DECEMBER, 2025

PARTICIPATORY

ARCHITECTURE OF

MEDIUM COMPLEXITY

PARTICIPATORY

ARCHITECTURE OF

MEDIUM COMPLEXITY

PARTICIPATORY ARCHITECTURE OF MEDIUM COMPLEXITY

AD2025

INSTITUTO TECNOLÓGICO DE ESTUDIOS SUPERIORES DE MONTERREY, CAMPUS QUERÉTARO.

TEACHING TEAM

RODRIGO PANTOJA CALDERÓN | ARCHITECT AND

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT

DIANA GARCÍA CEJUDO | MSC IN ARCHITECTURE

PEDRO MENDOZA | ARCHITECT

YETZI VERÓNICA TAFOYA TORRES | URBAN PLANNER

ANDREA MARÍA PARGA VAZQUEZ | EDITORIAL

VIVIANA MARGARITA BARQUERO DÍAZ BARRIGA | ARCHITECT

DANIELA CRUZ NARANJO | ARCHITECT

SANTIAGO LUJÁN CÓRDOVA | ARCHITECT

CARLOS GONZÁLEZ | ARCHITECT

UDO PAUL MUCHOW | ARCHITECT

ALLIANCES

IIT - ILLINOIS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY

ROGELIO CADENA, JUSTIN DEGROFF, DIRK DENINSON

STUDENT

ALFONSINA ESPINOSA AZUARA

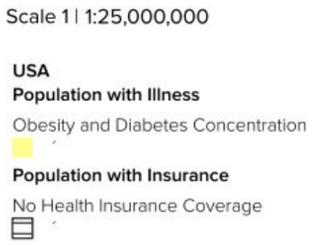

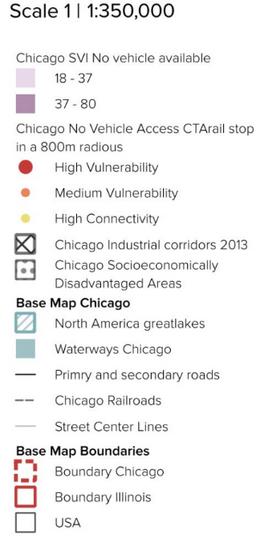

In Chicago, Latino adults face uninsured rates nearly three times higher than those of nonHispanic white residents. For thousands of families, this means living on the edge: a chronic illness or accident could immediately trigger financial hardship, limiting their access to even the most basic healthcare services.

Socioeconomic inequality

Immigrant population

Unequal access to services

1 in every 5 adults is uninsured

→ Postponement of medical care

Dental Care Medical Care

Mental Health

Integrated Well-Being

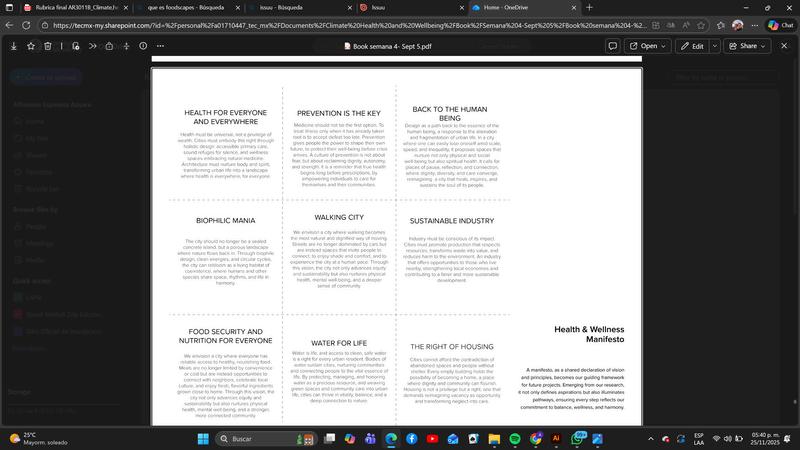

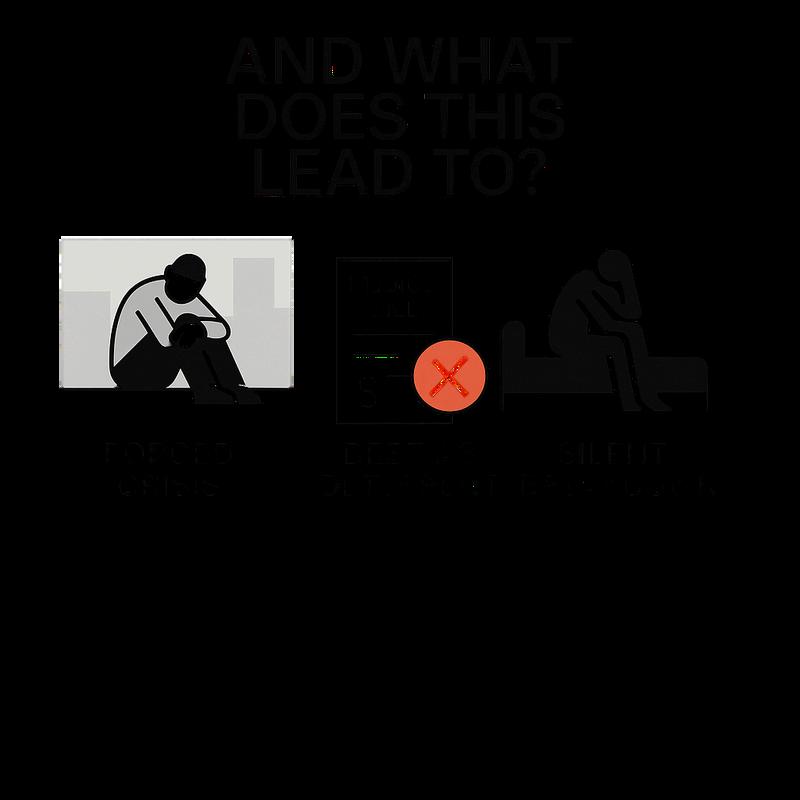

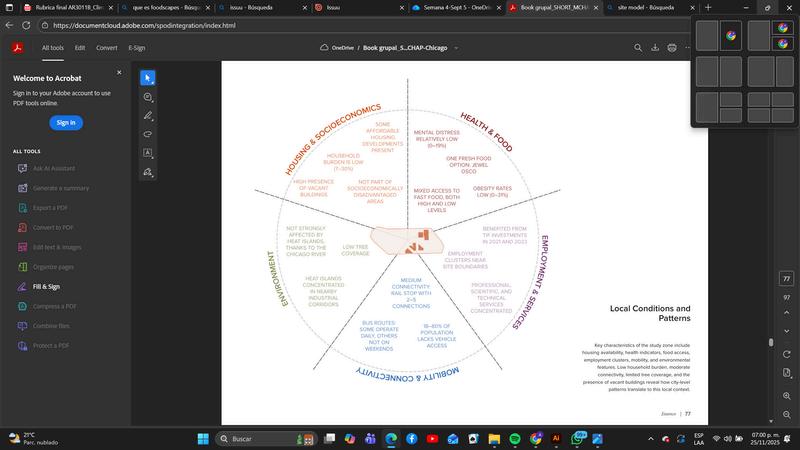

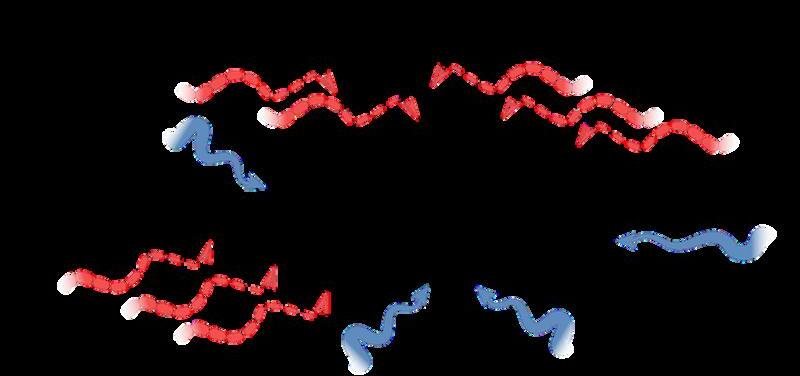

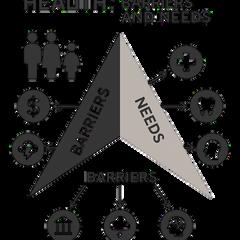

The diagram shows how socioeconomic inequality, a large immigrant population, and unequal access to services in Chicago contribute to a major healthcare coverage gap In some groups, 1 in 5 adults is uninsured, causing delays in medical, dental, and mental health care

To address this issue, the proposal introduces the Community Pocket Hubs neighborhood-scale centers that integrate essential healthcare services with community activation and social programs. Their purpose is to support accessible preventive care while strengthening social cohesion.

The final outcome illustrated is integrated well-being, achieved through improved access, prevention, and community connection.

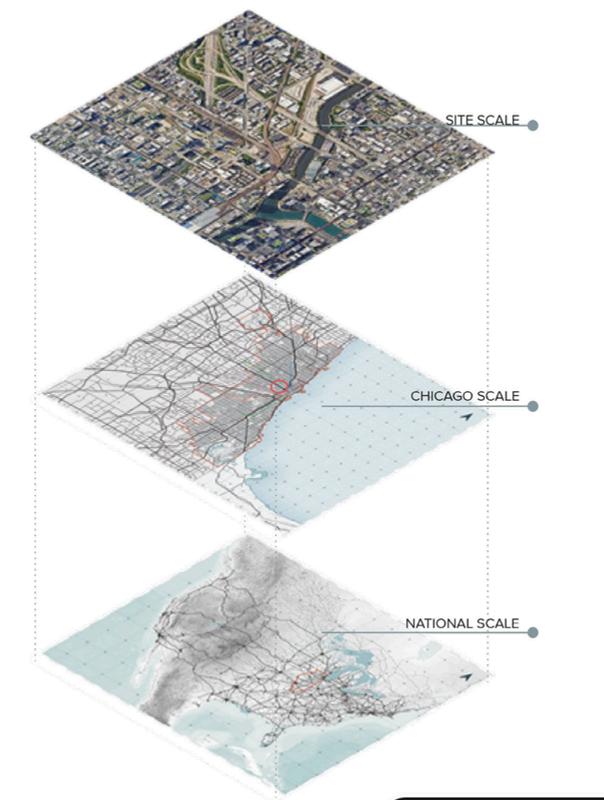

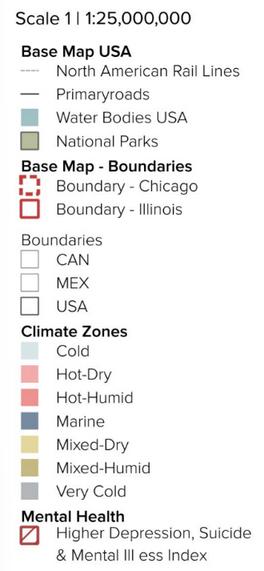

The U.S. healthcare system reflects a market-based model in which access to medical services is not universally guaranteed. The combination of unregulated pricing and complex administrative structures has produced one of the most expensive systems in the world, generating significant inequities in who can obtain timely and adequate care.

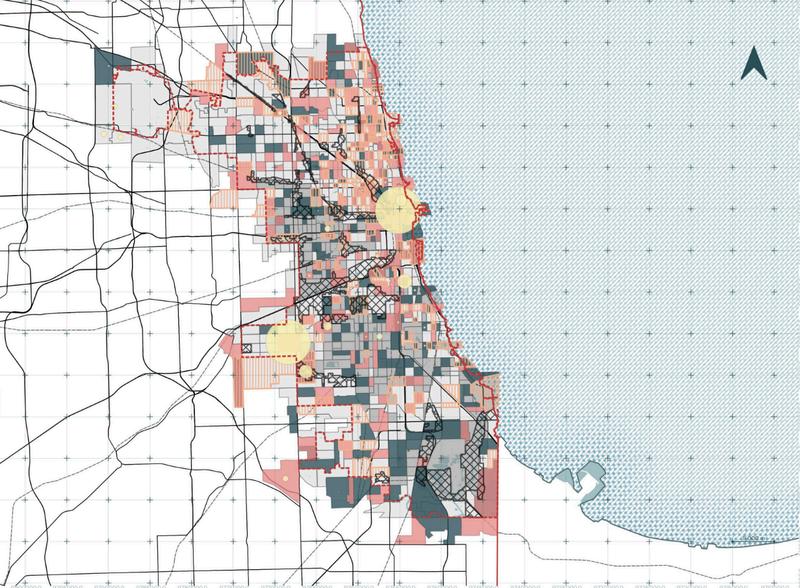

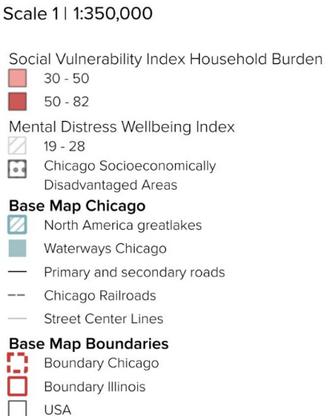

In major U.S. cities and especially in Chicago healthcare access has splintered into a pattern of urban medical segregation. High costs, insurance disparities, and uneven city planning have created neighborhoods where clinics, specialists, and mental-health services are almostabsent.

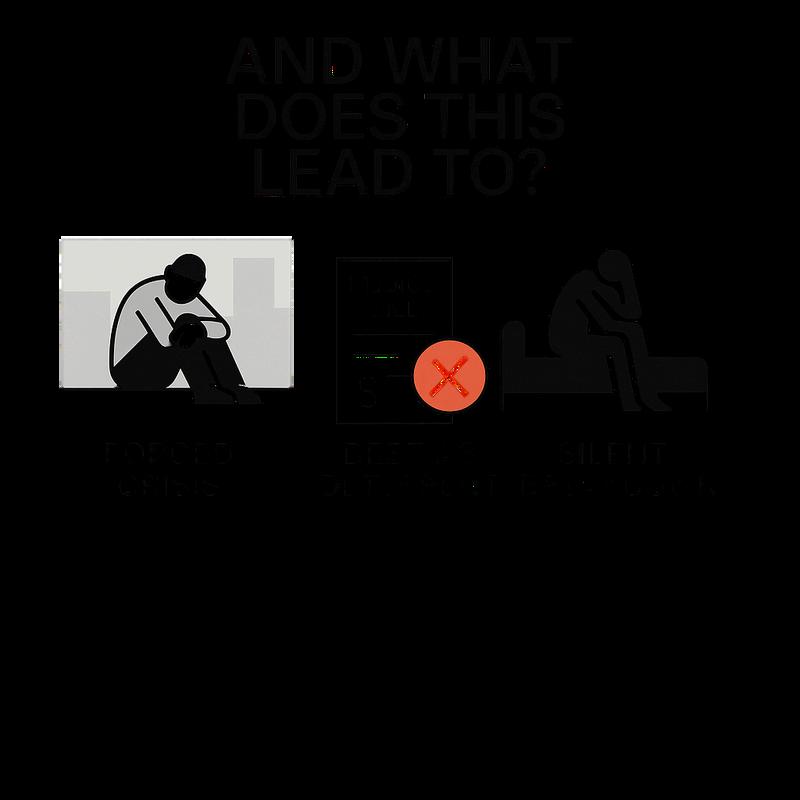

On Chicago’s South and West Sides, uninsured rates reach up to three times those of wealthier, majority-white districts. This forces residents to postpone care, endure silent deterioration, and face emergencies that generate crushing medicaldebt.

The issue is not simply about cost it is a structural urban failure that consistently leaves the same communities without the basic healthcare infrastructure required to preventavoidablesuffering.

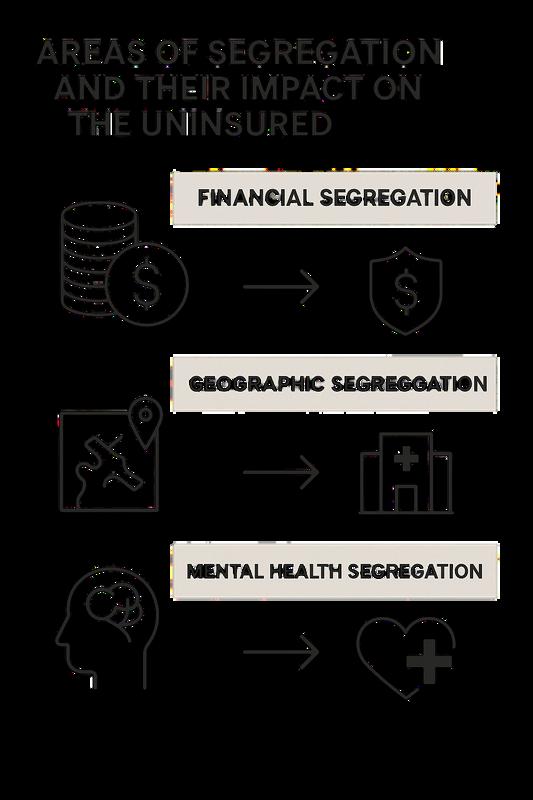

Medical segregation is the systemic, unequal distribution of healthcare resources and quality based on race, socioeconomic status, and ability to pay.

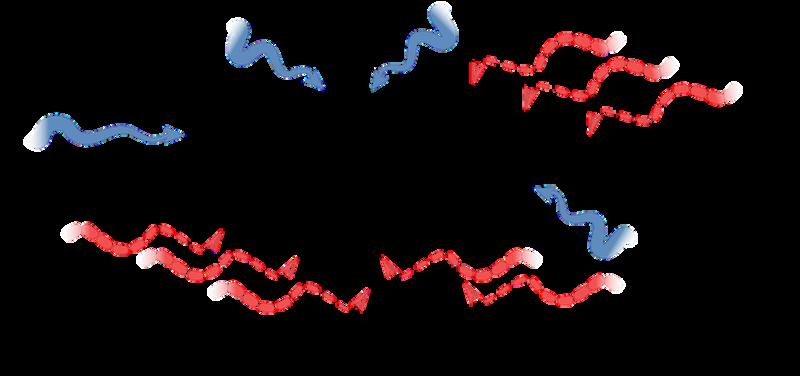

This diagram illustrates three structural forms of segregation that shape the lived reality of uninsured communities.

Financial segregation highlights how the cost-driven healthcare system restricts access to those who can afford high-tier coverage.

Geographic segregation shows how low-income neighborhoods often designated as “health deserts” lack essential medical and mental health facilities, forcing residents to rely on distant or overcrowded services

Mental health segregation underscores how psychological and psychiatric care remain inaccessible luxuries, leaving vulnerable populations without the support needed to maintain emotional and social wellbeing.

Together, these layers reveal how systemic barriers intersect, reinforcing inequality and limiting access to even the most fundamental forms of care.

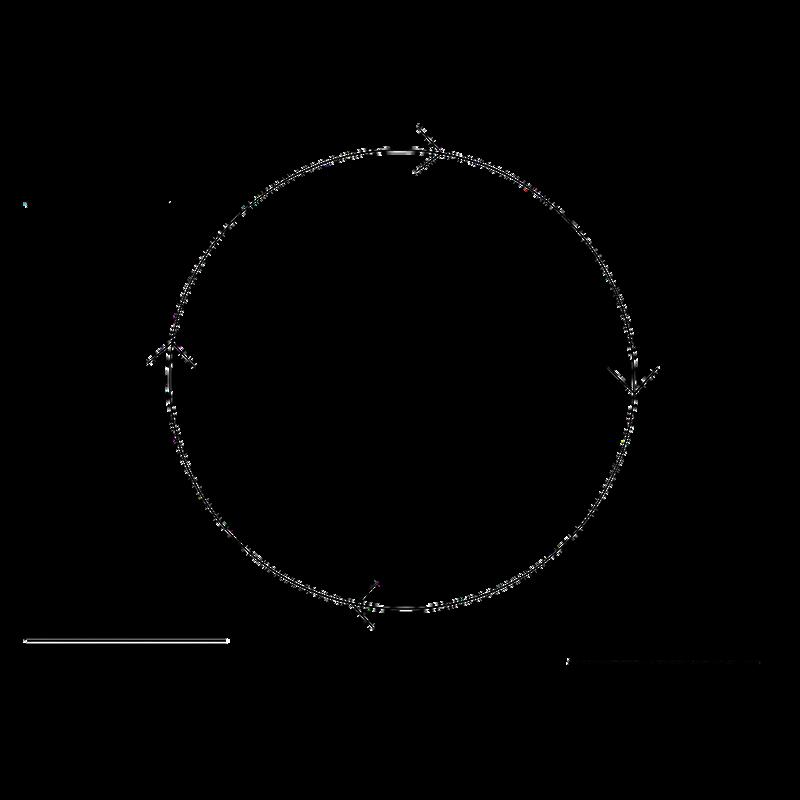

This diagram illustrates how vulnerable populations become trapped in a repeating loop of health exclusion. In the United States, 11% of adults remain uninsured, but the burden is far greater in marginalized groups: among Hispanic adults, the rate rises to 24.6%, and in several Chicago neighborhoods such as Little Village or Brighton Park it reaches 26–27%

Without insurance, people avoid seeking care due to cost, leading to silent deterioration until conditions become emergencies. Emergency visits then generate overwhelming medical debt, deepening financial instability. This debt pushes individuals further away from the healthcare system, causing relapse and renewed exclusion, which restarts the cycle.

The circular nature of the diagram emphasizes how each stage reinforces the next, creating a structural trap that disproportionately affects low-income and minority communities.

RUIN AND MASSIVE DEBT

MASSIVE

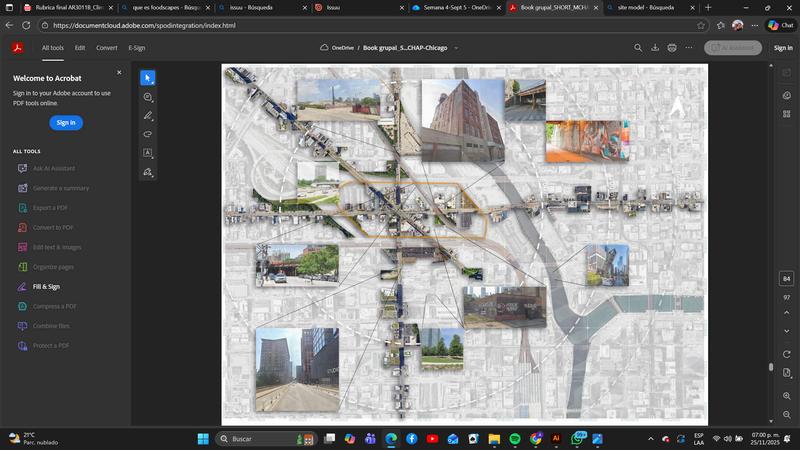

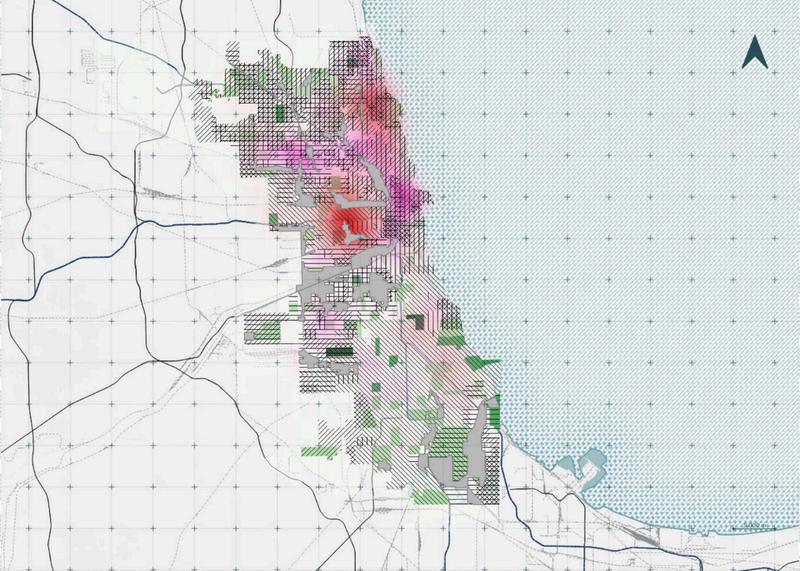

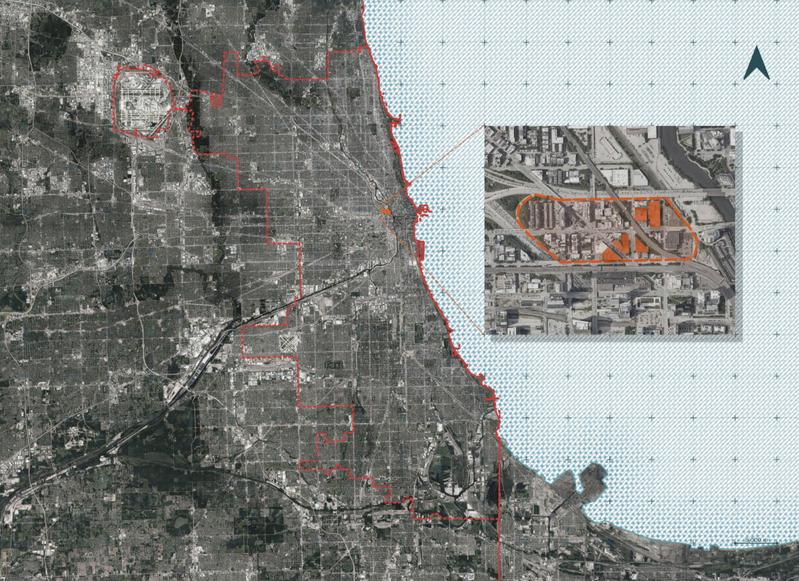

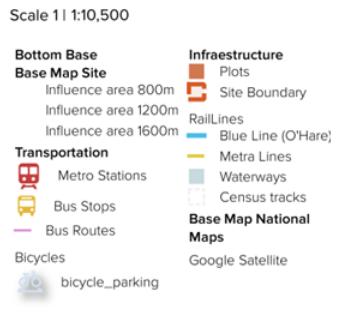

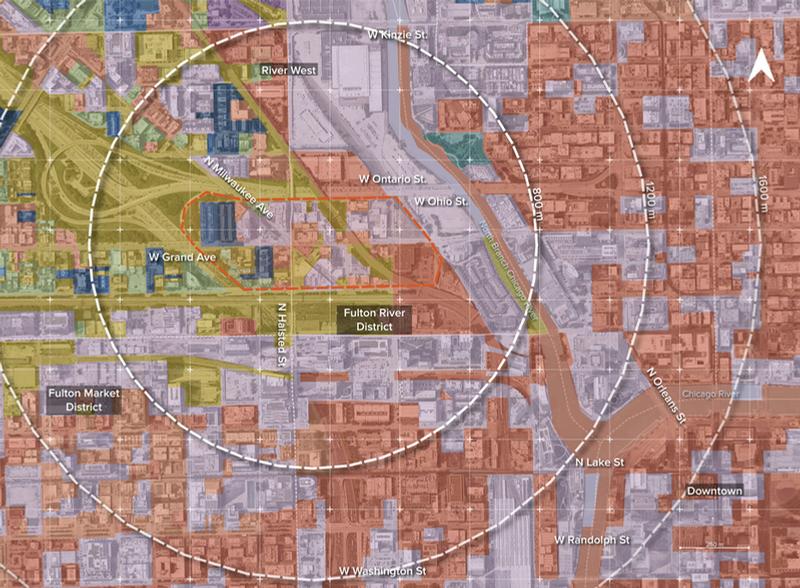

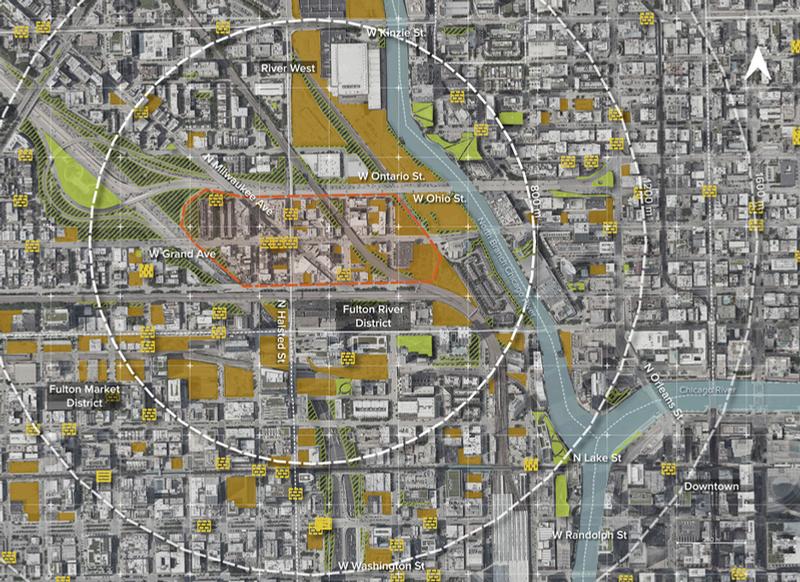

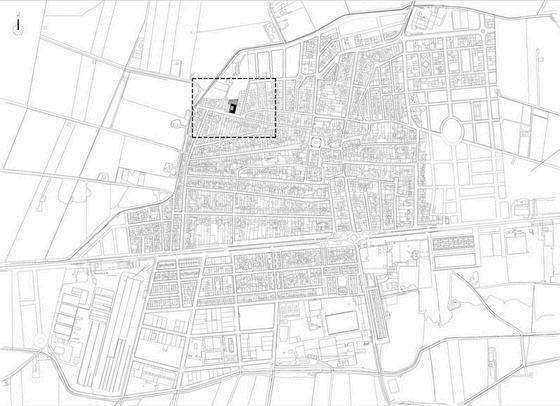

The study area, located in Chicago’s northwestern edge near Downtown, has evolved into a high-income, predominantly white enclave. Over the past two decades, massive reinvestment has reshaped the district, replacing industrial infrastructure and working-class immigrant communities with high-density housing, retail clusters, and tech-oriented office spaces. This wave of adaptive reuse marks a shift in Chicago’s economic priorities: historic industrial shells have been converted into creative workplaces and lifestyle developments, while the area’s original cultural and economic identity has been systematically displaced.

Primary

Railway

Housing

Roads Site

Prevailing winds from the west Buildings

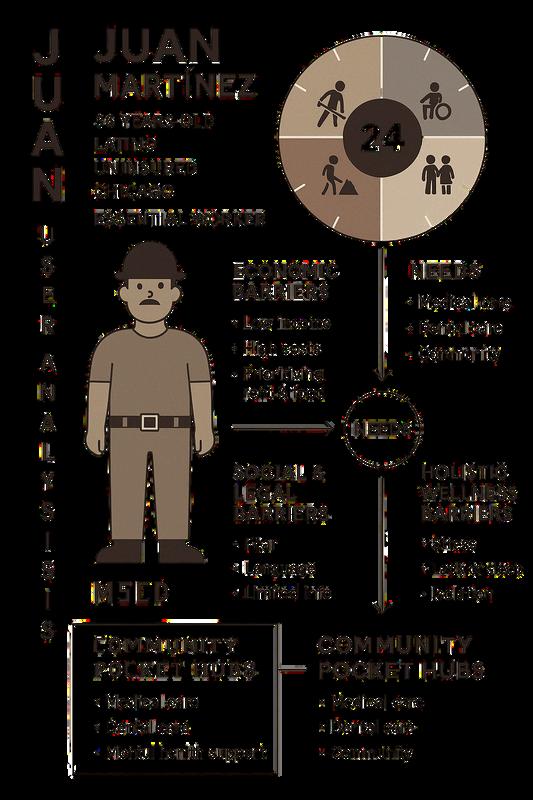

36 YEARS OLD LATINO

UNINSURED CHICAGO ESSENTIAL WORKER

ECONOMIC BARRIERS

LOW INCOME

HIGH COSTS PRIORITIZING

RENT & FOOD

SOCIAL & LEGAL BARRIERS

FEAR LANGUAGE

LIMITED INFORMATION

NEEDS

MEDICAL CARE

DENTAL CARE

COMMUNITY

HOLISTIC

WELLNESS

BARRIERS

STRESS

LACK OF SLEEP ISOLATION

BRIDGINGTHEHEALTHEQUITYGAP

DESCENTALIZED COMMUNITYHEALTH MODEL

BRIDGINGTHEHEALTHEQUITYGAP

BARRIERS HUB ACCESS

INTEGRATED,BARRIER-FREECARE

ESSENTIALMEDICALCARE

DENTALSERVICES

MENTALHEALTHPRIORITYCARE

SOCIALCOHESION

Workshops and community spaces fostering well-being and community support.

In a city where health is treated as a commodity, what is the true cost of being uninsured? The Community Pocket Hubs project is defined as the design of a zerocost, integrated community health center, a direct architectural and social intervention confronting the systemic inaccessibility of healthcare in Chicago. Conceived to break the vicious cycle of sickness and debt, the Hub critically merges essential access to medical, dental, and psychological care, eliminating the economic barrier that forces vulnerable populations to postpone care until illness becomes a crisis. Beyond clinical provision, the design intentionally integrates workshops and socialization spaces to act as an anchor of resilience, addressing the mental health crisis and social isolation. By being strategically situated in an area of rapid gentrification, the Hub establishes itself as a beacon of equity, asserting the right to health above economic profit.

INACCESSIBLEHEALTHCARE

CHOICEBETWEENHEALTH&

FINANCIALRUIN

CYCLEOFSICKNESSANDDEBT

POSTPONEDCARE

WORSENINGILLNESSES

MENTALHEALTHCRISES

SOCIALISOLATION

COMMUNITYPOCKETHUBS

ZERO-COST,INTEGRATEDWELLNESSCENTER

ARTWORKSHOPS

SOCIALIZATIONSPACES

FOSTERINGBELONGINGANDEMOTIONALWELL-BEING

ANCHORFORCOMMUNITYRESILIENCE

ARTWORKSHOPS

SOCIALIZATIONSPACES

FOSTERINGBELONGINGANDEMOTIONALWELL-BEING

STRATEGICALLYLOCATEDINAREAS

RESTRUCTUREDBYGENTRIFICATION

THERIGHTTOHEALTHABOVEECONOMICPROFIT.

HOLISTICWELLNESSBARRIER

CHRONICSTRESS

ISOLATION

UNADDRESSED

PHYSICAL CONDITIONS

SOCIAL&LEGALBARRIER

LACKOF RESOURCES

UNDER-SERVED COMMUNITIES IMMIGRANT CHALLENGES

ECONOMICBARRIER

LOW-INCOME STATUS UNINSURED POPULATION HIGH HEALTHCARE COSTS

Ensuringa secureand protected environment. Providing accesstocare andsupport.

Fostering connectionand inclusion. Facilitatingease ofusefor everyone.

The Community Pocket Hubs model transcends Chicago's borders, establishing itself as a deeply replicable and urgently needed architectural and social prototype on a global scale. Within the United States, it offers a proven solution to mitigate financial, geographical, and mental health segregation in countless cities and healthcare deserts where access to health remains a privilege. Internationally, the design can be adapted by developed nations with fragmented systems or by communities facing migration crises, serving as critical urban survival infrastructure for refugees, immigrants, and any vulnerable population. Essentially, the Hub demonstrates that a comprehensive, zero-cost, human-centered health model is universally applicable and vital for transforming health into a fundamental right in any global context.

The Community Pocket Hub is conceived as a self-sustaining social infrastructure, operating under a mixed funding model similar to that of subsidized community clinics. Its long-term maintenance is supported through a combination of public subsidies, private donations, institutional partnerships, and community-based programs, ensuring economic viability without compromising accessibility.

A portion of the building’s operation is sustained through government support for public health and social services, particularly in the medical, psychological, and dental care areas. This funding allows services to be offered at low or no cost for vulnerable users while maintaining professional standards of care.

In parallel, the project integrates a donation-based support system, involving:

Non-profit organizations

Healthcare foundations

Private donors

University and research institutions

These contributions strengthen equipment renewal, specialized programs, and preventive health initiatives. The inclusion of coworking spaces and affordable housing units generates a controlled internal revenue, which is reinvested directly into the building’s maintenance, basic operation, and public spaces. This creates a closed economic loop, where productive and residential programs financially support the social and health infrastructure.

Finally, the park, garden, and common areas are maintained through a shared-management model, where local institutions, residents, and service users participate in basic upkeep, reinforcing the project’s role not only as a healthcare facility, but as a collective urban asset.

A public place for people to meet, socialize, learn, and access recreational or support services.

To make “the healthy choice the easy choice” by shaping environments that naturally encourage better habits.

These center are becoming community wellness hubs that promote holistic health including clinical, behavioral, and pharmaceutical care.

The project targets the Life Radius the area around one’s home where people spend most of their time.

Entering the center is the first step toward well-being.

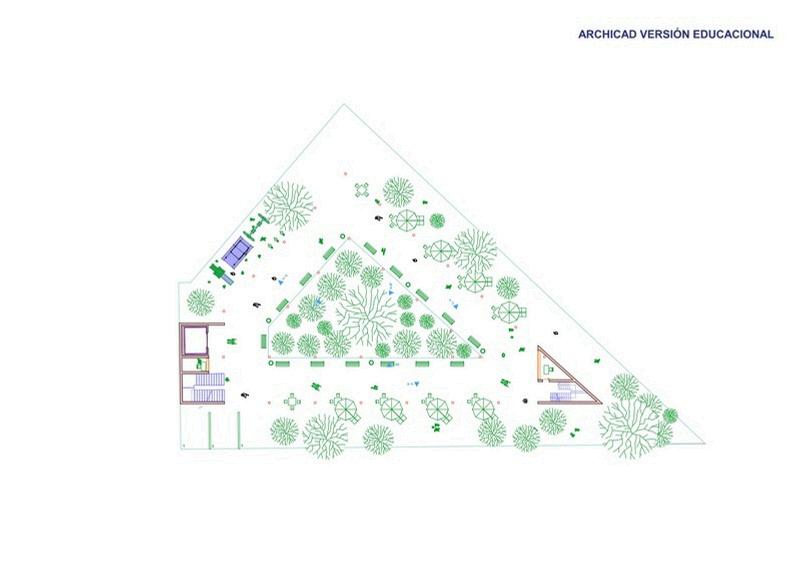

LANDSCAPESTRATEGIES

NATIVE, DROUGHTTOLERANTSPECIES

LOW-MAINTENANCE

PLANTING SUPPORTING LOCALBIODIVERSITY

POLLINATOR-FRIENDLY

VEGETATIONCORRIDORS

SHADED STRUCTURES: GREEN PERGOLAS, TRELLISES, OR VINE SYSTEMS

PHYTOREMEDIATION USING

HYPERACCUMULATOR SPECIES

SOIL DETOXIFICATION + ORGANIC MATTER

RESTORATION

MICRO-TOPOGRAPHYAND

POROUS SUBSTRATES TO IMPROVEDRAINAGE

ON-SITE COMPOSTING TO STRENGTHEN SOIL HEALTH

RAINWATER HARVESTING INTEGRATED WITH BUILDINGROOFS

ROOF RUN-OFF COLLECTION + GREYWATER REUSE FOR IRRIGATION

PERMEABLE SURFACES (PAVERS, GRAVEL BEDS, POROUSCONCRETE)

BIOSWALES + LINEAR WETLAND STRIPS FOR STORMWATER MANAGEMENT

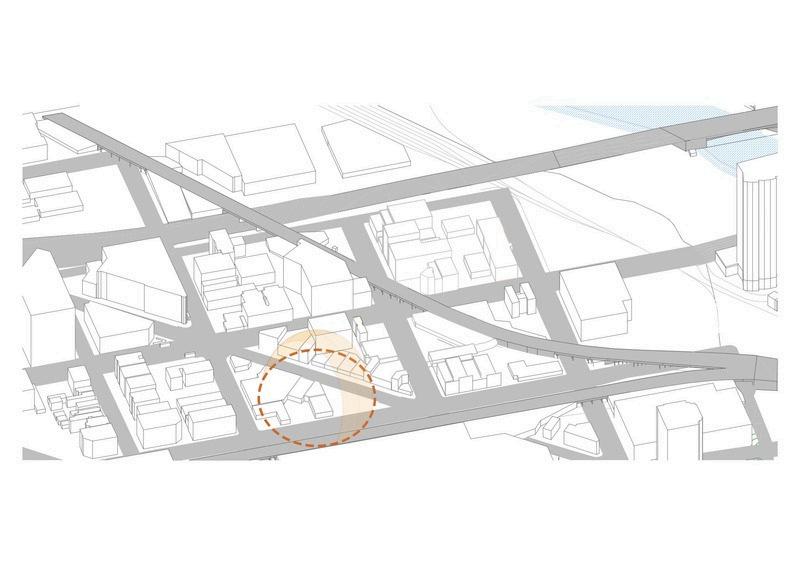

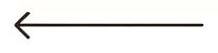

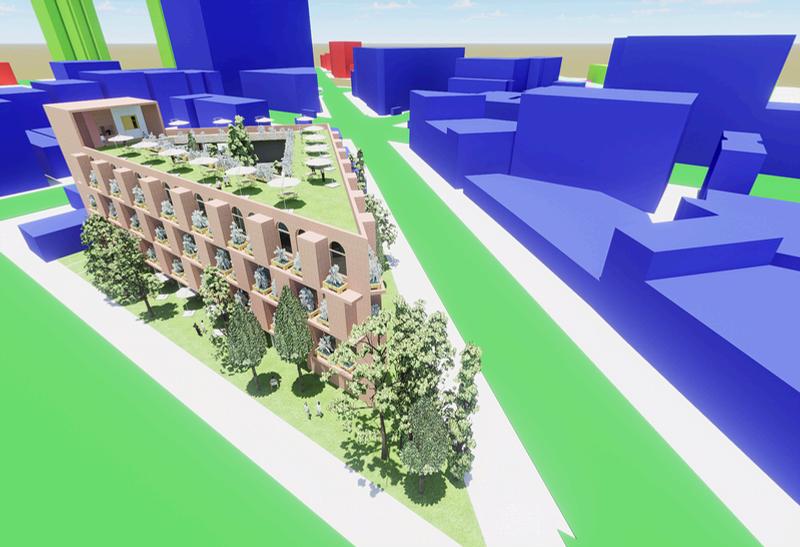

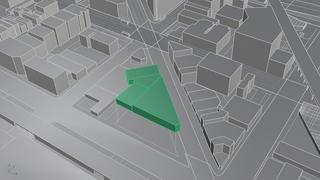

The Community Pocket Hub is located at the intersection of Milwaukee Avenue and Hubbard Street, a highly trafficked urban corridor with constant pedestrian and vehicular flow. The presence of bus stops both at the corner of the site and directly across the street establishes this location as a strategic mobility node, ensuring direct accessibility for the local and floating population. The surrounding area presents a pronounced urban heat island effect, caused by high building density, impermeable surfaces, and a lack of vegetation, alongside a critical shortage of accessible green areas. In addition, a clear deficit in integral healthcare services particularly medical, psychological, and dental care directly impacts the quality of life of those who work in and move through the area daily. For these reasons, the site is understood as a point of urban tension, where mobility, environmental stress, and social vulnerability converge, making it an ideal location for a Community Pocket Hub focused on health, care, and climate relief.

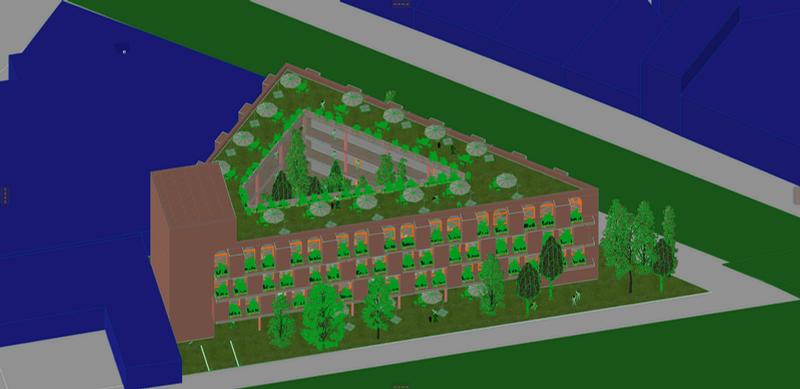

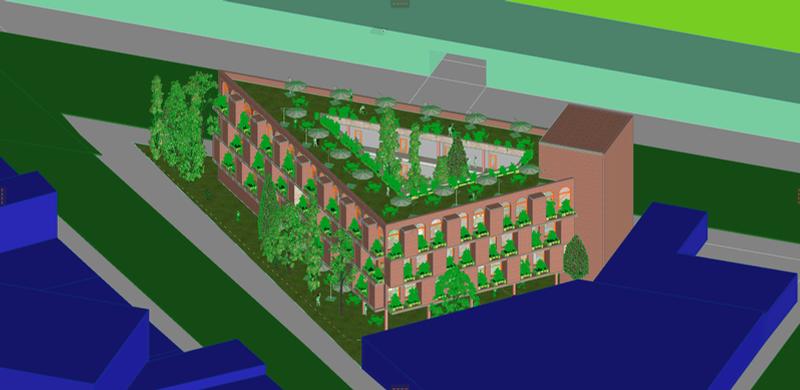

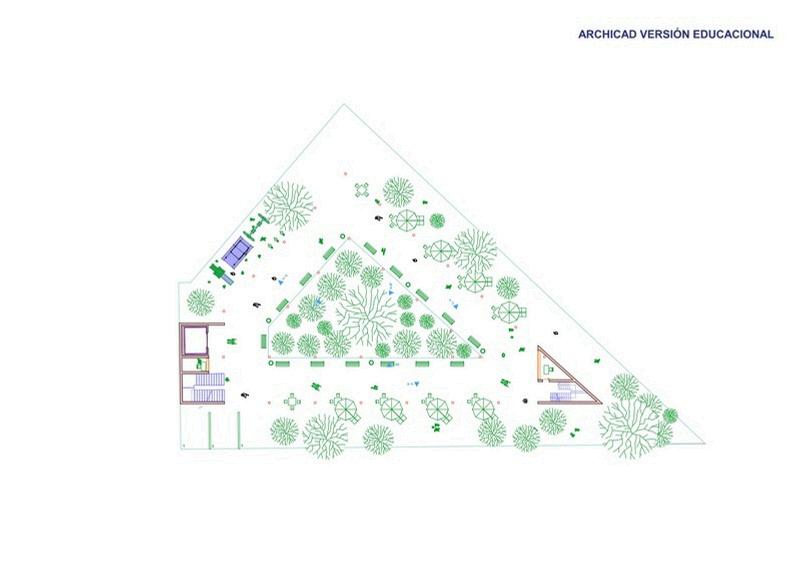

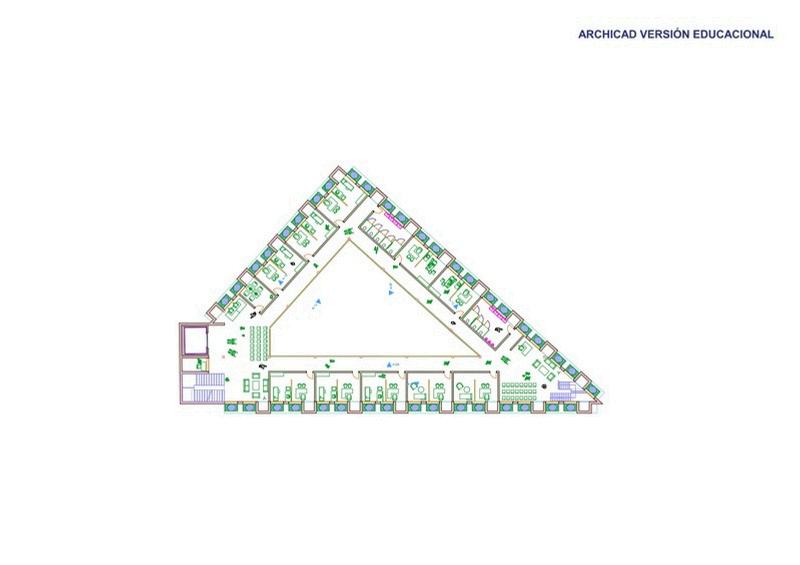

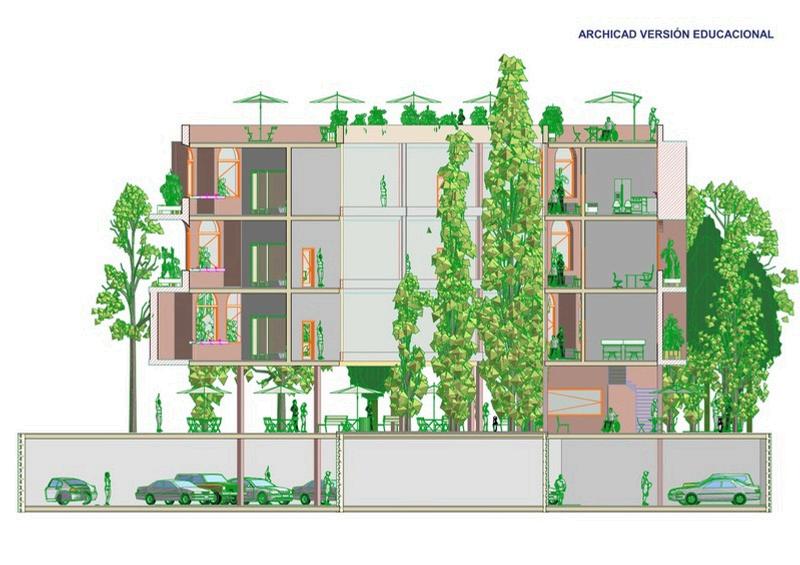

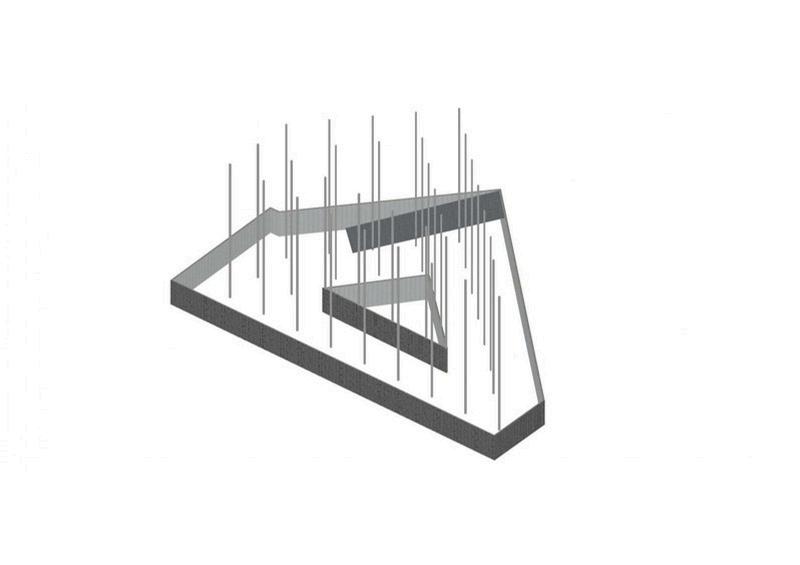

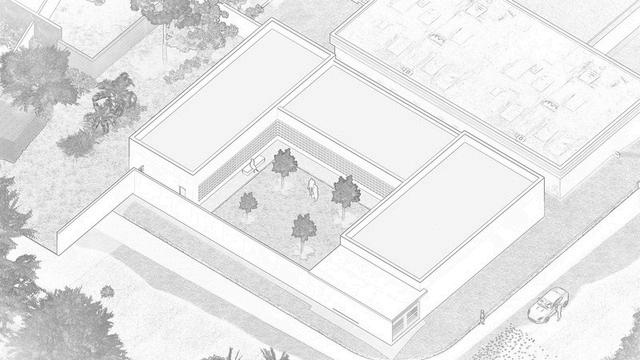

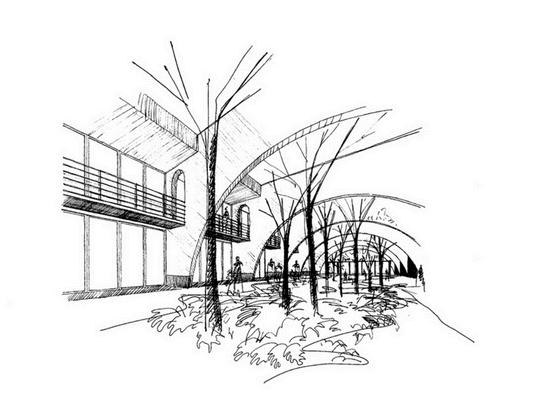

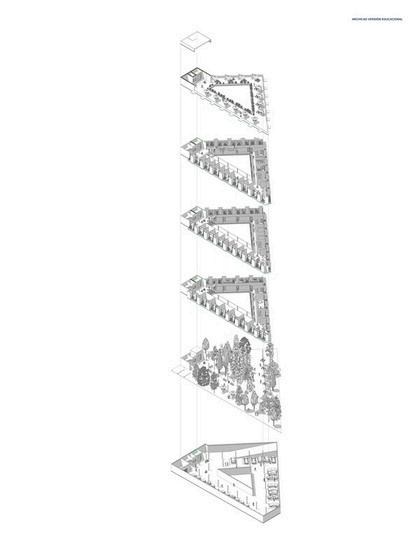

The form of the building responds directly to the almost triangular geometry of the site, shaping a volumetry that adapts to its limits and urban pressures. The project is conceived as a direct response to the scarcity of services in the area, concentrating medical, psychological, and dental care as the functional core of the building. The decision to allocate the ground floor as a park and garden emerges from the lack of green spaces, allowing the public realm to extend into the site as a true urban breathing space. Accessible housing is integrated in the upper levels in response to the artistic and creative character of the area, recognizing artists, cultural workers, and the floating population as key users. The steel structure supported by 33 columns makes it possible to completely free the ground floor, ensuring transparency, visual continuity, and allowing people arriving by bus to recognize and understand the project without the need to enter it, removing both physical and symbolic barriers. The building is organized through a vertical gradient of privacy, from the public park at ground level, to the semi-public health and coworking spaces, and finally to the private residential levels. A central garden is integrated as the thermal, visual, and therapeutic heart of the project, reinforcing the relationship between physical health, mental well-being, and architecture. An underground parking facility is incorporated to support users who arrive by car, strengthening the project’s overall accessibility. The building is conceived not as an isolated object, but as an urban care infrastructure, where the historically invisible user becomes the central axis of design.

Public

FIRST FLOOR FIRST FLOOR

GARDEN

INFORMATION POINT

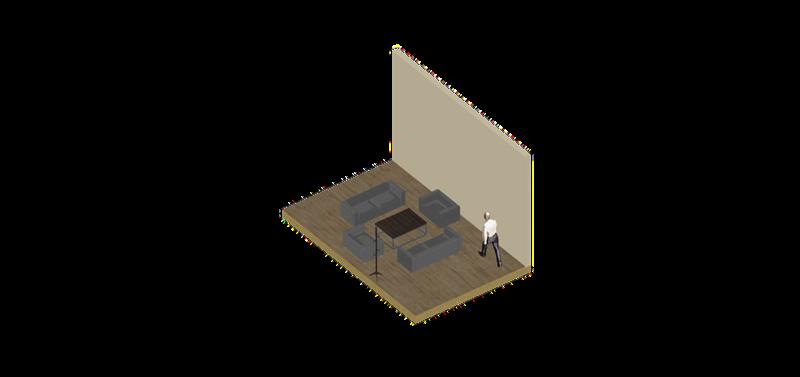

WAITING AREA

DRAWING

PAINTING

COMPUTING / COMPUTER ROOM

DANCE ROOM

MULTIPURPOSE ROOM

VISUAL ARTS ROOM

LIBRARY

COMMUNITY KITCHEN

OFFICES

CO-WORKING

WOMEN’S RESTROOMS

MEN’S RESTROOMSSTAIRS

ELEVATOR

ACCESS CONTROL

STAIRS

PARK / JARDEN

PLAYGROUND EQUIPMENT

STAIRS

ELEVATOR

ACCESS CONTROL

EMERGENCY PARKING

RAMP (DOWNWARD ACCESS TO THE PARKING)

UNDERGROUND PARKING AREAS

INDOOR PLANTER

STAIRS

ELEVATOR

ACCESS CONTROL

MECHANICAL ROOM

RAMP (DOWNWARD ACCESS TO THE PARKING)

FIFTH FLOOR FIFTH FLOOR

ROOF

FOURTH FLOOR FOURTH FLOOR

GARDEN ROOFTP GARDEN

ELEVATOR

ACCESS CONTROL STAIRS

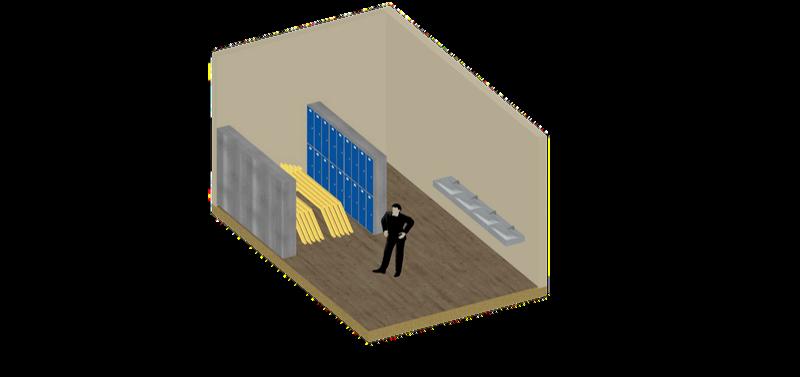

GARDEN INFORMATION POINT HOUSING / DWELLING SHOWERS

CHANGING ROOM CO-WORKING

LIVING ROOM

WOMEN’S RESTROOMS MEN’S RESTROOMSSTAIRS

ELEVATOR

ACCESS CONTROL STAIRS

GARDEN

INFORMATION POINT

WAITING AREA

MEDICAL OFFICE

PSYCHOLOGY OFFICE DENTAL OFFICE OFFICES

WOMEN’S RESTROOMS MEN’S RESTROOMSSTAIRS ELEVATOR

ACCESS CONTROL STAIRS

ACCESS 1

TOTAL AREA: 68.5 SQUARE METERS

ACCESS VIA STAIRS AND ELEVATOR

INCLUDES A CONTROL BOOTH

THIS CONFIGURATION IS REPEATED

ACROSS 6 LEVELS

PARKING TYPOLOGY

TOTAL AREA: 1881 SQUARE METERS

CAPACITY FOR 33 VEHICLES

4 ACCESSIBLE PARKING SPACES FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

ACCESS VIA ELEVATOR AND STAIRS

INCLUDES A CONTROL BOOTH FOR ENTRY AND EXIT MANAGEMENT

THIS LEVEL ALSO INCLUDES THE MECHANICAL ROOM

THIS PARKING AREA IS LOCATED ON LEVEL -1

SECONDARY ACCESS TYPÓLOGY

TOTAL AREA: 36.62 SQUARE METERS

INCLUDES A CONTROL BOOTH

ACCESS VIA STAIRS

THIS CONFIGURATION IS REPEATED

ACROSS 4 LEVELS

PARK / GARDEN TYPOLOGY

TOTAL AREA: 1,935.91 SQUARE METERS

ACCESS VIA ELEVATOR AND STAIRS

INCLUDES A CONTROL BOOTH FOR ACCESS MANAGEMENT

THIS AREA IS LOCATED ON THE GROUND FLOOR

ROOF GARDEN TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 750 SQUARE METERS

14 TABLES FOR 4 PEOPLE EACH

ACCESS VIA ELEVATOR AND STAIRS

SEMI-PUBLIC USE

INCLUDES A GARDEN AREA

LOCATED ON LEVEL 4 (ROOF)

DRAWING CLASSROOM

TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

PAINTING CLASSROOM TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

MULTIPURPOSE ROOM TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 72

SQUARE METERS

PLASTIC ARTS

CLASSROOM TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 24

COMPUTER CLASSROOM

TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

SQUARE METERS LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

DANCE / MOVEMENT

STUDIO TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

OFFICE TYPOLOGY X3

TOTAL AREA: 12

SQUARE METERS

EACH

LOCATED ON 3 LEVELS

LIBRARY TYPOLOGY X1

COMMUNITY KITCHEN TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 24 SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

COWORKING TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 24 SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 1

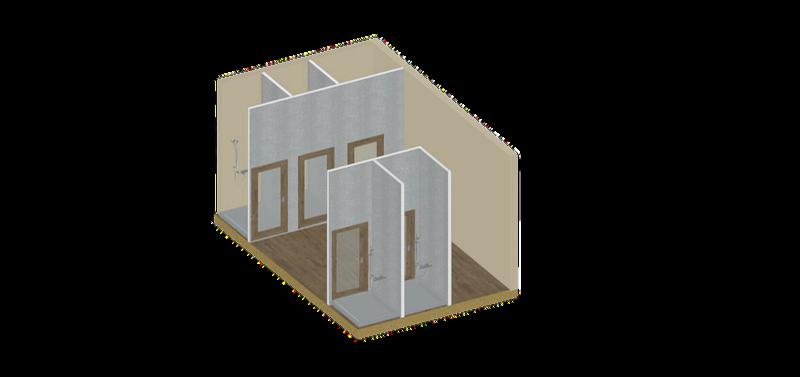

WOMEN’S RESTROOM TYPOLOGY X3

TOTAL AREA: 24 SQUARE METERS EACH

5 TOILET STALLS, INCLUDING 1 ACCESSIBLE STALL FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

LOCATED ON 3 LEVELS

MEN’S RESTROOM TYPOLOGY X3

TOTAL AREA: 24 SQUARE METERS EACH

3 TOILET STALLS, INCLUDING 1 ACCESSIBLE STALL FOR PEOPLE WITH DISABILITIES

3 URINALS

LOCATED ON 3 LEVELS

WAITING AREA

TYPOLOGY X4

TOTAL AREA: 22

SQUARE METERS

EACH LOCATED ON 4 LEVELS

SECONDARY ACCESS TYPOLOGY X1

TOTAL AREA: 70 SQUARE METERS

INCLUDES RECEPTION DESK

EQUIPPED WITH SEATING FOR WAITING AREA

FUNCTIONS AS A WAITING AREA

GENERAL WAITING AREA

TYPOLOGY X3

TOTAL AREA: 54 SQUARE

METERS EACH

INCLUDES A RECEPTION DESK EQUIPPED WITH SEATING FOR WAITING AREA USERS LOCATED ON 3 LEVELS

MEDICAL CONSULTATION

ROOM TYPOLOGY X6

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS EACH

LOCATED ON LEVEL 2

PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSULTATION ROOM TYPOLOGY X2

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS EACH

LOCATED ON LEVEL 2

DENTAL CONSULTATION

ROOM TYPOLOGY X2

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS EACH

LOCATED ON LEVEL 2

COWORKING TYPOLOGY

X1

TOTAL AREA: 36

SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 3

HOUSING UNIT

TYPOLOGY X7

LOCATED ON LEVEL 3

COMMUNITY SHOWERS

TYPOLOGY X1

5 SHOWER CUBICLES

TOTAL AREA: 24

SQUARE METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 3

CHANGING ROOM TYPOLOGY

X1

TOTAL AREA: 24 SQUARE

METERS

LOCATED ON LEVEL 3

1.UNDERGROUND PARKING AREAS

2.INDOOR PLANTER

3.STAIRS

4.ELEVATOR

5.ACCESS CONTROL

6.MECHANICAL ROOM

7.RAMP (DOWNWARD ACCESS TO THE PARKING)

1.PARK / JARDEN

2.PLAYGROUND EQUIPMENT

3.STAIRS

4.ELEVATOR

5.ACCESS CONTROL

6.EMERGENCY PARKING

7.RAMP (DOWNWARD ACCESS TO THE PARKING)

1.GARDEN

2.INFORMATION POINT

3.WAITING AREA

4.DRAWING

5.PAINTING

6.COMPUTING / COMPUTER ROOM

7.DANCE ROOM

8.MULTIPURPOSE ROOM

9.VISUAL ARTS ROOM

10.LIBRARY

11.COMMUNITY KITCHEN

12.OFFICES

13.CO-WORKING

14.WOMEN’S RESTROOMS

15.MEN’S RESTROOMSSTAIRS

16.ELEVATOR

17.ACCESS CONTROL

18.STAIRS

1.GARDEN

2.INFORMATION POINT

3.WAITING AREA

4.MEDICAL OFFICE

5.PSYCHOLOGY OFFICE

6.DENTAL OFFICE

7.OFFICES

8.WOMEN’S RESTROOMS

9.MEN’S RESTROOMSSTAIRS

10.ELEVATOR

11.ACCESS CONTROL

12.STAIRS

1.GARDEN

2.INFORMATION POINT

3.HOUSING / DWELLING

4.SHOWERS

5.CHANGING ROOM

6.CO-WORKING

7.LIVING ROOM

8.WOMEN’S RESTROOMS

9.MEN’S RESTROOMSSTAIRS

10.ELEVATOR

11.ACCESS CONTROL

12.STAIRS

1.GARDEN

2.ROOFTP GARDEN

3.ELEVATOR

4.ACCESS CONTROL

5.STAIRS

The project is structurally anchored by a perimetral retaining wall at the basement level, which contains the surrounding soil and acts as the primary foundation system for the building above. At the center of this level, a large planter void allows trees to develop deep and unrestricted root systems, ensuring long-term ecological stability. An additional open corner within the site operates under the same principle, enabling vegetation to emerge directly from the ground and reinforcing the continuity between landscape and structure.

Above this base, the building is supported by 33 steel columns, each measuring 30 cm in diameter, which sustain the five elevated levels of the project. Each floor reaches a height of 4 meters, providing generous spatial proportions that enhance natural ventilation, daylight penetration, and thermal comfort. Vertical circulation is resolved through a universal-access elevator, while each level integrates an access-control station, ensuring both security and functional organization throughout the building.

The building’s material strategy integrates brick, wood, steel, and latticework to articulate an architecture that is simultaneously robust, warm, and welcoming. Material selection is guided by criteria of durability, sustainability, and cultural resonance, reinforcing the idea that community care must be expressed through dignified architecture rather than minimal solutions. This palette establishes a balance between permanence, transparency, and human scale.

The exterior envelope is composed of brick walls, giving the building a warm, tactile, and timeless character that resonates with Chicago’s industrial and architectural heritage. In contrast, the walls facing the interior courtyard are resolved through glass framed panels, allowing full visual continuity with the central garden and ensuring that nature remains a constant presence across all levels of the project. Openings are strategically positioned to maximize natural light while controlling glare and reducing heat gain, optimizing environmental performance and user comfort.

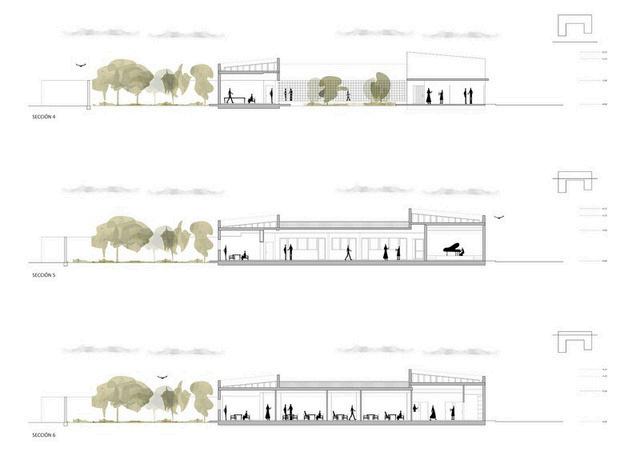

Location: Puebla de la Calzada, Badajoz, Spain

Architect: APT Arquitectos

Year: 2023

Area: 410 m2

The program integrates primary healthcare with spaces dedicated to health promotion and wellbeing. It includes medical and nursing consultations, multipurpose rooms for prevention activities, and support areas. Its key feature is a Community Focus, designed as a social meeting and activation point to encourage healthy habits and community cohesion. Spaces are flexible to adapt to different uses.

The material selection emphasizes sustainability and contextual integration. Ceramic Brick is used on the façades, providing a warm, traditional texture related to vernacular architecture. Exposed Concrete offers structural solidity. The design prioritizes systems that maximize natural light and cross-ventilation, reducing the need for artificial climate control.

The structure is simple and modular to allow for programmatic flexibility. It uses a Portico Structure (columns and beams) that frees the internal walls, making future modifications easier. The construction is optimized for sustainability and reduced environmental impact.

The design is based on the duality of privacy and openness. The building is organized around interior courtyards (patios), which function as "lungs" for light and ventilation, and as transitional spaces. Circulation is clear, and the Indoor-Outdoor Connection is achieved through courtyards and large windows, creating an welcoming and therapeutic environment (Biophilic Architecture).

The project responds to the social and urban needs of its location. It seeks Urban Insertion with a respectful scale, avoiding a cold institutional image. By creating an attractive public space, it contributes to the social and physical betterment of the site, acting as a driver for comprehensive community development.

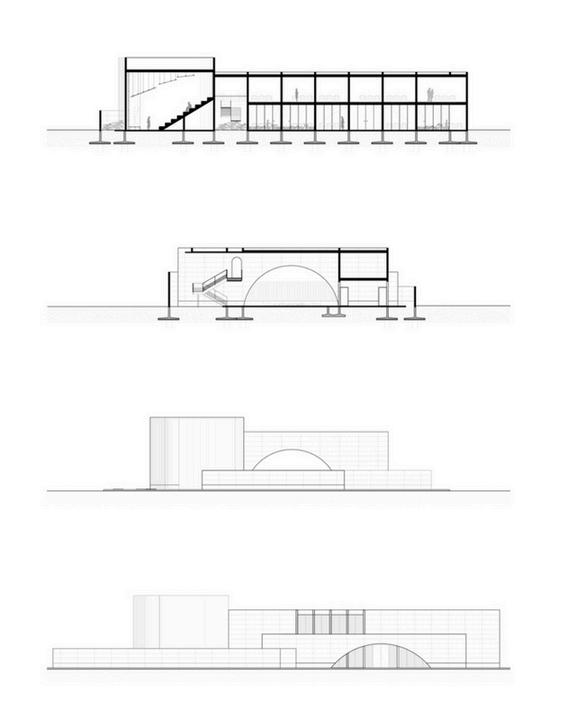

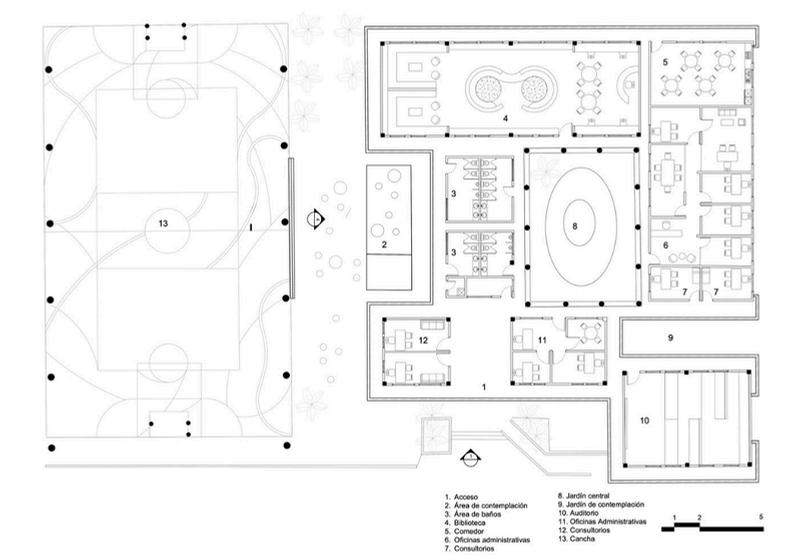

Location: Jalpa de Méndez, Tabasco, México

Architect: CCA

Focus Community Mental Health and Inclusion

Year: 2022 (not finished)

Area: 1240 m2

The CDC focuses on cultural and educational development to foster social integration and inclusive development, forming part of a larger public space revitalization project (El Campestre Recreational Park).

Core Focus: Cultural and educational development as a driver for social wellbeing.

Key Spaces: Multifunctional classrooms, workshops, meeting areas, and an outdoor auditorium.

Social Wellbeing: It promotes wellbeing by offering training opportunities and a safe space for community life, strengthening the social fabric and local economy.

The material selection emphasizes sustainability and contextual integration. Ceramic Brick is used on the façades, providing a warm, traditional texture related to vernacular architecture. Exposed Concrete offers structural solidity. The design prioritizes systems that maximize natural light and cross-ventilation, reducing the need for artificial climate control.

The structure is simple and modular to allow for programmatic flexibility. It uses a Portico Structure (columns and beams) that frees the internal walls, making future modifications easier. The construction is optimized for sustainability and reduced environmental impact.

The design is based on the duality of privacy and openness. The building is organized around interior courtyards (patios), which function as "lungs" for light and ventilation, and as transitional spaces. Circulation is clear, and the Indoor-Outdoor Connection is achieved through courtyards and large windows, creating an welcoming and therapeutic environment (Biophilic Architecture).

The project responds to the social and urban needs of its location. It seeks Urban Insertion with a respectful scale, avoiding a cold institutional image. By creating an attractive public space, it contributes to the social and physical betterment of the site, acting as a driver for comprehensive community development.

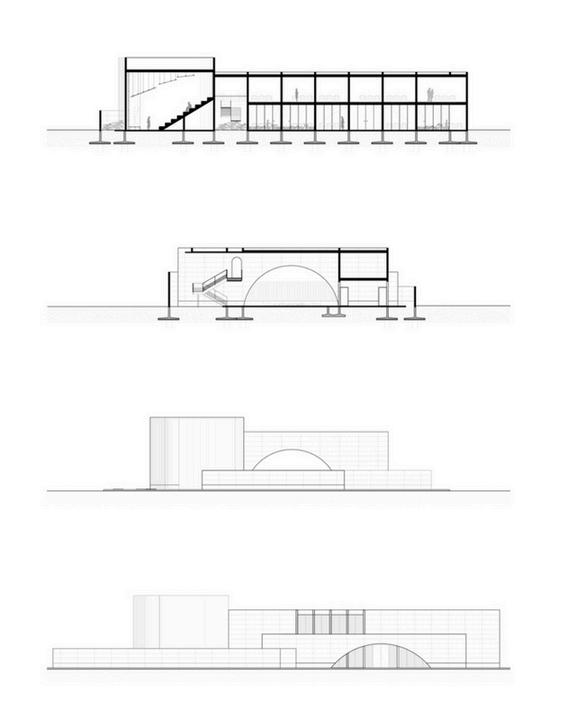

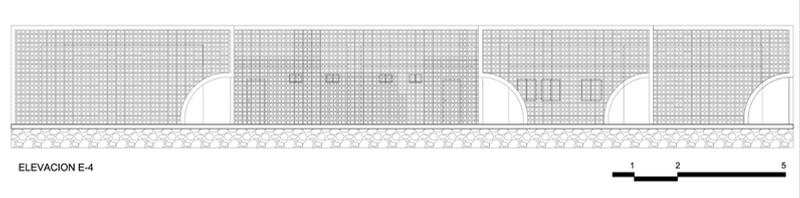

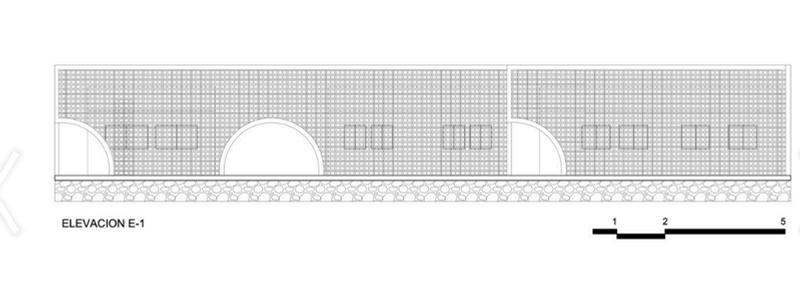

Location: Monterrey, Nuevo León, Mexico

Architect: Proyecto Reacciona

Year: 2022

Area: 840 m2

The center was rehabilitated from an old school to serve as a comprehensive community center focused on safety, mental health, and social development. The Secretary of Crime Prevention requested administrative areas, consultation rooms for psychological counseling, and a film/documentary viewing space. The design sought to create dynamic, multifaceted spaces that incentivize the development of multiple activities according to the community's needs.

The materiality strategy focused on unifying the old structure with the new intervention using color and a key architectural element: the latticework. The existing building was painted a solid yellow tone, which is visible through the perforations of the new ceramic latticework applied to the façade. The latticework functions as a dynamic veil that protects the interior from the intense sun of Monterrey and offers a sense of privacy while maintaining visual connection with the outside. The use of different forms and colors was key to generating dynamic and stimulating spaces.

The structural intervention involved reusing and adapting the existing masonry structure of the school. The main structural addition is the use of a large lattice wall that acts as a second skin, giving the building a new identity without modifying the original volumes excessively. This strategic use of the structural envelope maximizes natural light while protecting from solar heat gain.

The spatial logic revolves around creating a connection between the exterior and the interior to facilitate contemplation and community gathering. The vastness of the perimeter wall is interrupted by strategic extractions, creating openings that connect the inside and outside. A central landscaped area was created in the center of the project, allowing users to have a relaxation space at the door of each interior area. The entire perimeter features cylindrical benches designed to create spaces for contemplation and gathering.

The project is located in a highly dense urban area of Monterrey and is a direct response to the need for safe spaces and access to mental health services and community integration programs. The center is a resource for the local community, promoting a safer environment and offering psychological support and film/documentary viewing areas to foster social cohesion. The renovation sought to generate a differentiated and attractive image to stimulate attendance and community ownership.

PT Arquitectos. (2024, 18 de julio). Proyecto | Centro de la salud y el bienestar, Puebla de la Calzada, Badajoz. Proarquitectura. https://www.washingtonpost.com/es/post-opinion/

CCA | Bernardo Quinzaños. (2023, 22 de noviembre). Centro de desarrollo comunitario / CCA | Bernardo Quinzaños. ArchDaily México. https://www.archdaily.mx/mx/1010044/centro-de-desarrollo-comunitario-ccacentro-de-colaboracion-arquitectonica

Proyecto Reacciona. (2022, 31 de octubre). Centro comunitario Casa Nueva Esperanza / Proyecto Reacciona. ArchDaily México. https://www.archdaily.mx/mx/991354/centro-comunitario-casa-nueva-esperanza-proyectoreacciona

Servicio de Salud Metropolitano Sur Oriente. (s. f.). Modelo de salud mental y psiquiatría comunitaria COSAM La Platina. Gobierno de Chile.

Williams, D. R., & Collins, C. (2001). Racial residential segregation: A fundamental cause of racial disparities in health. Public Health Reports, 116(5), 404–416.

Betancur, J. J. (2011). Gentrification and social injustice in youth-oriented areas: The case of Pilsen, Chicago. Urban Studies, 48(4), 785–802.

Kellert, S. R., Heerwagen, J., & Mador, M. (2008). Biophilic design: The theory, science and practice of bringing life to building space. John Wiley & Sons.

Mindell, J. S. (2020). Health, well-being and the built environment. Springer.

Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning. (2024). Community data snapshot: Logan Square. CMAP.

Rhodes, K. V., Santin, O., Breyer, M., & Varela, M. V. (2020). Uninsured immigrants in Chicago: Characteristics and health care access. Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights.

CommunityHealth. (s. f.). Our impact and mission. https://www.communityhealth.org

Gehl, J. (2013). Cities for people. Island Press.

UN-Habitat. (2020). Integrating community facilities into urban planning. United Nations.

Whyte, W. H. (1980). The social life of small urban spaces. Project for Public Spaces.

Hernández, F. (2010). Arquitectura social y participación comunitaria. Gustavo Gili.

Sennett, R. (2018). Building and dwelling: Ethics for the city. Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Alexander, C. (1977). A pattern language. Oxford University Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1974). The production of space. Blackwell.

Jacobs, J. (1961). The death and life of great American cities. Random House.

World Health Organization. (2016). Urban green spaces and health. WHO.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Health equity in urban environments. CDC.

American Lung Association. (2024). State of the air: Chicago metropolitan area.

Environmental Protection Agency. (2023). Air quality and health impacts. EPA.

Northwestern University Institute for Policy Research. (2022). Health disparities in Chicago communities.

University of Illinois at Chicago. (2021). Urban displacement and neighborhood change in Chicago.

Logan Square Preservation. (2022). Community displacement report.

Chicago Department of Public Health. (2023). Healthy Chicago equity zones.

Chicago Housing Authority. (2022). Affordable housing and community development report.

McHarg, I. (1992). Design with nature. Wiley.

Hough, M. (2004). Cities and natural process. Routledge.

Beatley, T. (2011). Biophilic cities. Island Press.

Gehl Institute. (2022). Public life study: Chicago pilot.

Project for Public Spaces. (2015). What makes a successful place?

Carmona, M. (2019). Public places, urban spaces. Routledge.

Talen, E. (2012). City rules: How regulations affect urban form. Island Press.

36YEARSOLD

DESCENTALZED COMMUNTYHEALTH MODEL

BRDGNGTHEHEALTHEQUTYGAP COMMUNITY POCKETHUBS

BARRERS HUB ACCESS

BRDGINGTHEHEALTHEQUTYGAP

NTEGRATEDBARRER-FREECARE

ESSENTALMEDCALCARE

DENTALSERVICES

MENTALHEALTHPRIORTYCARE

SOCALCOHESON

Workshopsandcommuntyspaces fostengwe-bengandcommunty suppot WHUBBARDSTREET

https://youtu.be/IlQYcEfmzWg?si=3wgg roadGAtoXl3