Make the most of your Legion Membership

As a Legion Member, you take pride in the fact that your membership helps support and honour Canada’s Veterans.

Did you know that it comes with benefits you can use, too? Take advantage of all the benefits that come FREE with your membership.

Renew your membership to get all these benefits and more!

MemberPerks® unlocks $1000s in potential savings on offers and deals at stores and restaurants across Canada, including national chains, local businesses and online stores. Use the MemberPerks® app, print out coupons or shop online to save on electronics, travel, fashion, entertainment and so much more!

Your membership also gives you access to additional benefits, including:

• savings and deals from our Membership Partners

• a paid subscription to Legion Magazine

• exclusive members-only items at PoppyStore.ca

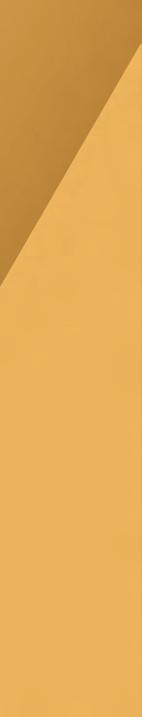

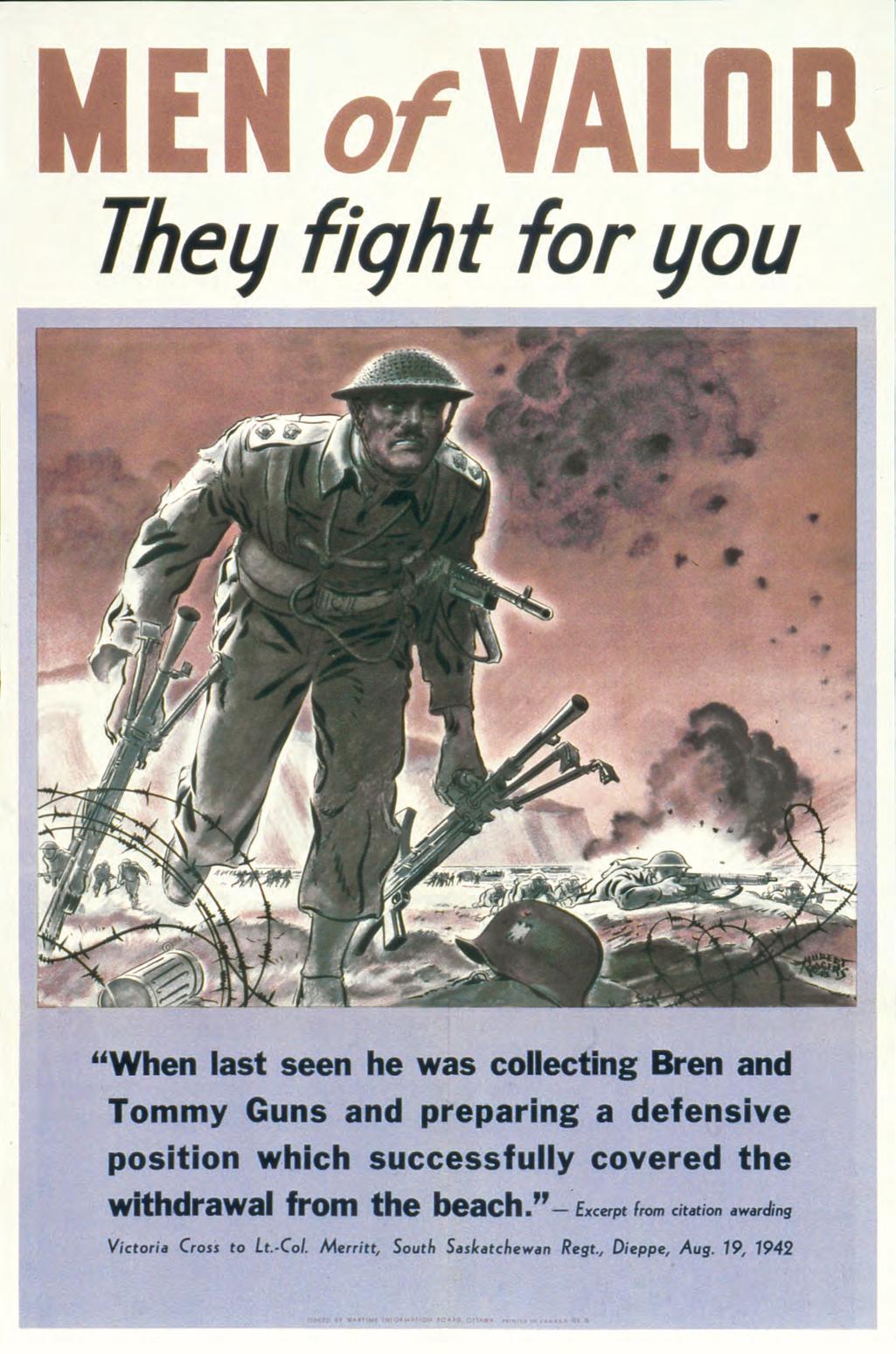

POSTER BOYS

Artist Reginald Rogers depicts the two-man boarding party of HMCS Oakville boarding U-94 in August 1942 for the Men of Valor propaganda campaign.

See page 50

Features

22 DIGGING IN

A deep dive into the evolution of tunnel warfare

By Stephen J. Thorne

30 SISTERS ACT

How the Great War’s Canadian nurses brought comfort and care to patients while enduring their own personal turmoil

By Alex Bowers

36 THE BOMBER BOOK

A wartime tome of fictional tales of Canadian airmen hits close to home

By George Case

42 JA, VI ELSKER DETTE LANDET

When Canada welcomed Norwegian mariners exiled from their homeland by the Nazis, it brought new meaning to the country’s de facto national anthem—“Yes, we love this country”

By Alex Bowers

50 MEN OF VALOR

A unique Second World War propaganda campaign highlighted Canadian bravery By

Robbie McGuire

56 IN SERVICE, TOGETHER

An exclusive excerpt from The Good Allies: How Canada and the United States Fought Together to Defeat Fascism During the Second World War

By Tim Cook

60 THE B’YS BACK Newfoundland repatriates an unknown First World War soldier

By Michael A. Smith

A visitor explores a tunnel dug by Japanese defenders of Iwo Jima during the Second World War. Donald Hudson/DVIDS/U.S. Department of Defense

A pair of Canadian nursing sisters pose for a photo overseas in May 1917. CWM/19920085-353

Vol. 99, No. 5 | September/October 2024

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Berkley Lawrence BOARD VICE-CHAIR Bruce Julian BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe

DIRECTORS Tom Bursey, Steven Clark, Thomas Irvine, Jack MacIsaac, Sharon McKeown, Brian Weaver, Irit Weiser Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Alex Bowers

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert

DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales

CANIK MARKETING SERVICES NIK REITZ 416-317-9173 | advertising@legionmagazine.com

MARLENE MIGNARDI 416-843-1961 | marlenemignardi@gmail.com OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR

Dyann

WEB

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2024. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Change of Address

Send new address and current address label, or, send new address and old address. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com/change-of-address. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S.

Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of Alliance for Audited Media and BPA Worldwide. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible. On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

We’re T

back?

he night he was first elected prime minister, a triumphant Justin Trudeau declared that Canada was poised to reclaim its rightful place in the world after more than nine years of Conservative anti-globalist isolationism.

“Many of you have worried that Canada has lost its compassionate and constructive voice in the world,” Trudeau told a boisterous victory rally on Oct. 20, 2015, in Ottawa. “Well, I have a simple message for you: on behalf of 35 million Canadians, we’re back.”

THIS PAST MAY, 23 BIPARTISAN U.S. SENATORS URGED TRUDEAU TO IMMEDIATELY DEVELOP A PLAN TO INCREASE CANADA’S MILITARY SPENDING.

Nine years later, the country is under fire for failing to hold up its end of bargains with both the North Atlantic Treaty Organization and the United Nations, and its military is in dire straits (see “Front Lines,” page 18).

Canada continues to fall well short of NATO spending minimums and hasn’t contributed meaningfully to the very UN peacekeeping missions it was a driving force in creating.

More than 125,000 Canadians have served and 130 have died on UN deployments since Lester B. Pearson, a Liberal, was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for his role in assembling an armed peacekeeping force to defuse the 1956 Suez Crisis.

Canada was a leading contributor to peacekeeping into the 1990s, when

its numbers peaked at 4,000. In 2016, and again in 2017, Ottawa pledged to renew its commitment and contribute substantially more to UN efforts.

After the 2019 election, Trudeau tasked his defence and foreign ministers to “expand Canada’s support for United Nations peace operations.” The Liberal party’s 2021 election platform included a pledge to “renew Canada’s commitment to peacekeeping efforts.” Its UN mission roster as of April 30, 2024, numbered 40.

Likewise, Canada has made repeated pledges to boost its military spending to meet NATO’s minimum two per cent of gross domestic product (GDP). It hasn’t.

According to NATO data, Canada spent 1.33 per cent of GDP on defence in 2023, ranking 27th in the 32-member alliance. In actual dollars spent, it’s seventh.

This past May, 23 bipartisan U.S. senators signed a letter urging Trudeau to immediately develop a plan to increase Canada’s military spending. And NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg has insisted the status quo is “not good enough.”

“I continue to expect that all Allies should meet the guidelines of spending two per cent,” Stoltenberg said in Ottawa this past June. “I know that this is not always easy... but when we reduce defence spending when tensions are going down, we must be able to increase spending, investments in our security, when tensions are increasing and are high as they are today.”

Stoltenberg praised Canada for its leading role in a Latvia-based deterrence force and the billions in aid it has provided Ukraine in its fight against Russian aggression, including air defence systems, battle tanks and fighter pilot training.

In July, Trudeau said Canada would reach NATO’s benchmark by 2032, noting it has increased military spending by $175 billion since 2015.

For Canada’s security, and its faltering reputation, it must make good on a promise it has repeatedly failed to keep. L

Exciting Transition from SimplyConnect to Rogers

Since 2017, Legion members have benefited from exclusive cell phone services through SimplyConnect, enjoying reliable, affordable cell phone plans and devices tailored to their needs, a reliable network, and best-in-class customer service

However, changes in communications technology, such as the 3G network shutdown in the U.S., outdated travel solutions, and limited data plans, have impacted the ability of SimplyConnect Legion customers to fully enjoy their service.

Furthermore, with the 3G network in Canada also phasing out in the future, it was important for The Royal Canadian Legion to endorse a reliable nationwide partner to offer simple and affordable 5G cell phone service - introducing the Rogers program for Legion members

Through this new partnership, SimplyConnect customers and Legion members alike can now upgrade to a 5G mobile plan on Canada's largest and most reliable 5G network while continuing to enjoy simple and affordable cell phone service. Key features include:

• Unlimited Canada-wide Talk and Text plans starting from just $20/month

• Unlimited Canada-wide Talk, Text, and data plans starting at $29/month

• For travelers, a new Canada + U.S. plan allows you to stay connected without changing your device or SIM card, and in over 185 countries with Roam Like Home for a low daily fee

• Competitive pricing on a wide selection of the latest devices from popular brands like Apple and Samsung at exclusive pricing, negotiated for you

By making the switch to Rogers, you will continue to enjoy affordable mobile plans with even greater benefits designed to meet your modern communication needs, on Rogers' 5G network, covering over 30 million Canadians from coast to coast.

• Sign up with no activation fee (Legion members see their activation fees credited thanks to this new program)

• Sign up worry-free with a 30-day satisfaction guarantee.

• Enjoy helpful features such as Spam Call Detect. It notifies users when they receive spam calls on their cell phone.

But, that’s not all, this exclusive partnership is provided by Red Wireless - your exclusive Rogers dealer. Their dedicated team of experts, called Account Managers, is prepared to assist you in selecting the right plan and device to suit your needs. They will guide you through a seamless switch, ensuring no activation fees and a 30-day satisfaction guarantee

Whether you're upgrading to the latest smartphone or looking for a cost-effective plan, their expert team is here to support you. Make the switch today to experience greater savings and amazing customer service. Stay connected with your loved ones, no matter where you are.

This program is brought to you by Red Wireless - your exclusive Rogers dealer, and is not available in stores.

Are you an existing SimplyConnect customer?

Visit www.redwireless.ca/simply-switch or call a dedicated Red Wireless Account Manager at 1-888-271-7206 and ask for your Rogers 5G SIM card to get started.

Are you a new customer?

Call a dedicated Red Wireless expert at 1-888-251-5488 or visit them at www.redwireless.ca/legion

Lest we forget T

hank you for the fine article (“The peacemakers,” July/August) concerning the Canadian military involvement in Vietnam control commissions that operated from 19541973. As a crew member of HMCS Terra Nova, which was deployed

from January-June 1973 in support of the Canadian contingent of the International Commission of Control and Supervision (ICCS), I believe another name should be added to the Canadian casualties of the Vietnam commissions.

On March 15, 1973, Leading Seaman Ned Memnook, a member of HMCS Terra Nova’s company, died in a Singapore hospital due to a viral infection. While not officially a part of the ICCS contingent, Terra Nova was dispatched to act as a communications relay for Canadian members of the commission and to provide an emergency escape

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

means for the Canadians ashore in Vietnam.

Memnook, a member of the Saddle Lake Cree Nation in Alberta, was one of serveral crew with Indigenous heritage who got sick and needed hospitalization. He was the only fatality. His body was returned to Esquimalt, B.C., where he’s buried at the Veterans Cemetery in Victoria. He was survived by his wife Frances and two children, Carolyn and Conrad. Memnook was the only member of the Terra Nova’s crew to receive the International Commission of Control and Supervision Vietnam Medal.

JOHN APPLER

VANCOUVER

ATTENTION CANADIAN MILITARY FAMILIES

Did you or a family member receive VAC disability benefits between 2003 and 2023? A class action settlement may affect you. Please read this notice carefully.

On 17 January 2024 the Federal Court approved a settlement in a class action involving alleged underpayment of certain disability pension benefits administered by Veterans Affairs Canada (“VAC”) payable to members or former members of the Canadian Armed Forces (“CAF”) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) and their spouses, commonlaw partners, survivors, other related individuals, and estates (the “Settlement”).

If you received any of the disability-related benefits listed below at any time between 2003 and 2023, you may be entitled to compensation under the Settlement. As the executor, estate trustee, administrator, or family member of a deceased class member who collected VAC-administered disability benefits, you may also be able to claim on behalf of the estate. If you are entitled to compensation under the Settlement and you have an active payment arrangement with VAC, such as direct deposit, you do not need to do anything to receive payment. If you are claiming on behalf of a deceased veteran of the CAF or RCMP, including as the executor, trustee, administrator of an estate, or a family member, you must submit a Claim Form to KPMG Inc., the administrator responsible for handling claims available at:

KPMG Inc.

C/O Disability Pension Class Action Claims Administrator 600 boul. de Maisonneuve West, Suite 1500 Montréal, Québec H3A 0A3

Online: https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/ E-mail: veteranspension@kpmg.ca

For assistance with submitting a Claim Form, please contact the Administrator’s dedicated call center at 1-833-839-0648, available Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM (Eastern Time).

The deadline to submit a claim is 19 March 2025. All eligible claimants are entitled to receive legal assistance free of charge from Class Counsel for purposes relating to implementing the Settlement, including preparing and/or submitting a claim to the Administrator.

You may contact Class Counsel for more information or for assistance with filing a claim, at info@vetspensionerror.ca, or 1-866-545-9920. To see the full text of the Final Settlement Agreement, please visit https://vetspensionerror.ca/court-documents/. WHO IS INCLUDED?

The Settlement covers members and former members of the CAF and the RCMP and their spouses, common–law partners, dependents, survivors, orphans, and any other individuals, including eligible estates of all such persons, who received—at any time between 2003 and 2023—disability benefits based on annual adjustments of the basic pension under s. 75 of the Pension Act (the “Class Members”). The terms of the Settlement are binding on Class Members. The Settlement includes releases of claims asserted in the certified Class Action.

WHAT ARE THE AFFECTED BENEFITS?

The Settlement affects prescribed annual adjustments of the following benefits:

• Pension Act pensions for disability, death, attendance allowance, allowance for wear and tear of clothing or for specially made apparel and/or exceptional incapacity allowance;

• RCMP Disability Benefits awarded in accordance with the Pension Act;

• Civilian War-related Benefits Act war pensions and allowances for salt water fishers, overseas headquarters staff,

air raid precautions works, and injury for remedial treatment of various persons and voluntary aid detachment (World War II);

• Flying Accidents Compensation Regulations flying accidents compensation;

• Veterans Well-being Act clothing allowance.

WHAT DOES THE SETTLEMENT PROVIDE?

The Settlement provides direct compensation to Class Members who receive (or have previously received) any of the Affected Benefits listed above, since 1 January 2003. Class Members will receive a single payment of about 2% of all Affected Benefits they have received since 1 January 2003. The total amount of compensation paid by Canada to the Class could be as much as $817,300,000. This is only a summary of the benefits available under the Settlement. The full text of

the Final Settlement Agreement (“FSA”) is available online at https://vetspensionerror.ca/ court-documents/. You should review the entire FSA in order to determine your entitlement and any steps you may need to take to access compensation.

HOW AM I PAID?

Eligible Class Members who are currently collecting VAC-administered disability benefits or pensions will receive a Settlement payment automatically through the same payment method they currently use to collect benefits, including by direct deposit.

Class Members who received Affected Benefits between 2003 and 2023 but who do not have a current payment arrangement with VAC will be required to make a claim with the Claims Administrator. This includes all Class Members who are deceased, and where an executor, estate trustee, administrator of an estate, or a family member is making a claim on behalf of that Class Member.

However, if a deceased Class Member has a survivor who is in receipt of VAC benefits and has a current payment arrangement, that survivor will automatically receive the deceased Class Member’s entitlement without the need to make a claim with the Claims Administrator.

HOW DO I MAKE A CLAIM?

If you do not have an active payment arrangement with VAC, you must submit a claim form with the Administrator.

You must submit a completed and signed Claim Form to the Administrator within the Claim Period. You are encouraged to use the Claim Form submission link available online at https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/. You may, however, submit your Claim Form to the Administrator using one of the following three methods: 1. online at https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca; 2. by e-mail to veteranspension@kpmg.ca; or 3. by mail to: KPMG Inc.

C/O Disability Pension Class Action Claims Administrator 600 boul. de Maisonneuve West, Suite 1500 Montréal, Québec H3A 0A3

You may download a copy of the Claim Form available online at: https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/download/Claim-Form.pdf.

If submitting electronically, the Administrator must receive your completed and signed Claim Form no later than 19 March 2025. If submitting by mail, your completed and signed Claim Form must be postmarked no later than 19 March 2025. For assistance with submitting a Claim Form, please contact the Administrator’s dedicated call center at 1-833-839-0648, available Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM (Eastern Time).

Please read and follow the instructions on the Claim Form. Class Counsel are also available, free of charge, to answer your questions and assist you with preparing your claim form.

The deadline to file a claim is 19 March 2025.

AM I RESPONSIBLE FOR LEGAL FEES?

You are not responsible for payment of legal fees. The Federal Court has approved Class Counsel’s fees (including HST) and disbursements to be automatically calculated and deducted from the Settlement amount you are entitled to receive before the payment is issued.

The Federal Court approved payments to Class Counsel equal to approximately 17% of each payment made under the Settlement for legal fees, disbursements, and HST.

The FSA contains additional details about Class Counsel fees, available online at https://vetspensionerror.ca/court-documents/.

Class Counsel are available to assist Class Members through the claims process free of charge.

FURTHER INFORMATION?

For further information or to get help with your claim, contact Class Counsel at: https://vetspensionerror.ca/ or Call: 1-866-545-9920 or info@vetspensionerror.ca

DO YOU KNOW ANY OTHER RECIPIENTS OF A VAC DISABILITY PENSION?

Please share this information with them.

Butterfly effect

Thank you for including an article in the July/August issue on my dad, Charles (Charley) Fox, and his encounter with German General Erwin Rommel. That moment 80 years ago certainly influenced the outcome of the Second World War. Dad always wondered if his backroad encounter with Rommel in France hadn’t occurred, might the highly popular general have been able to sway an earlier conclusion to the war. We will, of course, never know.

JIM FOX

VIA EMAIL

Blame Blair

Defence Minister Bill Blair is an embarrassment to Canada and NATO (Editorial, July/August). His reluctance to understand Canada’s defence budget deficits, personnel shortfall and the navy’s four-submarines debacle is not acceptable. Canada needs a strong leader with a persuasive voice to rectify these shortfalls. The country must be prepared to assist NATO as required.

STEPHEN JORDAN

VIA EMAIL

Muck up

I thoroughly enjoyed the excellent article “Licence to Plunder” (July/August) by Stephen J. Thorne. But, in the interest of historical accuracy, the terms England and the United Kingdom are not synonymous. The letters of marque were not issued by the King of England, as no such title exists. Since 1603, the British monarch has been the King of the United Kingdom. Similarly, the U.S. did not declare war on England in 1812 as England had ceased to exist as a country in 1707. They declared war on the U.K.

RON

ROSS

GUELPH, ONT.

CORRECTIONS

The Royal Canadian Legion 2024 national Cribbage Championships second-place pairs duo—Grant Graham and Darrell Gorvett—are from Perth Regt. Veterans Branch in St. Marys, Ont. In “The Greatest Landing” (May/June), the list of Royal Canadian Navy ships off Normandy on D-Day did not include HMCS Kitchener. The corvette escorted a second wave of American infantry at the Omaha landing area. And, in “The peacemakers” (July/August), the medal pictured is the International Commission of Control and Supervision Vietnam Medal, not the International Commission for Supervision and Control Indo-China Medal.

MEDIPAC TRAVEL INSURANCE

Exclusive HIGHLIGHT from LegionMagazine.com

attack against what was expected to be a weak and demoralized enemy with little equipment. Due to a failure of intelligence, however, it was doomed from the start. The Battle of the Scheldt was arguably the most critical battle

fought by the Canadian Army during the Second World War. Some historians believe that, after Normandy, it was the single most significant Allied campaign in Western Europe. Yet, for some strange reason, it remains relatively little-known. Readers can now learn more about this necessary victory in the special collector’s edition of Canada’s Ultimate Story titled “Canada and the Scheldt Campaign: The Necessary Victory,” written by frequent Legion Magazine contributor John Boileau. It can be found on

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /newsletter-signup

newsstands until Nov. 4, and online at https://shop.legionmagazine.com/. Accompanying the edition is a video on the battle, narrated by Canadian actress Cobie Smulders, known for her work in TV’s “How I Met Your Mother” and various Marvel superhero movies. Viewers will be transported to Europe in the fall of 1944 and shown how more than 40,000 Germans were taken prisoner and, ultimately, how the successful conclusion of the Battle of Scheldt became a testament to the quality, determination and skill of Canadian soldiers. Watch it on Legion Magazine’s YouTube channel. L

1 September 1880

The British Arctic Territories are ceded to Canada, becoming part of the North-West Territories.

3 September 1783

The Treaty of Paris (1783) is signed by representatives of Great Britain and the U.S., officially ending the American Revolutionary War.

4 September 1939

Pilot Officer S.R. Henderson, serving in 206 Squadron, Royal Air Force, becomes the first Canadian to participate in an operational sortie during the Second World War when he serves as the lead navigator in a bomber force attacking German warships.

5 September 1979

The first Canadian gold bullion coin, stamped with the maple leaf, goes on sale.

7 September 1850

The Robinson Treaties are signed. The British Crown agrees to pay the Ojibwa 2,160 pounds and annual payments of 600 pounds for lands on the northern shores of lakes Superior and Huron.

September

16 September 1939

The first convoy of the Second World War—designated HX-1—leaves Halifax for the United Kingdom. Eighteen merchant ships are escorted by HMC ships Saguenay and St. Laurent to a North Atlantic rendezvous with Royal Navy cruisers.

17 September 1944

8 September 1978

L’Anse aux Meadows, the site of a 1,000-year-old Norse colony in Newfoundland, is named a world heritage site.

10 September 1939

Canada declares war on Germany.

11 September 2001

Al-Qaida terrorists hijack four commercial jets, crashing two into the World Trade Center in New York City and one into the Pentagon in Washington, D.C.; passengers of the fourth plane force it to crash in Pennsylvania.

12 September 1846

Royal Navy ships Erebus and Terror of the Franklin expedition are trapped in ice in the Arctic.

Operation Market Garden, a bold but unsuccessful Allied attempt to shorten the war, begins.

18 September 1941

Vancouver’s Asahi baseball club plays its last game as Japanese Canadians are sent into exile or internment camps.

21 September 1995

The $2 coin—the Toonie—is unveiled.

23 September 1787

Mississauga chiefs sell 101,528 hectares of land—in the area of present-day Toronto—to the British for the modern equivalent of about $200,000.

14 September 1889

Nearly 400 Canadian voyageurs leave Halifax to participate in the Nile Expedition to rescue a British major-general trapped at Khartoum in the Sudan.

15 September 1762

Britain defeats France in St. John’s, Nfld., in the last battle of the Seven Years’ War.

25 September 1942

Canada joins the United States in combat against the Japanese in Kiska Harbor, Alaska.

28 September 1972

Canada defeats the Soviets in the eighth and final hockey game of the Summit Series.

October

2 October 1535

Jacques Cartier arrives at Hochelaga (now Montreal) on his second voyage to North America.

3 October 1914

The Canadian Expeditionary Force’s first contingent of 30,000 sails from Quebec to join the war effort in Europe.

4 October 1944

HMCS Chebogue is torpedoed by U-1227 in the mid-Atlantic and seven sailors die.

5 October 1970

13 October 1812

Major-General Isaac Brock dies during the Battle of Queenston Heights. Total British losses are 105 killed and wounded. There are at least 300 American casualties.

22 October 1940

Squadron Leader Ernest A. McNab is awarded the Royal Canadian Air Force’s first Distinguished Flying Cross for his service during the Battle of Britain.

23 October 1958

An earthquake near a coal mine at Springhill, N.S., traps 174 miners underground. Seventy-five die.

25 October 1973

British Trade Commissioner James Cross is kidnapped in Montreal by the Front de libération du Québec, beginning the October Crisis.

7 October 1918

The first of Canada’s 50,000 Spanish flu victims dies in Montreal.

9 October 1967

Reports from Bolivia state that Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara has been killed.

10 October 1970

Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte is kidnapped by the FLQ.

11 October 1918

Lieut. Wallace Algie leads the capture of two machine guns, an officer and 10 men at Cambrai, France, earning the Victoria Cross.

14 October 1914

The First Canadian Contingent begins to disembark after arriving at Plymouth, England.

16 October 1970

Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau invokes the War Measures Act in response to a deepening crisis in Quebec.

12 October 1915

British nurse Edith Cavell is executed for helping Allied prisoners escape occupied Brussels.

The second United Nations Emergency Force is established to supervise the implementation of a ceasefire in the Yom Kippur War.

17 October 1970

Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte is found dead in the trunk of a car seven days after being kidnapped by members of the FLQ.

19 October 1944

HMCS Bras d’Or vanishes without a trace in the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Thirty die.

21 October 1916

The first of three attacks are launched on Regina Trench by 4th Canadian Division.

26 October 1917

The Canadian Corps attacks Passchendaele Ridge. Fighting into November, the Canadians succeed, but suffer 15,654 casualties.

27 October 1915

King George V of Great Britain visits the Canadian Corps on the Western Front.

28 October 1790

On present-day Vancouver Island, Spain signs an agreement with Britain to end its Pacific Northwest monopoly.

30 October 2009

A landmine kills Private Steven Marshall while on foot patrol in Panjwaii district southwest of Kandahar, Afghanistan.

31 October 1995

Premier Jacques Parizeau resigns after a narrow loss in the Quebec sovereignty referendum.

By Alex Bowers

Lured by nature

How a veterans’ fly-fishing program has embraced the healing power of the great outdoors

G

ervais Jeffrey, 68, remembers when his fly-fishing journey began.

Just a boy at the time, he had been at a summer camp about three hours’ drive from Quebec City, a tranquil getaway run by his father’s boss. There, he watched the camp operator out on the water “catching all kinds of fish” while he, using lures instead of worms, caught nothing.

“One day,” Jeffrey explained, “I asked if I could learn what he did. [The operator] gave me a big grin and said, ‘Well, it’s about time you asked.’”

Sixty years later, and following more than four decades in the Canadian military, the army and navy veteran understands the true meaning of that moment.

“After I came back from Afghanistan in 2008, actually around the same time I was posted back to Quebec City, I used to go fly fishing on the weekends when I was tired and depressed. I felt directly connected with nature— the water running between my legs, feeling the currents, or sometimes not fishing at all and instead sitting or lying on a rock. It all brought a sense of liberty.”

Inspired to bring the same feelings to others, Jeffrey became involved in a U.S. fly-fishing project for fellow veterans. Then, in early 2019, he helped establish Heroes Mending on the Fly Canada, an organization catered exclusively to Canadian service members, first responders and their families.

With individual programs spread nationwide, Jeffrey, as national director, oversees a team of provincial co-ordinators and volunteers—most of whom are veterans—offering classes, trips and more.

Experience is never an issue, explained Jeffrey: “For beginners, we teach basic fly fishing and fly tying. There are casting classes, instructions on material care, setting up—everything.”

The group likewise supplies all the necessary gear for the first year for free. It’s merely one of several ways that the organization accommodates newcomers, regardless of their circumstances.

“One time,” noted Jeffrey, “we had a veteran with one arm. He needed adaptive equipment that could

enable him to fly fish and reel the line back. We got him the devices that were actually designed for people who had lost an arm.”

Finally, there’s the option of matching beginners with more experienced anglers. Such tutorials, alongside a general sense of camaraderie, play a critical role in the program’s mission—especially for service members, former and active, with post-traumatic stress disorder or who face other challenges.

“I was going to cancel due to anxiety,” Dave, a veteran attendee, wrote to Jeffrey after a Heroes trip. “On that first day I chose to wade into the water and fish by myself...you are always safe when you are by yourself.”

Once out there, however, Dave had gazed up at the evergreen hills, letting the cool lake wash over his senses. He felt his heart jump with excitement when the first fish broke the surface, and, at least momentarily, all worries disappeared. The day, he later recalled, “was probably the most peaceful...in a long time.”

Back at the fishing lodge, Dave found himself becoming more open with other veteran attendees: “we shared conversations of common experiences with regard to PTSD, which really brought to light the fact that the things I am experiencing, the sometimes cold and painful existence, is not solitary.”

Whether forming bonds akin to those in the service, sharing stories with like-minded individuals, or simply being immersed in nature, the program has helped hundreds of veterans coast-tocoast cope with difficulties.

Jeffrey is quick to assert that his organization should be seen as supplementary to conventional treatment options. Nevertheless, research does recognize the potential benefit of naturebased recreation. In one recent study, evidence suggested that fly

“WE’RE

.”

fishing could help alleviate PTSD symptoms and perhaps, under certain circumstances, contribute to post-traumatic growth.

What remains clear is the group’s year-round dedication. “We’re there for the veterans, and we’re there for their needs,” said Jeffrey.

Even in the winter, when there are fewer opportunities to be outside, the merits of fly fishing can continue by preparing for the season ahead.

“Fly tying can teach patience,” explained Jeffrey. “We practice our motor and concentration skills in order to place the material on the hooks, sometimes working in small groups while managing stress. Where people may otherwise have been sitting alone in their homes, they’re instead focusing on something that could be meaningful. Some of those guys have said it saved their lives.”

But challenges remain in raising awareness, having enough experienced volunteers for certain provincial programs, and,

fundamentally, ensuring the organization grows for the betterment of veterans’ health and wellness.

“Most of the money right now that we raise is the generosity of the Legion,” said Jeffrey, who also serves as president of Rockland, Ont., Branch. “Dominion Command supports us on the national side; so do the provinical commands, and then there are the Legion branches themselves.”

Sponsorship funds, Jeffrey is proud to note, directly benefit veteran attendees, enabling all participants to embrace the healing power of nature.

It is, according to Jeffrey, as important now as it ever was: “Some people think that because the Afghanistan War is over, everything is over, but we’re still losing veterans to suicide, to homelessness, to drugs, and other serious issues. We need to get those veterans on their feet again.”

For Jeffrey, Dave and fellow anglers, to have feet planted firmly in water—all the while surrounded by Canada’s natural beauty— can make all the difference. And it doesn’t matter the type of fish they reel in, because the real catch is finding peace of mind.

“Trout, salmon, pike, bass,” he listed off in reference to just some of his catches, past and present. “Whatever swims in the water, I would go fish for it.” L

Carignan takes command

Canada names its first female defence chief

Lieutenant-General Jennie Carignan, a 35-year military veteran who headed the forces’ topical professional conduct and culture directorate, became the first woman to serve as Canada’s chief of the defence staff.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau made the announcement on July 3, congratulating Carignan and saying “her exceptional leadership qualities, commitment to excellence, and dedication to service have been a tremendous asset” to the forces.

“I am confident that, as Canada’s new Chief of the Defence Staff, she will help Canada be stronger, more secure, and ready to tackle global security challenges.”

She officially became a full general and replaced the outgoing chief, General Wayne Eyre, at a change-of-command ceremony on July 18, 2024.

Carignan inherits a military in dire straits—understaffed, underequipped, underfunded and, when it comes to women, under-represented.

An internal Defence Department presentation dated Dec. 31, 2023, and recently obtained by CBC’s Murray Brewster says just 58 per cent of Canada’s armed forces could currently respond to a crisis if called upon by NATO allies.

Then major-general Jennie Carignan meets with colleagues on Feb. 7, 2020, while in command of a NATO mission in Iraq.

The presentation, which addresses issues from readiness and equipment to recruiting and ammunition supplies, says 45 per cent of the military’s equipment is considered “unavailable and unserviceable.”

“In an increasingly dangerous world, where demand for the CAF is increasing, our readiness is decreasing,” says the document.

The numbers are jarring:

• 55 per cent of Royal Canadian Air Force fighters, maritime aviation, search and rescue, tactical aviation, trainers and transport aircraft are considered “unserviceable;”

• 54 per cent of Royal Canadian Navy frigates, submarines, Arctic offshore patrol ships and defence vessels are not deployable;

• 46 per cent of army equipment is considered “unserviceable.”

But the biggest challenge, says the document, is “people shortfalls— technicians and support” along with “funding shortfalls—spare parts and ammo.” It says the military was short 15,780 regular members and reservists at the end of 2023.

Meanwhile, the federal government has started to reallocate hundreds of millions of dollars in defence money, forcing parts of DND to cut spending to pay for new equipment.

Kerry Buck, a career diplomat and Canada’s former ambassador to NATO, told CBC the numbers show that Canada is “falling further down the rank of allies.”

“It means that the gap is growing between our international commitments and our capacity,” said Buck. “It impacts our credibility at NATO for sure, but it impacts our security interests, too.”

Underlying some of the recruiting problems, particularly regarding women, are issues with which Carignan, a native of Asbestos, Que., is intimately familiar—professional conduct and culture.

The forces’ set a goal of increasing the percentage of women in its ranks from 14.6 per cent in 2016 to 25 per cent by 2026. In May 2023, the percentage was 16.48.

“The CAF will clearly not reach its female recruiting target by 2026,” said a 2021 article in Queen’s University’s Smith School of Business newsletter.

“There were no illusions that this was anything but a stretch goal,” it said. “The CAF’s own survey of Canadian women found that the military was second only to mining and banking as the least appealing career choice.”

An engineering graduate of Royal Military College Saint-Jean,

Carignan served in combat engineering regiments throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, including stints in the Golan Heights, Bosnia and Afghanistan, where she commanded a task force engineering regiment.

As a full colonel, she was appointed commandant of her alma mater in 2013.

She was promoted to brigadiergeneral in 2016, Canada’s first female general from a combat command. She was promoted to major-general in 2019 and commanded NATO forces in Iraq.

As a lieutenant-general, she became the Canadian military’s first chief of professional conduct and culture.

The job demanded nothing less than “leading institutional efforts to develop a professional conduct and culture framework that holistically tackles all types

Keep hearing & learning

Learning is lifelong, and discovering new hobbies and interests is part of what makes you, you. Whether it’s taking a new class, joining a discussion group, or learning a new language, your hearing plays an essential role in these experiences.

That’s why we encourage you to love your ears and take advantage of a FREE hearing test at any HearingLife clinic* –no referral needed. Plus, Legion Members and their family receive an EXTRA 10% off the final purchase price of hearing aids.**

of discrimination, harmful behaviour, biases, and systemic barriers”—essentially a mandate to prevent sexual assault in the military.

“It was a tall order,” Legion Magazine’s former news editor, Tom MacGregor, wrote in the Ottawa Citizen on July 5, 2024, “but insisted on by politicians and the public as, increasingly, sexual discrimination, harassment and generally poor conduct were cited by women as a major obstacle to attracting young women.

“The situation was not helped by the sexual conduct of several in the senior ranks in recent years.”

Carignan married a college platoon mate, Éric Lefrançois, in 1990. He eventually retired from the military to care for their four children, two of whom— a son and daughter—now serve in the Canadian forces. L

By David J. Bercuson

Recruiting agency

Canada’s military recruitment issues are hardly new— the country identified them nearly 30 years ago

“Tens of thousands of people want to join [Canada’s] military but we’re snubbing them,” wrote John Ivison in a column for the National Post at the end of May 2024. The piece confirmed information published by the Toronto Star earlier in the month that the Canadian Forces Recruiting Group had received 70,080 applications for the Canadian Armed Forces in 2023-2024, but enrolled only 4,301 new recruits. At a time when the CAF is running at least 16,500 below its current year enrollment targets, the articles raise serious questions about the country’s recruitment process.

When the armed services are so far below the optimum strength set for them by the government, it means that there aren’t enough senior personnel to train new recruits. A professional Canadian service person needs to not only know how to march and shoot, but also should be trained in a wide aspect of modern warfare technology, from working with drones to communicating using highly technical digital radios, not to mention deadly weaponry.

The lack of recruits also means there aren’t enough

personnel to fly the country’s military aircraft and fill its infantry battalions, nor enough sailors for its naval vessels or enough supply-andsupport workers to keep everything shipshape. And while Canada’s four 1980s-era submarines are barely seaworthy—having spent just 228 days at sea combined from 2000-2023—that hardly matters as there aren’t enough submariners to operate them.

In the fall of 1997, I was invited to, and participated in, the defence minister’s Monitoring Committee for the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. Art Eggleton, a former mayor of Toronto, had assumed the defence portfolio and received reports from a number of parliamentary investigations into many aspects of life in, and the performance of, Canada’s military in the aftermath of the so-called Somalia Affair.

In 1993, a Somali teenager had been beaten to death over several hours one night by Canadian paratroopers serving in a UN-backed humanitarian mission the African country. Members of the same regiment had previously shot a number of Somalis to death. The subsequent inquiries appointed to examine the CAF found there was plenty wrong. One of the main conclusions of the Special Committee on the Restructuring of the Reserves, for instance,

The Canadian Armed Forces’ current recruitment campaign, “This Is For You,” is generating applicants, but the military is struggling to enroll them.

was that the recruiting system just didn’t work. People wanting to join the reserves experienced lost files, a broken communication system, delays in medical examinations, transfers from the regular force that took months and, in some cases, years, and numerous other challenges. The recruiting system for the regular force was somewhat better, but stumbled, for example, on security clearance issues. Keep in mind, this was nearly 30 years ago. Many, if not all, of the same issues still exist.

Case in point: an individual who retired from the reserves as a captain several years ago, who held a PhD in security studies, was awarded the Order of Military Merit and served two tours in Afghanistan, considered returning to the naval service. He was eventually cleared to rejoin… as a cook. He declined the offer.

Canada’s recruitment system is broken in numerous ways, and has been for a long time. Auditor general reports from 2002 and 2006 found issues with training recruiting staff, the quality of the tools used to assess applicants and processing in general, which caused people to withdraw applications. They weren’t meeting recruiting targets 20 years ago and subsequently made no plans to meet them.

The system’s ultimate fault is that it’s not designed to attract the best and brightest who want to serve. Instead, it’s designed to keep the worst of this country’s young people from joining. In the words of the young former captain, it’s a defensive system designed to keep people out, not an offensive system designed to entice them.

The most significant challenge for Canada’s military isn’t the need

THE SYSTEM’S ULTIMATE FAULT IS THAT IT’S NOT DESIGNED TO ATTRACT THE BEST AND BRIGHTEST WHO WANT TO SERVE.

for modern kit, it’s the need for a smart cohort of young and educated people who want to challenge themselves for the most difficult job any country can offer—to go into harm’s way to guard those of us at home. Standing on guard is hard enough without having to claw through the narrow doors of a thoroughly broken recruitment system. L

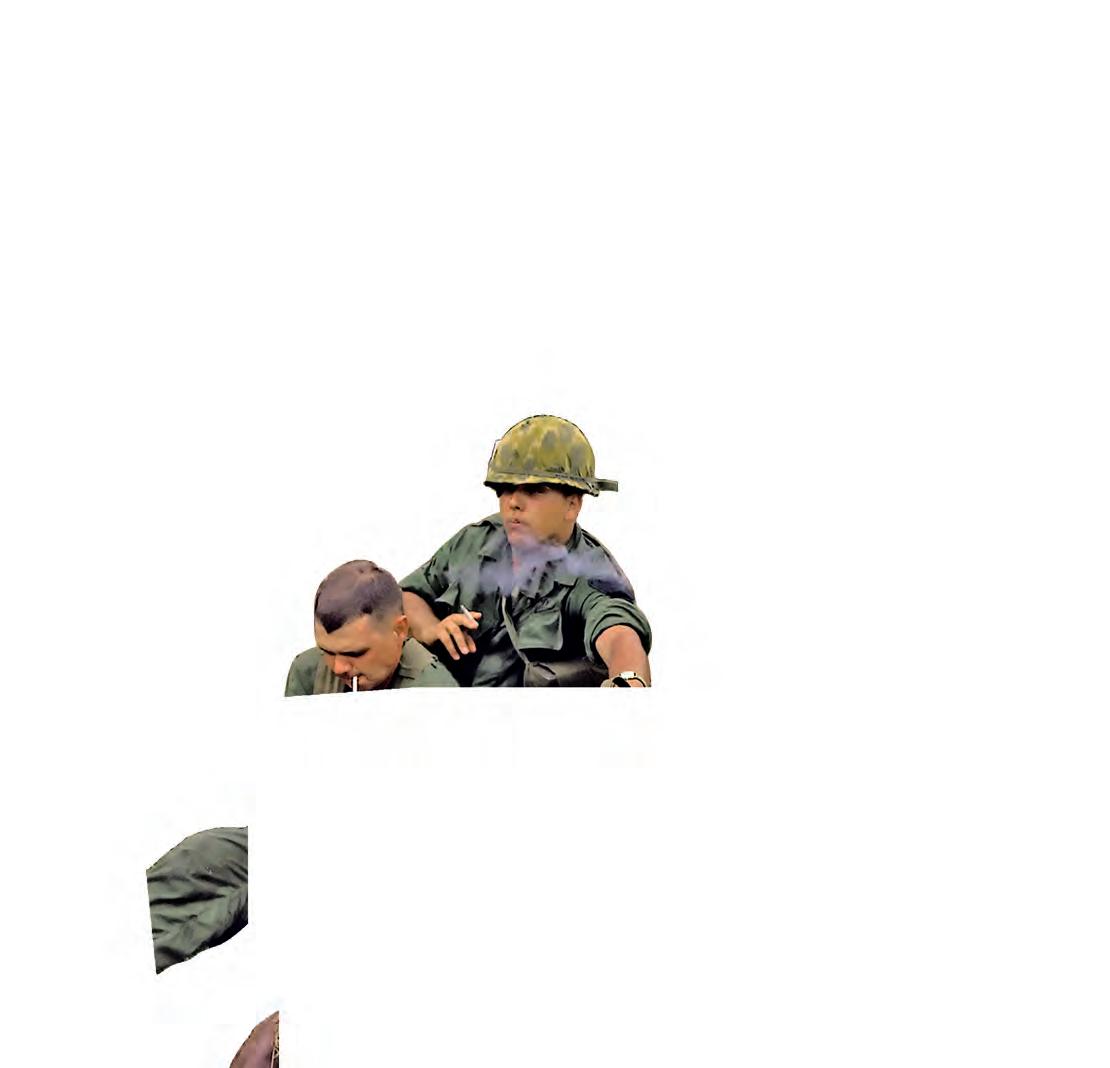

An American “tunnel rat” of Troop B, 1st Reconnaissance Squadron, 9th Cavalry, 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), is lowered into a Viet Cong tunnel on April 24, 1967.

By Stephen J. Thorne

For all the advances in humankind’s abilities to wage war, one particular tactic has bedevilled military strategists from ancient times to this day: tunnels.

Tunnels have figured in battles for millennia, from ancient Egypt through the ages of Macedonian and Roman conquest, two world wars, the Vietnam War and onward. They’ve provided cover, storage and surprise; overcome (or undermined) obstacles, optimized the strength of modest forces and maximized their hitting power. They remain hard to detect and difficult for anyone but their occupants to navigate.

Ancient Egyptians tunnelled beneath city walls; Assyrians were employing specialized engineering troops as early as 850 BC.

In his Histories, the Greek historian Polybius describes mining and

counter-mining during the Roman siege in 338 BC at the ancient Greek city of Ambracia, where its Aetolian defenders’ “gallant resistance” compelled the attacking forces to resort to mines and tunnels. This, in turn, brought what were, for their time, remarkable countermeasures.

“For a considerable number of days the besieged did not discover them carrying the earth away through the shaft,” wrote Polybius. “But when the heap of earth thus brought out became too high to be concealed from those inside the city, the commanders of the besieged garrison set to work vigorously digging a trench inside, parallel to the wall and to the stoa which faced the towers.

“When the trench was made to the required depth, they next placed in a row along the side of the trench nearest the wall a number of brazen vessels made very thin; and, as they walked along the bottom of the trench past these, they listened for the noise of the digging outside. Having marked the spot indicated by any of these brazen vessels, which were extraordinarily sensitive and vibrated to the sound outside, they began digging from within, at right angles to the trench, another tunnel leading under the wall, so calculated as to exactly hit the enemy’s tunnel.

“This was soon accomplished, for the Romans had not only brought their mine up to the wall, but had under-pinned a considerable length of it on either side of their mine; and thus the two parties found themselves face to face.”

The Aetolians then released smoke from burning feathers and charcoal, essentially unleashing an early form of chemical warfare.

“THE TUNNEL WAR IS ONE OF THE MOST IMPORTANT AND MOST DANGEROUS MILITARY TACTICS IN THE FACE OF THE ISRAELI ARMY.”

Despite the development of daunting countermeasures, however, tunnels became such an effective tactic that, early on, the very threat of them could inspire fear and capitulation.

Philip V of Macedon discovered the ground was too rocky and hard for mining during his siege at the fortified town of Prinassos in 201 BC. So, he ordered his soldiers to collect earth from elsewhere under cover of night and throw it all down at a fake tunnel entrance, suggesting the Macedonians were nearing completion of a tunnel system. When Philip then falsely declared that his army had undermined large parts of the town walls, its citizens promptly surrendered.

In the Middle East, archeologists recently uncovered a vast tunnel system under northern Israel believed to have been used by Jewish rebels fighting Roman occupation 2,000 years ago.

Indeed, tunnels are an age-old tool in the region where, during the Syrian Civil War in Aleppo in March 2015, rebels detonated explosives beneath the headquarters of the Syrian Air Force Intelligence Directorate, killing dozens.

Mining became standard in siege warfare and, by the 17th century, architects were including complex counter-mining measures into their geometric fortifications.

Ever more powerful artillery rendered sieges a shrinking element of warfare until new tunnelling tactics evolved during the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-05.

During the largely stagnant warfare on the First World War’s Western Front, sappers from both sides—Canadian miners among them—began tunnelling under enemy trenches, planting massive explosives beneath opposing armies, and literally blowing them to bits. The terrifying prospect of an undetected enemy suddenly and decisively taking out an entire frontline trench works and its occupants, without ever showing their faces, proved a formidable psychological weapon as well as a practical one.

On the Pacific island of Iwo Jima, a key stepping stone in the Allied march north during the Second World War, Japanese troops dug a network of tunnels and caves from which they mounted a suicidal defence that exacted a mighty price on the U.S. Marine Corps.

Two decades later, in the C ủ Chi District of Saigon (now Ho Chi Minh City), Viet Cong guerillas operated incognito from a vast tunnel network, mounting major operations that plagued American forces for much of the Vietnam War, including the pivotal Tết Offensive of 1968.

Today, tunnels figure infamously in the Hamas-governed Gaza Strip.

In the Palestinian enclave, the loose, easily dug subsoil is the stuff of legend. Its tunnels have confounded armies since Alexander the Great’s siege in 332 BC to Israel’s current offensive against Hamas militants.

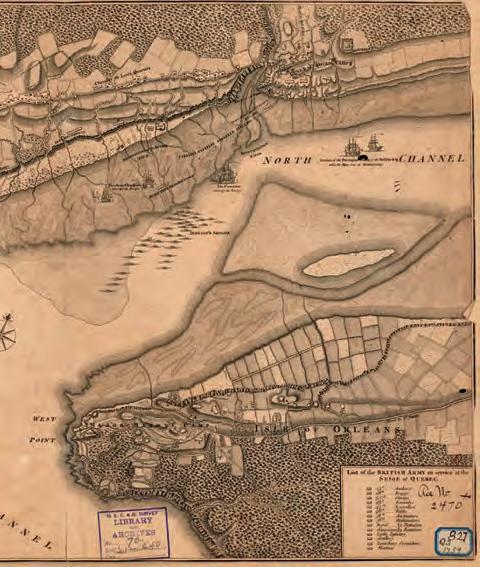

As Jean-Pierre Filiu writes in his book, Gaza: A History, Alexander expected a quick victory on the road to Egypt when he set out to take the fortified city on the Mediterranean Sea. It wasn’t to be. Instead, his Macedonian army was forced into what Filiu describes as 100 days of “fruitless attacks and tunneling,” the latter by both the defending Persians and his invading army.

The Gazan commander Batis had known Alexander was coming. He prepared, shoring up fortifications and building an extensive tunnel network. It took Alexander four attempts to overcome his enemy, and the Macedonian commander was wounded in the process.

Batis’ steadfast defence, and refusal to kneel before his ultimate conqueror, so infuriated Alexander that the usually compassionate victor ordered the men of Gaza killed, its women and children sold into slavery, and Batis dragged to death behind his chariot.

A Syrian soldier walks a tunnel during a battle with Assad regime forces in Aleppo, Syria, on Aug. 20, 2015. Fighters from the Democratic Front for the Liberation of Palestine press forward through a tunnel in the southern Gaza Strip on May 19, 2023.

Gaza’s tunnels have been infuriating prospective conquerors ever since. Ottoman Turks constructed tunnels during the First World War as they tried unsuccessfully to hold onto what had been for centuries a strategic link between Persia and Egypt.

The Gazan tunnel network expanded after Israel’s statehood in 1948, particularly once Hamas took power in the enclave in 2007.

Known as the Gaza metro, estimates of the size and scope of the tunnels vary. Daniel Rubenstein, former director of the U.S. State Department’s Office of Israel and Palestinian Affairs, has written that Israel discovered 100 kilometres of underground passages during the 2014 Gaza War, a third of them beneath Israeli territory.

Yaniv Kubovich, a journalist with the Israeli newspaper Haaretz, reported in 2021 that Hamas had since constructed “hundreds of kilometers of tunnels the length and breadth of the Gaza Strip.”

Senior Iranian officials, who were involved in the project, have estimated the network at 400 to more than 500 kilometres long.

The labyrinth is used to smuggle goods and people in and out of the

territory, while Hamas and other militant groups use it for a variety of purposes, including: to store weapons; gather and move underground; communicate, train and launch attacks from it; transport hostages through it; and retreat undetected by Israeli or Egyptian authorities.

“Most tunnels have several access points and routes, starting in several homes or in chicken coops, joining together into a main route, and then branching off again into several separate passages leading into buildings on the other side,” architect Eyal Weizman wrote in his book, Hollow Land: Israel’s Architecture of Occupation

Israeli defence officials estimated that in 2014, Hamas spent US$30 million-$90 million and poured 600,000 tonnes of concrete in building three dozen tunnels, some of them costing as much $3 million apiece.

Workers laboured 8-12 hours a day, earning US$150-$300 a month running jackhammers and digging down 18-25 metres

advancing 4-5 metres a day. The notoriously sandy soil required more durable levels of rooftop clay and reinforced concrete panels that were manufactured in workshops adjacent to each tunnel.

It was dangerous work. Hamas reported that 22 members of its armed wing died in underground mishaps—accidental explosions and passage collapses—in 2017.

Buried deep, the shafts are about two metres high by a metre wide, and have electric lights and fixtures. Some even have tracks for transport. They are sometimes booby-trapped.

Hamas is said to have addressed a host of potential challenges, including possibilities that Israeli forces could gas, flood, or blow up parts of the tunnels.

The passages have been used to launch raids, stage kidnappings and resupply the Palestinian resistance. Hamas terrorists used them during the Oct. 7, 2023, attacks on Israeli border communities in which they killed some 1,200 people, including at least seven Canadians, and wounded more than 2,500 others.

Palestinians move through a tunnel used for military exercises during a weapons exhibition at a Hamas-run youth summer camp in Gaza City on July 21, 2016. Soldier/artist Ted Zuber depicts Canadian troops and Korean labourers in a tunnel on the Korean peninsula on New Year’s Eve 1952.

An estimated 250 hostages were taken. Survivors have reported groups were transported and kept in the tunnel network.

Whatever can be said of Israel’s merciless response to the attacks, its defence forces have encountered a significant and complex problem in the Gazan tunnels.

“The tunnel war is one of the most important and most dangerous military tactics in the face of the Israeli army because it features a qualitative and strategic dimension, because of its human and morale effects, and because of its serious threat and unprecedented challenge to the Israeli military machine, which is heavily armed and follows security doctrines involving protection measures and preemption,” Adnan Abu Amer wrote for the Al-Monitor, a Middle East newspaper.

The tactic is to “surprise the enemy and strike it a deadly blow that doesn’t allow a chance for survival or escape or allow him a chance to confront and defend itself.”

Tunnelling took on new dimensions during the First World War when what was amounting to a protracted stalemate in France and Belgium inspired a rethink of underground warfare.

German pioneers blew the war’s first mine in late 1914. Isolated British efforts soon evolved into the formation of specialized tunnelling companies co-ordinated by John Norton-Griffiths, a millionaire entrepreneur, MP and mining engineer who had been advocating for subsurface tactics since the fighting began.

Norton-Griffiths was authorized to raise a tunnelling company in

TUNNELS BECAME SUCH AN EFFECTIVE TACTIC THAT, EARLY ON, THE VERY THREAT OF THEM COULD INSPIRE FEAR AND CAPITULATION.

February 1915, recruiting workers he had employed to extend Manchester’s sewage system. He had recognized that Manchester’s geology was similar to Flanders’ and that his miners could transfer the technique known as “clay kicking” to the front lines.

Norton-Griffiths had his first 18 clay kickers—the term inspired by the way the men worked— enlisted and tunnelling to the enemy within 36 hours.

“With his back braced the seated miner would use his legs to push an extremely sharp ‘grafting tool’ into

the clay,” explained Engineers at War, a website exploring all things related to combat engineering.

“Working from the bottom up the kicker would work 9 inches before fixing a set of timber, a bagger would bag up the spoil and a trammer loaded a tram taking the spoil to the surface. The process was almost silent and very fast.”

Four times faster than traditional mining methods in the firm clay of the Western Front, in fact. To maintain silence, no nails or screws were used to hold supporting timbers together; they relied

on the natural swelling of the clay to keep them in place. The process was unknown to the Germans.

Tunnelling capabilities rapidly expanded. On Sept. 10, 1915, the British government sent appeals for tunnelling companies to Canada, South Africa, Australia and New Zealand.

The Canadian Military Engineers raised four tunnelling companies; three served at the front with British formations under the Controller of Mines at General Headquarters. One of the units was formed from men on the battlefield; the two other front-line companies trained in Canada before shipping out.

Formed in Eastern Canada, No. 1 Tunnelling Company moved into the Ypres salient for further instruction in early 1916. By March, it was relieving the British 182nd Tunnelling Company near Armentières, then moved to The Bluff near St. Eloi in Belgium.

Mining operations peaked in 1916 when some 30 Allied tunnelling companies and 30,000-40,000 men were waging underground warfare, their tunnels protecting 50 of the 129 kilometres of British-held front line. Some 1,500 mines were blown in 1916 alone.

In the chalky soil of the Somme, Norton-Griffiths turned to coalmining techniques. He was allowed to bring in overaged recruits, whose experience would prove vital.

“Digging proceeded with pick and some mechanisation but many tunnel galleries and mine chambers still had to be completed by hand, cutting the chalk with bayonets to limit noise,” said the engineers’ site.

“In this way extensive systems progressed along and across the front lines; spearheading an enormous logistical effort to supply timber, explosives and other equipment whilst ensuring that spoil and any other sign of mining remained unobserved.”

British combat engineers blew up 19 mines under German lines on the Battle of the Somme’s first day, destroying fortifications and killing hundreds of German troops. But the tactic failed to secure the objectives British commanders had hoped for.

In fact, the craters they created became traps for Allied soldiers who poured into them only to become easy prey for German artillery and machine-gunners.

Tunnelling companies of Royal Engineers, many of them Welsh and north English coal

miners, had dug passages up to 17 metres down and almost a kilometre long, penetrating deep under key German positions.

In some areas they dug saps, or covered trenches, from the British front lines into no man’s land in efforts to shorten the attackers’ exposure to enemy fire once they launched their assaults.

Silence and secrecy were paramount. Both sides maintained underground listening posts to monitor enemy activity and progress.

“At first relatively rudimentary methods such as water in a glass and augers were used,” said the engineers’ site, “but by 1915 the introduction of geophones was enabling much more accuracy. Using these, tunnelling could be heard in clay from 100m and in chalk from a 240m distance.

“Establishing quiet relied fundamentally on discipline and attention to detail. British miners wore plimsolls underground, Germans remained in their hobnailed boots; British trucks and trams ran on rails screwed into place, German rails were nailed and by 1916 all British mine trolleys had self-oiling bearings.”

Nevertheless, British Captain Stanley Bullock of the 179th Tunnelling Company said his crews could hear German miners working toward them, creating the prospect of pre-emptive explosions or subterranean combat. The Brits finished a small chamber in which to plant explosives just before the Germans stopped their underground advance.

“I used to hate going to listen in that chamber more than any other place in the mine,” wrote Bullock. “Half an hour, sometimes once, sometimes three times a day, in deadly silence with the geophone to your ears, wondering whether the sound you heard was the Boche working silently or your own heart beating.

“THERE WAS AN EAR-SPLITTING ROAR, DROWNING ALL THE GUNS, FLINGING THE MACHINE SIDEWAYS IN THE REPERCUSSING AIR. THE EARTHLY COLUMN ROSE, HIGHER AND HIGHER.”

“God knows how we kept our nerves and judgment. After the Somme attack when we surveyed the German mines and connected up to our own system…we found that we were five feet apart.”

The charges were massive: some 25,000 kilograms of explosive at the site known as Lochnagar near La Boisselle, 18,000 kilograms each at H3 (Hawthorn Ridge) near Beaumont-Hamel and Y Sap in La Boisselle and, in three large mines opposite Fricourt: 11,000 kilograms at G15, 6,800 kilograms at G19 and 4,000 kilograms at G3.

There were others too, including lighter charges in shallower mines designed to remove smaller German positions such as machine-gun posts.

When they were triggered on July 1, 1916, the Lochnagar and Hawthorn Ridge mines were the largest ever detonated. They were deemed at the time to be the loudest artificial noises in history, reportedly heard as far away as London.

Fighter ace Cecil Lewis’s aircraft was hit by lumps of mud from the explosions at La Boisselle. “We were over Thiepval and turned south to watch the mines,” wrote Lewis.

“As we sailed down above all, came the final moment…the earth heaved and flashed, a tremendous and magnificent column rose up into the sky.

“There was an ear-splitting roar, drowning all the guns, flinging the machine sideways in the repercussing air. The earthly column rose, higher and higher to almost four thousand feet. There it hung, or seemed to hang, for a moment in the air, like a silhouette of some great cypress tree, then fell away in a widening cone of dust and debris. A moment later came the second mine. Again the roar, the upflung machine, the strange gaunt silhouette invading the sky. Then the dust cleared and we saw the two white eyes of the craters. The barrage had lifted to the second-line trenches, the infantry were over the top, the attack had begun.”

The officer in charge detonated the Kasino Point mine late when he saw that British troops had left their trenches and begun their advance. Instead of exploding upward, it sent debris outward over a wide area, obliterating several German machine-gun nests, but also causing casualties among at least four British battalions.

“I looked left to see if my men were keeping a straight line,” said Lance-Corporal E.J. Fisher of the 10th Essex Regiment. “I saw a sight I shall never forget. A giant fountain, rising from our line of men, about 100 yards from me.

“Still on the move I stared at this, not realizing what it was. It rose, a great column nearly as high as Nelson’s Column, then slowly toppled over. Before I could think, I saw huge slabs of earth and chalk thudding down, some with flames attached, onto the troops as they advanced.”

Planners ultimately decided the negatives of mining the Somme outweighed the positives, and opted against offensive mining in the Canadian attack on Vimy Ridge the following April.

The war’s most successful mining operation took place in 1917 during the Messines Ridge offensive on the Ypres salient, where 6,000 sappers and attached infantry prepared 19 mines and distributed nearly 450 tonnes of explosives across a 16-kilometre front.

Canadian tunnelling companies blew five of the mines during the battle in which engineers detonated all 19 at 3:10 a.m. on June 7, 1917, just before nine divisions from Britain, Ireland, Australia and

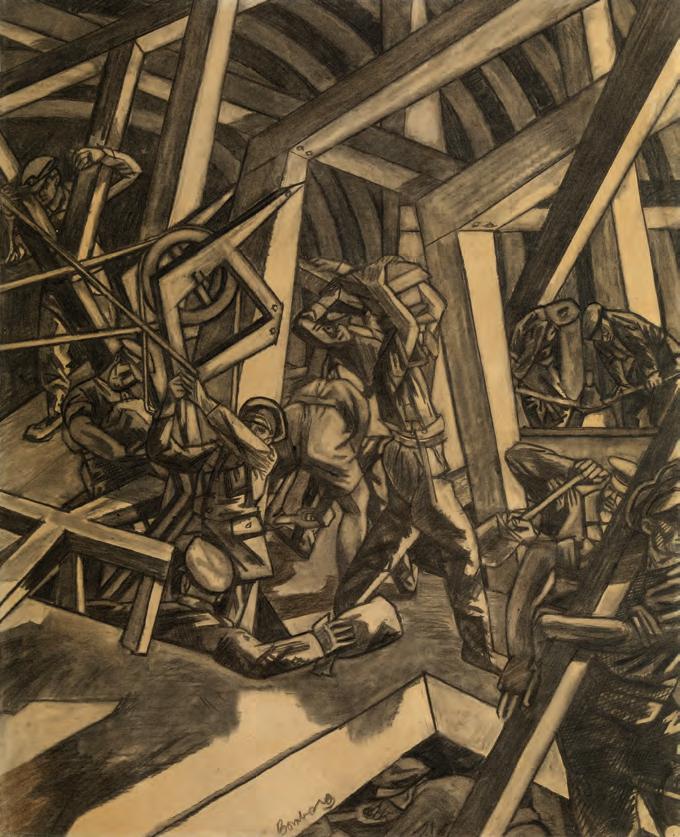

Sappers blow a mine beneath the German field fortification on Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt during the WW I Battle of the Somme on July 1, 1916. Artist David Bomberg depicts Canadian engineers building a tunnel near St. Eloi, Belgium, in 1918.

New Zealand assaulted German positions on the ridge.

“The [mining] effort was enormous, relying on successful dispersals of tons of spoil, accurate surveying of targeted German positions and the constant husbandry of many mines which had been laid and tamped over a year in advance,” said the engineers’ site.

“Time and geology combined to allow an extensive system which, when blown, destroyed an enormous area of ground and is thought to have instantly killed 10,000 Germans. The remaining defenders were profoundly disorientated and incapable of mounting any resistance to the British attack.”

Even some British troops amassed on the Allied line were concussed.

Messines essentially marked the end of large-scale offensive mining operations. Tunnelling companies were instead increasingly used to construct enormous subterranean systems of accommodation, headquarters, dressing stations and subways.

Nearly a century later, archeologists uncovered the labyrinth of tunnels at La Boisselle, finding poems and soldiers’ signatures etched into the walls along with hundreds of artifacts, including ammunition and discarded food tins.

“It is such an amazing piece of history and it’s so fresh,” genealogist Glen Phillips told the BBC in 2014. “The signatures have been there for nearly 100 years and because the tunnels have been sealed up, they are as fresh as the day they were made…like doodles on a notebook.”

Two of Canada’s three mining companies were disbanded in the summer of 1918 and their 1,100 tunnellers redistributed throughout Canadian engineer battalions.

During the war’s final Hundred Days Offensive in 1918, Allied sappers—including the last remaining Canadian mining company, the 3rd—removed more than 1,100 tonnes of explosives from German mines and booby traps.

It was during this final push with the 4th Canadian Division to prevent the demolition of bridges on the Canal de l’Escaut, northeast of Cambrai, in which Captain Coulson Norman Mitchell, a 28-year-old combat engineer from Winnipeg, earned a Victoria Cross.

On the night of Oct. 8-9, Mitchell led a small party ahead of the first wave of infantry to examine the canal bridges and try to keep them intact.

“On reaching the canal he found the bridge already blown up,” said his VC citation. “Under a heavy barrage he crossed to the next bridge, where he cut a number of ‘lead’ wires. Then in total darkness, and unaware of the position

or strength of the enemy at the bridgehead, he dashed across the main bridge over the canal.

“This bridge was found to be heavily charged for demolition, and whilst Capt. Mitchell, assisted by his N.C.O., was cutting the wires, the enemy attempted to rush the bridge in order to blow the charges, whereupon he at once dashed to the assistance of his sentry, who had been wounded, killed three of the enemy, captured 12, and maintained the bridgehead until reinforced.”

Mitchell continued cutting wires and removing charges, all while under heavy fire and the lingering threat that the explosives could be triggered at any moment.

“It was entirely due to his valour and decisive action that this important bridge across the canal was saved from destruction.”

He was the only Canadian combat engineer to receive a VC for First World War actions. L

How the Great War’s Canadian nurses brought comfort and care to patients while enduring their own personal turmoil

Sisters

ACT C

Anna Stamers, Margaret Macdonald and Jessie Brown Jaggard (opposite, top to bottom) played critical roles during the First World War as nurses, an in-demand role as this recruiting poster for the Voluntary Aid Detachments makes clear. The ward of a Canadian Casualty Clearing Station in Valenciennes, France, in November 1918 (bottom).

CBy Alex Bowers

Canadian Nursing Sister

Anna Stamers of Saint John, N.B., bound for England aboard Metagama, pondered her fate across the ocean.

Having graduated from her local nursing school in 1913 before accumulating two years’ relevant work experience, the Maritimer appeared prepared for the challenge ahead that June 1915—at least on the surface.

The reality, as is so often the case with conflict—regardless of specific roles and duties— seldom matched expectations.

Indeed, for Stamers and the 2,844 other nurses who served in the Canadian Army

Medical Corps (CAMC) during the First World War, destiny brought many of the same horrors witnessed and experienced by soldiers on the front lines. And like those soldiers, not every nurse would sail home.

Matron-in-Chief Margaret Macdonald (second from right) and nursing sister colleagues in wartime London. Gerald Moira depicts wartime action at the No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital in Doullens, France.

Such realities, however, were not without precedent.

While organized military nursing boasted strong roots in the 1853-1856 Crimean War, women had acted as battlefield caregivers long before the groundbreaking work of Florence Nightingale and Mary Seacole.

In Canada alone, Jeanne Mance and the nursing sisters of St. Joseph de La Flèche had tended to wounded troops in 17th-century New France. Canadian nurses had also served in the 1885 North-West Resistance, as well as during the 1899-1902 Boer War.

When war was declared in 1914, an influx of more than 1,000 applications showed that Canadian nurses were again willing to answer the call.

Like their male counterparts, motivations to serve varied, although adventure, duty, status, career aspirations and financial security were the most common factors. Unlike their arms-bearing comrades—a high proportion of whom were immigrants—some 83 per cent of WW I Canadian nurses were born in the country.

The earliest months of the war had nevertheless seen applicants whittled down to only the most eligible, a task carried out by Matron-in-Chief

Margaret Macdonald. Noted as the first woman in the British Empire to achieve the rank of major, Macdonald had initially selected just 100 nurses to join the CAMC.

Many more, not least the 27-year-old Stamers, followed when the desperate need for additional support became evident.

Among the requirements, those chosen were expected to be welltrained, experienced and display traits deemed appropriate for the dynamic, high-pressure environments they would soon encounter.

Almost always unmarried, the nurses’ average enlistment age was 29.9, making them slightly older than most soldiers in the Canadian Expeditionary Force (CEF)—sometimes dubbed their “boys” when admitted as patients.

Canadian nursing sisters, as they were called despite the lack of religious affiliations, were commissioned as lieutenants with equal pay to men of the same rank. This, along with the women’s sharp blue uniforms, white aprons, CAMC buttons, and two stars on the shoulder straps, became the envy of their British peers. Their distinctive appearance, meanwhile, earned them the affectionate nickname, Bluebirds.

A capacity for tenderness would be necessary once the women established themselves at hospitals and casualty clearing stations, the latter a short distance from the front and often well within range of enemy artillery fire.

Yet perhaps above all else, the Bluebirds required resolve to deal with the lethal efficiency of industrialized warfare—as they would soon discover.

Katharine (Kate) Wilson of Chatsworth, Ont., came to understand flesh torn from the body, muscles ripped to shreds, limbs turned gangrenous, and bones splintered into countless pieces. As part of No. 3 Canadian Stationary Hospital situated in the Dardanelles theatre in 1915, there was an equally deadly killer to contend with.

“Here,” wrote the Canadian nursing sister, “practically every man admitted was critically ill with fevers that left them eventually worn to skeletons.”

While disease itself was hardly a surprise, the global nature of the Great War brought with it varying health-care challenges. On the Western Front after the Second Battle of Ypres, it was gas; on the Greek island of Lemnos in

support of the ill-fated Gallipoli Campaign against the Ottomans, dysentery had run rampant.

On Sept. 25, 1915, the pestilence claimed 42-year-old Matron Jessie Brown Jaggard of Wolfville, N.S., a figure held in high regard by the nurses, and who left behind a grieving cousin in Prime Minister Robert Borden.

“Lying with the picture of her seventeen year old son smiling down at her,” Wilson recorded of the beloved matron’s death, “one night she closed her eyes for the last time and slept. In her service blue uniform...covered with a British flag...and carried by boys who knew and loved her, she was laid to rest. Forever she will remain in the hearts of those who were privileged to serve under her.”

With additional Canadian deaths anticipated, a makeshift cemetery was created. Beside these premature graves stood a sign reading: “For Sisters Only.”

Despite the daily reminder of a perceived fate while plagued by dust and flies, Wilson and her fellow nurses continued under increasingly difficult conditions.

Whether assisting medical or surgical procedures, performing therapeutic nursing techniques, maintaining wards, providing bedside care or carrying out administrative tasks, Bluebirds were typically the backbone of CAMC units.

They also found themselves on the front line of advances in medicine, be it dealing with infection or evolving perceptions around shell shock.

Moreover, when supplies became scarce and, particularly in the case of Lemnos, when temperatures could fluctuate dramatically, simple acts such as a few kind words or an encouraging smile were critical to patients’ morale.

Frequently, of course, compassion could do little to mend bodies shattered beyond healing. In these instances, nursing sisters might showcase their tenderness by joining chaplains in the final hours with dying soldiers.

Holding hands as their boys slipped away, the women could be mistaken for angels sent from above to guide lost souls to the next world.

But then it was on to the next bed, the next soul, as nurses—and all caregivers—found ways to cope with the intense emotional strain.

On Nov. 26, 1915, a freak storm struck Gallipoli. More than 200 troops drowned or froze to death in flash floods and a blizzard. Another 5,000 were evacuated from the peninsula for hypothermia and trench foot.