Talk to a dedicated Red Wireless expert - your exclusive Rogers dealer.

This program is provided by Red Wireless - your exclusive Rogers dealer. Subject to change without notice. Offer only available to new Rogers mobile customers. Taxes extra. Rogers Preferred Program. Not available in stores. Membership verification is required; Rogers reserves the right to request proof of membership from each Individual Member at any time. For plans and offers eligible for existing Rogers customers, a one-time Preferred Program Enrollment Fee of $75 may apply. A $75 Setup Service Fee applies to all upgrades. Existing customers with in-market Rogers consumer plans with 6 months or less tenure on their term plan switching to the plan above are not eligible to receive this discount. This offer cannot be combined with any other consumer promotions and/or discounts unless made eligible by Rogers. Plan and device will be displayed separately on your bill. © 2025 Rogers Communications. 1-888-251-5488

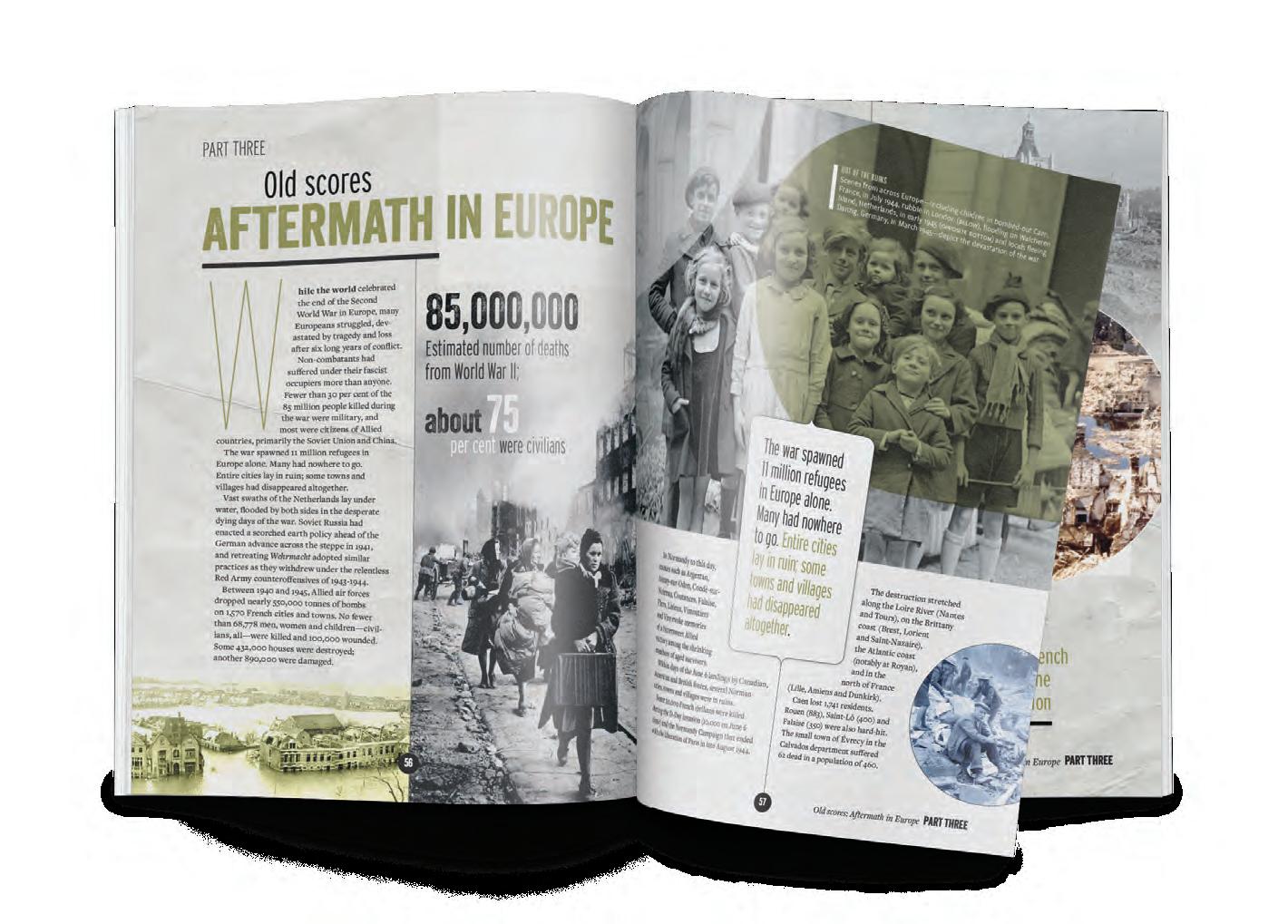

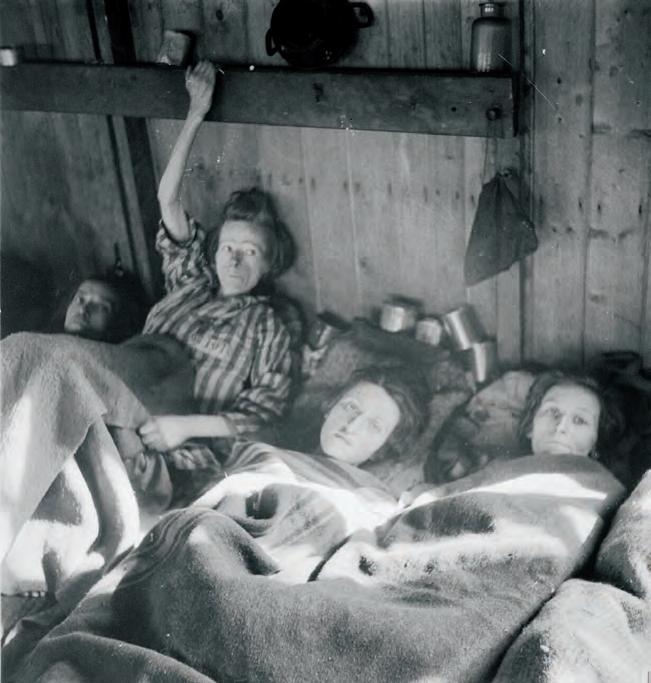

Despite living amid the battle for Caen, France, this group of local children is all smiles for Canadian photographer Ken Bell on July 10, 1944.

See page 52

18 A WAR BY ANY OTHER NAME

A look back at the key Canadian battle of the Korean War and the conflict’s future implications 75 years after it began

By Stephen J. Thorne

24 A FORMIDABLE PILOT

The legacy of Robert Hampton Gray

By Brad St. Croix

28 VILLAIN OR VICTIM?

For Japanese Canadian Kanao Inouye it’s a complex tale

By Alex Bowers

34 AFTERMATH

The trials and tribulations of the Canadian Army Occupation Force in Germany in 1945-1946

By J.L. Granatstein

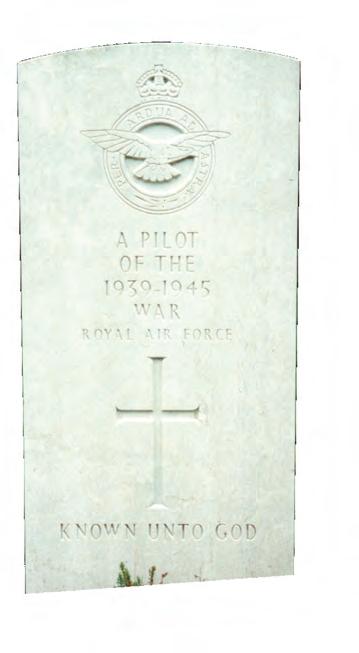

40 NO KNOWN GRAVE?

Tracking the final resting place of Canadian Battle of Britain casualty John (Jack) Benzie

By Andy Saunders

46 NOT AGAIN

A fiery footnote in history, the July 1945 Bedford Magazine explosion almost became a second Halifax disaster 27 years after the first

By Alex Bowers

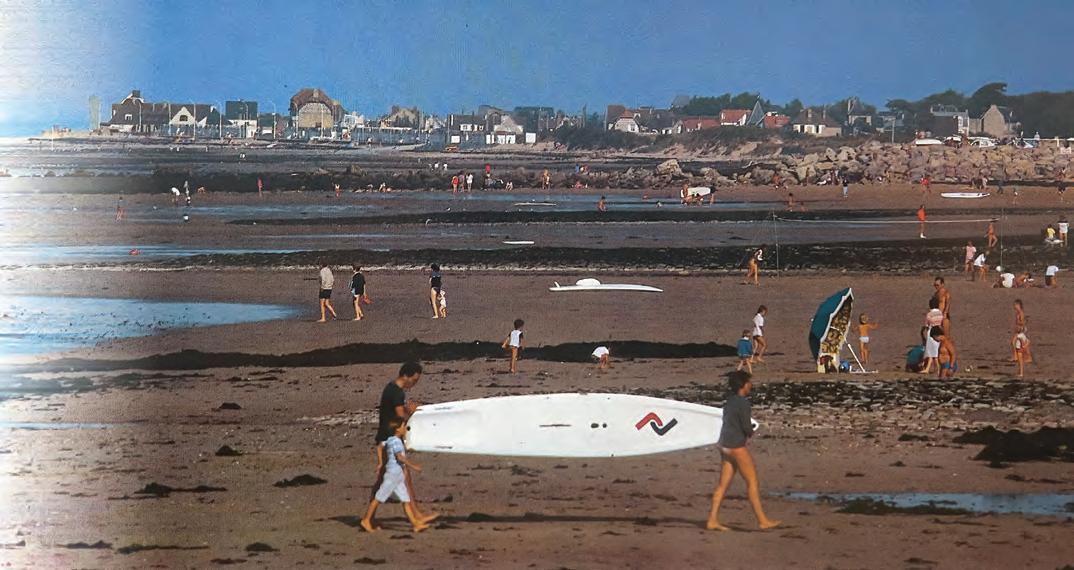

52 BACK TO THE FRONT

Canadian war photographer Ken Bell returned to European battlefields several times after the Second World War to reshoot some of the people and landscapes captured during the conflict

Words by Carla-Jean Stokes

THIS PAGE

An army truck lies on its side after the first explosion at the Bedford Magazine near Halifax in July 1945.

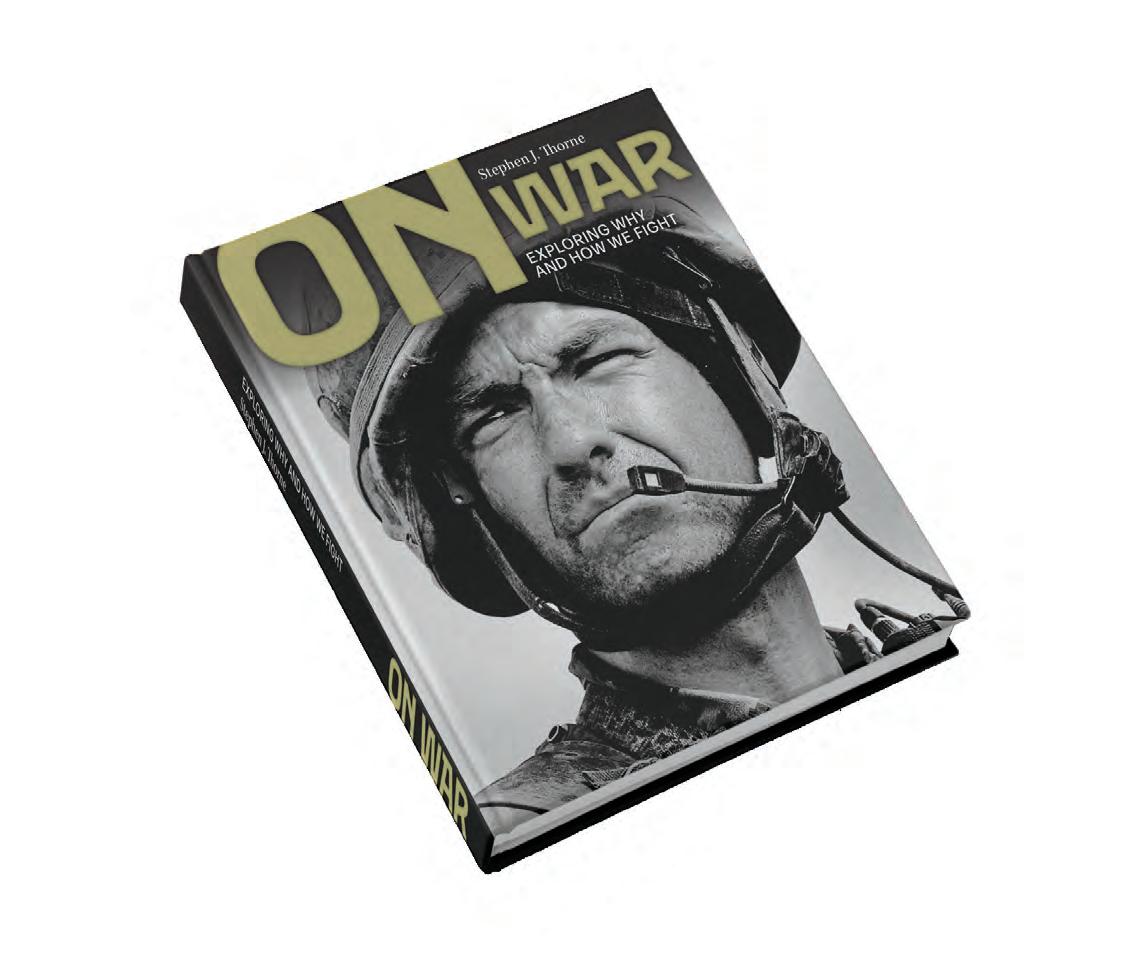

Nova Scotia Archives ON THE COVER

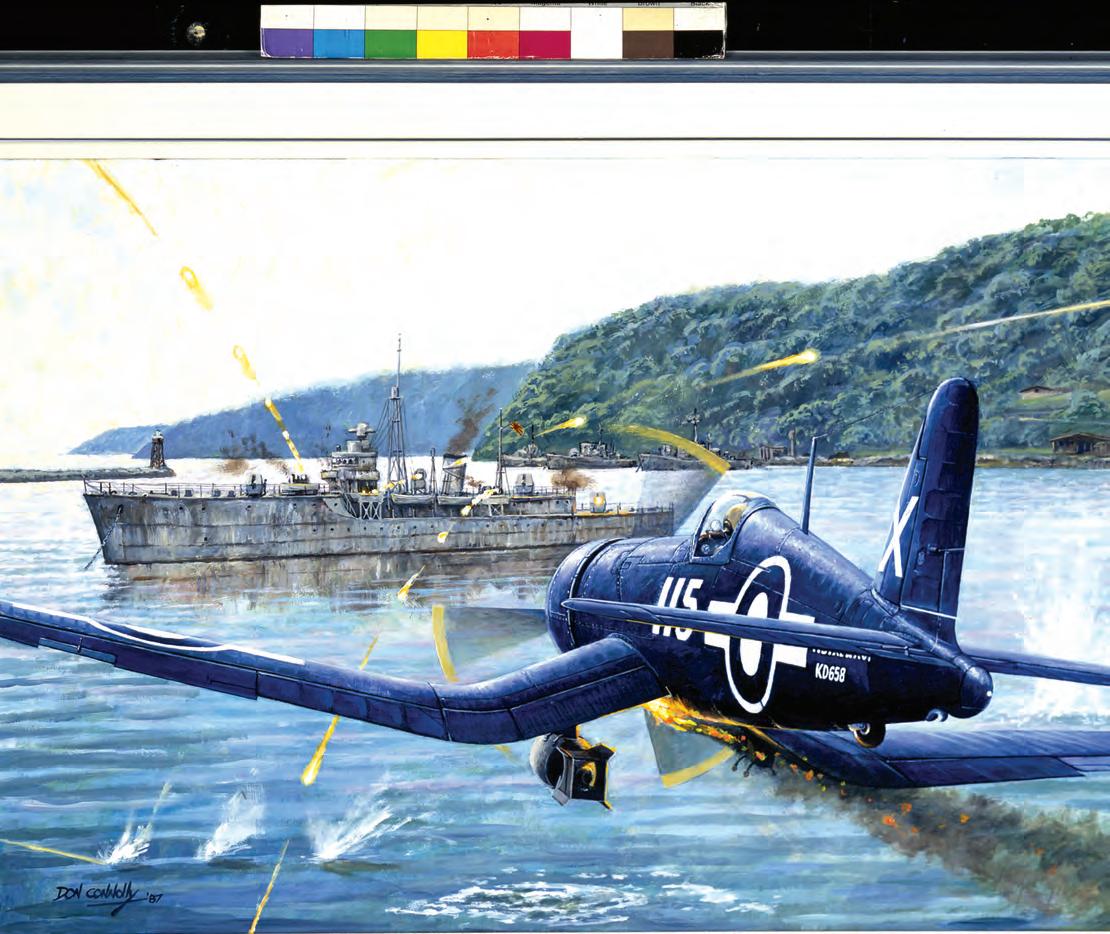

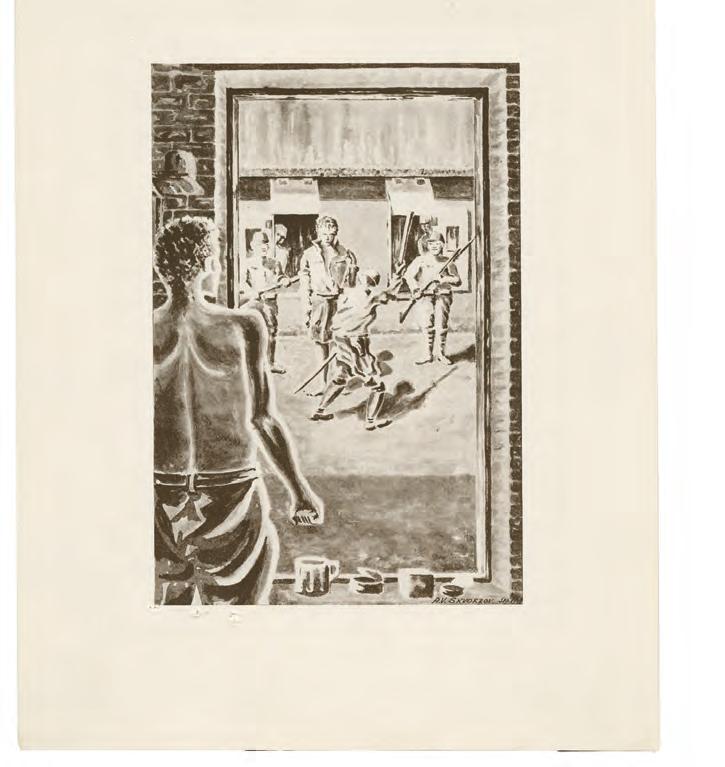

Artist Donald Connolly depicts pilot Robert Hampton Gray’s attack on a Japanese destroyer escort in Onagawa Bay on Aug. 9, 1945. The ship was sunk, but Gray died when his plane was shot down. He posthumously received the Victoria Cross for his actions.

Donald Connolly/CWM/19880046-001

the U.S. need to drop the atomic bombs on Japan?

J.L. Granatstein

Board of Directors

BOARD CHAIR Sharon McKeown BOARD VICE-CHAIR Berkley Lawrence BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe DIRECTORS Steven Clark, Randy Hayley, Trevor Jenvenne, Bruce Julian, Valerie MacGregor, Jack MacIsaac Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

ADMINISTRATION MANAGER

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

ADMINISTRATIVE AND EDITORIAL CO-ORDINATOR

Ally Krueger-Kischak

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Alex Bowers

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert

DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales CANIK MARKETING SERVICES NIK REITZ advertising@legionmagazine.com

MARLENE MIGNARDI marlenemignardi@gmail.com OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2025. ISSN 1209-4331

Subscription Rates

Legion Magazine is $13.11 per year ($26.23 for two years and $39.34 for three years); prices include GST. FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $14.36 for one year ($28.73 for two years and $43.09 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $14.11 for one year ($28.23 for two years and $42.34 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 Call 613-591-0116 or toll-free 1-844-602-5737.

The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Change of Address

Send new address and current address label, or, send new address and old address. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com/change-of-address. Allow eight weeks.

Editorial and Advertising Policy

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $12.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of Alliance for Audited Media and BPA Worldwide. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

From time to time, we share our direct subscriber list with select, reputable companies whose products or services we believe may interest our subscribers. To opt out of receiving these offers, please send your request, including your full name and address, to magazine@legion.ca. Alternatively, you can write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1, call 613-591-0116, or call toll-free 1-844-602-5737.

“It

’s quite encouraging to see that Canadians are paying more attention to defence and security issues,” the defence chief, General Jennie Carignan, told members of The Royal Canadian Legion’s leadership during a meeting in late April, two days before the federal election (also see page 60).

Owing no doubt in large part, if not entirely, to U.S. President Donald Trump’s repeated references to Canada as America’s “51st state” and his administration’s deranged tariff policy, Canadians seemingly took a renewed interest in the country’s sovereignty, manifest in national defence as a top campaign issue.

Both the minority-winning Liberals and the narrow-margin opposition Conservatives made several promises related to military investment during the election. And “analysts don’t see a whole lot of difference between the defence platforms of the two major parties,” wrote Chris Lambie of the National Post on April 26.

“WE HAVE A NEW U.S. ADMINISTRATION THAT’S ADOPTING A TOTALLY DIFFERENT POSTURE, AND WE HAVE TO ADJUST TO THAT.”

As a handy reference, here’s a brief summary of what Prime Minister Mark Carney’s Liberals pledged:

• a n $18-billion increase in defence spending over four years to meet NATO’s two per cent gross domestic product spending target;

• t he creation of a single agency to handle military procurement (the party made the same promise during the 2019 campaign);

• pay raises for military members, as well as to “rapidly (increase) the stock of highquality housing on bases across the country and (ensure) access to primary child care and health care—including mental health supports—for serving members and their families”;

• a modernization of the recruitment process “by streamlining security clearances and applying online, so that more applicants can get trained, faster”;

• a nd, to “integrate the Canadian Coast Guard into our NATO defence capabilities” to “exceed our commitment to spend at least two per cent of GDP on defence.”

“I think we need to be prepared to be underwhelmed by how much can change in just the next four years,” David Perry, president of the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, told the National Post. “The current defence procurement cycle, as an example, runs about 15 years from projects starting to being completed.”

Perry added that despite the promises, he didn’t expect much to change.

Ken Hansen, a military analyst and former navy commander, essentially agreed. “When the pinch is on for money due to things like COVID or trade wars,” said Hansen in the Post article, “then that’s where they’ll squeeze to get some money out so they can smear it around somewhere else.”

Preliminary data from Elections Canada indicated voter turnout was 68.66 per cent, a six per cent increase from 2021 and the highest it’s been since 1993. Clearly, something got Canadians to the polls. And it’s hard to imagine that Trump wasn’t a big part of that.

“We have a new U.S. administration that’s adopting a totally different posture,” General Carignan also told Legion leaders last April, “and we have to adjust to that.”

A nd so, Canadians who remain appalled by Trump, passionate about the country’s sovereignty, and invested in Canada’s military, may wish to heed the defence chief’s words—and likewise hold their newly elected MPs to their promises. L

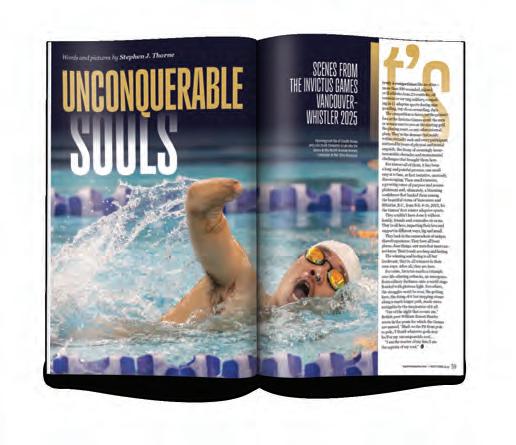

was really pleased to read the article about the Invictus Games held in Whistler and Vancouver this past February (“Unconquerable souls,” May/ June). It brought back many fantastic memories and, as a Games volunteer, it was an absolute thrill to have been part of such a unique and special sporting event. Meeting so many veterans and their families from around the world made it

The editorial from 1935 (“War — Neutrality — Canada,” May/June) is a reminder that ignoring the lessons of history is very dangerous. Politicians on both sides of the House have ignored the needs of Canada’s military for far too long. Canada depended on the United States, and it now needs to re-arm or face becoming Trump’s cherished 51st state. Wake up Ottawa!

PETER MARKLE

STOUFFVILLE, ONT.

Being a Newfoundlander by birth, I was particularly interested in the articles, “Who knit ya,” by Stephen J. Thorne, and “Somme memorial,” by Don Gillmor, in the May/June edition. I suspect that Gillmor’s article may have been edited down to fit the space because there was a misleading fact that requires clarification. While the Newfoundland Regiment did send a first contingent of 537 men to Britain for final training on Oct.13, 1914—who despite the slight lack of precision in the title became

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

all that much more special. One thing the article didn’t mention was that almost 2,900 applications were received and 1,900 international volunteers were chosen, many of whom were veterans as well. The Games wouldn’t have been possible without them. If the Games ever return to Canada, I will be first in line to volunteer again.

TED USHER COURTENAY, B.C.

known as the “First 500”—they were joined by a second group, which departed Newfoundland on Feb. 5, 1915, and a third, which left on March 22, to bring the regiment up to full strength before leaving for Gallipoli.

The second contingent, of which my grandfather, Howard Leopold Morry, was a member, also included roughly 500 men, while the exact number in the third contingent isn’t well documented. But, suffice to say, at least 1,076 officers and men landed on Kangaroo Beach in Suvla Bay on Sept. 20-21, 1915, to lend support to other British Empire forces who had arrived in Gallipoli on April 25, 1915.

CHRISTOPHER MORRY GREELY, ONT.

The claim that “Moscow, now under Vladimir Putin, is responsible for saving NATO in modern times, not Donald Trump” (“Face to Face,” March/April) is the kind of tortured nonsense that comes from Trump Derangement Syndrome. By pressuring his freeloading partners to step up their collective defence, Trump gave

new life to a moribund organization. Millions of Ukrainians have suffered and died in an unwinnable war. Trump’s iron will and adroit diplomacy will save Ukraine, too.

GARY M c GREGOR LADNER, B.C.

I have just finished reading your article “Unto the breach” (March/April) and I would like to point out that LanceCorporal Fred Fisher was a member of the 13th Battalion, The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) of Canada.

WILLIAM R. SEWELL POINTE-CLAIRE, QUE. L

In “Humour Hunt” (May/June), an editing error changed the word “destore”—to remove naval gear and supplies from a vessel— to “destroy.” As it turns out, the original message was likewise confused. The joke’s on us.

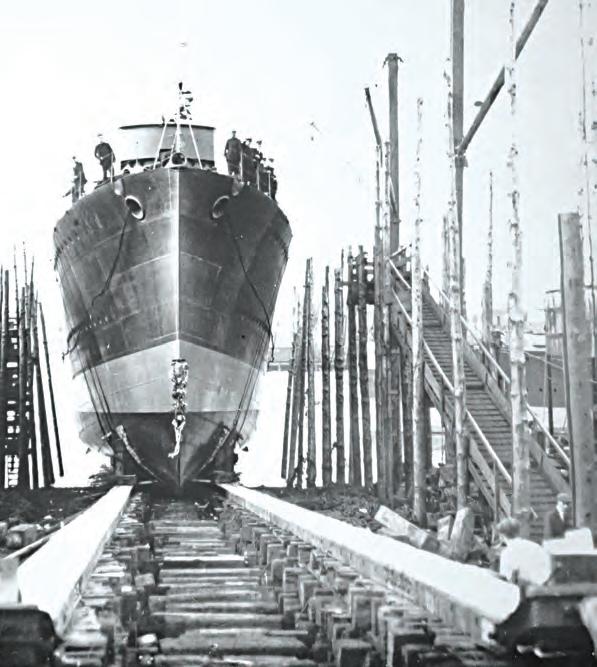

3 July 1931

11 July 1990

The first vessels specifically built for the Royal Canadian Navy, HMCS Saguenay and HMCS Skeena, complete their maiden voyages to Halifax. Both were commissioned at Portsmouth, England.

4 July 1944

Canadian forces advance under heavy fire toward Carpiquet airport on the outskirts of Caen, France.

5 July 1900

The Sûreté du Québec tries to dismantle a Mohawk blockade near Oka, Que. One officer is shot and killed, marking the start of the Kanesatake Resistance, also known as the Oka Crisis.

20 July 1871

B.C. joins Confederation on the promise of a rail link and representation in Parliament.

24 July 1927

The Menin Gate memorial to the missing in Ypres, Belgium, is unveiled.

For actions during the Boer War, Sergeant Arthur Richardson of Strathcona’s Horse earns the Victoria Cross. It’s the first VC awarded to a member of a Canadian unit.

7 July 1942

Operation Rutter, the original plan for the Dieppe Raid, is cancelled for numerous reasons, including reports of bad weather.

10 July 1943

1906

Charles K. Hamilton completes first powered and directed flight in Canada at Montreal flying a dirigible.

14 July 1976

Canada formally abolishes the death penalty.

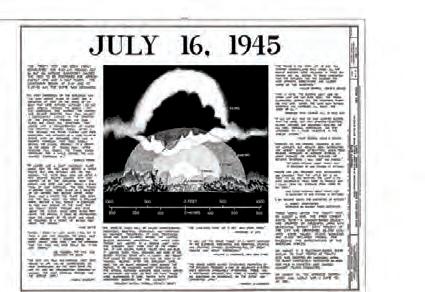

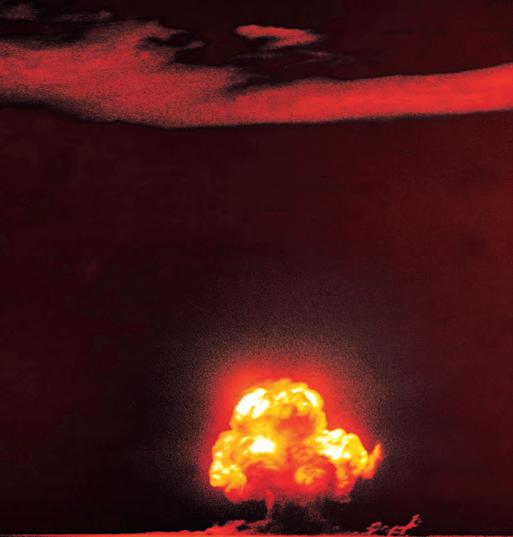

July 16 1945

An atomic bomb is tested in New Mexico (see “Face to Face,” page 58 and “O Canada,” page 96).

17 July 1812

British forces capture U.S. Fort Mackinac, which was unaware war had been declared.

Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily, begins. 1st Canadian Infantry Division’s participation represents the country’s first sustained commitment to the ground war against Germany.

25 July 1937

Two RCAF aircraft from 7 Squadron begin a month-long tour of the Arctic with Governor General Lord Tweedsmuir.

27 July 1953

An armistice ends three years of fighting in the Korean War. Some 26,000 Canadians served; 516 died and more than 1,200 were wounded.

28 July 1884

The Settlers’ Union issues a manifesto of grievances contributing to tensions that ultimately lead to the 1885 NorthWest Resistance.

29 July 1982

The CF-18 Hornet reaches Mach 1.6 on its first test flight in St. Louis.

30 July 1960

Prime Minister John Diefenbaker announces Canada will make a substantial contribution to a United Nations intervention in Congo.

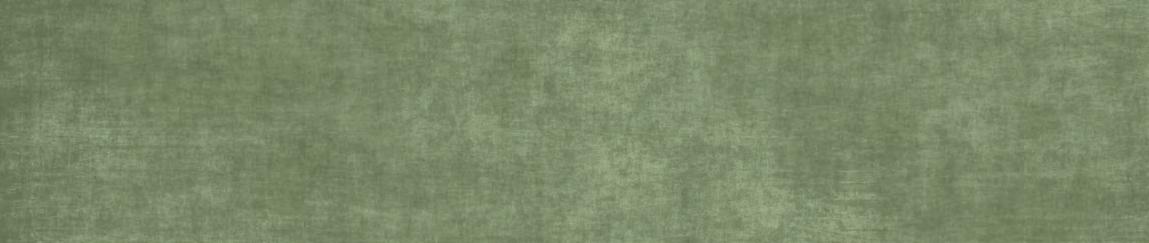

1 August 1834

The Slavery Abolition Act takes effect, outlawing servitude across the British Empire.

2 August 1951

HMCS Athabaskan sails for its second tour of duty in Korean waters.

3 August 1961

Tommy Douglas is elected leader of the New Democratic Party at its founding convention.

6 August 1945

An American nuclear bomb devastates the Japanese city of Hiroshima.

8 August 1918

In conjunction with other Allied forces, the Canadian Corps launches a major attack to the east of Amiens, France, beginning a period of operations known as The Last Hundred Days.

9 August 1945

Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray of Nelson, B.C., an RCNVR pilot, sinks a Japanese destroyer escort in Onagawa Bay. He is posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross (see “A Formidable pilot,” page 24).

10 August 1840

Louis Anselm Lauriat completes Canada’s first manned flight— in a hot-air balloon—in Saint John, N.B.

11 August 1755

British BrigadierGeneral Charles Lawrence orders the expulsion of the Acadians.

13 August 2008

Two Canadian aid workers, Jacqueline Kirk and Shirley Case, are killed in a roadside ambush in Afghanistan.

16 August 1812

The Americans surrender Fort Detroit to forces led by Major-General Isaac Brock.

18-20 August 1944

After days of fighting, Major David Currie accepts the surrender of German troops at Saint-Lambert-sur-Dives, France. He earned the Victoria Cross for his actions.

22 August 2006

A suicide bomber crashes into a Canadian military patrol in southern Afghanistan, wounding three and killing Corporal David Braun and a local girl.

25 August 1875

15-18 August 1917

Canadians capture Hill 70 at a cost of 9,000 casualties.

The Gazette; Wikimedia; CWM/ 199220044-995; LAC/PA-141664; Boston Public Library/Wikimedia; Backyardhistory.ca; CWM/19920085-663; Kylee Gardner/DVIDS/ Wikimedia

The North-West Mounted Police establish Fort Brisebois at the confluence of the Bow and Elbow rivers in Alberta. It’s renamed Fort Calgary the following year.

28 August 1928

Punch Dickins begins a 12-day, 6,400-kilometre pioneering flight in a float-equipped Fokker airplane over northern Canada.

29 August 1917

A mob of 5,000 begins a two-day riot in Montreal in protest of conscription.

The last U.S. troops leave Afghanistan, ending the nearly 20-year war.

What does life look like after the military? Perhaps you’ve started a new career, moved to a different city, or are balancing your income after a medical release. Now is the time to get expert financial advice on how to live better now and in the future.

Here are some of the things SISIP can help you with:

More money in your pocket. Financial success starts with managing your monthly cash flow. We’ll help you maximize your income, minimize your taxes, and make the most of your financial resources.

A path to your goals. Nothing can grow your money like a diversified, tax-smart investment portfolio. We’ll design a customized roadmap that lays out what you want to achieve and how you’ll get there.

Protection for your loved ones. Insurance provides cash to your loved ones when you are not able to do so. We’ll analyze your situation and recommend the ideal type and amount of protection for you.

As a veteran, you can talk to SISIP about financial advice, investing, insurance, pensions, and more. We exclusively serve Canadian Armed Forces members, veterans and their families both online and at bases and wings across Canada. You can count on us for unbiased advice because our financial experts are accountable to you and nobody else.

SISIP is here to help you make the right ones. Your pension. Your investments. Your insurance. Your cash flow. Your next career move. And beneath it all, a single question: “Am I making the right choices for my family and my future?”

That’s where SISIP comes in. SISIP has been serving CAF members and veterans for more than 50 years. Our only goal is to help you make confident, informed decisions about your finances. Here are a few ways we can help:

• Understand your pension options. Should you take a deferred annuity, an annual allowance, or a transfer value? We can walk you through your options and help you choose what’s right for your timeline and goals.

• Plan your transition. Starting a new career or moving to a new city? We’ll help you prepare your budget, manage your savings, and anticipate what comes next.

• Keep your insurance coverage. You have 60 days after releasing to switch to SISIP’s Insurance for Released Members without medical re-qualification. Don’t let your protection lapse without reviewing your options.

• Stay invested in your future. We can help you build a long-term plan that fits your new life stage, your new income, and your long-term goals.

• Get support when you need it. If you’re medically released, CAF long-term disability insurance can help you recover and retrain. We’re here to help you navigate the process and access the support you’re entitled to.

• Talk to experts who know. You’re still part of the CAF community, and we’re still here for you. From life insurance coverage to investing in retirement, your SISIP advisor is always just a phone call or email away. At SISIP, our financial advisors understand military benefits, pensions, and pay structures in a way most civilian advisors simply can’t. We know how to navigate the transition from full-time service to civilian life, and we’re ready to help you chart your next mission.

Just made the leap? Let’s talk.

Visit sisip.com or call 1-800-267-6681 to connect with your local SISIP advisor.

By Alex Bowers

e’re not providing mental health support services,” said TryCycle Data Systems founder John MacBeth. “We’re providing human connection,” he told a gathering of Legionnaires in August 2024.

In an increasingly digital world, authentic human connection has become a rarity. And just as modernity may hinder people’s sense of community, it may also be the anecdote needed, says MacBeth, for veterans to reach their optimal selves.

The evidence is in the Burns Way, an online peer-support tool for veterans developed by TryCycle Data and endorsed by the RCL, which since its launch has facilitated invaluable connections.

MacBeth’s vision was fully realized on Jan. 15, 2025, when the Burns Way opened its proverbial doors to veterans seeking comfort, guidance and camaraderie, as well as those best placed to offer it.

Its name honours the legacy of retired private Earl Burns Sr., who, on Sept. 4, 2022, died protecting his family and community amid a stabbing spree at Saskatchewan’s James Smith Cree Nation.

“We want individuals to build confidence in getting help for themselves through speaking to someone who’s worn their boots,” explained project lead Cameron MacLeod, “whether it’s RCMP, Canadian Armed Forces or a family member.”

Users, whether via the mobile app or on the Burns Way website, can hone their search for advocates most closely aligned with their own lived experiences.

“We want them to find the peer advocate who meets their needs, rather than just a peer advocate, explained MacLeod.

More than 200 applicants volunteered their time and services when the recruitment campaign began in November 2024, at least 50 of whom were initially selected to undertake standard and mental health first aid training prior to connecting with a fellow veteran.

The not-for-profit Burns Way, which steers clear of automated robots and artificial intelligence, or AI, that many public-facing parts of organizations currently use, recognizes the importance of anonymity and security as two vital factors that can often influence a veteran’s willingness to seek support. Thus, in delivering free, 24-hour assistance, the online portal requires neither an email address nor login details. Additionally, those choosing to create personalized profiles do so with a guarantee that no one else can access their information.

Only that which is voluntarily divulged to a peer advocate is known about an individual user. Once that conversation ends, the record is permanently deleted.

The fact that its users can remain anonymous addresses a major

concern of many former service personnel. The Burns Way also doesn’t fit the traditional mould of mental health services. It’s “not a crisis line,” MacLeod asserted. “Obviously, [under such circumstances], the peer advocate will respond. They’d then try to reduce the person’s anxiety, referring them to more formal support if intervention is required.

“[Our program] is not therapy, even if it might occasionally be therapeutic.”

Despite this, every peer is certified by Opening Minds, an affiliate of the Mental Health Commission of Canada, each having completed its “Mental Health First Aid— Veteran Community” course.

Elsewhere, MacLeod noted, the question of funding looms large. “From the outset, TryCycle Data Systems has supported the entire thing. They’ve invested more than three quarters of a million dollars into the Burns Way in cash and in-kind. So, we’re really looking to getting the program funded in a way that makes it sustainable.”

In June 2023, a proposal was submitted to VAC requesting $9.5 million annually for three years. To date, no formal commitment has been made.

“We know government is bound by rules, but they’ve been generous with their time and have worked with us to try and find a way of making this happen— we’ll have to wait and see.”

Following the success of the Talking Stick app, a previous TryCycle initiative that matches Indigenous Peoples in Saskatchewan with fellow Indigenous advocates, Macleod is hopeful the Burns Way will similarly flourish.

Regardless, one aspect of its mandate will remain: cultivating safe and secure support for Canadian veterans and their families.

“If you know of someone who’s struggling out there,” said MacLeod. “Tell them about us. Let them know someone is ready to listen. L

Enjoy up to 50% off accommodations at more than one million hotels worldwide when you sign up*—and it’s FREE! That’s incredible savings for you, your family and your friends.

Plus, a portion of all proceeds from hotel bookings at Legion Travel assist The Royal Canadian Legion and its efforts to support Veterans.

STAY, SAVE and SUPPORT—scan the QR code or visit legiontravel.ca/magazine today!

Free Membership

Sign up for instant access to amazing hotel deals with no hidden fees.

Exclusive Savings Travel in style or on a budget. Get access to up to 50% off hotels*, with our exclusive unpublished rates.

Travel Your Way

Book at over one million hotels in 155,000 cities in 220 countries. The world is your oyster.

By Stephen J.Thorne

quarter century ago, an unidentified Canadian soldier killed at the seminal First World War Battle of Vimy Ridge was ceremonially exhumed from his grave 8.5 kilometres away in Cabaret-Rouge British Cemetery and brought home to Canada.

Vimy, because it was there, in France in April 1917, that all four divisions of the Canadian Corps fought together for the first time, claiming—under unprecedented Canadian leadership—a victory that would propel the country to its rightful place in the war, and the world. Brought home, because Canadians—indeed, all secure, free-living people—need reminding of what it took, and still takes, to keep them secure and free.

More than 18,000 of the over 66,000 Canadians killed in the Great War were never identified, their names listed on the Canadian National Vimy Memorial (11,285) and the Menin Gate in Belgium (6,940). This soldier was destined to represent them all and the 27,000 who remain unidentified from the Second World War, 16 from Korea and undetermined others from the Boer War and other conflicts.

On May 28, 2000, the remains were laid in state at the Hall of Honour in Parliament before

they were interred in the shadow of the National War Memorial to lie in anonymity forever. It was the culmination of years of effort by The Royal Canadian Legion.

During the succeeding 25 years, the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier has become a focal point where, awakened by Canadians’ renewed sacrifices in Afghanistan, thousands of attendees have laid their poppies at the conclusion of the annual Remembrance Day ceremonies.

And, on May 28, 2025, veterans, serving military, dignitaries, schoolchildren and Legionnaires

Mounties place poppies on the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier (above). Retired brigadiergeneral Duane Daly, former Legion dominion secretary, and retired vice-admiral Larry Murray, Legion grand president, salute after placing their poppies on the tomb (left).

gathered to pay tribute to the Unknown Soldier and all his comrades, and lay their poppies on his concrete sarcophagus.

Gov. Gen. Mary Simon was there. So was former governor general Adrienne Clarkson, who had delivered a stirring speech at the tomb’s dedication 25 years earlier (see Legion Magazine May/June 2025).

“We cannot know him,” she said then. “And no honour we do him can give him the future that was destroyed when he was killed. Whatever life he could

> Check out the Front lines podcast series! Go to legionmagazine.com/en-frontlines

have led, whatever choices he could have made are all shuttered. They are over.

“We are honouring that unacceptable thing—life stopped by doing one’s duty. The end of a future, the death of dreams.”

Twenty-five years on, a chaplain with the Canadian Armed Forces, Lieutenant (N) Katherine Walker, delivered her own poignant words as Clarkson looked on.

“There are places that ask something of us,” Walker told the crowd. “Places we cannot pass by casually. This is one of those places.”

The Legion’s grand president, retired vice-admiral Larry Murray, spoke. So did retired brigadiergeneral Duane Daly who, as RCL dominion secretary at the time, first proposed the tomb idea after an eye-opening trip to South Africa.

There, he had found Canadian war dead buried where they fell, their graves—often single plots in farmers’ fields—marked by the granite stones that had served as ballast aboard the ship that brought them to their deaths so far from home.

Daly related the story of how Legion efforts to bring an unidentified soldier home for burial at the National War Memorial were

“THERE ARE PLACES THAT ASK SOMETHING OF US. PLACES WE CANNOT PASS BY CASUALLY. THIS IS ONE OF THOSE PLACES.”

stonewalled by successive governments, who pointed to Britain’s Unknown Warrior, interred at Westminster Abbey on Armistice Day 1920, saying he represented all the British Empire.

“Accepting the reality of the situation, the Legion remained undaunted,” said Daly, “and decided to take on the task of repatriating an unknown soldier itself” as a millennial project. A national survey reflected “overwhelming support” for the idea.

Design and costs posed major challenges from the outset: The initial budget was $500,000. It ended up costing nearly $2 million, much of it from federal coffers, but not because the federal government endorsed the endeavour. It didn’t.

Departmental budgets were arranged to ensure that it was adequately funded.

In a 20th anniversary interview with Legion Magazine, Daly said three public servants were critical to the initiative: Gerry Wharton, director ceremonial at Public Works and Government Services, came up with the design concept; Brad Hall of the Canadian Agency of the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, led the remains recovery in France; and Marc Monette, director of Public Works, Parliamentary Precinct, oversaw construction of the tomb and its placement. He also ran the design competition, won by Canadian artist Mary-Ann Liu.

Attention to detail was critical, from ensuring the granite came from the same Quebec quarry as the rest of the monument to finding a suitable gun carriage to transport the remains from Parliament Hill to the final resting place. The RCMP provided a gun carriage and mounted escort for the funeral cortège.

The soldier’s original stone marker was brought from Plot 8, Row E, Grave 7 in the Cabaret-Rouge cemetery to the Memorial Hall in the new Canadian War Museum where, at 11 a.m. each Remembrance Day, a beam of sunlight shines through a narrow window and illuminates it.

“This tomb is one eventuality of armed conflict,” said Walker. “And it reminds us that peace does not erase the traces of war.

“We gather here—not to glorify war, but to bear witness to its reality, and to honour what was asked of those who served. We gather to express how what they gave has immense value. That defines and allows for the very freedoms we now get to live out.” L

By David J. Bercuson

These days, Canadians have good reason to hit back at U.S. President Donald Trump and boycott American products from Heinz ketchup to Teslas. When it comes to Canada’s security and defence, however, Canadians ought to think very carefully about where their future lies and what measures they must take to maintain the country’s sovereignty and security.

Canada’s modern defence relations with the U.S. date back to the summer of 1940 after France was defeated by Germany and the North American continent was suddenly threatened by Nazi power. At that time, Canada was at war with Germany, but the U.S. was still neutral.

Nevertheless, President Franklin D. Roosevelt and Canadian Prime Minister Mackenzie King met at Ogdensburg, New York, on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River to initiate a new direction for both countries given the new threats to the world.

The pair agreed that the defence of North America demanded a joint Canada-U.S. arrangement and created the Permanent Joint Board on Defense (PJBD), which would initiate collaborative plans for continental security and report directly to the prime minister and the president. The agreement was renewed in 1946 by Resolution 37 of the PJBD to co-ordinate North American defence against the threat of

HMCS Harry DeWolf maritime task group, including French and U.S. naval vessels, in the North Atlantic on Aug. 11, 2023.

communism spreading under the influence of the Soviet Union.

This tie between the two coun tries was further strengthened by the creation of Norad in 1957. Now, there are hundreds of Canada-U.S. arrangements that govern shared security, dictated by the fact that the nations share a continent and by values of democracy. No president or his regime can invalidate those two basic facts.

As angry as Canadians may be with the current U.S. president’s lack of respect for their countries’ shared history, heritage and accomplishments, they must also understand that they rely on American satellites and radars to protect their aerospace, will soon rely on America’s help to secure Arctic sovereignty, in part by obtaining the best-in-class polar icebreakers, and not forget that the U.S. is their greatest investor. Exports to the U.S. accounted

for 19 per cent of Canada’s gross domestic product in 2023, which is by far the most common destination country for Canadian goods (70 per cent of all Canadian exports are destined for the U.S.).

How does such integration affect basic policy decisions? First, it can’t risk the existing positive working relationship between the Canadian and U.S. militaries. Second, the infrastructure and strategies to defend the continent must continue to be transborder, especially for air defences, sea approaches and the Arctic frontier. Plus, the ability to proffer military help in times of extreme natural disasters must continue. It also means that the time has

with a population of just 40 million. But that means Canada can’t afford to defend its borders and the world’s longest coastline alone. No matter the political stance of the administration in Washington, Canada must always make continental defence a priority, so that the U.S. won’t question its northern neighbour’s commitment to it.

In response to Trump’s Canadian sovereignty-related ramblings, the federal government has explored aligning itself with Europe when it comes to defence and security. What nonsense. Europe

create the sort of international defence structure that already exists in North American would likely take the better part of a decade, if it’s even possible.

Canadians must remember, there’s a reason their country has looked to the U.S. for defence equipment since the early 1950s: because it’s very good, if not the best, readily attainable, and owing to the transborder defence arrangements, is easily interchangeable.

So, buy Australian wines rather than American ones and vacation in the Caribbean instead of Florida or Arizona. But, now isn’t the time to disrupt the defence agreements that have kept North Americans safe and secure since the end of the Second World War. L

Korean

A look back at the key Canadian battle of the Korean War and the conflict’s future implications 75 years after it began | Stephen J. Thorne

Ask many a Korean War veteran what they remember most about their time near the 38th parallel and they’re as likely as not to tell you something about topography, sweltering heat or bitter cold.

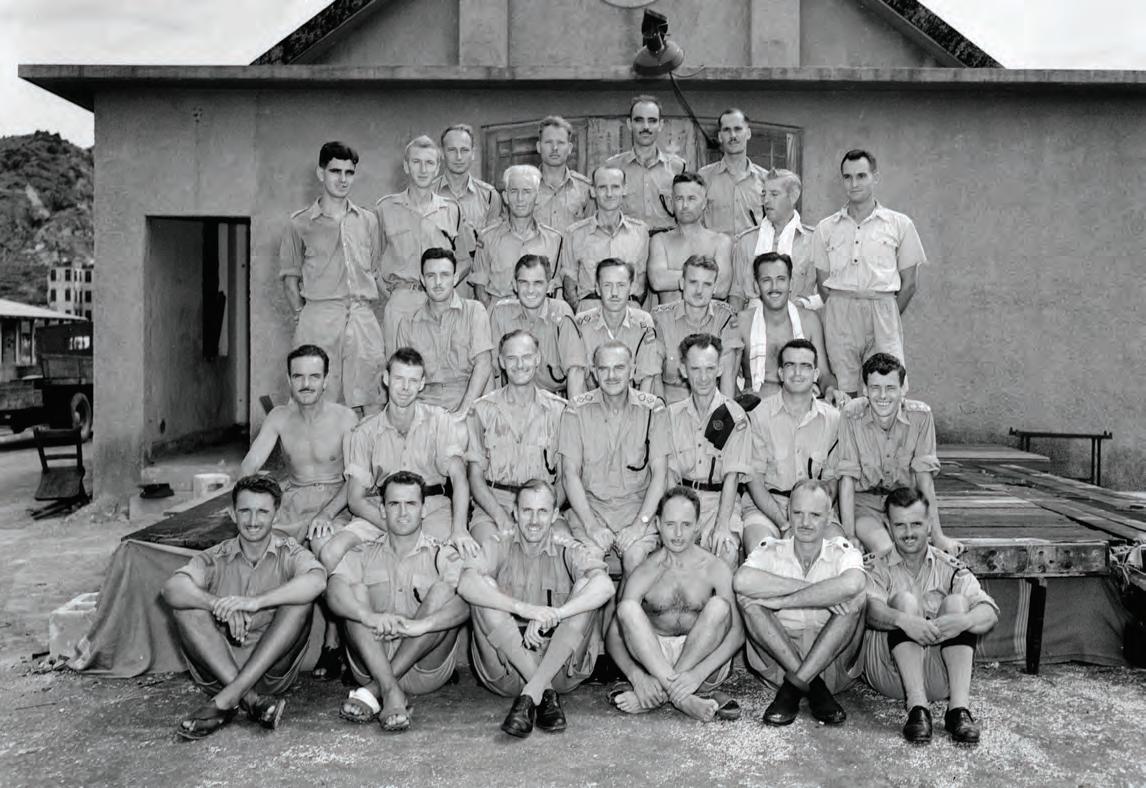

Ask the 1,500 men of the 3rd Battalion, Royal Australian Regiment (3 RAR), and 2nd Battalion, Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry (2 PPCLI), what they remember most, and those still living will likely take you back to the peaks overlooking the picturesque Kapyong Valley.

It was there, on the road to Seoul, that the 118th Division of the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army (PVA) launched the main element of its spring offensive in April 1951.

The Canadians and the Aussies were at the tip of the defensive spear, poised to bear the brunt of the three-day onslaught by up to 20,000 Chinese soldiers. Today, the battle is widely regarded as the most significant action fought

by either allied army in Korea, and Canada’s most famous battle since the Second World War.

Chinese casualties had begun to rise under relentless artillery strikes ordered by the supreme Allied commander on the peninsula, newly appointed U.S. General Matthew B. Ridgway.

The momentum of the war was shifting, and Kapyong was a lynchpin.

South Korean troops were establishing positions at the northern end of the Kapyong Valley when the PVA’s 118th and 60th divisions launched a local offensive at 5 p.m. on April 22.

Facing pressure all along the front, the South Koreans soon gave ground and broke, abandoning weapons, equipment and vehicles as they streamed southward out of the mountains. By 11 p.m., the South Korean commander had lost all communication with his units. At 4 a.m. the

next day, supporting New Zealand t roops were withdrawn, only to be sent back, then withdrawn again by dusk. The South Korean defences had collapsed, and on their way out they let the Canadians know the Chinese were coming.

“It was then, about mid-afternoon, that the rumour of the collapsing front acquired a meaning,” Captain Owen R. Browne, officer commanding ‘A’ Company, wrote in 2 PPCLI’s regimental journal.

“From my arrival until then both the main Kapyong Valley and the subsidiary valley cutting across the front had been empty of people. Then, suddenly, down the road through the subsidiary valley came hordes of men, running, walking, interspersed with military vehicles—totally disorganized mobs. They were elements of the 6th ROK (Republic of Korea) Division which were supposed to be ten miles forward engaging the Chinese. But they were not engaging the Chinese. They were fleeing!

“I was witnessing a rout,” continued Browne. “The valley was filled with men. Some left the road and fled over the forward edges of “A” Company positions. Some killed themselves on the various booby traps we had laid, and that component of my defensive layout became worthless….

“We knew then that we were no longer 10-12 miles behind the line; we were the front line.”

Some 40 million people died in the First World War; at least 70 million in the Second. By the time Soviet-backed North Korean forces crossed the 38th parallel into South Korea on June 25, 1950, folks didn’t want to hear any more about war.

And, so, when a U.S.-led United Nations coalition stepped in on the Korean peninsula, President Harry S. Truman and Prime Minister Louis St-Laurent called it a “police action,” an “intervention.”

The terms didn’t sit well with those who were there.

“There were 516 [Canadian] military guys dead over there,” George Guertin, a radio operator aboard HMCS Huron at the time, told Legion Magazine

“I don’t call that a ‘police action.’ Just an ugly little war.”

In fact, no war was ever declared, and for the next 40 years or so those happenings on the Korean peninsula were officially referred to as “the Korean Conflict.” There was a Cold War, all right, but God forbid another hot one.

To most all but those who fought it, Korea was “The Forgotten War.”

In Canada, the combatants weren’t formally recognized as war veterans until the late 1980s, when Ottawa decided the war was, in fact, a war. And it wasn’t until

1991 that veterans were awarded Korean War service medals.

Seven years later in the U.S., which provided the bulk of resources to the war effort, President Bill Clinton signed Public Law 105-261, Section 1067, which declared the “Korean Conflict” would henceforth be called the “Korean War.”

Semantics? No. The change had ripple effects throughout the coalition of countries that made up the UN force in Korea. It influenced such things as pensions and compensation for veterans, including the 26,791 Canadians who served.

Groups such as the Korea Veterans Association of Canada, which wasn’t formed until the 1980s, stepped up efforts to get vets the support they needed—and deserved. With numbers dwindling, the group folded in 2021 and was replaced by the more centralized and descriptive Korean War Veterans Association of Canada.

The recognition deeply affected many who had long felt their service had been taken for granted, if it had been recognized at all. While Vietnam War veterans would return to America to a hostile anti-war welcome in the 1960s and early ’70s, Korean War veterans of the 1950s got almost no public reception whatsoever.

Korea vets endured passive hostility in the form of veterans’ organizations that refused to recognize their service, resisted incorporating the Korean War on cenotaphs and generally belittled their contributions, all while overlooking the fact that about 16 per cent of all those who served in Korea also served in the Second World War. They knew what war was, and what occurred on the Korean peninsula between June 25, 1950, and July 27, 1953, was by all first-person accounts a war.

And the Patricias were decidedly in it.

With the disconcerting prospect of a superior force closing fast and ROK troops still pouring past them, the Canadians started digging trenches and positioning themselves on Hill 677 and along the 1.5-kilo metre ridge connected to it.

They were on the west side of the Kapyong River. On the other side of 677, atop Hill 504, were the Aussies, dug in and ready for a fight.

The New Zealand 16th Field Regiment was in artillery support, with troops of the British 1st Battalion, Middlesex Regiment, at the rear along with three platoons of the U.S. 72nd Heavy Tank Battalion—15 tanks—alongside the main road that split the valley.

“United Nations mountain warriors won their spurs today, holding their front and refusing to budge even though outflanked and encircled.”

“No retreat, no surrender,” the Patricias’ British-born commander, Colonel James Riley Stone, told his men.

The Chinese struck 504 first, engaging the Aussies of 3 RAR, infiltrating the brigade position, then hitting the Canadian front.

“They’re quiet as mice with those rubber shoes of theirs and then there’s a whistle,” said Sergeant Roy Ulmer of Castor, Alta. “They get up with a shout about 10 feet from our positions and come in.”

Waves of massed Chinese troops sustained the attack throughout the night of April 23.

The Australians and Canadians were facing the whole of the Chinese 118th Division. The battle was unrelenting through April 24.

“The Chinese employed all their familiar battle procedures in the attack—whistles, bugles, a banzai chorus, concerted action on the word of command and massed assaults followed one another in swift succession,” reported Bill Boss of The Canadian Press. “This was

familiar only by description for these United Nations troops who until now had fought mainly an advancing war against token resistance.

“Now it was grim reality.”

The fight devolved on both fronts into hand-to-hand combat with bayonet charges.

“The first wave throws its grenades, fires its weapons and goes to the ground,” explained Ulmer, who previously served as a company sergeant-major with The Loyal Edmonton Regiment during WW II.

“The country went from a war-torn, impoverished nation to a global industrial powerhouse in just two generations.”

“It is followed by a second, which does the same, and a third comes up. Where they disappear to, I don’t know. But they just keep coming.”

The Australians, facing encirclement, were ordered to make an orderly fallback to new defensive positions late on the 24th.

The Patricias were surrounded, too. “But they held,” wrote Boss.

Captain John Graham Wallace (Wally) Mills of Hartley, Man., a WW II veteran fighting his first action as a company commander, ordered his ‘D’ Company men into the slit trenches. Then the unit directed artillery and mortar fire on its own position several times during the early morning hours of April 25 to avoid being overrun.

“Guns and mortars rained hell on that hill from 2 a.m. to 6 a.m.,” Boss wrote, his censored copy of the day void of identifying specifics such as battalion and company.

“Torrents of hot metal fragments decimated the Chinese ranks,” said an account by The Loyal Edmonton Regiment Military Museum.

The Chinese kept hitting Ulmer’s position until 4 a.m. By then, the forward platoon had almost exhausted its ammunition.

“The sergeant hurled his bayonetted rifle like a spear at his enemy,” Boss reported. “While two gunners stood up and gave covering fire from the hip, the remainder withdrew—but only 50 yards. There the company continued the fight, dividing the remaining ammunition and holding out until the enemy pressure relented.

“I counted 17 dead Chinese within inches and feet of those troops today and approximately 50 graves of enemy buried in the heat of battle. There were uncounted enemy dead

where an intended rear and flank attack was thwarted.

“Another company fought at close quarters against waves of Chinese troops. This company shot and grenade[d] the enemy until its ammunition ran out.”

As the sun rose, 2 PPCLI, cut off from the rest of the UN forces, still held Hill 677. The Chinese had withdrawn. Ten Canadian soldiers were dead and 23 wounded.

Australian losses were 32 killed, 59 wounded and three captured. The New Zealanders lost two killed and five wounded. Chinese losses were pegged at between 1,000 and 5,000 killed and many more wounded.

That morning, U.S. transport planes dropped food, water and ammunition to the exhausted Patricias.

“United Nations mountain warriors won their spurs today, holding their front and refusing to budge even though outflanked and encircled,” began Bill Boss’s April 25 wire service account of the battle, placelined West Central Sector, Korea.

“It was a knock-down, drag-out battle with wave after wave of Chinese Communists who did everything but drive them from their positions.”

Five Patricias received valour medals and 11 were Mentioned in Dispatches for their actions at Kapyong. Mills, the commander of the unit that had called in the mortars and artillery on its own position, would be awarded the Military Cross for his actions.

A war, indeed.

Despite the belated shift at home four decades later, the recognition afforded Korean War veterans by Canadians pales in comparison to the gratitude and gestures the people and government of South Korea

have afforded them. The Koreans have awarded them medals, hosted pilgrimages and thrown annual parties in their honour.

South Korean representatives are unfailing in placing wreaths at the National War Memorial in Ottawa to mark Remembrance Day and anniversaries associated with the war and armistice. Visiting South Korean presidents take the time to pay their respects by placing wreaths no matter the season. President Yoon Suk Yeol did so in September 2022.

Some 2.5 million Koreans died, were wounded or disappeared during the three-year war, while 10 million families—a third of the population—were separated. Industry and infrastructure were gutted on both sides. By war’s end, Seoul had been taken and retaken four times. The sprawling city was left a ruin. South Korea had lost 17,000 businesses, factories and plants, 4,000 schools and 600,000 homes. The gross national product had declined 14 per cent and total property damage was estimated at US$2 billion.

Its air force virtually erased, the North bore the brunt of the fighting after September 1950. The U.S. Air Force dropped more than 350,000 tonnes of conventional bombs and almost 30,000 tonnes of napalm on North Korean cities, and fired 313,600 rockets and 167 million machine-gun rounds.

The North Korean leader, Kim Il Sung, said the country’s economy had been destroyed. It had lost 8,700 industrial plants, 367,000 hectares of farmland, 600,000 houses, 5,000 schools, 1,000 hospitals and 260 theatres.

Historian James Hoare reported that the North’s national income in 1953 was 69.4 per cent that of 1950; electricity production was reduced to 17.2 per cent of 1949 levels, while coal was down to 17.7.

“There had been a huge loss of able-bodied men either killed or who fled South,” wrote Hoare.

“Effectively, therefore, apart from the end of the fighting, both sides found themselves in the summer of 1953 with nothing to mark and nothing to celebrate.”

Some “conflict.”

Yet, for South Korea at least, the end of the war would mark the gradual beginning of a new age. The country would rebuild and far surpass anything it had known or could have expected before in terms of development and prosperity. It’s now a cultural phenom, a tech giant, and Seoul a sparkling jewel of southeast Asia.

“The country went from a war-torn, impoverished nation to a global industrial powerhouse in just two generations,” wrote Chung Min Lee in a November 2022 essay for the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

“Before this turn of events, no one could have imagined that South Korean actors would win an Oscar and an Emmy or that K-pop would reach a global audience.

“A country that relied on U.S. aid until the 1960s is now investing tens of billions of dollars

to build new electric vehicles, next-generation batteries, and semiconductors in the United States.”

While South Korea has its problems, too, it’s in its triumphs that the veterans of the Korean War take pride. They may not have left behind a united Korea, but their war preserved the South’s freedom and, ultimately, its means to prosper.

In a Dec. 1, 1953, telegram to the U.S. State Department, Arthur H. Dean, special U.S. envoy to the postarmistice political conference, effectively laid blame for the impending failure to reach a peace at the feet of South Korea’s president at the time, Syngman Rhee, who had refused to sign the hard-earned armistice and wanted to continue fighting.

“Rhee is presently very querulous,” wrote Dean. “Thinks he was tricked into armistice. Now thinks defense pact and economic program are dishonorable bribes to him not to unify Korea by force.

“He sees his lifetime dream of a unified Korea rapidly fading.”

Dean said he had the “distinct impression Rhee now feels the free world does not deserve a fighting Korea, that the rest of us have lost

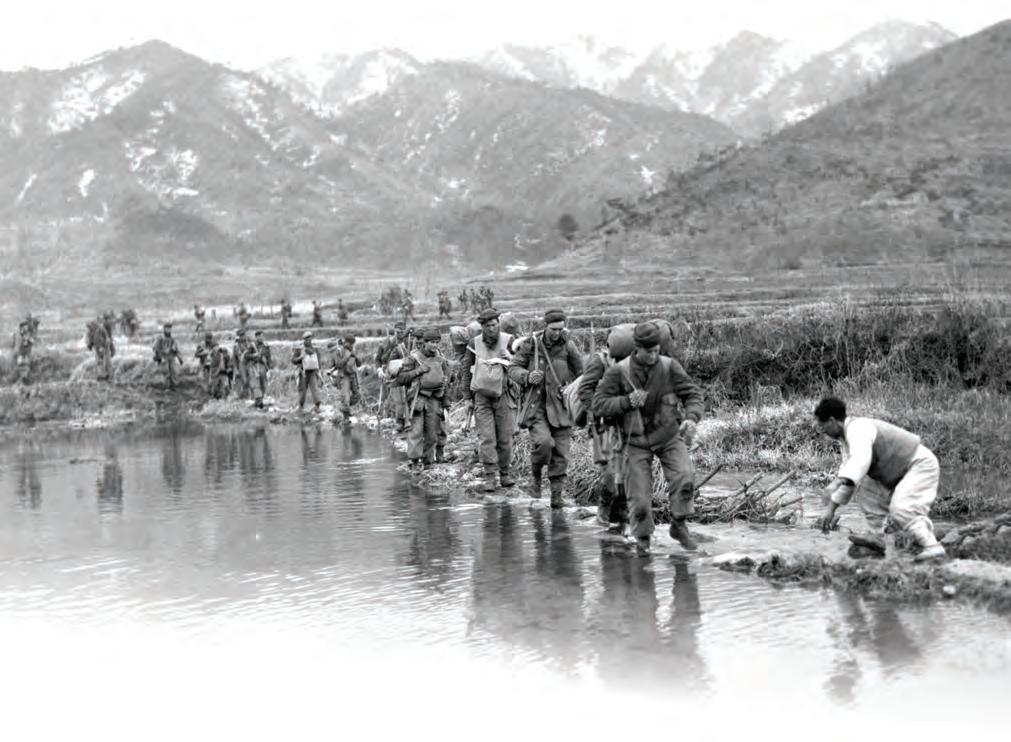

Korean ration-bearers pause near an active Royal New Zealand Artillery battery en route to 2 PPCLI positions.

our courage to fight Communism and he would be glad to see us go.

“He recites in detail every bit of concession we made to get an armistice and in working out a demilitarized zone and he is convinced, if we do not fight, [a peace conference] will merely result in yielding up one concession after another by our side to a final surrender of all Korea. Any constructive suggestions by us are, of course, outright concessions to Communists in [South Korean] view.”

And, so, the North of Kim Jong Un today remains a hostile neighbour— a hoarder of nuclear weapons, a source of regional instability, and a continuing threat to world peace.

It has conducted multiple missile tests and at least six times announced it will no longer abide by the armistice. It has violated its terms dozens of times, including via military attacks. Both sides conduct provocative military exercises.

In December 2022, five North Korean drones crossed the demilitarized zone into South Korea. South Korea scrambled helicopters and fighters to intercept them.

A South Korean helicopter fired on one of the drones, but none are known to have been taken down.

A UN investigation concluded both sides violated the armistice.

Some have advocated an armistice as the most efficient means to end the current fighting in Ukraine. But in a December 2022 essay, the Seoul-based American analysis site NK News said the example set by the Korean armistice doesn’t bode well for success in Eastern Europe.

“The Korean War armistice wasn’t meant to last forever, but an end-ofwar declaration, let alone unification, looks less and less likely every year,” wrote analyst James Fretwell.

“And that may be the key lesson to draw from the Korean War precedent: While ending active hostilities, the armistice laid out no clear path for a formal peace or unification. The result has been undying division— whether anyone wants it or not.” L

Artist Don Connolly depicts pilot Robert Hampton Gray attacking the Japanese ship Amakusa in Onagawa Bay on Aug. 9, 1945.

tBy Brad St. Croix

The Second World War in the Pacific began as it ended, with Canadians in the face of enemy fire. As the Canadians in the Battle of Hong Kong were some of the first Allied forces to fight against the Japanese in December 1941, Lieutenant Robert Hampton Gray of the Royal Canadian Naval Volunteer Reserve (RCNVR) was one of the last in August 1945.

Gray, like the defenders of Hong Kong and many other Canadians in the Pacific during WW II, ended up in that faraway theatre in a roundabout way.

From Trail, B.C., Gray enlisted in the RCNVR in July 1940 as an ordinary seaman. Soon after entering service, he was one of many enlistees chosen to go to Britain to train as a potential officer. A delay led him to transfer to the Fleet Air Arm to learn the ropes as a naval aviator. His training brought him back to Canada to Kingston, Ont., for a time in 1941. His subsequent service took him around the world. Gray served in Britain, South Africa and East

Africa before being transferred to 1841 Naval Air Squadron aboard HMS Formidable in August 1944. He was assigned to fly a Vought F4U Corsair with the group.

report that covered Gray’s first six months aboard Formidable. Lieutenant-Commander R.E. Jess, also an RCNVR aviator serving with the Fleet Air Arm,

“It is considered that with more sea experience he should develop well and be in every way suitable for higher Air Command.”

After being aboard Formidable for only a few weeks, Gray was Mentioned in Dispatches for his role in an attack on the German battleship Tirpitz on Aug. 29, 1944.

Gray’s leadership potential was quickly noted, and he was promoted to lieutenant and given command of a flight, comprised of four Corsairs. “It is considered that with more sea experience he should develop well and be in every way suitable for higher Air Command,” said a February 1945

said that despite Gray looking quiet “he was obviously the fighter type—aggressive almost to the point of recklessness. He had to be good to be a fighter pilot and he had to be good to do the things he did and live as long as he did.”

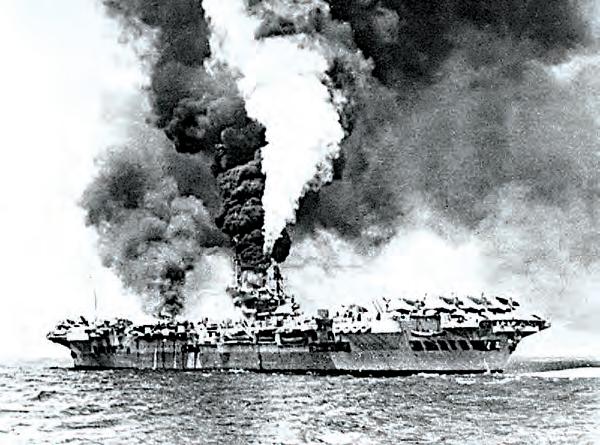

In April 1945, Formidable joined the British Pacific Fleet. The aircraft carrier supported the operation against Okinawa by attacking Japanese airfields and aircraft in the Sakishima Islands. On April 16 and 17, Gray led his flight in

Ipatrolling the area over the islands to protect other aircraft attacking ground targets. They encountered no enemy planes on either day.

On April 20, there was much excitement as Gray’s flight thought it had spotted an enemy aircraft, but it turned out to be a friendly Liberator bomber. For the rest of April and into May, 1841 Squadron continued these uneventful missions protecting other planes.

On May 4, Formidable faced one of the great scourges of the Allied navies during the war. It was attacked by two kamikaze aircraft.

“I really do think that I will be home before the end of this year and I hope to stay at home when I come next.”

The first hit the ship, while the second was shot down.

“Okinawa is, of course, the place where the Americans are having such a terrible time,” wrote Gray in a letter to his parents that same day. “It is fairly hard flying but not dangerous. We have had some trouble with the Japanese suicide bombers but have suffered very little damage.”

By July 1945, Formidable and its aircrews began to attack the Japanese main islands. Gray led a flight of planes that strafed airfields in the Tokyo area on July 18. Six days later, he led an attack on ships in the Japanese inland sea that damaged one merchant ship, and strafed two seaplane bases and an airfield.

On July 28, despite poor flying conditions due to rain and heavy clouds, Gray led another assault on the inland sea, where he bombed a Japanese destroyer, which was later reported to have sunk.

“For determination and address in air attacks on targets in Japan,” he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross. Because of his exemplary service in the Pacific, Gray was recommended for promotion to acting lieutenant-commander on July 31, 1945. His service record noted the advancement was deserved because Gray continued “to show his ability and skill as flight commander and has led his divisions in recent operations with undoubted success. Energetic and resourceful in his other duties and can always be relied on. A brave skilled and reliable pilot in action.”

For his actions at Onagawa Bay, Gray was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross. “Lieutenant Gray has constantly shown a brilliant fighting spirit and most inspiring leadership,” read his citation. Gray was the first and only member of the RCNVR to be awarded a VC. His was also the last Canadian VC-earning action.

His abilities as a pilot, of course, were well known to those who served with him.

“You will undoubtedly be hearing about us on the news,” Gray wrote to his parents on July 15, 1945. “I will be with those who are mentioned but do not worry, please. I really do think that I will be home before the end of this year and I hope to stay at home when I come next.”

On Aug. 9, 1945, around 8:30 a.m., Gray’s flight took off from Formidable. They were assigned to attack Japanese positions and aircraft at Matsushima airfield, located on the northern end of Japan’s main island near Sendai. Having discovered most of the airfield and aircraft there had already been destroyed, Gray turned his attention to vessels he had spotted in Onagawa Bay.

As the flight approached the bay, it took heavy anti-aircraft fire from shore batteries and at least five warships. Around 1 p.m., Gray peeled away from the formation and dove solo toward the Japanese Etorofuclass destroyer escort Amakusa. As Gray pressed an attack, his Corsair burst into flames, but he held steady until he was about 50 metres from the ship. He then released several bombs. At least one of them struck amidships, quickly sinking Amakusa.

“The bottom fell out of life on board after it happened and the victory when it came seemed so hollow somehow.”

Gray crashed into the bay moments later. This “fearless bombing run” cost him his life. His body and aircraft were never found. He was one of the last Canadians killed in action during the war.

Gray’s loss was heavily felt by those who knew him. In a letter to Gray’s parents detailing his final flight, Lieutenant-Commander Richard Bigg-Wither, commander of 1841 squadron, wrote: “That is the story—it hurts very much to write about. The bottom fell out of life on board after it happened and the victory when it came seemed so hollow somehow. He was so well loved by us all and simply radiated happiness wherever he went.”

In addition to his VC and DSC, during his service Gray was awarded the 1939-1945 Star, Atlantic Star, Africa Star, Pacific Star, Defence Medal, Canadian Volunteer Service Medal with clasp, and War Medal 1939-1945. It’s a unique medal set for a Canadian WW II veteran.

Gray has since been memorialized around the world. He is commemorated, along with 3,266 other Canadian war dead lost at sea, on the Halifax Memorial, as well as in many other communities across Canada. A monument to Gray was also unveiled near the location of his final attack and death, in Onagawa in 1989. It was damaged in the 2011 earthquake and tsunami but was repaired and moved to high ground near the town hospital the following year.

And Gray’s legacy continues to be honoured by the Canadian Armed Forces. HMCS Robert Hampton Gray, the RCN’s sixth Harry DeWolf-class offshore patrol vessel, was launched on Dec. 9, 2024. L

By Alex Bowers

Betrayal lies at the heart of the Treason Act 1351. Enacted during the reign of King Edward III (January 1327-June 1377), the medievalera law, still on the British statute books, protected the sovereign and his bloodline, punishing those who conspired against his rule.

?To “imagine the death” of His Majesty, “levy war” upon his divine authority, or “be adherent to the King’s enemies” were among the offences punishable by death according to the Norman French-language edict technically legislated in 1352.

The Treason Act was set not in stone, but on parchment. Its provisions were amended numerous times during the centuries, yet its framework largely remained the same.

In the Canadian colonies, it was used against Crown subjectsturned-American sympathizers during the War of 1812, its judgement applied by varying degrees ranging from imprisonment to hanging. It was similarly enforced amid the Upper and Lower Canada rebellions of 1837-1838, as well as after the 1885 North-West Resistance, facilitating the contentious execution of Métis leader Louis Riel.

Seldom without public controversies or legal complications, not to mention frequent moral incongruities, the age-old Treason Act endured one of its greatest tests at the 1945 trial of William Joyce, an American-born and Irish-raised Nazi propagandist known as Lord Haw-Haw for his anti-British radio broadcasts.

Joyce, an odious fascist who unquestionably deserved punishment for his actions, claimed he owed no allegiance to George VI since he wasn’t a British citizen. Despite this, prosecutors argued that his possession of a British passport under false pretences constituted loyalty to the Crown. Lord Haw-Haw was hanged.

Could someone be a traitor to a country not their own?

To what extent could nationality be open to interpretation? Had justice been legitimately served?

Such questions would be asked anew of Japanese-Canadian Kanao Inouye, nicknamed the Kamloops Kid for his British Columbian birthplace and Slap Happy Joe for his brutality against Canadian prisoners of war while serving Japan during the Second World War. Potential answers meanwhile, were, and are, unsettlingly nuanced.

A young Kanao Inouye with his family and, years later, in British custody in 1945 (opposite page). William Joyce after his arrest in Germany near the end of WW II (below ).

The duality of Kanao Inouye began in Kamloops, B.C., on May 24, 1916. Born that day, the fifth child and first son of Tadashi and Mikuma Inouye, the young boy’s parents were both Issei—first-generation Japanese immigrants—to Canada.

Tadashi, or Tow, served in the Canadian Expeditionary Force during the Great War, including at Vimy Ridge and Passchendaele, earning the Military Medal.

Back home, Mikuma registered Kanao’s birth with Japanese consular authorities, entitling him to a Japanese passport in what would later prove a fateful decision.

The household moved to the Vancouver area in time for Inouye to start school. His father, now a prosperous merchant in the import-export business, subsequently took the entire family to visit his ancestral homeland.

Tragedy struck when the patriarch died in Japan on Sept. 10, 1926. The late Tadashi had nevertheless afforded his son his first taste of Japanese culture.

Inouye remained an unremarkable student upon his return to Canada. Around 1935, with few other prospects, he again travelled to Japan for further education. There, the youthfully naive Nisei—a term applied to second-generation Japanese-North Americans— reportedly struggled to overcome perceptions of being a foreigner.

Inouye, perhaps unsurprisingly, was no stranger to overtly racist and xenophobic attitudes, having once been rejected from a child’s birthday party for being a so-called “little yellow bastard.” Nor were nativist views, misguided as they were, unfamiliar to him and, indeed, countless other Canadians of Japanese heritage.

Perhaps what he hadn’t expected was for the discrimination to persist in Japan.

On March 1, 1937, however, Inouye was conscripted into the

“YOUR MOTHERS WILL BE KILLED. YOUR WIVES AND SISTERS WILL BE RAPED BY OUR SOLDIERS AND ANYONE RESISTING WILL BE SHOT !”

masse—his former tormenters, as he saw it. Housed in awful conditions, enslaved by their Japanese captors, and deprived of adequate provisions, the hundreds of imprisoned compatriots were far from home.

Inouye intended to remind them of that.

Imperial Japanese Army, where he officially swore allegiance to Emperor Hirohito. A brief stint in Manchuria was eventually cut short by ill health.

Discharged on medical grounds in 1939, Inouye attempted a return to education until the same ailment prompted his withdrawal. He was now, seemingly, at his nadir. But like so many, the outbreak of war changed everything.

When Canada’s 1,975-strong ‘C’ Force, predominantly comprising The Royal Rifles of Canada and The Winnipeg Grenadiers, were thrust into the ferocious Battle of Hong Kong—a fight they would lose—Inouye had no notion of what impact it would have on his life. On Christmas Day 1941, the Allied garrison surrendered the British colony, with 1,689 Canadians among those captured.

Inouye was called to serve the emperor once more, now as a civilian interpreter.

With fluent English-speaking skills, the B.C.-born translator was clearly an asset. He first worked within Hong Kong’s Japanese Army headquarters before being reassigned to the island’s Sham Shui Po PoW camp in mid-November 1942.

It was here, for the first time in six years, that Inouye came face to face with Canadians en

“All Canadians will be slaves as you are now,” reportedly declared Inouye, later relayed by Signalman William Allister, to PoWs at Sham Shui Po, suggesting that Japan’s rising sun would soon fly proudly over Ottawa. “Your mothers will be killed. Your wives and sisters will be raped by our soldiers and anyone resisting will be shot!”

Accounts vary, some more corroborative than others, concerning the true extent of Inouye’s cruelty, but the fact he was sadistic in his treatment of Canadian prisoners was, and is, undeniable. “His craving for vengeance was awesome,” said Allister.

The Royal Rifles’ Henry Lyons recalled receiving a “son of a whore beating” for failing to retrieve a plank. The interpreter broke his collarbone with a rifle butt.

Inouye caught Gaston Oliver of the Grenadiers trading supplies with a sentry, forcing him to stand for two days and nights holding a full water bucket in front of him at arm’s length. Guards struck him with belts any time he faltered.

When Grenadier Arthur (Art) Ballingall didn’t salute a general— he had been carrying a water basin—Inouye struck him with the side of his sword. The Canadian PoW spent two months recovering in hospital with broken teeth.

For about two days, Inouye allegedly tortured Grenadier Jim Murray, tying him to a pole and beating him before then wedging lit cigarettes into his nostrils.

Not even men of the cloth were safe from Inouye’s ire, witnesses attested. Amid a diphtheria outbreak at the camp, during which period Vatican-supplied drugs hadn’t yet arrived, chaplain Eric Green inquired into their whereabouts. Lieutenant Frank Power watched helplessly as Inouye brutally laid into the Catholic padre.

The Japanese-Canadian interpreter had well and truly earned his dubious moniker as Slap Happy Joe, but it was his reputation as the Kamloops Kid that would endure. Far from outright dismissing his Canadian roots, he instead used them to his advantage, sneaking up on PoWs and criticizing the Japanese in unaccented English. If anyone agreed before he revealed the ruse, Inouye punished them.

The most consequential incident took place on Dec. 21, 1942, when British and Canadian prisoners assembled for roll call. Finding the Grenadiers’ ‘D’ Company two men shy, Captain John Norris took full responsibility for their absence by stepping toward the camp commandant. Inouye took control.

Living up to his moniker, Slap Happy Joe punched and pushed Norris to the ground. “Get up, you world conqueror,” he was reported to have said, “and take it like a man.”

Inouye, shifting blame elsewhere, next turned to Major Frank Atkinson. Kicking the Canadian in the knee, the interpreter was finally ordered to desist.

Remarkably, as a hospitalized Norris feared he might lose his sight in one eye—he didn’t—Inouye resolved himself to apologize for the assault; it went unaccepted.

The damage had been done, less to the victim and more to the perpetrator.

Inouye’s perceived vengeance spree ended in September 1943 after he was transferred out of Sham Shui Po. The following year, he joined the Kempeitai. Japan’s military police force had once tortured Inouye during his student days, but now, he could be the one inflicting techniques such as waterboarding on suspected Allied spies and Hong Kong residents. He continued serving as a police interpreter until February 1945. By that stage, with Allied victory inevitable, the walls had started to close in.

Inouye was one of 18,000 enemy personnel still in Hong Kong when the Japanese surrendered. With the island again a British colony, malnourished prisoners were freed from their camps, including 369 Canadians from Sham Shui Po. Others had been relocated, but in all, some 264 detainees of ‘C’ Force died. Many survivors wouldn’t forget the Kamloops Kid.

Around Sept. 10, 1945, Canadians at Ohashi PoW camp, located on the Japanese mainland, awaited their official liberation. The men were impatient to get home, understandably so, but news of their repatriation hadn’t been forthcoming.

Disappointed though they were, there was still cause for celebration: Word had reached Ohashi that Kanao Inouye, an all-too-familiar name among numerous prisoners, had been arrested the day before. The camp soon erupted in cheers.

Meanwhile, the mood in Ottawa was far less jubilant as authorities debated their involvement in planned Japanese war crime trials. Both Britain and the U.S. had expressed willingness to accommodate Canadian investigations, yet the federal government seemed to drag its heels until it eventually caved in to public pressure.

In January 1946, cabinet approved the Canadian War Crimes Liaison Detachment – Far East.

Headed by Lieutenant-Colonel Oscar Orr, the entire section

comprised just eight men. Of these, only four were officers, with second-in-command Major George Puddicombe the representative in Hong Kong.

Among their duties was bringing the Kamloops Kid to justice, supported by some 200 affidavits from former prisoners directly mentioning Inouye. Despite the lack of evidence that he had killed or disabled anyone, Puddicombe sought the death penalty for the Japanese-Canadian on the grounds of committing war crimes.

On May 22, 1946, the accused stood before a British military court presided over by Lieutenant-Colonel J.C. Stewart. The judge laid out three charges against Inouye, two related to his Dec. 21, 1942, actions and a third for his alleged conduct in the Kempeitai. The defence under Lieutenant John Reeves Haggan entered a not guilty plea.

Prosecuting officer Puddicombe launched into the case with a heavy reliance on affidavits, not least of former Canadian PoWs Norris

and Atkinson. Nevertheless, the testimonies from Inouye’s tenure in the Kempeitai proved the most damning.

Chinese witness Lam Sik, a w ireless operator once seized by t he military police, recounted Inouye attaching electrical wires to his ears before announcing, “This time, you are the wireless operation.” Rampal Ghilote, an Indian civil servant and accused Allied spy, recalled being hung from a beam by his hands. Mary Power, wife of another accused spy, remembered Inouye burning her with lit cigarettes until “I fainted and wet myself.”

Scrambling for an appropriate defence, Haggan attempted to portray Inouye as a victim of a Japanese culture, society and hierarchy in which he had merely been following orders. The tactic, combined with Inouye’s dismissals, lies and own accusations, failed to move the jury, nor indeed did the assertion that he had actually, or supposedly, cherished his prewar life on Canada’s West Coast.

The overall proceedings likewise had shortcomings, perhaps most notably in affording the defence negligible time to muster witnesses for its argument.

Such matters had long been disregarded. After some five days, Inouye, the Kamloops Kid, was found guilty on all charges.

“By your barbaric acts,” declared the court in delivering the death sentence, “you have destroyed your right to live.”

The noose awaited Inouye should he not appeal.

In a desperate attempt to avoid what seemed like the inevitable, Haggan petitioned that a military court held no jurisdiction over his client. His reason: Inouye was a Canadian citizen and, thus, a British subject as opposed to a foreign war criminal.

The ploy worked—almost too well—and the verdict was annulled.

In its place, however, law officials brought forward a new charge, one that acknowledged his nationality and the sufficient authority of a civil court to try the accused.

Inouye, in pleading not guilty to nearly 30 counts under the guidance of lawyer Charles Loseby, was now a suspected traitor according to the Treason Act 1351.

That trial began on April 15, 1947, presided over by judge Henry Blackall. Prosecuting the civil case was Henry Lonsdale and two police inspectors, while the jury, according to one witness, primarily comprised “whites and Chinese” of the Hong Kong citizenry who, two years earlier, had endured Japanese oppression.

In glaring contradiction to the defence’s previous stance, the former interpreter argued that he identified only with his ancestral heritage, that his childhood in B.C. was horrific, and that his mother had registered his birth with Japanese consular authorities. Inouye also suggested that in previously pledging his allegiance to Emperor Hirohito, he had effectively ceded any loyalty to the British Crown.

Such arguments fell short. Unlike the controversial case of William Joyce, or Lord Haw-Haw, there was little doubt of Inouye’s British subject status. It was likewise evident that the accused had taken no legal steps to formally renounce his citizenship after moving to prewar Japan. That he might have been too young or poorly educated at the time to understand the process wasn’t taken into account.

The fact that Inouye technically remained Canadian trumped any defence to the contrary, regardless of claimed allegiances or dual-citizenship nuances. He might have been an Emperor’s acolyte, but he was condemned as an enemy of the King.

For a second time, Inouye was sentenced to death.

At around 7:00 a.m. on Aug. 26, 1947, 31-year-old Inouye was escorted from his Stanley Prison cell. His fate, despite a series of last-ditch efforts, was sealed. It mattered not that he had recently obtained documents attesting to his Japanese civil status previously unavailable during the court case. It mattered

not that he had pleaded with the governor of Hong Kong, the Privy Council in London, nor the King of England himself. He would die for his Britishness, for his birthplace on Canadian soil. Any notion of Japanese civil status was deemed a moot point.

As Inouye approached the gallows, one thing remained irrefutable: the once-torturer of Canadian PoWs, suspected Allied spies and Hong Kong residents deserved punishment for his heinous crimes. The former interpreter had been objectively, unquestionably, cruel and abusive. Though he likely hadn’t killed anyone, the psychological damage wrought on his victims would outlast him.

Equally, however, some Japanese war criminals had received far more lenient sentences for far worse atrocities. They, too, were destined to outlast Inouye.

The prisoner, resigned to his imminent demise, cried out a final salute to the emperor: “Banzai.” Then the trap door was dropped, and the rope went taut.

So fell the Kamloops Kid. L

By J.L. Granatstein

Asthe end of the war in Europe neared, the Liberal government had to decide on several critical military issues. What would Canada’s role be in the war against Japan after Germany was defeated? How would soldiers be repatriated and in what order? What part, if any, would Canada have in the occupation of Nazi Germany?