the Climber

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra

2024 © VERSANTE SUD S.r.l.

Via Rosso di San Secondo, 1 – Milano, Italy

All rights reserved. No part of this work covered by the copyright herein may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means – graphic, electronic, or mechanised, including photocopying, recording, taping or information storage and retrieval systems – without the written permission of the publisher.

Translation into English by Francesco Bassetti

1st edition: May 2024

www.versantesud.it

ISBN: 978 88 55471 909

PIETRO DAL PRA and ADAM ONDRA ADAM

The Climber

Translated by Francesco Bassetti

YEARS

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

I DO IT MY WAY

La Dura Dura. Passing of the torch

FORE W ORD BY ERRI DE LUCA

I have known Pietro for a long time, and I was also fortunate enough to get to know Adam, the main character of this book. He would come and climb on the overhanging routes of the Grotta dell’Arenauta cave, which is found between the towns of Gaeta and Sperlonga, with his parents. At the time, this was my favourite climbing area and this young slender boy, less than ten years old, could make his way up routes that were unthinkable for someone his age.

Today Adam Ondra is considered the greatest rock climber of all time, with a long tick list of routes that few others have been able to match, and still one of the only people in the world to have climbed the hardest grade out there.

In a granite cave in Norway, he discovered and bolted a line that, to this date, only he has managed to free climb. What this means is that he used nothing but the rock in his progression to the top of the route, relying on the bolts solely as a safety measure with which to catch potential falls.

On a cold September day in 2017, Ondra climbed this still unrepeated line, from top to bottom without ever falling - as each fall would put an end to his free climb attempt.

He named the route Silence and proposed the grade of 9c, in a first for the world of climbing.

There are records established by athletes in the sporting world that remain unchallenged for decades, such as the 2.45-metre-high jump of the Cuban athlete Sotomayor. Although I have no idea how long Ondra’s record will remain unchallenged, I suspect that in the world of climbing the upper echelons of what is physically possible have been reached.

Pietro Dal Pra covers the life and achievements of this phenom, from his childhood to his great achievements later on in life. He does so with a precision and detail that is fascinating rather than discouraging to those that are not entirely familiar with the world of climbing holds and the movement required to get the best out of them.

Each chapter brings a new story, experience and adventure made up of different settings, people and a willingness to adapt to new rock types. Even without a profound knowledge of geology we all know that cliffs vary in their

conformations and consistencies, which in turn requires different styles and types of training if they are to be climbed.

Even though, as a reader, I already know that the conquests outlined in the book end in success, the narrative style keeps the reader hanging and conveys their rising crescendo. Pietro has an ability to set the scene, as if writing the script for a film, and in the process conveying the greatest of truths: what matters is the journey, the stops along the way, the failures, and the tenacity more than reaching the finishing line.

With Ondra’s own words and reflections accompanying us along the journey, we get an inside view of the person and the spectacular story of how he came to embody of the art of climbing.

Erri De Luca

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

FORE W ORD BY PIETRO DAL PRA AND ADAM ONDRA

Ring, ring.

‘Hi, Adam.’

‘Hey Pierin, how’s it going?’

‘All good. Listen, this is an important call: a few days ago, I was asked if I wanted to write your biography. My first reaction was to say no. But I then decided to buy a little time and think about it. We’d both have to be onboard with this… what do you think?’

‘Brilliant!’

‘Oh… great. But wait a minute, it’ll be a big job. It’s you we’re talking about, I’d have to give it my all and to be honest I don’t even know if I’m up to the task, I’m no writer! Also, you’d need to put some time aside for it and we both know you never have much of that to spare.’

‘Yeh, I get it but it would make me really happy to have you write a book about me. If you don’t who else will? A journalist that doesn’t even climb or know who I am?’

‘Ok, but I’m also a little lazy, I don’t know if I feel like sitting at a desk for months. It would be an uphill battle for me. Although challenging myself on something like this is kind of enticing: I guess I can’t say no.’

‘See, you’ve already given yourself an answer.’

‘Yeh, I guess! I knew you’d be like this, what a pain.’

‘Come on. It’s a great idea and someone has to do it sooner or later. Think about the pace at which the climbing world is changing; these youngsters don’t even know how it all started. It could turn out to be something important for future generations. Who knows, maybe someone will read it in thirty years time and think: “Really.. is that actually how it used to be?”’

‘Yeh you’re right, your story is also about a historical period and a richness that can’t just go forgotten. It can’t be left to the internet without a thread that knits it all together and gives it meaning. Alright let’s get to it, but you’re going to have to help me a lot, tell me your stories, and not just about the routes you’ve climbed - people know about those already. I want to write about you,

about climbing, and, big words here, the values that you represent. It’ll be a long process, not an onsight try, but a real long-term project. And you know that I never had the patience for projecting.’

‘Yeh, but it’ll turn into a beautiful route, as long as there is nothing more than the truth: no chipped holds!’

‘Of course, there’s no need for me to invent anything for it to be a good story. The most important thing is that it conveys the real meaning, or at least some of it…’

Now that the writing adventure is over, we hope that we’ve achieved some of what we set out to do.

Pietro

Dal Pra and Adam Ondra

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

INTRODUCTION BY ADAM ONDRA

Climbing has changed immensely from when I first started. The boom in climbing gyms has pretty much consolidated climbing as a mainstream sport and in the process far greater emphasis is now being placed on the performance and safety aspects. From a niche activity it became a mass sport and now even an Olympic sport. When I was growing up, the way people perceived climbing was completely diferent. I remember being met with blank faces when I told my classmates that I climbed, they had no idea what I was talking about.

Climbers back then were different: they had different lifestyles, different values, and a different mentality.

Both Pietro and I feel that many aspects of climbing that we both hold dear run the risk of being lost forever and that there isn’t much we can do about it. Climbing is changing, the times are changing, and we are both getting older – even though we are (both!) still young. I hope that, in holding this book in their hands and learning about my adventures, more people will understand and share the climbing values and beliefs that we hold dear.

Pierin is an amazing climbing partner, friend, and person. Although we are separated by a big age gap this has never conditioned our friendship. I have known him since I was only fourteen years old and, from the very first moment we tied in together, I could feel that we were on the same wavelength.

I knew that, as I grew older, I would become increasingly like him, and maybe even start to think like him. At least, that’s what I hoped and aspired to. I’m not sure the world idol really captures the way in which I looked up to him, but what is certain is that I have always considered myself lucky to count him as a friend, and proud in the knowledge that he felt the same way.

Today, almost twenty years on from when we first met, it’s safe to say that I have indeed become more like Pietro. I now drink cofee, I eat more than just power bars on big wall days, and my fingers are just about as fat as his. Sure, Pietro has a few more grey hairs on his head, but I’m not too far of having some of my own.

Most importantly, the way we think has become increasingly similar and I can think of no one more suited to writing a book about my life, climbing, and an approach and vision which may be on the brink of disappearing.

No easy task. And yet I trusted that Pietro would be up to it from the outset, just as I always trusted him unconditionally as a climbing partner on my first big walls, when I knew absolutely nothing about safety. Not that I’m now an expert: I still love climbing far more than the intricacies of safe and efficient ropework.

I like the fact that Pietro isn’t a ghost writer. He’s not simply writing a book about my life but weaving in parts of himself. A beautiful touch because he’s part of my story. Both directly and indirectly: as a climbing partner on some of my most important adventures and in the way he influenced me as a climber.

Just like me, Pietro started climbing at an early age. He was also considered a “wonderkid” – climbing hard routes at an unprecedented age, such as the first ascent of Mare Allucinante, 8b+, in 1987 at the tender age of sixteen. He came to sport climbing from an alpine climbing background which was passed down to him by his father. In those years sport climbing was still in its early years and competitions didn’t even exist.

When I first got started, sport climbing was already well established which meant that my initial experiences were at sport crags and climbing gyms. However, I was still influenced massively by my parents who were alpinists. Despite the word sport already finding its way into the label given to what we were doing, it was still a far cry from what the sport has become today.

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

Madagascar. Photo: Pietro Dal Pra

THE FIRST TEN YEARS

Pietro and Adam on Tough Enough, east face of Karambony, Tsaranoro massif, Madagascar.

Photo: Pietro Dal Pra

MADA G A S CAR. ADAM I S TOU GH ENOU GH

We don’t even bother to untie as we top out of the route and crawl up the last remaining rocky outcrops to the true summit. There, at the top of Karambony we embrace in happiness and satisfaction, finally stopping to take it all in. Sitting in silence at the top of this granite tower, our eyes drif over the magnificent hills and plateaus of Madagascar.

It’s not the first time I’ve seen that soft and intense look in Adam’s eyes after a climb. A unique way of looking out onto the world: narrow, squinting eyes that seem to want to filter and store the surrounding beauty and experiences that we’ve just been through. A beauty that takes on an even deeper meaning when you’re at the very pinnacle of what you’re capable of. Squinting eyes that seem to redefine what is possible and, at the same time, betray a suspicion that there is still more potential just beyond the horizon.

We got this far by chasing yet another dream: a wall of incredible beauty that was begging to be climbed.

It’s hard to imagine a more perfect vertical wall than the east face of Karambony. Standing below its towering faces leaves me breathless. Four hundred

metres of smooth granite that, upon closer inspection, aren’t perfectly vertical but ever so slightly undulating, like a gently billowed piece of fabric. And the colours couldn’t be more vibrant. Streaking down from above with no clear breaking lines they alternate from orange to brown and black, with the occasional dash of electric green sprayed here and there by the lichen. Truly fantastic.

On the more forgiving seams that run straight through the centre of this masterpiece, in 2005, the German climber Daniel Gebel and his partners established a new line, ground up, using a combination of free and aid climbing tactics. What they left behind was a route of both absolute elegance and staggering difficulty, which they gave both a provocative yet tantalising name: Tough Enough.

Two years later, François Legrand, a climbing legend from the turn of the century, became the first to attempt a free ascent of that line. Yet, try as he might, over half the route remained unsolved and a riddle for future climbers to decipher.

Not long after, Arnaud Petit, Stephanié Bodet, Sylvain Millet, and Laurent Triay - all seasoned and strong climbers from my generation who are no novices to the intricacies of climbing in Africa - were the next to attempt a free ascent of the route. They set up fixed ropes on the wall and allocated different pitches for each member of the team to work on. However, even for them, one of the pitches remained unsolved, leading to questions about whether it was even possible to free climb it at all.

A breakthrough moment came when Sylvain Millet rappelled down the route and spotted a weaker line - seemingly offering more holds - just to the left of the unsolved pitch. He promptly proceeded to bolt it creating an alternative, or bypass, from the original route. This new variation opened up the possibility for the French team to attempt a complete free ascent.

The four climbers continued to persevere in their attempts and, after about a month of hard work climbing up and down the fixed ropes or rappelling from the top to try each pitch individually, they finally achieved their goal: a free ascent of all ten pitches.

An achievement that, although exceptional in and of itself, also left room, at least theoretically, for Tough Enough to be climbed in a single ground up push from the base to the summit. The four climbers jotted down a sketch of the route which included proposed grades for each pitch: out of the ten pitches, only two were in the seventh grade, whereas five were believed to be between 8b and 8c. Within the somewhat exclusive circle of elite climbers that can dream of attempting such a hard route the legend of Tough Enough was born.

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

What is more, the French team didn’t just draw a rough sketch of the route on a piece of paper, they also produced a video documenting their adventure. Mesmerising images of the valley, rock face and climbing itself. As soon as I saw these images, I became transfixed. Although I would have loved to set myself the goal of climbing the route, not least of which for its incredible beauty, I was also realistic in the assessment of my capabilities: particularly considering the remoteness of the setting, those grades were beyond what I could hope to climb.

However, I do have a friend for whom these grades carry a very different meaning. And I’m pretty sure he’d love the challenge. I decide to give him a call.

A few months later I find myself meeting up with Adam at the airport in Paris. He has just finished competing at the World Cup in Bürs, Austria , and now has a three-week break before the next stage which will take place in Slovenia. This means that, at least for this autumn, I’m going to give up on my usual climbing trip to Sardinia. As we’re sitting on the plane, our flight passes over the Italian island and, out of an uncanny coincidence, I spot the canyons of Gorropu from the window, the place where Adam and I last climbed together. If it wasn’t for this new adventure in Madagascar I’d be down there right now, climbing where I truly feel most at home. I look down with a touch of nostalgia, but at the same time I’m excited to explore Madagascar, which I’ve been told is the “Sardinia of Africa”.

The owner of a company that is sponsoring Adam picks us up at the airport, takes us to his home, and the next day we visit the open market in Antananarivo. A cacophony of colours, smells, and sounds that are utterly new to us. Then, after a game of luggage Tetris, we squeeze into a jeep and head down to Fianarantsoa, where we shop for supplies before setting out for the remote valley of Tzarannoro.

It’s a wonderful place: sunny, open and with clean honest walls that seem to store no secrets. Once our jeep departs, I suddenly feel very alone, burdened with that load of responsibility which I’ve felt before when climbing with Adam. It’s just the two of us, at the foot of towering granite walls in a long-lost valley of Madagascar. No phone reception and no means to seek help. I’m thirty-nine years old, eighteen of which I’ve spent as a mountain guide, and I’m here with a partner who is only seventeen. Sure, his climbing skills are from another dimension, but he’s completely lacking in the experience needed for big wall climbing. It’s down to me to keep him safe. If anything happens, I’ll just have to put him in my backpack and carry him down, something Renato Casarotto once told me when I was a child. There’s no other option.

Tough Enough (8c, 380 metres) on the east face of Karambony, Tsaranoro, Madagascar.

Photo: Pietro Dal Pra

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

Above, dinner time in Madagascar.

Left, Adam rests on a portaledge on the east face of Karambony, Tsaranoro valley, Madagascar.

Photo: Pietro Dal Pra

THE COMPS

“Spraywall” - climbing walls filled with holds and endless bouldering sequences on which Adam trained regularly.

Photo: Bernardo Giménez

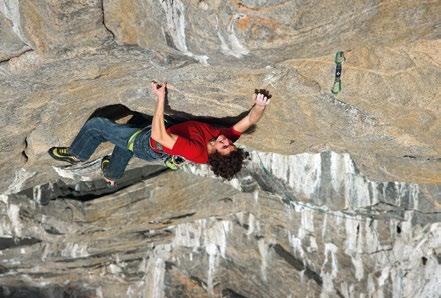

‘Light and with few muscles but still I’m able to climb hard routes that require a lot of strength.’

Marina Superstar 9a+/b, Domusnovas, Sardinia, 2009.

Photo: Vojtěch Vrzba

NOT J U S T FUN AND G AME S

2008 marks ten years of climbing for the young Czech boy. His first ten years. It’s also the year where I join him on the monstrous multipitch WoGü, in Rätikon, where I get to witness a climbing maturity and determination that I’ve rarely seen in anyone, let alone a child. A mixture of wisdom and the freshness of youth. Later on in life, Adam would sit down with me and put into words what that year truly meant for him:

‘That year, my climbing infancy came to an end.’

I can’t help but laugh. How can he call it an infancy? There aren’t many people out there who can claim to have achieved as much as he did in their early years!

But he insists, ‘Honestly Pietro, until then climbing was nothing more than a game.’

I try to dig below the surface and find some hidden meaning to what he’s saying.

Adam lays it out for me in the simplest way possible: ‘Before then, there was no pressure.’

Okay, I think I get it. In that early phase of his life, Adam was already fully committed to climbing but he also managed to retain a constant feeling of lightness and freedom.

So many holds have passed below his hands, kilometres worth of plastic and rock. And endless kilometres travelled by car, whether in the greyish ones of the Soviet era or the new red van. Countless nights spent sleeping in the Viano, in tents or simply out in the open air. Crags, villages, diferent languages, gyms in myriad cities meeting 6a to 9a climbers (the grade they climbed never change his attitude towards them), dinners cooked on camping stoves, dirty sleeping bags, weeks without showering, redpoints, ticks in guidebooks, notes scribbled into diaries or on 8a.nu. Worn down fingers, runouts, massive falls, and clipped anchors whose chains of gold brought immeasurable rewards. So much lightness, so little weight.

A life of wondrous adventure. A serious and intense game. But a game nonetheless.

The key that had ignited Adam’s engine were the competitions, those two trophies which he’d placed on the custom made shelf in his room in first grade. However, the fuel that had fuelled that same engine, keeping it running ever stronger, was the rock. The trophies multiplied and had to start being stored in the closet, there was no need to display and admire them. As they racked up they began to lose their value, and would never really mean as much to Adam as the first two. This was also because, after his first year of competing, Adam went on to win around ninety percent of the junior competitions he participated in. When he didn’t win it was usually because of silly mistakes, like stepping over an eliminate line that establishes where you should and shouldn’t climb on any given route.

The national competitions, the Czech Cup and Czech Championship, became a formality and little more than a weekend where you had to show up and top out. Then, at the age of fourteen, Adam is finally old enough to take part in the more important and official international youth circuit competitions, such as the European Cup and the Youth European Championship. Great, he thinks, now it’s getting serious and it’ll be a fight!

At his first international competition, whilst climbing on a qualifying route whose grade is probably around 7b, he makes easy work of the first half. Then, as he reaches a dihedral, he sees a distant foothold far out to the right.

‘Let’s make this fun, I’ll step out wide and let go of my hands,’ Adam thinks to himself. As he kicks his foot out right he hears murmurs rising from the crowd. Then, when he tries to get going again he can feel a tug from the belayer short roping him: he’s stepped over the eliminate line and has been disqualified.

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

Kyselina mravenčí IXc, Labák, Czech Republic.

Photo: Petr Piechowicz

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

Boží muka Xb (Font 8a), Labské údolí, Czech Republic. Photo: Petr Piechowicz

Above, Adam on Labák, Czech Republic. Photo: Petr Piechowicz

Below, climbing in Labské údolí, Czech Republic, 2007. Photo: Petr Piechowicz

RI S K S AND COMPETITION S

I like competitions because they’re a great way to measure who climbed best on a given day. Which isn’t the same as determining who the best climber is, but by no means less exciting. You can be exceptionally strong, but if you don’t have good technique or your mind is not quite ready to fully commit then it’s not easy to win. Climbing performance is composed of so many diferent elements. Power is one of them, but even when talking about power there are so many details and types. Being able to do many one arm pull-ups is certainly a good thing, but there are probably more important aspects to power in climbing than that.

Then there’s technique. The way you climb on an unknown route. The way you read the sequences. The pressure of the moment, knowing how hard you’ve trained, what shape you’re in, and dealing with the pressure of knowing that one tiny mistake could lead to a fall at any time.

I’ve always had an all-in approach when competing at World Cups and my first few years on the youth circuit were an important building block for my future career. On the youth circuit I was always expected to win and often found myself climbing badly, without the right flow. I knew I had to win and that I was capable of winning even if I climbed badly. It took the enjoyment out of climbing and I felt like I was just there to get the job done. I could never reach that state of complete consciousness that I’d get when I was climbing my hardest routes outdoors, when moves came by instinct or experience and my body felt like a perfectly synchronised machine whose performance was directed by intuition.

When I first entered the world of adult competitions, I was sixteen and it was a completely diferent story. I wasn’t even sure I was good enough to make finals, let alone get on the podium. There was very little pressure and I just wanted to give it my all. My first senior competition ended with a second place, just behind Patxi Usobiaga, at the World Championships in China in 2009. I climbed completely diferently from the junior circuit, feeling confident, fast and perfect. I was able to rely on my intuition, flying through most of the routes and not really noticing whether the moves were hard or not.

I just went for sequences without thinking twice. In some competitions this worked perfectly. In others, it led me to fall very low down on routes because my intuition failed me. There were times when I would jump for the next hold,

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

expecting it to be good, only to realise that it would have been better to reach it in a controlled and static way. In other cases, my focus on speed and using the least amount of power possible meant that I wasn’t being precise enough and I would slip unexpectedly.

The truth is that, if I want to win, I have to climb this way. I don’t have enough of a margin on the other competitors to win by climbing “safe”, hesitating or attempting to control each move. To win, I must accept the “risk”. The upside is the more I climb this way, the more I train my intuition and hence the more likely it is that I will be successful. This realisation has led me to climb without hesitation all the time: when I attempt hard onsights outdoors, when I warm up, when I climb an easy route just for fun at the end of a day. Occasionally I fall off very easy routes, but I feel no embarrassment in this. It’s just part of a constant and essential training process that brings me to the limit of what I am capable of.

Adam

Change 9b+, Flatanger, Norway. Photo: Petr Pavlíček

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

Above, The Dawn Wall. Fifth day: Adam celebrates sending pitch 14. Photo: Heinz Zak

Left, The Dawn Wall. Adam’s hands on the sixth day on the wall. Photo: Heinz Zak Next page, Silence 9c, Flatanger, Norway.

Photo: Bernardo Giménez

T H E NEVER-

ENDIN G CLIMB

Anders Ericsson, a Swedish psychologist who specialised in studying the psychological nature of expertise and human performance, formulated the TenThousand-Hour Rule afer monitoring a group of young violinists for over a decade. He argued that, if during repeated practice over an extended period of time a practitioner’s attention is completely focused on what they’re doing, then new brain circuits associated with that activity are created and that only in this way can excellence be achieved.

Ericsson wrote, ‘Improvement does not come from mere mechanical repetition, but from continuously refining one’s execution to get closer and closer to the goal.’

A somewhat simplistic summary of the Swede’s theories but even so, one that reminds us of the zen-like charm of practising a given expertise with so much love and dedication that it evolves into an art form. The appeal of the pursuit of perfection, practice to the point of automatism, whereby the body moves with animal-like flow and far beyond the realm of rational thought.

So it is for Adam, who has dedicated well over ten thousand hours to climbing, living each moment with unique dedication, concentration, and gut wrenching passion. He has absorbed all those moments, making them

beautiful and fulfilling experiences and finding motivation in whatever project he was pursuing at the time. All the effort he’s put into his development has never felt like a burden, but rather an opportunity.

Grades have certainly always been an important goal, but the individual climbing projects were always dreams that he pursued beyond the aspect of sporting performance. The grades were a way of stimulating himself to work towards pure excellence and then measuring it.

At twenty-three, Adam graduates, wins the World Championship, and shortly after climbs The Dawn Wall. At twenty-four, he clips the chains on Silence after a year of total dedication to the route. He’s satisfied in the knowledge that he gave that project his all. He’s reached the 9c grade. A new grade for himself and the world of climbing. A community that has recognised him as the best. But what others think doesn’t really matter to Adam; he has to answer to himself with facts.

A few months after his historic redpoint in Norway, Adam starts to feel as if there’s still something missing and that he needs to test himself once again. He wants to check whether he’s truly raised his own personal bar and where he stands in relation to it.

For this he goes back to his origins and his obsession with onsighting. There are two reasons: firstly, he’s still convinced that the most beautiful and pure qualities of a climber emerge when venturing out onto unknown holds, when one must be flexible in the mind and capable of adapting perfectly and immediately to the rock; secondly, and just as importantly, onsighting provides a complete test. On projects you can afford to make mistakes, there’s always another attempt. When onsighting or flashing all you get is one go. If you succeed, the pleasure of success is total. If you fail, the failure is definitive and you’ll never get another chance. With these conditions the pressure and stakes are far higher, which in turn makes it harder to channel your emotions in a constructive direction.

Having just one chance at success changes everything, and Adam knows it all too well. When he’s climbing on rock he appears cold, pragmatic, and rational. However, deep down he’s also a passionate climber who’s always had to deal with the battles of the mind and things like performance anxiety. As a child, without even realising it, Adam’s obsession with onsighting, and therefore giving himself only one shot at most routes, was slowly educating his mind so that it would become a valuable tool in his climbing arsenal and not a burden. His constant desire to test himself probably came naturally and wasn’t even a conscious process, but it ends up becoming the key to his

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

winning attitude in life, a sort of common denominator that spreads across different areas of his personality and well beyond climbing.

A pleasure, a need, a way of being. A desire with which he was born and which his cultural background reinforced and augmented. An attitude that found its purest form of expression in climbing, of which Adam has always appreciated a very specific aspect: the clear and defining line between success and failure. Whether on rock or on plastic, results in climbing are clear, unquestionable and transparent. Either you fall or you don’t. Black or white. Two extremes that can often come within a whisker of each other but which in the end remain separate, leaving no room for doubt. Extremes that are even more defined and ruthless when you choose to climb onsight.

Today onsight and flash climbing is becoming increasingly less popular. It seems incredible, but both beginner and strong climbers seem to devote most of their time to projecting, and therefore neglecting one of the most important aspects of our sport. When onsighting you’re constantly forced to step out of your comfort zone. In contrast, projecting and therefore focusing on a single route helps build a reassuring routine where you know what to expect. This isn’t necessarily a negative thing, indeed it does take strength and determination to commit to long term projects. Yet it also seems to be more about commitment and a certain stubbornness rather than courage and adventure.

Speaking to Adam about this trend in climbing you get the sense that he’s incredulous and almost disappointed that young people seem to no longer value or want to use onsight climbing as a benchmark. Adam knows exactly what it’s like to try the same route for months on end (and therefore the inner strength it requires), but he also realises that his climbing skills have largely come from choosing to snub projecting as a young climber.

‘Just think how far we’ve come in the last twenty years,’ says Adam. ‘The sheer amount of new routes available for young and strong climbers to try and onsight or flash. But instead they fixate on one line and try it over and over again until they eventually succeed, and in the process deprive themselves of new climbing and opportunities to improve.’

As a child Adam was a fundamentalist who considered onsighting to be the purest form of climbing. Even flashing was less attractive to him, he didn’t really understand it, his unwavering sense of ethics considering it a sort of compromise.

As Adam grew up, he gradually came to realise that flashing provides an indication of how well one knows oneself and their climbing. It requires a fundamental quality that is honed through years of climbing: imagination.

Climbing on holds that he’s never touched before implies studying the rock and others climbing on it; listening to them; internalising everything and translating it into a personal vision of those sensations. The closer his imagination can come to reality, the more the climb has been assimilated. It comes down to the ability to climb within oneself, just like imagining music without hearing or playing it.

The flash is an art within an art and an important benchmark, where once again you only get one chance.

9a+ is already a very high grade for Adam. It’s the first one on the grade scale that truly tests him every time; a difficulty where he cannot afford to make any mistakes. In fact, Adam has never climbed a 9a+ in less than three goes, which makes him think that flashing something in that grade may well be unattainable. But then again, impossible projects are the most enticing to Adam, where the uncertainty of success is the point itself.

Adam is constantly pursuing perfection and managing to flash a 9a+ feels like the perfect challenge. Super Crackinette is an exceptionally tough route, the hardest in Saint Léger du Ventoux, a historic crag in Provence. It has only been climbed by the renowned German climber Alex Megos. Short and intense, it revolves around thirty technical moves on tricky limestone holds, where perfect finger and body positioning are essential before you can pull on them uninhibitedly. It’s a full-fledged 9a+ with a climbing style that is anything but obvious. Perfect for Adam’s goal. As with Il Domani and Silence, Adam wants to test himself on routes of substance that have confirmed grades. Only this way can he feel like he’s fulfilled his dream.

It’s an early February morning, five months have passed since Adam’s feat in Flatanger, and he’s now standing under a wave of grey limestone in the gorges of Saint Léger. He’s tense. He’s been chasing this dream from the age of eighteen, failing several times before. If he falls, besides not getting a second chance, he’ll have wasted another precious opportunity, which is an additional psychological burden. Afer all, there aren’t that many of 9a+ routes lef for him to try and flash or onsight in Europe.

He’s already watched a video of the route and is now taking the time to observe two climbers as they take turns trying it. Adam listens to every detail, particularly when they tell him about the shape and size of the holds. He takes in their explanations and adapts them to the sensations that he imagines he’ll feel once he’s there. Lying down below the route he processes it with his eyes and all the power of his imagination, slowly making it his own.

Pietro Dal Pra and Adam Ondra ADAM

He analyses every detail, all the holds, the rests, and how he’ll end up using them. For each move he explores what he’ll feel, from the way he’ll have to contract his muscles, to the sensation from the tips of his fingers right down to the toes.

The start seems to involve stretching out on an initial, vertical crimps. He’ll have to be as fluid and dynamic as possible, without closing the angle of his arm too much. Adam then sees himself being a little more static and conservative on the subsequent metres of small underclings and crimps where he can bring his feet up high, using body tension and not just the force of his biceps.

Next he tries to feel the pressure on his finger in the mono and two-finger pockets where the crux begins; he’s never loved pockets and he knows he can’t afford to squeeze them too much, he simply has to pull down on them, allow his tendons to stretch and rely on the friction of his skin as it rubs against the edge of the pocket. He knows that the next distant and isolated foothold is fundamental for pulling his body to the left. Then he’ll go high with his right hand into a strange jam for the index and middle fingers that helps make the foothold feel more secure, before a sequence of two or three small crimps, holds that have always given him a certain sense of security. But it’s not over, next comes the final part of the crux: grab a rough edge by coming across with the left hand, press the thumb over the index and not the middle finger so that the wrist stays straight and the forearm aligned, and then with the bicep in the right position load up a final dyno to finish the crux sequence.

Most likely he’ll be at his limit, dancing on the edge between failure and hanging on where the biggest challenge is to remain calm and execute with precision. The stakes are high and the void between success and failure consists of tiny details which are first and foremost mental, then technical and finally physical. For the top section of the climb Adam tries to visualise staying calm and focused; surgically precise yet explosive.

Once the route has been dissected into its individual moves and down to the most minute details, Adam runs through it as a whole and tries to feel its physical and emotional rhythm. The holds are now a theory that he’s developed in his mind. Once he’s up there it’ll all be new to him and success will ultimately depend on not being caught off guard, particularly if the vision he’s created turns out to be different from reality.

For each section of the route he associates a breathing pattern, which at times must be long and controlled to help him calm down, and others focused on inhaling to fill up with oxygen and energy or exhaling with force to help claw himself back from the edge of failure.

Pietro has an ability to set the scene, as if writing the script for a film, and in the process conveying the greatest of truths: what matters is the journey, the stops along the way, the failures, and the tenacity more than reaching the finishing line.

— ERRI DE LUCA, from the preface