Published bi-annually by the United Architects of the Philippines

UAP National Headquarters Building, No. 53 Scout Rallos St., Barangay Laging Handa, Quezon City, Metro Manila 1103

UAP is not responsible for statements, views or opinions expressed in Arquitektura , nor do such statements necessarily represent the views of UAP , unless otherwise stated.

PDC Director

Joan S. De Leon- Tabinas, UAP

Publication Committee

John Lemuel G. Llacuna, UAP

John Immanuel R. Palma, UAP

Editorial Team

Diana A. Cabales, UAP

Kristy Marie O. Lagamon, UAP

(Photo: Ar. Jason Buensalido) On the Cover: Pangasinan Barangay Centers

Creatives, Media and Information

Michaela Y. Constantino, UAP

Fresca Adeline G. Colisao, UAP

Roseller P. Junsay Jr., UAP

Ways and Means

Ariel A. Tabang Jr., UAP

Contributors

John Immanuel R. Palma

Dr. Adolph Vincent E. Vigor

John Lemuel G. Llacuna

Arjay John Secugal

Deo Alrashid Trevecedo Alam

Jason Buensalido

Grendelle Joshua Basa

Joevic O Mondejar

Elritz Gallo

Keisha Plaza

Jon Medalla

Mark Pintucan

Gerald Harayo

Jankin Davies Y. Go

Welcome to the third issue of ARQUITEKTURA, the official trade journal of the United Architects of the Philippines! This issue delves into the heart of every architectural journey: Concept Creation

We often marvel at the finished structure, but the magic truly begins with a spark of inspiration. This issue celebrates that spark, showcasing the thought processes, inspirations, and innovative strategies employed by Filipino architects during this crucial, sleepless yet magical moment of every design project.

Our Creative Team focused on providing a platform that resonates. And we are proud to present thirteen (13) exceptional Filipino architects and their design teams from Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. They embody the very essence of concept creation—pushing boundaries and positively shaping our Nation’s built environment in varying scales.

Through insightful articles and captivating visuals, you’ll gain a window into their creative minds. Discover where they find inspiration, the tools they utilize, and the challenges they navigate to transform initial ideas into groundbreaking designs. Each architect’s journey is unique, and each story offers valuable lessons for aspiring and established professionals alike.

ARQUITEKTURA showcases the heart of the Filipino Architects. This third issue is the heartbeat of the UAP Professional Development Commission (PDC). And the testament of UAP’s dedication to support and celebrate the progressive architects and inspire the aspirants.

Libraries as Models of Architectural Adaptation

John Immanuel R. Palma

Enhancing Spatial Intelligence in Architecture Education

A Digital Leap Forward

Dr. Adolph Vincent E. Vigor

Architects in Education

Nurturing Future Builders Through Mentorship and Innovation

John Lemuel G. Llacuna

Rooted in Identity, Soaring in Creativity

The Power of Architectural Design Concepts

Arjay John Secugal

Bongao Municipal Hall

Deo Alrashid Alam

Pangasinan Barangay Centers

Jason Buensalido

Island Agora

Community Center

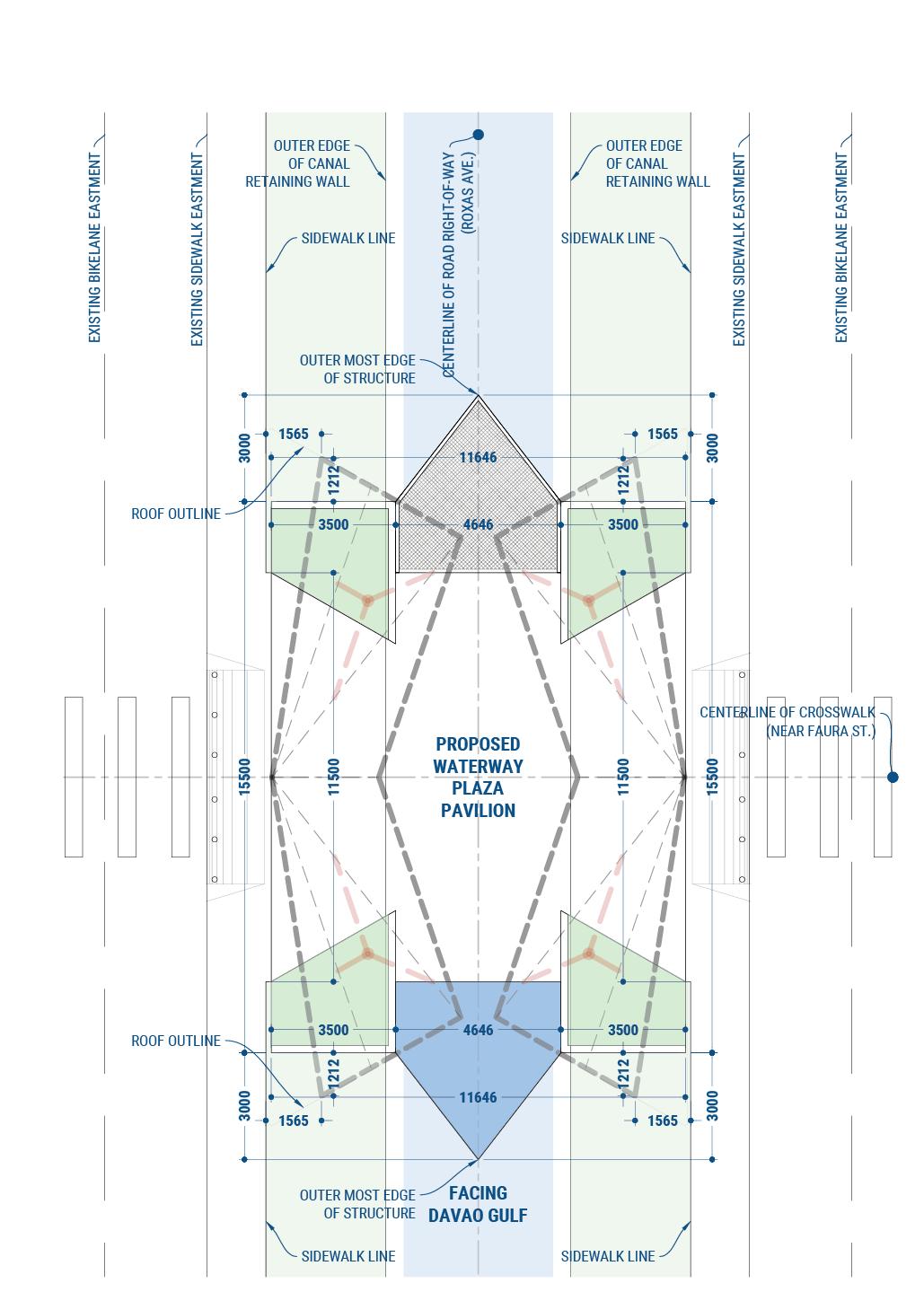

Jon Medalla

Proposed Two-Storey

MicroHouse “Concept Creation” in the Architectural Process

Grendelle Joshua Basa

Mark Pintucan

Re-envisioning Community and Faith

Joevic O Mondejar Elritz Gallo

Jankin Davies Y. Go

John Immanuel R. Palma

A dynamic professional in architecture, urban design, and landscape studies, he graduated Magna Cum Laude from the University of Santo Tomas with a Master’s in Architecture-Urban Design. Holding a Graduate Diploma in Landscape Studies from the University of The Philippines Diliman, they bring over a decade of experience as a Part-Time Instructor at Ateneo de Davao University and served as Chapter President for UAP Kadayawan-Dabaw, showcasing a commitment to industry progress. His expertise extends to notable projects in campus and library design, including the acclaimed Davao City Library and Information Center.

Adolph Vicent E. Rigor

A renowned academic and professional in architecture and technology education, with a distinguished career marked by scholarly excellence and practical expertise. Holding a Doctorate in Technology Education from the University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, he excelled with a remarkable GPA of 1.03. His doctoral research made significant strides in enhancing spatial intelligence among architecture students through a web-based interactive module.

As a Chartered Architect with the Royal Institute of British Architects, Dr. Vigor demonstrates his commitment to professional excellence. His credentials extend to being a registered and licensed architect, as well as a qualified Real Estate Broker and Real Estate Appraiser. His academic foundation is solid, with a Bachelor’s degree in Architecture from Mindanao Polytechnic State College and a Master’s degree in Project Management with Merit from the University of Liverpool. Dr. Vigor’s contributions to academia are noteworthy, with published scientific journal articles that explore various facets of architecture education. His research topics range from assessing interactive spatial intelligence modules for first-year architecture students to examining the use of statistical quality control charts in construction projects. He has also delved into the burnout and life satisfaction levels of architecture faculty during the COVID-19 pandemic and investigated the sentiments of fourth-year architecture students on the use of computer-aided design tools. His work not only advances the field of architecture education but also addresses contemporary challenges and leverages technology to enhance learning outcomes.

Ar. Deo Alam grew up in Zamboanga City, Mindanao, in the southern part of the Philippines. He moved to Manila for his tertiary education, graduated in 2006, and was certified as an architect in 2010. He has since practiced architectural design under the big names in the local architecture industry and led his own partnership firm. But starting his own company, Deo Alrashid Alam Design Architecture, is what represents him as an architect. Stakeholders have described his works as “bold creations that challenge the norm, and seek to define new standards of practice in architecture design build.”

Jason Buensalido is the Principal Architect and Chief Design Ambassador of Buensalido Architects and Barchan Architecture and Design. Both design firms that are committed to introduce fresh, bold, innovative yet contextual concepts to the Philippine design setting.

Along with his team, he bears the torch in contemporizing Filipino architecture and the local design scene with the goal to bring the nation global, by staying true to our identity. His company veers away from the conventional and com-mon, infuses function and innovation in all its creations, ultimately breathing new life into traditional design models and methods. It challenges and stretches the possibilities of design context in the Philippines.

Moreover, he hopes to bring positive change to the nation, communities, people’s lives through architecture - directly through his firm’s projects, and indirectly through multiple educational platforms that he is involved in such as a yearly design festival called B+Abble and a review center for the built environment called Foundree.

He is an alumnus of the University of Santo Tomas College of Architecture, as well as the Architectural Association Global School. He placed first in the Architectural Board Examination in 2005. Architect Buensalido also graduated as a Gold Medal Awardee for the Ateneo Graduate School of Business in 2014, is a Certified User Experience Practitioner by the British Computer Society, and was conferred as an ASEAN Architect in 2019.

Aside from his day-to-day projects, his firm has garnered several awards in multiple national and international competitions, such as Nayong Pilipino Cultural Park (Nayong Pilipino Foundation, 2002), Cultural Center of the

Philippines Masterplan (CCP and NCCA, 2005), Millennium Schools (DepEd, 2008), Pinakamagandang Bahay Sa Balat Ng Lupa (U.P. and La Farge, 2008), and a shortlist for the Design of the Artists Center and the Performing Arts Center for the Cultural Center of the Philippines in 2010.

In 2014, he wrote and published a book called ‘Random Responses: A Crusade To Contemporize Philippine Architecture’, a compendium of the firm’s past, future, built, unbuilt, small, and large scale projects, which is also his and Buensalido Architects’ “love letter” for Philippine architecture, which the firm believes still holds great relevance amidst the thematic, foreign, and non-contextual architectural styles in vogue in the country today. He has also recently used this understanding of design and space into visual art and sculpture, often exploring parametric patterns and phenomena of nature. He translates these into sculptural abstract forms that communicate the same essence of these phenomena, often extracting clues, learning, and questions from them, on how humanity can attain a sustainable existence.

In 2018, Buensalido+Architects was recognized as one of the T&C Design 50: Manila’s Top

Architects and Interior Designers by Town and Country Magazine; and has recently received the most nominations for multiple categories under the Kohler Bold Design Awards, while winning the award for the Culture Category thru APT Studios, a TV Studio in Marikina. They also won the grand prize for the M.A.D.E. (Metrobank Arts and Design Excellence) Awards for Commercial category for The Terraces at Dao, a company headquarters of a lighting equipment rentals business that sparkplugged the upliftment of the immediate community. Both awards were chosen among numerous submissions from design firms from all over the country, a sign that Philippine Architecture is yearning for a new direction toward positive change.

In 2019, he was included in the Generation T List 2019, an annual media platform organized by Asia Tatler and Philippine Tatler that connects, educates, and recognizes young leaders shaping Asia’s future.

In 2020, Buensalido+Architects was recognized as one of the Best Architects in the Philippines by Esquire Philippines.

In 2021, his firm had seven projects - the most projects to be nominated for the People’s Choice Awards for the Haligi Ng Dangal Awards organized by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts, reinforcing the relevance of their work in finding contemporary ways to showcase the Filipino Identity in Architecture.

In the same year, two of his projects got shortlisted in the World Architecture Festival - The Freedom Memorial for Futures Category - Competition, and The Interweave for Built CategorySchools and in the Best Use of Color Category. The Interweave received a ‘Highly Commended’ citation for both categories.

In 2022, B+A will evolve into Barchan Architecture - a new and more mature design collective,

structured to tackle larger and more significant projects, while still maintaining the heart and DNA of Buensalido + Architects.

In 2023, he was an awardee for Filipino Architecture during the Italian Design Day organized by the Italian Embassy and Philippine Italian Association. In the same year, his project - Pangasinan Barangay Centers - was shortlisted in the World Architect Festival for Future Project - Civic Category and won the WAFx Future Project Award for Ethics and Values.

UAP (United Architects of the Philippines), Asean Architect (AA), CBP (Certified B.E.R.D.E. Professional), AIA (American Institute of Architects), ME (Master of Entrepreneurship)

design@buensalidoarchitects.com www.buensalidoarchitects.com www.barchan.com.ph

Elritz Gallo

He is an architect with a diverse background including urban and regional planning, creative and technical writing, and project management. Currently, he serves as a key member of a dynamic team pioneering smart and creative city assessment metrics. He prefers his coffee with oat milk and sugar. He has a cat named Kai from the Japanese word “Kaizen” which means “continuous improvement”.

Jon Medalla

Jon Medalla is an architect, designer, entrepreneur, and artist based in Cebu City, Philippines. He has a Bachelors degree in Architecture from the University of San Carlos as well as special degrees from the HAN University and art-EZ University in the Netherlands. Jon founded his studio Prototecture in 2019 but still collaborates and works closely with his family’s architecture firm, Arkinamix, headed by his father and mother, Ar. Alex and Ar. Janet Medalla, and partner Ar. Ryan Rasines. Prototecture is a studio dedicated to the practice of essential design that is connected to nature, people, and the city. In 2023, Jon founded the industrial design studio, Grasscraft, which focuses on progressive bamboo furniture and product design.

Jon is an advocate of the solarpunk movement that envisions a world in which nature and technology come together in a holistic way to address the concerns of our current global condition and changing climate. Heavily influenced by eastern philosophy, Jon sees architecture and design as not just merely a medium of self-expression but as a sacred service and an act of transcendence. By deeply looking into the systems of nature, people, and our cities, Jon endeavors to manifest a more conscious built environment that doesn’t just perform better but that is greener and happier too.

When he isn’t designing, Jon is also a painter, an event organizer, and DJ (under the pseudonym Jon Meds) , as well as an advocate and participant in Cebu’s emerging creative scene.

Gerald Harayo

A graduate from the University of Mindanao College of Architecture and Fine Arts Education with the best thesis in his batch, Architect Gerald Canoy Harayo embarked

on a journey marked by quiet determination and unwavering commitment. His projects, ranging from commercial showrooms to residential buildings, reflect his keen eye for detail and his deep understanding of architectural principles.

Despite his accomplishments, Ar. Gerald C. Harayo remains grounded, never seeking the spotlight but rather focusing on the work itself. As an educator at the University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, he instills in his students not only the technical skills of architecture but also the values of humility and integrity.

Ar. Harayo is deeply engaged in architectural education and community development. As an esteemed faculty member at the University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines (USTP), he imparts his knowledge and passion to the next generation of architects. His previous roles as a department coordinator and currently the moderator of the United Architects of the Philippines Student Auxiliary USTP Chapter exemplify his dedication to fostering a culture of excellence and nurturing young talent within the academic sphere. During the academic year 2021–2022, Ar. Gerald C. Harayo, received the Student’s Recognition of Excellent Teaching award, which is given to USTP faculty members who have received exceptional performance ratings based on student assessments.

Ar. Gerald C. Harayo’s involvement in professional organizations such as the United Architects of the Philippines (UAP) CDO - Bay Area Chapter and the PIA Greater Davao Section and used to be a member and officer of Uap Kadayawan-Dabaw Chapter is a testament to his commitment to his profession and his community. His active involvement in these associations underscores his dedication to advancing

the architectural profession and promoting sustainable development practices. Speaking of sustainability, Ar. Harayo practices what he preaches. Currently pursuing a Master of Science in Sustainable Development, major in urban planning and sustainable development, he is committed to shaping a more environmentally conscious future through his work. Ar. Harayo devotes his free time managing the ARCHITECT STUDIO Facebook page and YouTube channel, where he explores various locations and architectural structures throughout Asia and the Philippines and shares his knowledge and ideas with a larger audience. Through his videos and posts, he seeks to inspire others and promote sustainable design and architecture, all with a humility that is characteristic of his approach to life.

Ar. Gerald Canoy Harayo may not be one to boast about his achievements, but his impact on the world of architecture and beyond is immeasurable. He is a shining example of how humility, dedication, and passion can lead to success, both professionally and personally.

In the words of Ar. Harayo himself, “Students must design as if the sky’s the limit.” It’s a philosophy that encapsulates his approach to architecture—pushing boundaries, embracing innovation, and striving for excellence at every turn.

Joevic serves as the Principal Architect, Planner, and Founder of Mondae Studio, their project portfolio currently includes Resort Planning, Residential Design, and various Master master-planned developments. Currently, he’s been involved with Bamboo Bootcamp, an organization that promotes awareness of bamboo propagation and its sustainable applications in construction. Outside of work, Joevic finds solace in spending his leisure time at the beach or anywhere with nature.

An individual who seamlessly bridges the worlds of architecture and writing. As the committee Cochairperson of UAP Publications and a dedicated Faculty Member at the National University College of Architecture, John intertwines his passion for design with the art of expression. Viewing architecture and writing as interconnected forms of art, he draws inspiration from the symmetry between structures and words. During his formative years, John nurtured his talent by crafting poems and short stories, a journey that has solidified his belief in a destined future as a writer.

Arjay John Barredo Secugal is a Registered and Licensed Filipino Architect and Master Plumber specializing in Tropical Landscape Architecture. He is currently an Assistant Professor in the undergraduate programs of National University- Manila, College of Architecture. He took his undergraduate studies in Bachelor of Science in Architecture at Adamson University- Manila where his research dwelt on the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) Complex—the proposal focused on providing spaces for training and job opportunities for Filipinos. Then he also pursued his Graduate Diploma in Landscape Studies and Master’s Degree specializing in Tropical Landscape Architecture at the University of the Philippines- Diliman. In his practice as an Architect, a Master Plumber, a researcher, and a professor, he became an experienced project and construction manager who worked with several fields and industries here in the Philippines and abroad. Currently, he is also the Owner and Principal Architect of A.S. Building Design Services, a design studio that offers a wide array of services related to architectural design & consultancy, site planning, interior fit-outs, plumbing design services, quality assurance & control services, and project management services.

Organizations:

• United Architects of the Philippines

• National Master Plumbers Association of the Philippines

• International Federation of Landscape ArchitectsYoung Landscape Architects Alliance

Jankin Davies Y. Go

Born and raised in Davao City— introverted in nature but a keen observer who communicates best in diagrams and drawings.

Architecture and design have always been his passion even before becoming a professional. He travels to learn and learns to have fun. A big coffee lover and sci-fi enthusiast. A graduate of Ateneo de Davao University and an ALE Top-notcher (Top 7). Go briefly rejoined his alma mater as a teacher but now a full time architect—focusing on his own design studio (and family) alongside his architect-wife.

Grendelle Joshua Basa is an architect focused on creating intimate spaces and delivering total brand experiences. A graduate of Ateneo de Davao University with a degree in BS Architecture, he has established a multidisciplinary practice in Davao City under the name Basa Architecture and Design Practice (BADPRACTICE).

His practice, BADPRACTICE, is a young studio, driven by a commitment to purpose and experience. He combines his architectural expertise with a keen understanding of brand identity to craft spaces that resonate with people on a deeper level. You can usually find him brainstorming ideas or sipping coffee in various local coffee shops around Davao City.

By John Immanuel R. Palma

Historically, libraries have been vessels for concept creation as it is a perfect space for ideas to ferment, collide and evolve. The library does not only function as instruments for the transmission of knowledge, but it is also where new ideas are birthed, and existing ones refined. Libraries are also bastions of community building. Their diverse offerings and communal spaces are intrinsic to community building. They transcend their role from mere repositories of information, bastions of quiet contemplation and individual study, to vibrant hubs where individuals and groups converge, ideas are exchanged, and community bonds are forged.

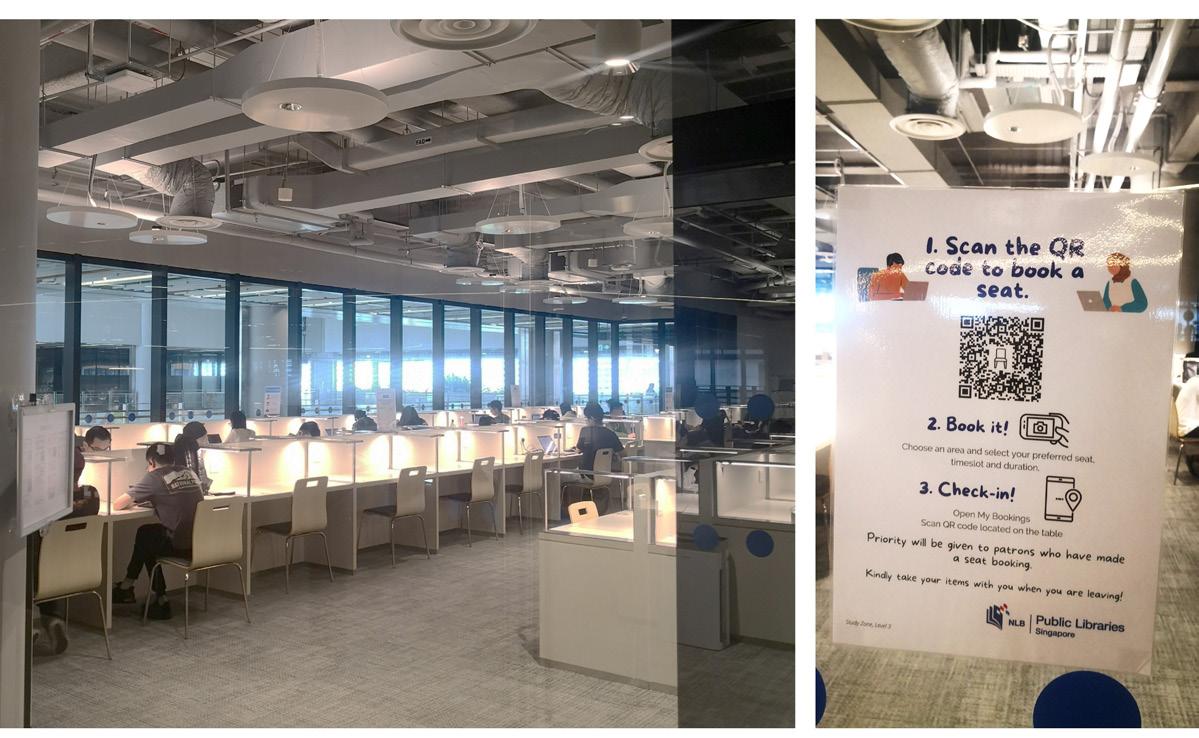

During the wake of the global pandemic, architecture has undergone a transformative paradigm shift, and this included the evolution of libraries. Traditionally resistant to rapid change, libraries have metamorphosed into dynamic spaces that prioritize safety, accessibility and the integration of innovative technologies. Architects, designers and librarians, grappling with the challenges posed by pandemic restrictions, undertook a comprehensive reimagining and review of library spaces to accommodate both in-person and remote users seamlessly. This metamorphosis is most conspicuous in the seamless integration of Hyflex capabilities, propelling these institutions into the forefront of adaptability, responsiveness, and inclusivity.

The safety and welfare of the library patrons and staff were the primary concern during the global pandemic. Beyond social distancing measures, libraries incorporated touchless technologies and automated systems for book checkouts. Automated kiosks equipped with RFID technology allow users to borrow and return books without physical interaction. This not only streamlines the borrowing process but also contributes to the overall safety of library spaces. Rigorous cleaning protocols were implemented, and spaces were reconfigured to allow for easy cleaning and maintenance. Contactless systems are indicative of libraries adapting to modern technological trends while prioritizing the health and well-being of their users.

John Immanuel R. Palma

The concept of a library as a haven has been amplified. Libraries are not only adapting physically to reduce health risks but also becoming centres for disseminating information about health and safety. Architectural changes, such as the creation of dedicated information kiosks and the integration of health and safety signage, reinforce the library’s role as a responsible and informed institution.

The architectural response to the pandemic goes beyond physical changes; it encompasses a comprehensive shift toward digital resources. Libraries have expanded their collections of e-books, online databases, and virtual research tools. These digital reservoirs are not mere supplements but integral components of the library experience.

The architectural transition toward a digital pivot involves reimagining storage spaces for physical collections and allocating more space for server rooms and data infrastructure. Architects and librarians collaborate to create an environment where users can seamlessly navigate between physical and digital realms, ensuring that the library remains a relevant and dynamic space.

The integration of Hyflex capabilities represents a paradigm shift in library architecture. This model, seamlessly blending in-person and online learning, has become an integral part of the architectural blueprint. Library spaces are now equipped and/or embracing cutting-edge technology to facilitate synchronous learning experiences. Collaborative zones feature interactive

screens, video conferencing facilities, and robust Wi-Fi, ensuring that students attending remotely can actively participate in group projects and discussions.

This deliberate fusion of physical and virtual learning spaces extends beyond the classroom. Libraries are redefining themselves as hubs of continuous learning, offering workshops and training sessions on digital literacy and virtual collaboration. The aim is to equip students, faculty, and researchers with the skills necessary to navigate an increasingly digital educational landscape.

Recognizing the diverse needs of its users, library architecture also embraced the concept of individual study rooms. These secluded spaces provide an environment conducive to focused study and contemplation. Equipped with ergonomic furniture, soundproofing, and advanced lighting controls, these rooms cater to those seeking solitude in the pursuit of knowledge. The incorporation of individual study rooms underscores the commitment of libraries to provide personalized learning experiences.

Library architecture is no longer static; it is dynamic, evolving, and responsive. Spaces within libraries are now designed with adaptability in mind. The goal is to create spaces that can easily be reconfigured to meet the ever-changing demands of technology and educational methods.

Libraries are now incorporating modular furniture, movable partitions, and flexible layouts. The oncerigid shelving systems are giving way to designs that can be easily reorganized to accommodate new

collections or create collaborative spaces. The emphasis on flexibility extends to technology infrastructure, with easily upgradable systems that can seamlessly integrate new advancements without major disruptions.

Libraries have transitioned from being repositories of knowledge to becoming active participants in the educational journey. Spaces within libraries are now designed as training grounds, offering workshops and tutorials on navigating the digital realm of resources. Architecture supports this shift by providing dedicated spaces for workshops, equipped with the latest technology for hands-on learning experiences.

The training spaces within libraries are not limited to technological literacy alone. Libraries are expanding their role in providing broader educational support, including academic skills workshops, research methodologies, and even soft skills development. The architecture supports the creation of multifunctional spaces that can adapt to diverse educational needs. The concept of maker spaces in libraries has also gained prominence. These collaborative areas are equipped with cutting-edge technology such as 3D printers, laser cutters, and other tools that empower users to engage in hands-on, creative endeavours. Maker spaces embody the library’s commitment to not only information consumption but also active knowledge creation. They are testament to the library as a dynamic hub for innovation and collaborative learning.

John Immanuel R. Palma

As architecture propels libraries into the future, these institutions stand not just as repositories of knowledge but as active participants in the educational journey. The response to the pandemic has been transformative, turning libraries into safe spaces that embrace technological innovation. The incorporation of Hyflex capabilities ensures that libraries are not only resilient in the face of unforeseen challenges but are also at the forefront of creating inclusive learning environments. This marriage of safety and technology positions libraries as harbingers of change in the broader landscape of architectural adaptation to the demands of the 21st century. The evolution of library architecture is an ongoing narrative, a testament to the resilience and adaptability of these institutions in the face of unprecedented challenges. In essence, libraries, as architectural entities, are not just adapting; they are thriving as crucibles of knowledge, community, adaptability, and innovation.

This article serves as an adaptation of a keynote presentation delivered by the author at the 15th DACUN Phil-BIST Conference and Fair. The presentation, titled ‘Evolving Library & Information Spaces as Safe Cocoons for Post-Pandemic Hyflex Modality,’ took place in Davao City last August 2023.

By Dr. Adolph Vincent E. Vigor

In the evolving landscape of architecture education, the integration of digital tools and innovative teaching methods is becoming increasingly crucial. Traditional approaches, heavily reliant on manual drafting and design, are gradually being overshadowed by the industry’s shift towards more advanced technologies like Building Information Modeling (BIM). This transition is particularly relevant for students in the Philippines, where the architecture curriculum has historically emphasized manual techniques for an extended period, potentially putting students at a disadvantage in a rapidly digitizing global industry.

One of the critical skills in architecture that has been identified as a crucial determinant of success in the field is spatial intelligence. This ability allows architects to visualize and manipulate three-dimensional objects and spaces in their minds, a fundamental aspect of design and problem-solving in architecture. Given its significance, there is a growing need to enhance spatial intelligence among architecture students to better prepare them for the demands of the profession.

Addressing this need, Dr. Adolph Vincent E. Vigor together with Dr. Sarah O. Namoco of the University of Science and Technology of Southern Philippines, and Dr. Mohd Bin Mohd Issa of the Universiti Sains Malaysia as advisers, conducted a study titled “Development, Implementation, and Assessment of the Web-Based Module to Enhance the Spatial Intelligence of Architecture Students.” The research focused on the development and assessment of a Web-Based Interactive Spatial Intelligence Module (WBISIM) designed for first-year architecture students. This innovative module, leveraging the capabilities of SketchUp, aimed to enhance students’ spatial intelligence by providing interactive, three-dimensional visualizations and exercises.

Dr. Adolph Vincent E. Vigor

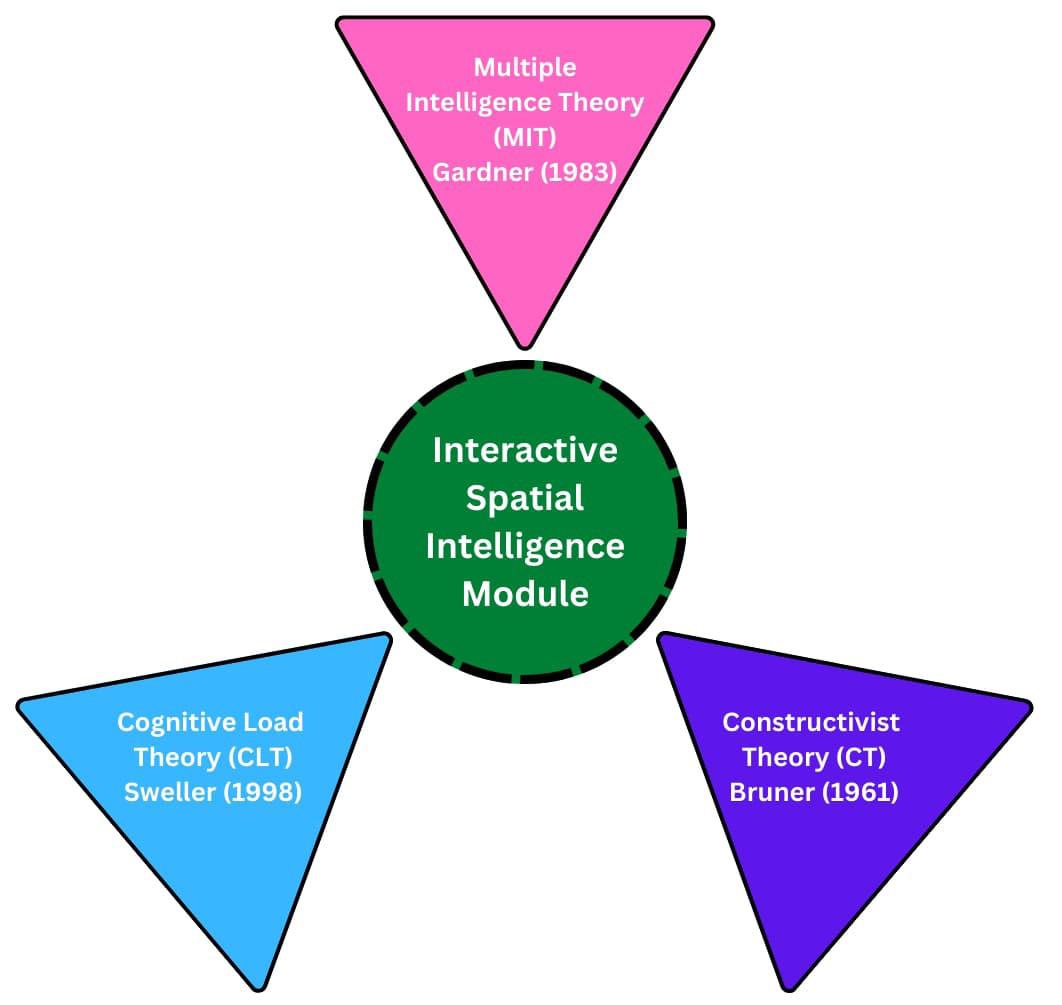

The study’s conceptual framework was grounded in three key theories: the Multiple Intelligence Theory, the Constructivist Theory, and the Cognitive Load Theory. These theories collectively underscore the importance of spatial intelligence in architecture and the potential of digital tools to reduce cognitive load, thereby facilitating a more effective learning experience.

The Multiple Intelligence Theory posits that there are eight types of intelligences, with spatial intelligence being one of them. Spatial intelligence is defined as the ability to generate

and manipulate mental images to solve problems. This type of intelligence is crucial in architectural design, as it supports the effective communication and evaluation of design ideas. High levels of spatial intelligence are required in architecture and other STEM disciplines to understand and create solutions in three-dimensional space.

The Constructivist Theory emphasizes that students construct their understanding of the world through experiences and reflection. In the context of architectural education, this theory supports the use of 3D images and models in teaching, making the design studio work collaborative, interactive, and process oriented. Engaging students in mental rotation activities, a core aspect of improving spatial intelligence, enhances their spatial understanding and creativity.

The Cognitive Load Theory is based on the idea that working memory can handle a limited number of simultaneous activities. It distinguishes between three types of cognitive load: intrinsic, extraneous, and germane. Intrinsic load is related to the inherent difficulty of the subject matter, extraneous load results from the presentation of information, and germane load pertains to the processing of new information into long-term memory. The theory suggests that cognitive load is significantly reduced when information is presented in a 3D format rather than a 2D form. Therefore, introducing 3D exercises and activities can greatly diminish the cognitive load on students, allowing for faster assimilation of information, which is crucial in architectural design studio work.

The WBISIM was meticulously designed to provide an immersive learning experience for students. It included a series of activities and exercises which lasted for 9 weeks that allowed students to interact with three-dimensional models and visualizations. For instance, in one of the module’s activities, students were shown rotating three-dimensional figures of architectural designs, such as a beach house or a modern residential building, along with their sun-path diagrams in 3D. Students were encouraged to explore these models in-depth, manipulate them, and compare their dimensions to human scale using the web-version of SketchUp integrated into the module.

This hands-on approach to learning, facilitated by the WBISIM, enabled students to actively engage with the material, moving beyond passive listening to actively doing. By allowing students to interact with objects from different perspectives and manipulate them as per the instructions given in the module, the WBISIM effectively became the center of learning, with the design instructor acting as a facilitator.

The study’s findings were promising. The experimental group, which used the WBISIM, showed a higher and more equal distribution of improvement in spatial intelligence levels and midterm grades compared to the control group, which followed conventional studio lectures. This improvement was statistically significant, with an ANCOVA result indicating a p-value of less than 0.001. Furthermore, thematic analysis of the experimental group’s responses revealed that the module was beneficial in enhancing their spatial visualization skills, crucial for their design courses. The experimental group, which used the WBISIM, exhibited a significant improvement in spatial intelligence and academic performance compared to the control group, which followed conventional teaching methods. This improvement was not only statistically significant but also reflected in the students’ enhanced ability to visualize and solve design problems.

Conclusion

The study conducted by Architect Vigor represents a significant step towards modernizing architecture education in the Philippines. By embracing digital tools like the WBISIM, educators can equip students with the necessary skills to thrive in a technology-driven industry. This research not only highlights the significance of spatial intelligence in architecture but also sets a precedent for integrating digital interventions in educational curricula to enhance learning outcomes.

By John Lemuel G. Llacuna

In the dynamic realm of architecture, education serves as the cornerstone upon which the profession’s future is built. With their wealth of knowledge and expertise, architects play a pivotal role in shaping the minds and talents of aspiring designers and builders. This article delves into the profound impact of architects engaging in education, exploring the multifaceted benefits, challenges, and the call to action for architects to embrace their role as educators.

John Lemuel G. Llacuna

Education, synonymous with knowledge and innovation, is fundamental to every profession, including architecture. As stewards of the built environment, architects possess a unique responsibility to pass on their wisdom and experiences to the next generation. Through education, architects continue the legacy of architectural excellence, fostering a culture of continuous learning and evolution within the discipline.

Engaging in teaching offers architects a plethora of personal and professional benefits. It catalyzes constant learning, exposing architects to fresh perspectives and novel approaches within the field. Moreover, teaching cultivates essential skills such as leadership, communication, and mentorship, enriching architects intellectually and emotionally.

Furthermore, the flexible nature of teaching allows architects to strike a harmonious balance between their professional commitments and personal aspirations. By investing in education, architects leave a legacy and contribute to the profession’s advancement and innovation.

Architects wield significant influence in shaping future designers’ and builders’ minds and talents. Through mentorship and guidance, architects ignite the creative spark in students, nurturing their innate curiosity and passion for architectural design. As educators, architects serve as mentors, imparting technical knowledge and invaluable insights gleaned from years of practice.

Architects in academia play a pivotal role in bridging the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application. By integrating academic principles with real-world experiences, architects equip students with the skills and confidence to tackle complex design challenges effectively. Through hands-on learning opportunities, students gain a deeper understanding of architectural theory, preparing them for the realities of professional practice.

Architects have the power to inspire and empower the next generation of designers and builders. By sharing their passion, enthusiasm, and experiences, educators ignite a spark of curiosity in students, motivating them to pursue careers in architecture and make meaningful contributions to the built environment. Through mentorship and support, architects guide aspiring designers on their educational journey, nurturing their talents and aspirations.

Transitioning from practice to academia presents challenges, from adapting to a new work environment to balancing competing responsibilities. However, architects can successfully navigate this transition with resilience, determination, and support. Effective time management, prioritization, and a commitment to maintaining a healthy work-life balance are essential for thriving in both the classroom and professional endeavors.

In conclusion, this article serves as a call to action for architects to embrace their role as educators and mentors. By investing in education, architects can shape the profession’s future and inspire the next generation of designers and builders. Let us seize the opportunity to leave a legacy for generations, fostering a culture of innovation, excellence, and mentorship within architecture. Together, we can nurture the talents and aspirations of future builders, ensuring a bright and sustainable future for the profession.

By Arjay John Secugal

In the constantly evolving field of architecture, where imagination and practicality converge, design concepts form the foundation of all architectural endeavors. Architects are like storytellers who weave narratives into the built environment, not merely as designers of structures. The strength and clarity of every architect’s idea and concept are the fundamental components of all their designs, whether they are working on towering skyscrapers, comfortable residential houses, or dynamic public spaces.

So why is establishing design concepts such an essential component of architectural practice? As a Filipino architect and educator, I have learned to appreciate the vital role that design concepts play in shaping the built environment and nurturing the innovative thinking of present and emerging architects.

In architecture, having a design concept is essential for several reasons. First, clarity of vision: a design concept provides the project with a

distinct direction and vision. It acts as a road map for the architect, directing the creation of the design and ensuring that all decisions align with a main concept. Second, coherence and unity: a well-thought-out design concept ensures that every component of the design comes together to form a cohesive whole. It prevents disorganized or chaotic designs by providing an outline for planning and merging different design elements. Third, meaning and purpose: the project’s meaning and purpose are derived from a well-defined design concept. It enables the architect to convey more profound significance, such as cultural, social, or environmental factors, beyond aesthetics alone. Fourth, client communication: by guiding clients in understanding the architect’s vision for the project, a well-defined design concept promotes effective communication. It allows clients to experience the intended outcome and serves as a starting point for discussion and feedback during the design phase. Lastly, inspiration and creativity: a design concept can be a source of inspiration and creativity for an architect. It promotes innovative solution-seeking and creative thinking by offering a framework for idea exploration and design development.

To emphasize, the clarity of design through a concept is fundamental—a clearly defined design concept is like a beacon showing the way through the complex layers of every design.

It offers a cohesive vision that guides everything, from material selection to space arrangement, ensuring coherence and harmony in the entire project. Moreover, design concepts give our creations meaning and purpose beyond mere aesthetics. The importance of design concepts requires deeper implications in the learning environment. As an architect and educator, I feel it is my responsibility to impart to students not just the technical skills of architecture but also the creative vision that drives the profession. We can empower students to think critically, think boldly, and translate their ideas into tangible manifestations of architectural grandeur through interactive tasks, case studies, and opportunities for discussion.

In a broader sense, it is hard to overstate the importance of design concepts in architecture—design concepts are the core of our profession, reflecting our values, principles, and aspirations, from creating our communities’ landscapes to nurturing the next generation of creative minds. Let us not waver in our commitment to produce design concepts that inspire, transform, and thrive as we move forward in the ever-dynamic field of architecture!

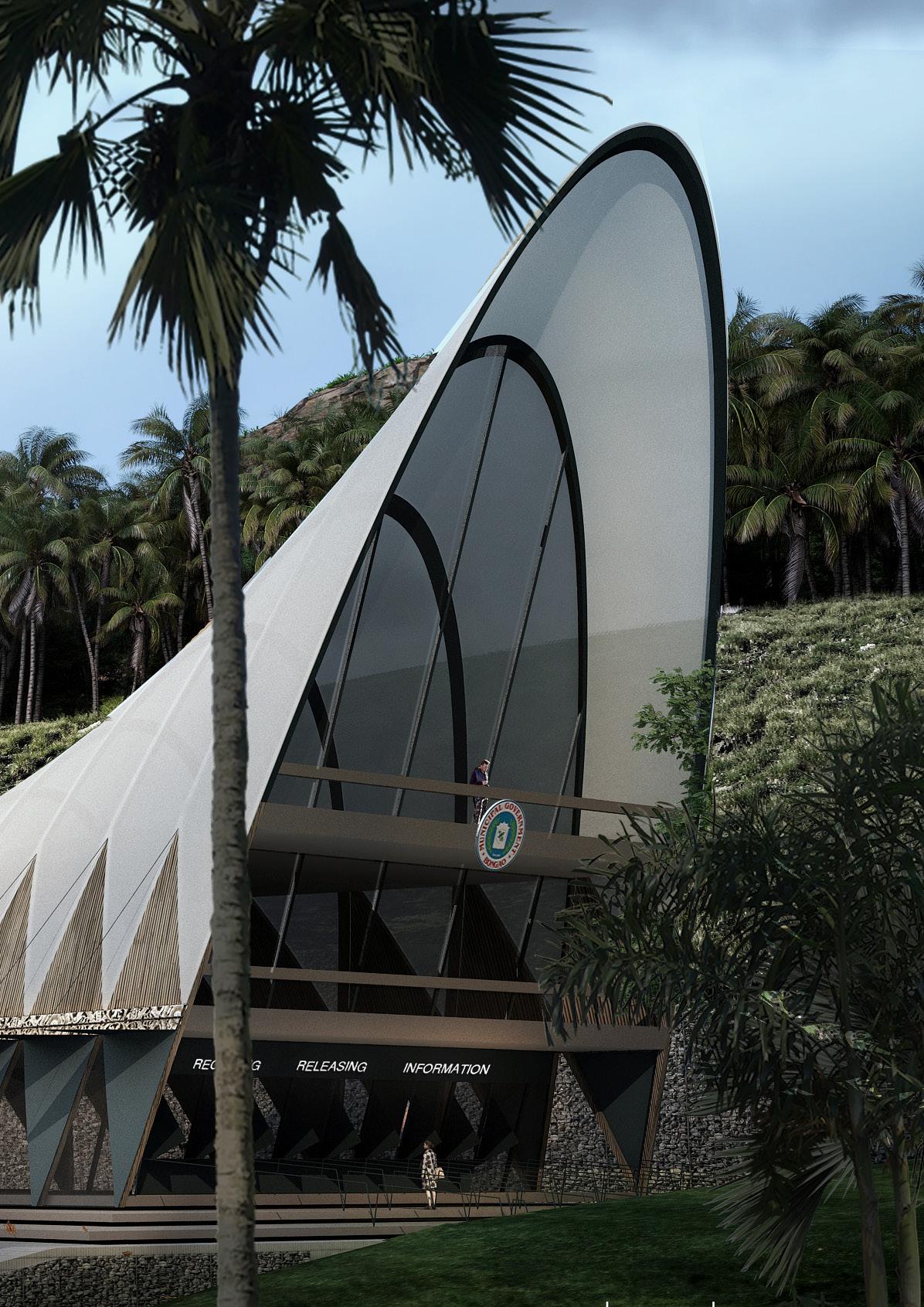

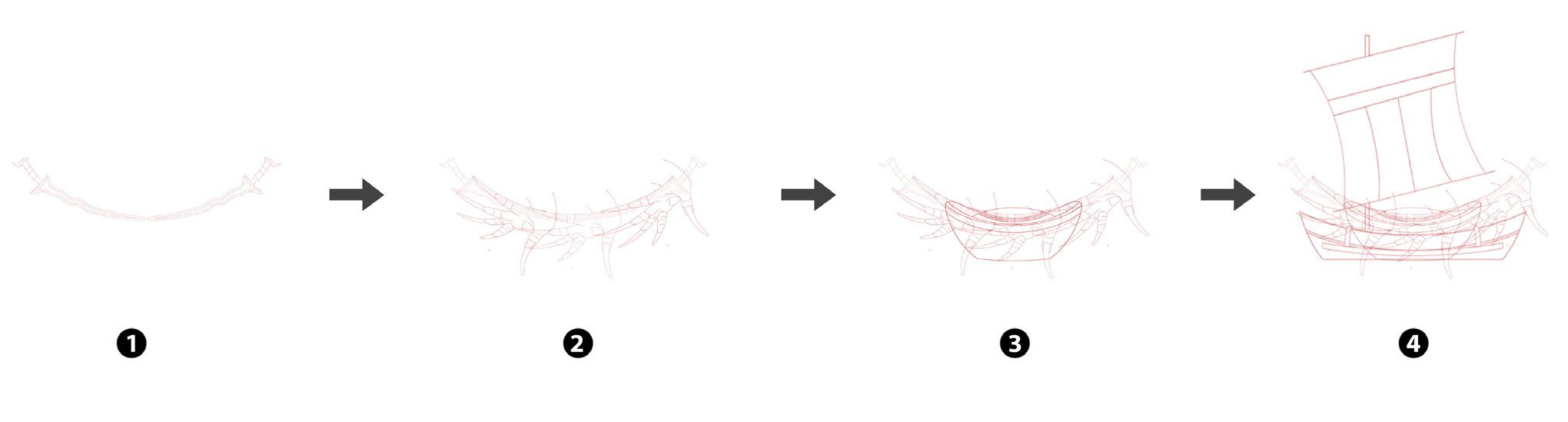

By Deo Alrashid Trevecedo Alam

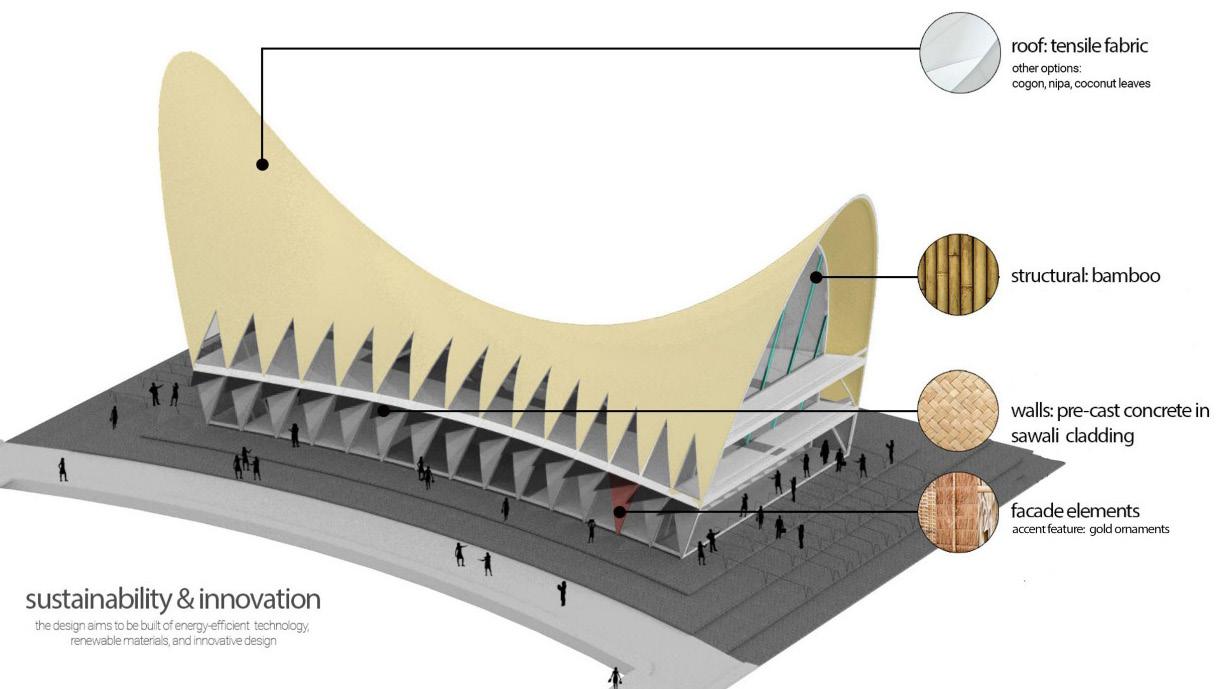

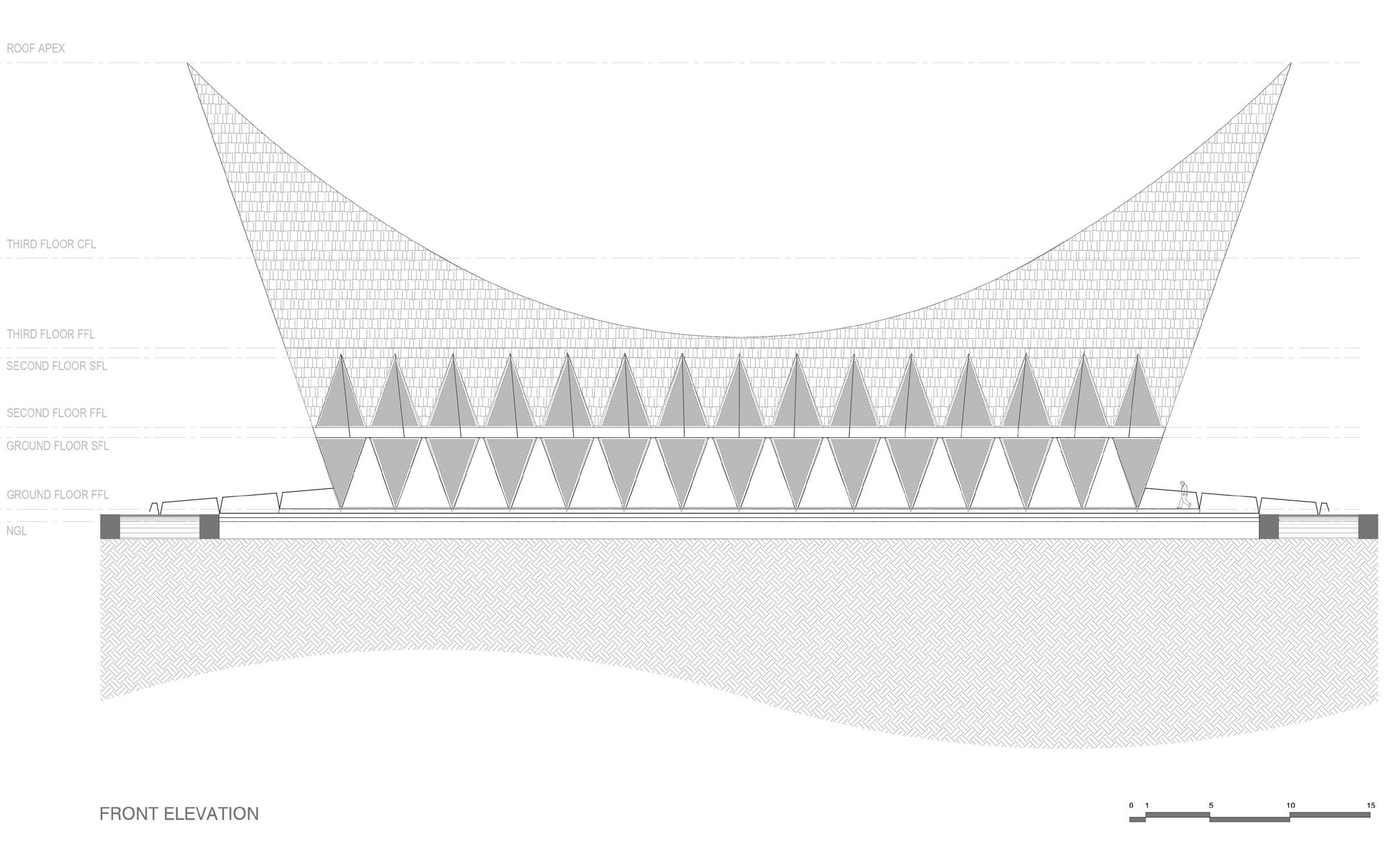

Situated at the base of Tawi-Tawi, the only mountain in Bongao, the municipality hall project combines geographically and culturally into the fabric of its surroundings. With consistent commitment to transparency and sustainability, the project deliberately uses local material such as clay bricks,coal and sawali to strengthen the region’s economy and provide sustainable employment opportunities for small businesses.

The design’s primary goal is to provide the community with a public building that they will feel belongs to them—that they are a part of it, that it will be efficient, and that they will witness the transparencyliterally and metaphorically-of their local government. To emphasize this, the architects intended to give the locals— including many tribes and societal sectors—a sense of ownership over it. To fit the project with the local environment and demands, the design process started with a thorough investigation into the history of Bongao Island and the native Mindanao tribes.

Rooted in a deep understanding of Bongao Island’s history and the diverse native Mindanao tribes, the design process prioritizes community ownership and inclusivity. The creative process relied on questioning, unraveling solutions through iterative inquiry, and guiding innovation towards trust, transparency, and inclusivity. For this project, the client’s brief played a pivotal role. The objective was to cultivate public trust in the local government and foster inclusivity within the community. This posed a fundamental challenge: how can we effectively communicate trust and transparency through the building design? Moreover, how do we promote inclusivity in an environment as culturally diverse as an island that serves as a melting pot of various cultures? Through this iterative process of inquiry, answers began to emerge, gradually unveiling layers of insight and understanding. Each question posed acted as a catalyst for exploration, guiding us towards innovative solutions that encapsulated the essence of trust, transparency, and inclusivity within the architectural design of the project.

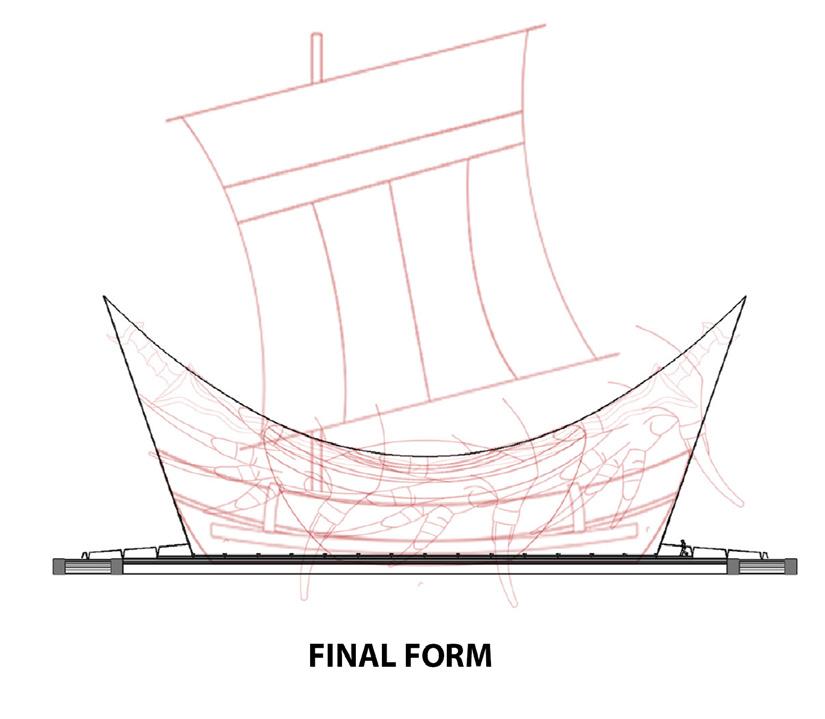

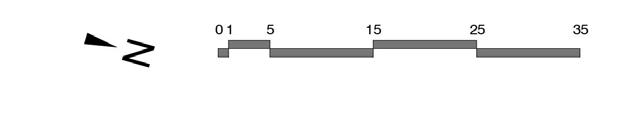

The form development of the Bongao Municipal Hall project reflects with the vibrant spirit of the vinta’s sails, the elegant curves of the sycee, the streamlined efficiency of the lepa, and the graceful movements of the pangalay dance, celebrating the rich tapestry of Filipino arts, culture, and maritime heritage. This combination of ideas creates a visually appealing and culturally relevant place that represents a harmonic blend of tradition and contemporary.

In its endeavor to enhance transparency, the project faced numerous challenges, in particular the deep psychological impact of distrust. Despite these obstacles, the initiative persisted, drawing inspiration from local heritage and treasures to shape its identity and ethics. Such inspiration came from the kris sword, known for its exquisite craftsmanship and symbolic representation of truth, freedom and freedom. The design of the project evoked the complexity of kris, including glass walls as a symbolic gesture of transparency, removing physical barriers, and promoting open communication between public and government officials. This design concept was not only rooted in practicality but also aligned with the principles of the Broken Windows theory, which posits that

maintaining and enhancing public spaces can reduce criminal behavior and promote civic pride.

In addition, the project was inspired by three iconic symbols – vinta, sycee and lepa – each bringing unique elements to shape its form and identity. First, the vinta, a traditional Filipino ship known for its colourful sails and polished design, brought a sense of fluidity and dynamic to the project. Taking into account the graceful lines and vibrant colours of the vinta, the architectural design includes elements of movement and energy, creating a visually striking and dynamic aesthetic. Second, the sycee, an ancient Chinese ingot traditionally used as a currency and developed through close commercial relations with the Sama people,

Embracing sustainability and cultural authenticity, the Bongao Municipal Hall project employs indigenous materials such as clay bricks, cogon, and sawali, sourced locally to support the region’s economy and honor its heritage.

influenced the architectural form of the project with its distinctive rectangular form and round edges. Reflecting the unique silhouette of the skyscraper, the design of the building incorporated smooth lines and curved accents, resulting in a sense of elegance and sophistication. Finally, the lepa, a historic vessel of the Sama-Bajau culture, inspired the form of the project with its smooth design and efficient use of space. Based on the curved shape of the lepa and the functional layout, the architectural design maximized space efficiency and maintained a sense of fluidity and movement, creating a harmonious balance between form and function. By integrating elements of these three iconic symbols, the form of the project reflects the fusion of cultural heritage and modern design principles, celebrating the rich maritime traditions of the Philippines while creating a visually remarkable and functional space that resonates with the local community.

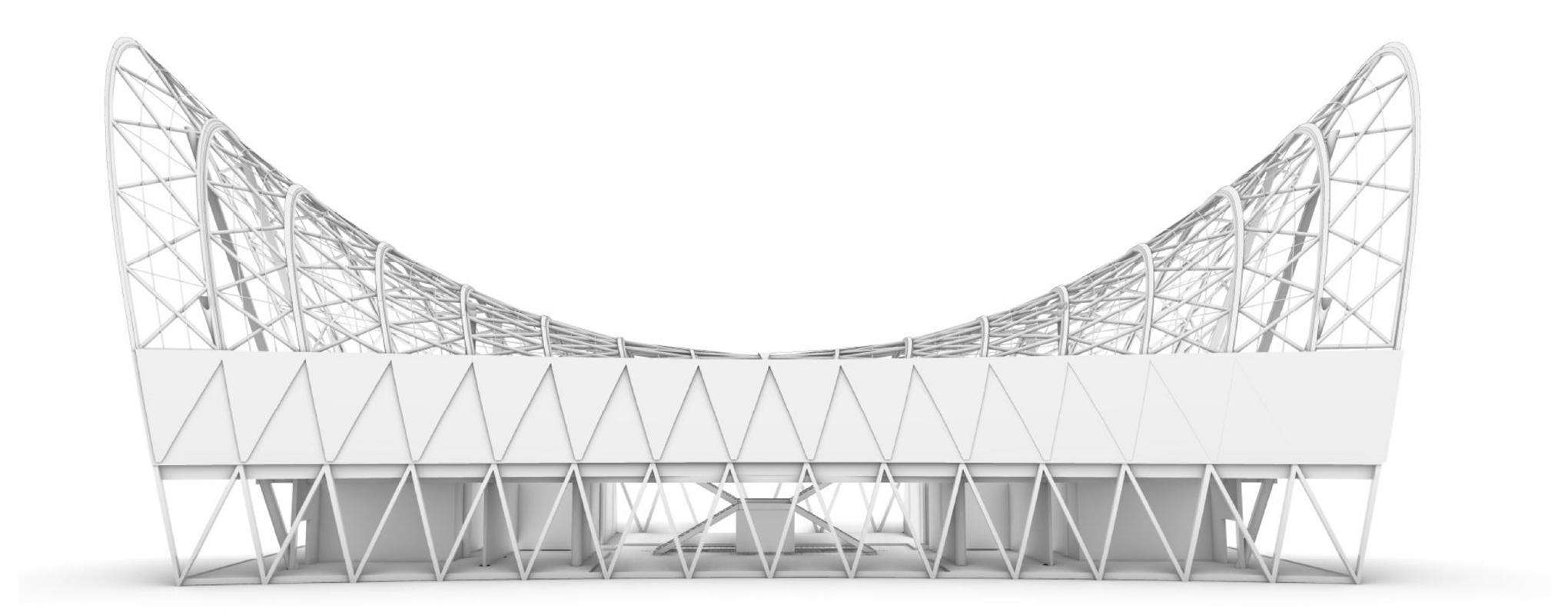

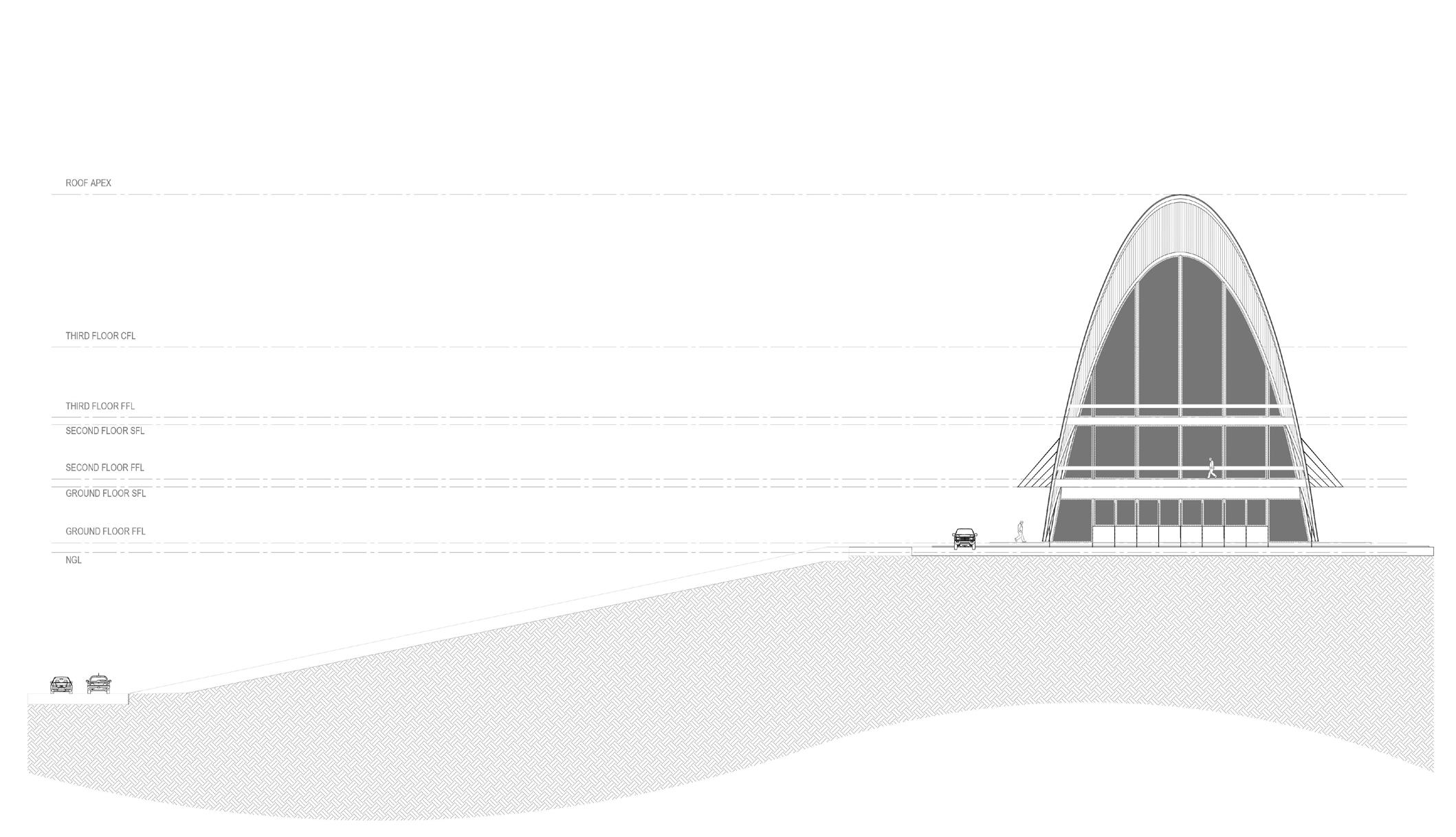

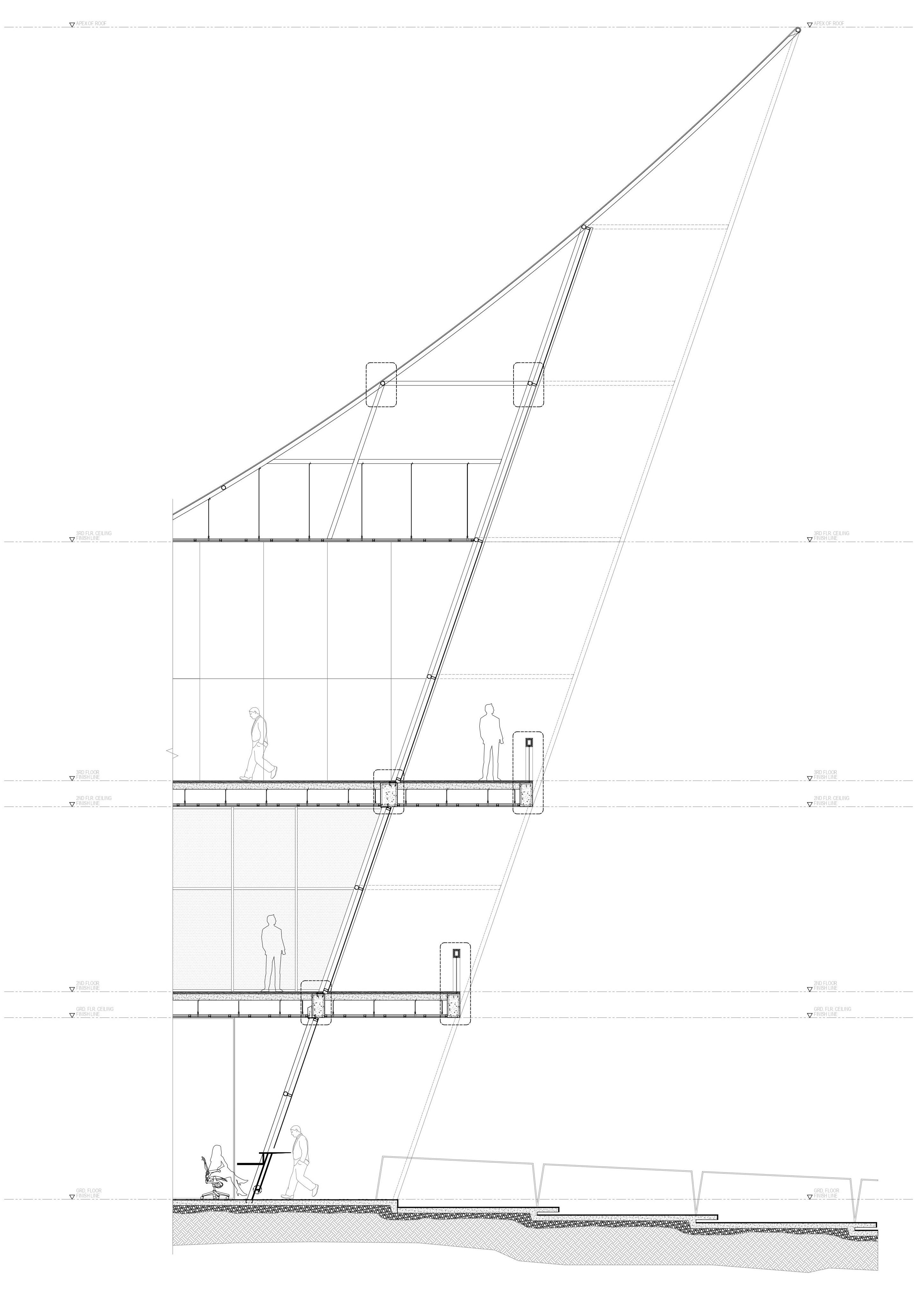

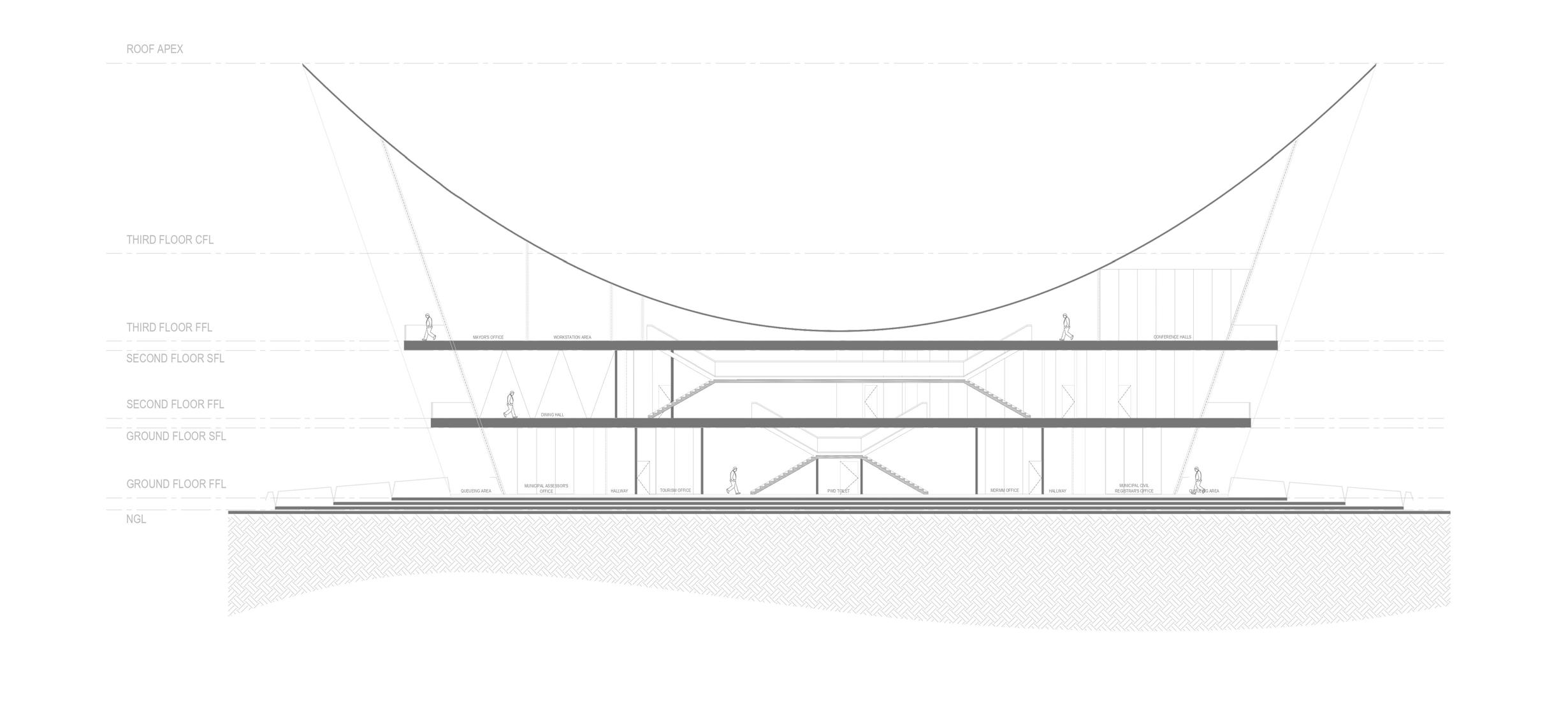

Moreover, the municipal building emphasizes the creation of healthy and open areas in addition to its cultural relevance. Glass walls were employed to increase the amount of natural light and make the workplace space feel larger and more welcoming. To improve the working conditions for government employees and foster a sense of pride and accountability, larger work tables were also placed. Tensile fabric roofing is one distinguishing element, allowing natural light to flood the third floor and lower-level pathways. To complement these design elements, the project’s team meticulously considered the psychological effects of colors, lighting, and materials, drawing inspiration from local weaving traditions to symbolize the ingenuity and resilience of the community.

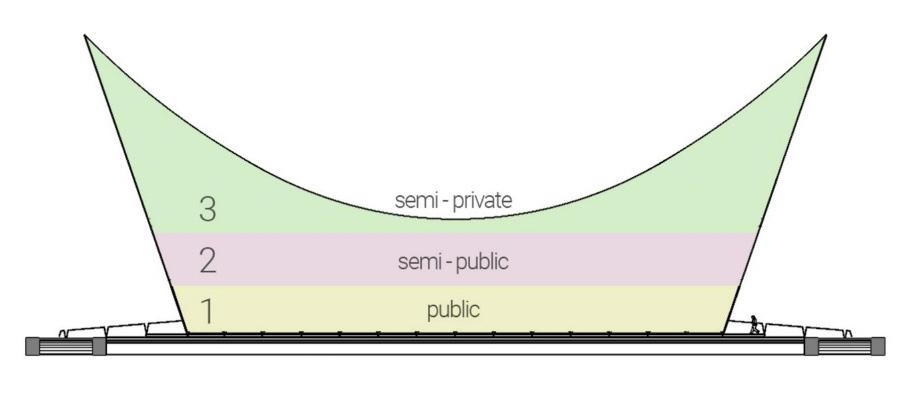

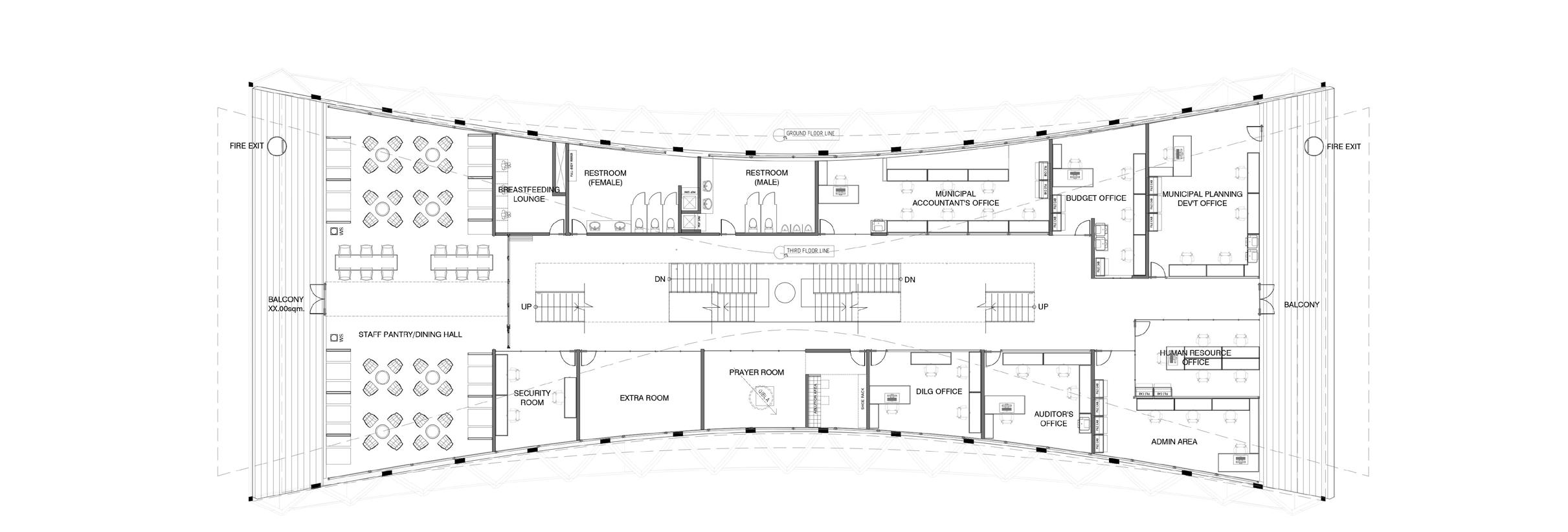

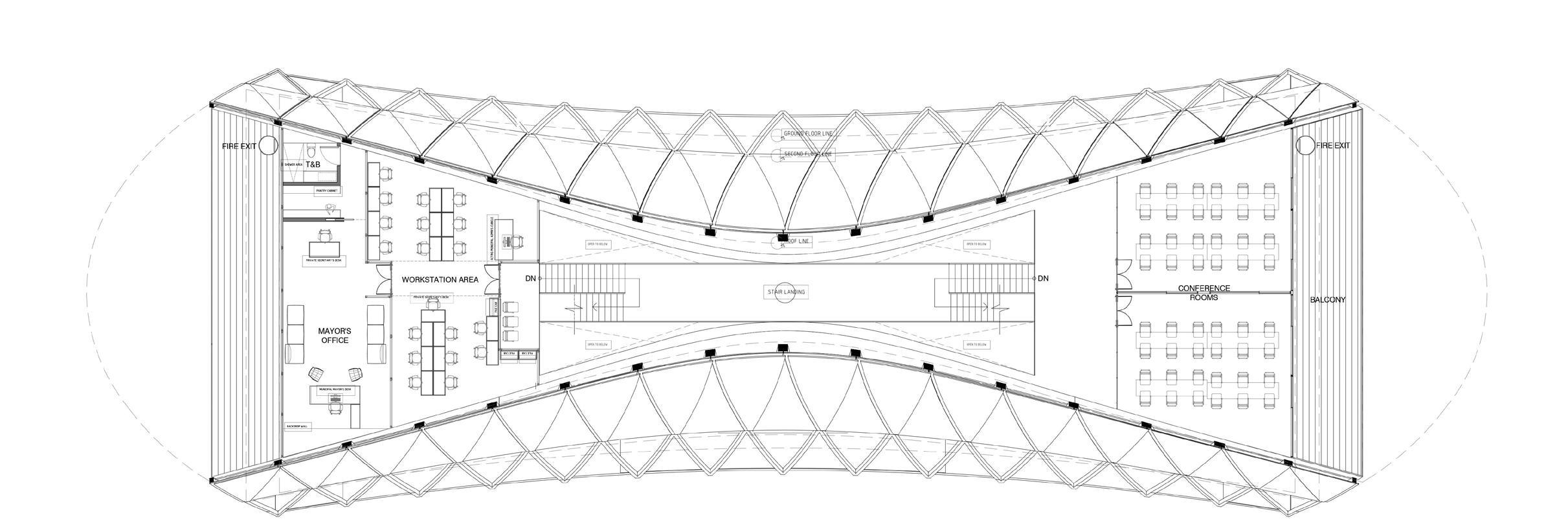

Strategically designed to optimize functionality and accessibility, the zoning plan of the Bongao Municipal Hall project reflects meticulous consideration of community needs and organizational efficiency.

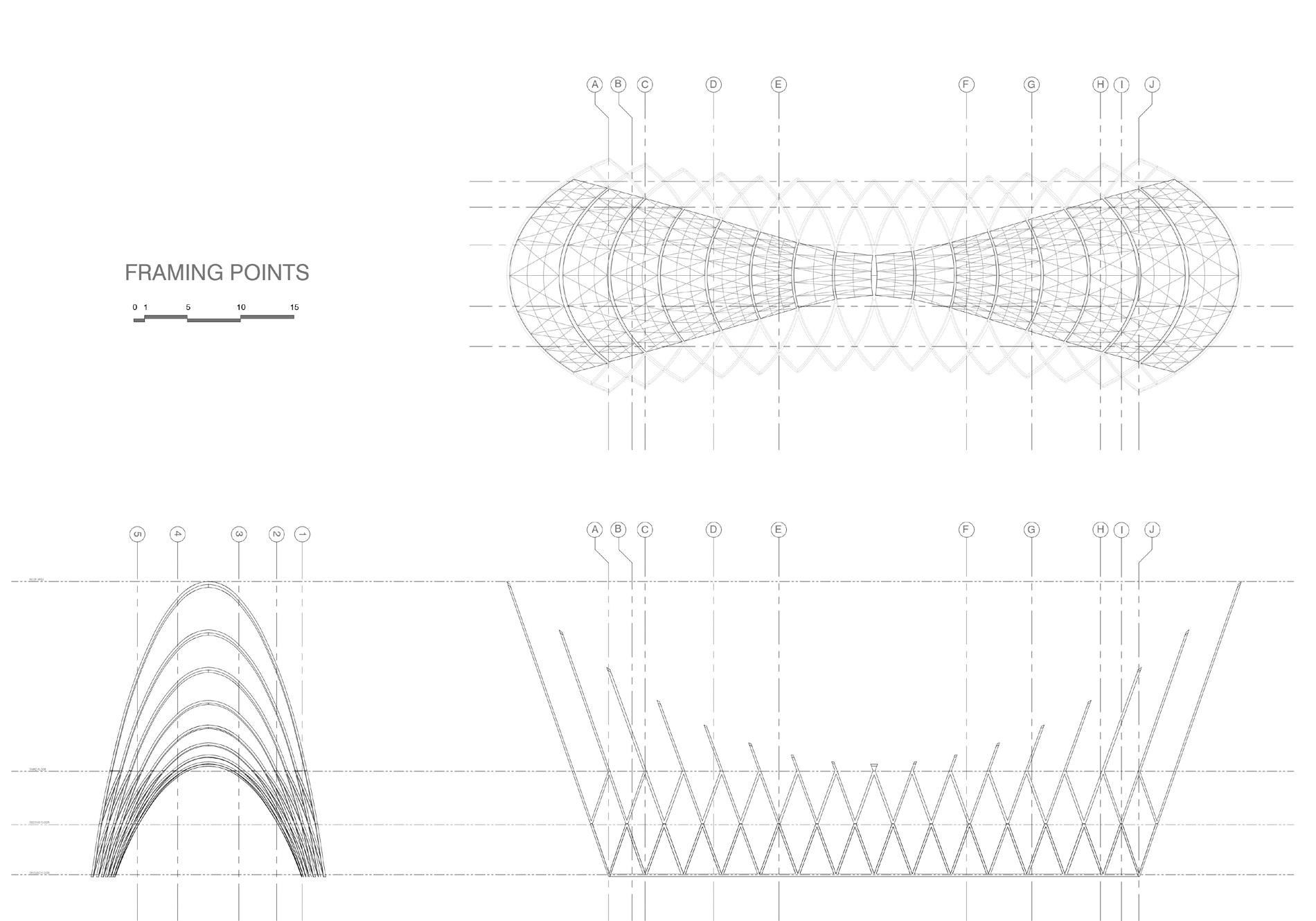

Structural engineering presented a substantial coordination difficulty, particularly for the roof design. Using an A-type framing, the roof achieves self-sufficiency, connecting to the main structure only by anchoring, assuring stability and cohesiveness. To address cooling difficulties on the third level, an additional tensile fabric layer was proposed to improve thermal comfort, while translucent roofing provides natural illumination, complemented with minimum general lighting for inclement weather or nighttime use.

The Bongao Municipal Hall, as a beacon of sustainability and civic involvement, is more than just a physical structure; it embodies the enduring concepts of transparency, efficiency, and community empowerment, promoting an inclusive and environmentally responsible future. It embodied values by creating a physical environment that stressed transparency, accessibility, efficiency, and community involvement, all of which are essential components in building confidence between the public and government. This hall motivates future generations by combining architectural brilliance and cultural significance to push for a better future.

Structural Design Concept

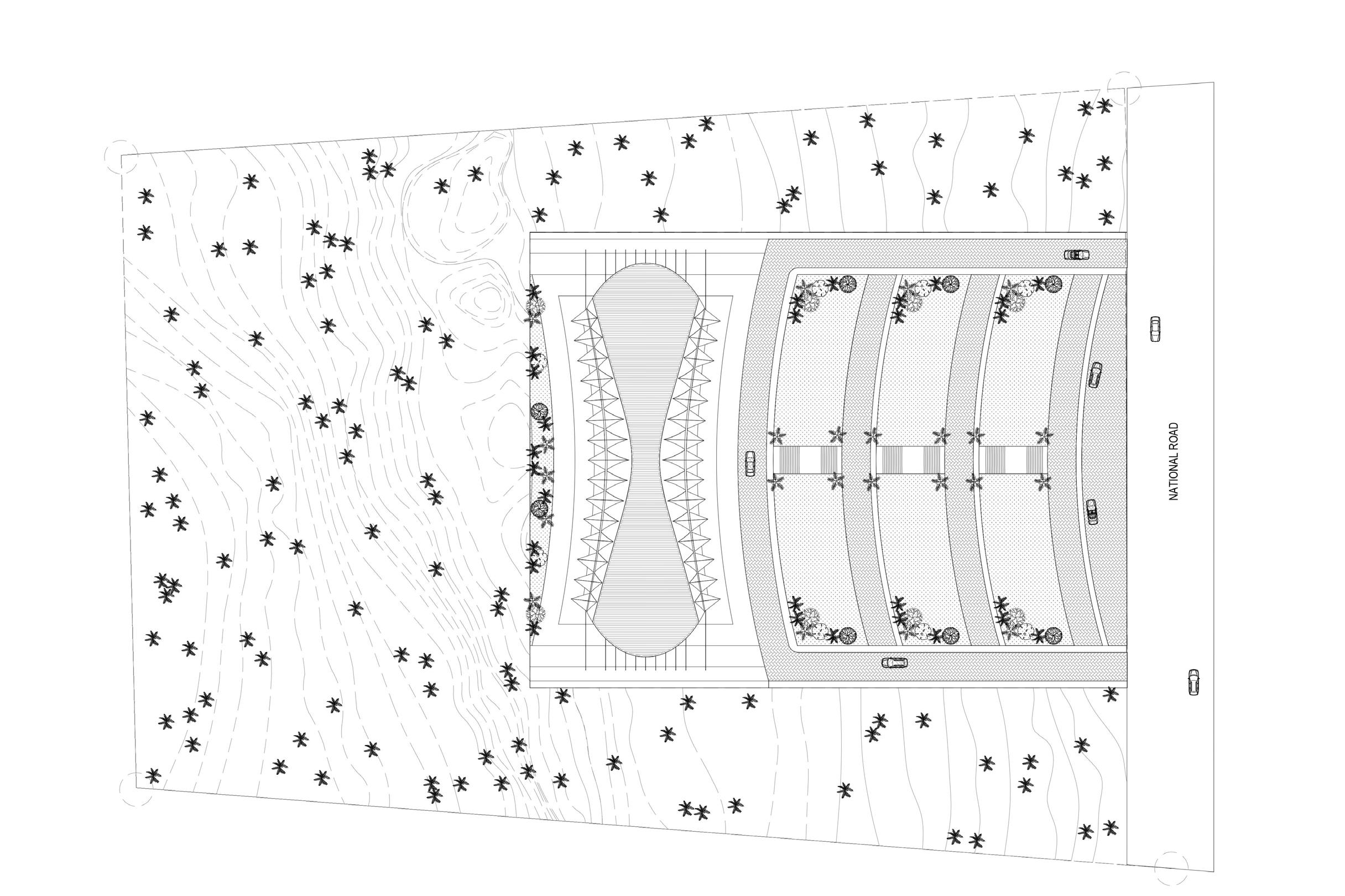

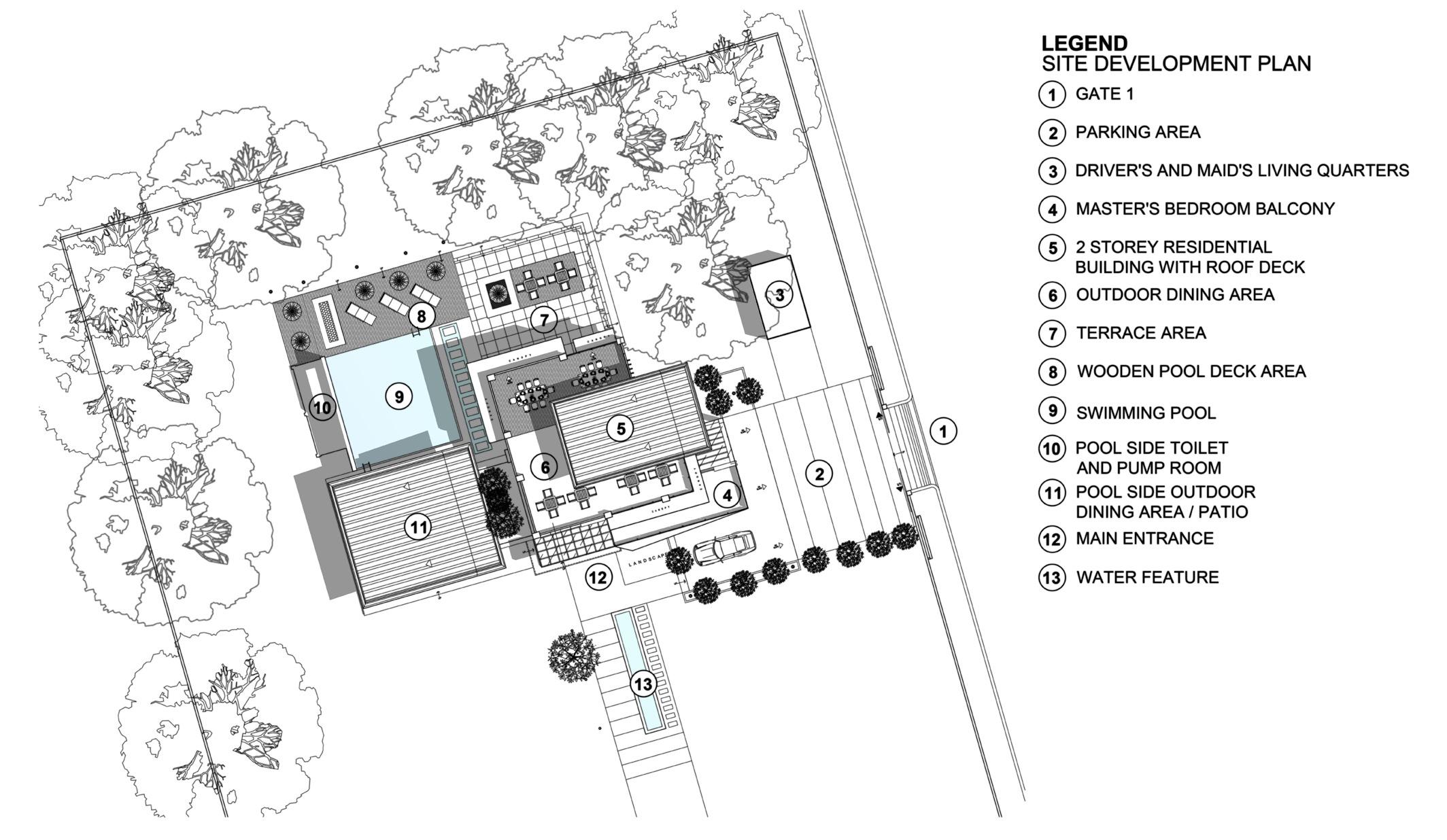

Crafted with community in mind, the site development plan for the Bongao Municipal Hall project integrates seamlessly with its surroundings, reflecting a commitment to transparency, inclusivity, and sustainable urban design.

Project Name

Year Completed

Project Location

Lot Area

Gross Built Area

Client

Photo Credits

Lead Architect

Design Team & Collaborators

Structural Engineering

Electrical Engineering

Sanitary and Plumbing Engineering

Bongao Municipal Hall

Under Construction

Bongao, Tawi-Tawi

9,293.37 sqm

2,453.95 sqm

Bongao Municipality

DADA

Deo Alrashid Trevecedo Alam

Julia de Santos

Ralph Avarez

Reymundo Alfonso

Nikko Arbilo

Marie Joy Camotuhan

Dianne Magsino

Lyka Reganet

Origenes Consulting

Engr. Ferdie Velasco

Engr. Maximo Ecleo

Balancing functionality with cultural resonance, the interior design of the Bongao Municipal Hall project creates a welcoming and efficient workspace, infused with local craftsmanship and inspired by the region’s vibrant heritage.

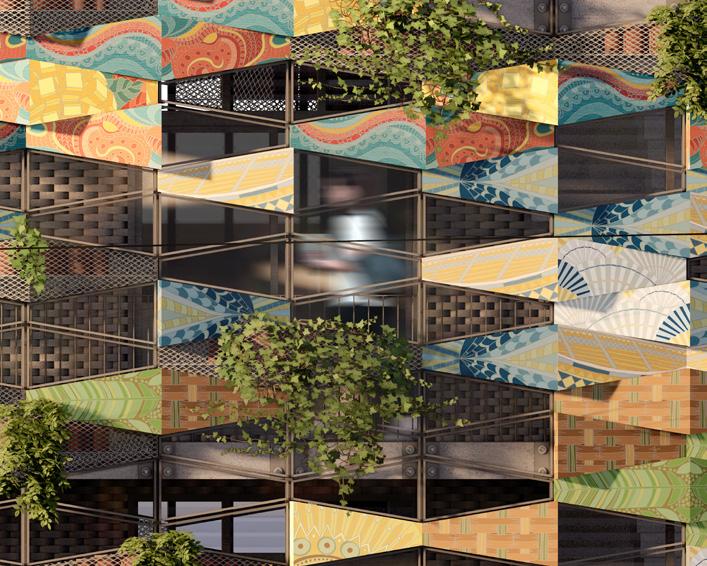

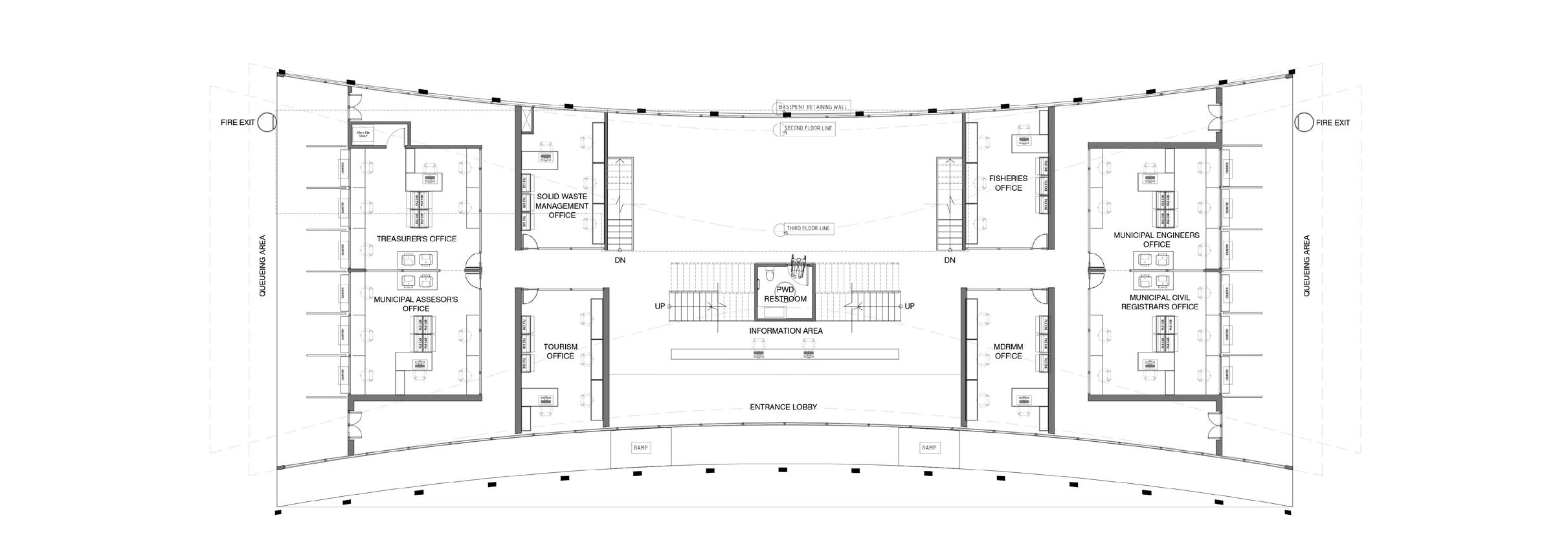

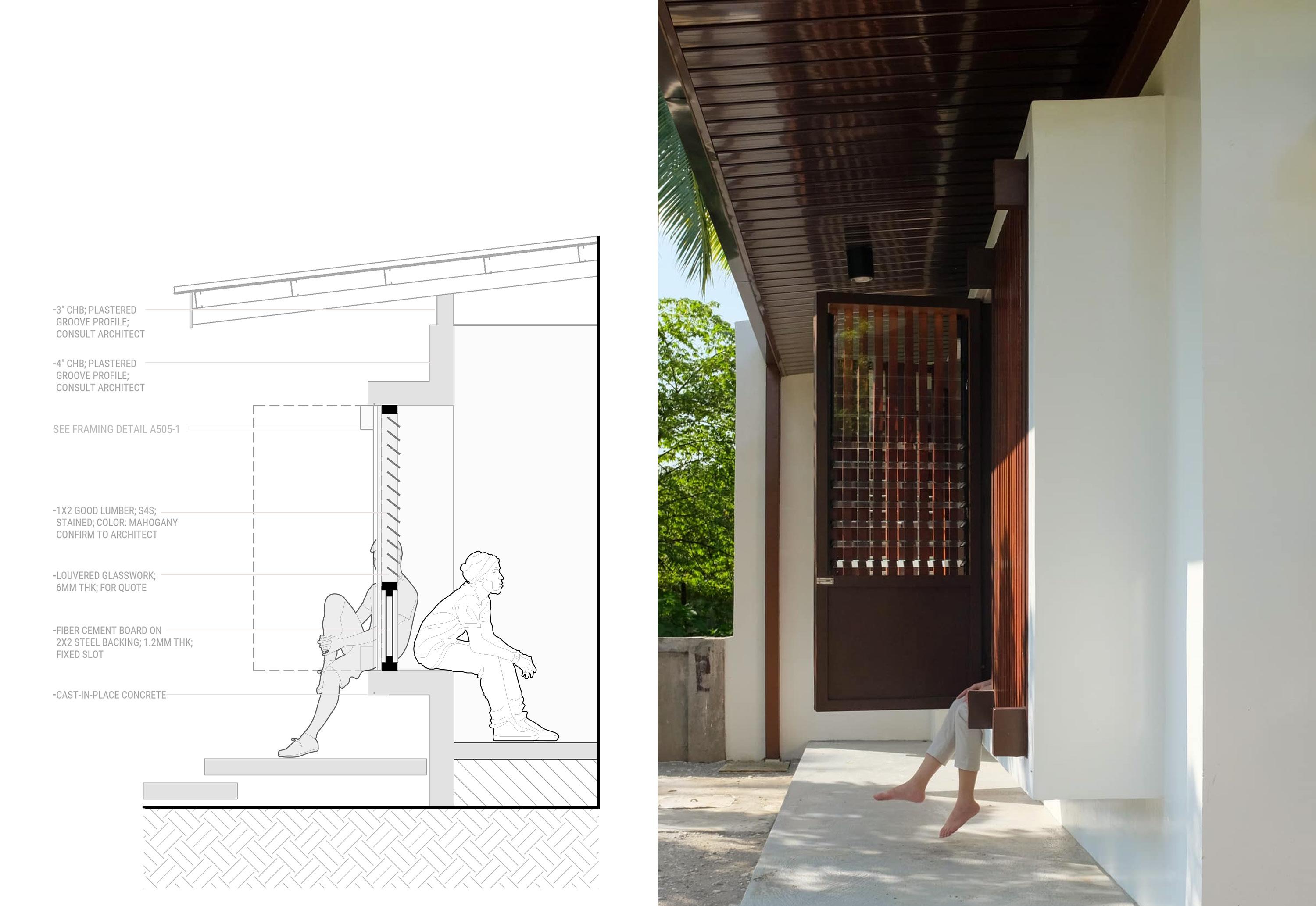

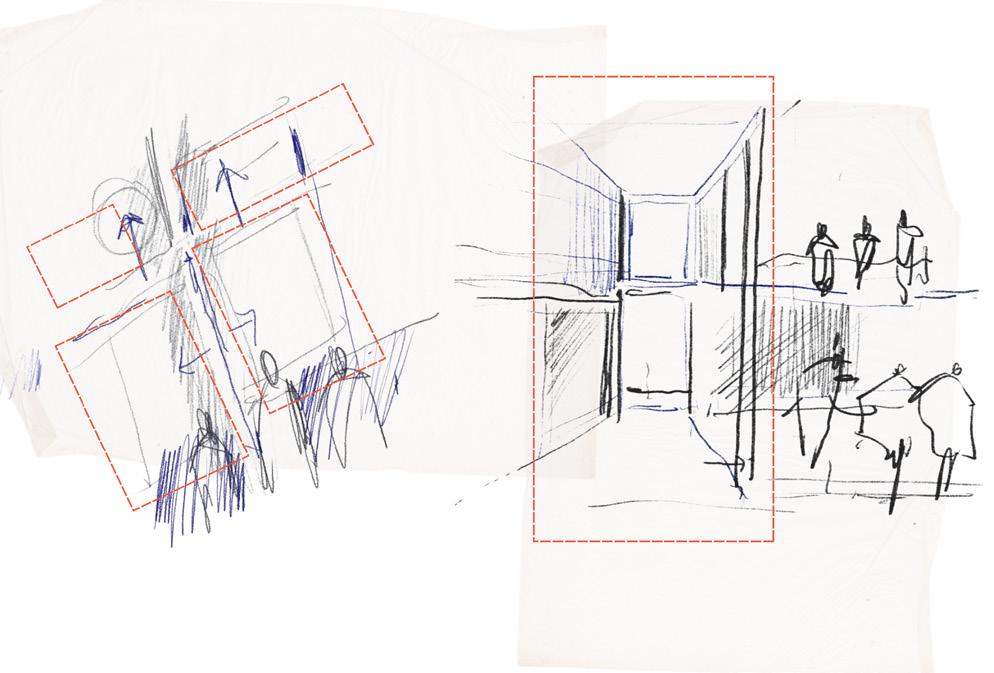

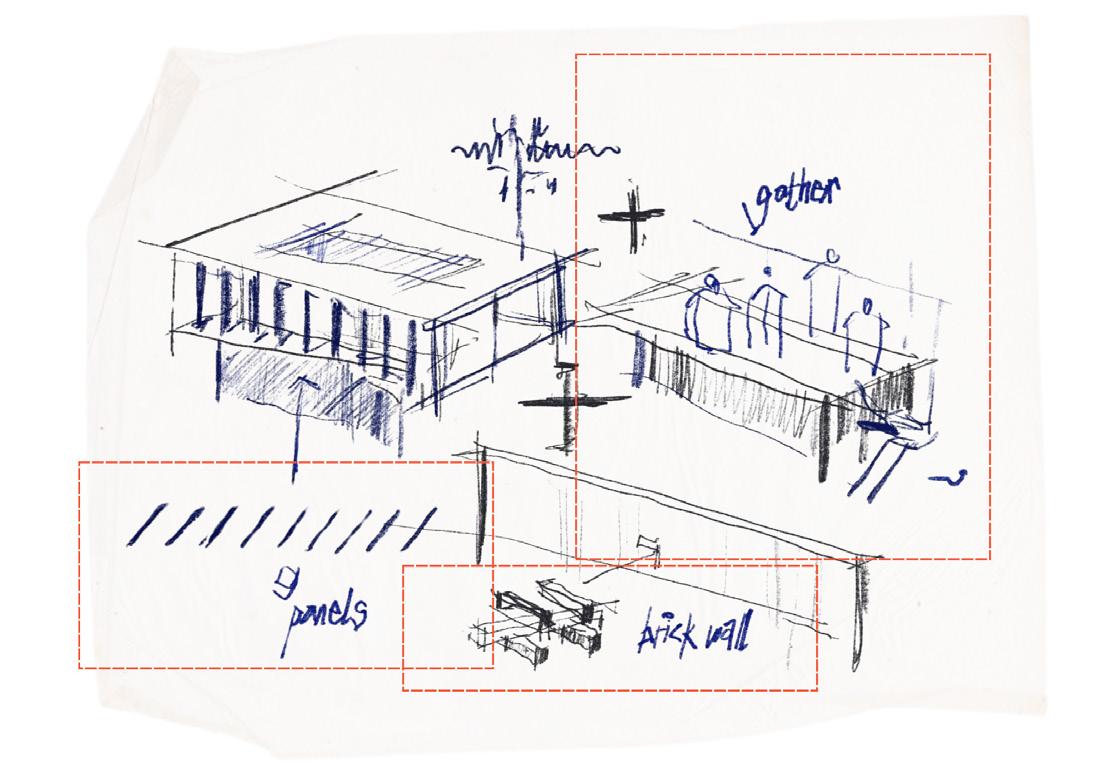

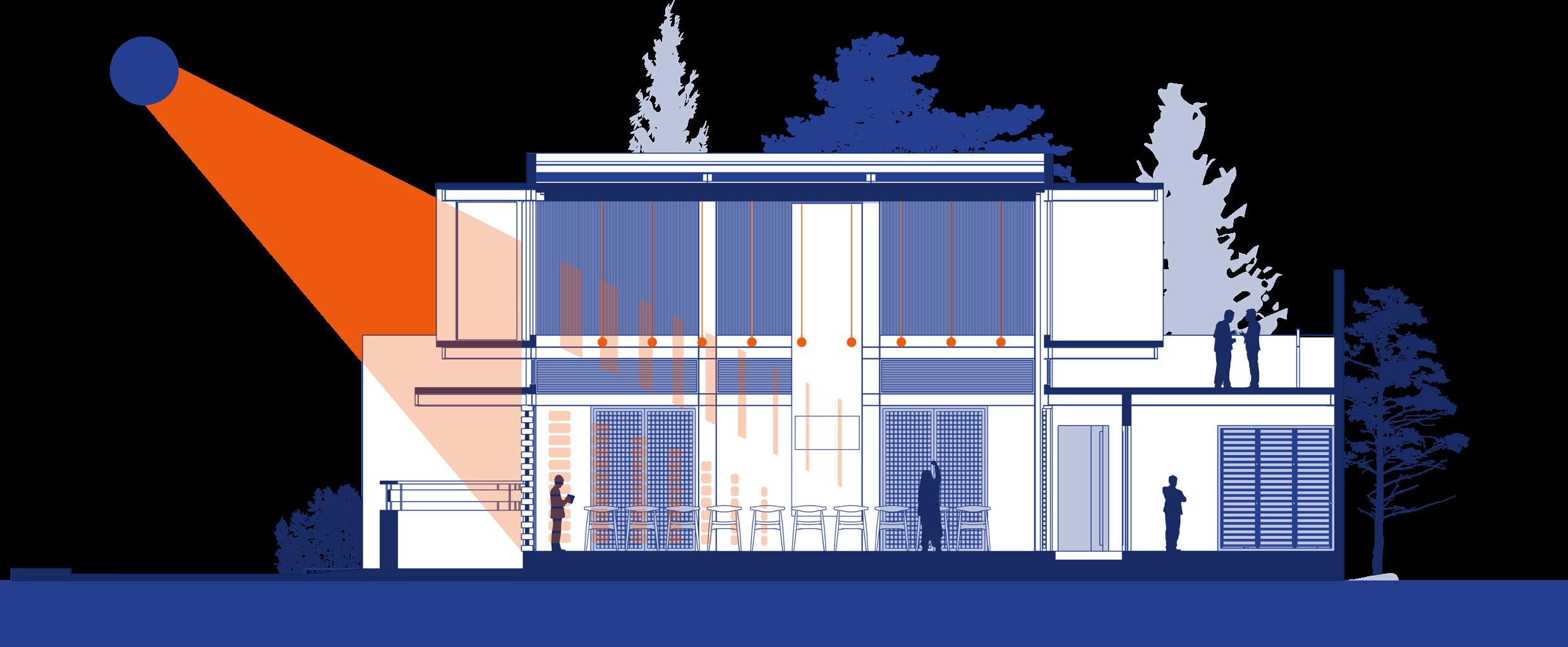

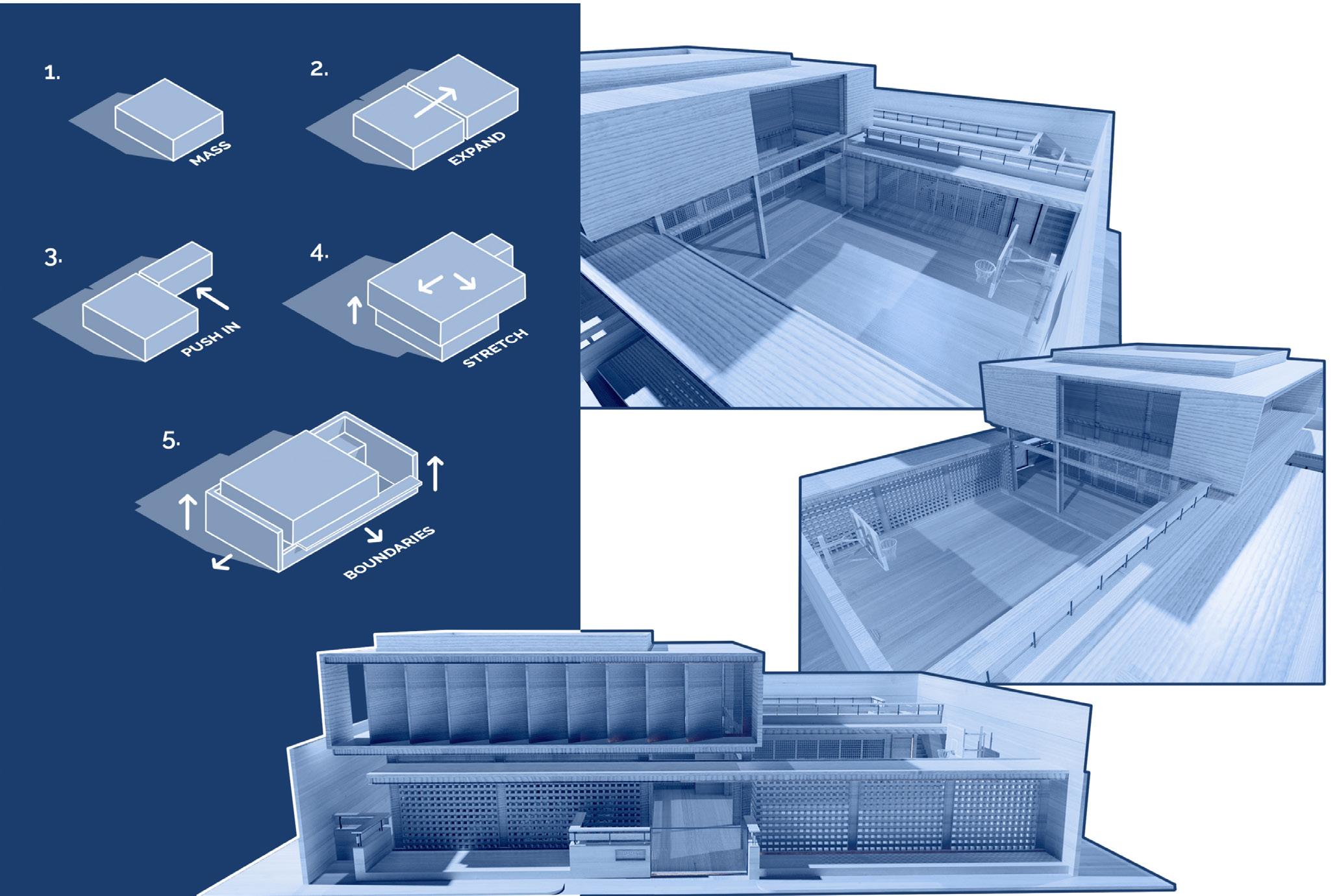

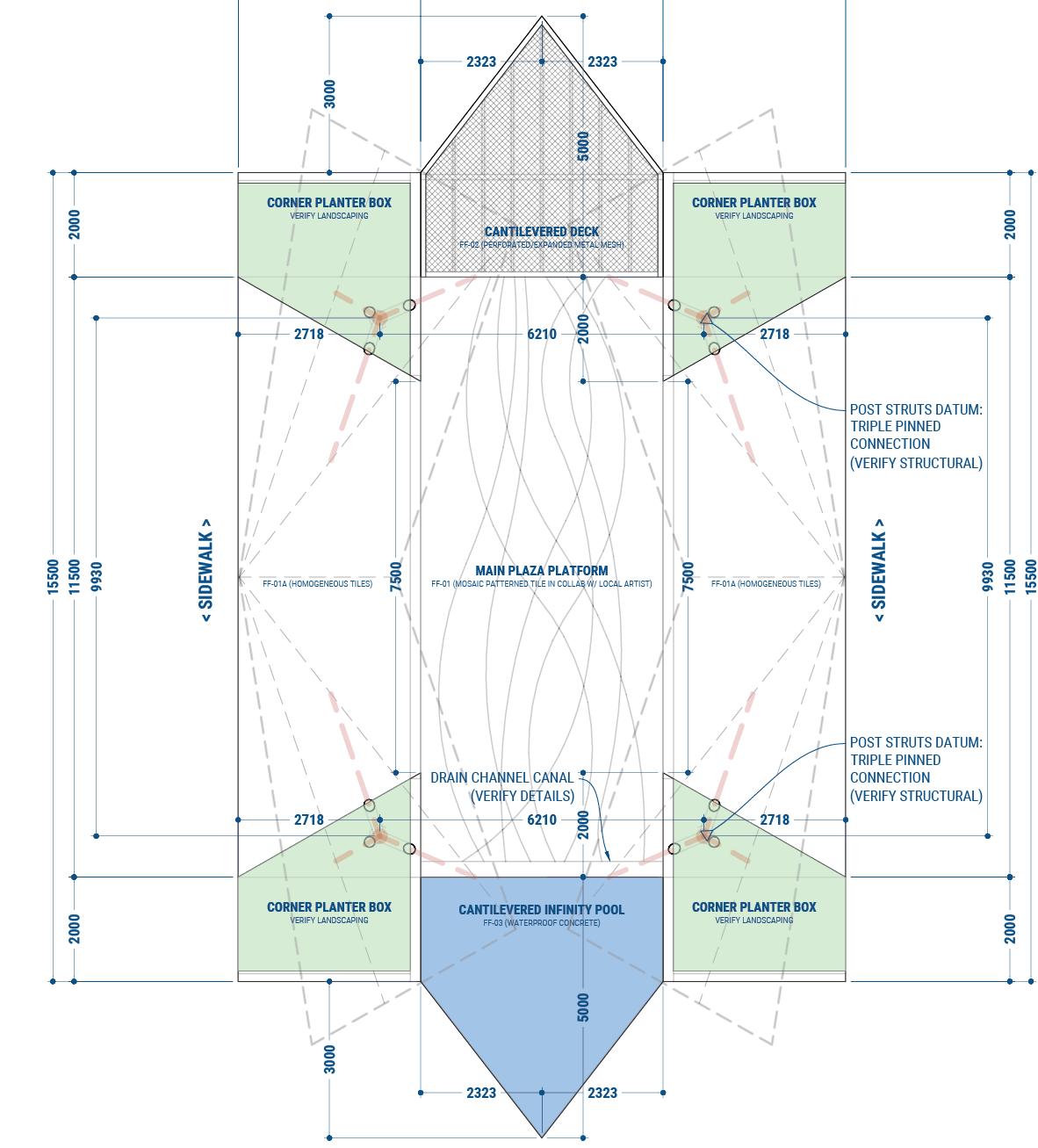

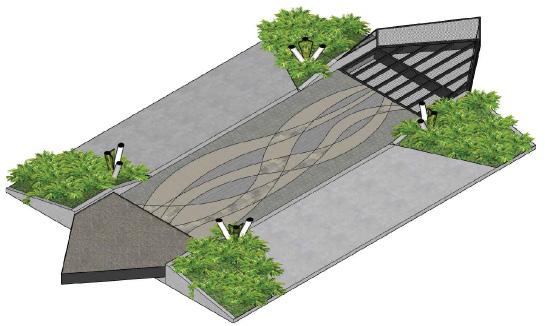

By Jason Buensalido

The barangay serves as the smallest and oldest unit in the Philippine government, a decentralized system that works because of our country’s geography. To this day, the barangay system empowers small close-knit communities to develop their own culture and autonomy through the operation of barangay centers. But despite the intent to decentralize power, a centralized authority is still felt with the current design of barangay centers, with the national government prioritizing speed, control, and cost, sacrificing the quality of these spaces. Centers are designed to be purely transactional, often devoid of identity, culture, and even basic human comfort. The Fourth District of Pangasinan recognized these failures and challenged us to find a way to standardize all 140 of their barangay centers while still maintaining the character of each and every location.

The project spans the entire Fourth District of Pangasinan which consists of 5 municipalities, namely Dagupan, Manaoag, Mangaldan, San Fabian, and San Jacinto. Pangasinan is one of the most culturally diverse provinces whose Fourth District has just earned the distinction of becoming a Creative Industries Hub, under its current representative, Rep. Toff de Venecia, who is known for championing the arts through his Creative Industries Development Act. Despite its vibrant culture, their barangay centers are not exempt from the same issues that stem from standardization initiatives.

The first catch is we were asked not to change the plans as these were already pre-approved by multiple authorities. We were also asked to continue using low-tech, conventional construction techniques, to secure cost and buildability. Also, to focus on the exterior, as a small first step to attract citizens towards the centers beyond mere transactions and as part of a larger, more drastic improvement to the design over the coming years. All these while working within the same budget allocated for the current design.

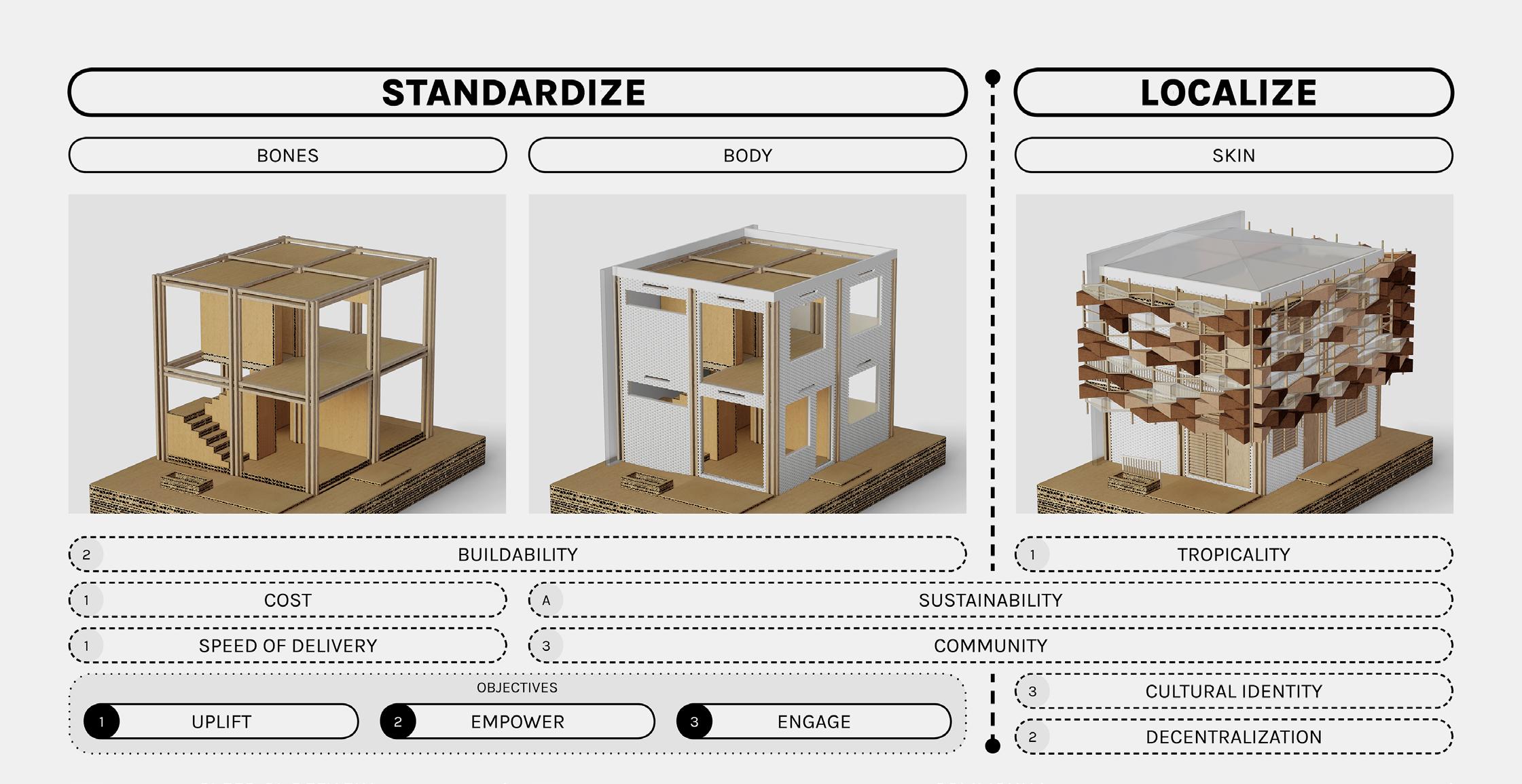

Reflecting on these challenges, we realized that these buildings are just like the people they serve. People have common values, yet we keep our own individual identities intact. And like people - buildings also have bones, a body, and a skin. Bones provide support, like a building’s structural frame. The body is our exterior shell, like the walls. While the skin, along with our clothing, provides our outermost identity and protects us from the elements, like a building’s outer screen. This framing of the problem helped us determine that while the bones and the body could be optimized for standardization, the skin could be reimagined for localization.

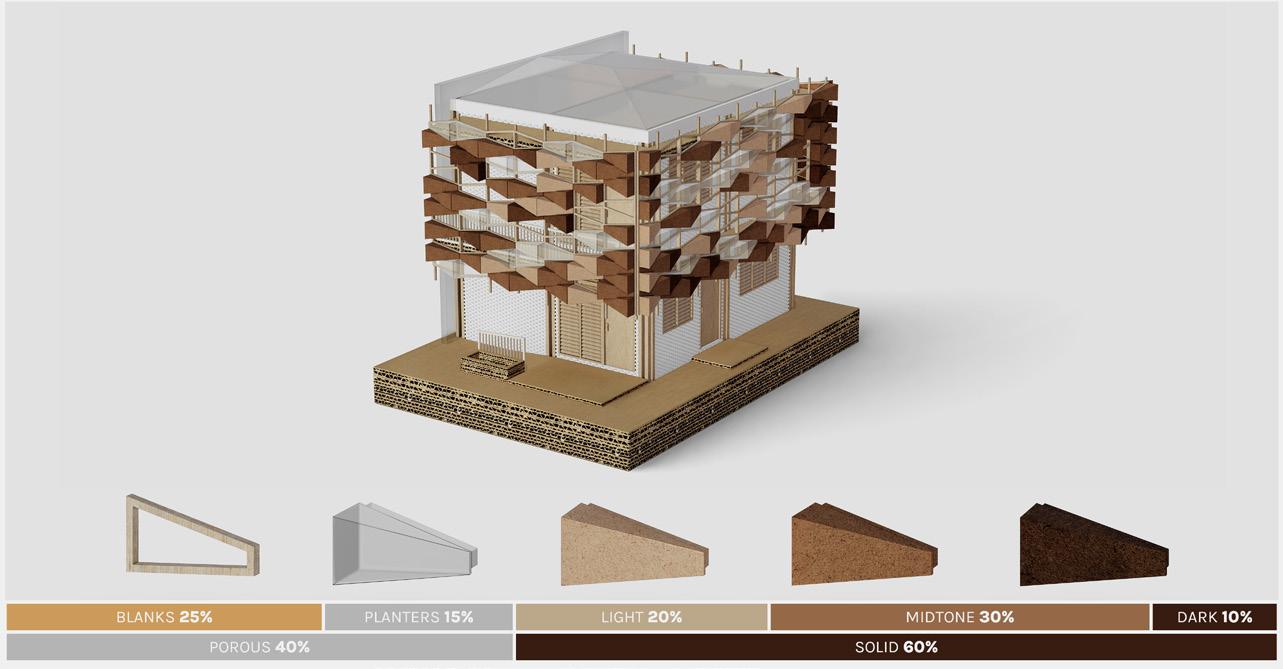

Starting with the standardization, we retained the post and lintel construction for the bones, but optimized the heights and roof slopes, to lower the costs. For the body, CMUs are still the standard in the country despite its inefficiencies. So, while we were asked not to touch the body, we shifted the material to brick, as brick is just as low-tech but is more sustainable, with thermal insulation that fits our climate better. Design-wise, its curved undulating form alludes to the ocean surrounding the coastal district. Establishing standardization through the bones and the body, we shift our focus on the skin next as we localize the building’s character to respond and reflect its eventual context.

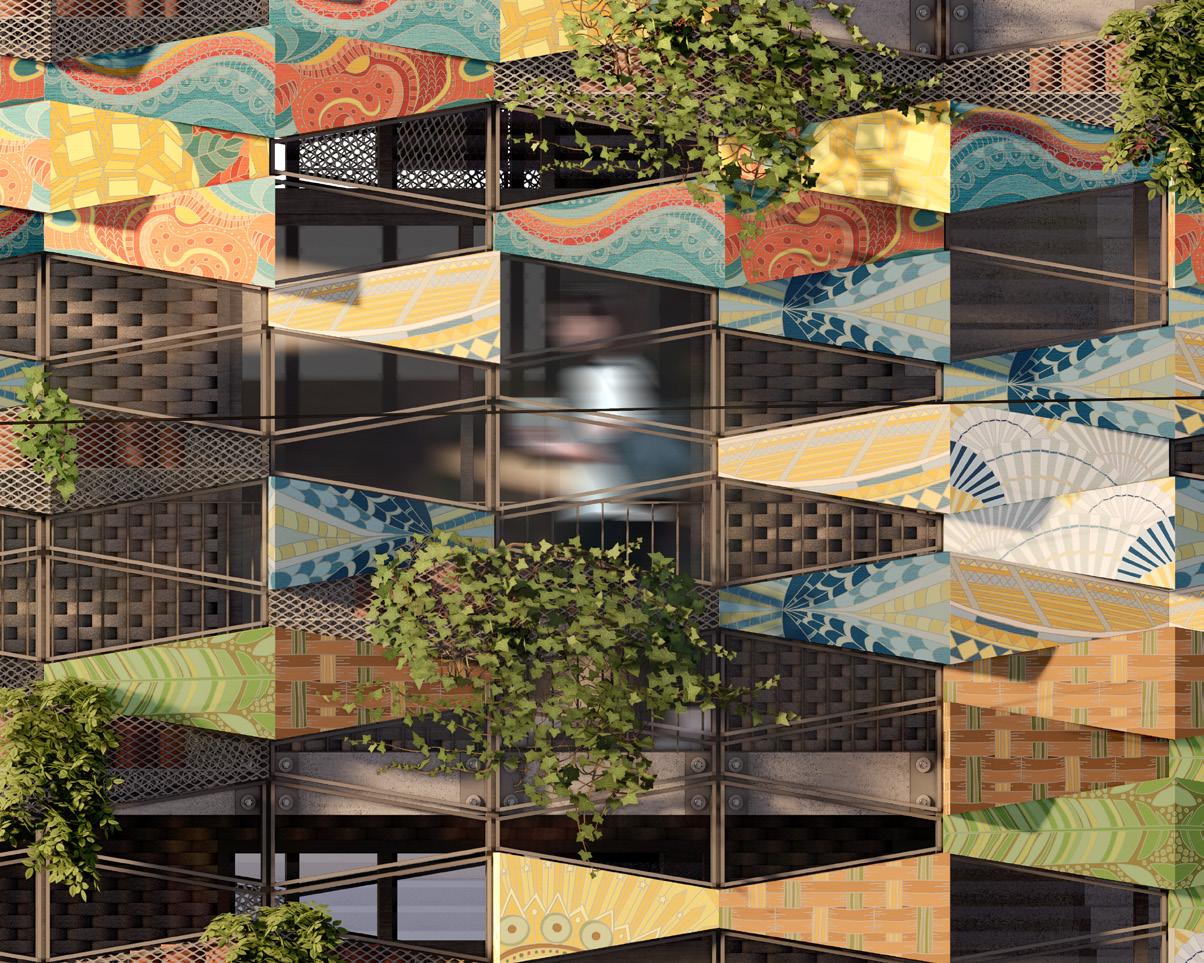

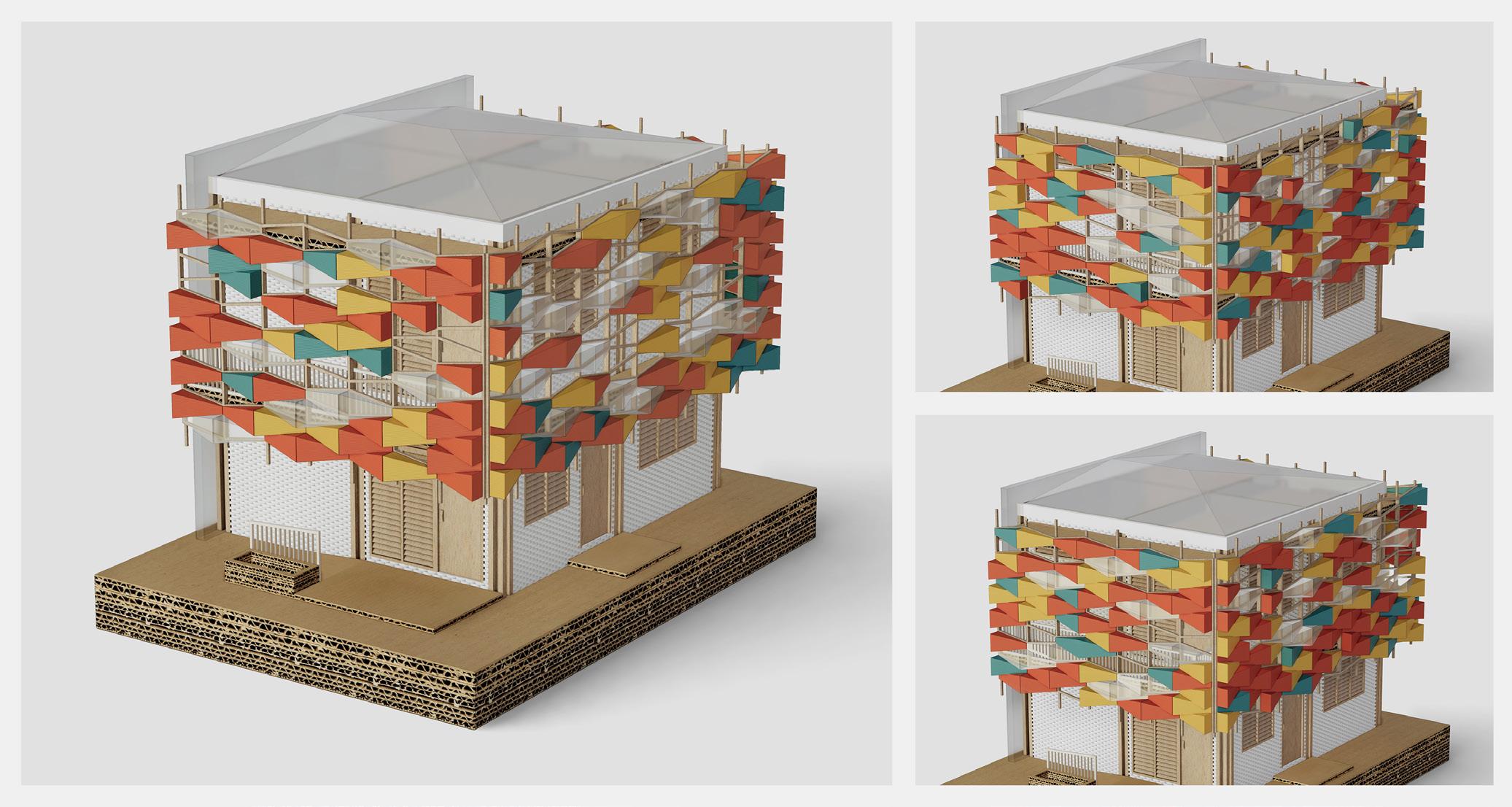

As a first step to localize the skin, we added features towards better thermal comfort, since the previous design lacked responsiveness to the tropical climate. We introduced canopies for shading and widened them to create wrap-around balconies as social spaces. This resulted in a larger and more usable, welcome porch underneath. We also converted the openings to jalousies to let in as much air as possible. The windows and doors were all made into modules to improve costs and

speed of fabrication. The skin is then introduced around the balconies as a brise-soleil, which further protects the interiors from the harsh sun, regardless of the orientation of the site where it would be built.

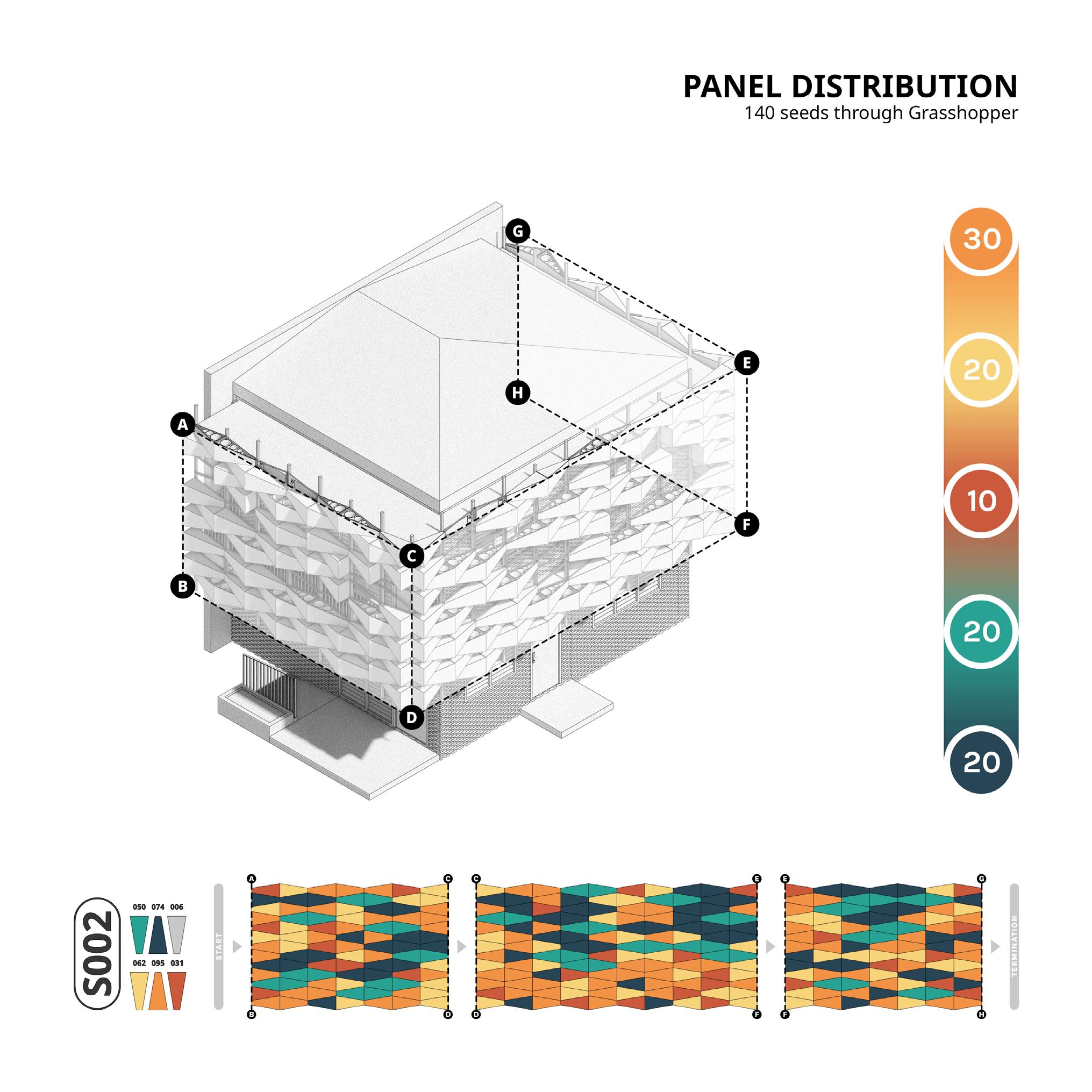

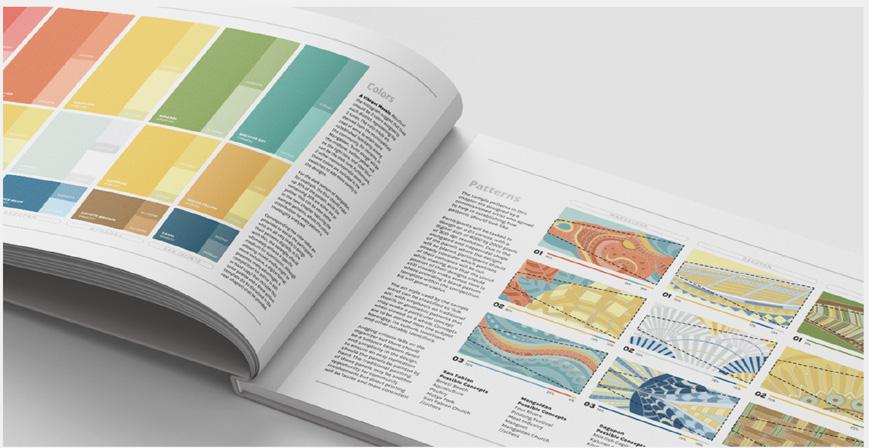

This lack of a specific site presents another concern: how will the standard skin reflect the character of each barangay? And for that we turn to the bigger picture of Pangasinan. Pangasinan is known for various industries where we tried to draw inspiration from for the skin. They have a rich agriculture industry where we studied crop arrangements; a traditional weaving industry where we studied the patterns and even their techniques. Combining the logic from all those, we were able to derive this diamond net-like grid, a nod to their massive fishing industry, born from having the longest coastline in the country. We developed this into a 3D network of modular panels that resemble a school of fish, an observation quickly made by the locals.

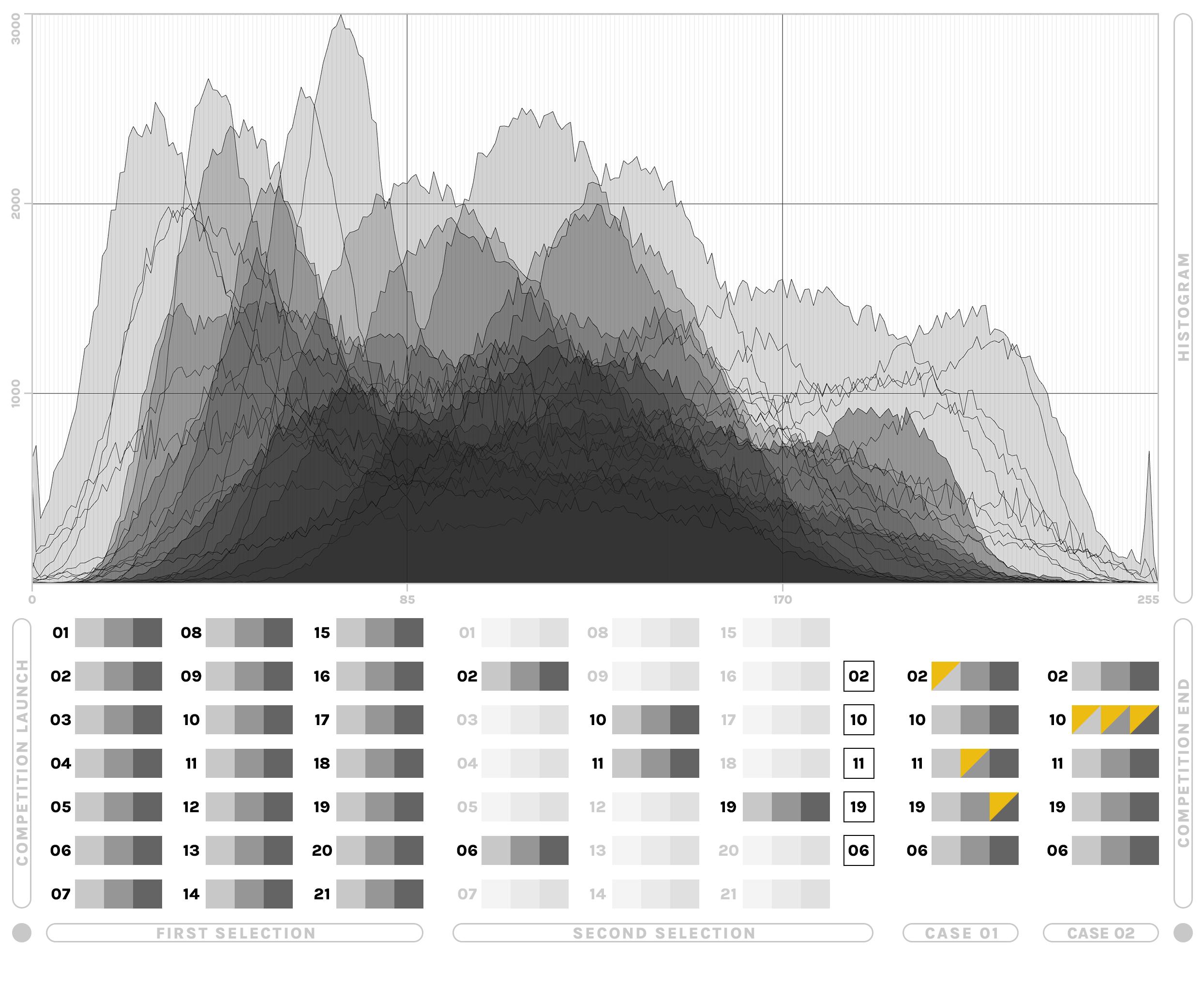

As you may notice, the facade is part solid to block heat, and part porous for daylighting. On the solid part, we borrow from the patterns of the local weaving industry, discovering a 20/30/10 tonality ratio across the patterns, which we were able to apply to the shading of the panels. We then combined this with the symbolic colors of each municipality to establish both distinction and familiarity. To further reinforce distinction, the skin is envisioned to be arranged differently per barangay. With the aid of a parametric approach and in consideration for daylighting, we developed hundreds of unique arrangements for each barangay and for each structure, akin to how our faces, colors, and the clothes we wear make us all unique.

Now, who better to reflect the uniqueness of these barangays than the residents themselves? This is where the hundreds of creatives from Pangasinan come in. The design of the panels will be crowdsourced through local art competitions, where the top 3 patterns will be awarded – one for the light, mid, and dark panels. The competition was launched last August 2023 and here are some of the entries.

As mentioned, the panels are modular, fabricated off-site, and shipped to the community where the residents of the barangay themselves can volunteer to help paint the winning patterns on the panels. The result is a building that is inspired by, designed, and crafted by the local community. The participatory approach demonstrated by the façade design of these standard barangay centers doesn’t just surrender a portion of the design to people who know most about the locality, but it also heightens the care people have for these buildings as they are made part of the process. The vision is that each barangay, with their own communities, can independently implement this standardized design on their own, without even needing us, the initial designers.

The objective to balance standardization with localization. The standardized bones and body address buildability, cost, speed of delivery; while the localized skin solves tropicality and identity

The hope is that what was formerly a transactional experience be transformed into a social space that encourages meaningful connections, resulting in an uplifting, dignified experience. By conceiving spaces that can be influenced and designed by people, even crafted by the people; we create an empowered community, reviving engagement toward barangay centers, as people start to see them as a reflection of their collective visions and values.

Skin iteration generated through a parametric approach

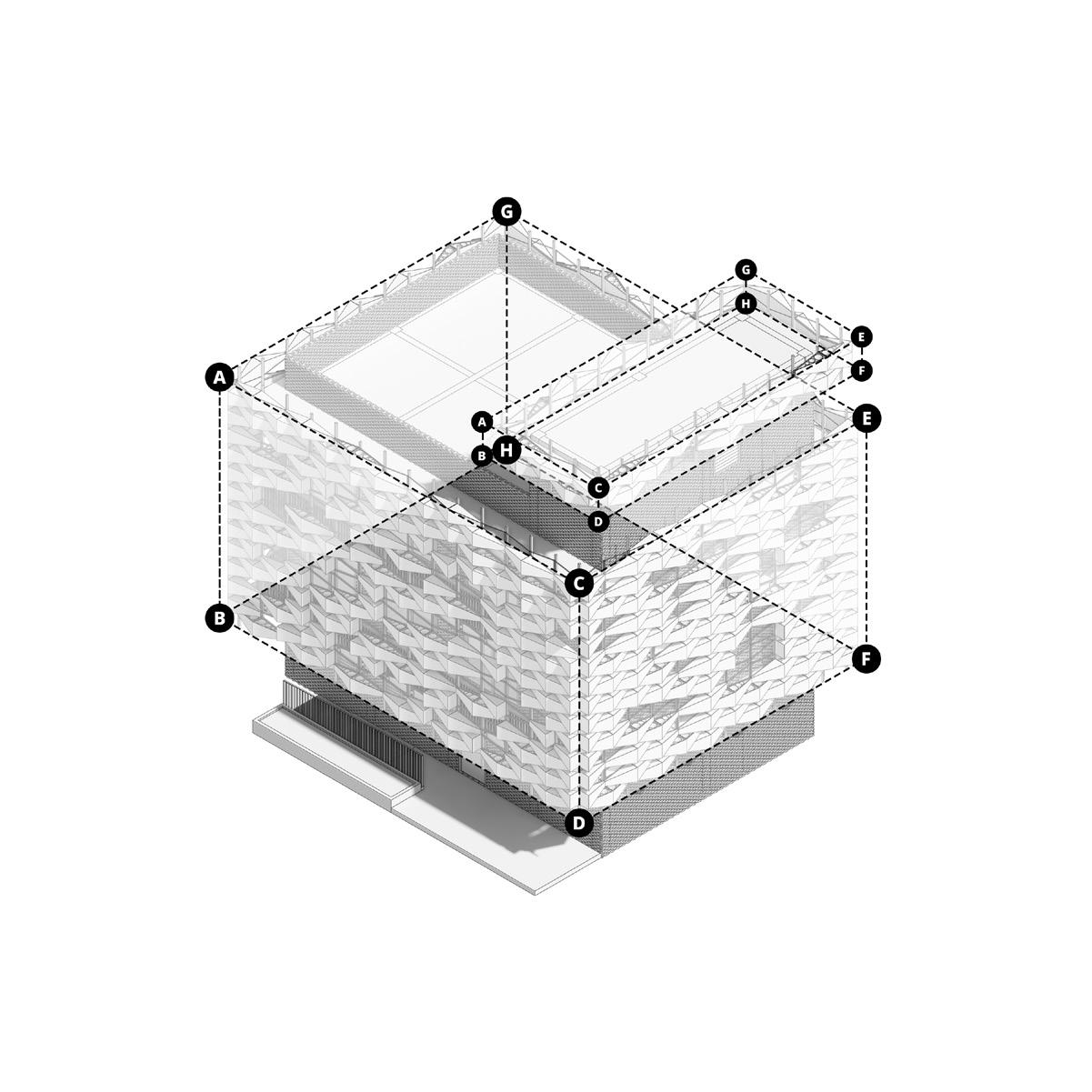

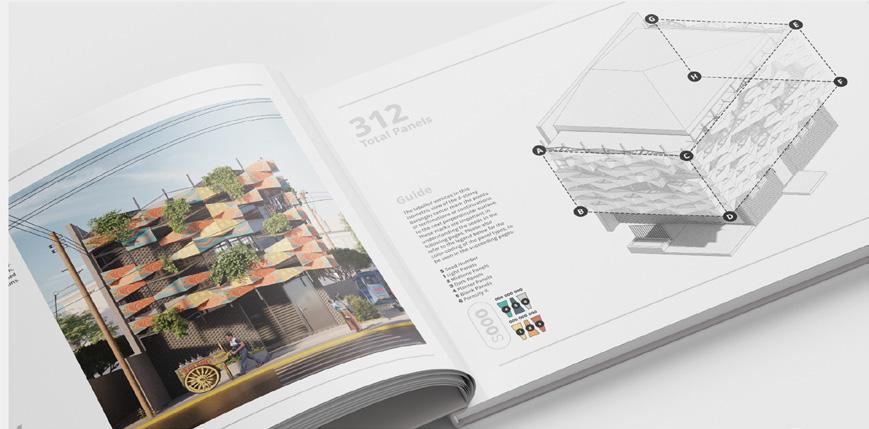

Isometric view of a 3-storey barangay center with guide points on surface termination and/or continuation

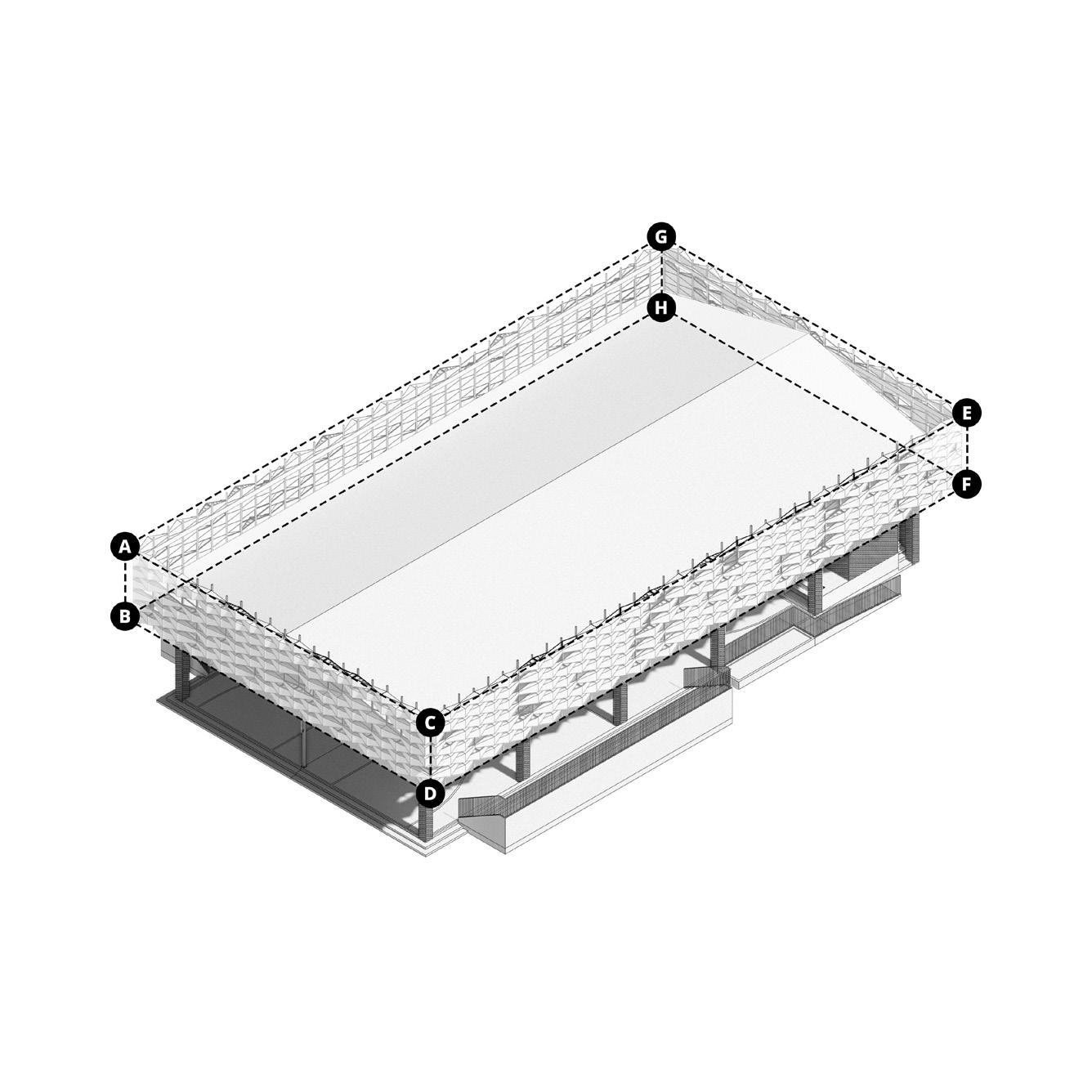

Isometric view of a multipurpose barangay court with guide points on surface termination and/or continuation

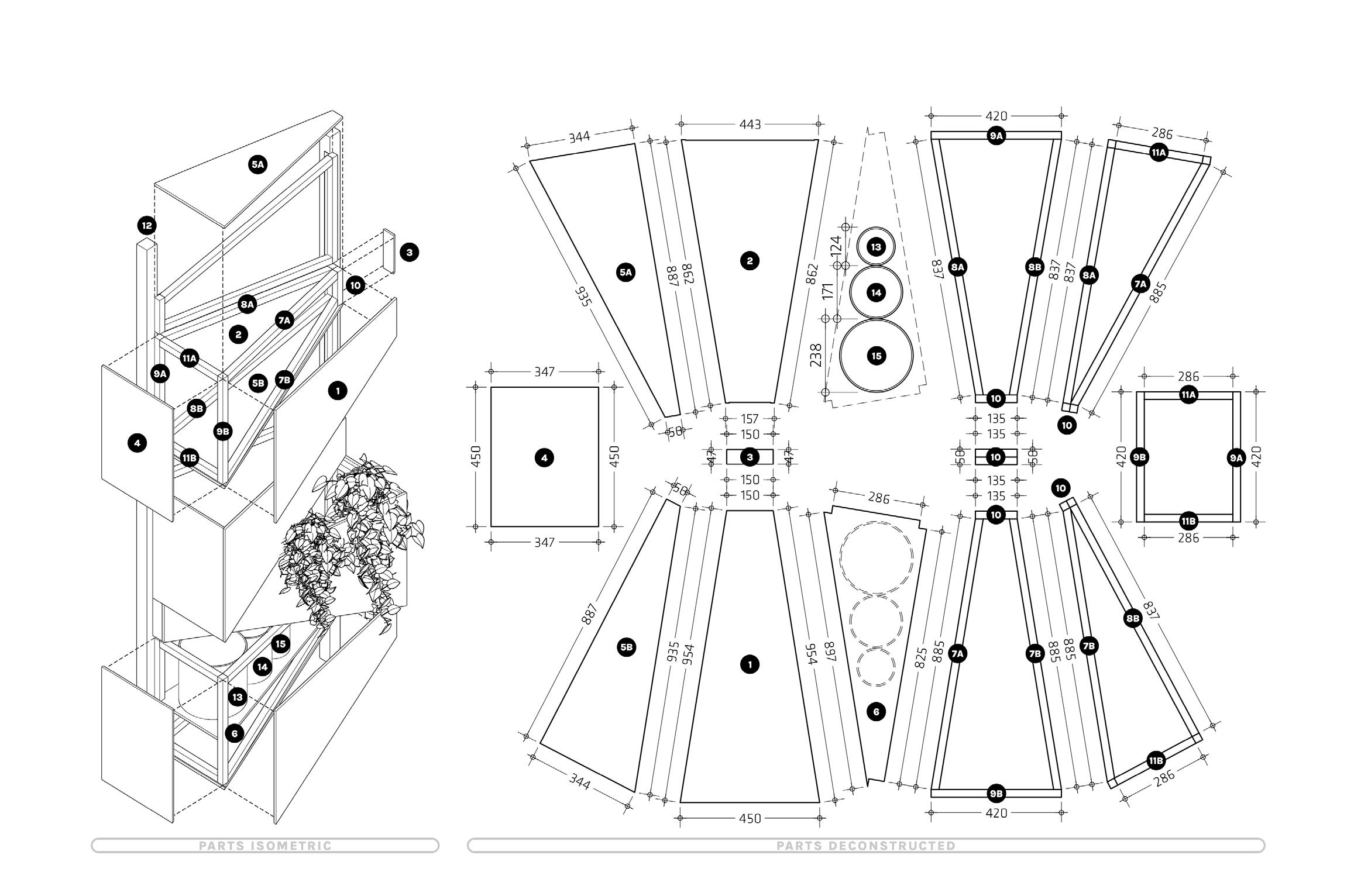

Deconstructed view of the panel surfaces and the tubular supports

Histogram of weaving patterns in the Philippines used as the basis for the distribution of patterns on the facade

Pattern visualization of the barangay centers in Mangaldan, Dagupan, and Manaoag, with the skins donning their specific municipality colors

Project Name

Year Completed

Project Location Lot Area Gross

Pangasinan Barangay Centers

2023 - Present (Construction Period)

Fourth District of Pangasinan

Various Sites

113.45 sqm (2-Storey)

412.27 sqm (3-Storey) 527.80 sqm (Multipurpose courts)

Barchan + Architecture (Buensalido + Architects)

Penthouse A, Greenbelt Mansion, 106 Perea St., Legaspi Village, Makati City

www.barchan.com.ph www.buensalidoarchitects.com

/barchanarchitecture /buensalidoarchitects

@barchan_architecture @buensalido_arch

@BArchan_Inc @buensalido_arch design@buensalidoarchitects.com

by

Architecture

Principal Architect

Senior Architects

Lead Design Coordinator

Project Architects

Client Engineering Consultants

Jason Buensalido

Emerauldine Eliseo

Marcelo Philippe Ramirez

Aramis Corullo

Lhouis Lanting

Miguel Razon

Aaron Espiritu

Fourth District of Pangasinan

KBL Structural Engineering Consultancy

Consibit Engineering Design

PD4 Creative Team

A visual summary of the project’s entire design and participatory process

By Grendelle Joshua Basa

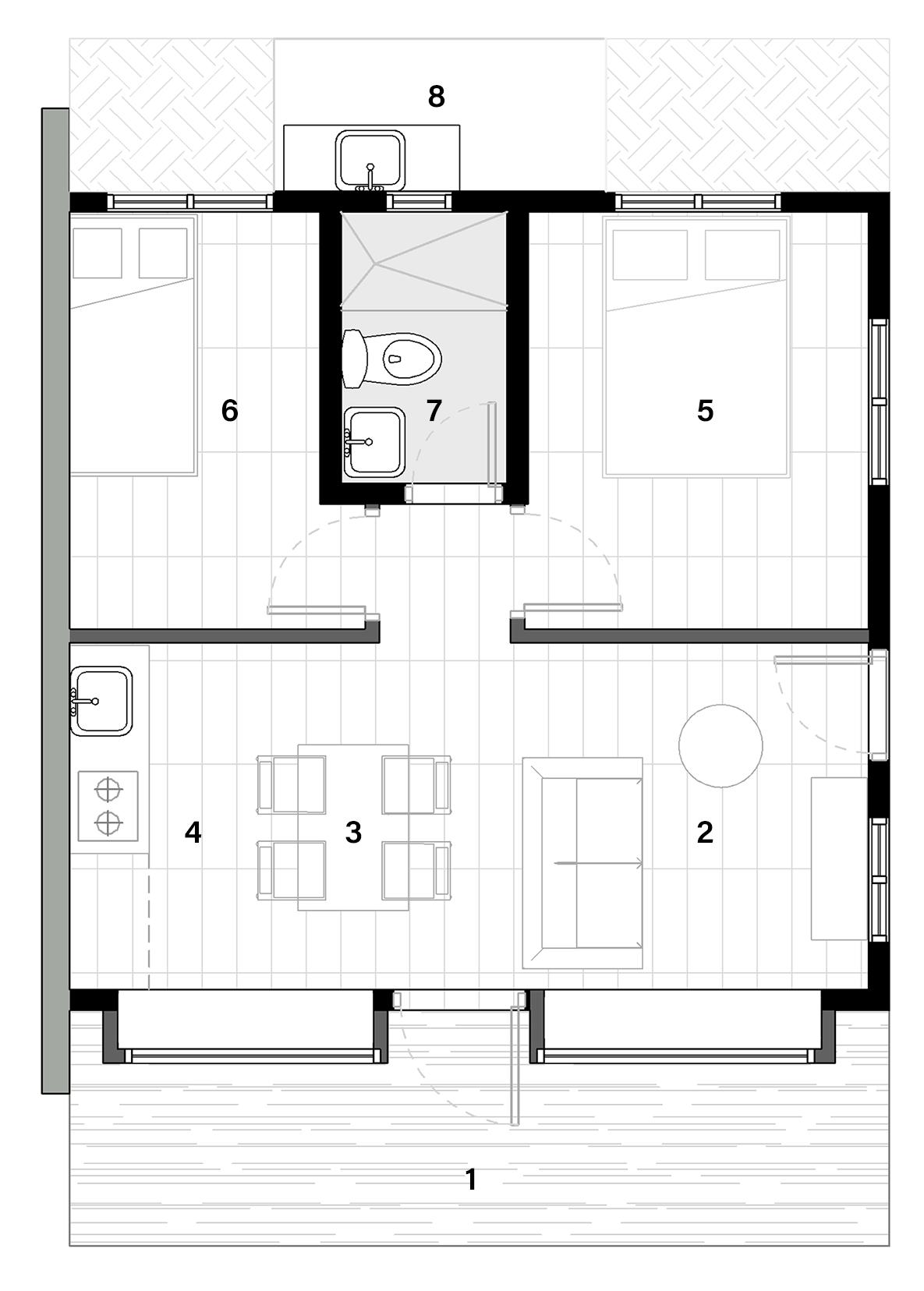

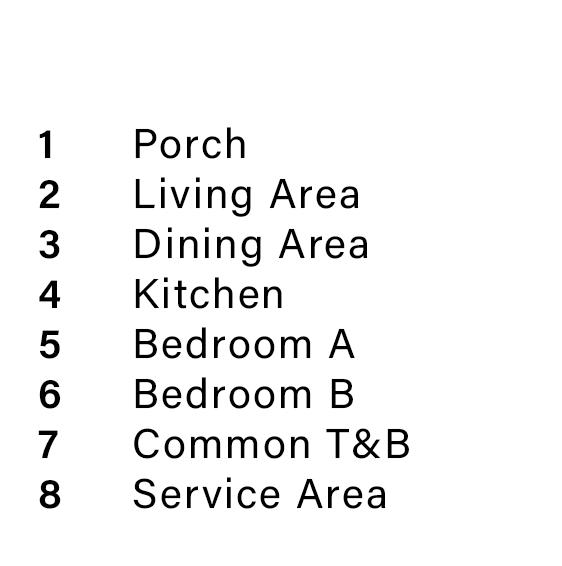

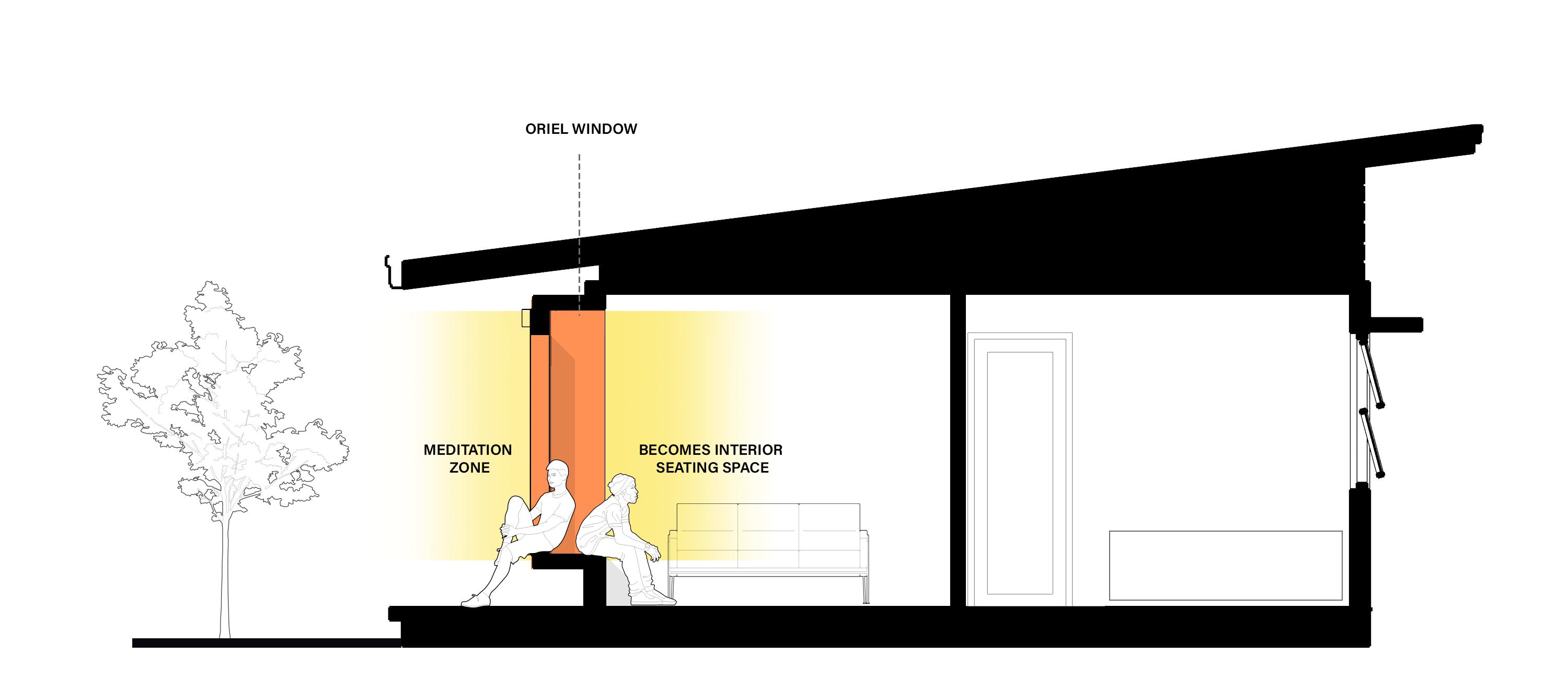

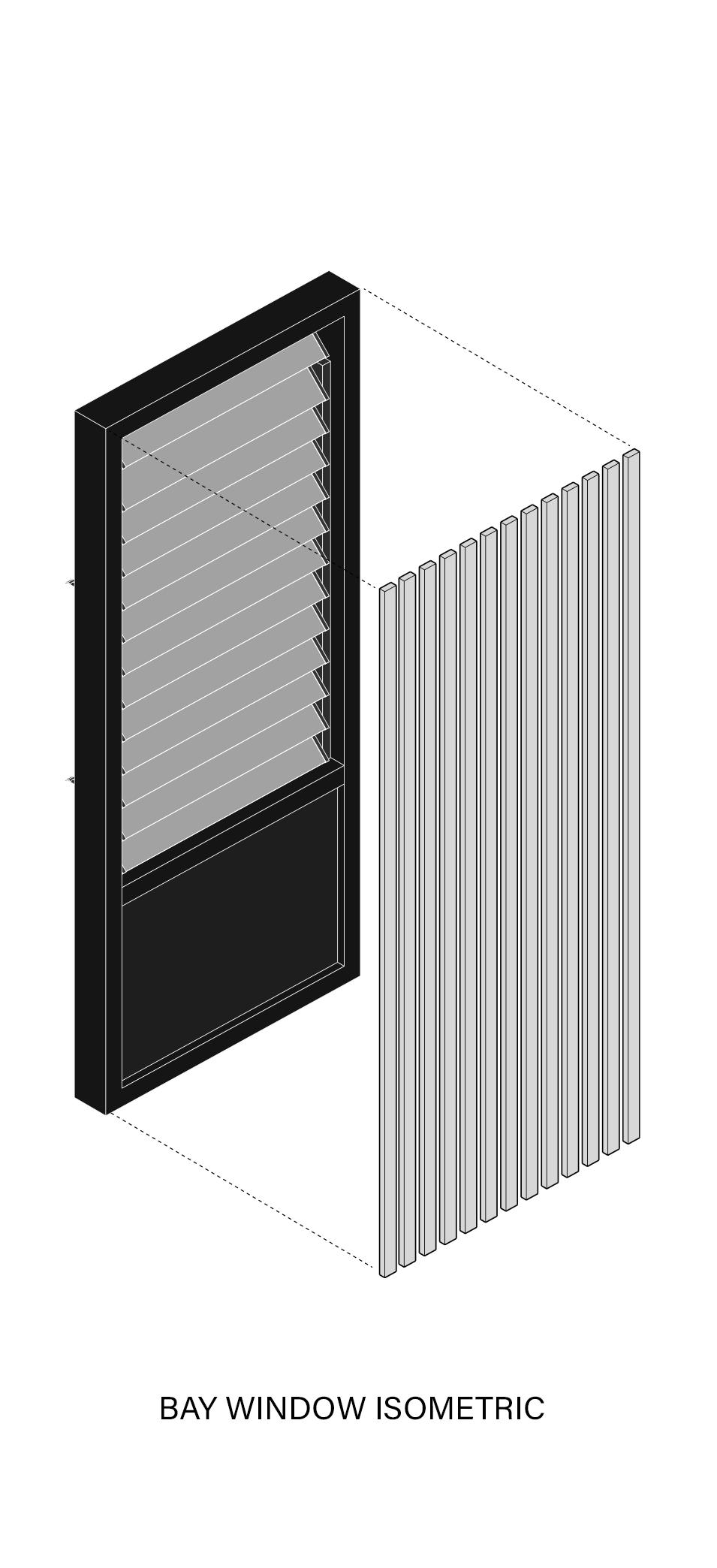

The project was built out of the clients’ desire to create a functional and tranquil living space for their grandparents amidst the budget and existing property area constraint. With a meager 36 square meters of possible building footprint, the design approach was aimed to maximize the space program and original intent, while maintaining a balance between functionality and budget considerations.

The core design challenge revolves on maximizing the interior space and its possible programs given the user-persona and site context, without expanding the building footprint.

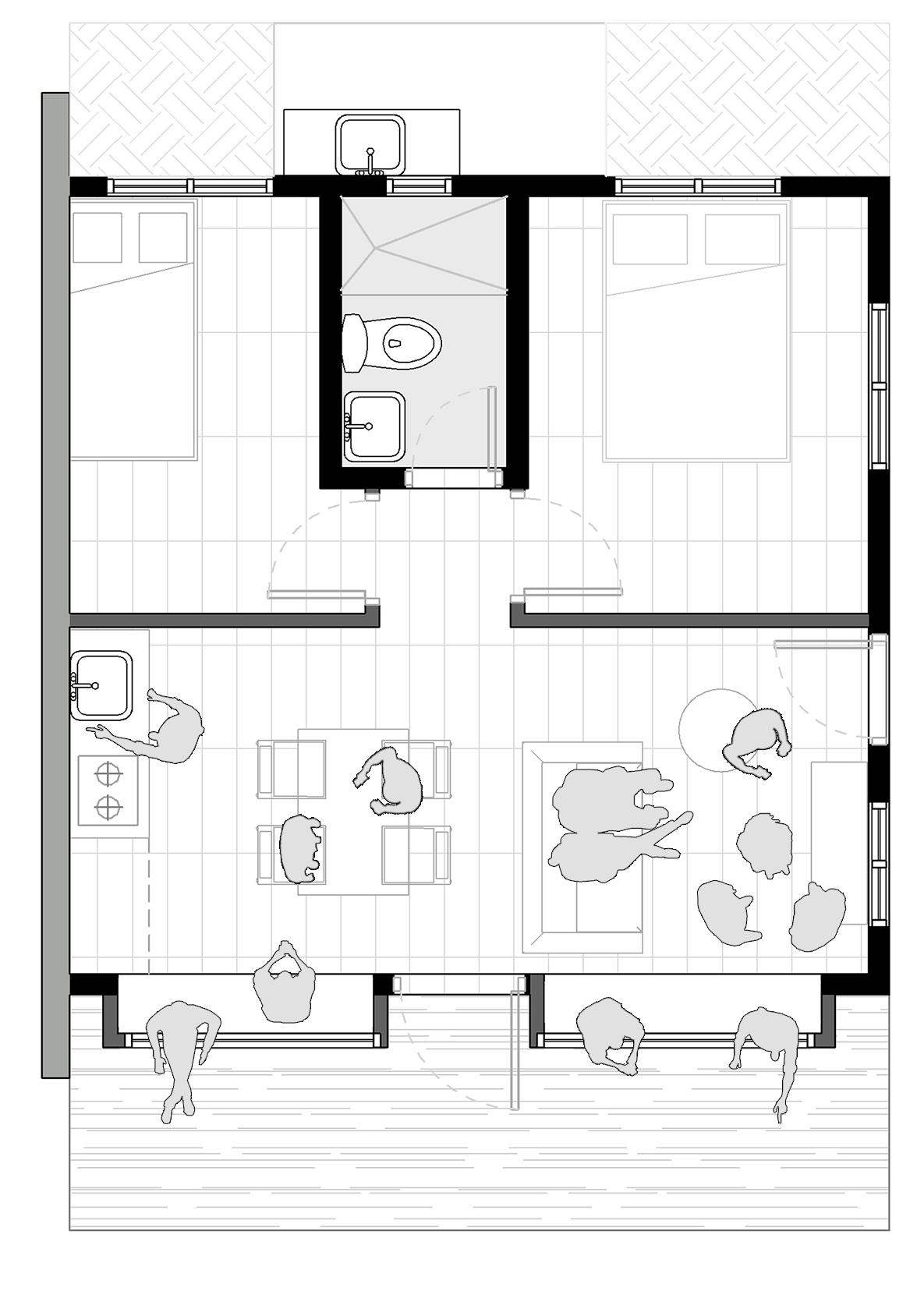

To address these challenges, a bay window is introduced, serving a multifaceted purpose. It not only maximizes the limited space but also offers area for the user’s meditation, functions as a versatile daybed, and adds depth and character to the overall architectural composition.

The solution also allows flexibility on its seating configuration amidst space restraint, a vital aspect for Filipinos who cherish SaloSalo culture or communal feasting. In effect, the architect is able to fit 2 bedrooms, central toilet & bath, ample-sized kitchen, 4-seater dining space, and living area with flexible layout configuration.

This architectural concept becomes a key functional feature and the defining identity of the entire structure.

The operable window of the bay window allows flexibility of airflow and sunlight filtering. The focus on developing and constructing the operable window is its ability to be flexible in filtering exterior elements. Once fully closed, the vertical wooden slats - sourced from a local woodcraft shop in the city – are able to provide partial privacy and a sense of enclosure to the openings. The jalousie windows serve as the next layer, controlling airflow and protecting against rain, all while allowing natural sunlight to filter through the glass.

Fully opening the operable window reduces the need for electric lighting during the day – which is significant given the area’s inconsistent electricity supply.

Overall, the project's alignment with the theme of Concept Creation lies in the architect’s approach to maximizing space, integrating cultural considerations, and prioritizing user comfort. Through thoughtful design intent and creative solutions, the architect has created a functional and tranquil living space meant for its users, embodying a concept that is both innovative and culturally relevant.

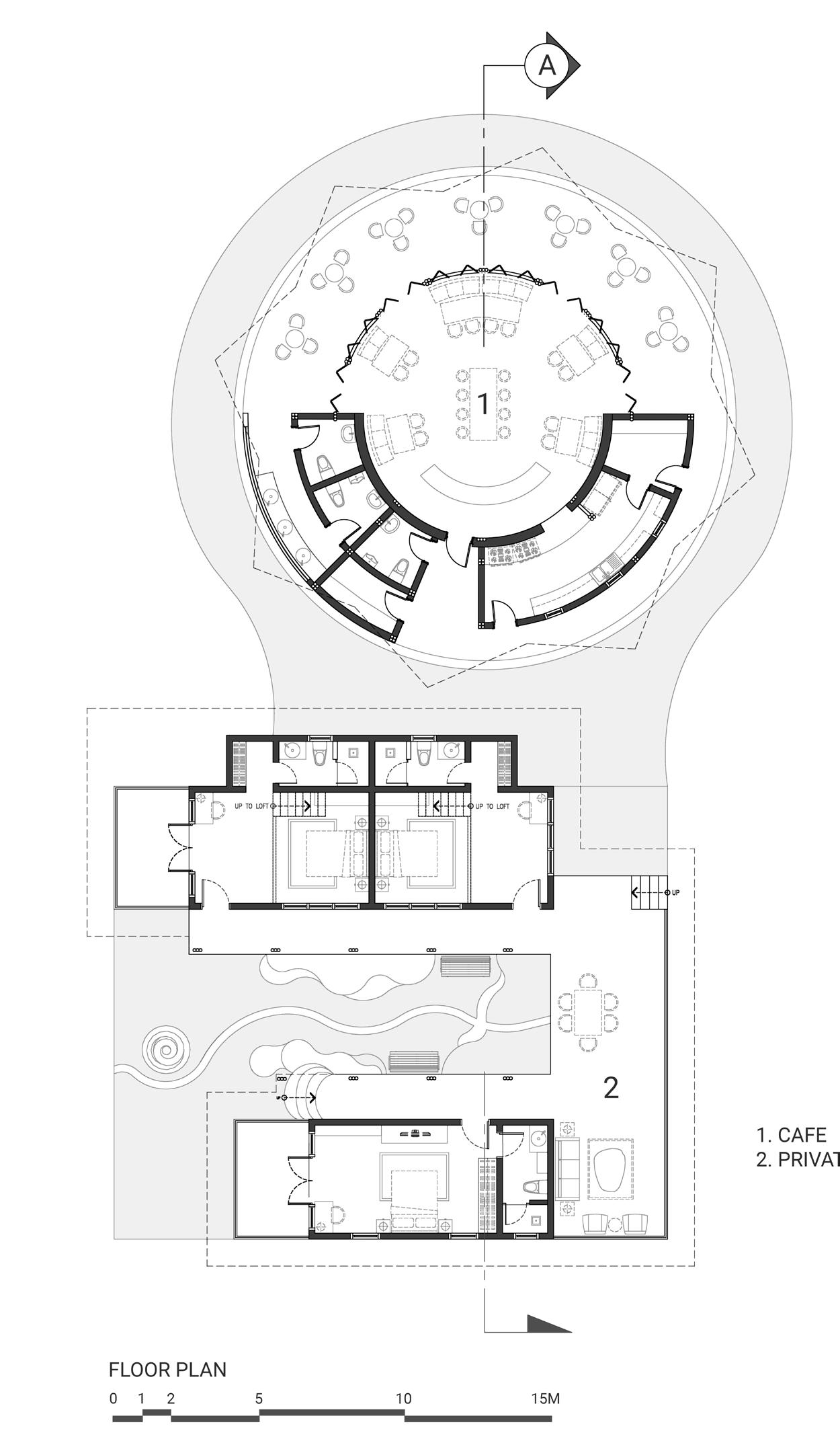

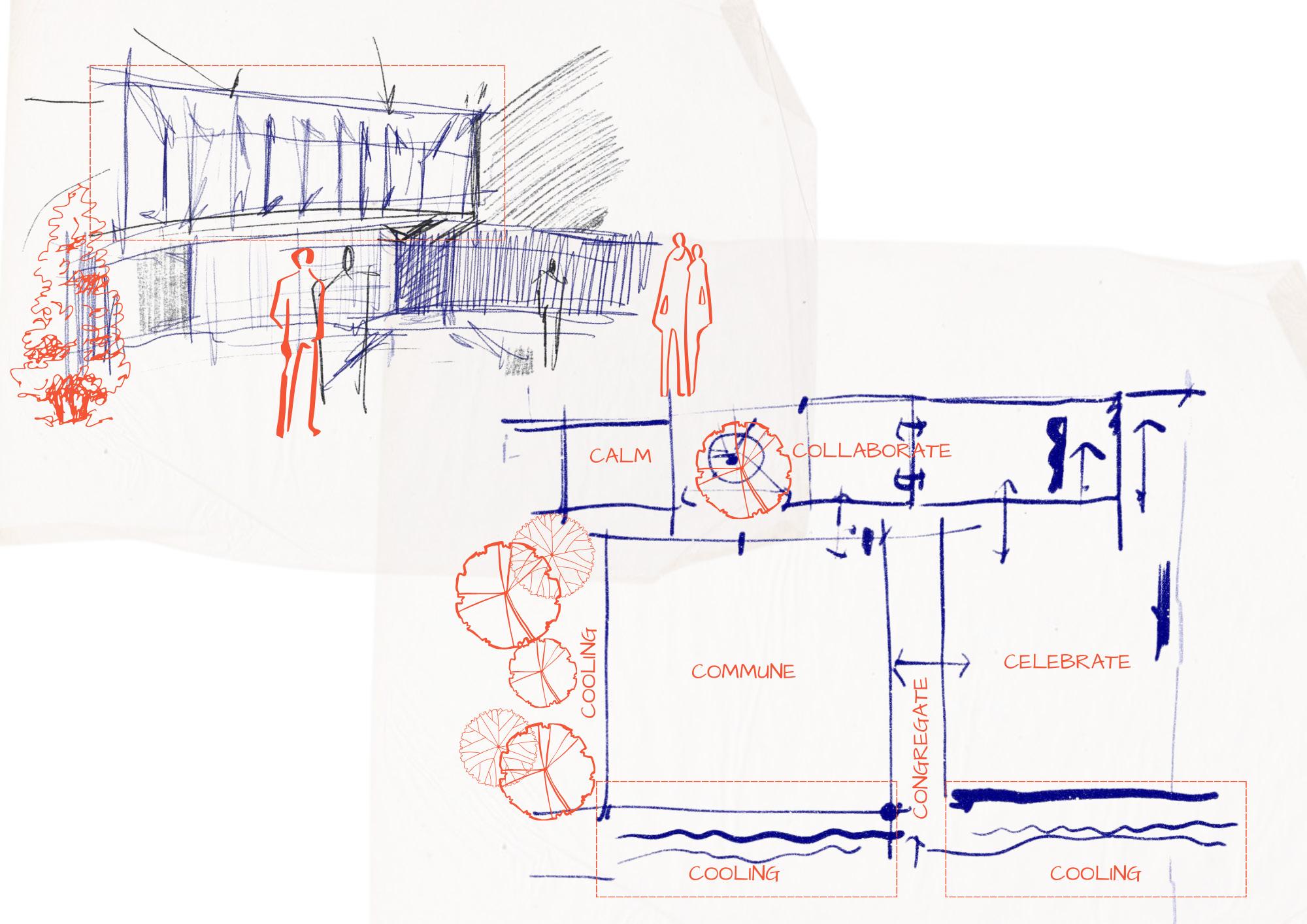

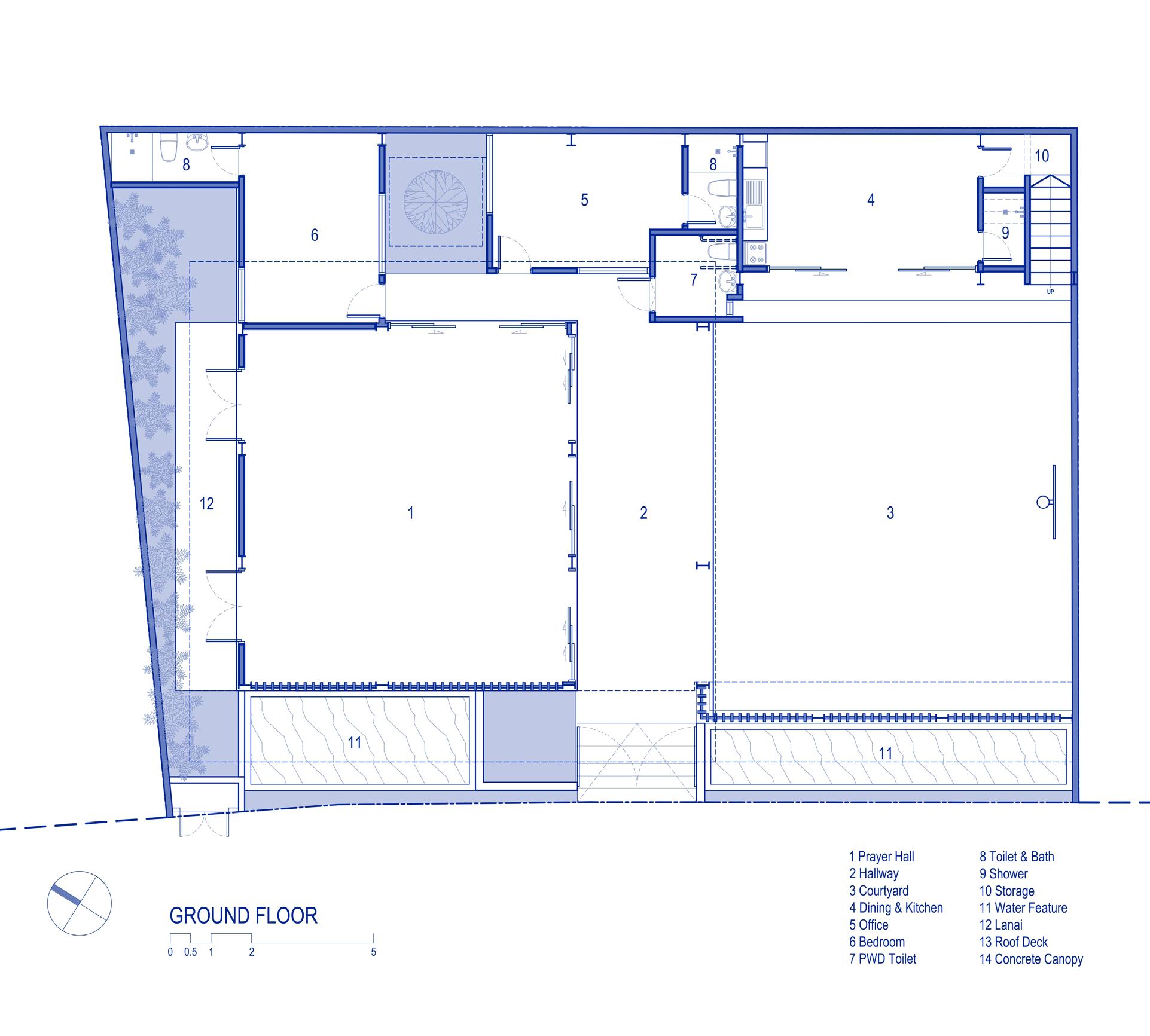

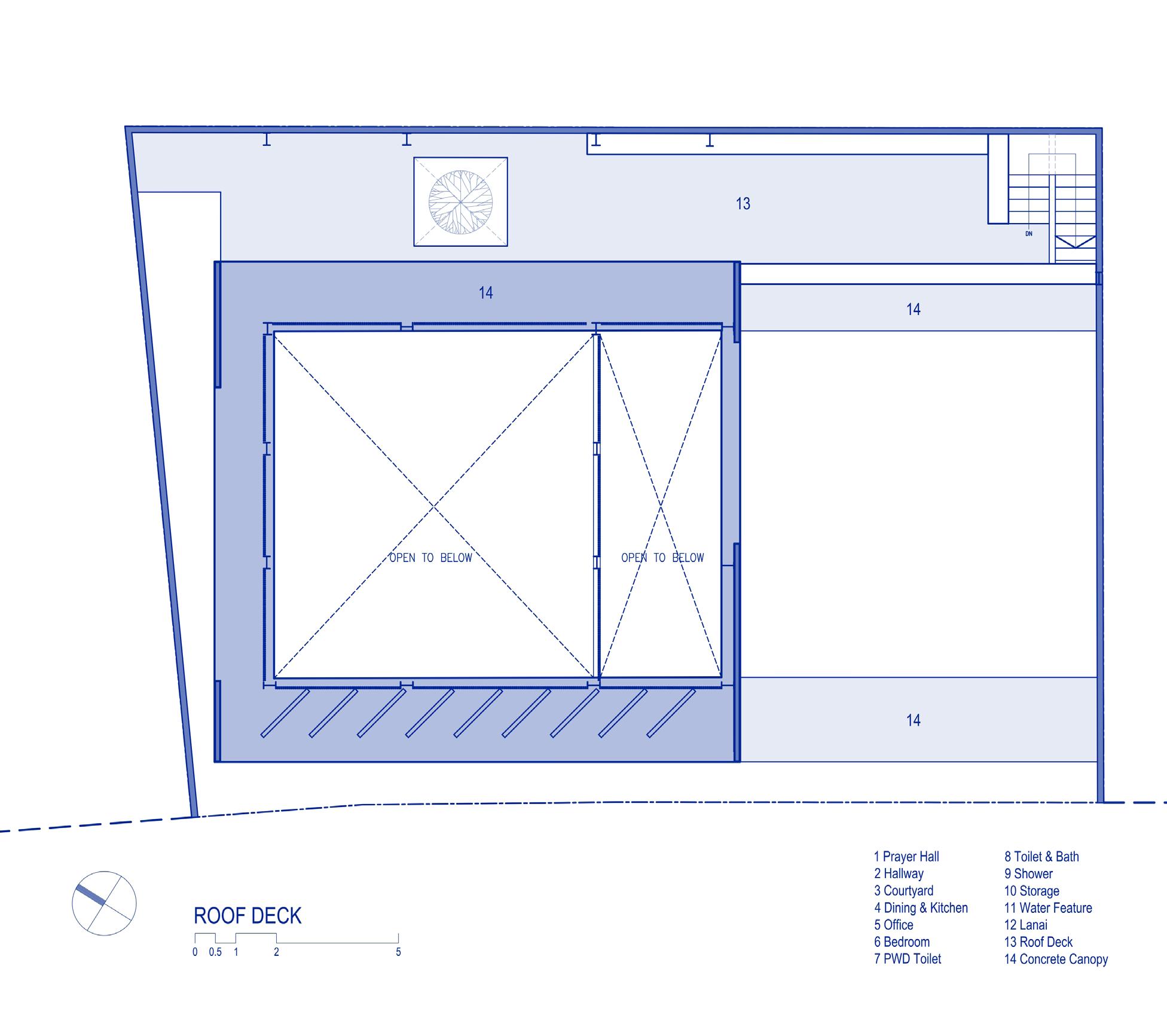

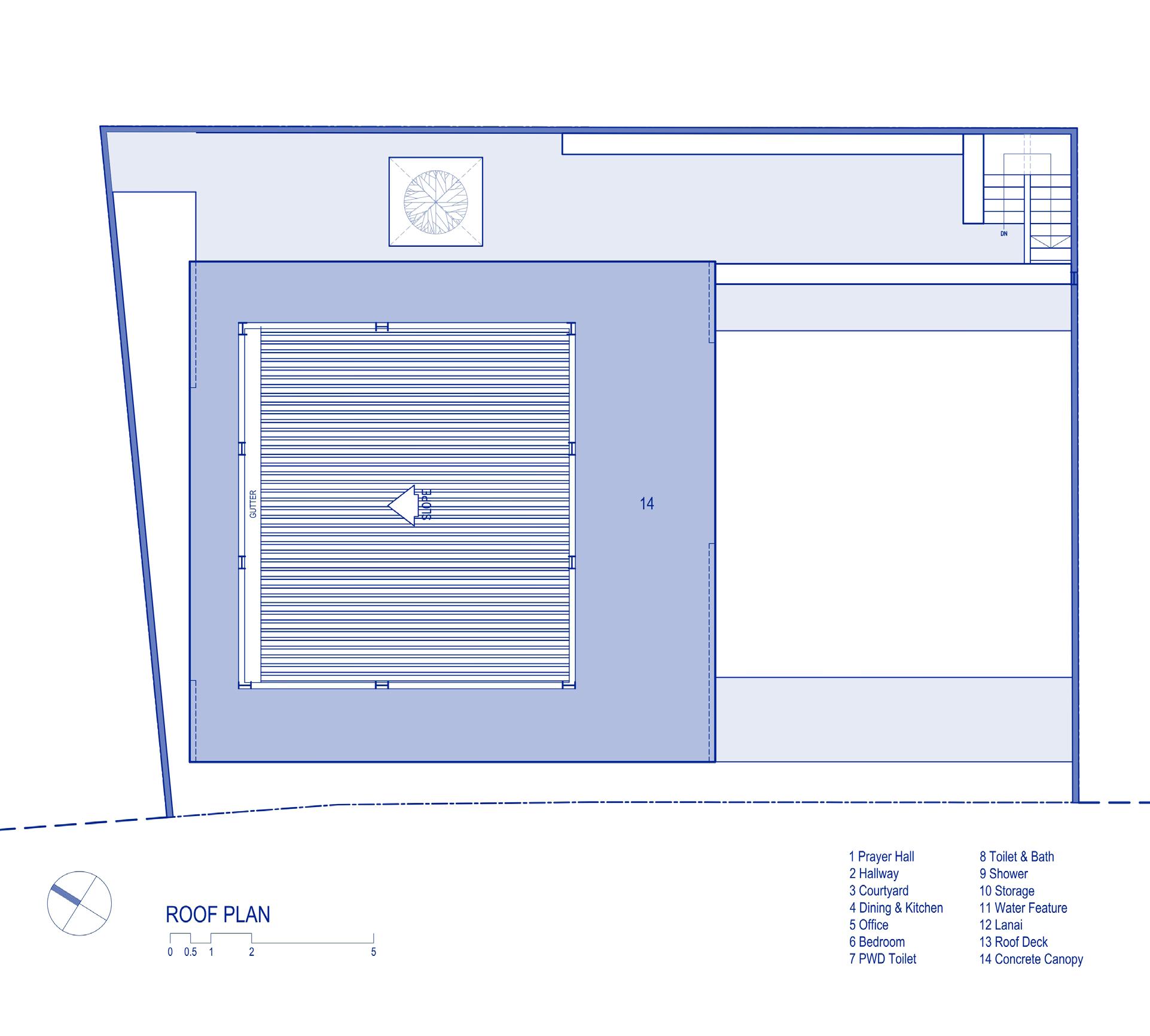

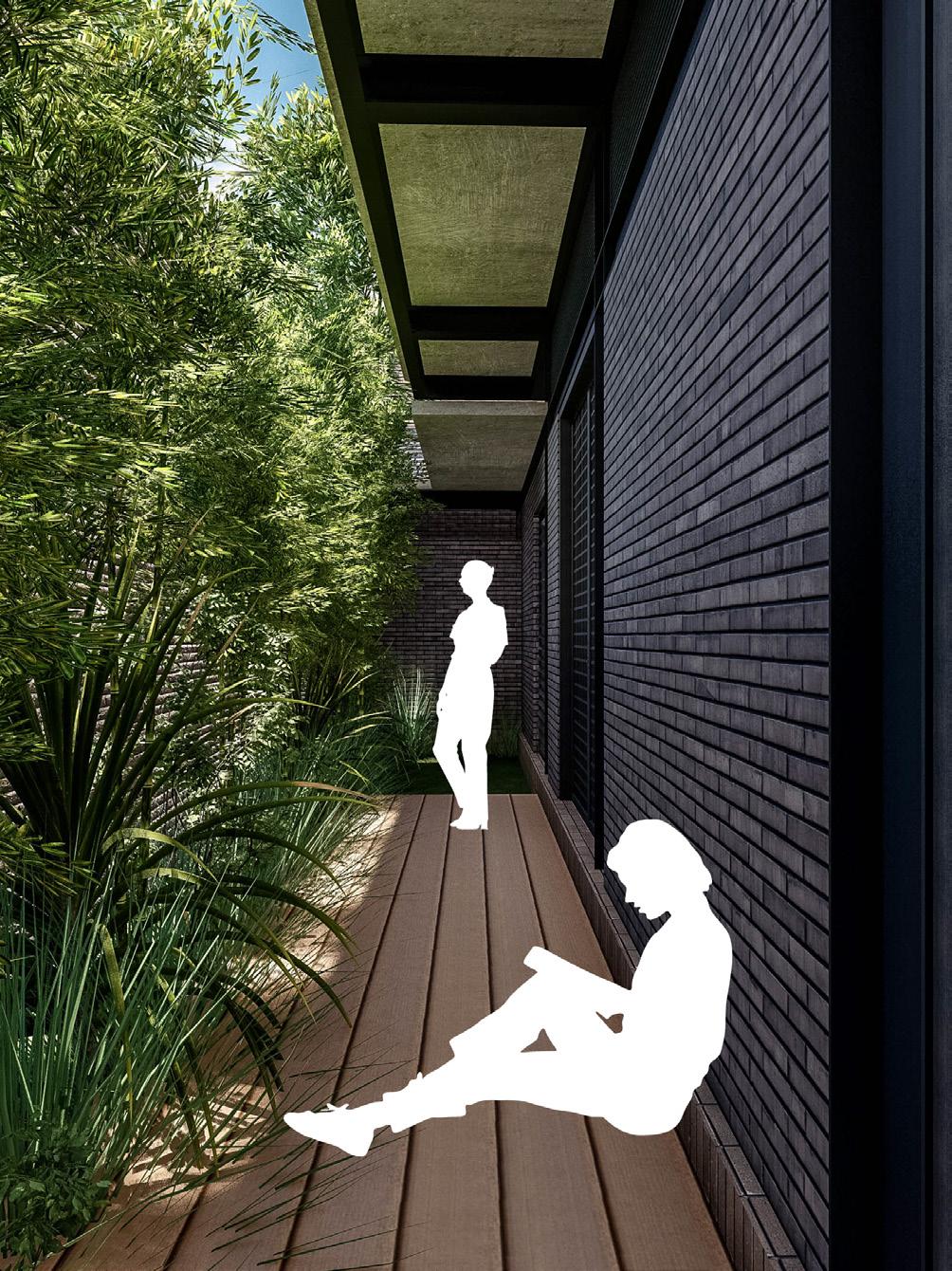

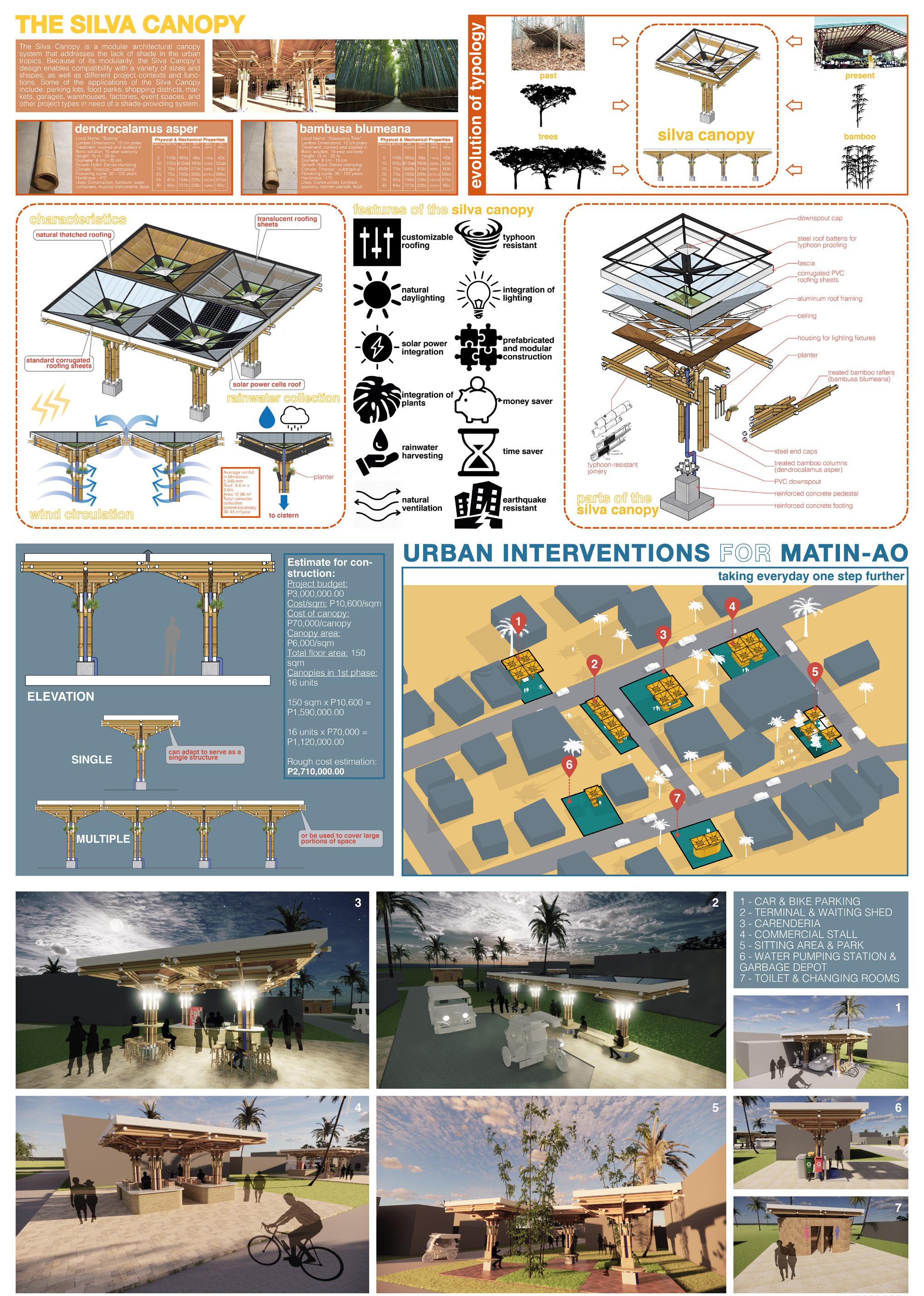

By Joevic O Mondejar & Elritz Gallo

A

contemporary café and residence project in Davao del

showcases the extraordinary versatility of bamboo—a local treasure that is often overlooked and underutilized.

Purple Leaf Farm, designed by Mondae Studio, is a residence and café complex built upon sustainability—both environmentally and economically. The impressive masterplan, covering an area of three hectares, seamlessly situates the urbanscape against the picturesque backdrop of Panabo, Davao del Norte. With the maximized use of bamboo at its core, this design will be the first of its kind in town, exemplifying a blend of architectural contrast and a harmonious planning approach. It is not just an infrastructure project–it is a testament to the spirit of collaboration that embraces the beauty of nature and

The project marries the concepts of a tropical contemporary café space and a residence. Nestled within a mango orchard, the boundaries between indoor and outdoor spaces are blurred with great panache. Guided by the expertise of Ani Landscape Architecture - a Landscape Design Studio based in Manila - that did the overall master plan of the site, the design not only preserves but embraces the natural terrain, orienting itself towards the tranquil creek and maximizing panoramic views of the verdant mango grove from the café area. The intent behind the layout of the central courtyard is deliberate to foster a sense of openness and connectivity with the surrounding landscape.

Skylights, clerestories, and oculi further enhance the spatial experience, allowing natural light and fresh air to permeate the interiors. To ensure privacy within the residential quarters, a meticulous “Security by Design” strategy is employed. This approach ingeniously utilizes landscaping elements to create visual and auditory barriers, while a low porous fence acts as a subtle yet effective physical deterrent, safeguarding the sanctuary within.

As the project harmonizes with the organic contours and natural features of the site, it also immerses both end-users and visitors in an engaging and educational experience of exploring the various treatments and applications of bamboo, a vital resource that proves its significance in the region.

The café component provides guests with the option to relax in a cozy indoor lounge or enjoy their meals alfresco flanked by the lush greenery. Meanwhile, within the residential component, an open-plan layout encourages fluid movement and interaction, with communal spaces designed for gatherings and social events.

Serving as the heart of the establishment, the kitchen serves a dual purpose as the culinary center and a transitional space connecting the private residence to the public café area.

As the residence transitions into an Airbnb amenity in the future, the kitchen will be transformed into a private area exclusively dedicated to servicing the café, ensuring smooth operations and reinforcing the business aspect of the client’s enterprise. Moreover, the adaptive arrangement maintains the distinction between private and public areas of the establishment, aligning with the project’s overarching goal of economic sustainability.

Inspired by the notion of balance and the allure of opposites, the design showcases disparate shapes and celebrates the intricate geometries and crafts native to Davao. This juxtaposition in both the café’s and the private residence’s designs serves to evoke a sense of visual intrigue. Reminiscent of a circle, the cafe layout draws in the eye with its leading fluid lines, while the rectilinear composition of its roof–a nod to the intricate details of traditional Davaoeño design–adds depth, complexity, and a sense of order. On the other hand, the nearby private residence’s simpler layout and curved roof provide a striking contrast to the café’s design elements, inviting viewers to compare and appreciate the distinct forms in action. This conscious interplay of curves and lines not only illustrates the harmony found in contrast but also enhances the overall coherence and aesthetic appeal of the design.

Overseeing the meticulous execution of the design, Mondae Studio ensured that every detail reflects precision and purpose. Utilizing indigenous materials and innovative techniques, such as bamboo connections and rammed earth materials, the structures stand as monuments of sustainability and ingenuity. Additionally, the color scheme is dictated by the natural materials employed in construction, including bamboo, nipa shingles for roofing, and the natural soil, echoing and complementing the organic palette of the surrounding environment.

Purple Leaf Farm embodies a pioneering vision for sustainable architecture in Davao del Norte. More than a café and residence, it symbolizes professional collaboration, cultural richness, and environmental stewardship. Effortlessly blending nature with contemporary design and harnessing bamboo’s endless potential, it sets a bold new standard for urban development.

By Gerald Harayo

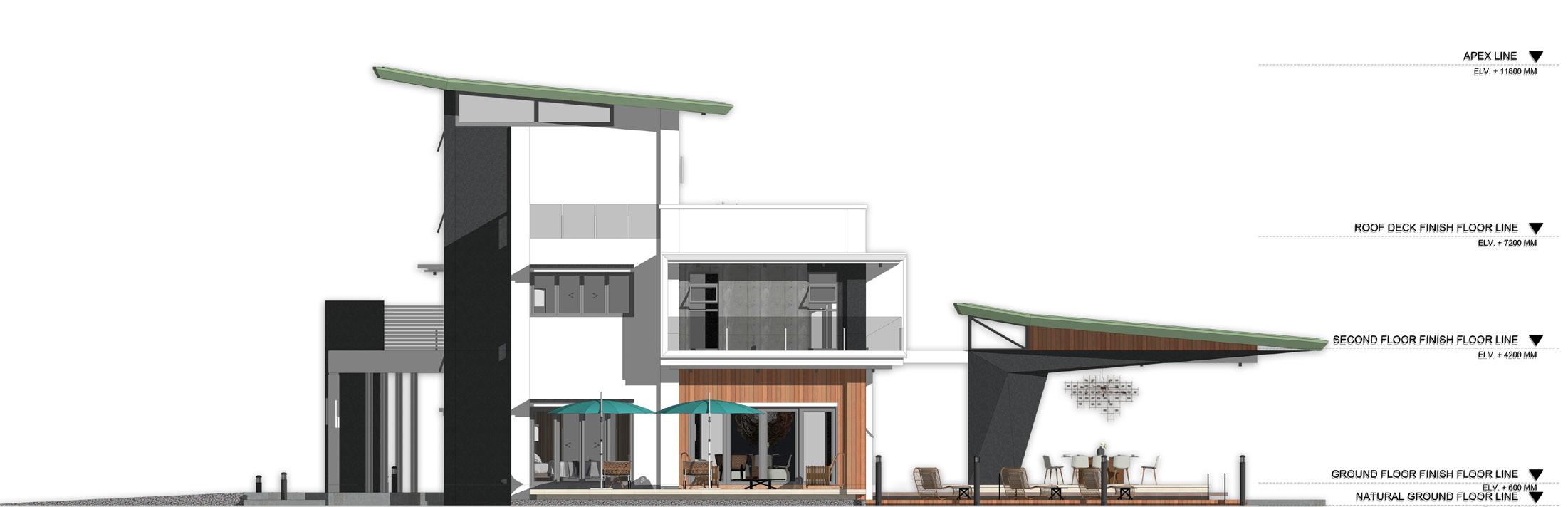

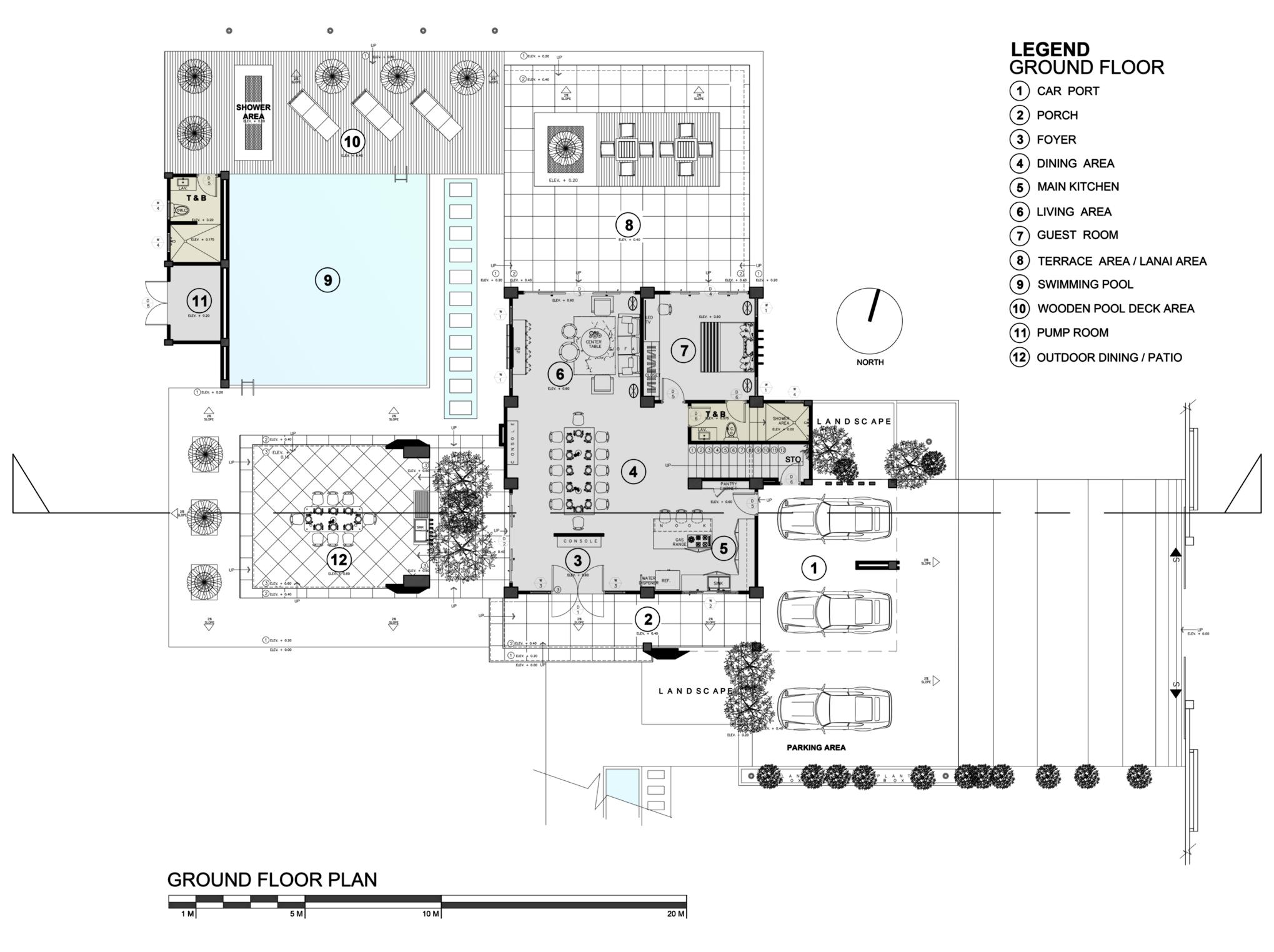

Nestled on a five thousand square meter lot located at Tacurong, Sultan Kudarat, Mindanao, a peaceful haven away from the city’s chaos, this spacious lot invites residents to escape into a tranquil oasis surrounded by nature. Its wide-open spaces offer ample opportunities for relaxation, and embracing the serenity of their surroundings. Encircled by verdant mango trees, the site brims with natural vitality, providing a tranquil retreat where residents can reconnect with nature’s rhythms. The lush greenery showcases the region’s rich biodiversity, fostering an appreciation for its natural beauty.

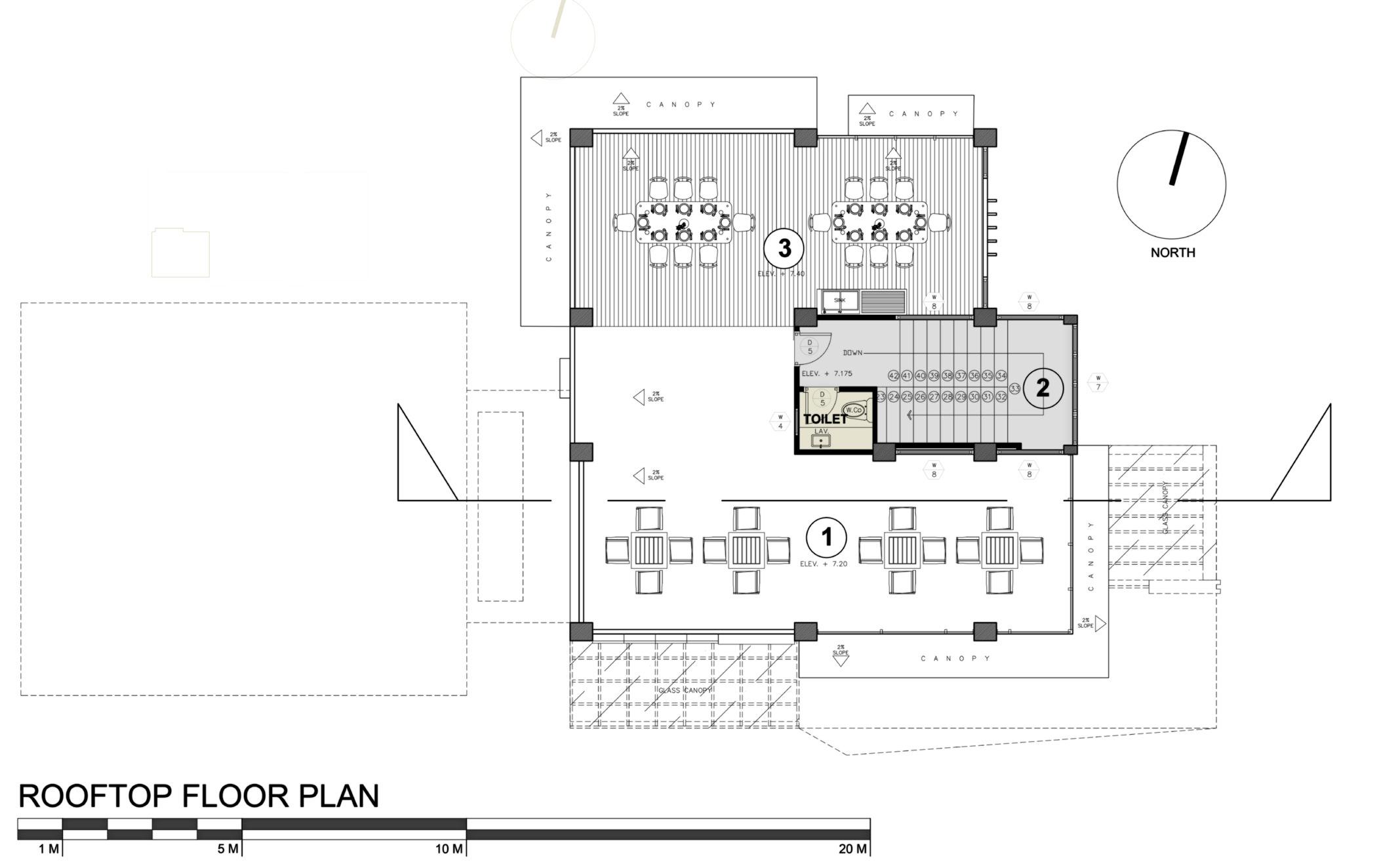

This proposed two-storey residential building with a rooftop combines contemporary architecture and inspiration from Japanese origami in an elegant manner. The design aims to provide a quiet and well-thought out living environment for a family of medical doctors based in Tacurong, Sultan Kudarat, Mindanao. It is located on a five thousand square meter lot surrounded by mango trees and lush vegetation which encourages unobtrusive indooroutdoor living through the use of large sliding doors and windows that bring in natural light and ventilation into the interior spaces to mimic a resortstyle home.

Exterior/ Façade Design

Inspired by the art of Origami, a Japanese paper folding technique, the front of the house features crisp lines and geometric patterns creating a striking yet peaceful presence, amidst the vibrant mango trees and natural surroundings. The facade is accentuated by sliding doors and windows that blur the distinction between indoors and outdoors allowing nature’s beauty to flow inside.

The architectural design of the exterior showcases a fusion of style with elements from nature resulting in a blend of practicality and visual appeal. The facade exhibits a combination of materials featuring tempered glass balconies complemented by stainless steel railings and fixtures that exude a touch of modern elegance.

To add visual interest and texture, the walls are carefully crafted with a combination of textured finishes and prefabricated accent walls near the facade, creating depth and dimension. These elements not only serve to enhance the architectural character of the building but also contribute to its overall visual impact.

At the main entrance, a statement solid wooden door commands attention, serving as a focal point of the design. Above the door, a vertical garden provides a refreshing burst of greenery, adding a touch of natural beauty to the façade and harmonizing with the surrounding landscape.

The outdoor dining and patio areas are ingeniously designed as cantilevered structures, imparting a sense of weightlessness and visual intrigue. This architectural feature not only enhances the aesthetic appeal of the building but also creates an inviting space for residents to enjoy the outdoors while being sheltered from the elements.

Throughout the exterior design, a palette of natural colors and wooden walls is employed, seamlessly blending the building with its natural surroundings and imbuing it with warmth and charm. This thoughtful use of materials and architectural elements creates a striking yet inviting exterior that perfectly complements the serene environment of Tacurong, Sultan Kudarat, Mindanao.

Gerald Harayo

The ground floor is meticulously planned for communal activities and leisure, emphasizing a sense of openness and connection with nature. The focal point is the swimming pool and patio area, providing a refreshing haven for family gatherings and entertaining guests. Additionally, a guest room on this floor offers cozy accommodation for visitors, ensuring their privacy and convenience.

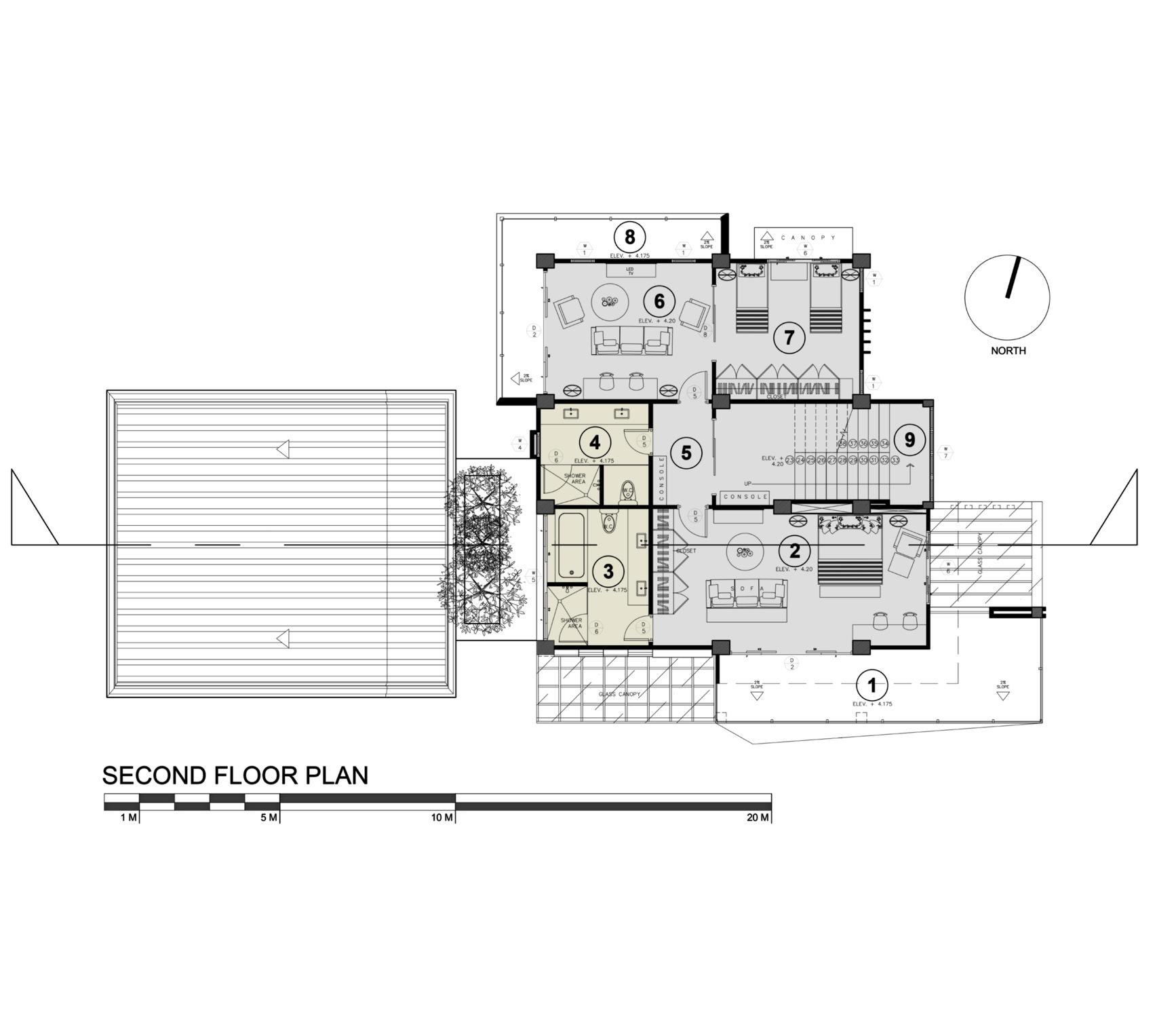

The second level of the family’s private quarters includes the anteroom leading to the children’s bedroom, a children’s playroom/study room, and a master’s bedroom with an en-suite bathroom and expansive windows framing scenic tree views. This layout reflects a thoughtful design that caters to the needs of both children and adults, providing spaces for relaxation, play, and study within the private domain of the residence. The master’s bedroom, characterized by its calmness and sophistication, serves as a sanctuary for the homeowners, offering a tranquil retreat with scenic views that connect the interior spaces with the natural surroundings. The inclusion of an en-suite bathroom enhances the functionality and privacy of the master suite, ensuring a seamless blend of comfort and elegance in this private realm of the home.

A spacious alfresco dining area graces the rooftop offering views of the property and its lush environment. This space serves as a spot for unwinding, hosting gatherings and immersing oneself in the beauty of nature.

My clients envisioned a space that not only embodied their affinity for contemporary design but also fostered a strong bond between their two daughters. They sought a home where their girls could grow together, sharing secrets, laughter, and dreams, spending countless hours playing, studying, and creating cherished memories in their shared room. This vision was to create an enduring legacy of sisterhood and togetherness.

To fulfill this vision, my client wanted a design featuring a children’s bedroom easily accessible from the master’s bedroom, with a sliding door separating the sleeping quarters and a versatile playroom/study room that could be transformed into an additional bedroom if necessary. This thoughtful layout allowed the sisters to have their individual beds while maintaining the closeness and connection of being in proximity to each other, fostering a sense of companionship and shared experiences.

Proposed Two-Storey Residential Building with Outdoor Dining Rooftop and Swimming Pool

Tacurong, Sultan Kudarat, Mindanao, Philippines

5,000 sqm

390 sqm

Kenchikuka Harayo Design

P.N. Roa Subdivision, Canito-an, Cagayan De Oro City

Gerald Canoy Harayo gerald.harayo@ustp.edu.ph

On Journal Theme

The theme of “Concept Creation” in the journal focuses on generating innovative ideas that form the basis of a design project. In my proposed residential house design, this is evident in:

Blending Contemporary and Japanese Origami Influences:

I integrated clean lines and geometric shapes inspired by Origami with modern architecture, creating a unique and cohesive design theme.

Prioritizing Serenity and Functionality:

I envision creating a serene and functional living space for a family of medical doctors and their relatives by carefully considering layout, materials, and spatial arrangements to promote relaxation and well-being.

Seamless Indoor-Outdoor Connection:

Large sliding doors and windows were strategically placed to maximize natural light and blur the boundaries between inside and outside, enhancing the connection with nature.

Thoughtful Spatial Planning:

Communal areas like the swimming pool and patio were designed for leisure and entertainment, while private quarters ensured privacy. A guest room on the ground floor accommodates visitors while maintaining privacy.

In summary, our project reflects innovative and cohesive ideas, from blending architectural styles to thoughtful spatial planning, all aimed at creating a harmonious and functional living environment for the occupants.

By Keisha Plaza

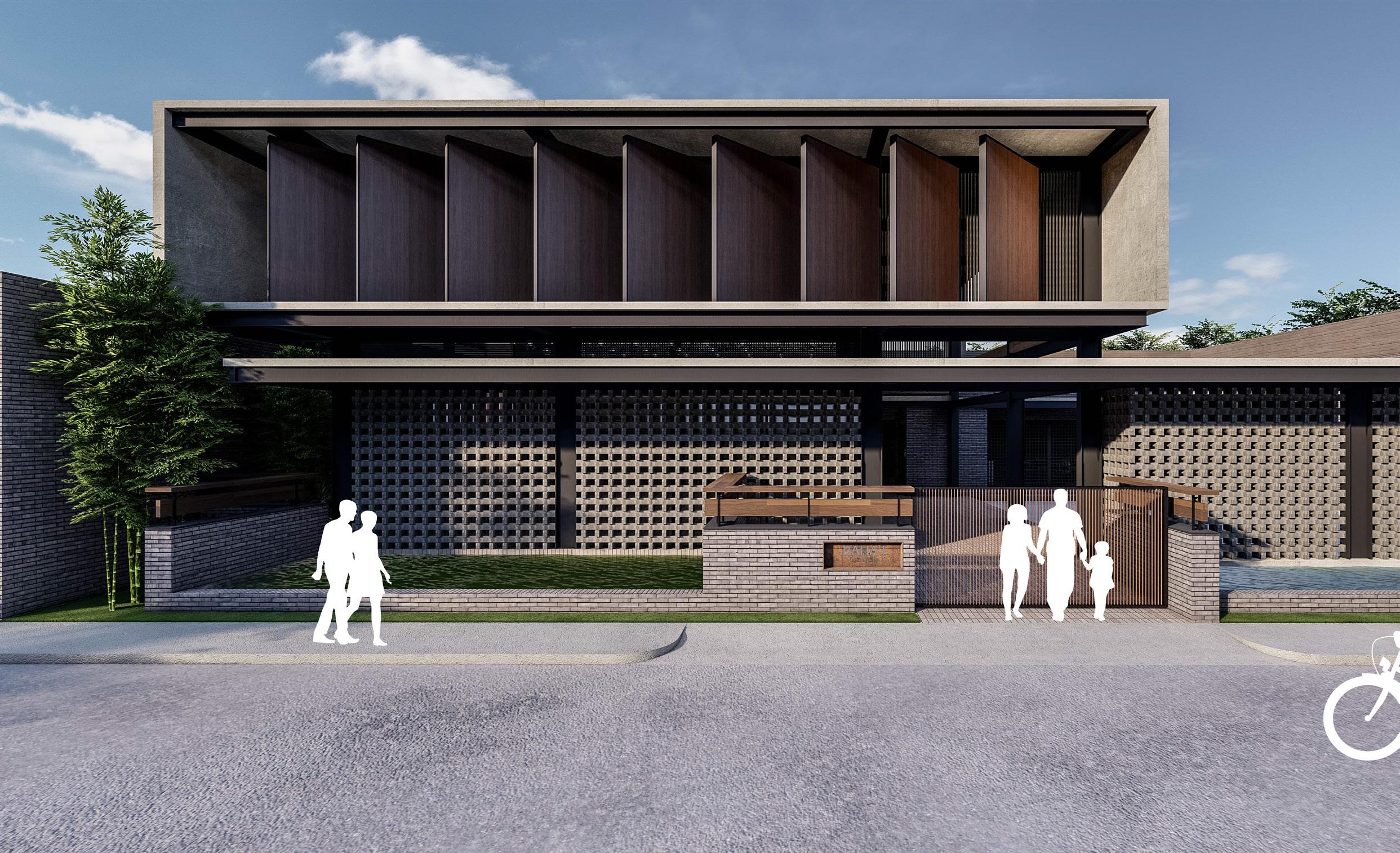

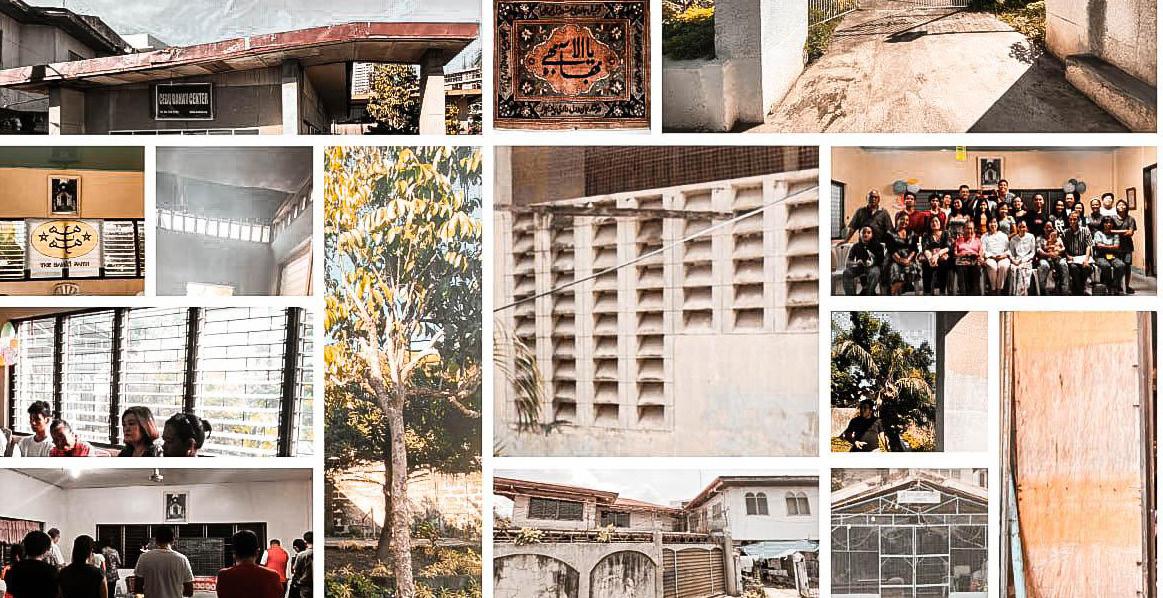

Nestled in a serene residential enclave of Midtown Cebu stands a beacon of faith and community - the Baha’i Center. This enduring edifice, originally established in the 1970s as a modest bungalow, has long been a testament to the resilience and spirit of its followers. The aftermath of Typhoon Odette, however, marked a pivotal moment for the center, compelling a reevaluation of its structural integrity and capacity to meet the evolving needs of its community.

The task initially centered on damage assessment and necessary repairs. Yet, it quickly became evident that simple restoration efforts would fall short of addressing the broader aspirations of the Baha’i community. Engaging deeply with the community and understanding the intrinsic values of the Baha’i faith prompted a bold departure from the original brief. The challenge was no longer about repairing an old structure but rather about conceptualizing a new architectural vision that would embody the principles of unity, spirituality, and a harmonious connection with nature - principles deeply rooted in the Baha’i faith.

The envisioned New Baha’i Center is more than just a physical space; it is an architectural manifestation of the community’s ethos, designed to reflect and amplify the collective spirit and values of its people. This project raises fundamental questions about the role of architecture in embodying faith and fostering a sense of belonging. How can design capture the essence of a community’s history and aspirations? What architectural language best articulates the values of unity and spiritual connection that are central to the Baha’i faith?

Project Name

Essence of the Site - To comprehensively document the site, we embarked on a visual journey, capturing its every facet through photography. Our aim was not only to record the physical attributes but to encapsulate the intangible essence of the place as well. Each image meticulously reveals the subtle nuances of mood, emotion, and ambiance, showcasing elements uniquely tied to the location. Together, these images from a curated essay that narrates the site’s story, vividly depicting its distinct character and spirit.

The proposed design for the New Baha’i Center is informed by a deep understanding of the Baha’i faith and a commitment to sustainability and inclusivity. The conceptual framework revolves around four pillars:

1. Honoring the Spirit of the Old

2. Embracing Unity and Symbolism

3. Harmonizing with Nature

4. Fostering Belonging and Service

Abstract Idea through Intuition - In this phase, we use intuition to shape an abstract concept, combining Baha’i elements, the existing structure, and community-inspired features into collages. These idea boards, both creative and functional, guide our design process. They visually represent our initial thoughts and goals, serving as the foundation for our architectural approach.

In laying the foundation for the New Baha’i Center, our design philosophy is anchored in deep respect for the site’s historical essence and the community’s rich traditions. This project is not merely about constructing a building but about creating a continuum—a bridge that connects generations. Our approach is twofold: to carry the echoes of the past and honor the soul of the original center, and to amplify its legacy through modern architectural language.