Max Harvey YE AR 12

the

GOLDEN RATIO and its repetition throughout nature

T

he Golden Ratio could be said to be as fundamentally important to our universe as any other constant such as Pi or Euler’s number, e. However a lot less is known about the value of the Golden Ratio and even less is known about why it exists and why it is mirrored across all fields of science and throughout our daily lives. The Golden Ratio’s appearances range throughout physics, chemistry, biology and even further into meteorology and architecture. So, first things first: what is the Golden Ratio and where does it come from? No doubt many of you are well acquainted with the Fibonacci sequence, which arises from the addition of previous terms in the sequence (1,1,2,3,5,8,13,21……..) and is used frequently to predict changing prices on the stock exchange by looking at long-term rises and falls which correspond to Fibonacci percentages such as 34% or 55% and then predicting future rises and falls. However, what may not be at first obvious is that the Golden Ratio arises from this seemingly basic sequence. Taking any two consecutive numbers and dividing the larger by the smaller will give a decimal answer between 1 and 2. A few examples are 5/3 which is approximately 1.67 and 13/8 which is approximately 1.63. Interestingly, as you use increasingly higher numbers in the Fibonacci sequence to obtain these decimals, the value that is obtained tends towards a value of 1.61803……. This here is the value of the Golden Ratio. It is often referred to as Phi and is an irrational number that, unlike Pi or e cannot be expressed approximately by a fraction. Putting it simply, the Golden Ratio is just a ratio between two things. It can also be found by splitting a length of wood into two pieces so that the length of the longer piece divided by the shorter piece is also

40

P O RT S M O U T H P O I N T. B LO G S P OT.CO M

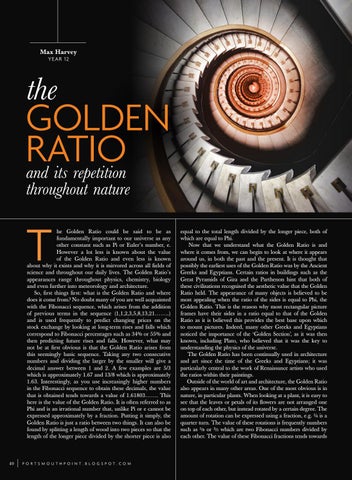

equal to the total length divided by the longer piece, both of which are equal to Phi. Now that we understand what the Golden Ratio is and where it comes from, we can begin to look at where it appears around us, in both the past and the present. It is thought that possibly the earliest uses of the Golden Ratio was by the Ancient Greeks and Egyptians. Certain ratios in buildings such as the Great Pyramids of Giza and the Parthenon hint that both of these civilisations recognised the aesthetic value that the Golden Ratio held. The appearance of many objects is believed to be most appealing when the ratio of the sides is equal to Phi, the Golden Ratio. This is the reason why most rectangular picture frames have their sides in a ratio equal to that of the Golden Ratio as it is believed this provides the best base upon which to mount pictures. Indeed, many other Greeks and Egyptians noticed the importance of the ‘Golden Section’, as it was then known, including Plato, who believed that it was the key to understanding the physics of the universe. The Golden Ratio has been continually used in architecture and art since the time of the Greeks and Egyptians; it was particularly central to the work of Renaissance artists who used the ratios within their paintings. Outside of the world of art and architecture, the Golden Ratio also appears in many other areas. One of the most obvious is in nature, in particular plants. When looking at a plant, it is easy to see that the leaves or petals of its flowers are not arranged one on top of each other, but instead rotated by a certain degree. The amount of rotation can be expressed using a fraction, e.g. ¼ is a quarter turn. The value of these rotations is frequently numbers such as 5/8 or 3/5 which are two Fibonacci numbers divided by each other. The value of these Fibonacci fractions tends towards