November/December 2022 Volume 47, No. 6 www.ttha.com

November/December 2022 Volume 47, No. 6 www.ttha.com

h, the glamor and the clamor that attend affairs of state seem to fascinate the rabble and impress some folks as great. But the truth about the matter on the scale of loss or gain, not one inaugural is worth a good, slow 2-inch rain.” —Sen. Carlos Ashley, 1949.

Well, it has finally rained, but not enough to absolve the drought that has darkened the state for months. First, we had a killing freeze in February of ’21 and then an ultra-dry summer of ’22. We don’t like such weather patterns, but they are not new to Texas.

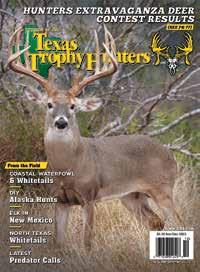

But first, let’s talk about the August Hunters Extravaganzas held in Houston, Dal las, and San Antonio. Attendees showed up in droves to see the many attractions: big rattlesnakes at the snake show; everything that goes with alligators at the show; some of the best bucks in Texas at the Annual Deer Competition; and all of the many attractions at the exhibitor booths. Folks enjoyed all the shows, which are get ting back to normal after the long period of COVID. We enjoyed seeing old friends, and making new friendships—a big part of each year’s shows.

Getting back to dry weather, most of us remember the long drought from 2005 to 2012, when ranchers hauled hay from East Texas, water holes dried up, creeks quit flowing, and old trees lost their root systems and fell over. The year 2011 was the driest in Texas history!

Texas also endured a long drought in the 1950s, I remember a 1957 “Cowpokes” cartoon by Ace Reid of Kerrville, showing a half-grown kid running to the house, crying and scared. He had never seen a rain!

Texas hunters usually hunt, regardless of the weather. Typically, the first day of dove season in September may be so hot, you could fry eggs on the rocks—or it may be raining.

Most hunters face any weather with determination, so what does the past dry summer mean to deer hunters? Well, if history repeats itself, deer will come to feed ers regularly, unless your hunting area gets a fall rain. Any rain will result in new ground forbs that may get the attention of hungry deer for a few days, but the deer will return to the feeders.

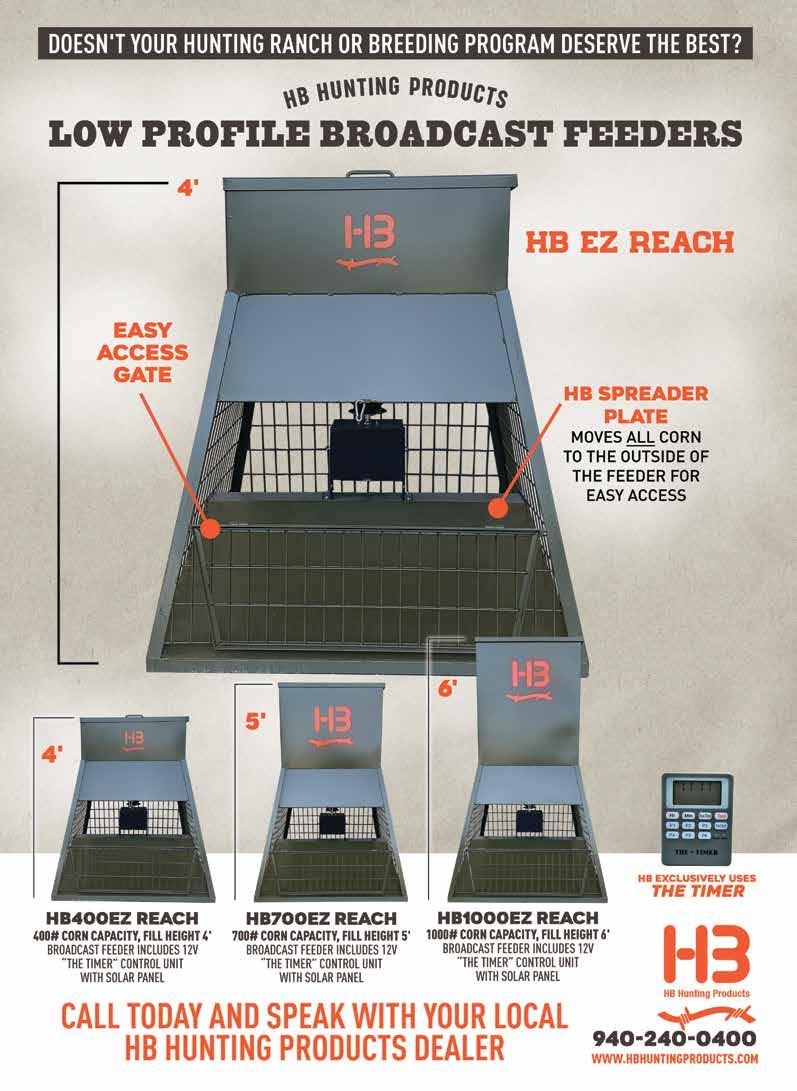

Protein pellets are high-priced, and corn at $12-14 a bag may be the highest ever. Deer do not need supplemental protein after Aug. 15, but corn gives bucks added energy during the rut. If I were carrying the ball, I would let the protein feeders run out, and keep as many corn feeders as your pocket will bear. Deer feed by habit, and if you lose deer from dry feeders, they may be slow in coming back.

With deer season here, most folks will forget the dry summer, and concentrate on getting a buck. Take the kids hunting when you can. There is an old saying: “Kids don’t get in trouble while hunting and fishing.” I’ll see you down the road.

Official Publication of

The Texas Trophy Hunters Association, Ltd.

700 E. Sonterra Blvd, Suite 1206 San Antonio, TX 78258 210-523-8500 • info@ttha.com

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer Christina Pittman 210-729-0993 • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Executive Editor Deborah Keene

Associate/Online Editor Martin Malacara

North Texas Field Editor Brandon Ray

East Texas Field Editor Dr. James C. Kroll

Hill Country Field Editor Gary Roberson

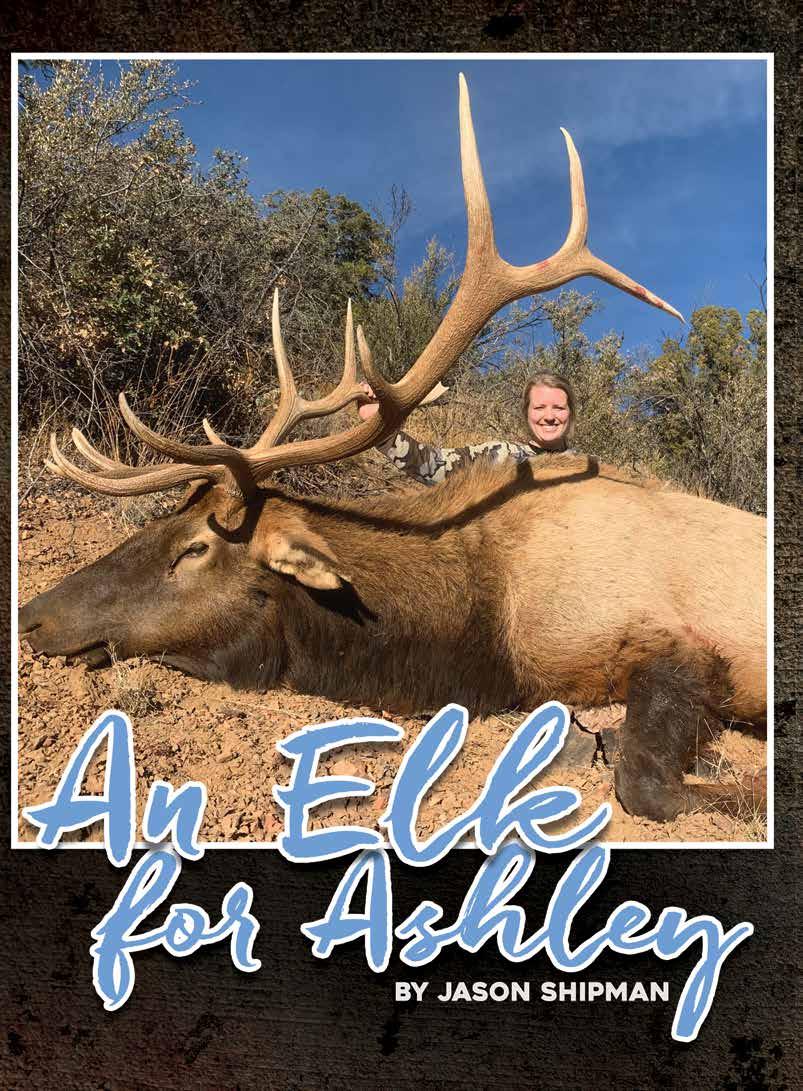

South Texas Field Editor Jason Shipman

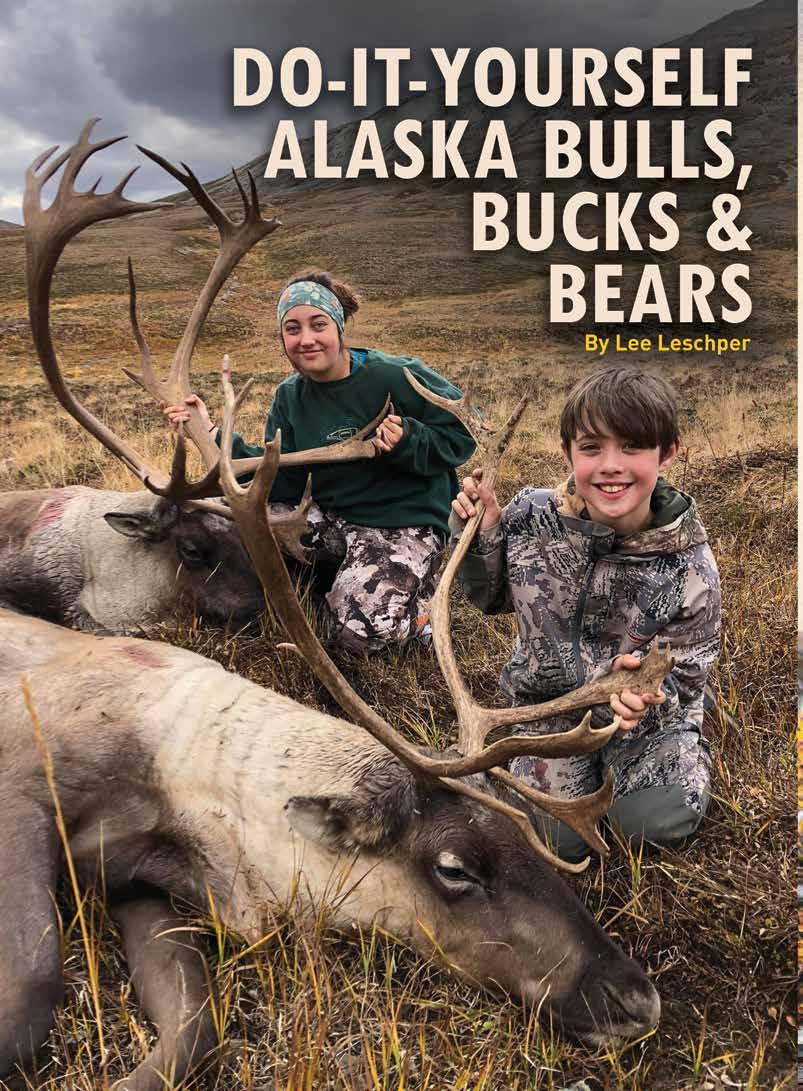

Coastal Plains Field Editor Will Leschper

Southwest Field Editor Jim Heffelfinger

Field Editor At Large Ted Nugent

Graphic Designers Faith Peña Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

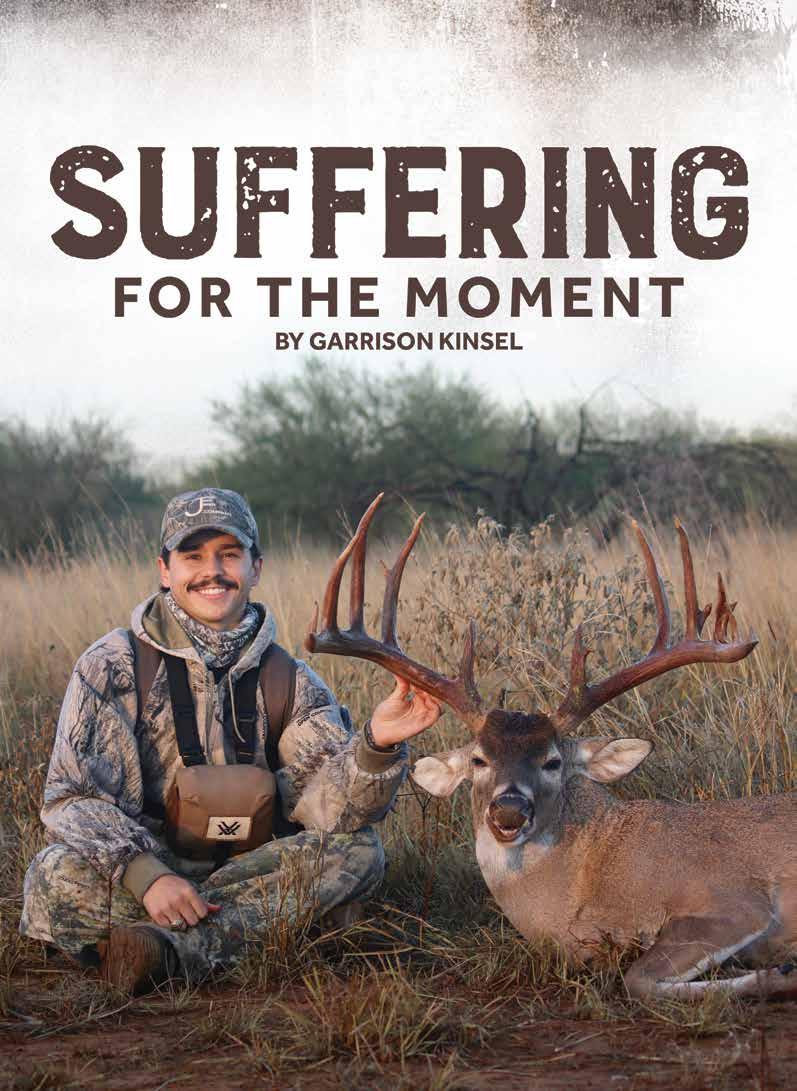

Bella Avolio, Leila Brown, John Goodspeed, Judy Jurek, Garrison Kinsel, Lee Leschper, James Nugent, Taylor Schmidt, Brian Stephens

Sales Representative

Emily Lilie 713-389-0706 emily@ttha.com

Advertising Production

Deborah Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Membership Manager

Kirby Monroe 210-809-6060 kirby@ttha.com

Director of Media Relations Lauren Conklin 210-910-6344 lauren@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events

Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

Administrative Assistant Kelsey Morris 210-485-1386 kelsey@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

TTHA protects, promotes and preserves Texas wildlife resources and hunting heritage for future generations. Founded in 1975, TTHA is a membership-based organization. Its bimonthly magazine, The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters®, is available via membership and newsstands. TTHA hosts the Hunters Extravaganza® outdoor expositions, renowned as the largest whitetail hunting shows in the South. For membership information, please join at www.ttha.com or contact TTHA Membership Services at (877) 261-2541.

must be accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope or return postage, and the publisher assumes no responsibility for loss or damage to unsolicited materials. Any material accepted is subject to revision as is necessary in our sole discretion to meet the requirements of our publication. The act of mailing a manuscript and/or material shall constitute an express warranty by the contributor that the material is original and in no way an infringement upon the rights of others. Photographs can either be RAW, TIFF, or JPEG formats, and should be high resolution and at least 300 dpi. All photographs submitted for publication in “Hunt’s End” become the sole property of the Texas Trophy Hunters Association Ltd. Moving? Please send notice of address change (new and old address) 6 weeks in advance to Texas Trophy Hunters Association, P.O. Box 3000, Big Sandy, TX 75755-9918. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, Texas Trophy Hunters Association, P.O. Box 3000, Big Sandy, TX 75755-9918.

TTHA member Howard Eaton likes to gather the family together for Sunday dinner. After attending this year’s Hunters Extravaganza in San Antonio, he thought it would be a hoot to grab some TTHA “headgear” and make the family wear it at the dinner table. Everyone agreed and his granddaughters were ecstatic with the idea. “We all indeed had big smiles eating Grandma’s pork chops,” he said.

Nicholas D.

season inspire him to write a poem for his

Whitewings are beautiful. The colors of whitewings are gray and a strip of white. When they fly it’s like watching a jet in the sky. So many good times.

When whitewing season comes about, it is time to pull your camo out. Caps, shirts, pants, and boots is the fashion of this time.

P.

it with us, and we’ll share it with you. Enjoy.

Now that whitewing season is here. Waiting patiently from dawn to dusk as they take flight.

Eating whitewings after a long day is the best part of the season. Cleaning them out in the field is just part of the fun that you feel. Next comes the jalapeño, cream cheese and bacon, wrapping and smoking them. Lastly whitewings fill my tummy with joy.

Col. David Sinclair is a pioneer of our hunting heritage.

David had an interesting, storied 40-year career as a Texas game warden before retiring in August 2012.

Since then, he has been a Texas legislative consul tant, first for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s executive office and currently with the Game Warden Peace Officers Association.

Born in Lubbock, David grew up and graduated high school in Abernathy in Hale County before attending Tarleton State University. His outdoor interests include hunting, fishing, and boating. Because of his love of the outdoors, his mother sug gested he look into becoming a game warden.

“All my personal outdoor recreation stopped once I became a warden,” David said, chuckling. He graduated from the 28th Texas Game Warden Academy at Texas A&M University in December 1972, then worked his first duty station at Crockett in Houston County. “Crockett was a great place to learn how to be a game warden,” he said. “I spent four years there.”

His next assignment, lasting 16 years, was Kerr County. “I got my wish working a whitetail hunting county with a bonus of exotic wildlife,” David said. “I loved the Hill Country.”

For 20 years, from the Pineywoods to the Hill Country, David was privileged to spend time protecting the resources he loves. “During my final 20 years, I enjoyed working in counties state wide in a position implementing positive changes for our great state,” he added.

David became a captain in 1993, and put in charge of all TPWD permitting. David realized many permits needed admin istration by entities other than TPWD law enforcement and took

Editor's note: This is the twenty-ninth in a series of pioneers to be recognized for their contributions, past and present, to Texas hunting. D avi D S inclair photo Sthe necessary steps to do so. He continued mov ing up the ranks until 2012 when, as a colonel, David became the interim director of law enforcement.

“I wanted to make a posi tive impact on anglers, hunt ers, and boaters in Texas with regard to statutes and regulations,” he said. “My last 20 years gave me the oppor tunity to help game wardens.”

A few of David’s efforts include enhancing game wardens’ inspection authority, increasing game and fish violation penalties, creating the whitetail deer harvest log on the back of hunting licenses—a suggestion from fellow warden Max Hartmann—and improving game warden salaries.

During his years at Austin headquar ters, David helped change countless hunt ing and fishing regulations. Constituents have seen regulations simplified while loopholes were closed for those trying to circumvent the law. “Penalties do have a positive impact in preserving Texas’ wildlife resources,” he said.

One of David’s proudest goals has been relocating the Texas Game Warden Me morial from the Texas Freshwater Fisher ies Center in Athens to Austin’s state capitol grounds. The relocation should be completed in 2023. The memorial honors 19 wardens who’ve given the ultimate sacrifice since 1919. Fallen game wardens are also recognized with designation as Texas game warden memorial highways.

When he’s not wrapped up with legislative activities, David also enjoys golfing with a bit of kayaking, in addition to hunting and fishing. “We’re working

our way around golf courses across the Hill Country,” David said. He also takes pleasure giving his time to the All Saints Presbyterian Church of America.

David’s family are outdoors oriented, too. His wife, Connie, loves to fish and kayak. His children, Darci and Duff, and stepson Chance are deer hunters. These days Darci enjoys hiking, paddle board ing, and being on the water.

For those asking how to interest young people in the outdoors, and possibly become a game warden, David said, “As a game warden, every day is differ ent, exciting, and for the most part, an adventure. There’s not a single day that I dreaded putting on my uniform and go ing to work. Not many people can claim that statement. It’s so fulfilling working as a game warden. You positively influence others, especially young people.”

David has always been, and continues to be, heavily involved with protecting Texas’ wildlife resources. “I’ve spent my adult life enforcing and writing laws to protect fishing and hunting,” he said.

For these reasons, we gladly salute David Sinclair as a pioneer of our hunting heritage.

How do you pass the torch? Share your photos with us. Send them to editor@ttha. com. Make sure they’re 1-5 MB in file size.

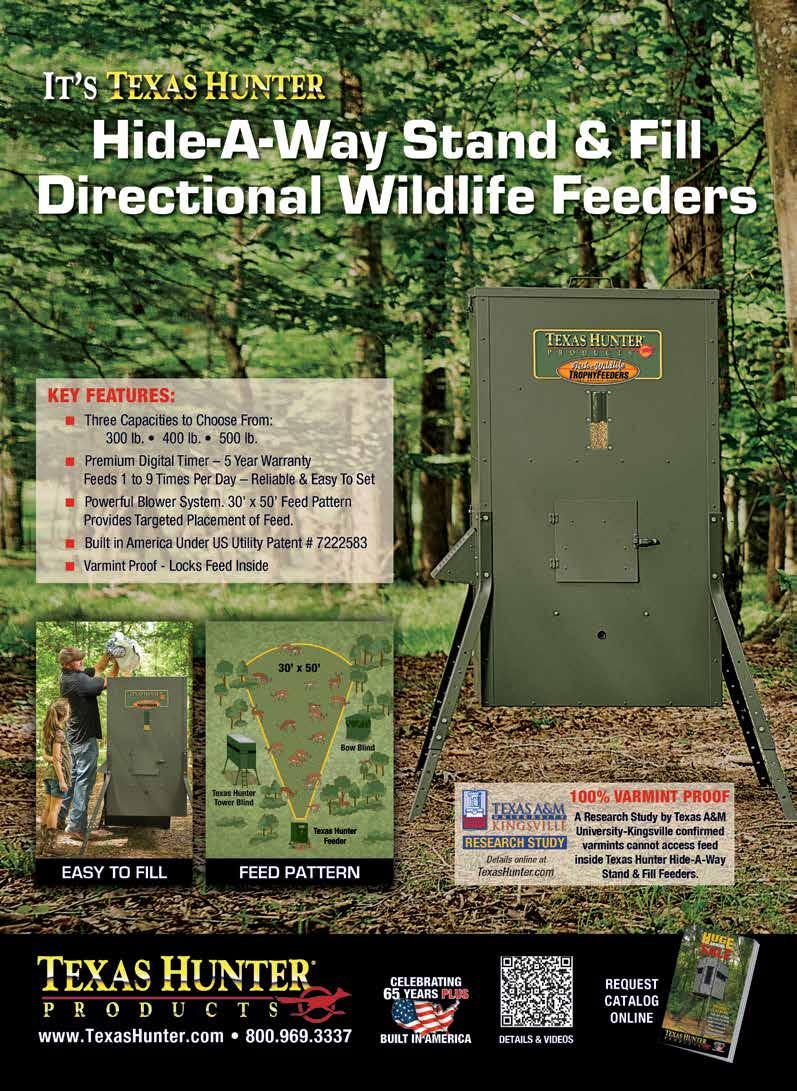

Do your part to preserve our hunting heritage. Share your passion with the next generation. Pass the torch. Photos Courtesy of Texas Hunter Products

The 2020 deer season was unusual and stressful for a lot of hunters because of the pandemic. Hunters had to choose between going hunting and staying inside, hiding from everything. It was a different deer season, but rather success ful because many hunters felt they were safer in the woods than in town. One of my close friends packed up and went to Real County to get away from the crowds and go without a mask. Life suddenly changed for all of us.

Deer hunters may be in for another unusual season, one associated with inflation. High prices for gas, feed, food, ammo, housing, cold storage—just to name a few items—will quickly empty your pocketbook. Two or three items that deer hunters must buy are gas, food and drink, and corn. Most hunters under 40 don’t know how to deer hunt without corn. Ammo may still be scarce, so no wasteful shooting with the old .270 or even the .223. This is not a good time to waste ammo.

I’m writing this in early fall, depend ing on the experts to tell us how much inflationary prices will affect us from September on through December. Most say everything associated with oil (gas, diesel, groceries) will be higher, and there’s little chance prices will get any cheaper this year. This means hunting will be more expensive in the fall and winter months. This may be the first year for “Biden Buck.”

Across the state, corn is selling for $12-13 per 50-pound sack. Some corner stores will show a $10-12 price tag, but for only a 40-pound sack, and the corn may be old and dirty. Any way you look

at it, corn will be a high-dollar item this fall, right along with gasoline and diesel.

Some friends say it’s already strain ing their pocketbook. Corn feeders that were going off 3-4 minutes, morning and evening, are now set for morning only at 2 minutes. On some leases and owner ships, it’s wise to keep a few feeders going all year. Right now, those are the folks looking closely at how much corn they’re feeding at $11 a sack. One of my friends said, “I’m using six 300-pound corn feeders. That is costing me $60 to fill one feeder.”

If I had to make a wild guess, I’d say corn might be somewhere around $12 a sack, gas and diesel might be about $4 per gallon—diesel maybe more—when dove and deer seasons roll around. Folks who travel long distances—round trip—to the hunt may decide to go less or stay longer. Hunters may even be less picky about shooting a buck because every trip to the hunt makes a buck more expensive.

So, the projections for hunting expens es this season don’t look too bright. Of course, deer hunters might let the kids go without shoes, cut family food, or move into a smaller house to protect their deer hunting. They will gripe, threaten to quit hunting, argue with family and friends about the cost, lean heavily on the meat they bring home, and even invite the preacher on a hunt.

But whatever it takes, Texas deer hunt ers will hunt every chance they get, and make it fit the budget. That’s the way it has been since time began, and it ain’t going to change.

—Horace GoreA surveillance zone covering almost 200,000 acres in Duval, Jim Wells, Live Oak and McMullen counties will be implemented for two years after feedback was received in the August meeting of the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commis sion. This zone will take effect prior to the 2022-2023 hunting season and TPW commissioners will consider the resulting data presented by Texas Parks and Wild life Department staff to assess the need for continued surveillance in the established zone.

This zone will include land between U.S. Highway 281 to the east, Farm to Market Road 624 to the north and U.S. Highway 59 to the west. The southern border follows a series of roads including County Road 101, Highway 44, County Roads 145, 172, 170, and 120.

This zone also includes the cities of Alice and Freer, as well as highways 59, 44, and 281 between the cities and the main body of the surveillance zone. This will provide a legal means for hunters to transport whole carcasses to deer-process ing facilities and/or CWD check stations located in those cities rather than having to quarter the carcasses first.

As of late August 2022, 376 captive or free-ranging cervids — including whitetailed deer, mule deer, red deer and elk — in 15 Texas counties have tested positive for CWD. First recognized in 1967 in captive mule deer in Colorado, CWD has since been documented in captive and/ or free-ranging deer in 30 states and three Canadian provinces.

Testing for CWD allows wildlife biolo

gists to get a clearer picture of the pres ence of the disease statewide. Proactive monitoring improves the state’s response time to a CWD detection and can greatly reduce the risk of the disease spreading to neighboring captive and free-ranging deer populations.

Hunters outside of established surveil lance and containment zones are encour aged to voluntarily submit their harvest for testing at a check station for free before heading home from the field. A map of TPWD check stations can be found on the TPWD website, along with more informa tion on CWD. To date there is no evidence CWD poses a risk to humans or noncervids. —courtesy TPWD

Editor’s note: We received the following letter before approval of TPWD’s new CWD surveillance zone, but due to our deadlines, couldn’t publish it until now. Nevertheless, we wanted to share it with our readers.

Editor:

TPWD is proposing the adoption of a new CWD Surveillance Zone in Duval and Jim Wells counties. The zone will consist of 644 square miles and over 400,000 acres. All in response to a single captive breeder deer testing positive a year ago. No other positive tests have been discovered in the area. Thousands of landowners and hunters are going to be blindsided by TPWD’s action, as it has not been adequately publicized.

The following was my objection I submitted to TPWD:

I am the owner of a 500-acre game fenced ranch in Jim Wells County. Today, by chance in a conversation with a wild life biologist, I was shocked to learn my property was going to be included in the proposed Duval County CWD Surveil lance Zone. I object to the proposed Duval County Zone as improperly noticed contrary to department policy and as overreaching.

I, as an affected landowner of record, was not provided any notice by the department and thus denied any involve ment in the creation or adoption of the Duval County zone.

It appears, without public comment and

involvement, the new zone was proposed and filed with the Secretary of State on June 4 for a possible adoption as early as Aug. 7, 2022. There were no press releases, social media announcements, public hearings, magazine publications, news stories, or mailings announcing the proposed zone or the research behind the proposal. In fact, the only mention of the department’s proposed actions I could locate on the internet was in the Texas Register. While constituting legal notice of the zone’s adoption, a single notice in the Texas Register clearly falls short of the department’s stated policy of “robust public awareness,” affording opportunity for public, and especially, landowner involvement.

Without a postponement of the proposed adoption of the Duval County Zone, nearly all other landowners in the 644 square mile/412,000-acre Duval County Zone are also going to be blind sided with the imposition of new regula tions affecting their land. All landowners in the new surveillance area must be afforded ample opportunity to review the department’s proposal and data and provide feedback without being limited to a single 5,000-character response on the department’s website. The adoption of the new Duval County Zone must be delayed and efforts made to provide robust public awareness.

Additionally, both the existence and the size of the proposed zone are overreach ing. It is my understanding the impetus for the proposed zone is a positive test of a single deer over a year ago in a high fenced breeding facility in Duval County. There is no credible evidence of any deer escaping or being released from the infected facility. Further, no free-ranging deer in the proposed area have tested positive.

I also understand there are 13 other breeding facilities in Duval County and no deer in the 13 breeding facilities have tested positive and no other deer transferred from the infected facility have tested positive. In response to the year-old case of the single Duval County captive deer testing positive, the department has in essence roped off a crime scene of 412,000 acres across two counties to do

a five-year investiga tion to confirm the absence of CWD in this massive area. This act is unreasonable, unnecessarily burdensome on landowners and their property values, and bears no reasonable relation to the location or the scientific probability of other cases in the area. If a zone is imposed, it must be more pre cisely and reasonably tailored to address the area surrounding the positive test for direct or indirect transmission rather than randomly following a path created by the highway department encompassing 644 square miles.

Accordingly, I respectfully request the department delay the adoption of the Duval County Zone until robust public awareness of the existence of the zone and the department’s data has occurred, public comment is received, and the zone is precisely tailored to address a legitimate area of concern.

George C. Noyes, San Antonio, TexasI think a positive note on Texas whitetailed deer is in order. We talk so much about CWD/scrapie, that we sometimes fail to look at deer from a positive angle. My 60-year experience with Texas deer and deer hunters is as follows:

1. Texas presently has an historically high whitetail population east of the Pecos River and south of the High Plains.

2. The quality of hunter-killed bucks in Texas is at an all-time high. Half the whitetail population, and half the whitetail harvest is in the 27-county Edwards Plateau of Central Texas—the Hill Country.

3. The average age of a hunter-killed buck in Texas is 31/2 years. Hunters presently take about 16% of the standing deer herd. Natural and man-made mortality accounts for another 5%. All losses are replen ished annually by year-old recruit ment. Some 98% of whitetails are subject to natural and man-made turnover every 3 to 5 years, which protects the herds from diseases and other mortality factors.

4. During the last 25 years, landown ers and hunters have placed more emphasis on quality deer. Genetic improvements from TTT, DMP permits, and breeding programs have added much to the quality of Texas whitetails.

5. Feeders have improved the deer harvest in Texas during the last 50 years, and trail cameras have increased the harvest of quality bucks in the last 20 years, espe cially in the dense forests of North and East Texas.

6. Whitetails are presently approach ing five million on 100 million acres of habitat.

7. Deer hunters have increased by 200,000 during the last 40 years, with 800,000 overall, but are not following the trend in Texas population of 30 million. The long, five-month deer seasons are con trolled by private landowners and a small percentage of the hunter-age population.

8. Approximately 22 million acres of deer habitat have been added in marginal deer ranges by high fences and/or supplemental feed ing; predation on Texas whitetails is low.

9. Biology/harvest of Texas deer herds—reproduction, hunting, natural mortality—creates natural barriers for clinically slow diseases such as CWD/scrapie, and anthrax outbreaks kill entire deer herds in small, isolated places in west ern counties, which are usually restocked with TTT permits. Blue tongue has never been a problem in Texas. Liver flukes, external parasites, and deciduous winter habitats limit whitetail numbers in East Texas.

10. Research has shown a small loop on the human protein protects it from rogue prions. Some folks are calling venison “America’s healthy red meat.”

11. Texas mule deer suffer from poor habitat, predation, and weather. CWD/scrapie has not shown any direct reduction in mule deer, but predation is a serious problem.

12. Stringent whitetail regulations have

caused many ranch owners to turn to exotics for additional and unique hunting, especially in South and West Texas.

The two distractions I see for the future of deer hunting in Texas are long, liberal deer seasons and bag limits for less than 10% of hunter-age Texans, and contain ment zones with stringent rules and regulations being created around a single positive for CWD/scrapie in breeder pens. The latest in South Texas involves 644 square miles in parts of four counties. These zones can be created anywhere, because Texas was the No. 1 sheep state for 100 years. I see these unnecessary zones as a deterrent to land values and deer hunting in the future.

P.S.: Deer hunting/lease revenue pays a lot of taxes, buys a lot of pickups, and sends a lot of kids to college! — HG

SCI Sues California over Canceled Youth Hunts Safari Club International is suing the state of California over AB 2571, which prohibits marketing or advertising of firearms to minors in the state. Because of its overly broad language, it does more than just violate constitutional freedoms. It threatens youth firearms training and education in the state. The law went into effect on July 1 and is already hav ing devastating effects on the hunting community.

For years, the SCI Orange County Chapter in California has hosted a Youth Quail Hunt. Started by Cliff and Toni McDonald, the hunt began with 17 youths in 2010 and has grown to 70+ in 2021. The three-day event teaches camping, conservation, hunting and harvest skills from start to finish at no cost to kids ages 8-15. For many, this is their first time hunting and a significant introduction to the outdoors. The weekend is held on the Mojave National Preserve, and the Cali fornia Department of Fish and Wildlife provides education and other resources at the event and has even created a special Early Season for hunters with junior hunt ing licenses in this area just to accommo date this hunt.

Due to AB 2571, this hunt—a critical youth program—has been canceled. Do nors, volunteers, and participants pulled out this year over fears that the new law

would expose them to up to $25,000 in liability—or more.

These fears are not unfounded as the law applies to any youth program that pro motes the use of firearms by a member of the “firearm industry” and imposes fines of $25,000 per impression, occurrence, or publication of prohibited communi cations. A law which was supposedly intended to reduce gun violence is only having devastating effects on the hunting community and eliminating youth from the outdoor lifestyle.

SCI, joined by Sportsmen’s Alliance, SoCal Top Guns, and the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation, lead the legal battle against this law that violates the free speech rights of hunters and puts well-established R3 efforts, like the Mojave Youth Quail Hunt, at risk. We’ll always defend your hunting freedoms regardless of age, species, or location. We stand first for ALL hunters. — courtesy SCI

On Aug. 7, the Congressional Sports men’s Foundation (CSF) submitted a comment letter, signed by 30 of the top sporting-conservation organizations, to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in support of efforts to expand hunting and fishing opportunities, but also to express concerns with the effort to phase out the use of traditional ammunition and tackle.

Earlier this summer, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service announced the 20222023 proposed Hunt Fish Rule. The proposed rule seeks to increase access for sportsmen and women across 54,000 acres within the National Wildlife Refuge System (NWRS). Unfortunately, the Hunt Fish Rule proposes to phase out the use of lead ammunition and tackle for expanded opportunities within nine NWRS units, effective in 2026.

In response to the proposed Hunt Fish Rule, CSF led a comment letter to express the support of the sporting-conservation community to strengthen access for hunters and anglers and to express the concerns from the community regarding seemingly arbitrary efforts to limit tradi tional lead and ammunition. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

By Dr. James C. Kroll

By Dr. James C. Kroll

Virtually every wildlife science student is required to take a course entitled, Population Dynamics; a course that covers, as the name implies, how to study the dynam ics of animal populations. Central to the various concepts is estimating the population size of the species you manage. The need to know how many individuals exist in the population is so ingrained in wildlife students, they tend to focus religiously on learning how to estimate population size. Years ago, I wrote an article for TTHA entitled, “Irrational Numbers,” which discussed how practicing biologists obsess with conducting population censuses. Later, I brought up the idea of metrics for deer management.

Yet, as I noted in these articles, estimating how many animals exist in a population is the “La Brea Tar Pits” of wildlife manage ment. This is because you will never accurately determine popu lation size for most species you try to manage, particularly true

for white-tailed deer. The fastest way I know to lose credibility as a deer biologist is to tell a landowner or hunter how many deer they have. These folks live with the deer over the years and usually know their herd quite well.

For some biologist who has not set foot on the place, to proclaim there are “173 deer” is a foolhardy venture. I learned this first hand when I was appointed as Deer Trustee (aka “Deer Czar”) of Wisconsin. The Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (WDNR) had completely lost credibility with the hunting public and landowners over how they were managing deer. Thought of as the Land of Aldo Leopold, the “Father” of American wildlife management, the WDNR enjoyed a high reputation among other state wildlife professionals as the best example of science-based management. In reality, what we discovered during our work in Wisconsin was they did not have reliable data on which to manage the state’s deer herds.

Ranch “X” is not a high-fenced prop erty, so the target buck-to-doe ratio is 1:2. Note that this trail camera survey, in fall 2017, showed disparities in sex ratio across the ranch. The average was on target, but six camera stations showed higher buck abundance than three others. The management goal then is to develop a nutrition and habitat strategy to even out the buck distribution. All of this is done without the need for census, other than camera studies. When compared on a year to year basis, true progress in the management program is measurable.

The focus of public animosity toward the WDNR was use of an Excel spread sheet model to the pre- and post-hunt deer population by region. The outcome of the model hinged on the abundance of yearling bucks in the harvest, presumed to be an indicator of the abundance of year lings in the population. Yet, the modern whitetail hunter had grown way beyond the sophistication of the agency biologists, preferring more and more not to shoot yearlings. Since it was presumed lower yearling abundance in the harvest meant a higher population estimate, leading to the agency becoming locked into a death spiral of erroneous population estimates (±123%), and demands for higher harvests placed on hunters, ultimately leading to a decline in the deer population. One of our principle recommendations was to aban don the model and replace it with more useful metrics for population management.

Before I discuss these metrics, let’s examine some of the many ways biologists have tried to estimate deer populations. When I attended college, the preferred method of census in Texas was the Hahn Cruise Line. In other parts of the country, managers used such methods as track counts and pellet counts. The Hahn Cruise Line was a modification of an old bird census technique, in which an observer walked a set transect across the property and recorded the number of birdcalls or flushes observed.

A lot of effort was expended determin ing the average distance the observer could either hear or see a bird. Application to deer census involved estimating how far the observer could see a white handker

These are the recruitment estimates from trail camera surveys for Ranch “Y.” It approached the targeted 70 percent recruitment in 2014, but the herd appears to be sustaining at 70 percent since 2016.

chief in the back pocket of another person. That average distance was used to estimate the area censused. So, if you knew the area you censused, counted the number of individuals seen, you only had to divide the number in area to come up with an estimate of population density. Once you had a density (acres per deer) estimate, you could divide that number into the acres of the property to obtain a popula tion estimate. Variations of the method were developed, using more sophisticated measurements and techniques, but the principles remained the same.

In a spotlight count, you use a pickup and one or two spotlights, requiring at least three people. The count is conducted at night, along a pre-determined and premeasured course, thought to best repre sent the habitats of the property being censused.

The Track Count method was developed for use in dense habitats, where a Hahn

Cruise Line could not be used. It was based on the assumption that a deer’s travel radius was approximately a mile. It was based on early telemetry studies and was burdened with a lot of issues. The observer used a drag to smooth a section of dirt road that may be several miles long. Then you waited 24 hours and walked the line and counted the number of deer tracks that crossed the road per mile. Again, the number was converted to a density (acres per deer) estimate, then converted to estimated deer population. The Pellet Count was even more strange in the assumptions assumed in the model. You walked a transect and counted the number of “fresh” pellet groups observed per unit of distance (mile). Using some pretty interesting calculations involving the number of times a deer defecates, the observer came up with a population estimate. Later, it was discovered there was a huge variation in the number of times a

deer defecates in 24 hours.

The Spotlight Count remains an ac cepted population estimation technique, especially for dense habitats. It is nothing more than a modified Hahn Cruise Line using spotlights and a pickup truck. It takes three people to conduct a spotlight count. You select a route across the prop erty that best samples the various habitats, then either travel the route prior to the count estimating the visibility distance you can see a deer at tenth-mile intervals, or you estimate how far you can see a deer at tenth-mile intervals while you are conducting the count. I conducted several research projects aimed at calculating a correction factor for distance observed, related to habitat, but later abandoned the method. Our calculated error was about plus-or-minus 30 percent.

Each year, hundreds of thousands (if not millions) of dollars get spent on helicopter counts, particularly in Texas. It

really is just a modification of the above techniques, and just as plagued by error. Again, I submit that these counts have average errors of about plus-or-minus 30 percent. This means if you estimate you have 200 deer, you have somewhere between 140 and 260 deer. I am one of the few biologists who has ever done a complete kill on large properties (2,000+ acres), and every time, the actual number of deer removed was up to twice as many as census predicted.

In Wisconsin, we concluded we did not need a population estimate. We needed to know how many deer hunters wanted to harvest, then develop a plan to increase, stabilize, or decrease the population. To do so requires development of metrics that tell you reliably how the deer herd and habitat is doing. After all, the deer and their habi tat are “more than happy” to “tell” you how they are doing. But, what are these metrics and how do you use them?

Analysis of trail camera data for 2018 for Ranch “X.” In this case, ranch management has set a recruitment goal of 70 percent, which was achieved in 2018; however, this is only the average across the ranch. Since the study was done on a grid pattern for nine stations, areas on the ranch where recruitment is subpar are clearly identified. The “trick” then is to develop a strategy to even out recruitment.

From a deer population standpoint, you need to know the following:

• Age structure of the buck and doe segments

• True recruitment

• Body condition

• Antler quality

We pioneered the use of trail cameras to obtain reliable information on both age structure and recruitment. Several years ago, we came up with the idea that deer could be aged live on-the-hoof with rea sonable accuracy. When we proposed this, many of our colleagues ridiculed the idea, adding, “Even if you could age them by sight, you could never teach the ‘common’ hunter/landowner how to do it accurately.” Well, after almost a 100,000 books and videos, it is now common knowledge that deer can indeed by aged. Using trail cam era studies of two weeks at the right time of the year, we can accurately construct the age distribution of bucks and does in the herd. This is one aspect of demographics; the structure of a population. We then can measure annually how the herd is doing in response to specific harvest intensities. After all, you do not manage a herd; you “fine-tune” it.

Trail camera studies also are useful in estimating the true recruitment of the herd. How many times have you heard a biologist talk about the “fawn crop,” usually expressed in fawns per 100 does, or percent fawn crop? In reality, knowing what the fawn crop is (fawns per 100 does in October) gives you incomplete informa tion. Fawn crop does not mean all that much to me; but the number of fawns that live to be one year of age and join the herd, means a whole lot.

Doe age structure for two consecutive years on Ranch “X.” The age structure of does is increasing, which tells us not enough does are being removed.

That is true recruitment, expressed as a rate. We strive for at least 70 percent recruitment. Anything less than 40 per cent guarantees you will not have mature bucks.

Body condition indices are developed by collecting data from every deer harvested from the property. Measurements such as dress weight, lactation rates (percent does in milk), age and body condition indicators such as parasite loads can provide annual metrics of body condition. In many areas, we conduct health checks in February under state permits to determine other metrics such as fetal counts, age distribu tion of fetuses, parasite loads and kidney fat indices.

Antler measurements on harvested bucks and pickup sheds can tell you a lot about how your management program is doing. Antler size and measurements can tell you, not only something about the genetics of your herd, but also the nutritional plane of your deer. Something as simple as the presence or absence of “pearls” (the small protuberances around the antler bases) can indicate the nutrition of your bucks.

The habitat also will tell you how the deer are doing. The much maligned

browse surveys can tell you much about the quality of browse and the intensity of use. Although they do not tell you any thing about the number of deer you have, browse surveys can tell you the relative abundance of your deer. We express this as “stocking level”: low, moderate or high. In managing deer at the statewide level, there are other metrics that can help in making decisions whether to increase, sta bilize or decrease the herd. These include numbers of deer/car accidents and farmer complaints about deer depredation on crops. Lyme disease in humans also has

been used as a metric for whether or not to decrease the herd.

So, you see that estimating how many deer you have, not only is not accurate, but you really do not need to know how many deer you have. The development and use of metrics for making management decisions and assessing progress of your management program are far more useful. In the process of conducting our studies in Wisconsin, we were surprised to learn Native American tribes had been using these methods for years, way ahead of their “white” neighbors.

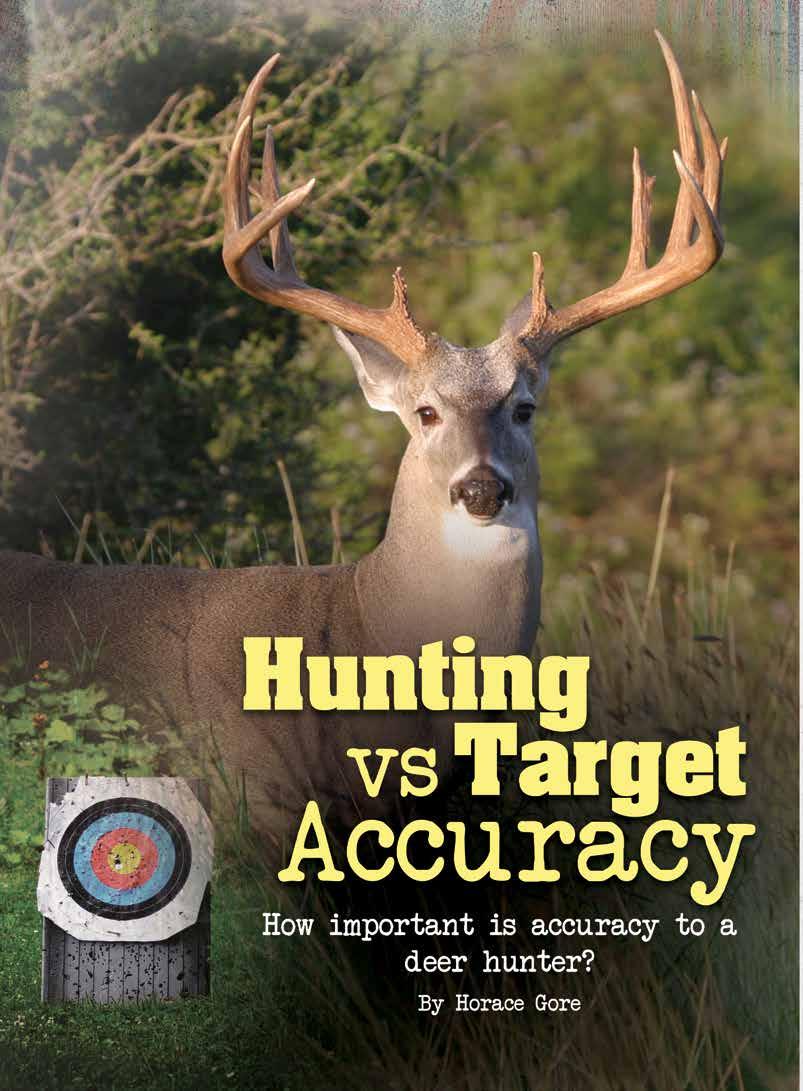

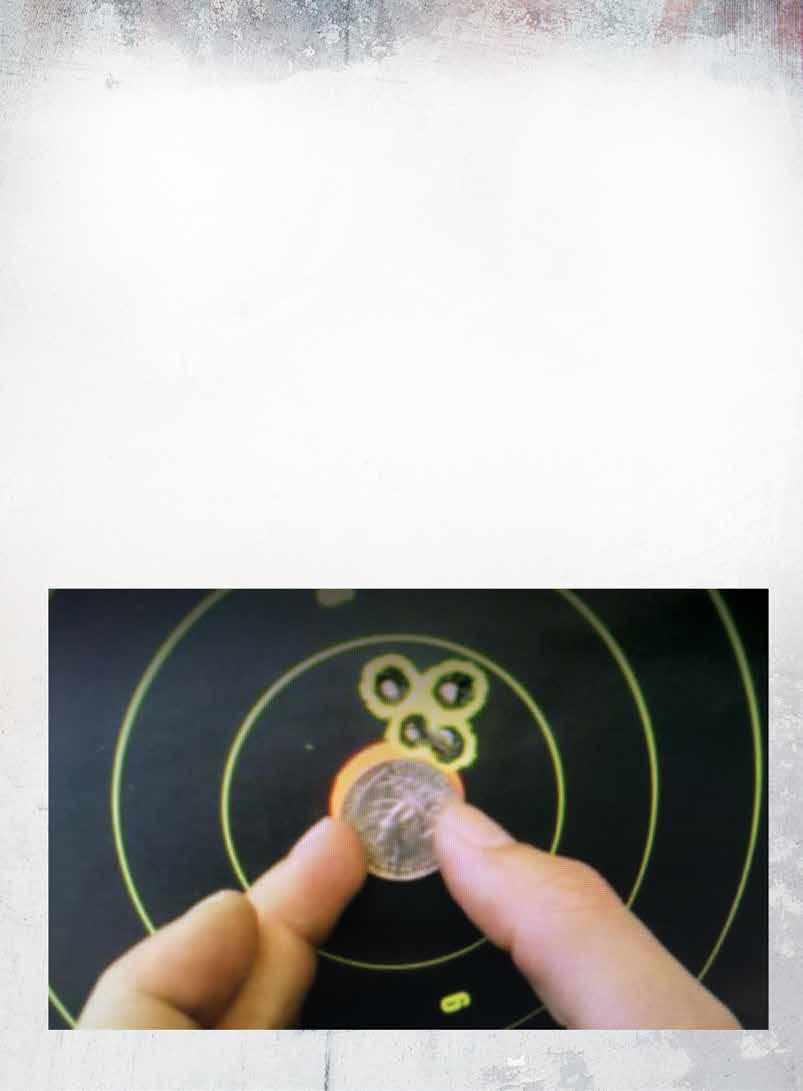

Is it possible that deer hunters get too concerned about accuracy in their favorite rifle? Should they be concerned if “Old Betsy” won’t put three shots in a group the size of a quarter at 100 yards? Most hunters get their advice from shooting pundits who write more than they shoot. Fact is, most deer get killed at less than 100 yards, and deer-size animals offer large target areas that are fatal and do not require target accuracy.

Back in the ’50s, my friend Edgar Woodly hunted in Gillespie County near Cherry Spring. He had a Sears Roebuck .270 made by High Standard and a 4-power Weaver scope. Before each season he would put up an 8-inch paper plate at about 75 yards, shoot three shots, and go to the target. If he hit the plate two times out of three, he was ready for the hunt, and he got his bucks every year.

Whoa! Don’t get me wrong. Bullet placement is paramount, but deer hunters have some leverage in what is hunting ac curacy. If the average aficionado of rifle shooting can put most of the shots in a 3-inch circle at 100 yards, such accuracy will result in a lot of dead deer. Under normal hunting conditions, deer hunters usually have a shooting rest of some kind, but it’s not like the shooting bench. A rest out the window of a pickup or deer blind will put bullets in a scattered group at 100 yards, but if they all fall in a circle of 3-4 inches, it’s meat on the table!

I’ve killed a lot of deer during the last 60 years, and I’ve had some fine deer rifles. A favorite is a Winchester Model 70 .270 in a custom walnut stock, with engraving by Tommy Kaye. The

Target accuracy is not needed in a good deer rif le, according to the author.

rifle has an aftermarket 22-inch light barrel that groups bullets about 2 inches at 100 yards. I tried everything to improve the group, but nada!

I liked the rifle so well, I just dismissed the fact it would not group well. During a period of 30 years, I used that rifle on many whitetails and mule deer from Mexico to the Rockies and never missed getting the buck. In fact, most were one-shot kills, and I never had a crippling loss. In that rifle, trigger pull and balance were more important than bullet groups.

Accuracy in a hunting rifle is important up to a point, but other factors are important to a good deer rifle. Trigger pull, balance (barrel length), a good scope, and proper ammo are probably more important than target accuracy. As a rule, white tails get killed at a closer distance than mule deer. But mule deer pose a big target with a good scope, and the hunter has time to pick a good gun rest. Mule deer are not hard to kill with proper bullet placement in rather large target areas—lungs, shoulder, etc.

In Texas, most deer hunters will kill their deer at less than 100 yards, and have some kind of shooting rest. The most important thing in getting the buck is not how accurate the rifle is, but the hunter’s ability to wait for a shot that will expose the base of the neck, the shoulder, or the lungs, directly behind the shoulder. A lung shot is best because it’s a 6-inch target that’s fatal and wastes very little meat. Another fatal shot is where the neck reaches the shoulder and is a 5-inch target. Shoulder shots are good if you don’t care how much meat you waste.

Most hunters can shoot a mild recoiling rifle better than one that rattles their teeth. Shots up to 250 yards can be accom plished with a .243, 7mm-08, 6.5 Creedmoor, or a .25-06, and the recoil will be tolerable. I believe a 7mm-08 with 22-inch barrel shooting 120- or 140-grain bullets at 3,000 fps may be the perfect Texas deer rifle. However, my daughter has made many one-shot kills with her .243, and I have hunted deer with a favorite .270 and .257 Roberts improved more than any other calibers. But they’re what I started with many years ago, and today I would probably select a nice 7mm-08 with a 3-9X Leupold scope and 3-pound trig ger, using 139-grain Hornady bullets. For some reason, Texas deer hunt ers think a South Texas buck is harder to kill than a Hill Country deer. More hunters in South Texas use 7mm Magnums than any other caliber. And the 7 Mag. has too much recoil for a lot of hunters. The ones I’ve shot kicked like a mule. The dog people who chase crippled deer from Del Rio to Browns ville tell me more bucks get crippled with the 7 Mag. than any other caliber in South Texas.

I suspect much of the problem is NOT accuracy, per se, but yanking the trigger and closing the eyes when they shoot. Bullet impact on a buck can be very erratic when the shooter is fighting the rifle. A mild-recoiling rifle with a good bullet of 100 to 150 grains, and a muzzle velocity of 2,900 to 3,000 fps will kill a South Texas buck faster than a dog can trot. It’s all in the mind, and bullet placement is the key to killing power.

A deer hunter should shoot the big gest caliber that they can shoot well. I’ve always liked the .270, but my friend Al Brothers likes the .264 Mag. Dean Davis likes the .25-06, and his dad Er nie likes the .270. Jerry Johnston likes the .300 Win. Mag., and James “Dr. Deer” Kroll likes the 6.5 Creedmoor. My daughter Donna likes either the .243 or 7mm-08, and she shoots both very well. Jimmy Gallagher likes his 7 Mag., and Bubba Schmidt of Gonzales likes his new 6.5 Weatherby Magnum. My friends shoot the rifles they shoot best.

The trend of rifles for Texas deer hunting is slowly, but surely, going from the larger calibers to the milder recoil ing calibers, and the top choice seems to be 6.5. The 6.5 Creedmoor, 6.5-284,

6.5 Swede, and the .264 Win. Mag. are popular these days. This doesn’t mean that the .30-06, .270, 7mm Mauser, .257 Roberts, .250 Savage, .300 Savage, .243 Winchester, 6mm Rem ington, .257 Weatherby—and other Magnums—are obsolete. It just points to the fact hunters are tired of being kicked around. Today’s hunters are looking forward to hunting with the milder calibers like the 7mm-08 that will kill a buck eating corn under a feeder at 75 yards very quickly and peacefully.

The author helped his wife, Tracey, celebrate beat ing cancer by arranging a whitetail hunt. She bow shot this buck, nicknamed “Fosgate,” at 24 yards.

My wife Tracey began bowhunting with me when we were 19 years old. She didn’t grow up in a hunting family, but she quickly discovered how exciting and rewarding it can be. With attending college, starting a career, and raising our three beautiful daughters, her participation has ebbed and flowed, but her enjoyment of bowhunting has never changed. Throughout the years, she has taken some nice whitetails, mule deer, blacktails and even bowhunted in Africa a couple times.

Sometimes life is good at dealing us a dose of perspective. Two years ago, our family was rocked by the news that Tracey had colon cancer. Her surgery and chemotherapy treatments were happening at the start of the pandemic.

When you face the kind of fear and uncertainty associated with cancer, you start looking for positive distractions—things to look forward to. I decided to get her a new custom Bowtech Solution SD and get her looking for ward to some good hunts with it. She quickly fell in love with her new bow. She hadn’t had a new bow since 2013 and practiced with it nearly every day leading up to the 2021 season. Her excitement got me fired up!

After she completed her cancer battle with a win, I looked forward to celebrating. On a small piece of land I managed for 7 years, I had a buck I’d been watching that was hitting his peak. He was a free-range buck any one would be excited about, a main frame 10 with matching split G2s, matching kickers, and a bonus kicker.

He was super symmetrical, and my years of low-pressure feeding and habitat improvement had him feeling comfortable in his routine. We named him “Fosgate.” I had high hopes and Tracey was obsessed with him.

As bow season rolled around, an unusual persistent north wind plagued us for the first week of the season. We needed a south wind. Once the wind started cooperating, Tracey sat three times, patiently wait ing for him to show. She didn’t want me to sit with her because she said I make her nervous when a target buck approaches because I start getting excited. I had watched this buck on camera so much I really wanted to see him in person and share the experi ence with her, so I promised to be a good boy.

On Oct. 12, 2021, we took every precaution imaginable to get into our stand location undetected. This involved taking a carefully chosen path to the blind, a slow, long walk and feet wrapped in plastic bags for the last 200 yards to avoid any possibility the buck would know we had walked through the area. Go ahead and poke fun. I’m laughing all the way to the taxidermist.

We were in the blind well before light. The anticipation as the darkness gave way to seeing dark-gray shadows you’d swear are deer moving made my heart race. Slowly, the blue light of the early morning revealed a slight movement I knew was a deer. I could see the bottoms of deer legs.

They carefully took a couple steps and paused. I could see an antler tip through the brush in my binos. I could hear my heart in my ears. Just as his head cleared the brush, I realized it was just a young buck.

I felt my entire body melt into my chair. I understood Tracey’s concern about me sitting with her. I’m a freak about big bucks and words can’t describe how badly I wanted her to get Fosgate. Could I follow through with my promise to stay calm if he actually walked out?

I had to have a quick and firm internal discussion with myself. “You calm down, mister,” I told myself as I wagged my finger incredulously—all in my head, of course. Just as I composed myself, I spotted movement coming from the trail where I had imagined Fosgate arriving on 1,000 times. I had pored over hundreds of trail camera pictures of Fosgate over his 6-year life, but I couldn’t have felt more amazed by how incredible he looked as he stepped out. This was the very first time I had seen him in person.

I snapped myself into immediate composure. I quickly glanced over at Tracey. In the low light inside the ground blind, I could see her eyes acknowledge my affirmation that it was Fosgate. All of her preparation, experience and nerves would be tested.

Fosgate approached with the most incredible caution I can describe. That blind had purposefully not been hunted in years, yet he remained hyper-vigilant. Every second felt like waiting for a bomb to go off. In these situations, even the

tiniest swirl of wind could trigger him or another approaching deer to blow the whole deal. Finally, he turned to the perfect position for a 24-yard opportunity. She drew, held, settled like a champion, and shot.

I used my cell phone to record video and didn’t get a good look at where the arrow hit. Tracey immediately asked, “Did I hit him good?” I wanted to jump for excitement, but for some reason we felt anxious. After watching and rewatching the video on my phone, we realized not only did she hit him, she had hit him perfectly.

As soon as we found her arrow, her pride was evident. As we followed a 50-yard blood trail that ended with Fosgate, I felt flooded with pride, emotion and thankfulness. Thankfulness that all the work over years had paid off with a giant buck for sure, but an over-riding thankfulness that I was living this very moment, with this woman I love so much and watching her win—again!

As if her fairy tale ending wasn’t enough, two weeks later she went hunting at the Charco Marrano Ranch in South Texas and shot another giant with her new bow. She shot her two biggest bucks ever, all during bow season! I thank the Lord for these experiences, for my family, and for every day He gives us together.

It’s the first rule in fishing: fish where the fish are. However, sometimes de spite our best efforts, the fish simply aren’t around. In those instances, we as anglers must stack the deck in our favor, and the easiest way to do that is to get our hands a little dirty.

Chumming often is thought of mainly as an offshore tactic, but in Florida and in some other Gulf coast locales, it widely is used for inshore situations. The method can take a variety of forms, but the ap proach is the same as you attempt to lure angling targets with a concoction consist ing of dead shrimp, bait fish or other small edibles that can be dispensed in a number of ways.

A July 1965 report from the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department archives offers a glimpse at bay chumming, most of which holds true to this day.

“Menhaden, anchovies, small sand trout and croakers can be cut up or run through a meat grinder to make chum. Trickled slowly but steadily overboard from an anchored boat, carried along the side of a good reef by the current, the chum line will almost certainly bring fish to the baited hook and have them excited enough to bite,” according to the report.

The description also detailed a common way to find your own live bait with a cast net.

“Menhaden, mullet, silversides, mollies, pupfish, killifish, small crabs and shrimp are common around bay edges, sometimes only a few steps from the shoulder of a road. Taken home and frozen whole or ground into meal, they make good chum and also serve to pre-chill your portable ice box on the way to the bay,” according to the report.

The report also discussed how to entice at least one species that typically lurks near bulkheads, oil wells, piers and other manmade structure.

“If the sheepshead won’t bite, try exciting them into a feeding mood by scraping the barnacles and other crusted animals off the pilings or rocks with a long-handled shovel or hoe taken along purposely for this trick.”

Black drum are great-eating fish. Some folks would say they’re better than redfish and flounder. Regardless of your stance, these fish hunt by smell, making chumming a great way to boat a limit of “puppy drum.”

There’s more than one way to skin a cat, as the old saying goes, and in the case of chumming, it’s all a matter of preference.

I had the opportunity to use chum bait bags packed with ground shrimp on an excursion out of Key West a number of years ago with great success. Patch reefs are common in Florida

and typically teem with fish, but during our outing the angling was slow, until the chum bags were flipped over the side. As the chum slowly crept from its putrid hiding spot, the bite almost instantly spiked. We went from flipping small jig heads tipped with shrimp to no avail to hooking up on every cast before the lure could even get near the underwater structure, catching yel lowtail snapper – which typically are wary of heavier line – and a variety of other reef dwellers.

The key to chumming is concentrating fish. The best way to do that is to create a scent trail that will maximize how many scaly denizens are attracted. That means however you put out chum, make sure it is allowed to work with the current and is above whatever location you’re working.

There are a number of tested approaches to chumming. The easiest on a shallow flat is to simply toss diced shrimp or bait fish into the water and wait a little while. The downside to this method is you may attract gulls and other birds that could also scoop up live or dead baits you throw out.

Other ways to brew a foul attractant are to make your own frozen mixture by plopping your bait choice into water and freez ing it to make a block that can be toted along in an ice chest. I’ve seen anglers who stuffed a milk carton halfway with diced bait fish and filled the rest with water before sticking it in the deep freeze. They then simply tied a line to the handle, popped the lid and threw it in the water when it was needed.

Another approach is to use a chum bag. There are specially made bags of mesh that are relatively inexpensive, but you also can use whatever you may have laying around such as a burlap sack or other porous container. You simply place your fro zen or fresh offering in the bag and cinch it closed before dump ing it overboard tied to a line.

Chumming will bring in anything that likes eating other critters – which can be irritating if less

White bass that school up can be easier targets for anglers. Chumming can help bring in schooling fish that are hungry and will latch onto much larger baits than you might think.

desired species such as hardheads or gafftops move in. However, many anglers dismiss the effectiveness of using chum for sought species including redfish, trout and even flounder. The two for mer species will gang up around any food source so chumming makes great sense, especially if the bite has slowed. Flatfish also will come to the smell of dead bait, especially if you’re fishing along drop-offs or small variances in terrain. Many anglers also may not consider their angling pursuits to include chumming but anytime you sling out multiple rods with cut bait of any form on the other end you technically are offering up chum.

One sure way to find speckled trout or redfish is to follow what veteran anglers term “slicks,” which are produced by feed ing fish just below the surface eating shrimp or small bait fish and essentially are moving chum balls. The game fish eat until they can’t anymore and have to spit out some of their prey, while parts of some of the bait fish and oils also will escape through the gills of trout and reds. This will leave a sheen on the surface, which sometimes can be large and is best discerned with a pair of polarized lenses. Seasoned anglers also will smell around when winds are up for what hints of watermelon, the aroma that emanates from these slicks.

The TPWD report summed things up nicely when discussing the implications of chumming.

“It may mean the difference between success and an empty stringer,” the report states.

I couldn’t agree more.

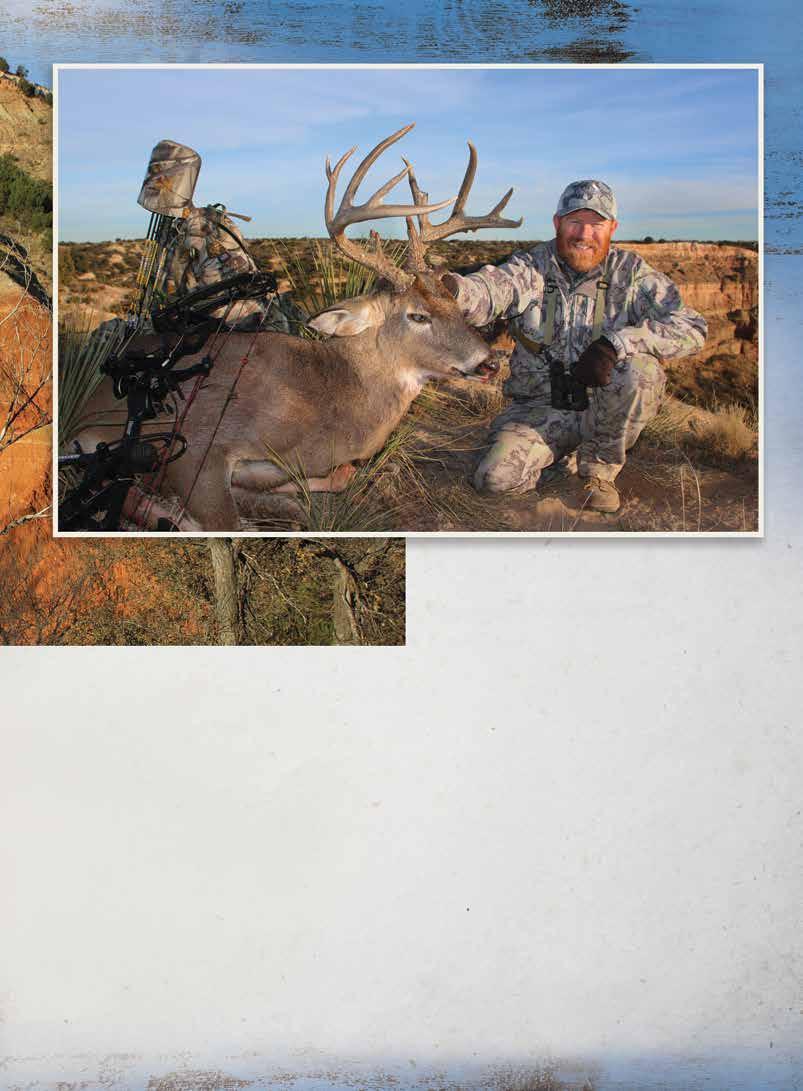

The first time I ever saw a mega-sized whitetail buck in rough canyon-country, it was totally by accident. It was after deer season had closed, late January if my memory is correct, and I was hiking through nasty red rock canyons and dry badlands calling winter coyotes. Up ahead, maybe 200 yards, a flash of white caught my eye. Through 10X binoculars I focused on the twitching tail of a beautiful 150-class buck. I felt like a ditch digger who’d just discovered a golden nugget in the muddy muck.

For the next half hour, I watched that buck meander through steep, rocky terrain more typical of mule deer or even aoudad sheep. That western whitetail was living in what I call fringe habitat, terrain with just enough groceries and water to sustain a low-density deer population.

Too often, we deer hunters hunt the easy places. We choose stand sites based on ease of approach from a nearby road, or hunt only the places where we see lots of deer. The problem is those places of convenience are often heavily trafficked and heavily hunted. Now think of the potential reward of hunting where it’s not so easy. Bucks are hunted less, so they have a bet ter chance of reaching prime antler growing years of 5, 6 and 7 years old. Because of a low human presence, those same bucks might be more inclined to move in daylight hours, too.

Since that first big buck sighting in broken canyon country many years ago, I’ve found other jumbo-sized bucks in unlikely

places. I shot my first big whitetail, a 160-plus buck with 13 scoreable points, in November 1998 after a lung-burning stalk in steep canyon country. Using my dad’s old .30-06, I dropped that buck near a small creek. The mass on his beams looked like something more common on a buck from Alberta, Canada.

According to Texas Parks and Wildlife biologist Todd Montandon in Canyon, Texas: “Whitetails’ range has been increasing westward across the Panhandle region for the last 15-20 years. I think the expansion is habitat driven. Over the years, brush has encroached throughout much of the Rolling Plains and canyon country. This encroachment has happened slowly for several reasons, the most influential one being a lack of wildlife which, historically prevented the spread of red berry juniper.

“CRP has also played a role in the increased range of white tails. Those areas where the landscape is dominated by cultiva tion makes it difficult for whitetails to fulfill all their habitat needs. As the CRP fields matured, they provided a corridor for wildlife to travel between areas of suitable habitat. Whitetails are so widespread because they are a habitat generalist, mean ing they are very adaptable and can tolerate a wider range of habitats.

“Within the canyon country, whitetails are typically more common as the habitat gets brushier. I hear from landowners and hunters that the whitetails have pushed the mule deer out of areas they were once common. What is happening is mule deer don’t have as high a tolerance for brush, so over time as

Rugged canyons like this offer a scenic backdrop for a deer hunt. Deer numbers are low in such places, but bucks have a good chance of reaching maturity.

the brush gets thicker, the habitat now favors whitetails.

“The effect of the current drought on the population will be evident with the success or lack thereof in the coming fawn crop. Last year, conditions were favorable leading up to fawning, so recruitment was a little above average. This year, however, habitat conditions during gestation have been poor across much of the region, so I would expect fawning percent ages to be lower this year in both whitetails and mule deer. As for competition, whitetails and mule deer diets are virtually the same in areas where the two overlap, so food and space could become limiting if population levels get high enough.

“The advantage is with whitetails in the brushier country and with mule deer in the rougher, more open habitat. Although, when you add aoudad into the mix in the steep country, there is even more pressure on mule deer. Whitetail densities are variable from ranch to ranch, but overall averages about 65 acres/deer in the caprock country and western Rolling Plains. Higher densities tend to be along riparian areas.”

Researching data from the Texas Big Game Awards (TBGA) is a good way to see where big bucks come from each year. The top TBGA non-typical whitetail taken in the Panhandle in 2021 came from Armstrong County on the rim of Palo Duro Canyon. Wyatt Arndt shot that buck as it chased a doe in short mes

quites near the edge of rough canyon terrain. The 6½-year-old buck gross-scored 198 5⁄8 and netted 1937⁄8 . Monte George took the Panhandle’s top typical in Ochiltree County. That giant buck gross-scored 1916⁄8 and netted 179. Two world-class bucks taken from counties with low deer numbers and rough terrain.

Some of my favorite rough country hunts have taken place in the Texas Panhandle, a landscape more like western prairies and winding river bottoms than the classic thick mesquites, cactus, and flat country that most people think of when they think of Texas. You find a variety of landscapes in the Pan handle. From steep canyons and rocky mesas to CRP fields and scattered agriculture to river bottoms lined with ancient cottonwoods and cow pastures dotted with short mesquites. The top of Texas holds a bit of everything. The bucks in these low-density populations often travel great distances, especially during the rut when they search for receptive does.

A couple years ago, a friend of mine in the northern Texas Panhandle spotted a big 160-class buck with a distinctive 5-inch drop tine on his left beam. A week later, while driving a backcountry road and glassing a CRP field, he spotted the same distinctive drop tine buck chasing a doe. The distance between

sightings was eight air miles.

The good news about these wandering nomads is that while there may be nothing of interest on your hunting property one day, a transient buck might pass through the very next day. When you see one of these big-racked nomads, it’s important to make the most of that opportunity because he could easily be gone tomorrow.

Back in 2015, a friend sent me a fuzzy cell phone picture of a stud buck. The non-typical buck had matching forks on both G-2s. We guessed his rack was 170-180 inches. He was courting a doe just across the fence from a property I hunt. The terrain consisted of a small creek, tall cottonwood trees and steep, colorful canyon walls. A month later, in early December, the same buck showed up on my trail camera at a corn feeder near the creek. I hunted that area for the next month, but never saw him. He was only on the camera the one day.

I remembered the advice from a wise friend whose killed many big bucks in his life. He said, “If a new buck shows up on your place, pay special attention to that date. There’s a reason that buck is there, either chasing does, looking for food, or avoiding pressure from another property. Be there at that same place on the same date next year.”

Sure enough, the next year, and only a couple of days from the same date the year before, he returned. I spent a few days in that ground blind, ultimately taking him with one wellplaced arrow on Dec.10, 2016. A cross section of his teeth conducted by Matson’s Lab in Montana indicated he was 8-9 years old. His rack was a little smaller than the year before, 160 inches counting the extras, but he still had 15 points and the distinctive forks on both G-2s, although his left side fork was broken.

Rough country bucks will visit corn feeders like other whitetails. Location is key. I like to put a corn feeder near water, like a meandering creek. Traveling bucks will parallel that water system and discover the free corn.

Because deer numbers are low, be very conservative in what you harvest. One of my favorite hunting spots is a wind ing creek under canyon walls. I can hunt about one mile of that river bottom. Speaking from years of hunting it, there’s usually about 15-20 resident deer that live in that one mile of habitat.

Taking only one buck per year ensures good bucks for the future. If I need meat, I’ll shoot does somewhere else. The buck to doe ratio is tight, approximately one to one. On a “good” sit in a blind I would be seeing six deer, and there are days when I see zero. The trade off is when you do see a buck, it’s often a mature buck with a fine rack.

Hunting low deer density, tough-terrain areas is not for everyone. But if you like wild country, beautiful scenery, ad venture, and the chance to see an Alberta-sized buck, it might be just the change you need.

This one will leave a mark

By Gary Robersonin events of all sorts in high school and college. This rugged lifestyle has afforded me to witness more than my share of bad wrecks, some that required hospitalization and oth ers that didn’t. Upon witnessing one of these “wrecks,” I remember thinking or hearing someone say, “That’s going to leave a mark,” knowing dang well the event would leave much more than a mark. Chances are there were numerous stitches and one or more broken bones. 2022 is a year that’s going to leave a mark on wildlife and the landscape of Texas.

I’m no stranger to dry weather. I was born in Castroville, Texas, in March 1953, during the drought of the 1950s. Since the seven-year drought went from 1950-1957, I guess you could say I was born in the middle of it. I don’t remem ber much about it because I was too young to burn prickly pear, which was about the only “cow feed” surviving on the ranch. I do remember in 1957 when the drought broke, my parents and grandparents were excited, and I saw Black Creek swell out of its banks for the first time.

I’m not going to blame just 2022 for the drought here in the Hill Country. 2021 had a lot to do with the wreck we’re in. While 2021 started out to be a pretty good year with av erage to above average rainfall in Menard County, someone turned the spicket off in June. While we had some fair rain in September, it wasn’t enough to saturate the ground. This has been the story for 2022 as well. It has rained, but gener ally less than a half inch at a time, which merely wets the surface. The excessive heat and wind that go hand in hand with a drought dry the shallow moisture in a day or two.

While I am the eternal optimist, I must say this deer sea son is shaping up to be substantially below average. Ranches overstocked with livestock and a high deer population are already losing animals. The only ranches where I see healthy deer and good antler growth are those that have an aggressive feeding program, which means 18-20% protein, free choice. Unfortunately, most hunters cannot afford to feed the deer herd with what it costs today.

This drought is not only retarding antler growth for this season, perhaps the greatest harm is how it will adversely affect the fawns born in a drought for the remainder of their life. Unfortunately, I have been finding dead fawns on ranches for the last two months while the fawns that lay around my house are in poor body condition. These deer not only have the luxury of eating Miss Deb’s plants, they wander off the hill and into Menard every evening where they spend the night consuming most anything green.

While the wildlife struggles to find enough food to survive, the toll that the wildlife and livestock are having on plant life will have the longest effects. One of my favorite plants native to Menard County and loved by deer is ephedra. Ephedra, also known as “Indian tea” or “Mormon tea,” is purported to have several me dicinal qualities. Picking the leaves and boiling them in water

Left: An ephedra plant looks more like tinder because of the lack of rain. Right: Rocky Creek is normally a spring-fed tributary of the upper San Saba River.

produces a naturally sweet brown tea that is supposed to aid with stomach problems and even treat syphilis. While I cannot attest to its healing qualities, I must admit that I do enjoy the tea from time to time.

The deer around my home have killed all but one of the ephedra plants that I knew grew on the 5 acres surrounding the house. Greenbriers that were once thick in several live oak mottes and shinnery thickets are gone, leaving a 2-inch stub. Hackberry saplings are dead because they have not been al

lowed to leaf out and older hackberry trees have a pronounced browse line. The Hill Country doesn’t have as many desirable woody plants for deer as the brush country, so those that are favored by deer and wildlife, may not survive.

While the loss of natural browse will be affected for several years, another huge is scar is the reduced flow from springs that water much of the Hill Country. There are six spring-fed creeks that feed into the San Saba River from the north between Menard and the headsprings at Fort McKavett. Today, there are only two that are still flowing, Clear Creek and Cogden Branch and to my knowledge, they have never gone dry.

Jacob’s Well in western Hays County has stopped flowing for only the fourth time in history. This spring feeds Cypress Creek that flows through Wimberly and an entire ecosystem has grown up along it, saying nothing about all the recreation it creates. While this spring has dried up in the past, today I fear that it will have a much more difficult time recharging due to the thousands of wells that have been drilled in the area for homesites. Fragmentation of large ranches into subdivisions has put an extreme burden on the groundwater supply.

Yes, 2022 is going to leave a mark, and one that we are not getting over anytime soon.

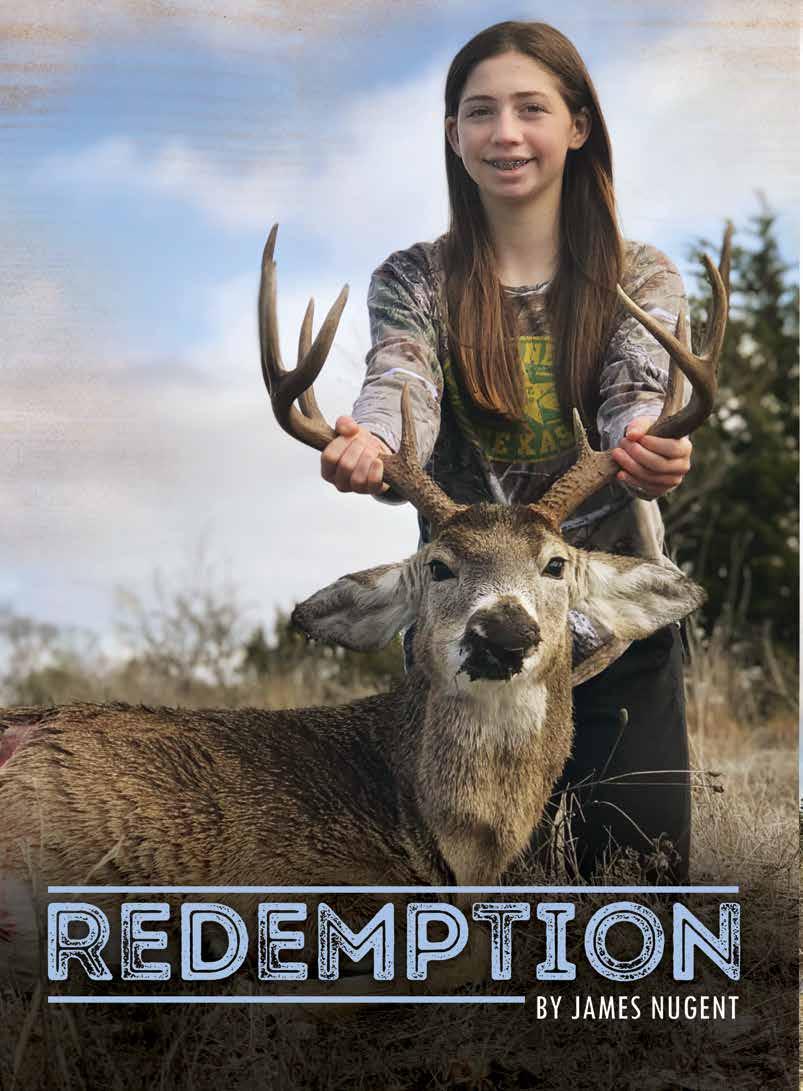

In 2019, the author’s niece, Mia, went home empty handed after her hunting trip. But nearly a year later, she would finally get herself a trophy buck.

Naturally competitive with maybe just a touch of sibling rivalry, my youngest niece, Mia, had been giving no shortage of reminders that she wanted to go deer hunting. Being the middle child and apparently never getting to do anything first—according to her—she didn’t have to think twice when I finally invited her to go to my deer lease for a chance to shoot a buck, especially before her big sister, Briley, did. At long last, the weekend after Christmas in 2019, Mia, her father Mike, and I packed up and made the five-hour drive to my deer lease, outside of Doss, Texas, for Mia’s first chance at a deer. Unfortunately, she would return home from her first hunt ing trip empty-handed.

Fast forward almost a year to the day, the same trio loaded up the truck to finish what we started a year prior. However, despite all of our best intentions, it turned out Mia would not be the first of her siblings to shoot a buck. Briley had claimed that title nearly two months prior, during the October 2020 youth weekend while hunting with their father. Even though she would have to go without bragging rights of being the first this time, she remained in good spirits and excited for the upcoming hunt.

We spent the drive to the lease recapping lessons learned from the year before and going over what to expect this time around, including what to look for in a mature buck, where to aim and when to squeeze the trigger. Arriving at camp after dark, Mia and Mike got to witness me exercise my not-soexpert-level breaking and entering skills because I had forgot ten the keys to the camper in the rush to get out of town. After cracking the less-than-vault-like camper security system, we settled in to rest up for the long-awaited morning hunt.

After a fairly sleepless night, or at least for myself, we arose before dawn and made our way to the blind after a light break fast, just as we did nearly a year before. This year we would be hunting out of a larger blind at a different feeder, which would more comfortably accommodate the three of us than the one we all managed to squeeze into the prior year. As the day slowly materialized out of the night, we watched silhouettes milling around the feeder in anticipation of their morning meal. Right on schedule, the unmistakable sound of the feeder through the predawn light signaled to all critters within earshot that breakfast was served.

Watching as the area around the feeder became the stage for nature’s star performers, we naturally gave extra attention to those sporting head gear, as we tried to determine if any of them would be worthy of the young huntress’ first buck. Just when it seemed no more room was at the breakfast table, in walked a noticeably older buck from stage right that ap peared on the downhill slide of his tenure. This old veteran had been spotted by other hunters earlier in the season and had an abnormally wide rack for the Hill Country, but his tine lengths fell a little short. After a brief discussion and thoroughly examining the candidate, Mia decided she wanted to take the shot at him.

As Mike and I kept our eyes on the buck through binocu lars, Mia carefully maneuvered the rifle out the window and positioned the stock to her cheek as if she had been doing it for

years. With all our eyes on target, we whispered to her to stay calm and reiterated where to aim and to slowly squeeze the trigger when she was ready. As the buck began to turn broadside, she confirmed she had a steady aim on him, and we gave her the greenlight to set the rifle to fire. Hearing the distinct click of the safety, we sat almost breath less as we anticipated her moment of truth. Suddenly, another buck appeared out of nowhere behind the wide-framed buck that seemingly dwarfed him in both body and antler size. Seeing this new brute, I may have let out a colorful word or two in my excitement. I quickly instructed her to not shoot the first buck because there was no doubt this was the buck she needed to take. Although not quite as old or as wide as the first buck, this bruiser had notice ably more antler mass and tine length and was unques tionably a mature deer.

Instructing Mia to take aim on the new buck, we reemphasized to her to stay calm and not rush the shot. As soon as he stepped clear and broadside, the morning silence broke as the shot rang out. The buck hunched up and stumbled forward, indicating Mia had hit her target. We watched as the wounded buck ran up the hill behind the feeder before disappearing into the brush. As we sat in disbelief of what had just happened and how quickly it transpired, it was hard to tell who was more excited through all the smiles and high fives.

After allowing adequate time for the buck to expire, we exited the blind and made our way towards the feeder to look for signs of blood to give Mia her first deer tracking lesson. Approaching the spot where the buck had been standing, we immediately found the crimson evidence we had hoped to find. Following in the direction we watched him run, we found the next few drops about 10 feet away. Continuing to search up the hill in the direction he ran, our hearts began to sink because we did not find another single drop of blood.

Scouring the terrain, Mike and I discussed finding someone with a deer-tracking dog. We agreed it would be best not to search too much and put too much of our scent down, just in case we could locate a tracking dog. With heavy hearts, we backed out and returned to camp to try to find someone in the area with a tracking dog. With no reception at the lease, we had to drive about 10 miles to get a call out.

After asking around, we called the only tracker close to where we were, only to find out he was on his way to track another animal hours from where we were. He wouldn’t be able to get to us for at least seven hours. Unable to make it to us in a timely manner, he instead instructed us to go back and keep looking, but to stay together as a group in order to minimize

adding any additional scent to the area.

On the drive back to camp, we barely spoke because hopes of recovering Mia’s deer began to fade with each passing minute. We returned to the hill to pick up the search where we had left off. Following the tracker’s instructions, we resumed the search for any signs of her deer. Reaching the plateau of the hill, the vegetation opened up, allowing for greater visibility.

Mia and Mike continued their search in one direction, while I decided to continue searching in the direction where I last saw the buck run. About 20 yards into my search on the plateau, my doubts and fears of not finding her buck instantly disap peared when I heard from a distance, “WE FOUND HIM!” Fol lowing the sound of their voices, I rounded a cedar bush to find the proud huntress and her even prouder father standing over a beautiful 10-point Hill Country buck that would even make the most seasoned hunter proud.