Orientalism and Postcolonialism in the Design and Development of Arab Cities

Supervisor: Dr Adam Walker

Word count: 9,987 (excluding the abstract, footnotes, and image captions)

Orientalism 1

The imitation of aspects in the Eastern world done by writers, designers, and artists from the Western world. The representation of Asia in a stereotyped way is regarded as embodying a colonialist attitude.

Postcolonialism 2

The critical academic study of the cultural, political and economic legacy of colonialism and imperialism, focusing on the impact of human control and exploitation of colonized people and their lands.

1 "Orientalism - New World Encyclopedia", Newworldencyclopedia.Org, 2022 <https://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Orientalism> [Accessed 20 June 2022].

2 "Postcolonialism | History, Themes, Examples, & Facts", Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022 <https://www.britannica.com/topic/postcolonialism> [Accessed 23 June 2022].

Abstract

Edward Said first criticized ideas the long-term effects of Orientalism on the Arab region in 1979, describing ideas of Orientalism as a racialized profiling of the East developed by Western powers in an effort to de-humanize the colonized and reassure itself of its power.

What is the role of Orientalism in 19th and 20th-century colonialism? How did this, in turn, affect the development of traditional Arab quarters and urban realms? What are the effects of this development on the rise of social inequities in the Middle East? How has the postcolonial era responded to the urban planning methods of the colonial period? What are the effects of modernday digital technologies on the development of this region? To what extent can a city be designed void of ideas of "the other" based on eastern and western views?

This dissertation aspires to answer these questions through investigating architecture and urban planning that resulted from Oriental views of colonial powers in the Middle East. It will do this through the exploration of imperial modes of urban development in this region from the late 19th Century to the present day. It examines forms of Orientalism concerning the colonial, postcolonial, modernist, neoliberal, and globalized design of urban centres. Thus, it helps expose the forces by which architecture is built through a system of meanings and experiences that reflect an epoch's cultural and critical values Through these investigations, the dissertation concludes with a manifesto to propose a reimagining of a contemporary Arab city.

Throughout this dissertation, I acknowledge that this is a large area of study that I do not claim to be able to unpack under the scope of this study.

Keywords

Orientalism, Colonialism, Postcolonialism, Occidentalism, Dual Cities, Globalisation, Cyber Cities, Neo-Feudalism

List of Figures

Case

Case Study: Cairo Case Study: Baghdad

Chapter 1 – Introduction

While the discourse of colonialism, postcolonialism, and Orientalism has been well-explored in various fields of history, it is often not discussed when analyzing the history of architecture and the cities we inhabit. Architecture has often been a vessel reflecting the entangled relationship between social, economic, and cultural change in the 19th and 20th centuries by colonial and noncolonial powers leading to the increasingly globalized present. In this colonial period, architecture was viewed as an instrument for the production of cultural change in various empire states. Following the empires' collapse and most states' independence, architecture shifted time and time again, reflecting the context and era of its construction.

Alongside colonial development rose ideas of "orientalism" that racialized the region in its discourse, developing a divide between the West and the East 3 This dissertation critically analyses the role architecture has played in the conquest and shaping of space and environments of everyday use as a result of orientalist ideas.

Architectural history and urbanism are undoubtedly strongly linked to ideas of race, civilization, and culture. It is within these terms that specific forms of Orientalism have developed pertaining to western discourse around the Arab and Islamic world. Chapter 1 begins by analysing a set of theoretical perspectives relating to these ideas of colonialism, and subsequently Orientalism, in architecture. Chapter 2, 3 and 4 then follow by tracing these critical analysis through a set of case studies in three different time periods in the modern-day development of Arab nations: the colonial period, when the British and French Empires were at their most powerful, and the postcolonial period, the period after WWII wherein states slowly began "gaining independence" I will look at the development of the Athens Charter in the early 20th Century 4 as a guide to developing these nations in a "one size fits all" format that seems to group all people of the Orient together.

Throughout these chapters, I will look at the relationship between the indigenous population and their foreign colonizers, and the way that has manifested in the development of urban forms in large cities, looking at utilizing this in understanding the relationship between culture, dominance, and urbanism.

Throughout my exploration, I will examine case studies from three cities throughout the Arab world: Algiers, Cairo, and Baghdad. These cities have been chosen as they are all some of the largest urban centres in the Arab world today and have been most influenced by French and British colonial powers and Western architects in their development. 5

Following the European empire phase, we are arguably still living in the age of industrial-capitalism colonization. 6 This dissertation will thus move on, in Chapters 5 and 6 , to investigate more broadly the rising trend of a shifting nature of colonialism from the traditional "conquest" sense to a more globalized version studied through the lens of capitalism and neo-feudalism. These inequalities are still seen today gentrified urban centres throughout the Middle East.

The dissertation will analyze these forms of urbanism in the modern-day period, with the onslaught of the digital age and the advancement of cyberspace. Modern-day architecture in this age of globalization is often built on a heightened sense of cultural encounter and rapid transfer of information and investments that inevitably affect the architecture of the region. I will look at case studies that have encouraged modern developers to look outside of current cities and move away

3 Edward Said, 1978. Orientalism

4 Le Corbusier and others, The Athens Charter (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1973).

5 Salam Mir, "Colonialism, Postcolonialism, Globalization, And Arab Culture", Arab Studies Quarterly, 41.1 (2019) <https://doi.org/10.13169/arabstudquar.41.1.0033>.

6 Martin Thomas and Andrew Thompson, "Empire And Globalisation: From ‘High Imperialism’ To Decolonisation", The International History Review, 36.1 (2013), 142-170 <https://doi.org/10.1080/07075332.2013.828643>.

from the risks of gentrification into creating developments of tabula rasas, such as the case of NEOM 7

The dissertation will then end with a development of a broadly defined manifesto that counteracts the Athens Charter in its terminology in creating a design model for oriental cities, looking at answering questions such as "How can the spatial discipline upon which orientalism was built move from a historical position of urban inequities, into a productive postcolonial spatial narrative?"

7 Merlyn Thomas and Vibeke Venema, "Neom: What's The Green Truth Behind A Planned Eco-City In The Saudi Desert?", BBC News, 2022 <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-59601335> [Accessed 26 March 2022].

Chapter 2 – Background Theories

Colonialism – A Brief Overview

This study starts with a view of British and French colonial imperialism in the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, where contemporary conceptions of East and West as oppositional and delineated regions have been formed on the basis of geopolitical expansions, conquests and strives for autonomy.

Ideas of British and French power and economic gain through imperialism began to take shape in the early 17th Century, reaching their territorial peak in 1921. 8 World War II brought change to the British and French Empires, with most countries demanding and gaining their own independence by 1963, following a decline of the empires from 1945 to 1997 Though both counties emerged victorious from WWII, global power had shifted to the United States and the Soviet Union. This pushed France to wage unsuccessful wars to keep its empire intact, waging wars in Algeria and Indo-China for decades.

On the other hand, Britain adopted a policy of peaceful disengagement. In 1960, British PM Harold Macmillan made a speech to the Parliament of South Africa, indicating that "the wind of change is blowing through this continent, and, whether we like it or not, this growth of national consciousness is a political act. We must all accept it as a fact." 9 This speech was met with various levels of discomfort in the UK and abroad, with the number of people under British rule outside of the UK falling from 700 million people in 1945 to 5 million in 1965.

8 Jessica Brain, "Timeline Of The British Empire - Historic UK", Historic UK <https://www.historicuk.com/HistoryUK/HistoryofBritain/Timeline-Of-The-British-Empire/>

9

(Cape

"Post" Colonialism

Following the establishment of states after WWII, there was a wave of celebration as a new "post" colonial" era began. With it came studies of postcolonial analysis into urbanism. These started in the 1980s with a study of the "post-colonial", looking at a time the implied the end of colonialism and a new future that exists despite it. However, as the field of study grew, the use of the hyphen diminished as people began to view it as a false notion of abstraction Rather, the "postcolonial" terminology was used, which signals the persisting impact of colonization across various epochs and their subsequent geopolitical implications. 10

One of the first users of this term was John McLeod, who argued against the use of the hyphen, stating that "The hyphenated term seems to be better suited to denote a particular historical period, like those suggested by phrases such as 'after colonialism', or 'after the end of Empire'. In its hyphenated form, 'post-colonial' functions rather like a noun: it names something which exists in the world. But I will be th inking about postcolonialism, not in terms of strict historical or empirical periodization, but as referring to disparate forms of representations, reading practices, attitudes and values." 11

Similarly, this dissertation will focus on the postcolonial version of the word, looking at an imperial impact that continues to affect modern-day geopolitics, economy and civilizations. Omitting the hyphen creates a comparative framework that is messier and allows for more variety in understanding colonialism and its effects, looking at utilizing this term to explain urban development with a "colonial wound" 12 and not despite colonial history. This dissertation will use these studies of postcolonialism in an orientalist context leading up to the modern period of neofeudalism and globalization, looking at the transformation of colonial cities. It will also begin to look at ideas of a post-colonial city and its potential success in modern-day urbanism.

10 Andrea Medovarski, "Unstable Post(‐)Colonialities: Speculations Through Punctuation", World Literature

Written In English, 39.2 (2002), 84-100 <https://doi.org/10.1080/17449850208589360>.

11 John McLeod, Beginning Postcolonialism, 1st edn (Manchester University Press, 2000).

12 Walter Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, And Border Thinking (Princeton Studies In Culture/Power/History) (Princeton University Press).

Orientalism

There is not a place on this Earth

Where I am not me, and you are not you

Then why shall we erect barriers

Upon bodies, minds and souls

It is through the eyes of difference, not deference

Which we see lands and peoples

Much time has passed, many people have passed

But these convictions remain

Of the inferior, the superior and the other

The eyes see, yet we are blind to it

The tongue speaks, yet voices are unheard

The heart bleeds, yet it must endure

How much longer can we allocate

The acceptance and rejection of each other

Based upon temporary and man-mad faculties

History is gilded

Its finery pretence

The truth is hidden and revealed in the sands of time

But the fortitude remands in the knowledge that

There is not a place on this Earth

Where I am not me, and you are not you

- Erum Ali, Us and Them 13

Conceptions of the postcolonial were all built on concepts of othering, or the transforming of a difference onto others in creating an ethnocentric group (us) of those that "belong" and an exotic one (them) of those who "belong to a faraway civilization that is thus demarcated from the norms established in and by the West" 14 Othering is due less to the difference of the Other than the point of view and discourse of the viewer of the Other. These were first utilized in the disciplines of phenomenology to identify the lack of familiarity or a state of being alien from the human occupation of the self by GWF Hegel in the late 18th Century 15 Otherization is not rare. It is something various societies have constructed using their available information (or lack of information) about one another. Homer often spoke of "faraway, dreamlike lands" 16. Herodotus spoke of a fascination with Persian society, and Renaissance explorers often wrote of the peculiarities of the civilizations they came across 17. All of these historians claimed to be objective However, they all seemed to demonstrate the superiority of Western culture to that of the "other" in writings of the colonist versus the native, the white man versus the person of colour, the West versus the Rest.

13 Erum Ali, “Us and Them”

14 Jean-Francois Staszak, "Other/Otherness", International Encyclopedia Of Human Geography, 2008 <https://www.unige.ch/sciences-societe/geo/files/3214/4464/7634/OtherOtherness.pdf> [Accessed 26 February 2022].

15 Peter Benson. 2022. "The Concept of the Other from Kant to Lacan | Issue 127 | Philosophy Now", Philosophynow.org <https://philosophynow.org/issues/127/The_Concept_of_the_Other_from_Kant_t o_Lacan> [accessed 13 January 2022]

16 Jean-Francois Staszak, "Other/Otherness", International Encyclopedia Of Human Geography, 2008

17 Ibid.

It is interesting here to note the geographical divide between the east and west. Homer, and ancient Greece are often noted as “the foundation of Western civilization” 18 despite their proximities to cultures and societal norms of the Orient. This artificial claim is further explored in Chapter 4, with the discussion of urban development in postcolonial era Arab nations.

Accompanying such views, the Orient is characterized by his barbarity, savageness, and race. Thus, views of Orientalism developed into the discourse through which the West constructs an "othering" of the Turks, Arabs, Persians, Indians, Japanese, etc., reducing them all to stigmatizing stereotypes. European historians often viewed orients as "beings with no conception of history, or Patrie" 20 and "no mental discipline for rational interpretation" 21. The West thus believes that they have the duty to dominate the Orientalists and save them from despotism, decadence, and vice.

Regarding societal development, ideas of postcolonialism and its connection to Orientalism were first presented in writing by Edward Said in 1978, where he examined the long-term effects of colonial hegemony and perceived thought constructs in the Arab region 22. His publication,

18 "Foundations Of Western Civilization: Greece | Scholarly Sojourns", Scholarlysojourns.Com <http://www.scholarlysojourns.com/all-sojourns/foundations-of-westerncivilization-greece/sojourn-overview-2/> [Accessed 23 June 2022].

19 On this drawing, Bacchus stated “Maps essentially tell the story of the land, which has deeper implications based on what is purposely portrayed and left out. Such a dynamic formed a foundation for this artwork, visualizing the messages maps contain (including historical erasures and the construction of other narratives)” (Maria Bacchus, “How the West Wants You to See the World).

20 Edward Said, 1978. Orientalism

21 Fernand Baldensperger, "Ou. s'affrontent I'Orienl el I'Occident intellectuels," in studcs d'histoire litthaire, 3rd seL (Paris; Droz, 1939). p. 230

22 Edward Said, 1978. Orientalism

Orientalism, is viewed as a critical text in the study of cultural politics. In it, he argues that the dominant European political system formed an unfamiliar notion of the Orient to subjugate it, creating a simplified subjective binary view of reality with the West viewed as "civilized" and the East as "primitive"

Therefore, in his work, Said broadly explained and criticized the systematic defamation of the East, where the West controlled the spread of misunderstandings of targeted texts alienating the east. In each case, this study shows the connection between postcolonialism and colonialism in the light of Orientalism.

Said also presents a regional crisis that "the West invented an imaginary Orient in an ongoing monologue to de-humanize its inhabitants and reassure itself of its own identity" 23, creating a perceived distinction between a world conceived of two unequal halves, the Orient and "the Occident".

Occidentalism, as written by Mignolo, is "the visible face in the building of the modern world" and "the overarching metaphor of the modern/colonial world system imaginary" 24 Said did not engage in defining Occidentalism to avoid it being seen as the opposite of Orientalism. His definition is much more in line with the finding that Orientalism and Occidentalism constitute two separate categories or schemata, which are divided by their individual characteristics. This depiction of the relationship between Orientalism and Occidentalism, therefore, is one of distinction, not one of opposition. A lot of the initial studies of Orientalism and occidentalism seem to present the idea that eastern and western cultures are opposites, with one single definite eastern culture and one opposing western one. This is, however, believed to be an outdated and absurd interpretation, as both cultures span across many regions with various attributes and should not be generalized.

23 Sing, Manfred, and Miriam Younes. 2013. "The Specters of Marx in Edward Said’s Orientalism", Welt des Islams, 53: 149-191 <http://dx.doi.org/10.1163/15700607-0532p0001>

24 Walter Mignolo, Local Histories/Global Designs: Coloniality, Subaltern Knowledges, And Border Thinking (Princeton Studies In Culture/Power/History) (Princeton University Press).

Orientalism in Urban Design and Architecture

Views of Orientalism in architecture can be viewed as having had a gradual transition from an Enlightenment attitude of curiosity and fascination to a more empirical one. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, oriental cities were first visited by explorers, with the first documentation being developed by Western travellers, showcasing a romantic love of ruins and heritage in the Middle Eastern world. A majority of the architects and architectural theorists of the late 19th Century were greatly interested in the development of the Orient

This interest later developed in the 20th Century into a form of imitation or appropriation, with "Oriental architecture" becoming a new form of design that was followed in the development of Western civilizations in Britain and France. These cultural appropriation projects began to appear throughout Europe, incorporating porcelain, textiles and fashion from the Middle East and Asia, further exotifying the "other" from this area.

The Royal Pavilion in Brighton, UK, is one such example of this discourse. Built in the style of Orientalist structures, it evokes the architecture of other cultures, yet with scant engagement beyond the surface, presenting as an inauthentic structure that fails to consider cultural and regional variations. The pavilion was built in the 18th Century as a place of seaside consumption and pleasure for King George IV. 25 Its design takes inspiration from Southeast Asian cultures in its exterior and East Asian for its interior, despite the fact that King George had never visited these destinations, only knowing these cultures as ones that are "different to his" It attracts the question

25 "History", Royal Pavilion, 2022 <https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/royalpavilion/history/> [Accessed 21 June 2022].

of whether King George and other orientalists aimed to show a sense of appreciation or boaster a sense of affluence with its design. This thus invites the debate of cases where orientalist architecture in a Western context began with a well- intentioned approach (despite poor practice), where the purpose is not to exploit or offend

While oriental architecture in the Occident continued to develop, architecture in the Orient, as a result of orientalist views, was portrayed through a culture of exploitation and intervention that reduced a variety of societies into a totalizing group of tropes and repetitive patterns. 26

When first visiting Orientalist cities in the 19th Century, Orientalists such as Robert Brunschvig and the Marcais brothers often described Middle Eastern cities as "irrational" and found the narrow streets to be a form of "nomadic chaos" perpetuated by its uneducated residents. Others, such as an unidentified French travelled wrote of oriental cities as being "the opposite to us in almost all respects", stating that "in our country, we are never at rest till we have invented some new fashion" and describing oriental planners as being "so far from studying to improve their understandings that in a manner they profess a glory in their ignorance" 27 .

Orientalists at the time, such as Afif Bahnassi, argued against this and in favour of the vernacular nature of these urban spaces, where the weather, humidity and social conditions forced a series of contained courtyards to allow for daylighting and airflow during the day and the trapping of cold air during the night. 28

Max Weber wrote about these concepts in the spatial design of cities by differentiating the Occidental and the Oriental City through the following features: the availability of a market (the urban economy of consumption, exchange, and production), a court of law, and political autonomy. 29

Following colonial and postcolonial development, these oriental concepts have come to be reflected in the systemic inequalities of the architecture and design of capital cities and urban realms following the independence of Arab nations from the imperial colonies (1922 – 1946).

The application of Orientalism into urban planning and architecture thus creates a distinction and divide between the East and West, slum and community, informal and formal, "bad and good" 30

The following chapters will explore oriental and postcolonial urban planning and architecture under the philosophies developed by Said, beginning with colonial gentrification in the 19th and 20th centuries, and concluding with an analysis of the effect capitalism, globalization, and cyberspace have had on the design and perception of the oriental city.

26 Sibel Bozdogan, "Orientalism And Architectural Culture", Social Scientist, 14.7 (1986), 46 <https://doi.org/10.2307/3517250>.

27 Tariq Khamis, "The Islamic City And Architectural Orientalism", The New Arab, 2015 <https://english.alaraby.co.uk/features/islamic-city-and-architectural-orientalism> [Accessed 31 March 2022].

28 Ibid.

29 Murvar, Vatro. 1966. "Some Tentative Modifications of Weber's Typology: Occidental versus Oriental City", Social Forces, 44: 381 <http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2575839>

30 Thomas Angotti, The New Century Of The Metropolis (New York: Routledge, 2013).

Chapter 3 – Architecture and Urban Planning in the Colonial Period

Development of Urban Design and Architecture in the Colonial Period

Architecture is a timeless medium that retains memories of the past, reflects values of the present and projects imaginaries of the future. From the very start of civilization, as it developed from spaces of basic shelter to modern-day monuments, architecture has evolved with a vast range of cultures and beliefs to reflect the socio-political, hierarchal, political, and technological advancement of its time. It provides cities with proof of civilization and history in a method to help contextualize our present, thus helping form the cultural identity of a region.

Initial development of cities started with "vernacular" building methods, which refers to a building form developed entirely using indigenous resources to meet the needs of local communities and climates. It is often referred to as a primitive building technique that is adaptive.

The development of Arab cities between 1900-1950 has been described as a period of transformation from the vernacular into a more internationalized form of architecture. During that period, there was a trend that viewed this colonial intervention as a "gift from Europe" 31. This notion that the development of Arab cities was induced by European powers can be linked to similar colonial ideologies in Latin America, Africa, and Asia. Cities in these regions were all developed in the early 1900s to include common traits that follow Occidental urban manifestos.

Colonial cities often develop with policies that aim to preserve and retain the local architectural styles and cultures. While it did start with good intent, this often led to the urban segregation of the colonizers from the colonized, where urban centres and "traditional quarters" are left to themselves, with new neighbourhoods built paradoxical to the urban centres. These followed theories written by sociologists such as Max Weber , who described European city-states as those formed with an independent urban bourgeoisie to allow for the development of modern capitalism, which contrasted with the features of the Oriental city 32 .

Weber built these views on his theories of the Protestant Work Ethic. In this theory, he referred to the role of religion in capitalism in the postcolonial era. He noted his observation that most owners of capital in Europe were of the Protestant faith rather than Catholic or any other religion. He attributed reasons for socio-economic disparity to certain "mentalities" held by different communities, where successful European Occident workers often belonged to the Protestant faith, which believed in the "inability to alter one's faith" and the lack of "control over salvation". 33 He believes that this, along with the belief that "God helps those who help themselves", has pushed Protestants to pursue a pious life dedicated to labour. This contrasted Weber's view of the Orient. While, according to Said, Weber never comprehensively studied Islam, the latter often expressed orientalist stereotypes when discussing Islam. In contrast to the Protestant ethic, Weber believed that Oriental Islamic beliefs lie on the basis that one's fate can be altered through atonement, and therefore the "most pious adherent of the religion became the wealthiest" 34. He emphasized this point on various occasions, stating "the ethical concept of salvation was actually alien to Islam". To

31 Thomas Angotti, The New Century Of The Metropolis (New York: Routledge, 2013).

32 Nader Naderi, "European Absolutism Vs. Oriental Despotism: A Comparison And Critique", Michigan Sociological Review, 8 (1994) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/40968982> [Accessed 31 March 2022].

33 Raluca Rusu, "The Protestant Work Ethic And Attitudes Towards Work", Scientific Bulletin, 23.2 (2018), 112117 <https://doi.org/10.2478/bsaft-2018-0014>.

34 Nader Naderi, "Max Weber And The Study Of The Middle East: A Critical Analysis", Berkeley Journal Of Sociology, 35 (1990), 71-88 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/41035498?seq=1> [Accessed 19 June 2022].

his orientalist view, Islam displayed characteristics of a feudal spirit due to its connection to "saints and magic" 35

Moreover, regardless of their attempted inclusion of traditional architecture in colonial urban design, and due to the endeavour to create a uniform Oriental city, Orientalist designers developed plans that lacked a distinction from one city to another and generalized the Orient based on biased notions based on an unstudied view of religion, culture and the civilization. Instead, it focused solely on the differences between Arab and European cities, creating a unified and generalized "otherness" of the region.

Similar studies were completed by Foucault in his writing of "the other" and heterotopias. He defines them as "real and effective spaces which are outlined in the institution of societies but constitute a counter-arrangement of attractively realized utopias" 36. As noted by Foucault, a significant change in the role of architecture is evident from the early 19th Century onward. From that period on, architecture and town planning became disciplines of cognitive order.

Oriental cities thus developed to reflect the rapidly growing Western states. In 1933, a group of prominent architects led by Le Corbusier developed the Athens Charter following the International Congress of Modern Architecture (CIAM). This charter became a manifesto of urban planning for colonial cities in the 20th Century, with the aim to "make modern architecture more efficient, rational, and hygienic" in the industrialized world. It highlighted the most common urban planning and design elements that shaped the formation of cities, including port development, garden cities, the dominance of vehicles in road planning, housing flats (as opposed to private houses), and the separation of city functions (including the development of central business districts) 37

35 Ibid.

36 Michel Foucault, "Of Other Spaces: Utopias And Heterotopias", Architecture /Mouvement/ Continuité, 1967.

37 Le Corbusier and others, The Athens Charter (New York: Grossman Publishers, 1973).

Case Study: Algiers

One of the cities to see significant development in the 1900s was Algiers. French occupation of Algiers began in 1830 and lasted 132 years, with the aim of developing it to become a new military city. During this time, Algiers was subject to changes in its social, economic, cultural, and spatial attributes. This period demonstrated ideologies built on the superiority of the Western civilization and the inferiority of the oriental one. Following this view, the urban planner became the colonial agent of change. In the first ten years of Algiers colonization, it was struck by a series of radical transformations, with reports stating that "the organization of space in Algiers must submit to the changing of institutions; the Christian commercial town cannot preserve the form of a pirate capital" 38. Some officers at this time wished to tear down the entire lower city and rebuild it 39 However, the costs and the protests of the local people became hindrances in achieving this.

38 Karim Hadjri and M. Osmani, "Planning Middle Eastern Cities", 2004 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203609002>.

39 Yasser Elsheshtawy, Planning Middle Eastern Cities (London: Routledge, 2010).

40 "The Streets Of Algiers Before 1830", Casbah-Algeria.Blogspot.Com, 2007 <http://casbahalgeria.blogspot.com/2007/12/map-of-algiers-medina-before-1830-t-he.html> [Accessed 31 March 2022].

Pre-colonisation, the three main roads of the Casbah (the traditional quarter of Algiers) were built to accommodate the passage of two donkeys 41. However, as the city was being developed for military use, the roads had to be widened to allow for the circulation of troops. Between 1830 and 1840, these streets were enlarged at the expense of existing shops and houses along the roads. The new roads were then lined with arcaded two and three storeys housing for European immigrants. Hence, traditional informal streets were quickly replaced by monumental streets with vertical regularities in their elevations.

Within the same ten years, a new and large square was developed at the intersection of the main roads of the Casbah, framed by arcaded Baroque-style buildings on three sides and a new "Hotel du Government" focal point. 42 This led to the vast urban gentrification that disadvantaged its users The new openness that came with the design of the Casbah was paradoxical to the traditional closed residential quarters and thus vastly uncomfortable for the local population, who prioritized private living quarters, thus moving away to the upper city as a result. This gave room to 20,000 new colonial residents, who favoured further destroying traditional houses and replacing them with housing blocks in the central areas.

41 Yasser Elsheshtawy, Planning Middle Eastern Cities (London: Routledge, 2010).

42 Karim Hadjri and M. Osmani, "Planning Middle Eastern Cities", 2004 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203609002>.

By the start of the 20th C entury, Algiers was almost in its final colonial form, characterized by a more traditional but gentrified Casbah and the new European quarters. This dual city paradigm –having both a 'traditional' settlement and a European one – is construed as a 'freezing of the image of a society in time and space', thus maintaining a bodily distinction between the conquerors and the occupied, rather than a natural assemblage of radically different experiences, or a synthesis of heterogeneity that generates new behaviour Following this, the "other" becomes the traditional settler, or the slum dweller and outcast, who has been forced to exit their own community and left to be powerless and unable to practice their daily life activities in the newfound confines of the city. Following WWI, the colonial authorities in Algiers appealed to many architects and planners for advice to increase colonial influence in Algiers, one of whom was Le Corbusier, by encouraging foreign travel.

Le Corbusier was often fascinated by the "exotic" city, recording travel notes of his visits to Istanbul and western Asia in his famous publication "Voyage d'Orient" This book of sketches followed young Le Corbusier on a six-month journey throughout the Islamic and East Mediterranean. 43

43 Cana Bilsel, "‘Le Corbusier In Turkey: From The Voyage D’Orient To The Master Plan Proposal For Izmir On The Theme Of A Green City", A Swiss In The Mediterranean: Le Corbusier Symposium, Cyprus International University, Lefkoşa, 2015, 54-64 <https://www.academia.edu/34580832/Bilsel_Cana_Le_Corbusier_in_Turkey_From_the_Voyage_d_Orient _to_the_Master_Plan_Proposal_for_Izmir_on_the_Theme_of_a_Green_City_Ay%C5%9Fe_%C3%96zt%C 3%BCrk_Atilla_Y%C3%BCcel_eds_A_Swiss_in_the_Mediterranean_Le_Corbusier_Symposium_Cyprus_Int ernational_University_Lefko%C5%9Fa_2015_pp_54_64> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

44 Zeynep Çelik, Urban Forms And Colonial Confrontations (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997).

This voyage has had an influential role in the establishment of Le Corbusier's early theoretical and practical work. References to Oriental Architecture appear in several of his writings and building projects, such as the Notre Dame de Ronchamp in 1955, where he was inspired by the sculptural mass of the Sidi Ibrahim Mosque in the Algerian countryside. 45

45 Zeynep Celik, "Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism", Assemblage, 1992, 58 -77 <https://doi.org/10.2307/3171225>.

However, when it came to constructing projects on oriental land (as opposed to building orientalinspired architecture on occidental land), Corbusier often began to look at Islamic architecture from a more colonial (rather than inspirational) point of view. Islamic architecture here became a challenge to him, where most of his projects for Algiers attempted to establish a confrontational dialogue with Islamic architecture through a colonial framework. 46

Le Corbusier first came to Algeria by chance in 1931, during which a new urban plan was developed for Algiers by Henri Prost. Le Corbusier greatly disapproved of the project developed, which he found to be too influenced by modernism, and developed Plan Obus as an alternate design 47

Le Corbusier was very proud of Plan Obus, which he believed would help "raise Algiers to the level of an international city" 48 with the help of the French colonial powers that could transform the city of Algiers to one of the great Mediterranean cities, such as Barcelona, Marseille, and Rome. Plan Obus presented a megastructure development while closely following the principles of the Athens Charter. Its brutal scale displayed a disregard for Oriental traditions in an effort to help the "Arabs" become civilized. Despite spending eleven years developing this plan, no portion of it was ever realized in Algiers, signifying a continued trend of the Western idealization and appropriation of design in a land of the "other" despite a lack of knowledge and understanding of the reality of its context and desires of its people.

Other cities at the time were subject to similar urban changes, with French urban planner Henri Prost stating that the plans he had been developing for Oriental cities were done so to have "the genius of order, proportion, and clear reasoning of our country" 49 .

46 Zeynep Celik, "Le Corbusier, Orientalism, Colonialism", Assemblage, 1992, 58 -77 <https://doi.org/10.2307/3171225>.

47 Ibid.

48 Brian Ackley, "Le Corbusier’s Algerian Fantasy: Blocking the Casbah | Bidoun", Bidoun, Undated <https://www.bidoun.org/articles/le-corbusier-s-algerian-fantasy> [Accessed 31 March 2022].

49 Yasser Elsheshtawy, Planning Middle Eastern Cities (London: Routledge, 2010).

Case Study: Cairo

Rapid colonial urban development was seen in Cairo, a British colony, long before the colonial period officially began. Similarly to Algiers, this started with the division of the city into an old and new quarter, being described as "a cracked vase whose two halves can never be put back together" 50 New public spaces were added in gentrification of traditional roads to allow for more parades, strolling, window shopping, and sports This development of new public spaces created a new urban divide in Cairo, where only a few literate communities were able to understand and make use of these spaces. Public spaces thus failed to accommodate public life in Cairo, with a flourishment of new cafes taking place despite the development of a new urban life. On a visit in 1911, British writer Hamilton Fyfe noted that "No city has a more active café life than Cairo," alluding to his admiration of these new urban spaces that present as places of connection but signify urban divides in the growing city. 51

The large open thoroughfares thus came to serve as sites of public politics in the struggle against the colonial experience. Public protests and demonstrations took place in 1879, 1919 and 1942 against this colonial gentrification 52 Despite this, changes continued to take place in Cairo, where various suburbs were founded for the European wealthy on the outskirts of the traditional quarters of Cairo. With these new modern developments came new forms of architecture that utilized modern technologies, mass production, and homogeneous materials

Thus, Cairo also came to be dubbed a "dual city" due to its divide between a modern European city and a historic core, creating a boundary between the different nationalities. Neighbourhoods, such as Ismaililyah, were developed at the time as "a capital from which Egyptians were excluded" 53

Most of these new neighbourhoods were designed with different historical styles, some being English Tudor, Bavarian Gothic, or local design vernacular (with the interior layouts drawing inspiration from British design practices) This illustrates orientalist views of utilizing the Orient as a form of "decoration", only withheld to the exterior of buildings. With the colonial period also came the widening of the street and introduction of the tramways in Cairo by WWI.

Moreover, following colonization, around 20% of the land in Egypt became owned by foreign investors, leading to small neighbourhoods such as Azbekiya showing a strange landscape of small grid-life developments surrounded by passageways particular of traditional design. 54 This strong paradoxical aerial of wealth versus poverty created a sense of inequality.

50 Mahy Mourad, "Heliopolis, Egypt: Politics Of Space In Occupied Cairo", The Funambulist, 2017 <https://thefunambulist.net/magazine/10-architecture-colonialism/heliopolis-egypt-politics-spaceoccupied-cairo-mahymourad#:~:text=Divided%20into%20old%20and%20new,Imperialism%20and%20Revolution%2C%20196 7).> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

51 Hamilton Fyfe, The New Spirit In Egypt (Edinburgh: W. Blackwood and Sons, 1911).

52 Ibid.

53 James Moore, "Making Cairo Modern? Innovation, Urban Form And The Development Of Suburbia, C. 1880–1922", Urban History, 41.1 (2014), 81-104 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/26398263?seq=1> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

54 Ibid.

Case Study: Baghdad

Mesopotamia was always a place enshrined in orientalist mystery and exoticism to western travellers and writers due to its proximity to Old Testament narratives and popular writings such as the Arabian Nights stores.

Similar to Cairo, the line after which colonialism is believed to have started in Baghdad is very blurred, with the first influences of colonialism on the architecture of Baghdad beginning in the early 19th Century with the construction of a British embassy. This monumental embassy was built in a prime location on the banks of the Tigris in Baghdad, which, similar to the Hotel du Government in Algiers, stood separate from the narrow streets of its surroundings, acting as a beacon of British influence in the Mesopotamian region. However, despite this building and the development of trade links, there was not a great deal of British urbanism until the early 20th C entury, where French and German ambitions for the region gave British occupiers anxiety, especially following the discovery of oil, fermenting the political desire to retain control of Baghdad

Following WWI, and under the establishment of the Public Works Department (PWD), headed by senior members of the Colonial Indian Civil Service and British Generals, various infrastructure

works took place in Baghdad. 55 Under PWD, British engineers designed a museum to house artefacts found by British surveyors in the region. The architectural significance of a museum in an urban realm presents a means to construct, curate, and assemble a version of history as defined by colonizers. Through the arrangement of objects, this space was used to improve the relationship with the local population, where "the attachment of colonizers to antiquity rather than to conquest attempted to form legitimacies with the British as custodians of local practice" 56

Following revolutions against colonialism, a new British-backed monarchy was established in 1921 57, with Faisal Hussein as King. In this era, monuments of power began to take form as "royal" monarchy architecture began to arise. One of the monumental works aimed at establishing this new nation was the design of King Faisal's palace.

The palace attempted to boost the King's credentials and develop a sense of permanency in Baghdad. 59 It was designed by colonizers using a language of exaggeration in its scale, with a strong symmetry, large entrances, large windows, and big arches that incorporated oriental design decorations on the outside and employed a distinctly British interior reflecting British notions of a royal domain and the cultural expressions of its designers.

While architecture should be developed as a means to foster relationships and lessen divides, it had the opposite effect in all three case studies Although the infrastructures developed in Baghdad and Cairo were opportunities for creating new nodes of connection (roads, railways and docklands) and offered a better sense of stability, they eventually began to signify power structures and the cultural expression of wealth and prestige.

55 Iain Jackson, "The Architecture Of The British Mandate In Iraq: Nation-Building And State Creation", The Journal Of Architecture, 21.3 (2016), 375-417 <https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1179662>.

56 Iain Jackson, "The Architecture Of The British Mandate In Iraq: Nation-Building And State Creation", The Journal Of Architecture, 21.3 (2016), 375-417 <https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1179662>.

57 Ibid.

58 Ibid.

59 Ibid.

Chapter 4 – Architecture and Urban Planning in the 20th century Postcolonial Period

Early Postcolonial Design in the 20th Century

Following the recognized establishment of Middle Eastern states in the mid-20th Century, they began to develop their own architecture and urban design styles under the influence of postcolonialism, capitalism and globalization. However, despite the end of colonialism, architecture and urban design continued to play an essential role in establishing political control. In his 1992 book Architecture, Power, and National Identity, Lawrence Vale explored the complexities of post-independence architectural production Here, Vale probes the question of the manufacture of a national style in the newly created states and wonders whether it is possible to design ex novo forms symbolic of national identity. 60

Other scholars at the time, however, were focused on the status of the existing architectures and the role colonial architecture continues to play in a postcolonial world. Al Sayed wrote in 1992 that "Colonial urbanism can only be understood in its true temporal framework. Once this framework ceases to exist, then its urban products can no longer be seen as colonial" 61. What, then, do these architectures become? Do they transform as the nation transforms into a more independent state? Or do they remain memories of the past even in the modern-day?

It can be argued that despite the imperial memories associated with them, colonial architectures have the power to be redefined as time begins to heal wounds of oppression.

Simultaneously with the redefining of occidental architecture, many Arab cities also began to develop their own architectural spaces with a rise in population. During the postcolonial period, populations of Cairo, Baghdad and Algiers more than doubled due to rapid economic growth.

Development initially began with a continued structuring of spaces as per colonial design principles. Following the end of the colonial period, the British Town and Country Planning Act of 1947 was adopted in many colonies 62. Land use planning standards, including land-use programme zoning, were based on the model of a low-density, green city that reflected the ideals of a colonial version of the Garden City combined with ideologies built under the Athens Charter.

The Garden City movement was developed in Great Britain as a method of urban planning in which self-contained communities would be surrounded by "green belts". Everything within this belt would include agriculture, housing, and industrial typologies of buildings. This would thus combine the proximity to industrial areas seen in urban environments and elements of connection to nature seen in rural communities. While this movement was adequate for towns with modest growth that were contained through rural-urban migration limits, it could not cope with the high urban growth rates seen since the independence of the oriental cities and under administrations with limited resources. 63 It began to play an unwelcome role in further creating polarised and segregated "dual cities" in North African states.

60 Martina Bernad, "Colonialism And Architecture – Postcolonial Studies", Scholarblogs.Emory.Edu, 1998 <https://scholarblogs.emory.edu/postcolonialstudies/2014/06/20/colonialism-and-architecture/> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

61 Nezar AlSayyad, Forms Of Dominance On The Architecture And Urbanism Of The Colonial Enterprise (Aldershot: Avebury, 1992).

62 Anthony King, "Exporting 'Planning': The Colonial And Neo-Colonial Experience", Urbanism Past & Present, 5 (1978), 12-22 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/44403550> [Accessed 21 March 2022].

63 Current Affairs, "The Need for A New Garden City Movement “Current Affairs", Current Affairs, 2022 <https://www.currentaffairs.org/2021/07/the-need-for-a-new-garden-city-movement> [Accessed 24 March 2022].

Case Study: Algiers

On July 5th, 1962, Algeria gained its independence following a war of independence that began in 1954 64. As a result of the Algerian political victory, roughly 300,000 European settlers left Algeria for France, leaving behind more than 98,000 houses and countless factories, businesses and farms vacant. 65

Following this began an issue of land privatization, public ownership and ownership through French investors that continues to this day. Following the vacating of various properties, local people in higher social classes rushed to take control of dwellings and urban spaces, leaving little behind for the poorer members of the community, who, as populations grew, resorted to living in government-managed housing that did not have access to proper services and sanitation systems. 66 Moreover, areas of the old town that were once left segregated for only Algerians in the colonial era became areas of residence for only the disadvantaged communities that failed to secure French-developed property in the Casbah.

This, along with the multi-party politics and capitalism, accelerated people's changing perceptions of their domestic space and continued to weaken the connection between the people and their lived space, intensifying disparities in social class in the postcolonial years

Case Study: Cairo

Cairo, on the other hand, gained its independence in 1922 (after 40 years of British occupation) 67 , with British political, military and economic influence continuing until the 1952 revolution that led to the first republican government in Egypt. Since then, urban population growth in Cairo has been very rapid and unprecedented

The first few decades of postcolonial 20th-century urban planning in Cairo continued to develop based on blind reproduction of occidental garden city and modular city concepts. Developments here have been reviewed as occurring under a theory of "urbanism exported through colonial dominance" 68 This theory was presented by Joe Nasr and Mercedes Volait in their book "Urbanism Imported or Exported" to explain the continued colonial dominance in urbanism presented through the lens of investment of European capital through indirect forms of colonialism that utilized Eurocentric resources and construction methods. 69

64 "Algeria - The Algerian War Of Independence", Encyclopedia Britannica, 2022 <https://www.britannica.com/place/Algeria/The-Algerian-War-of-Independence> [Accessed 23 June 2022].

65 Robert Parks, "From The War Of National Liberation To Gentrification - MERIP", MERIP, 2018 <https://merip.org/2018/08/from-the-war-of-national-liberation-to-gentrification/> [Accessed 18 June 2022].

66 Stephen Zacks and others, "Cultural Capital: The Ongoing Regeneration Of Algiers' Casbah - Architectural Review", Architectural Review, 2022 <https://www.architectural-review.com/essays/cultural-capital-theongoing-regeneration-of-algiers-casbah> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

67 "Egypt - World War I And Independence", Encyclopedia Britannica <https://www.britannica.com/place/Egypt/World-War-I-and-independence> [Accessed 23 June 2022]

68 Roberto Fabbri and Sultan Sooud Al-Qassemi, "Urban Modernity In The Contemporary Gulf", 2021 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003156529>.

69 Ibid.

Building materials remained to be concrete and steel, despite a pre-colonial local vernacular of successful mud-brick and stone houses in the region. As a result of colonization, dwellings continued to be built using industrial concrete, where concrete houses grew to become a symbol of wealth and affluence. 70

Case Study: Baghdad

Similar to Cairo, developments in postcolonial Iraq remained rooted in postcolonial principles throughout the 20th Century. While, with the age of the postcolonial, a majority of occidental architects resettled in their foreign nations, there were some architects, such as Le Corbusier, who continued to have an interest in orientalist cities and thus remained based in th e metropole, where he often completed works for newly independent nations.

Following the formal British independence of Iraq, a monarchy rule was appointed by Great Britain to rule over the country. Thus, Baghdad in the 1950s was the scene of a hopeful Western global convergence state. In 1954, the Iraqi Development Board appointed Constantin Doxiadis to develop a prestigious Baghdad master plan designed by Occident architects such as Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, and Frank Lloyd Wright. In this era, ideas of globalization in design began to develop in the Middle East, where the native elite continued to see the modern European architect as a triumphant and superior designer. 71

It is interesting here to again criticize the boundaries between the Occident and the Orient introduced in the first Chapter. While the Athens Charter and Doxiadis both, in a geographical sense, hail from locations of cultural, linguistic and physical proximities to Arab states, they are often referred to as quintessentially "occident" since the Treaty of Constantinople in 1832. 72 Divisions here are thus based solely on religion, with Christianity being a prerequisite of Occidentalism in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

While this new masterplan was developed, various anti-colonial movements were rising in Baghdad, which rejected continued ties to imperialism and believed that the government's support for internationalized architecture was indicative of the misplaced priorities of the elite. Thus, following the development of the Republic of Iraq, only some of these architectural plans were realized. 73 This aligned with a view where many residents of Oriental towns show disdain towards international designers implementing projects without understanding the local context.

70 Salma Samar Damluji and Viola Bertini, Hassan Fathy: Earth And Utopia (London: Laurence King, 2018).

71 Haytham Bahoora, "Modernism On The Margins: Le Corbusier's Baghdad Gymnasium And The Politics Of Discovery, Forthcoming, Aesthetic Practices And Spatial Descriptions: Configurations Of Micro, Macro, Meso," (University of Toronto).

72 Electra Peluffo, "The East And The West: Reciprocal Attraction", Electrapeluffo.Com <https://www.electrapeluffo.com/pdf/occidente_oriente_eng.pdf> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

73 Iain Jackson, "The Architecture Of The British Mandate In Iraq: Nation-Building And State Creation", The Journal Of Architecture, 21.3 (2016), 375-417 <https://doi.org/10.1080/13602365.2016.1179662>.

74 "Baghdad Gymnasium", Archnet.Org, 2022 <https://www.archnet.org/sites/345> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

75 Esra Akcan, "A Translation Movement", Cca.Qc.Ca <https://www.cca.qc.ca/en/articles/83798/atranslation-movement> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

Late 20th Century Design

Architecture in the postcolonial states raises the issue of who has the power to tell that history, as well as about the tensions between how buildings represent and potentially reconcile local and imported identities. The postcolonial 20th century period saw the publishing of Edward Said's Orientalism, as discussed in Chapter 1. While architectural studies were seldom affected by the criticism presented by Said, he did often speak about the role of the arts in establishing the view of the Orient. Said often described the representation of all things Islamic being done "in the service of imperialism during the colonial period", 76 where the first documented students of Islamic architecture were all Occident who travelled to the Orient following European military intervention in the area searching for "the thrill of fantasy" Despite their resistance to a hegemonic construct, Said explained in his 1993 publication "Culture and Imperialism" that this did not prevent them from falling into the trap of categorizing architectural history as "their" architecture based on their limited knowledge of the culture and religion that helped develop it. 77

Following the publication of Said's works, the study of Islamic architecture underwent a newfound renaissance throughout the globe. This was pushed for in the late 1980s due to the increased pressure in the oriental world to rediscover their heritage and culture and develop historicallyinspired architecture that counteracts the modernist architecture styles of the immediate postcolonial era (1950s and 1960s).

In the mid-to-late 20th Century, however, architects began looking at later practices that focused on regeneration and rediscovering a local architecture that aligns with modern developments. Concepts such as urban villages, sustainable communities and transport links arose, allowing for more significant movement and greater populations. While it was slow to be affected by postcolonial theory, rural vernacular architecture was back to being studied in the context and climate of Egypt, being seen as the most authentic self-expression of the colonized. In the 1950s and 1960s, architects often followed a top-down design method, where developers began investigating an "architecture without architects" where form followed social function rather than industrial and hierarchal aesthetics 78

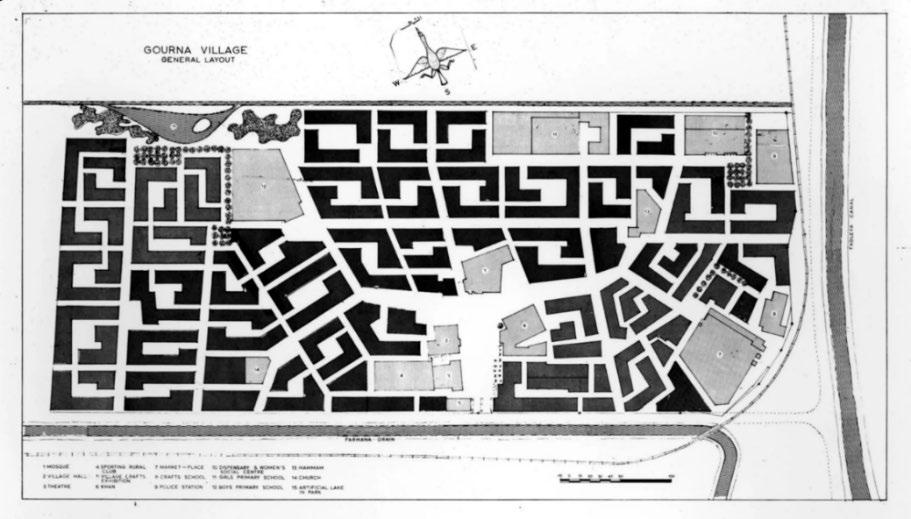

It was during this time that architects such as Hassan Fathy, now celebrated as a prominent architect in the Middle East, began his revival of vernacular architecture traditions to serve as a mode of sustainable design for social disparities.

Hassan Fathy's architecture developed with an anti-colonial development stance that rejected blindly following ideas of modernization. He often spoke about his desire to help architects in the Orient rediscover their craft, stating that designers have developed a trend where they "don't think, they just take and copy" the architectural trends set in Europe in the form of postcolonialcolonial-focused design. 79

76 Nasser Rabbat, "The Hidden Hand: Edward Said’S Orientalism And Architectural History", Journal Of The Society Of Architectural Historians, 77.4 (2018), 388-396 <https://www.jstor.org/stable/26771360?seq=1> [Accessed 22 June 2022].

77 Ibid.

78 Sibyl Moholy Nagy, Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture (New York: Horizon Press, 1957); Bernard Rudofsky, Architecture Without Architects (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1964); and Robert McCarter, Aldo van Eyck (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2015).

79 Salma Samar Damluji and Viola Bertini, Hassan Fathy: Earth And Utopia (London: Laurence King, 2018).

The late 20th Century, with the region's independence and rises in wealth, saw great Occidental interest in the oriental cities. This, along with rising capitalism, internationalism and neo-feudalism, pushed Arab cities at the time to develop a somewhat confused architectural language. International efforts to counteract the issues of postcolonialism began with the founding of the Aga Khan Award for Architecture. This aimed to develop an appreciation of Islamic architecture through its focus on vernacular revival and critical regionalism. 82 Over time, however, it has grown to focus on the current mounting issues in relation to environmental, social, and global challenges regarding the cyber and physical developments in architecture.

80 Ibid.

81 Ibid.

82 Ashraf M. Salama and Marwa M. El-Ashmouni, "Decolonisation Aspirations Of Architecture In Islamic Societies", Architectural Excellence In Islamic Societies, 2020, 189-213 <https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351057493-6>.