Supplying organic compost

Value added answer

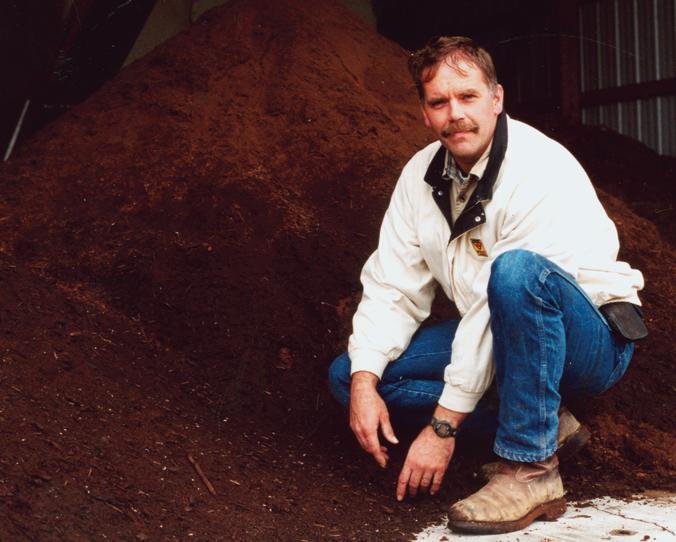

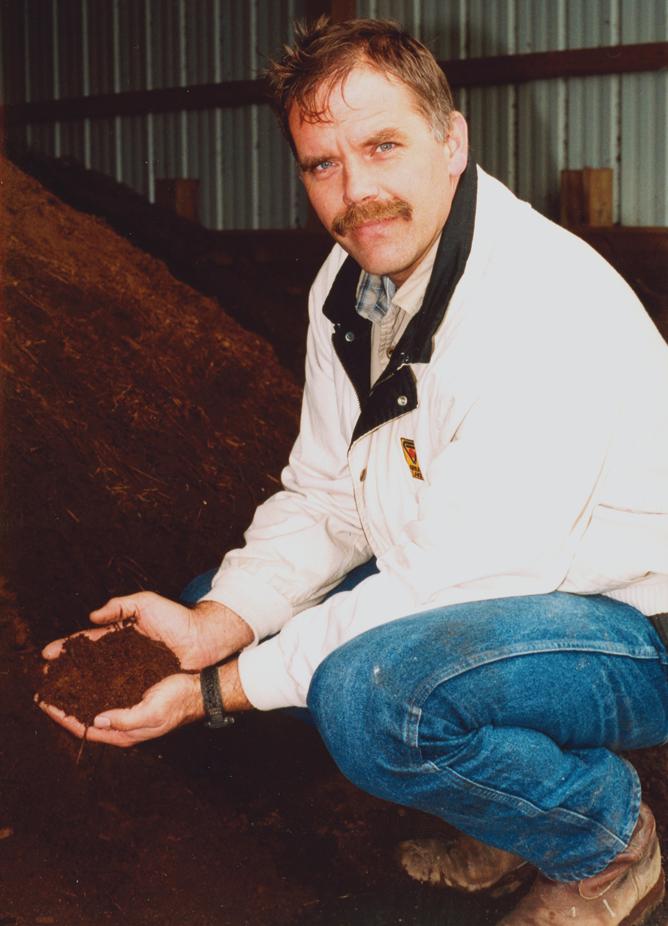

Mike Bronkema of Holland, Michigan, successfully transitions from construction worker to chicken farmer and commercial compost producer.

A profitable solution

As MOARK’s egg business grew, so did issues surrounding litter. They solved the problem by turning their waste management system into a nutrient business.

Manure digestion pioneers cash in on organic growing

Farm businesses pondering what they want to achieve financially by processing their manure through an anaerobic digester need look no further than Foster Brothers Dairy of Vermont to model their businesses after.

Major expansion at Fepro Farms

Canadian manure management pioneers Paul and Fritz Klaesi, who share a bio-digester between their dairy farms near Cobden, Ontario, are in the midst of a major expansion that should be finished by the end of the year.

Biogas production – it’s all in the mixing Engineers at Washington University in St. Louis, Missouri, have determined the importance of mixing in anaerobic digesters for bioenergy production, and animal and farm waste treatment.

Manure Manager takes a look at what’s out there in the market for: Compost equipment.

Guest column: Compost dairy barns – A closer look Wayne Schoper is a University of Minnesota Extension educator for Brown and Nicollet counties.

Cover: Interested spectators view a compost turner equipment demonstration during the 2007 Upper Midwest Manure Handling Expo, held in Wisconsin.

Published by:

Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. P.O. Box 530 Simcoe, Ontario N3Y 4N5 (800) 265-2827 or (519) 429-3966

Fax: (519) 429-3094

Editor

Margaret Land • (519) 429-5190, (888) 599-2228, ext 269 mland@annexweb.com

Contributing Editors

Tony Fitzpatrick, Treena Hein, Tony Kryzanowski, Diane Mettler, Candace Pollock, Wayne Schoper

Advertising Manager

Laura Cofell • (519) 429-5188, (888) 599-2228, ext 275 lcofell@annexweb.com

Production Manager

Angela Simon

Circulation Supervisor Diane Luke dluke@annexweb.com

Vice-President/Group Publisher

Diane Kleer • (519) 429-5177 dkleer@annexweb.com

Website: www.manuremanager.com

US Subscriptions:

$37 US one year

$64 US two years

International Subscriptions

$70 US one year

Canadian Subscriptions (GST included)

$37 Cdn one year

$64 Cdn two years

Canadian Publications Agreement #40065710

Return undeliverable addresses to: Annex Publishing & Printing Inc. P.O. Box 530, Simcoe, ON N3Y 4N5

Reproduction prohibited without permission of the publisher.

Printed in Canada July/August 2008

Volume 6 • No. 4

By Margaret Land

Compost – what a great topic to really bury yourself in – well, not literally.

A somewhat misunderstood process, composting consists of more than stockpiling piles of manure out behind the barn. Instead, it is the controlled biological decomposition of organic matter – such as animal manure –into a stable, humus-like product.

Composting can have numerous benefits for livestock production, including reductions of between 50 and 75 percent for dry matter, volume reductions as high as 85 percent, reductions in odor, flies, pathogens and weed seeds, plus a safe and effective way to deal with the issue of deadstock.

Earlier this year, I had an opportunity to view a poultry litter composting facility as part of the Growing the Margins energy conference, held in London, Ont., Canada. Cold Spring Farms, a division of Maple Leaf Foods, is an integrated turkey production and processing facility located near Thamesford, Ont. As a by-product of the company’s turkey production, the facility produces 8,000 tons of composted litter, comprised of wood shavings and straw, using an in-vessel composting system.

After barn cleanout, litter at Cold Spring Farms is either directed toward composting or sold as fresh manure to cash crop producers. Litter for composting is brought to a central facility where water is added to bring the moisture level up to 55 percent. The litter is then pushed into the composting facility and directed into one of three compost channels. A large compost turner that rides on rails is used to process each of the channels and a

crane system is used to transport the turner from one channel to the next.

Litter is retained in the composting facility for three to four weeks and is turned daily. Probes are used to monitor the temperatures in each of the channels. According to the facility manager, temperatures between 131 and 140˚F are required in order to kill any pathogens or weed seeds within the litter.

Once the composting process is completed, the litter is conveyed out of the composting facility and stored in windrows for curing. The windrows are turned every two weeks in the beginning, shifting to once every month by the end of the fourmonth curing period.

About 95 percent of the resulting compost is sold in bulk to high value horticulture producers, ginseng farmers, golf courses, landscapers and some home gardeners.

Readers will have an opportunity to learn more about composting – in relation to manure management – in this issue of Manure Manager with the help of Mike Bronkema, a Holland, Michigan poultry producer, and Robert Foster of Foster Brothers Dairy in Vermont. They’ll even learn how composting wasn’t the solution for handling litter issues at MOARK’s egg production facilities in southwest Missouri.

Don’t forget to read about the latest compost equipment offering in the Innovations section, starting on page 32.

The next issue of Manure Manager will feature the latest in manure management relating to dairy operations plus recent innovations in skidsteers/ loaders. Information and news from the 2008 Great Lakes Manure Handling Expo will also be featured..

By Diane Mettler

Not everyone can transition from construction worker to chicken farmer and commercial compost producer. But Mike Bronkema did just that in 1992.

Bronkema’s family farm is located on 160 acres in Holland, Mich. The family of six raises pullets — between 52,000 and 58,000 per batch every 17 weeks. They also raise 150 head of sheep and grow corn, soybeans, hay and oats.

In 1996, when Mike expanded the pullet operation, he ran into manure issues. “We were producing enough manure for well over 400 acres of ground,” he says. “With 160 acres available, we had to find another way to manage manure because we were exceeding our phosphorous limits.”

He tried hauling the manure to other locations, but that was problematic because the farm sits between two cities, roughly 20 miles apart. The semi-liquid manure sometimes dripped onto the road “and nobody likes that,” says Mike.

In 1998, the farm family made the decision to move to composting. After raising money, jumping through hoops

and educating officials, they installed a BW Organic in-vessel compost system in 2000.

Money, hoops and education

Grants helped pay for a large portion of the project. Equipment grants came from the Natural Resource Conservation Service (NRCS) but to be eligible the Bronkemas had to incorporate a number of environmental practices, including driveways, filter strips, and storm water runoff, among others.

The drum was secured through a low interest rate loan from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality. “And working with two departments — the Michigan Department of Ag and the Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) —we had quite a bit of regulation to work around.”

The Bronkemas were able to save a lot of money doing the work themselves, and Mike’s construction background came in extremely handy.

One of the frustrations, however, was educating the DEQ, as this was the first working composting endeavor they had worked through.

“They initially wanted to license us

as a landfill,” Mike says. “We had done enough testing with the final product though to show their issues disappeared in the composting process.”

Another issue the DEQ had was with the sawdust Mike was adding that came from a local furniture maker. Mike had to demonstrate that the sawdust contained no harmful chemicals.

One of the biggest frustrations, however, was when the DEQ said they didn’t like the amount of iron that was coming through from the manure. “All of a sudden we had an issue with a micronutrient that farmers use to grow crops,” says Mike, “They were saying it was an environmental issue and that it had to go to a landfill. So we had to educate them as to the difference between a waste product and a fertilizer.”

It was worth jumping through the hoops. Now the Bronkemas have an in-vessel system of composting that allows them to compost year-round.

“We can start the composting process in the winter, get through the main part of composting, which is the thermophilic stage, and then be able to

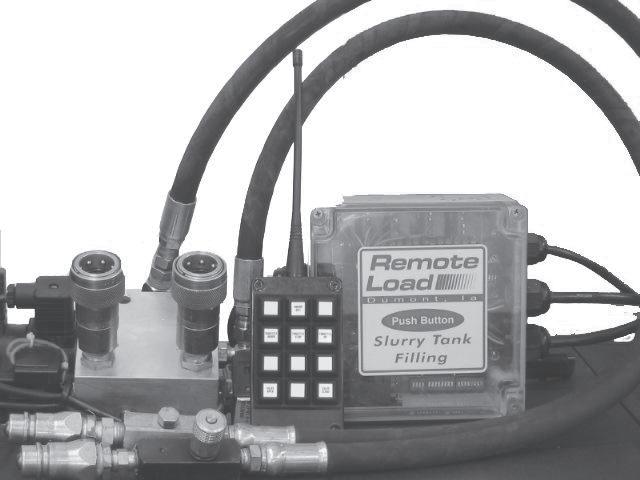

The composting unit is eight feet in diameter and 24 feet long and is rotated by a 1.5-hp, 230-volt electric motor. Manure is composted for 72 hours (three days), and then removed easily from three slide-gate unloading doors.

stockpile it on a pad for application in the spring or fall,” says Mike. “It turned manure in to a value added product to us.”

A big vessel

Mike installed a model 824 — one of BW Organics’ mid-sized models. It processes approximately eight yards of product a day. The rotating drum continually aerates and prevents uneven pockets during the composting process. The unit is mounted on an eight-inch I-beam frame with a slope built into the casters.

The insulated drum is eight feet in diameter and 24 feet long and is rotated by a 1.5-hp, 230-volt electric motor, which Mike says costs him about $3.50 a day to operate. Manure is composted for 72 hours (three days), and then removed easily from three slide-gate unloading doors.

A compost batch is composed of several ingredients, including 1,000 pounds of sawdust, 40 pounds of straw, and 3,000 pounds of chicken manure.

Mike says one of the reasons he’s able to add eight yards a day is because he’s using a product that’s easy to compost. Other products may take more time.

Mike initially sold the compost himself, but eventually turned to another composting farmer, Brad Morgan of Morgan Composting in Everett, Mich., who acts as his broker. “He moves my compost all over the state of Michigan, which is great,” says Mike. “And that allows me to spend more time raising my animals.”

Fortunately for Mike, the price of compost has steadily been increasing since the day he went into the business. At first, he was getting $10 to $15 a yard while it cost $8.50 to produce. Today, even using a broker, he’s getting $17 a yard.

The Bronkemas’ pullets create more manure than the operation can process at times. While it can take up to two weeks before the chicks are producing enough manure to process, by the end of their 17-week stay, they will have produced around 450 yards.

“As the chicks get older, we almost have to stockpile it or find a small site off site,” says Mike. “I’ve found a secondary composter that will use my extras throughout the year.

“Depending on how much moisture there in, among other things, we can compost up to 90 percent of the manure on site.”

Manure is collected from underneath the birds with custom-made scrapers designed for the 42-foot by 270-foot pullet barn. The manure is then placed in a Knight 2250 mixer wagon.

“The mixed compost is all measured by scale when we start,” says Mike.

He feeds the drum a “batch” and a half each day. A batch is composed of several ingredients. “We use 1,000 pounds of sawdust. We also like to add about 40 pounds of straw, which sometimes comes from our sheep barn. It adds a little manure to the mix, but generally doesn’t change our carbon to nitrogen ratio.” Lastly he adds 3,000 pounds of chicken manure.

He finishes each day by mixing a new batch. “I mix compost or fill the mixer wagon with manure and sawdust,” says Mike. “The manure sits there in the mixer wagon overnight with the temperature ramping up. In the summer it can go from an ambient temperature in the evening up to about 110 (degrees Fahrenheit) the next morning.”

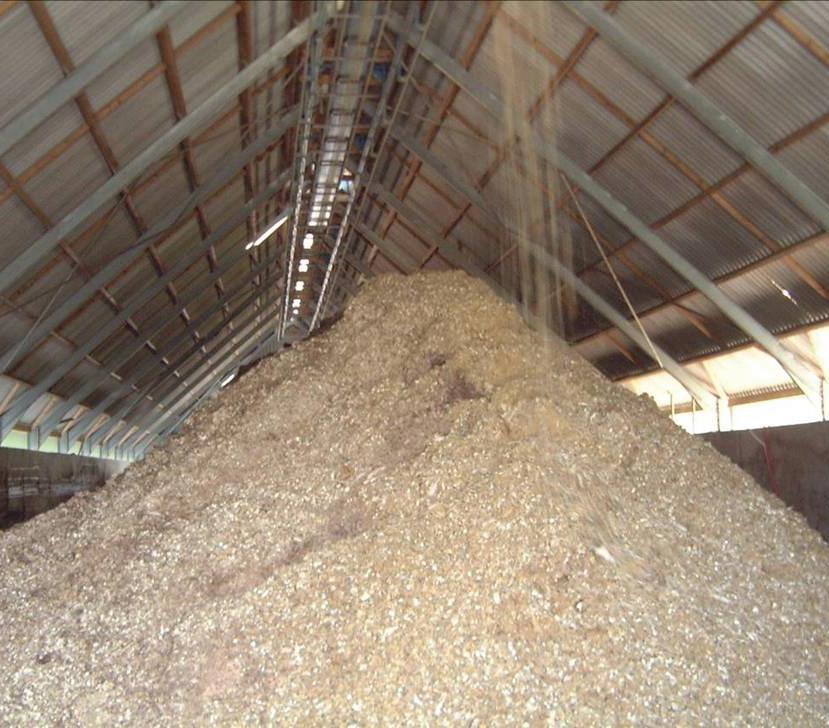

The compost is taken from the drum to an outdoor 100-foot by 100-foot gravel curing pad, designed to hold six months’ worth of composted manure. The compost remains on the slab for six months.

Bronkema family farm is located on 160 acres in Holland, Mich. The family of six raises pullets — between 52,000 and 58,000 per batch every 17 weeks. They also raise 150 head of sheep and grow corn, soybeans, hay and oats.

Each day, Mike Bronkema mixes a new batch of ingredients for the composter. The manure sits there in the mixer wagon overnight with the temperature ramping up. In the summer it can go from an ambient temperature in the evening up to about 110 (degrees Fahrenheit) the next morning.

The composter is located in a 24foot by 100-foot open barn, and is fed several times over the course of an hour. The compost will spend 72 hours in the drum at a minimum of 131 degrees Fahrenheit — the temperature and time required to kill the pathogens. In the summer, however, the temperature in the drum can get high as 140 to 144 degrees Fahrenheit.

From drum to dollars

The compost is taken from the drum to an outdoor 100-foot by 100-foot gravel curing pad, designed to hold six months’ worth of composted manure.

The pad has a three percent slope. “Any water runoff goes through a 50-foot by 160-foot grass filter before it reaches the fields.”

Mike’s pleased with the efficiency of the system. “We’re able to manage the

water runoff on the mat, catching the nutrients and harvesting them in the form of hay that is then been fed back to the sheep,” he says.

The compost remains on the slab for six months. “We generally put the compost on one side of the pad and then roll it across the pad, because it needs occasional turnings for it to get oxygen for the composting process,” explains Mike. “By the time it gets across the pad in six months, it’s generally at an ambient outdoor temperature.” And ready for sale.

Mike has been using the compost on his own fields now that they are at a healthy phosphorous level. He’s noticed since they started using their compost they’ve experienced healthier plants.

“With healthier plants, my animals are actually healthier, so we have less medical problems,” says Mike. “After eight years of composting I’m starting to realize what composting means to the environment. Instead of just a way to handle the manure, it means something to me in that it goes into my animals.

“Now if I’ve got healthy animals, what’s that gonna do for me?” Mike adds. “If I’m eating my animals, I should be healthier too, right?”

See the benefits

Agencies, companies and individuals are becoming more compost savvy. For example, Mike says that Michigan law has just changed, allowing mortality composting in a vessel system rather than just a static pile.

“The nice thing about the vessel system in doing mortality is that we get rid of all soft tissue in about three days in the unit,” says Mike. “It’s really the best way to get rid of mortalities.”

It’s not only been a sound environmental decision, but a good business decision as well.

“I spend the same amount of time I was spending loading manure into the manure spreader and transporting it to outlying fields as I do making compost,” he says. “The big difference is I’m getting money for the manure.

And he’s getting all the benefits from the nutrients. “Compost holds nutrients. It makes the nutrients available to the plants and animals in a way that they can use them,” says Mike.

He says you lose more nutrients spreading straight manure. “When you start putting compost out there, you hold your nutrients. All of a sudden you go from a welfare-type soil system to a workingbased nutrient system in the soil.”

Mike has reason to be proud of his farm. Many have praised the family’s efforts. In 2006 the Michigan Farm Bureau recognized them for proactive leadership in ecology management. In 2007, the American Sheep Industry gave them the Environmental Stewardship Award. And there have been others awards for their manure management.

“I guess I love compost,” says Mike. “The more I learn about compost, I see how it completes the life cycle.”

In 2006 the Michigan Farm Bureau recognized the Bronkema farm for proactive leadership in ecology management. In 2007, the American Sheep Industry gave the operation the Environmental Stewardship Award.

And even the DEQ is coming around. “We started out with skeptics in the DEQ that really didn’t even want composting. Now they are coming around asking us about the composting process.”

Good investment Mike is a true believer in compost.

The price of compost has steadily been increasing since the day the Bronkema family went into the business. At first, they were getting $10 to $15 a yard while it cost $8.50 to produce. Today, even using a broker, the farm operation receives $17 a yard.

By Diane Mettler

As MOARK’s egg business grew, so did issues surrounding litter. They solved the problem by turning their waste management system into a nutrient business.

MOARK, based in Southwest Missouri, has been in the egg business for nearly 60 years. As the business grew, so did litter issues. But they have turned adversity into profitability. Today, they have 2.5 million chickens and a turnkey nutrient business, which handles the 1,000 to 1,500 tons of litter produced each week.

No to composting

Three years ago MOARK was composting their litter, but it wasn’t working out.

“We had odor issues because of the sawdust we used,” recalls Hugh Vogel, MOARK’s byproducts manager. “It was heating up the manure and, because of that, it was enhancing our ammonia emissions.”

MOARK management discovered that by blending the different types of litter together, the company had a usable, stable, lower odor product with about 35 to 45 percent moisture content.

Because of those issues and pressure from Department of Natural Resources (DNR) and the community, they decided to stop composting altogether.

It was a small but vital observation that allowed the company to move away from waste management and turn to a more profitable business model.

The farm had 10 barns at each of its three different locations — all within a 40mile radius. The barns, they noticed, could be placed in three groups based on the manure moisture content:

• Those with 65 to 70 percent moisture content. These were the 30year-old barns that used older-style water nipples. The manure dropped onto belts and was removed three times a week, but there wasn’t enough air movement over the belt, so the litter remained wet.

• Those with approximately 40 to 50 percent moisture content. These were the newer barns with a new belt system. “Those belts have air tubes above the belts that blow air and dry that product,” says Vogel.

• Those with 30 to 35 percent moisture content. These were the new cage-free houses with the Big Dutch belts.

Hugh says they discovered that when they blended the three types of litter together, they had a usable, stable, lower odor product with about 35 to 45 percent moisture content. The product also didn’t heat up because there was no sawdust.

“And it spreads well,” says Hugh. “There are actually issues spreading the dry litter. It gets so dusty and light that you don’t get a good application pattern. So we like about a 35 to 40 percent moisture product because we get a good pattern. Otherwise you have to pelletize it or put it in a drill to get a good distribution.”

When it comes to mixing the manures, the process is fairly low tech. “We have some old slinger trucks that we sometimes put it in and then just throw it out,” says Vogel. “But usually just rolling it around with a pay loader is about the quickest and simplest.”

Spreading the litter on customers fields, however, is definitely high tech. Vogel says it was the Ag Chem machinery that allowed them to move from waste managers to a turnkey nutrient business.

“We use two Ag Chem TerraGator® spreaders,” says Vogel. “The difference is

MOARK, based in Southwest Missouri, houses 2.5 million chickens at three different locations all within a 40-mile radius.

in the way the product is distributed. They put down the manure as good as dry fertilizer spreaders. There are scales on the spreaders and a SGIS (GIS-based) program that tracks your application.”

Vogel is especially impressed with the European-designed spreader boxes. “I’ve been in the business for 30 years and I’ve never seen an applicator that does as good a job as they do as far as surface application.”

The MOARK pricing system is unique. Instead of paying by the ton, customers pay by the nutrient content.

“We sample the litter once a week and the turn around is about four days,” explains Vogel. “We make available the most recent analysis and then we discount the pricing enough so that nobody complains if it’s off five or 10 percent from the reading.”

MOARK has found the only variance from house to house has been the moisture. “If some of the houses happen to have a water leak it becomes wetter, others may be drier,” says Vogel. “And material can vary just because of the outside temperature being warmer. But by the time you blend everything together and you’ve done it for a few weeks, it’s pretty close to the same.”

Vogel has been responsible for putting together a computer program that is able to calculate the fluctuating market price of litter. He based the system on a pricing structure Oklahoma State University had created. Now a potential customer can go to a website (http://www.soiltesting.okstate.edu/Interpretation.htm) and see what the litter will cost them per ton applied.

MOARK’s product is extremely economical — even though prices were recently raised because of rising fuel costs. It runs between $30 and $35 per applied ton. That’s a bargain when commercial fertilizers are running about $70 to $80 per ton applied.

Turnkey package

Although some farmers have come to the farm to buy litter, the business model is a turnkey one. MOARK does everything — litter testing, soil testing, delivery and application.

Deliveries are made within a 60 to 80 mile radius and primarily to the larger operations that can handle the semis MOARK uses.

“We track everything,” says Vogel. “We track the nutrients, the soil tests, the field IDs, the GPS locations of each field, and

MOARK also operates a turnkey nutrient business, which handles the operation’s 1,000 to 1,500 tons of litter produced each week.

the nutrient production to make sure we’re not over applying.” Over application it turns out, isn’t their biggest challenge. “It’s the logistics of getting to the right place at the right time,” says Vogel. They have 12 employees handling the nutrient business, correctly applying up to 1,500 tons a week on 600 to 800 acres.

Another challenge is dealing with Mother Nature. “When weather patterns change, we have to adjust,” Vogel says. “This

MOARK employs about 12 people to handle its nutrient business, correctly applying up to 1,500 tons a week on 600 to 800 acres.

year has been really challenging, because in this part of the county it’s not only been raining, there have been tornados too.”

To be flexible, MOARK has a covered storage facility. On a big black top they can store up to 120 days worth. Vogel says if pressed they could possibly store 160 days’ worth.

Although the program is working well — odor is down, litter is affordable and it’s applied correctly — Vogel says there has been some resistance. Some people have had problems adjusting to a new type of business, and some resistance has come

understandably from waste management companies who are competing for the business.

But MOARK has had no problem finding customers and enjoys a number of repeat customers. Vogel does add that they are diligent when it comes to those who want to purchase the litter straight from the farm.

“We want to make sure they have the right kind of equipment to get the job done and they’re not going to have a pile of litter out in the field for a long time,” he says.

If it’s not broke, don’t fix it MOARK has no plans to change their current routine. But if they did, it would be with caution. “You’ve got to be careful how much and what you change in this business, especially if you’ve got something that works,” says Vogel. And

experiencing from the community “we had to have something that worked every day,” adds Vogel. “I don’t want to be negative about anybody’s product, but we just couldn’t find anything that worked for us.”

The choice to move from compost to a nutrient business looks to be a sound one. Three years ago, the farm was knee deep in complaints and embroiled in hearings. “That has all calmed down,” says Vogel, “So I’m going to have to say that we’re doing better, but there is still a complaint now and then.”

He’s discouraged though by the negative mentality of the public regarding big farms. Even thought MOARK works to educate the public, Vogel says things have changed. “Agriculture is different than it’s ever been in my lifetime. I don’t know how it’s going to end up. We’ve got

you have to take into account the litter that continues to accumulate. “If you make a change you have to make sure you’ve got that covered.”

Back in its composting days, MOARK had looked at scrubbers and technology of that kind, but didn’t find any products that would work consistently. “There needs to be some development in that area,” says Vogel.

To combat odors, they tried various sprays but, depending on the moisture content of the litter, they couldn’t find a product that was guaranteed to work every time. With the pressures they were

to figure out how to get along because I don’t think we want animal agriculture in another country that exports food to the United States.

“I think there’s some misconception in that people think that if they bust up the big producers that the problems will go away,” he adds. “But you have to take a look at how much food the big producers provide. I don’t think there’s enough small producers left to fill the gap. We’ve got to figure out how to communicate and change people’s attitudes and I don’t know how possible that is today.”

MOARK divides its manure based on moisture content with its driest litter registering at 30 to 35 percent moisture content.

The company’s wettest manure usually comes from its older barns that have older style nipple drinkers. The moisture content of the manure usually ranges from 65 to 70 percent.

By Tony Kryzanowski

Farm businesses pondering what they want to achieve financially by processing their manure through an anaerobic digester need look no further than Foster Brothers Dairy to model their businesses after.

This fifth-generation dairy, located in Vermont’s Champlain Valley, is definitely old school when it comes to anaerobic digestion of livestock manure, having operated their digester and had the capability to generate power from the captured methane gas since 1982. Today, it’s a proven example that anaerobic digestion is not only good for the environment, but can be extremely profitable as a subsidiary farm business with the right approach.

“It was new for the U.S. agricultural scene but it was an old, old concept that was used on a much smaller scale, particularly in China and India,” says Foster Brothers Dairy co-owner, Robert Foster. “Today, there is a lot more infrastructure to support the industry. Back then, a lot of it was by the seat of your pants.”

Back in the early 1980s, the dairy operated only one of 26 anaerobic digesters in the United States, but sometimes it really pays to be first off the mark. While the methane gas generated from an anaerobic digester is often touted today as the main potential cash cow for a farm business because of its ability to work as an energy source to generate power, Foster Brothers Dairy has cashed in on the composting potential of the separated solids manufactured from the digestion process. The solids generated from the dairy’s digester, combined with separated solids and manure from other farms, are composted on a 10-acre site on the dairy and are the foundation of a well-established organic soil, compost and growing mix business. The dairy owners started this business venture in 1989 on an old barn site.

The organic growing and landscaping products business is

managed by a subsidiary of the dairy operation called Vermont Natural Ag Products (VNAP). The compost is mixed with a variety of other materials, like sand and peat, and is marketed under the Moo Doo brand. It is sold through mom-and-pop-type retailers throughout the American Northeast, and to local landscapers. Last year, this subsidiary had nearly $2 million in gross sales, selling 750,000 bags of soil mix and about 10,000 cubic yards of bulk compost. It now has about 1,500 accounts from a business that basically grew through word of mouth. A marketing company now represents their line of products. They also produce a line of private label products sold through a chain of nine stores in the greater Boston area.

Foster Brothers Dairy also manufactures a separate line of compost products, which they do not claim is organic because the sources of raw material to produce the compost can not be verified as organic.

Greater public concern for the environment has definitely impacted positively on the dairy’s composting operation.

“I think there is a greater public awareness of the value of compost,” says Foster, “and that these are organic materials that are being recycled back into the environment. It certainly hasn’t hurt us a bit.”

Foster says there have been occasions, depending on the price for milk, when VNAP has brought in more income to the farm business than milk. It tends to fluctuate depending on the price of milk and input costs to operate the dairy.

While the anaerobic digester and composting operation have certainly helped out financially over the last several years, it wasn’t always a smooth ride. Foster says they have learned some lessons along the way.

Firstly, the manure digestion and composting processes can be integrated

but both have to be sized based on the raw material that’s available. Secondly, it is another enterprise that will take time and resources. For example, in addition to the cost of establishing the digestion and composting infrastructure, Foster Brothers Dairy now has 12 people employed in the composting operation alone. It is also important to have someone dedicated to the smooth operation of the digester, and the subsequent composting process, if one exists.

“If you are a dairy, you typically take care of the cows first,” says Foster. “The digester tends to be at the end of the line, so someone has to have the motivation to stay on top of it.”

The dairy farm covers approximately 1,500 acres. Today, there are a number of family members involved in the 380 milk cow operation, which averages production of about 29,000 lbs. of milk annually per cow.

Given the size of the operation, the dairy produces about 12,500 cubic yards of manure annually.

Foster Brothers Dairy hired a small company who had built an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) demonstration project to install their anaerobic digester. The family had a strong desire to minimize the impact of their dairy operations on the environment.

“I think it is part of the solution to creating a more sustainable society,” says Foster. “We’ve been trying to close loops as close to home as possible and that’s part of why we have gotten involved in this.”

The process starts with manure collection. There are four collection points around the dairy where the manure is pushed over the lip of the barn floor into a waiting wheeled manure spreader. The manure spreader delivers the manure to the digester building, with the longest distance being only about 750 feet. The manure is then dropped into the reception pit.

Anaerobic digestion is essentially a biological process, where bacteria living in a carefully controlled, oxygen-free and heated environment convert raw manure into methane gas, liquid and solid byproducts over a period of time. Foster Brothers Dairy operates a plug flow system where raw manure is fed into one end and, after about 29 days, it is converted into gas, liquid and solid byproducts.

“We basically use gravity, putting the material in one end and it goes down and comes out the other end,” says Foster. “It’s kind of the first in – first out theory, as

opposed to systems where you agitate all the time.”

The temperature within the digester is maintained at about 95 F. Heat is recovered from a dual fuel engine partially powered by the manufactured methane gas to keep the temperature in the digester steady. Methane gas is manufactured consistently throughout the digestion process and is captured and held as it rises by a flexible cover located over the digester. In a recent development, the cover has been divided into two bags to allow the facility to be used for full-scale research, with

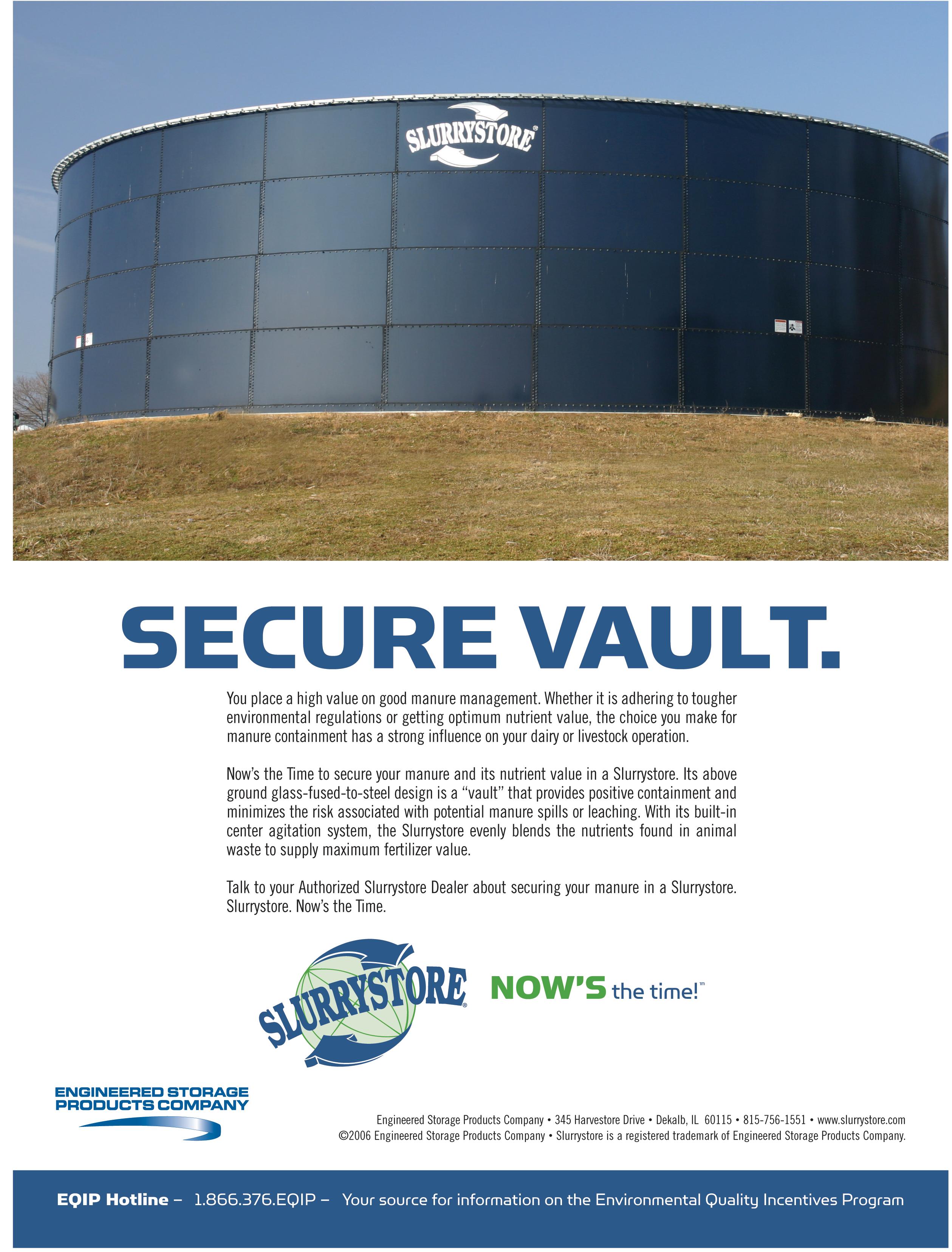

Engineered stay-in-place concrete forming systems that provide advanced architectural versatility and flexibility. Form your imagination with Octaform’s finished PVC forms and achieve superior construction.

Pre-cast, tilt-up and cast-in-place systems for barns, tanks, barriers and more.

one side acting as a control. The gas is transported to a separate building where it is scrubbed through a calcium carbonate filtering system and a water trap to remove hydrogen sulfide and moisture before it is fed as fuel into a Cat 3304 dual fuel engine. It is attached to a 125-kilowatt power generator. The engine operates on both diesel and methane gas, using between 25 to 30 percent diesel to methane under optimum operating conditions.

The dairy did originally have an engine that used methane gas exclusively as a fuel supply. It also initially generated

“We built our hog barn with Octaform and we can’t wait to see our next energy bill. We believe that the thermal mass will help reduce heating costs.”

™

• Finished surface when formed

• Easy to incorporate mechanical

• Sanitary and easy to clean, minimizing bacteria

• Solid walls allow for equipment mounting

• Straight and curved configurations

• Variable wall thicknesses

power that it sold to the public utility. However, once the price they were paid for the generated power dropped to five cents per kilowatt hour, which was less than the dairy was paying to purchase power from the state grid to operate the dairy, the Foster family decided to disconnect the generator from the grid and use the power being generated to supply their own dairy farm and three residences.

The solid material exiting the digester has a relatively high moisture content so it is processed through a FAN separator. All liquid generated by the separation unit is conveyed underground to a four million gallon capacity lagoon. Eventually, it is applied on cropland based on their nutrient management plan. The stockpile of largely pathogen-free solids that accumulates from the separator is trucked over to the composting operation located adjacent to the anaerobic digester.

The composing site is designed so it has complete water containment. A separate lagoon was constructed, which captures compost pad leachate. It is

used to maintain the 45 percent moisture content needed in the composting process as well as to irrigate cropland. The composting process takes about nine months – three months for the biological composting process to occur and six months to cure so that they are left with a stable product.

The Fosters’ early concern for the impact their dairy was having on the environment has helped to establish a template for other agriculture operations and to demonstrate what is possible by taking this alternative approach to manure management versus land spreading.

The farm business has realized a number of tangible and intangible benefits. For example, it is saving money by not having to purchase power off the grid, although the savings are reduced somewhat by having to purchase diesel fuel. Other benefits include reduced odor in a residential setting, the flexibility to apply nutrients through irrigation on

Foster Brothers Dairy – The flexible cover over the anaerobic digester at the Foster Brothers Dairy is where the methane gas collects. The gas is then transported to another building to scrub out the hydrogen sulfide and moisture before it is burned in a dual fuel engine to generate power.

a growing crop, and the availability of separated solids, which others may find beneficial as bedding material in a dairy operation.

By Treena Hein

Canadian manure management pioneers Paul and Fritz Klaesi, who share a bio-digester between their dairy farms near Cobden (northwest of Ottawa), are in the midst of a major expansion.

Construction of a second, much larger digester should be finished by the end of the year.

heat from the generator also provides supplemental winter heat to buildings on both farms.

About 20 years ago, the brothers moved with their families to Canada from Switzerland, where biogas technology is increasingly common and produces a significant amount of the country’s electricity.

The original digester was imported from Europe and cost $280,000 to install in 2003, although Paul Klaesi, an electrical engineer, and other family members contributed hundreds of hours towards the design and installation of the system not included in that cost. The anticipated payback was 10 years.

The system’s generator inputs electricity to the grid around –the clock, and the farms draw from the grid twice daily during milking when their power demand is high, so that the Klaesis have been billed only for net power used. The

At the start, the digester generated 400 cubic metres of methane and produced 750 kilowatt hours of electrical power per day – more than enough to meet the energy needs of both farms and their two houses.

Last year, however, two significant changes occurred.

In May 2007, the Klaesis finally received a Certificate of Approval from the Ontario Ministry of the Environment, allowing them to accept offfarm food wastes – commonly known as grease – into their digester. These wastes include deep-fryer grease, dishwasher residue, meal leftovers and food preparation wastes. Receiving the permit took more than 18 months, and that process is currently being streamlined.

In addition, in October 2007 the Klaesis signed an Ontario Power Authority (OPA) Renewable Energy Standard Offer Program Contract and Option Agreement. OPA, the agency controlling power generation in Ontario, has made this offer available to anyone generating renewable energy (from wind, biomass or biodigesters) who wishes to contribute to the province’s electricity grid for payment. The

In May 2007, the Klaesis received approval from the Ontario Ministry of the Environment to accept off-farm food wastes – commonly known as grease – into their digester.

rate currently sits at 11¢ per kW, with a 3.5¢ bonus per kW for contributions made during peak electricity demand times.

With the signing of this agreement and the incorporation of grease, “We now buy no power from the grid and sell three times what we use,” said Klaesi. “Some power flows back into the farm at peak milking time, which amounts to about $130 per month.”

Before they had a digester, the monthly electricity bill for the farms was $2,500.

At the same time, Klaesi does not believe the OPA contract rate supports digester cost-return adequately. He and about 30 other farmers have formed an association, called the Agri-Energy Producers Association of Ontario, to lobby the government for a boosted rate. The OPA has a rate review scheduled for this fall.

The old digester accepts 25 to 30 percent grease and 70 to 75 percent manure while the new facility will accept 40 percent grease and 60 percent manure mixture that has already been through the first digester.

“We haven’t had a ‘yes’ yet,” says Klaesi, “but they understand our concerns.”

A new digester is currently being built alongside the original one for several reasons. Klaesi says one of the biggest advantages of having a second digester

will be that all the farm’s manure will be “covered” – placed directly in their digester system – which means no open pit with associated odors. (The existing open manure storage pit must remain, however, as Ontario’s Nutrient Management Act specifies that each farm must be able to store 240 days’ worth of manure.)

Genesys Biogas Inc. of Ottawa, Ont., is doing most of the design work for the expansion and will assist in the construction. Genesys engineer Benjamin Strehler, who was also involved in the design and installation of the Klaesis’ original digester, says the new digester is similar to the old: continuous flow with twice-daily mixing and heated concrete walls. It will have a retention time of about 50 days, which is about double the original digester.

Manure from the 140 cattle in the dairy barn will continue to be placed into the original digester twice a day. The grease – delivered every three to four days, placed in a 50 m3 in-ground storage tank and pasteurized daily in 13 m3 batches for one hour at 70˚C (158˚F) – will be placed into the old and new digesters in a 1:2 ratio.

The old digester accepts 25 to 30 percent grease and 70 to 75 percent manure while the new one will accept 40 percent grease and 60 percent manure mixture that has already been through the first digester. Because the new digester is four times as large as the original (500 m3 versus 2000 m3), and because it accepts a greater proportion of grease, Strehler says it will be able to produce a whopping 10times more energy than the original. The farm’s 500-kW generator will eventually be replaced with a 2000-kW engine.

In terms of payback for the new digester, Strehler is optimistic it will occur within about seven years. However, this cost-return estimate could be lengthened if the Klaesis have to pay for off-farm waste. Right now, the grease is delivered at no charge by a company called Organic Resources, which is paid to collect it from restaurants.

Strehler admits that while it’s a possibility that digester operators like the Klaesis may have to pay for grease sometime in future, he says “I don’t think it’ll be anytime soon.” He says restaurant wastes present a problem for municipalities whether they process it with sewage or send it to their landfills.

“Grease is a nuisance that a lot of people are glad to get rid of,” he says, pointing out that Klaesis have had inquiries about accepting grease from as far away as Toronto.

Genesys expects construction of at least other two digester projects in Eastern Ontario to proceed this year (dairy and hog) and it could be even more than that, says Strehler.

“There is lots of interest now,” he concludes.

By Tony Fitzpatrick

Engineers at Washington University in St. Louis, Mo., using an impressive array of imaging and tracking technologies, have determined the importance of mixing in anaerobic digesters for

bioenergy production and animal and farm waste treatment.

They are studying ways to take “the smell of money ” – as farmers long have termed manure’s odor – and produce biogas from it. The major end product of anaerobic digestion is methane, which can be used directly for energy, converted

to methanol, or, when partially oxidized, to synthesized gas, a mix of hydrogen and carbon monoxide. Synthesized gas then can be converted to clean alternative fuels and chemicals.

The goal is two-fold; one is to have farms that grow their own energy by using readily available farm waste to power the farm, the other is to eliminate the environmental threat of methane, a greenhouse gas considered 22 times worse than carbon dioxide.

Dr. Muthanna Al-Dahhan, Washington University professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering; his postdoctoral fellow Dr. Khursheed Karim; and his graduate students Rajneesh Varma, Mehuld Vesvikar and Rebecca Hoffman, have determined that mixing is the most crucial step in the success of large, commercial anaerobic digesters that can react 15,000 gallons of manure. In addition to graduate students, numerous undergraduates have contributed to the research.

Dr. Al-Dahhan received a roughly $2.1 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy in 2001 to research anaerobic digestion. Since 2004, he and various collaborators have published no fewer than 16 papers on their anaerobic digester studies, and many will follow. The most recent paper is published in Biotechnology and Bioengineering 100 (1): 38-48, 2008.

“Each year, livestock operations produce 1.8 billion tons of cattle manure,” Dr. Al-Dahhan said. “If it sits in fields, the methane from the manure is released into

Dr. Muthanna Al-Dahhan (left) and graduate student Rajneesh Varma are researching effective ways to take agricultural waste and make biofuel out of it. They found the trick is in mixing and intensity, when it comes to commercial scale reactors.

the atmosphere, or it can cause ground water contamination, dust or ammonia leaching, not to mention bad odors. Treating manure by anaerobic digestion gets rid of the environmental threats and produces bioenergy at the same time. That has been our vision.”

A good mix

There are about 100 anaerobic digesters in operation in the U.S., but a remarkably high percentage — 76 percent — regularly fail. Dr. Al-Dahhan and his colleagues at WUSTL, Oak Ridge National Laboratory and ultimately the Iowa Energy Center based in Ames, Iowa, studied the configuration, design, hydrodynamics and mixing parameters of reactors and their effects on the treatment performance and bioenergy production.

“A systematic study had never been done before, so we wanted to get a notion of what was behind the high failure rates reported,” Dr. Al-Dahhan said. “We tested by gas injection, mechanical agitation, slurry circulation and liquid circulation and at different intensities. We found that, at laboratory scale (four liters), all of the different mixing modes performed adequately.”

They then went to Oak Ridge Laboratory to a pilot plant and tested a reactor that held 100 liters.

“As size increased, we found mixing plays a very important role in successful operations, Dr. Al-Dahhan said. “Intensity of mixing also is important. We found that if intensity of mixing is reduced, failure often is a consequence.”

Anaerobic digestion of manure is opaque, which means to understand the hydrodynamics of anaerobic digestion Dr. Al-Dahhan and colleagues developed a unique computer-automated, multiparticle radioactive tracking (MPRT) system, a novel dual-source gamma ray computed tomography (DSCT), and computational fluid dynamic simulation. These tools allowed the researchers to see where and under what conditions biochemical stagnant — or dead — zones occurred. They also analyzed mixing systems, hydrodynamics, shear effect and reactor configuration.

“We then used all of our knowledge to redesign the commercial digester at the Iowa Energy Center to make an efficient and long-lasting operation,” Dr. Al-Dahhan said.

At WUSTL, Dr. Al-Dahhan and his student Rajneesh Varma collaborated with Dr. Joseph O’Sullivan, a professor of electrical and systems engineering, on developing a new imaging reconstruction

algorithm and program for the developed DSCT. With his student Rebecca Hoffman, Dr. Al-Dahhan collaborated with assistant professor of energy, environmental and chemical engineering Dr. Lars Angenent, on microbiology techniques and measurement of organisms’ distribution.

“The research we’ve done provides the basis to scale up in the future, “ he said. “The process is complex, but we’re seeking to simplify it for use as a quick assessment and evaluation of the digester. The final goal is a simple system ready for use by farmers on site for bioenergy production and for animal and farm waste management.” Sizes from 16 to 34

Dr. Al-Dahhan (right) and graduate student Rajneesh Varma (left) discuss the data.

QuestAir supplying methane purifier for fuel project in California QuestAir Technologies Inc. announced recently that it is supplying an M-3200 pressure swing adsorption (PSA) system to the Biomethane for Vehicle Fuel project located at the Hilarides Dairy in Lindsay, Calif.

Phase 3 Renewables LLC (Phase 3) will integrate QuestAir’s PSA into a plant that upgrades a portion of the biogas generated from the anaerobic digestion of manure at the 9,000-cow dairy in California. Purified biomethane from the Phase 3 plant will fuel three heavy-duty milk trucks that have been outfitted with engines to run on biomethane fuel. The project, which is partly funded by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), is expected to be operational by this fall.

“We are very pleased to be part of this project, the first commercial scale plant in North America to produce renewable biomethane vehicle fuel from agricultural waste,” said Jonathan Wilkinson, president and CEO of QuestAir Technologies.

“California has the largest dairy herd in the U.S., producing nearly 30,000 tons of manure annually. This project demonstrates that this waste can be economically converted to renewable transportation fuel, reducing air and water pollution from manure, while also reducing emissions by replacing diesel trucks that service the industry.”

“This project continues our efforts to expand the markets for farm-based biogas production,” said Norma McDonald, owner and operating manager of Phase 3. “At today’s prices, the plant will produce more than $1 million worth of fuel. We’ve integrated QuestAir’s low-maintenance unit into a system that allows the farm to obtain substantial cost savings versus diesel fuel, while reducing operations and maintenance costs per vehicle.”

By Candace Pollock

A new tool is now available to Ohio pork producers to help them better manage the environment in their livestock facilities, potentially improving production and boosting overall savings.

Ohio State University Extension has designed a ventilation trailer, complete with all the bells and whistles found in typical mechanically ventilated livestock buildings, which simulates various ventilation system scenarios. The idea is to aid producers in fine-tuning their swine building ventilation systems, as well as troubleshooting specific problems.

“Most modern swine facilities depend on mechanical ventilation to make animals as comfortable as possible,” explained Glen Arnold, an OSU Extension educator in Putnam County. “The more comfortable the animals are, the faster they grow and the more productive they are. But it’s easy to lose track of proper ventilation maintenance – to warm the building more or to run the cooling fans longer than need be – or to miss small problems with the system that could be costing a producer money.”

Arnold said that producers could save on utility costs just by improving the efficiency of the system. “Producers can often save $2,000 to $3,000 a year or more in propane expenses just by tweaking the system to make it more precise

OSU Extension plans on offering barn ventilation training opportunities across Ohio later this year.

“We already completed three days of training in January, targeting about 100 pork producers, extension educators and industry personnel,” said Arnold. “We plan to offer additional training sessions throughout the year.”

The training will involve the ventilation trailer, classroom and hands-on exercises plus a training notebook participants can

take home and use in their own facilities

For more information about the OSU Extension ventilation trailer or to schedule a training session, contact OSU Extension swine associate Dale Ricker at 419-5236294 or e-mail ricker.37@osu.edu.

Phosphorous levels in the manure of swine and cattle can be altered by feeding dry distillers grains with solubles (DDGS), according to recent findings by researchers in Minnesota and Iowa.

Research indicates that by adding 20 percent DDGS to the nursery diet of pigs should result in the greatest reduction in phosphorus (P) in manure, if the diet is formulated based on available P.

According to Jerry Shurson, an extension swine specialist with the University of Minnesota, with DDGS, about 90 percent of the phosphorus present is digestible by the pig. Corn contains about 28 percent total phosphorus, and only 14 percent of that is available to the pig. So when DDGS is fed, there is a significant boost in phosphorus levels that are available. Adding a product, such as phytase, will make even more phosphorus available to the pig and reduce the amount of P in manure, Shurson says.

The opposite occurs with feedlot cattle, said Allen Trenkle, professor emeritus of animal science at Iowa State University. Grains contain more phosphorus than forages, he explained, adding that in the feedlot, there is going to be more phosphorus in the manure. Feeding DDGS to growing and finishing cattle fed high-corn diets will result in increased phosphorus excretion, he said.

The situation changes again when feeding DDGS to dairy cows. Lactating cows have a high phosphorus requirement, Trenkle said, which means farmers will need to supply supplemental.

Ag-Chem, an application equipment manufacturer for ag retailers and growers, has enhanced its website: www.agchem.com.

The site now includes a section dedicated to the TerraGator® Nutrient Management System™ (NMS), providing more information on proper application of bio-solid nutrients and the key role it plays in overall nutrient management plans.

The website provides information, photos and downloads on the fully integrated system. It includes the two TerraGator chassis models – the fourwheeled 3244 and the five-wheeled 9205 chassis. The SGIS GTA 500 software measures crop nutrient removals, soil test levels and environmentally sensitive areas to create application maps. The NMS system can then inject bio-solids directly onto grasslands, arable land, small grains and corn stubble with different types of application systems– dry, liquid and spinner – according to the prescribed maps.

“Ag professionals are increasingly being required to more closely manage the use and accounting of applied biosolids and manure,” says Arnie Sinclair, TerraGator NMS sales manager. “The website offers information on the fourstep process the TerraGator NMS uses to accurately apply those nutrients where they are needed in an environmentally friendly fashion.”

The TerraGator NMS handles a wide range of materials including poultry manure, bedding manure, cake biosolids, lime and lime sludge, compost and organic byproducts. The NMS can apply liquid or solid material easily and efficiently, up to 80 feet wide with some systems, and application rates easily adjust from one to 30 tons per acre. www.agchem.com

New multi-purpose disinfectant for swine Activon, Inc. recently released a new

Enivronmental Protection Agency (EPA)accepted disinfectant, EfferSan.

EfferSan is an effective, economical and versatile disinfecting and sanitizing agent designed for use in swine facilities and quarters. EfferSan contains hypocholorus acid, which penetrates cell walls and deactivates an organism’s primary energy-producing functions. When dissolved in water, it creates a mild, skin-friendly solution that eliminates and destroys a broad range of bacteria, even highly resistant strains.

EfferSan effectively disinfects in five minutes against Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, and Salmonella enterica, and will sanitize in one minute against Salmonella typhi on pre-cleaned, hard, nonporous surfaces. While many sanitizing chemicals are harsh on skin and surfaces, EfferSan solution has a near-neutral pH level that reduces irritation. The small four-gram tablet allows easy mixing, handling and storage. The tablets have a nonhazardous DOT rating and a three-year shelf life.

EfferSan is easy to apply and use with no rinsing required after application. Additionally, EfferSan controls odors while leaving no unpleasant odors or harsh residues.

www.effersan.biz

With the high price of today’s fertilizer, even application of manure and sludge is a necessity!

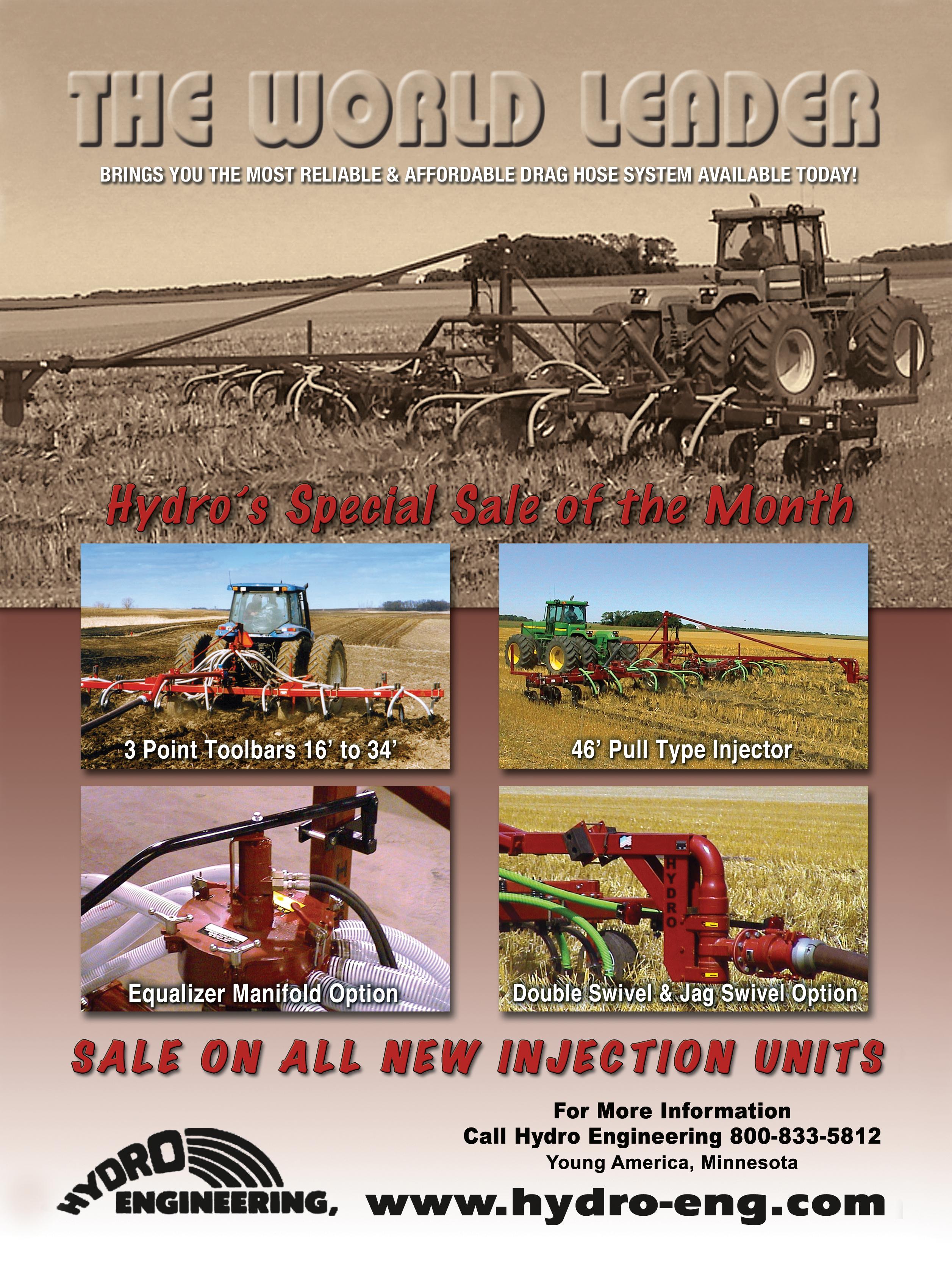

Hydro Engineering’s new PSI Transducer with digital readout head in the cab was developed to give the draghose injection toolbar operator a monitor to measure the manifold pressure reading down to one tenth of a PSI.

Hydro’s Equalizer Manifold requires 3 PSI for even distribution to all toolbar injectors. Tank wagon operators will find this instrument to be beneficial in determining if they have a plugged injector on the toolbar, as the PSI will rise when plugging occurs and a drop in PSI will tell when the tank is running empty.

Hydro Engineering’s new Battery Powered Hydraulic Pack can operate hydraulic valves for load stands that fill tank wagons or semi tankers and operate hydraulic dump valves on pumping units. This hydraulic power pack can be controlled by using a hard-wired push button, FM radio keypad mic or by using small key probe size remote transmitters.

For more information about these products, call Hydro Engineering Inc. at 1-800-833-5812.

www.hydro-eng.com

SEMA Equipment Inc., located in southeastern Minnesota, is the new U.S.

Tired of wasting time and energy running back and forth from the slurry tank to the agitation pump?

Would you like to control the agitation pump from the comfort of your tractor cab and not have to get out in the elements to make those extra trips?

Now you can with REMOTE LOAD! Control your agitation pump with a convenient hand held remote. Just pull your tank under the load stand, push a button and fill. When full, push another button and head back to the field. It’s that simple!

Instead of hiring someone to turn your agitation pump on and off, Get REMOTE LOAD!

It works 24/7 and never takes a break.

•

•

•

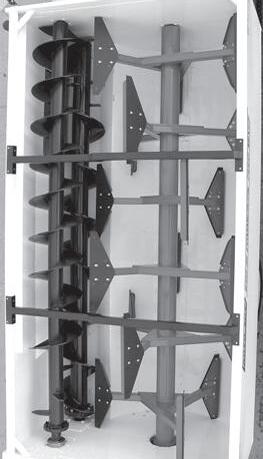

distributor for the Dutch Compost System. Developed by Dutch Industries of Pilot Butte, Sask., the Dutch Compost System is an in-vessel compost system designed to provide an “environmentally friendly” way to dispose of daily hog, poultry, road kill and cattle mortalities. The contained system controls odor, eliminates flies, eliminates leachate and destroys bones in less than a week. It works well year-round.

The system looks similar to a bulk feed bin. The hinged lid on the top of the insulated hopper opens and mortalities and carbon are dumped into the machine, using either a tractor with loader or an optional dump cart lift. When the machine is started, a stirring arm inside stirs and mixes the product. Special “teeth” within the machine destroy the hides and bones and blend the material with the added carbon. The system is designed so more material can be added daily until it is full. The tank can hold from to 3,000 to 5,000 lbs. of mortalities before it is full. When full, it takes about two days for the material to reach pathogen destruction temperature and for the composting process to be complete. At this point, the material can be unloaded with a conveyor for piling or spreading.

Some of the benefits of the Dutch Compost System include:

• Fly control,

• Odor control,

• Bone destruction,

• Discourages rodents and other animals,

• Self mixing (No routine turning),

• Insulated tank provides for year round use,

• Lower cost than incineration,

• Good for neighbor relations

• Environmentally friendly,

• Assists with biosecurity, eliminating the risk of disease spread from rendering trucks, birds and other animals,

• Optional heaters to help frozen materials break down quickly,

• Very easy to operate.

For more information, contact Jim Keune at 507-273-8536 or visit www.dutchcomposter.com.

Octaform Systems Inc., a producer of stay-in-place PVC concrete forming systems, has developed covers for tilt-up and pre-cast panels.

Structures such as barns will have walls with bare concrete exteriors. Octaform’s panel covers will be used as the walls’ interiors. The PVC panel covers are easy to sanitize as well as water and fire resistant, contributing to the optimal health of livestock and excellent preservation of grains. In addition, the finished walls improve lighting conditions by reflecting artificial and natural light.

“Pre-cast and tilt-up structures can now save their owners costs related to cleaning, lighting and maintenance,” said Ryan Bester, Octaform’s director of sales.

Tilt-up panels are formed on the ground at a jobsite, whereas pre-cast panels are formed and then transported to a jobsite. Octaform’s panel covers are made by connecting multiple PVC wall components to form a single cover. Builders can customize the length of their panels by increasing or decreasing the number of wall components.

For both the tilt-up and pre-cast applications, Octaform’s PVC covers are used as bases and cast into concrete panels with a maximum height of 30 feet. When the panels are built, their tops are left bare once the concrete is poured. After the concrete hardens the panel covers stay in place and the panels are tilted into position using a crane. They are then welded on to anchors already embedded in the concrete footing to form a structure’s walls.

The panel covers are available in three colors: white, beige, and light gray; custom colors are available upon request. The panel covers come in three profiles: flat, corrugated and octagonal. Insulation can also be added during construction of the panels to reduce heating and cooling costs.

Octaform Systems Inc. produces PVC stay-in-place concrete forming systems and provides pre-cast and tilt-up panel covers plus cast-in-place forms. www.octaform.com

AGCO Application Equipment Division recently announced HJV Equipment as a representative for Ag-Chem-branded products in eastern Canada.

HJV, which is based in Alliston, Ont., will now be the one-stop resource for RoGator and TerraGator application equipment sales, support and related spraying accessories for custom applicators and innovative growers located in Quebec, Ontario, New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island.

“We’re pleased to be associated with a company like HJV,” says Doug Daws, Ag-Chem director of sales. “As our dealer, they’ll combine our well-known sales team with a complete service offering designed to keep Ag-Chem equipment performing at its peak and maximizing customers’ uptime in the field.”

HJV Equipment has five full-service equipment locations in the company’s coverage area with numerous mobile technicians and overnight parts drop locations to support their customers.

“We’re extremely excited to add the Ag-Chem brand to our agricultural product line. Ag-Chem is a well-known, respected name in the sprayer industry, and we feel it allows us to offer a complete equipment solution to our customers,” says Brian Kennedy, sales manager for HJV Equipment. www.hjv.ca

➤ Manure Pits,Channels & Covers

➤ Suspended Slabs - up to 40’ clearspan

➤ Hog & Cattle Slats - up to 25’ clearspan

➤ Weeping Walls - manure separation

➤ Milking Parlors

➤ Strainer Boxes

➤ Commodity Storage

➤ Bridges

➤ Bunker Silos (8 types)

➤ Syloguard Concrete repair

➤ Retaining Walls

➤ L & T Walls up to 16’

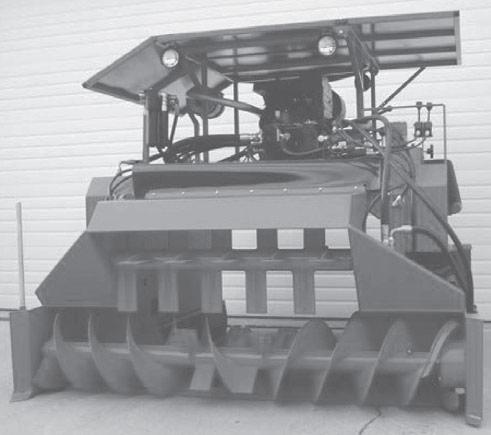

Layer manure can be composted in the pit of high rise layer houses using Brown Bear’s skid steer composting attachments to reduce or eliminate flies, odor and rodents while also reducing volume and moisture from the litter. This leads to ease of transport and ease of land application.

This same equipment can also be used to recycle litter from broiler houses by composting within the house. This system can pulverize, de-cake, sterilize and flash off the ammonia – all in one operation – within a few days time. Flocks do better on recycled composted litter showing less mortality, less blinding, increased feed conversion and increased bird weight at shipping. www.brownbearcorp.com

Backhus North America – a subsidiary of Backhus GmbH – turning solutions for professional composting, waste processing and bio remediation in North America.

Backhus offers a full range of solutions in four product lines:

Backhus Bridge Turner – This is the fully automated plant of the future. The centerpiece of this indoor system contains of a fully automatic turning unit. Based on computers, the flow of material as well as turning intervals are centrally operated. According to demand, the hydraulic bridge sets the turning unit with lowering drum in the right place.

Backhus Lane Turner – Built for the fully or semi-automated plant, this forward thinking waste management is for enclosed applications and indoor plants. The lane turner incorporates the proven plant technology of Backhus and offers high efficiency and turning performance and combines great economy, low maintenance and long life for composting, bioremediation and MSW treatment between lane walls or in tunnels.

Backhus 11.30 – The mobile trapezoid turner, the Backhus 11.30 is based on proven turning technology. This technology was developed in cooperation with universities and industry experts. The Backhus 11.30 meets the highest demands for trapezoidal composting. This turner is a true trendsetter and model of efficiency.

Backhus Windrow Turner – Dubbed the all-rounder, the windrow turner provides solutions for both up start and established operations. It is highly efficient turning in all

materials, utilizes an innovative, “one-hand” joystick and proven turning technology. www.backhus.us

An international marketing office for Sittler Manufacturing, Global Repair Ltd. provides compost equipment for nutrient recovery and soil regeneration, compost additives, consulting and education.

The company’s products provide sustainable solutions for agriculture, municipalities and industry. Global Repair offers compost windrow turners, compost/lime spreaders, trommel screeners, conveyors and baggers.

Technical backup includes a database for compost calculations, easy to follow instructional booklets and DVDs to ensure clients make the highest quality product.

Global Repair’s compost turners are reliable, efficient, economical, low-maintenance, and long-lasting. Extra-hardened, replaceable steel blades are uniquely positioned on the drum to allow for complete blending right to the base of the windrow. Material from the outside is brought inward and from the bottom to the top forming a peak position, allowing the windrow to have a chimney effect for CO2/oxygen flow. An optional nozzle watering system with a removable, folding tow-bar for a water wagon is available for models 507 & 509 and standard with model 512. Other features include: side scrapers that keep the form of the windrow; a swing cylinder to position the tractor close to the windrow; and a folding fleece roller on top of the machine that makes turning the compost and covering the windrow a one-person, one-step operation.

There are three turner sizes for seven-foot, nine-foot and 12-foot wide windrows. The company offers an optional, hydraullically assisted, (HA) model for operations not equipped with a creeper-gear tractor. Technical support, including database calculations and consultations for making quality compost available. All machines come with one-year warranty. www.globalrepair.ca

Midwest Bio-Systems(MBS) has introduced the CleanSweep tine design, further enhancing the results generated by the company’s Advanced Composting System.

Due to a near-concentric edge, the tines rotate the windrows more completely,

resulting in more complete gas exchange and more thorough rotation of the material between “hot” and “dormant” areas of the pile. Additional benefits to the design are lower maintenance and longer life due to reduced, more even, wear.

The improved material handling results in higher, more consistent, fertility content and lower toxicity in the resulting compost.

Midwest Bio-Systems, located in Tampico, Ill., provides its Advanced Composting Systems to customers around the world. Midwest is involved in every aspect of the composting business— building equipment, developing new technologies, consulting, and performing soil application research. www.midwestbiosystems.com

Green Mountain Technologies has taken its in-vessel control technology and created a skidmounted aeration system for Aerated Static Pile (ASP) facilities. The skid comes with blower, dampers and control panel all mounted and ready to connect to aeration plenums and biofilter. The modular skid design minimizes site installation and engineering costs and installs quickly.

The primary aeration control strategy utilizes a variable frequency drive to regulate blower speed to maintain constant duct pressure and minimize energy costs. Secondary aeration control is via zone dampers, which regulate volume of air flow to each ASP zone. The system can operate in either positive or negative aeration modes by manually or automatically switching suction and pressure connections to the blower. Processed air can be recirculated back to the piles or directed to a biofilter for odor control. The system includes a main control panel, field control panel (one for every four zones), and a J-box for each zone with a control damper and two temperature probes. All panel-to-panel communication is digital via Ethernet cable, which minimizes field wiring requirements. Wireless temperature probes are available for sites where cables could interfere with operations.

The ASP process requires no turning and less land area than windrows. First manure is blended with other feedstocks and water added to create a compostable mix. Then the material is stacked on top of perforated pipe sucks air down through the pile to maintain aerobic conditions and minimize odors. Air flow is regulated by computer controller and dampers to maintain sterilizing temperatures. www.gmt-organic.com

Avatar Energy, a renewable energy company with headquarters in Walnut Creek, Calif., has developed the world’s first scalable anaerobic digester to employ a tubular, modular design platform, geared to small-, medium-, or large-scale farms. Expanding the potential of a previously underused economic resource – organic waste – the digester will enable farmers to convert the methane in animal manure and crop residues to biogas energy that can power boilers and generators on the farm, and generate income from “green power” sales. Using a mesophilic plug flow system – the most reliable system in the digester industry – the Avatar anaerobic digester can also create secondary byproducts such as solids for odorless, pathogenfree animal bedding, a phosphorous-rich fertilizing sludge, and nitrogen-rich liquids for direct field application. These products can be used to cut costs on the farm as well as sold to create a stream of income for the farmer. Cost effective with rapid average payback, farmers will receive a five- to 10-year return on their investment in the system, which has a minimum 25-year lifespan. A moveable, non-fixed asset, installation is done above ground and utilizes minimal concrete. Additionally, the system is fully automated, inexpensive to operate, and requires very little maintenance.

Founded in January 2005, Avatar Energy is dedicated to

the development of technologies that increase profitability and sustainability of agriculture, protect the environment, and capture renewable energy. With corporate offices in Walnut Creek, Calif., and an R&D, manufacturing, and demonstration site in Burlington, Vt., Avatar Energy is poised to meet the changing demands of today’s farms. www.avatarenergy.com

The Compo*Starr system is an inline system that can process liquid or solid manure from any animal operation and produce a compostlike material that does not smell and has significant benefits as a soil amendment. The Compo*Starr takes a fresh feed of manure and mixes it with a feed stock of carbon source material such as saw dust or corn stalks to produce the compost-like material. These materials are conveyed through a long pipe, which is equipped with a proprietary auger that continually mixes the material allowing the natural compost conversion process to take place. Following a 72-hour processing time, finished material is available at the opposite end of the pipe. The Compo*Starr system can be trenched in underground, spread directly after being processed or stored above ground. Proper storage above ground will produce a fullfledged compost. The resulting soil amendment possesses most of the benefits of fully aged compost.

The Compo*Starr system will work with any type of animal management operation, including dairy, pork, beef, and equine producers and can be sized to accommodate the needs of varying-sized operations.

Gary Showalter – 866-540-7575

Donald Northcutt – 816-436-7666

Resource Recovery Systems of Nebraska, Inc. (RRSN) is a family owned corporation founded in 1976 specializing in activities associated with organic waste composting. The company sells new and refurbished KW self-propelled, straddle type windrow turners and leases turners for composting projects and bioremediation of explosive and oil contaminated soils. RRSN began operations by custom composting at cattle feedyards and operated a composting and bagging operation at

a terminal livestock market for more than 15 years.

KW models range in tunnel size from 5’ x 10’ to 8’ x 20’ with a range of engine horsepower from 200 to 600. Various options are available which include belt driven, clutch engaged drums, hydraulic driven drums, several tire sizes full tracks and 4-wheel drive. Engines are Caterpillar, Cummins or John Deere. KW composters have excellent residual and trade-in value.

Consulting services are offered for domestic and international projects. Teaming with an engineer is often very important. Projects include troubleshooting, revitalizing existing plants, designing the compost segment of the facility, problem solving and feasibility studies. www.rrskw.com

Industrial Telemetry Inc.’s patented BioMESH™ and BioMESH PLUS™ radio-based compost systems are designed to provide temperature information from compost windrows either on demand or on a scheduled basis. When used with the SCADA MESH™ board attached to the fan, the system is completely self-contained and can run autonomously.

The BioMESH probes have up to three thermistors in the shaft to give temperatures at different levels in the piles or windrows. SCADAMESH has a PLC on a chip, a processor and memory, and a MESH radio. The PLC is programmable via the radio network either locally or remotely via the Internet. The probes are battery powered while SCADAMESH is line powered using 12VDC. The system can output to any other system via either comma delimited format or XML.

www.industrialt.com

The latest addition to the MMI International line of heavy-duty commercial spreading products is the V-Bottom Compost Spreader. Like the MMI Commercial Manure Spreaders, the V-Bottom Compost Spreader is built tough for commercial use.

The V-Bottom Compost Spreader line features:

• All hydraulic drive with cab mounted variable control for the spinners and floor chain.

• Heavy Duty D88 Floor Chain

• Extra heavy-duty construction featuring 10 ga sides with tapered stakes and reinforced top rail.

• One-inch thick, corrosion and freeze resistant Poly Floor that provides extended wear and reduces commodity drag.

• Product capacities from 24.5 cubic yard to 35.7 cubic yard

• Infinitely variable spread patterns for all types of application needs.

• Adjustable rear door for variable product delivery.

• Hydrostat, PTO or tractor hydraulic power options available

V-Bottom Spreaders are available in truck, trailer or gator mounted configurations to accommodate all types of spreading requirements. www.mixerfeeders.com

The Wright composting system uses a system of fully enclosed, flow-through tunnels to transform organic wastes, such as agriculture byproducts and other organic wastes, into a soil-like material in a short time period, by controlling oxygen and moisture levels, reusing leachate and filtering exhaust air.

The Wright continuously loading systems represents the smallest possible footprint. The modular design provides maximum flexibility in siting tunnels and accommodating future waste quantities.

• Features include:

• Proven technology,

• Rapid thermophylic composting,

• Sequential loading and flow-through operation,

• Zero leachate discharge,

• Containment and treatment of all exhaust air,

• Automatic material and tray/floor advancement,

• Automatic control of airflow, temperatures, moisture and oxygen,

• Maintenance of oxygen levels above 15 percent and temperature levels within set point ranges. www.wrightenvironmental.com

The X-Act System composter monitors and maintains the critical elements of the composting process within ideal range; therefore, composting occurs at the fastest rate possible with the rotating vessel doing all the work. Because the guesswork inherent in traditional composting operations is eliminated, the compost produced is superior quality consistently.

In-vessel composters by X-Act Systems are large, robust rotating drums that compost huge volumes of organic waste

Features include: