This program is provided by Red Wireless - your exclusive Rogers dealer. Subject to change without notice. O er only available to new Rogers mobile customers. Taxes extra. Rogers Preferred Program. Not available in stores. Membership verification is required; Rogers reserves the right to request proof of membership from each Individual Member at any time. For plans and o ers eligible for existing Rogers customers, a one-time Preferred Program Enrollment Fee of $50 may apply. Existing customers with in-market Rogers consumer plans with 6 months or less tenure on their term plan switching to the plan above are not eligible to receive this discount. This o er cannot be combined with any other consumer promotions and/or discounts unless made eligible by Rogers. Plan and device will be displayed separately on your bill. ± Where applicable, additional airtime, data, long distance, roaming, add-ons, provincial 9-1-1 fees (if applicable) and taxes are extra and billed monthly. However, there is no airtime charge for calls made to 9-1-1 from your Rogers wireless device. Plan includes calls and messages from Canada to Canadian numbers only. On the Rogers Network or in an Extended Coverage area, excluding calls made through Call Forwarding, Video Calling or similar services. © 2024 Rogers Communications.

In what has become an impactful tradition of the national Remembrance Day ceremony, a person places their lapel poppy among others left on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier after the formal event.

See page 58

20 “17 DIFFERENT KINDS OF HELL”

Canada gets its first action of the Great War

By Stephen J. Thorne

28 “CANADIAN NOW STANDS FOR BRAVERY, DASH AND COURAGE”

In their first overseas battle, Canada’s soldiers proved their mettle

By John Boileau

34 THE MOBILIZATION MEN

Known derisively as zombies, thousands of Canadian men were conscripted—originally for home defence—under the WW II National Resources Mobilization Act. Late in the war, many were forced to the front lines.

By J.L. Granatstein

40 THE LAST SORTIE OF NN766

How one Lancaster crew met the demise of so many in Bomber Command

By Sharon Adams

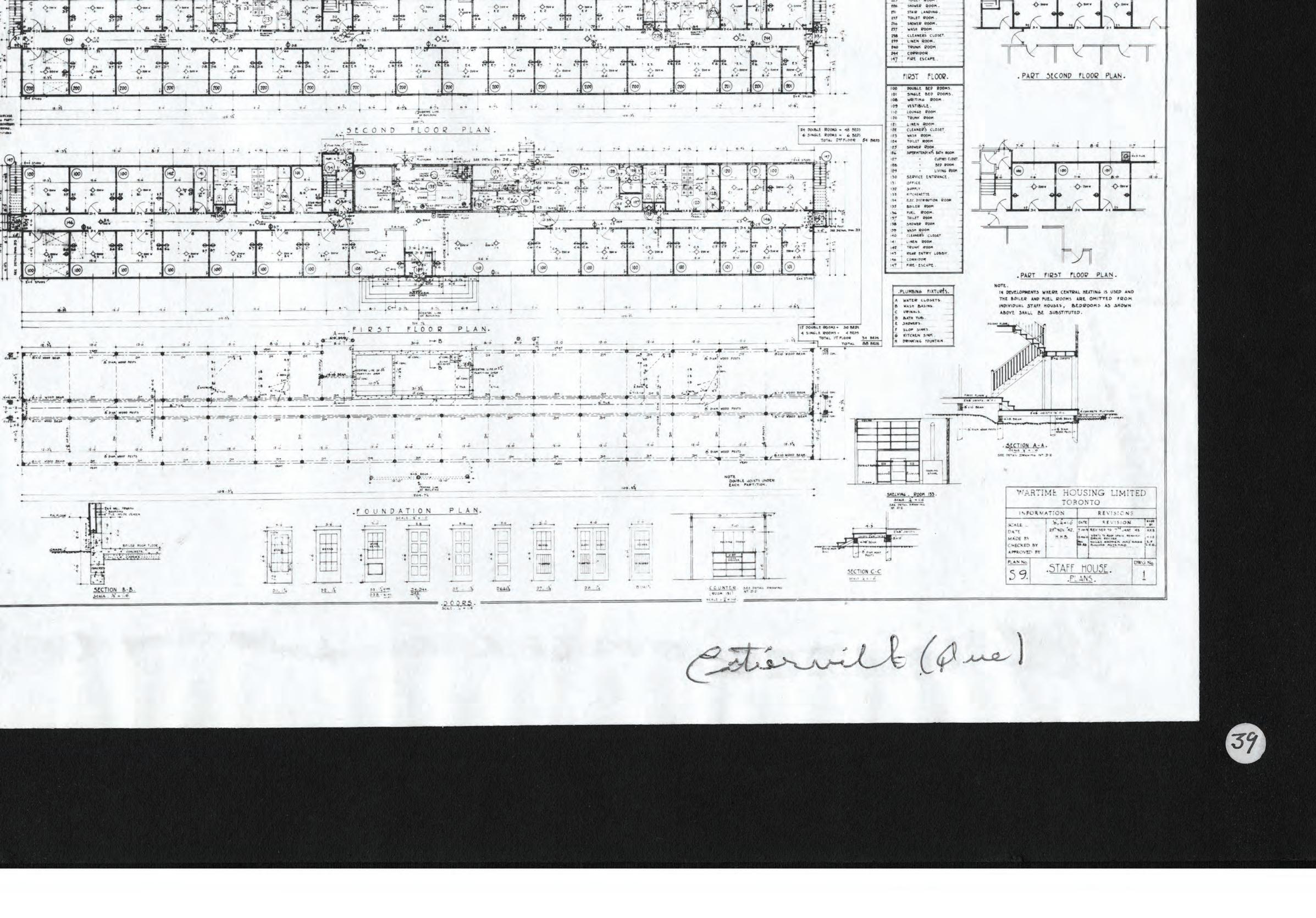

46 HOME MAKERS

Facing a housing shortage as Canadians gravitated to urban centres during the Second World War, the federal government got building

By Tom MacGregor

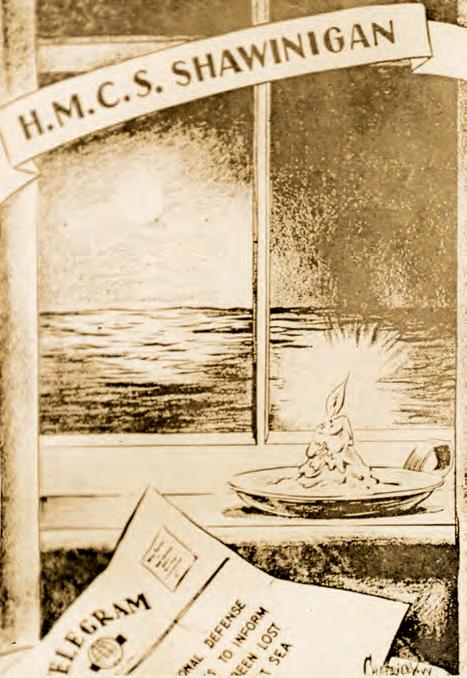

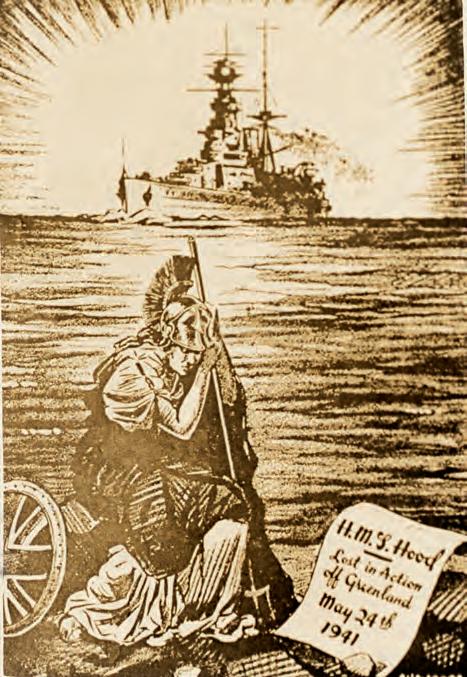

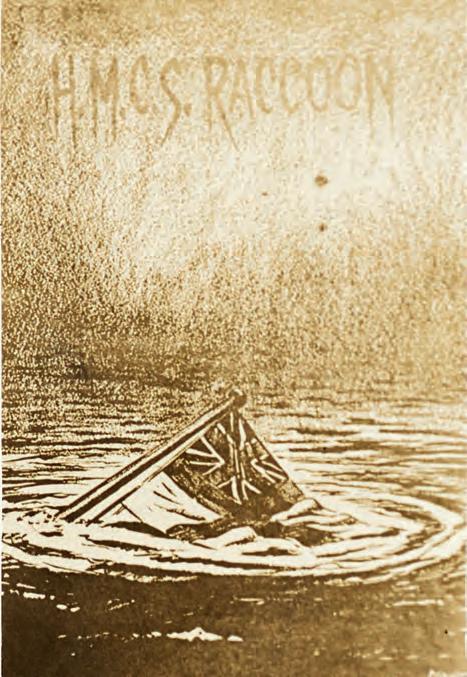

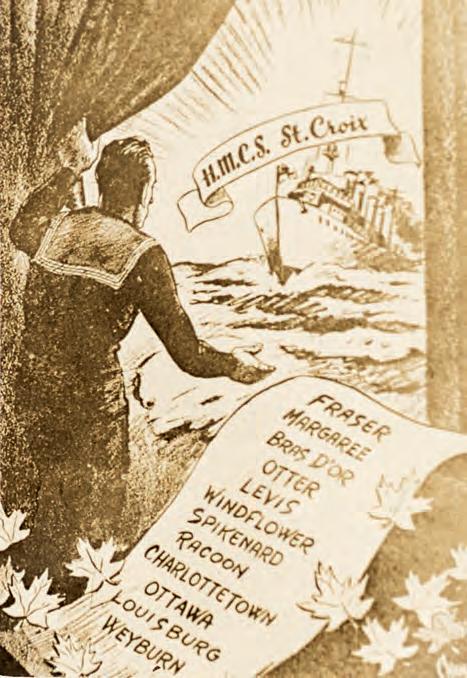

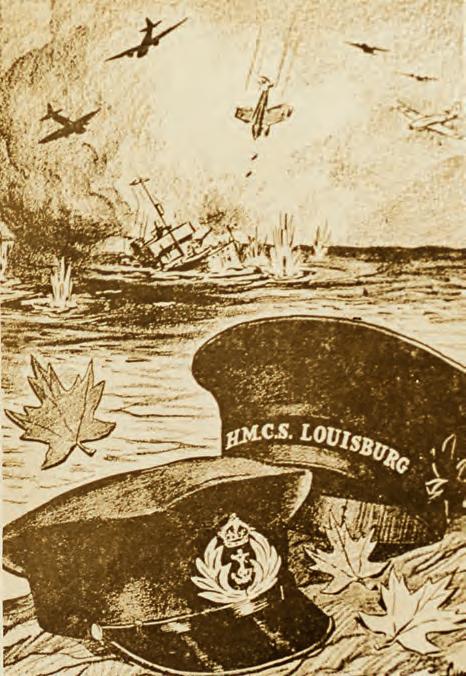

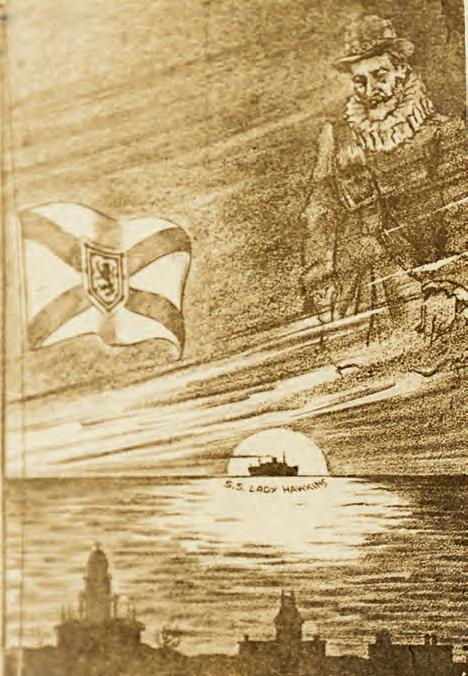

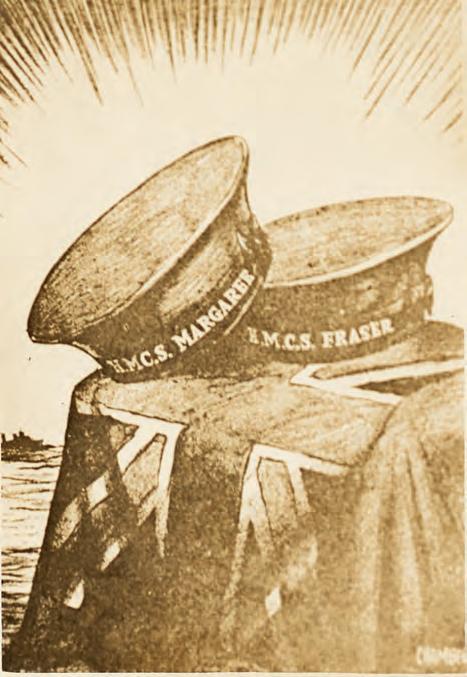

50 REMEMBERED AT SEA

During the Second World War, Canadian editorial illustrator Bob Chambers created a series of memorial cards to honour those Allied ships and their crews that didn’t make it home

By Stephen J. Thorne

58 DEDICATION TO REMEMBRANCE

As the faces of veterans change, Canadians gathered in Ottawa for the annual ceremony to continue their commitments to honouring military sacrifice

By Alex Bowers

63 LIFETIME OF SERVICE

In Toronto, a Korean War veteran remembers Story and photography by Stephen J. Thorne

THIS PAGE

Canadian troops march toward the Rhine in Germany in late March 1945.

LAC/5180096

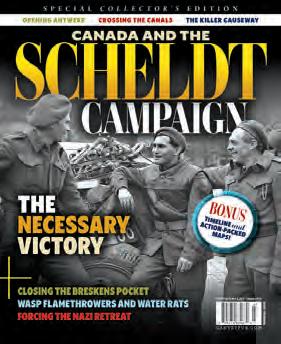

ON THE COVER

Lancaster NN766 plummets to the ground after a mid-air collision with Lancaster ND968 during an early January 1945 bombing run.

Gary Eason

56

Should Canadian ships sunk in war be considered war graves?

J.L. Granatstein

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Garry Pond BOARD VICE-CHAIR Berkley Lawrence BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe DIRECTORS Steven Clark, Randy Hayley, Trevor Jenvenne, Bruce Julian, Valerie MacGregor, Sharon McKeown Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Alex Bowers

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales CANIK MARKETING SERVICES NIK REITZ 613-591-0116 | 416-317-9173 | advertising@legionmagazine.com

MARLENE MIGNARDI 416-843-1961 | marlenemignardi@gmail.com OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER

Dyann

WEB

Ankush

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2025. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $13.11 per year ($26.23 for two years and $39.34 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $14.36 for one year ($28.73 for two years and $43.09 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $14.11 for one year ($28.23 for two years and $42.34 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Send new address and current address label, or, send new address and old address. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com/change-of-address. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $12.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of Alliance for Audited Media and BPA Worldwide. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and email magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

It’s because of members like you... that we receive letters like these:

“I can’t thank you enough for everything you did to make his last days and my life less stressful by coming to bat to help him receive deserved funding. Every penny went toward caregiving and other medical or travel expenses while he was alive and the last compassionate payment toward funeralhome expenses. I shall be indebted to you for the rest of my life.”

“Your hard work and perseverance on my behalf made it possible for me to receive a medical pension for on-going health issues. It has allowed me some peace of mind regarding my family’s well-being. In addition, the pension allows my wife and I to remain living in our own home and we are very grateful for that.”

nough is enough.

While one suspects the average Canadian bristles when their American neighbours interfere in the country’s affairs, its U.S. friends hit the mark hard with a criticism of Canada’s defence spending last year.

“We are concerned and profoundly disappointed,” wrote a bipartisan group of 23 U.S. senators to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau in May 2024, “that Canada’s most recent projection indicated that it will not reach its two percent commitment this decade,” referring to the military spending target NATO members agreed to earlier last year. “In 2029, Canada’s defence spending is estimated to rise to just 1.7 percent, five years after the agreed upon deadline of 2024 and still below the spending baseline.”

CANADA HAS LET ITS ONCE RESPECTED, EVEN REVERED, MILITARY BECOME A HOLLOW SHELL OF ANY FORMER GLORY.

The problem isn’t so much the critique, nor how accurate it is. The bigger issue is that Canada has let its once respected, even revered, military become a hollow shell of any former glory. Indeed, as it’s currently constituted, it’s more reminiscent of the ad hoc post-Confederation militia than a modern professional armed forces.

To be clear, this isn’t a criticism of the rank-and-file Canadians who’ve devoted their lives to fighting for their country. Indeed, the dwindling strength of Canada’s military is undoubtedly due in no small part to good people becoming increasingly

exasperated with their employer either appearing to simply not care about them or managing their business so poorly it feels like it.

Let us count the ways.

According to Defence Minister Bill Blair’s most recent public estimates, the Canadian Armed Forces are short at least 16,500 personnel. And about a year ago, the country’s top commander said he needed an additional 14,500 people on top of that to meet the military’s authorized strength. But that problem is easily fixed, no? No. Unfortunately, it isn’t. As our Eye on Defence columnist David J. Bercuson wrote in the September/October 2024 issue (“Recruiting agency”), Canada’s military recruitment system has been beset by issues for nearly 30 years. Today, as he wrote, it is “broken in numerous ways.” So, given three decades of problems, is it any wonder the forces aren’t up to strength? How is it possible it hasn’t been fixed?

Bercuson has also written repeatedly during the last few years about the disaster that is Canada’s defence procurement system. You name the equipment, from planes to pistols, it takes too long to get them and costs too much. The purchasing process became particularly politicized about 15 years ago, which contributed to delays and cost overruns, but it was already being managed with an outdated system then, too. The problem is evident. But a will to solve it seemingly non-existent. Combined, these issues are manifest on the ground most notably in the country’s commitment to peacekeeping. Such missions were once considered part of Canada’s identity—more than 125,000 Canadians have served in peace operations since 1956, but last year, only about 100 did. This despite the prime minister’s 2015 pledge to provide significantly more personnel to such missions.

To wit, Legion Magazine is also concerned and profoundly disappointed with the state of Canada’s military. The country deserves better, if for no other reason than to honour the sacrifices of those who’ve served it. L

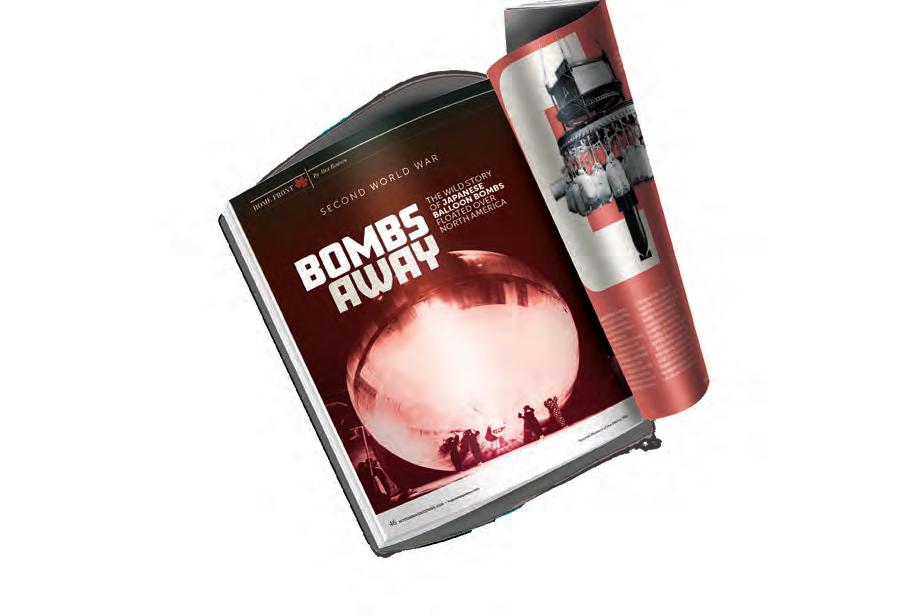

December 2024 issue. My father Sergeant Geoffrey Hart was discharged from overseas duty on Dec. 5, 1944, and in early 1945 was stationed at Currie Barracks in Calgary. One of his duties was to tend to the various balloon bombs that were found throughout the West. He had been trained in handling explosives while in the First Special Service Force. He was sent East for further demolition training. After returning, he did neutralize several of these bombs near Norman Wells, N.W.T., and Watson Lake, Yukon.

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

JOHN HART

MEDICINE HAT, ALTA.

J.L. Granatstein’s November/ December 2024 column (“Polar play”) laid bare the unvarnished sad truth about Canada’s supposed sovereignty. The stark reality is that the country has become a de facto American protected state. Individually and collectively, all Canadians are responsible for this indisputable abdication

of nationhood. Through neglect, indifference and the unspoken belief of American salvation when threatened, the country has surrendered its homeland security to a foreign government. Once a proud, strong and free nation, Canada has allowed its military capabilities to become so diminished, it is indisputably unable to defend itself or provide a meaningful contribution to western security through its international defence agreements. There

was a time when Canada was rightfully proud of its military heritage, its own defence and world stability, but it no longer enjoys the respect or admiration of its allies. Canada has forfeited its trust through years of military neglect and unfulfilled commitments.

If Canada ever expects to regain its position of reliability as a respected middle power on the world stage, it must explicitly provide the financial support, determination and unrelenting commitment to meet its national and international military obligations. Every Canadian must recognize and support this goal to shed the shackles of dependency on other countries. It will be a prolonged and difficult battle.

AL JONES ALMONTE, ONT.

Did you know that over 50% of men over the age of 40 suffer from erectile dysfunction?

Other symptoms that you may have could include an unwanted curve or bend or even an urgency to run to the bathroom and wake up at night frequently

We use the best technology available to treat erectile dysfunction

No pills, needles, or surgery! Ask us if your treatments may be covered by your current benefits program

Go to our website, email us, or call us to schedule an appointment

call: 1 877 866 VETS (8387) email: info@urogenvet.com www.urogenvet.com

As a Legion member and a graduate of the Royal Military College of Canada, I would like to draw your readers’ attention to some additional facts not mentioned in Don Gillmor’s “O Canada” column (“The Maple Leaf”) in the November/December 2024 edition. “One of the more well-received concepts considered by the committee,” notes the government website on the country’s flag, “was proposed by George Stanley, Dean of Arts at the Royal Military College in Kingston. Inspired by RMC’s own flag, Stanley recommended a concept featuring a single, stylized red maple leaf on a white background with 2 red borders.” I offer my salute to our college flag and to that of Canada.

CARL HUNTER WEST VANCOUVER, B.C.

I was completely shocked that there was no mention in Legion Magazine about the Canadian delegation that travelled to France in June 2024 to attend the 80th anniversary of D-Day and the Battle of Normandy events. Both veterans, my 96-yearold father-in-law was invited along with my spouse as his caregiver. It was the trip of a lifetime for my father-in-law as he has always dreamed of returning. They were also privileged to meet Princess Anne and Prince William, along with many other political representatives from both Canada and France. There were several veterans in attendance and sadly most, if not all, will not make it to another event. I believe the magazine missed a wonderful opportunity to recognize these veterans.

GAIL SPENST STURGEON COUNTY, ALTA.

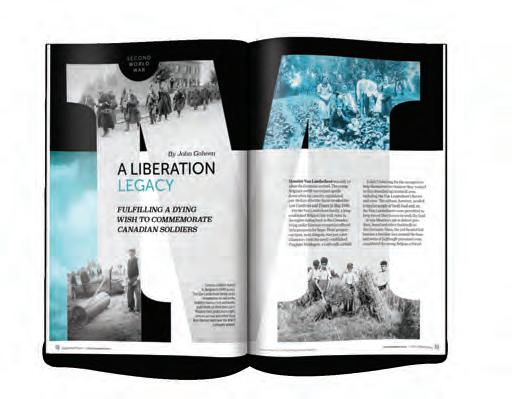

I found the article “A liberation legacy” in the July/August 2024 issue was well written and fascinating on so many levels. I’m glad this story will not be lost and will try to visit the museum the next time I’m in the area.

MIKE MECREDY BURLINGTON, ONT.

The Canadian contingent of the Nile Expedition left Halifax on Sept. 14, 1884, not 1889; also HMCS Bras d’Or vanished in 1940, not 1944 (re September/ October 2024 “On This Date”). In the November/December 2024 “Eye on Defence” column, an editing error identified HMCS Max Bernays as a Halifax-class frigate. It is, of course, a Harry DeWolf-class offshore patrol vessel. In “Moving toward 100” in the same issue, the location of the branch of former Royal Canadian Legion Dominion Vice-President Brian Weaver was incorrect. The Capt. Brien Branch is in Essex, Ont. L

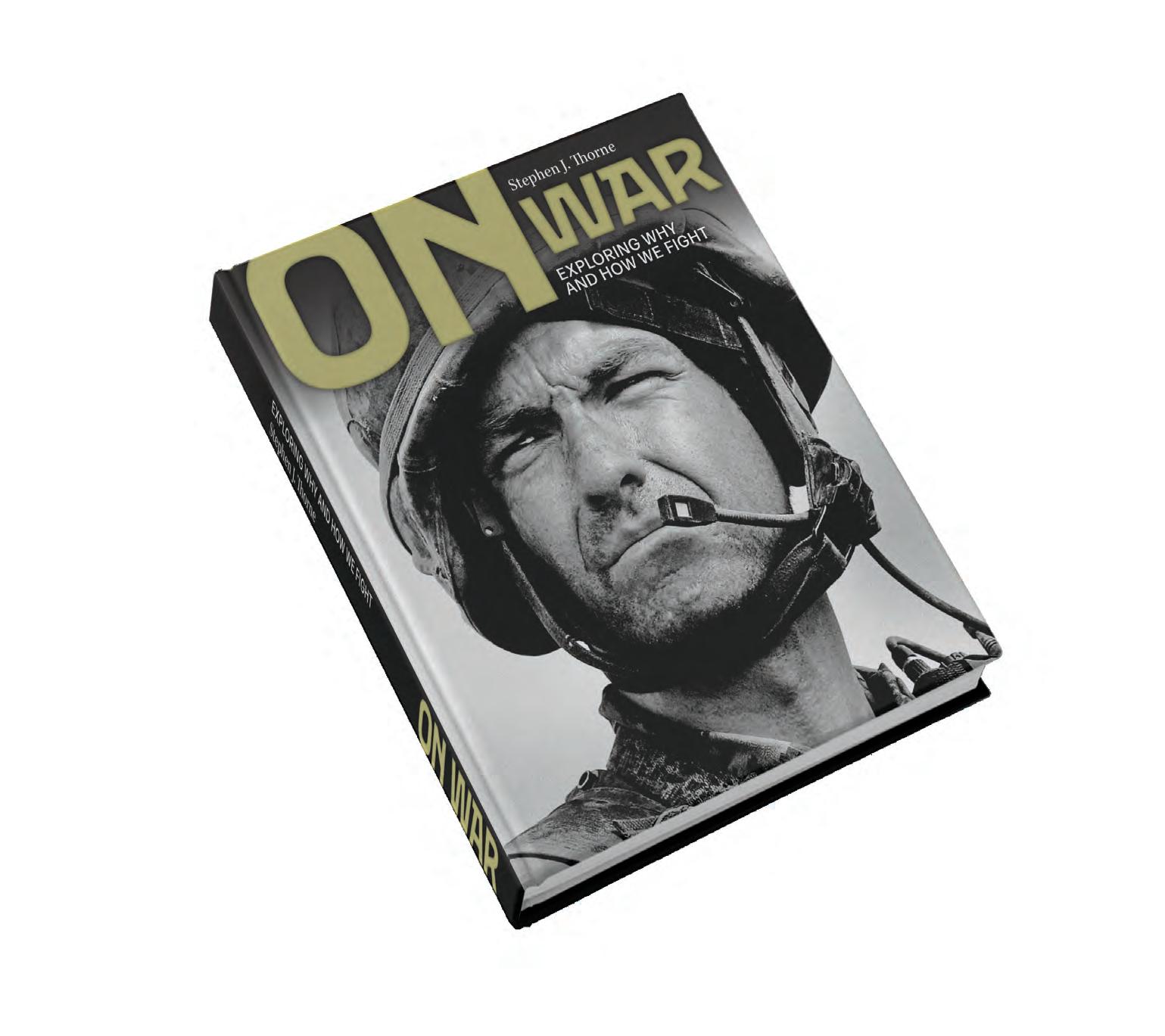

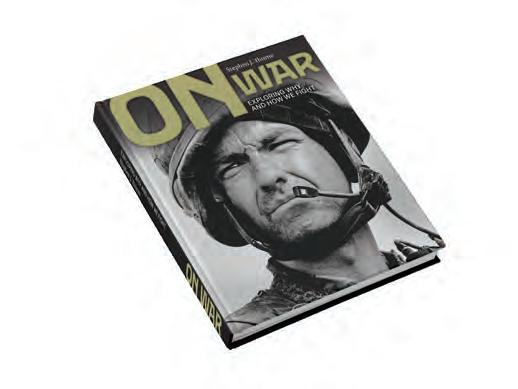

War, according to Legion Magazine senior staff writer Stephen J. Thorne, is humanity’s greatest failure. Its destruction has followed people for at least 20,000 years, with every conflict becoming more violent, more destructive and more efficient than before. Too much of the writing about war is technical facts, strategic theory and mounds of statistics. But in Thorne’s debut book, On War: Exploring why and how we fight, the former Canadian Press war correspondent who witnessed and wrote about fighting firsthand in Kosovo, South Africa and Afghanistan, addresses the humanity of such grand violence. In this curated collection of entries from his popular LegionMagazine.com

“Front lines” blog, Thorne goes beyond the numbers and jargon to delve into the deeper consequence of violence that facilitates the death and birth of countries, the obliteration of borders and the toppling of empires. The former wire-service reporter and overseas photographer explores conflict and war from fresh perspectives: how war is viewed from close and afar; front-line myths and manipulations; the puppet mastery of censorship and message control; the lifetime bonds between brothers- and

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /newsletter-signup

sisters-in-arms, which is forged in ways that can’t be duplicated; the bitterness, sweetness, tragedies and triumphs of this most confounding element of the human condition.

A native of Halifax, Thorne has been crafting award-winning stories and photography for 40-plus years. He has reported extensively from various war and conflict zones. Learn more about and buy On War at shop.legionmagazine.com. Plus, read more of Thorne’s weekly “Front lines” missives at www.legionmagazine.com. L

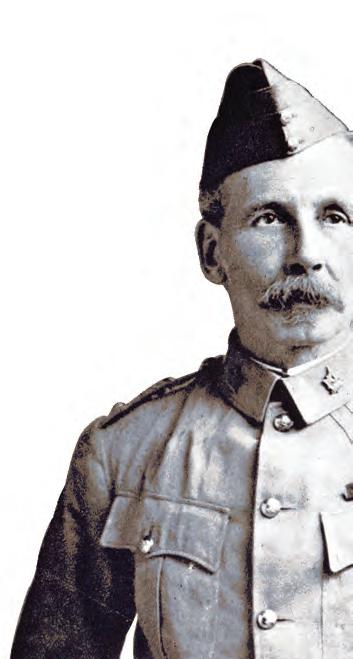

21 January 1945

Maj.-Gen. William A. Griesbach, veteran of three wars, dies.

2 January 1929

W.R. (Wop) May and Vic Homer deliver a diphtheria vaccine by Avro Avian biplane to Fort Vermilion, Alta.

3 January 1962

A Royal Canadian Air Force helicopter crew rescues 23 men from a freighter stranded off Ucluelet, B.C.

4 January 1951

Seoul falls to forces from the North for the second time during the Korean War.

5 January 1945

FO Norman Pearce of Portage la Prairie, Man., destroys six enemy vehicles while serving with No. 73 Squadron.

8 January 1916

Allies complete the withdrawal of troops from Gallipoli.

11 January 1914

Canadian Arctic Expedition ship Karluk sinks north of Siberia, leaving its crew stranded. Capt. Robert Bartlett embarks on a 1,000-kilometre journey to find help, resulting in a September rescue.

12 January 1910

The Naval Service Act is introduced by the federal government.

13 January 1943

HMCS Ville de Québec sinks U-224 in the western Mediterranean.

14 January 1952

HMCS Uganda, the only Canadian warship to fight the Japanese, is recommissioned as HMCS Quebec

22 January 1992

Roberta Bondar blasts off on the U.S. space shuttle Discovery on an eight-day mission.

23 January 1813

Wounded Americans are killed in a massacre by First Nations warriors at River Raisin.

24 January 1942

The Wartime Prices and Trade Board rations sugar to three-quarters of a pound (340 grams) per person, per week.

25 January 1951

HMC ships Nootka and Cayuga are fired on in Korea.

27 January 1987

Col. Sheila Hellstrom is promoted to brigadier-general, becoming Canada’s first female general.

28 January 1918

Lt.-Col. John McCrae, author of “In Flanders Fields,” dies of pneumonia and meningitis in Boulogne, France.

4 February 1945

I Canadian Corps departs Italy to support the Allied advance in Northwest Europe.

5 February 1856

The Victoria Cross, the Commonwealth’s highest award for military valour, is instituted.

8 February 1944

Near Littoria, Italy, Tommy Prince, disguised as a farmer, fixes a broken communication wire right under enemy noses.

13 February 2005

Defence Minister Bill Graham announces a doubling of the 600 Canadian Forces personnel in Afghanistan.

15 February 1965

The navy lowers the white and blue ensigns for the last time on ships and shore, replacing it with the new Canadian Maple Leaf.

16 February 1944

In Burma, a wounded Maj. Charles Hoey leads his company under heavy machinegun fire to capture a vital position; he is posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross for his actions.

6 February 1919

The last Canadian troops withdraw from Belgium.

7 February 1813

U.S. riflemen attack Brockville in Upper Canada, freeing prisoners, seizing stores and taking 52 hostages.

24 February 1944

HMCS Waskesiu sinks U-257 in the North Atlantic.

25 February 1916

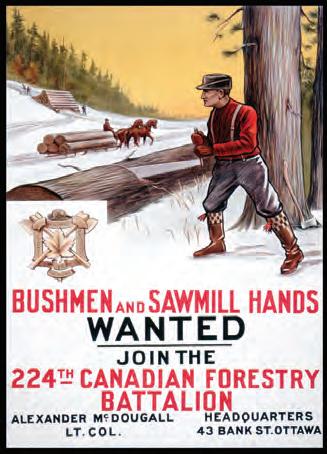

The 224th Canadian Forestry Battalion is authorized by the Department of Militia.

18 February 2010

John Babcock, last living Canadian First World War veteran, dies. Wilfred Reid May/LAC/C-057809; NASA/Wikimedia; George Hubert Wilkins/LAC/3407944; CWM/19710261-1031; Guelph Museums/Wikimedia; DND; Archives of Ontario/Wikimedia; Wikimedia; DND/LAC/3522606; CWM/19790262-033

19 February 1915

The Allies begin a naval attack on the Dardanelles.

20 February 1919

The Amir of Afghanistan is assassinated for supporting neutrality during the First World War.

21 February 1916

The Battle of Verdun begins.

23 February 1909

Canada’s first piloted heavier-than-air machine flight takes off in Baddeck Bay, N.S.

26 February 1943

Prime Minister Mackenzie King decides to nationalize the brewing industry—but a year later changes his mind.

27-28 February 1915

The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry launches its first trench raid of the war, near Ypres, Belgium (see “17 different kinds of hell,” page 20).

By Alex Bowers

How a Canadian War Museum oral history project is preserving and highlighting the post-military experiences of veterans

Able Seaman Alex Polowin’s war ended in Halifax.

Not yet 20, the D-Day veteran stared out toward the many ships “tied up with no crew,” the demobilization process well underway, and wondered, “Where now?

“That’s very, very frightening,” Polowin, a survivor of the Arctic convoys, recalled of the moment during his interview for the Canadian War Museum’s recently unveiled oral history project. “What am I going to do for the rest of my life?”

It was, and remains, a sentiment shared by countless Canadian Armed Forces members, a question not easily answered and yet, so immensely in need of addressing once military service draws to a close. It is, perhaps, a fear incomparable to that which is expected while the uniform is still on.

Such challenges have since been preserved and highlighted through the initiative entitled In Their Own Voices: Stories from Canadian Veterans and their Families.

Focused primarily on the post-military transition back to civilian life, the collection features more than 200 interviews with those whose trajectories were impacted by the Second World War and beyond to modern-day service, each account offering a personal insight into what can happen after that uniform comes off—and, potentially, contributing to a much broader blueprint for future veterans’ support.

“Most military histories end when the conflict or era being discussed

ends,” explained the project leader and the Canadian War Museum’s historian of veterans’ experience Michael Petrou. “But we understand that the ripples of war and military service continue much longer than that and typically shape the lives of veterans, as well as their families, in often profound and intimate ways.”

No stranger to such ripples, Petrou recalled his original curiosity being sparked in part by his WW II veteran grandfather, a figure he “was always fascinated by as a boy” and who

World War before returning home, only to be found by his mother hiding beneath the bed.

Or like Bruce Henwood, a former UN military observer who, in 1995, became a double below-knee amputee after his vehicle detonated a mine in Croatia and thrust him into a fight against insurers to receive the compensation he deserved.

Or Kelly Thompson, a Canadian captain compelled to enlist after the 9/11 attacks, but whose encounters with sexism and a career-altering wound left her untethered from her military identity until creative writing helped her feel grounded again.

In recording veterans’ accounts, Petrou recognized common themes across generations, conflicts and

“I SPOKE TO ONE VETERAN WHO SAID HE LIVED IN A CITY OF A MILLION PEOPLE WHERE HE FELT NO ONE KNEW WHAT HE DID.”

“right up until his death, [carried] a 1939 silver dollar in his wallet that was given to him by his high school teacher around the time he enlisted.”

Petrou rarely heard about the war’s lasting impact from his grandfather’s own lips, nor did he ever really ask much about the silver dollar he kept in his pocket.

Now, however, the In Their Own Voices project—started in early 2022 with an online exhibition unveiled in late 2024—has since captured the post-service memories, both positive and negative, of people with a similar dynamic.

People such as Max Dankner, who also served in the Second

eras, particularly that “losing someone close to you in war is universal” and how that imprints itself in a post-conflict setting. Camaraderie in the military was another oftdiscussed topic for interviewees.

Equally, the military-tocivilian workforce transition unearthed parallels.

“Veterans I’ve talked to often say that they learned useful skills in the forces,” said Petrou, acknowledging the instances where abilities were less readily transferrable.

But there were likewise marked differences.

“The Second World War veterans, for example, were part of a conflict in which almost the entire

country was involved; it was always visible,” noted Petrou. “Then you have the Afghanistan War, a conflict that we lost. I spoke to one veteran who said he lived in a city of a million people where he felt no one knew what he did.”

The diverse nature of the country, too, became a factor—and indeed an occasional challenge when Petrou travelled from coast to coast collecting first-hand accounts: “Even with over 200 interviews, it’s hard to get the totality of experience, be it anglophone, francophone, racialized communities, gender, service branches, conflicts, eras and more. To reflect that scope honestly was quite difficult.”

Nevertheless, each perspective, each story, has woven a tapestry of post-service experience that can shed light on a seldom examined aspect of military life, not only from veterans’ lips, but also those loved ones who shared in it.

In humanizing individual achievements and struggles, all the while hearing about them in their own voices, a compelling archive has been created that Petrou and the museum team hope will broaden understanding for generations moving forward.

Now is undoubtedly the time, especially for WW II-era service members.

“I interviewed somewhere between 40 and 50 Second World War veterans,” said Petrou. “Sadly, even over the last couple of years, many of them have died.”

They include Alex Polowin, whose memory lives on through the online exhibition where recordings and photographs lend a richness to his immortalized account.

Additionally, with plans underway to host a conference in 2025 and publish a “hybrid” academic-memoir book in 2026, the In Their Own Voices project will continue to grow, supported by The Royal Canadian Legion and the Legion National Foundation.

“The Legion has been a generous funder of the project,” said Petrou, “and has been a great supporter in terms of spreading the word and reaching out to people.”

Whether the archive could one day influence policy decisions is left to speculation for now. What’s certain is its potential as a valuable

resource for historians, authors, journalists, and the public, not least educators and students.

“My wish is that these transcripts and interviews have second, third, and fourth lives in ways we haven’t yet imagined,” said Petrou. “We’ll just have to see.” L

For Canadians who are heading south this winter

A Fokker Dr I, the WW I aircraft most associated with Germany’s legendary Red Baron, and a Sopwith 1-1/2 Strutter, both reproductions, perform at the Aero Gatineau-Ottawa air show in 2018.

There are few rivals in war who have shared the mutual regard and respect, even camaraderie, as those who flew aircraft during the First World War.

Theirs was a singular experience, the scale and intimacy of which were unique in the annals of conflict, even aviation, before or since. With it, a new chivalric tradition, vestiges of which persist to this day, was born.

Blazing trails in the skies in bare-bones, canvas-and-wood airplanes, they fought mano-amano, skill to skill, often just metres apart. And mostly without parachutes.

It was, after all, the first war in which aircraft played a major

role—initially for reconnaissance and artillery spotting, then bombing and fighting.

As fighter squadrons were formed and aerial conflict escalated, aces who scored five victories or more emerged. Personalities emerged with them, recognizable by their distinct aircraft and markings: Richthofen in his red Fokker triplane; Bishop in his Nieuport 17; Rickenbacker with his “Hat-in-the-Ring” Nieuport 28.

Early crews of rival reconnaissance aircraft exchanged nothing more belligerent than smiles and waves. As the products of their labours—death and destruction on the ground—became evident, they began tossing grenades and even grappling hooks at each other.

Battling freezing cold, buffeted by unpredictable winds and weather in flimsy, even delicate, airframes, and increasingly threatened by their rivals’ incursions, pilots began firing woefully inadequate handguns at enemy aircraft.

On Oct. 5, 1914, French pilot Louis Quenault became the first aviator to unleash machinegun fire on an enemy plane, propelling aviation into a new era. The dogfights escalated into desperate struggles over the mud-soaked trenches and wastelands of wartime Europe, the daily stakes as high as any could be.

“Now a dogfight is rather an exciting game actually,” pilot Thomas Isbell told the Imperial

Stephen J. Thorne

> Check out the Front lines podcast series! Go to legionmagazine.com/en-frontlines

War Museums. “You’d dive onto the first Hun you come across… and no sooner you’ve got your guns on him, someone else has got their guns on you.”

While soldiers on the ground wallowed in the mud, cringing under artillery bombardments and awaiting the next dreaded order to go over the top, pilots at least had days flying the wild blue—and good food and a warm bed to go back to.

At night, they would engage in the drunken, bittersweet celebrations and tributes to their fallen brethren, the ever-present prospect of fiery death or disfigurement lingering somewhere in the recesses of their collective consciousness, the price of a slight miscalculation, a moment’s loss of focus, or circumstances unforeseen. Over time, the underlying stress would do its work, chipping away at their psyches.

Still, those who flew belonged to an exclusive club whose members quickly came to understand the special place they occupied. The rare air above 10,000 feet brought on hypoxia, a potentially fatal high, but there were no borders, or rules, up there among the clouds.

In the Roberto de Haro novel Twist of Fate: Love, Intrigue and the Great War, the protagonist, a Louisiana Cajun named Quentin Norvell, describes the experience of flying in combat with the French Air Service during the First World War.

“There’s a bond between fighter pilots, even if we’re adversaries,” he says. “You see, we share the same things, the deafening noise of the engine which blots out our hearing, the speed and maneuverability of our planes, the sensation of flight, and the single purpose of defeating your opponent.

“There’s not enough time to think about hate. If I hate

anything…it’s the need for us to fight and kill each other.”

Indeed, opposing airmen went to astonishing lengths to help each other in the First World War, even warning the other side of where they were about to drop bombs and sending photographs of enemy graves.

near the Somme front in 1916.

Wilson had beaten out flames on his legs and arms after he was forced to crash-land his aircraft behind enemy lines.

Boelcke followed him down but, rather than hold him at gunpoint and send him away for interrogation, he shook

“THERE’S A BOND BETWEEN FIGHTER PILOTS, EVEN IF WE’RE ADVERSARIES.”

Alan Wakefield, head of photographs at the Imperial War Museums, told London’s Daily Mail in 2014 that such co-operation was far more common among pilots than those fighting on the ground.

“I know of cases where German pilots dropped notes and photographs of a crashed aircraft and its occupant, saying they’d buried him and asking for his name so they could make a headstone,” he said.

“In one instance, a German pilot dropped a note saying he was about to bomb an airfield and suggesting that those on the ground should get out of the way.”

Captain Gerald Gibbs, a British pilot awarded a Military Cross and two bars in six months, received adulatory fan mail from two German airmen whom he captured, then took to lunch. It was signed “with chummy German airman greetings.”

In another incident, the legendary Oswald Boelcke, regarded as the father of the German air force and the Red Baron’s mentor, formed an instant friendship with British pilot Robert Wilson, whom he shot down

Wilson’s hand, took him for coffee in the mess, and gave him a tour of his aerodrome. It was Boelcke’s 20th aerial victory.

Years later, Wilson described his encounter with Boelcke as “the greatest memory of my life, even though it turned out badly for me.”

“Flying in the First World War was almost like a gentleman’s club no matter which side you were on,” said war memorabilia auctioneer Matthew Tredwin.

“An unspoken camaraderie existed between Allied and German pilots.” L

By David J. Bercuson

Retired lieutenantgeneral Roméo Dallaire is a Canadian military icon. When he decided to donate his vast collection of letters, memos, documents and recordings in September 2024, no Canadian institution, not Library and Archives Canada or his alma mater the Royal Military College of Canada, was apparently interested in the archives. But, the United States Military Academy West Point in New York was and, thus, those Canadians who want to research the first-person accounts of the career of this extraordinary man have to go to the U.S. to do so. This is the very definition of irony.

Born in the Netherlands in 1946, Dallaire grew up in the east end of Montreal and joined the Canadian Armed Forces in 1964, attending Royal Military College and Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean, earning a bachelor of science degree. He first came to the Canadian public’s attention in 1993 when he was appointed to command the 81-strong United Nations Observer Mission UgandaRwanda (which eventually grew to about 2,000) and the betterknown United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR). Rwanda had been torn apart by

Major-General Roméo Dallaire speaks to the press at the UN Headquarters in New York City in September 1994 following his command of the UN mission in Rwanda.

a civil war between its government, largely comprised of the country’s Hutu ethnic group majority, and the rebel Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF), largely representative of the Tutsi ethnic minority. When UNAMIR was established, the civil war had become static, with the two sides separated by a demilitarized zone secured by troops of the Organization of African Unity.

The intention was to establish a new provisional government, bringing the RPF into a coalition with the ruling majority until democratic elections were held. UNAMIR soldiers, armed only with personal weapons, were to keep the two sides apart until that happened.

Dallaire and his assistant, Major Brent Beardsley, were the only two Canadians in the UN force. The rest of the peacekeepers consisted of 400 Belgian soldiers and a mixed group of predominantly African soldiers numbering about 2,000.

Dallaire arrived in Rwanda in late 1993 to take command of the mission. He soon discovered the Hutu were using broadcast media to set the stage for a mass attack on the Tutsi minority. Dallaire also learned that Hutu were gathering arms, mainly machetes, that were likely going to be used in the looming resumption of hostilities. He briefed the UN headquarters in New York of the situation and sought permission to take pre-emptive action, but his request was denied.

On April 6, 1994, the presidents of Rwanda and Burundi, both Hutu, died when their plane was shot down over the Rwandan capital of Kigali. Chaos ensued. Throughout Rwanda, machetearmed Hutu hunted down Tutsi and slaughtered some 800,000 people in a little more than three months until an RPF attack overran Kigali in July and the Hutu regime fled.

Dallaire was virtually powerless to stop the genocide, particularly after 10 Belgian peacekeepers were captured, tortured and murdered by the Hutu in the immediate aftermath of the presidential deaths. Belgium subsequently withdrew its troops. Dallaire’s most important action was to try to protect Tutsi wherever he and his shrinking force could actually accomplish something.

After Rwanda, Dallaire dealt with post-traumatic stress disorder. For years, he was haunted by what he had seen. In 2003, his book about the experience, Shake Hands with the Devil, was published. And, as he slowly recovered, Dallaire plunged into humanitarian work, particularly to publicize the plight of child soldiers. He also participated in the evolution of the Canadian military that continued well after

“ NO ONE IS A PROPHET IN THEIR OWN COUNTRY.”

the 1993 Somalia affair, in which Canadian peacekeepers had tortured and killed a local teen.

One of the lasting reforms to emerge from that process was the government’s decision that no Canadian military member could again receive a commission without a university degree.

Dallaire was appointed to the Senate in 2005 and served until 2014. And he has been showered

with awards and honours, largely because of his wide-ranging humanitarian efforts.

But, as Dallaire said at the event held to celebrate the donation of his archives to West Point, “there is a saying in French, that no one is a prophet in their own country.”

What has been left unsaid is that this turn of events is further proof of how apathetic Canadians are about the military history of their country. In 1994, Dallaire found himself in the middle of unimaginable horrors and despite wanting to take action, he was hamstrung by the UN bureaucracy. Now his own country has passed on his legacy to another. L

Check out David J. Bercuson’s new book, Canada’s Air Force: The Royal Canadian Air Force at 100, available now from University of Toronto Press.

Canada gets its first action of the Great War

By Stephen J. Thorne

Yfind much about Dickebusch in the annals of Canada’s First World War history. Granted, the name doesn’t have the same cachet to it as a Passchendaele, Somme or Vimy Ridge, but you would never tell that to the boys who were there.

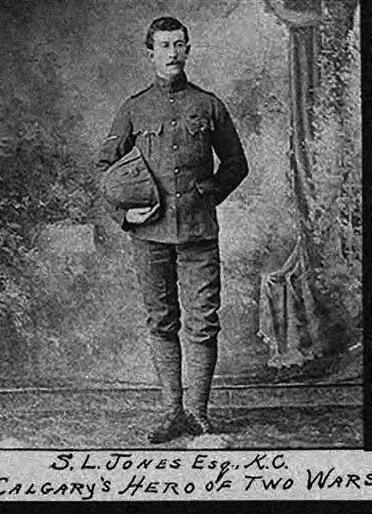

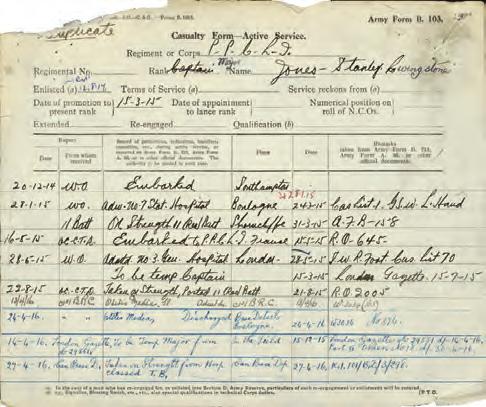

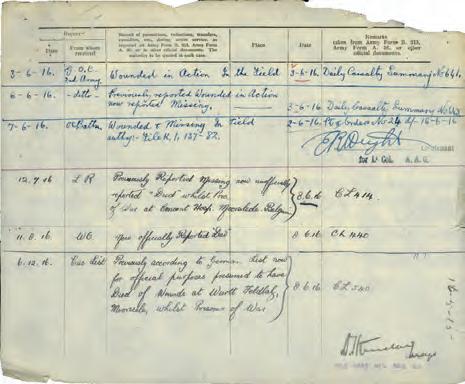

“The German guns suddenly opened on us, and for the rest of the day 17 different kinds of hell were all about us,” wrote Captain Stanley Livingstone Jones, 33, of Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (PPCLI), the first Canuck unit to see WW I action.

After two months of training in England, the Patricias had followed the No. 2 Canadian Stationary Hospital unit into France, arriving at Le Havre on Dec. 21, 1914.

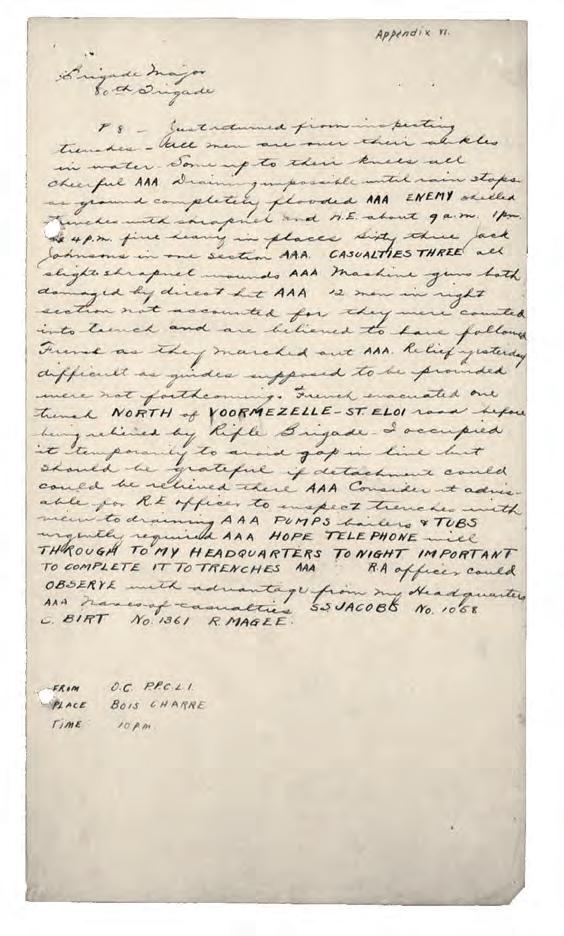

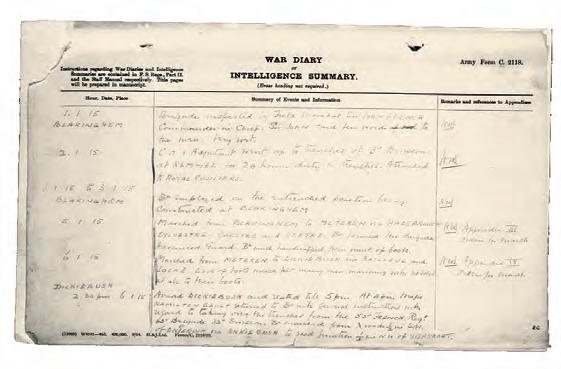

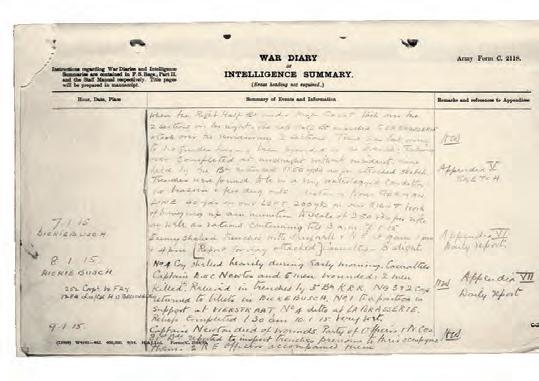

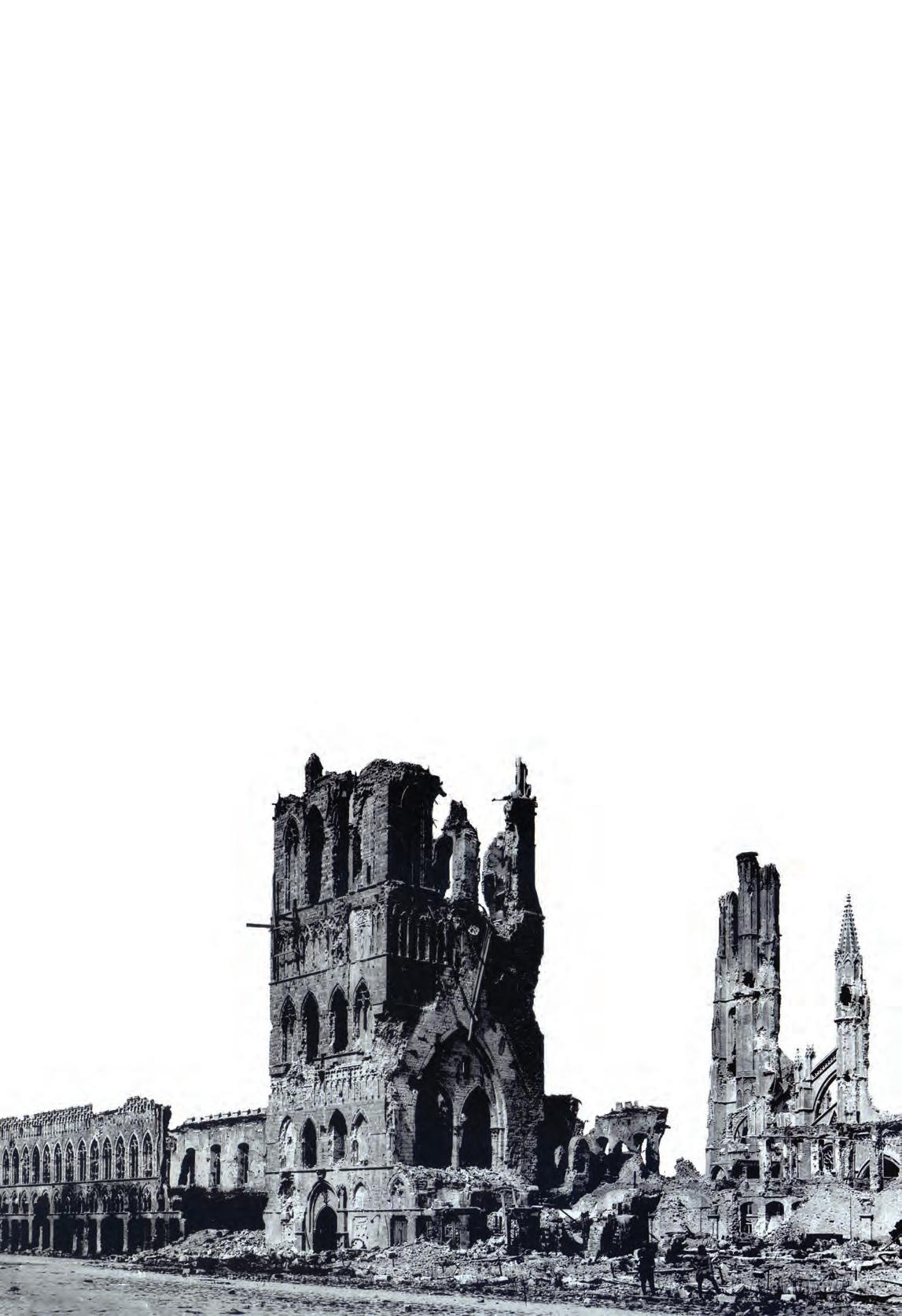

Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry fought Canada’s first battles of the Great War in January 1915 at Dickebusch near Ypres, Belgium (opposite). The unit’s war diaries (left) reference inferior equipment and replacing the infamous Ross rifle with the first Lee Enfields taken into front-line Canadian service (inset).

They were apparently illequipped when they moved into the line on Belgium’s Ypres salient on Jan. 6— thanks, no doubt, to Sam Hughes, the controversial federal minister of militia and defence whose cozy deals with suppliers and manufacturers tended to come at the fighting man’s expense.

The PPCLI had shed the troublesome Ross rifle and its nasty jamming habits in favour of the Lee-Enfield while still in England.

Clothing and footwear were another problem: Boots rotted and uniforms disintegrated in the notorious mud of the Western Front; trenching shovels were useless.

“Lack of boots much felt; many men marching with no soles at all,” says the Patricias’ war diary. “Arrived at Dickiebush [sic] and rested until 5 p.m…. The right half battalion under Major [Hamilton] Gault took over the two sections on the right…. Completed at midnight without incident.

“Trenches were found to be in a very waterlogged condition, no braisers and few dugouts. Distance from German line 40 yards on our left, 200 yards on our right.”

They were just south of the ancient trade centre of Ypres, about 15 kilometres from the French border. Here, the Allies were mounting a stand to prevent German forces from reaching Belgian and French seaports, some 35 kilometres away. The relentless shelling would reduce Ypres and its historic Cloth Hall to rubble.

The standoff would last almost the entire war, the German lines arrayed in a semicircle around Ypres, shifting with the ebb and flow of five major battles and multiple skirmishes in between.

The January 1915 action at Dickebusch appears to be one of those flare-ups, coming two months after the First Battle of Ypres, during which the German advance was stopped in October-November 1914.

There was some apprehension among the British about how the Canadians would adapt to the type and magnitude of the newly industrialized warfare, so different from their last go-round 14 years earlier in the Boer War. Any concerns, however, were soon allayed.

“This front has become a battle of inches and the slightest advance made out of the general scheme endangers our whole front,” a British officer told the Regina Leader-Post at the time.

“We were afraid the Canadians, in their enthusiasm, would carry out the rush tactics they employed so effectively in South Africa, but which would be fatal here.

“But the Patricias, rank and file, have shown themselves steady and their officers well trained.”

Indeed, for a forgotten battle, Dickebusch in January 1915 sounded pretty hot.

“Guns of every size and kind roared and spit back and forth, tipping up great holes in the earth and throwing mud and water high in the air,” Jones, himself a Boer War veteran, reported

in a Jan. 11 letter to his hometown Calgary Albertan newspaper.

“We escaped annihilation by only a few feet as the main bursts of shrapnel just cleared us.”

Two days after entering the trenches, the PPCLI took Canada’s first casualties of the war on Jan. 8.

“No 4 Coy shelled heavily during early morning,” says the history.

“Casualties Captain D.O.C. Newton and 5 men wounded: 2 men killed.”

By the time the war ended in November 1918, some 60,000 more Canadians would die, including Jones. And 172,000 would be wounded.

“TRENCHES WERE FOUND TO BE IN A VERY WATERLOGGED CONDITION, NO BRAISERS AND FEW DUGOUTS. DISTANCE FROM GERMAN LINE 40 YARDS ON OUR LEFT, 200 YARDS ON OUR RIGHT.”

A ruined village in the Ypres salient. Stanley Jones’ service records (below) trace his war journey from recruitment to capture and death.

The Patricias were relieved by the British 3rd Battalion, King’s Royal Rifle Corps (see “The King’s men,” page 26), and dispatched to billets in the village of Dickebusch, or the Flemish Dikkebus. It’s part of the present-day city of Ypres (Ieper), population 35,000.

Jones would take a bullet to his left hand later in January. He was wounded again by shrapnel to his right foot in May and a gunshot wound to the left foot in September.

By now a major, he was reported wounded once more, hit by shrapnel through his left lung during a German mortar and artillery barrage near Sanctuary Wood on June 2, 1916.

He “suffered for 36 hours from his wounds with no attention but the first aid given by a comrade,” Alberta’s Crag & Canyon newspaper reported on Aug. 5, 1916.

“The Germans then captured the ground where he lay and, at the risk of their lives, removed him to hospital. They gave him every possible attention.”

Jones died in German hands on June 8. He is buried in Moorseele Military Cemetery, 20 kilometres east of Ypres. His wife Lucile had followed him overseas and was nursing at a hospital in Champigny-sur-Marne, France. It wasn’t until July 11 that she learned of her husband’s fate. The words “burnt into my head like red hot coals,” she wrote in her memoir. It was days before she could read the rest of the letters that accompanied the news. One

was from Jones, mailed on June 4, two days after he was wounded.

“We may be separated for some time but our love will always hold us together,” he wrote.

The PPCLI would fight in what is most commonly regarded as Canada’s first major action, at the Second Battle of Ypres, in the spring of 1915. It was during this fighting between April 22 and May 25 that the Germans first deployed poison gas, hitting French colonials at Saint Julien on the battle’s first day and neighbouring Canadian troops two days later.

Jack Richard depicts Canadians in action at the Second Battle of Ypres in April/May 1915. Patricias march with the regimental pipes and drums in July 1917.

The Patricias had been on the line 12 days and taken 75 casualties, including 26 killed, when they fought a major engagement in the Second Battle of Ypres at Frezenberg in May 1915. Of 700 men who faced fire from three sides and stopped the German advance fighting from ditches and shell holes, 154 emerged in one piece under the command of the only able officer, a 39-yearold lieutenant named Hugh Wilderspin Niven, a wholesale hardware salesman from London, Ont., who had only just recovered from a bullet wound he had taken to his left forearm in March.

Niven was promoted to captain and awarded the Military Cross and the Distinguished Service Order (DSO) the following September. He would survive

a shrapnel wound to the chest in June 1916 and return to finish the war a major, receiving a bar to his DSO in January 1918. He died in 1969 at age 92.

Patricia Sergeant Walter Stamper was at Frezenberg, the PPCLI’s most celebrated battle honour and the origin of one of its unofficial mottos, “holding up the whole damn line.” Stamper wrote his wife and daughter in August 1916 after he was captured and eventually deposited in neutral Switzerland, where he would be interned for the duration.

This time, the Canadian prisoners of war didn’t get the same consideration afforded Jones.

“We were simply blown to pieces,” Stamper said. “There was just ten of us left in our Company, most of us unable to help ourselves;

those that were to [sic] badly wounded to walk they shot and bayoneted them. These, they made us lay on the ground beside them whilst they dug themselves in.

“All the time the shells and bullets were flying around us, and

“GUNS OF EVERY SIZE AND KIND ROARED AND SPIT BACK AND FORTH, TIPPING UP GREAT HOLES IN THE EARTH AND THROWING MUD AND WATER HIGH IN THE AIR.”

I can tell you I never expected to see any of you again. To amuse themselves they threw stones at us and called us swine, one of my men could not keep still as he was suffering so from a wound in the head, got up and was promptly shot by them through the stomach; he died about two hours later in great agony.

“We laid there from ten o’clock in the morning until six at night when we were fetched into the trench and robbed of everything we had. We were then taken back and threatened if we did not give information about our troops we should be shot. We were lined up three times for that purpose.”

They were eventually put on a train to Germany and given a starvation diet until relief parcels arrived and they were shipped off to Switzerland. There they were boarded in hotels and “smothered in flowers, chocolates, tobacco and cigarettes.”

In his paper “Birth of a Regiment: Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry 19141919,” historian James S. Kempling writes that the fighting that spring “marks not the death of the Originals but rather the initial birth pangs of a Regiment.”

“Nevertheless,” he continued, “by the end of the Frezenberg

battles the Patricias were in desperate condition. In May alone the battalion had 461 men struck off strength. Of these 219 had been killed and most of the remainder injured to the extent that they were unlikely to return to duty. A small number had been taken prisoner.”

The regiment would reconstitute and go on to fight at Mount Sorrel, the Somme, Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele (the Third Battle of Ypres) on into the Hundred Days Campaign that finished the war.

Of the 5,000 men who served with the regiment during the First World War, 1,300 never returned to Canada. Three Patricias would earn the Victoria Cross and the regiment would receive 18 battle honours.

During April 1916 fighting for the St. Eloi Craters five kilometres south of Ypres, elements of the Saskatchewan Rifles were billeted in reserve at the Patricias’ old haunt in Dickebusch. James Cameron McFadden’s grandfather, James Muirhead, was with the battalion.

In a Facebook post with a photo of his grandpa, great-granddad and great-uncle, who was killed at Ypres in 1916, McFadden said Muirhead rarely spoke of the war, but he was fond of one story about that favourite of infantry mascots—a dog.

“WE WERE SIMPLY BLOWN TO PIECES. THERE WAS JUST TEN OF US LEFT IN OUR COMPANY, MOST OF US UNABLE TO HELP OURSELVES.”

“Somewhere in a place that the men called ‘Dickie-Bush,’ [they] befriended a small dog, and it followed them wherever they were sent throughout the rest of the war,” wrote McFadden.

“They just called it ‘the DickieBush Terrier,’ after the place where it had joined them.

“When the war was over, they were told that they could not bring the dog home with them. One of the men scooped him up and hid him inside a duffel bag, and they all went onto the transport ship home to Canada. Grampa said that the last time he saw the dog, it was at the train station in Toronto. It was running after the man who had put it in the duffel bag.

“It followed him right up the steps onto a Pullman car, destined for a new home.” L

A soldier stands at a monument alongside Patricia Crater, where engineers and PPCLI took a German position during early fighting at Vimy Ridge.

Raised in 1756, the King’s Royal Rifle Corps had originally consisted of colonists recruited in British North America by what was then known as the antithetically named Royal American Regiment. This was during the Seven Years’ War— or the French and Indian War in North America. The unit existed for 200 years.

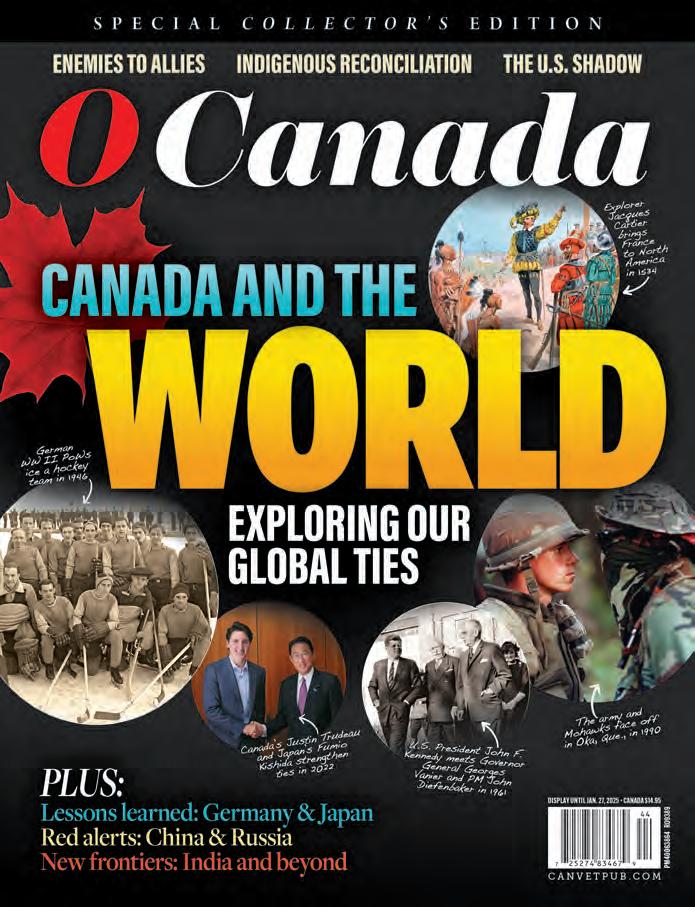

War may have made Canada, but it didn’t define it. To the eyes of many, the Great White North is the great conciliator. The objective third party. The voice of reason. The peacekeeper. During the course of 157 years— and more—the country has nevertheless made enemies and become their friend, made friends and become their enemy, and navigated relationships through good times and bad. Now, Canada’s Ultimate Story explores some of these key connections, the impact Canada had on them and their impact on Canada.

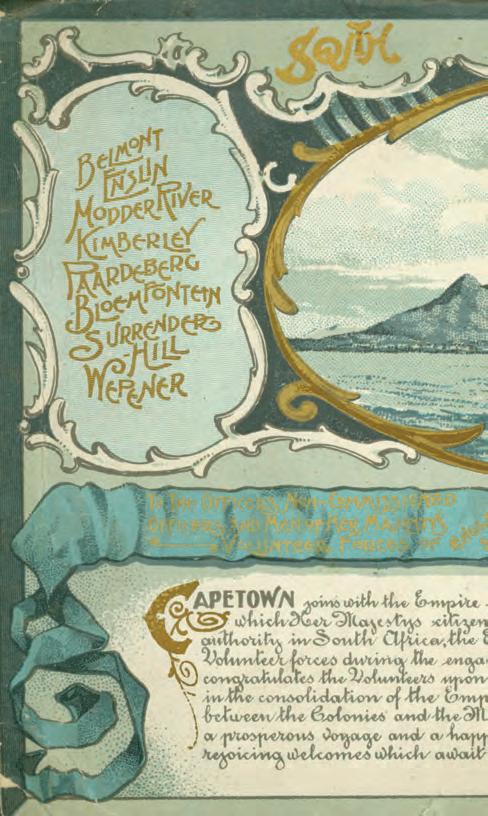

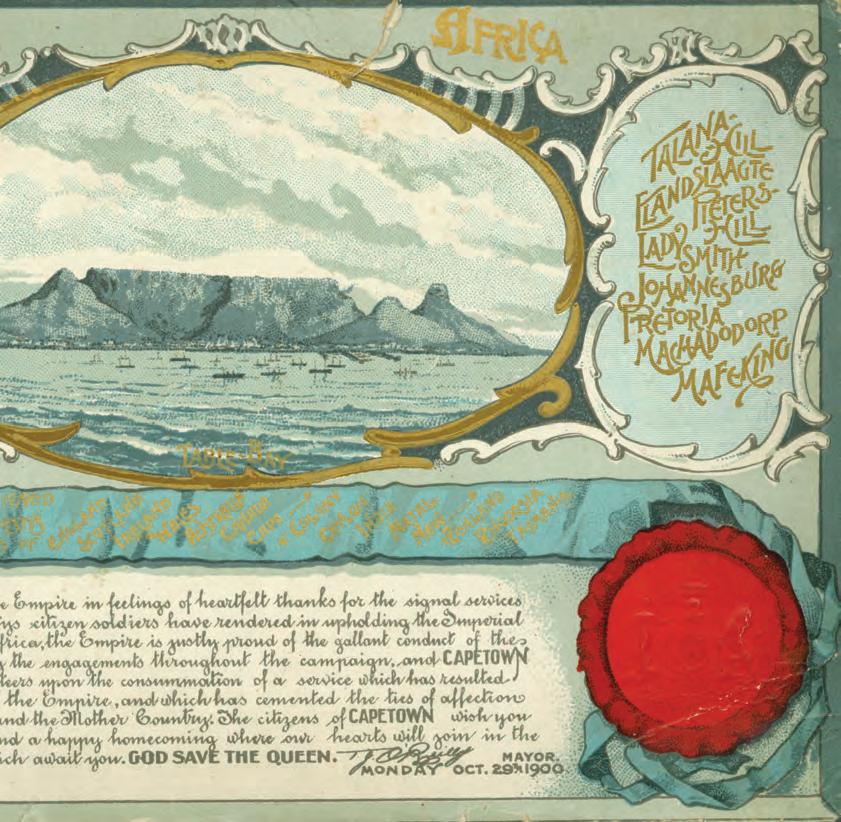

IN THEIR FIRST OVERSEAS BATTLE CANADA’S SOLDIERS PROVED THEIR METTLE

TBy John Boileau

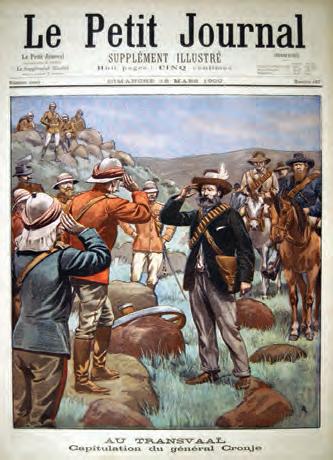

The newspapers called it “Black Week.”

Between Dec. 10 and 17, 1899, three columns of British regulars led by experienced generals were defeated at Stormberg, Magersfontein and Colenso during the opening battles of the Boer War. Citizen soldiers of the tiny Boer republics of Transvaal and the Orange Free State caused nearly 3,000 casualties as the Brits attempted to relieve the besieged towns of Mafeking, Kimberley and Ladysmith.

The public at home was shocked, while other European powers began to question the dominance of the British Empire. But that coalition had already answered the call and contingents from Australia, India, New Zealand, South Africa and Canada stepped in to help.

The conflict, also known as the South African War, had begun just two months earlier. In the wee hours of Oct. 11, 1899, Boer troops advanced south and east into the British territories of Cape Colony and Natal at the southern tip of Africa.

Canadians were sharply divided over sending troops to assist Britain. Generally, English Canadians were supportive, while French Canadians, seeing parallels between themselves and the Boers, were not. Wilfrid Laurier, the country’s first French-Canadian prime minister, opposed sending his brethren to fight in a war in which he felt no Canadian interests were at stake. But Laurier misjudged the overall mood of the country.

Throughout the summer and fall before the war, partisan newspapers whipped the public into a frenzy of Boer bashing. Laurier finally acquiesced to public opinion, or at least that of English Canada. In mid-October, he offered to send 1,000 volunteers to South Africa. The British promptly accepted. Recruiting started immediately. The 2nd (Special Service) Battalion of the Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry (RCR) was made up of volunteers—150 from the 1,000-man Permanent Force and the remainder from 82 militia units. Eight 120man companies were assembled in Victoria, Vancouver and Winnipeg for ‛A’ Company; London for ‛B’; Toronto for ‘C’; Ottawa and Kingston for ‛D’; Montreal for ‛E’; Quebec for ‛F’; Saint John, N.B., and Charlottetown for ‛G’ and Halifax for ‛H.’

Roberts’ praise acknowledged the Canadians as being “instrumental in the capture of General Cronjé and his forces.” The Boers reportedly dubbed them “fire eaters.”

1900. There, some 20,000 British soldiers were decimated by 8,000 Boers and forced to retreat.

Amazingly, authorities recruited, examined, organized, clothed, equipped, assembled and dispatched overseas the 1,039-man battalion in October in just 16 days. The government selected Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter, Canada’s most experienced soldier, to command the country’s first-ever overseas expeditionary force.

When the RCR arrived in Cape Town at the end of November, the Boers surprisingly held the upper hand and had British forces bottled up in Mafeking, Kimberley and Ladysmith. The day after the Canadians arrived, they moved north by train.

After pausing for a few days at various stops en route, the RCR reached Belmont on Dec. 9, just before Black Week began. At Belmont, the Canadians trained and performed outpost duties.

The defeats of Black Week were followed by the embarrassment of Spion Kop on Jan. 24,

The RCR moved to Graspan and joined 19th Brigade, part of a 35,000-man British force commanded by Field Marshal Frederick Roberts, the newly appointed commander in South Africa. The diminutive, one-eyed, 67-year-old Roberts, affectionally known as “Bobs” to his soldiers and the public alike, was one of Britain’s most capable officers. He had been sent to turn the tide.

In mid-February, the RCR began a gruelling, five-day cross-country trek across the veldt under Roberts. It was marked by thirst, hunger, heat and exhaustion. Roberts’ goal was the Orange Free State capital, Bloemfontein. But a Boer force of 5,000 men under General Pieter (Piet) Cronjé stood in the way.

The two sides met at Drift, a ford at the Modder River. While

Soldiers en route to the Boer War parade in Ottawa (opposite left). After early setbacks, British Field Marshal Frederick Roberts (opposite right) took command of the Imperial forces, while Lieutenant-Colonel William Otter (opposite bottom) led the Canadian contingent. An artist depicts the British defensive line during the Battle of Majuba Hill in February 1881 (below).

Cronjé dug defensive positions into the river’s north bank, he sent his wagons and the families about three kilometres further upriver to form a protective barrier called a laager

The Canadians’ initial experiences in battle on Feb. 18 weren’t good. The desperate fighting that marked Canada’s first overseas exchange of gunfire ended in failure, with 21 killed and 60 wounded. “Bloody Sunday,” as the soldiers called it, was Canada’s costliest engagement since the War of 1812.

After another abortive attack on Feb. 20, the RCR performed various outpost duties over the next few days, designed to keep the Boers from escaping. As the British gradually tightened a noose around the Boers and shelled their positions continuously during daylight, Cronjé moved closer to the laager and dug in positions

along both sides of the riverbank. Inside the circled wagons, which stretched in a three-kilometre arc along the north side of the Modder, conditions were deplorable.

The Canadians were in rough shape, too. Sickness, wounds and death had reduced the original 1,039-man battalion to 708. Those who remained were a bedraggled looking lot. Unable to wash or shave most of the time, they had been wearing the same lice-infested clothes for two weeks. Extremes of heat and cold, as well as insufficient rations, only added to their misery.

To make matters worse, hundreds of dead Boer animals floated downstream, their decomposing bodies polluting the water and filling the air with a sickening stench. When the Canadians got the odd rest day, they washed their bodies and clothes with river

water and used it for drinking and cooking. Illness struck.

On Feb. 26, the RCR relieved a British battalion in the front-line trenches opposite the west end of the Boers, only 550 metres from the dug-in farmers. The next day held special significance for both sides.

Feb. 27 nineteen years earlier, the Boers had triumphed over the British at the Battle of Majuba Hill. Their victory secured the former’s independence and humiliated the latter. The British army was anxious to avenge that defeat.

The responsibility for the attack fell to 19th Brigade, now reinforced by additional infantry units and a company of Royal Engineers. Because the RCR held the front-line trenches, they would lead the assault, assisted by the Brits. The green Canadians were about to undertake one of the most difficult operations in warfare: a night attack.

At daybreak, from the safety of their hastily dug new trenches, the tenacious Maritimers realized that they overlooked the enemy.

By 10 p.m., the forward RCR companies, ‛C’ through ‛H,’ were in position for the assault. Their trenches stretched northward for more than 300 metres from the riverbank. ‛A’ Company was sent south of the river, while ‛B’ Company was in reserve.

Shortly after 2 a.m. on Feb. 27, 500 Canadians climbed out of their trenches as quietly as possible and formed two lines six paces apart. The front line had bayonets fixed. To keep direction in the darkness, the soldiers advanced shoulderto-shoulder, “clasping the hands of those on our left and being clasped by the waist of those on our right,” according to a participant.

Around 2:45, when the Canadians were less than 100 metres from the enemy trenches, a soldier bumped into a tin can filled with rocks hanging from a wire. The primitive warning system alerted Boer sentries, who began firing. This was quickly followed by withering fire from the Boer lines as the farmers scrambled out of their dugouts. Fortunately, the sentries’ shots gave the Canadians enough time to throw themselves to the ground and avoid the worst of the barrage. British

engineers started to dig in while the Canadians returned fire.

Although the casualties from the first shots were surprisingly light, ‛F’ and ‛G’ companies, who were closest to the Boer lines, in some cases only 60 metres away, suffered the most. They sustained six killed and 21 wounded in the opening volley.

For the next 15 minutes, the two sides traded shots. The RCR front line kept up a steady fire, while the second line and the engineers dug in. Occasionally, a frustrated soldier in the second line dropped his shovel and crawled to the front rank to return a few shots in the enemy’s direction.

A few, paralyzed by fear, hugged the ground and didn’t fire at all. Suddenly, an authoritative voice from the left flank called out, “Retire and bring back your wounded!” Most of the soldiers were only too happy to oblige. The Canadian fire lessened, men stood up and ran to the rear. As they fled, fire from the Boers felled several of them.

Soldiers of ‛C,’ ‛D,’ ‛E’ and ‛F’ companies were soon crammed into their original trenches, which were now occupied by a British battalion. They remained there for

the rest of the battle. But the two companies from the Maritimes, ‛G’ under regular army Lieutenant Archibald (Archie) Macdonell and ‛H’ under Halifax militia Captain Duncan Stairs, either didn’t hear the order or purposely chose to ignore it. They stood their ground, along with a few Royal Engineers.

At daybreak, from the safety of their hastily dug new trenches, the tenacious Maritimers realized that they now overlooked the enemy. They could fire into the Boer dugouts along the riverbank, as well as into their laager.

When darkness began to fade around 4 a.m., several Boers emerged from their trenches to survey the battlefield. The Maritimers immediately opened up with well-disciplined fire that drove the enemy back into their holes. The Boers returned fire for about an hour or so, when suddenly those in the forward enemy trenches shouted out that they wanted to surrender. Initially, the Canadians continued to fire on the Boers. They had heard stories about Boers pretending to give up, only to open fire again. Around 6 a.m., a lone Boer climbed out of his trench carrying

Troops of the Royal Canadian Regiment cross the Paardeberg Drift in February 1900.

a white flag and walked toward the Canadians. All action ceased. Other Boers quickly followed, surrendering to ‛G’ and ‛H’ companies.

The leading British and Canadian troops advanced warily, bayonets fixed, past the Boer trenches and into the laager. Roberts arrived to accept Cronjé’s surrender. Most Boers never forgave him for capitulating, especially on the anniversary of their great victory at Majuba. Cronjé’s untimely and unexpected capitulation, with nearly 10 per cent of the entire Boer army, opened the way for the eventual Imperial victory.

Late that afternoon, as the RCR searched the laager for souvenirs and food, an honour the British

gave them in recognition of their role in the victory, Roberts rode over to congratulate the Canadians. He praised them and acknowledged them as being “instrumental in the capture of General Cronjé and his forces.” “Canadian,” he went on to state, “now stands for bravery, dash and courage.” The Boers reportedly dubbed the Canadians the “fire eaters.”

Once Roberts’ dispatches reached Britain, Canada and the rest of the Empire heaped praise on the soldiers of the RCR. Canadians had just won their first foreign

battle and the first significant Imperial victory of the war at a cost of 13 dead and 36 wounded. For his courageous actions during the battle, Private Richard Thompson was awarded a Queen Victoria’s Scarf of Honour (see “Artifacts,” September/October 2024).

The battle quickly became known as “The Dawn of Majuba Day,” avenging the earlier defeat. Many hailed it as a turning point in the conflict and the beginning of the reversal of British fortunes.

And Canadian soldiers played a full part in that victory. L

With Cronjé defeated, the RCR participated in the general Imperial advance on the Orange Free State and Transvaal capitals. By now, the Boers had decided that setpiece battles were not to their advantage and resorted to hit-and-run tactics conducted by roving bands of commandos.

On March 15, after a grueling march averaging 25 kilometres a day, the Canadians entered Bloemfontein

unopposed. Battles at Israel’s Poort, Thaba Nchu, Zand River and Doornkop Hill followed, opening the way to Pretoria. On June 5, the RCR, now reduced to 437 men, marched into the undefended Boer capital.

Lines of communications duties followed at various railroad stations until the regiment’s time was up. After almost a year in South Africa, the RCR returned to Canada and was disbanded.

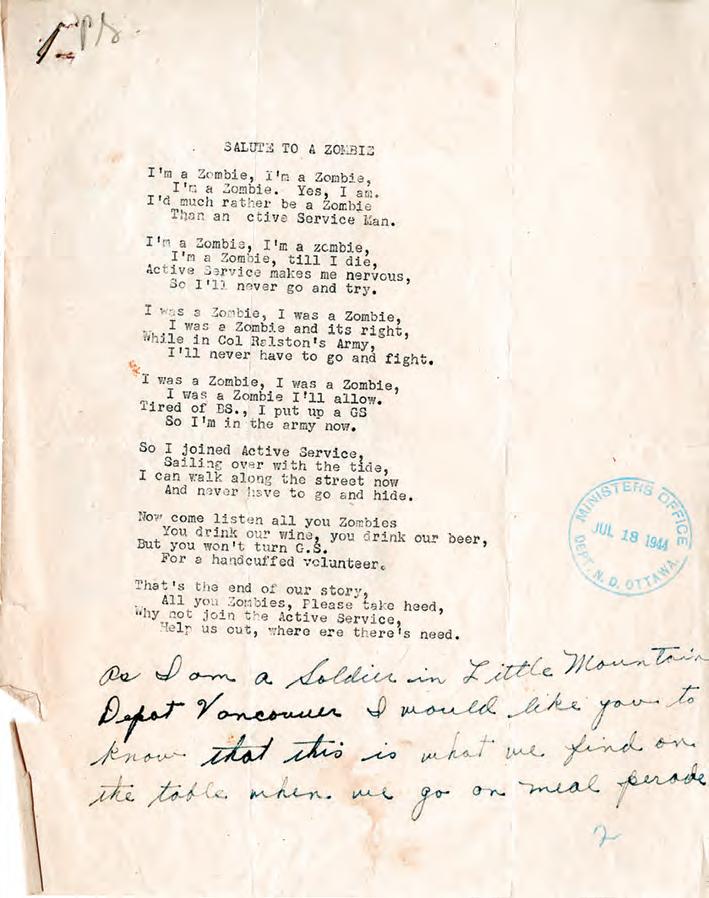

KNOWN DERISIVELY AS ZOMBIES, THOUSANDS OF CANADIAN MEN WERE CONSCRIPTED—ORIGINALLY FOR HOME DEFENCE— UNDER THE WW II NATIONAL RESOURCES MOBILIZATION ACT. LATE IN THE WAR, MANY WERE FORCED TO THE FRONT LINES

By J.L. Granatstein

Conscription was the political issue of the Second World War in Canada. And despite promises by the Mackenzie King government before the war to avoid it, the fall of France and public pressure forced the feds to pass the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) in June 1940, which authorized compulsory service for home defence.

But by 1944, after the D-Day invasion of France and the brutal combat in Normandy and the Scheldt estuary, casualties were high and trained infantrymen were in short supply. By November, the military was convinced that only the home defence conscripts could suffice for the needed reinforcements. King finally agreed to send 16,000 of the men who had become known by much of the public derisively as zombies—the soulless living dead of horror movies—overseas.

The pressure on the conscripts to “convert” to general service volunteers had been intense since at least 1942. And money was a factor in the efforts at persuasion. The home defence men weren’t entitled to a War Service Gratuity if they remained in Canada. If they went overseas, however, they would get an additional 25 cents for each day, $7.50 for each 30 days of service, and one week’s pay for each six months of service outside Canada. The additional remuneration was substantial.

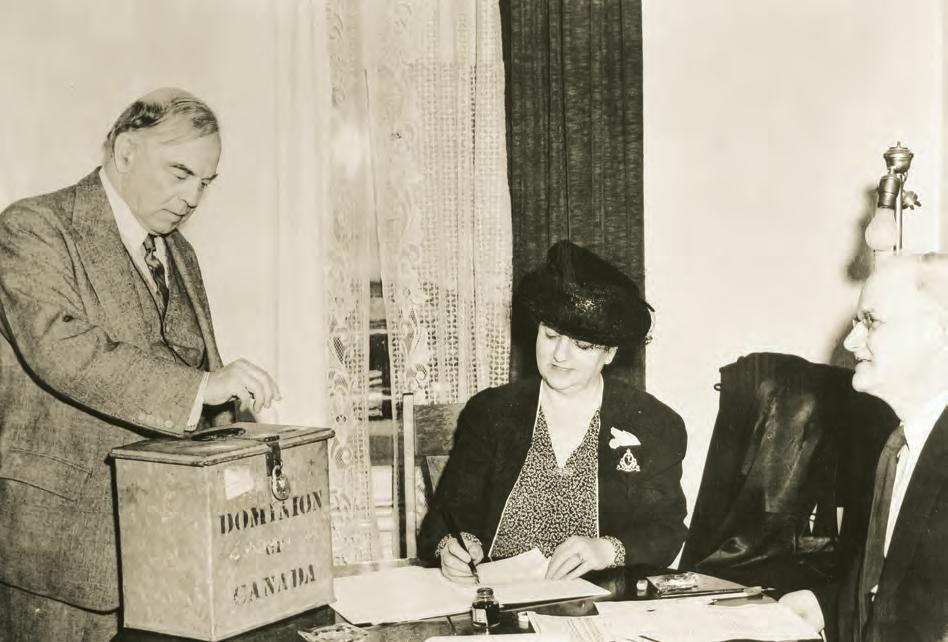

Conscripts served with units such as Le Régiment de Maisonneuve, shown (above) near Nijmegen, Netherlands, on Feb. 8, 1945. A recruitment campaign poster from 1942. Prime Minister Mackenzie King votes in the plebiscite on conscription on April 27, 1942.

Interestingly, the NRMA had much to do w ith enlistment for general service. By way of example, historian Terry Copp studied the 197 men of Le Régiment de Maisonneuve who were killed in action to determine, in part, how they had joined the war effort. Civilian volunteers numbered 130, while another three volunteered for overseas service after they received their conscription notices; 27 volunteered following their home defence service; 22 were zombies sent overseas for service; and there was no information on 15.

NOT EVERY ZOMBIE ACCEPTED THE DECISION. THERE WERE BRIEF MUTINIES IN BRITISH COLUMBIA TRAINING CAMPS. AND SOME 6,000 WENT ABSENT WITHOUT LEAVE.

Refining the data further, Copp focused on those Maisies killed in action who had enlisted in 1943-1944. There were 23 civilian volunteers; three volunteered on being called up; 16 joined after serving as home defence conscripts; 16 were zombies sent overseas; and there was no information on 14.

Of civilian volunteers then, some, and possibly many, did so when faced with home defence conscription. The same can be said about those who volunteered when they received their call-up notices. Those who converted after home defence service likely did so after being pressed repeatedly to volunteer, to get the benefits offered only to volunteers, or on being ordered overseas by Ottawa or even en route to England. Those who were ordered overseas might well have been hardline anti-conscriptionists throughout their service. What’s certain, however, is that the NRMA played an important role in persuading men to volunteer for military service.

Once the government ordered conscripts overseas, the rate of conversions, which had been stagnant for months, increased rapidly. There were 1,878 in December 1944, 1,692 in January 1945, 2,164 in February and 2,131 in March. The lure of veterans’ benefits was significant.

Men who believed in the cause but had made clear that they were only willing to fight overseas if the government had the courage to order them to do so, also converted after the government’s November 1944 decision.

But, not every zombie accepted the government decision. There were brief mutinies in British Columbia training camps. Some 6,000 soldiers ordered overseas went absent without leave after failing to return from pre-embarkation leave, though substantial

numbers returned to their units voluntarily; some men deserted from the trains taking them to their embarkation point, abandoning their rifles and kit; and one zombie tossed his rifle into the water from the gangplank.

All this made news around the world, greatly embarrassing the government, the high command overseas and many soldiers fighting in Italy and Northwest Europe. The latter wrote letters home denouncing the cowardly zombies.

Nonetheless, the NRMA was largely a success. In all, some 154,000 men had been drafted for home defence service, and about 60,000 converted to general service, about 6,000 transferred to other services, and thousands more were discharged for a variety of reasons. By early autumn 1944, there were an estimated 60,000 conscripts still serving, some in formed units, some in training or on courses, some seconded to help bring in the harvest. Trained infantry made up 42,000 of the group.

The widespread opinion in Englishspeaking Canada was that most of the home defence conscripts were francophones, but this wasn’t correct: 30 per cent spoke only English, 20 per cent spoke only French, 24 per cent were bilingual, and 26 per cent had another first language. They also came from across the country: 25 per cent were from Ontario, 39 per cent from Quebec, 24 per cent from the Prairies, six per cent from B.C, and 6 per cent from the Maritimes.

In other words, the home defence soldiers were generally representative of the Canadian population with only a slightly higher percentage of Quebecers.

Men who didn’t volunteer to fight had many reasons. Some feared being killed or grievously wounded, a rational enough reason in a bloody war. If family members had served during the Great War, many had heard stories of the horror of the trenches and didn’t want to go through their generation’s version of hell. Some were recently married or had young children and didn’t want to be separated from their families. Some were of ethnic origins that didn’t identify with the Anglo-centric views of the military or have any sympathy for the British Empire. Some had religious or cultural reasons for resisting military service. Simply put, not every Canadian wanted to fight.

But once the decision had been taken to order the zombies overseas, General Harry Crerar, the commander of First Canadian

Army, knew that he then had to deal with the possibility that the conscripts might not be welcomed by his men. How could this very dangerous possibility be averted?

Crerar decided that integration was the answer. He sensibly ordered conscripts arriving from Canada be integrated with volunteers in the normal reinforcement stream during their training in England “in order to avoid trouble when [their] draft reached units in the field.” And to avoid distinguishing the NRMA men from volunteers, he insisted on uniformity of dress and had the distinctive serial numbers of conscripts changed to conform with those of volunteers from the same military district in Canada. References to a soldier’s mobilization status were removed from his pay book, too.

At the same time, Canadian Military Headquarters in England worried that conscript non-commissioned officers wouldn’t be acceptable to units in the field and trouble might result if such NCOs tried to give orders to volunteer soldiers. The NCOs were duly reduced in rank.

After their refresher training in England, the now mixed groups of conscripts and volunteer reinforcements began to go to the continent and to infantry units. The battalions weren’t to know which reinforcements

In November 1944, home defence conscripts protest the government decision to send them overseas (opposite top) at a training base in Terrace, B.C. (opposite bottom). Conscripts bolstered infantry units such as Le Régiment de la Chaudière, shown here marching along a dike near Nijmegen, Netherlands in February 1945.

were NRMA men, though some figured it out. Lieutenant Donald Pearce of The North Nova Scotia Highlanders wrote on March 20, 1945, that: “There is, of course, a considerable prejudice against” the zombies. “But for some reason they have made excellent soldiers, so far; very scrupulous in the care of their weapons and equipment, certainly, and quite well versed in various military skills.”

The war diarist of The Loyal Edmonton Regiment also appeared to be aware of the presence of conscripted soldiers, writing:

“During the month our [Battalion] has [taken on strength] eight officers and 167 OR’s [and], among the latter, are approx 40 NRMA personnel. These men have in no way been treated differently than any other [reinforcements], in fact the majority of the

[Battalion] is not even aware of their presence here, and in the few small actions they have engaged in so far they have generally shown up as well as all new [reinforcements] do.”

By this stage of the war, volunteer reinforcements were either young or re-mustered from other trades and given refresher training as infantry. The war diarist of The Algonquin Regiment noted that: “our newcomers are beginning to fit nicely into the family and from the interest they have shown the [battalion] to date they have erased any poor impression they may have given a few days ago and our [officers] and NCOs are now firmly convinced that we have the makings of a fighting team worthy of upholding the name Algonquin.”

The commanding officer of the regiment said as much to reporter Frederick Griffin from the Toronto Star, noting his conscripted soldiers “were just as good any reinforcements we have had.

“Actually,” the CO continued, “nobody knows in the regiment who is a draftee and who is not, and after the boys have been in action, nobody cares.”

A March 15, 1945, story by Ralph Allen in The Globe and Mail had a similar assessment. The conscripts, wrote Allen, “acquitted themselves well on all counts, according to the veterans who fight beside them” in the savage battles on the Rhine-Maas front. “[In] the few cases where home defense soldiers have been introduced to combat at the side of men who knew them to be home defense soldiers, they have been given high marks for courage, training and discipline both by their officers and by their comrades.”

By all accounts, the zombies fought just as well as their volunteer comrades, and the soldiers’ disdain for them during the conscription crisis largely disappeared.

As events developed on the battlefield in the first months of 1945, the shortage of infantrymen that had produced the manpower crisis of late 1944 vanished, too. The men of

First Canadian Army fighting in Northwest Europe, hit so hard in Normandy and on the Scheldt estuary, were effectively removed from the gruelling battles for much of November and December 1944, and all of January 1945. They were almost completely unaffected by the last German offensive in December, the Battle of the Bulge. First Canadian Corps was also moved from Italy to join up with Crerar’s army and was out of action for some six weeks in the first months of 1945. These respites allowed the reinforcement stream to catch up with, and overcome, the losses that had appeared so threatening in the autumn of 1944.

“THERE IS A CONSIDERABLE PREJUDICE AGAINST” THE ZOMBIES. “BUT THEY HAVE MADE EXCELLENT SOLDIERS, SO FAR.”

This situation on the ground meant that of the 12,908 conscripts who had proceeded overseas, only 2,463 had been taken on strength by units of First Canadian Army by VE-Day, May 8, 1945. Infantry battalions received 2,282 of these men. Of these troopers, 69 were killed, 232 were wounded and 13 became prisoners of war. Had the fighting continued longer than it did and/or had major battles caused many more casualties, additional conscripts, possibly beyond the 16,000 the prime minister had indicated were required in November 1944, would have been

A home defence conscript sent Defence Minister Colonel James L. Ralston the copy of the lyrics to the song “Salute to a Zombie” left for him. Volunteers, such as these soldiers, continue to arrive in August 1944 as reinforcements, but too few to fill the ranks.

Private René Morin (left) was one of 69 conscripts killed in action overseas.

necessary. The late-war manpower crisis, in other words, disappeared even before Germany surrendered.

Private René Morin, an Acadian from Edmundston, N.B., was one of those 69 conscripts killed in action. Drafted in May 1943, Morin joined Le Régiment de Hull in B.C. after his basic training, then in January 1944 transferred to the Sherbrooke Fusiliers in May. After the decision to send conscripts overseas, he proceeded to England in one of the first waves of reinforcements. On April 7, Morin reported to the Royal 22e Régiment, which was fighting in the Netherlands near Apeldoorn. On April 14, a German hand-held anti-tank projectile struck and killed him instantly. Morin was one month shy of his 21st birthday. His time in action lasted just one week. L

How one Lancaster crew met the demise of so many in Bomber Command

By Sharon Adams

Jan. 7, 1945, nine Mosquito aircraft and 645 Lancaster bombers took off from airfields across the United Kingdom for grim duty over Munich.