action or at least a decision to reject discrimination. Our entering class had more than a tiny sprinkling of traditionally absent groups: people of color and white women like me. The faculty were egalitarian and encouraging to a fault, but not all the students. One of the guys I walked to classes with politely asked why I was taking a seat that could have been occupied by a man.

Michigan offered me a counterpoint to what I encountered when I transferred after my first year to Cornell Law School. My husband had taken a position in the history department there. Cornell was laissez faire in its approach to race and gender. There was one Black man in the graduating class on law review and a second in my class. The dean of admissions referred to them as “colored.” There were three other women in my own year. No woman had ever been on the faculty. When I would be called upon in class was completely predictable—if the issue involved an incompetent woman. The school’s squash court had a shower—for men. Most pernicious were the job ads that openly asked for male applicants. I nevertheless got a couple of interviews, which concluded when the interviewers said that they couldn’t possibly hire a woman because their clients would never accept it.

It’s hard to explain my feelings at the time. I was a faculty wife with limited prospects for employment outside Ithaca, New York. Some of the faculty had become friends. In class, I grew accustomed to my role as spokesperson for women in legal trouble. My budding legal knowledge was recognized outside the law school through invitations to give talks on the equal rights amendment. But it hurt that none of these friendly people had any concern for my chances at actually becoming a practicing lawyer or were concerned that their placement service was in direct violation of the law. I tore down discriminatory job ads and integrated the squash-court shower, but why didn’t I do more and why weren’t the law-school faculty concerned with violating the 1964 Civil Rights law??

The women’s movement in my small Cornell world focused then on issues like the Equal Rights Amendment, abortion, and lack of women on the faculty and even in some undergraduate programs at the university. The veterinary school, for example, accepted only two women per year on the theory that women weren’t suited for large-animal practice. The faculty club did not ad-

mit female faculty. There was no weight-room open to women—I was kicked out of the one I tried to integrate. Sadly, the fight for change was more like hand-to-hand combat than an organized campaign that reached across race and class to confront discrimination more inclusively and powerfully. I sensed broad agreement with Erich Fromm’s characterization of women in The Art of Loving, as the emotional center of the family, with the male as the intellectual leader. Higher education, in this line of thought, should be open to women, but it operated on the assumption that the goal was to produce well-educated wives and mothers, like the wives and mothers of many of the white male faculty. The possibility that the university could do more to encourage minority students by rethinking its recruitment and admissions processes remained largely off the table.

Being on the receiving end of sexism and misogyny of that era has relatively little in common with the racism of the present. For example, in my insulated white world, interactions with law enforcement were a non-issue. But at another level, some of the confidence-robbing characteristics of an environment that seemed blind to the intelligence and ambition of people who looked like me was dispiriting. The white men with PhDs who ran the university seemed unmoved by the tremendous gender and racial skew in their favor. The idea that more diversity might improve the quality of our lives together had few adherents.

A lot of this changed, sometimes quickly in the late 1970s. Cornell invested in a weight room for women and introduced a women’s studies major that brought in a few female faculty members on appointments shared with other departments, though this gave them service requirements in two departments and made them doubly vulnerable to a denial of tenure. In law-school classes after mine, the number of women began to grow significantly. But there was a general lack of appreciation for the way structures kept the status quo intact. The law school, for example, hired its first female faculty member a couple of years after my 1971 graduation, a bright, but naïve, recent graduate in her mid-twenties. During her first year of teaching, she fell in love with a divorced law student ten years older than herself and was promptly fired.

Becoming Professor Provine

After graduation, I took one of the few attractive options available to me: I became a lecturer and research associate at Cornell. I was the first woman in my department and of a status lower than the regular faculty, but it was fulfilling work for a couple of years. I realized that to ever go further, I would need a doctorate. My husband was on tenure track, and we were thinking about having children. I chose a PhD in political science at Cornell. I decided that

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

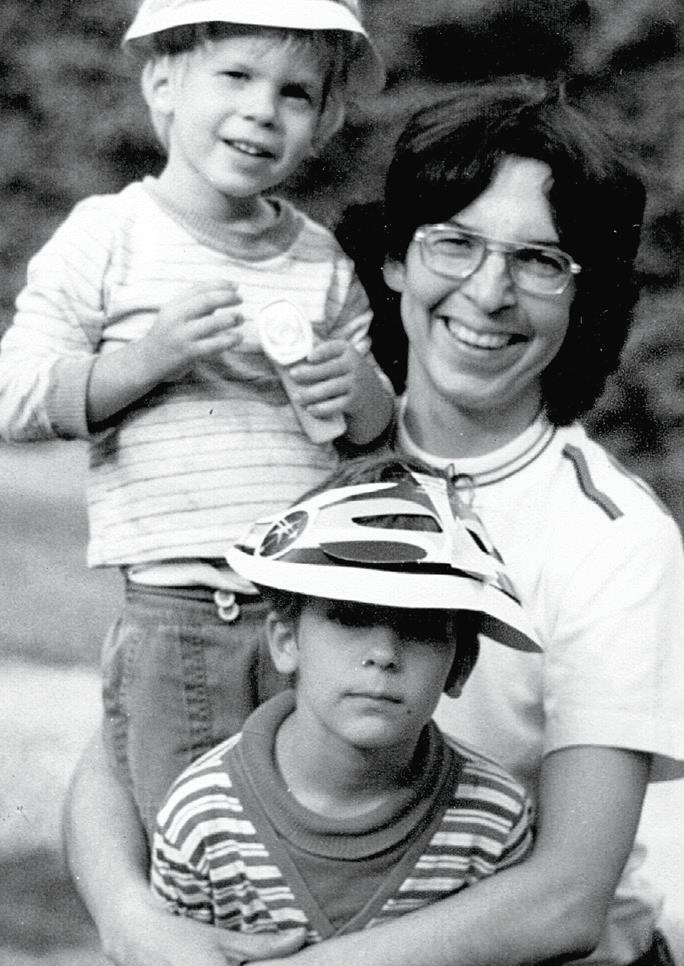

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir graduate school was the optimum time to have children, having heard terrible stories about inflexible tenure clocks for women faculty. Both my wonderful sons were born during my four years of graduate school. My mentors, of course, were men – both the political science faculty and the law school faculty were all male and all white in this period. These men, David Danelski, Ted Lowi, and Roger Cramton, were wonderfully supportive. The gender-inflected dynamics of this period came home to me when I went on the job market with my JD-Ph/D combo and received four Marie and her sons tenure-track offers. (Perhaps once again, I was a beneficiary of affirmative action as universities were beginning to realize that they needed women on their faculties.) My dilemma was that my otherwise supportive husband wanted badly to stay at Cornell. He made a perfunctory effort to find a position at the two schools I preferred, Ohio State and University of Texas at Austin, but nothing emerged. As a compromise, I took the offer from Syracuse University, a 50-mile commute from the rundown house we bought between Syracuse and Ithaca.

This was a busy time—the house needed a ton of work, the kids were 2 and 4, and I had a one-year deadline to put the finishing touches on my dissertation and graduate. I had a full teaching load. I soon discovered that I was being paid 13% less than a colleague hired at the same time and rank. My department chair refused to budge, and I could think of no way to appeal his decision. I was new at Syracuse University, which had no obvious office or procedure for addressing discrimination. And I was stung by the casual rejection of my complaint by my department chair. I also wonder if I did not actually feel accepted as a full-fledged member of the faculty. I don’t recall even discussing the matter with the one other woman in the department, hired a year before me.

Syracuse University was good to me. I published my dissertation on how the Supreme Court selects its caseload, (1) and then a book comparing lay and lawyer judges while serving as a local judge in my spare time, which grew

out of my election as a town justice. (2) The director of women’s studies and I were given a two-year leave to develop a university-wide policy on sexual harassment, which, much to our relief, was adopted and aggressively implemented. The University allowed me to spend time teaching abroad, first in Strasbourg, France, then in Madrid, Spain, with an additional summer in Geneva, Switzerland. I was also permitted to take a year off twice for having received two

Professor Marie Provine teaching Law at Cornell Law School. NSF grants. I took two year-long leaves in Washington, DC. I received a huge salary boost on one of these Washington years – apparently the result of a salary study on gender discrimination at Syracuse University.

I rose through the ranks and became department chair. One of my main goals in that role was to get the department to hire at least two African -American faculty. Helped by my brilliant, resourceful Black graduate student, Susan Gooden, we did succeed in finding two young men willing to be our first Black faculty. Their tenure was short, however. One of our hires was immediately recruited by the administration, and the other decided to move on. This was a bitter lesson in how inadequately prepared our department and University were for change. Ours was a naïve integrationist vision of welcome on the same terms as new white faculty, without regard to the nearly all-white university environment and the location in a declining industrial city sharply divided by race and class. I was more successful in moving an African-American colleague into our department on a half-time basis; he was tenured and already knew the score.

Law Is Raced

Ironically, research, rather than personal experience, helped me see how structurally embedded racial stereotypes are, and how resistant to change, even in the face of strong evidence of the injustices involved. In 1984 I became a Judicial Fellow, a one-year post in Washington DC to research issues involving the federal courts. Toward the end of my tenure there, I was alerted by a contact at the Federal Sentencing Commission to an unusual number of judicial retirements and requests for reassignments based on unwillingness to impose the harsh mandatory sentences that Congress had designed for offens-

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir es involving crack cocaine. A few district judges had sought to evade them on the grounds that the large racial disparities these mandatory sentences produced violated the Constitution’s equal-protection clause, but the appellate courts uniformly rejected this reasoning. The situation inspired me to leave my intellectual comfort zone, judicial politics, to determine how Congress came up with these penalties. Nothing in the legislation or its official description was helpful, but crude racial stereotypes were evident in much of the testimony and reports that Congress had examined. Concern about the vulnerability of white youth to drugs peddled by inner-city Blacks figured prominently in the congressional debate. The rhetoric about these drug sellers was dehumanizing — they were often characterized as rats or vermin. I struggled to find the right intellectual mooring for this research. Racist intent was an elusive framing, so I lay the project aside for more than a decade as life intervened, including divorce.

A few years later, I was invited to Washington to direct the Law & Social Sciences Program at the National Science Foundation. The law and society field, with its attention to social norms, economic injustice and societal structures, had long been a refuge for me from political science’s tight focus on the official organs of state power. I had taken leadership roles in the Law & Society Association and I was anxious to “give back,” but very unskilled in the ways of the NSF. Dr. Patricia (Pat) White, director of the Sociology program, in the cubicle next to mine, became my guide, mentor and friend. She educated me about the micro and macro aggressions prevalent at the agency and pushed me to use my power to challenge our biggest, most powerful grantee, The National Consortium on Violence Research. The Consortium had been accorded the unusual privilege of awarding NSF research funds to a group of criminologists according to its own criteria. My goal was to stop that passthrough relationship, which involved challenging the Consortium’s powerful director, Alfred Blumstein, a man with deep ties at NSF. This was unpleasant work, but it came with the enormous benefit of getting to know and love a handful of Black criminologists.

I was finally ready to return to the project on race and the war on drugs. I knew that I needed to draw attention to the animus toward Black citizens that Congress had displayed in adopting the penalties for crack, and to its long-standing indifference to the impact of these sentencing policies. The draconian drug penalties were still in place more than a decade after their enactment, still ruining young lives and creating massive misery. The outrageous indifference to the lives of its citizens propelled me to finally finish and publish Unequal Under Law: Race and the War on Drugs. (3)

The last stop on my academic journey was my 2001 appointment to lead Arizona State University’s School of Justice Studies. I felt fortunate to have a new husband willing to move, and to join an interdisciplinary faculty who were serious students of racial and gender injustice at both a global and local level. Arizona was then and remains, a state in transition with a racist legacy as bare as its rocky terrain. Our justice-studies majors were a mix of future social-justice warriors and future law-enforcement officers, a challenging mix. In my time there, ASU underwent a major transformation from being a rather laid-back refuge from academic elitism to an entrepreneurial powerhouse. The transformation of resources, space, and expectations for faculty included attention to the local social and racial environment, in contrast to other universities with which I had been associated. I found ready collaborators for my proposal to study the role of local police in enforcing federal immigration law, a research project inspired by the “attrition through enforcement” politics that dominated the state. The result was Marie Provine Policing Immigrants: Local Law Enforcement on the Front Lines. (4) My last major research leave was a Fulbright grant to study policies toward unauthorized immigrants in our northern and southern neighbors. My husband and I spent half the academic year in Canada and half in Mexico. That experience reinforced my interest in helping Arizona to finally welcome its proximity to the southern border and to embrace its racial and ethnic diversity. I left ASU in 2012 to pursue some decidedly non-academic interests, including painting and rescuing injured owls.

Academic life gives us a vocabulary to describe how society changes over time. But I find it surprisingly hard to draw conclusions. The obvious sexism during my youth is so old now that it isn’t even old-school. The race-segregated restrooms and drinking fountains that I saw in visiting Alabama, and closer to home in segregated settings, are history. My experiences abroad were lengthy enough to give me a firm sense that the United States is not the most sexist or racist nation on the planet, but possibly we worry more about it than most places. The flip side, of course, is the obvious unfinished work, and how embedded it is - in police work, anti-abortion hysteria, military interventions, etc. The country seems divided into those who want to shoulder the responsibility to do more, and those who fear or despise such efforts. But

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir

Provine | Commentary and Analysis/Memoir there is joy in this struggle. Taking the long view helps me to overlook the inevitable hiccups and uncertainties along the way and to remain optimistic about the outcome of the journey.

References 1. DMP, University of Chicago Press, 1980 2. DMP, “Judging Credentials: Nonlawyer judges and the Politics of

Professionalism,” University of Chicago Press, 1986. 3. DMP, University of Chicago Press, available in cloth and paper, 2007. 4. DMP, University of Chicago Press, 2016.

The requirements for our evolution have changed. Survival is no longer sufficient. Our evolution now requires us to develop spiritually - to become emotionally aware and make responsible choices. It requires us to align ourselves with the values of the soul - harmony, cooperation, sharing, and reverence for life.