veryone in Texas is tied up with football, while the ones who aren’t watching or attend a football game are deer or duck hunting. Texans must make choices between all the sports they love so well. The Texas Longhorns will play the Texas A&M Aggies on Nov. 28, so all bets are off for anything but football on that day.

This letter is the last one for the 50th anniversary year, and TTHA has had an exciting year with President and CEO Christina Pittman announcing the new Texas Trophy Hunters Foundation. TTHA also celebrated the 50th year with a new book for the occasion, “Stringtown to the Kokernot,” an autobiography by Yours Truly. The 304-page hardback refers to my early years in Arkansas and East Texas, 33 years with Texas Parks and Wildlife, and my 30 years with TTHA. Christina has a letter in it, addressed to all Texas Trophy Hunter members, celebrating our 50th Anniversary.

We threw a bash in San Antonio during the Hunters Extravaganza on Aug. 16, where Platinum Life Members, other members, and guests enjoyed a banquet of food and frolic. We gave awards to deserving personalities, and Christina thanked everyone who made the first 50 years of Texas Trophy Hunters a resounding success. Christmas is coming, so don’t forget to hang your stocking and put a special TTHA ornament on the tree. Dec. 25 is always a wonderful holiday, and I can remember many hunts on Christmas—quail, deer, ducks—that were all special hunts for the holiday.

Clement Clark Moore’s poem, “A Visit from St. Nicholas,” now known as “The Night Before Christmas,” began: “Twas the night before Christmas when all through the house, not a creature was stirring—not even a mouse. The stockings were hung by the chimney with care, in hopes that St. Nicholas would soon be there.” Old St. Nick was known for his generosity with children, and Santa Claus came from the 4th century saint at Christmas time. Santa Claus is Dutch for St. Nicholas.

Dr. Deer tells me buck quality in the nation’s deer herds is fading, but one of the states that’s holding deer quality is Texas. There are reasons for that, and private property is a big factor. See Dr. Deer’s Prescription on page 18.

The sport of hunting is having a hard time competing with all the other outdoor and indoor activities pulling on the interests of Americans. About 11.4 million deer hunters are helping to keep hunting alive, and Texas is still the No. 1 whitetail hunting state in the nation.

A lot of Texans are out hunting during these last two winter months of the year for deer, ducks, squirrels, and of course, hogs. Texas has a generous supply of rooters, and the hunter who wants some pork can usually find a wild pig. We call the feral hogs bad names, but when the chips are down, a hog hunt is a good way to salve your need for outdoor recreation and some good eating. Tally ho, the hog!

Let’s all enjoy the seasons, both Christmas and hunting. The last days of TTHA’s first 50 years will end soon, and we will begin the next 50 years of being “The Voice of Texas Hunting.”

Keep ’em running, swimming, and flying, and I’ll see you down the road.

Horace Gore, Editor

North

East Texas Field Editor

Graphic Designers Faith Peña

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

Sophia Berry, John Goodspeed, Riley Hornback, Judy Jurek, Fredrick Koehler, Dannielle Pope, Steve Southards, Eric Stanosheck

Advertising Production

Debbie Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Sales Representative

Tristan Summy 210-685-1205 tristan@ttha.com

Marketing Manager Logan Hall 210-910-6344 logan@ttha.com

Finance & Administration Manager

Laura Garcia

210-512-4927 laura@ttha.com

Events Manager

Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

Events Assistant Manager Natasha Delgado 210-512-8045 natasha@ttha.com

Membership Manager Valkyrie Myklebust 210-767-9759 valkyrie@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

TTHA staff spent the July 11 weekend contributing to flood relief for our fellow Hill Country neighbors. We delivered meat to Casey May, who cooked meals for those in need and for volunteers. We made multiple supply drops at Comfort High School, Center Point, and for Intrepid Care, which set up base camp in the Saddle Wood neighborhood for recovery opera-

Valkyrie Myklebust, our new Membership Manager, is a native Texan, calls Spring Branch her home, and is a graduate of Tarleton State University. If you need her help with any aspect of your TTHA membership, please call her at 210-767-9759, or email valkyrie@ttha.com.

tions along the Guadalupe River. With Intrepid Care, the TTHA and SCI San Antonio teams delivered and organized supplies and helped create “go buckets” for volunteers in the field to help with search and recovery efforts. It warmed our hearts to see people from all walks of life band together to help people overcome this tragedy.

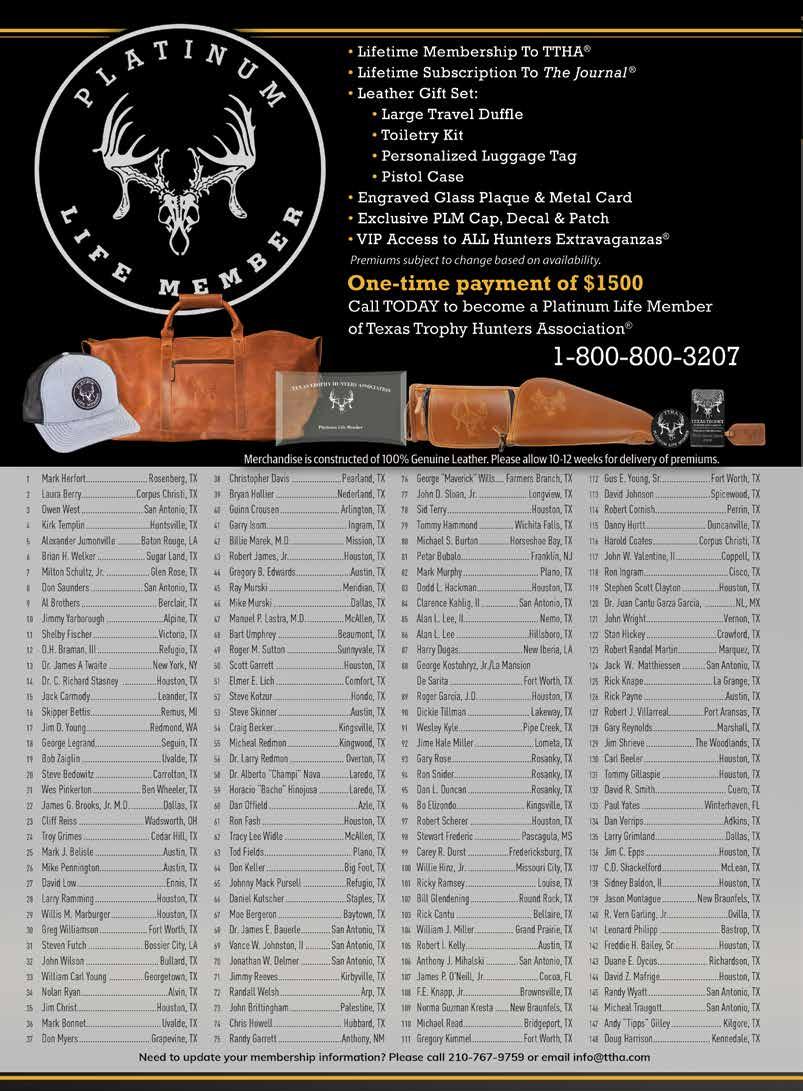

At our 50th Anniversary Banquet in San Antonio in mid-August, we bestowed honors upon a select handful of individuals who’ve supported the organization through thick and thin. Marty Berry received recognition for Artistic Contribution to The Journal, via his deer photography. Dr. Deer, James Kroll, received recognition as TTHA Educator & Advocate. Mark Herfort received recognition as Original TTHA Platinum Life Member No. 1. We thank these gentlemen for their unwavering support and their exemplary contributions that have enriched TTHA.

By Jake Legg

Ihad a hunting buddy in the old days—Harry Moss. We hunted deer every season, and both of us had taken our share of good bucks. One year, just before the opening of deer season, Harry came by, and we started talking about deer hunting. We pulled the cork, and Harry got to bragging about the

biggest bucks he had killed. “I feel plumb ashamed of all my big bucks,” he said with some concern. “I need to reform, and let you kill a big buck.”

Harry was a good deer hunter. His favorite rifle was a Winchester Model 70 in .257 Roberts, and he could put three in the paper no bigger than a quarter. I

saw him kill several bucks and they all dropped like a rock. My Remington 721 was a good shooting .270, but nothing to compare to his .257.

We sat around for an hour, talking about deer hunting and the coming season. Suddenly, Harry stood up, tipped his glass, and smiled. “Tell you what,

Hoss. From now on I’m going to shoot only bucks with eight slick points.”

I looked at Harry in disbelief. “Have you lost your mind? Only bucks with eight slick points?” This was not the Harry I knew.

“Yes. I have come to my senses. A buck with eight slick points is as hard to find as any buck, and from now on that’s the buck for me.” Harry put his glass on the table and leaned back. I could tell that he meant business. When Harry made up his mind, it was for good and ever more. I could see he would never kill any buck that didn’t have eight slick points.

The night was getting along, and finally Harry went to his pickup, mumbling something about “eight slick points” as he pulled away toward town. I sat for a while, thinking of what Harry had just said, and I knew Harry. He meant what he said. I knew I would never see him again with any buck that didn’t have eight slick points.

A few days before the deer season started, Harry came by, and we sharpened our knifes and discussed a hunting plan for the first day. There were a lot

of deer on the ranch, and we liked to sit in a big store-bought ground blind and watch for good bucks. That would be our plan for opening day, to hunt from a big ground blind near a corn feeder.

Nov. 16 came on Wednesday, and Harry and I sat in the blind before daylight. “You still stuck on the idea of eight slick points?” I asked as we pushed up the windows and placed a stick to keep them open. I had come out earlier and knocked the two wasp nests in the blind. We didn’t have anything against the wasps. We just wanted them to stay put when we got in the blind. Anyone knows wasps only sting when they’re protecting their nest, and when it’s gone, the wasps don’t attack.

Harry and I got settled in the blind, and I thought of ribbing him a little. “If you’re so sure of nothing but eight slick points, will you swear to that on a paralyzed oath?” Harry turned around in his swivel chair and replied, “If it will clear your mind of my intentions, I will swear.” We faced each other in the dim morning light, Harry raised his right hand, and said, “I swear on a paralyzed oath that I

will kill nothing unless it has eight slick points,” and rolled around to look out the window.

“Are we going to draw straws?” I asked Harry as I took a small flashlight out of my coat. “We always draw straws to see who gets the first shot. What about it?” Harry smiled and reached in his coat pocket and pulled out a small mesquite twig. “I’ve already thought about it.” He pulled off two pieces of the twig, one short and one long. He hid both in his fingers to show both to be the same and pushed them over to me.

“Draw. The short piece gets first shot.” I studied the two ends for a moment and pulled out the long twig. “You get the first shot,” I declared, and we leaned back in our swivel chairs, waiting for the feeder to go off.

The corn feeder was set to go off at 7, and it was right on time. We heard it spin, and I could see the dust float away from the corn in the distance. “Things will pick up, now,” I said.

Harry’s .257 stood in his corner with the bolt up. He liked to keep the bolt up and close it when he got ready to

shoot. As the sun rose, we could see a few does and small bucks mingling around the feeder. I kept thinking of a big non-typical staying in the area, an old buck that had a rack full of long points. I had gotten a glimpse of him just before season and his antlers were huge, but I hadn’t mentioned the buck to Harry.

The early morning fog had cleared a bit, as more deer became visible. The does had moved away from the feeder, as if to be evading some type of danger. Suddenly, a big buck emerged from the brush, and I saw immediately it was the big non-typical with multi-pointed antlers. Harry saw him, too, and reached for his .257 standing in the corner, closing the bolt and checking the safety.

I looked over at Harry and said, “You’re not going to shoot that big buck, are you? You swore on a paralyzed oath to shoot only bucks with eight slick points.” Harry smiled and replied, “You’re right, Hoss. I forgot. You go ahead and shoot him.”

In my mind, I had Harry over a barrel. I had drawn the long stem; he had the first shot at the biggest buck we had ever seen on the ranch; he had sworn to shoot only bucks with eight slick points; and now, he wanted ME to shoot the buck.

“No, No. I’m not going to shoot that buck!” I said with a grin on my face. “It’s

Harry’s Case knife that’s “sharp enough to shave hair off your arm.”

shoot bucks with eight slick points.” Harry waited until the old buck turned so that he could get his favorite shot, where the neck joined the shoulder. I sat in the swivel chair, wondering if Harry would actually shoot the biggest buck we had ever seen on the ranch.

Harry’s finger was on the trigger and the rifle roared—KA-BOOM. The 100-grain Hornady found its mark, as

his knife. He went through our usual ritual by pulling up his left sleeve to spit on his bare arm, rub it with his forefinger, and shave off the hair slick to show that his knife was ready. We stared out the blind window at the biggest buck we had ever seen.

“Let’s go out there and gut my buck. He looks like he has about 25 points, a typical 10 with long tines, and about 15

“I swear on a paralyzed oath that I will kill nothing unless it has eight slick points.”

- Harry Moss

your shot, so go ahead. You have had that ‘eight slick points’ on your brain till I’m sick of it. So, what are you going to do, now, Mr. Moss?” Harry studied the buck again through his binoculars, and slowly put his thumb on the safety. I watched in disbelief, as he pushed the rifle barrel out the window.

“You’re not going back on your oath, are you?” I quickly asked. “You swore on a paralyzed oath that you would only

the old buck fell in his tracks, kicked his back legs a few times, and lay dead.

“I can’t believe it. You went back on your paralyzed oath. You said, ‘no bucks that didn’t have eight slick points.’ How could you do such a thing?” I ragged Harry something terrible.

“Hold on, Hoss.” Harry kicked the empty hull from his rifle. “I believe I have some explaining to do.” He put the .257 back in the corner and pulled out

more long, odd points. I’m sure that we can find ‘eight slick points’ somewhere in his big rack.”

The morning was getting long as I held the buck’s front legs steady while Harry wielded his knife on the pelvis. He had put the shuck on me with the “nothing but eight slick points” and had even offered me the first shot. I had been bushwhacked, but what could I say? The old buck had “eight slick points,” and more.

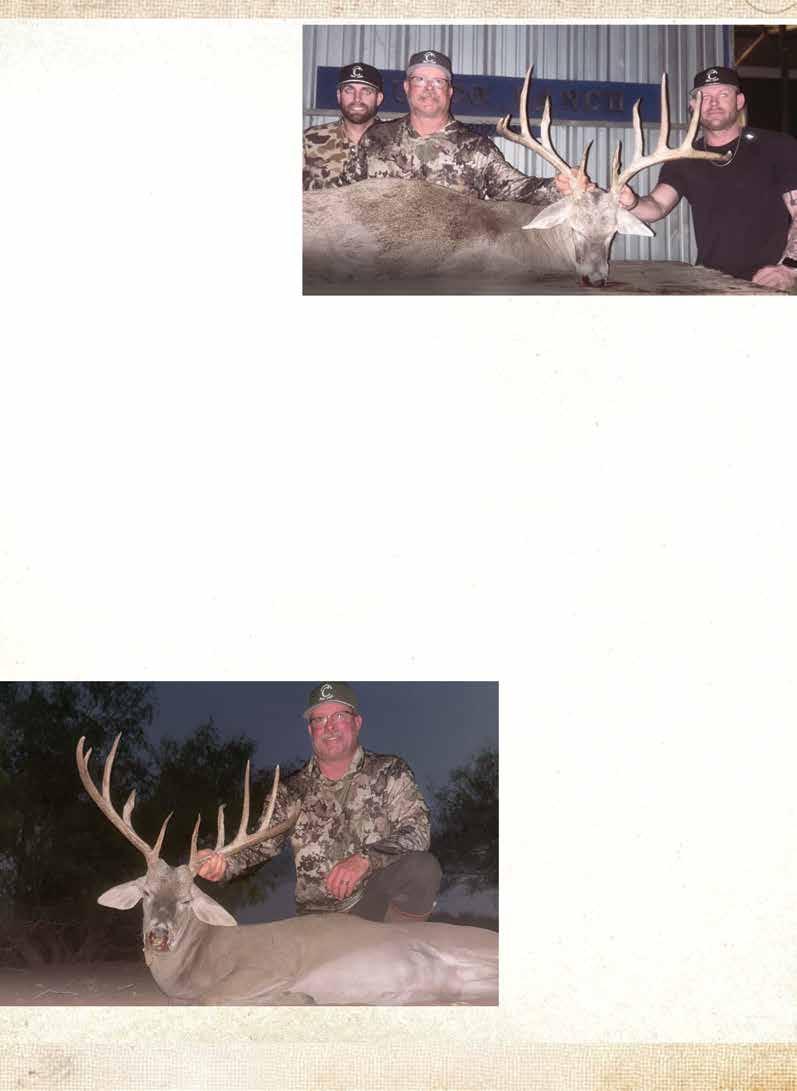

The Muy Grande Deer Contest reached a new milestone this year, celebrating its 60th anniversary awards ceremony. Freer is home to Muy Grande, the state’s oldest deer contest. Originally founded in 1965 by the late Leonel “Muy” Garza, the contest is still going strong and running smoothly thanks to co-owners Kenneth and Imelda Sharber, and the Garza family, with all of the sponsors and hunters who participate every year.

Muy’s No. 1 rule was, “Always take care of the hunters.” The longevity of the contest is proof the Garza family has followed through and taken very good care of the hunters. Of course, in return the hunters have taken good care of them, and everyone involved is considered to be a part of the “Muy Grande family.”

Aside from numerous awards highlighting the harvests of the prior season’s Muy Grande bucks, a handful of special awards are also presented. Among these are the Muy Grande Hall of Fame inductees. Muy started the hall of fame in 2007 to recognize individuals for their contributions to the hunting industry and the deer contest.

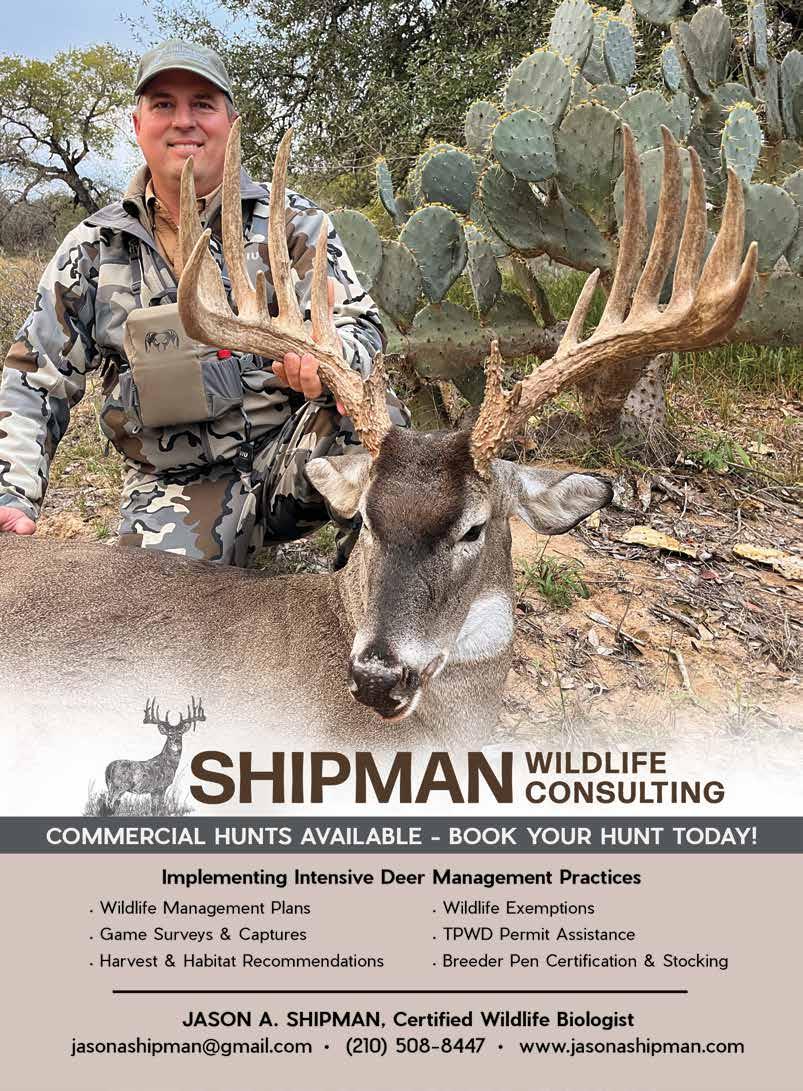

This year’s Muy Grande Hall of Fame inductees include Jason Shipman, John Goodspeed, John Morris Walker, Jr., Robert John Hart, and Edwin Espey Jr. Shipman is a private wildlife biologist and consultant with over 25 years of field experience and the South Texas field editor for The Journal of Texas Trophy Hunters. Goodspeed is a freelance outdoor writer and contributing writer for The Journal of Texas Trophy Hunters. Walker, Jr. is a seventh-generation landowner/rancher

and operates a local ranch brokerage service. Hart is a fourth-generation gunsmith well known for his custom guns and barrels. Espey, Jr. is a local landowner, rancher, and wildlife enthusiast.

A few years ago, Muy Grande established the Muy Grande Lifetime Achievement Award. This year’s recipient was Roy Hindes III. I can’t think of a more deserving person to receive this recognition than “Little Roy.” He operates the family ranch and is known throughout South Texas for his tracking dogs that have found hundreds of wounded deer. Many deer hunters owe him a debt of gratitude for finding their trophy bucks that would have otherwise been lost.

Many familiar faces attended the festivities, including Jerry Johnston, founder of Texas Trophy Hunters; Mark Herfort, TTHA Platinum Life Member No. 1; Elda Garza, Muy’s widow; and the rest of the Garza family. Shane Greenville, Kelly Kenning, and Daniel Adami provided some festive musical entertainment. Congratulations to this year’s inductees and awardees. —Bob Wire

The Texas Game Warden investigation known as “Ghost Deer” has reached a possible conclusion after two additional suspects turned themselves in on felony charges. This brings the total number of individuals implicated in the case to 24, with approximately 1,400 charges filed across 11 Texas counties.

Ken Schlaudt, 64, of San Antonio, the owner of four deer breeding facilities and one release site, along with facility manager Bill Bowers, 55, of San Angelo, surrendered to the Travis County District Attorney’s Office on charges of felony tampering with a governmental record. Both men allegedly entered false information into the Texas Wildlife Information Management System (TWIMS) to facilitate illegal smuggling of white-tailed breeder deer. They also face more than 100 misdemeanor charges related to unlawful breeder deer activities in Tom Green County.

The investigation has uncovered widespread, coordinated deer breeding violations including, but not limited

to smuggling captive breeder deer and free-range whitetail deer between breeder facilities and ranches; chronic wasting disease testing violations; license violations; and misdemeanor and felony drug charges relating to the possession and mishandling of prescribed sedation drugs classified as controlled substances.

Suspects charged in the case include: Evan Bircher, 59, San Antonio; Vernon Carr, 55, Corpus Christi; Jarrod Croaker, 47, Corpus Christi; Terry Edwards, 54, Angleton; Joshua Jurecek, 41, Alice; Justin Leinneweber, 36, Orange Grove; James Mann, 53, Odem; Gage McKinzie, 28, Normanna; Herbert “Tim” McKinzie, 47, Normanna; Eric Olivares, 47, Corpus Christi; Bruce Pipkin, 57, Beaumont; Dustin Reynolds, 38, Robstown; Kevin Soto, 55, Hockley; Jared Utter, 52, Pipe Creek; Reed Vollmering, 32, Orange Grove; Clint West, 56, Beaumont; James Whaley, 49, Sevierville, Tenn.; Ryder Whitstine, 19, Rockport; Ryker Whitstine, 21, Rockport; Claude Wilhelm, 52, Orange.

Cases are pending adjudication in Bandera, Bee, Brazoria, Duval, Edwards, Jim Wells, Live Oak, Montgomery, Tom Green, Travis, and Webb counties. The investigation began in March 2024 when game wardens discovered the first violations during a traffic stop. That incident led wardens to the much larger network of violations, resulting in one of the largest deer smuggling operations in Texas history. —courtesy TPWD

On July 4, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, the comprehensive bill that has been the focus of Congress since the beginning of the 119th Congress in January, was signed into law. While this legislation is a large and all-encompassing, there are a few particular provisions of note that will impact sportsmen and women across the country.

Most important, the Act omitted the mandate to sell-off certain federal public lands across 11 western states, which was an effort strongly opposed by the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation (CSF). While there were a number of

proposals to sell off public lands that were considered throughout the process of developing the Act, CSF strongly opposed the consideration of any public land disposal through this process. As a result of CSF’s efforts, the language to mandate the sale of certain public lands was ultimately removed from the final bill that became law.

The Act included a provision to reduce the $200 National Firearms Act Form4 tax stamp to $0 for the purchase of firearm suppressors and certain types of firearms. Prior to the enactment of the Act, each time an individual purchased a suppressor they needed to pay a onetime $200 tax stamp. Under new law, individuals will no longer have to pay the $200 for the tax stamp each time they purchase a suppressor, but they must still file the requisite paperwork and undergo the attendant background check.

Additionally, several of the Farm Bill’s conservation programs and previous investments made through the Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 are now officially considered to be part of the Farm Bill’s baseline. This means that current funding levels will serve as the base once Congress begins the hard work of writing the next iteration of the Farm Bill. Likewise, the Act’s language for these programs removed many of the climate limitations that, as pointed out by many within the sporting-conservation community, failed to include many key practices that benefit wildlife habitat and mitigate impacts commonly attributed to climate change. This bill also included $105 million to continue the successful Feral Swine Eradication and Control Program and, most important to hunters and anglers, included $70 million for the Voluntary Public Access – Habitat Incentive Program (VPA-HIP) which provides financial incentives for private landowners to voluntarily open their properties to public hunting access in many states.

Further, the Act includes significant forest management provisions to support the long-term sustainability of U.S. Forest Service (USFS) and Bureau of Land Management (BLM) lands by

improving forest resilience to wildfire and other threats through increased timber sales. Specifically, the reconciliation bill directs the USFS to increase the volume of timber sold over the next ten fiscal years by a minimum of 250 million board feet annually more than the prior fiscal year and directs the BLM to increase the volume of timber sold over the same period by a minimum of 20 million board feet annually more than the previous fiscal year. Additionally, the Act aims to provide stability by requiring the USFS to enter a minimum of 40 20-year timber sale contracts and requiring the BLM to enter at least five 20-year timber sale contracts. The mandated and incrementally increasing timber sales align with Executive Order 14225, Immediate Expansion of Timber Production; Secretary’s Memorandum 1078-006, Increasing Timber Production and Designating an Emergency Situation on National Forest System Lands; and the USFS’s new National Active Forest Management Strategy. After two and a half decades of relatively stagnant federal timber sales that resulted in overstocked, unproductive forests for wildlife, the increased timber harvests will improve habitat diversity and increase forest resiliency to support fish and wildlife habitat and access for hunters and anglers. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

Safari Club International proudly congratulates Brian Nesvik on his confirmation as the next Director of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS). His appointment brings a seasoned conservationist, decorated military leader, and proven wildlife manager to one of the most important conservation roles in the federal government.

“Brian Nesvik is a strong and experienced choice to lead the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service,” said W. Laird Hamberlin, CEO of Safari Club International. “His decades of service in wildlife management, coupled with his distinguished leadership as Director of Wyoming Game and Fish and as a Brigadier

General in the Wyoming Army National Guard, reflect a steady hand and a clear vision rooted in science, discipline, and public service. His leadership will be essential in guiding the Service through the complex challenges of modern wildlife management. SCI looks forward to working closely with Director Nesvik to ensure hunters and science-based conservation have a seat at the table.”

Nesvik brings over 38 years of combined experience in natural resource management and military service. He served as director of the Wyoming Game and Fish Department from 2019 to 2024.

—courtesy SCI

The Sportsmen’s Alliance Foundation and its partners, Safari Club International and the Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation, appealed a court judgment vacating the Fish and Wildlife Service’s (FWS) decision declining to relist gray wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountain region to the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The coalition of sportsmen’s groups have filed a notice of appeal and will continue to fight for sound wildlife management. This latest ruling in support of the activists’ petitions would seem to demand that until wolves are recovered across the entirety of the Lower 48, including active, protective, management throughout its historic range, that all wolves everywhere should remain protected under the Endangered Species Act.

Congress declared the wolves in the Northern Rocky Mountain region—Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, eastern Oregon and Washington, and north-central Utah—recovered in 2011. Since then, the wolves have thrived, and expanded into surrounding areas, including northern California, western Washington and Oregon, and Colorado. Several animal-rights organizations asked FWS to combine the recovered Northern Rocky Mountain wolves with wolves in the neighboring western states and list them as an endangered species.

“They asked FWS to use the wolf’s recovery against it,” said Michael Jean, Litigation Counsel for Sportsmen’s Al-

liance Foundation. “They want to push the boundaries of the recovered population to include the areas where it is currently expanding to dilute the overall recovery.”

FWS rejected the petitions from multimillion-dollar activist groups, including Center for Biological Diversity, Western Watersheds Project, WildEarth Guardians, Humane Society of the United States and Sierra Club. The inevitable lawsuits followed, and the Sportsmen’s Alliance intervened in each of them.

District Court Judge Donald Molloy in Montana’s District Court has now ruled against FWS’ denial of those petitions.

“We had to appeal this decision,” Jean continued. “This decision seems to hold that unless a species is not recovered across its entire historical range, then it has to stay listed—regardless of thriving populations. It’s difficult to see how the wolf, or other listed species, will ever be deemed recovered under that standard.”

“SCI is frustrated that the court ignored the reality of successful wolf conservation in the Western U.S. and instead ruled in favor of the plaintiffs’ arguments that are clearly biased against state wildlife management and counter to the law and the science,” said SCI CEO W. Laird Hamberlin. “SCI will appeal this mistaken ruling as soon as possible in order to defend legal, regulated hunting as part of science driven, state wildlife management programs for wolf species.”

“This ruling is the latest string of nonstop litigation by environmental groups seeking to frustrate the original intent of the ESA, which is to recover endangered species and return them to state-based management, not keep them perpetually listed and under the authority of the federal government,” said Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation President and CEO Kyle Weaver. “Whether it’s the wolf or the grizzly bear, once an animal receives ESA protections, it becomes nearly impossible to remove them, even if populations meet recovery criteria over an extended period of time. The ESA needs an adjustment to renew its focus on real species recovery.” —courtesy Sportsmen’s Alliance Foundation, SCI, and Rocky Mountain Elk Foundation

By Dr. James C. Kroll

The author says deer populations are high, but hunters only take about 6 million of the estimated 36 million animals. That’s less than 17% of the herd.

The estimated population of white-tailed deer in North America now stands at around 36 million. That’s pretty impressive, considering estimates of the pre-Columbian population are somewhere between 20-30 million. And, it’s estimated about 6.3 million deer are harvested annually, amount-

ing to about 315 million pounds of venison. The number of Boone & Crockett qualifying bucks from 2020-23 for the top 15 states and provinces was almost 1,000 (see sidebar). The average state record typical net score holds at around 194 inches (range=176-211 4/8, n=43). Given this information, why

Increa sing= 6, Decreasing= 7, Steady= 1, New= 1

Source: boone-crockett.org/top-trophy-whitetail-states-2023

should I even continue? Things look pretty good in the world of the whitetail and whitetail hunting, right? Let’s take a deep dive into the facts, beginning with the turn of the 20th century. In 1900, an estimated 300,000 whitetails were left in the continental U.S. How do we know this? How do we really know how many there are today? Well, we really do not. Both the 1900 number and the 2024 number are a best guess, maybe with a small amount of science thrown in. What’s important is that we do know there were very few deer left after the overexploitation into the 1800s.

Once folks realized deer were in danger of extinction, conservation-minded private landowners, hunters, and newly formed state agencies undertook an impressive restoration program, with Texas, North Carolina, Wisconsin and Michigan being the

most common stocking sources. In Texas, landowners deserve a great deal of the credit for supporting restoration efforts.

The goal was to restore deer populations, and little consideration was given to what subspecies they represented. So, most of the existing deer populations cannot be considered as truly “native.” For example, in Texas, large numbers of deer were moved over the state from South Texas and the Gulf Coast, two races of whitetails. Deer stocked in Georgia came from their coastal islands, Texas, and Wisconsin. Pennsylvania stocked deer from Michigan, Ohio, Kentucky, Maine, New York, and New Jersey, and even Pennsylvania deer breeders. Deer were sourced from wherever they could be found.

New game departments developed seasons and bag limits to protect growing populations. The Pittman-Robertson Act of

Texas reigns supreme by having the most deer in the U.S., with 5.2 million deer within its borders. Michigan ranks second at 2 million, with Alabama and Mississippi tied at third with 1.75 million. Wisconsin has 1.6 million deer, and Pennsylvania has 1.5 million deer.

1937 figured significantly as financial support for restoration. By the time I was born in 1946, a minimum of 11 states had established deer seasons, with deer populations in those states totaling approximately 304,000.

When I began my career in 1973, deer numbers had increased to at least 10 million, credited to protection and significant habitat improvement. In the Midwest, millions of acres once occupied by prairies were converted to agriculture by the early 1900s. In the Lake States—Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota—old growth timber had been cut, followed by massive wildfires, which led to lush growth of deer foods. In the South, southern pine and hardwood forestry adopted clearcutting as the preferred sylvicultural practice.

This also produced millions of acres of deer forage. So, as I began studying deer in the 1970s, high deer densities were common in much of the U.S. The mortality agents deer face today did not even exist. State game agencies were riding high on year after year reports of “record deer harvests.”

It quickly occurred to several of us young deer biologists that we had created a monster. In the early days of restoration, we had to change attitudes of hunters. Whereas, grandpa would have shot any deer in range, restoration discouraged shooting does so herds could grow. The attitude change became ingrained. We had focused on restoration, without considering that someday, deer would have to be managed. The “runaway train was building up steam, and it was about to roll over us.

Two different deer management models were developed for northern versus southern states. In the north, deer management was aimed at managing hunters rather than habitat.

Emphasis was on public hunting opportunities, while in the South and Texas, we saw a culture of private land ownership and hunting clubs. Quite logically, the latter focused on habitat management, as well as deer population management. Aldo Leopold knew full well the private landowner was the key to wildlife management; especially with 80% of the wildlife living on 60% of the land.

I wasn’t the only one worried about the future sustainability of deer and deer hunting. Several of my colleagues expressed the same concerns. Deer management at that point in time depended on a concept known as a “compensatory response.” Put simply, if you remove a large number of deer each year, the improvement in available nutrition would stimulate a larger fawn crop and recruitment.

The concept was solid until the world changed. In the mid ’70s, deer management was simple, and there were fewer limiting factors to consider. There were very few predators, low incidence of disease, and plenty of deer food. In short order, the perfect storm struck.

In much of the country, there were very few predators, especially coyotes. However, sheep and goat ranching in the Texas Plateau allowed coyotes to cross over that country eastward. In the North, wolf elimination had also encouraged coyotes, and they expanded eastward. By 1980, eastern deer populations were being attacked from the north and the southwest. Bear populations also were increasing, as were the large cats. An entire suite of predators developed, each with its unique specialty.

Then came a real killer—hemorrhagic disease. It had been reported in New Jersey and Michigan in late 1950, but had

been considered a minor mortality agent only showing up sporadically. That also changed, as the two most common strains underwent changes, and soon, EHD and its companion, Bluetongue, were significant mortality agents.

Then the land itself began to change. Gentrification gained a foot hold in traditionally rural areas. Intensive forest management relied heavy on herbicides, and clearcuts once flush with deer foods turned into nutritional deserts. Fewer landowners hunted or even allowed hunting. Compensatory response disappeared.

In 1994, Dr. Harry Jacobson and I were invited to the 3rd International Conference on the Biology of Deer to give the Plenary presentation. And boy did we do that! Our presentation was entitled: “The White-tailed Deer: The most managed and mismanaged species.” We outlined how deer management, as it had been practiced by states, was not working and that serious consequences would follow. To say our presentation was not well-received is an understatement, but it proved prophetic. We even predicted disease would soon be a problem.

Earlier, at Mississippi State University, my colleagues Drs. Jacobson and David Guynn came up with an ingenious new model for deer management. Since most of the deer lived on private land, why not develop a deer management research and assistance program, which involved the landowner?

The DMAP was the most effective deer management tool in history. It worked wonderfully, but there was one problem: There are only so many biologists to service demand. States that had adopted the program soon backed away due to heavy workloads.

Populations have continued to grow, with some minor declines in the late 1990s. Hemorrhagic disease became a serious issue, when a new strain, EHD-6 Indiana, showed up devastating local populations. Then, a new disease appeared that had been hidden from public attention for almost 30 years—chronic wasting disease.

When CWD magically jumped to southern Wisconsin from Colorado around 2001, it shocked the deer world. Gloom and doom prevailed, and massive efforts developed to “eradicate” it by “population reduction,” which fit well with a professional philosophy that we need much fewer deer. To date, thousands of deer have died since 2002, not from CWD, but the treatment for it. To date, no state has experienced a population decline scientifically demonstrated from CWD.

At the same time, there has been a significant decline in hunters. The cause(s) are complex factors, including urbanization, changing lifestyles, increased cost to participate, and loss of societal support for hunting. During all of this, deer populations ebbed and flowed.

The wildlife management profession has also changed, with fewer professionals hunting or fishing themselves. Hunters are looked upon less and less as necessary for population management, and the momentum worldwide is headed in the direction of “re-wilding” the deer woods. In recent times, support

for replacing or joining hunters with apex predators such as wolves, bears and lions has emerged. This has created a raging conflict between hunters, landowners, and resource management professionals.

So, what is the state of the union of deer management and hunting? There is a state of flux that concerns me. Yes, deer populations may be high, but hunters only take about 6 million of the estimated 36 million animals, less than 17% of the herd. Recruitment often is as high as 40%, and standard practice supports at least a 30% harvest. The habitat is deteriorating, even in places where trophy bucks have been the norm.

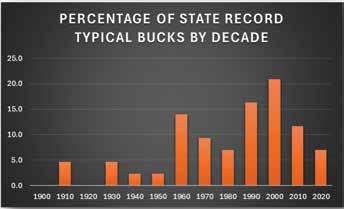

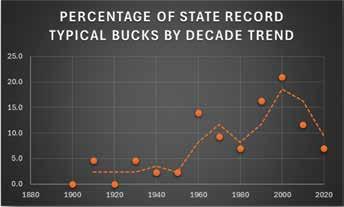

I also analyzed the records for 43 states with whitetails (see graphs) and looked at when each state record typical buck was harvested. It appears we reached the peak in new state records at the turn of the 21st century, but we are only halfway through the 2020s, so, time will tell. There are only two possible reasons: we either have reached the genetic limit for the species, or herds are more nutritionally and socially stressed.

In summary, we are at a crossroads in the history of deer hunting and management. There is no way we can continue to allow deer populations to increase. Sustainability is the key issue. As hunters, landowners, and professional managers, we soon will have to develop a new direction for our favorite recreation and our favorite animal.

We either make these change or settle for a world in which hunters are no longer regarded as critical to conservation. I prefer that there will always be a place for the hunter in our natural world.

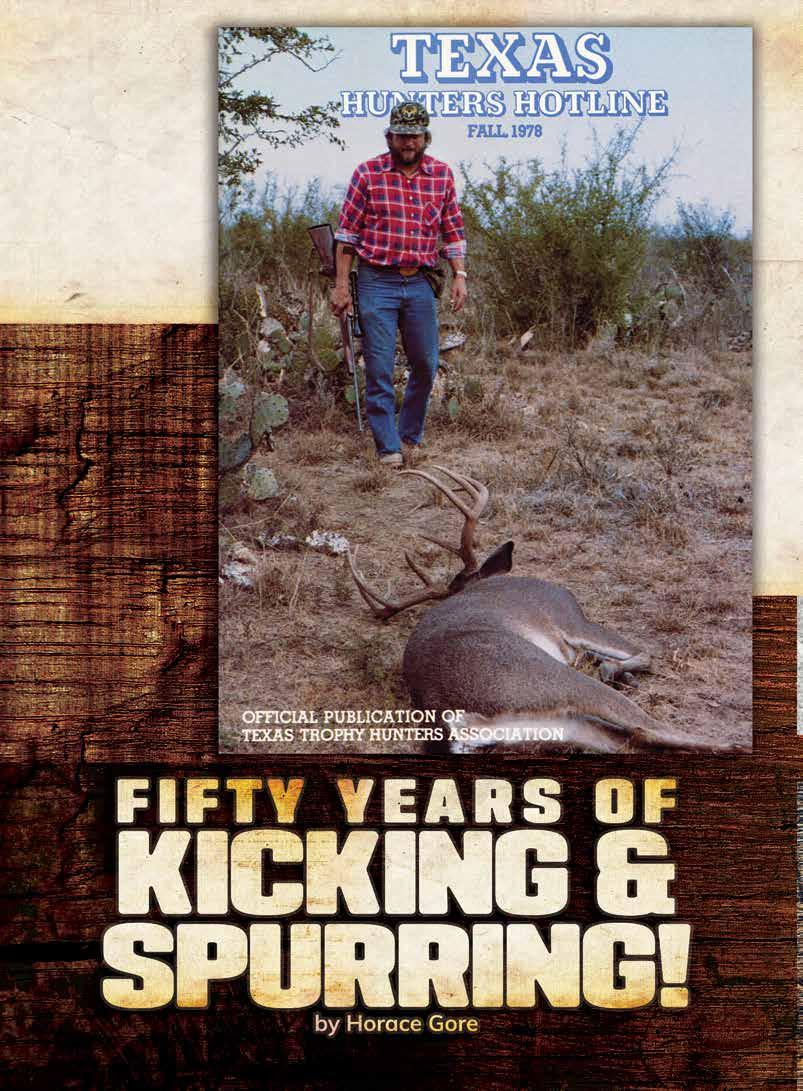

Left: TTHA’s founder Jerry Johnston and his big buck, circa 1978, on the cover of Texas Hunters Hotline, before he changed the name to The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters

Right: We celebrate 50 golden years of The Journal, and look forward to blazing a trail through the next 50 years.

Texas Trophy Hunters Association is 50 years old and still kicking and spurring as “The Voice of Texas Hunting.” The first 50 years was a resounding success, and we are now beginning a new 50 years of showing Texas and the world the exciting experiences of the hunt and the joys of the outdoors.

The “kicking and spurring” part of the title, is an old Texas phrase describing exactly what we were doing at TTHA when I joined the team in 1995: raising $350,000 for Operation Game Thief; weekly award-winning television shows; a magazine that reached 325 pages in 2003-2005; and three Hunters Extravaganza shows in Houston, Fort Worth, and San Antonio, with crowded aisles from Friday through Sunday. The record would show that Texas was enjoying the heyday of TTHA.

My second career with TTHA that started 30 years ago has

been a distinct pleasure. After 33 years with the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, and a lot of successful work with deer, quail, and wild turkey, I could have retired and spent the rest of my days hunting and fishing, writing, trading guns, and just loafing around. However, I picked up another career when Jerry Johnston called, and the wheels as editor of The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters started turning.

Jerry was in his 18th year after creating TTHA in 1975, and things were popping when I retired from TPWD in 1993. The Journal was growing, and Jerry needed an editor who knew the ropes of writing, hunting, guns, politicking, and had a respected knowledge of Texas wildlife.

I must admit I wasn’t too enthused about the offer from Jerry in September 1995. I was more interested in living on the vast Kokernot Ranch in Gonzales County and enjoying everything the ranch had to offer, which was the nearest

thing to heaven for a wildlife biologist and hunter. When Jerry agreed that I stay on the Kokernot and work a couple of days each week in the San Antonio office, I took the job as extra labor—30 years ago.

The thrills and excitement driven by TTHA have continued to promote hunting, shooting, conservation, and camping through the last 50 years, and now the Texas Trophy Hunters Foundation will push for membership, TTHA Chapters, wildlife research, and publicity that is needed for Texas hunting.

Safari Club International acquired Texas Trophy Hunters in 2021 and moved their operational headquarters from Tucson to San Antonio in 2024. The future looks bright for both SCI and TTHA as they work together not only for the benefit of the Texas hunting, camping and everything outdoors—but for hunting and conservation worldwide.

Everyone at TTHA is geared for the next 50 years. Hunters Extravaganzas are going strong; membership plans are in the works; an Outdoors Extravaganza will continue in Dallas; The Journal is the best hunting magazine in the Southwest; and the new TTH Foundation is pursuing needed goals.

Promoting hunting and the outdoors of Texas will be more difficult during the next 50 years because hunting and camping is challenged by a variety of activities that require decisions from the outdoor crowd. With 90% of Texans now living urban, TTHA is under more pressure to ensure that hunters will continue to buy licenses and enjoy the outdoors, despite all the pulls of urban living that are taking a toll on outdoor sports.

The growing whitetail population on 100 million acres of Texas habitats are a plus for deer hunters and worth $4 billion to the Texas economy. Some of the best bucks taken in the nation come from Texas, and the average of one deer harvested per hunter is the best of all deer hunting states. Some 800,000 deer hunters take that many deer, and Texans consume 15 million pounds of venison annually. In essence, deer hunting has never been better.

Dove hunters are now pushing 400,000 and spend some 2 million days afield shooting 15 million shotguns shells to take home 5 to 6 million doves each season. Both mourning and white-wing doves are consumed in specialty dishes for months after the season, and the future looks bright for dove hunting in Texas.

Although deer and dove make up most of Texas hunters, wild

turkey have their share of both spring and fall hunters. There was a time when turkeys were taken during deer season by hunters using rifles. Things changed when a spring season was approved for a first season in 1969. Today, some 100,000 spring hunters take about 50,000 birds, based on weather conditions and turkey reproduction. To say that the spring season has been a success would be an understatement!

Like any new hunting sport, Texans were slow to take up spring turkey hunting because they didn’t know how to hunt spring turkey. For the first 10 years, many hunters carried deer rifles and ambushed strutting gobblers. As time passed and hunters got the hang of calling in gobblers to the shotgun, the sport took hold from the Panhandle to Brownsville and the Pecos to the Brazos—that area where Rio Grande turkey flourish in Texas.

With 50 years of success in getting Texans into the wilds and promoting hunting and other outdoor activities, TTHA will be looking for ways to “keep ’em running, swimming, and flying” during the next 50 years. We will continue publishing an excellent Journal; push membership with Extravaganzas and the Foundation, and get the kids into the wilds of Texas by promoting hunting, fishing, shooting, and just enjoying the outdoors. Texas Trophy Hunters will continue to be “The Voice of Texas Hunting,” and that’s where we’ll be kicking and spurring for the next 50 years.

We look forward to promoting Texas whitetail hunting and sharing whitetail hunting stories for the next 50 years.

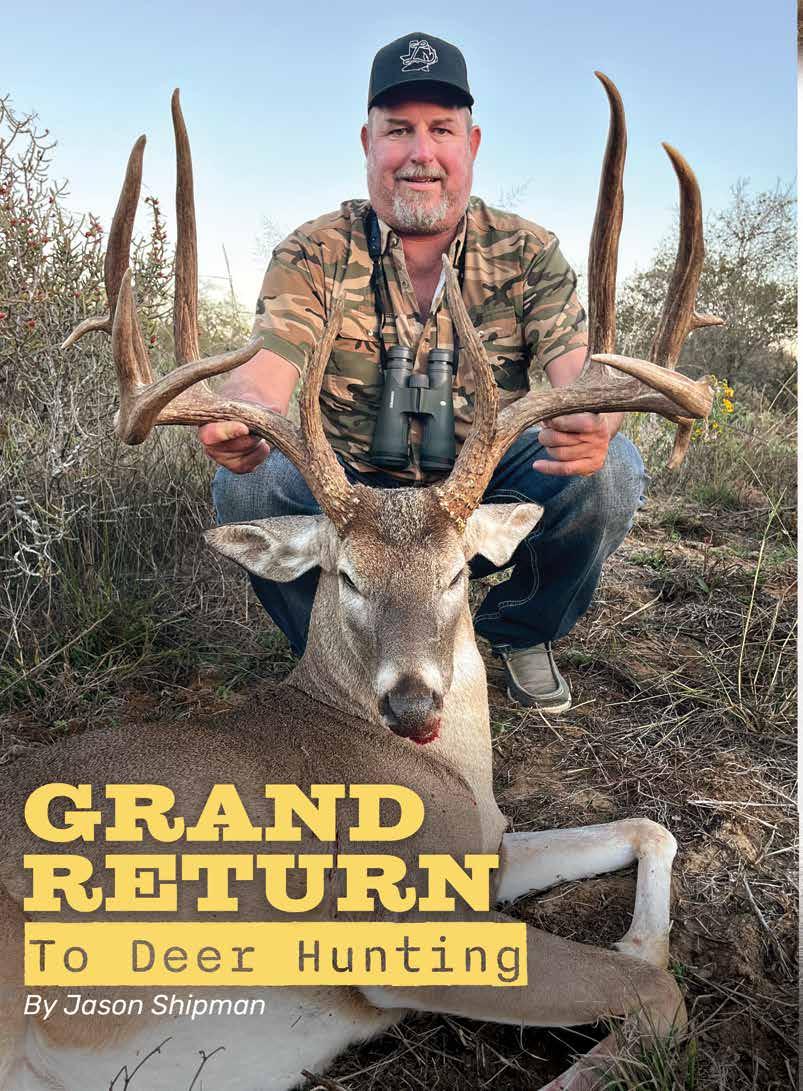

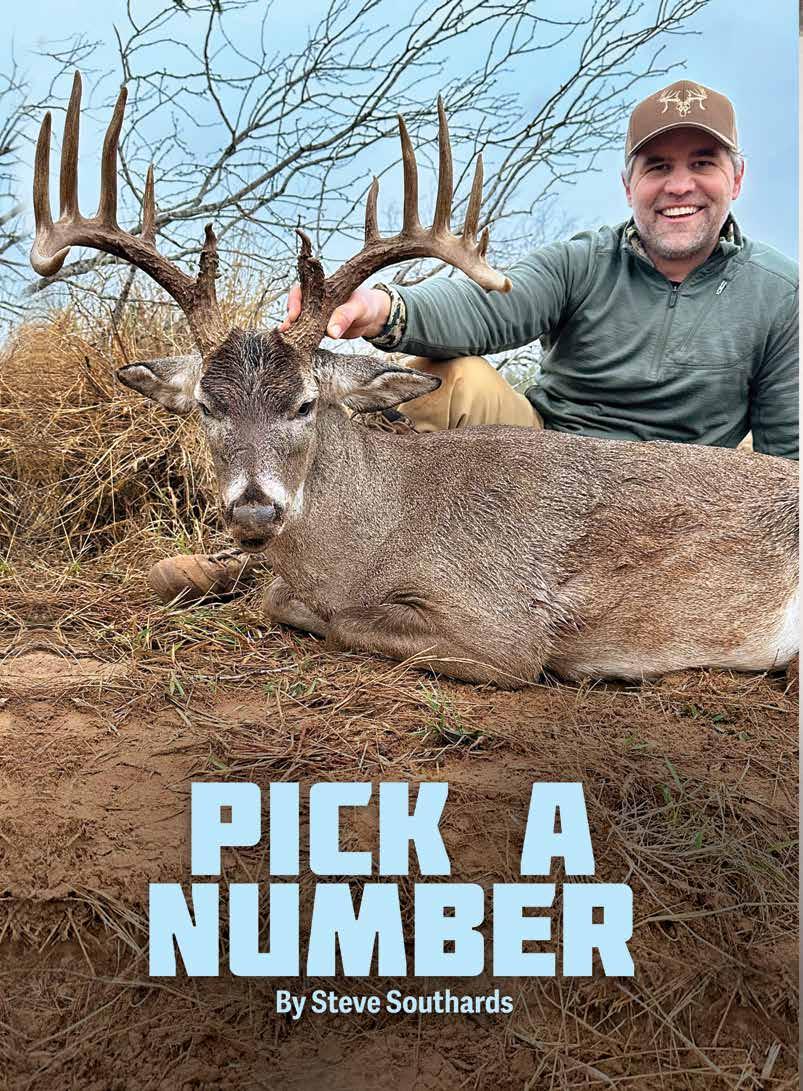

Ten years is a long time. It’s a decade to be exact, and quite awhile to sit idly by on the sidelines. We’ve all heard of someone making a grand entrance. This is the story of someone making a grand return. A comeback story of sorts.

John Naegelin grew up hunting and has been an avid deer hunter his entire life. He lives in Devine, located just south of San Antonio where the live oak trees make the transition into the brush country. He’s a farmer by trade and enjoys spending what free time he has hunting and fishing with his kids.

Throughout the years, John has enjoyed making lasting memories and has taken some great deer. About 10 years ago he killed an exceptional buck that was featured in The Journal. The buck was a big typical 10-point that grossed

194 5⁄8 and netted 1835⁄8 . The buck was entered in the Texas Big Game Awards and was later recertified by Horace Gore, an official B&C measurer, at 1831⁄8 net B&C. With an exceptional typical score, the buck was the third largest high fence typical killed in the state that season according to the TBGA standings.

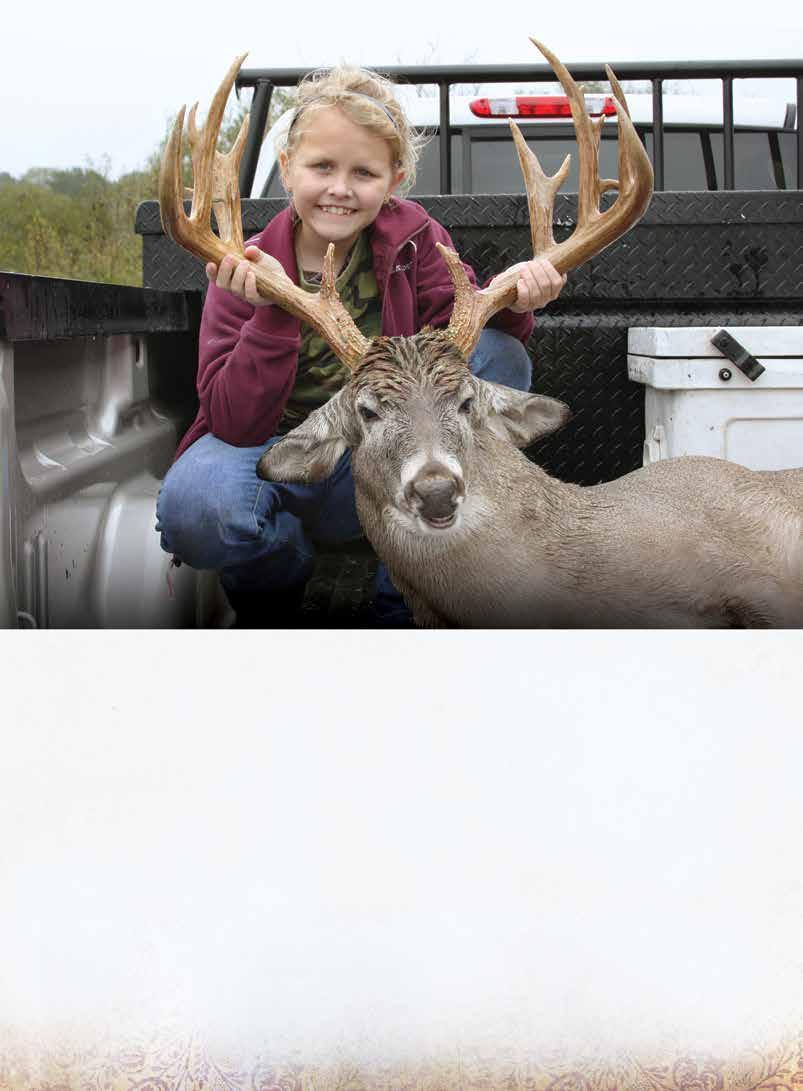

“After taking that big 10, I felt like I had topped out and decided to hunt with my kids for a while,” John said. At the time, his children, Ace and Khloe, were just beginning to hunt. “I still wanted to hunt,” he said, “but I redirected my efforts to my kids. I wanted them to be able to experience the opportunities.” John set his gun aside and forgot about it. For about the next 10 years he hunted with Ace and Khloe and helped them take some tremendous deer. “I watched them grow up hunting, and we had a great time,” he said. “I wouldn’t change a thing.”

Ace and Khloe are all grown up now. They still love to hunt but are old enough to do their own thing. For the past couple of years, John has felt the urge to hunt again. “I’ve had the itch to hunt big deer,” John said. Rather than ease back in to hunting, last season John made a grand return to the sport.

Last year, early in the hunting season, John learned of a huge typical framed buck on a ranch nearby. The old buck was extraordinary, and more important, the ranch owners were friends and agreed to allow him the opportunity to hunt the monster buck. “We had the discussion about hunting the deer and then the ball was in my court,” John said. “I didn’t have to think about it for a long time. The decision was easy. I was ready to hunt!”

John was out of town for a couple of days but planned to hunt the buck when he returned. “It was already mid-December. The rut was on, and the bucks were moving, but their patterns were fairly unpredictable,” John said. “Ace accompanied me, and the first evening out we saw some great bucks, but not the one we were after,” John added.

The next morning, they returned to the ranch and went to the same blind located in an area the old buck was known to frequent. “We saw more of the same, but the big buck was a no show,” he said. Around midmorning they decided to call it quits and head in. On the way back they saw the big buck that had been eluding them. “He was chasing a doe in some motte country. He was an absolute giant deer and a sight to behold. He was working that doe like a cutting horse,” John said.

The buck and doe were several hundred yards away, so they quickly made a plan to get closer for a shot. The wise old buck was aware of their presence and on to their game. “Every time we tried to get closer, he would move out a little farther,” John said. The buck didn’t exactly want to the leave the doe, but wasn’t going to cooperate with the hunters either. “The cat and mouse game went on for a while before we finally decided to ease out and return in the evening,”

That evening they returned to the same blind. It was close to the area where they had seen the buck that morning. “We hoped the doe would come in to feed or maybe the buck would come by to check for does,” John said. As the afternoon wore on, their wish came true when the big buck skirted the brush line they had been watching. “The buck was briskly walking and obviously on a mission. It did not appear like he was planning to stick around.”

As the buck went behind a motte of brush and out of sight, John quickly eased his gun out the window of the blind and readied for the shot. A few seconds later the buck reappeared, still keeping up the pace. The sun was setting and turned everything a beautiful golden orange hue. Suddenly the old buck stopped and looked up the hill at the blind as if he knew he’d just made a grave mistake. It was pictureperfect moment that would be etched in the hunters’ minds for eternity.

Knowing it couldn’t get any better, John quickly settled the crosshairs on the buck. At a distance of about 175 yards, the buck went down instantly as the gunshot broke the silence of the evening. A quick celebration followed as they waited a few minutes to be sure the fallen trophy had expired.

“Thoughts were racing through my mind as we made our way to the buck,” John

said. “I knew he was big, but everything happened so fast.” His anticipation grew and felt tense as they approached the downed buck. “When we got to him, I literally could not believe how big he was,” he said. “He was HUGE! I just knelt down beside him, grabbed his antlers, and admired him in amazement!”

The huge buck had excellent tine length including 9-inch brows and 15-inch G2s. Perhaps even more impressive was his huge frame with main beams just shy of 29 inches and almost 40 inches of mass. Additionally, the buck’s mainframe nine-point rack sported two kickers and a drop tine for added character. Simply put, John’s amazing buck had it all, and when everything was said and done, scored 203 4⁄8 gross.

With many years of hunting experience to his credit, John knew the kind of deer he had taken and offered a matter-of-fact explanation. “He is the buck of a lifetime and will certainly be hard to top,” he said, “but I love to hunt and look forward to the challenge of trying to best him. I just hope I don’t have to wait another 10 years.”

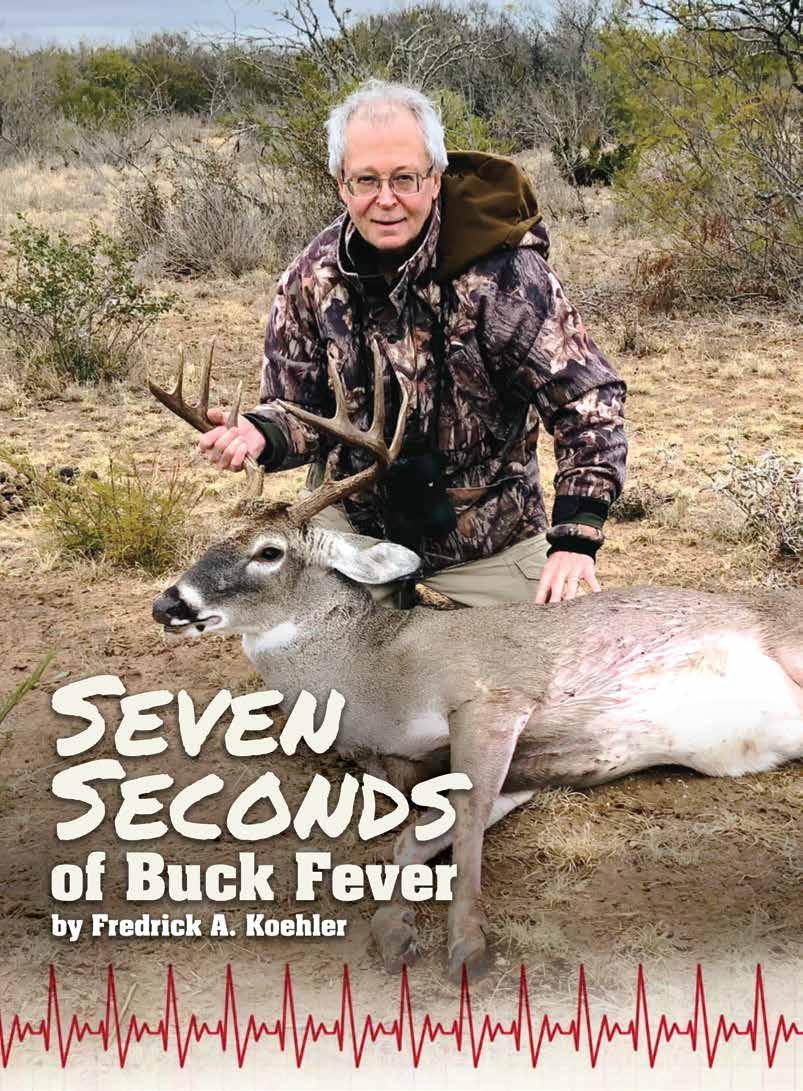

In the pre-dawn darkness, I climbed the steps of the elevated stand, assisted by my pocket flashlight, before 6 a.m. I used the light to load my rifle, hang my binoculars around my neck, and open the front and sidewindows. Then I fell back into the blackness of this early mid-December day. As predicted by my guide, Rusty, who just dropped me off, a coyote yodeled off to the northwest, answered by some yelping to the southeast. Twenty-five miles south of Uvalde, Texas, the mood was set for my first of three planned days of whitetail deer hunting. I settled into my chair and waited for daylight.

Out of my right-side window, the faint glow of dawn began to brighten the eastern sky. Many minutes passed and I began to discern the two senderos extending out in front of me. And then two dark forms took shape in the northwestern one, 40 yards out, and they seemed to jiggle or move in my binoculars—deer feeding. With time, I thought I glimpsed an antler on the edge of the larger mass. And then, too soon, before decent shooting light, the buck was gone. The other, a doe, remained.

Dawn came slowly, calm and partially overcast, about 50 degrees in temperature as I recall. I hoped to see more deer come out and eat the corn Rusty had poured out from the driver’s seat of his truck after dropping me off earlier in the dark. Two different spike bucks came out at different times in the next two hours. One walked a good ways in from the southeast. A fork horn also joined the doe.

Rusty had told me I could shoot a spike for meat or a mature buck, but not a forky. Just after 8, I gently stuck my rifle barrel out the right window and carefully leveled it at the spike’s chest 50 yards out on the northwestern sendero. Along the full breadth of that windowsill, I had a rock-solid rest. The deer looked up at my stand. I was tempted to shoot it for meat but held out. I wanted a bigger buck.

The deer drifted downrange. Three continued to feed intermittently in front of me at about 125 yards. I thought they’d be the only game I’d see that morning. I began to read the book I’d brought along in my rucksack on the bank-and-train-robbing history of the Dalton Gang in the early 1890s. Whenever I’m faced with the prospect of sitting in a deer blind for long hours, I always tote along a good book. It’s almost as important as my rifle. Suddenly, at exactly 8:45, a new development changed everything. A dark brown form dashed into the sendero, and it looked larger to my naked eye than the other three deer it joined. I grabbed my 15-power binoculars and instantly spotted five points on one side

of what seemed to be a symmetrical set of horns. It was just what I’d been waiting for.

I nearly panicked with pure, raw, wild excitement, jolted by a full slamming blast of adrenaline. In a mere split second, I was transformed into an entirely different hunter. That’s what big bucks suddenly appearing out of the blue can do to me.

Some decisions to shoot in hunting are dispassionate, debated, and slow in coming, but not this one. Somehow, I had the presence of mind to clamp my earmuffs on before seizing my rifle and aiming it out the right window again, but this time, with the speed of a man possessed. Yes, indeed, I was possessed. I had the burning desire to shoot this buck post haste.

I thrust my rifle firmly down along the right windowsill, slid off its safety and scrambled to find the animal in the 10-power riflescope. He must have heard me because he looked up at my blind when my crosshairs found his chest. I fired instantaneously. My rifle recoiled, and when it recovered, all four deer were gone.

I had a hunch they’d bolted east into the chaparral between the two senderos. But I saw no definite hide nor hair of any ungulate after the shot. The open ground in front of me became entirely devoid of game for the first time this morning.

Anxiously, I relived the shot, hastily hurling my rifle out the window to test the steadiness of its shooting rest. It seemed good, but nothing could

believed

the

rather hastily. He grappled with that feeling until his guide helped him track down the buck.

assuage the fact I’d reacted so furiously, engulfed as I was in 7 seconds of intense buck fever. I was drowning in self-doubt. Where once there was exhilaration, there was now angst.

I was distraught. I had fired too quickly. I heard no bullet hit. I was not sure where those four deer ran.

I convinced myself I had missed. I was so nervous, I ripped open my snack bag of corn nuts and chomped down on three different helpings in the next 15 minutes. I was too embarrassed to text or call my guide until I got down and looked for blood.

I climbed down and walked out and impetuously studied the ground, treading east between the two senderos, amongst the loose scrub, yucca plants, oak brush and scattered prickly pear cacti. No blood. Not a drop. I was despondent.

Any hope I had was fading fast. And in its place, heartbreak and despair. Reluctantly and gloomily, I texted Rusty, “I just shot at a 10-pointer. Come over.”

When he got there, he took one look at my long, drawn face and sensed my grief. I felt stupid telling him I thought the big buck ran east, because I really didn’t know for sure. I was certain we’d be looking for this deer the rest of the day.

But Rusty was unruffled. He’d been guiding me for nearly 10 years now and we have killed and found many deer together. I took him down the northwestern sendero and we cut east again based on my best guess. Less than two minutes later, and 40 yards away, Rusty howled out, “There he is!”

Out in the open, near the edge of the northeastern sendero lay my buck. Stone dead. Fully manifest. A vision of grandeur.

The feeling seized me, shook me, and shocked me. It was incredulous! I dashed over to the buck’s side. The great lump of woe growing within my throat disappeared.

I was beside myself with joy, excitement and relief. I shook Rusty’s hand most earnestly and enthusiastically. I could not be subdued. Without question, this was the high-water mark of my Texas whitetail deer hunt.

The buck was exactly as I had imagined from my snapshot glimpse of him through my binoculars right before my headlong shot. A 19-inch wide, perfectly symmetrical, South Texas 10-point buck, cleanly killed, with an estimated live weight, according to Rusty, close to 190 pounds. I was extremely pleased with this deer.

After cell phone pictures, Rusty eviscerated the buck and discovered my bullet had center punched its heart. I poked

my finger into that vital organ and found the hole’s diameter matched my index finger’s thickness. What a profound revelation to go from fearing I had missed and lost this fine buck, to finding it dead, shot through the heart, a half-hour later.

Things had gone from being Friday the 13th for me, to being Friday the 13th for the deer. It had been quite an eventful morning, and a particularly emotional one for me. Hunting takes me places like nothing else on Earth.

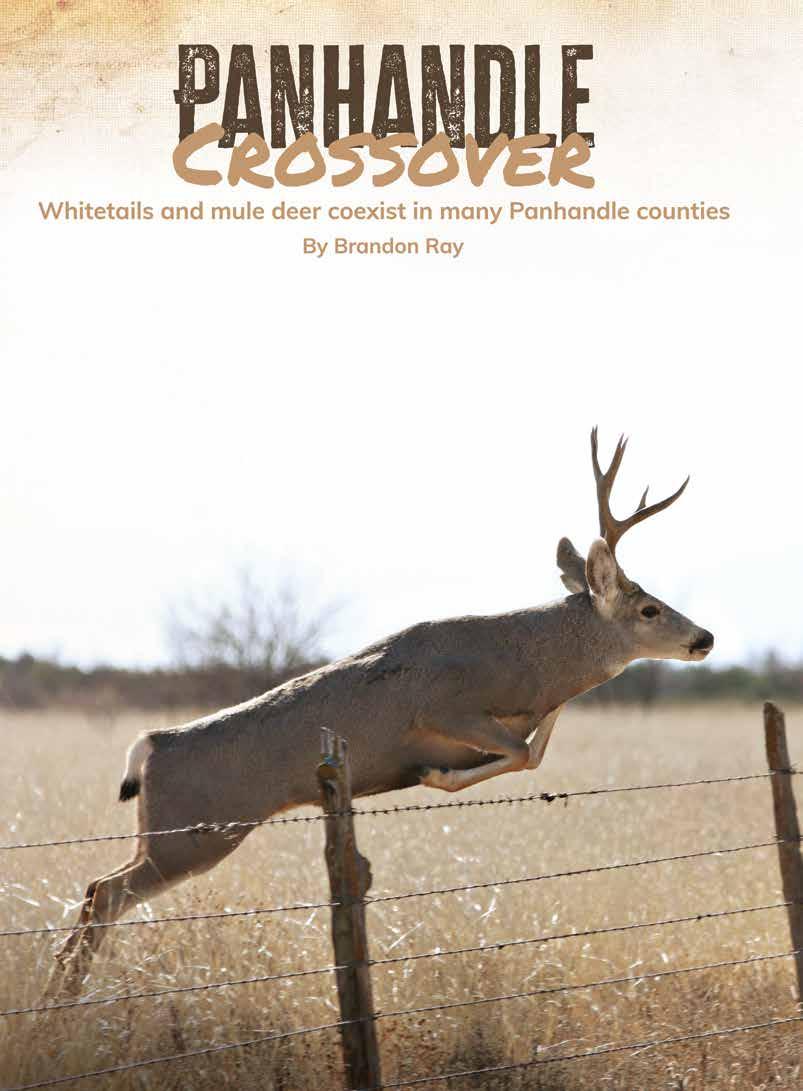

Not far from the muddy banks of the Canadian River, my spotting scope found a fine buck. I spied on him from an elevated bluff 600 yards away. Through the clear lens, I counted 12 typical points. The rack was 150 inches or better. The big-bodied whitetail stood near a corn feeder, under the canopy of an ancient cottonwood tree. Bow season had just started, and my friend waited on the right wind direction to hunt that creek drainage. With 20 minutes of daylight remaining, we backed out and drove back to the ranch headquarters.

As we crossed rolling, steep ravines dotted with mesquites and cholla cactus, a small herd of mule deer trotted out from one of those ravines. They stopped on the far side of the draw to look back. In the herd was a typical 10-point. His back forks were like giant sling shots, the front forks like crab-claws. His antlers were wide, spreading past his ears. I guessed his rack would score 160 inches. As daylight faded, the herd bounced like pogo sticks over the far ridge.

Encounters like that one in the northwestern Panhandle, seeing both deer species on the same afternoon, are what make hunting at the top of Texas so unique. The two species overlap in many Panhandle counties, although each deer species prefers slightly different habitat. Whitetail numbers are highest in the eastern counties and the further west you go the more likely you are to find mule deer. I asked Texas Parks and Wildlife Department biologist Shawn Gray for his insight on the overlapping range of whitetails and mule deer in the Panhandle.

“It used to be more on the eastern side of the Panhandle where the two species overlapped,” he

said, “but there are observations of white-tailed deer all over the Panhandle now. So, I would say the range overlaps across the entire Panhandle. Mule deer prefer more open country, a brush density of over 33% is generally not used by mule deer. In contrast, white-tailed deer are better suited to thicker brush densities.

“In broad terms, white-tailed deer will mostly be found in bottoms and drainages, while mule deer prefer the more open hilly topography, but you can find either in all habitat types in the Panhandle, just not as often as what they really prefer. Surveys from this past winter indicate an increasing trend in mule deer numbers, which is a very welcome change. White-tailed deer are also on an increasing trend. The main contributing factor to increasing white-tailed deer range across the Panhandle, is the impact of brush encroachment.

“Again, too much brush is better for white-tailed deer and

at 6½ years

significantly reduces the habitat quality for mule deer. Habitat is always the key. Obviously, they do interbreed, but it is uncommon. We recently conducted a mule deer DNA research project that spanned from the Trans-Pecos and Panhandle, we documented only 5% of interbreeding with white-tailed deer.”

There’s a location in the central Panhandle that I’ve hunted for 30 years. It’s a windmill surrounded by flat prairie dotted with a few mesquites and cedars. South of the windmill is a steep, brushy canyon with oak brush and mountain mahogany. For many years that location was a prime mule deer-only area. However, over the past 10 years, it has slowly started to include sightings of whitetails. And in the past five years, almost every time I hunt there, I see at least a couple of whitetails. What has changed? Over the past decade the brush on the flat area has significantly increased.

Thirty years ago, it had a 10-20% brush density around the windmill. Today, it’s probably 30-50% brush, therefore favoring whitetails. The mesquites were recently sprayed with Sendero herbicide, which should open the landscape and eventually make the habitat more appealing to mule deer again. Mesquite removal also benefits cattle grazing. In many locations a ranch manager must decide, “Do I want this area more favorable for whitetails or mule deer?”

Whatever county you hunt, know the season dates and antler restrictions for both species. Research season dates on the TPWD website. Since you might be looking for a big whitetail, but instead encounter a trophy-sized mule deer, be sure it is legal to shoot. For many Panhandle counties, there are now antler restrictions on mule deer to improve trophy quality.

Current counties included in the antler restrictions are Andrews, Armstrong, Bailey, Briscoe, Castro, Childress, Cochran, Collingsworth, Cottle, Dawson, Donley, Floyd, Foard, Gaines, Hale, Hall, Hardeman, Hockley, Lamb, Lynn, Lubbock, Martin, Motley, Parmer, Randall, Swisher, Terry, Terrell, and Yoakum

counties. A legal buck deer is defined as a buck with an outside antler spread of the main beams of 20 inches or greater. Mule deer antler restrictions do not apply to MLDP properties. Also, mule deer antler restrictions do not apply within any CWD zone.

Last fall, my daughter, Emma Ray, hunted a special Panhandle buck. For many years we watched that whitetail grow and evade us. He lived in classic Panhandle whitetail habitat; a river bottom flanked by mature cottonwood trees with mesquites and cedars in the surrounding flats. On that creek bottom, we rarely saw a mule deer.

Going into the 2024 season, Emma and I collected nine sheds from the old buck we called “Longhorn,” including a matched set from the previous year. He earned the nickname from his oddball rack that was always a big six-point with extra points around both bases. We jokingly said he looked like he was a crossbreed with one of the stray longhorn cattle that roamed that river drainage. Despite multiple attempts over the years to harvest that buck, we only had one previous close call.

In the fall of 2021, Longhorn came within 20 yards of our brush blind on a quiet evening in November. Emma was hunting with a crossbow. When she clicked the safety off, the smart buck heard the metallic “click” and bolted for the creek. He was no dummy!

It was our fourth sit in the creek bottom blind of the 2024 season when Longhorn finally made a mistake. At sunset, the old buck approached our blind in the company of two does. Broadside at 20 yards, Emma steadied her Browning .243 rifle over forked shooting sticks. She squeezed the trigger; the hit was solid.

Brandon and his daughter, Emma Ray, with Emma’s 2024 Texas buck. Many years of history made finally taking the 9½-year-old buck “Longhorn” extra special.

The following are the top three TBGA entries for typical and non-typical whitetails and mule deer from the Panhandle, Region 2, for the 2024 season. Over the past ten years, the top whitetails have usually come from the eastern counties and the top mule deer entries are usually from the southwestern counties. Look close at the numbers. These entries represent bucks as big as you might find anywhere in North America.

Typical Whitetail Hunter’s

J

Non-Typical Whitetail

Typical Mule Deer

Non-Typical Mule Deer

Hunter’s

Longhorn trotted 30 yards and tipped over. The old Panhandle buck’s back teeth were worn smooth as glass. Going off tooth wear and all the trail camera images we cataloged of him over many years, we estimated his age at 9½ years old. His rack carried 11 points.

Jeff Kelley’s focus for the 2024 season was a quality mule deer buck. Hunting in crossover country in the Panhandle, he saw both whitetails and mule deer, but a wide nine-point he’d seen the year before was his target. The buck was big-bodied with a distinctive, wide-antlered rack with short forks. A faint double throat patch also made the buck easy to identify from one year to the next.

It was during the early stages of the rut, Dec. 1 to be exact, when Jeff got his chance. Hunting from a pop-up blind near a feed station, the mature buck strolled within range at sunset following several mulie does. Jeff steadied his Bowtech bow and fired an arrow perfectly through the broadside deer’s heart. The big buck trotted a short 60 yards and tipped over. The bull-necked mule deer weighed an estimated 250 pounds live weight. The deer’s rack was 27 inches wide at its widest point and aged at 6½ years old.

The Texas Panhandle is home to more than just tumbleweeds and jackrabbits. Over the past 10 years, whitetails have expanded their range, mostly due to brush invasion. Whether you prefer hunting whitetails or hunting mule deer, trophy quality is excellent in this sometimesoverlooked region of Texas.

A fresh rub in the Panhandle. In many locations, unless you see the deer make the rub, you don’t know if it was made by a whitetail or a mule deer.

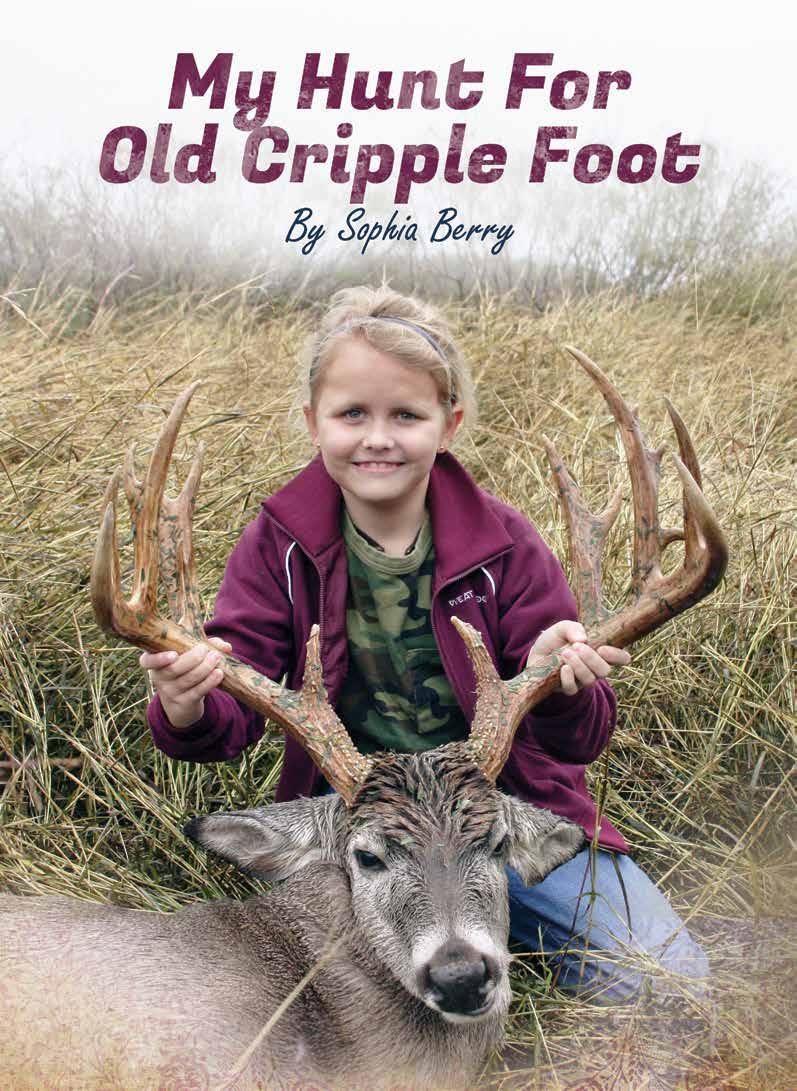

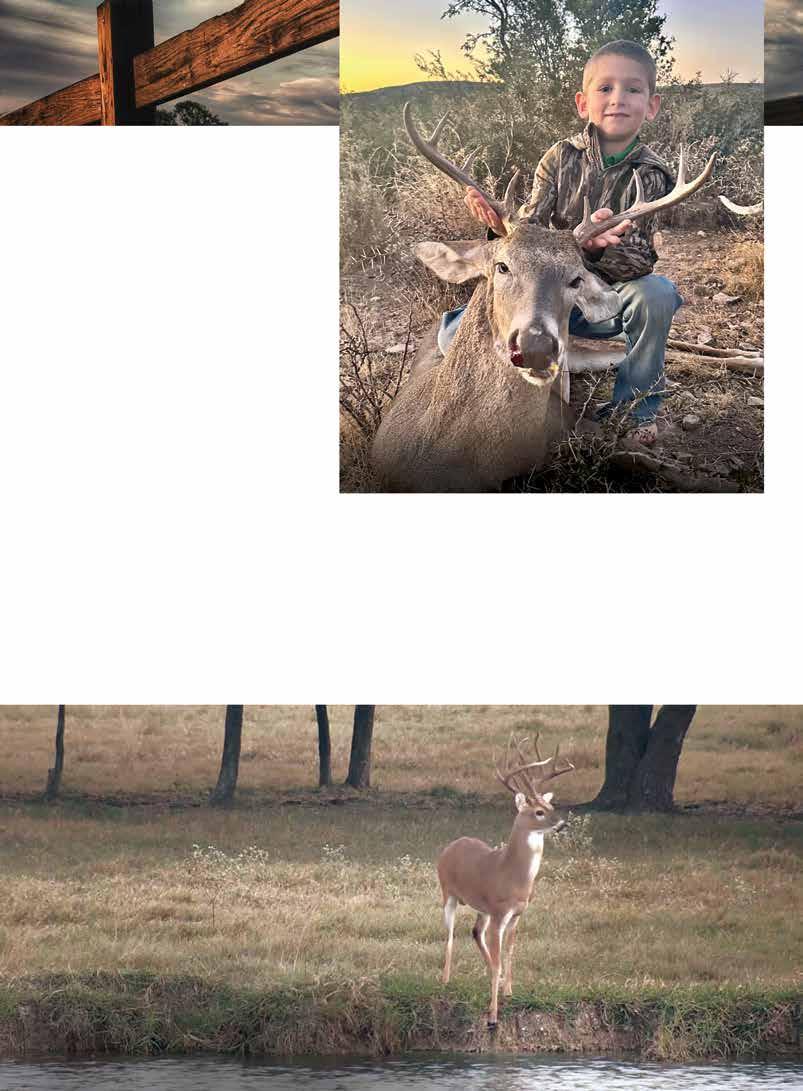

Editor’s note: This cover story appeared in our May/June 2010 edition.

My deer hunt started months before I killed the buck we’d call “Cripple Foot.” I asked my dad if he had seen a buck with 16 points that I could shoot this year. I wanted a buck with antlers over 15 points because one of my friends had killed a 15-point.

One day in November, Dad said he might have seen a deer for me to hunt, but there was one problem; he had 18 to 20 points. I told him that was no problem. Dad said we called him Cripple Foot because he was injured years ago in a fight and has favored his right foot ever since. Dad said he was very old now. He always had a 10-point rack, but with old age he had added kickers to his tines, giving him a lot more points.

We first tried to hunt Cripple Foot from a blind, but had no luck. We hunted from the blind about four or five times. It seems he did not like the corn we put out. We saw some other bucks, but my dad said I should be patient and keep hunting for Cripple Foot. So, I passed on buck after buck after buck.

On the day I shot my deer, I got up early, about 5:30 or so, and got dressed in my camo shirt over my brown long sleeved shirt with my jeans and boots. When I got downstairs I met Dad by the front door and Mom handed me my jacket and said, “Good luck,” as she hugged me goodbye. Dad and I got in his truck and headed off. We picked up breakfast on the way to our ranch.

It was cold and drizzling and my dad said it was a good day to find Cripple Foot. My dad said that we would be hunting out of the truck. I really prefer to hunt out of a blind. When I

killed my first buck two years ago, we hunted out of a blind. It was easier to rest the gun on the window and the deer are not scared, which gives you more time for the shot. My first buck was a 29½-inch nine-point. Dad said Cripple Foot would be even bigger.

When we got there we met up with Mr. Hubbard and his son Colton. While Mr. Hubbard and Dad got the corn feeder ready for our hunt, Colton and I talked about school, because we go to the same one. When my dad was ready, he showed me how to shoot a gun out of a truck because I had never done that before. I would be shooting a .243 Winchester.

This was the same gun I shot my first deer with two years before. I borrowed it from Dad’s friend, Mr. Ward. The stock had been cut off with a hacksaw and there was a soft pad on the butt of the gun. I felt comfortable with it and was ready to go hunting. Dad showed me how to place the gun on the mirror of the door and then we were ready.

I had shot this .243 only one time when I killed the wide nine-point when I was 9 years old. All of my other shooting was with a pellet gun and one of Dad’s .22 rifles.

We went into the pasture and started looking for Cripple Foot. My dad gave us a description of a buck that was with Cripple Foot and some does the evening before. Colton spotted that buck and then we saw the does. We parked the truck and waited for Cripple Foot to show himself. And he did.

When the big buck got close enough, I looked in the scope and my dad asked me, “Can you see anything?” I said, “I can see the white spot on his neck.” Then he told me to shoot. When I did, I blinked and my dad shut his eyes. When the gun smoke cleared, I saw that Cripple Foot had disappeared.

As my dad opened his eyes, he said, “Did you get him?” Mr. Hubbard, Colton, and I laughed and said he was down and then they all congratulated me. When I first saw the deer on the ground I could not believe my eyes. My dad said he was much bigger than the 175 inches that he had expected. I didn’t

know about that but I quickly counted 18 points and was very excited.

After that my dad took some pictures and told me that this deer was 11 years old, just about one month older than me. Then we said goodbye to Mr. Hubbard and Colton and headed home to show Mom the deer. She was so proud of me when she

a big buck. She had signed me up earlier in the year for the Muy Grande and made sure we were heading to Freer to enter my deer.

I wanted a buck with antlers over 15 points because one of my friends had killed a 15-point. One day in November, Dad said he might have seen a deer for me to hunt, but there was one problem; he had 18 to 20 points. I told him that was no problem.

saw Cripple Foot in the back of the truck, but not surprised. She said she knew I could do it.

We then left to find my Mammaw, Laura Berry. She really loves to hunt and had already entered a deer in the Muy Grande Deer Contest and won second in overall. She was so happy for me and kept hugging me and congratulated me for getting such

My uncle Roy joined us and we headed off to Freer. When we got there we went to the Muy Grande headquarters. They scored my deer and he ended up scoring 190. I answered lots of questions from other hunters and even let some of them take pictures with my buck. It’s funny how a big deer can make people so friendly. So far, I was in first place in the youth division. We left to go to another contest called Freer Deer Camp where my deer also scored first place.

When we were through in Freer, we left for Kingsville to go by Hibler’s Taxidermy and drop my deer off to be mounted before we headed home. What a day! I can’t wait for next year. Maybe we will get the chance to make the same trip again with a bigger buck!

“Come look!” came loud whispered words from the dining room. “Oh my gosh! Look at this buck!”

Have you ever experienced hearing those words coming from someone standing at a window in your house? Or perhaps you’re standing in the yard and suddenly you see a whitetail buck staring back at you. It’s also possible, depending on where you live, to see an axis, blackbuck, or any number of exotic animal species now free ranging across many areas of Texas.

It’s especially exciting when you most certainly were not expecting to see one. And it can be equally exciting IF you’re in an area where perhaps you may kill the buck legally and safely

A backyard buck refers to one that’s literally in the backyard of your property. It may be outside the house on a city lot surrounded by other homes. Or standing near the lodge, cabin or RV camp area on a 10,000-acre ranch. It could show up anywhere in between, whether a busy suburb or remote rural country but still inside what’s considered the yard area.

Backyard bucks and does can often be creatures of habit due to the three things they need most: food, water, and shelter. They are also capable of adapting however they need for survival. Most city and urban areas have green belt areas for a variety of reasons with one being for the

benefit of wildlife. Deer adjust to these quickly.

Texas has no state law regarding the amount of acreage required to legally hunt. However, in 1933, a law was passed allowing each county to prohibit hunting on lots or acreage less than 10 acres in unincorporated areas of the county in a subdivision. A subdivision being defined as any land tract previously part of a larger tract. Contact your county government to ask about any restrictive ordinance. Some counties or developments require owning 10.1 acres to legally hunt. Shooting may also be regulated to archery only.

Ordinances are enforced by sheriff departments, not state game wardens. Be aware there are laws about projectiles crossing property lines. Your bullet or arrow cannot cross a property line without landowner permission which is best to have in writing before hunting. It is also illegal to shoot toward a residence.

A wounded animal or bird cannot be legally pursued onto

neighboring property without landowner permission. A game warden cannot authorize it, only the landowner can. Trespassing laws come into effect as well as potential criminal negligence with possibly other violations. Know your game laws. Use common sense and always keep safety in mind.

Many towns and cities have deer and exotic populations living among thousands of humans, pets, vehicles, and skyscrapers. It can be amazing, and quite tempting when it’s a trophy animal.

Every year, game wardens check out reports of a subdivision or park’s “pet” buck, suddenly missing from its normal routine. It may have been found dead or headless with reports of possibly “who done it.”

Social media plays a big role in helping solve cases due to photos posted of outstanding live backyard bucks. Some may say exactly where the buck is located. When found dead, reported missing, or rumors abound of someone taking it, game wardens often check the internet. A posted trophy kill photo may easily match live deer pictures. The same applies to game wardens checking local taxidermists with good photos.

As stated earlier, backyard bucks may be on small or large acreage. One may be known to all residents or park visitors, especially if someone is feeding them. Tom, a New Braunfels homeowner on a quarteracre, lines his driveway daily with protein feed just to watch the deer.

For three years now, an awesome 12-pointer has been a regular visitor. Tom and the neighbors landscaped with greenery deer don’t find palatable, thus he feeds to enjoy seeing and helping sustain the deer in his tight urban suburb. He’d like to put it on his wall but cannot legally do so.

A huge 3,200-acre Brazoria County development hosts an over abundant deer population. It’s not unusual to see 50 or more whitetails grazing or bedded anywhere on the property year-round. During deer season, homeowners may take backyard bucks and

does using bows only on their own property in an effort to help control deer numbers.

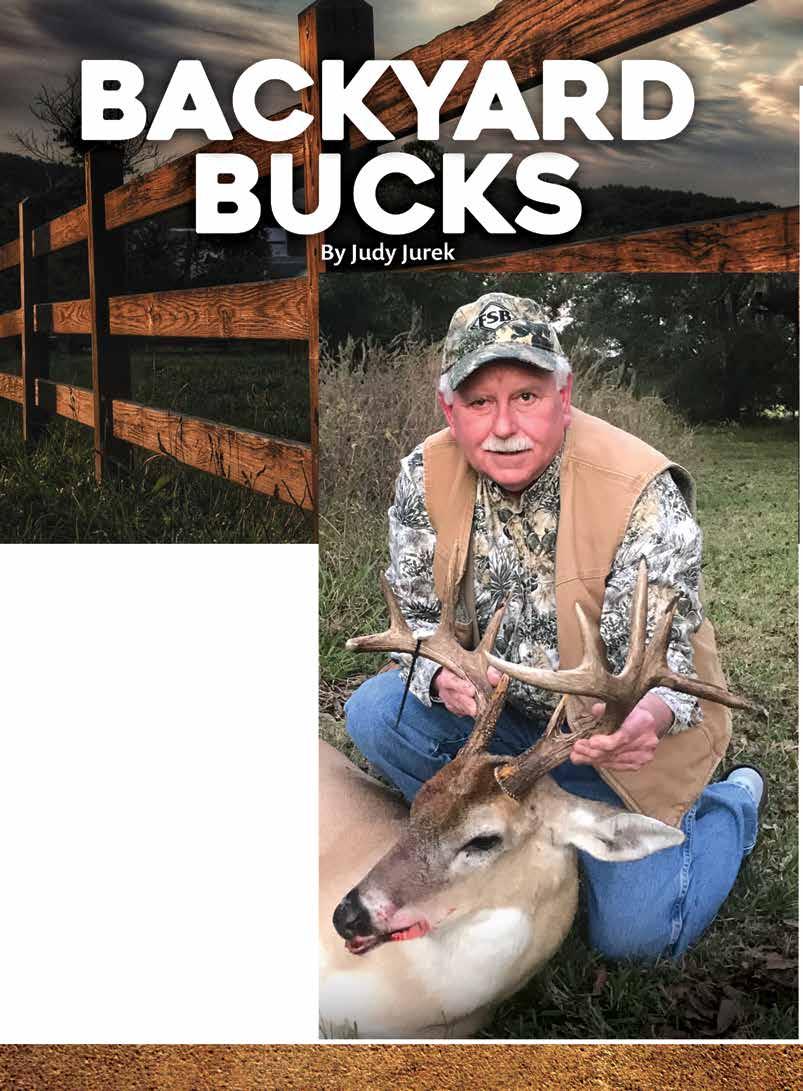

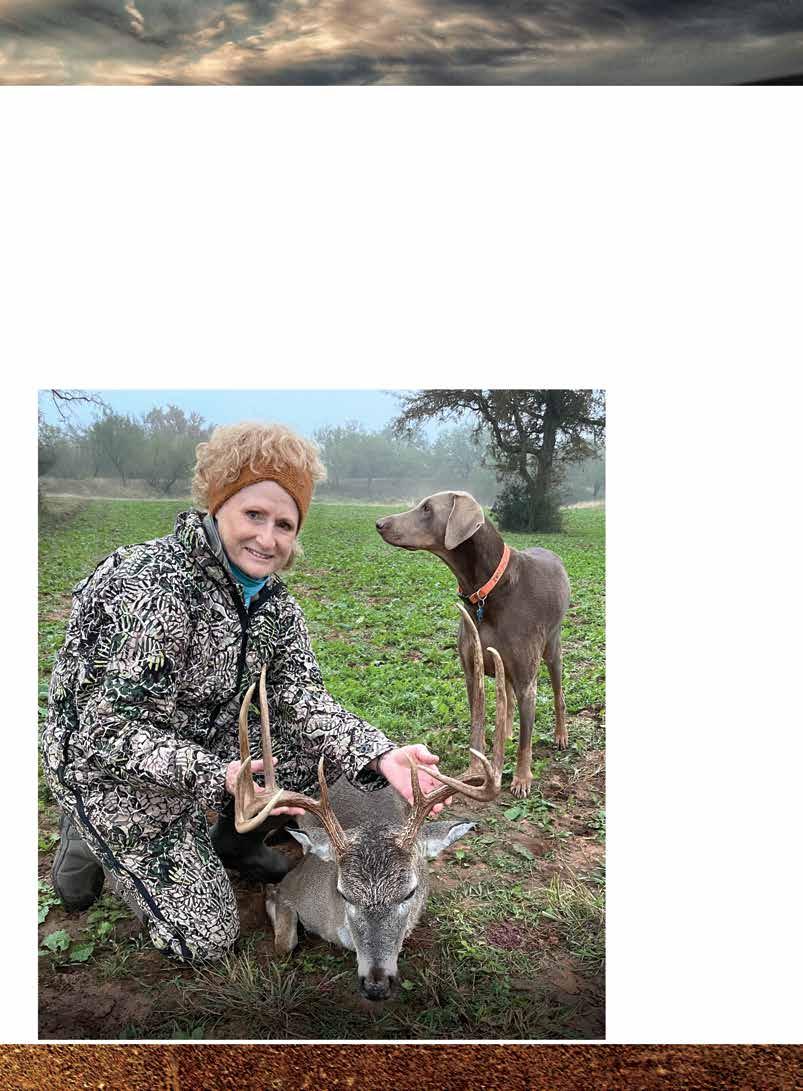

Veteran huntress Laura Berry was playing cards with a friend when a massive antlered buck appeared outside the ranch house. Berry was quick to get her rifle and add the buck to her always growing trophy room.

Jack and Johnice Anderson live on the Lakeway Air Park runway with no fencing. It’s not uncommon to see whitetail bucks and does in their backyard, as the deer are accustomed to airplane noise. In residing there for 34 years, few deer airplane incidents have occurred. Jack once landed on a deer, resulting in some damage to his plane, but the buck ran off apparently unscathed.

Val Verde County’s Riley family lives near the Devil’s River on a small tract. Mom Allison took a nice aoudad off the back porch. Dad Shon and two sons Jax and Sawyer have all taken backyard bucks while youngest son Ridge has hopes for one this season.

After years spent on a South Texas hunting lease, Charles Brookhouser took his best buck in his own backyard outside Van Vleck. He never expected to see a buck at his house worth shooting and mounting. The heavy typical 10-pointer sported an extra 5-inch tine straight off the main beam, more of a side tine than drop tine. His grandsons have benefited often hunting Charles’ 10 acres for both deer and varmints.

This writer took a nice typical 10-point on our Mills County 38 acres after seeing it several times from inside the house. It was dubbed the “Bedroom Window Buck” and featured in the July/August 2023 issue of The Journal. With binoculars at every window, my husband and I check feeders and look across the

This fine antlered backyard buck with kickers was well known in a rural Victoria County subdivision. Last season, a neighbor put it on his wall.

at deer and other wildlife all year long.

Backyard bucks, does, and even exotics, may be right in your backyard. Know your state game laws regarding legal hunting regulations. Be sure to check your county as well as your homeowners or property owners’ associations for ordinances and restrictions. Keep safety in mind at all times.

It’s also wise to know your surrounding neighbors in case you have a wounded animal. Remember, practice makes perfect for expert marksmanship for a quick, drop-in-their-tracks kill and no blood trailing. Keep your eyes open because you never know if a backyard buck might appear.

Igot my buck on the evening of Jan. 9, 2025, but the journey towards it began nearly 20 years ago when I met a friend named Larry. Larry and I were a part of the same church in Bradenton, Florida, and though there’s a gap in age, our love for God and the outdoors brought us together. Larry invited me to join him on a hunt at his brother’s ranch in South Texas. Having read about Texas hunting, I dreamed of experiencing it firsthand and assumed this bucket list hunt would be accomplished in retirement.

Little did I know this once-in-a-lifetime trip would happen in my early twenties and then become an annual hunt for close to two decades now. While I thought moving to Florida to become a youth pastor meant sacrificing my desire to hunt, it led to some of the best hunting and finest experiences of my adult life. To this day, that sandy soil in the South Texas brush country serves as a reminder of God’s goodness and the generosity of His people.

For many years, the focus has been on hogs, coyotes, does, and wily, old eight-point bucks. Finding a deer with those iconic chocolate-colored antlers, distinctive to South Texas, has been deeply satisfying. Over the years, my longtime friend Andy and I have made it a goal to find a unique management buck together, and we’ve made some great memories along the way.

Going into the hunt this year, Larry shared with Andy and me that one of us would have the opportunity to pursue a trophy buck. Knowing there were some nice bucks on the

ranch, Larry’s request was that the buck be special and, if possible, 160 inches or bigger. The ranch certainly has impressive deer, but with limited time and intel, seeing it all come together would be no small task.