uly 3 to August 11 are this year’s “dog days” in Texas. The flowers that bloomed in spring are beginning to wither in the summer heat. The big turkeys that gobbled their mating calls in March and April are silent. Cold blooded animals such as snakes, alligators, lizards and frogs may be the only critters in Texas that enjoy the hot weather. As a kid, I always looked forward to summer because we all took off our shoes until school started in September.

Many Texans enjoy early summer by celebrating Independence Day, which was declared a non-paid holiday in 1870, along with Christmas and New Year’s Day. In today’s world, a lot of holiday revelers don’t know why they celebrate July 4, so a brief history may be in order.

The 13 British Colonies of 1607, on the Atlantic Coast of North America, had gotten away from Henry VIII’s Church of England and heavy taxation, but were still burdened with British rules and new taxes. The colonies decided to break away from King George III and Parliament and form their own government as the 13 United Colonies, later to be known as the 13 United States.

In June 1776, Thomas Jefferson drafted a Declaration of Independence, and presented it to the Second Continental Congress for approval. The American Revolution against England had already started, and on July 2, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was adopted, but was not officially signed by the 56 delegates until Thursday, July 4. The British Parliament received the Declaration in November 1776, but the Revolutionary War was not over until 1783.

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, important signers of the Declaration, both died on July 4. In 1870, a non-paid holiday was declared for Independence Day, along with Christmas Day and New Year’s Day. All of these dates were made national holidays by the U.S. Congress in 1939 and 1941. Another note: The “Star Spangled Banner,” which was the American flag with 15 stars and stripes that flew over Fort McHenry in 1814 to signal victory over the British, was the basis for Francis Scott Key’s poem, inspired by the Battle of Baltimore. The poem, in song, was adopted as the National Anthem of the United States in 1931.

So, when you celebrate July 4 this year, or sing the National Anthem, think of the history of the dates—the end of control by the British Empire, and the beginning of the United States of America.

We’ve come a long way since July 4, 1776. We’ve had war with the British in 1812; the Alamo in 1836; the Mexican-American War in 1846; and the war between the North and South over cotton and slavery in 1861. Then there were the Plains Indian wars; the Spanish American War; World War I; World War II; Korean War; Vietnam War; Iraq; and Afghanistan. Now, we are facing a possible conflict with China over the sovereignty of Taiwan. It appears wars will continue to be a part of the price we pay for freedom in America.

Meanwhile, the “dog days” are coming, but a shade tree will give some relief. Some say the wheel was our greatest invention, but air conditioning might be a close second! For sure, we must endure two hot months, so go fishing or shoot a few clay birds and get ready for dove season. Think of the cooler days of autumn when hunting seasons begin. Hallelujah!

July/August

www.ttha.com 700 E. Sonterra Blvd, Suite 1206 San Antonio, TX 78258 210-523-8500 • info@ttha.com

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher

Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer Christina Pittman 210-729-0993 • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Executive Editor Deborah Keene

Associate/Online Editor Martin Malacara

North Texas Field Editor Brandon Ray

East Texas Field Editor Dr. James C. Kroll

Hill Country Field Editor Gary Roberson

South Texas Field Editor Jason Shipman

Coastal Plains Field Editor Will Leschper

Southwest Field Editor Jim Heffelfinger

Field Editor At Large Ted Nugent

Graphic Designers Faith Peña

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers

Jason Barrett, Bob Bauml, Jason Clayton, John Geiger, Clinton Goodpaster, John Goodspeed, Judy Jurek, Lee Leschper, Megan Luna, Andy Stephenson, Ralph Winingham

Sales Representative Emily Lilie 713-389-0706 emily@ttha.com

Advertising Production

Deborah Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

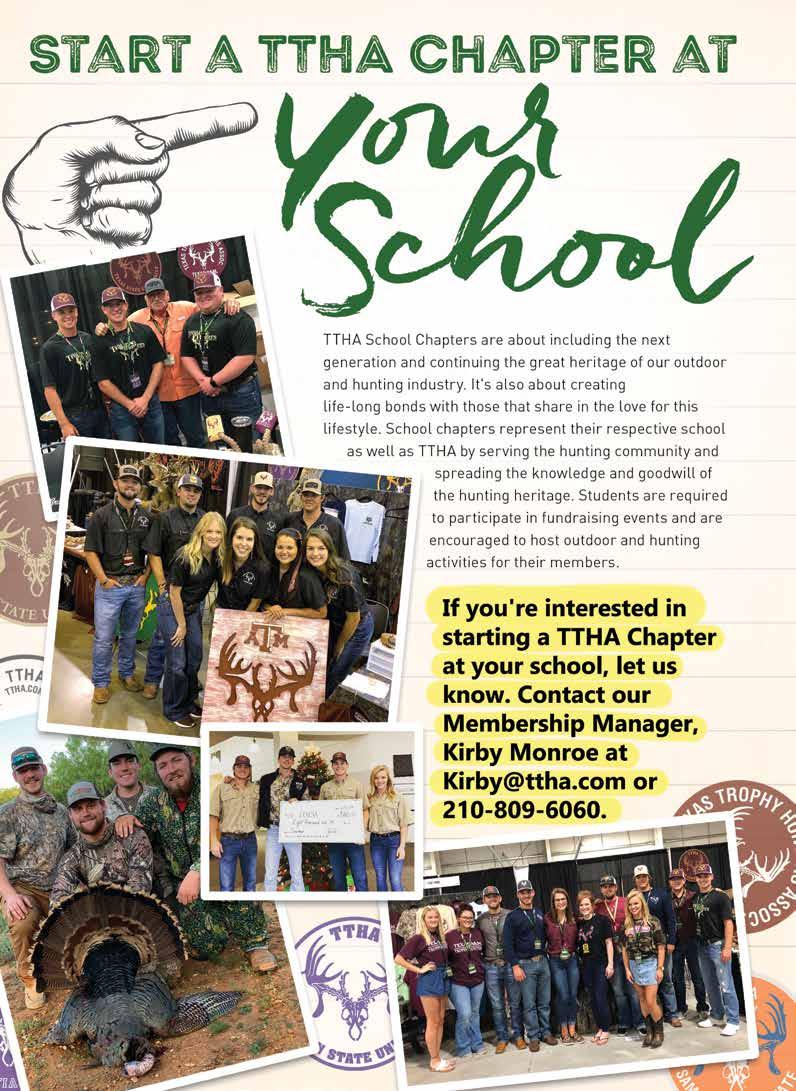

Membership Manager Kirby Monroe 210-809-6060 kirby@ttha.com

Director of Media Relations Lauren Conklin 210-910-6344 lauren@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

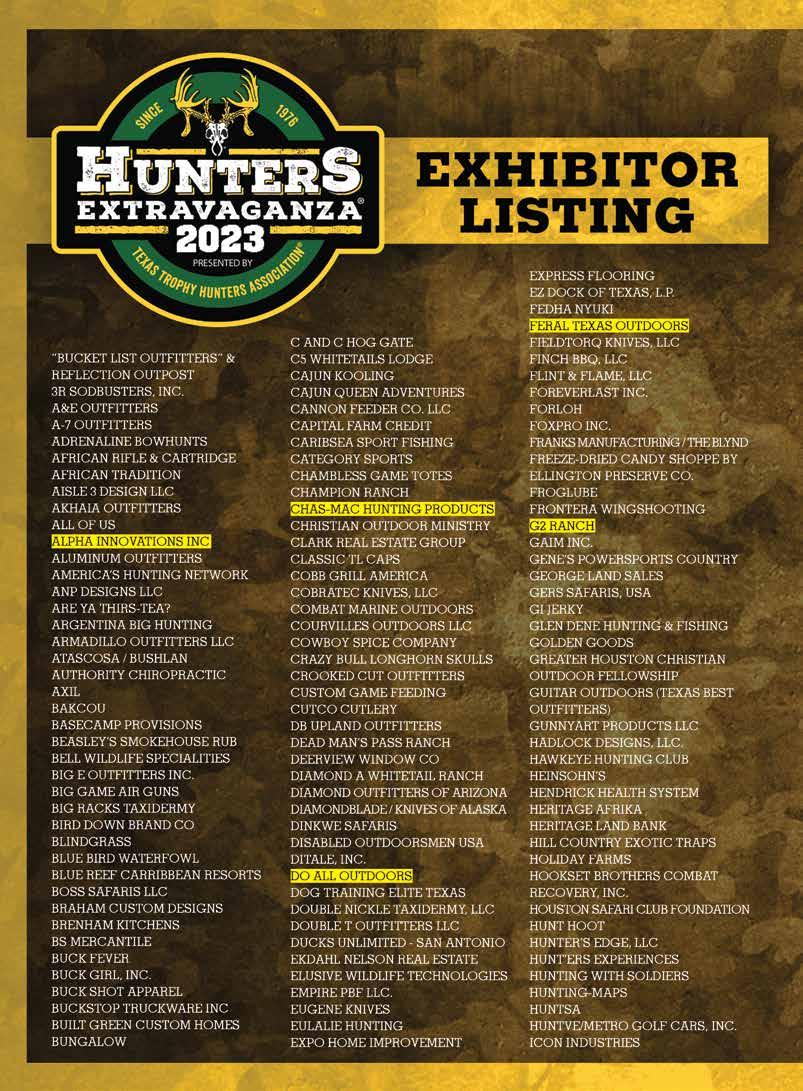

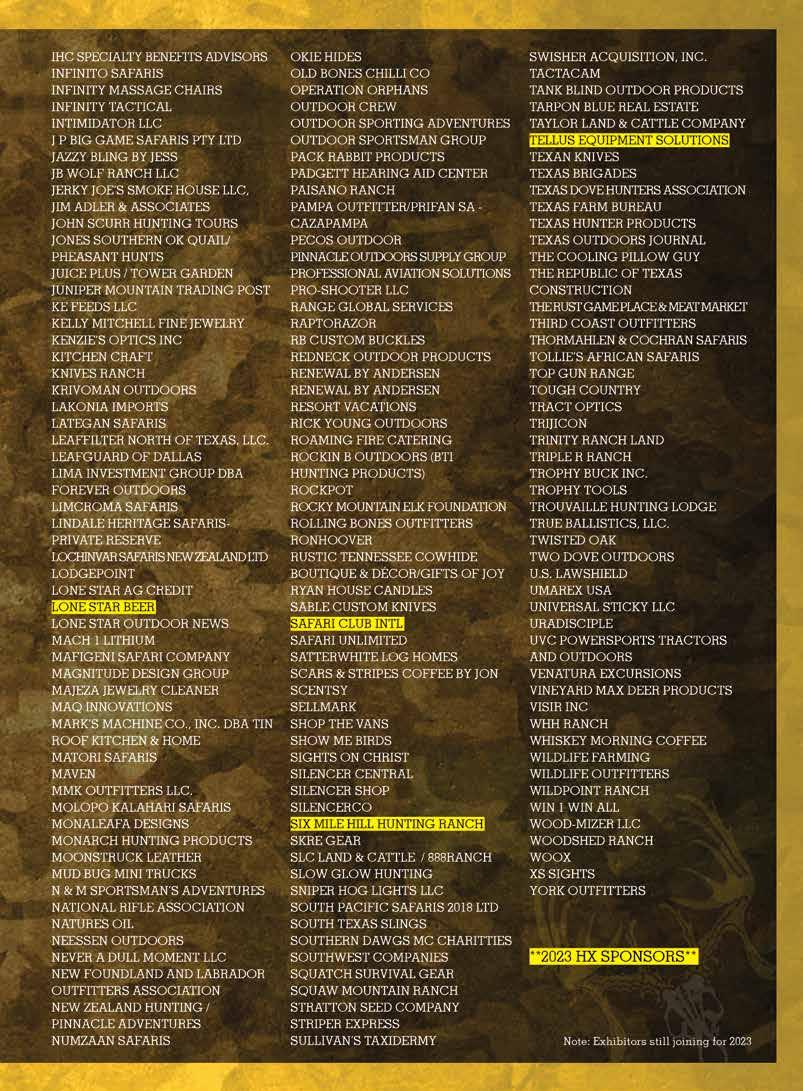

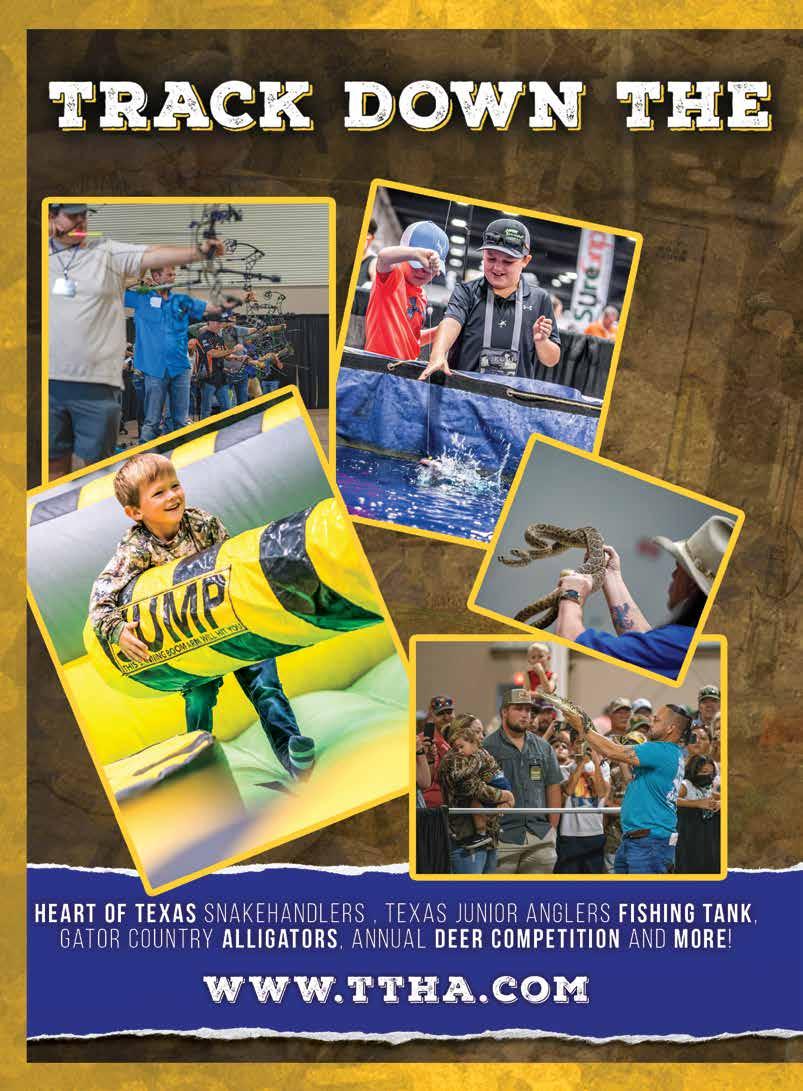

TTHA protects, promotes and preserves Texas wildlife resources and hunting heritage for future generations. Founded in 1975, TTHA is a membership-based organization. Its bimonthly magazine, The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters®, is available via membership and newsstands. TTHA hosts the Hunters Extravaganza® outdoor expositions, renowned as the largest whitetail hunting shows in the South. For membership information, please join at www.ttha.com or contact TTHA Membership Services at (877) 261-2541.

| By Jason Clayton

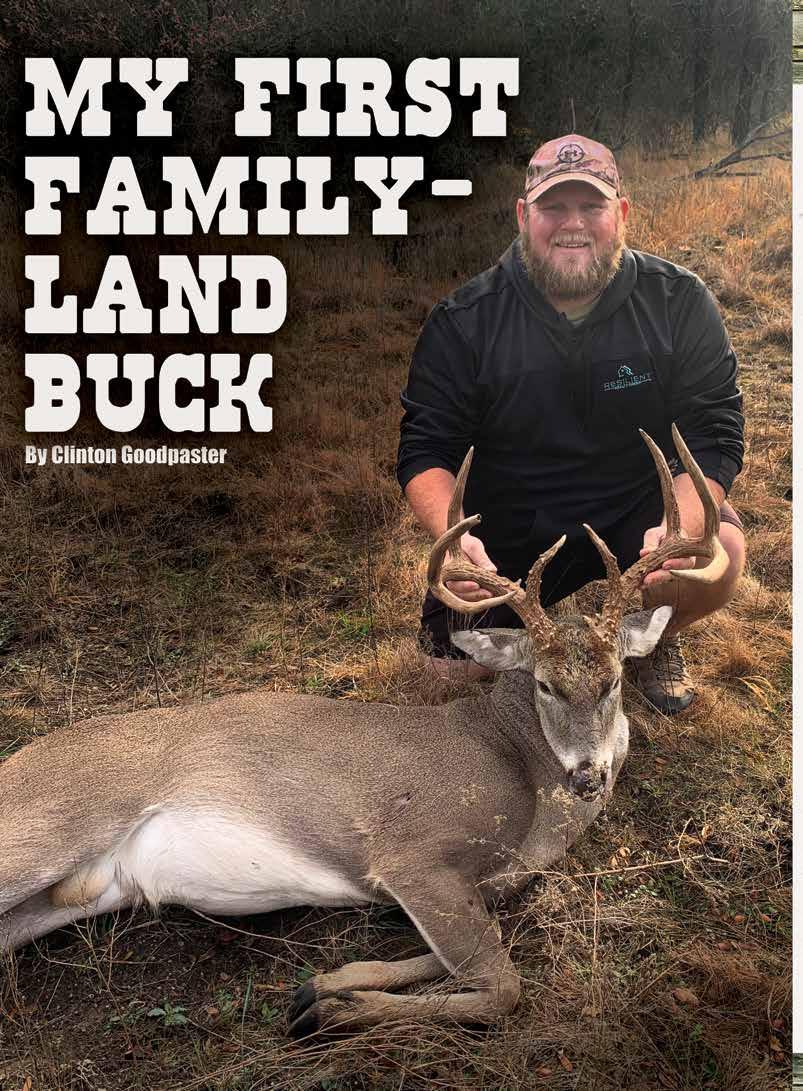

| By Clinton Goodpaster

| By Bob Bauml

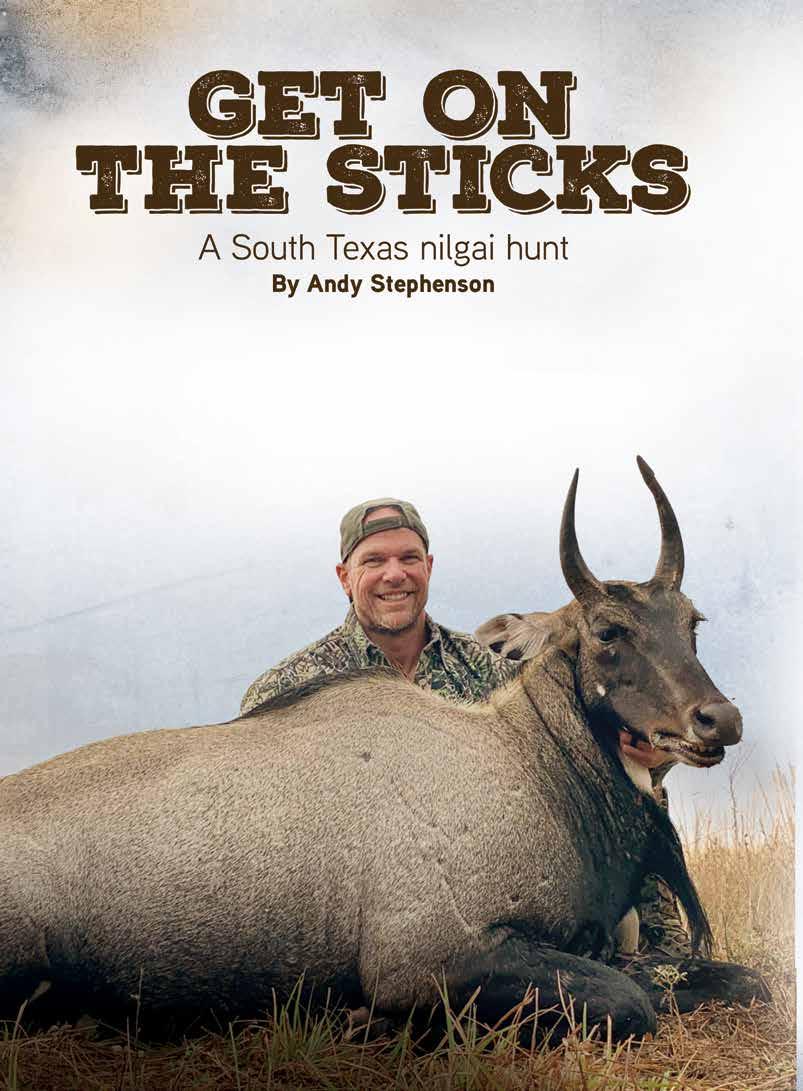

| By Andy Stephenson

accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope or return postage, and the publisher assumes no responsibility for loss or damage to unsolicited materials. Any material accepted is subject to revision as is necessary in our sole discretion to meet the requirements of our publication. The act of mailing a manuscript and/or material shall constitute an express warranty by the contributor that the material is original and in no way an infringement upon the rights of others. Photographs can either be RAW, TIFF, or JPEG formats, and should be high resolution and at least 300 dpi. All photographs submitted for publication in “Hunt’s End” become the sole property of the Texas Trophy Hunters Association Ltd. Moving? Please send notice of address change (new and old address) 6 weeks in advance to Texas Trophy Hunters Association, P.O. Box 3000, Big Sandy, TX 75755-9918. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, Texas Trophy Hunters Association, P.O. Box 3000, Big Sandy, TX 75755-9918.

TTHA member Natalia Reyes competed in her first national Archery Shooters Association Pro AM 3D tournament in Minden, Louisiana. The 10-year-old placed 4th in her class. She will compete in another national tournament in August. Meanwhile, she’s preparing for the 2023 Texas ASA State Championship in July. We wish her the best!

Lee Leschper (left) and Ralph Winingham participated at the annual Shoot for the Heart fundraiser for August Heart, a San Antonio nonprofit that has provided free cardiac screening for more than 62,000 high school athletes, to identify potential fatal and undiagnosed heart conditions. They have found more than 400 kids with potential heart issues, and undoubtedly saved some. Doré and Bart Koontz, the parents of 18-year-old athlete, August Koontz, who died in his sleep from an undiagnosed heart condition, founded the organization. Visit augustheart.org/ story/ to learn more.

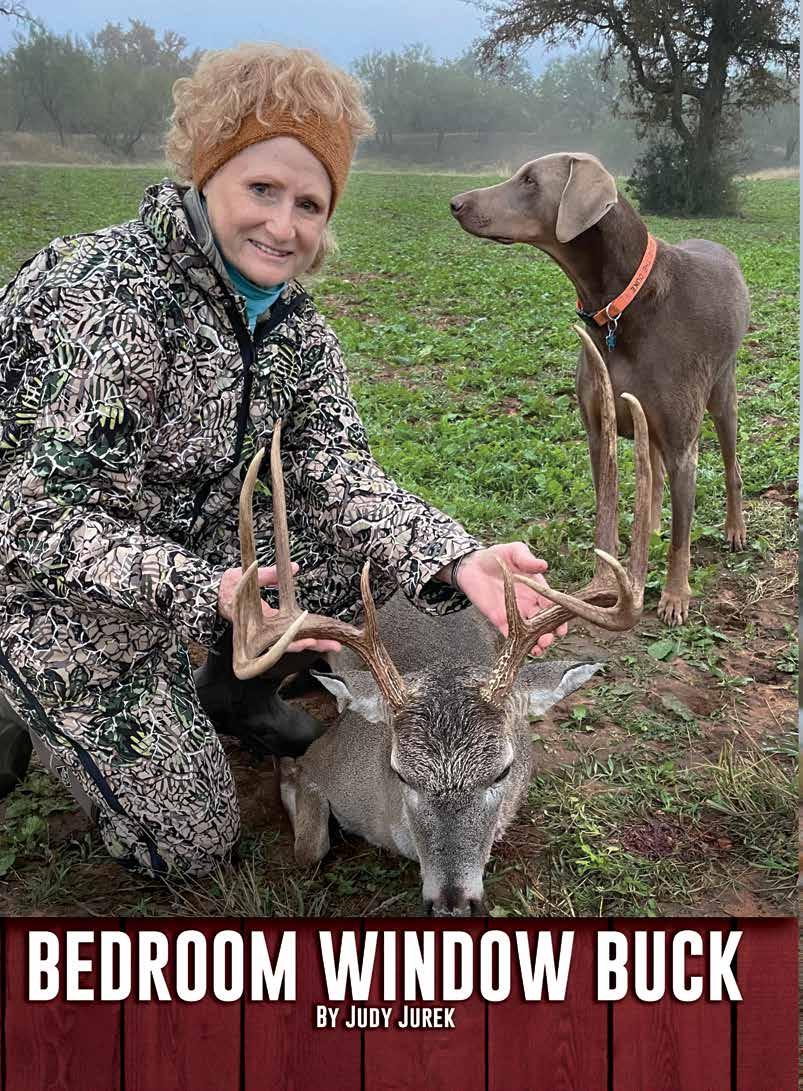

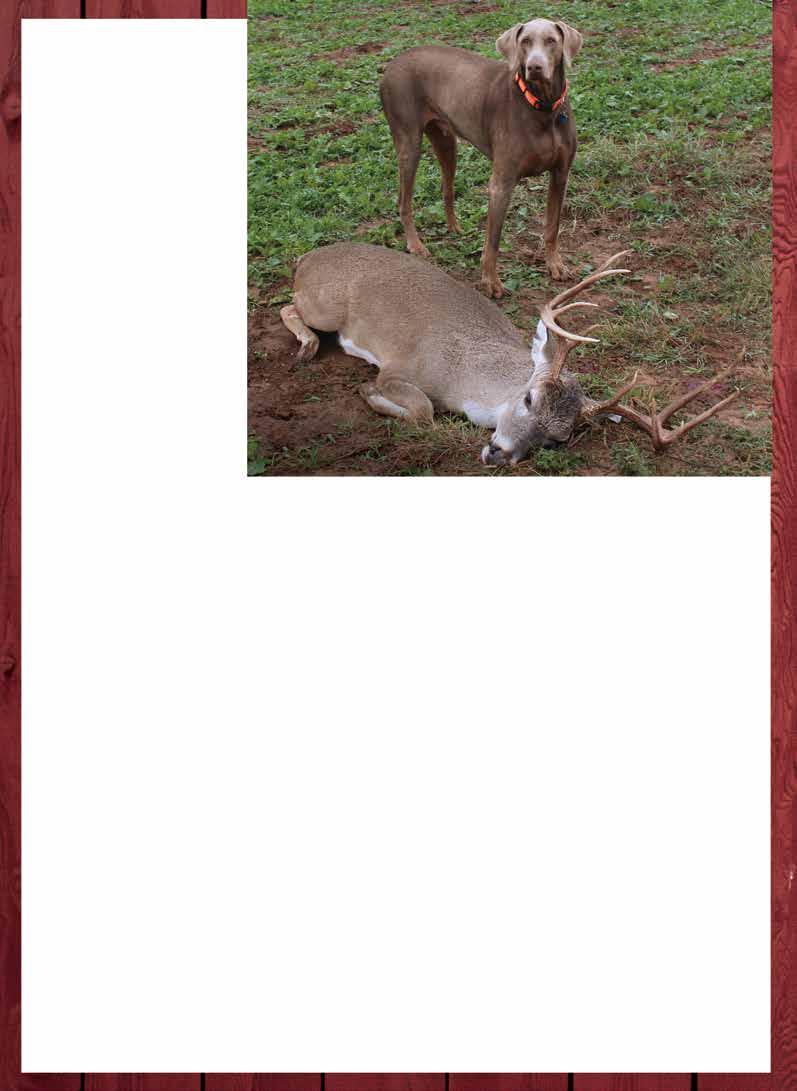

Judy Bishop Jurek is a pioneer of our hunting heritage. A longtime huntress and outdoor writer, Judy was raised in a hunting atmosphere, with her father and mother hunting deer, doves, and other Texas game. One of Judy’s first rifles was a .300 Savage with iron sights, handed down from her mother.

Judy was born in a farm family at Bay City, Texas, and raised prize cattle and showed appaloosa and quarter horses. “I had a sister, but I was daddy’s “tomboy” helper in raising livestock and in the shop,” she said. “I was always outdoors doing chores or helping where I could.”

Judy graduated from Bay City high school, and before long was married to a local farm boy, John Jurek. John is a hunter, and soon Judy was in deer camps or shagging doves. She loved the outdoors, and was soon hunting right alongside John. I have known both Jureks for over 30 years, and hunted with them on several occasions.

Back in the day, ladies were not so welcome in deer camps as they are today. John and Judy had to hunt by themselves, or be on a husband-wife lease. “I couldn’t find hunting clothes that fit me, but I managed to find appropriate outfits and boots,” Judy recalled. “Us [sic] gals were out of place at most hunting camps.”

Judy had several jobs around Bay City, but worked at Williams Energy for 26 years. After her long stint with Williams, Judy kept busy through the years, taking care of the house, cattle, and writing for newspapers and magazines. She became a member of Texas Outdoor Writers Association and eventually became a regular writer for The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters. In the meantime, She and John hunted South Texas for big whitetails, and Judy hunted axis deer and nilgai on occasion. Both Judy and John sported .300 Weatherby rifles, and were

hunting almost year-round for whatever was in season.

“I think I have written for every magazine with ‘Texas’ in their name,” Judy said. “I first wrote for The Journal in 1996, after John and I both killed 12-point bucks. Those were my first two stories as a Staff Writer.” Since then, Judy has been a regular contributor to The Journal

Judy is primarily a deer-hogdove hunter, but she got into exotics when she was asked to take an axis buck for the Texas Trophy Hunters TV show. After the axis hunt, she took a couple of nilgai on the King Ranch. Of course, the .300 Weatherby came in handy on the tough nilgai. Another unusual hunt was an invitation to bear hunt in Manitoba, Canada. “I like to eat what I kill, and I was not into bear hunting,” Judy recalled. “I turned down the hunt two times, but finally gave in.” The bear hunt on a concession in Manitoba was free, and Judy killed a black bear. “I didn’t care that much about killing a bear,” she said. “But I was hunting and I knew people back in Texas would ask about the hunt. So, I borrowed a 7mm-08 and brought back a bear cape and skull for mounting.”

Judy has had a .223 AR-15 platform rifle for many years. When she and John lived at Markham, and had a big herd of cattle, they carried the .223 for coyotes and hogs in the cow pastures. After hunting for years with the .300 Weatherby, Judy has now turned to the .223 for close range shots at deer and hogs.

In 2022, she took a big buck from her Mills County backyard with a neck shot from the little rifle. “That was my best buck in several years,” said Judy. The 10-point buck was old—one side of the

jaw showed 6½ and the other showed 7½. He had been injured on one hind leg, and the left antlers were slightly better than the right, but he was an excellent trophy buck.

Judy and I reminisced about the many years we both have hunted, and she remarked, “Things have changed so much since I started hunting. I remember going to the Houston Extravaganza in about 1978, and there were only four or five women at the whole show. Now, the crowd may include one-quarter or onehalf women at a given time.” Yes, many more females—old and young—hunt today. For women who have learned to shoot a shotgun, doves and turkey are exciting hunts. Today’s deer hunters include a lot of females, as shown by the big and little girls who bring bucks to the Hunters Extravaganza deer contests.

The hunting years have been good to Judy. She has promoted all manner of hunting through her writings in newspapers, various magazines, and especially The Journal. I know a lot of women in Texas who are expert hunters, and Judy is one of them. Her contributions to the sport of hunting and getting outdoors to enjoy the wilds of Texas makes Judy a pioneer of our hunting heritage.

Due to an unfortunate error from the printing press, page 108 in the May/ June issue of The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters has an incomplete photo of Eric Stanosheck’s Coues deer. We strive to produce a quality magazine for everyone to enjoy. But sometimes due to circumstances beyond our control, the high mark gets missed. We apologize to our readers, our members, and Mr. Stanosheck.

Even though it’s the middle of summer, it’s not too late to partake in the 100th anniversary of Texas State Parks. Events at state parks will occur throughout the year to help celebrate. Visit tpwd.texas. gov/state-parks to find listings of events hosted at state parks.

According to the Texas Parks and Wildlife website, Texas State Parks began in 1923, and has been dedicated to protecting the best parts of Texas’ vast natural and cultural beauty. Originally envisioned as a series of roadside stops for highway travelers, the Texas State Park system has grown to a network of parks, historic sites and natural areas that welcome millions of visitors every year. In 1923, Gov. Pat Neff appointed a Texas State Parks Board to begin locating sites for the establishment of a state parks system. In 1933, President Roosevelt charged the National Park Service to lend their services as part of his New Deal program.

The Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) built Texas’ park infrastructure, putting out-of-work Americans back on

the job. Texas State Parks transformed from a handful of undeveloped properties into a robust system of over 50 parks. Texans added camping, fishing, and hiking to their family traditions. Popular parks like Palo Duro Canyon, Garner, and Balmorhea were built by the CCC. While soldiers fought in World War II, Texas women kept parks operating. This opened the doors of change, elevating the roles of women in the workforce as leaders. Before the Civil Rights Act of 1964, African American citizens near Tyler and Bastrop State Parks successfully advocated for access to parks, regardless of the color of someone’s skin.

By the 1980s, parks were stretched to capacity. Thanks to significant public support for additional parks, the legislature expanded the system dramatically. Texans were becoming aware of the importance public lands played in maintaining a healthy environment. Parkland was acquired and managed to protect their habitat, uniqueness, and geological forms in order to preserve the land and the experience. Over 30 parks opened during this time, many protected for their unique resources, including Big Bend Ranch, Seminole Canyon, and Enchanted Rock.

Today over 630,000+ acres are devoted to Texas State Parks. Although Texas’ park system has expanded significantly in the last 100 years, 95% of Texas is still privately owned. This makes public land in Texas a precious resource for people and wildlife. Every inch of Texas public land is a seed of hope for future generations. —courtesy TPWD

The bipartisan Recovering America’s Wildlife Act (S. 1149) was reintroduced in the Senate by Congressional Sportsmen’s Caucus Members Sens. Martin Heinrich of New Mexico and Thom Tillis of North Carolina in late March. This legislation is a longstanding priority for the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation (CSF), which has served as a driving force behind Recovering America’s Wildlife Act since its conceptual stages in 2015.

Through their State Wildlife Action Plans, which serve as unique roadmaps to each state’s conservation needs, state fish and wildlife agencies have identified nearly 12,000 species identified as Species of Greatest Conservation Need (SGCN). These 12,000 Species of Greatest Conservation Need include many iconic species ranging from bobwhite quail, big horn sheep, monarch butterflies, to brook trout and arctic grayling. To address the conservation challenge facing these 12,000 species, the Recover-

ing America’s Wildlife Act seeks to provide approximately $1.4 billion annually to state, territorial, and tribal fish and wildlife agencies to proactively conserve SGCN before more costly and regulatory measures, such as listing under the Endangered Species Act may be necessary. Combined with a 25% non-federal match, Recovering America’s Wildlife Act would empower states to fully implement their State Wildlife Action Plans.

The Recovering America’s Wildlife Act was first envisioned in 2015 by the Blue Ribbon Panel on Sustaining America’s Fish and Wildlife Resources, which CSF served on as a leading group. Today, the Blue Ribbon Panel is represented by the Alliance for America’s Wildlife Act – a broad coalition working to advance Recovering America’s Wildlife Act. CSF President and CEO, Jeff Crane, has served as the legislative co-chair of the Alliance and the Blue Ribbon Panel since the concept of Recovering America’s Wildlife Act was first developed.

CSF thanks Senators Heinrich and Tillis for their continued support of fish and wildlife conservation as well as sportsmen and women through the reintroduction of Recovering America’s Wildlife Act. CSF looks forward to working with members of the Congressional Sportsmen’s Caucus, including Senators Heinrich and Tillis, to see a bipartisan, bicameral Recovering America’s Wildlife Act signed into law. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

Attendees of the 88th North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference, which wrapped up in April in St. Louis, got the first look at the results of the Hunting License Sales 2021-2022 report that documented a 3.1% decline in hunting license sales in 2022.

“We continued to track hunting license sales as one indicator of participation, and our results indicate that the impacts of COVID on getting people outdoors may be waning,” said the Council’s Director of Research and Partnerships, Swanny Evans, as he addressed the Hunting and Shooting Sports Committee

in St. Louis. “Hunting license sales are settling back to pre-pandemic levels.”

The study was a follow-up to the past two years’ Council to Advance Hunting and the Shooting Sports studies that documented a 4.9% increase in hunting license sales from 2019 to 2020 (otherwise known as the COVID-Bump) and a 1.9% decrease the following year from 2020 to 2021.

To continue monitoring sales trends in the wake of the pandemic impact, the Council revisited this study in early 2023 to identify ongoing changes and emerging trends in hunters’ rates of license purchases. Working with Southwick Associates, the Council collected monthly resident and nonresident hunting license sales data from 46 state wildlife agencies to quantify and compare 2022 to 2021 sales.

Among the 46 reporting states:

• Overall, hunting license sales decreased by approximately 3.1% in 2022 compared to 2021. Coincidentally, resident and nonresident license sales each were also down 3.1%.

• Just six of 46 states saw an overall increase in the number of licenses sold in 2022 compared to 2021.

• License sales were down overall in each of the four geographical regions (Northeast, Southeast, Midwest and West), with percentages ranging from -2.4 to -4.8%.

• The only months that saw overall increases in license sales – and slight ones at that – were February, and September.

• The surge in nonresident license sales seen in 2021 receded in three of the four geographical regions, with the only increase seen in the Northeast.

The report, which provides the most representative data on the current state of hunting license sales nationally and regionally, can be accessed on the Council’s website: cahss.org/our-research/ hunting-license-sales-2021-2022.

— courtesy Council to Advance Hunting and the Shooting Sports

Sen. Steve Daines

In late April, Congressional Sports -

men’s Caucus Member Sen. Steve Daines (R-Montana) reintroduced the Protecting Access for Hunters and Anglers Act, a bill to support the use of traditional ammo and tackle by sportsmen and women. This legislation is strongly supported by the Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation (CSF).

Specifically, the Protecting Access for Hunters and Anglers Act prohibits federal land management agencies such as the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Forest Service from instituting any restrictions on lead ammunition and tackle unless three triggers are met. First, any claims indicating a decline in wildlife populations at a specific unit of land where lead ammo and tackle is being restricted must be substantiated through field data from that unit. Additionally, the Protecting Access for Hunters and Anglers Act requires that any restrictions on lead ammo and tackle be consistent with the regulations of the impacted state fish and wildlife agency. Finally, the respective state fish and wildlife agency must concur with the need for regulation.

CSF maintains that any decision that seeks to limit the use of traditional ammo and tackle must be rooted in a scientific process, rather than emotional perception. The use of lead ammunition and fishing tackle should not be restricted by any arbitrary decisions that lack scientific justification. Additionally, non-lead ammunition and tackle options are often cost-prohibitive and not widely available, and as the markets have shown (primarily for ammunition), supply is still struggling to meet demand. Lastly, the inability to locate non-lead options, especially those that are reasonably affordable, has the potential to stave off participation, which in-turn may result in a loss of revenue for state fish and wildlife agencies through the American System of Conservation Funding.

CSF will continue to work to protect the use of traditional ammo and tackle for sportsmen and women. CSF will ensure that any efforts to restrict the use of lead ammo and tackle follow a science-driven process and have the sup -

port of the impacted state fish and wildlife agency, the entity best positioned to manage fish and wildlife. —courtesy Congressional Sportsmen’s Foundation

The Sables Education Programs are changing, but the mission remains the same. SCI Foundation and the Sables are committed to reaching educators, wildlife professionals, federal and state elected officials and others to educate them about the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and the impor tance of hunting as a socially and culturally acceptable activity. To do this, we are developing new programs that build upon the tradition of excellence established by the American Wilderness Leadership School in Wyoming. These programs include:

Inform educators, non-governmental organizations, corporations, state agency personnel and others about the role of hunting in conservation and society by bringing our message to them wherever they are. We will rely on partners and sponsors to implement custom programs that meet their needs. This can include American Wilderness Leadership School programming and more.

Working with SCI Government Affairs staff, provide educational programming and outdoor activities for federal and state legislators and their staff so that they are familiar with the North American Model and the economic, cultural and management importance of hunting in the United States. The first iteration of this program was successfully implemented in August with six U.S. representatives and 24 staffers in Montana.

More and more Americans now get their news and information from social media sources, including social media personalities (influencers and brand ambassadors). SCI Foundation will use the platforms and experiences of these

individuals to build social acceptance of hunting among young people.

Colleges and universities are key places to access younger generations and educate them about the role of hunting within the North American Model of Conservation. SCI Foundation will partner with university programs to bring our message to tomorrow’s leaders.

As the programs listed above are implemented, we will be monitoring their impact and costs. This gives us a chance to assess interest in this new approach, evaluate our curricula’s impact and reach, and determine the real cost. As with any program, we will be monitoring the results and adjusting, if needed, to reach the younger generations and pass on the importance of conservation and how hunting benefits land and wildlife conservation.

Opportunities to sponsor or partner with SCIF are available and critical to continuing to have an impact through these programs. SCIF staff will work with partners and sponsors to develop curricula specific to your location and important issues. Program length and content can vary, depending on your needs. We will also work with partner organizations to find suitable locations to host various events.

Please contact SCIF or Assistant Education Director Todd Roggenkamp at (520) 954-0664 or troggenkamp@ scifirstforhunters.org to learn more about these programs. All of our education programs rely on the interest and support of individuals, foundations, corporations and other conservation organizations.

—courtesy Vicky Swan, Sables president

SCI has been busy around the nation advocating issues important to its members, as well as all outdoor enthusiasts. Here’s a quick list:

Colorado: SCI joined two comment letters in support of Senate Bills 255 and 256. SB 255 would create a wolf depredation compensation account and SB 256 would prevent the reintroduction of gray wolves without a federal Endangered

Species Action Section 10(j) designation.

Florida: SCI encourages support of Senate Joint Resolution 1234 and House Joint Resolution 1157 propose to preserve in perpetuity hunting and fishing as a public right and preferred means of responsibly managing and controlling fish and wildlife.

Montana: SCI issued an action alert to Montana members regarding supporting HB 372, the constitutional right to hunt, fish and trap amendments.

New York: New York chapters signed onto letter supporting the “Make the Youth Deer Hunting Program Permanent” in the budget which builds off of a precedent set by the 2021 budget that expanded opportunities for junior hunters and would permanently authorize 12- and 13-year-old hunters to pursue deer with a firearm or crossbow when supervised by an experienced adult hunter.

Oregon: SCI joined a coalition letter in opposition to Senate Bill 348, regarding legislation that would require an expensive and exhaustive permitting process for the lawful transfer or firearms, impose a 3-day waiting period on firearm purchases, impose training requirements on Oregon’s law-abiding hunters and recreational shooters, restrict firearm purchases for Oregon’s youth hunters under 21 years of age, and restrict standard capacity magazines commonly found in the hands of hunters and recreational shooters.

SCI also joined a coalition comment letter in opposition to House Bill 2006, regarding restricting persons under the age of 21 from possession firearms and creating an obvious barrier to recruiting new hunters.

SCI issued an action alert to Oregon members regarding supporting House Bill 3086 with the -4 amendment, which would change the membership of the Fish and Wildlife Commission from a congressional district representation model to a watershed representation model.

Washington: SCI joined a coalition letter in opposition to House Bill 1143. HB 1143 would require a 10-day waiting period for firearms purchases and create new training requirements on Washington’s law-abiding hunters and recreational shooters. —courtesy SCI

In my first article (March-April 2023 Journal) I discussed how a growing movement exists for management of wildlife on private lands, spearheaded by families returning to either family land or acquiring new land on which to develop a family heritage of wildlife conservation through management. The real future of game conservation lies squarely in the hands of the private landowner, since government lacks neither adequate funding, nor the interest in land management. You do not have to be part of the “landed gentry” to become a wildlife manager, rather just willing to invest what you can in making a piece of land of any size better than you found it.

My second article (May-June 2023 Journal) highlighted what Jason and Stephany Woods and their family do to turn a leased property into a white-tailed deer factory and wildlife paradise. Working closely with a landowner who fully understands the commitment they are willing to make on another person’s land has indeed created a place where generations will reap the benefits of their hard work.

To quote Aldo Leopold: “Actually, game administration in this country has so far concerned itself almost entirely with two things: regulating abuses by the exercise of its police powers, and attempting to practice management on private lands without the co-operation of the owner. The latter attempt is bound to fail in the long run, because government cannot control environment on lands which it does not own.”

In this article, I will present an example of a family who purchased land in an area not yet thought of as a deer hunting mecca. Oklahoma is experiencing a modern-day land rush by families wanting to work a small piece of the Lord’s country.

Todd Waddle’s family recently purchased a half section—320 acres—of land in eastern Oklahoma, for the sole purpose of developing a family heritage focused on land stewardship, hunting and outdoor recreation. On the surface, their new land did not have the trappings of a game-rich property. Lying in a rural area of Oklahoma, the property had been managed for cattle, rather than deer. The

official ecological regionis the

In this area, Todd Waddle is planting brush species such as red cedar, Chickasaw plum, blackberry and sumac, with an outer edge of switchgrass.

northern extension of the Cross Timbers running north to south out of Texas. About a third of the area was “useless” because it is seasonally flooded. The woodlands in the uplands were mostly dominated by young, extremely dense stands of non-mast producing hardwoods that provided little in the way of wildlife food. The upland portions of the property consisted of over-grazed pastures, intersected by hardwood drainages and young stands of eastern red cedar. Remember, the Waddle family were faced with converting a cattle operation to wildlife habitat. Another challenge was the property was bordered on two sides by a public road that, shall we dare to say, encouraged visits by the hunting “night crowd.”

We began working with them here at the Institute after they attended one of the Dr. Deer’s Whitetail World Field Days a couple of years ago. Todd asked us to come to Oklahoma, and see what could be done. As with many of the new landowners we meet, there was no doubt he and the family had the will and enthusiasm to invest money and “sweat equity” in carrying

out our recommendations. Their “wildlife management staff” included the parents, the kids, some family relations and good friends—all dedicated the cause.

The first step was to take advantage of the wooded drainages which, if improved, could provide the main travel corridor across and around the property. As is traditional with the area, cattle were allowed in woodlands, devastated understory shrubs and herbaceous plants. Once cattle were removed, we

started thinning the drainage woodlands to allow sunlight to reach the understory. We also added edge species such as blackberry, dewberry, wild plum, sumac, honeysuckle and greenbriar; with an outer layer of switchgrass and gama grass.

Water is critical to deer management, and we recommended developing water in at least 80 acres of the property—including small ponds and artificial water. Food plots, both cool and warm season, were developed for at least 5% of the property. The original food plots were poorly developed and not planted to the most useful species and varieties. They also were underfertilized, so we recommended a soil analysis. Our standard for that part of the world is a cereal grain such as cold-hardy oats in the uplands and clover, chicory and oats in the lowlands.

Cover is critical for deer management, and a well-placed summer and winter thermal component helps hold deer on the property. We plant or encourage eastern red cedar for winter thermal and thinning hardwoods in the bottoms for summer thermal. The Waddles use both bulldozers and mulchers to create summer thermal cover and native foods in small patches in the bottomlands. The best way to deter folks seeing into the property from the roads is to plant layered, fast growing trees (red cedar), sumac, switchgrass as perennials and annuals such

as Egyptian wheat or sorghum/sudan grass a width of 25 or so feet from the road edge. The annuals will “hold the line” until the perennials develop.

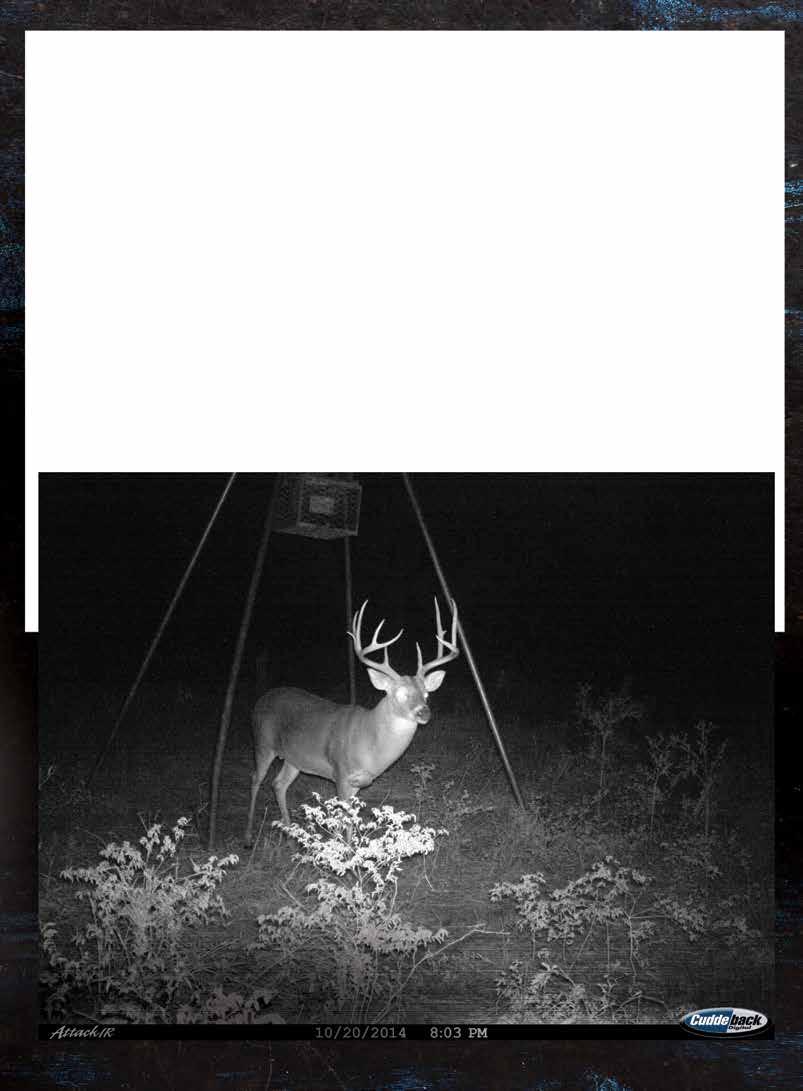

Deer herd management relies on year-round trail cameras at a density of one per 80 acres. We published an article some time ago on how to use trail camera photographs to obtain an accurate estimate of the deer population, demographics and density. As often happens, the owners were surprised to discover they had an estimated 84 deer, including 21 bucks, 42 does and 21 fawns, which is not a bad start for being in the early years. The family plans on signing up for the Oklahoma White-tailed Deer Management Assistance Program. It allows increased doe harvest eliminating antlerless days, including December.

In three years, the family are way into an ambitious management program that will pay off over the years in providing quality hunting, as well as the family heritage they seek for generations to come. Leopold was right when he expressed optimism about private landowners and game management. That is not to imply that public wildlife management does not have a place at the table; rather, that the role of the private landowner is critical in conservation in the 21st century.

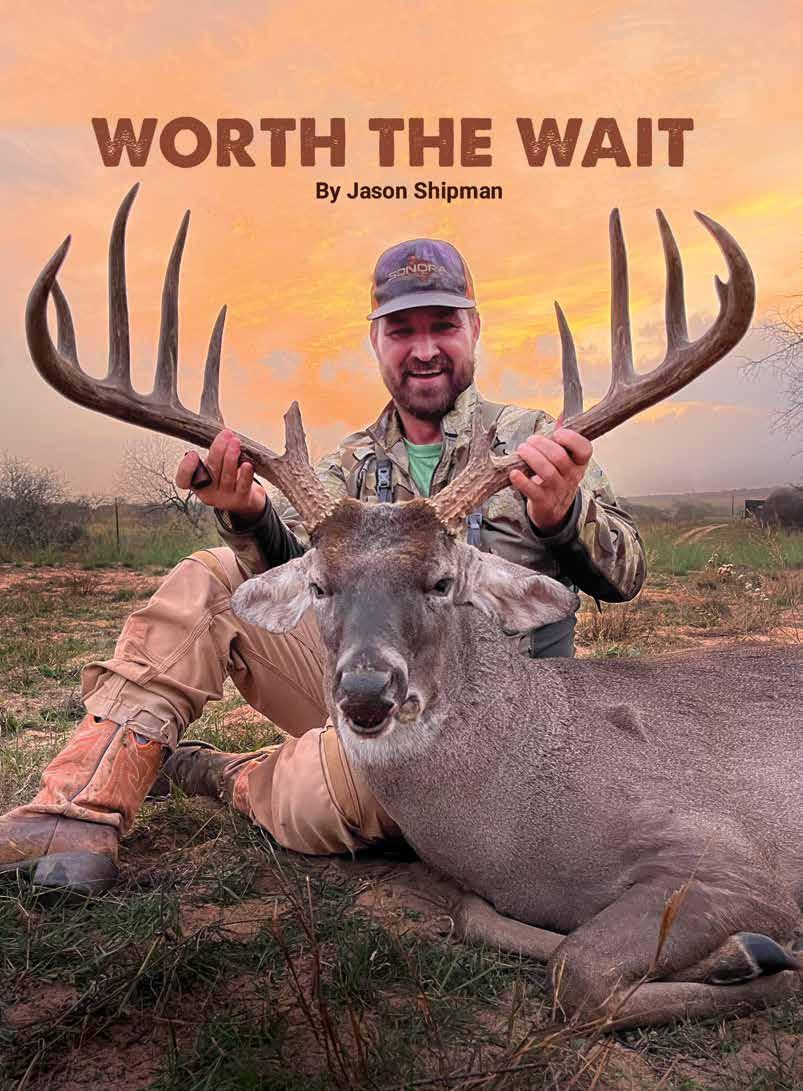

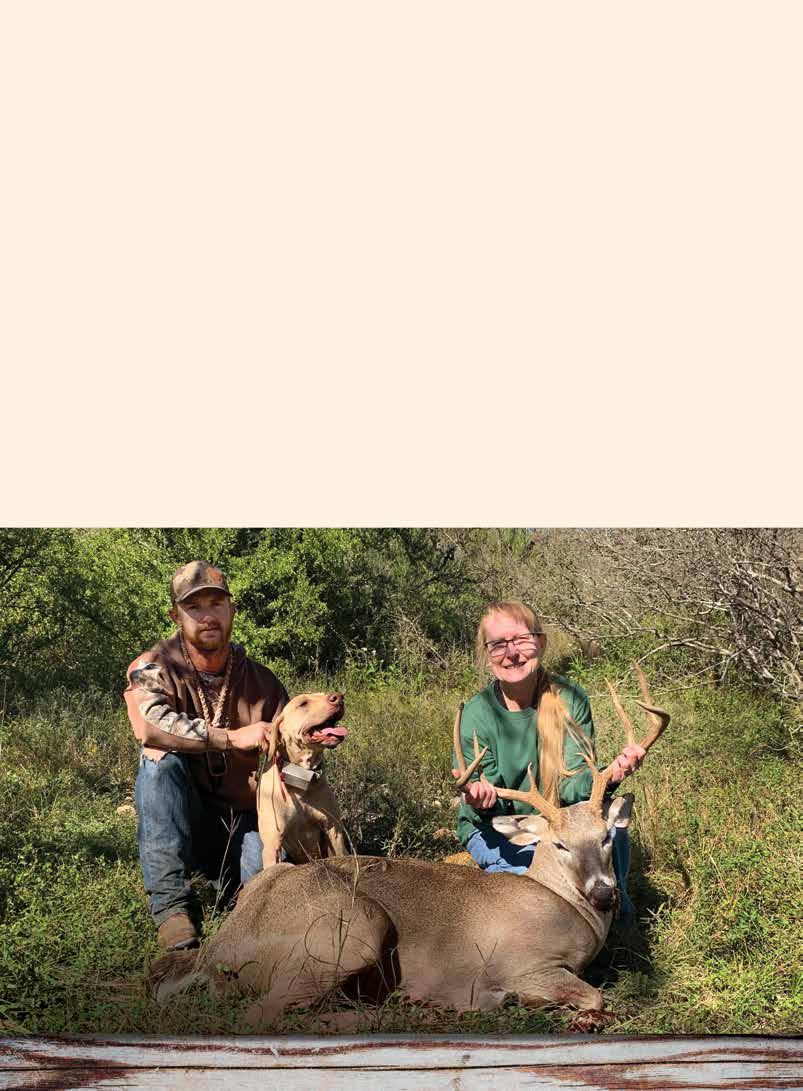

Brittain Griffith had to endure a long wait in order to get this wide trophy buck.

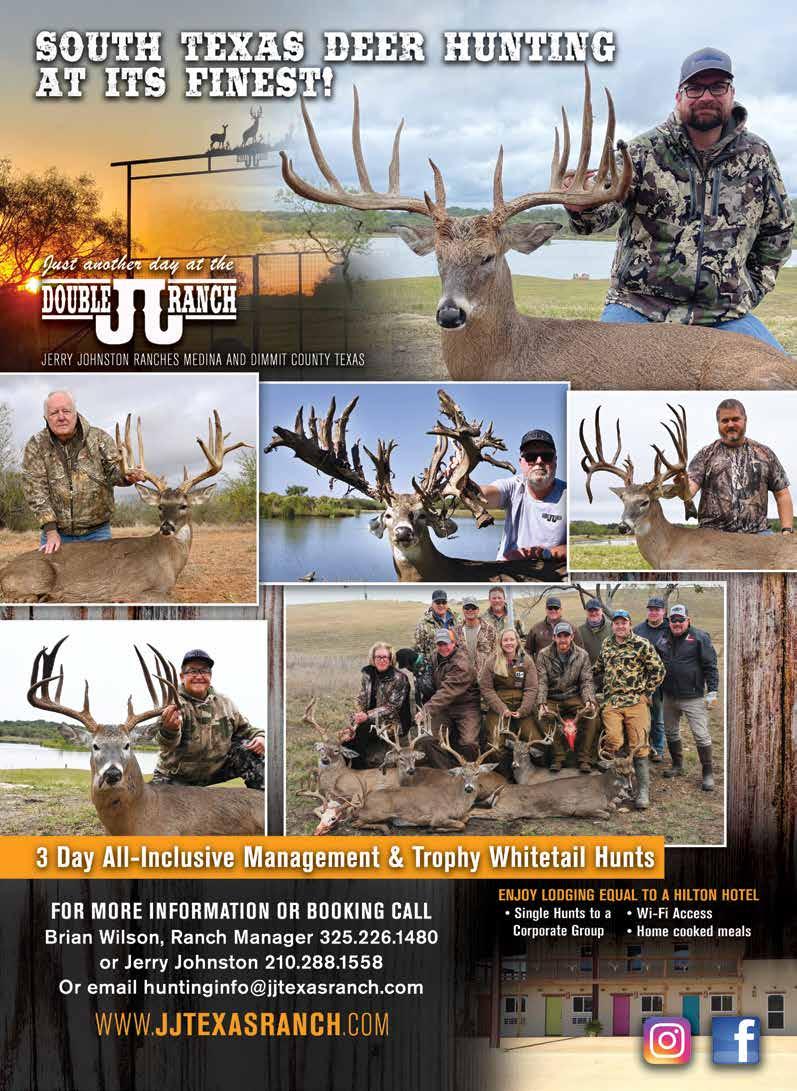

Brittain Griffith started out hunting deer with his granddad, “Dandy,” along the Neches river bottom in East Texas. While in high school and college, his interest shifted to duck hunting. Years later, his attention reverted back to his love of deer hunting and his efforts have since fueled his passion for chasing mule deer in the western states along with big whitetails in Texas. When it comes to hunting, you could say that Brittain’s path completed a full circle back to deer hunting.

Brittain is a self-professed mule deer fanatic, and as such, begins every hunting season out west in search of long-eared mulies. When mule deer season is behind him, he focuses on whitetails in the South Texas brush country. “I’ve hunted in South Texas for over 10 years, and have forged some great relationships and taken some exceptional trophy bucks during that time,” he said.

Last season, after striking out on a giant mule deer, Brittain returned to Texas dejected, but optimistic about hunting

whitetails with friends. “I knew it was going to be a tough year after the drought, but after taking care of things at home and work, I couldn’t wait to be hunting whitetails again,” he said.

A few weeks later, Brittain went hunting with some friends when a good buck caught his eye. “We were watching a real trophy buck—a massive 6x7—when we noticed another buck at the edge of the brush. He had a big, wide frame and really caught my attention. The buck was a standout and that’s saying a lot considering the company he was keeping,” Brittain said.

The old, wide buck stood motionless and partially concealed for what seemed forever. “The buck was impressive, and I was ready to shoot. Several times I considered trying to weave a shot through the scrub tree limbs. I envisioned dropping the huge buck in his tracks,” Brittain added.

Not wanting to take a chance, Brittain decided to play it safe and opted to wait and see if the buck would come out and join the other feeding deer. Being a wary adversary of sorts, the wise old buck surveyed his surroundings before simply turning around and walking straight away. “I just about lost it, watching

helplessly as the buck faded back into the brush,” said Brittain about his dilemma.

They hunted the next morning but to no avail, and the wide buck went unseen. Family and work commitments required Brittain to return home empty handed. “I had a sick feeling to my stomach and it was hard to leave without that buck,” Brittain said. It would be several days before a busy schedule would allow him to continue his pursuit of the buck.

“The wait was agonizing and the buck consumed my thoughts,” Brittain said. “I was going through all the what-if scenarios. What if I would’ve squeezed the trigger? What if he breaks his antlers in a fight? What if we can’t find him again? I rationalized that it was meant to be and could still possibly work out. Either way, I was going to try, and I couldn’t wait to get back to hunt.”

After a several days, and what seemed like a perpetual delay of game, Brittain finally went hunting again, in search of the wide buck. “The rut was in full swing, and we were on our way to a blind for an afternoon hunt, when we saw a big-framed buck with a doe in the brush and thought it could be him,” Brittain said.

“We quickly got into the blind and watched as deer began to filter out to feed. When the buck did not show, we began to glass the brush thinking maybe he was hiding with the doe,” he said. “We were finally able to find them in the thick cover, and the doe started to come out to feed, but the buck kept cutting her off. As they moved in and out of the brush it was then that we were able to determine it was indeed the wide buck I was after.”

Unsure exactly where the buck might step out, Brittain repositioned several times in an effort to prepare for a potential shot opportunity. “He had me guessing. I wasn’t sure where he was coming from and at one point I thought history was going to repeat itself, and he was going to slip out the back again,” Brittain said. This scenario played out for about an hour, with only brief sightings of the deer as the light began to fade.

Finally, the doe trotted out of the thick brush at about 150 yards with the big buck in tow. “He stepped out and was

everything I remembered, but I didn’t want to spend too much time looking at him,” Brittain quipped. Quickly, he focused on getting the rifle up. He wouldn’t miss an opportunity for a good shot. The rifle roared, and the .30-06 bullet went on its way, instantly dropping the huge buck.

“I was so excited, and it was such a relief to see him down,” Brittain said. A celebration began, as Brittain made his way to the fallen trophy. “He just kept getting bigger and bigger as I walked up and finally got my hands on him. I was actually a

little speechless and just in awe,” Brittain said.

The buck had a huge typical 6x6 frame, with good width, mass, and long, swooping main beams. “I reveled in the moment, as I had never killed a deer that wide,” Brittain said. “He’s had the look and was put together the way I’d envision a trophy whitetail. He was well worth the wait, and I couldn’t have been happier!”

Iwas the kid from Alpine, the cadet who traveled the farthest. In the summer of 2022, I had the opportunity to attend the 1st Battalion of South Texas Ranch Brigade at the Duval County Ranch in Freer, Texas. It was a fantastic program that provided hands-on education about ranch life, resource management, and proper cattle care. The camp was a delightful experience.

Throughout the five-day event, cadets learned the process of cattle marketing, beginning from a calf being born to when the beef is fabricated and sent to markets. The manager of the Duval County Ranch allowed us to vaccinate, deworm, ear tag, and castrate calves on the ranch. We also had the chance to observe a necropsy and ascertain knowledge of the fabrication process. Along with looking at the cow as a whole, we studied the necessary natural resources for the cow to be healthy. One day, cadets were taken to different locations on the ranch to obtain four grass species (either introduced or native) per herd. Herds are teams of four to five cadets that work together throughout the week to complete various competitions. After each herd had acquired the assigned plants, we then did calculations to determine how many acres of grazing land were needed per cow, based on the grass quantity and quality. We reviewed 21 different native and introduced plants during camp.

One of the main goals of the Texas Brigades camps is to turn us into conservation leaders through the analogy of turning coals into diamonds. We worked towards this through various leadership and team building games. These included activities like the human knot, making a pyramid out of cans with ropes, and discussing what develops a good leader. Being a good leader also requires good sportsmanship, which we exercised during the ranch competitions. The competitions entailed ranch chores, goat sorting, roping, and fence building. Another way that we competed together throughout the week was through daily trivia sessions, plant quizzes, and presentation etiquette. The summer camp was packed full of activities and education covering much of what is needed to be a land steward.

Cadets had an amazing opportunity to learn and make new friends that were interested in a lot of the same things. Every cadet was required to write a thank you note to two of our tuition

sponsors or donors, make an educational poster to present to their community, and assist in the making of their herd’s plant collection. Not only were we fed astounding information, but we also had some amazing experiences with the food provided. The first couple of days, there were some chuck-wagon folks that showed us original dutch oven cooking and some of their

favorite foods. Another day, the Texas Beef Council visited and provided burgers for us, and the day of ranch competitions, the Beef Loving Texans demonstrated how to grill a steak. As we were about to begin grilling our own steaks, it started raining and that ended our steak cooking.

One of the speakers gave a communications boot camp that not only taught us the benefits of proper communication, but taught us the proper way to communicate with people. We

reviewed the correct way to shake someone’s hand, methods to ask open-ended questions to keep a conversation going, the follow-up procedures of your presentation, and we were reminded to always enunciate and make eye contact. After the main portion of the communications boot camp, we did some interviews with another one of the presenters who asked us about our experience at camp. We were instructed on how to do a successful interview, and we then practiced a couple of improv interviews about ourselves.

Overall, South Texas Ranch Brigade provided a fantastic experience for teens wanting to learn more about ranch management and land stewardship. The week was extremely fun and exhausting. From writing about the sunsets and sunrises to getting a bucket of cold water dumped on your head after a leadership activity, South Texas Ranch Brigade never failed to amaze me with the amount of dedication each instructor and cadet gave to the camp. All of the staff and volunteers were energetic, excited to teach, and learn a little bit about each of the cadets. While it was a very activity-packed week, we had laughs and so many stories to be told about each and every one of us. This experience will always be a joy to look back on, and I look forward to next year to experience another Brigade camp all over again.

Texas Brigades is a conservation-based leadership organization which organizes wildlife and natural resource-based leadership camps for participants ranging in age from 13-17. Its mission is to educate and empower youths with leadership skills and knowledge in wildlife, fisheries, and land stewardship to become conservation ambassadors for a sustained natural resource legacy. There are multiple camps scheduled in the summers, focusing on different animal species while incorporating leadership development. Summer camps include Rolling Plains and South Texas Bobwhite Brigade, South and North Texas Buckskin Brigade, Bass Brigade, Waterfowl Brigade, Coastal Brigade, and Ranch Brigade. Visit texasbrigades.org or call 210-556-1391 for more information.

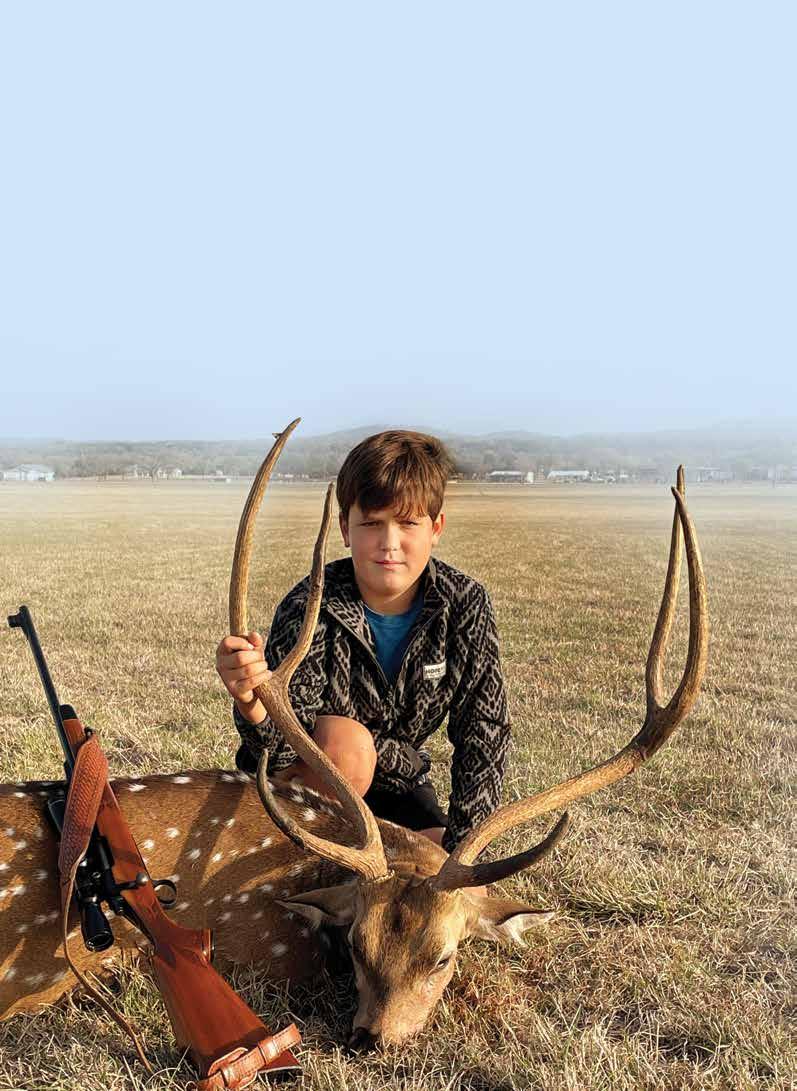

My son Cash was fortunate enough to have taken a gold medal class axis buck at our family farm. The buck’s exceptionally long secondary tines, called caudal tines, are unique. One side is even longer than the main beam, which isn’t common for this species.

One Sunday evening, my boys told us about a really nice axis buck they had seen while they were driving back to the house from feeding the livestock. Yes, these two drive and have been driving at the farm since they were about 6 years old. We’ve seen a few nice ones over the last few months, and taken some monsters in the past, but we had not seen this one before. The boys were very excited to show him to me, so later that evening we headed out to look for the buck.

We found a nice herd in a large thicket of cedar trees where we’ve seen others hanging out in the past. My oldest boy, Case, saw him first and was trying to point him out to me. Daylight was fading fast, and they have better eyes than I do. I had to reach for the binoculars.

Once we got a good look at him, I told the boys the buck was a good one. We also needed to work on a game plan for trying another day to see when we could try to catch him moving around ASAP. Axis like this one don’t hang around too long, sometimes by the deer’s choice, or because of other hunters. Cash had already staked a claim on him because Case had shot the last deer. Between my work schedule, school, and 4-H,

we were limited on how soon we would get the next chance to hunt for the buck. We had a few evenings the next week that would be the earliest opportunity for us, but unfortunately the weekday mornings are when the boys are “supposed” to get ready for school and I get ready for work.

While hunting one evening, we spotted the axis herd that the buck had been seen with. But he was not participating in their evening feeding, which wasn’t surprising because he was the herd bull. Those are typically the last to appear.

The next morning, I had to go to town for work and the boys were off to school. While Mom was heading down the road taking them to school, they saw the big axis buck we were looking for, walking across the hay field about 300 yards away. I got a call from the boys letting me know the buck was still around and how frustrated they felt because they had to go to school instead of hunting for him.

The next day we were eager to try and take this buck. I figured it wouldn’t hurt if Cash was a little late to school, but his mom didn’t feel the same, so we decided to see if we could get

Cash with his dad, Jason. During one previous attempt at this buck, Jason allowed Cash to be late for school in order to take the axis. Cash’s mom wasn’t happy, but Jason said it was worth the attempt.

lucky and catch him first thing at daylight. Needless to say, he was a no-show, and the boys were late to school. It was worth the try!

We hunted that evening and had two different axis herds come out to graze. As luck would have it, the buck came out last with one of the herds and managed to stay in the middle of them all. He didn’t present a clear shot. When he decided to walk off, he went in the opposite direction chasing a doe that caught his interest, which did not present a good, ethical shot for a youngster.

The weekend arrived and Cash and I grew more anxious. We planned to get an early start Saturday morning, in hopes the buck would cooperate. Around 7:30 we had an axis herd step out of the tree line about 200 yards away, and they were moving our way. One after another they kept walking out of the trees in a line following right behind each other.

The last one to walk out with the main herd was a mature doe. Knowing the bucks are the last to show, we were both excited and worried the buck may not show. I started scanning the brush for any movement, and standing in the cedars watching was the big axis buck with his head tilted back and nose in the air. Once we saw him, we knew he was glued to the doe and would follow. When he stepped out and started

his way towards the group to catch up, Cash caught buck fever. What made it even worse, Cash had to watch the buck slowly make his way up the field till he was in range and broadside to present a good shot. Once he was in range, I told Cash I would get the buck to stop and reminded him to relax, get a good rest for the rifle, and squeeze the trigger. Within a split second of me stopping the buck, the gun went off. I guess Cash was afraid he’d get away. I could tell Cash made a good shot and that the buck was hit hard by the way he lunged and ran about 20 yards before stopping and lowering his head. But I still had Cash chamber another round and told him to hold it on him in case he needed a follow-up shot. After about a 10-minute wait, we walked over to pay respect and admire the beautiful animal he has just taken, followed by some nice field pictures with the family.

As most who hunt know all too well, this is where the fun stops and the work starts. I can’t say Cash doesn’t complain, but he sticks with it. Cash and Case have been fortunate enough to have been brought up around hunting and have been taught the process of field dressing, as well as being fortunate enough to say their family processes their own animals for sausage, jerky, and more. There’s a greater level of appreciation for wildlife when someone is able to experience the full circle of stewardship and hunting. Job well done, son!

Members of Safari Club International, as well as Texas Trophy Hunters Association CEO Christina Pittman, traveled to Washington, D.C. to lobby on behalf of both organizations to ensure hunting and conservation maintain a vital role in our nation and abroad. Outdoors enthusiasts should be keenly aware of who is looking out for you and defending your freedoms to enjoy the great outdoors whether as a hunter, fisherman, hiker, biker, etc.

“Safari Club International raises monies for wildlife conservation, education, advocacy and humanitarian services not just internationally, but right here at home in the US,” said Jimmy Fontenot, past president of the SCI San Angelo, Texas, chapter.

“Our team of specialists within SCI are constantly researching, litigating, and literally fighting for YOU every day against the constant onslaught of anti-gun, anti-hunting agendas. I’m proud of our presence on Capitol Hill. I invite all of you to stand up for what you believe in and help protect our freedoms from the radical left. We can make a difference, but it will take all of us joining as one to make it happen.”

Here in Texas, you can participate by directly contacting your congressional representative, as well as Senators Ted Cruz and John Cornyn.

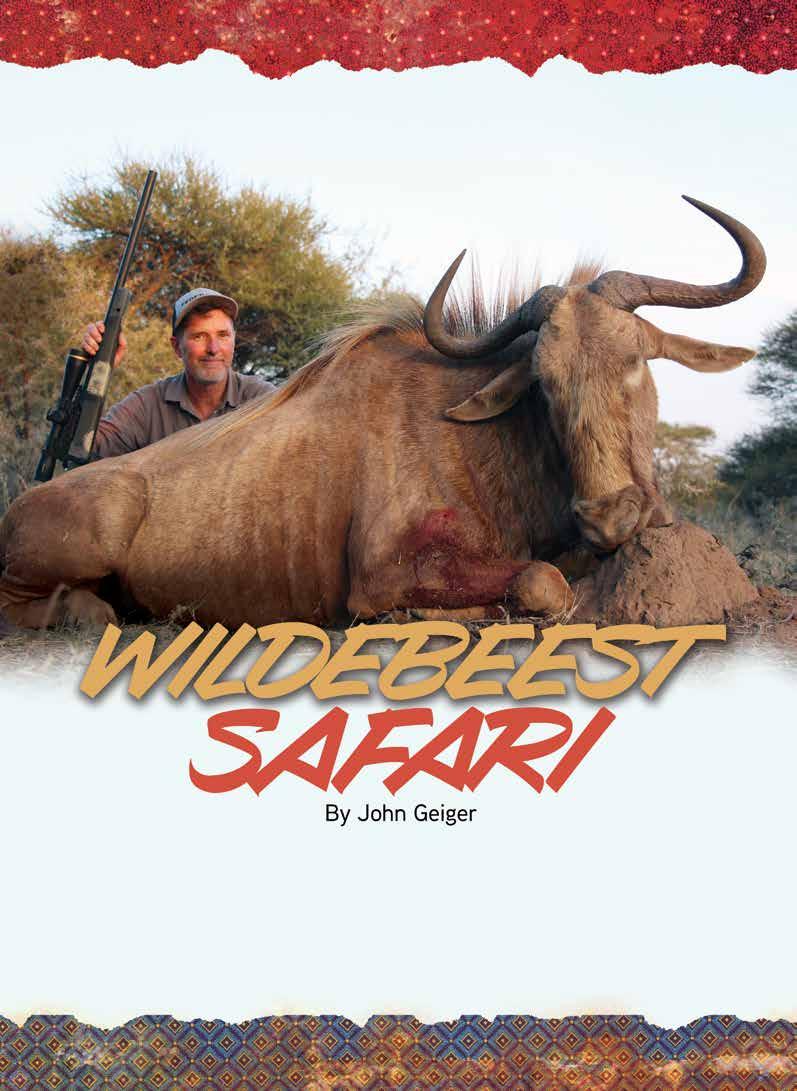

Ihave dreamed of Africa for my entire life. A magical place and land known for its vast country and incredible animals that inhabit the area. Watching so many different shows on TV throughout my childhood and life that depicted this part of the world like National Geographic, Jack Hannah’s Animal World, Animal Kingdom, and so many more, made me dream of one day exploring this amazing country.

The stories over the years from other hunters and a few dear friends able to go to Africa and hunt were extraordinary. The game animal pictures I saw and the stories I heard were hard to comprehend as a mere guy from Texas. Everyone I talked to that went to Africa to hunt had a great journey. Later on, I had the chance to watch Chuck Adams, Tom Miranda, and more extraordinary hunters bowhunt in Africa and take many beautiful, trophy African game.

I had the chance to visit with several outfitters from Africa at the 2021 Texas Trophy Hunter’s Extravaganza in San Antonio and came across Limcroma Safaris out of South Africa. After learning about their hunting safari and the way they operated and catered to the bowhunter, I booked my hunt for September 2022. Hans and his entire team truly had an experience for couples, small groups or individuals like me. Many of the professional hunters are avid bowhunters themselves. Al was great to explain his experience and why this is the place for me.

The day finally came for me to leave for Africa. I had spent

months planning my trip with last minute gear, new camo for the area that would help me blend in, tuning my bow and shooting to ensure I was accurate, getting new heavier cutting on impact broadheads, and even switching up my arrows to shoot a heavier arrow with forward weight for better penetration. I packed and left DFW on Sept. 18 and landed in Johannesburg, South Africa, on Sept. 19. After a good night’s sleep at Africa Sky Hotel, the Limcroma Safari van picked me up to take

me and four other hunters on a four- to five-hour drive to the hunting safari ranch and lodge.

We arrived at the hunting safari lodge and saw a gorgeous place that had all the old-style Africa I was looking for. I settled into my own private hunting hut, unpacked, and prepared my hunting gear for one week of Africa hunting.

We headed out that afternoon to hunt a waterhole. My guide,

Hardus, and tracker, Frances, were incredibly welcoming to their homeland. We hunted that evening out of a ground blind about 5 feet underground with a concrete shell that looked like a termite mound. We saw massive water buffalo, elands, wart hogs, and more, but nothing I wanted.

We finished the first hunt and came out to a glorious and striking sunset in Africa. I have never seen such a magnificent sunset in my life. It looked like an artist’s canvas and the colors were extraordinary. Hardus let me know how blessed they all were to have this every evening due to their location in the hemisphere. Sunsets are world renowned in Africa. We both opened a cold African beer from the cooler and headed back to camp. That evening our cook, James, made an amazing gemsbok stew with fresh vegetables and homemade cheesecake along with delicious South African red wine.

The next day we hunted a new area and another ground blind. Lots of animals came to the waterhole, but the wind would shift, and all animals would run off. Many young, great looking animals not old enough to shoot would come in, too. After a full day of hunting, I had my opportunity to shoot my first animal. A trophy blesbok came into with a herd and gave me a 20-yard broadside shot. I came to draw, shot, and nailed the animal! But it was a low shot like the ones I take while Texas whitetail

hunting. Even though the shot was a pass-through, we did not recover the blesbok. I shot 8 inches too low. You must shoot African game much higher in the shoulder because their vitals sit much higher than a Texas whitetail. I was very upset with

myself, but Hardus was supportive, and we went to shoot in camp more but practiced shooting higher.

We had a number of hunts over the next few days, hunting 10-12 hours a day. They were filled with African wind, heat, long days of hunting, and missed shots at gemsbok. African game herds would all come to a waterhole at the same time, so many times the desired trophy animal would be blocked by the younger animals or females and create zero-shot opportunity. Africa is hard hunting, and I had learned many first-time lessons.

I had a trophy impala come in at 18 yards and drew my bow but could not see my pin! Even though it was 1 in the afternoon with great sun, it was darker in the blind and my sight pin would not light up. I realized I would have to shimmy up to the window to get light on my pin. The impala had run off at that point.

I also learned an adjustable single pin bow was not appropriate for Africa. My Texas whitetail deer setup would not work because animals were at all different distances. It was difficult to keep adjusting my pins to draw and then need to let down

draw and re-adjust. Please learn from me and ensure you have a different bow setup for Africa with multiple pins to allow for a quicker shot.

Finally, towards the end of my week in Africa, luck and hard work would pay off. One evening as we finished the long day of hunting, a trophy-class waterbuck came to the waterhole. He was a brute and ran off all other game that came in, including a herd of sable and two roans. He was in for a while and finally gave me a 20-yard broadside shot. With calmness and ensuring I aimed higher, I shot and had a complete pass-through. Hardus and I watched as he ran off and watched him crash at what looked like about 100 yards away.

We waited a bit and called Frances to come get us and then started to look for the waterbuck. We saw good sign and we followed it right to where the animal was. I shot an SCI record for that region. We celebrated and took pictures, loaded the animal, had a cold beer with the sunset and headed back to camp. I finally shot an African trophy with my bow!

The next day we hunted again all day and saw numerous animals. We even had an African monitor lizard come to the waterhole, which made every animal run off. He actually got in the water trough and took an afternoon bath, then came out and walked right towards our blind. He was huge and bigger than an alligator. Hardus let me know how dangerous they are, because their mouths are full of sharp teeth and horrible bacteria that would kill a person. Luckily, he did not notice us and walked right past our blind.

Finally at the end of the hunt we saw a very old trophy blue wildebeest by himself. Hardus said he was an old bull kicked out from the herd by the younger bulls. He was awesome looking with his devil horns, gorgeous mane and tail, and coloring and ridge on his back. He was nervous and took over 2 hours to commit to come in. Once all the other animals had left and a group of warthogs came in, he finally committed to the waterhole. He stood broadside at 20 yards. I drew my bow, aimed, then shot. I hit him well and he ran off about 80 yards and crashed. Hardus and I waited a bit again and then called Frances to come get us. We could see the blue wildebeest down and Frances said he was happy he did not have to track the animal. We got pictures and loaded the animal to go back to camp. We watched our last sunset and drank what seemed like the coldest and freshest beer I ever had. I thanked God for this time in Africa and to Hardus who worked so hard to get me on trophy animals.

What an adventure and thrilling time! The hunts, the people, the culture, the food, the landscape, and the animals were all a lifetime opportunity. I am thrilled beyond words for this experience.

Only about 5% of Americans hunt, but 100% of us have ancestors who were hunters. Hunting is deeply and undeniably programed into our DNA. Even the vegan holding the anti-hunting protest sign is only there because her ancestors killed and ate animals for a couple million years. Our bodies are built to eat and process meat as evidenced by the way we store fat, the structure of our diges -

tive system, our tooth wear patterns, and chemical analyses of old bones. It’s clear we have been hunting and eating meat for a very long time.

Anthropologists have theorized we began to walk upright more than 4 million years ago so we could carry tools and

weapons. Also, the shift to a hunted protein diet fueled the development of our big brains, spurred on by the need to coordinate more elaborate, and sometimes abstract, hunt plans.

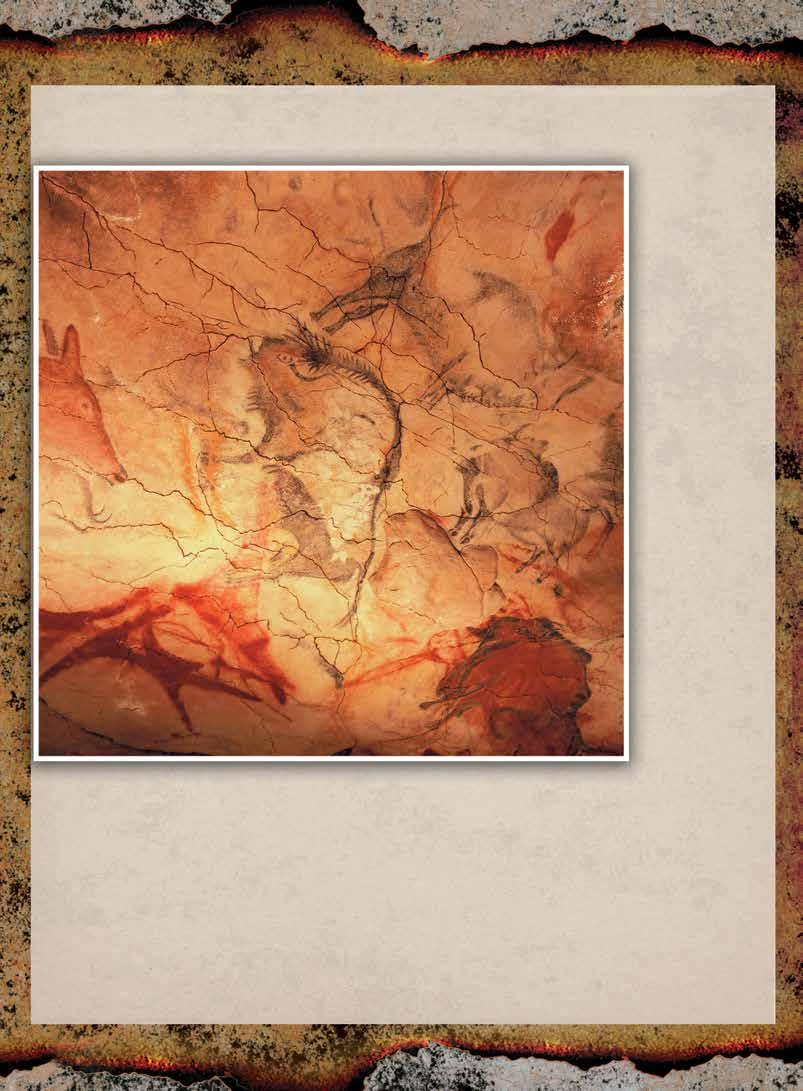

than female or young specimens. Researchers concluded the red deer, rhino, bison, and wild cattle skulls were placed in that section of the cave by Neanderthal hunters to display their hunting trophies. As I said, some of the things we like to do have deep genetic programming.

Sometime before 20,000 years ago, small bands of humans crossed the Bering land bridge in what is now Alaska and spread across the continent hunting and gathering their food supplies. These bands moved around to take advantage of seasonal food sources from the oceans or mountains or prairies. It’s hard to piece together details about them because they left very little evidence of their nomadic way of life. Archaeological evidence indicates these hunters had reached the Southwest and northern Mexico by 11,500 years ago.

Language became an important part of human development to tell hunting stories and orchestrate hunts effectively. Cave paintings depict hunting, not gathering, scenes. Hunting drove human evolution to make us who we are and why we have been so successful.

Certainly, early humans hunted for the meat, but we shouldn’t assume they were not admirers of beautiful, mature representatives of these species. Recently, a cave was discovered in Spain that contained an unusual assemblage of animal skulls without the jaws or any other bones from the animals’ bodies. This collection contained skulls that all belonged to individuals and species with large horns or antlers rather

The Clovis Culture, named after Clovis, New Mexico, left behind several big game kill sites that contain spear points and other tools such as scrapers and knives. Clovis definitely hunted some of the biggest game. Two sites in southern Arizona—Murry Springs and Lehner—had mammoth remains with several Clovis points embedded in their skeletons. There is evidence Clovis hunters were already using atlatls, a spear-throwing stick that helped them gain extra leverage for throwing their projectiles much harder and farther.

These early hunters roamed a landscape with the dire wolf, saber-toothed cat, horses, lions, camels, ground sloths, bison, and 100-pound beavers, all of which were native to North America before disappearing at the end of the Pleistocene. Deer were not as common and widespread at this time, but their remains have been found in association with Clovis artifacts. By 10,500 years ago, Clovis points disappear from

A bison depicted on the roof of Altamira Cave in Spain represents a prehistoric Facebook post of a hunt.the archaeological record.

Another hunting society, referred to as the Folsom complex, follows the Clovis culture in the eastern edge of the American Southwest. This culture is named after the Folsom, New Mexico, site that yielded the first distinctively fluted spear points that characterize this culture. The Folsom people were primarily hunters who seemed to concentrate on a now-extinct species of large bison (Bison antiquus). One archaeological site contained many bison skeletons with most missing the tail bones, indicating the hunters had skinned the animals and removed the tails with the hides. Around 4,000-5,000 years ago, this large form of bison evolved into the smaller bison (Bison bison) we know today. At that time, these formerly nomadic

to take advantage of what protein was available in their areas. It was sometimes more profitable to hunt closer to home for rabbits, armadillos, rodents, snakes, lizards, frogs, snails, and seafood. In most societies, men went hunting, while the women and children collected plants, cactus, acorns, mesquite beans, fruits and sometimes hunted small game. The Anasazi culture in the Southwest hunted, but also kept turkeys in a semi-domesticated state for eggs, meat, and feathers to make blankets and for decoration. Deer not only provided important protein and fat, but also raw materials for clothing, tools, jewelry, and ritual objects.

very long time.

Deer hunts were highly ritualized, with special observances beginning days before the hunt. Several different hunting styles have been described and they are all familiar to hunters today: still-hunts, ambushing, stalking, or driving deer. There were many rules and taboos regarding the handling and preparation of meat. For example, in some cultures, fresh deer meat from a mountain lion or wolf kill was considered a gift from the gods and eaten.

hunters began to focus their hunting on the smaller bison and medium-sized game. During this period, deer were beginning to assume a greater importance as a source of food and materials, a trend that continues to this day. From this time forward there appeared many different hunter-gatherer cultures occupying North America after the glaciers receded, until Europeans arrived.

Hunting was done primarily with the atlatl until about 3,000 years ago, when the bow and arrow came into common use. This improvement in weapons undoubtedly increased hunting effectiveness. Agriculture became more common and important, but diets were supplemented extensively with wild plants and animals. Some tribes focused on birds and small game

From the number of arrow and spear heads that have been found, there can be no doubt about the importance of hunting to all the diversified tribal nations spread across the continent. Many archaeological digs have yielded arrowheads embedded in deer bones, shoulder blades, and ribcages. Hunting parties would travel long distances for buffalo, turkey, deer, and elk. On longer trips, meat was dried before being transported home to help preserve it and reduce the packing weight. Some tribes are said to have made a practice of setting fire to the woods to attract animals to the newly burned areas.

These historic people hunted large dangerous game with true primitive weapons. One study of Neanderthal bones found their injuries were similar to the bone breaks suffered by rodeo bull riders. This makes sense when you consider these two groups of people were involved in similar activities around dangerous animals. We all come from a long line of brave hunters, but our hunting activities contribute to so much more now than simply protein for dinner. The future of conservation depends on making sure we are the ancestors to future hunters.

Is life an adventure, or what?

I can promise you the word boredom has never made its way into my adventurous life; you can be sure of that.

I see these poor, pathetic souls hopelessly locked into their handheld electronic zombie devices, and I can only feel sorry for them. Especially so many young people who have intentionally, or just mistakenly limited their view of the world, or worse, bypassed the possibilities that this incredible gift of life can provide.

I’m the first to admit the advantages of runaway technology when implemented intelligently and efficiently. Hell, I drive an 840 horsepower Dodge Challenger Hellcat SuperSport Widebody Redeye fire breathing fighter jet (based on the contents of the trunk) which happens to trounce the very best horsepower beasts of the so-called Muscle Car era of the 1960s and early ’70s.

And of course, I pound away like a madman on my state-of-the-art, pain-in-the-ass cellphone to keep in touch with family, friends, business associates and elected employees, the trick being knowing when to shut it down and escape the mayhem.

Which brings us to the point of this writing—the

healing powers of nature and the soul cleansing great outdoors lifestyle.

I have forever waxed poetic on the sanity safeguards of balancing one’s life’s pursuits between

Ted says he understands many outdoor enthusiasts focus on a few favorite activities. But he believes newcomers will stick with their new passions.

productivity and recreation, and in these crazy, treacherous, trying times in America and around the world, such prioritizing balance could not be more crucial.

The term recreation itself says it all: re-creating our energies, sanity and recharging our spiritual batteries.

Truly the joys of hunting, fishing, trapping, camping, boating and everything outdoors is by my evaluation, the ultimate re-creating powers available to mankind on planet Earth.

Nature certainly heals, but she heals most effectively when we actually participate as hands-on players, which of course is ultimately defined by hunting, fishing and trapping.

As we fight heroically to upright the good ship America, we will only be as effective as we are healthy, grounded, tuned in, and recharged.

I admit to being more gung-ho when it comes to bowhunting than any other outdoor activity, but I do indeed fish, trap, boat, birdwatch and dig my mitts deep into the throbbing heartbeat of the good earth as a farmer and rancher as often as possible.

Just the earthly act of planting food plots and trees each spring takes me far, far away from the increasing goofiness of the world, and as I wrap up each activity out there, I am genuinely rejuvenated and re-energized.

I love fishing for yummy panfish, shooting doves, waterfowl hunting,

small game hunting, big game hunting, turkey hunting, bowfishing, archery, rifles, handguns, shotguns, blowguns, slingshots, pretty much anything and everything out of doors.

We all have our favorites, but never underestimate the thrills of breaking the mold and trying something new. I would wager that many outdoor enthusiasts focus on a few favorite activities, and in my experience, when seeking new adventure and challenge, nine times out of 10 the newcomers stick with it, and in many instances, discover an exciting new passion that brightens their outdoor life.

Think outside the box as summer winds down and the magic of fall and winter brings us a new day, a new season, a renewed spirit and a much-needed upgraded hope for life, liberty and the pursuit of our favorite happiness.

Talk to your buddies, wander in a sporting goods store, walk up and down some new aisles and go for something new and different. Do it all! You won’t be sorry.

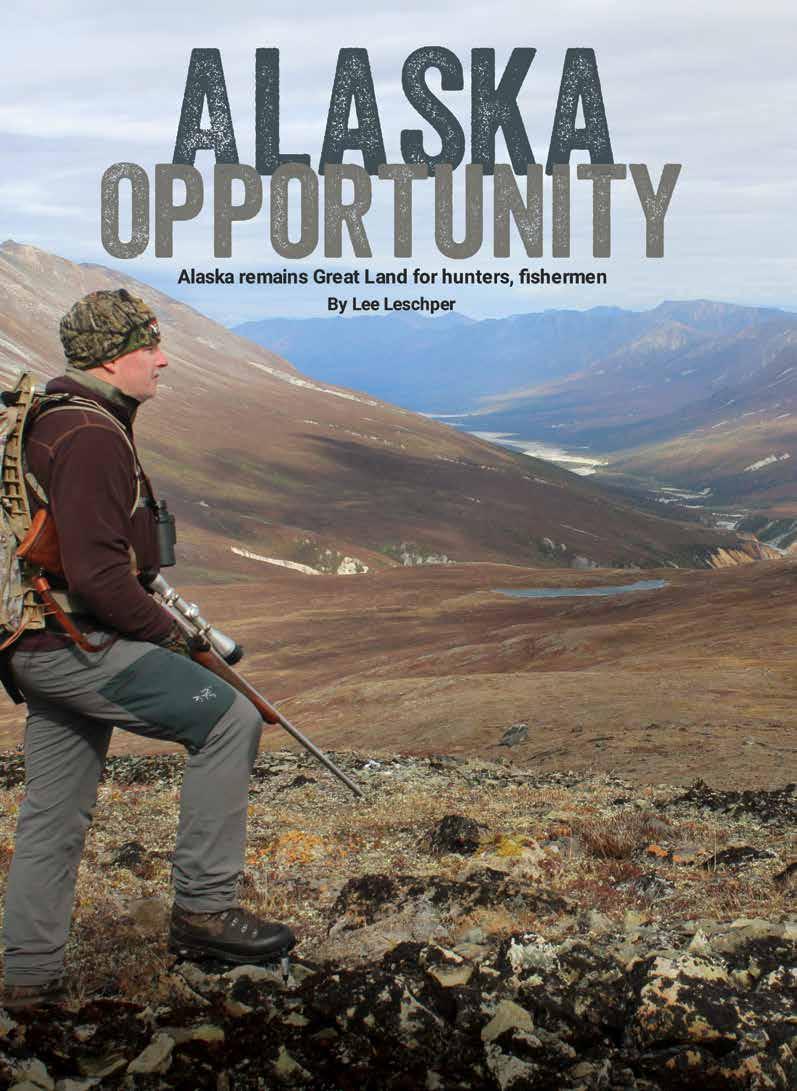

In a misspent life wandering the globe, chasing animals and fish, if I have one regret, it’s waiting till middle-age to set foot in Alaska. Work first brought me to the Great Land 20 years ago, and it remains home today. While I spend much of each fall in Texas and other points south, Alaska is always going to be my happy hunting and fishing ground.

John Muir, father of America’s national parks and the first advocate for wild places from Yellowstone to Alaska, visited Alaska often in the 1870s and 1880s, and wrote eloquently of his experiences. “To the lover of pure wildness Alaska is one of the most wonderful countries in the world. ... it seems as if surely we must at length reach the very paradise of the poets, the abode of the blessed,” he wrote in “Travels in Alaska.”

Alaska of 150 years later remains this place of wildness. So, let’s talk about you make the most of your first trip. To begin, don’t sweat the logistics. Yes, it’s 3,216 miles from San Antonio to Anchorage, but from Anchorage, you can drive north to Denali and eventually the North Slope, or south to the Kenai and Homer. Or you can take a quick flight to Kodiak or Bristol Bay or a million other destinations.

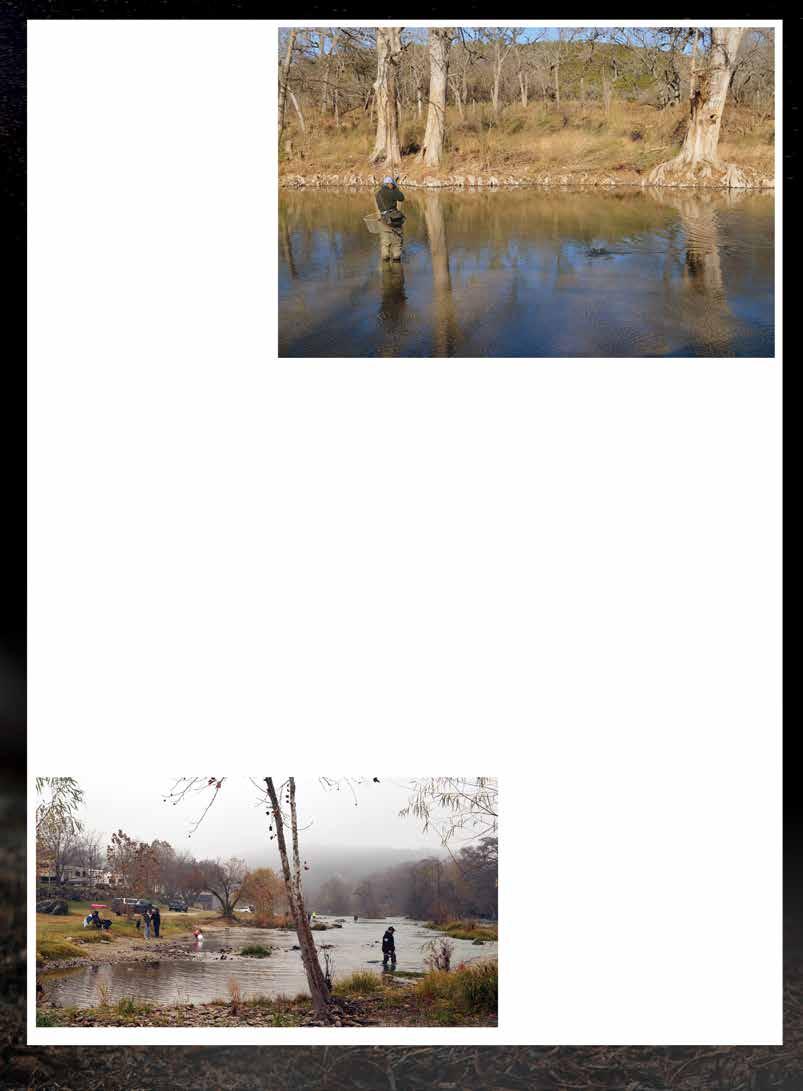

Next, remember every minute in Alaska is its own reward. While a 60-inch bull moose or 10-foot brown bear is still very possible and a worthy goal, the rewards are simpler. Wading in a river choked with salmon, or feeling the immovable force of a halibut as big as a Buick, your first view of a winter sky aflame with the aurora borealis, or seeing your first bear on the mountain side, lit by the sun and long hair blowing in the wind.

So, let’s talk about your first trip. Coming to fish for a week in the summer is a great start.

A week or more is a good idea, because even on a good trip

you’ll have days that are weathered out, or the salmon run is late or slowed by commercial nets. Expect incredible days and days you can’t even fish.

You can go it alone, fish the rivers solo, book your own saltwater charters, camp, or stay in local hotels. Or choose a package trip from one of hundreds of lodges that provides everything.

I recommend three days river fishing for salmon. Timing will determine which species, with late June to August for red salmon, or August and September for silvers.

Sadly, the legendary king salmon runs have so declined in recent years. Most are closed or restricted to catch-and-release, even the Kenai. You can still catch and keep a king in the hatchery runs in downtown Anchorage’s Ship Creek and the Kasilof on the lower Kenai Peninsula.

In addition to salmon, you need to plan a couple days on the saltwater, pursuing silver salmon, halibut, and rockfish, and after July 1, lingcod. Expect to see humpback whales and orcas, sea lions and seals and certainly sea otters. Plus, unique birds from bald eagles to puffins, all while fishing in view of glaciers and around iceberg.

There’s also world-class flyfishing for rainbow trout and Dolly Varden, which grow to almost unbelievable proportion by gorging on salmon fry, salmon eggs, and salmon flesh. Given time to head north to experience Denali National Park, you’ll also find superb grayling fishing throughout Denali country. Almost every trickle of water holds this fabulous fly rod quarry and in more remote fisheries they can grow to 4 pounds.

But enough about fishing. Once you’ve set foot in Alaska, you’ll want to come back to hunt. You need to prepare to pay, either in license and guide fees, or in blood, sweat, tears, and money.

For sheep, goats, and brown bear, nonresidents are legally required to hire a licensed guide. But there are plenty of great do-it-yourself options too, including caribou, moose, and black bear. There are 100 million acres of public land in Alaska you can hunt for little more than the price of transportation to get there.

There are excellent transporters with access to good country, whether by boat or float plane or super cup, that deliver you to the country hill, adventure, or camp, and after you hopefully have a successful hunt, pack your gear and meat, and haul you back to civilization. It does require planning. Starting today, I recommend looking at plans for 2025 or 2026, because the good transporters book up early.

The trip I always recommend for first timers is hunting Kodiak Island with one of the many boat-based operators. For a week, you live on a

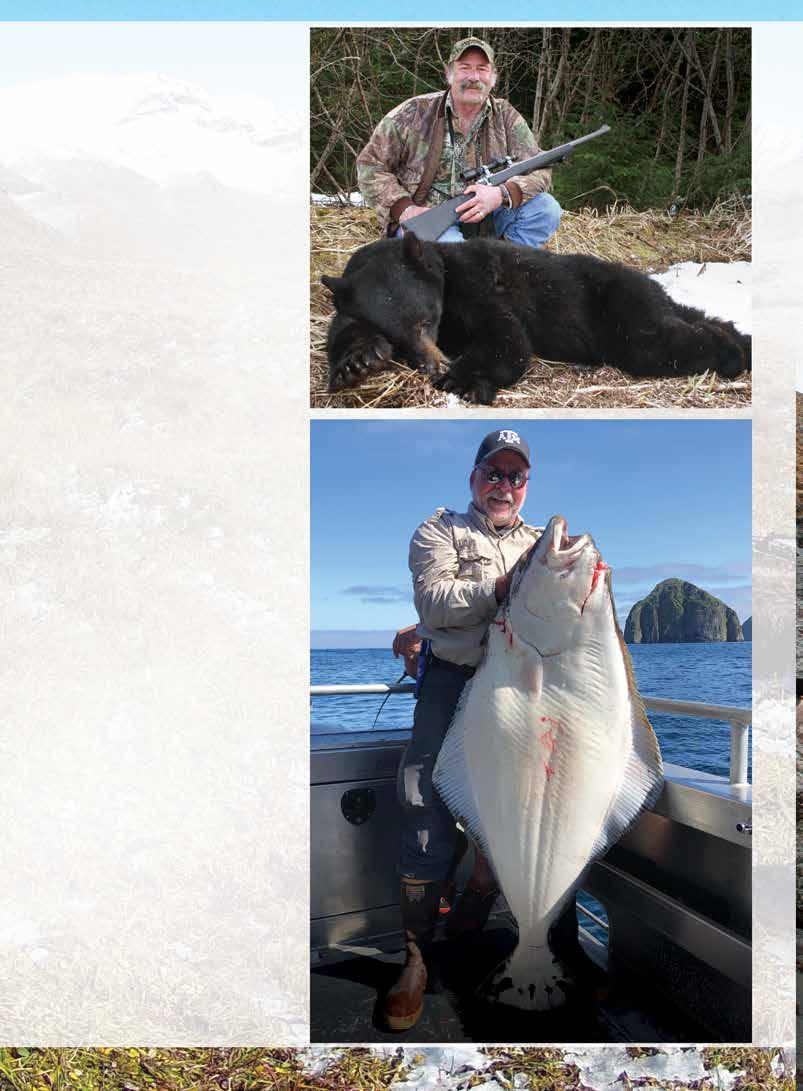

Larry Leschper with his first Alaska black bear, one of the species nonresidents can hunt without a guide.boat anchored in a remote cove, and run ashore by skiff each day to the island to spot-and-stalk the abundant and tasty blacktail deer. You can shoot three, while trying to avoid the largest brown bears on Earth.

Kodiak truly is a wildlife wonderland. After you’ve taken the limit on deer, you can hunt sea ducks, fish for halibut, and drop crab traps to catch Dungeness crab for dinner. A Kodiak trip like that costs less than an average Texas deer hunt today.

There’s another boat-based spring option, which is spring black bear hunting by boat in Prince William Sound out of Seward or Kachemak Bay from Homer. This is an April-May hunt for bears just out of hibernation with a big appetite. You base and sleep on the boat, cruise, and glass shorelines by day and when you see a suitable bear, go ashore, and make a stalk. There’s always time to fish midday as well when the bears aren’t active. A spring black bear hunt will cost you less than most exotic game hunts in Texas today.

There’s one other option I can’t close without mentioning. Every conservation organization in Alaska offers dozens of great hunts for auction and raffle fundraisers each year. Alaska Department of Fish and Game now also offers The Alaska Super Seven Big Game Raffle, with seven world-class hunts including

cash for travel or guide fees, with the $20 raffle fee going to Alaska conservation. Learn more at AlaskaSuper7Raffle.com. Somebody has to win, right?

Shopping for airfare will also require some homework. As I’m writing this, airfare remains at its post-pandemic peak, but with time and luck it’ll start to return to something more reasonable. We always recommend getting an airline credit card from one of the major airlines serving Alaska, whether it’s Alaska Airlines, Delta, United, and American, and using that card for a few months or a year to earn enough airline miles to make a trip from Texas to Anchorage.

Frankly, Alaskan airline miles are the true currency of Alaska, and you won’t find many Alaskans who don’t have one or more airline cards and a big bag of miles.

It’s fun to buy new gear for a trip to a new place like Alaska, but your Texas rifle, so long as it’s at least a .270 that you shoot well, will handle 95 percent of hunting in Alaska. As far as apparel, remember waterproof, waterproof, waterproof and layer, layer, layer. And cotton kills! Wet cotton blue jeans will give you hypothermia faster than a swim in Cook Inlet. Alaska is where cheap gear goes to die, so invest in good stuff.

You can find plenty of good reasons to not fish or hunt Alaska. Distance, cost, and those scary bears. But there’s one really good reason you have to go. It’ll change you forever. And you may just experience what John Muir did in southeast Alaska 150 years ago, when he cautioned as a senior citizen himself that a young man should not visit Alaska.

“Because once a man visits this place, he must choose first either to never leave, or second, accept that any place else he goes is going to be something less.”

So many of us look forward to our fall deer hunts, and each spring we fill our feeders with protein and whatever else we can feed to help our whitetails stay healthy. With all the exotics in Texas, we are very fortunate to hunt year-round if we so choose. Over the past 20-plus years, spring means turkey season, which means a lot to me and my crazy friends who like to chase these inconsistent, smart Rios of Texas. I had it said to me that if you’re a turkey hunter, you have to realize you will be unsuccessful more times than you will be successful. There are so many variables to contend with. Spring in Texas can be demanding for hunters, as we get high winds, hot days, cold days, and even sometimes a few rainy days. You are also dealing with turkeys that move from property to property looking for feed and water sources.

In the spring these same turkeys are also looking for romance. Most years we have green grass, blooming trees, and flowers of all kinds popping up on the Texas landscape. Where turkeys spend their winter can be entirely different than where they spend their spring.

One of my favorite things to do is take kids on their first turkey hunt. Our Rio Grande turkeys are typically aggressive birds, and when the time is right, it can be an adrenaline riddled exciting time for anyone new to calling in animals. Their defense mechanisms are

According to the author, if you’re a turkey hunter, you have to realize you’ll be unsuccessful more times than you’ll be successful. That’s why success feels so much sweeter.