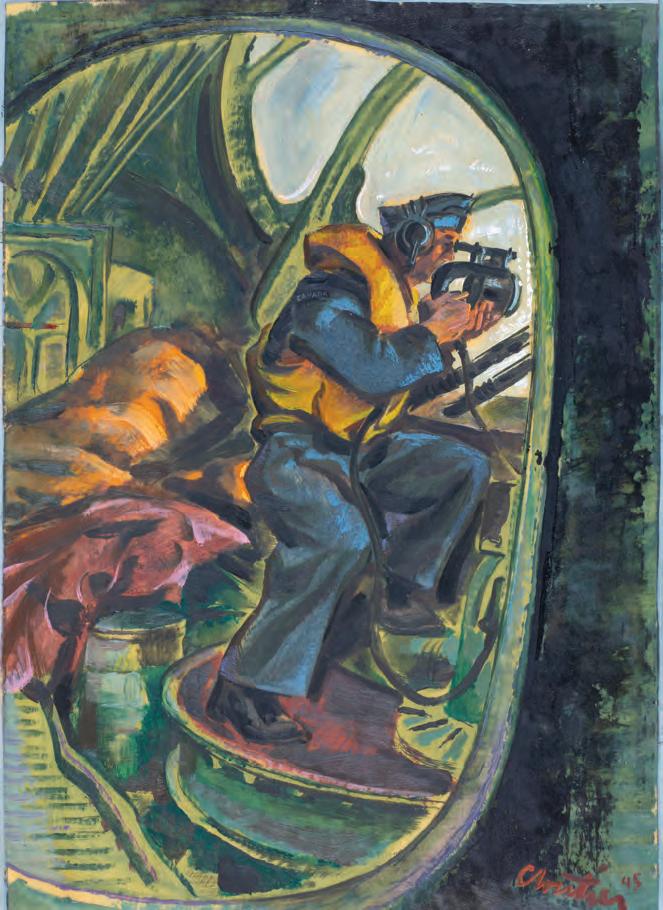

An unidentified sailor operates the signal projector aboard HMCS St. Laurent in 1940.

See page 44

22 THE SHOOTING STAR

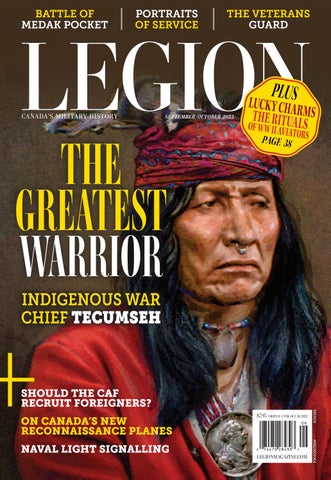

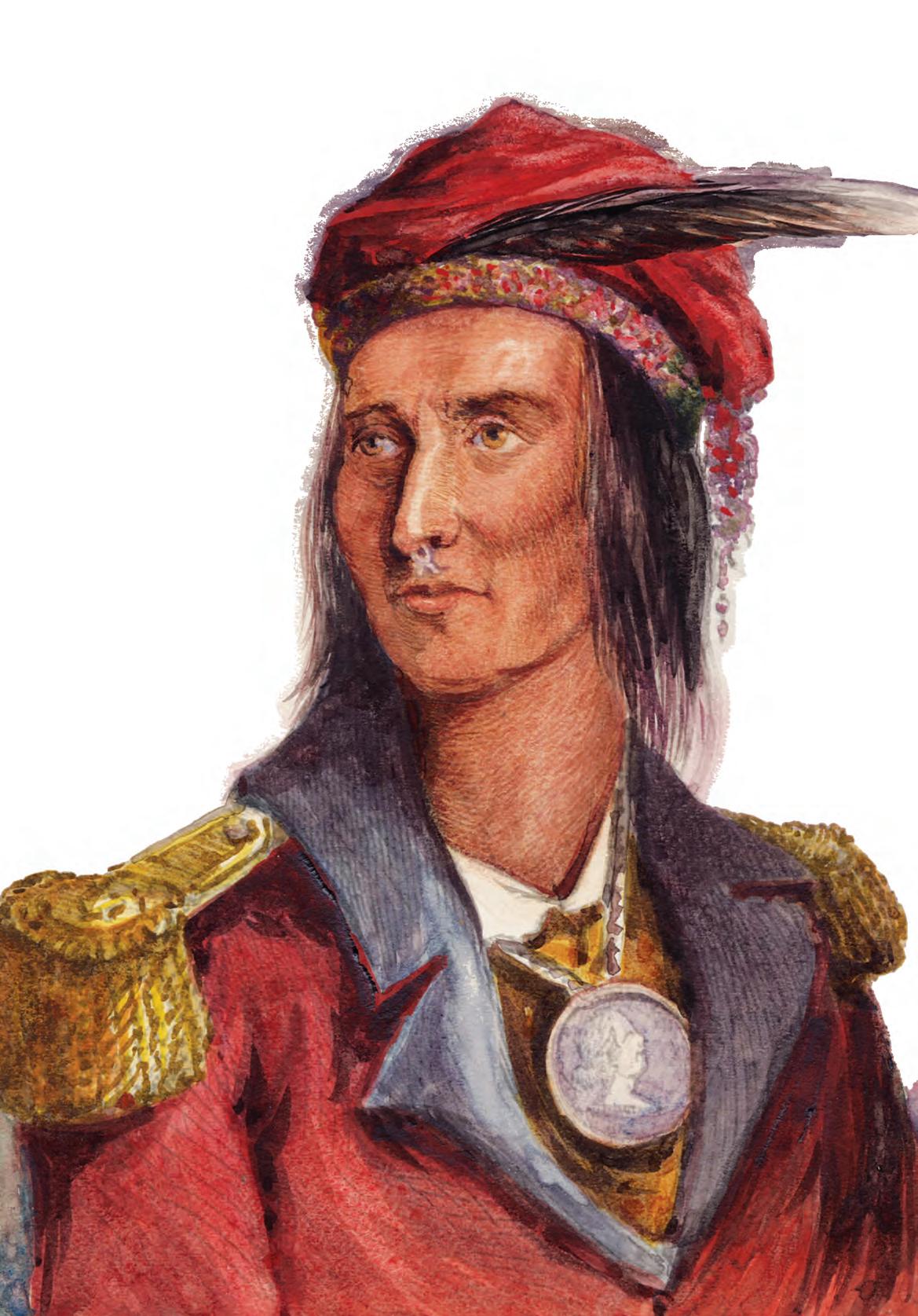

Celebrating the great Shawnee warrior Tecumseh

By Stephen J. Thorne

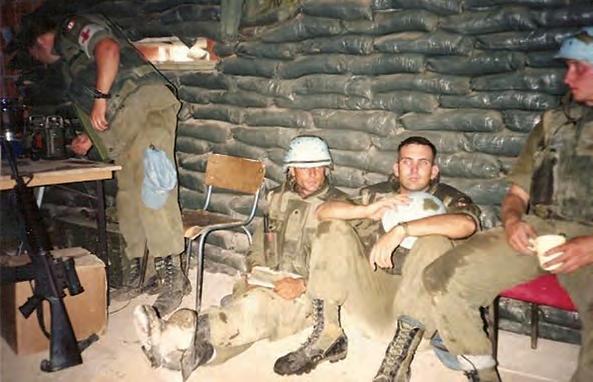

30 FIGHTING THE MONSTERS OF MEDAK

Canada’s key role in a gamechanging peacekeeping mission

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

38 CHARMED LIVES

With overwhelming odds against returning safely from a mission, Second World War Bomber Command aircrews resorted to superstition and ritual

By Graham Chandler

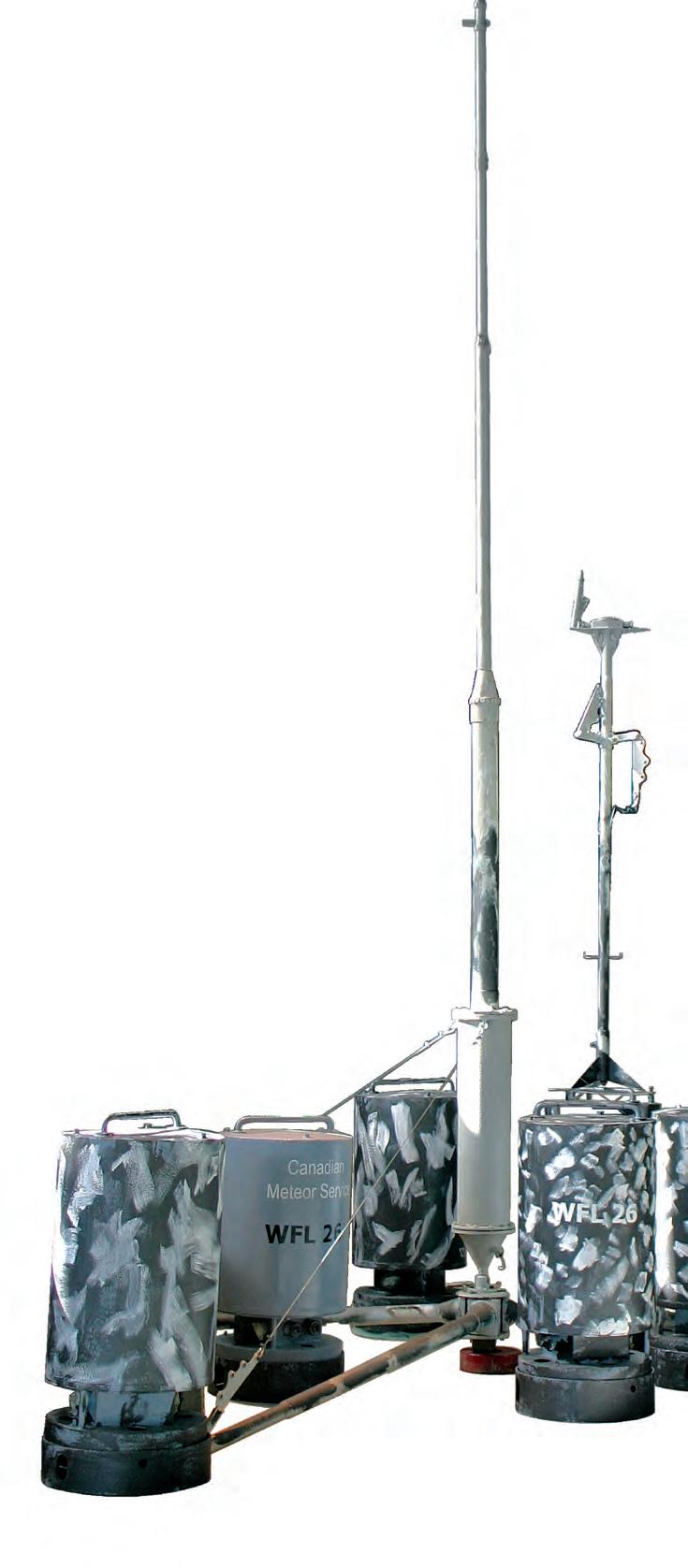

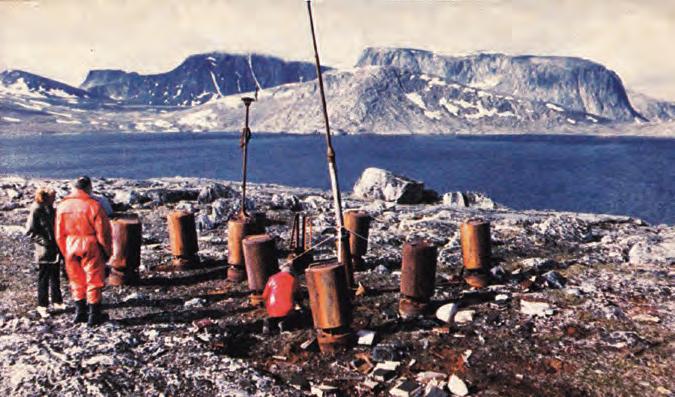

44 LIGHT MY WAY

Naval light signalling was an essential form of communication during the Second World War— and it may live on still

By Douglas Theedom

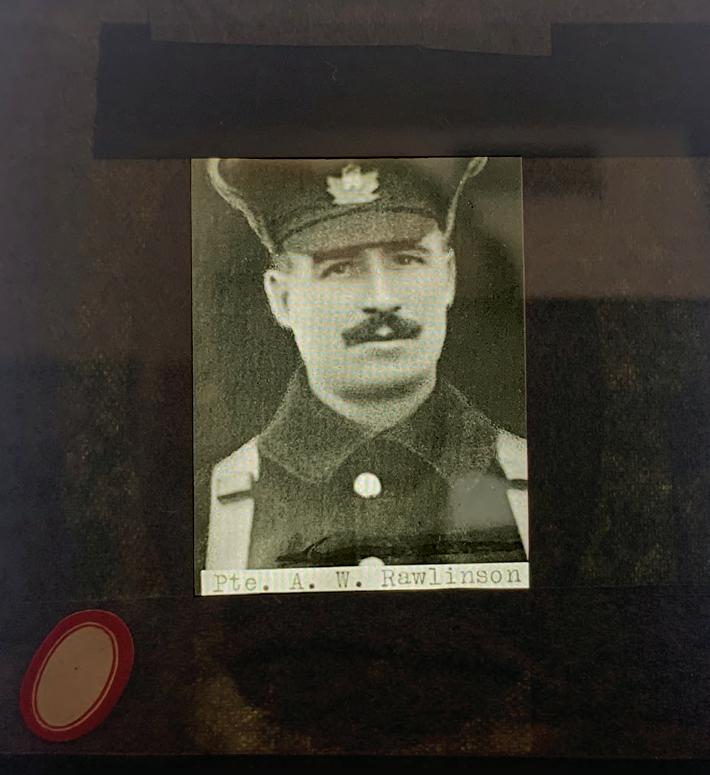

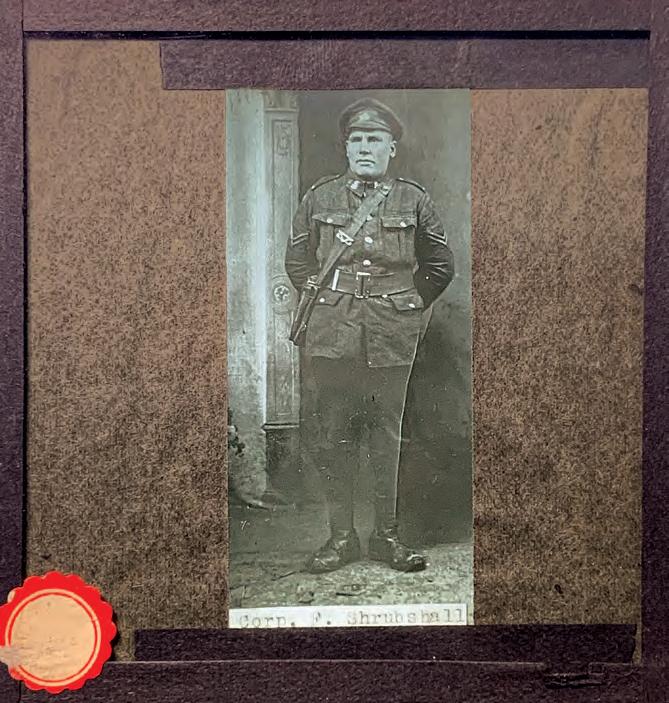

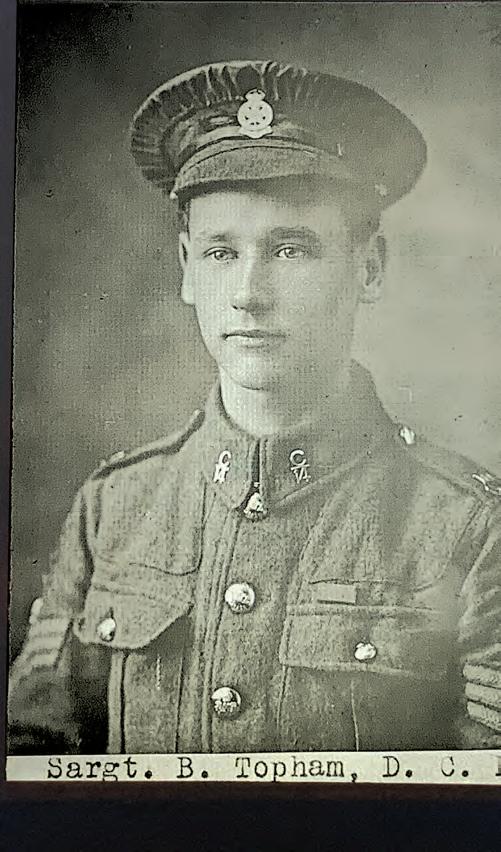

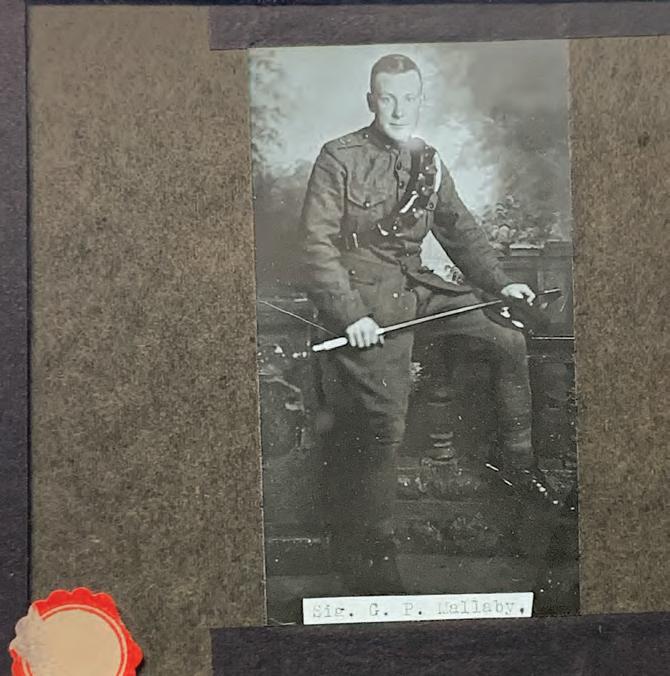

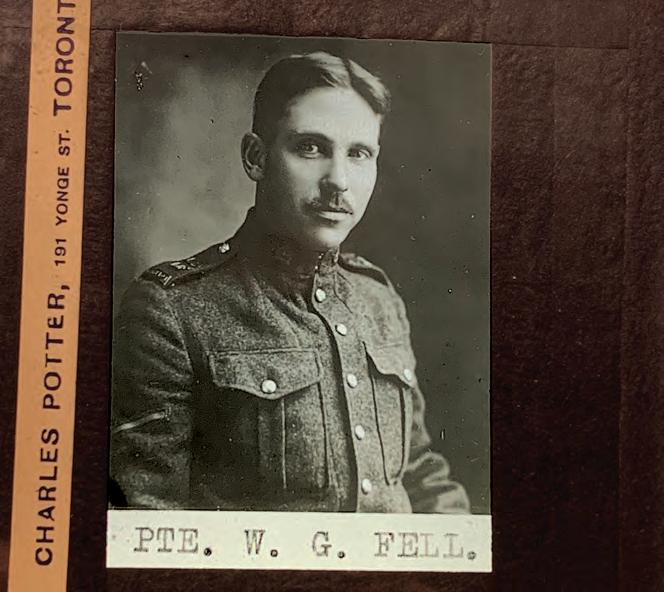

48 OFF TO WAR

A recently unearthed trove of photos captures Canadian men before they embarked to the Great War

By Stephen J. Thorne

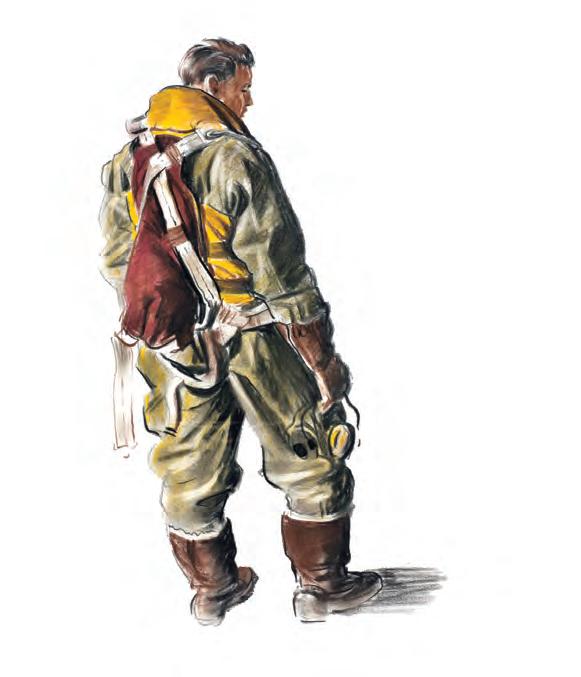

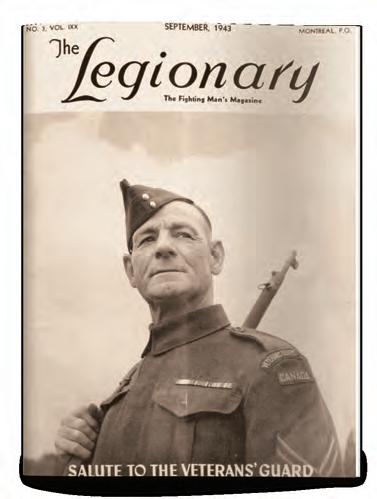

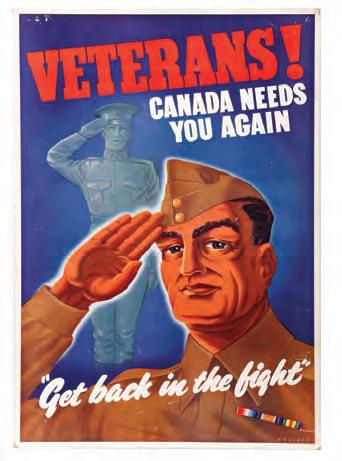

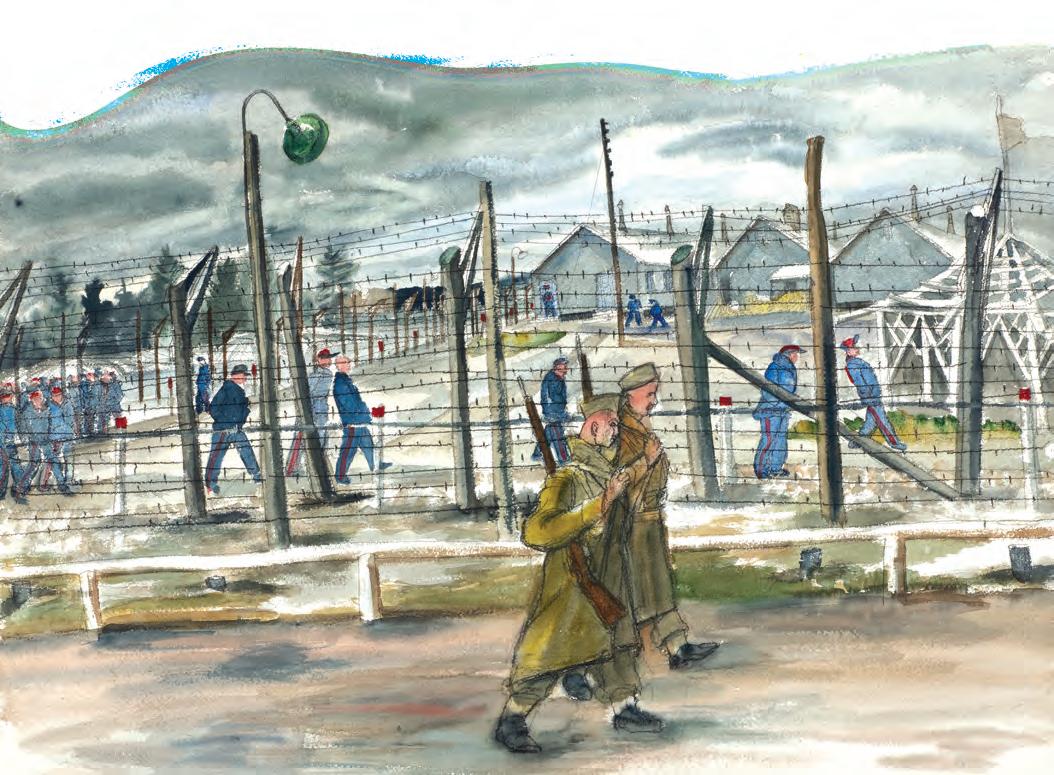

54 TO WAR ONCE MORE

The Veterans Guard of Canada enlisted Great War servicemen for critical tasks at home during WW II

By Serge Durflinger

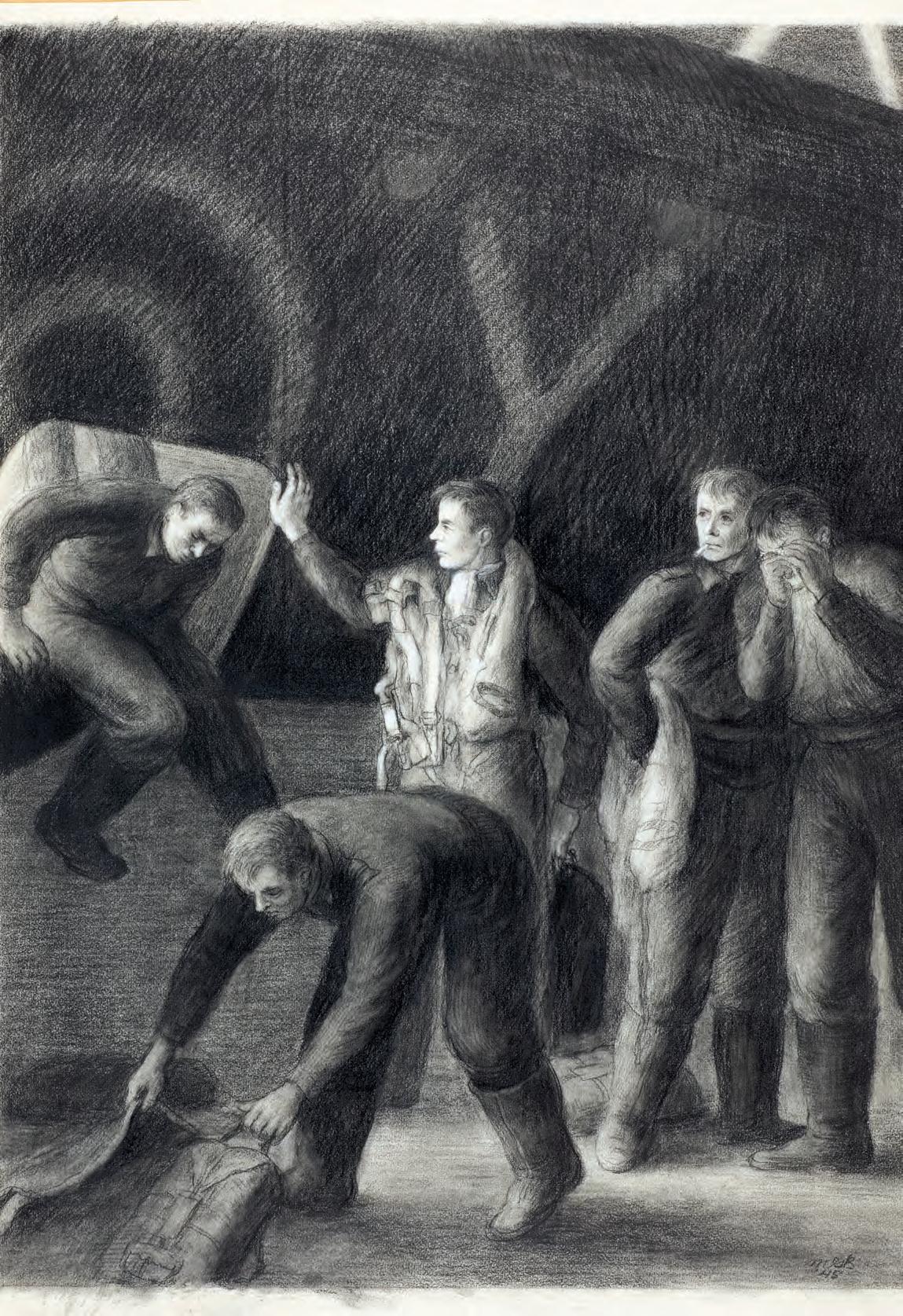

Aircrew and ground crew of No. 428 (Ghost) Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, pose with a Lancaster bomber in August 1944. DND/LAC/e005176190

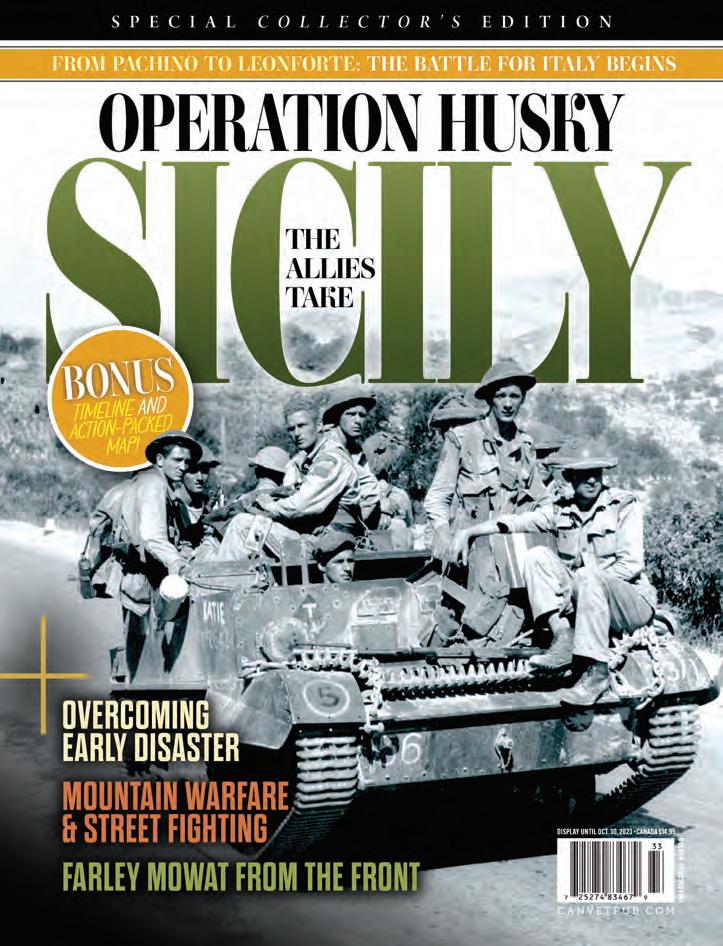

ON THE COVER

A modern portrait of legendary Indigenous warrior Tecumseh. Sharif Tarabay/LM

Forces?

These socks

Vol. 98, No. 5 | September/October 2023

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Owen Parkhouse BOARD VICE-CHAIR Bruce Julian BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe DIRECTORS Tom Bursey, Steven Clark, Thomas Irvine, Berkley Lawrence, Sharon McKeown, Brian Weaver, Irit Weiser

Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

INTERIM

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Lisa McCoy

INTERIM

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Jonathan Harrison

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin (on leave)

Sock Rocket. For each pair produced, three pairs are donated to agencies across Canada providing clothing to Canadian veterans.

Adult

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

STAFF WRITERS

Paige Jasmine Gilmar

Stephen J. Thorne

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert

Advertising Sales

CANIK MARKETING SERVICES

TORONTO advertising@legionmagazine.com

DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS INC mmignardi@dvtail.com OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER AND MARKETING CO-ORDINATOR

Dyann Bernard

WEB DESIGNER AND SOCIAL MEDIA CO-ORDINATOR

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2023. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Change of Address

Send new address and current address label. Or, new address and old address, plus all letters and numbers from top line of address label. If label unavailable, enclose member or subscription number. No change can be made without this number. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com. Allow eight weeks.

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of CCAB, a division of BPA International. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

As a Legion Member, you take pride in the fact that your membership helps support and honour Canada’s Veterans.

Did you know that it comes with benefits you can use, too? Take advantage of all the benefits that come FREE with your membership.

Renew your membership to get all these benefits and more!

MemberPerks® unlocks $1000s in potential savings on offers and deals at stores and restaurants across Canada, including national chains, local businesses and online stores. Use the MemberPerks® app, print out coupons or shop online to save on electronics, travel, fashion, entertainment and so much more!

Your membership also gives you access to additional benefits, including:

• savings and deals from our Membership Partners

• a paid subscription to Legion Magazine

• exclusive members-only items at PoppyStore.ca

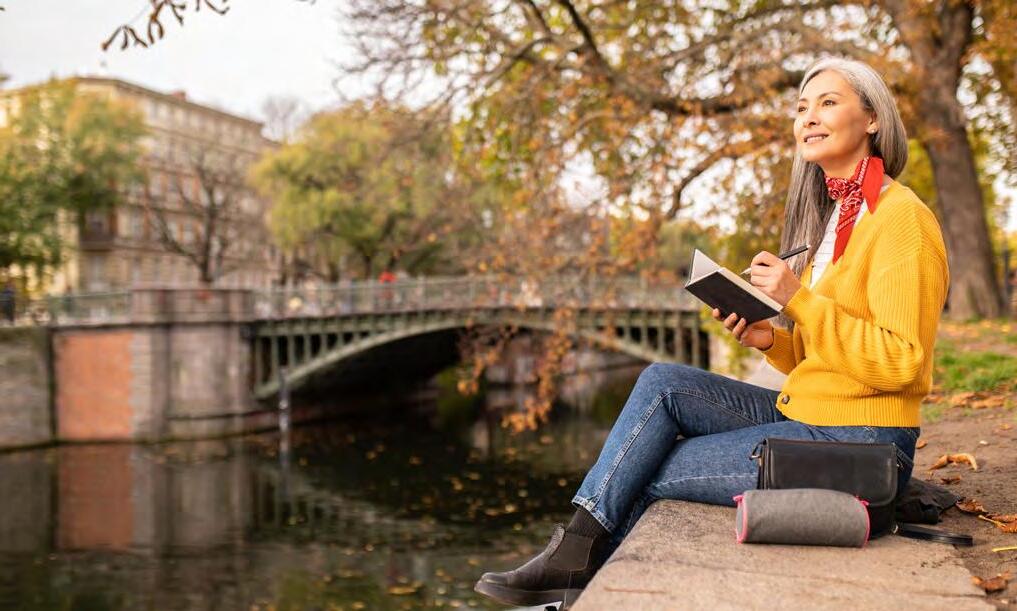

ack in early 2017, a young officer cadet from Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont., confronted the chief of the defence staff at an Ottawa conference and effectively took him to task over a particular challenge facing Canada’s female soldiers.

The ballroom was filled with mostly male academics, diplomats, policy-makers and military brass. They had been considering issues such as world order and the “unravelling” of NATO.

But Officer Cadet Melissa Sanfacon had other concerns on her mind. The future leader got right to the point, informing General Jonathan Vance that the recruitment policies he had just been trumpeting hadn’t been adequately thought through.

“When you speak about getting more women into the force, I’m wondering if at the same time there’s been any thought put to kit that can be actually useful and more suited to women in operations,” said Sanfacon.

She then pointed to the most

fundamental of military gear— body armour and rucksacks. She noted that the U.S. military had started issuing kit specifically designed for women while the Canadian Armed Forces had not.

The frame of her rucksack, she explained, was issued in 1982 for what was then the average soldier: a five-foot, 11-inch, 175-pound male. Sanfacon was four-foot-11 and 100 pounds.

“It’s not quite functional or practical,” she said.

Vance, who later pled guilty to obstruction of justice amid a sexual misconduct scandal, told Sanfacon he agreed with her and arranged a meeting with the army chief.

Six years later, Captain Sanfacon is executive assistant to the director general of Air and Space Force Development, and the issues have not gone away. Vance’s initiative to boost the proportion of women in the military by one per cent a year until it reaches 25 per cent is falling short. It was 14 per cent then; it was 16 in 2022.

And complaints about illfitting body armour for female soldiers have been increasing. But the equipment problems aren’t limited to women.

While its aircraft, ships and vehicles age out and big-money replacements are debated and deferred, even more fundamental equipment is apparently in short supply, or altogether unavailable to deployed Canadian troops, male or female.

In Latvia, Canadian soldiers engaged in live-fire exercises with NATO allies resorted to buying their own ballistic helmets equipped with built-in hearing protection/ headsets along with other personal gear to keep pace. The situation is added humiliation to a country that has fallen short of its NATO spending commitment and is 16,000 members shy of its desired strength.

The government has been justifiably timely and generous in its support for Ukraine’s struggle against Russian invasion—to the tune of more than $8 billion in 19 months. If Ottawa hopes to shore up the ranks and rescue the Canadian military’s reputation, it would do well to afford its own the same consideration. L

early 2023 survey by the Angus Reid Institute indicated that half of Canadians don’t have a will. If you’re one of them, Upper Canada Wills, the newest partner in The Royal Canadian Legion’s exclusive Member Benefits Package (MBP), can help. With offices across the country, local lawyers will walk you through the process of documenting your estate and discussing to whom you would like to leave your personal effects and property. They will ensure your will reflects your wishes. Legion members will receive

50 per cent off standard fees for wills and powers of attorney prepared by Upper Canada. Plus, for every will it arranges, the company will give the Legion a royalty for its veterans-support programs. Visit www.ucwe.ca/legion or call (647) 370-3777 to learn more. The MBP also boasts discounts on electric bikes, adjustable beds and related products, automotive repairs and consultation services, travel packages and specially designed travel insurance, online prescriptions, cellphone plans, eyewear, funerals and much more.

Other MBP partners include Teslica, Ultramatic, PEARL Fleet Vehicle Management, Blowes and Stewart Travel, Pocketpills, IRIS Eyewear, Medipac Travel Insurance, belairdirect car and home insurance, Rogers, HearingLife, Arbor Memorial, Canadian Safe Step Walk-in Tub Company, CHIP Reverse Mortgage and MBNA Canada Bank.

The ever-expanding collection of MBP partners are more than just another benefit of joining the Legion—the exclusive savings they offer can easily add up to cover the membership fee. L

is honoured to partner with the Royal Canadian Legion to provide members with a 50% discount on standard fees for the preparation of Wills and Powers of Attorney

In a recent study published in the Toronto Star it was found that more than half of all Canadian adults did not have a Last Will & Testament or Powers of Attorney.

The operating premise of our national business is that Canadians should have the Peace of Mind in planning their end of life decisions by using the expert advice of lawyers.

It is important that you have Peace of Mind knowing that your Last Will And Testament properly provides the

bequests to your family in accordance with your wishes. It is important that you have Peace of Mind in knowing that with properly drawn Powers of Attorney, decisions to be made for your healthcare and financial needs will be by someone you trust and can depend upon.

Lawyers will take you through the process for your estate documentation every step of the way. You will have person to person discussions on how you would like to leave your personal and real property to your family.

The Directors of Upper Canada WILLS are Legion members too. Our fathers were World War II veterans. As a partner in providing benefits to its members, we will give a royalty to the Royal Canadian Legion for every Last Will & Testament prepared. It is a privilege to contribute to an organization that means so much to us personally.

Legion members and their families can benefit from an exclusive discount on their car, home, condo and tenant’s insurance, on top of any other discounts, savings and benefits customers are already eligible for at belairdirect.

To take advantage of this offer, simply call us and mention you are a Legion member to get your exclusive premium.

Ijust finished reading the article “By enemy lines” (July/August) by Charles Wilkins. I usually start reading articles a little at a time, but when I started this, I couldn’t stop until I was finished. If there ever was an article about the horrors of war written in honour of a father, this is it. Thank you, Charles, for sharing what your father went through. It’s a lesson of how fortunate we are at the expense of those soldiers who fought for our freedom.

DAVID McBRIDE SOUTH ALGONQUIN, ONT.

Of all things that come in the mail, your magazine is one of the most appreciated. I read it cover to cover and I seldom differ with the information presented. However, I have two comments from the July/August edition. First, on Page 9, you remark that “the RCMP is the only police force in the Commonwealth, if not the world, that is a colour-bearing corps?” I do not believe this is so. The Canadian Heraldic Authority (CHA) has authorized and issued official “Police Colours” to several Canadian police services. I led the project for the Hamilton Police Service to obtain our Colour via the CHA through the Chief Herald more than a dozen years ago, and other police agencies have also done so. As a recognized “Colour,” it is entitled to all the respect and solemnity due any official Colour, military or otherwise.

Secondly, I enjoyed the article (“By enemy lines”) by Charles Wilkins about the story of his father in the Italian theatre during the Second World War. On the first page, though, there is a reference to “Taps” and “Reveille.” Both are

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1

American. The pieces are not like the Commonwealth ones, so it’s not a case of “alternative terminology” for the same thing, although they do serve the same function.

TIM FLETCHER GRIMSBY, ONT.

It was interesting to read staff writer Stephen J. Thorne’s perspective in his “Front lines” column (May/ June) on how Liberal governments “nurtured” Canada’s national identity in the 1960s and 1970s, specifically his reference to replacing the country’s flag. Although the Union

Jack was Canada’s official flag until 1965, it was the Red Ensign that truly embodied the spirit of the country, and accordingly it was universally adopted as our national banner and typically flown not only across the country, but throughout the world. This was the flag under which our military fought and died in both world wars and arguably was a symbol of strong national pride and unity. The “Great Flag Debate,” as the evolution to the Maple Leaf was known, was divisive. I suppose classifying it as a good initiative is a matter of opinion.

C.C. SPARLING CALGARY

The article “U-Boat Man” (May/June) by Stephen J. Thorne really captured my attention. The pictures really helped to tell an interesting story from both the Canadian and German perspective. I’ve been an affiliate Legion

member of the Maj. Hughes Branch in Rainy River, Ont., for eight years. I’m retired from the U.S. Army with a tour in Vietnam. As a member of both the American Legion and the U.S. Veterans of Foreign Wars organization as well, I’m disappointed that their magazines don’t have similar stories to

yours. Knowing your history is important.

JAMES A. HOVDA RICE, MINN.

CORRECTION

Re “On this date” (July/August), Winston Churchill first used the “V” salute on July 19, 1941.

“If it were not for the vicinity of the United States,” said U.S. President William Henry Harrison, then governor of Indiana in 1811, “[he] would perhaps be the founder of an empire that would rival in glory that of Mexico or Peru.”

The man Harrison was referring to was none other than the 18th/19th century visionary and hero Tecumseh. Born in March 1768 in a sprawling settlement of wigwams and bark cabins above present-day Ohio’s Mad River, the Shawnee warrior would come close to forming his own empire, while his very presence stoked fear in enemies and helped stave off intruding Americans.

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /en/newsletter-signup

In Legion Magazine’s latest “Military Milestones” video, listeners are taken back to a pre-confederation era of

instability and hostility in North America. Modern Canada was not yet formed, but the early heroes who helped shape the future country, and North America as it’s currently known, were there, including Tecumseh. His vast, multi-tribal confederacy, ranged from present-day Michigan to Georgia, and fought against colonial settlers.

Listen to journalist, author and storyteller Waubgeshig Rice, as he transports

you to another time and describes the life and influence of Tecumseh. Rice, an Anishinaabe, is from the Wasauksing First Nation near Parry Sound, Ont. His new novel, Moon of the Turning Leaves, will be published in October. It’s a return to the same world explored in his breakout bestselling novel, Moon of the Crusted Snow

You can also read the feature story on Tecumseh in this issue on page 22. L

Lancaster, B-25 Mitchell, C-47 Dakota and Canso aircraft just released in the Vintage Warbirds poster series 12" x 18"

2 September 1752

The United Kingdom adopts the Gregorian calendar. The U.K. and its territories had previously used the Julian calendar.

3 September 1894

The first Labour Day is implemented as a national holiday acknowledging workers’ rights.

4 September 2006

Pte. Mark Anthony Graham is killed and three dozen other soldiers wounded after U.S. aircraft mistakenly fire on a Canadian platoon in Afghanistan.

5 September 1979

The first Canadian gold bullion coin, stamped with a maple leaf, goes on sale.

6 September 1953

12 September 1846

The Franklin expedition ships Erebus and Terror are trapped in ice in Victoria Strait.

13 September 1814

American forces successfully defend Fort McHenry against heavy British naval bombardment in the battle that inspired the lyrics of the U.S. national anthem.

14 September 1857

Canadian surgeon Herbert Taylor Reade earns the Victoria Cross after coming under fire while tending wounded, then leading an attack on Indian rebels in the Siege of Delhi.

The last of 13,444 United Nations prisoners of war are released to the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission in Korea.

16 September 1974

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police swears in its first female officers.

17 September 1944

Operation Market Garden, a bold but unsuccessful Allied attempt to end the Second World War, begins.

18 September 1941

Vancouver’s Asahi baseball club plays its last game as Japanese Canadians are sent into exile or internment camps.

20 September 1943

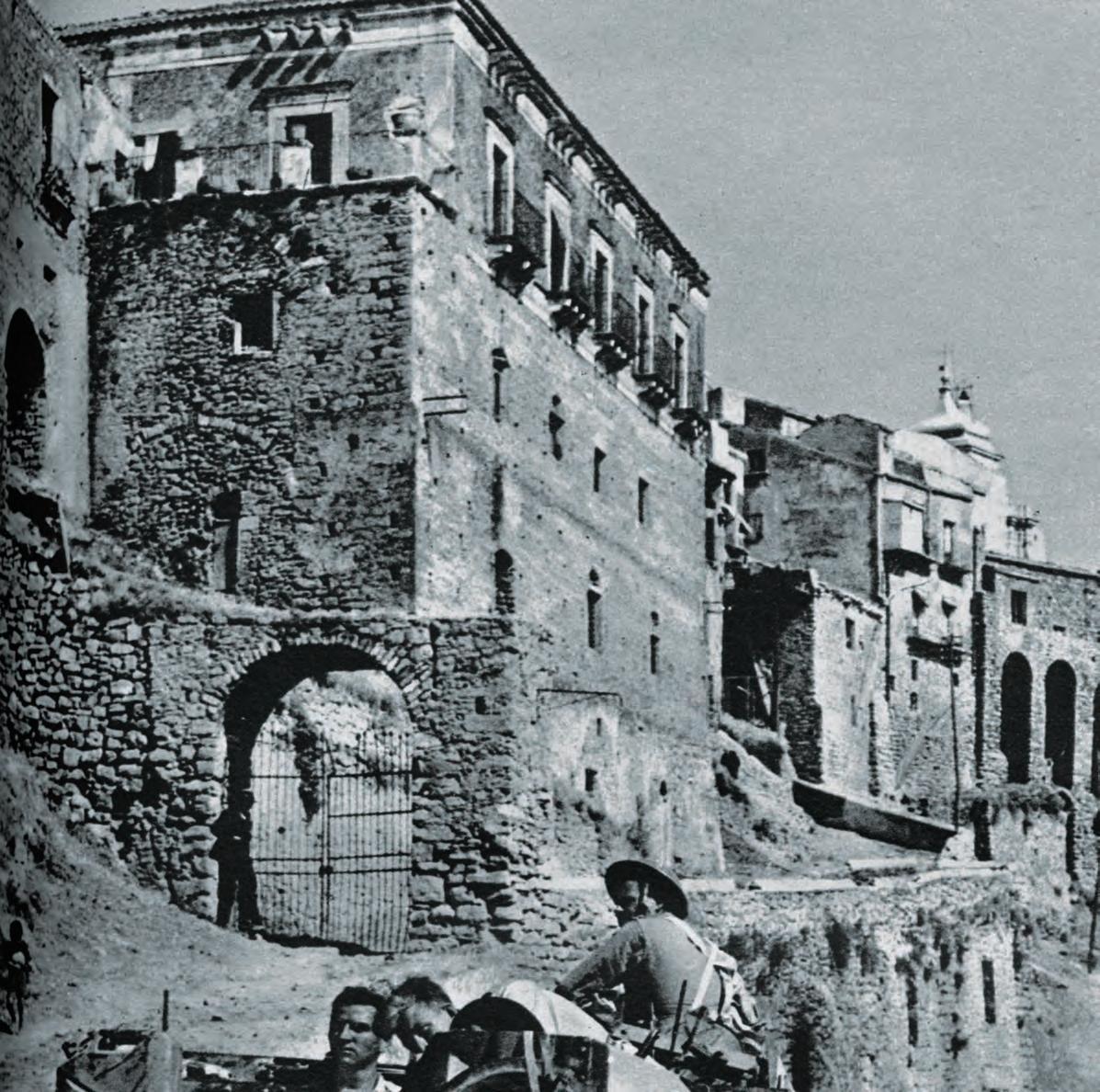

Canadian troops capture Potenza, Italy.

21 September 1902

Alberta’s first oil discovery is made in what is now Waterton Lakes National Park.

24 September 1960

The first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier, Enterprise, is launched by the U.S.

27 September 1973

The Soviet Union performs a nuclear test at Novaya Zemlya in the Arctic Ocean.

28 September 1972

Canada defeats the Soviets in the eighth and final hockey game of the Summit Series.

30 September 1946

Twenty-two Nazi leaders, including Joachim von Ribbentrop and Hermann Goering, are convicted of war crimes at the Nuremberg war trials.

8 October 1992

The modern-day Ottawa Senators play their first game.

9 October 1967

Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara is executed in Bolivia.

10 October 1918

2 October 1535

Jacques Cartier arrives at Hochelaga (now Montreal) on his second voyage to North America.

3 October 1914

The first contingent of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, numbering 30,000, sails from Quebec to join war efforts in Europe.

6 October 1939

Poland surrenders following its defeat at the Battle of Kock. German and Soviet forces gain full control of the country.

7 October 1963

U.S. President John F. Kennedy signs a ratified version of the Limited Test Ban Treaty on nuclear weapons.

After three days of heavy bombardment, 3rd Canadian Division clears the city of Cambrai, France.

11 October 2000

NASA launches its 100th space shuttle mission.

12 October 1915

Germans execute British nurse Edith Cavell for helping Allied prisoners escape occupied Brussels.

20 October 1671

Bachelors in New France are ordered to marry the Filles du roi, immigrant women from France, or lose their hunting, fishing and fur-trading rights.

22 October 1962

U.S. President John F. Kennedy alerts Americans to the Cuban missile crisis and establishes a naval blockade to prevent further weapon shipments to the island country.

23 October 1956

The Hungarian Revolution begins with a massive demonstration in Budapest.

26 October 1917

The Canadian Corps attacks Passchendaele ridge.

27 October 1961

The first Saturn rocket successfully launches.

28 October 1790

14 October 1918

A platoon of The Royal Newfoundland Regiment captures four machine guns, four field guns and eight prisoners during the Battle of Courtrai. Private Thomas Ricketts is awarded the Victoria Cross for his role.

On present-day Vancouver Island, Spain signs the Nootka Convention with Britain, which ends Spanish claims to a monopoly of settlement and trade in the Pacific northwest.

30 October 1995

Quebec citizens narrowly vote in favour of remaining a province of Canada in their second referendum on national sovereignty.

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

How a pilot team-fitness program showed connections between exercise and veteran mental

ood things come to those who sweat!”

The sentiment has been celebrated by both fitness gurus and health nuts for years, becoming a quote printed on T-shirts, wall decals and bumper stickers.

And while some might get tired of the kitschy cuteness of the “healthy body, healthy mind” tagline, there’s more truth to this trope than you might think. One University of British Columbia researcher decided to capitalize on it for the benefit of Canadian Armed Forces members and veterans, laying the framework for a new type of military health intervention.

Specializing in sport, exercise and performance psychology, Mark Beauchamp ran a pilot study in Vancouver called “Purpose After Service through Sport,” or PASS, from September to March 2020. The program sought to use team sports as a way for active and retired military members to better transition to civilian life and promote social connectivity and healthy lifestyles.

And the sport to do this? Ball hockey.

“It’s just turn up, sweat, socially connect and have fun,” said Beauchamp.

On any given night, self-refereed games of 10-20 players were held in a local armoury. Lasting about 45-60 minutes, the game was followed by refreshments in

the mess, where CAF members bonded over ice-cold drinks.

The program’s design seemed almost too simple. After all, it’s just a game and a hang with a beer—isn’t that what most Canadian weekends consist of? How was this supposed to benefit military members?

Well, beneath PASS’s seeming simplicity, a constellation of scientific fact bears its makeup, showing exercise to be vital to mind-body wellness. For instance, a 2022 review found that out of the nearly 1,300 experimental studies conducted on the effects physical activity has on mental health in the preceding 12 years, 89 per cent of them recorded a significantly positive relationship.

From the studies surveyed, the report surmised that 30-45 minutes of exercise three to five times per week delivered the greatest mental health benefits, with those who engaged in team sports reporting 20 per cent fewer “poor mental health days” each month.

Such scientific phenomena were essential to initiating PASS.

“[The data is] quite consistent now around the benefits of physical activity,” said Beauchamp.

This data came alongside Beauchamp’s team noticing that the transition back to civilian life can be especially difficult for CAF members. Losing military identity and the daily structure

cultivated in basic training and combat, many struggle with their new-found autonomy, leading to a host of mental challenges that are often exacerbated by issues with maintaining social connections and employment.

This is further compounded by a disconnect in the use of government-funded veteran health programs. A survey from 2010 found that a whopping 39 per cent of CAF members with mental health conditions were not receiving available services from Veterans Affairs Canada.

Since substantial evidence indicates that exercise and group identity correlate with boosting mental wellness and providing individuals with a sense of purpose, Beauchamp decided to create a military-specific program, inspired by the veterans he spoke with at his campus.

“After transitioning out of the military…some [veterans] struggle,” said Beauchamp.

A self-described “army brat” whose father served in the British army for 30 years, Beauchamp noted “you have some sense as to what army life is like.”

PASS, however, was one of the first military exercise initiatives open to all veterans, not just those who were wounded or sick. And to Beauchamp, bringing individuals who share the same military experience into a pro-team, pro-military environment—ball

hockey in an armoury—could create a sense of community and camaraderie many CAF members otherwise lacked in their daily lives.

“They come together on a sports field playing ball hockey,” said Beauchamp. “There’s this immediate sense that they’re talking the same language. They understand one another because they know what it’s like to serve in the military.”

The results were promising. PASS participants reported a boost in their mental health, with one telling study interviewers, “you’re doing something collectively and kinda suffering together which helps build/ forge bonds and friendships.”

Many participants really liked the way it simulated military structure, as well, with another commenting, “the army is kinda similar to [PASS], so it’s kind of like a work-hard, play-hard mentality….”

PASS also became a conduit for participants to learn about other veteran health programs and healthy habits.

“I think it sort of destigmatized [access to support],” said Beauchamp.

Seeing the overwhelmingly positive response to PASS, Beauchamp had sought to restart the program after the pandemic and even received monetary support from VAC’s Veteran and Family Well-Being Fund in 2021 to begin a multi-provincial, six-month initiative to bring hundreds of CAF members into sports this year. The fully fleshed out PASS program, taking the form of a multi-phase, randomized study, never reached fruition, however, and the grant was returned.

“We simply weren’t able to reach sufficient numbers to run the study,” said Beauchamp.

Still, those who worked on PASS believe it was worthwhile. Other veteran-health services such as

Soldier On, a similar initiative, have used PASS’s findings to strengthen their own programs.

“There are [sports-based] programs out there,” said Beauchamp, and “these programs can help veterans.”

More importantly, though,

Beauchamp believes there’s plenty left to explore regarding the benefits of physical activity for military wellness.

“We need to be open and listen,” he said. “It’s up to us as a community to see how we can best support [our veterans].” L

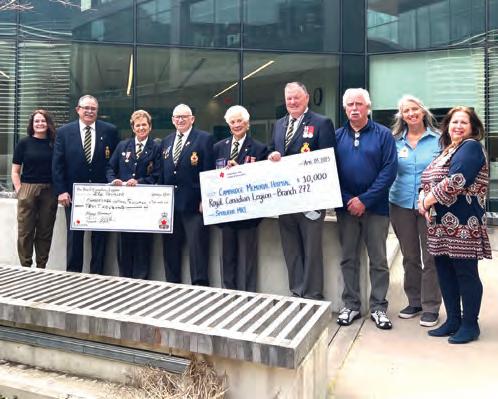

Addressing a longstanding bugaboo of one of the country’s most revered institutions headon, a former regional president of The Royal Canadian Legion delivered a firm message to its grassroots membership in May.

Marion Fryday-Cook was Nova Scotia/Nunavut Command president from 2019 through 2021. She’s now a member of the Legion’s national committee on equity, diversity and inclusion. She didn’t mince words when presenting a report on the organization’s draft plan to address what some consider the Legion’s single-biggest challenge.

“We’re moving into a new world,” Fryday-Cook told an all-white convention audience in Sydney, N.S. (also see “Nova Scotia/Nunavut bids farewell to long-time executive director” on page 61). “Somebody once said, we’re all volunteers and the Legion sometimes tends to eat its own and go after its own.

“It’s time, as members of The Royal Canadian Legion, we soften our thoughts; we are kind to each other; we look out for each other; and we look out for the veterans and their families in our communities, regardless

A Legion colour party leads a pre-convention parade past the Ashby Branch in Sydney, N.S., on May 21, 2023. Former command president Marion Fryday-Cook delivered a stern message on the evolving issue of equity, diversity and inclusion within the national service organization.

of our biases—time to throw those out the window.

“We are all Canadians. We are all human beings. We all deserve the dignity and the respect that we want from others.”

The highly respected FrydayCook, the command’s second woman president, received warm, if not rousing, applause for her efforts.

An aging Legion membership has been declining for years. Its rolls, which numbered 604,000 in 1984, had dropped to less than 250,000 by 2022 when membership rose 3.8 per cent, its first increase in three decades.

Yet, as with society at large, old ideas still prevail in some places and the Legion has resolved to address them.

Operation Harmony, aiming to promote a welcoming environment for all at Legions across the country, was formed in September 2021 to address issues surrounding equity, diversity and inclusion (EDI).

The committee’s draft strategic plan was approved by the Dominion Executive Council in April. It spent the summer developing a draft action plan to be presented to the council in September. If approved, it will go before the Dominion Convention in Saint John, N.B., next year.

“By doing these things that we have to do, we will bring in the next generation,” said council member Trevor Jenvenne. “If we don’t take these steps and do it expeditiously, there won’t be anyone to pass the torch to.”

The nine-page draft plan notes the Legion philosophy that a veteran is a veteran is a veteran “must be clearly understood to include the statement ‘regardless of age, ethnicity, race, nationality, disability, economic status, gender identity, sex and sexual orientation.’”

“If we accept this supposition,” it says, “we will give all veterans and non-veterans alike

> Check out the Front lines podcast series! Go to legionmagazine.com/frontlines

a clear indication that they will be supported and served by the Royal Canadian Legion regardless of their association with any equity-deserving group.”

The document acknowledges that, while the Legion has become increasingly diverse, it “has failed to keep pace,” largely due to challenges attracting younger, post-Cold War veterans and other potential members from racialized and LGBTQ+ communities.

Once an exclusively exmilitary organization, veterans and their families still made up about 75 per cent of Legion membership in 2020. Its core principles remain unchanged: service and remembrance.

The annual poppy drive raises about $20 million for veterans—buying hospital beds and equipment, providing meals and home services, and

supplementing the costs of such things as heating, housing, clothing, medicine and medical appliances.

It has advocated on veterans’ behalf since it was founded as The Canadian Legion of the British Empire Service League in Winnipeg in 1925. It was a voice for First World War veterans and helped win them pension and disability benefits.

It remains at the forefront of the continuing struggle for veterans’ rights, including those of the RCMP, and their families.

An RCMP veteran, a member of the Métis Nation and president of the Legion’s operational stress injury (OSI) special section, Jenvenne employed some tough talk when discussing inclusion with the council in Ottawa: Embrace EDI or die, he said. He told them that the organization’s leadership cannot be afraid to

alienate some older or intransigent members if it is to move forward and attract new generations.

“Those ones who feel alienated [by the EDI initiative] are not the ones we need in our organization. We don’t,” emphasized Jenvenne, one of about 23,000 Indigenous vets in Canada. “We as the younger veterans now are really the ones who are most important going forward.

“I hate to say it, but those individuals who are going to block this won’t be around when I’m here 30 years down the road.”

The Op Harmony committee has met with special advisers, hired a consultancy, and spoken to members and veterans. The consultancy sent out 99,000 emails to Legionnaires; 8,881 responded. It held three virtual town halls, conducted focus groups and consulted other veterans’ organizations worldwide. L

By David J. Bercuson

Canada is looking to replace its fleet of CP-140 Aurora aircraft.

Why look any further for a new surveillance-reconnaissance aircraft than the only available option?

M40 years ago, the Canadian Armed Forces acquired a fleet of CP-140 Aurora aircraft. At the time, they were top of the line and have since served the air force and navy well. But now that it’s time for an upgrade, Ottawa must choose between a reputably built aircraft or simply the concept of a model that will create jobs in the country.

The Aurora is a four-engine, maritime-surveillance, reconnaissance and anti-submarine aircraft. Its airframe and engines were designed by Lockheed Martin, and it boasts an electronics suite from the Lockheed S-3Viking. It’s a derivative of the P3 Orion, as the Americans call it, which first flew in the 1960s.

Over the years, the CAF has spent hundreds of millions of dollars upgrading the aircraft to keep it up-to-date, recently spending a final $52 million to ensure the fleet can fly for most of another

initiatives, which have improved the airplane’s surveillance and reconnaissance capabilities and strengthened perceived weaknesses in the airframe, have turned the Aurora into a capable airplane, though still an old one.

As military journalist David Pugliese reported this past May in the Ottawa Citizen, the federal government is now looking at a replacement for the Aurora and has approached Boeing to discuss purchasing 16 P8Poseidon aircraft—a military version of Boeing’s 737-7 airliner—under a provision that allows it to make a sole-source purchase if it deems there’s only one option that suits its needs.

The provision was used several times after Canada joined the war in Afghanistan, including, for example, its acquisition of the BAE Systems M777 towed howitzer in the early 2000s. Since it would take years for the P8s to be delivered, the recent

will allow Canada to deploy an acceptable maritime reconnaissance aircraft until then.

Enter Canadian business jet maker Bombardier, headquartered in Montreal. Knowing that Ottawa has approached Boeing, Bombardier, in partnership with General Dynamics which would supply electronics, is proposing to sell the CAF a maritime and surveillance aircraft based on its Global 6500 business jet.

Bombardier/General Dynamics noted that if Ottawa purchases its plane, the military would get a Canadian aircraft, built in Canada, which would also produce jobs in the country. The duo, as Pugliese reported, is urging Ottawa to “allow a competitive, fair and transparent procurement process.”

Boeing’s P8 is currently used by the U.S and Indian navies, as well as the air forces of Australia, the U.K., Norway and NewZealand.

Plus, the navies of South Korea and Germany have ordered U.S. has had the aircraft in full operation for more than a decade.

Buying the P8 would be a safe option for Canada given that it’s a proven aircraft. Purchasing the Bombardier/ General Dynamics option is riskier because it’s still a concept.

, Bombardier’s jets, now the company’s only line of business after it divested its rail transport unit in early 2021, are a hot commodity, responsible for quadrupling its profits since 2020. And the C-Series airliner it designed in the early 2000s—and for which Bombardier received roughly $1 billion in subsidies from the Quebec and Canadian governments—is considered an outstanding passenger aircraft. (It is now known as

the A220 and built by Airbus in Montreal and Mobile, Ala.)

Regardless, the P8 is already flying with six countries and has been ordered by two more who are certainly capable of choosing an aircraft that best suits their needs. This, of course, points to yet another facet of this complicated story. Whenever Canada orders new equipment for its military that is built to its narrow specifications—such as the CH-148 Cyclone maritime helicopter, which didn’t even exist as a military aircraft until the country ordered it—it seems to result in delays, cost overruns, technical failures and other costly disruptions.

Let’s face it, Canada’s military procurement record is abysmal, and no one seems to be able to fix it. One solution is to buy “off the shelf” as Ottawa did with the aforementioned M777howitzer. Had it purchased ready-made warships, the vessels might have been in harbour by now. When Canada replaces its current fleet of submarines, it will almost certainly have to buy an existing model.

Hopefully the government has learned its lesson. The P8 has been flying for more than a decade. It will certainly suit Canada’s requirements. There’s no need for a competition this time. L

That’s

By Stephen J. Thorne

He was a visionary and a pragmatist, a warrior and a diplomat, an enemy and a hero whose legend and likeness penetrated deep and long into the very culture he fought.

“The red men have borne many and great injuries; they ought to suffer them no longer,” declared the Shawnee chief Tecumseh in 1810. “My people will not; they are determined on vengeance; they have taken up the tomahawk; they will make it fat with blood; they will drink the blood of the white people.”

A powerful orator, his speech to the Osage Nation came as he sought to rally fewer than 100,000 Indigenous Peoples in the cause of halting an expanding population

of nearly seven million Americans, some 400,000 of whom were now living in traditional Indigenous territories west of the Appalachian Mountains. His recruitment campaign took him far from his frontier base on the Tippecanoe River in northern Indiana north into Canada and south to the Gulf of Mexico.

“Brothers, if you do not unite with us, they will first destroy us, and then you will fall an easy prey to them,” he warned the Osage three-quarters of a century before the last of the Plains Indians were forced onto reservations and into residential schools—and a way of life disappeared forever. It is now considered one of history’s great genocides.

19th-century

“They have destroyed many nations of red men because they were not united,” said Tecumseh. “They wish to make us enemies, that they may sweep over and desolate our hunting grounds, like devastating winds or rushing waters.”

Word of the Shawnee’s ambitions spread rapidly, leading William Henry Harrison, the governor of the Indiana Territory, to twice negotiate with the dynamic leader face-to-face.

Harrison characterized his adversary as “one of those uncommon geniuses who spring up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things.”

Tecumseh was, as writer Deborah Hufford put it, “one of the greatest Native American chiefs…a man of nearly clairvoyant vision who launched a massive campaign against whites marching west, the first—and last—best hope for Native Americans to save their ancestral lands.”

He would take his confederacy and ally with the British and Canadians in the War of 1812, only to die in battle a year later, his cause destined to be lost but, far short of his aims, his legacy as one of America’s most celebrated military foes and cultural heroes secure.

Tecumseh is believed to have been born in March 1768, possibly during a meteor shower, in a sprawling settlement of wigwams and bark cabins on the bluffs above present-day Ohio’s Mad River, northeast of Dayton. He was given the prescient Shawnee name meaning “shooting star” or “panther crouching for his prey.”

was difficult for young Tecumseh, he had already come to learn the lesson that life is nuanced in greys, not delineated in black and white. He had learned it from his father himself. He would come to envision a gentler society for his people and grew up with a strong sense of justice for all, including his enemies.

“A brilliant orator and warrior and a brave and distinguished patriot of his people, he was intelligent, learned, and wise, and was noted, even among his white enemies, for his integrity and humanity,” Alvin M. Josephy Jr. wrote in American Heritage magazine in 1961.

Tecumseh may have witnessed his first combat at the Battle of Piqua in 1780 near his home on the Mad River. He was 12 years old. At 18, he became a full-fledged warrior. The young man grew to nearly six feet tall, a handsome, imposing and muscular warriorpoet with an arresting presence.

colonial expansion. The whites brought more than guns and plows to the frontier territories. Smallpox and other diseases for which the Indigenous populace had no defence wiped out entire populations.

In the Great Lakes and middle Mississippi River regions, Tecumseh’s Shawnee were joined by Potawatomi, Winnebago, Kickapoo, Menominee, Odawa and Wyandot. Initially, he was met with strong resistance from chiefs who had already signed treaties.

In 1809, Harrison had negotiated the Treaty of Fort Wayne, which ceded more than 12 million hectares of land to the government. Tecumseh, who lived north of the area, maintained the deal was illegal. He met with Harrison in 1810 and 1811 and refused to recognize the treaty.

“The only way to stop this evil [loss of land] is for the red man to unite in claiming a common and equal right in the land, as it was first, and should be now, for it was never divided,” he told Harrison.

The Shawnee were fierce warriors and conflict imposed itself on his life from the beginning. His father, the war chief Pukeshinwau, would die in battle during Lord Dunmore’s War, a 1774 conflict pitting Shawnee and Mingo warriors against white settlers of the Virginia colony.

While dealing with his father’s death at the hands of the British

In 1790, when Tecumseh was 22, he fought alongside Chief Little Turtle against General Josiah Harmar in western Ohio. Fighting under order from then-president Washington, Harmar’s army lost. Nearly two hundred of his troops were killed or wounded in one of the U.S. military’s greatest defeats to an Indigenous force.

For more than a century, colonists had been pushing the Indigenous Peoples of eastern and southern North America west from their ancestral homelands in the regions of the Great Lakes and east of the Mississippi.

As a result, Tecumseh began building a vast, multi-tribal confederacy ranging from presentday Michigan to Georgia to fight

Harrison insisted the agreement was binding. Replied Tecumseh: “Sell a country?!? Why not sell the air, the great sea, as well as the earth? Did not the Great Spirit make them all for the use of his children? How can we have confidence in the white people?”

It’s believed he also reached out to South Appalachian Mississippian tribes, including the Cherokee, Muscogee (Creek), Choctaw, Chickasaw and Seminole.

“Where today are the Pequot?” he asked them. “Where are the Narragansett, the Mohican, the Pocanet and other powerful tribes of our people?

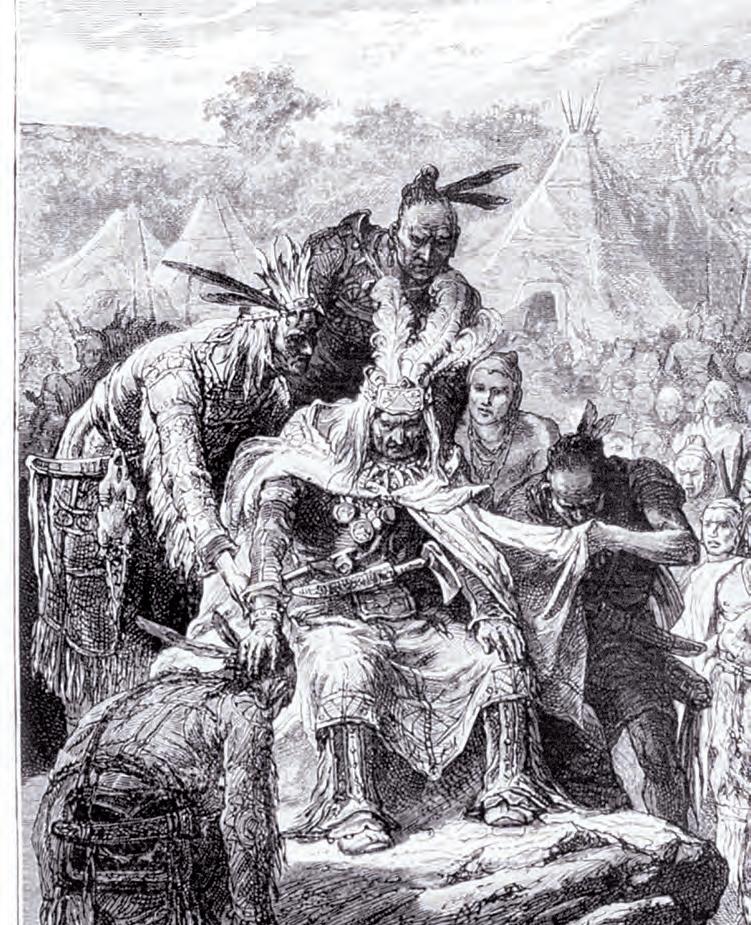

A wood engraving from the mid-19th-century depicts Tecumseh’s brother Tenskwatawa, known as The Prophet, meeting with other First Nations.

“They have vanished before the avarice and oppression of the white man...Sleep not longer, O Choctaws and Chickasaws... Will not the bones of our dead be plowed up, and their graves turned into plowed fields?”

Tecumseh’s cause was aided by his younger brother, Tenskwatawa, a religious visionary known as The Prophet who claimed to have powerful visions decreeing that tribes must unite to fight the evil spirits taking their lands.

Tenskwatawa then summoned a sunless sky, which was in effect realized in the form of a solar eclipse.

In 1808, the brothers established Prophetstown, where the confederacy would form its base at the confluence of the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers.

Trying to discredit Tenskwatawa, Harrison issued a challenge, reported by a newspaper of the day: “If he is really a prophet, ask him to cause the Sun to stand still or the Moon to alter its course, the rivers to cease to flow or the dead to rise from their graves.”

Known to the white pioneers as the “yaller devil,” Tecumseh, too, was said to have prophetic powers. Legend has it that when the Muscogee refused to join his alliance, he issued a threat: if they did not join him before he reached Detroit, he would simply stomp

his feet and the earth would shake down the great Mississippi and their villages would be destroyed.

Within days, on Dec. 16, 1811, the region was jolted by a massive earthquake—caused, says today’s U.S. Geological Survey, by the New Madrid fault system that spans five Midwestern states. The shaker was estimated to have been stronger than the one that destroyed San Francisco and killed more than 3,000 people in 1906.

Tecumseh’s confederation fought U.S. forces from August 1810 to October 1813.

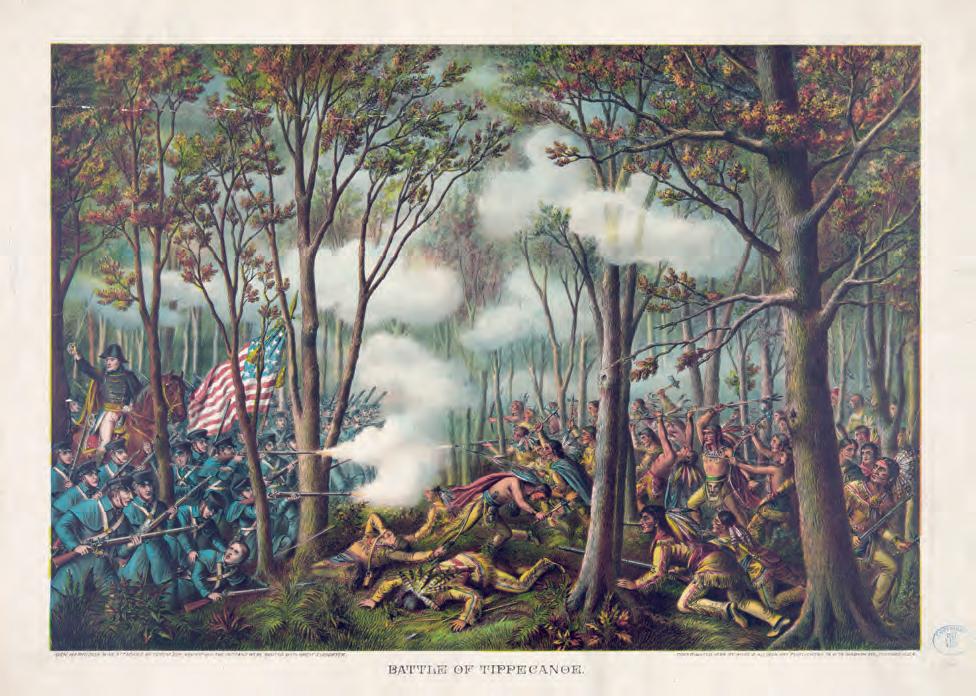

In November 1811, while the chief was away building his coalition among southern tribes, Harrison assembled some 1,000 troops and attacked Prophetstown, dealing the coalition a devastating defeat at the Battle of Tippecanoe.

In what some consider the first engagement of the War of 1812, the American troops burned the encampment to the ground after Tenskwatawa and its residents abandoned it.

The pragmatist in Tecumseh subsequently brought him into an alliance with the British who were likewise at odds with the Americans at the time.

A month after U.S. troops invaded Upper Canada in July 1812, MajorGeneral Isaac Brock travelled to Amherstburg to organize the British response, an attack on Fort Detroit. He met with Indigenous warriors to negotiate an alliance to fight the Americans. Tecumseh stood out among the assembled chiefs.

“I have heard much of your fame, and am happy again to

shake by the hand a brave brother warrior,” the Shawnee leader told him. Brock gave him his sash.

The British general was progressive for his time, saying of his Indigenous brethren in a July 22, 1812, speech: “But they are men, and have equal rights with all other men to defend themselves and their property when invaded.”

Brigadier-General William Hull had just led his forces into Canada. Haunted by Indigenous atrocities, he then withdrew back across the border to Detroit.

On Aug. 16, Tecumseh led a multi-tribal group of warriors and, with a combined force of Canadian militia and British regulars, surrounded the city’s fort. Brock could smell Hull’s fear and so, no doubt, could Tecumseh. The Indigenous warriors paraded past the fort for psychological effect.

Brock sent his adversary a surrender demand.

“The force at my disposal authorizes me to require of you the immediate surrender of Fort Detroit,” he wrote. “It is far from

my intention to join in a war of extermination, but you must be aware, that the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond control the moment the contest commences.”

With the prospect of imminent massacre by “hordes of howling savages” hanging over his head, the aging and ailing Hull surrendered the garrison and his 2,500-man army having barely fired a shot. He was rumoured to have been drinking heavily before the capitulation and is reported to have said that the Indigenous warriors were “numerous beyond example” and “more greedy of violence…than the Vikings or Huns.”

The attackers captured 33 cannons, 300 rifles, 2,500 muskets and the brig Adams, the only armed American vessel on the Great Lakes at the time. The British navy put it into service.

Brock sent the 1,600 captured Ohio militiamen south, providing them with an escort until they were

out of danger. Most of the Michigan militia had already deserted. The 582 American regulars taken prisoner were sent to Quebec City.

Hull was court-martialled in 1814 and convicted of cowardice and neglect of duty. He was to be shot but, in deference to his service in the Revolutionary War, President James Madison commuted the sentence and dismissed him from the army instead.

The British victory reinvigorated the beleaguered militia and civil authorities of Upper Canada, boost ing their prospects and morale, and it inspired tribes in Tecumseh’s confederacy to take up arms against U.S. outposts and settlers.

His warriors would go on to strike deep into the United States, attacking forts and sending terri fied settlers fleeing back toward the Ohio River. It wouldn’t be until after Tecumseh’s death that they would at last begin to “realize that a native of soaring greatness had been in their midst,” Josephy wrote. Harrison, recalled to

“IF IT WERE NOT FOR THE VICINITY OF THE UNITED STATES,” TECUMSEH “WOULD PERHAPS BE THE FOUNDER OF AN EMPIRE.”

Tecumseh and Major-General Isaac Brock oversee the American surrender of Detroit in August 1812 (left). The pair had exchanged sashes in mutual respect after first meeting earlier that year (above). Tecumseh readily joined the British in the War of 1812 after U.S. forces had razed his village in the November 1811 Battle of Tippecanoe (opposite).

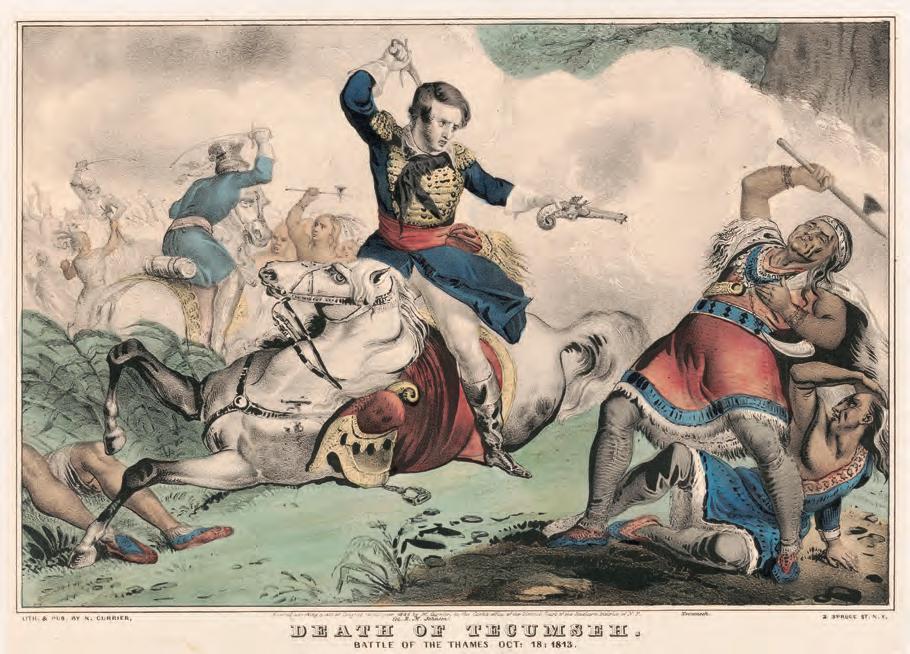

Tecumseh and his exhausted ranks took up positions in a patch of swampy woodland. The chief said he would retreat no farther. Having dispatched with the British, Harrison sent dragoons and infantry into the thickets.

After an hour of fierce fight ing, Tecumseh was killed, or so it is believed. He was never seen alive again—his ultimate fate dependent on which side was telling the story. For all practical purposes, however, his Indigenous resistance died with him.

Hungry for an American vic tory after a humiliating year of losses, the first reports from the Battle of the Thames claimed Harrison’s brave boys had over come 3,000 superb warriors led by the great Tecumseh.

The man who apparently had the most credible claim to killing him, a Kentucky cavalry com mander named Richard Johnson, eventually won a Senate seat, then

was key to defeating the Confederacy in the 1861-1865 U.S. Civil War, then led the American army against Indigenous nations in the continuing wars once fought by the Shawnee chief for whom he was named.

Sherman, like Tecumseh him self, was born in Ohio. According to the general’s memoirs, his father Charles, justice of the state’s supreme court, “caught a fancy for the great chief of the Shawnees, ‘Tecumseh.’”

Recognizable by his hag gard, battle-worn look in period photographs, Sherman was a

change than their historical areas and are more susceptible to extreme heat and drought.

On Dec. 2, 1820, the Indiana Centinel of Vincennes published a letter singing the praises of the great chief, and hearkening

on what might have been.

“Every schoolboy in the Union now knows that Tecumseh was a great man,” it said. “His greatness was his own, unassisted by science or education. As a statesman, warrior and patriot, we shall not look on his like again.” L

Kentucky cavalry commander Richard Johnson kills Tecumseh during the October 1813 Battle of the Thames (below), where Chief Oshawana (opposite top) served as his lead warrior.

He directed the U.S. Army as it crossed the Great Plains and employed the same destructive tactics in exterminating and relocating the last Indigenous nations. The Lakota, Cheyenne, Comanche and Apache all suffered significantly during Sherman’s 19th century Indian Wars.

“We must act with vindictive earnestness against the Sioux, even to their extermination, men, women and children,” Sherman once said. A year later, he issued an order permitting the Sioux’s “utter annihilation.”

“The more [Indians] we can kill,” said Sherman, “the less will have to be killed in the next war, for the more I see of these Indians, the more convinced

I am that they all have to be killed or to be maintained as a species of paupers.”

In his 1878 annual report to Sherman, General Philip Sheridan, who led American forces in battle against Indigenous warriors, acknowl edged the plight of Native Americans starving on reservations, where they lived on broken promises.

“We took away their country and their means of support, broke up their mode of living, their habits of life, introduced disease and decay among them, and it was for this and against this they made war,” wrote Sheridan, also a Civil War veteran.

“Could anyone expect less? Then, why wonder at Indian difficulties?”

Canada’s key role in a game-changing peacekeeping mission

It was just another companywide “smoker” at Camp Kananaskis in 1993, but Dangerous Dan was up to his old tricks again.

Acting major of Delta Company, 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI ), Dan Drew was at the base camp party in Sveti Rok, a Croatian village home to a defunct Yugoslav National Army base.

With cases of French wine and gallons of German and Croatian beer available, some Canadian troops saw these get-togethers as more than just a way to relax; it was a classic bacchanal, drunken revelry abounding.

“It was a breeding ground for alcoholism,” said Calgary Highlanders Sergeant Kurtis Sanheim.

Nicknamed “Dangerous” by his fellow soldiers, Drew had some madcap tendencies and access to liquor didn’t make those habits any better. Excessive alcohol consumption was already becoming a problem in 2 PPCLI, but Drew’s company was particularly infamous, boasting some of the battalion’s biggest drinkers.

So, during this smoker, the emotional residue accumulated from witnessing the human atrocities of Yugoslavia’s dissolution in the early 1990s surfaced in Drew as the night slowly expired.

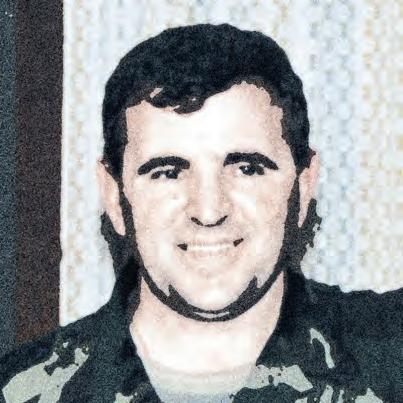

His company had known the monsters of the Croatian Medak area all too well—the civilian cries of ethnic genocide, the corpses burnt beyond recognition, the colonies of maggots that left carcasses wriggling with parasitic life. The company’s role in the United Nations Protection Force

was a thankless job that left them bewildered by humanity’s brutality.

“We were on the line too long,” 2 PPCLI Sergeant Sjirk Ruurds (Rudy)

Bajema said. “We were there for months without a break.”

Operation Medak Pocket, as the UN peacekeeping mission was known, would be the most significant combat Canadian forces had participated in since the Korean War—and yet, 2 PPCLI soldiers, reinforced by militias and other units, had received little to no attention from back home.

So, in that moment, Dangerous Dan decided to be the difference.

The lush landscape of Medak, a Croatian farming village, is photographed from the rear of an anti-armour platoon house (opposite). Kurtis Sanheim (blue cap) and team members ready an armoured personnel carrier in Croatia (above).

In one swift alcohol-drenched gesture, Drew fired his pistol into the night sky, emptying an entire magazine as a salute to his company. There was emotion in his gunfire, a heartfelt apology for the deafening silence of top brass.

And his soldiers didn’t just cheer, they went wild with loyalty for their company.

Unfortunately for Drew, however, the higher-ups didn’t see it that way, and he was demoted to administration company commander. Drew’s punishment, however, later became symbolic of 2 PPCLI’s post-operation experience: one of censorship, chaos and the failure of a system meant to protect soldiers.

Drew was one of more than 14,000 Canadians contributing to the UN peacekeeping force in the former Yugoslavia. The security group aimed to ensure

stable conditions for peace talks during the breakup of the country’s six republics in 1991. From 1992-1995, Canadians joined personnel from 36 other countries to mediate the messy divorce.

For years, the republics had coexisted peacefully, their similar languages, cultures and customs, along with a centralized communist authority, a binding glue. But the death of Yugoslavian leader Josip Broz Tito in 1980 and the end of the Cold War pushed each republic’s nationalist identity into global politics. The result? A new national order based on blood and religion.

When Serbia, the most powerful of the republics, tried to take the federation’s helm, Croatia, Slovenia and Bosnia fought back with their own declarations of independence, manic with nationalist-separatist sentiment. But Croatia and Bosnia were home to numerous ethnic Serbs, many who weren’t comfortable with the new nations

they found themselves in. They organized military coalitions against the new governments.

As the paramilitary operations formed, the Yugoslav National Army, propped up by Serbia, fought alongside them to keep Croatia and Bosnia in the Socialist federation. From 1992-1995, the combined forces were amateurish at best and homicidal at worst.

“They would go out and exterminate entire families, shoot them in their homes and outside their homes and line them up,” said Bajema. “I’d seen a bit of it before that. But on that scale, [it] was unprecedented.”

The UN entered the fray in 1992. In Croatia, the peacekeepers mediated a ceasefire between Croatia and its Serbian minority, establishing a buffer zone between the territories held by the two groups. The latter’s Republic of Serbian Krajina included the Medak Pocket, a farming region off the Adriatic coast. The agreement, however, was a far cry from a truce; for the Croats and Serbs, it was a temporary break they needed to increase their readiness for a bloodthirsty enterprise of land grabs, destruction and genocide, or ethnic cleansing.

Called to UN action, Canada readied its own operations, which included the full gamut of wartime weaponry. It was a new look when juxtaposed with the symbolic image of early peacekeepers.

“We were the poster boys for the United Nations,” said veteran Mark E. Meincke, a Canadian Armed Forces’ advocate. “They had a certain baby-hugging image of us that they wanted to maintain. They didn’t want us to be portrayed as the warriors that we were.”

So, in March 1993, 2 PPCLI headed to the region.

Initially, 2 PPCLI were given five months of in-theatre training. During that time, the battalion was a particular standout among the UN forces, particularly after Operation Maslenica in January

1993 when French troops were forced to abandon a UN-protected area against heavy Croat fire.

Witnessing the Canadian military’s skill, the UN force commander, French army General Jean Cot, assigned the Patricias to the theatre’s southern sector, supported by French troops.

According to historian Lee Windsor, it was a difficult assignment, not only within the larger mission, but in peacekeeping history.

Still, 2 PPCLI was ordered to establish a crossing line on the main road between the villages of Medak and Gospic and that they could pass it at noon on Sept. 16—until they were delayed by Croat forces.

Something seemed off about the Croatians biding for more time, however. Bombs bursting behind them, the Croats claimed their forces were exploding old mines.

“WE USED TO SAY THAT WE WERE TREATED LIKE USED TOILET PAPER, YOU KNOW, SHAT ON AND THROWN OUT.”

Indeed, on Sept. 9, the Canadians ended up in the middle of open warfare when 2,500 Croat soldiers invaded the Serbianheld Medak Pocket. For 12 hours, 9 Platoon, ‘C’ Company, felt the hellish rain of artillery and mortar fire, sometimes hitting within 50 metres of its location. Heavy shelling continued in the region for days.

Six days later, on Sept. 15, the Croats agreed to pull back to pre-Sept. 9 lines, thanks to UN mediation and international pressure.

But, in working to enforce the new positions, Canadian forces encountered Croat fire, comprised of “small arms, heavy machine gun and in some instances 20 mm cannon fire,” one government report stated. Firefights, up to 90 minutes long sometimes, also occurred during a 15-hour window. At the same time, Serbian forces were sniping at the Croats from behind the peacekeepers.

But as the sounds of rifle fire mixed with the rising smoke from the villages beyond the roadblock, the Canadians imagined what this meant: The Croats were killing Serbs in the communities.

Meanwhile, Lieutenant-Colonel Jim Calvin grew restless as the earth shook from explosions, demanding the Croats let the Canadians pass. Ready to play a “lethal game of chicken,” the

two sides loaded their weapons and locked onto each other.

However, without any supporting tanks or artillery to stand up against the Croatian 9th Brigade, nor the UN mandate to do so, 2 PPCLI were left to wait, forced to listen to the sounds of death that would later transfix decades-long nightmares for some soldiers.

After an hour waiting, Calvin realized that what he couldn’t breach with muscle, he could push with media. Armed with about two dozen reporters, the standoff was documented by the press, the journalists reporting on how Croatian forces were directly interfering with the UN agreement.

In what would be his “finest moment,” Calvin’s wager paid off, and an hour and a half after they were scheduled to

The UN High Commissioner for Refugees had indicated that the battalion’s operation could encounter thousands of Serbs in need of rescue from the wartorn region. That part of the mission could have been the most rewarding, a chance to save thousands of lives and prove that the endless mediations and mortar and artillery fire of midSeptember weren’t for nothing.

But what 2 PPCLI didn’t know, was that on the other side of the Medak-Gospic crossing line was not a rescue operation, but a murder scene.

“Nobody joins the army for medals,” said Sergeant Sanheim. “You join the army because you want to serve, and you want to do some good, and you want to help protect those that can’t protect themselves.”

One scene involved two bodies found in a brick chicken coop, bolted shut and still slowly burning. It looked like one person tried to escape, while the other was tied to a chair; both bodies, however, were so horribly charred and maggot-infested that they were beyond identification.

It was only through subtle context clues—long hair, feminine clothing, a purse—that their discoverers theorized that the duo were women. Moving the bodies proved challenging, too, as the limbs fell off when lifted and the heat radiating from the corpses melted the body bags. One warrant officer cooled the bodies by pouring bottled water on them so they could be more easily handled.

“I don’t think [they] ever really got over it,” said Bajema of the soldiers doing such work.

move in, his company cleared the line. Thereafter, 2 PPCLI’s sweep team would initiate their civilian rescue operation.

Remarked Bajema: “I think the leadership [of 2 PPCLI] was pretty bang-on.” Indeed, Calvin received the Meritorious Service Cross for, as his citation noted, carrying “out one of the most successful military operations in support of the humanitarian effort in this theatre.”

The battalion, however, would end up being required to gather evidence for a potential war-crimes prosecution, a new task the UN force had yet to standardize. This role, coupled with the sweep team’s lack of training in such endeavours and their limited experiences with death, made the smouldering flesh, poisoned wells and slaughtered livestock of Medak a grim reality check for many.

Sanheim in Croatia in 1993 (left). Canadian peacekeepers pause for a photo during their mission (centre). Sanheim, now retired, relives his tour as an actor for the 2022 short film Medak (right).

And, so, the sweep team routinely encountered heinous, cold-blooded war crimes. One elderly female victim had been dragged by a rope, had had her left breast slashed, fingers cut from her hand, legs broken and shot in the head four times, while one dead man appearing to be in his 60s had deceptively looked alive because of the sheer number of maggots on his corpse made it seem like his body was shaking.

The sweep team’s leader, Major Craig King, reported to journalist Carol Off for her book, The Ghosts of Medak Pocket: The Story of Canada’s Secret War on how many times the man had been shot: 24 times. “How many bullets in the back and in the head—shot at close range—does it take to kill a sixty-year-old man?” wrote Off.

Out of all these hellish scenes, none had rattled the sweep team as much as that of a blind elderly woman’s “grave.” Lying on top of a rabbit-fur coat, her body was found in a marsh and had been shot at least six times. The soldiers realized that her vulnerability had not been enough to save her—a disturbing truth for many.

The battalion’s hefty to-do list was compounded by a lack of running water nearby. Showers were out of the question, and since the sweep team was equipped only with kitchen gloves and surgical masks while moving bodies, they were often glazed with mud and bodily fluids.

Soon, UN officers and volunteers alike began finding more and more excuses to avoid going out with the sweep team and instead exercised their right to leave the corpsehunting business behind. Out of the thousands of potential Serbian lives that could have been saved, according to the UN, 2 PPCLI only found 16 bodies and no survivors.

The genocide had pulverized the sweep team’s morale, leaving it surrounded by weapons, war and the overwhelming question of “what if?”

The sense of failure from not finding any survivors, mixed with the guilt from not crossing the Medak-Gospic line sooner, had left a mental scar on the young soldiers, and it was starting to show.

“We felt we could have done more,” confessed Bajema.

While alcohol abuse became an increasing issue in the battalion, spurring such incidents

as Dangerous Dan’s pistol salute, other significant signs of combat stress began to surface, too.

One soldier, for instance, was found threatening a fellow officer with a bayonet and rifle during guard duty, while a Delta Company cook had cut his wrists and grilled his hands to escape the devastation. Other soldiers, however, went from miserable to mutinous. One private pounded a master corporal’s head against a concrete floor during a late-night smoker, while other soldiers exuded a “cowboy mentality,” digging graves for senior personnel and carrying extra rounds in case they might need them.

Later, it was discovered that as many as 12 soldiers had plotted to kill Delta Company members.

These instances weren’t a result of moral delinquency. The actions of 2 PPCLI members in battle and beyond had proven that a finer lot of peacekeepers couldn’t have existed. Instead, it was from the sheer helplessness and hopelessness of their situation—just as invalidated from the zero-survivor count as they were from Ottawa’s complete lack of contact with 2 PPCLI during the posting.

“[But] when they got home,” said Bajema, “they had to fight another battle.”

When some 2 PPCLI members arrived back in Canada in October 1993, their “hero’s welcome” consisted of a box of doughnuts, a coffee urn, and…silence.

“We used to say that we were treated like used toilet paper,” said Meincke, “you know, shat on and thrown out.”

Soldiers soon realized that most Canadians had no idea that the CAF was even in Croatia. And when soldiers tried to tell civilians about what had happened, people would flat-out deny the troops’ experiences.

“[They would say,] ‘well, if that was true, I would have heard about it on the news.’ Okay, narcissist,” Meincke quipped. “If you didn’t hear about it, it didn’t happen. Okay, centre-of-the-universe.”

Some believe that such a hushed homecoming was all strategy, however, aiming to quell military coverage in the wake of the Somalia affair. Earlier that year, media organizations had published graphic details of a Somali teen tortured and killed by Canadian paratroopers on a peacekeeping mission. The utter brutality of the teen’s treatment unravelled the CAF’s reputation for military competence and professionalism. According to historian Windsor, this fuelled a public perception that Canadian soldiers were “poorly trained, incompetently led, badly equipped and quite often racist.”

While the UN declared 2 PPCLI’s work in the former Yugoslavia an exemplary display of modern peacekeeping, the unit still felt tarnished by the Somalia affair. 2 PPCLI was silenced and some members felt shamed.

Sergeant Sjirk Ruurds (Rudy) Bajema on patrol in Croatia (left), sitting in his tent outside company headquarters (middle) and helmeted in HQ with fellow peacekeepers during an artillery shelling (right).

“It was a crappy time to be in the army,” noted Bajema.

This blow was compounded by the absence of post-deployment decompression programs for many reservists who had served with the Patricias in the Balkans and needed to move from station to station quickly.

“They kind of went like ghosts into the winds,” said Bajema.

So, unlike the First and Second world wars or even the Korean War, many 2PCCLI members had relatively very little time to transition back into civilian life, leaving them physically in Canada, but mentally still in Medak.

“[None of the soldiers] actually came home,” noted Meincke. “[A] hollowed out version of them came home.”

Without the validation combat soldiers often need to give moral legitimacy to their actions, many experienced broken marriages, homelessness and mental/physical illnesses. One of the most common health issues 2 PPCLI members dealt with was post-traumatic stress disorder, an illness that had, up until that point, largely been defined as such only in clinical circles.

And while veterans tried to bring this to the government’s attention, particularly in a 1998 letter written by Calvin to the head of the army, Parliament was silent on the matter. It was only when one veteran started talking to the media—a bold act given the military’s historically tight-lipped nature—that the government considered the matter. But not in the way veterans had hoped for.

Rather than receiving the longawaited thank-you they expected, 2 PPCLI members faced a vicious series of criminal investigations into leadership oversights and company discipline. Most soldiers deemed the inquiries “witch hunts” and suspected they were another political strategy to deny accountability.

“I felt like the government was abandoning us,” said Bajema.

While 2 PPCLI had received the UN Force Commander’s Commendation in 1993, one of only three such awards ever given to United Nations peacekeeping forces, it wasn’t until 2002—nine years later—that Governor General Adrienne Clarkson awarded the

battalion the Commander-in-Chief Unit Commendation in recognition of its “courageous and professional execution of duty during the Medak Pocket Operation.” Some members also finally received the pensions and health care services they needed, too.

“It [was] bittersweet,” said Bajema.

Additionally, 2 PPCLI’s thorough documentation of genocide, or ethnic cleansing, in the Medak Pocket set an international standard for UN peacekeepers, leaving its mark on how evidence for war crimes trials is recorded and documented.

Most importantly, though, the operation brought the concept of post-traumatic stress disorder and veteran mental health in Canada from fringe medical jargon to mainstream conversation, spurring a mental health awareness campaign that continues to grow.

And while there is still much work to be done on that front, Medak veterans such as Bajema, Meincke and Sanheim are still trying to make a difference. Meincke runs a nationally acclaimed podcast, “Operation Tango Romeo,” on veteran trauma recovery, while Bajema and Sanheim both spread awareness through talks on PTSD and participation in veteran peer support programs.

Said Bajema: “I couldn’t be prouder of all the guys who went through all that.” L

Courtesy Rudy Bajema

When Canadians went to fight in the First World War, they were initially led by two British generals, Edwin Alderson then Julian Byng. It made sense. The country had almost no military then. And it’s hard to develop a professional armed force if a nation doesn’t develop its own.

Fortunately, opportunities struck for Ontario-born militia man Arthur Currie and Byng eventually recommended he take command of the Canadian Corps. Currie led his countrymen to numerous key victories and became renowned for his planning, preparation and leadership.

Canada emerged from the conflict a changed country. Its participation led to many social programs and infrastructure projects that are still hallmarks of Canadian culture, largely, if not entirely, because Canadians themselves, like Currie, had first-hand experiences. That’s why, to start, the country should not allow foreign citizens at large to join the Canadian Armed Forces. Home-grown talent has always been critical to Canada’s development, militarily or otherwise.

To be clear, excluding foreigners from the CAF is NOT about questioning their experience, fortitude, commitment or trustworthiness. As with Currie, Canada long fought

Aaron Kylie says NO

to have its own citizens lead its forces and the country must continue to recruit, train and develop its own military members. The alternative is akin to a private army, like Russia’s Wagner Group or the U.S. Blackwater company, made up of guns-for-hire mercenaries.

THE ALTERNATIVE IS AKIN TO A PRIVATE ARMY, LIKE RUSSIA’S WAGNER GROUP, MADE UP OF GUNS-FOR-HIRE MERCENARIES.

If the goal extends beyond addressing the recruitment crisis to helping diversify the force, the country hardly needs to look beyond its borders. Canada is renowned as one of the most multicultural nations on the planet. Canadians reported more than 450 ethnic or cultural origins in the 2021 census. Some 52 per cent report European origins, while nearly four million Canadians noted Indo-Pacific origins, including 1.7 million from China, 1.3 million from India and nearly one million from the Philippines.

In total, one in four Canadians are part of a racialized group.

Plus, the CAF already admits foreign nationals in exceptional cases such as individuals on military exchanges or for those with high-demand specialized skills. So, there’s little need to expand such a policy. Also, a program introduced in 2014 allows foreigners on exchange, attached to or seconded to the CAF to fast-track their citizenship. More than a hundred such applications, from countries such as Hungary, Singapore, South Africa and the United Arab Emirates, have been approved.

And, while in the recent past many other foreign nationals have applied to the CAF, the majority have been refused as they don’t meet immigration, refugee or citizenship requirements. Should Canada really change those already accommodating rules just to fill out the ranks?

Of course, last year Canada began allowing all permanent residents to apply to the CAF. (It had previously accepted such applicants trained by foreign militaries.) In just one week after the change, half of new CAF applicants were permanent residents. Those were promising early results. The country should stick with the initiative and see what happens before allowing complete outsiders to serve the country. Canadians deserve it. L

> To voice your opinion on this question, go to www.legionmagazine.com/FaceToFace

Since November 2022, immigrants to Canada who have acquired permanent residence but are not yet Canadian citizens are eligible to apply to join the Canadian Armed Forces. This historical policy change was, for years, advocated by many, including myself. Previously, only Canadian citizens could join the CAF, with some exceptions such as the littleknown Skilled Military Foreign Applicant program, designed to recruit small numbers of foreign nationals with specialized skills such as trained pilots or doctors. Due to severe recruiting shortfalls, however, the CAF had no choice but to open its doors to all permanent residents of Canada who qualify. Indeed, the military is short approximately 16,000 members or about 15 per cent of its optimal strength. These recruiting challenges aren’t new, but they are becoming critical as the traditional pool of white men keeps shrinking. To be sure, the CAF does not reflect the ethnocultural and gender diversity of Canada’s workforce. Nor is it meeting its own employment equity goals: 16.1 per cent of the total force are women, compared to the 25.1 per cent goal; racialized Canadians make up 9.6 per cent, versus the 11.8 per cent target; and 2.8 per cent are

AARON KYLIE is the editor of Legion Magazine and the former editor-in-chief and associate publisher of Canadian Geographic. He is also the author of the Biggest and Best of Canada: 1000 Facts and Figures

is a professor in the department of defence studies at the Royal Military College of Canada and co-editor of the book The Power of Diversity in the Armed Forces: International Perspectives on Immigrant Participation in the Military

Indigenous Peoples, while the aim is 3.5 per cent.