EconomicPerspectivesisthePerseEconomicsmagazine dedicatedtostudentsrunbystudents.Publishedtermly, Economic Perspectives seeks to explore the complex worldofEconomicsonatheme-by-themebasis.

The Lent edition marks a change of theme, but also the editors. We bid farewell to Octavian, Varun and Ivan and introduce ourselves Ashvik, Sam and Richard as the new editors for the magazine. We are passionate to continue producing intriguing editions and are excited to start our tenure.

Moving away from broad economic concepts for this term's edition we chose the theme of Information to spark some nuanced but equally critical thought. Economics thrives on information. Policies shift, markets move, and decisions are made - all based on the information available. Yet, in an age of instant data frequently shifting information, understanding what truly matters has never been more challenging.

In this edition, we explore the importance of information on policymaking, the consequences of misinformation in markets and the rise of information as a powerful tool in the digital world. By exploring such concepts, we hope to uncover a deeper layer of economic thought, one that moves beyond broad concepts and uncovers the mechanisms that drive them.

We hope you enjoy this collation of 10 articles each exploring information from different perspectives, as well as 2 articles on current affairs exploring a tumultuous time in the global economy. Finally, we are pleased to announce the addition of a new section to the magazine which we hope will provide some interesting information about past economists and their work.

Thank you for joining us, we invite you to engage with this issue and through reading your reading, rethink how information, in all its forms, shapes the world around us.

Ashvik G, Sam R, Richard Z

Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) was established with aims to reduce US governmental bureaucracy through streamlining federal operations and reduce government spending – we have already seen DEI related contracts targeted resulting in layoffs in the federal workforce saving a reported $7 billion, and USAID’s budget cut by at least $6.5 billion. A proposal from DOGE (known as the Doge Dividend) suggests distributing 20% of savings through direct payments to citizens, and another 20% allocated toward reducing the national debt. Assuming DOGE reaches its goal of $2 trillion saved (admittedly a heavy assumption, if Musk continues at his current rate they would total just $100 billion by February 2026), this could mean around $5,000 for a taxpaying household per the DOGE rebate.

If implemented, the DOGE Dividend could have significant consequences across areas of consumer spending, inflation and public image. Below is an assessment of these potential impacts, compared to what similar historical policies have spelled out in the short and long terms.

In terms of consumer spending, clearly a sum of $5,000 per household could lead to a temporary boost in consumer spending (similar to the way stimulus checks operated in COVID-19). Whilst the lower income households are more likely to spend the majority of their dividend due to their generally higher marginal propensity to consume , higher income households may save or invest this payment – leading to capital market benefits but a less direct stimulus towards demand for goods and services.

By injecting a large amount of money into an economy where supply chains remain constrained, it is reasonable to assume there would be an inflationary risk if the increased spending caused by the dividend outpaces productivity growth; prices of goods and services would rise, offsetting the benefits to consumers. Furthermore, assuming businesses experience higher demand from a boost in consumer spending, they may increase wages to attract workers, fuelling possible further inflation and a wage-price spiral. A good demonstration of this is once again the post-pandemic inflation surge caused by stimulus payments in COVID which peaked at around 9% in June 2022

From a political standpoint, the dividend would likely garner short-term support among voters who experience the direct financial benefits – as well as it being met with support from those who remember the previous stimulus payments by

Reagan in 1981 as positive. However, this would soon be outweighed by the long-term concerns over inflationary changes, with voters blaming it for rising costs of living. There is also of course also those who argue that the government should permanently cut spending rather than redistribute the saved money as a one-time rebate.

To quantitatively assess whether Trump’s policy would be a good one, we can compare it to previous measures taken historically. As previously mentioned, COVID-19 stimulus payments in 2020 and 2021 similarly increased public and consumer spending – at the cost of excessive liquidity resulting in heavy inflation. This however is slightly differing from DOGE’s proposal, which would be financed by government savings rather than deficit spending.

Another similar policy is the Alaska Permanent Fund Dividend (APFD), which distributes a share of state oil revenue to residents in Alaska annually. The APFD has had positive effects on reducing poverty and strengthening economic stability, without massive inflationary consequences. Unlike the DOGE Dividend, the APFD is a sustained program rather than a one time payout – thus the effects on the economy are very different, a long term repeat payment provides a continuous incentive for investors to stay in the system and

therefore avoiding large dumps in consumer spending that could destabilise the market.

Therefore, it seems the best comparison to Trump and Musk’s plan is the tax rebates in Reagan’s presidency during 1981, where tax cuts put money back into the hands of taxpayers. As is expected from the DOGE Dividend, the tax rebates in 1981 had a mixed economic impact with short term boosts but long-term concerns, although these were over the widening deficit rather than inflation, as tax cuts are not equivalent to government savings.

To summarise, whilst the DOGE Dividend promises to temporarily stimulate consumer spending, the risk of inflation remains firmly at the forefront of the plan. Historical evidence further suggests mixed economic outcomes depending on how the policy is implemented – from my view, the shortterm superficial benefits of consumer spending increases and political popularity do not warrant the introduction of such a policy given the heavy inflationary consequences.

There are many ways a US-China trade war would affect the UK, both negatively and potentially positively. Negative effects include raised prices for consumers across the economy representing a significant increase in inflation analogous to the 2022 inflation spike seen following the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent oil embargo. Changes in the value of the dollar and Chinese yuan will have affects across the markets as the value of imported goods change and investment from China and the US are likely to decline as more money is lost to tariffs and higher costs of production resulting in lower profits for firms. Overall growth could be lower as global interest rates rise. However, this is not necessarily the case as the potential positive dynamics offer opposite effects. These may result from the diversion of trade originating in China from the US to other markets that could bring down prices across the economy as cheap imports become

readily available, reducing prices and inflation. British exporters could also see an increase in demand as gaps in the US market emerge where Chinese firms previously operated.

To fully analyse the effects of a US-China trade war, the best place to start would be to look at the effects of the first US-China trade war, fought during the first trump presidency from January of 2018 with the most action during the period from 2018-2020. The first war technically continued through the Biden administration before starting in earnest again in February 2025 after trump returned to power, but this 2025 rekindling is accepted as the second. The effects of the first trade war on the UK included slowed economic growth (economic growth fell from 2.7% in 2017 to 1.4% in 2018 and then 1.6% in 2019 - the primary years of the trade war) and lower investment due to increased uncertainty in the global economy while also likely worsening

Britain’s ability to restore economic strength after Brexit. On a more micro scale, British steel was quite significantly impacted as well as the aerospace industry as many firms sold components for good manufactured in the US that has previously often been shipped to China which due to the trade war demand had slowed causing knock on impacts for British firms. Although due to the rapid following of the trade war by the COVID19 pandemic and Brexit have made it less clear what effect the trade war had.

It is highly likely that similar effects will be felt again this time around with forecasts from the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) predicting lower UK economic growth due to higher global interest rates. Estimating UK GDP could be between 2.5% and 3% lower over five years and 0.7% lower this year. Furthermore, inflation is likely to rise due to increases in price caused by supply side shocks due to tariffs which would likely result in higher interest rates further contributing to slower economic growth and increasing pressure on the UK government to cut spending which would be highly unpopular and further damage the UK economy and standard of living. While there is also the risk that cheap Chinese made goods that where once destined to the US, could make their way to Britain in a technique known as price dumping, undercutting local prices and potentially as a result driving up unemployment as firms are forced to lay off workers due to reduced profits. Reductions in investment and business confidence are also likely due to higher uncertainty which, when the UK economy is already sluggish and badly in need of investment, could result in further issues for the UK governments attempts to restore the UK economy to growth. And there will of course be the impacts on British elements of global supply chains, with firms relating to the auto industry expected to be hit hard this time around. There is also the need to address that even if Britain is only affected minorly by the trade war, the significant effects on the US economy are likely to have knock on affects due to the US being the world’s largest economy in particular affecting the global stock market, financial markets and inflation across the world (including in Britain). Finally, importers may suffer shocks due to price increases

caused by the appreciation of the dollar.

However it is not a given that a US-China trade war will be all bad for the UK, in particular while dumping of cheap goods from China into the UK market may have adverse effects on firms, it is likely to have positive affects for consumers by lowering prices especially in areas where prices have risen due to Brexit, and lowering inflation. Exporters will also benefit from a stronger dollar making their exports more competitive while also making American exports in the UK market less competitive and bolstering UK firms. Furthermore, UK firms may be able to exploit gaps in the market created by the withdrawal of Chinese firms.

In conclusion, while the UK was not significantly affected by the first US-China trade war or at least had its effects overshadowed by the covid-19

pandemic and Brexit, this time is likely going to be different both due to the larger range of goods involved but also due to the size of the tariffs reaching 60%-100% in comparison with 10%25% the first time around. The most likely affects are a reduction in growth, with growth in 2025 decreasing by 0.7%. while also leading to higher interest rates and inflation. However, UK firms may be able to expand into gaps left by Chinese firms in the US market and the influx of Chinese goods with excess supply may in fact lower inflation in the UK and lower the wider cost of living among other affects. As such while Britain is likely going to be impacted negatively by the trade war some areas of Britain may find opportunities instead.

Hilm VdK, Y12

This trend has shown no signs of slowing down. Data is now collected in every facet of life. Every online interaction is recorded, every click and every scroll and this level of collection is not just limited to our devices. For example, every time you swipe a loyalty card, whether it be at Sainsburys or Boots, these companies are generating insights about your purchasing habits, utilising this data to increase your propensity to spend through targeted ads, coupons, and discounts.

It is clear how data has been monetised; these phenomena are nothing new, but will data come to play an even more significant role in the economy of the future? The key to this question lies in the recent technological breakthroughs such as large language and computer vision models. AI is set to revolutionise our society, with its ability to drive our cars, diagnose our illnesses and even write our essays! While we have all heard of the companies utilising AI such as OpenAI, Google and Tesla, less attention has been shown to those enabling the technology. These companies are the data brokers, collecting and trading billions of data points which are used to train AI models.

To understand why data commoditisation is so integral to the modern economy, it is first important to have a conceptual understanding of how machine learning operates. Machine learning drives AI advancements, and its success depends on vast, high-quality datasets, making data a crucial and valuable commodity. Some models are ‘trained’ through simple pattern recognition. For example, in the case of computer vision, they are presented with an image of an apple and told that what they are looking at is an apple. They are then shown millions of instances of apples so that they

‘know’ what apples look like. Then, when presented with the image of an apple they can, without being told, ‘see’ that it is an apple. The accuracy of the ‘vision’ of such a model depends upon both the quality and quantity of the dataset with which they are trained upon. Without access to these vast labelled databases companies have no ability to create and compete with companies that do, underlining the importance of this data.

This has led to the evolution of data labelling companies. Data labelling is the process of assigning descriptive tags to raw data such as images and audio to provide context that machine learning models can learn from. This is a crucial process that enables algorithms to recognise

patterns and make informed predictions, as without accurate labels, machines are unable to effectively understand the relationship within the data- compromising its performance. Data labellers have become akin to oil companies, ‘mining’ and ‘refining’ this valuable resource and selling it to those that require its use. Some of the key players in data labelling are companies such as Scale AI, Labelbox and Sama. These companies remain unknown and yet have garnered valuations in the tens of billions of dollars due to their importance in the supply chain of AI technology. They have captured this value owing to their lucrative, if ethically dubious business models. In the example of Scale AI, the company contracts tens of thousands of workers across low-income countries to manually label its data.

It is then clearer than ever that data is a valuable resource, and proprietary datasets should be seen as assets in the same way that an oil field might be. The implications of this realisation are widespread. For starters, it reinforces the

competitive advantage of large incumbents in mature industries. These companies will have been collecting detailed data on customers for many years, making it harder for new entrants to compete. The prime example of such corporations are the few largest hyperscalers such as Amazon, Alphabet, Meta, and Microsoft, who will have their already existing monopoly power on data entrenched because of the scale of their proprietary data. Closer to home, the obvious value of such data also raises questions about whether our governments should or could use national datasets. An interesting moral quandary has arisen regarding the NHS’ healthcare data. Utilising such data would undoubtedly unlock not only advances in healthcare and life sciences but also potentially a lucrative revenue stream for the struggling service. However, handing over such sensitive information to any third party, such as a pharmaceutical company, is viewed by some as morally reprehensible.

Data commoditisation drives AI progress and corporate dominance, creating both opportunity and ethical concerns. While it fuels innovation, issues like data monopolisation and exploitation pose challenges. Its value is clear, but careful regulation is needed to prevent misuse.

Sissi H, Y11

Demerit goods are goods that have negative impacts on consumer and negative externalities either of production or consumption. Unfortunately, these externalities are commonly ignored during the consumption/production process, leading to a misallocation of resources. For example, whilst a consumer may derive satisfaction from consuming the cigarette there is very little positive externalities of this consumption, benefits to a third party, instead they carry the burden of passive smoking which could lead a strain on the NHS which is a negative externality. This research paper attempts to evaluate whether government policies to reduce consumption, i.e. educate consumers to reduce information failure on the full impact of their consumption (the effect of passive smoking), a

plastic bag charge and taxation has been successful at reducing consumption.

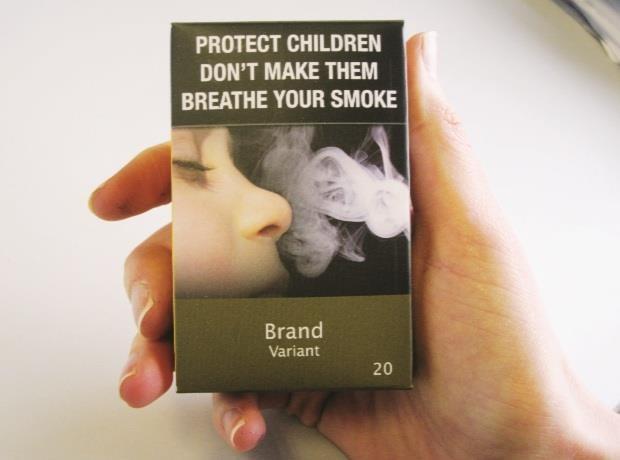

The first example this article will examine is cigarette consumption. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) investigated smoking rates in the UK. Between 1974 and 2014, male smokers have fallen dramatically from 51% to 20%, similarly with women from 41% to 17%. This staggering decrease can likely be attributed to stronger legislation to reduce information failure. For example, the photos below show how the cigarette packets have changed overtime. In the space of 100 years the two have become unrecognisable, and the effect this had on consumption is apparent. In 1991, the British Tobacco Industry went to European Court against the UK government and lost, it was to discuss the

packaging of cigarettes. Axel Gietz, director of corporate affairs, stated ‘No-one starts or continues to smoke because of the colour of the pack’ and they find the new legislation illegal as it takes away their trademark intellectual property.

Another example of theses bans removing trademark identity was the iconic Marlboro F1 McLaren. When the advertising of tobacco companies was banned the two had to use subliminal marketing, advertising that uses images or sounds that the conscious mind is unaware of to advertise as they had just signed a billion-dollar deal, these are also shown in the photos below.

This clearly shows that the government attempting to reduce cigarette consumption through stricter advertisement regulation and by educating children and adults on its effect has been successful leading to a decrease in smoking rates.

Another example of a product that is over consumed in the UK is single use plastics. It is estimated that in the UK 7.7 billion plastic bottles

are purchased each year, which is a clear example of negative externalities as many end up in landfill or the ocean. This could lead to environmental damage and negative impacts on marine live thus highlighting the negative externality. However, the UK in recent years has made strives to reduce single use plastic consumption, mainly plastic bags. Through schemes such as ‘’plastic free July’’ recycle now’’, society has attempted to highlight issues about not recycling and this has caused social norms to change, which is important in reducing their consumption. Furthermore, in 2015, the government implemented a 5p charge on plastic bags. This has had significant success with main retailers such as Tesco and Waitrose reporting that the number of bags sold a year went from £197 million in 2021/2 to £133 million in 2022/3. This clearly shows that the charge is working especially considering it is estimated that 7.6 billion plastic bags were used in 2014. Moreover, it is estimated that the average person in the UK now buys only two single use plastic bags a year compared to 140 in 2014 before the charge was introduced. The statistics clearly show that this charge has had large success so much so that in 2021 the charge increased to 10p. The environmental minister on the 31st of July 2023, said that ‘more than 7 billion harmful plastic bags have been prevented from blighting our streets and countryside thanks to the single-use plastic bag charge’. Therefore, it can be assumed that government policy which aims to tackle negative externalities of plastic bags have been very successful.

Finally, the UK government have taken measures to reduce alcohol consumption. Alcohol has many negative externalities including; strain on the public health care due to liver disease, strain on the police force due to public disorder, and on other families and healthcare systems due to drunk driving incidences. The government has taken measures to reduce these issues such as taxation on alcohol. For example, the tax rate for a litre of beer from 3.5%- 8.4% is £21.78. In theory an increase in price, due to the tax, should lead to a decrease in demand for the good as it becomes out of consumer’s reservation price, the maximum price consumers are willing and able to

pay for a specific good. Therefore, at a higher price there may be less consumers willing to pay that price than before at the lower price leading to a decrease in demand. Furthermore, advertising such as drink-aware, ‘think before you drink’ slogan, creating April as Alcohol awareness month, have all combined to highlight the issue with alcohol like addiction. In addition to this in 2018 the Scottish government implemented a MUP (minimum unit price for alcohol), essentially it is illegal to sell alcohol below a minimum price. Like taxation this higher price has been seen to reduce consumption by 7.7% compared with regions without the MUP. This policy has been seen as successful and thus Wales also adopted the MUP. However, it is important to mention that whilst higher price has seen a decrease in consumption it is mainly affecting low-income households, and an MUP can

create demand for a black-market to sell below the legal price. For example, since alcohol is addictive those addicted to it are not likely to substitute away from it, instead they would choose to still purchase alcohol and instead stop the consumption of necessities. For low-income households this impact could be worse therefore highlighting that although the government has been successful in reducing consumption, they have created other issues.

To conclude, it is very important for the government to reduce consumption of goods which create harmful negative externalities and, in some cases, have been very successful such as the plastic bags however, for addictive goods they have faced more challenges.

The rise of AI has been revolutionizing work across many industries, and finance itself stands much to benefit, as the industry is at the forefront of automation and data driven decision making. But the impact of AI is both threatening and constructive: it has the potential to not only enhance human roles but even replace them. However, new roles will appear too.

Artificial intelligence will undeniably affect jobs in the finance sector, is debatable whether its impacts will unilaterally affect junior versus senior roles, and to what extent would judgement versus execution be consequently reshaped.

Junior finance and accounting jobs can carry out repetitive tasks such as data collection, monitoring and analysis, graphs. AI will be able to automate these activities, which could lead to job displacement as such routine tasks, which could be

better executed without human error by ideally bias free AI models. However, this is not without its own issues, as AI models are typically trained on vast datasets that reflect historical and societal human biases. Selection bias may also arise, in cases of unrepresentative or incomplete data, which may lead the model to perform less accurately to marginalized groups. Even acknowledging the bias in AI, there is still a practical challenge of mitigating it without compromising the model’s utility. Junior jobs will likely upskill as a result and focus on more complex tasks and problem-solving that requires the human judgement.

Senior finance jobs executives exercise strategic thinking and leadership skills daily to make significant decisions. They perform more complex analytical work. AI may reduce the demand for

some senior roles if developed enough to handle high-level functions, which can aid senior roles with decision making through predictive models and automated data analytics, leaving the critical judgements to be made by those in senior positions who can expand their area of judgement. Senior professionals should monitor and adjust AI systems and focus on complex, human-centred decisions. The overseeing of the evolving AI, together with the prediction analysis may improve the decisional output, but also create additional functions and roles, inexistent before AI influence; for example, hiring AI bias and ethics managers or to maintain that models align with ethical standards and guidelines without showing implicit bias or perpetuating inequality. Another example of a job that could arise from the integration of AI models into financial workplaces would be a predictive data analyst that leverages AI models to forecast future trends and manage the machine learning.

AI’s impact of execution would likely be revolutionary, as artificial intelligence models can easily automate and execute operational tasks such as execution and processing of trade which would greatly improve efficiency and accuracy. The accuracy will lead to improved compliance and controls may need to change or reduce.

AI’s impact of judgement making may augment decision making but ultimately the final choice should rest with senior professionals, as though AI can provide insights based on data and trend analyses, human judgement remains essential, particularly in complex, multi-faceted financial decisions that involve knowledge of risks, market psychology and ethics. Senior professionals would still be required to provide their human intuition, which is crucial for complex negotiations and strategic decisions, whereas AI would assist with risk analysis, forecasting and valuations. professionals (both junior and senior) to concentrate of refining strategies, client relations, and market analysis.

In conclusion, AI will transform finance jobs by automating tasks and improving data analysis for better decision-making, but it won’t replace human expertise or final judgments. Rather than threatening jobs, AI will revolutionise the finance industry; professionals would be enabled to focus on higher value, judgement-based tasks, and strategic thinking.

Kiana M, Y11

A historical event due to government failure in this context is based on the economic and social outcomes, due to the government's failures, from their intervention or policies.

One historic event caused by government failure was the Great Depression. The US stock market crash on “Black Tuesday,” 29th October 1929 was where the US stock market collapsed, wiping out billions of dollars in wealth. Many investors had been buying stocks on the margin (borrowing money from banks to invest and paying off the loan later). When the stock prices fell, borrowers couldn’t repay their debts. This triggered further panic and stock selling, tanking the stock prices even more. Many banks had invested in the stock market or had loaned money out to investors, and when this money wasn’t repaid, the Banks went bankrupt, wiping out people’s savings, which led to a decline in consumer spending and investment. Without their savings, consumers spent less, which meant that businesses also suffered, as they had to cut production. This led to mass layoffs which

caused unemployment to peak at 25% in 1933, reducing consumer spending further. Moreover, the failure of monetary policies in the US, such as the Federal Reserve failing to provide enough liquidity to banks, but increasing the money supply to stimulate the economy, only led to further deflation and further economic decline. The Government allowed the Laissez-Faire policies throughout the 1920s, where it was believed that markets should self-regulate, with minimal Government interference, usually assuming competition and market forces would naturally prevent excessive risk-taking about bank lending. The government had little oversight on banks, until 1933, whilst the Federal Reserve was relatively weak, and didn’t act aggressively to curb risky lending. The Federal Reserve was designed to be more reactive, rather than proactive. They were hesitant to raise interest rates or tighten credits, fearing it may slow down the economic growth seen in the “Roaring 20’s”. As a result, this led to interest rates rising in 1928, which was too little, too late.

The collapse of the USSR in 1991 was the cultivation of multiple systemic failures. The Soviet Government relied on a centrally planned economy, which proved inefficient and unsustainable. The main reason was due to lack of incentive which discouraged innovation and productivity. The chronic shortages of necessities and consumer goods coupled with excessive military spending, which was 2% - 14% of its GDP, led to drained resources from the crucial civilian sectors, such as healthcare, education and infrastructure, which made the already unstable economy even more fragile. As a result, the lack of investment in civilian industries led to economic stagnation (a prolonged period with little or no economic growth), exacerbating the shortages of necessities and merit goods and services, that are essential for maintaining the living standards of the Soviet population.

AchartillustratingtheGDPpercapitafrom1921to 1991,withintheSovietUnion.

NotethelittlegrowthinGDPfromthelate1970s tothecollapsein1991.

The failure of government interventions under Gorbachev, who was in office from 1985 – 1991, had introduced Perestroika, an economic restricting policy. They tried to allow limited market mechanisms into the centrally planned system, which only created confusion and resistance. There was no legal framework for private businesses and sectors, which was worsened by the inconsistent

enforcement of Government policy, which led to the creation of black markets that thrived as people exploited the legal loophole between state control and new freedoms introduced. Instead of stabilizing the economy of the USSR, this reform weakened the central control from Moscow, fueling demand for independence among the Soviet Republics. The authoritarian Soviet Government had limited political freedom within the State, whereas the more open-minded Gorbachev had revealed the extent of corruption and past atrocities, such as Stalin’s purges and the Chernobyl cover-up. This undermined the trust between the people and the state, who saw the Government as corrupt and often incompetent which led to the growing nationalism in the Soviet States, illustrated by the movements in Lithuania, Ukraine, Georgia, and other Federations. Gorbachev’s Government, and the Government of his predecessors, had failed to suppress or accommodate the demands, leading to the breakdown of the Soviet Union in 1991.

In conclusion, both the Great Depression and the Collapse of the USSR illustrated the consequences of the government's failures in economic management and political governance. In the case of the Great Depression, the lack of regulatory oversight and inadequate monetary policies played a crucial role in the triggering of a financial crisis that led to widespread unemployment, poverty, and the decade-long economic downturn. Similarly, the collapse of the USSR was driven by the inefficiency and unsustainability of its centrally planned economy. The military overspending, failed reforms, and a lack of political freedoms ultimately led to the rise in nationalistic sentiments and movements within the Federations, which accumulated to the disintegration of the USSR. These events can highlight how government failures, whether through poor economic policies, or the inability to adapt to the changing needs of its people, can destabilize nations, leading to severe social and economic consequences.

Harry L, Y12

The foundation of economic activity markets effectively distributes resources and spur innovation. But markets don't always work flawlessly. When the free market is unable to distribute resources effectively, it results in market failure, which has negative social and economic effects. Asymmetric information and externalities are some of the elements that lead to market failures. These problems lead to inefficiencies, distort competition, and reduce economic welfare. This article explores the consequences of said problems and how governments and businesses combat these issues.

Asymmetric information can lead to market failure as it prevents markets from functioning efficiently. When buyers or sellers do not have complete or accurate information about a product, service, or market conditions, they may make poor decisions, leading to inadequate outcomes, especially if one party has more information than the other.

A notable example of asymmetric information would be the lemons problem, a concept introduced in 1970 by George Akerlof in the context of car markets.

A seller might know a car has hidden defects but may not disclose this information to the buyer.

The fear of buying a lemon (a low-quality car) reduces the price buyers are willing to pay. Therefore, sellers of peaches (a high-quality car) leave the market, leaving mostly lemons available. This leads to a cycle in which the distrust leads to

market failure. To counter this, businesses may obtain third-party inspections or offer warranties to prove their products' quality. Governments could also intervene by implementing regulations, such as the Consumer Rights Act 2015, to ensure businesses provide quality products.

The 2008 global financial crisis serves as a realworld example of how asymmetric information can lead to disastrous market failure. In this case, subprime mortgages were being handed out more freely than they should have, partly due to gaps in information about its potential effects.

Lenders knew that male borrowers taking out subprime loans would default on their loans. However, they downplayed the risk to borrowers and investors.

Borrowers were enticed by the low interest rates at the time, without being fully aware of the longterm financial burden that they were taking on as the rates rose significantly shortly after

As lenders were able to conceal the true risk, there was an inflation in the amount of subprime loans being handed out leading to inflated housing prices. Investors were also deceived as rating agencies gave high credit ratings to these mortgage-backed securities. Due to information asymmetry, they were unaware of the true risk. When the housing market collapsed, these investments lost their value leading to massive financial losses.

This crisis highlighted the importance of transparency in the financial market as well as

leading to tighter regulations from governments all around the world. In the UK this led to the creation of the FCA in 2013 to regulate financial markets.

A negative externality leads to market failure because the social cost of a good or service is greater than its private cost, but this additional cost is not reflected in market prices as consumers typically only consider their own benefit rather than society’s. As a result, firms and consumers overproduce or overconsume the good, leading to an inefficient allocation of resources. This causes harm to third parties who are not involved in the transaction. An example would be:

Example: When a steel manufacturing plant operates, it releases CO2, NOx and other harmful particulates that increase the effect of global warming and harm people.

Market failure: The factory does not bear the full cost of this damage, so it has no incentive to reduce its pollution. This could lead to the plant producing more steel than is socially optimal as it chooses to maximize what benefits it. This is an example of a negative externality of production, and it leads to an inefficient allocation of resources

Trafficcongestion

Example: If too many people are using their cars during rush hour, this could lead to traffic jams, resulting in longer travel times, increased pollution and greater fuel consumption.

Market failure: Car owners do not pay for the congestion they cause, so they have little incentive to reduce their driving and use other modes of transportation. This means that people are overconsuming the use of their cars, and this is an example of a negative externality of consumption.

Governments and policymakers must intervene to correct the market failure caused by negative externalities by taxing and regulating the goods to avoid overconsumption.

A positive externality occurs when an activity provides external benefits to society that are not reflected in market prices. Since individuals or firms do not capture the full benefits, they may underproduce or under consume these goods or services, leading to market failure.

Education

Example: When people pursue education, it can increase their money-earning potential as well as having benefits to society due to a more skilled workforce.

Market failure: Education may be under-consumed because people have imperfect information about its benefits or tuition could hinder them from joining. This is an example of a positive externality of consumption and this misallocation of resources leads to underconsumption

Researchanddevelopment

Example: If companies were to invest more in researching and developing new ideas and products, it could benefit their revenue as well as lead to developments in society

Market failure: However, this may be underproduced as R&D is expensive and can lead to information spills to other firms meaning that it is a risk. This is an example of a positive externality of production due to the firm's inability to capture the full societal gains.

To solve positive externalities and fix market failure, governments would have to intervene and provide public goods like schools, as well as subsidise businesses to promote societal gains and avoid under-consumption/production.

Conclusion

To conclude, information gaps and externalities are the main causes of market failure, which leads to societal losses for a community. However, if done properly, government interventions or other methods can solve most of these problems.

Chuk O, Y12

Do you ever find yourself in a group where everyone seems to share the same thoughts and opinions? This is a common on social media where we tend to follow accounts and people we agree with. We call environments like this - where you only get perspectives that reinforce your ownecho chambers.

Echo chambers are thought of as the catalysts behind many social economic outcomes such as the rise in violence and polarization, as well as lower social mobility and higher inequality, contributing towards information failures across society through the transmission of fake news and hyperbolic facts or figures.

We may happen to find ourselves in echo chambers as a result of confirmation bias – the human tendency to prefer the information or news we come across that coincides with our previous beliefs, that confirm and build onto our current views rather than challenging them.

Confirmation bias can work in three ways:

Research bias, when in pursuit for evidence to back up opinions by only going to sources that hold

similar views, which leads to heavy selectiveness when researching, avoiding anything that might challenge us. Information that conforms to what we already know and have absorbed is more digestible.

Interpretation bias, when a personal way of thinking causes misinterpretation of others regular actions as negative – often emerging when we actively search for reasons to disagree with something.

Memory bias, where your own views of a person can determine how many of their good moments you remember. If you view a person in a negative light, it makes it easier to gloss over better points of their past events in favour of believing things that conform with your own views, better solidifying them and making them appear as more truthful than they may in fact actually be.

By interacting with and engaging in media – often through liking or commenting - that follows a certain propaganda or side in society, we are essentially congratulating the platforms: “I like what you’re showing me, as I’m engaging with it!

Keep it up!” And that they do. Social media platforms will funnel more content that aligns to what we prefer onto our feeds. Confirmation bias subconsciously plays into the posts and news sources we are able to see, which then alerts the algorithms what media you interact with. Our biases shape how we both see the world, and how we are informed by the world.

And just like with conformation bias, echo chambers can ignite the spread of false stories. If you share a story that appeals to everyone else in your echo chamber, it can integrate into others feeds at fast speeds and be perceived with popularity, and thus engagement, which further spreads the information to the people at large –even if it isn’t true.

In social science, a theory that exists states that: “if those who are like minded are known to us, we will be drawn to segregate with such people.” There is a attribute to most of us of general conformity – if everyone around us says one thing there’s a greater chance we are to be swayed, having a certain obligation to “follow the pack”. If everyone around us in our echo chamber starts to discuss about the same piece of information perceived as fact, chances are, if it conforms with our views we won’t challenge it.

Echo chambers are one of the main hurdles from achieving nuanced views in our modern society.

In terms of economics, our own bias and selectivity in terms of the information we choose to intake determines how we view global economic decisions on both a macro and micro scale.

The cryptocurrency market, for example, have seen social media platforms playing crucial roles in the volatility of driving the value of crypto. Influential figures and echo chambers within these platforms can cause a rapid drive in the prices of these currencies. Take Bitcoin, for example. Erected in 2008 as the first digital currency, aiming to provide decentralized money that operates outside of the control of central banks. Over the years, influential political figures have shown endorsement towards currencies such as Bitcoin, which have contributed towards the value of the currency today, being over £68,000 for a single unit.

The Brexit referendum was another major political and economic event that had a decision impacted by echo chambers amplifying polarized views, which contributed towards the UK’s decision to leave the European Union. This decision has led to severe economic uncertainty and market unpredictability.

Uncertainty in the financial markets has also been accredited to echo chambers. The economic cycle (also known as the business cycle), which composes the cyclical upswing and downswing stages of widespread economic activity and growth, is controlled in some capacity by feedback loops between economic activity and the discussion and speculation that these activities incite. To name one activity, for example, a decrease in the price of stocks. This can ignite negative media response and chatter, as well and relight negative long standing stories, and theories. These stories, due to recency, are more freshly in the minds of people, which leads them toward pessimistic intuitive assessments, which conclusively can further this downward spiral. These initial price declines cause chatter to spread, causing still further price declines as well as reinforcement of this negative chatter.

So, how can we avoid ourselves from being informed inside the seclusion of echo chambers? To get around the algorithms you could follow some accounts that you don’t always agree with –that way the algorithms will learn to suggest different posts with a variety of nuanced viewpoints. You don’t necessarily have to actively search for the exact opposite opinion of your own, as this can be counter-productive, and lead you back into the echo chamber where your points feel more valued and shared. It’s important to question what we are reading at any given time.

People are social creatures. We thrive off of interaction and influences from others. The vast majority of information we will come across in our lifetimes has been passed down and recycled countless times, and with each transfer the chance is increasingly more probable that precision of detail can be lost in transmission.

Will J, Y12

Misinformation in financial markets can have severe economic consequences. It can have implications on the actions of investors, the overall stability of the markets and the efficiency of capital allocation. An excellent example of misinformation having profound impacts on financial markets and investors, is the Game Stop (GME) short squeeze in 2021 which this article will look into further.

public float had been sold short, meaning some stocks had been lent and shorted again.

What followed was the widescale spreading of misinformation on social media, namely Reddit, Twitter, YouTube and TikTok, regarding Game Stop.

In particular, one reddit forum, r/wallstreetbets, thought that Game Stop was being significantly undervalued after a false narrative that the company was in good health. This led to people on the subreddit buying up Game Stop shares, causing the share price to rise in the hope of triggering a short squeeze. This attempt by retail investors had historic success, with Game Stops stock skyrocketing to $483 per share, which was nearly 190 times the low it had reached 9 months prior. This made Game Stops stock incredibly volatile, and many retail investors attempted to take advantage

In January 2021, Game Stop was a struggling brick and mortar video game retailer. This was partially due to competition from digital game services as well as the ongoing affects of COVID-19, which reduced the number of people who were shopping in person. This led to a decline in Game Stops stock, which caused many major invests to start short selling the stock, believing it would continue to fall. Short selling is the process in which an investor borrows shares and immediately sells them, in the hope that they would be able to buy the shares back later at a lower price, and return the shares with interest to the lender, while making profit in the process. At one point on the 22nd January 2021, approximately 140% of Game Stops

of the inflated stock price, in order to make massive profits. At one point on January 25, over 175 million shares of Game Stop were traded in one day. Investors misunderstood the idea of short selling, misinforming other investors with the idea that major hedge funds, who had been short selling the stock were trapped, and would have to cover their positions at any cost, causing investors to believe that Game Stops stock could only increase. This caused an even greater artificial demand for the stock, and caused investors to hold their positions at highly unrealistic prices, believing it would rise. However, what investors weren’t aware of was that hedge funds had alternative ways of exiting positions, such as through options hedging, taking positions that offset the risk of a potential trade. Furthermore, false claims were spread online that hedge funds were going bankrupt. This prompted even more retail investors to purchase Game Stop stock, when in fact these hedge funds never went bankrupt, prolonging the squeeze and making retail investors overconfident. When Game Stop stocks eventually crashed, loosing over 80% of its value in two days retail investors on social media platforms encouraged people to never sell their stock, believing that hedge funds would be forced to cover the costs. These people were ignoring the market realities, keeping investors engaged that ultimately led to inexperienced investors suffering even more. Finally, conspiracy theories were spread that brokers including Robinhood were colluding with hedge funds, after they restricted the buying of Game Stop stock on the 28th of January, in order to protect Wall Street interests. Although this was not the case, Robinhood was actually facing a liquidity crisis and had to temporarily restrict trading.

So what were the economic impacts of the misinformation regarding the short squeezing of Game Stop? Well firstly, Game Stops stock became extremely volatile as a result of the short squeeze leading to severe market distortions and some retail and hedge funds making substantial profits, for example Senvest Management made a profit of $700 million exiting it’s position before the price crash. However, the opposite was true for many retail investors and the hedge funds that were shorting the stock. Hedge funds such as Melvin

Capital lost billions, and required a $2.75 billion bailout, contributing to it’s eventual shutting down in May 2022. In addition, Hedge funds were forced to liquidate other assets, to pay for their losses, destabilizing other stocks that were completely unrelated to Game Stop. Misinformation altered the behavior of individual investors, who were afraid of missing out on what seemed like guaranteed profits with mainstream media covering and promoting the story. This lead to herd mentality, and caused lots of investors to suffer massive losses after Game Stops stock crashed, with inexperienced investors panic selling. It was estimated that about $27bn in

had

The situation also brought broader economic implications, mainly distrust in the financial markets, with market manipulation and the belief that some platforms such as Robinhood were catering for Wall Street by restricting trading, which could reduce long term participation in the financial markets. It also misallocated capital towards Game Stop, which perhaps did not warrant this investment, leading to reduced capital efficiency.

In conclusion, it is clear that misinformation has the power to dramatically impact the financial markets, especially when amplified through social media. In an increasingly digital world, where more and more people are taking to investing, it is important to ensure misinformation is mitigated to avoid general volatility and price distortions in markets, which can impact investors behaviour and result in severe losses for investors.

Dylan

S, Y12

Have you ever wondered why large corporations like Amazon or Google transformed from garage startups into trillion-dollar giants shaping the modern world? From manoeuvring self-reinforcing data cycles to engineering digital lock-in, these companies utilized unique conditions to scale at an unmatched rate. For example, Amazon, in just 31 years, evolved from a $500 thousand online bookstore into a global titan generating over $500 billion in annual revenue. I am going to explore how big companies rises to power through how they collect, leverage and control information.

Information plays an important role in the rise of corporate giants through self-reinforcing information edge. Big companies that secure larger datasets early on can better forecast purchasing patterns for specific goods and services. This is generally through information such as search history, purchase history, geographical and demographical profiles. This allows firms to tailor their products and marketing strategies. This firstmover advantage means they can predict demand, personalize services, and fine-tune algorithms, making their products more appealing to the

consumers. As company grows, more data is generated that refines the algorithms and more consumers are attracted to the company which causes a self-reinforcing loop giving the company information advantage. As companies grow, more consumer interactions produce more valuable data for them. This refines and improves its algorithms which in turn improves user experience, thus attracting more consumers. Over time, this selfreinforcing cycle of information collection builds an economic moat.

As firms invest in special production processes and firm-specific expertise that improve productivity and reduce cost of productions, making their services or products more attractive. This growth process leads firms to achieve economies of scale, which refers to the cost advantage firms have when they increase their level of output. They spread fixed costs over greater output which reduces their per-unit costs but still maintain a profit margin. In contrast, smaller competitors struggle to match these efficiencies, meaning they either must charge higher prices to stay profitable or operate on thinner profit margins, making growth difficult. One example of this is the Clubcard loyalty scheme that tracks its consumer’s purchasing patterns such as

what, when and how often a purchase is made. This is explore in a case study of the scheme which shows that it “enables retailers to identify promotional impacts and ensure that both retailers and their suppliers can effectively target their marketing strategies” suggesting that these intellectual capitals reinforce its competing edge and forecast demand inefficiencies, thus further attracting more shoppers through better stock availability and tailored deals.

When consumer invest time, data, and personal preferences into a firm’s ecosystem, moving to another service becomes inconvenient due to existing information. This creates “sunk costs” where consumers lose access of certain personized features or data if they leave. Additionally, companies connect their products such as cloud storage, messaging platforms or subscriptions that are compatible to each other for it to work the best. This creates a compatibility advantage as switching to competitors will cost consumers functionality and convenience. This is the lock-in effect: when users become dependent on the company’s “ecosystem” and thus making it harder to switch to alternatives. This benefits and contributes to big corporations like Facebook through a higher user retention with steady revenue from existing consumers. One example of this is Amazon prime’s multi service package offer. Explored in “Amazon's Antitrust Paradox” which states that “Amazon’s integration across various business lines enables it to cross-leverage advantages in ways that bolster its dominance across markets”. It combines free shipping, Prime Video, Prime Music, exclusive discounts, and cloud storage all into one subscription, making it more valuable than standalone alternatives. Users usually subscribe to one service but often end up using other services and thus increasing their dependency on Amazon. There is also a high opportunity cost of cancelling the subscription as it loses multiple benefits at once, making it difficult for consumers

to justify leaving even if they don’t maximize all the benefits provided. This ensures strong customer loyalty and long-term revenue by making the ecosystem indispensable.

Unlike traditional retailers that set static prices and adjust them on occasions, large corporations take a different approach. Many, like Amazon, leverage AIdriven dynamic pricing to continuously optimize profits at scale. This is done through tracking demand changes and competitor prices through large datasets as mentioned earlier. A pricing algorithm that automatically modifies product prices to stay competitive. For example, when demand increases, price is increased to capture more consumer surplus, similarly when demand falls, prices drop to stimulate purchase while maintaining its profitability. Furthermore, while many digital services appear “free” such as Google search or Facebook, users indirectly pay through data collection and targeted ads. This transfers economic value to the corporations from consumer activity generates further profits, instead of users benefiting from their own data, firms monetize the personal information by selling insights to third parties for business marketing or for highly targeted advertising. This was shown by a study done by the University of Chicago where Amazon’s dynamic pricing system fluctuated based on competitor pricing and demand fluctuations. Furthermore, Meta (formerly Facebook) discloses in its annual reports that nearly all its revenue is derived from targeted advertising and converted user engagement into steady revenue.

In conclusion, information is the cornerstone of large corporation’s dominance, through leveraging big data pools, optimizing price models and package incentives, and successfully monetizing consumer behaviour, corporate giants reduce costs, increase profits and gain a lasting edge over competitors which allows them to grow and dominate the market.

Neil B, Y12

“Data is the new oil” – Clive Humby, 2006. Recently data and information has transformed like we could not have imagined and this statement by Humby, I think, is truer than ever. Data is being used in so many ways as a commodity whether it be for AI, advertising, or predictive modelling.

What is a commodity?

Commodities are raw materials used to manufacture other products rather than being sold to consumers. Examples include precious metals such as gold and other metals which are often used in the creation of technology such as smartphones. Commodities are also often unrefined meaning to be useful there needs to be an extra step such as refining of crude oil. There are many ways in which data is being used as a commodity.

Advertising

Advertising in the real world is simple as firms know that certain people who are more likely to

buy their products are likely to see ads in certain locations and so are able to strategically place ads to maximise revenue. An example is placing an advert for the latest Disney film outside a child’s toy shop. However, with the rise of the internet and with 80% of Americans using online shopping (US census bureau), it means firms have to advertise online. This is more complicated as firms have no idea about a person when advertising on a general app such as Facebook or Instagram so to solve this, firms either buy or gather information about each person using a website or app in order to tailor ads that they are more likely to buy. This means that data needs to be collected to build profiles of each person containing their age, gender, interests and hobbies . One reason this has happened is that advertising is expensive so firms try to cut costs as much as they can. Personalised advertising means there are fewer redundant ads that will never get someone to buy something which means fewer ads are needed for

the same outcome, effectively reducing the price of advertising. Data is being used as a commodity here as it is being collected and used in the production of another good in the form of advertising. This is analogous to crude oil being extracted and refined to be used in plastics and fuel.

Artificial Intelligence

AI can be split into predictive and generative. Predictive AI requires data as it makes predictions based on past events, examples include fraud detection and forecasting. Generative AI requires massive datasets, a lot more than predictive, as it mimics the data it has already been given, examples of generative AI include image and text generation AI. The more data you give to an AI, the better it will be in general which means AI development companies will try to obtain the most data possible. The demand for data, therefore, is derived from the demand for AI and in recent years this has only increased. The quality of data is also a factor in the

quality of AI as biases in the datasets will propagate into the results of the AI and they often reflect the negative stereotypes that society creates. This could be analogous to the purity of a metal.

Why is data a commodity?

Data is now like raw material, for example, it can be collected (like extracting oil) but isn’t useful until it is analysed (like refining a raw material) and it has many uses in AI and advertising. For a good to be a commodity, a unit of that good needs to be interchangeable with another unit which means it is fungible. I think this is how data has evolved the most into a commodity as in the past it would have mattered what the data contained however, now, with the rise of general purpose AI, any data that you train it on, will improve so it matters less as to what the data contains.

Data has evolved into the new oil.

The Cobb-Douglas Production Function is an economic model which explains how inputs (labour and capital) contribute to outputs (goods and services produced) in an economy and has many real-world applications such as giving information to businesses about the best areas of production to scale and thereby affecting their investment choices amongst others.

The formula for the Cobb-Douglas Production Function is : Q=ALαKβ

The formula is not too hard to understand, Q stand for total output or production, and this is made up of the product of the Labour input (L), which

measures how much labour has gone into the production a good, the Capital input (K), which is the quantity of capital (machineries, factories, infrastructure) that has helped produce a good, and the technology factor (A), which measures how efficiently the labour and capital inputs are used. The output elasticity of the factors is measured with α and β, and the sum of these also tells you about the returns to scale. If α+β=1, then when the inputs double, the outputs double and there is no change in efficiency. When this is greater than 1, as inputs grows, so does efficiency, and when it is less than 1, efficiency declines as inputs grow.

From this explanation of how the model works, it is

easy to see its real world applications. Firstly, it allows economists to compare economies and how they grow, by examining the Cobb-Douglas Production Function, it can be seen that a country like India’s output grows due to said country increasing its labour force, thereby increasing L, and also growing infrastructure (K). This is contrasted

The final way in which it can be used, is by businesses, to understand how scalable the production of certain goods is. Using the sum of α + β, businesses can work out whether it is worthwhile to invest with the goal of increasing production of a good or service, as it allows them to see how efficiency will scale with an increase in production. Therefore, it helps businesses make more prudent decisions when it comes to choosing when and where to invest their profits.

to a developed country such as the US, which relies in innovation (A) and increase its efficiency (α+β) to increase its production. This allows policymakers to see which areas of countries need developing and helping in order to allow them to grow at a faster rate.

Secondly, the model can also be used to measure trends in the manufacturing of products. For example, as humans are replaced with automation in factories, this is shown in the model by a decrease in L and an increase in K. The relationship between the two can be easily expressed as mathematical ratio which therefore can be used to examine trends in the production of goods.

However the model has some limitations, the model assumes constant returns, however real-world productivity varies, and so longer-term productivity averages must be used for the best results. Furthermore, it cannot fully capture external shocks which can happen to producers. For example, in Covid-19, when supply chains broke down and labour and capital didn’t function as expected and so therefore the model when used to predict inputs or outputs, broke down.

In summary, the Cobb-Douglas Production Function is a tool which allows economists and policymakers to examine how different factors of production contribute to the production of goods and services on both a macro and micro level. It will become even more important in the future as it will be used to help us understand the shift from humans to automation and how innovation drives output and production.

In Economics, we often take theory for granted however, someone had to develop it. In the following segment we will delve into the lives and contributions of some of the most influential economics in history. We will explore their upbringing, education, ideas and their impacts on modern day economics. Hopefully, this will allow you to gain a much more conceptual understanding of economics, after all, the more you know about the past, the better prepared you are for the future.

Friedrich August Von Hayek was born on May 8th, 1899, in Vienna Austria. Hayek’s father, August, was a physician and professor of botany at the University of Vienna while his mother, Felicitas, was the daughter of prominent civil servant. Despite a comfortable upbringing, Hayek did surprisingly poorly at school, once receiving a failing grade in mathematics, albeit this was not due to a lack of intellect but rather a lack of interest and problems with teachers. During WW1, Hayek served for the Austro-Hungarian army on the Italian front and was decorated for his bravery.

After this, Hayek decided to enrol in the University of Vienna to study law in 1921. He also studied under the Austrian Economist Friederich von Wieser and was awarded a second doctorate in political economy which kickstarted his career in economics. Following his time at the University, he met monetary theorist Ludwig von Mises, eventually joining von Mises’s private seminar, similar to Keynes’s, ‘Cambridge circus’. In 1927, Hayek became the director of the newly created Austrian Institute for Business cycle Research. He stayed in this position until, at the invitation of Lionel

Robbins, he travelled to England to present four lectures on monetary policy at the London School of Economics (LSE). These lectures ultimately led to Hayek’s appointment as the Tooke Professor of Economic Science and Statistics at LSE, a position he held until 1950.

Hayek became the best-known advocate of what is now known as Austrian economics. Much of his

work during the 1920s and 1930s focussed on the Austrian theories of Business cycles, capital theory and monetary theory, which he viewed as all being interconnected. Hayek argued that the major problem for any economy was how people’s actions are reflected by the market. He agreed with Adam Smith’s view on how remarkable a job the price system in free markets did in coordinating peoples actions, however Hayek also acknowledged that the market did not always work perfectly, and thus focussed his time on understanding why the market can fail to coordinate people’s plans, leading to large scale unemployment. One reason for this, Hayek argued was due to increases in money supply by the central bank. When the central bank injects money into the economy, this leads to an artificial fall in interest rates according to Hayek in his book, ‘Prices and production’. This is because the supply of credit increases relative to demand, resulting in the price of borrowing falling. Businesses would then make capital investments, trying to take advantage of the relatively low cost of borrowing, unaware that they were getting a distorted price signal from the market. In addition to this, Hayek suggested that long term investments, such as infrastructure projects, are more sensitive to interest rates than short-term investments. As a result, artificially low interest rates would cause malinvestment, excessive investment in the wrong areas, as businesses invest too much into long term projects compared to short term ones, and when interest rates would begin to rise again, many of these investments would fail leading to an economic downturn. Therefore, Hayek’s solution to prevent recessions was through avoiding creating artificial booms by manipulating interest rates through monetary policy. This idea is central to the Austrian Business Cycle Theory, which argues government interventions in credit markets inevitably lead to recession as it creates artificial booms.

Hayek and Keynes long fought over their differing models of the world developing at the same time. Most economist agreed that Keynes’s book, ‘General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money’ published in 1936 won the battle, it was generally

more accepted after the limitations of the free market were exposed by the Great Depression a few years earlier, although Hayek always disagreed with Keynes’s view. He believed that Keynesian policies to combat unemployment would ultimately result in higher inflation, as the central bank would have to increase the money supply faster and faster, causing rising inflation. This belief of Hayek’s is now accepted by mainstream economists, and supported by the Phillips curve, showing an inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment.

Hayek then turned to the debate on whether socialist planning could work in the late 1930s and early 1940s. His belief was that it could not. The idea of socialist economists was that central planning could work because planners could use given economic data to allocate resources efficiently. However, according to Hayek, the data does not and cannot exist in any single mind or number of minds and therefore it is impossible for the central planner to efficiently allocate resources. The advantage of the free market, he argued, is that each individual uses information that only they have, which influences the markets that in turn, creates this economic data, which otherwise wouldn’t be realised. This argument is now accepted by both mainstream and socialist economics. After witnessing Germany in the 1920s and 1930s, Hayek wrote, ‘The Road to Serfdom,’ a warning to Britain about the dangers of socialism. His argument was that government control of the economy amounted to totalitarianism, which should not be desired. “Economic control is not merely control of a sector of human life which can be separated from the rest,” he wrote, “it is the control of the means for all our ends.” This book was even praised by his old opponent, Keynes, who said he was virtually in agreement with all of it.

In 1950, Hayek moved to Chicago to become a professor of social and moral sciences at the University. It was here where he gave his view on the role of government in his book, ‘The Constitution of Liberty’. In this book, Hayek cemented his status as a classical liberal, criticizing socialism, advocating for democracy but a limited

state, supporting individualism and economic freedom and a strong defence of liberties. In his later years, Hayek returned to Europe teaching at various universities. He shared the 1974 Nobel Prize with Gunnar Myrdal, “for their pioneering work in the theory of money and economic fluctuations and for their penetrating analysis of the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena.” Hayek become even more radical with age, as a result of witnessing the stagflation and failure of Keynesianism experienced in the 1970s and influence of other free market libertarian thinkers like Milton Friedman, and began supporting the denationalisation of money, despite favouring central banking for most of his life. He

argued that private companies would have an incentive to maintain their own currencies purchasing power, if they all had their own distinct currencies, although this idea has never really been taken up. This was for multiple reasons, such as the highly entrenched government monopoly on money and difficulty in the practical implementation of denationalising money

Hayek published his final book, ‘The Fatal Conceit,’ in 1988. He passed away four years later in Freiburg aged 92, with a legacy as one of the most influential and prominent economists of the 20th century whose ideas have continued to have significant impacts to this day.

Karl Marx was a hugely controversial philosopher, economist and revolutionary socialist best known for his 1848 pamphlet, The Communist Manifesto. His political and economic theories developed into Marxism, the principles on which communism is founded.

Marx was born in 1818 in Trier, Kingdom of Prussia (northeast Germany). His family was affluent, owned many vineyards in the region, and his father was a lawyer, privately educating Marx in his early years. Karl later attended Trier High School, known to have employed many liberal humanists as teachers, likely swaying Marx’s first exposure to more radical political ideas, influencing him to write pieces on Christian and humanitarian devotion. Marx obtained his doctorate degree in philosophy in 1841 from the Jena University and studied humanities for a year at the University of Bonn, and law and philosophy at the University of Berlin. He believed that philosophy was necessary in any endeavour, he

was always interested in combining the two fields.

He moved to Cologne the following year, working as a journalist, where he wrote for the radical newspaper Rhineland News. Throughout his time in

this position, Marx expressed his early views of socialism and developing economic ideas, which inevitably attracted the attention of Prussian government censors, already marking himself as unemployable as a notable socialist radical. In 1843, he married his childhood friend, Jenny von Westphalen, who was part of the lower nobility. However, despite their initial prosperous backgrounds, Marx’s increasingly radical views caused his estrangement to most of his family and his consequent inability to gain employment, leading to his family with Jenny quickly becoming impoverished.

In 1844, the family moved to Paris, where Marx met Friedrich Engels, another revolutionary socialist, who was to become a lifelong friend. Marx wrote Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts during this time, his first delve into economics. In Brussels, 1845, Marx met many other like-minded political theorists as he became more active in the Communist League. In 1846, he joined the League of the Just, an initially secret radical, ChristianCommunist, international revolutionary organisation. The League’s main goals were, “the overthrow of the bourgeoisie, the rule of the proletariat, the abolition of the old bourgeois society which rests on the antagonism of classes, and the foundation of a new society without classes and without private property”.

Joining the League shaped Marx’s ideas monumentally, carving his beliefs of social classes and revolution which are so prominent throughout Marx and Engels’ 1848 The Communist Manifesto, which detailed their similar plans for revolution, leading to his expulsion from Belgium and Germany.

The Communist Manifesto essentially examined the conflicts Marx maintained were arising in a power struggle between the bourgeoisie (those who owned the means of productions of labour), and the common workers (the proletariat). Marx demonstrated through his works how the League acted truly in the interests of the proletariat, to violently overthrow capitalist society, replacing it with socialism, inspiring revolution.

Marxism itself is a social, political and economic philosophy. It examines the historical effects of capitalism on economic development and argued that a proletariat revolution was both inevitable and imminently needed to replace capitalism with communism; though not differentiating between socialism and communism. Marx was influential in the development of socialism too, advocating for shared ownership of means of production for workers and the rejection of private ownership.

His ideas were distinctly anti-capitalist, as detailed in Das Kapital in 1867, stating the inherent “selfdestructive” flaws in capitalism, leading to workers’ exploitation. Marx believed in two principles: the use value and the exchange value. The use value that goods possess was defined by their capacity to meet a human need, whilst exchange value was calculated by the amount of socially necessary labour to create those products, considering skills and technical advancement. In addition, the idea of the surplus value held importance to later theory and was defined as the difference between the labour cost (wages paid) and the value created during the labour process. He claimed that the surplus value is appropriated by the capitalists and is the exploitation inherent in the capitalistic structures.

Essentially, Marx defined capitalism as a mode of production where business owners (bourgeoisie) control all means of production, such as profits, raw materials, and the factories themselves, whereas the workers (proletariat) only are paid wages, with no personal stake or shares in profits. The proletariat would have minimal power in economy, as they were readily replaceable in periods of high unemployment. He predicted this would lead to the alienation of labourers from their work, turning them resentful to their bourgeoisie patrons. The bourgeoisie would respond by leveraging their position and power over social institutions (financial systems, academia and the government).

These inherent inequalities and exploitative economic relations would result in a revolution: the working class would take control of means of

production - capitalism would be abolished. This revolution would be led by “vanguard of the proletariat”, a select few who were enlightened and understood class structure of society, who would work to unite the working class by raising awareness and class consciousness.