This bronze statue of Mona Parsons, the only Canadian female civilian imprisoned by the Nazis during the Second World War, was created by Dutch-Canadian artist Nistal Prem de Boer and unveiled on May 5, 2007, in Parsons’ hometown of Wolfville, N.S. It depicts an emaciated Parsons dancing after her successful escape.

See page 44

16 UNTO THE BREACH

As the Germans unleashed warfare’s first major gas attack, untested Canadian troops hold a critical gap in the front during the Second Battle of Ypres

By Alex Bowers

24 CRERAR’S CAMPAIGN

General Harry Crerar oversaw just one major battle—but the decisive early 1945 advance into Germany’s Rhineland was critical to ending WW II

By Mark Zuehlke

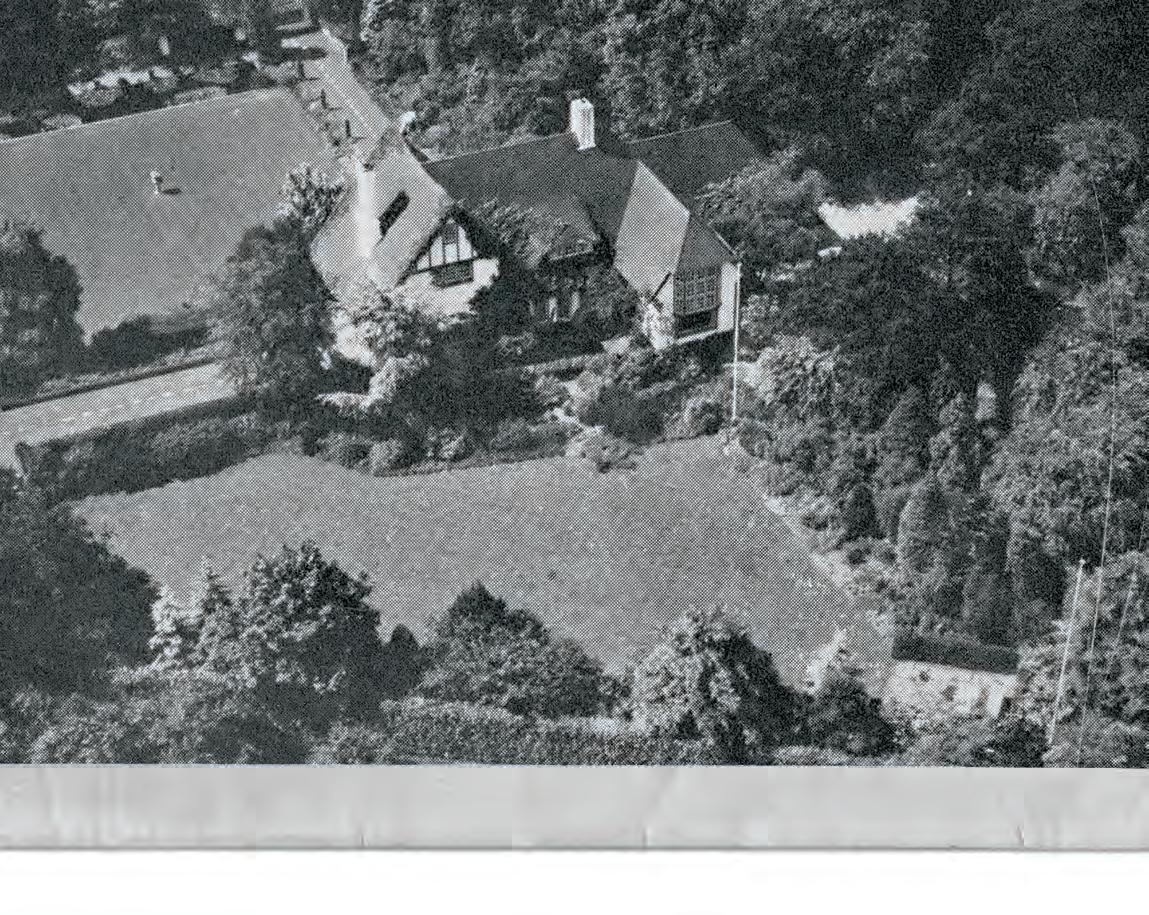

32 FIRST TROOP, CHARLIE SQUADRON, ROYAL CANADIAN DRAGOONS

Recollections from the diaries of a Canadian who helped liberate the Netherlands

By Charles Wilkins

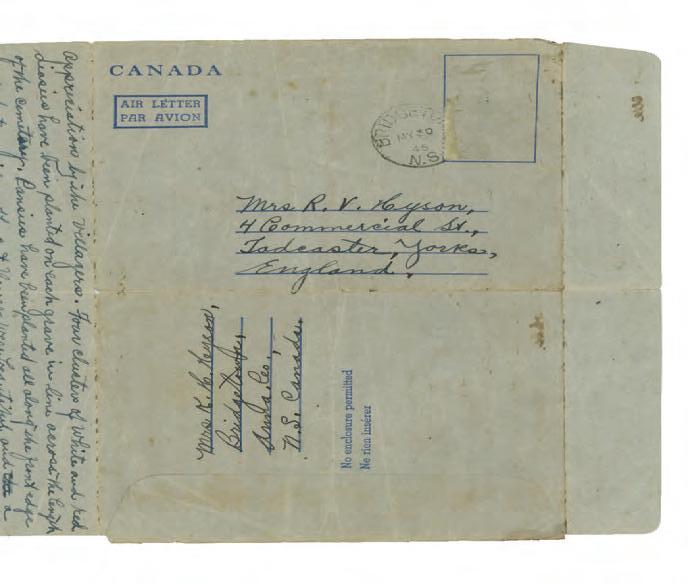

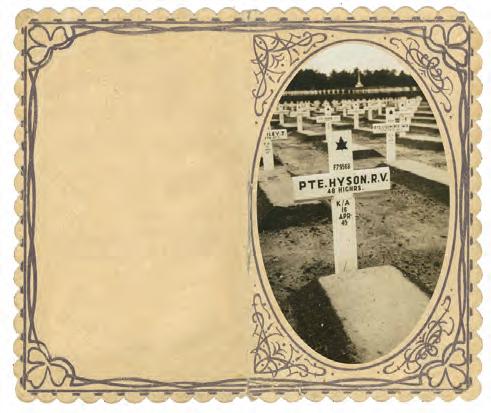

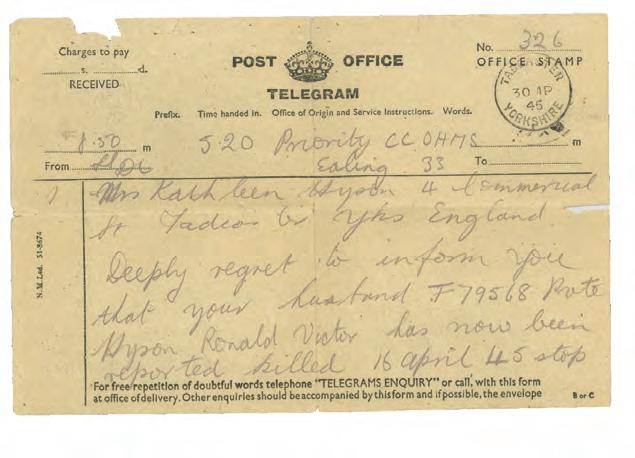

40 REGRET TO INFORM YOU

How the widow of a WW II soldier killed in action got the news

By Stewart Hyson

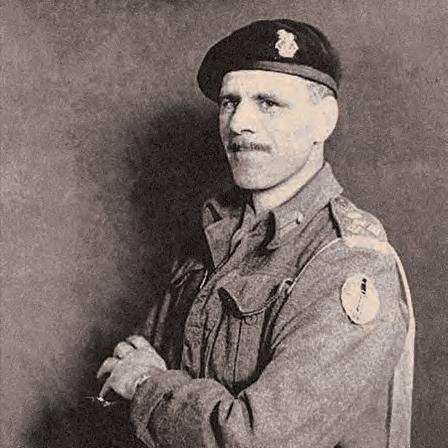

44 MOED EN VERTROUWEN

It means courage and confidence in Dutch. Mona Parsons, the only Canadian woman to be imprisoned by the German army during the Second World War, embodied the phrase.

By Alex Bowers

50 THE PLAN

Canada’s instrumental role in WW II’s British Commonwealth Air Training Plan

By Stephen J. Thorne

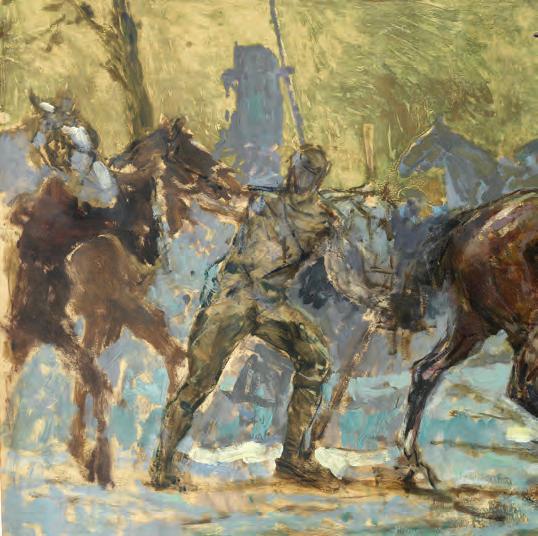

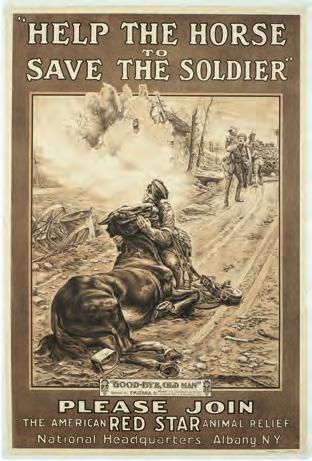

56 ART OF THE WARHORSE

First World War images of the trusty steeds in action

By Stephen J. Thorne

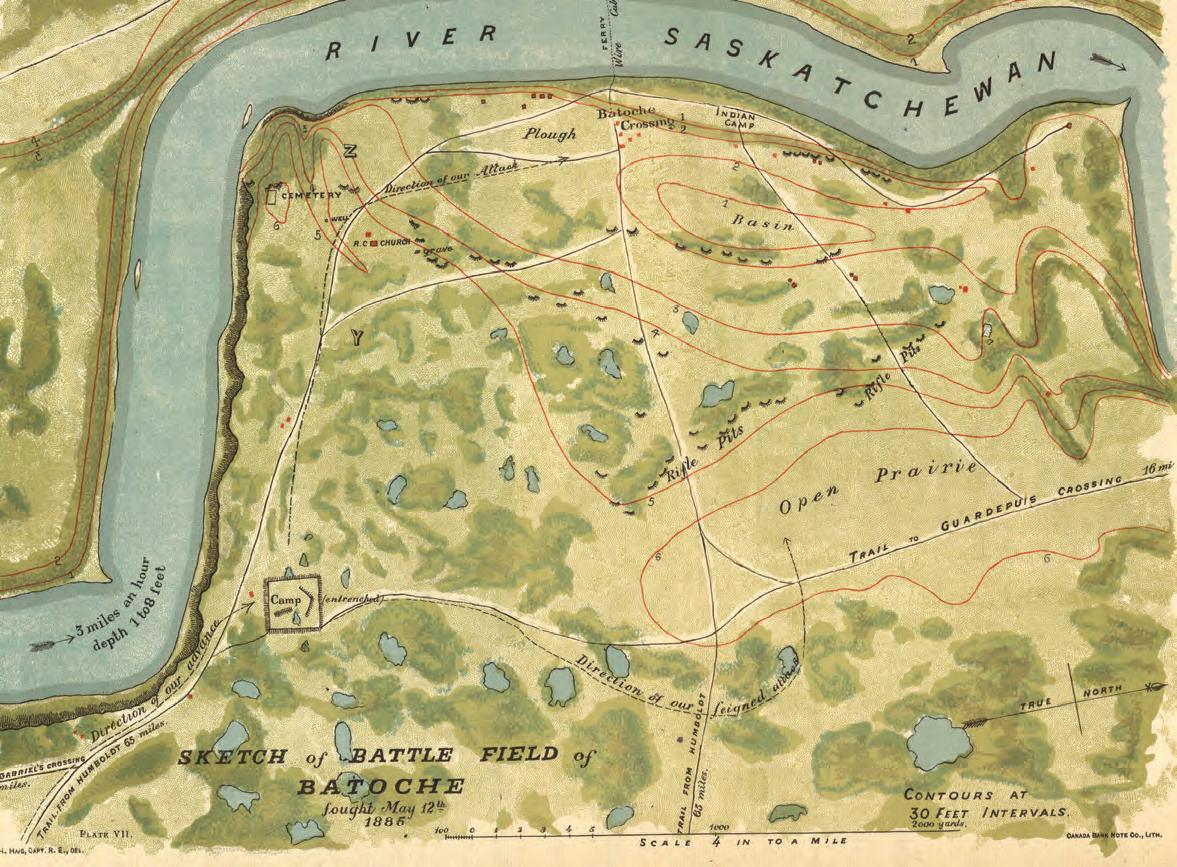

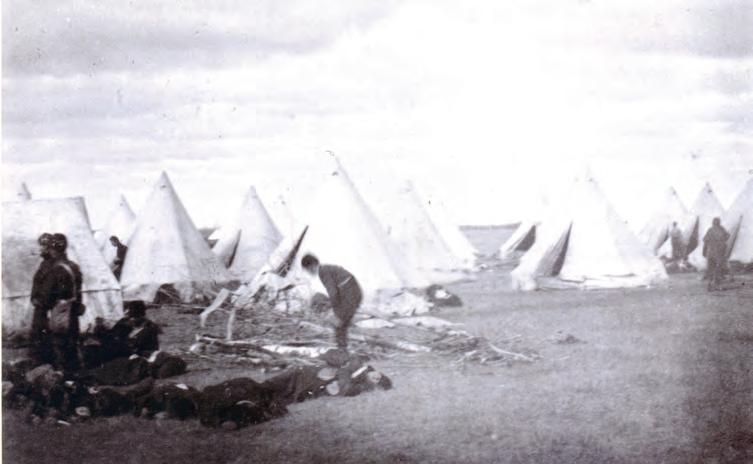

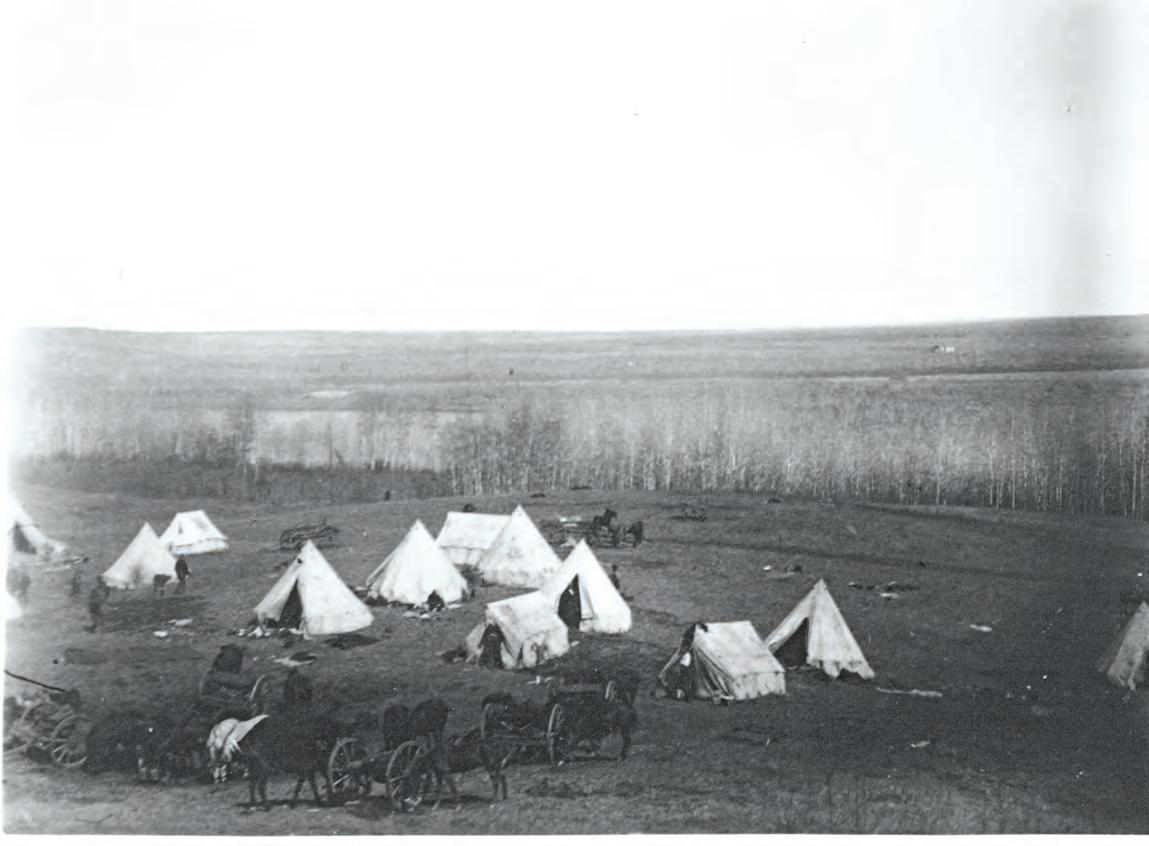

66 FISH CREEK IN FIRST PERSON

A visit to the site of one of the key battlegrounds of the 1885 Resistance offers a new perspective on the fight for the Canadian West

By Russell Hillier

THIS PAGE

Graduating pilots of the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan receive their wings at Ontario’s Camp Borden on May 16, 1941. DND/LAC/3232905

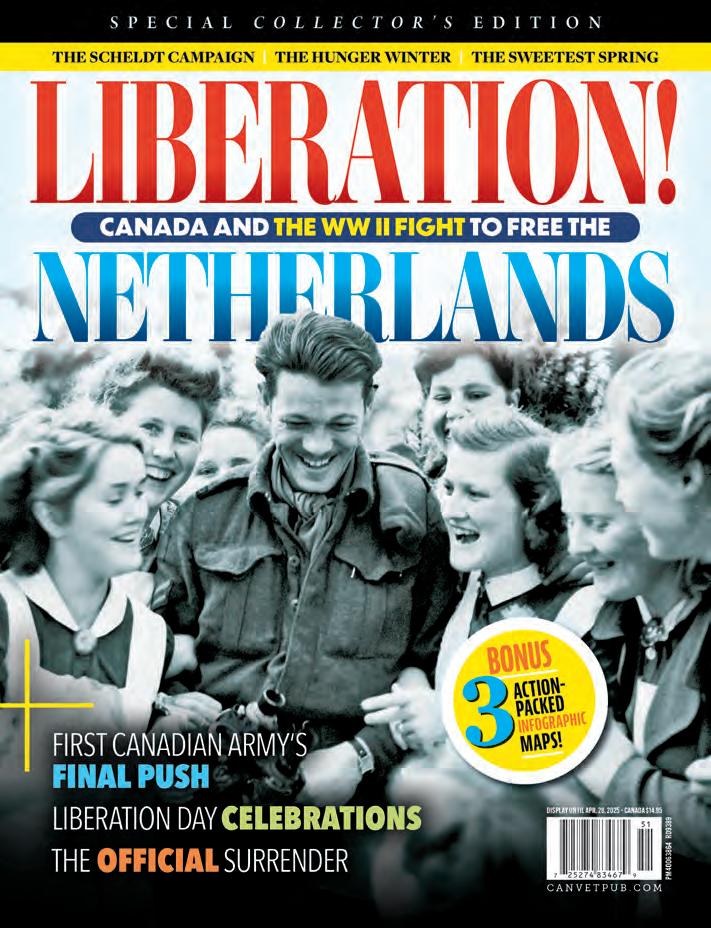

ON THE COVER

Infantrymen of The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment board an Alligator amphibious vehicle near Nijmegen, Netherlands, at the start of Operation Veritable on Feb. 8, 1945. Colin McDougall/DND/LAC/PA-190818

save

Vol. 100, No. 2 | March/April 2025

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Garry Pond BOARD VICE-CHAIR Berkley Lawrence BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe

DIRECTORS Steven Clark, Randy Hayley, Trevor Jenvenne, Bruce Julian, Valerie MacGregor, Sharon McKeown

Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

ADMINISTRATION MANAGER

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

ADMINISTRATIVE AND EDITORIAL CO-ORDINATOR

Ally Krueger-Kischak

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Alex Bowers

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales CANIK MARKETING SERVICES NIK REITZ

613-591-0116 | 416-317-9173 | advertising@legionmagazine.com

MARLENE MIGNARDI 416-843-1961 | marlenemignardi@gmail.com OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER AND MARKETING CO-ORDINATOR

Dyann Bernard

WEB DESIGNER AND SOCIAL MEDIA CO-ORDINATOR

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2025. ISSN 1209-4331

Legion Magazine is $13.11 per year ($26.23 for two years and $39.34 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $14.36 for one year ($28.73 for two years and $43.09 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $14.11 for one year ($28.23 for two years and $42.34 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Send new address and current address label, or, send new address and old address. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com/change-of-address. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $12.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of Alliance for Audited Media and BPA Worldwide. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and email magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

orale wins wars, solves crises, is an indispensable condition of a vigorous national life and equally essential to the maximum achievement of the individual.”

So wrote historian Arthur Upham Pope in the December 1941 edition of The Journal of Educational Sociology. He went on to quote Napoleon’s dictum that “in war morale forces are to physical three to one.”

It seems little has changed. “Maintaining morale in military operations is a vital element in maintaining the resilience and determination of members of the armed forces,” wrote Mioara Șerban in the March 2024 edition of Security & Defence Quarterly.

“THE BIGGEST DIFFICULTY WITH ATTRACTING RECRUITS, MAY BE THE CAF ITSELF.”

So, while there’s a glimmer of hope that Canadian military chaplains ranked morale among the country’s forces as “mixed” in 2024—upgraded from “mixed to low” the year before—defence department officials ought still to be very concerned about the issues continuing to dog the esprit de corps among Canada’s military members.

In the Oct. 29, 2024, briefing to defence chief General Jennie Carignan, growing workload, lack of housing and shortages of equipment were noted as continuing to contribute to the lagging mood. In some regions, lack of childcare and difficulties in finding doctors also impacted morale. (Improvements in pay and efforts to modernize the military were said to have helped boost attitudes.)

“Chaplains have reported that members are experiencing fatigue and low morale, largely due to personnel shortages,” the briefing, a copy of which was obtained by the Ottawa Citizen, noted. “Members frequently express concern about being tasked with duties or responsibilities beyond their rank.”

All this comes amid a recruitment crisis, with the Canadian Armed Forces short some 16,000 members of its authorized strength. Just weeks into her command, Carignan identified recruitment and retention of personnel her top priority. In August 2024, the defence chief issued a joint statement on the matter with CAF Chief Warrant Officer Bob McCann.

“We have had the privilege of working alongside many of you, witnessing your dedication and professionalism,” wrote the duo. “This spirit defines the CAF and makes us a respected institution at home and abroad.

“Without a strong and dedicated workforce,” they continued, “all the best capabilities, training, and plans mean very little.”

Of course, the two issues—morale and recruitment/retention—are intrinsically linked.

“The biggest difficulty with attracting recruits,” wrote Major Ian A. Creighton in a 2024 paper for a Canadian Forces College course, “may be the CAF itself.

“Years of neglect and chronic underfunding have contributed to the deterioration of equipment and infrastructure, which degrade operational capability and capacity. The result is not just a tarnished image but calls into question the legitimacy of the CAF.”

Indeed, the very challenges reportedly behind the sagging morale.

Legion Magazine supports a strong Canadian military, one that’s esteemed by Canadians and around the world. But no recruitment strategy will work until the attitude of the CAF’s rank-and-file is improved.

Want to improve morale? It’s simple. Listen to what you’re being told. Don’t overburden them. Ensure they get homes. Provide them with reliable equipment. If you build it, they will come. L

read with interest

Stephen J. Thorne’s Front Lines column “Unsinkable Sam” (November/December 2024). As a quirk of history, it’s worth noting that if Oscar/ Sam had been aboard Bismarck he would have been facing off against three English cats who were aboard HMS Prince of Wales. Blackie, for one, would later be seen being shooed away from the

As a former Royal Canadian Air Force fighter pilot, I am appalled, embarrassed, ashamed and angered over the way our military, especially our air force, has been neglected by successive governments. The last nine years under Prime Minister Justin Trudeau have been particularly abhorrent. It started with Trudeau’s campaign promise to not buy F-35 fighters recommended by the previous Conservative government. That was in 2015. Now, nearly a decade and billions of dollars later, the defence department is buying the very same aircraft. Meanwhile, the country only has about 40 combat-ready pilots. But, never mind, it’ll train new pilots to fly them. But wait, Canada just deactivated its pilot training squadron. No matter, it will just have one of its allies, such as the United States, train them. At great cost.

One of the prime responsibilities of the federal government is to keep Canadians safe. The current government has abrogated that responsibility. Hopefully, a responsible

government that will correct the shameful degradation in equipment and personnel of Canada’s military will win the forthcoming election.

RICHARD KISER

CALGARY

I have noted in your magazine criticism of the federal government relating to the state of the Canadian Armed Forces (all of the defence department, really). Columns by David J. Bercuson, J.L. Granatstein and others have laid out the many shortfalls. It’s perfectly justified criticism. But, I haven’t read a single word t hat offers a real solution.

On recruitment: what about compulsory military service? It has been talked about, but what about some analysis? Other countries are considering it again, having ditched it years ago. On procurement: other than complain, what can be done now?

Maybe it’s time to stop complaining and start to suggest a way forward. Your staff are as expert as a nyone in government, and some of them have

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

feet of Winston Churchill during a meeting in Newfoundland during the Second World War.

MICHAEL RALPH ST. JOHN’S, N.L.

Ed note: Read more about Blackie and other military ship cats at www.legionmagazine.com/ in-defence-of-cat-ladies-andgentlemen-the-tale-of-unsinkablesam-and-other-seafaring-felines.

military experience. I would like to see some well-considered suggestions or proposals.

RETIRED LT.-COL. JOHN M c NAIR KINGSTON, ONT.

Ed note: Numerous readers responded to “The B’ys Back” (September/October 2024) by Assistant Editor Michael A. Smith to point out that Newfoundland’s Red Ensign was not an official flag, but rather a merchant marine tool used to denote a ship’s origin, and questioned why it was used during the repatriation ceremonies for Newfoundland’s unknown soldier. From 1904 to 1931, the Dominion’s Red Ensign— which included the colonial badge—was used so commonly by government and civilians that it was considered the de facto flag. And during the First World War, families of Newfoundland soldiers and sailors killed in action received letters of notice with two flags adorning them: the Red Ensign and the Union Jack. On May 15, 1931, the Newfoundland legislature officially adopted the Union Jack as the colony’s official flag. L

The origins of Legion Magazine can be traced back almost 100 years to the publication of the first issue of The Legionary. The magazine took its current name in 1972. In the intervening years, the ways it shared stories evolved. And in recent times with the advent of digital technologies, it expanded its offerings to include immersive and interactive web stories, topical videos narrated by Canadian icons and a podcast series.

The latest change is the introduction of a new weekly web post. “The Briefing” features Q&A interviews conducted by staff writer Alex Bowers with a who’s who of the Canadian military experience

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /newsletter-signup

and culture—both high profile and under-the-radar experts. From veterans to serving personnel, from politicians to professors, from historians to curators, from authors to advocates and more, Bowers’ discussions will delve into all aspects of Canada’s military history.

To get notified about each week’s latest interview (and much more), sign up for Legion Magazine’s e-newsletter, if you haven’t already, at www.legionmagazine. com/newsletter-signup. L

1 March 1928

Two British destroyers are transferred to the Royal Canadian Navy and renamed HMC ships Vancouver and Champlain

2 March 1951

National Defence publishes its first Korean War casualty list. Today, the names of 516 Canadians are inscribed in the Korean War Book of Remembrance.

5 March 1995

The Canadian Airborne Regiment officially disbands; its 600 paratroopers parade one final time.

7 March 1951

In the Korean War’s Battle of Maehwa-san, two companies from 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, assault and secure Hill 532.

8 March 1996

The United Nations peacekeeping mission in Rwanda ends in failure after more than two years.

9 March 1812

A British spy’s letters are presented to the U.S. Congress, sparking the War of 1812.

11 March 1876

Sub-Constable John Nash becomes the first member of the North-West Mounted Police to die on duty. He is accidentally killed in Fort Macleod, Alta.

24 March 1975

The beaver becomes an official symbol of Canada.

12 March 1908

Toronto native F.W. (Casey) Baldwin becomes the first Canadian to fly a heavier-than-air flying machine in Hammondsport, N.Y.

13 March 1915

No. 2 Canadian General Hospital crosses the English Channel to France.

25-26 March 1952

Chinese forces attack a Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry platoon holding Hill 132 and a Royal Canadian Reserve outpost on Hill 162. They end up withdrawing as the Canadians hold their positions. Eight Canadians die, while 13 are wounded.

17 March 1945

HMCS Guysborough is torpedoed and sunk by U-868 in the Bay of Biscay off France, resulting in 51 casualties.

20 March 1944

General Harry Crerar assumes command of First Canadian Army. He will go on to lead troops into France, Belgium, the Netherlands and a final assault on Germany.

takes delivery of the first Canadair CF-104 Starfighter.

3 April 1916

2nd Canadian Division relieves British troops at the Battle of the St. Eloi Craters in its first major engagement of WW I.

5 April 1955

Winston Churchill resigns as U.K. prime minister.

7 April 1868

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, one of the Fathers of Confederation, is assassinated by Fenians in a rare Canadian political assassination, and the only one of a federal politician.

10 April 1972

13 April 1945

Canada and more than 70 other countries agree to ban biological weapons.

12 April 1961

Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin becomes the first human to travel into space and orbit Earth, aboard spacecraft.

Private Léo Major rushes a German position after the death of his friend and almost singlehandedly liberates the Dutch city of Zwolle.

15 April 1993

George Frederick Ives, last known survivor of the Boer War, dies at 111.

18 April 1910

The 14th Boston Marathon is won by Canadian Fred Cameron with a time of 2:28:52.

19 April 1904

The Great Fire of Toronto destroys most of the city.

20 April 1934

Heinrich Himmler is appointed assistant chief of the Gestapo, Nazi Germany’s secret police, in Prussia.

21 April 1945

Allied forces capture Ie Shima, Okinawa, in five days.

22 April 1963

Lester B. Pearson is sworn in as Canada’s 14th prime minister.

23 April 1949

The Chinese Red Army captures Nanjing.

24 April 1974

The U.S.S.R. performs a nuclear test at Sary Shagan.

25 April 1945

A bombing mission on Obersalzberg, Germany, is the final combat operation for the majority of Bomber Command squadrons involved.

26 April 1933

Jewish students are barred from attending school in Germany.

27 April 1959

The last Canadian missionary leaves the People’s Republic of China.

By Alex Bowers

was one of those strange coincidences,” explained Cheryl Forchuk, assistant scientific director at the Lawson Health Research Institute in London, Ont.

“I happened to be at one of our [homeless] shelters talking to people about strategies to lift them out of poverty, and two individuals were veterans. We had an interesting conversation about the difficulties of transitioning to civilian life.”

Forchuk left the shelter with that conversation vivid in her mind. It remained with her the next day at a committee meeting in Ottawa where, in a curious turn of events, the broad topic of veterans without permanent housing surfaced.

One thing led to another, and “we were able to get funding to do Canada’s first national study related to veterans experiencing homelessness,” said Forchuk.

Travelling coast to coast to interview dozens of veterans, Forchuk and her research team began developing principles based on the accumulated feedback.

Among the conclusions was the need for a housing-first model

that would stabilize service members by providing housing before any other issue is tackled.

“From all the homeless projects we’ve done, it’s clear that people can’t deal with their problems while they’re still on the street,” said Forchuk.

Equally important is peer support. Many veterans expressed the desire for greater assistance from people who understood the military and homelessness.

Forchuk’s study also determined the need for veterans to maintain structure in accessing homeless services.

“If I heard it once,” she said, “I heard 100 times the phrase ‘loosey-goosey’ [when discussing homeless shelters]. While these sites are trying to be accommodating, they couldn’t be more opposite to military routine. There are no rules, there is no specific breakfast time, and the veterans often need that.”

Forchuk’s team likewise encountered hurdles, not least a fundamental lack of Canadian research and an overreliance on U.S. research. This, of course, wasn’t an American shortcoming

in acknowledging the military culture differences between both countries; rather, it was a decidedly Canadian omission in factors of contextualizing veterans’ homelessness north of the border.

Where U.S. studies suggested that post-traumatic stress disorder was a leading cause of homelessness, Forchuk found that many Canadian veterans tied their challenges to alcohol dependency, in part the result of the Canadian military’s drinking culture.

It was, the team recognized, a complex addiction issue that benefited from a harm reduction over an abstinence model of treatment. Nevertheless, in laying bare the glaring cross-border divide, it became increasingly evident that a similar one-size-fits-all strategy extended to demographic disparities within Canada itself.

“I was really concerned about the lack of women [represented in the study],” said Forchuk, who identified female veterans in only two locations before the research findings were published in 2015. “I made a point of talking to them regularly, and they said that the systems were really set up for men.”

In 2018, a national survey tallied roughly 32,000 people experiencing homelessness in 61 communities across Canada (both in sheltered and unsheltered locations, as well as in various transitional programs), 19,536 of whom actively participated in the project; 4.4 per cent of respondents said they were veterans of the Canadian Armed Forces; of those, 82.7 per cent were male and 14.1 per cent female.

What were the exclusive lived experiences of the latter? How can they be addressed and why had so few come forward when research was carried out prior to 2015?

Now, with $1.2 million in federal government funding, Forchuk’s team is in the process of finding answers by conducting first-of-itskind research that focuses on the experience of female veterans.

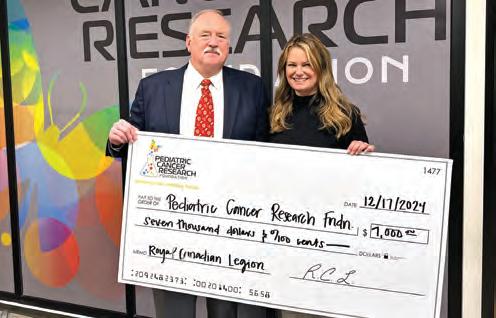

Like with the previous study, Forchuk’s team is continuing to travel across Canada—to locations selected in partnership with The Royal Canadian Legion and other veteran-serving groups— for an expected four-year period. Their aim is to gather information that could ultimately shape programs, inform policies and, fundamentally, provide tailored solutions for female veterans.

Already, conversations with former personnel have highlighted some of the issues, explained Forchuk.

“In London, for example, many [female veterans] had kids where it wasn’t good to take them into a group environment [of shelters]. More recently, new programs offer tiny homes that just aren’t suitable for kids.”

“Some women,” she added, “are dealing with sexual trauma. So, to put them in a room or

building full of men, let alone if they have kids, is not appropriate.”

However, with hopes for interviewing at least 100, ideally 150, female veterans, Forchuk is wary about generalizing their respective experiences.

“I don’t want to say, ‘This is a solution for all women,’ she said. “We must drill down. We must understand the differences between having kids and not having kids, between Indigenous and nonIndigenous individuals and between trans women. We might say that these are some broad experiences, but they must be further condensed.”

And yet, challenges identified in Forchuk’s first study linger— namely, affording individuals the space to self-identify as veterans. It is, seemingly, one area where there’s little difference between male and female interviewees, noted Forchuk: “Many feel they don’t deserve the title [of veteran]

because of how far they’ve fallen. They feel it’s part of their recovery to reclaim that status again.”

As much as peer support has been emphasized, the role civilians play in helping veterans, regardless of sex or gender, cannot be diminished.

“The Legion is a huge partner [in finding would-be candidates],” said Forchuk, “but everyone can assist. If someone asks to borrow your couch because they’re in a situation, talk to them. If someone is doing super well now, but they had been homeless, have them reach out as it could be a way of helping other women.”

Homing in on solutions is, unsurprisingly, the cornerstone of the study, although the Lawson Health Research Institute also recognizes the profound importance of giving female veterans a long-overdue voice.

“It’s about hearing people’s stories,” suggested Forchuk. “It’s about bearing witness, of knowing they’re out there.” L

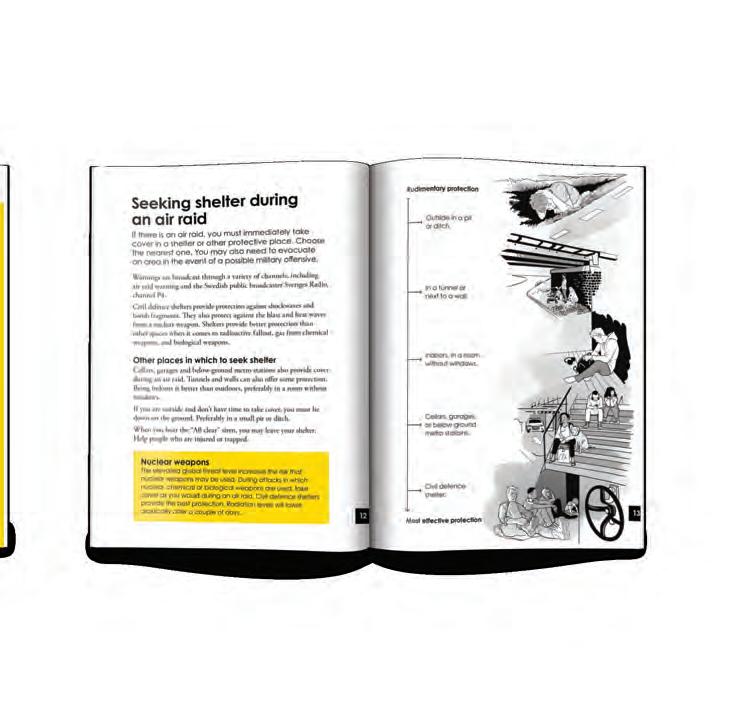

Asthe rhetoric escalates and violence spreads, Nordic countries have issued formal instructions to their citizenries on how to prepare for war and other crises.

“ We live in uncertain times,” declares a Swedish government booklet distributed to households across the country. “Armed conflicts are currently being waged in our corner of the world.

“If Sweden is attacked, everyone must do their part to defend Sweden’s independence—and our democracy…. In this brochure, you learn how to prepare for, and act, in case of crisis or war.”

Tensions mounted recently after Russian President Vladimir Putin lowered the threshold for a nuclear strike. The move followed a Ukrainian strike deep inside Russia with U.S.-made ATACMS missiles— supersonic conventional weapons.

The Moscow doctrine deems any attack by a non-nuclear power supported by a nuclear power a joint attack, and any attack by one member of a military bloc an attack by the entire alliance.

Announced on Nov 1,000th day of the Ukraine war, Russia also included a broader definition of what constitutes a mass attack on the motherland from aircraft, cruise missiles and unpiloted drones.

The war has entered what some Russian and western officials say could be its final and most dangerous phase as Moscow’s forces advance at their fastest pace since the first weeks of the invasion. And it’s doing so amid post-election uncertainty over the future of critical U.S. support to Ukraine.

The current state of U.S.Russia relations has been termed an all-time low, or their worst at least since the 12-day Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962.

“Now the danger of a direct armed clash between nuclear powers cannot be underestimated,” said Sergei Ryabkov, Russia’s deputy foreign minister overseeing arms control and U.S. relations. “What is happening has no analogies in the past, we are moving through unexplored military and political territory.”

Sweden’s “In case of crisis or war” has been updated due to what the government in Stockholm describes as a worsening security situation.

in size due to what the government in Stockholm calls the worsening security situation.

“Military threat levels are increasing,” it warns. “We must be prepared for the worst-case scenario—an armed attack on Sweden.

“We can never take our freedom for granted. Our courage and will to defend our open society are vital, even though it may require us to make certain sacrifices.”

It says Sweden is already under attack from cyber warriors, disinformation campaigns, terrorism and sabotage.

Swedish authorities produced a similar document, “If War Comes,” during WW II. It was updated during the Cold War.

But one message has since been prioritized: “If Sweden is attacked by another country, we will never give up. All information to the effect that resistance is to cease is false.”

Finland, Norway and Denmark— all bordering on the strategic Baltic Sea—have also issued

> Check out the Front lines podcast series! Go to legionmagazine.com/en-frontlines

pamphlets, booklets and/or online advisories addressing the spectre of crises, including war, and how to respond to them.

Sweden joined NATO in 2024 after Moscow expanded its war in 2022. Finland had joined a year earlier, while its neighbours, Norway and Denmark, like Canada, are founding members of the defensive alliance.

Finland already has a long history with Moscow’s hegemonic aspirations, dating to the Finnish War of 1808-’09 when Russia invaded and took what was then the eastern part of the Kingdom of Sweden. It formed the Grand Duchy of Finland, an autonomous piece of the Russian Empire.

The empire collapsed during the Russian Revolution of 1917. Finland seceded and declared its independence. A civil war ensued, pitting German-aided conservatives on one side and Bolshevik-backed socialists

on the other, resulting in full, if not fragile, sovereignty in May 1918.

On Nov. 30, 1939, Joseph Stalin’s Red Army launched a costly invasion into Finland aimed at creating a buffer around Leningrad.

By the time the fighting stopped and a treaty was signed, threeand-a-half months had passed and Moscow had gained more territory than it had demanded prewar.

But in a scenario that sounds uncannily familiar in these Ukrainian war times, Finnish defenders knocked out almost 2,000 Russian tanks. The Soviets had lost up to 168,000 soldiers killed or missing and more than 207,000 wounded or sick.

Moscow’s prestige had taken a hit, while Finland’s was elevated.

“Finland has always been…prepared for the worst possible threat, war,” says its digital brochure,

“Preparing for incidents and crises.”

“Military defence is built on conscription and the support of the whole society to national defence. All Finnish citizens have a national defence obligation, and everyone plays an important role in defending Finland.”

The online document addresses varying degrees of defence, outlines civilian responsibilities, describes the minute-long rise and fall of an air-raid warning, and points people to civil defence shelters.

“Everyone aged 18 or over but under 68 living in Finland is obliged to participate in rescue, first aid, maintenance and clearing tasks or other civil defence tasks.”

Ilmari Kaihko, associate professor of war studies at the Swedish Defence University, told the BBC that his native Finland, which shares a significant border with Russia, “never forgot that war is a possibility.” L

ust weeks after he was elected for a second term as U.S. president, but nearly two months before his inauguration, Donald Trump threatened to raise tariffs on Canadian imports by 25 per cent. Surely, it’s only a matter of time until he pressures Canada to do more militarily to help safeguard North America and the West at large.

With the U.S. engaged in an arms race with China, which has been increasingly asserting its sovereignty claims over international waters, the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the instability in the Middle East, the world grows more dangerous.

some $13 billion over five years and $4.4 billion annually after that. Then there was the national child-care plan introduced in 2021 that the parliamentary budget officer estimated will cost close to $28.3 billion by the end of next year. In these three initiatives alone, Ottawa has added billions to t he national budget; the national debt, meanwhile, is already an estimated $1,532.3 billion.

Go to our website, email us, or call us to schedule an appointment

call: 1 877 866 VETS (8387) email: info@urogenvet.com www.urogenvet.com

This past November, for instance, the federal government implemented a GST break which runs until mid-February and will cost between $1.5 and $2.7 billion. That largesse followed a new national dental care program, which was rolled out at the end of 2023 and had an estimated price tag of

And for defence? The feds promised in July 2024 that the country will spend two per cent of its gross domestic product (GDP) on its military by 2032—seven years from now. In the meantime, Canada will continue to rely on its fleet of 12 30-plus-year-old Halifax-class frigates, its four 1980s-era submarines with no under-ice capability, and the 30-year-old fleet of tactical helicopters. Note, too, the country has no real troop air defences and has a deficit of some 16,500 military personnel. Even though there were 70,080 applicants in 2023-24, only 4,301 were accepted.

The state of Canada’s defences has gotten so bad that Defence Minister Bill Blair has made clear his willingness to increase his department’s budget much quicker.

“My goal is to do it as quickly as possible,” Blair told CBC in late January, “and I’m increasingly confident we’ll be able to.”

Indeed, facing continuing criticism of military spending in the days immediately following Trump’s January inauguration, Blair indicated the government would meet the two per cent target by 2027, five years earlier than promised.

“We’ve been working hard to accelerate that spending to get the job done,” Blair continued. “But that’s in Canada’s national

interests, it’s not just in response to threats made by what we’ve always considered our closest ally and friend.”

Still, Canada will have to face the inevitable: how to achieve the two per cent of GDP minimum? There are no easy solutions, especially for a government that continues to bloat the country’s debt with tax breaks and new social programs.

Sure, dental care is a worthy cause for Canadians who don’t already have it. And so is child care. But, in light of the geopolitical powder keg around the world right now, it would seem Canada doesn’t have its priorities straight. Indeed, should some disaster occur in the North that the country can’t handle because it has neither the

ships nor the aircraft to respond adequately, will Canada continue to undermine its sovereignty by begging others for help?

The country’s priorities are set by the federal government, one that long ago decided that investing in social programs was far more important t han the nation’s defence. Canadians can get rattled at Trump’s sometimesridiculous pronouncements, but when business and trade groups, premiers, and many everyday Canadians realize the country isn’t doing enough for its own defence, it also becomes apparent something must be done.

If Trump has his way, as he often does, something will change—and soon. L

As the Germans unleash warfare’s first major gas attack, untested Canadian troops hold a critical gap in the front during the Second Battle of Ypres

By Alex Bowers

Gas! Gas! Quick, boys! An ecstasy of fumbling Fitting the clumsy helmets just in time; But someone still was yelling out and stumbling And flound’ring like a man in fire or lime… Dim, through, the misty panes and thick green light, As under a green sea, I saw him drowning.

—from “Dulce Et Decorum Est” by Wilfred Owen

“The very essence of spring was in the air,” wrote Canadian Lieutenant-Colonel George Nasmith about Belgium’s Ypres salient on April 22, 1915. “I felt as if I had to go out into the open and watch the birds and bees, loll in the sun, and do nothing.”

An analytical chemist from Toronto, the 4' 6" intellectual had been deemed ineligible for combat service due to his small stature. Undeterred, he had instead received authority to organize a laboratory for testing the troops’ drinking water.

On April 22, having travelled close to the Allied front line “to see what ‘No Man’s Land’ was like,” Nasmith ran into his friend Captain Francis Scrimger, the medical officer of the 14th Battalion (Royal Montreal Regiment). Sharing pleasantries, he and another comrade eventually pushed on until “our attention was attracted to a greenish yellow smoke ascending from the part of the line occupied by the French.”

Without any sense of urgency, both lit cigarettes and observed the expanding cloud as it drifted

forward at roughly eight kilometres an hour. It was only after Nasmith noted that it contained streaks of brown that he grew more concerned.

“That must be the poison gas that we have heard vague rumours about,” he surmised as the reality dawned on him. “It looks like chlorine, and I bet it is.”

And it was coming straight

The sight was horrifying omewhat expected horror.

Essentially outlawed by the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, neither the Central Powers nor ntente were outright opposed to the use of poison gas. An ambitious Germany, however, was the first to act on it on a large scale.

Experiments with weak irritants had previously fallen short of expectations. German chemist Fritz Haber then stepped up with the idea of using chlorine. Moreover, to circumvent the convention’s stipulation that gas must not be fired from exploding shells, he suggested releasing it through trench-installed hoses.

The intended target would be the Ypres salient. Considered a symbol of Allied tenacity, the front there jutted into German territory and acted as a buffer zone for the logistically critical Channel ports. Eliminating the salient would have enveloped as many as 50,000 Entente troops, including the relatively fresh and largely inexperienced 1st Canadian Division that defended part of the line.

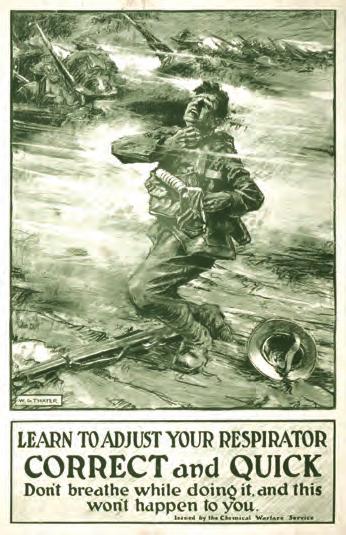

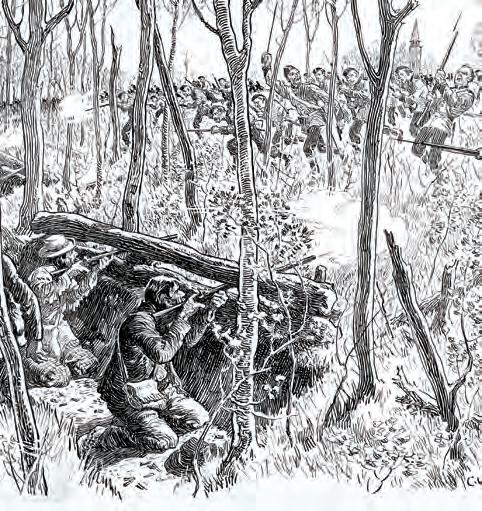

Artist Jack Richard depicts action during the Second Battle of Ypres. A British war poster circa 1915.

There were other motivations, but fundamentally, the first mass use of lethal chemical warfare was perceived as a means to break the deadlock on the Western Front. Combined with artillery

barrages and numerically superior forces, the Germans hoped that gas could eradicate the proverbial thorn in their side.

The Canadians were barring the way by mid-April 1915, wedged between the British 28th Division on the right and North African

“That must be the poison gas that we have heard vague rumours about. It looks like chlorine, and I bet it is.”

in places, seeped into every crevice, penetrating shell hole after shell hole before rolling through the 45th Algerian and 87th French Territorial defences.

“One had a sensation as if some beautifully horrible natural event was taking place,” recalled Leisterer of the sight. “The impression was tremendous.”

The three infantry brigades of 1st Canadian Division were led by brigadier-generals Arthur Currie, Malcolm Mercer and Richard Turner. The cover of a late May 1915 issue of British newspaper The Sphere depicts gassed troops in the trenches.

infantrymen of France’s 45th (Algerian) Division on the left. The formation’s overall command fell to British-born Lieutenant-General Edwin Alderson. Nevertheless, its three infantry brigades were led by Canadians: brigadier-generals Malcolm Mercer (1st Brigade), Arthur Currie (2nd Brigade) and Richard Turner (3rd Brigade), the latter a Victoria Cross recipient for actions during the Boer War.

As the enemy installed more than 5,730 steel canisters brimming with 160 tonnes of chlorine behind parapets and sandbags and waited for the right moment to turn on the taps, the Allies tried to confront the growing evidence of what was to come.

On April 13, German Private August Jäger deserted to the French lines, where he revealed information about the cylinders. He further explained that the enemy’s upcoming offensive would be signified by three red flares dropped from an

the gas. It proved unsuccessful.

Nervous anticipation built during the subsequent days until finally, if devastatingly, a German spotter plane fired the three red flares on the 22nd. With it came an intense artillery bombardment against the Entente lines and the city of Ypres itself. Worse, at around 5 p.m., the cloud of gas emerged, bolstered by an advantageous wind. It was, in the eyes of Fritz Haber, “a way of saving countless lives.”

German Sergeant Leisterer watched the hundreds of gas canister valves open with morbid fascination. Following a distinctly ominous hissing noise, the soldier of Reserve-InfanterieRegiment 233 then watched as the “whitish gas drifted from the long tubes over the parapet. Soon it took on a yellowish green colour, rolling in an interminable cloud, sneaking across the earth towards the [Entente] trench.”

The monstrous haze, stretching some six kilometres and reaching up to 30 metres high

In reality, the effects were as heinous as they were almost instantaneous. Inhaled fumes damaged and destroyed the alveoli—tiny air sacs in the lungs—and caused fluid discharge that impaired oxygen exchange. The chlorine mixed with these bodily fluids and water vapour to form tissueburning hydrochloric acid.

Victims began to drown within themselves, seared from the inside out. Screaming and begging for mercy, some French and North African soldiers dropped their rifles and fled only to drag out their misery by running in the wind’s direction; others writhed on the ground in agony, choking and vomiting greenish slime.

“Their eyeballs [were] showing white,” described McNaughton as a six-kilometre gap opened in the Entente line. “They literally were coughing their lungs out.”

Nine Canadian artillerymen who had been in the Algerian sector were killed, their fate a slow and ugly one amid the lethal cloud.

Elsewhere, entire Canadian battalions had mere minutes to prepare for their own dose, although the gas had gradually dissipated by that stage, sparing most from its deadliest effects. Despite this, irritated eyes were still rubbed

raw as blurry, yet unmistakable, figures appeared on the horizon. The Germans were advancing. And it was up to 1st Canadian Division to stop them.

The enemy threat was met by force, dashing German expectations that the Ypres salient would fall with ease after unleashing their not-so-secret weapon.

The Canadians, together with surviving Algerians, fought on.

Among those in the firing line were the men of 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada), who quickly shifted their defensive axis to plug the gap on their flank. Aside from a few overrun positions, the outnumbered troops held their ground.

Back at 3rd Infantry Brigade headquarters, an increasingly disorientated BrigadierGeneral Turner struggled to maintain order. The VC holder was proving to be the wrong man for the hour. Orders from his HQ, which was also under fire, sometimes varied from panicky to confused to entirely out of touch with events on the ground. Unfortunately, his shortcomings were most felt by the troops engaged at the front.

Fisher was but one example. The 14th Battalion machinegunner had poured rounds into the German ranks since the attack had commenced. When all other crew members were killed, the St. Catharines, Ont., native refused to retreat. In doing so, Fisher bought time for the Canadian artillery to withdraw to safer positions.

seized several British guns. From midnight on April 22-23, the 10th and 16th battalions counterattacked in an audacious yet flawed offensive. Advancing in the dark, the 1,600-strong force encountered an unmarked fence within sight of the strongpoint objective. The men overcame the hurdle, but not without alerting its German occupiers.

Those same soldiers, still retching from the gas, learned to rely less on brigade-level instructions and more on the men beside them on the parapet. Fighting in often isolated and desperate pockets, the Canadians struggled to turn the enemy tide.

In such dire circumstances, the heroics of individual soldiers— both seen and unseen—occurred throughout the salient. Nineteenyear-old Lance-Corporal Fred

He was later killed in the battle, his body never recovered. He received the Victoria Cross for his actions, Canada’s first of the war. Three more VCs were presented to Canadians for efforts at Second Ypres. Deserving though each recipient was, many brave acts went unnoticed, unrecorded and unrewarded.

Alas, German inroads were still being made, notably at Kitcheners Wood where enemy forces had

Flares, then muzzle flashes, illuminated the Canadian soldiers caught out in the open. Enduring a hail of small-arms fire, the t wo battalions launched a bayonet charge, sustaining horrendous casualties until they reached the forest. Survivors took few prisoners, but they did recapture four British artillery pieces. The Canadian defence of Kitcheners Wood would continue to be a bloodbath. Another scene of devastation took place atop Mauser Ridge, a Germanheld position overlooking the entire battlefield.

Brigadier-General Mercer’s 1st and 4th battalions were tasked with dislodging its enemy defenders. When French support failed to materialize, however, the 6 a.m. assault on April 23 descended into chaos, with the Canadian troops having to cover around 1,500 metres in broad daylight.

“Ahead of me I see men running,” recounted 1st Battalion’s Private George Bell. “Suddenly their legs double up and they sink to the ground. Here’s a body with the head shot off. I jump over it. Here’s a poor devil with both legs gone, but still alive.” More than 900 casualties were sustained during the doomed attack.

Command miscalculations aside, the Canadian infantry was having to deal with the ever-inefficient Ross rifle, a weapon prone to jamming that could fail men at the

least opportune moment—usually after rapid-firing in the heat of battle. It wasn’t uncommon for troops to discard these rifles, replacing them with British Lee Enfields or even German Mausers when available. Most weren’t so lucky, left to hope that their primary source of protection would hold out.

By nightfall on April 23, the Entente overall—and the Canadians, in particular—were also holding out. There had been gains and losses, tactical victories and defeats, but Ypres remained in friendly hands for the time being. With British reinforcements having plugged gaps in the line, all was not yet lost. Even German prisoners appeared to express grudging respect for their adversaries, one of whom later remarked to his Canadian captors: “You fellows fight like hell.”

Armed with chemistry, Lieutenant-Colonel Nasmith— still suffering from the gas attack on the 22nd—found a different means to fight.

Being caught in that menacing cloud had come with its upsides, if only from a purely scientific perspective, as he was now inclined to believe that chlorine had been combined with “perhaps an admixture of bromine” as an extra irritant.

Through coughs and splutters, Nasmith reported his findings to Allied officials, becoming the first person to formally identify the gas’ chemical compounds. He wouldn’t be the last to gain such insights borne of first-hand experience.

At around 4 a.m. on April 24, the Germans launched a second gas attack against the Canadian lines, primarily directed at 8th and 15th battalions. The blanket of death was smaller yet denser than before, but it was also widely anticipated.

Canadians with scientific back grounds, having seen brass buttons tarnished green two days earlier, warned that the discolouration

could result from chlorine. Soldiers familiar with the smell of chlorinated water in tea-making were just as capable of identifying the substance. Jointly, these independent intuitions left men scrambling for improvised respirators, typically a cloth or handkerchief soaked in ammonia-rich urine to neutralize hydrochloric acid. Anyone unprepared or unwilling to perform such an unpleasant act of self-preservation risked an agonizing death.

This crude method saved most— but not all—victims, with many survivors plagued by health challenges for the rest of their shortened lives. More pressing was the German horde again advancing toward the battered and bruised defenders. Canadian formations throughout the salient offered a stout resistance, ensuring the enemy paid for every inch of ground. Yet slowly, incrementally, the sheer weight of German opposition became overwhelming as some gassed troops began to buckle.

Communications had broken down. So, too, had much of the command structure. And while

there remained strongholds, the floodgates had opened.

The situation wasn’t helped by Brigadier-General Turner, who, in his battle-fatigued state, misinterpreted divisional orders and pulled his men back amidst a bitter struggle. Unable to disengage the enemy as they withdrew, the Canadians were thrust into a maelstrom and harassed further in new, weaker positions.

But for every folly, there was heroism. Lieutenant Edward Bellew, the 7th Battalion (1st British Columbia) machine-gun officer, played a vital role in the fighting retreat. Disregarding his own wounds, he and a comrade spat rounds into the German force until his loader was killed and he ran out of ammunition. Bellew next destroyed the spent weapon under fire, retrieved a rifle with bayonet attached, and charged at the enemy, somehow surviving to be captured. He earned the Victoria Cross.

Like falling dominoes, 3rd Brigade’s withdrawal mounted pressure on Lieutenant-Colonel Currie’s 2nd Brigade, prompting its commander to make the controversial decision of leaving his men to personally request British assistance. Destined for greatness later in the war, his judgment on April 24 was, and is, hotly debated.

Artist Eric Kennington depicts a blinded soldier recovering from the effects of mustard gas. The early evolution of 1915 gas masks.

Anyone unprepared or unwilling to perform such an unpleasant act of self-preservation risked an agonizing death.

consciousness, where the Second Battle of Ypres would eventually stand with the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele as a symbol of Canadian fortitude. In holding the line, these men had sacrificed much for a salient far from home.

“When the people of the little villages through which we passed saw the name ‘Canadian’ on our car,” remembered LieutenantColonel Nasmith, “they nudged each other and repeated the word ‘Canadian.’ It was the name in everybody’s mouth those days, for it was now general knowledge that the Canadian division had thrown itself into the gap and stemmed the German rush to Calais.”

It had come at a cost of 6,036 Canadian dead, wounded and captured.

Survivors left behind friends, comrades and parts of themselves they could never retrieve. For John Armstrong of 3rd Canadian Field Artillery, the horrors he encountered were encapsulated by a lone, injured horse walking past “with just the lower part of a man’s body in the saddle. From the waist up there was nothing.”

Further horrors lay ahead before the battle ended on May 25, 1915, by which point numerous individual engagements had taken their toll on the Entente forces. For Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, that month’s Battle of Frezenberg became a particularly harrowing clash when the unit was almost annihilated in defence of the Ypres salient. Nevertheless, like the Canadian veterans of

remainder of the battle, attended hundreds of patients without rest. On April 24, having learned that hundreds more lay dying in forward positions, the doctor went to them. Scrimger saved lives well into the next day, all under heavy fire, until his position became untenable, leaving him with little choice except to evacuate the wounded. When one injured captain couldn’t be transported, Scrimger stayed with him as artillery fire edged closer, setting the building ablaze. The slight medical officer carried the soldier away, past enemy patrols, to the relative safety of another aid station. His gallant efforts were later acknowledged with the VC. Courage came in many forms during the Second Battle of Ypres, from the privates in the trenches to the gunners and stretcherbearers in the field. Mistakes had been made, but almost all the Canadians had stood tall in their first major fight of the war. Each soldier found ways to cope with what they had experienced. For Lieutenant-Colonel John McCrae, mourning the loss of a friend, it was in writing a soon to be famous poem. L

Among the families impacted by the more than 6,500 Canadian casualties during the Second Battle of Ypres were the Braithwaite sisters of Hamilton: Marjory, Mary and Dorothy. Two of the trio married officers in the First Canadian Contingent.

Marjory married Lieutenant Trumbull Warren, a Royal Military College graduate, president of Toronto’s Gutta Percha & Rubber company and member of the 48th Highlanders of Canada. Trumbull went overseas with the 15th Battalion (48th Highlanders of Canada) as a captain and the unit’s adjutant.

Mary wed Captain Guy Melfort Drummond, the son of wealthy Montreal industrialist George Alexander Drummond, a partner in Redpath Sugar. The younger Drummond was a successful businessman, too, and a prewar officer in Montreal’s Black Watch. When the war broke out, the newly married Drummond volunteered to go overseas as a member of the 13th Battalion (Royal Highlanders of Canada).

By John Boileau

On April 20, after Canadian units had occupied positions along the Ypres salient, a huge German howitzer shell wounded Warren near Ypres’ Cloth Hall. He died shortly afterward. Drummond was allowed to attend his brother-in-law’s burial.

Drummond returned to the trenches on April 22, just as the Germans launched the Second Battle of Ypres. As he led an attack to close a gap in the line caused by the collapse of French colonial troops overcome by the first major gas attack, a bullet struck him in the neck. Drummond died instantly and today lies in Belgium’s Tyne Cot Cemetery. Marjory and Mary became widows within two days of each other.

Their unmarried sister Dorothy sailed from Canada to offer support to her siblings. She travelled on Lusitania and marked her 25th birthday aboard on May 5. Two days later, the cruise liner was torpedoed by U-20. Dorothy survived in the water for a short time, but eventually drowned. Her body was never recovered; a large stone cross marks her empty grave in Hamilton.

In England, Drummond voluntarily reverted to the rank of lieutenant to serve at the front. In April 1915, he was in Belgium’s Ypres salient as a company second-in-command. While their husbands served at the front, Marjory and Mary moved to England, a practice followed by many officers’ wives.

Toronto for service personnel, for which she was appointed an Officer of the Order of the British Empire.

Marjory and Mary became widows within two days of each other.

Mary also remarried, to British Captain Tom Stoker, a relative of Bram Stoker of Dracula fame. L

Three Canadian soldiers watch as a plume of smoke from an artillery shell rises above the rubble-strewn city of Ypres, Belgium.

In the fall of 1944, Canadian troops led bitter fighting to secure access to the critical port of Antwerp, freeing the Scheldt estuary and the approaches to a key supply hub as Allied forces prepared to enter Germany and bring the Second World War to an end.

The Scheldt victory also liberated a sliver of the occupied Netherlands, but more epic combat lay ahead. Ultimately, the year 1945 will prove a happy one, as the sufferings of the Dutch populace, ravaged by almost five years of hardship and a bitterly cold winter of starvation, are brought to a bloody end.

Now available on newsstands across Canada!

GENERAL HARRY CRERAR OVERSAW JUST ONE MAJOR BATTLE—BUT THE DECISIVE EARLY 1945 ADVANCE INTO GERMANY’S RHINELAND WAS CRITICAL TO ENDING WW II

By Mark Zuehlke

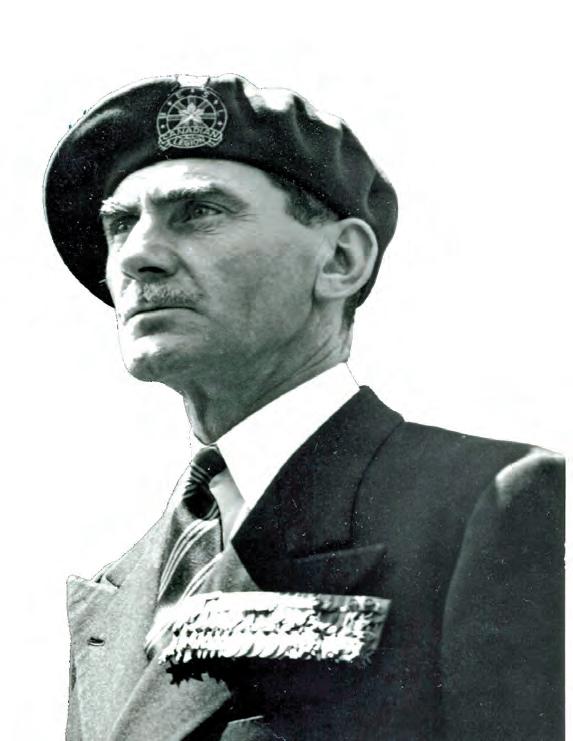

ONIn February 1945, Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds and Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery meet with General Harry Crerar (above, right , and opposite bottom). Crerar with infantrymen afield.

Jan. 16, 1945, Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery summoned General Harry Crerar to his tactical headquarters. In his usual terse manner, Montgomery told Crerar the time had come for the Allies to engage the Germans in “a potentially decisive…operation.” That operation was the Rhineland Campaign, which aimed to capture a narrow wedge of ground south of the Rhine River that ran to the east of the Netherlands’ Groesbeek to Wesel—a distance of about 65 kilometres.

This would be the first part of Germany targeted by the Allies. First Canadian Army’s Crerar was to lead the British-Canadian advance southeast from Groesbeek along the Rhine’s southern shoreline to link up with a U.S. Ninth Army drive northeast from

the Maas River to Wesel. What was anticipated to be a large number of German divisions concentrated to hold this ground would be crushed between the two closing Allied armies.

At the same time, this region of the Rhineland would provide British 21st Army Group with a launching point to cross the Rhine. Once on the opposite bank, the British would push into Germany’s industrial Ruhr valley, while the Canadians would move westward into the Netherlands to begin liberating it.

Crerar wouldn’t just have First Canadian Army’s II Canadian Corps and I British Corps under his command. Added in was Lieutenant-General Brian Horrocks’ XXX Corps from British Second A rmy.

This was going to be a juggernaut smashing into the Germans on a very narrow front. Montgomery hadn’t given t he task to Crerar willingly. It fell to the Canadian because of the alignment of the British forces.

The Canadians were on the 21st Army Group’s left flank, so—as the man on the ground— Crerar had to command. Montgomery’s relationship with Crerar had been fraught since the Canadians had come under Montgomery’s command in southern England. Montgomery also considered Crerar incompetent.

Miles Dempsey. It was a move that suited both corps’ commanders, Canadian Lieutenant-General Guy Simonds and British LieutenantGeneral John Crocker. Each had their own issues with Crerar’s competency and personality.

At 55, Crerar was a Great War veteran who had ascended to army command via a series of staff positions. He had put in a brief stint leading I Canadian Corps in Italy, but this only further soured his relationship with then-Eighth Army commander Montgomery. The corps command had been a necessary step for Crerar to become Canada’s overseas army commander.

HORROCKS SOON HELD THE CANADIAN IN HIGH REGARD. HE CONSIDERED CRERAR “MUCH UNDERRATED, LARGELY BECAUSE HE WAS THE EXACT OPPOSITE TO MONTGOMERY.”

Crerar was methodical, hardworking, and detail oriented. He favoured multi-page, complex operational directives, the very kind of products shunned by Montgomery. In his manner and dress, he was formal and a stickler for regulations. Montgomery, meanwhile, favoured informal dress and had a habit of wearing a black beret, even though he had never served in an armoured regiment.

While Crerar and Montgomery were polar opposites, the Britishborn Simonds tended to mimic Montgomery, including wearing the same headwear. Montgomery had long considered Simonds a protege and respected his abilities as a soldier and commander. This meant he was happy that Simonds was effectively in command of the Canadians in Normandy. Simonds,

Monty wrote, was “far better than Crerar” and “the equal of any British Corps Commander.”

Crerar, he noted on the other hand, was “very…stodgy, and… very definitely not a commander.”

For his part, Crerar seethed that Montgomery’s clear attempts to keep him away from his army reflected the “Englishman’s traditional belief in the superiority of the Englishman.” No “Canadian…is ever rated as high as the equivalent Britisher.”

Montgomery, however, couldn’t keep Crerar isolated for the war’s duration. Accordingly, on July 23, 1944, Crerar established an army headquarters in Normandy. Due to the narrow battlefield, however, Simonds continued directing II Corps operations in the drive to Falaise and in ultimately closing the gap that

consigned thousands of Germans to either death or capture.

Thereafter, the Canadians advanced up the French coast under Crerar. Save for a short pursuit of German divisions to the Seine, what was to be known as the Channel ports Campaign required little direction from army headquarters. Instead, it consisted largely of sieges by individual divisions of port cities—such as Le Havre, Boulogne and Calais.

Crerar’s major battlefield debut should have come during the Sept. 13-Nov. 6, 1944, Scheldt Campaign, which aimed to open the huge Belgian port of Antwerp to Allied shipping. On Sept. 25, just as that operation was developing into a major fight, Crerar was diagnosed with dysentery and a possible blood disorder and evacuated to England. He wouldn’t

recover until Antwerp was open and the guns had fallen silent.

First Canadian Army spent a harsh winter holding a line from Walcheren Island in the Netherlands along the south bank of the Maas River (as the Dutch called the Rhine there) east to near Groesbeek by the German border. Fighting was sporadic and isolated, but still costly at times for both sides. Meanwhile, on Dec. 16, Crerar had started planning Operation Veritable— the offensive into Germany’s Rhineland—at Montgomery’s direction. That initiative, however, fizzled immediately: a German offensive smashed into the Ardennes region the very same day and had the thin American line there reeling. The ensuing Battle of the Bulge became the focus of all Allied activity at the time and raged through to Jan. 16, 1945.

The original plan for Veritable was to have been launched sometime in January when the

battlefield and approaches to it would have still been frozen, enabling tanks and vehicles to move relatively easily across the hardened ground. The German offensive had thwarted that, and Montgomery consequently selected a Feb. 8 start. After the worst winter weather Europe had experienced in 50 years, lingering rains and melting snow were expected to render the battlefield a muddy quagmire.

But, from General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander of the Allied forces in Europe, down the ranks, the Allies were in a hurry to seize the Rhineland and prepare for the advance into Germany’s heartland.

At Canadian army headquarters, Crerar and his staff faced an unprecedented logistical challenge. With three corps under his command, Crerar had at his disposal 449,865 soldiers as opposed to the army’s normal compliment of about 150,000.

Infantrymen of The North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment board an Alligator amphibious vehicle at the start of Crerar-led Operation Veritable on Feb. 8, 1945. Canadian Guy Simonds (opposite left) tended to mimic British commander Bernard Montgomery while Crerar was their polar opposite.

Montgomery had bolstered XXX Corps to five infantry divisions, two armoured divisions and four armoured brigades. Second British Army, meanwhile, was stripped down to four divisions and three independent brigades. Everything else went to Crerar.

Now, Crerar’s penchant for detailed planning proved invaluable. The army’s requirements were vast and needed to be identified and precisely provided. Ammunition of 350 different varieties ranging from 105-millimetre shells to .303-calibre rifle cartridges had to be assembled. Awed, Crerar noted that if all this ammo “were stacked side by side and five feet high, it would line a road 30 miles.”

The numbers were staggering: 2.3 million rations, 5 million litres of petrol for just the first four days, 13,000 kilometres of communication cables, 85,000 smoke generators, some 800,000 maps and 500,000 aerial photos. More than 35,000 vehicles soon jockeyed toward position with 1,600 military police trying to prevent gridlock. And in addition to maintaining roads suffering from increasing wear and tear, engineers built new ones crudely surfaced by laying logs side by side. This required 18,000 logs and, while providing bumpy going, prevented vehicles from miring in mud.

The sheer might under Crerar’s command was necessary for success. With no chance of achieving surprise, the army would launch a frontal assault against well-prepared and strengthened positions—initially the vaunted Siegfried Line.

Horrocks and his ballooned XXX C orps were to open Veritable w ith only 3rd Canadian Infantry Division advancing on its left flank. As the launch date approached, Horrocks fought an unexplainable illness that made him irritable. Horrocks was impressed that Crerar patiently excused his bad-tempered behaviour.

In fact, Horrocks soon held the Canadian in high regard.

He considered Crerar “much underrated, largely because he was the exact opposite to Montgomery. He hated publicity, but was full of common sense and always prepared to listen to the views of his subordinate commanders.”

Crerar also showed an ability for grasping and considering the complexities of the modern battlefield. He carefully monitored the logistical expansion. Endless hours were spent establishing, Crerar

wrote, that “the technique of the fire preparation for the assault was worked out in order to ensure the closest possible integration of movement with overwhelming fire both from artillery and the air…I gave instructions to my senior officers that once the operation began, commanders… must be seized with…keeping the initiative, maintaining the momentum of the attack…through the enemy without cessation.”

Members of The Royal Winnipeg Rifles leave Niel, Belgium, on Feb. 9, 1945 (right). A column of Churchill tanks and other vehicles advance at the start of Operation Veritable the previous day (opposite top), while Canadian infantrymen assemble near Nijmegen, Netherlands, that day (opposite bottom).

Ground objectives were to be seen as no more than a means to an end. Before the attack, every soldier was to be briefed so he understood his tasks and their importance to achieving victory.

Crerar repeatedly made it clear that while winning the Rhineland was important, the greater purpose of Veritable “was to destroy the enemy.” Defeating the Germans was insufficient, Crerar and his headquarters staff reiterated. They must be killed or taken prisoner. Therein lay true victory, because this would leave the enemy so weakened that capturing the rest of G ermany should go quickly.

On Feb. 8 at 10:30 a.m., following a prolonged artillery and aerial bombardment that had pounded German positions throughout the Rhineland, Crerar unleashed the massive juggernaut stationed on the Dutch-German border. Fifty thousand soldiers, supported by 500 tanks and 500 of the specialized tanks of British 79th Armoured Division, led. As the Canadians and British slammed into the defending Germans, the battle descended into nightmare with heavy casualties on both sides.

There was to be no surcease, no pause. As one infantry battalion ran out of steam or was shredded by enemy fire, another leapfrogged it. On the left, 3rd Canadian Infantry Division—already nicknamed “the water rats” for its role fighting in the flooded terrain of the Scheldt— used amphibious Buffaloes and Weasels to move through a wide swath of submerged land after the Germans had blown dikes along the Rhine River. After two days of hell, however, the Siegfried Line—built over years to defend the Rhineland—was broken.

The Germans fell back into a series of prepared defensive lines that had to each be taken in turn. As their casualties mounted, the overall intent of the offensive was achieved. More German divisions were fed in because Hitler refused to cede any of his country’s ground. One after another, Germany’s best remaining divisions in the west were committed—and slaughtered. When Veritable ran out of steam on Feb. 22 in front of a road running north to south from Calcar to Goch, Germany, Crerar allowed a brief pause. Four days later, he launched Operation

Blockbuster, led mostly by the Canadians. In front of the dense Hochwald Forest, it seemed the advance might falter—the woods bristling with Germans holding entrenchments with fanatical determination. But Crerar threw more Canadian battalions into the narrow Hochwald gap, and they fought through and took Xanten. Nearby, they met up with U.S. Ninth Army and ended the campaign.

The Allies paid a terrible cost in the campaign—15,634 casualties, 5,304 of which were Canadian. The German decision to defend the Rhineland proved a disastrous folly. First Canadian Army took 22,239 prisoners with another 22,000 killed or suffering long-term wounds. Including those taken and killed by the Americans, total German losses were tallied at 90,000. Thereafter, First Canadian Army fought smaller engagements while advancing through the Netherlands and into northern Germany. There would be no other major campaign for Crerar to plan and fight. But in the Rhineland, he won his battle. The end of the war would soon follow. L

BY CHARLES WILKINS

By

the time First Troop, Charlie Squadron, of The Royal Canadian Dragoons reached the northern Netherlands in late April 1945, the Second World War was into its final days, and the Netherlands had been under savage Nazi occupation for five years.

In cities such as The Hague and Amsterdam, where the Germans had set up blockades to prevent the arrival of food, an average of 300 Dutch citizens a day were dying of starvation.

On farms, both in the Netherlands and across the border in Germany, Dutch captives, some of them adolescents, were performing slave labour to produce food for the German military—and were barely fed themselves.

In German factories, Dutch and eastern European prisoners, invariably under armed guard and sometimes shackled to the machinery, produced battle gear and munitions for the German fighting forces.

My dad, Lieutenant Charles Hume Wilkins—Charlie, to the men in his platoon—was part of First Troop, Charlie Squadron, and the diary he kept as the Canadians rolled deep into northern Holland paints a rousing and memorable picture not just of the horrors experienced by the Dutch under Nazi occupation, but of the sheer joy, the wild sense of celebration that exploded among the Dutch citizens as the Canadians appeared, sweeping the last of the occupying Nazis either back across the border into Germany or into prisoners’ cages, where the captured German soldiers got a taste of the treatment they themselves had been dishing out.

“And, indeed, they had been dishing it out,” wrote my dad in a late-April diary entry that goes on to describe a reconnaissance mission he led into the west German borderlands near the village of Friesoythe. In their armoured cars, the Canadians came across a rundown concentration camp, where the Nazis had locked Polish and eastern European prisoners in crowded cages and left them more or less to starve.

“Mere bags of skin and bone,” my dad called the prisoners, noting that “the newspaper stories of atrocities were coming true before our eyes— but they were still hard to believe.”

With the arrival of the Canadians, northern Dutch towns such as Steenwijk and Franeker were freed not just of uniformed German soldiers, but of the presence of the reviled Gestapo, the Nazis’ plain-clothed secret police. In Steenwijk, members of my dad’s platoon captured a Gestapo agent who had been responsible for the deaths of several local boys and locked him in a truck, barely able to prevent the townsfolk from tearing the truck apart in their ambition to tear up the agent himself.

As celebrations welcoming the Canadians rocked the thousandyear-old city of Leeuwarden in the north, a young man named Freddy Ringnalda invited my dad to dinner at his parents’ home. While the family and their Canadian guest ate a sumptuous celebratory meal, Fred explained to my dad that

six months earlier he had escaped Gestapo agents who had come to the factory where he worked, intending to arrest him and put him to slave labour in a nearby German munitions factory.

Fred had escaped the secret police by the narrowest of margins when a factory foreman caught wind of the Gestapo’s approach and, as they were entering the factory by the front doors, ordered Freddy to lie down on a wheeled dolly, covered him with a tarp, and spirited him by elevator into the basement and out a shipping door at the back of the building.

Not that Freddy’s escape brought any sort of real freedom; he was obliged, rather, to spend the remainder of the war hiding in a musty and lightless attic under the eaves of his parents’ home.

Some of the diary’s tales describe events so theatrical and satisfying and, for my dad at least, so personal that their outcomes and the people involved would affect his life for decades to come.

Near Heerenveen, for example, a battle-weary Dutch Resistance fighter, “just a kid but a strong one,” named Pete Toxapeus approached Charlie Squadron, offering muchwelcomed services as a translator and navigator, and proceeded to facilitate the Canadians’ journey on a landscape where they knew neither the language nor the geography nor the social customs. So appreciative was my dad of Pete, and vice versa, the two remained friends long after the war. Indeed, during the 1950s, Pete crossed the Atlantic by ocean liner for the sole purpose of reuniting with and, in effect, thanking my dad.

However, in those last brutal days of the war, travelling with the Dragoons, the young resistance fighter was a kid known less for amicability than for toughness and fearlessness—and for a trait not always noted, much less emphasized, in more formal or discreet histories of the war: that of a low-key desire for vengeance, at an all but personal level.

FOR AMICABILITY THAN FOR TOUGHNESS AND FEARLESSNESS— AND FOR VENGEANCE.

Pete’s aptitude for payback was triggered not just by the plight of his own people, but by the mistreated or enslaved citizens of half a dozen other countries occupied and brutalized by the Nazis. On a mop-up excursion across the border in Germany, for example, Pete and the Canadians learned of a German farmer who had been ruthless in his treatment of several Czech and Polish prisoners, including an 11-year-old Polish boy. On April 28, 1945, my dad recorded that “Pete paid an early morning visit to the erring farmer, and put him into a state of fright that he will remember as long as he remembers anything.”

Given the oppression suffered by the Dutch, it’s no wonder that when their Canadian liberators got to, say, Leeuwarden, a city of more than 100,000 people, the Canadians were surrounded by screaming children and teenagers throwing bouquets of tulips; and by young women who, clad in their spring dresses, hair flying, took the non-plussed Canadians in their arms, encouraging them to dance, to feast, to party in streets packed, day and night, with celebrating Netherlanders.

“At about noon the day after our arrival in Leeuwarden,” wrote my dad, “we rode away towards the east, and in a couple of hours reached a tiny village called Oldekerk. Here, too, there was a fiesta going on in honour of the liberation, and all afternoon and evening the grassy field where we harboured was full of admiring men and women. As in Leeuwarden, the girls here were lovely; half the men in the troop fell in love with somebody before the day was out.”

While the romance, as presented by the diary, is both sweeping and dream-like, it’s also humanized and anchored by the most meticulous and homey of details. “Towards supper-time,” wrote my dad, “I brought out a round of Dutch cheese that Fred Ringnalda had given me as a parting gift, and proceeded to cut a good-sized wedge out of it in the well-known Canadian manner. There were half a dozen girls crowding our picnic site and they all burst out laughing, took the cheese away from me and showed me how to shave a piece off, very thin, as the Dutch do.

“I couldn’t help admitting that they were right—the shavings seemed to have a more delicate flavour than a bigger piece.”

The diary describes the Dutch celebrants as “all but maniacal in their desire for whatever tobacco

the Canadians had to share,” and notes the capability of the young men and women to roll “an Oldekerk slim,” a cigarette “barely thicker than a toothpick,” but nonetheless significant to the v illage’s robust celebrations.

“Meanwhile, out on the road,” the diary continues, “the celebrating Dutchmen crowded around the armoured cars and climbed onto the sides, pleading for cigarettes— to the point where it was almost disastrous to give one away, in that the gift brought twenty more men clutching for the coveted tobacco.”

As the narrator of all this drama and history—and, in a sense, curator of the diary—I must pause for a moment to say that the reason for publishing the story now, during the spring of 2025, is that exactly 80 years have passed since the Dragoons, among other Canadians, rolled into the Netherlands; since my dad sat by Dutch roadsides and barns, or in the safety of his armoured car to pen the extraordinary diary that brings to life that final Canadian mission of the Second World War.

One of the diary’s most adamant and prevalent motifs, I must emphasize, was that the march into the Netherlands was a story not just of triumph and romance, but of caution and suspicion and fear. Pockets of Nazi soldiers still hid in the villages, or along the roads, determined to inflict a last crack of the whip on the allied enemies of the Reich.

In one village, the Germans piled tree trunks across the road. When my dad got out to begin clearing them, the road exploded within metres of him, and the air was full of lead. “I was lucky to escape back into the armoured car,” he wrote, “by pounding on the side door until my gunner, Braden, opened it and I dove inside.”

On the same day, the Canadians came to a gathering of Dutch women and children parading beneath a

Red Cross banner strung across the road. “We sent a scout forward, who came running back, head down, with word that behind every tree up ahead, a Jerry infantryman was waiting with a faustpatrone [a hand-held anti-armour weapon, capable of piercing an armoured car]. The Dutch villagers had been forced to parade beneath the Red Cross sign as a means of dissuading the Canadians from firing as we approached.”

At the town of Holten, due east of Amsterdam, Charlie Squadron encountered what the diary describes as “a pocket of fierce loyalists to the Reich,” eventually forcing them to raise the white flag of surrender on the village church tower.

“When our infantry brought back prisoners, we were surprised to discover they were just teenagers, paratroopers, who had fought like madmen, holding up the Canadian armoured car advance with dogged courage; one soldier cannot help admiring another, and I could hardly do less than admire such determination.”

It is not your average soldier who writes so appreciatively of the courage and persistence of his opponent. My dad, I hasten to add, was not an average soldier (one could ask, what soldier is?).

Back home in Canada, he was a poet, an opera-lover, a birdwatcher. He loved books (by the time he was 16, he had read every one of the approximately 300 novels in the Hespeler, Ont., library). A descendant of peace-loving Quakers, he wasn’t only non-violent, but almost pathologically non-competitive.