SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012

SEPTEMBER/OCTOBER 2012

Energy with Synergy

New York dairy hands biogas production reins to Florida-based green power producer.

Options abound for sub-surface drainage management

The Michigan Land Improvement Contractors Association and MSU Extension recently held a farm drainage and nutrient management field demonstration in Jonesville, Mich.

The right move

RCM digester offers multiple benefits to the Roach family dairy in New York state.

Maintaining manure flow biggest challenge in cold weather at two Wisconsin dairies.

Sand-laden manure handling and separation in freezing conditions

Are you and your manure system prepared?

Using wastewater as fertilizer

Researchers have developed a chemical-free process that enables the recovered salts to be converted into organic food for crops.

Nutrient management plans: A study in cause and effect

Researchers from the University of Connecticut and the U.S. Department of Agriculture track what happens when four dairy farms implement NMPs during a several year time span.

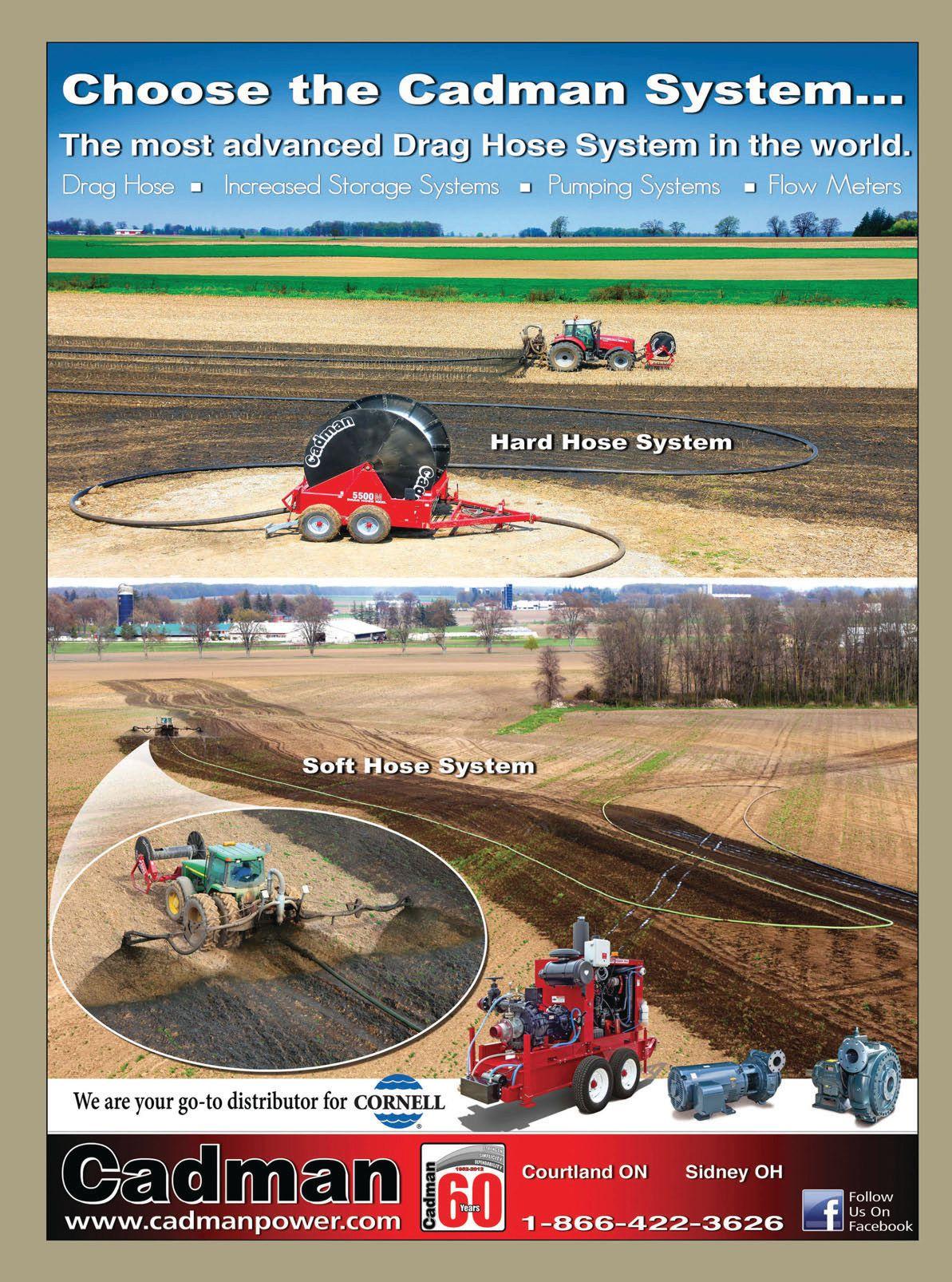

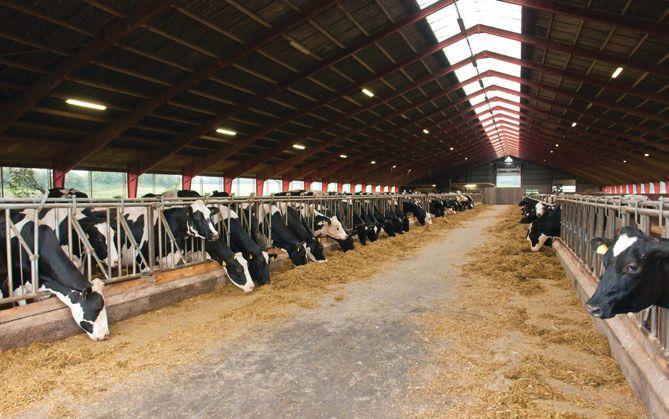

Cover: Synergy Dairy, a 2,400-head dairy operation in New York state, recently brought its new anaerobic digester online. The $7 million digester and biogas-based power-generation system is owned and operated by Florida-based company CH4 Biogas LLC.

Photo by Margaret Land

Published by:

Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. P.O. Box 530 Simcoe, Ontario N3Y 4N5

Editor

mland@annexweb.com

Contributing Editors

Tony Kryzanowski, Diane Mettler, Natalie Rector, Andrew W. Wedel

Advertising Manager

skauk@annexweb.com

Sales Assistant

mburnie@annexweb.com

Media Designer Brooke Shaw

VP Production/Group Publisher Diane Kleer dkleer@annexweb.com

President Mike Fredericks mfredericks@annexweb.com

Publication Mail Agreement #40065710

RETURN UNDELIVERABLE CANADIAN ADDRESSES TO CIRCULATION DEPARTMENT, P.O. BOX 530, SIMCOE, ON N3Y 4N5

e-mail: subscribe@manuremanager.com

Printed in Canada

Circulation

e-mail: subscribe@manuremanager.com

Tel: 866-790-6070 ext. 211

Fax: 877-624-1940

Mail: P.O. Box 530 Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

Subscription Rates

Canadian Subscriptions

$35.24 Cdn, one year (with GST $37.00, with HST/QST $39.82)

$47.00 USD, one year

Occasionally, Manure Manager will mail information on behalf of industry-related groups whose products and services we believe may be of interest to you. If you prefer not to receive this information, please contact our circulation department in any of the four ways listed above.

No part of the editorial content of this publication may be reprinted without the publisher's written permission. ©2012 Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. All rights reserved. Opinions expressed in this magazine are not necessarily those of the editor or the publisher. No liability is assumed for errors or omissions.

All advertising is subject to the publisher's approval. Such approval does not imply any endorsement of the products or services advertisted. Publisher reserves the right to refuse advertising that does not meet the standards of the publication.

By Margaret Land

I’m sure most of you are now in the midst of your busy fall period, emptying lagoons and pits of accumulated manure in preparation for fall planting or providing a boost of nutrients to the soil before the dormancy of winter.

For what it’s worth, I am also busy preparing for my “crunch” time – about five to six months of editorial nightmare involving overlapping deadlines, backto-back trade shows and conferences plus my personal favorite (not): lots of air travel. I’m not a very good flyer, which doesn’t go over well with my pilot husband or fit in with a job that requires traveling throughout the U.S. and Canada – two fairly large countries. After all, you can only drive so far. But I work through my discomfort because after the travel comes something I enjoy immensely – learning.

I’m an information junkie, which makes sense considering I entered the writing profession. I love to gather more and more information and knowledge about anything and everything that interests me – including manure management – and share it with others. So I was excited when information regarding a new conference involving manure and its relation to air, water, soil and climate bounced into my inbox.

The Livestock and Poultry Environmental Learning Center, which comprises manure and nutrient management experts from universities across the U.S., is hosting From Waste to Worth: Spreading science and solutions, a national conference aimed at integrating research, education and Extension efforts related to managing the environmental aspects of livestock and poultry production. The five-day conference will include workshops, tours, posters, a trade show and oral presentations.

“Our livestock and poultry learning center on eXtension.org prides itself on connecting the nation’s best research-based science and top scientists to the people that need the information,” said Dr. Mark Risse, a professor with the University of Georgia and chair of the new conference. “We believe this conference will attract both groups and encourage dialogue between those that generate and use the information.”

“Representatives of commodity groups, environmental agencies, regulatory and policy agencies, government agencies, farmers, producers, technical service providers and consultants should … attend the conference,” added Jill Heemstra with University of Nebraska Extension.

From Waste to Worth will take place April 1 to 5, 2013, at the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Denver, Colo. For more information, visit www.extension.org/63747.

Speaking of shifting from waste to worth, Toto, a Japanese company famous for its toilets (and not the American rock band from the 1970s and ’80s), recently unveiled its newest creation – a motorcycle that runs on manure. The Toilet Bike Neo is based on a three-wheeled, 250 cc trike, and sports a fancy toilet seat (it’s decoration, you can’t actually “use” it). The hog runs on biogas fuel collected from livestock manure and wastewater that has been purified and compressed. And while journalists and writers have been having a field day writing headlines announcing the “green machine,” I’m just going to poo-poo the toilet humor.

See you at the shows.

By Tony Kryzanowski

New York dairy hands biogas production reins to Florida-based green power producer

New York dairy farmer John Noble is excited about the potential of a new, three-stage, anaerobic digestion and biogas power-generation system that has been installed on the 2,400-head Synergy Dairy farm he owns with a group of neighboring farmers. He says it represents a new generation of technology that extracts more methane gas from the farm’s manure and produces more power than its counterparts.

The $7 million anaerobic digester and biogas-based power-generation system, which came online at the

MAIN: A new, three-stage, anaerobic digestion and biogas power-generation system has been constructed and is now online at Synergy Dairy farm, located about 40 miles east of Buffalo, N.Y. Contributed photo

INSET: The $7 million anaerobic digester and biogas-based power-generation system is owned and operated by a Florida-based company called CH4 Biogas LLC. Contributed photo

The AgriInvest program helps you manage small income declines on your farm. Each year, you can make a deposit into an AgriInvest account, and receive a matching contribution from federal, provincial and territorial governments. You can then withdraw the funds when you need them the most.

To benefit from the AgriInvest program for 2011 you must: submit your 2011 AgriInvest form; have or open an AgriInvest account at a participating financial institution of your choice; and make your deposit to your AgriInvest account at your financial institution by the deadline shown on your AgriInvest Deposit Notice.

Application deadline for 2011 is September 30, 2012.

Please note: If you miss the application deadline, you can still submit the form by December 31, 2012. However, your maximum matchable deposit will be reduced by 5% for each month (or part of the month) your application is received after September 30, 2012.

For more information, call 1-866-367-8506 or visit www.agr.gc.ca/agriinvest.

Le Programme Agri-investissement vous aide à gérer la légère baisse de revenu de votre exploitation agricole. Chaque année, vous pouvez déposer un montant dans votre compte Agri-investissement et ainsi recevoir une contribution de contrepartie des gouvernements fédéral, provinciaux et territoriaux. De cette façon, vous pouvez retirer les fonds lorsque vous en avez le plus besoin.

Afin de profiter du Programme Agri-investissement 2011, vous devez :

soumettre votre formulaire Agri-investissement 2011; détenir ou ouvrir un compte Agri-investissement dans l’institution financière participante de votre choix; faire un dépôt en respectant la date d’échéance indiquée sur votre avis de dépôt Agri-investissement.

La date limite de présentation des demandes de 2011 est le 30 septembre 2012.

Remarque : Si vous dépassez la date limite, vous avez quand même jusqu’au 31 décembre 2012 pour soumettre le formulaire. Cependant, la contribution de contrepartie maximale sera réduite de 5% pour chaque mois (ou partie du mois) suivant le 30 septembre 2012, si votre demande est reçue après cette date.

Pour obtenir de plus amples renseignements, composez le 1-866-367-8506 ou consultez le www.agr.gc.ca/agriinvestissement.

TOP: Synergy Dairy cleans out the manure from its three dairy barns three times a day to supply the digester. All the manure is collected in a holding area before being pumped to feed the nearby digester. Photo by Margaret Land BOTTOM: A group of neighboring farmers own the 2,400-head dairy operation that supplies manure to the anaerobic digester. Contributed photo

beginning of 2012, is owned and operated by a Florida-based company called CH4 Biogas LLC.

When asked how much more methane gas and how much more power the company’s technology is able to produce, Lauren Toretta, vicepresident of CH4 Biogas, says, “We assume 10 percent more because it is a complete mix system. This is an improvement on an existing technology.”

In addition to a complete mix system, she adds that CH4 is also achieving production gains because of computer controls the company has built into the system.

The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (NYSERDA) provided $1 million in incentives to help build the facility.

This isn’t Noble’s first experience with this method of manure treatment. He was among the first dairy farmers to install and operate an anaerobic digester to manage his manure on a neighboring dairy farm called Noblehurst Dairy about 10 years ago. The engine, generator and some PVC pipes from that installation were recently destroyed by fire, but that hasn’t dampened Noble’s enthusiasm for responsibly treating manure generated by dairy farms using anaerobic digestion to capture biogas from manure and then using it to generate power.

Noble says the anaerobic digestion installation at the Noblehurst Dairy did serve a useful purpose as a way to treat raw manure and as a source of power. When operational, it generated power about 85 percent of the time and the dairy was able to offset its power costs based on the amount it produced. The power generated from burning the biogas resulted in about 135 kilowatts per hour. Annually, the digester produced about 850,000 kilowatts.

The anaerobic digester tank is still functional and is being used by Noblehurst Dairy to separate its solids

LEFT: The digester produces a treated solid byproduct that Synergy Dairy uses for bedding in its barns. The facility will produce about 17,500 cubic yards of bedding material annually. Photo by Margaret Land RIGHT: The dairy was separating the manure previously and then composting the solids for two weeks before reusing it for bedding. Now, it can dispense with that composting step and use the dry bedding material from the digester immediately. Photo by Margaret Land

and liquids from 40,000 gallons of manure per day, but the biogas is not being captured. Noble is negotiating with potential system suppliers to replace the biogas collection and power-generation system to get that installation back up and producing power. Both Noblehurst Dairy and Synergy Dairy are located about 40 miles east of Buffalo.

Noble says the new, privately owned, CH4 anaerobic digester and power-generation system installed at Synergy Dairy is in a whole different category compared to his old digester. First, it is 10 times larger, capable of producing 1.4 megawatts of electricity per hour and processing 1.9 million gallons of manure and organic food waste a year.

“It’s really built to handle additional food waste and it almost requires the additional food waste to generate the gas needed,” says Noble. By collecting this food waste and treating it, CH4 Biogas also derives an extra income from tipping fees.

Second, CH4 Biogas, operating as Synergy Biogas LLC, is the owner and operator of the anaerobic digester and biogas power-generation system. Synergy Dairy simply leases some land to the biogas power producer and supplies the company with its manure.

Given his experience operating his old digester, Noble prefers it that way. He says that the dairy’s expertise is producing milk while CH4 Biogas is an expert in the generation of biogas from manure and production of power.

“We saw it as a win-win situation,” says Noble. “Probably the first lesson we learned from operating the Noblehurst Dairy digester was how difficult it is to operate and get hooked onto the grid as a small power-generation player.”

He adds that managing the Noblehurst Dairy digester was also a commitment that was not without its challenges to keep running.

“Our folks had some interest in engineering and it was an interesting project to pursue,” says Noble, “but the maintenance requirements were fairly high. However, we walked into this knowing full well that it would be a 10- to 15-year payback, and it was a net cost savings for us of about $50,000 to $60,000 per year in bedding for the animals and about the same amount in power costs.”

Noble describes a digester as a finicky stomach. Controlling the feedstock going into the digester and maintaining consistent temperatures are critical for achieving optimum biogas generation. Keeping biological activity balanced in the tank throughout

the year when temperatures could fluctuate from -10 F to 100 F was also a challenge.

Partnering with CH4 Biogas on the new digester project as simply the manure supplier has relieved the dairy owners of that management responsibility. Noble adds that there is an opportunity to profit-share if the installation is “wildly successful”.

The Synergy Biogas LLC facility is New York state’s first biogas project that will process both animal and food wastes.

Synergy Dairy cleans out the manure from its three dairy barns three times a day to supply the digester. It converted its manure transportation system from a flush to a scrapper system because the new digester required a drier manure product. It flows into a small storage tank that feeds the digester as needed.

Toretta says that tanker trucks collect liquid food waste such as whey from nearby dairy plants and oils and fats from bakeries and food manufacturers as much as 60 miles from the Synergy Biogas facility to complement the manure provided by Synergy Dairy.

The combined slush is transferred to a large receiving tank and macerated using two submersible mixers to gain

LEFT: The Synergy Dairy digester facility is capable of producing 1.4 megawatts of electricity per hour. The dairy is also able to purchase power from Synergy Biogas LLC at a discounted rate. Photo by Margaret Land

RIGHT: The Synergy Biogas LLC facility is New York state’s first biogas project that will process both animal and food wastes. By processing food waste, the facility is diverting about 1.14 million gallons of food waste from landfills and wastewater treatment facilities. Photo by Margaret Land

even consistency. The mixture is then pasteurized.

“The pasteurization step is unique,” Toretta says. “It kills the pathogens that come in through the waste. We then allow the right bacteria to do their job and maximize gas output.”

Pumps transfer the mixture into a 2.2 million gallon anaerobic digestion tank where the digestion process occurs over a three-week period. The captured biogas flows through a scrubber that removes hydrogen and other impurities. The biogas is then warmed in a heater and then flows to a compressor.

According to Noble, the digested mixture actually proceeds through a third tank where it sits for a week to 10 days to capture even more biogas before it is separated into liquid and solid by-product streams. The gas, which is collected only in the second and third tanks, is burned in a GE Jenbacher J420 biogas engine. It is designed to run around the clock with as much as 95 percent uptime.

Toretta says because the facility is producing power almost all the time, the company is looked on favorably by other dairy farms and utilities.

Synergy Dairy benefits from this arrangement in several ways. The digester produces a treated solid byproduct that Synergy Dairy uses for

bedding in its barns. By not having to purchase bedding material, this saves the dairy between $150,000 and $200,000 per year. The facility will produce about 17,500 cubic yards of bedding material annually. The dairy was separating the manure previously and then composting the solids for two weeks before re-using it for bedding. Now, it can dispense with that composting step and use the dry bedding material from the digester immediately.

The dairy is also able to purchase power from Synergy Biogas LLC at a discounted rate once it ramps up to full production. The plan is to install a second biogas-powered generator that will be used to supply the dairy. Noble believes that it will provide 100 percent of the dairy’s power needs, and will cut its power costs by about half.

The odor emanating from the nutrient-rich liquid by-product exiting the digester and stored in the dairy’s lagoon is also significantly diminished, making for better relations with neighbors. The dairy can store about 10 million gallons in two lagoons on the farm site. The liquid byproduct represents a source of organic fertilizer when it is land applied either using drag-hose systems or tanker trucks on neighboring farms. Some of the crop

farmers benefiting from this fertilizer source are also investors in the dairy.

“We pay to have them land apply the manure and then they give us a credit back for the value of the nutrients,” says Noble. One of the challenges the dairy has to deal with is more liquid by-product because of the additional food waste used in the process. It may require the construction of more storage lagoon capacity.

The environmental benefits are not only producing a safer form of organic fertilizer and reducing the dairy farm’s base load greenhouse gas emissions by about 8,500 tons of carbon dioxide annually, but also by processing food waste, Synergy Biogas LLC is diverting about 1.14 million gallons of food waste from landfills and wastewater treatment facilities.

As the digester ramps up to full biogas production, Synergy Biogas LLC is processing about 60,000 gallons per day consisting of about two-thirds dairy manure and one-third organic food waste. The goal is to process about 100,000 gallons per day.

Toretta says CH4 is just beginning the roll out its system and has its sights set on other opportunities in New York.

“New York has a lot of opportunity because of the importance of and focus on agriculture,” she concludes.

By Natalie Rector

In August, the Michigan Land Improvement Contractors Association and MSU Extension held a farm drainage and nutrient management field demonstration in Jonesville, Mich., near the Ohio and Indiana borders. Bruce and Jennifer Lewis hosted the event at their Pleasant View Dairy. Nearly 1,000 farmers and contactors came from all over the tri-state area and beyond.

In-field demonstrations included a sub-surface irrigation system, a wood chip bioreactor, water control structures and land shaping. Educational sessions and demonstrations showcased new tillage equipment, cover crops and nutrient management.

The goal of the field day was to create awareness of options in both new technologies related to drainage systems and management practices that can be employed to reduce losses of nutrients to surface waters, improve yields and reduce the risks of uncertain weather events. Soil types, slopes and producer goals will determine which option will work best on any individual farm.

Four new drainage machines were on site installing a contour drainage and sub-irrigation system, while Dr. Richard Cooke from the University of Illinois guided the installation of a bioreactor. Dr. Larry Brown of Ohio State University and Phil Algreen from Agri Drain demonstrated and explained how water control structures could be used for controlled drainage, and Nate Cook from AGPS demonstrated land shaping with GPS outfitted bulldozers. Larry Geohring from Cornell University came from New York to speak about proactive management practices to keep manure out of sub-surface drainage systems.

Bark bed bioreactors remove nitrogen in drainage water before it is released to surface waters. Bioreactors can be applied to existing systems and can be installed without

losing land from production. Water control devices control the water level in the soil and ultimately create less outflow of water during the non-growing season and therefore, less loss of nutrients. True sub-irrigation manages the water table over the growing season, and additional water can be added through the sub surface tile system during dry periods and thus increase yields. A subsurface drainage system helps manage risk in this era of variable weather patterns.

Along with ensuring successful yields and timely field operations, the management practices displayed during the field tour also included the latest in tillage methods and tools such as vertical tillage, cover crops and their use in combination with manure applications. Tile drains are designed to drain water, and when manure is liquid enough, it acts like water. Shallow tillage operations prior to liquid manure applications can disrupt the macro-pores and cause manure to be adsorbed and held in the soil rather than reaching subsurface drains while conserving surface crop residue. Tillage is one option that is readily available on most farms. Cover crops assist in absorbing, retaining and recycling manure and fertilizer nutrients. Bioreactors and water control devices provide added protection of surface waters if crop nutrients do reach tile drains.

Field day participants were able to see, listen and discuss the options available, and interact with resource people to determine what practices might be most applicable for their farming operation.

ABOVE: Tillage is one practical way that farmers can break macro pores in the soil and reduce the risk of liquid manures reaching sub-surface drains. Various forms of tillage equipment were displayed. Photo by Natalie Rector

In the beginning, the Roach family pulled spreaders with tractors to help distribute their dairy cattle manure to the operation’s 1,200 acres.

By Diane Mettler

Tom Roach had been working at dairies for years when in 1981 a small farm he’d worked for in New York State became available. He and his wife Diane purchased it and have been running it as a dairy every since.

Like other farms, over the course of years, the farm gradually expanded its operation. Tom began milking between 250 to 300 cows. Then it was 400, then 500.

“We never bought any more cows, we just kept them,” he says.

With expansion came the need for more buildings.

“We would get way overcrowded, build another barn, then get way overcrowded and build another barn,” says Tom.

Today the farm houses five milking barns and 1,550 cows – 1,300 of which they are milking. As the family grew to be a large CAFO, they faced lots of the manure management issues that come with a large farm. The Roaches recently installed an RCM (round heated mixed digester), but prior to that they had tried just about everything.

No stone left unturned

“First we pulled spreaders with our tractors, then we started custom-hiring people to truck for us,” says Tom.

After that, and for the next few years, the Roaches used an irrigation system.

“We used the big guns that spray the manure up in the air, but that didn’t work very well,” says Tom. “The problem was, it was too easy to get runoff and odor. It was also labor intensive. It cut down on the compaction, but it wasn’t a lot faster than spreading.”

Roach spreads on approximately 1,200

acres, which includes their neighbor’s acreage, so it was important to find a good solution.

After the irrigation system, Tom hired someone in the area with a dragline system, which seemed to do the trick. “We had enough flow and we had the underground pipe from the irrigation, so it worked fairly well for us.”

Today, the Roach farm has its own dragline system with about two miles of hose. “We have someone else do our trucking though,” says Tom. “They truck the manure to the fields we can’t reach with the dragline.”

Judging by the results of the CAFOrequired tests, this system is working out

The Roach dairy farm also tried distributing manure to crop land using hose and irrigation guns, similar to this system. “The problem was, it was too easy to get runoff and odor,” says Tom. “It was also labor intensive. It cut down on the compaction, but it wasn’t a lot faster than spreading.”

Eventually the Roaches decided to construct an anaerobic digester to process the manure from the dairy’s 1,550 cows. Contributed photo

A benefit of the Roach's digester is energy production. The farm can produce all its own power and sell some back to a utility. Currently, the digester is producing about 350 KW and in the winter about 150 KW. Being able to save on electricity bills means that the digester will probably pay for itself in three to five years. Photo courtesy of RCM International

summer, and it gets soaked up pretty fast in the fields with little odor. You can’t say that you don’t smell it at all, but it’s not terribly offensive; it won’t make your eyes water.”

Another benefit of the digester was the energy production. The farm could produce all its own power and sell some back to the utility.

“Right now we’re producing about 350 KW. In the winter we only use about 150 KW, but that increases in the summer with the fans blowing,” says Tom.

Being able to save on electricity bills means that the digester will probably pay for itself in three to five years. But Roach is quick to point out that quickly paying off the digester takes into consideration the farm’s ability to secure New York State Energy Research and Development Authority and U.S. Department of Agriculture grants.

Of the two, the most valuable was the NYSERDA Renewable Portfolio Standard (RPS) program, which provided a performance-based incentive of 10 cents per kWh produced by the engine over three years. At that rate, it adds up quickly.

“I’m not sure if you just purchased the digester outright without the grant money how long it would take to pay for itself – or if it could,” says Tom.

Choosing the digester

When it came time to choose a digester, Tom chose the RCM International complete digester because he had seen a couple in operation. Within 10 miles of his farm there were four in operation, which, he says, speaks to the incentives.

“We checked them out and then made our decision.”

The system is pretty simple.

“Manure from the barns works its way from a continuous pit in one barn to a reception pit. From there the manure is pumped to the digester with a dual piston pump,” explains Tom.

About 52,300 gallons a day flow into the mesophilic digester, designed by RCM International, which has a retention time of approximately 28 days. The digester can handle a total volume of about 1,501900 gallons a year.

There were numerous reasons for installing a digester. One was to be green and a good environmental steward, but another was

Manager well. But there is always room to improve. For that reason, Tom and Diane purchased a digester to incorporate into the system.

to control odor so the farm could spread in the summer without complaint from neighbors about the smell.

“We can get rid of a lot of our manure in the summer when the crops are growing, but the odor is a problem if we don’t digest,” says Tom. “Because we separate and digest, the manure is fairly liquid in the

The digester is a circular aboveground concrete tank 120 feet in diameter and 18 feet in height with the liquid level of 16 feet. The digester tank has an in-tank heating system and four-inch extruded foam insulation surrounding the tank. Five mixers are inserted through the top of the digester tank.

From the digester manure overflows into a tank.

“In that tank there’s a pump that pumps the manure to two DODA

The PUMPELLER Hybrid Turbine revolutionizes manure pump performance. Incredible intake suction pulls solids into the cutter knives, reducing the toughest crust to nothing in just seconds. The turbine combines the high-volume mixing of a propeller agitator with the power and reach of a lagoon pump, the resulting hybrid design radically outperforms both.

separators,” explains Tom. “We use most of the solids from the separators for bedding, and we spread some. And the liquids go into the first lagoon of a two-stage lagoon.”

The first stage holds approximately one million gallons and the second, larger lagoon holds around five million gallons.

“We originally started with one small lagoon and then we needed more storage, so instead of tying the two together, we made it a two-stage lagoon system.”

The argumentfor the two-stage lagoon system, he says, is that phosphorus stays in the first lagoon. “We often truck the manure out of the smaller lagoon further away and then, from the larger lagoon, manure is draglined closer to home, so we’re getting the phosphorus further away from the farm. That’s the plan anyway,” he says.

The installation process took about a year and a half and was completed Aug. 9, 2010.

“That was the difficult part,” says Tom. “When you’re paying for things, and buying equipment, and not seeing any benefit coming back for over a year, it’s difficult.”

One of the reasons it took so long was that they had to co-ordinate not only the equipment coming but the crews. At times there were up to 25 men on the job site. Tom couldn’t take time off from the farm to manage the project and hired a construction manager, Thad Young. Thad had worked on a farm with a digester, was familiar with the installation process and helped move things along so Tom could focus on the cows.

Young took care of any permitting, construction and other issues that arose. One issue that Tom hadn’t anticipated was the three-hour time difference between RCM headquartered out of California and Roach’s farm in New York. It left limited hours to communicate.

On the bright side, Tom was able to take advantage of local talent. Because there had been digesters installed in the area, there was an electrician already familiar with the programming and electrical work.

“I certainly couldn’t have done it myself. I’m not a mechanic or an engineer or any of that stuff. I’m a dairy man,” he says.

Now that everything is in place, Roach’s electricity production is handled via net metering – a system owner receives retail credit for at least a portion of the electricity they generate. Until this year though, farms could only get credit on one meter. In Tom’s case it was favorable because the farm’s

main meter was at the diary.

“Now the law says they have to give farmers credit on every meter that’s in our name within so many miles,” says Tom. “In my case, it takes care of all of them. We have 12 meters and so we can offset on all the meters, not just the one.”

Another adjustment the farm is going through due to the digester is new bedding. Prior to the installation the farm was using shredded paper. Today it is using manure solids It’s been a challenge to make the switch, but, Tom says, they are figuring out how to make it work.

The last advantage of the digester, however, helps offset the challenges. They can use the heat from the digester to heat all the water needed for washing and, Tom says, “that’s a big thing.”

“We probably use 500 gallons of water a day. Before we were using at least 100 gallons of fuel oil a week for heating water. We’re not doing that any more and it’s saving us money.”

In the end, he says, the digester was definitely the right decision.

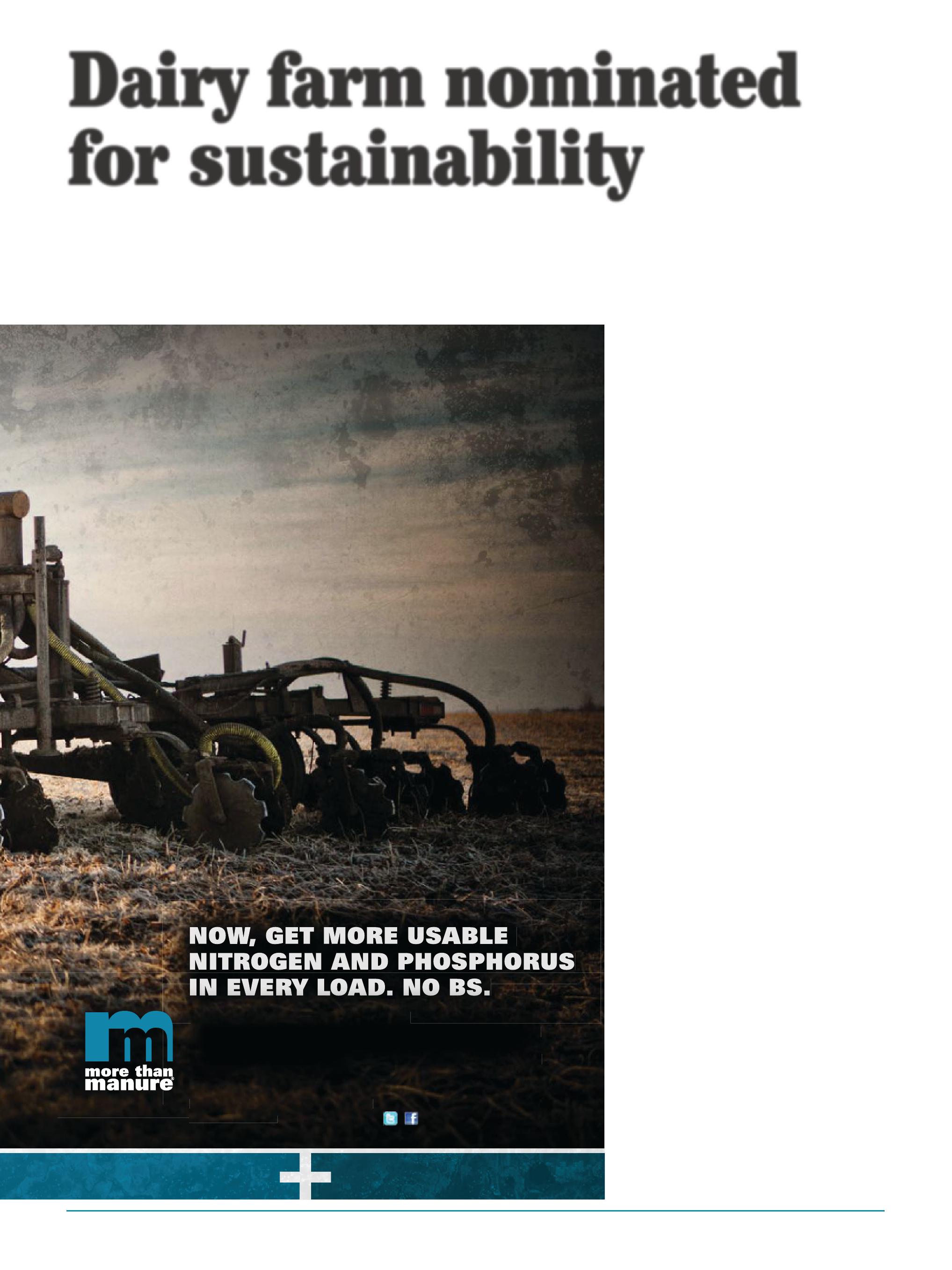

Adairy farm in the Edmonton, Alta., area is doing its part to help improve the operation’s environmental footprint and was recently nominated for

national recognition for doing so.

Lakeside Dairy, a 170-cow farm near Legal, Alta., is taking clean drywall that would normally go to landfill and putting it to use on their farm through

bedding and composting.

According to Alberta Environment, about one pound of drywall waste is produced for every square foot of new house built in Alberta. From a 2,000-square-foot house, that means that about a ton of drywall waste will be shipped to landfill. The 30,000 houses forecasted to be built in Alberta in 2012 alone translate to the weight of a cruise ship. The effects of drywall in landfills include the production of hydrogen sulfide gas.

Lakeside Dairy has been able to demonstrate the benefits of mixing the clean, ground drywall with wood shavings to use as cow bedding. The bedding is composted with manure and chicken litter from a neighboring farm, additional drywall, and then used as a fertilizer for the fields. All the drywall is brought in from local housing construction sites.

The sulfate in the drywall decreases the pH of the manure, reducing ammonia and greenhouse gases by up to 90 percent or as much as 3,000 tons of CO2-equivalent annually. When the mixture is spread on the land, it adds sulfate and calcium, and retains nitrogen.

Ultimately, Lakeside’s use of recycled gypsum helps to divert more than 1,200 tons of drywall scrap from landfill annually, providing a local urban company with a business opportunity in drywall recycling.

About 80 percent of the farm’s fertilizer needs are met through their compost.

“Sustainability is successful on our farm because it is profitable. The practices with the largest impact do not require large capital investment and generate financial and labor savings that are immediate and provide opportunities in the future,” says Jeff Nonay, president of Lakeside Dairy.

Lakeside was one of four finalists from across Canada for the national Dairy Farm Sustainability Award. This award evaluates environmental sustainability, financial viability, social benefits, and the reproducibility of practices on other farms.

By Tony Kryzanowski

Wet manure, sand bedding and freezing cold temperatures – these are three ingredients that don’t mix well. Without careful management, this combination quickly results in frozen manure in the barn or between the barn and the lagoon. Dairy farms located in colder climates have had to develop various methods to keep the manure melted and flowing.

States like Wisconsin must contend with cold temperatures for at least four months a year. In the coldest months of December, January and February, it can get as cold as -25 Fahrenheit on occasion, but typically hovers in the -10 to +15 Fahrenheit range. A normal year also yields about 24 to 36 inches of snow.

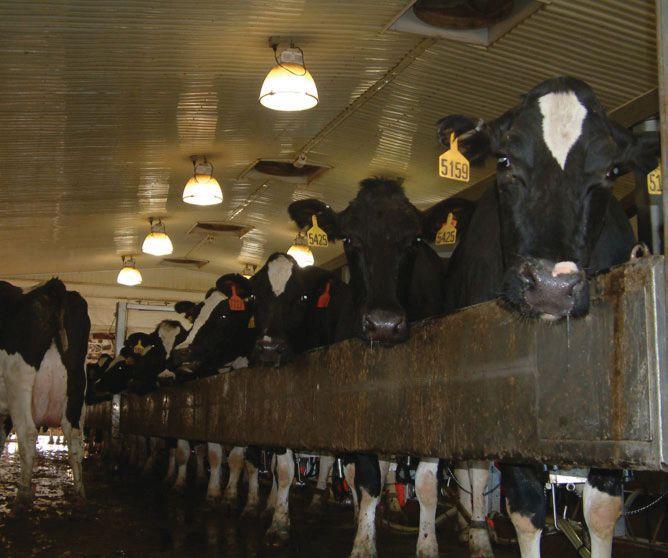

Blue Star Dairy’s Arlington operation is located in the Madison, Wis., area. It is one of three dairy farms owned by Walter, Louie, Arthur, Craig and Brian Meinholz. The Arlington dairy consists of two head-tohead, four-row barns and 1,200 cows, which produce about 18 million gallons of manure annually. The dairy uses sand bedding for its cows in this operation.

At present, the dairy’s barn manure is handled entirely by gravity flow. The waste

generated from the parlor and milking area, which includes the clean parlor and holding area flush water, collects in one lagoon. Water is neither added to the manure gathered nor collected from the free stall area. It collects in a separate lagoon.

Walter says the dairy farm has taken several steps to ensure that manure from the free stall area in particular maintains a “milkshake-like consistency” – no matter what the temperature is outside – to ensure consistent flow into the lagoon and to prevent the sand from settling out. First, they have installed barn insulation, which helps to maintain some heat during the coldest weather. Normally, the temperature in the barn stays above 26 Fahrenheit for part of the day. Manure freezes below that temperature. Second, the dairy uses a very fine sand for bedding, which helps to keep it in suspension both in the underground channel, which transports the manure to the lagoon, and in the lagoon itself.

Manure in the Arlington dairy is scraped using a tractor with a rear rubber blade. Below the barn floor, the dairy has a nine-foot-wide, seven-and-a-half foot deep, and 420-foot-long channel covered in concrete that slopes about one foot every 100 feet so the manure will gravity flow into the lagoon. Manure is deposited into the channel three times a day.

The goal at the dairy in terms of managing the manure in cold weather is to avoid letting it freeze in the channel. To accomplish this, the Meinholzes cover the channel opening with a piece of plywood

with rubber on the edge like a trap door. A chain is attached to the plywood cover to lift it and put it back in place as needed. A gate keeps cows away from the opening.

“Since the channel is greater than seven feet deep, we seem to have some built-in warmth,” says Walter.

The dairy has embarked on a new sand separation project, which will allow it to recycle about 95 percent of its sand. Recycling that sand will also result in less wear and tear on their pumps when the manure from the lagoon is land applied and less sand settling in manure haul tankers.

“We are setting it up as a closed-loop, flush/flume system so we are going to have mechanical sand separation,” says Walter. “Up (until) now, we have always used new sand. We’re set up with our gravity flow system and it was very practical on a smaller herd. As you grow bigger, most farmers go to sand separation. We had no moving parts until now when we’ll have all kinds of moving parts.”

The new system will require water flow to flush the manure from the free stalls through a 24-inch manure pipe to carry it to the sand separation system. The system will be enclosed in a 72-by-158-foot building.

A seven-foot-deep, 420-foot-long channel delivers the barn manure by gravity at from the barns to the lagoon at the Blue Star Dairy barn in Arlington, Wis. The opening of the channel is visible as it reaches the lagoon. Contributed photo

The wastewater from the milking parlor is also being collected in the sand separation building and will be used as part of the separation system. The building will house both the sand separation equipment and storage to allow the sand to dry.

Komro Sales, located in Durand, Wis., is providing the sand separation system. It consists of McClanahan augers, DariTech Inc. rotary drums to separate the manure solids from the sand, and Houle pumps. The system is equipped with a series of rotary drum screens so that a portion of the water used in the system is clean enough to reuse. The sand is separated out. Ultimately, the Blue Star Dairy system reunites the water and the solid manure streams in the storage lagoon.

“My understanding is that it takes very little heat to keep it above freezing,” says Walter. “You are only keeping the building at, like, 35 to 40 degrees. The experience of people that have them is that it’s not a big fuel draw. The big expense is the fact of having an insulated building.”

He adds that the pipeline transporting the manure from the barns to the sand separation building will also have to be

Kifco offers a full line of traveling irrigation systems, pto pumps, slurry pumps & primary pump packages

With outstanding service & support through the largest network of authorized dealers, there’s only one name you can trust

Iowa Select Farms seeks an Environmental Compliance Officer to work out of our Iowa Falls location. This position would be responsible for coordinating the activities of the Nutrient Management - Environmental Department to ensure that records are accurately kept, management plans are filed accordingly, and custom applicators are supplied with the necessary information to apply nutrients. Ultimately, the Environmental Compliance Officer must ensure that Iowa Select Farms is compliant with all state regulations regarding use, storage, transportation and application of manure.

Iowa Select Farms offers a competitive salary and benefits package, including health, life, disability insurance, 401(k), paid vacation and holidays.

Check us out at www.iowaselect.com or call 1-888-826-7447 ext. 263 EOE

deep enough to ensure that the contents won’t freeze.

So Fine Bovines is a dairy about an hour north of Madison, Wis. It manages a herd of 670 head and consists of three barns, each equipped with sand bedding and scraper systems to transport the solid manure that collects in grated gutters to reception pits, each with varying degrees of holding capacity. Wash water is pumped directly to the lagoon, which results in a manure slurry. The dairy has been using sand bedding since 1994.

The dairy operation has a four-row barn housing 220 cows, a six-row barn housing 140 cows, plus an additional 80 special-needs cows and a three-row barn housing another 150 late-lactation cows. The six-row barn is divided between twoyear-old cows and special-needs cows. The manure generated in the special needs area is scraped to one end of the barn where a barn cleaner takes over to transport the manure across the building into a reception pit capable of six months’ worth of storage. The pit has that much storage capacity because there are fewer specialneeds cows. All told, the herd generates

annually.

barn manure ends up in a six-million-

where

about 750 feet.

about seven million gallons of manure annually. All the barn manure ends up in a six-million-gallon lagoon capable of about eight months’ worth of manure storage. A portion of the manure is land applied in fall over corn silage cropland, worked in, and replanted with wheat as a cover crop. A portion is also land applied in spring before planting season.

The manure from the three-row barn has a reception pit with enough capacity for one day’s worth of manure, and it is conveyed into a spreader that transports the manure to the lagoon. The manure slurry from the six-row and four-row barns is transported to the lagoon using a 12inch underground piping system. Manure transported from both barns connects at a

central collection point in the pipeline where a Houle piston pump automatically propels it to the lagoon. The distance from the barns to the lagoon is about 750 feet.

“Because the lines are six to seven feet below ground, the material in the pipes doesn’t freeze,” says So Fine Bovines co-owner Jeff Buchholz. He owns the dairy with Jim Kruger. Moving the sand through the pipe at any time of the year presents its own challenges. Therefore, So Fine Bovines has come up with an innovative approach to keep the pipeline clear.

“Once a day, we blow air through it to clean it out,” says Buchholz. “Sand has a tendency to want to settle out in pipes, so you need to be able to blow them out.”

So Fine Bovines fills a 1,000-gallon

liquid propane tank with air using an air compressor and, through the use of a connector hose, the air in the tank is used to blow out the pipes.

“There are actually four risers in the pipeline where you can inject air to blow it through,” says Buchholz. “At 750 feet, that’s probably close to the maximum distance for conveying the manure and if we weren’t blowing air through the pipeline daily, it would probably plug up with sand.”

If the manure does freeze, the dairy’s contingency plan is to load the manure into a spreader with a Bobcat until the temperature is once again warm enough so that it will flow through the barn floor grate and into the channel leading into the reception pits.

By Andrew W. Wedel, P.E.

Ask someone from South Dakota at what temperature handling sand-laden manure (SLM) becomes problematic and you’ll get one answer –probably something in the neighborhood of prolonged periods below 0 F. Ask someone from North Carolina the same question and you’ll surely get a different answer – probably, nights with temperatures below freezing. To be sure, every producer has a varying level of tolerance and preparedness for freezing conditions. No matter where you are located, the laws of nature stipulate water freezes (converts from a liquid to a solid) at 32 F or 0 C. Manure, as excreted, is roughly 85 percent water. With freezing temperatures just a few weeks away in some places, take a few moments to evaluate whether or not you and your manure system are prepared.

Expectations and preparations

First, it’s important to recognize the freestall barn environment is part of a SLM handling and separation system. To maintain an optimal barn environment, it is necessary to maintain some air exchange when cold weather hits. In order to preserve barn air quality, avoid completely closing all air inlets such as curtains and doors, even as temperatures drop. This is less of an issue with the advent of controlled-environment freestall barns. In any case, remember, it’s about the cows and their environment even if the ideal environment is achieved at the expense of allowing manure to freeze.

Start with freeze-prevention basics. Are above- and below-ground

pipes adequately insulated and buried, respectively, and buildings with separation systems equipped with heating systems in good working order? Find the ground-frost depth for your location at http://nsidc.org/cryosphere/ frozenground/images/NA_permafrost. jpg. It’s important to set some reasonable expectations before prolonged freezing conditions occur. In the most extreme circumstances, manure will freeze on freestall alleys and be immovable by rubber tire scrapers or vacuum tanks. On these days, options are limited to handling manure as a solid, which means scraping with a steel blade such as a loader bucket. Under these conditions, manure will appear freeze-dried and indeed behave as a solid.

Avoid scraping frozen manure into reception tanks, since once in a reception tank, frozen SLM will remain frozen due to the insulating capability of the earth. Furthermore, when manure freezes solid, sand grains are locked in the solid structure and cannot be readily dispersed, which is why attempting to separate sand from frozen manure

can be futile. Instead of attempting to separate sand from frozen manure, some producers will scrape the manure out of the barn onto a concrete pad where the daytime radiation will liquefy (melt) manure at such time, making it suitable for separation. Of course there are circumstances where there is no end in sight for sub-zero F weather, so provisions should be in place to convey SLM directly to long-term manure storage for future land application.

Viscosity is the key

Don’t wait for manure to freeze solid to begin addressing the effects of temperature change on conveyance and separation systems since manure viscosity increases as temperature drops. Loosely speaking, viscosity is a measure of a fluid’s resistance to flow – the more resistant to flow, like tomato ketchup, the higher the viscosity. As temperature decreases from 80 F to 32 F, water viscosity doubles. This means two things in the world of conveyance and separation. The first is colder water (higher viscosity) requires more

power to pump than warm water. This phenomenon will go unnoticed provided pumps are sized to account for higherviscosity material. Far more noticeable is the effect of viscosity on conveyance and separation systems. When manure is more viscous, it has a reduced capability to entrain and convey solids. To compensate, water flow volume must be increased or fresh water added. Separation systems also rely on water to dilute manure. Dilution reduces the viscosity of as-excreted manure thereby allowing sand to settle. Accordingly, the viscosity of the dilutant (manure storage or other process water) must be sufficiently low to reduce manure viscosity. Cold water makes for a poor dilutant when compared to warm water. Cold or frozen manure can be added to separation systems, but sand recovery is reduced since sand grains are not easily dispersed from the manure mass and thereby unable to settle. Most producers agree the limiting manure consistency for properly performing sand separation is “slushy” – that is, semisolid.

The negative effects of cold weather on conveyance and sand-manure separation can be minimized using closed-loop water-recovery systems that are housed in a structure maintained at just above freezing. Closed-loop systems do not warm water, per se, but do maintain a more consistent dilution water viscosity, and therefore, consistent handling and separating system performance. Some systems acquire dilution water from manure storage, which is subject to changes in viscosity simply due to weather. In a closed-loop system, the dilution water comes from manure liquids as extracted by liquid-solid separators.

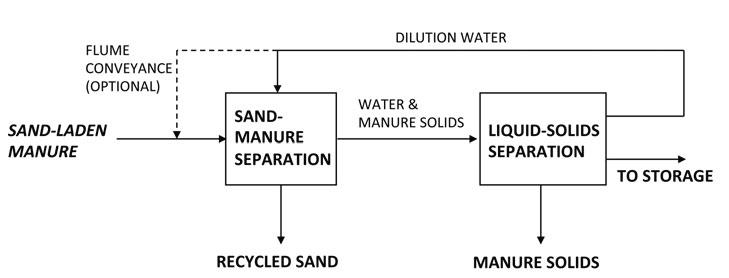

The diagram (Figure 1) shows a closed-loop conveyance and separation system. SLM is delivered to a sandmanure separation system either by scrape or by flume. Water, liquids and solids discharged from the sand-manure separator are pumped to a solids separator. Liquids from the liquid-solids separator are used for sand-manure dilution water and perhaps flume water.

As sure as the sun rises, freezing conditions will eventually occur; however, despite this certainty, oftentimes our level of preparedness

and planning suggests we didn’t know it was coming. Start by understanding the not-so-obvious effects of cold weather on manure handling – that is, how viscosity effects things like conveyance and separation. Consider closed-loop conveyance and separation systems to minimize the effects of cold weather. Avoid compromising air quality in freestall barns by completely closing air inlets in an attempt to facilitate manure handling. When all else fails and manure

does freeze solid, plan to have an alternative method for handling sandladen manure. This could mean scraping directly to long-term storage for eventual land application or stockpiling until conditions are suitable for separation. In any case, be prepared.

Andrew W. Wedel is a professional engineer. He is the general manager of the agriculture division of McLanahan Corporation, based in Holidaysburg, Penn.

The Basque Institute for Agricultural Research and Development in NeikerTecnalia, Spain, has set up a mobile environmental monitoring unit to assess in situ greenhouse gases and ammonia emissions on farms.

The results of the measurements will be used to evaluate the effect of best available techniques (BAT) at farm level to reduce the environmental impact on the air and soil. The initiative is co-funded by the Interreg Atlantic Area Programme through the Batfarm European project.

The mobile laboratory is equipped with equipment to take and keep samples in optimal conditions. A photoacoustic gas analyzer will be used to monitor in situ gas emissions. The mobile laboratory will work for one month in a pig farm near Vitoria-Gasteiz, Spain. The effectiveness of various additives to mitigate ammonia and greenhouse gases will be assessed during slurry storage.

The project aims to estimate the environmental and economical efficiency of different environmental technologies implemented on swine, poultry and cattle farms in the European Atlantic Area. Five Atlantic research centres and universities are also involved in the Batfarm project along with Neiker-Tecnalia: Teagasc (Agriculture and Food Development Authority of Ireland), Cemagref (France), ITG Ganadero (Spain), University of Glasgow Caledonian (United Kingdom) and the Instituto Superior de Agronomía (Portugal).

The intensive production model yields considerable economic returns but has numerous environmental problems, such as the release of pollutant gases (ammonia, nitrous oxide and methane) into the atmosphere, and the contamination of soil and water by nitrates. Once the project is over, farmers will be able to choose those technologies that best fit their environmental requirements. The members of the Batfarm project are currently developing a software program to select the best environmental techniques.

A nutrient management specialist with Manitoba Agriculture, Food and Rural Initiatives (MAFRI) reports in-crop applications of liquid swine manure fertilizer can result in up to a 10 percent yield increase over the standard fall application.

In-crop manure application was among the topics discussed recently as part of a field clinic in soil and manure management at the University of Manitoba’s National Centre for Livestock and the Environment. Clay Sawka, a nutrient management specialist with MAFRI, says most manure fertilizers in Manitoba are typically applied in the fall but, by applying in-crop, farmers can spread out their workload and hopefully provide nutrients when the crop needs it most.

“Generally we see liquid manure being applied to the grass crops that can stand a little bit more damage,” says Sawka. “Just like your lawn when it gets cut, the growing point is below the ground so we can go in there and apply manure to those crops in about the two-to-five-leaf stage, so early in the year when we still have lots of time to bounce back from any impact of the traction or the implement itself.

“We’ve had reports of up to a 10 percent increase in yields over the standard fall application of 100 percent of your nutrients,” he says.

“These guys are generally putting down starter N with their seed and then topping up with the remaining 100 to 120 pounds of nitrogen and seeing about a 10 percent bump in yields.”

Conditions are very important.

“You have to have the right conditions so that manure is not still lingering around in the surface,” says Sawka. “If the soil is too wet, you see a little bit more compaction issues, some more disturbance from the rolling tines going through, so you want to try to time it with the crop conditions, that two-to-five-leaf stage, as

well as trying to not hit the soil when it’s too wet. Drier soil conditions are much better.”

Sawka acknowledges there will be years when in-crop application works and years when it doesn’t so it’s a gamble to try to apply all of your manure in that narrow two-to-five-leaf window.

He says when it works it works well but there might be years where you just can’t get on there because the soil conditions just aren’t right.

The Association of Equipment Manufacturers (AEM) has elected two new directors: Tiago Bonomo, president and CEO of McCormick USA, joins the AEM AG Sector Board, and Daniel Miller, president and CEO of Manitou Americas Inc., joins the AEM CE Sector Board. Both fill unexpired terms.

AEM’s AG Sector Board and CE Sector Board are the association’s board-level groups that determine and recommend strategic direction and develop and direct programs, services and activities focused on their respective industry sectors.

AEM directors help set the guidelines and operating policies of the association on behalf of its members in areas including public policy, equipment statistics and market information, trade shows, technical and product safety support, global business development, education and training, workforce development and worksite safety and educational materials.

AEM is the North America-based international trade group representing the off-road equipment manufacturing industry, and its members manufacture equipment, products and services used worldwide in the agriculture, construction, forestry, mining and utility sectors. The group is headquartered in Milwaukee, Wis., and has offices in the world capitals of Washington, D.C.; Ottawa, Canada; and Beijing, China.

For more information on AEM and its activities, go online to www.aem.org.

The National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) recently voted to amend its standards for animal housing facilities, requiring fire sprinkler systems in newly constructed and some existing facilities.

The NFPA is a standard-setting organization, and its uniform codes and standards are widely utilized by state and local governments to set building and fire codes, by insurance companies as minimum standards to maintain coverage and by international organizations.

The recent change is a substantial expansion of the standards for animal housing. In the past, the sprinkler requirement has applied only to facilities such as zoos, veterinary clinics and pet shops. But the new revisions would cover all barns and any other facilities where animals are kept or confined.

The National Pork Producers Council believes the overly broad fire codes have the potential to significantly increase the cost of new barn construction and maintenance and could subject producers to biosecurity risks during annual sprinkler system inspections. NPPC is in the process of filing with NFPA an appeal of the decision to amend the animal housing standards.

The Agricultural and Environmental Research Unit (AERU) at the University of Hertfordshire has been awarded a research contract to review chemical additives used in livestock diets and to critically evaluate their potential for delivering environmental benefits such as reducing waste gases that may contribute to climate change.

Livestock productivity is dependent on the animals being well-kept and healthy, and this depends on them receiving adequate nutrition. Existing evidence shows that livestock feed can be improved by the use of feed additives that not only improve diet and health but can also be used, for example, to increase milk yields, suppress the oestrus (female reproductive) cycle or even improve digestion in livestock. When properly used in a well-managed environment, many of these additives can substantially improve performance and farm profitability.

The study, funded by the European Food Safety Agency (EFSA), is to be completed by spring 2013. It will undertake a thorough, critical and systematic review to produce a global inventory of current feed additives that offer environmental

benefits. This information will support the current European regulatory process on feed additives, and will help develop more sustainable policies in this area.

“Feed additives must meet the necessary safety standards, but they can also help to deliver environmental benefits,” said Dr. Kathy Lewis, reader in agri-environmental science. “They have an important role to play in delivering sustainable increases in productivity but can be used to improve digestive processes in livestock which will reduce waste production including methane, ammonia and other metabolic gases.”

Wastewater from large dairy farms contains significant concentrations of estrogenic hormones that can persist for months or even years, researchers report in a new study. In the absence of oxygen, the estrogens rapidly convert from one form to another; this stalls their biodegradation and complicates efforts to detect them, the researchers found.

The study, led by scientists at the Illinois Sustainable Technology Center, is the first to document the unusual behavior of estrogens in wastewater lagoons. The study appears in the journal Environmental Science & Technology.

Just as new mothers undergo hormonal changes that enable them to breastfeed, lactating cows generate estrogenic hormones that are excreted in urine and feces, said ISTC senior research scientist Wei Zheng, who led the study. In large confined animal feeding operations (CAFOs), the hormones end up in wastewater. Farmers often store the wastewater in lagoons and may use it to fertilize crops.

Federal laws regulate the flow of nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus from CAFOs to prevent excess nutrients from polluting rivers, streams, lakes or groundwater.

Environmental officials assume that such regulations also protect groundwater and surface waters from contamination with animal hormones and veterinary pharmaceuticals, but this has not been proven.

Hormone concentrations in livestock wastes are 100 to 1,000 times higher than those emitted from plants that treat human sewage, and large dairy farms are a primary source of estrogens in the environment, Zheng said. Recent studies have detected estrogenic hormones in soil and surrounding watersheds after dairy wastewater was sprayed on the land

as fertilizer.

“These estrogens are present at levels that can affect the (reproductive functions of) aquatic animals,” Zheng said.

Even low levels of estrogens can “feminize” animals that spend their lives in the water, causing male fish, for example, to have low sperm counts or to develop female characteristics (such as producing eggs), undermining their ability to reproduce.

Hormones that end up in surface or groundwater could contaminate sources of drinking water for humans, Zheng said.

“The estrogens may also be taken up by plants – a potential new route into the food chain,” he said.

When exposed to the air, estrogenic hormones in animal waste tend to break down into harmless byproducts. But the hormones persist in anoxic conditions.

While conducting the new study on dairy waste lagoon water in the lab, the researchers were surprised at first to see levels of three primary estrogens (17 alpha-estradiol, 17 beta-estradiol and estrone) fall and then rise again in their samples. Further analysis revealed that the estradiols were being converted to estrone, undergoing the normal first step of biodegradation. But then the process reversed itself: Estrone was reverting to the alpha- and beta-estradiols.

“We call this a reverse transformation,” Zheng said. “It inhibits further degradation. Now we have a better idea of why (the estrogens) can persist in the environment.”

The degradation rates of the three hormones in the wastewater solution were temperature-dependent, and very slow. After 52 days at 35 C (95 F) – an ideal temperature for hormone degradation, Zheng said – less than 30 percent of the hormones in the solution had broken down.

The fluctuating levels of estrone and estradiols may lead to detection errors, Zheng said, giving the impression that the total estrogen load of wastewater is decreasing when it is not.

“We need to develop a strategy to prevent these hormones from building up in the environment,” he said.

For the latest news and information affecting manure handling and management, visit www.manuremanager.com.

Challenger recently introduced the MT700D Series, available in two models. The tractors are powered by 8.4L diesel engines, built for smooth operation and longer life.

With the powerful engine and Challenger’s Mobil-trac system, the MT700D Series tractors put power to the ground. A new cab and controls make operating a Challenger easier.

The AGCO Power 8.4L diesel in the MT765D is rated at 285 PTO/350 engine HP, while the MT755D engine is rated at 260 PTO/327 engine HP. Both diesel engines feature a single-piece cast iron block with wet cylinder liners. This enables the engine to handle high-horsepower loads without overheating, and extends its service life. Four valves per cylinder, improved fuel regulation and combustion from a new pump and injectors help maximize engine efficiency.

The power plant achieves Tier 4i emissions standards and maximizes power output while minimizing exhaust treatment costs by varying the diesel exhaust fluid (DEF) rate based on real-time emission measurements.

Challenger’s Mobil-trac five-axle undercarriage system with oscillating mid-wheels minimizes compaction while maximizing traction and pulling power to work in the most demanding environments.

Standard polyurethane midwheels provide long life in abrasive environments and where long transport distances are required. Gauge settings, ranging from 72 to 160 inches, plus a wide selection of track widths, allow Challenger tractors to fit the

requirements of a wide range of farming operations.

With 110 cubic feet of space, the new cab provides high visibility and comfort, and enhances the Mobil-trac ride. Other features include a 59 GPM hydraulic pump option and 37 GPM flow per hydraulic remote to provide the hydraulic capacity needed for large planters and tillage equipment.

www.Challenger-ag.com

Custom manure applicators and owner/ operators of farms spreading liquid manure with tankers and drag-hose systems will want to check out a new remote engine controller, Broadcaster 1.

The controller offers real-time data that doesn’t require cell phone coverage. New from Sunova WorX, the technology was launched at the North American Manure Expo in Prairie Du Sac, Wis., on August 22.

“Broadcaster 1 is different from any other engine controller currently on the market because it uses a digital radio signal to communicate rapidly with the engine it is controlling,” explains John Van Lierop, owner of Sunova WorX Inc., the company that researched, developed and manufactures the technology. “We have extensively tested Broadcaster 1. It covers a distance of two miles with the capacity to extend this range to provide liquid manure handlers control over the tractor and independent engine at the manure pump. It is cost-effective. It will save labor costs and time.”

Broadcaster 1 communicates back and forth with the engine controller using a digital radio signal providing real-time data displayed on the remote controller, including engine RPM, PTO, intake and outlet pressure, engine temperature and oil pressure, and acts as an emergency shutdown. Since it doesn’t require cell phone coverage, as it is an independent system, there are no additional user or network fees. The data is shown at both the engine controller and remote on an LCD screen, which is backlit for nighttime use. Broadcaster 1 will work on both dragline and tanker manure spreading systems and

has options available for boost pumps to increase distances for drag hoses.

Sunova WorX Inc. is a family-owned company located in Lakeside, Ontario, Canada.

www.sunovaworx.com

Spreading manure to fertilize fields has long been an inexact science, with some areas receiving too much and others too little. Now, farmers can take precise distribution to the next level with the MS23 Series of side-discharge manure spreaders from Frontier Equipment.

Four models are available to fit any size of livestock operation:

MS2320 (2,000 gallons)

MS2326 (2,600 gallons)

MS2334 (3,400 gallons)

MS2342 (4,200 gallons)

Standard equipment on all models includes a 40-inch-wide side-discharge expeller beater; an automatic chainoiler system; a left-side, poly-lined tank; highway lighting system; remote grease system; and shear bolt protection.

The automatic oiler system keeps the drive system chains working smoothly by releasing oil each time the discharge door is raised. All extra equipment is nearby when needed. A scraper holder and jack storage area is conveniently located on the left side of the spreaders.

www.BuyFrontier.com

Nuhn Industries has sold a prototype machine to the largest milk supplier in

the world. It will go to their new facility in China, and if successful, the sale will expand to all of the company’s other operations in China. Eventually, the machine will be implemented in many of the supplier’s facilities around the globe.

This marks Nuhn’s first time competing on a worldwide scale. The company went up against international bidders for the job and was selected, presenting a conceptual machine that was a customized solution to meet the specific needs of the customer.

Nuhn’s vice-president, Ian Nuhn, designed the prototype, and promised to deliver.

“We couldn’t have done it without our workforce,” said Nuhn. “Everyone has given one hundred percent effort in the last month toward this initiative.”

The buyer chose Nuhn Industries over the other international corporations for their technology, expertise and experience in the field of manure management, said Nuhn, adding it was an honor for the homegrown family business, which began as a blacksmith shop in 1902.

Before the deal was finalized, Nuhn Industries welcomed a delegation from China. The group gathered information about the project and the requirements of the buyer. The biggest challenge was the extremely tight turning radius that would be necessary on the prototype.

Ian Nuhn recognizes the benefits of this experience for his business. “It gave us the opportunity to develop new technology,” he said. “We now have a power steering module, and this can be applied to the North American market as well.”

Ian and company president Dennis Nuhn traveled to China in September to commission the unit. While there, they examined other opportunities for continued growth into the Chinese market. It is part of Nuhn Industries’ objective to develop a strong international presence.

Sewage sludge, waste water and liquid manure are valuable sources of fertilizer for food production. Researchers have now developed a chemical-free, eco-friendly process that enables the recovered salts to be converted directly into organic food for crop plants.

Phosphorus is a vital element not only for plants but also for all living organisms. In recent times, however, farmers have been faced with a growing shortage of this essential mineral, and the price of phosphate-based fertilizers has been steadily increasing. It is therefore high time to start looking for alternatives. This is not easy as phosphorus cannot be replaced by any other substance. But researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB in Stuttgart, Germany, have found a solution that makes use of locally available resources that can be found in plentiful supply in the waste water from sewage treatment plants and in the fermentation residues from biogas plants. The new process was developed by a team of scientists led by Jennifer Bilbao, who manages the nutrient management research group at the IGB.

“Our process precipitates out the nutrients in a form that enables them to be directly applied as fertilizer,” she explains.

The main feature of the patented process, which is currently being tested in a mobile pilot plant, is an electrochemical process that precipitates magnesiumammonium phosphate – also known as struvite – by means of electrolysis from a solution containing nitrogen and phosphorus. Struvite is precipitated from the process water in the form of tiny crystals that can be used directly as fertilizer, without any further processing. The innovative aspect of this method is that, unlike conventional processes, it does not require the addition of synthetic salts or bases.

“It is an entirely chemical-free process,” says Bilbao.

The two-meter-high electrolytic cell that forms the centerpiece of the test installation and through which the waste

Researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute for Interfacial Engineering and Biotechnology IGB in Stuttgart, Germany, have developed a process to take wastewater and create magnesium-ammonium phosphate – also known as struvite. Struvite is precipitated from the process water in the form of tiny crystals that can be used directly as fertilizer, without any further processing. Contributed photo

water is directed contains a sacrificial magnesium anode and a metallic cathode. The electrolytic process splits the water molecules into negatively charged hydroxyl ions at the cathode. At the anode an oxidation takes place: the magnesium ions migrate through the water and react with the phosphate and ammonium molecules in the solution to form struvite.

Because the magnesium ions in the process water are highly reactive, this method requires very little energy. The electrochemical process therefore consumes less electricity than conventional methods. For all types of waste water tested so far, the necessary power never exceeded the extremely low value of 70 watt-hours per cubic meter. Moreover, long-duration tests conducted by the IGB researchers demonstrated that the concentration of phosphorus in the pilot plant’s reactor was reduced by 99.7 percent to less than two milligrams per liter. This is lower than the maximum concentration permitted by the German Waste Water Ordinance (AbwV) for treatment plants serving communities of up to 100,000 inhabitants.

“This means that operators of such plants could generate additional revenue from the production of fertilizer as a sideline to the treatment of waste water,” says Bilbao, citing this as a decisive advantage.

Struvite is an attractive product for farmers because it is valued as a highquality, slow-release fertilizer. Experiments conducted by the Fraunhofer researchers have confirmed its effectiveness in this respect: crop yields and the uptake of nutrients by the growing plants were up to four times higher with struvite than with commercially available mineral fertilizers.

The scientists intend to spend the next few months testing the mobile pilot plant at a variety of waste water treatment plants before starting to commercialize the process in collaboration with industrial partners early next year.

“Our process is also suitable for waste waters from the food industry and from the production of biogas from agricultural wastes,” adds Bilbao.

The only prerequisite is that the process water should be rich in ammonium and phosphates.

It seems practical on the surface. Nutrient management plans (NMPs) should supply plants with ideal amounts of nutrients, minimize runoff and maintain or even improve the soil condition. And the farmer behind the plan would work with a set of conservation practices designed to reduce harmful pollutants while still obtaining optimal crop yields.

However, many U.S. concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) now produce excess manure nitrogen and phosphorus compared to the actual nutrient requirements needed by cropland. The Clean Water Act required several agencies, including the U.S. Department of Agriculture, to develop a unified strategy to minimize the effects of CAFOs on water quality and public health. Yet, each state continues to operate under a different set of guidelines for NMPs, with most heavily suggesting farmers develop field-by-field records of nutrient applications. Currently, only Delaware and Maryland have laws requiring all farmers to implement NMPs.

In a new study, funded in part by the Agricultural Food Research Initiative of the National Institute of Food and Agriculture, researchers from the University of Connecticut and the U.S. Department of Agriculture tracked what happened when four dairy farms implemented NMPs during a several year time span. The scientists compared pre-plan practices with recommended management plans to evaluate whether manure and fertilizer management has a significant effect on the nutrient status of soil and corn tissue. Numerous factors were considered, including the number of livestock, cropland acreage, nutrient status of the cropland, manure production, manure management, and fertilizer management.

During the first year, each farmer kept field-by-field records for manure and fertilizer applications, but made no changes to the management of nutrients. The information collected, developed a field-by-field recommendation for manure and fertilizer management, in the

Researchers from the University of Connecticut and the U.S. Department of Agriculture tracked what happened when four dairy farms implemented nutrient management plans over several years.

subsequent implementation years. The rate of manure recommended was based on the amount of phosphorus needed by the crop, which researchers estimated from soil test results. If the farm had excess manure after fulfilling the crop’s phosphorus needs, recommendations were made to apply manure at a rate equal to the amount of phosphorus expected to be removed by the crop. If the farm still had manure left over, it was to be applied to fields to meet the nitrogen requirement for the crop and to fields with a low potential to export phosphorus to water bodies. Chemical fertilizer recommendations were made after all manure was allocated.

Soil samples were routinely collected by farmers or crop advisers and analyzed at the University of Connecticut Soil Testing Laboratory. Samples were taken from the surface 30-cm layer in late spring when the corn was 15 to 30 cm tall. The samples underwent pre-sidedress nitrogen tests (PSNTs), which indicate how much nitrogen is available in the soil.

Cornstalk samples were also collected for corn stalk nitrate tests (CSNTs), which

provide a retrospective assessment of a season’s nitrogen management. Farmers collected 15 cornstalk samples from each field during the period ranging from one week prior to harvest through one day after harvest.

In the end, results were surprisingly mixed, with little decrease in the concentrations of nitrate in PSNTs and CSNTs tests. The documentation of improvements in nitrogen and phosphorus management after the implementation of NMPs also proved to be a difficult task and for many reasons. But researchers suggest, by digging deeper and for a longer period of time, all may come closer to the needed outcome.