TOP CROP MANAGER

WHAT’S IN A NAME?

Fababean is still the preferred host crop for pea leaf weevil.

PG. 28

PHYTOPHTHORA ROOT ROT

Defense is the best option.

PG. 10

DIVING DEEPER INTO SOYBEAN QUALITY

Overcoming low protein concerns in Manitoba

PG. 38

Fababean is still the preferred host crop for pea leaf weevil.

PG. 28

Defense is the best option.

PG. 10

Overcoming low protein concerns in Manitoba

PG. 38

Providing earlier nodulation, longer on-seed survival and enhanced performance in challenging conditions.

For more information visit your BrettYoung retailer or brettyoung.ca/biologicals.

PESTS AND DISEASES

28 | Pea leaf weevil: what’s in a name? A pea leaf weevil by any other name would still prefer fababean as its host crop. by Jennifer Bogdan

THE EDITOR 4 Looking ahead to a bright future by Stefanie Croley

UPDATE 49 Environment has biggest impact on soybean production by Bruce Barker

PESTS AND DISEASES

10 | Managing Phytophthora root rot in soybean Defense is the best option. by Bruce Barker

Inter-row stubble seeding by Carolyn King PESTS AND DISEASES

Safeguarding Prairie pulses from nematode impacts by Carolyn King PULSES

Optimizing field pea yield and protein by Donna Fleury

GOVERNMENT SEEKS FEEDBACK ON CANADA GRAIN ACT

SOYBEANS

38 | Diving deeper into soybean quality Could a better indicator of end-use quality overcome the low protein concern for Prairie soybean? by Carolyn

King

The mystery of the chickpea health issue by Bruce Barker

Exploring pest and clubroot interactions by Jennifer Bogdan

Beneficial crop rotations by Donna Fleury

The federal government is asking Canadian grain farmers, handlers, processors and exporters to share their views on the Canada Grain Act, the legislative and regulatory framework for grain quality assurance in Canada. The consultation will be held online until April 30.

Readers

STEFANIE CROLEY EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Irecently had the pleasure of interviewing Curtis Rempel, the vice-president of crop production and innovation with the Canola Council of Canada, for an on-demand session for the Top Crop Summit. And if you’ve ever had a conversation with him, I’m sure you’ll understand why I say it was a pleasure.

Besides being a wealth of knowledge, Rempel offered a realistic perspective on growing canola, specifically regarding the challenges and opportunities that Canadian canola producers have faced and continue to deal with. Between trade disputes, disease risks and terrible weather, the last couple of years in particular haven’t been easy – and Rempel not only acknowledged that, but also offered support, encouragement and solutions.

I don’t want to spoil the whole interview – you’ll have to register for the Top Crop Summit, to be held Feb. 23 and 24, to see it for yourself (visit TopCropSummit.com to catch this and several other valuable sessions and conversations). But one highlight I will share was Rempel’s outlook on innovation, which I found to be especially poignant this time of year. When we chatted about some of the challenges for canola growers going into 2021, Rempel discussed several – weather, of course, among many others. But he was also quick to point out the myriad opportunities for canola growers, specifically surrounding biofuels and plant protein.

“There’s clearly a global trend for plant-based proteins. That doesn’t diminish animal proteins,” he said, quoting the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations in saying highly bio-available protein is a basic human right. “That really has kicked off a renewed interest in protein,” he added. “It takes good protein to make good protein, so in the animal feed space, canola protein still has an amazing fit for monogastric, for dairy and for aquaculture.” And on the human side, as many look for other ways of increasing protein content in their own diets, Rempel recognizes that plant-based protein is clearly a staying trend.

As valuable as Rempel’s comments and advice were, what struck me most about our conversation was his realistic, practical and balanced approach, specifically by acknowledging both the challenges and opportunities growers are facing. Farming is hard. We can’t pretend the skies are always blue, but we can recognize that it’s not all doom and gloom either.

Unfortunately, in our current climate, encouragement can be hard to come by some days, especially without the regular opportunities to have great conversations with like-minded people. My interview with Rempel reminded me just how much I’m missing that this winter, especially without the usual conference circuit, and how I need to actively look for new opportunities to connect with the industry.

If you find yourself also missing out on real conversations right now, send me an email –I’d be happy to jump on a Zoom call with you. Sure, it’s not quite the same as chatting over a coffee break at a conference like we might normally do at this time of year, but with the right perspective, it’s the next best thing.

Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of

related groups whose products and services

believe

be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com • Tel: 800 668 2374

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher’s

A simple, low-cost way to give a boost to field pea standability.

by Carolyn King

Field pea lodging is a big problem in productive growing environments. “When the crop is very badly lodged, growers can take as much as five days to harvest a quarter section of peas,” says Sheri Strydhorst, an agronomy research scientist at the University of Alberta. “After a couple of experiences like that, you can see why a grower might say, ‘I’m never growing peas again!’”

She notes, “In a 2011 survey by Alberta Pulse Growers and Alberta Agriculture, 38 per cent of growers said harvest difficulty was their main barrier to increasing pulse acres. It was also the reason why 46 per cent of growers stopped growing pulses and 42 per cent of growers had never grown pulses.”

Clearly, growers need solutions to this problem. So Strydhorst led a study to assess two possible ways to try to reduce lodging in field pea: inter-row seeding into standing stubble; and plant

growth regulators (PGRs).

Inter-row stubble seeding involves planting a crop between the rows of standing stubble from the preceding crop. Strydhorst was interested in this practice because some previous research and field-scale demonstrations in Australia and Canada had shown that it improved pea standability, but there was limited information on how it affected pea yields. “In the Alberta context, Steve Larocque with Beyond Agronomy had been working on inter-row seeding. He found that, although the peas might lean over, the wheat stubble is like a little bit of a fence that helps the peas from lying completely flat on the ground.”

Regarding PGRs, Strydhorst knew from her own research and

ABOVE: Strydhorst’s study found that field pea planted between rows of tall standing wheat stubble (right) had better standability than pea planted into no standing stubble (left).

Cereals? Canola? Honestly, you’d die of boredom. Lentils, on the other hand, are the jigsaw puzzle of prairie crops, a season-long agronomic challenge that only a rare breed of farmer has the skill and nerve to pull off. We get it, and we want to help. With two modes of action from Groups 14 and 15, Focus® herbicide delivers extended control of key grassy and broadleaf weeds. The kind of powerful, sustained weed control you’ve always wanted is here.

other studies that foliar applications of PGRs can help reduce lodging in cereal crops. “Although no PGRs are registered for use on field pea in Canada, I began to think we should see if PGRs might reduce lodging in pea crops,” she says.

“A little work had been done on field pea in India using a product with the same active ingredient as Manipulator, but results varied. A greenhouse study in Alberta had found that Ethrel reduced pea height, but as a greenhouse study it didn’t assess the effects on lodging under field conditions. So we wanted to look at the effects of PGRs on field pea standability in more depth.”

The main funders of Strydhorst’s project were the Alberta Crop Industry Development Fund and the Alberta Pulse Growers.

The field experiments took place at three Alberta sites – Bon Accord, Lacombe and Falher – all highly productive environments.

She notes, “To give you a sense of how frequently lodging is happening in these types of environments, in our research plots we had extreme lodging 25 per cent of the time, conditions where harvesting would have been really difficult. We had moderate lodging 38 per cent of the time. And we had no lodging the rest of the time, and that happened in very dry conditions.”

In the inter-row experiments, the project team grew AC Foremost wheat in the year prior to field pea. The wheat stubble was cut to heights of zero, 20 and 30 centimetres. In 2015 and 2016, they seeded CDC Meadow, a commonly grown pea with typical lodging resistance, in between the wheat stubble rows.

The 20- and 30-centimetre stubble heights produced very similar results.

“These tall stubble heights significantly improved field pea standability compared to the zero stubble height. Where we had lodging pressure, the tall stubbles reduced lodging between six and 23 per cent,” she says.

This improved standability occurred despite the fact that the pea plants in the tall stubbles tended to be taller. “Compared to the

zero stubble height, those standing stubbles increased the height of the pea plants about 83 per cent of the time. At maturity, those plants were one to four centimetres taller, so not drastically taller. We think this height increase is due to the plants elongating at early growth stages to find light between the stubble rows.”

She also notes, “The standing stubbles didn’t impact pea yields, and the 1,000-kernel weights increased in two of six site-years, so we were quite happy with that.”

On the downside, the tall stubble plots had lower seed protein in two of the six-site years. In one case, the reduced protein content was likely due to pea leaf weevil feeding on the root nodules, resulting in decreased nitrogen fixation. In the other case, unusually wet growing conditions increased yields, and Strydhorst thinks there was a small nitrogen dilution effect where the higher yields were compensated by lower protein.

The PGR experiments were conducted in 2015 and 2016 with CDC Meadow, and in 2017 with both CDC Meadow and AAC Lacombe, a high-yielding pea cultivar with typical standability. The project team evaluated three PGRs at two rates on the two cultivars. None of the PGRs are registered for use on field pea.

“The PGR results were very disappointing. The first PGR had no impact at all on any of the agronomic traits, yield or quality,” Strydhorst says.

“The other two PGRs had really negligible effects on standability. They did not consistently affect plant height, and they didn’t have an impact on maturity or significant effects on protein content. And where there were any responses, those responses were incredibly small and inconsistent.”

Pea yields were reduced when the PGRs were applied under the drought conditions that occurred at Bon Accord and Falher in 2015, when growing season precipitation was about half the long-term average. She notes that yield reductions also occur in other crop types when PGRs are applied under dry conditions.

Strydhorst concludes, “We don’t recommend PGRs as an agronomic tool for improving standability of field peas. This result was disappointing, but it’s better that we find it out in small plots than in farmers’ fields.”

Based on the project’s results, inter-row stubble seeding can be an easy, low-cost practice to help reduce lodging in field pea. It requires a GPS guidance system, but Strydhorst thinks most Alberta farm operators have a GPS system on the tractor that they use for seeding.

“Producers just need to cut their wheat stubble at a tall height. They should avoid heavy harrowing because they need to keep that stubble standing nice and tall; the wheat crop needs to be harvested under very good conditions with excellent straw and residue spreading,” she explains.

“Then in the spring when they are seeding their pea crop, they simply use their GPS to nudge their seed drill so the openers are in between the wheat stubble rows.”

She adds, “At the end of the day, what growers really need is a better standing pea. Breeding for standability is definitely a goal in pea breeding programs. Although we’re not there yet, growers should be on the lookout for new pea varieties with improved standability. In the meantime, inter-row stubble seeding provides a bit of a boost to standability that could help.”

CEREAL PRE-SEED HERBICIDES

CANOLA PRE-SEED HERBICIDES

Start strong with Corteva Agriscience, the industry leader in pre-seed crop protection. Visit your retailer today to book your Corteva Agriscience products for 2021.

Early Order is back for a limited time. Book by March 15th, 2021 and SAVE up to 18% with Flex+ Rewards*.

Find out more at flexrewards.corteva.ca *Minimum 300 acres per category. How you start determines where you finish.

Defense is the best option.

by Bruce Barker

Once you have Phytophthora root rot (PRR), it’s not going away. As a result, strategies to reduce the impact of PRR on soybeans are the best option.

“An important factor with this plant pathogen is the production of the thick-walled oospores that are adapted for overwintering and survival under adverse environmental conditions –they are able to survive for long periods of time in soil,” says Debra McLaren, research scientist, crop production pathology with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Brandon, Man.

Phytophthora root rot, caused by Phytophthora sojae, is a root and stem disease that attacks primarily soybeans. It is referred to as a water mould, or Oomycete and overwinters in the soil as oospores, which germinate and produce sporangia that release zoospores. Zoospores can swim short distances of about one cm. They are attracted to root exudates from soybean roots. The zoospores infect the soybean root, causing root and stem rot. As the zoospores are motile, soil must be flooded or saturated with water for the zoospores to swim.

The disease is now becoming more of a concern on the Prairies, and the importance of disease surveys for assessing the incidence and diversity of this pathogen cannot be overemphasized. Surveys of Manitoba fields have been conducted since 2014. Saskatchewan was added in 2017 and Alberta in 2019. In Manitoba in 2016, 40 fields were surveyed, and 38 per cent had PRR. In 2017, 35 per cent of 89 fields had PRR, and in 2018, 30 per cent of 96 fields had PRR. That dropped to five per cent in 2019.

In Saskatchewan in 2017, two of 25 fields surveyed had PRR and one out of 15 in 2018. None of the 17 fields in 2019 had the disease. In Alberta, PRR has not been detected in these surveys.

Results for the 2020 survey have been delayed due to restrictions in place because of COVID-19. McLaren says the drop-in incidence in 2019 was likely due to the drier growing season.

“Warm soils and periodic rains at weekly intervals where saturated soils develop are ideal conditions. It commonly occurs on heavy, compacted soils, and in low and wet spots in the field,” McLaren says. “2019 was a dry year so we probably saw fewer issues.”

Other favourable conditions include soils that have an impervious shallow hardpan that is subject to saturation and flooding. It can also occur in well-drained fields where the pathogen is present and soils are saturated from seven to 14 days of heavy rain or irrigation.

Unlike other root rot pathogens, PRR can infect soybeans at any development stage. Early in the season, seedlings can be attacked and killed in the ground or soon after emergence, causing seed rot,

pre- and post-emergent damping off and reduced stands. Water soaked lesions on the seedling progress up the stem causing yellowing of leaves. The plant wilts and dies, but leaves remain attached.

Mid- to late-season symptoms cause stunting, as well as root and stem rot. A chocolate-brown canker develops up the stem. The plants wilt, leaves turn yellow, droop and remain attached to the stems after the plant dies.

“The most diagnostic feature with Phytophthora root rot is the dark brown canker that begins below the soil level and moves up the

We’ve captured it! 3 modes of action, 1 powerful product.

Turns out, you really can capture lightning in a bottle when you re-think what’s possible in pulse disease control. Say—like putting together three high-performing modes-of-action for the first time. Count on Miravis® Neo fungicide to deliver consistent, long-lasting control so you can set the stage for healthier-standing, higher-yielding, better quality pea and chickpea crops.

Lightning in a bottle?

More like, “a better crop in the bin.”

For more information, visit Syngenta.ca/Miravis-Neo-pulses, contact our Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682) or follow @SyngentaCanada on Twitter.

Always read and follow

stem,” McLaren says. “This is different from stem canker, another soybean disease, where there is green tissue above and below the canker.”

The disease can be patchy in the field, reflective of soil moisture conditions. Yield losses vary depending on the field, environmental conditions, and soybean variety but amount to $50M annually in Canada. In the U.S., McLaren says yield losses can range from eight to 11 per cent

Genetic resistance to P. sojae is available. There are different major “Resistance to P. sojae” (Rps) genes available in soybean varieties, and these major genes can prevent the disease from developing. Phytophthora sojae occurs in the soil as populations of different races and therefore it is critical to determine the current races of P. sojae in Canadian soybean fields so that growers can select the best varieties for their operations.

McLaren works with Richard Bélanger at Université Laval in Quebec on a nationwide screening program to determine the current races of P. sojae that are in soybean production regions across Canada. McLaren’s team screens the samples collected in the western Canadian survey for PRR. Every isolate of P. sojaeis screened against soybean lines, each containing a different Rps gene, to confirm the isolate’s race or pathotype. There are more than 50 described races, but many more pathotypes reported throughout the U.S. and Canadian soybean production regions. Because there are so many races and the numbering system previously used has no biological meaning, plant pathologists have moved to a pathotype designation that lists the Rps genes that can be overcome by the P. sojae isolate. For example, ‘pathotype 1a, 1c, 7’ was originally called Race 4. This pathotype can overcome Rps genes 1a, 1c, and 7.

In Ontario and the U.S. prior to 1990, simple pathotypes that were only able to defeat one or two Rps genes were identified. Over time, pathotypes that are able to overcome more Rps genes have developed, and different pathotypes have been reported within the same field.

This shift in pathotypes is partially because of selection pressure. Many soybean varieties have a single major Rps gene. Growing a variety with the same Rps gene over the years allows other pathotypes to evolve in the field to eventually overcome that Rps gene. Tight rotations and higher rainfall over a few years can speed up the shift.

“Some of the resistant genes have been effective for many years with a single gene having lasted for eight to 15 years. But it seems

like weather changes and increased precipitation means the races are evolving and are becoming more complex,” McLaren says.

From 2014 to 2016, ‘pathotype 1a, 1c, 7’ was predominant in Manitoba. In 2017 the predominant pathotype had shifted to ‘1a, 1b, 1c, 1k, 7’ (race 25). In 2018, the predominant pathotype was able to overcome two additional Rps genes: Rps1b and Rps3a. Screening results for 2019 and 2020 are ongoing but have been delayed due to COVID-19. Seed Manitoba lists the varieties with resistance to PRR, and the major Rps gene(s) the variety carries. Genes that are available include 1a, 1c, 1k, 3a or 6 either as a sole resistant gene, or stacked with another resistant gene. Several varieties registered in Manitoba carry a single Rps6 gene. These lines would be effective against all pathotypes identified in the surveys of Manitoba soybean fields.

“Major resistant gene can help protect against specific pathotypes throughout the entire growing season so the plant is protected from seedling as well as mid and late-season infections,” McLaren says.

In parallel with the screening program, Laval University is developing a molecular diagnostic assay to help growers select the cultivars with the proper Rps genes for their specific field.

Another type of resistance, also invaluable in limiting the damage caused by P. sojae, is partial resistance, also known as quantitative resistance. It is controlled by several minor genes, is a non-race specific resistance and places less selection pressure on P. sojae populations.

“It is believed to have broad-spectrum effectiveness against all races of the pathogen, but it is incomplete resistance because some level of disease can still occur,” McLaren says.

When diverse pathotypes are present, partial resistance can provide additional protection that major genes cannot when overcome by the diverse pathotypes. However, partial resistance develops after the cotyledons and first true leaves are visible and because it takes time to develop in the plant, seed treatment with a fungicide for early season protection against PRR is an important management tool. McLaren says under high disease pressure, seed treatments have increased yield in partially resistant cultivars. And under lower disease pressure, a susceptible variety with partial resistance can yield as much as a resistant cultivar.

A resistant cultivar with an Rps gene that is effective against the predominant strains in the field is the foundation of disease management. McLaren says research is continuing with the collection and characterization of isolates of P. sojae from western Canadian soybean fields to provide information to growers on the pathotype diversity that exists. In addition, research to develop molecular tools that can be used to reduce the time required for pathotype determination in a field is ongoing at the Université Laval and will be available to research partners in Western Canada in the near future.

Reduced tillage can increase the risk of disease because no-till areas are more easily saturated, creating a better environment for the pathogen. Arguably, though, reduced tillage may bring other soil benefits that may outweigh the increased disease risk. Field activities that reduce compaction are also a good strategy. The disease is usually worse in tractor tracks and at headlands.

Practices that encourage healthy plant stands can also reduce the impact of the disease. And while extended crop rotations of four years or more do not eliminate the pathogen, some reduction of oospores can occur, and there are other rotational benefits that can help reduce other disease pressures.

“Once you get the disease, it will be there for a long period of time. A combination of these different management tools and strategies can help reduce the impact of the disease,” McLaren says.

looking for six women making a difference to Canada’s agriculture industry. Whether actively farming, providing agronomy or animal health services to farm operations, or leading research, marketing or sales teams, we want to honour women who are driving the future of Canadian agriculture.

PRE-SEED

GROUP 2 GROUPS 4, 6, 27

GROUP 2 GROUPS 2, 6, 27

We’re guessing you didn’t get into farming for the thrill of controlling weeds. That’s where Bayer cereal herbicides come in. With a wide roster of solutions, you can be sure there’s one that’s right for your operation, no matter what cereal you’re growing.

Research is laying the groundwork for managing these often undetected or misdiagnosed pests.

by Carolyn King

Nematodes are often overlooked as a possible concern for Canadian crops, especially on the Prairies.

“Farmers don’t come to us and say, ‘I’ve got a nematode problem’ because the visible symptoms of nematode impacts are very subtle,” explains Mario Tenuta, a professor of soil ecology at the University of Manitoba. “So, we have to go looking for nematode problems.”

Tenuta is now leading a five-year project (2018 to 2023) to look into nematode problems on Prairie pulse crops.

“Not much is known about nematodes on pulses on the Prairies. However, we know from other areas of the world that nematodes can seriously impact pulse yields, and pulses have been grown on the Prairies for long enough that populations of nematode species that attack pulses might have built up to damaging levels.”

His project aims to improve understanding of the possible threat from these microscopic, worm-like plant parasites and to lay the groundwork for reducing the spread of these pests, decreasing the risk of yield impacts and preventing market access issues.

Funders of this project include the Alberta Pulse Growers, Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers, and Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership’s Pulse Science Cluster.

Tenuta’s current project builds on the findings from previous studies by his University of Manitoba research group and his western Canadian colleagues.

For example, from 2014 to 2016, they surveyed 93 yellow pea, chickpea and lentil fields in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, sampling pulse plants, weeds and soils in these fields. They found 20 genera of plant-parasitic nematodes in the surveyed fields. Several fields had high enough numbers of some of these nematodes to potentially cause problems for pulse crops and/or crops grown in rotation with pulses.

One of the most concerning nematodes found in the survey is Pratylenchus, the root-lesion nematode. Through molecular analysis, Tenuta’s group has identified the Pratylenchus species on the Prairies as Pratylenchus neglectus. He says, “We found this nematode in about 20 per cent of the surveyed fields. Moreover, in some

fields, it occurred in pretty high numbers, particularly in Alberta.”

Like other root-lesion nematodes, Pratylenchus neglectus causes root damage, such as brownish lesions, fewer root hairs, and reduced lateral roots, in susceptible hosts. This damage can reduce the transport of water and nutrients to the aboveground parts of the plant, leading to symptoms like stunted plants, yellowing foliage, and lower yields. The nematode’s feeding damage can also

provide entry points into the root for other pathogens.

To find out whether Pratylenchus neglectus is an issue for Prairie pulses, Tenuta’s group has been working on various studies with Sya ma Chatterton and Frank Larney at AAFC Lethbridge, Alta., and Tom Forge at AAFC Summerland, B.C.

Tenuta’s group assessed the nematode’s ability to attack and repro duce on chickpea, lentil, pinto bean, soybean, yellow pea, canola and spring wheat in a growth chamber study. Because earlier studies by various researchers had shown that different crop varieties may have different susceptibility levels to the nematode, this study used the variety most commonly grown on the Prairies for each of the seven crops.

“We found that Pratylenchus neglectus really liked to grow, repro duce and build up its numbers on soybean,” Tenuta notes. Although canola, chickpea, pinto bean and wheat were also good hosts to the nematode, soybean was clearly the “winner” in enabling the nema tode to increase its population rapidly.

“As a result of those findings, we are now investigating whether this nematode is building its populations high enough to reduce soy bean yields,” he says.

“So in 2019, we started a field study at AAFC’s Lethbridge sta tion. I call it a micro-plot study because we are using very small field plots where the AAFC group added the nematode to the soil and then planted the soybeans in that soil. Then they came back and retrieved the soil and the plants, and we did the analysis for the nematode.”

As in the growth chamber study, the 2019 field data indicated Pratylenchus neglectus could reproduce on soybean and reduce the growth of soybean plants. Unfortunately, an early frost meant that soybean yield impacts could not be reliably determined that year. The researchers didn’t conduct the study in 2020 due to COVID restrictions, but they plan to continue it in 2021.

The nematode’s ability to increase its numbers on soybean plants also has implications for other crops in soybean rotations. Tenuta explains, “If the numbers build up to 1,000 or 2,000 of these nematodes per kilogram of soil, we think Pratylenchus neglectus could be problematic for a wide range of crops. I suspect this is the situation with potato, where potato production is affected when this nematode is at very high levels in the soil.”

Tenuta’s group is also continuing to conduct host studies with different crop types. Rotations with non-hosts could be a useful tool in controlling Pratylenchus neglectus because this nematode cannot persist for long periods in the soil without hosts.

He concludes, “Within two years, we expect to have much more information on the damage caused by this root-lesion nematode, its importance in Prairie pulse production and how to manage it with crop rotation.”

Disentangling a Ditylenchus duo

In recent years, Tenuta’s research group has been tackling – and resolving – a serious nematode issue for yellow pea exports from the Prairies.

“The stem and bulb nematode, Ditylenchus dipsaci, is a quarantine pest. That means many countries, including Canada, do not allow the importation of soil or plant materials, including grains, that contain this nematode,” he explains.

“A nematode species that was thought to be Ditylenchus dipsaci was found at a very small frequency in Prairie field pea shipments to India. India enforced the quarantine very strictly, and those shipments had to be diverted to other ports and fumigated, which was

No matter how challenging your needs, V-FLEXA is your best ally for agricultural trailers, tankers and spreaders. This latest-generation product features VF technology, which enables the transport of heavy loads both in the fields and on the road at lower inflation pressure. V-FLEXA is a steel-belted tire with a reinforced bead that provides durability, excellent self-cleaning properties and low rolling resistance even at high speeds.

V-FLEXA is BKT’s response for field and road transport with very heavy loads avoiding soil compaction.

For info:

Western Canada 604-701-9098

Eastern Canada 514-792-9220

very costly. Furthermore, it delayed delivery of the shipments to India, which sometimes meant the contract terms weren’t met.”

Tenuta’s group worked with the Prairie pulse grower associations and Pulse Canada on this issue. First, his group collected samples of peas, weeds and soils from yellow pea fields across the Prairies. When they found Ditylenchus nematodes in a sample, they used molecular identification to determine the specific Ditylenchus species because several Ditylenchus species look really similar to Ditylenchus dipsaci

They discovered that the Ditylenchus nematode in Prairie pea fields is actually Ditylenchus weischeri

Then in a greenhouse host study, Tenuta’s group determined Ditylenchus weischeri does not attack peas, other pulses or other Prairie field crops.

However, it really, really likes Canada thistle. “When we surveyed thistle plants across the Prairies, we found that almost every plant had Ditylenchus weischeri,” Tenuta notes.

“It turns out that there would be a little bit of thistle flowers in the pea exports. The nematodes being found by the Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) in the pea export shipments were really Ditylenchus weischeri in the thistle flowers in the grain,” he explains.

“We published our findings and informed CFIA and AAFC. CFIA altered their analysis of export shipments to recognize the weischeri nematode. Previous exports reported to have dipsaci were reanalyzed and were actually weischeri. To my knowledge, CFIA hasn’t found dipsaci in pea exports.”

Tenuta’s current project includes further Ditylenchus research. “Although we were a little set back by COVID, we are now screening other crop types, particularly vegetable crops, to see if any of them are susceptible to Ditylenchus weischeri. We just want to be even more confident that this nematode is not an issue for agricultural crops.”

His group is also working on Ditylenchus dipsaci, the quarantine pest. “This nematode can be devastating for onions, garlic, and

other bulb crops like ornamentals such as daffodils, and there can be issues on alfalfa. It is a very serious problem in garlic fields in Eastern Canada and the northeastern United States,” he notes.

“Although not much garlic is grown on the Prairies, there is some. So I was concerned that some local garlic growers might get Ditylenchus dipsaci in their fields, and that it might spread from there by wind or machinery to neighbouring pulse fields.”

Tenuta’s group issued a call to Manitoba garlic growers to find out if any growers were having possible Ditylenchus dipsaci symptoms in their garlic. “A couple of growers contacted us, and we got samples of their garlic. The garlic bulbs were devastated, rotting and chock full of the dipsaci nematode. It turns out that these growers were getting their garlic cloves for seed stock from Ontario,” he explains.

Tenuta’s group hopes to conduct workshops or online presentations for Prairie garlic and onion growers about this issue, to help these growers and ensure that dipsaci doesn’t get into Prairie pulse crops.

“With just a small investment of time and effort in getting the word out to the folks who grow garlic and onions locally on the Prairies, we can safeguard a very big pulse market,” he says.

“Garlic growers can buy certified, disease-free seed stock. Or they can dip the garlic into hot water for a very specific time at a specific temperature, to kill the nematode without damaging the seed stock.” Garlic growers can contact Tenuta for more information.

Tenuta’s research includes another important pulse nematode: soybean cyst nematode (see “Forewarned is forearmed: Soybean cyst nematode in Manitoba” originally published in the December 2019 edition of Top Crop Manager). He notes, “Manitoba has a few fields with this nematode. Right now, the numbers are really low and not affecting soybean yields. But the nematode will definitely spread. So we are continuing our surveys to determine its distribution and population levels. And we are continuing outreach to soybean growers about managing the pest, including biosecurity to limit its spread, crop rotations and resistant soybean varieties.”

“Scouting for nematode problems is tough. They can be very difficult to diagnose. In general, nematodes tend to cause a weak-performing crop,” Tenuta notes.

With root-lesion nematodes like Pratylenchus neglectus and other nematodes that attack plant roots, he suggests looking for symptoms related to poor root health like stunted or yellowing plants, delayed canopy closure, patchiness of problematic areas in the field, and low yield in those areas. You can also dig up the affected plants and look for symptoms like root lesions, root rots, lack of fine roots, and in the case of soybean cyst nematode, small cysts on the roots.

For nematodes that attack plants’ aboveground parts, such as some Ditylenchus species, look for symptoms like stem twisting or swelling.

Many dfferent problems can cause weak-performing crops, and it can be challenging to find a commercial lab set up to identify different nematode species. So if you see possible nematode symptoms in your pulse field, Tenuta suggests contacting your provincial crop production specialist or diagnostic lab, or your provincial pulse grower association. If they think your plants may have a nematode problem, they can contact Tenuta to arrange for sample testing and diagnosis.

Phosphorus is the most likely nutrient to be limiting field pea productivity and can provide sizeable yield benefits when applied as fertilizer.

by Donna Fleury

Field peas are an important pulse crop for Saskatchewan growers, providing both rotational and diversification benefits. With the increasing consumer demand for plant-based proteins, researchers and industry are interested in exploring potential management options to more consistently achieve high protein levels in field peas while optimizing yield.

In 2019, a comprehensive field pea fertility study was initiated at multiple Saskatchewan locations by Agri-ARM and Saskatchewan Pulse Growers agronomists. The objectives were to evaluate the yield and protein response of yellow field pea to various rates and combinations of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and sulphur (S) fertilizer across a range of Saskatchewan environments. The six study sites were located near Swift Current, Outlook, Scott, Indian Head, Yorkton and Melfort. Seed yield and seed protein concentrations were evaluated.

“For field peas, P is the main nutrient that growers need to be concerned about for fertilizer management. Generally, N fertilization in field pea production is not recommended unless soil residual

levels are extremely low, and responses to S appear to be rare,” explains Chris Holzapfel, research manager at the Indian Head Agricultural Research Foundation (IHARF). “Peas, like most other legumes, can convert atmospheric N2 to available forms utilized by the crop through the process of N fixation, with maximum benefits generally achieved when mineral N (soil plus fertilizer) levels are low. However, we were interested in evaluating various fertilizer application treatments to test the yield and protein responses, and therefore included varying P and S rates in addition to several N fertilization strategies. We also included an unfertilized control and an ultra-high fertility treatment to represent those two extremes.”

For the study, the source of P was monoammonium phosphate (11-52-0) and S sources were ammonium sulphate (21-0-0-24). The

TOP: Field pea fertility trials near Indian Head in early August 2020, about two weeks before harvest.

INSET: Field pea fertility trials near Indian Head in early August 2019, about two weeks before harvest.

• Enhanced Fusarium control

• More uniform plant stand

• Increased yield potential*

Visit agsolutions.ca/InsureCerealFX4 or call AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273) to learn more. Start your season with

on yield, which is not surprising as the selected sites were generally low in P. The lowest yields were in the unfertilized control, while the highest yields were achieved with a balanced but not excessive fertility package of 17-40-0-10 kg N-P2O5-K2O-S per hectare (/ha) as sidebanded monoammonium phosphate and ammonium sulfate.”

The responses to P fertilization varied across locations and environments, however yields were increased by up to 12 per cent when averaged across all six sites. The most responsive sites showed yield increases with P fertilization ranging from 11 to 31 per cent. Statistically, yields did not differ significantly amongst any of the fertilized treatments where a minimum of 20 kg P2O5/ha was applied. As well, yield increases beyond the 20 kg P2O5/ha rate were never statistically significant, and under most conditions it is unlikely that rates exceeding approximately 40 kg P2O5/ha would be justified. An important exception could be when the fertility objective is for long-term building of residual P levels. A balanced, but not excessive P fertility package probably resulted in healthier plants and roots, which could have indirectly resulted in better fixation and accumulation of N and frequently increased yield.

“We also saw a significant location and fertilizer interaction with the protein response, similar to seed yield, indicating that the protein response to fertilizer varied with the environment,” Holzapfel adds. “The study showed that P had the biggest effect on protein, and there was a significant overall linear increase in protein with increasing P rate; however, these responses were small, inconsistent, and could be due in part to the elevated N levels at the highest P rates. The results also showed that regardless of formulation, there was no benefit to additional N for either yield or protein, beyond what is supplied with modest rates of P and S fertilizers. This study did not provide any evidence that an in-crop application of N, or slow release N products, are likely to benefit an otherwise healthy and well-nodulated pea crop with respect to either yield or protein. Any responses to N that did occur were small and/or negative. Negative protein responses to N fertilization are at least as probable as positive responses.”

When averaged across locations, S responses were not significant, however S deficiencies can potentially occur on a site-specific basis. For example, a positive yield response to S rate did occur at Yorkton even though soil test levels were high. It is unlikely that S deficiency has been an important yield limiting factor for many field pea producers in Saskatchewan, however if deficiencies have been observed in the past for either field peas or other crops, applying a small amount of S may be beneficial.

N source for all of the treatments was urea (46-0-0), except for one treatment where polymer coated urea (ESN; 44-0-0) was used. Seeding equipment varied across locations, but all sites utilized notill drills with side-band capabilities and the field peas were always seeded directly into cereal stubble. All fertilizer was side-banded with the exception of one treatment that included an additional in-crop broadcast urea application during the late vegetative crop stages. All sites used the same seed source and variety CDC Spectrum, with target seeding rates of 100 viable seeds per square metre, adjusted for seed size and percent germination. All treatments received the full, label-recommended rate of granular inoculant.

“Generally, the results from the 2019 trials are more or less what we expected, taking into consideration that specific responses and requirements can vary across the study sites,” Holzapfel says. “The observed fertilizer responses were largely consistent with past research and current recommendations for western Canada. Overall, the results showed that P had the largest and most consistent impact

“Overall, the study results support the use of soil tests and suggest that of the major nutrients, P is the most likely to be limiting field pea productivity and can provide sizeable yield benefits when applied as fertilizer,” Holzapfel says. “The fertilizer responses in the study were largely consistent with past research and current recommendations for Western Canada. Soil testing can help predict what the likelihood of response to individual nutrients is and also help growers set longterm fertility goals, whether that is to build, maintain or deplete residual P levels. Although growers with a strong history of peas or lentils in their rotation may see reduced benefits to inoculation, I still always recommend inoculating since die-backs of native rhizobia can occur, particularly in areas affected by flooding, drought, or disease. Good nodulation is so critical for a healthy, high-yielding pea crop that it is not worth risking a failure by failing to inoculate.”

These exact trials were repeated in 2020 at all locations except Outlook, and Holzapfel says the team will be re-analyzing the data and providing an updated report later this winter.

by Bruce Barker

It’s a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma, as Winston Churchill once famously said. The same phrase could be used to describe an emerging health issue in chickpea that was first noticed in 2019 and was more widespread in 2020.

“There are some well-known health issues in chickpea in Saskatchewan, such as Ascochyta blight, insensitivity to Group 11 fungicides, and delayed maturity because of the indeterminate nature of growth. None of these issues appear to be the primary cause of the emerging chickpea health issue,” says Michelle Hubbard, plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Swift Current, Sask.

Gravelbourg, Assiniboia and Coronach were the worst-hit areas in 2019. These areas were dry early in the season and wet later on. Early symptoms showed leaf tip chlorosis, and edges could also be chlorotic. There were varying levels of white spotting on the leaves that could have been surfactant burn. Secondary growth in the leaf axils on the main branch could also be wilted and chlorotic.

There was discolouration with purpling or browning of the leaves, combined with whitening or death of the leaves. Entire branches or the entire plant could dry up and die.

Adding to the puzzle, some affected plants had rotted roots but others had healthy roots. There were also reports of nodules being affected.

Hubbard says in 2019, the symptoms were often widespread in a field, while in 2020 some fields had patchy areas in low spots, compacted areas, knolls and rocky areas. Some fields, however, were completely wiped out.

Initially in 2019, CDC Orion chickpea seemed to be hit much worse than CDC Leader. That year, the samples were collected fairly late in the summer, resulting in all samples having high levels of Ascochyta blight that were insensitive to the Group 11 strobilurins.

“In 2019, we came up with the idea that, assuming Ascochyta blight was playing a significant role in the damage, that maybe the genetic resistance in CDC Orion had been overcome,” Hubbard says. “We found no significant difference on how CDC Orion and CDC Leader responded to Ascochyta blight in growth chamber tests.”

Another suspected cause in 2019 was damage from residual herbicides, like Group 14 saflufenacil (Heat). However, no clear symptoms of herbicide damage, such as mottled chlorosis or necrosis, were observed. And some affected fields had never seen a

Group 14 herbicide.

A task force has been set up to study the issue, including Hubbard, Banniza, weed scientist Shaun Sharpe with AAFC in Saskatoon, soil scientist Jeff Schoenau at the University of Saskatchewan, James Tansey, provincial insect specialist with the Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture, and agronomy manager Sherrilyn Phelps with the Saskatchewan Pulse Growers. Saskatchewan Pulse Growers has a factsheet on their website that provides an in-depth look at the issue.

More extensive sampling was conducted in 2020 on behalf of Saskatchewan Pulse Growers around flowering to early podding,

and analysis was conducted for herbicide residues, nutrient levels, and foliar and root pathogens. Root and leaf samples were collected from 16 fields with one to three samples collected in each field. Eight fields had both healthy and unhealthy areas, which were sampled separately for analysis. Agronomic practices were also collected.

The most severely affected areas in 2020 were in the same general area as 2019, but mild symptoms were also observed in the Swift Current area. In the survey, the percentage of field impacted ranged from less than 10 to 100 per cent.

The samples were analyzed for nutrient content. Nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium, calcium, sodium, zinc, manganese, iron, copper, boron and aluminum content were compared between healthy and unhealthy samples. Total nitrogen and potassium were slightly lower than the normal range, but there was no difference between the healthy and the unhealthy samples. Micronutrient concentrations were generally above the critical levels and not related to apparent differences in plant health.

“The potassium levels were low according to the diagnostic criteria, but the stage of sampling is an important consideration as the criteria was for the vegetative stage and not the early reproductive state,” says Schoenau. “In terms of comparing healthy and unhealthy plants, there weren’t any differences that appeared to be a smoking gun for the issue.”

Aluminum toxicity was also raised as a possibility, but Schoenau says this issue usually shows up on low pH (acid) soils where there is a lot of soluble aluminum. Schoenau says the symptoms of aluminum toxicity are a reduction in root growth and root pruning. This hasn’t been the case with the chickpea health issue.

“I don’t see anything that points to metal toxicity to think that might be the issue,” says Schoenau.

The samples were analyzed for herbicide residues in the tissue. The herbicides screened are commonly used in chickpea production, and included ethalfluralin, flumioxazin, imazethapyr, Metribuzin, quizalofop-p-ethyl, clethodim, saflufenacil and trifluralin. Sharpe says when herbicide residues were detected, there were no differences between health and unhealthy plants.

Metribuzin residues were detected in seven of 16 fields. In four out of five fields with healthy and unhealthy plants, metribuzin residues in the unhealthy plants were a bit higher than the healthy plants. Sharpe says this could suggest that metribuzin could play a role in some fields.

“We were concerned about metribuzin because we do know that it does have an influence on Ascochyta severity, but the disease survey by Michelle Hubbard did not find this to be the case,” Sharpe says.

Ethalfluralin residues were found in two fields, saflufenacil at low levels in five fields, sulfentrazone in four fields, and trifluralin in four fields. Sharpe says that because the 16 fields had different herbicide use patterns but have similar symptoms, herbicide residues can’t be the direct reason for the health issue.

Clethodim, quizalofop, imazethapyr and flumioxazin were not detected in any of the fields sampled.

“I believe with the range of symptoms we are seeing, we could be seeing many little cuts [factors] that are causing stress to chickpeas,” Sharpe says.

In addition to moisture stress and poor chickpea tolerance to metribuzin, herbicide carryover from rotational crops, usually wheat, could add another little cut. Group 4 fluroxypyr and clopyralid, and Group 2 herbicides commonly used in wheat might be carrying over to add to chickpea stress. Sharpe plans to investigate this further in 2021.

The 2020 samples were screened for a wide range of root and foliar diseases, and viruses. Hubbard says there were no consistent trends in the percentage of pathogens detected or in abundance of pathogens between healthy and unhealthy plants. Additionally, Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Verticillium dahlia were not detected.

Eight viruses that are transmitted by aphids were also screened for. Only lettuce mosaic virus and peanut stunt virus were detected in two samples each.

The Saskatchewan Crop Protection Lab received a sample of chickpea that had feeding damage on the nodules. Tansey says two species of insects were found including Delia platura (seedcorn maggot) and a dark-winged fungus gnat (Sciaridae).

The seedcorn maggot has a wide host range, so Tansey says the confirmation of feeding on chickpea was not unexpected. The previous crop was canola, and the insect likely carried over from that crop.

“It seems very likely that, given the large numbers present, they weren’t feeding on nothing, so it is very likely they found an alternate host [on chickpea],” Tansey says.

The dark-winged fungus gnat was surprising, since it is a fungus feeder, and is typically associated with mushroom production. Tansey says the seedcorn maggot feeding coupled with the wet

weather could have led to increased fungal hyphae growth, which the gnat could have taken advantage of as a food source.

“However, they were tunneling in the nodules, so there is much more to this story,” he adds.

During the fall of 2020, soil samples were collected and will be analyzed for other pathogens. The soil will also have a nutrient, pH and electrical conductivity analysis conducted, and will be screened for nematodes.

Hubbard, Sharpe and Schoenau hope to collaborate on a greenhouse trial to look at potential interactions between environment, herbicides and disease. Another survey may also be conducted in 2021.

Looking forward to the remainder of 2021, there are still many questions to be answered, including whether the health issue will even occur – especially given its mysterious nature. That leaves chickpea growers in a tough spot regarding chickpea acreage.

“Unfortunately, we don’t have all the answers, so I can’t make a definitive recommendation. But if I was a farmer in those hard-hit areas, I would keep my chickpea acres muted, and follow all the recommended production practices. Keep track of what you can. Scout around that flowering stage to look for the issue,” Hubbard says. “If I was a grower outside those hard-hit areas, I would be less worried and plant as much chickpea as you would normally, but don’t increase your acreage and be careful with all your production practices.”

And as a final suggestion, Hubbard encourages chickpea growers to try a chickpea/flax intercrop to see how it compares with monocrop chickpea for both Ascochyta blight and the mysterious health issue.

A pea leaf weevil by any other name would still prefer fababean as its primary host crop.

by Jennifer Bogdan

The name “pea leaf weevil” drums up thoughts of an insect gnawing away in a crop of field peas. But as many fababean growers have found out in recent years, this weevil doesn’t stop in its tracks at the pea field borders. Finally, some much-needed research on pea leaf weevil in fababean, including the first-ever economic threshold, is coming to conclusion through the work of Asha Wijerathna, a PhD candidate in the department of biological sciences at the University of Alberta.

“Pea and fababean are becoming increasingly popular in Alberta, with more area of growth every year. Along with this increase in host plant acreage, pea leaf weevil populations have been expanding their range to the northern and eastern regions of Alberta, causing damage to these crops. While research on this insect exists for field pea, very little was known about its effect on fababean on the Prairies. Therefore, there was a need to understand the impact of pea leaf weevil on fababean in order to mitigate potential damage,” says Wijerathna.

Under the supervision of Héctor Cárcamo, research scientist at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Lethbridge, and Maya Evenden, professor in the Biological Sciences Department at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, Wijerathna conducted eight experiments in Alberta from 2016 to 2018, including a focus on the host preference, yield impact and management of pea leaf weevil in fababean.

Fababeans: Where spring adults prefer to arrive and larvae happily thrive

Pea leaf weevil adults were found to have different host preferences during different times in their life cycle. Adults in the fall, when they are reproductively inactive, did not have a preference in host

ABOVE: Adult pea leaf weevils are reproductively active in the spring, preferring fababean over field pea as their reproductive host.

• STATE OF THE ART DIGITAL PROGRAM

• CROP PLANNING AND SAMPLING

• FIELD SCOUTING AND RECORD KEEPING

• SATELLITE IMAGERY

• INTEGRATES WITH MULTIPLE PLATFORMS

AVAILABLE AT

crops when given the choice between field pea and fababean. However, reproductively active adults in the spring preferentially chose fababean over field pea.

Wijerathna explains: “Fababean produces more nodules compared to field pea. Since the larvae feed on nodules, female weevils may choose fababean over field pea to support larval development. We still don’t know how adults are able to discriminate between hosts, but adults do respond to both fababean and field pea host volatile compounds so perhaps adults use volatile composition to choose between two host plants.”

Spring adults also fed more than the fall adults. Wijerathna attributes this finding to the reproductive status of the weevils – since weevils need to feed on their reproductive host in order to become reproductively mature, it makes sense that spring-dispersing weevils feed more compared to fall-dispersing weevils.

Interestingly, when the spring adult weevils fed on alfalfa prior to being introduced to fababean and field pea, the weevils stopped exhibiting a preference for fababean. “Because this previous experience of feeding on alfalfa may have affected weevil host acceptance and preference, it’s possible that fababean and alfalfa may be used as potential trap crops in managing pea leaf weevil,” Wijerathna adds.

Wijerathna also tested adult feeding and larval development on seven different legume species, all inoculated with their corresponding inoculant strain: field pea, fababean, alfalfa, lentil, chickpea, soybean and lupin. The results showed that adults will feed on all of

the host plants, except for chickpea, and feeding is very minimal on lentil. Larvae were found to develop only on field pea and fababean, and to a much lesser extent, soybean.

Wijerathna clarifies that there is still a lot to be understood when it comes to larval development on host species. “We know that larvae feed on Rhizobium leguminosarum biovar viceae, associated with root nodules of pea and fababean. Yet, lentil does not support larval development despite having this same Rhizobium, and adults do not feed much on lentil. The leaf and nodule characteristics may have something to do with this, but more research is required to understand why. We also do not know if other Rhizobiu strains support larval development. Adult weevils will feed to a lesser extent on soybeans, which use a Bradyrhizobium japonicum inoculant strain, and we did find some, although very few, larvae feeding on these nodules. Again, these findings need further research,” she says.

Out of the two primary host crops, field pea and fababean, higher numbers of larvae were able to develop on fababean. “Both hosts support more larvae when infestation occurred at the later seedling stage (fifth unfolded leaf stage) compared to the earlier infestation stage (third unfolded leaf stage) because the root systems of the crops are larger at that time, and more nodules mean more food available for the larval population. Fababean produces more nodules compared to field pea, which is the reason for higher larval capacity in fababean,” Wijerathna explains.

New economic threshold determined, although foliar insecticide ineffective for control

Similar to field pea, Wijerathna found that foliar feeding by adults on fababean plants can potentially decrease yield, but it is the feeding damage by larvae on the root nodules that causes the more significant yield reduction.

Wijerathna found that a seed treatment containing thiamethoxam reduced both adult and larval damaage, thereby

Currently, few management options exist for controlling pea leaf weevil in fababean. One option is to attempt to use a foliar insecticide (lambda-cyhalothrin, in this study) to control adult weevils before egg-laying takes place. The results showed that foliar insecticide was ineffective in protecting fababean yield and therefore is not a recommended strategy for pea leaf weevil management. These conclusions are consistent with multiple research studies and field-scale observations conducted in western Canada on pea leaf weevil in field pea.

A second option is to use a seed treatment containing an insecticide. Wijerathna found that a seed treatment containing thiamethoxam reduced both adult and larval damage, thereby protecting fababean yield.

During this experiment, Wijerathna was able to calculate an economic threshold for pea leaf weevil in fababean, a first for this insectcrop combination. The economic injury level (and threshold) for pea leaf weevil was 15 per cent of fababean seedlings with terminal leaf damage. But if foliar insecticides are ineffective in controlling wee-

vils, how useful is this economic threshold to farmers?

“The effectiveness of foliar insecticide could vary with many factors such as peak flight time of the weevil to the fields and weather conditions. Therefore, any attempt at spraying should be done with a prior knowledge of weevil density and this is where monitoring for adult damage and using the economic threshold is important. Another way to make use of this economic threshold is for evaluating how effective your insecticide seed treatment is at protecting seedlings from adult damage,” Wijerathna suggests.

Cárcamo agrees. “I think the best we can do is say that this is really only a nominal action threshold because we are using the prices of insecticide that we know are not protecting yield. But this is all we have to give producers an idea of what level of damage is serious enough to reduce yield, and for them to think about ways to mitigate the risk damage in the future – basically, use seed treatments or grow a crop that is not susceptible, such as lentils,” he says.

Canola affected by diamondback moth or clubroot negatively impacts bertha armyworm.

by Jennifer Bogdan

Bertha armyworm is a cyclical, generalist insect pest that has adapted to using canola as its preferential host crop. Diamondback moth is a specialist on brassicaceous plants such as canola and can undergo multiple generations depending on when they arrive on the southerly winds that carry them to the Prairies. Clubroot, another specialist, is a devastating root disease of canola when susceptible varieties are grown and is increasing its spread across the Prairie Provinces. Individually, these pests can take a serious toll on a canola crop if not managed properly, but what happens when they act on canola together?

Chaminda Weeraddana, a former PhD student at the University of Alberta in the department of biological sciences and currently working as a post-doctoral fellow in the department of entomology at the University of Manitoba,

now has the answers. As part of his PhD thesis, Weeraddana studied how the generalist bertha armyworm (BAW) is impacted by a canola host crop that has already been affected by the specialists diamondback moth (DBM) or clubroot (CR). “A canola crop is impacted by more than one stressor at a time under field conditions. However, most of the research has focused on testing the direct influence of only one stressor, but this is not realistic under field conditions. We need to understand multiple interactions in order to understand the ecology of BAW in canola fields. Then we can incorporate these findings into integrated

ABOVE: As part of his research, Chaminda Weeraddana analyzed the volatile organic compounds between clubrootinoculated susceptible and resistant cultivars to study their effect on bertha armyworm.

RANCONA® TRIO seed treatment for pulse crops takes disease protection and improved crop emergence to new levels. By combining three powerful fungicides that provide both contact and systemic activity, with the superior coverage and adhesion of RANCONA advanced owable technology, you have a seed treatment that delivers more consistent protection under a wider range of conditions. Because when more seed treatment stays on the seed, you get more out of your seed treatment. Ask your dealer or UPL representative about RANCONA TRIO, or visit ranconatrio.ca.

pest management of BAW in canola. Because of the overlapping life cycles of BAW, DBM and clubroot in canola on the Prairies, I thought it would be important to study their interactions,” Weeraddana explains.

All of the experiments took place under greenhouse conditions. For the diamondback moth experiments, the standard check cultivar Q2 was used. For the clubroot experiments, a susceptible canola cultivar (45H26) and a resistant canola cultivar (45H29) were either inoculated with clubroot pathotype 3, the predominant pathotype found in Alberta at the time of the research project, or were mock-inoculated with sterilized water.

Clubroot-infected plants exhibit reduced overall fitness due to galls imepeding water and nutrient uptake, perhaps making them less desirable as a host plant.

In my experiments, I introduced BAW a short time after feeding by DBM, which is similar to the field conditions. However, this short time may not have allowed the plant to mount defences against oviposition by BAW,” Weeraddana explains

Egg-laying by bertha armyworm was affected by clubroot but not by diamondback moth

Female BAW moths were able to distinguish between CR-infected canola and uninfected susceptible canola, possibly from the volatile organic compounds (VOCs) emitted by canola under attack by the pathogen. As a result, the female moths laid fewer eggs on the CRinfected susceptible canola cultivar. Clubroot-infected plants are also smaller with fewer leaves which could be less attractive to a female moth who lays her eggs mostly on the underside of leaves. In addition, clubroot-infected plants exhibit reduced overall fitness due to galls impeding water and nutrient uptake, perhaps making them less desirable as a host plant. On the resistant canola variety, there was no difference in egg-laying on the pathogen-inoculated and mock-inoculated canola.

Weeraddana also inoculated the susceptible canola variety with a low dose of inoculum to see the effect of a mild clubroot infection on egg-laying. The result was a trend toward BAW moths laying fewer eggs on these plants. “Because the plant morphology (leaf differences, etc.) from this mild infection was not severely affected, it is possible that the female BAW moths were still able to detect volatile cues from the plant since reduced egg-laying was consistently observed, but it was a non-statistical trend,” he says. Contrary to the clubroot experiment results, female BAW moths did not have an egg-laying preference between the DBM-damaged canola or the undamaged canola. “DBM has a short life cycle and completes several generations per field season in the Prairies. Although earlier DBM generations occur prior to BAW infestations, later in the season, feeding activity of both species co-occurs in canola fields.

Bertha armyworm development was suppressed by diamondback moth and clubroot

Bertha armyworm larvae grown from eggs laid on clubroot-infected susceptible canola developed into smaller pupae and then into adults with smaller wings. The same result held true for BAW larvae that fed on DBM-damaged canola. Small wings tend to equate to lower reproductive capabilities as well as reduced dispersal by the moth. Pupal weight and adult wing size of BAW were not impacted by the clubroot-inoculated resistant variety. When given a choice, BAW larvae preferred to feed on the undamaged canola rather than on the DBM-damaged canola. Weeraddana speculates that this observation could be tied to glucosinolates in canola. “Glucosinolate metabolites on their own are not toxic to specialist insects; however, glucosinolate metabolites are toxic to generalists. Brassica specialists like DBM have evolved mechanisms to detoxify glucosinolate metabolites, whereas generalist feeders have not and can experience negative consequences from consuming these hydrolyzed glucosinolate products. Bertha armyworm may have adapted to detoxify some, but not all, glucosinolates present in Brassica species,” he explains.

Plant hormone changes due to clubroot infection may influence egg-laying

The presence of the clubroot pathogen had an influence on plant hormone levels particularly in the susceptible cultivar. Salicylic acid and its conjugates were much higher in CR-infected canola at the pre-flower stage (five weeks old; usually at seven to eight weeks, canola starts flowering in greenhouse conditions), and this observation was even more pronounced in the susceptible variety. This is the first study to report an increase of salicylic acid in susceptible canola following clubroot infection. “In our study, female BAW laid fewer eggs on CR-inoculated susceptible plants that had higher levels of salicylic acid and its conjugates in the pre-flower growth stage, suggesting that salicylic acid may accumulate in the plant and negatively influence egg-laying by BAW,” Weeraddana says.

Weeraddana’s findings help form a strong knowledge base that is key to understanding how BAW performs when its canola host has already been affected by another insect or disease. Ultimately, more research involving the interactions between different pest species will contribute to more effective integrated pest management approaches to help western Canadian farmers manage common insects and diseases in their crops.

Secure your profits with leading crop protection solutions that cover you from pre-seed to post-harvest.

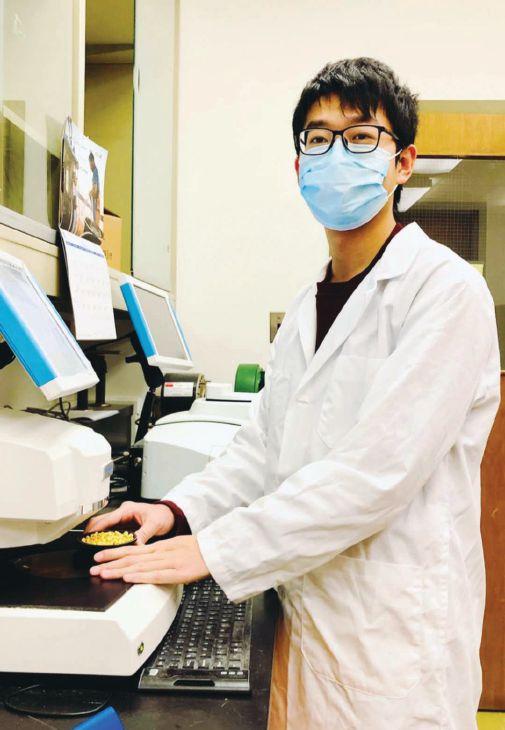

Could a better indicator of end-use quality overcome the low protein concern for Prairie soybeans?

by Carolyn King

Crude protein, a commonly used indicator of soybean protein quality, tends to be lower in soybeans grown in more northerly areas. And that’s a concern for Manitoba soybeans. However, it turns out that crude protein levels may underestimate the feeding value of the protein in northern soybeans.

So, a Manitoba project is working with an alternative indicator of protein quality that is based on certain nutritionally essential amino acids, the compounds that make up proteins. And the preliminary results look very promising for protein quality in Manitoba soybeans.

The University of Manitoba’s James House is leading this project, which started in 2019. “We have been engaged in a program here at the university focusing around the quality of plant-based proteins. As part of that, we established the capacity to measure protein quality including amino acid composition and protein digestibility. Those are really important factors in the nutritional impact of plant proteins and in the marketing of plant proteins,” explains House, a professor and head of the University’s Department of Food and Human Nutritional Sciences.

“As part of that research, we engaged with the soy sector because there were some concerns over lower protein content in Manitoba soybeans and in particular the fact that certain soy crops were receiving discounts because their protein contents didn’t reach the minimum standard established by the particular purchaser. There was a real economic incentive for the sector to take a closer look at this issue.”

He adds, “Low protein is not just an issue for Manitoba soybeans. It is basically a north-south issue – the further north you go in the soybean-growing regions, the lower the protein content typically is.”

The Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers (MPSG) is very aware of the issue of low protein levels in northern-grown soybeans. MPSG has been supporting various protein-related soybean studies and is collaborating with House on this project. The Western Grains Research Foundation and the Canadian Agricultural Partnership are helping to fund the project.

Along with the north-south trend in protein levels, there has also been an overall decline in protein content in North American soybeans over time, notes Cassandra Tkachuk, an MPSG production specialist. “We suspect this decline might be due to breeders selecting for higher yields while potentially sacrificing

protein levels; researchers have found an inverse relationship between soybean yield and protein.”

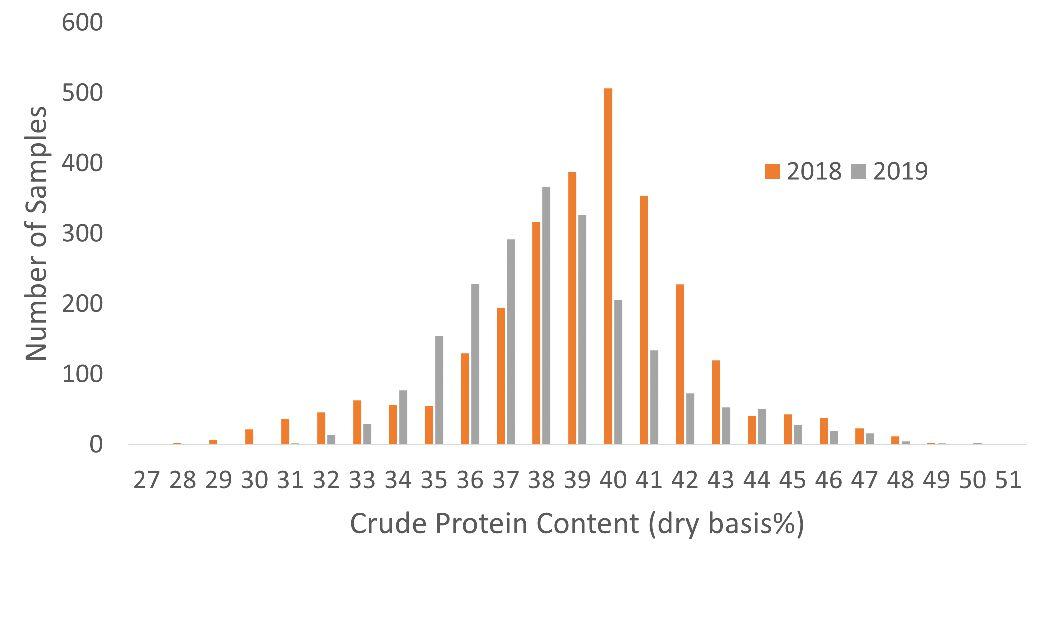

On the positive side, Canadian researchers are working to get a better understanding of the reasons for the north-south protein trend and to improve protein levels in Prairie-grown soybeans. In fact, as the line graph shows, protein content in western Canadian soybeans has had an overall upward trend since 2006 –although western protein levels remain lower and more variable than those in Eastern Canada.

For canola growers in the West, ea beetles are a familiar problem. In recent years, growers across Western Canada have reported high annual ea beetle populations and as a result, heavy crop damage.

When not properly managed, ea beetle damage can have a severe economic impact. According to the Canola Council of Canada, crop losses of up to 10 percent are reported in areas of high insect pressure. Overall, the combined severity of ea beetle damage across North America is estimated to exceed $300 million*.

To ght back against this chronic pest issue, growers need to be ready with the best management tools available to ensure they can mitigate losses and start their season off strong.

Bayer’s new BUTEO™ start insecticide seed treatment provides superior and immediate protection for canola against both striped and crucifer ea beetles.

“Flea beetles take advantage of the early growing stages when the plant is most vulnerable,” says Andrew Chisholm, Trait and Trait Launch Manager at Bayer. “The damage these insects can cause in the seedling and early vegetative plant stage can impact the crop for the rest of the season and lead to signi cant yield loss. But BUTEO start offers the early defense the crop needs to grow in strong.”

Early ea beetle damage can cause poor plant stands, delayed maturity and reduced yields. BUTEO start is designed to be an early-stage solution, protecting the plant from day one. The Group 4D insecticide ( upyradifurone) delivers rapid uptake and systemic translocation

from cotyledon to leaf margins, encouraging stronger plant stands. The powerful seed treatment also enables a quicker-growing canopy and uniform owering, even in dry conditions.

BUTEO start is designed to give growers the targeted pest control they need. The seed treatment not only reduces the need for in-crop rescue treatments but also works well in combination with leading base seed treatments and cutworm treatments, so growers can customize their pest management strategies to their needs.

“In a busy season, growers have many challenges to focus on, but signi cant crop loss from ea beetles damage doesn’t have to be one of them,” says Chisholm. “As trial results have demonstrated, BUTEO start’s ef cacy and performance is something canola growers can count on.”

In research trials held across areas with strong ea beetle pressure, BUTEO start continually demonstrated superior performance, with BUTEO start treated canola showing signi cantly lower levels of damage over two weeks after emergence compared to other industry seed treatments. Canola that was treated with BUTEO start also grew in with stronger plant stands and developed fuller canopies. Importantly for Western Canadian growers, BUTEO start showed exceptional control against the novel striped ea beetle, which is especially prevalent across the Canadian prairies.

To protect your canola investment with BUTEO start, talk to your local Bayer representative or visit BUTEOstart.ca to learn more.

Source: Bayer Market Development Trials (photos taken July 7, 2020, Carseland, AB). Treated seeds were seeded the same day. * Source: Knodel, J.J. and Olson, D.L., 2002. Crucifer- ea beetle: biology and integrated pest management in canola. North Dakota State Univ. Coop. Ext. Serv. Publ. E1234. North Dakota State University, Fargo, ND

Tkachuk notes that Manitoba soybeans are grown mainly for the meal, with the oil as a byproduct. So the livestock feed market is very important for the province’s soybeans, which means that protein quality is very important.

Although crude protein content is relatively easy to measure, the problem with using it as the sole indicator of protein quality is that soybean meal with a higher protein content does not necessarily have higher amounts of the particular amino acids needed in animal rations.

“Livestock nutritionists don’t really formulate diets around crude protein any more. They formulate around the amino acid content, making sure the animals have the correct levels of the digestible amino acids [for good health and growth],” House explains.

“Typically, nutritionists are using soybean meal to balance the amino acid profile coming from the main ingredient in livestock diets, which is normally a cereal grain, particularly corn, wheat or barley. The amino acids that tend to be the most important ones to add to cereal-based rations [for pigs and poultry] are lysine, threonine, cysteine, tryptophan and methionine.”

And that’s where another indicator comes in: the Critical Amino Acid Value (CAAV). CAAV is the sum of those five amino acids, measured as a percentage of crude protein. It was developed in the U.S. as an indicator of protein quality in soybean meal for livestock feeding.

“The Critical Amino Acid Value concept was brought to our attention based on what our neighbours to the south are doing. Soybean growers in states like North Dakota, Minnesota and South Dakota are also dealing with this low protein issue. They initiated research a few years ago looking at these critical amino acid value levels,” Tkachuk notes.

House says, “Interestingly, the U.S. researchers have found that as protein levels go down, you actually maintain or increase the levels of those really critical amino acids that tend to be limiting in a cereal grain diet.” So, soybeans from the northern U.S. are competitive with soybeans from more southerly regions in terms of these key amino acids for livestock rations.

House and MPSG want to see if this U.S. finding also holds true for Manitoba soybeans. One of the project’s objectives is to determine the crude protein and amino acid levels in Manitoba-grown soybeans.

House’s project team is analyzing samples from the MPSGfunded annual soybean variety performance trials in 2018, 2019 and 2020. The trials include herbicide-tolerant and conventional soybean varieties grown at multiple Manitoba locations.