ear Members:

Texas Trophy Hunters Association is deeply shocked and saddened by the recent news of the attempted assassination of President Donald Trump. We unequivocally condemn this violent act and extend our heartfelt prayers to President Trump and all the victims affected by this tragic event.

In these troubling times, we stand united with the victims and their families, offering our support and prayers for their swift recovery and well-being.

As a community committed to keeping our hunting heritage alive, we promise to promote, protect, and preserve the values that bind us together. Acts of violence have no place in our society, and we must continue to uphold the principles of respect, unity, and solidarity.

Let us all keep the victims and our president in our prayers, and work together to foster a safe and supportive environment for all.

Sincerely,

Christina Pittman President & CEO

Graphic Designers Faith Peña

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

Benno Bauer, Jason Clayton, Kennisyn Drosche, John Goodspeed, Judy Jurek, Lee Leschper, Bobby Parker, Eric Stanosheck, Brian Stephens, Ralph Winingham

Emily Lilie 713-389-0706 emily@ttha.com

Marketing Manager Logan Hall 210-910-6344 logan@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events

Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

Administrative Assistant

Courtney Carabajal 210-485-1386 courtney@ttha.com

Advertising Production Deborah Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Membership Manager Kirby Monroe 210-809-6060 kirby@ttha.com

Events and Chapter Services Manager

Donicio Rubalcava, CMP 210-889-1543 donicio@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

Despite the summer heat, hunting aficionados showed up in San Antonio to celebrate the opening of the new TTHA/SCI headquarters on June 29. Both organizations hosted an afternoon of fun, food, and fellowship at the open-house event. “Texas Trophy Hunters Association welcomes Safari Club International’s business office to San Antonio, Texas,” said TTHA President and CEO Christina Pittman. “TTHA is excited

to have two forces under one roof to amplify the impact on wildlife conservation and hunting advocacy.”

“We are excited to launch this endeavor in the Lone Star state, and look forward to a productive future in a pro-hunting political environment that will contribute to our organization’s growth and its wide-ranging advocacy activities for years to come,” said SCI’s CEO W. Laird Hamberlin.

Texas Trophy Hunters Association is proud to relaunch our Member Discount Program (see page 81). This revamped program offers our members unparalleled savings on premier outdoor and hunting gear. It not only aims to elevate our

members’ outdoor experiences, but also provides an exciting opportunity to collaborate with companies in the industry who want to reach Texas hunters and outdoorsmen and women directly. Contact kirby@ttha.com for more information.

By Horace Gore

Don Gilchrist is a pioneer of our hunting heritage. He grew up in the small town of Ben Wheeler in Van Zandt County, a farming town of some 400 residents. Don’s father was a hunter, and had Don sitting on a pond shooting doves when he was 10 years old.

“Dad sat me down in a good spot and handed me a single barrel .410 and a box of shells,” Don said. “Dad came back about sundown, inquiring about my doves. I had one mourning dove and a lot of empty .410 hulls on the ground.” Since that day, I have had a shotgun or rifle in my hands, looking for a place to hunt.

Don grew up in a county that is referred to as the Gateway to East Texas. He spent a lot of time hunting fox and gray “cat” squirrels, bobwhite quail, doves, and whatever else he could find. Like a lot of East Texas kids, Don knew how to thump a watermelon, bale hay, pick peas, and hunt at an early age.

Van Zandt County is famous for declaring war on the United States of America. After the Civil War, Gen. Philip Henry Sheridan sent troops to quell the uprising, and the Van Zandt citizens won the battle. But after their win, the locals got high on “shine” and eventually lost the war. The most famous place in Van Zandt County is the “First Monday Trades Day,” the largest flea market in the United States. The well-attended monthly event has been held in Canton, the county seat, for 150 years. Watermelon farming was good around Ben Wheeler, and Don had a close friend, Randall Preston, whose father was big in the watermelon business. As time passed, the watermelon business took the Prestons to Frio County where they bought a farm near Pearsall. Don soon learned Frio County had a lot of quail, and before long he was in Pearsall hunting with Randall. “I wore out a Browning auto 20-gauge on quail hunts,” Don said.

Don and his first wife, Sharon, developed a successful business in Ben Wheeler and raised four children. They continued

to visit with the Prestons in Pearsall, and Don did a lot of quail hunting in Frio County. A farm came up for sale near the Prestons, and Don and Sharon bought the property, which was primarily raw ranchland with few improvements. They didn’t

do much with the land, and soon after, Sharon became ill and died of renal disease.

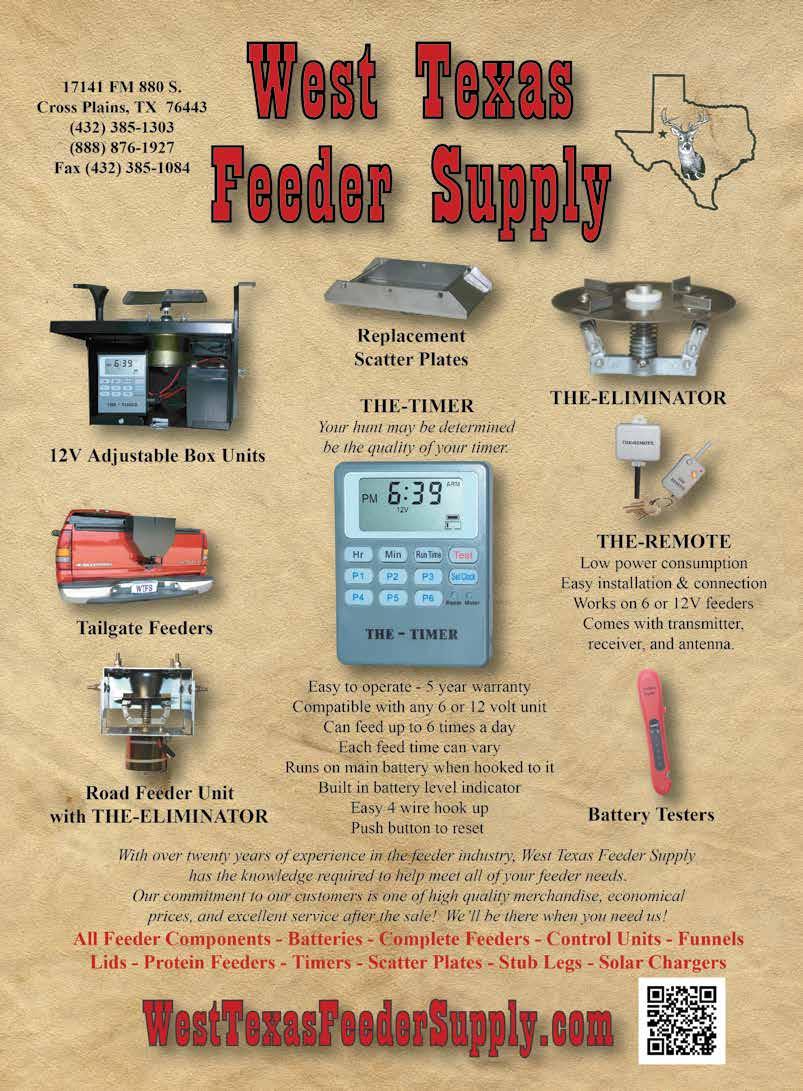

Later on, Don married Sandy, his present wife, and they eventually pondered on what to do with the ranchland. They talked about developing or selling it, but Sandy wanted to develop. They began to build on the property—a lodge and other buildings—and soon Don and Sandy had established the G2 Ranch, a year-round hunting and entertainment venture. Along with white-tailed deer, the ranch has a variety of exotic game as well as bird hunting. The facilities are also available for other festive occasions.

The ranch entertains hunters from a wide range of places, but Don says about 40% of their clients are from the southeastern states. The other 60% come from Texas and adjoining states. Hunters come to the ranch for a range of exotics including axis, blackbuck, fallow, aoudad, nilgai, and native whitetails. A cadre of guides are available to provide the best in trophy hunting. “Of course,

Don and Sandy Gilchrist developed their ranchland into a lodge and other buildings, establishing the G2 Ranch as a year-round hunting and entertainment property.

our trophy whitetail bucks are the first choice of most hunters,” Don quipped. September is a big month for the ranch when hunters converge on the sunflower fields to hunt whitewinged and mourning doves. Don and Sandy have the best in dove hunting, and most of their hunts are booked long before the season opens. “We can accommodate a dozen or a hundred hunters, and white wings are our specialty,” Don said. “Sandy and I started out, hoping to get carloads of dove hunters. Now, they come by the busload and by airplane.”

Don had this to say about the excellent exotic hunting on G2: “Hunters who are new to exotics like to take a good axis buck, or maybe a blackbuck or a fallow buck. Those are probably our first-choice animals.”

Don noted as hunters develop more interest in exotics, they want something a little different. “We have them all,” Don said. “Our repeat hunters want a wide choice to choose from—even a big blue-bull nilgai, sable, or greater kudu on occasion.

Don not only hunts deer, quail, and doves, he makes a lot of hunting available to the many guys and gals who come to his ranch for a variety of game. He and Sandy are longtime friends of Texas Trophy Hunters, and that’s why we’re proud to call Don a pioneer of our hunting heritage.

Do your part to preserve our hunting heritage. Share your passion with the next generation. Pass the torch.

How do you pass the torch? Share your photos with us. Send them to editor@ttha. com. Make sure they’re 1-5 MB in file size.

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission has approved updates to the chronic wasting disease containment and surveillance zones. Containment zones refer to areas where CWD has been detected and confirmed. Surveillance zones identify areas where, based on the best available science and data, the presence of CWD could be reasonably expected.

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department will replace mandatory check station requirements with voluntary testing measures beginning Sep. 1 in the following containment and surveillance zones:

• CZ 1- Hudspeth and Culberson counties

• CZ 2- Deaf Smith, Oldham and Hartley counties

• CZ 3- Bandera, Medina and Uvalde counties

• CZ 4- Val Verde County

• CZ 5- Lubbock County

• CZ 6- Kimble County

• SZ 1- Culberson and Hudspeth counties

• SZ 3- Bandera, Medina, and Uvalde counties

• SZ 4- Val Verde County

• SZ 5- Kimble County

• SZ 6- Garza, Lynn, Lubbock, and Crosby counties

Mandatory CWD testing remains in place for SZ 2 due to the additional detections of CWD in free-range mule deer outside of CZ 2. In response to these detections, TPWD will additionally expand the geographical coverage of two containment zones in the Panhandle. TPWD will eliminate two surveillance zones – SZ 10 and SZ 11 – in Uvalde

Additional amendments have been adopted to modify surveillance zones to include only portions of properties within a two-mile radius around a CWD positive deer breeding facility—the physical facility, not the boundaries of the property where the infected facility is located.

Zone information can be found on the CWD webpage on the TPWD website. . —courtesy TPWD

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission approved statewide deer carcass disposal regulations during its May meeting, in an effort to reduce the risk of transmission of chronic wasting disease across the state. For most hunters, these new regulations do not change how they currently care for their deer after harvest.

“Proper disposal of all potentially infectious material is critical for reducing the risk of disease transmission,” said Blaise Korzekwa, TPWD’s whitetailed deer program leader. “These new regulations provide hunters more options when it comes to processing their deer to reduce that risk. If CWD is not managed and efforts are not made to mitigate potential spread of the disease, the implications for Texas and its multibillion-dollar ranching, hunting, wildlife management and real estate economies could be significant.”

The new regulations, which will take effect during the upcoming hunting season, will allow hunters to debone a carcass at the site of harvest, provided proof of sex and tags are maintained

until the hunter reaches the final destination. By leaving the unused parts at the site of harvest, the chance of spreading CWD to other parts of the state is greatly reduced. Meat from each deboned carcass must remain in whole muscle groups (not chopped, sliced or ground) and maintained in a separate bag, package or container until reaching the final destination.

These disposal measures apply only to unused carcass parts from native deer (white-tailed deer and mule deer) harvested in Texas and being transported from the property of harvest. If carcass parts from native deer species are not being transported from the property of harvest, these carcass disposal rules would not apply.

Because many hunters take their harvest to a commercial processor, it will be the processor who properly disposes unused parts. For hunters processing deer at home, disposal in a commercial trash service is preferred, but other options are available.

Acceptable disposal options include:

• Directly or indirectly disposing the remains at a landfill permitted by the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality to receive such wastes

• Burying the carcass at a depth no less than 3 feet below the natural surface of the ground and covered with at least 3 feet of earthen material

• Return to the property where the animal was harvested.

For more information, visit the CWD webpage or contact a wildlife biologist. —courtesy TPWD

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission approved regulations banning canned hunts and implementing trapping standards for mountain lions during its May meeting. These changes are the first in more than 50 years regarding management of mountain lions in Texas and move the state toward more modern hunting and trapping standards.

“The passage of these regulations is an important step toward better management of mountain lions in the state,” said Wildlife Diversity Program Director Richard Heilbrun. “The regulations support ethical hunting and trapping practices while continuing to provide flexibility for landowners to manage mountain lions.”

The Commission unanimously voted to approve the measure, which included the banning of canned hunts, meaning the capture and later release of a mountain lion for the purpose of hunting or pursuing with hounds.

After concerns were raised that some mountain lions are left to perish in traps, which many consider to be inhumane and potentially damaging to the reputation of trapping, a 36-hour trapping standard was also adopted. This regulation ensures that live lions are not kept in traps or snares for more than 36 hours.

The initial proposed regulation during the March Commission meeting included an exemption to the 36-hour trapping standard for snares fitted with a breakaway device. The proposed regulation was modified in response to public feedback received during the comment period to remove the breakaway device exemption and replace with a blanket exemption for snares set vertically with a maximum loop size of 10 inches or less.

Consequently, if a mountain lion is inadvertently captured in a snare set vertically with a loop that cannot exceed 10 inches in diameter, the 36-hour requirement does not apply.

Mountain lions are relatively uncommon, secretive animals. In Texas, mountain lions are primarily found in the Trans-Pecos, the brushlands of South Texas and the western Hill Country.

For more information, please visit the

mountain lion or fur-bearing animal regulations pages on TPWD’s website. —courtesy TPWD

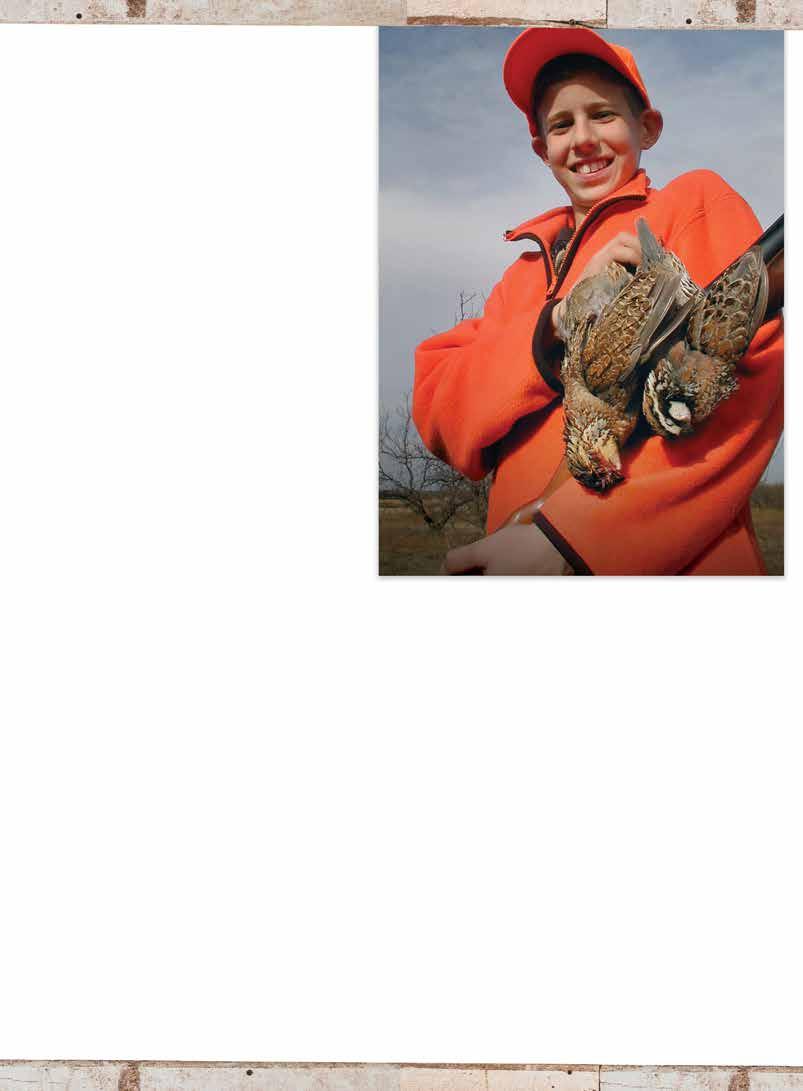

The FDA has approved a drug for parasite control in wild quail populations. The FDA concluded the drug integrated into a medicated feed is safe and effective in controlling parasites in wild quail in their natural habitat. For instance, eyeworm parasite infection levels in the Rolling Plains region of West Texas have been documented at over 60% and cecal worms have been documented at up to 90% levels throughout Texas.

The medicated feed crumble integrating the drug will be known as “QuailGuard.” In labeling instructions, the FDA recommends the medicated feed be in the form of a crumble and not generally broadcast but offered through strategic feeding stations and appropriate feeders.

QuailGuard is a field-tested medicated feed crumble made from a proprietary blend of grains, minerals, vitamins, and amino acids combined with the active drug ingredient, Fenbendazole. It has been proven to be palatable and effective throughout the FDA registration process. In addition to parasite control, the formulation has multiple health benefits to quail.

Based on field research, the recommended application is for QuailGuard to be distributed with strategic feeders for a 21-day period in the spring and a 21-day period in the fall. The FDA does not recommend it for broadcast feeding. Using a 50-pound bag per application and one feeder per 200 acres, QuailGuard will cost approximately 50 cents per acre for treatment once a feeding strategy has been set up. An example of strategic feeding stations employing QuailSafe technology has proven to be effective in treating wild quail for parasites in multiple FDA-approved demonstration sites.

The approval follows nine years of research and application in coordination with the FDA by Dr. Ron Kendall, professor of environmental toxicology at the Wildlife Toxicology Laboratory at Texas Tech University. Park Cities Quail Coalition and the Rolling Plains Quail Research Foundation primarily provided funding for the research. The funds were raised by sportsmen concerned about the declining huntable populations of wild quail in Texas and beyond.

“This was a momentous project involving over a decade of research and ultimately involving dozens of highly credentialed professionals and has resulted in the publication of 44 scientific research papers so far,” Dr. Kendall said. “I am a quail hunter myself and feel passionately that QuailGuard will contribute to quail conservation and sustainability efforts.”

“We are proud to have funded this research with money raised by hunters,” said Raymond Morrow, president of Park Cities Quail Coalition. “Wild quail naturally have a high mortality rate. It makes sense that high levels of parasites in their eyes and gut contribute to quail mortality. We hope all grassland birds in this region will benefit from this advancement.”

“Of course, habitat and weather are the most important factors. However, eyeworms and cecal worms on quail have reached pandemic levels in parts of Texas and this is the first solution to this significant factor in quail decline,” said Joe Crafton, QuailGuard’s president. “This is another sportsman-led conserva-

tion success story and only the second wild animal ever approved by the FDA to be treated in their natural habitat with a medicated feed product.”

—courtesy Park Cities Quail Coalition

The National Elk Refuge in Wyoming provides habitat and winter grazing for thousands of elk in western Wyoming. The Refuge was founded to provide winter forage, including supplemental winter feed, to help elk through Wyoming’s harsh winters after development in the Jackson area cut off prior migration corridors. The Refuge has been feeding elk in the winters since 1912. The Refuge is currently updating its Elk and Bison Management Plan and considering whether to continue, reduce, or phase out the supplemental winter-feeding program.

SCI strongly opposes any option that would arbitrarily cut-off feeding without providing alternative forage or reopening migration corridors, given the likelihood of mass starvation, cratering of the Jackson elk herd, and increased humanwildlife conflicts. SCI is currently engaged in litigation, along with the Wyoming Outfitters and Guides Association, to defend the adaptive phase-out of feeding against animal rights groups that seek to speed up the end of feeding. In May, SCI participated in a stakeholder

meeting to raise our concerns and push for the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to consider a broader range of alternatives in the environmental analysis supporting the new management plan. SCI was the only group in the session representing sustainable use of elk and seeking to maintain feeding, so our participation was key in developing a record for the Service’s decision-making.

SCI will continue to promote responsible management of the National Elk Refuge and to oppose any top-down decisions that would shirk the Service’s duty to protect and preserve the elk who depend on the Refuge for winter feed— and who have no other options, given human development and the reintroduction of wolves. —courtesy SCI

The International Hunter Education Association-USA (IHEA-USA) announces the expansion of its partnership with Savage Arms to advance firearm education and safety initiatives.

“Savage is proud to continue our support of IHEA and their focus of safely educating the next generation of hunters. Worldwide, IHEA has helped educate tens of thousands of new hunters every year. The safe hunting practices that are taught by these great instructors are creating a strong, safe future for our hunting lifestyle,” Savage Arms said in a statement.

Former President Donald J. Trump stopped by the Hunters’ Embassy on June 13, and was eager to thank Safari Club International for representing sportsmen and women worldwide and defending the right to hunt. “It was an honor to have the president spend time at the Hunters’ Embassy to share his support,” said Ben Cassidy, SCI’s executive vice president of international government affairs and public relations. “He even called the embassy a ‘beautiful building.’ His visit certainly threw the press pool outside through a loop.” —courtesy SCI

As part of the expanded partnership program, Savage Arms will include a promotional card with every firearm sold, encouraging customers to sign up for the Firearm Fundamentals online courses, provided by IHEA-USA. The courses teach safe firearms usage, which are built with and adopted by many state wildlife agencies. These courses give new hunters and firearm enthusiasts a solid foundation in firearm safety and handling.

In addition to promoting the Firearm Fundamentals course, the promotional cards will provide an option to donate to IHEA-USA directly, further supporting the organization’s efforts to promote hunting safety and conservation. This move underscores Savage Arms’ dedication to hunter education and safety, aligning perfectly with IHEA-USA’s mission to provide comprehensive training and resources for new hunters.

IHEA-USA Executive Director Alex Baer said, “We are incredibly grateful to Savage Arms for providing this opportunity to educate firearm owners with the Firearm Fundamentals Courses. Savage Arms has been a long-standing partner of IHEA and the Conservation Industry with their support of hunter education instructors, and this partnership further demonstrates their dedication to safety and responsible gun ownership. The Firearm Fundamentals online courses were created to help new gun owners understand their contribution to the North American Model of Conservation, and to quickly gain confidence through an education focusing on safe firearm handling, transportation, storage, and even range expectations. We hope this partnership benefits Savage Arms customers and helps to create safer, more knowledgeable firearm owners.”

The Firearm Fundamentals Online Courses, accessible to participants in hunting and shooting sports, are comprehensive online courses that equip participants with essential knowledge and skills that will create confident and satisfied gun owners. As more hunters enroll in the course, state agencies will benefit from a more educated and safetyconscious hunting community, contributing to improved safety nationwide. Visit ffcourse.org.

By Dr. James C. Kroll

In the early 1970s, I began presenting seminars in response to the growing demand for information about managing white-tailed deer. By today’s standards these talks were pretty generic, covering the usual age, nutrition and genetics components to management. It was my opinion the greatest challenge was getting bucks past their first year of life.

“Can I safely say, every Boone and Crockett buck once was a yearling?” was my favorite question. To my surprise, the most common response was, “If I don’t shoot him, someone else will!” I would come back with, “Well, if you let a yearling buck walk, his chances were certainly higher than if you shot him.”

That is indeed true, but at that time we had no idea what the true survival rate was for bucks. In Texas, we tend to have opinions on deer management colored by what I call the “South Texas mindset.” That is, deer management takes place on large properties. In the real world, however, folks try to manage for better bucks on 40-acre and 80-acre tracks. After 50 years, we now have more data on factors affecting buck survival, so this

According to author, the principal mortality agents for bucks has been disease, fighting and accidents. In the 2020-21 season, he lost two mature bucks to accidents where he conducts deer research. This buck died during the February 2021 “snowmageddon” when the deer tried to walk between two trees, got his hips caught, and froze to death.

column is about what we know.

I just finished an exhaustive investigation on the state of knowledge about buck mortality factors, rates and survival. It’s an understatement to say the literature is very confusing on these subjects. There are a host of variables influencing mortality, ranging from climatic conditions to hunting pressure to social norms for hunters. In “natural herds,” buck morality takes a “U-shaped” form, with highest death rates in the early and late periods of life.

In general, most studies agree the highest mortality of bucks and does is from birth to about one month of age. There is a reason why does have two fawns. It’s the magic number needed to produce at least one fawn each year. The primary causes, in order, for fawn mortality are starvation, predation, and disease. Under poor nutrition, does cannot produce enough milk to feed both fawns, leaving one or both to die. Fawn survival in 2020 for much of South Texas was quite low, due to very dry conditions, which translated to poor quality and quantity of forages.

In other areas of the country, fawn survival was very high due to abundant rainfall during the nursing period.

Predation is a hot topic today, and it should be. Predators are increasing at alarming levels—especially the larger predators such as lions and bears—creating an “additive” impact on survival. Bears can take as much as 50% of the fawn crop, because they are highly adapted to finding fawns, even in thick cover.

It’s reported that sheep and goat ranching in the Texas Hill Country allowed the coyote to cross the Edwards Plateau and invade the southeastern and eastern portions of the U.S. Coyotes have moved farther and farther north in the last two decades, creating concern among biologists who once asserted that coyotes were not a real problem. Disease can be a significant problem, especially in conjunction with poor nutrition. Bacterial and viral diseases are common killers of fawns, followed by parasites such as pinworms.

The second highest natural mortality period, especially bucks, is the first year after weaning. However, mortality is not uniform among bucks and does. The reason being that yearling bucks tend to relocate, exposing them to strange places and increased mortality. That’s one reason young bucks tend to “pal up” with another buck one year older, in a tight relationship lasting as long as both survive. Most of the scientific studies have focused on mortality of younger bucks, frankly because in many states there are no mature bucks to study.

After a buck reaches his second year, natural mortality is quite low, sometimes less than 5-10%, and I often have said after 21/2 years, a buck is pretty much immortal until 61/2 years and older. In fact, an Oklahoma study concluded: “…males >3.5 years old tended to die from non-human causes (e.g., fighting, predation) more frequently than did younger deer.” (Ditchkoff, et al. 2001). The key word here is “natural,” because in most of the whitetail’s range, the number one mortality agent after the first year is hunters. Many areas exist where hunters annually take as much as 50% of the yearling bucks.

That trend has lessened in recent years, primarily due to the education of hunters by media such as this magazine, conservation organizations such as the Quality Deer Management Association—now the National Deer Alliance—and outdoor programming. According to QDMA, yearling buck harvest has dropped from a high of about 60% in 1989 to 30% in 2018. Even so, states such as Wisconsin, Maryland, Massachusetts, New York, and Illinois harvested 40-50% of their yearling bucks in 2018. It’s interesting Wisconsin considers any buck greater than 18 months of age, as an “adult.”

It also is a state which considers yearling bucks with spikes less than 5 inches in length. When we consider just bucks, hunters in many areas are indeed the primary mortality agent. Yet, studies conducted in states with high buck harvest rates tell us little about the question, what is a buck’s potential survival if I do not shoot him as a yearling?

In order to arrive at an answer, we have to look at the handful of studies conducted on either un-hunted populations or ones where age management is deeply ingrained. The five states with the highest percentage of 31/2+ year old bucks in the harvest are Mississippi (77%), Louisiana (75%), Arkansas (72%), Oklahoma (66%), and Texas (65%), all states where management is very popular. Texas probably is number five due

Bowman, J. L., H. A. Jacobson, D. S. Coggin, J. R. Heffelfinger, and B. D. Leopold. 2007. Survival and Cause-specific Mortality of Adult Male White-tailed Deer Managed Under the Quality Deer Management Paradigm. Proc. Annu. Conf. Southeast. Assoc. Fish and Wildl. Agencies 61:76–81

Ditchkoff, S. S., E. R. Welch, Jr., E. R. Lochmiller, R. E. Masters, and W. R. Starry. 2001. Age-specific causes of mortality among male white-tailed deer support mate-competition theory. J. Wildlife Management 65(3):552-559.

Webb, S. L., D. G. Hewitt, and M. W. Hellickson. 2007. Survival and Cause-Specific Mortality of Mature Male White-Tailed Deer. J. Wildlife Management 71(2):555558.

Elder, W. H. 1965. Primeval deer hunting pressures revealed by remains from American Indian middens. J. Wildlife Management 29(2): 366-370.

to there being more dyed-in-the-wool trophy hunters, willing to let even middle-aged bucks walk.

The Oklahoma study referenced earlier reported annual mortality for older bucks to be 0.26-0.38 annually, with most mortality coming from non-hunting factors. Bowman, et al. 2007, reported on a study on managed herds in Mississippi, concluding: “… if <2.5-year-old bucks are passed up … will be available for harvest during the next season because these bucks have very little natural mortality.” In South Texas, a study by Hewitt and Hellickson, on an intensively managed ranch, reported, “Average annual survival of the known-aged 1998 cohort was 82% with 52% of [bucks] surviving to 6.5 years of age.”

There is almost nothing known about un-hunted deer herds. The only information we have about natural deer herds comes from studies on the middens (trash piles) of Native Americans. According to one study (Elder, 1965), 20-26% of deer killed by Native Americans were 61/2 years or older. For such a high percentage of bucks to reach that age, annual mortality has to be very low.

Finally, at our research facility near Nacogdoches, for 38 years we have harvested only a handful of bucks. In those years, the principal mortality agent for bucks has been disease (hemorrhagic and pneumonia), fighting and accidents. It’s amazing how many accidents deer have. In the 2020-21 season, we lost two mature bucks to accidents, one during the February “snowmageddon,” when it tried to walk between two trees, got its hips caught and froze to death.

The answer to the question about what happens to a young buck if you let him walk, is clear in my mind. He has an acceptable chance of reaching an older age when he will have the largest antlers his genetics will permit. This is true even in areas where landholdings are small. So, there’s no excuse for not passing on yearling bucks, provided hunters are willing to do just that. But that is a topic for another column.

The Coues white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus couesi) is named after Elliot Coues, an Army surgeon and naturalist who served a tour of duty in the “sandbox” of the American Southwest in the late 1800s. Elliot pronounced his last name “Cowz,” and would roll over in his grave if he heard how badly hunters butcher his name. Trying to correct that mispronunciation is probably a lost cause at this point, because 90% of non-biologists pronounce this deer “Cooz.” I’m not a grammar Nazi, but if I had a deer named after me, I would want it pronounced correctly.

“Cooz deer,” as they are often called, are simply a miniature version (subspecies) of the white-tailed deer found in the East. There is only one species of white-tailed deer, but it shows a lot of variation throughout its range of distribution. This variation is simply due to local populations adapting to habitat, nutrition, or climatic conditions. Through the years, many of these various kinds of whitetails have been described as official subspecies, complete with multi-colored maps showing well-defined distributions. Currently there are at least 38 subspecies of white-tailed deer that have been described in North and South America. Most of these descriptions were based on only a few individual

specimens and have not been evaluated sufficiently to see if they are really valid. But, the Coues’ whitetail differs both physically and genetically from other whitetails.

Coues white-tailed deer is often called the “Arizona Whitetail” because of its distribution throughout central and southeastern Arizona. It is also found in scattered populations throughout other areas of the southwestern United States such as southwestern New Mexico, and in the Mexican states of Sonora, Chihuahua, Durango, and Zacatecas.

Throughout their range, whitetails live in relatively rough, wooded terrain with steep canyons. Typical Coues whitetail habitat is mixed oak woodland, but they can be found anywhere from ponderosa pine/mixed conifer at 10,000 feet elevation down to the upper limits of semi-desert grassland. Although elevations with the highest deer densities vary among different mountain ranges, most Coues whitetails are found between 4,000 and 7,000 feet. Their distribution in the mountains is determined by the availability of good quality browse and water in dry seasons. At lower elevations, there is considerable overlap in habitat use with desert mule deer.

In most areas of the West, mule deer are found in high elevation mountains and whitetails live in valleys and along rivers. However, in the Southwest, whitetails are found in the

mountains and mule deer in the grassland, shrubland or desert valleys surrounding the mountains. Coues whitetails don’t migrate because they don’t need to with light and sporadic snow events. But, they do shift to areas lower on the mountain or to south-facing slopes after big snow storms, and then filter back to their home ranges in a week or so when the snow melts.

This little version of white-tailed deer has been generating a lot of interest nationwide among hunters looking for a different challenge and some fantastic landscapes. This is the only one of 38 whitetail subspecies that has its own Boone and Crockett Record Book category. To highlight the physical differences between Coues and other whitetails, consider that a mature buck field dresses at 90-100 pounds, and it takes only 110 points to make the all-time Boone & Crockett record book for the typical category. The current World Record Coues whitetail scores 144 1⁄8 Boone & Crockett points and has not been surpassed in more than 60 years despite a lot of effort by people with high-dollar optics and long-range rifles. In South Texas, a buck scoring 144 points won’t even make it to a taxidermist.

I went from being a biologist on a trophy ranch in South Texas to manage Coues in southern Arizona and it took some time before I was getting excited about a 100-point whitetail buck. They are amazing animals, however, and easy to fall in love with. Outdoor Life editor Jack O’Connor proclaimed the Coues white-tailed deer to be the most beautiful of the North American big game.

Because an average whitetail buck from elsewhere could be the new Coues deer world record, the Boone and Crockett Club funded a series of studies to look at just how genetically unique Coues whitetails are by looking at differences in their genes. That research resulted in a genetic test to identify true Coues whitetails that is used by the Pope and Young and Boone and Crockett clubs to maintain the integrity of the permanent trophy record categories.

The predators of this small deer currently, or in the past, include Mexican wolf, jaguar, southwestern grizzly bear, black bear, mountain lion, and coyote. You can understand why these open country whitetails are more than a little jittery and “twitchy.” They are considered one of the hardest big game animals in Western North America to sneak up on with a bow.

Hunting is done in classic western spot and stalk style by “glassing up” deer with binoculars and then stalking to within

range. This is a different experience than most whitetail hunting in the country. Even the way we refer to antler points is western count, where you ignore brow tines and only count one side of the rack. No other type of whitetail is counted that way. Successful hunters find areas of thick brush near open hillsides to catch bucks that slip out of the cover to grab a bite to eat. Getting away from roads and finding areas of habitat with the least disturbance offers the best chance to find older bucks that have not been messed with. During dry periods, hunting at or within a mile of a water source also increases your chances. Rut occurs in mid-January in “Cooz country” so if you are not from the Southwest, you are probably wanting to come here that time of year. If you are lucky enough to hunt the rut with archery tackle or rifle, you will see plenty of mature bucks moving around all day long.

It’s hard to beat the grand landscapes of the Southwest and this unique type of deer. It’s ironic that Elliott Coues was famous for collecting thousands of animal and plant specimens for museums while he was stationed in the Southwest, and yet he never shot a specimen of his namesake deer. Humans inherently like to collect different versions of things, and the more unusual or local, the more appealing it is. That’s certainly true with deer and one of the reasons that every Grand Slam of deer varieties will always include the “Cooz” deer.

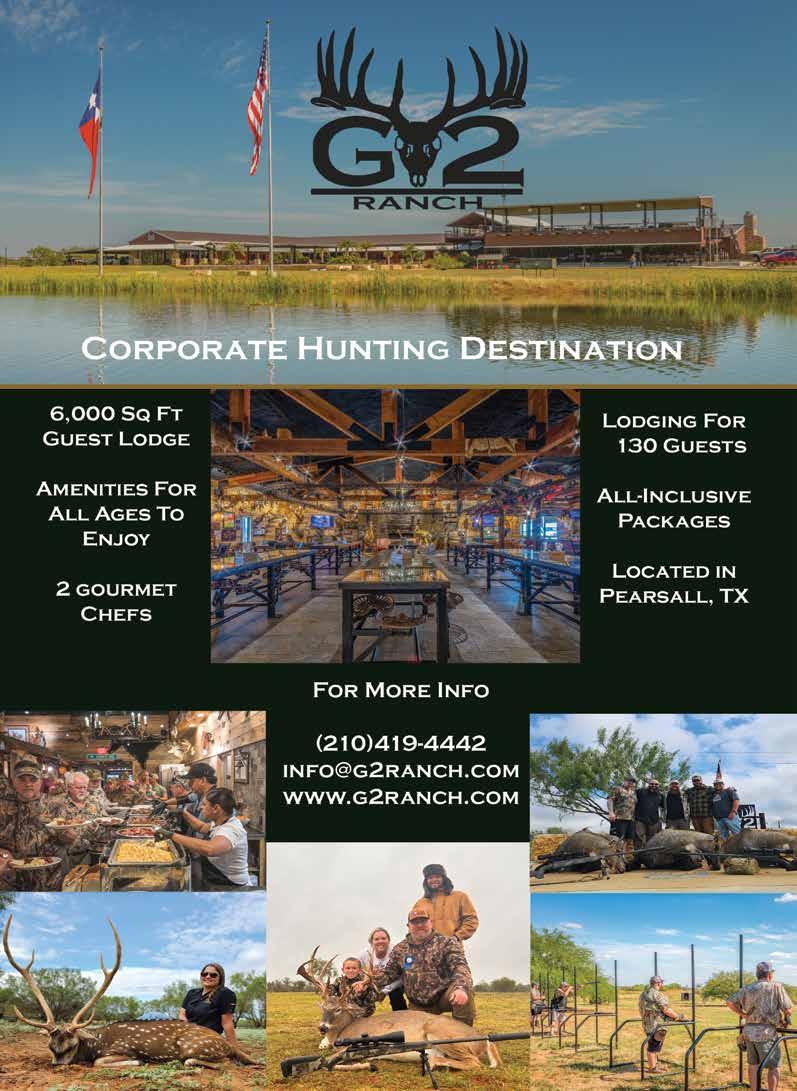

Dove season is open, but the summer sun is hot, so let’s find a cool place and dwell for a moment on a famous writer, adventurer, and hunter named Ernest Miller Hemingway. Aside from novelist James Albert Michener, “Papa” Hemingway may have been one of the most influential writers of the 20th century, having plied his literary art to a long list of novels and short stories. I was a wildlife advisor to Michener in 1984 while he wrote “Texas,” and I have a pretty good library of Hemingway selections. Both Hemingway and Michener were Nobel Prize winners, and both led unusual and adventurous lives. Hemingway’s Nobel Prize in Literature came in 1954 with “The Old Man and the Sea,” when he was living in Havana with his fourth wife, Mary.

Hemingway led an unpleasant life as a youth in suburban Chicago, because his mother dressed him—for whatever reason—as a girl. He left the family as a teen to get away from both his mother and father. As a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star, Ernest began a long career as a writing correspondent and novelist.

After volunteering at 19 as an ambulance driver with the Red Cross during World War I, and getting wounded, young Hemingway ended up in France and Spain, where he rubbed elbows with the likes of F. Scott Fitzgerald, Gertrude Stein, and Max Eastman.

“The Sun Also Rises,” was Hemingway’s first novel, published in 1926, and centered around a group of young “lost generation” expatriates as they hobnobbed through the night lights of Paris and the bullfights of Madrid. It was at this time that Hemingway requested that his friends call him “Papa,” as opposed to a first name that he distained.

Hemingway became a master with words, and he usually wrote about his experiences: war-time ambulance driver; bullfights in Madrid; yachting and fishing; four wives; African safaris; and World War II. Before leaving Cuba and building a home in Ketchum, Idaho, in 1959, Hemingway had lived in Chicago, Paris, Key West, Madrid, and Havana. His challenges with Africa’s dangerous Big Five; two plane crashes; diseases; women; and booze, influenced Hemingway to be one of the greatest novelists of our time.

Deep sea fishing, shotgun shooting, and big game hunting were Hemingway’s favorite pastimes. He had a safe full of expensive firearms, and spent a lot of time on his yacht “Pilar,” a rather lavish 38-foot boat. Papa’s Caribbean cruises were instrumental for his novel, “To Have and Have Not.”

Hemingway used a unique writing style that purred with excitement in his many novels and short stories. Two stories that stand out to me—“The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber” and “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”—were both made into Hollywood movies. I highly recommend “Macomber” and the safari scenarios that pit a wealthy coward, his pretty, sexy wife, and a worldly, red-faced guide against African lions and buffalo that

end with an unusual bullet hole in Macomber’s head.

But what about Hemingway’s “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”?

In his 66-page short story, which contrasts distinctly from the movie, the principal character is a faded writer named Harry Street, who lies dying in a tent on the African plains. An unkept thorn injury has infected Harry’s leg, and the bloodless dead flesh of gangrene causes Harry to become delusional as he drifts in and out of the past.

Harry’s wealthy, but unloved wife cares for him as he lays on a cot with his smelly, gangrenous leg, knowing he has let the soft life ruin his literary career. As Harry lies dying, he dreams

The inspiration for one of his best-known stories, the imposing Mount Kilimanjaro.

of the writing he has failed to do. Since this story wasn’t considered a regular for Hemingway’s repertoire, it’s interesting to see how he came to write one of his best short stories.

Hemingway and his second wife, Pauline, had been on safari in Tanganyika (now called Tanzania) in East Africa, and had returned to New York to a waiting press. Hemingway was 35; at the pinnacle of a literary career; and all of New York wanted to know what his next venture would be. In typical Hemingway fashion, he announced, “I’m going to Key West and make enough money to go back to Africa.” He and Pauline spent a few weeks visiting and partying in New York before going home to Key West.

Hemingway was more popular and well-known in 1934 than President Roosevelt. Pictures and comments about the African safari were in all the New York newspapers, which were read by one of the wealthiest women in America.

Helen Hay Whitney was a rich woman who lived in a mansion on lower Fifth Avenue and owned a 435-acre estate on Long Island. A widow at 58, Whitney had a string of racehorses; had won the Kentucky Derby; and was known far and wide in social and horse racing circles.

The lady sent Hemingway a note, “Come by for tea,” and he went by as requested. As they drank bourbon and branch (tea), she explained the visit. “Ernest, you don’t need to make any money for Africa. I will give you all the money you need for your next safari, and more—if I can come along with you and Pauline.”

Hemingway later remarked, “Helen Whitney was a nice, rich lady, but I turned her down.” He supposedly never visited the woman again, although there were notes left by Whitney’s son that read,

“Helen always enjoyed her visits with Ernest Hemingway.” Back in Key West, Hemingway kept thinking about the rich woman’s offer—and maybe more— and what would have resulted if he had taken her generous African safari proposal.

Hemingway was not a saint, by any stretch. He was the epitome of a burly, bearded, outdoorsman: a boozer, fighter, and womanizer. He often quipped that politics, women, drink, money, and ambition were the five downfalls of writers. His use of many of these failures in his writing is evidence Hemingway had experienced most of them.

His writing and lifestyle had made Hemingway famous, and back in Key West, he kept thinking about a fictitious writer with great potential, who is led astray by money, never to know the height of success that might have been. His lingering thoughts of Helen Hay Whitney and the free-standing, snowcapped, volcanic mountain—the highest in Africa—led to “The Snows of Kilimanjaro.”

Hemingway worked back and forth on “Snows” for two years, and in 1936, the short story was first published in Esquire magazine, and later in book form in 1938. Some critics called the story a masterpiece, while others said it rambled. However, the majority felt that, although a short story, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” was clearly one of Hemingway’s best.

I first read “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” many years ago, and just recently read it again. Through the years, I have been puzzled with the epigraph: “Kilimanjaro, a 19,710-foot peak, thought to be the highest point in Africa. Near the western summit is the dried, frozen carcass of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude.”

What was Hemingway’s source for this dynamic description of a leopard carcass nearly three miles high near the snowy summit of a dormant volcano—a frozen leopard preserved for eternity? Had something caused the leopard to lose its way? Did Hemingway see himself as the leopard?

I have always suspected Hemingway had previous knowledge of such a leopard carcass, and recently I discovered the answer. In 1926, a mountain-climbing Lutheran pastor named Richard Reusch had found the frozen carcass of a leopard at 18,500 feet, along with a distant carcass of a goat. Hemingway apparently heard the leopard story while on safari in (formerly) Tanganyika in 1934, and tied the “lost” leopard and Helen Hay Whitney to his scenario for a short story.

Hemingway pondered the thought of a wealthy woman and a soft life causing a successful journalist to lose his ability to write—to lose his way—just as the leopard had lost its way. He pictured someone like himself, trying to pick up the pieces of a

flaunted literary life, and knowing that he never could.

And then, in “The Snows of Mt. Kilimanjaro,” we have Hemingway’s protagonist Harry Street, a successful but floundering writer on safari with his rich wife in East Africa, dying of gangrene on the dry African plains in the shadow of the snowy summit of Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Harry’s wife is asleep from exhaustion, as he lies on his cot, looking at the purity of the mountain’s high snowcap, while a hyena and a community of vultures witness his death. Like the leopard, Harry had lost his way by taking the wrong trail with a wealthy, unloved wife named “Helen”—as in Helen Hay Whitney of New York. Ah, the essence of Hemingway’s unvarnished satire.

In 1920 Paris, Ernest Hemingway regularly patronized Harry's New York bar with many of his well-known expatriate friends. As was normal for a 21-year-old, Ernest was a regular with a girlfriend named Mary. It's questionable what Hemingway's interest was in Mary, but they were at the bar quite often.

Mary didn't like the smell of whiskey on Ernest's breath—giving him holy-hell when he smelled of corn liquor. One evening, Hemingway and a bartender at Harry's confronted the issue.

BARTENDER: You need to drink something with no whiskey smell, like vodka.

HEMINGWAY: I don't like straight vodka. I might drink it if it was

mixed with something to kill the vodka taste, like tomato juice.

BARTENDER: Yes, and add something that will give it a bite, Worcestershire sauce. HEMINGWAY: I like a good bite, and something tangy, like a little lime juice, a pinch of salt, cayenne, and black pepper.

BARTENDER: This all sounds good, and some ice, and a few drops of tabasco should give you a racy cocktail that nobody can smell.

Over 100 years ago, Ernest Hemingway and Fernand Petiot concocted the cocktail known today as "Bloody Mary." Hemingway was noted as saying, paraphrased, as he sipped the vodka-strong, tangy, tomato-based drink that would solve Mary's bitching: "This 'Bloody Mary' has licked my problem." The name stuck, and exists to this day.

The original recipe for the Bloody Mary was published in 1921 in "Harry's ABC of Cocktails," and is still served, sometimes for a hangover, in Harry's New York bar in Paris, France, and all over the world.

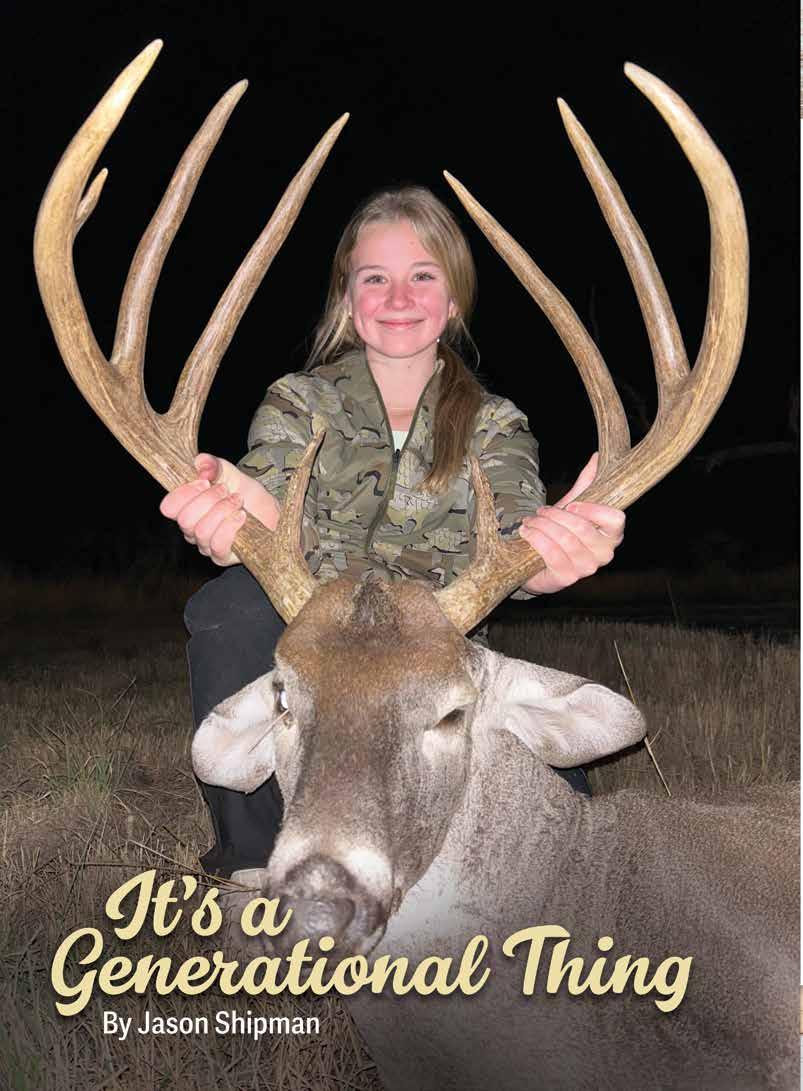

is another up-and-coming hunter. Just look at the fabulous trophy buck she took on one of the family’s ranches.

Hunting has been a favorite pastime of the Moy Family for as far back as they can recall. The Moys are a rather large family, and the majority of them call Falls City home. Located southeast of San Antonio, the rural area has a heavy emphasis on agricultural practices, including farming and cattle. White-tailed deer, feral hogs, wild turkey, and excellent wing shooting provide a lot of hunting in the surrounding region where wildlife habitat is interspersed amongst the local farms.

The Moy family runs a third-generation water well company, Thomas Moy & Sons Water Well Drilling Inc., servicing and drilling wells throughout South Texas. Thomas Moy, Sr. started the business in 1944, and passed it to his sons, Thomas Moy, Jr. and Johnny Moy. The brothers are still involved in the business, but their sons, Thomas “Tres” Moy III and Joshua Moy, are now the third generation to run the family business.

Aside from water wells, Thomas Moy, Jr. and Johnny Moy always had an interest in cattle and hunting. Throughout the years, they acquired a number of ranches and focused on running successful cattle and wildlife management programs. In addition to hunting their ranches, the brothers have pursued trophy whitetails throughout South Texas and Mexico, and even hunted abroad.

Just as their business has passed from one generation to the next, so has their love of hunting. Tres Moy loves to take his daughters, Isla and Olivia, hunting. Isla is the oldest, just turning 13, and in addition to hunting, she enjoys cheerleading and volleyball.

“Isla is growing up to be a well-rounded young lady,” Tres said. “She likes the girly things as well as the outdoors, and has spent enough time deer hunting with me to understand our management at the ranches. She killed her first buck when she was 5 years old, and has taken many since then. Quite an accomplished hunter.” Tres continued, “I just go along for the ride since she started hunting with me,” he said with a laugh. Last year, while hunting with her dad, Isla capitalized on an opportunity and took her biggest buck to date.

At the beginning of the 2023 hunting season, a big nine-point had been seen at one of the family’s ranches. “We knew the buck. He was an older buck that just kept getting a little bigger each year,” Tres said. “The family discussed the buck, and we decided that Isla would hunt him.” Until this point, Isla had only taken does, culls, and management bucks. “I had really been quietly hoping and wishing for an opportunity at a trophy buck I could hang on the wall,” Isla said.

Their first chance to hunt for the big nine-point was an evening hunt. Tres, Isla, and Olivia went to a blind where the buck had been previously seen. “The buck came out but just wouldn’t cooperate. There were a lot of deer feeding and he was continually moving. It was just tough to get a shot,” Tres said.

“I tried to get comfortable for a shot, but the sun was in my eyes, and I was a little nervous,” Isla said. They left the blind at dark, without having fired a shot and felt a bit dejected. They hoped the next hunt would bring a change of luck.

Early next morning, they went to the same blind early before daylight and watched as the old, big-bodied nine-point jumped into the feed pen. Tall grass and the panels enclosing the feed pen to exclude cattle and hogs obstructed any chance of a clear shot. “We sat there and watched him eat,” Isla said.

“We were hoping he would leave the feed pen and go to a group of deer that was nearby,” Tres said. “However, when he jumped out, he walked straight into the brush and disap -

peared.” After a long wait, the hunters were confident the buck had left the area, so they decided to go eat a late breakfast.

That evening, Tres and Isla returned to the same blind, confident they would see the buck they were after. Olivia’s patience had run out, and she went hunting with her cousins in a different blind. “We hadn’t been sitting long, when the big nine-point stepped out and started walking toward us. I told Isla to shoot him as soon as she felt comfortable,” Tres said.

At about 125 yards, the buck stopped and turned broadside. Isla was ready and squeezed the trigger on her .270. The buck showed little sign of being hit, but buckled from the bullet before disappearing into the thick brush. “The shot felt good, and I said a little prayer to make my bullet fly straight as we waited,” Isla said.

After a 15-minute wait, they made their way over to where the buck had been standing, but didn’t find any sign of a hit. “I started to get really nervous,” Isla said. They worked their way into the brush where the buck had gone. “We found him right away,” Isla added. “He had gone about 30 yards before piling up in a cactus.”

“Isla had the biggest smile when she walked up to her buck,” Tres said. “She was so happy and excited. He was so much bigger than we expected.”

“I couldn’t believe I got the chance to shoot him! He was perfect,” Isla said. They took a couple of photos before loading up the buck to show everyone. They took another round of photos with the rest of the family. The deer measured 1675⁄8 gross.

“The deer had a huge body and based on our observations, we figured he was old,” Tres said. “His body size threw us off a little. He had a big frame with 28-inch main beams and tines over 14 inches. Everyone in our family does their part to make the business and ranches successful for future generations. We all enjoy hunting together and we couldn’t be happier for Isla and her buck.”

By Kennisyn Drosche

Six years ago, while knowing little to nothing about cattle, I started showing heifers. Very quickly, I discovered I loved being around and working with cattle. However, I had one issue I thought that seemed to slow me down. The issue I had in mind was I did not come from a family involved in the ranch or livestock industry, and I had no idea how to go about becoming a part of it. That was until I discovered Texas Brigades, and more specifically, Ranch Brigade. Ranch Brigade, a Texas Brigades program, is a five-day educational program that teaches youth about land stewardship, livestock production, and so much more in the classroom and in the field. Ranch Brigade helped me learn things about the ranching and cattle industry that I had been wanting to know for years. While at Ranch Brigade, I learned everything from land stewardship to the pasture to plate process. I was taught about the many types of grasses and which ones are common in the area.

Along with this, I learned about grassland management and why it is so important to the health of our ranches. Aside from learning about grasses and how to be a land steward, I learned

all about the livestock industry. I gained knowledge about livestock production and how to properly handle livestock so that they are in a low-stress environment. My favorite part about camp was learning how to vaccinate, castrate, and brand cattle.

Not only did I learn how those things work, but I got to participate hands-on in these activities. These were things that I had been very interested in learning, and I am so thankful that this camp gave me the opportunity to experience this. Even though I had so much fun learning and doing activities such as vaccinating, I also found it interesting to learn about cattle digestive systems and cuts of meat. We even got to cook and eat our own steaks.

I believe having fun is an important part of learning, and Ranch Brigade made sure that happened through competitive events. These games were not only fun, but great learning opportunities. They included roping, post hole digging, sheep sorting, and a relay race. Even though I had initially wanted to go to camp specifically to learn about the ranching and cattle industry, I am so thankful for the people I met who made Ranch Brigade so great.

All the volunteer instructors were extremely helpful and made learning so easy. Along with that, I also got to participate in teambuilding activities that led me to making friends that will last a lifetime. Even after camp concluded, Texas Brigades hosted follow-up networking and outreach opportunities that gave me the chance to reconnect with camp volunteers and fellow cadets, in addition to making new acquaintances.

After returning from camp, I knew I wanted to go back as an assistant herd leader. To do so, I am currently working on many activities, such as displaying the poster I made at camp in a variety of different places. Ranch Brigade taught me that it’s very important to go out and be an advocate for our land and livestock industries. Although that is a very important part, it is also important to make sure that we are extending our knowledge and learning how to do our best in things such as natural resource management and livestock production. To expand my knowledge, I am excited to be doing things such as attending cattle conferences and range tours.

Walking out of camp, I felt like I had discovered so much about the industry that I had wanted to be involved in for years. In just five days I had learned more than I ever thought I could in such a short amount of time. Not only does Texas Brigades tell you what you need to know in the classroom through experienced individuals, but the hands-on activities help ensure you understand.

In the end, I learned that I did not have to come from a

After camp concluded, Texas Brigades hosted follow-up networking and outreach opportunities that gave the author a chance to reconnect with camp volunteers and fellow cadets.

Ranch Brigade taught the author that it’s important to advocate for land and livestock industries.

family in the ranching industry to be involved with it. It truly showed me I want to be a part of the ranching and livestock industry for the rest of my life. Moments and lessons at Ranch Brigade are something I will forever use in life. I am so grateful that this Texas Brigades program gave me the opportunity to know how to become involved in the ranching industry, and the confidence to know I can do amazing things within it. In five days, I truly became a different person.

Through Texas Brigades, I have become a better leader, public speaker, and most importantly, a better individual. I highly encourage everyone to look into a Texas Brigades summer camp because it is an experience that will undoubtedly change your life.

Texas Brigades is a conservation-based leadership organization which organizes wildlife and natural resource-based leadership camps for participants ranging in age from 13-17. Its mission is to educate and empower youths with leadership skills and knowledge in wildlife, fisheries, and land stewardship to become conservation ambassadors for a sustained natural resource legacy. There are multiple camps scheduled in the summers, focusing on different animal species while incorporating leadership development. Summer camps include Rolling Plains and South Texas Bobwhite Brigade, South and North Texas Buckskin Brigade, Bass Brigade, Waterfowl Brigade, Coastal Brigade, and Ranch Brigade. Visit texasbrigades.org or call 210-556-1391 for more information.

At Camp Verde Ranch near Camp Verde, Texas, we have managed for trophy whitetails and a healthy, productive deer herd for over 30 years. Intense culling of undesired genetics, high protein supplemental food, and allowing prime bucks to reach full age potential are the principles we follow. Our goal is to have two to three trophy bucks each season on 1,300 acres.

We made the switch from protein pellets to cottonseed 15 years ago with good success. Under our MLDP management program assisted by outdoorsman Mike Leggett and overseen by state biologist Johnny Arredondo, we have grown trophy deer that are harvested after full maturity.

We brought in 30 does from South Texas 12 years ago on a Triple T permit, which is the only outside genetics in 40 years. Otherwise, these are genetically improved Hill Country deer benefiting from a long-term management plan.

My son Robb and I switched from rifles to bow hunting in the Hill Country a few years ago. Last season (2022) Robb was hunting for an old 15-point buck we call “Groucho,” but the buck didn’t show over Thanksgiving week. Being from out of state, that’s Robb’s only time to hunt here.

The 2022 season was my third year to hunt Groucho, a beautiful buck that we seldom saw except on trail cameras. I had seen the deer only twice in three years, after many hours

of sitting in all kinds of weather. And I’m stealthy! I did get one shot at him, but I got excited and hit the feeder leg with my arrow. Yes, there’s still the hole in the leg. It’s amazing how a 170-pound deer can hide behind a feeder leg.

In December 2022, Groucho broke his antlers fighting, including his left main beam halfway out. We didn’t see much of the old buck, and hoped that he survived the winter.

In September 2023, we put cameras back out and Robb liked a big non-typical buck that showed up at two blinds. Another old deer with three main beams also showed up and we finally realized it was Groucho. His third beam grew out the side where he broke his main beam off the year before, causing much stress to his pedicle.

After a May hospital stay for a shoulder replacement, I was intent on strengthening my shoulder in order to draw a bow. Groucho was about 8+ years old now and was feeding at the same blind consistently, which he has never done. I was doing all I could do to be able to accurately draw and shoot a bow before the 2023 deer season.

I finally allowed myself to go after Groucho. On my second hunt where he was feeding, he came in. I knew that I would get only one arrow, so I waited several minutes until he was finally broadside. I pulled full draw, and put my broadhead in his liver. The old buck ran a considerable ways, but we found him stone dead. Last season was the fourth year I had hunted this buck, and it’s hard to describe the feeling I had when I walked up to the old Monarch.

My son Robb came last Thanksgiving, and the third time out, his big non-typical buck showed up. He had 15 points, eight on his right and seven on his left; truly an exceptional buck. I was at the ranch house when he texted me with a picture of his buck with the arrow still in him.

We both got our great bucks with bows last season after striking out in the 2022 season. Robb’s 7½-year-old deer grossed scored 171" and my estimated 8½-year-old buck scored 207" with a third beam. I sent my buck’s teeth to Matson’s lab in Montana to get a true age, which came back as 8½. His teeth were too worn to estimate beyond eight years. I felt like sending a couple of my own teeth as well just to check my age.

The best part of the two hunts last season are the memories between father and son. Those memories will last forever for Robb and me. I want to thank our team starting with Mike Leggett for his professional leadership, and for serving as our MLDP agent.

Ranch manager Joey Connell oversees the ranch operations, blind construction, and blind movement. Joey also checks numerous camera cards to track the many bucks for age and movement. Joey also brings many years of experience in the outdoors.

Francisco “Pancho” Prado has worked 36 years for the ranch, and is tireless with his work filling feeders, and so many other ranch duties. Pancho is very proud of the ranch.

I also want to thank my wife Risa, who does her share of hunting old and unique deer, and who is also completely supportive of our management program. She knows wildlife and deer management. She’s also a cat lover.

Team Camp Verde is an amazing team working together for great results and having fun with the deer management program.

Hunter Jake Henriksen glassing the Texas Panhandle for pronghorns at sunrise on opening morning. A tripod-mounted spotting scope and 10X40 binoculars are key tools for this game.

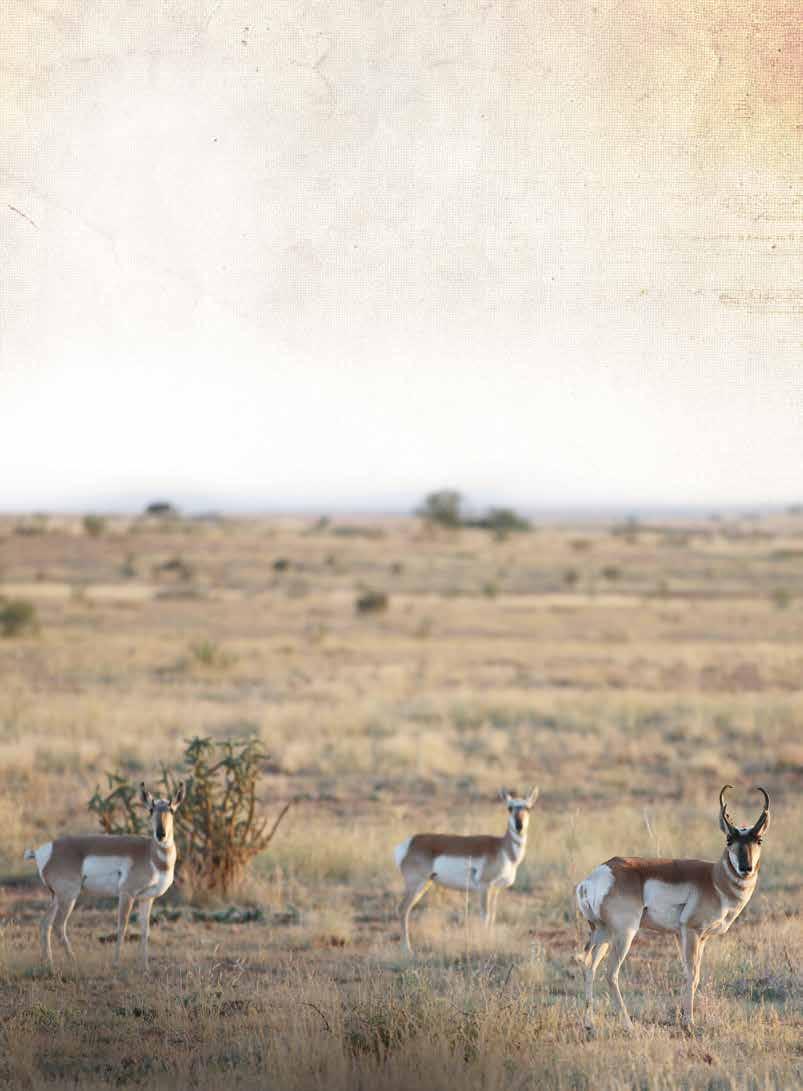

Ilove the wild country where pronghorns live. The unobstructed views of the horizon; the smell of dirt and sage; colorful sunsets; prickly yuccas and cholla cactus; and of course, the animals themselves. It’s a place as opposite from civilization as hot and cold. Long views are like therapy when you’ve been crowded in the city too long.

Windmills replace skyscrapers, grass is better than concrete, and the wind replaces the sound of zooming cars. One of my favorite places to hunt pronghorns is the Texas Panhandle. A hunt from 2022 ended with a heavy-horned buck in my crosshairs.

The two pronghorn does were like guard dogs on either side of my target buck. Despite a stealthy approach, as soon as I peeked over the hill, the two does spotted me. They stared hard, as if they were ticking time-bombs about to explode. I slid my rifle over my bulging backpack, a support as solid as a sandbag. As I lay prone, I dialed the scope’s magnification up to 10X. The buck stood broadside at 275 yards. After a deep breath, I let half the air out and squeezed the trigger. Boom! Hit through both lungs, the buck stumbled, then he dropped in a prickly yucca plant. Walking down the hill towards my buck, I felt small in such a vast landscape.

Texas pronghorns are found primarily in the Trans-Pecos and Panhandle regions. Drought in recent years has limited fawn recruitment. According to Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Pronghorn Program Leader Shawn Gray, pronghorn numbers across the state are as follows:

“Things are looking up for pronghorns in both regions. The populations either remained stable (Panhandle) or increased (Trans-Pecos) last summer from the previous year. We got some late winter moisture and so far, some spring moisture this year, so I am hoping we will have a shot in the arm when it comes to fawn production this summer. The 2023 survey numbers were as follows: Panhandle at 12,873 and the Trans-Pecos at 6,865.

A pronghorn buck and two does in the Texas Panhandle.

The western Edward’s Plateau is at 142. The statewide total estimate in 2023 was 19,880. The 2024 Texas season will open on Sept. 28.”

Texas’ pronghorn hunting on private lands is controlled by permits issued by TPWD. After summer surveys, TPWD issues permits to landowners requesting tags, if herd numbers are large enough to support a limited buck harvest. Landowners can sell hunting by way of the permits, use them for friends or family or choose not to use some or all of the permits. TPWD biologists set pronghorn permit issuance rates to maximize hunting opportunity while maintaining a level of older aged bucks for hunters who seek mature pronghorn.

This management philosophy is rooted in population sustainability and, to a lesser degree, sociological factors. However, I’ve always recommended ranchers use half of the permits they are issued, because permits are not issued based on “trophy” bucks seen during surveys. The season starts every year on the Saturday closest to Oct. 1, and lasts approximately two weeks.

Pronghorns are not large animals. A mature buck will have a live weight of 100-150 pounds. Mature bucks will have black horns, black cheek patches, and black on the bridge of the nose. Does are tan and white, and smaller in body size. Peak breeding usually occurs in September, but some years you’ll see herd bucks aggressively chasing off rival bucks from their harem of does into October.

Gear for this game includes quality 10X40 binoculars, rangefinder, and a spotting scope. Wear comfortable lace-up leather boots with merino wool socks, and be prepared to hike prickly terrain in search of animals. For a hands-and-knees stalk, leather gloves and thick pants like those from Carhart can ward off cactus and burrs. Top destinations for trophy-sized bucks include Hartley and Dallam counties in the northwestern Panhandle, and Hudspeth County in the Trans-Pecos.

Whatever rifle you use for deer hunting will certainly bring down a pronghorn, but heavy Magnums are unnecessary. My preference is a midweight bolt action rifle chambered in .243 or

.25-06. Top that rifle with a simple 3-10X40 scope and practice with it! Yes, pronghorn country is big, but by using the swales and rolls on the prairie, and some stealth and patience on a stalk, it’s usually possible to sneak inside 300 yards.

The focus of last year’s annual Texas pronghorn adventure was getting my girlfriend, Lisa Armbruster, a handsome buck. Lisa is as fanatical about hunting pronghorns as I am. She’s hunted them successfully with bow and rifle in New Mexico and Texas. She enjoys our annual visit with the Brown family at their scenic Panhandle ranch. Lisa Lu loves the big country, watching bucks chase does and especially cooking pronghorn meat, her favorite wild game for the table. She has even built her own pedestal base from cholla cactus to display one of her mounted pronghorns.

The afternoon before the season opened, we scouted the north end of the ranch. Near a windmill and a patch of headhigh chollas, we found a small herd. They were only 200 yards off the two-track road, but the chollas were so thick that we could only see glimpses of tan and white. Standing in the bed of my truck for added elevation, I dialed the focus ring on my tripod-mounted spotting scope. I found a black-faced buck amidst the forest of chollas. His horns were about 15 inches tall with good mass and prongs that cupped forward. I guessed his horns at 76 inches, maybe more.

Two smaller bucks were circling the herd of six does, but the big-bodied, black-faced buck was clearly in charge. “That’s a great buck,” I said to Lisa Lu as we both stared through our

binoculars. “Let’s start here in the morning.”

Sunrise opening morning was spectacular with colorful orange and red streaks over the horizon. We started at the cholla patch but found nothing. A mile to the west, we found the same tall, heavy-horned buck from the night before, now chasing a single doe. We cut the distance in half, then ditched the truck for a stalk.

At first, we gained ground quickly, but once inside 400 yards, the doe caught us slipping behind a patch of mesquites. She took off at a trot, taking the big buck with her. They ran a half-mile farther west, then ducked under a barbed-wire fence onto the neighboring ranch. We spent the rest of the morning watching that buck follow that doe around just across the property line.

After lunch, we glassed some new country and saw a handful of does and one average buck. Multiple coveys of blue quail scattered near the road as we traveled. We went back to the boundary fence and found our target buck bedded with the doe a mere 50 yards across the fence line. We respect boundaries, so we just watched and waited to see if the buck would cross to our side. They never did, and day one ended without firing a shot.

Day two started with more glassing. The mornings were cold enough to require a fleece jacket, but by lunchtime, the sun would heat the prairie and a T-shirt was enough. It took some time behind the spotting scope, but we eventually found the big buck from day one. He was very content with his girlfriend just across the fence, on the neighbor’s ranch.

I found the doe first, her colorful tan and white hide glowing

The following list comes from the official entries in the Texas Big Game Awards (TBGA) for the 2023 season. The top three pronghorns for the Trans-Pecos and Panhandle regions are listed. It takes a minimum net score of 70 inches to qualify for the TBGA.

Hunter’s

1.

in the slanting early-morning light. Closer scrutiny through the spotting scope revealed the big buck bedded nearby. Only his black horns were visible over a patch of dead mesquites. Lisa Lu and I watched from a distance for a couple of hours, eating trail mix and napping in the sun, but they never crossed the fence.

After lunch, we had a decision to make. Should we spend more time hoping the 15-inch buck comes back to our side, or go look for something else? We decided to spike out to the west to a far-off windmill where we’d always found pronghorns in years past.

Glassing due west, I spotted two pronghorns a mile away: a buck and a doe. Through the spotting scope I could see lots of black on the buck’s head, even through the shimmering heat waves. We cut the distance, looked closer at the buck again, then decided it was worth a stalk.

Inside 300 yards I could tell the buck had short, but heavy horns. Lisa Lu and I debated it. Do we take this buck or spend more time hoping the across-the-fence buck comes back? This was a short weekend hunt, so time was ticking.

Lisa Lu steadied the .243 rifle over the top of my tripod-mounted spotting scope. With the buck broadside at a laser-ranged 170 yards, she tugged the trigger. It was a perfect shot. The Hartley County pronghorn had 13inch horns with heavy 6½-inch bases, and gross-scored 73 inches.

We filled out the permit, snapped some pictures, then gutted the buck. Chef Lisa Lu wanted the meat cooled

on ice ASAP, so we headed for the ranch headquarters to skin the buck in the shade.

On the way there, we glassed the boundary fence and spotted the 15-inch buck and doe, still very content on the wrong side of the barbed wire. Maybe we will find him on the right side of the fence this fall. Chasing Texas pronghorns is a hunt I look forward to every year.

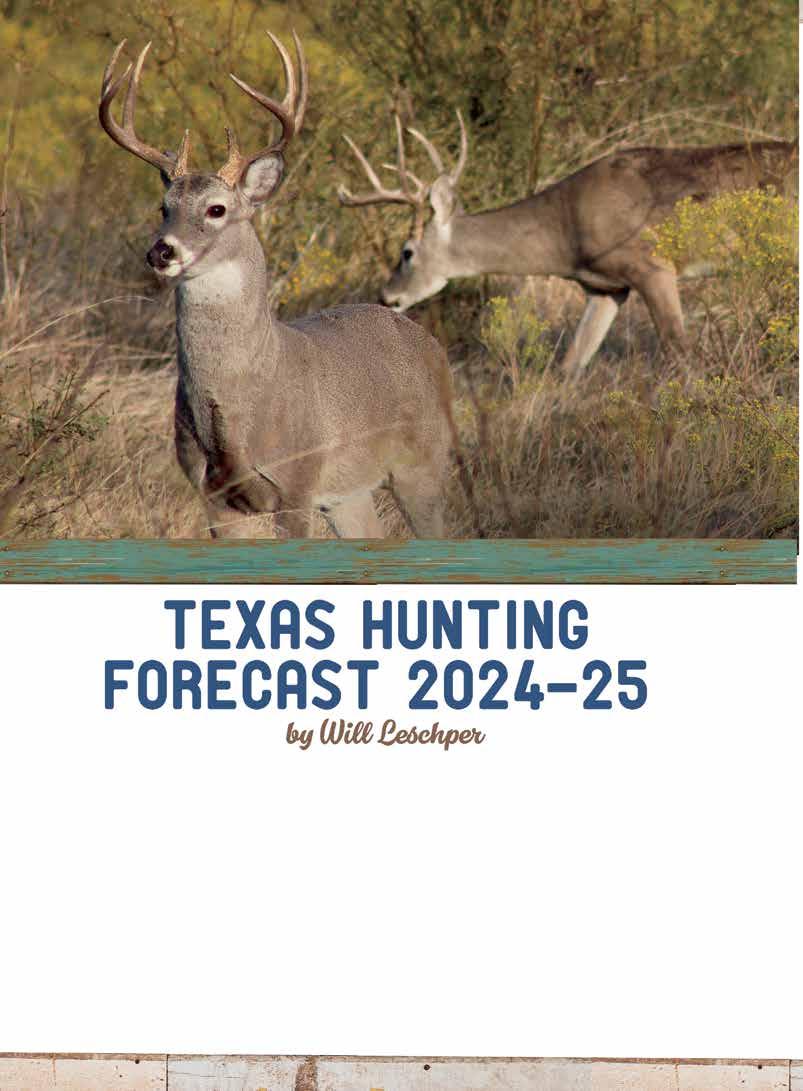

The Texas deer hunting outlook always includes quantity and quality of bucks. There will be no shortage of healthy bucks.

The Lone Star state is blessed with an abundance of hunting opportunities for both small and big game. And hopefully, as always – with a little help from Mother Nature – the overall outlook has shaped up to be good for deer, doves and a host of other wildlife during 2024-25 hunting frameworks. Here is a preview for Texas’ most sought-after species for upcoming fall and winter hunting seasons.

The Texas deer hunting forecast can almost always be summed as being good, no matter what curveballs Mother Nature has thrown at the whitetail population. The Lone Star state is blessed with the highest whitetail populations in the country, offering hunters quantity and quality, no matter where you may be hunting.

As always, the prognostication offered in the summer ahead of deer seasons is typically based on how the weather treated

bucks and does in the preceding winter and spring months. Moisture of any kind, including snow up in the Panhandle and Rolling Plains regions, is beneficial to helping deer make it through the previous fall and winter, especially in years of drought that lingered through summer and into hunting seasons.

That being said, much of the state experienced El Niño rains through the spring and summer. Many ranchers say their pastures and brush are doing well, and both does and bucks should be in excellent condition when seasons open.

Blaise Korzekwa, white-tailed deer program leader for the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, is tasked with helping to oversee the crown jewel of hunting species, along with a host of biologists who put in time throughout the year working with landowners and hunters. He said things are looking up in many ways for deer this year.

“Aside from portions of the Edwards Plateau and southwest

Texas, the rest of the state should expect above-average fawn recruitment and antler growth this season,” Korzekwa noted.

“Historical statewide fawn recruitment will produce a good number of middle-age and mature bucks this season. Given that well over half of the state experienced good rains this year, hunters will have a great opportunity at harvesting a quality buck this season. Overall, the Texas deer population is a robust 5.3 million white-tailed deer that is rebounding from drought conditions during the last two years.”

It should be no secret that the whitetail hot spots for numbers are the Edwards Plateau (Hill Country), South Texas, Pineywoods and Lower Plains. However, the area between Austin, San Antonio and Houston, and heading up north toward the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex (roughly bounded by Interstates 10, 35 and 45) also is continuing to see a rise in whitetail figures and shouldn’t be overlooked as a hunting locale for those residing in the larger cities.

Korzekwa noted that increased deer management has become the norm statewide, regardless if you’re hunting 100 acres or 1,000, which is good for the whitetail population as a whole.

Korzekwa said that while the annual expectations can vary somewhat, there remain two certainties in Texas deer hunting: There will be no shortage of animals, and hunters should plan to fill as many tags as they deem fit, which helps control a population that continues to increase, regardless where you’re hunting.

Texas dove hunting – like Texas deer hunting – is tops in the country in terms of both hunter participation and the number of birds that flood through the Lone Star state. This year should again be on par with other dove frameworks that see millions of combined mourning doves and white-winged doves from Amarillo to Brownsville.

“The success of any dove season is centered on nesting conditions and bird production that always rests on adequate

moisture and good range conditions,” said Owen Fitzsimmons, dove program leader for TPWD. He noted that hunting seasons during the past decade have actually seen somewhat diminished harvest figures, though this year could see an upswing in both doves and hunters.

“Dove hunting in Texas has been known to be cyclical with multiple-year periods of exceptional harvests followed by years of below-average hunting,” Fitzsimmons said. “However, there is no reason to think we won’t see good numbers of mourning doves again statewide, and good numbers of white wings in their traditional areas of South Texas and down into the Rio Grande Valley. We also continue to see increases in white wings in other areas of the state.”

“September storms almost always spring up as dove seasons start, which could be detrimental to hunters looking to utilize standing grain crops and consistent water sources such as ponds and stock tanks,” Fitzsimmons noted. “However, We should have good sunflower and farmland fields this year and a very good crop of young mourning doves, which are numerous in early season harvest. Texas hunters traditionally take a high proportion of young doves in the first 2-3 weeks of the north and central zones. In a nutshell, look for good dove seasons.

Texas duck and goose hunting has traditionally always been among the best in the country, for a variety of reasons, namely the number of birds that migrate south to escape colder temperatures. That being said, this year is likely to again be on par with other recent seasons that have seen tougher hunting and simply smarter birds that aren’t frequenting their typical haunts.