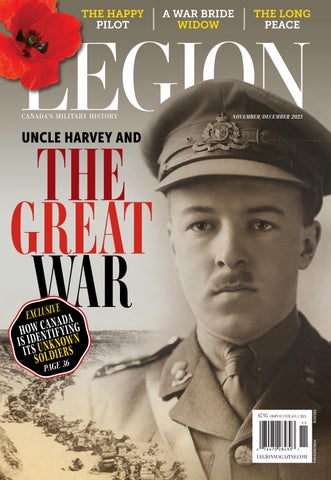

THE GREAT WAR

nally have all of the

✓ First walk-in tub available with a customizable shower

✓ Fixed rainfall shower head is adjustable for your height and pivots to o er a seated shower option

✓ High-quality tub complete with a comprehensive lifetime warranty on the entire tub

✓ Top-of-the-line installation and service, all included at one low, a ordable price

G

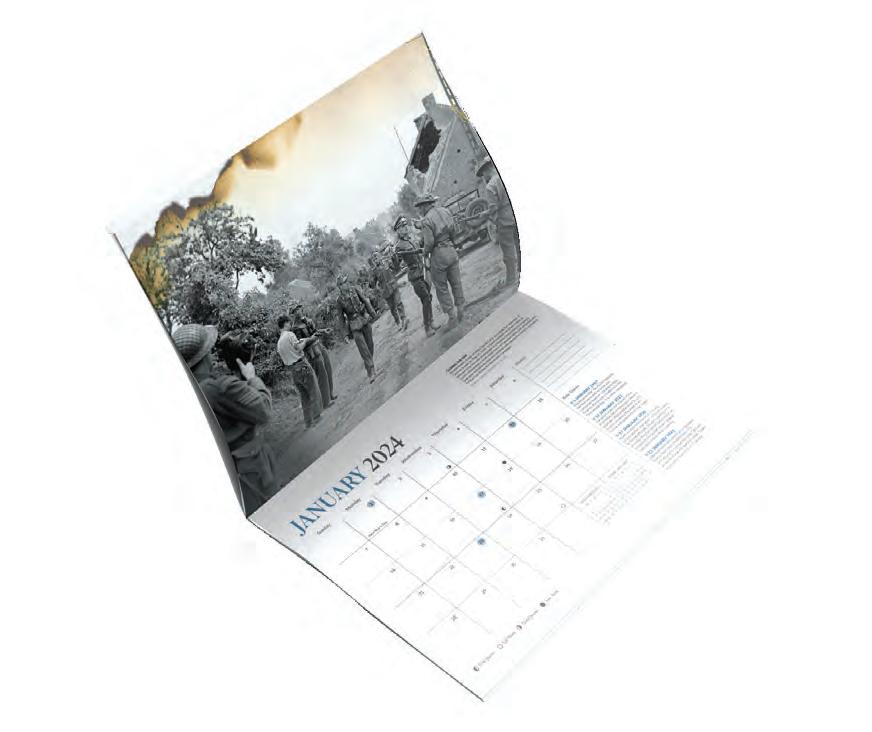

General discontent

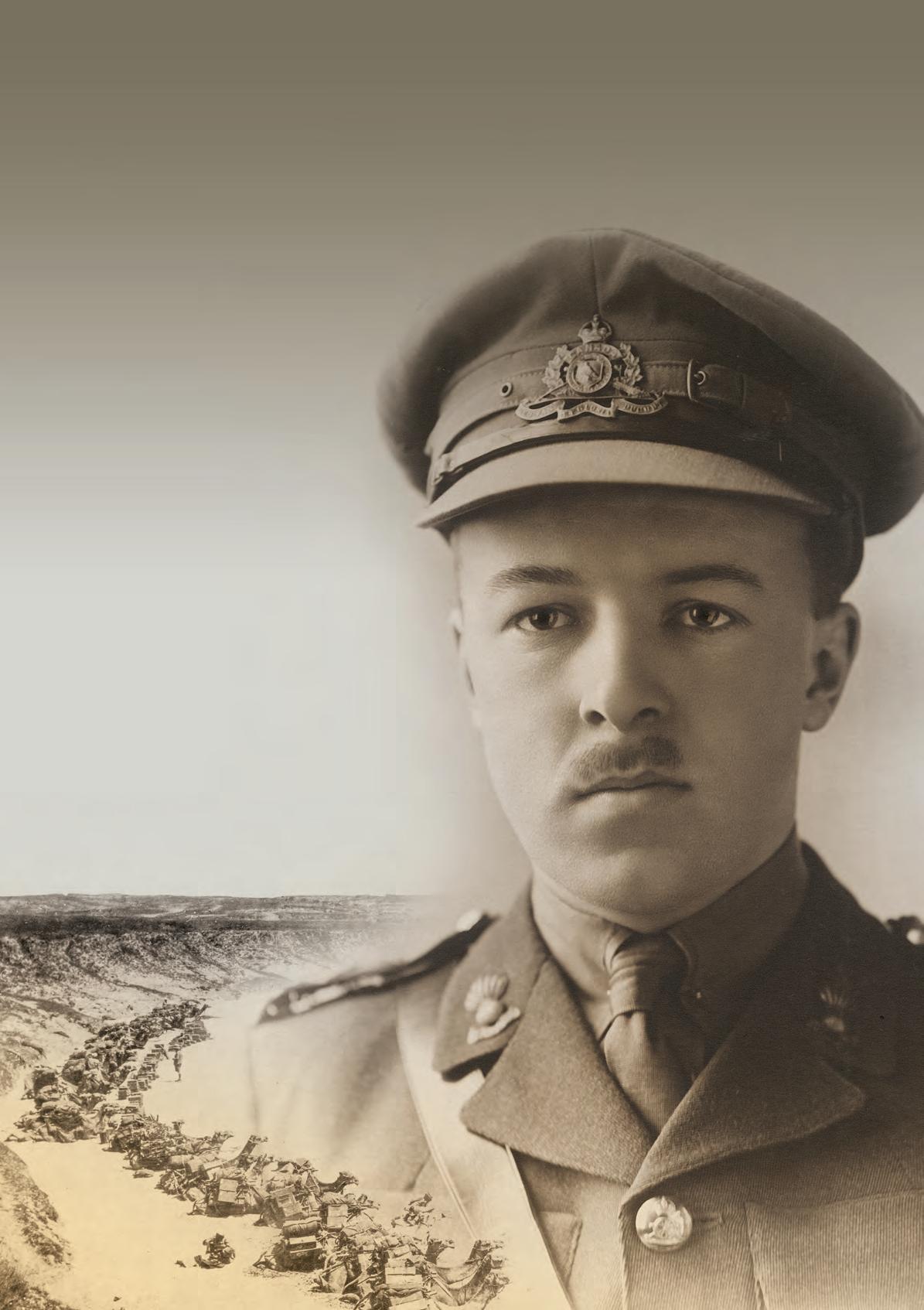

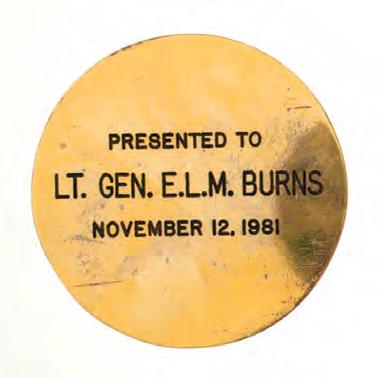

While in command of I Canadian Corps, Lieutenant-General Eedson L.M. Burns consults a map in Italy on Sept. 23, 1944. While a great military mind, he was notoriously disliked by his men and other officers.

See page 30

Features

24 THE HAPPY PILOT

A granddaughter learns the wartime secret(s) of the gruff former Royal Air Force flyer she knew growing up

By Kallan Lyons

30 DOWN BUT NOT OUT

A military man of high intellect but a lack of charm, Eedson L.M. (Tommy) Burns never stopped fighting

By J.L. Granatstein

36 LOST, NOW FOUND

How Canada’s once unknown war dead are being identified By Stephen J. Thorne

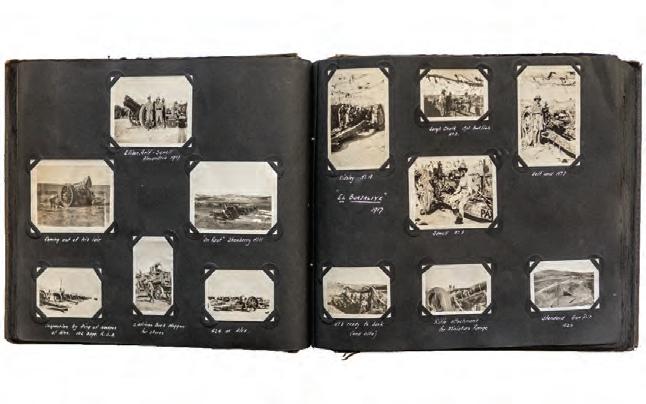

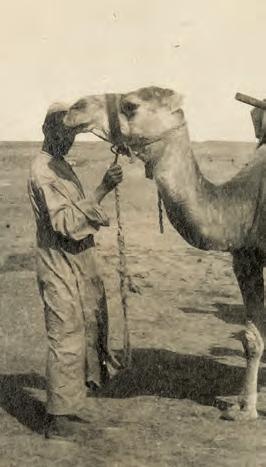

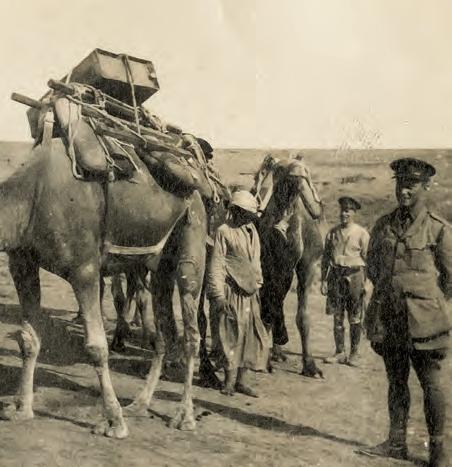

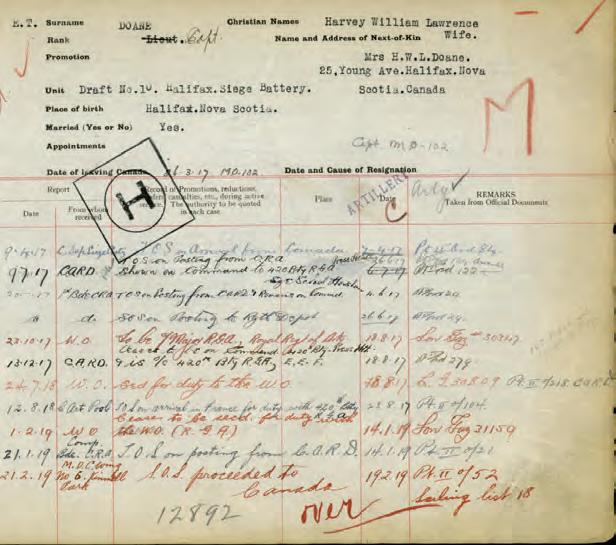

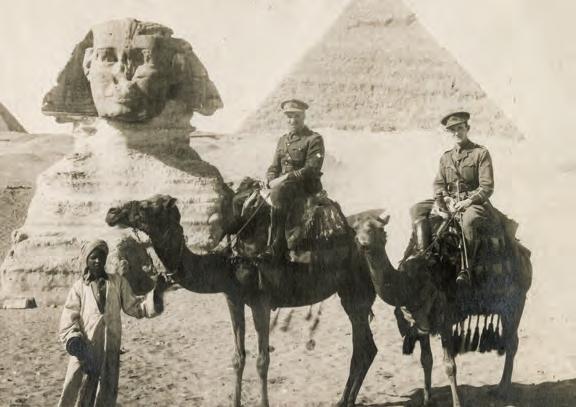

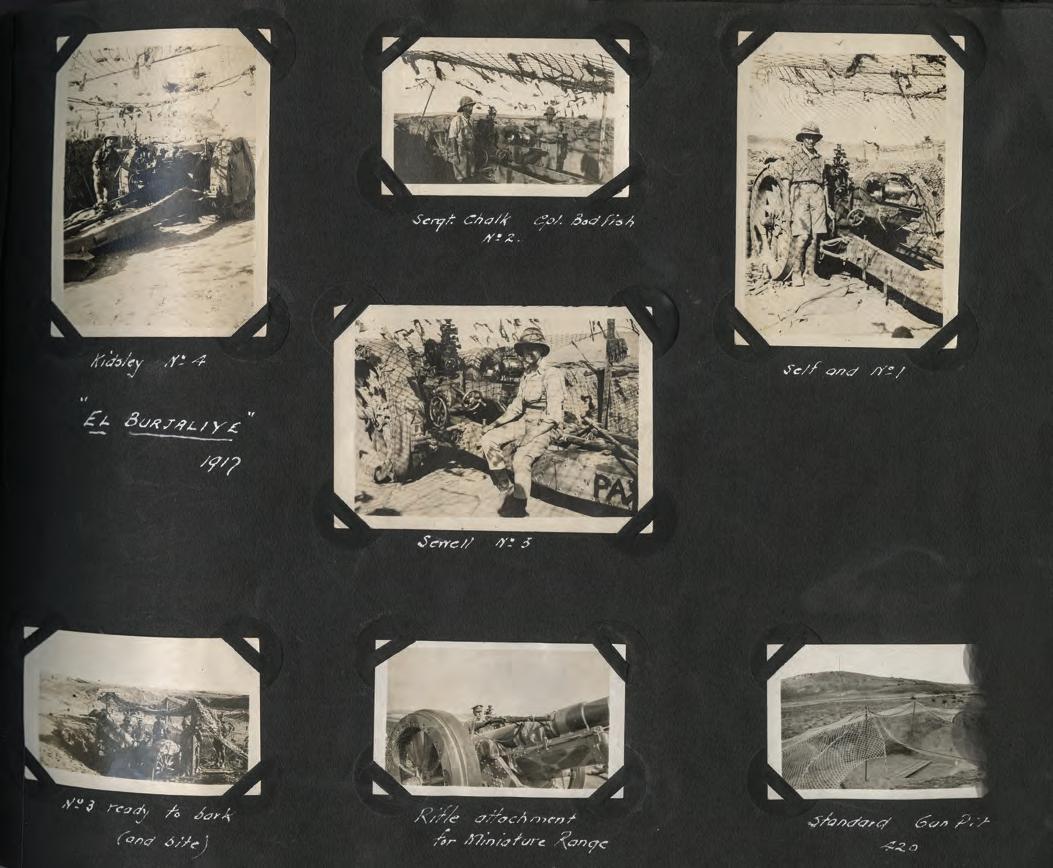

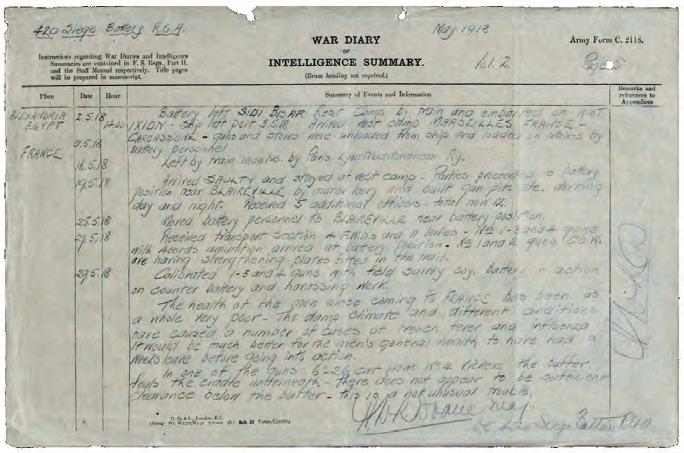

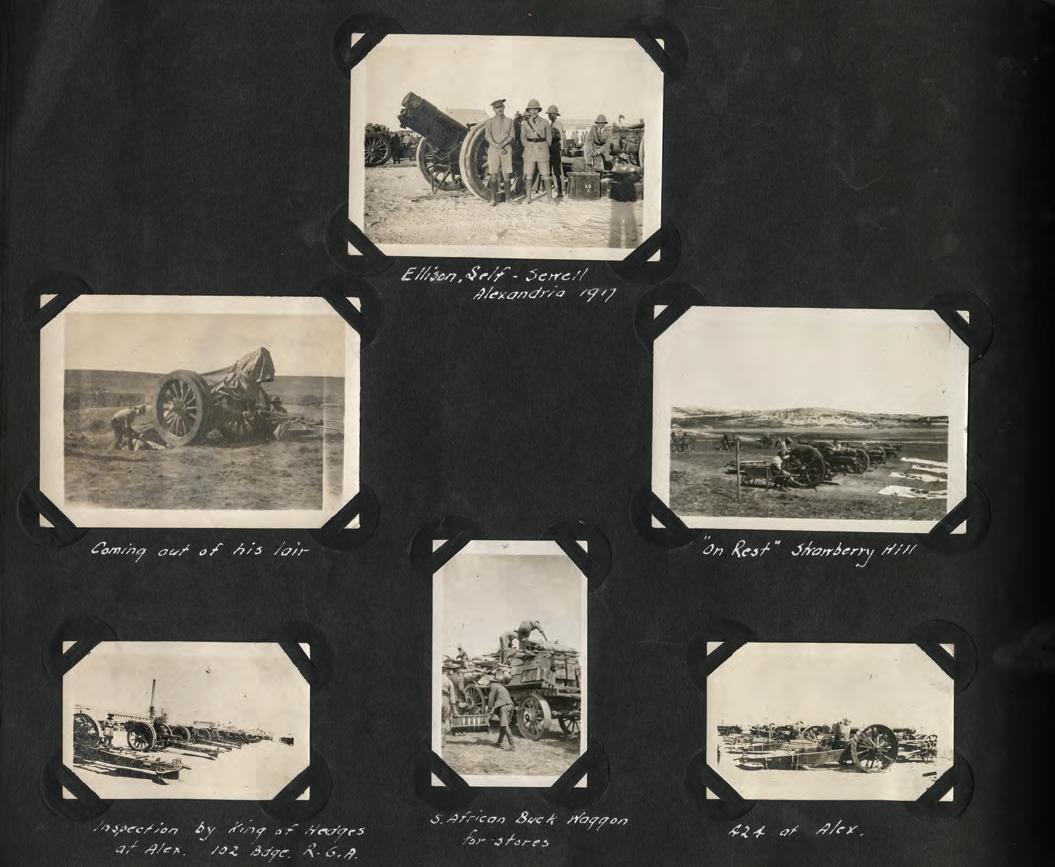

46 UNCLE HARVEY’S PHOTO ALBUM

Recollections of a cherished relative from a First World War scrapbook By

Stephen J. Thorne

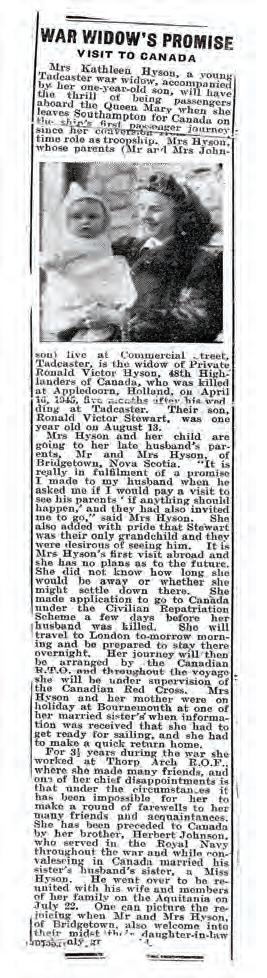

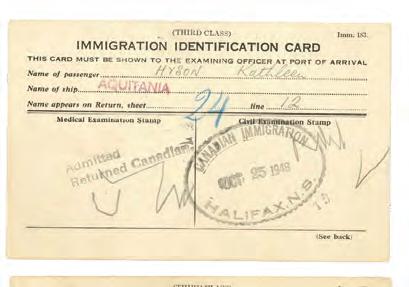

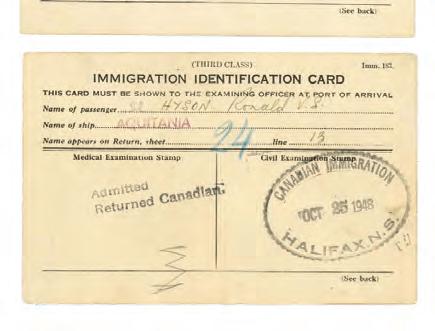

54 A WIDOW’S WALK

The story of a war bride of a Canadian soldier killed in action—and how she eventually lived a full life in Canada By

Stewart Hyson

THIS PAGE

War brides and their children en route to Canada from England in April 1944.

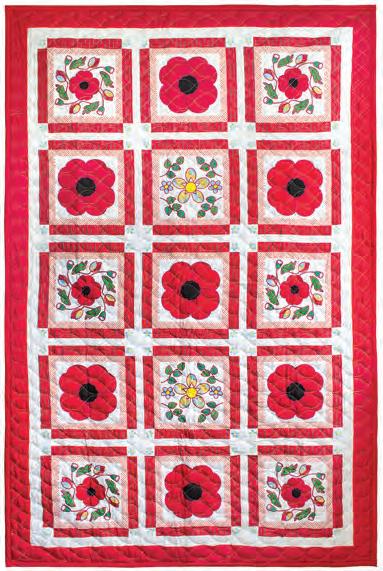

Lieutenant W.J. Hynes/DND/LAC/PA-147114 ON THE COVER

A wartime portrait of Harvey William Lawrence Doane, author Stephen J. Thorne’s great-uncle. He collected a trove of First World War images from his service in a cherished scrapbook. Courtesy Mary Doane

COLUMNS

18 MILITARY HEALTH MATTERS

Art direction By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

20 FRONT LINES

The myth of the "Long Peace" By Stephen J. Thorne

22 EYE ON DEFENCE

Playing politics By David J. Bercuson

44 FACE TO FACE

Should Canada have repatriated its war dead? By Stephen J. Thorne and Paige Jasmine Gilmar

88 CANADA AND THE NEW COLD WAR Treaty talk By J.L. Granatstein

90 HUMOUR HUNT Flag flap By John Ward

92 HEROES AND VILLAINS

Paul Triquet and the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division By Mark Zuehlke

94 ARTIFACTS

Street

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar 96

By Don Gillmor

Vol. 98, No. 6 | November/December 2023

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Owen Parkhouse BOARD VICE-CHAIR Bruce Julian BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe DIRECTORS Tom Bursey, Steven Clark, Thomas Irvine, Berkley Lawrence, Sharon McKeown, Brian Weaver, Irit Weiser

Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ASSISTANT

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

DESIGNERS

Sophie Jalbert Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales

CANIK MARKETING SERVICES

TORONTO advertising@legionmagazine.com

DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS INC mmignardi@dvtail.com

OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER AND MARKETING

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2023. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST.

FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Change of Address

Send new address and current address label. Or, new address and old address, plus all letters and numbers from top line of address label. If label unavailable, enclose member or subscription number. No change can be made without this number. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of CCAB, a division of BPA International. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

Make the most of your Legion Membership

As a Legion Member, you take pride in the fact that your membership helps support and honour Canada’s Veterans.

Did you know that it comes with benefits you can use, too? Take advantage of all the benefits that come FREE with your membership.

Renew your membership to get all these benefits and more!

MemberPerks® unlocks $1000s in potential savings on offers and deals at stores and restaurants across Canada, including national chains, local businesses and online stores. Use the MemberPerks® app, print out coupons or shop online to save on electronics, travel, fashion, entertainment and so much more!

Your membership also gives you access to additional benefits, including:

• savings and deals from our Membership Partners

• a paid subscription to Legion Magazine

• exclusive members-only items at PoppyStore.ca

We shall not sleep

There’s a lot of desecration going around these days— of honour, of purpose, of memory. And politics, in their various forms, are at the root of it.

A genuine Canadian war hero died this past August, without the recognition many say he deserved. Instead of the Victoria Cross some expected he would receive for actions in Afghanistan, Jess Larochelle was awarded a Star of Military Valour. Badly wounded, Larochelle was key in suppressing an October 2006 Taliban attack (see “Obituaries,” page 68).

A campaign to review his decoration with the intent of upgrading it to a VC was rejected on a technicality: valour awards must be considered within two years of the related action. Canada began revamping its honours and awards system five decades ago aiming to distance it from its British roots. When the new decorations were unveiled, there was no VC. It was only after pressure from The Royal Canadian Legion and others that Ottawa

produced a Canadian version of the Commonwealth’s most-coveted valour decoration in 1993. But it has never been awarded, a victim of agenda. And a desecration of honour.

In this issue, David Bercuson (“Eye on Defence,” page 22) casts a critical eye on Canada’s military procurement system, which has for decades been plagued by delays, indecision, politics and patronage. Among the casualties: replacements for aged Sea King helicopters and the CF-188 Hornet.

In many cases, it appears an overemphasis on Canadian content rules have trumped practicality—and tend to have more to do with collecting votes than prioritizing national interests.

Writes Bercuson: “The real lesson: when the country’s leaders play politics with the defence procurement process, all Canadians lose.” A desecration of purpose.

In France, the Canadian National Vimy Memorial was defaced this past August by an apparent

environmental activist. The towering limestone monument on the site of Canada’s seminal victory at Vimy Ridge is considered an eloquent protest against war. It bears the names of 11,285 Canadians who died in France and have no known grave.

In Ottawa in 2022, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier was blanketed by an American flag months after a protester danced on the grave and another urinated on the adjacent National War Memorial.

Such acts show blatant disregard for, and ignorance of the intent of, such monuments, whose messages are not to glorify war, but to honour the dead—and, in the case of the Vimy Memorial, to silently protest its waste and injustice.

The defacing of such memorials is a desecration of memory.

The answers? Education. Investment. Action. Canada needs a well-equipped and able-bodied military whose accomplishments and sacrifices are recognized and appreciated. As the plaque on the Vimy Memorial concludes of those who served, we must ensure “that their sacrifice will never be forgotten.” L

Newest partner promises affordable wireless services

Canada has among the most expensive wireless phone rates in the world. But members of The Royal Canadian Legion looking for affordable and reliable cell services have a new option to help limit such costs: the latest partner in the RCL’s exclusive Member Benefits Package (MBP), Red Wireless. A Rogers’ authorized dealer, Red Wireless boasts a team of dedicated experts who can advise you on the best smartphone and related plan. It also offers unlimited Canada-wide calling and texting plans starting as low as $20 per

month. And, if you’re a frequent traveller, Red has roaming options in more than 180 countries.

You can also bring your own device and still enjoy the 5G network and infinite data with no overage charges. Visit www.redwireless.ca/ legion or call 1-888-251-5488 to learn more.

The MBP also delivers discounts on wills, electric bikes, adjustable beds and related products, automotive repairs and consultation services, travel packages and specially designed travel insurance, online prescriptions, eyewear,

funerals and much more. Other MBP partners include Upper Canada Wills, Teslica, Ultramatic, Blowes and Stewart Travel, Pocketpills, IRIS Eyewear, Medipac Travel Insurance, belairdirect car and home insurance, HearingLife, Arbor Memorial, Canadian Safe Step Walk-in Tub Company and CHIP Reverse Mortgage. Combined, the continually growing group of MBP partners offer exclusive savings that can easily cover Legion membership dues— just one more bonus to joining the RCL. L

Rogers discount for Legion members

Legion members like you are looking for simple, affordable and reliable cell phone service designed with their needs in mind.

Look no further! As an endorsed Legion partner, Rogers is committed to providing affordable cell phone plans, smartphones, and tablets all on Canada’s largest 5G network.

Brought to you by Red Wireless - your exclusive Rogers dealer, our dedicated team of experts is here to help you select the right device and plan for your needs

Stay in touch with your loved ones with unlimited Canada-wide talk & text starting from $20/mo. or one of our affordable data plans to use your device on-the-go. If you often travel to the U.S. or escape the Canadian winter, pick our new Canada + U.S. plan, a perfect plan for Snowbirds

You can also travel seamlessly in 180+ countries with Roam like Home. No need to switch devices, SIM cards or get a temporary phone number.

Need a new device? Choose from Apple iPhone, Samsung and other brands and discover new affordable ways to get your device. Already have a device you love? No problem, bring your own device and enjoy our plans without commitment. With a fast and reliable 5G network, plans with unlimited calling, texting, and Infinite data with no data overages, as well as features like Spam Call Detect to notify you when you are receiving a spam call, you will never have to worry about your cell phone service.

This program is brought to you by Red Wireless - your exclusive Rogers dealer.

Sign up worry-free with no activation fee and our 30-day satisfaction guarantee

Call a dedicated Red Wireless expert at 1-888-251-5488 or visit us at www.redwireless.ca/legion

Glass Poppy Ornament in Velvet Box

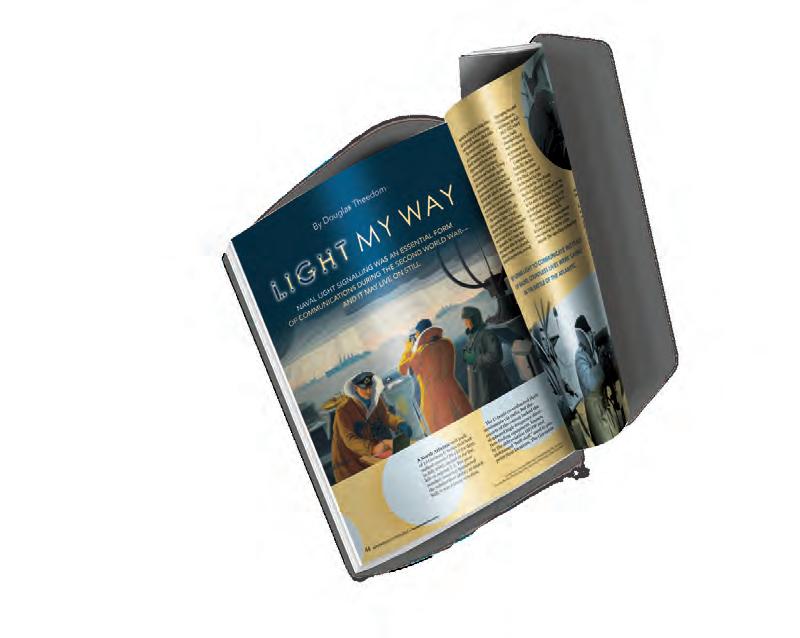

I Light fantastic

received the September/ October issue of Legion Magazine and was most interested in the “Light my way” article. I was a convoy signalman during the Second World War attached to the Royal Navy. The Canadian navy followed the same protocols almost exactly.

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

I remember receiving my very first message in a North Sea convoy from a destroyer

Lagging jets

I read with great interest David Bercuson’s article “Buyer beware” (Eye on Defence, September/ October) on a possible replacement for the CP-140 Aurora aircraft. Bercuson maintains that the P8 Poseidon, based on the Boeing 737-7, is widely used and is the safe choice for Canada. If a rapid decision was needed, I would agree.

However, is the Poseidon really the only choice? First, it’s an old airframe. Second, its sensor suite is an issue. I believe the reliability of the Bombardier Global makes it a better choice. It also has a military variant, having been selected as an early warning aircraft by both the United Arab Emirates and Sweden. The Global could also be fitted with the most modern sensor suite for surveillance-reconnaissance.

Bercuson mentions government subsidies to Bombardier, but these pale in comparison to U.S. financial support to Boeing. I appreciate Bercuson’s insights and I’m sure he would agree that no matter which aircraft is selected, the sensor suite must be top-of-the-line.

PIERRE ST-AMANT LEFAIVRE, ONT.

escort. I was inexperienced and nervous and made a mistake that cost our signal crew a weekend leave. I never guessed at a word after that.

I eventually got nicknamed “Steady light Smurthwaite” and by the end of the war, I considered myself an expert in sending and receiving messages by light in Morse code. We used Sperry searchlights for long distances, but mostly

It’s nice to see that the Aurora aircraft are going to be replaced. Kudos to the teams that have kept the aircraft in service for 40 years. I am disappointed, though, that we will be going through the same procurement process that causes delays in getting new equipment. No matter which aircraft the government decides to purchase, the taxpayer will be footing the bill.

The P8 seems to be proven in its abilities, but purchasing it would suggest to me that the government will reward companies that disrupt Canadian busi-

used Aldis lamps, which were convenient and movable. Our shore stations were later staffed by the Women’s Royal Navy Service—they were just as good, if not better, than the men. I imagine that today’s methods of communication will certainly mean that light signalling is a dying naval trade. Semaphore even more so.

STAN SMURTHWAITE ELMIRA, ONT.

nesses that compete with foreign companies. The purchase of the CH-148 helicopter may have had its problems, but it illustrates that the government can work with industry and make something that suits Canadian requirements. Canada has the capability to build it own equipment. The country needs to stay on top of its game when it comes to replacing aging military equipment. Many people may not like the idea of spending millions on military equipment, but think what the alternative could be.

If the P8 is chosen, the government should insist much of the aircraft is manufactured by Canadian companies. What better way to stimulate an economy than employing Canadians?

ROGER MAGARIAN REVELSTOKE, B.C.

Dress mess

What an outstanding read! (Canada and the New Cold War, September/October). As a retired chief warrant officer, it makes me proud that other people see the state of our military much the same way as I feel when it comes to our serving members. It’s hard to believe what they go through and still proudly and professionally serve our country. As author J.L. Granatstein indicated, how the folks in positions of power in Ottawa felt that the changes made in dress and appearance regulations would greatly increase recruitment is beyond me.

REX PITCHER

BEDFORD, N.S.

I completely agree with J.L. Granatstein on the new Canadian Armed Forces dress regulations. I live near 19 Wing Comox in B.C. and volunteer at the base, and I’m saddened by what I see of our soldiers in uniform, especially the length of hair for many of the men.

It’s a sloppy, unkept and unprofessional look. Is that what the image of Canada’s military on the world stage is to be now? Shame. And to allow coloured hair, men in skirts? Come on. This will do nothing to improve recruiting.

TED USHER

COURTENAY, B.C.

The greatest warrior

The feature story about Tecumseh in the September/ October issue (“The shooting star”) was great. After reading Killers of the Flower Moon and The Inconvenient Indian, I have become quite interested in the plight of Indigenous Peoples of North America. It’s sad to see what has happened to them as a result of colonization.

PAUL LEDUC

FENELON FALL, ONT.

Aw, shucks…

I am a new member of The Royal Canadian Legion living in Paris, Ont. My grandfather served Canada in an artillery unit in Belgium, Holland and Germany during the Second World War. I am proud of his service. I recently started getting Legion Magazine and have been pleasantly surprised by its quality. It’s full of excellent,

well-researched, thoughtful articles and features. And unlike many other magazines, it isn’t full of advertisements or image-heavy puff pieces. I’m proud to support the Legion and glad that there’s such a great editorial team producing such an excellent magazine.

JEREMY E. PARSONS PARIS, ONT.

Image conscious

It’s unfortunate that Gilbert Alexander Milne’s D-Day landing photo has become the iconic image of Canadians on D-Day (“The eyes of war,” July/August). It perpetuates a false understanding of the landings. On June 6, 1984, my father, Archie McQuade, escorted Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau on his tour of the beach at Bernièressur-Mer. Forty years earlier, Dad landed on the beach at 7:30 a.m., as a rifleman in ‘D’ Company of The Queen’s Own Rifles. When one of Trudeau’s assistants told the PM that this was where our troops landed with their bicycles, Dad immediately countered: “What the hell are you talking about? We didn’t have any goddamned bicycles! We fought!” The assistant started to challenge my father, but Trudeau stopped him, saying he wanted to hear what my dad had to say. Dad then told Trudeau what really happened that day.

RICHARD McQUADE

TORONTO

CLARIFICATION

In “Fighting the Monsters of Medak” (September/October), Mark E. Meincke was used as an independent source and was identified as a veteran and “a Canadian Forces’ advocate.” Any other interpretation of his service was not intended.

Communist troops of the North Korean People’s Army attack the South on June 25, 1950. They are in Seoul in less than a week. A United Nations coalition resolves to stop them, and

Canada joins what is, by any definition, a war. For three years, Canadians fight iconic battles on land, sea and in the air; 516 die and when the killing is over, the more than 26,000 survivors spend years fighting for recognition. They call it a “police action” and the “forgotten war,” but for those Canadians who fought in Korea between 1950 and 1953, neither time nor circumstance can erase the memories of what they saw, smelled and experienced in the hills and valleys around the 38th parallel and beyond.

Written by Stephen J. Thorne and narrated by Canadian wrestling legend Chris Jericho,

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /en/newsletter-signup

watch the story of Canadian soldiers in Korea in Legion Magazine’s latest video in its Canadian Military Moments series, Korea: War without end. The video transports viewers to the Korean peninsula and its hillsides, and shows why this was indeed a war, what the Canadians accomplished, what they sacrificed, and the legacy of the conflict. Watch it at www.youtube.com/legionmagazine. And if you want to dive deeper into the “forgotten war,” get a copy of Canada’s Ultimate Story, Korea: The war without End at canadasultimatestory.com. L

3 November 1534

November

9 November 1918

German Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicates his throne in the closing days of the First World War and flees to Holland.

11 November 1918

The Allies sign an armistice with Germany near Compiègne, France, to end the First World War.

13 November 1942

King Henry VIII becomes Supreme Head of the Church of England following the passage of the Act of Supremacy by the U.K. Parliament.

4 November 1920

Airmail service begins between Canada and the U.S.

5 November 2006 Saddam Hussein is sentenced to death.

6 November 1861

James Naismith, the inventor of basketball, is born in Almonte, Ont.

8 November 1939

An assassination attempt on Hitler in Munich fails, but eight die and 57 are wounded by the explosion meant to kill him.

The five Sullivan brothers from Waterloo, Iowa, die after the cruiser USS Juneau sinks. The U.S. Navy subsequently changes its regulations to prohibit close relatives from serving on the same ship.

20 November 1945

The Nuremberg war crime trials of 24 former Nazi leaders begin.

14 November 1666

The first experimental blood transfusion, between dogs, takes place in Britain.

15 November 1985

The Anglo-Irish Agreement, aiming to quell conflict in Northern Ireland, is signed by British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and her Irish counterpart Garret FitzGerald.

17 November 1869

The Suez Canal is formally opened after more than 10 years of construction.

18 November 1477

The Dictes and Sayengis of the Phylosophers is the first Englishlanguage book published in England.

19 November 1942

The Soviets begin a massive counteroffensive against the Germans at Stalingrad.

22 November 1943

Chinese Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek, U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill meet at the Cario Conference to discuss the war with Japan.

26 November 1917

After the National Hockey Association disbands, the Montreal Canadiens, Montreal Wanderers, Toronto Arenas, Ottawa Senators and Quebec Bulldogs form the National Hockey League.

30 November 1829

Two schooners pass from Port Dalhousie to Port Robinson in Upper Canada symbolically opening the Welland Canal and directly linking lakes Erie and Ontario.

December

3 December 1943

Of 400 casualties at Monte la Difensa in Italy, 27 Canadians die and 64 are wounded.

5 December 1812

HMS Plumper sinks in the Bay of Fundy; 42 lives are lost, along with gold and silver.

6 December 1907

Lieut. Thomas Selfridge makes Canada’s first recorded flight carrying a passenger on a heavier-than-air craft.

8 December 1915

Punch Magazine publishes “In Flanders Fields.”

11 December 1813

Bodies of women and children are found after U.S. forces burn the town of Newark (present-day Niagara-on-the-Lake, Ont.).

12 December 1942

The Knights of Columbus Hostel in St. John’s burns down, killing 99 and wounding 109. German sabotage is suspected.

14 December 1939

The Soviet Union is expelled from the League of Nations after invading Finland.

16 December 1941

The original HMCS Calgary is commissioned in Sorel, Que.

20 December 2019

The United States Space Force is founded as an armed branch of the military.

21 December 1898

Pierre and Marie Curie discover radium.

24 December 1968

Apollo 8 orbits the moon, becoming the first manned space mission to achieve the feat.

22 December 1775

The Continental Navy, forerunner to the U.S. Navy, appoints Esek Hopkins as commander-in-chief and its officers are commissioned.

25 December 1952

Queen Elizabeth II gives her first Christmas broadcast on BBC radio.

27 December 1831

Charles Darwin sets sail on HMS Beagle, beginning the voyage on which he would formulate his theory of evolution.

28 December 1918

For the first time, women are allowed to vote in Britain’s general election.

29 December 1940

Germany begins dropping incendiary bombs on London.

31 December 1857

Ottawa becomes capital of Canada.

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

Artdirection

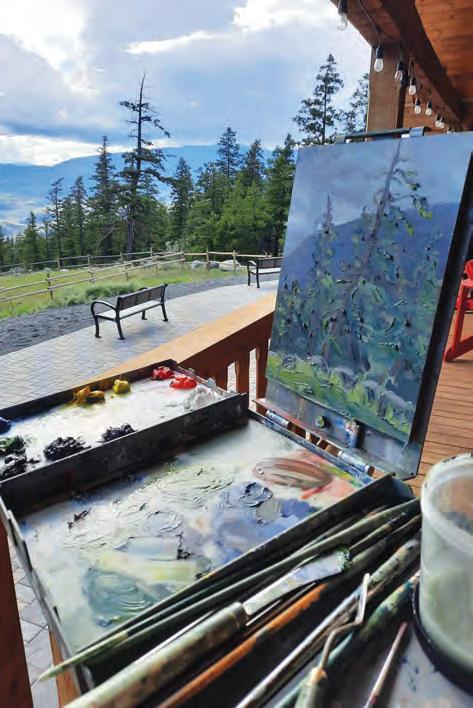

Enlisting the creative forces can be its own conscription crisis. To be imaginative is a state of existence, a life’s purpose. In many ways, it’s the opposite of the analytical, orderly way of armed forces’ thinking.

Alongside the results-driven culture of the military, being creative can be intimidating for soldiers and veterans. But with a job as nerve-fraying as serving in the Canadian Armed Forces, any outlet that relieves stress, from football to fingerpainting, can be welcome.

Chief Warrant Officer Chris Hennebery of The Royal Westminster Regiment felt something had to change when he saw Canadian Armed Forces’ members shy away from the prospect of art therapy.

“Serving for as long as I have, I’ve developed quite a family within my unit,” he said. “A lot of them were struggling.”

But rather than shrug off their struggle, the Vancouver-based reservist decided to use his

How one Canadian soldier is enlisting creativity to counter operational stress injuries

entrepreneurial knack and artistic skill to create the Veterans Artist Collective, a non-clinical art therapy program for veterans struggling with operational stress injuries (OSIs) such as post-traumatic stress disorder or traumatic brain injuries (TBIs).

“Working with your hands can be a great tool for mastering your mind,” said Hennebery, who holds a fine-arts degree. “There’s a form of soft therapy to it.”

Researchers have found that artistic activities can enhance mood and lower levels of cortisol, a “stress hormone.” Professionally guided art therapy, for instance, has been found to help reduce symptoms of PTSD and brain injuries, as well as aid in processing and clearing traumatic memories.

“Art therapy bypasses our usual judgments, filters and censoring that we often do when we talk,” art therapist Youhjung Son told Legion Magazine. “That’s why it’s often one of the best ways we can get in touch with the part of ourselves that we don’t even know, understand or suppress.”

Son also notes that art programs such as Hennebery’s collective can be better focused, more flexible and better tailored to people’s needs than formal art therapy.

“Shamans, guides, elders, medicine men and healers who used creative means to help people are not considered trained therapists,” noted

Son in her art therapy program’s blog, Thirsty for Art. “But are they not therapists in their own context?”

During the throes of the pandemic, Hennebery put his art initiative into motion, catering to a need further compounded by COVID’s psychological ramifications. His vision: a multi-day getaway in a peaceful location for veterans to break routines and bad habits using an artistic medium, specifically painting.

“We’re trying to get them to commit, to be immersed in it,” he said. “We take all the excuses away and just have that opportunity to be quiet, to concentrate and give themselves over to the process.”

Michael King, a master of plein-air, or painting in nature, facilitated the workshop, which was held at Honour Ranch, a mental-health retreat for CAF members and first responders dealing with OSIs, in Ashcroft, B.C.

Major

“[Veterans] are dealing with so much shit that if listening to me takes away that shit for five minutes, and then they can paint for another 10,” said King, “that’s a success.”

The collective’s first retreat was an absolute hit. And believing that the program could be more than a one-hit wonder, Hennebery dedicated himself to the program, sometimes ponying up the money to pay for retreats, cooking all the meals for attendees and even sleeping on the couch to fit an additional guest into one of the cabins.

“I really enjoyed myself and all the attendees did,” he said. “It was just brilliant.”

Still, Hennebery wanted to expand his initiative from painting to metal forging, hoping to boost male turnout since the art retreats were dominated mostly by women.

“When we think of creative practices, lots of guys say, ‘that’s not me. I was in the infantry. That’s not what we do,’” noted Hennebery, citing the importance of genderspecific health care, a characteristic that can heighten the effectiveness of some wellness services.

“Some of these guys say that the last time they did anything creative was when they were in elementary school. That’s why the axe-forging was really important.”

Joining forces with navy veteran Will Steed of The Forge Co. in Beaumont, Alta., Hennebery started an axe-forging retreat, which also showed promising results.

“We are seeing real, meaningful change,” he said. “And at the end of the day, I think that’s all we’re trying to achieve.”

The demand for retreats for both arts continues to build. Indeed, there’s currently a waiting list of 120 people. What accounts for the success? Hennebery recounted the journey of one attendee who had served in the infantry for eight years and was diagnosed with PTSD and TBI. “He had told me, ‘When I saw this [program], it literally

stopped me from deciding to take my own life.’ And he’s still axe forging.”

Hennebery plans to retire from the military in a year, hoping to replace “one service with another” by dedicating his time to expanding the collective to include creative writing and music programs. He also wants to

increase the number of attendees per retreat, as well as get consistent funding from government.

“We’re not trying to change the world,” Hennebery confessed. “We’re just trying to give some veterans and serving soldiers an opportunity to try something new.”

MEDIPAC TRAVEL INSURANCE

The myth of the “Long Peace”

Have the last seven decades really been a Pax Americana

Some historians describe the period between the end of the Second World War and now as the “Long Peace,” or Pax Americana, based on the fact there have been no major wars involving the great powers. Proxy wars, yes; “major” wars, no.

They qualify this by describing it as a time of “relative” peace, implying that the Cold War—four decades of living with the prospect of nuclear annihilation hanging over the planet—was a good thing and that regional conflicts are inconsequential.

As American as that might sound, the concept is not limited to our neighbours south of the 49th.

In 2012, the Norwegian Nobel Committee unanimously voted to award the European Union the Nobel Peace Prize for contributing to “the advancement of peace and reconciliation, democracy and human rights in Europe” for six decades.

This despite the bitter ethnically and religiously based wars that raged in Eastern Europe, notably the Balkans and Chechnya, after the collapse of the Soviet Union and communism in the 1990s. Never mind the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 or the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968—mere incidents, apparently.

According to the Council on Foreign Relations, a U.S.-based

think tank, there are at least 26 hot wars and simmering conflicts in the world today, including the 20-month-old—some say nine-year-old—war in Ukraine; the potential powder keg developing over Chinese territorial claims in Taiwan and the South China Sea; and wars, civil wars and conflicts in Africa, the Middle East, the Indian subcontinent and Southeast Asia.

The Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project, meanwhile, reported 19 countries met its criteria for high or extreme levels of conflict severity at the start of 2023. For the week of July 15, 2023, it recorded 2,350 incidents of political violence worldwide, including battles. And that was down 16 per cent from the previous week.

Some 21.3 million people currently serve in armed forces around the world (China tops the list at 2.4 million, followed by the U.S. at 1.4 and India at 1.3). Fourteen of the world’s 20 largest militaries are in developing nations.

Two billion people currently live in conflict-affected areas and climate change is creating new reasons to go to war.

Humanity’s penchant to fight and kill one another is at least as old as recorded history.

The New York Times reported in 2003 that humans had been entirely at peace for just 268 of the past 3,400 years, or an estimated eight per cent of humankind’s documented time on Earth, which spans about 5,000 years. Estimates of the total number of people killed

Canadian armoured reconnaissance troops patrol in the mountains west of Kabul in 2003.

in wars during that time vary widely between 150 million and a billion.

The Canadian perspective on war is often shaped by American policy and experience. Since 1946, up until at least the Donald Trump administration, the U.S. laid claim to the title of global police officer—the defender of democracy and human rights, even when the very exercise violated international law and human rights.

Between its founding in 1776 and 2020, America was at peace for just 15 years, according to one news outlet. It has been been involved in at least 105 wars and rebellions, four of which still involve U.S. forces: Niger, Syria, Somalia and Yemen. More than 650,000 Americans have died in combat.

The Americans currently have between 160,000 and 170,000

active-duty personnel deployed in “non-combat” roles in at least 36 countries, nearly 40,000 of whom are assigned to classified missions and an additional, undetermined number participating in actual wars—more, apparently, than we know.

A November 2022 report by New York University School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice says the Americans have been involved in many more wars during the past 20 years than the Pentagon has disclosed to Congress.

“Afghanistan, Iraq, maybe Libya,” says the report by the law and policy think tank. “If you asked the average American where the United States has been at war in the past two decades, you would likely get this short list.

“But this list is wrong—off by at least 17 countries in which the United States has engaged

in armed conflict through ground forces, proxy forces, or air strikes. For members of the public, the full extent of U.S. war-making is unknown.”

And that includes American lawmakers. Congress’s understanding of its forces’ involvement in overseas wars, adds the 39-page report, is often no better than the public record. The U.S. defence department provides congressionally mandated disclosures and updates to a limited few.

“Sometimes, it altogether fails to comply with reporting requirements, leaving members of Congress uninformed about when, where, and against whom the military uses force. After U.S. forces took casualties in Niger in 2017, for example, lawmakers were taken aback by the very presence of U.S. forces in the country.”

Pax Americana, indeed. L

By David J. Bercuson

Playing Insights from a brief history of Canada’s military procurement processes

politics

In

1977, the Royal Canadian Air Force began to look for an aircraft to replace the three-decade-old CF-101B Norad interceptor and the CF-104 NATO fighter, whose lowlevel nuclear strike mission was being phased out. To do so, the government launched the “new fighter aircraft” competition under the direction of the future defence chief, Brigadier-General Paul Manson, then commanding officer of 441 Tactical Fighter Squadron. Manson was an energetic leader, outstanding pilot and superb administrator who quickly organized tests. The Aeronautical Engineering Test Establishment was responsible for overseeing the competition and the budget for the purchase was about $2.4 billion to procure between 130 and 150 aircraft, including two place-training aircraft. Five to eight top Canadian fighter pilots and radar operators

or navigators flew existing U.S. and European fighters and one plane that was still in development. Specifically, the options included: the Grumman F-14 Tomcat, a U.S. Navy swingwing, twin-engine fighter; the McDonnell Douglas F-15, a new U.S. Air Force twin-engine fighter; the Panavia Tornado, a twin-engine interceptor/ ground attack fighter developed by Italy, Britain and Germany; the French Dassault Mirage F1, a single-engine interceptor; the American General Dynamics F-16, a single-engine fighter; and the U.S. Navy’s prospective YF-17, a McDonnell Douglas fighter not yet in production, but eventually to be built as the F/A 18 Hornet. The latter—known in Canada as the CF-188 Hornet—was announced winner in 1980, three years after the competition began. The first aircraft arrived

in Canada in 1982, destined for decades of outstanding service.

The CF-188 procurement was not the only large defence purchase done without a hitch. When Canadian troops shifted their role in Afghanistan in 2003 to act as peace enforcers around the capital of Kabul, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Paul Martin purchased new M-777 howitzers, with a brace of GPS-guided shells, to shore up Canada’s longer-range capabilities.

In 2009, Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper’s government leased the Israeli-built Heron unmanned aerial vehicle under a license agreement with Canadian company MDA with no squabble at all. The Harper government subsequently initiated a purchase of four

Canadian soldiers

(later five) Boeing Globemaster III heavy airlifters and, in 2007, leased 20 Leopard II tanks from Germany for service in Afghanistan, as well as 100 refurbished L eopard IIs from the Netherlands.

But in 2010 when the Harper government announced t hat it planned to purchase 65 L ockheed-Martin F-35 stealth fighters, opposition MPs began seriously questioning t he lack of competition for the expenditure. A report by t he auditor general on the matter, which considered t he still-in-development fighter a completed production aircraft, was released t wo years later and projected impossibly expensive costs for the purchase. In 2014, t he CBC's “The Fifth Estate” labelled t he aircraft a “turkey.” It was the final nail in the coffin. The plan was k illed by the same Harper government.

This past January, the government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, who had sworn Canada would not buy the F-35, decided to do just that—nine years after the original initiative died.

The F-35 situation is somewhat reminiscent of the plan to replace Canada’s Sea K ing helicopters, which began in 1986. It was killed by Jean Chretien’s Liberal government in 1993 only to be revived two years later. It ultimately dragged on until the replacement Sikorsky CH-148 Cyclone entered service in 2018—some 30 years after the process started.

What can Canadians conclude from these examples? When the country has its back to the wall in an international crisis—emphasis on crisis—federal governments of both political parties can move quickly to outfit the Canadian Armed Forces w ith equipment t hat’s needed.

Legion and Arbor Alliances

In the case of the CF-188, the Cold War was the motivating factor, along with the need to assure the U.S. that Canada would do its part to defend North A merica with the best aircraft available. Even supposedly antimilitary Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau knew that. Martin’s government needed no acute tactical thinking to buy M-777 howitzers when Canada pledged to keep the Taliban out of Kabul. A nd the Harper government acted quickly to acquire Heron drones, new Hercules tactical transports and buy and lease new tanks.

Too bad it quickly abandoned the F-35 purchase, only to have it re-emerge almost a decade later under Justin Trudeau’s government. The real lesson: when the country’s leaders play politics with the defence procurement process, all Canadians lose in the long run. L

happy The

By Kallan Lyons

A GRANDDAUGHTER LEARNS THE WARTIME SECRET(S) OF THE GRUFF FORMER ROYAL AIR FORCE FLYER SHE KNEW GROWING UP

Opilot

Courtesy Kallan Lyons

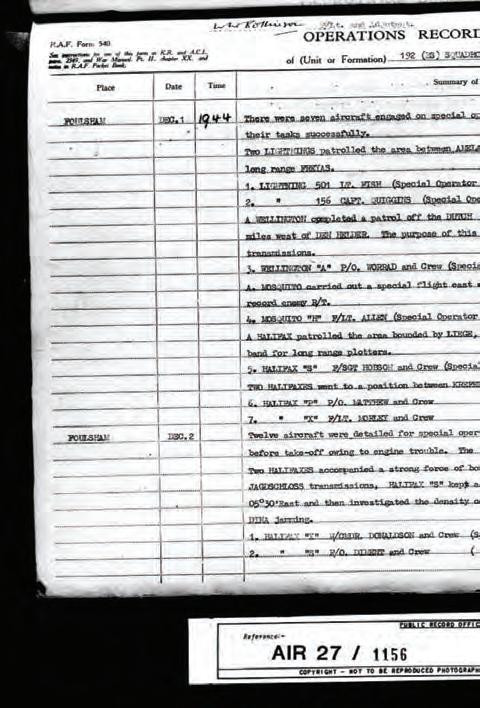

On a bitter cold evening in 1944, eight men took off from Royal Air Force station Foulsham in Norfolk, England, in a four-engine Handley Page Halifax heavy bomber and ascended 6,100 metres into the dark. Rear Gunner Bernard (Bernie) McNicholl sat silent and alone in his Perspex dome, scanning the sky for any sign of a flitting shadow. Three years prior, the 15-year-old was itching to finish high school in Montreal. Now he waited for the enemy to appear—poised to fire four Browning guns that protruded like stingers from the plane’s tail.

From his turret, McNicholl could usually spot enemy aircraft 350 metres away. Suddenly a crew member yelled: “Fighter coming in on us!”

O

“Corkscrew, starboard, go, go, go!” McNicholl roared into his headset. The bomber plummeted to the right and dove, rolling 60 degrees in the opposite direction before once again starting its ascent.

“What was that?” the pilot’s voice crackled over the intercom.

“There’s good news and bad news,” McNicholl replied.

Arnold (Smitty) Smith (opposite page) served with the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. Flying Officer Smith is third from right with his crew in this wartime photo. Bernard (Bernie) McNicholl served with Smith as a rear gunner.

The good news: the Allied bomber had just flown by a German night fighter. The bad news: “The fighter pretty near crashed into us,” said McNicholl. “I bet you we were 10 feet apart.”

McNicholl and my grandfather Arnold Smith—“Smitty” to his crew and family—were among hundreds of Canadians who served with the Royal Air Force during the Second World War. I knew very little about my grandfather’s RAF career when I was growing up beyond the simple fact that he was a bomber pilot. So, in the fall of 2018, I drove from my home in Vancouver to Chilliwack, B.C., to visit then 92-year-old

McNicholl to learn more. (McNicholl died this past July.)

When I arrived at McNicholl’s home, a small, animated man swung open the door and ushered me inside. I had met him only once before, when I was a child, but he immediately felt like family. As we made our way to the living room, he grabbed something off the kitchen table to show me. It was a Halifax bomber model he had built.

McNicholl and Smitty met in Lossiemouth, Scotland, in early 1944. As the youngest crewman, McNicholl looked up to Smitty and the pair bonded quickly. Both had no siblings and had had difficult childhoods.

They flew with 192 Squadron in special duty RAF 100 Group on a top-secret mission: electronic warfare. Their plane carried very few bombs and gathered radar frequency, with a rotating eighth crew member who operated the equipment.

“Every crew thought they were the best crew, but we were, no argument there,” said McNicholl. “Because they used to pick us for the bad trips, too.”

McNicholl spoke highly of my grandfather, a “great low-level pilot” who had never flown a plane before the war. “Smitty didn’t panic,” said McNicholl. “Your grandfather could fly that aircraft like a fighter.”

Smitty, 30 at the time, was one of the eldest on board, and as confident in his aviation skills after less than two years of training as he was in carpentry, a trade he had practised since his teens. Never one to do anything half-heartedly, he was out to impress. Indeed, after meeting a Canadian Red Cross worker—who would become my grandmother— during a stopover in London, Smitty decided to put on a show.

“As we went by Croydon hospital, the ladies were hanging out the windows waving towels at him,” said McNicholl. “When I went by in the rear turret, I was looking up at them. That’s how low we were flying.”

The squadron’s mission was arguably more dangerous than that of many bomber crews, who would fly to a target, drop bombs and go home. After circling for hours collecting frequencies, the data was sent to a jamming squadron to block German radars. While readily scanning for fighters, McNicholl would turn the turret so that it would catch the wind and move the plane. Smitty would correct it to indicate he was awake. Good communication and reflexes were key to their survival. McNicholl says he owes his life to the way his shouted warnings were translated into action by his pilot.

Of course, the fact that McNicholl lived to share this tale is momentous: as is well-known, only 25 per cent of bomber crews completed a first combat tour of 30 missions. Remarkably, in June 1945, Papa’s special-ops crew completed, without a casualty, 30 top-secret missions over Germany.

In 1995, a largely intact RAF Halifax bomber was exhumed from the bottom of Lake Mjøsa in Norway and brought to Canada. The 25,000-kilogram plane had been sitting in its boggy grave for some 50 years when Canadian pilot Karl Kjarsgaard began its recovery.

“The Halifax was the most important airplane in [Canada’s] aviation history,” he told me during a visit to the Bomber Command Museum of Canada in Nanton, Alta. “The Lancaster has always got the glory as the beautiful bomber that did everything in World War II,” continued Kjarsgaard, also the museum’s curator. “But Canadians flew 70 per cent Halifax, 20 per cent Lancaster and 10 per cent Wellington.”

Most RAF bombers shot down by the enemy were attacked by night fighters from the rear or

underneath. There was and it was seen as the weak-

enemy plane had snuck up on them that near-fatal night in 1944.

If RAF crewmen weren’t killed in the air, they were likely to be seriously wounded in crashes or to become prisoners of war. Few in Bomber Command made it to the end of the war unscathed.

Despite the immense losses, Kjarsgaard said the Handley Page Halifax played a huge part in the Allied victory, even if it was overshadowed by the Lancaster heavy bomber. In part, the Merlin engine used in earlier Halifax models couldn’t provide enough horsepower for the plane to perform as designed, garnering it a poorer reputation. In 1942, however, the Halifax Mark III was powered by a Hercules engine and the bomber became a jack of all trades. While the Lancaster could carry more bombs, the new and improved “Halibag,” as it was affectionately known, was ideal for special operations— as assigned to 192 Squadron.

Kjarsgaard speculated that my grandfather’s crew survived thanks to a combination of chance, talent and teamwork. Still, there’s one thing he’s sure of: “Your family exists because of a Halifax.”

In 1997, my family took my grandfather to the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum near Hamilton, Ont. I was 10 years old and didn’t fully appreciate the trip’s significance. In one photograph from the visit, my sister and I are standing next to my grandfather in front of an Avro Anson—a plane used for RAF training. My mother captured a rare moment that day: my grandfather— with his white cane in one hand, the other resting on the nose of the plane—grinning from ear to ear.

He was lauded a hero in his hometown of Centreville, N.B, a tiny village northwest of Fredericton, but my mother says her dad never talked about the war. She always knew, however, that he had a special bond with his crew. “The squadron was everything to him,” she told me. I couldn’t help feeling a twinge of jealousy when I heard that. I longed for the loving relationship my friends had with their grandfathers. Papa Smitty, as I called him, was impatient, short-tempered and extremely fastidious. I constantly tiptoed around him and was, admittedly, a bit scared of him. Even my mother found him intimidating.

As a teenager, when my mom would drive the family car, my grandfather would inspect it upon her return. He would insist she put the seat and mirrors back in the positions she had found them and park it so that the two front wheels sat in the little divots in their gravel driveway. She did her best to please him, but still felt that he didn’t trust her. One time, Smitty secretly put coins

“I know I can be a pilot. I’ve been driving a taxi for over a year and a half, and I haven’t killed anybody.”

on both sides of the dashboard, right up against the window. My mother never noticed until the day she returned home and was asked how fast she had been driving.

“You must have been going pretty darn fast,” she recounted him saying. “The coins are on the floor.

“I got to the point where I knew enough to put them back,” she recalled with a laugh, then paused. “I think of that now— he couldn’t have survived the war flying a Halifax bomber if he hadn’t been that precise.”

In 2005, the world’s first restored Halifax was unveiled by Kjarsgaard and his team at the National Air Force Museum of Canada in Trenton, Ont. Smitty, unfortunately, didn’t live long enough to see it. He died less than a year after our trip to Hamilton, at the age of 83.

“My personal tribute to the bomber boys is to save as many Halifaxes as I can,” said Kjarsgaard.

Smith met the women who would become his wife, a Canadian Red Cross worker, during a stopover in London. Smith (centre) with crewmen, including McNicholl (back right).

Arnold Smith never dreamt of becoming a pilot. Instead, he became a taxi driver, driving full speed from town to town picking up passengers. To avoid being drafted into the army or navy, the New Brunswick farm boy drove to Moncton, N.B., in the fall of 1942 and enlisted in the Royal Canadian Air Force.

I recently received a package from my mother that held the missing pieces to Smitty’s story. Inside were five compact disks with converted audio recordings from old tapes.

In the 1980s and ’90s, my uncle James Smith sat down with Smitty to capture his wartime memories. When I pressed play, my grandfather’s gruff voice filled my ears for the first time in more than 20 years.

“I said, ‘I want to be a pilot,’” he recalled. “They asked, ‘What makes you think you can be a pilot?’ I said, ‘I know I can be a pilot. I’ve been driving a taxi for over a year and a half, and I haven’t killed anybody.’”

Two weeks after he enlisted, Smitty was on a train to Montreal. He learned to fly on Wellingtons at No. 11 Elementary Flying Training School in Cap-de-Madeleine, Que. He was flown to Lossiemouth shortly before his 30th birthday and assigned the task of finding a crew. All he needed were six people to join him.

At the time, Smitty had recently injured himself in a bicycle mishap after a night at the pub and thought

“Every crew thought they were the best crew, but we were, no argument there.”

his banged-up appearance might deter others from wanting to fly with him. He stood idly by for a couple of days until wireless operator Reg Bastow approached him after deciding the other pilots looked too young. Next, they found mid-upper gunner John (Johnny) Matulack and bomb aimer Jack Martin, who, after a few too many drinks, had been left behind by his previous crew.

Meanwhile, aspiring pilot McNicholl had allegedly been grounded for being too dangerous and reckless (or possibly had to re-enlist because he was originally underage), and navigator Ed Moran

was even older than Smitty (most crews were in their late teens or early twenties). Unable to find a flight engineer, they picked up Jock Young at the next base. They were a band of misfits, made up of five Canadians, one Englishman and one Scotsman.

“If you want to take a chance it’s all right with me,” Smitty told them.

The crew trained on Halifaxes. When they finished in Lossiemouth, they were granted a seven-day leave before heading to London. But the leave was cancelled.

“Instead of going to London, we were put on another aircraft, a Lancaster—the first and only time I was near one—and flown to the squadron to which we were attached,” Smitty recalled. “And the thing that shook us up, we were an RAF squadron, instead of RCAF.”

During the big raids, Smitty’s Halifax was among a dozen other planes from 192 Squadron that were the first to fly out and the last to return.

“In one case we were over Berlin, and we circled for 35 minutes.

Just round and round. I think there was supposed to be 1,000 bombers,” said Smitty.

One night, while flying over France, he felt an unexpected bump. He asked the crew if they had seen anything, assuming they may have touched another aircraft. No one had a clue until Matulack shouted, “I think we lost our dingy.”

“When we got back we found out it was gone,” Smitty told my uncle. “And the rudder and the elevator both had been hit—must have been the CO2 bottle because they were both badly dented. Would have been a bad situation if it had inflated.”

As chance would have it, whether it was evading a freak accident,

Courtesy Kallan Lyons

fighting to stay awake through the thick fog or corkscrewing past a night fighter, Smitty knew he would make it to the end.

“In a way, it’s luck,” he said to my uncle, who asked how he managed to survive. “But I knew in my mind that I was not going to be killed in war, or even be made a prisoner. It’s self-confidence, that’s all.”

The first and last five trips were the most dangerous, he said. Back at the base, he remembers speaking to an Australian pilot in his squadron who told Smitty he feared he wouldn’t complete more than five trips. On the young man’s fifth mission, his plane was shot down and the crew all died.

“I told the boys all along: ‘We’re coming back tonight; we’re coming back every night.’ And after two or three trips, they believed me. I never had the least doubt in my mind.”

On May 8, 1945, the crew received their operational wings for surviving a full tour of operations.

Smitty wanted to join the military after the war, but by then he was too old. He went home to Centreville and worked as a customs officer until retirement. Meanwhile, McNicholl went on to have a lengthy military career. The aircrew reunited in Winnipeg every four years. Their duties remained top secret for decades after the war.

The Smitty from my childhood has few redeeming traits, but a couple of details upended what I thought I knew about my grandfather—one of which wasn’t caught on tape. Instead, I heard it from McNicholl: the squadron wanted to nominate Smitty for a Distinguished Flying Cross in recognition of his devotion while flying during active duty.

Smith and crew pose in a wartime image. He flew mostly Halifax bombers, similar to this one (left) at the National Air Force Museum of Canada in Trenton, Ont. The author and her sister during a 1997 visit with Papa Smitty to the Canadian Warplane Heritage Museum near Hamilton.

Out of the 20,354 DFCs awarded during the Second World War, 4,018 were awarded to RCAF members and 247 were awarded to Canadians in the RAF.

“He said no,” McNicholl told me, “not unless the whole crew gets it.”

The other item that stood out was from my uncle’s interviews with Smitty. When I finished them, I called him.

“I haven’t listened to those for a long time,” he said.

My uncle revealed that he had had very few conversations with his father throughout his life. He had been just as surprised as I was by what he learned in the recorded chats. I told him that by listening to Smitty’s stories, I felt like I understood him better.

“That was part of my hope with those tapes, too,” he said. “That other generations would have some sense of him.”

There is one moment in the recordings when my grandfather revealed a startling truth about himself, one that challenges the assumption that, were it not for the horrors of war, he would have lived a much happier life. The truth is, my grandfather yearned for the existence that most (people in combat) wanted to leave behind.

“The most exciting and happiest time of my life was in the service,” he admitted. “It was the last thing I wanted, was the war to end.” L

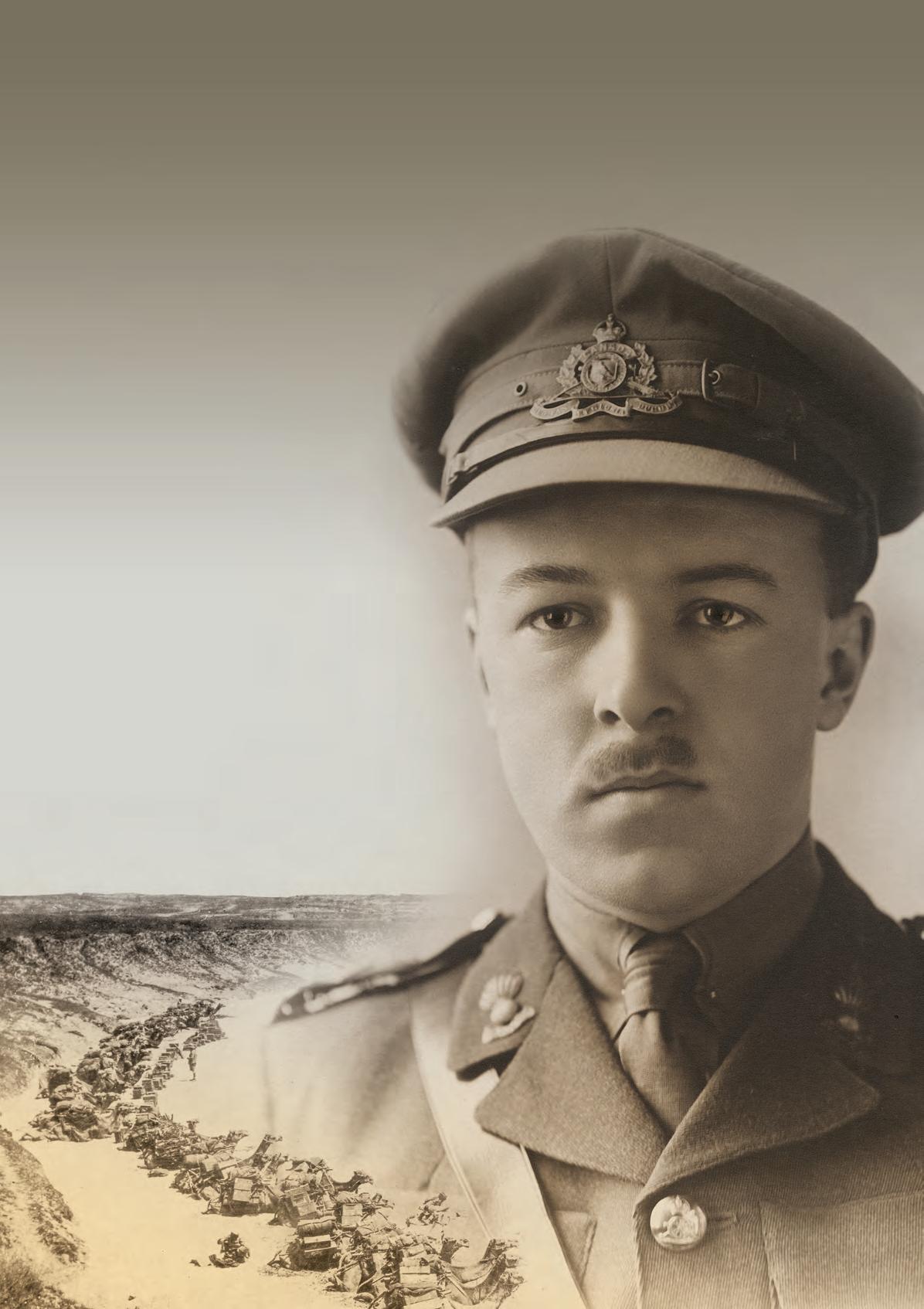

By J.L. Granatstein

NOT

DOWN but out

A military man of high intellect but a lack of charm, Eedson L.M.

(Tommy) Burns

never stopped fighting

“Things have reached a crisis here,” Major-General Christopher Vokes wrote a friend in England on Nov. 2, 1944. “Personally I am absolutely browned off. In spite of no able direction we have continued to bear the cross…. I’ve done my best to be loyal but goddamnit the strain has been too bloody great.” Vokes was the general officer commanding of the 1st Canadian Division in Italy, and the subject of his ire was the commander of I Canadian Corps, LieutenantGeneral Eedson L.M. Burns. Relations between Burns and his key subordinates had reached the breaking point, and Burns, soon relieved of command and reduced in rank to major-general,

was posted to rear area duties in Northwest Europe. How had matters reached this point?

Burns was 47 years old in 1944. Born in Montreal, he had attended Lower Canada College and entered the Royal Military College in August 1914 where he picked up the nickname Tommy, after the famed Canadian world heavyweight boxing champion of the time.

He did well academically in his first and only year at the college, but took a wartime commission in the Royal Canadian Engineers (RCE) as soon as he turned 18 in June 1915 and trained as a signals officer. He went to England with the 4th Division in August 1916, then to France.

Wounded twice, he was awarded the Military Cross for laying and repairing signal cables under heavy fire. By the end of the war, Burns was a staff captain attached to the 12th Infantry Brigade under its acting commander, Colonel J. Layton Ralston. “They say he looks more like 35 than 21,” his mother wrote to the commandant of the military college in 1919, an indication that Burns’ war experiences had weighed heavily.

Burns nonetheless stayed in the army, joining the tiny Permanent Force as a captain in the RCE. Quickly recognized as a comer, Burns became a major in 1927 and took the examinations for staff college, scoring the top mark among the Empire-wide applicants. He went to the British Army Staff College in Quetta, India (now Pakistan) in 1928-29. He was deemed “a very popular officer” with “a great sense of humour,” a “strong and imperturbable” character and an “ability to express himself well on paper.” Few others, however, would see a great sense of humour in Burns.

On his return home, he soon worked for Colonel Harry Crerar at National Defence Headquarters where he devised

new methods of aerial photography that mapped much of Canada, and for which he was promoted to lieutenant-colonel and made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire in 1935. Promotion was glacial in the interwar army, but Burns was on the fast track.

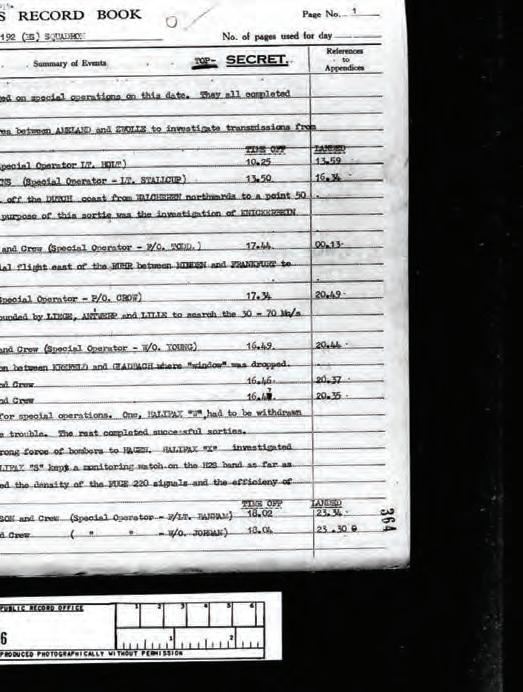

Tommy Burns was not only a soldier. As his Staff College assessment had noted, he expressed himself well on paper. In the 1920s, under the pseudonym Arlington B. Conway, he wrote articles on the military for Henry L. Mencken’s The American Mercury magazine. Mencken was a sharp critic of

their nostrils,” he wrote. “They look on the horse as a romantic symbol of personal superiority.”

Another article noted that it was impossible to develop initiative in infantrymen: “if the ranks of the infantry were filled with intelligent men, it is unlikely that they would long submit willingly to being used as it is intended to use infantry.”

Burns’ writing was not limited to military subjects. He wrote short stories, a play and even a novel with Madge Macbeth, a well-known Ottawa writer. The Great Fright: Onesiphore Our Neighbor was published in 1929. The book, a part written in prose that was of fashion, attracted little notice. Using a pseudonym, Burns had hoped he would stay anonymous. Nonetheless, advertising for the novel used his photograph and name, but none in National Defence Headquarters noticed. Neither did reviewers or readers. Burns also frequently wrote articles and reviews for Canadian , the military’s semi-official journal.

Posted to Montreal in a senior staff role in 1938, published an

A young Burns poses with his father (opposite left). Later, he took command of I Canadian Corps in Italy (opposite right) in March 1944 from Lieutenant-General Harry Crerar (below, left). In 1929, Burns co-wrote a novel under the pseudonym A.B. Conway.

article on the use of tanks in battle that drew a spirited response from Captain Guy Simonds, another officer on the rise.

Burns called for a division to be made up of one armoured and two infantry brigades. Simonds argued that armour should be kept in reserve, not decentralized, and used when needed for a major attack. Their exchanges continued and were arguably the high point of interwar military thinking in Canada.

Soon after the first of these articles appeared, Burns was in England attending the Imperial Defence College, the route to high command. The coming war interrupted his course, and Burns moved to the Canadian High Commission, assisting future Governor General Vincent Massey and future Prime Minister Lester Pearson with military

matters until Crerar, now a brigadier, arrived to set up the Canadian Military Headquarters in Britain.

As his principal staff officer, Burns did the heavy lifting, and Crerar soon had him promoted to colonel and took him back to Canada when he became chief of the general staff. Again, Burns’ workload was massive, and he had arguments with Ralston, now defence minister. Ralston told one of his confidants that Burns and another staff officer were “as stupid as wooden Indians.”

That comment, however, did not dissuade Crerar who made Burns responsible for organizing the development of the army’s new armoured units, and Burns was frequently in Montreal overseeing the development of the Ram tank. Soon, he returned to England

Down but never out, Tommy Burns managed to overcome

as brigadier general staff of the Canadian Corps under LieutenantGeneral Andrew McNaughton, who was also satisfied with his work.

Two key Canadian wartime generals supported Burns, but his rise was disrupted when a letter he wrote was intercepted by military censors.

During his time in Montreal, Burns had had an extramarital affair. Short, pudgy and not particularly handsome, Burns nonetheless was substantially successful at seduction. But this missive to his mistress, while full of sappy love talk, also commented on politicians, war strategy and British generals, as well as referring to McNaughton’s opinions of a particular senior officer.

Burns was lucky to escape a court martial, but he was returned to Canada, sharply rebuked by Crerar and Ralston, and busted to colonel. Still, he was named officer administering of the Canadian Armoured Corps, a post that required frequent visits to Montreal—and his girlfriend.

Burns returned to England as brigadier general staff of the Canadian Corps under Lieutenant-General Andrew McNaughton.

Promoted to brigadier in early 1942, Burns took command of an armoured brigade in the still-forming 4th Canadian (Armoured) Division. He went with it to England in October.

His full redemption came in May 1943 when Burns, on the recommendations of Crerar and McNaughton, became a major-general and commander of 2nd Canadian Division. It was a difficult assignment as the division had been shattered in the abortive Dieppe Raid the previous August. In his nine-month stint in command, Burns made progress in rebuilding the division.

Favoured as he was by his superiors, not everyone was impressed with Burns. In mid1943, one of Ralston’s advisors wrote appraisals of senior officers overseas and was unflattering in his review of Burns.

“Exceptionally high qualifications but not a leader,” said the review. “Difficult man to approach, cold and most sarcastic. Has probably one of the best staff brains in the Army and whilst he will lead his Division

successfully he would give greater service as a high staff officer.”

That was exactly right.

In late 1943, Crerar took command of I Canadian Corps in Italy, and in January 1944, Burns became general officer commanding of the 5th Canadian (Armoured) Division, replacing Guy Simonds, who returned to Britain to command II Canadian Corps. Soon to replace McNaughton in Britain, Crerar wrote that “if Burns acts up to expectations he will undoubtedly be my recommendation for Corps Commander.”

Burns again had little time in his new post, certainly not enough to acquire experience in action.

The British believed that first-hand battle knowledge was key—and six weeks in command of the 5th was not enough time to get it. Burns nonetheless became Corps commander and acting lieutenantgeneral on March 20, 1944.

Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese, commander of the Eighth Army, was not pleased to have the untried I Canadian Corps in his group. He initially thought Burns satisfactory, but after the battle in May to crack the Hitler Line in Italy, he changed his mind. While the Canadian divisions had fought well, there were huge traffic jams that delayed the advance. Leese blamed Bert Hoffmeister’s 5th Division and Burns’ staff. He tried to have Burns replaced, ideally with a British general.

Generals of the 1st Canadian Army, including Burns (second row, fifth from right), sit for a group portrait in May 1945 (opposite top). Burns poses with British Lieutenant-General Oliver Leese and Polish Lieutenant-General Wladyslaw Anders and again with Major-General Christopher Vokes in Italy (opposite bottom). In the aftermath of the Suez Crisis, Burns (left) visits HMCS Magnificent in 1957 (bottom) while in command of the UN Emergency Force. He received the Distinguished Peacekeeper’s Award for that work.

“Neither Burns nor his Corps staff are up to Eighth Army standards,” wrote Leese. Still, Crerar remained a strong supporter and, after much palaver, Burns retained his position by replacing some of his staff. His division commanders, Vokes and Hoffmeister, were at first willing to continue to work with him, but by the autumn they had changed their minds.

Burns’ Corps had cracked the Gothic Line in Italy at the end of August 1944, arguably the most successful Canadian action of the war. But, his British superiors, his two division commanders and some of the Corps’ senior staff officers had had it with him. Still, Crerar again tried to save Burns. No one, however, could remember Burns smiling—the troops called

him “Smiling Sunray” in derision—and he could not inspire his subordinates. He was a sarcastic, dour personality who seemed to only criticize. Burns, said Vokes, “lacks one iota of personality, appreciation of effort or the first goddamn thing in the application of book learning to what is practical in war & what isn’t.”

Hoffmeister, meanwhile called the relationship intolerable and said he had lost all confidence in Burns. Burns had won major battles in the field, but his personality defects did him in. As Ralston’s confidant had presciently written a year earlier, Burns “will never secure devotion of his followers.”

His hand forced, Crerar replaced Burns with Charles Foulkes on Nov. 10.

Burns spent the rest of the war in minor posts in Northwest Europe. After the conflict, he joined the Department of Veterans Affairs, eventually becoming its deputy minister. He wrote a fine study of Canada's military workforce problems during the war and, in 1954, he was named to head the United Nations Truce Supervision Organization on the Arab-Israeli borders. Burns was in that job

during the 1956 Suez Crisis and, on the spot, was given command of the UN Emergency Force, the first large peacekeeping operation.

When the Egyptians objected to accepting Canadian infantry in the UN force because they were indistinguishable from the invading British—they wore the same uniforms, their regimental names were redolent of the Empire and their flag had the Union Jack in the corner—Burns persuaded Cairo to let Ottawa provide logistics and signals personnel instead.

That move was much appreciated by the federal government and in 1958 Burns was promoted to lieutenant-general. Two years later, he was made the government’s disarmament adviser. Burns died in 1985, his sacking in 1944 almost forgotten.

Down but never out, Tommy Burns managed to overcome his personality defects and achieved great success. He had served in the Great War with distinction, advanced through the Permanent Force in the interwar years, and served in high command during the Second World War. His postwar career and life were extraordinary. If he was cold and critical, his intelligence and drive shone through nonetheless. L

How Canada’s once unknown war dead are being identified

A view of the French village of Loos from a crater on Hill 70, where Harry Atherton was killed in action on Aug. 15, 1917. His fate was unknown until combat engineers clearing First World War munitions stumbled on the remains of a Canadian soldier. Authorities confirmed his identity in October 2021.

Lost,

now found

By Stephen J. Thorne

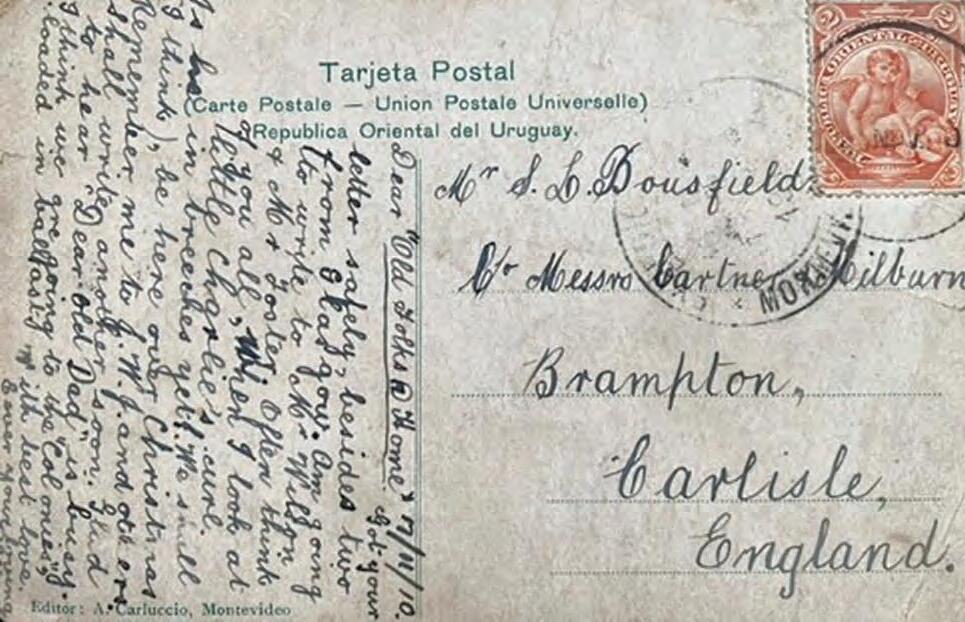

Captain Scott McDowell was just a young boy, eight or 10 years old, when he first heard the name Percy Bousfield, a great-great-uncle who went to sea at 14, sailed the world, then joined the army and died on the Western Front in 1916.

The remains of Corporal Bousfield, a 20-year-old signaller with the 43rd Battalion (Cameron Highlanders of Canada), were not accounted for, his last resting place unknown. But his legend lived on in family lore.

His maternal grandmother was

a Bousefield and McDowell heard the stories many times growing up, though he never knew investigators were searching for his relative. Or that he was an unknown soldier, his name among more than 54,000 missing British and Empire combatants listed on the Menin Gate memorial in Ypres, Belgium.

A career military intelligence officer, McDowell happened to have transferred to the Canadian Forces’ Directorate of History and Heritage as a war diaries officer in August 2022, working in a nondescript brick building in

Ottawa. Three months later, he and his colleagues were summoned to an all-hands town hall. It was during the meeting that senior staff coincidentally announced an investigation team had identified the grave of Corporal Frederick Percival Bousfield.

“The world stopped spinning for a moment,” McDowell told Legion Magazine. “I was like, ‘Oh, my gosh, that’s Percy.’ I was gobsmacked. The odds of it are effectively zero. It’s completely insane. I didn’t hear a single word the rest of the town hall.”

Corporal Frederick Percival Bousfield

Bousfield was killed at Mount Sorrel in Belgium on June 7, 1916. The hill in the Ypres Salient was taken from the Canadians, then recaptured during two weeks of intense fighting. Allied units sustained 8,430 casualties in 12 days.

“At the time he was off duty, but he was not content to be idle and despite the terrible hurricane of shells he was doing magnificent work in helping our wounded,” his one-time company captain, Horace John Ford, wrote Bousfield’s mother.

“It was while lifting one of his helpless comrades that a shell burst right at his feet, so you see

“The world stopped spinning for a moment. The odds of it are effectively zero. It’s completely insane.”

that brave lad experienced no pain whatever, and although his death is a grievous pain to his loved ones, yet they can glory and thank God for the manner of it. He was doing humane work to relieve suffering and doing it nobly and well and without fear or thought of reward.”

English by birth, Bousfield’s remains were buried in a temporary grave alongside others behind a cottage near the church in Zillebeke not far from where he died. It was marked by a simple wooden cross, which would be replaced by one of the now-familiar pale white or grey tombstones that adorn British and Empire war plots once the battlefield graves were relocated.

Thousands of similar temporary plots were hurriedly created on or near First World War battlefields. Given the stagnant nature of the fighting, they were often trodden over repeatedly, damaged by shellfire and flooded by rains. Many were overrun, first by advancing enemy and later by the Allies pushing eastward again. Plots were inevitably destroyed, and the locations of many registered and otherwise documented graves were obliterated.

So it was with Bousfield’s remains.

On Sept. 14, 1923, a headstone at Bedford House Cemetery, near Ypres, was recorded as “A Corporal of the Great War—Canadian Scottish—Known Unto God.” The remains had been transferred with others from Zillebeke the previous February. They were not identified, the date of death unknown, although the other graves were confirmed as Mount Sorrel casualties.

“I regret to have to inform you that although the neighbourhood South-East of Ypres, in which Corporal F. P. Bonsfield [sic] was reported to have been buried has been searched, and the remains of all those soldiers buried in isolated and scattered graves reverently reburied in cemeteries in order that the graves may be permanently and suitably maintained, the grave of this soldier has not been identified,” said a 1927 letter from what was then called the Imperial War Graves Commission, later the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

And so, Percy Bousfield was lost, but not to memory. For a 20-yearold of his time, he had lived an

Frederick Bousfield’s memory has lived on in family lore. Pictures, postcards, letters and souvenirs from the former seaman are plentiful. Bousfield was sailing the world when his family immigrated to Canada from England in 1912 and settled in Winnipeg.

incredibly full and well-documented life and, for almost a century after, pictures, letters and tales of his adventures and his noble death circulated among his family.

Then in October 2019, the History and Heritage Directorate received a report from the commission detailing the potential identification of Grave 68, Row C, Plot 11 in Enclosure No. 4 at Bedford House.

The commission, which manages more than 1.1 million war graves in over 23,000 locations in 150 countries and territories, had received three “very in-depth reports” from independent researchers suggesting the grave was that of Corporal Frederick Percival Bousfield.

The directorate launched its own investigation involving the Canadian Forces Casualty Identification Program, the Forensic Odontology Response Team and the Canadian Museum of History. They reviewed war diaries, service records, casualty registers and grave exhumation and relocation reports. They concluded the grave could only be that of Corporal Bousfield. No other candidate matched the details of the partial identification.

Renée Davis is a civilian historian at History and Heritage and a principal researcher for the Casualty Identification Program. She and a small team of historians and co-op students conduct the research and analysis of graves cases, which differ significantly from the identification of found remains.

“Usually this is a headstone for an unknown, but for whatever reason there is a unit identifier or a date of death or anything along those lines that sparks [an independent researcher’s] interest,” she explained in an interview.

“And so, they start doing a bit of research and submit a report to the Commonwealth War Graves Commission.”

Marjorie Bousfield/Bousfield family archive (5); Mary

And so, Percy Bousfield was lost, but not to memory. For almost a century after, tales of his noble death circulated among his family.

The commission then conducts a preliminary analysis into the merits of each case and submits a report to the country involved, including the independent researcher’s findings, as well as their own, along with its recommendations.

It’s at this stage that Davis’s team steps in. They investigate and write the reports, making recommendations to Canada’s Casualty Identification Review Board on whether to positively identify gravestones. They do not conduct exhumations.

Davis said her team is able to positively identify two in 10 headstones that are brought to their attention. Eleven of the 46 identifications they’ve made so far were from grave markers, the rest from remains. The vast majority are First World War, in which there were a far greater proportion of missing in action than in WW II.

At this writing, the Casualty Identification Program had 40 active investigations involving remains and 38 involving graves.

“You feel very connected to these individuals in a very tangible way,” said Davis. “Sometimes the cases work out, like this one, and you feel absolutely wonderful.

“But other times, more often, there’s not enough to definitively say it is this person, and that can get a little gut-wrenching at times.”

No other candidate’s profile matched the sparse details of Bousfield’s.

“The family was so fortunate that Percy was a corporal because his stone identified him as a corporal, Canadian, and the records said he was with a

family historian, McDowell’s second-cousin Marjorie Bousfield. “So that really narrowed it down.