Let me begin this letter by an nouncing Texas Trophy Hunters is doing all we can to help the folks in Kerr County who have endured the biggest Guadalupe River flood on record. We thank our members for do nating supplies to send to the stricken area, and TTHA/SCI are still taking donations to help the folks in the disas ter area. Our prayers are with everyone who lost loved ones in the flooding.

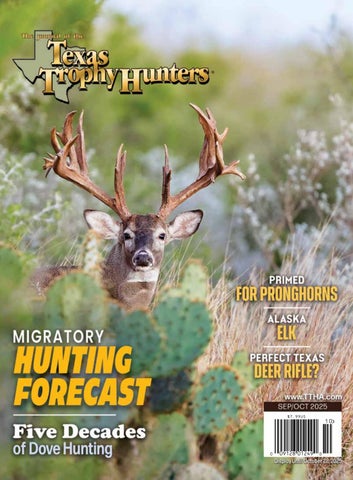

And now to the hunting scene. Texas dove and duck hunters are cleaning up “Old Betsy” and looking for cheap shotgun shells. Wing shooting seasons for mourning and whitewing doves and blue-winged teal are upon us as the first hunting seasons of the year. Dove seasons open for the North and Central zones on Sept.1, by treaty, and the South Zone opens Sept. 14. Teal season is short this year, running from Sept. 20-28.

Lone Star dove hunters are nearing 400,000 when you add up the hunters in all three zones, and when the smoke clears—no pun—about 6 million doves will be in the pot. Hunters have found more ways to cook doves than you can shake a stick at, and most of us have eaten our share of dove breasts laced with Louisiana hot sauce and bacon wrapped with onion and jalapeños. Add an after-hunt Bloody Mary, and you have the best that dove hunting has to offer.

For hunters who have never hunted teal ducks in September—you have a treat coming. I recall our small group of Gonzales hunters who would gather at Eagle Lake for our annual teal hunt. The eight or nine hunters with their three to four retrievers would spend a Saturday morning shooting the fast little flyers as they dipped and dodged through the morning mist. I had a good Lab and usually ended up with several hunter’s bag limits, but we seldom lost a bird. The teal hunts were a hoot!

Hold on, Hoss. Doves and teal are just the start. Our “modern-day” deer seasons kick off with archery and MLDP permits in late September and the regular deer season opens Nov. 1. Smart hunters will check seasons and bag limits carefully for their hunting area. It seems that as time passes the deer hunting regulations get thicker and stickier.

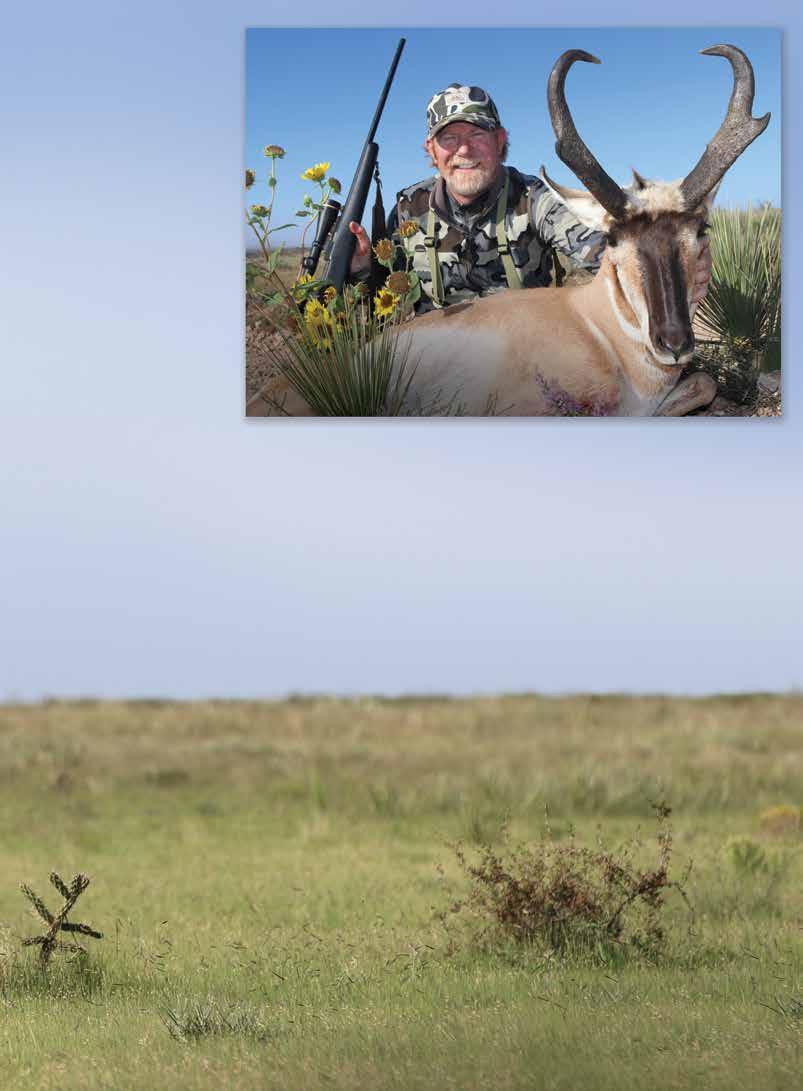

Hunters who chase the open plains pronghorn antelope need to mark their calendars for Sept. 27 through Oct. 12. There’s nothing quite like hunting the pragmatic pronghorn on the open prairies of West Texas and New Mexico, where most Texas hunters spend their antelope-hunting time and money. Acting like a coyote and stalking a herd buck is near the top of hunting experiences, so try your luck at getting a good 14-inch buck for the den wall.

In general, wildlife has fared well during 2025, and hunters can expect good hunting seasons. As usual, deer hunters will be more concerned about corn and gas prices than a good place to hunt. Texas is also the No. 1 dove hunting state in the nation, and dove hunters will enjoy the best in all three zones.

In the meantime, let’s keep ’em running, swimming, and flying by being good sports and obeying the game and fish laws. I’ll see you down the road.

Horace Gore, Editor

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer Christina Pittman • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Graphic Designers

Faith Peña

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

Christian Chatellier, John Goodspeed, Carol Heughan, Chad Jones, Judy Jurek, Lee Leschper, Heath Siegel, Eric Stanosheck

Advertising Production

Debbie Keene

210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Sales Representative

Tristan Summy 210-685-1205 tristan@ttha.com

Marketing Manager

Logan Hall 210-910-6344 logan@ttha.com

Finance & Administration Manager

Laura Garcia

210-512-4927 laura@ttha.com

Events Manager Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

Events Assistant Manager Natasha Delgado 210-512-8045 natasha@ttha.com

Membership Manager

Valkyrie Myklebust 210-767-9759 valkyrie@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

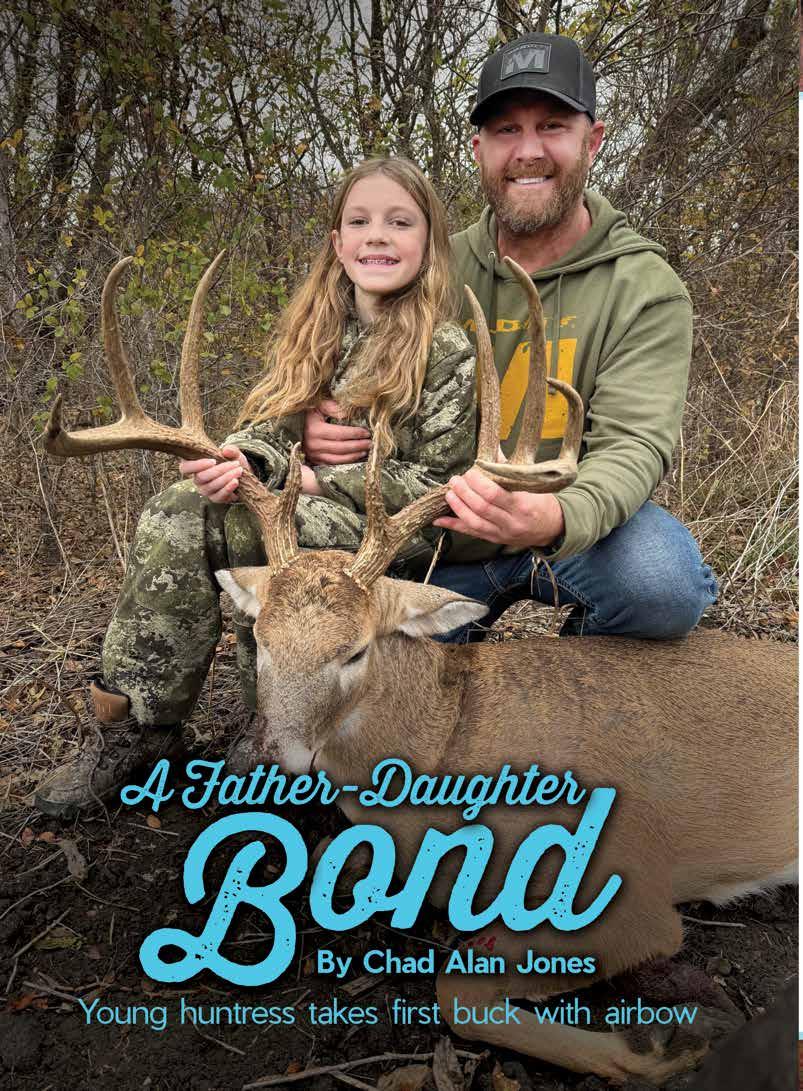

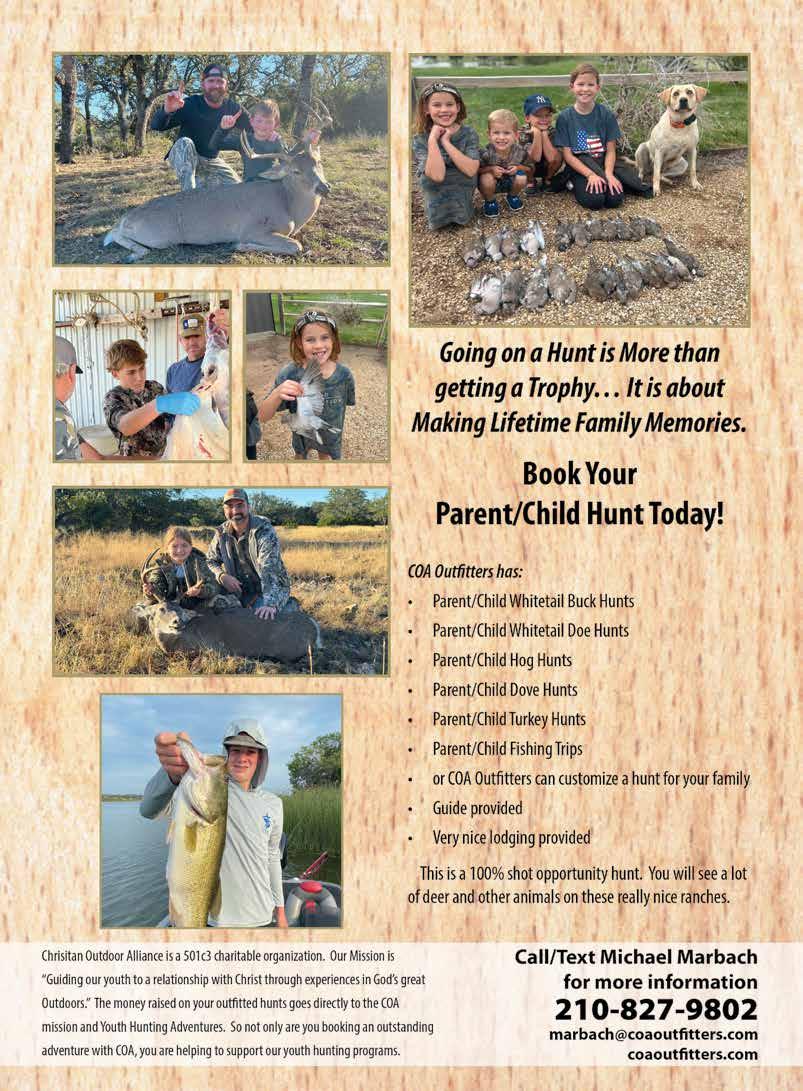

Each year during the month of August, deer hunters of all ages from Texas, Mexico, and out-of-state, bring their bucks to the Hunters Extravaganza Annual Deer Competition in Houston, Fort Worth and San Antonio. Young hunters proudly enter their trophy—sometimes their first buck—hoping to win a prize. TTHA is proud to recognize some of these young hunters and their trophy bucks.

BBy Horace Gore

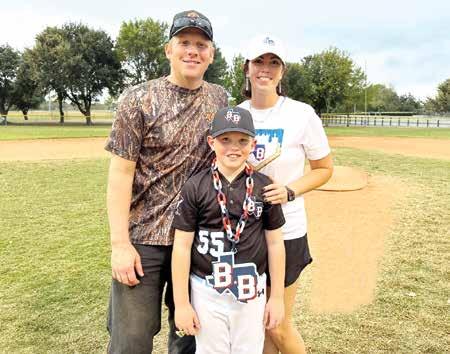

rock Brown is the 9-year-old son of Randall and Amanda Brown of Benbrook, in Tarrant County, and a Trophy Hunter of Tomorrow. In January 2024, Brock got his best buck of a “long” hunting career—a perfect eight-point netting 1452⁄8 B&C. The big eight-point was not Brock’s first buck. He has taken three bucks—a six-, eight-, and nine-point—since taking his first spike at 5½ with his dad. The Browns have friends who own deer hunting property in Tarrant County, and whitetail hunting is a family forte!

Brock just finished third grade at Great Hearts Elementary in Fort Worth. He loves the outdoors, hunting and fishing, but also enjoys baseball and football. Brock has twin brothers, Parker and Hudson, who are one year younger. When Brock got the big eight-point

Brock Brown took his perfect eight-point, netting 1452⁄8 B&C points, in January 2024. Brock just finished third grade at Great Hearts Elementary in Fort Worth.

with exceptionally long brow tines in 2024, the family decided to enter the buck at the Annual Deer Competition at

the Fort Worth Hunters Extravaganza. To their surprise, the entry period had expired when they got to the show. They

were encouraged to take the buck to the San Antonio show only a week away, so the family made the trip to San Antonio with Brock toting his big eight-point.

Brock entered the North Texas, openrange rifle category. The competition was keen, but Brock’s buck won the Best Perfect 8 category with a high score of 1452⁄8 B&C. It was Brock’s first entry in the Annual Deer Competition, but it probably won’t be his last.

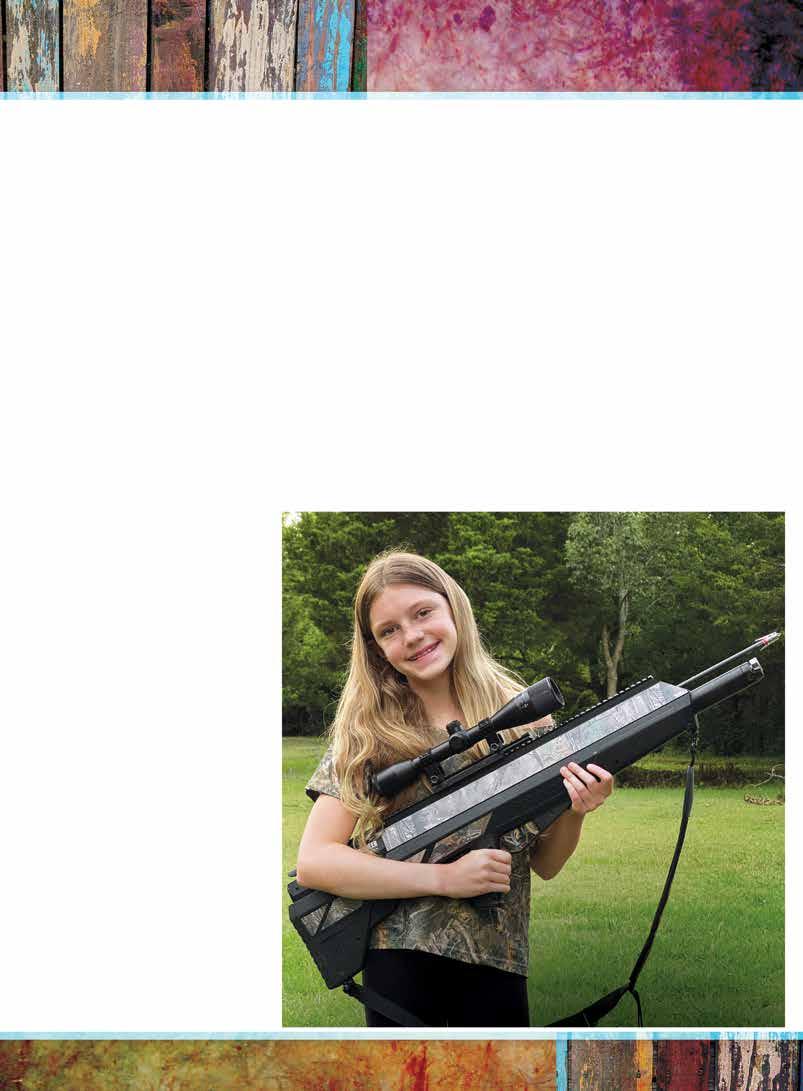

Brock was 7½ years old when he took his big eight-point. Since his first spike buck, which he killed with his dad’s rifle, Brock has hunted with an AR-15 platform rifle in 7.62x39-caliber—much more fitting to his young age and physique. The cartridge is of Russian origin, designed for automatic rifles. The velocity and energy is close to the Winchester .30-30, which was originally made for lever-action rifles. Recoil is minimal with the capability of taking an adult whitetail up to 100 yards. The rifle has a 4-12X Vortex scope, and Brock has taken each of his last three bucks with one shot from his “personalized” deer rifle.

The 2023-24 deer season was waning for Brock and Randall. They had seen the good eight-point several times, but Randall was cautious and wanted young Brock to get a good shot. Finally, the opportunity came one evening when the buck showed up to the feeder, and Brock got a close shot.

The buck took the bullet behind the shoulder, and the buck fell about 65 yards from the blind. It was Brock’s best buck to date, and Randall saw that it might score well because the antler points were evenly matched with long brow tines.

The Browns took a roundabout trip to the Fort Worth Extravaganza and then a long jaunt to San Antonio the next weekend—but the effort was worth it. Young Brock was a happy hunter. The Brown family were all proud of Brock’s buck winning the Best Perfect 8 category.

Since then, Brock has taken a ninepoint in the 2024-25 season, and plans to be in the deer blind when the 202526 season begins this fall. Randall will have his hands full with Brock and his twin brothers who are 8. Then, there is Amanda who took her first buck—a 10-point—last year. The Browns are quite a deer hunting family, but for now we congratulate Brock as our Trophy Hunter of Tomorrow.

loves the outdoors, hunting and fishing, but he also enjoys baseball and football.

Kory Gann Named TPWD Big Game Program

Wildlife biologist Kory Gann of Seguin has been promoted to Big Game Program Director for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. Gann, whose dad was a football coach, has lived in several towns in Texas. He was born in San Antonio, graduated from high school in Sealy, and went to Texas A&M University to earn a bachelor’s degree in wildlife science.

Gann obtained a master’s degree in range and wildlife management from the Caesar Kleberg Wildlife Research Institute at Texas A&M UniversityKingsville. While in graduate school, he participated in research projects related to white-tailed deer. TPWD hired Gann as a district biologist in 2015, taking

over for the late Randy Fugate in Brooks, Kenedy, and Kleberg counties. Gann also spent time as a district biologist in West Texas and the Laredo area, and for the last 2 years, he worked as a regional wildlife health specialist in the Big Game Program. Gann is well versed in all aspects of wildlife science.

Gann got into whitetail hunting at an early age with his dad, who had deer leases in the Hill Country and South Texas. He has hunted deer and game birds most of his life. His hunting and interest in wildlife has followed him through his many years as a wildlife professional.

Gann’s wide range of knowledge in wildlife science and his varied field work in South and West Texas put him in line for a recent promotion to Big Game Program Director in Austin. On May 1, he was promoted to the position and will continue to live in Seguin and commute to Austin with an established routine.

“I’m very excited about this opportunity and the chance to work with and support TPWD staff, landowners, and other external partners across the state of Texas,” Gann said. “I’ve enjoyed my time with the Wildlife Division in the field, and I look forward to the challenge of my new position.”

Gann and his wife Whitney, who is also an employee of TPWD, have fulltime jobs keeping up with their professional duties while attending the needs of their daughter, Carter, who is just over one year old. Seguin is a good place to raise a family, and the couple have many good days ahead. Texas Trophy Hunters Association congratulates Gann on his new job. — Horace Gore

In May, U.S. Sens. Tommy Tuberville and Mike Crapo introduced the Sporting Goods Excise Tax Modernization Act (S. 1649) to close a loophole that allows foreign manufacturers of fishing and archery equipment to evade conservation excise taxes by selling direct to consumers in the United States. A similar version of the bill (H.R. 1494) was recently introduced in the House by CSC Co-Chair Congressman Jimmy Panetta and CSC Member Rep. Blake Moore, demonstrating strong bipartisan and bicameral support for protecting conservation funding.

“The American System of Conservation has been vital to restoring and protecting the abundant fish and wildlife resources we have in this country today,” said CSF Senior Director of Fisheries Policy, Chris Horton. “We’re grateful that Senators Tuberville and Crapo are leading the effort on the Senate side to protect the unique and highly successful Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration Programs while safeguarding the competitiveness of U.S. based manufacturers and importers of fishing tackle and archery equipment.”

A study published by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2024 acknowledged the importance of the excise taxes on fishing and archery equipment for fish and wildlife conservation while also highlighting the challenges with collecting these taxes when products are sold direct to consumers via electronic commerce. The GAO further recommended Congress make online marketplaces facilitators, not the individual consumer, responsible for collecting the

sport fishing and archery equipment excise taxes.

The Sporting Goods Excise Tax Modernization Act will meet the GAO’s recommendation and protect a cornerstone of conservation funding in the U.S. CSF looks forward to working with our champions in both the House and Senate to ensure the bill becomes law.

A critical component of conservation funding in the United States is based on excise taxes collected at the manufacturer level on fishing and archery equipment, which funds the Wildlife and Sport Fish Restoration (WSFR) Programs. It is estimated that tens of millions of dollars in excise tax revenues are currently being avoided through direct-to-consumer sales of foreign fishing and archery equipment facilitated by online marketplaces. The Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation (CSF) has been working with the American Sportfishing Association and Archery Trade Association and Members of the CSC to develop a solution. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

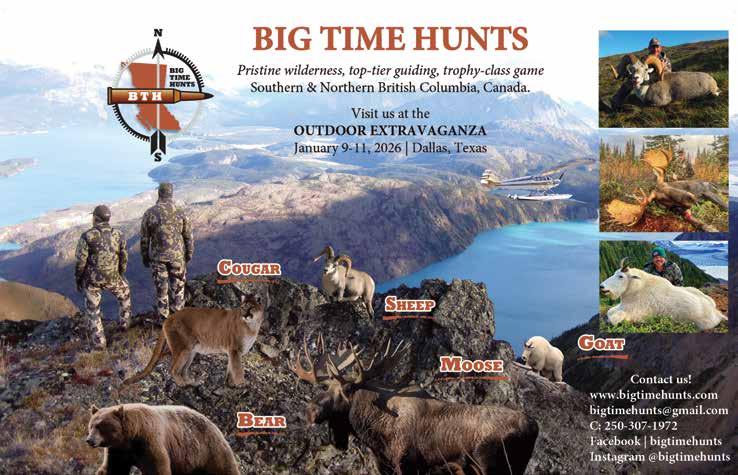

Alaska’s rugged wilderness draws hunters worldwide, many of whom rely on professional guides and outfitters to navigate its challenging terrain in the pursuit of iconic big game species like brown bear, moose, and Dall sheep. These guided hunts, often the culmination of years of preparation, are a cornerstone of Alaska’s outdoor economy and cultural heritage. Ensuring these services operate ethically and sustainably while protecting existing businesses has been an ongoing conversation among the Alaska Outdoor Community, including during events like the annual Sportsmen’s Rendezvous and among members of the Alaska Legislative Outdoor Heritage Caucus.

Alaska Senate Bill 29, introduced by Caucus Co-Chair Senator Jesse Bjorkman during the 34th Legislature, aims to strengthen the Big Game Commercial Services Board by permanently establishing an Executive Administrator position to serve as the volunteer Board’s principal executive officer. SB

29 also guides the Board to establish qualifications and duties for the Executive Administrator. Currently the Alaska Big Game Commercial Services Board is responsible for regulating and overseeing all commercial big game hunting and transportation services in Alaska. Their oversight includes licensing, guide/ outfitter examinations, regulations and standards, disciplinary actions, policy development, and conservation coordination with the Alaska Department of Fish and Game. Proponents of SB 29 hope that creating a permanent ongoing administrator will ensure continuity, stability and industry confidence.

Supported by coalition partners like Safari Club International and the Alaska Professional Hunters Association, SB 29 has passed out of the Alaska State Senate and has moved to the House Resources Committee. The Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation has been following the bill closely as it progresses through the state legislature and is working with our Caucus members and coalition partners to ensure that the policies enhance wildlife conservation and support sustainable access to Alaska’s big game hunting opportunities for sportsmen and women. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

In May, SCI filed its final brief in three lawsuits in which anti-hunting groups seek to put recovered gray wolf populations back on the Endangered Species Act list. That concept is absurd. Wolves in Idaho, Montana, and Wyoming have far exceeded recovery goals and their populations have grown substantially since they were removed from the ESA by Congress in 2009. But animal rights groups will not stop until they see these large, healthy wolf populations back under federal control. SCI has fought this battle for over 20 years. We continue to fight.

SCI’s brief emphasized that wolf populations in the Western U.S. are healthy and expanding. It emphasized that changes in state law, prompted by frustration with the impact that wolves

have on livestock and prey populations like deer and moose, do not threaten these wolves. And it pointed out legal deficiencies in the plaintiffs’ arguments.

SCI defends the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s decision not to relist these wolves in partnership with Sportsmen’s Alliance Foundation and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation. SCI also recently completed briefing in another legal challenge involving gray wolves, where we partnered with the NRA.

In that case, SCI and the NRA appealed a California district court’s ruling that rejected the Service’s removal of wolves across the lower 48 States from the ESA’s coverage. That California court, like a number of courts before it, did not find fault in the science underlying the Service’s decision. Rather, the court held technical issues with the ESA kept wolves under federal management. But no one—not even the plaintiffs in these lawsuits—can deny that wolves are biologically recovered in their primary habitat in the lower 48 states.

SCI has defended the delisting of gray wolves in at least 16 cases since 2003. Litigation has for decades kept the country’s largest wolf populations under federal control. That has caused significant damage to deer and other wildlife across the Great Lakes states. It has led to significant loss of livestock and even pets and hunting dogs. Ever expanding and unmanaged wolf populations benefit no one—except the animal rights groups that fundraise off photographs of wolves and hyperbole that wolf populations will be “exterminated” under state management.

For these reasons, and many more, over 100 SCI members took to Capitol Hill on May 15. SCI members lobbied for the “Pet and Livestock Protection Act,” which will mandate the reissuance of a final rule removing the gray wolf in the lower 48 states from the ESA lists. Passage will assist in proper administration of the ESA. It will allow the Service to focus its limited resources on species of much greater conservation concern.

SCI is unique among pro-hunting clubs in having in-house legal counsel, ready to go to court to defend science-

based decisions when it comes to gray wolves and other species. SCI’s legal team, as well as our state and federal lobbyists, will continue to push for the removal of wolves from the ESA lists. And we know our members will continue to stand with us in this longtime effort. —courtesy SCI

SCI unequivocally opposes language from the recent federal budget reconciliation process proposing the sale of federal public lands in the Western United States.

SCI vigorously supports access to federal public lands for hunting, fishing, recreational shooting, and other outdoor pursuits. The Senate proposal threatens this access.

SCI acknowledges the importance of providing affordable housing and other services to American families, as well as the challenges faced by communities in states with high levels of federal land ownership. Furthermore, SCI has previously engaged in numerous lawsuits challenging federal landowners that have not supported state wildlife management authority or arbitrarily reduced hunting, fishing, recreational shooting, and access rights. But federal lands provide extensive wildlife habitat and recreational access. Sale of these lands cannot be conducted without adequate safeguards for protecting hunting, fishing, and other access. Nor should any such sale occur unless the proceeds are reinvested in conservation.

Accordingly, SCI opposes any land sales that do not incorporate:

• A thorough review of the recreational and ecological values of any land proposed for sale

• A public process involving both residents and the broader sporting community

• Consideration of other options such as land transfers or exchanges

• A process by which proceeds from any such sales, if they occur, be set aside for conservation

To protect America’s hunting heritage,

SCI encourages members of Congress to reconsider using the budget reconciliation process as a vehicle for land sales. If Congress determines that there are some public lands for which potential sale is appropriate, lawmakers should consider other options available to them, including developing a separate bill creating broader public engagement and evaluation of compliance with the Federal Land Policy and Management Act and Federal Lands Transaction Facilitation Act, to serve that purpose.

Federal public lands are of critical importance to protect wildlife populations and their habitats. Congress must prioritize these values in the current debate. —courtesy SCI

Through its National Request for Proposals Program (RFP), the National Wild Turkey Federation is helping fund research involving translocated and surviving Eastern wild turkeys across East Texas. Researchers are using GPS data and state-specific breeding, nesting and roosting information to provide habitat management recommendations at a scale that can support Texas Parks and Wildlife Department’s Eastern Wild Turkey Super Stocking Project and broader wild turkey conservation efforts.

Thanks to support from dedicated partners, such as the Bass Pro Shops and Cabela’s Outdoor Fund, Mossy Oak and NWTF state chapters, the RFP program is an aggressive, annual effort to fund critical wild turkey research projects nationwide.

“Across the southeastern United States, we are seeing a decline in wild turkeys, especially in this zone of eastern Texas,” said Nicholas Bakner, post-doctoral researcher at the Tennessee Technological University. “For the past few years, Texas has been reintroducing birds from other states to reestablish populations in these areas.”

Bakner and his team want to see how translocated female birds from other states are responding to existing habitat conditions, which will help identify suitable release areas. Through this work,

they will be able to identify critical habitats, their availability and the potential for habitat restoration to increase turkey distribution and abundance in the region. This project will also be identifying areas where habitat limitations exist, enabling researchers to implement more effective habitat management strategies.

Using data collected over the past decade, researchers can develop a comprehensive habitat suitability model for wild turkeys in West Texas. When wild turkeys were captured and processed using rocket nets baited with cracked corn between January and March of 2016 through 2024, all individuals, regardless of age or sex, were given a leg band and a GPS transmitter that took one location nightly at midnight, and hourly locations between 5 a.m. and 8 p.m. until the battery died or the unit was recovered.

Researchers also conducted nest and brood surveys of any banded females suspected to have had brood success to gather survey data that will be used, along with other relevant variable data, to evaluate habitat suitability.

“When it comes down to looking at habitat suitability, this model identifies critical areas,” Bakner said. “We know from GPS data from across the southeastern United States, that there is a limitation in brooding habitat. Only about 7% of hens are successfully producing a brood, and we’re seeing as low as 10% nesting success in some of these areas. We need reproduction in order to supplement a population, which is why the brooding and nesting portion of this habitat suitability model are important. If we could use this model to identify areas of improved nesting habitat, this would help our efforts in recruiting new birds into the population.”

The research is being conducted on both private and public lands.

“I hope that we find areas that are pocketed with different types of brooding and nesting habitat,” Bakner said. “We can write all these scientific papers, but I want to able to integrate it into management. I’m hoping that we can find those pockets, identify what’s critical in those areas, and then transfer that to on-the-ground habitat management.”

—courtesy NWTF

By Dr. James C. Kroll

Dehydration is one of the primary causes of fawn mortality. By providing year-round water sources, the game manager can greatly improve fawn survival.

The white-tailed deer remains unchallenged as one of the most adaptable big game species in the world. Its range extends from the tip of South America to the edge of the northern Tundra. This covers a diverse range of habitats and climates, including tropical forests, scrublands, grasslands and temperate forests of all types.

Temperatures where whitetails live can rise to 100°F plus, or fall to subzero. When you combine diverse habitats and climates, it is no wonder that there are at least 38 subspecies; with the smallest—Florida Key deer—weighing in at only 55 pounds, and the largest—northern woodland or boreal whitetail—reaching over 400 pounds.

Managing diverse habitats and subspecies can be quite a challenge, one I have accepted many times in my five-decade career. I am sure each deer biologist has his or her favorite subspecies and habitat, but for me, it’s got to be the ones that live in the hottest, driest places on Earth—the desert brushlands of northern Mexico. I have managed whitetails over a great part of their range, and each place carries with it management challenges.

I like challenges, and each place where I have managed deer herds presents its own unique challenge. I would not have it any other way. For example, my interest in whitetails in the northern portion of the Lower Peninsula of Michigan was, not only the terrible winter conditions, but the fact a portion of the region is a place where bovine tuberculosis is endemic, presumably acquired from untested cattle from Mexico.

Managing whitetails is an adaptive proposition, where you first figure out the limiting factor(s) to true recruitment.

Farther north from the TB endemic area, I dealt with migration issues created by deep winter snows and harsh temperatures. There are properties in the upper Lower Peninsula and the Upper Peninsula totally devoid of deer during part of the year. There are properties there where I know exactly how many deer we have in January, a big zero. They can be found miles away in bedding grounds dominated by conifers.

Farther south to the Mississippi Delta, deer also migrate, this time to escape flooding caused by spring rains farther north and hurricanes farther south. I once managed a property just south of Memphis where, at one time, I again knew exactly how many deer we had—zero.

Thankfully, in each of these cases, we solved the problem first by identifying the limiting factors, then developing innovative ways to mitigate challenges. We reduced TB infection rates to “undetectable” in the upper Lower Peninsula. We stopped the migration and increased recruitment and survival in the bitter cold areas. We figured out ways to get the deer back safe and sound to the Delta. That’s one of the things I cherish about deer management. There is no such thing as “cookbook” management. It’s about being able to adapt.

Yet, the greatest challenge to date in my career has been developing a sustained population management program in the northern deserts of Mexico. Ranchers in this region routinely deal with annual rainfall, as low as 12 inches. Ponds routinely

go dry, creeks and rivers dry up, once again causing deer to migrate. Then there is the fact many of the browse plants are drought-deciduous, meaning, when it gets dry, the woody plants drop their leaves and go dormant. This does include the fact that the weedy plants deer would like to eat, “roll up their tent, and go home.”

Whitetails often adopt a drought strategy of just surviving, with little successful reproduction, hoping for the better times that come eventually in harsh climates. The lifespan of deer is geared to survive until good times. They are the ultimate survivor species, and they always seem to find a way to survive long enough to reproduce.

So, why even worry about helping them? Deer are the No. 1 big game species in the Americas, with some 80% of hunters pursuing this most adaptable of game species. It is our nature to try to mitigate the negatives.

We often have talked about the difference between fawn crop and recruitment, because there is a significant difference between the two. Biologists often measure the productive capacity of a deer herd by the fawn crop: the number of fawns surviving to weaning. Many times, however, we have seen herds, notably in the Midwest, with very high fawn crops, yet very poor recruitment.

The term “recruitment” refers to the number of fawns per doe that live to be one year of age, the time when they are recruited

into the herd. Fawn mortality rates from the time of weaning can be quite high, depending on many factors, including winter stress, predation, and disease. In managing the ranch herd, we recommend following the steps we have taken many times to reach the goal of identifying limiting factors.

In 1828, agricultural scientist Carl Sprengel first recognized in any biological system, health is affected by many factors, but there usually is one that has the greatest impact. Popularized later by Justus von Liebig, this scientific law became known as Liebig’s Law of the Minimum. If we identify all of the factors that limit population growth, the one in least supply is “the” limiting factor. Hence, in deer management— and particularly in herd management— we attempt to identify all the potentially limiting factors, then develop strategies to reduce or eliminate the impact of this factor.

Managing diverse habitats and subspecies can be quite a challenge, one the author has accepted many times in his fivedecade career.

In northern Mexico, it clearly is rainfall. But how have I coped with this deficit in a practical and economically efficient manner? First and foremost, we always consider in a management plan what to do about natural forage production. Deer love early succession plants and thrive after a disturbance. Using a roller-chopper we knock down the browse plants to stimulate regrowth, plus fracture a dense silty soil to allow what little moisture we get to infiltrate the soil.

Chopping is not for every soil, and there is an art to identifying which areas are suitable. We must prepare a property for the rare times when it does rain, trapping as much moisture as possible. Prescribed fire is seldom the solution, because many areas just won’t carry a fire.

There is confusion about supplemental feeding in the drier portions of the whitetail range. Some landowners think of it as “replacement feeding,” instead of “supplemental feeding.” Reality is, setting up a few feeders around the place and feeding part of the year does not constitute either of these. We conducted a research project on a very large Mexican ranch, the size of which allowed us to separate large pastures to study the impact of supplemental feeding with a balanced pellet ration, plus corn.

Our true recruitment goal is set at 70%, so reviewing the results of this study for this specific ranch, we settled on a preferred feeder density of one per 750 acres. The high rate of feeding was for pastures where we were managing intensively, so we kept the feeder density high. This was average true

recruitment over 7 years. The range was from 39% to 78% over that study.

Deciding on the density for your program will depend on the recruitment goal and the economics of the strategy. Our studies indicate that, on average, a deer will consume 1.8 pounds of feed per day. At say $0.25 per pound, that’s $0.45 per deer per day. Does not seem like much, right? Well, compute the cost of feeding 100 deer per day, and it increases to $45 per day, or $16,425 per year.

As you reduce the density of your feeders, you obviously are feeding a smaller and smaller portion of your herd, so there is “cost-benefit” to consider. On one of the ranches we manage, the true recruitment under feeding at an average density of 500 acres per feeder, over 7 years has been about 50%. You need at least 40% to produce adequate numbers of mature bucks

What about water? One of the primary causes for fawn mortality is not predation, it’s starvation and dehydration. By providing year-round water sources at a one per 200 acres, we have greatly improved fawn survival. However, this is far easier to recommend than to do. There is the cost of getting water to the stations, and the constant maintenance and repairs they create. We double up on benefits to other wildlife by also pairing water troughs with low ground waterers so quail and other species, even rattlesnakes, can also get water.

Managing whitetails is an adaptive proposition, where you first figure out the limiting factor(s) to true recruitment, then develop a workable, economic plan to mitigate the negative factors. Managing deer in the eastern and southern U.S. has its challenges, but it is the areas with severe climatic conditions that take real management. I love the challenges and finding the solutions have taught me so much about our favorite game animal—the white-tailed deer.

By Horace Gore

on Adams’ telephone rang, and he dropped the Gonzales Inquirer and answered. Jim Martin, who ran a large ranch on BLM land near Roswell was calling about a good pronghorn antelope that he and his son, Charlie, had seen— maybe 16 inches—in the south pasture.

Jim wanted to know if Don wanted to come to New Mexico and hunt the trophy pronghorn. “Well, I haven’t been antelope hunting in a long time. My daughter might want to hunt. She’s taken a few deer and hogs.”

“I guess the price has gone up,” Don

quipped, and Jim replied, “Don, you’ve never spent a dime on an antelope hunt—maybe a few dollars on gas, and our supper in town.” They talked a little more about a hunt.

Don yelled to his tomboy daughter, “Bessie, do you want to go antelope

Pronghorns depend on eyesight and speed to evade enemies and have a danger perimeter of about 250 yards that gives them the edge in any chase.

hunting at Roswell?” Bessie Faye had just turned 17 and was an avid hunter. “Of course, I want to go,” she yelled back from upstairs. “Did you hear that?” Don asked Jim. “Looks like we will see you in antelope season!”

The high school senior was delighted as she came down the stairs. “When will we go?” Don picked up the weekly paper again and replied, “New Mexico antelope seasons are about the time school starts.”

“Can I take my deer rifle?” Before Don could answer she asked, “Is pronghorn hunting anything like deer and hog hunting?” Don interrupted her questions. “Yes, your 7mm-08 will do just fine, and

no, antelope hunting is nothing like deer or hogs at the feeder. Pronghorns live on the open prairie, and you need to slip up on them to get a shot.”

Bessie’s next question: “How do you slip up on them in the open?” Don replied, “You act like a coyote.” His answer surprised Bess, and she walked away thinking, “How do you act like a coyote?”

As the pronghorn hunt got closer, Don told Bessie that unlike deer hunting, she would have to make a longer shot at a herd buck. “We will sight your Winchester in 3 inches high at 100 with 139-grain Hornady spire points, and you can hold dead-on for any shot up to 275

yards.”

Don reviewed the three 2-day pronghorn seasons, and they picked the August hunt before school started. They would drive out on Friday and be ready to hunt on Saturday morning.

“Where will we stay?” Bessie asked. “Right out on the prairie,” Don replied. “We’ll take our pop-up tent and camp at a windmill,” Don surmised. “After supper, we’ll lay on the prairie and look at the stars, and in the morning, you can wash your face in windmill water.”

Don and Bessie Faye had practiced shooting from the prone position at a 200-yard antelope target made from cardboard. He figured that would be the kind of shot that they would get at a herd buck. Bessie remarked to her dad, “Shooting is different when I’m lying on the ground. My eye is closer to the scope, and my aim is steady.”

Bessie read up on the American pronghorn. She found the unique mammal was the only one of its species that lives on open prairie. Pronghorns are fleet at 50 miles per hour, but are easy to bring down with a well-placed shot.

The teenager also learned that the pronghorn depends on eyesight and speed to evade enemies and have a danger perimeter of about 250 yards that gives them the edge in any chase. Bucks have sheath horns made of hair over a permanent core that are hard during breeding season, when it’s common to see several does with a dominant herd buck. After breeding season, the outside sheath slides off leaving the blade-like core to form another sheath horn.

The August New Mexico pronghorn season came, and Don and Bessie drove from Gonzales to Roswell. With out-ofstate hunting licenses, they drove to the Martin ranch to visit with Jim and Charlie before the hunt. Jim assured them the

big pronghorn was still somewhere near the south windmill where they would camp.

Charlie reminded Don that it would take patience to stalk the old buck. He winked at Bessie Faye and said, “Don, you and Bessie will have to act like coyotes.” It was the second time Bessie had heard that remark. Jim and Charlie would catch up with the hunters at one of the two windmills on Saturday evening.

The Gonzales hunters set up camp at the south windmill. Bessie fixed a hunter’s supper of fried bologna and pork and beans, topped off with canned peaches. They warmed windmill water in the skillet and washed up everything, saving some fried bologna for sandwiches the next day.

After supper, they sat under a halo of bright stars and talked about the next day’s hunt. After they got into their summer sleeping bags with the tent flaps folded back, Bessie found a satellite moving through the stars. She drifted off to sleep wondering how they would act like coyotes.

Early on Saturday, the hunters drank coffee and ate sweet rolls. Bessie drifted off behind the tent and came back ready to go after her first pronghorn. They would hunt together and glass the small herds looking for a good buck. Don reminded Bessie to pack her leather gloves with the sandwiches and toilet paper.

The duo walked and glassed all morning—no “safari hunting” from vehicles in New Mexico. They were both tired and thirsty at noon when Don glassed another windmill in the distance. As they headed toward the water, Don spied a herd of pronghorns with his binoculars. The herd had a buck, but they were far away.

Don and Bessie got to the windmill; tested the water and drank their fill. They rested for a while in the scant shade and ate their sandwiches. Don continued to glass the faraway herd as Bessie went behind the bushes. When she came back her dad remarked, “Your buck may be with that herd—you know, the one Jim and Charlie talked about.”

Don wanted a closer look, so the hunters took a fast clip toward the herd. They made good time after Don took both rifles so that Bessie could keep up on the grassy landscape.

When the hunters were about 400

yards from the resting herd, they sat on the ground for a breather. As Don got up to a crouch he told Bessie, “Stay low behind me and take your rifle off your shoulder. We’ll have to act like coyotes to get this old buck. He can outrun a coyote, but he can’t outrun a bullet.” They continued to move in a crouch for another hundred yards.

Don stopped and they both sat down. “They see us,” Don said as he glassed two does and the herd buck that were standing, with three does still resting. Don took off his hat and said, “Bessie, put everything on the ground but your rifle and gloves.” Don laid his rifle and hat with Bessie’s things. They put on their gloves and Don kept his binoculars.

Hunters have to act like coyotes to get close enough for a shot on old pronghorn bucks.

The herd was about 300 yards—too far for Bessie. Don motioned to her, and they got on hands and knees with the rifle and binocs under Don’s chest. Both stayed low for about 50-60 yards and lay prone on the ground. Don whispered to Bessie, “Don’t look. Keep your face down.” He took a quick glance through the binocs to see all the antelope standing and staring. The buck looked to be about 250 yards.

Don whispered, “Take a quick look— can you shoot from here?” Bessie peeked at the herd and got her first good look at the buck. She visualized the distance she had been shooting prone at the cardboard target and said, “I can hit him from here.”

Bessie and Don lay flat facing the herd. Don shifted the rifle to Bessie, and she shed a glove for a prone shot above the short gramma grass. With the crosshairs about halfway up behind the buck’s shoulder, Bessie squeezed the trigger.

The Winchester roared, and the pronghorns ran. Both hunters jumped up, looking for the buck. Don patted Bessie on the back and said, “Good shot, kid,” as he pointed to the buck’s white belly in the distance. Bessie had taken her first American pronghorn. She bolted

the hull from her rifle and picked it up with her left hand, thinking to herself, “Now I know what acting like a coyote really means!”

Don went back for his hat and rifle and the other things. Bessie walked to the buck and admired his strange horns and body color—orange and white. The mature buck had black horns and face, with small, pointed ears and white rings around the base of his neck—unlike any animal Bessie had ever hunted. Don returned and took photos of his proud daughter and her pronghorn, after she had filled out her landowner permit.

Don’s watch showed 3 p.m. when they turned the gutted pronghorn belly-down to drain it, and walked back to the windmill. Jim and Charlie found them, and they drove over to get the buck. More photos were taken, and they soon had Bessie’s trophy skinned with choice cuts of meat in the ice box. Charlie rough scored the horns at 79 3⁄8 —a good 15inch New Mexico pronghorn.

Charlie put the head and cape in a garbage bag with ice and water for the trip back to Gonzales. “Keep the eyelids and nose out of the sun,” Charlie warned. Back at camp, Bessie slept well that night under the New Mexico stars with her pronghorn rifle tucked away in the tent.

Don passed on two antelope bucks on Sunday—smaller than what he had on the wall. They broke camp for Gonzales, but not to fret. Don had been lucky before, and young Bessie Faye was all smiles with her first American pronghorn.

By Judy Bishop Jurek

With permission to hunt both sides of this fence, one hunter quickly repositioned to enable recovering doves on the other side.

What’s changed across Texas in the last 50 years of dove hunting? Depends on who you talk to and where they may hunt in the great Lone Star state. On one hand, not much has changed, as dove hunting is perhaps the easiest type of hunting to enjoy. Necessary items are a license, shotgun, ammunition, and permission to hunt on a particular property. It’s pretty simple if you have doves flying.

On the other hand, dove hunting has somewhat revolutionized this past half century. Hands down, it’s the most popular wing shooting in Texas today. Although always a co-ed sport, more women and children head to dove fields nowadays than in past decades. One reason is the simplicity of the hunt, as well as more dove hunting opportunities today across the state.

Weaponry has helped change the dove movement. Shotguns abound in a variety

of lengths, weights, and styles, making shooting easier and more pleasant. This is especially true for females and youngsters lacking the physique to enjoy dove hunting without tiring from a heavy shotgun or creating a bruised shoulder.

Another item that’s greatly motivated hunting in general is camouflaged clothing, specifically geared for women and children. Camo isn’t necessary for dove hunting, but helps conceal hunters on fence lines or in the shade. Lightweight, cool fabrics are available in every style, size, and fit.

Hunters sweat in the Texas heat while shooting aerial acrobatic doves. However, our fall weather is often unpredictable, and a cool front can drop temperatures and rain. So it’s wise to carry a jacket in your gear.

This ol’ hunter has noticed changes over the years in how people hunt. Dove

hunters today are more concerned about safety, using eye and hearing protection for themselves and family, than hunters did in the past. I grew up never using either but do so now, especially if I’m in a hunting group.

When many people hunt in close proximity, a single stray lead pellet can be a problem. Ear plugs can be useful, too. It’s a blast to have lots of hunters in the same field, but keep safety at the forefront. Many hunters today carry and use insect repellent, especially for ticks and chiggers. Gnats are a nuisance when you’re sweating, but there’s not much you can do about the pesky critters.

Not yet big enough to handle a shotgun, future hunter Ridge Riley happily participated in a dove-hunting adventure by picking up downed birds.

A dove-hunting crew today wears much camouflage and often use more than one buggy to navigate a hunting area.

It’s easy to make an outing much more pleasant. Take a chair or stool to relax if doves stop flying. Wear a hat or cap to shade your face. Pack snacks with plenty of water for you and your faithful retriever, if you’re lucky enough to have one fetching your downed doves.

Some hunters prefer hunting in large groups. Others prefer being with a small number of hunters. It helps having a few friends along to surround a field or create a shooting line to keep doves moving.

Tailgate parties have always been popular, but please reserve alcoholic beverages until after all shooting is done. It’s also sensible and advis-

Once he figured out his purpose, the author’s Doberman, named Zarr, became a faithful dove retriever, never missing a single bird.

able to keep each hunter’s birds separate in case a game warden appears. When there’s a huge dove pile, it may be hard to tell, and justify, who killed how many, and tickets may come flying faster than the doves.

Hunters can legally hunt both morning and afternoon but cannot exceed your daily

bag limit. Double dipping, as in taking a dove limit same day morning and evening, is illegal. Don’t be greedy or a law breaker.

Something that hasn’t changed in 50 years of dove hunting is the hunt. There will always be days when your shotgun is fast and furious, getting dove limits in short order. But don’t forget those days when doves are scarce, and shooting is less.

The age-old adage is often true: “You should have been here yesterday.” A fantastic hunt can be followed by a terrible one, back-to-back. It happens. It’s possible because doves are finicky.

The slightest change in weather can affect feeding and flight patterns. A heavy shower can drive doves away, because they don’t like getting their feet wet. A tropical weather system almost always arrives just as the September dove season opens, so it’s good to have a backup plan.

Dove hunting can be strange. We once hunted a prime South Texas pond with shady mesquites. Across the road 100 yards away, a disked milo field was covered with doves feeding and flying. Our eight hunters were totally disheartened at sunset when only a handful of doves passed our way. Disappointing was an understatement.

I experienced my best dove hunt ever near the town of Alice. Five adults and two teen hunters scattered around the bottom of a huge 20-foot-deep caliche pit. In one corner was a shallow water pool. Two hours before sunset doves came into the water and covered us up. We couldn’t reload fast enough, and our gun barrels got hot.

Each dead bird was clearly visible against the white caliche. Someone would holler, “Hold your fire! Grab and count your doves!” We all limited out in record time, and it was easy picking up spent hulls—a courtesy hunters should always perform. We had three very memorable hunts before a heavy rain changed it all.

Camaraderie is a common thread whether an outing is with a few hunters or a crowd. Dove hunting’s outstanding quality hasn’t changed in 50 years. Doves fly fast, and shotgun blasts don’t seem to scare them. An hour before sunset can be great in good dove country.

Dove hunting should not be about bagging your limit, but rather having a fun outdoor outing making memories. Your next hunt may be your best, so have fun, be safe, and enjoy the outdoors.

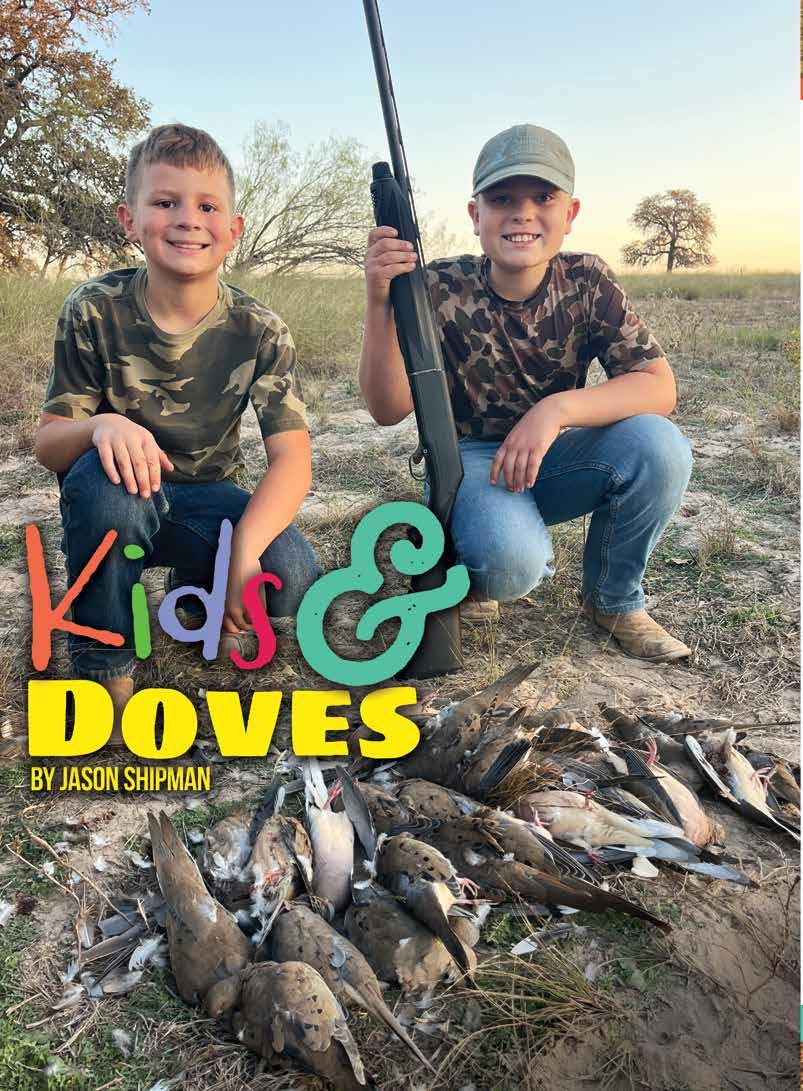

Dove season marks the beginning of all the hunting seasons in Texas. It’s the real hunting opener so to speak, and a warmup for things to come. After a long hot summer, hunters are eager to grab a shotgun and get out in the field to test their wingshooting skills.

The numbers are telling. According to Texas Parks and Wildlife estimates, approximately 400,000 hunters harvest 6 million birds every year, with an annual economic impact of $300 million to the state. Roughly 30% of the national harvest of mourning doves and 90 percent of the national harvest of white-winged doves occurs in Texas. Everything is bigger and better in the Lone Star state, and that holds true with dove hunting.

Dove hunting appeals to so many people for several reasons. It doesn’t require much of a commitment in terms of preparation, time, or money. Affordable hunting opportunities abound. An afternoon off work can easily be turned into a good dove hunt.

Pavilion style hunts have become popular, and generally cater to large numbers of hunters over sunflower fields. These hunts often include a steak dinner, and sometimes even live music. In addition to offering lodging, many outfitters offer day hunting options for the budget minded.

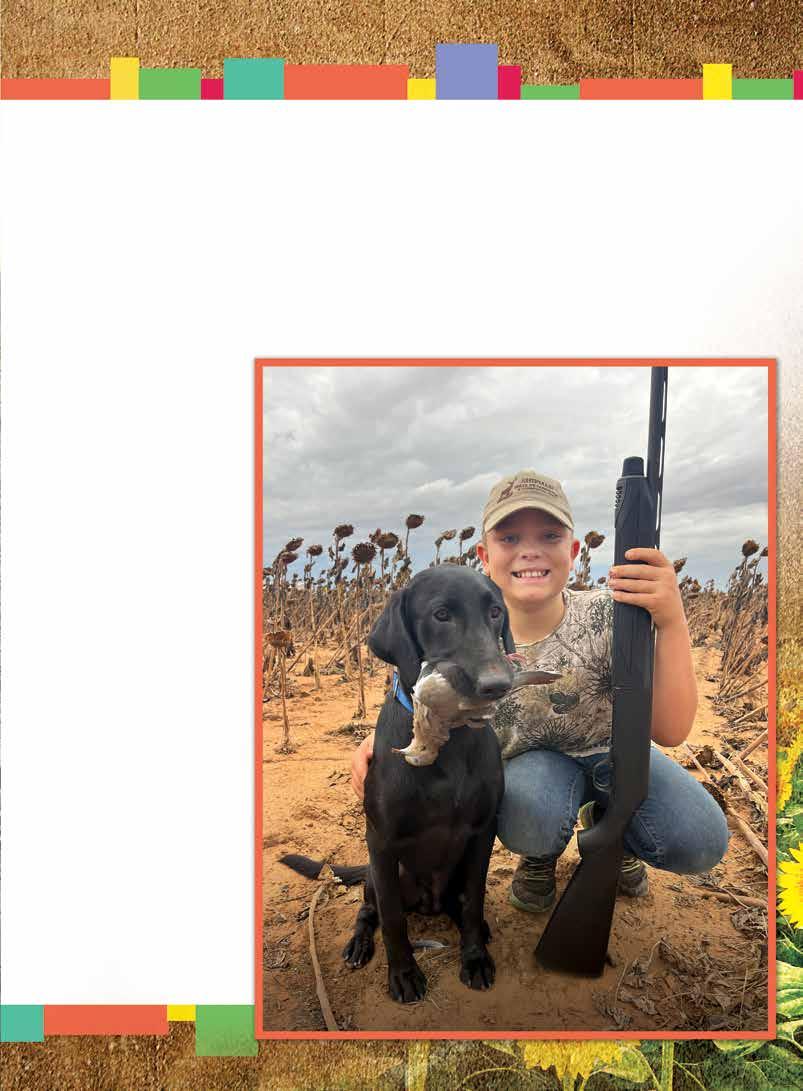

Dove hunting is a social event, and more enjoyable in the company of friends and a good dog. The more the merrier, and it’s fun for all ages. Perhaps the best thing, it provides a great introduction for new hunters. Bird hunting is a great way to start kids hunting. A single shot .410 or 20-gauge is simple, yet effective, and a great shotgun option for a young hunter just starting out.

Gun safety is a priority for everyone and cannot be stressed enough. Care should be taken to provide instruction to newcomers on basic firearm safety. Additionally, game laws including licenses, endorsements, HIP certification, hunter education, seasons, bag limits, shooting times, shotgun plugs, etc., should always be adhered to.

Specifics aside, someone new to dove hunting should set up for success. Pass shooting high flying white-wings is not a great place to start. Consider starting with easier shots around a pond or MOJO decoys and allow confidence to build as wingshooting skills develop.

I have enjoyed many a bird hunt with my kids. It has been very rewarding to see their progression. I have taken care to always involve them in the hunts and let them decide when the time was right for them to actually grab a shotgun and start hunting. We’re still in the process, but generally I start them out with a 20-gauge single shot until they’re proficient before transitioning them to a youth model gas operated semiautomatic 20-gauge.

Based on experience, I believe this option offers the least amount of recoil and is therefore the most comfortable to shoot. Brooke, 13, began shooting last year and was a quick study. Hunter, 11, has been at it for a few years and is very accomplished. Tristan, 9, is ready to pick up a shotgun this year. I would be hesitant betting against Hunter in a wingshooting or sporting clays match. He’s a crackerjack shot and there’s a good chance he’ll take your money.

Joking aside, it’s always a pleasure to see them having fun while hunting, as well as watching the dog work. Our black Lab named “Doc” is arguably the best dog I’ve ever had, and times are good. Doc is young, but has a great “onoff” switch and loves to hunt. He’s a very obedient dog and retrieving is a breeze for him. Our ongoing joke is that Doc took Tristan’s job as our retriever. Not to worry though, because Tristan was ready to hunt anyway.

The kids and I, like many other hunters, look forward to opening day. Afternoon hunts over water holes or on planted fields always provide great action and never seem to disappoint. Additional areas we like to target are treelines, fencerows, and flyways between feeding, watering, and roosting locations. We generally put out a couple of mojo decoys that draw the birds in like a moth to a flame. Of course, some hunts are better than others in terms of numbers, but they’re all good.

After the hunt we always have a great time cleaning the birds. This time is always accompanied with a fair amount of stories and good laughs. I’ll admit that some of these stories might get stretched a bit, but it’s all part of the fun. Back at home we relive the hunt experience yet again at the dinner table while feasting over the family favorite: bacon-wrapped doves.

Countless, unforgettable memories have been made with my kids in the field, including many firsts, and I’m sure they’ll never miss a dove hunting season. It’s deeply ingrained within them and so the hunting tradition will continue and live on. This season, be sure to make time to take your kids, or for that matter, anyone who may have an interest, on a dove hunt. Whether the birds fly or not, I guarantee the good times and camaraderie shared are sure to be a rewarding experience. Get out there, go hunting, and have fun!

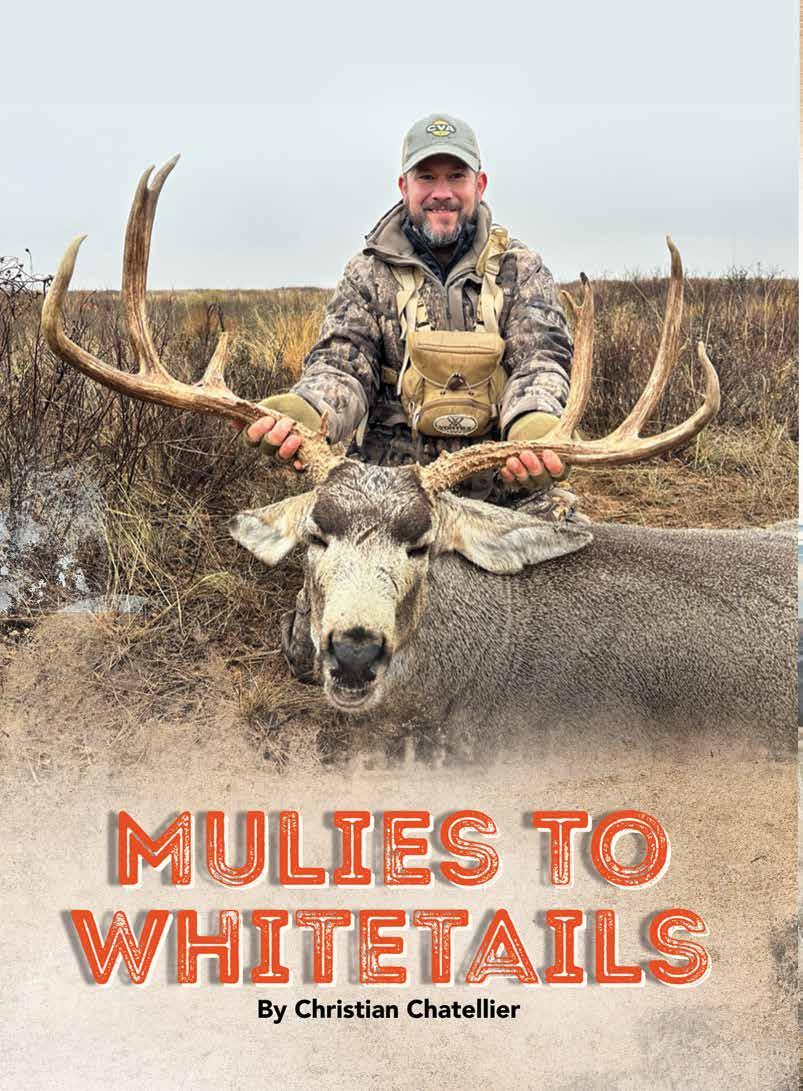

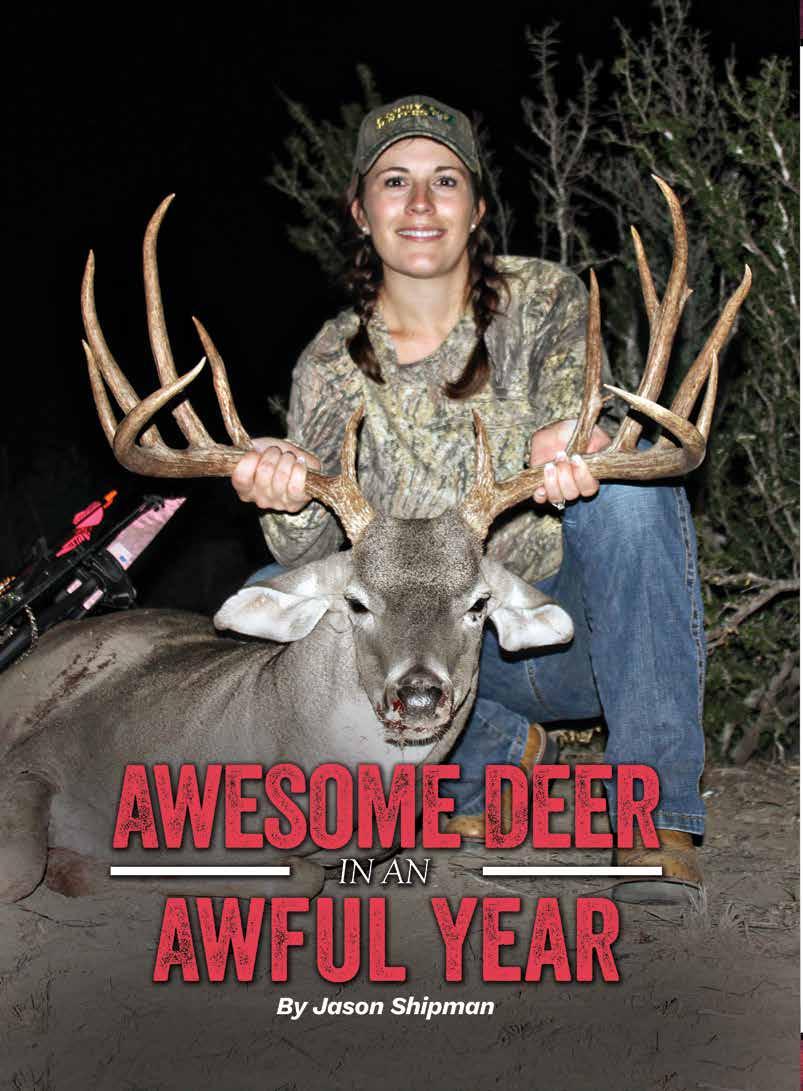

The 2023-24 season started out normal as usual. Being an industry veteran with Dead Air Silencers, I started the season with demos, shows, and training events, but eventually found time to scout and get ready for hunting season. With a love for hunting North and West Texas, I found myself trying to fit in a few hunts as well as a Colorado elk hunt. All this being way different from how I was raised hunting.

I’m from a small town in South Louisiana. I grew up hunting in the swamp for deer and ducks. You were lucky to see a deer each season, and really lucky to see one with a good set of antlers. I can remember hunting in Alabama with a good friend of mine and his family. We worked in law enforcement, so we only had a few days at a time to work the farm, scout and hunt.

But that was the beginning of my trophy hunting. They taught me about deer herd management, correct feed schedules, stand placement, and hunting the wind. This really started my strategic journey to hunt trophy animals. It also started my

desire to learn more about deer management.

After leaving the Louisiana State Police and serving in Iraq for five years, I missed lots of hunting time. Upon my return from overseas, I found myself in a Mississippi hunting club hunting trophy deer. After that season I returned home to Louisiana with the largest deer I had taken to date. A 176-inch whitetail taken with a muzzleloader. Shortly after that, I took a job in Texas where I met my wife and planted my roots.

I started working in the outdoor industry on the real estate side selling large hunting ranches in Texas. I attended many outdoor management classes and deer management classes. I was fortunate enough to get invited to help on a ranch and guide hunters. That was a true turning point and opened my eyes to the Texas hunting lifestyle. This is how I was able to get into the outdoor industry after guiding a group of industry personnel on a hunt. I’m truly blessed.

For the ’23-’24 season I had planned a hunt in Colorado for elk during second rifle season. It’s usually pretty busy up there

at that time, so I also booked a rifle mule deer hunt the day after Thanksgiving in the Texas Panhandle. I was also helping a friend of mine in the industry at his ranch in North Texas. He has worked his ranch intensely for whitetail hunting and a family atmosphere. Again, I’m truly blessed.

So a few friends flew to the Texas Panhandle. One drove out with his camper for us to stay in. We got set, ate dinner and sat around talking about hunting. Our outfitter Justin with JWP came in and went over our times and plans. We had hunted with Justin before and knew all would be great.

The weather came in, including the sleet and rain. The low temps were in the teens that morning. Our good friend T.J. had also come along to hunt. He had beaten the odds with cancer and started his last round of chemo. He was excited to be there.

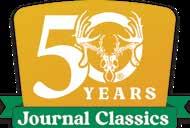

That morning, we were scouting and seeing lots of deer. The first being the buck I wanted to take from last year, “Wide Load.” He was a main frame eight mulie, but had broken his G2 on the right side, which had a split. I have pics earlier of him and video. We split up in two side by sides to cover more ground. We got a call T.J. had shot a deer, and we were all so excited for him. We were spotting deer on a large hillside when another call came in that T.J. went down and wasn’t breathing. Our hunt turned into a nightmare.

After medical help got to us, which takes a very long time due to the area and weather, T.J. had passed away due to a blood clot. We spent the day at the hospital speaking to doctors and the family back home, as we were a day away from Louisiana. We all packed up and decided to head back home to be with the family. My friends told me, however, to stay and hunt because he would want that. “We will go back home and come back maybe one day,” they said, “but he would want you to

hunt your deer. Just get it on camera.”

That was a hard evening. We decided to go back out to retrieve our gear at the ranch. The Lord would have it that the first thing we saw was Wide Load! We prayed and decided to go after that deer. After a few hours and the sleet coming back we were able to get on the deer and take him. With my outfitter helping run the camera, I was able to take him with the CVA 6.5 PRC and the New Dead Air Nomad Ti silencer. The other deer just stood there not knowing what the shot was. What an animal. The ups and downs were tremendous. What a venture.

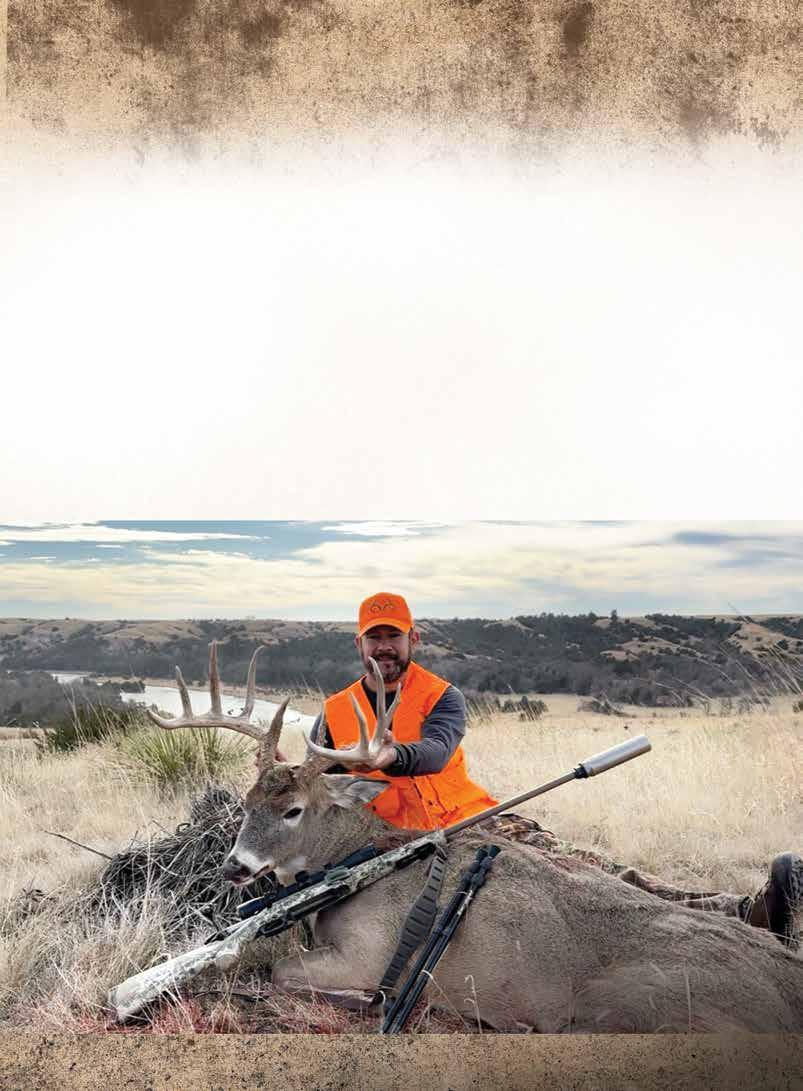

The next week I found myself filming in Nebraska by myself. I only had three days to make it happen. On day one I watched deer and took notes. Day two was another turn. I was watching a gorgeous sun rise one like I had never seen before.

I got a call that my grandfather who taught me to hunt had passed away. I was heartbroken, but it’s God’s will. I was filming a large deer rutting when a car came by on the ranch road and scared them all away. I walked down a ridge behind my location to set up and the deer I was watching popped up. I took him with only two hours left before I had to leave. What a deer. A main frame 10. My first Nebraska buck.

A few weeks later I ended up with my North Texas hunt with a dear friend at his camp. We had hunted some, but we passed on several bucks that were just not mature or not what we wanted to take. This is a fair chase large farm. The last day it started to storm, but we had to get out there and hunt, so I sat alone in a tower blind and at first light, the deer we had pictures of appeared. I took him, using the new silencer. All the other deer stayed around and did not get scared. Amazing what hunting with a suppressor can do. And that finished the season for ’23-’24.

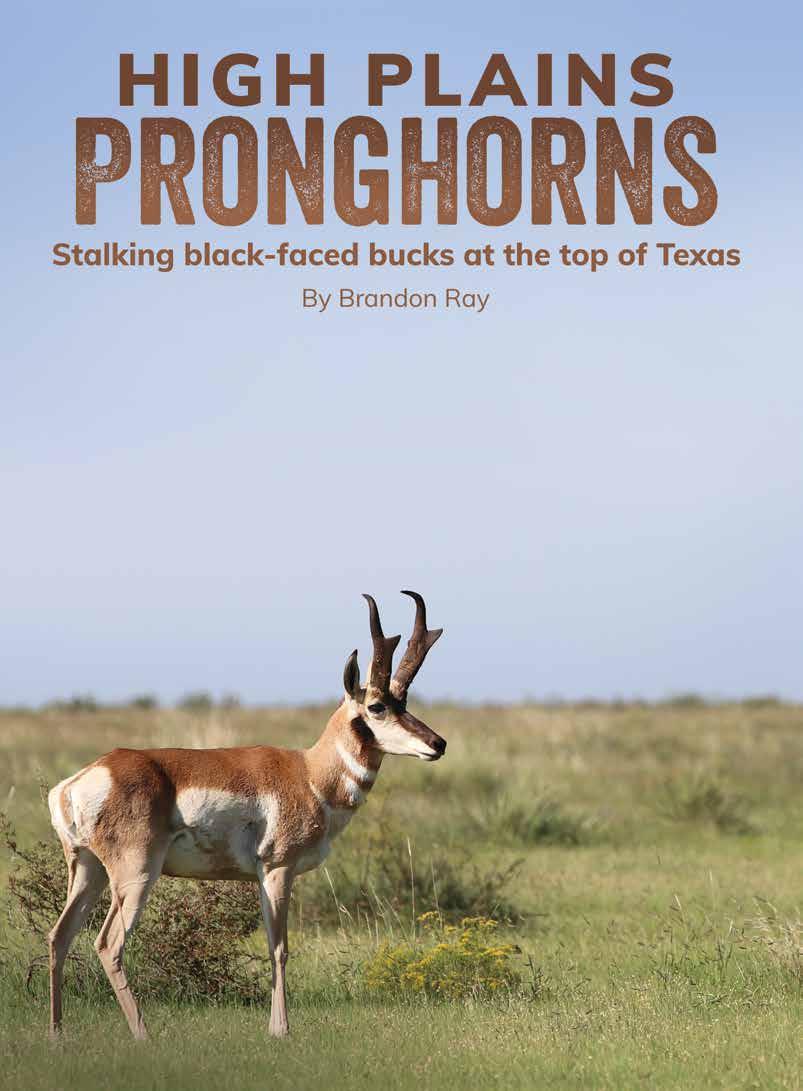

Irecently read an old article in the September 1943 issue of Outdoor Life, titled “The Incredible Antelope” by famed gun writer, Jack O’Connor. It starts as follows:

“A couple of friends of mine drove up in front of my house one day with two buck antelope. They almost caused a traffic jam, and one passer-by, who stood gaping at them, said, “Good Lord, there just ain’t any such deer!”

That is about the usual reaction to a first sight of that amazing creature, the pronghorn. The average American is used to looking at deer, and when an antelope comes along he isn’t prepared for it.

A big buck antelope feeling his oats, prancing along with his rump patch extended so he looks as if someone had tied

a sofa pillow on his rear end, his red mane up, his fantasticlooking black horns coming just above his eyes, looks like nothing else in the modern world-except an antelope.”

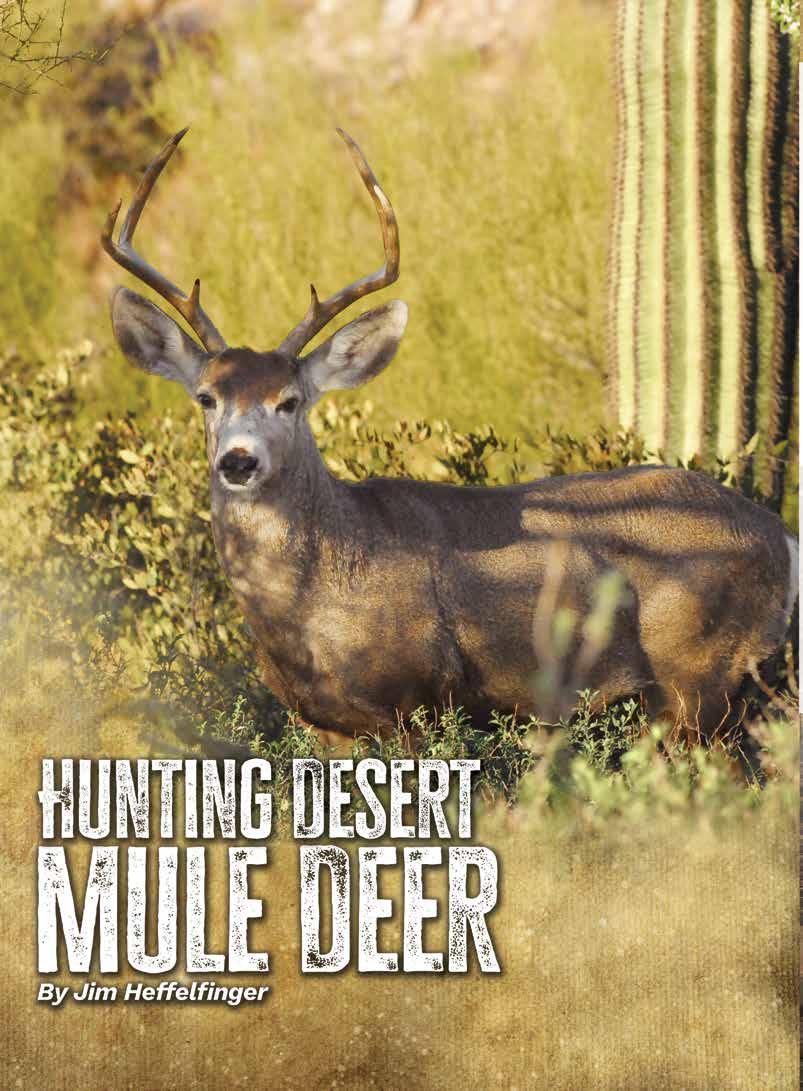

O’Connor had a way with words. Truly, there’s nothing else like Antilocapra americana, the scientific name for pronghorn. They’re unique to the American West and the only horned animal to shed their horn sheath each year. In Texas, huntable numbers exist in the Trans-Pecos, western Edward’s Plateau region, and the Panhandle. Hunting gets controlled by permits issued to landowners. After summer surveys, TPWD issues tags to landowners who request them and that have huntable numbers. Top locations for big bucks include Hudspeth County in the Trans-Pecos and Dallam and Hartley counties in the Panhandle.

A mature pronghorn buck photographed on the plains.

I asked Shawn Gray, TPWD program leader for pronghorn and mule deer, for the current numbers and health of the state’s herd.

“As of last summer, our aerial surveys estimated around 19,500 pronghorns statewide. For the Trans-Pecos, numbers were around 4,500 and holding on even under terrible drought. We believe our intensive management actions regarding brush control, removing restrictive fencing barriers, and predator management are helping keep numbers stable until we can build herds back with higher fawn production when rains finally come back. In the Panhandle, numbers are close to 15,000 pronghorns and have stabilized since the previous couple of years of decline from drought.

“We are also working on doing more habitat management focusing on mesquite removal in some areas of the Panhandle as well as predator management in the northwest Panhandle to build back the herds faster to use for more translocations to new areas of the Panhandle with prime pronghorn habitat and continuing to supplement herds in the Trans-Pecos and western Edward’s Plateau. Dates for the 2025 season are set for October 4-19.”

A pronghorn hunt starts with your eyes. Plan on spending lots of time peering through optics, scouring the horizon for tan-colored, blocky shapes and then evaluating bucks for horn size. Wear 10X40 binoculars with a comfortable bino harness around your neck. If your optics have a built-in rangefinder,

that’s even better. Last year, I used Sig Sauer’s Kilo series 10X binoculars with a rangefinder to pin down the exact distance to my buck and hold my crosshairs accordingly for an accurate shot.

Next, bring a variable-powered spotting scope. The added magnification of a spotter saves time when evaluating bucks far in the distance. Is he big enough for a stalk or not? The spotter will tell you and save boot leather.

I use mine mostly on a window mount from the truck, but a small tripod stays stashed in my backpack for long hikes from the rig so I can steady the scope for accurate field-judging. Last year’s spotter was a vintage Cabela’s Big Sky ED model. I bought the mint-condition scope on eBay for under $300. It has a variable-powered eyepiece that adjusts from 20-60X and a 66mm objective.

Pronghorn country is prickly. Yuccas, chollas, prickly pear cactus and sand burrs will all attempt to ruin your day. It’s also rougher than it first appears. Use swales in the prairie, ravines and clumps of brush to conceal your approach. On a long crawl, you will appreciate thick, canvas-type pants from Carhartt or Levis, leather gloves and even leather patches sewn on the elbows of your camo shirt or jacket or the knees of pants. Whatever rifle you use for deer will work fine for pronghorn. You don’t need a Magnum. A mature pronghorn buck only weighs 110-150 pounds live weight. My go-to antelope calibers are the .243 Win. and .25-06 Rem.

Top that midweight bolt action rifle with a 3-10X scope, and practice with it. I sight mine in about 2-inches high at 100 yards and know the exact hold over for shots out to 300 yards. The wind always blows in pronghorn country, so monitor the wind speed and direction before squeezing the trigger. Windy conditions and long shots would be a viable reason for carrying a bigger caliber and heavier bullets, despite the target animal’s smallish size.

My goal, however, is always to get as close as possible. In 30 years of pronghorn hunting, I can only remember one buck I’ve shot slightly past 300 yards. Most were taken under 150 yards by using rolls in the landscape, or decoys to get close.

Anticipation was running high for last year’s annual Texas Panhandle pronghorn hunt. At daybreak on September 28th, while shuffling gun cases and backpacks in a big, flatbed pickup, rancher R.A. Brown said, “There’s a good buck south of headquarters I’ve seen a couple of times. We can start there.”

We found the target buck in a large flat. A few scrubby mesquites and patches of yuccas dotted the otherwise bleak prairie.

The buck was with a single doe, cocking his head side to side and staying close to her. Through the spotting scope from 700 yards away, he looked good.

We guessed his horns at 14 inches with decent mass. The pair were alert, staring at us hard for ten minutes. Finally, they bedded down. “What the heck,” I said as I grabbed my rifle and spotting scope. “I’ll just try a stalk and see if I can get close enough.”

Bent at the waist, I put a large clump of yuccas between me and the bedded antelope. That cut the distance by 100 yards. From there, it was all on hands and knees. I would scoot the short tripod and scope ahead of me, then crawl to the next clump of yuccas or small mesquite.

Finally, winded and dirty from the long crawl, I sat up and checked the distance with my rangefinder. It said 298 yards. I knew from lots of practice; I could hold the horizontal wire of my crosshairs even on the buck’s backline and the bullet from my .243 would drop right into the kill zone.

I slowly eased up onto my knees, setting up the short tripod and resting my rifle stock over the top of the spotting scope. The doe stared and then stood up. Next, the buck was on his feet. When he turned broadside, I took a deep breath and touched it off.

Both antelope ran a short 20 yards and stopped. The buck started to wobble and then tipped over. It was 9:28 on opening morning and we were already taking photos.

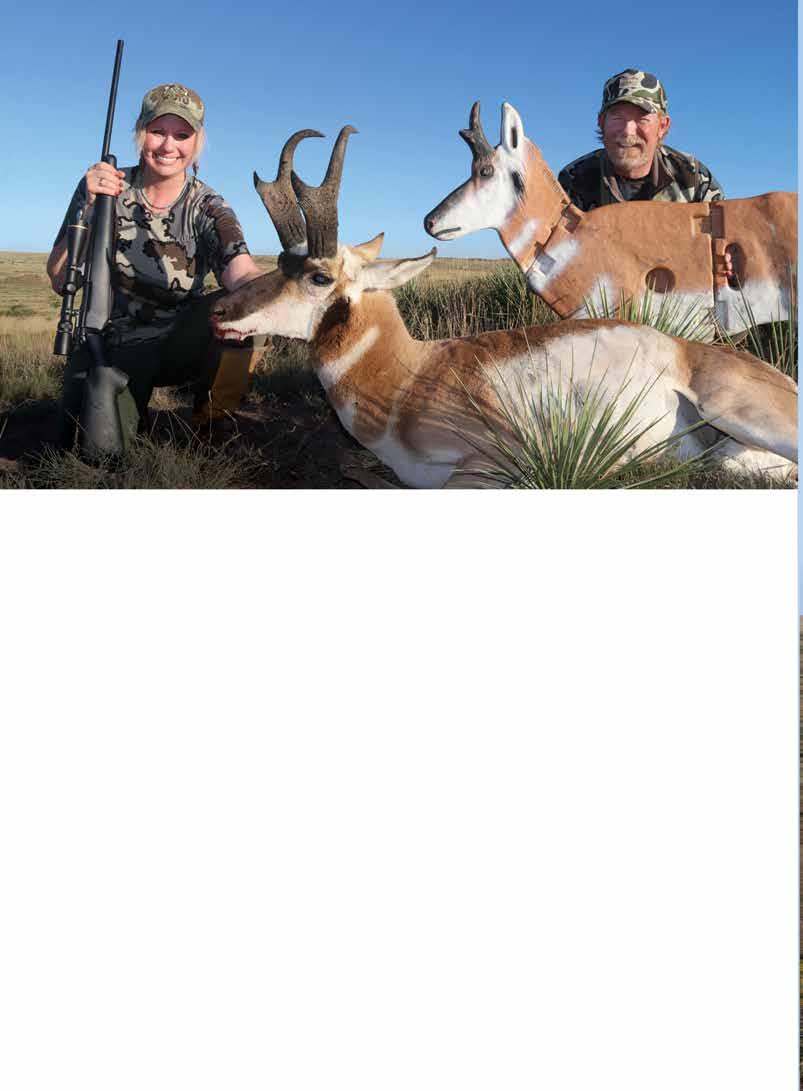

Sweet Lisa Armbruster has hunted antelope with me for years. Most of her bucks have been taken behind a decoy. Why? I asked Lisa Lu what the attraction is to hunting pronghorns and specifically to using decoys.

“I love everything about antelope hunting. I like the big country, the way the grass and sage smell and I like the fact you can stay out and see animals all day. The weather is nice in antelope season with cool mornings and warm afternoons. To me, hunting antelope is more exciting than sitting in a blind, like most deer hunting.

“Antelope are so unique and my favorite wild game to eat. I like hunting with a decoy because when you make a long stalk and a buck comes to the decoy, you feel like you have really earned your shot. Most of my shots over decoys have been close, under 50 yards.”

The following are the top three pronghorn entries in the Texas Big Game Awards (TBGA) from the 2024 season. The minimum net score to qualify for TBGA is 70 inches.

Hunter’s Name County Gross Score Net Score

1. Dan McBride Hudspeth 87 3⁄8 85 4⁄8

2. Bill Wilson Brewster 85 3⁄8 84 2⁄8

3. Steven Wolfe Hudspeth 85 84 1⁄8

Obviously, take precautions when using a decoy. On private land, let other hunters on the ranch know where you’ll be using a decoy. I’ve used plywood silhouettes of a cow, homemade antelope buck and doe decoys, and commercially offered decoys, all with various degrees of success. I’ve never been able to get within bow range with cow decoys, but between mid and late September during the rut, I’ve been able to lure mature bucks in under 50 yards using small buck or doe decoys.

It was late afternoon on day two of the season when we spied a heavy-horned buck with a small harem of does. He was constantly circling his four does, trying to round them up. As we watched, he trotted over a small bluff and down into a valley out of sight. It seemed like the perfect opening to make a decoy attempt.

Lisa Lu and I made the stalk until we peered over the back of our vintage Mel Dutton decoy and into the valley below. The buck was alone, looking away from us at roughly 150 yards. It only took a few seconds for him to spin around and notice the

decoy silhouette. He stared for five long seconds, then started uphill towards us at a steady, fast walk. When my rangefinder said 40 yards, I whispered to Lisa Lu, “When he turns broadside, shoot.”

The buck gawked, facing us head on, then he started to circle to the downwind side. His mane bristled up and he had rage in his eyes. When he got to 20 yards, I grunted with my voice, and he stopped. Lisa Lu steadied the .243 on her shooting sticks, then sent the bullet on its way. The buck stumbled and went down next to a spiny yucca.

The big-bodied pronghorn had a handsome black face and thick horns. Even though they were only 13½ inches tall, the 6½-inch bases pushed his gross score to 76 inches.

Hunting pronghorns is one of my favorite fall traditions. Whether you belly crawl and make a 300-yard shot or try a decoy and fool one inside bow range, it’s always a good time. As O’Connor once wrote, “it looks like nothing else in the modern world-except an antelope.”

The author glassing big country in the Texas Panhandle in search of pronghorns. Tools for this game include 10X40 binoculars, a tripod with variable power spotting scope, and an accurate rifle.

The Texas dove hunting landscape has changed drastically over the years, as with every other outdoor pursuit here in the Lone Star state, but mostly for the better. Yes, the economics of a good dove outing have certainly risen, as with the accompanying gear that most folks now tote afield.

However, at its core, hunting for mourning doves and whitewings remains a relatively inexpensive and low-impact way of kicking off fall hunting seasons while allowing an easy entry for youngsters and first-timers to experience what truly can be a grand pastime. If there’s a single piece of advice to offer, it would be to invite the next generation of hunters along and show them what the great outdoors truly has to offer. After all, they’re the ones who will be stewards of what we as hunters will pass on to them.

The largest impact on dove hunting for the better is the vast expansion of the whitewinged dove population in the past couple of decades, especially into and near large urban centers with healthy populations of eager hunters. Years ago, pursuing whitewings was very much a hunt that centered on one specific area of our sprawling state –the Rio Grande Valley – which meant that unless you called deep South Texas home, you probably had to log a lengthy

Whitewings can be found concentrated in and around most metro areas in the state, providing good hunts not far from many large cities.

road trip to make it down to prized dove havens not far from the Mexican border.

However, following a devastating freeze in December 1983 that killed the nesting valley citrus groves, the whitewing population started expanding north — first into areas such as Kingsville and Corpus Christi — and later into Uvalde, San Antonio, and Austin. As of today, the larger cousins of mourning doves have migrated across most of the state and can now be found in almost every county in Texas.

As biologists note, roughly 90% of the breeding population resides in or near urban areas. Simply put, you now don’t have to go far to get into huntable numbers

of whitewings. They’ve come to you. Texans are adept at bagging doves of all varieties, especially whitewings, with an annual mixed harvest of 6 million from overall populations of 30 million mourning and 12 million whitewings. Most of the recent expansion out of The Valley, according to biologists, was due to hard freezes that decimated citrus groves. After those freezes, and with increased human encroachment and other factors, whitewings began to migrate out of deep South Texas, first appearing in the San Antonio metro area, and later moving farther north, east and west.

TPWD’s 2000 spring breeding survey – it’s hard to believe that’s 25 years ago – showed just how things had changed from the previous decades. The agency estimated roughly a half-million whitewings in the Lower Rio Grande Valley and about 700,000 across the rest of South Texas.

Today, the overall Texas breeding population numbers more than 12 million, according to TPWD. Most of that population prefers nesting and roosting in urban areas with large trees and consistent food and water sources. By comparison, the mourning dove breeding number is typically almost three times that in good years, providing most of the daily bag limits for a majority of hunters.

Texas accounts for 30% of the total mourning doves and 85% of the total white-winged doves killed in the U.S. each year, far more than any other state, for obvious reasons. It’s not uncommon for hunters in the Pineywoods, Hill Country

The spoils of a good dove hunt are enough to make anyone smile, no matter their age.

and Rolling Plains to bring home at least a few whitewings in their daily aggregate bag limit.

The obvious advantage to the whitewing

expansion is that it has provided additional hunting opportunities for hunters around urban areas all the way from Brackettville east to San Antonio and Tyler,

Practice makes perfect when dove hunting, no matter which version of the species may be flying. Don’t wait until opening day to pull out the shotgun.

with northern expansion to Big Spring and Brownwood. Even Houston and the Dallas-Fort Worth hunters get a few shots at whitewings where sunflower and corn are available to whitewings.

Public hunting can be tough based on a number of factors, but TPWD provides most of its numerous dove hunting opportunities near urban sprawls that can be accessed using an annual public hunting permit. If you don’t have a dove lease or access to private land, the public hunting options provided by the agency are certainly less expensive and can be quite good if new waves of

Years with good moisture levels help provide grain crops whitewings thrive on and will usually keep migrating birds for much of the season.

migrating birds cooperate.

Aside from The Valley and urban areas, whitewings in recent years have also expanded their range across Texas’ coastal counties in a big way. Starting at Port Mansfield and heading up to Victoria, the I-69 corridor has become among the notable hot spots for great whitewing hunts, featuring a variety of terrain that can hold doves all season.

The same can be said for the State Highway 35 corridor beginning north of Corpus Christi all the way up to south of the Houston sprawl. That area is usually considered more of a traditional waterfowl haunt. However, it has become synonymous with excellent dove excursions, especially in years with good moisture that aids standing agricultural grain crops.

If you’re hunting doves, it’s always an occasion to also target the early teal season in September in traditional hot spots along the coast that offer great bay hunting opportunities when the waterfowl counts are good.

And, if you’re anywhere near the coast, it’s always customary to schedule some time for the saltwater flats in pursuit of speckled trout, redfish and flounder. Wing shooting may be the main draw, but it’s

Doves and windmills in Texas go hand in hand. If you have consistent sources of water, you’re going to have consistent flights of birds.

hard to think of a better cast-and-blast combo than bringing home a couple of limits of doves and couple of limits of fillets. If you’re looking to spoil yourself, friends or family – or all the above – many fishing guides and outfitters today specialize in offering dove and waterfowl hunting as part of their outdoors repertoire. It may truly be the Golden Age of dove hunting in Texas! Sure, the cost of every

hunting excursion seems to be more expensive, but pursuing doves of all legal varieties – including those invasive Eurasian collared doves (that have no season or bag limit restrictions) – is one of the easiest and relatively inexpensive ways to enjoy the start of fall hunting seasons with friends and family.

Here’s to another exceptional year of Texas hunting at its finest!

By TTHA Staff

Hunters can plan on taking a high percentage of young doves early in the season, with mature doves becoming more common after early October.

The Journal has attempted to predict fall hunting for several years, using information from the field staff of Texas Parks and Wildlife Department to lay out the prospects for doves, waterfowl, whitetails, and quail. Time has shown the most important predictions for the benefit of most fall hunters lies in migratory game birds.

How do you predict the coming deer season for the No. 1 whitetail hunting state in the nation? In general, deer hunters are more concerned about the price of gasoline and corn than the predictions for good hunting. The general trends in whitetail hunting go from good to better, so in the future we will skip whitetails in this fall hunting forecast.

Upland game birds and animals usually follow weather trends, and local hunters know how the weather has been, so we will leave upland game to the local hunters across the state.

Two important species of migratory birds that have the interest of hundreds of thousands of hunters are mourning doves and teal ducks. Both move from north to south in regulated patterns, with teals—bluewing, green-wing and cinnamon—arriving on coastal prairies in mid-August. Mourning doves have set patterns of migration, and all migratory bird hunting seasons are determined by The Migratory Treaty Act signed with Canada in 1918. Mexico joined the treaty in 1936 to include all of North America.

Migrating game birds travel from north to south based on weather patterns and food supply. Predicting

when blue-winged and greenwinged teal arrive on the coast, or when other migrating geese and ducks will leave breeding grounds in northern provinces determines when hunting seasons open and close.

Mourning doves often have varying migratory patterns, and a high percentage of birds do not migrate at all. For this reason, many young doves are hardly out of the nest when hunting begins by treaty on Sept. 1. Research has shown

that doves actually migrating south to Texas do so sometime near Oct. 15. Therefore, hunters can plan on taking a high percentage of young doves early in the season, with mature doves becoming more common after early October.

The historic freeze of Dec. 18-30, 1983, caused a major shift in white-winged dove habitats in Texas. The gulffreezing, fish-killing temperatures destroyed the citrus orchards and nesting grounds of the Rio Grande Valley whitewings. At generally the same time, corn and domestic