Well, another year is in the can, and I’m trying to remember any good that came with 2024. Of course, we voted in a new president. We’re winding up another good deer season, and the state is exceptionally dry. Other than politics, 2024 was a year of hurricane disasters and hopes for the future.

In the last 12 months, I got a little longer in the tooth. We lost music stars Toby Keith and the incomparable Kris Kristofferson. And Al Brothers and I celebrated 66 years as bueno compadres at the annual Wayne Spahn barbecue at Gonzales.

Texas Trophy Hunters concluded its 48th year of Hunters Extravaganzas, with SCI joining in to power the deer competition. The annual shows in Houston, Fort Worth, and San Antonio have a long history of bringing outdoor enthusiasts together for fun, frolic, and the best in outdoor gear.

The coming year will be big for TTHA, as the association celebrates its Golden Anniversary, and many activities will show 50 years of the “Voice of Texas Hunting.” The Journal staff has printed a new book, “Stringtown to the Kokernot,” as a keynote publication for the anniversary year.

The past year was good for Texas hunters. Rainfall was double that of 2023, bringing good habitat conditions for all manner of wildlife. Ground-nesting birds such as turkey and quail prospered in the wetter environs. White-tailed deer showed exceptional antlers, and many “Trophy Hunters of Tomorrow” bagged their first buck. The various deer contests across the state were chucked full of big bucks from Texas, Mexico, and out-of-state.

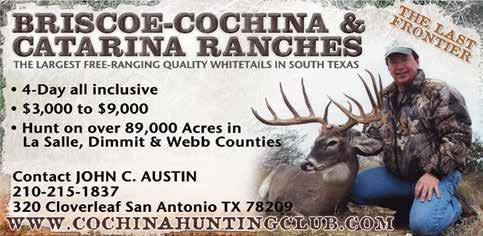

Texas is arguably the capital of whitetail hunting in America. The habitat is here; the deer are here; and the hunters are here, making for the best in deer hunting in the nation. The success rate of one deer per hunter is the highest anywhere, putting Texas in a realm of its own as a deer hunting state.

Some big things are coming in 2025. TTHA and SCI will conduct an Outdoors Extravaganza in Dallas. The three-day hunting, fishing, and outdoors event will be held Jan. 10-12 at the Kay Bailey Hutchison Convention Center, with an expected attendance of thousands of outdoor enthusiast in and around the East Texas area.

A brand-spanking new Hunting and Fishing Extravaganza will debut in MidlandOdessa for April 11-13, 2025. TTHA will host a three-day hunting and fishing show at the Midland County Horseshoe Arena with all of the attractions Texans are familiar with at Hunters Extravaganzas, plus a good showing of fishing gear that will be attractive to the Midland-Odessa fishing crowd. Don’t miss this “first” for the Midland-Odessa area in 2025.

As you can see, 2025 will be a big year, so mark your calendar and be there for the biggest and best of TTHA when we celebrate our 50th Anniversary in 2025. It will also be my 30th year with TTHA, so we can celebrate together. In the meantime, keep ’em running, swimming, and flying by being good sports, and obeying the rules. I’ll see you somewhere down the road.

Horace Gore

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer

Pittman • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

George Blitch, Seth Johnson, John Goodspeed, Judy Jurek, Lee Leschper, Paul Nuñez, Eric Stanosheck, Elizabeth Yates

Sales Representative Emily Lilie 713-389-0706 emily@ttha.com

Marketing Manager Logan Hall 210-910-6344 logan@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events

Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com Graphic Designers

To

Advertising Production Deborah Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Membership Manager Kirby Monroe 210-809-6060 kirby@ttha.com

Did you know in the past 6 years, the Texas A&M chapter of Texas Trophy Hunters Association has seen over a dozen marriages come out of the chapter? When you mix countless hours of time spent together, with shared values and passions, it creates the perfect recipe for love. So, if you’re looking for someone special, or a special whitetail, look no further than the collegiate chapter of Texas Trophy Hunters Association on your campus. Want to start one on your campus? Email kirby@ttha.com for details. Happy Valentine’s Day!

Mason William Monroe made his world debut Oct. 30, 2024. The first child of TTHA’s Membership Manager Kirby Monroe and her husband Tyler entered the world weighing 7 pounds, 8 ounces and 20½ inches tall. Welcome to the TTHA family, Mason. Looks like you’re already off to a great start.

Known by most folks simply as

“The Chap,” its name is sometimes whispered with reverence. To deer hunters across Texas and elsewhere, it’s a very special place, where a whitetail buck hunt has been called the best public hunt in Texas. The Chaparral Wildlife Management Area is perhaps the most popular public hunting place in the entire Lone Star state’s vast Texas Parks and Wildlife Department system. Being randomly selected by drawing to hunt on the area is the dream of many Texas hunters.

Nestled in both Dimmit and La Salle counties, The Chap spans 15,200 acres featuring the best natural South Texas brush country. Once a part of the historic Light family cattle ranch, the department purchased it in 1969 with Pittman-Robertson funds. The Rio Grande Plains ecological area serves as both a research and demonstration area while also allowing for planned public hunting.

A wildfire in 2008 burned approximately three-quarters of the WMA. It’s taken many years to grow back from the devastation, in addition to rebuilding a research facility, water supply, and fencing. The main office, however, was spared.

The Chap is a research facility. There is still much to learn every day about our native Texas wildlife. Rotational grazing, controlled burns, and studies

of almost every animal, bird, tree, bush, and grass are just a few aspects examined, explored, and recorded here and at other WMAs across Texas.

Whitney Gann is The Chap’s South Texas ecosystem project manager. Raised in Sugarland, this lady loves science. Her post graduate work included two years of pronghorn research in Alpine before joining TPWD. She’s been at The Chap nearly seven years.

“South Texas research is not the same as other parts of the state,” Whitney said. “We have the risk of exotic grasses with some wildlife species here that may not be in other parts of the state. Currently, Texas A&M is conducting a five-year javelina project. There’s little information on the South Texas collared peccary that we call javelina. They’re interesting and often misunderstood.”

Every year TPWD publishes the Public Hunt Drawing System covering over 1 million acres for adults and youth hunters. As this issue is printed, all public hunt drawings for the 2024-2025 season have occurred.

Each area lists the hunt types and species offered with last year’s statistics of number of applicants, number selected, and success rate. Some places are more

popular due to accessibility, accommodations, and location to major cities.

E-Postcard selection hunts and special hunt package drawings for exotic and native animals also occur on TPWD managed lands and specially leased private properties.

Dates for submission may vary. Go to www.tpwd.texas.gov/huntwild/hunt/ public for more information.

“Much of the javelina research, trapping and tagging, is conducted at night due to cooler temperatures,” she added. “Aerial, spotlight and cameras are all being used. The intent is to learn life history, life cycles, harvest planning, and how to manage them as a resource.”

Whitney likes being part of research. “A prime purpose of The Chap, as well as other WMAs, is hosting educational field days. Area schools bring classes of all aged students to expose them to nature and wildlife. Study projects take place for higher learning institutions,” she said, adding, “UT-Austin is studying and banding green jays at present.”

Long before deer breeding and supplemental nutrition became commonplace in Texas, the Chaparral WMA became known as the best place for the average hunter to possibly take a trophy whitetail buck. Deer hunting on TPWD land involves registering for annual drawings for a limited number of slots (see sidebar).

Hunting’s important role is two-fold by providing opportunity for hunters as well as managing the carrying capacity of the habitat. Each year game surveys are conducted while monitoring drought, rainfall, and habitat conditions. Harvest numbers are based on recruitment (fawn crop) and the number of mature animals observed during an annual survey. South Texas has good years and bad, thus harvest numbers may fluctuate year to year.

These factors determine if and when public hunts will take place, as well as the harvest goals for each species. They help establish the number of hunters and standby opportunities. Being selected for a Chap hunt is a thrill that also comes with many challenges.

In 1992, The Chap conducted its first ever four-day hunt. The goal offered hunters more days to take mature bucks, not

hunts also allow unlimited coyotes and feral hogs. The ePostcard multi-species entries must possess an Annual Public Hunting Permit (APH). Some hunts allow for quail and rabbit hunting.

If selected to hunt a WMA or state park (SP), you’ll be notified and must pay for your spot(s) in advance. No refunds. If unable to make the hunt date, it’s a great courtesy to advise the WMA you or your group won’t show. By cancelling, you may allow standby hunters, but if TPWD isn’t advised, they cannot release your spot(s). Standby hunters, if selected, pay their fee and hunt immediately.

It’s always advisable to call the WMA or SP beforehand to see if there may be standbys. Some places do not offer any and a call may save you a trip.

just the first antlers encountered. This writer and husband John were drawn as standby hunters. John killed a 6½-year-old typical 12-pointer. With a 24-inch spread, it grossed 165 6⁄8 . At the time, his was the largest ever killed on the high fenced area.

Outdoor writer and author Larry Hodge of Athens was once drawn for a buck hunt on the famed Chap. “The biggest buck I’d ever seen that I could legally shoot walked out—and I missed!” Larry said with exasperation. “Just plain ol’ buck fever! I still dream about that buck, that shot, that day as I know it won’t happen again. But it’s still a great moment in my life.”

The Chap isn’t just about hunting big whitetail bucks with archery or gun. This year’s categories included javelina, youth only antlerless/spike hunts, and either-sex deer hunts. Most

The 2023-2024 season totaled over 7,000 adult and youth-only applicants for seven different hunts. Approximately 143 permits or groups were allowed to hunt, achieving a 50% success rate for six of the hunts (one exempted success rate).

Today’s technology offers many features that enable hunters to prepare for a hunt. With different apps, an area and terrain can be studied in advance of hunting a particular pasture. Plan ahead for weather changes, and above all, practice and know your shooting ability. Obey the Boy Scout rule and “be prepared.”

Whether successful or not, hunting The Chap is a grand opportunity and a bargain. In fact, public hunting on any TPWD land can be relatively light on the pocketbook compared to private guided or lease hunts.

Mark your calendar now to check TPWD’s public hunting in August to apply for your chance to hunt the Chaparral WMA. Non-hunters should check on wildlife management field days, workshops, and nature tours. The Chap’s roadways and trails offer driving, hiking, biking, primitive camping, and wildlife viewing from April 1 to August 31.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department officials announced the retirement of Wildlife Division Director John Silovsky effective Oct. 1, 2024, after more than 10 years with the agency. After a successful first career as a wildlife biologist with the Kansas Department of Wildlife, Parks, and Tourism, Silovsky came to TPWD’s Wildlife Division as a district leader in Tyler in June 2014. He was promoted to TPWD’s Austin headquarters as the wildlife deputy division director in February 2019, and into the wildlife division director role in November 2020. He is an avid hunter and angler, and now gets to spend more time enjoying outdoor pursuits.

Effective Oct.1, 2024, Meredith Longoria, TPWD’s wildlife deputy division director, was temporarily promoted into the interim wildlife division director role while the position is advertised and until it is filled on a more permanent basis, officials said. Meredith has a bachelor of science in biology and a master of science in wildlife ecology from Texas State University. Meredith’s approximately 20-year career with the TPWD wildlife division has encompassed a variety of positions that include deputy division director, non-game and rare species program leader, conservation initiatives specialist, and private lands biologist.

“John Silovsky has retired from two careers, and we wish him well,” said Journal Editor Horace Gore. “The wildlife division is an important part of TPWD, and we welcome Meredith in her role as interim division director,” he added.

—TTHA staff

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department announced the winners of the 2024 Big Time Texas Hunts. Kevin Hirt, of Garden City, won the newly added Trans-Pecos Aoudad Adventure, a challenging freerange hunt with professional guides for a mature male ram in the Chihuahuan Desert. A portion of the proceeds from this hunt goes directly to desert bighorn sheep restoration and research efforts. Hunting aoudad positively impacts bighorn sheep by lowering the number of competitors and reducing the spread of disease and grazing pressure on the habitat.

Winners from other categories include:

• Big Time Bird Hunt — James Sanford, Brenham

• Exotic Safari — Stephen Reid, Odessa

• Gator Hunt — Roger Wooley, Graham

• Nilgai Antelope Safari — Christopher Shrum, Canyon Lake

• Premium Buck Hunt — Larry Tatom, Kingsland

• Texas Grand Slam — Lynn Betts, Pleasant View, UT

• Ultimate Mule Deer Hunt — Robert Pennington, Bulverde

• Whitetail Bonanza — Curtis Luchak, Freeport; Cynthia Day, Wolfforth; Jeffrey Manley, Houston; Sandra Compton, Santa Fe; Winfred Menzel, Fort Worth

• Wild Hog Adventure — Douglas Carvan, Cedar Creek

The 154,032 entries raised more than $1.39 million to support wildlife research, habitat management and public

hunting across the state.

“We want to congratulate the winners, but also thank all the hunters who bought an entry, and the outfitters and TPWD wildlife biologists who created and executed the hunts,” said Janis Johnson, TPWD marketing manager. “This year we added a new hunt, the TransPecos Aoudad Adventure, which generated a lot of interest. The Big Time Bird Hunt saw the addition of wildlife game chef, Jesse Griffiths, to the turkey hunt as a guide and chef and was a tremendous hit with Texas hunters.”

Entries for the 2025 Big Time Texas Hunts go on sale May 15.

—courtesy TPWD

Denise Welker, a longtime supporter of SCI and SCI Foundation, has been elected president of Weatherby Foundation International. The Weatherby Foundation presents the prestigious Weatherby Foundation Award annually and will do so at a Jan. 22 Gala during the SCI Convention in Nashville.

Welker has led SCIF’s Women Go Hunting program as chairperson. The program has unified many women in the hunting world and has grown year over year. Women Go Hunting events are also scheduled during the SCI Convention.

“I am very excited to be a part of bringing Weatherby to SCI,” said Denise, who’s also a Texas Trophy Hunters Association Platinum Life Member. “My hope is that SCI members will join us at the Weatherby Gala on Jan. 22, 2025, to celebrate Eduardo Negrete, our Weatherby Award winner this year. Our Gala

and auctions are how we raise funds to support our mission, which is to educate youth and the non-hunting public on the beneficial role of ethical sport hunting and its contribution to wildlife conservation and to protect our constitutional rights to do so.”

Denise also has received numerous hunting awards, including SCI’s Diana Award in 2017, the SCI Fourth Pinnacle of Achievement, the Zenith Award and the Crowning Achievement Award. Denise and her husband Brian, SCIF President, received the Beretta and SCIF Conservation Leadership Award in 2020.

She most recently achieved SCI’s World Hunting Award and is now pursuing SCI’s World Conservation & Hunting Award, the highest award in the SCI World Hunting Award program.

“I am excited that Denise Welker was named president of the Weatherby International Foundation,” said W. Laird Hamberlin, SCI and SCIF CEO. “Denise is the right person to guide the Foundation, which has entered into a new partnership with SCI that we will see on Wednesday night during our convention in January. SCI and SCIF congratulate Denise on her election and the Weatherby Foundation board on this forwardthinking choice.” — courtesy SCI

On Oct. 8, Safari Club International announced the launch of Sporting Conservation International, an inclusive, forward-thinking parent corpora-

tion that will protect and advance the conservation of wildlife and wild places by unifying conservation’s most active and passionate stakeholders – hunters, anglers, wildlife scientists, and the men and women around the world who make up the outdoor sporting community –under one roof.

As threats against science-backed conservation and the right to hunt and fish become more severe and global than ever before, Sporting Conservation International will allow affiliate organizations aligned with this critical mission to coalesce under a single corporate entity. In doing so, Sporting Conservation International will be a global powerhouse for advocacy and wildlife conservation, creating a cohesive outdoor sporting community that is better equipped and more resourceful than our opponents.

Sporting Conservation International’s member and affiliated organizations boast an audience of millions of individuals among Safari Club International, Safari Club International Foundation, Texas Trophy Hunters Association, Cinegética, and other aligned entities and companies operating in the U.S. and internationally. Moving forward, any entities similarly focused on hunting, angling, shooting sports, conservation, or the outdoor lifestyle are also eligible to become part of Sporting Conservation International.

Organizations that become part of Sporting Conservation International will retain their brand identity while securing significant operational cost savings and access to additional marketing and sales opportunities at other affiliate organizations’ dozens of conventions and events. For example, one of the first affiliate organizations saved $180,000 in printing and publication costs during its first year after acquisition.

Importantly, members of Safari Club International will see no changes to the facets of the organization they know and love. For example, Safari Club International’s infrastructure, including the national organization’s relationship with its local chapters and members, will remain unchanged. They will still be part of Safari Club International and enjoy the same autonomy in operations as in

the past. Moreover, Safari Club International’s Annual Hunters’ Convention and Ultimate Sportsmen’s Market will remain under the direct control of Safari Club International and will be unchanged by the formation of Sporting Conservation International.

“United we stand, and divided we fall,” said Safari Club International and Safari Club International Foundation CEO W. Laird Hamberlin. “The formation of Sporting Conservation International is a landmark development for the hunting, shooting, angling, and outdoor life advocacy community. As we converge and build under this banner, I am thrilled about the victories that lie ahead in the battle to safeguard our rights and ensure responsible wildlife and habitat conservation in the U.S. and around the world.” — courtesy SCI

On Oct. 21, Secretary Tom Vilsack of the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) issued a Secretary’s Memorandum that will direct agencies within USDA to improve and conserve terrestrial wildlife habitat connectivity across the country.

This effort will help bolster the conservation of migratory wildlife habitat by providing direction to enhance interagency coordination within the USDA as well as interdepartmental coordination with other important entities such as the Department of the Interior and state fish and wildlife agencies. This memo provides direction to important USDA agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Farm Service Agency, and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service to implement science-based decision-making as it relates to conserving and restoring wildlife habitat connectivity. This effort builds upon other actions by USDA to conserve migratory wildlife habitat such as the USDA Migratory Big Game Initiative, which has leveraged existing programmatic funding to conduct voluntary conservation efforts

in Montana, Idaho, and Wyoming.

“CSF thanks the USDA for initiating this effort that will help enhance conservation for migratory wildlife and their associated habitats,” said Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation President and CEO Jeff Crane. “CSF will continue to prioritize wildlife connectivity through Interior Secretarial Order 3362, the Wildlife Highway Crossings Pilot Program, USDA’s Migratory Big Game Initiative, the Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships Act, and now the USDA Secretarial Memo.”

Wildlife migration and habitat connectivity continues to be a top priority of the CSF. In September, CSF’s Director of Federal Relations, Taylor Schmitz, testified before the House Natural Resources Committee Subcommittee on Water, Wildlife, and Fisheries on the Wildlife Movement Through Partnerships Act (H.R. 8836). This legislation seeks to solidify Department of the Interior Secretarial Order 3362, which seeks to conserve big game migration corridors and winter range across 11 western states, by providing much-needed funding and expanding this effort nationwide.

Additionally, CSF was a main driver behind the Wildlife Crossing Pilot Program contained in the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, which marked the first time that federal funding was dedicated by Congress to build critical infrastructure for wildlife across roads and highways. Additionally, Taylor Schmitz serves as the Chairman of the American Wildlife Conservation Partners. During his chairmanship, AWCP released Wildlife for the 21st Century, which includes a standalone recommendation related to the issue of wildlife migration. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

The American Wildlife Conservation Partners (AWCP) – comprised of the nation’s top 52 sporting-conservation organizations that represent America’s hunter-conservationists, professional wildlife and natural resource managers,

outdoor recreation users, conservation educators, and wildlife scientists – released Wildlife for the 21st Century, Volume VII (W-21). This comprehensive publication focuses on solutions to conserve wildlife and their habitats across the nation, bolstering public access, and protecting our outdoor traditions.

The recommendations in W-21 will aid policymakers in the next Administration and the next two Congresses in making decisions on sporting-conservation issues and practices that are vital to current and future generations of sportsmen and sportswomen and other conservationists.

“I am proud to have worked alongside the members of AWCP to develop a thoughtful and comprehensive set of priorities that are contained in W-21. AWCP is a unique and collective force, and it is through our coordination, communication, and vision that the priorities in W-21 will be recognized,” said Taylor Schmitz, AWCP Chairman and Director of Federal Relations for the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation. “While this document is intended for the next two Congresses and presidential administration, there are numerous W-21 priorities that can be delivered on in 2024, and we look forward to making that a reality”

Every four years since AWCP first convened in 2000, the partners have put forth their collective priorities in Wildlife for the 21st Century, which serves as the roadmap for AWCP’s vision for wildlife and sportsmen and sportswomen. Although the 52 partner organizations of AWCP may have diverse primary missions, the recommendations contained in W-21 Volume VII represent a consensus amongst the AWCP organizations and shared commitment to advancing and promoting pro sporting-conservation priorities.

The specific recommendations made by the AWCP are featured in nine distinct sections of the report. Each recommendation includes detailed descriptions of the issues and action items to address the issues. These recommendations encourage collaboration and cooperation between federal agencies, state fish and wildlife agencies, and private landowners. The recommendations support the implementation of sound, science-based

conservation efforts.

• Recommendation 1: Funding for Conservation – Protect and secure permanent and dedicated conservation funding

• Recommendation 2: Access – Enhance access for hunters, shooters, and other outdoor recreationists

• Recommendation 3: Wildlife Migration – Institutionalize and support wildlife migration corridors and seasonal habitats

• Recommendation 4: Energy Development – Ensure wildlife and habitat goals are integrated into planning, development, and operations of all energy sources and impacts are mitigated

• Recommendation 5: Private Land Conservation – Incentivize private landowners to conserve wildlife and habitat and provide access for hunting

• Recommendation 6: Active Management of Federal Lands –Increase active management of federal lands and reduce litigation through collaboration

• Recommendation 7: Species Conservation – Achieve greater results from an improved Endangered Species Act

• Recommendation 8: Wildlife Health – Support and assist state fish and wildlife agencies in addressing wildlife health challenges

• Recommendation 9: Climate Change -Sharpen climate policy focus on habitat conservation, restoration, and carbon solutions

The recommendations act as a blueprint for decision makers to lead policy changes that will make a meaningful difference to ensure our country’s unique outdoor heritage remains and thrives for years to come.

While the focus of W-21 is the incoming Administration and new Congress, several of the priorities are still being considered in the current Congress. Wrapping up some of these issues in the 118th Congress will open the opportunity to achieve even more of the recommendations in the coming years.

courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

By Dr. James C. Kroll

In the 1960s, I was a young student biologist at Baylor University, working on my degree in zoology. In those days, biologists were trained classically, with considerable “in the field” experience. We spent weeks in the summer, traveling around the U.S., Mexico and Central America, collecting reptiles, mammals and birds for the Strecker Museum on the Baylor campus. Later, I would even expand my work into South America and Madagascar, describing new species of lizards.

Our days in the field would be spent roaming over the landscape, turning over rocks and logs, hoping to find a new species of snake or lizard. But I somehow always returned to Mexico. Those are some of the greatest days of my life, and it was when I fell in love with Mexico.

I have always favored deserts and tropical forests for some reason; don’t ask me why. I guess it’s the wild and unforgiving nature of these places and their menageries of strange creatures that survive against all odds. Northern Mexico has some of greatest true wilderness left on the planet, and the Sierra Madre country has been my favorite place on Earth now for over 50 years.

I decided that one cannot spend their life roaming around the globe, so I decided my interests would be focused on the western slopes and country north to the U.S. border in what we call the “Mexican Frontier,” including the states of Coahuila, Chihuahua, and Sonora.

It was on a trip to the Sierra Del Carmen (Sierra Maderas del Carmen) that I had my first encounter with a Mexican whitetail. I was working my way through some of the thickest thorn brush you can image, when I broke out into a small opening surrounding of all things, a spring. I must have been moving quietly because to my surprise, I saw a buck drinking from the spring.

I had spent my younger days pursuing Texas whitetails in the Hill Country with my family, and in spite of my interests in non-game animals, I’d become fascinated by white-tailed deer. The buck at the spring did not seem to mind my presence, so I just remained on the edge of the brush and studied him.

He was rather small, even to a man who had hunted whitetails in the Hill Country, with big, alert ears and eight-point rack. He was grayish in appearance and seemed to blend well with the thick brush. I must have watched him for several minutes, while he continued to “tank up” on water. Then, he turned with water dripping from his chin, wagging his long tail wagging, and faded into the brush. I know it was a special moment in my life, since I can remember every detail after all these years of studying whitetails.

carminis). Forty years later, I would produce a segment of North American Whitetail TV on the elusive subspecies, whose range extends into the Big Bend National Park, Sierra del Carmen Mountains, and Sierra del Burro Mountains.

Some years later, I hiked through the mountains in the northwest corner of the Mexican state of Chihuahua, when I had a similar encounter with another of Mexico’s “special” whitetails, the Coues deer (Odocoileus virginianus couesi). I have a set of antlers mounted just above where I have coffee each morning. One of my dearest memories is hunting Coues deer with my friend and colleague, Jesús Fimbres, of the “original”

Returning to camp, I tried to find information on what deer that was, but in those days, not much information was readily available on whitetail subspecies. When I returned to Waco, I was able to look up the subspecies of whitetails, discovering I had met a Carmen Mountain whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus

Rancho Grande in Sonora. Later, I will refer back to how Jesús manages his deer.

The Coues is one of the most unique whitetails on Earth, and there is a lot of “magic and mystery” to this small deer. Few hunters have pursued them, and few ever will; as it has

become a “cult following” to be a Coues hunter. The average deer hunter, as with the Carmen Mountain whitetail, does not appreciate a deer for which the world record typical is “only” 144 1⁄8 inches, killed by Ed Stockwell of Pima County, Arizona.

I have a fine set of Coues antlers above my chair in the living room, and I have lost count of the folks who come into the room, look at the huge whitetail mounts, and ask, “Why do you have that little buck in here with all these big whitetails?” I just smile, and go on about my business.

Heck! The average deer hunter does not even know how to pronounce the name of the subspecies. It was named after Army surgeon and naturalist, Dr. Elliot Coues, stationed at Fort Whipple in the Arizona Territory, and the first to scientifically describe the species in the late 1800s. Dr. Coues pronounced his name “cows,” not “cooz,” so the small group of avid Coues hunters know immediately whether or not you belong to the club.

rare for me to ethically hunt. At 77 years, I think my days for pursuing such a slam are slim. It’s just enough to be able to say

The good doctor’s set of Coues antlers from his Mexico hunt.

I have seen seven of them. So, I will spend the rest of my editorial space, discussing the management of Texas whitetails that inhabit the northern border with the U.S.

While discussing one of my favorite subspecies of whitetails, I feel like I’m intruding on Jim Heffelfinger’s territory, who in my opinion, is one of the greatest deer experts in the country. You may have seen some of the many literary contributions to The Journal by Jim over the years. So, I hope you excuse my intrusion, Jim.

In all, Mexico has at least 10 subspecies of whitetails, including:

• Texas whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus texanus)

• Acapulco whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus aculpulcensis)

• Sierra Del Carmen whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus carminis)

• Coues whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus couesi)

• Mexican whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus mexicanus)

• Oaxaca whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus oaxacensis)

• Sinaloa whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus sinaloae)

• Mexican Lowland whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus thomasi)

• Northern Veracruz whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus veraecrucis)

• Yucatan whitetail (Odocoileus virginianus yucatanensis)

I have always toyed with the idea of hunting the “Mexico Grand Slam” from this list, but alas, some of them are too

When it comes to deer hunting and management, Mexico has been like the “little brother” of American deer hunting. I have spent the latter part of my career, trying to do something about that. Mexico has one of the best environments for private land deer management, in my opinion.

I have worked with biologists all over the U.S., but have never encountered more experienced, knowledgeable and downright helpful biologists than those in Mexico. For two decades, I have worked closely with these great guys, and call many my friends.

Organizations such as ANGADI (Asociacion Nacional de Ganaderos Diversificados Criadores de Fauna), which translated means, National Association of Diversified Cattle and Wildlife Breeders, represents many far-thinking Mexican ranchers who are as interested in managing for ecological diversity as big antlers. Not only have these folks modernized deer hunting in Mexico, they have changed the way deer are managed south of the U.S border. Their key to success has been the goal of keeping Mexican deer “Mexican.” And they’re doing incredibly well. In future columns, I will discuss just how these folks in Mexico are creating a deer hunting nation.

By Horace Gore

Ihave long enjoyed shooting a Winchester Model 70 .270 on North American game, but it hasn’t always been that way. When I was young and money was scarce, I shot any rifle I could beg or borrow. In my days at Texas A&M, I had a $40 war relic Enfield .30-06 that I “sporterized” with a Weaver J2.5 scope on a side mount. My Enfield “deer” rifle was accurate, and I took 15 deer with it, including my first yearling buck in Brazos County in 1958.

I eventually traded the old Enfield .30-06 for a Remington 721 .270 that I used on deer and pronghorns. As I traded up, I got a “tack-driving” Winchester standard Model 70 in .270 from Ernie Davis that I used on big game from the Rockies to Mexico. My good friend, Dean Davis of Gonzales, has the rifle now, and I’m satisfied that it’s in good hands.

Jack O’Connor’s promotion of the .270 sparked my interest about 65 years ago. I looked to Jack for shooting advice, and his regular column in Outdoor Life hooked me on the .270, which has enough hydrostatic shock and bone-busting power to bring down any animal I ever shot at. Handloaded with 60 grains of H4831 in Winchester cases, and a 130-grain Hornady Spire Point, the 24-inch barrel shot the bullet at 3,140 fps, and was deadly from 50 to 300 yards.

The Winchester .270 cartridge will be 100 years old in 2025, and is still a favorite of Texas hunters in both factory and custom rifles. The Remington Model 721 was an economical version in .270 I liked very much. I recall a new Model 721 being $87 in 1964, and a used one will bring $500 today. A clean, used Winchester Model 70 in .270 will sell for three times that much.

Jack O’Connor grew up hunting with his grandfather in Arizona Territory and used a .30-06 and 7mm Mauser for wild sheep, Coues whitetails, mule deer, and other game. When Winchester developed the .270 in 1925, and brought out in their Model 54, Jack bought one and liked it. Eleven years later, Winchester brought out the .270 in their Model 70 with a completely revamped stock, action, and trigger, and Jack liked it even better.

In 1936, the new Model 70 in .270 really caught the journalism professor/outdoor writer’s interest, and Jack used the .270 exclusively after moving to Idaho. He ended up working for Winchester and promoting the rifle and caliber as “The Rifleman’s Rifle” for the next 30 years. Jack was responsible for Winchester developing the Model 70 Featherweight in .270 and the new .308 and .243 cartridges, with 22-inch barrels light enough for the mountains.

Many of us whitetail, mule deer, and pronghorn aficionados have enjoyed the .270 in a variety of rifles, and this probably comes from successful hunts with no regrets. My personal preference for the Winchester Model 70 in .270 came from its killing power, mild recoil, crisp trigger, and good design.

My hunting exploits with the .270 go from Wyoming to Mexico, and several places in between. I have used a standard Winchester Model 70 to take whitetails, mule deer, pronghorn, elk, aoudad, and several deer-size exotics such as the Japanese sika and India’s spotted axis.

In 1990, I traded for a fine custom Model 70 .270 from Joe McBride in Austin that turned out to be one of my favorite rifles.

The rifle had good walnut wood and checkering, and was even finer after Robert Bueltel cut the barrel to 22 inches and Tommy Kaye graced it with whitetail motif engraving on the floor plate and trigger guard. Later, Tommy added a nice pronghorn and “pineapple” engraved the bolt knob.

For 20 years, I used this custom Model 70 .270 on whitetails, mule deer, pronghorns and hogs. The lightweight barrel wasn’t too accurate, but I killed everything I shot at, which proved to me that a hunting rifle does

Here are some popular Texas deer cartridges, with the .270 Winchester third from right: Left to right are the (1) .222 Rem., (2) .243 Win., (3) 7mm-08 Rem., (4) .257 Roberts, (5) .270 Win., (6) .30-06 Springfield, and (7) .300 H&H Magnum.

not have to be a tack driver. The .270 with hand loads would hit a golf ball-size target with every shot at a hundred yards, and that was good enough for me.

Even though I never used the .270 on nilgai, I wouldn’t hesitate to shoot one with a 150-grain Nosler bullet if the distance was no more than 250 yards. Unless the shooter is close enough to shoot a nilgai where the neck joins the shoulder, most nilgai are taken with a bullet directly through the shoulder blade and into the lungs. This requires a heavy, deep penetrating bullet.

I’ve never seen a bull nilgai fall in his tracks, so don’t fret if he throws up his tail and runs 150 yards before collapsing. For long-range shooting at nilgai, I would leave the .270 and other similar rifles at home and depend on a heavier .30 caliber bullet to penetrate the shoulder bone and destroy the lungs—a little much for a .270 at 300 yards.

Bull elk can be taken with a .270 and good, deep penetrating bullets. A young bull taken with my .270 while mule deer

hunting in Wyoming took two 130-grain Sierra bullets—the first to stop him, and the second to put him down. My other bull and several cow elk were taken with a .300 Weatherby and a .264 Win. Mag.—both very good Magnums. Of course, the bottom line is to put the bullet in a vital spot, and the rest comes with a good skinning knife.

So, I was drawn to the .270 at an early age by a persuasive and articulate gun writer. I say this with respect, because Jack O’Connor was my idol during my formative years of hunting, shooting, and writing. I never met him, but I owe a lot to the world’s greatest gun editor.

I have read nearly everything Jack wrote about guns and hunting, and I’m confident in his early days, he liked his Springfield .30-06 as well as he liked the Winchester .270. The difference was he eventually became an employee of Winchester, and his rifle preferences were driven by the monthly check and paid hunting trips. On eight African safaris, Jack still relied on his Winchester Model 70 .30-06 for bigger horned game, but on the North American continent, Jack relied exclusively on his custom Model 70 in .270.

After hunting big game with a .270 for a half-century, I would recommend it to anyone. The key to success with the .277 caliber is to use proper bullets for the game you are after. In my case, all the deer, elk, exotics, pronghorns and hogs I’ve taken with the Winchester .270 would feed a small army, and each hunt always ended with a smile.

I took my final trophy whitetail buck in 2016 with my new Jack O’Connor Commemorative Super Grade Winchester .270. I went hunting with Marty Berry and Jason Shipman in Live Oak County. The heavy eight-point that grossed close to 160 B&C fell to a handloaded 130-grain Hornady SST bullet and 60 grains of H4831 in Winchester cases, my favorite .270 handload recipe for many years.

Today, hunters have many good rifle cartridges to choose from, but if you select the .270 in a good rifle, you won’t go wrong. The venerable cartridge has proven itself for 100 years, and I expect it’ll be a caliber of choice for another 100 years.

Texas Trophy Hunters Association has kept Texas hunting in focus for 50 years. Jerry Johnston had a vision for an organization that would promote interest in white-tailed deer and deer hunting in Texas. To that end, he founded TTHA, and developed it into a household name for Texas hunters and wildlife enthusiasts across the Southwest.

TTHA celebrates the slogan, “The Voice of Texas Hunting,” and hunters and outdoor folks all over Texas recognize the skull logo designed by Jerry immediately after he founded the association. TTHA’s mission is “to unite all segments of the hunting community to promote, protect and preserve Texas’ wildlife resources and hunting heritage for future generations.”

In 1975, Gerald Ford was president, and the Dallas Cowboys were in their 16th season under coach Tom Landry. That same year, Jerry hosted the inaugural Texas Trophy Hunters Association meeting at the El Tropicano Hotel in San Antonio—a small meeting attended by a group of dedicated deer hunters and landowners. I was there, representing Texas Parks and Wildlife as a biologist in its wildlife division. A few attendees brought deer heads, knives, guns, and arrowhead collections to show and tempt others into buying. The rest is history.

With the help of friends and associates, Jerry’s new association took off like a rocket, with membership drives, a quarterly publication called Texas Hunters Hotline, and trade shows called “conferences.” These shows, later given the title of “Extravaganzas,” got folks together to be entertained and see—and buy—the latest in hunting gear and deer hunting paraphernalia. Other facets of the shows were hunting seminars, and a popular deer contest where hunters could enter their deer heads and compete for prizes.

And now, as a company of Safari Club International (SCI),

TTHA continues to promote Texas hunting with a bi-monthly Journal, an annual Bucks and BBQ Cook-off, and Hunters Extravaganzas held annually in Houston, Fort Worth and San Antonio. An Outdoor Extravaganza will debut Jan. 10-12 in Dallas, and a Hunting and Fishing Extravaganza will be held April 11-13 in Midland. This year—2025—Texas Trophy Hunters celebrates its 50th anniversary as the largest association of its kind in the Southwest.

I have been on the TTHA team for 29 years, having retired from Texas Parks and Wildlife after 33 years, and joining the

team at TTHA in September 1995. My job was to edit and write for The Journal, assist Brian Hawkins with television productions, assist with Operation Game Thief banquets, and be the chief judge for the Hunters Extravaganza Deer Competition.

At that time, the Extravaganzas were hunter oriented, and attendees were mostly adults. The deer contest was popular, and there were few problems with people evading the rules because the only prizes were a jacket and certificate for the division winners. Later, when MCMI owned TTHA, prizes were increased to various expensive hunting items, and more contestants tried to duck the rules, hence, my job as judge of the deer contest.

I had known Jerry for several years, and had hunted deer and doves with him in South Texas when he started TTHA in 1975. As a wildlife biologist, and upland game program leader with TPWD, I helped Jerry with matters of importance between TTHA and the state agency. After I retired, and Jerry called me in 1995, I was very honored to join his team in San Antonio.

TTHA has a proud conservation history. In 1981, the 67th Legislature established Operation Game Thief (OGT) to discourage game and fish violations and poaching. Jerry and TTHA organized fundraising banquets to promote the program. The result was three consecutive banquets totaling $350,000 to help fund the new OGT program. During the last 50 years, TTHA has promoted, protected, and preserved hunting; outdoor recreation; and the Second Amendment.

The bi-monthly magazine, The Journal of the Texas Trophy

Hunters, has content that encourages hunting and quality habitat and nutrition through food plots and supplemental feeding. The Journal has articles and suggestions for deer management and antler quality. The bottom line for The Journal is to promote hunting and boost hunting interest. The magazine also emphasizes youth hunting to keep kids off the street and in the woods.

For several years, the Trophy Hunters TV show, which aired on the Outdoor Channel, promoted the

best in big game, upland game, and waterfowl hunting. The show was a video extension of the passion and philosophy expressed in the pages of The Journal, and often delved into social and economic issues of deer management. The television show was also a forum for filming hunts featuring wounded warriors coming back from war.

One of the keys to TTHA’s success has been the Hunters Extravaganzas, held annually in three major cities: Houston, Fort Worth and San Antonio. These trade shows highlight the newest innovations in hunting gear, and the business of hunting in general.

The annual shows draw between 40,000-50,000 outdoor enthusiasts in August, and get hunters and wildlife enthusiasts ready for the fall hunting seasons. Today, attendees to the Extravaganzas include men, women, and many young people of all ages.

A main feature of each show is the deer competition and its awards. Some of the biggest and best whitetails and mule deer taken in Texas, Mexico, and out-of-state, are displayed in competition for an array of prizes. However, the original intention of the deer contest was to get trophy bucks to a venue like Hunters Extravaganzas so attendees could view them.

tional preferences, but the association has continued to grow in many ways. Several high school and college chapters have been organized to participate in activities sponsored by the organization. In 2011, TTHA created the Bucks and BBQ Cook-off. With only 40 teams involved at the beginning, the cook-off teams now

that is a leader in protecting the “Freedom to Hunt.” SCI’s motto is “First For Hunters” with an office in Washington, D.C., and active chapters around the world. The new offices for membership and business operations are located in San Antonio, Texas.

In its 50th anniversary year, TTHA is

Nationwide, many organizations such as Ducks Unlimited, Pheasants Forever, Coastal Conservation Association, Texas Bighorn Society, National Wild Turkey Federation, to name a few, have objectives to save or promote the existence of a species.

TTHA’s objectives are quite different. It promotes hunting recreation, conservation, and the wise utilization of an abundant population of game birds and animals such as deer, doves, wild turkey, and exotics. Without hunting and excise taxes on guns and ammunition, there would be no wildlife conservation. TTHA also helps landowners realize a monetary return for their conservation efforts.

TTHA is being courted by genera-

number over 100, competing for cash prizes. In its 14th year, the annual event is sanctioned by the Champions Barbecue Alliance.

In February 2020, Christina Pittman became president and chief executive officer of Texas Trophy Hunters. Christina had been director of sales, and also director of trade shows—Hunters Extravaganzas—for eight years prior to her promotion. Christina and her husband Matt are hunters, and their youngsters, Ava and Gunnar, are tagging along. Christina is in charge of all TTHA programs under the guidelines of SCI and will continue to direct the statewide trade shows.

SCI purchased TTHA in 2021, and it has become a subsidiary of the internationally known conservation organization

going strong among competitive organizations, and some folks describe TTHA as the best hunting organization in the Southwest. The Hunters Extravaganzas, as well as The Journal, are regionally known for exemplary quality and exposure. Trophy Hunters TV is gone, but TTHA is using outdoor podcasts to promote the Association and hunting.

The Hunters Extravaganzas have never been better, as wildlife enthusiasts get ready for another half-century of Texas Trophy Hunters, The “Voice of Texas Hunting.” People everywhere are excited about the quality of Texas hunting. And we hope to inspire every Texan to join Texas Trophy Hunters, go and enjoy the outdoors, and attend our shows and events.

The buck of a lifetime—the culmination of many deer seasons in Mexico and South Texas—is the kind of whitetail that would cause one hunter to hang up his whitetail rifle for good. What a way for a hunter to go out with a bang, literally and figuratively. The hunter had said, “If I ever kill a 200 B&C buck, I will quit hunting whitetails.” He stood over a 209-inch typical buck lying in the Webb County brush.

The hunter, Larry Hlavaty of Hillje, wasn’t raised in a hunting family. He began hunting deer at age 25, as his wife’s family were hunters, and had encouraged him to take part. Like many hunters of a long-ago era, Larry’s first bucks were small, but typical of the Wharton County coastal prairie and the Hill Country where he learned to hunt.

It didn’t take long for Larry to develop a passion for whitetails: living, breathing, hunting, and guiding for large antlered bucks. As he gained experience, his quest for bigger, better bucks also increased. About the same time, hunters began learning about Boone and Crockett scoring versus simple antler spread and points. Managing for quality bucks, and supplemental feeding became important aspects of hunting.

In the 1990s, Larry began hunting the Cuevas Ranch in Coahuila, Mexico, where he and a partner operated Rio Bravo Safaris. Over his many years of hunting and guiding, Larry gained a reputation for accurately judging whitetails on-the-hoof, while putting clients on great bucks.

When the partnership dissolved, Larry returned to hunting and guiding in South Texas. For the last seven years, he and friends have managed and selectively harvested bucks on a 7,000-acre Webb County ranch.

Larry loved hunting big bucks, but had become quite particular over the years. He expressed pleasure and satisfaction with each hunt and outwitting a clever mature buck. He also enjoyed every guided hunt, happy to put hunters on their first or very best buck.

Over the years, Larry became a legend to many, simply for his hunting expertise. He’s also legendary for his wisdom, good-humored nature, and patience with anyone and everything. Getting in a hurry has never been on Larry’s agenda.

As antler scores continued to increase due to supplemental feeding and herd management, Larry took a different approach to buck hunting. The lease he shared with others has a rotation setup; only one true trophy buck per year is killed on the lease, and must be an older deer. Family and friends help keep total numbers in check by killing does and bucks not fulfilling trophy status requirements.

Larry had the top rung of the rotation, although he hadn’t killed a buck in 13 seasons. He couldn’t make himself take a buck smaller than anything he’d already killed in Texas and Mexico. Each season he allowed the next person in the rotation to take the annual trophy buck. If that person declined, it went to the next in line, and so forth.

This system worked well with all lease members. It was another factor that played into Larry being called “The Legend.” He stuck to his beliefs and passed many trophy bucks on to others over the years.

On the Webb County lease, a young typical buck appeared with much potential. All of the hunters kept a sharp eye out for this particular whitetail. Each year his typical antler width and mass increased dramatically.

The buck at 5½ was most impressive, although he sported an extra main beam with points. The hunters believed he would score close to 200 B&C. However, they wanted to give the buck another year. Larry hoped the buck would return to being more

typical. He wasn’t fond of the extra beam. Larry’s optimism was answered as the buck grew impressively thick mass on a 12-point main frame in 2023. The buck became known as “The Legend” long before his antlers hardened. Everyone believed the buck would positively gross 200 B&C, and possibly more.

Always the hunter, Larry had remarried a few years back. His wife, Kathy, was a hunter but also enjoyed traveling. Larry retired from farming and spent a lot of time on the deer lease when he wasn’t having adventures with Kathy and grandkids. He’d made up his mind that if he ever killed a 200 B&C buck he would quit hunting white-tailed deer for good.

As the 2023 deer season opened, Larry stated he’d like to take The Legend. All hunters began trying to pattern this buck, and on Nov. 11, Larry pulled the trigger of his 7mm PRC rifle, and the big buck fell hard in the Webb County cactus. At age 6½, the buck sported 16 scorable points with an inside spread of 252⁄8 inches. The main beams were 244⁄8 and 257⁄8 inches.

The right side G1 measured 83⁄8 inches, G2 at 115⁄8 and G3 over 12 inches. The left side’s G3 and G4 were over 11 and 10 inches respectively. Circumference added 18 inches with abnormal points putting in 87⁄8” for a gross score of 2096⁄8 B&C. Larry made the rounds of numerous deer contests with the score varying a bit either way but all over the 200 mark.

Long-time friend and lease member Gary Lott said, “It was unbelievable when Larry said he was going to quit hunting whitetails. We’d gone to Africa in 2021 and New Zealand in 2022, so it was a shock to hear him tell us he was giving up deer hunting.”

“However, Larry taking a 200-class buck was the pinnacle of his whitetail career,” he added. “He said he’d never take another one like it and that’s probably true. He’s ready to travel with his Kathy, enjoy the grandkids, and hunt other things besides whitetails. We’re happy for him but sure gonna miss him!”

Darell Hoffer of El Campo has known and hunted with Larry for many years. “We call Larry The Legend simply for the number of people’s lives he’s touched through hunting and guiding. He’s guided people from across the U.S., Mexico and elsewhere,” he said.

“Every season Larry passed great bucks. We all thought he was a bit crazy to do so,” Darell added, with a laugh. “At the same time, everyone who hunts with him continues to learn more about deer. When he said he was going to hang up his gun on whitetails, I was in total disbelief, but I totally respect his decision. He’s gone out with a big bang!”

When asked about his buck and quitting hunting, Larry modestly said:

“He’s a pretty good deer. I don’t think I could get a bigger whitetail. I’ve enjoyed the folks I hunt with, but the lease is costing a lot of money. And I’m not going to quit hunting entirely.

“I’ve hunted Africa and New Zealand, and now I’ve booked a Canadian mule deer hunt in Saskatchewan. I’m even considering going after an elk sometime. Between Kathy and I, we have seven grandkids. It’s fun to travel, see new places, do new things I didn’t do while I was busy farming or going after whitetails.”

A 209-plus B&C majestic whitetail became the highpoint of an illustrious hunter who’s considered an icon to countless outdoors men and women. What a way to go out with a bang. Congratulations, Larry.

Seth admits hunting in a national forest is not an easy task. You have to work a bit harder to earn your trophy buck.

Isat against a big red oak; my feet soaked with creek water on a crisp 37-degree morning. Family obligations had kept me out of the woods the last few weeks and I began to wonder if I would find my opportunity this season. After a 90-minute drive, and a 45-minute walk, I could hear the heavy steps of a whitetail buck about to cross within 25 yards of my setup. His head hung low, but his senses were high as I raised my rifle.

Hunting in a national forest in Texas is no easy task. It’s usually made up of 80-degree sits in a large, monotonous forest riddled with pines. How is a hunter expected to narrow down a buck’s path in these expansive woods without feeders, food plots, and a permanent box stand? The answer is simple. You work for it.

Over the years, hunting over 600,000 acres of national forest in Texas has proved the most challenging, and yet, the most rewarding adventure I’ve ever had. Hunting the big piney woods without many limiting factors, effort is often what puts you in the right spot at the right time.

You may find yourself in one of four Texas national forests, chasing the elusive trophy whitetail. I can tell you; it’s no easy task. Texas public land is limited, given the size of our state, but offers tremendous opportunities, nonetheless. You can choose to camp overnight in designated camp areas, or make the drive out on a cool, low-pressure morning, in hopes of encountering a mature buck. East Texas is the setting of the majority of our national forest which is usually comprised of pine thickets, ravines, dirt bike trails, and the occasional pipeline right of way. It’s up to you on how you choose to tackle this intimidating timber. However, I have found a few tactics helpful to me over the years.

I’ve discovered selecting relatively small chunks of land around 500 acres in size helps to remove the vast, intimidating landscape. Scouting an area and becoming intimate with its deer herd, habitat, access, and pressure, are key to staying on the deer. Sometimes, it takes several years to learn a property well enough to understand how the deer use it. Scouting becomes key and putting in hours in the stand helps you to make

micro movements to ensure you’re in the right areas. However, circumstances such as drought, controlled burns, and hunter pressure, often force you to pivot inside your hunting zones.

This particular area was an area I had scouted during the late season the year before. In December, I had found multiple doe groups were using this peninsula within this creek system for bedding. There were a few features that funneled movement across the landscape, which I was able to identify. There was also a huge scrape outside the doe bedding, which indicated to me that bucks were monitoring the activity in and out of the doe bedding area. In my experience, bucks will lay out scrapes, or scrape lines outside of doe bedding areas for the does to use when they come into heat. Once the does begin to frequent the scrapes, it’s an indication the doe is in estrous.

After monitoring this area for over a year and a half with multiple trail cameras, I learned bucks were often cruising near this bedding area, checking the crossing doe trails. The timing of these photos, and the increased activity, provided insight on when this doe, or doe group, began to come into estrous. Oddly enough, this area seemed more active approaching the latter part of the rut.

On Nov. 22, the day before Thanksgiving, I found myself with an unfilled buck tag and the better part of the season behind me. Family obligations and out-of-state trips had kept me out of my stomping grounds during the prime hunting times in Texas. I had not been in the woods in over 10 days, and the discouragement began to set in.

I knew my best opportunities would be to rely on my historical knowledge of prior seasons. In this instance, I remembered this particular area I had been monitoring the year before. I was hopeful the consistent doe bedding would provide the lure of a cruising buck through the nearby funnel on his way to find his mate. That morning, I woke up at 2:30 a.m., poured myself a hot cup of coffee, and set out. It was, after all, over an hour and a half from my house to the parking area I needed to get to. The morning was cold, and the drive was long, crowded by my thoughts of wasting my time and effort for another public land hunt that yielded no reward. However, relying on my plan, detailed knowledge, and the blessing of a north wind, I pressed on.

Recent rains had swelled the area creeks to an impressive level. My access was dependent upon moving from sandbar to sandbar for over half a mile to access the area where I needed to be. This kept my scent low, my steps quiet, and my disturbance undetected. As I neared my exit point along the creek, a few last steps resulted in a cold blast of creek water pouring over the top of my boots. The rains had caused me to underesti-

mate the creek banks as I stumbled to gain my footing. I sat on the creek bank and removed my rubber boots to empty my soaked socks, another hiccup in an already doubtful sit in these unforgiving woods. I pressed on, and made my way downwind of the bedding area I had planned to hunt. Positioning myself about 8o yards off the bedding edge, I chose to sit on the ground near a deadfall. On this hunt, I chose to bring my trusty .2506 rifle instead of my bow.

As I tucked myself into the tree trunk, I heard the familiar hoof cadence of a heavy bodied deer approaching from my right side. He was close. Too close for my liking with the amount of time he gave me. The mature buck worked his way from east to west, scent checking the north wind blowing from the doe bedding. As he passed behind a towering pine, I raised my rifle to my knee, and with one last breath, I took the 22-yard shot. To my surprise, the buck bolted. He ran until I lost sight of him through the brush about 50 yards away. How could I miss that shot? Why didn’t he go down right here? Had I somehow managed to screw this up?

After a few panicked phone calls, I made my way over to the scene. I saw no sign except a few kicked-up leaves. I got on my hands and knees and crawled down the trail for 20 yards without any sign of blood. It’s times like these I really hate being color blind!

As I backtracked the trail over and over, I decided to push beyond the last marker I used before I lost sight of him. As I swung around the edge of some creekside sea oats, there he lay; a stud of a nine-point in full rut. His beautiful brown coat glistened in the broken sunlight just peeking through the brush.

The national forest can be ruthless, exhausting, discouraging, yet honest. Any time you’re fortunate enough to take one of these bucks, it’s a truly rewarding experience.

In northern areas like southeast Alaska, retaining areas with a closed forest canopy is important during harsh winters to intercept snow and allow Sitka blacktails to move around in their habitat.

Mule deer habitat stretches from northern Mexico through Canada’s Yukon Territories, into central Alaska, and east into the prairies and agriculture of the Great Plains. They do very well in the hot deserts of the Southwest, the boreal forests of Canada, and the coastal rainforests of the Pacific Northwest. Because they thrive in such a wide variety of habitats, it is not easy to describe the types of habitat they prefer, but the one common denominator associated with preferred mule deer habitat is disturbance of the vegetation.

Deer are selective feeders, which means they don’t just walk along and vacuum up all green plants in their path. They have small, pointed mouths for a reason, and that is because they eat select plants and plant parts. Rather than eat grass like cattle, they feed on forbs (broad-leafed weeds) and shrubs. Both forbs and shrubs regrow and flourish after they have been disturbed.

Without some disturbance, mature forests provide less forage for mule deer because the dense tree canopy shades the forest floor, and the all-important shrubs and forbs can’t grow. When we say disturbance, we mean disturbing the soil and existing vegetation to knock the growth cycle back to a younger growing phase. New plant growth is higher in nutrition, easier to eat, and more easily digested. So having a lot of this type of growth, instead of tough old plants, is a great way to get more nutrition to deer. This renewed flush of new plant growth delivers nutrition to deer, which translates into higher

reproduction, higher survival of adults, and bigger antlers.

Direct habitat disturbance naturally came in the form of fire, wind damage, avalanches, hurricanes, rock slides, and tornados. In addition, human caused habitat disturbance, such as logging, fire, mechanical, and chemical treatments can be used to create this beneficial disturbance that is so important to restoring and maintaining robust deer populations. Weather patterns, especially precipitation, drive deer population fluctuations in the short-term, but landscape-scale habitat improvement will make long-term gains in mule deer abundance. Historically, heavy livestock grazing and suppressing wildfires increased the number of shrubs on rangelands, which increased the browse available to mule deer year-round. More intensive timber harvest back in the day also opened canopies of dense forest and allowed sunlight to reach the forest floor to create a flush of forbs and beneficial shrubs. All this disturbance, along with the advent of effective game laws allowed mule deer populations to increase across their range, probably reaching all-time high levels in the late 1940s through early 1960s. This era of disturbance created mule deer abundance on the landscape that may never be reachable again because of long-term habitat changes.

One thing that should be clarified, when we say disturbance, we are not talking about disturbing the deer in their habitat. Disturbance of deer is not beneficial and is a point of great

discussion and consternation among mule deer managers in areas with a lot of recreational disturbance. Mountain bikers, hikers, shed hunters, off-highway vehicles, bird watchers, and all outdoor recreators have the potential to alter a deer’s ability to use the best habitat. Managers are currently trying to grapple with how successful we have been in getting people outside to enjoy nature.

One of the dangers of soil and vegetation disturbance is that it often holds open the door to invasive species. Many invasive plant seeds are already in the soil or nearby in the environment and all they need is a little disturbance to gain a foothold and spread. Cheatgrass flourishing after a fire is a great example of this, but there are other problematic invasive plants like red brome, yellow star-thistle, Medusa’s head, Lehmann’s lovegrass, knapweed, and many more that have to be considered when planning to disturb the vegetation and soil.

In the most general terms, disturbance is a good thing for improving mule deer habitat, but there are areas like southeast Alaska with a high snowfall where it is more important to maintain an old-growth forest canopy to intercept snow so the deer can simply move around. They may not have much food in these areas, but they can survive harsh winters and

venture out for food nearby. Some environments, like the Southwest deserts, did not evolve with fire, or other forms of disturbance. When large fires do occur, they can seriously degrade the quality of desert mule deer habitat for a very long time.

Habitat projects involving brush control must be careful to not remove too many existing trees and shrubs that deer need for thermal and screening cover to get out of the hot sun and cold wind. Sunlight onto the ground is a good thing for deer habitat, but as they say, all things in moderation. This highlights the importance of planning habitat improvement in a mosaic pattern across the landscape so the deer have more food in disturbed areas and yet retain cover nearby. Sometimes concerns for another species—especially endangered species—may obstruct our ability to disturb habitat for the benefit of deer.

Managers are constantly struggling to satisfy all the state and federal requirements that have to be met before disturbing the soil or vegetation on public land in the West. These restrictions are not a bad thing because they were developed to protect wildlife habitat. But when simply trying to reintroduce natural and historical levels of disturbance, it can seem like an obstacle. When the tree canopy shades the forest floor, less high-quality forage is available to deer.

The consistent theme in maintaining preferred mule deer habitat is to maintain large portions of the landscape in early stages of vegetation growth with a good mixture of water and cover. This will not happen without active and well-planned management. Future changes in long-term climate, shorter-term weather trends, and human developments all add challenges to the long game of continually making habitat better. We all need to work together to improve the capacity of habitat to support robust deer populations into the future. The focus has to be on land activities that promote a positive influence on deer reproduction, survival, and landscape connectivity.

Of course, habitat management is not a simple case of disturbance. We need the right amount precipitation to drive the rejuvenation of vegetation, and we also have to have proper grazing management after treatment. However, disturbance is a pervasive cornerstone that determines where deer prefer to be and where they are most productive. Building mule deer herds up to management objectives can only be accomplished through a continual process of paying attention to what deer need, what is lacking, and what tools will achieve our goals.

Hunting is and always has been an integral part of the culture of Texas, so it makes sense that hunting organizations should be located here.

Two of the world’s greatest organizations of hunters are now together under one roof in Texas, a move that will help assure a bright future for hunting, not only in the Lone Star State, but worldwide.

Safari Club International has moved its Member and Business Services operations from Tucson, Arizona, to San Antonio where it now shares offices with Texas Trophy Hunters Association.

SCI, for more than half a century, has been the leader in protecting the freedom to hunt and promoting sustainable wildlife conservation worldwide.

Currently, SCI has 10 Chapters in Texas: Austin, Brazos Valley, Brush Country, Fort Worth, Houston, Lubbock, San Angelo, San Antonio, Texas Hill Country and West Texas.

I encourage all TTHA members to join SCI and to join an SCI Chapter. The more you know about SCI, the more there is to like. And we also encourage all SCI members to become part of TTHA.

It is all about hunters getting together and helping assure that the hunting culture and lifestyle continue for future generations. There are powerful forces trying to stop all hunting forever, so we are all in the fight together to save hunting.

That’s why it was so heartening when several hundred SCI and TTHA leaders, members and local San Antonio community members last summer celebrated the Grand Opening of SCI’s Member and Business Services office and TTHA’s new headquarters in San Antonio.

“This move to San Antonio is much more than simply a geographic relocation of operations,” SCI President John McLaurin told many who came to enjoy the day with food, music and tours of the new facility.

“It is a necessary part of long-term strategic planning that will keep SCI at the forefront of protecting the freedom to hunt and promoting sustainable use of wildlife

conservation worldwide,” he said.

The new offices in the heart of Texas and the United States are expected to be a turning point in the organization’s history to improve its ability to advocate on behalf of hunters in the U.S. and around the globe.

SCI’s presence in San Antonio represents a new era for the organization, as it assumes a more central geographic location for its stakeholders and membership while simultaneously allowing for even closer collaboration with the advocacy staff who work from SCI’s Hunters’ Embassy in Washington, D.C., home to the Armand & Mary Brachman Advocacy Center.

SCI’s headquarters in Washington, D.C is called the Hunters’ Embassy because it is located literally on Capitol Hill where SCI staff advocates for hunting in Congress, in the courts and throughout the federal agencies. No other organization of hunters does as much for hunting on the legislative and legal fronts than SCI.

Meanwhile, SCI’s office in San Antonio was fully operational on July 1, the start of the organization’s new fiscal year. SCI and TTHA, a subsidiary of SCI, are working collaboratively from this location.

Texas is the perfect place for SCI’s new business and member services office. We are excited to launch this endeavor in the Lone Star state and look forward to a productive future in a pro-hunting political environment that will contribute to our organization’s growth and its wide-ranging advocacy activities for years to come.

Numerous vendors were part of the Grand Opening of SCI’s Member and Business Services office in San Antonio.

SCI also is expanding its presence in Canada, Mexico and throughout Central and South America. No matter where they are in the world, hunters share a common passion, a common way of life.

Many elected officials, such as Texas State Representative Barbara Gervin-Hawkins, Texas Wildlife Division Director John Silovsky and industry leaders like Brandon Maddox, founder and CEO of Silencer Central; and Jason Vanderbrink, CEO of The Kinetics Group (formerly Federal Ammunition), attended the celebration. SCI ambassadors Kristi Titus, Nick Hoffman and many others also attended.

Now that the celebrations are over, we are working hard every day to make TTHA and SCI the best organizations of hunters on Planet Earth. This began several years ago when SCI and TTHA joined forces.

Since then, the SCI family of organizations has continued to expand. For example, SCI currently is in a joint venture with Cinegetica, the biggest hunting show in Spain. Elsewhere in Europe, SCI is engaged daily on the political front where we advocate for hunting in the various legislatures and courts.

Also, SCI is active throughout Africa where SCI works with professional guides and outfitters, as well as governmental agencies. SCI’s sister organization, SCI Foundation, works closely on conservation initiatives with governments and nongovernmental agencies throughout Africa to assure that there will be wildlife in wild places there forever.

What all of this means for TTHA members is that now there are more things for hunters in Texas to be involved in, and that Texas will be at the heart of the pro-hunting movement for decades to come.

Now is a great time to be proud to be a hunter, to be proud of being part of TTHA and, I hope, to be proud to be a part of SCI.

I invite all TTHA members to go to the SCI website and see what we’re all about. I am certain that there are things of interest there for all hunters.

As I repeat constantly, the future of hunting and of TTHA and SCI rests on six pillars: Advocacy, Event Services (Conventions and Extravaganzas), Membership, Hunting, Chapters and Conservation.

And as the year progresses, plan to attend any or all five of the TTHA Extravaganzas, as well as the SCI Convention in Nashville, Tennessee, Jan. 22-25, 2025. I hope to see everyone at these important events that help raise the funds necessary to save hunting.

Above all, I thank all TTHA members for being part of one of the greatest organizations of hunters on Earth. Your dedication to hunting is critical and it is appreciated.

From a young age, I’ve dreamed of going on a hunting trip to South Africa. I was always fascinated by the hunting shows on TV and by the wildlife featured in National Geographic. As the years passed, I came to the realization that financial commitment and life would make this a bucket list trip I may never scratch off.

I always try to attend the Hunters Extravaganzas every year. I always enjoy meeting and talking with the outfitters and learning about new places and what they offer. Fortunately, I was at Hunters Extravaganza a few years back and came across an outfitter who had several clients that had just returned from their safari trip. These gentlemen were, let’s just say, up in years. One of the gentlemen, who I believe could see the excitement in my eyes for this trip, pulled me aside and said, “Don’t wait till you’re as old as me and struggle to enjoy this trip. Do what you must do, and make it happen.”

His advice rang in my ears for a few more years. So, I finally decided to just make it happen and booked my first trip. It was educational to say the least. I met the outfitter and professional hunter (PH) who made this second trip epic, not only for me, but my friend Anthony Alvarado and his two sons. Yes, I did say second trip.

My first trip was a nice family vacation. However, as with some outfitters, you get an education on what to ask, what to confirm, and get a learning experience in general. The mystique and fascination has not diminished after my first experience. If anything, it made my desire to do it again more obsessive.

I was captivated by the atmosphere, the people, and the