Canada’s most grown clubroot-resistant hybrids.

If you farm in an area that’s affected by clubroot, you can’t risk using half measures. InVigor® hybrid canola is the leader in managing this rising challenge, offering multiple hybrid options with rst- or secondgeneration clubroot resistance. And you can expect high performance without compromise, because all our hybrids come with patented Pod Shatter Reduction technology.

For more information, contact BASF AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273) or visit agsolutions.ca/InVigor.

Mind your ‘Ps’ and ‘Ns’ and ‘Is’ when it comes to lentil fertility in the Brown, Dark Brown and thin Black soil zones. Phosphorus (P) can be a limiting nutrient in lentil production, but nitrogen (N) and inoculants can also affect lentil yield and profits. A recent Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture ADOPT (Agricultural Demonstration of Practices and Technologies) project looked at these three fertility inputs and how the latter two interact to impact production.

There are more options for cereal growers.

Shedding light on photosynthetic efficiency. 22

Searching novel genes for resistance to rusts, bacterial leaf streak and tan spot. 24

Putting a known stripe rust resistance gene to work again.

The first Canadian field trial is being conducted in 2024.

Using accelerated breeding to bring new varieties to producers.

The greatest benefits are yield and income stability.

Using cover crops like fall rye to regulate soil moisture in Manitoba.

by Kaitlin Berger

The farm show I attended this summer happened to fall during a sweltering week in July. It was the perfect recipe for dust-covered boots and sunburns. Ducking under one of the tents at the Agriculture and AgriFood Canada booth, I found a brief break from the sun – and a fascinating conversation with a plant breeder.

He walked me through the plots of durum in front of us, explaining the features of varieties from 1971 to 2024. Some focused on high protein concentration. Others offered excellent standability or resistance to wheat stem sawfly. He left me with the reminder that plant breeders are a proactive group. Whether growers are facing disease, insect pests, devastating weather events or specific consumer demand, their goal is to have varieties that are ready for it.

This conversation reminded me of the first time I heard about CRISPR/ Cas9 (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) from my co-worker with a science background. I was a writer and a fresh graduate with an arts degree. I didn’t initially perk up when she started talking about the genetic code of plants, but I was hooked by the end of our conversation. A few days later, I was engrossed in the topic, listening to podcasts about CRISPR and hearing the exciting possibilities of using it to edit certain pieces of DNA to enhance or remove characteristics in a plant. It was another example of the scientific community’s agility, anticipating solutions to problems that may arise in the future.

Plant breeders are constantly looking ahead - like most farmers. That’s good news and something to think about as you’re watching the yield monitor...

Farmers have a similar perspective, constantly anticipating the next challenge. While you might not be thinking about plant breeding tools when you’re in the thick of harvest with late nights combining and hauling grain, you’re likely evaluating your crop’s yield, making judgments about its quality and determining what you can do better in the future.

Whether it’s using tools to speed up the breeding process or bringing varieties with better disease resistance to the market, plant breeders are doing what they can to provide more and more options to Canadian growers. The flax breeder on page 12 is looking at accelerated breeding techniques in flax. You can also read about a wheat breeder on page 22 who is searching for new resistance genes to rusts, bacterial leaf streak and tan spot.

Plant breeders are constantly looking ahead – like most farmers. That’s good news and something to think about as you’re watching the yield monitor under the harvest moon.

@TopCropMag

and

subscription inquiries or changes, please contact Angelita Potal, Customer Service Administrator Tel: (416) 510-5113 | Fax: (416) 510-6875 Email: apotal@annexbusinessmedia.com Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

Western Field Editor BRUCE BARKER (403) 949-0070 bruce@haywirecreative.ca

National Account Manager QUINTON MOOREHEAD (204) 720-1639 qmoorehead@annexbusinessmedia.com

National Account Manager REENA UPPAL (437) 922-7359 ruppal@annexbusinessmedia.com

Account Coordinator JULIE MONTGOMERY (416) 510-5163 jmontgomery@annexbusinessmedia.com

Group Publisher MICHELLE BERTHOLET (204) 596-8710 mbertholet@annexbusinessmedia.com

Audience Development Manager SERINA DINGELDEIN (416) 510-5124 sdingeldein@annexbusinessmedia.com

Team Lead/Media Designer BROOKE SHAW CEO SCOTT JAMIESON sjamieson@annexbusinessmedia.com Printed in Canada ISSN 1717-452X

BY KAITLIN BERGER

For growers considering cereal varieties for 2025,Top Crop Manager has compiled a list of options. All information comes from the respective seed companies.

CDC Envy is an early maturing CWRS. Yielding 114 per cent of Carberry in the Western Canadian Parkland registration trials, CDC Envy offers good standability and reduced plant height with an MR rating for stripe rust, an I rating for Fusarium head blight (FHB) and stem rust and an R rating for common bunt and leaf rust. This is a good replacement for those who have grown AAC Redberry and are looking to advance yield and standability with early maturity.

TriCal Surge is a spring forage triticale with excellent forage and silage yield potential, and forage quality attributes. It has later maturity, shorter stature with improved lodging resistance.

AAC Prairie is a two-row malting barley with the highest enzyme activity since AC Metcalfe, surpassing it. It has good yield potential (102 per cent CDC Copeland) and standability, short straw, an MR rating for smut, stem rust and net blotch and an I rating for FHB resistance. It’s listed on the Canadian Malting Barley Technical Centre (CMBTC) recommended variety list.

AAC Lariat is a two-row feed barley with exceedingly high yield potential (104 per cent CDC Austenson), shorter straw, better lodging resistance, plumper grain and good feed quality parameters with an R rating for smut, stem rust and net blotch resistance.

AB Maximizer is a two-row feed/forage barley with excellent yield potential (102 per cent CDC Austenson), good lodging resistance and earlier maturing than the check. It has improved forage quality over CDC Cowboy and AB Cattlelac, an R rating for surface-borne smut and stem rust and an I rating for FHB, scald, spot and net blotch resistance.

Kalio is a white milling oat with early maturity (-4d vs CS Camden) and good yield potential (96 per cent CS Camden), shorter stature and good lodging resistance

with the best resistance to crown rust in its class, rated as MR. An approved milling oat variety by Richardson Milling, it has excellent milling quality.

AAC Darby VB is a very early maturing midgetolerant wheat. It’s a high-yielding, awned, hollowstemmed spring wheat with good protein, an I rating for FHB and an MR rating, or better, for all rusts.

CDC Anson has the shortest straw available. It is a new white milling oat with very high yield potential and the best standability available. Its very short plant height is shorter than CS Camden and AC Summit. It has outstanding milling characteristics with high plump percentages, low thins, excellent groat percentage, high beta-glucan content and total dietary fibre content and

has seen early end-use demand.

SU Performer is a hybrid fall rye with exceptional versatility, winter hardiness and high, consistent grain yields alongside excellent forage production. It delivers yields reaching 123 per cent of Hazlet and 104 per cent of Trebiano. With options for marketing, milling, distilling, ethanol and feed, it offers flexibility in end-use options, matures early, stands strong, and its shorter height simplifies management.

SU Cossani is a profitable, sustainable hybrid fall rye option. As the go-to for dry, sandy soils, it thrives under stressed conditions with consistently high yields. It’s a top performer with up to 120 per cent of Hazlet’s yield,excelling in milling, distilling, ethanol and feed markets. Its improved ergot rating and aggressive tillering ensure sustainability in crop rotations. It matches Hazlet’s winter survival and stands out with rapid establishment, early maturity and exceptional standability.

AB Standswell is a six-row, general purpose barley and the first nitrogen-use efficient barley in Canada, nine per cent more efficient than most barley varieties to protect yield under limited nitrogen. It’s a semi-dwarf with good lodging resistance, a smooth awn with high grain and forage yields and it’s seven per cent higher than the seed guide check and three per cent higher than the forage check.

AAC Spike is a CWRS with exceptionally short strong straw and an excellent disease package, well suited to high moisture, high fertility areas. It has an MR rating to FHB, R ratings to leaf, stem and stripe rust, and good resistance to pre-harvest sprouting.

AAC Westlock is a CPSR, a great fit in traditional CPS growing areas. It’s 8 cm taller and yields 105 per cent of AAC

PRINCE GEORGE Wednesday, Oct. 23

Foothills Boulevard Regional Landfill

6595 Landfill Rd., V2K 5H3

QUESNEL Thursday, Oct. 24 Four Rivers Co-operative 1280 Quesnel Hixon Rd., V2J 5Z3

VANDERHOOF Monday, Oct. 21 Four Rivers Co-op 1055 Hwy. 16 W., V0J 3A0

VERNON Tuesday, Oct. 22 Growers Supply Co. 1200 Waddington Dr., V1T 8T3

WILLIAMS LAKE Friday, Oct. 25

153 Mile Fertilizer

#80-5101 Frizzi Rd., V2G 5E4

Penhold with an MR rating to FHB and R ratings to leaf, stem and stripe rust.

ORe BOOST is a forage oat with an upright leaf structure that promotes leaf retention and improves compatibility with companion species in a forage blend. Higher stem density allows finer stems for improved forage quality. Sold with a VUA (Variety Use Agreement), it has strong straw and late maturity for a wide harvest window.

CDC Durango is a two-row rough awned feed barley. This is the CDC Austenson with higher yield and stronger straw, an average yield of 104 to 106 per cent of CDC Austenson with an I rating to FHB.

Alotta is a red-seeded, special-purpose wheat, suitable for feed or ethanol. Alotta has short strong straw and exceptional yield potential averaging 127 per cent of AAC Brandon with an MS rating to FHB and R ratings to leaf, stem and stripe rust.

Southern Alberta

BARNWELL

Tuesday, Oct. 22

Independent Crop Inputs Inc. N.W. of 27-9-17 West of Hwy. 4, 94035 Range Rd. 17-3, T0K 0B0

BARONS Thursday, Oct. 24

South Country Co-op Ltd. 123014 Range Rd. 234, T0L 0G0

BENALTO Friday, Oct. 25

Benalto Agri Services Ltd. 38531 Range Rd. 2-4, T0M 0H0

BROOKS Friday, Oct. 25

South Country Co-op Ltd. 7th St. and Industrial Rd., T1R 1B9

CARSELAND Monday, Oct. 21

Cargill 263026 Township Rd. 221, Corner Hwy. 24 & Agrium Rd., T0J 0M0

DRUMHELLER Monday, Oct. 21

Kneehill Soil Services Ltd.

700 South Railway Ave. W., T0J 0Y0

DUNMORE

Thursday, Oct. 24

AgroPlus Inc. 2269 - 2nd Ave., #22, T1B 0K3

FOREMOST

Wednesday, Oct. 23

AgroPlus Inc. 199 1st Ave. W., T0K 0X0

FORT MACLEOD

Wednesday, Oct. 23

Nutrien Ag Solutions 250 Boyle Ave., T0L 0Z0

HANNA

Wednesday, Oct. 23

Hanna UFA Farm & Ranch

Supply Store

601 1st Ave. W., T0J 1P0

HIGH RIVER

Friday, Oct. 25

Nutrien Ag Solutions 498012 – 122 St. E., T1V 1M3

HUSSAR

Tuesday, Oct. 22

Richardson Pioneer 151 Railway Ave., T0J 1S0

INNISFAIL

Thursday, Oct. 24

Central Alberta Co-op 35435 Range Rd. 282, T4G 1B6

LETHBRIDGE COUNTY

Tuesday, Oct. 22

Parrish & Heimbecker Wilson Siding 75006 Hwy. 845, T1K 8G9

LOMOND

Monday, Oct. 21

South Country Co-op Ltd. 115 Railway Ave., T0L 1G0

OLDS

Wednesday, Oct. 23

Olds UFA Farm & Ranch

Supply Store 4334 46th Ave., T4H 1A2

OYEN

Thursday, Oct. 24

Richardson Pioneer 1 mile East on Hwy. 41, T0J 2J0

THREE HILLS

Tuesday, Oct. 22

Richardson Pioneer 503 - 3rd St. S.W., T0M 2A0

VETERAN Friday, Oct. 25

Richardson Pioneer 400 Waterloo St., T0C 2S0

WARNER

Monday, Oct. 21

Nutrien Ag Solutions

Junction Hwy. 4 & Hwy. 36, ½ mile N. on the Access Rd., T0K 2L0

Northern Saskatchewan

BIGGAR

Tuesday, Oct. 8

Parrish & Heimbecker 12 km West of Biggar on Hwy. 14, S0K 0M0

BRODERICK

Friday, Oct. 11

Rack Petroleum Ltd. Broderick Access and Hwy. 15, S0H 0L0

CARROT RIVER Tuesday, Oct. 8

Richardson Pioneer 265 2nd St., S0E 0L0

HAFFORD

Wednesday, Oct. 9

AgriTeam Services Inc. 11 km West of Hafford on Hwy. 340, Turn North on Jackson Rd., S0J 1A0

HUMBOLDT Thursday, Oct. 10

Humboldt Co-op 10564 Crawley Rd., S0K 2A0

IMPERIAL Friday, Oct. 11

Richardson Pioneer 1 mile North on Hwy. 2, S0G 2J0

KINDERSLEY

Wednesday, Oct. 9

Simplot Grower Solutions 907 11th Ave. E., S0L 1S0

MEADOW LAKE

Monday, Oct. 7

Meadow Lake Co-op 513 9th St. W., S9X 1Y5

MELFORT

Wednesday, Oct. 9

Nutrien Ag Solutions 810 Saskatchewan Dr. W., S0E 1A0

NEILBURG

Friday, Oct. 11

Nutrien Ag Solutions 300 Railway Ave. E., S0M 2C0

NORQUAY Tuesday, Oct. 8

Norquay Co-op 13 Hwy. 49 E., S0A 2V0

NORTH BATTLEFORD Thursday, Oct. 10

Cargill Ltd. 12202 Durum Ave., S9A 2Y8

PORCUPINE PLAIN

Monday, Oct. 7

Nutrien Ag Solutions

Hwy. 23 W., S0E 1H0

PRINCE ALBERT

Thursday, Oct. 10

Lake County Co-op 4075 5th Ave. E., S6W 0A5

ROSETOWN Thursday, Oct. 10 Rack Petroleum Ltd. 3 miles North East of Rosetown on Hwy. 7, 32 Airport Rd., S0L 2V0 ROSTHERN Friday, Oct. 11 Blair’s Crop Solutions N.E. 33-42-3 West of the 3rd, 2 km West of Rosthern, S0K 3R0

SPIRITWOOD Tuesday, Oct. 8

Simplot Grower Solutions ½ mile on Hwy. 24 N., S0J 2M0

WILKIE Monday, Oct. 7 Nutrien Ag Solutions 1½ miles West of Wilkie on Hwy. 14, S0K 4W0

WYNYARD Wednesday, Oct. 9 Wynyard Co-op Assoc. Ltd. 571 South Service Rd., S0A 4T0

YORKTON Monday, Oct. 7

SynergyAG 21 Rocky Mountain Way Rd. (Hwy. 9 S.), S3N 4B2

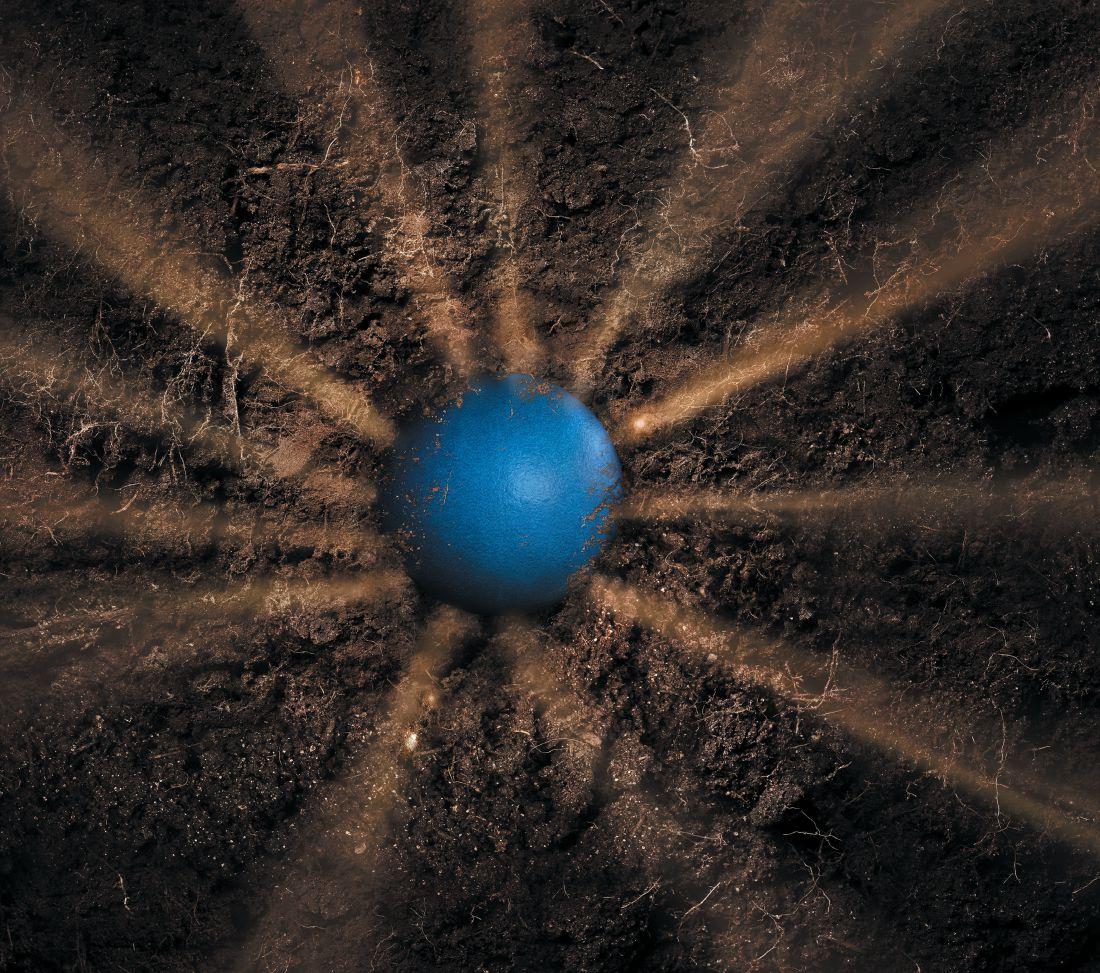

Shedding light on photosynthetic efficiency in canola.

BY PETER HOHENADEL

Canola breeding has come a long way since Canadian researchers isolated and bred low erucic acid Brassica napus plants in the 1970s. Canadian canola growers have benefitted from the introduction of herbicide-resistant traits, as well as specialty oil, drought tolerance, season length and, of course, ever-increasing yield.

It may seem like we have reached the limits of what can be achieved through canola breeding. But a new day has arisen on the opportunity to increase canola yields through more efficient use of sunlight. A research team at the University of Alberta (U of A) has been assessing photosynthetic efficiency in canola since 2021.

The project is led by plant scientist, Linda Gorim, from the faculty of Agricultural, Life and Environmental Sciences at the U of A, where Gorim also serves as the Western Grains Research Foundation (WGRF) chair in cropping systems. The research project was 80 per cent funded by Results Driven Agriculture Research (RDAR), the largest producer-guided funder of agriculture research projects in Alberta. Contributions from Alberta Canola Producers Commission and WGRF rounded out the project funding.

Beginning in 2021, Gorim’s team assessed 170 canola breeding lines to determine if any of these plants demonstrated exceptional photosynthetic efficiency compared to two, commercially available canola hybrid checks. In other words, they looked for plants that were able to capture more sunlight and convert that light into photosynthesis, a plant’s innate ability to convert light into food.

This was not a controlled experiment in a greenhouse or under irrigation, but plants grown in a

real-world environment. “That complicates our data analysis since drought and other variables were factors to consider,” says Gorim.

Each year, the team assessed the Brassica lines and checks using a handheld device called a MultispeQ meter, developed at Michigan State University. The light-emitting device measures the amount of light that passes through the leaf. Any light that does not pass through is converted to food through photosynthesis. Readings on the MultispeQ meter are taken in the field and uploaded to a smartphone app for analysis.

Typical commercial canola hybrids show 40 to 45 per cent photosynthetic efficiency, but researchers found one promising line at 55 per cent.

Gorim says commercial canola hybrids typically retain 40 to 45 per cent of the light that hits the leaf surface. The rest of the light is reflected or dissipated as heat energy. “We were looking for a needle in a haystack,” Gorim adds. “So even if we find five promising lines, we will have achieved our goal.” For example, one promising line they assessed showed photosynthetic efficiency of about 55 per cent, a significant increase over current commercial hybrids.

That laborious fieldwork is now complete. Analyzing the mountain of data falls to U of A master’s candidate, Fernando Guerrero-Zurita, who has been working with Gorim on this project. “Plants make their own food through photosynthesis,” Guerrero-Zurita explains. “There are components in the leaves, hairs and stomata that can capture light for photosynthesis. If we can optimize those components within the leaf, we can

We’ve developed the high yielding, straight cut hybrids you demand. Our 2025 canola seed lineup is our best performing ever. We’re not holding back. We’re ready to be your #1 canola seed.

capture more light and increase biomass.”

“We don’t expect to beat the commercial hybrids in yield,” Guerrero-Zurita adds. “But some of the lines we assessed had more partitioning of biomass than the checks. That’s very promising.”

Gorim says the research team has learned to recognize visual traits that may signal increased photosynthetic efficiency. “Our data should help us to determine visual clues such as whether there are more stomata on the bottom or top of the leaf. We may also learn that photosynthetic efficiency is determined in part by whether leaves have more or fewer hairs, which are important for temperature control.”

A core outcome of this research project is a better understanding of all the factors that may affect photosynthetic efficiency. “We’re still early in the development process,” Linda Gorim cautions. “But with the capabilities of molecular technology and artificial intelligence, it will be simpler to incorporate photosynthetic efficiency into a commercial breeding program, once we identify a line with exceptional ability to convert light into food.”

The U of A photosynthetic efficiency project is just one example of the in-field diagnostics now available through the PhotosynQ project out of Michigan State. Gorim says there are now about 20,000 diagnostic projects in play around the world, many of them in underdeveloped countries. “Those countries may be disadvantaged by the scarcity of plant tissue labs,” she says.

With the handheld MultispeQ device, it takes less than three minutes for a producer to assess whether a plant is photosynthesizing efficiently. Previously, by the time a producer received lab results, it could be too late to remedy a crop development situation. Thanks in part to seed money from organizations like the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the use of this in-field diagnostic tool is getting a lot of traction in the underdeveloped world, according to Gorim.

Closer to home, it’s not hard to imagine that a device like the MultispeQ meter that costs $3,000 in 2021 may cost 20 per cent of that in five years. That could open the door to reducing Canadian canola growers’ dependence on plant tissue labs, and enabling those growers to diagnose their crop in-field with a handheld device and smartphone app. The tool has already been widely used to assess photosynthetic efficiency in wheat, and there’s no practical barrier to assessing this trait in pulse crops, for example.

ABOVE Master’s candidate, Fernando Guerrero-Zurita, assesses biomass in canola breeding lines.

The Canola Council of Canada has set a yield improvement goal of 30 per cent, and the U of A project may help the industry achieve this goal. “As we start to see the effects of climate change, it would be great if crop production could benefit in some way from the additional light and heat we are experiencing,” says Linda Gorim. “Photosynthetic efficiency has the potential to achieve that. My hope is that commercial breeders can work with plant physiologists to come up with new canola hybrids with better photosynthetic efficiency and higher yield potential.”

“Ultimately, it doesn’t matter how much nitrogen you put on a crop,” she adds. “If the crop is not using sunlight efficiently, then we’re not going to be able to push yield as fast as we want to.” Thanks to this research project, commercial breeders will soon know a lot more about how to let more sunshine into canola – without affecting the plant’s physiology.

Trusted solutions like TRIBUNE™ nitrogen stabilizer, ANVOL™ nitrogen stabilizer and SUPERU™ fertilizer deliver higher active ingredient concentrations that low-rate products can’t match. See how other stabilizers stack up to proven solutions that defend your nitrogen and your bottom line.

BY KAITLIN BERGER

The past few years have seen flax acres waning in Western Canada. Straw management for flax can be a hassle for farmers and – with competition from the Black Sea region, Russia and Kazakhstan –the price for Canadian flax is less attractive. While flax remains an excellent option for diversifying crop rotation, it’s difficult to compete against the choice to grow canola. Research to improve flax varieties is crucial for ensuring flax is an attractive option to include in rotation –and the accelerated breeding approach holds promising results.

“Whenever I’m doing extension to the farmers, I always put the emphasis, stress to them, keep your rotation,” says Bunyamin Tar’an, the Saskatchewan ministry of agriculture strategic research program (SRP) chair in chickpea and flax breeding.He recommends a four-year rotation, growing oilseed such as canola, flax or mustard, as well as pulses between two years of cereals.Reducing this rotation is a recipe for new disease development, whether it’s Aphanomyces in pulses or blackleg in canola.

The agronomic implications of growing flax are positive, but Tar’an says it has to be economical for farmers. While flax has the economic advantage of relatively low inputs, the yield tends to lag. Tar’an attributes this to the fact that flax originally was domesticated for fibre – not for seed or oil – and today’s flax varieties are still geared toward strong fibre in the straw. “I’d like to change the morphology of the flax to be geared for seed formation, and that’s how the yield will improve in the future,” he says.

To develop improved varieties, Tar’an is investigating a new technique

called accelerated breeding. While it’s already being used in other crops including cereals, Tar’an’s goal is to determine if the rapid cycling of plant growth will work for flax. The project began in 2022 and is in year three of four, funded by the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture (Agriculture Development Fund), Western Grains Research Foundation, SaskFlax and the Manitoba Crop Alliance. Tar’an works closely with Megan House, who is responsible for coordinating the project on a daily basis.

The accelerated breeding technique exposes the plants to extended daylight, so they can complete their lifecycle in a very short time. “In a way, you put the plants under stress, so that the plants will flower early and then produce few seeds and complete its life cycle very quickly,” says Tar’an. Under normal conditions in Western Canada, a plant might experience 17 hours of daylight on the longest day of the year. Accelerated breeding hosts the plants in a growth chamber or greenhouse and exposes them to 22 hours of daylight with a two-hour dark period.

The first stage of the project focused on optimizing the conditions for growing the plants, ensuring they still produced a reasonable number of seeds. They explored light intensity and spectrum, whether there were differences between how flax varieties responded. “Some species are sensitive to the day length,” says Tar’an. “Once you expose them to a long day like this, they’re not even flowering.” It’s not as simple as introducing germplasm from tropical regions or a wild species that is good for disease resistance to try to

diversify the varieties in Canada. They must be able to flower under long days or accelerated breeding conditions.

The results look promising for speeding up the process. The standard breeding process under controlled conditions used to produce three generations per year with an average of four months from seeding to harvest. Accelerated breeding techniques have doubled the outcome, allowing for six generations per year.

While the process for crossing in the breeding has been reduced from four months to 2.5 months by making the cross under 22-hour light and high temperature, the success rate of crosses under accelerated breeding is only about 65 per cent for some cultivars. By the fourth year of the project, Tar’an hopes they’ll know if the technique is feasible on a routine basis.

Accelerated breeding has some other significant implications for flax, specifically for future research projects. Most projects start with the plant population development to create inbred lines where researchers examine for visual traits such as maturity, plant height or seed size and link them with their genetic makeup. This population development usually takes about two years, but accelerated breeding could decrease the

process to one year. “That’s a big savings,” says Tar’an.

Pairing accelerated breeding with molecular markers is another game-changer. Molecular markers allow researchers to select specific traits using a tiny piece of young leaf at an earlier stage. “Some DNA markers have a 99 per cent accuracy, so you don’t even have to grow the plants to maturity to make a selection,” says Tar’an. For this project, Tar’an uses molecular markers to select for resistance to rust and powdery mildew and combine them with yellow seed colour in flax.

The standard breeding process is long, usually taking 10 to 12 years from crossing until a variety is created. Between 2020 and 2023, three new flax varieties for improved yield were released – and Tar’an’s accelerated breeding program shows promise for increasing flax variety options for producers.

Flax brings diversity to rotations in fields across the Prairies. As new varieties are created at a quicker pace, Tar’an hopes the incentive for farmers to grow flax will increase too. “It’s not just about the agronomy,” he says, “but also yield, quality and the economy, about how we can deliver it to be desirable for farmers.”

12:00PM ET

The Influential Women in Canadian Agriculture program honours women who have created lasting impacts on Canadian agriculture. Since 2020, the program has recognized 33 women who have positively contributed to the industry, whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services, completing research, leading marketing or sales teams, and more.

The program receives dozens of incredible nominations every year, highlighting just how many influential women are working within Canada’s agriculture industry.

Join us in our annual virtual summit on October 22 at 12 p.m. ET. Featuring our hand-selected group of honourees and other prominent ag trailblazers, this free event will provide a platform for the exchange of knowledge and ideas as our guests share their thoughts through interactive sessions.

The greatest benefits are yield and income stability.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Too hot. Too dry. Too wet. Too cold. These extremes in weather can impact flax and chickpea production differently. To see if intercropping chickpea and flax could reduce disease pressure, stabilize yield, and expand where these crops could be grown outside of their normally adapted area, research led by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) is looking to develop agronomic practices that could encourage adoption of intercropping.

“Producers need regionally relevant, multi-site data on the potential benefits of flax-chickpea intercropping,” says research scientist, Bill May, at AAFC Indian Head, Sask. “This data will facilitate sound decision-making and potentially increase returns to producers.”

Chickpea is a high-value crop, but is susceptible to Ascochyta blight, late maturity, green seed and problems with harvestability. While Ascochyta blight can be controlled with fungicides, it can still result in total crop failure, and fungicide insensitivity to strobilurin fungicides has been confirmed on the Prairies. Chickpea is best adapted to drier areas of the southern Prairies and its adaptation further north is hindered by disease pressure and later maturity.

Flax is more suited to northern areas of the Prairies where moisture is less of a limiting factor in crop growth. However, pasmo disease is a major limitation.

ABOVE A chickpea-flax intercrop trial establishes seeding rate recommendations.

There are several reasons why intercropping could make sense. Earlier research at Redvers, Sask. found intercropping could drastically reduce the need for a fungicide application to control Ascochyta blight. Pasmo disease in flax might be lower, and reduced flax density in the intercrop could make flax residue management with baling or burning not necessary.

To develop a greater agronomic understanding of chickpea-flax intercropping, a three-year study was conducted at five sites in Saskatchewan in 2017, 2018, 2019, 2021 and 2022. The five locations were at Indian Head, Redvers, Swift Current, Melfort and Saskatoon with Indian Head and Redvers covering the full five years and the remaining sites the latter three years.

The objectives were to develop an agronomic system for intercropping chickpea with flax in Saskatchewan to determine if the area of adaption for chickpeas and/ or the economic area of production for flax can be expanded by utilizing a chickpea-flax intercrop. Other objectives were to determine if intercropping can be used to reduce disease pressure in chickpeas and/or flax, and to improve the agronomic performance of chickpea and/or flax.

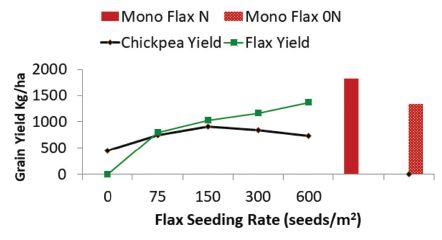

The seeding placement compared was alternating rows or intermixed with both crops in the same row. Five flax seeding densities were compared at zero, 7.5, 15, 30 and 60 seeds per foot square (zero, 75, 150, 300

and 600 seeds/m2) which equated to approximately zero, five, 10, 19 and 38 pounds per acre. A flax monocrop seeded at 60 seeds/ft2 (600 seeds/ ha) was also included in the trials.

Two nitrogen (N) rates of zero and 53 pounds per acre (zero and 60 kg/ ha) were compared to see how flax responded to N rate.

The trials were seeded into wheat and canary seed stubble using a no-till cropping system. The flax variety used was CDC Glass, and the Kabuli chickpea variety was Leader. The target plant density for chickpea was four plants/ft2 (40 plants/m2) adjusted for germination and estimated field mortality at 30 per cent.

Weed control included an Authority (sulfentrazone) application prior to or up to three days after seeding, and in-crop broadleaf herbicides were applied depending on the weed spectrum at each site. The trials were inoculated with the Ascochyta rabiei pathogen.

With a massive amount of data to analyze, the researchers are still sifting through the research to confirm trends. May says that flax seeding rate has the largest impact on the intercrop. Chickpea plant density dropped, as expected, as flax seeding rate increased to around 15 seeds/ft2, but then leveled off at higher seeding rates. Also as expected, flax plant density increased linearly as flax seeding rate increased.

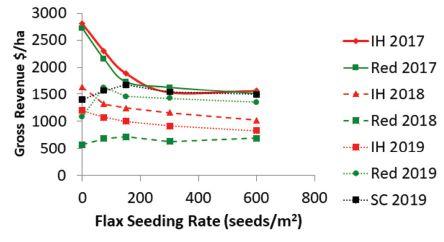

“As the flax seeding rate increases, chickpea grain yield decreases but the overall economic return appears to be fairly stable once the seeding rate reaches 15 viable seeds per square foot,” says May.

An example comes from the Redvers 2022 site. Chickpea yield in a monocrop was 404 pounds per acre (454 kg/ha) rising to 661 lb/ac (743 kg/ha) at the 7.5 seeds/ft2 and to 808 lb/ac (908 kg/ha) at 15 seeds/ft2. As the flax seeding rate continued to increase, chickpea yield remained statistically similar to the yield at 15 seeds/ft2. For flax yield, it increased with seeding rate rising from 694 lb/ac (780 kg/ha) at the 7.5 seeds/ft2 seeding rate up to 1,220 lb/ac (1,373 kg/ha) at the highest seeding rate.

Yield trends between mixed and alternating rows of the intercrop across the range of flax seeding rates seemed to be similar.

No clear trends emerged with N rate. Six site-years had the highest flax yield with the 53 lb N rate, six were similar between zero and 53 lb, and one site had the highest yield at zero lb N. Chickpea yield response to N rate showed a similar pattern with five site-years having the highest rated with zero lb N, five with 53 lb, and three having similar yield with the two N rates.

There was also a trend for chickpea green seed to decrease as the flax seeding rate increased. For example, in the chickpea monocrop, green seed was as high as 17 per cent at Redvers in 2019, with the remaining seeding rates statistically similar ranging from 1.4 to 5.1 per cent green seed. Other sites had similar trends and support the theory that a flax intercrop will reduce green seed levels in chickpea.

Under low disease pressure there was a trend that increasing the flax seeding rate decreased disease incidence in chickpea.

Gross revenue calculations have been done for the 2017 through 2019 and 2021 sites. Generally, gross income stabilized around 15 seeds/ft2 flax seeding rate, although there was some variation between sites. Indian Head and Redvers 2017 sites had very high gross returns with monocrop chickpea, but other sites had intercrop returns more similar to the chick-

pea monocrop.

For growers new to chickpea-flax intercrop, May recommends a full seeding rate of chickpea and a 30 seeds/ft2 seeding rate of flax. If successful, the flax seeding rate could be cut to 25 seeds/ft 2 of flax. The reason is that chickpea needs to be sown deeper into soil moisture at least one inch deep, which can reduce flax emergence. This is the case with both crops being placed through the seed opener.

However, if a farmer can run the chickpea down the fertilizer knife and the flax sown shallower with the seed opener, the 25 seeds/ft2 seeding rate might be adequate.

Phosphate fertilizer (MAP) is also recommended as a starter fertilizer. If the intercrop is being placed through the seed opener, then MAP could be side-banded. If the crops are being placed separately, then a safe seedrow rate of MAP could be placed with the chickpea.

May says that the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF) started conducting field-scale trials on the intercrop in 2023. He says it was their highest gross crop grown in the trials in 2023.

“Stability of economic returns is the greatest advantage to the intercrop,” says May. “But we had dry to normal years during the research. We need to have some normal to wet years to understand where the intercrop can be adapted. In wet years, we have had zero chickpea yield.”

cover crops like fall rye to regulate soil moisture in Manitoba.

BY JOEY SABLJIC

Cold, wet and waterlogged soils are just a fact of life in many fields across Manitoba early in the growing season, and growers have no choice but to wait out the moisture.

The biggest challenge is that it can be weeks before soils are dry enough to be able to walk fields, let alone drive in with equipment. That means the already short growing season gets shorter, and precious time that could be spent growing a profitable crop is lost.

Afua Mante, an assistant professor in the Department of Soil Science at the University of Manitoba, is exploring how cover crops, like fall rye, can be used to improve soil trafficability – the ability of soils to carry vehicular traffic and withstand the weight of machinery. This way, growers can get into their fields faster, without getting bogged down to the axles or causing serious compaction.

“Soil trafficability is a major issue under our climate at the beginning of the growing season – especially in the heavy, clay soils of the Red River Valley area,” explains Mante. “For farmers, it’s incredibly difficult and frustrating, as any day delay has ripple effects on plans.”

The main idea behind Mante’s work is surrounding fall rye. Growers seed fall rye in the late summer for the following spring. The fall rye then puts on enough biomass so that it can take up moisture. At the same time, the rye’s root system forms natural channels that help with water movement down into the soil profile.

“It’s about achieving a good balance – you’re removing the excess moisture that prevents you from getting onto your fields, while still storing that moisture deep in the soil profile for drier periods,” says Mante.

She adds that, for the fall rye to be effective at regulating excess water, it needs enough of a chance to establish, so that it can actively remove water and create the root system channels.

Much comes down to the timing, and Mante and her fellow researchers are trying to nail down the ideal seeding date for fall rye, so that it has between

four to six weeks to establish before the temperature drops to around 10 C.

ABOVE Afua Mante explores how cover crops can be used to improve soil trafficability.

“The conventional recommendation has been to seed fall rye on or around the week of September 15. But by the time you get to that date in Manitoba, we have less chance of having four to six weeks for good establishment before the temperature cools down,” says Mante. “Our field work is showing us that it’s too late to give fall rye a good head start, so you won’t see any major improvements in regulating moisture.”

Mante notes that, even if the fall rye isn’t quite developed enough to deal with surface water, growers are still helping to build up soil carbon and microbial communities.

New pre-mixed formulation – now available in bulk.

It doesn’t get simpler than this. Centurion® ADV herbicide delivers the effective grassy weed control you trust, now in a convenient pre-mixed formula with built-in adjuvant. It also offers peace of mind with a Performance Support Guarantee in the unlikely event of weed escapes1. So why mess with anything else? Visit agsolutions.ca/CenturionADV to learn more.

1 When adhering to specified rates outlined in the product label.

While Mante is focused on the impact of cover crops on early-season soil water regulation and trafficability, she says growers need to reimagine the way they use cover crops to protect their soils year-round.

The use of cover crops in Manitoba is a well-known and proven practice for preventing erosion during the off-season.

But in addition to erosion prevention, Mante says that cover crops – when seeded at harvest, or inter-seeded with canola, soybean or cereal crops – help to build and preserve root channels that move moisture away from the soil surface and into the soil profile. This helps reduce the risk of drought conditions during the season.

Specifically, having well-established cover crops can also reduce the potential damage from high-intensity rainfall that often follows dry periods.

“It’s the drought periods that we have to be more concerned about. Because around that time, it gets dry and goes on for a few days or weeks. Then, suddenly we’ll receive 40 millimeters of rainfall in the span of an hour,” explains Mante. “And the rate of

What’s

At Pioneer® brand seeds, innovation drives everything we do. From the scientists in the lab to your local teams with boots on the ground, we collaborate tirelessly, gathering and analyzing billions of data points annually. All to ensure we’re delivering industry-leading solutions to the farmers and families who count on us every day. Visit Pioneer.com/WhatsNext to see how we’re innovating the future of farming.

Optimum® GLY is the highest yielding glyphosate-tolerant trait on the market, created to unlock agronomic excellence.

Pioneer® brand canola hybrids with the Optimum GLY trait allow you to make the herbicide applications you need without impacting the yield potential of the hybrids you love.

Cover crops can help mitigate the risk of drought conditions by preserving root channels that move moisture away from the soil surface.

deformation of the soil under such a condition is huge compared to if you took your time and allowed water to move through over two or three days.”

This soil deformation leads to surface crusting, which essentially seals off the soil to water and increases runoff.

“If that water isn’t percolating through deep soil layers to store water for drought conditions, then your soil is going to be at greater risk,” says Mante.

Trafficability and soil structural protection are one aspect of a larger ongoing cover crop project at the University of Manitoba, with funding support from the Sustainable Canadian Agricultural Partnership program, Manitoba Crop Alliance, Manitoba Canola Growers, and Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers.

Mante is part of a team that includes Yvonne Lawley, Department of Plant Science and Francis Zvomuya, Department of Soil Science.

Together, the researchers are exploring ways cover crops can be integrated into farm management practices to support agronomic goals while also improving

soil health for sustainable crop production and a healthy environment.

“When you think about these soils across the province, they have been in production for a long time,” says Mante. “While intensive agricultural practices have been instrumental in the progress we have made as an industry, we also recognize that these practices are associated with risks such as soil compaction, salinization and erosion. For that reason, we need to adopt beneficial management practices that reduce these risks and ensure our soils can support crop production and other ecosystem services.”

Continued research is essential. As much as cover crops have the potential to bring major benefits, timing is still a challenge since they need to be seeded after harvest – and that can be difficult following certain crops in Manitoba.

Mante also cautions that the positive effects of cover cropping – like moisture regulation – aren’t going to be seen or felt instantly. “We need patience,” says Mante, “and a systems approach that takes the entire year, the climate, soil characteristics and agronomic practices into account to first allow the soil to heal.”

Searching novel genes for resistance to rusts, bacterial leaf streak and tan spot.

BY DONNA FLEURY

Wheat varieties with good disease resistance packages to control rust diseases, one of the major challenges for wheat production, are currently available to growers. However, the spread and emergence of new pathogen races can overcome genetic resistance. Wheat breeders and researchers continue to search for new resistance genes to keep genetic resistance effective.

“In our Cereal Breeding Lab (CBL) at the University of Alberta (U of A), our focus is primarily on variety development for Western Canada. However, we also include a few projects in the program that are more focused on genetics,” explains Gurcharn Brar, assistant professor and wheat breeder at U of A and an affiliate assistant professor in plant science at the University of British Columbia (UBC). “In 2023, we initiated a three-year project to search for new traits and resistance genes for wheat rusts, tan spot and bacterial leaf streak (BLS) to add to breeding programs underway.”

Brar is the project lead and moved the project from UBC to the CBL program when he moved to U of A in early 2024. The project is funded by Western Grains Research Foundation, Manitoba Crop Alliance, and the Saskatchewan Wheat Development Commission.

Resistance remains the most economical solution for controlling rust in wheat, making the search for novel genes important. There are new races of the rust pathogen that continue to evolve and defeat the existing

race-specific resistance in current varieties. “Rust pathogen races have evolved and gained virulence against a few important leaf rust resistance genes that were very effective even five years ago,” notes Brar.

In this project, Brar’s team is searching for novel traits and resistance genes for stripe, leaf and stem rust which could potentially be used in building rust resistance in CWRS and CPS wheat. “We are also focused on finding new genes for resistance to tan spot and other leaf pathogens as well as bacterial leaf streak (BLS), an emerging disease that we have little information about under Canadian conditions,” says Brar.

They are screening about 700 lines from the Plant Gene Resources of Canada (PGRC) wheat diversity panel for resistance to rusts, tan spot and BLS races/ strains, explains Naveen Kumar, U of A postdoctoral fellow. “The diversity panel encompasses geographical and phenological diversity, which is important because, for plant breeding, we are hunting for variation in genes,” says Kumar. The phenotyping of the panel will be conducted at different field screening nurseries that represent hot spots for the diseases. The diversity panel will be screened for stripe rust in Creston, B.C.

ABOVE Researchers Gurcharn Brar (L) and Naveen Kumar (R) assessing field plots being screened using the wheat diversity panel for resistance to rusts, tan spot and BLS races/strains.

and Abbotsford, B.C.; leaf and stem rusts in Morden, Man. and Saskatoon, Sask.; BLS in Vancouver, B.C.; and tan spot in Edmonton, Alta.

“We have also genotyped the same panel to help identify genomic regions that confer disease resistance for these diseases,” says Kumar. “This process will provide robust data that can be used for genome-wide association mapping for identification of SNP markers associated with resistance to rusts, tan spot and BLS.”

The goal of the study is to be able to determine which of these markers correlate strongly with the phenotypes in the field and then develop DNA molecular markers for the genes that can be used in the breeding program. “We are conducting intensive phenotyping and screening in the field and also screening for different rust races in the greenhouse,” adds Kumar. “Although tan spot in wheat is a priority-two disease, we will be screening the diversity panel to identify as many traits as possible, including other leaf spotting diseases that are common in wheat and non-race-specific resistance. Identifying novel sources of resistance will help breeders take them into their breeding programs to keep genetic resistance as an effective and sustainable disease management tool.”

Getting the most from your acres comes down to the smallest details, and we’re ready to prove we’re up to the challenge – even on your toughest acres. Whether it’s developing, researching, testing or getting to work in the field, PRIDE Seeds is there with you every step of the way.

BECAUSE

Brar is optimistic that they will be able to find a few novel genes for each trait that can be moved into breeding programs. However, this process will take some time. “The materials we are screening are landraces that come from all over the world and don’t necessarily have the same set of agronomic or end-use quality traits that we prefer for Canadian wheat varieties. Once we identify good accessions, we will use multiple rounds of crossing to bring only desirable traits forward into progenies that can be used in Canadian wheat backgrounds for variety development. New varieties from this process are expected to take about 15 to 20 years before they are available.”

Brar encourages growers to select varieties with a good disease package even if the yields might be slightly lower. It comes down to math and the risks of growing a variety without a good disease resistance package. In a higher disease risk year like 2024, growing a good disease-resistant variety can eliminate the need and cost of a fungicide application.

“Although pathogens are evolving, our Canadian wheat breeding programs and pathologists continue to do a really good job of building resources to protect against disease epidemics,” says Brar. “Through this and other projects, we continue to identify and select new and novel sources of resistance and resources to strengthen disease breeding programs. We are excited to be able to bring competent varieties to the market and dedicate our work for Alberta and Western Canadian wheat growers. We are trying to build a breeding program that wheat growers can count on and be proud of over the long term.”

Putting a known stripe rust resistance gene to work again.

BY LEEANN MINOGUE

Stripe rust (Puccinia striiformis f.sp. tritici) has caused yield loss for Prairie wheat growers since the early 2000s. Its spores blow in from the Pacific Northwest, typically landing in southern Alberta. Stripe rust also reaches Saskatchewan and Manitoba from the Mississippi Valley.

Despite years of research, André Laroche, a research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at the Lethbridge Research and Development Centre (Lethbridge RDC), is still fascinated by the interactions between these pathogens and plants. When stripe rust pathogens encounter wheat plants, they can mutate one or a few of the proteins they secrete (among dozens or hundreds), making it harder for the plant to recognize them.

If the wheat plants recognize stripe rust, they can initiate a defense reaction. In some cases, this causes the pathogen to secrete another protein that interrupts the wheat plant’s defense mechanism, Laroche says. If that works, the pathogens can invade the wheat and take over and multiply themselves.

“[It’s] an arms race where the pathogens always mutate and evolve,” says Laroche. Breeders can add resistance genes to wheat, but these pathogens mutate quickly. Varieties with just one resistance gene probably won’t last more than two or three years before their resistance is overcome, Laroche says. Varieties with two or three resistance genes have longer lives.

The issue is that researchers have only identified a limited number of wheat genes that confer resistance to stripe rust, and haven’t yet sequenced the genetics of each of these genes.

New resistance genes have traditionally been found by searching for resistance in related plants, then crossbreeding cousin plants with wheat. This was done from the 1940s through to the 1970s, but many people with this expertise have retired. “We know how to do it, but it’s not easy,” says Laroche.

When related plants are bred with wheat, “some

ABOVE

André Laroche is a research scientist with AAFC.

plants, at the beginning, look more like the wild cousin than wheat,” Laroche says. These plants are backcrossed with wheat for several generations to produce a resistant wheat plant, a process that takes 10 to 12 years.

With funding from the Alberta Wheat Commission and SaskWheat, and internal funding from AAFC, Laroche and his team are testing a more efficient method of finding resistance genes by tweaking known, defeated, resistance genes to make them effective again.

The team used site-directed mutations to modify a resistance gene (Yr10). They then bombarded immature wheat embryos with DNA from the modified gene, expecting a small percentage of these embryos to develop into plants with modified DNA. The transformation work was carried out with John Laurie, a collaborator and colleague at Lethbridge RDC.

“[It’s] an arms race where the pathogens always mutate and evolve.”

When Top Crop Manager reported on this study in 2020, Laroche said he hoped to develop six to eight genetic variants of Yr10. Now he reports that they have developed 12 variants that may one day be used in new wheat varieties, and eight have been tested.

The team was still growing out the final plants in the summer of 2024. Once the plants are grown out in growth chambers to the three-leaf stage, they’ll be

tested against the stripe rust pathogen.

This work has not gone as smoothly as they had hoped. COVID-19 shut them down for close to a year. When the lab reopened, there was a major problem with the transformation in plants.

When the team added modified DNA to wheat embryos, they also added a genetic marker, a herbicide-resistant gene, so they could easily see if the plants had taken in the new genetic material. If the grown plant was herbicide-resistant, it had the modified DNA, and the transformation was successful. This worked before COVID, but afterwards, it just didn’t.

After much debate, stress, and re-calculating, they found a work-around. They replaced the herbicide-resistant gene with a hygromycin resistance gene that enabled selection of tissues based on antibiotic resistance at the Morden location. At the Lethbridge location, they replaced it with a red fluorescent protein gene that would allow identification of putative modified plants by shining a light on them.

The percentage of transformation varied from 0.5 per cent to 2.7 per cent, a low value but high enough to obtain some results. Now, they’ll grow out plants from the seven of their new genetic variants, then

challenge them against genetic isolates of the stripe rust pathogen.

If any of these variants prove to be resistant, the researchers will not only have developed new resistance genes, but they will also have proven that this method works and can be used to develop resistance against other pathogens.

This genetic manipulation process was a proof-of-concept study, Laroche says. It will not be used to breed new resistance genes into commercial wheat varieties. Laroche and other wheat researchers are fully aware that genetically modified wheat is not accepted by all of Canada’s export markets. “There is no need to bring out the perfect wheat if it cannot be grown and exported,” Laroche says.

Eventually, wheat breeders will be able to add some of these new resistance genes to wheat varieties that include two or three resistance genes. Laroche isn’t sure yet if a new variety could be based on three tweaked variants of Yr10, or if breeders will need to mix the tweaked genes with other resistance genes.

As for how new genes will be added to existing high-performing wheat varieties, Laroche leaves us with a cliffhanger, saying that John Laurie is working on a method to simplify the movement of genes. “It would be used eventually to move these modified wheat genes back into wheat with no issue of the plant being genetically modified,” Laroche says. “There are new tricks coming up. In five years, there will be different options.” 24_007769_Top_Crop_Western_Edition_OCT_CN Mod: August 6, 2024 6:11 PM Print: 08/16/24 page 1 v2.5

The first Canadian field trial is being conducted in 2024.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Ready. Set. Go. Since the Canadian Food Inspection Agency announced in May 2023 that gene-edited seeds would be regulated the same as conventionally bred seed varieties, researchers in Canada are investigating how gene editing could be applied to Canadian crops. Leading the early race are researchers at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) at Lethbridge, Alta. working with spring wheat.

“With bread wheat being a hexaploid, we figured that gene editing could be used to fine-tune the circadian clock control of metabolism and plant development. Our initial goal under the International Wheat Yield Partnership project was to increase yield, but we are now also interested in drought tolerance and disease resistance,” says John Laurie, research scientist with AAFC at Lethbridge.

Laurie, working with co-lead André Laroche, is using CRISPR/Cas9 and HI-Edit gene-editing technologies to target specific genes that control the circadian clock in wheat. Because wheat is a hexaploid – it carries six total genes of two A, B and D genes each – gene editing allows a much more precise way of developing new alleles than the conventional method of using chemical or radiation to produce random mutant alleles.

Alleles are different versions of the same gene; they can be thought of as variation of traits such as eye colour. For example, if you have two blue eye alleles, your eyes will be blue. But if you have one allele for brown eyes and one for blue eyes, your eye colour will be decided by which allele is dominant.

Laurie was first introduced to the plant circadian clock while doing postdoctoral work at the University of Nebraska. He is targeting the core circadian clock in wheat, which number about a dozen, with some being more important than others. Laurie says these core

ABOVE John Laurie and André Laroche are working on the first gene-edited wheat field trial.

circadian clock genes regulate about one-third of all genes over the course of a day. Roughly 30,000 genes are under their influence. The core clock genes govern daily activities like photosynthesis and secondary metabolism, and are important in plant environment interactions and in plant development and flowering. This impacts traits like date of heading and spike characteristics.

“In knowing its importance in plant growth and development, I decided that the circadian clock would be a good target for gene editing. Much work had been done in model plants to define the core clock genes, setting the stage for gene editing in wheat,” says Laurie. “The value of Ppd-1 alleles in breeding programs worldwide set precedence and provides validity for doing this work.”

Ppd-1 is a famous wheat gene that has many different

natural alleles. Ppd-1 is a core clock gene and its mutant alleles have been important for wheat breeding programs worldwide, says Laurie. Like the variation seen in the natural Ppd-1 alleles, he is now using gene editing to fully study the circadian clock and its potential for crop improvement. Essentially, Laurie is tweaking how a wheat plant perceives and reacts to daylight hours, like turning the volume up or down on a radio.

Laurie’s work first started in growth chambers and then moved to greenhouse trials. He has been editing the circadian clock in wheat under a large project funded by AAFC and part of the International Wheat Yield Partnership. The team has produced several edited alleles in two core clock genes.

“Of the many edited wheat lines that we generated, we saw lines that flowered earlier, lines that flowered later, lines that were taller than controls, lines that were shorter than controls, lines with more tillers and lines with interesting spike characteristics in greenhouse and growth cabinets,” says Laurie.

Eight lines have been selected for field testing in

2024 to see if these differences could be seen in the field as well. The eight lines are being grown in duplicate alongside four checks. One of the checks is the line that the gene-edited lines are derived from, so they are genetically identical except for the single gene-edited allele. The field testing is being done on small plots that can be hand-seeded and grown in isolation at the Lethbridge Research and Development Centre.

“As far as I know, it is the first gene-edited wheat trial in the field in Canada,” says Laurie.

BY BRUCE BARKER

Set aside your beliefs about bees. While managed honey bees play an important role in producing honey and pollinating crops, wild or native bees are often better pollinators.

“Honey bees get too much credit for pollination. They are actually pretty poor pollinators. The hundreds of species of wild bees contribute a lot more to pollination,” says Jason Gibbs, associate professor in the department of entomology at the University of Manitoba.

Gibbs says he has nothing against honey bees, as his father is a retired beekeeper in Ontario, but rather highlights the importance of wild bees in pollination. He says most bees don’t sting, are solitary, and about 70 per cent of them nest in underground burrows. Most aren’t black and yellow, and most don’t make honey.

Gibbs recently led a survey of bees in Manitoba that was published in The Canadian Entomologist journal in 2023. The researchers recorded 392 species or morphospecies of bees in Manitoba, which was 154 more species than reported in 2015. This was a 64.7 per cent increase in the known species richness, which was likely the result of intensive sampling in areas previously under sampled.

The wild bee population is a diverse group. Gibbs highlights several of the species, such as Andrena, which includes over 50 species in Manitoba. Andrena is an important early spring pollinator, and pollinates blossom crops such as apples, cherries and blueberries.

Another very common wild bee is Lasioglossum, the sweat bee. This bee has more than 60 species in Manitoba. It’s called the sweat bee because it will land on your arm and drink sweat from it on hot days. This tiny black bee is often ignored. “It is incredibly abundant. If you have a lawn, I guarantee that you have sweat bees in it. And it is one of the most disturbance-tolerant bees. If you sweep canola, you will likely find sweat bees,” says Gibbs.

Many bees are specialists, like cellophane bees that

only pollinate Dalea. Unfortunately, not enough is known about wild bees to know what their ecological status is or if it is changing.

“I think we can generally assume that wild bees are doing poorly because of habitat decline,” says Gibbs. “Unfortunately, not a lot of bee habitat is readily available in cultivated areas.”

That loss of habitat from tree lines, fence rows and sloughs have all contributed to population and species richness decline. A recent research study looked at wild bee species abundance and richness (diversity) as impacted by natural habitat area and pesticide use. In areas of little natural habitat and high pesticide use, species abundance and richness were low. But Gibbs says the study found that if a lot of natural landscape was present, bees still did well despite high pesticide use.

Another research study that Gibbs was involved in looked at the establishment of floral strips around organic and conventional fields. These floral strips contained 15 species of forbs and four species of grasses. The capture rates of ground beetles, syrphid flies and bees in floral strips was significantly higher than in the control with unmodified field edges. There were no significant differences between organic and conventional management.

“The best thing you can do for pollinators is to keep the habitat you have. Forested areas, shelterbelts, fence rows, these are important habitat areas for pollinators,” says Gibbs. “Bee diversity is more important than overall populations.”

One crop that has a diverse species richness is sunflower. As a native plant species, a large number of pollinators have adapted to sunflower, including sunflower specialists.

Wild bees are a key part of integrated crop pollination that combines the integration of pesticide stewardship, horticultural practices and habitat enhancement with the integration of wild bees, managed honey bees and alternative managed bees.

Managed bees include species like honey bees, bumble bees and blue orchard mason bees. Honey bees, of course, are cultivated to produce honey from agricultural crops like canola, alfalfa, buckwheat and native flowers. The blue orchard mason bee is used primarily in fruit orchards like apples and cherries. The bumble bee is used primarily in greenhouses.

Gibbs says that honey bees visit flowers in a different manner than wild bees, resulting in less effective transfer of pollen between flowers. An example is alfalfa pollination. The shape of the alfalfa flower requires it to be ‘tripped’ open to make the reproductive parts accessible. When the flower is tripped, it slams the pollen onto the bee.

“Honey bees don’t like that. It’s like getting punched in the face. But the alfalfa leaf cutter bee is strong with a thick head and doesn’t mind getting in there to get pollen,” says Gibbs. “And a lot of crops are like that.”

Pollination experiments have shown the value of pollinators to canola seed production and weight. Plants that were bagged to prevent pollination had significantly lower number of seeds per flower and lower seed weight than when pollination was allowed – at both the field edge and the centre of the field.

ABOVE Floral strips provided a habitat to encourage a diversity of wild bee species.

Managed bees also differ in how they pollinate. Honey bees tend to spread out over the field. Leafcutter bees don’t like to fly too far from their hives and have fewer visits per hour to flowers further away from their shelter.

Gibbs summarizes that wild bees contribute to pollination services and are part of an integrated crop pollination system. The benefits to Manitoba agriculture are hard to measure and will vary.

“The benefit from wild bees depends on the crop and the broader landscape and natural habitat. They need that natural habitat or an introduced or enhanced flower habitat for species richness and diversity,” says Gibbs.

by Bruce Barker, P.Ag | CanadianAgronomist.ca

Strip-till equipment moves residue to the side leaving strips of bare soil about eight inches (20 cm) wide. The soil between the strips is left undisturbed with the residue providing soil and water conservation benefits. In Manitoba, strip-till is often conducted in the fall so that the strips warm up more quickly in the spring.

A two-year research project was conducted in 2015 and 2016 at Carman and Portage la Prairie, Man. by Magdalena Rogalsky at the Department of Soil Science at the University of Manitoba. The objectives of this study were to determine if starter phosphorous (P) fertilization would improve early corn development and increase yields, whether side-banding P in the spring near the seed would outperform fall deep-banded P applications, and if the agronomic benefits of starter P fertilization would be greater in strip-tillage than conventional tillage due to slower diffusion and root uptake of P in the strip-tillage system.

The field sites were selected based on good surface drainage and low to medium Olsen extractable P soil test. The Carman site was rated low in P fertility (5 to 8 ppm) and the Portage la Prairie site was medium (11 to 14 ppm). Soil samples were also analyzed for nitrogen (N), potassium (K), sulfur (S), and micronutrients, and additional nutrients were applied as needed. Nitrogen was broadcast applied in the spring with a urease inhibitor with a target rate of soil plus fertilizer of 222 lb N/ac (250 kg N/ha).

After harvest in the year preceding corn, the conventional tillage treatment was tandem disced while the strip-till treatment utilized a Yetter strip-till unit with eight-inch (20 cm) wide strips on 30-inch (76 cm) centres. Three of the site-years had wheat stubble and the fourth had barley stubble.

The P fertilization treatments were a control with no added P, and two application rates of 27 lb P2O5/ac (30 kg P2O5/ha) and 54 lb P2O5/ac (60 kg P2O5/ha) of monoammonium phosphate (MAP, 11–52–zero).

Fall and spring P application timing was compared. In the fall, P fertilizer was applied as a deep-band four to five inches (10 to 13 cm) below the soil surface in the strip-till treatment. On conventionally tilled plots, the fall-banded fertilizer treatment applications were first cultivated with a tandem disk, and then P fertilizer was deep banded with the strip-till unit so that fall-banded fertilizer treatments were similar for both tillage systems. These fall fertilizer bands were marked with flags so that the corn could be planted directly over the bands in the spring.

The second application timing was a spring side-banded P treatment that was placed two inches (5 cm) to the side and one inch (2.5 cm) below the seed with the corn planter for both the conventional and strip-till treatments.

In the spring, corn was planted without additional tillage, but a burndown herbicide application was applied at two of the site-years. Corn hybrid Dekalb 26-28RIB Genuity VTDoublePRO was planted with a corn planter about 1.75 inches deep (45 mm) on 30-inch rows. Appropriate corn herbicides were applied in-crop.

Compared to the unfertilized P control, spring side-banded P was more consistent in increasing early-season biomass, early-season plant tissue P concentrations, and P uptake at V4 growth stage than the fall deep-banded treatments. Reduced days to silking and grain moisture at harvest was similar between the fall and spring application methods. Additionally, throughout the growing season, corn response to side-banded P was more consistent than fall deep-banded P. These responses, though, varied across site-years and declined throughout the growing season.

The 54 lb P2O5/ac rate of starter P fertilizer produced greater early-season response at the V4 growth stage than the 27 lb P2O5/ac rate. Days to silking, grain moisture, and yield were similar for both rates of P when averaged across all site-years, tillage systems, and application methods.

The highest overall average grain yields were produced with spring side-banded P application compared to the control and fall deep-banded P treatments. Averaged across all site-years, tillage systems and P fertilizer rates, spring side-banded P significantly increased grain yield by an average of 7.4 bu/ac (467 kg/ha) compared to the unfertilized control. Spring side-banded P also outyielded the fall deep-banded treatments by an average of 7.5 bu/ac (470 kg/ha). Fall deep-banded P treatments were not significantly different from the unfertilized controls.

Comparing tillage systems, tillage did not generally affect early-, mid-, or late-season measurements. Grain yield and grain moisture content at harvest were also similar between conventional and strip-tillage. Strip-till averaged 149 bu/ac (9,372 kg/ha) corn yield and conventional averaged 148 bu/ac (9,290 kg/ha) across all site-years, application methods and P fertilizer rates.

Overall, starter P side-banded at planting is beneficial for corn growth, maturity, grain yield, and grain moisture compared to fall deep-banded P. Strip-till corn performed similar to conventionally planted corn and is a promising practice for soil and moisture conservation in southern Manitoba. Bruce Barker divides his time between CanadianAgronomist.ca and as Western Field Editor for

Stay tuned for early bird registration!

The Top Crop Summit is the chance for farmers and agronomists to hear practical applications from the latest research in agriculture. The 2025 event will provide helpful insight on weeds, pests, soil and water, and more – a variety of topics to provide a strong foundation for making the growing season a success. Both days will provide exclusive access to firsthand knowledge from experts in the field, as well as valuable information to improve decisions affecting crop production. The second day’s theme gives attendees the chance to dive deeper into factors that promote better management of soil and water. Feb.

Prairieland Park Trade and Convention Centre, Saskatoon, SK February 25-26, 2025

With Canada’s most complete canola seed protection.

Your best start begins with Lumiderm™ insecticide seed treatment. Lumiderm provides the most complete seedling protection, giving your crop the best start possible.

Premium control of early season cutworms

Proven crucifer & striped flea beetle protection

Excellent early season seedling stand establishment

Increased plant vigour and biomass

Book today and Win the Start with Lumiderm.