Establishing a Statewide Food and Product Innovation Network (FPIN) in Hawaiʻi

Proof of Concept Study

June 2025

Prepared by: University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center

Submitted to:

Agribusiness Development Corporation

Establishing a Statewide Food and Product Innovation Network (FPIN) in Hawaiʻi

Proof of Concept Study

June 2025

Prepared by: University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center

Submitted to:

Agribusiness Development Corporation

Kimi Makaiau, Principal Investigator

Jonathan Malu Stanich, Project Designer

Daniel Luna, Project Designer

Hannah Valencia, Project Designer

Logan Shiroma, Graduate Research Assistant

Joyce Lin, Student Assistant

Cost Estimator: J. Uno & Associates

2410 Campus Road Room 101A Honolulu, HI 96822 http://uhcdc.manoa.hawaii.edu

The University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center (UHCDC) is a service learning program and teaching practice established and led by the University of Hawaiʻi (UH) School of Architecture that provides a platform for applied research, planning, placemaking, and design. UHCDC involves UH faculty, staff, students, and partnered professionals across UH campuses, departments, and professional disciplines.

This project was made possible by the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism and the Agribusiness Development Corporation, with support and collaboration from the Office of Senator Donovan Dela Cruz.

UHCDC extends its sincere appreciation to the many individuals, organizations, and agencies who contributed their time, insight, and expertise to the development of the Food and Product Innovation Network (FPIN). This work was shaped through a collaborative, statewide process that included site visits, surveys, interviews, charrettes, and public engagement activities conducted over the course of the planning phase.

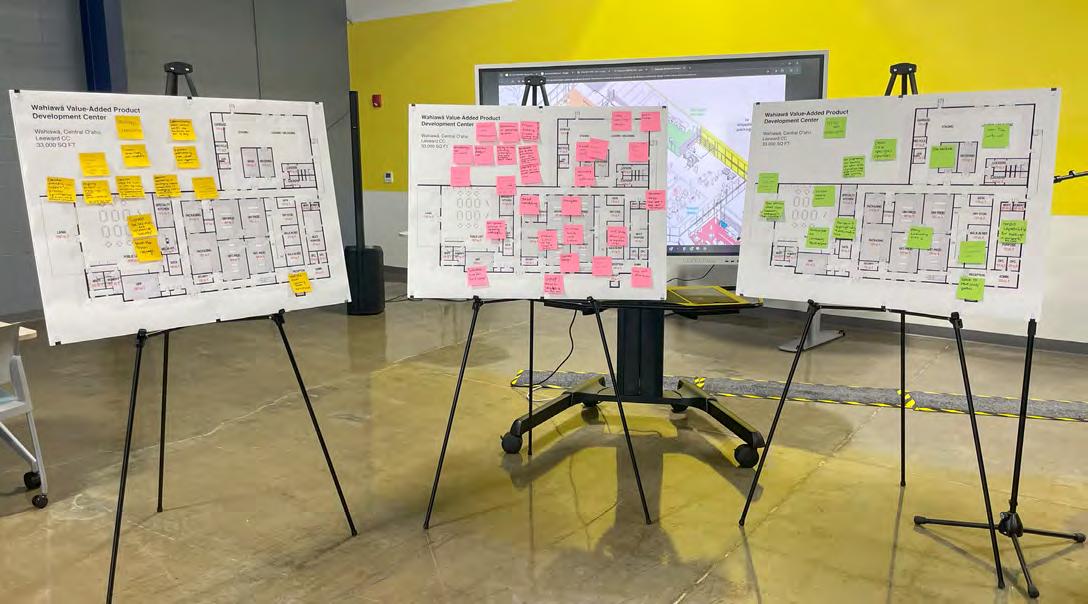

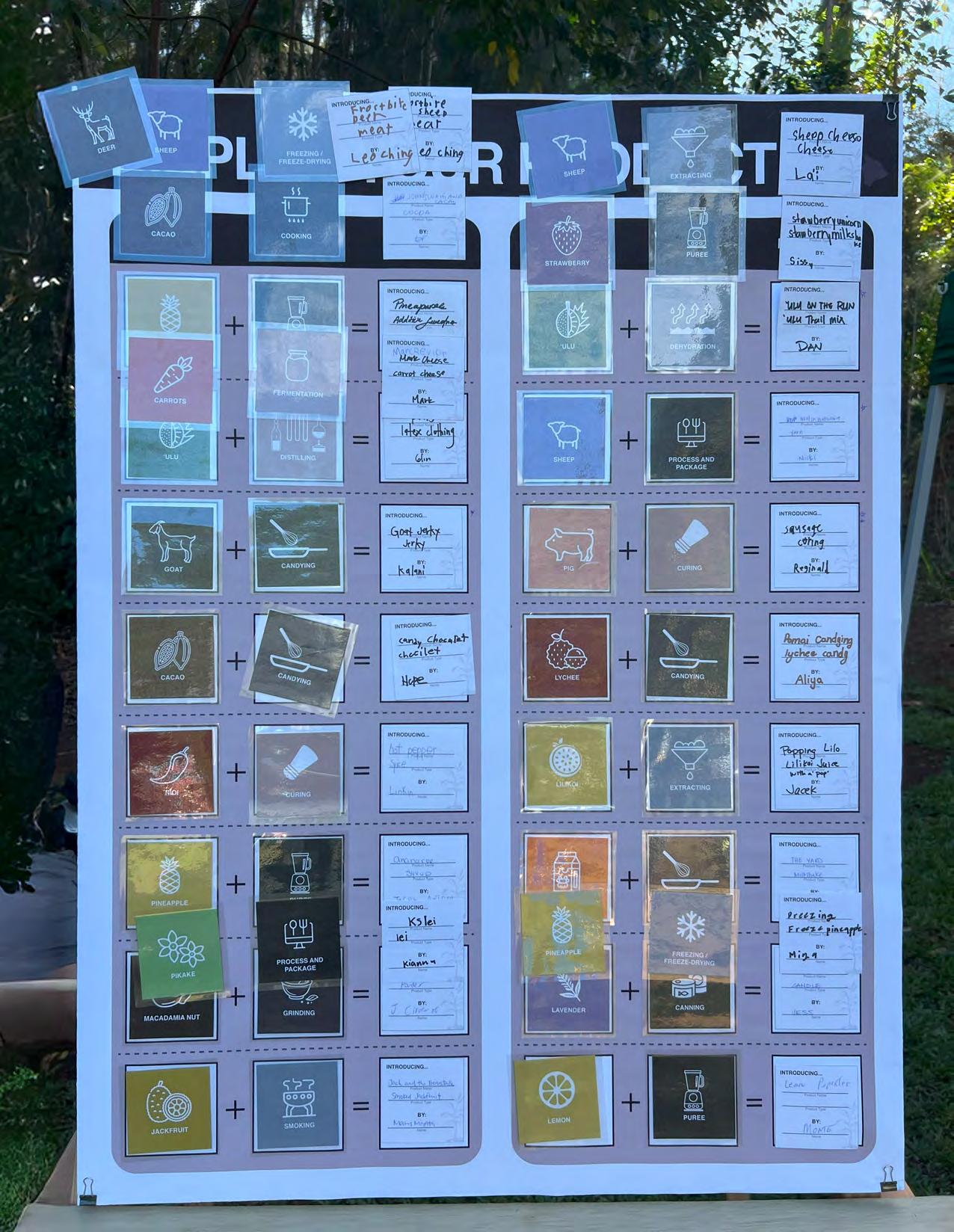

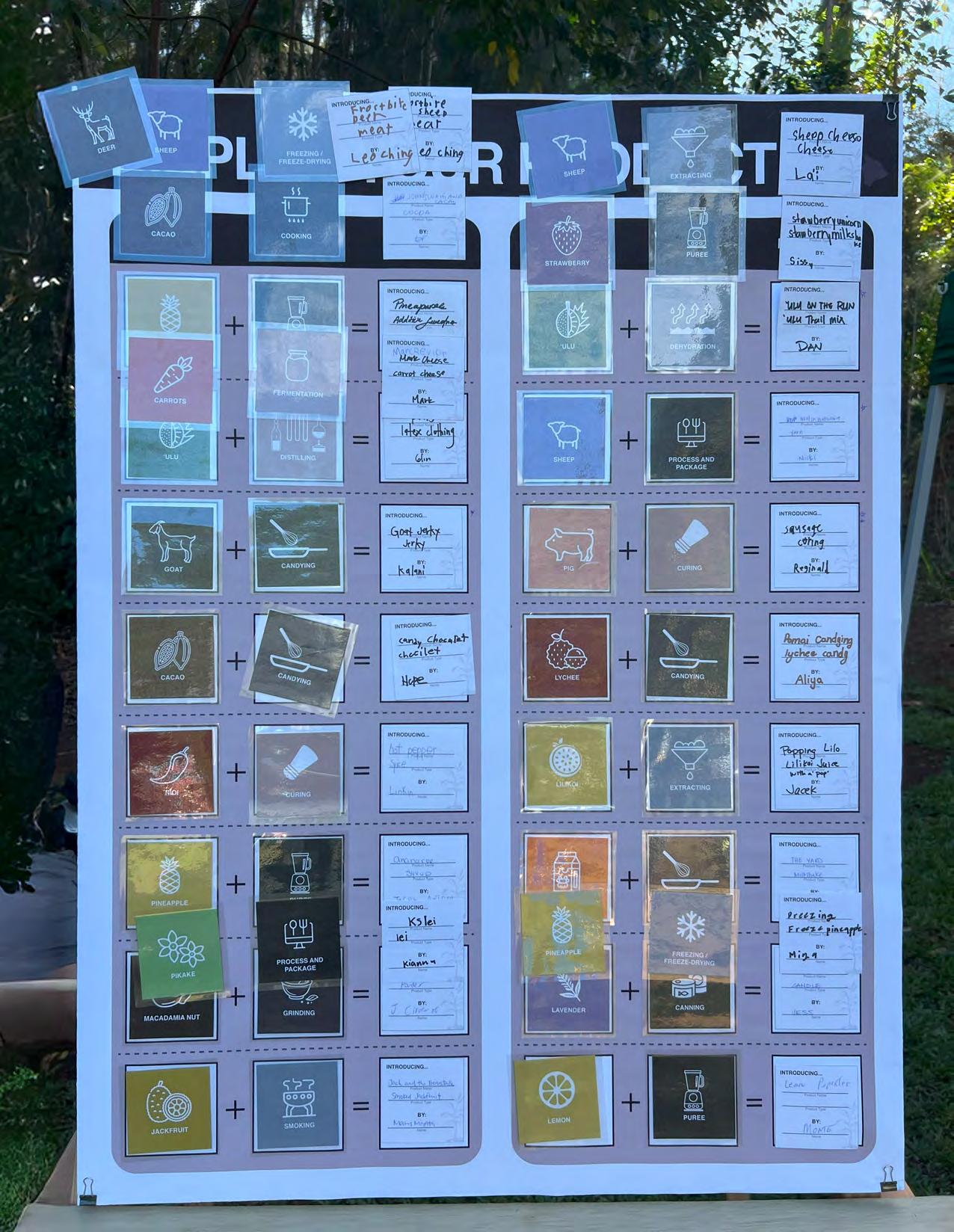

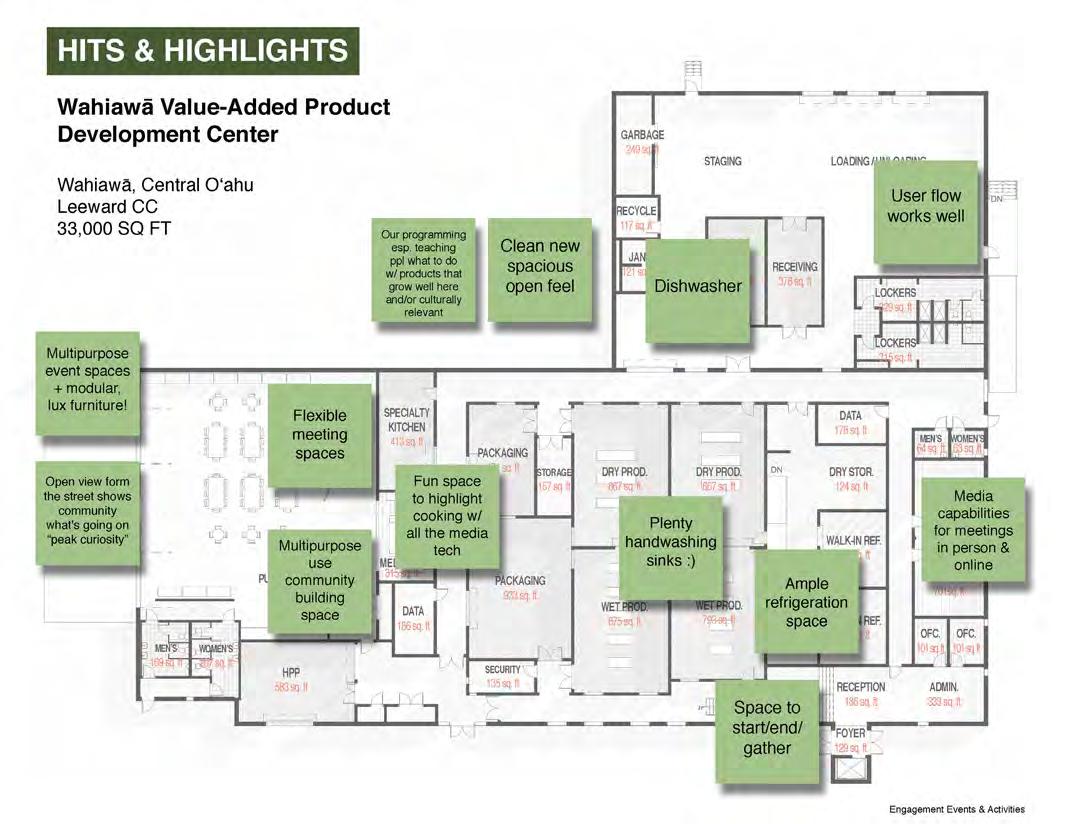

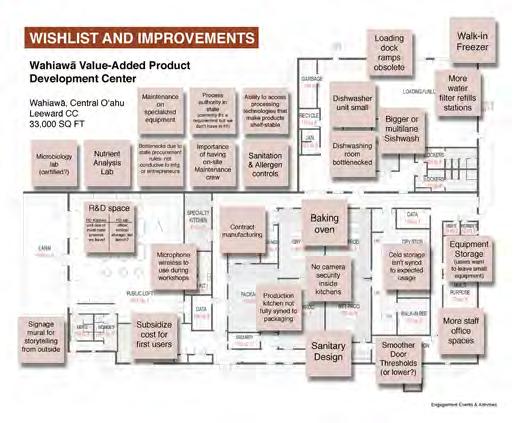

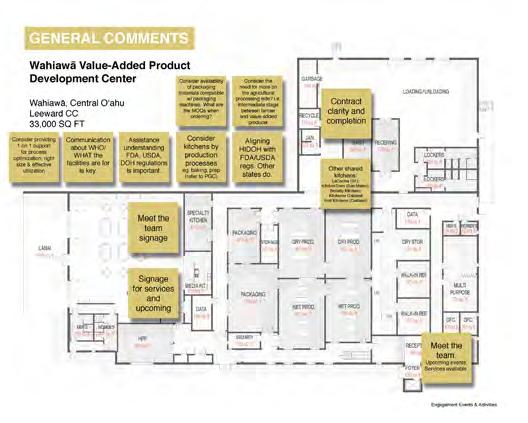

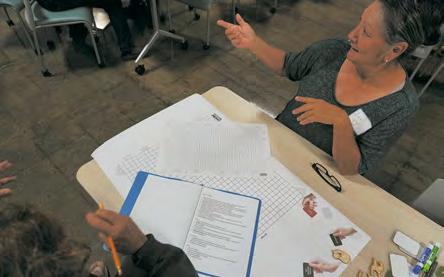

Mahalo to the Wahiawā Value-Added Product Development Center staff for participating in targeted design charrettes that informed critical aspects of the FPIN pilot facility. We also like to recognize the entrepreneurs from Leeward Community College’s ʻĀina to Mākeke cohort for their involvement in the facility design workshop, where their practical knowledge and entrepreneurial experience helped shape programming and layout strategies. Additionally, UHCDC acknowledges the Maui Food Innovation Center at UH Maui College, whose team and incubator program participants provided operational insights and precedent guidance that informed statewide facility planning.

Stakeholder engagement included participants from across the public and private sectors, including but not limited to: value-added food producers, small business owners, agricultural cooperatives, culinary and ag-tech educators, community colleges, nonprofit organizations, regulatory agencies, and government officials. Each stakeholder brought a unique perspective, and their collective input was critical to aligning FPIN facilities with local business needs, regulatory realities, and regional development goals.

While it is not possible to name every contributor individually, UHCDC expresses its deep gratitude to all who engaged in this process. Their participation has helped ensure that FPIN is grounded in the values, challenges, and opportunities that define Hawaiʻi’s food system today—and that it remains responsive to the communities it is intended to serve.

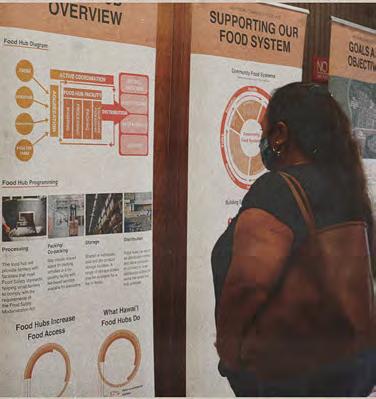

The Hawaiʻi Food and Product Innovation Network (FPIN) is a statewide initiative led by the Agribusiness Development Corporation (ADC) intended to further Hawaiʻi’s agricultural, food security, and economic diversification goals. Legislatively established in 2024, the network provides for open-access food and valueadded product development facilities across the state that will enable businesses to scale up new products from research and development to manufacturing and commercialization. These facilities will provide shareduse processing infrastructure, technical expertise, advanced manufacturing equipment, and business support services that enable entrepreneurs to scale from research and development to full-scale production and commercialization. The network is also designed to strengthen the visibility and competitiveness of Hawaiʻimade products in local and global markets.

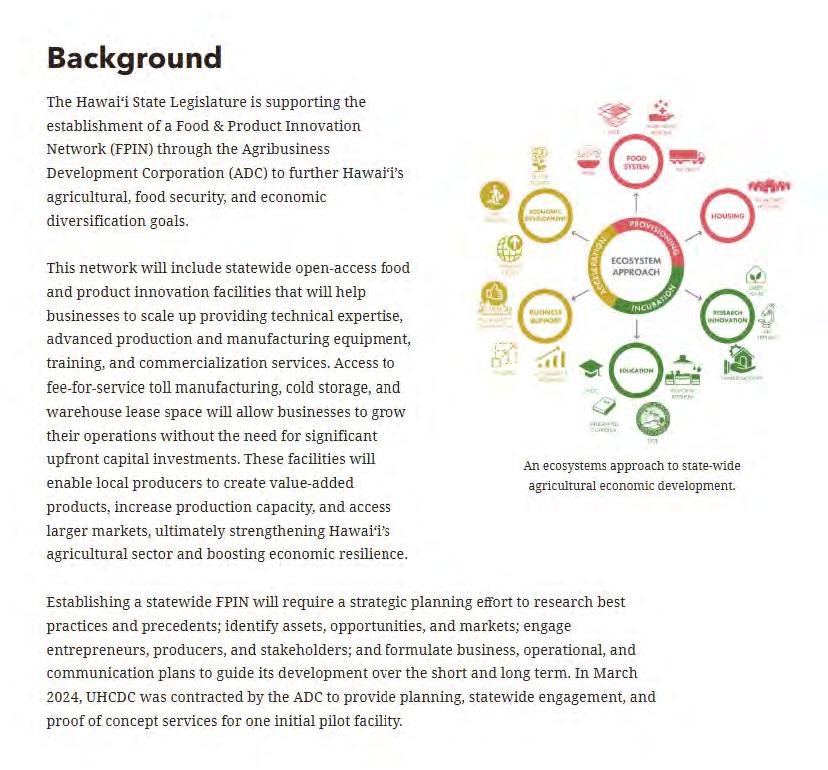

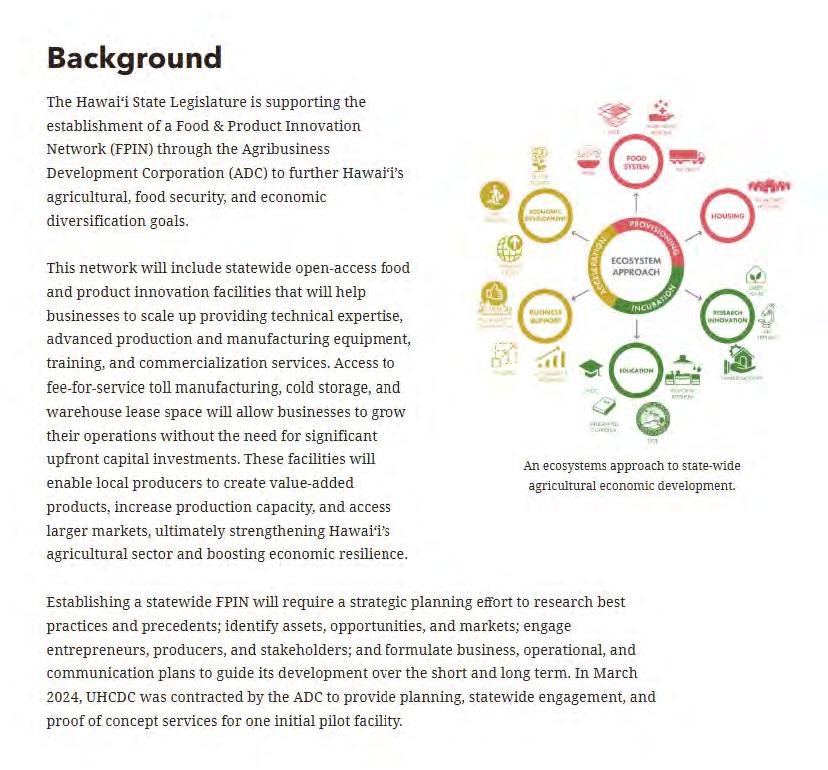

FPIN is further structured through an ecosystem approach of development that leverages the unique assets, capacities, and aspirations of a region to stimulate economic activity and improve long-term resilience. This includes bridging components of the food system with research innovation, educational pathways, business support, workforce housing, and economic development.

The following report is a summary of the planning and design process conducted by the University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center (UHCDC) from March 2024 - April 2025. UHCDC engaged in a collaborative planning process that involved precedent research and discussions, statewide stakeholder engagement, design research, and facility prototyping incorporating potential future user insights .

The general goals of this research was to articulate the broader vision of the statewide network, create a framework that could be utilized in the development of facilities statewide, document the implementation process and conceptual planning for an inaugural production facility, and finally, to provide recommendations that would allow for more efficient and inclusive development of both the network and future facilities.

This document is organized into six primary sections:

1. Introduction;

2. Defining the Network;

3. Strategic Planning Framework;

4. Implementation Process;

5. Proof of Concept, and

6. Conclusion.

This section orients readers by providing a background on the initiative, its need to align statewide food systems goals, vision, objectives, and defines the priority production function of value-added processing. This includes both food-based and non-food based products. It also describes the systemic challenges faced by Hawaiʻi’s agricultural producers including high costs related to land, labor, and logistics; limited availability of manufacturing infrastructure; and competition from low cost import products. This section culminates with a case study of Hawaiʻi’s ancestral value-added product, poi, its cultural significance, and exemplifies traditional circular resource management.

The section provides an overview of global frameworks that have established models from which Hawaiʻi can draw upon. It analyzes precedent models including New Zealand’s Food Innovation Network, the European Institute of Innovation and Technology, and Singapore Food Story, that demonstrate how regional specialization, openaccess infrastructure, and cross-sector collaboration can support value-added innovation. The network is designed to create a sustainable and resilient agricultural economy by building a seamless pathway from education to export. It also details how an integrated ecosystems approach to development along with a convergence of key partners will be critical to statewide implementation and success.

This section presents the methodological framework used to guide all future FPIN facility development. It includes two integrated tracks: Engagement and Facility Planning. Its intent is to strengthen statewide collaboration, support inclusive planning, adapt processes to diverse regional conditions, and guide-decision making.

The engagement track incorporates interviews, workshops, site visits, and outreach events that ground planning decisions in local needs, opportunities, and capacities. A comprehensive site selection model was developed to evaluate parcel eligibility, zoning compatibility, proximity to agricultural activity, logistics access, infrastructure readiness, and potential for expansion. Facility types are organized along a spectrum of shared use, ranging from public kitchens to semi-private manufacturing suites and contract processing spaces. The framework integrates best practices from global models, along with technical and regulatory requirements for facility design.

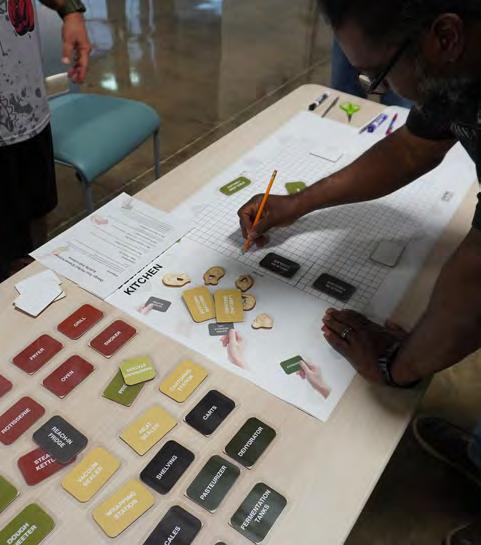

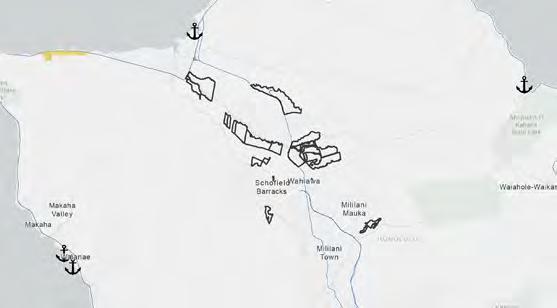

Utilizing the Strategic Planning Framework process, UHCDC documented activities for Engagement and Facility Planning to guide conceptual plans for an inaugural pilot facility in Wahiawā on the island of Oʻahu. UHCDC facilitated a multistage process that included community outreach, institutional collaboration, and participatory design activities. Key contributors included staff from the Wahiawā Value-Added Product Development Center, faculty from Leeward Community College, and food entrepreneurs from across the islands.

Stakeholder input shaped decisions related to spatial layout, equipment selection, user flow, and compliance considerations. Design priorities addressed infrastructure constraints, state procurement processes, packaging and storage coordination, and training programs. The process confirmed the value of iterative planning that integrates end-user feedback from early concepts through detailed facility planning.

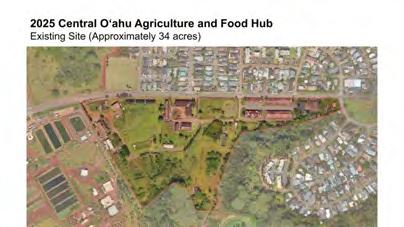

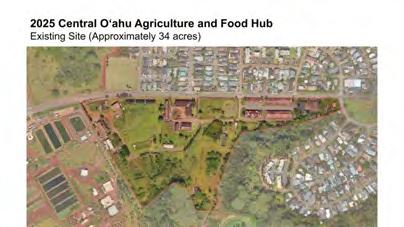

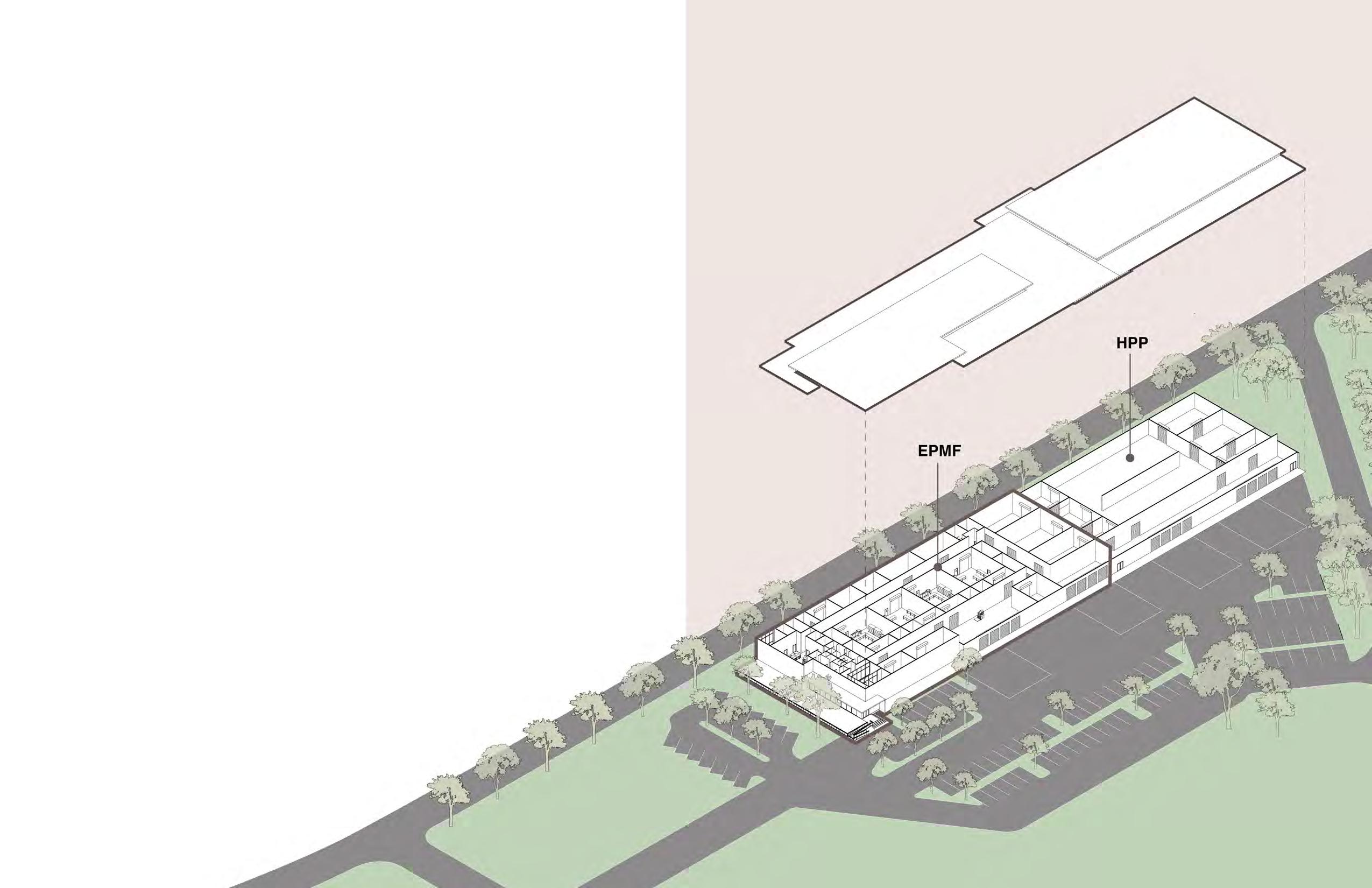

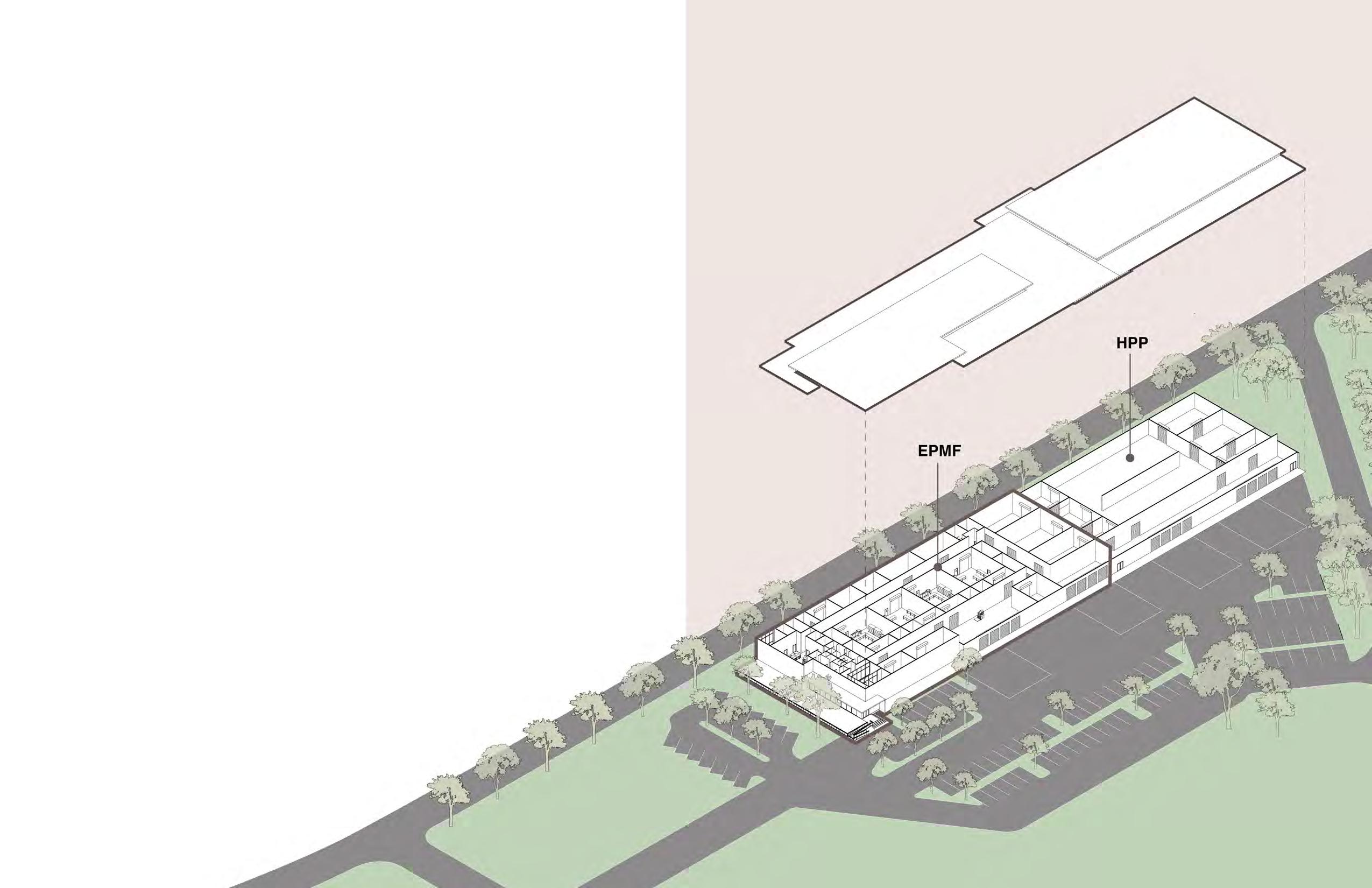

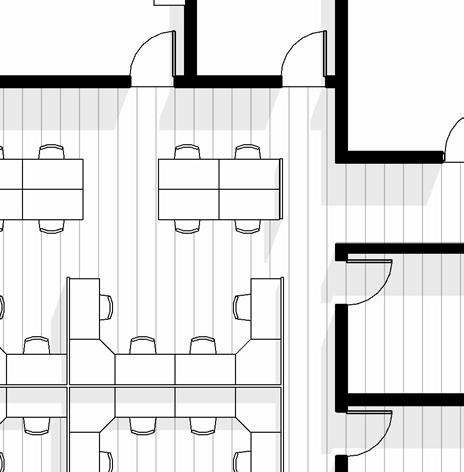

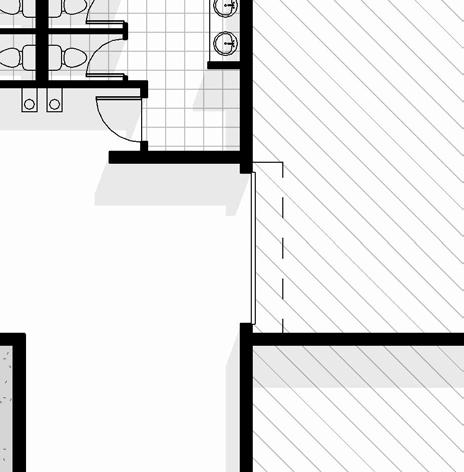

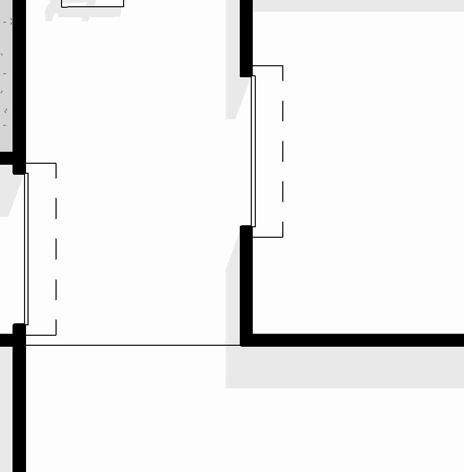

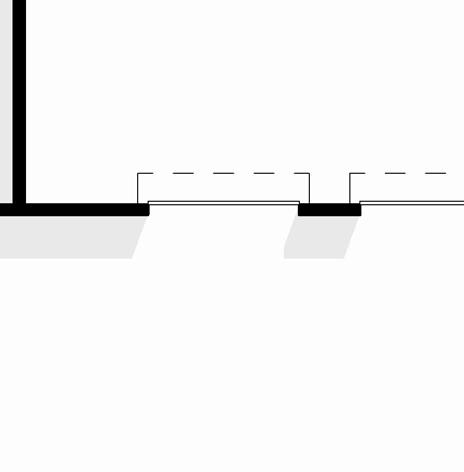

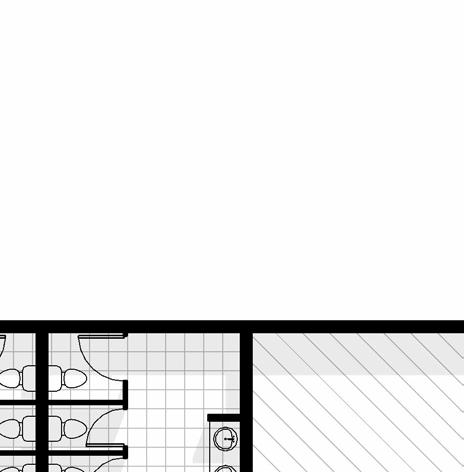

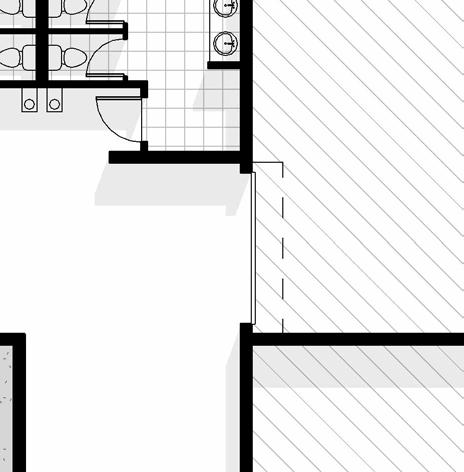

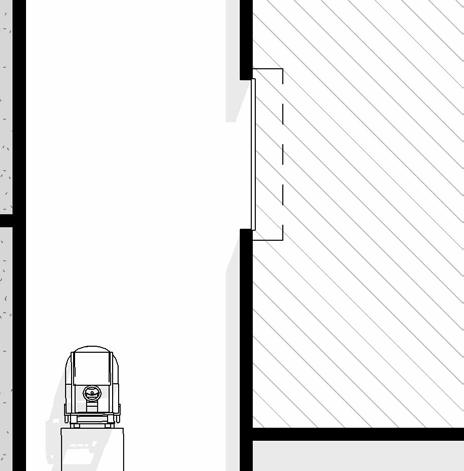

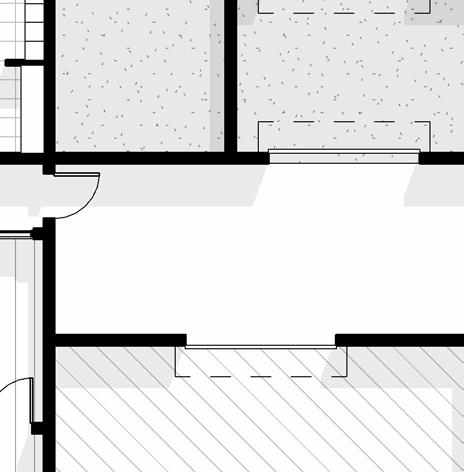

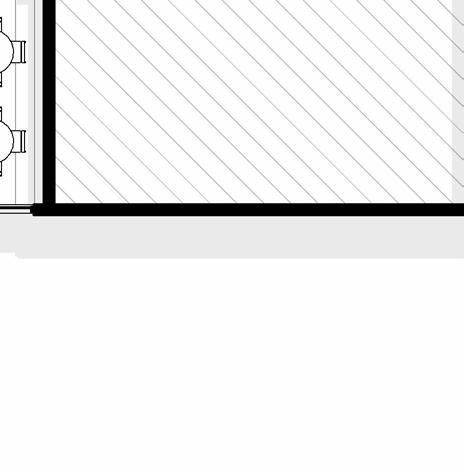

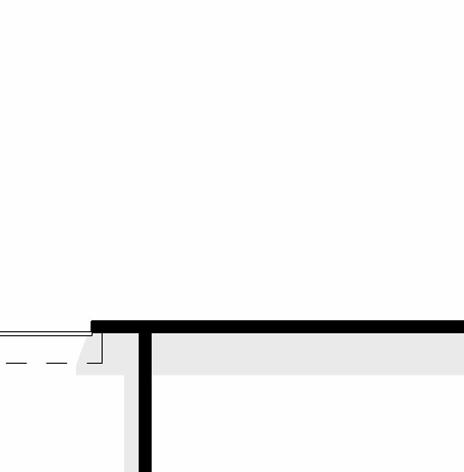

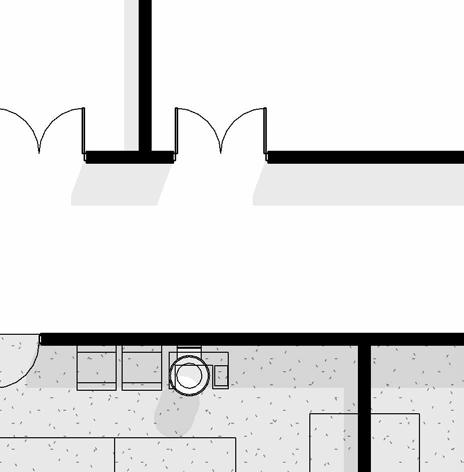

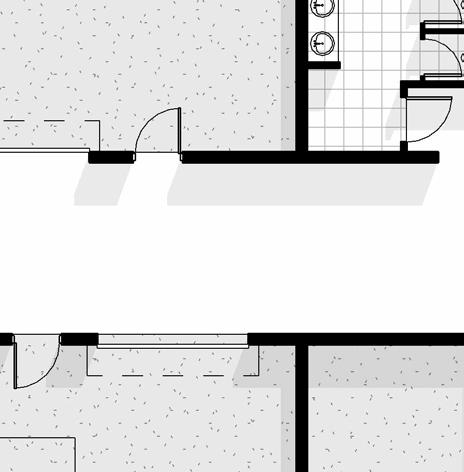

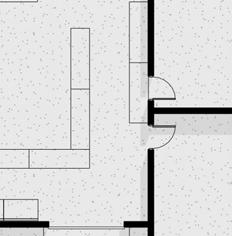

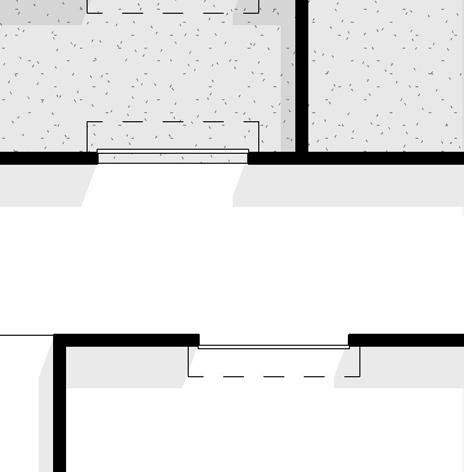

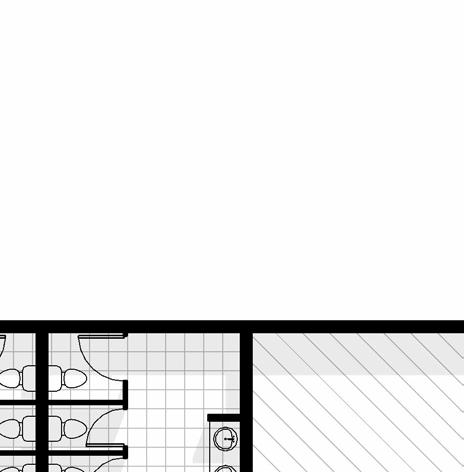

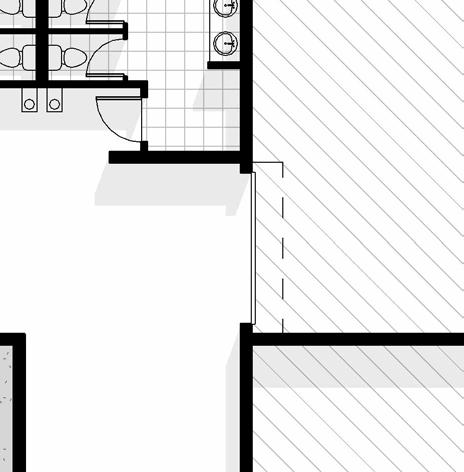

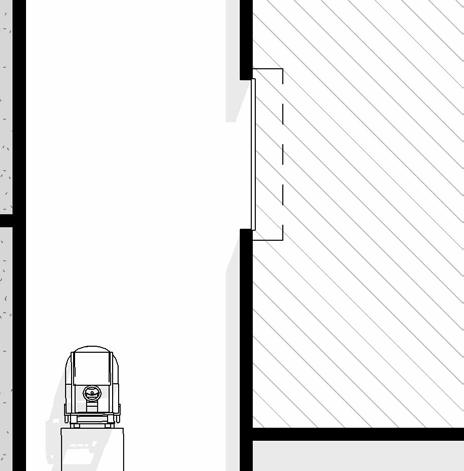

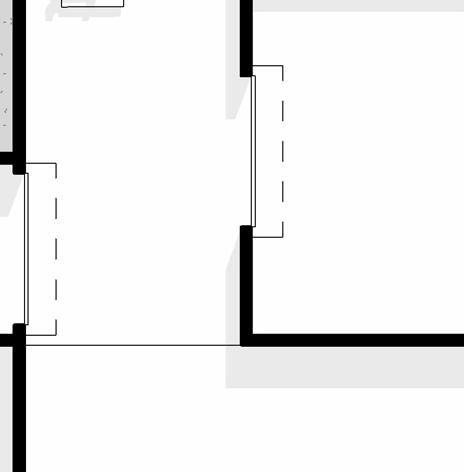

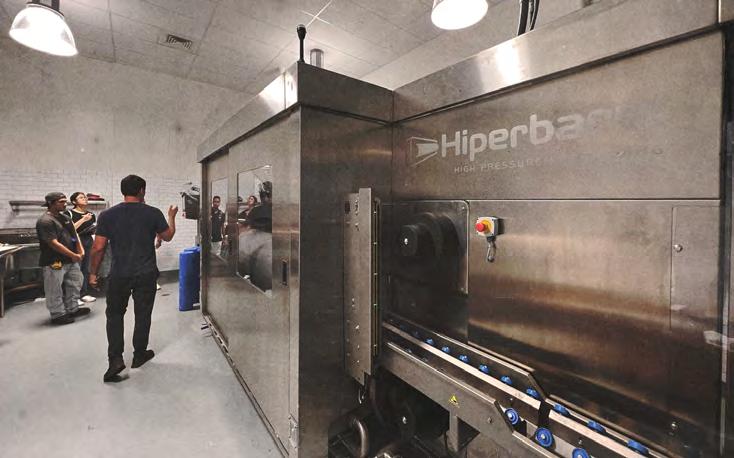

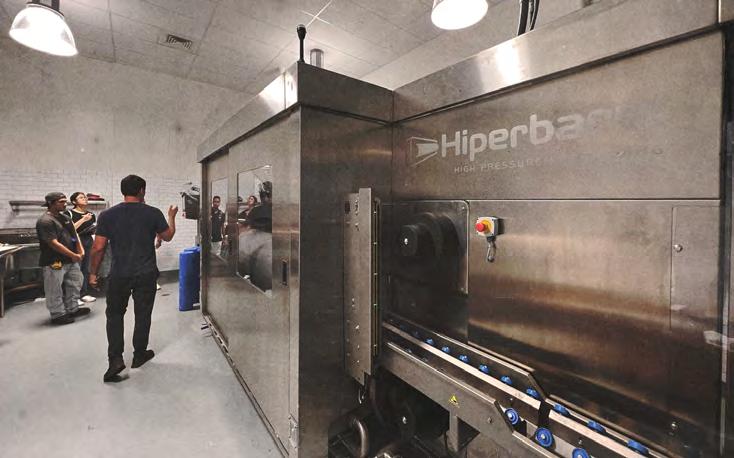

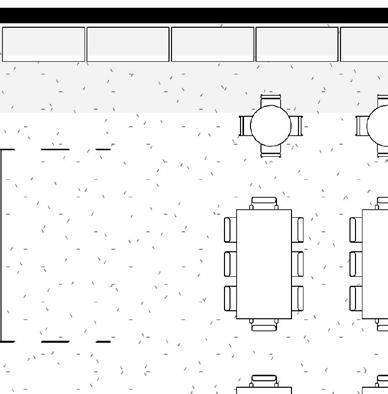

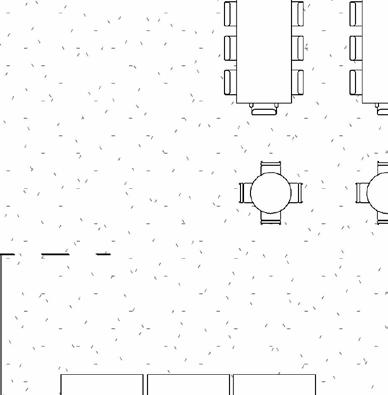

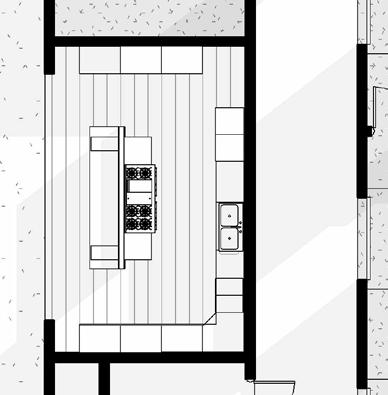

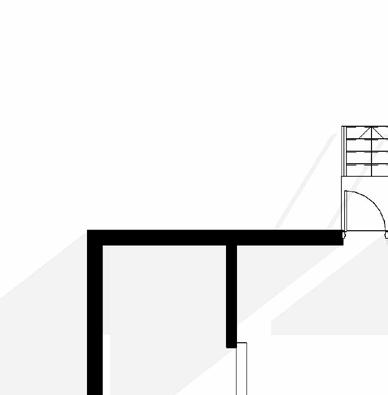

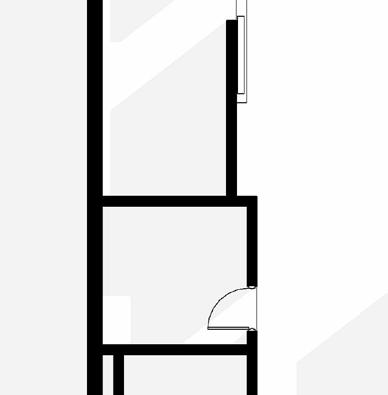

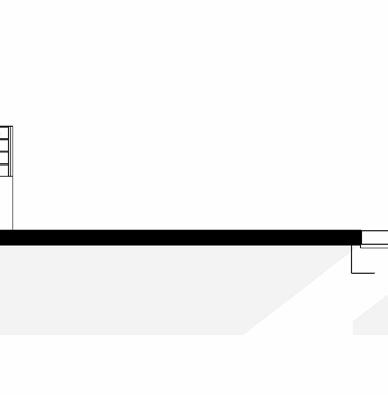

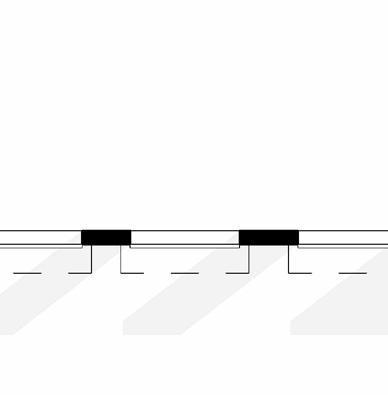

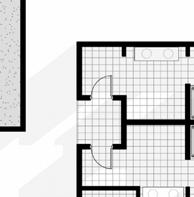

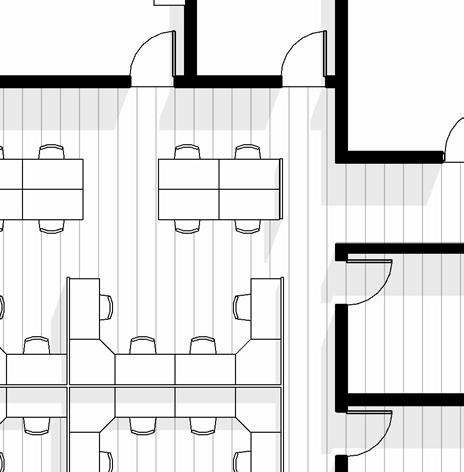

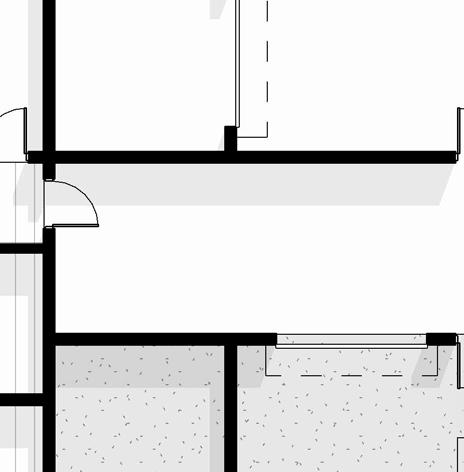

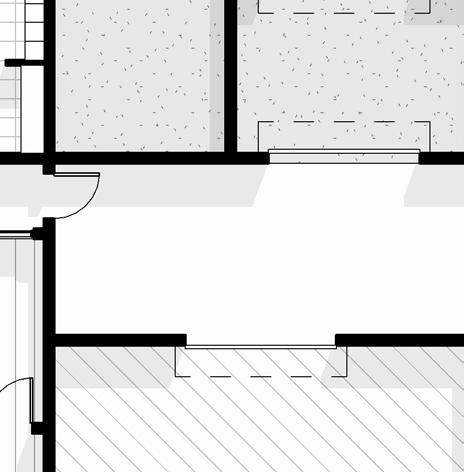

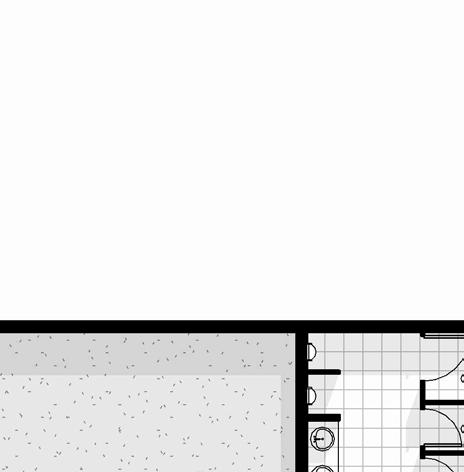

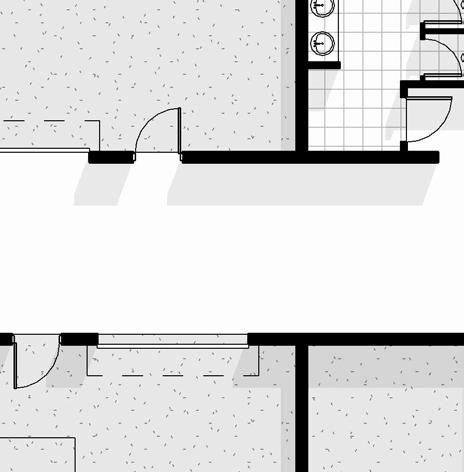

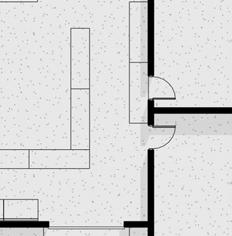

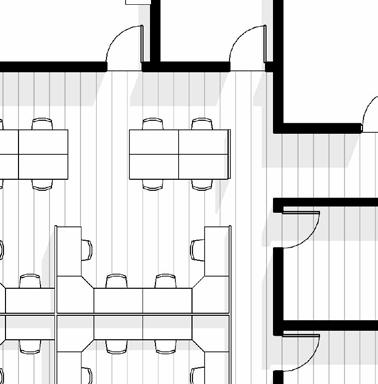

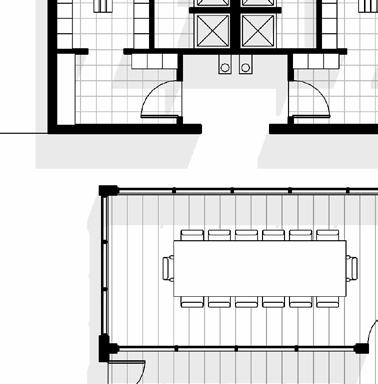

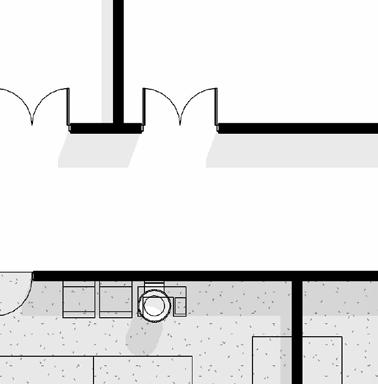

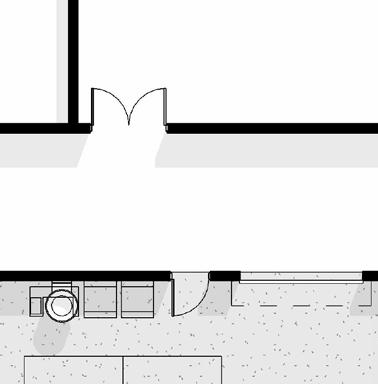

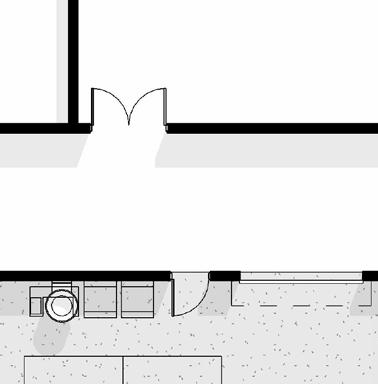

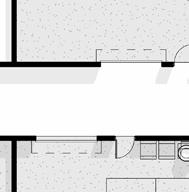

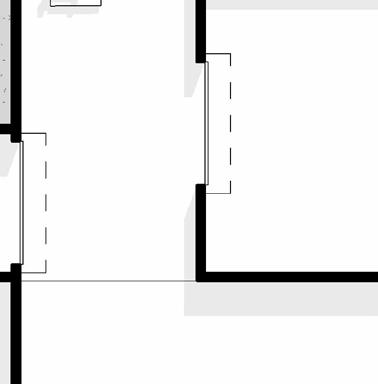

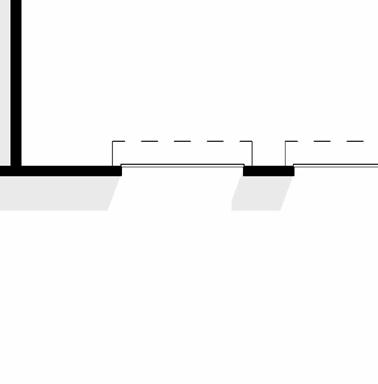

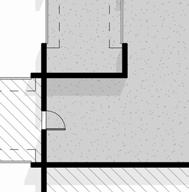

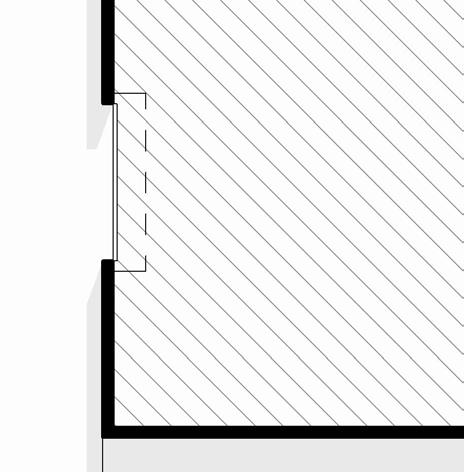

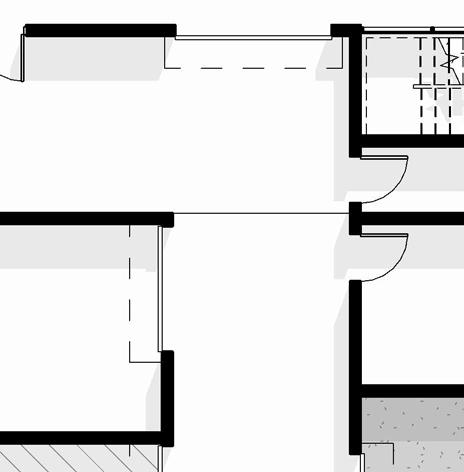

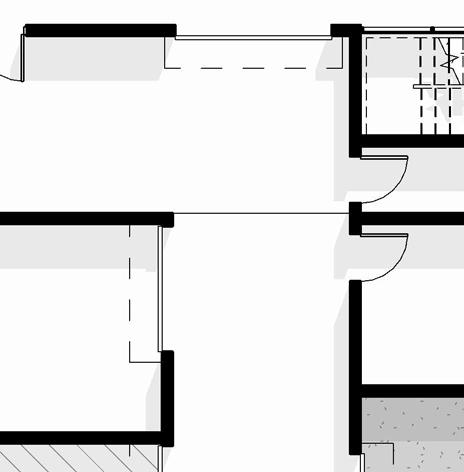

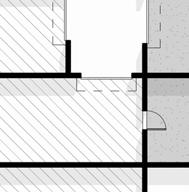

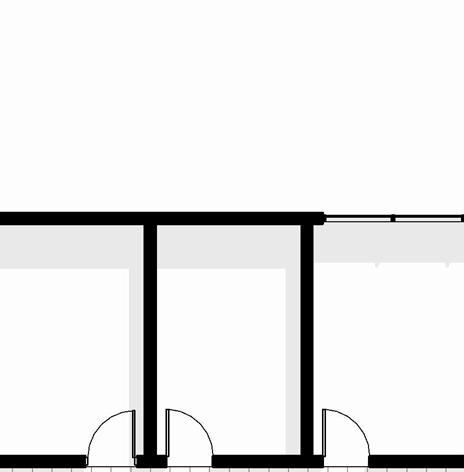

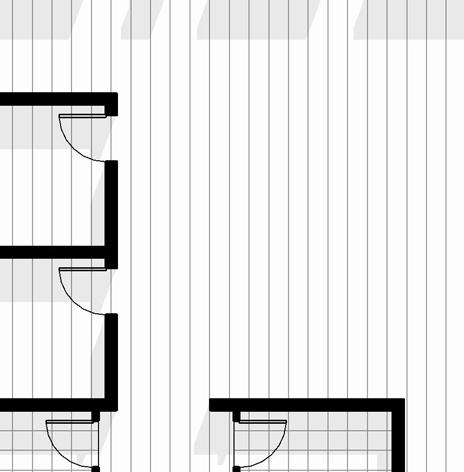

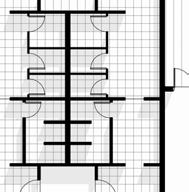

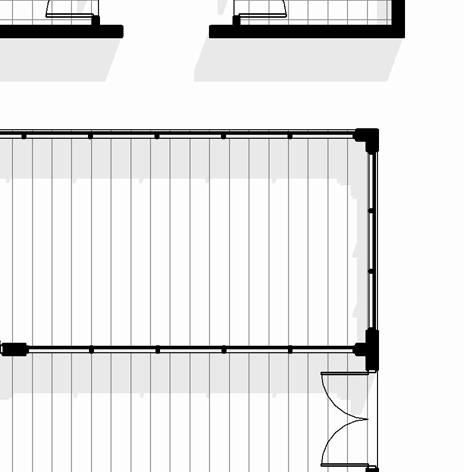

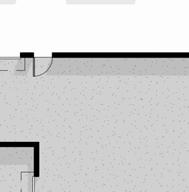

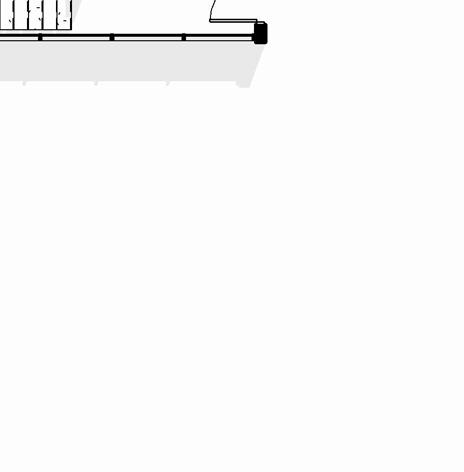

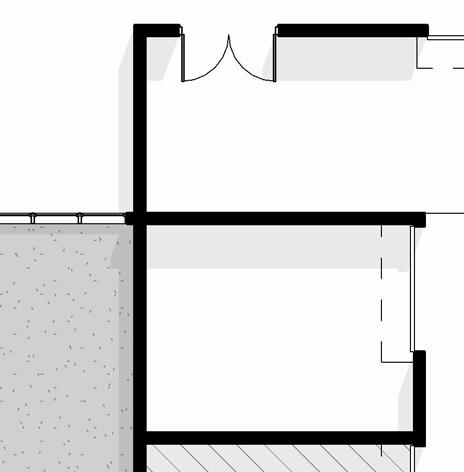

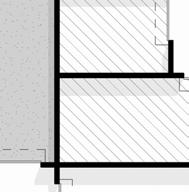

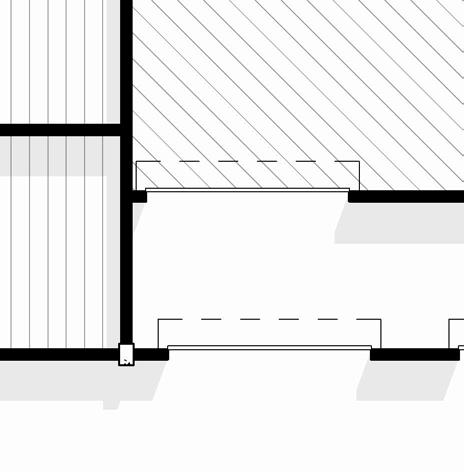

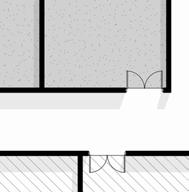

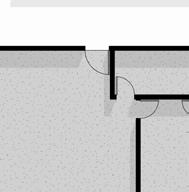

Proof of Concept describes a scope of work that includes stakeholder involvement, applied research, conceptual planning, and design investigation that informs annual budget requests and procurement of design professionals. Through the Implementation Process, the Entrepreneur Product Manufacturing Facility (EPMF) was developed. This inaugural FPIN facility is envisioned at 34,000 square feet, and includes modular production suites, dry and cold storage, food safety laboratories, and shared logistics spaces. Located adjacent to a high-pressure processing facility at the Central Oʻahu Agriculture and Food Hub, the EPMF is intended to streamline workflow, support regulatory compliance, and reduce startup costs for small and mid-sized producers. Scenario testing of this facility validated the spatial organization, production sequence, and regulatory zoning. The project demonstrates a scalable model that can be adapted to other regions across the state, reinforcing the FPIN vision of regional resilience through value-added product development.

In closing, recommendations for both the broader FPIN and EPMF are provided that offer strategies on governance and funding, infrastructure and operational readiness, partnerships and communication, and workforce development. These recommendations lay a foundation for programming and planning a strong Hawaiʻi agricultural sector and boosting economic resilience.

• Develop a flexible facility typology that accommodates a range of users from small-scale entrepreneurs to export-ready manufacturers.

• Prioritize the use of ADC-controlled lands and infrastructure assets to reduce development costs and expedite implementation.

• Co-locate FPIN facilities with educational institutions to align training, workforce development, and product innovation.

• Design facilities to accommodate a range of operational models, including open-access kitchens, leasable production bays, and tollprocessing services.

• Incorporate regulatory input early in the design process to facilitate permitting, compliance, and certification for food safety.

• Ensure regional adaptability while maintaining consistent statewide standards for infrastructure, operations, and service delivery.

• Through targeted investment in infrastructure, education, and coordinated programming, FPIN provides a foundation for a more resilient, innovative, and self-reliant food system in Hawaiʻi.

Introduction

Background

Meeting Statewide Food System Goals

Vision

Purpose of the Network

Objectives

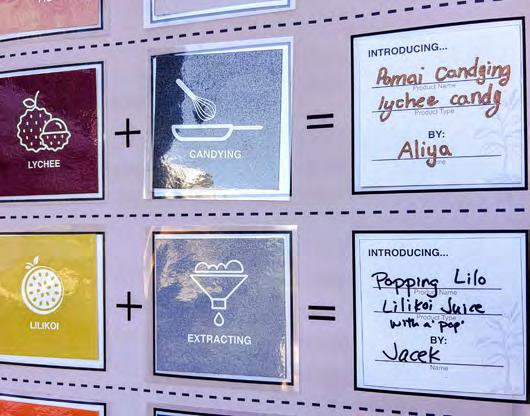

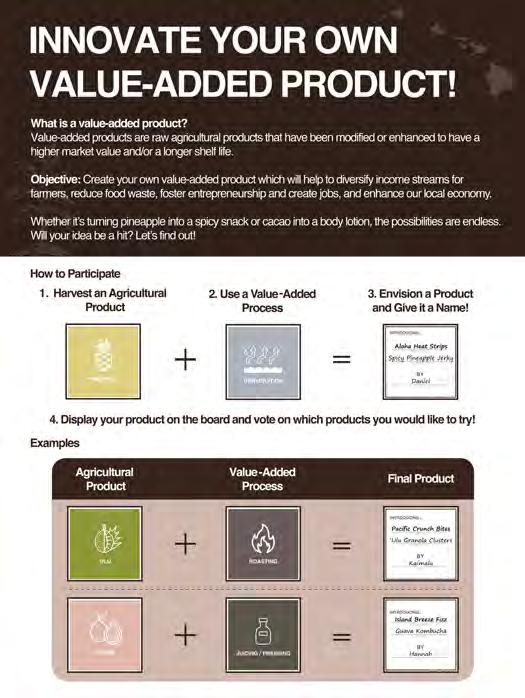

What are Value-Added Products?

Case Study: Hawaiʻi’s Ancestral

Value-Added Product

Overview

Precedent Networks

Regional Economic Development - An Ecosystems Approach

Education to Export Pathway

Identifying Stakeholders and Allies

Overview

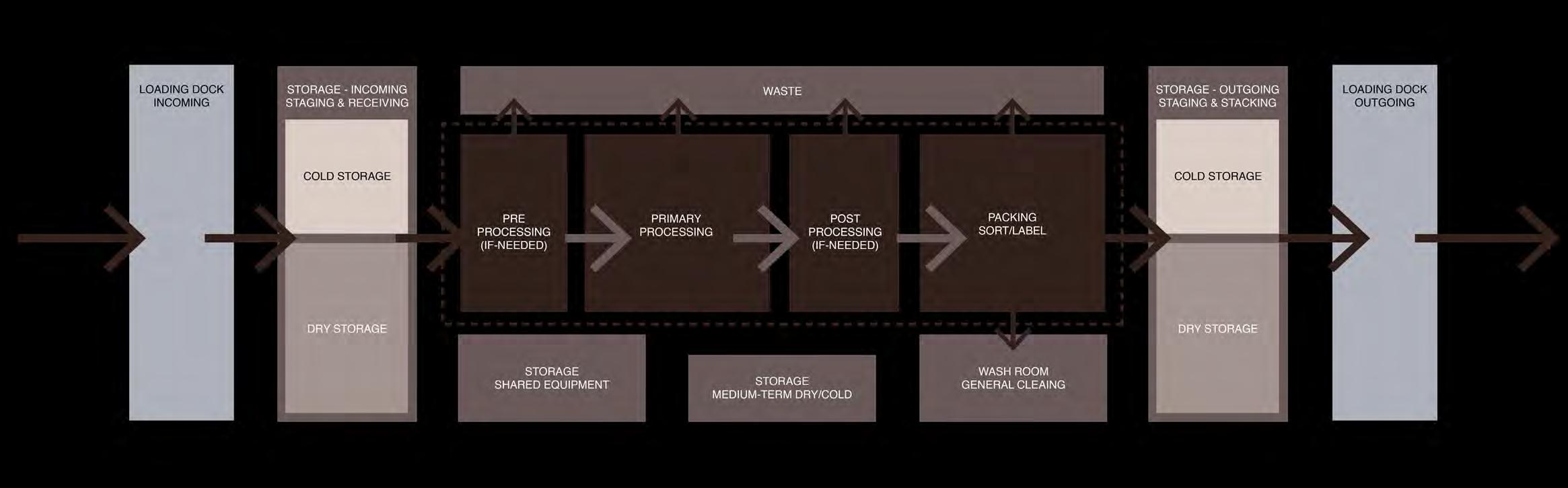

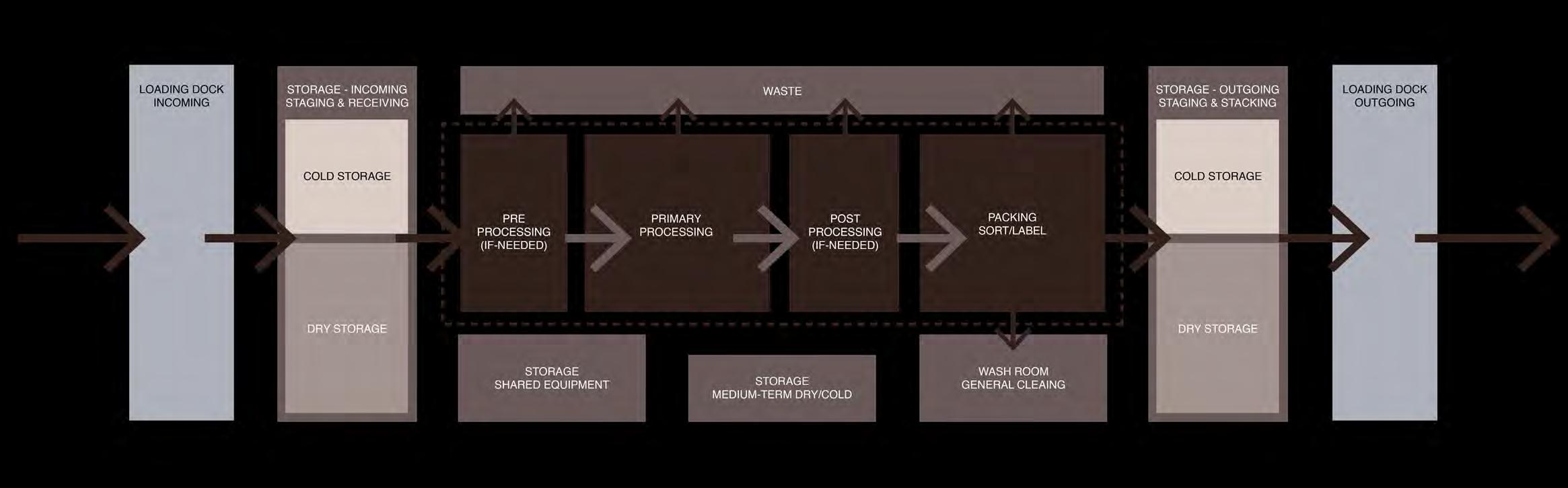

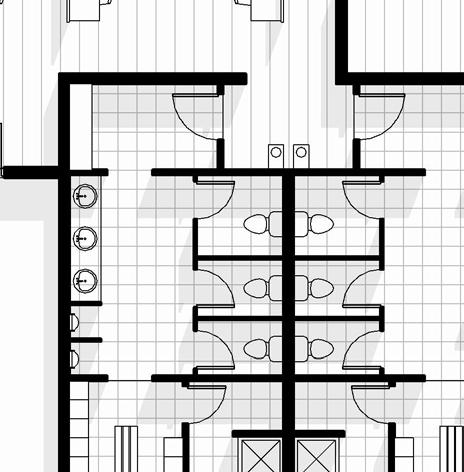

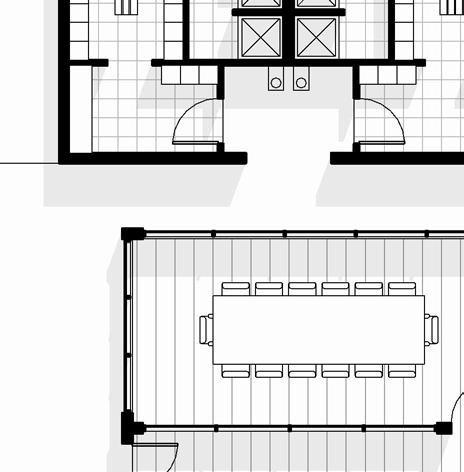

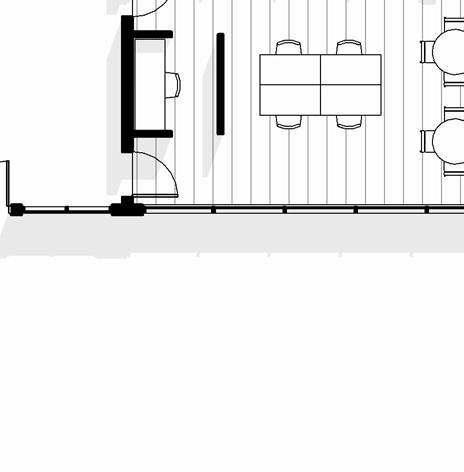

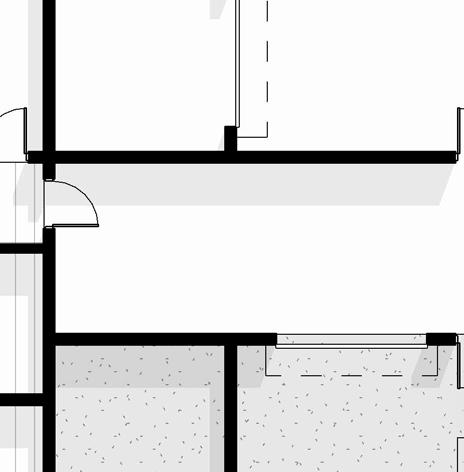

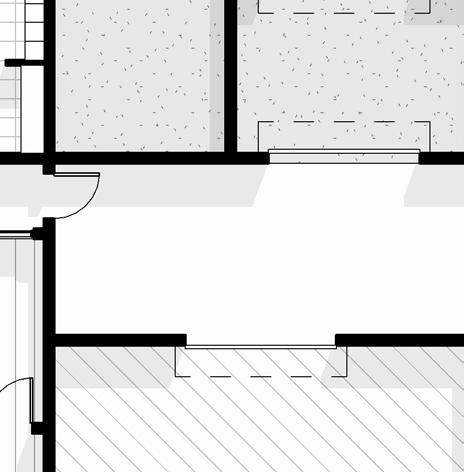

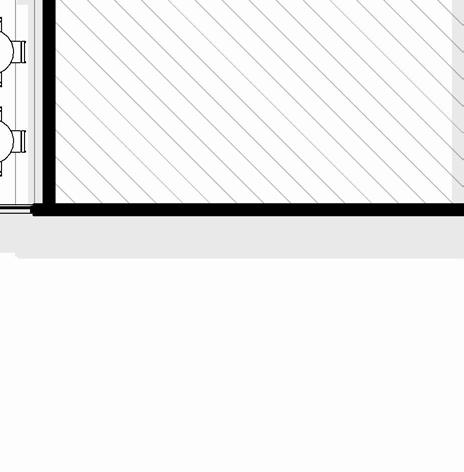

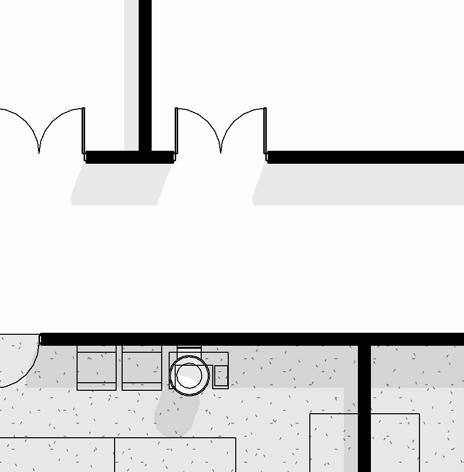

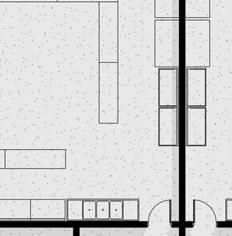

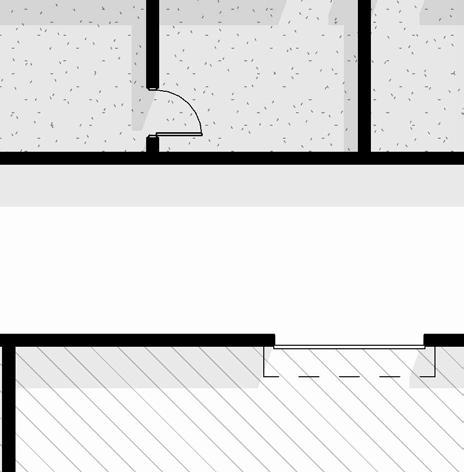

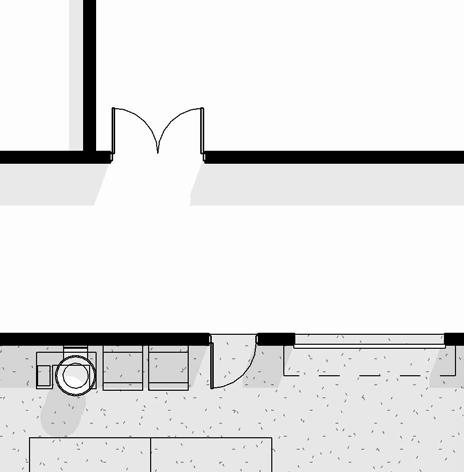

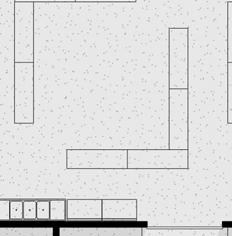

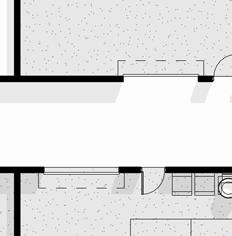

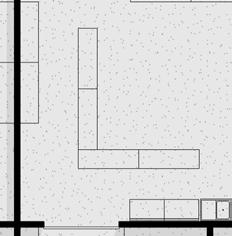

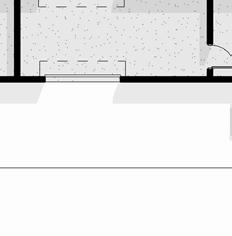

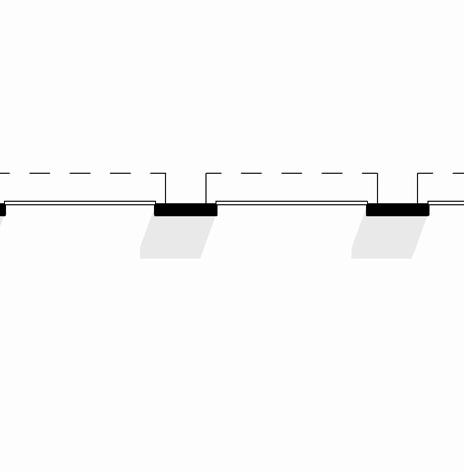

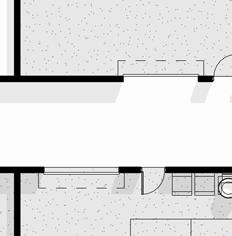

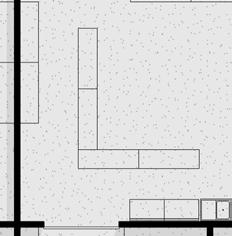

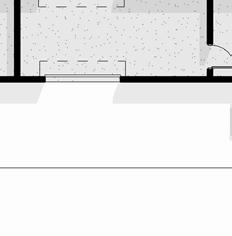

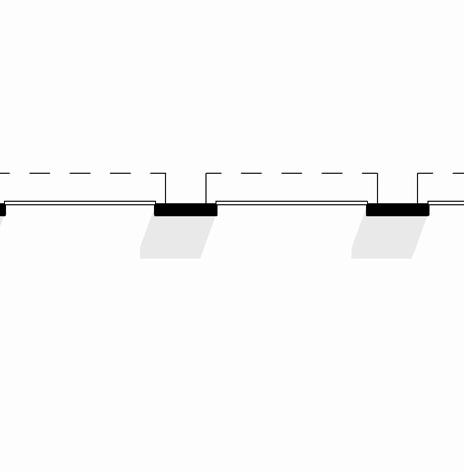

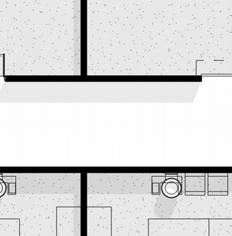

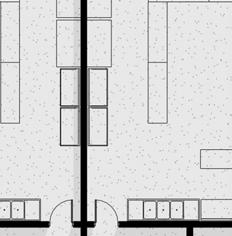

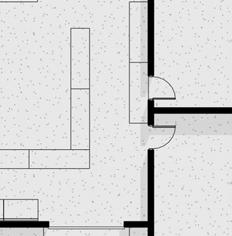

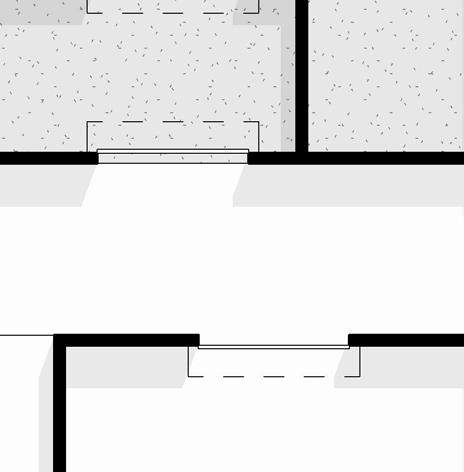

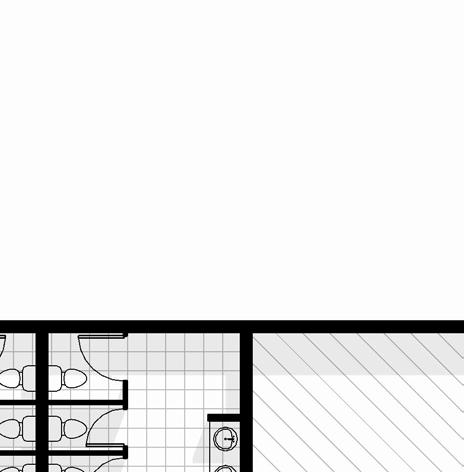

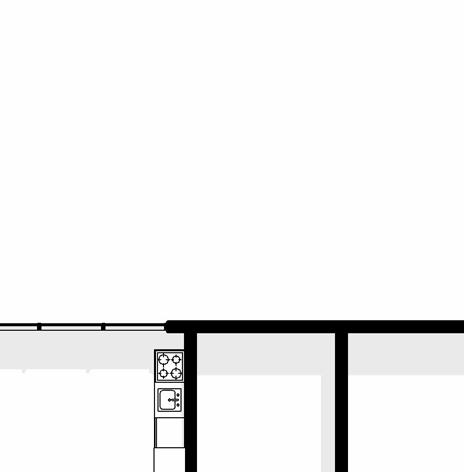

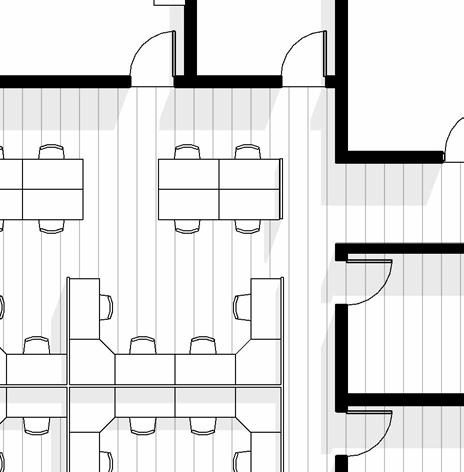

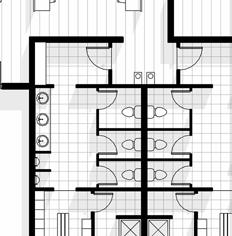

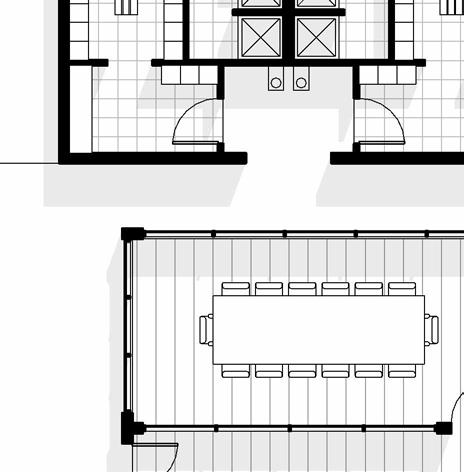

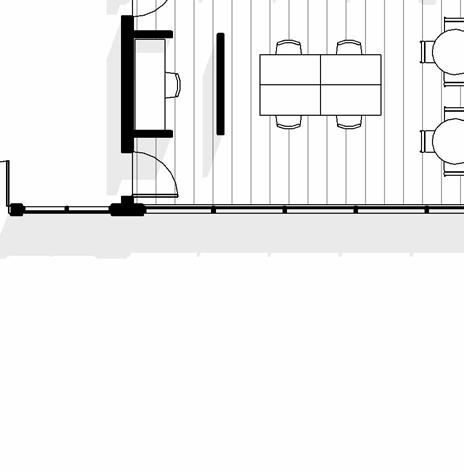

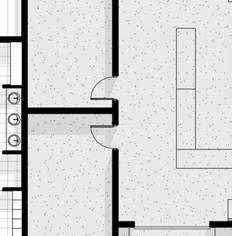

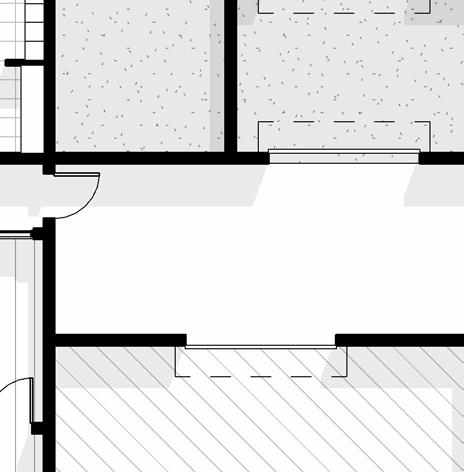

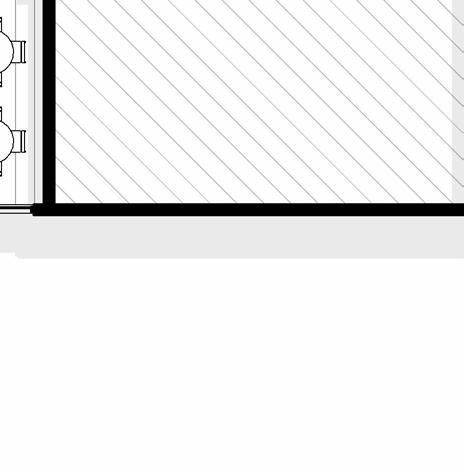

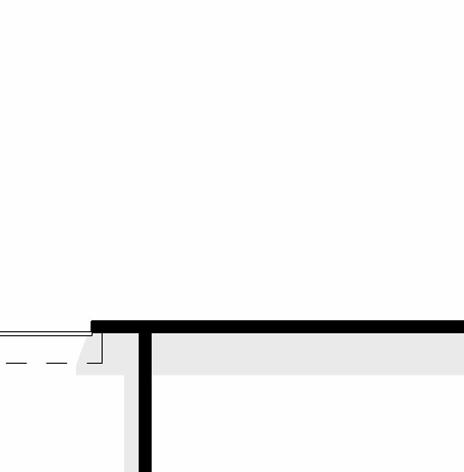

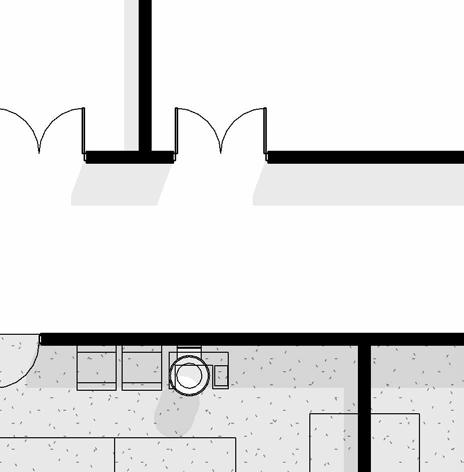

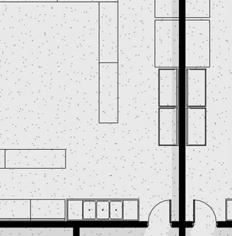

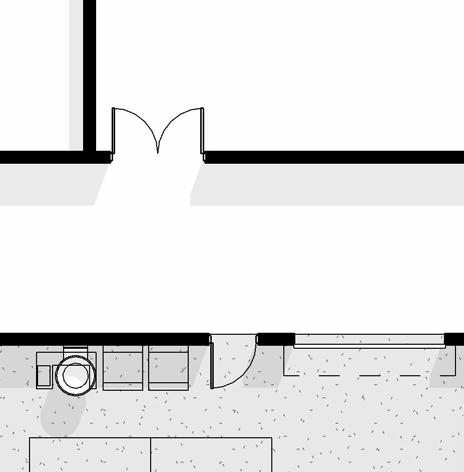

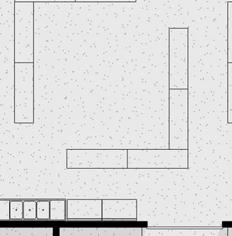

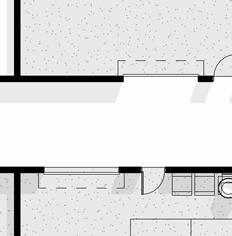

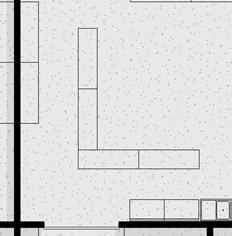

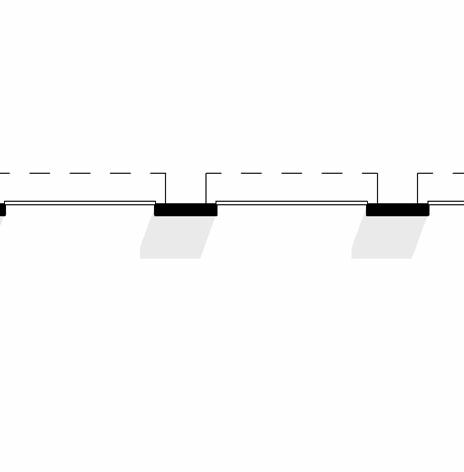

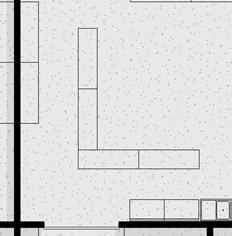

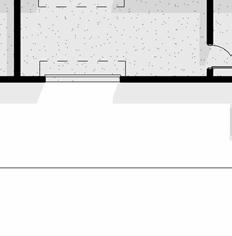

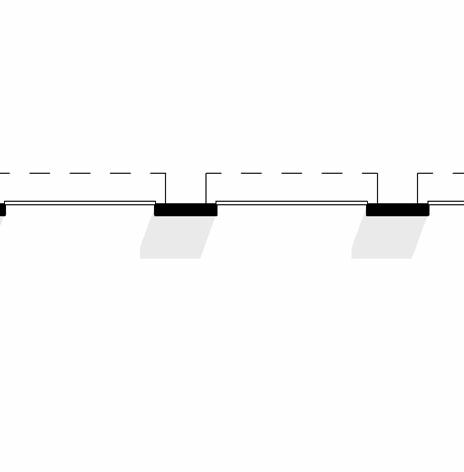

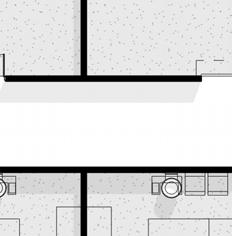

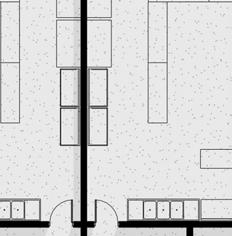

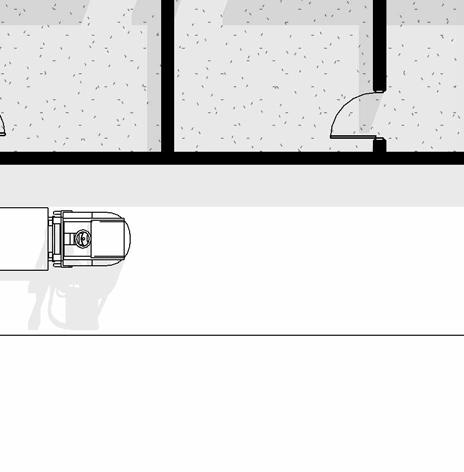

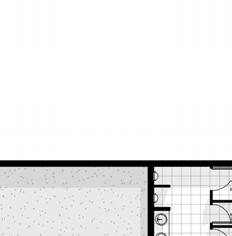

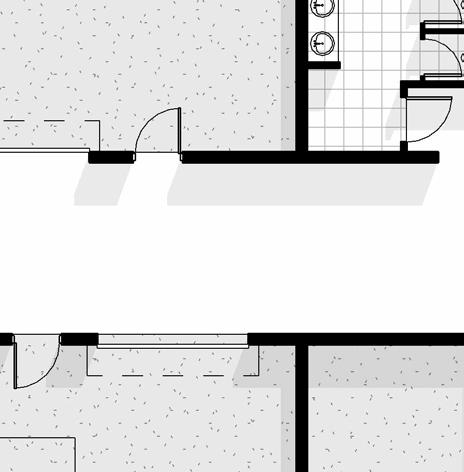

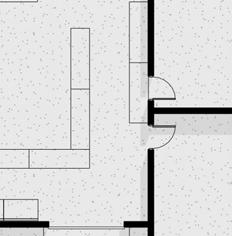

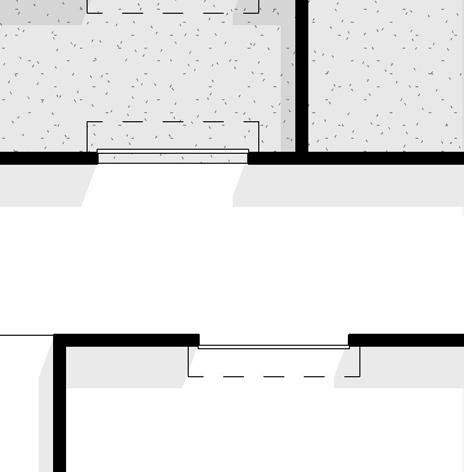

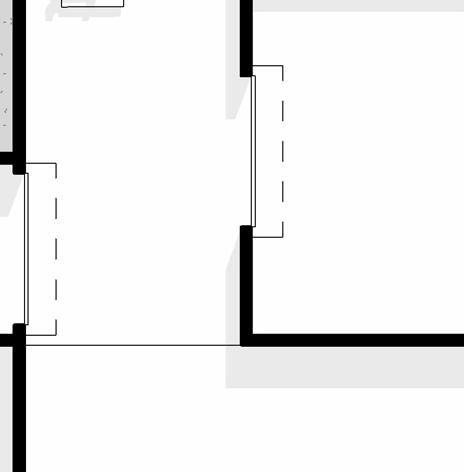

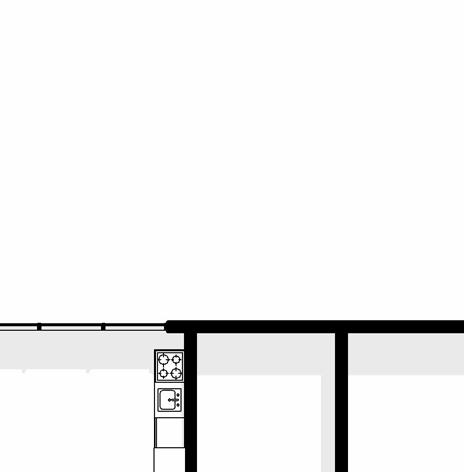

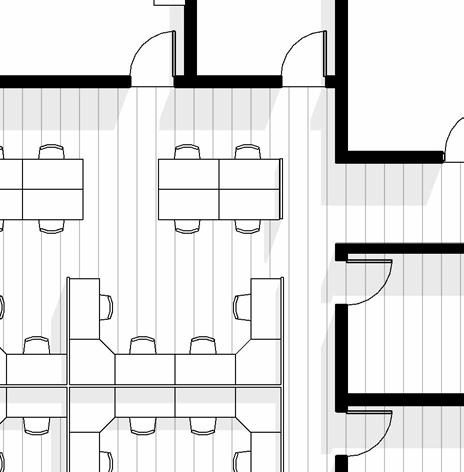

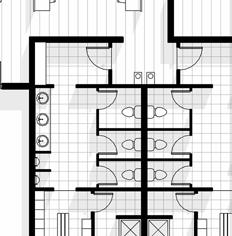

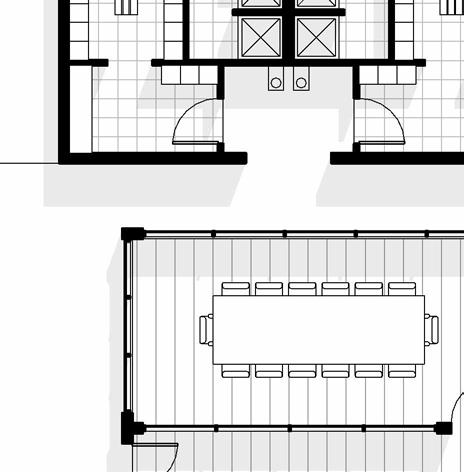

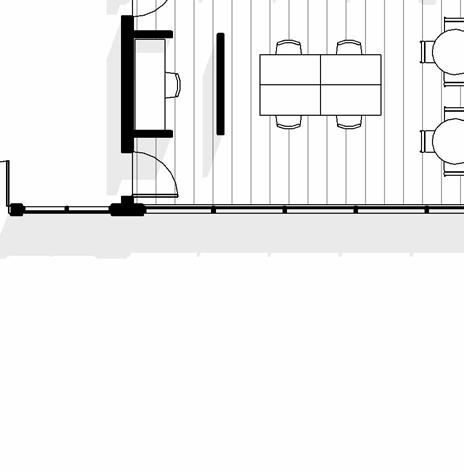

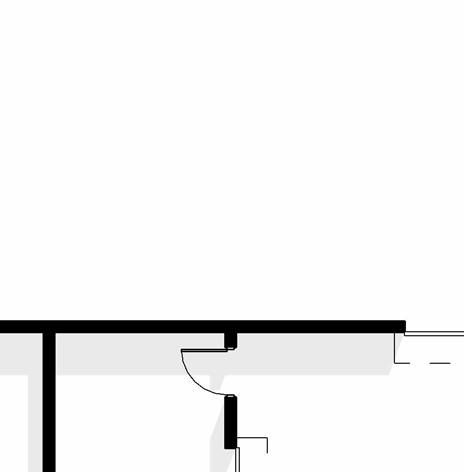

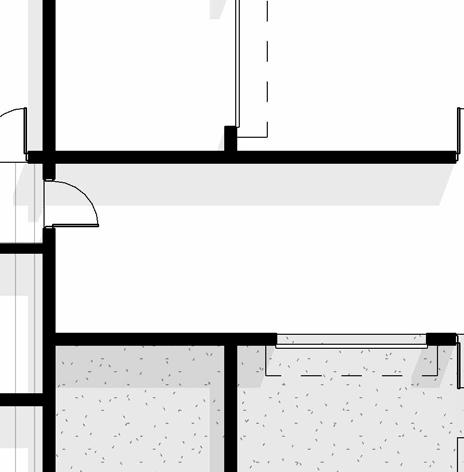

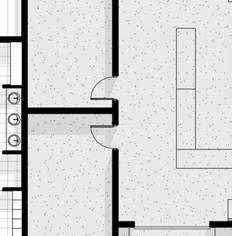

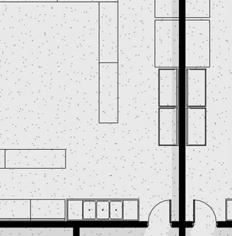

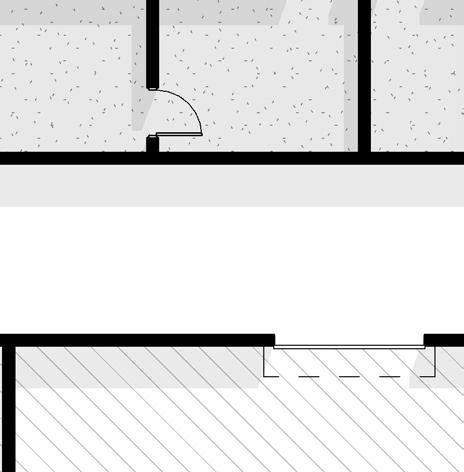

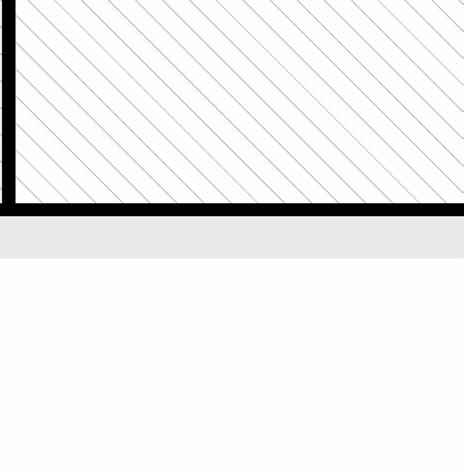

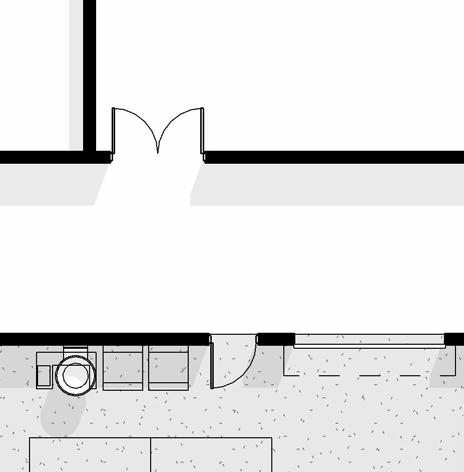

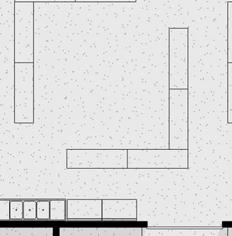

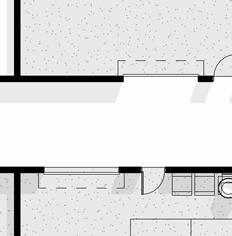

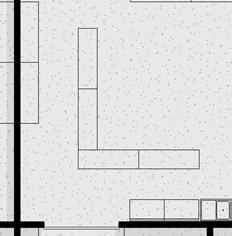

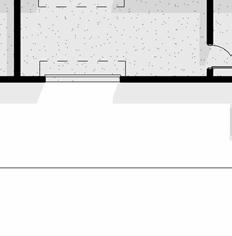

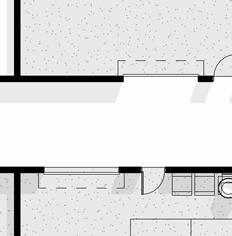

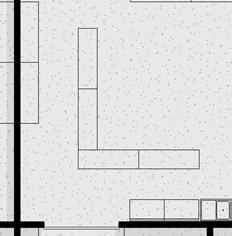

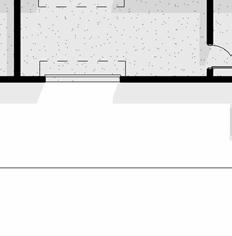

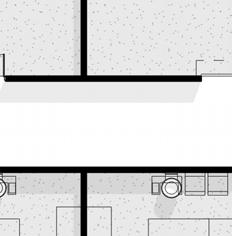

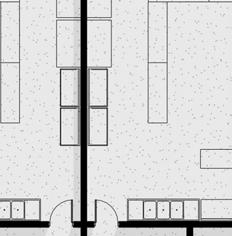

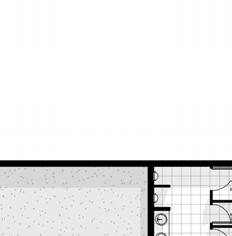

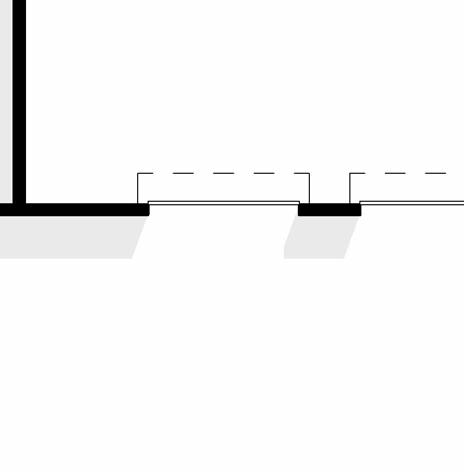

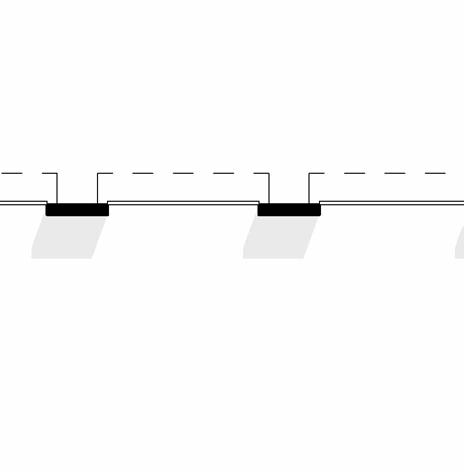

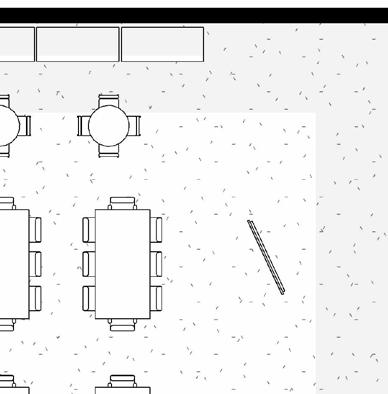

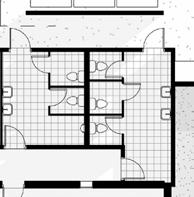

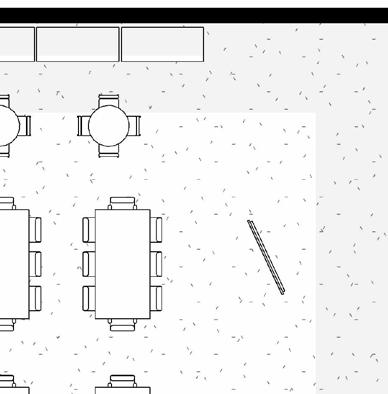

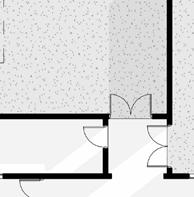

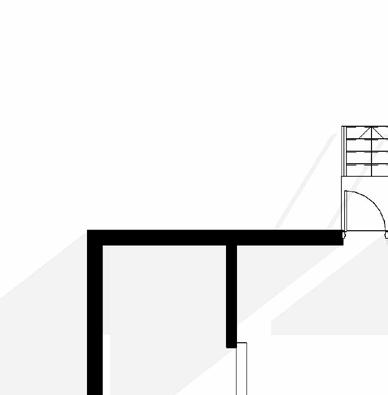

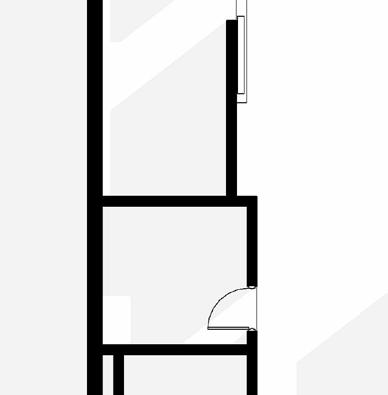

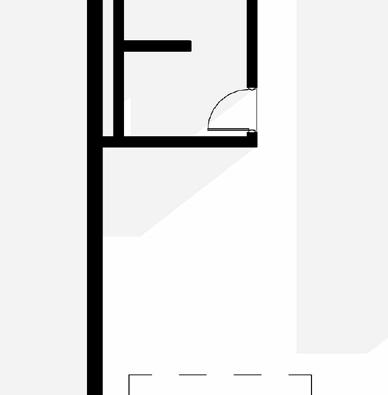

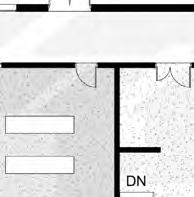

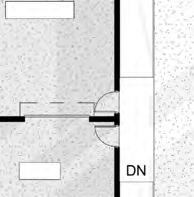

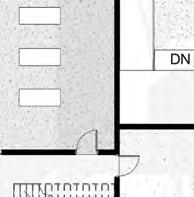

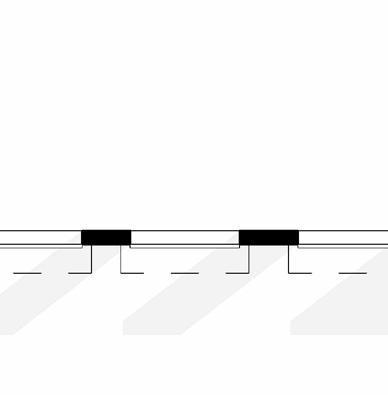

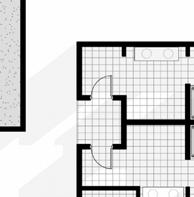

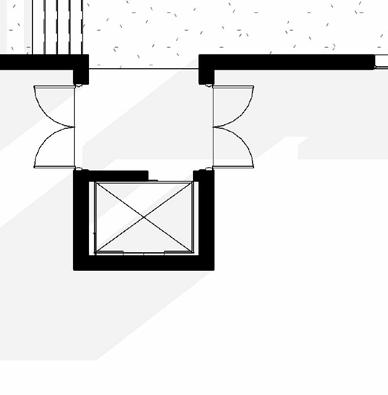

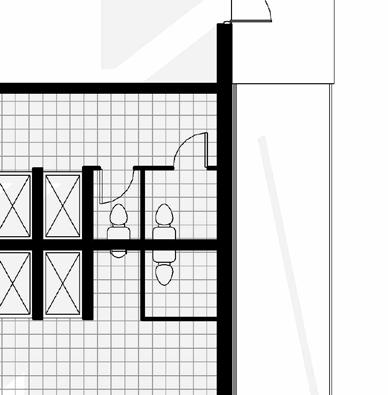

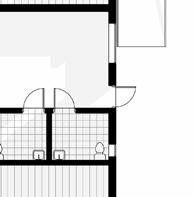

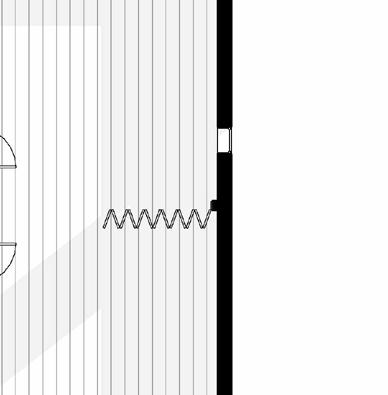

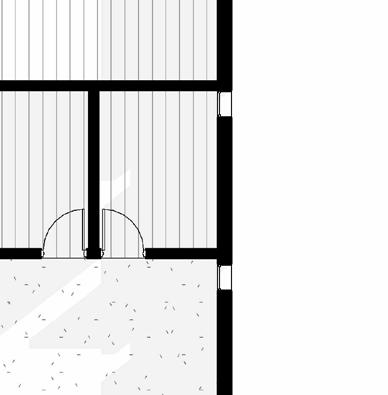

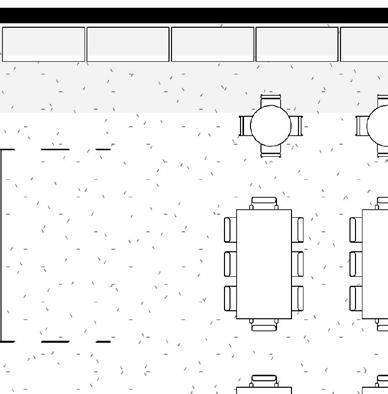

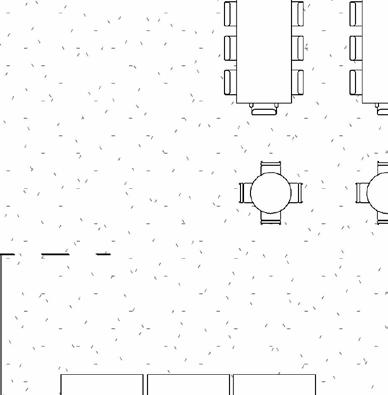

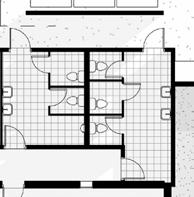

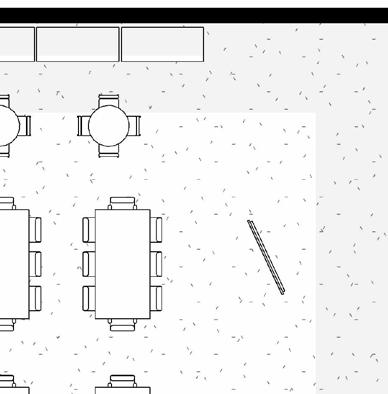

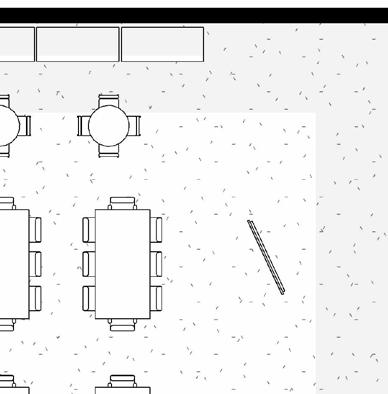

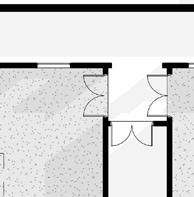

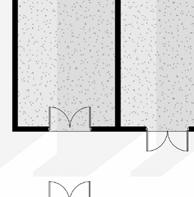

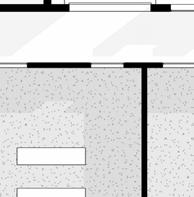

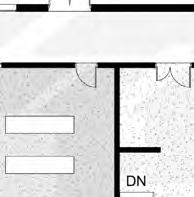

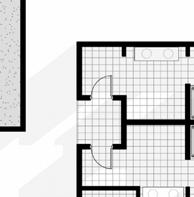

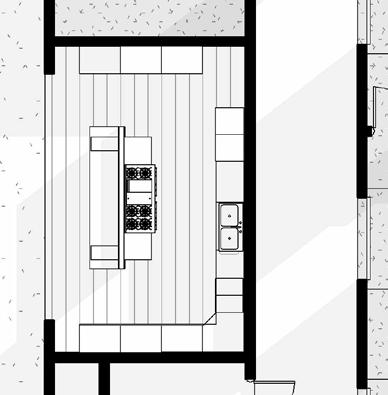

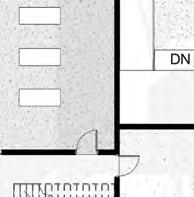

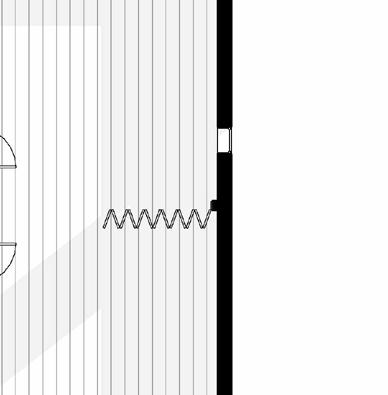

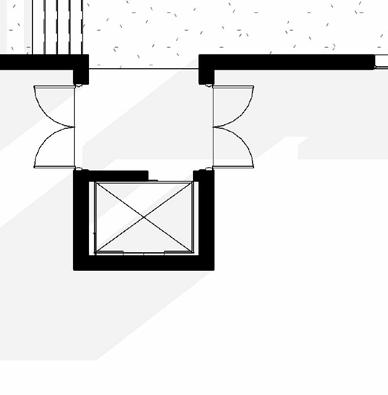

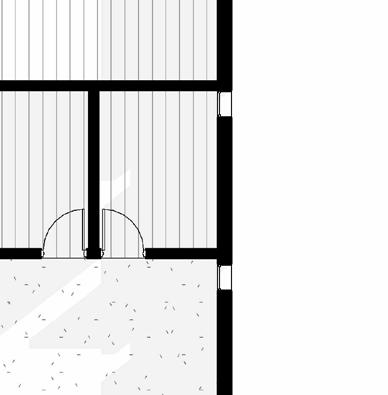

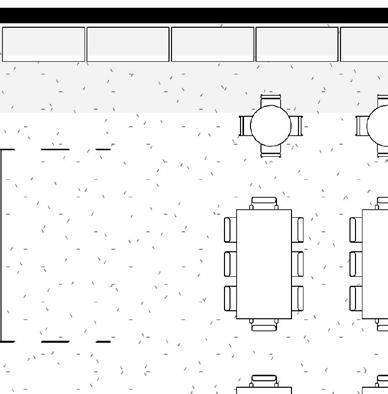

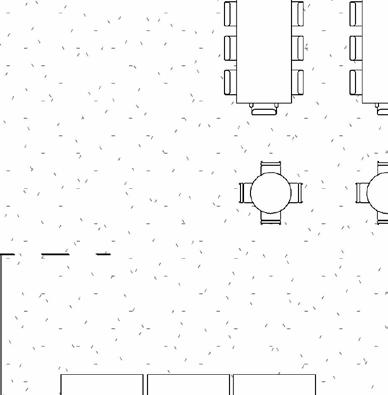

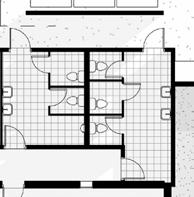

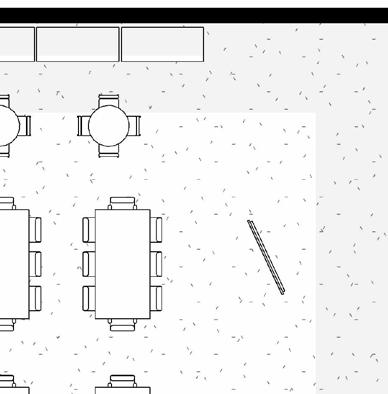

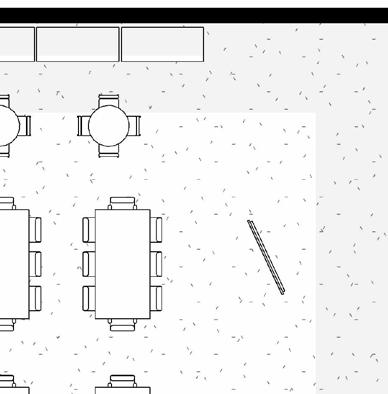

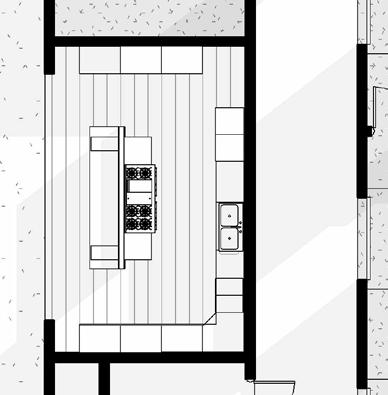

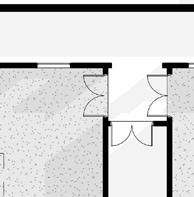

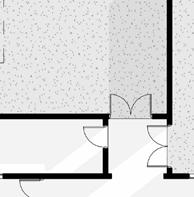

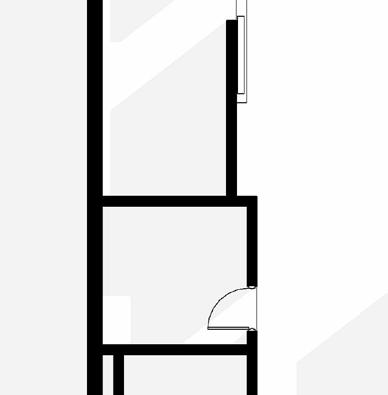

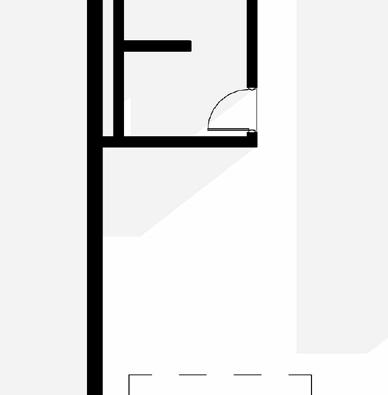

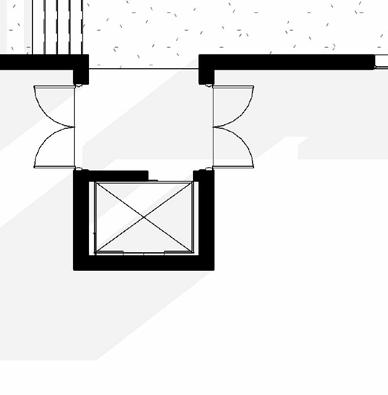

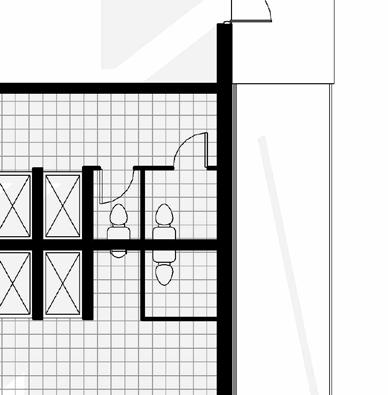

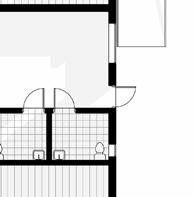

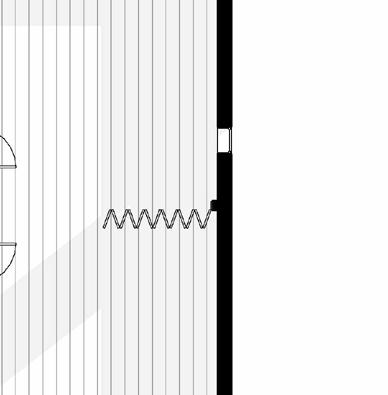

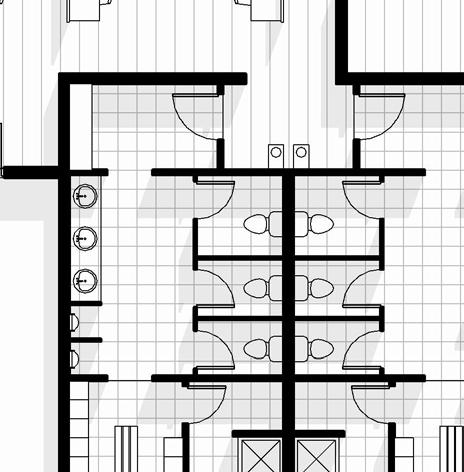

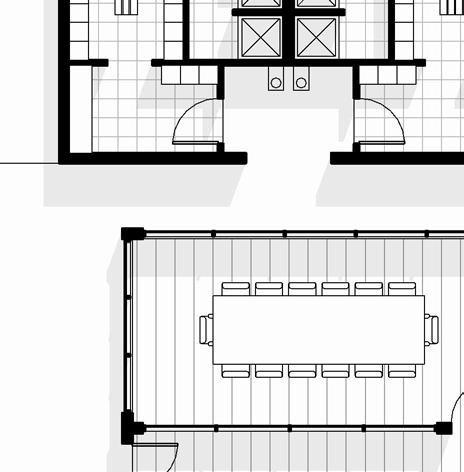

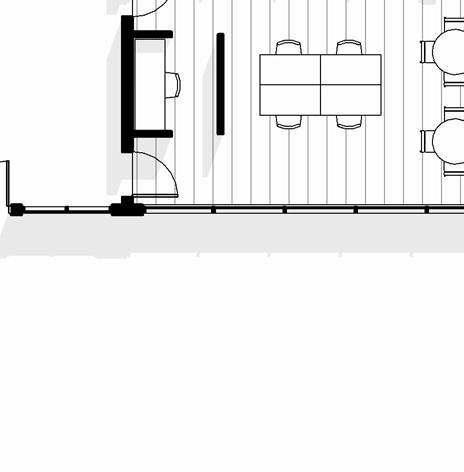

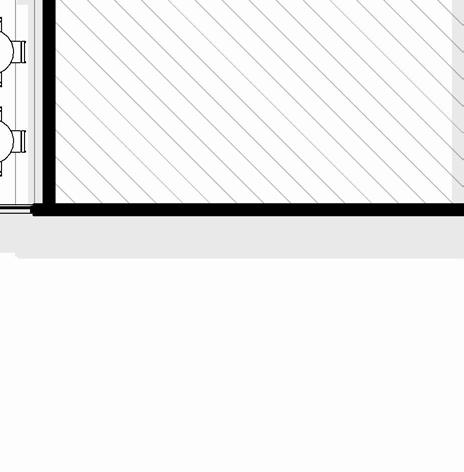

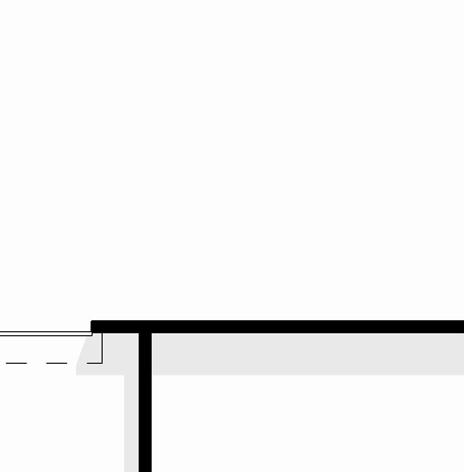

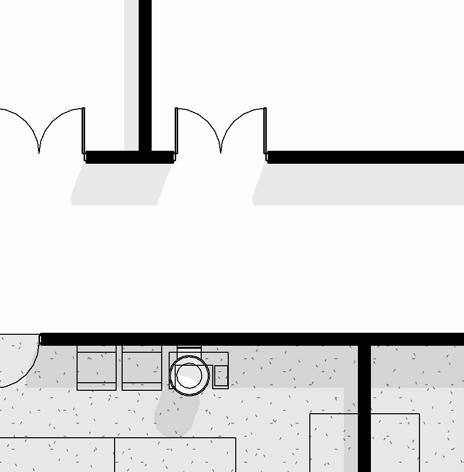

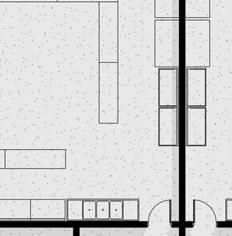

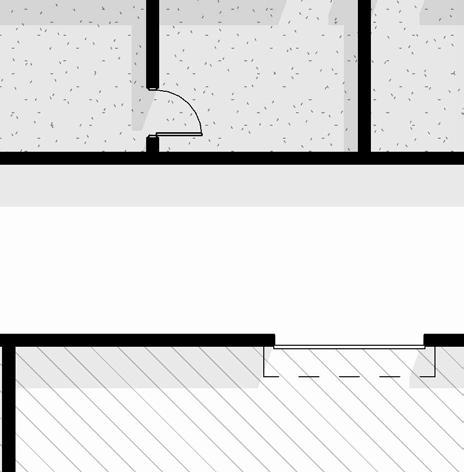

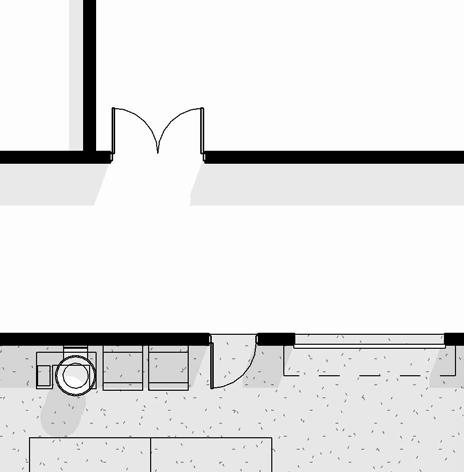

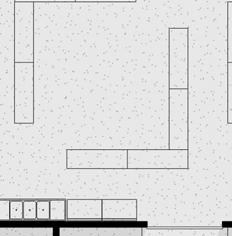

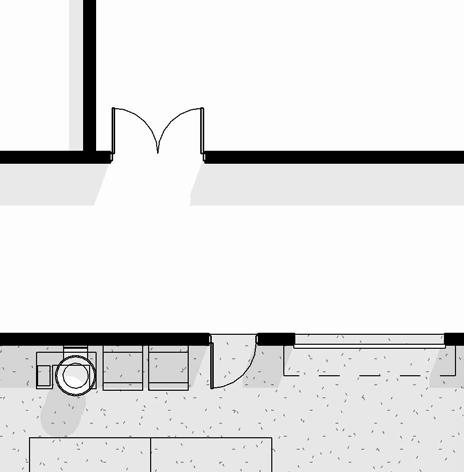

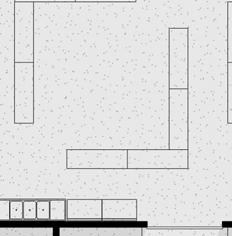

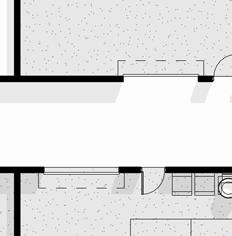

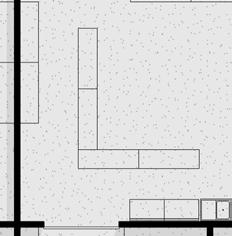

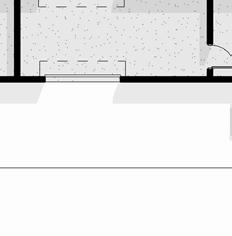

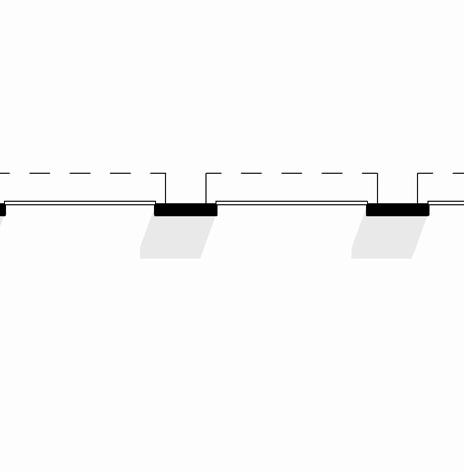

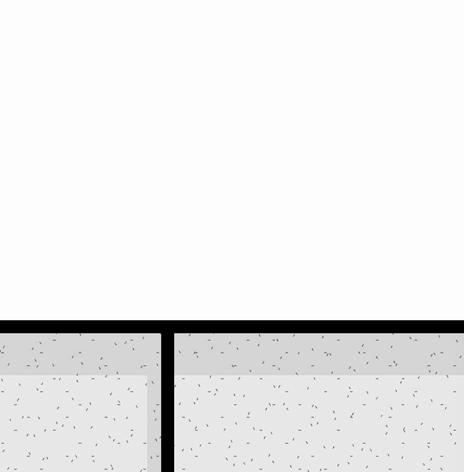

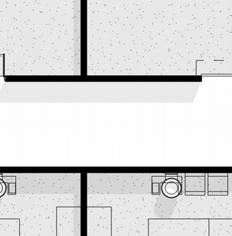

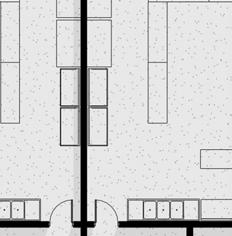

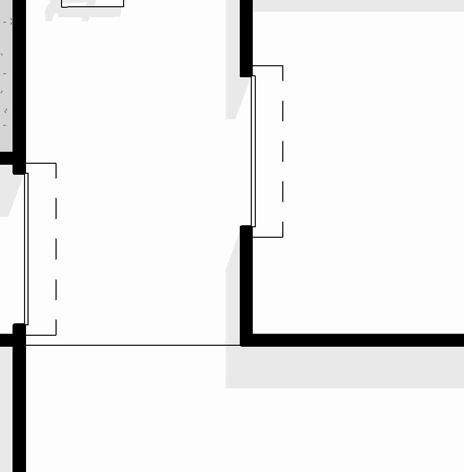

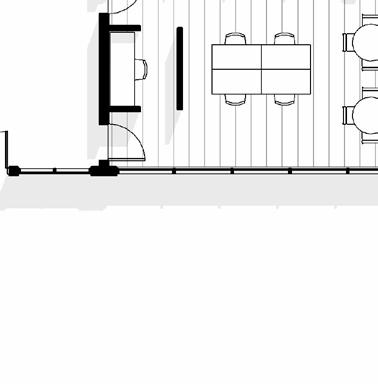

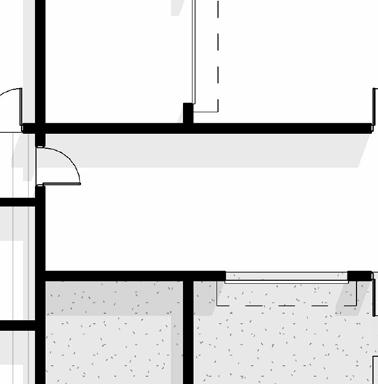

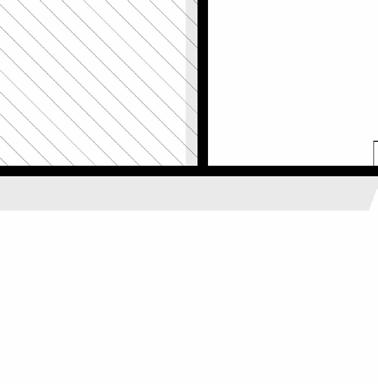

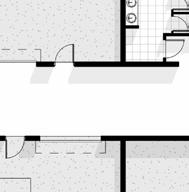

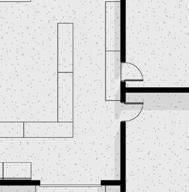

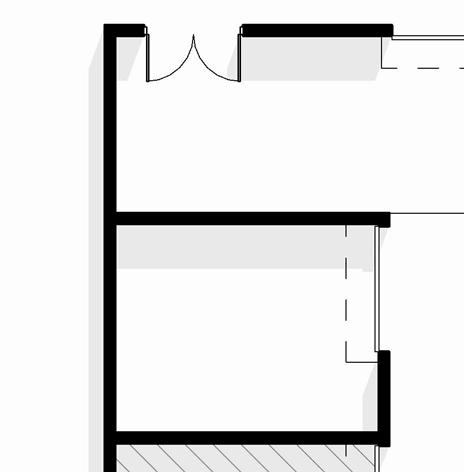

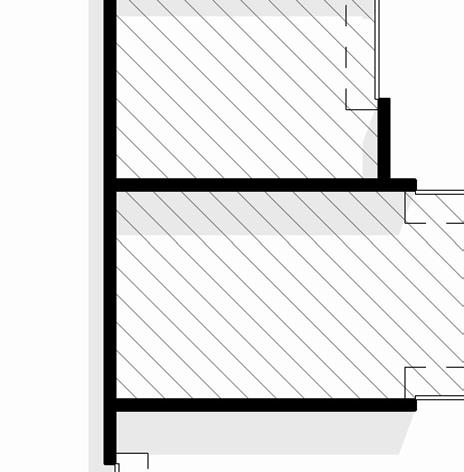

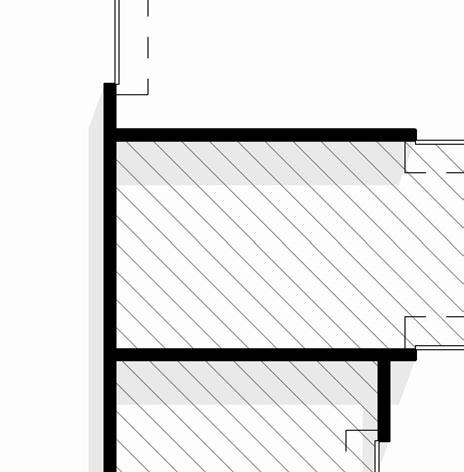

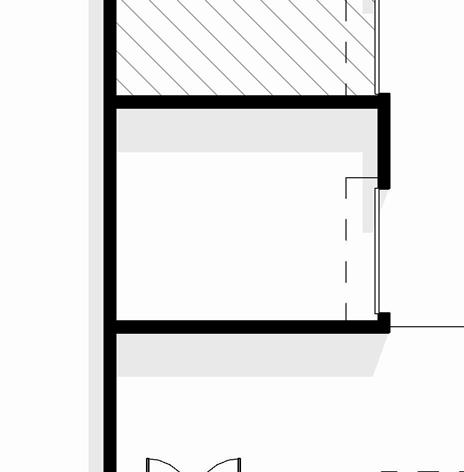

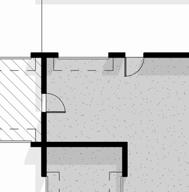

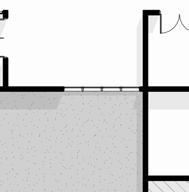

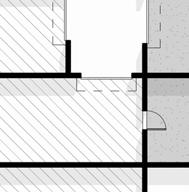

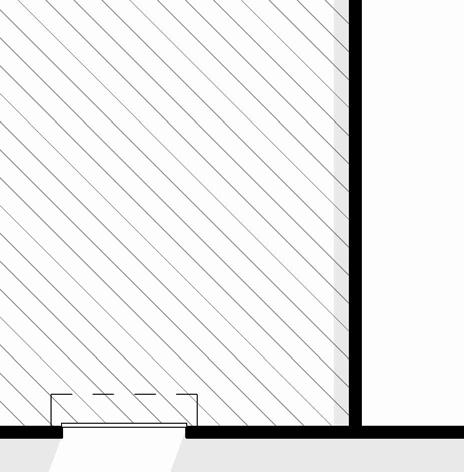

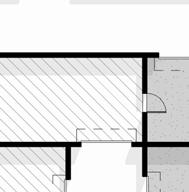

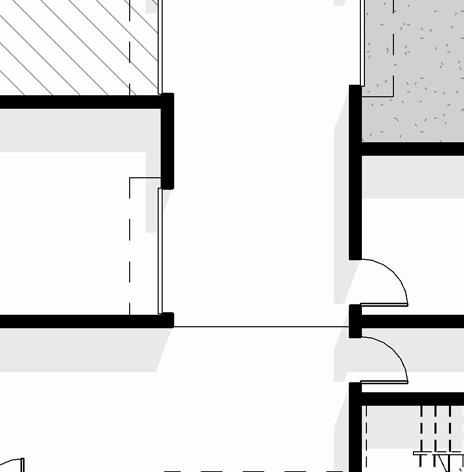

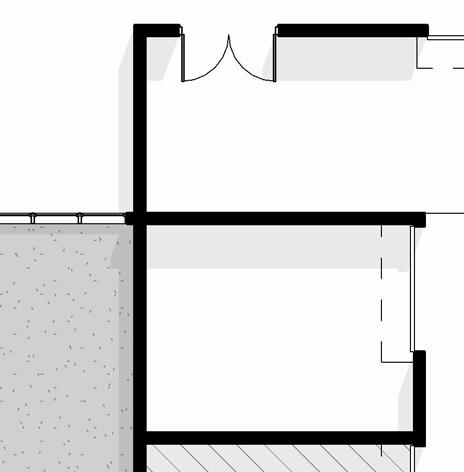

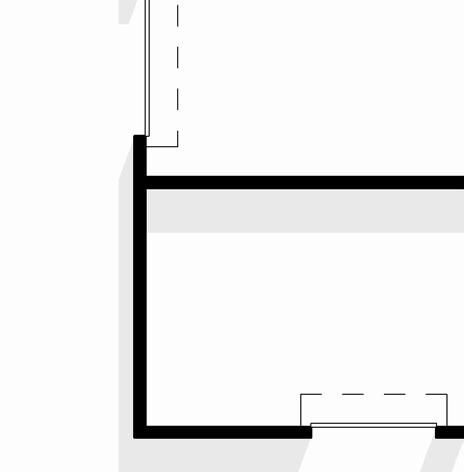

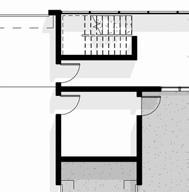

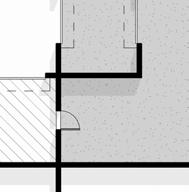

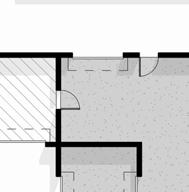

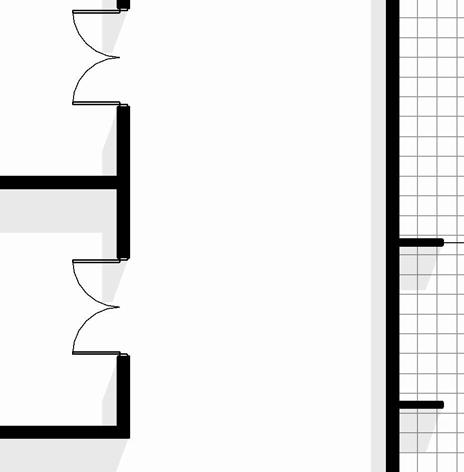

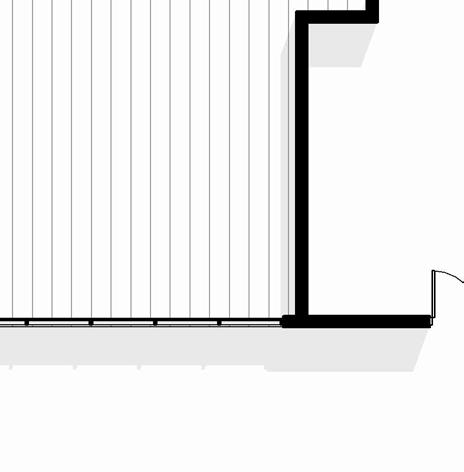

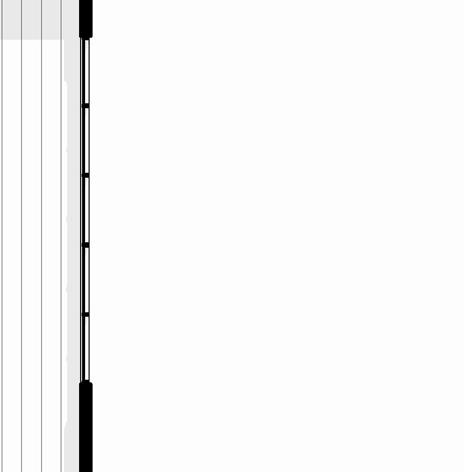

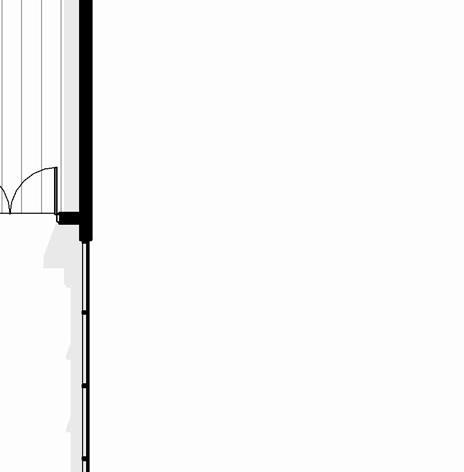

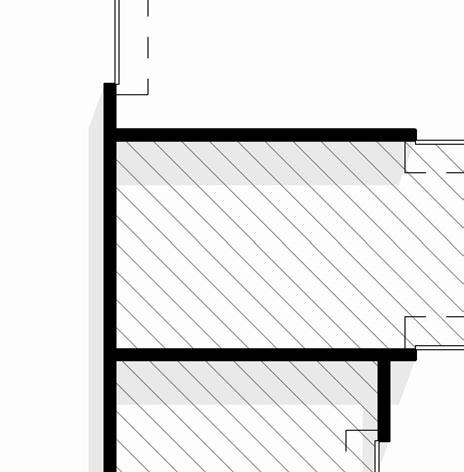

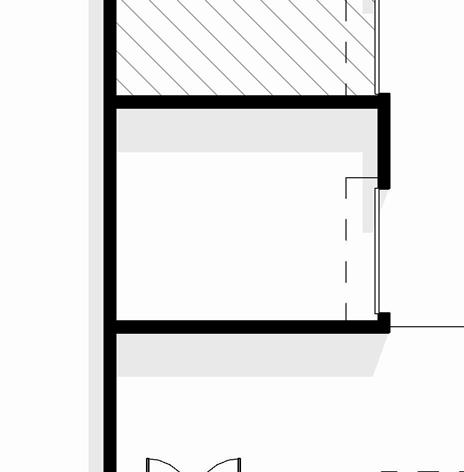

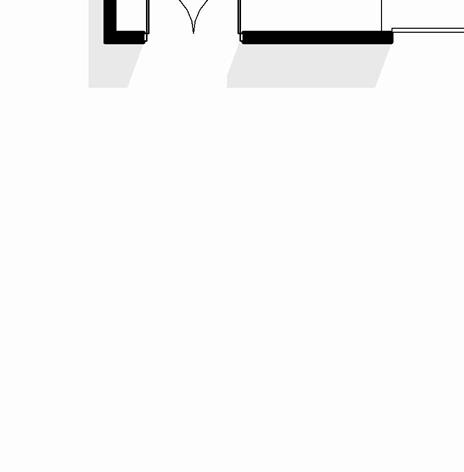

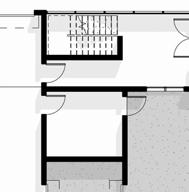

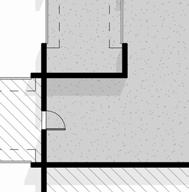

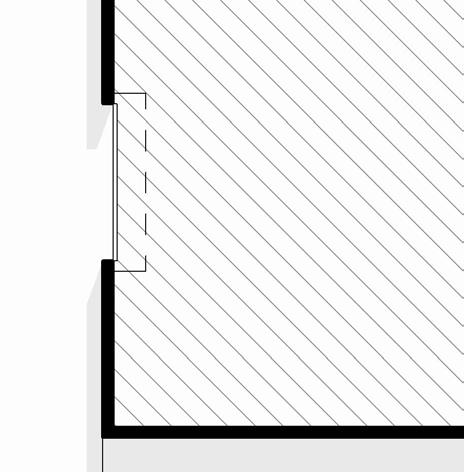

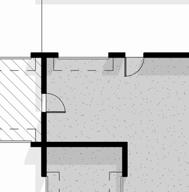

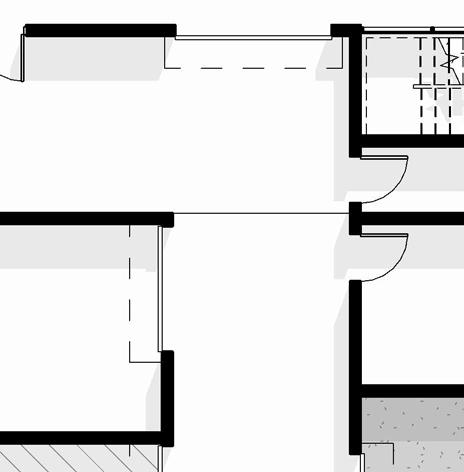

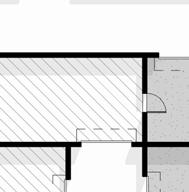

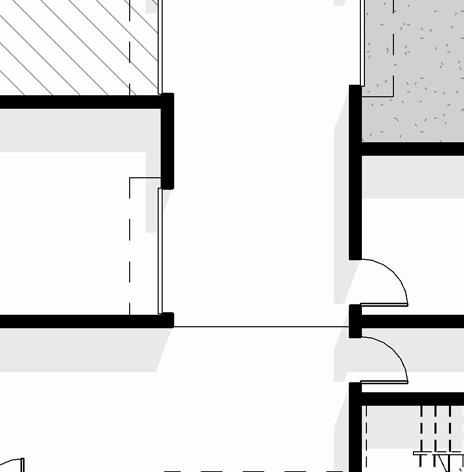

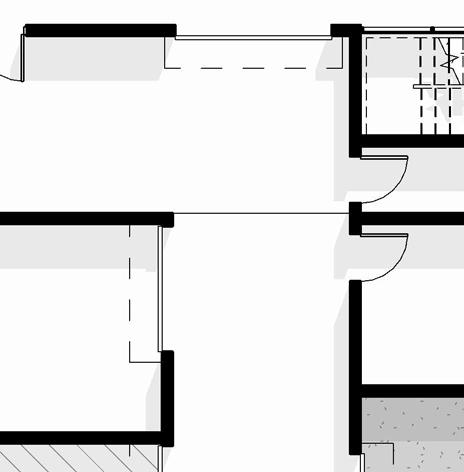

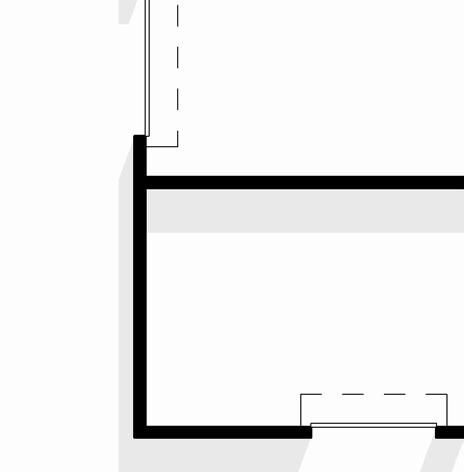

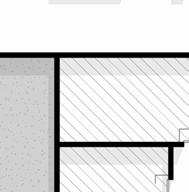

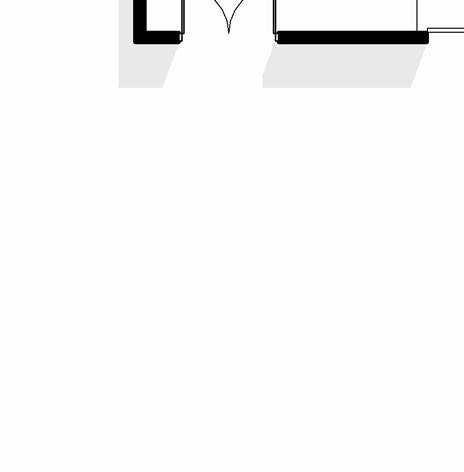

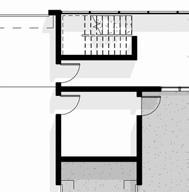

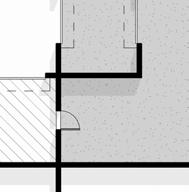

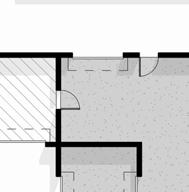

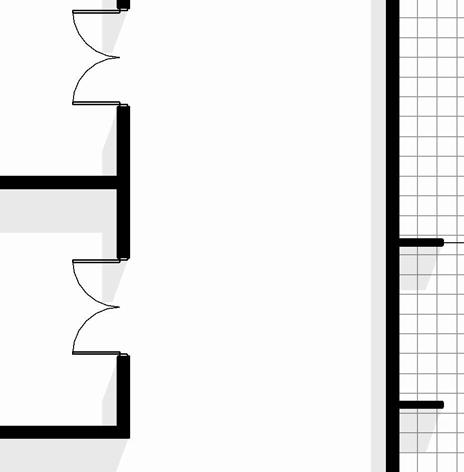

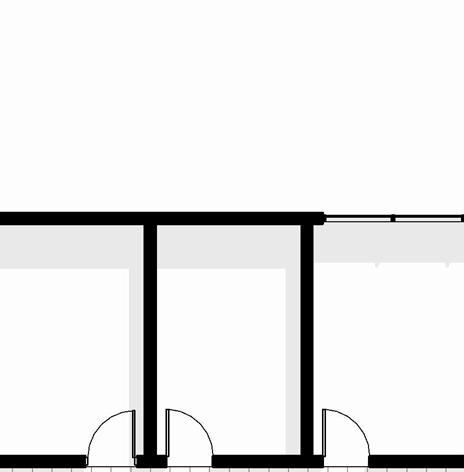

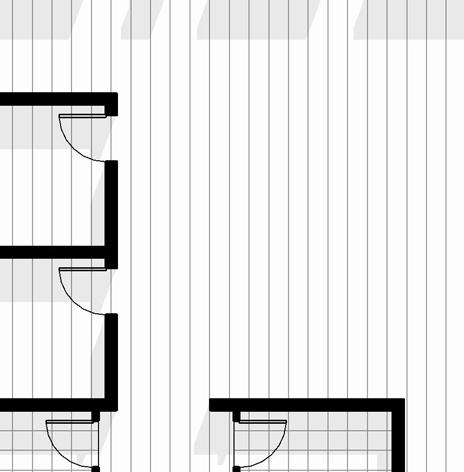

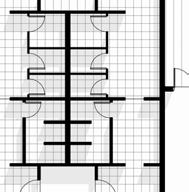

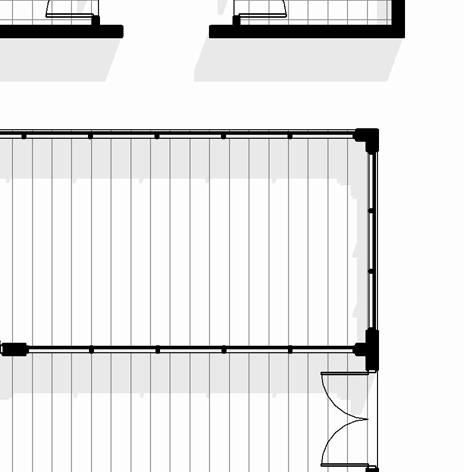

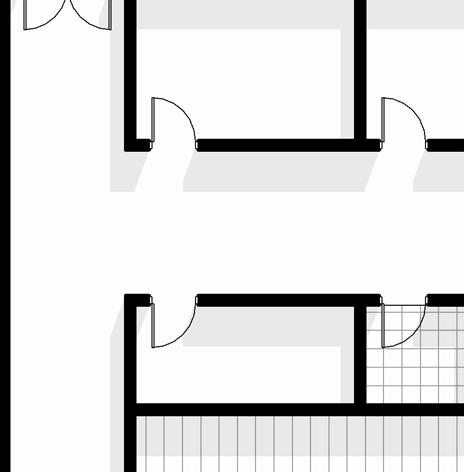

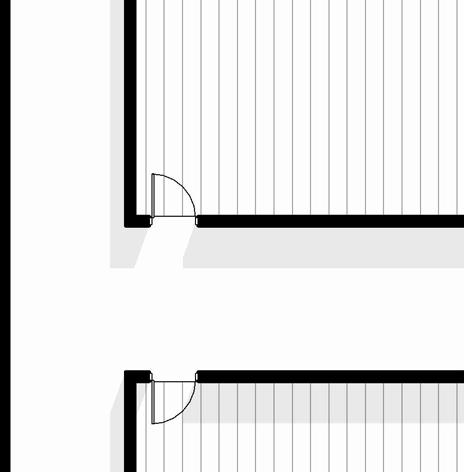

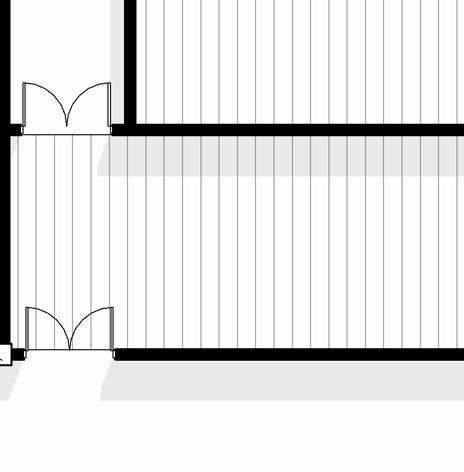

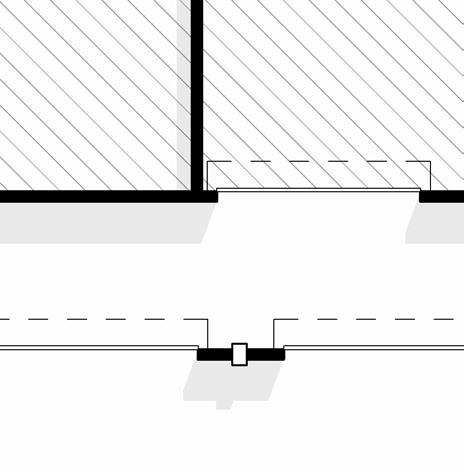

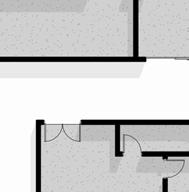

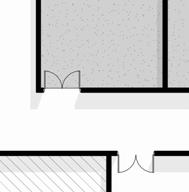

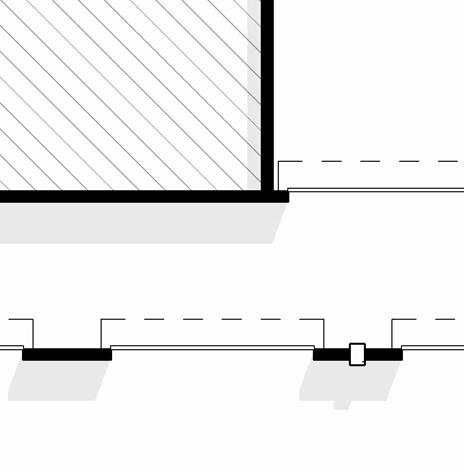

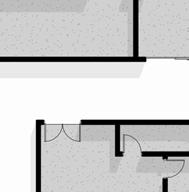

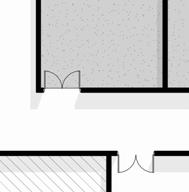

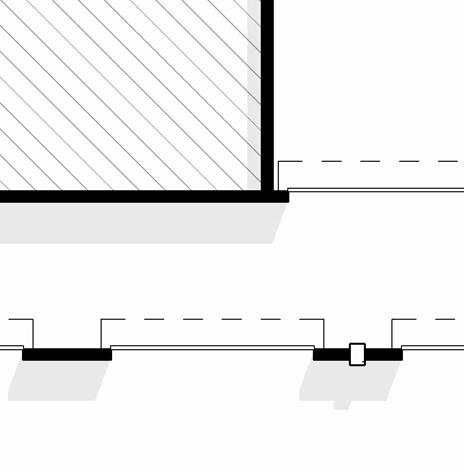

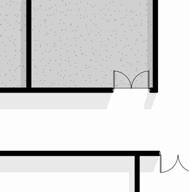

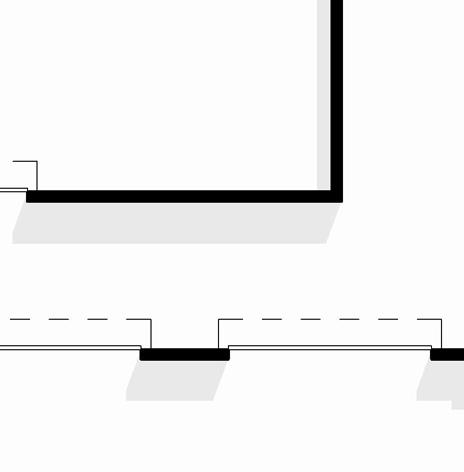

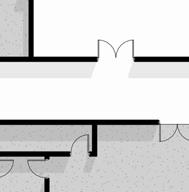

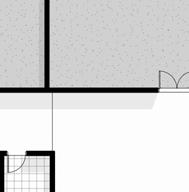

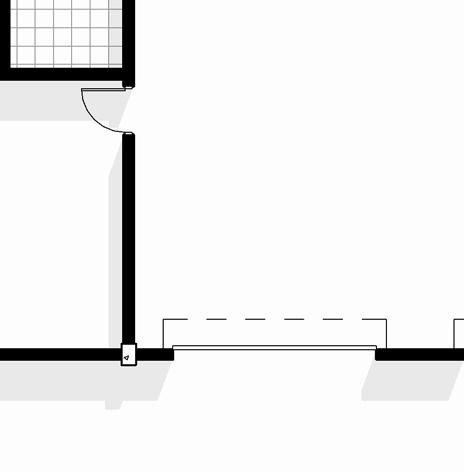

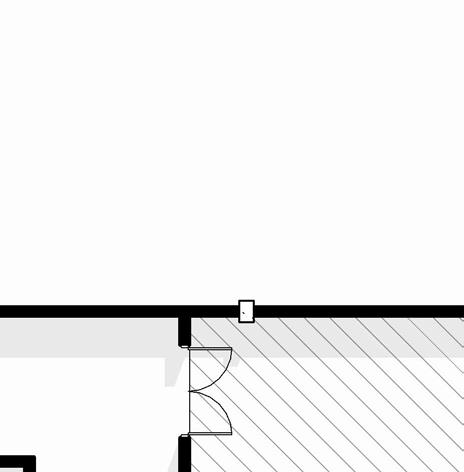

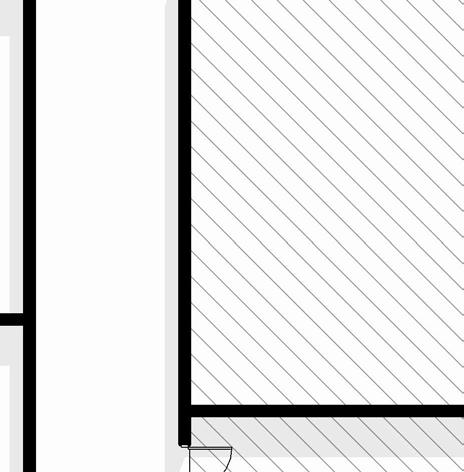

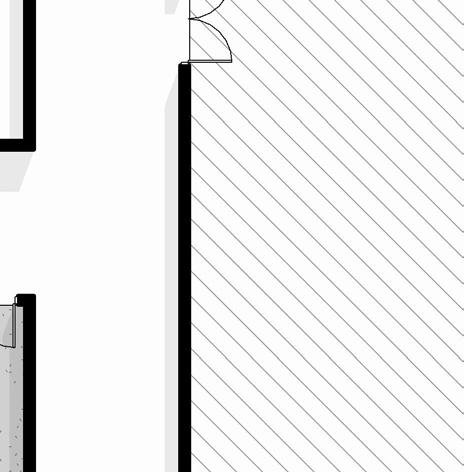

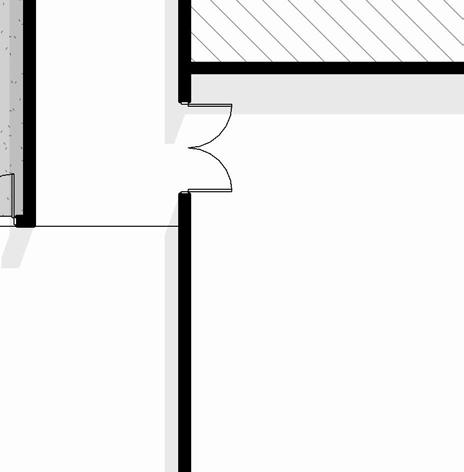

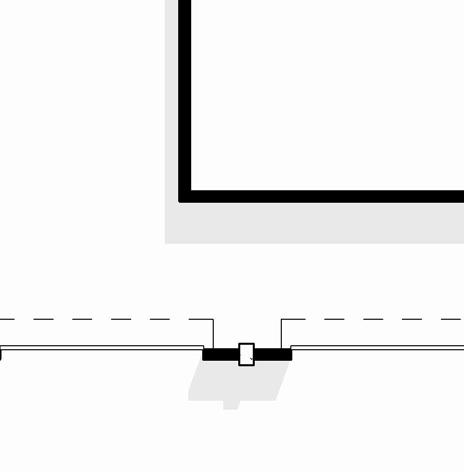

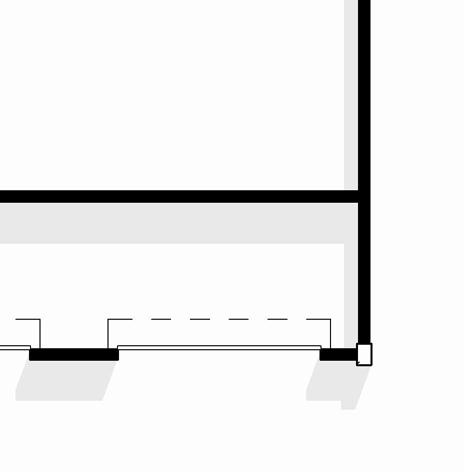

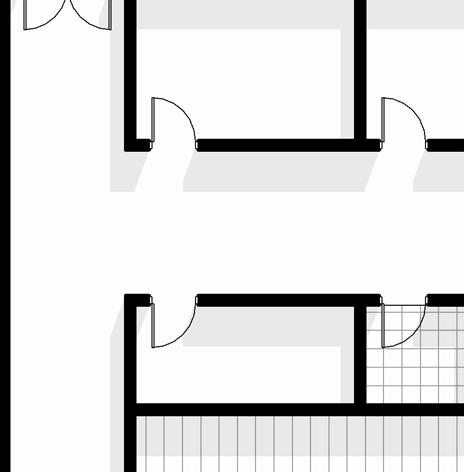

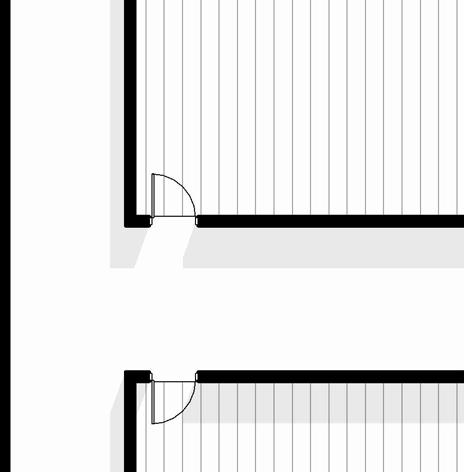

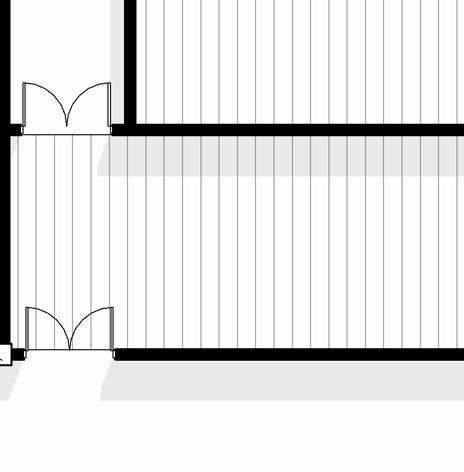

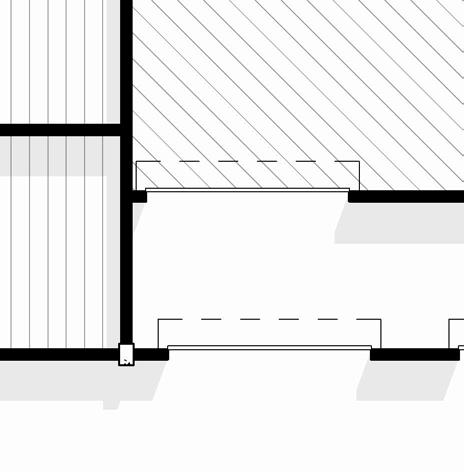

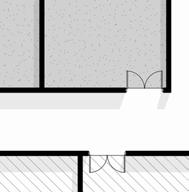

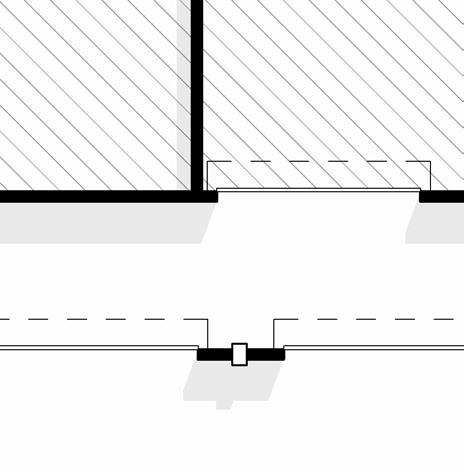

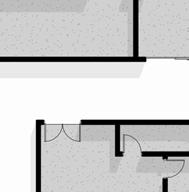

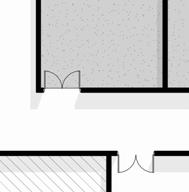

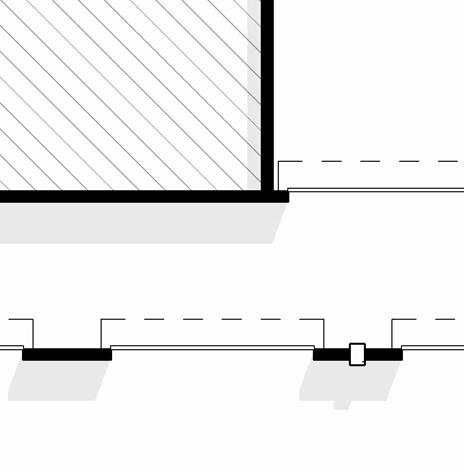

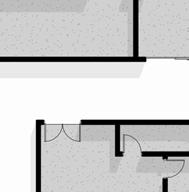

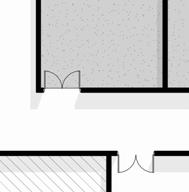

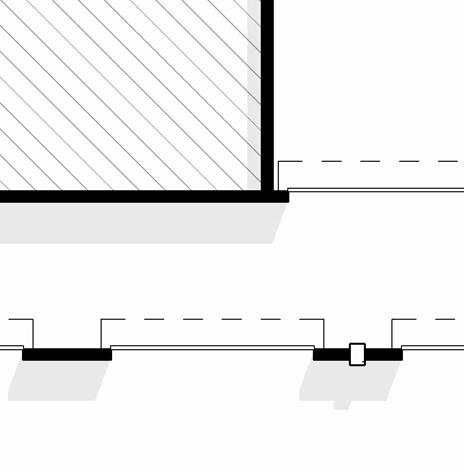

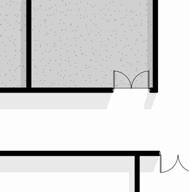

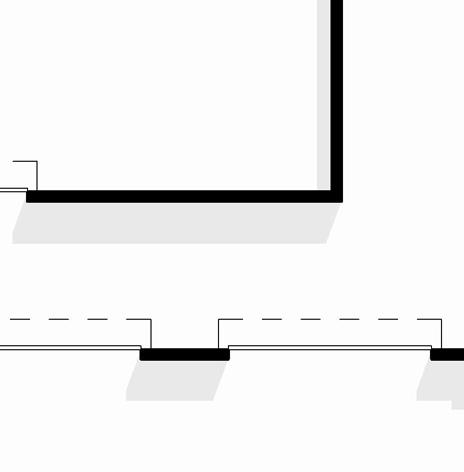

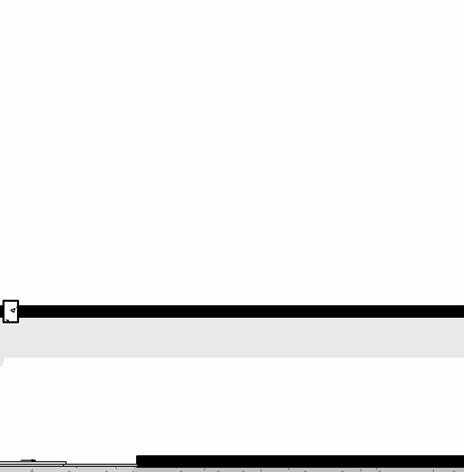

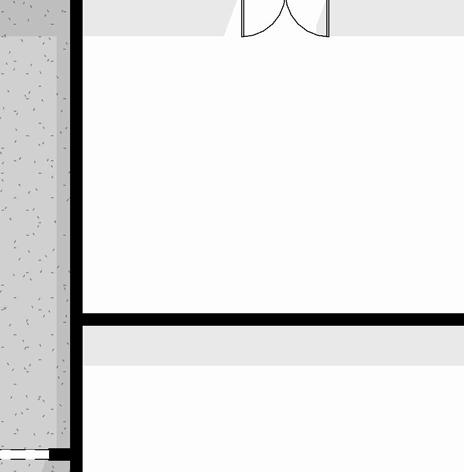

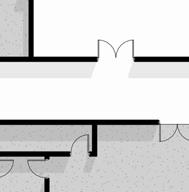

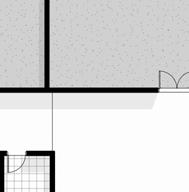

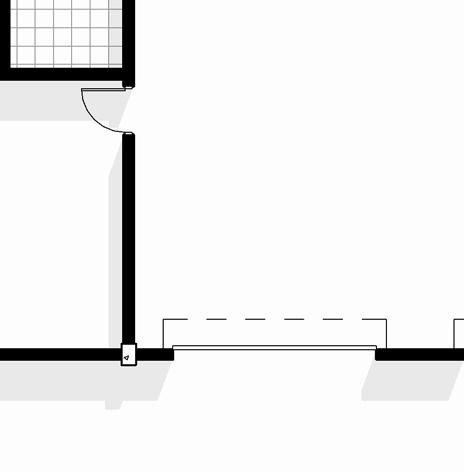

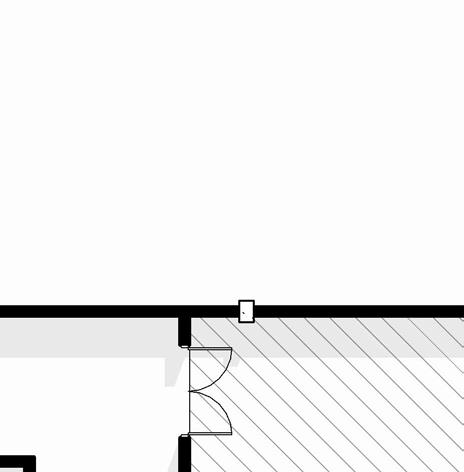

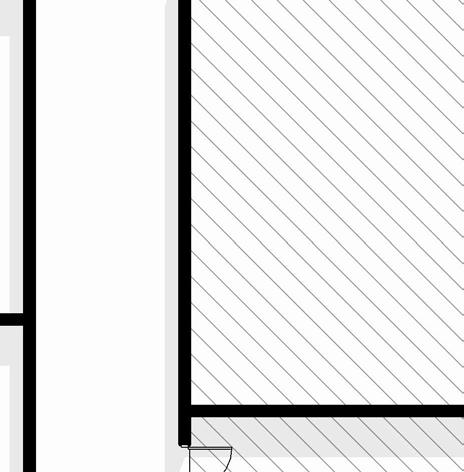

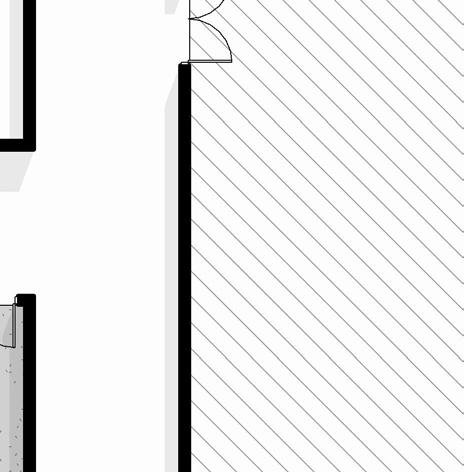

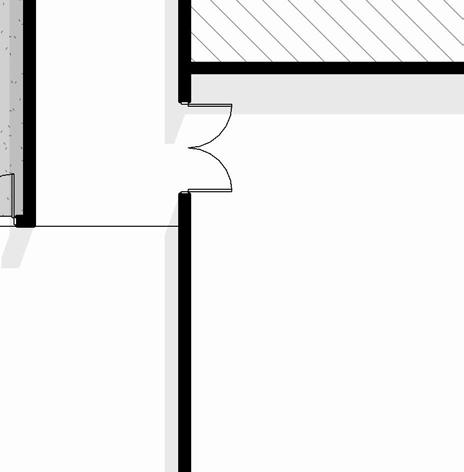

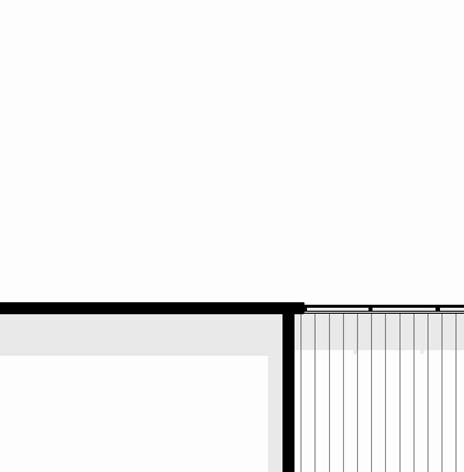

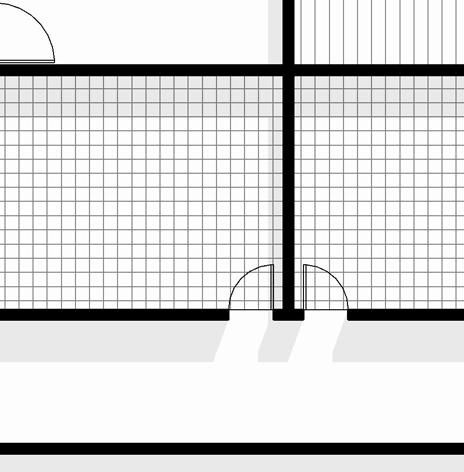

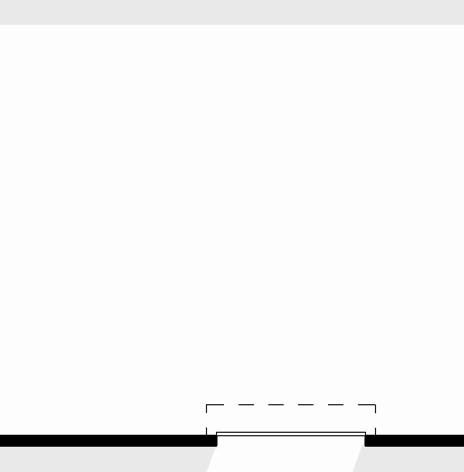

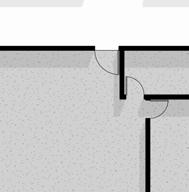

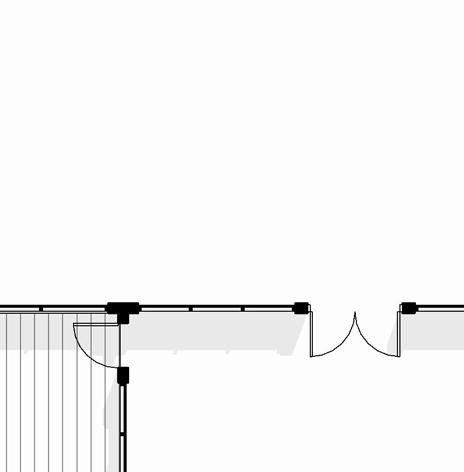

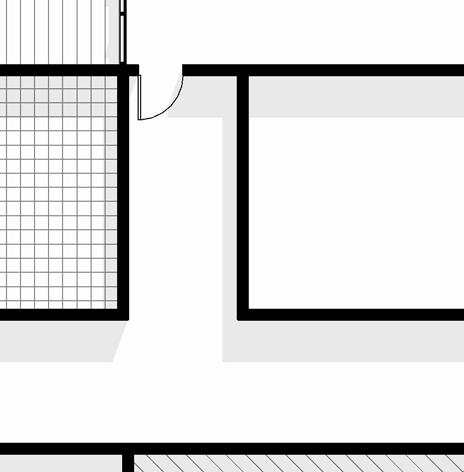

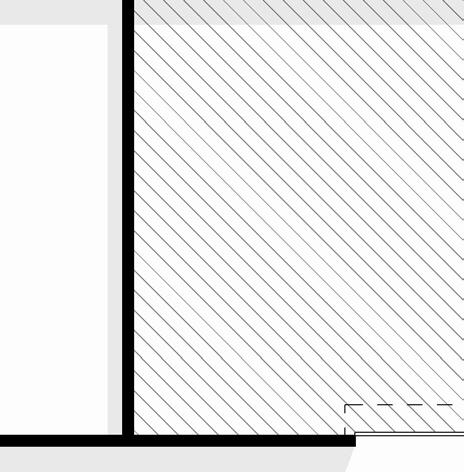

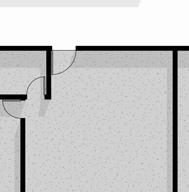

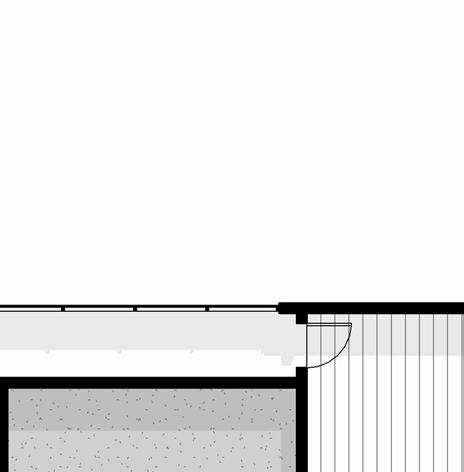

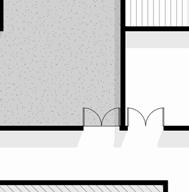

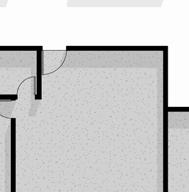

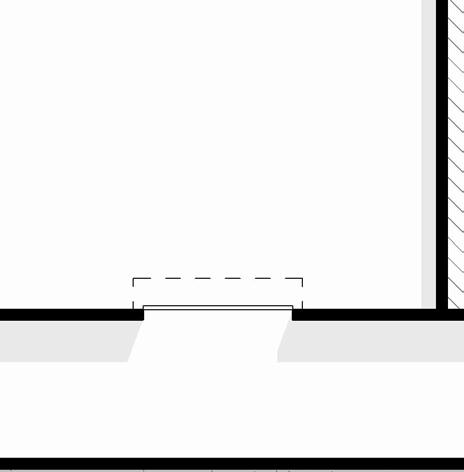

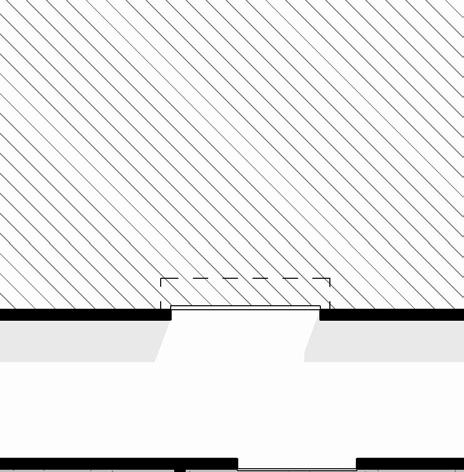

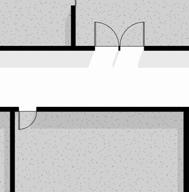

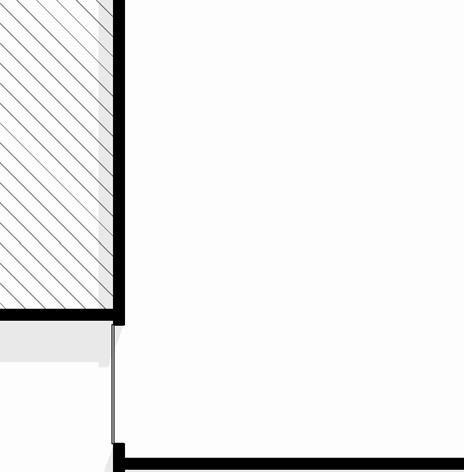

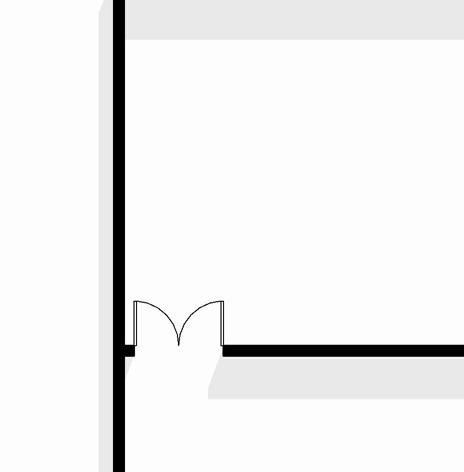

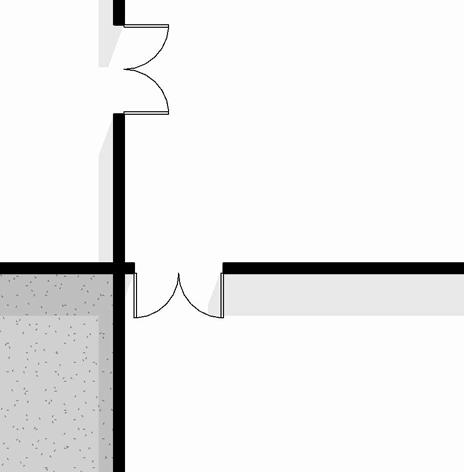

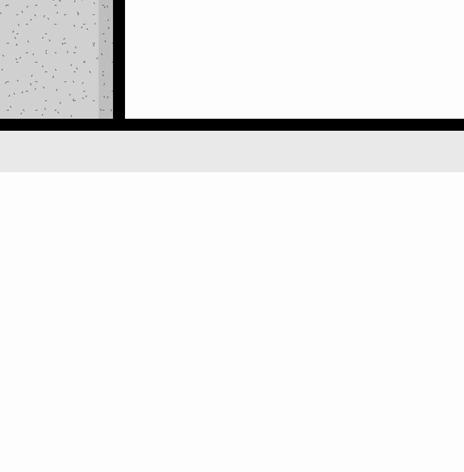

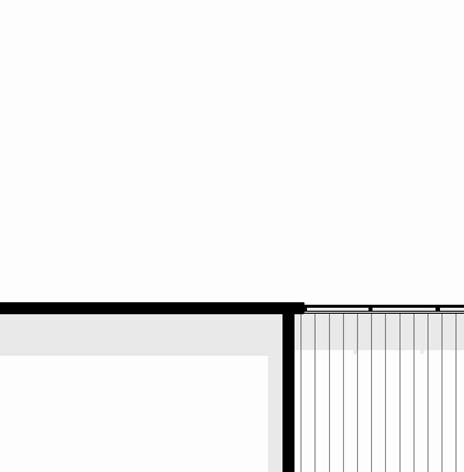

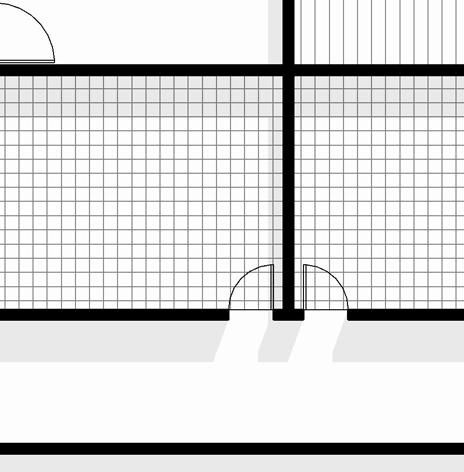

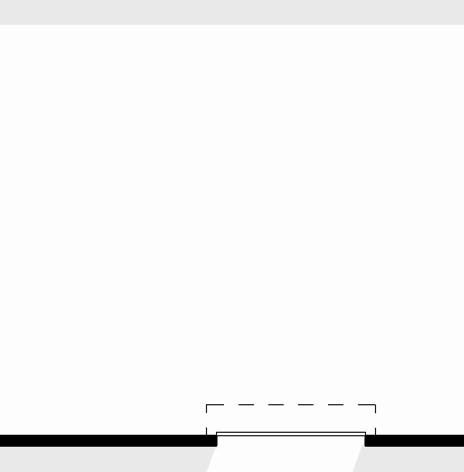

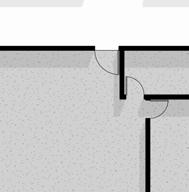

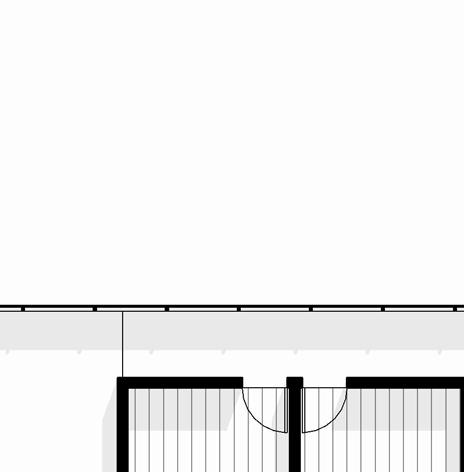

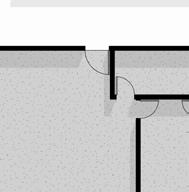

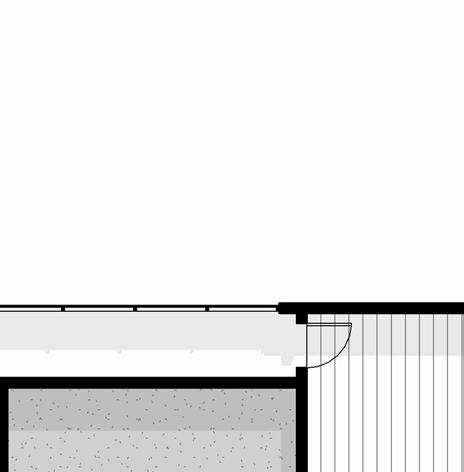

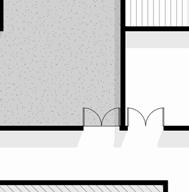

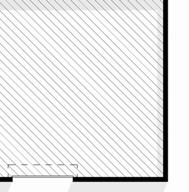

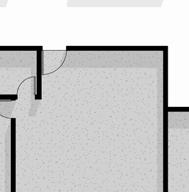

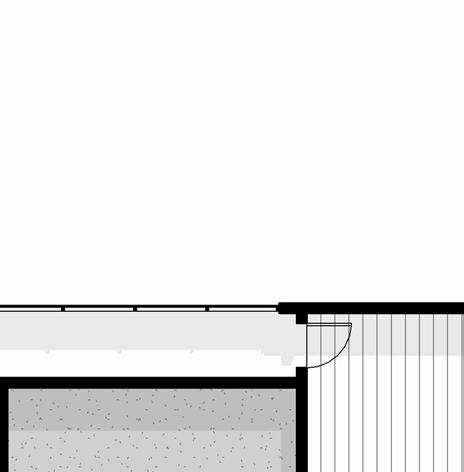

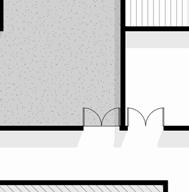

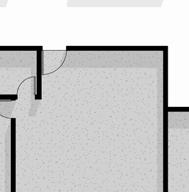

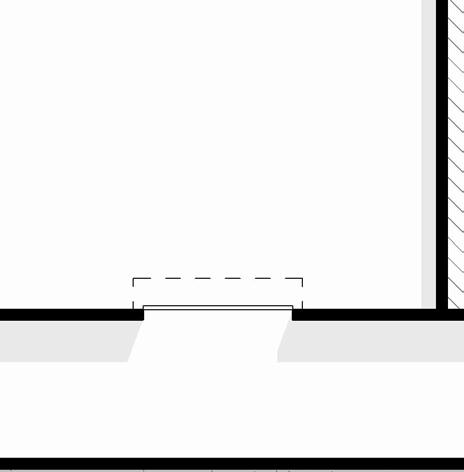

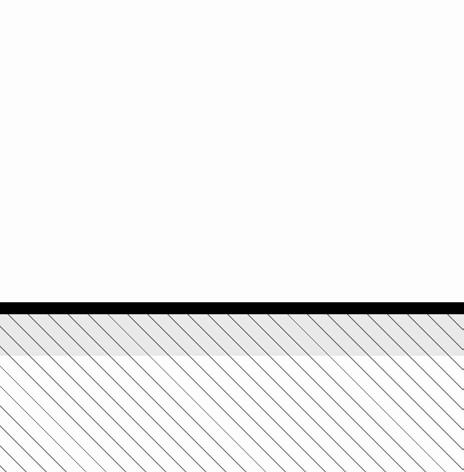

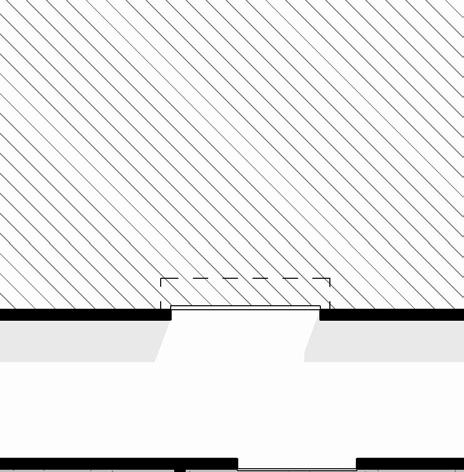

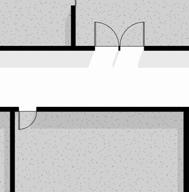

Facility Description

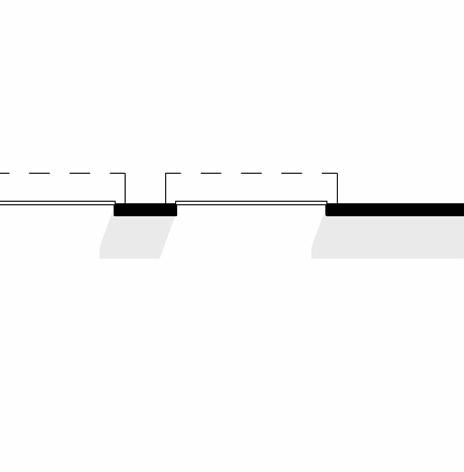

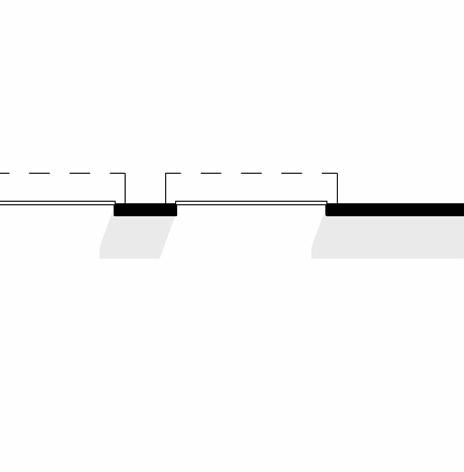

Design Considerations

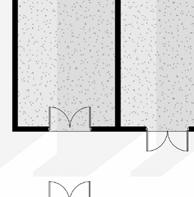

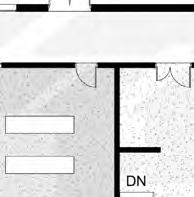

Facility Program Flow

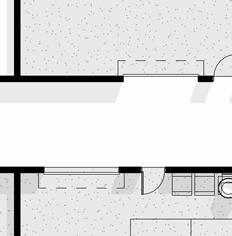

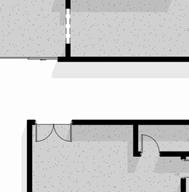

Scenario Development

Program Adjacency

Program Inventory

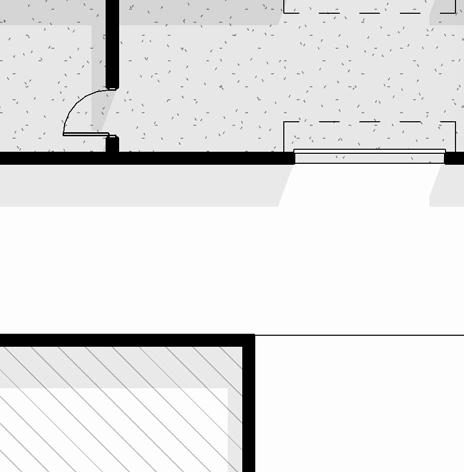

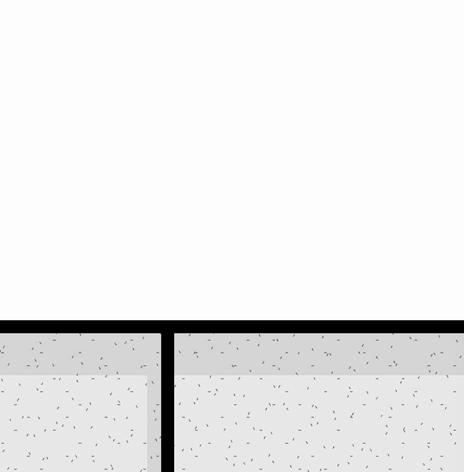

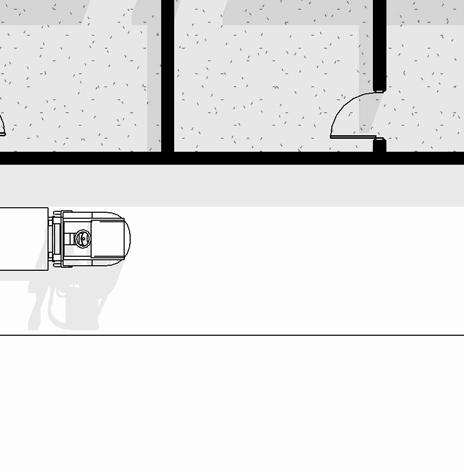

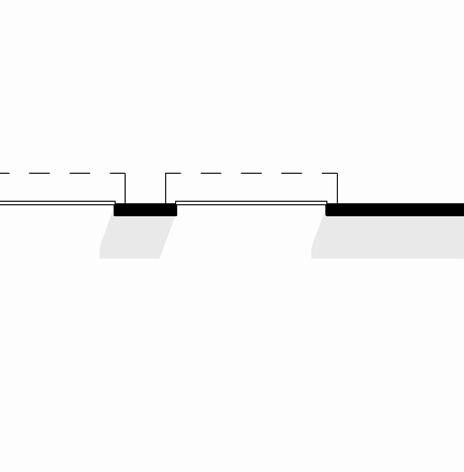

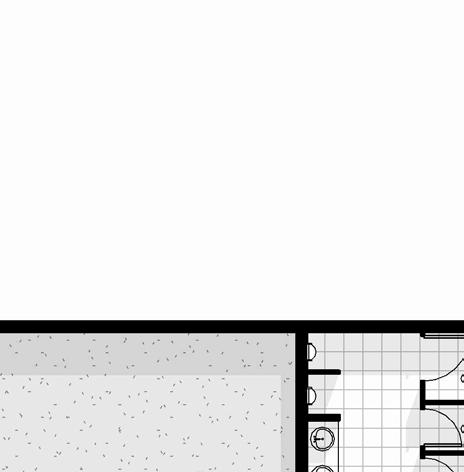

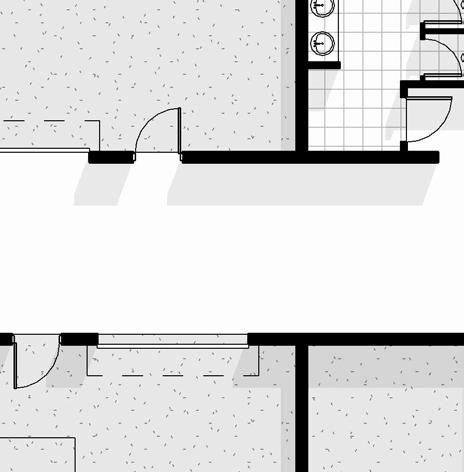

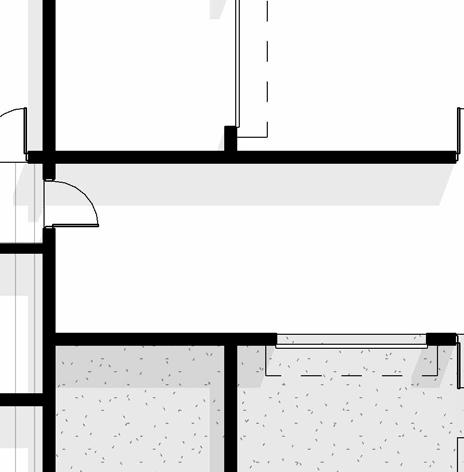

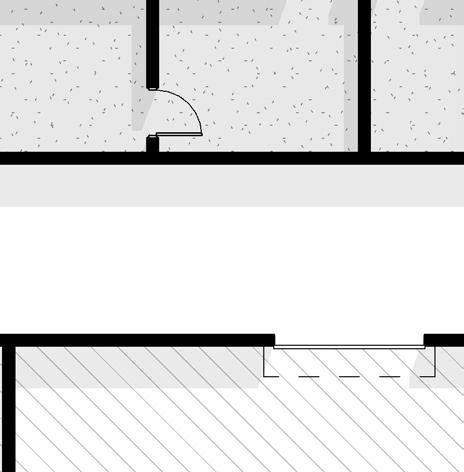

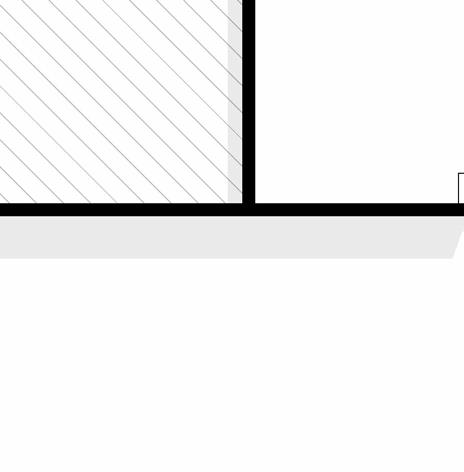

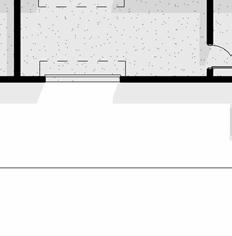

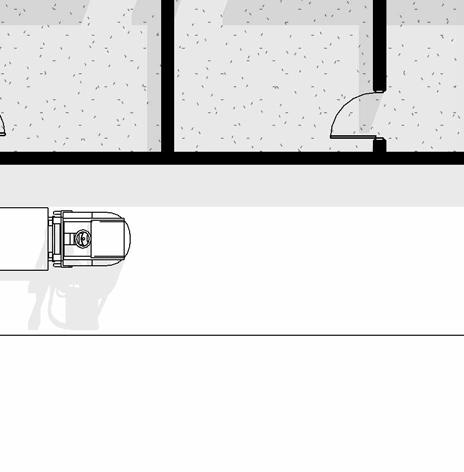

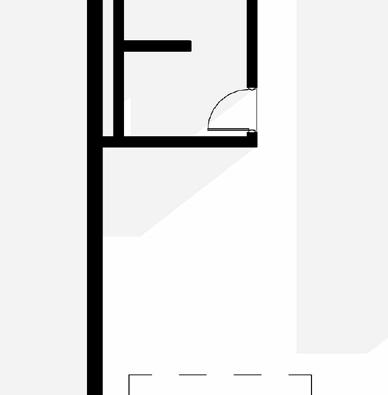

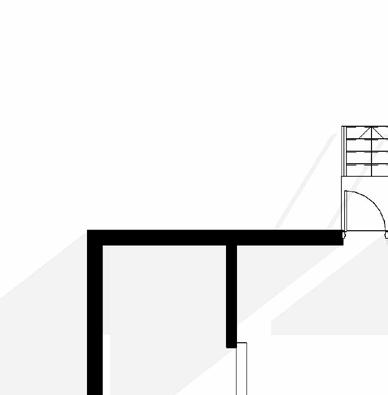

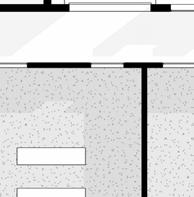

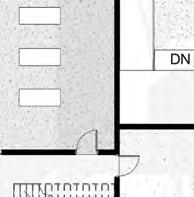

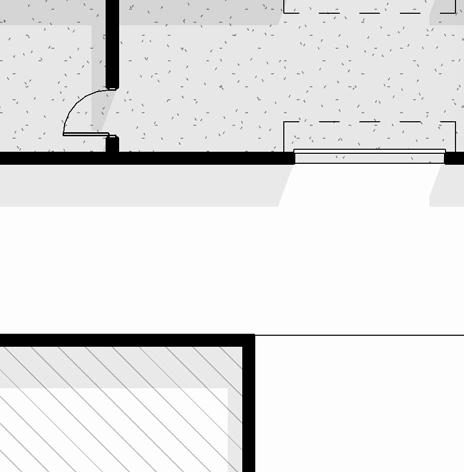

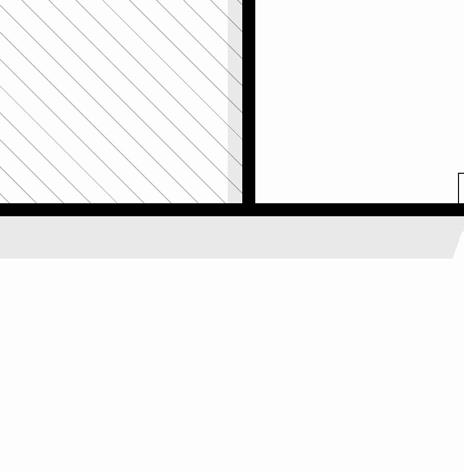

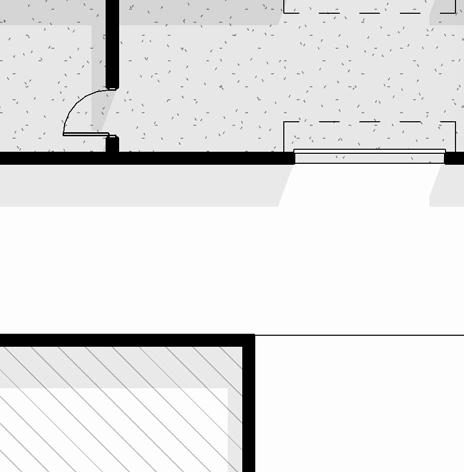

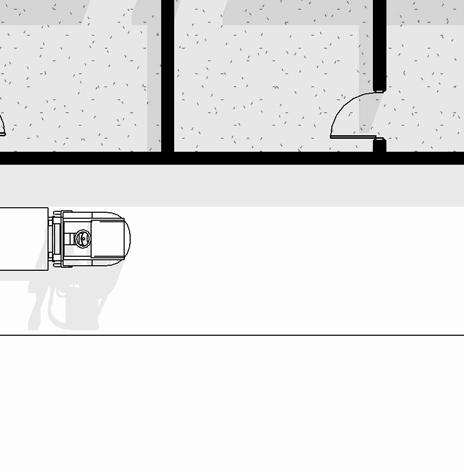

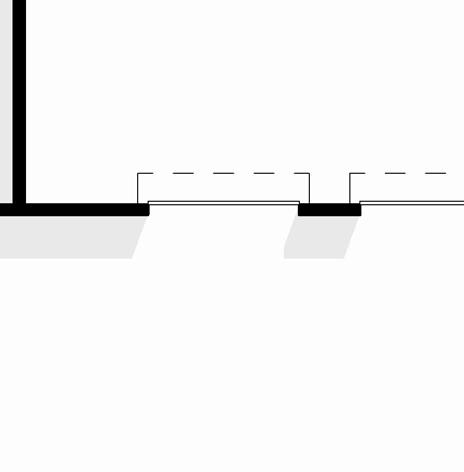

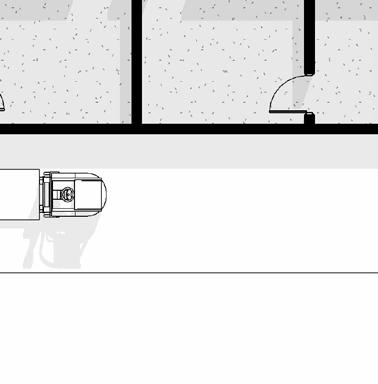

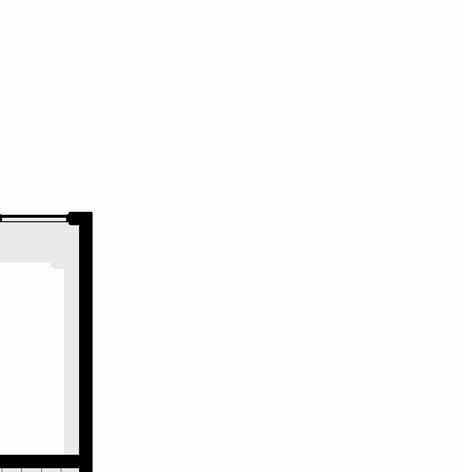

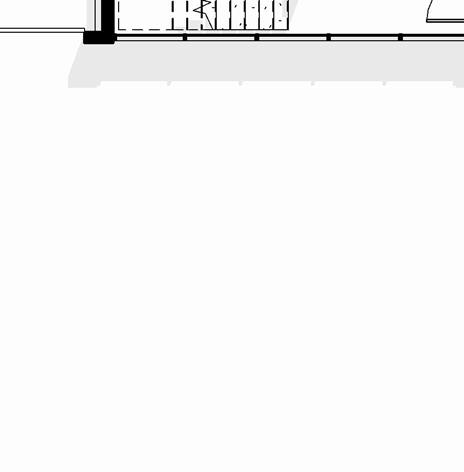

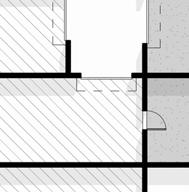

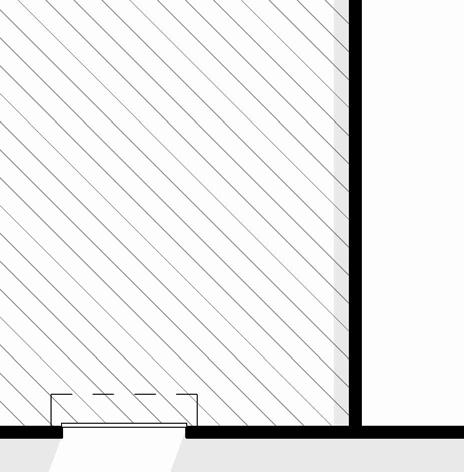

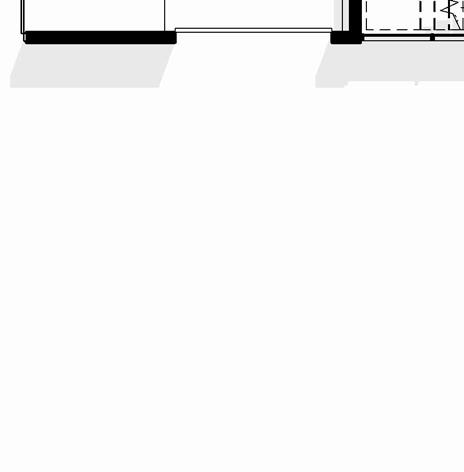

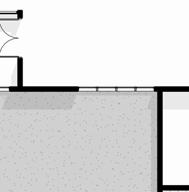

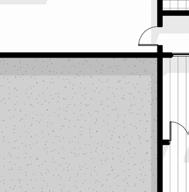

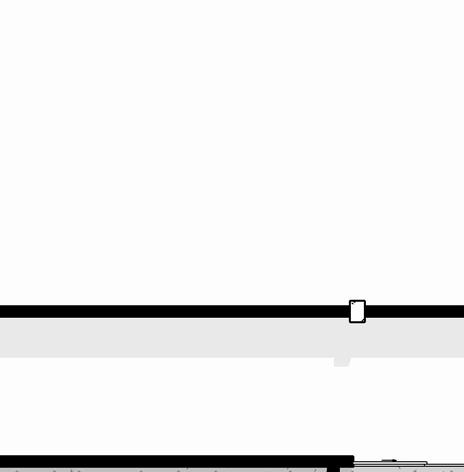

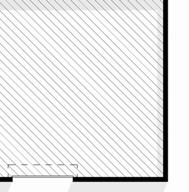

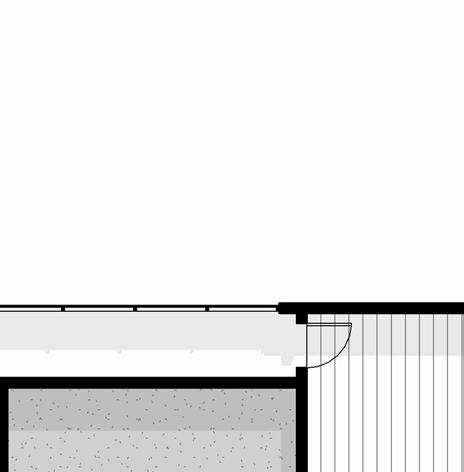

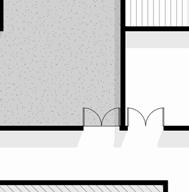

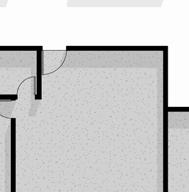

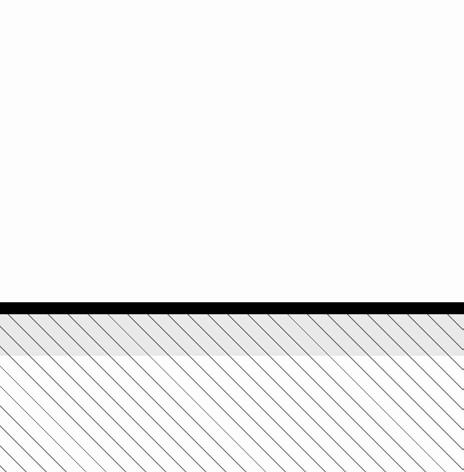

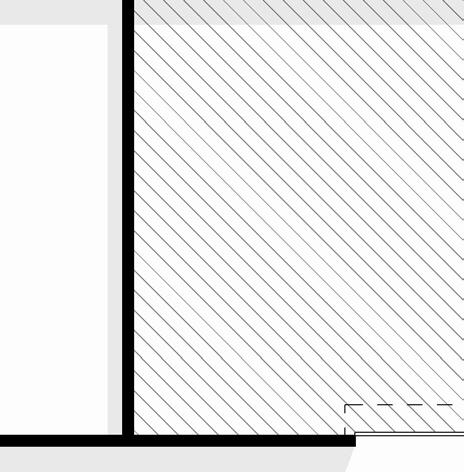

Site Context

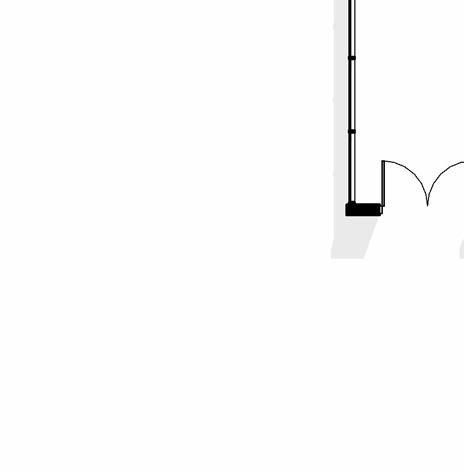

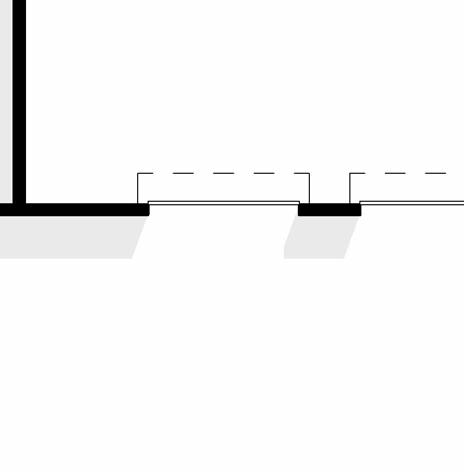

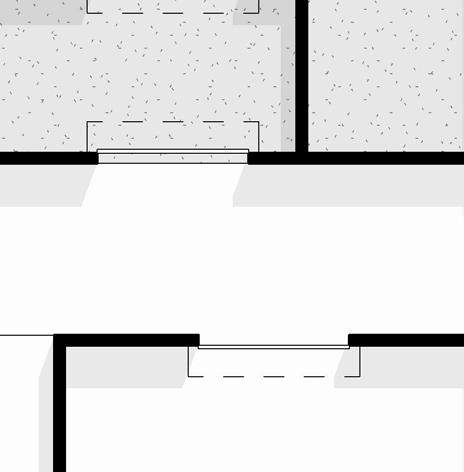

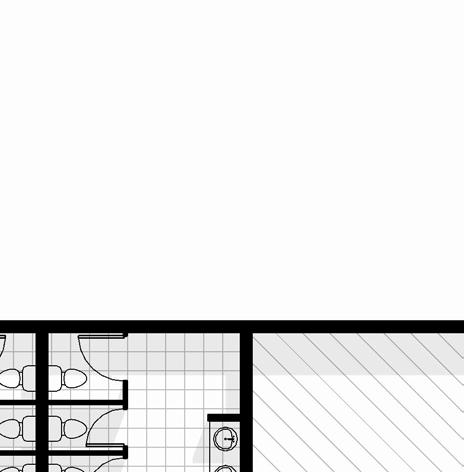

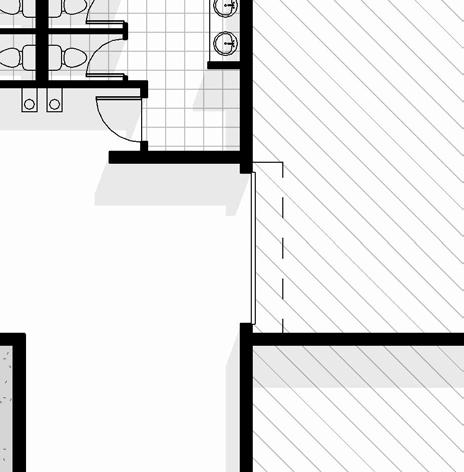

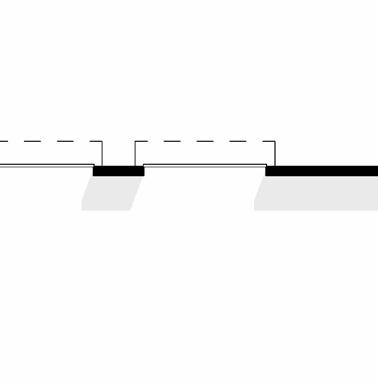

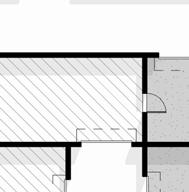

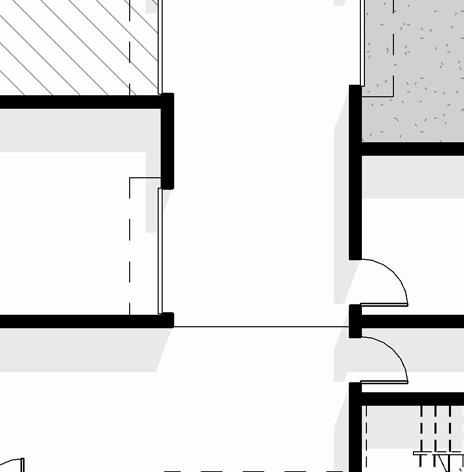

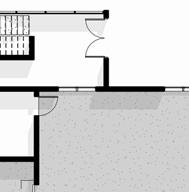

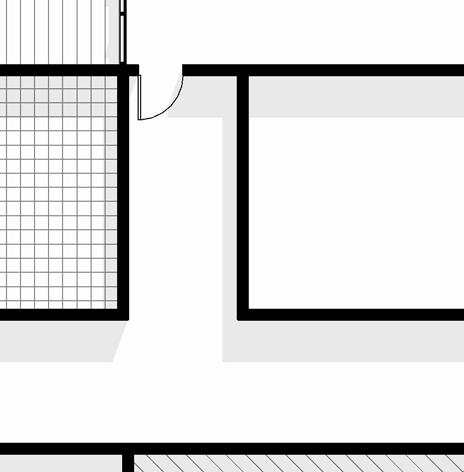

EPMF Layout

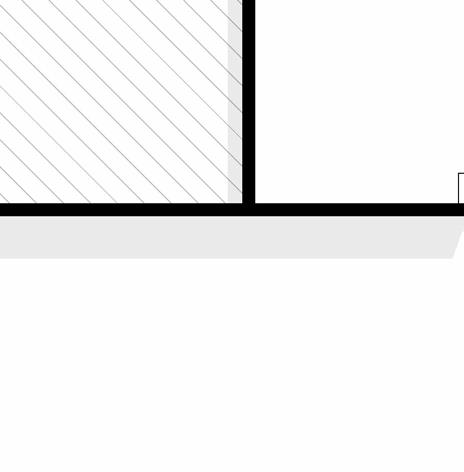

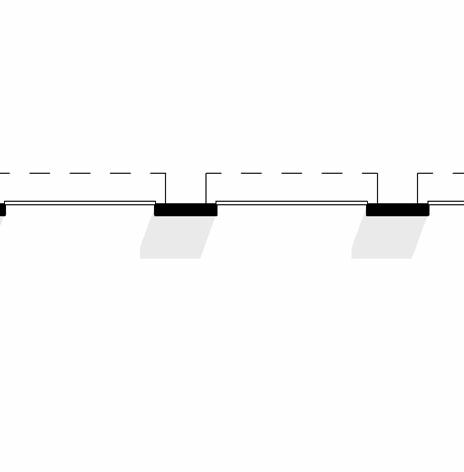

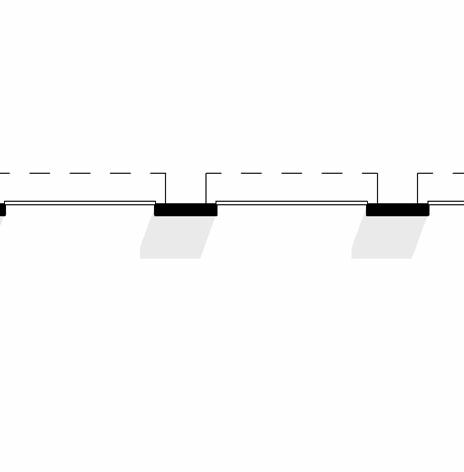

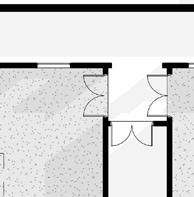

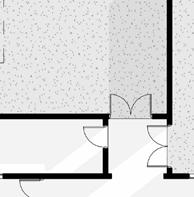

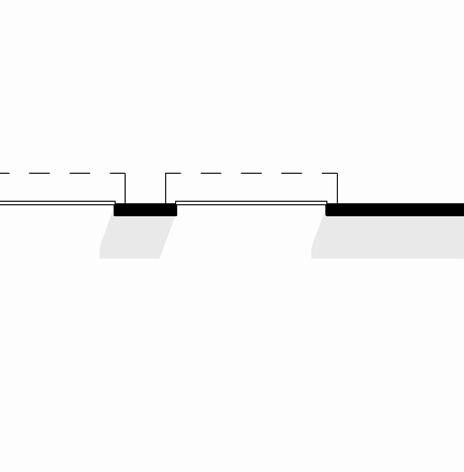

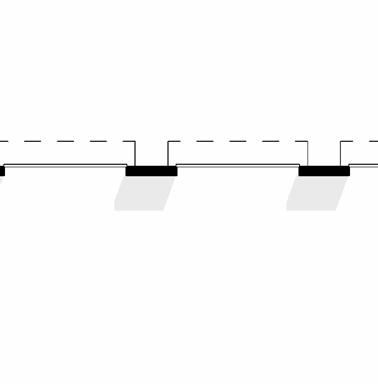

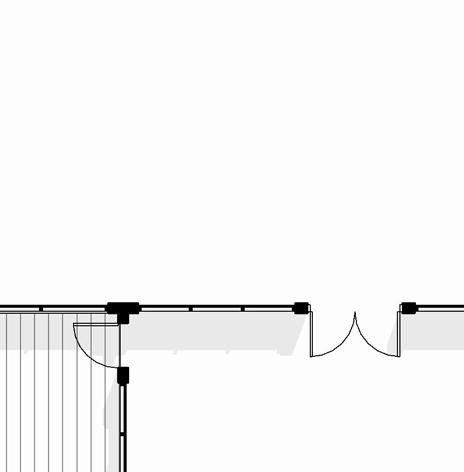

HPP Facility Connection

Conclusion

FPIN Recommendations

EPMF Recommendation

References

A: Meeting Summaries

B: Site Visits

C: Precedent Studies

D: WVAPDC Staff Design Charrette

E: ʻĀina to Mākeke Alumni Design Charrette

F: EPMF Design Scenarios

Agribusiness Development Corporation

current Good Manufacturing Practices

Co-Location Centers

Central Oʻahu Agriculture and Food Hub

Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism

Department of Education

Department of Health

Department of Transportation

European Institute of Innovation and Technology

Entrepreneur Product Manufacturing Facility

Federal Drug Administration

Food and Product Innovation Network

Hawaiʻi Department of Agriculture

High Pressure Processing

Kapi‘olani Community College

Knowledge and Innovation Communities

Leeward Community College

Maui Food Innovation Center

New Zealand Food Innovation Network

Pacific Gateway Center

Proof of Concept

Research & Development

Singapore Food Agency

Singapore Food Story

Singapore Institute of Food and Biotechnology Innovation

Small and Medium-sized Enterprises

University of Hawai‘i Community College

University of Hawai'i Community Design Center

U.S. Department of Agriculture

Wahiawā Value-Added Product Development Center

In order to meet Hawaiʻi’s agricultural, food security, and economic diversification goals, a strategic planning effort was undertaken by public leaders, stakeholders, and elected officials. The intention was to create a network of statewide open-access food and product innovation facilities to help businesses scale up new products from research and development to manufacturing and commercialization.

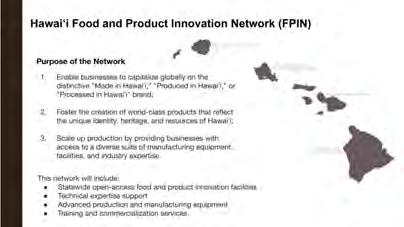

In 2024, the Hawaiʻi State Legislature passed Senate Bill 2500, establishing a food and product innovation network within the Agribusiness Development Corporation (ADC) to support statewide economic diversification and value-added product development. The network would allow Hawaiʻi businesses to capitalize globally on the “Made in Hawaiʻi,” “Produced in Hawaiʻi,” or “Processed in Hawaiʻi” brand; foster the creation of world-class products that reflect the unique identity, heritage, and resources of Hawaiʻi; and scale up production by providing businesses with access to a diverse suite of manufacturing equipment, facilities, and industry expertise (Hawaiʻi State Legislature, 2024).

Hawai‘i’s agribusiness sector is undergoing a decisive transition. The economic transformation of Hawai‘i’s agricultural sector began in the late 20th century with the large-scale downsizing of sugar and pineapple plantations. This transition released tens of thousands of acres of arable land and substantial irrigation infrastructure, creating both the need and the opportunity to reposition agriculture as a diversified and resilient pillar of the state’s economy. However, realizing this potential has been impeded by systemic challenges, including competition from cheap imports, fragmented infrastructure, competing land uses, and the high costs associated with land access, labor, and logistics.

In the decades since, Hawaiʻi has become increasingly reliant on imported food, with estimates indicating that more than 85% of the state’s food supply is sourced from outside the islands (Hawaiʻi Department of Business, Economic Development & Tourism [DBEDT], 2012). This dependency renders the state highly vulnerable to supply chain disruptions, global market volatility, and climate-induced impacts. Local agriculture continues to face a spectrum of structural challenges. Limited food processing infrastructure constrains the ability of farmers to add value and access broader markets. Climate change exacerbates risks through more frequent droughts, floods, and wildfire events, intensifying the need for resilient infrastructure and land management practices. Concurrently, workforce shortages, high housing costs, and the declining availability of skilled agricultural labor hinder operational continuity and expansion. Food insecurity remains a persistent issue for many residents, further highlighting the importance of strengthening Hawaiʻi’s agricultural sector. In this context, the need to develop resilient, sustainable, and diversified agricultural systems has never been more urgent (State of Hawaiʻi, Commission on Water Resource Management, 2019).

This imperative aligns with a growing body of state-level initiatives and policy frameworks that underscore the need to build a more self-reliant and circular food system. The Hawai‘i 2050 Sustainability Plan, revised in 2021, outlines a comprehensive vision for food resilience, calling for increased local food production, protection of agricultural

lands, and equitable access to healthy food. Similarly, the Aloha+ Challenge, a statewide commitment to achieve six sustainability goals by 2030, includes a focus on local food production as a core metric of economic resilience and environmental stewardship.

Complementing these plans are statutory procurement mandates that commit public institutions to sourcing a significant portion of their food from local producers. These include the state mandate to source at least 30% of food locally by 2030 and a longer-term goal to reach 50% by 2050 (Hawaiʻi State Office of Planning and Sustainable Development, 2021). Collectively, these benchmarks reflect both the urgency and the strategic intent behind statewide efforts to reduce dependence on imports and increase food security through targeted investment, regulatory reform, and coordinated action across sectors.

In this policy landscape, agencies like ADC play a pivotal role. Their statutory mandate to facilitate land and infrastructure access, support value-added production, and coordinate regional agribusiness development directly supports these broader food system objectives. Through initiatives such as FPIN and regional processing hubs, the agency provides the foundational infrastructure and strategic coordination necessary to translate highlevel goals into measurable outcomes. These efforts represent not only a response to current vulnerabilities but also a proactive investment in Hawai‘i’s long-term agricultural, economic, and environmental sustainability.

The long-term vision of FPIN is to establish a resilient, place-based innovation ecosystem that catalyzes agricultural, economic, and food system transformation across the Hawaiian Islands. FPIN aims to enable local producers and entrepreneurs to transition from small-scale operations to globally competitive enterprises by providing access to a statewide network of open-access facilities and coordinated support services. By institutionalizing a flexible, iterative strategic framework, FPIN is poised to evolve alongside community needs, emerging markets, and climate resilience demands. It serves not only as a response to current systemic gaps but also as a forwardlooking investment in Hawaiʻi’s economic future.

1. Allow businesses in the State to capitalize globally on the “Hawaiʻi made”, “Made in Hawaiʻi”, “Produced in Hawaiʻi”, or “Processed in Hawaiʻi” brand;

2. Create world-class products; and

3. Scale up production by providing the businesses with access to a diverse suite of manufacturing equipment and industry expertise (Hawaiʻi State Legislature, 2024).

1. Offer a range of resources within the wider network to support innovation and business development, including courses and events relating to food and value-added product development, entrepreneurship, marketing, branding, business management, workforce development, intellectual property protection, and other topics;

2. Provide new product development support from early-stage trials to commercialization by establishing a network of facilities with equipment of various scales, providing expert advice, and offering resources tailored to the regional economies;

3. Provide low-risk commercial production with appropriate certifications for exporting products and selling products locally;

4. Provide recommendations on process optimization by offering advice and networking, identifying and testing equipment, planning trials, and analyzing results;

5. Increase exports by securing facilities and developing compliance programs for off-shore markets; provided that each county shall have no more than two food and product innovation network facilities that produce products labeled “Hawaiʻi made”, “Made in Hawaiʻi”, “Produced in Hawaiʻi”, or “Processed in Hawaiʻi”;

6. Develop entrepreneurs to grow the State’s economy;

7. Prepare businesses to scale up and achieve autonomous business success and sustainability;

8. Establish pathways from early-stage innovation through commercialization, including pilot testing, certification, and support for accessing capital and distribution channels;

9. Facilitate partnerships with research institutions, educational organizations, and private sector partners to strengthen innovation pipelines, technology transfer, and applied research opportunities; and

10. Engage with national and international partners, including foreign innovation networks, to support shared learning, exchange of best practices, and cooperative programming that advances innovation, sustainability, and commercialization outcomes. (Hawaiʻi State Legislature, 2024).

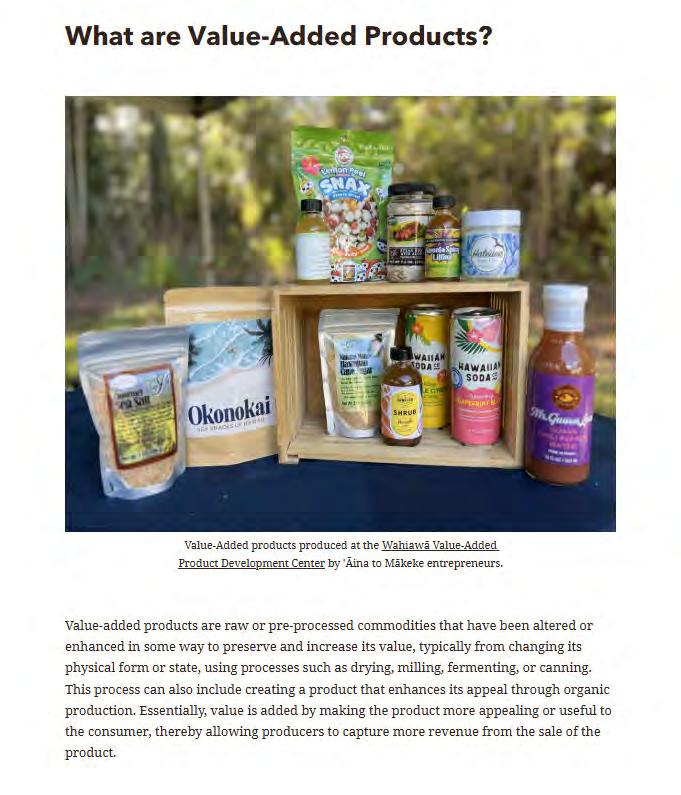

To support the development of competitive, high-quality products, FPIN prioritizes value-added production as a key strategy for increasing local economic returns and market differentiation. Value-added products are raw or minimally processed commodities that have been modified or enhanced to increase their market value (U.S. Department of Agriculture, 2011). This typically involves transforming the product’s physical form through methods such as drying, milling, fermenting, canning, or baking. In some cases, value may also be added through production attributes such as organic certification, regional branding, or cultural significance. By capturing more of the supply chain locally, valueadded production allows producers to retain a larger share of revenue while offering differentiated products that meet diverse market demands.

Value-added production in Hawaiʻi spans a wide range of food-based and non-food-based goods, each contributing to local economic diversification and resource optimization. These types of products reflect growing interest in sustainability and circular economies. FPIN supports both categories as integral components of a robust regional innovation ecosystem.

Food-Based Products:

These include processed or preserved items derived from locally grown agricultural inputs. Common examples are:

• Shelf-stable goods such as jams, sauces, dried fruits, and baked products;

• Fermented items like kimchi, kombucha, or soybased products;

• Specialty items including locally sourced chocolate, coffee, and honey;

• Frozen or ready-to-eat meals with local ingredients.

These products not only extend shelf life and reduce waste, but also enable producers to expand their reach to institutional, retail, and export markets.

Processed and Packaged Foods

Processed and Packaged Foods

Beverages

Beverages

Snack Foods

Snack Foods

Dairy Products

Dairy Products

Meat and Seafood Products

Meat and Seafood Products

Baked Goods

Baked Goods

Functional and Health Foods

Functional and Health Foods

Ethnic and Specialty Food

Ethnic and Specialty Food

Prepared and Ready-to-Eat Meals

Prepared and Ready-to-Eat Meals

Organic and Natural Products

Organic and Natural Products

Non-Food Products:

These include goods derived from agricultural byproducts or natural resources. Examples include:

• Body care and cosmetic products made from macadamia oil, kukui, or other botanicals;

• Biodegradable packaging, natural dyes, and fiberbased materials derived from crops such as hemp or banana;

• Nutraceuticals and wellness products incorporating locally sourced ingredients with functional properties.

Supporting these product types expands the utility of agricultural production, reduces waste streams, and opens new market sectors for Hawaiʻi-based entrepreneurs.

Textiles and Fibers

Textiles and Fibers

Cosmetics and Personal Care

Cosmetics and Personal Care

Essential Oils and Aromatherapy

Essential Oils and Aromatherapy

Herbal and Medicinal Products

Herbal and Medicinal Products

Biofuels and Energy Products

Biofuels and Energy Products

Crafts and Handmade Goods

Crafts and Handmade Goods

Building Materials

Building Materials

Paper and Packaging Materials

Paper and Packaging Materials

Animal Feed and Bedding

Animal Feed and Bedding

Biochar and Soil Amendments

Biochar and Soil Amendments

Poi represents one of the earliest and most enduring examples of value-added food production in Hawaiʻi. Derived from taro (kalo), poi is created through a traditional process of cooking, pounding, and fermenting the corm (stem) to produce a shelf-stable, nutrient-rich staple. This transformation increases digestibility and extends the product’s usability, aligning with key principles of value-added processing. Beyond its technical qualities, poi carries deep cultural significance within Native Hawaiian communities, where it has long served as a staple food and symbol of connection to ʻāina, kūpuna, and communal well-being. The continued practice of poi production reflects Indigenous knowledge systems that integrate food preservation, environmental stewardship, and cultural identity (Dinnan, 2020; Kūpuna Kalo, n.d.).

The traditional production of poi involves multiple transformative steps:

Cleaning: Kalo is harvested below the kōhina (corm line), allowing the upper huli (kalo top) to be replanted. The corms are then cleaned of roots (huluhulu), washed, and sorted to remove the loliloli (watery) or pala hu (overripe) corms. This process is carried out in two stages:

1. Pohole – scraping away rough skin and roots;

2. Ihi – detailed cleaning of root eyes and removal of rot.

Cooking: The cleaned corms are steamed in an imu (underground oven) until tender. This method preserves nutritional integrity while enabling efficient processing. The act of cooking and preparing kalo for poi is known as kahu ʻai, referring to one who stewards food through its preparation and preservation stages.

Pounding: After cooling, the cooked corms are kuʻi (pounded) using a traditional pōhaku ku‘i ʻai (stone pestle) and papa ku‘i ʻai (wooden board). The pounding process proceeds through distinct stages:

1. Naha or pakiki* – breaking or crushing of the kalo into large pieces;

2. Mokumoku – separation into many pieces;

3. Paʻi paʻi - slapping the pieces together;

4. Pili – adhesion into a single mass to form paʻi ʻai (dense paste);

*Acknowledge varying terminology and regional naming systems.

Mixing: Water is gradually added to paʻiʻai to produce poi of desired consistency, ranging from poi paʻa (firm) to linalina (a silk-like state with no lumps). The act of mixing is described by terms such as hoʻowali (to add water and soften) and kūpele (to knead or rework the poi), reflecting both technical skill and textural nuance.

Fermenting: Poi naturally ferments over time, acquiring a tangy flavor and enhanced shelf life. This fermentation not only reduces spoilage, but also produces probiotic benefits, contributing to gut health without the use of artificial additives.

The traditional process of making poi is highly efficient— minimizing waste, extending food usability, and exemplifying circular resource management. Beyond its functional attributes, poi exemplifies a model of sustainable, place-based food production. By converting a fresh agricultural input into a preserved and value-added food product, traditional poi making demonstrates how ancestral practices can inform contemporary strategies for food system resilience. Its efficient, regenerative approach supports both ecological stewardship and cultural continuity, offering valuable insights for modern product development.

This section outlines the core components that structure FPIN. It provides a framework for understanding how the network is designed, who is involved, and how valueadded production is supported across regions and sectors. Each spread introduces a key element of the system, from global precedents to local implementation strategies.

It begins with a review of global precedent models that inform the FPIN’s design. Examples from New Zealand, the European Union, and Singapore demonstrate how open-access facilities, public-private partnerships, and cross-sector coordination can strengthen regional food systems and support business growth.

Building on these models, the next component explores Hawaiʻi’s ecosystem approach to regional economic development. This place-based strategy emphasizes investment in infrastructure and programming that align with each island’s agricultural assets, industry needs, and long-term resilience goals. It is designed to reduce barriers for small and medium-sized enterprises while ensuring local economic benefits are retained.

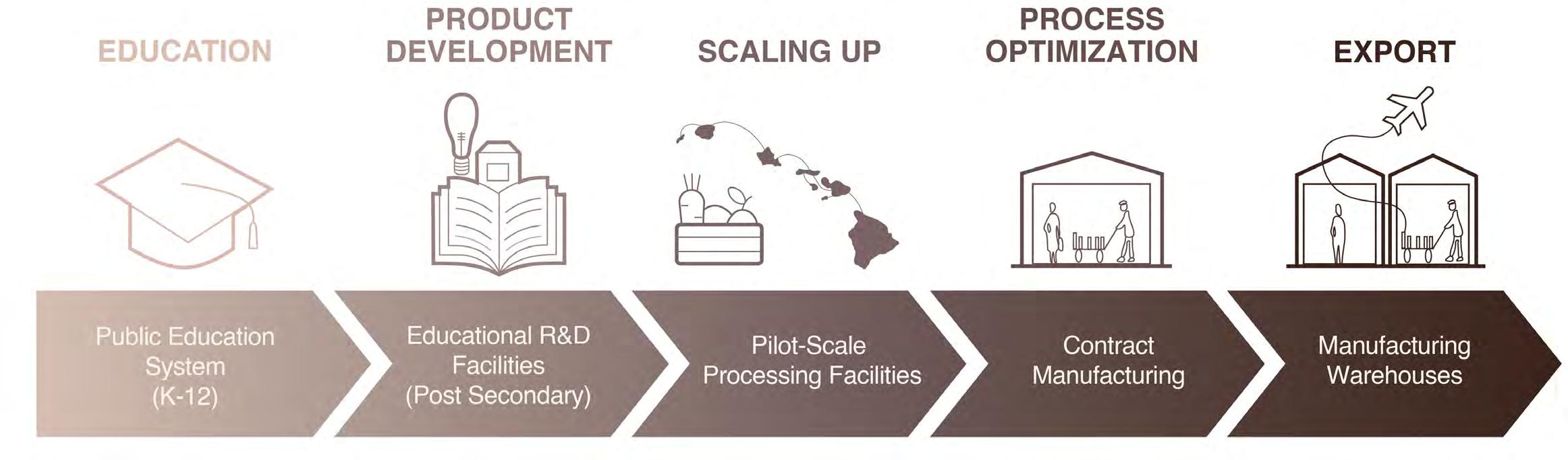

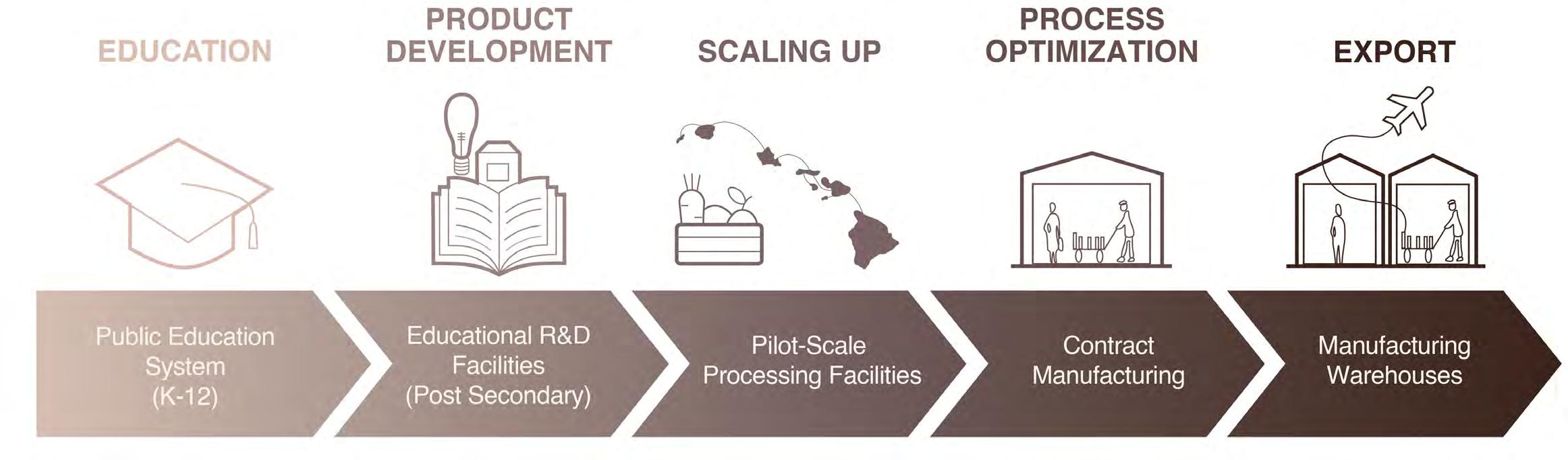

Hawaiʻi’s emerging Food and Product Innovation Network is designed to create a sustainable and resilient agricultural economy by building a seamless pathway from education to export. This initiative begins by integrating agriculture education into the public K-12 curriculum, sparking an early interest in food systems and sustainability. Postsecondary institutions then provide hands-on learning through food and product development centers, featuring test kitchens and technical support, while offering trainings, certificate and degree programs. As businesses grow, pilot-scale processing facilities, contract manufacturers, and warehouse lease spaces provide the resources, expertise, and infrastructure needed to scale operations, ultimately positioning local products for success in global markets.

A stakeholder framework identifies the key actors involved in planning, implementing, and sustaining the network. These include producers, educators, regulators, policy makers, and community partners, each playing a role in maintaining compliance, ensuring relevance, and supporting equitable access.

The final component maps how resources, services, and decision-making processes flow throughout the network. This value network framework illustrates the interdependencies that connect producers, facilities, regulators, and support systems.

Precedent networks serve as critical references for understanding the design, operation, and impact of existing food innovation ecosystems. By examining established models from other regions, the Hawaiʻi FPIN can identify transferable strategies, structural elements, and implementation practices that support value-added production, entrepreneurship, and economic resilience. These case studies provide insight into governance structures, facility typologies, funding mechanisms, and collaborative frameworks that have been successful in enhancing agricultural innovation and commercialization.

This report highlights three international models: the New Zealand Food Innovation Network (NZFIN), European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT) Food, and the Singapore Food Story (SFS). Each precedent offers a distinct approach to regional capacity-building and sector development of varying scales.

“We’re here to help innovative, ambitious food businesses scale up and commercialise new products”

NZFIN is a nationally coordinated system of openaccess food innovation hubs. It was established to support the growth, export readiness, and technical advancement of New Zealand’s food and beverage sector. NZFIN provides shared access to state-ofthe-art processing equipment, food-safe facilities, and applied research services that help businesses develop and commercialize new products (Ministry of Business, Innovation and Employment, 2021).

The New Zealand Food Innovation Network (NZFIN) is a national network of open-access food innovation facilities strategically located throughout New Zealand. The network was established to support food and beverage businesses’ growth, development, and export by providing access to 5 state-of-the-art facilities, technical expertise, and commercial services. The NZFIN integrates government agencies, research institutions, industry bodies, and business incubators to accelerate the commercialization of new food products and processes, enhance sustainability, and drive economic growth within the food sector.

Sources:

innovative, ambitious food busicommercialise new products”

NZFIN is composed of five regionally specialized centers: The FoodBowl (Auckland), FoodWaikato (Hamilton), FoodPilot (Palmerston North), FoodSouth (Canterbury), and FoodOtago (Dunedin) (New Zealand Food Innovation Network, n.d.). Each facility is tailored to regional agricultural strengths and provides businesses with access to technical expertise, scaleappropriate equipment, and collaborative spaces for product development and testing (FoodBowl, 2020). The network is supported by partnerships among government agencies, universities, and industry, making it a strong model for Hawaiʻi’s proposed islandbased FPIN framework.

Food Innovation Network (NZFIN) is a open-access food innovation facilities throughout New Zealand. The network support food and beverage businesses’

1. FoodBowl

Specialized in supporting growth food businesses

2. FoodWaikatao Graduation facility production.

3. FoodPilot (Palmerston Research facility designed port food and beverage nies in product development, cess optimization, commercial production

4. FoodSouth

Focused on scale-up food and beverage

• Demonstrates the effectiveness of a geographically distributed, governmentsupported network of open-access facilities tailored to regional agricultural strengths;

5. FoodSouth (Otago) Offering multidisciplinary expertise and capabilities and develop processes ucts.

• Emphasizes public-private collaboration, integrating government agencies, research institutions, and industry partners to accelerate product development;

6. NZFIN

• Provides scalable infrastructure and technical services that reduce barriers to entry for small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs);

Hawke’s Bay Business viding business development sistance.

• Illustrates the role of specialized hubs in supporting both local market access and global export readiness;

• Serves as a strong precedent for Hawaiʻi’s island-based approach to regional innovation, particularly in the deployment of shared-use production facilities and targeted expertise.

University

1. FoodBowl (Auckland)

1. FoodBowl (Auckland)

Specialized in supporting highgrowth food businesses and exporters.

2. FoodWaikatao (Hamilton)

Graduation facility for spray dried production.

The largest NZFIN Hub, FoodBowl has seven processing food-grade spaces for pilot scale R&D trials and commercial manufacturing.

3. FoodPilot (Palmerston North)

2. FoodWaikato (Hamilton)

Research facility designed to support food and beverage companies in product development, process optimization, and scale-up to commercial production.

(Auckland) supporting highbusinesses and ex(Hamilton) for spray dried (Palmerston North) designed to supbeverage compadevelopment, proand scale-up to production. (Christchurch) scale-up support for beverage companies. (Otago)

Owned by New Image Group, FoodWaikato operates as an independent product development and spray drying facility.

3. FoodPilot (Palmerston North)

4. FoodSouth (Christchurch)

Focused on scale-up support for food and beverage companies.

5. FoodSouth (Otago)

Massey University’s FoodPilot enables research and development, as well as small scale manufacture.

4. FoodSouth (Canterbury)

Offering multidisciplinary research expertise and capabilities to trial and develop processes and products.

6. NZFIN Navigator

The South Island’s largest Hub, FoodSouth has five food-grade processing spaces for product development and scale up.

5. FoodOtago (Dunedin)

Hawke’s Bay Business Hub, providing business development assistance.

In partnership with the University of Otago, FoodOtago delivers new product development and analytical services at a benchtop scale.

multidisciplinary research capabilities to trial processes and prod-

Hub, prodevelopment as-

EIT Food is a pan-European innovation network focused on building a more sustainable, healthy, and trusted food system. It operates under the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT), an European Union body established to foster innovation through cross-sector collaboration and strategic funding (EIT Food, n.d.).

EIT Food operates through eight thematic Knowledge and Innovation Communities (KICs), each organized around five to ten co-location centers (CLCs). These centers function as collaborative workspaces—labs, university campuses, and business incubators—where researchers, entrepreneurs, and businesses engage in joint innovation and commercialization efforts (European Institute of Innovation and Technology, 2021).

• Demonstrates a multi-tiered innovation model that combines centralized funding with decentralized, place-based implementation through co-location centers;

• Leverages diverse funding instruments such as grants, public-private partnerships, low-interest loans, and prize competitions to support businesses at all stages of development;

• Establishes clear performance frameworks and innovation principles, including impact tracking, commercialization plans, and minimum cofunding requirements;

• Prioritizes cross-sector collaboration among academia, industry, and government to accelerate technology transfer and market integration;

• Serves as a precedent for integrating strategic oversight with regional action, offering a scalable framework for tracking and evaluating innovation outcomes over time.

The SFS is a national initiative led by the Singapore Food Agency (SFA) to strengthen the country’s food security and build a future-ready agri-food ecosystem. Developed in response to Singapore’s dependence on food imports and limited land availability, the initiative integrates innovation, research, and infrastructure to increase local food production in sustainable and hightech ways. It emphasizes urban agriculture, alternative proteins, food waste valorization, and next-generation food safety systems, positioning Singapore as a leader in agri-food technology and resilience (Singapore Food Agency, 2023).

• Models a government-led, research-intensive approach to food innovation in a land-and resource-constrained environment;

• Integrates urban agriculture, novel food technologies, and high-value research & development (R&D) through a centralized yet multi-agency framework;

• Prioritizes food security and economic resilience by investing in alternative proteins, vertical farming, and next-generation food safety systems;

• Highlights the importance of co-located innovation infrastructure (e.g., Agri-Food Innovation Park) and coordinated funding programs to support commercialization;

• Offers lessons for Hawaiʻi in aligning agrifood innovation with national sustainability, workforce, and export goals within a compact regional footprint.

The Singapore Food Story is a coordinated framework of research institutions, government agencies, and private sector partners working across three pillars:

Anchored by the Agri-Food Innovation Park at Sungei Kadut and research centers such as the Singapore Institute of Food and Biotechnology Innovation, the initiative provides shared R&D infrastructure, co-location opportunities for agri-tech companies, and direct funding for innovation through the SFA’s Food Innovation Product Commercialization Programme . These efforts are supported by cross-agency partnerships with Enterprise Singapore, A*STAR, and the Economic Development Board, aligning national policy with technology-driven food production goals (Singapore Food Agency, n.d.).

The three precedent networks (NZFIN, EIT Food, SFS) demonstrate that successful innovation ecosystems combine physical infrastructure with coordinated governance, flexible funding, and sustained stakeholder engagement. Their diverse models offer adaptable strategies for Hawaiʻi’s FPIN, particularly in structuring regionally distributed facilities, fostering public-private collaboration, and supporting entrepreneurs from earlystage ideation through export readiness.

Category

Network Structure

Primary Objectives

NZFIN

Regionally access hubs

Support SME export readiness

Key Facilities

Funding Model

Governance Model

Five regional specialized technical services

Government-supported infrastructure

Commercialization

Support

Relevance to FPIN

Public-private strong regional

Access to consultation, manufacturing

Place-based aligned with diversity

Regionally distributed openhubs

Centralized oversight with decentralized implementation

SME growth, scale-up, readiness Drive food innovation, sustainability, and entrepreneurship

regional hubs with specialized equipment and services

Government-supported infrastructure and partnerships

5–10 co-location centers per KIC (labs, campuses, incubators)

Centralized national strategy with multi-agency partnerships

Strengthen food security, develop future foods, advance food safety

EU-backed grants, public-private co-funding, competitive prizes

Agri-Food Innovation Park, R&D institutions like SIFBI

Public investment through SFA, with support from Enterprise Singapore and A*STAR

Public-private collaboration with regional coordination

Structured innovation principles with top-down metrics

Government-led, researchintegrated strategy pilot facilities, expert consultation, and scale-up manufacturing services

Place-based network approach with Hawai‘i’s regional

Structured pathways from research to market, post-funding tracking

Model for standardized evaluation, funding diversity, and layered governance

Industry co-location, funding for commercialization of novel products

Integrated innovation for food system resilience in landconstrained contexts

Regional economic development is a place-based strategy that leverages the unique assets, capacities, and aspirations of a given area to stimulate economic activity and improve long-term resilience. In Hawaiʻi, this requires moving beyond the state’s heavy reliance on tourism and hospitality towards industries that more closely reflect local priorities, resources, and identities. Agriculture, aquaculture, forestry, and product innovation represent alternative sectors that the Hawaiʻi State Legislature has identified as priority areas to pivot towards over the coming decades.

FPIN supports this diversification by investing in distributed infrastructure and programming tailored to each island’s strengths. By providing access to shared manufacturing spaces, cold storage, technical expertise, and market access support, regional FPIN facilities can provide the tools and resources needed to activate these opportunities, reducing barriers to entry for small and medium-sized enterprises. State-led investments reduce the risk for private actors, establish essential infrastructure, and ensure that economic assets remain beneficial to local communities.

A central component of this approach is the integration of workforce development and educational pathways that prepare residents to participate in and benefit from emerging economic sectors. FPIN facilities are designed not only as production spaces, but also as learning environments that connect students, entrepreneurs, and transitioning workers with applied training in food innovation, processing, and business development. This alignment between infrastructure and education ensures that regional investment is accompanied by talent development, strengthens the local labor pool and supports long-term economic self-sufficiency.

Together, these investments lay the foundation for more diverse, place-based economies that complement existing sectors, retain local value, and generate new capacities and pathways for economic resilience.

SECTOR GROWTH

GRANTS AND LOANS

ACCELERATOR PROGRAMS PRODUCT EXPORT

ACCELERATOR PROGRAMS

FOOD SYSTEM

VALUE ADDED PROCESS DISTRIBUTE

HOUSING

LAB/ TESTING PROCESS

EDUCATION

UHCC DOE

INTEGRATED CURRICULA

INTERN PATHWAY

WORKFORCE HOUSING

INCUBATION

RESEARCH INNOVATION

REGIONAL INNOVATION

KITCHEN

TEST PLOTS

Early education programs will introduce the fundamentals of food systems, farming, and environmental stewardship through classroom instruction and hands-on outdoor activities. This curriculum would prepare students for careers in agriculture, food science, and agribusiness, while fostering an understanding of the importance of local food production and sustainability for Hawaiʻi’s future.

Post-secondary institutions offer an array of certified kitchens and technical support to help students and entrepreneurs develop products from local ingredients. In addition to providing state-of-the-art equipment, these facilities offer hands-on training and guidance in food safety, packaging, and business development. Together, these programs and resources play a critical role in transforming innovative ideas into market-ready products.

FPIN supports small and with access to pilot-scale spaces that bridge the batch experimentation production. These facilities on product testing, food safety validation equipment, giving businesses launchpad to prepare compliance. Public-private may be necessary at facility operations, technical specialized equipment

and growing enterprises pilot-scale processing the gap between smallexperimentation and commercial facilities allow for handspackaging trials, and validation using semi-industrial businesses a critical prepare for scaling and Public-private partnerships this stage to support technical training, and equipment access.

As products move closer to market, FPINenabled contract manufacturing spaces provide access to full-scale, shared-use production lines. Entrepreneurs can produce at volume without having to own or operate their own facility. These spaces are essential for refining processes, increasing efficiency, and meeting the consistency, safety, and scalability requirements needed for wholesale distribution and export. At this stage, partnerships with private manufacturers and co-packers will likely be required to expand capacity and deliver cost-effective services to growing businesses.

As businesses grow, publicly constructed manufacturing warehouses will address a critical need in Hawaiʻi by providing affordable and accessible warehouse space for lease. By offering flexible leasing options, these warehouses can bridge the gap between smallscale production and full-scale manufacturing, helping position local businesses for success in both domestic and international markets. The development and operation of these facilities will depend on collaboration with private sector partners to ensure long-term viability and costsharing in infrastructure delivery.

and

At the heart of FPIN is a systems-based understanding that resilient regional economies emerge through the coordinated efforts of diverse and interdependent stakeholders. Identifying these actors is foundational to defining the network itself (Dentoni et al., 2022). In planning for successful FPIN facilities and components, four primary stakeholder groups must first be identified. These groups are:

Users: Such as farmers, producers, and entrepreneurs who directly engage with FPIN infrastructure and services.

Industry Experts: Researchers, technical advisors, and sector specialists who provide critical knowledge and innovation support.

Statewide and Island-based Communities: Community members and organizations whose participation ensures the network remains culturally grounded, locally responsive, and equitably distributed.

Educational Partners: Schools, colleges, and universities that support workforce development, applied research, and food systems education.

Policy Makers and Public Entities: Those who establish the regulatory and funding frameworks that enable network growth.

Each group brings unique assets and perspectives, and FPIN functions as an integrative platform to align these diverse interests toward shared goals. Mapping and activating these relationships is essential to building a distributed, collaborative system that advances local production, strengthens regional economies, and retains value across Hawaiʻi.

1. ADC facilities to be developed in Kekaha, on the island of Kauaʻi; a to-be-determined location on the island of Hawaiʻi; and additional facilities on the islands of Maui, Molokaʻi, and Oʻahu to expand regional support and enhance statewide coverage;

2. The foreign-trade zone facility in Hilo, on the island of Hawaiʻi;

3. The University of Hawaiʻi Maui College’s Maui Food Innovation Center (MFIC), on the island of Maui; and

4. The University of Hawaiʻi Leeward Community College’s Wahiawā Value-Added Product Development Center (WVAPDC) on the island of Oʻahu.

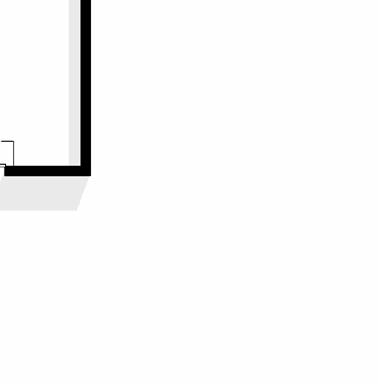

This diagram illustrates a generalized network of key actors and relationships within the FPIN. It shows how stakeholder groups including users, policy makers, industry experts, educational partners, and community members interact through flows of resources, services, and information. While not exhaustive, it provides a high level view of core system functions and connections across the statewide network.

Capital Investment/ Management Aid

Policy Makers (Legislature, County Council)

Mandates/ Initiatives

Facility Infrastructure (FPIN sites, cold storage, HPP, R&D kitchens)

Shared-Use Space, Cold Storage

Export & Logistics Services (Ports, customs, brokers)

Packaged Product

Primary Producers (Farmers, ranchers, aquaculture)

R&D/ Innovation

Community Advocacy Groups (Nonprofits, cultural leaders)

Research Institution (UH, CTAHR, private labs)

Product Development Support

Education & Training Programs (DOE K-12, UHCC, workforce dev.)

Public Education

Public Funding/ Programs Policy Influence/ Engagement

Grants/ Loans/ Incubation

Business Support Services (Grants, CDFIs, funders)

Raw Inputs/ Ingredients

Workforce Development

Curriculum & Technical Research

Distributors & Aggregators (Food hubs, transport)

Retailers & Institutional Buyers (Schools, hotels, grocers)

Processors and Manufacturers (Shared-use kitchens, co-packers)

Certification & Compliance Bodies (Food safety, organic, labeling)

Freight & Logistics

Freight Trade Regulations

Inspection/ Labeling Compliance

Compliance Requirements

Regulatory Agencies (DOH, FDA, USDA)

Scientific Validation/ Policy Input

Consumers (Local and international)

Oversight

The Strategic Planning Framework is a flexible, adaptable guide for developing food and product innovation facilities across Hawaiʻi’s islands. It was created in response to the need for a cohesive, statewide network that could respect and build upon the unique agricultural conditions, resources, and communities of each region.

The Strategic Planning Framework offers a clear, iterative process that supports decision-making at all stages of development, from early groundwork to facility design. This framework outlines broad steps that can be scaled and adapted based on local conditions. It encourages collaboration, asset mapping, stakeholder engagement, and integrated planning, allowing islands to move at a pace appropriate to their resources and needs.

The primary objectives of the Strategic Planning Framework are to:

• Strengthen Statewide Collaboration

• Support Inclusive Planning

• Adapt to Diverse Island Conditions

• Guide Decision-Making from the Ground Up

The University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center (UHCDC) has actively utilized this Strategic Planning Framework through the establishment of an inaugural FPIN facility in Wahiawā, Oʻahu, named the Entrepreneur Product Manufacturing Facility (EPMF). This facility is intended to be the first of the FPIN Facilities planned across Hawaiʻi, and serves as a tangible example of how the framework functions in practice. Detailed insights and outcomes from the Wahiawā implementation are discussed comprehensively in the “Implementation Process” and “Proof of Concept” section of this report, serving as a reference point and shared learning resource for future initiatives.

The Strategic Planning Framework comprises two interconnected, concurrent, and iterative processes:

Effective engagement ensures that facilities respond directly to the needs and expectations of local communities, businesses, and stakeholders. Engagement activities inform all aspects of the planning and design process, providing critical insights, validation, and refinement. Key activities within Engagement include:

1a. Stakeholder Identification

Identifying and categorizing the individuals, groups, organizations, and institutions that are impacted by, or involved in, the FPIN initiative.

1b. Outreach and Communication

Development and dissemination of materials, online platforms, and interactive tools to clearly articulate FPIN goals and facilitate continuous dialogue.

1c. Site Visits, Workshops, and Charrettes

Structured engagement sessions that involve stakeholders directly in the planning process, incorporating their input into decision-making and facility conceptualization.

1d. Engagement Synthesis

Systematic analysis and synthesis of collected data and feedback to inform strategic decision-making and facility planning priorities.

Facility Planning encompasses technical research, regulatory analysis, design decision-making, and professional design practices, all informed by the outcomes of Engagement. This phase transforms stakeholder-informed strategies into tangible, contextually appropriate, and operationally feasible facility plans. Key activities within Facility Planning include:

2a. Site Selection and Asset Mapping

Identifying suitable locations based on strategic metrics, existing community assets, agricultural inputs, land availability, and infrastructure.

2b. Precedent Research and Regulatory Analysis

Examine best practices, global precedents, health and safety guidelines, and regulatory considerations to establish high-quality and compliant facilities.

2c. Strategy Synthesis and Decision-Making

Combining insights from engagement and research phases to determine the facility’s programmatic needs, scale, users, and equipment requirements.

2d. Professional Design

Collaboration with professional consultants, design experts, and operations managers to create detailed design solutions, facility layouts, and construction documentation.

Engagement is an ongoing and iterative process that ensures planning and design decisions are rooted in the knowledge, aspirations, and needs of local stakeholders. The Engagement phase of the FPIN Strategic Planning Framework establishes the foundation for creating facilities that are community-responsive, industryinformed, and culturally grounded.

Engagement is particularly critical to the success of FPIN given Hawaiʻi’s geographic diversity, cultural richness, and distinct regional economies. Building trust, fostering long-term relationships, and integrating the expertise of those working within local food systems are essential to creating facilities that are resilient, sustainable, and embraced by the communities they serve.

The engagement process seeks to involve a broad crosssection of stakeholders, including farmers, value-added producers, food entrepreneurs, educators, researchers, institutional buyers, policymakers, and community organizations. Each group brings unique insights that shape how FPIN facilities can best support local business development, agricultural sustainability, and regional economic resilience.

Multiple methods are used to gather stakeholder input and facilitate collaboration, including site visits, workshops, design charrettes, interviews, surveys, and public outreach initiatives. These tools are selected and adapted based on regional needs to ensure participation is accessible, meaningful, and impactful.

Through continuous and adaptive engagement, each FPIN facility becomes not only a place of production but a reflection of community vision, collaboration, and innovation.

Within the Strategic Planning Framework, the Engagement Process is fundamental to ensuring that facility development reflects the real needs, opportunities, and aspirations of Hawaiʻi’s communities.

The objectives of the Engagement process are organized into three core goals:

Hawaiʻi’s agricultural producers face complex conditions—such as reliance on imports, high production costs, and limited infrastructure. The planning process will:

• Identify critical gaps in infrastructure, training, and support systems;

• Understand the operational realities and barriers faced by local entrepreneurs and agricultural producers;

• Develop strategies that strengthen local value chains and contribute to statewide goals for food security, economic resilience, and sustainability.

A thriving FPIN depends on the strength of its relationships across sectors, scales, and islands. Meaningful engagement ensures this by:

• Connecting educational institutions, industry experts, producers, and businesses to align workforce development with market needs;

• Fostering collaboration between small, medium, and large businesses to create opportunities for scaling, mentorship, and innovation;

• Elevating diverse community voices and regional perspectives that are central in the shaping of the FPIN.

Sustainable facility development requires that stakeholders are involved not only at the start but throughout the life of the network. Engagement aims to:

• Develop facilities, programs, and resources that are accessible, relevant, and responsive to community needs;

• Create decision-making processes that embed continuous stakeholder feedback and learning;

• Build long-term partnerships that enable FPIN facilities to evolve alongside Hawaiʻi’s agricultural economy and entrepreneurial ecosystem.

Effective stakeholder identification is a critical early step in the Engagement Process. While the broader FPIN vision includes a wide array of statewide partners, each region must define which individuals and institutions are essential to their own process.

Stakeholder identification is not a checklist but a dynamic, ongoing effort. This guide is intended to help designers ask the right questions, prioritize early outreach, and understand how stakeholder relationships evolve throughout facility planning. The process is adaptive and scalable. The goal is to support inclusive, informed engagement that reflects the needs and assets of each community.

These are not rigid steps but useful principles that can guide the discovery process across different island contexts:

Start with Key Sectors

Consider categories like producers, educators, regulators, food safety experts, distributors, and non-governmental partners. Use these as an initial framework for outreach.

Prioritize Practical Connections

Focus early efforts on stakeholders with direct relevance to facility design, workforce readiness, and compliance, such as State of Hawaiʻi Department of Health (DOH) staff, commercial kitchen operators, or agricultural extension agents.

Map Regional Assets and Gaps

Take stock of what already exists (e.g., facilities, services, producers), and note where there are missing voices or infrastructure challenges. This helps target engagement toward areas with the greatest need or opportunity.

Use a Networked Approach

Leverage existing relationships and events. Stakeholders often lead to new connections—site visits, conferences, and agricultural networks are good entry points.

Seek Diverse Perspectives

Include stakeholders across scale, background, and business stage. A range of viewpoints—from kūpuna to emerging entrepreneurs—can shape more relevant and equitable outcomes.

Engage Regulators Early

Initiate dialogue with permitting and compliance agencies as soon as possible. Early regulatory insight can shape design choices and avoid costly revisions later.

• Who is currently producing or supporting value-added products in your region?

• What food businesses, processors, or entrepreneurs could benefit from shared-use space?

• Which agencies oversee permitting, licensing, and food safety compliance?

• What educational institutions or programs offer training in culinary arts, agriculture, or business?

• Where does food aggregation, distribution, or resale already occur?

• Which organizations work directly with under served food entrepreneurs or small farms?

The matrix below serves as a flexible tool to help planners identify and prioritize stakeholders based on their function and relevance to early phases of facility planning. While not exhaustive, it provides a starting point for understanding which individuals and groups may be essential to include and when.

Stakeholder

Producers & Value-Added Entrepreneurs

Established producers; current or potential facility users

Regulators & Policy Agencies

Workforce Development & Education Institutions

Food Aggregators & Distribution Networks

DOH food safety staff; Building permitting offices

Early-stage entrepreneurs; small farmers exploring processing

County economic development offices; Agricultural development corporations

Community college culinary or agricultural programs; workforce training centers

Regional food hubs; cooperatives; major distributors

Community Knowledge Holders & Advisors

Kūpuna with land, farming, or cultural knowledge

DOE K-12 agricultural/ culinary education coordinators

Community members with future business interest

Funding & Business Support Entities

Agricultural loan offices; grant managers; CDFIs (community lenders)

Farmers markets organizers; small logistics companies

Cultural organizations; resilience hub leaders

Regional planners; zoning boards (if facility expansion is planned)

Private training nonprofits; apprenticeship programs

Informal aggregation groups; ad-hoc distribution efforts

Local nonprofits focusing on food security or youth programs

Small business incubators; venture accelerators

Private lenders; philanthropic foundations

This matrix is intended to be adapted based on local context. Not all stakeholder types or tiers will apply to every region and not all stakeholder types are covered. Use it to track who has been engaged, where gaps remain, and which relationships may become more important as the planning process evolves.

To support a consistent and adaptable engagement process across regions, the Strategic Planning Framework organizes methods into four primary categories: Outreach, Site Visits, Workshops, and Previous Relevant Engagement.

These categories offer flexible ways to engage stakeholders identified in earlier phases of the process. Each method can be adapted depending on who you are engaging, the goals of the interaction, and the resources available. No single method is required; instead, planners are encouraged to select and tailor approaches that are appropriate to their regional context.

Outreach includes any public-facing or direct communication efforts intended to raise awareness, share project goals, and invite participation. This method is especially effective when engaging community members, early-stage entrepreneurs, policy makers, or stakeholders unfamiliar with the project.

Common tools:

• Project websites and online surveys

• Printed flyers or mailers

• Presentations at community events or industry conferences

• Community websites, informational videos or physical exhibits

Site visits provide firsthand insight facilities, workflows, challenges, and They are an essential method for engaging professionals, regulators, educators, facility users. Site visits can be both (to learn) and relational (to connect and

• Educational institutions and workforce centers

• Shared-use kitchens, food hubs, manufacturing spaces

• Farms, producers, and processors

• Facilities in other regions or industries precedent research

insight into existing best practices. engaging industry educators, and potential both observational and build trust).

workforce training or processors industries for

Workshops are structured, participatory sessions that invite stakeholders to co-create aspects of the FPIN facility. They are well suited for gathering input from potential users, small business owners, educators, and community leaders. Workshops can range from informal design activities to targeted charrettes or stakeholder working groups.

Common formats:

• In-person or virtual design charrettes

• Hands-on activities (e.g., “Design Your Kitchen” sessions)

• Collaborative mapping or facility programming exercises

• Focus group-style discussions around specific user needs

In some cases, planners can draw on engagement work that has already taken place in the region. This includes surveys, interviews, public feedback sessions, or prior research efforts that align with FPIN goals. Referencing existing work reduces redundancy and respects participants’ time.

Examples include:

• Past community food system planning

• Surveys from previous agricultural or commercial kitchen initiatives

• Reports from partner organizations or county departments

• Educational program feedback or alumni assessments

Engagement methods are most effective when selected based on who is being engaged, what insights are needed, and what resources are available. This matrix offers general guidance for aligning methods to stakeholder types and planning objectives.

Not all methods are needed in every region. The purpose of this tool is to help planners think strategically about how and when to involve different voices in the process— whether that means a workshop with entrepreneurs, a one-on-one meeting with regulators, or drawing from existing community plans.

Engagement methods should be flexible and culturally responsive. Below are suggestions to help adjust these tools to fit different conditions:

Limited Staff or Time?

Use short interviews or focused round-table sessions in place of larger workshops.

Low Internet or Digital Access?

Prioritize printed flyers, in-person meetings, or community announcements instead of online surveys.

New or Unfamiliar Stakeholders?

Start with informal one-on-one conversations or site visits to build relationships before inviting broader participation.

Engagement Fatigue or Previous Planning Overlap?

Reference existing reports and community feedback before initiating new outreach. Acknowledge earlier efforts and show how current engagement builds on them.

Broad Region with Uneven Access to Facilities?

Consider regional approaches: conduct outreach in multiple districts, visit diverse facility types, and balance in-person with remote methods where necessary.

Producers & Value-Added Entrepreneurs

Flyers, social media, project updates, talk

Regulators & Policy Agencies

Workforce Development & Education Institutions

Email introductions, briefing memos, meetings, presentations

Presentations at campus events, outreach instructors

Industry Experts / Operators Conference panels, professional outreach

Food Aggregators & Distribution Networks

Emailed briefs, inclusion advisory outreach

Community Knowledge

Holders & Advisors

Community newsletters, flyers, radio, StoryMap

This matrix identifies common engagement methods on time, capacity, and community dynamics.

Outreach Site Visits

media, website talk stories

Facility tours, direct visits to kitchens or production sites

Workshops

Co-design sessions on kitchen layout, business needs

Previous Relevant Engagement

Surveys from past training programs

introductions, meetings,

One-on-one meetings at agency offices or facilities

Not typically used

campus to

Campus or lab tours, visits to culinary/ag programs

Collaborative curriculum planning workshops

panels, targeted outreach

Tours of peer facilities (local or international precedents)

inclusion in outreach lists

Tours of aggregation sites, ride-alongs with distributors

Technical roundtables or operations-focused charrettes

Notes from previous permitting or compliance reviews

Institutional reports, workforce strategy documents

Assessments from previous facility or program evaluations

Workflow mapping or packaging/labeling strategy sessions

Hub strategic plans or feasibility studies

newsletters, StoryMap

(Less common; only if connected to ag land or food spaces)

Visioning or values workshops, product pathway mapping

Community planning documents, prior food access work

matched with stakeholder types. Use it to guide early planning and decision-making. Methods should be adapted based

Engagement synthesis is the process of translating stakeholder input into actionable facility planning decisions. It connects what was heard, including needs, gaps, and aspirations, to what needs to be designed. Without structured synthesis, valuable input risks becoming anecdotal or disconnected from design and operational choices.

This phase helps to assess and interpret data collected during outreach, site visits, and workshops to identify shared priorities, infrastructure needs, and the scale of opportunity. This includes:

Understand whether the region would benefit from a small R&D facility, a mid-scale shared-use kitchen, or a largescale agriculture processing warehouse.

Identify whether the priority is business incubation, product development, storage and logistics, or manufacturing at scale.

Specifying

Assess production types, process flows, and technical needs based on what types of businesses are present or anticipated.

Determine how shared or private the facility needs to be—what level of access control, management, and customization is appropriate.

All core resources are shared, access is time-based

• Users book access hourly/ daily

• All equipment, space, and utilities are shared

• High coordination, low entry barrier

Examples of facilities that may operate this way:

• Community kitchens

• Shared cold storage

• Classroom or test labs used by multiple groups

Shared access, but with orientation, programs, oversight

• Access still time-based rotational

• May include onboarding, coaching, or guided scheduling

• Often includes business, technical, or educational support

Examples:

• Incubation kitchens

• Educational R&D

• Food hubs with centralized intake systems

The Shared Use Spectrum is a framework for evaluating how a facility access to fully private control—that can apply to a range of facility

Each position on the spectrum represents a different configuration from left to right on the spectrum, these elements shift from fully shared

Facilities do not need to conform strictly to a single category. A successful private suites or embedding a toll-processing service within a food The Shared Use Spectrum is intended as a flexible planning guide—supporting producers.

with user programs, or

time-based or onboarding, guided business, educational kitchens labs centralized

Facility services are provided on behalf of users (not user-operated)

• Shared equipment operated by trained staff

• Fee-for-service or toll models

• Users may not enter production zones

Examples:

• HPP or contract packaging centers

• Managed distribution hubs

• Campus-operated pilot processing labs

Tenants have private space but share infrastructure and systems

• Lockable units or suites within shared facility

• Shared use of utilities, logistics, admin systems

• More autonomy, moderate coordination

Examples:

• Leaseable suites in a kitchen incubator or ag warehouse

• Shared classroom with dedicated storage or lab bench

• Multi-tenant education or processing hubs

User owns and controls all aspects of the facility

• No shared access

• Fully customized operations

• High investment, maximum autonomy

Examples:

• Privately owned manufacturing facility

• Independent distribution center

• Standalone classroom or test site operated by one entity

facility operates across five degrees of shared use. The spectrum describes a range of operational models—from fully shared cility types; kitchens, warehouses, educational spaces, aggregation hubs, or R&D centers.

configuration of shared elements, such as equipment, physical space, infrastructure, staffing, and administrative systems. As planners move shared to fully private.

successful FPIN site may combine elements from multiple categories—for example, combining an open-access kitchen with semifood hub. New or hybrid categories may also emerge over time in response to specific regional needs or innovative partnerships. guide—supporting informed, place-based decision-making that can scale with the needs of Hawaiʻi’s diverse communities and

The facility planning phase of the Strategic Planning Framework transforms stakeholder engagement into concrete spatial and operational strategies. Building on input from producers, educators, and industry experts, this phase outlines the analytical tools, research methods, and technical criteria necessary to shape facilities that are responsive to local conditions and aligned with regional and statewide goals.

Facility planning is not a one-size-fits-all process. Just as Hawaiʻi’s communities vary by island, crop profile, and infrastructure capacity, the facilities that support them must be adaptable, contextually appropriate, and strategically located. This section provides a flexible yet structured roadmap to support that process—helping planners make informed decisions about site selection, facility type, layout, equipment, and operational model.

By establishing shared methodologies such as asset mapping, precedent analysis, and suitability screening, this section ensures that all future FPIN sites are guided by consistent principles while remaining adaptable to regional needs. This includes both early-stage research and high-level design criteria, as well as tools for evaluating program requirements and technical feasibility.

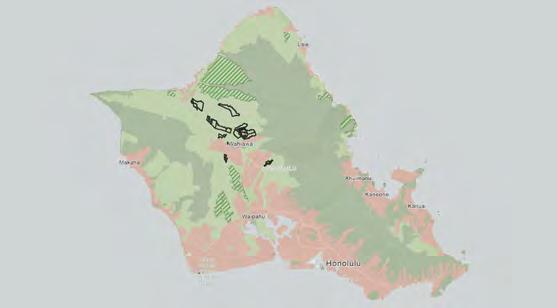

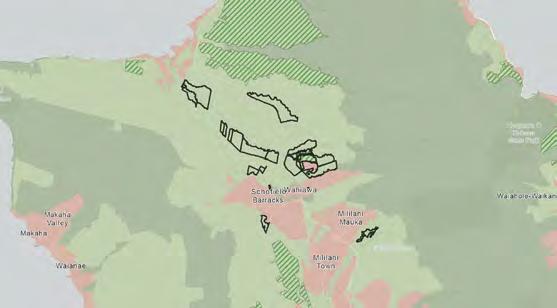

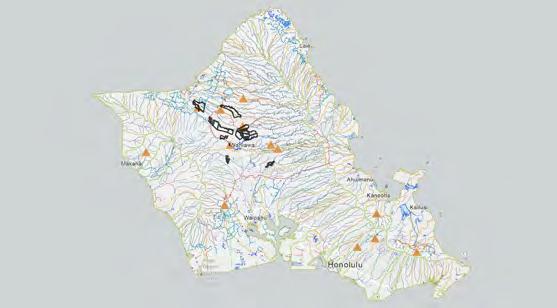

In the FPIN pilot project on Oʻahu, this framework was used to assess agricultural assets, analyze community and regulatory inputs, and develop a conceptual design for a shared-use manufacturing facility. Lessons from that process have informed the planning guidance offered in the following pages.

Facility planning, as defined here, is more than a technical exercise; it serves as the bridge between vision and implementation. It ensures that each FPIN facility is designed not only to meet current needs but also to evolve with its users, technologies, and regional economies.

Site selection is a critical first step in facility planning, as it establishes the physical context within which all subsequent design, operations, and business strategies must perform. A well‐chosen site optimizes access to raw materials and markets, aligns with regional economic assets, meets zoning and utility requirements, and supports community goals.

The FPIN site selection process is organized into two distinct tiers. Tier A uses a series of filters to eliminate parcels that are unsuitable for development due to issues such as ownership constraints, zoning incompatibilities, or poor integration with existing agri-business infrastructure. The parcels that advance to Tier B are then evaluated using a set of suitability metrics that quantify how well each site aligns with FPIN’s operational, logistical, and strategic goals. This two-tiered structure produces a list of candidate sites for which community members, leaders, and designers can then evaluate and ultimately choose the final preferred site for the future FPIN facility.

Tier A serves as the initial screening criteria in the FPIN site selection process, systematically narrowing the full universe of parcels to only those that are viable for public-sector food and product innovation infrastructure.

The first filter evaluates land control, requiring that parcels be either state-owned or readily acquirable from a single large landowner. This ensures that sites can be secured and developed under a public-interest mandate.

The second filter verifies agricultural zoning or compatibility, ensuring that the proposed facility use can occur with minimal regulatory friction.

The third filter requires proximity to agribusiness assets, including nearby crop lands, existing food hubs, educational pilot kitchens, and agricultural research nodes. This ensures that the selected site is embedded within an existing production and innovation ecosystem.

The final filter excludes all parcels that are identified as in a potentially hazardous area, including sea level rise zones and areas prone to erosion and flooding.