Hālawa Correctional Facility

Proof of Concept Study

June 2024

Prepared for:

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

By:

The University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center

Proof of Concept Study

June 2024

Prepared for:

Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation

By:

The University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center

We would like to thank the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation for this opportunity, especially Director Tommy Johnson, Wayne Takara, Terry Visperas, and Hal Alejandro for their guidance and support throughout this continuously evolving process. Special thanks to Warden Shannon Cluney at the Hālawa Correctional Facility (HCF) and his staff, Correctional Industries, and Aaron Ackerman from Bowers & Kubota.

Project Team:

Cathi Ho Schar FAIA, Associate Professor, Principal Investigator

Creesha Layaoen, Research Associate

Dean Matsumura, Research Associate

Jonathan “Malu” Stanich, Research Associate

Kiana Dai, Student Assistant

Kaylen Daquioag, Student Assistant

Thanh Nguyen, Student Assistant

Haixin Ruan, Student Assistant

Kaimana Tuazon, Student Assistant

Hannah Angelika Valencia, Student Assistant

Introduction

In 2017, the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (formerly known as the Department of Public Safety), contracted the University of Hawaiʻi Community Design Center (UHCDC) to co-develop a Strategic Sustainability Master Plan for correctional facilities statewide. UHCDC gathered teams from the School of Architecture, College of Engineering, and Social Science Research Institute to work in collaboration with a separately-contracted professional team led by Bowers & Kubota (BK). The outcomes of this planning effort led to three research reports prepared by UHCDC and this proof of concept study for the Hālawa Correctional Facility. This proof of concept study applies the findings from planning, research, and engagement to the design of three underutilized spaces within the prison as pilots for healing-center facility improvements.

Overview

The Hālawa Correctional Facility (HCF) is a medium security prison that houses a little under 900 incarcerated individuals and employs approximately 200 correctional staff. HCF sits on a 31-acre lot near Kamanaiki Stream in the upper part of Hālawa Valley. HCF is made up of two facilities: the medium security

facility (MCF) which was built and opened in 1987 and the special needs facility (SNF), the former City and County Jail, which originally opened in 1961 and was transferred to the State in 1975.1 These facilities are located at 99-902 Moanalua Road, ʻAiea, Hawaiʻi, 96701.

The facility is situated in Hālawa in the easternmost ahupua‘a of the moku (or kalana) of ‘Ewa. Before the introduction of Western values, ideas of land ownership, as well as commercial endeavors of the 19th century, Hālawa was centered around the natural resource and wahi pana of Pu‘uloa (Pearl Harbor), with its extensive shoreline and estuaries that were home to numerous loko i‘a (fishponds) and lo‘i kalo (pondfield complexes).2 Hālawa was known for its abundance in resources and ancient sites. The valley’s landscape included varieties of upland kalo, ʻawa groves, medicinal herbs, feathers for cloaks, and pili grass for thatched homes, and dozens of fishponds. It was also dotted with ancient temples, house sites, cave burials, and a number of sites associated with royalty.3

The current boundaries of the Hālawa ahupuaʻa extends from Ford Island Bridge, northeast along the ridge line between ‘Aiea and Hālawa Heights neighborhoods, to the top of the Koʻolau Mountains, parallel to the H-3 highway to the corner of Moanalua Ahupuaʻa, then southwest through Moanalua Freeway and includes the ʻewa end of the Honolulu International Airport “reef runway.” 4

Today, Hālawa encompasses Hālawa Valley, ʻAiea, Crosspointe, Hālawa Heights, Foster Village, Waimalu, Salt Lake, Puuwai Momi and Pearlridge. These neighborhoods consist of various residential housing types (condominium, low-density, public, military),

and high-density commercial buildings.5 The nearby Pearl Harbor Naval Base, Camp Smith, and Red Hill Fuel Tanks represent the high level of military use in the area. Several large projects including the Aloha Stadium redevelopment and the relocation of the Oʻahu Community Correctional Center will continue to shape the region in the next decade and could present opportunities for alignments with HCF.

HCF is the largest prison facility in the State of Hawaiʻi that houses general population inmates. A portion of that population is sent to the Saguaro Correctional Center, a multi-level security facility in Arizona that is contracted to house inmates from DCR.6 The Saguaro facility only accepts individuals who meet

certain behavioral requirements, leaving HCF with a population of men with behavioral risk factors and those who are en route to or from Arizona. These men are kept closer to their families, however they are subject to harsher physical conditions, more acute staffing shortages, and access to significantly fewer programs.

The majority of the Hālawa Correctional Facility population is part Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (55.8%).7

This over representation of Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders remains consistent throughout Hawaiʻi’s criminal justice and correctional system. Numerous task forces have called for a new vision for corrections that supports traditional Hawaiian cultural practices and restores individuals to their families, community, and the land (ʻāina).8 This proof of concept study explores how small pilot projects can begin to embed this into an existing facility.

The 31-acre property is zoned as Residential District (R-5) and is adjacent to other zones such as Intensive Industrial (I-2), General Agriculture (AG2), and Restricted Preservation (P-1). The property abuts undeveloped hillside owned by the Queen

Emma Foundation, leased by Hawaiian Cement to the North and industrial properties to the South.9 Hillside blasting at the nearby quarry causes periodic seismic disturbances.10 The Medium Security Facility (MCF) consists of four (4) living modules, a Special Housing Unit (SHU), an infirmary, and support entities that include Correctional Industries, Food Service, Chapel Services, a Learning Center and an indoor Gymnasium. Each module houses approximately 100 individuals, within an 80 square foot cell, typically shared by two individuals.

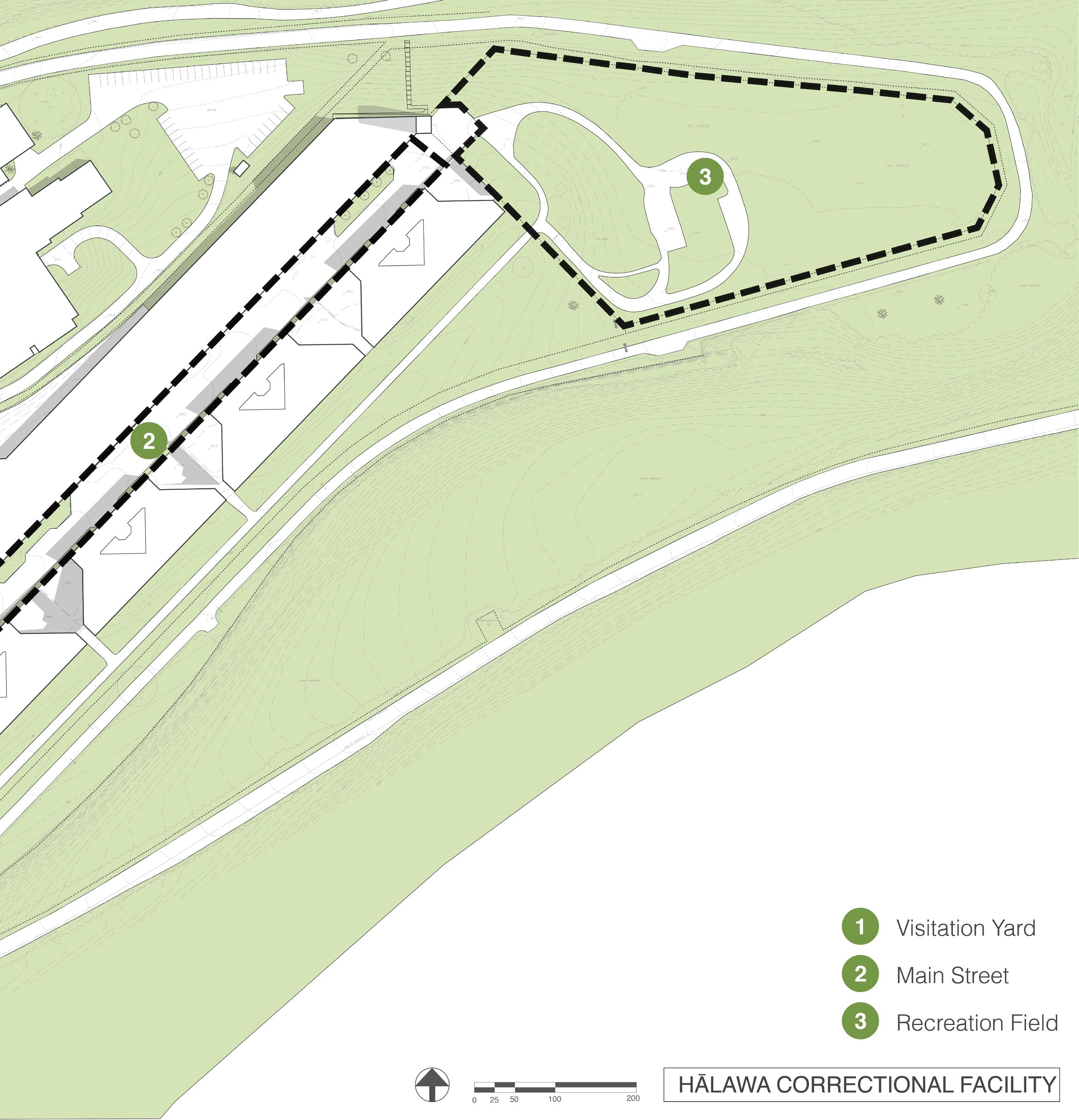

As a result of their strategic planning process, Bowers & Kubota selected the HCF facility and three underutilized sites within it, for this proof of concept study. The three focus areas are shown and described below.

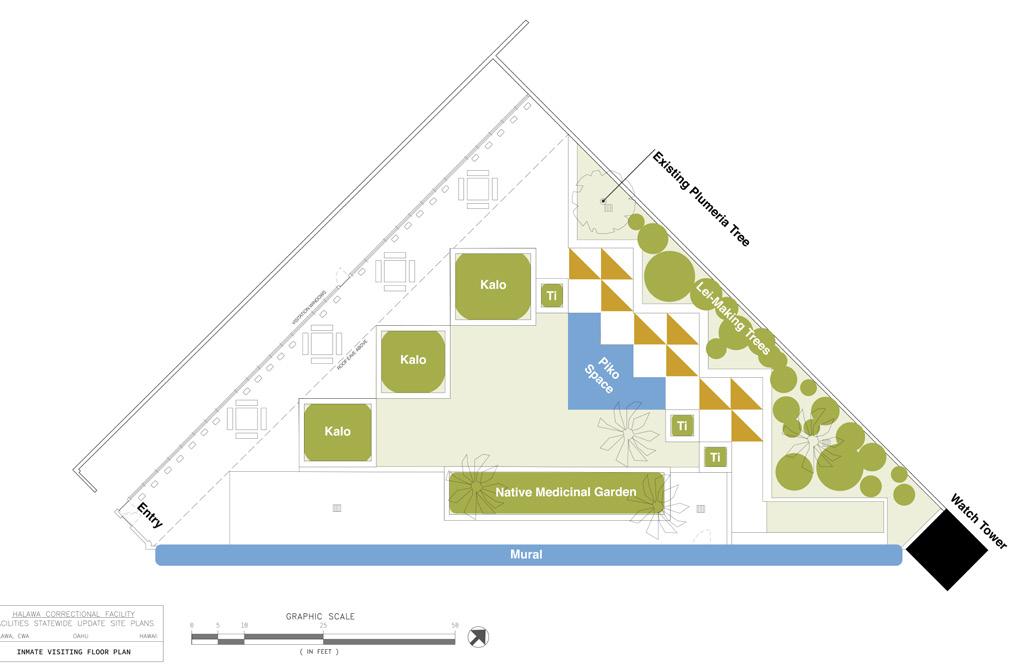

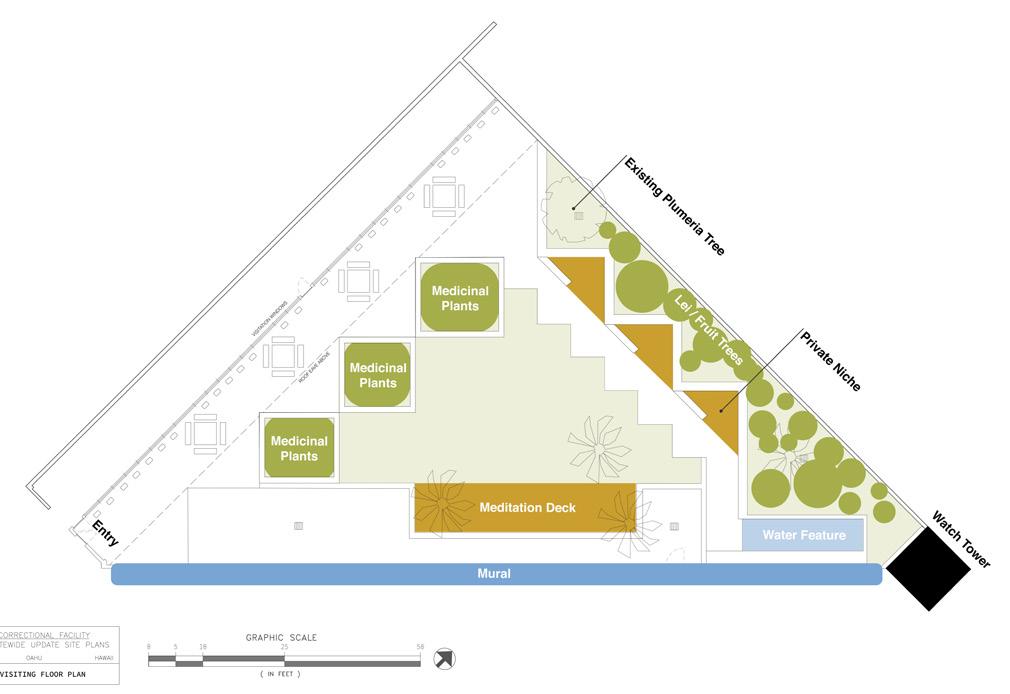

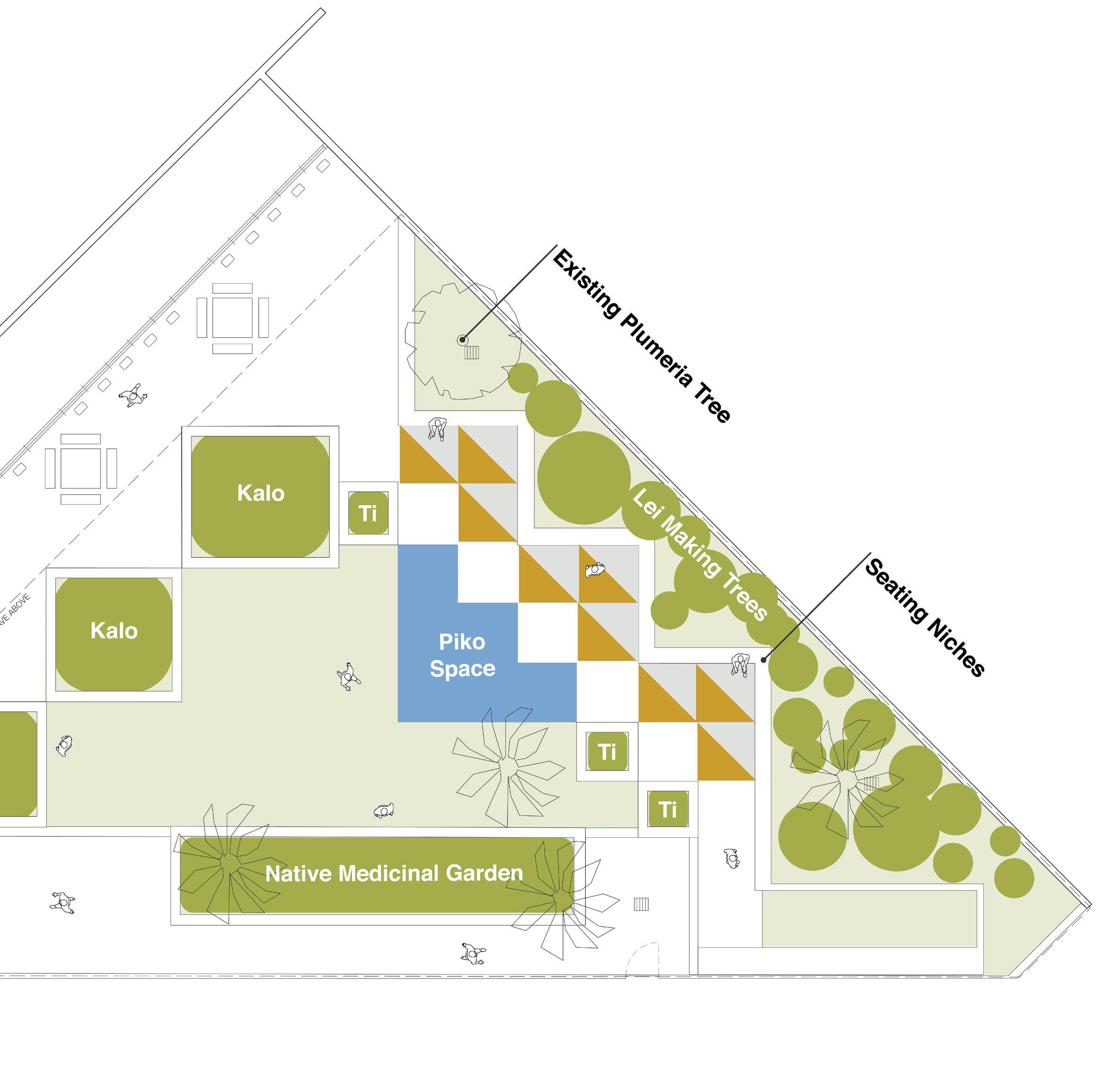

The visitation yard is a triangular open air courtyard adjacent to the facility’s entrance. Currently, the visitation yard is not in use because contact visits have not resumed. There are over 20 visitation windows and 4 concrete picnic tables in the space. The planters in the yard are overgrown with weeds. The grass in the center is dead. The trees are surviving. There is no security screen above the courtyard to completely secure the area, however the courtyard is fully visible from the observation tower.

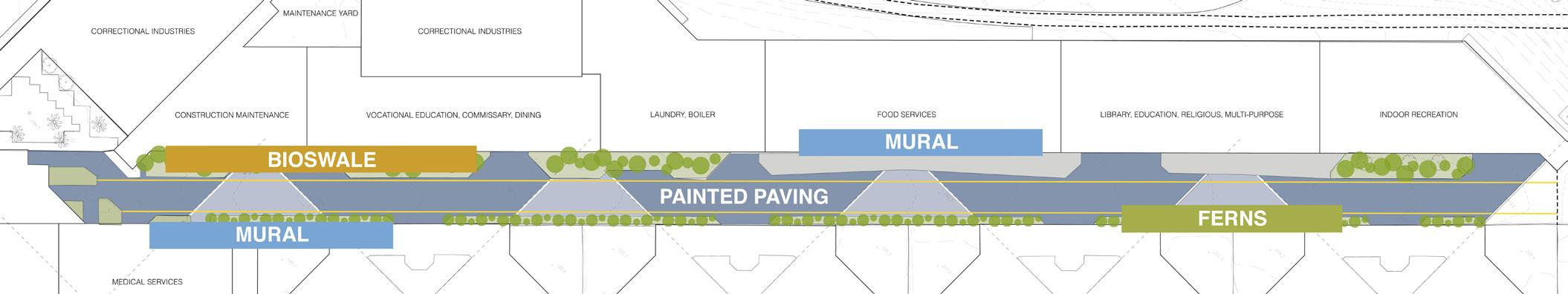

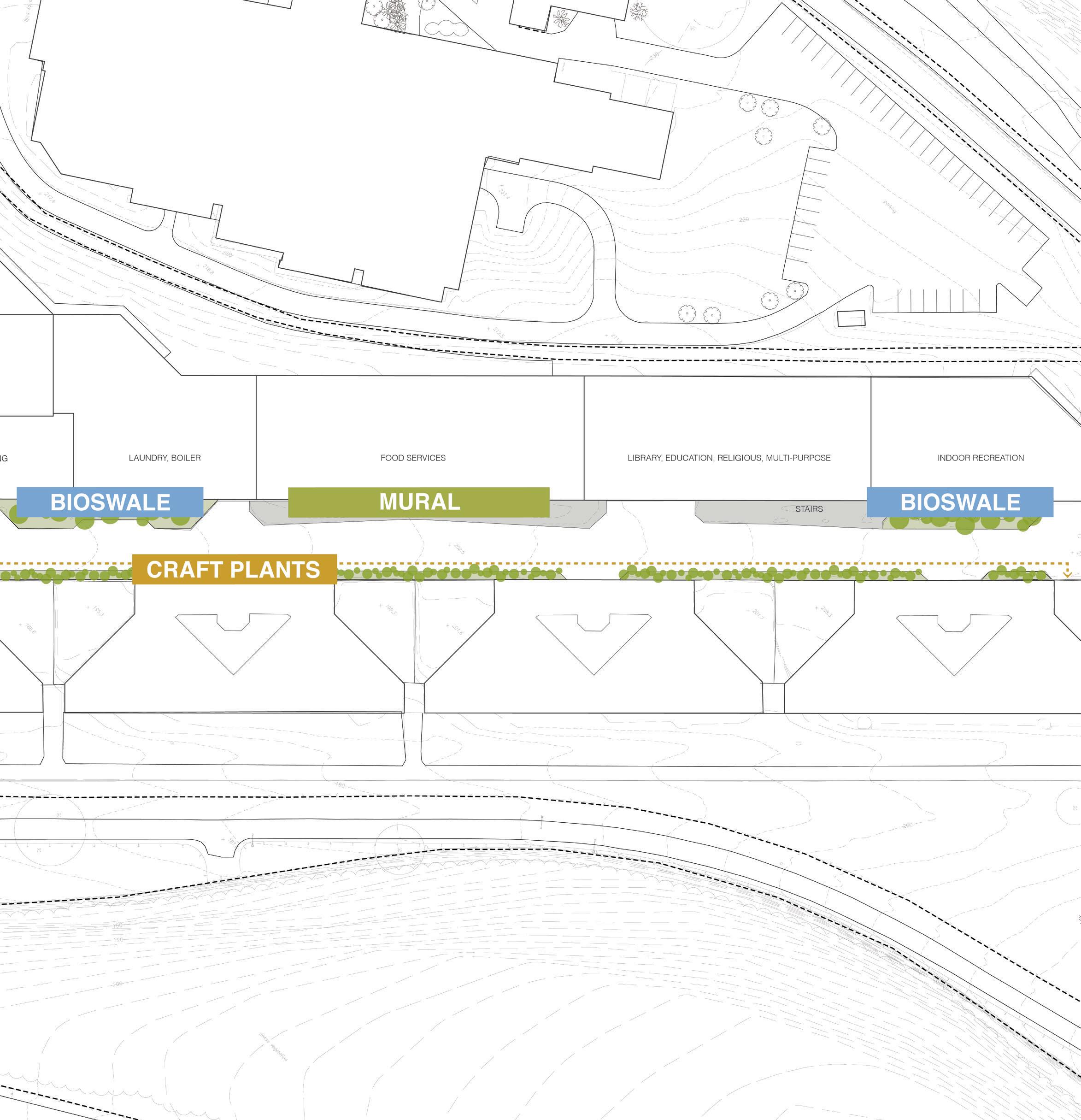

Main Street is the primary thoroughfare within the facility, which runs along the center of the campus, dividing it into two halves: the programs and services building to the West and the housing modules to the East. Along the thoroughfare, large landscape areas abutting the buildings remain mostly barren with a few ti leaf plants as the exception. Some of these areas are prone to flooding.

The recreation field is located at the easternmost part of the property at the end of Main Street. It is currently not used because the security fence needs repairs. A new fence project is currently in the design phase, which will secure a small part of the area. The concrete ball courts connected to each module are the only other recreational space that the men have access to.

Prior to this UHCDC HCF-focused work, Bowers & Kubota engaged every correctional facility warden and staff to identify future capital improvement projects based on immediate needs and longer term plans. UHCDC continued this engagement with HCF, with multiple meetings with the HCF warden, staff, incarcerated men, members of Bowers & Kubota, Correctional Industries, and DCR. This feedback was used to develop design principles that were then applied to the final proof of concept designs for the project.

The principles are:

• Start with low intensity, low maintenance projects that can succeed.

• Introduce spaces that support cultural values, knowledge, and practices, especially through art and music.

• Jointly invest in the health and wellbeing of staff and incarcerated individuals.

• Bring families together in environments designed for keiki and kūpuna.

• Create educational, productive, and performative landscapes that offer learning and job training opportunities.

This proof of concept study applies the findings from planning, research, and engagement to the design of three underutilized spaces within the prison to enhance rehabilitation of residents and wellness of staff.

The visitation yard is an unused, completely enclosed, and secure outdoor space that was re-envisioned as a "kīpuka" or refuge for staff and residents. Murals, loʻi, lāʻau lapaʻau plants, seating, and a stage area support self-reflection and expression, and connections to ʻohana, ʻāina, and akua in a safe and maintainable setting.

The main street proof of concept design focuses on normalizing the pedestrian experience for the HCF men, as this is the central open space used to access most of the spaces within the facility. Improvements to the main street include re-purposing the barren existing planters with bioswales to help retain water and reduce flooding. The planters would be planted with several low-maintenance plants that also have historical and cultural significance. The design and

maintenance of these native bioswales would provide incarcerated individuals with the opportunity to develop skills in sustainable landscaping.

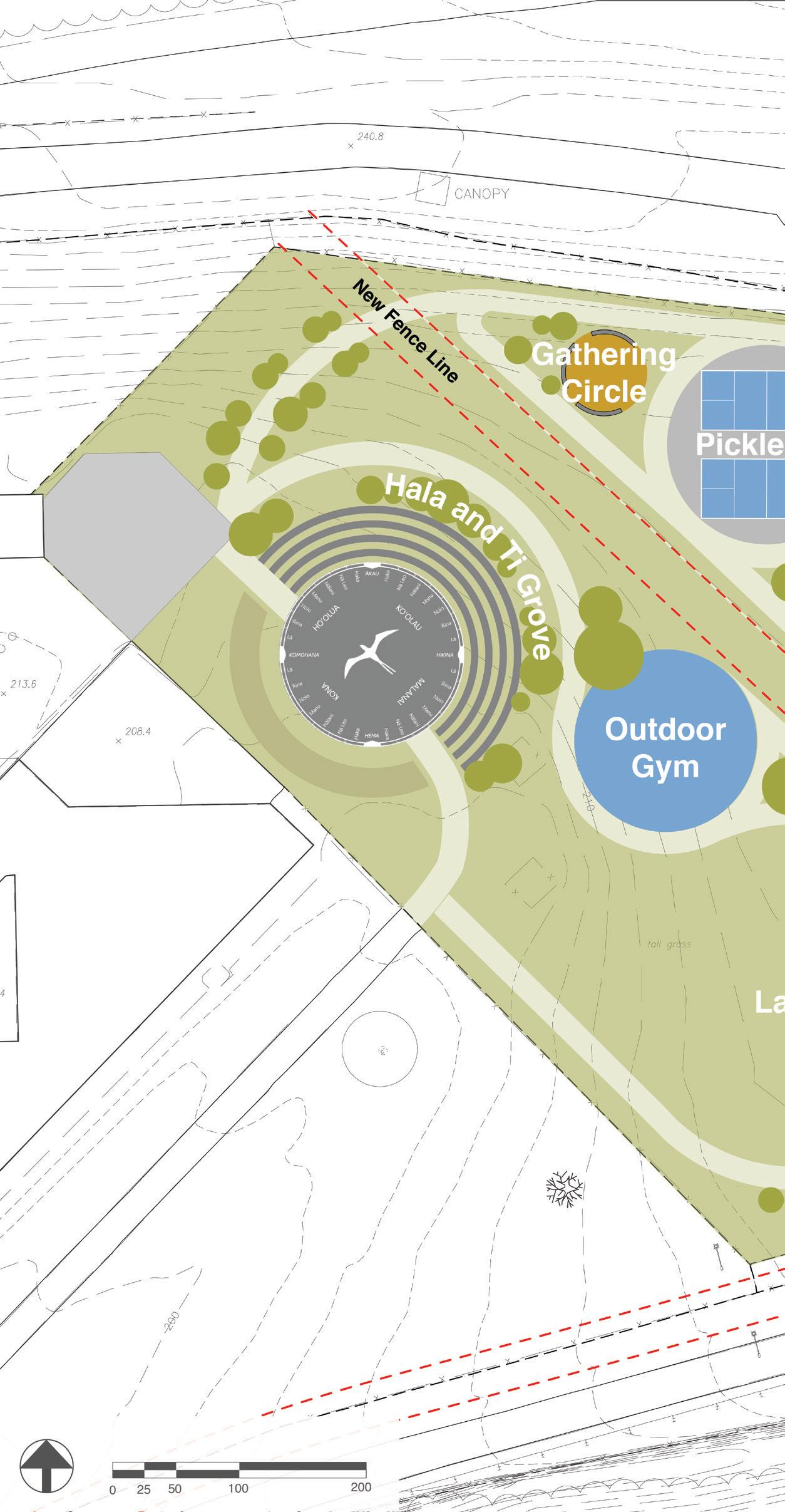

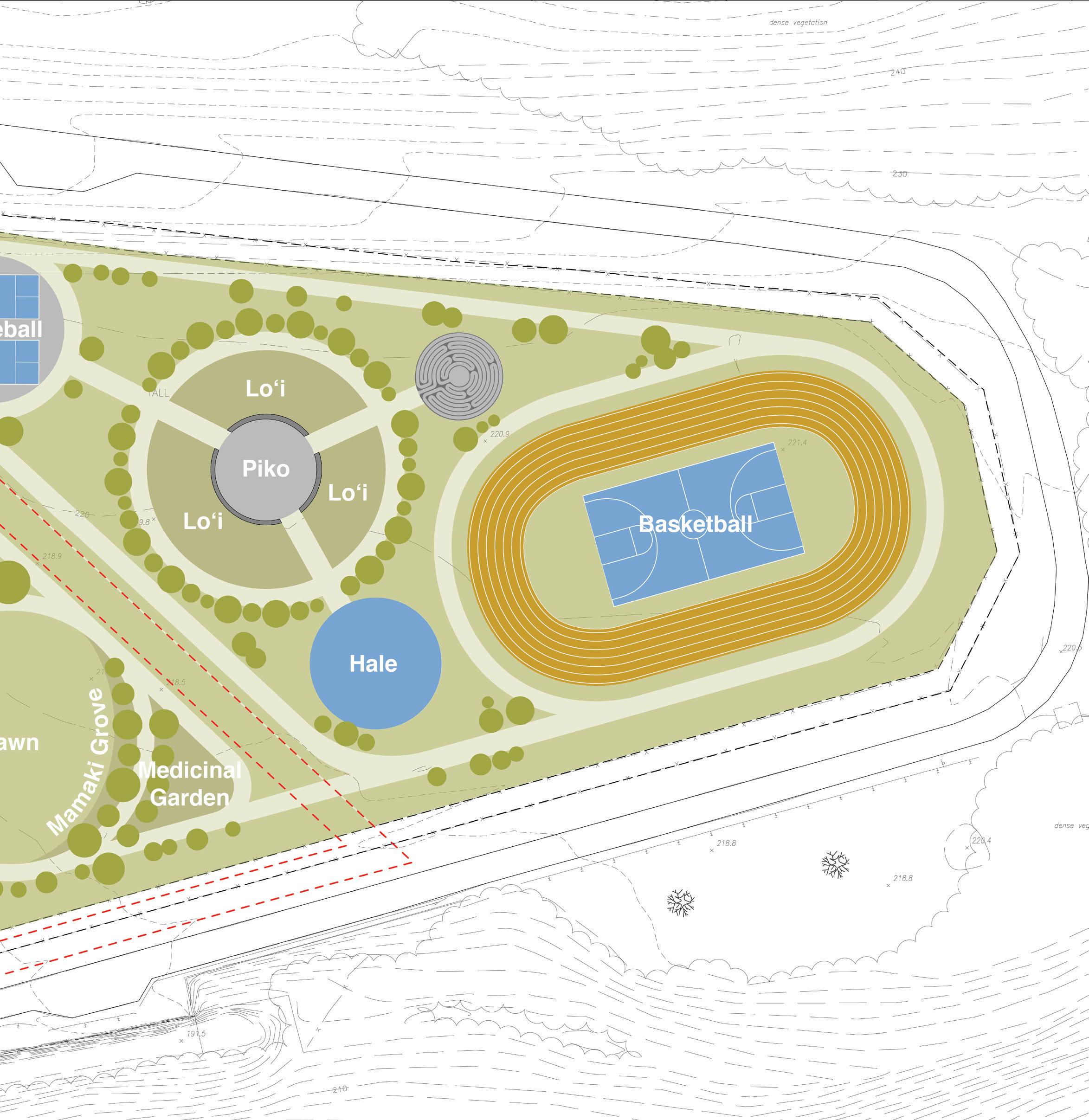

The recreation field has long been an underutilized area of interest for HCF, which has been waiting on funds to replace the perimeter fence. With the fence work underway, this proof of concept design proposes simple performance, sporting, gathering, and reflecting areas that allow staff and individuals to strengthen their physical, mental, and social skills.

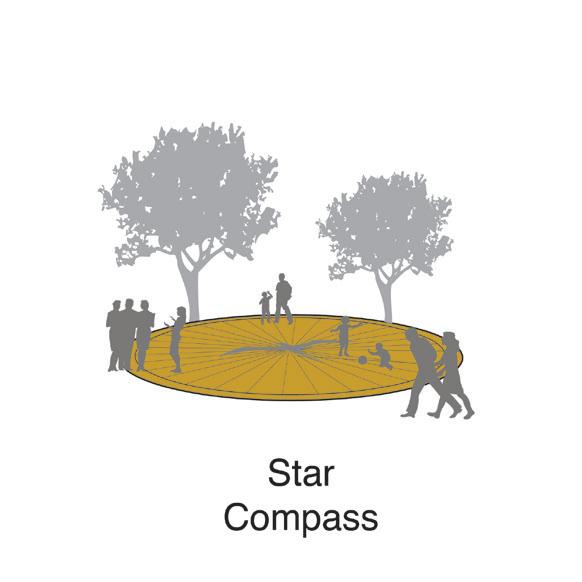

Phase 1 looks at the area within the proposed new fence line, and proposed a Hawaiian Star Compass stage, an exercise equipment area, a medicinal garden, Mamaki grove, and a continuous walking path. Phase 2 would expand and provide additional types of spaces that promote health and recreation.

The visitation courtyard and main street improvements were identified as priorities for the facility. Recommendations for next steps include: research other art and mural programs and partners, request appropriations for healing-centered proof of concept projects in the prison, develop maintenance criteria,

hire a design-build team for implementation, host staff family events in the new visitation courtyard to inaugurate the new space, strategically reintroduce family contact visits for eligible incarcerated persons, and with success, expand to other underutilized spaces. There are examples and evidence of the positive impact of these types of spaces in Hawaiʻi and across the nation, to support these small investments that enhance the wellbeing of everyone living and working in the facility.

2.0 Methods

1 2 3 4

Strategic

Strategic

This proof of concept work for HCF is connected to UHCDC studies that were completed between 2018 and 2020, all intended to support the Strategic Sustainability Master Plan led by Bowers & Kubota.

The UHCDC’s social enterprise study identified bee-keeping as a low cost, high-yield option for new programs. The waste and recycling study produced diverse recommendation specific to each facility. The cultural competence study resulted in a framework that looked at agency alignment, community partnership, equitable representation, holistic health, and relationship-building as core goals.

In parallel to this UHCDC work, Bowers & Kubota engaged wardens and staff at all eight facilities to solicit information and perspectives to identify near, mid, and longer term capital improvement projects for each facility and for the system. See the engagement diagram (Figure 9).

The information that Bowers & Kubota collected from this process, through meetings and surveys, led to the identification of HCF as the focus of this proof of concept design work. The areas within the facility were also pre-selected by Bowers & Kubota, based on their communications with the HCF team.

CULTURAL PRACTITIONER

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

KAUAʻI COMMUNITY CORRECTIONAL CENTER

MAUI COMMUNITY CORRECTIONAL CENTER

Figure 9. Diagram of engagement.

HAWAIʻI COMMUNITY CORRECTIONAL CENTER

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

UHCDC PROOF OF CONCEPT DESIGN

INCARCERATED INDIVIDUALS

HĀLAWA CORRECTIONAL FACILITY

BOWERS + KUBOTA

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

WOMEN’S COMMUNITY CORRECTIONAL CENTER

OʻAHU COMMUNITY CORRECTIONAL CENTER

WAIAWA CORRECTIONAL FACILITY

KULANI CORRECTIONAL FACILITY

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

CORRECTIONAL INDUSTRIES

Building on UHCDC’s Cultural Competence Study, Social Enterprise Study, Engineering Waste Study and Bowers & Kubota’s strategic and planning work.

The proof of concept designs for the three focus areas are based on design principles that emerged from multiple research efforts. The first research process began in 2018, with a series of interviews with cultural practitioners, scholars, and leaders to develop a cultural competence framework and toolkit

for correctional planning and design. This framework and toolkit provided foundational self awareness, knowledge, and tools to develop the process and outcomes of this work.

On August 9, 2022, UHCDC met with Hālawa warden and staff members to visit the site and understand priorities and perspectives.

UHCDC hosted a second workshop on August 11,

2022 with Bowers & Kubota, their biophilic consultant, Correctional Industries, and DCR. Participants brainstormed potential programming and design strategies for each focus area, and then ranked them through dot voting. These ideas were then synthesized into 2-3 conceptual designs for each area, 10 total. UHCDC presented these designs to HCF staff on July 10, 2023, which included the warden, facility superintendent, and chief of security.

Kumu Malina Kaulukukui, a social worker, cultural practitioner, and kumu hula who taught women to dance at the Women’s Community Correctional Center, joined the team to share her insights on the design of these spaces for cultural practices and healing.

A third workshop was held on August 2, 2023 with the HCF warden and 9 incarcerated individuals who shared their stories and perspectives, as well as feedback on desired life skills, job skills, program incentives, and what they need most to succeed. The warden generously hosted this over a three hour period, which allowed the team to use sorting cards for small group conversations, dot votes for prioritizing, and sticky notes for brainstorming. This data was aggregated and documented anonymously.

The team engaged the men to develop understandings, not research findings. What the team understood, from the 9 men, was that family came to the top of their priority lists. The most powerful and raw moments in these conversations relate to family. Family visits, however, are something universally supported by the staff, due to concerns

about contraband. The desire for spaces that promote culture, art, and music is shared by staff and incarcerated men. Same for health and wellbeing. There was also interest in learning about technology and sustainability to be better prepared for the outside world and to be able to give back in meaningful ways. All this led to the development of the following design principles for this project.

1. Start with low intensity, low maintenance projects that can succeed.

2. Introduce spaces that support cultural values, knowledge, and practices, especially through art and music.

3. Jointly invest in the health and wellbeing of staff and incarcerated individuals.

4. Bring families together in environments designed for keiki and kūpuna.

5. Create educational, productive, and performative landscapes that offer learning and job training opportunities.

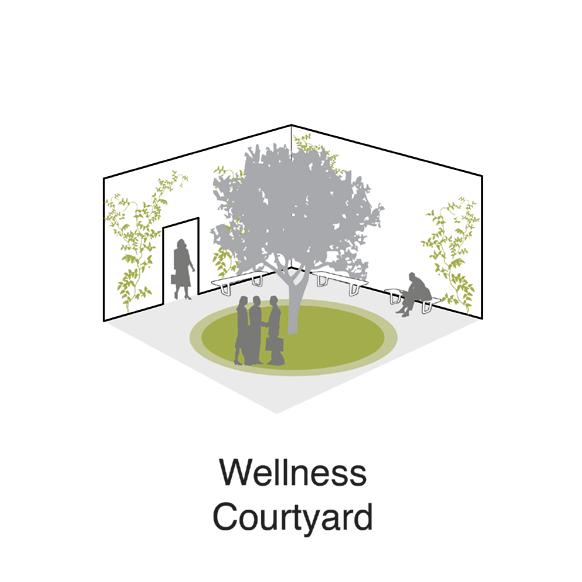

Wellness Courtyard Family Playscape

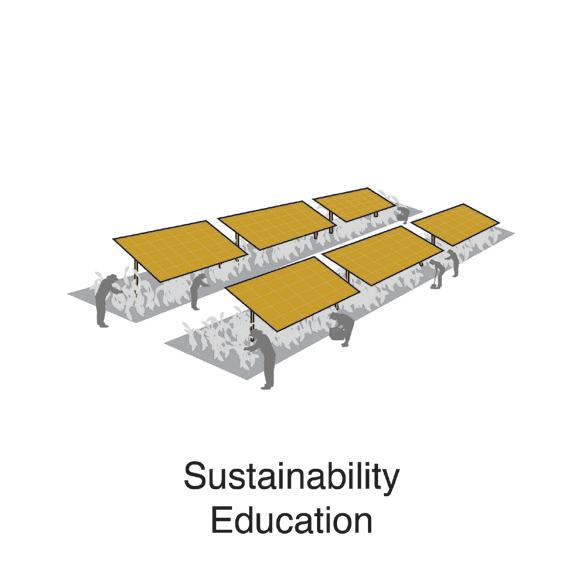

Sustainability Campus

Health and Recreation Landscape

3.0 From punitive to healingcentered.

The visitation courtyard is re-imagined as a wellness courtyard, or a kīpuka, used by correctional staff, incarcerated individuals, and family members of both, to reconnect individuals to their inner selves, each other, their ʻohana, their culture, and their place. As an unused, enclosed, and secure space, improvements to the visitation courtyard would not disrupt operation or require additional security.

[Hawaiian Dictionary, Pukui] kī.puka (n.)

1. Variation or change of form (puka, hole), as a calm place in a high sea, deep place in a shoal, opening in a forest, openings in cloud formations, and especially a clear place or oasis within a lava bed where there may be vegetation.

“In the Hawaiian mind, a sense of place was inseparably linked with selfidentity and self esteem.”

- George Kanahele

The square planters would be re-purposed for kalo beds, other planting areas would be dedicated to lāʻau lapaʻau plants, lei making trees, and a small performance or gathering area. The space could be used by incarcerated individuals only, incarcerated individuals and their family members, staff only, or staff and their family members.

Hālawa is a blank canvas.

The courtyard is enclosed by tall, unpainted concrete walls. The wall facing the visitation windows would feature a mural depicting the cultural history of Hālawa Valley or other themes, collaboratively conceptualized by artists and HCF men. Partnerships with individual artists, State Foundation for Culture and the Arts, POWWOW!, or UH, and joint applications for external grants and donor support, would open up alternative sources of funding for labor and materials.

The design proposes an informal stage area, where storytellers, magicians, or singers might come for a family day or where cultural and spiritual rituals might take place.

Reports show that correctional officers have a life span of 12-14 years less than the average individual.11

Research data shows high rates of trauma, depression, anxiety, divorce, and suicide amongst correctional officers, as well as significantly decreased life spans. As a kīpuka, the courtyard would be reserved for staff at different times of day, to provide respite, alleviate stress, and reduce absences and vacancies.

Main Street is a wide concrete avenue separating two continuous concrete buildings. Men circulate up and down this street to access education, food, or health services. The corridor is envisioned with bioswales filled with native plants and painted graphics that soften the only “civic” open space that the men experience day-to-day. The native plants included are pili grass, kalo, ʻilima, and loulu. All of these plants have historical, cultural significance and uses and can help inmates learn and connect to places.

“Mohala i ka wai, ka maka o ka pua. Flowers thrive where there is water, as thriving people are found where living conditions are good.”- ‘Olelo No‘eau

The painted ti leaf lei is meant to be a supportive environmental graphic rather than a punitive one. The ti leaf symbolizes blessings, protection, appreciation, and respect. A different re-imagining of the yellow line could also be developed through a partnership with an artist and painted with the help of HCF men.

Sustainable practice programs reduce environmental impacts while also providing opportunities for practical training and skills.12

The empty planter areas would be used as bioswales to retain water, and to support low maintenance flood tolerant native plants. This could be integrated into a sustainability program that teaches native landscaping and green infrastructure.

planters.

Studies have shown that art and photographs displaying nature scenes help in the reduction of stress, blood pressure, pain management in prison staff and inmates.13

Certain entries could be painted and color coded to help break up the continuous concrete walls, and to help distinguish one part of the facility from the others. For example, the kalo leaves and green entryways were shown for the cafeteria area.

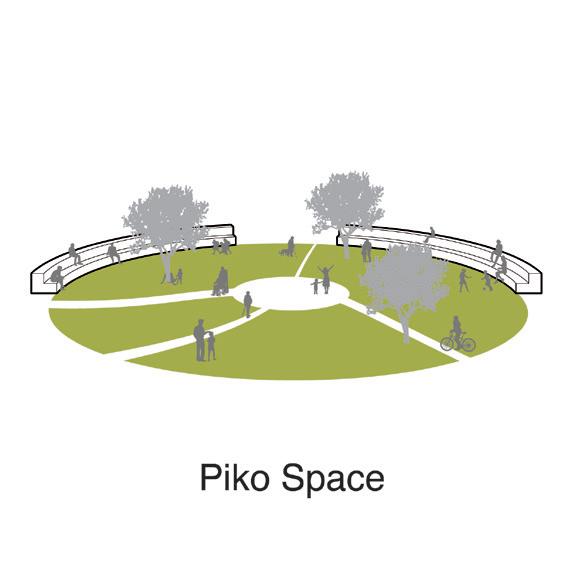

The Recreation Field consists of programs and spaces that encourage individuals to be active and healthy by taking an approach that connects these aspects in a continuous loop. Further demonstrating the importance of healing and connection, spaces such as performance, sporting, gathering, and reflecting areas, are provided to give individuals opportunities to strengthen their physical, mental, and social skills in an outdoor setting.

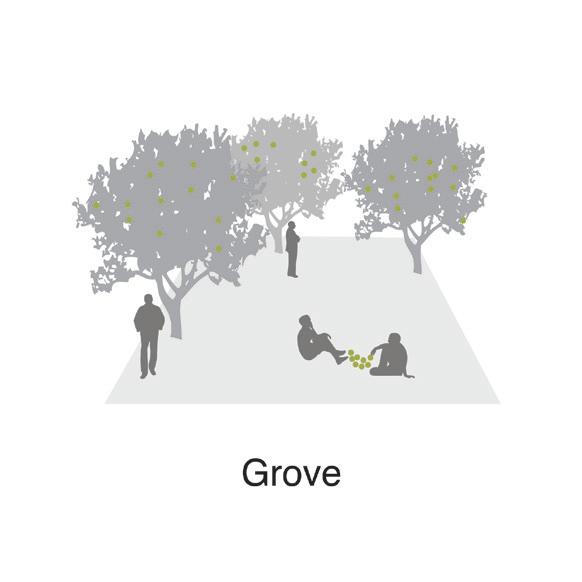

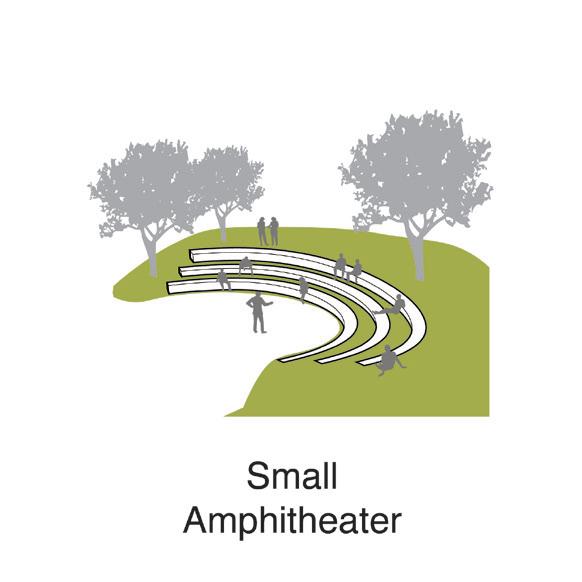

The first phase of the Recreation Landscape looks at the smaller section within the proposed new fence line. This section would include a small natural amphitheater, a Hawaiian Star Compass stage for music and other performances, an exercise equipment area shown in blue, an area for a medicinal garden, a Mamaki Grove, and a continuous walking path for exercise. These are all envisioned as low maintenance outdoor spaces that would only require weed whacking. Perhaps the inmates that contribute to the maintenance of the recreation field are the ones that get more free time to enjoy them.

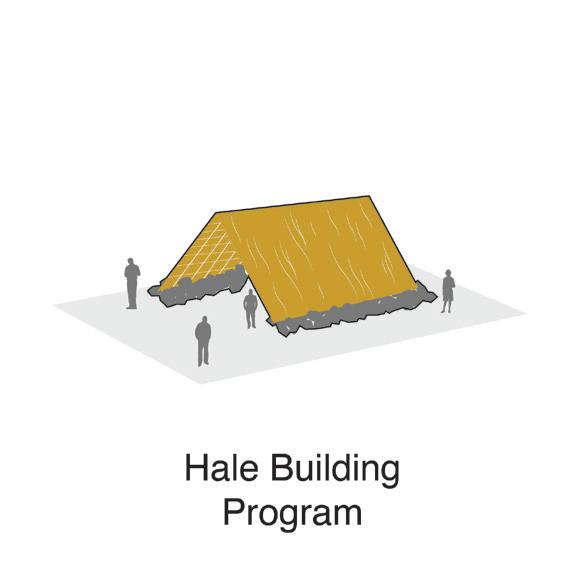

The second phase looks at the rest of the recreation field area, and proposed smaller areas for different kinds of recreational activities. These include a small gathering circle for socializing, a pickleball court, a piko area for Makahiki type of activities, a maze based on Catholic rituals, a hale building area, a short track, and a basketball court.

All of these amenities would also be used by correctional staff, and provide an incentive to come to work.

Research suggests that prison arts programs have a correlation between positive behavioral changes, selfconfidence, motivation, and self-discipline.14

This is a view of the entry/transition area right when entering the recreation field. This field would include an amphitheater to fit 100 or so individuals and a stage, with the large concrete wall as a backdrop (shown here with a mural). This could be a space for the guest performers and concerts.

“Findings suggest that prison-based exercise programs constitute a feasible and useful strategy for improving the physical and mental health status of prisoners”15

In this scheme, there could be exercise equipment installed around the circle allowing people to do cycles or rotations.

“I draw, I paint, I create, I inspire.” - Kiana Kalima, Women’s Community Correctional Center

artist

In November 2023, two murals were unveiled at the Women’s Community Correctional Center (WCCC) in Kailua. The murals were a result of a collaboration between local artists and WCCC residents.16 This effort was initiated by the Women’s Prison Project (WPP), and was funded by donations from WPP members, with materials donated by Hardware Hawaiʻi in Kailua and the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (DCR) in hopes of promoting tranquility and liveliness to WCCC. Four residents

assisted the artists and during the process, learned how to use paints, blend colors and textures to create paintings that have become a source of inspiration for themselves and others.17

Here are our preliminary recommendations for the next steps to advance the visitation courtyard project:

• Research other art/mural programs in corrections, select willing local partners, and develop a program that integrates inmates into the conceptualization and painting of a mural in the visitation yard.

• If there is interest in doing this at all facilities,

request an appropriation for healing-centered proof of concept projects in every facility, in line with the transitioning of the department. Appropriation to include design, construction, and assessment. Partners might pursue a grant for this. A single small mural (depending on the condition of the wall) can be done for $10K, more would be needed to develop a program for this. An estimate would be needed for the landscape work.

• If this is on DCR’s agenda, message the proposed improvements to stakeholders to build political will and support for the project, for example, in the DCR newsletter, social media, or hearings. People appreciate hearing about positive healing-based projects led by DCR.

• Develop maintenance criteria for the visitation yard that ensures that designs consider landscapes that are feasible to maintain via a workline or with existing maintenance staff.

• Hire a design-build team to design the courtyard. Explore opportunities for incarcerated persons to assist with building and landscaping.

• Host staff family events to inaugurate the new courtyard space. Provide HCF staff with something to be proud of at their workplace.

• Strategically integrate programmatic use of the space by incarcerated persons. Start with those who successfully participated in the mural or landscape efforts. Allow individuals who choose to participate in other programs to use the visitation courtyard (lāʻau lapaʻau, lei making, hula, yoga/ meditation, etc.)

• If contact visits resume, strategically re-introduce family visits for eligible incarcerated persons, ensuring that all security measures are still in place.

1 “State of Hawaiʻi Department of Correction and Rehabilitation Annual Report 2023.” Department of Public Safety - Hawaii.gov. Accessed February 10, 2024. https://dps.hawaii.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/PSD-ANNUALREPORT-2023.pdf.

2 “Hālawa Ahupuaʻa,” Kamehameha Schools, accessed February 3, 2024, https://www.ksbe.edu/assets/site/special_section/regions/ewa/Halau_o_ Puuloa_Halawa.pdf.

3 Manalo-Camp, Adam Keawe. “Through the Eyes of Hālawa.” Ka Wai Ola, November 1, 2022. https://kawaiola.news/moomeheu/through-the-eyes-ofhalawa/.

4 “Hālawa Ahupuaʻa,” Kamehameha Schools.

5 “Hālawa Area - Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) Plan: Existing Conditions Report,” City and County of Honolulu, 2015, https://www.honolulu. gov/rep/site/dpptod/Halawa_docs/Final_Existing_Conditions_Report_112515_ low.pdf.

6 “Saguaro Correctional Center,” Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, 2012, https://dps.Hawaiʻi.gov/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/ PSD-WEBSITE-INFORMATION-POSTING-FOR-AZ1.pdf.

7 Ibid.

8 “The Native Hawaiian Justice Task Force Report - Oha.org.” Accessed October 16, 2019. https://www.oha.org/wp-content/uploads/2012NHJTF_ REPORT_FINAL_0.pdf.

9 “City and County of Honolulu, HI.” qPublic.net - City and County of Honolulu, HI - Report: 990100300000. Accessed February 16, 2024. https://qpublic.schneidercorp.com/Application aspx?AppID=1045&LayerID=23342&PageTypeID=4&Page ID=9746&KeyValue=990100300000.

10 Thompson, David. “Field Guide: Honolulu behind Bars.” Honolulu Magazine, October 13, 2020. https://www.honolulumagazine.com/field-guidehonolulu-behind-bars/

11 Hart, Dionne. “Health Risks of Practicing Correctional Medicine.” AMA Journal of Ethics 21, no. 6 (June 1, 2019). https://doi.org/10.1001/ amajethics.2019.540.

12 “Sustainability in Prisons Project 2023 Annual Report.” Sustainability in Prisons, 2023. http://sustainabilityinprisons.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/ SPP-2020-Full-Annual-Report.pdf.

13 Farbstein, Jay, PhD, FAIA, Melissa Farling, AIA, LEED AP, and Richard Wener, PhD. “Effects of a Simulated Nature View on Cognitive and PsychoPhysiological Responses of Correctional Officers in a Jail Intake Area”. Washington, DC: National Institute of Corrections, 2009.

14 Brewster, Larry. “The Impact of Prison Arts Programs on Inmate Attitudes and Behavior: A Quantitative Evaluation.” Justice Policy Journal 11, no. 2 (2014). https://www.cjcj.org/media/import/documents/brewster_prison_arts_ final_formatted.pdf.

15 Sanchez-Lastra, Miguel Adriano & de Dios, Vicente & Ayán, Carlos. (2019). Effectiveness of Prison-Based Exercise Training Programs: A Systematic Review. Journal of Physical Activity and Health. 16. 1-14. 10.1123/ jpah.2019-0049.

16 Ordonio, Cassie. “Oʻahu Prison Debuts Transformative Murals Painted by Inmates and Local Artists.” Hawaiʻi Public Radio, November 10, 2023. https://www.hawaiipublicradio.org/local-news/2023-11-08/oahu-prison-debutstransformative-murals-painted-by-inmates-and-local-artists.

17 “PSD News Release – WCCC & Women’s Prison Project Unveil New Wall Murals.” PSD NEWS RELEASE – WCCC & Women’s Prison Project unveil new wall murals. Accessed February 16, 2024. https://governor.hawaii. gov/main/psd-news-release-wccc-womens-prison-project-unveil-new-wallmurals/.