PattieLovett-Reid

Pattie Lovett-Reid Chief Financial Commentator,

Bank

Youthful reflection

Corporal Emily Solberg-Wells, recently returned from a deployment to Latvia, waits to place a wreath on behalf of the Lord Strathcona’s Horse (Royal Canadians) at the 2023 Remembrance Day ceremony in Nanton, Alta.

See page 62

Features

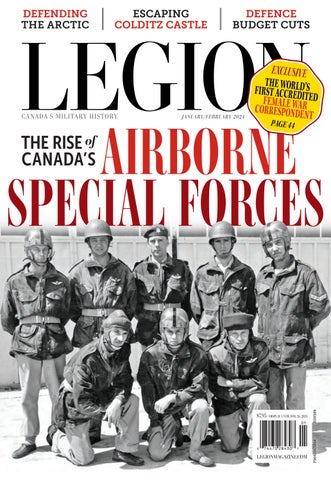

20 “BRING US THE GODDAMNED CANADIAN”

How Canadian officers seconded to the British Army under the Canloan program fought for their comrades— and respect

By Alex Bowers

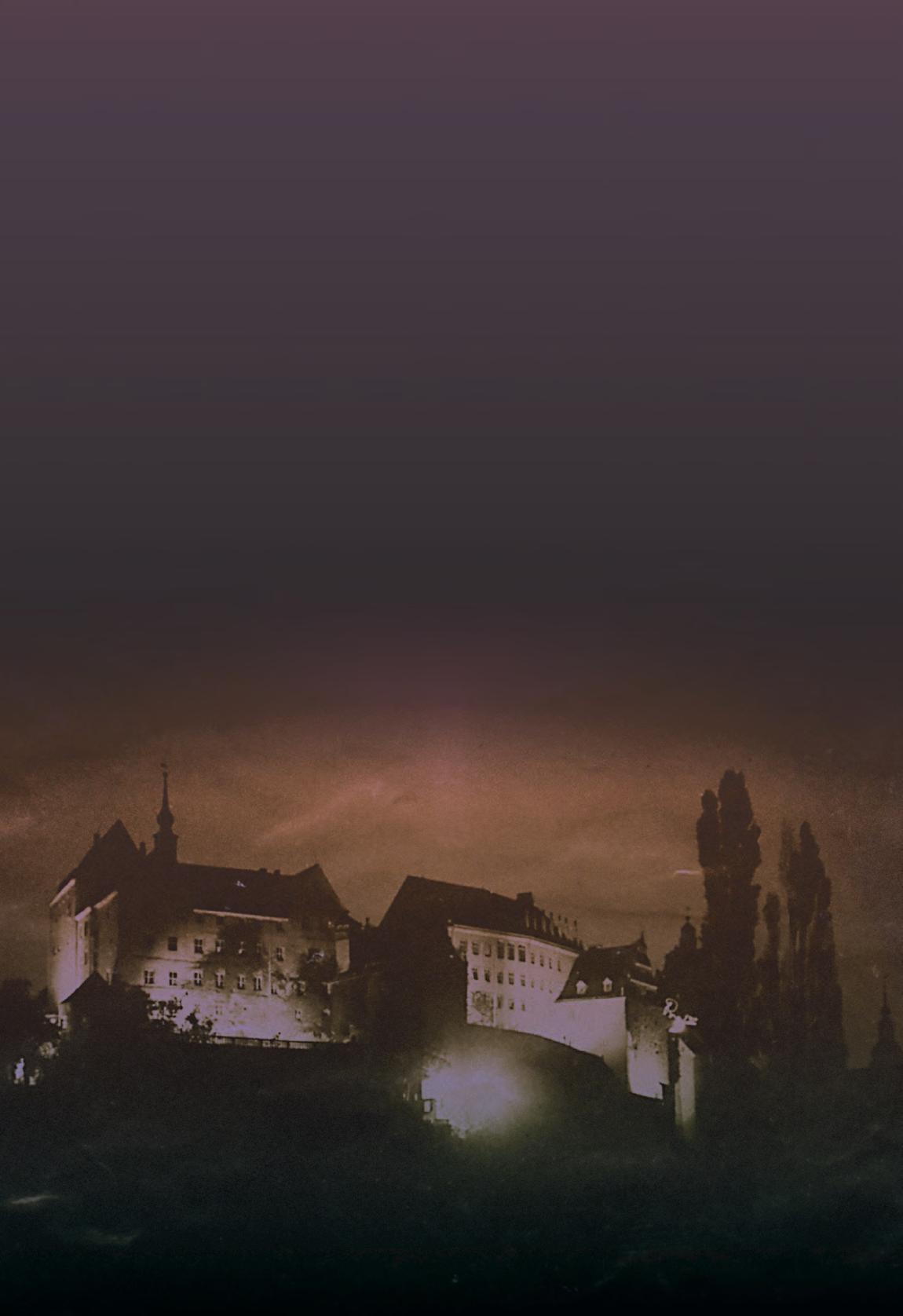

26 THE CASTLE

Allied prisoners of war who had a penchant for escape were often sent to Schloss Colditz—but even the legendary German keep couldn’t stop many from attempting getaways

By Ed Storey

32 ROGUE CO.

The story of Canada’s short-lived postwar Special Air Service

By Stephen J. Thorne

38 THE BACTERIUM BATTLE

How the Canadian Expeditionary Force fought for cleanliness during the Great War

By Robert Smol

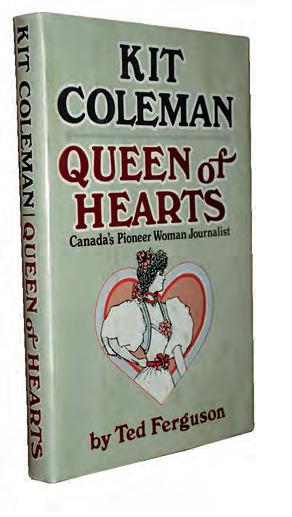

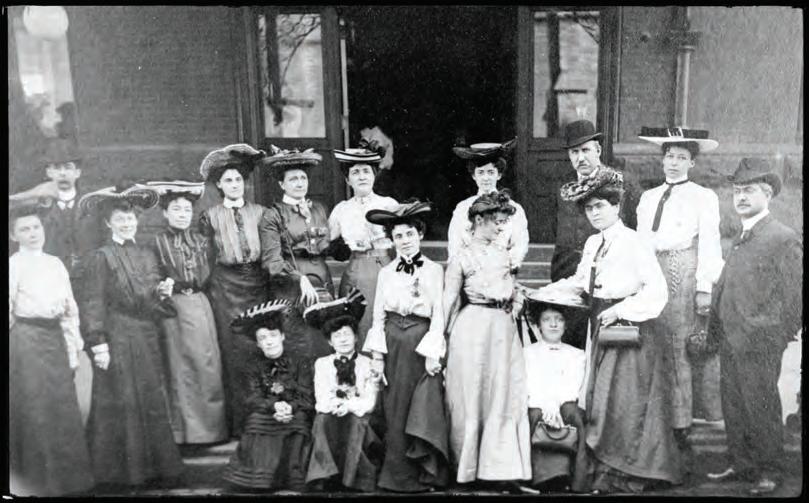

44 KIT UP!

The story of Kathleen (Kit) Coleman, North America’s first female war correspondent

By June Coxon

52 ICONS OF THE AIR

A collection of warbirds that symbolizes 100 years of the Royal Canadian Air Force

Photography and words by Stephen J. Thorne

58 REMEMBRANCE FOR ALL

A diversity of voices reflect on military sacrifice at the annual ceremony in Ottawa

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

62 A MEMORIAL STORY

In Nanton, Alta., home of the Bomber Command Museum of Canada, Remembrance Day inspires the tale of a WW II crewman killed in action

By Stephen J. Thorne

1st Canadian Parachute Battalion Association Archives/ Bernd Horn

Vol. 99, No. 1 | January/February 2024

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Owen Parkhouse BOARD VICE-CHAIR Bruce Julian BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe DIRECTORS Tom Bursey, Steven Clark, Thomas Irvine, Berkley Lawrence, Sharon McKeown, Brian Weaver, Irit Weiser

Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Paige Jasmine Gilmar

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert

DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales

CANIK MARKETING SERVICES

TORONTO advertising@legionmagazine.com

DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS INC mmignardi@dvtail.com

OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER AND MARKETING CO-ORDINATOR

Dyann Bernard

WEB DESIGNER AND SOCIAL MEDIA CO-ORDINATOR

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2024. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST.

FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Change of Address

Send new address and current address label. Or, new address and old address, plus all letters and numbers from top line of address label. If label unavailable, enclose member or subscription number. No change can be made without this number. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of CCAB, a division of BPA International. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

Make the most of your Legion Membership

As a Legion Member, you take pride in the fact that your membership helps support and honour Canada’s Veterans.

Did you know that it comes with benefits you can use, too? Take advantage of all the benefits that come FREE with your membership.

Renew your membership to get all these benefits and more!

MemberPerks® unlocks $1000s in potential savings on offers and deals at stores and restaurants across Canada, including national chains, local businesses and online stores. Use the MemberPerks® app, print out coupons or shop online to save on electronics, travel, fashion, entertainment and so much more!

Your membership also gives you access to additional benefits, including:

• savings and deals from our Membership Partners

• a paid subscription to Legion Magazine

• exclusive members-only items at PoppyStore.ca

Symbolic

meaning

“In

these places, recalling history has an exceptional value. Today, the burial and memorial sites of the First World War have become places of contemplation and celebration of the memory of the dead, the symbolism of which glorifies peace and reconciliation.”

“ THIS RECOGNIZES THE GLOBAL IMPORTANCE OF THESE SILENT CITIES TO ONGOING COMMEMORATION OF THE WAR DEAD.”

So said UNESCO last September upon announcing the inclusion of 139 First World War cemeteries and battlefields in France and Belgium in its list of world heritage sites.

And while the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization’s designation doesn’t make the locations any more important, it does serve to remind regular people the world over of the sacrifices made on these hallowed grounds more than 100 years ago—and the importance of remembrance.

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial, the Beaumont-Hamel Newfoundland Memorial and the St. Julien Canadian Memorial are among the sites with Canadian and Commonwealth connections.

“I find those cemeteries very powerful places, sites of memory and sites of mourning,” Tim Cook, chief historian at the Canadian War Museum in Ottawa, told the Ottawa Citizen following the announcement.

“You feel the weight of history there. I’ve never met a Canadian who hasn’t been physically moved by the experience,” said Cook. “The cemeteries have always held a significant and a haunting place in the Canadian imagination.”

The sites are all located on the Western Front of the 1914-1918 Great War, and vary in scale from large necropolises, with the graves of tens of thousands of soldiers of numerous nationalities, to smaller, discrete cemeteries and even singular memorials.

The proposal for the UN designation, which recognizes places of “outstanding universal value to humanity” and deserving of protection “for future generations to appreciate and enjoy,” was made by Belgian and French officials. It includes 51 areas managed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, such as the Menin Gate (Ypres) Memorial that bears the names of more than 54,000 soldiers whose graves are not known, and the Tyne Cot Cemetery where the nearly 12,000 burials make it the largest Commonwealth war graveyard.

“We are thrilled that a significant number of our iconic cemeteries and memorials along the former Western Front have been awarded world heritage status,” said Claire Horton, the commission’s director general.

“This recognizes the global importance of these silent cities to ongoing commemoration of the war dead,” continued Horton, “and brings with it significant, and tangible, benefits—not least the opportunity to engage wider and more diverse audiences.”

Indeed, in a day and age more than a century later when such memorials are being vandalized in protest of non-related social issues, politicians are increasingly unaware of wartime history and Canadians at large seem apathetic to the country’s military, such recognition can be integral in reminding all of the sacrifices our forebearers made in the name of peace and prosperity.

“Anything that is done to recognize the service and sacrifice of our soldiers during the First World War and after, it’s very important,” historian and author Frank Gogos told the Citizen. “And, of course, it’s all about commemorating our dead so that we don’t forget the atrocities of war.” L

It Injustice

was with great sadness that I learned of the passing of Jess Larochelle (“Obituaries,” November/December). Jess was a true Canadian hero who deserved much more than he received. I was also disappointed to read that the push to get his Star of Military Valour upgraded to the Victoria Cross was thwarted by a technicality. I wonder how many technicalities

The government’s failure to review Jess Larochelle’s commendation for bravery and to consider it be upgraded to a Victoria Cross revulsed me. How a technicality, such as “nominations for bravery decorations must be submitted within two years,” should negate Larochelle’s qualifications for the highest order, defies belief. We are talking about a true Canadian hero’s devotion

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

Larochelle overlooked that day when he single-handedly saved so many lives of his pinned down company all while being severely wounded himself? Technicalities are created by, and changed by, the federal government of Canada. Tell your MP you want the application for Larochelle’s upgrade to be revisited.

EPPY M c RAE NEWBURY, ONT.

to duty under the most horrific circumstances now being judged by a Directorate of Honours and Recognition acting on the faceless direction of a military edict.

As a Canadian veteran, I’m ashamed of the current condition of Canada’s military. The lack of funding by the government is responsible for the degradation of the country’s standing force. The good news is that Canada

still has heroic patriots such as Larochelle. The bad news is the nation doesn’t know how to honour them properly. Sadly, Larochelle passed away at age 40, no doubt in part at least because of his war injuries. All the more reason his memory should be perpetuated and saluted, posthumously, with Canada’s highest military honour.

RICHARD KISER

CALGARY

Re repatriation

In the November/December issue, Paige Jasmine Gilmar made the case for repatriating Canada’s war dead (“Face to face”). While I have no concerns with repatriating bodies today, I think Gilmar overlooked many important points of world wars-era repatriation. My father was shipped overseas before I was born and died in 1944 on my parent’s seventh wedding anniversary. The last thing my mother was concerned about was flying a body across enemy-held territory or shipping it across enemy-infested seas. It was far more important to have food and fuel. Grief psychology has a place, but when a country is at war, there are far more important matters to consider than where a body is buried.

PETER GOWER KINGSTON, ONT.

Out of date

One of the greatest pleasures of being a member of The Royal Canadian Legion is receiving Legion Magazine. It has much information about well-known aspects of Canada’s military history and even more interesting items about lesser-known events. However, as of late, I find the “On this date” section to be wanting. For example, the November/ December edition had information on only 17 of 30 dates in November. This is understandable, as there is only so much space in the magazine. My concern, though, is the actual content.

Of the 17 dates, only three have a connection to Canada’s military history. The others don’t fit the magazine’s “Canada’s military history” tagline. We have an extensive military history. I’m sure there is at least one event in every date of the year where something related to Canada’s military happened.

G. PAUL KARCHA

WOLFVILLE,

N.S.

Teslica Inspire N1S

Fan mail

I wanted to thank Legion Magazine for the varied and wonderful articles. I first began reading the magazine because my dad, Garnet Sproule, a WW II vet, always received it. He loved the “Humour Hunt” section and the “Last Post.” When I became a social studies and history teacher, I used many of your articles and encouraged students to find out more about veterans in their families. The September/ October 2023 issue was deeply moving. The pictures and biographies of the men captivating.

JANE SPROULE GIBSONS, B.C.

Just over two years ago while at a dentist appointment, I happened upon an issue of your fine magazine. I subscribed later that evening. Whether it is page 1 or page 100, the stories ring true through every issue. These men and women

are owed a debt beyond just gratitude, rather it should be an apology from every Canadian who has, in one way or another, disparaged the country’s military. The experiences shared, painfully in many instances, speak volumes about the valour and integrity the fraternity of warriors we begrudgingly acknowledge all too infrequently. The phrase is often overused, but in sincerity say to you all “Thank you for your service.” A special nod to all those who contribute, in whatever fashion, to mold this endeavour into the polished magazine it is.

JOHN B. KEYLOR GLACE BAY, N.S.

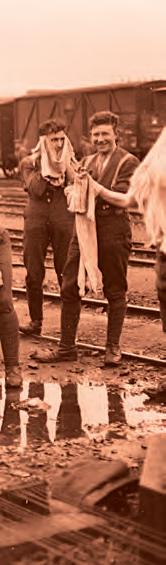

Exclusive HIGHLIGHT from LegionMagazine.com

Railways played an integral role in many parts of the Second World War. From carrying soldiers and munitions to the front or people to safety, trains kept the war effort moving. Some were a sign of death, while others were a sign of health and hope. The latter were hospital trains. Not unique to WW II, though they were instrumental in saving lives in history’s deadliest conflict. A new book, A Different Track: Hospital Trains of the Second World War, by Alexandra Kitty, introduces

readers to the nurses who ran them and the factories that built them. At www.LegionMagazine.com

you can read an excerpt from the book and be transported to a little-known facet of the war.

Every week, the magazine’s website publishes exclusive content, including the “Front Lines” blog by staff writer Stephen J. Thorne and “Military Milestones” by staff writer Paige Jasmine Gilmar. Thorne’s missives delve into important happenings in the military

Legion and Arbor Alliances

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /newsletter-signup

world, ranging from hunting down unmarked graves to what happens to recovered Nazi artifacts. Gilmar’s entries, meanwhile, explore significant moments in Canada’s armed history, for example, Victoria Cross recipients such as Philip Eric Bent and Colin Fraser Barron or the early struggles of the country’s navy. Plus, there are special posts, like Kitty’s excerpt. Visit www.LegionMagazine.com to read past posts or sign up for the weekly e-newsletter so that you never miss the latest content. L

January

21 January 1945

Maj.-Gen. William A. Griesbach, Canadian-born veteran of the Boer and First and Second world wars, dies.

5 January 1998

Ice storm knocks out electricity in Quebec and Ontario.

7 January 2009

Trooper Brian Richard Good is killed and three other Canadian soldiers wounded by an improvised explosive device north of Kandahar, Afghanistan.

8 January 1916

Allies complete the withdrawal of troops from Gallipoli.

9 January 1953

Marguerite Pitre, the last woman executed in Canada, is hanged in Montreal for abetting the bombing of a passenger plane.

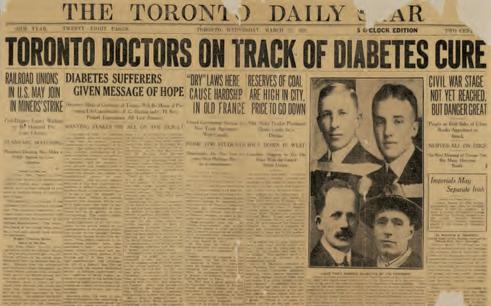

11 January 1922

22 January 1944

Allied forces establish a beachhead at Anzio, Italy.

23 January 1943

No. 164 Squadron, RCAF, is formed in Moncton, N.B.

25 January 1945

The Battle of the Bulge ends.

13 January 1942

Canadian fighter pilots arrive in Singapore, part of a force of 50 Hawker Hurricanes.

15 January 2006

A Canadian diplomat is killed and three Canadian soldiers are wounded after a suicide bomber strikes a military convoy near Kandahar, Afghanistan.

17 January 1991

Operation Desert Storm is launched against Iraqi forces occupying Kuwait.

Canadian Frederick Banting uses insulin to treat diabetes in humans for the first time when he injects 14-year-old Leonard Thompson.

18 January 1995

27 January 1916

Manitoba is the first province to give women the vote and the right to run for office.

28 January 1973

Canada begins sending military personnel to Vietnam under the International Commission for Control and Supervision.

29 January 1942

A film is broadcast of a disturbing hazing by the Canadian Airborne Regiment at Canadian Forces Base Petawawa in Ontario.

19 January 1989

Canada’s first female combat soldier, Heather Erxleben, completes her training at CFB Wainwright, Alta.

Eight Royal Canadian Air Force members are among those killed in the first bombing raid on the German battleship Tirpitz

February

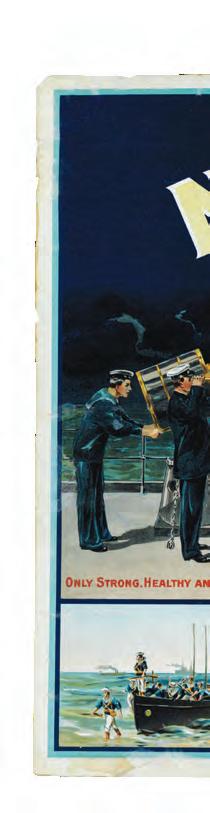

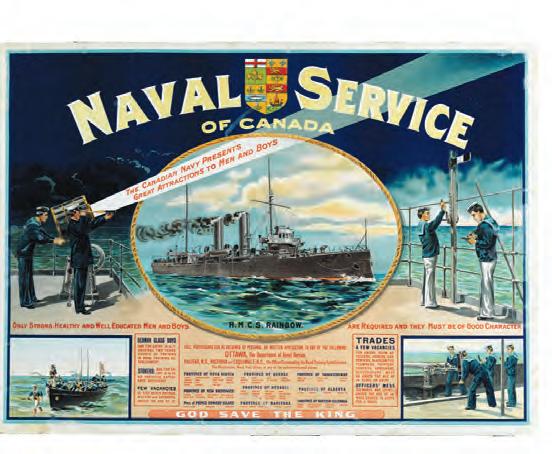

1 February 1911

Recruiting posters for the Naval Service of Canada are displayed in post offices across Canada for the first time.

2 February 1943

German forces surrender at Stalingrad.

3 February 1942

The Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force is renamed the RCAF Women’s Division.

4 February 1945

I Canadian Corps departs Italy to support the Allied advance in Northwest Europe.

5 February 1944

12 February 1918

Lieutenant Hugh McKenzie’s posthumously awarded Victoria Cross for action at Passchendaele is announced in The London Gazette

13 February 1988

The Calgary Winter Olympics officially open.

14 February 1940

No. 110 Army Cooperation Squadron sails from Halifax for Britain.

A German mortar kills 19 members of The Perth Regiment near Ortona, Italy, as they line up for supper.

7 February 1813

U.S. riflemen raid Elizabethtown, Upper Canada (present-day Brockville, Ont.). They free prisoners, seize stores and take 52 hostages.

8 February 1944

Near Littoria, Italy, Tommy Prince, disguised as a farmer, fixes a broken communication wire right under enemy noses (see “O Canada,” page 96).

16 February 1944

In Burma, a wounded Major Charles Hoey leads his company under heavy machine-gun fire to capture a vital position; he is posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

17 February 2002

HMCS Ottawa joins the Canadian Naval Task Group, part of the multinational anti-terrorism campaign in the Persian Gulf.

21 February 1951

The Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry advances through snow and rain north of the village of Sangsok in Korea.

24 February 1944

While escorting a convoy, the Canadian frigate Waskesiu sinks U-257 in the North Atlantic.

25 February 1932

Austrian immigrant Adolf Hitler gets German citizenship.

26 February 1938

The battleship USS New York is outfitted with the first true radar device.

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

Musical Medicine

How music therapy helps heal veterans

1999’s

youngsters grew up to a distinctly North American musical craze, which wasn’t the ragged bliss of grunge, nor the urban poetry of hip hop. For many who were born at the end of the 20th century, the fad that gave them their first taste of song was not a revolutionary new genre, but a classical one. It was dubbed the Mozart effect. It all started in the spring of 1993 at the University of California, Irvine. Researchers curious about the relationship between music and memory launched a study analyzing the effect the renowned classical composer’s music has on the brain. After playing 10 minutes of Mozart’s

“Sonata for Two Pianos in D major, K. 448” for one set of participants and silence or relaxing sounds for another, the researchers tested the spatial-reasoning skills—the ability to think about and manipulate objects in three dimensions—of both groups. Project lead Francis Rauscher and his team made a startling discovery: participants who listened to Mozart showed a sizable increase in spatial reasoning for 10-15 minutes afterward.

Though the study was quick to point out that the impact was both modest and temporary, the media mutated the Mozart effect into a panacea, with parents and journalists alike purporting that children listening to classical music could increase their IQs, grade point averages or even the possibility of getting into university.

Still, the study brought widespread credence to the age-old belief that music can positively affect a person, inspiring a new fascination for music therapy programs and music research. Without the Mozart effect, music programs such as Music Healing Veterans Canada (MHVC) might never have been created.

“The demand was there,” said Jason Costello, the organization’s co-founder and national director, “and we believed we could help.

“The best reviews I have gotten are from members who have credited the program with saving their lives,” said Costello, “giving them a tool to cope with issues they are experiencing.

Founded in 2016 by Costello, Brian Doucette and a group of Canadian Armed Forces members, the healing program uses the side effect-free medicine of music for active and retired military members ranging in age from mid-20s to mid-70s, as well as first responders, medical providers and personnel from the Correctional Service of Canada and Canada Border Services Agency.

“The variety brings such a value to the room,” said Ottawa chapter lead and veteran Ken Fisher.

Conceived from the bare-bones formula of get up, get out and play, the program consists of meeting once a week in the evening to decompress with a like-minded group and receive music instruction from a thoroughly vetted music instructor.

But the sensationalism slowed down when the public realized that enhanced spatial reasoning simply came from “enjoyment arousal.” So, if someone didn’t like Mozart’s music, they would be immune to the effect and, by the same token, someone enjoyed listening to, say, Led Zeppelin, they would experience a Led Zeppelin effect. It all came down to personal preference, because what an individual likes what mentally stimulates them.

“It’s a safe environment,” said Fisher. “Everybody understands that people are there for their own reasons.”

With three Ontario chapters— Kingston, Ottawa and Upper Ottawa Valley—and a fourth in North Bay in the works, Music Healing starts participants with a loaner guitar and a 10-week beginner program to cement the foundational knowledge of playing an instrument. Once that’s complete, the musicians can continue attending classes, jam with others and perform live if they

wish. The project is non-clinical, but its priority is tapping into music’s innately therapeutic value.

“I can tell you that music makes a difference,” said Fisher.

Indeed, numerous studies have proven that learning to sing or play a musical instrument can lower blood pressure and slow heart rates, combat cognitive decline and decrease the effects of dementia, arthritis, pulmonary disease, Parkinson’s, depression, anxiety, insomnia and more. Playing an instrument can even help fend off viruses and heal injuries faster, with consistent musical training permanently restructuring the brain for the better in most cases.

“When you’re in pain all day, it’s tough to be in a good mood all the time,” said Fisher, who has dealt with operational stress injuries himself after serving for 40 years on the regular force. “So, when I’m at Music Healing, I think it’s the fun part of my day.”

Group music lessons can be particularly effective for the psychological wellness of veterans and first responders, since research has proven that situations that safely simulate service—such as working with a group to achieve a collective goal—have therapeutic benefits.

“I miss the camaraderie that I had when I was in the forces,” said Fisher. “But at Music Healing, everybody understands that people are there for their own reasons. I don’t have to worry about people judging. I don’t have to explain anything to anybody.

“Usually, I’m the loudest singer, and I probably have the worst voice. But nobody says, ‘Shut up.’ Nobody says, ‘Hey, you can’t sing.’”

Sponsored by Spartan Wellness, a medical cannabis program serving veterans, first responders and donations from the public, Music Healing subsists off the generosity of local communities and businesses to support some 300 participants. While the initiative is not actively looking

to expand, Fisher said the Ottawa chapter is in the process of forming a partnership with the University of Ottawa’s music department.

The school plans to offer piano lessons for 18 Music Healing students while surveying the health impacts. So, while playing a musical

instrument might not guarantee a higher IQ, it does help some veterans in a meaningful way.

“I hate going out of the house, and I don’t want to leave the house on Thursday night,” admitted Fisher, “but when I get to Music Healing, I wish I could stay there forever.” L

War words

How we talk about fighting and remembrance

The language of war and remembrance is couched in euphemism, hyperbole and a healthy dose of gilded lilies. In short, a lot of overused words and hackneyed phrases that tend to glorify and obfuscate, comfort and satisfy.

In war, politicians and military mucky-mucks use alternative language to soften the reality of, or maintain support for, humankind’s greatest failure—phrases or words such as “collateral damage” for civilian casualties, “enhanced interrogation techniques” for torture, “ethnic cleansing” for genocide, and “conflict” for war.

The remembrance period is rife with such well-worn words as “sacrifice,” “bravery,” “noble,” “heroes” and that most-misunderstood of phrases, “lest we forget”—old-reliables delivered with great solemnity, earnestness and gravitas; take-homes that make people feel good about their societal debts for another year.

Most of these terms and phrases emanate from 1914-18, the first industrialized war, when combatants and non-combatants were killed in unprecedented numbers.

The scale of death and destruction, the sight of disfigured survivors in the streets of cities and towns awakened the general public to the horrors of war.

Bill Black (left), representing Korean War veterans, and James Sookbirsingh of the Submariners Association of Canada place a wreath at the National War Memorial on Remembrance Day 2020.

The “war to end all wars” also transformed war art and literature, far less of which glorified the subject in the aftermath of 20 million wartime deaths, the Erich Maria Remarque book, All Quiet on the Western Front a prime example.

But the Great War didn’t alter the language surrounding it.

The first Armistice Day was observed in 1919 after King George V circulated a Nov. 9, 1919, letter throughout the Empire calling on its dominions and territories to mark “the victory of right and freedom” and for “the brief space of two minutes, [make] a complete suspension of all our normal activities.”

This was to happen at the precise moment the Armistice ended the fighting—the 11th hour of the 11th day on the 11th month.

“During that time, except in rare cases where this may be impractical, all work, all sound

and all locomotion should cease, so that in perfect stillness the thoughts of every one may be concentrated on reverent remembrance of the glorious dead.”

And so, a tradition was born.

Of course, silence wasn’t enough. People had to talk—and not usually the people who were there but, most often, the people who sent them, and their ilk. There were politicians and preachers, poseurs and potentates.

The language was still laced with Old World ideas and phrases— the oratorical equivalent of a 19th century painting dripping with shredded battle flags and glory, rooted in a time when Britannia ruled the waves and half the world with an iron fist and navy rum.

Even the phrase “lest we forget” has its roots in ancient Biblical tradition.

“Only take heed to thyself, and keep thy soul diligently,”

says the King James Bible version of Deuteronomy 4:9, “lest thou forget the things which thine eyes have seen, and lest they depart from thy heart all the days of thy life: but teach them thy sons, and thy son’s sons.”

In 1897, Rudyard Kipling borrowed the concept in his poem “Recessional,” written for Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee: Lord God of Hosts, be with us yet,

Lest we forget—lest we forget!

“Lest we forget” soon became the rallying cry for, not just Nov. 11, but what became the annual period of remembrance leading up to it. Somebody forgot, however, because in 1939 they did it all over again— a world war, that is—and this time some 53 million people died. Those speeches didn’t change and neither did the escalating cycle of war. The weapons became more

efficient, the causes more obscure, the atrocities almost mundane to an increasingly uncaring world. And, still, the language remained the same.

The speech makers would have you believe the warriors died gloriously for king and country, freedom and democracy. The fact is, many signed up not knowing what they were getting themselves into and, in the end, most fought for a more personal, indeed intimate, reason: They couldn’t, in their heart of hearts, let down the men on either side of them. That commitment, and those bonds, are deep and everlasting—a connection that only they can know.

As time passed and societal mores evolved, veterans became more candid, forthright and unvarnished in their recollections of war and their attitudes toward it.

Literacy, once the domain of the more educated officer corps, had become common by the First World War and the rankand-file wrote more explicit letters, memoirs and histories.

Media coverage of the Vietnam War brought the public to the front lines and perceptions of war evolved. Still, the language of remembrance did not.

It has been shown that a large proportion of present-day Canadians know relatively little of the country’s military history or the events that perpetuated it, and the deficit in historical awareness isn’t unique to this country.

The question is, how does a society remember something for which it has no knowledge?

The answer, it seems, lies in those same ancient texts: “Teach them thy sons, and thy son’s sons.” And daughters. L

By David J. Bercuson

Picking priorities

When will the federal government focus on defence?

Ifthere is anyone left in Canada who still believes the current government has any understanding of the importance of defence for the country, Sept. 28, 2023, should set them straight. Governments usually reserve late-week business for announcements they hope will get little attention and this one was no exception.

On that day, defence chief General Wayne Eyre and Deputy Minister of Defence Bill Matthews told the Commons defence committee that the national defence budget would be cut by about $1 billion, just as other departments will also cut their budgets in an effort to tackle the country’s

estimated $40-billion deficit for fiscal 2023-24 and the accumulated $1.13-trillion federal debt.

Coincidentally, former defence minister Anita Anand is now in charge of making this nation’s budget problem go away as the president of the Treasury Board, a position she assumed after a summer 2023 cabinet shuffle. Anand announced that she would be seeking $15 billion in cuts from departmental budgets during the next five years, a tiny fraction of Canada’s national debt.

Okay, she has to start somewhere, especially with such a profligate government. According to the Fraser Institute, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s Liberal

government has logged the five highest years of per-person spending in the country’s history. But given the state of the national defence budget, and the huge shortfall between what Canada needs to spend both to improve continental defence and to help strengthen NATO in the face of Russia’s aggression against Ukraine, any cuts to the defence budget are astounding.

At a meeting this past July, NATO members agreed that they must each spend “at least two per cent” of their gross domestic product on defence. Canada, represented by the prime minister himself, endorsed the resolution, despite reports that indicate he proclaimed months previously that the country would never achieve the spending target.

How does he know that? His government made the choice. And he chose long ago to make defence spending optional. Deciding not to raise the defence budget

Canadian Armed Forces personnel helping to train Ukrainian soldiers gather in the U.K. to commemorate the one-year anniversary of Russia’s 2022 invasion.

is not pre-ordained by some existential power or authority. It happens because people in power make the decision. Choices are made to spend money on health, dental and child care, and to compensate Indigenous Peoples for past wrongs, among other governmental priorities.

These may be perfectly worthwhile policy choices when a government is properly administered, when there are surpluses, when there is room to manoeuvre, when one item can be delayed a year or two or three, while another item is addressed sooner. And in the case of defence, which is one of the main reasons to have an organized government, all other choices must be second.

This is a fact that Canadian governments have forgotten since well before the end of the Cold War when Canada started

increasingly relying on the U.S. for its defence. In essence, that habit is a huge subsidy that the Americans hand Canada every year. Canadians sing about “The true North strong and free,” but it’s the Yankees who help pay for it and free up money for Canada to spend on other priorities.

On the current government’s list of spending choices, defence is not high. It seems as urgent as say, spending on national parks. If the budget for Parks Canada is going to get cut, why not defence as well? Spread out the pain that the government itself caused because of its own reckless accounting. So, it delays purchases that must be made now, and waits

to make them a decade later when the costs increase. Or they put, for instance, the country’s already out-of-date submarines into dry dock for refits. As far as the current government seems to be concerned, defence is nice to have, not need to have. So, if there are other ways to spend money, they will come first.

It is seriously time for NATO —and the U.S.—to put real pressure on the Canadian government. From sanctions to trade embargoes, Canada deserves the whipping it would surely get. And if Canadian citizens don’t enjoy the punishment, there will be another election sooner or later. L

Hearing loss can change much more than how you hear and perceive the world. Hearing aids support your brain by helping it to process sound, keeping you mentally stimulated,

By Alex Bowers

CANADIAN THE GODDAMNED BRING US

How Canadian officers seconded to the British Army under the Canloan program fought for their comrades—and respect

HEAPS

LIEUTENANT LEO HEAPS, drifting gently from the heavens in his parachute over the Netherlands, felt he shouldn’t be there.

Above him an early afternoon sun shone brightly that Sept. 17, 1944. Below, the fields of Wolfheze—a Dutch village—were bursting with sunflowers, their sight catching the 21-year-old Canadian officer’s eye.

All seemed relatively quiet. No enemy gunfire; just the droning sound of innumerable C-47 transport aircraft dropping their cargo of airborne troops sent into action for Operation Market Garden.

Except Heaps of Winnipeg was neither on a Canadian mission nor even under Canadian command. This was the British 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, a part of the 1st Airborne Division.

And it was his first jump, ever.

Things started to unravel— literally—when Heaps’ kit bag broke loose, showering his belongings across the countryside. He then realized his trajectory was sending him toward a cluster of pine trees, their uninviting branches edging ever closer.

But it was too late.

In a sense, however, Heaps was not alone.

He, like 672 other Canadian officers seconded to the British Army under the Canloan scheme, was indeed exactly where he needed to be—even if his immediate circumstances were less than ideal.

By the fall of 1943, following a succession of costly campaigns, British forces had been plunged into an acute labour crisis. Authorities needed to fill the ranks of lieutenants and captains. No stone was left unturned.

The expansion of the Canadian Army, meanwhile, had created a surplus of junior officers, a situation caused by an almost too efficient promotion system and the disbandment of home defence formations.

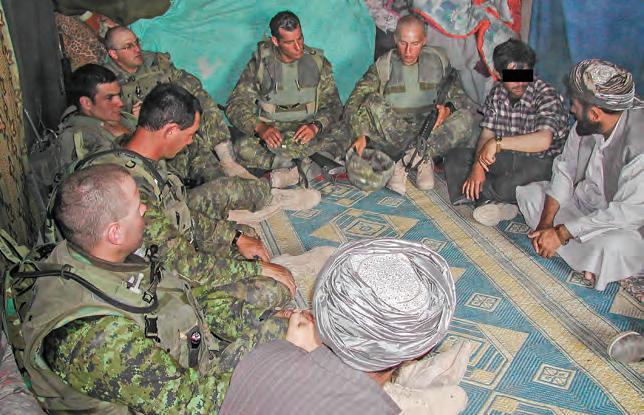

Paratroopers of the 1st Airborne Division (left), including Canadian Lieutenant Leo Heaps (below, standing far right), descend over the Netherlands in September 1944. Several Canadian officers similarly served under the Canloan program with other British units such as the 15th (Scottish) Infantry Division, shown here near Nijmegen, Netherlands, in February 1945.

It seemed only a matter of time before one of those stones was used to kill two birds, realized in full in September 1943, when Ottawa requested that the Canadian Military Headquarters in London determine whether the British Army could absorb any of these officers.

Ultimately, both countries came to an agreement.

The primary condition laid out by the British was that the bulk of the transferred officers would be subalterns (below the rank of captain), although a proportion could be captains at a rough ratio of 1:8 in favour of lieutenants.

For the Canadians, there were several conditions: that the Canloan scheme be entirely voluntary; that officers should be loaned with the understanding that they could be recalled if required; that Canada should be responsible for pay; that age limits should meet Canadian Army criteria; that their service be restricted to the European and Mediterranean theatres (excluding a few exceptions to the rule further down the line); and that Canada would select volunteers that the British Army would accept without question.

It was likewise agreed that any junior officer deemed worthy of promotion could rise through the British ranks, and any deemed unsuitable for service could be returned to the Canadian Army after a trial period.

Given estimates suggesting up to 2,000 potential candidates, not only infantry, but also a small number of ordinance officers, there were high expectations for the initiative and calls went out across the country. Many answered.

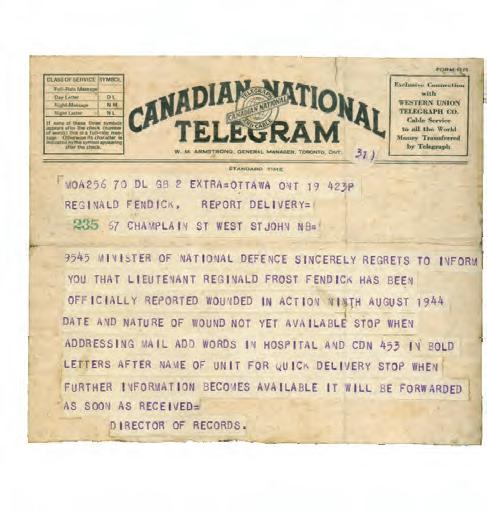

That didn’t alleviate the inevitable culture shock. Fendick and his colleagues occasionally misunderstood each other’s accents and turns of phrase.

FENDICK

LIEUTENANT REGINALD (REX) FENDICK

of The Saint John Fusiliers (Machine Gun) walked through the mess doors in Prince George, B.C., to a commotion.

All he had wanted was a hot drink and a bedtime snack after enduring hours on the bus from leave in Vancouver. Now, he was being asked if he wanted to join the British Army, a strange turn of events that Sunday in March 1944.

Tired of home defence duties and the National Resources Mobilization Act conscripts (nicknamed “zombies” for their unwillingness to serve overseas), it seemed like the perfect opportunity for someone like him.

The reasons for participating in the program, of course, differed between officers—be they naturalborn Canadians, Americans who had crossed the border, or even Britons who had emigrated prior to the war. However, as a rule of thumb, boredom and disillusionment with service in Canada were leading factors in the decision-making process, often coupled with the

fundamental desire to be part of the invasion of Western Europe.

Thus, the New Brunswicker was gone by the end of the month—along with five of his willing comrades—en route to Camp Sussex in his home province.

There, a facility designated A-34 Special Officers’ Training Centre had been established as an intensive, three-week refresher course commanded by Brigadier Milton Gregg, a WW I Victoria Cross recipient.

The centre’s syllabus stressed physical fitness, weapons training, night operations, field works— including mines and booby traps— infantry tactics, leadership and personnel management. Additionally, officers were expected to have a basic grasp of British regimental traditions and even mess etiquette.

Fendick was far from the only individual to find the instruction tedious, even if Gregg was highly respected.

It was during Fendick’s time at Sussex that he met Leo Heaps, feet planted on a desk as he tore folded paper to create a string of paper dolls. “If they’re going to treat us like

children,” Heaps reasoned, “we may as well behave like children.”

Still, the refresher course at A-34 served its purpose, providing Canloan officers with an opportunity to hone their skills and bond before departing for Britain in nine groups or “flights.”

Fendick joined the largest group of 250 officers on May 3, comprising the entire second intake, and arrived in Liverpool on May 11. From there he travelled to the Grand Central Hotel in the Marylebone area of London.

“We were assembled in a large lobby…with many small tables set up around all sides of the room, each manned by one or two British staff officers and clerks,” the young Canadian lieutenant later wrote.

“Each table had a sign over it, naming one or more British regiments. We were invited to go to the table of our choice, where we were told which regiments and battalions had vacancies, and we were invited to choose our unit.”

Pleased to find space in the King’s Own Scottish Borderers, which was affiliated with his former Saint John Fusiliers, Fendick

Lieutenant Reginald (Rex) Fendick served with the King’s Own Scottish Fusiliers under the Canloan program. He was wounded in August 1944, but recovered and fought again in the Korean War.

soon found himself bound for southeast England in preparation for Operation Overlord.

He, like all Canloan officers, was then provided with a distinct identification number—his being CDN 453—that became unique to the scheme, and a “Canada” flash emblazoned on his British battledress.

Where possible, successive groups of subalterns were similarly afforded the chance to join affiliated British regiments, the most successful being The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada, its members joining the United Kingdom’s Black Watch. Elsewhere, soldiers from The Seaforth Highlanders of Canada served in the British Seaforth Highlanders, as did some of those once belonging to the Pictou Highlanders.

But that didn’t alleviate the inevitable culture shock. Though glad to be commanding his own platoon of lowland Scots, Fendick and his colleagues occasionally misunderstood each other’s accents and turns of phrase. At one stage, it took a Midlander English sergeant to translate.

The use of the word “colonial” by superiors also became a source of frustration among a few Canadian lieutenants and captains.

Yet despite the odd hurdle, Canloan officers adapted to their circumstances, ironed out any personal difficulties and became integral to their respective formations, earning the rightful respect of their comrades.

In Fendick’s case, his familiarization period proved short. Anticipating the need to replace casualties after D-Day, he was sent to a Reinforcement Holding Unit and instructed to wait.

His moment would come, but for now, staring out to sea from Folkestone, Fendick saw the vast armada crossing the English Channel. It was early June 1944, and the Canloan scheme was about to face its first true test.

ROBERTSON

LIEUTENANT LEONARD

ROBERTSON—designated CDN 192—was in the armada.

Originally attached to The Dufferin and Haldimand Rifles of Canada, he had been posted to the 2nd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment.

On June 6, he hit Sword Beach, one of two Canloan platoon commanders in ‘C’ Company (the other, CND 118 Captain James (Mac) McGregor).

The landing craft ramp dropped and Robertson, along with a couple of his men, charged ahead, only to realize when it was already too late, that they had not yet reached the shore. The trio had unwittingly launched themselves into the water, its depth luckily shallow enough to recover and wade ahead.

Meanwhile, “Bullets, shrapnel and what have you was flying around like a swarm of angry bees,” the lieutenant noted.

One of his privates was struck and fell. Robertson grabbed the wounded soldier and dragged him the rest of the way, mindful of the bodies floating face down in the wake, their blood flowing freely from fatal wounds.

Unfortunately, the private was struck again.

Urgently needing to get off the beach, Robertson organized his platoon and pushed forward through the maelstrom.

It mattered not that his life, upbringing and experiences more than 4,800 kilometres away differed from those of the British troops beneath him. The moment called for leadership, and that’s what the Canadian officer could provide.

Venturing inland by June 7 brought little respite, with Robertson’s 15 Platoon and Mac’s 14 Platoon confronting a German pillbox.

“Mac had gone up to the entrance and called on them to surrender,” said Robertson. “They didn’t give him a chance, but cut him down with a burst of gun fire hitting him in the chest and stomach…Mac was dead.”

McGregor was the first Canloan officer recorded as killed in action. He would not be the last.

Between D-Day and the end of August 1944 in Normandy, 77 Canloan officers were killed or died of their wounds on patrols, in slit trenches and throughout various operations. More would come. But they had likewise established themselves to be capable and valued leaders with the clear capacity to inspire courage and fortitude in the British Second Army soldiers they commanded.

Canadian Lieutenant Leonard Robertson (above, second from left) hit Sword Beach on D-Day with the 2nd Battalion, East Yorkshire Regiment.

M

acLELLAN

LIEUTENANT C. ROGER

M acLELLAN—designated CDN 554—of New Glasgow, N.S., and a Canloan officer in the British 2nd Battalion, Glasgow Highlanders, was about to prove those very same capabilities in the battle for Ghent in the Netherlands.

It was Sept. 10, 1944, and his platoon had been tasked with clearing houses around the Canal du Nord.

As was the case by then with so many Canloan officers after the relentless combat of several months, MacLellan—previously of the Pictou Highlanders—had cultivated a strong bond with his men.

He needed only to wave his left arm and bellow, “Follow me,” leading from the front as always, and his sections would fall into place.

Yet it was not long until a German machine gun opened up on them in the street. Enemy rifle fire joined the cacophony, and the platoon was pinned down. But MacLellan maintained his nerve.

With his left section in position to provide covering fire, he ordered an aggressive response. Their intense pressure appeared to be tipping the scales until MacLellan’s left section spied an 88mm gun. Repeated attempts to neutralize the position seemingly failed— even with the surprise arrival of tank support. And all the while, casualties were mounting.

MacLellan ordered the evacuation of the wounded as he and

two men covered a withdrawal. The lieutenant was the last to leave, carrying his Sten and a Bren through a blanket of smoke.

Unbeknownst to the officer at the time, the platoon and armour combined had succeeded in silencing the German artillery. Noteworthy, too, had been MacLellan’s “great coolness and ability…[and] utter disregard for his own personal safety,” noted his Military Cross citation. Canloan officers across multiple British regiments earned many such accolades, including 41 Military Crosses (MC), among several other honours from the French, Belgians and Americans.

Few British soldiers, no matter the rank, doubted qualities of their Canadian numbers by that stage. In one instance, D-Day veteran Robertson—himself a Military Cross recipient—asked his men to choose between a British and Canloan officer for a replacement. Their decision was unanimous: “Bring us the goddamned Canadian.”

Moved to Geel, Belgium, after his MC-earning actions, MacLellan participated in a church parade before listening to a padre’s sermon. Midway through the service, however, he and his men felt reverberations coming from outside. Everyone filtered through the doors and stared up into the sky, awed by the sight of countless aircraft almost shrouding the horizon. It was Sept. 17, 1944.

The mossy ground cushioned Heaps’ parachuted descent.

Miraculously, he was unscathed. The Winnipegger—designated CDN 415—dusted himself off.

His duties, unlike most subalterns, were to take on special assignments at his liberty, the result of there being no other rank-appropriate positions available. The first came the next day, having been instructed to take a jeep laden with supplies and a wireless operator to Arnhem bridge.

Joined by a Dutch guide, they promptly got into trouble when the vehicle’s steering wheel came off in Heaps’ hands, hurling the three of them into an embankment—though for the most part they were unharmed.

The determined lieutenant then flagged down a Bren carrier, hitched a ride and continued into the devastated city of Arnhem.

Major-General Roy Urquhart watched with bemusement as the mismatched party arrived at his beleaguered headquarters, an encounter made stranger still when Heaps, believed by the commander to have a “charmed existence,” reported news from elsewhere along the front.

The Canadian’s role thereafter shifted from supplier to messenger. Over the coming days, Heaps acted as a vital communications link between the divisional headquarters at Hartenstein Hotel and, wherever humanly possible, the often isolated and increasingly desperate pockets of airborne troops. He even—on his own initiative—crossed the River

Canadian Lieutenant C. Roger MacLellan (left) with fellow Canloan officers Kip MacLean and Ken Coates at a training facility in June 1943.

Rhine in a dinghy more than once, intent on contacting the forward elements of XXX Corps, which was expected to bring much-needed relief to the overwhelmed force.

His luck ran out, however, while guiding the 4th Battalion, Dorset Regiment over the Rhine. The unit was set to launch a midnight attack to bolster the battered airborne, but Heaps was pinned down by enemy fire after making the crossing. Despite slipping into the water to escape, he was captured.

Heaps spent a brief period in a prisoner-of-war holding camp, undoubtedly acutely aware of his Jewishness, and befriended a couple of British prisoners.

En route via train to Germany, armed with a tiny silk map, a box of matches, a button compass, a pair of nail clippers, a blanket and a tin of chocolate, the three cut a barely man-sized opening in a carriage porthole and jumped.

But Heaps’ story would not end there.

The Canloan officer made it back across Allied lines, whereupon he received authorization to team up with the Dutch resistance and help retrieve fellow evaders in the wake of Operation Market Garden.

Not only did he receive the Military Cross for his exploits, but he left behind a legacy synonymous with the success of the Canloan program.

The Canadian Army encountered many of its countrymen serving in British units during its campaign to liberate the Netherlands, including as it moved toward the Rhine River near Xanten, Germany, in March 1945.

That small yet significant legacy, fostered by Heaps and his fellow Canloan officers, remains a great source of pride in military circles on both sides of the Atlantic—albeit largely unknown on a grander scale.

Fendick shared Heaps’ so-called charmed existence when his carrier struck a mine in August 1944. He sustained serious wounds, but was evacuated to hospital, recovered and was sent back to action. He later fought in the Korean War and eventually rose through the ranks to lieutenant-colonel.

Robertson also suffered from a series of minor wounds that required treatment. Within a couple of weeks, however, he also returned to his unit and continued to serve with distinction. One of his postwar achievements included serving as vice president for the Canloan Army Officers Association.

MacLellan returned to his education after the conflict. Qualifying as a research scientist in entomology, his work contributed considerably to agricultural pest management procedures. MacLellan likewise rejoined the service, commanding the West Nova Scotia Regiment from 1960-1962.

Finally, Heaps ran unsuccessfully for political office, but found another avenue for service when he organized efforts to assist refugees amid the 1956 Hungarian revolt—a feat he repeated with locals during the Vietnam War. In addition to becoming an esteemed art dealer, he authored several books, notably Escape from Arnhem and The Grey Goose of Arnhem. These individuals, in many respects, were fortunate. There was a 75 per cent casualty rate in the nearly 700-strong—623 infantry officers and 50 from the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps— Canadian group seconded to British regiments in the summer of 1944. Of those, 128 never returned home. Their sacrifices have been recognized through the Canloan National Memorial in Ottawa, a similar monument at 5th Canadian Division Support Base in Gagetown, N.B., and a plaque at the residence of the British High Commissioner to Canada.

Perhaps above all else, they are remembered by the ever-dwindling number of British veterans who, recalling the outstanding leadership of their Canloan comrades, still hold Canada’s wartime contribution in high regard. L

They had established themselves to be capable and valued leaders with the clear capacity to inspire the British Second Army soldiers they commanded.

Allied prisoners of war who had a penchant for escape were often sent to Schloss Colditz— but even the legendary German keep couldn’t stop many from attempting getaways

BY ED STOREY

A wartime image of Colditz Castle.

Colditz is perhaps the best known of all the Second World War German prisonerof-war camps. Several books, a movie and a television series have all immortalized Offizierslager (Oflag) IV-C

Colditz as a facility where British officer PoWs taunted (“goon-baiting” as they called it) their guards and planned elaborate escapes involving tunnels, detailed disguises and even a glider.

Many turned their plans into reality. Those who didn’t make a “home run” back to Britain but got recaptured, however, returned to face a stint in solitary confinement before reuniting with their fellow prisoners. The jail was a miserable, cramped and

Cdamp castle where a nearstarvation diet along with gloomy weather drove some of the incarcerated to madness—and others to suicide.

Schloss Colditz is in the German town of the same name near Leipzig and Chemnitz in the state of Saxony. It’s on a hill spur overlooking the river Zwickauer Mulde, a tributary of the Elbe River.

First built in 1158, the castle was destroyed and rebuilt twice, taking on its current Renaissance-era appearance between 1577 and 1591.

In its early days, the Schloss was used as a hunting lodge.

In 1694, it was expanded with a second courtyard and a total of 700 rooms.

From 1803-1829 it was a workhouse for the poor, and then it was converted into a sanatorium for wealthy patients. It served in this capacity for more than a century until the Nazis gained power in 1933. They converted the castle into a political prison.

After the outbreak of the Second World War, the Schloss was transformed into a high-security prisoner-ofwar camp for officers who were escape risks or regarded as particularly dangerous. The facility’s population was initially cosmopolitan, consisting of PoWs from Poland, France, Belgium and the Netherlands. Beginning in late 1940, the first British Belgian and French prisoners gather in a Colditz courtyard.

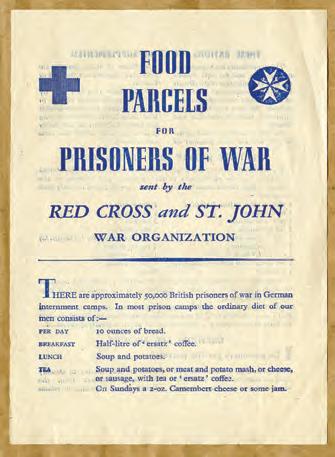

British prisoners of war at Colditz in April 1945 (above). A pamphlet detailing how Canadians could help PoWs. A prison portrait believed to be of Lieutenant C.D. Mackenzie and Canadian Pilot Officer Howard (Hank) Wardle (immediate left).

Kenneth Lockwood (far left, left), one of the first British held at Colditz, with an unidentified Polish prisoner. David Stirling (below), founder of the British Special Air Service, was one of Colditz’s most notable detainees.

began to arrive, and during the next three years each contingent competed to see who could escape most often.

By 1943, Colditz was largely a British camp with some Americans, all other nationalities having been moved to other locations. The term British, of course, was quite

broad and encompassed Commonwealth personnel from Canada, Australia and even India. Some notable prisoners included British fighter ace Douglas Bader, New Zealand Army Captain Charles Upham, the only combat soldier awarded the Victoria Cross twice, and David Stirling, founder of the wartime Special Air Service. Along with these officers were several British of other ranks who served as cooks and batsmen and weren’t included in any of the escape plans.

One of the first Canadian prisoners at Colditz was Pilot Officer Howard (Hank)

Wardle, of Dauphin, Man., who had joined the Royal Air Force in March 1939.

Wardle’s Fairey Battle light bomber had been shot down near Crailsheim, Germany, on April 20, 1940, while he was conducting a reconnaissance mission with 218 Squadron. Wardle was captured and, after being interrogated at a Luftwaffe barracks, he was detained at Oflag IX-A/H in Spangenberg, Germany. In August, he escaped the camp, but was recaptured the following day and transferred to Colditz.

On Oct. 14, 1942, Wardle, along with three British officers—including Captain

On Oct. 14, 1942, Wardle, along with three British officers, successfully escaped Colditz .

Patrick (Pat) Reid whose 1952 memoir, The Colditz Story was the basis for the film of the same name— successfully escaped Colditz. Wardle and Reid crossed the Swiss frontier at Singen, Germany, a known border weak spot, four days later.

In late 1943, Wardle made his clandestine journey to Spain, paid for by the British, arriving in the Spanish village of Canejan just before Christmas 1943. Wardle returned to England via Gibraltar on Feb. 5, 1944, and was awarded the Military Cross on May 16. He passed away in Ottawa in January 1995, aged 79.

Not all Canadians held at Colditz were as lucky as Wardle, however. Captain Graeme Delamere Black, was one of seven men of No. 2 Commando who were captured in September 1942 after Operation Musketoon, the destruction of the German-held power plant in Glomfjord, Norway. Originally from Dresden, Ont., prior to the war Black had served with the Queen’s York Rangers (1st American Regiment) and, after moving to London, he joined the South Lancashire Regiment (Prince of Wales’s Volunteers) before volunteering for the commandos. All seven of the PoW

commandos were held in Colditz before they were executed under Hitler’s Commando Order—a directive that all captured Allied commandos be killed without trial—on Oct. 23, 1942.

Years of captivity at Colditz also took a terrible mental toll on many prisoners and Flight-Lieutenant Frederick Donald Middleton of Dauphin, Man., was no exception. One of three brothers who enlisted in the RAF in 1937, Middleton’s Hampden bomber of 50 Squadron was shot down over Norwegian waters on April 12, 1940. Taken prisoner, he arrived at Colditz with Wardle after

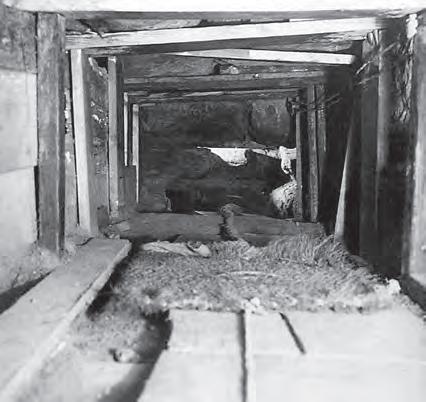

German officers pose with a rope, made of knotted bedsheets, from a failed escape attempt. French PoWs dug this tunnel—ultimately 44-metres long— under the castle’s chapel in 1942 in another foiled breakout.

As they advanced to the castle, the troops were surprised to learn that it held some 250 Allied PoWs who had been watching the whole battle from the windows.

British PoWs

Jim Rogers and Giles Romilly (above), the latter specially guarded because he was the nephew of Winston Churchill’s wife. A Colditz guard climbs a homemade rope in re-enacting an unsuccessful escape.

an unsuccessful escape from the PoW camp in Spangenburg. While at Colditz he suffered severe depression and attempted suicide numerous times.

Middleton was then transferred to a mental hospital for PoWs and, once deemed well, he was sent to Stalag Luft III. There he helped dig the “Harry” tunnel renowned in the 1944 “Great Escape,” but the route was discovered before Middleton got his turn to use it.

In 1945, Middleton returned home a shadow of his former self, weighing less than 100 pounds and suffering what today would

likely have been diagnosed as post-traumatic stress disorder. While Middleton recovered physically and began to live a normal life to the best of his ability, he never truly regained his emotional health. Sadly, for some, there was just no escaping from Colditz.

Interned at Colditz were also several prisoners called prominente, or German for celebrities, all relatives of Allied VIPs. Two were particularly noteworthy: Giles Romilly, a journalist who was captured in Narvik, Norway, and was the nephew of Winston Churchill’s

wife Clementine; and British Commando Michael Alexander, who claimed to be the nephew of Field Marshal Harold Alexander to avoid execution, though he was merely a distant cousin.

By March 1945, the number of high-profile inmates had swollen to 21. With the Reich collapsing on all sides, they were to be used as bargaining chips with the Allies. In early April, the prominente were all transported out of the castle by the SS. After a harrowing trip south, they were liberated by the advancing American 7th Army outside of Innsbruck, Austria, in late April.

The liberation of the prison itself began on April 15, as advancing elements of the 3rd Battalion, 273rd Infantry Regiment, approached from the southwest. A sharp, day-long firefight ensued as SS troops and Hitler Youth desperately tried to stem the attack. Some

20 Americans died in the street fighting.

By the next morning, however, the Germans had left, the white flags were up and, as they advanced to the castle, the troops were surprised to learn that it held some 250 Allied PoWs who had been watching the whole battle

Return

to Colditz

For the average Canadian, Colditz is slightly off the beaten trail, located as it is in the former East Germany. The site has always fascinated me, and I first visited in the spring of 1994 while on leave during a year-long deployment with the United Nations Protection Force Headquarters in Zagreb, Croatia. I was travelling with a Belgian colleague, and we found a sleepy little town just emerging from four decades of Communist rule.

Reminiscent of the Balkans, the town was in decent shape, though

from the windows. Two days later, the freed men left the Schloss for the last time and, after spending an evening in Erfurt, they were flown back to Aylesbury, England.

The infamous Colditz Castle had finally been physically escaped for the last time. L

Colditz Castle (bottom) and the unsuccessful French escape tunnel (below) in more current times.

much of it needed work other than the newly established gas station and car dealership. The castle still had its foreboding wartime look, but the small museum dedicated to escape was in a building outside the walls and most of the outer courtyard rooms were being used as a youth hostel.

A return visit with my father in 2015 revealed a town that had been refreshed and modernized, boasting old-world European charm perfect for a quiet getaway. Everything was bright and shiny. The Schloss, still

a hostel, had been restored; and its updated museum, now inside the castle, had become a popular site, especially for British tourists, offering comprehensive tours by knowledgeable guides.

Ed Storey

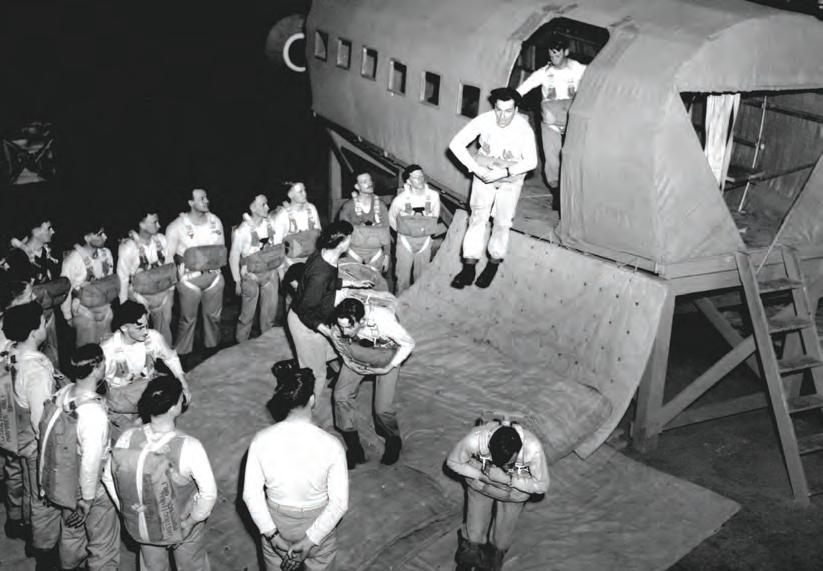

THE STORY OF CANADA’S SHORT-LIVED POSTWAR SPECIAL AIR SERVICE

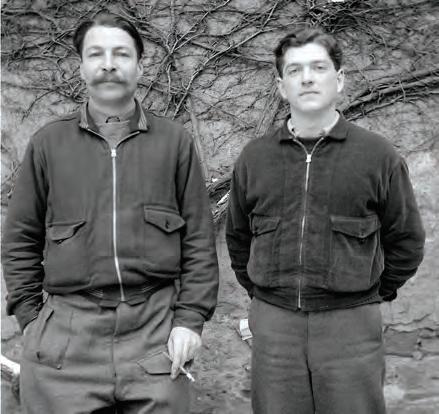

An unconventional crew of Canadian SAS Company commandos pause from their training at Rivers, Man.

During the Second World War, a desertbased commando unit of the British Army employed bold, innovative guerilla tactics to wreak havoc on German forces in North Africa. The Special Air Service and its exploits, including present-day counterterrorism, hostage rescue and other covert operations, are the stuff of rogue heroes. This is not that story.

This is the tale of the Canadian Special Air Service Company, a distinctly different organization made up of airborne soldiers whose initial role in postwar Canada was non-military: airborne firefighting, searchand-rescue and aid to the civil powers.

“The story of the Canadian SAS Company is actually surreptitious,” wrote Bernd Horn in his 2001 paper,

A Military Enigma: The Canadian Special Air Service Company, 1948-1949.

“The army originally packaged the subunit as a very benevolent organization.

“Once established, however, a fundamental and contentious shift in its orientation became evident—one that was never fully resolved prior to the sub-unit’s demise. With time, myths, often enough repeated, took on the essence of fact.”

SAS members expected to form a special operations unit practised in long-range reconnaissance, deep penetration raids through enemy lines in conventional warfare and supporting guerrilla or irregular forces in unconventional warfare.

The unit had no insignia of its own. Assembled as the Cold War was declared, its 125 infantrymen came from the country’s three regiments, some of them war veterans from the vaunted 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion or the Canada-U.S. First Special Service Force, famously known as the Devil’s Brigade.

They retained their original regimental badges and underwent rigorous preparations for their anticipated role as a highflying elite force. They trained in rope work, survival, mountaineering, improvised demolitions, skiing and foreign languages.

The Canadian Special Air Service Company lasted but two years, its only operations a 1947 Arctic rescue and flood relief in B.C. in 1948 .

They were chosen for their “superb physical condition…demonstrated initiative, determination and self-reliance.”

And they had to be unmarried.

“Exercises were reportedly rigorous, with scenarios usually involving an airborne raid on a fixed enemy installation,” reported canadiansoldiers.com. “At least one member of the Company was killed during a public parachute demonstration.”

They were commanded by a decorated Devil’s Brigade veteran, Captain Lionel Guy d’Artois, a temporary appointment who, after his wartime commando unit folded, volunteered to join the Special Operations Executive in 1943. He jumped into France under the codename Dieudonné and spent the rest of the war organizing, arming and operating with units of the French Resistance.

d’Artois’ tenure as acting officer commanding of the new unit proved short. The search for a permanent replacement was still going when the unit was shut down.

An unidentified parachute candidate (top left) undergoes a medical exam at the Canadian Parachute Training Centre in Shilo, Man., in March 1945. Captain Lionel Guy d’Artois, head of the Canadian SAS (top right, centre), was widely regarded as a grand old man of the Canadian airborne. Airborne troopers (below) board a Dakota at Rockcliffe, Ont., in 1948.

The Canadian Special Air Service Company lasted but two years, its only credited operations a 1947 Arctic rescue mission for which d’Artois, the lone SAS soldier involved, was awarded the George Medal, and flood relief in British Columbia’s Fraser Valley in 1948, the only time the service functioned as an entire unit.

The military disbanded the SAS in September 1949 and created the Mobile Striking Force, a larger and more conventional airborne unit. Some SAS members were retained as instructors, augmenting existing training establishments until the strike force was formed. Others returned to their regiments.

d’Artois went on to serve with the Commonwealth occupation force in Japan, then did an operational tour with the 1st Battalion, Royal 22e Régiment, during the Korean War.

“ Something was clearly amiss . Either the sub-unit was named incorrectly or its operational and training focus was misrepresented.”

The story of the Canadian Special Air Service Company might be all but lost to popular history, however the facts ring familiar today, when Canada’s military is mired in controversy, recruitment is languishing and the government wants to cut the defence budget by almost $1 billion.

Then, as now, the military’s role in civil affairs and crisis response was up for debate and funding was in short supply.

In the immediate aftermath of the Second World War, the powers that be in Ottawa had little concept of what they wanted to do with the country’s armed resources.

The vast, sparsely populated land that had entered the war with meagre military might ended it with the world’s third-largest navy and one of the largest air forces. Its shipbuilding industry, virtually non-existent in 1939, was among the planet’s biggest. Yet all of it was reduced to nominal strength after the fighting ended.

Even the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, a standout in the formative

years of airborne warfare, was disbanded six weeks after Japan surrendered. Global affairs were changing fast and so were opinions on how to address them.

“Notwithstanding the military’s achievements during the war, the Canadian government had but two requirements for its peacetime army,” wrote Horn.

“First, it was to consist of a representative group of all arms of the service. Second, it was to provide a small but highly trained and skilled professional force which, in time of conflict, could expand and train citizen soldiers who would fight that war.

“Within this framework paratroopers had limited relevance. Not surprisingly, few showed concern for the potential loss of Canada’s hard-earned airborne experience.”

In the austere postwar climate of minimum peacetime obligations, Horn added, the fate of Canada’s airborne soldiers, who would typically form the core of any commando unit, “was dubious at best.” The Canadian Parachute Training Centre in Shilo, Man., had stopped prepping new jumpers virtually as soon as the war in Europe ended in May 1945. Its future hung in the balance as it awaited a final decision on the direction the postwar army would take.

“No one knew what we were supposed to do,” recalled Lieutenant Bob Firlotte, who had been hand-picked to serve at the centre, “and we received absolutely no direction from army headquarters.”

Nevertheless, senior staff worked to keep abreast of airborne developments and

perpetuate the links forged with American and British airborne units during the war. Horn called their efforts “the breath of life” that the airborne advocates needed.

Their advocacy would eventually pay off after a National Defence Headquarters study revealed that British peacetime policy was based on training and making all infantry formations air-deliverable. Americans and Brits alike made it known they would welcome an airborne establishment in Canada capable of “filling in the gaps in their knowledge.”

These “gaps” included the problem of standardizing equipment between Britain and the U.S., and addressing the need for cold-weather research.

“Canada seemed to be the ideal intermediary for both needs,” wrote Horn. “It was not lost on the Canadians that co-operation with its closest defence partners would allow Canada to benefit from an exchange of information on the latest defence developments and doctrine.”

A test facility might not be a parachute unit, but it would allow the Canadian military to stay in the game. Ultimately, National Defence opted to form a joint parachute training school and airborne researchand-development centre in Rivers, Man.

“For the airborne advocates,” said Horn, “the Joint Air School, [later to become the Canadian Joint Air Training Centre] became the ‘foot in the door.’ More important, the JAS…provided the seed from which airborne organizations could grow.”

Still, the concept of a special operations force, which showed such promise in the fleeting Devil’s Brigade, was all but lost entering the Cold War—“a patchwork of activities, few of which were co-ordinated in any fashion,” according to Sean M. Maloney, a history professor at Royal Military College in Kingston, Ont.

Once the army’s permanent structure was established in 1947, impetus to expand airborne capability began to stir at the Joint Air School. In May 1947, the school proposed the Canadian Special Air Service Company with its clearly defined benevolent role.

The army backed the idea, calling the unit’s inherent mobility a definite public asset for domestic operations and a potential benefit to the country. The SAS, it said, would provide an “efficient life and property saving organization” capable of moving to any point in Canada in 10-15 hours—not unlike the role the military’s present-day Disaster Assistance Response Team plays on the world stage.

The official Defence Department report for 1948 noted that co-operation with the Royal Canadian Air Force in air searchand-rescue would meet International Civil Aviation Organization requirements.

The initial training cycle consisted of four phases, covering research and development (parachute-related work and field skills); airborne firefighting; air search-andrescue; and mobile aid to the civil power (crowd control, first aid, military law).

“Conspicuously absent was any evidence of commando or specialist training which

An SAS member (opposite) wrestles with his parachute after a training jump. SAS recruits practise landing rolls.

the organization’s name implied,” wrote Horn. “The name of the Canadian subunit was a total contradiction to its stated role. It was also not in consonance with the four phases of allocated training.

“Something was clearly amiss. Either the sub-unit was named incorrectly or its operational and training focus was misrepresented. Initially no one seemed to notice.”

The director of weapons and development added two additional roles when he forwarded the request for the new organization to the deputy chief of the general staff: “public service in the event of a national catastrophe” and “provision of a nucleus for expansion into parachute battalions.”

“This Company is required immediately for training as it is these troops who will provide the manpower for the large programme of test and development that must be carried out,” the proposal noted.

There was no mention of special forces or war fighting. But by October 1947, mission creep began to rear its head. Embedded in an assessment of potential benefits that the company could provide to the army was an entirely new idea.

“The formation of a SAS Company,” the report explained, “is in line with British Army Air Group post war plans; whereby the SAS is being retained as a small group integrated within the Airborne Division. This provision is to keep the techniques employed by SAS persons during the war alive in the peacetime army.”

It appeared last in the list’s order of priority but, in practice, it would soon become the primary objective.

Things changed virtually as soon as the defence chief approved the SAS proposal in January 1948. “Not only did its function as a base for expansion for the development of airborne units take precedence, but also the previously subtle reference to a war fighting, special forces role, leapt to the foreground,” said Horn.

“The shift was anything but subtle. The original emphasis on aid to the civil authority and public service functions, duties which could be justified to a war-weary government and a budget conscious military leadership, were now re-prioritized if not totally marginalized.”

Horn described the change as partially a case of gamesmanship, allowing the strong airborne lobby within the Canadian Joint

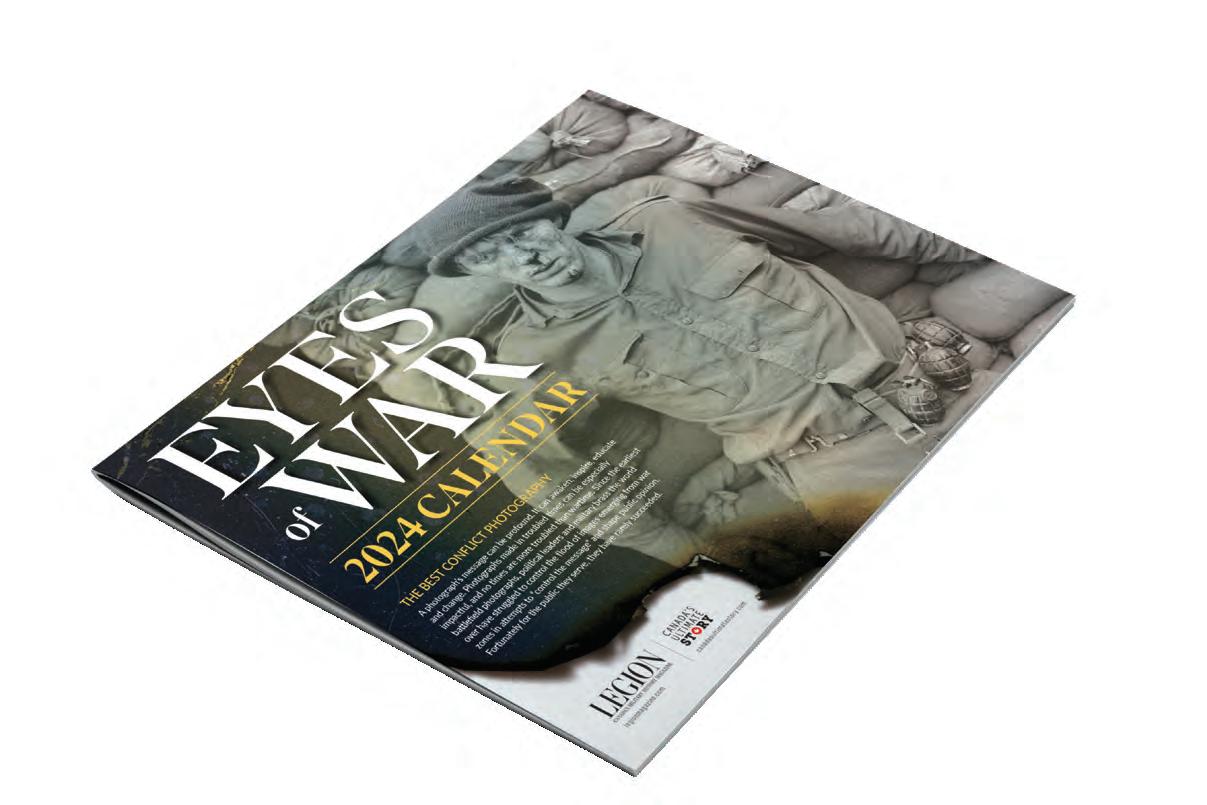

Air Training Centre and others in the army with wartime airborne experience an opportunity to perpetuate a capability that they believed was at risk.