TOP CROP MANAGER

Three different powerful herbicide Groups have been combined to make one simple solution for cereal growers. Infinity ® FX swiftly takes down over 27 different broadleaf weeds, including cleavers and Canada fleabane. And if you’re worried about resistance consider this: you’re not messing with one wolf, you’re messing with the whole pack.

Source: Bayer Eastern Canada Trials (2017-2018)

Managing western bean cutworm to decrease DON severity

PG. 7

Expanding production of the high-value crop

PG. 14

Storage tips for growers

PG. 20

• SCOUT AND ELIMINATE TARGET INSECTS

•

Target insects that cost you. Leave the ones that help you. When insects like Western bean cutworm start to invade your corn, you need proven performance. Use Coragen® insecticide for extended residual and fast acting control of key insects. Enjoy the flexibility of multiple tank-mix partners and application timing - hot or cool temperatures. Best of all, Coragen® insecticide is easy on beneficials and pollinators1 Mission

7 | Mycotoxins in corn linked to WBC Research reveals corn hybrid, insecticide and fungicide recommendations to manage WBC and DON. by

Julienne Isaacs

FROM THE EDITOR

6 Moving and shaking by Stefanie Croley

PULSES

10 Pulses show promise for Eastern Canada by Julienne Isaacs

FEBRUARY 2019 • EASTERN EDITION

14 | Malting barley for northern Ontario Opportunities and challenges for expanding production of this higher-value crop. by Carolyn King

CEREALS

24 Size matters by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

TOP CROP MANAGER’S WEBINAR SERIES

FOCUS ON: STORAGE

20 | Dealing with DON

Storage tips and support for growers. by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

TRUCK REVIEW

26 GMC Sierra wins the Canadian Truck King title by Mario Cywinski

Top Crop Manager’s webinar series has wrapped up and all four webinars are now available online. Learn about the latest cover crop best practices or new strategies for blackleg management. Review last year’s corn season and how you can prepare for the upcoming season. Uncover new research revealing spring wheat can go in the ground earlier than recommended.

Stay on top of the latest in cover crop, corn, spring wheat and blackleg management. Each webinar is approved for one CCA-CEU.

Catch up all on the recordings at www.topcropmanager.com/webinars.

Readers will find numerous references to pesticide and fertility applications, methods, timing and rates in the pages of Top Crop Manager. We encourage growers to check product registration status and consult with provincial recommendations and product labels for complete instructions.

STEFANIE CROLEY | EDITOR

We’re barely through the first two months of 2019, but it’s safe to say this growing season is kicking off on a strong note – a welcomed sign after the tough conditions Canadian farmers experienced in 2018.

Several significant announcements have been made these last few weeks in terms of investments and new products for the coming year; a sure indication that research, innovation and stewardship are alive and well in agriculture. Here’s a quick recap . . .

Producers across the country breathed a collective sigh of relief in early January when Health Canada announced that after careful vetting of eight objections, the re-evaluation decision made in 2017 that glyphosate is safe when used according to product label direction will stand. Health Canada, in a statement, says the scientists involved “left no stone unturned in conducting this review,” adding those scientists had access to all pertinent information from multiple sources.

This good news was preceded by the news that China has granted regulatory approval of Bayer’s TruFlex canola with Roundup Ready technology. In a statement, Bayer’s trait launch lead Jon Riley noted the company has waited five years to introduce this product to farmers in Canada and the United States. Despite being approved in Canada since 2012, seed developers cannot commercialize traits until they are approved in major markets in order to align with the Canola Council of Canada’s Market Access Policy.

Further into January, Syngenta announced it had received registration for Tavium Plus VaporGrip Technology, a new herbicide for Roundup Ready 2 Xtend soybeans. The company says the dicamba-based pre-mix herbicide will provide broad-spectrum control of weeds including glyphosate-resistant Canada fleabane and common and giant ragweed. Corteva Agriscience also announced commercial sales of Enlist E3 soybeans to begin in 2019, introductory quantities of Qrome corn products through the United States Corn Belt, and the licensing of LibertyLink canola. And Nufarm’s GoldWing herbicide label expanded to include lentils, chickpeas, fababeans and other beans for pre-seed burndown control.

Plans for significant investments to Canadian agriculture research were also recently unveiled. Notably, the Alberta Wheat Commission announced more than $2.6 million in funding for 22 wheat research projects, aimed at improved farm profitability. These projects will be funded as part of the Canadian National Wheat Cluster, a five-year federal matching program under the Canadian Agricultural Partnership. Additionally, the Canadian Field Crop Research Alliance will receive an investment of $4.1 million over five years to support two national projects, one on oat and one on corn. This investment is funded under the AgriScience Program (Projects) and follows the Government of Canada’s investment of up to $5.4 million to the Canadian Field Crop Research Alliance for a soybean project.

These events taking place within the first six weeks of the year, combined with the many novel projects we’ve covered in this issue, speak to the current state of Canadian agriculture: our innovation game is strong. Though spring may not be on the horizon quite yet, producers will have an array of tools at their disposal come planting time. Here’s hoping the rest of the year continues to ride this positive wave.

Crop Manager will mail information on behalf of industry related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

Annex Privacy Office privacy@annexbusinessmedia.com • Tel: 800 668

Research reveals corn hybrid, insecticide and fungicide recommendations to manage WBC and DON.

by Julienne Isaacs

The 2018 growing season was one of the worst years on record for Fusarium graminearum infection in Ontario corn, according to Jocelyn Smith, a research associate in insect resistance management and field crop pest management at the University of Guelph Ridgetown Campus. High Fusarium infection levels meant high levels of mycotoxin contamination, particularly deoxynivalenol (DON), which can render grain unmarketable for food, feed and fuel end-uses.

Fusarium is nothing new for Ontario producers. But a growing body of research points to interlinkages between Fusarium infection, DON accumulation and western bean cutworm (WBC), a relatively new-to-Ontario pest of field corn. Although WBC injury has been shown to cause four to 15 bushels per acre (bu/ac) yield losses, its effect on grain quality and mycotoxin contamination is of greater concern.

Smith is the first author on a newly published research paper that suggests WBC can exacerbate Fusarium infection and thus DON concentrations in corn.

When Bt corn first became available in Ontario, Smith says, research conducted by Art Schaafsma showed that controlling European corn borer with Bt corn resulted in lower DON levels in grain.

“Insect feeding creates wounds in the plant tissue that provide more entry spots for fungi like Fusarium species to infect,”

Smith explains. “Insects may also spread fungi as they move around the plant while they feed.”

Western bean cutworm has been present in Ontario for about a decade. By 2011, says Smith, a major problem had developed: the pest had become resistant to corn hybrids with the CRY1F gene (Herculex 1, SmartStax), which had been thought to control the pest.

“In a very short time we had very poor control of western bean cutworm in Ontario, and we observed more ear mould and more DON in areas that had western bean cutworm infestations,” she says.

Smith and Schaafsma decided to instigate a research study to establish the pest’s resistance to the CRY1F gene as well as to evaluate the relationship between WBC and Fusarium incidence and resulting DON levels.

The study ran between 2012 and 2014 on three large field-scale sites in southwestern Ontario. Each year of the study, the researchers planted hybrids with and without the CRY1F trait as well as a VIP3A hybrid with similar agronomic characteristics.

The researchers relied upon natural pest pressures for the study, and measured WBC injury, ear mould symptoms and DON in the grain, as well as yields, each year. They also included different pesticide treatments with a high-clearance sprayer: insecticide alone, fungicide alone, and an insecticide-fungicide tankmix, each applied at different timings.

In total, they ended with nine site-years, but opted to use data from only six of those because Fusarium and WBC levels were low in some years of the study, explains Smith.

“We also tried to develop a relationship or model that could indicate how much WBC injury it would take to see concerning

“But insect control is not the only thing you need to consider,” Smith explains. “You need to consider Fusarium susceptibility of corn hybrids. You could still have DON issues in a hybrid that is relatively resistant to WBC if it is susceptible to Fusarium via silk infection.”

But the VIP3A trait plays a role in that it reduces WBC incidence early after hatching from the egg mass, says Smith, so fewer insects feed on the ears when silk infection has already happened.

In the study, the researchers tested two insecticide treatments – DuPont’s group 28 insecticide Coragen (chlorantraniliprole) alone, and Syngenta’s pre-mixed insecticide Voliam-Xpress, which contains the active ingredients lambda-cyhalothrin and chlorantraniliprole (Group 3 and 28). They applied these either alone or in combination with fungicides.

Traditionally, to control WBC, producers are advised to spray insecticides at 95 per cent tasseling. In the study, when insecticides were sprayed alone, the researchers used this timing. They also sprayed insecticides at this timing and then fungicides later, at full silking, and there was a final treatment where both were sprayed as a tank-mix between 95 per cent tasseling and full silking.

“We had lower DON levels when we sprayed an insecticide/ fungicide tank-mix versus a fungicide alone,” Smith says. “Based on these results and subsequent years of research, we recommend producers apply an insecticide/fungicide tank mix when there’s as much fresh silk as possible.”

It’s important for producers to be aware of the link between WBC injury and DON, Smith emphasizes, which has implications for scouting.

“Growers need to scout to see whether western bean cutworm egg masses are present in the field and consider whether environmental conditions are favourable for Fusarium infection around silking time before deciding whether to spray an insecticide/fungicide tank-mix,” she says. “We don’t want to jump to the conclusion that we should do this every year.”

“But the bottom line was that regardless of the hybrids we tested, the incidence of WBC injury –basically, whether there was any feeding – did increase the amount of DON.”

levels of DON in the grain, but that turns out to be really complicated and at this point we don’t have enough parameters in the model to do that,” Smith explains.

“But the bottom line was that regardless of the hybrids we tested, the incidence of WBC injury – basically, whether there was any feeding – did increase the amount of DON. The severity of feeding didn’t have a significant effect – just the fact that injury was there. Even a small nip from a caterpillar could increase DON.”

Because there was no difference in WBC injury between CRY1F and non-Bt hybrids, the study confirmed that the CRY1F Bt trait does not control WBC. The least amount of damage was seen in the plots planted with the VIP3A hybrid.

In 2018, for example, WBC was not a major issue in some parts of Ontario. Egg counts were lower in historical problem areas, but conditions were perfect for Fusarium infection, Smith says. So an insecticide application would not have provided an economic advantage when WBC wasn’t present.

Another important recommendation to note, Smith says, is that fungicide group matters: triazole fungicides are much more effective at controlling DON than strobilurin fungicides. For best control of Fusarium infection, triazoles should be applied at full silking, before silk browning.

Producers should start scouting for WBC in the third week of July and continue scouting every five days for up to three weeks during the moth flight period. The economic threshold for WBC egg masses in Ontario is five per cent, but producers should count this cumulatively; for example, if a producer finds one per cent egg masses on their first scouting day and several days later they count four per cent egg masses, they should consider that the threshold has been reached.

*Performance may vary from location to location and from year to year, as local growing, soil and weather conditions may vary. Growers should evaluate data from multiple locations and years whenever possible and should consider the impacts of these conditions on the grower’s fields.

Monsanto Company is a member of Excellence Through Stewardship® (ETS). Monsanto products are commercialized in accordance with ETS Product Launch Stewardship Guidance, and in compliance with Monsanto’s Policy for Commercialization of Biotechnology-Derived Plant Products in Commodity Crops. These products have been approved for import into key export markets with functioning regulatory systems. Any crop or material produced from these products can only be exported to, or used, processed or sold in countries where all necessary regulatory approvals have been granted. It is a violation of national and international law to move material containing biotech traits across boundaries into nations where import is not permitted. Growers should talk to their

by Julienne Isaacs

It was during a 2013 vacation to Prince Edward Island, where Chris Chivilo grew up, that he and his wife, Tracey, had the idea to support the development of the pulse industry in Atlantic Canada.

“Looking around, some of the crops hadn’t been grown when I was raised on P.E.I., such as grain corn and soybeans,” Chivilo says. “Seeing that those crops were doing well, I thought for sure we could grow fababeans, which were hot out west at the time. We’d also started growing them in northern Ontario. We thought, let’s try some on P.E.I. and see if they do well.”

Chivilo is president and CEO of W.A. Grain and Pulse Solutions, based in Innisfail, Alta. With six cleaning and processing plants in Western Canada, the company is one of Canada’s biggest pulse exporters.

Last year, the company opened its $8 million pulse processing plant in Summerside, P.E.I. – the first such facility in Atlantic Canada, and the sole reason producers in the Maritimes can now seriously consider putting pulses in the rotation.

The plant’s establishment followed on the heels of a four-year

Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada research collaboration study solely funded by the Chivilos to investigate basic agronomy for a variety of pulses on PEI.

Prior to the plant’s arrival, marketing opportunities for pulses were almost nil, according to Aaron Mills, the research scientist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada who is leading the study. “The market opportunities developed by W.A. Grains are what is driving the increase in pulse acres in the region,” Mills says.

Mills had been looking into the development of alternative rotation crops for potato producers since 2011, including pulses, when the Chivilos approached him with an offer to support pulse research on the Island.

“For a lot of these emerging crops, they have fairly established production practices in Western Canada, but it’s totally different in Eastern Canada, so we needed to start with the basics,” Mills says.

ABOVE: Ag Canada research scientist Aaron Mills is leading a study in pulse growing options for Atlantic Canada.

The Maritime Provinces, led by P.E.I., are Canada’s biggest potato exporters. A threeyear rotation is mandatory for potato growers on the Island. Mills says a typical rotation used to be potatoes followed by barley underseeded to red clover, with the clover allowed to grow the third year.

But Mills says there’s no typical P.E.I. rotation anymore and notes the emergence of several crops new to the region, including cover crop mixtures, soybeans and pulses. Soybean acres, for example, have jumped from 18,000 acres in 2008 to more than 50,000 seeded acres in 2018.

The reality is that there are few profitable rotation crops for non-potato years, and this is where there is a potential for pulses, says Mills.

Soybeans add economic value to the rotation but very little value to the soil in terms of residue or organic matter. Added to this, soybean yields aren’t high and beans don’t come off the field until late-October or mid-November, when most producers would prefer to have everything put away in the bins.

Disease and wireworm pressure are also growing problems for potato producers across Atlantic Canada. For this reason, interest in mustard as a biofumigant has been increasing, says Mills.

“Wireworm is so terrible that growers are looking for alternative crops that act as biofumigants to control pest populations. Mustard is one of those crops,” he says.

Mustard has traditionally been used as a plough-down crop, but Mills’ team is conducting trials to see if the plant’s biofumigation effects are retained if the seed is harvested. “That way, you can get a crop off and have time to put in another crop of mustard or buckwheat to cover the soil in the winter,” he explains.

Enter pulses, specifically peas, which work well as a rotation crop before mustard, because the pea crop is off the field by the middle of August, leaving time to put in mustard or buckwheat. The same goes for fababeans, although they mature a bit later, says Mills.

His research team is also looking at intercropping mustard and peas, which is commonly done in Western Canada. “One of the classic mixtures that used to be grown on P.E.I. was peas, oats and barley. The new peamustard mixture would be another way to keep diversity in the rotation,” Mills says.

Recently, Mills began an AAFC-funded study looking at carryover effects of peas, fababeans and soybean on winter wheat,

Seeding rate data for the average of the 2017 and 2018

Seeding rate data for the average of the 2017 and 2018 growing seasons. The low, medium and high seeding rates are 75, 100 and 125 seeds/m2 respectively, or 160, 210, or 260 lb/ac; the x-axis shows different pea varieties. Limerick and Raezer are green peas, and Lacombe and Saffron are yellow pea varieties.

with a focus on soil health metrics and nutrient carryover.

But the work goes beyond peas and fababeans. During the W.A. Grains-funded project, the team has been working to hammer out the agronomy for chickpeas, lentils, black beans and pinto beans in their field trials. Pulses that perform well in initial field trials are carried over into AAFC projects.

Weather conditions present an obvious challenge for pulses in Atlantic Canada. Mills says springs have been getting later in the Maritime Provinces and pulses have been going in the ground later than hoped.

Generally speaking, weather conditions on PEI are more akin to Europe than Western Canada, so Mills’ team is looking into planting European pulse varieties, which can stand up to wetter, temperate conditions better than many varieties developed in the west.

But Mills says his research team’s initial goal was not to evaluate varieties, but rather get a sense of which pulses appear to do well in Atlantic Canada and to generate basic agronomic data, including specific recommendations for plant population, spacing, fertility and herbicide options. Now that they have completed a lot of the development work, they can analyze how specific pulses perform in rotation with potatoes.

Along with peas and fababeans, chickpeas, black beans and pinto beans also show promise. 2018 was unseasonably hot and dry, but the team’s chickpeas and black beans performed well. The lentils were planted too late and did not pod up, and the team ran into harvesting issues with their pinto beans, but Mills says both crops will be planted again in 2019.

Mills says that it is likely that disease will someday become a major issue for pulse producers in Atlantic Canada, like it is in many parts of Western Canada, so they are recommending fungicide application as part of general management practices. “We haven’t seen disease levels high enough to result in economic losses, and the yield data is surprisingly good – in short, we’re in the honeymoon phase here for these crops,” he says.

His team has A-base funding to continue work with pulses until 2021 and plans to do further work on intercropping with pulses in potato rotations.

This year, Chivilo’s Summerside plant took in 10,000 tonnes of peas and beans, a figure they hope will rise by 50 per cent in 2019.

“Farmers want choices, good choices that won’t cost them money,” he says. “I would encourage farmers to look at all the choices and, when it comes to adding pulses into the rotation, weigh the benefits to their land and bottom line.”

Opportunities and challenges for expanding production of this higher-value crop.

by Carolyn King

The Northern Ontario Agri-Food Strategy, released in 2018, identifies malting barley as one of the crops with growth potential for the region. Grower organizations, researchers and others are working to help northern growers capture this niche market opportunity.

“I think malting barley gives farmers in our region an opportunity to diversify within a crop that we know we can grow, to diversify their markets and potentially, depending on the market and the year, get a premium for what they are growing,” says Stephanie Vanthof, administrator of the Northern Ontario Farm Innovation Alliance (NOFIA).

For successful malting barley production, the crop needs the right growing conditions and special management to meet the strict requirements for the malt market. For example, the grain’s protein content must be within a particular range specified by the malting company. The grain must also have good germination, so damage from preharvest sprouting is not acceptable. As well, the grain should be disease-free and should have little or no fungal toxins like

deoxynivalenol (DON) from Fusarium head blight.

Northern Ontario’s relatively drier and cooler weather mean that this region is probably the best part of the province for growing malting barley, according to Duane Falk. He is a professor emeritus in plant agriculture at the University of Guelph and has been breeding barley for over 30 years.

“Barley originated in a dry climate, so it doesn’t particularly like southern Ontario’s more humid conditions. That is why disease resistance has been the biggest challenge for the breeding programs because fungi and bacteria love humidity. Also, barley is a cool-season plant and the north is a little cooler during the peak of the summer,” Falk explains.

He also notes, “Another advantage over southern Ontario is the north’s higher latitude; it is almost parallel to Western Canada. Almost all the Canadian breeding work on malting quality is being

ABOVE: Lakehead University’s Sahota is conducting nitrogen and sulphur management trials for malting barley as part of the Northern Ontario Farm Innovation Alliance (NOFIA) project.

done in the west, so the western-adapted varieties are currently the best sources of malting quality [although that may change in the future as eastern Canadian breeders put more emphasis on quality]. And plants like barley, wheat or oats are fairly daylength-sensitive, so when you move them north or south, it disrupts their natural adaptation. But if you

move them east or west on the same latitude, it doesn’t bother them. So western varieties tend to do well in northern Ontario.”

Nicole Mackellar, manager of market development with Grain Farmers of Ontario (GFO), identifies another important factor: “There definitely seems to be interest from northern farmers in growing malting barley,

and they have experience in growing some speciality crops. For instance, a lot of the milling oats grown in the province are grown in eastern and northern Ontario.”

“I think there is a good opportunity for malting barley in northern Ontario. For instance, some northern growers have uniquely close proximity to a large end-user, Canada Malting Company in Thunder Bay, so they don’t have to truck their crop far distances,” explains Joanna Follings, cereals specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA).

As well, Falk notes that Canada Malting’s Montreal plant buys some malting barley from eastern Ontario, so high quality malting barley from northeastern Ontario might find a market there.

However, Follings cautions, “Craft malting capacity is limited in Ontario, even though the craft brewing industry in Ontario continues to grow and there is a demand from the craft brewers for barleys from Ontario.”

“Across the province we have only three commercial craft maltsters in operation today. And they are processing very low volumes [of malting barley] and most of them are already at their capacity,” Mackellar says. None of the three craft malt houses are in northern Ontario.

She also points out, “One of the things we have heard from every one of the maltsters that we’ve had discussions with is there is a lot of interest in using Ontario-grown malting barley, but 1) there needs to be enough supply, and 2) that supply needs to be at a consistent quality year in and year out. So identifying varieties that are suited to northern Ontario and fine-tuning some of the agronomics for growing malting barley are quite important.”

In recent years, northern Ontario’s agricultural research stations have been working to develop local agronomic and varietal information to help malting barley growers achieve consistent yields and quality.

The New Liskeard Agricultural Research Station (NLARS), a University of Guelph facility, has conducted various malting barley trials over the years because of the area’s suitability for the crop. “Compared to southern Ontario, our lower humidity means that disease pressure isn’t as high, although you still need fungicide applications,” explains

Nathan Mountain, cropping systems research technician at NLARS. “Another advantage is that currently not a lot of corn is grown in our region compared to the south, which in part reduces the prevalence of Fusarium head blight.” Also, the New Liskeard area lies in northeastern Ontario’s Clay Belt, which has good soil for crop production.

NLARS’s recently completed malting barley trials include a collaboration with SeCan in 2016 to evaluate seven varieties, and a comparison of two varieties, two seeding rates and five nitrogen rates from 2014 to 2016 that was part of an Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada multi-site project.

Mountain says, “We’re close to getting the agronomics nailed down for malting barley, but we still need a little more research to help farmers.”

Tarlok Sahota, director of the Lakehead University Agricultural Research Station (LUARS, formerly the Thunder Bay Agricultural Research Station), explains that the Thunder Bay area has several advantages for malting barley production – Canada Malting as a buyer, the research station to provide information for local growers, and good growing conditions.

Sahota has been conducting malting barley trials at the station since 2014. He focused on variety trials as a starting point because genetics play such a big part in achieving top yields and quality. Canada Malting conducted the malting analysis for these trials.

Along with identifying varieties suited to the area, like CDC Bow, Bentley, AAC Synergy and CDC Copeland, these trials showed that the area can produce good quality malting barley. He says, “For example, kernel plumpness for malting barley should be at least 80 per cent. In our 2014 and 2015 trials, we had averages of 91.5 to 96.2 per cent. We also had zero to very low levels of undesirable traits like preharvest sprouting, weed seeds and disease.”

Sahota identifies some factors that contribute to this high quality. “Thunder Bay is located on Lake Superior, which has a moderating effect on the temperature. Barley likes cooler growing conditions and in particular it prefers cooler temperatures at night.” The Thunder Bay area also tends to be less wet and humid than some of the other cereal-growing areas in the province, and many of the cereal fields in the area are tile drained. As well, the area has productive soils.

The University of Guelph’s Emo Agricultural Research Station (EARS) has done some malting variety testing, with Canada Malting providing the quality analysis. Manager Kim Jo Bliss says, “The trials we conducted a few years ago were mainly because Canada Malting in Thunder Bay was interested. Canada Malting sources a lot of its barley just west of us in Manitoba, so they are driving right by our area, the Rainy River District, and they know that crop production here is increasing.”

Bliss notes, “The biggest challenge that I see with growing barley in general in our district is the lack of drainage because we tend to get a fair bit of rain.”

A major malting barley project is currently underway in northern Ontario, building on the foundations of the earlier trials at the three research stations. NOFIA is managing this three-year project (2018 to 2020), which includes research trials at NLARS, EARS and LUARS, and on-farm trials by the Rural Agri-Innovation Network (RAIN).

“We know northern climates and northern conditions differ from southern Ontario and the rest of the province, but even within the north the conditions differ quite a bit,” Vanthof explains. “And to get the right specs for malting quality, the production practices around

malting barley can be a little more intensive, so it is really important to give the farmers the best management information possible to increase their chances of having really high quality malting barley.”

The project is funded by GFO and the Canadian Agricultural Partnership (the Partnership), a federal-provincial-territorial initiative. The Agricultural Adaptation Council assists in the delivery of the Partnership in Ontario. Canada Malting is also a key partner, conducting all the malt quality analysis for the project.

NOFIA’s Emily Potter, who is managing the project, explains that the research trials involve two studies. One study is assessing the performance of 10 malting varieties; they include heritage varieties and dual-purpose feed and malting varieties. The varieties were selected based on their performance in previous trials at the New Liskeard and Thunder Bay research stations. The other study is comparing the effects of different sulphur and nitrogen fertilizer treatments on malting barley yields and quality.

The three research stations are collecting data from the trials on such factors as days to maturity, plant height, grain yields, straw yields and thousand kernel weight. Canada Malting is measuring characteristics like protein content, preharvest sprout, germination and energy.

RAIN’s on-farm trials are testing malting barley varieties. Mikala Parr, research technician, notes, “We had two sites in Algoma in 2018. Due to seed availability, we were only able to plant one variety of dualpurpose malting barley at each site. But next year, we will have two to three varieties per location.”

Sahota is the project’s technical lead and he designed the two studies in the research trials. The fertilizer study is a 7x3 trial. The nitrogen

The easy way to manage your farm

Analyze your data. Plan your strategy. Then track your performance. AgExpert Field gives you the details you need to know to make the best business decisions.

It’s all new. And seriously easy to use. Get it now and see.

fcc.ca/AgExpertField

treatments are zero, 35, 70 and 105 kilograms of nitrogen per hectare applied as urea alone and the same rates applied as a combination of urea and ESN (3:1 on a nitrogen basis). The sulphur treatments are zero, 8 and 16 kilograms of sulphur per hectare. The treatments are applied to CDC Bow, the top performer in Sahota’s previous trials.

In his past cereal research, Sahota has found that using urea plus ESN (Environmentally Smart Nitrogen, polymer-coated urea) can be effective, and he has experimented with different proportions of the two products to determine the optimal ratio. He says, “Urea provides nitrogen earlier in the season to get the crop off to a good start, and ESN provides nitrogen later in the season during grain fill.” In his experience, the yield boost from ESN tends to more than make up for ESN’s higher cost. Also, ESN is safer than urea for seed-placed nitrogen applications.

Falk is pleased to see that both sulphur and nitrogen are included in these trials. “With nitrogen, you need enough fertilizer to get reasonable yields but not so much that the protein content exceeds the malting company’s specifications. So you need to know your soil type and how your particular situation responds to nitrogen,” he says.

“Sulphur rates are much more of an unknown because up until about five or 10 years ago, we never worried about sulphur. We were getting free sulphur fertilizer from the smoke stacks of all those coalfired power generators. Most of our crops mine the sulphur from the soil, and now we are going to have to figure out how to replace it or work with lower sulphur levels.”

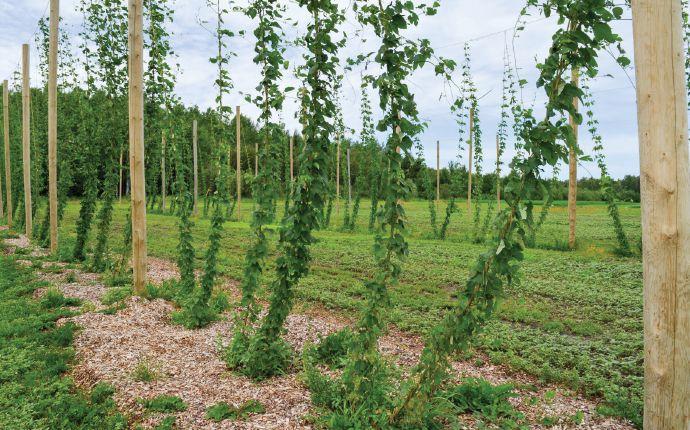

At EARS, Bliss is exploring the possibility of producing hops, another key ingredient in beer. “Hops is a new crop for us so we have taken a lot of advice from people with experience in hops production and then made it work for the equipment and staff that we have. In some ways, we’re learning as we go,” she explains.

“We have set up a small hops yard with two varieties. We planted half of the yard in 2017 and the other half in 2018. In 2018, we harvested the hops from the ones planted 2017. They did really well.” Bliss is planning to send some samples for quality testing to look at the effects of earlier versus later harvesting.

“It is a demonstration to see if it will work and if it is something that people in our district are interested in growing. And people are interested – lots of people came to our station in 2018 to see the hops yard,” she says.

“The whole craft brewery business is so big right now, and craft

breweries tend to want local hops if that is an option. We have Lake of the Woods Brewing Company in Kenora and Sleeping Giant Brewing Company in Thunder Bay. And a brewery is being built just across the river from us in Minnesota, and there is talk that one might be built right in our district.”

“Malting barley is a unique opportunity, but new growers need to really do their research on the management requirements because it takes more management than feed barley. Start out small before diving in,” Follings recommends.

Bliss offers a few tips: “Use well-drained fields or tile-drained fields. A fungicide would definitely be helpful. And use good crop production practices to try to avoid anything that is going to set the crop back.”

Mountain notes, “In a wet fall, taking the crop off early and carefully drying it down can help reduce some of the pre-harvest sprouting.”

Mountain, Follings, Mackellar and Falk all emphasize that it is crucial to have a contract for malting barley before you plant it.

“You need to know exactly what the malting company wants,” Falk says. “That means working closely with Canada Malting or a craft maltster, having a contract in place with the company, and understanding exactly what the requirements of that contract are before planting.”

Mackellar adds, “We’ve seen examples in the U.S. where there has been a surge in interest in growing malting barley and some farmers have tried growing it for the spot market. Unfortunately, they ended up getting burnt because there wasn’t enough market share available.”

A grower’s contract with a malting company will specify such things as the barley variety to grow, the quality specifications such as protein content, and the price for the grain. Typically, malting companies require between about nine and 12.5 per cent for beer making. However, Sahota and Mountain point to recent news reports that China wants between 12.8 and 13 per cent protein. Grain with slightly higher protein might also be suitable for making malt for the distillery market.

“If the barley doesn’t meet the requirements in the contract, then there will either be a penalty or maybe the company will not want it at all,” Falk explains. “So the farmer also needs to have a plan B [such as a feed barley buyer] because the crop doesn’t always work out for malting quality. For instance, if it rains for a week just before harvest, you’re going to have sprouting because malting barleys are bred to sprout rapidly and uniformly, and they will do that in the field almost as well as they do in the malt house. And if it sprouts in the field, nobody is going to want to see it in a malt house or a brewery.”

What would it take for northern Ontario growers to successfully increase production of malting barley?

“In northern Ontario, there is a lot of scope for expanding agricultural production,” Sahota notes. “Farmers are clearing land and tile draining their fields. If northern farmers have research and extension support from the government and other organizations, then production will probably continue to improve.”

“For many farmers in northern Ontario, malting barley is probably a new crop. So it is really important is to make sure good agronomic research and resources are available,” Mackellar says.

Follings adds, “Research like the current project to refine fertility recommendations and test varieties is great because it gives growers

better information on how to successfully grow malting barley.”

Developing malting varieties specifically for northern Ontario would probably not be economically practical because the growing area is relatively small. “However, there may be the possibility of working more closely with the western breeders,” Falk notes. “Perhaps we could get some of them to do some evaluation and selection of earlier generation material at sites around northern Ontario, to identify lines that do really well in northern Ontario but might not be the very top performers in Western Canada. [Then those top northern lines could be included with the top western lines in the next stage of the breeding process, which is the quality analysis.]”

Follings, Falk and Mackellar believe that increasing craft malting capacity would also be vital for success. “Expanding the craft malting industry in northern Ontario will be a critical component to move the malting barley industry forward in the region,” Mackellar says.

Although some malting barley from northern Ontario might find buyers at the craft maltsters in southern and eastern Ontario, she explains that craft malt houses tend to be “hyper-local,” tightly focused on their very immediate area.

She notes, “I know there have been several conversations about other craft malting operations starting up. Perhaps someone who is a craft brewer or has friends in the craft brewing industry and has a keen interest in developing an all-Ontario value chain for the craft beer industry, might take this on.”

GFO is currently investigating possible alternative markets for barley when it doesn’t meet malting specifications. Mackellar says, “Feed is one of the main markets that could provide an alternative; we are also looking into the possibilities available within the food

sector – consumers are interested in food barley particularly because of its health benefits, which could provide additional marketing opportunities.”

Mackellar also points out that another essential factor for success would be adequate pricing all along the malting barley value chain so that all the players feel they are getting a reasonable price for their product.

The price for malting barley influences growers’ decision about whether to try to produce the crop. For example, in the Thunder Bay area, barley for malt and barley for livestock are competing with each other. Sahota notes, “Almost all of our producers are livestock producers, and 98 per cent of those are dairy farmers, so they are growing barley for silage or feed.”

The price also affects crop management decisions. Falk says, “If malting barley is worth more, then growers will invest in more management and inputs, and probably get better crops.”

“Grain Farmers of Ontario sees opportunities for malt barley not only in northern Ontario but across the province. We are involved in a number of discussions and initiatives that are providing support both from a market development and research perspective,” Mackellar notes.

“For instance, we have been engaged in a number of industrywide discussions with growers, researchers, seed companies and malting companies, talking about how we can advance this opportunity. Malting barley will probably never be a tremendously large industry for us in Ontario, but I think there is definitely an opportunity to tap into this niche market which hopefully will bring a premium to our farmers.”

Late summer rains produced perfect conditions for ear moulds in corn. Producers across Ontario were reporting higher-than-normal levels of DON, levels that hadn’t been seen since 2016. In response, the province steps in with storage tips and support for growers.

BY Trudy Kelly Forsythe

Wet conditions during the latter part of the 2018 growing season in Ontario resulted in higher than normal levels of Deoxynivalenol (DON) in corn crops, particularly in the west and southwest of the province.

“We do a pre-harvest survey every year,” says Ben Rosser, corn specialist with the Ontario Ministry of Agriculture, Food and Rural Affairs (OMAFRA). “It’s always present in some parts of the province, but this year it was higher than normal with a larger area affected.” He says they saw a similar situation in 2006.

DON is a type of mycotoxin caused by Gibberella ear rot. While some livestock can consume corn with higher levels of DON, severely infected corn causes limitations for making feed, which in turn affects the saleability of the crop. There is also a health risk if the mould is inhaled, so producers should handle infected grain carefully.

The 2018 grain corn ear mould and vomitoxin (DON) survey, conducted in collaboration with OMAFRA field crop staff, the Grain Farmers of Ontario (GFO) and members of the Ontario Agri-Business Association (OABA), revealed that 60 per cent of the 146 samples collected tested at less than two parts per million (ppm), 15 per cent at two to five ppm and 25 percent above five ppm. Comparatively, OMAFRA’s field crop team reported in its 2018 corn seasonal summary, six to eight per cent of samples tested above five ppm in more recent elevated years.

The final report is available on the Field Crop News website: fieldcropnews.com/2018/10/2018-grain-corn-ear-mould-and-vomitoxin-don-survey.

James Dyck, an engineering specialist for crops systems and environment for OMAFRA, says there is not a lot of difference when it comes to best practices for storing corn affected by DON as when storing a regular crop. However, if a corn crop is infected with DON, it is compromised, which puts it at higher risk of mould spreading in storage.

Agricorp’s corn salvage benefit program, announced in midNovember, provides additional support for cases where DON levels are higher than 5.00 ppm in harvested corn. This benefit can help producers cover costs to harvest and then market, use as feed or find an alternative use for damaged corn. Watch for more info in the March issue of Top Crop Manager East.

“Depending on level of DON they have and how it looked when it went in, there could be residual mould or it could be a little wet, making the conditions for DON to continue to increase,” Dyck says. “The higher the DON levels going into the bin, the higher the risk is of it continuing to mould.”

The solution: dry it, aerate it and monitor it.

• Dry it: Dyck recommends drying corn in a heated air dryer to dry it quickly and neutralize the mould still on the kernels. “Put it in dry,” he says. “If you want to store into July and August, dry it an extra per cent. Fifteen per cent is normally dry enough so that moulds don’t grow.”

• Aerate it: Use aeration to keep grain cold. “Keep it below 5 C to give grains the best chance of keeping moulds away,” Dyck advises. “This is more challenging in the spring.”

• Monitor it: If the corn is questionable going into the bin, Dyck says to keep an eye on it in the bin and move it as soon as possible. “It’s the same as with a regular crop, just at a higher risk,” he says.

Rosser recommends segregating DONinfected corn from other corn if possible and he suggests cleaning the corn before storing it.

“Past research has demonstrated the ability to reduce DON levels in corn by removing fines which tend to have higher DON levels,” he says, explaining research is ongoing. OMAFRA staff have worked with a couple of growers this fall to investigate the ability of decreasing DON levels by using different on-farm grain cleaners. “We clean corn with moderate levels of DON, measure DON levels in the uncleaned corn, in the cleaned corn, as well as in the fines.”

Trial results are pending.

Several organizations have announced initiatives to support producers during this stressful time, including Agricorp, the crown corporation that delivers business risk management programs to Ontario agricultural producers on behalf of the provincial and federal governments; the Ontario Corn Committee (OCC), which is made up of

representatives of Agriculture and AgriFood Canada, OMAFRA, the University of Guelph, the Ontario Soil and Crop Improvement Association, the Canadian Seed Trade Association; and the Grain Farmers of Ontario, which represents Ontario’s 28,000 barley, corn, oat, soybean and wheat farmers.

The OCC has undertaken two initiatives to provide guidance to farmers with respect to DON. The first is the collection of samples from each plot in several OCC trials across southwestern Ontario during the 2018 fall harvest. The samples will be analyzed for DON with the goal to provide insight into:

• factors associated with DON production,

• the range in tolerance among hybrids to mycotoxin accumulation,

• the consistency of hybrid tolerance across environments,

• what growers can do to reduce their risk for next year, and

• research or testing the OCC could undertake to improve the knowledge about hybrid response to Gibberella and/or management practices to reduce the risk of DON accumulation.

The OCC also established a working group tasked with recommending actions and/or research that the OCC can implement this year to assist the industry in reducing the risk of a similar crisis in the future and investigating a system to develop hybrid ratings.

The GFO proposed a number of ideas to government, including financial support, with the goal to help alleviate farmer-member concerns around testing protocols, cash flow, storage of corn and harvest bottlenecks, new markets for high DON corn and support for on-farm testing and technology.

“Farmers are facing an outbreak of DON in corn beyond what we have ever seen,” Markus Haerle, GFO chair, said in a GFO media release dated Nov. 15. “The grain value chain in Ontario counts for 40,000 jobs and this issue could impact everyone. Our farmers face major financial losses that could have devastating impacts on their businesses and the businesses of others across the grain industry.”

The GFO is also supporting a number of creative solutions to do with testing, exploring markets and storage, the latter of which it says it is prepared to support with $240,000 to purchase grain baggers for temporary storage solutions.

I don’t crave special attention. But I got it when I needed it.*

I grow hybrid seed corn and have a tight window to harvest – or I get docked. Time equals money, so I couldn’t afford the downtime when a failed push rod caused severe engine damage. My John Deere dealership understood that. They quickly tracked down a short block and accessories, and two technicians worked through Friday night until 4 a.m. when missing parts halted progress. Still, the team kept going. They tracked down the missing parts on Sunday morning at one of their other stores, finished building the engine, and brought a mobile service crane truck out to my farm to install the engine.

I was back picking corn by Sunday afternoon.

I’m not the largest farmer in our area. But when I needed them, I was the most important person to my John Deere dealer.

Key to increasing corn yields lies in growing bigger corn kernels.

by Trudy Kelly Forsythe

Increasing corn yields isn’t just about planting more plants or growing more kernels per ear of corn. It’s also about making sure each kernel of corn is the biggest it can be.

“In the past, we achieved higher yield by focusing on higher plant densities,” says Dr. Tony Vyn, a professor of agronomy at Purdue University in Indiana. “At today’s plant densities, yield gain is achieved more by increasing kernel weight.”

Modern hybrids, while producing slightly less kernels per plant at the much higher plant densities than was common 30 or 50 years ago, produce bigger kernels as one part of the equation to increasing corn yields. Vyn also recommends focusing on an incremental approach to the integrated management of nutrients and tillage to achieve bigger kernels of corn.

While potential kernel number establishment begins early in the growing process, kernel weight is a function of the early growth of kernels after a successful pollination. The first 10 to 14 days after pollination is when kernel endosperm cells divide rapidly. Specifically, Vyn says, growers want a lot of divided endosperm cells the first two weeks after successful pollination.

To increase this growth-filling period, growers need to grow healthy plants to meet the kernel needs from ongoing photosynthesis and new nitrogen and phosphorus uptake. The alternative is for corn plants to re-mobilize nitrogen from their leaves and other plant parts to meet kernel needs. However, this decreases yield potential.

With proper management, growers can ensure the corn plants meet their nitrogen needs from the soil rather than remobilizing it from the plant. This will make the corn leaf solar panels work longer, extending the grain-filling period and resulting in bigger corn kernels.

“It’s a race against time,” Vyn says. “If you want heavier kernel weight, you need new sugar production from efficient photosynthesis.”

The way to get there, besides planting corn with good, stay-green potential, low disease risk and any warranted fungicide application, is to work with your nutrient management program so the plants have adequate nitrogen and phosphorus. Vyn recommends growers consider a late-season nitrogen application for a portion of their nitrogen input.

“At the V12 stage, provide the last 30 to 40 pounds per acre and keep phosphorus available because, at the end, grains will accumulate over 80 per cent of total plant phosphorus,” he says. “I am not recommending in-season phosphorus application, but high initial levels of both nitrogen and phosphorus in early grain fill are important to meet the objective of high kernel weight.”

Vyn expects the average Ontario farmer is meeting their phosphorus needs through pre-plant and starter applications. “There is

more starter fertilizer used today in Ontario than used across the central Corn Belt because Ontario farmers realize it’s an effective strategy,” he says.

With 50 per cent of total phosphorus going into the corn plant after silk emergence, Vyn says banded phosphorus application is able to meet the needs of early season roots relying on the soil. He recommends growers err on the side of practical nutrient management and make decisions about phosphorus management based on season-long availability, taking into account issues like cold temperature stress early in the season and warm nights later in the season.

“You can’t do anything about air temperatures, but there can be challenges for achieving kernel weight because hot nights are going to respire more sugars away,” Vyn says. “Warm nights cut the linear period of grain fill short and can also limit kernel weight gain per day.”

Generally, effective kernel weight gain only goes as long as 50 days from pollination, although growers would like to have weight gain occur for 60 days. If warm nights occur, growers need to ensure roots are able to access sufficient water to keep leaves cool.

“Water availability is an important part,” he adds. “Soil structure is also important.”

To this end, limit soil compaction by planting on systems that reduce compaction so roots can go deeper. Strip-tillage systems with automatic guidance controlled traffic result in less compaction be -

low the soil where seeds are placed. Vyn recommends strip-till or minimum-till practices combined with nutrient banding to ensure consistent nutrient availability for all plants.

“I am a promoter of systems with more consistency in soil physical structure and soil nutrient availability so every plant in a high-density system has equal access to water and nutrients,” Vyn says. “These practices together will provide more uniform nutrient distribution.”

He also stresses the importance of crop rotation.

“Crop rotation is more important in times of stress conditions during the growing season,” he explains. “Corn yields are five to 10 per cent higher following soybean and require less nitrogen than following a corn rotation.”

Growers are also doing well if they regularly include winter wheat in their rotations.

“You do not grow consistently big corn in a continuous corn practice,” Vyn says. “You can’t get around it by applying more nitrogen and sticking with it for number of years. Adding wheat helps with subsequent yields in corn-soybean rotations.”

Vyn’s recommendations come from corn hybrid era comparison studies as well as comprehensive reviews of almost a century of corn nutrient uptake research he conducted with former graduate students. Research is now focused on alternate nutrient band placements, pre-season and in-season nutrient applications, and endosperm cell counting and kernel nutrient uptake during grainfill period to see how deterministic each are to final yields. Other projects involve fall and spring strip-tillage comparisons to no-till and conventional tillage and plant-to-plant uniformity studies.

know good food comes from right here in Ontario. Ontariofresh.ca has the platform to connect you to buyers, and the Greenbelt Fund has the tools and resources to get your products onto the plates of more Ontarians.

It’s a matter of fit for purpose and this challenge tests trucks through real-world situations.

by Mario Cywinski

The Canadian Truck King Challenge (CTKC) crowned the 2019 GMC Sierra 1500 Denali as its champion. CTKC is unique in that it tests the trucks using real-world situations. There were two days of testing for five Automobile Journalists Association of Canada (AJAC) judges, who scored each 4x4 truck using 20 subjective test categories.

“The field of 2019 half-ton pickups was competitive, with trucks from GM and RAM, while the F-150 received major upgrades, including offering a 3.0L diesel engine, that we ran back-to-back with gas engines from RAM, GM, Toyota and Nissan. Towing is where the diesel feels best, but the raw horse power of GM’s 6.2L V8 is hard to ignore,” said judge Stephen Elmer, from The Fast Lane Truck. “The performance exhaust on the Toyota Tundra TRD Pro barks when you accelerate, while Nissan’s 5.6L V8 has a strong exhaust note with loads of power. In the end, the GMC Sierra came out on top.”

This year, manufacturers that took part were: General Motors with its GMC Sierra 1500 Denali and Chevrolet Silverado 1500 LTZ; Ford with the F-150 Diesel Lariat; FCA with the RAM 1500 Limited; Nissan with the Titan PRO-4X; and Toyota with the Tundra TRD Pro.

The Sierra and Silverado were equipped with a 6.2L V-8 engine with Dynamic Fuel Management and mated to a 10-speed automatic transmission. F-150 was equipped with a 3.0L Power Stroke V-6 diesel engine mated to a 10-speed automatic transmission. Ram 1500 featured a 5.7L HEMI V-8 engine mated to an eight-speed automatic

transmission. Tundra offered a 5.7L V-8 engine mated to a six-speed automatic transmission. The Nissan Titan was equipped with a 5.6L V-8 engine mated to a seven-speed automatic transmission.

“Unlike typical road tests and reviews, CTKC evaluates each entry as a working truck – not simply driving it around empty, but with a hefty payload and significant towing load,” said judge Clare Dear, with Autofile.ca. “The format helped reveal characteristics that might otherwise have gone unnoticed, such as the towing capabilities of Ford’s new 3.0L diesel engine and the RAM’s unique load-levelling air suspension. The findings of the Challenge are a must-see resource.”

Third-party company, FleetCarma, used data recorders on each of the vehicles to measure real-word fuel economy under each part of the challenge (empty, payload and towing). The winner of the Fuel Economy Challenge was the Chevrolet Silverado 1500 with a 6.2L V-8 engine.

The days of one truck being better than others are over. The differences in engine, features and packages between trucks are getting smaller and smaller. Today, it’s a matter of fit for purpose, what are you going to use the truck for, and what is important to you. Judge Éric Descarries, with Auto 123, noted, “This time, the winner has to be the consumer.”

BlackHawk® combines the burning power of Group 14 with the systemic action of Group 4 in broad-spectrum burndown that helps control ragweed, fleabane and other tough winter annuals in soybeans, cereals and corn. Tank mix with glyphosate for faster and greater weed control than glyphosate and Group 2 herbicides alone. This all-in-one jug comes with the only multiple mode of action on the market for convenience and strong performance every time.

ADMIRE® /// ALIETTE ® /// ALION® /// BETAMIX® ß /// BUCTRIL® M /// CALYPSO® /// CONCEPT® /// CONVERGE® FLEXX /// CONVERGE XT /// Country Farm Seeds /// Croplan® /// DECIS® 5EC /// DEKALB® /// ELITE /// ENVIDOR® /// ETHREL® /// FLINT® /// FOLICUR® EW /// General Seed Company ® /// GENUITY® ROUNDUP READY ® 2 YIELD ® SOYBEANS /// GENUITY VT TRIPLE PRO® RIB COMPLETE® CORN /// INFINITY® /// Legend Seeds Canada /// LUNA SENSATION™ /// LUNA TRANQUILITY ® /// /// Maizex Seeds /// MOVENTO® /// Northstar Genetics /// NORTRON® SC /// OBERON® /// OPTION® LIQUID /// PARDNER® /// PICKSEED /// Pride Seeds /// PRIWEN® /// Prograin /// PROLINE® /// PROPULSE ® /// PROSARO® XTR /// PROSeeds /// PUMA® ADVANCE /// REASON® /// ROUNDUP READY ® 2 CORN /// ROUNDUP READY 2 XTEND ® SOYBEANS /// ROUNDUP XTEND® /// SCALA® /// SeCan /// SENCOR® STZ ///SENCOR480///SENCOR 75DF /// SERENADE ® SOIL /// SERENADE OPTI /// SIVANTO™ PRIME /// SMARTSTAX ® RIB COMPLETE® CORN /// STRATEGO® PRO /// TITAN® ///TITANEMESTO® /// TRILEX® EVERGOL® /// TRILEX EVERGOL SHIELD /// VELUM® PRIME /// VIOS® G3 /// VT DOUBLE PRO® RIB COMPLETE® CORN /// XTENDIMAX®