Buck Mortality By Dr. James C. Kroll

I

n the early 1970s, I began presenting seminars in response to the growing demand for information about managing white-tailed deer. By today’s standards these talks were pretty generic, covering the usual age, nutrition and genetics components to management. It was my opinion the greatest challenge was getting bucks past their first year of life. “Can I safely say, every Boone and Crockett buck once was a yearling?” was my favorite question. To my surprise, the most common response was, “If I don’t shoot him, someone else will!” I would come back with, “Well, if you let a yearling buck walk, his chances were certainly higher than if you shot him!” That is indeed true, but at that time we had no idea what the true survival rate was for bucks. In Texas, we tend to have opinions on deer management colored by what I call the South Texas mindset. That is, deer management takes place on large properties. In the “real world,” however, folks are trying to manage for better bucks on 40-acre and 80-acre tracks. After 50 years, we now have more data on factors affecting buck

survival, so this column is about what we know. I just finished an exhaustive investigation on the state of knowledge about buck mortality factors, rates and survival. It is an understatement to say the literature is very confusing on these subjects. There are a host of variables influencing mortality, ranging from climatic conditions to hunting pressure to social norms for hunters. In “natural herds,” buck morality takes a “U-shaped” form, with highest death rates in the early and late periods of life. In general, most studies agree the highest mortality of bucks and does is from birth to about one month of age. There is a reason why does have two fawns. It’s the magic number needed to produce at least one fawn each year. The primary causes, in order, for fawn mortality are starvation, predation, and disease. Under poor nutrition, does cannot produce enough milk to feed both fawns, leaving one or both to die. Fawn survival in 2020 for much of South Texas was quite low, due to very dry conditions, which translated to poor quality and quantity of forages.

Author photo

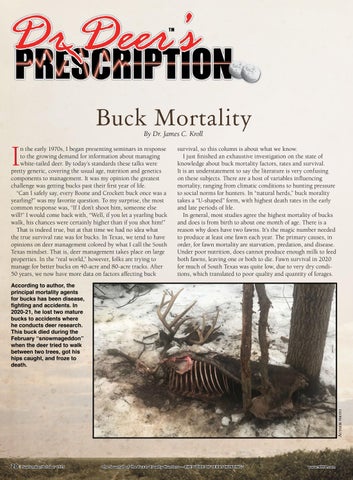

According to author, the principal mortality agents for bucks has been disease, fighting and accidents. In 2020-21, he lost two mature bucks to accidents where he conducts deer research. This buck died during the February “snowmageddon” when the deer tried to walk between two trees, got his hips caught, and froze to death.

20 |

September/October 2021

The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters — THE VOICE OF TEXAS HUNTING®

www.TTHA. www. TTHA.com com