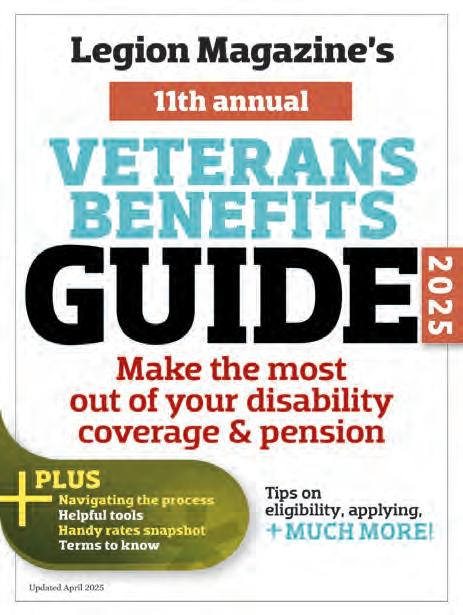

Michael Villagran of the U.S. wheelchair rugby team chases down the ball versus France at the 2025 Invictus Games in Vancouver. A retired U.S. Army specialist, Villagran lost his right leg to a Taliban bomb in 2012.

See page 58

18 WHO KNIT YA?

How the Second World War road to victory in Europe changed Newfoundland By

Stephen J. Thorne

26 GOING OVERBOARD

Looking back on the Halifax VE-Day riots

By Alex Bowers

34 THINK AGAIN

Re-examining Canada’s role in D-Day

By Marc Milner

38 SPIRIT SQUAD

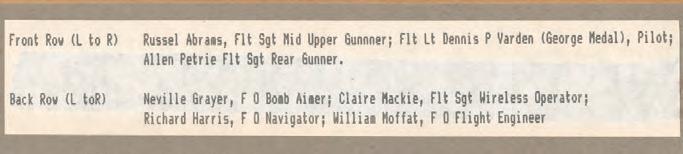

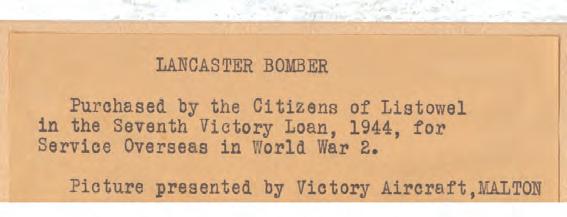

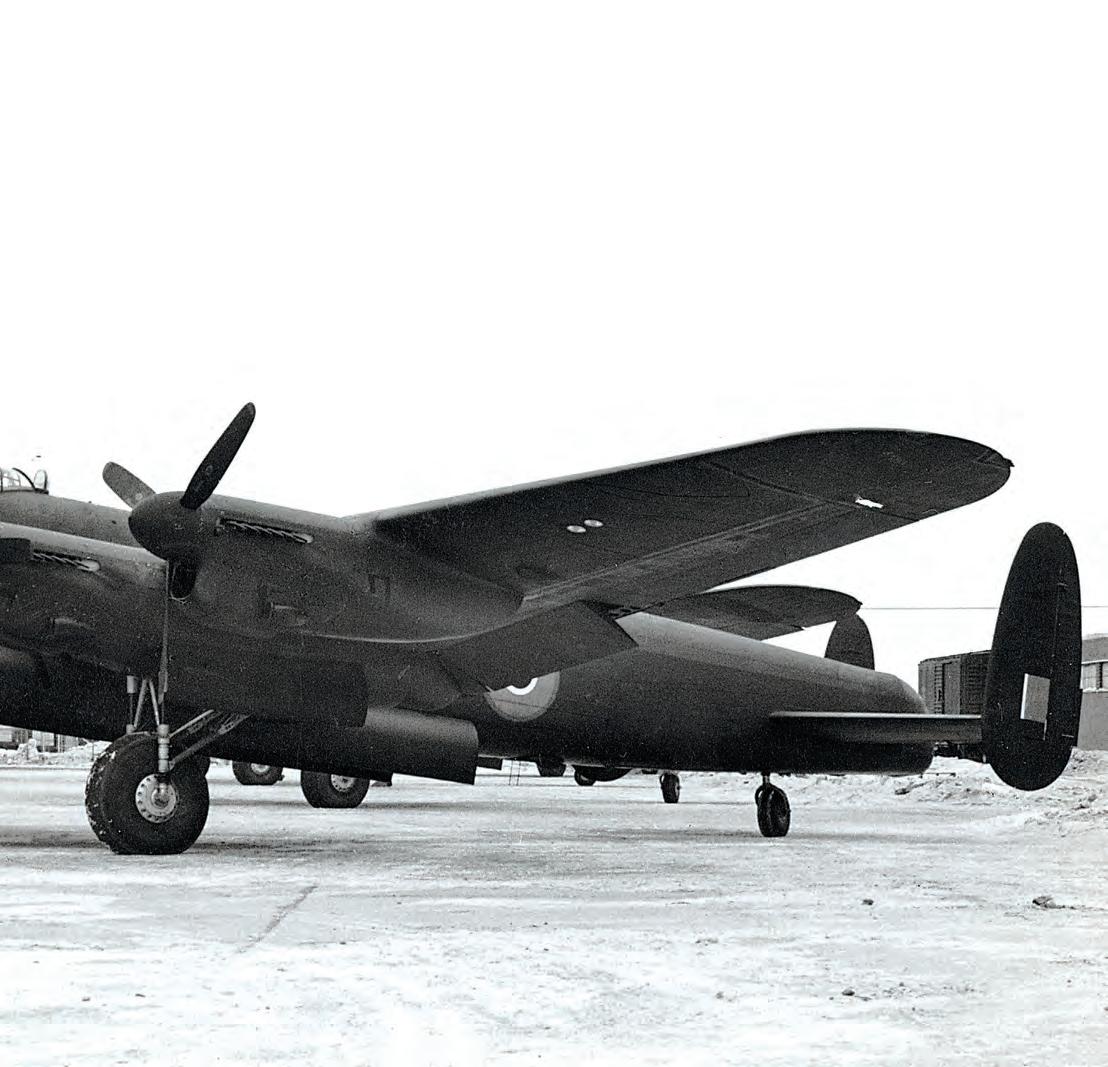

Solving the mystery of how a seemingly random bomber crew photo ended up in the archives of a small-town Ontario school library By Wendy van Leeuwen

42 OPERATION IMPACT

20 years ago, Canada joined the international fight against Islamic State militants

By Mark Zuehlke

48 A EULOGY FOR CANADA’S UNKNOWN SOLDIER

25 years ago, on May 28, 2000, the governor general delivered this speech at the ceremony unveiling the country’s Tomb of the Unknown Soldier By

Adrienne Clarkson

52 THE AMERICAN INVASION

How the British and their Canadien subjects turned back the 1775-76 attack on the Province of Quebec

By Serge Durflinger

58 UNCONQUERABLE SOULS

Scenes from the Invictus Games Vancouver-Whistler 2025

Words and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

THIS PAGE

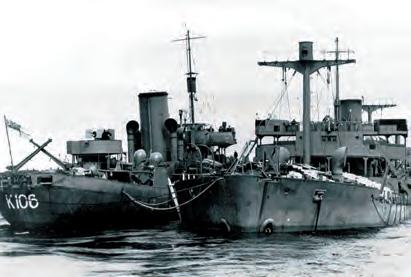

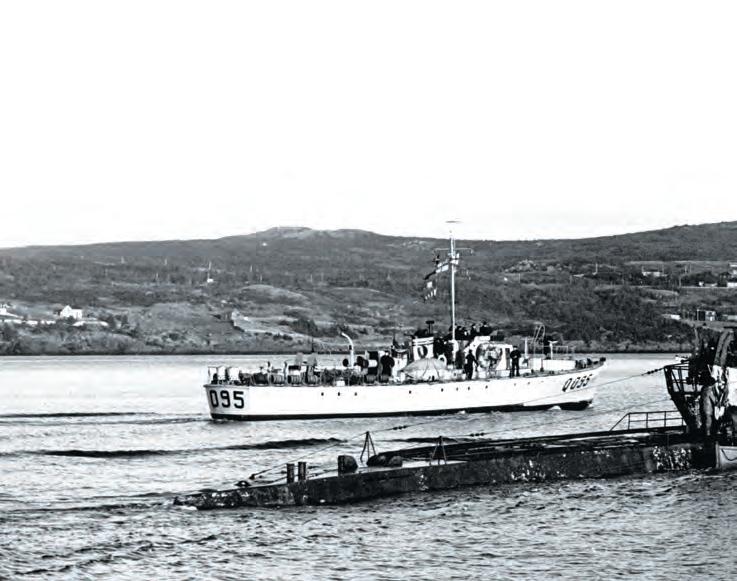

U-190 is escorted into the harbour at St. John’s, Nfld., on June 3, 1945, after surrendering to the Royal Canadian Navy weeks earlier. Gerald P. Murison/DND/LAC/PA-128268

ON THE COVER

Personnel of The Royal Canadian Artillery approach Bernières-sur-Mer, France, on D-Day, June 6, 1944. Ken Bell/DND/LAC/PA-137523

12

MILITARY HEALTH MATTERS

From shunned to celebrated By Alex Bowers

14 FRONT LINES

Guilty by association? By Stephen J. Thorne

16

EYE ON DEFENCE

Fool’s game By David J. Bercuson

32 FACE TO FACE

Were naval leaders to blame for the Halifax VE-Day riots? By Alex Bowers and Stephen J. Thorne

88 CANADA AND THE NEW COLD WAR

On the flank By J.L. Granatstein

90 HUMOUR HUNT

Decoding typo By John Ward

92 HEROES AND VILLAINS

Douglas Haig and Crown Prince Rupprecht By Mark Zuehlke

94 ARTIFACTS

Canada’s U-boat By Alex Bowers

96 O CANADA

Somme memorial By Don Gillmor

Vol. 100, No. 3 | May/June 2025

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Garry Pond BOARD VICE-CHAIR Berkley Lawrence BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe Steven Clark, Randy Hayley, Trevor Jenvenne, Bruce Julian, Valerie MacGregor, Sharon McKeown Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

ADMINISTRATION MANAGER

Stephanie Gorin

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

ADMINISTRATIVE AND EDITORIAL CO-ORDINATOR

Ally Krueger-Kischak

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Alex Bowers

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales

CANIK MARKETING SERVICES NIK REITZ advertising@legionmagazine.com

MARLENE MIGNARDI marlenemignardi@gmail.com

OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER

Dyann

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2025. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $13.11 per year ($26.23 for two years and $39.34 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $14.36 for one year ($28.73 for two years and $43.09 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $14.11 for one year ($28.23 for two years and $42.34 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Change of Address

Send new address and current address label, or, send new address and old address. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com/change-of-address. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $12.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of Alliance for Audited Media and BPA Worldwide. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and email magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

ar clouds are darkening on the international horizon. What is Canada’s position? No Canadian wants war—no sensible Canadian. That is an indisputable fact. As a nation Canada will never of itself do anything knowingly to provoke war. We desire to live at peace. But, alas for the tragedy that seems inevitably to pursue defenceless nations, their misfortune and extinction have been due to their living in a world made up of powerful people whose ideals are not quite so lofty.

THAT PAYMENT WOULD BE EITHER THE ANNEXATION OF CANADA OR, AT THE VERY LEAST, A HUGE SLICE OF OUR TERRITORY.

How less secure is the expectation of perpetual peace for a nation that has direct economic contacts with almost every other country in the world and whose interests, in great part, are in conflict with theirs? No different from other nations, Canada has engaged actively and aggressively in economic warfare. And someone has said that this is inevitably the prelude to armed conflict.

I have frequently read and heard that “even if the British Navy can not protect Canada, the United States will not permit Canada to be invaded or Canadian trade destroyed.” This doctrine is the counsel of the weakling, the product of a painful inferiority complex. Apart altogether from the contempt it engenders among selfrespecting Canadians, it is a fool’s paradise.

In the first place, Canada has no undertaking that the United States would do anything of the sort. The United States is dominated by a national sentiment. If the United States is indisposed to jeopardize that, the man must be a lunatic who imagines the republic will jeopardize it for the sake of Canada.

But, assume by an impossible stretch of the imagination, that the United States became altruistic to the point of insanity and decided to “Protect Canada.” Would the service be rendered for nothing? It has to be remembered that we do a great deal of bragging about our inexhaustible resources and the great potential wealth that lies concealed beneath the surface of our soil. Services costing American lives, American ships and American money would have to be paid for. That payment would be either the annexation of Canada or, at the very least, a huge slice of our territory. We should keep continually in mind that priceless story in the Scriptures of the man who cast out one devil and took in seven.

We render no service, either to ourselves or our country by sidestepping these unpleasant facts. We are utterly and absolutely defenceless. In the past 15 years, anyone who let a peep out of him to promote national security was pounced upon by professional and amateur pacifists who branded him a “militarist” and an “enemy of peace.” The popular thing has been to court the illusion of perpetual peace, to forget the lessons of history and to proclaim that a disarmed nation, by virtue of its defencelessness and the high moral principles it incorporates, is much safer from aggression than a nation not disarmed.

This is an excerpt from a piece originally published in the September 1935 edition of The Legionary magazine, this publication’s predecessor. L

“Letters” (March/April), retired lieutenant-colonel John McNair rightly takes issue with some of the arguments put forward by certain opinion writers in the magazine as they pertain to issues of defence preparedness. He is right to concur with them that more needs to be done in resourcing the military in areas of recruiting, retention and procurement. However, he’s also correct to point out that columnists David J. Bercuson and J.L. Granatstein, among others, continually fail to provide concrete solutions.

Your magazine continues to impress me. I had a great chuckle reading “Beaver fever” (March/ April) and the line “like many Canadians the beaver is industrious and lacks a dental plan.” Yet, I have a negative response to “beaver fever” as I contracted it a few years ago and it still lingers in my digestive system.

WILL PERRY

VIA EMAIL

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

If they are being honest with Canadians, they must propose just how much more we will be asked to pay in federal income tax. They might indicate, too, which current federal transfers to provinces, including for health care and equalization, they want to see reduced. Also, they forget to mention that under prime minister Stephen Harper Canada’s defence spending fell below one per cent of gross domestic product at one point. Lots of blame to go around.

GAVIN PUGH REGINA

As usual, I quite enjoyed opening my latest copy of Legion Magazine and devouring the content. However, as a proud owner of a Lynx scout car, I wanted to point out that the vehicle you identified as a Staghound in “First Troop, Charlie Squadron, Royal Canadian Dragoons” (March/April) is actually a Ford Lynx 11.

PETER DUGGAN

VIA EMAIL

I read with great interest “Ripples of service” by Alex Bowers in the January/February issue. After my military service, I provided musical services with four regimental bands between 1955 and 1988. The groups were deeply involved in Canadian military and Canadian affairs. In the mid-1990s, 12 out of 16 bands were eliminated, thereby cutting one of the most culturally

interesting and important functions dear to military and Canadian authorities. Incidentally, the Canadian Armed Forces dropped from 78,000 to 62,000 members around that time. That indicates to me that music making in the military may have played a greater role than previously thought.

NICOLAS DE VRIES DARTMOUTH, N.S.

After general Roméo Dallaire’s service to the Canadian military, specifically to the United Nations during Rwanda’s brutal civil war, Canadians should be ashamed that national archives and library institutions allowed his collection to leave the country and go to the United States Military Academy West Point (re “Oh, Canada,” January/ February). To say Canadians haven’t been supportive of our military for many years is an

understatement, and this is just another example.

As a Canadian whose grandfather and great-uncles served in the First World War, whose father served in Bomber Command during the Second World War, whose brother was a career soldier during the Cold War, whose husband served in the Royal Canadian Air Force, and whose nephew is presently serving in our armed forces, which included a mission in Afghanistan, I want to apologize to General Dallaire and thank him for his service to our country. “Oh, Canada,” indeed.

CHRISTINE LANG

SHANTY BAY, ONT.

Well, Canadians no doubt did fight well in South Africa (re “Face to Face,” September/ October 2024, “Should Canadians continue to pay tribute to

the Boer War?”). No doubt they fought like Canadians. However, there was nothing glorious about the Boer War. It was one of the last big grabs of an already fading empire. It just was naked British aggression.

DENNIS PEACOCK CLEARWATER, B.C.

I just read your excellent article “The Plan” in the March/April Legion Magazine. A caption in the story mentioned that the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan pilots completed training on Harvard 4s built by Canadian Car and Foundry. In fact, wartime Harvards were built by Noorduyn in Montreal. Canadian Car and Foundry built Harvard 4s for training at their plant in Fort William, Ont., in the early 1950s.

GERRY KOSORIS

KAKABEKA

FALLS, ONT. L

1 May 1888

8 May 1945

On Victory in Europe Day, a ceasefire takes effect at 11 p.m. after the Germans formally surrender.

9 May 1937

The Canadian Coronation Contingent stands sentry at St. James and Buckingham palaces in England, the first Canadian military personnel to do so.

10 May 1915

Lord Stanley appointed Governor General of Canada; serves from June 11, 1888, to September 6, 1893, and later donates hockey’s Stanley Cup.

2 May 1945

U-2359 is sunk by British, Norwegian and Canadian Mosquito aircraft.

4-5 May 1971

A clay landslide destroys 40 homes and kills 31 residents of Saint-JeanVianney, Que.; three members of the Canadian Armed Forces are decorated for daring rescues.

The Curtiss Aviation School in Toronto begins training pilots; 128 military airmen graduate before it closes in 1916.

13 May 1861

Queen Victoria asks her subjects to remain neutral in the U.S. Civil War.

4 May 1943

18 May 1785

The communities of Parrtown and Carleton amalgamate to form Saint John, N.B., Canada’s first incorporated city.

Trainee navigator Kenneth Spooner takes over for an unconscious pilot, saving three lives, but crashes. He is posthumously awarded

19 May 1918

Lieutenant Katherine MacDonald is the first Canadian Nursing Sister killed in action, at No. 1 Canadian Hospital, Étaples, France, during an enemy air raid.

20 May 1971

Francis Simard is given a life sentence for the murder of Quebec Labour Minister Pierre Laporte, kidnapped by the Front de libération du Québec.

28 May 1916

The Canadian government is advised to abandon the Ross rifle, which often

7 May 1867

Dr. Campbell Douglas of Grosse Île, Que., leads three trips through heavy surf in Little Andaman Island, Bay of Bengal, to rescue several men. He is awarded the Victoria Cross.

1918, resumes at Camp Borden near Barrie, Ont.

17 May 2006

Captain Nichola Goddard is the first female Canadian soldier killed in combat.

30 May 1915

The German Fokker Eindecker (monoplane) aircraft is fitted with synchronized machine guns that fire through the arc of the propeller blades.

1 June 1866

2 June 1916

Canadian positions are hit by German shellfire at the northern edge of Sanctuary Wood, near Ypres, Belgium.

3 June 1885

In the Battle of Loon Lake (in present-day Saskatchewan), NorthWest Mounted Police led by Major Sam Steele attack Cree warriors. Part of the North-West Resistance, it is the last military engagement fought on Canadian soil.

13 June 1916

12 June 1940

The 1st Brigade of the Canadian 1st Division lands in France; they are forced to leave days later when France surrenders to the Nazis.

Troops under command of MajorGeneral Arthur Currie counterattack at Mount Sorrel in Belgium, restoring front lines at the cost of 8,000 Canadians killed, wounded or captured.

HMCS Edmundston rescues 31 crew from SS Fort Camosun after an attack by a Japanese submarine off the coast of Washington.

21 June 1951

The Royal Canadian Regiment, Lord Strathcona’s Horse and Royal Canadian Horse Artillery patrol in Korea.

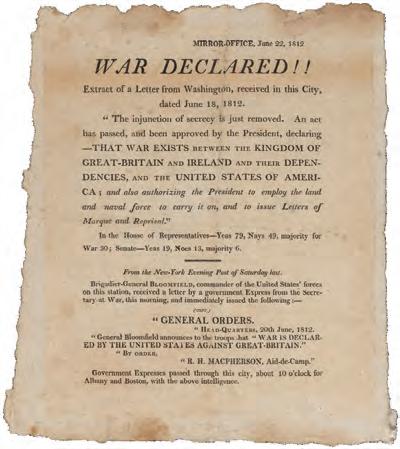

23 June 1812

Great Britain revokes the restrictions on American commerce, thus eliminating one of the chief reasons for going to war.

4 June 1742

The naval ship Le Canada,

14 June 1617

The first French family to cultivate land in Canada settles near today’s Quebec City.

16 June 1993

Canada withdraws its peacekeepers from Cyprus, ending a 29-year mission during which more than 25,000 Canadians served and 28 lost their lives.

17 June 1932

25 June 1950

North Korea invades South Korea.

26 June 1945

Canada is one of 50 countries to sign the United Nations Charter. On Oct. 24, the UN replaces the League of Nations, which was created by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.

27 June 1946

The Canadian Citizenship Act receives royal assent. Effective Jan. 1, 1947, it confers citizenship on all Canadians, regardless of their place of birth.

29 June 1996

Oil tanker Cymbeline explodes in Montreal.

From the Space Shuttle Columbia, Canadian astronaut Robert Thirsk talks with students at Maple Grove Education Centre in Nova Scotia.

By Alex Bowers

Desiderates Meliorem Patriam. “They desire a better country.” It’s the Latin motto of the Order of Canada, and what appointees are said to exemplify. Diane Pitre, a veteran of the Canadian Armed Forces, 2SLGBTQI+ purge survivor, and now member of the Order, embodies that sentiment. It was 2018, and Diane Pitre was a special guest for a film screening in her home province of New Brunswick. Family members were in attendance, aware, if only to a certain degree, that she featured in the documentary called The Fruit Machine

Directed by Sarah Fodey, the film details the events and impacts of the 2SLGBTQI+ purge that robbed many thousands of Canadian Armed Forces personnel of their dignity, identity and livelihoods from the 1950s to the 1990s.

The documentary’s title, aside from being a derogatory reference toward people of the 2SLGBTQI+ community, refers to a genuine, governmentsanctioned device that could purportedly reveal the sexuality of test subjects who, after being shown pornographic pictures, were determined to be “homosexual” if their pupils dilated.

Canadian veteran Pitre was never hooked up to the machine, its use having been phased out in 1967 for its scientific infeasibility, but she still had her own story to tell.

“I went on stage afterward,” she recalled, “and everyone was shocked. I spoke to my family as if we had forgotten the audience. My aunt asked, ‘Why didn’t you tell us?’ I replied, “because I didn’t want to lose you like I’d lost so much else.”

Pitre had wanted to serve her country since she was a child. In light of her father’s absence— he died when she was just three months old—Pitre always admired her uncles, one a Second World war veteran of The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment and the other having fought in Korea before becoming a peacekeeper.

Pitre wished to follow in their footsteps, enlisting at age 18 on Nov. 9, 1977, whereupon she commenced her training to become an air frame technician.

“It was everything I ever dreamed of,” she recalled—until it wasn’t.

Believing at the time she conformed to stringent societal norms surrounding sexuality, Pitre knew “nothing at all” about the CAF’s discriminatory policies toward 2SLGBTQI+ personnel. Seemingly, she had little reason to.

For several decades, however, the Canadian government believed certain individuals were more vulnerable to being targeted by Soviet blackmail. Armed with flawed logic that the so-called “character weakness”

of 2SLGBTQI+ members could lead to the release of state secrets, supposed suspects within the military, RCMP and federal public service endured investigations, persecution and ostracization.

The human rights-suppressing campaign became known as the Purge, and it employed many of the same tactics against fellow Canadians that authorities feared the Soviets were using. Pitre was just the latest of an untold number to undergo interrogation.

“I was instructed to go to Halifax without knowing why, and two guys picked me up at the airport. They were completely silent as they drove me to an undisclosed wooded area in an industrial park. I wondered if I was in with the wrong people.

“They got out the car at a warehouse and started questioning me: ‘Who’s the man in the relationship?’ ‘Do you masturbate in front of a mirror?’ Questions like that.”

Pitre was released after three days. Though temporarily permitted to remain in the military, she lost her security clearance on “suspicion of being a homosexual” and was thus forced to retrain as a supply technician. Nevertheless, on Sept. 24, 1980, having been subjected to incessant surveillance, Pitre was discharged.

“I had done a good job and was going to be promoted to corporal before my time, but a captain told me that wasn’t happening and threw my papers in the garbage.

“I left the base totally devastated. I was disconnected. It was surreal. How could I be a threat to my country for just wanting to serve? Why would Canada do that?”

Change arrived in 1992 following the precedent-setting court case of veteran and Purge survivor Michelle Douglas, who sued the Defence Department for infringing on her rights. The historic lawsuit led to Douglas receiving a settlement of $100,000

and, ultimately, the revoking of Canadian Forces Administrative Order 19-20, the policy that helped enable the harmful practices.

But for too many, the damage had already been done. Lives had been ruined during successive decades; others lost to suicide. What’s more, discrimination wouldn’t just end overnight. Pitre, who had dedicated years to advocating for an official apology, was joined by a growing number of voices demanding greater justice.

Nov. 28, 2017, proved to be the turning point. That day, a class action filed against the government on behalf of Purge survivors reached a settlement, which was ratified in June the following year, of $145 million. The compensation package, which awarded between $5,000 and $50,000 to most claimants while committing to reconciliation and memorialization measures, accompanied the assurance that service records would include disclaimers regarding the nature of discharges.

That same day, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stood in the House of Commons and delivered the words Pitre had long waited—and fought—for.

“To the victims of the Purge… we betrayed you. And we are so sorry,” he announced. “You were not bad soldiers, sailors, airmen and women. You were not predators. And you were not criminals. You served your country with integrity, and veterans you are.”

For Pitre, who embraced the apology even if its lateness “made me a bit angry,” the fight continues. In 2019, she founded the Rainbow Veterans of Canada to “provide a supportive and safe space for CAF veterans impacted by the LGBT Purge along with other CAF veterans who identify as 2SLGBTQI+, while educating and advocating for the rights, benefits and recognition our members deserve.”

As the Rainbow Veterans’ co-chair, Pitre considers placing a wreath at the National War

Memorial as one of her “proudest accomplishments.” In the same capacity in 2024, she joined representatives in symbolically breaking the ground for the 2SLGBTQI+ National Monument due to be completed and unveiled later this year in Ottawa.

“We worked so hard to make ourselves better for Canada because we were told we were not worthy of Canada,” said Pitre. “We were a disgrace, we were a threat. But now, with the work we’ve all done, I can finally see that it was about making Canada better.” L

Eighty years on, Dutch name

425,000 suspected Nazi collaborators

The Netherlands National Archives is opening its files on some 425,000 suspected Nazi collaborators eight decades after the Holocaust took the lives of 102,000 Dutch Jews.

War In Court, a project of the Netherlands-based Huygens Institute, released a list of the names online after a law restricting public access to the archive expired Jan. 1, 2025. The archives’ more detailed digitized versions were expected to follow.

“This archive contains important stories for both present and future generations,” the institute said in a statement. “From children who want to know what their father did in the war, to historians researching the grey areas of collaboration.”

The institute is helping digitize 32 million pages of dossiers that include details on suspects and witnesses, as well as members of the Dutch Nazi party and some 20,000 Dutch citizens who enlisted in Nazi Germany’s armed forces.

Comprising files from the Special Criminal Jurisdiction, which began investigating suspected collaborators in 1944, the archive also contains the names of people acquitted. The expired law has

Collaborators and moffenmeiden (‘Kraut girls’) are rounded up and publicly humiliated by the Dutch Resistance following the liberation.

been described as more restrictive than Italy’s, an Axis country whose wartime past is far more controversial than the Netherlands’.

Seventy-five per cent of the Netherlands’ Jewish population was deported to death camps between 1940 and 1945. While stories abound of heroic attempts to hide Jews from SS squads, collaborative police, Dutch bounty hunters and others, the darker stories of betrayals by neighbours, friends and co-workers are less known.

Historian Hans Renders of the University of Groningen told the BBC that only about 15 per cent of collaboration cases went to court. “So, if a name appears in the [archive], it is not certain that the person was ‘wrong.’”

A planned online release of the first eight million pages of detailed scans was postponed after the Dutch data protection authority intervened. All documents are expected to be digitized by 2027.

People with a research interest, including descendants, journalists and historians, have been able to submit requests to consult the actual files at the national archives. Now the public can, too.

The forces of Nazi Germany invaded the Netherlands in May 1940. Five years of brutal occupation followed, during which at least 106,000 Dutch Jews were robbed of their property and belongings and transported to death camps such as Auschwitz and Sobibor.

The identification and roundup of Dutch Jews was largely enabled by the efforts of a Dutch public servant, Jacobus L. Lentz, head of the Population Registration Office in the Hague.

The history is still fresh in the Netherlands and throughout much of Europe, where a total of six million Jews were systematically killed in what

> Check out the Front lines podcast series! Go to legionmagazine.com/en-frontlines

the Nazis dubbed the “Final Solution.” Another six million Roma, political foes, people with disabilities and other minorities across Europe died in Nazi gas chambers and by other means.

The most famous of the Netherlands’ wartime Jews was to be Anne Frank, the young girl whose diary chronicled two years in hiding before she and her family were outed to authorities. Frank, 15, died with her sister in a concentration camp in 1945.

Who betrayed her family remains a mystery—and still a sensitive topic.

In 2022, Amsterdam-based publishers Ambo Anthos ceased printing and recalled the book The Betrayal of Anne Frank: A Cold Case Investigation after an outcry over its findings.

Researched by a team of historians and investigative

experts and written by Canadian Rosemary Sullivan, the book said it’s likely Arnold van den Bergh, a Jewish notary in Amsterdam, gave up the Franks to save his own family. The accusation spawned a wave of criticism from experts who contend there’s not enough evidence to reach such conclusions.

According to the Dutch central statistics bureau, in 1939—the year the Second World War broke out—the Netherlands’ population was 8.7 million, making just under five per cent of the country suspected collaborators.

While the vast majority of those named are dead, the move after so many years is certainly not without controversy in the Netherlands for several reasons, foremost among them relatives’ concerns over what they might disclose.

The Dutch government in wartime exile developed laws to prosecute suspected collaborators after the peace; some 156,000 faced varying punishments, while 329,000 cases were settled without prosecution and dismissed.

Separate archives were merged once the Special Criminal Jurisdiction concluded its work in the early 1950s. The consolidated dossiers and files were named the Central Archives of the Special Administration of Justice (CABR).

They were under the purview of the Dutch justice ministry until 2000, when the files were transferred to the national archives.

Said national archives director Tom De Smet: “Collaboration is still a major trauma. It is not talked about. We hope that when the archives are opened, the taboo will be broken.” L

By David J. Bercuson

When U.S. President

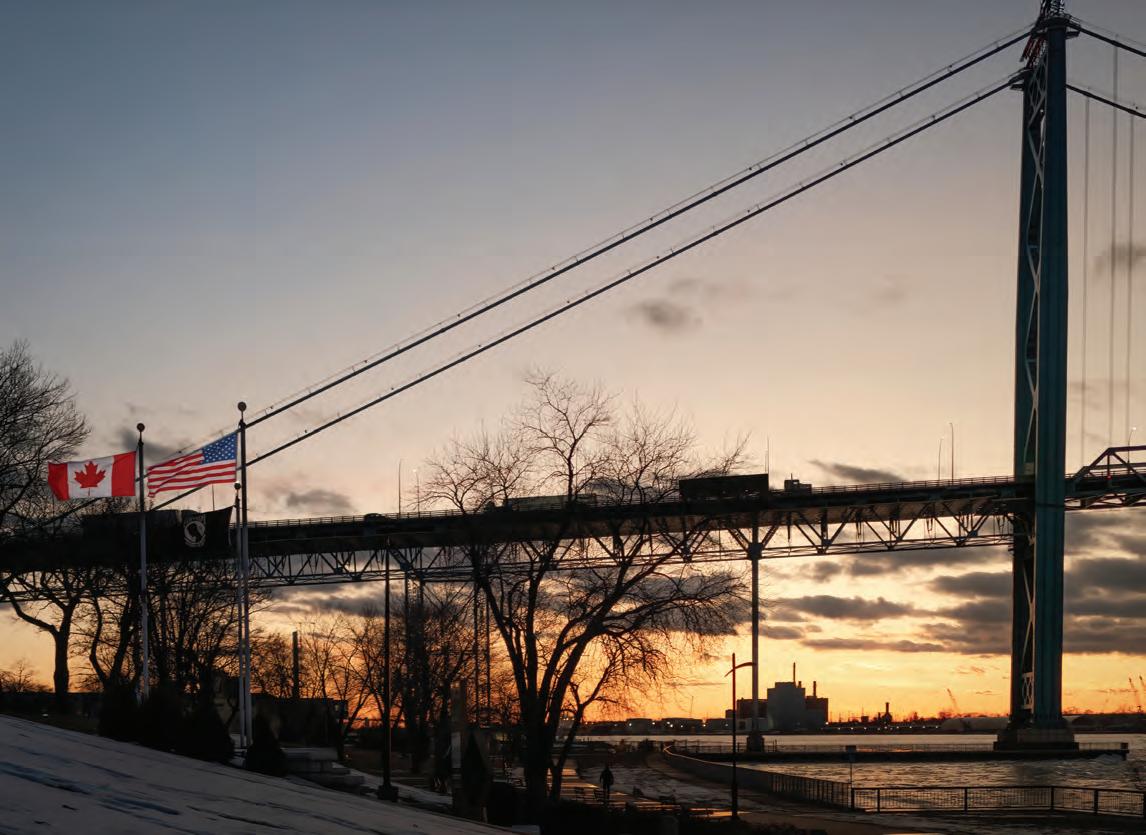

Donald Trump started a trade war by imposing a 25 per cent tariff on almost all Canadian goods bound for his country (with the notable exception of only 10 per cent on Canadian oil, gas and electricity), he fired the opening salvo of a conflict that Canada hadn’t anticipated.

It’s clear from Trump’s words that he has little regard for Canada’s sovereignty; no respect for a country, like his, that went from living under Britain’s thumb to being one of the more influential, secure and selfsustaining nations on Earth. Indeed, he seems to think that Canada is some sort of factitious creation that shouldn’t exist and that should join the tender mercies of the U.S.

“You get rid of that artificially drawn line, and you take a look at what that looks like,” said Trump in a January 2025 news conference. “That would be really something.” He followed the remark with a social media post including a map that erased Canada.

What does a trade war have to do with Canadian defence? Everything.

It’s the latest aggression in a series, including, but not limited to, threats to Canada’s Arctic region manifest by the growth and modernization of Russia’s military in the North and China’s stated designs on exploiting the area’s resources; and, as the National Cyber Threat Assessment 2025-2026 stated, “Canada is

confronting an expanding and complex cyber threat landscape.”

The country has done little to address these challenges, while it has spent (and borrowed to spend) nearly $300 billion on social welfare programs (nearly half of all government spending).

Canada’s defence spending as a percentage of its gross domestic product (GDP) ranks it among the bottom six NATO members— and one of the countries below it is Iceland, which has no military. While Canada has been pressed for years by its NATO allies to increase its military budget, the answer has always been delay, delay, delay. NATO countries agreed in 2014 to commit two per cent of their GDP to military expenditures.

At the time, Canada was spending less than one per cent of its GDP on defence. In 2024, it spent 1.37 per cent. In July, it promised to meet the mark by 2032.

That’s no way to earn respect in a world where power is largely measured by what a state can do to protect itself and to project strength to advance causes that it considers vital to itself and its allies.

The causes advanced by Trump for this war—illicit fentanyl and illegal immigrants flowing from Canada to the U.S.—are completely fabricated. Statistics from U.S. Customs and Border Protection indicate that just 43 pounds of fentanyl were seized at the Canadian border in 2024—about 0.2 per cent of the total border authorities caught. Meanwhile, about 1.5 per cent of people caught illegally entering the U.S. entered from Canada, according to American border officials.

Of course, at this moment, no one knows how this trade war will progress. But, buying Canadian wherever possible should be one

rallying point of the country’s defence. True, many goods we use in Canada—everything from orange juice to F-35 fighter aircraft—come from the U.S., but most of Canada’s other NATO allies also build reliable weaponry. (As for oranges, Israel and Brazil produce some good ones.)

The trust that Canada thought it had been building with the U.S. during times of both war and peace since the middle of the 19th century has been broken. When the British colonies that preceded Canada adopted the U.S. rail gauge and the decimal currency at least a decade before Confederation, it was a sign of where Canadians believed their future lay.

Canadians bled beside Americans during two world wars, in Korea and in Afghanistan. Canada supported the democratic and self-governing values the U.S.

espoused, which on a global level were first championed by President Woodrow Wilson, who, in an address to Congress in February 1918 said: “What we are striving for is a new international order based upon broad and universal principles of right and justice.”

But, given the current president’s rhetoric, Canada would do well to be suspicious of modern American leadership.

“The United States will once again consider itself a growing nation,” Trump said in his inauguration address this past January. “One that increases our wealth, expands our territory…and carries our flag into new and beautiful horizons.”

The two countries share the majority of a continent. But, most of the northern half belongs to Canada, and it’s safe to assume that Canadians will always “stand on guard.” L

Second World War

By Stephen J. Thorne

Nestled away on the top two floors of a four-storey stone-andbrick building overlooking the St. John’s waterfront, just a few metres from the Newfoundland National War Memorial, is a piece of Second World War history unlike any other.

Fifty-nine precarious steps up the back of the former warehouse, the Seagoing Officers’ Club, established by Captain Rollo Mainguy—a B.C. native commanding Canadian navy destroyers in the British colony of Newfoundland—is the stuff of legend.

Opened in January 1942, the warm-wooded refuge with its planked floors and beamed ceilings became home to a growing number of crests, etchings and artifacts deposited by its clientele on behalf of their ships.

On virtually every vertical surface emerged a unique gallery of the Battle of the Atlantic, a time when Newfoundland had, for all intents and purposes, become the “Gibraltar of America” that its former prime minister, Robert Bond, predicted it would be.

War was transforming the world—including this grand island affectionately known as The Rock.

“Perhaps nowhere…was there a garret exactly like the Crow’s Nest,” wrote Joseph Schull in his 1950 book Far Distant Ships. “Reminiscences went round the world, and doubtless still are on the wing, of the loud and smoky room where ships’ crests and bells and trophies hung thick on the

Captain Rollo Mainguy in the Seagoing Officers’ Club in September 1942.

A retreat and a respite for Allied naval and merchant marine officers between sailings on the North Atlantic run, it became forever known as the Crow’s Nest after a Canadian army colonel, gasping from his upward trek, mopped his beaded brow and uttered the immortal words: “Crikey, this is a snug little crow’s nest.”

wall and where women were allowed on Tuesday nights only, provided they do not clutter up the bar.”

The club is still there, now a refurbished Canadian national historic site, a living testament to the ships and men who fought the war’s longest battle and, by their presence alone, acted as catalysts helping usher the island into the modern world.

Among the Crow’s Nest artifacts is the periscope from U-190 (see “Artifacts,” page 94), one of the last German subs to surrender, on May 11, 1945—three days after VE-Day. Canadian warships brought the boat into St. John’s before it was moved, examined and scuttled off Halifax—but not until the periscope was salvaged and eventually brought back to the port where, for many, the war began, and ended.

Poking out of the building’s roof, the signature element of the U-boat war now provides, not the silhouette of another victim, but a sweeping view of downtown St. John’s and a sheltered, tranquil harbour populated by fishing trawlers, oil service vessels and coast guard ships—all of it very different from what came before.

For those fortunate enough to be granted passage through its door, the Crow’s Nest is an intimate history of an era of great turmoil and transformation. But the living legacy of WW II in Newfoundland can be found in virtually every corner of the province where the wartime forces of Canada and the United States, in very tangible and lasting ways, changed the course of the former colony’s history.

The Jan. 24, 1934, telegram from a magistrate in the outport of Burgeo, Nfld., to the justice minister on the other side of the island amounted to a desperate cry for help.

“ABOUT FORTY MEN [CAME] TO ME IN STARVING CONDITION,” it said.

“I CONSULTED RELIEVING OFFICER WHO INFORMS ME NOTHING CAN BE DONE THEIR ALLOWANCE WILL NOT BE DUE TILL EIGHTH AND NINTH FEBRUARY STOP IMPOSSIBLE THESE FAMILIES EXIST FOURTEEN DAYS WITHOUT FOOD STOP CAN ANY ARRANGEMENTS BE MADE HELP OUT SITUATION IF NOTHING I FEAR CONSEQUENCES.”

Government documents in Ottawa were describing Newfoundland as Canada’s “first line of defence” and “the key to the western defence system.”

There were few phones. It would be another 31 years before the broad, U-shaped arc of the Trans-Canada Highway would connect Port aux Basques on the island’s southwest corner to St. John’s, 900 kilometres away in the southeast.

Remote, weatherbeaten and chained to the make-and-break of a fickle fishery controlled by a handful of merchants in St. John’s, Depression-era Newfoundland was a Dickensian nightmare, and worse, for a disproportionate number of its 289,000 residents.

“Newfoundland was hit very hard by the Great Depression,” Carmelita McGrath wrote in Desperate Measures: The Great

Depression in Newfoundland and Labrador, a 1996 history produced by the province’s writers’ alliance.

“Many people were out of work or had very low wages. Hunger was a real problem…. More and more people were forced to apply for public relief.”

“The dole,” as it was known, didn’t come in the form of cash; it consisted of what were essentially food stamps redeemable at local merchants for specific goods.

“Many people said that you could not live on the dole. Often, people ran out of food before their next ‘relief order’ would allow them to get more. Most people hated the dole. They wanted work. They wanted to choose what they ate.”

McGrath describes how the Depression upset the delicate balance that was survival in Newfoundland at the time: life on the edge.

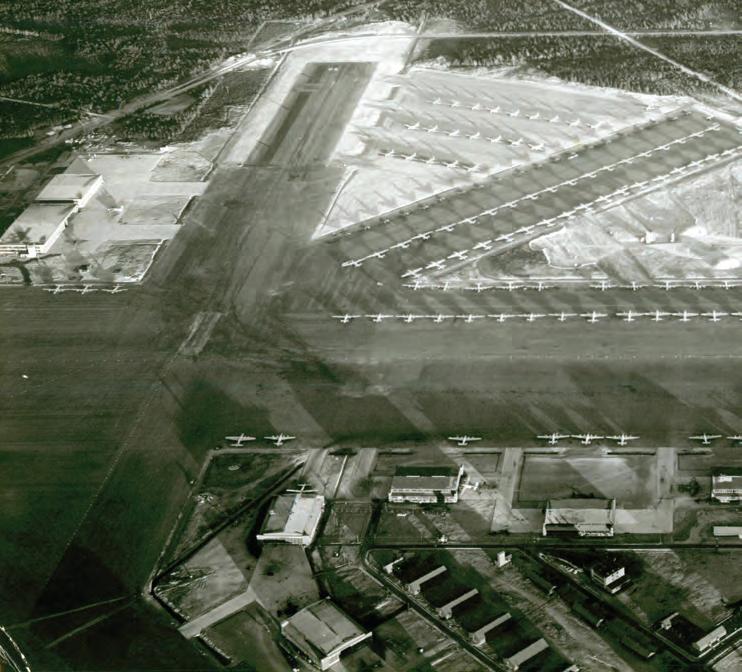

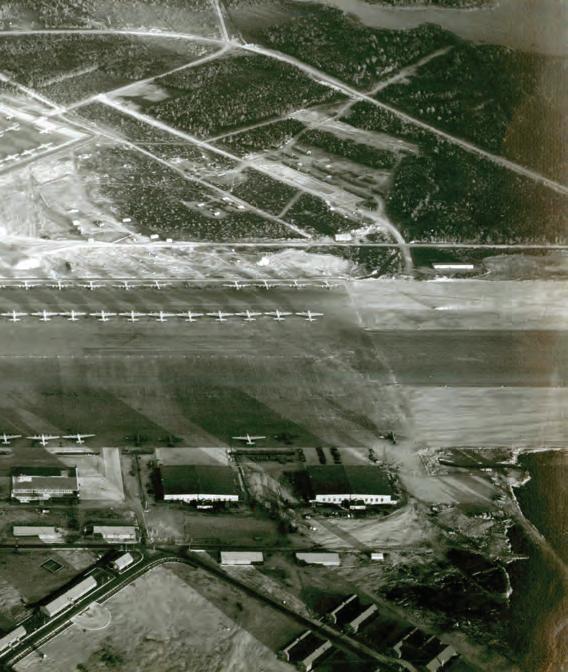

Dozens of planes, mostly bombers, line the Tarmac at the Royal Canadian Air Force base in Gander, Nfld., in 1944. Naval personnel of S.S. Miss Kelvin pose with a recovered mine in St. John’s, Nfld., in July 1942.

“On one side of this edge is a certain amount of security,” she explains. “There is enough food, decent housing, heat and comfort. On the other side of the edge there is little security, hunger, poor housing, cold and discomfort.

“During the Great Depression, more and more people were pushed over the edge.”

Largely descendent from British, French, Spanish and Portuguese fishermen, Newfoundlanders are a rugged, passionate people. Eventually, dissatisfaction—indeed, desperation—boiled over. There were demonstrations, riots, even looting.

The government, however, was up to its ears in debt.

Newfoundland had given up its status as a dominion of the British Empire in 1934 to be governed by a six-member commission appointed out of London. Now a colony, it was kept afloat by loans and grants from the British Treasury.

It all changed in the spring of 1940 when, after defeating virtually all of western Europe, Hitler’s forces stood poised to invade Britain.

On this side of the pond, government documents in Ottawa were describing Newfoundland as Canada’s “first line of defence” and “the key to the western defence system” should the Nazi advance come this far.

As for Newfoundland itself, the colony was all but defenceless. It had virtually no troops, no guns, no fortifications, and the government didn’t have the funds to provide them. Britain was in no position to help.

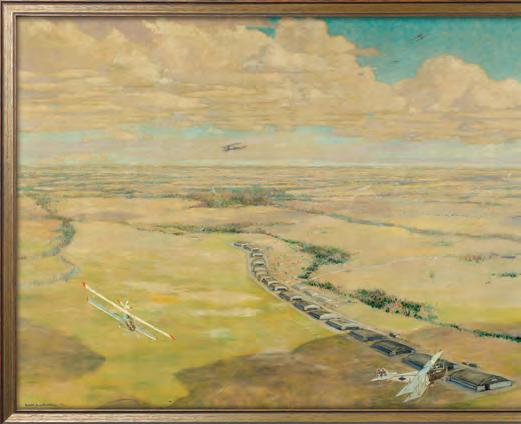

On Nov. 10, 1940, seven Hudson bombers manufactured in Burbank, Calif., took off from the airport at Gander and headed out into the night across the Atlantic. They were the war’s first transatlantic ferry flights, 13 years after Charles Lindbergh made his famous solo crossing.

The crews disembarked the next morning—Remembrance Day— at Aldergrove, Northern Ireland, wearing poppies. “At a single stroke, Newfoundland had become ‘one of the sally-ports of freedom,’” says a Canadian War Museum history.

Indeed, “in a very short time,” wrote historian Paul W. Collins in a 2015 paper for the provincial government, “Newfoundland boasted five military and civilian aerodromes, two naval bases, two seaplane bases, plus five army bases.”

During the next five years, tens of thousands of Canadian and American military personnel were to be posted throughout the island and Labrador.

“As the Colony’s entire population stood at less than 300,000 and Newfoundland’s capital (and largest) city boasted a mere 40,000 souls,” wrote Collins, “this ‘friendly invasion’ held tremendous economic, social, and political repercussions for Newfoundland— many still felt today.”

“This infusion of cash into the Newfoundland economy had a huge impact on the people of Newfoundland both directly and indirectly.”

Overlooked as a “liability” when Confederation was struck in 1867 (Newfoundlanders didn’t want Canada, either), the island was now regarded as an “essential Canadian interest” and an important part of the “Canadian orbit.” Prime Minister Mackenzie King argued in September 1939 that not only was the defence of Newfoundland “essential to the security of Canada,” but guaranteeing the colony’s integrity would actually assist Britain’s war effort.

Ottawa, however, did not act until Nazi Germany overran France and British soldiers were driven off the beaches of Dunkirk, at which point it dispatched a battalion of The Black Watch of Canada to protect Newfoundland’s Botwood seaplane base and the airfield at Gander, where it also stationed five Douglas Digby bombers and crews from 10 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force.

Shortly after, Canadian contractors started building Camp Lester on the outskirts of St. John’s. Brigadier Philip Earnshaw, the newly appointed Commander, Combined Newfoundland and Canadian Military Forces, arrived in November.

By the end of 1940, nearly 800 Canadian soldiers were posted throughout the Newfoundland capital and surrounds, ready to defend against any German attack. Canadian troops would also protect Lewisporte (considered a likely enemy insertion point), Rigolet and Goose Bay Air Station (the world’s largest airport by 1943). They also operated artillery and radar installations along the coasts of both the island and mainland.

The Royal Canadian Navy arrived in Newfoundland and set up a Naval Examination Service to control shipping entering St. John’s Harbour.

The British were woefully short of destroyers for convoy escort duty after losing significant numbers during the doomed Norwegian Campaign the previous winter, in the evacuation at Dunkirk in May, and at the outset of the Battle of Britain when the Luftwaffe was attacking Channel shipping.

Prime Minister Winston Churchill appealed to U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt in May 1940 for “forty or fifty of [his] older destroyers” to fill the breach until new construction replaced the losses.

Roosevelt was amenable, but the Japanese attack on the American base at Pearl Harbor was still more than 18 months away and the U.S. was officially neutral. A simple transfer would contravene international law and inflame isolationist sentiment in the U.S.

As a solution, Churchill proposed that Britain, as a gesture of friendship, lease base sites on British territory in the Western Hemisphere to the Americans, and Washington reciprocate with the requested destroyers.

“Unfortunately, such a remedy was a bit too subtle for American policymakers, who preferred a more direct and documented swap,” wrote Collins. “This presented the British with difficulties of their own as a straight exchange of assets could alienate the territories concerned, as well as upset many in the United Kingdom.”

Ultimately, a compromise gave the British their gesture and the Americans their business deal. Leases were given “freely and without consideration” in Newfoundland and Bermuda, while similar facilities were traded in Jamaica, Trinidad, British Guyana, St. Lucia and Antigua for the 50 destroyers.

The United States would go on to develop facilities in Newfoundland at St. John’s (Fort Pepperell/ Camp Alexander), Argentia (Argentia Naval-Air Station/Fort McAndrew), Gander, Stephenville (Harmon Air Force Base/Camp Morris) and Goose Bay.

There were also numerous artillery/radar sites granted around the island. By war’s end, tens of thousands of U.S. servicemen were stationed throughout Newfoundland and Labrador, and hundreds of thousands of U.S. military personnel and passengers had passed through the various American facilities throughout the colony.

By the summer of ’42, Collins reports, the Canadians had turned St. John’s into a well-defended harbour and home base for the five corvettes, two minesweepers and four Fairmile patrol boats of the Newfoundland Defence Force.

It was also home to the Newfoundland Escort Force, renamed the Mid-Ocean Escort Force—about 70 warships protecting the transatlantic convoys ferrying personnel and materiel to the war fronts. It would also include British escorts sailing out of the U.S. naval base at Argentia, on Newfoundland’s south coast.

Two Canadian corvettes, Chambly and Moose Jaw, recorded the force’s first U-boat kill, U-501, off the southeast coast of Greenland in September 1941. It was during this action that the recently commissioned Moose Jaw famously rammed the damaged sub, ending the German’s first and only war patrol (11 of 48 crew died).

Near Torbay, outside St. John’s, the RCAF had begun building an airbase that in postwar years would become the province’s main airport. Canadian military aircraft protected the city, and the iron ore mines on Bell Island, and patrolled convoy routes east of Newfoundland.

The RCAF group headquarters took up residence alongside the navy at the Newfoundland Hotel in St. John’s. RCAF Air Station Torbay opened in October 1941 with two runways; four

Hudson bombers arrived from Nova Scotia in November.

Passenger traffic between Canada and Newfoundland and the railway known as the “Newfie Bullet” had become so congested that in February 1942 the Commission of Government approved regular Trans-Canada Airlines service to and from Canada.

The RCAF developed more facilities at Gander and Goose Bay and made use of the island’s two American aerodromes. RCAF personnel also ran an expanding number of radar stations and an early-warning system.

By 1943, some 5,000 Canadian navy personnel were stationed in St. John’s. Thousands more were at the Buckmasters’ Field Naval Barracks just outside the city. Others would eventually be billeted at new facilities in Harbour Grace, Bay Bulls, Botwood, Corner Brook, and Red Bay and Goose Bay in Labrador.

“The most stunning impact of all this military activity was economic,” declared Collins. “During the fall of 1943 (the peak year of construction) over 20,000 Newfoundlanders were employed in building the various facilities.

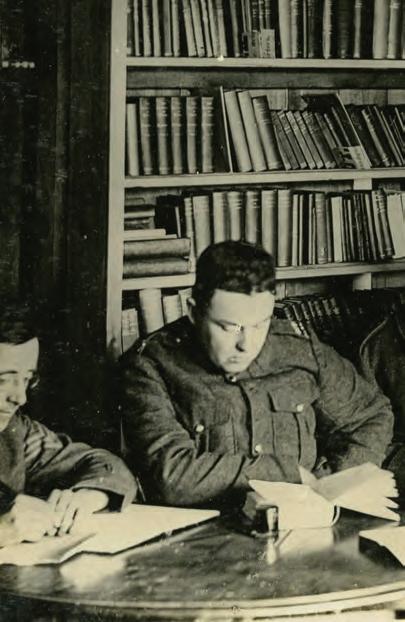

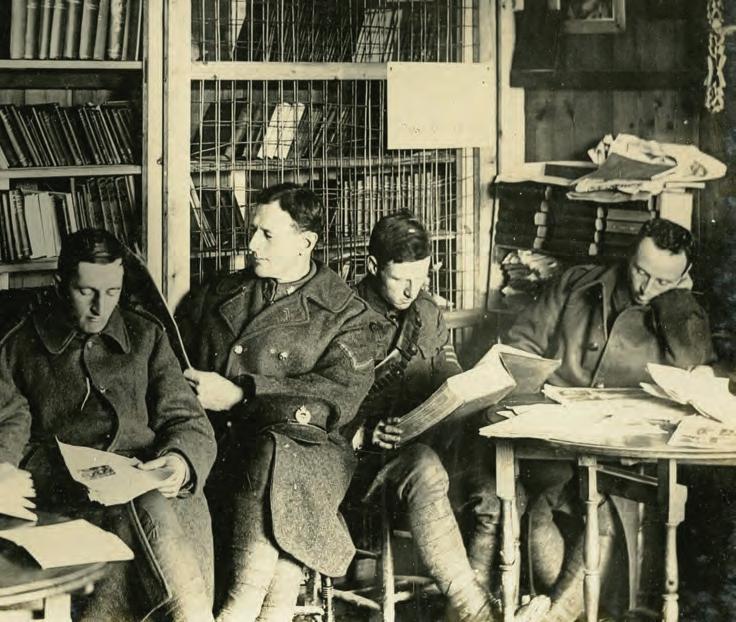

Personnel pass the time at Royal Canadian Air Force Station Gander, Nfld., circa 1945.

“Over the course of the war years, the U.S. invested $114,000,000 (USD) on their facilities in Newfoundland, and the Canadians $65,000,000 (CAD). Further, military personnel rose to upwards of 29,000 (13,000 US, 16,000 CA) in 1943, all of whom purchased local goods and services.

“This infusion of cash into the Newfoundland economy had a huge impact on the people of Newfoundland both directly and indirectly.”

In 1939, Collins continued, nearly 50,000 Newfoundlanders received some form of government assistance; by 1942, for the first time since the Commission of Government was struck in 1934, unemployment was “virtually wiped out.”

Tens of thousands of Newfoundlanders were working on base construction, support and supply. While the Americans tended to supply their bases via direct shipments from the U.S., the Canadians sourced theirs locally.

The cost of living rose dramatically during the war years. Though the Commission of Government tried to implement wage-and-price controls, local employers were still forced to match wages paid by the two occupying forces or lose workers.

“Whereas pre-war, only the merchant, professional and political/bureaucratic elite of the Colony could afford a comparable standard of living to that of the United States and Canada, by 1942, most residents of Newfoundland now tasted the benefits of the booming wartime economy.”

Government revenues, mainly from customs and excise taxes, also rose considerably during the war years. In 1939, the expected deficit was $4 million ($84.6 million in

Dancers celebrate VE-Day aboard HMCS Burlington in St. John’s, Nfld. Allied merchant ships in the harbour decorated with flags mark the end of the war in Europe.

2025 Canadian dollars). The 1940-41 fiscal year yielded a surplus of $796,531 ($15.3m) on revenues of $16.3 million.

In 1941-42, the commission recorded a $7.2-million surplus (about $131.8 million in 2025 Canadian dollars) on revenues of $23.3 million; in 1942-43 it had a $3.7-million surplus ($66.3M) on revenues of $19.5 million; in 1943-44, it came in with a $6.4-million surplus ($113.9M) on $28.6 million in revenues; and in the final fiscal year of the war, it recorded a $7-million surplus ($123.8M) on revenues of $33.3 million.

By war’s end, the Newfoundland government had a cumulative budgetary surplus of some $29 million (about $512 million in 2025).

At 10:30 a.m. on May 8, 1945, the siren atop the Newfoundland Hotel began wailing as it had every Thursday morning since 1939, reminding citizens that they were at war. On this joyous Tuesday, however, it marked the end of the greatest conflict the world had ever seen.

In homes across the city, in coastal outports, and at outposts in Labrador, families, service personnel and others gathered around radios to listen as Aubrey MacDonald of the Broadcasting Corporation of Newfoundland held a microphone out a window of its top-floor studio in the Newfoundland Hotel. The streets of the city were flooded with celebrants.

“You are hearing the rejoicing, the unabated rejoicing of our people in St. John’s which has followed spontaneously the great announcement by Prime Minister, Mr. Winston Churchill, that the war in Europe has ceased in an Allied victory,” he said.

“Listen to the whistles, the steamers, the church bells, as our people greet them in great jubilation. The town is bedecked with bunting. Flags are flying. And just now, our people are releasing the pent-up emotions in a torrent of joyous emotion.

“The war in Europe is over!”

And so, too, to a large degree, were the days of Newfoundland’s failing economy and starving populace.

The revenues from its wartime boom had allowed the commission to make significant investments in education, infrastructure, health care, pensions for disabled veterans and their families, and even loans and gifts to Great Britain.

The colony also inherited vast amounts of military property and infrastructure. In St. John’s alone, this included two hospitals, the RCN/RCAF headquarters, a naval barracks complex, a tactical training centre and numerous other area properties.

RCAF Air Station Torbay eventually became St. John’s International Airport.

St. John’s Harbour was also transformed. Once what Collins describes as “a tangle of decrepit wharves and finger-piers,” the RCN brought the moorings along the harbour’s Southside to naval standards—in most cases upgrading the owners’ properties with paving, fencing, access, etc. The navy built new facilities such as HMC Dockyard, now the Port of St. John’s shipping terminal,

and a fuel tank farm, which was sold to Imperial Oil in 1946.

Three hospitals—in Gander, Botwood and Lewisporte—were added to the health-care system. A fourth, the U.S. Memorial Hospital in St. Lawrence, was officially opened on D-Day’s 10th anniversary, a gift from the U.S. government to the people of St. Lawrence and Lawn who rescued and cared for survivors of the February 1942 disaster in which two U.S. naval vessels, Pollux and Truxtun, ran up on nearby rocks in a storm.

Hundreds of kilometres of roads were laid during the war. The Newfoundland Railway was expanded with new rail lines and rolling stock. Modern communications systems were installed and augmented, navigational beacons were upgraded, and Long Range Navigation (LORAN) added.

During succeeding decades, the Americans—and to a lesser degree the Canadians—closed facilities at St. John’s, Argentia, Botwood, Lewisporte, Gander, Stephenville and Goose Bay, passing title to federal, provincial or municipal governments.

Collins says the social impact of the war’s “friendly invasion” was also substantial.

“With the arrival of thousands of young men in communities throughout Newfoundland, many away from home for the first time, social interaction between the genders was inevitable,” he wrote.

“Scores of local women attended the various functions both on the bases themselves…and also at local entertainment facilities and hostels that sprang up at St. John’s and communities across the Island.”

Marriages, pregnancies—and sexually transmitted diseases— increased dramatically until U.S. authorities stepped in and prohibited local marriages, even sentencing some love-struck young bucks to prison terms.

“The Canadians, while not encouraging such unions, did not prohibit them, and seldom did a week go by that the St. John’s Evening Telegram did not announce an engagement or marriage between ‘a local girl’ and a visiting serviceman.”

When it was over, locals tended to join their spouses in Canada or the United States. Some would return to Newfoundland and raise families.

The friendly invasion changed Newfoundland and its people, who in turned changed the “invaders,” many of whom had never been far beyond their own villages and towns.

The colony never returned to dominion status. In 1948, fearful the United States would make a play for ownership of what was now recognized as a strategic chunk of North American territory, Britain and Canada conspired to omit the American option from two referendums on the colony’s future.

With Joey Smallwood at the helm, confederation with Canada edged out British rule and outright independence in a result whose legitimacy is in some quarters debated to this day. Newfoundland entered Confederation on March 31, 1949.

For years, it would be considered a “have-not” province, the breeder of Alberta oil workers and recipient of billions of dollars in equalization

“The war in Europe is over!”

payments from its wealthier siblings. Until, that is, offshore oil and gas propelled the renamed province of Newfoundland and Labrador to a payer between 2008 and 2024.

In today’s changing and onceagain increasingly volatile world, the province’s strategic importance, at the intersection of the Arctic and eastern approaches to the continent, cannot be overstated.

Nor can the value of its people who, in 75 years, have changed Canada, too.

“Among English-Canadians, at least,” author and historian Gwynne Dyer, a dyed-in-thewool Newfoundlander, wrote in a 2003 royal commission report on the province’s place in Canada, “Newfoundlanders have come to be seen as a slightly different breed of human beings who add interest and value to the Canadian mix.

“There is a clear perception among urban Canadians in particular that both the place and its people are in some sense special. If you were to press them as to what that really means, they would reply using

Able Seaman Donald Albert Douglas, like all liberty-loving Canadians, was jubilant at the news: the bloodshed in Europe—if not the war overall—had finally ended.

It mattered not that the May 7, 1945, announcement had been leaked earlier than authorities had intended. Cheers soon rang out across the city of Halifax and neighbouring Dartmouth as spontaneous celebrations erupted in the streets.

The 19-year-old from Belleville, Ont., who was serving in the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve thought little of his duties aboard HMCS Cobalt. Who, anyway, would need a sick berth attendant when the greatest issue, both over the coming hours and on VE-Day, was ensuring that service personnel and civilians alike savoured the moment?

Douglas reflected on his parents and how they would mark the historic occasion back home. He wondered, too, what he would write of his own experiences.

His medical skills, it would transpire, were destined to be critical. The young corvette crewman’s next letter to family, meanwhile, would be laced less with exuberance

and gratefulness and more with horror, angst and sheer disgust.

“If we live to be 100,” he penned in the immediate aftermath of what was to become the Halifax VE-Day riots, “…we’ll shudder at the thought of it.”

The Maritime port had long been a powder keg.

Effectively on the front lines throughout the Battle of the Atlantic, Halifax was a hub of wartime activity from the conflict’s onset. Allied convoys transporting munitions, supplies and troops assembled and departed from its harbour; local industry was booming; and civilians grew accustomed to the sea of uniforms.

As soldiers, sailors and airmen flooded into the city, the overall population swelled by an estimated 60 per cent between 1939 and 1944. Initially, these military men and women received a warm Nova Scotian welcome, but such hospitality was eventually replaced by ambivalence.

One of the primary causes was a fundamental lack of accommodation. Halifax’s infrastructure couldn’t keep pace with the rapid growth of Canada’s forces and, thus, had maintained its prewar, small-town semblance. Service personnel sought billets within the city, competing with civilians in a bidding war that bred contempt. Most landlords were fair in rent

Aprices, although the more devious inflated rates for uniformed newcomers, who often found themselves sardined into small apartments under spartan living conditions.

The situation became so dire that plans were hatched to place posters at Canadian railway stations urging visitors to avoid Halifax unless on official business. It was, according to one naval officer, an “overcrowded hellhole.”

Another issue was an increase in rationing. Partly due to the city’s enormous military presence—some 13,000-18,000 naval personnel alone resided there by May 1945—Haligonians felt these shortages more acutely than most. Then there was alcohol. Antiquated liquor laws meant that personnel had startingly few opportunities to enjoy a drink. Wet canteens on base and government stores in Halifax were perhaps the best options, but even those came with certain limitations, not least the ban on liquor possession and consumption in barracks.

Those less fazed by legality could instead visit bootleggers and speakeasies.

Once, the privately-owned Ajax Club had quenched the thirst of innumerable sailors, only for Halifax’s temperance lobbyists to force its closure in early 1942. That perceived slight against naval ratings was neither forgiven nor forgotten.

“If we live to be 100,” he penned in the immediate aftermath of what was to become the Halifax VE-Day riots, “…we’ll shudder at the thought of it.”

Resentment between residents, who became jaded by the strain on local facilities, and military members, who felt gouged by landlords and stifled by archaic rules, continued to fester, occasionally exhibited in alcohol-fuelled offences ranging from vandalism to property destruction to theft and assault.

On Dec. 2, 1944, a tram became the target of naval ire, having come to epitomize all that was considered wrong with Halifax. The streetcars were old, congested and uncomfortable, not to mention scarce. Inebriated sailors smashed windows and damaged the vehicle’s interior.

The incident further shook public trust in military and civic authorities whose shared role it was to counter escalating displays of misdeeds and indiscipline.

There was even precedent for precaution. At the time of the Great War, the arrest of a drunken sailor

A streetcar, set ablaze by rioters, burns on the evening of May 7, 1945. Despite the signs of trouble, RearAdmiral Leonard W. Murray allowed sailors free rein on VE-Day.

on May 25, 1918, resulted in City Hall being besieged; then, on Feb. 18-19, 1919, a racially motivated mob rampaged through the streets after a returning war veteran abused a Chinese restaurateur.

The question was what could be done this time around?

Preparations for VE-Day had begun in September 1944 amid hope that the war would be over by Christmas.

Municipal and military officials gathered for a series of meetings spanning several months, their collective goal to co-ordinate celebratory plans and, above all else, to ensure that jubilations couldn’t descend into violent unrest.

A committee was appointed to organize efforts, headed by Civil Defence Director Osborne R. Crowell. Other key figures

involved in preparations included Mayor Allan MacDougall Butler (who succeeded Jack Lloyd in May 1945); Police Chief Judson Jeffrey Conrod; Captain C. Balfour, commanding officer of the local naval barracks; Lieutenant-Commander Reg Wood, who led the navy shore patrol; and Rear-Admiral Leonard W. Murray, commanderin-chief of the Canadian Northwest Atlantic Command, the only Canadian to preside over an Allied operational area. Thanksgiving church services, remembrance ceremonies, military parades and firework displays were all agreed upon in due course. However, these genteel affairs were then combined with a slew of decisions that would prove fateful. Committee chair Crowell focused less on arranging entertainment and more on curtailing boisterousness. Elsewhere, Chief Conrod met with the provincial liquor commission and, together, discussed whether alcohol-selling outlets should close on VE-Day, a measure ultimately adopted. Naval barracks commander Balfour, meanwhile, announced “open gangway,” meaning that naval ratings not on duty could join in the merrymaking at will. Such perceived free rein was arguably aided by the navy shore patrol’s Wood, who intended for his men to stay in reserve to answer emergency calls in force rather than have them monitor the streets. This move was approved by Murray, who planned to curb arrests for fear of “a serious riot.”

The measures didn’t cease there. Soldiers and sailors were implicitly discouraged from participating in civic events, with Murray maintaining the belief that having wet canteens open could “go a long way towards keeping the crowds of service personnel off the streets where they might do harm.” Those who did venture farther afield would find 44 of 55 eateries and all 11 theatres closed on VE-Day, deemed a necessity by most establishment owners, despite some pleas to the contrary, after realizing that the stretched-thin police were ill-equipped to provide protection.

Whereas the Canadian Army and Royal Canadian Air Force imposed strict schedules and rules of conduct on their garrisons, the Royal Canadian Navy’s guidelines were comparatively lax. Nevertheless, it took more than a sailor’s presence to cultivate discontent.

Added to the spectre of anarchy was mayoral inexperience and, of course, the frayed nerves of a war still being fought in nearby waters until May 7, 1945.

The question now was whether the guardrails would hold.

It started as it was always meant to start.

Spilling into the streets for an impromptu party, Haligonians ignored dense fog and torrential rain to mark victory in Europe, even if VE-Day was earmarked for the following day, May 8. The clouds later parted as bunting sprouted from windows, flag masts and telephone poles, only amplifying the jovial atmosphere throughout Halifax.

Mayor Butler declared the 7th a civic holiday before promptly removing his car from the area for “security reasons.” Though most service personnel remained on duty, more than 9,000 naval ratings were expected to join the evening festivities.

In the meantime, the planned shuttering of cinemas, cafés

and restaurants went ahead. Liquor stores likewise closed, freeing bootleggers to charge a premium of $15 per two-bit bottle of rye. Plus, in accordance with the agreed-upon police policy, enforcers prepared to gather and respond to trouble in strength.

That trouble seemed almost negligible until 9 p.m. when the wet canteen at the primary naval barracks at HMCS Stadacona shut down. The site had been well stocked with 6,000 bottles of beer, and the drunk naval ratings now released into the streets sought new methods to sate their feisty mood.

What would appear then than one of the despised streetcars. The naval shore patrol’s Wood glimpsed the disturbance from a Stadacona window, mustered 30 officers and hurried to the scene. He discovered the tram had escaped with minor damage. But it was merely the beginning of an exceedingly long night.

On Citadel Hill’s eastern slope, a crowd of 15,000 marvelled at a two-hour fireworks display launched from Georges Island and naval vessels. During the quieter interludes, however, came the equally distinct din of smashing glass.

Sailors, joined by scores of civilians, ran amok through downtown Halifax. The naval ratings harassed streetcars along Barrington Street by disconnecting their electricity supply, leaving them stranded to the whims of well-lubricated mobs. Hundreds of rioters surrounded one tram, ejected its driver and passengers, shattered windows, tore out seats and attempted to topple it. They eventually set it ablaze.

The task of restoring order fell to a police squad driven to the scene by Constable Fred Nagle. His arrival did little except fuel greater chaos. Nagle himself sustained injuries when the mob flipped his vehicle, forcing all other passengers to make a hasty exit while he remained trapped. The officer watched in unbridled horror as

a sailor set the police wagon on fire. Caught in an inferno, Nagle’s bids for freedom were prevented by an individual shoving him back into the car. Thankfully, if belatedly, another sailor saw sense and pulled him out.

The next target soon became the firefighters tackling the flames, as rioters hacked at water hoses with axes stolen from the fire truck. Perhaps fearing the onset of sobriety, the crowd then shifted its attention to plundering the liquor stores.

The outlet on Sackville Street was the first hit when three merchant mariners threw a flagpole through the plate-glass storefront. Two more shops, on Hollis and Buckingham streets, were looted around midnight. The overwhelmed police, powerless to halt proceedings, stared impotently as the horde of uniforms and civilian accomplices extricated thousands of wine, beer and spirit cases.

The pandemonium continued with a range of criminal acts, from robbing the Wallace Brothers’ shoe store to foiled efforts to dump Nagle’s gutted patrol wagon into the harbour. Finally, in the early hours of May 8, the disorder fizzled out.

But the worst was yet to come.

Memories of the Great War riots paled compared to what Haligonians confronted on their streets the next morning. Due to the lateness of the previous night’s events, many had been unaware of the destruction wrought. They saw it now.

The signs were everywhere: shattered glass, strewn merchandise, devastated storefronts, and the wretched stench of stale booze, vomit and charred wood. Then there were the perpetrators, some of whom lay drunk in the gutters. As such, legitimate concerns were raised about whether the scheduled VE-Day celebrations would provoke further unrest. Rear-Admiral

“I’m ashamed that I’m in the Services and that I’m Canadian and I don’t mind telling you.”

Murray, who inexplicably hadn’t been informed about the previous evening’s rampage while it took place, had since been apprised of the situation. He determined that his sailors still deserved their day; they had fought for it.

Mob mentality began anew shortly after 1 p.m., when the naval barracks’ wet canteen ran dry, once again forcing naval ratings into the streets. The men first vented their frustration on the canteen itself, hurling bottles and rocks at its windows. They then shifted their focus to a tram on Barrington Street.

Hijacking the streetcar, nearly 150 intoxicated sailors clambered inside or perched outside, with the remainder of the throng following behind as it lumbered downtown. Their numbers were eventually augmented by personnel of the Women’s Royal Canadian Naval Service, civilians and even children. They joined in smashing windows en route before abandoning the wrecked tram.

Additional streetcars, liquor outlets and shops soon faced the same fate. But, perhaps the most significant misfortune befell Keith’s Brewery, when a thirsty, 4,000-strong horde descended on its Lower Water Street warehouse. Despite having barricaded the gate, security couldn’t protect the complex’s entire perimeter. Two dozen rioters breached it, emboldening hundreds more to swarm through. Colonel Sidney Oland, the brewery’s owner, resolved himself to the path of least resistance, offering free cases of stock. The decision paid off as satisfied intruders left the business largely undamaged.

“This is to thank you for your service to your country,” remarked Oland in donating 118,566 bottles of beer to the swarm as it formed an orderly queue.

Drunkenness, theft and vandalism weren’t the only crimes and misdemeanours taking place throughout Halifax. At Cornwallis Park (since renamed), for instance, couples were engaged in public fornication. Elsewhere, sailors sold stolen liquor in a cemetery.

Yet, the band played on at the Garrison Grounds ceremony, where about 20,000 Haligonians gathered for the scheduled events. Murray, who attended the service, devised a plan for the parade’s 375 naval ratings to march downtown. There, they would assist the shore patrol and police in quelling the violence.

And it may have worked, too, had someone thought to tell the parade officer in charge. Instead, 100 peeled off from the march and joined the rioters.

To make matters worse, Chief Conrod neglected to order his own officers to stay on duty after their shifts ended. The accidental oversight meant that 40 men—an entire platoon’s worth—returned to their homes at 4 p.m.

Seaman Donald Albert Douglas, HMCS Cobalt ’s 19-year-old sick berth attendant, wouldn’t receive the same luxury, having been tasked with erecting an emergency ward to treat the wounded. The sailor laid claim to a “clear conscience” amid the turmoil as his short-staffed team “worked like pack horses.”

At 7 p.m., Douglas and two assistants “who were nearly sober” commandeered an army ambulance

and headed into Halifax. Weaving past shattered glass, the trio saw “shoes, boots, chesterfields, clothes, cash registers, pots, pans and nearly everything you could imagine on the street.”

Their first patient was unconscious after “someone had taken the jagged end of a broken bottle and just slashed his face to pieces.”

The team had just heaved the man into the ambulance when a soldier approached and offered to drive.

Countless others—including naval ratings—likewise volunteered their services across the city, whether in quelling the riots or providing medical assistance.

Over the next few hours, Douglas’ mismatched band of helpers made repeated trips into Halifax and provided aid to dozens.

“I got one fellow,” he wrote later, “who had had a broken bottle shoved into his back and twisted till it made a hole.”

Enough was enough for civic and military authorities. Mayor Butler, who had proposed enacting martial law without success, and Murray, who had at last conceded that more needed to be done, declared VE-Day celebrations over at 6 p.m. and imposed an overdue curfew two hours later. Bolstered by shore patrol officers armed with 150 axe handles and an incoming army contingent from Debert, N.S., both leaders boarded a sound truck and, touring the streets, ordered everyone to return home or back to base.

The streets of a battered Halifax began to empty, perhaps due to the authoritative voices that bellowed through speakers— or perhaps because the rioters were all rioted out.

Regardless, it would be one hell of a hangover.

“I’m ashamed that I’m in the Services and that I’m Canadian and I don’t mind telling you,” wrote a disillusioned Douglas to his parents on May 9, 1945.

Service personnel and civilians alike walk past looted businesses in Halifax on VE-Day.

Emotions were evidently high in the aftermath of the Halifax VE-Day riots, but one question was already at the fore: who was to blame?

Crammed into jail cells were masses of miscreants, 152 of whom had been arrested for drunkenness and another 211 for the likes of robbery, looting and possession of stolen goods. Those goods included 6,987 beer cases, 1,225 wine cases, and 55,392 spirit bottles from the liquor commission of Halifax; another 30,516 quarts of beer from Keith’s Brewery; and an additional 5,256 quarts of beer, 1,692 quarts of wine, and 9,816 spirit quarts from the commission in Dartmouth, where a smaller riot had occurred. Plus, 207 businesses pillaged and another 564 establishments damaged.

Were these imprisoned individuals the sole perpetrators of a destructive spree costing some $5 million? No, it would be deemed—it went higher than that.

Two people had died during the two chaotic days, while at least 29 sustained serious injuries, with many more minor ones.

Someone, surely, in the upper echelons of command would need to take responsibility for such casualties, not to mention the physical carnage.

That person became RearAdmiral Murray, who, through a Royal Commission inquiry under Justice Roy Kellock—a militant teetotaler—endured an estimated 2,243 questions only to be later found at fault for virtually the entire debacle.

It was a view that corresponded with an ever-broadening consensus that sailors, who indeed comprised a sizable proportion of rioters, had mainly been left to their own devices while naval authorities and, therefore Murray, remained passive.

That was probably true to a certain degree, but the verdict failed to recognize the unique and unfortunate circumstances that made it possible. Civic authorities—from the municipal to the federal level—had done little to relieve pressures placed on overcrowded Halifax. The city’s military-civilian relationship was at an all-time low when the riots broke out—with

Haligonians sharing a proportion of fault for that deterioration. And the fateful decisions, actions (and inactions) of others, be they in positions of power or simply on the streets, contributed to the disorder. It mattered not: a scapegoat had been chosen.

An unrepentant Murray was relieved of command. With his hard-earned reputation forever tarnished—rightly or wrongly—the former rearadmiral committed himself to self-imposed exile in England, where he subsequently retrained to practise law. The renowned Battle of the Atlantic veteran died on Nov. 25, 1971, at age 75.

Halifax’s naval bonds were repaired with time. The heroic RCN response to the July 18-19, 1945, Bedford Magazine explosion did much to restore that relationship, with sailors playing a vital role in mitigating its impact. It almost certainly helped, too, that the city’s VJ-Day celebrations, when they at last occurred on Aug. 15, 1945, were a far quieter— and less riotous—affair. L

Knowing your people is a fundamental tenet of good leadership—knowing their capabilities, shortcomings, foibles, their collective state of mind.

That navy brass in the Halifax of May 1945 believed concerts and sports would mollify thousands of antsy sailors, most of whom had just survived the longest battle of the war, was at best naive, at worst negligent.

And once things went south on Halifax streets, the navy did little to stop it.

“The disorders which actually occurred on May 7 and 8 owe their origin, in my opinion, to failure on the part of the Naval Command in Halifax to plan for their personnel,” wrote Justice Roy Kellock, head of a royal commission on the riots.

Kellock said the situation escalated and continued for two days because navy brass allowed it to. He said they were “passive” and left remedial action until it was too late.

Typical of grey old 1940s Halifax, city police were ill-equipped to address the onslaught, during which mostly navy ratings caused some $5 million in damages (more than $88 million today). Two people died.