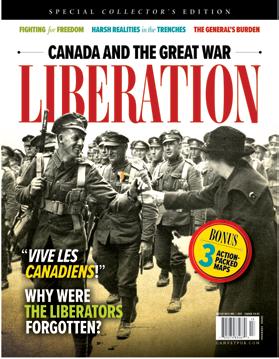

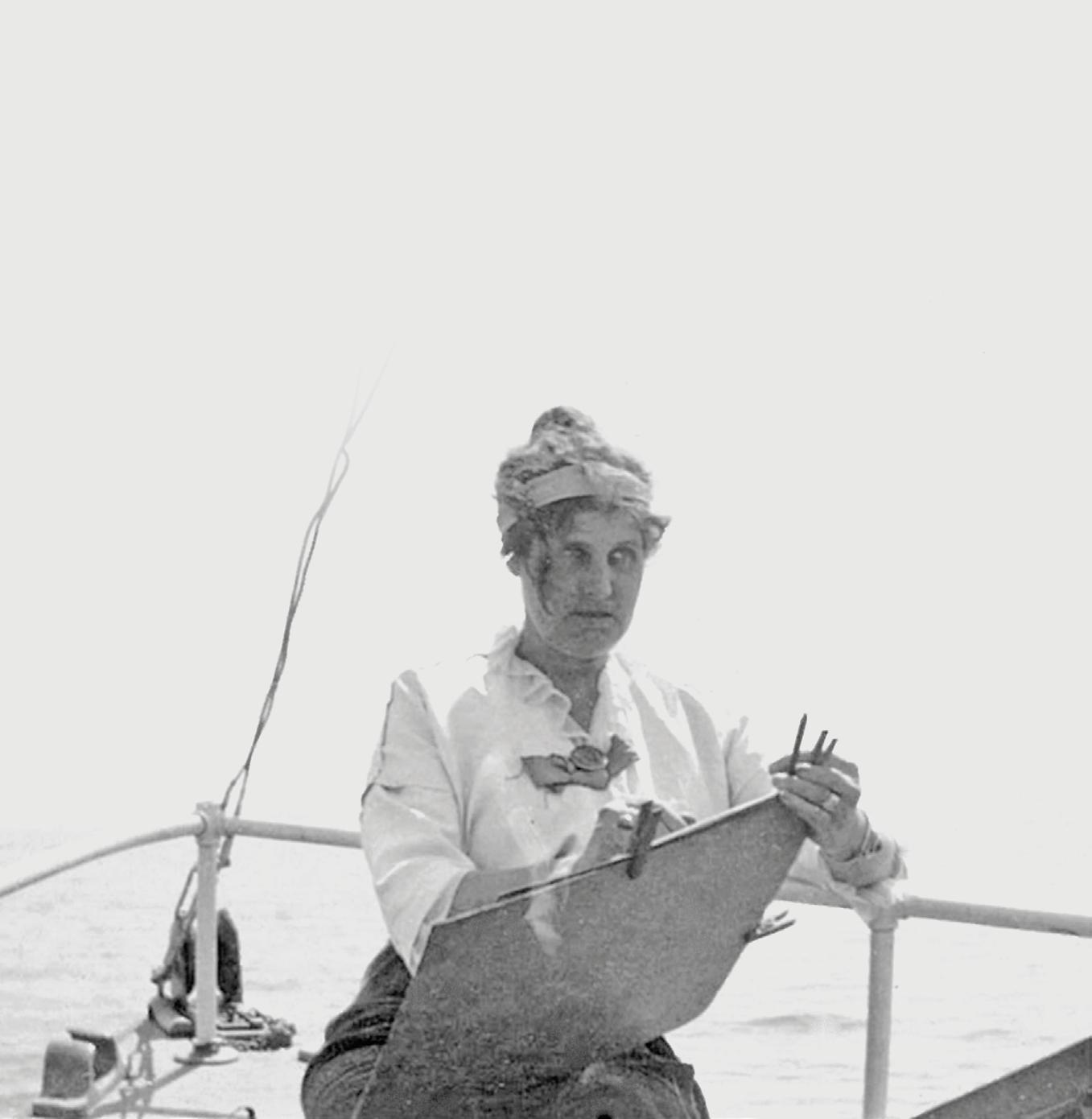

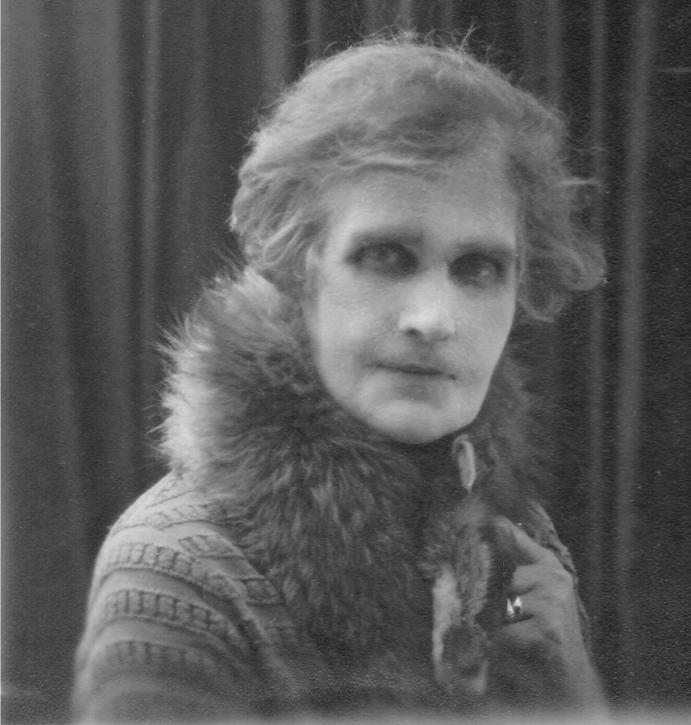

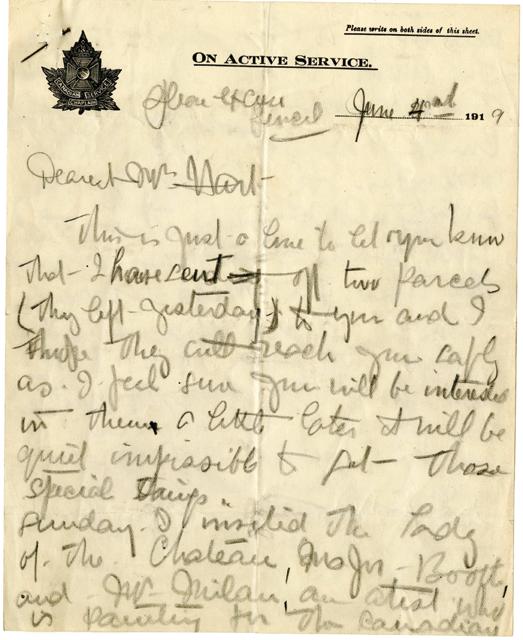

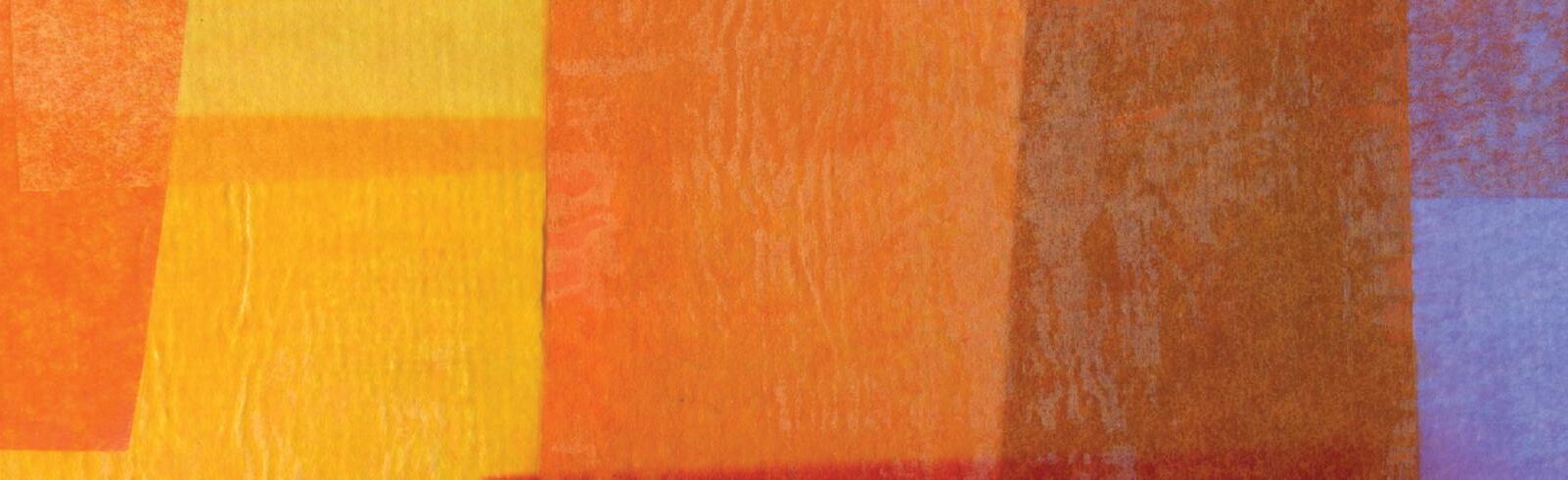

Regarded as Canada’s first female battlefield artist, Mary Riter Hamilton painted “Sanctuary Wood, Flanders” in 1920 during a postwar tour of the Western Front.

See page 52

Reflections on the country’s role in Afghanistan 10 years after it left

Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

28 IT TAKES A VILLAGE

The new Legion Veterans Village in Surrey, B.C., is offering unheralded opportunities for military health care

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

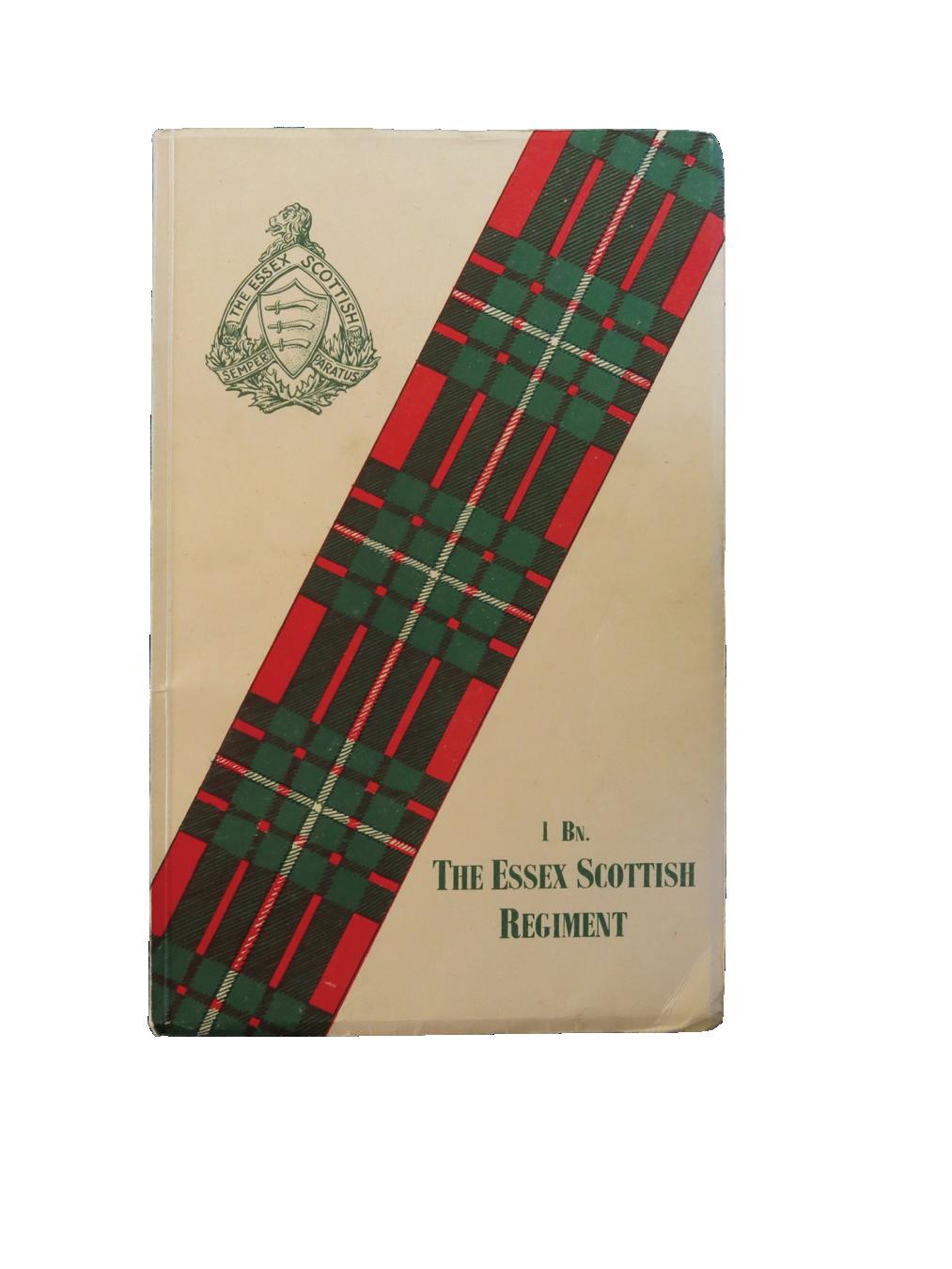

34 THE GHOSTS OF KENLEY

Reliving the Canadian connections to a critical Royal Air Force base Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

42 SECURITY SYSTEM

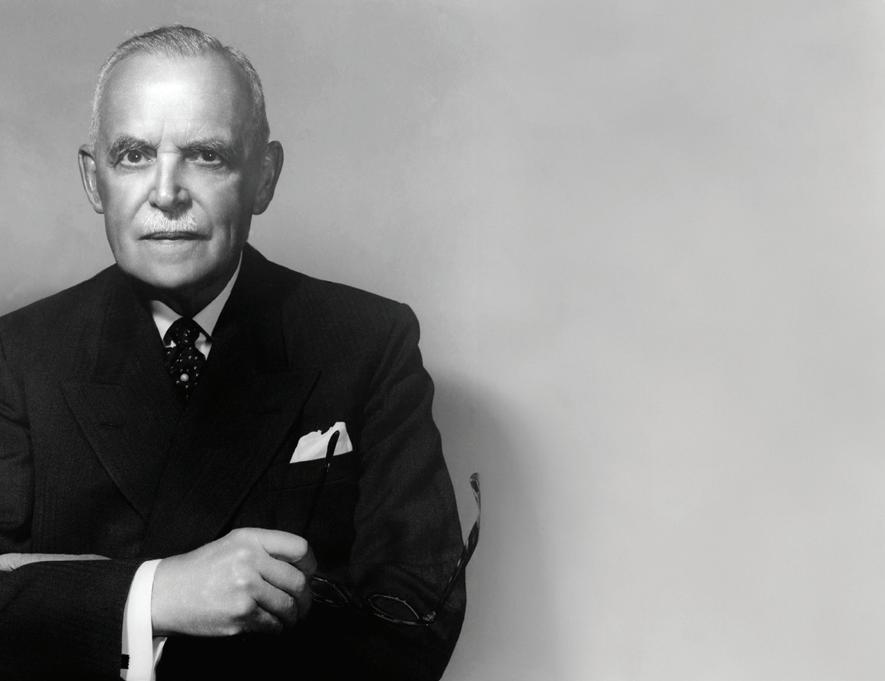

For 75 years, the North Atlantic Treaty Organization has worked to quell conflict By

John Boileau

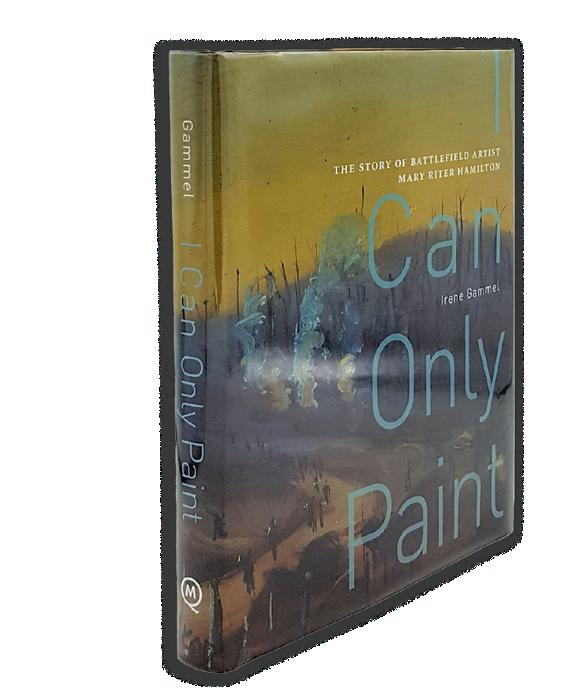

52 DRAWN TO WAR

The First World War art of Mary Riter Hamilton By Irene

Gammel

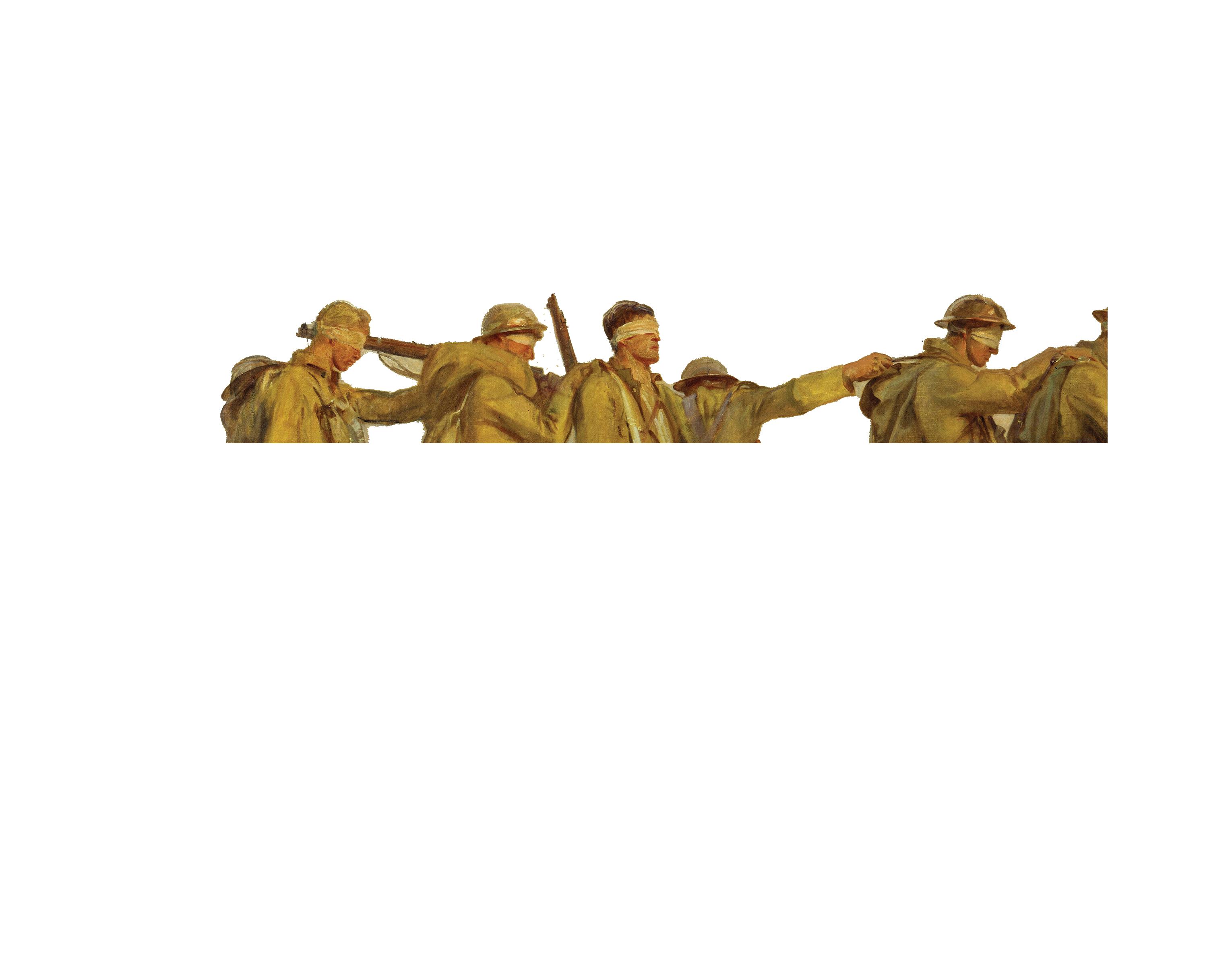

60 THE BLIND SIDE

How soldiers who suffered vision impairment in the Great War changed the outlook for their lot By Serge

Durflinger

Overgrown berms surround a Second World War blast pen at the dormant Royal Air Force base in Kenley, England. Stephen J. Thorne/LM

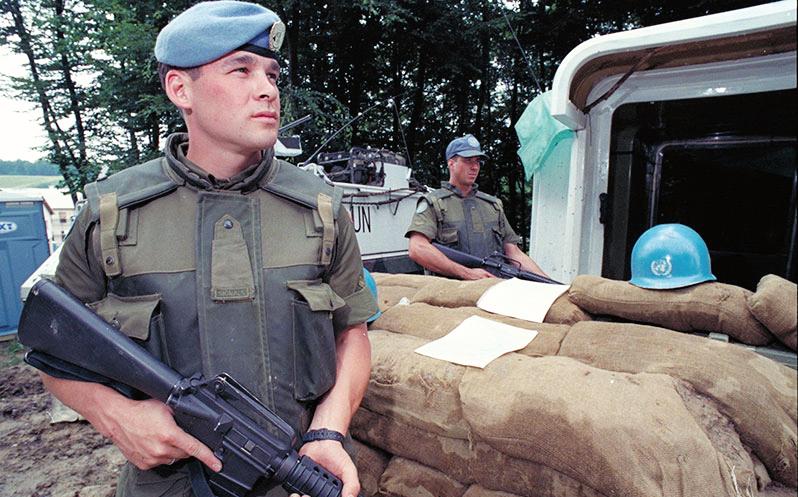

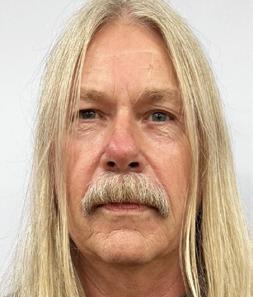

Members of the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment Battle Group, conduct a reconnaissance patrol in Afghanistan in 2003. The gunner, Sergeant James (Jimmy) MacNeil, was killed in 2010 during his fourth deployment to the country. Warrant Officer Mark Boychuck (second from left) died in 2019 at Canadian Forces Base Gagetown in New Brunswick. He had served three tours in Afghanistan and one in Bosnia. Stephen J. Thorne

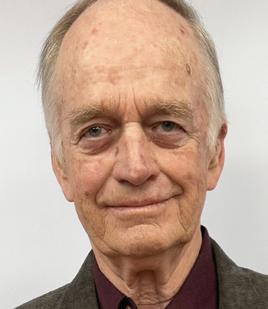

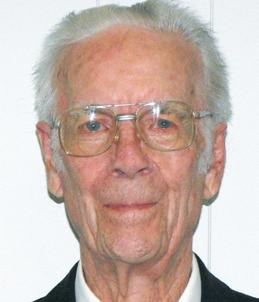

BOARD VICE-CHAIR Bruce Julian BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe DIRECTORS Tom Bursey, Steven Clark, Thomas Irvine, Berkley Lawrence, Sharon McKeown, Brian Weaver, Irit Weiser

Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Paige Jasmine Gilmar

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert

DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales

CANIK MARKETING SERVICES

TORONTO advertising@legionmagazine.com

DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS INC mmignardi@dvtail.com

OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER AND MARKETING CO-ORDINATOR

Dyann Bernard

WEB DESIGNER AND SOCIAL MEDIA CO-ORDINATOR

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2024. ISSN 1209-4331

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST.

FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Send new address and current address label. Or, new address and old address, plus all letters and numbers from top line of address label. If label unavailable, enclose member or subscription number. No change can be made without this number. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com. Allow eight weeks.

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of CCAB, a division of BPA International. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

“L

ooking for Canadian veterans.”

The request was simple enough.

Late this past November, the French Embassy in Canada issued a communique searching out Canadian veterans still living who took part in the liberation of France 80 years ago. “He could be eligible for the Legion of Honour, the highest national French distinction,” it continued.

IT’S HARD TO FATHOM THAT NO CANADIAN HAS ENGAGED IN ACTIONS WORTHY OF THE COUNTRY’S TOP MILITARY HONOUR IN NEARLY 80 YEARS.

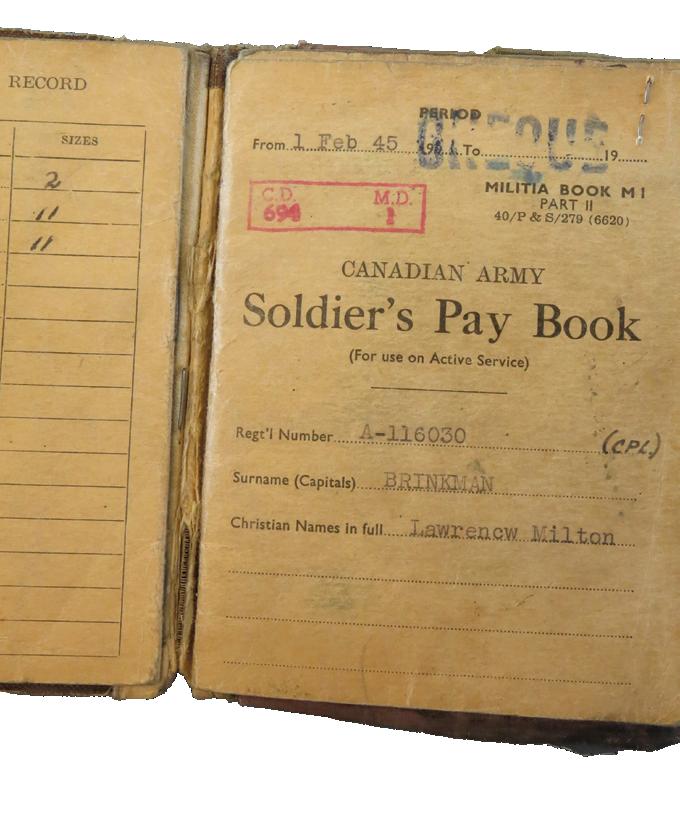

Weeks later, French Ambassador Michel Miraillet presented Second World War veteran Jim Spenst, 97, the decoration during a small ceremony in his hometown of Estevan in southern Saskatchewan. Spenst enlisted with the Royal Canadian Army Service Corps on Remembrance Day 1943 at just 17. He went overseas in June 1944 and helped transport materiel to troops in Belgium and France before returning to Canada in December 1945. “I went in a boy and came out a man,” said Spenst.

“This is a nice day for me, and it was an extraordinary opportunity,” said Miraillet after the presentation. “It’s very symbolic. The French have not forgotten what the Canadians did during the First World War or the Second World War.”

As France prepared to commemorate the 80th anniversary of D-Day, it was, and is, actively working to identify more veterans who qualify for the honour. The distinction cannot be awarded posthumously. During the last decade, nearly 1,300 Canadians have received the medal.

“I think that it’s tremendous for France to recognize the great work that our veterans do,” local Conservative MP Robert Kitchen told Discover Estevan following the ceremony.

Canada’s Victoria Cross, meanwhile, the country’s highest military decoration, has never been awarded—31 years after it was established in February 1993. And its British predecessor, created by Queen Victoria in 1856, was last earned by a Canadian, Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray, in August 1945. Still, nearly 100 Canadians received it. So, it’s hard to fathom that no Canadian has engaged in actions worthy of the country’s top military honour in nearly 80 years. Even more so when a foreign country is searching out the last living Canadians to have fought on its soil in the Second World War to grant them its highest commendation—no matter their sacrifice.

Legion Magazine has covered for years now the campaign to have Jess Larochelle’s October 2006 actions in Afghanistan, recognized with the awarding of the first Canadian VC. Although alone, severely wounded and under sustained enemy fire in an exposed position, he provided covering fire to protect the lives of many of his comrades.

Larochelle received the Star of Military Valour for his conduct. But despite an effort backed by a 15,000-name petition, the endorsements of at least three living VC recipients and several highprofile former Canadian soldiers to have the award upgraded, Lieutenant-Colonel Carl Gauthier, head of the military’s Directorate of Honours and Recognition, told Legion Magazine last year that a timelimit technicality on bravery decoration nominations means it will never happen. Larochelle died this past August.

Fortunately for living WW II vets, France is ensuring they know how much their service meant before it’s too late. L

On the wings of a burgeoning aviation culture of hinterland stick jockeys, airmail pilots and high-flying adventurers, the Royal Canadian Air Force emerges from 100 years of war and peace as a respected, if not feared, hunter, protector and humanitarian presence in troubled skies the world over. The fascinating story of the RCAF is one of passion, promise and perseverance. Now

find the argument for Canada to buy more weapons and increase spending on the war machine curious coming from some Legion Magazine contributors (“Eye on defence,” “Face to Face” and “Canada and the New Cold War,” January/ February). The wonky British subs Canada bought and spent millions on to manage two weeks of use in 2023 should be a sign that the country needs to rethink its strategy. The option of having nuclear-powered subs

I agree with Assistant Editor Michael A. Smith (“Face to face,” January/February). Yes, we do need nuclear submarines. My neighbour in Sooke, B.C., is an electrician on Canada’s current subs and tells me they are poor and outdated. Canada needs to go to nuclearpowered submarines for its next fleet of the vessels, full stop. I spent seven years in two separate stints posted to CFB Esquimalt. During the time, I had neighbours working on HMCS Victoria counting with their fingers the number of days, not months, they spent underwater. It’s disgusting!

MASTER CORPORAL KELLY CARTER RED DEER, ALTA.

with nukes aboard so that, should the mainland be obliterated, Canada could still do damage to the other side is addled logic.

Given the magazine’s coverage of sick and elderly veterans, its writers are surely aware that millions in Canada don’t have access to a family doctor. Why is that? Can Canada as a civilized country not train enough doctors? When my family moved to the country in 1974, we had the choice of three family doctors. There was also a post office,

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

There are several problems with Peggy Mason’s argument about nuclear-powered submarines. First,

bus service, railway, four gas pumps and general stores, even a laundromat in our community. Plus, a public school, three working sawmills within 24 kilometres, a craft store and more. All now gone.

The country has progressed into a backwater where people have the option of booking to see a nurse practitioner once a week by appointment. My point is simply: spend it on what we need and drop out of the war machine.

PAUL WHITTAKER GILMOUR, ONT.

it seems she is bent on appeasing the Chinese, ignoring the main reason for the subs, Canada’s Arctic sovereignty. Second, she talks about the cost, disregarding the fact that our defence is shamefully underfunded and a budget increase is needed whether we get the subs or not.

PIERRE ST. AMANT

LEFAIVRE, ONT.

I would like to suggest Legion Magazine readers send emails to bill.blair@parl.gc.ca or postage free letters to “Hon. Bill Blair, PC, MP, Defence Minister, House of Commons, Ottawa,” in support of Indigenous war hero Tommy Prince being promoted posthumously to Lieutenant (“O Canada,” January/February). He was denied that rank three times because of his heritage. He was entitled to that field promotion, so Canada should give it to him now.

JOE KOOPMANS

EDMONTON

I just read the article “Should Canada repatriate its war dead?” (“Face to Face, November/ December 2023). To my utter surprise, writer Paige Jasmine Gilmar referenced the lost love of her grandmother, Lois Mae’s, “soon to be husband,” George Henry Lloyd from Wingham, Ont. He was my uncle. My grandma, Minnie, his mother, took his death especially hard and yearned to visit his grave in Harrowgate, England. My grandparents finally made the trip across the Atlantic in the early 1950s. I had the privilege to get there twice, as well. I was

For almost four years, the forces of Nazi Germany occupied Europe while the Allies fought in Africa and the Pacific. But on the night of July 9-10, 1943, the Canadians, fighting as an independent unit for the first time, at the insistence of Prime Minister Mackenzie King and the Canadian military headquarters in Britain, slogged into the interior of Axis-occupied Sicily as part of Operation Husky. It was the first stage of the Allied liberation of Europe.

not aware of Lloyd’s fiancé until I read the article. I can’t explain why, but this revelation makes me feel so relieved and happy that he had this connection. It must have been a huge comfort to him knowing he had her in his life, imagining his future with her while in training. Your article conjured up many emotions. I have profound respect for the men in my family who served and sacrificed so much for us.

JOHN WELWOOD KINCARDINE, ONT.

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /newsletter-signup

Six weeks later, the fighting in Sicily ended, on Aug. 17—one month, one week and one day after it began. Fascist Italian troops and the forces of Nazi Germany were eradicated in Sicily, Mediterranean transit routes were opened to Allied merchant ships for the first time since 1941, and mainland Italy became the Allies’ next objective. Learn more about Operation Husky with Legion Magazine’s new five-part interactive website. Scroll through maps, images and primary sources that tell the story of the events that changed the tide of war in Europe and cemented Canada’s role in it. Check it out at https://legionmagazine. com/features/operation-husky/.

There’s an accompanying video, too, narrated by Canadian survival expert Les Stroud, that relates Canada’s part in Sicily. Watch it at www.youtube.com/ LegionMagazine. L

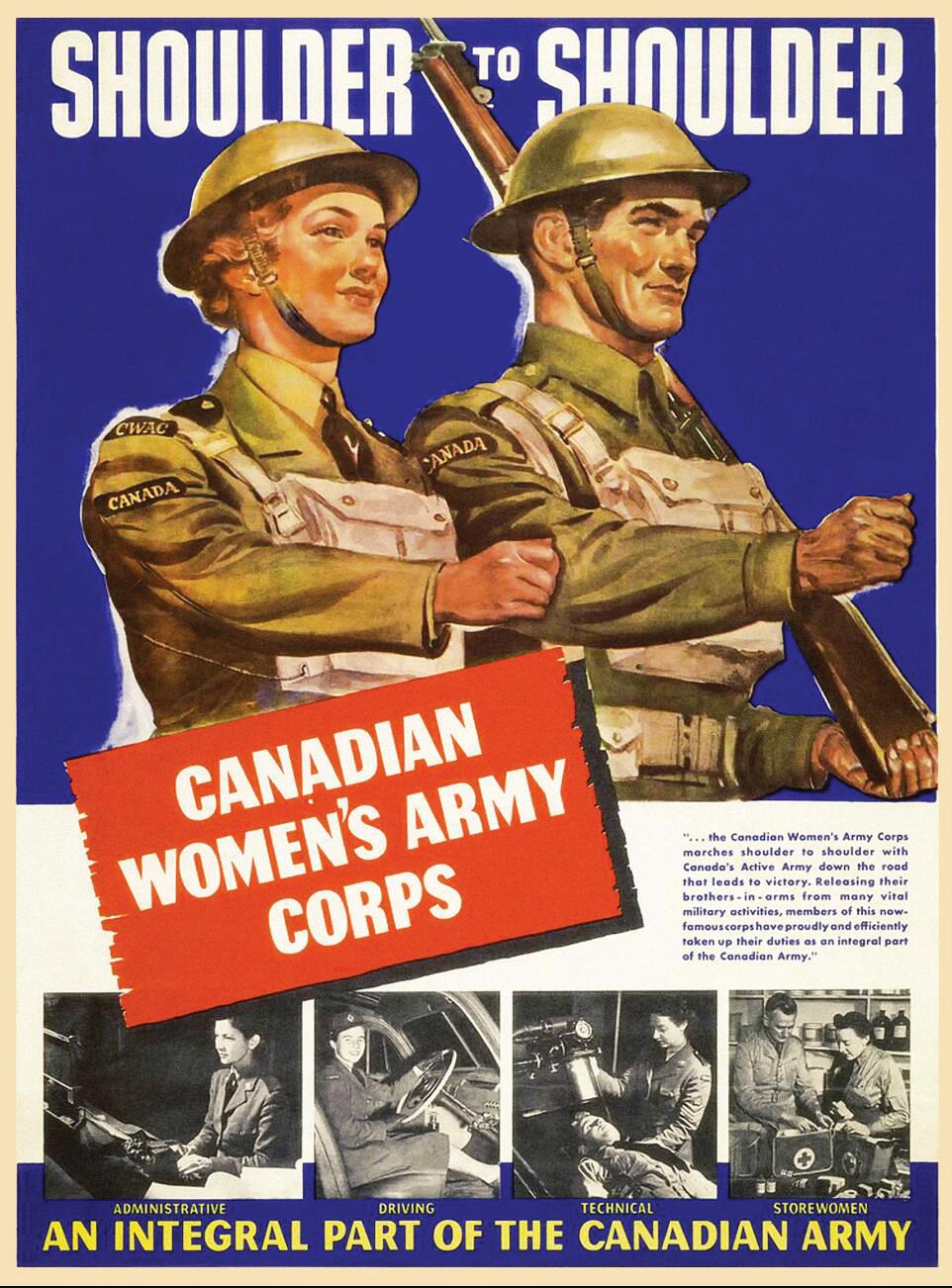

1 March 1942

The Canadian Women’s Army Corps is granted full army status and becomes an integral part of the Canadian Militia. Prior to this, only nursing sisters were admitted into the country’s armed forces.

2 March 2011

HMCS Charlottetown heads for Libya to provide humanitarian assistance amid civil war.

3 March 1838

A small British force led by Capt. George Browne intercepts and repulses American invaders near Pelee Island, Upper Canada.

8 March 2001

The Royal Canadian Navy authorizes women to serve on submarines.

9 March 1925

The first Royal Air Force operation conducted independently of the British Army or Royal Navy is led by Wing Cmdr. Richard Pink.

10 March 1944

HMC ships St. Laurent, Swansea and Owen Sound, along with HMS Forester, destroy U-845 in the North Atlantic.

12 March 1964

5 March 1945

Some 700 Allied bombers destroy Chemnitz, Germany.

7 March 1936

Nazi Germany sends troops into the Rhineland, bordering Belgium, violating the Treaty of Versailles.

Canada commits peacekeepers to the United Nations mission in Cyprus; more than 25,000 personnel serve there over the next 29 years.

13 March 1951

18 March 1885

Métis at Batoche, Sask., are warned that Canadian soldiers are on their way to arrest Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont.

19 March 1964

Sgt.-Maj. Walter Leja receives the George Medal for bravery in dismantling FLQ bombs in Montreal.

23 March 1965

Fifteen RCAF aircrew are killed when their Argus patrol plane crashes during a night exercise off Puerto Rico.

24 March 1975

The beaver becomes an official symbol of Canada.

27 March 1918

Wounded several times in an aerial dogfight in which he shot down three enemy planes, Alan Arnett McLeod crash-lands in no man’s land. He is awarded the Victoria Cross.

Communist forces begin a withdrawal across all fronts in the Korean War.

14 March 1984

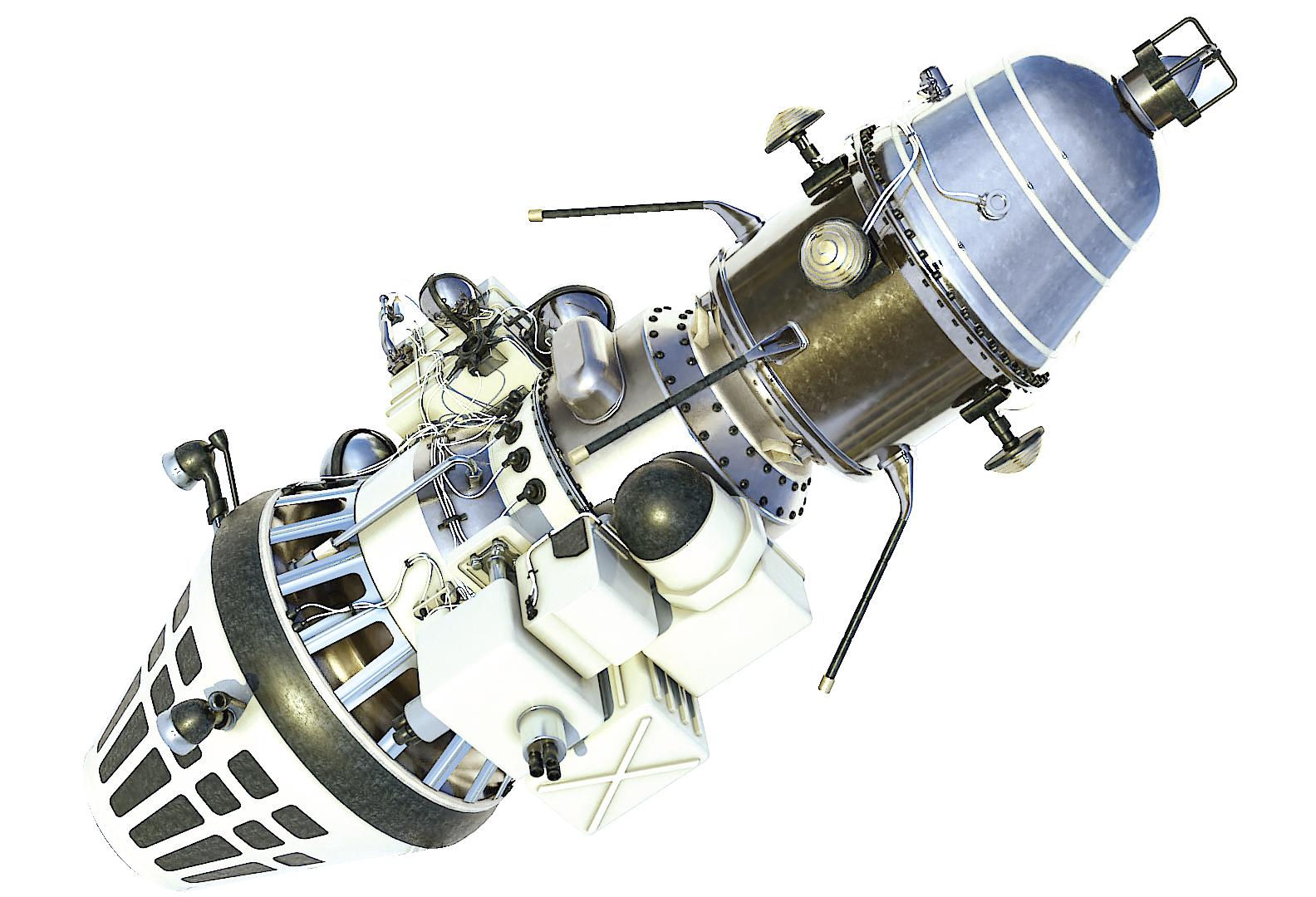

NASA announces Marc Garneau as one of seven astronauts on space shuttle Challenger Later that year Garneau became the first Canadian to go to space.

15 March 1990

RCMP officer Baltej Singh Dhillon becomes the first officer to be allowed to wear a turban in uniform.

1 April 1924

The Royal Canadian Air Force is established.

2 April 1885

Cree warriors, led by war chief Wandering Spirit, kill nine settlers at Frog Lake as part of the NorthWest Resistance in what was then the District of Saskatchewan.

3 April 1945

The First Canadian Army captures the German town of Zevenaar.

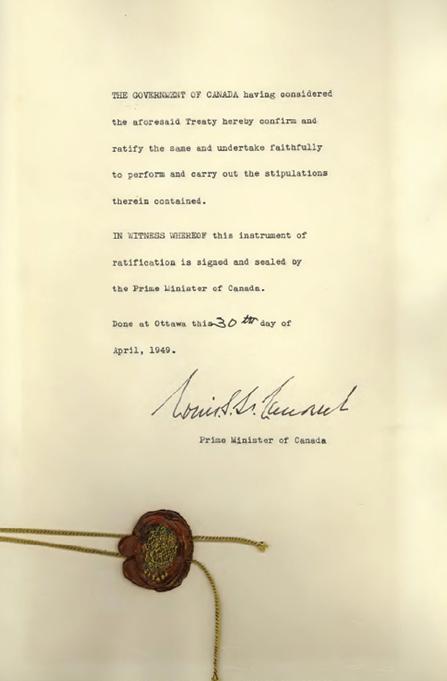

4 April 1949

The North Atlantic Treaty, which forms the legal basis of NATO, is signed by member countries. (Also see “Security system” on page 42.)

7 April 1991

HMC ships Athabaskan, Protecteur and Terra Nova return home from service in the Persian Gulf War.

10 April 1945

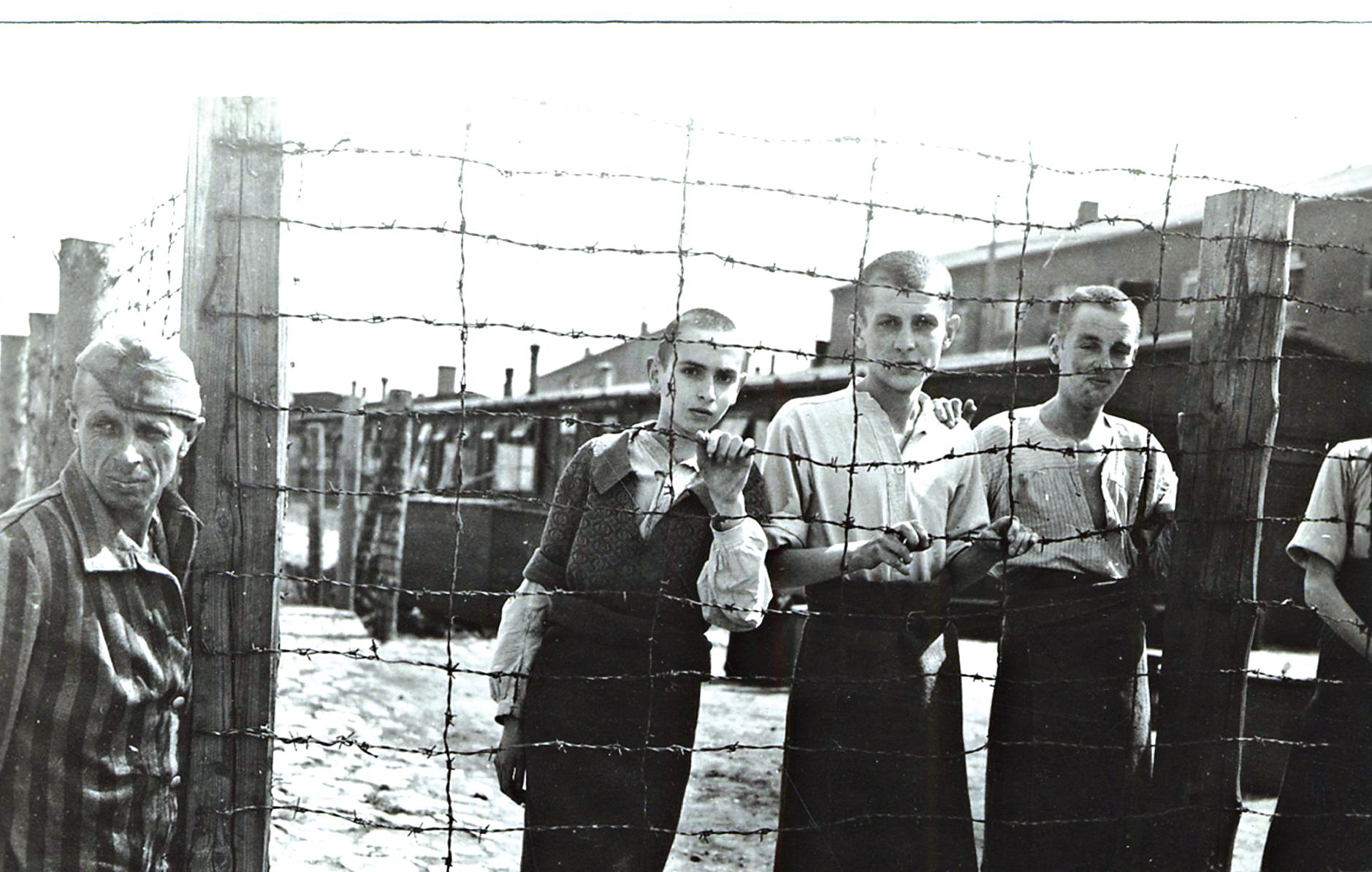

The Nazi concentration camp of Buchenwald near Weimar, Germany, is liberated by U.S. troops.

18 April 1943

No. 14 Squadron, RCAF, supports the U.S. Eleventh Air Force bombing Japanese installations on Kiska in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands.

20 April 1953

Prisoners of war are exchanged between North Korean and United Nations forces at Panmunjom as Korean War fighting grinds to a halt.

13 April 2011

Under a hail of bullets, Cpl. Brian Belanger drags a wounded Afghan soldier to cover and administers first aid after an ambush in Afghanistan. He is awarded the Medal of Military Valour.

16 April 1945

Canadian minesweeper Esquimalt is torpedoed by German submarine U-190 off Halifax and sinks before it can send a distress signal; 44 die, while survivors are rescued by HMCS Sarnia

21 April 1997

The CAF launches Operation Assistance in response to flooding along Manitoba’s Red River.

24 April 1992

The United Nations establishes a peacekeeping mission to Somalia in which Canada would infamously participate.

25 April 1915

Under heavy fire at Saint-Julien, Belgium, Capt. Francis Scrimger protects a wounded officer with his own body. He receives a Victoria Cross for his action.

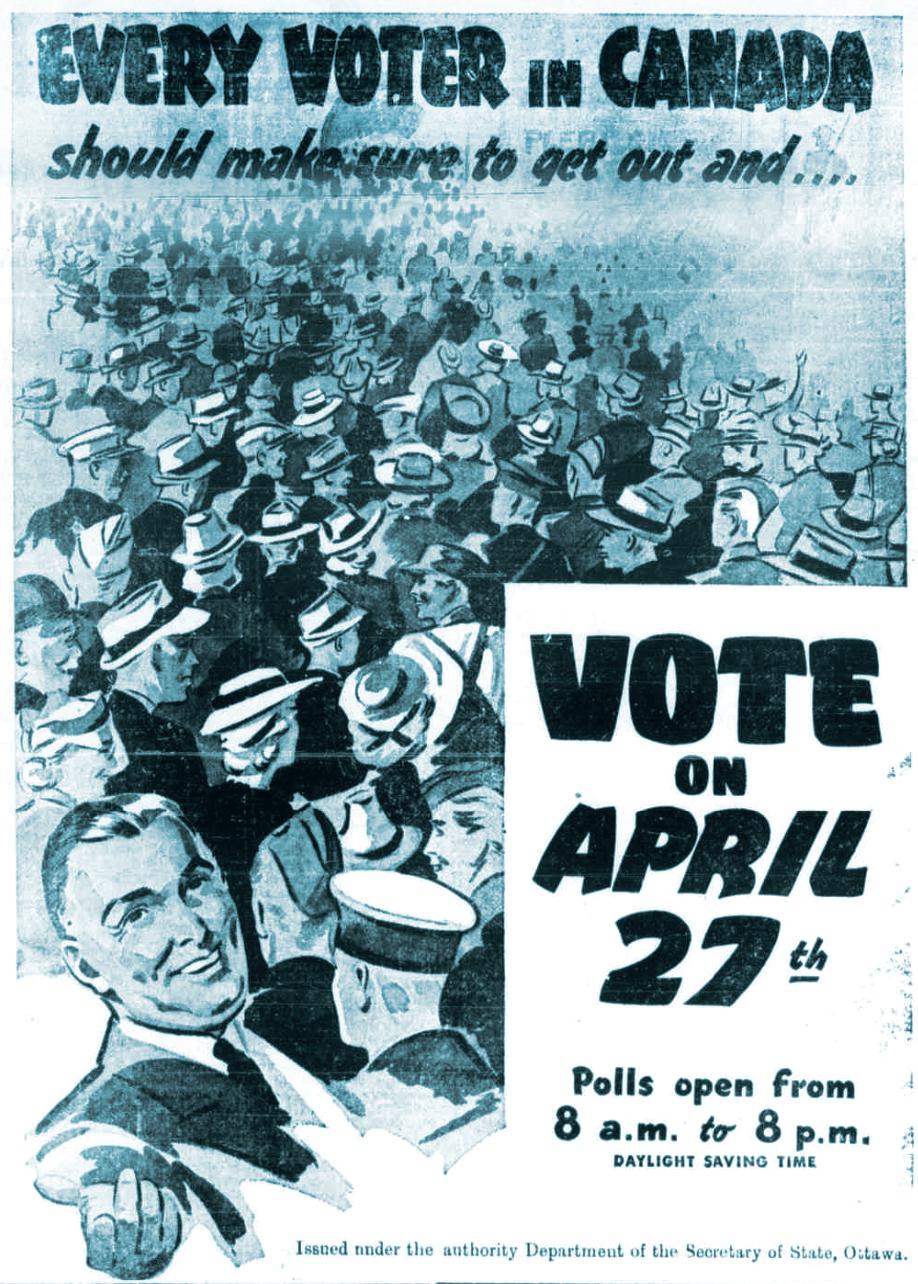

27 April 1942

Quebec votes “Non” in a national conscription plebiscite.

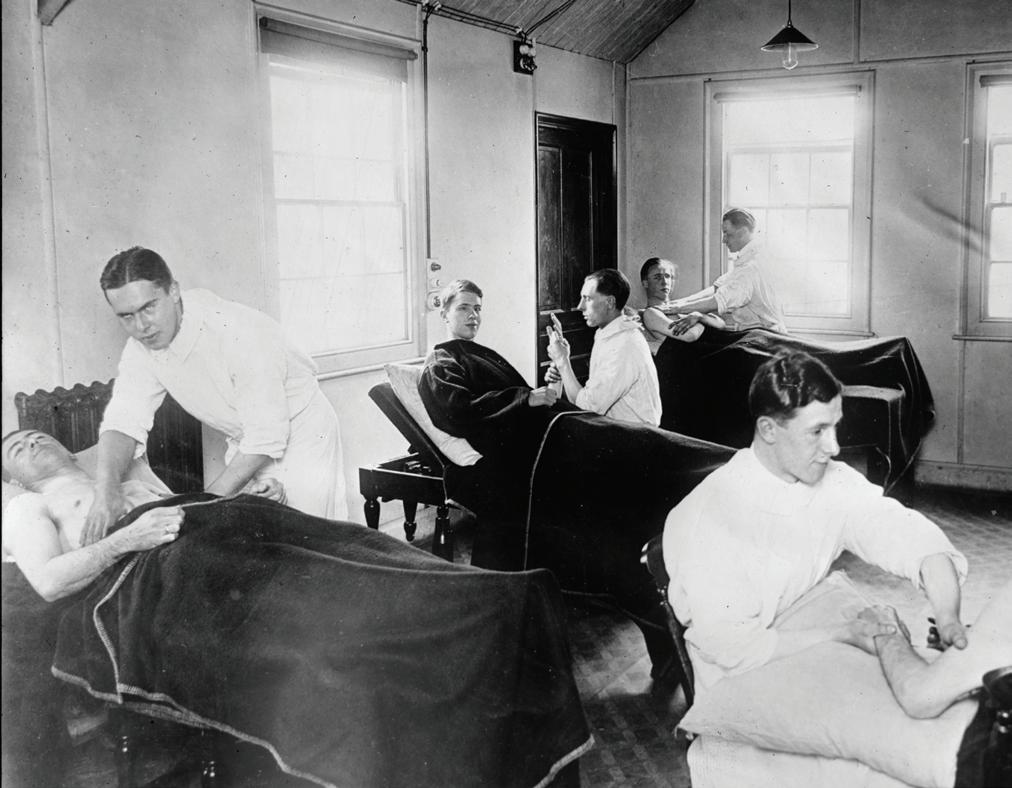

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

Hallucinogens such as ketamine appear to help address PTSD, but Veterans Affairs Canada won’t fund clinical trials to test them

Two hundred and fifty per cent. That’s how much higher the rate of suicide for male Canadian veterans under the age of 25 is than for the general population according to Veterans Affairs Canada. It’s a dramatic statistic that suggests a dramatic new approach to treatment might be needed.

Other veteran demographics don’t fare much better, with suicide among female veterans 200 per cent higher than the general population and male veterans over age 25 at 50 per cent higher. The situation is attributed to high frequencies of post-traumatic stress disorder and operational stress injuries (OSIs), and traditional therapeutic techniques have done little to counter the problem. Indeed, the remission rate for PTSD and OSIs is stagnant at 30-40 per cent. Still, Veterans Affairs Canada sticks by the typical psychotherapeutic approaches as the be-all and end-all, the infallible panacea until something conclusively better shows up.

But the something better VAC has been waiting for may have already arrived; in fact, it has been an option for years. The use of

medically prescribed psychedelic drugs for severe, treatmentresistant PTSD or OSIs are yielding promising results in preliminary studies. So much so, that in a November 2023 report on the topic, the Senate subcommittee on veterans affairs recommended that VAC immediately implement a robust research program on psychedelics to “ensure…that those veterans most likely to benefit from it are given access to treatment with the best scientific support available.”

Introduced in the 1960s, the psychedelic ketamine allows people to feel detached from their body or environment, while also relieving pain. Used widely in pediatrics, emergency medicine and intensive care, ketamine has been named an essential medicine by the World Health Organization for its versatility and high-ranking safety profile. When ketamine was shown to hold rapid antidepressant effects in a 2000 study, it kickstarted what Canada’s largest ketamine provider, the Canadian Centre for Psychedelic Healing, called the “psychedelic renaissance.”

“I did a ketamine treatment with a patient, and in one treatment, 70 per cent of his symptoms went away. And within two treatments, he had no symptoms,” said Dr. Mario Nucci, the centre’s founder. “I just can’t do that with any other form of care.”

Ketamine hacks into the areas of the brain responsible for thoughts and feelings while in a resting state and rewires unconscious and uncontrollable thinking patterns. It helps create new and additional connections in the brain.

Randomized control trials have shown that the drug provides benefits for chronic PTSD, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social and generalized anxiety disorders, chronic pain, treatmentresistant depression, addiction and eating disorders. With success rates as high as 70-80 per cent, the Psychedelic Healing centre suggests that ketamine is a therapeutic goldmine for OSIs and has even launched its own pre-pilot study on PTSD remission rates in Canadian veterans using ketamine therapy. “Veterans don’t allow for chinks in their armour,” said Ian Ruberry, the centre’s CEO. “It takes the ketamine to let that guard down so that they can feel safe.”

Canadian veteran Corey Pettipas is an activist for ketamine therapy. He served nearly 13 years with the Royal Canadian Navy, starting in April 2008, first as a naval combat information operator and then as an electrical technician. From the Gaddafi uprising in Libya to South American drug busts, Pettipas was unnerved by the moral mess that often came with intelligence operations. He was medically discharged with PTSD in 2021.

“My PTSD is really complicated because it has a lot to do with information and seeing how people used the information we had in an abusive way, how it needlessly put lives at risk,” Pettipas told Legion Magazine. Discussions

about suicide were frequent on his ship, especially after one of his shipmates overdosed.

After his release, Pettipas experienced a number of therapies and suffered debilitating side-effects from many of the associated drugs. He also felt as though he was being chastised and shamed during some psychotherapy sessions. But after his service dog was injured and a friend died of a fentanyl overdose, Pettipas was finally prescribed something that actually helped: ketamine. “I was shown how beautiful I was in those first sessions,” he said. “I was handed my autonomy on a golden platter.”

Even in the face of scientific studies supporting its effectiveness, VAC maintains that psychedelic psychiatry isn’t an “evidencebased practice.” And Alexandra Heber, its chief psychiatrist, noted

in the Senate report that “based on our review of the literature and deliverations...[we] do not recommend the use of psychedelics or psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy at this time.” VAC, meanwhile, did not immediately respond to a Legion Magazine request for further comment.

The Senate report said VAC was “ill-suited to the leadership role it should be taking,” stating that its inability to adopt new practices such as psychedelic therapy is unnecessarily putting lives at risk in favour of a wait-and-see approach. VAC’s inaction is particularly noteworthy when both the U.S. and Australia have funded studies on the clinical usage of psychedelics.

Pettipas’ situation is a direct result of VAC’s stance. Its policy only covers the costs of ketamine therapy for treatment-resistant depression and it won’t cover

psychotherapy that takes place during ketamine treatment or if the treatment is prescribed for conditions such as PTSD. VAC has deemed Pettipas ineligible under both criteria. “They are adopting a wait-and-see policy because being progressive costs money,” said Pettipas.

His wellness has been impacted by his ongoing struggle to have VAC cover the cost of his ketamine therapy. He said the organization owes him thousands of dollars and he’s prepared to take VAC to court to recoup his expenses and have the treatment recognized for his condition.

“I sacrificed so much for my country that I can sacrifice myself now,” said Pettipas. “To prop this door open with my heart and soul so other veterans can get this psychedelic therapy that’s going to save their lives.” L

“When our brother passed away, we reached out to Ultramatic for advice on reselling his Ultramatic twin bed. [Beds still working after 40 years!]

Maria answered our call. She suggested we consider donating the bed to a Veteran. So she kindly researched the contact information for several Legion branches in our area of BC.

Since our family members have a long history of military service and Legion membership, we were immediately in support of this idea.

We are very impressed with the culture of care at Ultramatic and their willingness to go the extra distance to support not only their customers but also Veterans in need.”

OnApril 22, 1915, Canadian and Algerian troops holding the line on the Ypres Salient watched as an ominous yellow-green cloud rose from the opposing German trenches and, carried by a light northeast wind, approached low and slow.

The cloud was, in fact, more than 160 tonnes of poisonous chlorine gas and as it rolled over the French colonials on the Canadians’ left flank, the Algerian soldiers began choking and gasping for air. Some turned and ran, but the gas followed them. The nearest Algerians made for the Canadian trenches across the road.

“Our trenches were shortly filled with them crowding in from out left,” said Lieutenant-Colonel

Ian Sinclair of the 13th (Royal Highlanders of Canada) Battalion. “They were mostly blind and choking to death, and as fast as they died were just heaved behind the trench.”

The attack during the Second Battle of Ypres—the first successful incidence of modern chemical warfare—had the desired effect, opening a 6.5-kilometre gap in the Allied line, which the Canadians promptly filled as best they could. But the Germans were unprepared for such success and their advance stopped short.

Two days later, it was the Canadians’ turn as a six-metrehigh wall of gas swept over their trenches north of the Belgian trade centre that had become a

roadblock to the German advance to the sea. The town is known today by the Flemish Ieper (EE-per).

“The Canadians…got badly gassed,” recalled Bert Newman of the Royal Army Medical Corps. “In the end you could see all these poor chaps laying on the Menin Road, gasping for breath.”

In their first two weeks of fighting around Ypres, the Canadians suffered some 6,000 casualties, a third of the division. A thousand lay dead on the battlefield, many of them gas victims.

“On the front field one can see the dead lying here and there, and in places where an assault has been they lie very thick on the front slopes of the German trenches,” Canadian LieutenantColonel John McRae wrote less than two weeks before he authored the poem, “In Flanders Fields.”

Gas attacks directly killed or wounded nearly 1.3 million soldiers in the First World War.

Fritz Haber, the German scientist who came up with the diabolical weapon, is a study in contradiction, a Jew who converted to Christianity in 1892 to secure his

> Check out the Front lines podcast series! Go to legionmagazine.com/frontlines

career, whose work not only caused misery and death to untold numbers of people in two world wars, but also saved—and continues to save—countless millions. A scientific institute in Israel bears his name.

In 1918, three years after his weapon was introduced on the battlefield at Ypres, Haber was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for developing the HaberBosch process, a method of synthesizing ammonia from nitrogen and hydrogen that remains fundamental to the large-scale synthesis of fertilizers—and explosives.

Developed with German chemist and engineer Carl Bosch, Hader’s fertilizer process proved a milestone in the annals of industrial chemistry. The production of nitrogen-based products such as fertilizer and chemical feedstocks, previously dependent on extracting ammonia from limited natural deposits, now became possible using an easily available, abundant base—atmospheric nitrogen.

The ability to produce far larger quantities of nitrogen-based fertilizers in turn supported much greater agricultural yields. Today, the annual world production of synthetic nitrogen fertilizer based on the Haber-Bosch process exceeds 100 million tonnes and the food base of half the world’s population depends on it.

Yet Haber was a fanatical nationalist whose chemical weapons development is said to have contributed to the May 1915 suicide of his first wife, trailblazing scientist and women’s rights activist Clara Immerwahr.

He continued working on chemical weapons even after the 1918 armistice. Two of his children killed themselves after WW II, before which Zyklon A, a pesticide developed at Haber’s institute, spawned Zyklon B, the chemical the Nazis used to exterminate more than a million Jews and other “undesirables” in the 1940s.

In a not-so-improbable twist of fate, several members of his extended family died in Nazi concentration camps.

Despite his contributions to the German cause, his Jewish ancestry caught up with him and, after 1933, Haber lived out his life in exile.

Haber once said, “during peacetime a scientist belongs to the world, but during wartime he belongs to his country.” A veteran of mandatory service 25 years earlier, Haber rejoined the military at the outbreak of WW I. He was promoted to captain and appointed head of the war ministry’s chemistry section.

He immediately assembled a team of more than 150 scientists and 1,300 technical personnel. A special gas-warfare troop was formed (Pioneer Regiments 35 and 36) under the command of Otto Peterson. Haber and Friedrich Kerschbaum served as advisers. Haber recruited physicists, chemists and other scientists to the cause.

Future Nobel laureates James Franck, Gustav Hertz (both in physics) and Otto Hahn (chemistry) served as gas troops in Haber’s unit. Haber seized on chlorine gas largely because it was heavy and settled downward. His teams also developed other deadly chemicals for use in trench warfare, including mustard gas.

Haber was on hand when the chlorine was released outside Ypres. He defended the weapon against accusations that it was inhumane, saying that death was death, regardless of how it was inflicted.

In his studies of the weapon’s effects, Haber noted that exposure to a low concentration for a long time often had the same effect— death—as exposure to a high concentration for a short time. He formulated a simple mathematical relationship between the gas concentration and the necessary exposure time. This relationship became known as Haber’s rule.

Haber died in January 1934, at just 65 years old. He has remained the object of much criticism from the science community for his involvement in developing chemical weapons.

Yet in 1981, the Minerva Foundation of the Max Planck Society and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem established the Fritz Haber Research Center for Molecular Dynamics, based at the Institute of Chemistry of the Hebrew University. Its purpose is the promotion of Israeli-German scientific collaboration in the field of molecular dynamics. The centre also houses the Fritz Haber Library. L

By David J. Bercuson

While everyday Canadians are otherwise preoccupied, the country’s navy is

Last fall, Vice-Admiral Angus Topshee, commander of the Royal Canadian Navy, released a YouTube video warning that the navy is in a critical state with old ships and a serious shortage of sailors to operate them. He also told a defence leadership symposium that the navy “could fail to meet readiness commitments.”

Topshee’s message can’t be a surprise to anyone who has watched the decline of the RCN during the last two decades. For a nation as dependent as Canada is on maritime trade—at least 20 per cent of the country’s $757.4 billion in exports travel by sea—the navy’s collection of small-but-highly-capable modern Halifax-class frigates, old-but-still-functioning command

destroyers, Kingston-class coastal defence vessels, obsolete Britishbuilt, diesel-electric submarines, and oiler/replenishment vessels was a minimum requirement. Today, that minimum can’t be reached. And it won’t be for at least another decade, if not longer, based on the current plans for upgrades and replacements.

The frigates, while trusty, are now out-of-date, as are the Kingston-class vessels. Plus, there’s currently only one oiler/replenishment ship, a converted merchant that’s barred from any conflict zone; the submarines are barely functioning, having tallied just 228 sea days combined since 2019, and while there are two new Arctic offshore patrol vessels in service, they can’t operate in the winter

and they have already encountered problems with engine-cooling and drinking-water systems. On top of the equipment shortcomings, the navy is 1,200 personnel short of requirement, with vacancy rates in some positions above 20 per cent.

It’s bold for Admiral Topshee to tell the public how bad the situation is. But it may be worse: none of the projected replacement vessels— two new oiler/replenishment ships and 15 surface combatant vessels, are even being built yet. And while the navy is pushing for new submarines, there seems to be no plan for acquiring them, or ensuring that they can operate under ice—a critical function for working in the Arctic. Canada’s navy is falling to pieces. And nothing but money—boatloads of it—can save it.

Canadians can blame the country’s sclerotic military procurement program for the problem. But even if that mysterious witches’ brew of a challenge

was solved, the basic issue would remain. For decades, Canada has consistently prioritized social welfare programs, such as dental and pharma care, over defence. Indeed, national security isn’t treated with any urgency. In fact, the defence budget is slated for a nearly $1-billion cut.

Canadians choose every day to live in this wonderful country, but the politicians they vote for don’t spend as much as they could on defence and all three services suffer the consequences. So, why not let it all go, save some money and nestle under the tender wings of the United States?

The Americans fund defence at a far greater rate anyway.

A fine idea in theory, but perhaps not in execution. In a Wall Street Journal article published last December with the headline “The U.S. Can Afford A Bigger Military. We Just Can’t Build It,”

Greg Ip argued, in a nutshell, that China can build ships far more quickly than the Americans.

“In terms of industrial competition and ship building, China is where the U.S. was in the early stages of World War II…we just don’t have the industrial capacity to build warships…in large numbers very fast,” Ip was told by Eric Labs, a navy analyst for the U.S. Congressional Budget Office.

What that means for Canada is simple. Add Canada’s Pacific, Atlantic and Arctic coasts—combined, the longest coastline in the world—to the U.S. Navy’s areas of responsibility and its capacity

to watch, guard and defend would shrink its overall ability dramatically. And that’s not even accounting for the U.S. Navy’s current global commitments. It would get stretched very thin very fast, particularly when China is outbuilding the U.S. every year.

Should Canadians not shoulder a reasonable share of responsibility for the defence of the country’s own waters? Does Canada not need to contribute to guarding freedom on the seas in troubled parts of the globe? The answer is simple. The country needs to prioritize the welfare state of its navy. L

STORY

AND PHOTOGRAPHY

BY STEPHEN J. THORNE

Members of the 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Battle Group land in the embattled region of Tora Bora, Afghanistan, on May 4, 2002, just metres from the spot where Osama bin Laden was last confirmed alive by Westerners before he was killed by a U.S. Navy SEAL team in May 2011.

OOver the course of three Canadian army tours in their parched and war-ravaged homeland, Alex Watson came to know and respect the longsuffering Afghan people for their courage, resilience, devotion and unfailing courtesy.

As a CiMiC (civilian-military cooperation) officer, Watson became intimately acquainted with the citizens and culture Canadian troops were sent to protect.

Ten years after Canada withdrew its troops from Afghanistan, with the country now in the hands of the Taliban and 20 years of progressive reforms gone in a virtual instant, Watson’s reflections over a series of interviews are poignant reminders of the conflicting legacies left by Canada’s longest war.

In Kandahar in 2002, he was a young captain with the 3rd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry Battle Group. He was among the first Canadians charged with the task of reaching out to Afghan villagers, fostering trust and cultivating a network of informal allies, not to mention alert eyes and ears.

The relationships he developed were unique.

“I loved it,” he told Legion Magazine. “There is not a single place in the world where I would rather have been doing my job.

NOT A SINGLE AFGHAN, IT SEEMED, WAS IMMUNE TO WAR’S IMPACT OR HAD ESCAPED THE

.

“I view it as nothing less than a privilege that I got to do the job that I did in Afghanistan, to meet the Afghans that I met—some of whom are lifetime friends—and, the biggest privilege of all, to command Canadian soldiers in combat.”

Afghans were entering their third decade of war at the time, having survived the 1979 Soviet invasion and almost 10 years of internal strife that followed. After the Soviets left, the country was gripped by a series of civil wars that ended with the Taliban, who ultimately opened Afghanistan’s borders to militant leader Osama bin Laden and his al-Qaida terrorists-in-training.

“The past quarter century devastated this country more than any other on earth,” former U.S. diplomat G. Whitney Azoy wrote

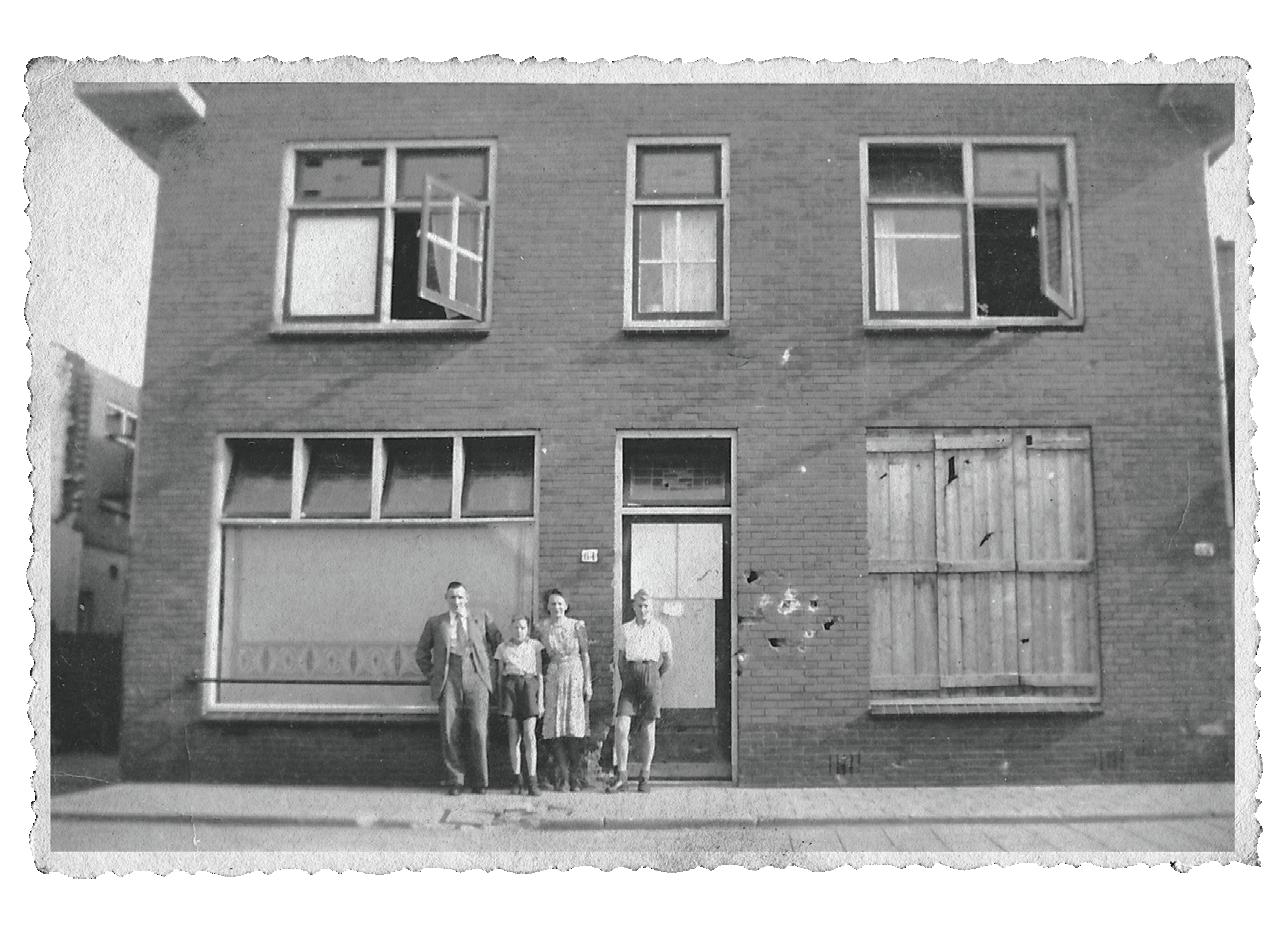

Captain Alex Watson (below and opposite) did three tours in Afghanistan, liaising with local commanders and elders in 2002 before mentoring an Afghan National Army battalion through multiple firefights. Captain Americo Rodrigues (above), an army doctor attached to the 3rd Battalion, Royal 22e Régiment Battle Group, conducts a medical clinic in a remote Afghan village in 2004.

in 2002 for the second edition of his book Buzkashi: Game and Power in Afghanistan. “No country in all history has proven more resilient. No people alive today are more worthy of admiration, respect, and support.”

As a 10-year drought neared its end, Afghanistan was caught up in the post-9/11 war that was supposed to set it free. It was Watson’s job, in part, to convince Afghanis that the coalition forces of which he was part were not simply following the waves of Mongol, Macedonian, British and Soviet invaders who had come before.

The country was in ruin, its neighborhoods reduced to rubble, its infrastructure gutted and its landscape peppered with more than 10 million landmines.

The dusty villages surrounding Kandahar and beyond, some without so much as a water well, were populated by stoic survivors of war, injury, disease, poverty, drought and malnutrition. The life expectancy of Afghan males in 2002 was 47 years. The infant mortality rate was among the world’s highest. They remain so.

“I did often think that I was looking back on how western society would have looked several hundred years ago,” Watson recalled. “I was reading a book about medieval Europe and how probably if you were walking down the street in Europe at that time many people would have broken bones that had never been set. Or the consequences of ravaging disease, if it hadn’t killed them, would be visible in scars that

“I VIEW IT AS NOTHING LESS THAN A PRIVILEGE THAT I GOT TO DO THE JOB THAT I DID IN AFGHANISTAN , TO MEET THE AFGHANS THAT I MET.”

had never properly healed. Looking at the Afghans, you saw a much rougher society [than ours]…. People lived with permanent discomfort.”

Not a single Afghan, it seemed, was immune to war’s impact or had escaped the devastation of profound loss. Death, in all its forms, was everpresent. Still, they moved forward, scratched livings from nothing, built homes from the cracked clay beneath their feet and rebuilt lives out of the tragedy and hardship.

They managed this not because life in Afghanistan was cheap, said Watson, but because it was the only way they knew how to cope. Islam’s rites of quick burial helped, but Watson said Afghans also seemed to “force upon themselves a more limited period of mourning because they had to.”

Soldiers commented repeatedly on how industrious and resourceful a people the Afghans were. Unlike some others they had protected as UN peacekeepers in other parts of the world, seasoned Canadian troops found Afghans reluctant to allow others to do work they could do themselves.

True to the traditions of the dominant Pashtun culture that had

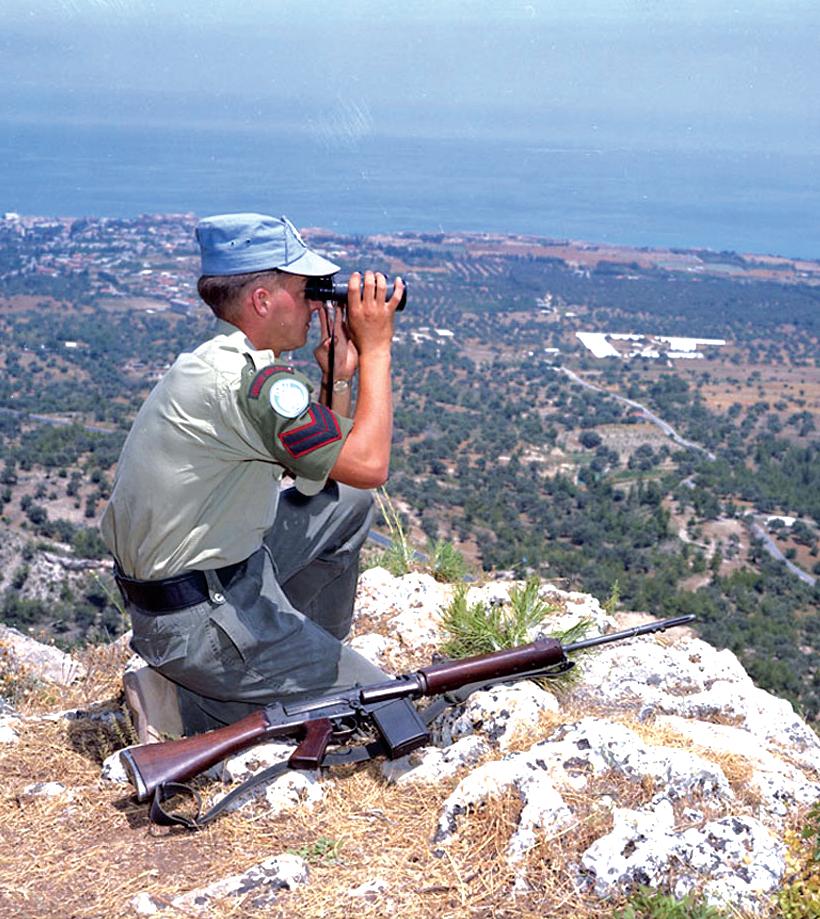

Reconnaissance troops from the 3rd Battalion, The Royal Canadian Regiment Battle Group conduct a mountain patrol west of Kabul in 2003. A Canadian sniper team from the 3 PPCLI Battle Group, wearing specialized British fatigues, surveys the terrain near the Afghan-Pakistan border.

thrived on the frontiers of the land for centuries, Afghans opened their homes to Watson and others, serving guests acid-strong tea and whatever foodstuffs they could muster, despite their own hardships and sufferings. They lived by the tenets of Pashtunwali, an ancient code of conduct predating Islam whose central dictum is hospitality to all, regardless of race, religion or economic status. Under Pashtunwali, a guest must not be harmed nor surrendered to an enemy.

Kandahar had been a waypoint on the Silk Road, and Afghans remain to this day born-and-bred traders, machinists and merchants.

“Everything became a dealmaking process,” said Watson. “Everything was subject to negotiation. I found that initially maybe jarring. Then I started to enjoy it. I didn’t take offence that everything became a bargaining opportunity.

“They could sell sand to a camel, I think. I admired that sort of entrepreneurial aspect to their society, although I got taken to the cleaners a few times due to my own naïveté.”

On his third tour in 2009, Watson, by then a major, was given a small company of Canadian troops and assigned to mentor an Afghan National Army battalion which, for all intents and purposes, he commanded.

Having fought alongside Afghan militia and national soldiers alike, he already respected the Afghans’ “very principled, faith-driven” warrior culture—not savage and incendiary like that of al-Qaida and Islamic State militants.

The men in his battalion, though largely from the ethnically distinct north, treated civilians in the south ethically and respectfully, and they proved effective at gathering intelligence. They were light and quick. Their practised eye could pick out bombs and other threats better than their Canadian mentors.

Watson recalled walking ahead of about 200 Afghan and Canadian troops along a high-risk route in Zhari district when suddenly two young Afghans scurried past him with metal detectors in hand, determined that their Canadian would not step on a landmine.

“That sort of affection and two-way loyalty, I remain very, very touched by,” he said. “It’s that very tangible fraternal bond between soldiers and it’s something I don’t really have in my life now outside of my own family.”

Watson left the army in 2016, two years after Canada’s withdrawal.

He is now a federal drug and gang prosecutor, married with children.

At the time of Canada’s withdrawal in 2014, University of Ottawa international affairs professor Roland Paris was already dismissing military claims that the mission had been a success.

“This much seems clear: the international mission to stabilize Afghanistan following the toppling of the Taliban regime in 2001 has not succeeded,” he wrote in the March 2014 issue of Policy Options, the online journal of the Institute for Research on Public Policy. “Early hopes for a democratic renewal gave way to mounting disillusionment, corruption and violence.

“Although important gains were achieved in national development indicators—including the number of children in school, women’s rights, and access to health care— these improvements rested heavily on the presence of an enormous foreign military and a deluge of aid money, all of which is now waning.”

As the last American and other coalition troops withdrew in 2021 and the conclusive Taliban offensive gained momentum, retired major Brian Hynes, who served two tours in Afghanistan, in 2002 and 2004-2005, said it felt “like Srebrenica all over again.”

The United Nations had declared the besieged enclave in eastern Bosnia a “safe area” under the protection of Canadian peacekeepers when Bosnian Serb troops massacred more than 8,000 Bosniak Muslim men and boys in July 1995.

Afghanistan’s collapse was “not a surprise,” said Hynes, who was with The Royal Canadian Regiment when it became the first UN force in Srebrenica in 1993.

Afghanistan was “a lost cause from the get-go because we were never staying,” he said. “That’s the message, really: If you’re going to go to war, you’re either there for the whole thing or you don’t go.”

“THIS

MUCH SEEMS CLEAR: THE INTERNATIONAL MISSION TO STABILIZE AFGHANISTAN FOLLOWING THE TOPPLING OF THE TALIBAN REGIME IN 2001 HAS NOT SUCCEEDED.”

It’s March 13, 2002, and 3 PPCLI, including a Canadian sniper in British fatigues, launches Canada’s first combat assault since the Korean War on a mountain called the Whale’s Back.

As Afghan National Army units collapsed, their troops simply laying down their weapons and going home while Talib fighters took district after district with relative ease in their march to Kabul, Watson said he had conflicting feelings.

“One is this emptiness, this ennui, about wasting a decade of my life,” he said. “The second is a great fear and sadness for the people of Afghanistan, for whom I developed great affection.

“Third is that I’m fired up. I wish I were there, with my guys and my Afghan battalion, 1/1/205. My team didn’t lean on U.S. air power in 2009-2010, and we wouldn’t need to again. We could take them with small arms, just like last time.

“I realize realistically I’m old and battered, but I still feel that surge for combat in a righteous cause.”

Today, with social reforms and other progress stifled under a harsh fundamentalist regime, he still thinks of those youthful, underdeveloped Afghan troops, their big eyes peering out from beneath oversized Kevlar helmets, trusting absolutely in his commitment, education, judgment and equipment.

“I struggle to this day, philosophically in an existential sense, because every time that I planned an independent operation for my Afghan battalion and then led that operation, an Afghan soldier was either horribly wounded or died,” he said.

“The trite answer is that’s the nature of the job. But these were like little dudes; they were teenagers, man. And I don’t have the answers for what sort of expenditure of resources is appropriate to achieve a mission.

“I do know that every single area I operated in is all under Taliban control now. So, I guess I’ve answered my own question.”

A member of the 3 R22R Battle Group approaches a village north of Kabul.

Desert cam uniforms weren’t available at the outset of Canada’s participation in Afghanistan, but the faded and dusty forest green proved ideal in much of the country’s terrain.

“ THERE HAS BEEN LITTLE INSTITUTIONAL RECKONING , NO LESSONS-LEARNED REPORTS—AT LEAST NONE THAT WAS PROACTIVELY PUBLICLY RELEASED.”

More than 40,000 Canadian soldiers, sailors and aircrew served in Afghanistan. At least 158 are known to have been killed in action, along with a diplomat, four aid workers, a government contractor and a journalist. Thousands of other Canadians were wounded and dozens of veterans of the conflict have since died by suicide.

The mission cost taxpayers more than $18.5 billion and the country spent another $3.9 billion on humanitarian assistance.

“Many Canadians seemed to think that a victory in Afghanistan would be ours to achieve,” said Tom Bradley, who served two tours with Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians). “But the victory parade was never ours to have; it was the Afghans who would achieve that goal. The Afghans

would determine the time and place and what it would look like.

“Unfortunately, despite years of advance warning that the patience of the electorate in the West was running thin and that the military and political support for Afghanistan would come to a close, it seems that the Afghan political class and their supporters in the West choose to avoid looking at what the consequence of this change would mean for both the Afghan people and their country.

“Instead, they chose a standard political solution: pretend it’s not going to happen and carry on as if change only happens to others,” added Bradley, who retired from the regular force a lieutenantcolonel in 2011. “Unfortunately, the Afghans will now pay the price for that hubris.” And did.

“There has been little institutional reckoning, no lessons-learned reports—at least none that was proactively publicly released,” Renée Filiatrault wrote seven years after Canadians left Afghanistan. “But a reckoning is necessary so that mistakes are not repeated and successes might be.”

Filiatrault, who served as a foreign service officer in Afghanistan with Task Force Kandahar in 2009-2010 and is now advising her fourth defence minister, said returning diplomats and other civil servants had little opportunity to share what they learned.

“Some didn’t even have jobs to come back to. Those who did confronted issue fatigue from officials around them who no longer wanted to hear about Afghanistan and discouraged references to it.

“The lack of caretaking of this expertise, and of people generally, meant the government struggled to retain the right people and to recruit those interested in hardship postings or conflict resolution in the future. A cadre of officials with civilian-military and intheatre experience was lost.”

There has since been an exodus of knowledge and experience from Canada’s troubled armed forces, and the defence minister’s newest adviser says Canadian bureaucrats and legislators retained little from the war in Afghanistan.

She said the lack of expertise was even more stark on the political side, and it has gotten worse. “Politics is a game for the young, and roles are temporary,” she said. “Most current advisors were not out of grade school on September 11, 2001.” L

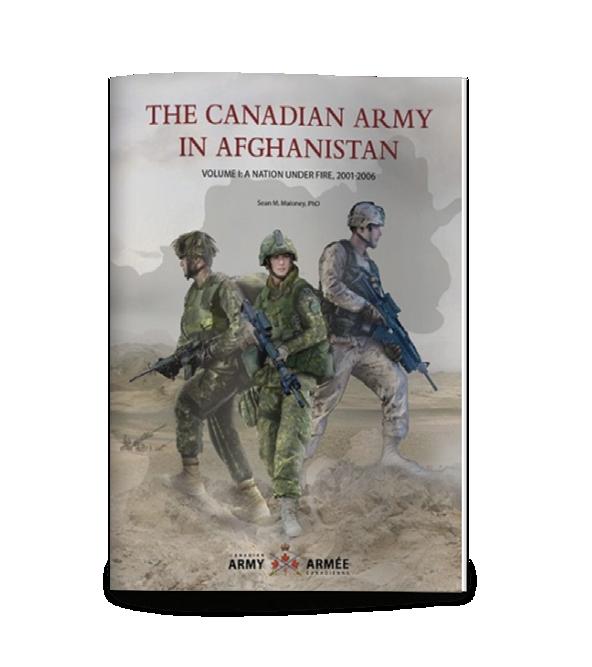

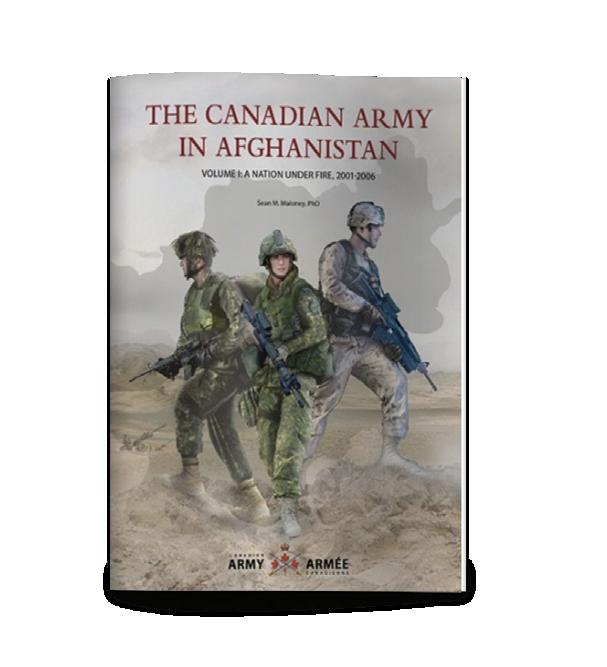

Written by Royal Military College historian Sean Maloney, The Canadian Army in Afghanistan, a comprehensive, in-depth account of Canada’s war in Afghanistan, was quietly published by the federal government last summer. But only 800 English and 800 French copies of the three-volume history were printed, making its availability limited. However, after many veterans complained, the books were posted online this past November. Visit www.Canada.ca and search for “The Canadian Army in Afghanistan” to access the series.

Retired captain Trevor Greene stood stage-left, a laser-like focus on the opposite side of the platform. Fitted with a backpack and waist-down exoskeleton, he cut a formidable figure, an iron soldier, if you will, set against the harsh hues of LED lighting and a white curtain backdrop. It was Sept. 17, 2015, at Simon Fraser University’s Surrey, B.C., campus and Greene was going to walk in public for the first time in nearly a decade. Deployed to Afghanistan with the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada in 2006, Greene’s journalism experience made him a suitable choice for a civil-military cooperation officer. Tasked with securing and expanding infrastructure assistance to villages throughout the war-ravaged Kandahar province, Greene was having tea with the elders of Shinkay on March 4, 2006. He had removed his helmet in respect.

But a 16-year-old member of the Taliban interrupted the meeting, thrusting a home made axe into Greene’s head. The ambush and ensuing chaos consumed the village. The assail ant was quickly dispatched by the

Retired captain Trevor Greene, fitted with a robotic-like exoskeleton from the waist down, walks across a stage at Simon Fraser University’s Surrey, B.C., campus on Sept. 17, 2015. The new Legion Veterans Village in Surrey aims to offer veterans such as Greene similar advanced medical care.

Coupled with post-traumatic stress disorder, Greene was left riddled with health challenges that made day-to-day life incredibly difficult. But, Greene defied all odds, thanks to months of surgeries, therapies and alternative treatments.

“It was wonderful working with Trevor. He was such a hard worker,” said Pauline Martin, one of Greene’s physiotherapists and the CEO of Neuromotion, a B.C.based chain of rehabilitation clinics that offer the latest technologies for

those with severe neurological conditions. “He wanted answers to questions about what he could do to get better at home, what he could do to fix things.”

Greene’s robotic exoskeleton—built by Israeli-based ReWalk Robotics and funded initially through Project Iron Soldier, a campaign first spearheaded by Grade 12 student Rebecca Lumley and The Royal Canadian Legion’s

“THE REGULAR HEALTH-CARE SYSTEM IS NOT EQUIPPED TO ADEQUATELY SUPPORT A VETERAN .”

B.C./Yukon Command—stimulated and exercised his lower body while building new neural pathways for physiological and psychological recovery.

Legion Veterans Village is a $312-mil lion project that provides integrated health care and housing for veterans and first responders. Located in the heart of downtown Surrey, the building celebrated its grand opening in February 2023 after years of planning, design and construction.

“We’ve been unwavering,” said Rowena Rizzotti, a founder and current leader of the facility. “We’ve met every single Monday morning for eight years.”

Greene decided to put his healing to the test that day on stage in 2015. With Debbie guiding his walker and ReWalk training director Jay Courant stabilizing his exoskeleton’s movements, Greene took about 14 paces to the podium.

“His inspiration is his purpose right now,” said Martin. “It’s really valuable. Seeing other people working so hard is motivating.”

Funded by the RCL’s local Whalley Branch, the provincial government and Lark Group of Companies, a locally based development and construction firm, the village boasts a multi-faceted staff, many of whom were impressed after witnessing the community’s ability to fundraise to address gaps in veteran health care.

Surrounded by other dignitaries, President Tony Moore of The Royal Canadian Legion’s Whalley Branch cuts the ribbon at the Veterans Village grand opening on Feb. 8, 2023.

While his first steps were understandably a little uneven, Greene found his stride and moved confidently toward centre stage. After completing the milestone feat, Debbie slowly helped turn Greene to face the audience to reveal a smile—a grin born from pride and happiness of achieving what once seemed improbable.

The local Legion then announced that Greene soon wouldn’t be the only veteran capable of similar such advances; others could receive the same state-of-the-art health care through a new, revolutionary project: the Legion Veterans Village.

“The regular health-care system is not equipped or prepared to adequately support a veteran,” noted Rizzotti, who trained as both a nurse and a paramedic and has more than 35 years of experience in executive leadership in the industry.

Unlike the U.S. Veterans Health Administration, which provides integrated, veteran-specific health care, former CAF members are funneled into a system with long waiting times, confusing paperwork and red tape that often leaves them frustrated.

“When you leave the service and become a civilian, you essentially are just like any other Canadian,” said Rizzotti. “And so, a primary care physician, a rehabilitation provider, a mental health practitioner and other agencies don’t talk to each other.

“For a veteran who has suffered as a result of their service, it’s very difficult for them to navigate that system, and there’s no support and assistance really.”

Plus, because some general practitioners who veterans are matched with have little exposure to military-specific health concerns, they can deliver inferior treatment. And that can lead some veterans to develop a mistrust for health-care providers.

“Veterans fall between the gaps, and some of that is what results in tragic outcomes,” said Rizzotti.

Before Greene got involved with Project Iron Soldier, for example, he was part of this unfortunate narrative—his initial doctor dismissed his prospects for recovery. But Greene’s walk across the stage, and the village’s initiative at large, prove that anything is possible.

Wanting to help inspire other veteran success stories like Greene’s into existence, Rizzotti’s team met with close to 100 clinicians, veterans and veteran families when the project first launched to learn about the most critical challenges in veteran health care and housing. Rizzotti was determined to understand every issue and pitfall.

“It was very raw. It was very honest,” said Rizzotti of the feedback they received. “Leaving the service, they felt quite abandoned.

“We’re really not supporting them the way they need to be supported, yet we still have expectations that they’re going to show up and support us.”

Rizzotti’s team then defined generalizable trends from the responses that it hoped to remedy and spent the next four years building a consortium of stakeholders.

“It needed every single type of partner because of the project’s complexity,” noted Rizzotti.

After approving Michael Green Architecture’s building design in September 2019, a two-phase construction plan was initiated. Its design inspired by the Canadian National Vimy Memorial, the first stage was completed in four years. The 20-storey

building, boasting red-and-black design accents, includes 91 affordable units, 171 regular apartments, the new Whalley Legion Branch and a Centre of Clinical Excellence, a cutting-edge health facility for veterans and first responders.

The affordable units are owned and operated by VRS Communities, a nonprofit housing service. There are studio and one- and two-bedroom suites, 10 of which have features to aid mobility, such as wheelchair accessible kitchens and bathrooms. The apartments, all with modernist design, are available to anyone, but preference is given to veterans, first responders and Legion members.

In part an attempt to help address veteran homelessness, Rizzotti recognizes that just because the units are lower than market price, doesn’t mean veterans can afford them.

“The market is so high right now that even the affordable housing is still too costly,” said Rizzotti.

While many of the affordable apartments are currently vacant, VRS is working with Veterans Affairs Canada and other agencies on further subsidies for the many veterans interested in the housing and health care.

“We’ve been working on a number of applications to generate more support for veterans having financial hardships,” said Rizzotti.

The facility includes 91 affordable modern apartment units, available to anyone, but with preference given to veterans, first responders and Legion members. Its Centre of Clinical Excellence, meanwhile, promises cuttingedge health services for veterans and first responders.

“WE WANT TO MAKE SURE THAT VETERANS AND FIRST RESPONDERS HAVE THE BEST OF THE BEST ACCESSIBLE TO THEM.”

On the other hand, the building’s regular units have proved popular. Both the affordable and regular apartments have a symbiotic relationship, with the hundreds of thousands of dollars generated from the latter going into veteran housing and health care.

The Whalley Legion hall that opened in 1960 to much fanfare was, 60 years later, in need of a facelift. The new open-concept, 975-square-metre facility at Legion Veterans Village boasts an upscale casual dining restaurant and bar, full-service kitchen, cadet assembly hall, banquet room, lounge and billiards area, and a military library. And with its streamlined architectural designs, it’s a community centre for the modern age.

“Legions are always likened to old men in dark and dingy places drinking beer,” said branch President Tony Moore. “Now, we still drink beer, but it’s not dark and dingy. It’s beautiful.”

Careful consideration and craftsmanship can be found throughout the facility,

most notably from the illuminated, handcarved glass of the Vimy Memorial that leaves a sparkle and glow in visitors’ eyes when they first walk into the branch.

But perhaps what makes the new facility so special is its associated Centre of Clinical Excellence, which hosts arguably one of the most integrated continuums of veteran health care programs in Canada.

“We’re seeing people being taken out of wheelchairs and getting to walk for the first time,” said Moore. “That is really fantastic.”

Operated by an interdisciplinary health-care group that uses state-ofthe-art digital technology to personalize its patient services, the centre focuses on advancing evidence-based care.

Lorne Friesen, the centre’s chief executive officer, noted that the team is developing services that will offer patients virtually continuous connection to their health-care providers. For instance, clients may wear heart-rate monitors that will provide data simultaneously to the centre. Other devices

could allow the centre’s practitioners similar real-time contact with their patients on a range of other medical issues, too.

“We will be rendered one of the first organizations in Canada to be able to offer this full suite of services,” said Friesen.

No bureaucratic bilge in sight, veterans and first responders can be easily matched with a range of medical professionals that specialize in their treatment. The centre offers primary care, lifestyle medicine, mental health, addiction and chronic pain services, a dental practice and the aforementioned Neuromotion clinic that worked with Trevor Greene.

Neuromotion is best known for its robotassisted gait rehabilitation and robotic legs. The company also has other innovative technologies to help get former military personnel moving again, all of which co-ordinate and refine motor skills and movements.

According to Friesen, the centre’s revolutionary medical care will also include pioneering procedures for psychological conditions, such as sensory reality pods for ultra-realistic exposure therapy and ketamine therapy, which uses a psychedelic drug known to help with treatment-resistant depression.

“We’ve made a very large investment in technology to support the centre,” said Friesen. “We want to make sure that

veterans and first responders have the best of the best accessible to them.”

The centre is also a hub for academic institutions, offering internships and training for those studying engineering, neuroscience or social sciences. Under the guidance of top leaders from the University of British Columbia, Simon Fraser University, Vancouver Coastal Health and the CAF, the facility aims to become a hotbed of research.

“We want to research and publish all of our findings because we want to be able to shift current practices,” said Rizzotti. “We want to demonstrate that these improvements can happen.”

Only a few months after the facility’s grand opening, the research program received a big boost with $500,000 in funding from VAC for a personalized therapeutics program focused on treating long-COVID symptoms in veterans.

With the first phase of Legion Veterans Village complete, its second is now underway: an additional 26-storey tower that will include 400 more condominium apartments, the sale of which should generate even more funding for the village’s veteran facilities.

“It’s already doing amazing things,” said Rizzotti, “and it’s going to do extraordinary things.” L

Legion Veterans Village may serve as a model for the next evolution of Royal Canadian Legion branches. So says one of the facility’s founders, Rowena Rizzotti, and Whalley Legion branch President Tony Moore, whose group was one of the key funders of the project.

While Legion halls have survived for nearly 100 years as key local community centres, the existing business equation in many places of bars and meat draws is showing its age. Replicating the Veterans Village concept elsewhere could help modernize

local branches, grow membership and prevent branch closures.

It might also attract younger veterans by providing a one-stop shop for health care, housing and a sense of community. Local branches, meanwhile, would get consistent funding from members, governments and developers.

“There’s a new generation of veterans, and the old Legion model isn’t necessarily conducive to the younger population,” said Rizzotti.

Legion membership rates could also get a boost from associated health-care programs, particularly

given that those offering such services are eager to share them with military families as well as nonmilitary Legion members. Indeed, the concept has also caught the interest of some existing Legion members in other parts of the country.

“We received hundreds of inquiries from veterans across the country,” said Rizzotti. “Our hope and our dream is to share our model as a template in hopes of replicating it. We want to create a movement where we are impacting veterans’ lives across Canada.”

At Veteran Village’s grand opening, partner companies in the facility’s health centre displayed some of the advanced technology they’re working with for clients, like robotic legs. The building also includes the Legion’s new Whalley Branch.

by Stephen J. Thorne

Thirty-eight WW II pilots and ground crew lie is the Whyteleafe churchyard in Kenley, including Canadian Spitfire pilot Leonard Burke. Blast pens (opposite) are among the remnants of the once-critical air force base.

It’s Aug. 15, 1940. The Battle of Britain has been raging in the skies over the English Channel and the home islands for more than a month, the criss-crossing contrails of Spitfires and Hurricanes, Bf 109s and 110s weaving chaos high above.

Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe is trying to neutralize a desperate Royal Air Force and its Allies before Adolf Hitler launches a Channelborne invasion of the last bastion of democracy in Europe. The continent has fallen, and German fighters and bombers have taken up residence at airfields all over occupied France.

Already a veteran of the Battle of France, 19-year-old Corporal Frederick Victor (Vic) Bashford of Portsmouth, England, is an aircraft electrician with 615 Squadron, a local auxiliary unit stationed at Royal Air Force Kenley.

The First World War airfield is perched on a hilltop, on the fringes of London in the verdant county of Surrey, England. It overlooks the hamlet of Kenley and neighbouring Croydon to the north and the village of Whyteleafe in the south.

The site’s Canadian connections date to its earliest days in the summer of 1917, when the Canadian Forestry Corps felled trees and cleared land on Kenley Common after it was requisitioned under the Defence of the Realm Act of 1914.

Now, with another world war upon them, Bashford and the pilots and maintainers of 615 have been a busy lot. Kenley is at the front line of one of the great battles in British history, among three airfields along with Croydon and Redhill that will form 11 Group, Sector B. The region will bear the brunt of the German onslaught.

The airfield at Middle Wallop, 120 kilometres west, was hit hard the previous day. Two 615 pilots, Peter Collard and Cecil Robert Montgomery, are among the dead.

On this day, Squadron Leader Ernest A. (PeeWee) McNab of 1 Squadron, Royal Canadian Air Force, is flying with an RAF unit on his first combat mission and shoots down a Dornier bomber over the Thames estuary.

Hundreds of German aircraft have been attacking airfields and radar stations throughout the exhausting day—Hawkinge, Lympne and Manston; Rochester, Eastchurch and Worthy Down; Rye, Dover and Foreness.

Out over the English Channel, the air fighting is furious and, in many cases, the Allied pilots are vastly outnumbered.

It’s sometime around 6 p.m. when Bashford wanders over to Whyteleafe Bank, the bluffs overlooking the village in the valley below. In the distance, he hears the faint buzz of airplanes approaching from the south.

As the hum gradually approaches a roar, Bashford

strains to see whether the aircraft are friends or foes. He counts 15. He notes that they’re twin-engine planes, perhaps friendly Bristol Blenheims. But then he makes out the long canopies, the tapered, shark-toothed noses and engine cowlings, and—the dead giveaway— the twin stabilizers on the tails.

It’s clear they’re not friendly. They’re heavily armed, bomb-laden German Bf 110s, fighter-bombers known as Zerstörer (destroyers) coming up the valley low and fast.

From his vantage point on the bluffs, Bashford is soon looking down on the squadron as it passes, the black crosses on the wings and fuselages, the swastikas on the stabilizers clear just metres away. He can see the faces

KENLEY IS AT THE FRONT LINE OF ONE OF THE GREAT BATTLES IN BRITISH HISTORY.

of the two-man crews, the pilots peering forward, the rear-facing gunners positioned mid-fuselage. They belong to Gruppenstab/ Erprobungsgruppe (test wing) 210, based in Marck, near Calais, France, a few short kilometres from the narrowest point of the Channel. It will be their leader’s final mission. They bypass Kenley—indeed, they may not even realize it’s there, flying as they are below the ridgeline—and continue seven kilometres north to Croydon, home to the lone RCAF squadron in Britain at the time. As it happens, 1 Squadron is away training, minus its two senior officers, temporarily seconded to the RAF. Some historians will later argue that Kenley was the intended target that day, mistakenly missed as the Germans instead rained devastation on the Croydon airfield and its surrounding London suburb. Regardless, both sides pay a heavy price. Hurricanes from Croydon and nearby Biggin Hill bring down most of the Germans, including the unit commander Hauptmann Walter Rubensdörffer and his gunner.

Some of the attacking aircraft crash into the heavily populated suburbs around Croydon and Purley. The Bourjois perfume factory takes a direct hit; 60 people die and more than 180 are injured. The Aug. 15 raid is the first to hit Greater London, causing waves of grief and anger.

The hilltop airfield at Kenley is targeted three days later in what is supposed to be a staged attack led by a dozen Junkers 88s, followed by 27 Dornier 17s, then nine lowflying Dorniers of the Luftwaffe’s 9th Staffel out of Cormeillesen-Vexin in northern France.

Poor weather, however, plays havoc with the complex operation, delaying some aircraft and hampering their form-up near Calais.

The Dorniers of the 1st and 3rd Gruppen are six minutes late, but overtake the Junkers of the 2nd Gruppe anyway. This has ominous consequences for the low-flying 9th Staffel, which arrives at Kenley first and finds the airfield disconcertingly intact and ready for a fight.

Bashford, who had been conducting routine aircraft inspections that morning, first sees three Dorniers

barely clear the top of the hangars. He watches as the four-inch antiaircraft gun, some 50 metres away, opens fire. It’s about 1:15 p.m., and he’s sprinting for the air-raid shelter in the back of a blast pen.

Led by Hauptmann Joachim Roth, the planes are coming in at 30 metres—so low that the station armourer, Warrant Officer Edward George Alford, can clearly see their crews and fires two futile rounds from his service revolver.

Four of the German aircraft are nevertheless destroyed by ground fire and fighters; the rest are all damaged. But their handiwork is devastating to Kenley. And there’s more to come.

“After the low level attack had passed over, I went up on to the roof of the Armoury and found that no one was hurt but one of the armourers had burnt his hand through catching hold of the barrel of the G.O. Gun to recock it to remedy a stoppage due to a misfire,” Alford writes later. “I told him to report to the Sick Bay, but a glance in that direction told me that no such place existed.”

The onslaught resumes minutes later as the main group of 27 Dorniers begins high-altitude

Faded markings and cracks sprouting grass dot the base’s aged runway. Many of the WW II personnel would undoubtedly have passed through the gate to the local cemetery en route to the airfield.

bombing. More than 150 explosives miss the airfield and wreak death and destruction on the surrounding area, hitting railway lines and damaging roadways. Houses in Whyteleafe and Caterham are destroyed or badly damaged.

By the time the last flight of Junkers 88 dive bombers arrive, Kenley airfield is a smoking ruin. The last wave of Germans head for their alternative target, 25 kilometres away at West Malling.

Bashford emerges from the shelter to find the hangars burning, their contents destroyed. The man who had driven the ground crew back from lunch, believed to be Leading Aircraftman Thomas Holroyd from Liverpool, is slumped behind the wheel of his lorry, killed instantly by a Dornier’s bullet that had entered through the open passenger-side window and hit him in the face. The lorry itself is undamaged.

Five new Hurricanes, still awaiting their squadron markings, sit riddled with bullets and shrapnel outside the hangars.

One Kenley pilot is killed in the air, another on the ground, along with nine aircraftmen and two soldiers.

Throughout the day, the Luftwaffe targets airfields at nearby Biggin Hill, Hornchurch, North Weald, Gosport, Ford and Thorney Island, along with the radar station at Poling.

German losses are tallied at 69-71 aircraft destroyed, 31 damaged, 94 crew killed and 40 captured. The Allies lose 27-34 fighters in the air and 29 on the ground; 62 aircraft are damaged; 10 pilots are killed. Aug. 18, 1940, comes to be known to both sides as The Hardest Day.

Croydon and Kenley will rebuild. Kenley, in fact, is dispatching fighters the next day after the craters are filled in and Alford earns a George Medal cleaning up the 150 unexploded bombs that litter the airfield. Kenley—indeed, the whole area— is critical to Britain’s defence.

Over the next two months, the Battle of Britain tapers off. By the following spring, Hitler has turned his attention eastward to the Russian steppe, the air war has shifted to the continent and the Allied bombing campaign is escalating. The airfields of southern England, especially, become home to dozens of Commonwealth and other Allied fighter squadrons, including Canadian. During the war, eight RCAF units take up residence at Kenley alone, along with British, Australian, Kiwi, Polish, Czech, Belgian and American.

Beginning in the summer of 1942, my father, an RCAF medical officer, was posted with 401 or 416 squadrons at Kenley, Redhill and Biggin Hill, all within a 20-kilometre radius—20 minutes, more or less, by train from London’s Victoria Station. In all, he spent 31 months overseas with fighter, maritime and bomber squadrons in England, Scotland and Northern

Ireland, tending to airmen of multiple nationalities. He was even summoned to care for a member of the extended Royal Family while serving with Bomber Command at Topcliffe, England, in 1944.

Like so many before and after him, Flight Lieutenant Edward L. Thorne likely arrived at Whyteleafe Station and humped his duffel along the winding laneway up Whyteleafe Hill toward RAF Kenley. Perhaps, as some did, he took a short detour along Church Road to the Whyteleafe (St. Luke) Churchyard, with its “Airmen’s Corner,” in which 38 WW II dead are now buried.

A Canadian motorcycle driver and two pilots lie there: Sergeant Leslie Burk of Lindsay, Ont., Flight Sergeant Leonard Joseph Burke of Tignish, P.E.I., and Sergeant Ross Alexander MacKay of Vancouver. Many more died

“IF I HAD A PENNY FOR EVERY PERSON WHO HAS COME UP TO ME AND PROUDLY SAID THAT THEIR HOUSE HAD CANADIANS BILLETED THERE, I’D BE A RICH WOMAN.”

flying out of Kenley, their remains buried in far-flung parts of the British Isles, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany. Others were lost and never found.

Kenley boasted some of the great British and Commonwealth pilots, including the legless British ace Douglas Bader, Canadian aces George (Buzz) Beurling, Hugh Godefroy and Lloyd (the Angel) Chadburn, along with the RCAF’s first Black-Canadian commissioned officer and fighter pilot, 401’s Junius Hokan of St. Catharines, Ont., who died in September 1942.

Then there was the leading Allied ace in Europe, Briton Johnnie Johnson, who amassed 34 aerial victories along with seven shared, three shared probables, 10 damaged, three shared damaged and one destroyed on the ground. His victims were all German fighters—14 Bf 109s and 20 Focke-Wulf Fw 190s, the most kills of the vaunted German aircraft credited to a single pilot.