TOP CROP MANAGER

MANAGING LEAF DISEASE IN SILAGE

Diverse rotations are key

PG. 8

WEATHER WOES

The impact of a challenging harvest

PG. 14

SUPPORTING AG PRODUCTION

Unfarmed spaces help bring benefical insects to boost yields

PG. 24

Diverse rotations are key

PG. 8

The impact of a challenging harvest

PG. 14

SUPPORTING AG PRODUCTION

Unfarmed spaces help bring benefical insects to boost yields

PG. 24

Enforcer ® works fast to take out tough weeds in cereals.

Knocks down your toughest weeds

Including cleavers, chickweed, wild buckwheat and kochia (Group 2-, 4-, and glyphosate-resistant biotypes)

Convenient and flexible to use

Spray when it works for you with a wide window of application and an all-in-one formulation

Excellent compatibility with the leading cereal grass weed herbicides Gentle on wheat and barley crops

Enforcer D performs best in the brown soil zone while Enforcer M is best suited for the dark brown and black soil zones of western Canada on cereals Made for Western Canada

Ask your local retailer for more information. 1.800.868.5444 | Nufarm.ca | NufarmCA

8 | Managing leaf disease in silage

Adding diversity to rotations is a relatively low-cost strategy for reducing leaf disease development and improving productivity.

By

Donna Fleury

ON:

14 | Weather woes

The impact of the challenging harvest of 2018 on prairie producers.

By Mark Halsall

24 | Unfarmed spaces supporting agricultural production

Abundance and diversity of native pollinators and beneficial insects can contribute to canola yield.

By Donna Fleury

MARIE-CLAUDE BIBEAU NAMED NEW AG MINISTER

Quebec MP Marie-Claude Bibeau was named the new federal Minister of Agriculture during Justin Trudeau’s cabinet shuffle on March 1, 2019. Former Minister of Agriculture, Lawrence MacAulay, is now Minister of Veterans Affairs.

Readers

During planting, the transmission went out on our three-year old 8320R. We’re small farmers, so we didn’t expect our John Deere dealer to drop everything and send a technician 40 miles to our farm, but that’s what happened. The service manager quickly identified the problem and a truck was on its way to haul the tractor to their shop. Technicians worked through the night and were able to track down the parts needed through the John Deere parts depot. We were back in the field only two days after we called our dealer! And that’s why we’ve been John Deere customers for more than 40 years – because they’ve gone the extra mile for us. We just thought you should know.

*Real story from John Deere customer shared in a letter to John Deere

Chairman/CEO

STEFANIE CROLEY | EDITOR

We live in an era of constant connection, where it can be difficult to focus on the task at hand without looking ahead to what’s coming up next. Agriculture is no different, and, perhaps, has always been this way – I don’t know any farmers who aren’t thinking about scouting or spraying before seeding has completely wrapped up. Producers are always on the hunt for the best possible strategies and solutions for problems that haven’t yet happened, and the industry is a reflection of that with constant innovation and development in the works.

Researchers at the John Innes Centre in Norwich, U.K., with assistance from colleagues in the United States and Australia, have developed a new way to quickly recruit disease resistance genes from wild plants and transfer them to domestic crops.

According to a release from the John Innes Centre, the technique, called AgRenSeq or speed cloning, enables researchers to search a genetic “library” of resistance genes discovered in wild relatives of modern crops. This assists researchers in identifying sequences associated with disease-fighting capability. The next step is to clone the genes and introduce them into domestic crops to protect them against troublesome pests and pathogens.

While this process has been done before, speed cloning will allow researchers to do it in a matter of months – record timing, compared to the 10 or 15 years it would take to accomplish using conventional methods, according to Dr. Brande Wulff, one of the project’s leaders in Norwich.

In field trials using wild wheat, researchers were able to successfully identify and clone four resistance genes for stem rust pathogens over a period of a few months. The team collected 151 strains of a wild grass and inoculated the population with the stem rust pathogen, then screened plants to identify those resistant and susceptible to the disease. After comparing the collected information with the DNA sequences of the plants, the team was left with a so-called library of resistance genes.

This breakthrough in technology could mean significant advancements in the fight against crop disease from a scientific level in the coming few years – especially timely news given the leaf disease theme of this issue. As you’ll read in this issue, Canadian scientists are on par with those previously mentioned, making great strides in the fight against serious disease threats. Of particular note, André Laroche’s study on stripe rust on page 18 is just one example of how Canadian researchers are leading the charge when it comes to disease research.

It’s important to stay focused on what’s currently happening, but just as imperative to anticipate what’s about to happen. As your season begins, take a note from the research playbook and look for ways to improve what’s to come.

#40065710

rthava@annexbusinessmedia.com Tel: 416.442.5600 ext. 3555 Fax: 416.510.6875 or 416.442.2191 Mail: 111 Gordon Baker Rd., Suite 400, Toronto, ON M2H 3R1

SUBSCRIPTION RATES

Top Crop Manager West – 9 issues Feb, Mar, Mid-Mar, Apr, June, Sept, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $48.50 Cdn. plus tax

Top Crop Manager East – 6 issues Feb, Mar, Apr, Oct, Nov and Dec – 1 Year - $48.50 Cdn. plus tax

Potatoes in Canada – 1 issue Spring – 1 Year $17.50 Cdn. plus tax

Occasionally, Top Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office

privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com

Protect your pulses from the rising threat of disease.

One of the most prominent challenges facing pulse growers today is the rising threat of disease in Western Canada. When conditions favour its development, you could lose up to 50% of your yield1,2. It’s time to take a stand against this issue with the aid of new Dyax™ fungicide. Thanks to a higher rate of the active ingredient Xemium®, Dyax provides more consistent and long-lasting disease control. To learn how it can help you fight for your right to grow pulses, visit agsolutions.ca/dyax today. 1 Saskatchewan Pulse Growers, 2017. 2 Manitoba Agriculture, 2017. Always read and follow label directions. AgCelence, AgSolutions, and XEMIUM are registered trade-marks, and DYAX is a trade-mark of BASF; all used with permission by BASF Canada Inc. DYAX fungicide should be

Adding diversity to rotations is a relatively low-cost strategy for reducing leaf disease development and improving productivity for silage producers.

by Donna Fleury

Leaf disease development and yield losses are a serious concern for silage producers, including scald, net blotch and spot blotch. With a priority of increasing productivity without having to add a lot of inputs, researchers have been investigating potential low-cost, low-input options including rotational diversity to manage leaf disease development.

“We were trying to mimic as much as possible what a typical silage production system might be, which in the past has normally been barley, often with the same variety grown for a few years in a row on the same piece of land,” explains Kelly Turkington, plant pathologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) in Lethbridge, Alta. “As a consequence, there could be very significant development of leaf disease in that type of system. In some of our earlier research in the late 90s, we found that simply rotating barley varieties could result in a dramatic decrease in leaf

disease and a corresponding increase in productivity compared to growing the same variety year after year. However, the best results were from including a non-host crop such as triticale in rotation, which significantly decreased leaf disease and increased yields. In 2008, we initiated a long-term study to investigate the impacts of adding diversity in rotations to leaf disease development in silage systems.”

The project was designed as a three-year rotational sequence repeated three times at two sites in Lacombe and Lethbridge. The project compared eight replicated treatments at each location in a three-year rotational sequence, including: continuous Sundre barley; barley rotation with different varieties; mixture

TOP: The intercropping treatment with spring triticale, with the variety components changing each year, Lacombe, 2010.

INSET: The continuous Sundre trials, Lacombe, 2010.

of the same three barley varieties; mixture of three different barley varieties each year; an intercrop of same varieties and either spring or winter triticale; and an intercrop of different varieties and either spring or winter triticale.

Sundre, a six-row high yielding feed variety with an excellent scald resistance package was used in the continuous barley treatment and in the third year of the rotational sequence for all treatments. For the three-way variety mixture and intercropping treatments, each variety was seeded at 100 seeds per square metre (seeds/m2) and mixed together to end up with a target seeding rate of 300 seeds/m2. All of the trials were direct seeded in the spring using a ConservaPak Seeder or equivalent. To more easily facilitate leaf disease assessment in the three-way barley variety mixture, the treatments included a two-row, a six-row (Sundre) and a hooded or non-awned variety.

“With each different treatment, we tried to add more diversity into the system for comparison,” Turkington says. “For example, using a winter triticale in the intercrop creates an understory of triticale foliage along the soil surface to help intercept disease spores being released from old infested barley stubble on the soil surface. A non-host crop increases the distance between susceptible crop components, and also acts as a barrier to disease development. If a net blotch spore lands on a non-host oat or triticale leaf, the spore would die and not be able to contribute to disease development in the crop. Similarly, in barley variety mixtures,

the genetics of one variety may potentially trigger a defense, while another may be more susceptible to virulent spores, overall reducing the disease load or rate of disease development.”

Over the nine years of the project, researchers conducted leaf disease rating assessments for net blotch and total leaf disease at the end of year three in each of the rotations, including 2010, 2013 and 2016. The assessment for leaf disease was conducted on Sundre barley in each treatment and rated for percent leaf area affected on the penultimate leaf, or the second leaf from the head. “Overall, we were trying to determine if we would be able to see a trend of reduced disease development as we added diversity,” Turkington explains. “The results confirm that as diversity increased, net blotch disease levels were reduced and crop productivity increased. The highest levels of disease were measured in continuous barley, with disease assessments showing above 80 per cent of the leaf area affected. Simply by changing barley varieties each year in rotation, disease levels dropped to approximately 70 per cent and using barley mixtures dropped it to 60 per cent. Using different barley components in the mixtures brought disease levels down even further.”

Let’s make it 100%

LEFT: Continuous Sundre treatment, flag-1 leaf, Lacombe 2016.

MIDDLE: Sundre in the barley variety mixture treatment where the barley varieties changed each year over the three-year rotational cycle, Lacombe 2016.

RIGHT: Sundre in the intercropping treatment with spring triticale and where the variety components of the intercrop changed each year, Lacombe 2016. This treatment and the barley variety mixtures where the varieties changed each year also were the most productive.

Intercrops using the same varieties each year had significantly lower disease levels than continuous barley, but more disease than where the variety component was changed each year. There was also an indication of lower disease with winter triticale as compared to spring. Researchers suspect that the understory of the winter triticale leaf material may have helped intercept net blotch spores and spores of other barley pathogens.

The trials also included a comparison of wet and dry yield weights of silage harvest for each treatment. On a wet weight basis, the trend in productivity followed the trend in disease, with increasing diversity showing increasing productivity.

“Although there was a trend of slightly higher productivity with barley variety rotation or the same barley mixtures on a wet weight basis as compared to continuous Sundre, the results were not always significant,” Turkington says. “However, productivity on a wet weight basis was higher with the mixture of different barley varieties each year and with the intercrops, both spring and winter triticale.”

In comparison on a dry weight basis,

the treatment with the highest tonnage was the intercrop of barley, oat and spring triticale. Spring triticale typically produces more biomass including crop head and grain at harvest, whereas the winter triticale does not when seeded at the spring timing. For the other treatments, there were very similar patterns for dry weight silage, with significant increases in productivity with barley variety rotation and barley mixtures compared to continuous barley. Overall the trends and results were similar between the Lacombe and Lethbridge sites, although disease levels were quite a bit lower at Lethbridge. As well, the barley variety mixture with different components tended to do among the best of the treatments at Lethbridge, although the intercrops also performed quite well.

“The results from our earlier work in the mid-’90s and this longer-term comparison study confirm that adding diversity in terms of an intercrop or barley mixtures can provide a relatively low cost strategy for reducing disease development and improving productivity,” Turkington says. “It’s a good reminder that even with the newest varieties and improved genetics with a great dis-

ease package, the challenge remains that if you grow that resistant variety continuously for two, three or four years, you are going to see a shift in the pathogen population to more virulent pathotypes.”

These same principles apply to swath grazing, which can also benefit from more diversity in rotation to reduce leaf disease development, and also to corn silage. Even with little or no history of corn production in a field, as the rotation is pushed in terms of repeating the same crop and potentially the same hybrid variety for a few years, growers can expect to see a shift in pathogens and an increase in disease development. “Adding diversity not only reduces leaf disease development and increases productivity over the long term, it also protects and extends the effectiveness of the disease resistance genetics packages included in the varieties,” Turkington adds. “Adding more diversity to rotations and selecting varieties with good resistance packages is a relatively low-cost, low-input strategy for reducing disease development and improving productivity that can be readily implemented in a continuous silage production system.”

Take control of your straight-cut canola harvest and optimize desiccation. Reglone® Ion is a true desiccant that works on contact for faster dry down than other harvest aids. A desiccated canola crop can be cut and threshed more easily, so you can start combining sooner, run faster, and get more acres done in a day.

Watch out for herbicide carryover and injury after a dry 2018.

by Bruce Barker

We’ve been here before. Farmers with a long enough memory will remember the droughts of the early 2000s when herbicide carryover – then mainly from Group 2 herbicides –impacted the following crop unexpectedly. Since then, research conducted by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC) and by herbicide manufacturers has helped to define the risk of unexpected herbicide carryover.

“Rainfall after application is key to herbicide degradation. The period from June through August is when most herbicide breakdown occurs because soil microbes break down herbicides and require adequate soil moisture and warm soil temperatures,” says Eric Johnson, who conducted herbicide carryover research when he was with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada in Scott, Sask.

Generally, at least four inches (100 millimetres) of rainfall during this summer period is required to lower the risk of unexpected herbicide carryover and residual herbicides. Higher rainfall reduces the risk even more. Less than three inches of rainfall means a very high risk of carryover.

Some Group 2s (sulfonylureas) and Group 5 herbicides are degraded by chemical hydrolysis. Most other herbicide Groups with soil residue are degraded by soil microbial activity. Both mechanisms require adequate rainfall during the summer growing season; however, moisture requirements for hydrolysis to occur are generally lower than microbial activity.

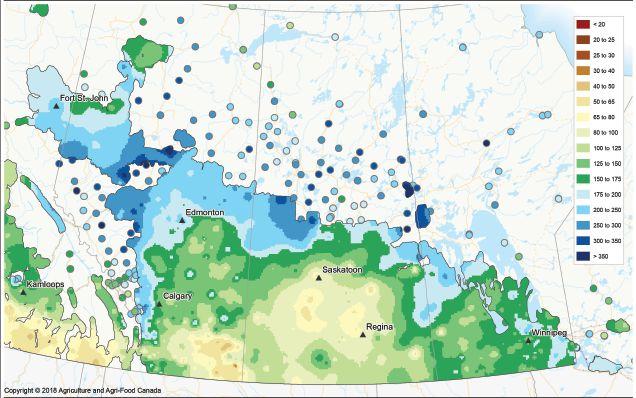

Clark Brenzil, weed control specialist with Saskatchewan

ABOVE: Group 2 imidazolinone herbicide damage showing interveinal chlorosis on new wheat leaf.

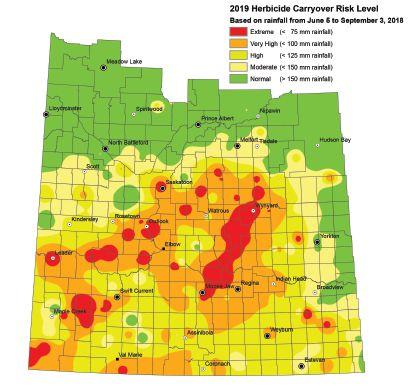

Generally, less than 77 millimetres (mm) of rainfall means a very high risk of herbicide carryover. Areas on the map that are yellow or orange represent areas that received less than 80 mm of rain during the summer months and are at an elevated risk for herbicide carryover.

Agriculture, developed an Herbicide Carryover Risk Map for 2019. The map shows areas of concern where risk of herbicide carryover is greater than normally expected. It details what producers in each risk area should consider when selecting crops where residual herbicides were applied the previous year. The map can be found on Saskatchewan Agriculture’s website and is included at the top of this page.

A larger scale map for the Prairies from AAFC can also help guide farmers in their recropping decision process. Large areas in southern Alberta, and a few pockets in Manitoba are also at risk.

Saskatchewan, Manitoba and Alberta Agriculture’s Guide to Crop Protection include a chart of residual herbicides and recropping restrictions. These restrictions are for ‘normal’ years with adequate rainfall after herbicide application. In dry years, these restrictions may not apply, and growers should consult

The map shows areas of concern where risk of herbicide carryover is greater than normally expected.

with the herbicide manufacturer for further guidance if they received low rainfall in 2018.

For example, in areas that were dry in 2017, some growers experienced unexpected Odyssey (Group 2) carryover in 2018 on wheat even though wheat planted one year after Odyssey is generally safe with adequate rainfall.

Additionally, growers who have had two successive dry years may be at increased risk of ‘herbicide stacking.’ Small amounts of residual herbicides can build up over several dry years to cause unexpected crop damage as well. Again, consult herbicide manufacturers for guidance on recropping.

Producers in Western Canada saw the harvest of 2018 start, stall, stop, and start up again. A cold, wet fall with early snowfall led to a challenging harvest and crop quality concerns. Crop insurance agencies discuss how the conditions and claims stack up to what the Prairie provinces have seen in previous years.

BY Mark Halsall

For many growers in Western Canada last year, cold, wet fall weather and some early snowfalls led to a challenging harvest in 2018. While thousands of acres were left unharvested, the number was less than what was experienced in the difficult harvest season of 2016, according to crop insurance agencies in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba.

Zsuzsanna Sangster, insurance product coordinator for Alberta’s Agriculture Financial Services Corporation (AFSC), says about 260 claims for unharvested acres were submitted to her agency in 2018.

That’s up from the 189 claims for unharvested acres processed by the AFSC in 2017, but it’s a far cry from the 2,255 claims recorded in 2016.

Sangster recounts a lot of Alberta farmland was snowed under in 2016, which led to the unusually high number of unharvested acres that year. So when cold temperatures, rain and snow settled in during harvest time in much of the province in 2018, there were fears it could happen again. Fortunately, that wasn’t the case and warmer weather in late October enabled most farmers to complete their harvest.

Shawn Jaques, CEO of the Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation (SCIC), says it was a similar situation last year in northern Saskatchewan, which experienced a later than normal harvest due to snow in September that persisted into October.

“Southern Saskatchewan had a really good harvest. There was warm, dry weather and they got the crop off no issue, but harvest was delayed in the northern grain belt,” he says. “Having said that, we had some warm and sunny weather in mid to late October and producers got back out in the field and finished combining.

“Despite all those challenges in harvest conditions, something like 99 per cent of the crop got harvested and producers were able to pull off an average to above average quality crop.”

Jaques says the SCIC insures about 30 million acres of farmland in the province. Of that, approximately 130,000 acres were left unharvested. “There’s definitely some crop left out,” he says, “but compared to 2016 when we had 1.6 million acres left out, it’s not that many acres.”

In Manitoba, about 100,000 acres of farmland were left unharvested in 2018, according to David Van Deynze, vice president for the Manitoba Agricultural Services Corporation (MASC). However, Van Deynze notes that’s only a small fraction of the overall number of seeded acres in Manitoba, which totals around nine million acres.

“Most years there’s always a few acres that go unharvested, and 100,000 acres is not uncommon,” he says.

Van Deynze, with Manitoba Agricultural Serivces Corporation, says the challenging harvest did lead to quality issues for some producers, but the province also had good yields overall.

Jaques, CEO of Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation, says the unharvested acres in 2018 are less than what the province saw in 2016.

“We are proud that over the last five years our customers have made AG Direct Hail the fastest growing hail insurance provider on the Prairies.”

Below is a Q&A with CEO Bruce Lowe, on how AG Direct Hail Insurance has quickly become the preferred crop hail insurer for thousands of hard-working Prairie farmers.

Q: Am I correct that AG Direct Hail is going into its sixth season providing private line crop hail insurance to Prairie farmers?

Bruce: Yes. And we remain the only exclusively direct and online choice for crop hail insurance on the Prairies.

Q: How has it been going?

Bruce: We are proud that over the last five years, our customers have made AG Direct Hail the fastest growing hail insurance provider.

Q. That is impressive. Why do you think farmers are choosing AG Direct Hail over the other private line insurers?

Bruce: In our first couple of years, I would say that our growth was primarily driven by our attractive rates. Because we are direct and online, farmers apply for a policy directly from us on our website, and we eliminate the middleman or broker. The other private line companies rely on brokers or agents to sell their policies and pay them about 12% commission. “No broker” means we don’t layer that 12% onto the cost of a policy from AG Direct Hail Insurance.

Q. So it’s your rates that are fueling your growth?

Bruce: Initially yes but our customers tell us there are many other reasons why they choose to purchase a policy with us and why they return year after year.

Q: What other factors would a farmer consider when purchasing a crop hail insurance policy?

Bruce: One of the most important considerations is the claim process. I say “process” because we handle every claim with the same urgency and seamless attention to detail. From the moment a policyholder files a claim online, they experience the AG Direct Hail difference. They get an email confirmation indicating we have received their claim. Our Claims Office calls within 48 hours after receipt of the notice of loss to schedule an adjustment. A highly skilled, experienced adjuster attends the claim within our internal goal of two weeks depending on the crop and growth stage. Immediately after the proof of loss is signed, a cheque is mailed or a direct deposit issued. We are exclusively backed by Allianz Global Risks Insurance; Allianz is the second largest insurance company in the world and a gold standard reinsurer. The AG Direct Hail claims process emulates that same high standard.

Q: So price and claims handling are important. What else?

Bruce: Because there is no middleman, our customers develop an unmatched relationship with us. AG Direct Hail policyholders know that if they have questions or want to discuss their coverage or claim,

they can call toll free and speak to me, Ellen, Beth, Sarah, Megan…. the entire team is available seven days a week. We are not a broker that will sell you a policy from some random company..….we are your private line insurance company. Customers also tell me they like the convenience of buying hail insurance 24/7 and how easy our website makes it to apply for a policy online.

Q: It sounds like you spend a lot of time interacting with your customers.

Bruce: Absolutely and we love it. I believe that any private line insurer that isn’t openly and actively looking for feedback directly from farmers doesn’t have a clue about what is important. We communicate with…. and I’m not exaggerating….thousands of farmers at tradeshows, conferences, on the phone and via email. Why? How else would we know what’s important to them? In many respects, AG Direct Hail was built with and by farmers. They told us what they wanted in a crop hail insurance provider. We conducted an end-of-season customer satisfaction survey and 98% of our policyholders were satisfied or very satisfied with their overall experience this past season…..that is how we measure success.

Q: So how can a producer learn about AG Direct, check rates, and then apply?

Bruce: Producers simply have to go to www.agdirecthail.com to simply create an account. There is no obligation when creating an account but it is required before viewing our rates in the spring.

Q: You also have a toll-free number?

Bruce: Yes. We are available seven days a week. Simply call us at 1 855 686-5596 We would be pleased to speak to farmers who would like to know more.

Q: Anything else that you would like to share with Prairie farmers, Bruce?

Bruce: Yes. After five years and almost 3,000 claims, we have NOT had a single hail claimant refuse to sign a proof of loss. Why? I believe it’s because we have the most knowledgeable and experienced crop adjusters in the industry. They are committed to thoroughly inspecting the damage so that our customers receive a loss payment that accurately represents their loss. We can sleep well at night knowing we always treat our customers fairly and with respect and integrity.

Shawn Jaques, CEO of the Saskatchewan Crop Insurance Corporation, says any time a farmer is unsure about what kind of impact weather will have on their crop insurance, the answer can usually be found a phone call away.

“If you’re experiencing a weather challenge on your farm and you think it’s going to impact the production of your crop, contact your local crop insurance office and we can help you out,” he says.

“We can work through and answer any questions that you may have on how your insurance coverage will be impacted by whatever weather event you’re facing, whether it’s harvest challenges in the fall or dry conditions in the summer or maybe establishment issues in the spring.”

Van Deynze says many Manitoba producers struggled “because the weather wasn’t great through September and parts of October. But at the end of the day, producers were able to successfully harvest almost all of their acres.”

“They managed to find some short windows at some tough times, I would say from mid to late October, when they were able to scratch and claw their way to get most of it,” he adds. “Farmers are a resilient bunch and they put a crop in the ground with the intention to harvest it, so they generally do whatever they need to do to make that happen. They just stayed at it.”

Van Deynze says growers with unharvested acres are sometimes faced with a difficult decision in the spring on whether to try to market the crop, bale it for feed, or destroy the crop entirely.

“If they decide to bale or destroy it in the spring because it’s deteriorated to a point where they’re not going to bother harvesting it, they should call us before they bale or destroy anything so that we can properly evaluate [the situation] and inform them how that impacts their insurance,” he says.

“If they’re going to combine their crop, then they just need to update us after combining it to tell us what yield they actually did get. Then we can run the numbers comparing it to their coverage and determine whether they’re in a claim position or not.”

Van Deynze says the challenging har-

vest in 2018 did lead to quality issues for some producers, but he adds average yields in Manitoba ended up being quite good, which dampened the number of claims submitted through the MASC’s yield-based insurance program.

“In some cases, they didn’t get that last bit of crop off in the condition they wanted to. But overall it was above-average year from our perspective for producers,” he says. “Overall, growers had enough production typically in the bin that they didn’t generate a lot of claims this year. Our numbers are relatively low from an insurance perspective for 2018.”

Van Deynze acknowledged that many producers had to incur extra costs as a result of wet harvest conditions.

“A lot of drying happened from what I understand,” he says. “Some of the crop was probably taken off tough and had to put it through some sort of drying or aeration [process] to make sure it stays in condition through the winter here.”

Sangster says some Alberta growers saw lower grain yields in 2018 because of adverse weather conditions, especially in the southern part of the province due to drought conditions in the summer. She says about 4,500 AFSC clients submitted post-harvest production insurance claims.

Sangster notes that the biggest impact of the 2018 weather was on crop quality. “Grain quality was affected this year, so producers may not be able to get top prices when marketing their grain due to grade,” she says.

Jaques says some Saskatchewan growers also experienced quality losses, especially with grain crops harvested later in the fall. The extremely dry summer in some of parts of Saskatchewan also contributed to significant yield losses for some growers, he says.

“We do have about 7,900 post-harvest claims that were registered across the province for different causes of loss,” Jaques says, adding that this number is “probably slightly below average.”

When the harvest of 2018 started, stalled, stopped, and started up again, it was difficult to imagine how it would end. The unpredictable weather that brought early snow also gifted two weeks of warm weather allowing producers to wrap up harvest and avoid a repeat of 2016.

Three different powerful herbicide Groups have been combined to make one simple solution for cereal growers. Infinity ® FX swiftly takes down over 27 different broadleaf weeds, including kochia (up to 15 cm) and cleavers (up to 9 whorls). And if you’re worried about resistance, consider this: you’re not messing with one wolf, you’re messing with the whole pack.

By Carolyn King

Canadian researchers are working towards a real-time forecasting system for major airborne wheat pathogens in Western Canada. The goal is to provide timely, accurate information to help growers in making disease management decisions. One of the diseases the researchers are working on is stripe rust. And their first step in that work was a project to develop a better method for counting stripe rust spores, for an improved forecasting process.

This project and other stripe rust research activities are helping to provide tools that growers need to fight this fungal disease, which can cause devastating yield losses in susceptible wheat varieties.

Stripe rust has emerged as a major concern in the western Prairies over the past two decades due to changes in the pathogen.

“Stripe rust has always been present in the irrigated area of southern Alberta. Until recently, this pathogen liked cool nights and high humidity, so the microclimate of southern Alberta under irrigation was perfect for the disease,” explains André Laroche, a research sci-

entist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada (AAFC). His research relates to stress biology in plants, including stress from different fungal diseases. And since he is based in Lethbridge, he has always been involved in some stripe rust research, such as contributing to the development of resistant wheat varieties.

“Soft white wheat is a class of wheat bred specifically for this area; it has fantastic yields under irrigation. So in the soft white wheat breeding program, stripe rust resistance has always been a number one priority.

“But for the wheat classes grown on dryland in Alberta, stripe rust wasn’t a problem because the conditions weren’t suitable for the pathogen to develop and spread.”

That situation began changing in 2000, as new stripe rust races replaced the older races across North America.

“In southern Alberta before 2000, the end of June would come with nice, warm days, and stripe rust would stop proliferating be-

ABOVE: Stripe rust pustules are scattered over the leaf surface in young plants.

cause the conditions were too dry and too hot. But starting in 2000, people began seeing stripe rust in late June and all July, indicating the presence of new isolates that were more aggressive and better able to survive in warmer weather. And some of these isolates were defeating some known stripe rust resistance genes,” Laroche says.

“Then in 2003, southern Alberta had a stripe rust epidemic. It was a real shock – suddenly stripe rust could develop outside the irrigated lands. The wheat fields were yellowish orange; you could see the disease from the car as you were driving by.

“Most of the other classes of wheat didn’t have any stripe rust resistance genes. A few lines had resistance because there are a few genes that confer resistance to leaf rust and/or stem rust and also confer resistance to stripe rust. But these stripe rust resistance genes were not widespread in the Canadian wheat germplasm.”

Stripe rust, also called yellow rust, is caused by Puccinia striiformis. The pustules are yellowish orange, with each pustule containing a mass of thousands of spores. In young plants, the pustules are scattered over the leaf surface. On the higher leaves of older plants, the pustules run in stripes parallel to the leaf veins.

Like the two other wheat rusts – stem rust and leaf rust – stripe rust requires a living host to survive. So conditions on the Prairies are not usually suitable for the pathogen to overwinter. For the most part, the spores are carried by the wind into the Prairies from warmer regions.

Laroche explains, “There are two pathways for the spread of rust in North America. The most important pathway for the western Prai-

ries is the Pacific Pathway where the spores are blown from Mexico to California and then along the coast to Oregon and Washington State. From there, the spores move inland into southern British Columbia and the Lethbridge area, and then into eastern and northern Saskatchewan, and into central Alberta and infrequently in the Peace River area.” As the disease works its way northward on this pathway, the spores cause infection in wheat fields along the way, producing more spores that can be carried further north.

These days on the Prairies, stripe rust levels still tend to be highest in southern Alberta, but severe outbreaks have sometimes occurred in parts of Saskatchewan.

“The small airborne spores can travel at least 1,000 kilometres. Often, they come down with showers or thunderstorms. This is great for the spores because they need high humidity to germinate. If they land on a susceptible wheat plant, the spores will germinate and infect that plant,” he notes.

“The life cycle takes about two weeks. Initially, a few small areas in fields here and there are infected, depending on where the spores landed. But after two or three life cycles, the disease affects large areas.”

Like the other wheat rusts, stripe rust can reproduce sexually and asexually. Sexual reproduction in all three pathogens takes place on alternate host species, not on wheat. For stem and leaf rust, sexual reproduction is responsible for most of genetic variation in the pathogens’ populations. That variation is key to enabling these two pathogens to adapt to changing conditions, such as defeating resistance genes in wheat. Their asexual reproduction processes produce much less variation – each generation is almost the same as the

SHIPPING

ORDER BY 6 PM FOR SAME DAY SHIPPING

previous generation except for occasional random mutations.

Stripe rust is different. Its alternate host is barberry (which is also stem rust’s alternate host), but that was only determined about a decade ago. Laroche suspects that scientists took over 100 years to identify its alternate host because sexual reproduction may not be as important for this pathogen. Instead, it appears to have an unusually high degree of mutation in its asexual reproduction process, enabling it to overcome control measures such as genetic resistance in wheat.

To track the spread of airborne pathogens for disease forecasting systems, air samples are collected in the field and then analyzed to identify and quantify the pathogens present. These days, this analysis is usually done using PCR, a DNA-based approach. But PCR is difficult to use with stripe rust.

Laroche explains, “To use PCR, we first have to break open the spores to release the DNA. The spores of rust pathogens and even more so for stripe rust are difficult to break open – stripe rust spores are amazingly thick.” Consequently, stripe rust spores take much

longer to prepare for PCR testing, and quantitative recovery of DNA is more difficult. So, it is challenging to provide the timely results needed for disease forecasting.

In addition, there is the worry that the stripe rust spores might not be properly broken open, which would reduce the reliability of the forecast. He notes, “From our work over the years, we know that the spores of some stripe rust isolates are more difficult to open than others; we don’t have any theory at this point as to why this is the case. But when you’re collecting samples in the field, you don’t know whether the spores will be a little easier or more difficult to break open. So our protocol is always for the most difficult spores.”

Laroche’s project involved an innovative method to detect and quantify stripe rust spores. This method uses an antibody that reacts to the specific proteins on the surface of the stripe rust spores, so the spores don’t have to be broken open. The Western Grains Research Foundation and Saskatchewan Wheat Commission funded this three-year project, which started in 2015.

Laroche had obtained the antibodies about five years earlier. He collaborated on that work with his AAFC-Lethbridge colleague Claudia

Sheedy, who has expertise in antibodies. The antibodies were produced using the techniques involved in making antibodies for medical uses.

To develop the new detection method, Laroche and his research team tested the antibodies on different stripe rust isolates. They used samples from infected plants that they were growing in the greenhouse and from air samples collected in the field. They figured out how to accurately quantify the number of spores based on the colour intensity of the antibody reaction. And they assessed the effectiveness of this antibody approach.

Their results show that the antibody method is a sensitive, faster and more reliable way to quantify stripe rust spores. The antibody is highly specific to stripe rust; the presence of other pathogens doesn’t interfere with the antibody’s ability to detect stripe rust spores. The antibody method takes only about 3.5 to 4 hours; in contrast, the PCR approach takes about a day and a half of lab time because of the extra time needed to break open the spores and extract the DNA. And the antibody method reliably determines the number of spores across a range of spore sample sizes relevant for a disease forecasting system.

The field samples offered a special challenge. Air sampling equipment for spore collection can capture lots of other airborne things – pollen, insects, dust, dirt and so on, as well as many different species of spores. In particular, Laroche and his team wanted to be sure that their method was robust enough to handle the sometimes large amounts of dirt in these samples.

He says, “We made some minor modifications to our protocol, and we determined that, yes, we can still detect the spores with our antibodies, even when the amount of dirt is in vast excess of the number of spores.”

Laroche’s detection research is an essential first step for forecasting stripe rust. Currently, growers make decisions about fungicide applications by scouting their wheat fields for symptoms, which start to appear about one to two weeks after the spores arrive. A real-time, reliable forecasting system could provide earlier information to growers about whether

Get a more complete and faster bur noff when adding Aim® EC herbicide to your glyphosate. This unique Group 14 chemistry delivers fast-acting control of your toughest weeds. Aim® EC herbicide also provides the ultimate flexibility, allowing you to tank-mix with your partner of choice and no fear of cropping restrictions.

Fire up your pre-seed bur noff with Aim® EC herbicide.

Save up to $5.50/acre with FMC

or not spraying would be warranted.

Since most western Canadian wheat varieties do not have strong resistance to stripe rust and the pathogen is good at overcoming resistance genes, fungicide applications are very important for managing this disease.

“With stripe rust’s ability to mutate in every life cycle, the pathogen is able to adapt and eventually defeat the resistance genes. When a single new resistance gene is released in commercial cultivars, the pathogen will overcome that gene within two or three commercial years. So if you have a plant that is resistant today, it might not be resistant next week or next year.” He adds, “That’s why it is important to bring at least three stripe rust resistance genes together in a wheat variety to help to preserve the effectiveness of these genes.”

The pathogen’s relatively high mutation rate also means it can more easily develop resistance to fungicide chemistries. “This has been experienced in Europe a number of times. Nowadays, only two fungicide groups [Group 3 and Group 11] are effective against stripe rust [in North America],” notes Laroche.

“If you apply a fungicide when it is not really needed, you favour the development of biotypes of the pathogen that have resistance to that fungicide. So the potential danger is: what do you do on the day when you have stripe rust that has become resistant to the remaining two chemistries? You will have lost your last tool to fight the pathogen.”

A reliable forecasting system would enable growers to apply fungicides only when needed. That would help maintain the effectiveness of the current fungicide chemistries as well as reducing stripe rust yield losses, lowering fungicide input costs, and minimizing any environmental impacts from the fungicides.

Western Canadian researchers are currently working on the other components of the stripe rust forecasting system. And they are developing forecasting systems for stem rust, leaf rust, powdery mildew, tan spot and Fusarium head blight.

Laroche is also involved in other stripe rust research. Some of this work is focused on learning more about the pathogen. For instance, he and his research team are examining the genetic differences between different stripe rust isolates. This work confirms that stripe rust populations have a remarkable amount a genetic variation. He says, “This pathogen is very plastic and can change about 2 to 10 per cent of its genes quite rapidly.”

Another area of his research aims to increase understanding of stripe rust resistance and susceptibility mechanisms by examining gene expression. “When we infect a susceptible wheat plant, we see a huge response of the stripe rust genes as they invade the plant and make their reproduction very successful,” he explains.

“When we infect a resistant wheat plant, we see a little bit of rust development. Very few of the pathogen’s genes are expressed. But many wheat genes are expressed; these genes are obviously involved in protecting the plant against that pathogen. So we are gaining information on how a plant with given resistance genes defends itself against the pathogen.”

Laroche also works on identifying new stripe rust resistance genes. For example, his team screens wild relatives of wheat, such as intermediate wheatgrass, for resistance to the disease. He says, “These wild wheatgrasses usually are quite resistant against many diseases. At least 70 per cent of the known disease resistance genes used in our current wheat cultivars originated from wild relatives of wheat.”

However, crossing wheat with its wild relatives to bring in resistance genes is a time-consuming, complicated process. So Laroche’s group develops DNA markers that are used to screen for the resistance genes in each generation of the breeder’s plants, making the screening process much faster and more efficient.

Stripe rust presents a formidable threat, with its more aggressive races that are better adapted to warmer temperatures and its ability to defeat control measures. Laroche’s research is contributing to the development of new tools so western Canadian growers can more effectively manage this yield-robbing disease.

Together, Richardson Pioneer and Syngenta are bringing quality varieties to Western Canadian Farmers.

We are committed to providing you with reliable products and sound agronomic advice. That is why we have partnered with Syngenta, offering our customers products they can trust. SY Obsidian and SY Sovite are Canadian Western Red Spring wheat varieties which combine competitive yields with an excellent disease resistance package.

Book your seed with Richardson Pioneer today.

Abundance and diversity of pollinators and beneficial insects can contribute to canola yield.

by Donna Fleury

Pollinators and beneficial insects can be important contributors to crop production and yield for prairie crops like canola. Natural habitats and uncultivated spaces can improve the abundance and diversity of these native beneficial insect communities. Researchers are interested in learning more about the role that unfarmed spaces have in supporting these insect communities and the potential for increasing crop yield.

“We have several projects underway in our lab, including an understanding of how natural and agricultural landscapes may affect the ecosystem services of pollinators and beneficial insects and crops,” explains Paul Galpern, associate professor in the department of biological sciences at the University of Calgary. “From a landscape perspective, we are interested in looking at small unfarmed areas that may border or be included in cultivated fields and what difference that might make. We questioned whether these messy bits, such as small wetlands, fence lines, remnant grasslands, forested areas or shelterbelts or other unfarmed spaces in and around cultivated fields were good for yield.

We wanted to know if more of this type of habitat would make a difference in the field across major prairie crops.”

In a recent project, Galpern and his team looked at crop insurance data since 2012 in Alberta to determine if there were any differences. The available data was a larger aggregated set at the county or municipality level. “Our analysis showed that in municipalities that tend to have more unfarmed or complex areas in their fields, these areas have a small positive association with yields. We found that canola yields are higher than average in municipalities with more unfarmed areas in their fields, after controlling all other variables such as weather, climate and varieties,” he says. “This shows there is a correlation between these factors, but we will need to dig deeper to determine if this works at an individual field level and what mechanisms are involved. We have evidence from many stud-

ABOVE: Maintaining in-field wetlands, natural habitats and unfarmed spaces can improve the abundance and diversity of native beneficial insect communities, with possible pollination benefits for farmers growing crops such as canola.

ies in Europe that more uncultivated or unfarmed spaces in a farmed landscape improve habitat for pollinators and other beneficial insects that pollinate crops such as oilseed rape, and that these have a small effect on yield. We expect to see similar results in canola in Canada and that’s why we are looking.”

In another large landscape-level study across agroecosystems in southern Alberta, Galpern and his team looked at the impacts on yield from beneficial insect visitation. They studied the role of natural habitats near canola fields as reservoirs for pollinators and natural enemies of canola pests, as well as the capacity of these beneficial insects to increase seed yield through pollination and pest reduction. Across a wide area, they sampled beneficial insects (including pollinators, and predators of insect crops such as beetles and spiders) and developed estimates of abundance and diversity, and of crop yield to determine how these unfarmed features impact insect communities. To better understand habitat required by pollinators such as native bees for nesting and foraging and to quantify the role of in-field wetlands, researchers also sampled native bees at three distances from the wetland margin into the surrounding cropland (zero metres, 25 metres and 75 metres) across the season in three field types (canola, cereal and perennial grassland).

“As part of the project, we were trying to measure what we call spillover effects, such as native bees or predatory beetles and spiders that are using wetlands or unfarmed spaces as homes and nesting sites, and eventually move out into the crop to feed as pollinators or to attack crop pests such as flea beetles or others,” Galpern explains. “Our results showed evidence that pollinators are based in wetlands, nesting in the margins and spilling over into the fields. We found that native bee abundance and diversity decreased further away from the margin of wetlands in both canola and cereal fields. This shows there is a positive benefit of maintaining in-field wetlands and unfarmed spaces, with possible pollination benefits for farmers growing crops such as canola.”

Although there are clearly benefits to pollinator and beneficial

insect abundance and diversity by keeping these unfarmed areas intact, Galpern adds the next question is do these landscape features provide enough benefits or services to make it worthwhile for growers to maintain them in their fields? When we add all of the pieces of the puzzle together, the benefits are not zero, but does it add enough yield or other conservation benefits to encourage growers to keep them on the landscape?

There may be other reasons to keep these unfarmed spaces, such as the impacts and benefits for carbon sequestration or other sustainability measures that may be monetary or for social license. For example, the rotational footprint of crops across Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba is estimated to be twice the footprint of the United Kingdom. So even a small increase in yield or other conservation ecosystem services will have a measurable impact on any of those metrics, whether it is carbon storage, sustainability or crop yield and food production.”

Galpern and a small group of colleagues from across the Prairies have come together to continue to explore these questions in this relatively new and evolving area of research where little is known. “We are really interested in big data in my lab, so we are looking at the opportunity to work with growers and leverage the information they are collecting through precision agriculture systems to help us look for patterns and answer questions,” Galpern adds. “For example, with enough precision harvest data, we hope to identify these trends as yield halos around wetlands – essentially areas of higher yield around unfarmed patches. We are also looking to see if there is an increase in yields per acre in fields that have more wetlands and other unfarmed spaces within their margins.

“We want to be able to look at not just yield benefits, but also profitability benefits and what does it mean for the overall bottom line. Growers care about both the economic and the environmental bottom lines, as do consumers and the public. I believe it is possible to have a win-win across agriculture land in the prairies and uses these unfarmed spaces to find a sustainable balance between conservation and farming.”

Prosaro XTR fungicide. The best just got even better.

Prosaro® XTR is here and it’s better than ever. How much better? How about a whopping 14% over untreated*. So regardless of disease pressure, in wet or dry weather, give your wheat and barley yields a big-time boost come harvest. Protect your cereals and your bottom line with Prosaro XTR.