DECOLONISE! DEMOCRATISE! DECARBONISE!

Instruction Manual

Instruction Manual

Under international and national carbon trading policies, carbon offsets give companies, financial institutions and governments the option to spend money on “emissions-saving projects,” instead of reducing their own emissions at source. This was first introduced at the 1995 Kyoto Protocol, after which policies of carbon offset began to emerge in the United Kingdom and the European Union in 2001 under the “Climate Change Levy”.

This introduced a climate tax on heavily polluting companies. It presented a method where companies could get a discount on the emissions tax if they elected to make reductions through participation in a new “carbon trading scheme”. This trading scheme recruited 54 sectors of the UK economy, giving participants the decision to take action to manage their emissions, or to reduce their emissions below the target, allowing them to release carbon allowances that they could then sell or save for the future. Markets emerged where participants can also buy and sell allowances from each other. Alongside this scheme emerged the REDD scheme, which aimed to help corporations offset their carbon in developing countries around the globe.

Not only have these schemes largely failed in their creation of sufficient carbon emissions, they also further the capitalist agenda of forestry and agri-business that has been emerging since the start of the postcolonial era in the mid-20th century

Since 2021, there region has been under threat of being destroyed by the carbon offset market. Foresight, a company registered in the Shard in London, bought up farms in the area to plant commercial, non-native conifers over the existing hillside in order to sell off carbon credits to their financial investors for profit.Thus, farmers are finding themselves priced out of good quality farming land as many can simply not compete with the new prices.

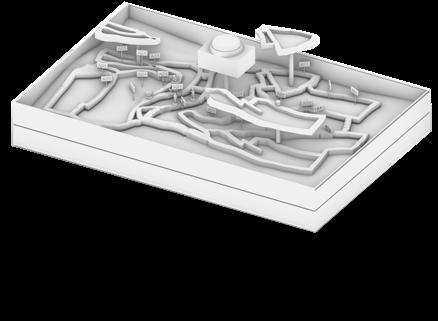

The set-up of the game is based on the Cwrt-y-Cadno valley in Wales.

To set up the game, follow the steps below 3 4

1 2

Open the board game and place on the centre of all players.

Place the floating pieces, an indicated in the image on the left to above the allocated spaces using the wood pole.

Place the risk and lobby cards on their chosen spot on the board.

Place all characters at their starting spot.

The first step in playing Capital Rewilding is to get given a character. Each character is a combination of game statistics, roleplaying hooks, and the player’s imagination and strategic planning.

Each player can choose a category (human or non-human), after which they must role the dice to determine their character role. Each character is accompanied by their own set of policies and characteristics, explained in the character cards. Throughout the game, this character becomes each player’s representative in the game. Players of the same category then become part of a larger team that plays within this game, collaborating together to win the game for their team.

Human:

1. Landowner

2. Corporations

3. Private Sector Sellers

Non- Human

4. Sheep

5. Squirrels

6. Pine Martens

Human:

1. Landowner

2. Corporations

3. Private Sector Sellers

Non- Human

4. Sheep

5. Squirrels

6. Pine Martens

In addition to the character card, the players will have the chance to perform actions through the use of 2 main cards

Following this, the human characters will have the added advantage of utilising these cards:

1. Land Card

2. Risk Card

3. Lobbyist Card

4. Policy Notice

5. Commoning Card

1. Land Card

2. Risk Card

3. Lobbyist Card

4. Policy Notice

5. Commoning Card

Whenever a player lands on an unowned property, they may put a bid on that property at its printed price. Each land is associated with a selling waiting period, once that period passes, a dice roll determines whether the player was successful in their purchase or whether more complications have arose.

If no other complications occur (such as the need to pay extra costs), the player may then receive the Land Ownership Card showing ownership. If the player does not wish to buy the property, it can be sold it at auction to the highest bidder. The buyer pays the policymaker the amount of the bid in CRC or carbon credits.

Following the sale, the owner may then begin carbon offsetting as based on the rules of their player card.

When a player lands on property owned by another player, they must either pay rent to the owner, or chose to buy the land at 3 times the cost despite ownership. This process is then similar to the one described above. If they do not wish to buy it, the owner of the land collects rent from the player in accordance with the list printed on its Land card.

It is an advantage to hold all the Land cards in a block because the owner may then charge double rent for properties in that group. The owner may not collect the rent if they fail to ask for it before the second player following throws the dice.

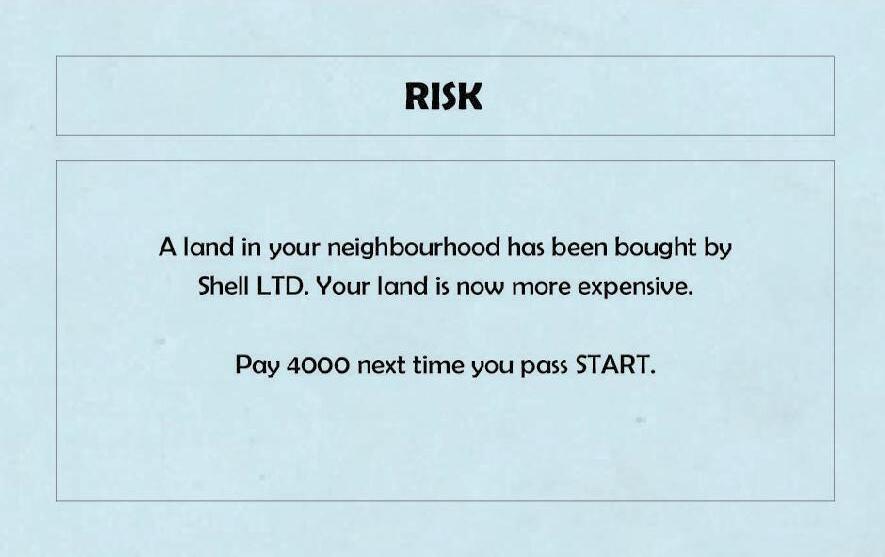

When you land on These spaces, take the top card from the deck indicated, follow the instructions and return the card facedown to the bottom of the deck.

These cards are randomly distributed to the game players at the start of the game, helping them understand and empathise with ideas of commoning.

Landowner: Plant a tree on your site

According to the rules, if a small amount of trees are planted on the land, additional woodland cannot be created on the land. Thus, this land becomes unsellable to any corporation.

Landowner: Speak to MP.

Attending a protest can help hault the sale of a land to a corporation.

Landowner: Demand maintenance check of corporation’s land.

A maintenance check of bought land is needed every 5 rounds. If a corporation fails, they must pay a fine of give up the land.

Corporation: Publish a greenwashing document.

The publishing of this document would prevent the action of any landowner’s lobbyist cards for 2 rounds.

The game follows two groups of players, the landowners and the corporations. It is based on emissions trading policies and land-regulations in the UK that have been built on capitalist ideas regarding green-washing and carbon offsetting through the rise of mandatory and voluntary carbon markets.

The aim of the game for the corporations is to collect as much pieces of land as possible, while the aim for the landowners is to protect their land from foreign investment.

1

At the start of the game, all players must roll the dice to determine their character, as described in page 7. An additonal player, or one of the existing players, must be made policymaker.

2

Following this, each player is given a sum of 500-1000 CRC of play money, as described in the following pages. Additonally, all players are given 10 carbon credit tokens at the start of the game.

3

The players must then place their character tokens on the board as indicated by their character guide.

Clockwise and starting with the policymaker, each player in turn throws the dice. The player with the highest total starts the play, moving clockwise around the board the number of spaces indicated by the dice and the players character guide.

4

After the first player has completed their play, the turn passes to the left. The tokens remain on the spaces occupied and proceed from that point on the player’s next turn. Two or more tokens may rest on the same space at the same time.

According to the space the character token reaches, the player may be entitled to buy landor obliged to pay rent, pay taxes, draw a Risk or Summit card, or fall down the ladder, where the player is taken back to a point on the edge of the board (near the starting point).

5 When reaching a point of intersection, players can chose to go down whatever path they prefer based on the land they hope to reach.

Intersections that allow to rise to the next level require a payment of 50 CRC as a minimum per player (based on the level cards presentes), which must be paid upon decision to rise to the level.

6

At any point during the game, the players (in teams or individually) may request to use one of the three lobbyist card they are allocated. Landowners may choose to protest a sale, start a petition, or contact an MP, while corporations may chose to publish a research document, attend private climate conferences, or change their business plan.

7

The game ends with a victory for the corporations when all properties on the board are owned. It ends with a victory for the landowners when they manage to keep their land despite attempts from the other team.

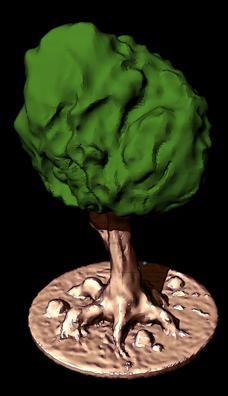

Upon having the ability to plant or forest a piece of land, human players then have the ability to chose a type of tree, based on their desired output.

Conifer trees are 200 CRC and allow the player for a quick return in terms of the carbon sequestration that they are able to complete. Conifers also allow players the chance to earn an income every turn as this will produce softwood that is used in construction.

This tree will then positively impact the Pine Marten character, who will be able to utilise this land for food when they land on a site with this piece of land.

Broadleaf trees, on the other hand, are 100 CRC. They take twice the amount of time to sequester carbon as the conifer trees, bringing in only half of the income that conifer trees are able to bring in. They do, however, allow both pine martens and squirrels to reside on them.

The aim of the corporation here in this game is to acquire land rights to the farming lands they encounter. With a starting salary of 3x that of the farmer, they are able to invest their money in land or carbon credits. They are also able to advance up to Levels 1-3, getting access to more premium land as well.

As a human player: they are able to earn a an income eveytime they are close to their starting START point. This rent can then be used to buy cards, credit and land.

They are also able to move at two speeds, giving them the chance to move two squares at a time if they roll an even number on the dice.

Farmers are able to win as a team once they have secured full neighbourhoods (earning a trophy) or managed to bankrupt the other players. The player with the most worthy lands is the winner at the end of the game.

The aim of the farmer in this game is to win back rights to their land. They play in collaboration with one another to keep their owned lands while maintaining rent at a moderate rate.

As a human player: they are able to earn a an income eveytime they are close to their starting GO point. This rent can then be used to buy cards, credit and land. This income is determined by the amount of lands that they own, and thus the amount of agricultural income they would be having as a result of their jobs.

They are also able to move at two speeds, giving them the chance to move two squares at a time if they roll an odd number on the dice.

Farmers are able to win as a team once they have places farmhouses on every neighbourhood, earning a trophy. The player with the most worthy land at the end of the game is the winner.

Sheep work with the farmers to gain a shared income for sheep grazing land. They play in collaboration with one another to keep their owned lands while maintaining rent at a moderate rate. They are able to attack sites of less than 3 trees, ruining the trees if rolling a number greater than 4.

As a non-human player: they are able to earn a an income eveytime a player passes by their land, using the money earned to pursuade other players to achieve their goals.

The aim of the sheep is to encourage players to keep the land unforested in their sites. They win when they are able to land on a single site per neighbourhood which has their land of choice.

Squirrels work with the human players to gain a shared income for broadleaf forest land. They play in collaboration with one another to keep their owned lands while maintaining rent at a moderate rate. They are able to attack sites of less than 3 trees, ruining the trees if rolling a number greater than 4.

As a non-human player: they are able to earn a an income eveytime a player passes by their land, using the money earned to pursuade other players to achieve their goals.

The aim of the squirrel is to encourage players to forest their lands with broadlead trees. They win when they are able to land on a single site per neighbourhood which has their tree of choice.

Pine martens work with the human players to gain a shared income for conifer forest land. They play in collaboration with one another to keep their owned lands while maintaining rent at a moderate rate. They are able to attack sites of less than 3 trees, ruining the trees if rolling a number greater than 4.

As a non-human player: they are able to earn a an income eveytime a player passes by their land, using the money earned to pursuade other players to achieve their goals.

The aim of the pine marten is to encourage players who are buying land to use the conifer pine trees in their sites. They win when they are able to land on a single site per neighbourhood which has their tree of choice.

When landing on the policy square, each player must press on the buzzer to be given a policy that they must adhere by.

This task is beyond the control of the player and cannot be debated.

Following research into the site and its human and nonhuman inhabitants, this game inspires users to begin understanding and developing a common as a solution to disputes on what to do with the land.

Common Land is privately owned land with ‘Rights of Common’ over that land, most commonly to graze animals.

First enshrined in law in the Magna Carta in 1215, Common Land traditionally sustained the poorest people in rural communities who owned no land of their own, providing them with a source of wood, bracken for bedding and pasture for livestock.

At one time nearly half of the land in Britain was Common Land, but from the 16th century onwards the gentry excluded Commoners from land which could be ‘improved’ through agriculture. That is why most Common Land is now found in areas with low agricultural potential, but areas which we know hold value for high conservation significance and natural beauty.

Commoning involves a group of stakeholders having “commoners rights” to graze their animals and develop their businesses on a shared piece of land – the common – without fences or boundaries between them.

While the common itself belongs to a private player, a variety of others can utilise it based on written agreement

But the heritage of commons isn’t just about commoners and livestock, it’s about some of the UK’s most spectacular landscapes, its most valuable biodiversity, its geology and pre-history, and its history of settlement and industry. And beyond that it’s also about natural systems such as the water and carbon cycles, which shape and support our everyday lives locally, nationally and internationally.

Following research into the site and its human and nonhuman inhabitants, this game inspires users to begin understanding and developing a common as a solution to disputes on what to do with the land.

Common Land is privately owned land with ‘Rights of Common’ over that land, most commonly to graze animals.

First enshrined in law in the Magna Carta in 1215, Common Land traditionally sustained the poorest people in rural communities who owned no land of their own, providing them with a source of wood, bracken for bedding and pasture for livestock.

At one time nearly half of the land in Britain was Common Land, but from the 16th century onwards the gentry excluded Commoners from land which could be ‘improved’ through agriculture. That is why most Common Land is now found in areas with low agricultural potential, but areas which we know hold value for high conservation significance and natural beauty.

Commoning involves a group of stakeholders having “commoners rights” to graze their animals and develop their businesses on a shared piece of land – the common – without fences or boundaries between them.

While the common itself belongs to a private player, a variety of others can utilise it based on written agreement

But the heritage of commons isn’t just about commoners and livestock, it’s about some of the UK’s most spectacular landscapes, its most valuable biodiversity, its geology and pre-history, and its history of settlement and industry. And beyond that it’s also about natural systems such as the water and carbon cycles, which shape and support our everyday lives locally, nationally and internationally.

A collective win of the game is achieved when a form of commoning is established on the land on site. The images on the right represent an example of how this can be achieved. It takes a base of lands that are public (owned by the policy makers), and privatised (owned by corporations and single farmer families). It then utilised concepts of commoning to allow for empathetic understanding of how a plot of land can be used to include various different members of the community, both the humans and nonhumans.

Players are encouraged to then ask themselves:

What did you think of the interactive design methodology as a method to understand and control the future of the carbon offset market and ideas of commoning?

How does the incorporation of both human and non-human characters influence your understanding of this issue?

Who was there a perceived “bad guy” in this game? Why?

What would you change about the game rules to allow for a more “fair” method to monitor and manage the carbon offset system? What do you think about the Woodland and Peatland management codes?