March and April bring on a marvelous reset of nature, as the drabness of winter fades into the regrowth of spring. It seems everything and everybody welcomes the songs of birds, the new leaves on the many trees and shrubs of Texas, and the emergence of new creatures such as young squirrels, mockingbirds, turkey poults, cardinals, and the diminutive wrens. Spring is a good time of year in Texas.

The millions of female Mexican freetail bats inhibiting the caves and overpasses of the Hill Country have come back from Mexico to rear their young in several big caves, as well as the walls of bridges in Austin and San Antonio. The male bats hang out (no pun intended) in bachelor groups far away from mother bats and their single “pup.”

When evening shadows fall, the millions of bats take to the skies, devouring all the mosquitos and other winged pests that make up their diet. Sad to say, many young bats that fall to the waters of Lady Bird Lake in Austin end up as fish food for bass and catfish, but that’s the call of nature. However, millions of young bats make it to flying time, and visitors look in awe at the clouds of bats swarming from their summer haunts into the Texas skies.

Texas spring is not only for Mexican freetails, it’s the season for Rio Grand turkeys to fill the air with their challenging calls that lure spring turkey hunters to match their wits with old mating toms. Over 100,000 turkey hunters will enter the wilds of the Edwards Plateau and the Panhandle with their turkey calls and shotguns as they chase one of Americas favorite game birds.

Spring is also the time of migration of the many songbirds that Texans enjoy. One of the biggest migrations involves the meadowlark—none one week, but thousands the next week. Other noticeable migrants are mockingbirds, cardinals, wrens, blackbirds, scissor-tailed flycatchers, and bluebirds, to name a few.

Some areas of Texas have migrating populations of sandhill cranes, barred owls, and piliated woodpeckers. These species come south to Texas in October and stay until the weather warms in March, and they all go back north for the summer with the many species of migrating waterfowl and songbirds.

As a hunter for many decades, I always had wishful thoughts about spring turkey season. Some 40 years of chasing gobblers (1970-2010) gave me many memorable hunts for one of the most wily birds in North America. It’s no wonder Benjamin Franklin wanted to name the wild turkey as our national bird, but was voted down in favor of the bald eagle.

Spring has sprung, so take time to enjoy the flowers. It might be a good time to look for shed antlers or take the cane pole and can of worms to the fishing hole. There are a lot of things to do in the spring, so get out there and enjoy the wild areas of the great state of Texas.

Horace Gore

info@ttha.com

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer Christina Pittman • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

John Goodspeed, Art Griepp, Judy Jurek, Jake Legg, Ron McWilliams, Kaylee Scott, Eric Stanosheck, Mark Wengler

Sales Representative Emily Lilie 713-389-0706 emily@ttha.com

Marketing Manager Logan Hall 210-910-6344 logan@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events

Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com Graphic Designers

To

Advertising Production Deborah Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Membership Manager Kirby Monroe 210-809-6060 kirby@ttha.com

Anyone recognize this device? If so, send us your best guess to editor@ttha.com. We’ll reveal the answer in our next issue.

Journal Editor Horace Gore sat ready with his trusty pen to autograph copies of his latest book, “Stringtown to The Kokernot,” at our inaugural Outdoors Extravaganza, which kicked off in Dallas in early January. Horace also

shared a special moment with Jerry Johnston and Christina Pittman at a special banquet after day two of the Extravaganza. Christina honored Jerry and his TTHA legacy, which is now in its fifth decade.

In 1975, Jerry Johnston had finally gotten all his ducks in a row. He was ready to announce his new venture—Texas Trophy Hunters Association. The idea of starting an association to celebrate Texas’ No.1 game animal—the Texas whitetail—was coming to fruition with the first meeting at the El Tropicano Hotel to kick-off what Jerry hoped would be a success.

Jerry had arranged for the publication of the association’s new magazine called Texas Hunters Hotline, which would come out as a mostly black and white 32-page quarterly publication in the July, August, September (fall) issue. To be sure, the small magazine needed a shot in the arm, but interest grew as deer hunters became TTHA members and offered their hunting stories to the magazine. Jerry and family members did the rest.

Jerry was a deer hunter, and most of his friends were, too. In the early ’70s, he had been selling leases for the American Sportsman’s Club (ASC) for quite a while and had been so successful that he was awarded a new rifle for his top sales list. In his many travels with ASC, Jerry had talked to Ray Scott several times about Ray’s success in founding B.A.S.S. (Bass Anglers Sportsman Society) in 1967. Jerry thought if Ray could form a society of bass fisherman, he might do the same with white-tailed deer hunters.

While Jerry worked for ASC, he thought about ways to start an association celebrating the white-tailed deer and Texas deer hunting. Then, in the summer of 1975, Jerry’s dream became a reality when he founded TTHA as the first association of its kind in the Southwest.

The quarterly magazine was a necessity for the success of the organization. As the membership increased, so did the interest in deer hunters telling the story of their hunts in the magazine. Jerry had some close friends who were happy to contribute to the magazine, and it became the “flagship” of the association for about six years.

also included in Texas Hunters Hotline.

Above: Buddy Mills created this special “logo buck” cover photo. Opposite page: The debut cover photo of the first Texas Hunters Hotline magazine.

Jerry edited the magazine content, which included deer hunts, regulations from Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and other pertinent information for deer hunters. As the membership grew, hunting articles on turkey, doves, and varmints were

In 1982 Jerry pursued a 501(c)(3) non-profit status for TTHA and changed the name of the magazine to The Journal of the American Trophy Hunter. The magazine had grown in page count with advertising and additional story material, and had taken on more color and photos that increased the magazine’s appeal. It soon had features and ads totaling 125 pages and was growing fast. During the early ’80s, Jerry realized TTHA had bloomed into a new “first” for the Southwest—something that had never been done before.

TTHA continued to grow as the association’s publicity made the rounds of the wildlife world, and Jerry added more staff and printed more magazines. The Hunters Extravaganzas, originally called conferences, were a huge success. Jerry saw where the money was and tried to establish Hunters Extravaganzas in several locations in Texas and other states, but the problems of

spreading out prevailed, and Jerry settled on three locations for his trade shows: Houston, Fort Worth, and San Antonio.

After a few years of attempting to get TTHA recognized as a non-profit association, Jerry considered the proposal a lost cause, and put all his attention to memberships and contributions to the hunting community. One of his new ideas for

advancement in 1987 was to change the magazine’s title to The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, which is what you see today in the mailbox and on magazine racks around the country.

Some critics say today’s Journal is the premier hunting and outdoor magazine in the Southwest. The content and color stand out in the cover of each Journal, which often shows the photographic artistry of businessman-rancher Marty Berry of Corpus Christi. A select group of outdoor writers—who we consider the best in Texas—contribute various articles and photographs from their vantage points across the state.

People who read The Journal—hunters, campers, bankers, landowners, day-laborers, and more—say it’s never thrown away. After a few weeks at home, most copies end up in hunting camps, doctor’s offices, local libraries, pickup dashboards, and outhouses. To wit, The Journal is never trashed. You often see a large collection of old Journals in a bookshelf or stashed away in a den or trophy room, but I know of only one TTHA member who has every copy of Texas Hunters Hotline, The Journal of the American Trophy Hunter, and The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, since day one.

Owen West of San Antonio is Platinum Life Member (PLM) No. 3, and has worked the floor of Hunters Extravaganzas from the day they started. Owen has a copy of every magazine that has been published by TTHA since the first Texas Hunters Hotline in the fall of 1975. Many of the magazines through the years have been passed around or donated to various causes, but Owen has them all.

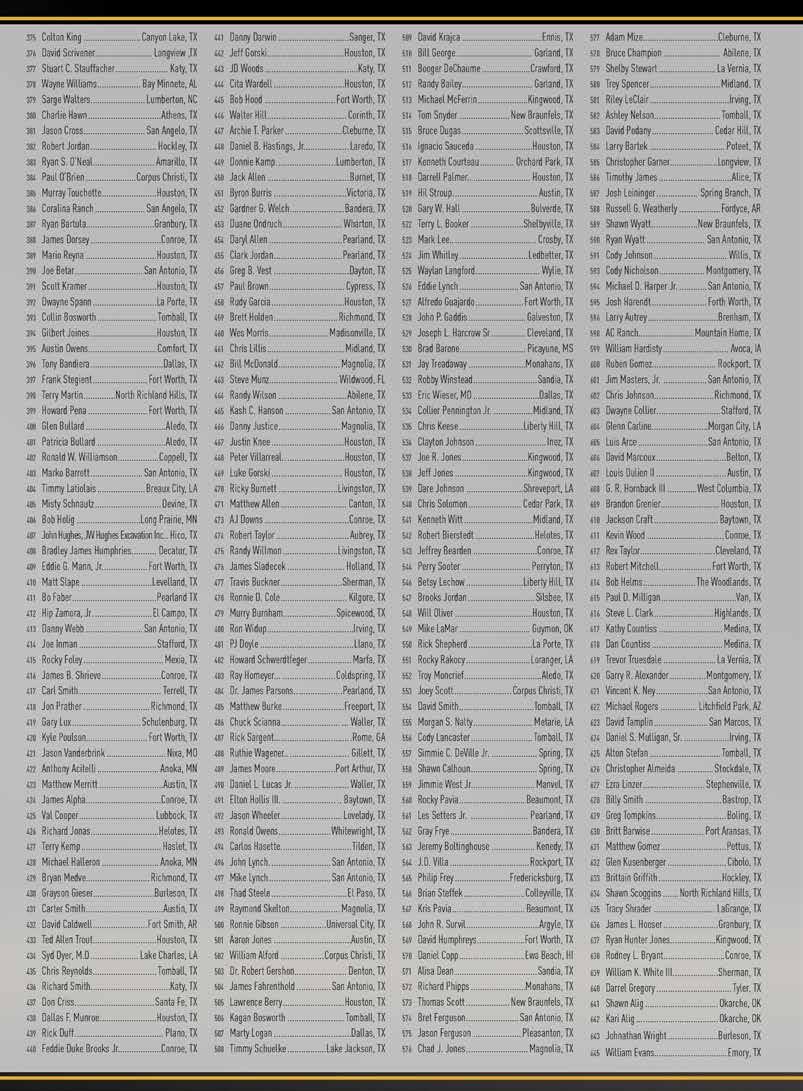

Since we’re talking about Texas Trophy Hunters PLMs, the top 10 include some remarkable Texas hunters. Mark Herfort of Rosenberg is No. 1 and Laura Berry of Corpus Christi is No. 2. Another friend of TTHA is No. 6, Brian Welker of Sugarland. Milton Schultz, Jr. of Glen Rose is No. 7 and Al Brothers of Berclair is No. 9.

The thousands of PLM members fill five pages of each issue of The Journal, and more get added every year. Our TTHA members—old and young—have been reading and contributing to Texas Hunters Hotline and the Trophy Hunters Journals for 50 years, with many hunting seasons to come.

In this golden anniversary year of TTHA, we congratulate all our members across Texas and America. Let’s keep them running, swimming and flying by being good sports and contributing to wildlife conservation through hunting and fishing in Texas, the USA, and around the world.

Christina Pittman, president and CEO of Texas Trophy Hunters Association, announced the launching of the Texas Trophy Hunters Foundation at the Outdoor Extravaganza hosted by TTHA/SCI, held in Dallas on Jan. 10-12 at the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center. The initial and spacious trade show brought hunters and outdoor enthusiasts together with international and statewide outfitters in an atmosphere of hunting, camping, and fishing that is the biggest and best of its kind in Texas.

Vendors and outfitters from worldwide consortiums were present to promote their hunts and provisions for extended safaris and jaunts to all parts of the globe. Hunting and fishing destinations were well represented by Africa, Alaska, Argentina, Asia, Australia, Brazil, British Columbia, New Zealand, Spain, and Texas—to name a few.

The Outdoor Extravaganza opened on Friday, then held an elaborate banquet on Saturday night where W. Laird Hamberlin, CEO of Safari Club International and SCI Foundation, introduced Pittman, who announced the TTH Foundation and its founding sponsors, Brian and Denise Welker of Sugar Land. Pittman also brought Jerry Johnston, founder of Texas Trophy Hunters Association, to the microphone, where Johnston praised the affiliation of SCI and TTHA and reminisced on TTHA’s 50th anniversary.

“Denise and I are longtime TTHA Platinum Life Members and have always loved this unique association,” said Brian Welker, president of SCI Foundation. “We are very proud to be a part of the TTH Foundation inaugural year, introducing the contribution from SCI Foundation as well as our personal contribution. As time goes by, we hope many more TTHA members will feel so inclined to contribute to this new Foundation.”

Brian added, “I first met Jerry and Horace (Gore) after winning a membership drive for TTHA in 1977. I was honored with a free-range trophy whitetail hunt on the San Ramon Ranch in South Texas. Even though I was just 22 years old, they treated me as an equal, and with great respect. Two finer men you could never meet.”

Pittman noted the Foundation will waste no time in getting into action. “We will invest in groundbreaking wildlife research to ensure the sustainability of Texas wildlife,” she said. “One of the most inspiring parts of our mission is our educational scholarships and college chapters in universities like Texas A&M, UT-Austin, Texas Tech, Texas State, and many others. With the launch of the Texas Trophy Hunters Foundation, we are taking our commitment to the next level. Our mission is simple yet powerful: to help and inspire through wildlife research and educational scholarships,” she added.

Denise Welker, newly elected president of Weatherby Foundation International, said, “I’m very excited to see what the future holds for the TTH Foundation. Deer hunting in Texas is where I discovered

my hunter’s heart, as Brian was teaching me and our sons to become hunters.”

The banquet concluded with a live auction that brought over $75,000 for the Foundation. “As we celebrate 50 incredible years, I am filled with pride to announce the launch of the Texas Trophy Hunters Foundation,” Pittman said. “This milestone marks a new chapter in our commitment to the future of Texas wildlife and the next generation of conservationists.” —Horace Gore

Alan Cain has been selected as the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Wildlife Division director. Cain began his more than 24-year career with TPWD in 2000 and has progressively held roles of greater complexity and responsibility, including wildlife biologist and district leader in South Texas, white-tailed deer program leader and most recently the big game program director.

“Alan has a proven track record as a leader who can strengthen relationships and build trust with private landowners and stakeholders, enabling our agency to manage public resources in a predominantly private lands state. This will be accomplished on a strong foundation of applied science and with the collaboration of public, non-profit, and private partners,” TPWD Executive Director David Yoskowitz said. “Alan will be a valuable addition to the agency’s senior leadership team and lead a talented team of wildlife professionals inside TPWD to help fulfill our agency’s mission.”

During Cain’s tenure with TPWD’s Wildlife Division, he has successfully

led or been a critical team member in designing and implementing impactful programmatic and regulatory changes, including enhancements of the Managed Lands Deer Program (MLDP), development of the Land Management Assistance application to administer the MLDP, mandatory harvest reporting and digital tagging applications, expansion of antlerless deer hunting opportunities, and working on Chronic Wasting Disease policy, management, and regulations.

“TPWD is a leader in conversations on evaluating and implementing solutions for pressing issues including wildlife disease management, habitat loss and fragmentation, game and non-game wildlife stewardship, and hunting access and opportunity for rural and urban Texans,” TPWD Chief Operating Officer Craig Bonds said. “Cain’s professional experiences, institutional knowledge, and relationships have positioned him to take on the role of Wildlife Division director.”

Cain is a certified wildlife biologist through the Wildlife Society and has been a member of the Texas Chapter of the Wildlife Society since 1991, serving as its president in 2011. He is a current member and past chairman of the Advisory Board for Wildlife Management Academic Program at Southwest Texas Junior College in Uvalde, previously served on the Texas Big Game Awards Scoring Committee and Measurer, Boone & Crockett official measurer, TPWD Mentor Program, and is a graduate of TPWD’s former Natural Leaders Program.

Cain earned his bachelor’s degree in wildlife management from Texas Tech University and a master’s degree in range and wildlife management from Texas A&M University-Kingsville. He held a research associate position at the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute in Kingsville before beginning his career with TPWD. —courtesy TPWD

The Boone and Crockett Club announced in December that it will create a new category in its big game records for javelina (collared peccary, Pecari tajacu), the first new category created since 2001. The proposal to include a new big game category for javelina was brought forward to B&C’s Big Game Records committee by a working group made up of wildlife managers from Texas, New Mexico, Arizona, and Mexico as well as other hunting conservation groups. Last week, the Committee voted unanimously on the proposal during the Club’s annual meeting in Charlotte, North Carolina. That vote is the first step in the process, which will now require creating specific measuring protocols and establishment of minimum scores.

“The decision to add javelina as a trophy species was years in the making and reflects not only the growing appreciation for the species among hunters and wildlife managers, but can bring conservation benefits to javelina and the places it lives,” says Mike Opitz, chair of the Club’s Big Game Records Committee.

The Boone and Crockett Club has been measuring North American big game since 1895 with the original vision for the records program to create a record of what was thought to be the vanishing big game in the country. The big game record book, Records of North American Big Game, was first published in 1932 and serves as a vital record of biological, harvest, and location data on hunter-taken and found trophies based on the principle that the existence of mature, male specimens is an indicator of overall population and habitat health. While often misunderstood, this vision of a “trophy” is not to celebrate the suc-

cess of a hunter but rather the success of conservation efforts and selective hunting that leads to the presence of larger, older animals on the landscape.

In the proposal’s introduction, the agencies wrote: “Collared peccary (Pecari tajacu), also known locally as javelina, are an important big game animal in the southwestern United States and Mexico. They are managed alongside other big game species, including requirements that hunters follow all regulations in pursuit of the animal across all jurisdictions. This is the first step in taking an animal under the “fair chase” ethic; a concept that originated with the Boone and Crockett Club. This ethic demands an elevated level of respect for the unique and diverse species of big game on the landscape. We propose the creation of a new javelina category in the Records of North American Big Game, building upon the growing interest in javelina hunting and recognizing this unique North American big game species. There is a feeling of pride from hunters who have taken a “Boone and Crockett” animal. This results in increased desire for conservation of that species and the landscapes in which they live. In this way, the Boone and Crockett Club is a leader in conservation by holding hunters to a high standard of fair chase and recognizing the largest and most magnificent individuals of native North American big game species.”

The general criteria for adding a category to the records program is: there are extensive geographic areas where the proposed category occurs, the animals occur in good number, suitable boundaries can be drawn, the game department(s) managing the proposed category are in favor of setting up the category, the scientific evidence supports this category. The last time a new category was created was adding nontypical categories for both Columbian and Sitka black-tailed deer 23 year ago, though the last time a new species was added was in 1998 when California’s tule elk were added.

“As we work on establishing minimum scores, we’ll work with the states and Mexico to come up with a minimum

that strikes the balance between a mature specimen worthy of recognition and a good representation of a mature javelina across its range,” said Kyle Lehr, Boone and Crockett Club’s Director of Big Game Records. “We need to determine if a mature javelina in, say Texas, is quantifiably different than one in Arizona.”

—courtesy Boone and Crockett Club

SUNAGAWA, Japan — A gunshot rang out on a recent morning in a meadow in northern Japan. The brown bear slumped in the cage, watched by a handful of city officials and hunters. The bear had been roaming around a nearby house and eating its way through adjacent cornfields, so officials and hunters in Sunagawa city had set a trap with a deer carcass to lure the voracious creature.

“For me, it’s always a bit deflating when a bear gets caught,” Haruo Ikegami, 75, who heads the local hunters’ association, told Reuters news agency hours beforehand.

Japan is grappling with a growing bear problem. A dwindling band of aging hunters is on the front line. A record 219 people were victims of bear attacks, six of them fatal, in the 12 months through March 2024, while more than 9,000 black and brown bears were trapped and culled over that period, according to Japan’s environment ministry.

Both species’ habitats have been expanding; the ministry estimates that the number of brown bears in Hokkaido, Japan’s northern island, more than doubled to about 11,700 in the three decades through 2020. Restrictions on hunting practices and greater emphasis on conservation contributed to a surge in bear sightings over recent decades, according to Japan’s Forest Research and Management Organization. With Japan’s rural areas experiencing rapid demographic decline, bears are venturing closer to towns and villages and into abandoned farmland, an environment ministry expert panel said in February. But bear expertise among local governments is spotty, and Japan’s reliance on

recreational hunters to protect settlements looks unsustainable as its population ages, according to Reuters interviews with almost two dozen people, including experts, hunters, officials and residents.

Many called for changes to the way Japan manages human-bear conflict to address safety concerns while ensuring a future for the bears. In Hokkaido cities and towns like Sunagawa, Naie, Iwamizawa and Takikawa, which Reuters visited in October, some residents wonder what will happen when hunters can no longer do the job. Sunagawa’s city government told Reuters that efforts to capture the bear were complicated by its proximity to homes and deliberations about what to do once the animal was trapped.

Although some hunters stalk bears as a hobby, Ikegami reckons not many are thrilled about culling trapped bears for local governments. “I don’t want people to think of hunting as something fashionable. What we do is difficult. It’s a big burden to take a life,” Ikegami said.

The burden is both mental and monetary. The hunter that shot the bear in Sunagawa would get about 8,000 yen (about $50), perhaps enough to cover fuel and expenses but little else, Ikegami said. Hunters also risk clashing with authorities. Ikegami’s guns were seized by Hokkaido authorities in 2019 after they deemed his attempt to shoot a bear near a house was ill-judged. He is battling in court to have the weapons returned. The Hokkaido safety officials involved in the matter declined to address Reuters questions about the case.

In response to increased bear attacks, Japanese government officials this year proposed relaxing rules around gun use to make it easier for hunters to shoot bears in urban areas. Local governments of Sunagawa, Takikawa, and Iwamizawa told Reuters that regional and national authorities could go further to address the problem. This could include promoting the recruitment of hunters and improving their conditions, among other ideas.

Japan’s environment ministry said it subsidizes efforts to train local officials and conduct bear drills in towns, but added that regional differences in

human-bear conflicts called for tailormade approaches. The Hokkaido government’s wildlife bureau said it ran various initiatives to incentivize and recruit hunters, including promotional events and training people in how to handle brown bears. Katsuo Harada, an 84-yearold hunter, said that ultimately, Japan should create a system where hunters are paid enough to support a family. “Unless they’re paid properly, we can’t nurture the next generation of hunters,” he said. —courtesy Reuters

LUNENBURG, Va. — A Virginia man died after a bear in a tree shot by one of his hunting partners fell on him, state wildlife officials said. The incident occurred Dec. 9 in Lunenburg County, which is between Richmond and Danville, Virginia’s Department of Wildlife Resources said in a statement. A hunting group was following the bear when it ran up the tree, the department said. As the group retreated from the tree, a hunter shot the bear. The animal fell onto another hunter who was standing about 10 feet from the bottom of the tree.

The department identified the man as Lester C. Harvey, 58, of Phenix, Virginia. An obituary for Harvey, a married father of five with eight grandchildren, said he was a self-employed contractor and avid outdoorsman. —courtesy Associated Press

Laredo police arrested a man Dec. 6 for shooting at hogs with a shotgun in the parking lot of the Flying J Travel Center truck stop. The Laredo Police Department said the emergency call center received a report about a man shooting from a silver pickup truck in the parking lot of the Flying J Travel Center at 1011 Beltway Pkwy. Officers located and detained the suspect. Albert Torres, 31, admitted to shooting at the hogs and claimed he was authorized to do so by the Flying J manager. Police arrested and charged Torres with discharging a firearm, unlawful carrying of a weapon, and possession of a controlled substance. —courtesy Laredo Morning Times

By Dr. James C. Kroll

There is an old saying among cowmen that if you take a cow from East Texas to South Texas, it will gain weight; but if you take a cow from South Texas to East Texas, it will starve to death. This saying originated from the partial truth that the forages of eastern Texas are less “strong” (nutritious) than the ones in South Texas. Although the per-acre forage yield is much higher, as well as potential tree and shrub growth, in East Texas they are not as nutritious.

So, what is the problem with eastern Texas? The higher rainfall supports more growth, but it also leaches out critical nutrients. Yet, when asked, “Where is the best place to grow deer?” I still say East Texas. The potential for producing more deer on less acreage is far greater. Why? It’s easier and less expensive to improve soil nutrition than it is to provide more water.

I began my deer research back in 1973, after reading a book by a German scientist named Dr. Ukermann, on roe deer

Left: Landowner/hunter Dr. Bob Lehmann harvested this fantastic 2051⁄8-inch monster from his East Texas property in the 2024 season. The buck was 5 years old and was born and grew up on the property. Dr. Bob and his manager, James Miller, plant well-distributed warm- and coolseason plots. The buck was harvested while feeding on a plot of forage oats.

management. He had developed some models to predict the productive capacity of land for roe deer, the species “Bambi” was written about.

As a forestry professor, I was very familiar with the concept of “site index” for land regarding expected tree growth; and had wondered if such a thing could be produced for deer? In a nutshell, site index is the expected height of a tree, planted today in a specific location, in a set number of years; usually 50.

Site index is most influenced by the amount of available moisture in the soil. A site index of 70 means the average tree planted today on one soil type would reach 70 feet in height in 50 years, and another soil type with a calculated site index of 90 would have trees grow 90 feet tall in the same time period. So, it seemed to me the ability of a specific piece of land to produce trees could also predict forage yield, which in turn affects the number of deer the land will support—in effect a deer site index. Along the way, this quest took me a very long way, ending up in the longest continuously running research project in deer food plots to date.

When properly planted and managed, food plots can significantly improve the nutrition of deer in areas with at least 30 inches of annual rainfall. Much of the eastern half of Texas, east to the Atlantic Ocean, and due north into Canada falls into this category (see map). Our research has demonstrated a mere 3-5% (3-5 acres per 100 acres) of your land can significantly increase nutrition and productive capacity, effectively increasing deer site index.

So, why are not most landowners who manage deer planting more food plots? There are many reasons, but the most common is lack of education on food plot planting, coupled with confusion and misinformation created mostly through social media. I decided to write this column to help clear up some of the confusion.

I recommend you plant 3-5% of your property to food plots, but where do you plant? Obviously, you want to find the best

When properly planted and managed, food plots can significantly improve the nutrition of deer in areas with at least 30 inches of annual rainfall (in green), including eastern Texas.

places to grow forages, and that eliminates high, dry places or low, excessively wet places. There are three general soil textures: sand, silt and clay. Pure sand is very droughty. Clays have the smallest particle size, making them cling to water and nutrients. Silts have intermediate particle size, providing better water and nutrient availability. The perfect soil has equal portions of sand, silt and clay, and are called “loams.”

If you visit https://websoilsurvey.nrcs.usda.gov, you can develop a custom soils map for your property. You can then look up the characteristics of each soil type to find the perfect places on your property for planting food plots. Try to distribute food plots evenly over your property. A good location for a food is near the center of your property, where you can designate a sanctuary for your deer. Include plantings of conifers such as pines and cedar in large clumps adjacent to a food plot for cover.

One of the most wasted resources in the U.S. are rights-ofway (ROW). You cannot grow trees within a ROW, but you can plant food plots. A 30 feet wide ROW that runs just 30 feet across your property contains almost a quarter acre.

Deciding what to plant in your food plots is probably the most difficult, yet important decision you make. There is no

such thing as a magic bean. There are certain plant varieties that can be easily cultivated on your soils that deer will use— that will supplement the native nutrition when deer need it.

There are two stress periods for most geographic areas: late summer-early fall, and late winter-early spring. Few plants will be actively growing during each of these periods, so that means you will have to consider two different types of plants: warm season and cool season. Warm season plants include peas, soybeans, summer clovers and pseudo-clovers, alfalfa and herbaceous plants such as barley, and winter peas in the South. In choosing each of these, you must study the soil type needs of each plant using your soils map.

The first thing you must do is to collect soil samples from each plot at least three months ahead of planting. Visit your nearest agriculture extension service office for advice on how to collect soil samples or go on-line, where there are dozens of resources that teach you how to do it. Your soils analysis report will provide information as to how much fertilizer and/or lime each plot will need prior to planting.

It seems logical that cool season plants need to be planted during or just before the cool season (fall-winter), and warm season plants should be planted in spring or early summer. It is critical you follow directions for when to plant each variety. Not planting on time or too early can be quite costly.

Here’s an example. A few years ago, I gave talks at the Hunters Extravaganzas on planting successful food plots. I warned people not to plant cereal grains before the last week of September and the first week of October. Rainfall is unpredictable

during these times, and so are pests. A couple of folks argued they always succeeded by planting the opening weekend of dove season. Later, they sent photographs showing lush oat growth in their plots. Shortly after, I got a panic call from one of them, asking what could be done about army worms. These pests are devastating and had completely destroyed their plots. I kindly gave them the recommendation to replant.

I could write an entire book on this final topic because it probably is the most confusing aspect of food-plot planting. You could spend literally hundreds of thousands of dollars on farming equipment for planting and maintain food plots. However, let me keep it very simple. All you really need is a modest-sized tractor tailored to your size property and a few implements, including harrow or disk, about 5-6 feet wide, a seed/fertilizer spreader, and a rotary mower or “bushhog.” You can have a very successful food plot program, using just these three implements and your tractor.

You can go low-till, and buy a $20,000 drill, plus a few more thousand in specialized implements, but you really do not need them. There are tractor and implement packages offered at dealers each year for new equipment. Start small and add implements as you need and can afford them.

I hope you have learned planting food plots can be easy and effective in supporting your deer management program on your land. All it takes is planning, matching your food plot varieties to your soils and climate, planting on time, and using and the right equipment. It’s all about details. Trying to take shortcuts will lead to nothing but failure.

By The Old Hunter

Between the World Wars, about six major deer rifles were used in Texas: .30-06, .300 Savage, .250 Savage. .257 Roberts, and .30-30. In 1925, Winchester introduced the .270 in the Model 54, and in 1936, did so with the “rifleman’s rifle”—the Winchester Model 70—a traditional Texas deer rifle. After World War II, the soldiers came home, and a variety of guns began pouring out of the major firearms factories.

From the 1950s to the ’60s, Remington made pump rifles in most popular deer calibers of the time, and Winchester even veered off and made a hammerless lever gun and semiautomatic (Model 88 and 100) that were basic failures. Remington’s pump guns faded, and the popular 721 and 722 models were replaced by the popular Model 700 in 1962. Browning brought out some fine bolt and semiauto rifles for the discriminating hunter. Winchester introduced the Model 70 Featherweight rifles in the ’50s in two

new calibers, the .308 and .243, which swept the deer hunting world. Savage made their Model 110 in all popular calibers, and were one of the first to offer a left-hand bolt rifle. The ever-popular “wildcat” .25-06 was made legit by Remington in 1969.

Belted Magnum cartridges originated in Europe, where technicians thought a strong belt on the rear of a Magnum case was necessary for head spacing correctly in the barrel chamber. Up to the mid ’50s, about the only belted Magnums sold in the U.S. were rifles in .300 Holland & Holland and the excellent Weatherby Magnums—all with Magnum-length actions.

Then, Winchester shortened the .300 H&H case to fit a standard-length bolt action and developed calibers such as .264, .300, .338, and .458—all belted Magnums. Remington retaliated in 1962 with a double-plus, its popular 7mm Magnum in a brand-new Model 700 Remington

rifle. With a wide variety to choose from, hunters started a Magnum craze that lasted 50 years.

The Win. .264 and the Rem. 7mm Magnums were very competitive, but the race was soon settled because of bullet weights, 100 and 140 in the .264 as opposed to 140, 150, 160, and 175 in the 7mm Mag. The end result, the 7mm Mag. in a variety of rifles left the .264 Mag. standing at the gate.

The .338 Mag. was popular as “the elk rifle” for a while, and the big .458 mangled everything, including hunters, from Alaska to Africa. However, through the years, only Winchester’s .300 Mag. has stood the test of time. In fact, if Texas hunters had only one rifle for everything from whitetails to nilgai, they would do well with a .300 Win. Mag. fitted with a good recoil pad, and a variety of ammo to fit the hunt.

When the new 7mm Mag. cartridge emerged in 1962, a magic spell fell over

South Texas deer hunters who were already shooting bigger calibers at South Texas bucks. As a result of good advertising, many hunters shelved their venerable .30-06, .270, and .25-06 rifles, and bought the new Remington 7mm Magnum. Old dependable whitetail rifles like the .300 Savage and .257 Roberts were cast aside like a worn-out shoe.

Within a few years, practically every notable deer hunter south of San Antonio toted a scoped 7mm Magnum and a box of 150-grain ammo. There were stories about hunters shooting a buck so far away that the meat spoiled before they could get to it.

With everything on the plus side, the 7mm Mag. had one flaw—recoil. Some hunters of lesser stature and others who had a tendency to flinch could not effectively shoot the Magnum. Only the most zealous hunters could handle the 7mm Magnum’s 20 pounds of recoil, as opposed to 16 or 17 pounds for the .270, .308, and .30-06, or 12 to 13 pounds for the popular .25-06, 7mm-08, and .243.

The new Remington rifles had stock dimensions and trigger pulls that made shooting without flinching almost impossible. However, some hunters who could

afford custom-built rifles with after-market triggers and better fitting butt stocks reported good results from the 7 Mag.— even from lady hunters and youngsters.

The problem of “kick” eventually cooled the Magnum popularity, as recoil-sensitive hunters went back to less powerful cartridges that were just as effective and more pleasant to shoot. Some hunters solved the problem of recoil by putting a muzzle brake on their 7 Mag., but the muzzle blast from this combination was revolting to both the shooter and bystanders.

An interesting aspect of the powerful 7mm Rem. Mag. was crippling loss of South Texas whitetails. Some hunters simply could not shoot the 7 Mag. without flinching, or they “stretched the barrel” on long shots, both resulting in crippled deer.

Hunters who crippled high quality or high-priced bucks often looked for a dog handler to find the crippled buck. Enter Roy Hindes III of Charlotte, a rancher who kept good deer-trailing dogs and would find a crippled buck for a price.

For many years the term “call Little Roy” was heard at South Texas deer camps, meaning to call Little Roy Hindes

and “Jethro” to find the buck. The same could be said of Gary Machen and “Bull,” although Machen used Bull mostly for finding bucks for the family and close friends. In answer to my question several years ago, Roy Hindes III said the most common rifle for his wounded bucks was the 7mm Mag.

So, where are the Magnums today? Well, the 50-year craze has subsided somewhat, but many South Texas deer hunters still shoot a variety of Magnums: .264 Win. Mag., 7mm Rem. Mag., .300 Win. Mag., and a variety of Weatherby Magnums. However, most of the Magnums used today were obtained several years ago, and the sale of Magnum calibers other than the .300 Win. Mag. has slipped through the cracks.

I must confess that I have often bragged on my Winchester .264 Mag. and custom .300 Weatherby and .257 Weatherby Mag. rifles after a terrific shot. The rifles did very well on elk, nilgai, whitetail and mule deer, and the .257 Weatherby was a “peach” on whitetails and pronghorns. I might have taken all of these animals with my favorite .270 in a pinch, but the Magnums served me well.

Many recoil-sensitive deer hunters

have left the Magnums and gone back to their .30-06 or .270, or a mild mannered 7mm-08 or a .243. With the advent of comfortable blinds, trail cameras, and corn feeders, hunters have found that all Texas whitetails fall fast from closer shots, milder “kick,” and more accurate bullet placement.

Today, there is a different kind of “Magnum.” Hornady, Nosler, and others have developed new cartridges with no belted case that are designed to fit short actions and the popular AR-15 platforms and magazines. However, other than being short and fat, the new “beltless” calibers have the same physical attributes

The .300 Winchester Magnum has a belted case (arrow) like many of the older Magnum cartridges. The author notes that the .300 Win. Mag. has remained a popular chambering in Texas big-game rifles.

and recoil of the old Magnums, and a new twist on how these new cartridges can defy gravity.

Hunters who may be swayed by outlandish propaganda should think back at all of the elk, deer, pronghorns, exotics, and even hogs they have shot at 1,000 yards—none! Then, compare slick ads to all the game animals that you have taken at 100 to 200 yards with your reliable old .30-06, .270, 7mm-08, or .243. You might be obliged to go to the closet or safe and pet the old rifles that have served you so well, and so long.

We all know Magnums can do well on the bigger game animals, even a mule deer or pronghorn across the canyon. However, there are a dozen less rugged calibers that are pleasant to shoot and will put a Texas whitetail, exotic, or hog on the skinning rack in style.

Mitch Nelson cut his teeth hunting whitetails on the family hunting lease at Sonora. “Our family leased and hunted the same ranch for over 30 years,” he said. “I hunted there with my father, grandfather, and my uncles and cousins. All of my first hunts were at the lease, including my first buck when I was seven years old.” A small, basketracked eight-point buck Mitch shot while sitting on his dad’s lap in his grandfather’s blind would be the first of many.

Later in life, Mitch graduated from Texas A&M University with a degree in agriculture economics before landing a solid job in the offshore oil and gas exploration industry. After finishing school, he would begin dating the love of his life, Ashley Griffin. They were married and had a family of three children—Mark, Kate, and Ellen— and now reside in Tomball. Over the years, life became busier with faith, family, and careers taking precedence. However, hunting and more specifically teaching their children to hunt, still remained a priority.

As it turned out, Mitch wasn’t the only hunter in his young family. Ashley is an accomplished huntress in her own right, and has some great bucks and a huge bull elk on the wall to her credit. Ashley was raised in much the same manner as Mitch and grew up learning to hunt on her family’s ranch in Dimmit County near Big Wells.

Los Sueños Ranch is located in the heart of great whitetail country. The low-fenced ranch is a special place, not just by measure of the game, but in terms of the people that steward the property. Ashley’s parents, Alan and Barbara Griffin, are gracious hosts and have shared the ranch and its resources with countless guests throughout the years. Their dedicated ranch manager, Carlos Rivera and his wife Mary, work hard to keep things running smoothly.

The ranch operates as a working cattle and hunting property. Emphasis, however, has always been on the wildlife management program. The ranch consistently produces its share of trophy deer, including an official Boone & Crockett qualifying

buck in 2012 that measured a whopping 200 6⁄8 net non-typical. Several other great deer have been taken, but the memories made have been equally important. The family strives to share the ranch with others, especially first-time hunters, and regularly entertains guests from their church group in addition to extended family and friends.

As you would imagine, Mitch and Ashley spend quite a bit of time at the ranch. Throughout the years Mitch has had many opportunities to take trophies, but has refrained from doing so, instead insisting that others have the opportunity. Mitch is a very considerate and selfless person, always putting others ahead of himself. It is perhaps what makes the story of his hunt last season even sweeter.

For several years, the family watched as a promising buck with great potential grew into an amazing typical 6x6 trophy. “He was a beautiful buck,” Alan said. “The entire family wanted Mitch to hunt that deer, and I had to virtually force him to do

so. No one was more deserving of the opportunity. It took some convincing, but finally Mitch reluctantly agreed.”

The buck had been spotted on cameras, and frequented about three different stands. The problem was the buck only moved and fed at night. Getting a shot at the deer would prove even more difficult than getting Mitch to agree to the task. Several weekends were spent hunting with the kids and alternating between the three stands with no luck. The buck continued to show up on the cameras at night but there were no daylight sightings.

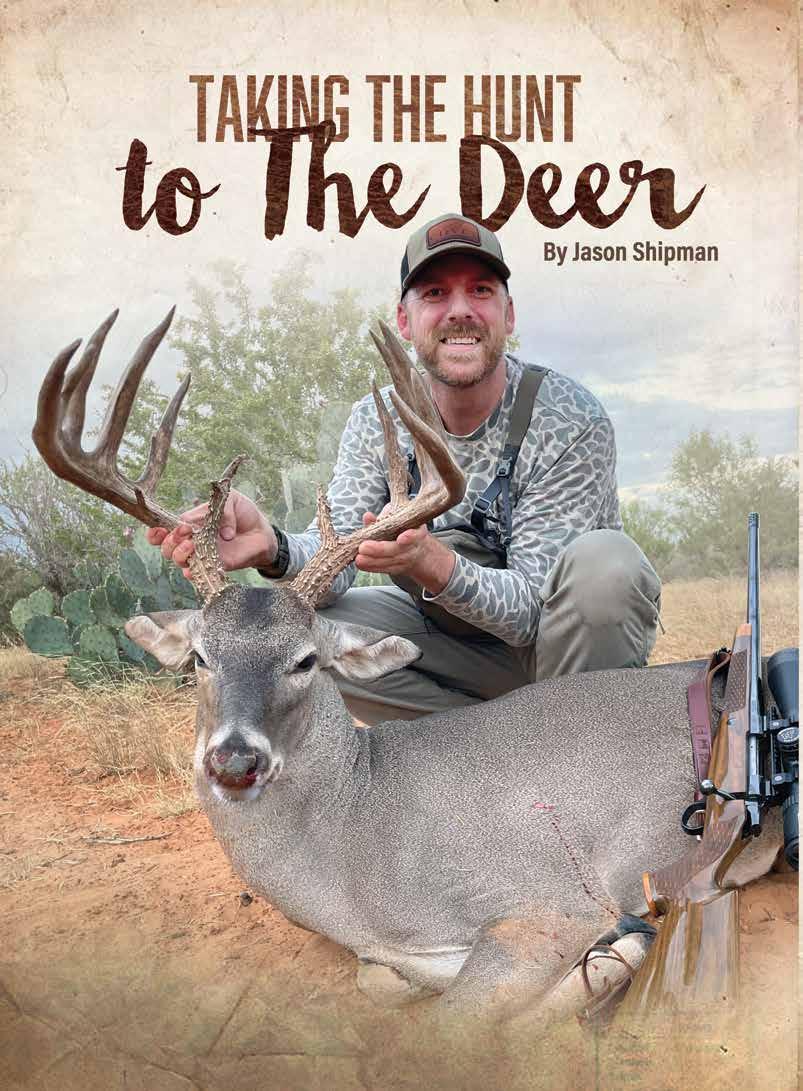

“We had the old buck figured out, and knew he probably bedded in a creek drainage located in his core area,” Mitch said. “We decided to change our tactics and take the hunt to the deer.” They decided to forgo the traditional box blind hunting stands and opted to set up two tripods adjacent to the dry creek bed. “The kids really enjoyed helping set up the tripods and were thrilled with the whole experience of something new,” Mitch said.

The following weekend a cold front blew in and conditions were perfect to hunt the new dual tripod stand location. “It was an afternoon hunt and Alan went with me,” Mitch said. “He sat in the second tripod over my left shoulder.” Everything seemed perfect as the wind blew in their faces and several deer began to feed in front of them. Things did not go as planned when a doe approached downwind. “She winded us and ran everything off. We had about 45 minutes of daylight left and decided to sit it out,” Mitch said.

Just minutes before dark, a buck emerged from the brush along the creek. “It was not the buck we were after,” Mitch said. “But it was a buck that we had seen with him.” Instinctively, Mitch got his rifle up and readied for a shot. The next buck that stepped out was the big buck they were after and had hunted for several days. “We watched as he fed facing away from us for a few minutes. He finally turned broadside and gave me the opportunity I had been waiting for,” Mitch said.

The brush was thick along the creek, and they were hunting in tight quarters. The distance was a short 80 yards as Mitch squeezed the trigger on his Sako .300 Winchester Magnum. The gun was a wedding gift from Ashley, engraved with his favorite scripture, 1 Corinthians 10:31. At the shot, the big buck dropped in his tracks, and was a fitting end to a wonderful hunt and story.

“We watched and waited a few minutes before getting down to go take a look at him,” Mitch said. “As we walked up to him, the first thing that caught my attention was his mass and dark chocolate antlers. I thanked Alan for the opportunity, and we got the rest of the family on the phone to let them know we

had finally taken the “Night Shift Buck.” I couldn’t have been happier!”

Everyone was elated for Mitch’s success. They took a few photos in the field before loading the buck up and heading back to the ranch headquarters. With the excitement of the hunt, Saturday night steaks would run a little later than usual. Mitch’s buck was his best to date, and would later be measured at 1716⁄8 , proving that good things come to those who wait.

Editor’s note: Jerry Johnston relates this tale about a huge South Texas buck, and the hunter who shot the buck, country superstar George Strait, which appeared in The Journal’s 1988 November-December issue. Enjoy!

As the 1987-88 deer season came to a close, country and western singer George Strait had taken an 18-point monster South Texas whitetail buck that would win the most points division of Leonel Garza’s Muy Grande deer contest. The shy country boy from Pearsall, Texas, would later take the buck to Cotulla to enter in the Los Cazadores Trophy Whitetail Contest, only to find that hunters must enter the competition prior to bringing in their entries.

George’s deer would have scored extremely high, as the Los Cazadores contest chooses the winner by gross Boone and Crockett score.

George is not unlike any other hunter just because he’s a noted country singer. He’s just as proud to take a big ol’ buck as your or I would be. In fact, if he’s anything, he’s publicity shy.

His disappointment and anguish that he hadn’t entered Los Cazadores “prior to,” would linger in his mind for a month or so, but I’m sure George got over it. We’ve all suffered similar deer hunting symptoms of remission of one sort or another ourselves. Haven’t we?

George won the third annual Los Cazadores deer contest and had to take a polygraph test, per contest rules at the time for the winners.

It would be less than a year later when George would awake Thanksgiving morning on his ranch in South Texas. Weather wise, it was an average cool, but not real cold morning. A full buttercup moon was at its peak the night before. Not what any trophy hunter would call ideal timing to catch an ol’ buck off guard in South Texas.

Like any dyed-in-the-wool South Texas hunter, George knew that around noon or late morning would be his best shot to hunt. So as it was, he wasn’t up before light as usual. After breakfast and a little coffee, he would visit with his ranch foreman and talk of ranch work and how the deer were moving. It wouldn’t be until nine o’clock that morning when he would head out to the pasture to hunt a little before noon. It was still cool that morning, and like any hunter, he thought there might be hope of seeing something. After the normal “see you laters” and “good lucks,” he drove off through the heavy South Texas brush.

His path would take him past a root-plowed area that sometimes drew deer to tender young sprouts of weeds. As he approached the area, he slowed down to creep, so as not to disturb any deer that might be still feeding from the night before.

What went through George’s mind and what he saw, only he could tell. Over 300 yards away stood a tremendous high-antler buck, feeding among several does. The ignition key was slowly turned off, the truck door came open ever so slowly, and with a careful rest across the hood, a single shot rang out.

The huge buck buckled as the hissing shot made a solid whop! The buck went down, but was still crawling. George chambered another round and let loose again. Another solid hit was heard, but the buck still kept crawling. Finally with a third shot, the big buck was motionless.

I’m sure ol’ George’s heart was thumping as he carefully measured off 380 walking steps to the downed trophy. He raised the head of the monarch and counted 14 points. The tines were tall and rugged. I’m sure it looked “Book” to him!

Being biologically and management minded, he checked the deer’s teeth for wear. He judged the deer to be at least 7½ years old. After gutting the buck, he returned to show off the buck to his son and ranch foreman. It was evident to all, the buck would surely make “Book”!

I’m sure as George drove into Cotulla, memories of the disappointment from the year before must have gone through

his mind. This year would be different. He had entered the Los Cazadores contest early.

Later in Cotulla, official scorer and Los Cazadores Whitetail Tournament board member Darwin Avant would score the Strait buck at 191 gross Boone and Crockett points, with a net score of 1832⁄8

I’m sure many of you reading this story have only one thought of entering this competition, or you might not have known that you must register prior to entering, much the same as George thought in 1987. If you can afford it, do it now! You might just be the one that brings in a buck that could rival George’s great buck!

Remember, this contest is based on gross Boone and Crockett points. When a man takes a “Book” deer in South Texas on Thanksgiving Day, there’s no telling what may come out of the brush this season, plus, we have a longer season for South Texas hunters. On the other hand, George; if you’re reading this, you may just be getting warmed up.

Contestants with bucks to be entered in the Los Cazadores contest should stop by the “chuck box” grocery store in downtown Cotulla on South I-35.

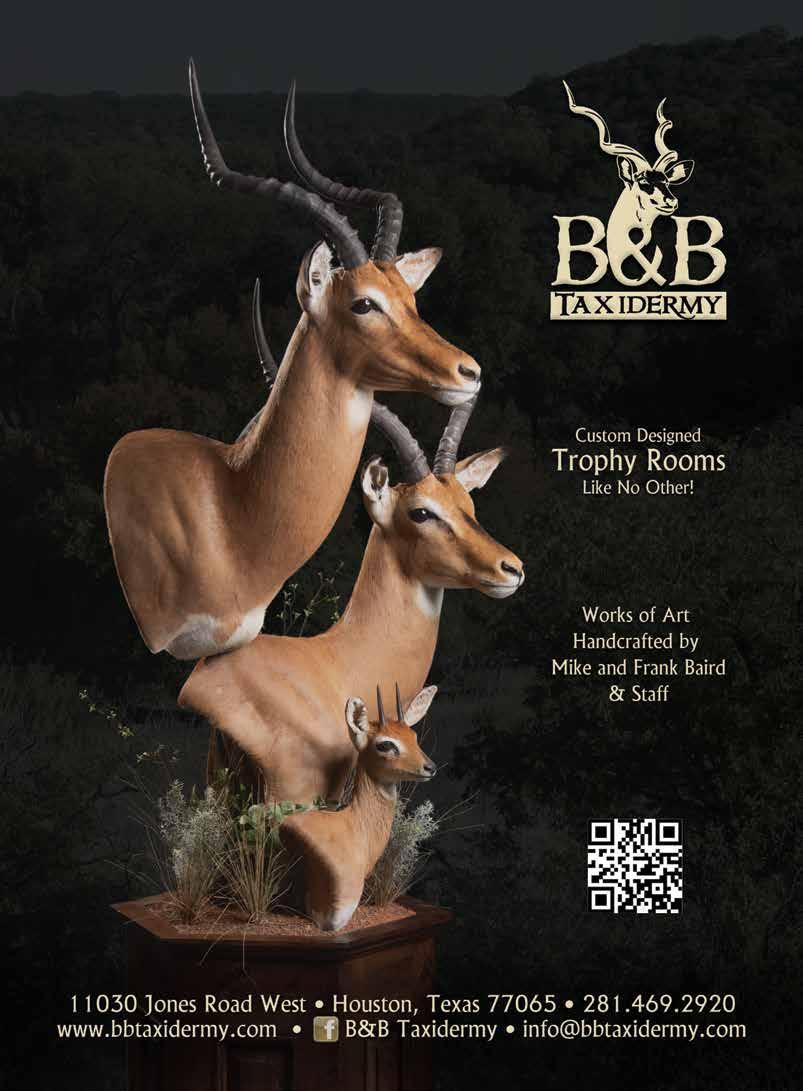

This scimitar-horned oryx is just one of many exotics that

Four miles north of Mason located in the Llano Uplift and Central Mineral Ecoregion lies one of the state’s most unique wildlife management areas (WMA), Mason Mountain. The high fenced 5,301 acres contains diverse terrain from limestone hills to granite soils and deep sands. Blackjack oak, post oak, live oak, and Texas oak dominate the landscape with scattered mesquite, a bit of cedar, and assorted brush and grass species.

WMAs are for research and Mason Mountain is no exception. Research and wildlife are their chief priorities. Native and exotic wildlife call it home. Land management practices such as controlled burning take place along with various demonstrations year-round for professionals, K-12 students, and university study groups.

Hunting is just one tool used for studies and controlling numbers. Whitetail deer populations here are much lower than most Hill Country properties as they strive for one

deer per 12-15 acres. Dove hunting, requiring a hunting license and Annual Public Hunting Permit, takes place in certain areas during dove season.

Gemsbok and scimitar-horned oryx also call Mason Mountain WMA home. TPWD offers hunt packages for both. In 2024 these hunts garnered 34,764 applicants. Nearly 3,000 hunters applied for Mason Mountain WMA whitetail hunts selected by drawing.

Worried that Mason Mountain’s history might not be preserved, Mark Mitchell of the TPWD Wildlife Division researched and interviewed various people to put together written documentation. Mitchell also serves as the current manager of Mason Mountain, where he’s been since 1999. He has a vast knowledge of the area, topography, and wildlife.

Originally the property was known as the Thaxton Ranch, settled in the late 1800s as a working livestock ranch. The family lived in Mason, and few structures were created on the ranch. There are several stories regarding the family and land, but sadly, none could be verified.

In the early 1960s to the 1980s, the property, consisting of approximately 8,500 acres, belonged

to Ferd Slocum. He ranched and hunted but later leased the grazing and the property was over-grazed. The ranch was sold to a buyer group in 1982, and 2,500 acres across Blackjack Road was sold.

The remaining acreage was sold to C. G. Johnson in 1984. Johnson had previously donated what is now Elephant Mountain WMA near Alpine to Texas Parks and Wildlife. A passion for conservation and wildlife with specific interest in desert bighorn sheep led to his generous gift to Texas. He did not want Elephant Mountain to be a park but held for wildlife research, management, and hunting as it is today.

Johnson divided his Mason Mountain ranch into eight high-fenced pastures, and stocked 16 exotic species including zebra, elk, ibex, nilgai, sable, impala, oryx, waterbuck, blackbuck antelope, and axis deer. Earthen dams were constructed to improve water sources, add irrigation to certain fields, and keep shallow lakes filled.

Johnson wanted a place for he and his friends to hunt, but he would not offer the ranch to commercial hunting. He preferred to raise and sell some animals to other ranches. He added working pens, improved structures on the ranch, and had a nice lodge with a view built. In the mid-1990s, Johnson wanted a ranch closer to his Houston home and began the donation to TPWD.

Journal Editor Horace Gore, a retired TPWD whitetail biologist, was a close friend to Johnson. Gore spent many days spring turkey hunting and guiding turkey hunters. One of his pleasures with “C.G.” was competing with their .22 rifles, shooting at various targets from the lodge porch.

“I have fond memories of Mason Mountain. Mr. Johnson was a fine man, and we shared some great sunrises and sunsets hunting spring turkeys on this exceptional place,” Gore said with a smile. “Mason Mountain had Rio Grande turkeys thicker than fleas on a javelina.”

The gift suggestion was met with resistance from TPWD Commissioners because state resources were thin at the time. After much discussion, officials determined the property was too valuable to pass, partly due to its centralized location. It took two years and much effort on Johnson’s part to complete the transaction.

The exotics on the WMA presented a problem for TPWD.

Over the years, various programs were implemented, including guided hunts to generate income but also remove animals for management purposes. Today, whitetail deer, gemsbok oryx and scimitar-horned oryx are the main species. A handful of axis, one greater kudu cow, one blackbuck antelope, and a couple aoudads share parts of the ranch.

“Most folks don’t realize there can be problems with exotics,” Mitchell said. “Some species don’t get along with other animals or people, while certain ones like gemsbok and scimitar, can interbreed so we keep them separated.”

“As a research facility we decided to reintroduce collared peccary (javelina), blacktail prairie dogs, and Texas horned lizards to the area. All were once native to central Texas.” Mitchell said. Success has been limited but he says they currently have about six javelina herds of approximately ten animals each.

“Our prairie dogs number about 60, but they are hard to count,” Mitchell said. “This is our most successful stocking so far and we’re excited that two burrowing owls are using the prairie dog town as well.”

“The Texas horned lizard is fragile and very difficult to count as they’re spread out over a mile. Texas Christian University is doing the lizard research and all the work. We provide the area and facilities as needed for them. It’s an interesting project.”

The WMA is not open to the general public. Mitchell stated he cannot imagine what it would look like with thousands of visitors per year like Texas’ state parks and nature areas. However, in November 2022, an additional 200 acres near the entrance gate were purchased.

This property increased public dove hunting opportunity and is open for public self-guided tours to observe Hill Country wildlife management practices. Some demonstrations are also held there. Please call Mason Mountain WMA for more information regarding access to this area.

As with other WMAs across Texas, Mason Mountain is vital to our heritage and preservation of wildlife along with the pristine, native landscape.

We’re thankful to folks like the late C. G. Johnson for his foresight and generosity.

I’ve invited Dad several times over the past few years to come hunt, but he wasn’t particularly interested. Hosting two weekly church services in his barn and maintaining multiple rental properties on his 4½-acre farmstead, he’s the busiest nonagenarian you’ll ever meet. If the weather wasn’t idyllic, or if he felt he couldn’t afford to get away for a few days, he wouldn’t commit to the long drive.

I asked him if he had hunted as a young man and the only time he could recall was once around 1954. He was the driver and managed to chase a nice buck to the waiting hunters. That was as close as he’d come to his own hunting success. Sometime in the late ’70s, a pastor friend of his took him hunting in East Texas. He sat uncomfortably all day in a treestand and decided if that was hunting, it wasn’t for him. Around the same time in suburban Houston, Dad found a doe trapped and suffering in a field fence. The sheriff was called, and he agreed to let Dad take her. I guess you could argue he’d “taken” a deer before, but that hardly counts.

Growing up on a farm in South Dakota during the dust bowl years, he was well acquainted with raising and slaughtering livestock, but killing for sport is anathema to his gentler sensibilities. This season, my invitation took a different approach. Instead of asking if he wanted to come “hunt,” I offered him an opportunity to come “harvest” some venison instead. And just for good measure I suggested, “If that’s something on your bucket list, I’d like to get that done for you.” He accepted tentatively at first, but the kernel once planted began to take root. Over the next several weeks whenever we spoke on the phone, he made it clear he was planning on it. He kept me updated on his preparations, like when he made the trip to Academy to get his hunting license, or when he arranged for his generous lady friend to drive him up. I could tell he was truly looking forward to it.

In order to make the experience as comfortable as possible, I picked up a little .308 Ruger and quickly worked up a light recoiling load, then fitted an extra soft butt pad.

On my 41-acre ranchette in southern Coleman County, I have a semi-finished barndominium. A couple years ago I installed a window upstairs in the sleeping loft then set up a corn feeder and trail

camera just inside the tree line about 100 yards away. Don’t judge me for my lazy man’s deer blind, but to my way of thinking it’s not for hunting so much as just filling the freezer with doe meat. Besides, who wouldn’t want to roll out of bed, grab a cup of coffee, and be on-stand without so much as changing out of your pajamas?

Friday night we sat at that window, watched a couple deer casually feed, and rehearsed how the morning’s hunt would go. I got Dad settled behind the gun and carefully lined up the tripod rest in the direction of the feeder. I showed him a video on the virtues of the high shoulder shot, and we discussed at length where to aim. All we needed was a good night’s sleep and for the deer to follow the script.

Dad’s friend, Sharron, joined us, and we settled in well before dawn. A muzzle brake inside the open window could be deafening so we donned ear plugs, which for 92-year-old ears made any further communication between us dicey at best. Legal shooting light had barely arrived when Sharron announced,

“Here they come.” A doe/fawn pair were indeed headed toward the feeder, albeit not from the anticipated direction.

Three of us crowded around one window meant the deer were out of my sight until they advanced a bit further into the field. Dad quickly readjusted the tripod so he could point in their direction. I tried to tell him to wait for them to come all the way to the feeder.

Either he couldn’t hear me, or was too caught up in the moment because in the next instant, he had already pulled the trigger. If you’ve ever been hunting with an impatient kid, you’ll understand. I looked up just in time to see the doe jump 6 feet in the air then quickly disappear into the nearby brush.

Dad, not familiar with the bolt action, urgently tried to get me to load another round in the gun so he could shoot it. Who was this killer sitting with me? I hesitated, but being an obedient son, obliged. However, by the time we managed to chamber another round, everything had headed for cover.

Dad was positively giddy. Having seen her reaction to the shot, I thought it was very likely the doe was hit hard and wouldn’t require tracking. So, we headed down to put our hands on her.

But when we did, we found nothing. No hair, no blood, nor the torn-up ground to indicate where she had launched herself. I was still confident she hadn’t gone far, and for the first half hour or so, I trudged between the prickly pear and mesquite thorns but found nothing.

I called for reinforcements. My buddy Mark, who was hunting on the other end of the property, returned to help us search. We decided our best chance was to put Mark high up in the bucket of the tractor so he could glass down into the scrub for any sign. He’d glass, then we’d move the tractor a bit, then he’d climb in again to glass some more. Finally, while walking ahead of the tractor, he spotted some blood right in the middle of the path, about 150 yards from where she’d been shot. It was

very sparce and not particularly encouraging, but with diligent searching, we eventually found her nearly 300 yards from where she started her final sprint.

Praise God; what a relief. We loaded her in the tractor bucket and met Dad back at the house where I promptly “bloodied” his cheeks, then got the all-important trophy picture. I think the smile on his face says it all.

We dropped the deer off for processing and found she weighed in at 92 pounds. That’s exactly one pound for each of his 92 years. When we got back to town, he saw my wife and said, “You can call me Nimrod, a mighty hunter before the Lord.”

I’m not sure I’ve turned him into a hunter, but once he gets all the breakfast sausage and jalapeño cheese summer sausage back from the processor, he may decide “harvesting” venison IS for him. Will we go again next year? I don’t know, but I hope so. He says it fulfilled a bucket list item, so maybe we need to up the ante next year and add a buck to his bucket list.

Texas has thousands of everyday deer hunters who take thousands of everyday bucks each deer season. They take more eight-point bucks than 10-point, more typical antlers than non-typical, and most typical bucks have antlers with show normal antler development.

Although Texas hunters take a lot of high-quality bucks, the average whitetail will probably score less than 125 gross and have brow tines less than 4 inches. For the 200,000 typical bucks taken in the 27-county area called the Hill Country, you could probably count all of the brow tines over 4 inches on your fingers and toes.

A majority of the state’s bucks come from the Edwards Plateau and East Texas where 2½- and 3½-year-old bucks are more common than not. With all this said, Texas hunters take some 400,000 whitetail bucks from a variety of habitats each season, with an assortment of antlers that would fill a large photo album. Occasionally, a hunter will take a buck with odd antlers that no one has seen before. Enter Sarah Parker of Fort Worth with her “super-brow” buck.

Sarah hunts the bottom land habitats of the Clear Fork of the Brazos in Shackelford County. In 2023, she hunted for a buck with rare brow tines like many of us have never seen—straight up 12-inch brows that match the long G-3 and G-4 on each beam. A peek at the photos in this story will show what we mean by “rare.”

Antler characteristics vary, but the typical whitetail buck has two brow tines, G-1, much shorter than the other tines, and develop close to the antler burr. The next longer point is the G-2 that appears close to the curve of the main beam, and additional points—G-3, G-4, etc.—spaced regularly toward the tip of the beam.

Typical points are more often matched from side to side, than not. Sarah’s ninepoint was nothing like any whitetail buck that has ever been brought to the Hunters Extravaganza in 50 years of deer competition. The long brow tines are unlike any antlers many of us—who have seen thousands of typical bucks—have ever seen. I got Sarah’s story on this rare whitetail she killed on a 3,000-acre ranch that she and

her husband manage for a friend.

Sarah grew up in Fort Worth and married Juston Parker, also of Fort Worth, who had spent a lot of time in Shackelford County as a young man, working for his uncle near Moran. Juston is involved with oil and fracking, and also guides hunters on properties in and around Shackelford County.

Some years ago, Juston and Sarah made a deal with the owner of a 3,000-acre ranch along the Clear Fork to manage the wildlife and watch over the place in exchange for hunting

privileges. This arrangement has worked well through the years, and the Parkers—Juston, Sarah, and their daughter Hannah—have enjoyed deer, turkey, hog, and varmint hunting. The ranch runs cattle, and has not been hunted commercially. Sarah spends as much time as she can on the ranch, feeding the wildlife and carefully watching some of the deer as they grew older—one buck in particular that showed extreme brow tines when he was two years old.

Sarah is a hunter, par excellence, and has taken all manner of game animals with her .300 PRC Custom Magnum. She also shoots a 7mm STW Magnum, and both rifles have muzzle brakes to counter recoil. Anyone who is familiar with either of these “hot” calibers can see Sarah doesn’t fool around when it comes to firepower. She uses the custom 7mm and .30 caliber Magnums on ranch whitetails and hogs, as well as larger animals such as elk, nilgai and oryx on local high-fenced ranches.

Hannah is also an avid hunter. She spends her time between the ranch and college at Denton. Hannah also has a favorite 7mm STW with a muzzle brake that she uses to whack a lot of native and exotic game.

When deer season opened in 2023, Sarah had her eye on the unusual buck with foot-long brow tines and planned to sack him with her .300 PRC if she got a good shot. The buck was thought to be 5½ years old, and Sarah wanted to get the unusual deer before he wandered onto a neighboring ranch and got killed by one of the many hunters. She had watched the buck for three years, and knew a lot of his daily habits.

“In early October, we had seen the buck in velvet, and he was just outstanding. I told Juston that I wanted to take him when the season opened,” Sarah said. “I got carried away with looking for the buck, and on one occasion I scared him so bad that he practically disappeared! I lost him in the wild, and didn’t see him for a month.”

“The season opened, and I took the .300 PRC to my favorite blind, while Juston went to a blind that offered a long shot in some open country. I was having fun with a young deer that had come to some corn that I had thrown. He wasn’t afraid of me, and we were eying each other, when my phone rang and Juston said, ‘Your boy is here!’”

“I’m coming,” Sarah told Juston and started her exit from the blind so as not to disturb her little friend. With rifle and gear in hand, Sarah journeyed back to her truck and headed toward Juston’s blind. She parked a good distance away, and took notice that the wind was in her favor as she walked toward the blind, looking for the buck.

“I had a good idea where the buck might be because he had come by the stand before season and spent a lot of time in some tall prickly pear. I slipped up to where I thought he might be, and there he was in the pear—his antlers so tall I could see him clearly. Without hesitation, I got him in the Night Force scope and pulled the trigger on the .300 PRC. The buck dropped in his tracks, in the middle of the prickly pear patch! We had a

won first place in the Adult Female-Open Range Division at the San Antonio Hunters Extravaganza.

hard time getting him out of the prickly stickers, but it was worth it.”

Sarah is no stranger to the Hunters Extravaganza Annual Deer Competition. She found her TTHA membership card and took the buck to Fort Worth to enter the Adult Female-Open Range Division. To her surprise, she got to the show too late to enter the buck by 4 p.m. on Saturday evening. However, the San Antonio show was scheduled for the following weekend, so Sarah took the deer to San Antonio and won first place in the Adult Female-Open Range Division.

Our hats are off to Sarah, a seasoned hunter who can hold her own on any hunt. We hope to hear from Sarah and Hannah in the future as they sniff the trails of Shackelford County, looking for signs that will get them a big whitetail, a rank old boar, or even a long beard for the Thanksgiving or Christmas table.

Bruce Brady, left, guided clients and friends such as Kevin Howard, right, for many longbeard turkeys.

By Gary Roberson

Bruce Brady from Brookhaven, Mississippi, was my mentor and turkey hunting partner for many years. When we weren’t calling for clients, we were calling for friends and family. On many occasions, I witnessed hunters doubling on multiple birds.

Bruce taught me the rules of ethical turkey hunting that a true sportsman should observe. Here are a few of the rules I live by when hunting turkeys in the spring.

Rule #1: Only kill a turkey that has been called within shotgun or bow range. If you can’t trick him, he beats you. Try to improve your game and go after him another day.

Rule #2: When calling multiple birds, pick out the dominant bird (strutting gobbler). When it’s clear to kill him and only him, take the shot. Never wait until several birds line up so that you can kill multiples with one shot.

Rule #3: Doubling up is best described when multiple birds respond to calling and the first hunter takes one bird, and his/her partner takes the second. Doubling is an ethical practice in the hunting woods.

Rule #4: Never spook turkeys around the roosting area. For this reason, I don’t hunt turkeys until about an hour after sunrise and stop hunting them about 30 minutes before sundown.

Rule #5: Never shoot a hen or a jake; longbeards only.

Rule #6: This is my personal view and not one that’s accepted by all true turkey hunters. Never use a decoy. I try to set up, so the gobbler has to come looking for me rather than depend on a decoy to close the deal. Again, if I can’t call him into shotgun range, he beats me, and I tip my cap to him. It’s all about sportsmanship.

In the years hunting with Bruce, I had witnessed several of our hunters double on gobblers. I have seen Bruce and his wife double, Bruce double with

his kids and a couple of his grandkids. But with all of the birds Bruce and I called, we had never doubled.

In spring 1998, Bruce and I were hunting with his grandson, Matthew Mooney, on the Gainer Ranch, north of Menard. About mid-morning, we called two longbeards. While it took nearly an hour to convince them we were the “real deal,” we finally saw them strutting through the agarita and mesquite, nearing shotgun range. I sat behind Bruce and Matthew and made one last series of soft yelps to bring the big strutter within 35 yards of Matthew.

At the report of his 20-gauge, the second bird alerted and raised his head without taking flight or running. Bruce made him pay for his mistake. This was the first time Bruce had ever doubled with his grandson.

We hunted again that afternoon and finally raised a bird on the eastern side of the ranch. As luck would have it, turkeys were moving in our direction as they made their way to the roost along Celery Creek about half a mile to the west. There was one big live oak tree surrounded by scattered agarita and wild persimmon bushes. I told Bruce this tree would be where we would need to set up because it was large enough to conceal him and Matthew. I would take cover off to the right side of the tree, under a dense persimmon.

Since the birds seem to be moving in our direction, we called sparingly. When we did call, I could hear two or perhaps three birds answering. After half an hour, I could see numerous turkeys moving through the scattered cover, headed directly to the lone live oak. There were six hens closely followed by two longbeards, and approximately 30 steps behind the two gobblers was a third longbeard.

I could see that Bruce was on his gun, tracking the strutter. Something was wrong, because he was letting them get way too close as a couple of the hens had already passed to his right. But I realized

what he was trying to accomplish. He was waiting to take the shot in hopes the gobbler in the rear of the flock would get into shotgun range so he and I could double.

At 11 steps, Bruce almost decapitated the lead tom. I was ready to take a shot at the gobbler on the wing as the flock had taken flight to the west and I expected him to follow suit. To my surprise, the tom broke running to the east. I leveled on the back of his head and took the shot at about 45 steps. This is when things got really interesting.

Instead of rolling up in a ball of dust and feathers, the old boy took flight, but not the kind of flight you would expect. Being somewhat idled with a BB to the brain, he took off like one of Elon Musk’s rocket ships not headed away, but straight up. I have seen doves get a pellet to the brain do this same maneuver on several occasions. I cranked off the other two rounds from my shotgun, but if I made contact, the bird didn’t show it. I leaned the empty shotgun against the persimmon and gave chase to a gobbler

still attempting to gain altitude.

Twenty-six years ago, I was still able to break into a run and the race was on!

At an elevation of approximately 70 feet, the rocket lost propulsion, cupped his wings and began his descent, flying in a tight circle. I came up with a great idea. I would try to catch the tom out of the air, a feat I had never seen or even heard of.

Running and trying to avoid rocks, bushes and prickly pear while keeping an eye on the earth-bound bird was more than I could handle. Approximately five steps short of where the bird would make landfall, this hunter hung his toe on a rock, which brought him to the ground. I rolled a couple of times and about the time I made it to my knees, the tom hit the ground with a heavy thud.

Disappointed I didn’t make the catch, I jumped onto the back of the gobbler to salvage what I could of the event. To my surprise, there were no broken wings or legs, and the fight began. I had to keep his feet pinned to the ground because he was trying his best to hit me with his spurs. I finally wallowed around and got

Gary’s guidelines say never to wait until several birds line up so that you can kill multiples with one shot.

astride of the tom as if riding him, which freed up my hands to grab his neck. He was pretty good at pecking me until I got both hands on his head and neck.

By this time, Matthew had made it ringside and laughed and whooped himself into hysterics. I wasn’t enjoying the event too much until I finally broke the old bird’s neck. I had the situation in hand by the time Bruce arrived. laughing so hard he was crying.