ecause July and August are hot months, outdoor activities are best done in early morning and just before dark. But if you sweat, don't worry, because sweating is good for you! You can still have good times outdoors, but you just have to plan better when it’s 100 degrees in the shade.

In my younger days, I spent time in the hot summer cutting firewood on a deer lease in Brown County. The fireplace in Austin was a cozy place in winter, and I was glad to have a place to get oak wood. July and August are also good months to fix up the deer blinds and cut brush for shooting lanes. Of course, you can go to Hawaii or Bermuda, if you have the money. “Bidenomics” is taking most of mine. Oil keeps going up. It’s over $80 a barrel, and climbing as I write this. With gas over $3 a gallon, I’m reminded of the old phrase during the big war—“Is this trip necessary?” It’s interesting that regular gas is cheapest south of I-10, and east of the Pecos. It appears gas prices follow the economy index, which is higher north of I-10 and I-20. Be that as it may, gas is always something to consider on a hunting trip. I used to drive 100 miles to hunt doves, but such trips are not economical these days. Such a trip today would cost $45 just for gas.

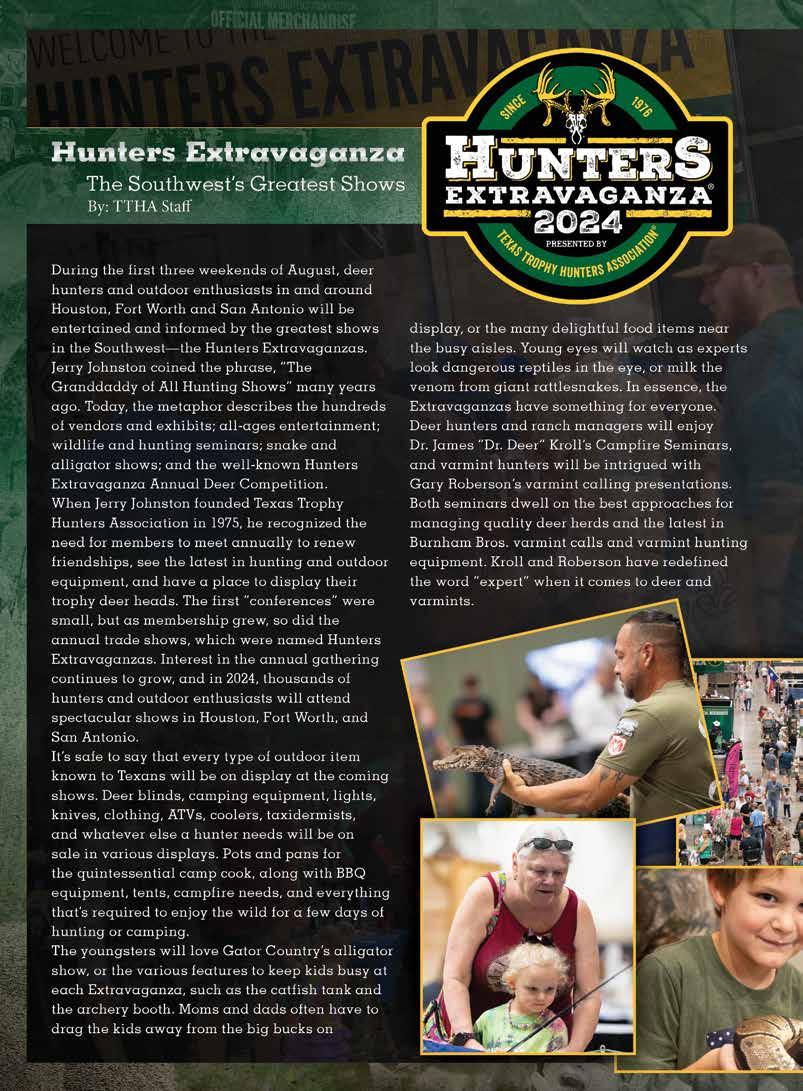

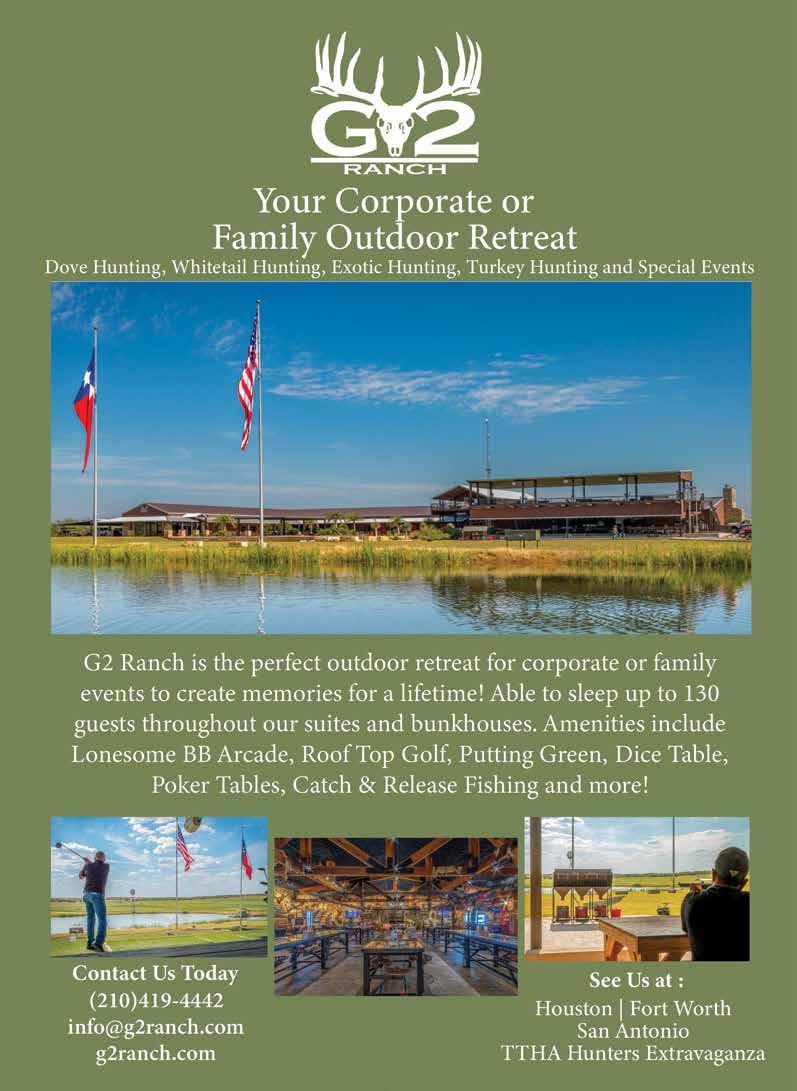

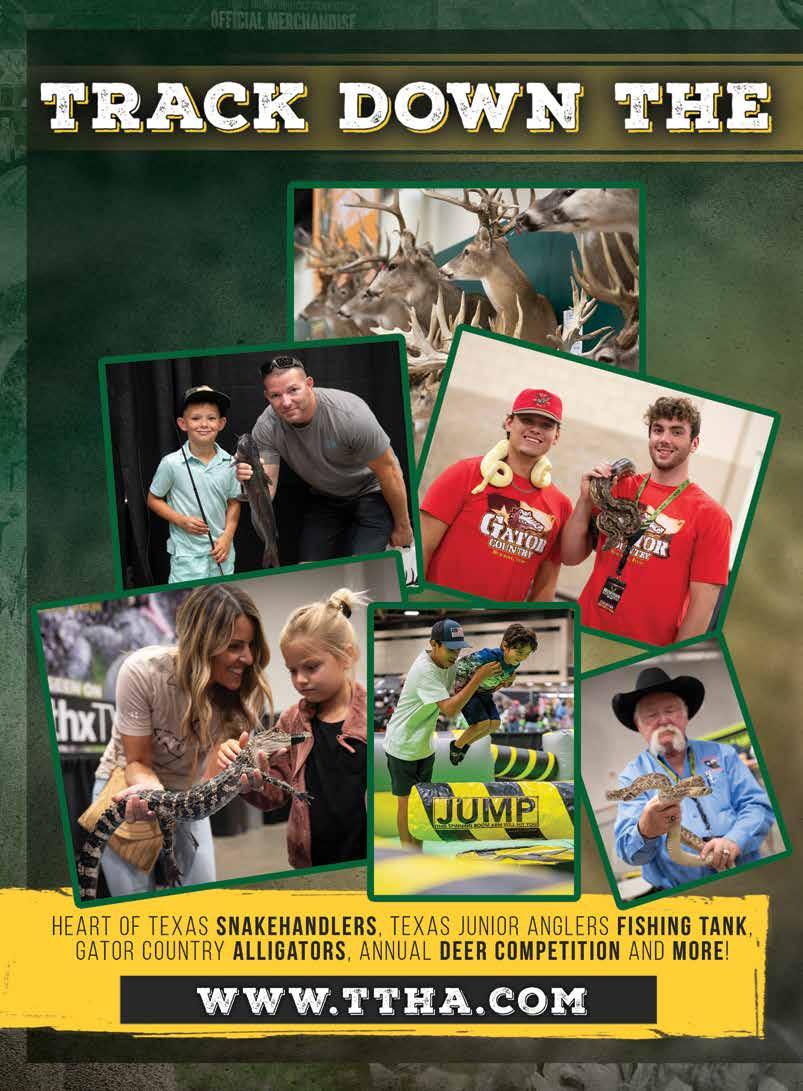

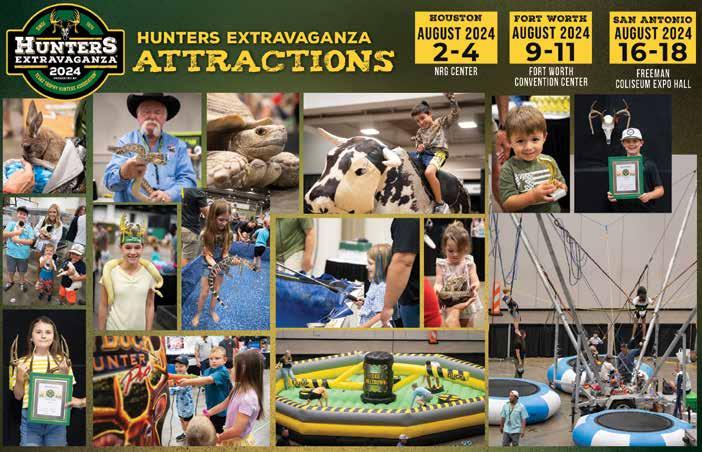

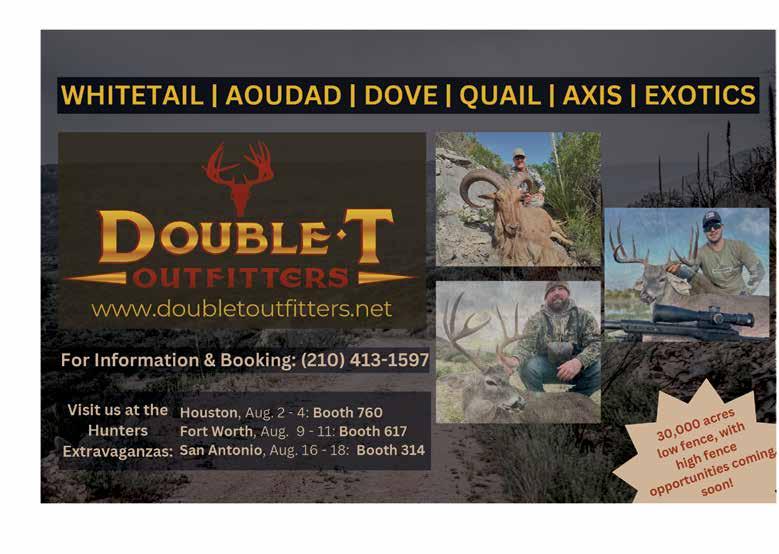

August will be a big month for Hunters Extravaganzas, and we hope to see everyone at one of the shows in Houston, Aug. 2-4; Fort Worth, Aug. 9-11; or San Antonio, Aug.16-18. Each show has something for everyone, so mark your calendar. The cool shows are a good place to be in August to meet old friends and find out from the vendors what’s new for hunting and the outdoors.

When you celebrate July 4, think about the time lapse since we declared independence from Great Britain 248 years, or about 13 generations ago. We can thank Henry VIII and his Church of England, and the rebellious taxes on everything from paint to wool by King George III, known as the “Mad King.” Religion and taxes were the two major components that drove Puritans to the New World, and we should all be thankful for that.

Dove season is just around the corner, so now is a good time to start thinking of a good place for opening day, and renew any old acquaintances that might get you a good hunt. Clean up “Old Betsy,” or whatever you call your favorite shotgun, and look for a good buy on shells. Dove season kicks off the fall hunts, and some 300,000 doves hunters will be in the field in the North and Central zones on Sept. 1. Another 100,000 will join the dove crowd when the South Zone opens later in September.

2024 has been a good year, so far. General rains have been good enough to give us good dove and deer seasons, the two most important hunting seasons in Texas. Make room for the kids in both seasons, and you will be glad later on. And keep ’em running, swimming, and flying by being good sports, and I thank you kindly.

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher

Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer Christina Pittman • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Executive Editor Deborah Keene

Associate/Online Editor Martin Malacara

North Texas Field Editor Brandon Ray

East Texas Field Editor Dr. James C. Kroll

Hill Country Field Editor Gary Roberson

South Texas Field Editor Jason Shipman

Coastal Plains Field Editor Will Leschper

Southwest Field Editor Jim Heffelfinger

Graphic Designers Faith Peña Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers Kristina Brabston, Craig Boddington, John Goodspeed, Judy Jurek, Noah Lavender, Robbie Placino, Brad Ruiz, Eric Stanosheck, David Stoddard

Sales Representative Emily Lilie 713-389-0706 emily@ttha.com

Marketing Manager Logan Hall 210-910-6344 logan@ttha.com

Membership Manager Kirby Monroe 210-809-6060 kirby@ttha.com

Advertising Production Deborah Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

Administrative Assistant Courtney Carabajal 210-485-1386 courtney@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, 1982 ISSN-08941602, is published bimonthly (a total of 6 issues) by The Texas Trophy Hunters Association Ltd. 700 E. Sonterra Blvd., Suite 1206, San Antonio, TX 78258, Phone (210) 523-8500. All rights reserved. Periodical postage paid in San Antonio, Texas, and Additional Mailing Offices. Subscriptions: $35 per year includes membership in TTHA. Phone (210) 523-8500. Advertising: For information on rates, deadlines, mechanical requirements, etc., call (210) 523-8500. Insertion of advertising in this publication is a service to the readers and no endorsement or guarantees by the publisher are expressed or implied. Published material reflects the views of individual authors and does not necessarily reflect the official position of the association. Contributions: should be sent via email to editor@ttha.com, or mailed to the Editor, Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, 700 E. Sonterra Blvd., Suite 1206, San Antonio, TX 78258. They must be accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope or return postage, and the publisher assumes no responsibility for loss or damage to unsolicited materials. Any material accepted is subject to revision as is necessary in our

Deer hunters bringing their trophy heads to the 2024 Annual Deer Competition at Houston, Fort Worth, and San Antonio will see new scoring system changes for the popular Extravaganza buck contest. All three deer contests will feature both Boone and Crockett (net) scores, and SCI gross scores. All deer will be scored using the Trophy Scan system, with matching score sheets for each deer.

SCI will conduct the contests, using all of the original TTHA methods of accepting deer heads, scoring, exhibit-

ing, and presentation of winners and prizes on Sunday evening at 4 p.m. Rules for entering the contests will be unchanged, only the methods of scoring, which use a new scanning technique.

We urge contestants to bring their 2023-24 harvested bucks, or best-in5-years trophies. Texas, Mexico, and out-of-state harvested white-tailed deer will be accepted from TTHA members, along with Texas mule deer. It’s a fun time for all, so bring your buck and enter!

—Horace Gore

By Horace Gore

Kathryn Coleman of Richmond, Texas, is a pioneer of our hunting heritage. She grew up in the Houston area and went to Lamar High School. Graduating in 1952, Kathryn went to Baylor University in Waco, graduating in 1956 with a business degree. She returned to Houston, working with business interests. Part of her work involved the National Cash Register Company, and setting up programs for businesses as computers came into use.

Kathryn married Joe Coleman, who graduated Baylor Law School in 1957, and they continued to live in Houston. “I never hunted anything until I married Joe,” Kathryn said. “Joe had field trial English setters, and I followed him and the dogs in training and at quail field trials. I didn’t hunt deer until 1960 when we began hunting deer together in several counties: his home county of Freestone, and Frio, Dimmit, and other South Texas counties.”

“I killed my first buck in 1960 in Frio County,” she added. “It was a little pencil-horned spike that I shot with a Winchester .30-30 carbine. Joe had the taxidermist put the spike antlers on a nice, colorful board with all information—who, when, and where it was killed—with a remark, ‘Proof you can improve.’”

After that first deer, Joe got Kathryn a .243 and she used it for several years. When the .260 Remington came out in 1997, Joe had a custom rifle made for her, and she has used that .260 for all her big South Texas bucks. “I love my rifle,” Kathryn told me. “It’s deadly on everything I shoot at, it’s very accurate, and the recoil is pleasant.” Kathryn got her best buck with the .260 Remington in Dimmit County.

Kathryn Coleman

Kathryn laughed when she talked about her early days and deer hunting with Joe. “Joe made sure I had good, warm hunting clothes,” she said. “In those days, all of the warm underwear was big and fluffy, and after I got all my clothes on, I looked like a blimp!” Kathryn said Joe got her some electric socks for her cold feet. The socks had wires that ran up each leg to the waist, where a battery box would attach to the belt. “The electric socks worked very well,” she added. Kathryn wears knee-high boots while hunting and elsewhere in the outdoors, so I asked how she got started wearing the boots. “Well, Joe wears dress boots every day when he’s working at the law office, and I like to wear boots, too,” she said. “A lady bootmaker in Raymondville would come around to hunting camps and measure your feet and

send you a pair of boots. Well, I don’t know how many pairs of boots she made for me and Joe, but it was several. Each pair was perfect and fit like a glove.”

Kathryn and Joe raised two kids, John David and Kathryn Ann, and took them to the deer blind at an early age. One of Kathryn’s friends asked, “You don’t shoot a rifle with that baby in the blind, do you?” The kids grew up on chicken fried venison, and Kathryn always had a good stash of deer meat. John David hunts in South Texas from his home in Temple, and Kathryn Ann is employed at Baylor University and lives in Waco.

The Muy Grande Deer Contest in Freer has always been special to Kathryn. She has taken bucks to the contest from the beginning, when she was one of the few female hunters to enter a buck. “I’ve had my share of wins in the female divisions at Muy Grande because there were only a few women entered in the contests,” she said. She and Joe also won several times at Muy Grande as a

Kathryn and Joe with their trophy bucks. She has used her custom .260 Remington rifle for all her big South Texas bucks.

husband-and-wife team.

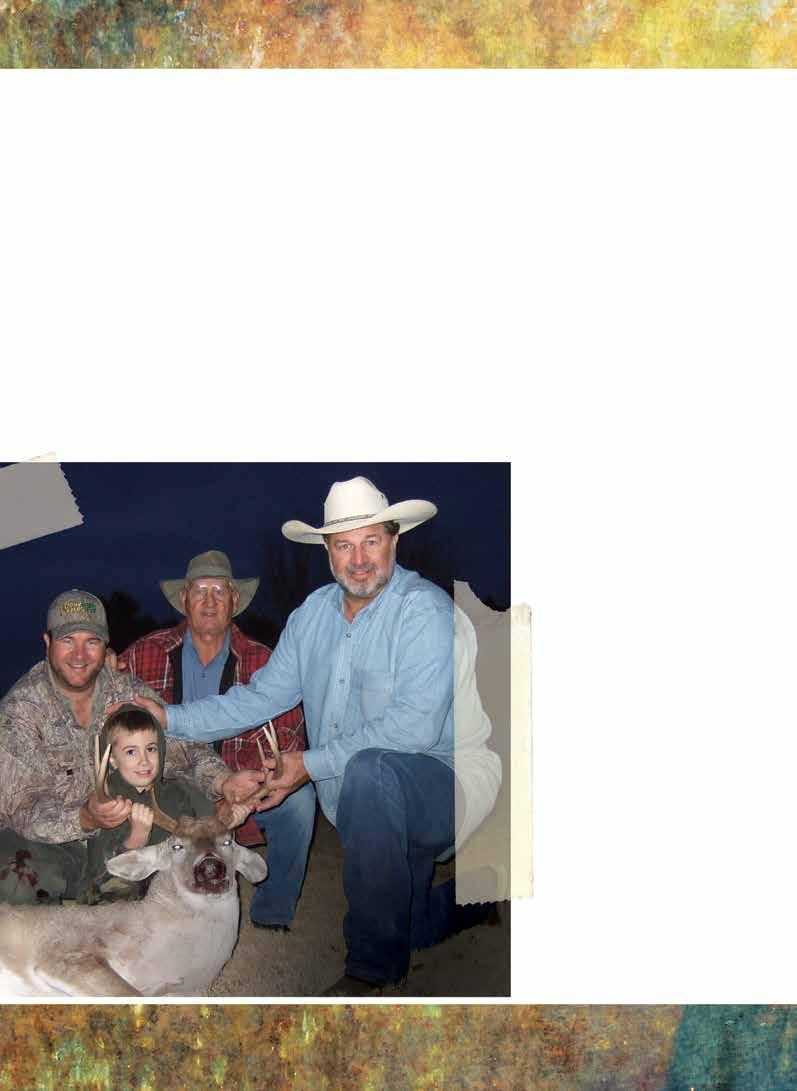

Muy Garza (center) inducted Kathryn and Dr. James Kroll into the Muy Grande Hall of Fame in 2011. The author said it was difficult to tell which recipient had the most pride that day.

“I’ve taken some big bucks to Muy Grande through the years,” she said, “and some were unique—big six-point; drop tines; wide spread; non-typical. I’ve taken them all.” She noted she had killed several typical 180s, but never a Boone and Crocket buck. “Joe has a big B&C buck, but I haven’t killed one. It’s not fair,” Kathryn said.

One of the highlights of her hunting career was being inducted into the Muy Grande Hall of Fame in 2011. Two honorees received the prestigious Hall of Fame Award, and it was difficult to tell which one was the proudest: Kathryn or Dr. James “Dr. Deer” Kroll.

Kathryn and Joe are longtime friends of Texas Trophy Hunters and have added much to Texas hunting and the outdoors. She’s a deer hunter, par excellence, and has shared her love of hunting with Joe and their many friends. It’s an honor to recognize Kathryn as a pioneer of our hunting heritage.

Do your part to preserve our hunting heritage. Share your passion with the next generation. Pass the torch.

How do you pass the torch? Share your photos with us. Send them to editor@ttha. com. Make sure they’re 1-5 MB in file size.

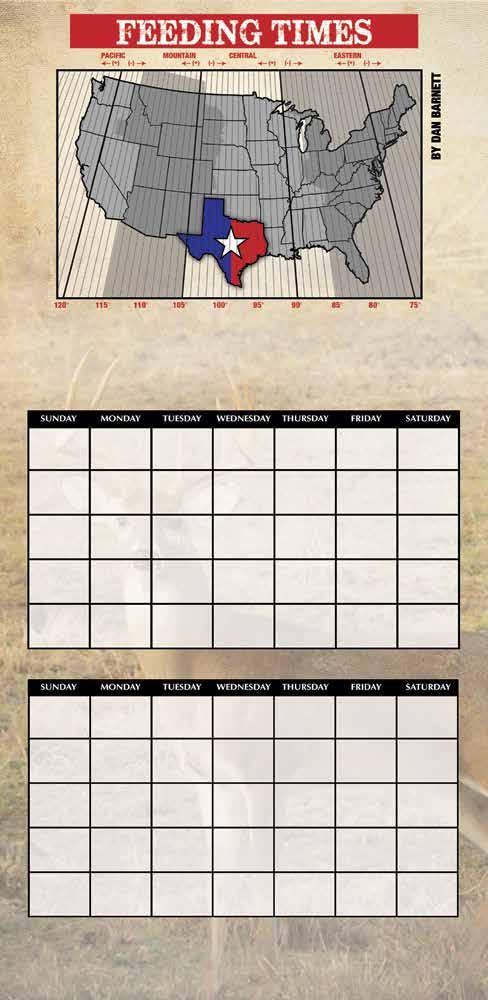

TPW Commission Approves 2024-25 Statewide Hunting, Migratory Game Bird Regulations

Texas Parks and Wildlife Commissioners also approved in late March other changes to the 2024-25 Statewide Hunting and Migratory Game Bird regulations:

• Change greater white-fronted goose daily bag limit restrictions from two in the aggregate to a simplified dark goose daily bag limit of five in the western zone.

• Change the Special White-winged Dove Days season structure due to calendar progression.

• Change the season structure of the second segment for dove in the north zone to allow later dove hunting during the holiday season.

• Require statewide mandatory harvest reporting for all wild turkeys during all seasons and counties to improve harvest data for their management.

• Close the spring-only hunting season for wild turkeys south of Highway 82 in Fannin, Lamar, Red River and Bowie counties due to ongoing wild turkey restoration by TPWD, NWTF and landowners.

• Close all wild turkey hunting seasons in Bell and Williamson counties east of Interstate 35 (I-35) and in all of Milam County to allow the restocking of wild turkeys for population restoration by TPWD and landowners.

• Remove references to Rio Grande and Eastern wild turkey subspecies in regulations and replace with “wild turkey” to simplify county regulations.

• Reduce the wild turkey hunting season length and annual bag limit in Brew-

ster, Jeff Davis, Pecos and Terrell counties west of the Pecos River; Comal, Hays, Hill, McLennan, and Travis counties east of I-35, and Guadalupe County north of I-10 to a spring-only season from April 1-30 and a one gobbler (male turkey) annual bag limit to be more proportionate with wild turkey populations.

• Change desert bighorn sheep hunting season from Sept. 1 – July 31 to Nov. 15 – Sept. 30 to allow for safer flying conditions during TPWD aerial surveys.

• For properties enrolled in the Harvest Option of the Managed Lands Deer Program, allow youth to harvest bucks with a firearm for the same days that correspond to the early youth-only season for county regulations.

• Expand doe days in 43 counties in the Post Oak Savannah and Pineywoods ecoregions to better manage white-tailed deer populations.

• Expand youth-only seasons in the fall to include Friday for white-tailed deer, squirrels and wild turkeys to allow greater hunting opportunity for youth.

—courtesy TPWD

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Commission voted unanimously to eliminate the light goose conservation order, making Texas the first state to have done so. Commissioners also approved at their March 28 meeting the lowering of the daily bag limit for light geese from 10 to five, standardize possession limit for light geese to three times the daily bag limit, and extend the regular goose season for light geese by 19 days in the Eastern Zone.

Owen Fitzsimmons, webless migratory

game bird program leader for Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, along with his staff, recommended removing the order and implementing other associated items.

“Liberalized hunting regulations and near year-round pressure on these birds across their range have resulted in significant changes to mid-continent light goose distribution and behavior, both in Texas and throughout the flyway,” Fitzsimmons told commissioners at their March 27 work session.

Fitzsimmons cited data on declining geese populations in the state, as well as a decline in hunter participation. He said the light geese population has gone from a high of 19 million in 2007 to less than 3 million in the most recent estimate, a decline of 86% over a 15-year period.

“That decline is not due to the conservation order or regular season harvest,” he said. “In fact, researchers have now concluded that the conservation order, and the liberalized regulations associated with it, have been largely ineffective at reducing light geese as intended. The recent decline, instead, is primarily due to very poor recruitment of young birds into the population. Climate change is impacting seasonal timing in the Arctic, creating a mismatch of resources during the very limited summer breeding window, and the young birds are simply not surviving to adulthood.”

Horace Gore, retired wildlife biologist with Texas Trophy Hunters noted that Texas rice production has gone down drastically in the last 15 years because of water shortages. “White geese are rice geese, Gore said. “The number of white geese around Eagle Lake and other rice farming areas is determined by rice acreage, which also determines the number

of geese that winter in Texas.”

“Goose hunters hardly ever go out and kill 10 snow geese,” he said about the bag limit, adding he has hunted snow and speckle-belly (white-fronted) geese for many years. “Season length has more effect on harvested geese than daily bag limits, and we have to understand that all waterfowl hunting in Texas has decreased during the last two generations.”

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service established the light goose conservation order in 1999 as a way to manage a growing light goose population and decrease overgrazing in their nesting habitat in the Arctic. But 25 years later, the order is no longer necessary and not compatible with current conservation needs in Texas, according to Fitzsimmons.

“For 25 years, this population of geese have been the most pressured game birds in North America,” he said. “They are hunted nearly year-round across their entire range. The proposals here will alleviate some of the pressure on Texas birds.” —TTHA staff

Study: Early humans used wood splitting 300,000 years ago to hunt animals

Early humans used sophisticated crafting techniques such as “wood splitting” to hunt and to clean animal hides, a new study has revealed. Using new cutting-edge imaging techniques such as 3D microscopy and micro-CT scanning for the first time, scientists from the Lower Saxony State Office for Cultural Heritage (NLD) and the Universities of Reading and Göttingen examined the oldest complete hunting weapons known to humankind. The weapons, believed to be 300,000 years old, were found during archaeological excavations in Schöningen, Germany, in 1994.

The research, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, identifies how pre-Homo sapiens hunters re-sharpened broken points of spears and throwing sticks. Other tools were made by splitting wood, a behavior previously thought only to be practiced by our own species, Homo sapiens. Some tools made from split wood were likely used not for hunting, but to soften and smooth animal skins.

Dr. Dirk Leder, from NLD, said, “There is evidence of much more extensive and varied procedures of spruce and pine woodworking than previously thought. Selected roundwoods were worked into spears and throwing sticks and brought to the site, while broken tools were repaired and recycled on-site.”

Dr. Annemieke Milks, from the University of Reading, said, “What surprised us was the high number of point and shaft fragments coming from spears and throwing sticks that were previously unpublished. The way the wooden tools were so expertly manufactured was a revelation to us.”

At least 20 spears and throwing sticks were among the weapons found at Schöningen three decades ago. In the years that followed, extensive excavations yielded numerous wooden objects dating from the end of a warm interglacial period 300,000 years ago. The findings suggested a hunting ground on the lakeshore.

The wide range of woodworking techniques used on the weapons and tools show the importance of wood as a raw material 300,000 years ago. The Schöningen finds bear witness to extensive experience in woodworking, technical know-how and sophisticated work processes. Project leader Professor Thomas Terberger, who works at the NLD and the University of Göttingen, said, “Wood was a crucial raw material for human evolution, but it is only in Schöningen that it has survived from the Paleolithic period in such great quality.”

Schöningen is therefore part of the internationally outstanding cultural heritage of early humankind. Only recently, the site was included in the nomination list for UNESCO World Heritage Site at the request of the state of Lower Saxony. courtesy phys.org

Oppose Catalina Island Conservancy Attempt to Eradicate Mule Deer

Safari Club International (SCI) and SCI California Coalition staunchly oppose the Catalina Island Conservancy’s unscientific proposal to eradicate the mule deer population from the island. Both

organizations are advocating for reasonable alternatives, such as an expanded program of legal, regulated hunting, that would balance public enjoyment of wildlife with harvest opportunities for lean, organic sources of protein.

California Gov. Gavin Newsom has a long history of disrespecting hunting and hunters’ ethical, sustainable, and critical role in wildlife management. Yet his administration and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife are comfortable with an aerial slaughter plan to kill thousands of deer wantonly.

Before such extreme measures are even considered, SCI believes it is critical to determine the carrying capacity for mule deer and bison on the Island. SCI demands peer-reviewed studies to assess the feasibility of coexistence with native fauna. Sadly, the Conservancy’s record of this type of scientific approach is poor. For example, in the instance of bison management, the Conservancy first established a birth control program, then it reversed course and proposed introducing additional bison to expand genetic diversity in the herd. With respect to the deer population, residents and non-Conservancy-affiliated biologists question the Conservancy’s methodology for population estimation.

The Conservancy’s use of cherrypicked information to make consequential decisions is alarming. Mule deer provide significant benefits to Catalina Island residents, and their impact on Island vegetation is not significant—despite Conservancy claims. The Conservancy’s plan to eradicate deer on the Island has been rejected at least twice due to lack of data and scientific support. It should be rejected again, especially as it does not meet the standard for a “Scientific Collection Permit.”

“If Gov. Newsom and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife care about science-based conservation, they will reject the Catalina Island Conservancy’s foolish deer mule eradication proposal immediately,” said SCI CEO W. Laird Hamberlin. “Proper management of the deer mule population via regulated hunting and other tried-and-true methods, not ill-founded aerial slaughter,

will ensure ecological harmony on Catalina Island.”

“Mule deer have thrived on the Island for a century, while thousands of sportsmen and women have participated in regulated hunting seasons since then,” noted SCI California Coalition’s Legislative Coordinator Lisa McNamee. “We stand ready to collaborate with the Department to create sustainable, prohunting deer and bison population management strategies once this proposal is no longer on the table.” — courtesy SCI

The Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission voted April 9 in support of a black bear hunting season beginning in December 2024. The season will take place in the Tensas River Basin bear management area—home to the state’s largest and most rapidly expanding black bear subpopulation. Safari Club International (SCI) proudly supports this vote as it is the first black bear hunting season in Louisiana since the 1980s and recognizes the success of recovery efforts for the species.

From the early 1990s through 2016, the Louisiana black bear was listed on the Endangered Species Act (ESA) and was the only black bear species ever to be ESA listed. However, the Louisiana black bear has recovered due to strong collaboration between the state, the federal government, and private landowners. Under the state’s newest management plan, hunting is a welcome addition to the collection of appropriate management tools that help maintain the population at a healthy level and keep bears within their core habitat.

SCI, Safari Club International Foundation (SCIF), and SCI’s Chapters have steadfastly supported Louisiana black bear recovery and conservation. SCI was the only organization to defend the 2016 removal of black bears from the ESA list and successfully obtained a dismissal of the lawsuit twice. Maria Davidson, SCIF’s Large Carnivore Program Manager, has over 25 years of experience managing the black bear recovery

program and is the former Large Carnivore Program Manager for the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission. SCI’s Acadiana Chapter has contributed thousands of dollars to critical black bear recovery programs and incentivizing rewards for bringing bear poachers to justice.

“We are thrilled with the Louisiana Wildlife and Fisheries Commission’s vote to open a black bear hunting season. The best available science has proven that regulated hunting is the only method to manage bear populations in suitable habitats,” said SCI CEO W. Laird Hamberlin. “A new season would be conducted in a manner that safeguards the long-term viability of Louisiana’s black bear population while providing a new hunting opportunity in the Sportsmen’s Paradise.” — courtesy SCI

On April 9, the House of Representatives passed H.R. 6492, the Expanding Public Lands Outdoor Recreation Experiences (EXPLORE Act), on a voice vote, a clear sign of the widespread support for this legislation and outdoor recreation, including hunting, fishing, and recreational shooting. This bipartisan legislation is strongly supported by the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation (CSF) and is led by Congressional Sportsmen’s Caucus (CSC) Co-Chair and Chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee, Rep. Bruce Westerman, along with nearly two dozen other Representatives, many of whom are CSC Members.

H.R. 6492 is complementary to another comprehensive package known as the America’s Outdoor Recreation Act, which is led in the Senate by CSC Co-Chair Sen. Joe Manchin and CSC Member Sen. John Barrasso. The EXPLORE Act includes a number of longstanding CSF priorities, including an important provision that CSF has been spearheading for the last five years that will increase recreational shooting opportunities. Specifically, the range access language contained in the EXPLORE Act requires the U.S. Forest Service and the Bureau of Land Management to have a minimum of one free and public target shooting

range in each of their respective districts. The Range Access Act also helps improve conservation funding through the Pittman-Robertson Act, which is the largest source of wildlife conservation funding for state fish and wildlife agencies.

The EXPLORE Act will also assist federal agencies in efforts to prevent the spread of aquatic invasive species, which pose a serious threat to native aquatic ecosystems and the economy. Once established, aquatic invasive species are difficult, if not impossible, to eradicate, and significant resources must be invested annually in population management. The bill provides federal land management agencies with the authority to carry out inspections and decontamination of vessels entering or leaving Federal land and waters. However, CSF worked to include language that will not prohibit boating access in the absence of a federal, state, or partner’s inspection station. Additionally, this legislation includes language that will help improve future federal land agency planning decisions and would enhance user planning efforts. Specifically, the Improved Recreation Visitation Data section directs certain federal land management agencies to capture various recreation visitation data. This section also establishes a real-time data pilot program to make available to the public real-time or predictive visitation data for federal lands, helping sportsmen and women with their trip planning efforts.

Furthermore, the EXPLORE Act contains another longstanding CSF priority that would streamline the permitting process for small film crews (six individuals or fewer) conducting filming or photography on federal lands. Under current law, small film crews are treated the same way in the permitting process as large-scale Hollywood productions. However, this legislation will make it clear that no additional film or photography permits are required for those small film crews, in accordance with other applicable laws and permit regulations. This provision will make it easier for sportsmen and women, outdoor production companies, and others to promote and share their federal land recreational experiences. — courtesy CSF

By Dr. James C. Kroll

Each year we receive hundreds of questions through social media on an array of topics related to whitetailed deer. Always among the top five questions are those related to deer parasites. So, I am devoting this column to providing you with facts about the most common parasites that afflict our favorite big game animal.

According to the CDC, parasites are “… organisms that live on or in a host and get their food from or at the expense of the host. Parasites can cause disease in humans.” Simply put, they are “free-loaders,” making a living at another organism’s expense. Sometimes they are benign and have little real impact on the host, while others can lead to poor health or even death. The majority of parasites do not have the goal of killing the host, since what good would that do for the parasite? So, what is their relevance? In deer management, more often than not, we use parasite presence or densities as a health and deer population indicator, because they often are what we refer to as “density dependent.”

Parasites are classified as one of two types—ectoparasites and endoparasites. The preface “ecto” means outside and “endo” inside. The ectoparasites either attach to or roam freely around the outside of a deer’s body, generally feeding either on blood or waste products such as skin and hair. Endoparasites must enter the deer’s body by some means, then complete its life cycle within one or more organs. Since I have spent the last two decades performing necropsies (animal autopsies) on several thousand deer, I have a pretty good idea which ones are most common and most significant. Let’s take a look.

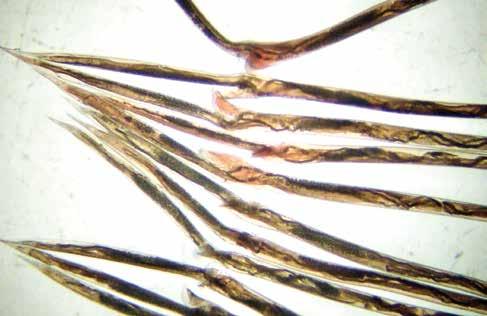

The two most common ectoparasites are ticks and keds; with a total of nine species being reported for whitetails. I think it’s safe to say, your first impression of parasites on your deer is when you spread that buck’s hind legs and begin to gut him. There are two types of creatures encountered—those that hold fast to the skin and those that try to run away. Simply, the first are ticks and the second, keds. Ticks are arachnids with eight legs and keds are insects with six legs. There are four species of ticks and three native species of keds known to afflict whitetails: most notable are Ixodes scapularis (black-legged tick), Amblyomma americanum (Lone Star tick), Lipoptena mazamae (neotropical deer ked), and the imported L. cervi (European deer ked), arriving in North America about 1900.

Ticks are known to transmit several diseases, most notably Lyme Disease (named after Lyme, Connecticut); which in spite of being around for 5,300 years, took many years for the medical profession to recognize. The disease is caused by Borrelia bacteria, most commonly carried by the black-legged or deer tick. The Lone Star tick has not been shown to transmit Lyme, but is responsible for other human diseases, such as Ehrlichiosis, STARI, and tularemia, among others.

When I began my career in eastern Texas, deer populations were exploding, and it was nothing to find as many as 80-90 imbedded ticks

on one deer. Years later, there are fewer ticks; some say due to fewer deer and fire ant predation. The life cycle of ticks involves three stages. An engorged female full of eggs that drops off her host. The larvae go through two stages, each with a separate blood meal, then become adults, after as much as 3 years. Native Americans regularly burned the forest to rid themselves of the pest.

Keds have a more complicated life cycle, beginning with a wingless adult living on the host. The female gives “birth” to a single fully developed larva that cements itself to a deer hair and pupates. She lives about 120 days and produces some 10-12 “young” during this time. The pupa hatches in three weeks, equipped with wings to fly to another host; then sheds its wings. They have piercing mouthparts that lacerate the skin of the deer, so the fly can lap blood. Although tick-borne pathogens have been reported in deer keds, there is no proof yet of transmission to humans or other animals.

Each year we receive dozens of inquiries that go like this: “I shot this deer and hung him up in the camp, only to come back and find some ugly fat worms lying on the ground beneath him. Can I eat this deer? ” They are the larvae (maggots) of the common nasal bot fly (Cephenemyia spp). Even if you have not seen them, you no doubt have experienced their effect, when you hear deer snorting and sneezing in the woods. Here is what is happening:

The nasal bot fly lays its already hatched larvae on a deer’s nose, which crawls into the nose and sinus cavities of the host.

Once there, they use hooks on their heads to hold on to the sinus lining. They remain for up to 10 months, feeding presumably on nasal secretions. Once mature, the larvae drop out of the nose, burrow into the litter, then pupate in

3-9 weeks. They transform into flies that cannot eat and start the process all over again. There has never been any evidence these parasites hurt the deer other than irritation. Nasal bots create no human health concern, and have no effect on the wholesomeness of venison.

Now, let’s turn to the endoparasite-some that can create significant health issues for deer. I am amazed how little attention hunters give the “insides” of a deer, unless something really “gross,” like a large abscess catches their attention when field dressing.

Liver flukes are endoparasite flat worms (Trematodes), which got their name from Old English for “flounder.” The ones infecting deer are the “large American liver fluke,” Fascioloides magnus. They draw attention when a hunter slices up a deer liver for cooking, only to find thick-walled chambers filled by dark black liquid and strange-

looking creatures that curl up on their edges. They are flat, football-shaped, measuring 15-30mm wide by 30-100mm long. Flukes do not have sexes, but are hermaphroditic. Their eggs pass out through the digestive tract in feces. In the environment, they undergo a complicated journey through snails to reinfect deer by ingestion of plants with larvae attached. Fluke infection is mostly around wet areas. I have never seen a deer, even heavily infected, die from live flukes; although other ruminants are not so lucky; especially sheep.

Round worms belong to the group called nematodes, which infect both plants and animals. Several species of nematodes have been reported for ruminants: 32 for whitetails. However, there really are only three I have found that cause significant problems—the barber’s pole worm, thread worm, and lung worm. I consider the latter two to be relatively rare, so let’s focus on the most common, the barber’s

pole worm.

Deer are ruminants with a fourchambered “stomach,” consisting of the rumen, reticulum, omasum and abomasum. The pH in the true stomach (abomasum) can drop to 2.1-2.2; obviously a pretty hostile environment. Yet, that is precisely where the barber’s pole worm, Haemonchus contortus, thrives. The life cycle of this worm starts with freeliving larvae from feces and ends with a parasitic adult phase, when they are incidentally eaten, completing the cycle. When I began my career, there was a lot of research correlating stomach worm numbers to deer density. It generally was thought to be true, although it has not always been the case. Because they are aggressive blood feeders, they cause “haemonchosis,” a condition caused by blood loss. Symptoms are anemia, weakness, enlarged lymph nodes, and swelling of the lower jaw from edema. Most of the serious cases are reported for warmer, wetter areas of the whitetail range.

So, there you have a brief primer of the most common whitetail parasites I have encountered. There are several more, but don’t be concerned. Deer are animals, and being such, they are susceptible to a host of diseases and parasites, just as humans. The take home message though, is the wonderful creatures called whitetailed deer have faced many threats over the millennia and come out on top every time. I seldom worry about them anymore.

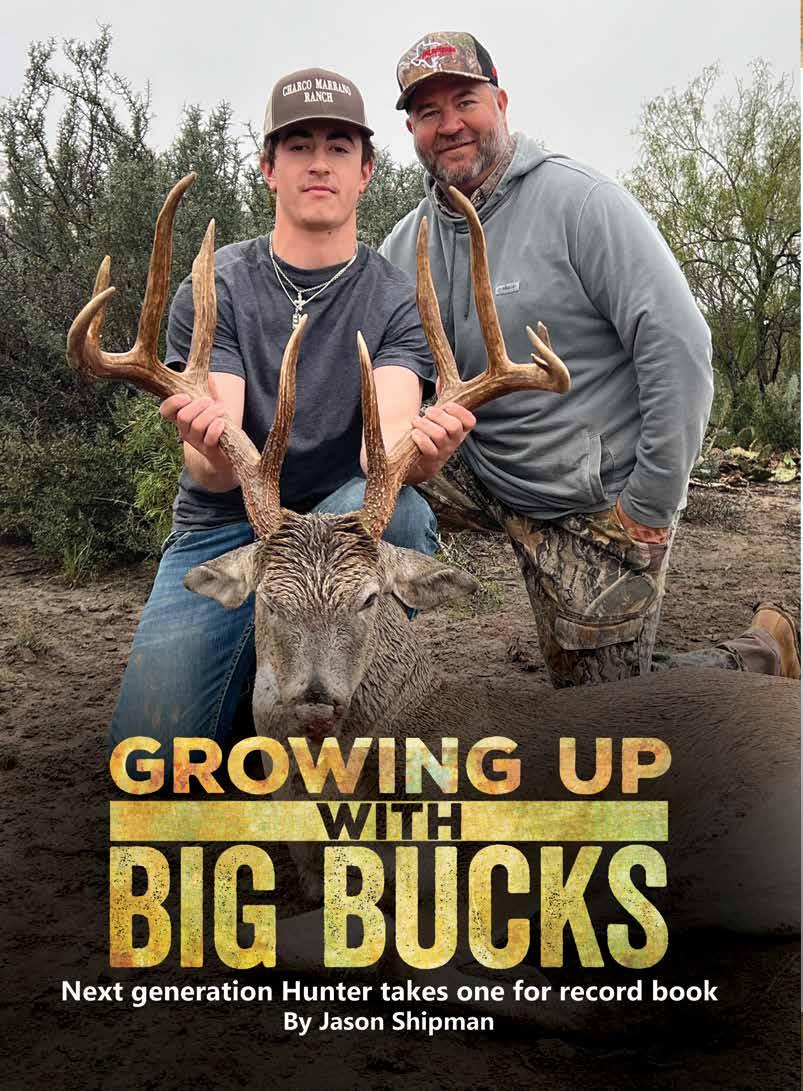

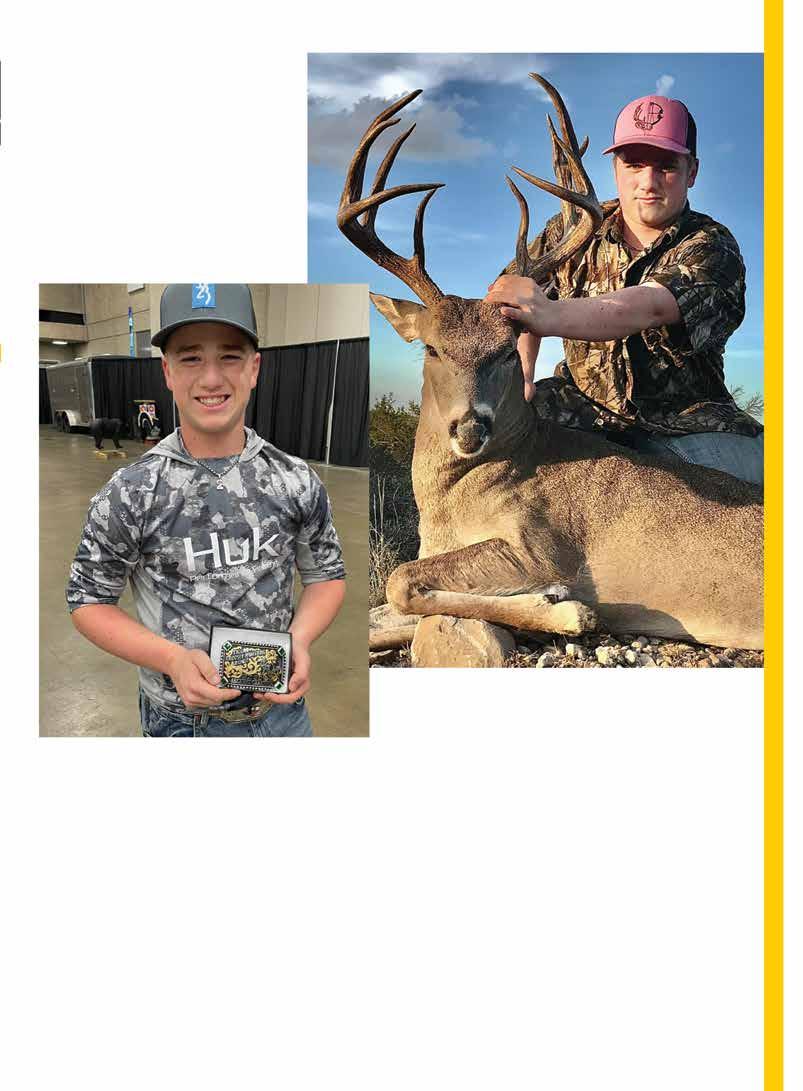

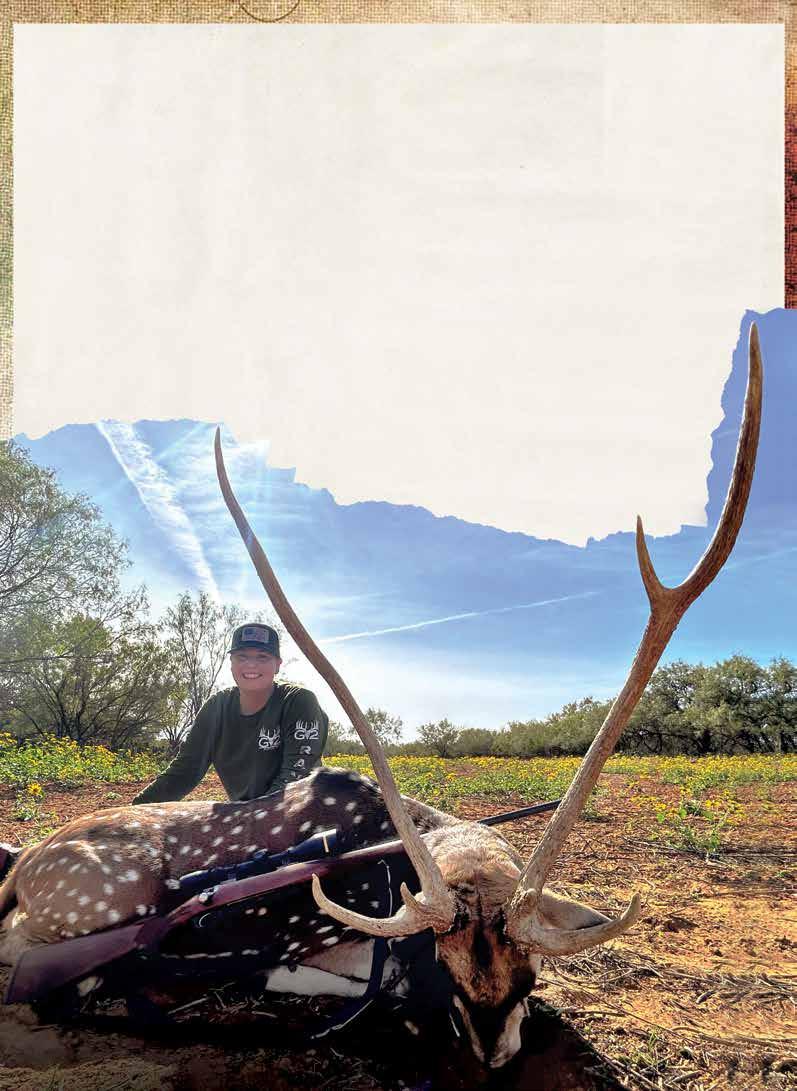

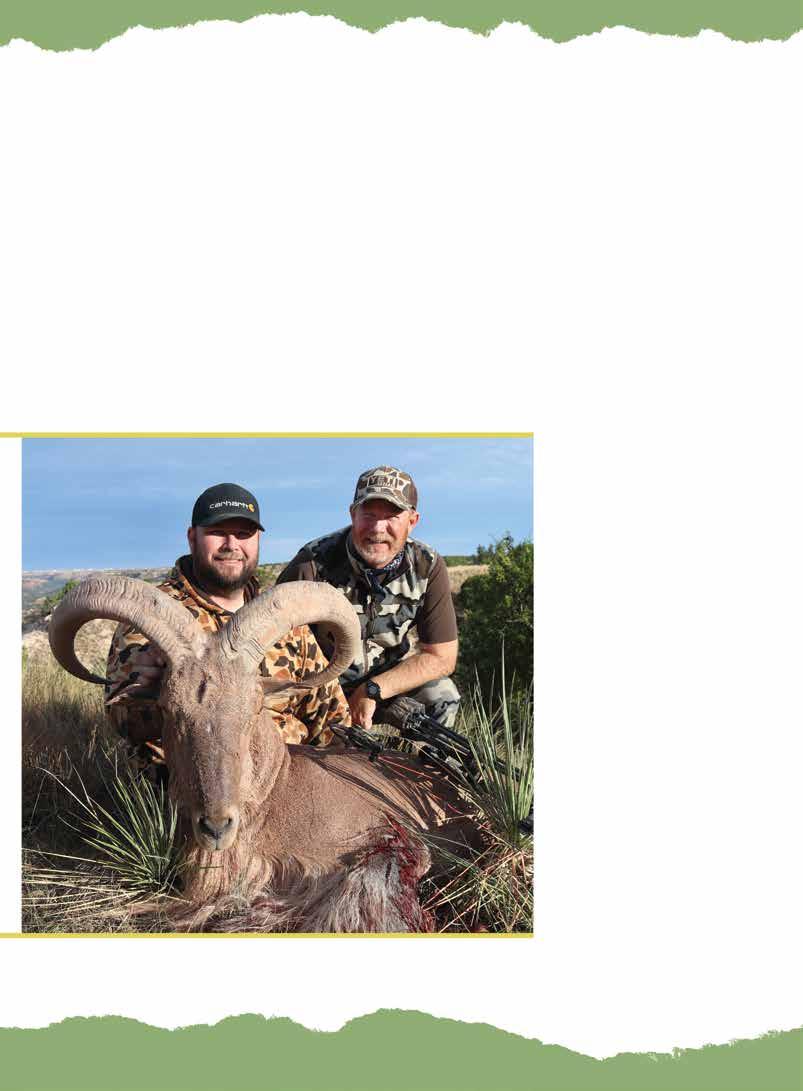

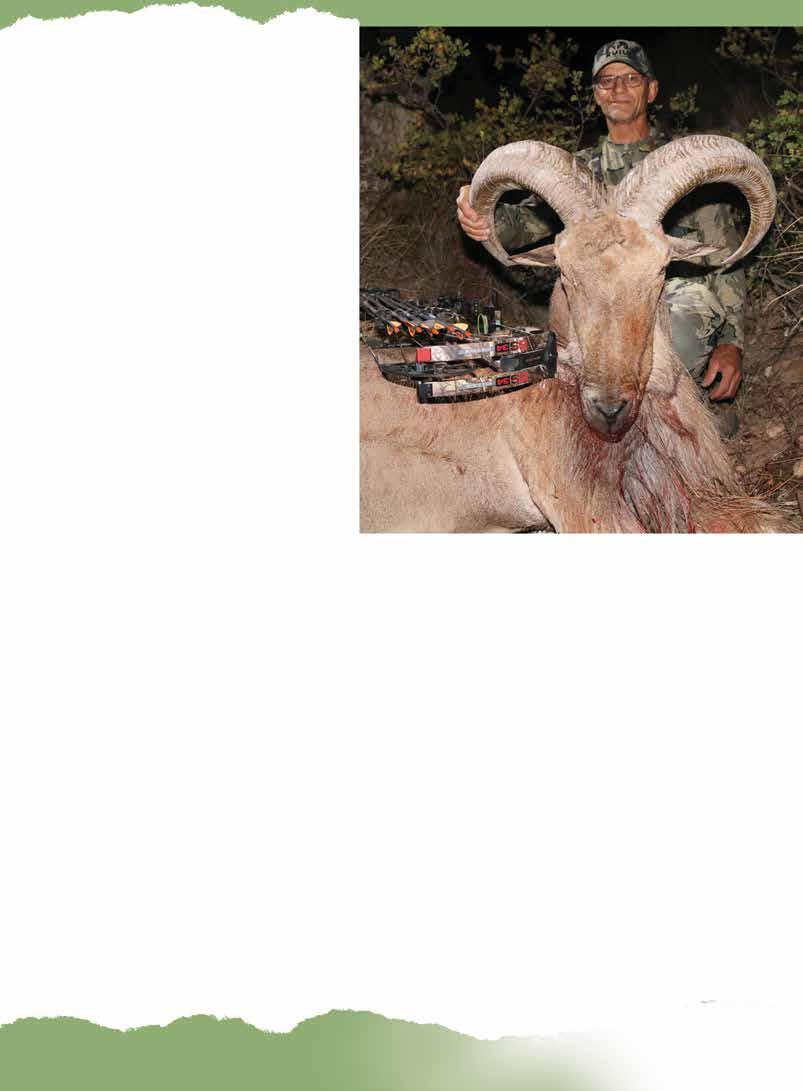

José has seen his fair share of big bucks taken on the Charco Marrano. And now he can proudly take his place with other family members with his own B&C record buck.

Cody “José” Hunter is a deer hunter, par excellence, and last season in La Salle County, José took the best buck of his young hunting career.

Fall is a magical time of the year for Texans who enjoy the thrill of the hunt. Approximately 800,000 hunters pursue and take some 800,000 deer per season. Although many outstanding typical and non-typical bucks get taken each year, only two to four (at most) bucks will have what it takes to make the Boone and Crockett all-time records book.

Without exaggeration, the odds of killing a B&C buck in Texas are less than 1 in 100,000, considering that Texas hunters take 400,000 bucks per year. Those are slim odds, even from a state that’s historically a top producer of record book qualifiers.

The Hunter family has been fortunate to take several record book bucks on their Charco Marrano Ranch, southeast of Cotulla in La Salle County. Dedication and hard work implementing their wildlife management program over the past 25 years has led to tremendous success. Some of these bucks have been featured in past editions of The Journal Last season, José took the sixth book buck the ranch has produced, and this is the story of the young trophy hunter’s progression. José grew up in the Cibolo area and has enjoyed playing sports, hunting, and fishing. His parents, Travis and Jennifer Hunter, ensured he could go to the ranch as much as possible with Gramps and Granny, Phil and Jackie Hunter, along with the rest of the family.

There are eight grandkids in the family, and they’re known for their nicknames. José earned his moniker at age 4, while on the way to the ranch one afternoon with Gramps. “I was telling a story and probably stretching it a little,” he said. “Gramps kept saying, ‘No way, José! No way, José!’ and the nickname stuck. Everyone called me José from then on.”

When he was just 6 years old, José cut his teeth deer hunting. “All I wanted to do was hunt,” he said. “The ranch rule for the kids was that you had to shoot three hogs and three does in a row before you could hunt a buck.” José is the oldest of the grandkids and the first to honor the rule and be eligible for buck hunting.

Travis took young José hunting on a wet, overcast day when a nice eight-point buck stepped out at about 50 yards. “He was

Little did 6-year-old José know the blind where he shot his first buck would be the same one to later produce a

following a doe in and out of the brush along the sendero,” José said. “About the third time he came out, my dad made a noise and the buck stopped. I shot him with a .204 Ruger, and he ran about 30 yards into the brush before piling up.”

Cameraman Brian Hawkins caught everything on video. Trophy Hunters TV featured the video. It was a great day for the Hunter family. José was on top of the world and couldn’t have been prouder of his first buck. His smile in the old photos proves it.

That first buck would become one of many as José continued hunting. Over the next 13 years he would kill a dozen more bucks including a couple of pretty nice ones, scoring around 150. “As I got older, I began enjoying guiding and helping others get a deer,” José said.

Time has flown by, and little José is now 19 years old. Last

year he graduated from high school and began working in the family’s construction business. “I’m busy with work, but without school and sports, it’s actually been easier for me to spend time at the ranch again,” he said.

Last hunting season while at the ranch, José heard Gramps and his dad talking about a big 10-point the family had been watching. “They told me I was going to hunt that buck, and I thought they were joking. That was until we started hunting him,” José said. “I was excited to have the opportunity to hunt the buck. He was special to me because I was one of the first to spot him when he was a younger buck. We would also be hunting him at the same stand where I got my first buck,” he added.

The hunts started off slow with no sightings of the big buck. “I probably hunted a dozen times for the buck with various family members. He just wouldn’t cooperate,” he said. “We hunted Thanksgiving weekend and were unsuccessful, so we went back to town to work. A couple of days later, my cousin called and said he’d seen my buck. My dad and I quickly made plans to return to the ranch.”

Anticipation was high when they climbed into the familiar blind for an evening hunt. “We didn’t see him or really any-

thing that evening and were kind of disappointed,” José said. The next morning, José and Travis returned to the blind early. “We saw a few deer including a big non-typical buck, but not the deer we were after,” he said.

They were about to head in for breakfast when Travis excitedly whispered, “Oh my goodness, he’s right here!” The big typical 10-point they had been desperately hunting for stepped out of the brush a scant 40 yards away. “We stayed motionless and watched as the buck turned and walked away from us down the sendero,” José said.

Never one to miss an opportunity for a good ribbing, Travis whispered, “You don’t have to shoot him.” José turned and looked at his dad who was smirking and said, “I’m shooting him!” With that he got his .300 PRC ready and put the crosshairs on the big buck’s shoulder. The distance was about 100 yards and at the shot the buck wheeled around and ran 20 yards before falling over within sight.

“I’ll admit I was really nervous, but we knew he was down, and I was relieved,” José said about the aftermath. Eager to share the experience with the family, they quickly made a call and waited for everyone to arrive before going to take a look at the fallen trophy. After a short wait, the entire family arrived and organized chaos ensued.

“We knew the buck was big, but he looked so much bigger when we walked up to him,” he said. “His mass was impressive, and he had long brow tines!” A big batch of photos were taken while the story of the hunt was shared.

After the required drying time, José’s buck scored 1716⁄8 net typical and qualified for the B&C all-time record book. The beautiful typical buck was 7½ years old. José killed him within a stone’s throw of where he killed his first buck, and where it all began.

Travis has also taken some big bucks. “It took me a little longer to get a buck like that, but I couldn’t be happier and prouder of José,” Travis said. While extremely happy with the success of the hunt and his giant typical, José insists the hunt was about more than just the antlers.

“The experience of the hunt and opportunity to share it with everyone made it memorable for me. Qualifying for the book is just icing on the cake,” José said. “I look forward to helping the rest of the family and guests get big deer in the future!”

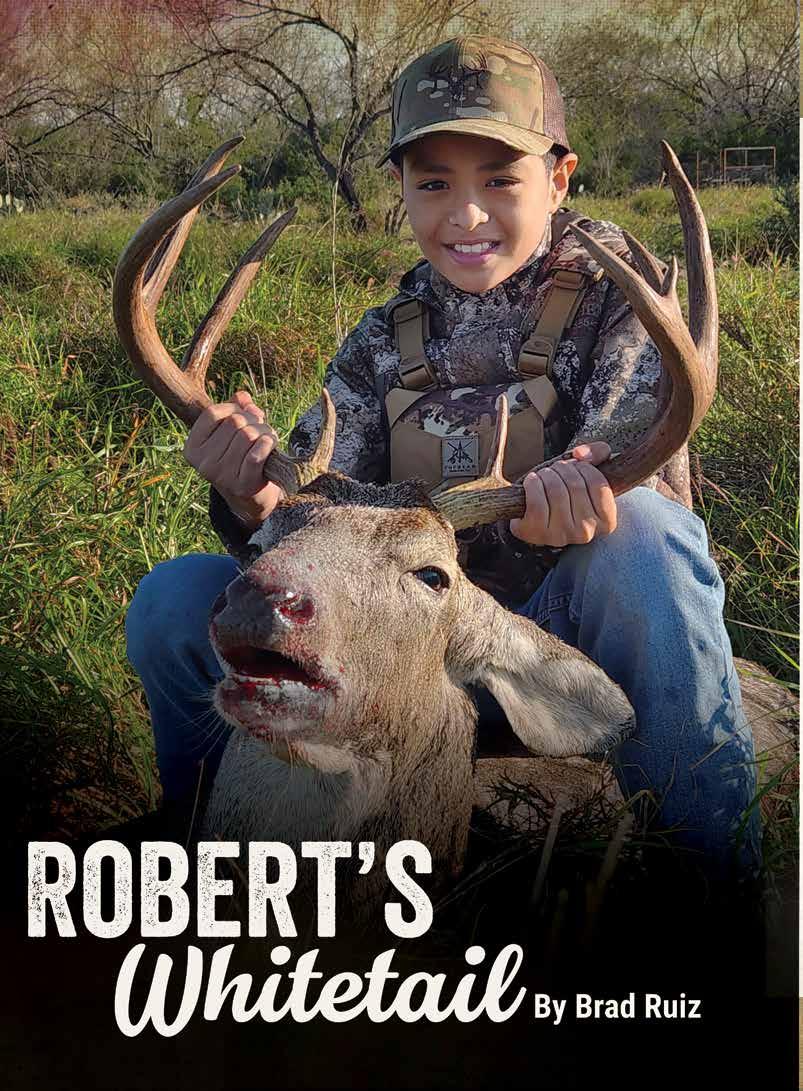

My son Robert is 10 years old, born and raised in San Antonio, Texas. Robert has worked his way from hunting javelinas, coyotes, hogs, and now whitetail deer. When Robert isn’t in the brush, he also loves to spend his time fishing at the coast and finding new fishing spots. When Robert was about 5 years old, he would ask me, “Dad, when can I go hunting with you?” I would tell him, “Soon, son. Soon.”

Not too long after Robert completed his hunters safety course, he was ready to hit the brush. He loves hearing old hunting stories from when I was a kid or hearing what it was like hunting with Grandpa Robert. I told him it’s no different from now, but it was a whole lot cheaper then. He makes sure to write down on the calendar when the Hunters Extravaganza will be for the month of August, and reminds me when the Extravaganzas end, we’ll have three more months until hunting season.

My father has a good, close, longtime friend, Manuel Garza. Growing up as a kid I had some great hunting experiences with my father and Manuel. Now that I’m 40 years old, I’ve now become the hunting guide for Robert.

The way my son’s whitetail hunt started was by helping Manuel on his low fence cattle ranch, located in Starr County, deep in South Texas. I help tend the cattle, do welding repairs, anything and everything, to keep the ranch in order. Manuel told me one day while I was at the ranch, “I have seen some good-looking bucks when I come to check on the cows. There’s one in particular that I think would be a great first buck for your son. It’s a good looking eight-pointer—he looks wide and has chocolate brown antlers.”

Afterwards, the 2023 hunting season was in full swing. We arranged a date to hunt, but had no luck spotting the eightpoint buck. I then told Robert, “We’re going to have to come

back and stay a few more days to hunt a little harder for this buck.” Robert agreed.

During Christmas break, Manuel called and told me, “I was out on the ranch yesterday evening and I saw a 10-point buck—heavy in mass and has good spread with tall tines. You need to get on him soon.” I then prepared to gather my things to make the trip to the Garza ranch to hunt this bigger buck.

We arrived at the ranch late in the evening to prepare for the morning hunt. About 5:15 we were in the deer blind and we let things quite down and settle. As morning light started to make its way in the sky, we saw a six-point buck that quickly appeared, only to head back in the brush. Soon after, I then hit my rattling horns to see if we could get any activity going.

I then saw something move to my left that came quickly to a halt. It was only a curious coyote that heard the crash of

my rattling horns. By then it was about 8 a.m., and the wind seemed to pick up from all directions. As Robert and I patiently glassed with our binoculars, carefully looking at every detail, Robert said, “Dad, maybe someone else shot him.” I then told him, “We need to give it some time. Be patient.”

I rattled once more, crashing the horns a little harder, hoping the wind would be in our favor. And about 15 minutes later, I saw something catch my eye to my left, and with great surprise, it was the buck Manuel had seen the evening before. I took the time to look at him for a bit and then slowly reached over

and tapped Robert. I said, “Look to my left. Try not to get too excited.”

I looked at Robert’s reaction and saw his eyes had grown big. I then told him, “Reach for your rifle while I open the widow to the blind.” As I opened the window, Robert then placed the rifle on the ledge.

I asked him, “Can you see him clearly?” He then said, “Yes

Dad, but he won’t stop walking.” I let the buck take a few more steps, then I grunted. The buck stopped to look, standing broadside. Robert quickly delivered the shot at about 80 yards and dropped the buck in his tracks.

Robert could not believe what had just happened. I turned to congratulate him, and he gave me a great hug and told me, “Dad, I’ll never forget this day.” I then told him, “Neither will I, little man.”

We then made our way to the buck and soon after, took a few pictures of Robert with the buck. By then it was about 10 a.m., so we loaded the buck in the truck and made our way back to San Antonio. I then asked Robert what he would like to do with the meat. He quickly said, “Dad, let’s get some beef jerky made.” “Sounds good,” I said.

We went to our favorite meat market to get the meat processed. I then explained to Robert, “This is all part of taking a deer, but now that you shot your first buck, I think it would be best to mount it.” So right after we left the meat market, we made one more stop at the taxidermist to start the mounting process. What an exciting day it was for Robert and me.

I want to thank my dad for getting me hunting at a very early age. And now, I get to pass it on to my son. But most of all I want to thank my great friend Manuel for making this father and son hunt a memorable hunting experience for years to come.

By Noah Lavender

What is a Texas Brigades summer camp? It’s a special five-day experience for youth ages 13-17 or incoming high school seniors. Camps focus on team building, leadership, conservation, wildlife principles, and having a fun week. I want to tell you all about my experience with this amazing summer camp.

I’ve only attended one camp so far, the North Texas Buckskin Brigade, but I know for sure I’ll be going back this summer. When I arrived at camp, I wasn’t a person that loved public speaking. Or talking to people. Or really anything that included talking to a random stranger. But within two days, I had talked to almost every single person there, made new friends, and had a blast!

When I first arrived, I went straight to the main classroom to take my hunter’s education test. We watched a video called

“Shoot or Don’t Shoot,” which makes you decide if you can shoot an animal or not. You have to base your decision off these three questions: Is it safe? Is it legal? Is it ethical? We would decide the answers to these three questions and then give an explanation for each answer.

After a bit of time passed, everyone else arrived at camp. We played a short icebreaker game to get to know each other a little better, then we all picked out our group (herd) names. We named our group the “Muy Grandes.” Later that afternoon, we all hopped on a bus and headed towards the barn to observe a deer necropsy. We all pulled out our notebooks and pens to start taking notes, which would come in handy the next day.

The next day, we woke up at about 5:30 a.m. and quickly cleaned our rooms before heading out for the day’s activities. Every day, members from our instructor team would come into our room for an inspection to ensure we kept things clean and tidy at the facility. Then later in the day, they would announce the winners. Depending on which placing your herd gets, you can receive anywhere from 2-10 points. These points would come in handy later when determining the Top Herd award.

We did our first trivia session this day about all the things

we had learned so far. For this first trivia, we were allowed to use our notes, but this luxury would be taken away. We did more trivia later in the day, worked on our designs for a large poster, then went to bed. This concluded a busy second day.

On day 3, we woke up even earlier and headed towards the pond. During sunrise, we wrote in our camp journals about camp and the scenery around us. After that, we went to some of the coolest activities of camp, the drop net demo, the rocket net demo, and a controlled burn demo.

The drop net is a net set up on four large poles with another one in the middle, supporting the net. The net was attached to a wire, which was attached to a pedal that sets off the rest of the trap. Once triggered, the net would drop down and capture whatever animal is below it. This net is more so intended for deer, moose, and other tall animals.

At the pond, campers wrote in their camp journals about camp and the scenery around them.

The rocket net, my personal favorite, is a net attached to some explosives in smaller pools on the ground. Like the other net, the rockets were attached to a wire, leading to a foot pedal. Once triggered, the rockets and net would fly through the air, capturing any animal below it. This net is used for rabbits, raccoons, and other smaller animals.

The controlled burn demo was very neat. The instructor used a thing called a drip torch, which drops fuel that ignites vegetation. After that, we got to go play some games to cool us off. We also practiced our marching, which is a big part of Texas Brigades summer camps. That was the end of a long third day.

On day 4, we went to the shooting range. We learned how to safely operate rifles and archery equipment. This was my first experience ever handling a firearm, and I enjoyed the opportunity very much. We also practiced marching some more and learned how to score deer antlers.

Then, of course, we learned about more plants. That night, it was time for the most extreme thing we had done at camp: poster night. This is the night where you stay up late completing your poster display and wake up at 5 a.m. the next morning. Although you have to push through it, it’s definitely one of my favorite times at camp. I love designing and writing, so this was practically heaven for me, no matter how long I had to stay awake.

On the last day, it was the time to use all of the knowledge and skills we gained from camp. We had competitions, antler scoring, labeling the parts of a deer jaw, shooting competition, trivia, marching, and so much more! It was eventually time for graduation. I won the Top Journal award, and I got a cool, leather-cover notebook as a prize. Our parents came to pick us up, and I slept the whole ride home.

Now, I’m doing things to earn points and get to go back to camp as an assistant herd leader, which means I’ll get to help with the camp. I’ve hung up flyers, shown off the poster I made on poster night, told people about Texas Brigades, and so much more. I can’t wait to go back to camp next year, and I hope I’m able to inspire others to join me.

Texas Brigades offers nine camps across the state. Applications are available Nov. 1. Visit texasbrigades.org for more information.

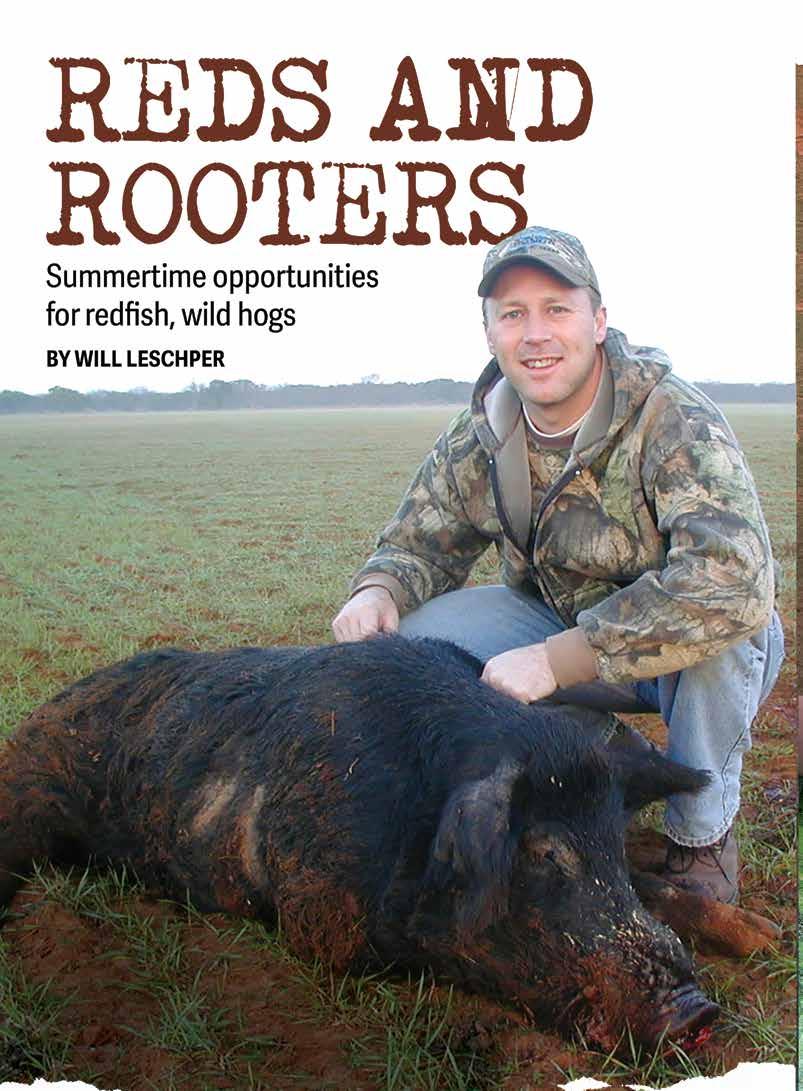

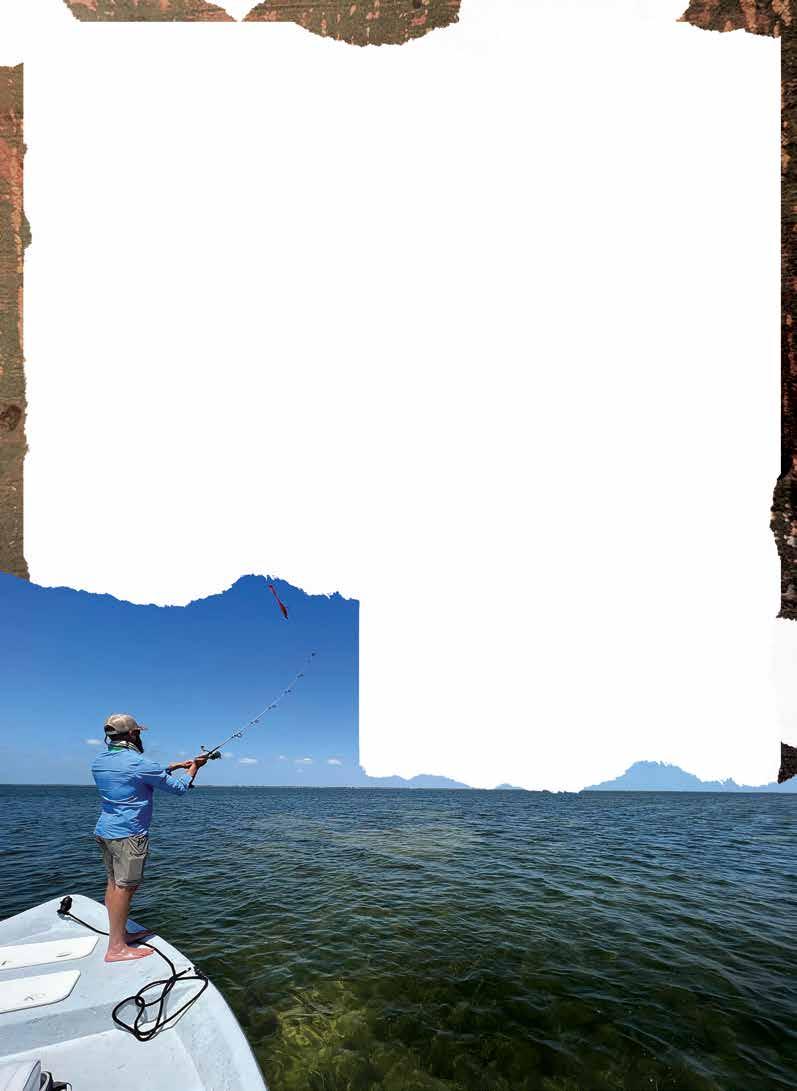

Summer fishing during the middle of the day isn’t just tough—it’s downright dangerous. It doesn’t take much to overheat and take all the fun right out of the pastime. However, if you’re looking to find the magic hour, any success you have clearly will be both audible and visible.

Concentrating early and late during the dog days of summer near the surface by throwing topwater lures often will provide amazing angling action in almost any body of water for species ranging from largemouths and smallmouths to stripers, redfish and speckled trout. Regardless of whether you’re angling on one of the biggest lakes or bays in the state or on a small family stock tank, the opportunities to see a big fish bust the surface while snatching your bait are better than average during the cooler parts of the day, which may mean it’s only 80

By Will Leschper

degrees instead of 100.

When most anglers think of topwater baits, they often have visions of time-tested thick plugs such as the Pop-R or Zara Spook spitting or chugging along, but lure companies today offer no shortage of imitations designed to attract fish to the surface, and with some variations, you can tailor an offering to changing water conditions in almost no time.

Working topwater lures into or near vegetation or other standing objects can be tricky, but many of these lures can be adapted to cut down on problematic hookups. With at least two or even three treble hooks on what typically are hefty lures, it certainly can be easy to snag anything from vegetation and clothing to a fish’s gills or eyes, which could contribute to mortality.

You don’t typically think about snags on open saltwater flats when you’re casting to redfish and trout, but if you’re using treble hooks, you’ll almost always find an accumulation of grass when you bring back a topwater, even if you can’t see any floating near the surface.

To cut down on snags, consider replacing treble hooks with single hooks. Many pro anglers fish topwaters with a treble in front and a single hook in back, which makes a lot of sense, especially if they’re probing thick vegetation or cover, or even if they’re trying to cut down on light grass. If it’s really a problem, consider using a pair of single hooks or even just a single barb.

Other topwater lures that allow anglers to alter their fishing presentations are buzz baits and spinner baits, which most often come with interchangeable blades that can

be switched out in a pinch to match conditions. Saltwater spinner baits have gained in popularity in a number of notable skinny water hot spots, and they’re designed to be rustproof, which certainly is a useful concept.

Boat docks and pilings are some of the best places to drag a topwater bait even during the hottest parts of the day, and since you don’t necessarily have to hit fish on the head for them to strike, you don’t usually have to be a top-flight flipper or pitcher. Other freshwater hot spots to think about are areas such as riprap, rocky points and standing timber, where fish tend to congregate before moving deeper as temperatures rise.

One approach to frog fishing or chunking a weedless lure is to bounce it off objects in the water. The theory is the added sound mimics a critter trying to get out of an area in a hurry and the fish will home in and strike simply out of reaction. Another theory on topwater fishing is it’s best during cloudy, overcast days or in low-light conditions, which negate a fish’s ability to get a clear look at a lure that’s making a lot of noise but may not fit the preferred shape of a usual meal.

While that’s a keen observation in many circumstances, it’s not rooted in fact. I’ve observed redfish suntanning—with their backs out of the water—strike a variety of lures on crystal clear flats without a hint of cover in the sky. In

those situations, it’s obvious that if the fish are even somewhat hungry and you don’t spook them, you’ve got a number of options to get them to strike.

Topwater fishing is amazing when the fish are willing to rise, and even a small bass or redfish can produce a booming strike. While their aim usually is true, they often miss their mark. The faster you hum a lure across the surface, the less likely a fish is to suck it down, so it’s good to slow down and vary your retrieves. Some fish will go a long way to track down a fastmoving lure while others won’t even give a slow-moving bait a second look.

Many times you’ll actually see a fish hit before you feel its weight, so you often must wait before ripping in the opposite direction. That especially is true in shallow water situations when you actually see a fish target, chase and slam your offering.

In the case a fish blows up on a lure but doesn’t take it, pitch it right back where the boil occurred, unless you can still see your target. Most bass pros often keep multiple rods at the ready when topwater fishing equipped with a flipping lure such as a Texas-rigged lizard or crawdad pattern for follow-up shots.

Though most anglers use a bait-casting setup for topwater fishing, it’s as easy to work many baits with a spinning outfit. For many topwater situations, the preferred rod is a heavy, fast-action stick equipped with a high-speed reel, which is good if you’re attempting to quickly horse a fish out of thick cover. However, you can fish most topwater baits with a medium, moderate-action rod and do just as well.

I’ve seen fish of all sizes thump lures of all sizes. Among the most exciting was a day lousy with white bass on Lake Texoma, when schools of 2-pound fish were exploding out of the water to hit 10-inch plugs rigged up more for stripers. Days like that are impossible to forget.

With a little effort, even the hottest days will turn out to be downright cool!

By Horace Gore

Iserved in the 86th Ordnance Battalion at Fort Hood in 1956 when Winchester introduced the .243 in their Model 70 bolt rifle. The .308 Winchester had been out since 1954—a sporting cartridge emerging from the military 7.62 NATO cartridge. Winchester technicians got smart, and necked down the .308 to .24 caliber, hence the .243 that hit the market like a whirlwind. The mild recoil and fast 100-grain bullet made the .243 a success as a deer and pronghorn rifle.

I used the .243 more on pronghorn antelope than whitetails, but my daughter, Donna, used a Winchester Model 70 in .243 to take a half dozen big bucks—all one-shot kills. We both found the 100-grain bullet was best for deer and hogs, while the 85-grain handload was excellent on pronghorns.

In the Southwest, the .243 was advertised as a “do-it-all” caliber for coyotes, whitetails, mule deer, and pronghorns. Hunters could use the factory 80-grain bullet on varmints, and the 100-grain on bigger game—a winner all-around. The pundits advertised the new cartridge as the best thing since sliced bread. The fast little bullet was praised for its killing power, while being light on recoil and muzzle blast. But for some, the cartridge came before its time.

In the ’50s, the popular deer rifles were .30-06, .300 Savage, .257 Roberts, .270 Winchester, and .30-30 carbine. When the Winchester .308 and .243 arrived, they were immediately accepted by hunters, and soon the two rifles were showing up in deer camps. The .243 was praised as a “Super Deer Rifle” by all, except South Texas deer hunters.

The .243 was not accepted in South Texas because deer hunters thought it was too small for the big brush country bucks. Hunters below I-10 stayed with their .30-06 and .270,

and referred to the .243 as a “popgun.” However, recoil-shy hunters such as wives, girlfriends, and kids, along with coyote hunters, bought the .243, and South Texas gradually took to the 100-grain cartridge for deer.

Then in 1962, the 7mm Magnum in the new Remington Model 700 rifle appeared, and the Magnum craze took over. The new .264 Win. Mag. and 7mm Rem. Mag. became the rage, and the little .243 was hardly ever seen on a South Texas deer hunt.

The .243 continued to be popular in the Hill Country and other deer hunting circles, as more females and youths took up deer hunting, and didn’t like the teeth-chattering Magnums, or even the .30-06 or .270. As a rule, hunters who shot a .243 at deer, pronghorn antelope, or even a coyote, soon pushed the .30-06, .270 or .300 Magnum toward the back, and kept the .243 up front.

By the turn of the century, the Magnum craze ended, and hunters began looking for milder deer and antelope cartridges in shorter barrels. The .243 gained renewed popularity in 22-inch barrels, along with new cartridges such as the 7mm08 and the 6.5 Creedmoor. Hunters in deer blinds discovered milder cartridges were very effective on deer and other medium-sized game, and that bullet placement was more important than a big bullet at high velocity.

Today, a good cadre of deer hunters tote a .243, which has gained popularity because of better factory ammo. Good rifles, good scopes, and good bullets have put the .243 in the top 10 deer rifles in the nation. It’s a deer cartridge that has been vindicated as one of the best mild “game-getters” for Texas whitetails. You won’t go wrong with a good .243.

Brandon with his solo, do-it-yourself pronghorn from a tough hunt in New Mexico in August 2023.

The afternoon sun sat on my shoulders like an anvil. The air was dusty and too hot. The temperature was 110 degrees. New Mexico’s badlands are prickly in the summer months, but that’s where you find some of the world’s biggest pronghorns. Because I’m a pronghorn fanatic, I make the trip to the desert almost every summer.

It was two weeks until opening day, but I wanted boots on the ground to see what quality of bucks or lack thereof were available this year. I’d just spotted a bachelor herd of five bucks a quarter mile away from my truck window. Squinting into the spotting scope eyepiece, sand and grit in my teeth, I could tell one of the bucks was bigger in body size than the others. When he lifted his head, I noticed his handsome, coal black face markings and heavy, short horns. After three hours of bouncing around the rocky two-track roads on this middle-of-nowhere ranch, I finally found a quality buck.

From my scouting time, I could verify herd numbers were half of what they were just two years earlier. Rumor was the rancher allowed heavy hunting by a local outfitter the two seasons since I’d been on the ranch. The month before, talking to the rancher on the phone, I was hesitant to pay the hefty trespass fee without seeing the land in person, but with no luck in the public land draw, this was my only option in 2023. I was promised I’d be the only bowhunter on the ranch in archery season, but more hunters would follow in rifle season. As predicted, numbers were disappointing and the few bucks I did see were young. With several thousand acres to hunt, I now had only one buck I felt was worth my tag. Scouting revealed the truth.

So why scout? First, pronghorn populations fluctuate with environmental factors like drought or changes in ranching practices, like brush removal, increased hunting pressure or

rotation of cattle grazing. An area that may have lots of antelope one year may have only a few animals the next. Find out early before you waste limited hunting days. Pronghorns are more visible than deer or elk. They inhabit mostly open, rolling terrain and they’re active all day. With good optics, it’s possible to glass most of the bucks in a specific area over the course of a couple of attempts. For me, my goal is to find out what a realistic, top-end buck looks like for that area and that year. Once I’ve scouted an area thoroughly, I feel like I can confidently decide what size buck to hold out for. If my goal is an 80-inch buck, but the biggest I’ve seen while scouting is a 70-incher, it’s time for a reality check.

Obviously, it’s not always possible to scout a week or two before opening day if your hunt area is far from home. If distance makes early scouting impossible, I suggest getting there one or two days before opening day. Basic gear like 10X40 binoculars, a spotting scope with a window mount, and several trail cameras will help locate bucks.

Learning boundaries is important. Whether you’re hunting a private ranch or public land, spend time getting to know the boundaries. Old school paper maps will work, or you can use a modern phone app like OnX maps. The app will show boundaries for public land, private land, and even the landowner’s name for each parcel of land. Besides learning fence lines, focus on the terrain. Especially for bowhunters, terrain with some rolling hills or pockets of brush or cactus will be better suited for stalking than featureless terrain. Finally, make notes of windmills and waterholes. Just because a waterhole is marked on the map, that doesn’t always mean it will be holding water. Inspect the mud around waterholes for heart-shaped antelope tracks. Trail cameras set near windmills or dirt ponds can show what time of day bucks quench their thirst. In my experience, midday from 10 a.m. to 2 p.m., or the last two hours before dark are when most pronghorns go to water. However, I’ve had

bucks water at every hour of the day, so when I guard water I sit all day.

On my 2023 New Mexico hunt, I traveled to the ranch two weeks before the archery opener. I’d hunted the ranch before, but wanted to see first-hand what conditions were like in the drought. I also wanted to set blinds and trail cameras. I spent the afternoon mostly driving and glassing. I set blinds and five trail cameras at three different water tanks.

The day before the opener, I drove back to New Mexico. Cattle destroyed one blind and knocked over two of my five cameras. I had a spare blind in my truck and repositioned bumped cameras. Cameras at the two windmills where I’d seen the most antelope on my first scouting trip confirmed the big buck I’d spied in late July was indeed watering at both locations. The two water tanks were roughly 1½ miles apart, but both were in the same large pasture. I found no puddles or seeps anywhere else in the pasture. There seemed to be no pattern to which water tank my target buck would visit, but four of the previous seven days he was on camera at one of the two waterholes. Mostly, I had hundreds of pictures of black cows. Despite driving and glassing diligently the afternoon before opening day, I did not see my target buck.

Opening day, I had a decision to make: which of the two waterholes to sit? I decided to sit at the north water tank because that was where I’d laid eyes on the buck while scouting. His most recent trip to water was at that blind.

As the sun chinned itself over the eastern horizon, I sat ready in my popup blind. A cooler full of drinks and snacks sat by my feet. My backpack contained two books, magazines, a notepad, pen, camera and my phone with a solar charger.

I sat in that blind for 14 hours. The high temperature was 95 degrees. One average-sized buck with both horn tips broken came to water at 6:30 p.m. I snapped his picture with my camera as he slurped water for two minutes nonstop.

A large covey of 40 blue quail came to water at sunset. By dark, I was weary, dehydrated, and a bit delirious after the all-day sit. In the dark, on the way to town, I stopped by the middle water tank to check my trail camera.

There, on the screen at 8:44 that morning, was ol’ short-and-heavy horns with the other four small bucks he traveled with. I would have another tough decision for day two: which blind to sit? After a burrito for supper at the gas station, I fell asleep in my hotel room with my boots on.

On day two, I decided to sit at the middle water tank since all five bucks had been there the day before. A long 13 hours passed under the beating sun. The high temperature was 93. A herd of black cows visited the water two different times, but other than a few pronghorn silhouettes far off in the distant heat waves, no pronghorns came to water.

With maybe one hour of shooting light remaining, and no pronghorns visible from my blind, I made the tough decision to

bail. Even though the last hour is often the best hour at water, I felt like I should have at least been able to see my target buck on the horizon if he planned to drink before dark. Visibility was a mile in every direction. I grabbed my bow and backpack and trotted north towards the other waterhole, stopping occasionally to glass. Maybe I could find my target buck and execute a stalk before daylight ended.

I covered the 1½-mile distance across sandy, cactus-covered terrain quickly. I saw no pronghorns along the route. When I eased over the rocky ridge, binoculars to my eyes, I could see down into the long ravine where the north windmill tank sits: the blind where I’d spent opening day. There in that small valley, only 100 yards from the water, I spied the herd of five bucks. They had just quenched their thirst and were now headed towards the yuccas and rolling hills. They appeared to be headed to a saddle between two brushy hills.

The bucks were 200 yards from my position. Using the roll of the terrain, I duck-walked behind a small hill to cut the distance. Hunkered down behind a waisthigh clump of yuccas—arrow nocked—I

saw black horns bobbing over the hill like antennas. I drew my 61-pound Mathews bow and waited.

First, the four small bucks walked by single file, then the bigger-bodied, older buck with short, heavy horns followed. From 36 yards away, my 409-grain Easton Axis arrow tipped with a Slick Trick broadhead sailed through the mature buck’s chest. Success at last!

My 2023 New Mexico pronghorn had heavy, short horns that

measured 132⁄8 inches long. Most of a pronghorn’s score comes from its mass. He had bases and second mass measurements both over 6 inches. By the beam of my headlamp, I secured my tag, gutted the buck, and used an arrow to prop open the chest cavity to cool.

Exhausted, I walked to my parked truck a mile away where I guzzled cold water, then drove back and loaded my pronghorn. I took down blinds, stopped in town to buy extra ice for the cooler full of meat, and started the long journey home to Texas. Like it usually does, scouting and hard hunting paid off.

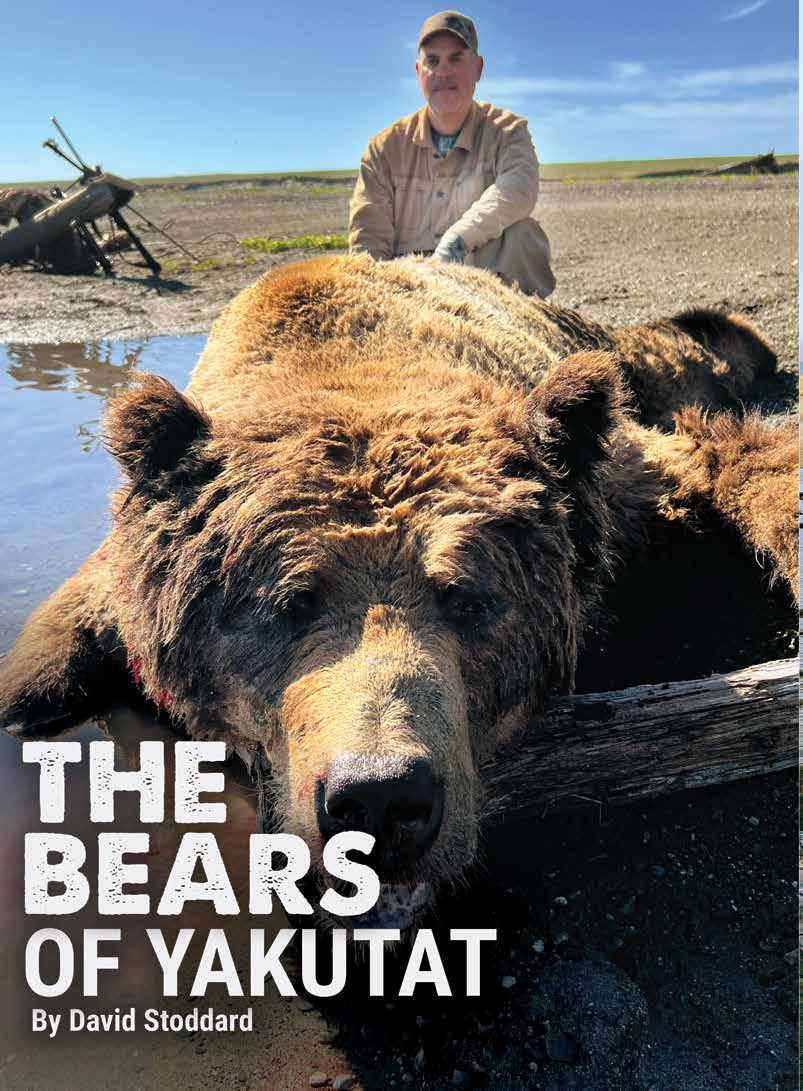

Eric Stanosheck

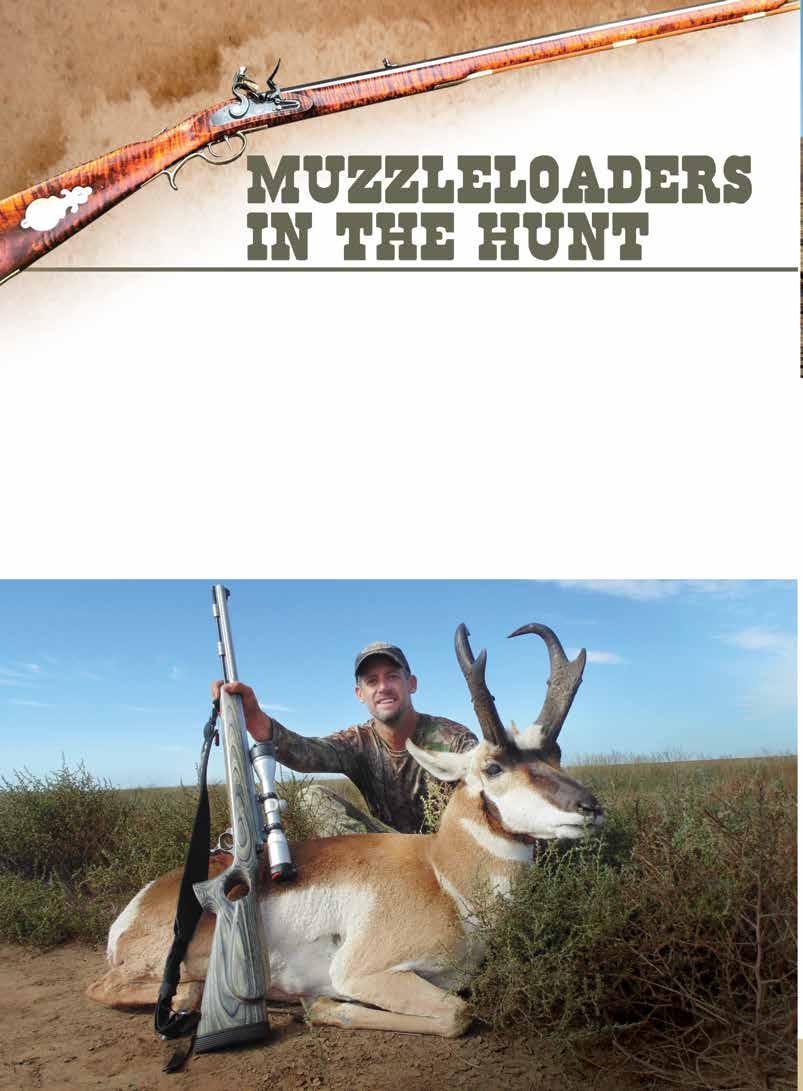

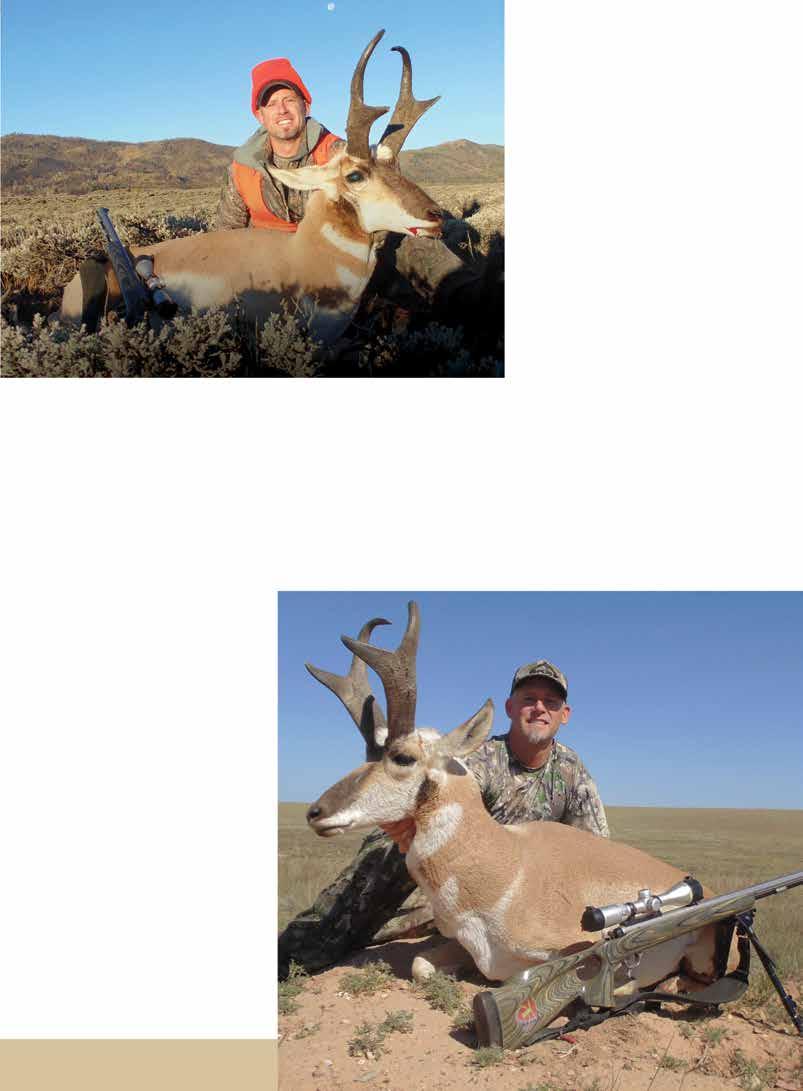

he American pronghorn has always been one of my favorite big game animals to pursue with the muzzleloader each fall. Rare is the day that you don’t see animals while hunting for them, but it’s their 60 mph top speed, amazing eyesight, which is equivalent to high-powered binoculars, and wide-open country they call home that makes them a very worthy opponent in the game they force you to play. Most of us who hunt with muzzleloaders do it for the additional challenge, and what better species to chase than the fastest and most skittish big game animal in North America.

Opportunities abound if you know your way around tag allocations in western states. Many have either landowner tags

for purchase or opportunities to draw tags with only a few accumulated permit points. I’ve taken pronghorns in nine of the 16 states with hunting seasons, but for consistent opportunities each fall, you don’t have to look much further than Texas, New Mexico, Colorado, or Wyoming.

Wyoming is the only one of those states that doesn’t have landowner tag options, which allow you to hunt each year. However, there are more pronghorn in Wyoming than there are people, so finding animals is not too difficult once you get a tag.

I obtained a tag for my last Texas hunt by calling landowners from a list that is released in August. I only had 1,100 acres to hunt and there wasn’t a single pronghorn on it opening day of

season. Fortunately, I had driven all of the roads within 10 miles the prior day and I knew there were plenty of animals around, so I waited for the hunting pressure to push a great buck and his harem onto the property.

I easily took the buck at 125 yards right in the middle of the pasture. Sitting and waiting for hours is not the typical way I like to hunt a pronghorn buck, but it worked to perfection given the limits of my land access. That buck is still the largest Texas buck on my wall.

New Mexico has great potential for monster pronghorns. I have been blessed to take three Boone and Crockett bucks in that state with my muzzleloader. All were in completely different units of the state in back-toback years, using landowner permission and over the counter tags bought at the local Walmart. I usually use guide/outfitter information and connections, because they generally have access to the best land and know the available bucks. However, just driving around to ranches and knocking on doors has worked many years for me as well.

My buddy Aaron Bauer with Spot & Stalk Outfitters always steers me the right way in New Mexico when I want a high-quality hunt. Pronghorn seasons are only three days long, so it’s never a problem to squeeze a hunt on the calendar.

My New Mexico bucks have all been spot-and-stalk and involved

many hours both in the crawling and stalking as well as removing cactus stickers from my knees and hands. Pronghorn have tremendous eyesight and New Mexico generally has limited terrain to use in your favor when shooting a limited distance weapon. This requires many blown stalks, and changing to new plans.

I recently crawled within 80 yards of a bedded buck in nothing more than six-inch-tall grama grass and made a great shot off my bipod. The buck has the big-

gest prongs I’ve ever seen at just under 7 inches. You will sometimes question your sanity when you come face to face with a prairie rattlesnake as you are slithering across the prairie in pursuit of a big pronghorn buck.

Colorado has landowner tags available in many units and it only takes a bit of dedicated research to put a tag in your pocket each season. I’ve hunted quite a number of units in the state, but I prefer the higher elevation hunts.

My best buck was a border-hopper and actually was one I became very familiar with in mid-summer on a scouting trip. Not only was this buck a no-brainer for Boone and Crockett, he was actually very predictable in his route, marking territory on both sides of the Wyoming/Colorado line. After establishing his home turf in July, I returned in October and shot him at less than 100 yards on opening morning, exactly where I had seen him every day back in July.

Opportunities abound if you’re interested in chasing the prairie speedsters called American pronghorns. So, get out there and burn some powder while enjoying an early fall hunt and get the kids into the challenge and enjoyment of black powder hunting. Pronghorns are a challenge you’ll embrace, especially when you have the limitations of a muzzleloader.

PRODUCTS AND VENDORS AT THE

Make sure you stop by the TTHA Merchandise Booth at any of the Hunters Extravaganzas to pick up the latest gear. We have something for the little ones and all the way up to the seasoned hunter. Don’t forget we offer members a discount on TTHA gear. Not a TTHA member? Join today! See details on page 44.

The Corn Feeder is a high-quality, affordable corn feeder featuring the licensed MB Ranch King Blinds feeder assembly housing. It’s available in a 500-pound capacity (based on corn weight) made with galvanized metal (hopper: 14-gauge, funnel: 14 gauge, sides: 20-gauge, and lid: 18 gauge). The assembly housing features THE-ELIMINATOR spinner plate that keeps all the corn from being exposed before distribution, which makes it hog and ’coon proof. It spreads the corn evenly up to 25 feet, keeping it away from the feeder. It comes completely assembled with the PLAN-B timer, 12-volt battery, and solar panel. It has a 50-inch fill height, making it easy to fill from the ground. Visit bosshawgmfg.com.

bosshawgmfg.com

mavenbuilt.com

Maven’s S.3 20-40X67mm spotting scope provides a high-powered solution across a wide range of magnification levels with a smaller objective lens. Choose between the variable magnification zoom eyepiece for field use or a fixed reticle eyepiece to aid in target and competitive shooting scenarios. It incorporates fluorite glass, and ensures razorsharp clarity from edge to edge; exceptional performance in low light conditions; and delivers vivid, distortion-free, and brilliantly bright images. TTHA Member Discount Offered. Visit mavenbuilt.com.

Domain’s Bad Habit Attractant is specifically formulated to attract deer and provide an enhanced nutritional profile through key ingredients, such as protein, fat (energy), vitamins and minerals. Enhanced with berry infused flavor and aroma, this powerful attractant will attract deer from longer distances and help increase consumption as a means of optimizing nutrient availability. Bad Habit can be fed on its own or mixed with corn or feed, and can help provide the nutritional foundation for your deer management program. Sold in 20-pound, 7-pound, and 3-pound bags.

TTHA Member Discount Offered. Visit domainoutdoor.com/ collections/feed.

domainoutdoor.com/collections/feed

The Reveal Pro 30 has no glow flash; built-in GPS; new internal storage with optional SD slot; new on-demand video requests; new improved image sensor; new cellular firmware updates; new pre-installed antenna; new internal SIM card; new multi shot: 5 photos; new live aiming in app; 1080p FHD video; faster photo sends; and improved battery life. Visit tactacam.com/cameras.