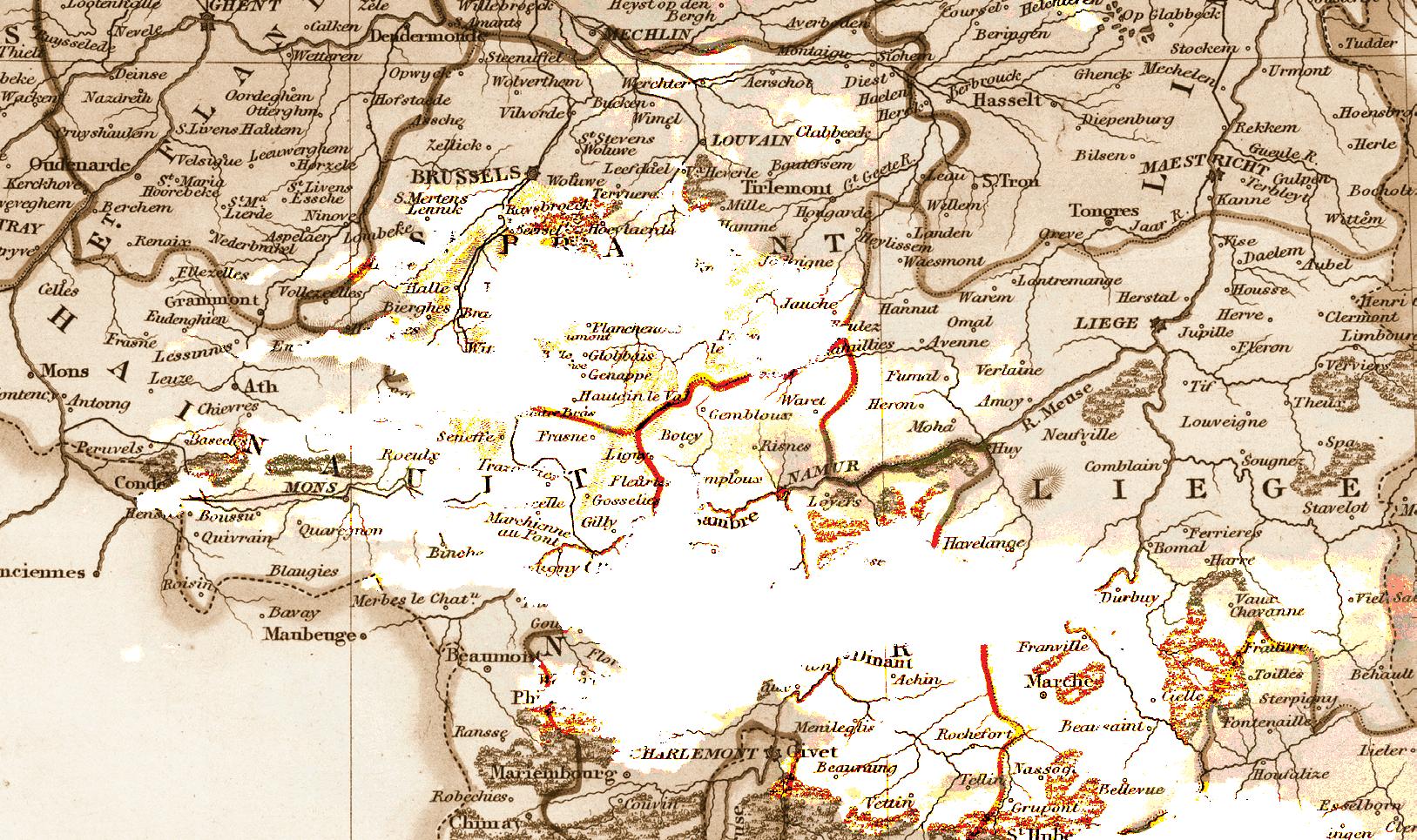

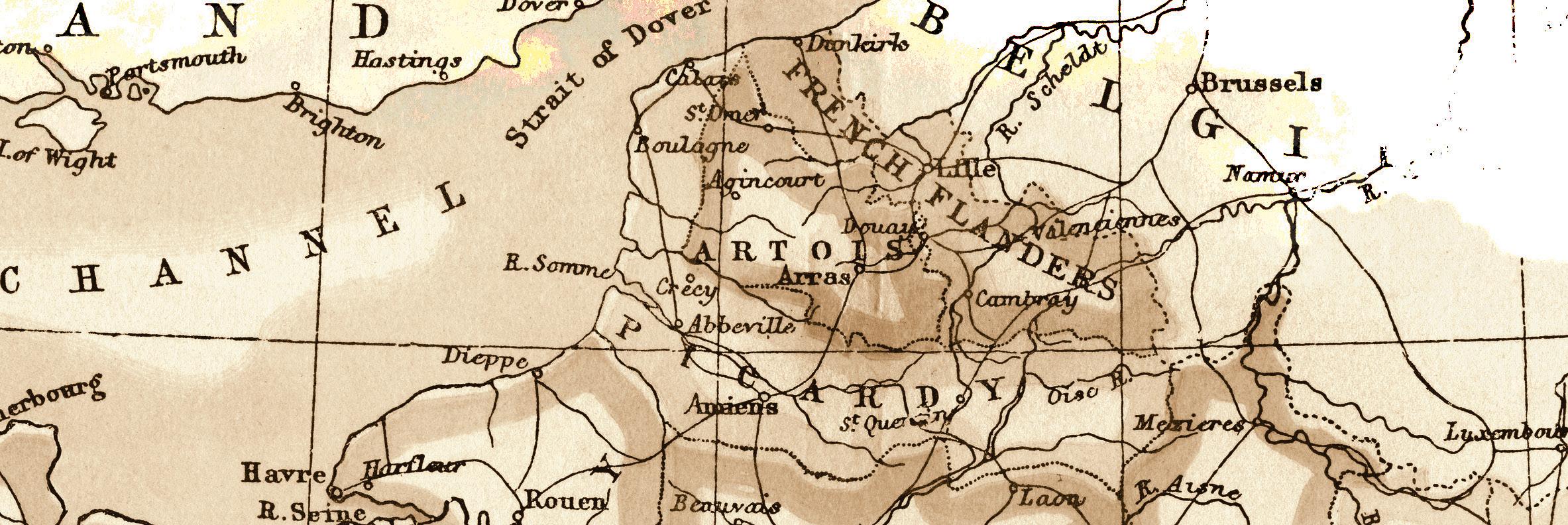

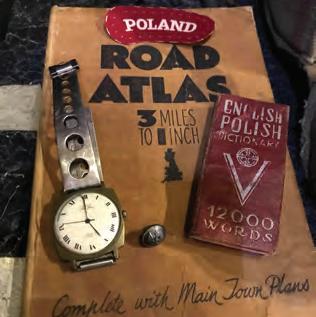

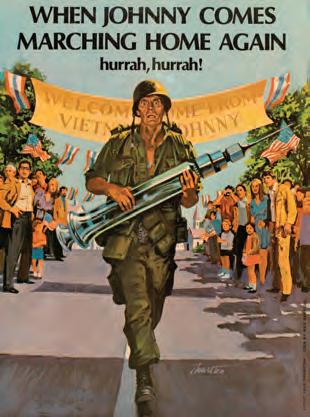

Military members of the Canadian delegation to the International Commission move ashore in South Vietnam as part of the truce supervisory mission.

See page 44

18 LICENCE TO

Privateers played an important role in wars throughout the 18th century

By Stephen J. Thorne

26 “THOSE DAMN WOMEN”

Canadian female fighter jet pilots first took to the skies 30-plus years ago—but few have followed in their vapour trails

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

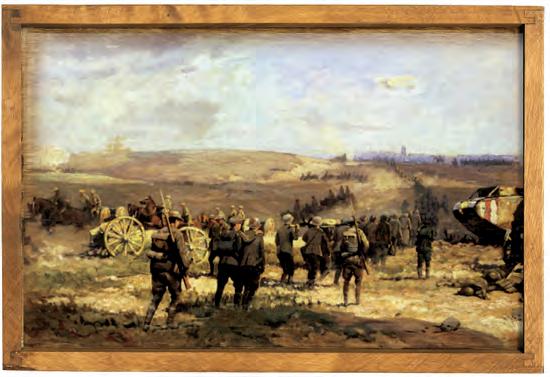

32 THE WEIGHT OF WAR

Insights into Canada’s First World War experience from the 2023 Legion Pilgrimage of Remembrance

By Aaron Kylie

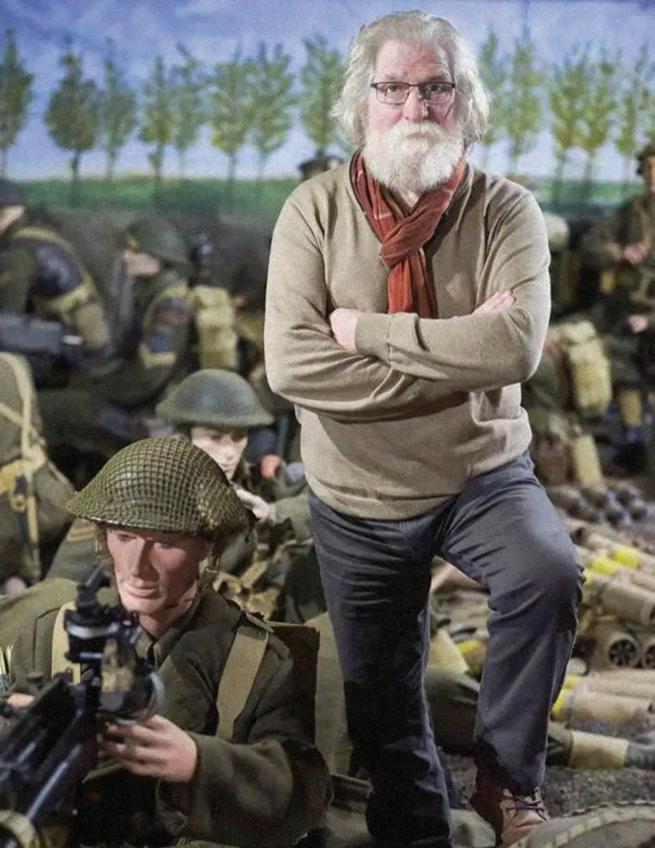

38 A LIBERATION LEGACY

Fulfilling a dying wish to commemorate Canadian soldiers

By John Goheen

44 THE PEACEMAKERS

During their lengthy truce supervisory mission in Vietnam, Canadian military personnel played many roles

By John Boileau

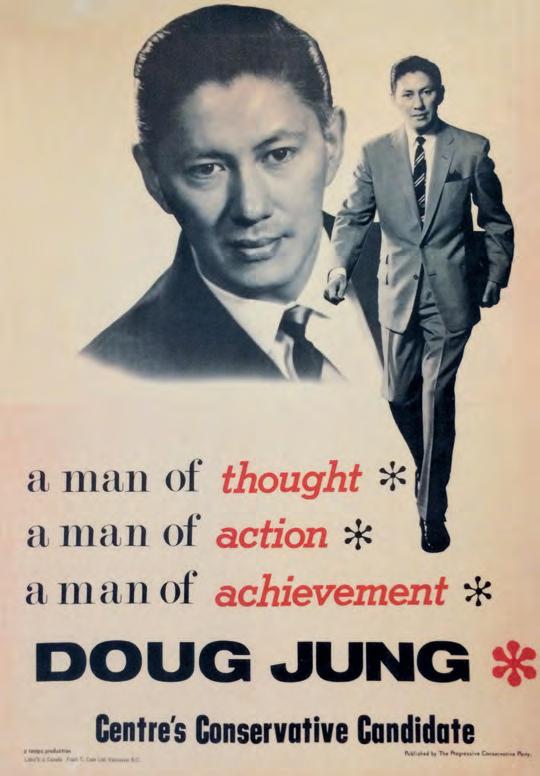

50 SPECIAL OPERATIONS

How Douglas Jung went from a man with no country to Second World War intelligence service and a postwar citizen of firsts

By Sharon Adams

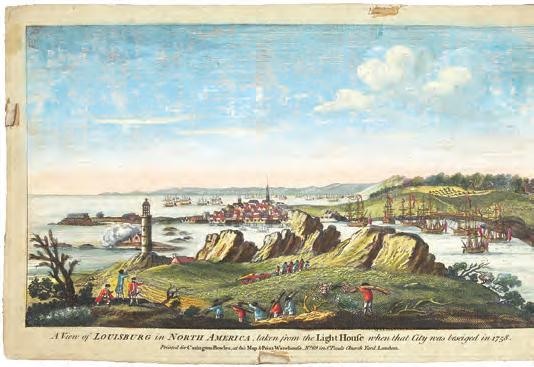

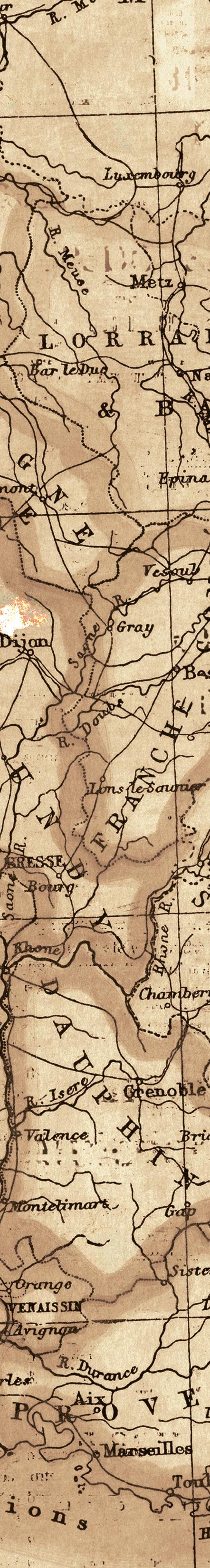

56 THE FORTRESS

For much of the 18th century, Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island dominated access to North America

Photography and words by Stephen J. Thorne

Re-enactors march on the ramparts of the reconstructed 18th century fortress at Louisbourg, N.S.

Stephen J. Thorne/LM

ON

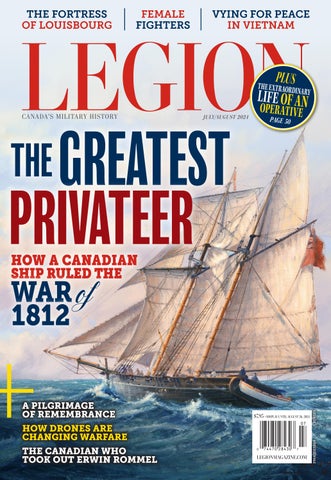

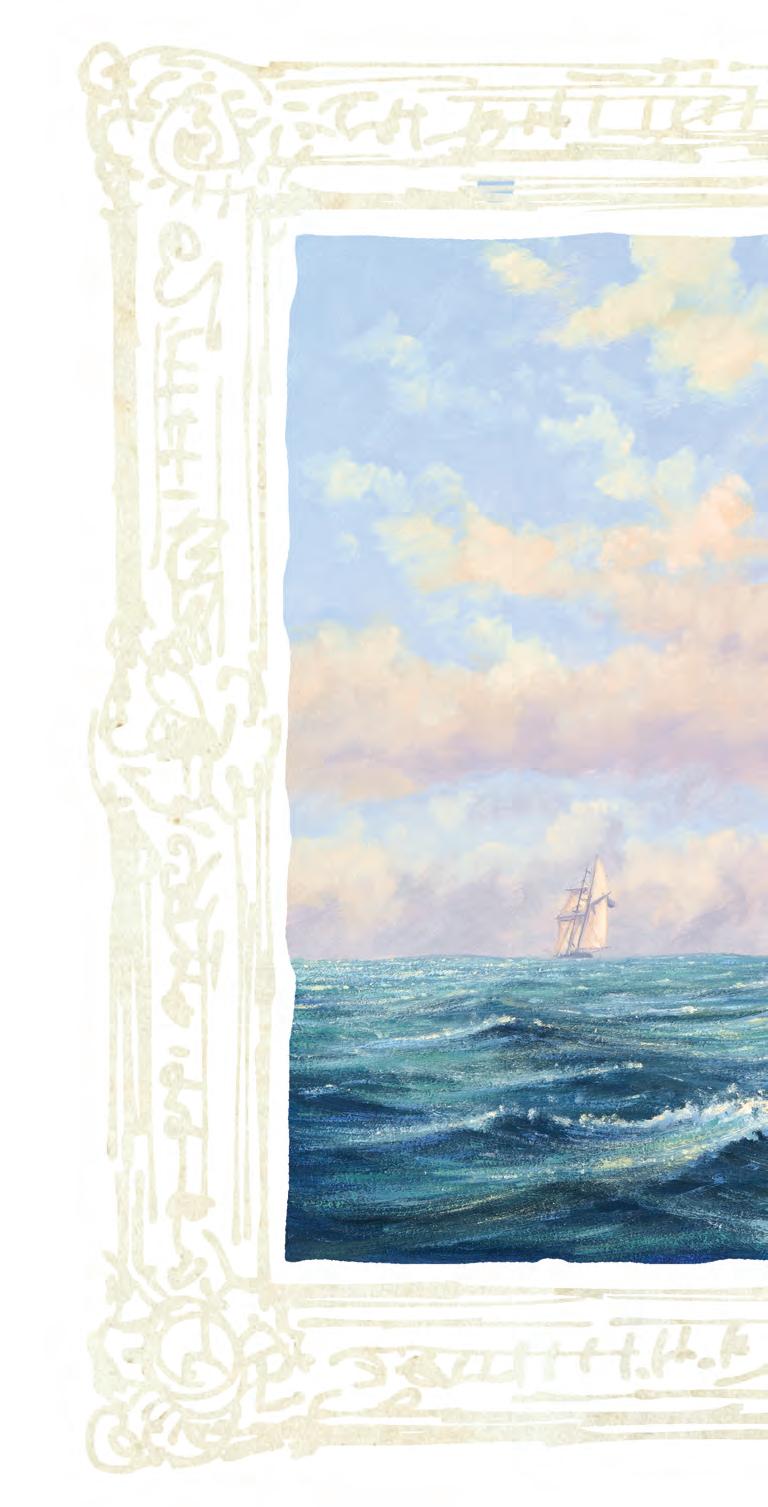

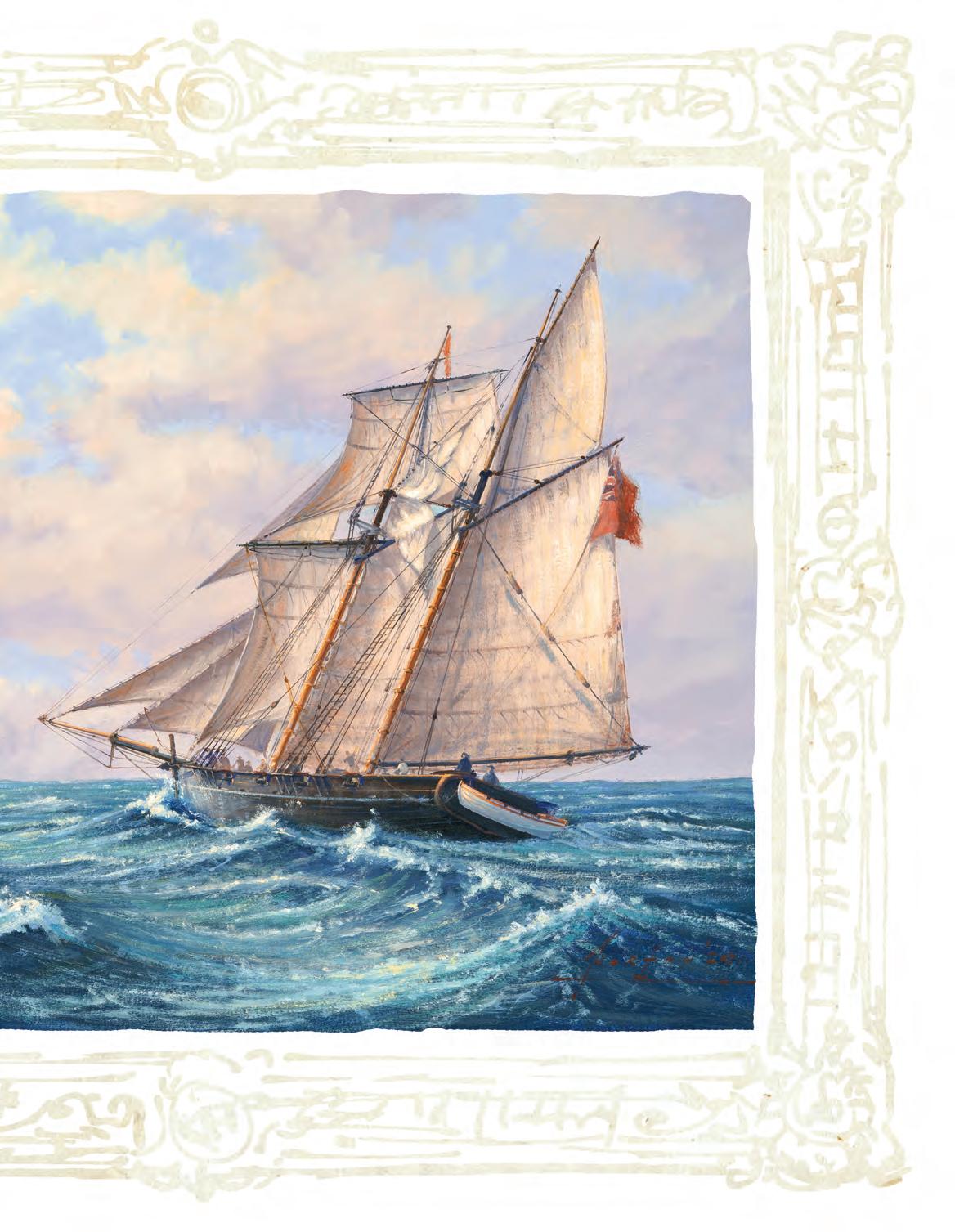

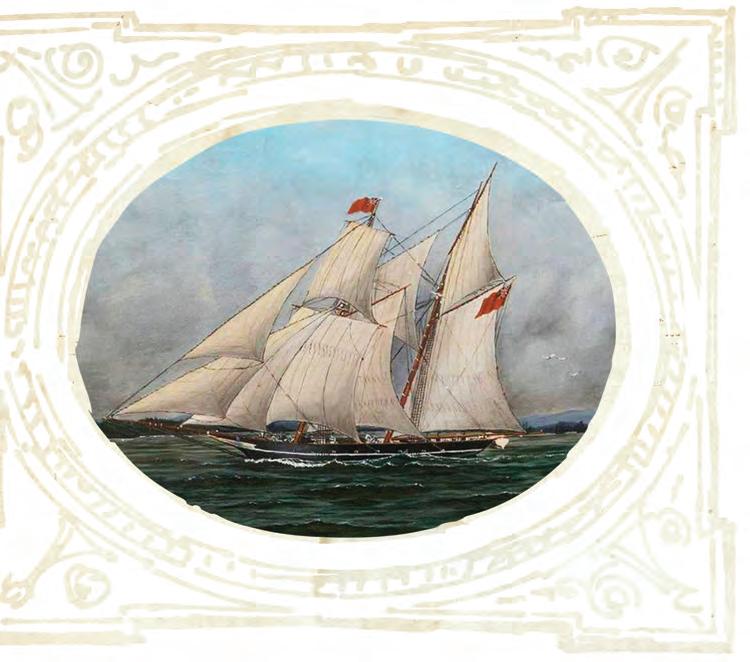

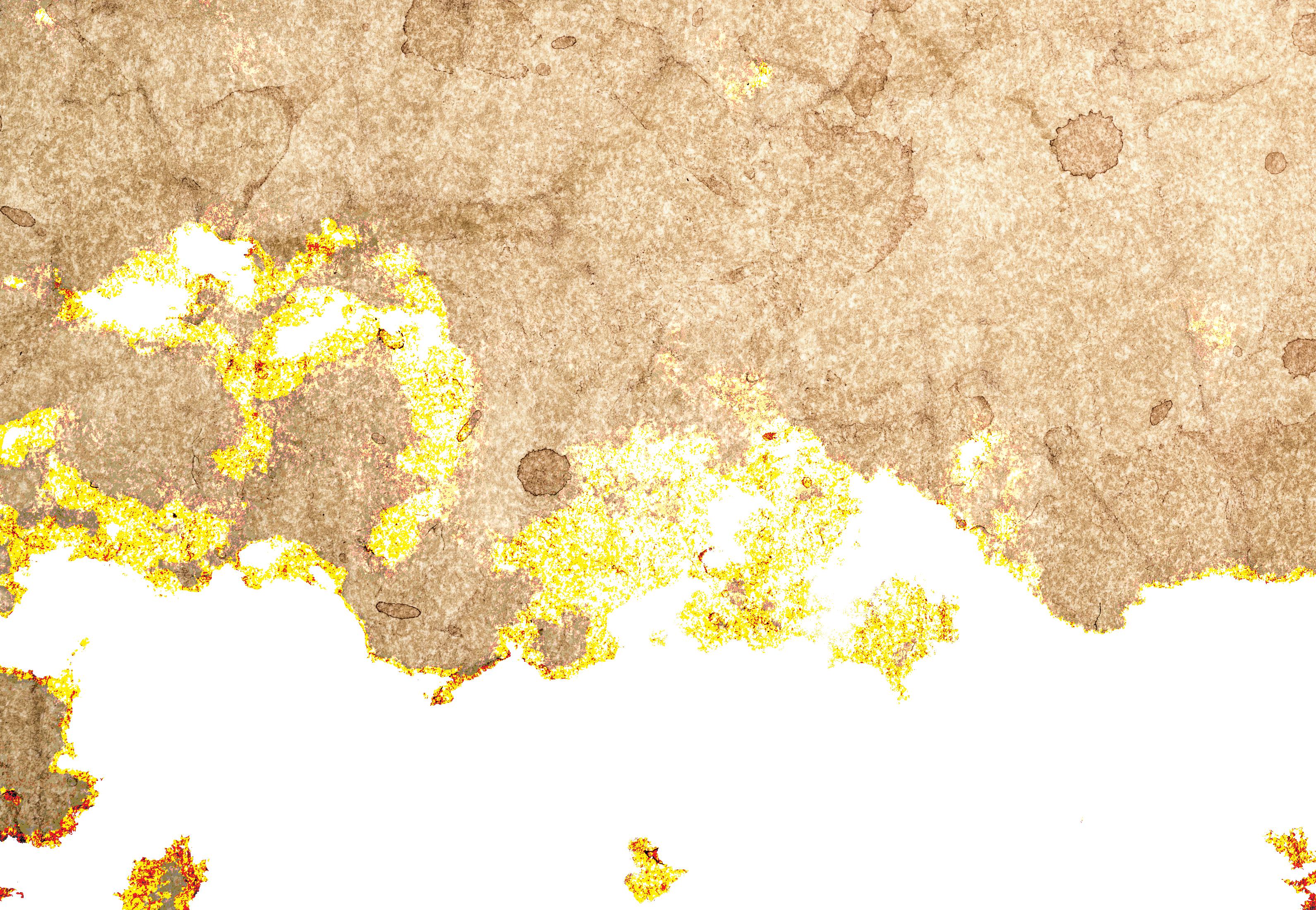

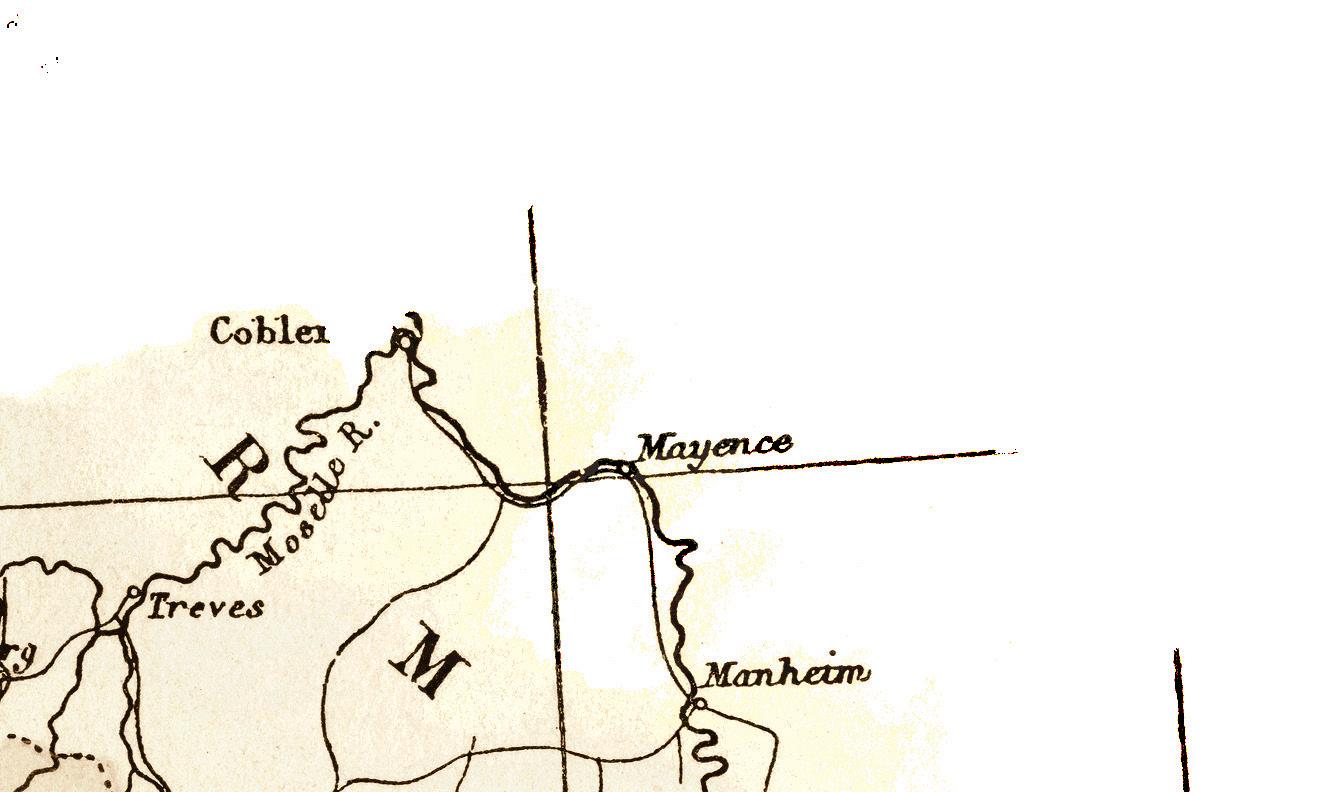

“Stern Chase” by renowned, modern-day, Canadian marine artist John M. Horton (www.johnhorton.ca) depicts the notorious privateer Liverpool Packet chasing a prize off the Massachusetts coast during the War of 1812.

John M. Horton

fail to make the most of its

Vol. 99, No. 4 | July/August 2024

BOARD CHAIR Berkley Lawrence BOARD VICE-CHAIR Bruce Julian BOARD SECRETARY Bill Chafe

DIRECTORS Tom Bursey, Steven Clark, Thomas Irvine, Jack MacIsaac, Sharon McKeown, Brian Weaver, Irit Weiser Legion Magazine is published by Canvet Publications Ltd.

ADMINISTRATIVE

SUPERVISOR

Stephanie Gorin

SALES/

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Lisa McCoy

ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT

Chantal Horan

GENERAL MANAGER Jason Duprau

EDITOR

Aaron Kylie

ASSISTANT EDITOR

Michael A. Smith

SENIOR STAFF WRITER

Stephen J. Thorne

STAFF WRITER

Alex Bowers

ART DIRECTOR, CIRCULATION AND PRODUCTION MANAGER

Jennifer McGill

SENIOR DESIGNER AND PRODUCTION CO-ORDINATOR

Derryn Allebone

SENIOR DESIGNER

Sophie Jalbert

DESIGNER

Serena Masonde

Advertising Sales CANIK MARKETING SERVICES

TORONTO advertising@legionmagazine.com

DOVETAIL COMMUNICATIONS INC mmignardi@dvtail.com

OR CALL 613-591-0116 FOR MORE INFORMATION

SENIOR DESIGNER AND MARKETING CO-ORDINATOR

Dyann Bernard

Ankush Katoch

Published six times per year, January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October and November/December. Copyright Canvet Publications Ltd. 2024. ISSN 1209-4331

Legion Magazine is $9.96 per year ($19.93 for two years and $29.89 for three years); prices include GST.

FOR ADDRESSES IN NS, NB, NL, PE a subscription is $10.91 for one year ($21.83 for two years and $32.74 for three years). FOR ADDRESSES IN ON a subscription is $10.72 for one year ($21.45 for two years and $32.17 for three years).

TO PURCHASE A MAGAZINE SUBSCRIPTION visit www.legionmagazine.com or contact Legion Magazine Subscription Dept., 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116. The single copy price is $7.95 plus applicable taxes, shipping and handling.

Send new address and current address label, or, send new address and old address. Send to: Legion Magazine Subscription Department, 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1. Or visit www.legionmagazine.com/change-of-address. Allow eight weeks.

Opinions expressed are those of the writers. Unless otherwise explicitly stated, articles do not imply endorsement of any product or service. The advertisement of any product or service does not indicate approval by the publisher unless so stated. Reproduction or recreation, in whole or in part, in any form or media, is strictly forbidden and is a violation of copyright. Reprint only with written permission.

PUBLICATIONS MAIL AGREEMENT NO. 40063864

Return undeliverable Canadian addresses to Legion Magazine Subscription Department 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 | magazine@legion.ca

U.S. Postmasters’ Information

United States: Legion Magazine, USPS 000-117, ISSN 1209-4331, published six times per year (January/February, March/April, May/June, July/August, September/October, November/December). Published by Canvet Publications, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. Periodicals postage paid at Buffalo, NY. The annual subscription rate is $9.49 Cdn. The single copy price is $7.95 Cdn. plus shipping and handling. Circulation records are maintained at Adrienne and Associates, 866 Humboldt Pkwy., Buffalo, NY 14211-1218. U.S. Postmasters send covers only and address changes to Legion Magazine, PO Box 55, Niagara Falls, NY 14304.

Member of Alliance for Audited Media and BPA Worldwide. Printed in Canada.

We acknowledge the financial support of the Government of Canada. Version française disponible.

On occasion, we make our direct subscriber list available to carefully screened companies whose product or services we feel would be of interest to our subscribers. If you would rather not receive such offers, please state this request, along with your full name and address, and e-mail magazine@legion.ca or write to Legion Magazine, 86 Aird Place, Kanata ON K2L 0A1 or phone 613-591-0116.

on’t get me wrong. It’s important, but it was really hard to convince people that that was a worthy goal.” So Defence Minister Bill Blair said in a speech this past May to the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, a foreign affairs think tank, about conversations with cabinet colleagues about funding Canada’s military to NATO’s standard of two per cent of the country’s gross domestic product (GDP).

THE GOVERNMENT DOESN’T WANT TO INCREASE MILITARY SPENDING BECAUSE CANADIANS AT LARGE DON’T WANT THEM TO

Blair called that expectation a “magical threshold” and said: “Nobody knows what that means, [cabinet] didn’t know how much that is and they didn’t know what we were going to spend the money on, so I couldn’t make a defence policy argument to meet the spreadsheet target.”

So, Canada’s defence minister couldn’t explain to his colleagues that two per cent of the country’s $1.927 trillion GDP is $38.54 billion? He couldn’t explain the current $26.5 billion defence budget is 1.38 per cent of GDP? He couldn’t explain that the military is an estimated 16,500 members under strength? He couldn’t explain that Canada’s four submarines spent just seven and a half months, combined (!), at sea between 2000 and 2003? He couldn’t explain that there’s a miliary housing crisis? He couldn’t explain that there are critical equipment shortfalls?

We can’t possibly imagine what Canada’s military would spend the money on, either. Nor do we believe cabinet members are that simpleminded.

Let’s get it straight: the government doesn’t want to increase military spending because Canadians at large don’t want them to. MPs serve their constituents—and ultimately try to give them what they want.

The defence chief, General Wayne Eyre, who is set to retire this summer, has similarly been steadfast in standing up for his charges throughout his tenure. Just before Minister Blair’s May speech, Eyre was having difficulty answering questions at a town hall meeting about how the government’s latest cuts and funding reallocations in the defence budget squared with promises made in April’s defence policy statement to increase spending.

“We’re being asked to suck and blow at the sa me time,” Eyre told about 1,300 Forces’ members. “This year on the operations and maintenance side, we are facing some challenges. And you talk about confusion—I don’t have complete clarity yet either, as the finance staff continue to analyze the impact of this year’s federal budget.”

In February, the government outlined defence spending reductions of $810 million in fiscal 2024-25, $851 million the following year and just under $981 million in 2026-27. The new defence policy subsequently promised an additional $81 billion for the miliary in the near-term and more than $73 billion during the next two decades.

Despite the confusion, the minister and the defence chief apparently agree that the NATO target is a red herring.

“I don’t care about percentage of GDP in terms of spending,” Eyre said at the town hall. “What I care about is, what does the armed forces and the department produce as an output metric, which is capabilities and readiness?”

On that score, Canada is failing. At the very least, it’s long past time the country’s leaders clear up that confusion. That’s a worthy goal, no? L

Comments can be sent to: Letters, Legion Magazine , 86 Aird Place, Kanata, ON K2L 0A1 or emailed to: magazine@legion.ca

The use of a service dog can help many struggling veterans (“The dogs of postwar,” May/June). Having had pets during my military career and afterward helped me. They give you unconditional love and support and can be trained to be more attentive. Post-traumatic stress disorder is no joke, and any way you can cope and have comfort is good. I have noticed

In “Heroes and Villains” (May/June), it states that the North Nova Scotia Highlanders were supported by tanks of Les Fusiliers de Sherbrooke. They were supported by The Sherbooke Fusiliers

a difference in my mental and physical health since I lost my dog. Even simply having the routine of feeding, going for walks and interacting with others is helpful. I think the cost of caring for a dog is where the approval of service dogs for veterans gets hung up. People need help affording and training their pet.

S. DEDLA FORT SASKATCHEWAN, ALTA.

Regiment, which had been formed by the union of The Sherbrooke Regiment and Les Fusiliers de Sherbrooke Regiment. After the war, The Sherbrooke Fusiliers Regiment once again returned to the two former regiments.

JACK R. GARNEAU SAWYERVILLE, QUE.

I loved the article by Andy Sparling about the RCAF Streamliners in your May/June issue (“Sentimental journey”). As someone who has read numerous biographies of famed musicians, this ranks as one of the best stories ever, an example of how “ordinary” people achieved something extraordinary, then went back to their lives.

INTA

LIEPINS

SAINT JOHN,

N.B.

In the “Humor Hunt” section of Legion Magazine (March/ April) there was an item about the Halifax VE-Day riot. My late father was in the navy and in the city at the time and had shared some interesting observations about the incident. It’s true that

there wasn’t a good relationship between Halifax residents and the navy. The citizens considered the sailors unruly and the sailors felt that the local merchants gouged them on purchases. In dad’s opinion, the worst thing that the city did was close the bars. If they had remained open, the sailors would have let off some steam, had a few drinks, and things would have subsided. He said that no one had much money anyway. When the trouble started, it’s true that the majority of the rioters were sailors, but there were also members of the other services involved, as well as some civilians who saw what was happening and wanted to get in on the action. He didn’t condone it, but the Halifax riot was a situation that, in his opinion, could have been avoided.

ROBERT J. RUSSELL VICTORIA

I was strolling through Atlantic Superstore and noticed Wing Commander Hugh Godefroy staring skyward from the cover of Legion’s special issue RCAF

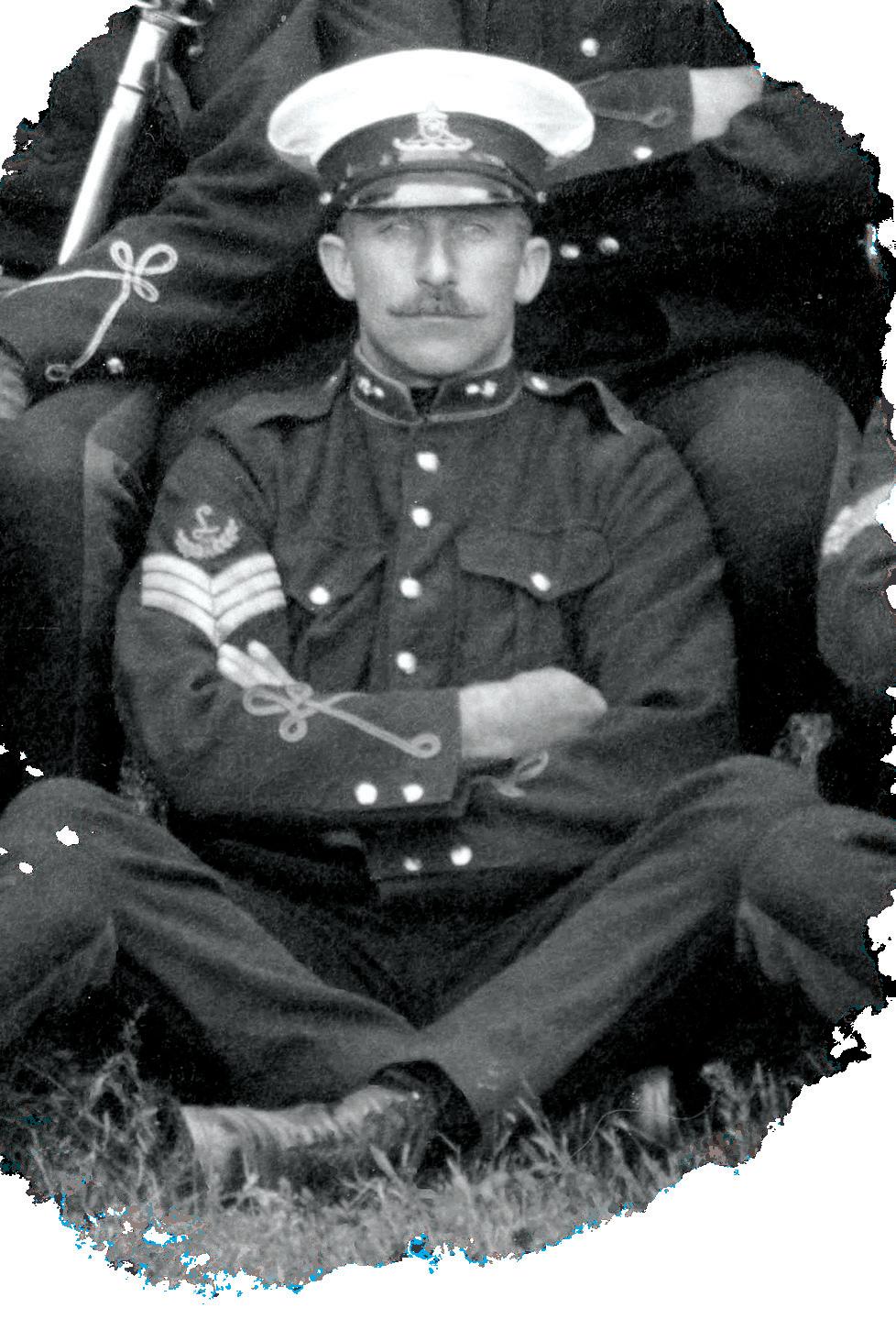

Much of military history comes from battles mythicized over time or recent atrocities that people are still trying to contextualize. Sometimes

historians can overlook decades of military work between wars that were critical to keeping world peace.

Many such operations took place as Canada took on a peacekeeping role with the United Nations on the world stage. One of the many Canadians who were deployed overseas for the military during peacetime was Sergeant Lech Kwasiborski. In the summer of 1974, he was serving in Egypt (pictured) when a Canadian transport flight of the United Nations Emergency Force II (UNEF II) was shot down by missiles fired from Syria, killing all nine aboard. It was an event that took Kwasiborski 50 years to process in his own words.

In a web-exclusive memoir available on LegionMagazine.com,

nial of the Royal Canadian Air Force (Winter 2024). The first time I met Godefroy, he slapped me on the butt. Why? He had just delivered me into this world in a small hospital in Grand-Mère, Que., and that slap was my cue to start breathing. He was our family doctor until we moved to Montreal when I was five, so I don’t have a lot of memories of him. He transferred his practice to the U.S., returned to Canada— my mother became his patient again, I had moved to Toronto— and went back to the U.S. where he passed 22 years ago. Godefroy wrote an account of his wartime endeavours, Lucky 13, in 1983.

KEVIN FINCH VIA EMAIL

Get notified of all the latest updates on legionmagazine.com by signing up for our weekly e-newsletter at www.legionmagazine.com /newsletter-signup

Kwasiborski remembers the events leading up to his Egyptian summer, how peacekeeping doesn’t guarantee safety and how, for him and many others, luck can play a major role in life.

As Aug. 9, now National Peacekeepers Day in commemoration of the ill-fated UNEF II flight, approaches, Kwasiborski reminds readers not to forget the sacrifices of peacetime Canadian military personnel. When peacekeepers are deployed, they’re often not met with peace. During the summer of 1974, Canada lost 11 peacekeepers, four military personnel in active training and six cadets. And as Kwasiborski describes in his reflection, a chance change of plans kept him from being included in the tally. L

On 17 January 2024 the Federal Court approved a settlement in a class action involving alleged underpayment of certain disability pension benefits administered by Veterans Affairs Canada (“VAC”) payable to members or former members of the Canadian Armed Forces (“CAF”) and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (“RCMP”) and their spouses, commonlaw partners, survivors, other related individuals, and estates (the “Settlement”).

If you received any of the disability-related benefits listed below at any time between 2003 and 2023, you may be entitled to compensation under the Settlement. As the executor, estate trustee, administrator, or family member of a deceased class member who collected VAC-administered disability benefits, you may also be able to claim on behalf of the estate. If you are entitled to compensation under the Settlement and you have an active payment arrangement with VAC, such as direct deposit, you do not need to do anything to receive payment. If you are claiming on behalf of a deceased veteran of the CAF or RCMP, including as the executor, trustee, administrator of an estate, or a family member, you must submit a Claim Form to KPMG Inc., the administrator responsible for handling claims available at: KPMG Inc.

C/O Disability Pension Class Action Claims Administrator 600 boul. de Maisonneuve West, Suite 1500 Montréal, Québec H3A 0A3 Online: https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/ E-mail: veteranspension@kpmg.ca

For assistance with submitting a Claim Form, please contact the Administrator’s dedicated call center at 1-833-839-0648, available Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM (Eastern Time).

The deadline to submit a claim is 19 March 2025. All eligible claimants are entitled to receive legal assistance free of charge from Class Counsel for purposes relating to implementing the Settlement, including preparing and/or submitting a claim to the Administrator.

You may contact Class Counsel for more information or for assistance with filing a claim, at info@vetspensionerror.ca, or 1-866-545-9920. To see the full text of the Final Settlement Agreement, please visit https://vetspensionerror.ca/court-documents/. WHO IS INCLUDED?

The Settlement covers members and former members of the CAF and the RCMP and their spouses, common–law partners, dependents, survivors, orphans, and any other individuals, including eligible estates of all such persons, who received—at any time between 2003 and 2023—disability benefits based on annual adjustments of the basic pension under s. 75 of the Pension Act (the “Class Members”). The terms of the Settlement are binding on Class Members. The Settlement includes releases of claims asserted in the certified Class Action.

The Settlement affects prescribed annual adjustments of the following benefits:

• Pension Act pensions for disability, death, attendance allowance, allowance for wear and tear of clothing or for specially made apparel and/or exceptional incapacity allowance;

• RCMP Disability Benefits awarded in accordance with the Pension Act;

• Civilian War-related Benefits Act war pensions and allowances for salt water fishers, overseas headquarters staff,

air raid precautions works, and injury for remedial treatment of various persons and voluntary aid detachment (World War II);

• Flying Accidents Compensation Regulations flying accidents compensation;

• Veterans Well-being Act clothing allowance.

The Settlement provides direct compensation to Class Members who receive (or have previously received) any of the Affected Benefits listed above, since 1 January 2003. Class Members will receive a single payment of about 2% of all Affected Benefits they have received since 1 January 2003. The total amount of compensation paid by Canada to the Class could be as much as $817,300,000. This is only a summary of the benefits available under the Settlement. The full text of

the Final Settlement Agreement (“FSA”) is available online at https://vetspensionerror.ca/ court-documents/. You should review the entire FSA in order to determine your entitlement and any steps you may need to take to access compensation.

Eligible Class Members who are currently collecting VAC-administered disability benefits or pensions will receive a Settlement payment automatically through the same payment method they currently use to collect benefits, including by direct deposit.

Class Members who received Affected Benefits between 2003 and 2023 but who do not have a current payment arrangement with VAC will be required to make a claim with the Claims Administrator. This includes all Class Members who are deceased, and where an executor, estate trustee, administrator of an estate, or a family member is making a claim on behalf of that Class Member.

However, if a deceased Class Member has a survivor who is in receipt of VAC benefits and has a current payment arrangement, that survivor will automatically receive the deceased Class Member’s entitlement without the need to make a claim with the Claims Administrator.

If you do not have an active payment arrangement with VAC, you must submit a claim form with the Administrator.

You must submit a completed and signed Claim Form to the Administrator within the Claim Period. You are encouraged to use the Claim Form submission link available online at https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/. You may, however, submit your Claim Form to the Administrator using one of the following three methods: 1. online at https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca; 2. by e-mail to veteranspension@kpmg.ca; or 3. by mail to: KPMG Inc.

C/O Disability Pension Class Action Claims Administrator 600 boul. de Maisonneuve West, Suite 1500 Montréal, Québec H3A 0A3

You may download a copy of the Claim Form available online at: https://veteranspensionsettlement.kpmg.ca/download/Claim-Form.pdf.

If submitting electronically, the Administrator must receive your completed and signed Claim Form no later than 19 March 2025. If submitting by mail, your completed and signed Claim Form must be postmarked no later than 19 March 2025. For assistance with submitting a Claim Form, please contact the Administrator’s dedicated call center at 1-833-839-0648, available Monday to Friday, 8:00 AM to 8:00 PM (Eastern Time).

Please read and follow the instructions on the Claim Form. Class Counsel are also available, free of charge, to answer your questions and assist you with preparing your claim form.

The deadline to file a claim is 19 March 2025.

AM

You are not responsible for payment of legal fees. The Federal Court has approved Class Counsel’s fees (including HST) and disbursements to be automatically calculated and deducted from the Settlement amount you are entitled to receive before the payment is issued.

The Federal Court approved payments to Class Counsel equal to approximately 17% of each payment made under the Settlement for legal fees, disbursements, and HST.

The FSA contains additional details about Class Counsel fees, available online at https://vetspensionerror.ca/court-documents/.

Class Counsel are available to assist Class Members through the claims process free of charge.

FURTHER INFORMATION?

For further information or to get help with your claim, contact Class Counsel at: https://vetspensionerror.ca/ or Call: 1-866-545-9920 or info@vetspensionerror.ca

DO YOU KNOW ANY OTHER RECIPIENTS OF A VAC DISABILITY PENSION?

Please share this information with them.

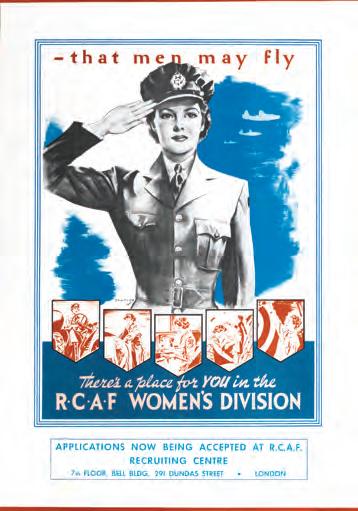

2 July 1941

An Order-in-Council authorizes the creation of the Canadian Women’s Auxiliary Air Force, which was renamed the Royal Canadian Air Force Women’s Division in 1942.

4 July 1955

A group of anti-submarine torpedo specialists take flight as sonar operators for six Sikorsky H04S-3s in a new navy antisubmarine helicopter squadron.

5 July 1950

HMC ships Cayuga, Athabaskan and Sioux depart for Korea.

6 July 2003

8 July 1944

The 9th Canadian Infantry Brigade (9 CIB) takes part in Operation Charnwood, the British I Corps’ final assault on Caen, France.

9 July 1943

The 1st Canadian Infantry Division and the 1st Canadian Army Tank Brigade arrive to join the invasion armada of nearly 3,000 Allied ships and landing craft during the assault on Sicily.

10 July 1943

17 July 1944

Canadian Spitfire pilot Charley Fox strafes a black car, wounding German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, known as the Desert Fox (see “Heroes and Villains,” page 92).

Canadian troops come ashore near Pachino close to the southern tip of Sicily and take up the left flank of five British units as part of Operation Husky.

18 July 1925

Mein Kampf, Adolph Hitler’s blueprint for the Third Reich, is published.

11 July 1973

Operation Caravan, Canada’s role in the French-led United Nations Organization Stabilization Mission in the Democratic Republic of Congo, comes to an end.

Canadian Forces’ Hercules aircraft begin food-relief missions in response to the drought-induced famine in West Africa.

12 July 1812

American General William Hull invades Upper Canada from Detroit.

15 July 1870

The Hudson’s Bay Company sells the region known as Rupert’s Land—a quarter of North America’s landmass—to Canada for $1.5 million.

19 July 1870

Franco-Prussian War starts.

20 July 1974

Turkey invades Cyprus. Two Canadian peacekeepers die and 30 are wounded foiling attempts to capture the airport.

22 July 1943

Canadian soldiers capture the Italian town of Assoro.

24 July 1942

A German U-boat wolf pack attacks convoy ON-113. While five Allied ships are sunk, HMCS St. Croix takes out U-90

26 July 1758

The French fortress at Louisbourg surrenders to the British (see “The fortress,” page 56).

12 August 1917

2 August 1990

Iraq invades Kuwait. Canada joins a U.S.-led international coalition in response, contributing a naval task group and later, an air task group.

3 August 1981

Egypt and Israel sign a peace treaty, the Sinai is returned to Egypt and a multinational force begins peacekeeping.

8 August 1918

The Hundred Days Offensive of the First World War begins with the launch of a major attack east of Amiens, France.

HMCS Shearwater and submarines CC-1 and CC-2 are the first Canadian warships to pass through the Panama Canal.

16 August 1900

In South Africa, Boer troops withdraw at news of approaching British reinforcements, bringing an end to the Battle of Elands River.

17 August 1943

Sicily is liberated; Canada incurs 2,310 casualties, including 562 killed, in the campaign.

9 August 1974

Nine Canadian peacekeepers die when their Buffalo aircraft is shot down by Syrian missiles.

10 August 1930

Bellanca aircraft enter service with the RCAF.

11 August 1718

Frederick Haldimand is born. As governor of Quebec, he helps resettle United Empire Loyalists and Six Nations of Iroquois in Canada following the American Revolution.

18 August 1944

HMC ships Ottawa, Kootenay and Chaudière sink U-621 in the Bay of Biscay.

20 August 1915

The Newfoundland Regiment leaves for the Mediterranean.

21 August 1853

HMS Breadalbane is trapped and crushed by ice, sinking in the Northwest Passage. Its crew of 21 is rescued by sibling ship, HMS Phoenix

22 August 2001

The defence minister announces that Canada will deploy troops to NATO operations in Macedonia.

24 August 1814

British troops march into Washington, D.C., and burn public buildings.

25 August 1944

In Italy, Canadian, British and Polish forces attack the Gothic Line.

28 August 1992

Canada announces 750 troops to aid the United Nations Operation in Somalia.

30 August 1945

HMCS Prince Robert sails into Kowloon, Hong Kong, liberating Canadian prisoners of war.

By Alex Bowers

here’s a swing bridge, and all they tell you to do is walk,” said retired master corporal Mike Trauner. “Just walk in a straight line across the bridge.”

Beginners, he explained, have on ly a light breeze rocking the flimsy span back and forth. “But for me...the bridge is just swinging wildly out of control.”

Trauner, an Afghanistan combat veteran who uses prosthetic legs—the result of two improvised explosive devices detonating under him on Dec. 5, 2008—recalled grabbing the handles to gain stability before pushing on.

Yet despite the almighty gusts, despite the swaying structure and despite the seemingly perilous risk of falling, he remembered being unafraid.

The bridge, in reality, never truly ex isted. Nor did the wind.

But in Trauner’s case, alongside other Canadians who returned from Afghanistan with lifechanging wounds, the so-called Caren (Computer-Assisted Rehabilitation Environment) system has brought—and for some still brings—a virtual reality capable of producing tangible results.

One of only two such facilities in Canada, The Ottawa Hospital’s Caren lab has, since being installed in 2010 in partnership with the Canadian Armed Forces, enabled patients to push boundaries in a sa fe and controlled setting.

The technology, monitored by a collaborative team of rehabilitation experts, psychologists, occupational therapists, physiotherapists, researchers and more, encompasses an entire room dominated by a large projection screen. A moving platform, which can tilt in different directions depending on the patient’s movements, and a remote-controlled treadmill add to the immersive experience as participants are secured in a harness attached to a fall-restraint system.

“It allows us to simulate so many different environments besides flat-level ground walking,” explained Dr. Nancy Dudek, medical director of the hospital’s amputee program. “It likewise affords a great degree of comfort knowing that if it doesn’t go as planned, [the patient] is not going to sustain injuries.”

Considered an accompaniment to other aspects of the rehabilitation process, the virtual reality program captures data that medical professionals can assess and adapt according to the patient’s needs. Its scope, meanwhile, can reach beyond combat-related wounds to the likes of traumatic brain or spinal cord injuries, neuromuscular disease, mental health conditions or chronic pain.

“The Caren system can be just as beneficial to, say, a 28-year-old

who happened to be in a civilian motor accident as to a 28-yearold member of the Canadian Armed Forces wounded in the field,” said Dr. Dudek.

And then there are the scenarios themselves, which can cater to individual circumstances, goals, interests and requirements. While some, such as traipsing across a rickety bridge, bear an arguably closer resemblance to fantastical video games, others draw inspiration from everyday life.

A three-dimensional map of downtown Ottawa is just one example, where crowds throng the streets, vehicles drive by and obstacles can spontaneously present themselves. “The idea is to give [patients] mental challenges, which is what happens in the real world when somebody walks in front of you or you have to suddenly move,” noted Dr. Dudek.

Another, Trauner recalled, placed him on a boat. Here, balance and weight dispersal become critical as patients navigate around a series of buoys, all the while building confidence in their abilities and those of their prosthetics.

Bushra Saeed-Khan also remembered cruising over virtual waters during her rehabilitation. On Dec. 30, 2009, the 25-year-old Canadian diplomat was only eight weeks into a one-year assignment when her light-armoured vehicle encountered an improvised explosive device near Kandahar.

“There were 10 of us [in the vehicle]. Five of us passed away immediately, and five of us survived,” explained SaeedKhan, whose wounds resulted in the loss of a leg, while the other was severely damaged.

By the time she arrived at the rehabilitation centre in Ottawa, Saeed-Khan’s recovery had extended beyond the physical and into mental barriers.

“I was still knee-deep in my rehab and surgeries...for the

first few months,” she said, “until I reached a point where I almost felt I started to stagnate a bit. I wanted to go back home and back to work. But there was still this fear of being back in the community because I was so comfortable in the rehab centre. It was accessible, it was safe.”

The Caren system helped her push physical boundaries.

The program’s importance to mental health, as Saeed-Khan herself recognizeed, cannot be overstated: “It took me a few efforts to trust the Caren system. But it helped me figure out what was possible and what was not.”

Whether walking over uneven ground in a virtual forest or steadying herself on a virtual bus, each accomplished task brought Saeed-Khan closer to the life she hoped to lead. Even when specific

scenarios—and their varying difficulty settings—posed challenges beyond her new circumstances, the diplomat remained grateful for the clarity that came with knowing her limitations.

One of Saeed-Khan’s long-term goals, however, posed an entirely different challenge with a unique set of considerations: motherhood.

“Not only did I want to physically have [children] if possible,” she said, “but just play with them and engage with them. Everything I did at the rehab centre, every surgery, every exercise, I wondered how it would affect that.”

Beyond the rehabilitation lab, trials and tribulations awaited Saeed-Khan over the subsequent years as the prospect of pregnancy was complicated by her past wounds. Nevertheless, in 2018, she and her husband welcomed their daughter into

the world. More recently, SaeedKhan gave birth to a son.

“They’re like mini Caren systems,” she joked of her five-year-old and two-year-old children. “They’ve just got to push you sometimes.”

In part due to her virtual reality journey, together with The Ottawa Hospital’s dedicated team that helped her along the way, Saeed-Khan eventually returned to work. She is currently posted to the UN in New York.

Trauner’s sporting career continues to flourish. In 2023, the veteran served as games ambassador at The Royal Canadian Legion’s National Youth Track and Field Championships, a position he will take on again in 2024.

“I think the military made me the person I am today,” said Trauner. “But ultimately, in a way, the Caren system fine-tuned me.” L

Stephen J.Thorne

Itis a blight on the hypocritical, arguably corrupt and highly politicized International Olympic Committee that the 1936 Olympic Games were ever allowed to take place in Nazi Germany. But the controversial call gave one Black athlete a grand platform on which to upstage Adolf Hitler and the racist policies of his fascist regime.

Jesse Owens’ achievements at the Berlin Games would not change the course of history. They wouldn’t prevent a world war or the Holocaust. They wouldn’t even alleviate racism in his native United States.

“When I came back to my native country, after all the stories about Hitler, I couldn’t ride in the front of the bus,” said the sharecropper’s son from Oakville, Ala. “I had to go to the back door. I couldn’t live where I wanted.

“I wasn’t invited to shake hands with Hitler, but I wasn’t invited to the White House to shake hands with the President, either.”

But his four gold medals did humiliate “the master race” and “single-handedly [crush] Hitler’s myth of Aryan supremacy,” wrote ESPN columnist Larry Schwartz.

Berlin’s selection as the Games’ host city took place in 1931, two years before Hitler was appointed chancellor. But the evil nature of his Nazi regime became evident immediately, and by 1935 German Jews had lost virtually all their rights.

Still, the Games went ahead— some countries, including the

U.S., even removed Jews from their teams to avoid offending Germany’s Nazi regime.

“Politics has no place in sport,” declared Avery Brundage, future IOC president and head of the U.S. Olympic Committee at the time. Brundage nevertheless became a Nazi apologist and one of Berlin’s biggest backers after a 1934 “fact-finding” trip to Germany.

The issue was argued in Canada, too.

In November 1935, the University of Manitoba hosted a debate on whether the country should attend the Berlin Olympics. Attendees voted 90-20 to boycott.

Participation proponents argued that a withdrawal would antagonize Germany and compound Nazi hostility toward Jews. They claimed IOC bans on racial and religious discrimination would protect minorities. Opponents said competing represented tacit support for Nazi racial policies.

In a Nov. 1, 1935, piece, Vancouver Sun columnist Hal Straight said the Berlin Games should be cancelled altogether.

“ The Olympics do not belong to Hitler, nor Germany,” he wrote. “ They belong to the world and are just being staged in Germany to that country’s request because it brings great beneficial returns. Hitler is being done a favor.”

> Check out the Front lines podcast series! Go to legionmagazine.com/en-frontlines

Canadian Olympic officials ignored the protests. The annual meeting of the Amateur Athletic Union of Canada, held behind closed doors in Halifax, did not air the issue. Its resolutions committee instead suggested following Britain’s lead and attending the Games.

According to the Vancouver Holocaust Education Centre, the resolution was approved without discussion. Canada would send 79 men and 18 women to Berlin. They earned a gold medal, three silver and a bronze.

Fifty-one countries—14 more than participated at Los Angeles in 1932—gave Hitler what he wanted. The U.S. even switched out two Jewish relay runners, Sam Stoller and future New York broadcaster Marty Glickman, for Owens and Ralph Metcalfe.

Spain, on the other hand, boycotted Berlin and staged its own parallel “People’s Olympiad,” attended by some 6,000 athletes from 49 countries.

By the time the Games were held, German Jews had lost citizenship and were banned from universities and many fields of work,

their businesses boycotted and vandalized. They were regularly harassed in the streets, and worse.

The persecution and violence would escalate until, finally, in 1941, the Nazis implemented the “Final Solution,” a euphemism for the systematic extermination of Europe’s Jewish population.

German team bans on Jewish and Romani athletes were condemned internationally. The pressure gained such momentum that the Nazis allowed a part-Jewish athlete, 1928 fencing gold medallist Helene Mayer, to return to the German team. She won silver in Berlin.

Owens became an instant superstar in Berlin, in spite of it all. German fans chanted his name whenever he entered the Olympic stadium and mobbed him for autographs in the street. He took gold in the 100 metres, long jump, 200 metres and 4×100 relay—proof, the international press would declare, that the Nazi “master race” was a myth. Owens would be given a tickertape parade in Manhattan. Afterward, he wasn’t allowed to pass through the main doors of the Waldorf Astoria. He was

forced to go to the reception honouring him in a freight elevator.

He struggled to find work and took on menial jobs as a gas station attendant, playground janitor and manager of a drycleaning firm. He sometimes raced against motorcycles, cars, trucks and horses for cash prizes before he filed for bankruptcy and was convicted of tax evasion.

A lifelong Republican, his fortunes turned in 1955 at the hand of President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who made Owens a goodwill ambassador and sent him to India, the Philippines and Malaya to promote physical exercise and American culture.

In 1972, the emerging civilrights icon travelled to Munich for the Summer Olympics as a special guest of the West German government. He was greeted by Chancellor Willy Brandt and boxing legend Max Schmeling.

Berlin would be the last Games for 14 years. On Sept. 1, 1939, the forces of Nazi Germany invaded Poland, sparking a world war that would become the deadliest and most destructive conflict in history. L

By David J. Bercuson

anada’s military has long been plagued with procurement problems. It took 30 years to go from the Progressive Conservative’s announcement to order replacement helicopters for the aging CH-124 Sea King to when the last of that venerable aircraft retired. And it will be nearly a decade until the succeeding fleet is fully operational.

That lengthy drama began in 1993 when Jean Chretien’s Liberals won the largest majority in the country’s history. The Conservative government that preceded his, first under Brian Mulroney then Kim Campbell, had concluded a long competition to find a Sea King replacement. Its choice was the EH-101, built in Britain by AgustaWestland.

The Tories had ordered 35 of the helicopters in 1987, but Chretien had campaigned, in part, on a promise to cancel the contract because, he said, they were too elaborate and expensive.

Not long after this, a search was initiated to replace the Sea Kings; it took 10 years to get to the preliminary approval stage with a civilian Sikorsky design (the S-92). The government intended to buy the S-92 as a military helicopter, dubbed the CH-148 Cyclone, with major modifications that would enable it to perform at sea in rough weather, with shipborne landing pads that danced and jumped with every wave that crashed against a ship’s hull.

The first Cyclone was delivered in June 2015, but continuing delays—caused mostly by the civilian-to-military-purpose conversion—mean Canada still doesn’t have all the helicopters it ordered; the navy is awaiting the final two aircraft now. Thus,

it took 30 years from the cancellation of the EH-101 to receive the penultimate CH-148s.

During most of that time, the Sea Kings continued to fly even though maintenance costs grew yearly, as did downtime due to maintenance, which resulted in mission delays.

So, how has the CH-148 fared since it went into service? Constant problems, some of them serious, have plagued the aircraft. For example, early this past February, the CBC’s Murray Brewster reported that some Cyclone main rotor blades were “defective [and] could rip apart in flight.” Known as “debonding,” it’s described as when “the skin of the blade peels off while the helicopter is in the air.”

But this is only the latest in a growing list of problems with the CH-148. Others? The estimated life-cycle cost of the Cyclone has risen from $14.8 billion to $15.9 billion, all while its weapons

systems are becoming rapidly obsolete. Then there was the April 2020 crash of a Cyclone into the Ionian Sea, apparently at full speed, that took the lives of six Canadian sailors.

A lawsuit against Sikorsky filed by the families of the dead crew alleges that the incident was caused by a failure of the aircraft’s flight-control system. Sikorsky denies the allegations. The root of the problem, however, lies in the initial decision to purchase the civilian S-92 and convert it to military use. The latter is much harder on any vehicle—land, air or sea—than the former. That’s why military trucks are large, with strong tires, robust frames and engines, and designed to run well in all types of weather and no matter the condition of the road, or lack thereof, or the circumstances surrounding them. The same essential characteristics are necessary for military helicopters.

There are no exceptions, and such designs aren’t cheap. In the case of replacing the Sea King after Chretien’s decision to cancel the EH-101 contract—which cost the government $478 million in penalties, by the way—there were several viable off-the-shelf candidates that could have been selected. For example, the U.S.-built Black Hawk is now flown by 34 countries.

Perhaps that family of utility military helicopter was considered too expensive or didn’t have the carrying capacity of the S-92/ CH-148 aircraft. But, when reflecting on the last 30 years and seeing how difficult the conversion from civilian to military configuration was, some people in Ottawa might well question the decision to buy the Cyclone in the first place.

When it comes to military procurement, the proverb “better safe than sorry” means all that much more. L

Stephen J. Thorne

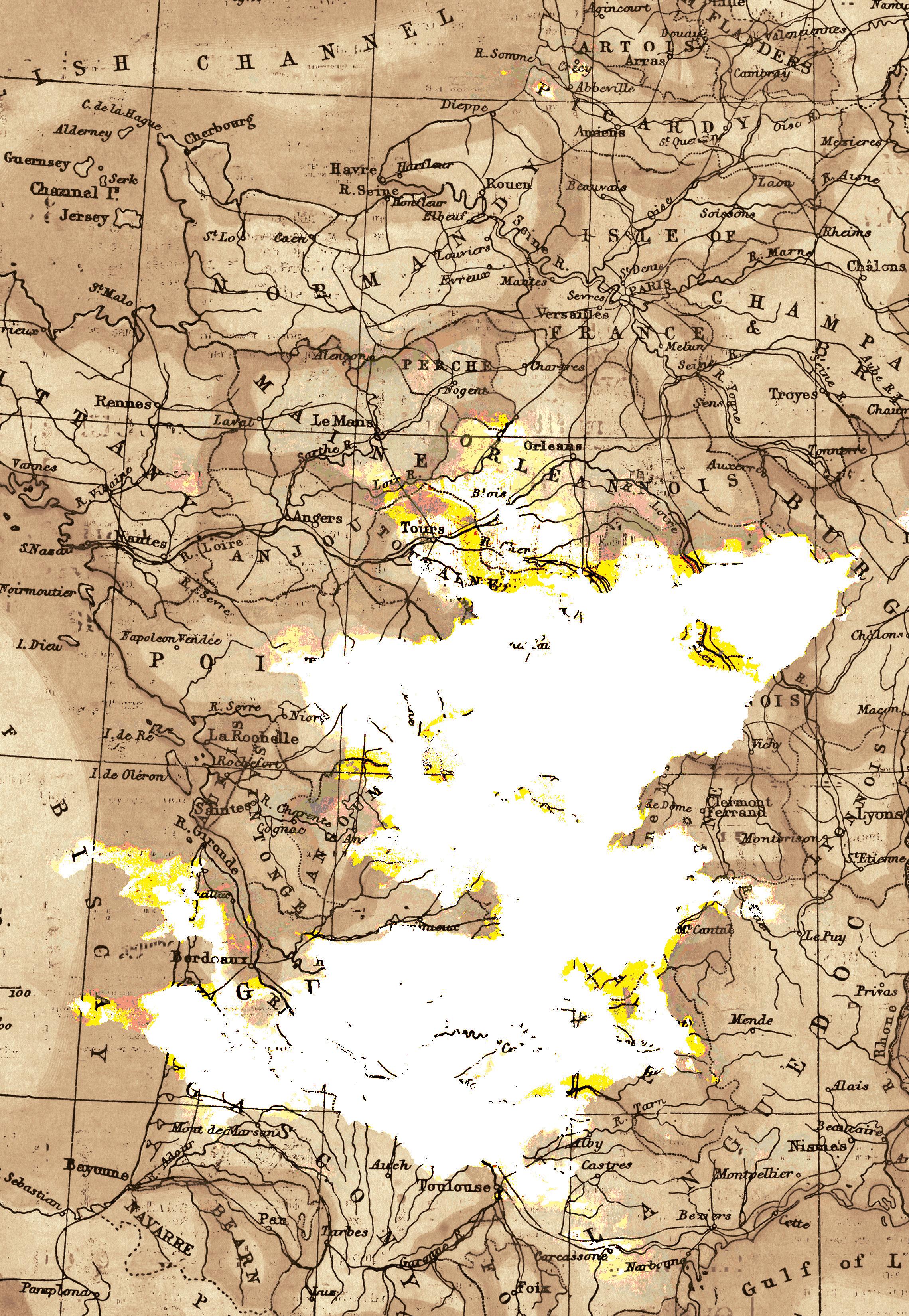

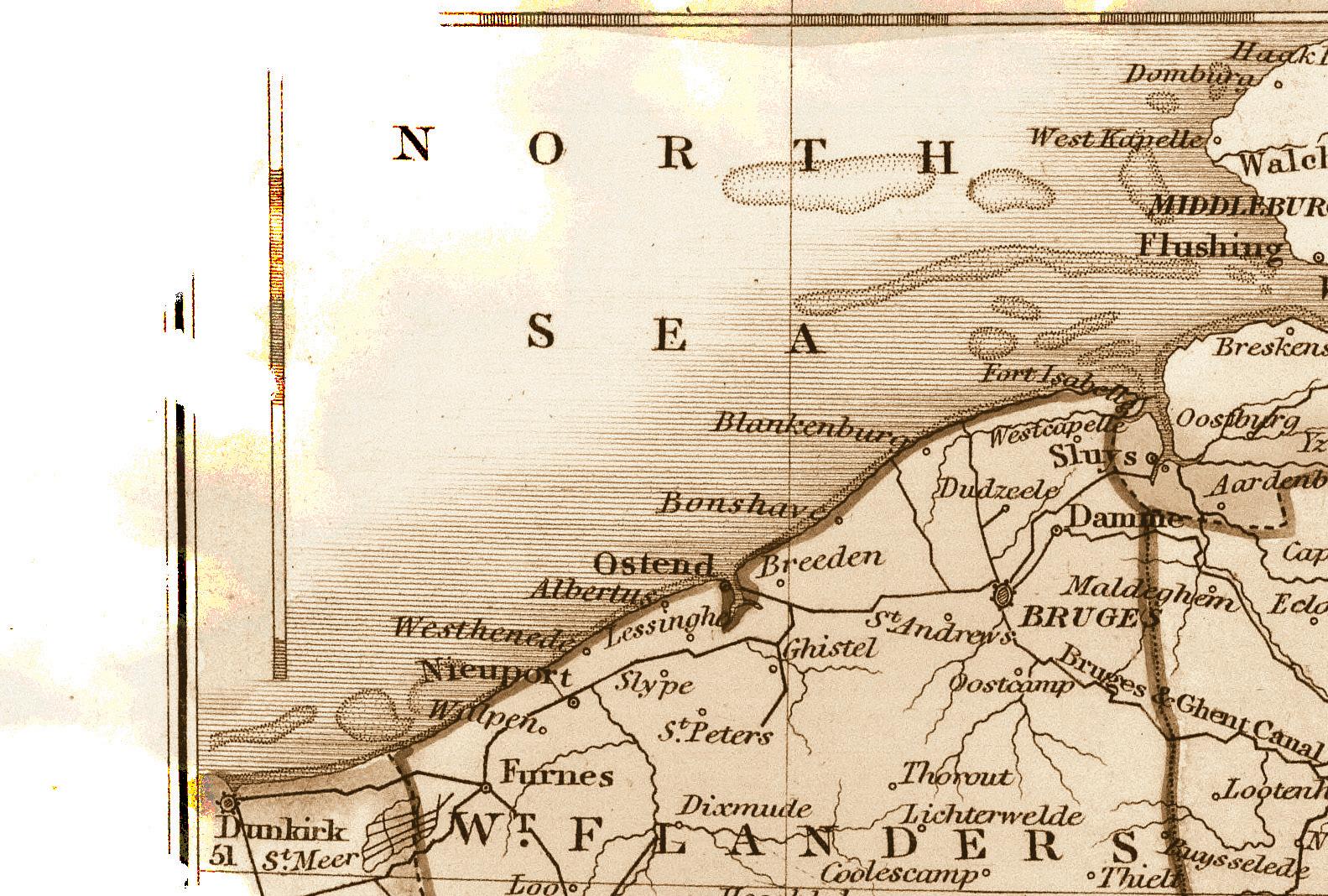

the War of 1812.

God damn them all, I was told We’d cruise the seas for American gold We’d fire no guns, shed no tears

Now I’m a broken man on a Halifax pier

The last of Barrett’s privateers

—“Barrett’s Privateers,” by Stan Rogers

may have been the best investment Enos Collins, Benjamin Knaut and John and Ja mes Barss ever made.

In 1811, the merchants of Liverpool, N.S., purchased Severn, a former tender to a Spanish slaver captured by the Royal Navy, for a few hundred British pounds (tens of thousands of dollars today). Lucky for them, war broke out with the United States a few months later, and the boys were in business, big-time.

They renamed the Baltimore clipper-style schooner Liverpool Packet, and initially ran mail

between their hometown and Ha lifax.

With the outbreak of the War of 1812, however, they acquired a letter of marque from the king of England and embarked on the most successful privateering spree mounted by any of the 40-odd

Canadians licensed as maritime mercenaries during the conflict.

Liverpool, with its sheltered harbour on the province’s South Shore and boundless access to the region’s rich sailing stock, was considered the privateering capital of British North America at the time and the speedy, upstart Packet, with its five guns and 45 crew, proved a formidable presence along the New England coast.

During its war-long spree, the ship captured some 50 American vessels and their cargoes, then worth between $262,000 and $1 million (equivalent to the 2023 purchasing power of C$4.8M-$18.6M).

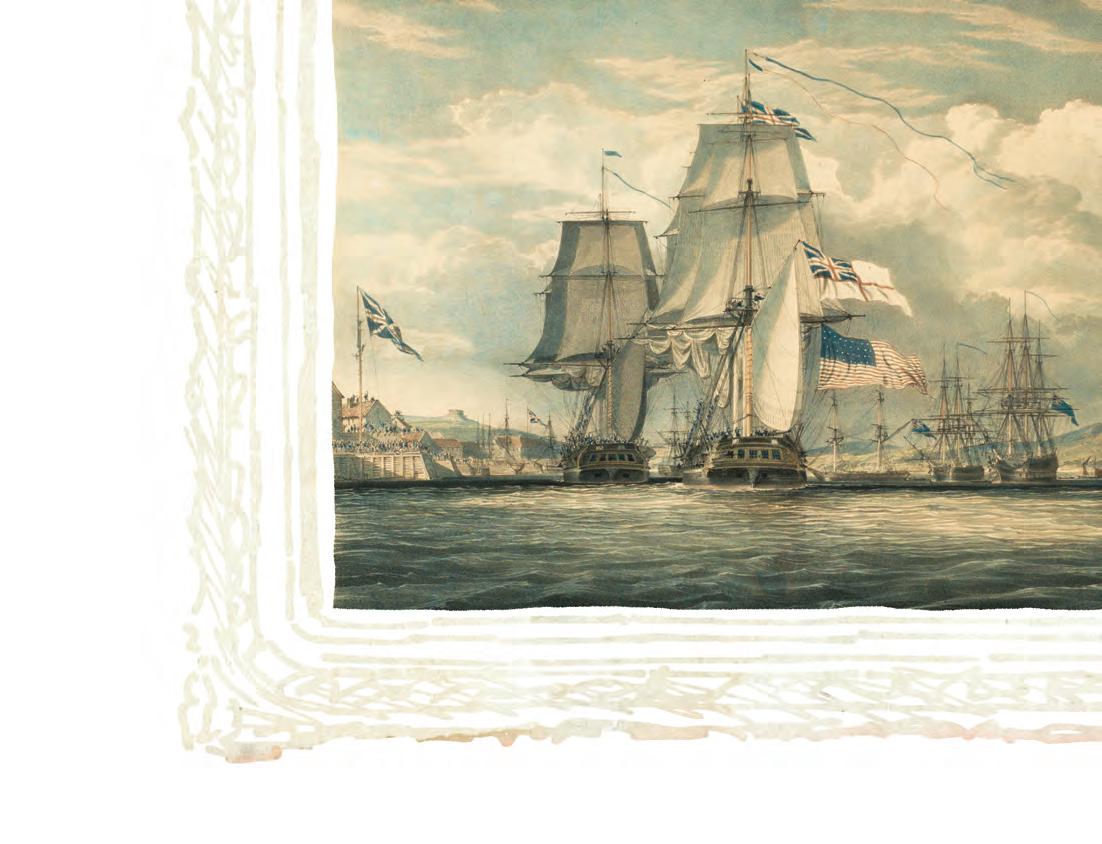

Classic naval engagements such as the Battle of Lake Erie and the clash between HMS Shannon and USS Chesapeake, which ended with a captured Chesapeake paraded up Halifax Harbour, earned much of historians’

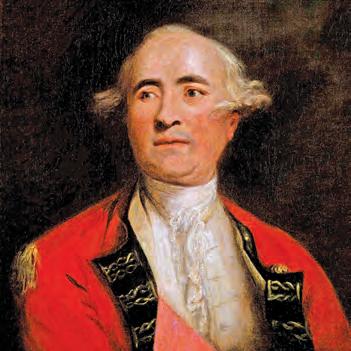

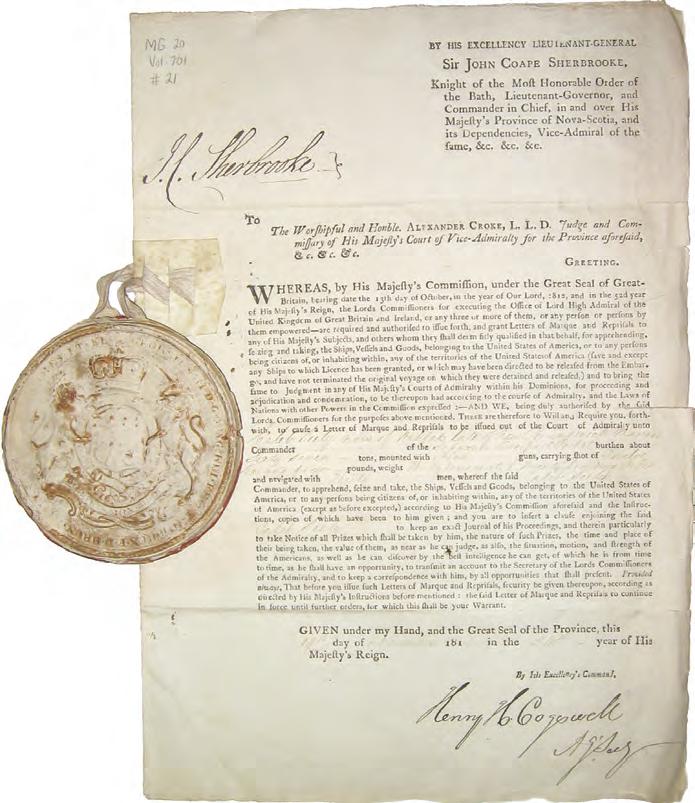

Enos Collins (opposite), Packet ’s principal owner, was rumoured to be the richest man in Canada when he died in 1871. One of the ship’s letters of marque— its licence to plunder. HMS Shannon escorts its war prize, USS Chesapeake, up Halifax Harbour on June 1, 1813.

attention. But skirmishes between what were at their core small, souped-up cargo and fishing vessels were a continuing feature of the last great conflict between the U.S. and Britain.

Colonial privateers had played a key role in the 1775-1783 War of Independence, capturing hundreds of British vessels and seizing coveted muskets and gunpowder for the Continental Army.

During the War of 1812, it’s estimated that American privateers captured millions in British commerce, much of it off the British Isles. By 1814, British maritime insurance firms were routinely charging a whopping 13 per cent on shipments between England and Ireland. The Naval Chronicle reported that was triple what it was when Britain was at war with “all of Europe.”

The British monarch and his representatives issued some 3,000 letters of marque during the Napoleonic Wars, which included the period 1812 through 1815.

The documents—licences to plunder—represented gains for everyone involved, save the hapless victims. They essentially legitimized the practice of piracy against an enemy country’s sea-going vessels, no matter how innocent they might be. By seizing and looting merchant ships, fishing boats, whalers and others, privateers interfered with commerce, disrupted supply, distracted naval resources and, in some cases, made themselves fortunes.

The golden age of piracy was long over. Names such as Blackbeard, Calico Jack, Henry Morgan and Samuel (Black Sam) Bellamy had become the stuff of legend, their long-lost treasures lying at the bottom of the Caribbean or buried, perhaps, beneath Nova Scotia’s Oak Island.

A century after the Jolly Roger terrorized seafarers around the world, the needs and desires of the English king had bestowed a measure of legitimacy on the

practice, and opportunists were more than willing to cash in.

“The privateers of Nova Scotia played an integral role in closing American ports during the War of 1812,” wrote James H. Harsh in The Canadian Encyclopedia. “They were a valuable source of intelligence for the Royal Navy on American strength and ship movements.”

For the privateers, however, the benefits were less certain.

Their handpicked crews were made up mostly of volunteer fishermen with dreams of fame and fortune. None was offered wages; their rewards were to be shares in the prizes they captured.

Yet 15 of the 40-some commissioned privateering ships from New Br unswick and Nova Scotia failed to capture a single prize; another 10 took just one each. The rest made fortunes for their owners.

And none more than Liverpool Packet.

The 53-footer (16-metre) was at anchor in Halifax Harbour on June 27, 1812, when the British frigate Belvidera arrived in port bearing news of the American declaration of war with England nine days earlier. The ship had on board 17 casualties from a day-long fight with five American ships.

Packet ’s crew hastily loaded five rusty cannons aboard their vessel and made for Liverpool to await Britain’s response to the American challenge—and an anticipated letter of marque. By mid July, the Nova Scotia coast was swarming with American privateers, who were capturing merchantmen almost daily.

Packet would acquire its licence to raid and captured at least 33 American ships in the war’s first year. The ship, first commanded by an aging John Freeman—a privateering veteran of the French and Spanish wars—and later a younger but seasoned mariner, Joseph Barss Jr would lie in wait near Cape Cod, Mass., attacking U.S. vessels headed to Boston and New York.

“All awake!” trumpeted Boston’s Columbian Centinel newspaper on Dec. 19, 1812. “The Liverpool Packet has again raided our coast.” The privateer returned to Liverpool two days later with a pair of prizes in its wake.

Enemy ships weren’t the only perils Packet faced. A storm that month forced Barss to take the ship out into the open ocean where he could ride it out. “At midnight tremendious Gails and Sea on,” noted a logbook, “the seas breaking over the vessel from Stem to Stearn.”

But the rewards proved astounding.

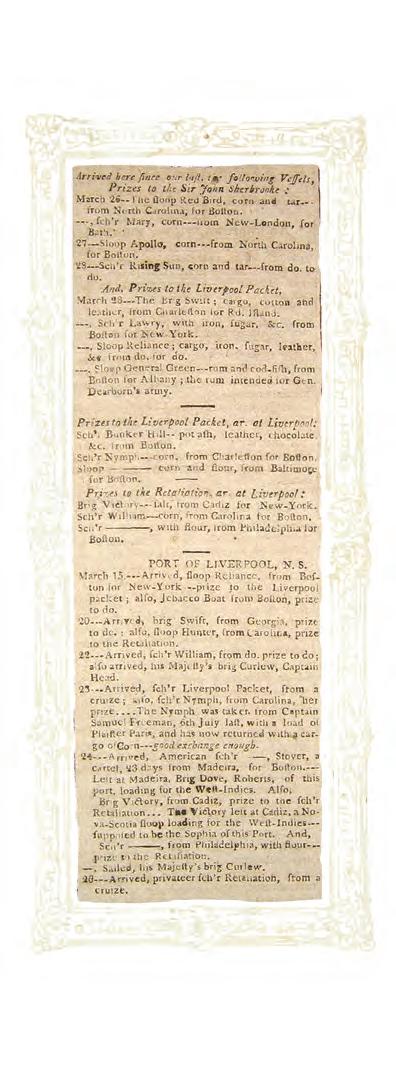

A list of prizes published in the Nova Scotia Royal Gazette on March 31, 1813, includes four taken on March 28 alone: the brig Swif t, captured while en route from Charleston, S.C., to Rhode

Island with a load of cotton and leather; the schooner Lawry with a load of sugar, iron and cotton bound for New York from Boston; and the sloop Reliance, headed for an undetermined destination with iron, sugar, leather and cotton. It also captured the sloop General Green, destined for Albany, N.Y., from Boston with codfish and rum for the army of General Henry Dearborn.

Other prizes taken by Packet were anchored at Liverpool, including the schooner Bunker Hill loaded with chocolate.

Packet ’s owners were so inspired

Thorn. With a displacement of 273 tons, the warship had 18 guns and was crewed by 150 men. It has been said that it achieved the fastest success of any Canadian privateer, but estimates of its prizes vary widely.

Its notoriety spread far and wide, Packet earned the nicknames New England’s Bane and The Black Joke, a moniker borne by several infamous slave ships.

Packet was a veteran privateer by the spring of 1813 and three months out of port when its run of good luck took a turn: it came upon the American privateer Thomas out of Portsmouth, N.H.—twice Packet ’s size, wielding 15 guns with a crew of 100.

The five-hour chase began in light winds at 9 a.m. on June 9. Packet ’s crew dumped all but one of t he ship’s short-range guns overboard to lighten their load, and moved their one remaining six-pounder to the stern. As their pursuer closed, they fed the cannon with six-pound shot, then tried a four-pound ball wrapped in canvas. It split the muzzle.

“At 2 p.m., coming up with the chase very fast, the schooner hoisted her colours and commenced firing her stern chasers,” Liverpool historian George E.E. Nichols related in a 1904 presentation entitled “Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers.”

“Overtaken by the American, she rounded to, struck her colours and ran alongside the Thomas. In the act of veering, she fouled the Thomas, and thinking their opponents about to board their vessel, the respective crews engaged in a hand to hand encounter.

“After striking her colours, the officers and crew of the Thomas repeatedly fired into the Liverpool Packet and threatened to give her crew no quarter. Greatly outnumbered, they were compelled to surrender, but not

its

spree, the ship captured some 50 American vessels and their cargoes.

before several of the crew of the Thomas had been killed.”

Three weeks later, the American ship was taken by a British frigate after a 32-hour chase. It was brought to Halifax and sold to Liverpool privateers, the largest shareholder among them Barss’ father, Joseph Sr., a Queen’s County representative in the House of Assembly.

The Thomas of Portsmouth became the Wolverine of Liverpool. It took eight prizes before the year was out.

Meanwhile, Joseph Jr. was taken to Portsmouth, where he was kept under armed guard

for several months before John Coape Sherbrooke, lieutenantgovernor of Nova Scotia, a former British army general and namesake of the aforementioned privateer, secured his release.

Liverpool Packet was converted to an American privateer and eventually renamed Portsmouth Packet. But in October 1813, HMS Fantome, an 18-gun brigsloop, encountered the schooner off Mount Desert Island, Maine.

A chase ensued, lasting 13 hours before Fantome seized its quarry and brought the prize to Halifax. Packet was repurchased by its

Thomas Hayhurst depicts Packet in full sail. The Nova Scotia Royal Gazette of March 31, 1813, reports the prizes taken in recent months by privateers Sir John Sherbrooke and Liverpool Packet

former owners, its Liverpool name restored. It resumed its plundering under the command of Caleb Seely.

Packet ’s second letter of marque is now held in the Nova Scotia Archives.

Dated Nov. 19, 1813, it authorized Seely and his ship “to apprehend, seize and take, the Ships, Vessels and Goods, belonging to the United States of America, or to any persons being citizens of, or inhabiting within, any territories of the United States of America…according to His Majesty’s Commission.”

As part of his privateering duties, Seely was ordered to take note of “the situation, motion, and strength of the Americans, as well as he can discover by the best intelligence he can get.”

Packet closed the year with three more prize vessels to its credit.

The ship had a successful 1814, too, capturing prizes in May and June, then taking two more alongside Shannon near New York and Bridgeport, Conn. Packet worked often with British naval vessels through the end of the war.

Barss was appointed skipper of his former captor, Wolverine, in 1814 and sailed as a trader to the West Indies. The Americans considered his mere presence on the high seas a violation of his parole, however, and his seafaring days ended on his return to Liverpool in August.

American privateers continued their campaign off the Americas, their commissions issued on a per-voyage basis by the Continental Congress and state governments.

Working out of ports like Savannah, Ga.; Elizabeth City, N.C.; and Mobile, Ala., skippers such as John Peter Chazel, Hugh Ca mpbell and Herman Perry sailed fast schooners and brigs along the continent’s east coast raiding merchant vessels.

American privateers didn’t limit their prey to British merchants, either. Records show they also captured Swedish, Spanish, Portuguese and Russian ships.

Believed to be the most successful of the Americans was a six-gun schooner dubbed Saucy Jack, owned by Charleston, N.C., merchant John Everingham. On its maiden voyage, Saucy Jack, captained by Thomas Jervey, took the brig William Rathbone, along with its 14 guns and a cargo worth about C$7M today. Though the British ship, known as a West Indianman, was later recaptured, the incident was a harbinger for the American’s successes under three different captains.

The log of Saucy Jack’s last and most successful privateer skipper, Chazal, tells of a bloody encounter with the 540-ton, 10-gun British trader Pelham between Cuba and Santo Domingo on April 30, 1814.

“In the act of boarding, Stephen Dunham, one of our seamen, was shot dead and our First Lieutenant, Dale Carr, mortally wounded while fighting on the enemy’s deck,” Chazal wrote. “At the same time our second Lieutenant Lewis Jantzen and John St. Amand, Lieutenant of Marines, was severely wounded, together with 7 of our men. Making our loss 2 killed and nine wounded, 8 of which badly.

“On board the Pelham there were 4 killed and 11 wounded; among the latter, the Captain and his Chief Mate (since died).”

With hostilities over and privateering all but ended by the Treaty of Ghent and shifting Royal Navy policy, ship owners from both sides, including Everingham, tended to go back to what they knew best, merchant trading.

Privateers who continued raiding after their commission expired or a peace treaty was signed could face piracy charges. The penalties were harsh—convicts were hanged at the beach in Halifax, then tarred and hung in chains (gibbetted) at the harbour entrance as a warning to other mariners.

Thus, combined with an expanding naval role on the high seas, privateering all but disappeared by the end of the 19th century.

“The Liverpool privateersmen were of excellent stock, all leading citizens of the community, well and favorably known to British

naval officers of the time,” Janet E. Mullins wrote in The Dalhousie Review. “When the wars were over, many filled positions of honour as members of parliament, judges, ship-owners, merchants.”

Packet ’s owners sold their feisty little ship in Kingston, Jamaica. Its fate beyond that is unknown. Several ships have since carried its name.

The vessel’s success helped launch the great fortune of its principal owner, Enos Collins, who would go on to co-found the Halifax Banking Company, which merged with the Canadian Bank of Commerce in 1903.

Born to a merchant family in Liverpool, he had sailed on a few privateering escapades to the West Indies in his youth. He was rumoured to be the richest man in Canada when he died in 1871 at the age of 97. L

In 1904, Liverpool, N.S., native and passionate amateur historian George E.E. Nichols gave a presentation entitled “Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers,” which included a strident defence of the practice that, by some, was considered immoral.

Private vessels of war, he noted, operated under strict regulations set down by the Crown. None could go on a prizehunting cruise without first obtaining a licence, known as a letter of marque.

no one taken or surprised in any vessel, though known to be of the enemy, were to be killed in cold blood, tortured, maimed or inhumanely treated “contrary to the common usages of war.” Prisoners were not to be ransomed;

privateers were not permitted, under peril, to fly any colours usually shown by the king’s ships. They were required to fly a Red Ensign;

The Feb. 9, 1913, edition of The New York Sun commemorates the privateers of a century before. George E.E. Nichols’ 1904 “Notes on Nova Scotian Privateers” sought to clarify the history and correct some negative interpretations of the trade.

To obtain one, a ship’s owners had to meet a series of requirements and undertakings: their vessel’s tonnage, armament, ammunition, etc., together with the names of the owners, officers and men were to be registered with the Admiralty Court—in Nova Scotia’s case, in Halifax;

a regular account of captures and proceedings had to be kept in a logbook and any potentially valuable information obtained about the enemy reported;

bail with sureties (guarantors) was required either on behalf of the owners, if residents, or the captain. The amount varied according to the number of crew. If they exceeded 150 men, 3,000 pounds sterling [about C$500,000 today] was required, while fewer than 150 demanded half the cost.

Prizes were to be taken to the most convenient port in the dominions of the Crown, where they would be adjudicated upon by the Court of Admiralty. Once declared a legitimate seizure, the captors were permitted to sell the vessel and its cargo in an open market “to their best advantage.” The proceeds were typically distributed by percentage between the privateers’ sponsors, shipowners, captains and crew. And a share usually went to the issuer of the commission (the Crown).

“ ”

Canadian female fighter jet pilots first took to the skies 30-plus years ago— but few have followed in their vapour trails

By Paige Jasmine Gilmar

Captains Jane Foster and Deanna (Dee) Brasseur stand atop a CF-18 in 1989 shortly after they became Canada’s first female fighter jet pilots.

nthe early 1980s, a man who signed himself as “Ex Aircrew Earl Everson” had a lot to say about the 1979 Servicewomen in Non-Traditional Environments and Roles (SWINTER) Aircrew Trial. Conducted over six years, the purpose of the initiative was to test the effectiveness of mixed units in operation, as the roles for women in the Canadian Armed Forces continued to expand. However, many airmen such as Everson didn’t take too kindly to the evolution of what some considered to be “the most exclusive boys’ club in Canada.”

“I sure don’t go for the Air Force having these girl pilots,” wrote Everson in a letter to the editor of a military newspaper in 1981. “I don’t feel too safe underneath with women pilots.

“You know what they’ll be doing, don’t you? All the time the aeroplane is trying to land, they’ll be patting down their hair and pulling out their eyebrows and looking into their mirrors and putting on eye-makeup and all during the whole landing, that’s what.”

This was the cultural climate that greeted the trials’ female applicants.

“There was me with my volunteer hand,” said Deanna (Dee) Brasseur, “and I got picked.”

Born in 1953, Brasseur grew up to the sights and sounds of Chipmunk trainer airplanes taking off from her father’s air force base near London, Ont. She joined the forces in 1972 and was selected for the initial SWINTER Aircrew Trial. As a result,

she was the first of three women to earn her operational military wings and became Canada’s first female fighter pilot.

“It’s been a heck of a road,” she told Legion Magazine. “It’s been a long and challenging and hard course.”

For women such as Brasseur, the road to equality was, and remains, a bumpy one, despite the services’ goal to increase female representation in the military to 25 per cent by 2026. In fact, the air force has only had seven women fighter pilots since 1989.

By 1971, Canadian women had been in uniform for more than 85 years, though their roles had been primarily limited to wartime nursing. While female employment opportunities in the military expanded out of necessity during the Second World War and the Korean War, such growth remained largely temporary and the future of woman in the forces was uncertain.

Following the 1970 report from the Royal Commission on the Status Women in Canada, the Defence Department lifted its cap of 1,500 servicewomen and gradually expanded employment opportunities for them to nontraditional positions such as vehicle drivers and firefighters. Nevertheless, females still couldn’t fill combat positions (like piloting or aircrew), be on sea duty or in remote locations.

When the Canadian Human Rights Act passed in 1977 and with the military facing the very tangible reality of recruitment shortages in the 1980s, in January 1979 the defence minister announced “a limited experimental basis in near combat roles on land, sea, or in the air” for women.

And yet, despite calls to create greater employment options for females in the military, women didn’t jump at the new opportunity dangling in front of them. In fact, out of some 6,000 women in the armed forces in 1979, only 11 applied to the SWINTER trials (including those for army and navy), Brasseur among them.

So, it became the first of many hurdles the program’s women had to overcome.

“You knew you were on trial. Every step you took, people were watching,” said Brasseur. “If you had one button on your uniform undone, somebody would notice that.

“It’s like being thrown to the wolves.”

When SWINTER began, though, Air Command made a firm declaration: women would be treated the same as men. Circumstances, though, proved this would be impossible; female participants were working against more than just their sex.

A media blitz followed the announcement of trials and the program’s female students became the centre of attention. With non-stop calls, interviews and photo sessions, jealousy eroded potential friendships between male and female co-workers.

“The boys were saying, ‘If we’re all supposed to be equal, how come you guys are covered by the media and we’re not?’” said Brasseur. “Oh, poor boys!”

What’s more, because many of the women who joined the program were already ranking military officers well acquainted with most of their instructors, there was a perceived power imbalance with the mainly young male recruits in the trial.

“We saw that as brown-nosing,” one former male colleague of Brasseur’s was quoted as saying in Shirley Render’s No Place for a Lady: The Story of Canadian Women Pilots 1928-1992. “We had our own problems trying to adjust to military life and worrying about washing out. Most of us saw them as ‘those damn women.’”

With so many factors complicating men’s adjustments to the new culture, the reception to female recruits was mixed, with beliefs ranging from “it was high time that women were admitted” to “the military was going to pot.” Indeed, the airmen even went so far as

“ ”

You knew you were on trial. Every step you took, people were watching. It’s like being thrown to the wolves.

to refer to the last all-male class to graduate as the “LCWB,” or the “last class with balls.”

“I have all these people telling me I shouldn’t be doing it,” said Brasseur. “They think I should be barefoot, pregnant and in the kitchen.”

Retired Royal Canadian Air Force pilot Micky Colton, who joined the SWINTER program in 1981, said attitudes during the initiative’s early years were sour.

“There was this misconception,” she said, “that if girls were meant to fly, they would have been born with wings on their back.

“My wings were quite hidden.”

Both female and male trial participants had difficulty understanding what was expected of them. With no role models to imitate, many women experienced loneliness and had to experiment with different behaviours to be taken seriously, from acting like “one of the boys” to employing a healthy sense of humour.

Brasseur joined the military in 1972 at 19 and was among the first three women to earn military wings in 1981.

Meanwhile, instructors were worried about going too hard or too easy on the women (though they often leaned toward the former) while getting over preconceived notions of what women could and couldn’t do. Similarly, male students were confused about whether to act like colleagues or gentlemen with their female counterparts, especially during the program’s social events.

Sexual harassment and assault were also a reality for some of the women. One reported that instructors “kept humming songs like Let’s Get Physical or You’re Having My Baby to get a reaction out of me… we put up with a lot of shit and abuse.”

Colton noted that men engaged in sexually inappropriate conversations in front of her (such as talking about their genitalia while she was in the cockpit), while Brasseur confronted sexual assault when a commanding officer tried to grope her at a restaurant. “You feel betrayed,” said Brasseur, “by somebody you thought you liked or was a nice person.”

They toppled the popular masculine myth about the alleged shortcomings of women in a man’s world. They became good solid military pilots. ”

Colton recalled a poignant memory that best summarized the attitudes and perceptions women had to overcome at the time. While stationed in Europe, her crew met another crew for dinner. As everyone loosened up after a few drinks, the other crew’s first officer, who was older and outranked Colton, began disparaging her.

“There was a lot of profanity in it,” she sa id, ‛you know, you effing woman; you shouldn’t be on airplanes; what the eff are you doing? you should be at home.’

“It was, like, biblical,” she laughed. “The whole table went quiet. Nobody even breathed.”

Anti-female sentiment gripped more than just the air force’s culture, however. Sexism was a systemic issue that affected more than just the military’s policies and procedures.

From ill-fitting uniforms to doctors who knew relatively little about women’s physiology, the very fabric of the military had been built for men. This was particularly true regarding policies on marriage and family.

Officials viewed marriage as potentially problematic. While wives traditionally followed their military husbands who occupied different postings, female pilots whose husbands were also pilots faced the possibility of not seeing their spouses for months. Colton, who was, and remains, married to a pilot remembered their time apart none too fondly.

“We spent some time apart,” she said. “There was some separation anxiety in there. It was a really long year. Let’s just say that.”

Even female pilots with civilian husbands still faced the same mobility issues, with their husbands usually having jobs that made it more difficult for female officers to transfer.

Worse, though, was the air force’s inconsistent policies on pregnancy, with some pilots claiming that the military often punished women for motherhood. Female pilots faced limited maternity leave, no paternity leave and rejections to requests to be put on the ground to ease bodily strain during their pregnancies.

“I only got four months off when I had my baby and then I had to go back to work,” said Colton. “It was very hard to turn over somebody that small to daycare.”

In October 1985, the SWINTER Aircrew Trial concluded and the results were, for all intents and purposes, deemed successful. Twenty-one women got their wings and proved that females had their place in the air force.

“They toppled the popular masculine myth about the alleged shortcomings

of women in a man’s world,” wrote Render. “They met the standards and became good solid military pilots.”

While Defence Minister Perrin Beatty declared that women could serve as pilots, navigators and flight engineers in July 1986, other questions remained: Could women go into combat? Could women become fighter pilots?

Citing a lack of evidence on the operational effectiveness of mixed-gender crews in action, the CAF announced another trial. But while Air Command prepped for a 10-woman combat program—with Brasseur once again being one of the first to sign up—so few female pilots volunteered that by July 1987, the trial was cancelled. All areas of air force employment, including fighter pilot, were now open to women.

More than that, though, a paper published by National Defence in 2022 asserted that the forces fail to provide female-specific recruitment strategies and sustainment plans so that women join and stay in the military. Brasseur, for her pa rt, recommended more fleshed-out and publicly known incentive programs.

For instance, inflexible and fragmented policies spur women to choose between work and their family lives and service couples or women in nontraditional families/marriages often get little support from the CAF.

Sexism was still a challenge, however.

“We don’t get basic training and say to the guys, ‘Okay, guys, you have to hate women; they’re no good; they can’t do anything,’” said Brasseur. “We get attitudes, values and perspectives toward women from the general population.”

And even though Brasseur opened the door for future female fighter pilots, few have even dared to step onto the welcome mat.

With the number of female fighter pilots since 1989 left in the single digits, an overarching question remains: why? For Brasseur, the answer is based on changing cultural attitudes toward values of service.

“It makes it harder to recruit forces,” she sa id, “if your societal value of service to the country is not part of your makeup.”

“We need more family-friendly help,” said Ontario MPP Karen McCrimmon, who was the forces’ first female navigator and the first female to command a squadron, “like military family support networks and military family resource centres. I don’t think we fund them well enough yet.”

Even strategic documents are too generalizable and aren’t usually developed to an operational level. According to the 2022 paper, policies need to be truly holistic and ensure they don’t unfairly disadvantage certain military members.

McCrimmon also believes these policies can be informed by greater health and sociological research on serving women, an area that’s sorely lacking in scientific literature.

“We need research,” she said. “The fighter pilot, it’s hard on the human body. I don’t think people who’ve never done it realize how challenging it really is because none of that research is there.”

“Until you get equality in numbers,” said one female pilot, “you don’t truly get equality in attitude.” L

Trial in 1981. She became the first female pilot to reach 5,000 flying hours in a CC-130 Hercules. Richard Singer of Lockheed congratulates Colton on the achievement.

By Aaron Kylie

The Canadian National Vimy Memorial was the last stop of the 2023 Royal Canadian Legion Pilgrimage of Remembrance. Pilgrims pose for a group photo at the St. Julien Canadian Memorial in Belgium.

Now it feels personal. Whether you’re in the medieval courtyard of Abbaye d’Ardenne in France, where the Nazis brutally executed 18 Canadian prisoners of war less than 48 hours after D-Day; or you’re standing on an unmarked dirt track in a wheat field just east of a tiny French hamlet where Lieutenant Reginald Barker died valiantly saving five of his Canadian comrades from being ruthlessly gunned down by SS troops around the same time; or you’re at

the Adegem Canadian War Cemetery in Belgium standing over the grave of Sergeant William S. Hawthorne, who died on Sept. 9, 1944, at the age of 26, honouring the epitaph on his marker: “His grave we may never see but may some kind friend say a prayer at this sacred spot for me;” when you stand on these hallowed grounds, you gain a new appreciation of the weight of war—and remembrance.

Some two dozen Canadians, including select rank-and-file members of

The Royal Canadian Legion, provincial RCL representatives, a trio of Legion headquarters’ staff, and guests, participated in the organization’s biennial Pilgrimage of Remembrance in July 2023. The 14-day tour of First and Second World War sites in France and Belgium focused exclusively on Canadian battlefields, cemeteries and memorials and unmarked rural roadside battle sites—where few, if any, other such excursions stop.

“It’s John’s middle-ofnowhere tours,” said John Goheen, the pilgrimage’s voraciously knowledgeable guide-cum-narrator. (Or, as one pilgrim put it: “I’m beginning to realize that every field tells a story.”) An avid military historian and former school principal from Port Coquitlam, B.C., Goheen is an expert storyteller, bringing life—and equally evocative death—to staid granite monuments and quiet abandoned hillsides alike.

The pilgrimage was, of course, much more than history lessons. A camaraderie developed among attendees

recounting was compelling, but three in particular, when combined, manifest an intriguing snapshot of Canada’s role in WW I.

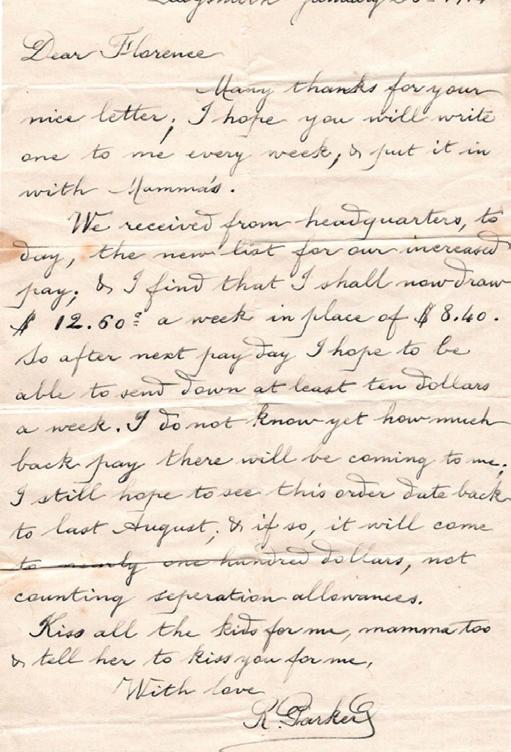

Just steps from famed John McCrae’s plot in the Wimereux Communal Cemetery in the small French town on the Strait of Dover, lies the far-lessfamous Sergeant Robert Parker of Victoria.

Sergeant Robert Parker of Victoria died on May 31, 1915, from wounds suffered during the Battle of Festubert. In a letter home

just months earlier he wished “that the war come to a speedy end.”

The tombstone of Private Russell Bernard Tobin in the New British Passchendaele Cemetery. Pilgrims Anastasia Dufour (left) and Madonna Jackson salute during a cemetery service.

(what would a day be without another joke from Padre Paul?); friendships were made and rekindled (Louison earned the nickname Google); fun and frivolity reined on bus rides (particularly with faa-thur at the back of the bus); bus drivers were loved (yeah Jaco!) or loathed (unnamed for his protection); refreshments were imbibed and solemn formal ceremonies were held.

Still, among the jampacked days, what stood out were the stories of those who made the ultimate sacrifice. And while a story of the tour could be told in dozens of different ways, guide Goheen involved participants in a particularly memorable part of the pilgrimage: relate the story of a First World War soldier at his gravesite. Each pilgrim’s

Parker’s tombstone, like all those in the Wimereux burial ground, lies flat. The sandy soil is too unstable for upright markers. Nearly 110 years after Parker’s death, pilgrim Ken Pendergast, an executive member of B.C.’s Prince George Legion Branch, is standing over Parker’s final resting place.

Pendergast, now 79, joined the Royal Canadian Air Force at 17. After a few years of service, he ended up in Prince George, eventually building a career as a top provincial forestry bureaucrat, then consultant. He retired in 2007, though in addition to his work with the Legion, he’s a consummate helping hand with numerous other community organizations. Word is, if you need a local volunteer to make it happen, you call Pendergast.

Mid-July 2023, Pendergast has the rapt attention of his fellow pilgrims as he shares details of Parker’s life and service.

Heeding the country’s call to arms, the five-foot, five-inch carpenter enlisted on Sept. 22, 1914, four months shy of his 39th birthday. Despite a reluctance to take older men with families—he was married with seven children, his youngest just five months,

his eldest 14—Parker had militia experience, having served for 12 years in the 5th Regiment, Canadian Garrison Artillery. He was also born in Caen, France, though he grew up as part of the city’s wealthy English population, so there was likely strong dual patriotic duty at play.

As a teenager, he and his older brother, Herbert, immigrated to Canada, settling on a farm near the Qu’Appelle River valley east of Regina. After marrying, he moved to Victoria with most of his in-law’s family in 1901.

“The war came, and he had to go,” his last surviving child, Gladys George, told an interviewer in 2005. She was two years old when her father sailed with the first Canadian contingent overseas in late September 1914. She would never see him again.

The following spring, Parker was assigned to the 7th Battalion (1st British Columbia). He joined shortly after the 7th had fought in Canada’s first major action in the Great War during the Second Battle of Ypres. Its men had watched as the Germans unleashed the first-ever gas attack on April 22. Then days later, as it fought to hold the line northeast of Saint Julien, the battalion had been decimated. Just about a third of its troops answered roll call on April 25. Parker was among a group of reinforcements for the 7th that arrived at the front on May 7.

The 7th was soon back in action at the Battle of Festubert, considered the second major engagement fought by Canadian troops

during the war. The First Canadian Division joined a wider British attack on the German front line near the French village on May 18. The offensive’s costliest day for the Allies was six days later.

Parker’s 7th suffered among them on May 24.