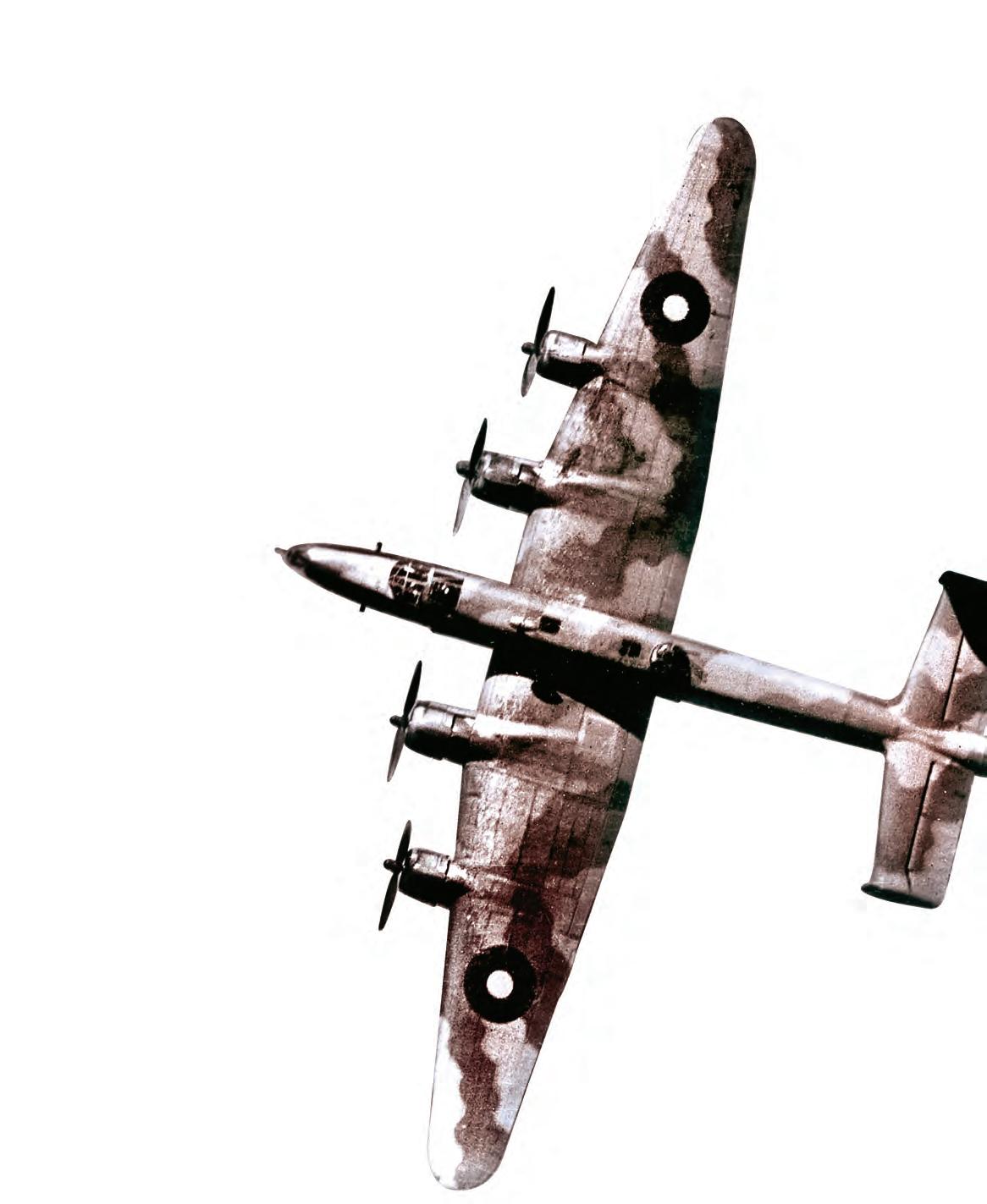

At an airfield in northern England, crew from No. 405 Squadron, RCAF, stand with their Wellington bomber—nicknamed “Berlin or Bust.”

See page 28

16 A GREAT VICTORY

Planned and executed with precision, the attack on Vimy Ridge redefined the Canadian Corps as an elite formation

By J.L. Granatstein

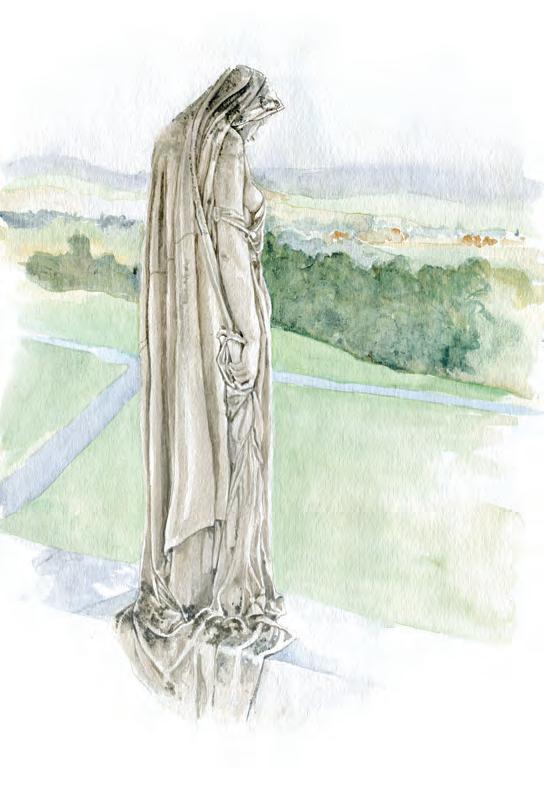

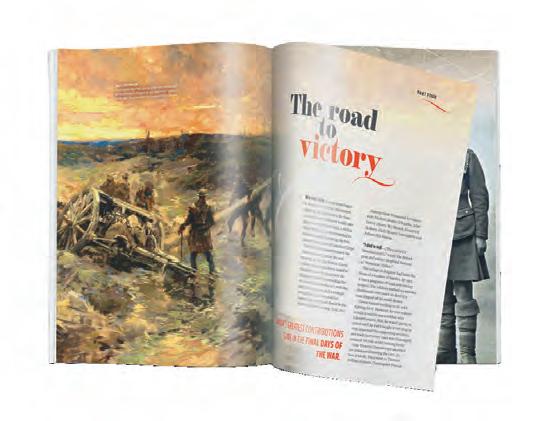

22 ART OF VIMY

War artists of all stripes trekked to the cratered grounds following the iconic battle

By Stephen J. Thorne

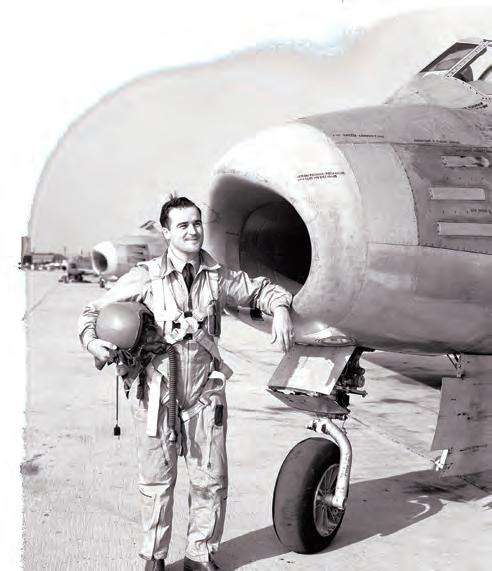

28 FLIGHT OF THE PATHFINDERS

Crack teams of navigators and pilots marked targets from the air, in the dark and under fire

By Sharon Adams

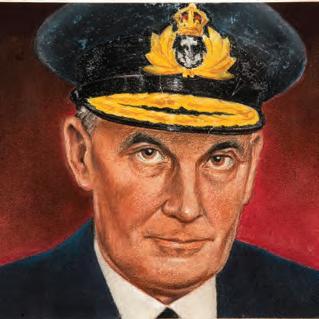

36 SAVIOUR OF CEYLON

Patrolling over the Indian Ocean, pilot Leonard Birchall and his aircrew spotted an approaching Japanese fleet

By John Boileau

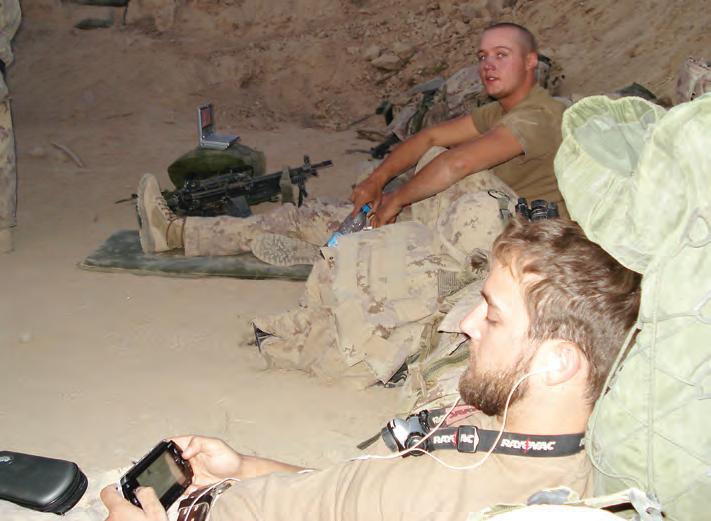

46 DANGER CLOSE

Wounded by a rocket-propelled grenade, Private Jess Larochelle fought off Taliban attackers at a strongpoint near Pashmul, Afghanistan

By Stephen J. Thorne

54 PLACING THE DISPLACED

An early refugee support group helped open Canada to victims of Nazi persecution

By Valerie Knowles

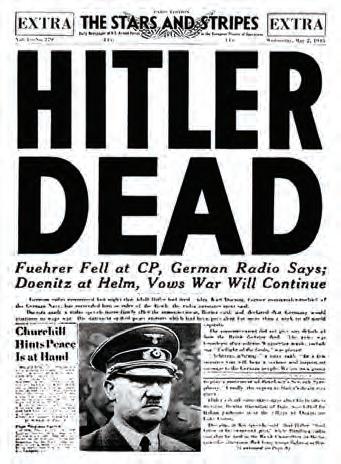

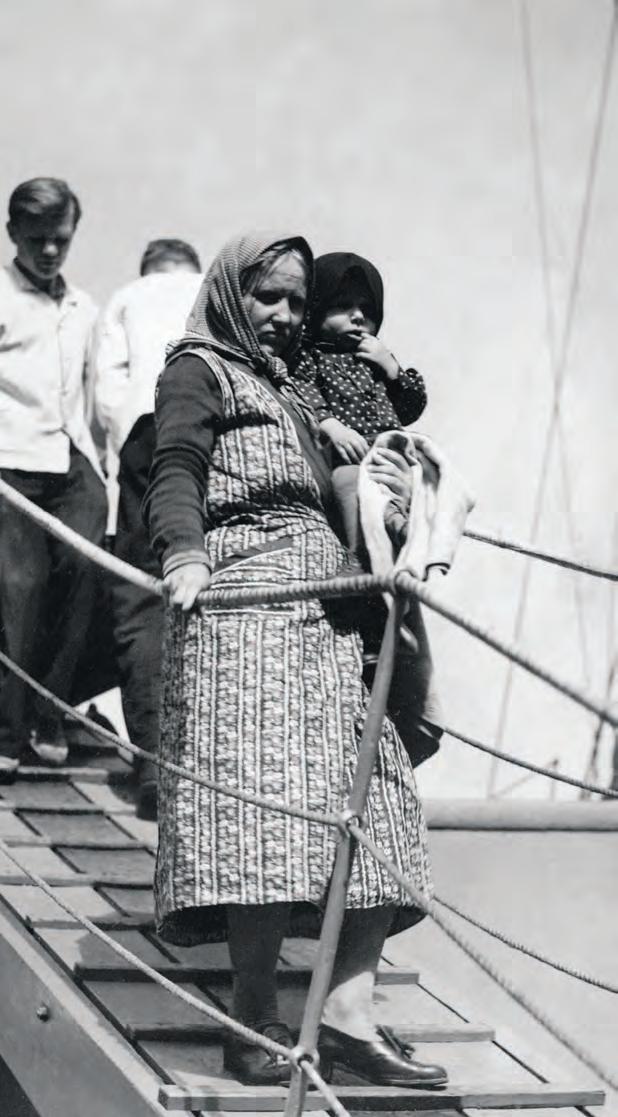

THIS PHOTO

Undeterred by restrictive immigration policies of the time, the refugee Loeffler family, photographed in 1939, homesteaded at Edenbridge Hebrew Colony near Melfort, Sask. LAC/3367859

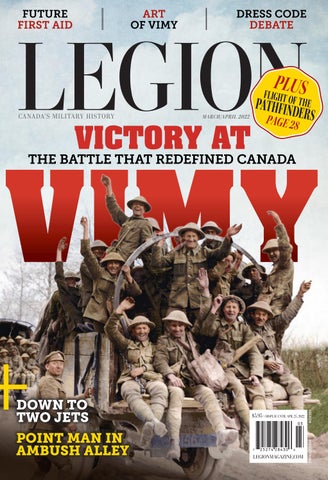

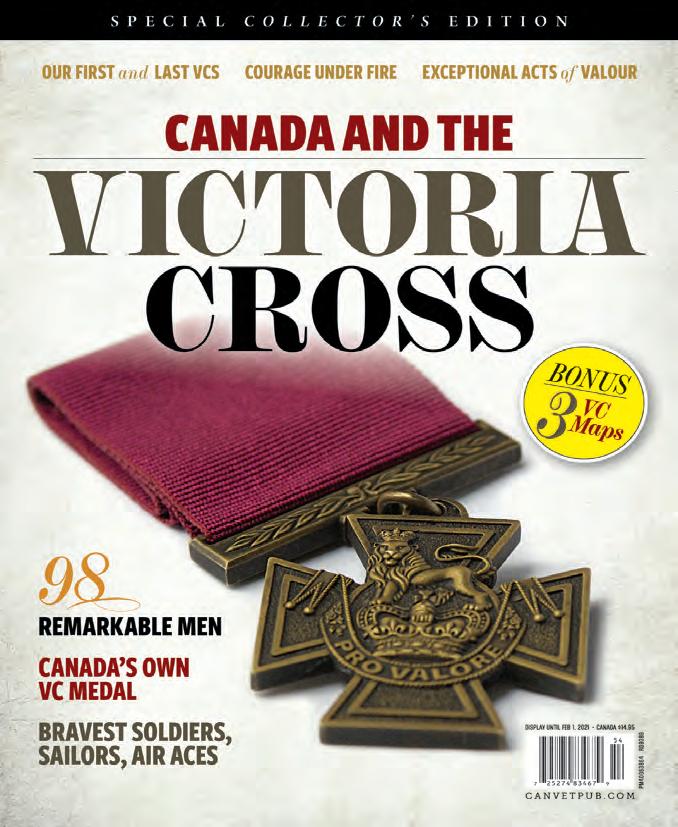

ON THE COVER

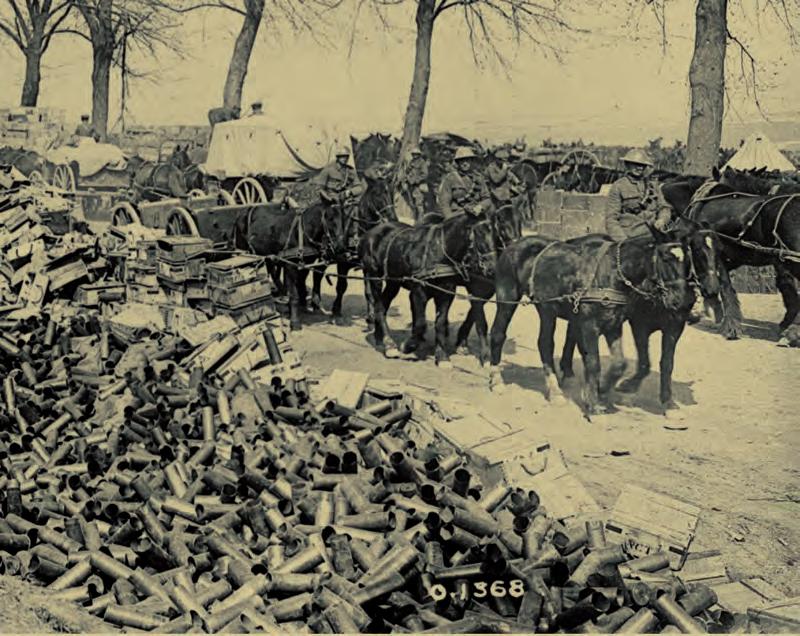

Canadian troops return triumphant from the Vimy front, their celebrations tempered by the loss of comrades.

William Ivor Castle/LAC/3194757/Colourization: The Vimy Foundation

Vol. 97, No. 2 | March/April 2022

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Owen Parkhouse BOARD VICE-CHAIR Bruce Julian BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe

DIRECTORS Tom Bursey, Steven Clark, Thomas Irvine, Berkley Lawrence, Sharon McKeown, Louise Tardif, Brian Weaver, Irit Weiser Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jennifer Morse

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

RESEARCHER/ ADMINISTRATIVE

ASSISTANT

Mike D’Angelo

EDITORS

Eric Harris

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Trevor Oattes

STAFF WRITERS

Sharon Adams

Stephen J. Thorne

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jason Duprau

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Jennifer McGill

DESIGNERS

Derryn Allebone

Sophie Jalbert

Advertising Sales

CANIK MARKETING SERVICES

SENIOR DESIGNER AND MARKETING CO-ORDINATOR

Dyann Bernard

WEB DESIGNER

Ankush Katoch

WEB AND SOCIAL MEDIA

CO-ORDINATOR

Mauricio Dimate

TORONTO advertising@legionmagazine.com

DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS INC mmignardi@dvtail.com

OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2022. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $5.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Send new address and current address label. Or, new address and old address, plus all letters and numbers from top line of address label. If label unavailable, enclose member or subscription number. No change can be made without this number. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com. Allow eight weeks.

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $5.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of CCAB, a division of BPA International. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine,

613-591-0116.

he federal government is planning to apologize in July for the treatment of Black volunteers who served with the segregated No. 2 Construction Battalion during the First World War.

Black men, some of whom came from the United States and Caribbean to sign up with the Canadian Expeditionary Force, faced racism and often insurmountable obstacles in their efforts to join regular infantry units. While about 700 eventually did, the bulk of Black volunteers were relegated to support duties with No. 2 in France.

DOING SO RINGS HOLLOW, HOWEVER, IF MEANINGFUL AND EFFECTIVE MEASURES AREN’T TAKEN.

It will not be the first military- or war-related apology to be issued. Far from it.

Most recently, on Dec. 13, Ottawa apologized to victims of sexual misconduct in the military (see page 58). Other apologies preceded it:

• on Sept. 22, 1988, the federal government apologized for interning Japanese Canadians during the Second World War;

• on Nov. 7, 2018, Ottawa said sorry for turning away Jews who arrived in Halifax Harbour in 1939 seeking asylum in the face of rising Nazi atrocities;

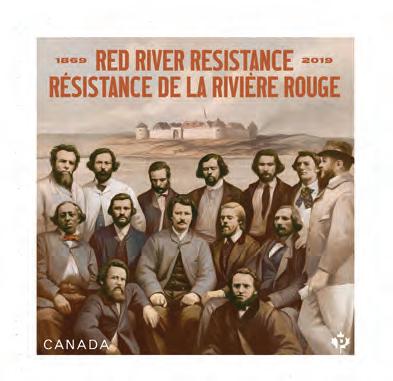

• on Sept. 10, 2019, it apologized to Métis veterans who had been denied their rightful benefits;

• and on May 27, 2021, the government issued a mea culpa for the internment of Italian Canadians during the Second World War.

For many, such apologies come a day late and a dollar short. Of the 937 Jewish refugees sailing port to port in 1939 aboard MS St. Louis in what became known as “The Voyage of the Damned,” 254 eventually were killed in the Holocaust.

The government’s apology to Japanese Canadian internees and their families included $300 million in compensation and $24 million for a race relations foundation to “ensure such discrimination never happens again.”

But no amount of compensation four decades after the fact could make up for the suffering inflicted on 22,000 Canadians of Japanese descent whose property and belongings were confiscated and sold. To add insult to injury, they had to pay for their own internments; their full citizenship rights were not restored until 1949.

“We cannot change the past,” said Prime Minister Brian Mulroney in 1988. “But we must, as a nation, have the courage to face up to these historical facts.”

Doing so rings hollow, however, if meaningful and effective measures aren’t taken to right what caused the wrong in the first place.

The Canadian military has “faced up” to sexual misconduct on numerous occasions and commissioned two studies into the problem. Scandals at the topmost ranks and a steady stream of courts martial alleging sexual misconduct suggest comprehensive change remains elusive.

Likewise, systemic racism in Canada won’t end with an apology.

Hopefully, by acknowledging the wrongs of the past and making amends, Canadians will cast a more critical eye on events of the present and engineer real and lasting change. There can be no better acknowledgement of the sacrifices Black soldiers made more than a century ago—overseas and at home. L

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or e-mailed to: magazine@legion.ca

Thank you for the two excellent articles in the January/February edition, “Are we disarming?” and “Defence on the cheap.” As a member of the Legion and having three family members in the Canadian Armed Forces, they sure rang a sour note. Our military situation is sad and depressing and should be to all Canadians. Sadly, it is of little concern to many. You can bet if Canada was an isolated country and did not have the might of the United States military next door to it the situation would be different. We would have an up-to-date and strong military. Having military equipment that is dated and useless can only lead to fatal

results. Then will someone in the government take notice? Probably not. As stated in the article by David J. Bercuson, if we stand by, we are fools.

BILL SHOLDICE, MISSISSAUGA, ONT.

In reading the article regarding the Lytton Branch and its situation (“Lytton Branch destroyed by wildfire,” November/December 2021), a couple of thoughts have occurred to me. I am wondering if thought has been given to helping them by staging (for lack of better wording) a community barn-raising party? I would think that among Legion membership and friends there must be an extensive number of active and retired tradespeople who would be willing to volunteer to help rebuild and others with no particular skill set who would happily be the “grunts” needed to help out. This would dramatically lower their costs and potentially speed up the timing of their rebuild. It also occurs to me that if this could be co-ordinated to happen quickly, the rebuilt building could become the community “command centre” for the larger task ahead of rebuilding the entire town. Much better to change a discouraging situation into a statement of commitment for the whole community of Lytton

and the nearby First Nations as well as demonstrating, once more, the value of the Legion.

BILL AAROE, MAPLE RIDGE, B.C.

“Fujita’s blade” (November/ December 2021) reminded me of a professor I had at Seneca College in 1967, George Suzuki. At the time, he was a reserve officer in Toronto. That year, he had returned a sword surrendered to him by a Japanese officer at the end of the Second World War as his own centennial project. I have wondered about the story, especially as Japanese Canadians, to my knowledge, were not enlisted nor did Canada have much of a presence serving in the Pacific other than those in Hong Kong and a few other areas.

ROBERT TUCKER, OWEN SOUND, ONT.

“Defence on the cheap” (January/ February) is a reminder that there is an old lesson to be re-learned in Canada from the sorry epilogue of the Avro Arrow. National security cannot be procured on the cheap. Political leaders in democratic countries have always tended to shy away from that unpalatable truth. And yet, how many times in recent history have those same politicians, who shrank from asking the electorate to spend money on national security, unhesitatingly asked the country’s youth to lay down their lives to restore it?

Our country seldom recognizes the very people who have provided us the rights and freedoms that so many now take for granted. We must never give up what these brave men and women fought and died for.

JOHN FEFCHAK, VIRDEN, MAN.

Advertisement

In the text with the photo essay on Canada’s participation in the Korean conflict (“Into the fire,” March/April 2021), I was surprised to not see any mention of Lieutenant-Colonel Herbert Fairlie Wood. He produced at least four great books, two dealing with Korea: Strange Battleground: Official History of the Canadian Army in Korea and The Private War of Jacket Coates, a novel about one typical representative soldier and the military experience in general. It helped me understand my father and my stepfather and is still a damned good read.

JOHN WIZNUK, SATURNA ISLAND, B.C. L

The Snapshots caption on page 83 (January/February 2022) incorrectly located Lancaster, N.B., Branch and Portland, N.B., Branch. We apologize for the error.

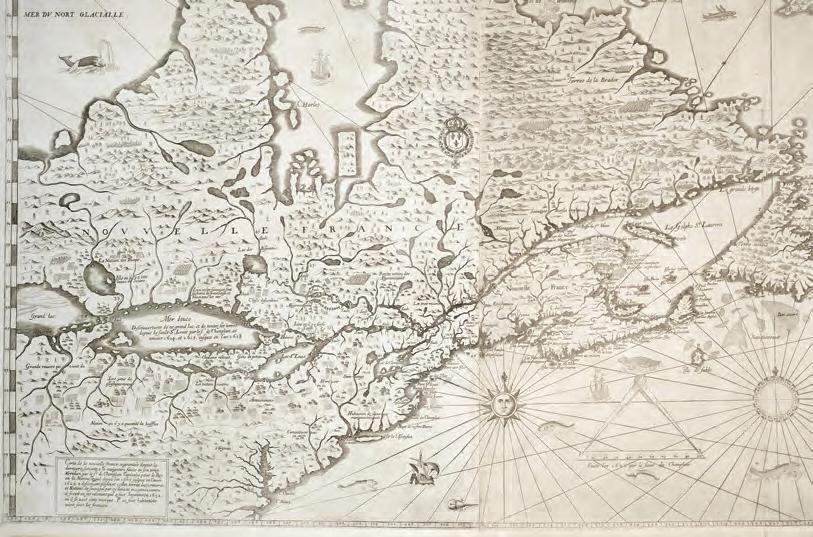

1 March 1633

After three years of English occupation, Samuel de Champlain is reinstated as the commander of New France.

2 March 2011

HMCS Charlottetown heads for Libya to provide humanitarian assistance.

5 March 1891

John A. Macdonald leads the Conservatives to victory in what would be his final general election; he dies just three months later.

6 March 1945

Operation Spring Awakening, the last major German offensive of the Second World War, begins.

7 March 1951

8 March 2001

The Royal Canadian Navy begins allowing women to serve on submarines.

9 March 1915

Redford Mulock is the first Canadian to qualify as a pilot in the British Royal Naval Air Service.

10 March 1992

Citing his “unique and historic role,” the House of Commons declares Métis leader Louis Riel a founder of Manitoba.

11 March 1876

North West Mounted Police sub-constable John Nash is accidentally killed while on duty near Fort Macleod, Alta. He is the first person commemorated in the RCMP Honour Roll for those killed in the line of duty.

20 March 2009

Four soldiers are killed, eight wounded in roadside bombings near Kandahar.

21 March 1918

The entire German army attacks the British front between St. Quentin and Arras with a heavy artillery bombardment of explosives and gas.

24 March 1945

The 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion drops behind enemy lines in Germany as part of the crossing of the Rhine River.

28 March 1918

The anti-conscription Easter Riots begin in Quebec City and culminate in Canadian soldiers firing at civilians, killing four and injuring dozens.

Two companies from 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry launch an assault on Hill 532 in South Korea.

12 March 1930

First World War ace Billy Barker dies in a plane crash near Ottawa.

13 March 1971

FLQ member Paul Rose is sentenced to life imprisonment for the murder of Quebec politician Pierre Laporte; he is later released after a report reveals he was not present at the crime.

17 March 1945

HMCS Guysborough is torpedoed and sunk by U-868 in the Bay of Biscay off France, resulting in 51 casualties.

30 March 1951

RCAF Flt. Lt. Omer Lévesque is the first British Commonwealth pilot to shoot down a German Focke-Wulf Fw-190.

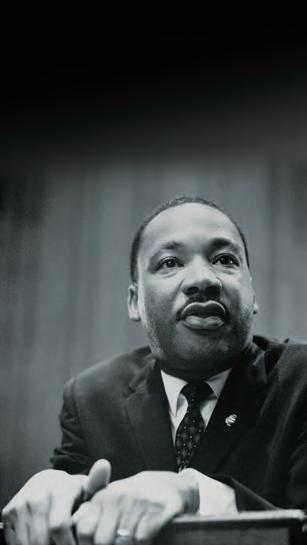

4 April 1968

12 April 1946

Harold Alexander is sworn in as Canada’s 17th governor general.

15 April 1865

U.S. President Abraham Lincoln dies of his wounds hours after he is shot by John Wilkes Booth.

Martin Luther King Jr. is assassinated in Memphis, Tenn.

5 April 1958

Ripple Rock is blown up to ease sailing of the Seymour Narrows in British Columbia; the event remains one of the largest non-nuclear explosions in history.

24 April 1945

Indigenous war hero Tommy Prince receives the U.S. Silver Star Medal for leading a two-man reconnaissance mission deep behind enemy lines.

25 April 1967

9 April 2007

Queen Elizabeth II rededicates the refurbished Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France.

10 April 1937

The Foreign Enlistment Act is enacted to prevent Canadians from volunteering for service in the Spanish Civil War.

11 April 1951

Gen. Douglas MacArthur is replaced by Gen. Matthew Ridgway as commander of the United Nations forces in Korea.

16 April 1874

The House of Commons moves for the expulsion of Louis Riel.

18 April 2007

M.Cpl. Anthony Klumpenhouwer becomes the first reported member of Joint Task Force 2 to die in the line of duty.

19 April 2020

The perpetrator of the 2020 Nova Scotia shootings is shot and killed by two RCMP officers.

21 April 1918

German flying ace Manfred von Richthofen—the Red Baron—is killed in action; the RAF credits Canadian Capt. Roy Brown with the victory.

The Canadian Forces Reorganization Act passes, unifying the army, navy and air force into one service with common uniforms and ranks.

26 April 1860

The Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada regiment is formed in Toronto.

27 April 1945

Benito Mussolini is captured by Italian resistance fighters; he is executed the next day.

28 April 1952

Dwight Eisenhower resigns as NATO commander.

30 April 1945

Adolf Hitler dies by suicide in Berlin.

By Sharon Adams

The challenges of battlefield medicine are about to change for Western allied nations, now that the focus of threats has migrated to China, Russia, Iran and North Korea.

Unlike counterterrorism operations, future battlefields are likely to have larger fronts, see more use of long-range ballistic and cruise missile strikes, and produce more blast and burn casualties.

The United States military is looking for solutions to gaps it sees in providing medical care in future multi-domain operations, which now include space and cyberspace along with land, air and sea theatres.

It anticipates fighting may be dispersed on multiple, perhaps larger and simultaneous, fronts. Personnel could face combat in large cities and remote and hostile environments that are difficult to reach.

The U.S. military also realizes it will not always have air superiority in every situation—and that has medical consequences.

Air superiority in recent conflicts reduced the time to evacuate wounded from battlefield

to hospital to between 45 and 90 minutes, said retired Colonel Will Schiek, former brigade commander of the Walter Reed Army Medical Center, in a seminar for the Association of Military Surgeons of the United States titled “Future Readiness: Medical Battlefield Operations and the U.S. Army.” During the Vietnam War, evacuation took anywhere from four to 12 hours, he said, and in the Second World War, often more than 24 hours.

Loss of air superiority means future medical personnel could be spread thin and medical resupply sketchy. For the wounded, it means longer waits for evacuation, longer waits to get to sophisticated medical care and a lower survival rate.

“Force health protection and health services support to the warfighter will be challenging,” said Gary R. Gilbert, medical intelligent systems manager at the Telemedicine and Advanced Technology Research Center (TATRC), in an article on the U.S. army’s website.

Unmanned automated equipment is high on the list of desired support technology for a combat environment, as tasks like delivering essential supplies and transporting wounded can be done in areas far too dangerous for human pilots.

Robots could be deployed to pick up the wounded in dangerous situations and, after treatment by a medic, an unmanned aircraft could carry the wounded to a field hospital. But work is needed on the human-computer interface so medics in the field can easily operate this equipment.

“Unmanned and autonomous platforms have the potential to completely rewrite the medical doctrine for how we conduct emergency resupply of unmanned and autonomous platforms, including whole blood products delivered directly to the point of need,” Colonel Daniel R. Kral, former TATRC commander, said in Gilbert’s article.

To ensure availability of supplies, the U.S. is considering reinstituting a practice from the Cold War, when medical material was pre-positioned in order to be quickly available if needed.

Attacks could come with limited warning and on a larger scale, making it important that “critical medical supplies are in place before the first wave of combat casualties requires treatment,” said Brent Thomas in an article titled “The Future of Combat Casualty Care: Is the Military Health System Ready?” and published by RAND Corp.

Medical stations may be targeted, interrupting the flow of patients from front lines to field hospital to theatre hospital to safe territory. Even if there is a cache of supplies nearby, field hospitals may suddenly need more beds, operating rooms, critical care wards and staff. The military is

looking for innovative ways to provide what’s needed if it can’t be delivered by traditional aircraft.

Since most combat deaths in the field are caused by blood loss and airway obstructions, new methods are needed to slow or stop hemorrhage and support breathing. Front-line troops need to be trained in their use as well as other life-saving interventions that have, until now, been administered by medics or farther from the front.

New methods to store blood and new blood substitutes are also needed.

Canada has mobile surgical resuscitation teams to provide advanced care closer to the front, and they can be seeing to patients within an hour of arrival. In a 2015 article in the Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, their biggest logistical concern was cold chain storage for blood products.

Also on the wish list is a small, hand-held device loaded with medical information that can be used in the field to guide people at the front through lifesaving medical procedures.

If casualties need to be held longer near the battle zone, innovative ways to fight infection will also need to be developed.

If wounded need longer for evacuation, they must also be concealed from enemy eyes and ears, both close to the front lines and in field hospitals. The U.S. army is investigating ways for mobile hospital units to move more frequently.

And a final jarring note for families: in case of death, it may not be possible to evacuate remains, requiring a return to burying personnel in theatre and registering their graves for later recovery.

We all have to wrap our heads around what new and different warfare might bring. L

FRONT LINES By Stephen J.Thorne

A Canadian soldier on NATO operations alongside the Kabul national bakery, its façade pocked by battle damage.

Eighteen years of alliance operations in Afghanistan were doomed by mission creep, as allied nations poured undue effort and resources into helping rebuild the country rather than focusing on their core objective of defeating terrorism, said the head of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization.

Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg recently said that NATO went into Afghanistan to prevent terrorists from continuing to use the country as an operations and training base. On that score, it succeeded—at least for now.

But Stoltenberg said it must be recognized that “over the years, the international community set a level of ambition that went well beyond the original aim of fighting terrorism. And, on that, we were not able to deliver.”

U.S.-led forces, including Canadians, entered the country within weeks of the 9/11 attacks in 2001, quickly establishing a foothold and driving surviving Taliban and al-Qaida into the mountains

of neighbouring Pakistan.

Acting on the credo that an attack on one is an attack on all, NATO established the Kabulbased International Security Assistance Force in 2003 as enemy fighters regrouped and battles gradually escalated.

While coalition troops were combating a relentless insurgency, however, they were also helping build and train a national army said to be 300,000-strong. Allied nations were streaming billions of aid dollars into Afghanistan, helping establish democratic institutions and building roads, schools and other infrastructure.

“That broader task proved much more difficult, so we must ensure that our levels of ambition remain realistic,” Stoltenberg said in Latvia on Dec. 1, after chairing a meeting in which foreign ministers discussed a report on lessons learned in Afghanistan.

Afghan army and national police were “hampered by corruption, poor leadership and an inability to sustain their own forces,” he said.

“For the future, we must ensure that NATO training efforts create more self-sustaining forces.”

The Afghan National Army quickly collapsed as the final coalition withdrawal approached and Taliban fighters advanced districtby-district, province-by-province last August. Allied nations evacuated more than 120,000 people in the frantic days after the Afghan capital fell, most borne by the Americans.

Canada, which ceased combat operations in 2011 and withdrew its training mission in 2014, got 3,700 people out before the emergency airlift was abandoned. Most were Canadian citizens or special visa holders.

A co-ordinated suicide attack by Islamic State–Khorasan Province (a Taliban enemy also known as IS–KP or ISIS–K) killed at least 182 people, including 169 Afghan civilians and 13 U.S. military personnel, in mid-evacuation at the Kabul airport on Aug. 26. At least 150 others were wounded.

U.S. forces launched an airstrike the next day that they claimed killed

Stephen J. Thorne

three suspected ISIS–K members in Nangarhar Province. On Aug. 29, a second U.S. drone strike took out a suspected ISIS–K vehicle in Kabul. It turned out to be an Afghan aid worker. Ten Afghan civilians were killed, including seven children.

“We should explore how to strengthen NATO’s ability to conduct short-notice, largescale, non-combatant evacuation efforts,” said Stoltenberg.

Mission creep is defined as “the unintended but almost inexorable tendency of military actions to broaden beyond their original scope,” according to a paper delivered during a 2020 conference at the University of Windsor in Ontario.

“The road to hell may indeed be paved with good intentions but that hardly means we should give up good intentions,” said “The Problem of Mission Creep: Argumentation

Theory Meets Military History,” a paper co-authored by three experts from Oslo and one from Waterville, Maine.

“Rather, it means we should be prepared to look for exit ramps whenever we find ourselves going down that road.”

“WE SHOULD BE

Questions surrounding the NATO coalition’s escalating involvement in Afghanistan began around a 2006 surge in fighting.

“Has NATO, the world’s most powerful military alliance that saw off the Soviet threat and brought two Balkan wars to an end, bitten off more than it can chew in trying to pacify lawless Afghanistan?” wrote

Gareth Harding for United Press International in February 2006.

The somewhat rhetorical question came after the Kabul-based alliance opted to fan out into the unstable south, where U.S.-led forces had their hands full fighting an increasingly aggressive enemy out of Kandahar. The decision boosted NATO’s presence from 9,000 to 15,000.

“A growing number of military experts believe the bloc is sleepwalking to disaster in the mountains of the Hindu Kush,” added Harding.

Details of NATO’s December report on mission creep were not immediately released, although Stoltenberg promised to publicize its main findings.

The document was assembled by NATO’s 30 deputy national envoys, led by several experts and the alliance’s assistant secretary general for operations, John Manza. L

about slipping? With the Safe Step walk-in tub, you just sit down and relax – no more worries about falling. And with luxuries like temperature control and powerful hydrotherapy to soothe away your aches and pains, it’s a whole new bathing experience, like having your own personal spa. Call us right now to find out more, and for a limited time save $1600 – plus get our Exclusive Shower Package with height-adjustable showerhead, free!

By David J. Bercuson

Canada will now decide between Lockheed Martin’s F-35 Lightning II (top) and the Swedish Saab JAS 39 Gripen (above) to replace its CF-18s.

Dec. 1, 2021, the federal government dropped the Boeing Super Hornet from the competition to replace the aging McDonnell Douglas CF-18 Hornet fighters with up to 88 new aircraft beginning in 2025. That left only two contenders in the competition: the Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II and the Swedish Saab JAS 39 Gripen. Thus, 11 years after the Stephen Harper government announced that Canada would acquire 65 F-35s and six years after Justin Trudeau announced that, if elected, his government would

never buy the F-35, Canada is back on track to do just that.

Canada’s slow and often confusing effort to replace the Cold War-era CF-18 shows that military procurement in Canada is as mixed up, politically dominated and inefficient as ever, certainly as it was in the hunt to replace the aging Sikorsky CH-124 Sea King helicopters with Sikorsky CH-148 Cyclones. That process took almost 20 years.

Observers appeared to be surprised by the government’s decision that the Boeing Super Hornet was not in compliance with the air force’s requirements for a new fighter. Experts had forecast that the final two fighters in the competition would both be American. The multinational Eurofighter Typhoon never officially entered the competition and France’s Dassault Rafale also declined to take part.

But Boeing long ago blotted its copybook in Ottawa by filing a petition claiming Bombardier had unfairly benefited from Canadian government subsidization of the CSeries jetliner and seeking to have tariffs placed on American airline purchases of the new aircraft. The move forced Bombardier to effectively sell the CSeries to Airbus, which took over the aircraft as the A220 and is making a significant success of it. It marked the beginning of Bombardier’s withdrawal from the passenger aircraft industry, though it still produces business jets.

The F-35 has been controversial from the beginning of the program in the late 1990s, mainly because of inflated costs and problems in the development of new technologies.

But more than 20 years after the aircraft was conceived, it has been purchased by the United States air force, navy and marines, the Royal Air Force, the Royal Australian Air Force, the Israeli Air Force and the air forces of another half dozen countries.

The Gripen is currently flown by Sweden, South Africa, the Czech Republic and will be acquired by Brazil. The basic Gripen design dates to the 1980s, but the aircraft on offer is a beefed-up and modernized version of the original.

The Gripen is probably the better aircraft for Arctic operations, but the current state of CanadaU.S. relations will probably kill any chance of Canada buying it. Despite trade agreements, the administration of President Joe Biden is making a significant effort to keep electric vehicles manufactured in Canada out of the

U.S. market. It has given Canada little relief from Trumpera tariffs, imposed a punishing tariff on Canadian softwood lumber, and made Canada look like a second-rate ally in Washington, compared to Australia and Britain.

Under these circumstances, will Ottawa choose the Gripen over the F-35? Not likely.

To some extent, Canada has deserved Washington’s ire. Canada’s defence expenditure in 2020 was 1.4 per cent of gross domestic product, while other NATO nations have been making serious attempts to reach the longstanding NATO goal of two per cent.

The U.S. government recently chided Canada on its failure to increase its UN peacekeeping operations, which in the Trudeau era have fallen to a single mission in Mali and a current deployment of less than 60 Canadian service personnel on UN missions.

So by 2025, or likely later, expect the first F-35s—in matte gray with low-visibility roundels—to be stationed at one of Canada’s two fighter airfields: at CFB Cold Lake in Alberta and CFB Bagotville in Quebec.

And, over the next decade, expect a similar convoluted replacement process to be repeated for surface combatant ships, submarines and even the trusty old Second World War-era Browning Hi-Power pistol. L

By J.L. Granatstein

PLANNED AND EXECUTED WITH PRECISION, THE ATTACK ON VIMY RIDGE REDEFINED THE CANADIAN CORPS AS AN ELITE FORMATION

The victory at Vimy Ridge in April 1917 is the one military story that most Canadians know. Some of our best writers—journalists and historians alike, from Pierre Berton to Tim Cook—have written books on Vimy and the event has been celebrated in textbooks, in the federal government’s material for new citizens, on our money and in the

stunning Canadian National Vimy Memorial in France. Celebrations on the 90th and 100th anniversaries attracted thousands of high school students who raised money to travel to Vimy, and the CBC devoted hours to broadcasting the event to those at home. After more than a century, Vimy remains firmly set in the Canadian consciousness.

The war was not going well for the Allies in the spring of 1917. The Russians were tottering and the Americans, who had recently joined the war, would take months to train and equip troops and get them to the front. The endless toll of dead and wounded at Verdun and the Somme and the mounting financial costs of total war had left Britain and France—and Canada

too—near the breaking point.

The enemy was also suffering because of food and materiel shortages caused by the British naval blockade, and German casualties were enormous. But if the war had ended on April 1, 1917, the Germans—occupying most of Belgium, large parts of northern France and huge swathes of Russian territory—would certainly have

Canadian troops return triumphant from the Vimy front, their celebrations tempered by the loss of 3,598 comrades killed and 7,004 wounded. Their commander, Lieutenant-General Julian Byng (bottom), inspects one of the German guns captured during the battle.

been deemed the victor.

Field Marshal Douglas Haig, commanding the British Expeditionary Force that included the four divisions of the Canadian Corps, planned a big push in the Arras sector for April. The Canadians, commanded by British Lieutenant-General Julian Byng, were ordered to take Vimy Ridge, the long and well-fortified feature that

protected much of the industrial and mining industries in German-occupied France.

This was a difficult task— earlier Allied assaults on Vimy had failed with heavy losses and the Germans seemed well prepared to hold on no matter what the Allies could do.

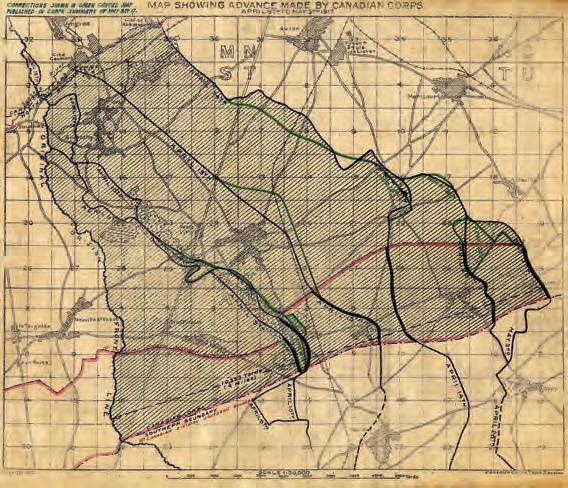

A period map (right) illustrates the boundaries, objectives and strongpoints confronting the Canadians between April 9 and May 3, 1917. Members of the 8th Battalion (90th Winnipeg Rifles) conduct bayonet practice (below) with bags of straw on Salisbury Plain.

But orders were orders, and Byng and his staff began to plan. In January, Byng sent Major-General Arthur Currie, commanding the 1st Canadian Division, as a member of a British delegation that visited the French armies to learn how they had fought at Verdun.

Currie’s report stressed the importance of artillery counter-battery preparation that eliminated the enemy guns, and he noted that the French had perfected the creeping barrage that moved effectively just ahead of the advancing troops. He saw that they had developed platoons capable of independent

manoeuvres with distinct sections of machine-gunners, rifle-grenadiers, bombers and riflemen. Unlike the Canadians, the French no longer attacked in waves; instead, platoons could support their own advance with fire and movement and bypass enemy strongpoints. Currie was also deeply impressed with the rehearsals and reconnaissance that the French conducted prior to an attack, so much so that the soldiers became “as familiar as possible with

the ground over which they were to attack.” He pointed out that the French pulled the assault forces out of the line for special training and ensured that the men were “re-equipped, re-clothed, fed particularly well, had entertainments provided for them, and consequently returned to the line absolutely fresh and highly trained.”

Currie also admired the French practice of distributing maps and photographs widely, not only for senior officers well behind the lines as was the practice in the British Army. Soldiers needed to know where and why they were attacking and what was expected of them. On his return, Currie recommended that the Canadians emulate the French, and Byng listened and acted, changing the training and organization of the infantry platoons, cutting their number of soldiers down to 35 or 40, the most a junior officer could manage to lead.

The attack at Vimy, thanks in part to Currie’s report, was preceded by unheard of training in fire and movement supported by the specialist roles and, as the official history by G.W.L. Nicholson noted, “a

full-scale replica of the battle area was laid out…to the rear” where units from platoons to divisions “rehearsed repeatedly,” so often that some soldiers grumbled about “their officers’ silly games.”

Forty thousand maps were distributed, and a new artillery plan was launched: the guns began their battlefield preparation two weeks before the attack, and the heavy artillery concentrated its fire on the enemy batteries. The Germans certainly knew an attack was coming, but they did not know when. Moreover, tactical surprise would be achieved by moving troops into specially created tunnels dug into the chalky ground very close to the frontline trenches and maintaining the tempo of gunfire until just before the assault.

and horses reached the front through pipelines; signallers buried telephone lines to survive enemy shelling; and the tunnellers carved out large alcoves for battalion and brigade headquarters.

Byng’s plan was ready by March 5. His four divisions, fighting together for the first time, would be positioned in order with the 1st Division on the right and the 4th on the left. There were four objectives, each designated by a coloured line on the map: the entire ridge and the enemy’s second line were to be seized in just under five hours. There were 863 guns in support and the gunners had the new No. 106 fuse that could cut the enemy’s barbed wire. The rolling barrage was to advance in 50-yard steps. Ammunition for the guns came forward in profusion (they would fire more than a million shells between March 20 and the capture of the ridge), much of it hauled by newly laid tramlines. Water for men

“I am a rifle grenadier,” Private Ronald MacKinnon of the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry wrote in a letter home. “We have a good bunch of boys to go over with and good artillery support, so we are bound to get our objective alright.” MacKinnon was killed in the battle.

The attack began at 5:30 a.m. on Easter Monday, April 9, with snow and sleet blowing in the Germans’

faces. With what Lieutenant Stuart Kirkland described as “the most wonderful artillery barrage ever known in the history of the world,” the enemy guns and trench lines were hit with high explosives and gas, destroying more than 80 per cent of the German guns and keeping the infantry sheltering in their dugouts.

“The guns all opened at the same moment with a roar like a terrible peal of thunder,” wrote Harold McGill,

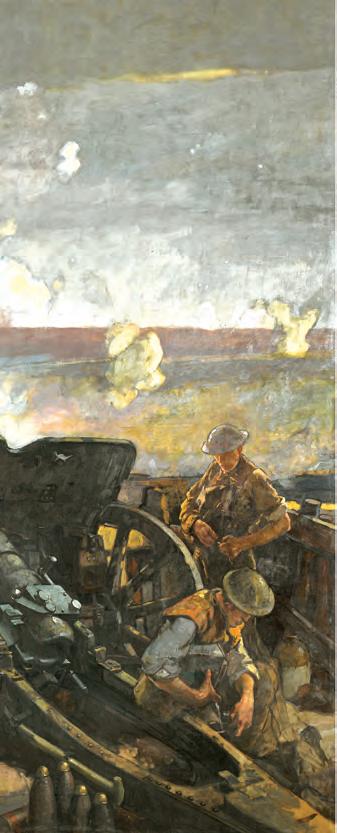

Canadian artillery members fire a captured German 4.2-inch gun at retreating enemy during the battle.

BEEN IN YET.”

The 29th Battalion (Vancouver) advances across no man’s land despite German barbed wire and heavy fire at Vimy.

a medical officer of the 31st Battalion (Alberta), “and for miles all along the German trenches there was the most wonderful display of fireworks caused by our bursting shells.”

The 15,000 infantrymen who led the attack moved steadily forward behind the rolling barrage, their handful of supporting tanks unfortunately unable to move forward because of shell holes and sticky mud.

The 1st Division reached the German front line, held by Bavarians, and found most of the defenders still in their dugouts. Mop-up troops soon arrived, and Currie’s soldiers reached the Red Line, their second objective, by 7 a.m., although enemy snipers and machine-gunners were beginning to exact their toll.

The 2nd Division moved quickly across its first objective, the Black Line, and encountered heavy fire only at its second objective which it controlled by 8 a.m. By 9:30, the reserve brigades of the two divisions were

moving toward the third objective, the Blue Line.

“Our troops advanced as cool and steady as when they had previously practised,” said McGill, but, in fact, it frequently took great courage to take the objectives. Sergeant Ellis Wellwood Sifton of the 18th Battalion (Western Ontario) charged a machine gun that fired on his men, bayoneted its crew, and held off riflemen moving down the trench toward him by using his own rifle as a club. He was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross.

The 3rd Division had a relatively easy time, taking its first two objectives quickly. Billy Bishop, a young pilot in the Royal Flying Corps whose victories were still to come, watched what to him seemed to be men wandering casually across no man’s land. He could see shells falling among them, but the others continued going forward.

The ground had been torn up by two weeks of shelling, and many of the landmarks intended to help

situate the attackers had been destroyed. Some units, advancing too quickly, were hit by the Canadian barrage. Many had close calls.

“[We] were able to extricate our men without getting hurt ourselves,” wrote Major Percy Menzies of the 3rd Division’s 4th Battalion, Canadian Mounted Rifles. “All this time we were troubled by our own shells bursting short, but I was never touched.”

The 4th Division faced real difficulty. Its main objective was Hill 145, which had four lines of strong defences and deep dugouts on the reverse slope. The attack by the 11th and 12th brigades, each with an additional battalion, took the first line, but the Germans in the heavily manned second line of trenches forced the troops back with repeated counterattacks.

Hill 145 remained in German hands until the newly arrived 85th Battalion (Nova Scotia Highlanders) took it that night. The next day, the 44th and 50th battalions followed the barrage in

a mad charge down the steep eastern slope, and the 4th Division had the Red Line.

Now all that remained was The Pimple, the northern tip of the ridge.

In the early morning of April 12, the 10th Brigade, attacking in the teeth of a gale, surprised the Germans manning the hill. By 6 a.m. after hand-tohand fighting, the brigade had taken The Pimple.

From the crest, the Canadians could see eastward as far as the suburbs of Lens, a coal mining town, and the Canadian artillery, struggling forward through the heavy mud, took up new positions to the east

of Vimy Ridge. The Germans’ supposedly impregnable position had been taken and the Canadian Corps’ success was hailed in Paris, London and at home.

Byng was the first beneficiary of the victory. Promoted to full general, he received command of the British Third Army. His successor, Currie, received a promotion, a knighthood and command of the Canadian Corps in June, a position he would hold until the war’s end.

The battle was a costly but limited success. The ridge had been taken, but the Germans were not routed. There was no breakthrough—no cavalry had been made available to

In Canadian popular history, Vimy is sometimes painted as a war-winning victory. MajorGeneral Arthur Currie’s Canadians had done something that the Allies previously could not: they had scaled the heights of the ridge and defeated the Germans.

Byng to exploit success. In five days of fighting, the Canadians suffered 10,602 casualties, including 3,598 killed—enough that Prime Minister Robert Borden, in London at the time, began to realize that conscription would be needed. Many soldiers were proud of the victory.

Vimy was “the greatest thing the Canadians have been in yet—wonderful,” said Captain William Fingold of the YMCA. “Of course, there have been heavy losses, but it was a great victory.”

Others were just happy to have survived: “It was a hell on earth,” wrote one soldier, “and I am very lucky to be here today.” L

But realists know that Julian Byng, a British general, not Currie, commanded the Canadian Corps in April 1917. We know that most of the ridge the Canadians attacked from the west rose gently with the big drop behind the enemy trenches and on the reverse slope. We understand that there was no breakthrough, no cavalry sweeping through the enemy rear, and that the Germans simply retired several kilometres east to their next defence line. We remember too, that the Canadians suffered 10,602 killed and wounded at Vimy, the greatest losses in any single action in our history, and the killing continued for another year and a half. The myths far outpaced the reality.

But Vimy did matter. The Canadians began the war as amateurs, but at Ypres, Saint-Éloi and the Somme, they had learned how to fight.

After Vimy, the soldiers understood they had done something great and knew that their battalions, brigades and divisions had come to maturity and made the Corps an elite formation. The war would continue, and the confidence and determination earned at Vimy turned the Canadians into some of the best Allied troops of the Great War. Canadian troops hold a memorial service in September 1917 for the men of the 87th Battalion (Canadian Grenadier Guards) who fell at Vimy. Over the course of the war, impromptu cemeteries sprang up all along the Western Front. Reburials and more elaborate memorials would come later.

By Stephen J.Thorne

wasn’t over yet and already Vimy Ridge was being hailed back home as a seminal battle that could forever change Canada’s place in the world.

The Easter 1917 success where others had failed marked the first time all four Canadian divisions fought together. Ideas of what the battle was—and wasn’t —evolved over the ensuing decades. But it wasn’t until 1967 that BrigadierGeneral Alexander Ross anointed Vimy “the birth of a nation.”

Such declarations moulded Canadians’ perceptions and blurred the lines between the myths and the realities of Vimy Ridge. Speeches, ceremonies and writings tended to reinforce the myths in a country anxious to define its identity.

A nation may not have been born on Vimy Ridge, but Canada did come into its own after the four-day battle. It took on its most significant role of the conflict and earned postwar seats at the Paris Peace Conference and the newly formed League of Nations.

Vimy became, in retrospect, a rite of passage for Canadian soldiers, as well as for war artists of all stripes who trekked to the cratered grounds in the months and years that followed to record their impressions in paint, charcoal and pencil.

Australian captain and celebrated artist William Longstaff painted “The Ghosts of Vimy Ridge” between 1929 and 1931, depicting the spirits of Canadian Corps soldiers on the ridge, having left their earthly battles, and the soaring memorial, behind.

He drew on the words of the monument’s designer, Walter Allward, who said in 1921 that his work had been inspired by a wartime dream in which dead soldiers “rose in masses, filed silently by and entered the fight to aid the living.”

“Without the dead we were helpless. So I have tried to show this in this monument to Canada’s fallen, what we owed them and we will forever owe them.”

A gift to Canada from John Arthur Dewar of the Dewar distillery family, Longstaff’s painting was made while the memorial was still under construction. Except for periods it was on loan, it has hung in Parliament’s Railway Committee Room since February 1932. L

Painted by Richard Jack in 1919, “The Taking of Vimy Ridge, Easter Monday 1917” (top left) depicts the crew of an 18-pounder field gun firing at German positions as the wounded move past toward the rear. The Lens-Arras road along the crest of the embattled ridge (left) is a desolate place as painted by Gyrth Russell in February 1918.

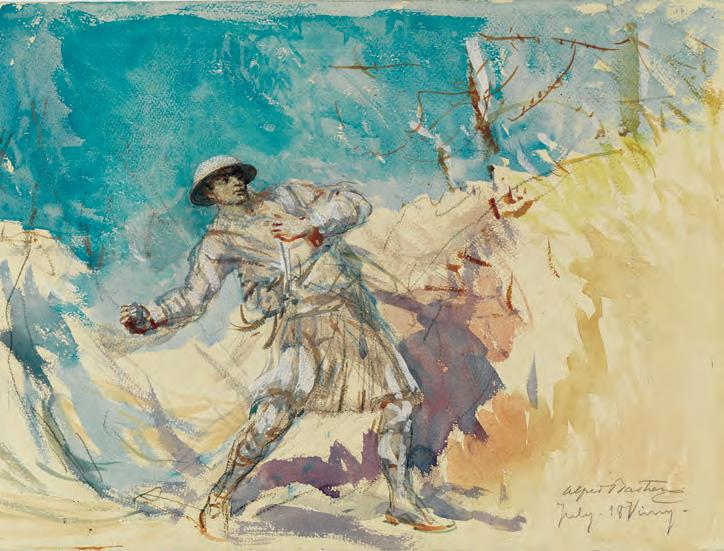

A picture may be worth a thousand words, but Group of Seven artist Frederick Varley told his wife that his art could not say a thousandth of what he saw at Vimy. “We are forever tainted with its abortiveness and its cruel drama,” he wrote to her before painting a burial party at work after the battle in “For What?” (top right). “It is foul and smelly—and heartbreaking. Sometimes I could weep my eyes out when I get despondent.” A Canadian Highlander throws a grenade from the safety of a trench (above right) in a watercolour by Lieutenant Alfred Bastien, one of the more prolific painters of the war.

The impressions of the battlefield were still fresh when another Group of Seven artist, A.Y. Jackson, painted “Vimy Ridge from Souchez Valley” (left) in his London studio in 1918. Jackson described his impressionist style, learned in Europe before the war, as “ineffective” for painting conflict.

Female war artists were rare but not unheard of. Elizabeth Southerden Thompson—Lady Butler after marrying up—specialized in paintings of British military campaigns and battles dating from the Crimean and Napoleonic wars. In 1918, she rendered the dramatic watercolour “Cede Nullis: Bombers of the 8th Canadian Infantry on Vimy Ridge, 9th April 1917” (below). Cede Nullis is Latin for “yield to no one.”

By Sharon Adams

Crack teams of navigators and pilots marked targets from the air, in the dark and under fire

At the beginning of the Second World War, when Germany learned it would never persuade Britain to remain neutral or sign a peace treaty, sterner measures were adopted. The Nazis decided try to bomb and starve Britain into submission.

The Luftwaffe attacked industrial targets while the Kriegsmarine went after the island nation’s supply lines. An army invasion was planned as the next step.

Royal Air Force Bomber Command, Britain’s only means at the time of taking the fight into Germany, was tasked with destroying as much of that as possible.

At first, Britain’s bombing campaign was a dismal failure.

But attacking Britain while fighting the war on other fronts would take all of Germany’s industrial might—coal for industrial furnaces, steel for ships and aircraft, raw materials for munitions and factories to make them, railways, highways and canals to move supplies, troops and materiel, as well as fuel processing facilities to power vehicles.

It began with daylight raids against military targets—warships and airfields. But when the Netherlands capitulated after Rotterdam was reduced to rubble in May 1940, Bomber Command was ordered to attack German targets in the Ruhr valley, Germany’s industrial heartland.

Targets in Europe were well-defended, turning daylight raids into suicide missions, so Bomber Command moved to night attacks. But technology for night navigation was primitive.

An Avro Lancaster (above) flies through flak tracers in a bombing raid on Hamburg, Germany. Air Vice Marshal Don Bennett (opposite top) commanded the Pathfinders. Fire ravages a German aircraft plant (opposite bottom) bombed late in the war.

Early in the war, navigation for bombing raids was a hit-or-miss affair, the emphasis on miss. While heading for targets on the continent, navigators would climb into a Perspex bubble on top of the aircraft, take a half-dozen timed photos of the stars, then go to the navigation charts to work out where the aircraft was.

“If you were lucky,” said navigator James McCloy in a 2003 documentary, The Men Who Lit Up Germany. It was “the sort of thing that mariners had been doing for years,” but ill-suited for precision bombing by fast-moving aircraft. “On the ground I found the best I could do was fix the position of the aerodrome within five miles [eight kilometres]. In the air, I’d have been lucky if I’d gotten 20.”

Before navigation aids, crews had to rely on dead reckoning—estimating their position by aircraft and wind speed, flying time and compass. Calculations were easily disrupted by wind.

An examination of bombing in June and July 1940 showed only one in three British bombers got within eight kilometres of their targets; over the Ruhr River, it was one in 10. With no moon, the figure dropped to one in 15. In the year ending May 1941, it was found that 49 per cent of bombs had fallen in open country.

It is one thing to navigate over foreign territory during the day and “quite different doing it in a heavy bomber, at night, under total blackout conditions, sitting above 9,000 or more pounds [4,000 kilograms] of bombs and flares, over unfamiliar and hostile territory, while being shot at from the ground or attacked by enemy fighters,” recalled navigator Donald M. Currie of North Vancouver, B.C. Precision bombing was simply impossible given the limitations of technology and lack of experienced crew—in 1940 many navigators didn’t get much time to gain experience. Royal Air Force bomber crews, which included many Canadians, were lost faster than they could be replaced.

Success lay in the development of better technology to help aircraft fix their positions and find their targets—and better attack techniques.

One of those techniques was marking targets from the air.

Bomber Command navigators and pilots with the best records for accuracy were cherry-picked for a crack unit—No. 8 (Pathfinder Force) Group—whose job was to fly ahead of a main bomber formation to drop flares to mark targets and illuminate the way for bombers. The Pathfinder Force, numbering about 20,000 men (and women, in ground jobs) was commanded by Air Vice Marshal Don Bennett, an Australian described as an outstanding pilot and superb navigator equally capable of stripping a wireless set or overhauling an engine.

Pathfinder crews led 51,053 sorties, flying Halifax, Lancaster, Stirling, Wellington and Mosquito aircraft with the best crews and up-to-the-minute technology continually upgraded throughout the war.

Over the course of the conflict, the British pioneered external navigation systems that used precisely timed radio signals to allow navigators to fix their positions and ground-scanning radar to identify targets at night and in bad weather.

Beefed-up fireworks produced brilliant white flares for illumination and target markers with names as colourful as their glow—Red Blob and Pink Pansy. Rear-facing aerials (called Boozers) warned the pilot when aircraft were being monitored by enemy radar.

The Pathfinders’ first operation on Aug. 18-19, 1942, was not a success, as winds caused the aircraft to drift north and targets were incorrectly marked. The second foray was little better.

But at the end of the month, Pathfinders came into their own in a raid on Kassel, Germany, marking targets for 306 bombers that destroyed 144 buildings and damaged more than 300, including three aircraft factories. Their record improved from there.

Led by Pathfinders, bombers came within five kilometres of targets 73 per cent of the

time during the Ruhr campaign in 1943 and by the end of the war that record had improved to 95 per cent, said Will Iredale, author of The Pathfinders: The Elite RAF Force that Turned the Tide of WW II.

“Pathfinders would drop flares and identify the target, then others would drop coloured flares on each side and we would fly between the flares,” recalled Joseph (Jo) Forman in his memoir on the Canadian Letters and Images Project website. “We had three minutes leeway at each turning point and over the target,” said Forman. “Naturally we did a lot of pastoral bombing.”

Currie volunteered for Pathfinder training, attracted by the challenge of navigation. “They used two navigators rather than one and the attrition rate was much higher than the main force, so we might be called earlier.”

about raids was leaked to the enemy and feint raids on nearby towns drew fighters away from main targets. Bits of aluminum and other material (called window or chaff) were dropped in clouds to swamp readings on enemy radar.

The first Pathfinders arrived over targets two to six minutes before the main force, dropping illuminating flares and releasing barometric markers that would go off at different altitudes and drift downwind. But there were other Pathfinders within the mass of aircraft to continue marking the target, as flares and target indicators had short lifespans and could be blown off course.

“It’s a dangerous job,” William Douglas Watson wrote home to his family in May 1944, “but you have all the tops in equipment and crew. Advancement is really fast too.”

The letter did not tell them why— the survival rate was grim.

Bombs pour from an Avro Lancaster on a thousandbomber raid over Duisburg, Germany, in October 1944.

Currie was assigned as navigator/observer to No. 635 Squadron, RAF. Five of eight crew on his first operation were Canadians, including the wireless operator, two gunners and the pilot, Len Moore of Niagara Falls, Ont., who had already completed one operational tour with Bomber Command.

Currie was teamed with a British navigator/ plotter. “We operated in a completely blackedout compartment,” working by weak lamplight and the glow of equipment. “We sat side by side on a narrow bench and unless we made an effort to pull the blackout curtain…we saw nothing but our instruments for hours on end.”

New Pathfinder crews were broken in slowly, starting out in a support role carrying the same bomb load as the main force.

“Exceptional standards had to be met before a crew could qualify for the next step,” Currie recalled. Once they had proved themselves, crews undertook more and more demanding marking duties.

In June 1943, Bomber Command tested very-high-frequency radio equipment that allowed communication among aircraft in attack formations. This allowed a lead Pathfinder, which became known as the master bomber, to alert other Pathfinders to re-mark targets when the first flares drifted off course, and to radio corrections to bombers.

It was one of many tweaks to attack techniques. Enemy airfields were attacked prior to raids to dilute the available fighter force. Enemy radar was jammed. False intelligence

Only 16 per cent of Bomber Command crews survived their tour of 30 operations. To make the most of their extra training, Pathfinder crews, many of whom had already completed one Bomber Command tour, signed on for 45 operations (which had been reduced from 60 to encourage volunteers).

“Each man got an immediate promotion in rank and a pay rise—danger money,” wrote Iredale. “And they earned every penny of it. Over the next three years, 3,600 were killed in action. An individual Pathfinder would be lucky to still be alive after 12 sorties. The loss rate was so great that 50 new crews had to be recruited every month.”

Flak and enemy fighters were a constant danger, but so was equipment failure.

“One thing that airmen can never overlook in weighing the scales of survival is Lady Luck,” said Flight Lieutenant Bill Davies, a navigator who settled in Toronto after the war, quoted in Jean Portugal’s We Were There.

On a clear night in February 1945, his crew was off the coast of Sweden, returning from marking a mission to bomb an oil installation.

“The mid-upper gunner shouted there was a Ju 88 sitting out on the starboard beam with his cockpit light on. It was so plain to see and so easily recognized.” It was also a ruse readily recognized by gunner Michael McCrory of Hamilton, Ont.

McCrory started advising the pilot to corkscrew and “warned us to watch out for a Ju 88 friend who would sneak up behind, completely blacked out, and

open fire. And that’s what happened.”

They were hit, “but the discipline of the crew was excellent.” Skill got them to the safety of cloud cover, despite the loss of two engines. Then a third engine failed.

“We had to get back to base on one engine.” They slowly descended to an altitude of 150 metres—and heading down—when they were still 650 kilometres from England. The pilot prepared to ditch the plane in the North Sea, at its most unforgiving in winter. Davies shook hands with his friend, navigator George Blick.

“All we had on was ordinary shoes in the Nav section and a simple sweater and battledress, Mae West [life preserver] and parachute, and a helmet and oxygen gear and two pair of gloves. So we weren’t going to last very long.”

Suddenly the dead engine started on its own and was nursed back to life by the captain and engineer. “We managed to get home on two engines.”

Getting hit by bombs from their own group was another danger.

“We were all supposed to fly at specific height, but many crews decided they would fly higher” to avoid mid-air collisions, recalled Davies, whose crew was horrified to see a Halifax barrelling toward them in January 1945.

“We screamed…and managed to dive, missing this aircraft by a few feet. A huge bomb, possibly a 4,000-pound [1,800-kilogram] cookie, just missed us in front. The

skipper pushed the stick forward and the Halifax skimmed over the top of us. We could only suppose [this pilot] was very, very late and had cut a corner.”

And that wasn’t the only time they saw bombs cascading past them, he said.

It wasn’t unusual for strong winds to blow bombers off course, as happened to Ed Moore’s crew on a raid on Berlin.

“It became obvious when Pathfinder flares went off behind us that the actual winds were very much stronger,” the veteran of 26 missions said in an Edmonton Journal interview in November on his 100th birthday.

“We turned around and dropped our bombs on target about 25 minutes late. Common sense should have dictated the bomb be jettisoned and a course set for home. Nevertheless, we all agreed with our skipper-pilot who said, ‘We have come this far, we will drop the bombs in the right place.’”

Pathfinders were first to arrive at targets, where they were the focus of searchlights of ground defence crews. Master bombers faced the most danger. Their job was to circle the target, co-ordinate the attack, and broadcast instructions to other

Squadron Leader Reg Lane (at left) piloted the first Canadian-built Avro Lancaster bomber to Britain.

Precision bombing was simply impossible.

aircraft. They remained over the target longer and their radio transmissions could be tracked by defences and night fighters.

“It was when the master searchlight got you that you knew you were in trouble,” recalled Wing Commander A.J.L. Craig, who flew 73 operations, 41 as master bomber. “All the other searchlights would point at you, and then every gun in the area would take aim.” It was known as being ‘coned’ and pilots had a devilish time escaping.

“The good side to it was that most of the other bombers nearby would get a free run and thank you later, if you made it back to base. The reality was that most people who were coned were shot down.”

In April 1943, No. 405 (City of Vancouver) Squadron joined the group—the only Royal Canadian Air Force unit in the Pathfinder Force (although Canadians served in every squadron).

Bennett was opposed to differentiation within the force and had already refused a request for the formation of an Australian squadron.

“Each man got an immediate promotion in rank and a pay rise— danger money.”

“I insisted that the crews of this so-called Canadian squadron must not be more than 50 per cent Canadian, [but] I did agree that the CO would always be a Canadian, and it started off under the command of Wing Commander [John] Fauquier, a thoroughly ‘press-on’ type if ever there was one,” wrote Bennett.

John Fauquier of Ottawa had been a bush pilot before the war and had already completed 35 bombing operations before taking command of 405 Squadron in February 1942. He was a hard taskmaster, but many considered him Canada’s greatest bomber pilot.

On Aug. 17, 1943, Fauquier was deputy master bomber during a raid on a German rocket base on the Baltic coast, passing over the target 17 times, guiding bombers. He was awarded the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) for that operation, which delayed the use of the rockets by a year.

When he retired in 1944, after flying 38 sorties as a Pathfinder, he was awarded a Bar to the medal and a promotion to commodore.

Retirement didn’t suit Fauquier. He requested his rank be lowered so he could fly a third tour of operations. He went on to No. 617 Squadron, RAF—known as the Dambusters— where he earned a second Bar to his DSO.

Fauquier was one of many notable Canadian Pathfinders.

Reg Lane of Victoria received a Distinguished Flying Cross (DFC) following 30 sorties on his first Bomber Command tour,

during which he attacked the German battleship Tirpitz at mast height. He remained with No. 35 Squadron, RAF, when it was selected to join the Pathfinders.

On the final run of his second tour in April 1943, Lane was coned over Frankfurt, escaping the searchlights and antiaircraft fire with a steep dive of more than 300 metres. He was awarded the DSO.

After a four-month break from operations, Lane returned to the sky, taking over command of 405 Squadron from Fauquier. He often served as master bomber, notably circling the city while under fighter attack for 40 minutes during the Battle of Berlin.

In May 1944, Lane was awarded a Bar to his DFC on a raid to Caen, France, as master bomber on his 65th mission just prior to D-Day. After his third tour, Lane went on to operational tactics, rising to lieutenant-general after the war and serving as deputy commander-in-chief at Norad before retiring in 1976.

Squadron Leader Ian Bazalgette of Calgary was one of three Pathfinders to earn the Victoria Cross. On Aug. 4, 1944, on his 58th mission, he was master bomber in a daylight raid on a V-1 storage cave near Saint-Maximin, France. His Lancaster was hit by flak before arriving at the target.

The aircraft ablaze, two other master bombers out of commission, Bazalgette continued on to mark the target, then ordered the crew to bail out. He fought to land the burning aircraft in order to save two wounded crew and avoid crashing in the village of Senantes.

Wireless operator Chuck Godfrey bailed out and watched the bomber go down.

“I could see it all,” said Godfrey, quoted on the Bomber Command Museum of Canada website. “He did get it down in a field…but it was well ablaze and with all the petrol on board it just exploded.” The three still on board were killed.

Bazalgette was one of 10,000 Canadians killed serving with Bomber Command.

Fifty-five thousand Allied men and women lost their lives serving in the bomber forces. Pathfinder crews were well aware of the risks.

“On the walks out to the trucks that used to take us to the pads where the Lancs were sitting, you’d see one or two vomiting like mad,” recalled Davies. “They were the bravest of the lot. They really were so frightened they had almost no control. But they went.

“There was a widespread feeling of pride… morale could not have been higher. The mere thought of going back to the main force was seen as almost the end of the world.”

The Pathfinders’ contribution to the end of the war is incalculable. They improved bombing precision and allowed Bomber Command to increase the intensity of raids and to destroy many targets in a single raid on one city. Raids on the Ruhr valley alone resulted in declines of metal processing by 46.5 per cent in 1943 and 39 per cent in 1944.

More importantly, the bombing campaign opened a second front long before D-Day, said Albert Speer, German minister of armaments and war production.

“Defence against air attacks required the production of thousands of anti-aircraft guns, the stockpiling of tremendous quantities of ammunition all over the country, and holding in readiness hundreds of thousands of soldiers, who in addition had to stay in position by their guns, often totally inactive, for months at a time.”

Not only did the Axis lose factories and war materiel, but huge numbers of troops and labourers were tied up defending against bomber raids and rebuilding afterward. Speer called the air war “the greatest lost battle on the German side.” L

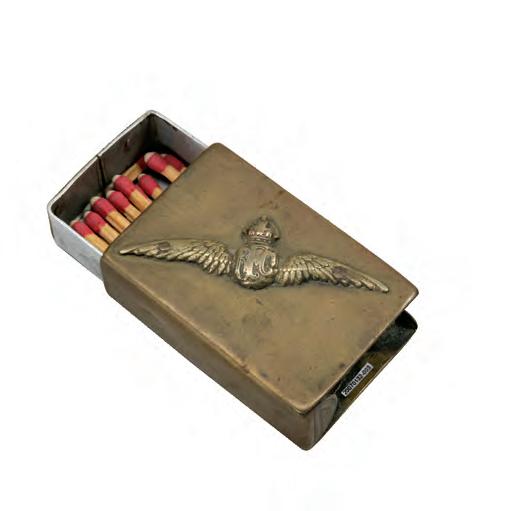

A crew (opposite) of 405 Squadron, RCAF. John Fauquier (above, clockwise) commanded 405 Squadron; Charles Godfrey was issued this membership card when he joined the Pathfinder Association Club after the war; master bomber Ian Willoughby Bazalgette died trying to save fellow crew members.

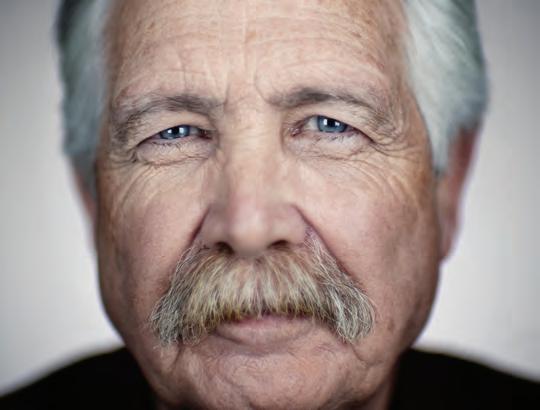

By John Boileau

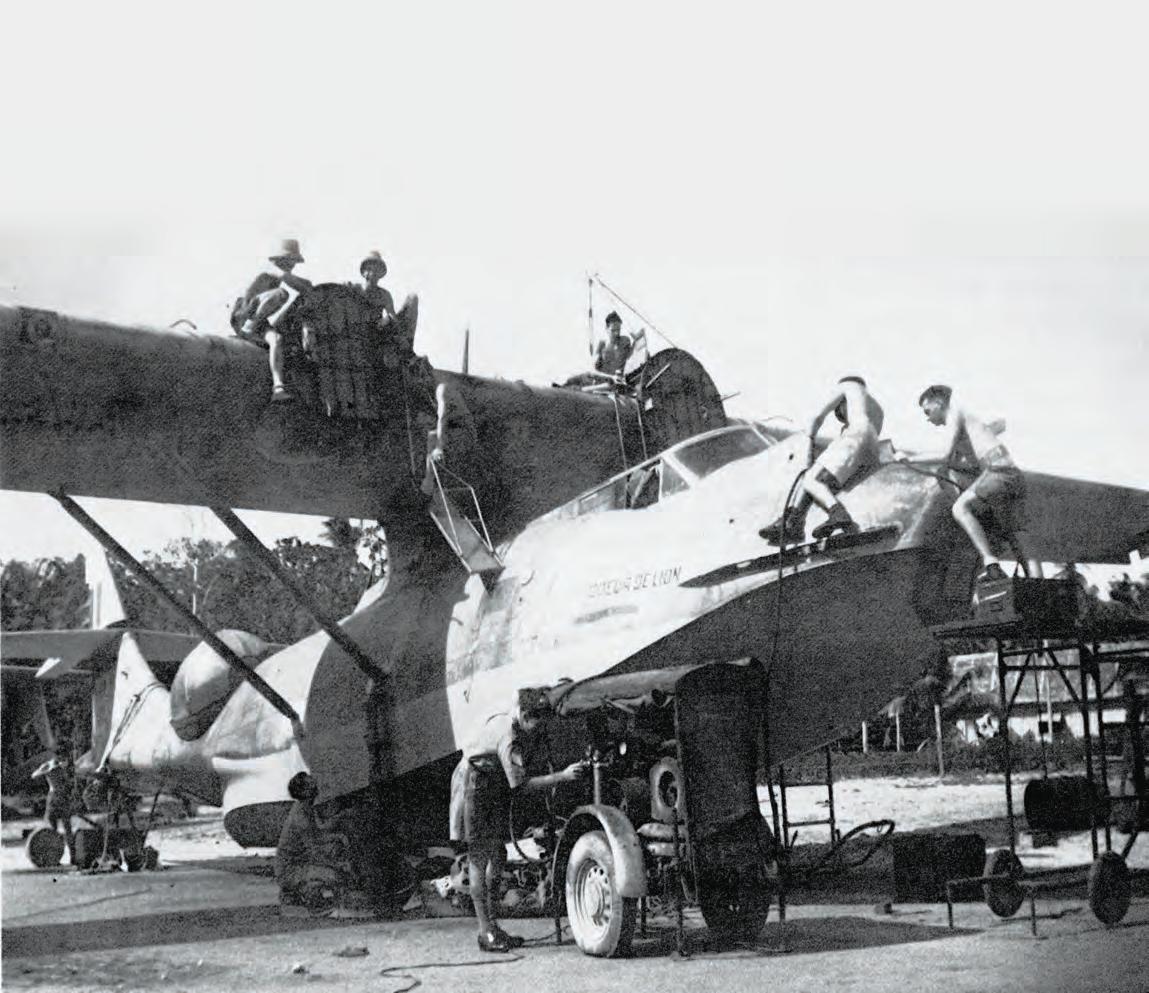

Known as the “Saviour of Ceylon,” Leonard Birchall (opposite) commanded 413 Squadron, RCAF, and its four Consolidated Catalina flying boats (inset and below) at its base in Koggala on Ceylon’s south coast. Birchall piloted the Catalina, ultimately shot down, that warned of an incoming Japanese fleet.

Admiral James Somerville (right), commander-inchief of the British Eastern Fleet, relocated his ships to the Maldives as Japan advanced in the region. Birchall, who had piloted Supermarine Stranraer flying boats (below) on defensive patrols out of Dartmouth, N.S., at the outbreak of the war, was part of a small contingent left on guard in Ceylon.

Ithad been a long, uneventful flight. After 12 hours of scanning the vast Indian Ocean without luck, the pilot of the Royal Canadian Air Force Catalina flying boat decided to return to base. Suddenly, the navigator cried out; he had seen something on the horizon. The pilot banked and headed toward the sighting.

It was a Japanese raiding fleet heading for Ceylon (Sri Lanka). As the radio operator sent a warning message to alert the island, Japanese fighters swarmed the flying boat. Cannon shells tore through the aircraft and set it on fire, forcing the pilot to crash land.

Six of the nine crewmen survived and were picked up by a Japanese ship. Their next three and a half years were spent in the horrors of prisoner of war camps.

But had their warning message gotten through?

At the end of February 1942, No. 413 Squadron, RCAF, was told it was being sent from Scotland to Ceylon. The slow speed and immense endurance of the unit’s Consolidated Catalina flying boats allowed them to stay airborne for 24 hours. The crew consisted of two pilots, flight engineer, navigator, four to six wireless operators/ air gunners and maintenance personnel.

The Catalina’s armament included four to six depth charges on wing mounts (enough for one attack) and four .303 machine guns: one in the nose, one in each of two side “blisters” and a fixed one in the tail. Detection of enemy vessels depended mainly on the time-proven “Mark I eyeball.”

On March 28, the first aircraft reached the squadron’s base at Koggala on Ceylon’s south coast, where a large lake served as a runway and base for the flying boats. The military situation was tense.

British forces were in full retreat in Burma. Attacks on India, Ceylon or the British Eastern Fleet could be next. That was exactly what the Japanese were planning: they had dispatched a large fleet to attack Ceylon.

Admiral James Somerville, commander-in-chief of the British Eastern Fleet, wisely withdrew most of his ships from Ceylon on March 30. They sailed to a new secret anchorage in the Maldives, southwest of Ceylon. With all Royal Navy warships and many fighter aircraft far from Ceylon, it left the responsibility for reconnaissance and visual

early warning of a potential Japanese attack to a few RAF Catalinas and the four flying boats of 413 Squadron.

Before dawn on April 4, Catalina A rose into the air and made history. Under the command of Canadian Squadron Leader Leonard Birchall, among its eight crewmen was another Canadian, Warrant Officer Bart Onyette, the aircraft’s navigator.

Birchall, a 26-year-old native of St. Catharines, Ont., had graduated from Kingston’s Royal Military College in 1937 and then trained to be an RCAF pilot. He first served in Dartmouth, N.S., on anti-submarine patrols. By the time he was posted to 413 Squadron in 1942, he was an experienced pilot.

Birchall’s assigned patrol sector was the southernmost one, some 560 kilometres south and east of Koggala. After a dozen unproductive hours of scanning the vast waters stretching in all directions, Birchall was just about to return to base at 4 p.m. when Onyette spotted “specks” on the southern horizon. Birchall immediately headed toward them.

They were Japanese vessels.

Birchall flew directly toward the ships to count and identify them, fully realizing the closer he got, the less chance he had of escape. Slowly, Japan’s 1st Air Fleet came into view.

The fleet consisted of five aircraft carriers, plus battleships, cruisers and destroyers. The carriers had more than 300 modern combat aircraft embarked, including several first-rate Mitsubishi A6M Zero fighters, which could outperform any Allied fighter in Asia at the time.

The enemy’s primary aim was to neutralize British naval and air resources in the Indian Ocean to secure Japan’s western flank. Birchall’s radio operator immediately

began sending a coded transmission to Ceylon, containing details of the fleet.

But by then, with no clouds in which to hide, Birchall had been seen. As many as 12 Zeros swarmed in for the kill. Birchall later noted, “All we could do was to put the nose down and go full out, about 150 knots.”

When the operator was partway through his required third transmission, enemy cannon shells destroyed the radio, blew the operator’s leg off and set the aircraft on fire. The Catalina began to break up. It was too low for the crew to bail out, but Birchall managed to crash land safely on the water—just before the aircraft’s tail fell off.

Everyone but the operator evacuated the aircraft, although two crewmen were seriously wounded. Because they were unconscious, they were floating on the surface and unable to dive when Japanese fighters continued to strafe the Catalina and the airmen struggling in the water.

As the other survivors swam away from burning gasoline and the potential for exploding depth charges, the fighters strafed them and the Catalina, sinking it and killing

A.M. Bell and W.R. Meadows.

At Pembroke Dock in Pembrokeshire, Wales, in March 1942, members of 413 Squadron pose in front of the Catalina that Birchall (back row, seventh from left) piloted.

the unconscious crewmen. Just as sharks began to approach the remaining six airmen, including the two Canadians, a Japanese destroyer finally fished them out of the water.

Three of the survivors were badly wounded and Birchall himself had shrapnel in a leg.

In response to questions from a Japanese officer, who “spoke perfect English,” Birchall identified himself as the senior officer. He was immediately beaten to the deck.

Every time he got up, he was beaten down again. The Japanese wanted to know if the Catalina’s crew had sent a report about their warships. But Birchall maintained only the wireless operator would know—and he had been killed.

In fact, the operator was one of the badly wounded airmen.

“He immediately became an air gunner,” Birchall later related, “and stayed that way for the entire war.” Just as he thought the Japanese were starting to believe him, they produced a radio intercept from Colombo asking Birchall’s Catalina to repeat its message.

The crew were all beaten and locked up. The message from Birchall’s aircraft had been garbled, but its meaning was clear: a Japanese attack was coming. When Somerville received this news, he ordered Colombo’s large harbour cleared of all shipping.

Unfortunately, the British had grossly underestimated the capabilities of Japanese aircraft—especially the range—and when 91 enemy bombers and 36 escort fighters appeared on the morning of April 5, RAF aircraft were still on the ground.

Forty-two fighters, mostly Hurricanes, scrambled to intercept them. The Japanese lost only seven aircraft to the RAF’s 19, but the aerial dogfights distracted the Japanese attackers from their primary mission and the port was only lightly damaged.

Although the Japanese had sunk some warships and merchant ships at a cost of 17 aircraft, they cancelled further major forays toward the west. The fleet sailed back to the Pacific.

Birchall spent the next three and a half years as a prisoner of war in Japan and moved through four camps. Solitary confinement and daily beatings were routine; limited rations constituted a starvation diet. All prisoners, including sick ones, were forced to work.

Birchall’s natural leadership emerged, and he quickly earned the respect of other prisoners. When it came to food—the most essential commodity of all—he insisted that officers’ meals be displayed for all to see. If anyone thought an officer had been given more or better food, that individual had the right to exchange his ration for the officer’s.

Cigarettes were a valuable commodity, bringing momentary relief to the PoWs. Birchall gave up smoking and convinced the other officers to do the same and donate their cigarette rations to the men.

Birchall was almost tortured to death for attacking a guard who was beating a prisoner, but he did not stop looking after his men. He led them in a sit-down strike and refused to work until the guards agreed not

to beat or otherwise mistreat the very sick. Birchall’s captors could not break his spirit and he was an inspiration to his comrades.

American troops freed Birchall after Japan surrendered. The diaries he kept while a prisoner and his testimony were used as evidence in war crimes trials of Japanese soldiers.

On Feb. 2, 1946, newly promoted Wing Commander Birchall was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire. His citation noted that as senior Allied officer in PoW camps, he “continually displayed the utmost concern for the welfare of his fellow prisoners…. Birchall continually endeavoured to improve the lot of his fellow prisoners…. The consistent gallantry and glowing devotion to his fellow prisoners of war that this officer displayed throughout his lengthy period of imprisonment are in keeping with the finest traditions of the [RCAF].”