Lana‘i Long-Term Kūpuna Care Facility Needs Assessment Report

PREPARED BY Department of Urban & Regional Planning University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

IN PARTNERSHIP WITH University of Hawai‘i Community Design Center & Social Science Research Institute University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa

Table of Contents

2 Acknowledgments

3 5 6

10

Background and Methodology

Background 3 Purpose 3

Methodology 4

Survey of existing facilities and services 4

Interviews 4

Focus group 5 Limitations 5

Profile of the Study Population

Precedent Study Results

Existing Facilities and Services 10

Qualitative Study 12

Interviews with service providers 12

Interviews with family caregivers 13 Interviews with kūpuna 14 Focus group 15

Conclusion and Recommendations

Appendix: Interview Guides

21

19 17

References

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the study participants for being generous with their time and sharing their stories and insight on health care for kūpuna on Lānaʻi. They gratefully acknowledge the assistance provided by Robin Kaye, Valerie Janikowski, and Jared Medeiros, and thank Hale Makua Health Services and Lānaʻi Community Benefit Fund for supporting the project.

2

Background and Methodology

Background

By 2030 one in five Americans will be over the age of 65, and 70% of older adults in the U.S. will need long-term services and supports (LTSS) for two to four years.1 Despite widespread agreement that older adults and individuals with disabilities should have LTSS to be able to live independently as long as possible, caregiving can be onerous for family members. A recent report by the American Association of Retired Persons (AARP) states that 53 million family members provide unpaid care for vulnerable seniors and individuals with disabilities which often comes with financial and emotional costs (AARP, 2020). The COVID-19 pandemic exposed fissures in the nation’s long-term care systems as nursing homes struggled to protect older adults and saw an exodus of frontline workers (Abrams et al., 2020). Chronic problems such as underfunding and understaffing due to low pay, employment benefits, worker exhaustion, and inadequate workforce training to address cognitive conditions such as dementia has brought attention to alternatives such as receiving home- or community-based care.2

While some have underscored the need to reimagine long-term care by focusing on resident-directed care in homelike settings instead of traditional nursing homes (Afendulis et al., 2016), others have cautioned against assuming preference for home care since it depends on varying levels of functional and cognitive impairment; the costs for expanding

home- and community-based services should take this into account (Guo et al., 2014). The recent federal boost to support in-home care for older adults and individuals with disabilities, although temporary, presents opportunities to add to the menu of alternatives to traditional elder care options.3 These considerations help frame the broader context for this study on Lāna‘i.

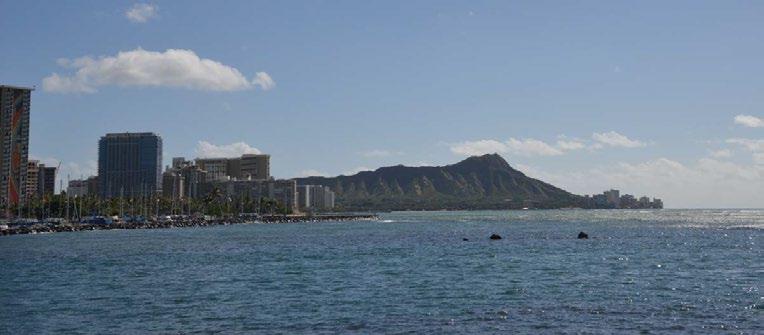

About 25% of Lāna‘i’s population of about 3,000 is over the age of 60. Yet, there are limited long-term care facilities for its kūpuna. These include an apartment complex for seniors (without medical care) and a hospital that has an emergency room, four acute care beds, a laboratory, X-ray, and 10 beds dedicated for long-term care (skilled nursing and intermediate care). Lāna‘i Kina‘ole provides home health care and a hospice is available for in-home and in-patient services. However, Lāna‘i has no residential facility (adult residential care home or foster family home) with attached health care and/or social services for its kūpuna. Also, it has an excellent County-run senior center but no adult day care or adult day health care facility. Informal studies done in 2013 and 2016 pointed to the need for a long-term kūpuna care facility. The community hosted an adult foster care home workshop in November 2015. About 25 individuals participated; however, the barriers of retrofitting old plantation homes – and permitting – were too difficult for the community to overcome. In 2020, the Hawaii State Legislature

awarded a $75,000 grant-in-aid to help meet Lāna‘i Kinaole’s operating needs.

Purpose

The purpose of this qualitative study was to conduct a needs assessment by gathering and analyzing data through in-depth interviews and a focus group, an inventory of existing facilities, and a review of precedents for a long-term kūpuna care facility on Lāna‘i. The assessment, in turn, will provide the basis for a proof of concept for a such a facility. Together, the deliverables will assist the community in decision-making and in seeking government and/or private capital for establishing a long-term care facility on Lāna‘i. The goal of the needs assessment were to: i) learn about the current status of long-term care on the island and the gaps in services and supports; ii) explore alternatives for the type of long-term care facility appropriate for Lāna‘i’s kūpuna; and iii) make recommendations as appropriate.

The study addressed the following questions:

Is there a need for a long-term kūpuna care facility on Lāna‘i?

☐ Survey of existing facilities and kūpuna care providers

☐ Interviews and focus group discussion with kūpuna and their families or caregivers, service providers

3

What type of facility would be best suited for Lāna‘i?

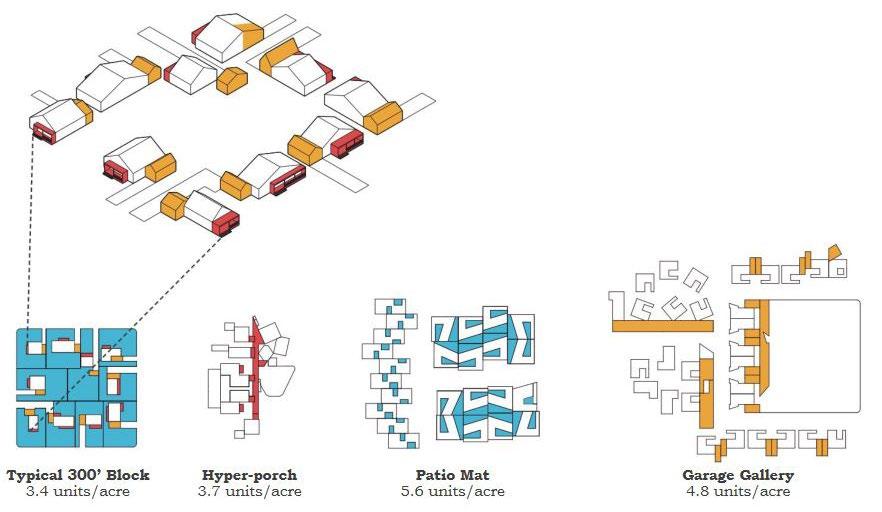

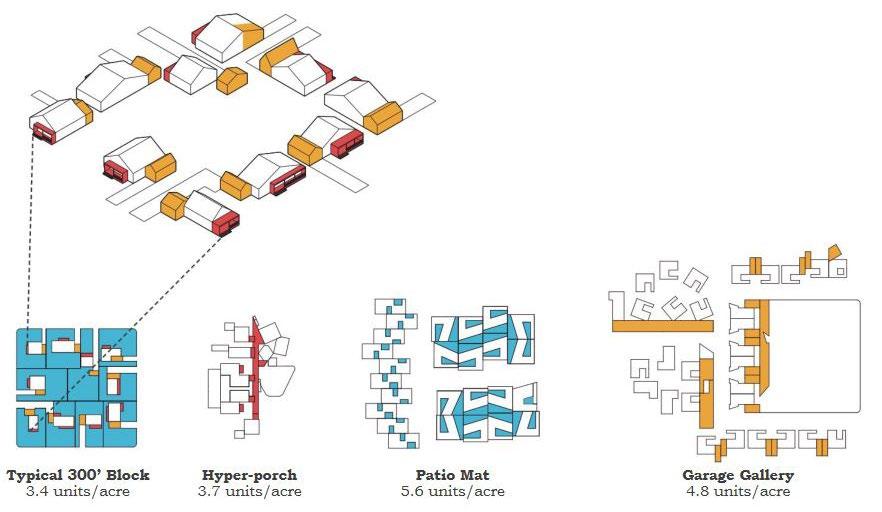

☐ Precedent study of small long-term care facilities (approx. 12-15 beds)

Methodology

Data collection included recruiting three groups of participants – kūpuna, family members who are caregivers, and service providers – for in-depth interviews and a focus group discussion. With assistance from Lāna‘i Kina‘ole, Lāna‘i Community Health Center, and residents who are older adults, information about the study was shared in the community to recruit participants. Thereafter, a snowball sampling technique was utilized to ensure robust participation from diverse groups. The team completed 47 in-depth interviews, a focus group with 6 participants, a site survey of existing facilities, and a precedent study. Each of the interviews lasted between half an hour to an hour. The focus group lasted two hours. They were conducted between the months of November and December of 2021. The majority were done in-person; however, in some cases, they were done virtually (via Zoom) or over the phone to accommodate participants’ preferences. The project was reviewed by the University of Hawai‘i Institutional Review Board and granted exempt status.

A survey by Lāna‘i Kina‘ole to assess the need for an adult day care center was also completed in December 2021 and informed this study.

To lay the groundwork, the team consulted an expert at the University of Hawai‘i’s Center for Aging and a core group of older adults on Lāna‘i. In addition, a review of existing literature provided direction for the themes to be included in the assessment. The methodology followed a participatory approach by conducting in-depth interviews and a focus group.

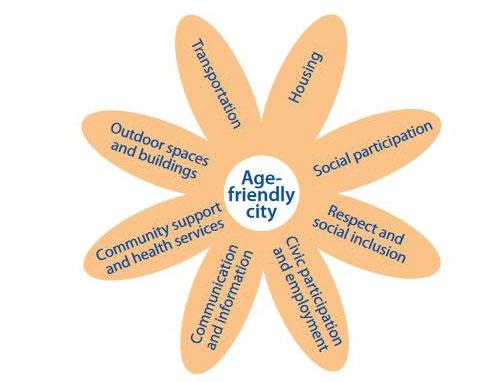

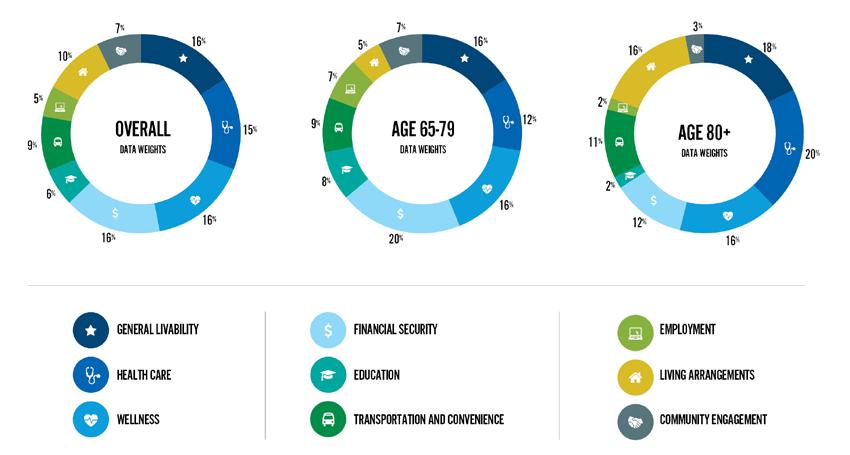

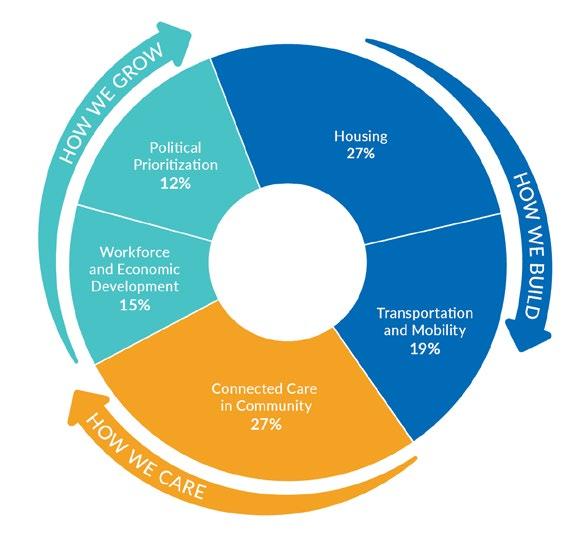

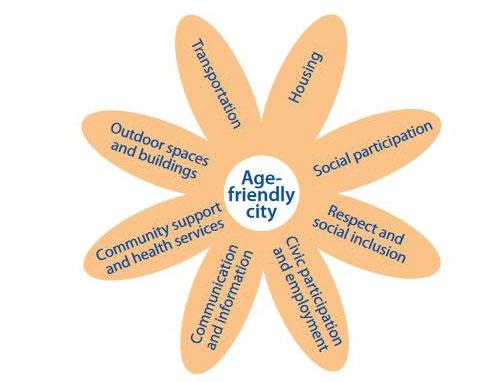

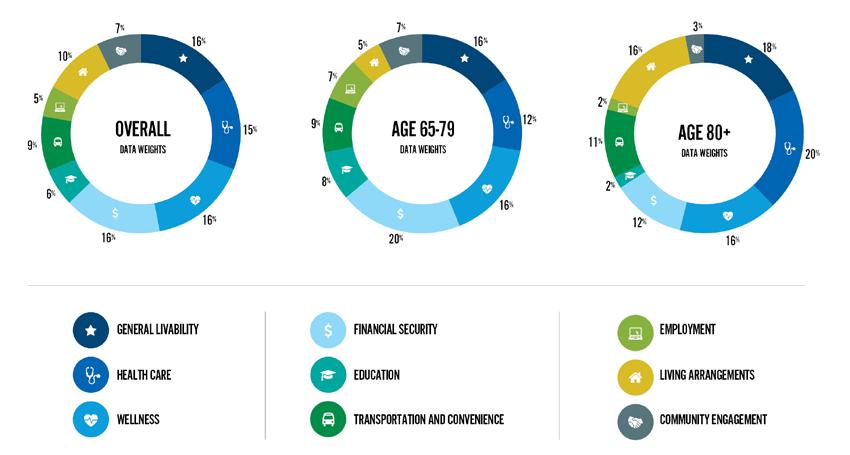

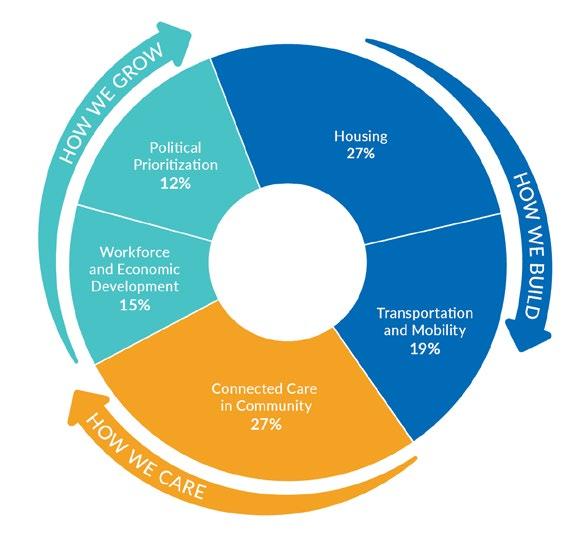

It utilized frameworks developed by the World Health Organization (2007; 2018) and the domains of livability framework outlined by the AARP Network of AgeFriendly States and Communities (Table 1) as a starting point for designing the interview guides for each group of participants. According to the WHO (2018, p. 1), age-friendly environments:

☐ recognize the wide range of capacities and resources among older people;

☐ anticipate and respond flexibly to aging-related needs and preferences;

☐ respect older people’s decisions and lifestyle choices;

☐ reduce inequities;

☐ protect those who are most vulnerable; and

☐ promote older people’s inclusion in and contribution to all areas of community life.

Overall, creating such environments

calls for collaboration among sectors (health, long-term care, transportation, housing, and social services) and actors (government, service providers, family members, faith-based organizations).

Survey of existing facilities

This included a visit to the existing facilities that serve kūpuna on Lāna‘i to learn about the space requirements, services and programs offered, and management. Among the sites visited were the Lāna‘i Community Hospital (restricted due to COVID-19), the Senior Center, Lāna‘i Kina‘ole, Lāna‘i Community Health Center, and Hale Kūpuna O Lāna‘i.

Interviews

An interview guide was designed to gather information from kūpuna, family members who are caregivers, and service providers to understand the domains of livability on Lāna‘i (Table 2). The three interview guides were shared with a

Table 1: Eight Domains of Livability for Age-Friendly Communities

1 Housing Availability of housing for older adults, aging in place, and home modification programs. Comfortable home environment, preventing falls and accidents, being able to get around, assistance with yard work, repairs, and other chores.

2 Transportation Safe and affordable modes of public and private transportation. Transportation to health care appointments, grocery store, cultural/ religious events, errands, and senior center.

3 Social Participation Access to leisure and cultural activities and opportunities for older adults to participate in social life with peers and younger people. Participating in activities with others in the community, exercising, having someone to talk to when lonely.

4 Respect & Social Inclusion

5 Civic Participation & Employment

6 Community Support & Health Services

Intergenerational gatherings and activities to learn and share experiences.

Encouraging paid or volunteer work for older adults and opportuni ties to engage in decision-making processes relevant to their lives. Assistance with job training, job search, and voting.

Access to home-based services, programs, and services for active aging and wellness. Assistance with personal care, prescription medicine, and cleaning.

7 Outdoor Spaces & Buildings

8 Communication & Information

Accessibility to safe recreational facilities. Safe places to gather, safe sidewalks, and outdoor areas.

Promotion of and access to the use of technology to keep older adults connected to their community, friends and family. Knowing what services are available and information/assistance applying for health insurance or prescription coverage.

Source: WHO (2007); https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/network-age-friendly-communities/

4

core group of older adults and service providers on Lāna‘i for comments and revised before conducting the interviews. Each guide had two broad sections: the existing status of long-term care and participants’ vision for long-term care on the island. The former included questions to assess the domains of livability for kūpuna and unmet needs whereas the latter focused on learning about their preferences for the type of care facility.

Focus group

A focus group was conducted in December 2021. The questions were open-ended and limited to only a few. They were intended to learn about the lived experiences of kūpuna on Lāna‘i and elicit their views about specific needs related to long-term care.

Limitations

The main limitation was the uncertainty about conducting in-person interviews during the COVID-19 pandemic especially with older adults who are considered high-risk. Moreover, due to funding and time constraints, the number of in-depth interviews and focus groups had to be limited. Despite achieving data saturation, recruiting participants from different racial/ethnic groups for the purposive sample was challenging as was recruiting those whose native language is not English. These included Micronesians and Filipinos whose work schedule and/ or inability to find child care or elder care made it difficult for them to participate.

Kūpuna

of Respondents

Asian American 33

Japanese 11

Filipino 22

Native Hawaiian 5 Hispanic/Latino 5

Puerto Rican

White 44 Multiethnic 11

White, Filipino

Family Caregivers

Asian American 29 Japanese 23 Filipino 6

Native Hawaiian 35 White 18

Multiethnic 18 Hawaiian, Filipino Japanese, Filipino Hawaiian, Spanish, Chinese, Filipino

Service Providers

TOTAL INTERVIEWS

Profile of the Study Population

This needs assessment was designed to benefit the kūpuna of the island of Lāna‘i. In Native Hawaiian culture and society, kūpuna are elderly members of the community who play important and active roles as sources of wisdom and knowledge for younger generations (Browne et al., 2014; Braun et al., 2021).

Other definitions of the elderly based on age and assessment of physical health, however, can be more arbitrary. For instance, to receive Medicare and Social Security benefits, the age requirement is 65 years and older. In other social programs, and for some federal, state, and county agencies, 60 years and older are considered elderly.

Table 3 presents the demographic profile of Lāna‘i's population. The island cares for more kūpuna per capita than the county, state, or even the nation. Specifically,

5 #

%

18

17

12

47 Table 2: Analytic Sample of Participants

almost a third of the population in Lana‘i, or 31.4%, are aged 60 years and older, a higher proportion than that of Maui County (24.2%), the entire state of Hawai‘i (24.2%), and the national population (21.8%). Female seniors outnumber males also at a proportion higher than in the county (53.1%), state (54.7%), and nation (55.7%).

The composition of the kūpuna population in Lana‘i provides clues to the type and level of elderly care needed on the island. For instance, more than one in ten seniors, or 13.4%, are in the oldest cohort (85 years old or older). This is again a higher proportion than in the county (8.2%), state (11.2%), and nation (8.8%).

In terms of race and ethnicity, Lana‘i’s population is predominantly Asian, with 69.6% identifying as either Asian or part-Asian. Among them, residents who identify as Filipino are the largest population group at 39.2% or more than a third of the population. Native Hawaiians and other Pacific Islanders comprise almost a fifth or 19.4% of the population.

Almost a third of the total population, or 32.8%, do not use English as their primary language. In this group, more than one in five, or 22.9%, speak English less than very well.

At the state level, the kūpuna population follows a nationwide trend of growth.

Table 3: Demographic Profile of Lāna'i’s Population

Total Population 324,697,795 1,422,094 165,979 2,730

Pop.: ≥ 60 y.o. 70,885,955 343,700 40,216 856

% of Total Pop.: ≥ 60 y.o 21.8 24.2 24.2 31.4

% of Elderly Pop., 60-64 y.o. 28.4 26.2 27.7 31.4

% of Elderly Pop., 65-74 y.o. 41.7 41.9 44.7 40.4

% of Elderly Pop., 75-84 y.o. 21.1 20.7 19.4 27.2

% of Elderly Pop., ≥ 85 y.o. 8.8 11.2 8.2 13.4

% of Total Pop.: Male, ≥ 65 y.o. 44.3 45.3 46.9 38.9

% of Total Pop.: Male, ≥ 65 y.o. 55.7 54.7 53.1 61.1

Pop. of Single-Race Individuals

% of Total Pop.: NH or other PI alone 0.2 10.1 10.9 6.8

% of Total Pop.: Filipino alone 0.9 15.1 18.8 39.2

% of Total Pop.: Japanese alone 0.2 12.0 6.4 10.3

% of Total Pop.: White alone 75.0 32.8 45.4 22.3

Pop. by Race: Single- or Mixed Race

% of Total Pop.: NH or other PI 0.4 26.0 25.6 19.4

% of Total Pop.: Am. Indian / AK Native 1.7 2.4 2.4 0.7

% of Total Pop.: African American 14.0 3.6 1.9 3.0

% of Total Pop.: Asian 6.6 56.4 46.5 69.6

% of Total Pop.: White 75.3 43.0 52.1 26.7

% of Total Pop.: Other 5.5 2.6 2.4 2.3

Source: 2019 American Community Survey

Between 2020 and 2030, the number of older adults 60 years and above will increase by 17% and represent 28% of the State’s total population while the number of older adults 85 years and above will increase by about 32% (EOA, 2019).

In response to the expected challenges from these demographic trends, the needs assessment primarily focused on individuals 60 years and older. For a better understanding of the existing long-term services and supports, family members caring for kūpuna and service providers were also included in the study.

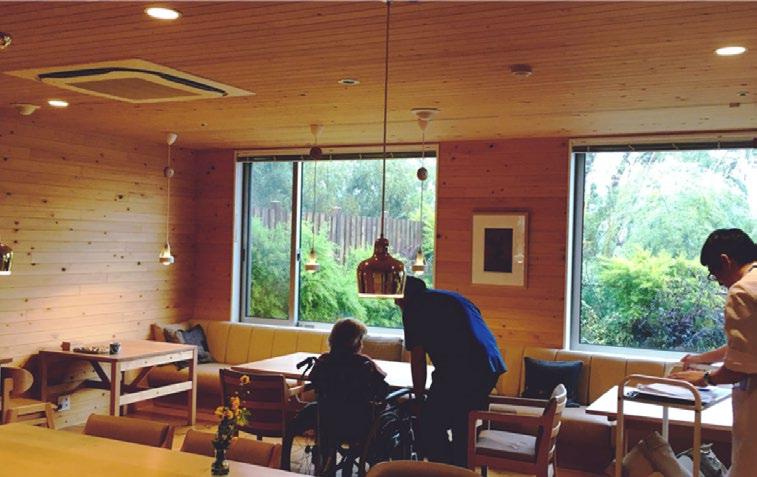

Precedent Study

The purpose of the precedent study was to examine best practices and models of long-term care that could be considered for Lana‘i. A review of existing literature on long-term care for older adults provided insight into the different approaches to care, particularly ones that highlight the role of design in promoting social connections such as ibasho, which follows eight principles: (1) elder wisdom, (2) normalcy, (3) community ownership, (4) multigenerational, (5) demarginalization, (6) culturally appropriate, (7) resilience, and (8) embracing imperfection, change, and flexibility. The concept encourages a transition from the medical model that places emphasis on safety, cleanliness and efficiency, to socio-medical and inclusive/empowerment models that break away from strict routines and promote meaningful engagement through individual choices (Kiyota, 2018).

Ibasho encourages working with stakeholders to design socially integrated communities where elders do not feel marginalized and are able to live an independent life by aging in place. 4 Other

US Hawai'i Maui Lāna'i

6

Approach

Model

Care Type

Ibasho

Empowerment Community

Person-Centered

Socio-Medical

Individualized

Person-Centered

Socio-Medical

Individualized

Precedent Ibasho Hub Ho‘oNani Place Hale Makua Long Term Care

Location

Japan, Philippines, Nepal

Est. 2010

Facility Type

Mission Statement Management & Funding Services Provided

Community Facility

“Ibasho partners with local organizations and communities to design and create socially integrated and sustainable communities that value their elders. We create a place where elders find the opportunities to contribute to their community members of all ages.”

65-1267B Lindsey Rd, Kamuela, HI 96743

Est. 2004

Care home

“To graciously serve our residents with loving comfort and safety in their Ho’oNani home.”

472 Kaulana St, Kahului, HI 96732

Est. 1946

Long-term care home

“As a leader in customized care, we inspire well-being and independence, distinguished by the quality of our team, while striving to improve the lives of those in our care through compassionate personalized health services in our homes and yours.”

Non-Institutional

Socio-Medical

Individualized

Evergreen Villas The Greenhouse Project Lunalilo Home

900 E Harrison Ave, Pomona, CA 91767

Est. 2003

Alternative to traditional skilled nursing care

“GHP partners with organizations, advocates, and communities to lead the transformation of institutional long-term and post-acute care by creating viable homes that demonstrate more powerful, meaningful, and satisfying lives, work, and relationships.”

501 Kekauluohi St, Honolulu, HI 96825

Est. 1883

Type II expanded adult residential care home

“Founded more than 130 years ago, Lunalilo Home’s vision is to be a nurturing and vibrant kauhale for all kūpuna. In fulfillment of the trust of King William Charles Lunalilo, the sixth reigning monarch of Hawai’i, our mission is to perpetuate the legacy of King William Charles Lunalilo to honor, tend to, and protect the well-being of elders.”

Community-run and -owned; donations and fund-raising

Venue for community activities

For-profit LLC

Offers a day center for elders who do not require long-term care

Daily activities (e.g. music, games, personalized exercise, group outings and review of current events)

Afternoon tea and happy hours give residents and their guests an opportunity to chat and share their stories

Private non-profit corporation

☐ Adult day health, care home, home health, & rehab programs

☐ Personalized meals & snacks

☐ Laundry and housekeeping

☐ Respite care; a safe, secure environment for a period of 3-30 days for caregivers needing a break

☐ Beautician/barber services

☐ Choice of religious services

☐ Free aids and services to those with disabilities to communicate effectively (e.g., qualified sign language interpreters, written info in other formats)

☐ Free language services to those whose primary language is not English (e.g., qualified interpreters, info in other languages)

Non-profit organization

Three meals per day. Meals may be enjoyed in the dining room or arranged for take-out

Chaplaincy services and interdenominational worship support residents’ spiritual growth

Private non-profit; Trust fund

☐ Long-term care

Expanded care (ICF/SNF)

Hospice care

☐ Adult day care services, respite care, and a meals-togo program for seniors living independently

Clients & Beneficiaries

Facilities and programs benefit not only the elderly but the whole community

Open to all seniors

Open to all seniors

Seniors across 32 states; GHP has built nearly 300 homes with more in development

Open to seniors; subsidies for indigent Native Hawaiian kūpuna

7

☐

☐

Medical Collective Collective

Table 4: A Comparison of Long-Term Care Precedents

Number of Beds

Total Area

Other Physical Aspects of the Facility

Ibasho Hub Ho‘oNani Place Hale Makua Long Term Care

No beds

Varies

Japan: old farmhouse donated by the Ozawa family that was disassembled, moved, and reconstructed by local craftsmen (mostly elders); a café that includes a vegetable garden, a farmer’s market, and a children’s day care

Philippines: concrete multipurpose hall, corrugated galvanized iron sheet roof; café located beside the community basketball court, meeting rooms, vegetable garden

Nepal: village as Ibasho; no single dedicated building; activities were held throughout the village, in the women’s building, chaurati, old age home

Gathering place built at the vegetable farm, structure made of bamboo, which would be relatively safe in the event of an earthquake

Ibasho hub used for meetings and for storing farm equipment, vegetable garden

5

344 (maximum capacity)

Evergreen Villas The Greenhouse Project Lunalilo Home

20 (2 Villas in Evergreen Villas, with 10 residents in each Villa)

Data not available

☐ Open-plan common area

Shared dining space and kitchen

3 bedrooms that serve 5 fulltime residents

3 baths

Private lāna'i's and outdoor seating areas

Data not available

31 acres

42 5 acres

Number of Staff, Part- & Full-Time

Staff Training

N/A; facility is run by volunteers who are also the beneficiaries

N/A

6 (part-time or full-time status unknown)

Open-air environment with each room overlooking vibrant courtyards Unknown

Green House homes are small in scale, self-contained, and selfsufficient, with elders at the center

Each home includes private rooms and bathrooms for all elders, and outdoor spaces that are easy to access and navigate

Open kitchen where all meals are prepared and served at a communal dining table

☐

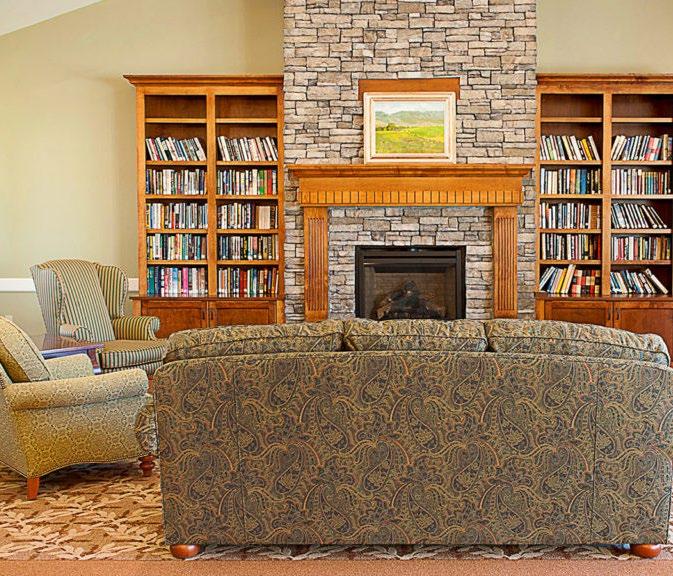

The main building, constructed in 1918 of steel and concrete, and recently renovated, has wood floors, two fireplaces, and a grand staircase

☐ Open grounds

☐ Fireplace room with koa rocking chairs

☐

Dining room with French doors

☐ Air-conditioned ohana room for hosting activities

☐ Sun lānai and garden with Koko Head view

☐ Farm-to-kūpuna garden beds

Attention to Special Needs

Facility is multi-purpose, no known specialized features for special needs

Trained, professional care staff is on duty 24 hours a day

Staff oversees daily medications and individual dietary preferences as well as making sure the medical program set by each resident’s physician is carefully followed

The floor plan was specially designed to provide a safe and welcoming environment for elders with physical or mental limitations

Experienced, licensed and certified staff

Varies by facility

Unknown

Registered dietitians oversee dietary needs and preferences

Social workers who help maintain and enhance the quality of life

Around-the-clock nursing care and support

Assistance with activities of daily living and personal care

Small, self-managed team of care partners - registered nurses and Certified Nursing Assistants

Trained, professional care staff is on duty 24 hours a day

Offers wheelchair services for residents recovering from a surgery or illness

Provides care for residents with dementia

8

☐

☐

☐

☐

Attention to Special Needs

Ibasho Hub Ho‘oNani Place Hale Makua Long Term Care

Special care for residents with dementia or Alzheimer’s disease

Maintenance level physical therapy

Evergreen Villas The Greenhouse Project Lunalilo Home

Programs

Livelihood and fundraising projects

Community capacity-building projects (e.g. disaster resilience and preparedness seminars)

Community improvement projects, e.g. renovation of existing community facilities

Daily activities (e.g. music, games, personalized exercise, group outings and review of current events)

Afternoon tea and happy hours give residents and their guests an opportunity to chat and share their stories

☐

Ethnic/cultural entertainment

Community outings

Table games

Cooking sessions

Support groups

Art groups

Computers for use in activity centers

Organized fitness programs, independent exercise, and recreational outings organized by residents

Respite care

Adult day care

Meals-to-go foodservice

Resident Services Subsidy Program

Proximity to Other Services & Mobility Options Community Partnerships

Ibasho houses are located within communities; the focus is proximity to services and care provided by the immediate community

Transportation available for health care appointments and attending religious services, as requested.

Transportation available for medical appointments.

Green House houses have access to our extensive and closeknit network of adopters. This community gives you the benefit of experience; peer mentoring and interaction; and conferences, webinars, and assistance to help you sustain the strength and vitality of your homes.

Private sector donors, local community, local government, military, other non-profit organizations

Member of the Kona-Kohala Chamber of Commerce, a nonprofit organization that consists of nearly 500 business members representing a variety of industries and sectors.

Cost, (e.g. out-of-pocket expense)

No cost. The program is funded through donations and revenue from fundraising activities and the facilities are co-maintained by beneficiaries themselves, members of the community, and volunteers.

About $4500-$5500 monthly according to Seniorly

Medicare and Medicaid certified.

Accepts insurance from Kaiser Permanente, HMSA, Veterans Administration, and most private insurance companies including HMOs.

Skilled Nursing private room: $365/day

Skilled Nursing semi-private room: $345/day

Intermediate Care private room: $355/day

Intermediate Care semi-private room $335/day

Residents have easy access to the diverse educational and cultural offerings at the nearby Claremont Colleges and venues throughout the Los Angeles area.

More than 10 miles away from downtown Honolulu where most other medical and care facilities are located.

Closest facilities are the Hawaii Kai Retirement Community Phase I and II, and the Hale Malamalama skilled nursing facility.

Partnerships with Native Hawaiian and local organizations and nonprofits.

GHP aims to provide quality care to elders "without regard to the ability to pay"

Evergreen Villas accepts Medicare. Cost varies depending on the type of care residents are receiving (Life Care vs. Continuing Care):

Costs range from $6,358 to $7,605 per month, plus a one-time nonrefundable $500.00 community fee.

Accepts Medicare and Medicaid.

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

☐

9

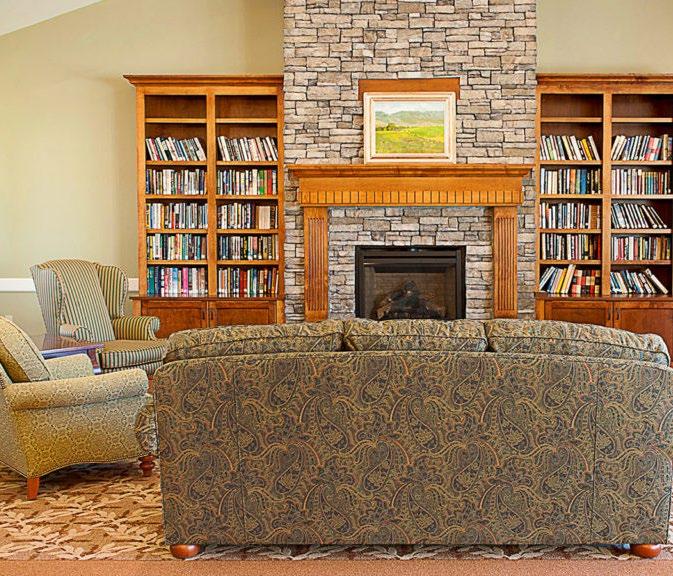

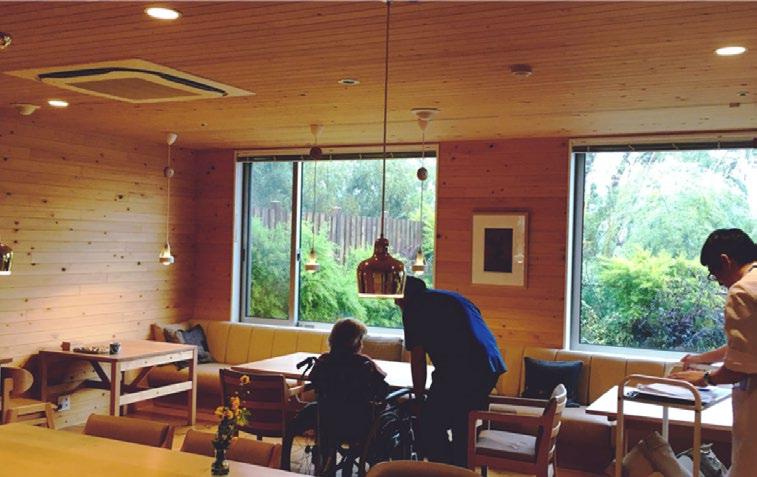

Figure 1. Long-Term Care Precedents: (1) Ibasho, (2) Ho‘oNani Place, (3) Hale Makua Long Term Care, (4) The Green House Project: Evergreen Villas, and (5) Lunalilo Home.

Note: Images from respective organization websites.

precedents presented in Table 4 are the Green House Project, Ho‘oNani Place, Hale Makua Health Services, and Lunalilo Home.

The Green House Project, founded in 2003, offers a non-traditional model with 10-12 beds, a homelike environment that affords its residents a flexible schedule and a balance of communal and private quarters. Homes are typically licensed as skilled nursing facilities and meet all applicable federal and state regulatory requirements. Green Houses are staffed by a team of support workers, shared nurses, and clinical workers. Hale Makua Health Services provides a continuum of care to meet the changing needs of Maui’s kūpuna and Lunalilo Home integrates core Native Hawaiian values in its recreational, cultural, and spiritual activities.

Institution-based models for longterm care such as nursing homes have been pummeled recently. They have been implicated in the high death toll among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic5 (Grabowski, 2020). Alternatively, small-home models have been found to provide higher quality of care compared to traditional nursing homes (see Gawande’s book Being Mortal). Green House residents, for instance, were found to be less likely to contract or die from COVID-19.6 Initial studies have indicated that COVID-19 incidence and mortality rates are less in Green Houses/small nursing homes compared to traditional nursing homes with <50 and ≥50 beds (Zimmerman et al., 2021). However, there has not been a systematic evaluation of such homes to be able to indicate a significant difference in the outcomes between the two.

The precedents illuminate a range of programs and services for short- and longterm care. They were selected primarily for their emphasis on a holistic model

of care that pays particular attention to cultural and contextual nuances and their appropriateness for smaller, close-knit communities with a storied past like Lāna‘i’. While not all elements of the precedents are equally relevant for Lāna‘i’, they are meant to inspire discussion about developing location-specific plans and programs.

Results

Existing Facilities and Services

The existing facilities provide health and social services for kūpuna on Lāna‘i. In addition to site observations and meetings with the key service providers on the island, the in-depth interviews and a focus group provided useful insight about the current status of services and supports to present a nuanced picture of long-term care on the island. Lāna‘i Community Health Center, Lāna‘i Kina‘ole, and the Senior Center play a pivotal role in the community.

Senior Center

The Senior Center (satellite of Kaunoa Senior Center on Maui) was built in 2010. It replaced a community library. Its hours are Monday to Friday from 7.45 am to 4.30 pm (pre-pandemic). The Center offers programs to promote the health and wellness of Lāna‘i’s kūpuna. It includes a large gathering room for shared activities, a smaller reading room, exercise equipment and computer stations, a kitchen, and office space for its staff. It hosts social and recreational programs that focus on healthy aging, whole-person wellness, and personal growth. The primary programs are:

☐ Congregate Nutrition Program which is a contract with the Department of Education and the Leisure

2 3 4 5 1 10

Program which entails field trips and excursions for seniors.

☐ Meals on Wheels which provides meals to homebound seniors and their caregivers. The Maui County Office on Aging does assessments of individuals eligible to receive these meals.

☐ Assisted Transportation which provides free transport to stores, the post office, pharmacy, and doctor’s appointments for those eligible. This service is provided by Maui Economic Opportunity, Inc. (MEO) which has been providing transportation services in Maui County since 1969.

The Senior Center receives funding through the Maui County Office on Aging Title III Nutrition Services Program (federal program). It has two full-time positions, a facilities manager, a grantfunded program nutrition aide, and a senior services aide who oversees the Assisted Transportation program.

Lāna‘i Kina‘ole (Kina‘ole)

Kina‘ole provides home- and communitybased services (home health and home care). Their services are tailored to individual clients. Home health care includes services that require a registered nurse such as wound care, administration, and management of medication, including intravenous medication, lab/ blood collection, and health monitoring. Currently, it has 23 patients and about 18 on the waitlist. There are three Registered Nurses who supervise three Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs) to support Activities of Daily Living (ADL) and Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL). In addition, they host outpatient services such as a chiropractor and a podiatrist twice a month. The Maui County Office on Aging refers patients to Kina‘ole and is their primary source of funding. They are unable to accept Medicare but provide a sliding scale fee based on income for several of their services. Although they do not offer mental health services, they refer clients

to such services and help facilitate them when needed.

Lāna‘i Community Health Center (LCHC)

LCHC provides health and wellness services for all groups, with a particular focus on those who live at or below 200% of the federal poverty level and the under-/ uninsured. It offers primary care services, telemedicine (cardiology, nephrology, dermatology), ultrasound, and optometry. It is the only place on the island that offers dental care. Kūpuna who do not have dental insurance are able to use a sliding scale fee to receive affordable dental care

including dentures. The Center also has two licensed psychologists and, as part of their telemedicine program, offers telepsychiatry (in partnership with the Department of Psychiatry at UH Manoa JABSOM and Sound Mind Psychiatry LLC) for patients who need behavioral health care. It has 4 nurse practitioners and a staff of about 60 members. Its outreach coordinator assists patients with applications for Medicare and Medicaid benefits. The Center provides services in different languages and serves about 70-75% of the island’s population; LCHC

Figure 4. Lana'i Community Health Center

11

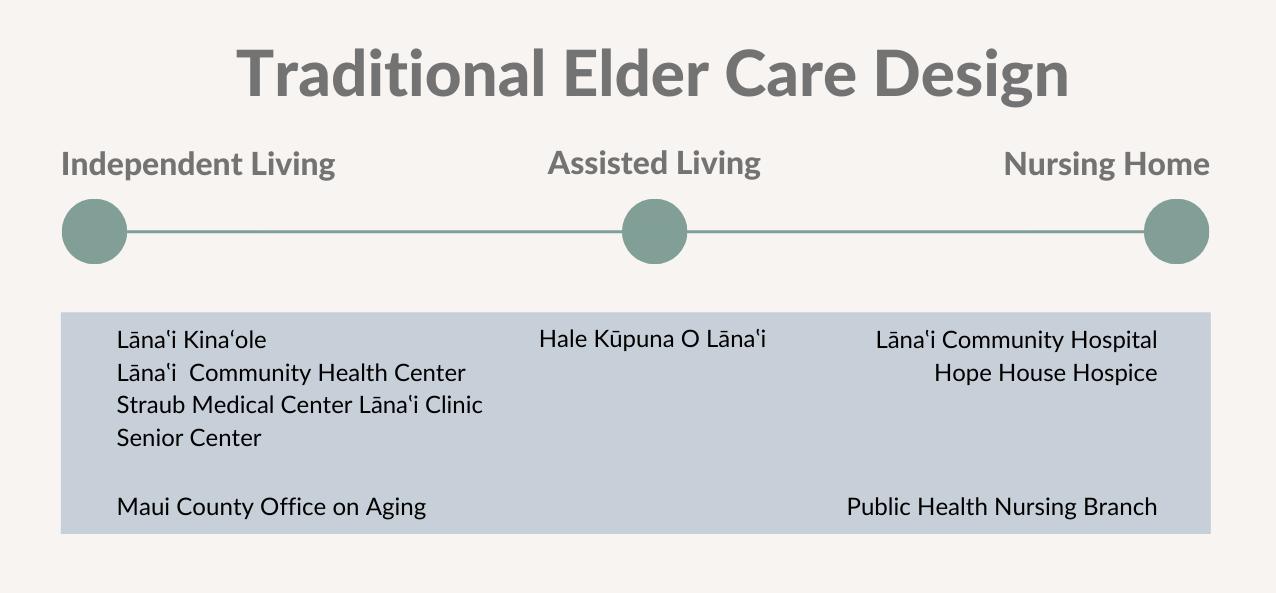

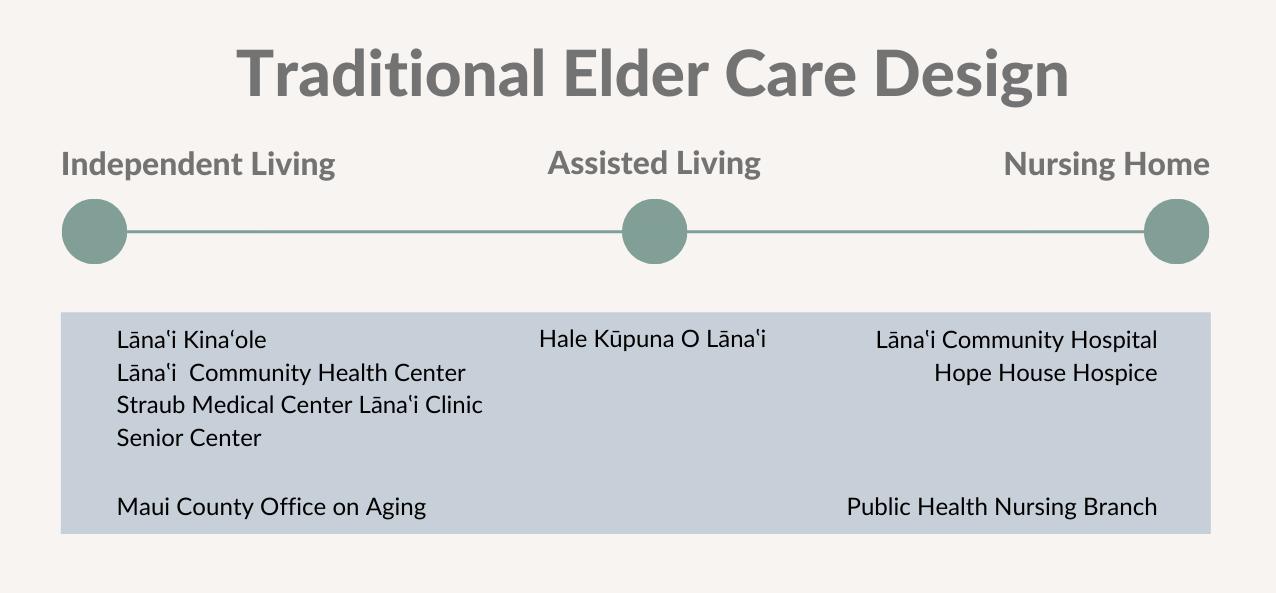

Figure 2. Traditional Elder Care Design for People with Similar Physical and Cognitive Capacities

Figure 3. Lana'i's Senior Center

is governed by a board of community members. Its focus is on providing comprehensive health and wellness services (medical, behavioral, dental, optometry, and outreach) for Lāna‘i residents. It also offers a fitness program with free classes (Zumba, yoga, boxing, soccer, gymnastics, tai chi, kung fu).

Straub Medical Center Lāna‘i Clinic Straub Medical Center Lāna‘i Clinic opened its doors in December 1991. It offers primary care services such as physical examinations, preventative health maintenance, and diagnosis and treatment of illness and injury for infants, children, adolescents and adults. It also includes well-baby and well-child services. It has two doctors who are involved with home health and hospice care. The doctors do home visits when patients are unable to come to the clinic. In the past, they coordinated with the MCOA staff members. They now coordinate with Kina‘ole. During the COVID-19 pandemic, they offered telehealth services and taught kūpuna to navigate their health services such as refilling their prescriptions remotely through MyChart, a patient portal. Currently, Straub has between 2,200 to 2,400 registered patients; the same patients could also be registered at the LCHC; moreover, patients may have relocated to another island but continue to call for care. The physicians see between 16 to 20 patients on average daily. A typical day for the physician includes office visits (routine visits of 20 mins or 40 mins for more complicated cases), home visits when needed, and after-hours telephone calls.

Hale Kūpuna o Lāna‘i

Hale Kūpuna O Lāna‘i is a senior housing complex with 23 one-bedroom units (522 sq.ft) and a manager’s unit. Eligibility is based on income, medical expenses, and disability. Rent for a one-bedroom unit is 30% of qualified annual income and includes grounds and building

Figure 5. Hale Kūpuna o Lana'i maintenance, utilities, pest control, and one reserved parking stall per unit. The complex also houses a community center and a coin-operated laundry facility. Currently, there is a long waitlist.

Lāna‘i Community Hospital

The only hospital in town offers 24-hour urgent and limited emergency care, as well as skilled and long-term care services. There are 10 beds for long-term care of which only a handful are for acute care. Residents have to qualify for a bed based on criteria. There is a waitlist and few alternatives. Although Lāna‘i patients are given priority, when available, beds are available to patients from Maui. X-ray and lab services are closed on holidays.

help kūpuna live independently in their homes. Services include homemaking, personal care, case management, homedelivered meals, transportation, health education, and educational workshops for caregivers. It relies on partner agencies and organizations in the Aging Network for service provision. It also offers legal services through contracts with the Legal Aid Society of Hawaii and has a new contract with Silver Bills, a concierge bill management service.

State Public Health Nursing Office Public Health Nursing Branch (PHNB) is the branch under the Community Health Division, Health Resources Administration within the Department of Health. PHNB administers the public health nursing services through the Public Health Nursing Sections, statewide. The staff of PHNB is made up of public health nurses (registered nurses, licensed practical nurses, para-medical assistants, health aides) in the public schools, and clerical support staff. Lāna‘i Public Health Nursing provides services to the island to address the root causes of poor health and chronic conditions. These include case management, community and public health services, home visits, tuberculosis testing, and vaccinations. There is a vacancy for a public health nurse on Lāna‘i.

Qualitative Study

Interviews with Service Providers

Figure 6. Hope House Hospice

Hope House Hospice

The hospice is in transition with a possible change in management. Hospice care is provided in-home. Kina‘ole has certified nurse aides for such care.

Maui County Office on Aging (MCOA)

MCOA provides services and resources to

In-person interviews were conducted in November and December of 2021 with 12 key informants who represent health care providers on Lāna‘i. The interviewees included a physician, nurse practitioner, registered nurse, care managers, certified nursing assistants, and volunteers.

The unmet needs and preference for

12

the type of long-term care identified by participants are described below.

Limited services

Long-term care services on Lāna‘i are very limited. Besides the 10 beds at the hospital, patients rely on the LCHC and Kina‘ole to meet their health care needs and have no alternative but to go off-island for specialized medical care. The vacancy for a public health nurse has limited the ability to conduct assessments. The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the situation.

The norm on Lāna‘i is for family members to care for their kūpuna; however, they often need assistance and, in many cases, they are unable to provide the type of care required for those with moderate to severe mental illnesses such as dementia and Alzheimer’s. They also require assistance if they have full-time employment with little to no flexibility in their schedule. Occasionally, family members can arrange for help from volunteers in the community. This is, however, limited to personal care needs (e.g., bathing and hygiene, meal preparation). According to the service providers interviewed, the kūpuna are generally aware of services. They communicate with each other and share information, primarily by word of mouth. Often, the non-native English speakers find it difficult to understand the information they receive from service providers. They are embarrassed to ask and call family and friends for clarification. The Senior Center, LCHC, and Kina‘ole collaborate. They share pamphlets, give talks, and provide referrals.

Impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic made it impossible for families to visit patients in the hospital. Although iPads were provided to facilitate virtual interaction, kūpuna with dementia or on feeding tubes were unable to use them and it was not

“We had a ton of volunteers and still have several volunteers out there. The community just kind of rallied together. It was really something that was incredible. Volunteers would pick up groceries in the morning and do a contact free delivery and just leave the groceries on the porch.”

viable. It was also difficult for patients who needed specialized care or medical procedures to travel to Maui or O‘ahu due to the restrictions. Some had to postpone care (e.g., mammograms). There was an increase in demand for services that strained the capacity of existing care facilities. Service providers delivered games, adult coloring books, fresh vegetables and fruits from farmers, and conducted routine wellness check-ups. They also distributed COVID-19 handouts and translated them as necessary. When clients were in quarantine, they assisted with mail pick up, food delivery, and grocery shopping. The community also rallied to assist those affected. MCOA care managers had to prioritize those needing home visits as their staff was teleworking during the pandemic. During the pandemic, programs like Meals on Wheels were delivering meals including to those who would typically come to the Senior Center for congregate meals.

Vision for long-term care

The service providers saw the possibility of rehabilitating an existing building such as “Social Hall,” increasing the hospital’s capacity, prioritizing home health care while continuing to support telemedicine services post-pandemic. Home visits provide a true assessment of the client and their provider which is different from meeting patients in the office. If a long-term facility were to be built, it should consider short- and long-term care. Having an adult day care center and respite care is important. It provides family caregivers an option when they have to leave the island for a

few days and prevents caregiver burnout. Service providers also suggested home modifications and increasing the number of trained staff and physicians to meet the demand. They reiterated the importance of providing opportunities for social interaction for kūpuna with programs to support mental health and wellbeing such as those being offered at the Senior Center. Most preferred to see such a facility located centrally so that patients feel connected to the community.

Interviews with Family Caregivers

In-person, virtual, and phone interviews were conducted in November and December of 2021 with 17 family members who are caregivers, several of whom were above 60 years of age. The participants included those who live on Lāna‘i, O‘ahu, and the Continental U.S.

The unmet needs and preference for the type of long-term care identified by participants are described below.

Limited services

Family caregivers typically assist with daily needs such as cooking, cleaning, grocery shopping, and medication. They rely on Kina‘ole for services that require medical expertise. The MCOA also provides homemaker services for a limited number of hours per week based on their assessment. Caregiving is especially challenging for family members with full-time employment.

“When she [mother] lost her husband her neighbor would bring her things. She would talk to her because she knew she was lonely. I don't think anybody else really realized that. I think maybe some family and friends stopped by but I don't know that she reached out or knew about any other resources that she could have utilized at the time.”

13

Some reported using vacation time for caregiving which negatively impacts their quality of life. They receive some respite care from Kina‘ole but this is typically insufficient. Others reported that some family caregivers are reticent about asking for assistance. They also mentioned the existence of elder abuse. Those with health insurance to cover long-term care send their kūpuna to foster homes, assisted living facilities, or nursing homes off-island. However, the costs are prohibitive and not all families can afford such health care. Most importantly, they prefer to receive care on Lāna‘i and remain among family and friends. The participants also mentioned the emotional stress of considering off-island options for their kūpuna who wanted to age in place.

“Four years ago is when he [father] fell into a major depression. So that's when we had him come live with us which required 24 hour care because he was slipping and going further and further into depression. So between myself, my son, partner, my brother and his family, we had to rotate our schedules to make sure someone was always home with him.”

Family caregivers highlighted the need for an adult day care center, and more staff to conduct routine wellness check-ups. They also mentioned the challenge of taking the kūpuna off-island for specialized care, especially when they are wheelchairbound and find it uncomfortable to travel in a small aircraft to Maui or O‘ahu.

Impact of COVID-19

Several of the family caregivers mentioned that the COVID-19 pandemic isolated the kūpuna and diminished their quality of life considerably. They saw depression among the kūpuna. The closing of the Senior Center during the pandemic was especially difficult for many who felt disconnected. Moreover,

the pandemic did not allow family and friends to say goodbye to their loved ones.

Vision for long-term care

The types of facilities that the family caregivers thought would be appropriate included an adult day care center, nursing home, respite care, and a combination of short- and long-term care. They emphasized that such a facility should not be too large and institution-like. Rather, it should be welcoming and home-like. They also highlighted the possibility of expanding existing facilities, for instance, by increasing the number of beds for long-term care at the Lāna‘i Community Hospital. According to them, for the kūpuna to enjoy good health, it is important to ensure they can socialize and stay in their homes for as long as possible by making home modifications, as necessary. For caregivers, having access to respite care is essential to prevent burnout from caregiving. The types of spaces the participants envision are similar to those mentioned by the kūpuna. However, several emphasized the need to have secure spaces to accommodate those with mental illness.

Interviews with Kūpuna

In-person interviews were conducted in November and December of 2021 with 18 kūpuna. The kūpuna interviewed ranged in age from 62 to 86 years. While some were born and raised on Lāna‘i, others had moved due to family reasons and for the quality of life a small community offered. The majority of those interviewed had health insurance (Medicare, HMSA, Kaiser Permanente, supplemental plan).

The unmet needs and preference for the type of long-term care identified by participants are described below.

Limited services

The kūpuna highlighted the insufficient services on Lāna‘i and the limited options for long-term care. There are only 10 beds available for long-term care so those who do not have family on Lāna‘i often have to consider moving away. This tends to affect their wellbeing by triggering stress. The only senior housing complex on the island has a waitlist of about 250 applicants. The participants identified their primary challenge to be the need to make frequent trips to Maui or O‘ahu for specialized health care. This has become increasingly difficult with only one airline operator on

14

Figure 7. Preferences for Types of Spaces in an Elder Care Facility

“He [uncle] walks across the dog park every day to pick up some food and get the newspaper. One day he collapsed. He just became too weak. That created an emergency because he became bedridden and there was absolutely no caregiver you could hire on Lāna‘i for help. That's one problem.”

the island. Moreover, Medicare does not cover travel expenses so those without supplemental insurance have to pay out of pocket. The trips typically require a family member to accompany the kūpuna as they are unaccustomed to getting around in Maui or O‘ahu and often feel vulnerable. The participants reported relying on Kina‘ole for home-based care. Kina‘ole staff provides services such as routine wellness check-ups and homemaker services. However, they are understaffed and, therefore, unable to meet the demand for home-based services. Some kūpuna receive basic care from family members whereas others reported having difficulty as family members were away or busy with work and unable to provide care.

The kūpuna value social interaction with family and friends. Volunteering helps maintain social relations in the community, especially when family members are busy and unable to spend time with them. The kūpuna are typically active between 7 am and 3 pm. They spend their day watching television, talking to and visiting friends, volunteering, and engaging in activities such as reading, knitting, walking, or fishing; however, activities such as fishing are less frequent due to the risk of accidents. Some visit the Senior Center; others take the MEO shuttle to visit stores or take day trips to Maui, which allows them to socialize.

The kūpuna reported experiencing a

sense of insecurity as Lāna‘i transitioned from a plantation town to a tourist destination. While safety is not a concern, they perceived a change in their environment from the days when they were a close-knit community to the present day when they have to get accustomed to being around strangers.

Impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic isolated the kūpuna and diminished their quality of life considerably. The Senior Center was closed due to restrictions imposed by Maui County leaving them with no alternatives for socializing. Services from MEO did not cease but there were modifications to the schedule that caused disruptions in services such as the Maui shopping trips.

Vision for long-term care

Most participants preferred homebased care and expressed a desire to live independently as long as possible before transitioning to a facility. Their vision for long-term care included facilities such as an adult day care center, assisted living facility, and nursing home. The types of spaces they envision in such a facility are a combination of private and communal spaces that allow them to gather with family and friends (e.g., picnic, bbq), play games, watch movies, do arts and crafts projects, and exercise. Some outdoor spaces mentioned were gardens, walking paths, and water therapy pools. Programs with educational content were also mentioned. Most preferred a location close to the town square due to ease of mobility and access to amenities, and support intergenerational programs.

Focus Group

The focus group comprised of six participants – kūpuna and a family caregiver – five of whom have lived on Lāna‘i for more than 50 years. The family caregiver was born and raised on Lāna‘i

“I've been in Lāna‘i since 1966.

The biggest change is that there are many strangers. When we go out now we don't know everybody. Before when we went out it would be odd if you saw somebody you didn't know. It is different now.”

but moved away during her adult life before returning to care for her mother. The group collectively lamented that the Lāna‘i they knew when they were younger has changed. They described the island as a place where they could roam freely, a good place for kūpuna and children, and safe. Neighbors would check in on each other. People would leave their car keys in the car but not anymore. Today, they see many strangers. One participant stated, “The company [Pulama Lāna‘i ] is only taking care of their priorities, they are forgetting the seniors.”

The kūpuna prefer to live independently in their homes for as long as possible before transitioning to a long-term care facility. They, therefore, emphasized the need for more services. As one participant said, “I tell my children don't you dare make me go someplace now. I said this is my home. I'm gonna stay here. I said…if I die…you just cremate me and scatter my ashes.”

On a typical day, the kūpuna spend time at home doing household chores (laundry, yard work, cooking), watching television, engaging in activities that help maintain their cognitive ability (e.g., doing puzzles, Sudoku, reading), and talking to and texting their children and friends. They would not prefer living with their children because they do not want to intrude on their lives or burden them with caregiving. Living independently allows them to enjoy a healthy relationship with their children.

15

Limited Services

The group felt that there is a general lack of information about the services available and how to access them. They are available when one asks but not otherwise. They also mentioned that some family caregivers do not want others to know their business; there is still the stigma around mental health issues and elder abuse. Socializing is very important for the kūpuna. Trips to Maui and around town on the MEO shuttle allowed them to talk story. Some would go to Maui almost every month, sometimes twice a month, or even three times a week. Kina‘ole is unable to keep pace with the demand for services despite going much beyond their capacity. The DOH is still waiting to fill the position vacated by the public health nurse who resigned. One of the challenges of attracting candidates is affordable housing. The participants stated that the County should provide subsidized housing for staff as they do for police officers on Maui.

Impact of COVID-19

Despite the high vaccination rate among the kūpuna on Lāna‘i, the Senior Center was closed under the restrictions imposed by Maui County. The MEO shuttle

experienced some disruptions in the schedule. For some, not being able to socialize at the Senior Center, visit friends, or go to Maui was depressing as they faced isolation.

Vision for long-term care

According to the group, adult day care is a community need. It would allow the kūpuna to be dropped off and picked up when family caregivers have to work. They would be well taken care of in such a facility and have the opportunity to socialize. Outdoor spaces could include gardens, exercise areas, and walking paths. Indoor spaces could have rooms where the kūpuna could enjoy sewing, reading, playing games like hanafuda (Japanese card game), and watching television or movies. Since the kūpuna prefer to continue living at home, assistance with home modification, repair and maintenance (e.g., carpenters, electricians, etc.) and homemaker services are essential to support aging in place. Encouraging adult foster care homes that each serve a handful of people, are certified, and recruit dedicated and compassionate staff could provide an alternative for those who prefer living in a home-like environment.

“ The facility should be somewhere flat so they [kūpuna] can get around. That would be somewhere near the town center, near the park, I think. That way they can enjoy. You know, those older guys, they want to see what they remember and know from 20 years ago. And they can still enjoy watching the kids playing around the park, hitting baseballs and throwing the football around. I think the older people definitely need to see the younger people in action. So I don't think it's good to be like, oh, let's tuck them away in a corner.”

16

Conclusion

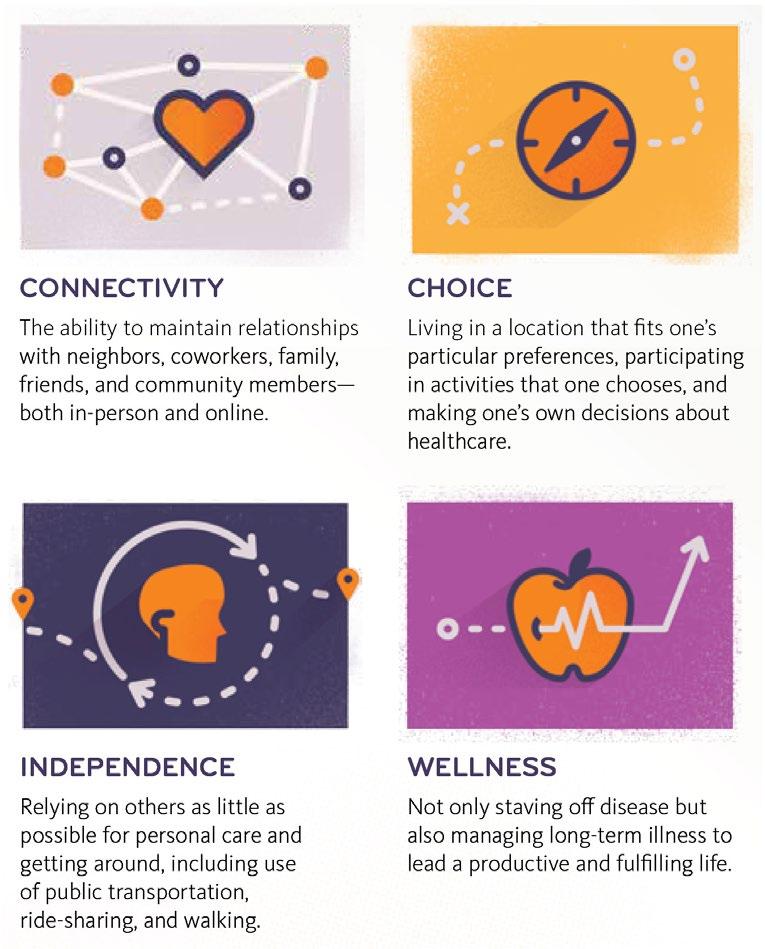

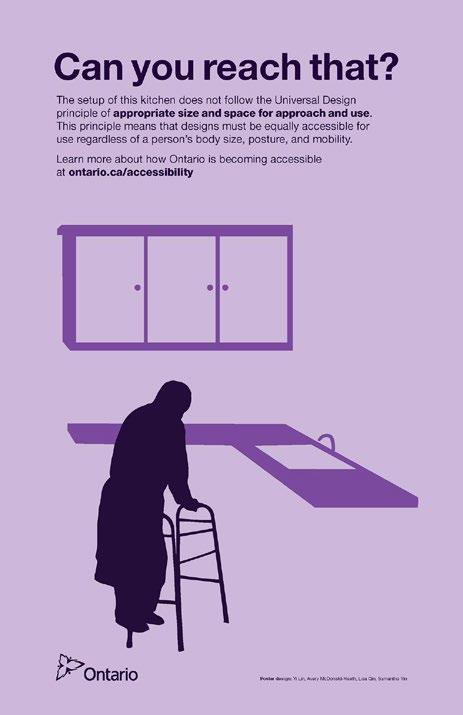

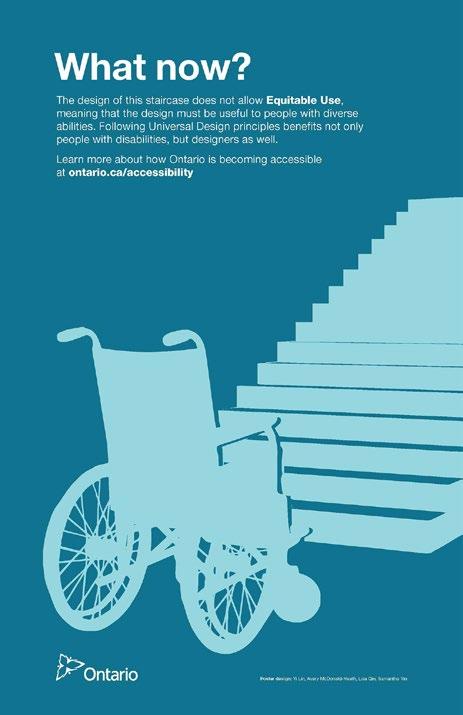

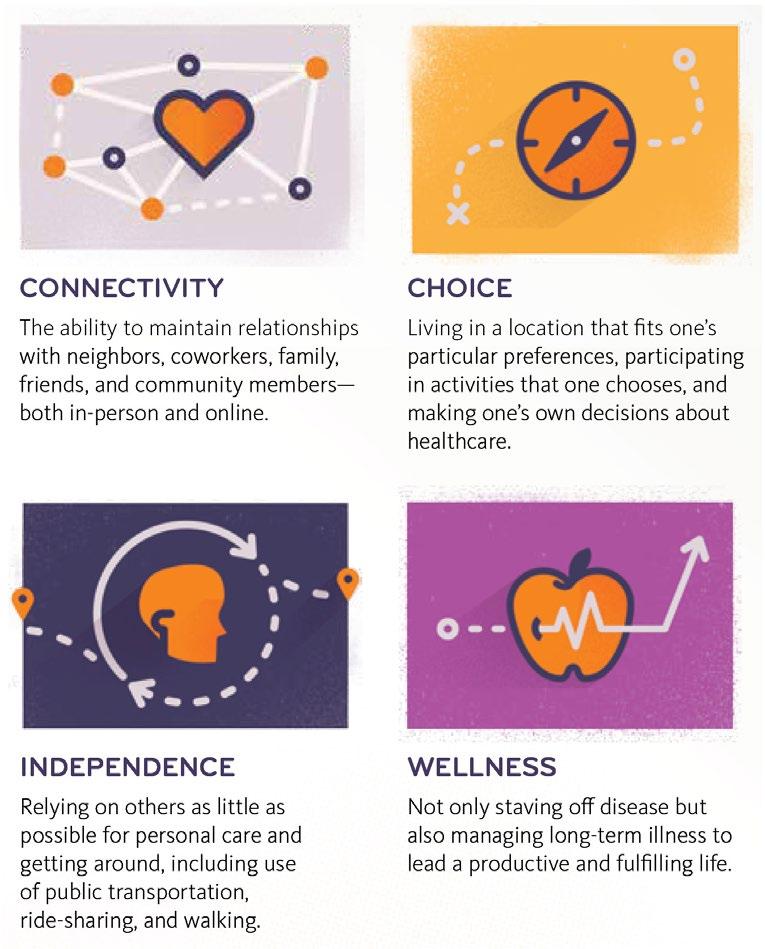

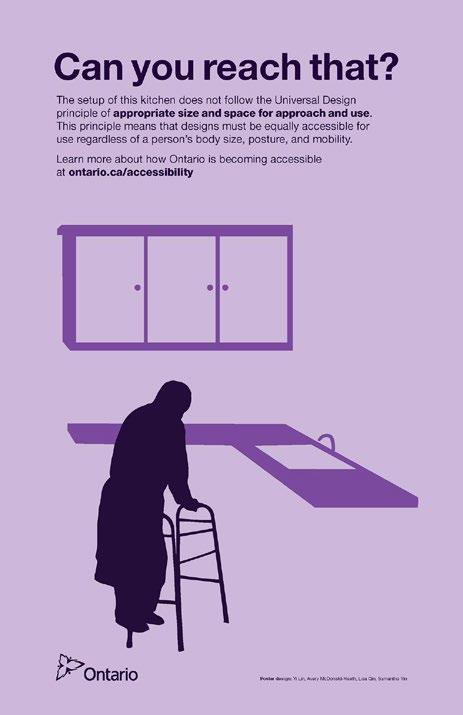

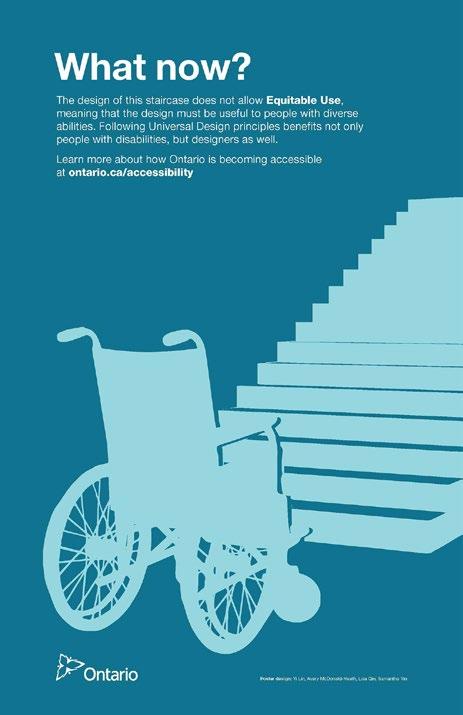

The growing aging population of Lāna‘i will increase pressure on health care and social services. It is important to design age-friendly communities based on universal design principles that are intended to be inclusive regardless of an individual’s physical limitations. This qualitative study provides insight into the status of long-term kūpuna care on the island based on in-depth interviews with kūpuna, family members who are caregivers, and service providers, a focus group, and a survey of existing health care facilities conducted between November and December 2021. The results indicate that the majority of the kūpuna interviewed preferred to remain independent in their homes as they age. This provides an opportunity to explore strategies to support healthy aging.

All three groups of study participants mentioned the lack of long-term care alternatives on the island. They stressed the need for adult day care or adult day health care, expanding home care, and a facility on Lāna‘i that offers long-term care for kūpuna who can no longer live independently. They preferred any new facility to be located centrally for a sense of connectedness to the community. They also mentioned the language barrier in accessing English-language resources, the need to support health literacy, and the barriers to recruiting and retaining a high-quality workforce on Lāna‘i. The caregivers and service providers underscored the need for short- and long-term care. The kūpuna described the importance of aging in place and, therefore, the need to have home care and support services such as home modifications, and assistance with housework.

The study provides a reasonable assessment of needs in the community despite its limitations. The inadequacy of long-term care reported in this study is reiterated in the results of an online survey of 184 Lāna‘i residents conducted in 2021 which finds that while respondents are satisfied with the quality of services currently offered, they are concerned about the availability of senior services which they perceive to be worse than on the other islands. The majority of respondents (75%) see the need for more long-term care options. There was strong support for adult day care (87%) and adult day health care (79%) along with other short- and long-term care options.

Below we outline seven main recommendations based on the needs assessment. Broadly, these call for enhancing existing services, exploring opportunities for Medicaid-funded home- and community-based services, strengthening the bridge between health and social needs, and providing a new facility to meet the growing need for short- and long-term care on the island.

Build new facility

Expand home care

Locate facility in town

specialized transport services

communication and coordination

Develop affordable housing to support health care workforce

Solicit input from stakeholders

17 Recommendations

1.

2.

3.

4. Provide

5. Improve

6.

7.

1Build new facility

Option A

An adult day health care center could fill the gap in care between home and institution (Figure 2). Such a center will provide ADL assistance and social and companion services for older adults allowing them to continue living independently while providing respite and support for family members who are caregivers. This is well-suited for Lāna‘i’s close-knit community where kūpuna generally feel safe, and can rely on their families, friends, and neighbors. However, being unable to age in place due to the limited health care services on the island coupled with the high costs associated with seeking health care offisland causes anxiety among the kūpuna and their family members. Such a facility would address the community's needs and supplement the services provided by the Senior Center.

Option B

A small skilled nursing care facility (12-15 residents) could address the transition from home-based care to a long-term care facility (Figure 2). Given the nature and size of Lāna‘i’s community and its aging population, the facility could be modeled after the Green House. Alternatives such as a facility that houses both short-and long-term care should be considered.

2 Expand home care

Home care could provide homebound patients quality, patient-centered care with the requisite case management. Functional impairments affect the ability to access medical care, particularly for those who do not have family members on the island. Having access to shortand long-term care in their homes could help avoid institutionalization. Technological advancements and a push for robust social services that pay for

health, not just health care, encourage the expansion of home care tailored to individual needs allowing the kūpuna to continue living at home. Treatment of non-life-threatening conditions, X-ray, bloodwork through home care could lessen the pressure on hospital beds and reduce readmissions. Telehealth and telemonitoring can increase access to care. Wraparound programs such as Safe at Home, The Lifetime Home, or engaging a Certified Aging-in-Place Specialist (CAPS) offer home remodeling to reduce risks. Expanding home care on Lāna‘i is, however, tied to workforce development and the availability of affordable housing to recruit and retain a high-quality workforce.

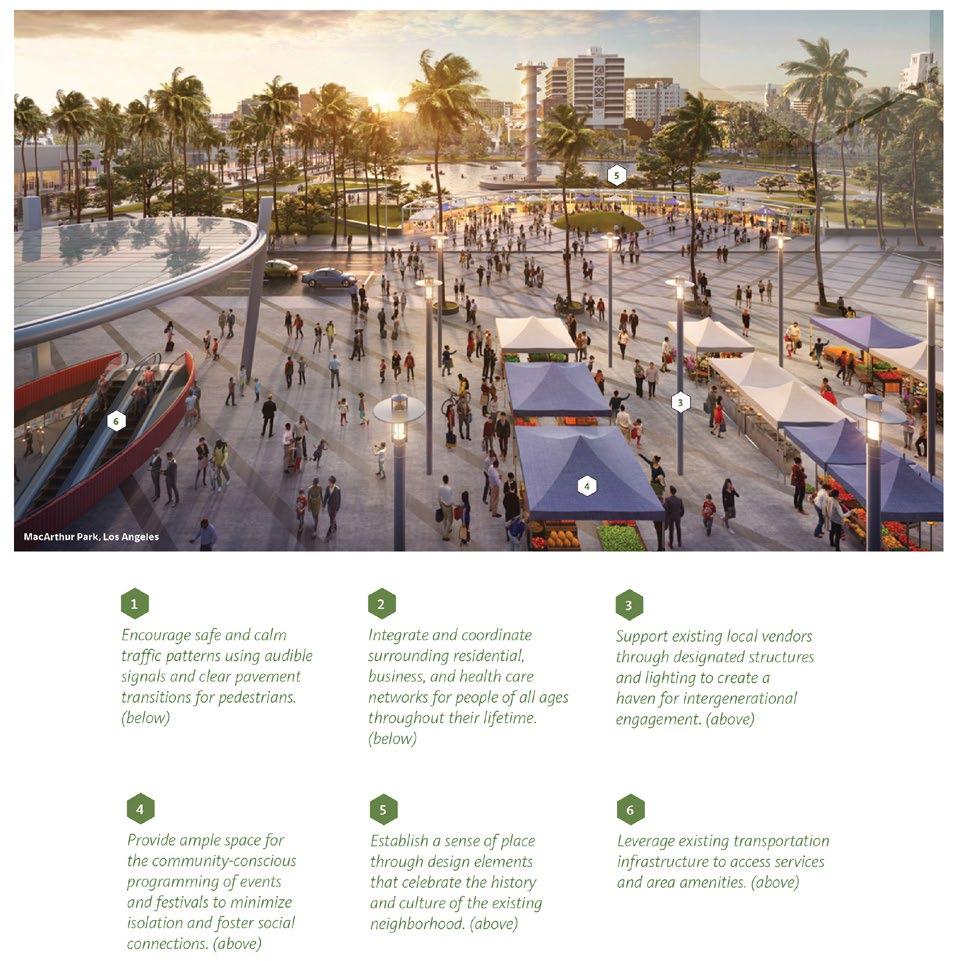

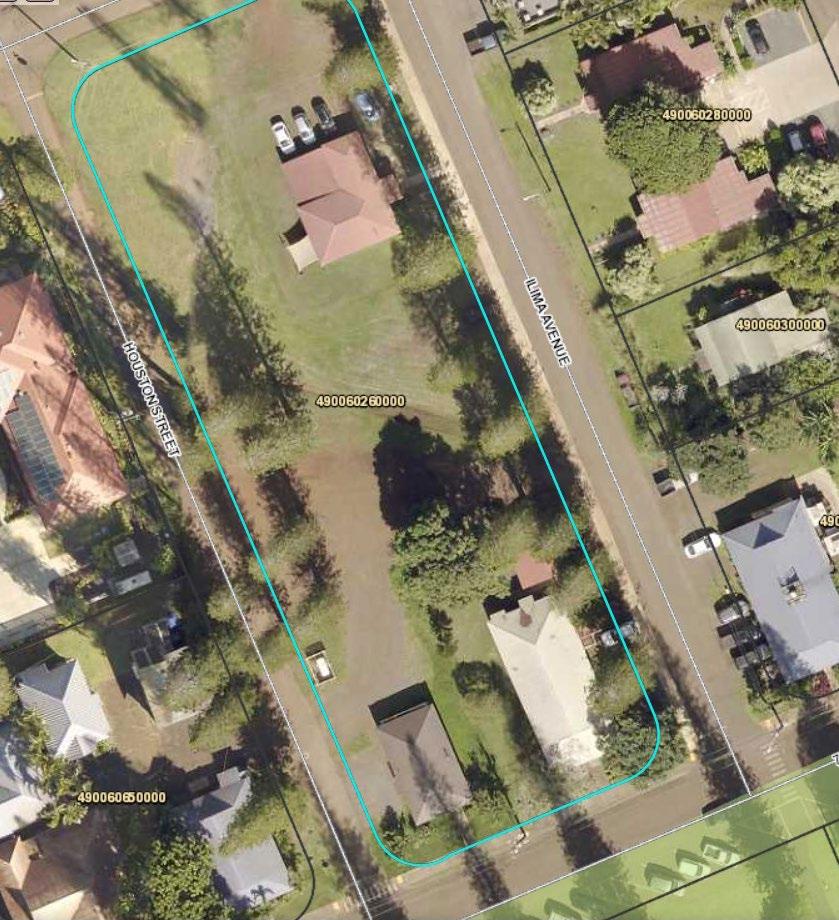

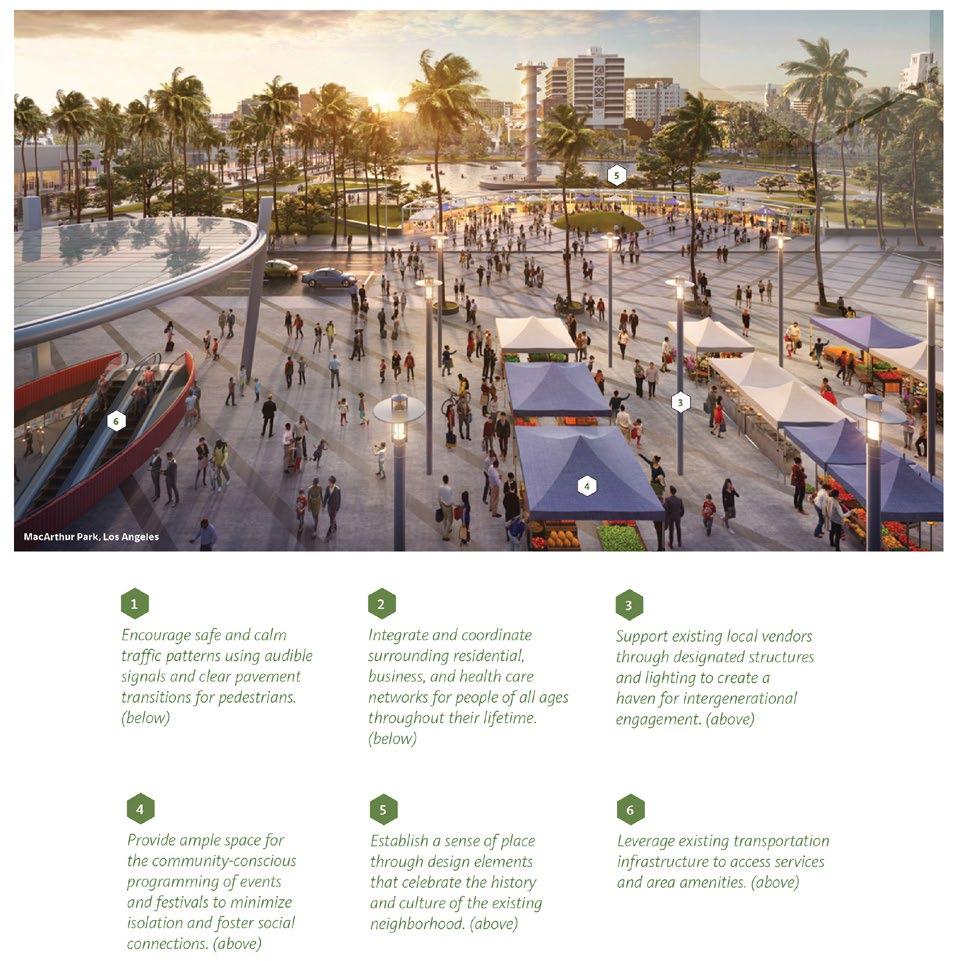

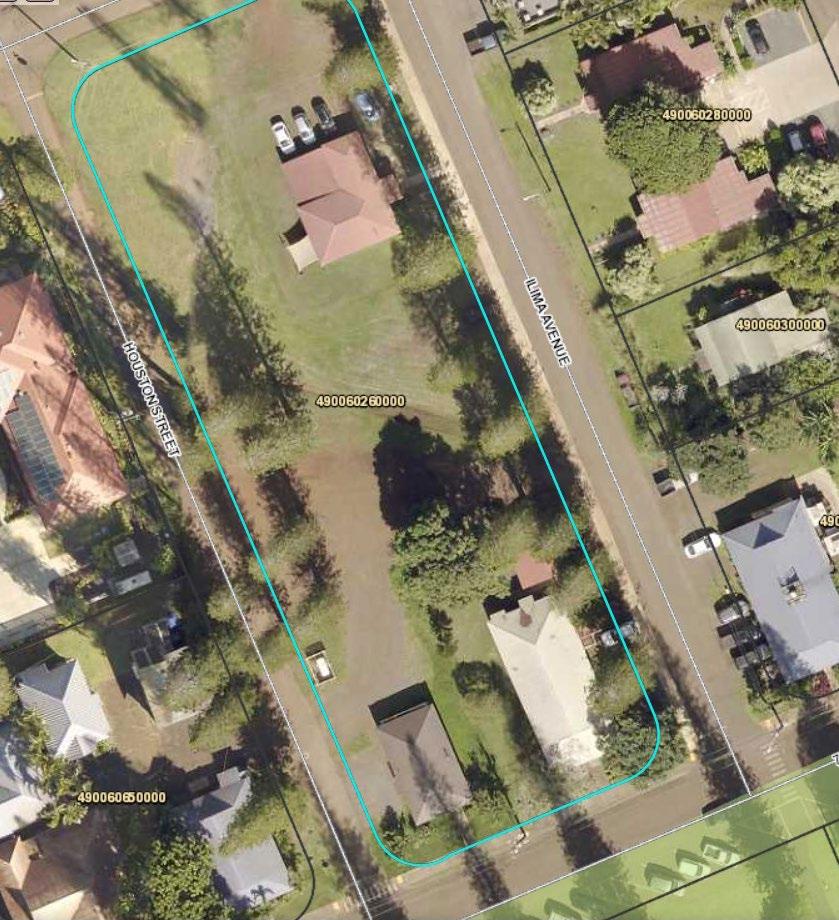

3 Locate facility in town

The location of a new facility close to the town center, if feasible, will assure Lāna‘i’s kūpuna that they are an integral part of the community. The facility could be housed on an empty lot or consider adaptive reuse of an existing building. Paying particular attention to land use and design choices can enhance health through the design of spaces that foster social interaction and physical activity. Adjacency to open space, and convenient access to transport services and other neighborhood amenities are important considerations. Spaces should support active participation by older adults and be non-institutional, flexible, and multifunctional with provisions to adapt them to evolving needs. Wayfinding for individuals with disabilities (e.g. landmarks, plantings to enhance wayfinding for those with cognitive impairment) and well-lit streets with well-marked crosswalks and sidewalks are important for safety and to reduce the risk of falls and injuries (see Hunter et al., 2013). The design should also consider accessibility, visitability, and universal design principles.

4 Provide specialized transport services

Reliable transport services play an important role in maintaining independence, assisting with shopping, visiting family and friends, running errands, and providing access to health care services, and social and cultural activities. On-demand transport and mini ride-shares or volunteer-driver programs with easily available information about pick-up and drop-off should be considered with the new facility.

5 Improve communication and coordination

Strengthening coordination among service providers, kūpuna, families, and caregivers by providing a portal or an information hub with age-friendly navigation in languages commonly spoken in Hawai‘i will provide comprehensive information about the range of services available and how best to access them, making health care information accessible for all and thereby improving health literacy.

6 Develop affordable housing to support health care workforce

Affordable rental housing is critical for attracting a high-quality workforce and is a key consideration that should be coupled with staffing existing health care facilities or a new facility. This is important in stemming high levels of turnover and job vacancies, especially when competing with higher-paying hospitality jobs. The lack of rental housing creates severe challenges by limiting alternatives for families moving back to Lāna‘i or trying to find housing for private caregivers for their kūpuna. Workforce development is another critical need. The shortage of health care workers is a

18

national dilemma. This is amplified on Lāna‘i where rental housing is scarce. The high cost of living on the island also presents challenges for health care workers who not only need to adjust to the high cost but also to life on a rural island with limited opportunities for social activities unlike on the more populated neighbor islands.

7 Solicit input from stakeholders

Engaging stakeholders – kūpuna, family members and/or caregivers, and service providers – by hosting a codesign workshop will tailor preferences and design decisions and leverage existing community assets. Widespread community support and visibility of proposed plans and programs are critical. It is important to design with rather than for the kūpuna by tapping into their wisdom to unlock innovative strategies instead of pathologizing old age. This could help reimagine the future of elder care design. Combining stakeholder input with precedents and best practices outlined in the American Planning Association’s Policy Guide on Aging in Community and the Urban Land Institute’s Building Healthy Places Toolkit could offer architects, planners, and public officials strategies for creating agefriendly communities.

References

AARP (2011). Aging in Place: A State Survey of Livability Policies and Practices. AARP Public Policy Institute. Washington, D.C.

Abrams, H. R., Loomer, L., Gandhi, A., & Grabowski, D. C. (2020). Characteristics of U.S. nursing homes with COVID 19 cases. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 68(8), 1653–1656. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.16661

Afendulis, C. C., Caudry, D. J., O’Malley, A. J., Kemper, P., & Grabowski, D. C. (2016). Green House adoption and nursing home quality. Health Services Research, 51, 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12436

American Planning Association. (2015). Planning aging-supportive communities (PAS 579). Retrieved March 6, 2022, from https://www.planning.org/publications/ report/9026902/

Braun, K. L., Browne, C. V., Ka’opua, L. S., Kim, B. J., & Mokuau, N. (2013). Research on indigenous elders: From positivistic to decolonizing methodologies. The Gerontologist, 54(1), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnt067

Browne, C. V., Mokuau, N., Ka’opua, L. S., Kim, B. J., Higuchi, P., & Braun, K. L. (2014). Listening to the voices of Native Hawaiian elders and ‘ohana caregivers: Discussions on aging, health, and care preferences. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology, 29(2), 131–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10823-014-9227-8

Executive Office on Aging Annual Report for SFY 2019. (n.d.). Retrieved March 6, 2022, from https://health.hawaii.gov/opppd/files/2019/12/EOA-Annual-LegislativeReport-2019.pdf

Gawande, A. (2015). Being Mortal: Illness, Medicine and What Matters in the End. WF Howes Ltd.

Grabowski, D. C., & Mor, V. (2020). Nursing home care in crisis in the wake of covid-19. JAMA, 324(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.8524

Guo, J., Konetzka, R. T., Magett, E., & Dale, W. (2014). Quantifying longterm care preferences. Medical Decision Making, 35(1), 106–113. https://doi. org/10.1177/0272989x14551641

Hunter RH, Potts S, Beyerle R, Stollof E, Lee C, Duncan R, Vandenberg A, Belza B, Marquez DX, Friedman DB, Bryant LL. (2013). Pathways to Better Community Wayfinding [Internet]. Seattle, WA; Washington, DC: CDC Healthy Aging Research Network and Easter Seals Project ACTION. Available from: www.prc-han.org

Kiyota, E. (2018). Co-creating environments:empowering elders and strengthening communities through design. Hastings Center Report, 48. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.913

The Global Network for age-friendly cities and communities. (n.d.). Retrieved March 6, 2022, from https://www.who.int/ageing/gnafcc-report-2018.pdf

Global age-friendly cities: A guide (n.d.). Retrieved March 6, 2022, from https://www. who.int/ageing/publications/Global_age_friendly_cities_Guide_English.pdf?ua=1

Zimmerman, S., Dumond-Stryker, C., Tandan, M., Preisser, J. S., Wretman, C. J., Howell, A., & Ryan, S. (2021). Nontraditional Small House nursing homes have fewer COVID-19 cases and deaths. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(3), 489–493. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2021.01.069

19

Notes

1 https://aspe.hhs.gov/basic-report/what-lifetime-risk-needing-and-receiving-long-term-services-and-supports

2 Luterman, S. It’s time to abolish nursing homes. The Nation (11 August 2020); https://www.thenation.com/article/society/abolishnursing-homes/

3 CMS Issues Guidance on American Rescue Plan Funding for Medicaid Home and Community Based Services | HHS.gov

4 “Aging in place is the ability to live in one’s own home and community safely, independently, and comfortably, regardless of age, income, or ability level” (see http://www.cdc.gov/ healthyplaces/terminology.htm). It offers numerous benefits to older adults including life satisfaction, health and self-esteem, all of which are key to successful aging (AARP, 2011).

5 https://www.aarp.org/ppi/issues/caregiving/info-2020/nursing-home-covid-dashboard.htm

6 Tan, R. Nontraditional nursing homes have almost no coronavirus cases. Why aren’t they more widespread? Washington Post (3 November 2020); https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/green-house-nursing-homes-covid/2020/11/02/4e723b82-d114-11ea-8c5561e7fa5e82ab_story.html

20

Appendix: Interview Guides

About the Study

INTERVIEWER: This study will explore the long-term care needs of kūpuna and family members who are caregivers. It will also include insight from Lāna'i's health care service providers to understand the medical, social and economic needs of its kūpuna. The goal is to develop principles for the design of a facility that is holistic and well-aligned with the everyday needs and cultural values of the island’s kūpuna. [Interviewer to provide consent form before proceeding]

Questions for Service Providers

Section I: Current status of long-term care and services

1. Tell me about your organization.

2. What types of services do you offer? For kūpuna? Describe.

3. How many patients do you have the capacity to serve? How many would you say you are currently serving?

4. Do you coordinate with the Executive Office on Aging and/or the Maui County Office on Aging and their assistance programs and services? Explain.

5. Do the kūpuna you typically serve have health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, military, no insurance)?

6. What are their primary health and/or personal care needs? Describe.

7. What types of care are you able to provide? Describe.

8. Do you offer programs that encourage intergenerational activities with kūpuna? Do you offer financial counseling? Information about legal services?

9. Is there a need for affordable housing among the kūpuna?

10. Are there recreational facilities available in the community where kūpuna can go to exercise or engage in physical activity besides the Senior Center?

11. How many hours a week of care would you say you provide?

12. Are there other long-term care options available to them? If yes, what are they?

13. How aware would you say kūpuna and/or their caregivers are about services that are available? How do newcomers find out about the services

you provide?

14. How has COVID-19 affected your service? Those you take care of?

15. Could you describe a typical day in your care routine?

16. Do you engage volunteers to provide services and information to kūpuna and caregivers?

17. Do you offer support services for caregivers/family members? If so, what types?

Section II: Vision

18. What would you change about the current care situation, if possible?

19. Based on your experience, what would you consider important for the wellbeing of the kūpuna (e.g. a sense of belonging/connectedness, a homelike environment, privacy, connection with nature, etc.)? Describe.

20. As a service provider, what would you like to see in a long-term care facility? Describe.

21. What type of care (e.g. home-based, community-based) would you say is well suited for the kūpuna you work with? Why?

22. What would you prioritize in the design of this facility in terms of needs? Cultural values? Quality of life?

23. What types of spaces would you like to see (e.g. indoor, outdoor, transitional)? For staff? Activities for kūpuna?

24. Do you know of other long-term care facilities that could serve as a model?

25. If such a facility were to be built, where would you like to see it located? Why?

26. What do you think about intergenerational care?

27. Is there anything else you would like to share?

Questions for Family Caregivers

Section I: Current status of long-term care and services

1. Tell me about yourself.

2. How many kūpuna members do you provide care for? How old are they? With whom or where do they live?

3. Do they have health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, military, no insurance)?

4. Are you their primary caregiver?

5. What made you begin caregiving?

6. What are their primary health and/or personal care needs? Describe.

7. How do you gather information about services for kūpuna?

8. What type of care are you able to provide? Describe.

9. How many hours a week would you say you spend on caregiving?

10. How does having to care for kūpuna affect your life? Your work?

11. Are there other long-term care options available to them? If yes, what are they?

12. What kinds of activities do kūpuna need assistance with?

13. What do you think of home health care in your community? (e.g. is it meeting kūpuna’s needs?)

14. What would you change about the current care situation, if possible?

15. How has COVID-19 affected you? Those you take care of?

16. What would you consider important for the well-being of your kūpuna (e.g. a homelike environment, privacy, connection with nature, etc.)? Describe.

17. How are health and health care needs of kūpuna being met in your community?

18. In general, are there barriers to

21

physical and/or mental and emotional health care?

19. If kūpuna feel isolated, lonely, or depressed, what type of help is available to them?

20. Have you ever felt overwhelmed when providing care (physically, financially, and/or emotionally)?

21. Have you ever felt the need for assistance in caring for your kūpuna family member(s)?

22. Do other family members assist you in caregiving?

Section II: Vision

23. What would you like to see in a longterm care facility? Please describe.

24. What type of care (e.g. home-based, community-based) would you most prefer for your family member? Why?

25. What you would prioritize in the design of this facility in terms of needs? Cultural values? Quality of life?

26. What types of spaces would you like to see (e.g. indoor, outdoor, transitional)? Activities?

27. Do you know of other long-term care facilities that could serve as a model?

28. If such a facility were to be built, where would you like to see it located? Why?

29. What do you think about intergenerational care?

30. Is there anything else you would like to share?

Section III: Demographics

» Age » Gender

» Race [White, Black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, American Indian, Native Alaskan, Other]

» Ethnicity

» Marital status

» Household size

» Annual income level [range]

» Education level

» Primary language spoken in the household

» Current employment status [e.g. working full-time/part-time, looking for work, homemaker, other]

» Members in the household who are employed

» Have you ever served in the United States Armed Forces (military,

National

Questions for Kūpuna

Section I: Current status of long-term care and services

1. Tell me about yourself.

2. How long have you lived in this community? How would you say things have changed over the years?

3. What are your living arrangements? (Interviewer to note down type of housing – e.g. single family, condo/ townhome, apartment, senior living)

4. Do you currently own or rent your home?

5. Do you have a primary caregiver or a service provider? If so, who?

6. Do you have health insurance (Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, military, no insurance)?

7. What are your primary health and/or personal care needs? Please describe.

8. What are some of the long term care options available to you? Please explain.

9. What plans, if any, would be in place if your current caregiving situation changes? Do you have a plan?

10. How has COVID-19 affected you? Your family? Friends?

11. Prior to COVID-19, were you able to interact regularly with others in the community? With family?

12. Did you have access to local services and shops? Which ones did you visit most frequently?

13. Describe how you typically get around. Is transportation readily available when you need it (e.g. to get to medical appointments, religious services, shopping, etc.)?

14. Are there any barriers, if any, to accessing transportation?

15. Do you feel safe in your community (e.g. from theft, burglary, fraud, etc.)?

16. Do you know where to go in case of an emergency?

17. Do you have concerns about dealing with legal issues (e.g. preparing a will/trust, Social Security benefits, financial debt, etc.)?

18. What would you consider important for your well-being (e.g. a sense of belonging/connectedness, a homelike

environment, privacy, connection with nature, etc.)? Describe.