4 minute read

The River Derwent | Charles Brownson

The River Derwent

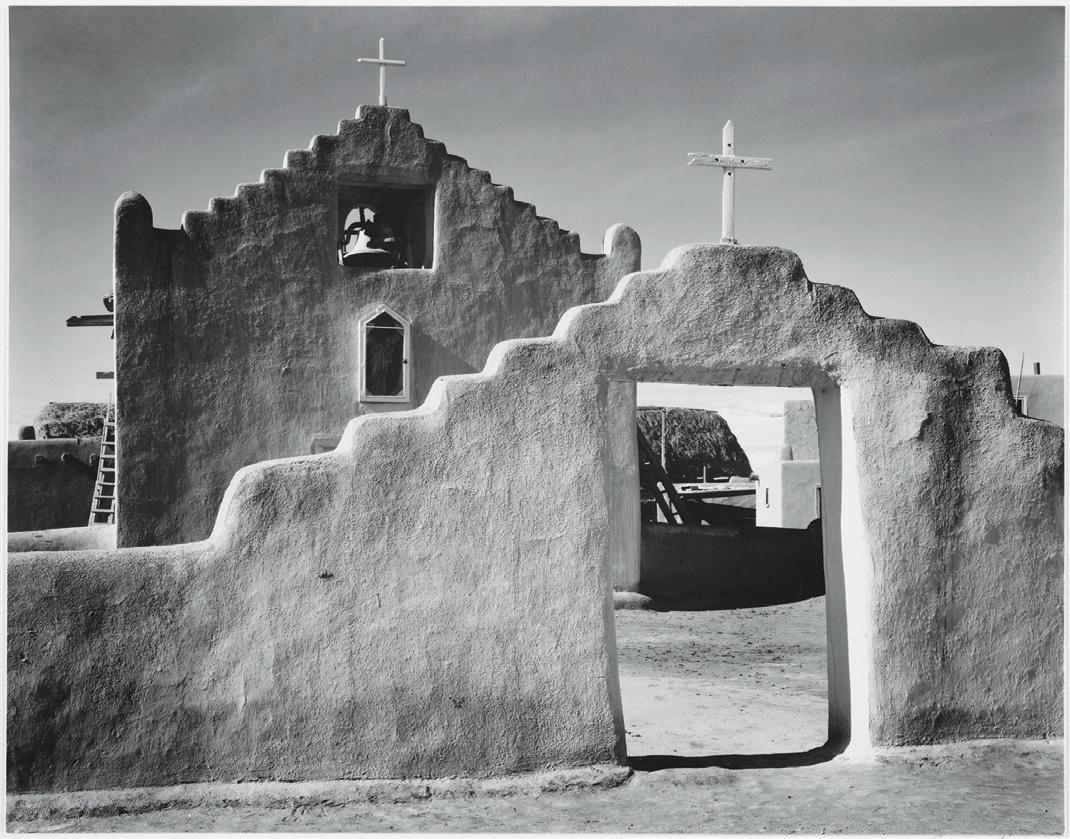

She’d heard the old mission had been restored, put back into place so to speak, its grubby old age wiped off like a fogged mirror she might say, and had come to see for herself.

Advertisement

From the front it was no whiter than before. Unless you are a mission Indian your approach is coy. Circling down from a rise some miles away where the road falls out of the underside of the city,

you see it off to the right, white in the morning sun. Plaster, of course. Not a big building, but as noticeable as an exposed shoulder among brown suits. Country roads lead around to the face.

There’s no mission square. Just a dusty parking lot, and an arched gate with a small bell under which you pass. A low wall, whitewashed. Some Indian girls, children that is, were selling guidebooks there as usual.

Poetry

You pay what you like. On a Thursday morning, October, no cars but hers, she gave a dollar. From the front the central bell tower, the white wings, seemed unchanged.

A shop had once been there, fitted under the dark lintels. She found it now on the plaza in back, bought water there and signed the guest book only Derwent. Outside she sat on a bench in mesquite shade.

They who had made this place, the mission Indians who were the people who owned this place, whose girls now stood out front in the dust with coffee cans.

They built it for themselves. In seventeen fifty something. She drank their water, warm water, under the mesquite and didn’t want to be more precise.

In the mercado a bodega was serving good bean burros in the hot white air but she didn’t want any of that either. A breeze rattled the tree overhead. It was their church

Some foundation’s money rebuilt this, bought the research and the skills, but not the burros or the Guatemalan rugs in the mercado.

Had the first old friar kept a pariah dog? Once, territorial jails were built by the men

themselves because there was no prison yet for them. Did those men feel the lash of creation?

But this new work was good. She saw it was good, knowing nothing. Why then had she come? Past times worry us, worried to make a shrine but that someone was here before, polishing and tidying up, putting to rights

some stuff. She knew that. She was that kind of historian. Inside their mission now the intricate decorations had been cleaned, repainted in the original heavy red and green garish to the protestant eye.

Scary reliquaries, gaunt carvings painted blood and gold with big dark eyes. Masses of wavering candle flames and stiffened lace concealing dwarves in glass coffins, pulpits and dark crooked lintels grow from the narrow walls. You feel you could reach right across.

She wasn’t much for church architecture. Didn’t know how the parts were—apse, crossing— was there a rood screen? Or was that Byzantine. Best to keep such things screened off. She was the kind of historian who

would want to know how they had lived, what changes the missionaries had made, why they needed a church when there was a perfectly good religion already. She would want to know about dogs

and games, and if they also made rugs for tourists at train stops without a purpose but only to sell their things: Rugs using the new aniline dyes, heavy greens and reds made from coal tar in factories.

Poetry

Poetry

The sort of historian she was is one who wants to taste the daily life. Maybe she should go for one of those burros after all. Beans and chilis were not the friar’s food alone.

She drank the water which might have gone for their beans and squash. Maybe the friar thought he was helping to make adobe for something more than just another church, already here.

She didn’t understand these things, really. She was a woman from somewhere in England, presumably—or time was, given her name. Derwent. One of that old tribe, perhaps.

She herself was only from the place where she was last. The academic life takes you everywhere. An itinerant life like the early printers setting up wherever there was no press, needing only a few tools to build one

as did the people whose church it was. Who built this place out of their own adobe. Whose dogs left their paw prints on it. Now restored, and all the clay of generations since wiped off.

They hadn’t neglected a cemetery of course. Would leave no one unburied. And a school which was in the opposite wing. Years of teaching here she might have worked, carrying children from one side to the other.

The River Derwent as the English call it, always putting the particular last,

is about forty-five miles long. It comes down from the Howden Moors in the Pennines between Manchester and Sheffield

where they make good steel, to Derby and Burton, from whence it provides the salts, that is minerals, which brewers use who have only bad water. To bear a river’s name is to bear a kinship With a passage washing her from birth to death,

a flow, an infusion, a dispersion which is the meaning of religious experience. One stands at the confluence, waiting, and somehow there is always more water coming.

Charles Brownson