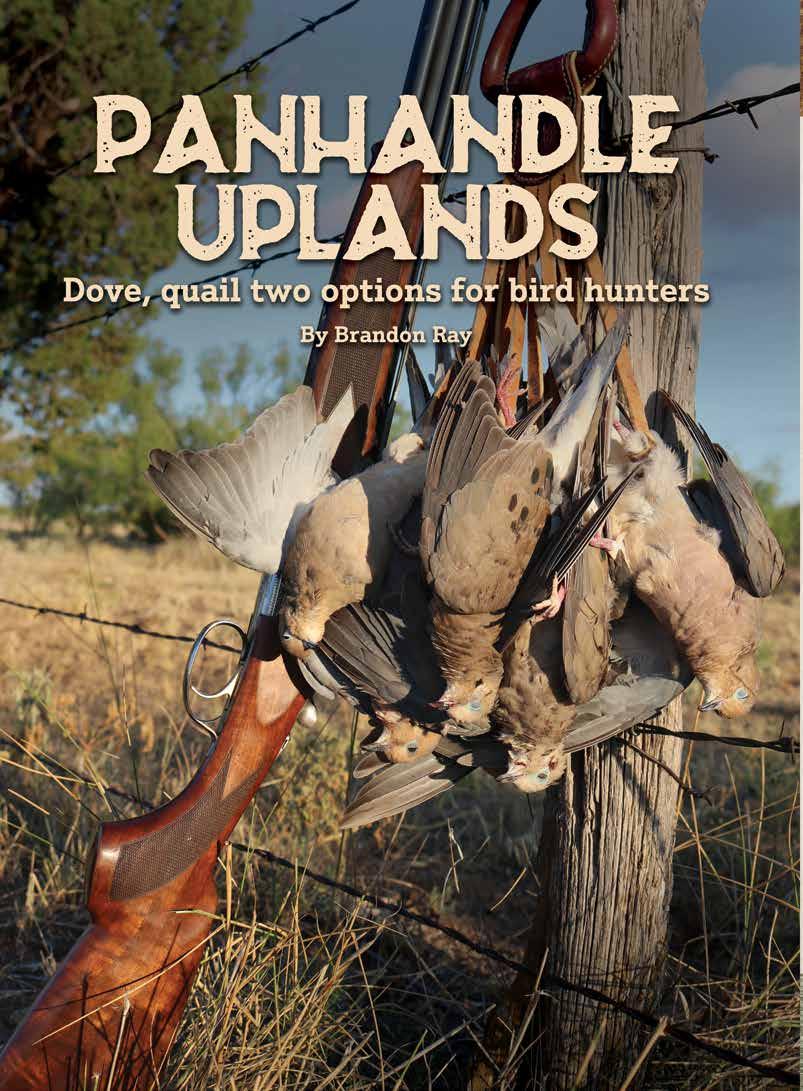

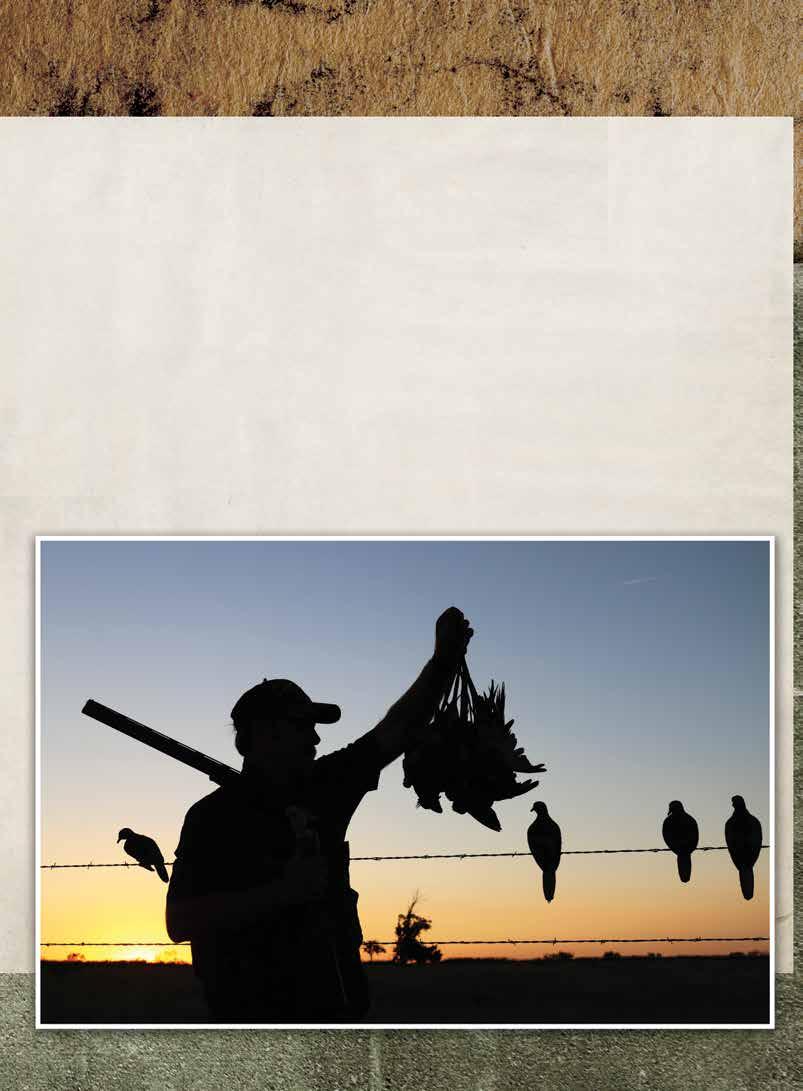

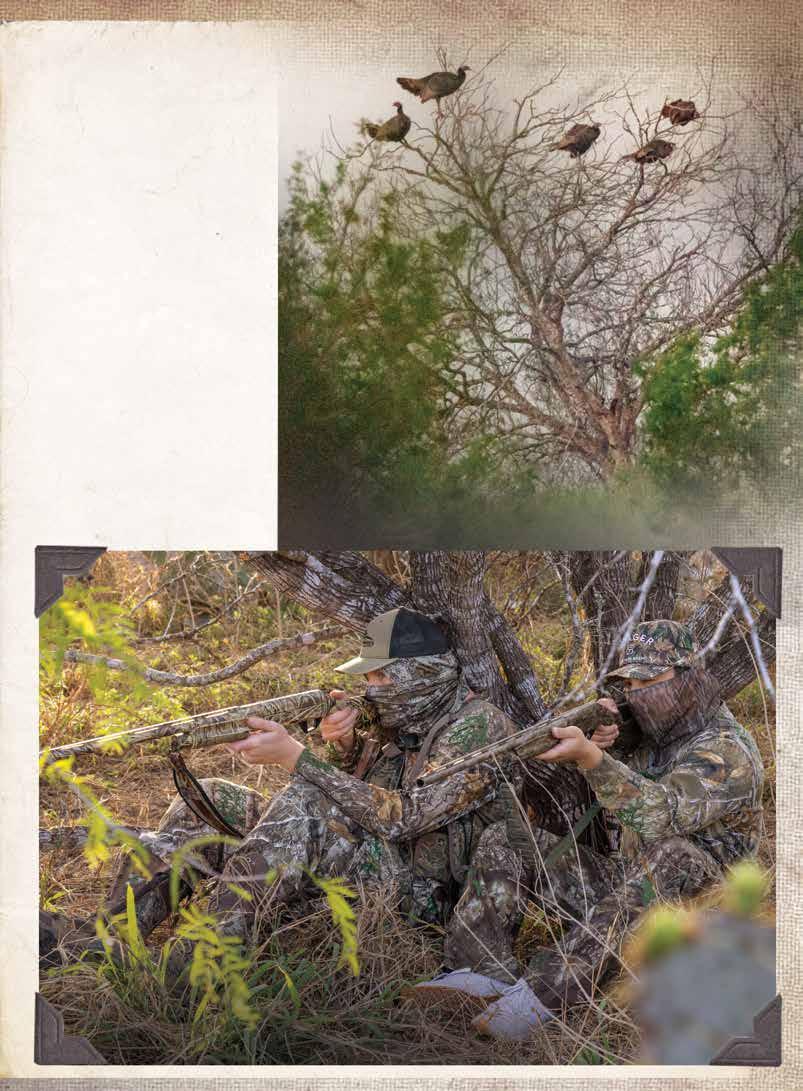

exas has had another dry year. We just can’t get caught up on rainfall. The dry weather is hard on deer, turkey, and other wildlife that live on the ground, but doves do quite well during drought, and teal season will open to conditions that are questionable for ducks. So, the dog days of summer will be dry and hot for both man and beast.

On July 4, we will celebrate our 249th year of independence from England, and things could be better than the weather. Our nation’s economy is floundering with a national debt of $36 trillion—that’s with 12 zeros—and the new administration is trying to get us back on an even keel with the rest of the world. Our two-party system despises each other. Times have been much better.

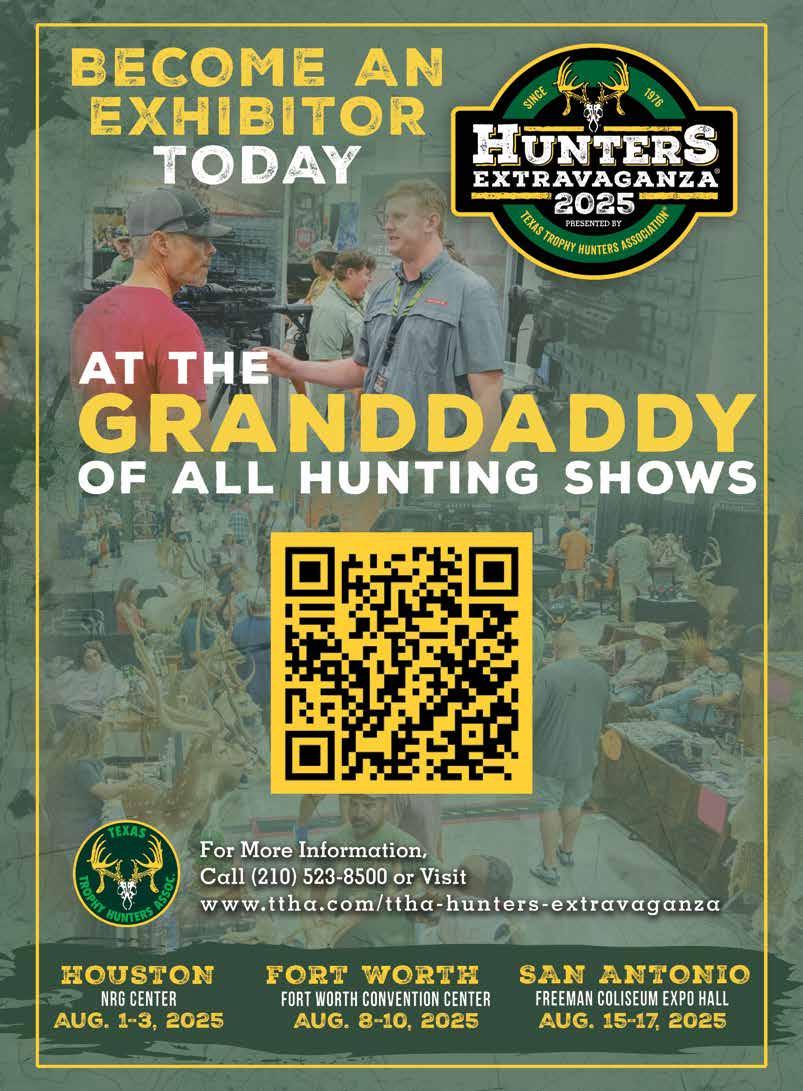

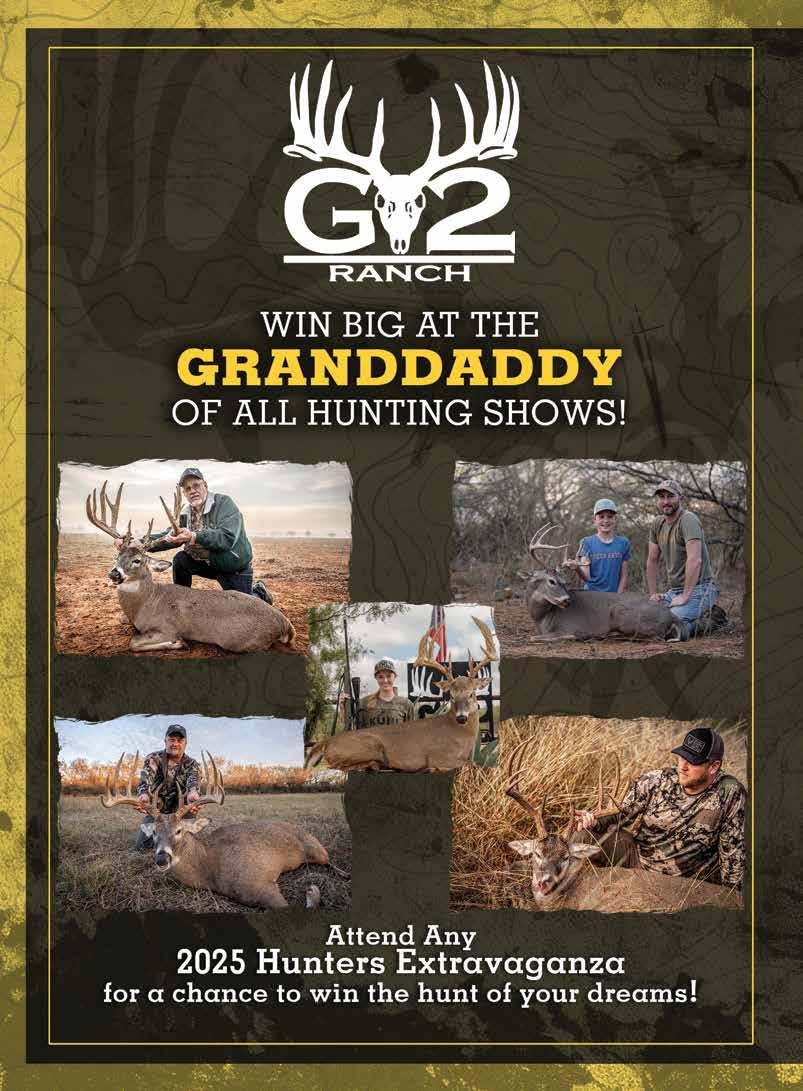

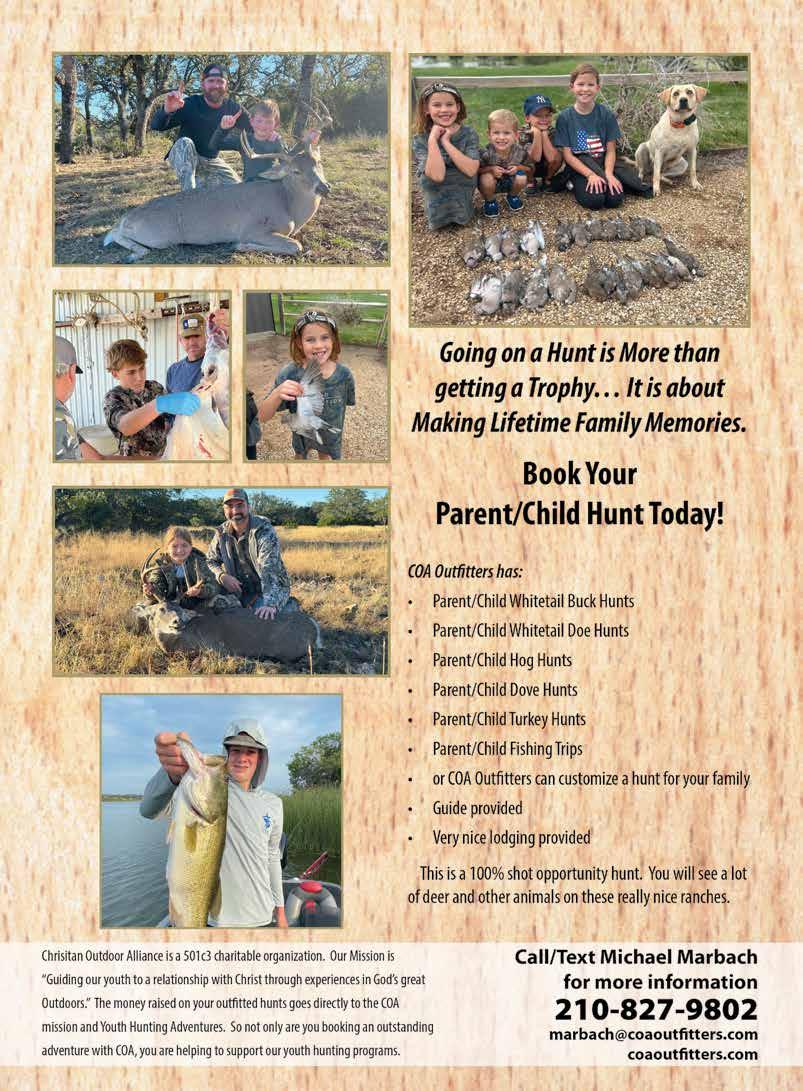

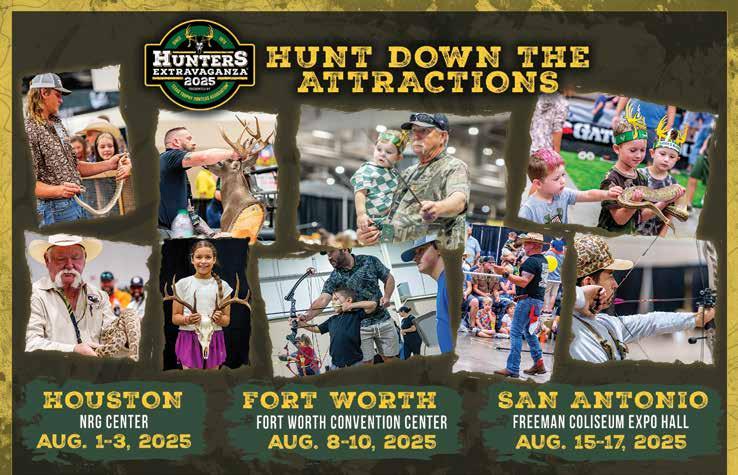

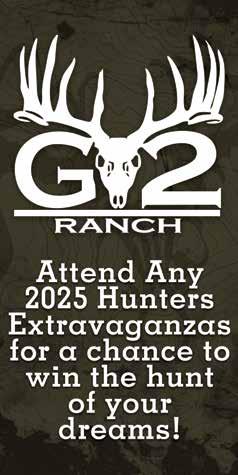

Texas Trophy Hunters’ 50th anniversary is in full swing, with the exciting Hunters Extravaganzas coming in August. Folks who love the outdoors and hunting look forward to the trade shows in Houston, Fort Worth and San Antonio that have everything for hunting, fishing, and camping. The venue aisles are full of the best in outdoor equipment, and the kids enjoy all the things that make kids happy. The Extravaganzas make the dog days of August more enjoyable for the whole family. Dove season is just around the corner, so it would be wise to start looking for a good buy in shotgun shells and other things you will need for dove hunting. You might even want to call the landowner where you hunt and invite the family out to dinner. Dove hunting spots are not easy to get, and you shouldn’t take your dove hunting for granted. And the coming Extravaganzas are the perfect place to gear up for the hunting seasons.

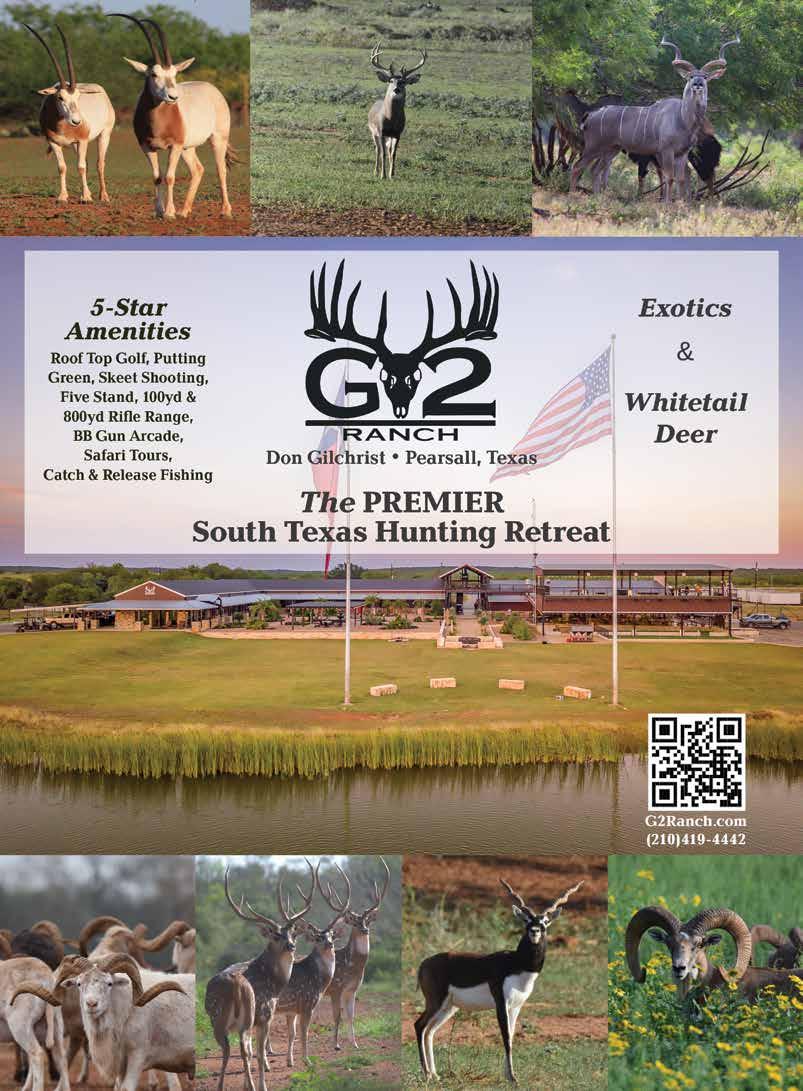

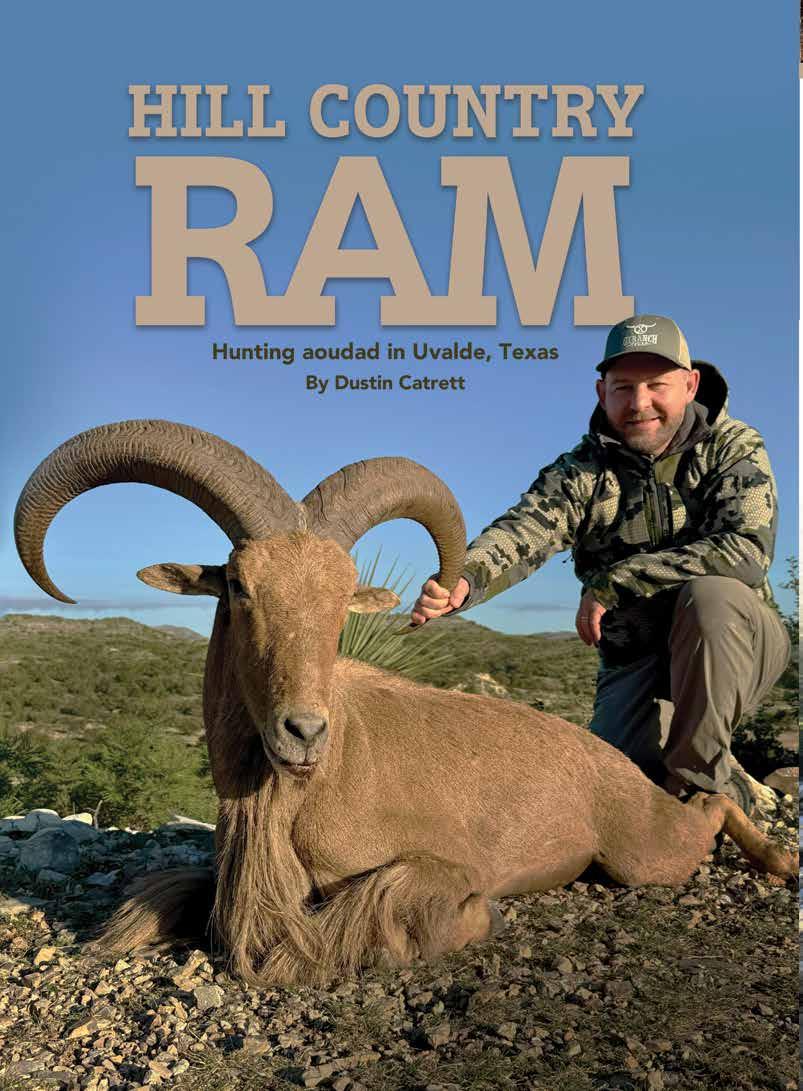

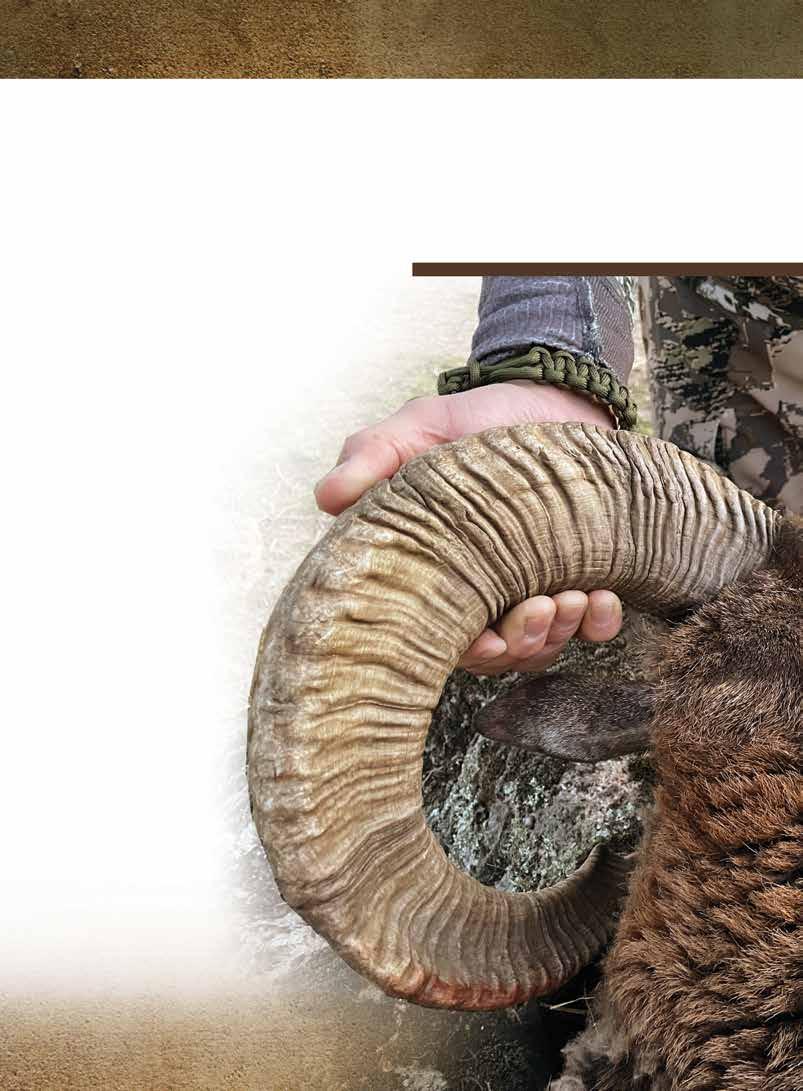

Texas has a lot of “Texotics,” and late summer is a good time to hunt for axis, nilgai, aoudads, and marauding wild hogs. Many hunters take advantage of the offseason hunts, and exotics and hogs are there for the taking. Guided hunts for nilgai are available in South Texas, axis are plentiful in many Hill Country counties, and aoudads offer good hunting in the Hill Country, West Texas, and the canyon areas of the Panhandle. Any hunts should be well planned for summer heat, with a wise choice of heavier caliber rifles for nilgai and aoudad.

July and August are good times to clean up the deer camp and get deer blinds ready for the coming deer season. Wood needs cutting, blinds need repairing and cleaning, brush needs cutting for shooting lanes, and it’s not too early to clean out the wasp nests. While you’re at your favorite hunting spot, you may want to check your rifle for proper sight-in.

The old adage that “dog days of summer just hold the year together” is true only if you have nothing to do to keep you busy during the hot days. Enjoy the holiday and think of all the good things you can do to make ready for the fall hunting seasons. Kids can find a swimming hole, and it’s not too late in the year to cut a watermelon with friends and neighbors.

Horace Gore

info@ttha.com

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer Christina Pittman • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Graphic Designers Faith Peña

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

Dustin Catrett, Tret Darr, John Goodspeed, Parker Hause, Judy Jurek, Bob Newland, Jack Orloff, Eric Stanosheck

Advertising Production

Debbie Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Sales Representative Tristan Summy 210-685-1205 tristan@ttha.com

Marketing Manager Logan Hall 210-910-6344 logan@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events

Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com Events Natasha Delgado 210-512-8045 natasha@ttha.com

Finance & Administration Manager Laura Garcia 210-512-4927 laura@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

The 2025 Hunting & Fishing Extravaganza in Midland April 11-13 brought together outdoor enthusiasts from across the West Texas region for a fun weekend. Hosted at the Midland County Horseshoe Pavilion, this year’s event featured a variety of hunting outfitters, apparel, fishing gear and more, giving attendees the chance to connect with the lifestyle they love. Country music legend Mark Chesnutt’s performance gave fans a chance to enjoy his iconic hits. We’re thankful to everyone who came out, and we’re already looking ahead to 2026. We hope to see you then!

—Logan Hall

It’s here – the original Texas hunting show is back

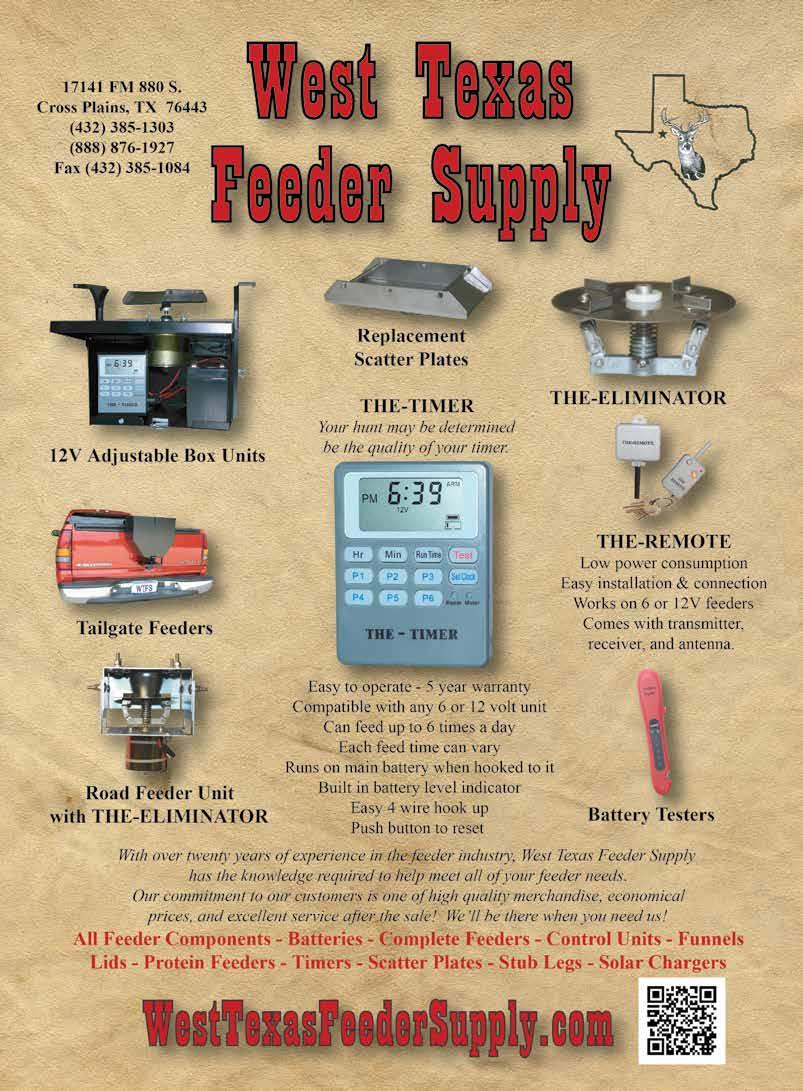

Kick-off your 2025 hunting season(s) with us at the Hunters Extravaganzas in Houston, Fort Worth and San Antonio. Discover the latest and greatest in camo, blinds, feeders, ATV’s, optics and so much more. Enjoy a seminar from hunting/outdoor experts, or even book your dream hunt. Bring the family; bring your friends. There’s plenty of fun for the kids, too. You won’t want to miss it! More details starting on page 32.

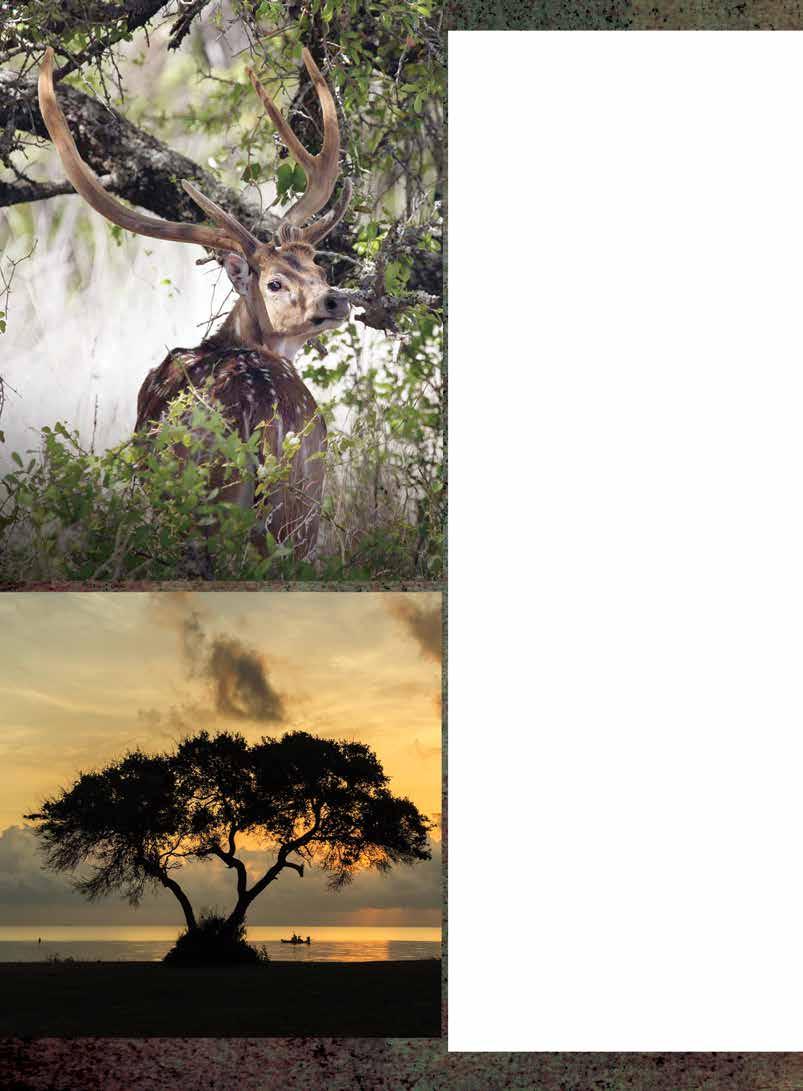

Despite their size, nilgai are quite elusive afield.

By Horace Gore

Agnes Ann “Aggie” Goodman shifted her position on the passenger side of the pickup so the fore end of her 7mm Mauser lay steady against the sandbag and rearview mirror. She had the 2-minute Lee dot in the 6-power Leupold scope centered on the nilgai’s shoulder.

This was Aggie’s first nilgai hunt, and she didn’t want to foul up her shot at a “blue bull.” She pushed the safety off and waited, as she thought about what Jack had told her: “Put the bullet square into the bull’s shoulder, and right through both lungs.”

The old bull stood near some scrubby live oak, which would give him quick escape. His dark body formed a silhouette against the oaks, offering Aggie a broadside shot. She thought this would

be her only shot—albeit a long one. Aggie had been practicing at a 250-yard target and had been scattering the bullets in a 6-inch group—good enough to kill a Kenedy County nilgai bull.

The bull looked at the truck, but had not bolted. Aggie had confidence, knowing Jack had sighted the handloaded 160-grain Nosler in for a long shot, 3 inches high at 100 yards, “dead-on” at 250 yards, and 6 inches low at 300 yards.

Jack Morgan, Aggie’s “soon-to-be,” had guessed the distance at about 250 yards, a safe distance for the lone nilgai bull. The ranch had limited hunting, and the nilgai were not exceptionally wild at a safe distance. Jack looked at the bull through his binoculars as he said, “Put

the dot high on the bull’s shoulder.”

Aggie had a steady rest on the sandbag as her finger felt the trigger. She took a deep breath and slowly squeezed it for the one, and probably only shot at the distant bull. The 7mm roared and Aggie lost sight of the antelope, as she bolted another round and put the safety on.

Jack had his binoculars on the nilgai as it wheeled in the loose sand and ran—with tail high in the air—veering toward the scrubby live oaks. Jack felt good about the shot, knowing a bull hit well through the lungs often throws up his tail and runs until his air plays out. The bull went through the live oaks and disappeared behind a grassy knoll. Jack took Aggie’s trembling hand, and they waited.

The idea of a nilgai hunt had started when Aggie’s grandfather had given her his custom 7mm Mauser as a college graduation present. The old man had carried the Mauser from the Rockies to Mexico over the years, taking all manner of big game. He knew Aggie wanted the Mauser, and now she had it.

The rifle was exquisite, with French walnut wood, fine checkering, aftermarket tang safety, and light 22-inch barrel. The 6-power Leupold scope had a 2-minute Lee dot on thin crosshairs. This meant the dot covered 2 inches at 100 yards, and 6 inches at 300 yards.

Aggie’s grandad loved the old Mauser and had talked about shooting 140-grain Hornady spire points at deer, pronghorns, and hogs, but preferred the 160-grain Nosler for aoudad and elk. She had heard him say with a grin, “My Mauser and 160-grain Noslers would kill an elephant if the sun was right! I’m sure it will do well on a bull nilgai.”

Now, Aggie hunted nilgai with her beloved Jack and Gramp’s old Mauser, with his handloads of 160-grain bullets at 2,650 fps. Jack was not new at nilgai, having taken a good bull on one hunt and a fat cow on another. He knew the ins and outs of nilgai hunting and had put Aggie on this big bull that ran hell bent for leather after she put a 7mm Nosler bullet through both lungs.

Aggie and Jack sat in the pickup wondering how far the bull would run before collapsing. Jack had guessed the horns at 8 to 9 inches—good for an old bull that could weigh 500 pounds, or more. But Aggie wasn’t interested in the horns, just the unique hunt with her new gifted 7mm Mauser.

The nilgai antelope they hunted in South Texas are native to India, and many animals were brought to American zoos in warmer climes after World War

I. The San Diego Zoo had an excess of nilgai in the mid-1920s, and the King Ranch bought some to stock the ranch for meat consumption—not trophy hunts. Nilgai meat is outstanding, but now the big antelope are prized as exotic trophies.

Jack started the pickup and began the drive up the incline. The truck almost stalled in the deep sand, but Jack finally got to harder ground. Aggie leaned as far as she could against the windshield, and sighed with relief when she saw the big, dark bull laying in the grassy flat 100 yards ahead.

Jack stopped the truck a few yards from the bull and surprised Aggie with a kiss as he remarked, “Good shot, Babe!” Both were excited as they got out to check where Aggie’s bullet had hit the bull, and to measure the horns. Jack called back to ranch headquarters for help in getting the big bull back to the skinning shed.

Aggie watched as Jack spread his hand on the short, black horns. “Close to 9 inches,” Jack surmised as Aggie ran her finger up one horn and felt the sharp point. “Are these real horns—not like pronghorns?” she asked. Jack assured her they were real as he felt the Nosler bullet under the hide, where it had lodged after going through both shoulders.

“The difference in your nilgai’s horns and a world-record is about an inch,” Jack joked as they sat in the truck waiting for the ranch cowboys to come and load the big antelope. Everyone would have a lot of work ahead. A mature bull takes a lot of effort to load, hang, gut, skin, and cut up for the freezer.

Before long, a flatbed truck came down the sendero and backed up to the nilgai. Two ranch hands got out and put four thick, wide boards together

from the ground to the truck bed, and then turned the bull’s rear towards the boards. The electric winch whined as the cable attached to the hind legs pulled the big animal up the boards and onto the truck bed. Aggie heard the cowboys talking, “Muy bien! El es un gran toro.” She knew enough Spanish to know they were admiring her nilgai.

“We couldn’t have gotten the bull out of the pasture without the boards and winch, could we?” Aggie asked as the cowboys drove away with her nilgai. “Not hardly,” Jack quipped. “Nilgai hunting ain’t for the weak and feint hearted.”

Aggie could hardly believe how long a bull nilgai is when you pull it up by the hind legs for gutting and skinning. “That bull is twice as long as I am tall,” she remarked as Jack and the cowboys got out the knives and saw. An hour later, two large chests with meat were iced down, and the cape and head were ready for the taxidermist.

“I like his blue hide and the whitetipped ears and cheek spots,” Aggie said as she rubbed her fingers through the coarse hair of the cape. “If he had been closer, I would have shot him in the white spot,” she bragged as she touched the large white area on the bull’s neck. Jack remarked as Aggie admired her trophy, “Not much for horns, but hell to shoot and put on the ground.”

Aggie had found the big tuft of hair below the white spot on the nilgai’s neck, and remarked to Jack, “He’s got a beard like a turkey!” Jack just smiled, as he rubbed some dirt on his Buck knife blade and wiped it clean on his pant leg. They had started the hunt early and the sun was below the edge of the skinning shed. Jack glanced over at Aggie—her red hair gleaming in the evening sun as she sat admiring her new rifle. It had been a good day.

On Feb. 27, a tragic helicopter crash claimed two lives near Uvalde. The accident occurred around 1:20 p.m. near Cline, located in Kinney County just west of Uvalde. The pilot, William Garrett Robertson of Uvalde, and passenger Earl Blakely Hunnicutt of Florida, were the only occupants in the helicopter involved in the fatal accident. The two men were flying in a Robinson R44 and conducting a routine flight. The exact cause of the accident is unknown at this time and is still under investigation.

Hunnicutt was 53 years old and visiting from Florida. It was reported that he was well-known locally and involved in charity work as well as programs supporting veterans and first responders.

Robertson, known by those close to

him as “Garrett” or “Gee,” was 31 years old and flew for Holt Helicopter of Uvalde. Robertson was passionate about flying and was an extraordinary pilot with a prestigious educational background and numerous certifications. Robertson had a Bachelor of Science degree in aeronautics with minors in helicopter operations safety and aviation flight safety from the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University in Prescott, Arizona. He was a certified flight instructor and held a commercial certificate as well as a second-class medical.

When Robertson wasn’t busy with work, he lived life to the fullest. He enjoyed spending time with his family and liked to hunt deer, hogs, and ducks as time permitted. Many fond memories were made with his brother in the field.

A pilot’s infatuation with flight may perhaps best be summarized by a quote from none other than Leonardo da Vinci. “Once you have tasted flight, you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward, for there you have been, and there you will always long to return.” Robertson’s enthusiasm was contagious. He never arrived at a scheduled job on time. He arrived early and with a smile. His work ethic and commitment to aviation were second to none, and he felt at home in the air.

Robertson’s love of aviation was eclipsed only by that for his wife, Maci Robertson, and their beautiful baby daughter, Emma Dawn Robertson. Robertson was a friend to all whose paths he

crossed. His selflessness and humility left a mark on many. Countless heartfelt tributes were shared at his celebration of life ceremony. The outpouring of love and support shown by those who knew him speaks volumes to his character. Robertson lived his dream and died doing what he loved. He will be greatly missed by all.

Donations may be made to the Garrett Robertson Memorial Fund at TXN Bank to help the young Robertson family during this difficult time. —Jason Shipman

Gov. Greg Abbott appointed Tim Timmerman and reappointed Bobby Patton to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission for terms to expire Feb. 1, 2031. The appointment went into effect May 21.

Timmerman of Austin is the owner of Timmerman Capital LLC and numerous real estate investment and development entities. He is the president of the Colorado River Land Trust, board member for Central Texas Community Foundation, Austin Area Research Organization, YMCA of Central Texas and Texas Business Leadership Council. He’s also a member of the Texas A&M University Chancellor’s Century Council and the Texas A&M Legacy Society. Additionally, he is the former vice chairman of St. David’s Round Rock Medical Center and a former board member of the Austin Chamber of Commerce. Timmerman received a Bachelor of Business Administration from Texas A&M University and a Master of Business Administration from The University of Texas at Austin.

Patton of Fort Worth is president of Texas Capitalization Resource Group, Inc. He is a member of the State Bar of Texas, the UT Development Board, UT Marine Science Institute, the UT Liberal Arts Advisory Council and a director of the Fort Worth Stock Show & Rodeo. Additionally, he is the former chairman of the PGA Tournament Committee for Charles Schwab. Patton received a Bachelor of Business Administration from UT Austin, a Juris Doctor from St. Mary’s Law School, and a Master of Laws from the Southern Methodist University Dedman School of Law.

These appointments are subject to senate confirmation. — courtesy TPWD

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department is expanding digital license and tag options to all recreational hunting, fishing and combo license and tag types. TPWD introduced digital licensing and tagging in 2022 for harvested deer, turkey and oversized red drum.

Options have since expanded to allow resident hunters and anglers to purchase a fully digital license for the super combo (Items 111, 117), youth hunting (Item 169) or lifetime combo (Item 990), Hunting (Item 991), or Fishing tags (Item 992). Customers can also purchase other products such as the exempt angler tag (Item 257), bonus red drum (Item 599) and spotted seatrout tags (Item 596).

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission approved expanded digital license and tag amendments during its March meeting. The new digital options will go into effect on Sept. 1 but will be available for purchase Aug. 15, when 2025-26 licenses go on sale. —courtesy TPW

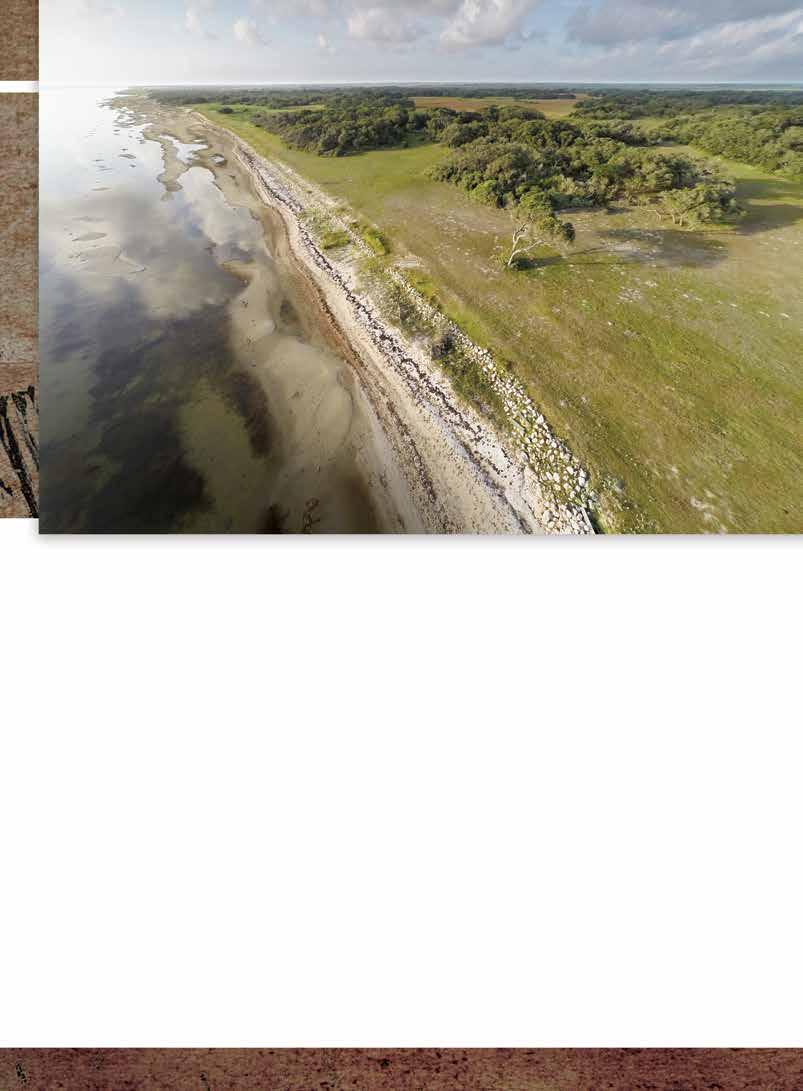

For the first time in almost two decades, the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department has added a new Wildlife Management Area to its East Texas inventory. The property, comprising approximately 6,900 acres in Anderson County, will become the Trinity River

Wildlife Management Area. Trinity River WMA is the newest addition to the Middle Trinity River Ecosystem Project, which includes Gus Engeling, Richland Creek, Big Lake Bottom and Keechi Creek WMAs. Together, these properties protect more than 38,000 acres in East Texas. The newly acquired property also adds 11.3 miles of Trinity River frontage, giving TPWD more than 25 miles of riverbank conservation along this important corridor for migratory birds.

The management and restoration of the Trinity River and Richland Creek WMAs gives TPWD the opportunity for “wall-to-wall” bottomland conservation across the entire east-west width of the Trinity River basin on more than 21,000 contiguous acres. These efforts will aim to slow waters during flooding events, allowing for natural river sediment to settle across the floodplain rather than downstream in areas where concentrated deposits cause environmental problems.

“The establishment of the Trinity River WMA presents an opportunity for the conservation and management of an ecologically unique and important habitat,” said TPWD Executive Director David Yoskowitz. “Partnerships with organizations like the Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and Knobloch Family Foundation make historic land purchases like this possible.”

The late Jackie Gragg, whose family owned the property, enjoyed seeing the blooming dogwood trees at the nearby Gus Engeling WMA and had a vision of her land being managed and protected in a similar fashion. The Gragg family worked closely with TPWD staff over the course of a year and a half to make this new WMA a reality.

During the 88th legislative session, $10 million in Migratory Game Bird Stamp Funds were appropriated to TPWD for the acquisition of new wildlife management areas. A portion of these funds, along with a grant awarded to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Foundation from the Knobloch Family Foundation, provided the primary match for a Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration grant from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

“The 88th Legislature’s appropriation

of Migratory Game Bird Stamp Funds has allowed TPWD to conserve more lands and bring greater access to even more Texans,” said TPWD Wildlife Division Director Alan Cain.

TPWD will work cooperatively with many partners to fund and prioritize habitat restoration on the new WMA. Wetland restoration and creation will be a primary effort, along with work focused on rebuilding bottomland hardwood on the Trinity River. Prairie restoration efforts will occur on the upland acres on the northern end of the property. When appropriate, outdoor recreational opportunities, including hunting and fishing, will be available to the public. —courtesy TPWD

Safari Club International submitted a detailed report in January to the Trump transition team identifying the key priorities that will expand public land access for sportsmen and women, modernize wildlife management, and promote stronger and more effective state, federal, and international partnerships.

President-elect Donald Trump’s decisive victory marked a global win for sportsmen and women and now sets the stage for unprecedented opportunities to safeguard hunting traditions and advance sustainable-use conservation. SCI is wasting no time capitalizing on opportunities to work side-by-side with the incoming administration on behalf of hunters, anglers, and outdoor enthusiasts everywhere.

Among a list of critical priorities, SCI is urging the Trump administration to:

• Protect public access to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting on federal lands while ensuring guided opportunities on remote public lands remain available.

• Modernize the Endangered Species Act by delisting recovered species like gray wolves and grizzly bears, allowing resources to focus on at-risk species.

• Defend hunters’ rights by maintaining access to traditional ammunition and fishing tackle.

• Strengthen statefederal collaboration in wildlife management by improving consultation processes and reducing unnecessary litigation.

• Support global conservation efforts by engaging with international partners, particularly in regions like Southern Africa, to enhance sustainable-use programs that benefit local communities and wildlife.

“SCI is ready to partner with the Trump administration to advance science-based conservation, protect hunters’ rights, and ensure America’s public lands and wildlife resources remain a thriving legacy for future generations,” said SCI CEO W. Laird Hamberlin.

“SCI’s priorities reflect a shared vision with the Trump administration: preserving America’s outdoor heritage while promoting effective conservation practices,” said SCI President John McLaurin. “With strong leadership in the White House, the future looks bright for sportsmen and women around the world.” —courtesy SCI

Doug Burgum as New Secretary of the Interior

Safari Club International (SCI) congratulates former Gov. Doug Burgum (R-North Dakota) on his confirmation as U.S. Secretary of the Interior. With a strong record of executive leadership and a deep appreciation for America’s hunting heritage, Secretary Burgum is the ideal champion for the rights of sportsmen and women across the country and a trustworthy steward of sound conservation policies rooted in science and sustainable use principles.

As the leading voice for hunters and anglers on Capitol Hill and the nation at large, SCI looks forward to working with Secretary Burgum and the Trump administration to ensure the Department of the Interior implements critical reforms that will enhance access to public lands, modernize wildlife conservation policies, and strengthen partnerships at the federal, state, and international levels. SCI’s key policy priorities include:

• Protecting public access to hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting

on federal lands while ensuring guided opportunities on public lands remain available.

• Modernizing the Endangered Species Act by delisting recovered species like gray wolves and grizzly bears, allowing federal resources to focus on genuinely at-risk species.

• Defending hunters’ rights by maintaining access to traditional ammunition and fishing tackle.

• Strengthening state-federal collaboration in wildlife management by improving intergovernmental consultation processes and reducing unnecessary litigation.

• Supporting global conservation efforts by engaging with international partners, particularly in regions like Southern Africa, to enhance sustainableuse programs that benefit local communities and wildlife.

“With Secretary Burgum at the helm of the Department of the Interior, we have a leader who understands the importance of protecting America’s hunting traditions while advancing science-based conservation,” said SCI CEO W. Laird Hamberlin. “SCI is eager to partner with President Trump and his administration to expand hunting access, reform outdated regulations, and defend the rights of sportsmen and women across the country.”

“Secretary Burgum’s confirmation is a win for every hunter and angler who values access to our public lands and responsible wildlife management,” said SCI President John McLaurin. “We look forward to working with the Department of the Interior to safeguard America’s outdoor heritage and ensure all citizens can go afield free from the kind of crippling regulations that were commonplace with the previous White House.”

—courtesy SCI

On Jan. 23, two important bills to bolster conservation and public lands were introduced by Members of the Congressional Sportsmen’s Caucus (CSC). Both these bills were priorities for the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation (CSF) in the 118th Congress and will remain

priorities in the 119th Congress.

Led by CSC Member Rep. Zinke and Rep. Beyer, the bipartisan Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships Act (H.R. 717), which CSF testified before the House Natural Resources Committee this past September in support of, would codify an important effort to conserve habitat for migratory wildlife across the country.

The Keep Public Lands in Public Hands Act (H.R. 718), another bipartisan bill led by Rep. Zinke and CSC Member Rep. Vasquez, would establish more congressional oversight over the disposal of public lands managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) and the U.S. Forest Service (USFS).

The Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships Act, is a critical step forward towards conserving and restoring habitat connectivity for our nation’s wildlife. This legislation seeks to codify the highly successful Secretarial Order 3362 that sought to conserve big game migration corridors and winter range across 11 western states. However, this legislation broadens this scope across the entire country and all wildlife species that migrate or move as part of their annual cycle would be eligible for funding. This legislation respects the rights of private landowners while providing these important stakeholders with voluntary options to expand conservation across their lands as they see fit.

The Keep Public Lands in Public Hands Act requires congressional approval for the sale or transfer of publicly accessible lands that are greater than 300 acres and water accessible lands that are greater than five acres. Under current law, Congress does not need to provide oversight over the sale or transfer of parcels of FLPMA identified parcels regardless of size. This legislation establishes an important threshold to maintain public access for sportsmen and women while recognizing that smaller, less recreationally important lands are suitable for disposal. This legislation does not prevent or prohibit the transfer or sale of public lands, nor does it undermine important land transaction programs that help increase access such as the Federal Lands Transaction

Facilitation Act. Rather, this legislation establishes an important threshold to ensure that important recreational lands and water are scrutinized and approved by Congress before being sold or transferred. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

Congressman Introduces Endangered Species Act Amendments Act of 2025

Safari Club International commends House Natural Resources Committee

Chair Bruce Westerman, R-Ark., for introducing the Endangered Species Act (ESA) Amendments Act of 2025. This long-overdue legislation is a major step in bringing the ESA into the 21st century, ensuring it works to recover species and promote collaboration with landowners, conservationists, and the sporting community, instead of allowing for endless litigation cycles and bureaucratic overreach.

For decades, environmental and animal rights groups more interested in

control than conservation have hijacked the ESA. The ESA Amendments Act of 2025 restores the law’s original intent— helping species recover, not locking them in perpetual regulatory limbo. This bill injects much-needed common sense into federal wildlife policy by streamlining the delisting process for recovered species, rewarding effective international conservation efforts, and aligning U.S. import-export regulations with proven science-based practices.

ESA Reform of this kind is part of SCI’s 2025 Policy Priorities, which it relayed to the Trump administration earlier this year. SCI is committed to advocating for policies that protect hunting and conservation as essential tools for species recovery. SCI urges the House of Representatives and Senate to swiftly pass the ESA Amendments Act of 2025 to ensure that science, not an uninformed political agenda, guides future conservation efforts.

“Congressman Westerman’s legislation puts collaboration science and results

ahead of politics and obstruction,” said SCI CEO W. Laird Hamberlin. “Groups like the Center for Biological Diversity have spent years using the ESA as a weapon to block conservation success. They’re stuck in the past and unwilling to acknowledge when recovery efforts work. This bill corrects that and puts data a willingness to work with those on the ground, living with listed species, including in foreign countries at the forefront of conservation policy.”

“This legislation is a win for hunters, conservationists, and wildlife species alike,” said SCI President John McLaurin. “America’s sportsmen have funded the most successful conservation programs in the world, and it’s time the ESA recognized those achievements instead of pointlessly erecting meaningless roadblocks to sustainable-use hunting and wildlife conservation. Chairman Westerman’s bill brings the law back in line with real-world conservation success.” —courtesy SCI

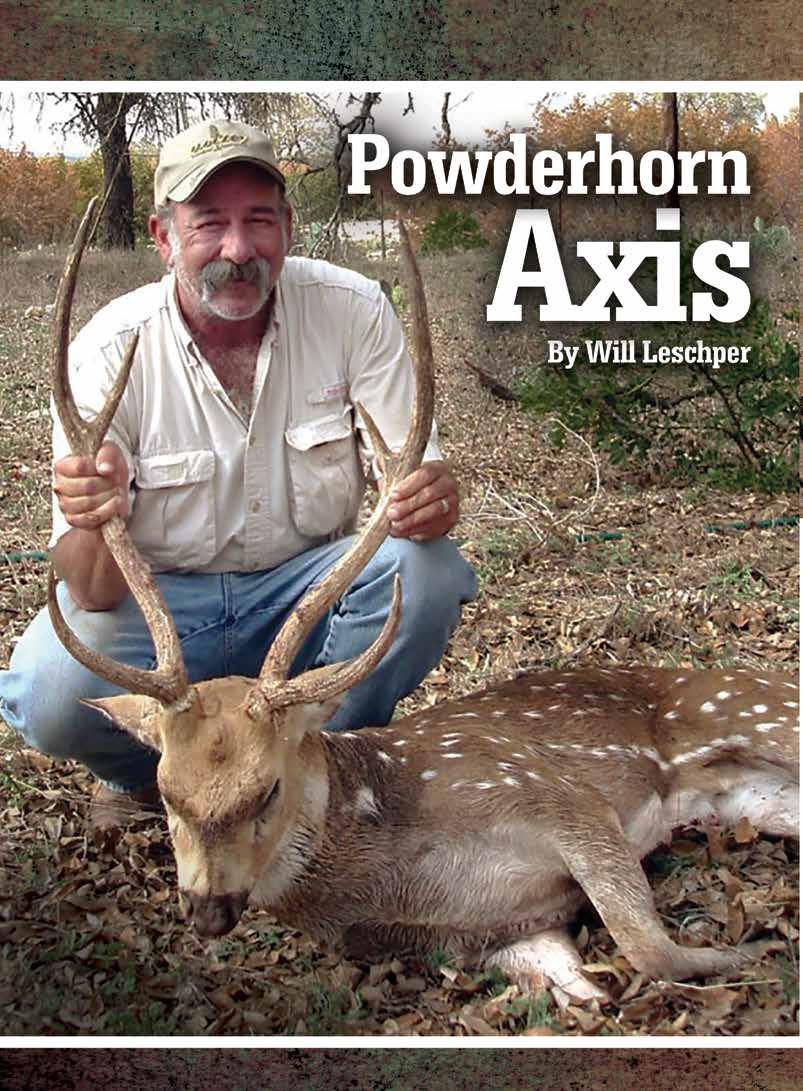

By Dr. James C. Kroll

While attending Texas A&M University, the author took part in a venison preference study, which concluded that axis venison was far superior to any other cervid.

Ibegan my deer hunting career in the early 1960s when I went on my first deer hunt at the invitation of my high school biology teacher, Mr. Victor Rippy. He was an enthusiastic man, filled with wonder and enthusiasm for the natural world. He was one of many to whom I would owe credit for where I am today. I dedicated my first book, “A Practical Guide to Producing and Harvesting White-tailed Deer,” to him and we remained friends until he died a few years ago. He had an altitude stroke while climbing a Colorado mountain, and never got over the damage.

My first deer hunt was great for lots of reasons, but mostly because I took my first buck. I had bought a surplus M-1 1903 Springfield rifle in .30-36 caliber that came coated in military grease. I think I paid about $10 for it. I was told by somebody—tongue-in-cheek—that Teddy Roosevelt once used this rifle, so I felt pretty good about having it.

In late December, we were hunting a day lease on what I remember to be the Elmo Wilson Ranch near Hunt, Texas. We stayed in a barn that had been equipped for hunters and I remember it being quite cold. The next morning, I sat against a tree when I saw a buck slipping across a sheep pasture. Without

hesitating I lifted up the Springfield, peered through the iron sights, and pulled the trigger.

The buck fell in his tracks. Then, I suddenly noticed that the pasture was full of sheep. I quickly looked for white bodies on the ground. And finding none, I breathed a sigh of relief.

That first hunt, with help from several fine gentlemen, launched a career most young men only dreamed of in those days. It also fostered a love for the Hill Country, especially the great area surrounding the Guadalupe River headwaters. Over the last 60-plus years, every time I have the chance, I take a trip to my beloved Hill Country and Kerrville.

My favorite activity each visit has been to drive the exactly 100 miles around the basin, composed of State Highway 39 west out of Kerrville, through Hunt, then to the junction with US Highway 83, turning north about 10 miles, and back to the east on Highway 41 past the Y.O. and Priour ranches to State Highway 27, and back south into Kerrville.

It was during these drives in the 1970s I started noticing more and more ranches being high fenced. At first, my goal was to count the number of whitetails I observed, but then new animals became more obvious. The area can legitimately claim

ownership to being one of the “deerest” places in the Lone Star state and can also take credit as being the birthplace of exotic game ranching. Men like my friends Charlie Schreiner III and Dale Priour were instrumental in bringing exotic species to the Hill Country.

A great number of exotics originated from the San Diego Zoo Park in California. These species quickly became known as “Texotics,” a term made popular by Thompson Temple of Kerrville. For well over 50 years, the Y.O. Ranch conducted an annual exotic sale that played a big part in getting exotics distributed statewide.

Among the many non-native animals I observed on my trips were strange, orange-colored deer covered with large white spots, and the bucks had high, six-tine antlers. It was the axis deer (Axis axis) or chital from the Indian subcontinent.

I noticed right away that axis appeared to be the most populous exotic species that had the odd habitat of running around in large herds in the middle of the day. To make things more interesting, there were males in the herd that were growing velvet antlers and others that had fully hardened antlers. These

Axis compete with whitetails for nourishment by eating forbs and brush. Unlike whitetails, axis eat grass and typically are more active during daylight hours.

were very interesting deer, to say the least.

By the time I entered graduate school at Texas A&M University, the “golden age” of exotics was in full swing in the Hill Country. While at TAMU, I took part in a venison preference study, from which we concluded that axis venison was far superior to any other cervid. My fellow graduate student Elizabeth Cary Mungall completed her doctoral research on Texas exotics and has published at least two books on the subject. She was glad to educate me on the strange spotted deer from India, Nepal, Bhutan, Bangladesh, and Sri Lanka.

The chital is a tropical species, ranging over 8-30°N latitude. They evolved in tropical forests and grasslands, where the vegetation could range from lush to sparse, depending on the rainy season. Their primary predator was another brightly colored species, the Bengal tiger.

When you consider the predatory efficiency of the tiger, you can understand why chital are colored the way they are, why they run around in large herds, and why they are mostly diurnal. In fact, I can think of no deer species more adapted to avoiding predation than the chital.

It’s not surprising why they were brought to Texas in the early 1930s, but this was not the first time they had been transplanted from Asia. In 1867, several chital were brought as a gift to Hawaii’s King Kamehameha V. Soon they were released on Molokai, and then Lanai in 1920. Each time they were moved to new habitats they thrived, and in 1932 axis were released on high-fenced ranches in the Hill Country. Later they would also be transplanted to the Texas Coast, Deep South, and Florida.

Today, it’s estimated at least 10,000 live in Texas alone. They are broadly pre-adapted to survival, and the only place I have not seen them survive is in eastern climes, where some factors, maybe predation, or rainfall and humidity, generally suppresses population growth.

So, axis deer could be called a real success story for a game animal—but not so fast. Early on, professional wildlife managers and particularly state agencies began worrying about the potential for serious competition between axis and native whitetails. Ironically, Texas Parks and Wildlife began a study on the Kerr Wildlife Management Area, immediately next door to where I killed my first whitetail buck, on the potential competition between axis and whitetails.

There was room for concern. Axis deer are different in many ways from whitetails, including being able to breed throughout

the year. However, the most worrisome characteristic that they could do what whitetails could not—eat grass. The white-tailed deer is not well-suited to grass-eating, not having the digestive system to do so. Conversely, the axis can eat grass, forbs, and brush in competition with whitetails, a source of real concern.

The Kerr WMA confined six deer of each species in high fenced areas and monitored what happened to each population. In three years, whitetail populations began to decline, while axis numbers dominated, then leveled off to axis only. For an area such as the Kerr WMA where numerous species of grasses dominate the understory, this study created some legitimate red flags about axis deer.

In spite of this competitive discovery, more ranchers began stocking axis as an alternative income source from hunting. After all, Texas whitetails are available for hunting only about three months of the year, while axis are available 12 months. That alone is an understandable economic strategy, but axis soon escaped into the wild.

Today, axis bodies are seen on Hill Country roads, and even South Texas. Axis and automobiles do not mix well. Efforts to reduce axis populations have been implemented everywhere axis have been stocked. Hawaii, with no predators, has managed to reduce their herds from 60,000 to 18,000, but fall far short of extermination.

The Gillespie County AgriLife Extension and Hill Country Alliance have launched the Axis Deer Control Project and encourage landowners and hunters to participate. The Alliance recently posted that local landowner, Ronnie Ottmers, expressed his concerns about the population growth of axis deer. “Over three nights, we counted 347 white-tailed deer and 546 axis deer along our transects. It’s ridiculous,” he said.

So, what is the solution if one is needed? Some landowners like axis while others detest them. I do know that axis numbers can be brought down, when you give a landowner a reason. During the days of exploding interest in growing huge whitetails, my annual trips around the Guadalupe Basin yielded almost no axis sightings.

Then, as interest in whitetail breeding has waned, axis numbers began to increase. There is no easy solution. Land prices in Texas, especially in the Hill Country, have become insane. In order for a rancher to keep his/her land in livestock agriculture, there will have to be profitable animal systems.

We tried many years ago to install a venison production industry centered on exotic species, but traditional commodity interest groups have worked against us with great success. Perhaps, if the Texas AgriLife Extension Service wants to really help, they should focus on venison. The pessimist side of me sees a Hill Country where an exotic species is dominant, and whitetails are scarce. Only time will tell.

Everything is big in Texas, including “Big Buck” contests held across the state, which considers itself the “Deer Hunting Capital of America.”

By Jake Legg

uck contests have long been a part of Texas deer hunting. The major competition is in South Texas, where bucks exceeding 160 B&C have been common at several contests since Leonel “Muy” Garza devised the first competition at his Texaco gas station in Freer. Garza originally called the affair a buck contest in 1965, but an outdoor writer from San Antonio told Garza that it was a “Muy Grande Buck Contest,” and the name stuck. The oldest buck contest in Texas has long been the Muy Grande at Freer.

Through the years, buck contests have come and gone—three being the Texas Gulf Coast contest in Kingsville, Los Cuernos de Tejas in Eagle Pass, and the Freer Deer Camp in Freer. There have been other short-lived contests, such as Texas Whitetail Classic, El Monstruo del Norte, and Comal County Deer Contest. Today, there are five longtime deer competitions that are annually enjoyed by hundreds of whitetail hunters.

Besides the Muy Grande in Freer. the Cola Blanca contest in Laredo is also a historic event, as is ANGADI Los Gigantes of Nuevo Laredo, Mexico. The Los Cazadores Deer Contest started in Cotulla in 1987, but moved to Pearsall many years ago and combined with a sporting goods store, gun room, and taxidermy studio. One of the original aspects of Los Cazadores was the $5,000 cash prize for the best buck, which has been deleted. The Hill Country has a big buck contest with Trophy Game Records of the World in Kerrville. This contest has its own rules and scoring system as noted below.

All contests with exception of Trophy Game Records use modified Boone and Crockett scoring systems—mostly B&C scoring without deductions for symmetry. A wide variety of categories and divisions are used in all contests, giving hunters of all ages several ways to win trophies and prizes. Each contest has its own rules for entering a buck, and most bucks are scored on the spot.

In most contests, deer are accepted from Texas, Mexico, and out-of-state. One or two contests have categories for javelina, wild hogs, coyotes, and bobcats. Contestant rules vary for sign-up and some contests have time limits for entering a buck.

The most unusual out of all the deer

contests comes from the big buck contest of the Trophy Game Records of the World. This contest has its own unique scoring system using centimeters and antler measurements. In The Journal, they do not report scores, but name the top place winners in several categories.

Two prominent statewide deer contests are the Hunters Extravaganza Annual Deer Competition and the Texas Big Game Awards. Texas Trophy Hunters Association started its Annual Deer Competition in 1995 as a way of getting a large collection of bucks for public viewing. TTHA members bring their Texas, Mexico, and out-of-state whitetails and Texas mule deer to the three Extravaganzas each August in Houston, Fort Worth, and San Antonio to compete for prizes in a variety of categories.

TTHA’s deer contest began with a B&C net score for all whitetails and mule deer—both typical and nontypical. Prizes include certificates, jackets, and valuable hunting paraphernalia. Hunters of all ages, from far and wide, bring their deer trophies to the popular competition, which has long been a drawing card for extravaganza attendance.

In 2021, TTHA became a corporate subsidiary of Safari Club International, which has its own patented scoring system. In 2024, SCI powered the scoring of all deer, using Trophy Scan to measure antlers in the Hunters Extravaganza deer contest. At present, both B&C and SCI scores are used in a twin-system of scoring. SCI gives awards to both SCI and B&C winning contestants. The Texas Big Game Awards began in 1992 as a way

Big buck contests are important to Texas deer hunters as a way of defining a trophy buck, as well as hunting for a prize-winning trophy. They’re a major attraction in small towns.

of recognizing top quality game animals and habitat conservation in Texas. The awards program was initially founded and administered by Texas Parks and Wildlife, but was later transferred to Texas Wildlife Association for administration and awards. The program started with whitetails, mule deer, and pronghorn, but has since added javelina and other game animals to the awards program.

Contests such as Muy Grande, Cola Blanca, ANGADI, Los Cazadores, and Trophy Game Records have an awards banquet in the spring following deer season. Several contests put on quite a show with food, music, and celebrities from the hunting world. Many winners frame their certificates for the home or office, and others proudly wear jackets or vests from Texas Trophy Hunters, Muy Grande, Cola Blanca, ANGADI, and Trophy Game Records.

Big buck contests are important to Texas deer hunters as a way of defining a trophy buck, as well as hunting for a prize-winning trophy. Most contests have numerous categories for adult and youth, men and women, young and old. Some of the awards banquets are plush with a variety of recognition, awards, food, and entertainment. Big buck awards programs are a major attraction in small towns, bringing in hunters from a wide area.

Texas has 60 years of big buck contests—some extravagant and some small—that will continue as young hunters fill in after the old hunters have hung up their rifles. Whitetail hunting garners some 800,000 hunters who add a lot of money to the Texas economy and provide millions to wildlife conservation in a state that brags about being the “Deer Hunting Capital of America.” Texans don’t like to brag, but if the shoe fits, we will wear it.

Nolan

cancer survivor, has gratitude for his doctors, family, and friends who helped him overcome his fight with cancer so he could get back to the things he enjoys most: baseball and hunting.

Life is a beautiful thing, but sometimes we get preoccupied and take things for granted. The time we have goes by fast, and along the way, things can change in an instant. On occasion, we’re reminded exactly how fragile things like our health can be.

For young Nolan Cernosek, this happened while running bases in a baseball game. The 15-year-old had just finished his freshman year at New Braunfels High School and playing select baseball. He focused on athletics, and at 6 feet 5 inches and 235 pounds, he was fit and as strong as an ox. But while rounding third base and heading for home plate, he lost his footing and his femur snapped.

For the young athlete, it seemed like a huge setback as he waited in the hospital with his parents, Nathan and Sarah Cernosek. However, things took a turn for the worse when the doctors informed them a tumor had actually caused the break. Shortly afterwards, doctors diagnosed Nolan with a rare form of bone cancer called osteosarcoma.

The prognosis was grim, but Nolan stayed strong and determined to win his battle with cancer. “I was not in this alone. I had tremendous support from my family and

friends,” Nolan said. Everyone rallied behind him, and in a show of support, his friends at school adopted the slogan “Nolan Strong.” Treatments at the MD Anderson Cancer Center quickly began and consisted of chemotherapy 4 days a week. Surgeries followed, and ultimately most of his femur was replaced with a titanium rod.

For Nolan and his family, the entire process felt like it lasted for an eternity. After two years of enduring treatments and surgeries, prayers had been answered when he was declared cancer free. Preventative treatment is currently ongoing as Nolan tries to settle back into some form of normalcy.

This past year Nolan returned to sports, albeit in a limited capacity. His willpower and determination continue to drive him, and he never ceases to amaze those around him. He has started pitching again for the New Braunfels High School varsity baseball team. In addition to sports, he has a renewed interest in spending time outdoors and more specifically, hunting.

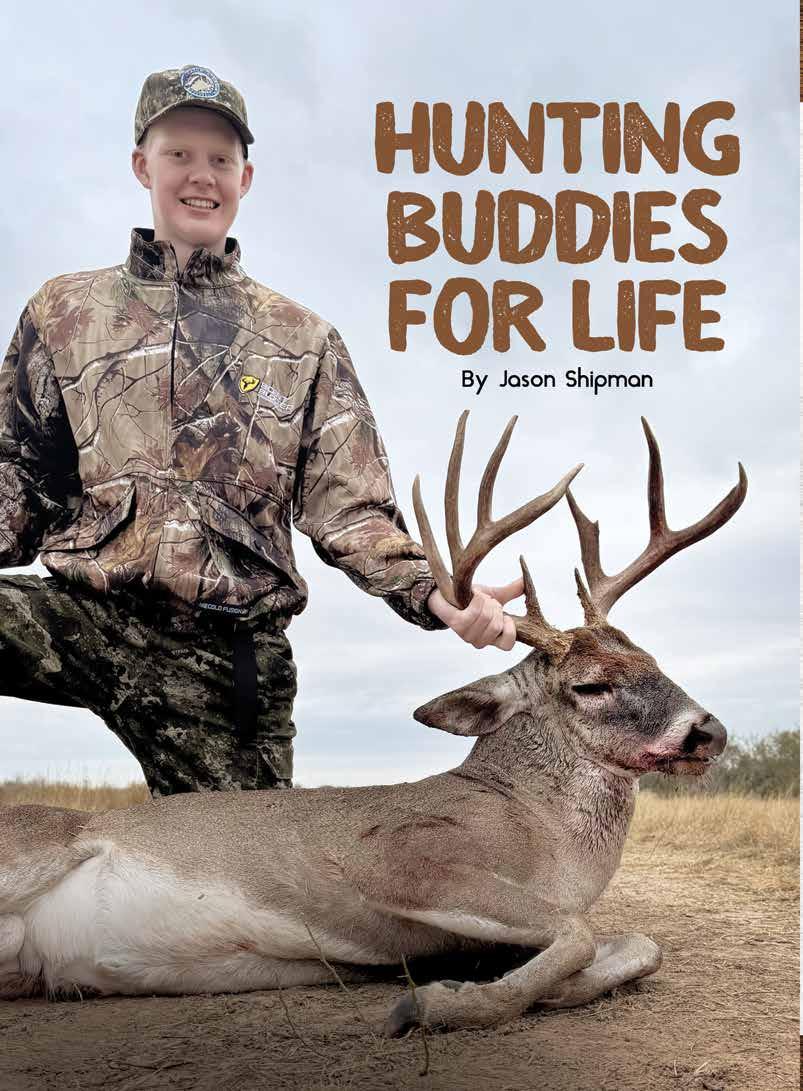

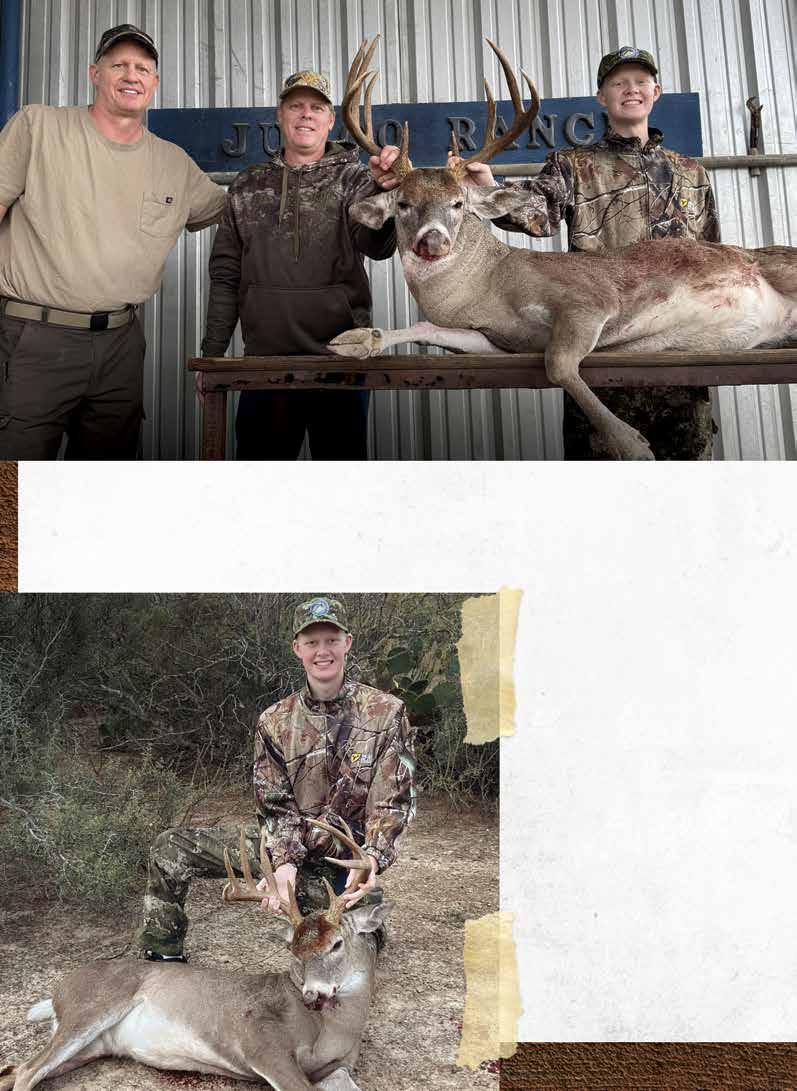

Nolan had enjoyed hunting in the past and took his first buck years ago with his dad and uncle, Matt Cernosek, at the Junco Ranch in Webb County. “Nolan has always liked to hunt, but it wasn’t necessarily a priority for him,” Matt said. “However, when we got him back down to the ranch this year, his interest was renewed.”

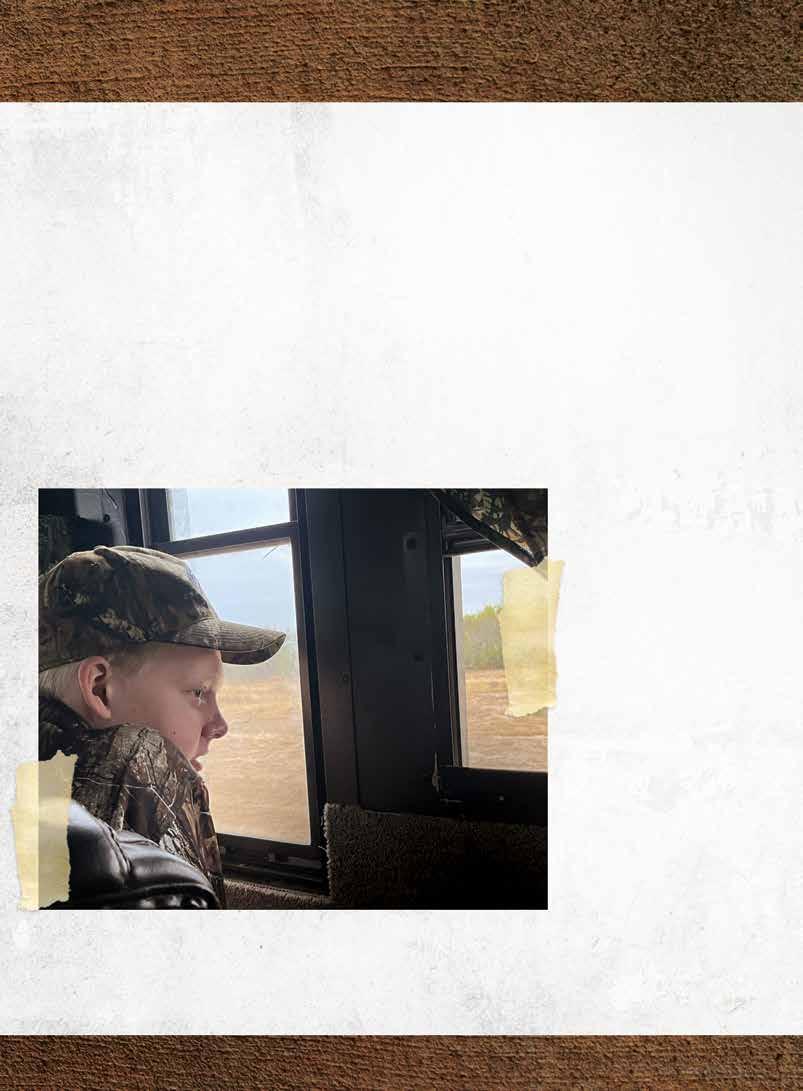

This past hunting season, around the middle of December when the bucks were on the move, Nolan and Nathan made plans to meet Uncle Matt at the Junco to deer hunt. It would be the first opportunity Nolan would have to hunt in South Texas since his cancer diagnosis. Nathan and Matt have shared a lifetime of hunting experiences together, but this hunt with Nolan would be their most memorable.

Upon arriving at the ranch, the trio wasted no time getting set for the afternoon hunt. “We were looking for a massive nine-point that frequented the area. I really wanted Nolan to get a chance at him,” Matt said. Late in the evening, a buck crossed the sendero at quite a distance, but with good optics they could tell it was the big nine-point they were after. Shortly thereafter, the buck reappeared closer and in range, but only his head and back were exposed in the thick cover. Not wanting to take a risky shot, they elected to wait and ended up returning to camp empty handed. Nolan got little sleep during the long night. “I couldn’t quit thinking about that buck,” he said. Morning finally came and Nolan, Nathan, and Matt went back to the same blind. Several deer fed about, as the buck they were after returned. “He appeared at some distance again, but this time he worked his way in and joined the other feeding deer,” Matt said.

Uncle Matt carefully pushed the suppressed .300 Winchester Magnum out the window of the blind as Nolan got ready for the shot. “I was really nervous and started breathing heavy,” Nolan said. Matt, realizing the situation, looked at Nolan and whispered, “You beat cancer! You fought to live life! You’ve got this!”

Nolan quickly put things into perspective, and he calmed

Nolan felt buck fever coming on, but his uncle told him, “You beat cancer! You fought to live life! You’ve got this!”

down. The distance was about 130 yards when the big-bodied nine-point turned broadside. Nolan got the crosshairs on the buck and made a good shot. The buck took the bullet and lunged forward to disappear into the brush. “We heard him crash back in there, but gave him a few minutes before going to take a look,” Nolan said.

The hunters felt a little concerned when they arrived where the deer had stood and found no blood or sign of a hit. However, they found where the buck had torn the dirt out when hit and followed the tracks into the brush to quickly find the expired buck. “Nolan made a perfect heart shot, and I watched as he and Nathan walked up to the buck,” Matt said. Everyone felt relieved and excited at the same time as they all examined the fallen trophy. “Nolan is an inspiration to all of us. He’s been through a lot. His mother and I cherish him and couldn’t be prouder of him,” Nathan said.

Nolan’s buck was estimated to be 61/2 years old and scored 154. As Nolan posed with the buck for pictures, his smile told the story. “I am so grateful and thankful for the experience. I can’t wait for next season!” Nolan said. Overcome with joy and emotion, the hunters relished the moment as they snapped photo after photo to capture the memory forever. Back at camp, they relived the hunt as they recounted the story, declaring they would be hunting buddies for life.

By Parker Hause

The Texas Brigades has been the highlight of my summer for the last several years. I have been to a handful of their summer camps, and they never disappoint. This year, I attended the Ranch Brigade at the Warren Ranch in Santa Anna, Texas. Unlike the other Texas Brigade camps where you learn about specifically wildlife conservation, at the Ranch Brigade we got to learn about the cattle industry.

Upon arrival at camp, we were all assigned to a herd. A herd is a group of cadets—first time camp attendees—and their leaders. Throughout the week of camp we competed, learned, and bonded together, all working towards winning Top Herd. Competition is a prominent aspect of the Texas Brigade camps. It promotes the idea that team building and leadership skills are the key to success.

The first thing we did at camp was learn about bovine anatomy through the necropsy of a heifer. The stomach of a cow is unique to that of deer or other ruminants because it almost strictly digests grass with the help of bugs in their stomach. Not only did we explore the anatomy and bodily processes of cattle, but we also analyzed the grasses they consume.

On the second day of camp, we ventured into the old roaming lands of the Indians to collect plants that cattle encounter daily. We dirtied our hands and shovels until we accumulated a collection of about 20 different plants. We then placed our cow forage into a plant press to be compiled into a book later in the week. The Natural Resources Conservation Service came out to camp that day to demonstrate their rangeland survey techniques as well. After instruction from them, we went into the field and did our own surveys to practice.

My personal favorite part of camp was when we worked cattle in the chute ourselves. This was hands-on learning to the extreme. We castrated, vaccinated, and branded the bulls ourselves, which significantly impacted our ability to do so in the future. We were shown a new way to castrate bulls than what many of us already knew. Instead of placing an elastic band around the scrotum or just chopping the testicles off, we methodically slit the bottom of the scrotum and slowly pulled them free. This practice resulted in less bleeding than other methods because it allowed the membrane around the testicle to clot easier.

Another memorable moment at camp was the ranch competitions. There were four: roping, sheep sorting, ranch chores, and post hole digging. Each herd had the opportunity to win a competition, and at the end, the points were distributed based on the performances. At the end of camp, my group, “Angus,” won Top Herd!

This camp motivated me to continue my journey as a conservation leader. Immediately, I volunteered in a Kids

Conservation Day where I led a group of 9- to 10-year-olds through a day of shooting rifles, driving ATVs, and learning about wildlife conservation. I was lucky enough to have been assigned to a group of cadets at Ranch Brigade that bonded well, and were all willing to extend our experience in the ranching industry. We organized a trip to the R.A. Brown Ranch where we learned about their bull development program and worked cattle as well. Along with this, we shared our Texas Brigade experiences with Woodson ISD, and were interviewed by the Graham and Breckenridge newspapers.

Since then, I have continued to further my influence on my community. I have done many presentations and activities to promote Texas Brigades and expand my knowledge on ranching and wildlife conservation. All of these events and projects contribute towards my Book of Accomplishments. A Book of Accomplishments is a compilation of completed activities, which is then submitted to Texas Brigades for evaluation in order to become an assistant leader and receive college scholarships.

I have been to the Bass Brigade as an assistant leader, and it’s another amazing opportunity for leadership development. Not only do you get to renew your knowledge from the prior camp, but you get to lead a group of cadets along the way. This allows assistant leaders to practice and learn new leadership skills, which apply to other aspects of life as well. The Texas Brigades has significantly influenced my personal character and has allowed me to become a confident ambassador of conservation in my own community.

When I first began to attend the Texas Brigades, I was simply a hunting-andfishing-loving every-day kid. However, after being a part of the program long enough, I have genuinely developed a

passion for conservation of the natural resources that our great state has to offer. The Texas Brigades’ mission is to create conservation leaders in every community. They have accomplished this goal by educating their cadets about wildlife conservation, developing their leadership skills, and sending them off into their communities to share what they learned at camp. The Texas Brigades program is doing the world of conservation a great deed by preparing us, the next generation.

Texas Brigades is a conservation-based leadership organization which organizes wildlife and natural resource-based leadership camps for participants ranging in age from 1317. Its mission is to educate and empower youths with leadership skills and knowledge in wildlife, fisheries, and land stewardship

to become conservation ambassadors for a sustained natural resource legacy. Texas Brigades hosts nine summer camps throughout June and July. The application period for camp runs Nov. 1 through March 15 of each year. Visit texasbrigades.org or call 210-556-1391 for more information.

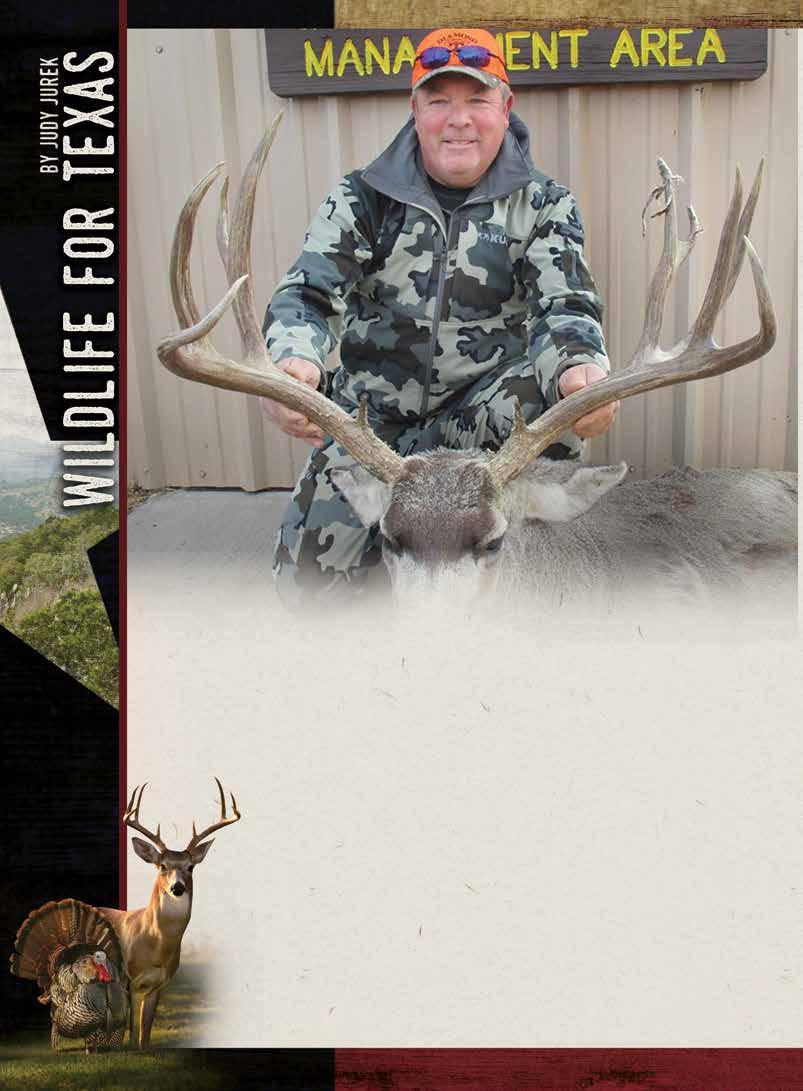

By: Judy Jurek and Jake Legg

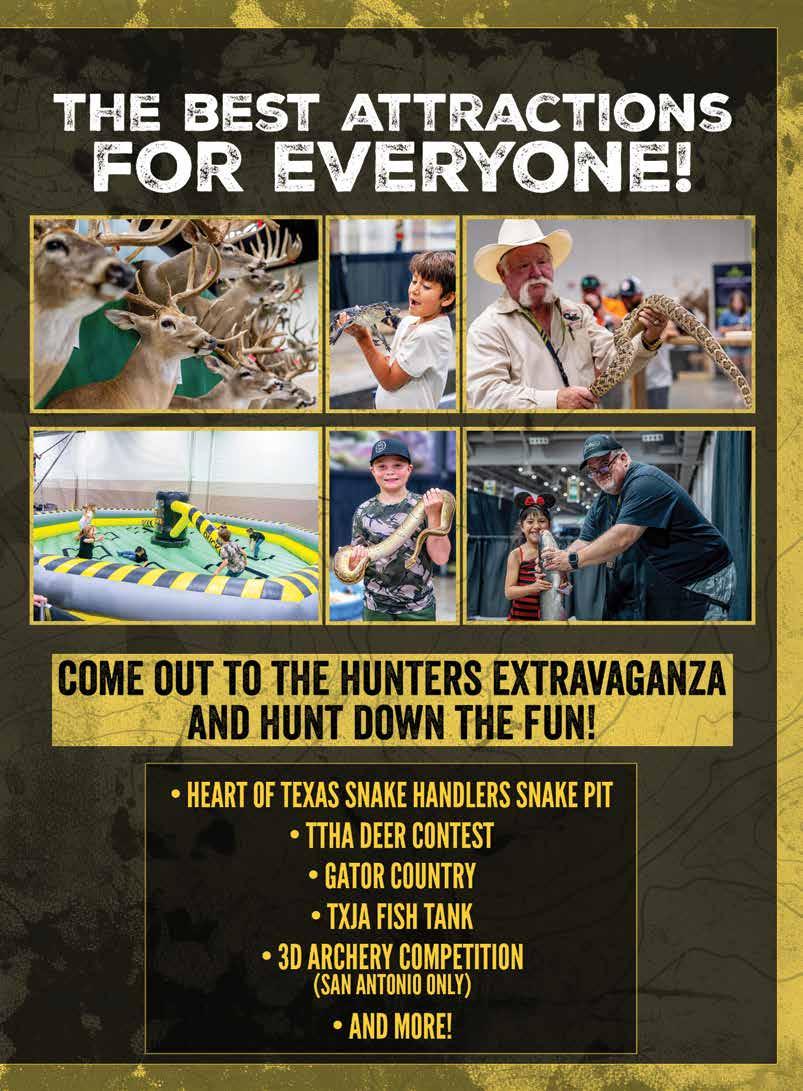

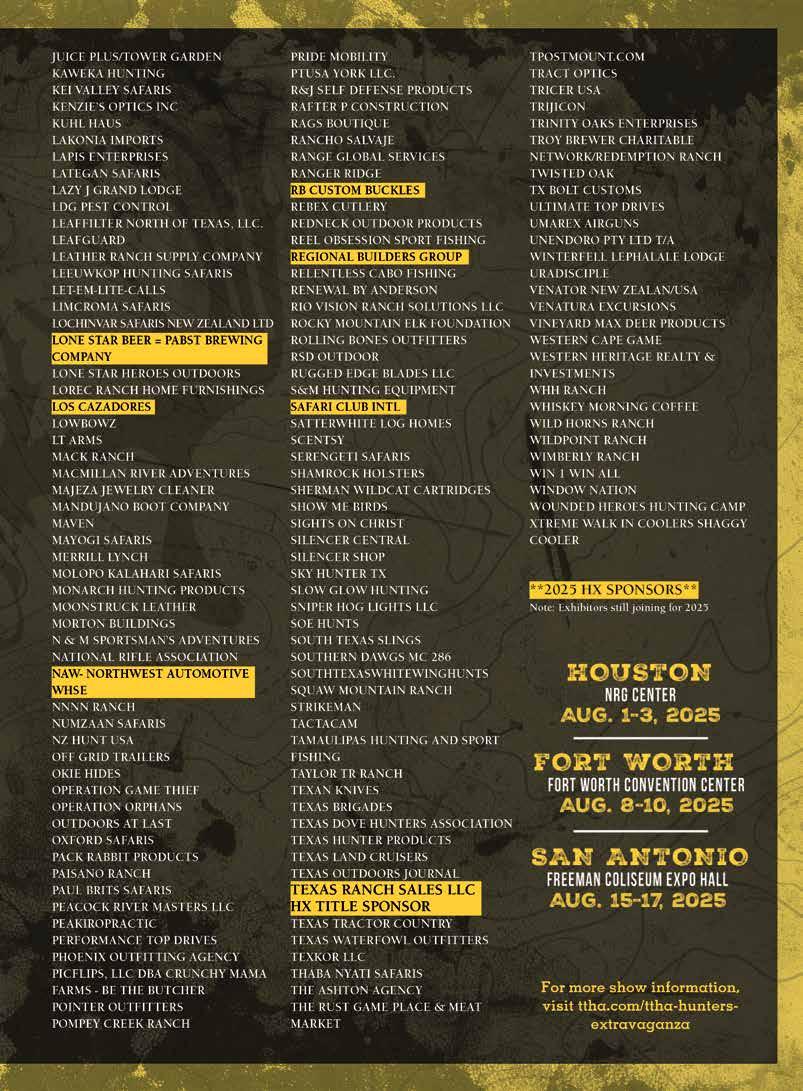

The Hunters Extravaganzas, the granddaddy

50th Anniversary of Texas Trophy Hunters Association, all shows are bigger and better than ever. You must go see for yourself just how Grrrreat the Extravaganzas are in Houston, Fort

Extravaganza in the past, it’s time to mark your calendar to make one of the shows this year (see sidebar). They’re the biggest and best hunting shows in the Southwest, with more fun and

To be exact, they’re known far and wide as trade shows with a fl air. It’s an adventure for the entire family because there’s truly something for everyone. They may be dubbed hunting shows, but they’re way more than just hunting. The many vendors and events are for hunters and

If you’ve never attended any of the three sidebar). They’re the biggest and best hunting frolic than you can shake a stick at. trade shows with a fl air. It’s an adventure for the many vendors and events are for hunters and non-hunting folks alike, as you will see. Bring the kids. Gator Country will once

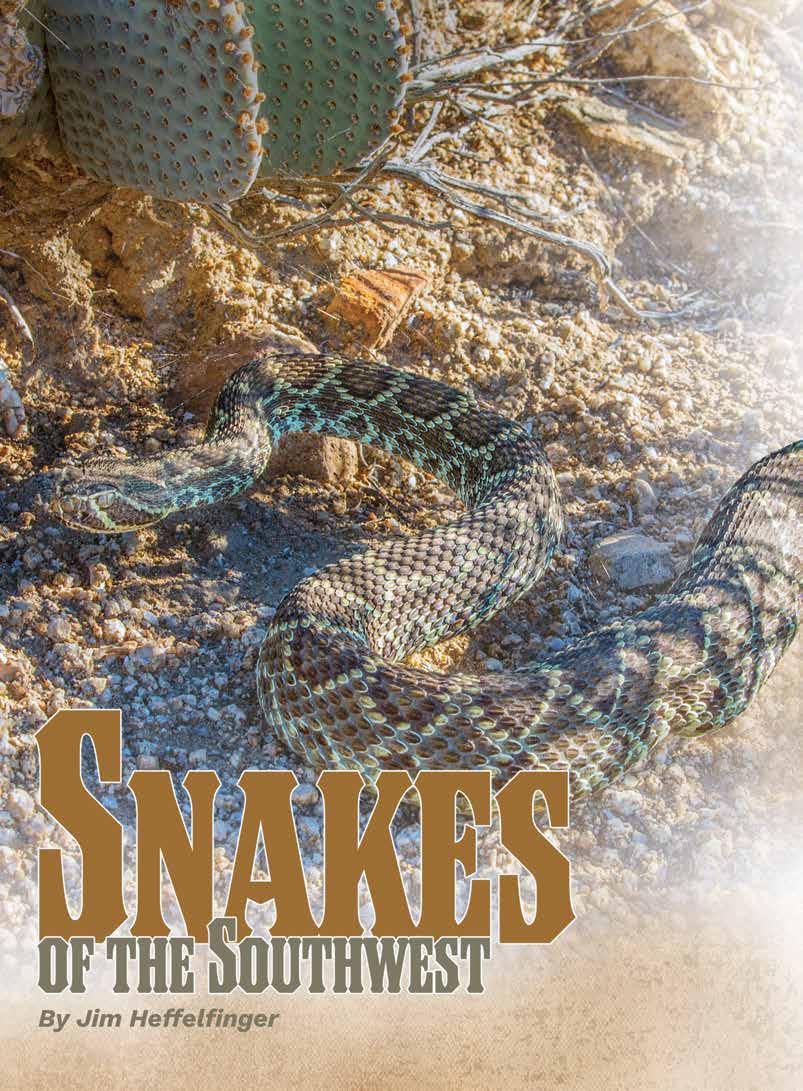

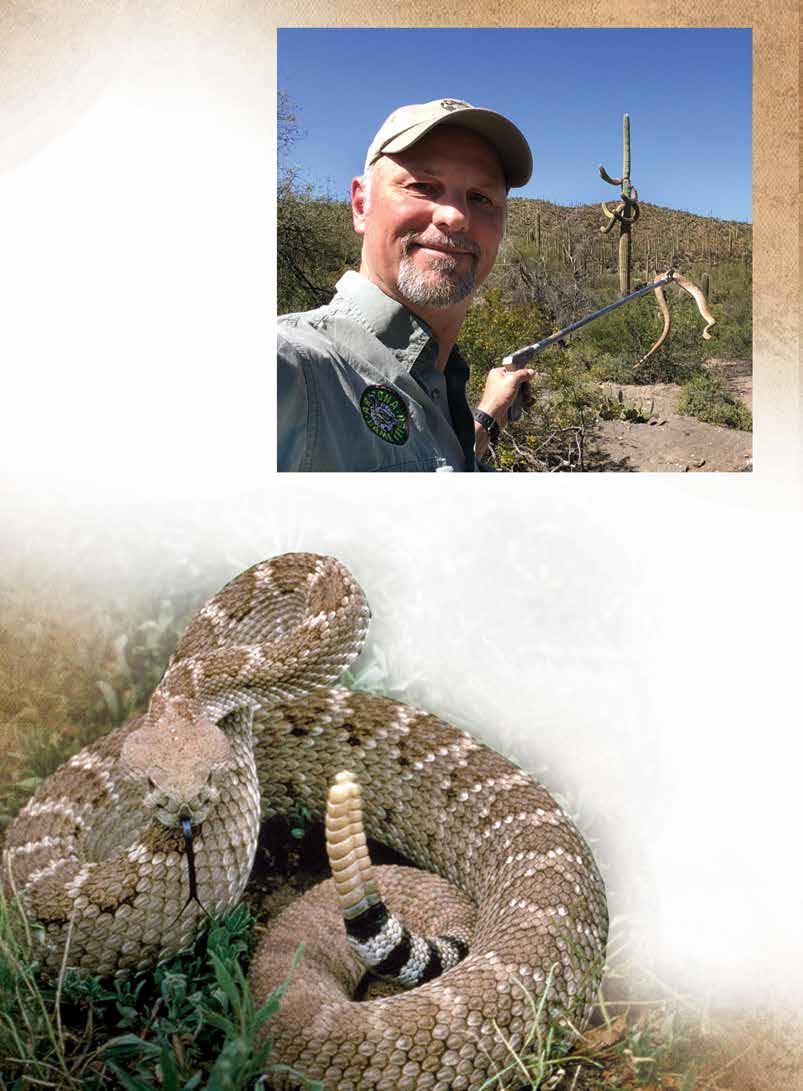

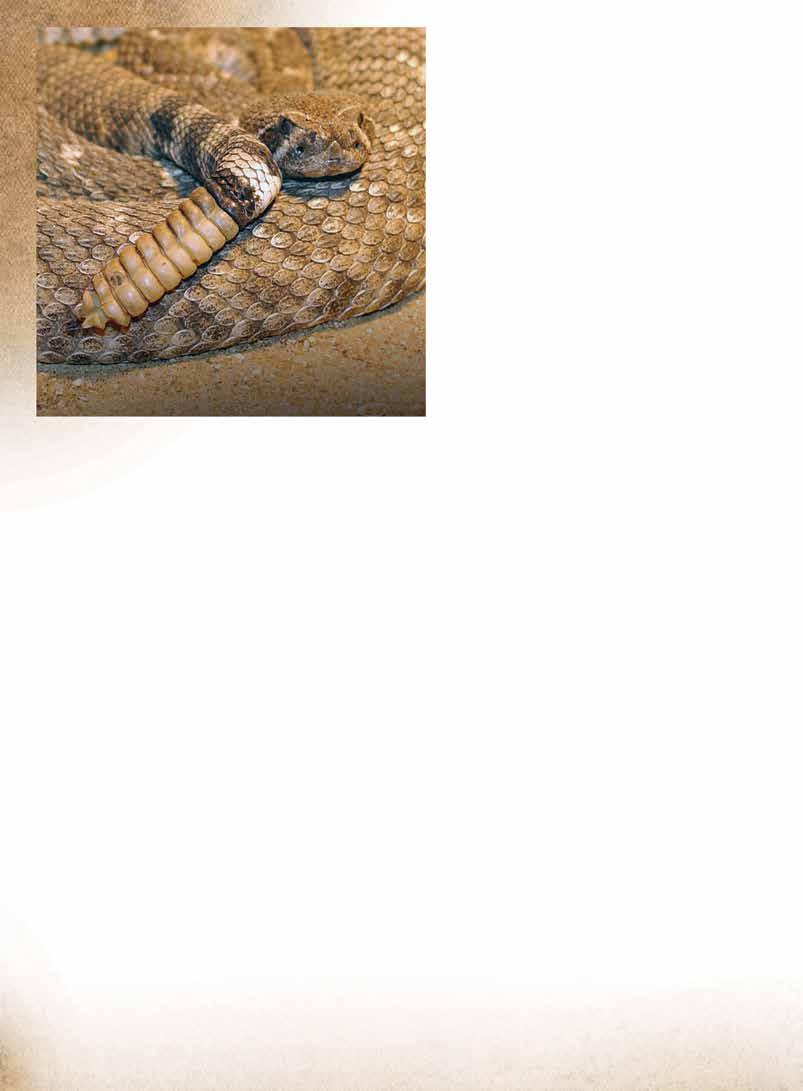

Handlers will feature a pit full of rattlesnakes.

again display their reptilian rascals, putting on presentations for everyone to learn more about these prehistoric swamp creatures. A fi shing tank sponsored by the Texas Junior Anglers allows youngsters to test their casting and catching skills. The Heart of Texas Snake Handlers will feature a pit full of rattlesnakes. Learn more about Texas’ four poisonous snakes: rattlers, cottonmouths, copperheads, and coral

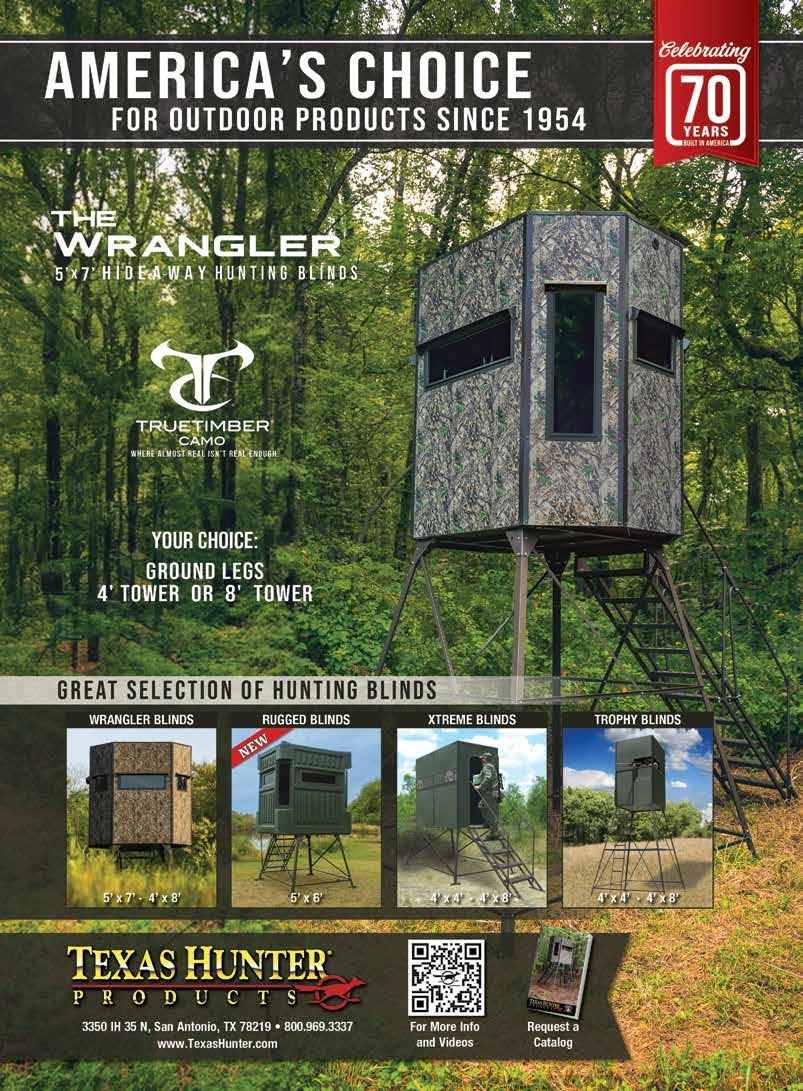

Countless vendors will have fi rearms, scopes, binoculars, rangefi nders, game cameras, hog lights, hunting blinds, and many other things too numerous to name. Many will be available to look at—or through—and otherwise give a hands-on chance to examine your next “toy” for

snakes. The snake show is a blast. to look at—or through—and otherwise give a hands-on chance to examine your next “toy” for hunting or the outdoors.

Ladies, you’re most welcome right along with the men. These days, camoufl age clothing is

always in vogue, not just for hunting, and the Extravaganzas will most certainly have plenty to choose from—just pick your pattern. From handbags and jewelry to home décor with or without animal hides. With so much to perceive, you may fi nd yourself in a diffi cult decisionmaking mode.

Besides food vendors, merchants will have samples of jerky, sausages, cheeses, dips, and other delicious items for taste testing, as well as candy and nuts of all kinds and assorted fl avors. You’ll also fi nd multiple items to help you clean, process, freeze, cook, and serve the wild game you bring home each season.

Need a fl ashlight or pocketknife, or the latest, most innovative item for scouting wildlife or hunting? What about a chance to win fi rearms, a dream hunt, or four-wheel drive buggy? If you’re looking for your own hunting or vacation property, realtors and fi nancial vendors will be available. It’s all here and more.

always in vogue, not just for hunting, and the to choose from—just pick your pattern. From handbags and jewelry to home décor with or samples of jerky, sausages, cheeses, dips, and candy and nuts of all kinds and assorted fl avors. You’ll also fi nd multiple items to help you clean, hunting? What about a chance to win fi rearms, a dream hunt, or four-wheel drive buggy? If you’re looking for your own hunting or vacation property, realtors and fi nancial vendors will be available. It’s all here and more.

Naturally, a huge part of the Hunters Extravaganzas are outfi tters and guide services. Whether you want to hunt in Texas, North America, or maybe Africa, South America, or New Zealand, you may fi nd exactly what you’re looking for. If you don’t see what you want, it’s not impolite to ask.

America, or maybe Africa, South America, or New Zealand, you may fi nd exactly what you’re looking for. If you don’t see what you want, it’s not impolite to ask.

Need a great taxidermist for mounting your next trophy? Again, you’ll be at the right place. Large, small, standing, lying down, fl ying, jumping, fi ghting—you name it, someone can preserve your memory in whatever way you envision. A good mount of your big buck or aoudad helps warm the atmosphere when your friends arrive. Speaking of bucks, don’t forget the big buck contest. It will feature many outstanding of all hunting shows, are back. In the than ever. You must go see for yourself just how Worth, and San Antonio!

Need a great taxidermist for mounting your next trophy? Again, you’ll be at the right place. Large, your memory in whatever way you envision. A good mount of your big buck or aoudad helps warm the atmosphere when your friends arrive.

Speaking of bucks, don’t forget the big buck contest. It will feature many outstanding

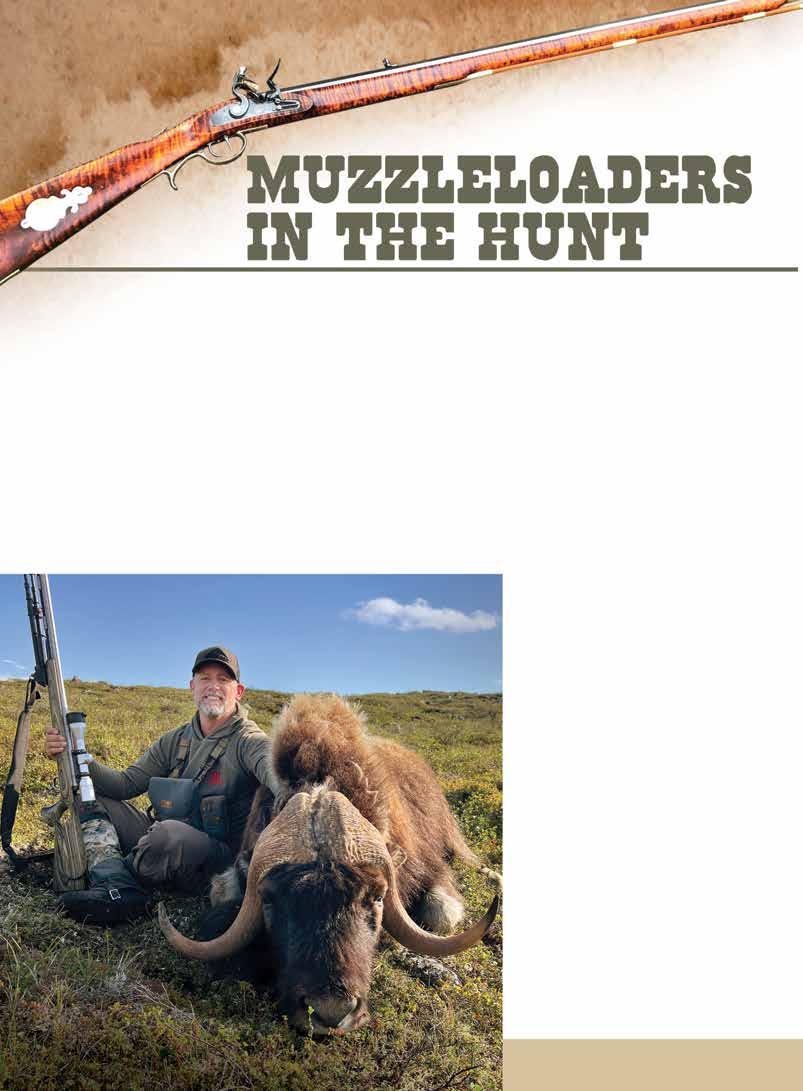

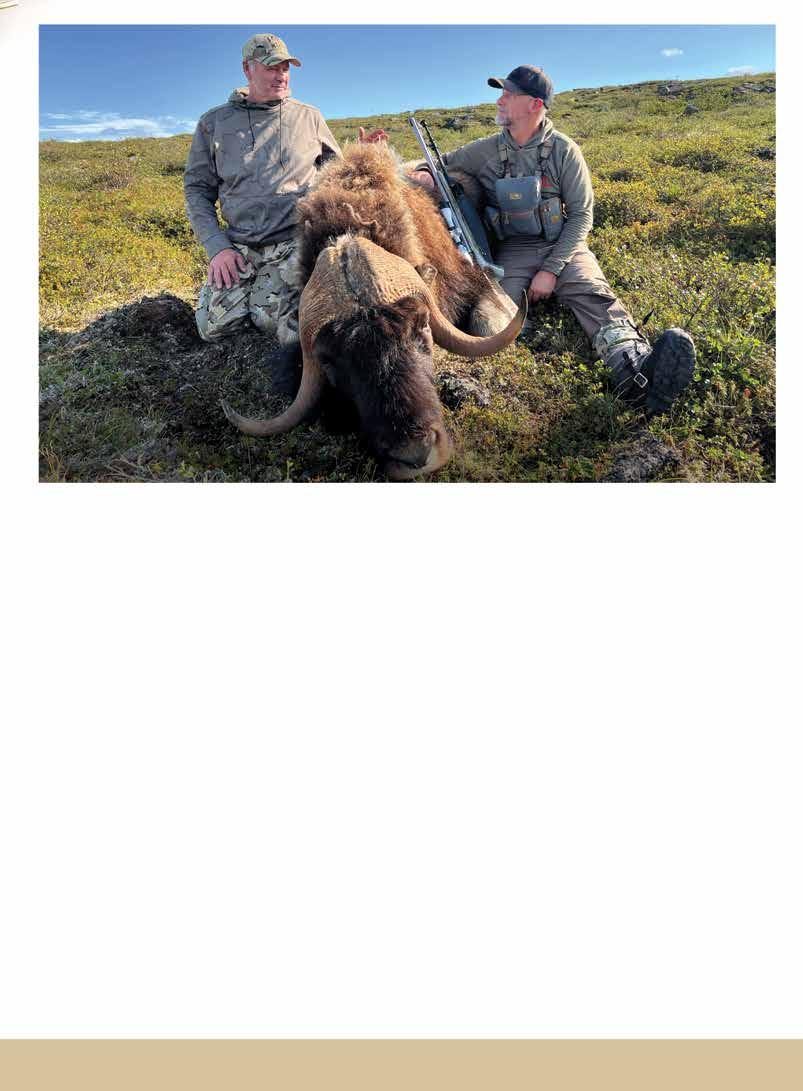

Tret with his grandfather and the deer Tret shot on his first muzzleloader hunt, using his grandfather’s muzzleloader.

The towering pines of East Texas stood silent, their needles damp from the morning dew. I sat perched in the old wooden stand, gripping my grandfather’s muzzleloader with a mix of reverence and anticipation. The air was crisp, carrying with it the familiar scents of pine, earth, and the faint hint of black powder. This was the land my grandfather had hunted on for decades, and now, with his treasured firearm in my hands, I would step into a tradition that runs deep in our family.

This was my first muzzleloader hunt in East Texas. It was more than just about taking a deer—it was about connection. Connection to the land, to my grandfather’s legacy, and to a style of hunting that requires patience, skill, and respect for the animal. I’d planned to take a whitetail deer with my grandfather’s old muzzleloader, an older model Traditions 209, the very firearm he had passed down to me.

However, as is often the case with hunting, unexpected challenges arose. The old gun had issues with misfiring and proving unreliable at the moment I needed it most. My grandfather, ever the prepared and experienced hunter, handed me his trusted newer CVA Optima .50 caliber muzzleloader. “Take my gun just in case you see one,” he said, ensuring I wouldn’t face disappointment due to equipment failure. Though it wasn’t the same as using his original muzzleloader, the sentiment remained. This hunt would continue the traditions he and my father had instilled in me since I was a child.

The morning stretched on in stillness, interrupted only by the occasional rustle of squirrels in the underbrush. I took deep, slow breaths, keeping my focus sharp and my senses attuned to the forest around me. Then, just as the golden light of the rising sun began to filter through the trees, movement caught my eye. Two does stepped cautiously into the clearing, making their way to the feeder, their ears twitching as they scanned the area.

My heart pounded as I slowly raised the muzzleloader, steadying my breath as my father had taught me. I carefully studied the two, deciding on the larger one. This was the moment I had been waiting for.

Tret planned on using this Traditions 209 muzzleloader, a gift from his grandfather, but the gun wasn’t working properly on the day of the hunt. So he used his grandfather’s newer model muzzleloader.

With a deliberate pull of the trigger, the hammer snapped forward, igniting the powder in an instant flash. Smoke billowed around me, momentarily obscuring my vision. The distinct scent of burnt powder filled my nostrils as I leaned forward, heart still pounding. As the smoke cleared, I saw her drop just a few yards from where she stood.

The shot was true. This marked my first East Texas harvest, my first muzzleloader shot, and my first time hunting on my grandfather’s land—a trifecta of milestones that made the moment unforgettable. The forest seemed to pause with me, as if recognizing the weight of the occasion.

I have taken my fair share of deer throughout the years, but this one was special. It brought back the memories of my very first deer—the buck fever, the heart-pounding adrenaline, and the overwhelming joy and excitement when I saw the deer lying on the ground. This moment felt like a full-circle experience, connecting that initial thrill to a deeper, more profound ap -

preciation for the hunt. I took a few moments to collect myself, allowing the significance to sink in before climbing down from the stand.

As I heard my grandfather pull up in his Honda Pioneer, I climbed out of the stand and joined him on the way to the harvest site. There she was, lying peacefully on the pine needlecovered floor of the woods. I couldn’t help but notice the look of excitement and pride on my grandfather’s face—a look that mirrored my own feelings. He had been hunting the East Texas woods long before I was born, and now we were sharing this moment together.

We stood there for a moment, soaking in the weight of the experience—an unspoken understanding passing between us. Together, we admired the doe, acknowledging the significance of the hunt, the responsibility it carried, and the gratitude we felt for the harvest. Then, with care and respect, we lifted the carcass and placed it in the back of the Honda. As we drove back to the house, the hum of the engine was accompanied by easy conversation, laughter, and the warmth of a shared tradition. This was more than just a hunt. It was a memory etched in time, a bridge between generations, and a moment neither of us would ever forget.

Pulling up to the shop, we knew the real work was about to begin. My grandfather and I, side by side, armed with a couple of sharp knives and a steady rhythm of old country music playing in the background, set to task. Within an hour, the doe was carefully cleaned of her hide, her meat prepared and portioned with care. Sharing this process with him made it all the more meaningful.

He guided me through each step with the same patience and wisdom he had always shown, weaving stories from his own hunting days into the task at hand. The innards were disposed of respectfully, and the succulent cuts were packed for transport back home. The process was as much a ritual as the hunt

itself, a moment of reverence, gratitude, and connection—to the harvest and to my grandfather.

As we cleaned up, my grandfather wiped his hands on his worn leather gloves and looked over at me with a nod of approval. “You did good,” he simply said, but in those three words, I heard so much more. I heard pride, tradition, and the passing of knowledge from one generation to the next. That morning in the East Texas Piney Woods was more than just a first muzzleloader hunt. It was a rite of passage, a bond with my family’s past, and the beginning of a lifelong respect for the sport and the land that sustains it.

From all the teachings I was presented in hunting with my father till now has truly helped in making me into the outdoorsman I am today. Being able to further my knowledge, love, and passion for the sport that so much of us love and endure is a past time many of us get to enjoy as kids with our fathers and grandfather. During the ride back to the house, I knew this wouldn’t be the last time I walked these woods with my grandfather’s muzzleloader in hand. The sun had risen higher in the sky now, casting long shadows across the pines, but in my heart, I knew this moment would remain forever bright.

Sometimes we find ourselves forgetting the small things—the lessons, the moments, and the traditions our sport was built upon. From those long mornings in the blind with our fathers, where we likely spent more time playing with a Game Boy than actually hunting, to moments like this—where even after years of experience and countless harvests, there’s always something new to learn and memories to make. And for that, I am forever grateful to my father. He’s the one who introduced me to the world of hunting, who passed down his knowledge and passion, and who first ignited that spark in me. What began as a flicker has since grown into an uncontrollable bonfire, fueling my love for the outdoors and carrying forward the traditions that will forever bind us through generations.

Each year during the month of August, deer hunters of all ages from Texas, Mexico, and out-of-state, bring their bucks to the Hunters Extravaganza Annual Deer Competition in Houston, Fort Worth and San Antonio. Young hunters proudly enter their trophy—sometimes their first buck—hoping to win a prize. TTHA is proud to recognize some of these young hunters and their trophy bucks.

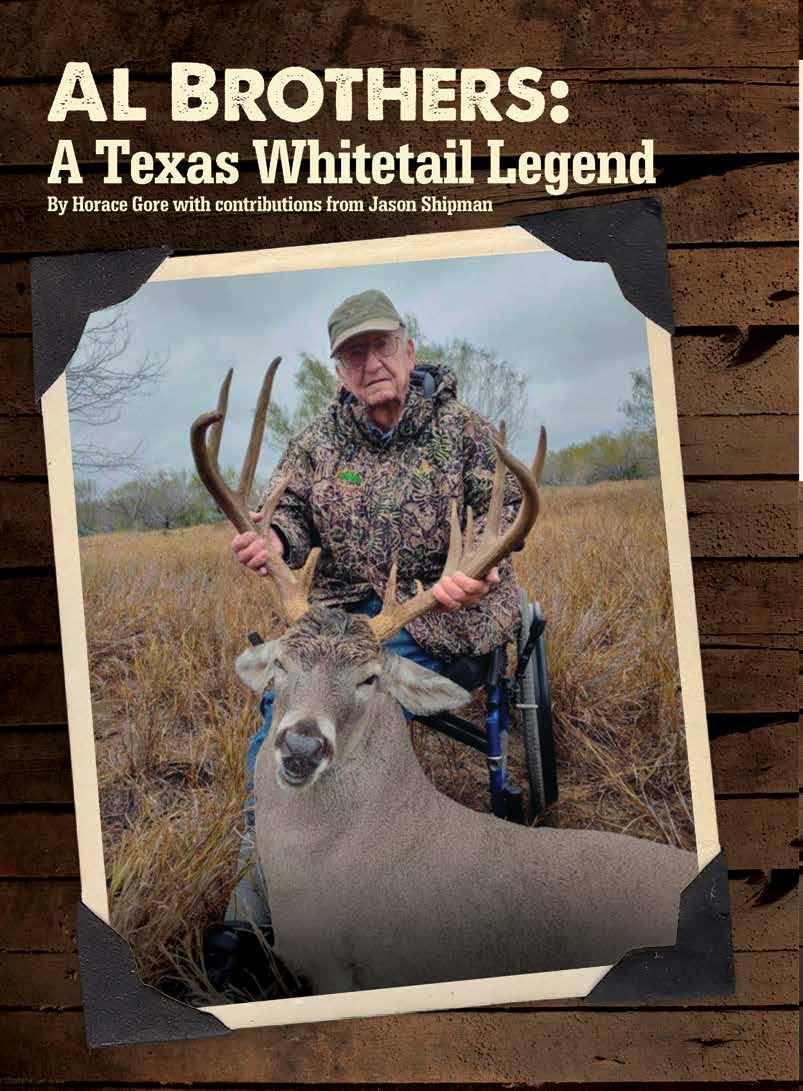

By Horace Gore

The Newman family lives in the small community of Maydelle on State Highway 84 between Rusk and the Nueces River in Cherokee County. The Newmans are a hunting family that finds deer hunting along the Nueces a pleasurable outdoor sport for parents, kids, and kin. The oldest boy, Ty, is 14 and took his sixth buck during the 2023-24 deer season. His sister Tenley is 12, and took her first buck during the same season.

Ty and Tenley attend Rusk Junior High where Ty is in the eighth grade and Tenley is in the sixth grade. Ty likes baseball and football. Tenley likes soft-

ball and plans to play volleyball next year. Of course, both like to hunt. Ty hunts doves, quail, ducks and deer. At 12, Tenley is interested only in deer.

Both hunters took their bucks to the 2024 Fort Worth Hunters Extravaganza and entered the Annual Deer Competition. This story is about Ty and Tenley, their deer hunts, and the results of the deer competition at Fort Worth. Meanwhile, their little brother Tripp, 9, is chomping the bit to get his first buck, and we hear from hunter talk that he may have taken a 10-point last season. Stand by!

Ty and Tenley both hunt with family adults on a large deer lease that lies on both sides of the Nueces River. Their hunts in this story occurred on the Cherokee County side, where Ty hunted with his grandfather, Rodney Newman, and Tenley hunted with her father, Jacob. The hunts were both from high blinds near corn feeders, but the hunts were quite different as we shall see.

Shortly after the deer season opened in 2023, Tenley let it be known that she wanted to deer hunt. She had a scoped .243 deer rifle and was ready for the challenge. Jacob agreed to take her for her first buck. The weather was good, and deer were coming to the feeder.

Ty had his grandfather’s .308 ready when this trophy stood broadside, and Ty quickly felled the buck with a bullet just in front of the shoulder.

On the morning hunt, a shooter buck showed up near the feeder and Tenley was nervous about taking her first shot at a buck. She missed. The deer whirled and disappeared into the woods. Both Jacob and Tenley were disappointed with the hunt, but Tenley was anxious to return for another chance at the buck.

An evening hunt had Jacob and Tenley back in the blind, hoping for a shot at the buck she had missed with her .243 earlier in the season. Jacob hoped Tenley would settle down and make a better shot if the buck reappeared. She had shot the gun several times and her aim appeared good with the light recoil of the little rifle.

Their hunt was short, as the buck Tenley had missed before came out of the

woods in early evening and meandered toward the feeder. When the buck was close enough for a good shot, Tenley raised her .243 and poked the barrel out the blind window. While getting adjusted for the shot, she breathed on the scope glass and it became fogged. “I can’t see through the scope,” she said to her dad. Without hesitation, Jacob switched her .243 for his .300 short Mag. Tenley found the buck in the scope and put a bullet through the buck, which wheeled and bounded into the brush.

“Did I get him?” Tenley asked as she looked up at her father with a small trickle of blood running down to her nose. “You sure did, and looks like the rifle recoil got you!” The scope mark on Tenley’s forehead took a little out of her good shot, but Jacob knew that her first buck wouldn’t be far into the timber. After a short wait, the father-daughter duo left the blind to follow the blood trail to

the dead buck. Tenley was excited with her first buck, which would later score 134 5⁄8 gross B&C.

Ty wasn’t after just any buck—he wanted to take one of the biggest bucks he has seen on the lease to the skinning rack. He and Grandfather Rodney were in a high blind just east of the Nueces where they had sat morning and evening for several hunts with no luck in getting a shot at the big buck. Jacob was not taking any chances by letting Ty shoot the buck with his .22-250. Although Ty had taken two bucks with the little rifle, Jacob wanted his son to use Rodney’s .308 if he got a shot.

Patience was rewarding on a cool evening when the big buck followed some does to the feeder. After all the

hunts and no deer, Ty was nervous, but this was not his first buck—just his biggest. He had his grandfather’s .308 ready when the buck stood broadside, and quickly took advantage of the shot. Both Ty and Rodney were surprised at how quick the buck fell as the 150-grain bullet cut hair just in front of the shoulder.

“I was aiming for the shoulder and hit the buck at the base of the neck,” Ty said, as he and Rodney came up to examine the dead deer. “None of my other bucks fell that fast.” They rolled the buck over to see if the bullet had emerged after the shot, and Ty immediately saw a gaping hole where the bullet has passed through. “He probably didn’t know what hit him,” Ty said as Rodney shook his hand and patted his grandson on the back.

Rodney looked at the antlers, which were typical with several odd points. “He’ll gross good, but he has several deductions. I would guess him to be about 170 or so gross.” Ty had already thought about the Fort Worth Extravaganza if he got the buck, and now it was decision time. Both he and Tenley wanted to take their bucks to the deer competition, so when the time came in August, Jacob loaded up the family for Fort Worth.

Tenley’s buck had several deductions and did not score “net” very well. Her gross of 134 5⁄8 ended up 1132⁄8 net, so no big prize. Her brother’s buck followed the same pattern of deductions and scored 168 6⁄8 gross, but fell to 1361⁄8 net. However, the folks liked the looks of Ty’s buck, and he won the People’s Choice Award.

Both bucks made a good addition to the array of antlers for attendees to view. You can bet the Newsom hunters will be in the deer woods of Cherokee and Anderson counties this fall (2025) looking for good bucks: Jacob, Rodney, Ty, Tenley, and Tripp.

TTHA congratulates Ty and Tenley for their good bucks and wish all the Newmans good luck in the deer woods of Cherokee and Anderson counties. TTHA is always proud to hear stories of young hunters like Ty and Tenley and their quest for America’s favorite cervid—the whitetailed deer.

Ty’s buck scored 1686⁄8 gross and 1361⁄8 net and won the People’s Choice Award at the Fort

Tenley was excited about her first buck, which would later score 1132⁄8 net B&C.

By The Old Hunter

“I’d like to shoot a .30-06, but I can’t take the recoil!”

How many times has recoil been a factor in what rifle a deer hunter shoots? “I need the extra punch of a 12-gauge, but the recoil just kills me!” The chant often heard from many wing shooters who are recoil sensitive. It is a fact that recoil or “kick” is a problem with many hunters in the U.S., and the problem has been dealt with in many ways: weight, barrel length, stock length, recoil pads, trigger, and muzzle brakes.

One way to deal with recoil in a rifle caliber is to shoot the caliber that you shoot best—both for accuracy and recoil. For example, any rifle caliber and bullet that carries 1,000 pounds of energy at striking distance will kill any deer-sized animal.

The need for a .30-06 with 18 foot-pounds (fp) of recoil over a 7mm-08 with 13 fp is in the mind of the shooter and is not necessary to kill a deer or hog at normal hunting distances. The same is true for the .270 at 17 fp of recoil over a .25-06 with 13 fp of recoil. The popular .243 with 100-grain bullet has 9 fp of recoil—half that of a .30-06. “Kick” often determines a hit or miss when the shooter is expecting to get zapped, so don’t shoot a caliber that makes you flinch, and miss your target.

Texas deer hunting has changed during the last 50 years. When hunters hunted from tree limbs alongside a wheat or oats field or sat on a bucket watching a long sendero, they sometimes felt a larger caliber was needed for an occasional long shot. Today’s deer hunter sits in a comfortable blind equipped with a good gun rest, looking at a feeder that is usu-

ally less than 70 yards away.

A deer coming to the feeder is normally shot at close range and a long list of rifle calibers with less than 15 fp of recoil will suffice, if the shooter can hit a grapefruit at feeder distance. These calibers include the .22-250, .243, .25-06, 6.5 Creedmoor, 7mm-08, and 7mm Mauser, to name a few. So, shoot the biggest caliber that you shoot best, and you won’t go wrong.

Shotgun recoil is another matter. It may surprise you to see the difference in recoil when a rifle or shotgun fits you. Stocks too long or too short have a lot to do with recoil. A good recoil pad and the type of ammo you shoot also play a big part in shotgun recoil. Dove hunters should shoot light loads, while waterfowl hunters need heavier loads.

You should shoot the shotgun gauge that you like and shoot best. Make sure the gun fits you and choose shotgun shells that you shoot best. If you can’t shoot heavy loads, then shoot light loads. Pick the combination of gauge and ammo that you shoot best, and you will do better on quail, doves, or ducks, or skeet.

Tip: Check your dominant eye. If you’re right-handed, close your left eye and point your finger at an object. Keep your finger on the object and close your right eye. Your finger should be to the right of the object when you look through your left eye.

Another tip: Keep both eyes open when shooting a shotgun if your dominant eye matches your dominant hand.