TOP CROP MANAGER

RESISTING FALL FROST

Tannin-containing fababeans less damaged by frost PG. 10

SOYBEANS ON THE PRAIRIES

Improving short-season varieties

PG. 20

CANOLA BEFORE PULSES

Is biological nitrogen fixation affected?

PG. 34

Tannin-containing fababeans less damaged by frost PG. 10

Improving short-season varieties

PG. 20

Is biological nitrogen fixation affected?

PG. 34

Step up to a new level of cleavers control.

For years, managing cleavers in canola has been a challenge. But not anymore. New Facet® L herbicide puts you in control of cleavers to help safeguard the yield potential of your InVigor® hybrid canola. Visit agsolutions.ca/FacetL to learn more.

directions.

10 | Resisting fall frost damage

Tannin-containing fababean varieties less damaged by frost. by Bruce Barker

4 The power of people by Stefanie Croley

PULSES

6 Resarching fababean agronomy by Bruce Barker

PESTS AND DISEASES

16 Twospotted spider mites suck in soybeans by Bruce Barker

20 | Growing soybeans on the Prairies Saskatchewan researchers are improving short-season soybean varieties. by Mark

Halsall

26 Pea aphids overwhelming pulses by Bruce Barker

SOIL AND WATER

29 Do you need to inoculate your soybeans every year? by Carolyn King

FERTILITY AND NUTRIENTS

40 Fixing nitrogen in dry bean by Carolyn King

34 | Growing canola prior to pulse crops Is biological nitrogen fixation affected? by Donna Fleury

46 For bees, butterflies and landscape health by Carolyn King

49 Hitting malt barley quality by Bruce Barker

PULSES

52 Searching for root rot control in pulses by Bruce Barker

Readers

Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration

labels for complete instructions.

STEFANIE CROLEY | EDITORIAL DIRECTOR, AGRICULTURE

Technology in agriculture has made countless advancements over the last few decades. These innovations can drive efficiency and process, but can anything truly replace a human?

I recently tuned in to The Calgary Eyeopener podcast, featuring highlights from the CBC Radio Calgary program, where host David Gray interviewed Will Evans, a farmer from Wales, U.K., and host of the Rock and Roll Farming podcast.

Evans, a multigenerational farmer, aims to share the human side of agriculture through his podcast. He visited Edmonton in January, attending and speaking at the FarmTech conference, and is passionate about telling the story of agriculture through the people most involved in it.

Much like their Canadian counterparts, Evans says farmers in the U.K. are focused on soil health and regenerative agriculture. And, of course, technology is making all the difference. “We’re really on the cusp of a fourth agricultural revolution in terms of robotics and technology on farms and how it can drive us forward,” Evans said in his CBC interview.

But, he said, it seems as though the challenges are mirrored too.

“I think, speaking to Canadian farmers here over the last few days, [it’s] very similar [to] issues we’re having in the U.K. in terms of finding people to work on farms.

“It’s changed a lot certainly from my father’s generation, when there [were] a lot of small family farms around us. A lot of them are gone now. They’ve been swallowed up by the neighbours . . . a lot of the [larger farms] are really driving in efficiency and have incredibly high standards of animal welfare. It’s not as simple as ‘big farms are bad, small farms are good,’ but it certainly has changed a lot over the last generation.”

He’s not wrong. Advancements in technology and equipment have provided numerous benefits, including efficiency and precision. But to me, smart farming goes hand-in-hand with the shift in farm labour and dynamic. Yes, the benefits are proven – but that also means that the operator needs to be willing to adopt and understand the technology.

In addition, finding someone qualified to take over the farm has been a longstanding challenge for many Canadian farmers. Much like Evans has observed in the U.K., small farms with no one to succeed them often get purchased by a neighbour – in fact, the majority of respondents polled in our 2019 Succession Planning Survey revealed they have no succession plan in place (you can read more about that on www.familyfarmsuccession.ca).

The bottom line? Engaging the next generation is more important than ever, and it’s encouraging to see government and industry recognize and respond to this. In January, MarieClaude Bibeau, Canada’s minister of agriculture and agri-food, announced the launch of the Canadian Agricultural Youth Council, a group of young Canadians who will be asked to provide input on agriculture and agri-food issues.

It’s 2020. We know technology isn’t going anywhere. But if we want to keep up with smart farming, we need the right people to help.

Fax: 416.510.6875 or 416.442.2191 Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

SUBSCRIPTION RATES Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues Feb, Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, June, Sept,Oct, Nov and Dec

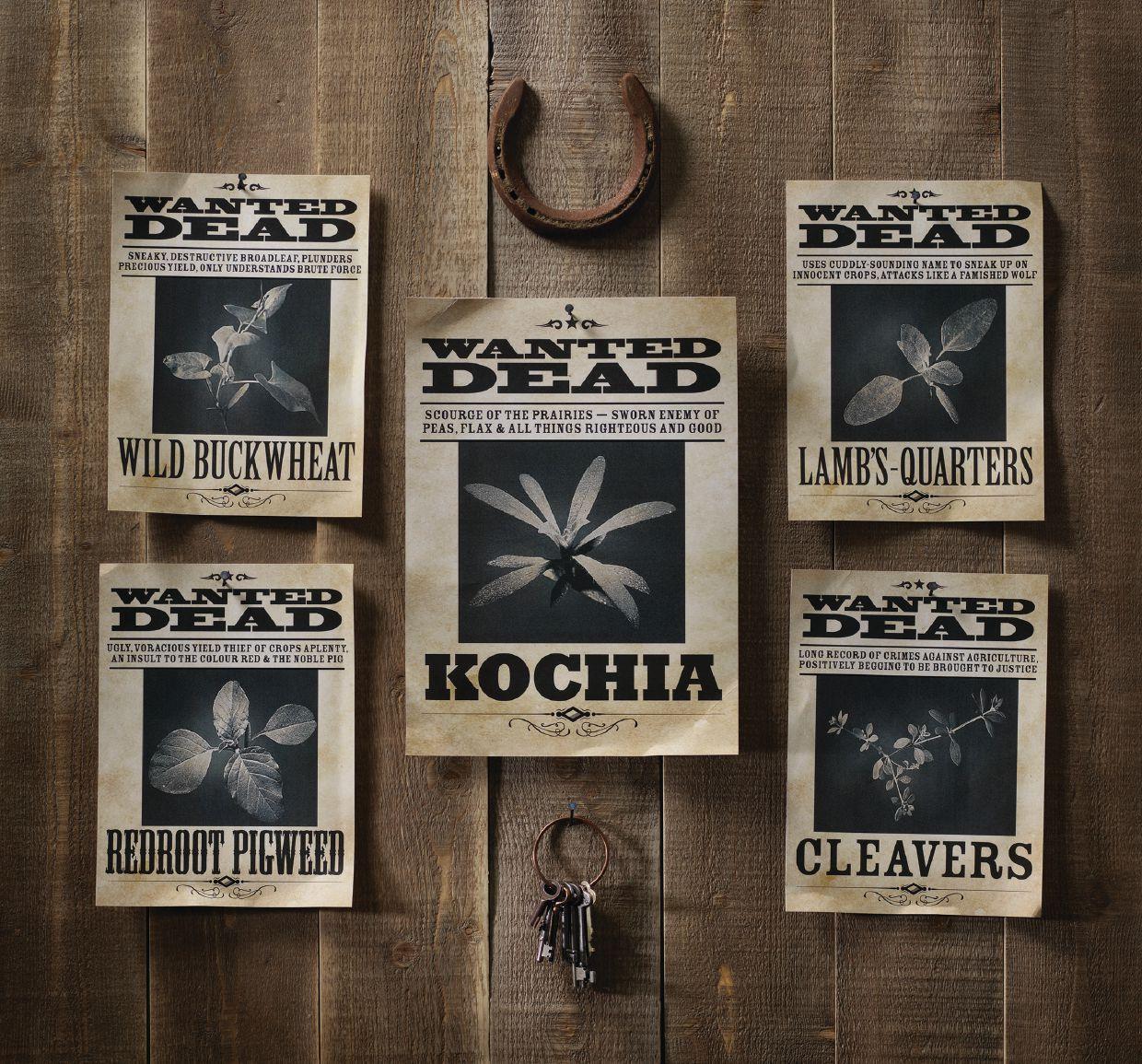

When you apply pre-emergent Authority® 480 herbicide, you’re after kochia and you mean business. But it’s not like the other weeds can jump out of the way. Yes: Authority® 480 herbicide controls kochia with powerful, extended Group 14 activity to protect peas, flax and other crops. It also targets redroot pigweed, lamb’s-quarters, cleavers* and wild buckwheat.

Authority® 480 herbicide. Gets more than kochia. But man, does it get kochia.

Save on Authority® 480 with FMC Grower CashBack.

*Suppression.

fungicides and nutrient management investigated.

by Bruce Barker

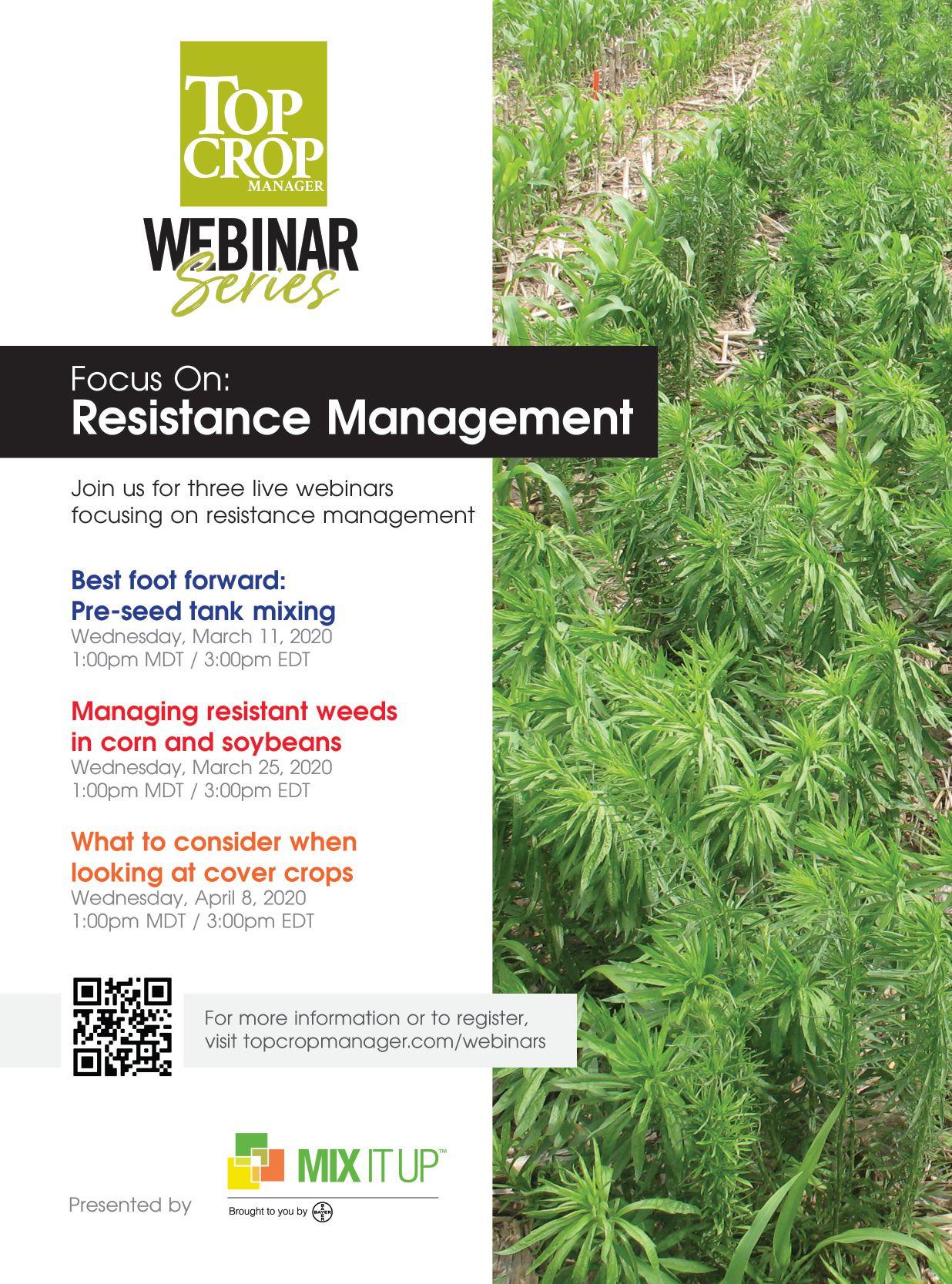

When Alberta fababean acreage hit 110,000 acres in 2015, growers had a lot of questions. With funding from Alberta Pulse Growers, pulse research scientist Robyne Bowness Davidson with Alberta Agriculture and Forestry at Lacombe, Alberta set up three research trials to help build a better understanding of fababean agronomy.

“There were some gaps in knowledge that we wanted to fill in. The research gave us some interesting results and, in some cases, surprises,” Bowness Davidson says.

The research project began in 2016 and ran for three years. Trials were established looking at herbicide residues, fungicide use and nutrient management. Additional funding was secured to carry on the herbicide and fungicide trials in 2019 and 2020. Trial locations included Falher, Edmonton (St. Albert), Lacombe and an irrigated Lethbridge site.

Herbicide trials looked at carry-over risk

The herbicide study included two components. The first was application of three cereal herbicides, Infinity, Prestige and Everest, on wheat in the year prior to fababean. The herbicides were applied at label rate, plus twice the label rate and, for some products, three times the rate. None of the herbicides have fababean as a re-crop the year following applications, so the research team wanted to see if crop emergence, plant height, flowering, maturity and yield would be affected.

Generally, at 14 and 21 days after emergence, plant stands were not significantly impacted. Plant height, flowering date and maturity were not significantly impacted by the wheat herbicides, either. Yield was not significantly impacted at Falher, St. Albert or Lethbridge. However, at Lacombe, the label rates of Prestige and Everest

had similar yields to the control with no herbicide application, but the other treatments had significantly lower yield.

Bowness Davidson says the significantly lower yields with Infinity and double rates of Everest and Prestige were unexpected, since the fababean plants did not show any signs of reduction in plant stand, height, flowering or leaf discoloration.

In general, Bowness Davidson says that growing fababean after Infinity, Everest, and Prestige has the risk of leaf damage and lower yield, especially under dry conditions. The research showed that fababean can sometimes grow through initial herbicide residue injury, but can also have reduced yield even if crop injury was not observed.

“The challenge with fababean is that, because it has traditionally been a smaller acreage crop, there hasn’t always been a lot of recropping research done. As far as recropping goes, fababeans are pretty wimpy at the seedling stage. If you can’t grow pea or lentil after a residual herbicide, I would be careful about growing fababeans,” Bowness Davidson says.

The second component looked at four preseed burndown herbicides applied prior to seeding, or five days after seeding at label rate and twice the label rate. The herbicides were Cleanstart (registered), Heat (not registered), Express SG (registered with caution on sandy and low organic matter soils) plus glyphosate, and Express SG plus 2,4-D.

At Falher, Lacombe and St. Albert, plant stand was not significantly affected. However, at Lethbridge, Express SG plus 2,4-D had a negative impact on stand establishment when applied according to label directions. But when Express SG plus 2,4-D was applied five

Turns out, you really can capture lightning in a bottle when you re-think what’s possible in pulse disease control. Say—like putting together three high-performing modes-of-action for the first time. Count on new Miravis® Neo fungicide to deliver consistent, long-lasting control so you can set the stage for healthier-standing, higher-yielding, better quality pea and chickpea crops.

Lightning in a bottle?

More like, “a better crop in the bin.”

We’ve captured it! 3 modes of action, 1 powerful product. For more information, visit Syngenta.ca/Miravis-Neo-pulses, contact our Customer Interaction Centre at 1-87-SYNGENTA (1-877-964-3682) or follow @SyngentaCanada on Twitter.

Always read and follow label directions.

days after seeding, damage was much less severe. That was a surprise.

“After the first year I jokingly said the plots must have been mislabeled. But when it happened again, we knew something was going on,” Bowness Davidson says. “I talked to a few weed scientists and nobody could really come up with a reason.”

Visually, Bowness Davidson says that Express SG plus 2,4-D, in general, showed more injury at the seedling stage. The seedling injury increased at twice the label rate, which can occur with sprayer overlaps. At Lethbridge, consistent with the plant stand reduction, plant height was significantly reduced when Express SG plus 2,4-D was applied according to label directions.

Yield was not impacted by the pre-seed herbicides at the Falher or St. Albert locations. At Lacombe, preseed herbicide application done according to label rates did not significantly lower yield, but higher rates or application after seeding reduced yield. At Lethbridge, Express SG, especially when tank-mixed with 2,4-D, had significantly lower yields of between 32 and 56 per cent when applied at label rate and at recommended preseed timing.

Bowness Davidson says the results suggest that Express SG should not be used in the Lethbridge soil zone because of the damage observed when it was applied according to label directions. At Lacombe, some visual damage was observed, and she cautions to use Express SG carefully. At St. Albert and Falher, where moisture conditions were favourable, Express SG was safe on the crop, but under dry conditions or low soil organic matter, caution is recommended.

Six fungicides were applied at early signs of chocolate spot disease or at mid-flower at recommended label rates. The fungicides applied were Lance, Acapela, Vertisan, Priaxor, Headline and Delaro. Overall, disease levels were low during the three years of 2016, 2017 and 2018 because of the hot, dry weather. Chocolate spot averaged 1.5 to 3 out of 7 on the disease rating scale of 1 (no disease) to 7 (death of the plant).

Generally, all the fungicides lowered the disease ratings compared to the control plots. There was a trend of higher yield with fungicide application, but it was not significant.

The fungicide trial was carried forward into 2019 and will be completed in 2020. In 2019, Bowness Davidson says chocolate spot pressure was high because of the late summer and fall moisture con-

ditions. Again, the fungicides worked well, and did increase yield, but she hasn’t had a chance to run the statistics.

“I can definitely say the fungicides worked in 2019, and worked well, but I haven’t determined if they would have provided an economic return,” Bowness Davidson says.

The nutrient trials had three components. The first looked at starter fertilizer applied with the seed with phosphorus (P) at 30 kilograms per hectare (kg/ha), potassium (K) at 30 kg/ha and sulphur (S) at 15 kg/ha. Crop and yield responses varied by location, depending on soil test levels.

At Lacombe (marginal soil test K), there was a significant plant height and yield (20 to 32 per cent) response to K in all three years. In 2017, P application provided a yield response at Lethbridge (high soil test P) and Falher (marginal soil test P). At all other site years, no additional trends were observed. There was no response to S at any location.

Micronutrient application was investigated in the other two components. Boron was applied at 11.2 kg/ha, molybdenum was applied at 49.4 g/ha and manganese was applied at 2.8 kg/ha with the seed at planting. Foliar trials included boron applied just before flowering, molybdenum applied twice (pre-emergence and at the 4-6 node stage) and manganese applied once at the 4-6 node stage. Combination products Precede (5-19-4-4.0Zn-1.0B), Releaf (4Ca-1Mg + Transit-S + TE) and 42Phi (4Ca-1Mg + Transit-S + TE) were also compared.

Bowness Davidson says that none of the micronutrient trials provided a significant response, except for Lethbridge in 2016 where Precede, Releaf and 42Phi produced higher yield. However, given the cost of the micronutrients, the application of these combination products was not economical.

The nutrient trials were not carried forward into 2019. Based on the three years of nutrient trials, Bowness Davidson says there were some consistent results.

“Phosphorus and potassium are important nutrients for fababean production. It’s important to maintain soil fertility at an adequate level for high yields,” Bowness Davidson says. “For the micronutrients, this study suggests that they are not necessary for improved production and yield in fababean.”

Tannin-containing fababean varieties less damaged by frost.

by Bruce Barker

There’s something about tannins that help protect fababean seed from damage when Jack Frost comes calling.

Boris Henriquez found that out when frost hit two Alberta Agriculture and Forestry (AAF) research experiments one September evening.

“At first we thought the differences in frost damage could have been because of differences in maturity. Maturity had a little bit to do with it, but it turned out that tannin-type varieties had way less damage than the zero-tannin varieties,” says Henriquez, a senior pulse crops technologist with AAF in Edmonton.

The two experiments were set up to evaluate the adaptability of non-registered European varieties in Alberta and the agronomic performance of newly registered varieties in Alberta. The frost event hit three sites in central Alberta, lasting 13 hours with temperatures dropping to -3 C in Morinville, -5.2 C in Barrhead and -6.5 C in Vegreville.

Noticing the differences in frost damage between the 10

varieties in the two experiments, Henriquez had his summer students put together a trial to assess the differences in frost damage between the varieties. They randomly collected 100seed samples from the harvested grain for each variety, and assessed frost damage by visually determining the number of damaged seeds (blackened).

In Experiment 1, assessing European varieties, average frost damage ranged from 7.7 to 48.2 per cent. In Experiment 2, frost damage ranged from 8.6 to 54 per cent. However, the zero-tannin varieties had 2.2 times more frost-damaged seeds than normal tannin varieties in Experiment 1, and 4.5 times more in Experiment 2. These differences were found after accounting for differences in maturity.

For example, in Experiment 2, the zero-tannin variety Snowbird had 30.6 per cent frost-damaged seed while the tannin-

ABOVE: Undamaged (left) and frost damaged fababean.

There’s one thing we all do when we drive by another farmer’s field — we compare our crop to theirs. It’s obvious to us that keeping an eye on what other farms and producers are doing is valuable, but how do you put that to work?

Benchmarking with real data from your farm, and the farms around you is a great way to evaluate your own farming practices by comparing them to the best practices of your most profitable neighbours.

It’s not just a quick fix to bag a bit more profit. Benchmarking is all about continuous improvement and refining your operation to get the best results over time.

Because success is relative, sometimes it’s hard to be objective about how your farm is doing, but data doesn’t lie. When you compare yourself to other farms you might be surprised at how your practices actually stack up. Like the old saying goes – you don’t know what you don’t know.

Taking a look at actual data from your peers will reveal where you’re excelling and can provide insight on how to stay ahead. It will also show you where you’re coming up short of the average.

Looking at what the top 25% of farmers in your area are doing might help clear up some roadblocks you’re hitting when it comes to growth. A benchmark is an excellent place to start.

Seeing the best practices from the top growers in your area can also act as a compass when you’re planning your year.

Letting you know exactly where you stand against farms in your area is part of our quote process, and part of helping you be a great farmer. Our data is accurate and covers not only market trends from the past ten years, but average input costs, fixed costs, revenue, and more.

Global Ag Risk Solutions has been in business for nearly ten years, covering thousands of Western Canadian farms and growing. All of our claims are paid out quickly and we’re backed by trusted reinsurers (many of which reinsure Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba crop insurance too). You can trust Global Ag Risk Solutions. We’re here to help you be the best farmer you can be.

containing variety Malik had 7.8 per cent frost-damaged seed. Tabasco, another zero-tannin variety, had 44.5 per cent frostdamaged seed.

Distribution of frost damage in Experiment 1 and Experiment 2 in central Alberta

“I looked through the scientific literature and found a couple papers in Cryobiology [journal] that linked tannins to frost resistance, but the effects of tannins in preventing frost damage haven’t been studied very much,” Henriquez says.

Henriquez says the papers indicated that a possible mechanism explaining the role of tannins in frost protection is their activity as a supercooling promoting agent or anti-ice nucleating agent (antiINA), which prevents intracellular ice formation and subsequent damage.

Although the frost event did cause damage to the seed, the average yield from frost-damaged varieties was similar to the other years in Experiment 1 when frost did not occur. Henriquez says the varieties were close enough to maturity that yield was not affected. Other research has found yields are not affected by frost when 30 per cent of the plants had the lowest pods turn black. However, he did observe that as the level of frost increased, the yield of affected varieties decreased, and this occurred more with the zero-tannin varieties.

Henriquez says that further research on understanding how tannins help to reduce frost damage could assist plant breeders in selecting for this trait. If combined with earlier maturity, the selection for tannin-containing varieties that are more resistant to frost could reduce the risk of commercial downgrading. In the end, greater frost resistance could help improve marketability to the human and livestock markets.

Here are our unbeatable tank-mix options for a better burndown for your canola, cereal, pulse and soybean crops.

Group 4, 14

Group 4, 14

• Helps manage volunteer canola, narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, kochia and more

• Control of Group 2- and glyphosate-resistant weeds and volunteers

• Has activity on volunteer canola, kochia, cleavers, wild buckwheat, wild mustard and more

• Control of Group 2, 4-, and glyphosate-resistant weeds and volunteers

Take action against weed resistance when you apply a pre-seed tank-mix product with your glyphosate. Be rewarded when you choose one of Nufarm’s pre-seed tank-mix products:

• Controls cleavers, kochia, lamb’s-quarters, narrow-leaved hawk’s-beard, volunteer canola and other broadleaf weeds when tank-mixed with glyphosate

• Flexibility to move from pulses to cereals with one product

complete offer details, please visit GrowerPrograms.ca

Sign up today to start saving – Nufarm.ca/grower-programs

BY

The tiny arachnid causes sporadic damage under hot and dry conditions.

by Bruce Barker

How can a tiny mite about 0.4 millimetres long cause economic losses in soybean? They simply suck the life out of the plant, cell by cell. The twospotted spider mite (Tetranychus urticae) feeds on soybeans and many other plants, and populations build under optimum conditions of high temperatures and low humidity. In 2018, and to a lesser extent in 2019, the spider mite caused some localized economic damage to soybeans.

“The twospotted spider mite typically becomes more numerous under drier conditions. Heavy rain can wash them off plants, and wetter conditions allow a fungal pathogen to attack the spider mites to help keep the populations down,” says John Gavloski, Manitoba Agriculture and Resource Development’s entomologist.

The twospotted spider mite goes through four life stages of egg, larva, nymph, and adult. Under optimum conditions of high temperatures and low humidity, the life cycle can be completed in as little as five to seven days, although under normal temperatures

and humidity, it usually lasts about 19 days.

The adult twospotted spider mites typically move into soybeans in the spring from grassy waterways, roadsides, and other grassy areas. Mating and egg-laying soon follow and continue throughout the mite’s life. The adult spider mites feed on soybean leaves by piercing leaf cell walls and sucking out the cell’s contents. Extensive damage means the leaf no longer contributes to plant growth and development. In addition to soybeans, they may also be present in dry beans, corn, alfalfa and some vegetables and ornamentals.

Gavloski says feeding damage is most often noticed at field edges, and because the spider mite is so tiny, leaf damage is the first indication of a spider mite infestation. Soybean leaves show a yellow discoloration or stippling. The leaf may have a mottled or

TOP: Spider mites caused localized economic damage to soybeans in 2018 and 2019.

INSET: More research is needed to develop action thresholds for the twospotted spider mite in Western Canada.

BY

Take

sand-blasted appearance and can turn bronze to brown in colour. Field edge infestations may increase after adjacent wheat fields are harvested or if roadside ditches are mowed.

Other crop stresses such as soybean cyst nematode, nutrient deficiencies and other insects that cause leaf yellowing should be ruled out. While spider mites are very small and can easily be overlooked, which makes field identification difficult, the presence of stippled leaf damage and webbing are clues they may be present. Pulling some of the affected plants and shaking them over a tray or piece of cardboard can help to isolate and increase movement of the twospotted spider mite, which makes them easier to see.

The twospotted spider mite typically becomes more numerous under drier conditions. Heavy rain can wash them off plants, and wetter conditions allow a fungal pathogen to attack the spider mites to help keep the populations down.

the upper canopy, and when lower leaf yellowing is common.

The most susceptible stages of soybean are the R4 (full pod) through R5 (beginning of seed fill). Once soybeans reach R6 (full seed or green bean stage), spider mite feeding will have less impact on yield.

To determine the level of plant injury, sample plants at least 100 feet into the field while walking in a “U” pattern. At 20 different locations, select two plants and look for stippling on the leaves.

More research is needed to develop action thresholds. Gavloski says a widely used nominal action threshold at the R4 to R5 stage is to apply an insecticide when heavy stippling occurs on lower leaves with some stippling progressing into the middle canopy, when mites are present in the middle canopy with scattered colonies in

Dimethoate (Cygon, Lagon) is the only registered insecticide for spider mites in soybean in Canada. It has a 30-day pre-harvest interval. Rather than a blanket application across an entire field, spraying field margins where the insect pressure is usually heaviest might be an option. Dimethoate is a broad-spectrum organophosphate insecticide that can also be damaging to beneficial insects and predators. As a result, Gavloski stresses to only spray once thresholds are reached at the correct stage.

“You might be able to only spray the field edges, and it is important to only spray at the susceptible R4 to R5 stage because, once the crop reaches R6 when the seeds are fully formed, there is less impact from spider mite feeding,” says Gavloski. “And spraying earlier can harm generalist predators, like the lady beetle and minute pirate bugs that feed on spider mites. It’s important to try to encourage those populations by only spraying when necessary.”

5 YEAR LEASE PROGRAM

What does $22.50 per acre in canola savings look like on your farm? Over a 5 year period, you almost can’t afford not to.

Brian said they saved $22.50 per acre using their new seeding system. YOU DO

Start the season stronger than ever with squeaky clean fields.

• Powerful pre-seed control: Clean out Group 2 resistant cleavers and hemp-nettle plus other tough broadleaf weeds with the most powerful pre-seed option for your wheat and barley.

• Just GO: Spray when you need – on big or small weeds or in cool or dry spring conditions.

• Extended control: Provides trusted control of volunteer canola flushes.

• Convenient packaging: Paradigm’s innovative GoDRI™ formulation makes it easy to mix and handle.

For more information call our Solutions Center at 1-888-667-3852 or visit Paradigm.corteva.ca.

Saskatchewan researchers are looking to improve short-season soybean varieties and their profitabilty.

by Mark Halsall

Soybeans have been grown in Eastern Canada for many years, and the crop is now gaining popularity among farmers in the West. However, there are challenges involved in adapting the crop to the shorter, colder, and drier growing seasons on the Canadian Prairies.

In Saskatchewan, where soybeans first emerged as a new crop rotation option about 10 years ago, researchers are working to gain a better understanding of short-season soybeans and which varieties may be better suited to growing conditions on the Prairies. The goal is to make soybean production more consistent and profitable for Western Canadian soybean producers.

One of the questions being examined is why short-season soybean varieties have a lower percentage of seed protein than their longer season counterparts. Diane Knight, a professor in the College of Agriculture and Bioresources at the University of

Saskatchewan, is looking at nitrogen fixation as a possible reason why.

“It may be that that the growing season [in Saskatchewan] simply isn’t long enough for the plant to acquire the amount of nitrogen that it needs for protein development,” she says.

Knight notes some research from the United States indicates that nitrogen found in soybean seed protein preferentially comes from biological fixation and not from fertilizer put down with the seed.

According to Knight, it takes more energy for a soybean plant to fix nitrogen than it does to take it up, so one of the things

ABOVE: Tom Warkentin, soybean breeder and professor in the department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan.

• Enhanced Fusarium control

• More uniform plant stand

• Increased yield potential* Visit agsolutions.ca/InsureCerealFX4 or call AgSolutions® Customer Care at 1-877-371-BASF (2273) to learn more. Start your season

she’s studying is whether there’s sufficient time for short-season soybeans to attain enough nitrogen through biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) for optimal protein development.

For her research, Knight is looking at the impact of cold temperatures on BNF in soybean and how nitrogen uptake rates differ for different growth stages. She is also examining root nodules of soybean plants to see what types of nitrogen-fixing rhizobia are present there, and whether they’re coming from applied inoculant or naturalized populations.

Knight says about a dozen or so short-season soybean varieties supplied by different seed companies, as well as a couple of new varieties supplied by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, are being evaluated as part of the five-year project that started in 2018.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is figure out whether or not some of these varieties are better than others [at nitrogen fixation], and if so, why are they better,” Knight says.

Another soybean project being led by Rosalind Bueckert, a professor in the department of plant sciences at the University of Saskatchewan, is assessing the effect of cool temperatures and abiotic stress on yield formation in a range of soybean varieties suited to very short seasons.

This research is aimed at identifying traits for varietal improvements to better equip short-season soybeans to beat the cold.

Tom Warkentin, a professor in the department of plant sciences

Wild oats can make your fields stand out for the wrong reason. Varro®, a Group 2 herbicide, provides control of wild oats and other tough grass weeds while helping manage resistance on your farm.

Varro – for wheat fields worth looking at.

at the University of Saskatchewan who specializes in pulse crop plant breeding and genomics research, has been working with AAFC soybean breeders for the past decade to develop new varieties suited to northern soybean areas like Saskatchewan.

For his current project, which began in 2018 and concludes in 2023, Warkentin is collaborating with Elroy Cober at the AAFC’s Ottawa Research and Development Centre and Louise O’Donoughue from CÉROM, a grain research program based in Montreal.

Their goal is to produce high-yielding, early maturing soybean cultivars suited for production in northern latitude regions and to validate early maturity gene performance to improve the breeding process for short-season varieties.

“We’re in the early stage of this particular round,” Warkentin says. “We have good breeding lines that are showing promise, and we plan to release varieties in the not-too-distant future.”

Warkentin believes having soybeans that are especially welladapted to the Prairie climate is particularly important in Saskatchewan.

“Soybean is a crop that tends to have a narrow adaptation, so through breeding over the last hundred years, breeders have selected shorter duration varieties and as they have done that, the crop has

moved north from the southern U.S., to the central U.S., to the northern U.S., to Canada,” he says.

“To make soybean adapted to Saskatchewan, we need even shorter duration varieties than what are needed in the Red River Valley of Manitoba.”

Warkentin maintains having soybeans that are particularly well-adapted to the Prairie climate will no doubt benefit Western Canadian farmers.

“Crop agriculture in the Canadian Prairies is heavily based on wheat and canola. Healthy crop rotations need more than two crops, and soybean is another option to go from two to three,” he says.

“Another benefit is that soybean, along with other pulse crops, fix nitrogen, and that’s desperately needed . . . to make agriculture more sustainable,” he adds. “Neither wheat nor canola fix nitrogen, but soybean does. We need more N-fixing crops for a proper rotation in this region.”

Knight agrees that there’s much interest in diversifying crop rotations to include soybeans in Saskatchewan and other Prairie provinces, and she maintains one reason soybeans have become more attractive to farmers is because of the relatively high value of the crop.

The best o ence is a good defense. With Prospect™ herbicide, your canola will have the best start possible. Prospect tank mixed with glyphosate will give you game-changing performance against the toughest broadleaf weeds, including cleavers and hemp-nettle.

Ask your retailer or visit Corteva.ca to learn more.

Lentil and fababean are the pest’s latest casualties.

by Bruce Barker

Pea aphids are commonly found in many pulse and legume crops, but are occurring at economically damaging levels more frequently in the last few years. In 2019, the sapsucking insect devastated lentil and fababean crops in some areas of the Prairies.

“Typically, this past year we saw pea aphids on lentil crops, but also some infestations later in the year on fababean,” says James Tansey, provincial entomologist with Saskatchewan Ministry of Agriculture in Regina.

Peas, lentils, fababeans, chickpeas, dry beans, alfalfa, and clover are host crops of pea aphids. Peas and lentils are preferred hosts, but when these crops start to dry down, the pea aphids can fly to nearby fababean crops. Similarly, when alfalfa is harvested, the pea aphids move to pea, lentil and fababean fields.

Pea aphids can overwinter on the Prairies, but large infestations that cause economic losses are usually the result of pea aphids blown in from the United States. The insect is also a reproducing machine. Females can reproduce without mating and have seven to 15 generations per year. One female can produce 50 to 150 offspring in a summer.

“I would say pea aphids have been a real problem the last three

Introducing the new 8 S eries Trac tor s, now available with wheels, t wo track s and the all-new four-track con figuration A ll built with more comfor t and convenience thank s to a larger, re fined c ab, plus added p ower and legendar y reliabilit y W hat ’ s more, they ’ re completely integr ated with precision ag technolo gy T hey make it eas y for you to t ake advant age of precision ag solutions to help increase your yields, lower your cost s and improve the e f ficienc y of ever y job. T hey ’ re full y integr ated, full y c ap able and – thank s to the best dealer net wor k in the industr y – full y supp or ted

S o if you ’ re ready to t ake your op eration for ward, t ake time to see your John Deere dealer to day

Severe infestation causing wilting of fababean. years. Some of the infestations have been pretty horrific,” says entomologist Tyler Wist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Saskatoon. “There were some fababean fields that had such high density that there was literally zero yield. The plants were basically sticks without pods.”

Wist, along with entomologist Sean Prager at the University of Saskatchewan’s plant science department and M.Sc. grad student Ningxing Zhou are conducting research on scouting and economic thresholds for lentil and fababean.

In lentils, a nominal threshold has currently been adopted from North Dakota. It suggests that insecticide application is recommended when 30 to 40 aphids per 180-degree sweep are captured, few natural enemies are present, and aphid numbers do not decline over a two-day period.

“If aphid numbers aren’t declining, that is an indication that the natural predators are not able to reduce or hold the infestation in check. In that case, pea aphid numbers can increase rapidly, so spraying might be warranted,” Tansey says.

No economic threshold levels have been established in fababean.

The current economic threshold for peas was developed in the early 1980s at AAFC Winnipeg using the large-seeded yellow pea variety Century. The economic threshold is two to three aphids per eight-inch (20-centimetre) plant tip, or nine to 12 aphids per sweep, based on the price of peas at $5.71 per bushel, and the cost of control at $6.73 to $9.25 per acre. Spray application timing is when 50 per cent of plants have young pods. While Zhou’s research isn’t looking at pea thresholds, Wist says the threshold could use a re-evaluation with current varieties.

As part of her M.Sc. research project, Zhou is literally counting a million aphids. Trials were set up to assess yield losses in lentil and fababean that occur at various pea aphid densities and timing. She measures cumulative aphid days, which is the number of aphids over time. This helps to provide an assessment of the cumulative impact on the crops. Zhou saw some massive numbers, especially

on fababean with infestations as high as 1,500 per plant.

“In the first year, we went really wide with our assessment dates so that we could measure the pea aphid impact at different points in the growing season. But with the last three dates, the aphid populations were too high,” Zhou says.

Prager says the yield losses measured are occurring because of pea aphid feeding. While some aphids are known to be vectors for viruses, Zhou screened for the pea mosaic virus in her trials and did not find any.

Wist says that having established the high end where pea aphids cause too much damage, the research is moving forward to establish the low end where an economic threshold could be established. In fababean, pea aphid populations of 300 to 800 per plant seriously impacted yield. In lentil, yield losses were showing up in the 150 to 600 pea aphids per 180-degree sweep.

“We’re also looking at the best scouting method. In lentil, 180-degree sweep is preferred, but in fababean it looks like numbers per plant works best. Sticky cards were utterly useless,” Wist says.

One of the reasons research-based economic thresholds are so important is to minimize the impact of insecticidal applications on beneficial insects. Aphid predators include ladybeetles (adults and larvae), lacewings (primarily larvae), hoverflies or syrphid flies (larvae), minute pirate bugs (adults and nymphs), and damsel bugs (adults and nymphs). A seven-spotted ladybeetle adult can eat 48 aphids per day, and larvae can eat 71 to 72 aphids per day.

A parasitic wasp in the Aphidiidae family can also attack pea aphids. The female wasp lays an egg inside an aphid, and when the egg hatches the larva eats the aphid from the inside out. When the larva pupates, the parasitized aphid swells up, turns tan/copper in colour, and the body becomes mummified.

“Natural enemies can reduce the populations pretty quickly. If you see copper-coloured aphid mummies on the plants, the pea aphid population is being hit pretty hard,” Tansey says. “That’s why this research on economic thresholds is so important. Spraying only when needed helps maintain the populations of beneficial insects and can keep aphid infestations under control.”

Evaluating the persistence of soybean rhizobia in Manitoba soils.

by Carolyn King

In many traditional soybean-growing areas, rhizobial inoculant is not used every year,” says Ivan Oresnik, a professor of microbiology at the University of Manitoba. Does that mean that Manitoba soybean growers could sometimes skip inoculating their crop with nitrogen-fixing bacteria? Research led by Oresnik, plus on-farm studies, are helping to answer that question.

Bradyrhizobium japonicum (B. japonicum) bacteria are used in commercial soybean inoculants. These bacteria form a symbiotic relationship with a soybean plant, forming nodules on the plant’s roots and converting nitrogen from the air into nitrogen compounds that the plant can use. B. japonicum can also exist in the soil as free-living bacteria, without having a relationship with a plant.

Oresnik and his research group have been working on B. japonicum studies since 2008, mainly with funding from the Mani-

toba Pulse & Soybean Growers (MPSG). Back in 2008, soybean production was just starting to take off in Manitoba, and people were still wondering how well B. japonicum would survive the cold Prairie winters because the bacteria are not native to Western Canada.

One of Oresnik’s MPSG projects, which started in 2010, involved developing a PCR test to rapidly count the population of B. japonicum in soil samples – a helpful tool for getting a better handle on how long these bacteria persist in the soil. Over the next few years, Oresnik and his group developed and fine-tuned this quantitative PCR (qPCR) test.

Then starting in 2016, they partnered with an agricultural consulting company to see if their qPCR test could be used to predict

ABOVE: On-farm trials are helping to establish the best practices for soybean inoculation in Manitoba.

when a soil’s B. japonicum population was high enough that the next soybean crop would not need to be inoculated. In this two-year project, they compared inoculated and non-inoculated soybean crops in fields with an established soybean history at several Manitoba locations.

“The long and the short of that study was that Bradyrhizobium japonicum was everywhere [in all of the study fields],” he says. Whether or not a commercial inoculant was applied, all the soybean crops had sufficient nodulation for successful nitrogen fixation.

Most recently, Oresnik and his group have been examining if and how the crop rotation influences the level of B. japonicum persisting in a field.

“Plants engineer the soil microbial community around their roots by the different compounds their roots exude into the soil. Different plant species have different tastes, if you want to think of it that way, so their exudates attract different types of microbes,” he explains.

So, the persistence of B. japonicum is

likely influenced by the crop rotation’s effects on the microbial community and whether this community’s diverse interactions help or hinder the survival of B. japonicum.

As part of this MPSG-funded study, Oresnik and his group are also examining whether some portion of the B. japonicum population in a field might lose their nitrogen-fixing capacity over time. He explains that the group of symbiosis genes that enable B. japonicum to form root nodules and fix nitrogen occur together in a large genetic package, called a symbiosis island.

This symbiosis island is detachable from the bacterium’s genome. “Research in other regions shows you can get genetic transfer events where the symbiotic island will move to a closely related species,” he notes. Manitoba soils have native bradyrhizobial species that could potentially take up B. japonicum’s symbiosis island and integrate that island into their own genomes.

“However, just because the symbiosis island has moved to another bacterial species doesn’t mean that those genes will work efficiently in that other species. Sometimes you start getting bacteria that can nodulate and fix nitrogen with your crop, but they are not efficient at this and they are not the species in your commercial inoculant. We don’t have that problem here yet, and I don’t know if it will happen here.”

Oresnik piggybacked his study on a pre-existing soybean rotational project led by the University of Manitoba’s Yvonne Lawley. Her project started in 2013 and the rotations include: continuous soybean; corn-soybean; canola-soybean; and wheat-canola-corn-soybean.

Oresnik says, “Our study’s objectives were: 1) to quantify the population of rhizobia that overwinter in the soil in Manitoba; 2) to compare the effect of the frequency of soybean in a four-year crop rotation on populations of rhizobia that overwinter in the soil; 3) to evaluate the microbial community and determine the functional categories of bacteria that are present; and 4) to evaluate the impact that the frequency of soybean in a rotation has on the rhizobial/microbial population and how these affect overall soybean yield.”

The fieldwork took place in Carman, Melita and St. Adolphe in 2017, when all the plots were in the soybean phase of

their rotations. Oresnik’s group collected soil samples before seeding, at emergence, at pod development and at full maturity. Also, for comparison, they obtained soil samples that had been archived when Lawley’s project started in 2013.

Oresnik’s group extracted DNA from the soil samples. Then they used their qPCR test to quantify the B. japonicum population and they used a different PCR test to look for one of the bacterium’s nodulation genes to see whether the B. japonicum bacteria still had their symbiosis islands. The DNA samples were also analyzed to characterize the rest of the soil bacterial community.

If you want to change your inoculant strategy, then consider testing it in a portion of your field. For instance, if you are double inoculating and want to try single inoculation, then double inoculate most of your field and leave a strip of single inoculation.

started. The other two sites already had a history of soybean production before her project.

Oresnik and his group are currently wrapping up their work on the study’s first two objectives. Their results confirm their previous finding that B. japonicum has now become an established part of most Manitoba fields where soybean crops have been grown more than one or two times.

Their findings also show that B. japonicum survives the winter but its population declines over the years in a predictable way. “Based on these decay curves, you could predict how much of the bacterium’s population will remain if you last grew soybean the previous year, two years ago, three years ago, or four years ago,” he says.

These decay curves varied somewhat from field to field. The population decline was steepest for the Melita location, which had never had a soybean crop before Lawley’s rotation project

The results also show that the crop rotation influences the B. japonicum numbers: the population was highest in the continuous soybean plots and lowest in the canola-soybean plots. However, the rotation did not significantly affect soybean yields.

Oresnik and his group are currently analyzing the very complex bacterial community data. He says, “You might have something like 10,000 species of bacteria in a gram of soil. A single bacterial species doesn’t define what will happen; it’s really the village effect [with many different interactions affecting different functions].” He notes that the soil bacterial community is important for all crop types because the bacteria drive the nutrient cycles in the soil.

He concludes, “Our findings so far suggest that if you had an inoculated soybean crop in a field the previous year, you wouldn’t need to inoculate this year. If you grew soybean two years ago, and you’ve grown it previous to that, then you probably still don’t

non-inoculated control.

In both types of fields, the product, formulation and rate did not affect yields or nodulation. The rate comparison was single versus double inoculation. A double inoculation involves using two formulations or placement techniques. For instance, a grower might use a liquid inoculant on the seed and a granular inoculant in-furrow as a way to ensure successful inoculation.

So, in this study, double inoculation did not provide an additional benefit. However, the study’s small plot conditions were very favourable for inoculum survival, which might not always be the case under field conditions.

MPSG is evaluating soybean inoculant strategies in two ongoing studies through its On-Farm Network. “We have a double inoculant versus single inoculant study, more on the western side of the province, and single inoculant versus no inoculant study on the eastern side of the province where more soybeans have been grown or have been grown for longer,” explains Serena Klippenstein, the MPSG production specialist for western Manitoba.

Most of the double versus single inoculant trials have been in fields with at least two years of soybean. Only two trials have been in fields with little or no recent soybean history, but the results from those two trials suggest double inoculation might help yields in such fields.

“Our recommendation for fields with little or no history of soybeans is to double inoculate,” says Klippenstein. “That’s because there is no way to be sure exactly what the conditions are in the field for survival of the inoculum.”

need to inoculate, but you might choose to inoculate just to be sure.”

His advice to growers is to follow MPSG’s recommendations for soybean inoculation.

Studies and recommendations

MPSG has been working on a number of studies that are helping to nail down the best practices for soybean inoculation in Manitoba.

In an MPSG plot study in Melita, Carberry, Carman, Roblin and Beausejour

from 2014 to 2016, 14 inoculant treatments were compared, including different inoculant products, formulations and rates, and a non-inoculated control. The study included fields that were new to soybeans and fields with a history of soybeans.

The results showed that, for fields with no soybean history, inoculant treatments increased nodulation and yields. For fields with a history of soybean, there was no difference in yield or nodulation between inoculant treatments and the

She notes that MPSG has developed a checklist of four criteria that a field should meet before the grower shifts from double to single inoculation: the field has had at least two previous soybean crops; those crops nodulated well; the most recent soybean crop was grown within the past four years; and the field has had no significant flooding or drought conditions over that time.

For fields with a history of soybeans, the trials so far have shown that double inoculation is usually unnecessary. She says, “In the double versus single inoculant trials, we found that only two of 32 on-farm trials had a significant yield increase with double inoculant on fields with at least two years of soybean history.”

In the single versus no inoculant study, soybeans did not get a yield boost from inoculation when grown in fields with a history of at least three well-nodulated soybean crops and where the most recent soybean crop was grown within the past four years. She says, “[None] of the 27 onfarm trials had a significant yield difference with inoculation.”

MPSG has not yet created a checklist for switching from single inoculation to no inoculation, but Klippenstein says they hope to develop that in the future.

“If you want to change your inoculant strategy, then consider testing it in a portion of your field. For instance, if you are double inoculating and want to try single inoculation, then double inoculate most of your field and leave a strip of single inoculation. The results will give you a better picture of the rhizobia situation in that field and also maybe in other fields on your farm with similar conditions and field histories,” she advises.

“Similarly, if you’re currently single inoculating and you have had some really good soybean years with good nodulation and the environment has been favourable for rhizobia to continue living in the soil, then maybe it is a good time to single inoculate most of your field and leave a non-inoculated strip. Then you can dig up a few of those soybean roots and see what is going on.”

Klippenstein explains that MPSG encourages farmers or their agronomists to check the nodulation in all their soybean fields every year. The protocol for assessing soybean nodulation is available on the MPSG website. She summarizes, “You dig up a few of your soybean plants at the R1 stage (beginning bloom) and cut open the nodules. If the nodules are reddish pink inside, then they are healthy and fixing nitrogen. If you have at least 10 healthy nodules per plant by R1, then you are good to go for the rest of the season. If you don’t have 10 healthy nodules by R1, you likely won’t have enough nitrogen fixation later in the season. In that case, you may want to consider adding nitrogen fertilizer as a rescue treatment between the R2 (full bloom) and R3 (beginning pod).”

She adds, “Checking the nodulation in your soybean field not only helps you for the current growing season, but it also gives you information about where the field’s rhizobia populations are at, which can help inform your inoculation strategy for the years ahead.”

Clean fields lead to higher yields. That’s why farmers trust Simplicity™ GoDRI™ to get the job done right. For convenience, performance and outstanding wild oat control in wheat, the choice is Simplicity. For more information, call the Solutions Center at 1-800-667-3852 or visit SimplicityGoDRI.Corteva.ca

15,

by Donna Fleury

Planning crop rotations in a cropping system is important for optimizing yields and profits, and providing a break in weed, disease and insect pest cycles. Growers are increasingly considering the inclusion of a pulse crop in rotation for several reasons, but most importantly for their ability to acquire a large proportion of their nitrogen (N) needs from biological N fixation (BNF). Questions remain around which crops would be recommended in rotation prior to a pulse crop, and what the considerations might be.

“In our research work on pulse crops, one of the main goals is to determine where they fit in rotation for the best advantage,” says Diane Knight, professor and researcher at the University of Saskatchewan. “In some previous projects, both in the field and in growth chamber studies, we compared either mustard or canola

in rotation just before pulse crops or a cereal crop such as wheat, barley or oat. The results were mixed, where, in some cases with canola in rotation, there was a depression in the N fixation in the following pulse crops, and in others there was not. It wasn’t clear why this occurred part of the time but not all of the time. In most cases, the differentiation was in the Brown soil zone, which tends to have lower organic matter, and may be the reason the Dark Brown and Black soil zones with generally higher organic matter levels didn’t show similar results.”

In a two-year study, graduate student Lara de Moissac conducted a series of field experiments, along with a controlled

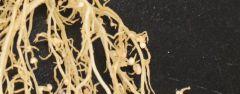

Second-year field pea crop in the controlled environment experiments.

environment experiment to study in more detail whether or not biological N fixation in pulse crops is impacted by canola as the previous crop. The 15N isotope dilution method, which measures N2 fixation in plants, was used to estimate BNF in pulse crops grown on oilseed and cereal stubble across soil zones in Saskatchewan. Soil samples were collected from each rotation to identify soil properties affecting BNF in pulse crops.

In collaboration with farmers, several commercial fields from across the Brown, Dark Brown and Black soil zones were selected for the study. “At each site, paired fields were seeded to a Brassica, either mustard or canola, and a cereal, which tended to be wheat in most areas, along with at least one barley and oat,” explains Knight. “The farmers managed the crops using their regular agronomic and cropping practices. In the second year, a pulse crop –usually pea or lentil – was seeded across all of the paired fields. This allowed us to measure the BNF of the pea or other pulse crop, and compare the results across soil zones to determine whether or not the previous crop had any impact. We took soil samples at each location to determine soil characteristics, as well as conducted a soil microbial analysis.”

In addition, a controlled environment experiment was performed to determine if stubble quality (i.e., wheat and canola) affects N-mineralization potential before and after a pulse crop is grown. In this study, the canola and wheat crops were grown on two different soils from the Brown and Black soil zones. The soil with crop stubble for each experiment was put under freezing conditions to simulate winter field conditions, followed by seeding CDC Meadow pea across all experiments. Along with the growth characteristics and BNF measures, the study also measured N-mineralization and immobilization to determine whether or not N may be more available faster from cereal stubble compared to canola stubble, which may explain the boost or depression in N fixation. Soil microbial analysis was also completed.

“We have just wrapped up the field trials and controlled environment experiments, and the final data analysis is

2020-01-09 11:03 AM

underway,” Knight says. “We expect to have the final results available in 2020. From the preliminary observations, the data shows that there are some differences between the results from Brassica compared to wheat stubble, but it is not all of the time. Where there are negative impacts from the Brassica crops, it seems to be mostly in the Brown soil zone. One exception was a field site near Wilkie in the Dark Brown soil zone, however we expect the negative impact was disease-related in this case and not the soil zone. Disease assessments were completed and this was the only site where we saw any impacts.”

To be able to analyze the microbial communities in the various soils, a PLFA analysis was used, which analyzes the phospholipid fatty acids (PLFAs). Phospholipids are only present in living soil microbes and can be used as biomarkers to determine the living microbial types and abundance in the soil. The PLFA analysis provided details on the various microbial communities, including gram-positive, gramnegative, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), fungi, actinobacteria, other eukaryotes and others. Sampling

Canola and other Brassica crops are often thought to have negative impact on soil health, but the trial’s results proved otherwise.

“The preliminary soil microbial analysis results provided some of the most interesting observations so far,” Knight adds. “Brassica crops such as mustard and canola have often been assumed to have a negative impact on soil health due to some negative allelopathic effects. Brassica crops are also not considered to be mycorrhizal crops. However, across all of our analysis the preliminary results show that the total soil microbial communities are higher in the oilseed crops than in the cereal crops, as were the levels of AMF soil microbes. These results are counter to what we assumed we would see, and although we are still not sure why, the results were fairly consistent across all of the sites.”

Knight expects to have more complete information once the final data analysis for both the field trials and the controlled environment experiments are completed. The question of whether canola or mustard crops affect BNF in the following pulse is expected to be better understood. The final details will provide information to help growers finetune their cropping systems and rotations, and in particular where to put things, or where not to, for the best results.

Finally! One box, one pass, one easy decision.

Rexade™ is pure performance – today’s complete grass and broadleaf weed control for wheat and the only one pass decision you need to make.

For more information, visit Rexade.Corteva.ca

Towards more effective rhizobial inoculants for dry bean varieties.

by Carolyn King

Afew years ago, microbiologist Ivan Oresnik learned from Manitoba Agriculture’s provincial pulse specialist Dennis Lange that dry bean growers usually apply nitrogen fertilizer to this crop rather than relying on rhizobial inoculants. As a rhizobia expert, Oresnik’s off-the-cuff response was: “We should be able to fix that.”

Excitingly, proof-of-principle experiments by Oresnik and his research group at the University of Manitoba indicate that there could indeed be an easy solution to this longstanding issue in dry bean production.

As legume growers know, rhizobia bacteria have the ability to form nodules on the roots of a compatible legume host and to convert nitrogen from the air into nitrogen compounds that the host plant can use. However, dry beans are usually much poorer

at nitrogen fixation than most legume crops, so they need nitrogen fertilizer to produce good yields.

“Improved nitrogen fixation would allow bean growers to use less fertilizer, which could reduce their input costs. And it would decrease the risk of nitrogen losses to the environment, which can have effects ranging from greenhouse gas emissions to eutrophication [excessive nutrient levels] in water bodies,” Oresnik says.

Better and better rhizobial variants

His research usually looks at rhizobia from an academic perspec-

Multiple modes of action deliver both fast burndown and extended residual.

Just when you thought the best couldn’t get better. New Heat® Complete provides fast burndown and extended residual suppression. Applied pre-seed or pre-emerge, it delivers enhanced weed control and helps maximize the ef cacy of your in-crop herbicide. So why settle for anything but the complete package? Visit agsolutions.ca/HeatComplete to learn more.

Always read and follow label directions. AgSolutions, HEAT, and KIXOR are registered trade-marks of BASF. © 2020 BASF Canada Inc.

tive, focusing on their molecular microbiology, rather than investigating agricultural applications. But after talking with Lange, he started delving into the published research on rhizobia in dry bean production.

As he read more and more about it, he began to wonder if it might be impossible to develop better rhizobial strains for dry bean.

However, Oresnik had an idea: he knew that some researchers were using adaptive evolutionary approaches to improving organisms and he thought such an approach might work with rhizobial strains. Adaptive evolution refers to the tendency for beneficial traits to become more frequent in a population as the environment selects for those individuals in each generation that are best able to survive, thrive and reproduce.

Oresnik explains that naturally occurring mutations develop in bacteria because of mistakes during their reproduction. He thought that, in rhizobia bacteria, some of these mutations could result in better nitrogen fixation through adaptive evolution. Furthermore, he thought this adaptive process could be helped along if you specifically selected rhizobial variants with superior nitrogen fixation for the next generation.

So, Oresnik led a proof-of-principle study to see if this approach would work.

In this greenhouse experiment, Oresnik

and his research group used a strain of Rhizobium etli called CFN42. Rhizobium etli is the main rhizobial species that nodulates with bean plants. CFN42 is a well-known, agriculturally important strain that has been studied by scientists. As well, CFN42’s genome has been sequenced, so its genome could be compared with the genomes of any better-performing variants that might be developed through the experiment.

The first step in the experiment was to inoculate Envoy navy bean plants with CFN42 and then grow the plants under nitrogen-deficient conditions. That resulted in plants with yellowish green foliage and tiny, ineffective-looking nodules scattered over their roots.

“An effective rhizobium nodule is big and spherical and it has a pink tinge. If the nodule is small and not pink, then it is not really fixing nitrogen,” he explains. “And it’s easy to tell whether a bean plant is nitrogen-deficient or sufficient. If it is nitrogendeficient, the plant goes a completely pale, pale yellowish green. If it has enough nitrogen, then it’s dark green.” So CFN42 had some interaction with the plants but it did not result in effective

“An effective rhizobium nodule is big and spherical and it has a pink tinge. If the nodule is small and not pink, then it is not really fixing nitrogen.”

Three different powerful herbicide Groups have been combined to make one simple solution for cereal growers.

Infinity® FX swiftly takes down over 27 different broadleaf weeds, including kochia (up to 15 cm) and cleavers (up to 9 whorls). And if you’re worried about resistance, consider this: you’re not messing with one wolf, you’re messing with the whole pack.

nitrogen fixation.

Next, Oresnik’s group selected the largest of the tiny nodules, crushed them, and used them to inoculate a new set of Envoy plants. They repeated this step for about eight cycles.

“By the time we did this step about three times, we began getting nodules that were looking pink and bigger,” he says. “Somewhere around cycle five, we were starting to get large, effectivelooking nodules that were clustered on the roots right below the crown, and the plants looked really healthy and green. The change was very striking.”

To confirm these results, they replicated this whole process three times, starting with inoculation of CFN42 and going through eight cycles of selection. Each time, they ended up with large, effective-looking nodules and healthy, green plants.

So, under greenhouse conditions, they have proven that it is possible – and surprisingly easy – to develop more effective rhizobial variants in this way.

“From an academic perspective, I am really excited, because no one has ever selected [for rhizobial strains] in this way,” Oresnik says.

In 2020, Oresnik and his group will be starting the next stage of this research. They will be using the same multi-cycle selection process, but they will be working with local rhizobia.

“CFN42 was originally isolated in Mexico. I suspect this strain

may not work well in the field here,” he explains. “So, I want to test rhizobial strains collected more locally, because they are more likely to be better adapted to our environment and more competitive.”

These local rhizobia may not necessarily be Rhizobium etli. He notes, “Beans are relatively promiscuous when it comes to rhizobial interactions. A number of different species can sort of work with beans, including Rhizobium phaseoli, Rhizobium etli, Rhizobium tropici, Rhizobium gallicum, and Rhizobium giardinii, and some species of Bradyrhizobium.”

And there could be other rhizobial species or subspecies that also work with beans. “All rhizobial species have up to maybe 40 per cent of their genetic component in very large plasmids [packages of DNA]. And a lot of the genes necessary for nitrogen fixation as well as the genes for nodulation tend to be on plasmids that can be mobile, so they can move from one bacterial species to another. So, it becomes very hard to tell what is and what isn’t a different species. For instance, you can move one plasmid into a Rhizobium phaseoli and it will work fine on peas.”

Oresnik will also be trying to make an additional improvement in the rhizobial variants through the multi-cycle selection process. “I want to see if it is possible to evolve strains that can be effective at lower temperatures, in an effort to allow earlier planting/inoculation.” Sometimes it can take several weeks after seed germination before the rhizobia are able to start fixing nitrogen, especially under stressful growing conditions like cold

temperatures. If the rhizobia could start fixing nitrogen sooner, the young crop might get off to a stronger start.

As soon as Oresnik and his group have developed some rhizobial variants that perform well on bean plants in the greenhouse, they’ll test those variants in the field. The goal is to identify the variant that is most effective at fixing nitrogen and boosting bean yields under Manitoba conditions.

“Improved nitrogen fixation would allow bean growers to use less fertilizer, which could reduce their input costs. And it would decrease the risk of nitrogen losses to the environment, which can have effects ranging from greenhouse gas emissions to eutrophication [excessive nutrient levels] in water bodies.”

Along with developing more effective rhizobial variants for bean growers, Oresnik also wants to understand why they are more effective.

“As a second component of the project, I want to determine what kind of mutations are occurring to allow the bacteria to become better at nitrogen fixation. That could increase understanding of some of the mechanisms of the plant-microbe interaction.” So, he will be sending some of the original strains and their variants for genomic sequencing.

The Manitoba Pulse and Soybean Growers are funding this research, along with some support from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Larger implications

Oresnik’s approach to developing more effective rhizobial variants has the potential to be much easier and faster than breeding

bean plants that are better at fixing nitrogen – especially since nitrogen fixation in legume plants is controlled by many different genes.

“The plant breeding process takes a long time. If I’m right about this method – and I think we’ll know that when we start figuring out what the actual mechanisms are – then microbiologists could collaborate with bean breeders, working with the breeders’ penultimate lines before commercial release. They could possibly very quickly come up with inoculum tailored for each specific bean variety,” he notes.

“And I think we should be able to apply this same approach to rhizobial inoculants for new lines of all legume crops. This would improve the effectiveness of biological nitrogen fixation for all these crops and further enhance the sustainability of legume crop production, benefiting growers and the environment.”

by Carolyn King

Converting lower productivity areas on farms into pollinator habitat can enhance the environmental health of an agricultural landscape. So, a Farming Smarter project is looking into some of the practicalities of growing such pollinator havens to provide information and advice for interested farmers.

Awareness that bee populations worldwide are under threat from such stresses as disease, habitat loss and pesticides has sparked interest in creating pollinator sanctuaries. “Farmers are constantly working to improve their knowledge and understanding of what is happening in the soil, and with the plants and the whole ecosystem,” says Jamie Puchinger, the assistant manager at Farming Smarter, an applied research organization.

“Farmers recognize that pollinators are important to our industry in particular. And they are interested in helping to conserve pollinators and in seeing what they can do on their farms, and using areas that are not prime production land.

“So, if we find some pollinator-friendly seed mixes that can go as reclamation on an oil-and-gas service road, or as a buffer strip around a slough, or as soil cover for pivot corners, or things like that, then farmers could add extra plant species to enrich the biodiversity in those areas.”

Puchinger, who is leading the project, explains that pollinator sanctuaries could provide multiple benefits. “Some of the benefits we are looking at are: conserving our natural insect pollinators, of course, and with that we can also enhance local biodiversity, promote soil conservation, and provide some year-round habitat for other wildlife species, and there is also the potential for these areas to be used as additional forage for livestock.”

So, for best results, pollinator plant stands should provide an ongoing food source for a diversity of local pollinators throughout the growing season. And the stands should also be easy for farmers to establish and maintain for multiple years under the local growing conditions, and should provide good soil cover, livestock forage, and habitat for local species of reptiles, amphibians, birds and mammals.

The project is a one-year pilot study funded through the Canadian Agricultural Partnership. The overall objective is to develop suitable pollinator mixes that can be used for the maintenance of pollinator populations in southern Alberta. The fieldwork took place in 2019 at a site with Dark Brown soil in the Lethbridge area.

Puchinger and her project team planted seven different seed mixtures and single-species stands: a custom-made annual/perennial mix; a custom-made perennial mix; a custom-made annual

The project’s plots included several custom-designed mixes that focus on crop species.

mix; a commercial pollinator mix from a local seed distributor; a wildflower mix from a local retailer; sainfoin only; and alfalfa only. They also compared an early and a late seeding date for each plant stand option, to evaluate the effect of seeding date on stand establishment and competitiveness.

The three custom-made pollinator mixes were designed by Saikat Basu, a field agronomist working on the project. He says, “The annual mix has annual clovers, vetch and Brassica crops. The perennial mix has crops like alfalfa, sainfoin, perennial clovers, sweet clovers and perennial grasses. And the annual/perennial mix has a combination of both.”

Basu explains that he focused on using agricultural crops in

Cereals? Canola? Honestly, you’d die of boredom. Lentils, on the other hand, are the jigsaw puzzle of prairie crops, a season-long agronomic challenge that only a rare breed of farmer has the skill and nerve to pull off. We get it, and we want to help. With two modes of action from Groups 14 and 15, Focus® herbicide delivers extended control of key grassy and broadleaf weeds. The kind of powerful, sustained weed control you’ve always wanted is here. Save on Focus® herbicide with FMC Grower CashBack.

these mixes for several reasons. “My experience in surveys and field research indicates that wildflower seeds are difficult to establish, expensive and not easily available, and they run the risk of becoming weeds. Furthermore, since they do not have much commercial value, they are not preferred by our farmers.

“In contrast, the crop seeds are easily available, easy to establish and comparatively cheaper. [Many pollinating insects will feed on the pollen and nectar provided by the legume and Brassica crops in these mixes.] Plus these mixes provide more than just benefits for pollinators. Several of the crops have value as forage for livestock and as cover crops to prevent soil erosion and to provide phytoremediation. Many of the crops are very competitive with weeds and can grow in places that are less suited to regular crop production, such as areas along fencelines and roadsides, areas that are hard to reach with farm equipment, and areas along water bodies and irrigation canals.”

Puchinger and her team collected data on such factors as: plant emergence dates, plant density, canopy closure, survival of the different species in each mix, crop biomass and heights, and weed counts and biomass.

They also monitored flowering timing in the plots to establish a floral calendar for southern Alberta conditions and to see which plant stands would be better at providing a continuous source of pollen and nectar throughout the season.

As well, they used sticky cards to sample the insects visiting the plots. This winter, an insect taxonomist will be identifying the species of bees and other insects on the cards.

Although Puchinger and her team haven’t analyzed the data yet,

their field observations provide an initial look at what happened during the growing season. From what Puchinger saw, almost all the mixes planted at the first seeding date turned out really well; however, the wildflower stand was spotty. “Growing native flowers from seed is tough, so getting them established is more of a challenge than getting our commercially grown crops to establish.”

Basu saw many different pollinators visiting the plots. “I found a wide diversity of bees, including honeybees and native bee species such as the Nevada bumblebee, orange-belted bumblebee, brown-belted bumblebee, mining bee, and sweat bee, which are all common in southern Alberta. There were also moths and butterflies such as checkered butterflies, pollinating beetles such as black blister beetles, and flies like hover flies and drone flies.”

Puchinger says, “Once we dig into the data this winter, we can see which stands were most successful, which of the treatments provided the longest window for foraging by pollinators, and those kinds of things.”

Then Farming Smarter will look at preparing a grant application for a new project to investigate this topic a little more deeply. In particular, they are interested in the possibility of expanding the project into different parts of Alberta to find mixes that work well in other regions.

Puchinger is hopeful that the pollinator mixes composed mainly of commercial crops will make it easier for Alberta farmers to increase pollinator habitat. “A lot of these crops are being grown in the different regions of Alberta anyway. So, you’re just adding some plant diversity each year, to enhance the stand’s value for pollinators and the environment.”

Licence to spray.

This season, elite growers are being briefed on a new secret weapon for barley in the fight against the prairie’s toughest weeds.

• Cross Spectrum Performance

Get leading Group 1 grass control plus unparalleled broadleaf control of cleavers, hemp-nettle, wild buckwheat, kochia and many more.

• Total Flexibility With Arylex™ active fl exibility, you can apply on your own terms. Early, late, big or small.

• Easy Tank Mixing

Tank mixed with MCPA, count on 3 chemical families in the Group 4 mode of action for e ective resistance management.

Get briefed at OperationRezuvant.Corteva.ca

by Bruce Barker

Hitting malt barley quality is part science, part luck, and part karma. To look at the science part of the equation, research led by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research scientist John O’Donovan (retired), from Lacombe, Alta., investigated the effect of seeding date and seeding rate to see if high yield and malting quality could be more easily achieved.