March/April

March/April

As a hunter of long vintage, I sometimes reminisce about the sounds of nature—the squeals, howls, hoots, gobbles, and cackles coming from denizens of the wild. From 12 years old, I have spent much time in the woods and fields of Texas, listening to the sounds of the animals and birds that have been an important part of my life.

I’m prejudiced when it comes to nature. The poor souls in New York City or Philadelphia who have never heard a pack of hounds in the chase; the eerie calls of the giant pileated woodpecker; the howl of a coyote; or the morning gobble of a wild turkey have missed a part of living.

I feel fortunate to have been raised to appreciate the wilds of Texas—hunting and hearing all that the fields and forests have to offer a woodsman. I’m proud to have seen and heard it all—or, at least, all that was important to me.

Spring has “sprung” in South Texas, and creeps towards Dallas and Amarillo. Early daffodils are blooming, the birds are singing, and the turkeys are gobbling. Crappie fishing is at a peak, and baseball is just around the corner. Spring is great in Texas!

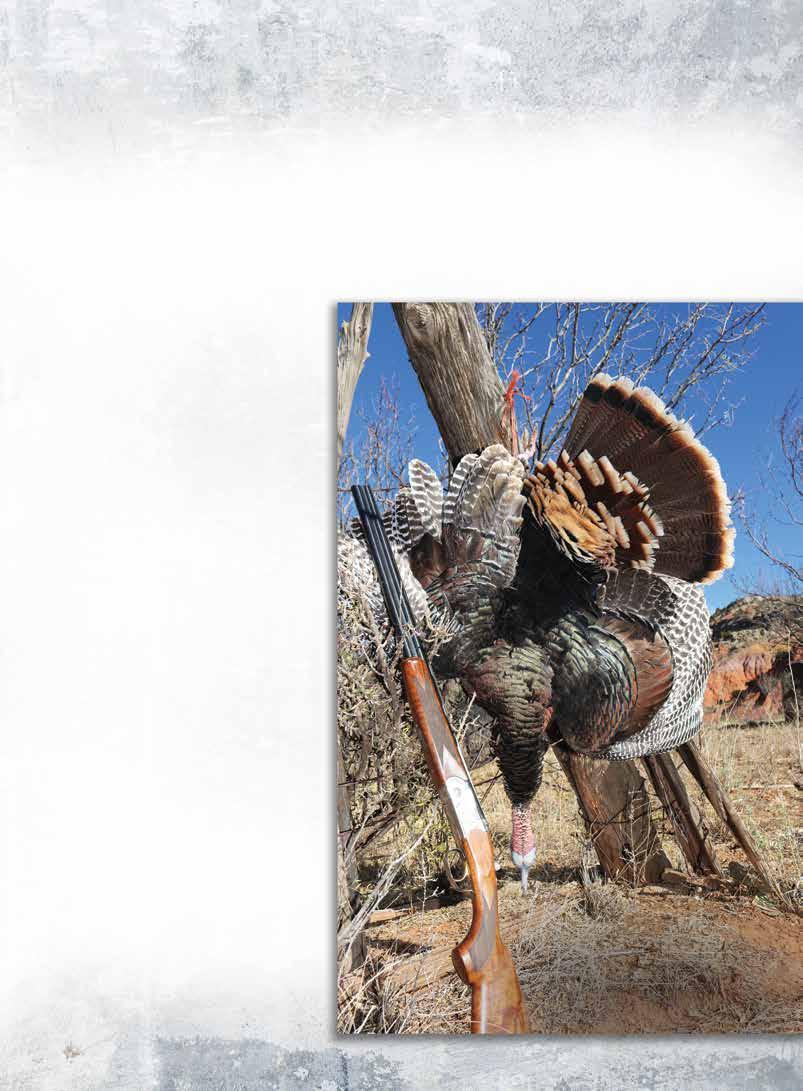

Now that deer season is over, hunters’ minds will turn to exotics and Rio Grande turkeys. March is a good time to hunt nilgai and axis, and the April calls of the wild turkey will lure a few 100,000 nimrods to various parts of Texas west of the Brazos to chase the elusive turkey gobbler.

I was a good turkey hunter for over 30 years, and I know “Old Tom” pretty well. He’s a wild and wary creature, but his traits of love often cause his demise. An old gobbler can’t resist the seductive yelp of a lovelorn hen, imitated by the call of the hunter, and each spring, thousands of Texans tote shotguns and heavy gobblers to the truck. In many ways, there’s nothing more exciting than spring turkey hunting. There are other things to do in the spring if you’re not into exotics or turkey. Shed antler hunting can be enjoyable before the grass and weeds hide the discarded head bones of whitetail bucks. The dry weather that Texas has experienced in the last year or two makes it easier to find off-white antlers on the green turf. It’s almost as enjoyable as looking for arrowheads or four-leaf clovers.

“If I had a flower for every time I thought of you … .” Alfred Lord Tennyson, the English poet-laureate, had it right. Spring IS the time when a young man’s fancy turns to thoughts of love. This is a good time of the year, so enjoy it to the fullest.

Founder Jerry Johnston

Publisher

Texas Trophy Hunters Association

President and Chief Executive Officer Christina Pittman 210-729-0993 • christina@ttha.com

Editor Horace Gore • editor@ttha.com

Executive Editor Deborah Keene

Associate/Online Editor Martin Malacara

North Texas Field Editor Brandon Ray

East Texas Field Editor Dr. James C. Kroll

Hill Country Field Editor Gary Roberson

South Texas Field Editor Jason Shipman

Coastal Plains Field Editor Will Leschper

Southwest Field Editor Jim Heffelfinger

Field Editor At Large Ted Nugent

Graphic Designers Faith Peña

Dust Devil Publishing/Todd & Tracey Woodard

Contributing Writers Zoe Barilla-Deuschle, Luis DeLa Garza, John Goodspeed, Judy Jurek, Christopher Stanley, Kim Tackett, Lynn Zarr, Nick Zinsmeyer, Ralph Winingham

Sales Representative Emily Lilie 713-389-0706 emily@ttha.com

Advertising Production

Deborah Keene 210-288-9491 deborah@ttha.com

Membership Manager Kirby Monroe 210-809-6060 kirby@ttha.com

Director of Media Relations Lauren Conklin 210-910-6344 lauren@ttha.com

Assistant Manager of Events Jennifer Beaman 210-640-9554 jenn@ttha.com

Administrative Assistant Kelsey Morris 210-485-1386 kelsey@ttha.com

To carry our magazine in your store, please call 210-288-9491 • deborah@ttha.com

TTHA protects, promotes and preserves Texas wildlife resources and hunting heritage for future generations. Founded in 1975, TTHA is a membership-based organization. Its bimonthly magazine, The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters®, is available via membership and newsstands. TTHA hosts the Hunters Extravaganza® outdoor expositions, renowned as the largest whitetail hunting shows in the South. For membership information, please join at www.ttha.com or contact TTHA Membership Services at (877) 261-2541.

30 Tribute Buck for Granddad

| By Luis DeLa Cerda, with Texas Harper

39 The Saw Tooth Buck

| By Lynn Zarr

58 Three Generation Buck

| By Christopher Stanley

83 Big Boy

| By Kim Tackett

91 DIY Elk Success

| By Nick Zinsmeyer

Ella Hawk is a young, up-and-coming big game huntress. Read all about her on page 25.

accompanied by a self-addressed stamped envelope or return postage, and the publisher assumes no responsibility for loss or damage to unsolicited materials. Any material accepted is subject to revision as is necessary in our sole discretion to meet the requirements of our publication. The act of mailing a manuscript and/or material shall constitute an express warranty by the contributor that the material is original and in no way an infringement upon the rights of others. Photographs can either be RAW, TIFF, or JPEG formats, and should be high resolution and at least 300 dpi. All photographs submitted for publication in “Hunt’s End” become the sole property of the Texas Trophy Hunters Association Ltd. Moving? Please send notice of address change (new and old address) 6 weeks in advance to Texas Trophy Hunters Association, P.O. Box 3000, Big Sandy, TX 75755-9918. POSTMASTER: Please send change of address to The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, Texas Trophy Hunters Association, P.O. Box 3000, Big Sandy, TX 75755-9918.

The Dallas Safari Club selected Jim Heffelfinger as the winner of its 2023 Conservation Trailblazer Award. This award celebrates the monumental contribution of wildlife professionals to the field of game and non-game wildlife conservation, including wildlife and habitat management, applied research and policy.

Heffelfinger received the award, plus a $10,000 contribution in his name toward the conservation project he selects, during a banquet at the 41st Annual DSC Convention and Expo held January 5-8, 2023.

Heffelfinger currently serves as Arizona Game and Fish Department’s wildlife science coordinator and as an adjunct faculty and full research scientist at the University of Arizona. He has also worked for private landowners, the USDI Bureau of Land Management, and multiple universities as a wildlife research assistant and wildlife biologist. Heffelfinger was a regional game specialist for the Arizona Game and Fish Department for more than 20 years.

“Jim is a foremost expert on deer in the United States. He is a consummate professional who diligently stands on the side of science and not emotion or politics. The impact of his expertise, leadership with the scientific community, and ability to take complex scientific information and communicate it to a diversity of audiences make Jim worthy for consideration of this prestigious award,” said Casey Stemler, big game migration coordinator for the Department of the Interior.

For more than 30 years, Heffelfinger has focused primarily on big game and various deer species. He’s the chair of the Western Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies’ (WAFWA) Mule Deer Working Group. He authored his own book, “Deer of the Southwest,” led the writing of the North American Mule Deer Conservation Plan, and is lead editor of the upcoming book “Ecology and Management of Black-tailed and Mule Deer in North America.” He’s also been instrumental in helping coordinate and implement the Department of Interior’s Secretarial Order on big game winter range and migration, both in Arizona and with other WAFWA state agency biologists.

Additionally, Heffelfinger has also written more than 300 magazine articles, including in The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters, and 20 book chapters in regional, national and international publications. He has published dozens of scientific papers and has written TV scripts for outdoor TV shows. He’s participated in approximately 25 podcasts and maintains his own website called deernut.com.

“Given his incredible body of work and ability to communicate with broad audiences that has manifested into profound conservation impact, coupled with a long list of existing peer recognition and achievement awards for that work and impact, I simply could not think of a better qualified candidate for the DSC’s Conservation Trailblazer Award,” Edward B. Arnett, CEO of The Wildlife Society, said. — courtesy Dallas Safari Club

Barry Hogan is a pioneer of our hunting heritage. He’s a visionary of sorts, and as such has been successful in many aspects of life. He built an industry-leading company as well as an outstanding ranch and wildlife program, which he has selflessly shared with many other aspiring hunters and outdoor enthusiasts.

A lifelong love affair with wildlife began at an early age for Barry. “I grew up in the southwestern suburbs of Houston in a sea of suburban brick homes and hardly a place reminiscent of the outdoors,” Barry said. “It was my father and uncle who instilled in me a passion for hunting and fishing. My uncle took me bass fishing and my father taught me at an early age to shoot and took me dove and duck hunting. These experiences created a foundation for me, but it was the stories they told during our holiday gatherings of their outdoor exploits that really lit my fire!”

The recollected stories detailing youthful outdoor adventures were contagious. As a young teenager, Barry would ride his bike, and later a motorcycle, to nearby creeks and bayous where he would wander and explore with a BB gun or .22 at his side. “Later I developed close relationships with friends whose families operated cattle ranches in the South Texas brush country. Our friendships centered around our mutual love of the outdoors,” Barry said. “It was there I acquired my introduction to deer hunting and although we mostly hunted for does, I remember rattling up and killing my first buck, a nice 10-point.”

Not only did his South Texas friends introduce Barry to whitetail deer and quail hunting, they did even better when they also introduced him to a lovely young lady named Liz in 1974. Liz had grown up in the Rio Grande Valley. The two hit it off instantly and Liz became Mrs. Hogan.

Around the same time, quite a bit was happening in Barry’s life. “My father had a business of fabricating small modular

crude refineries. In 1977 he and I built a small refinery in South Texas that specialized in recycling petroleum waste sludges,” Barry said. That business led Barry to a long career of developing and operating petroleum waste recycling and reduction technologies culminating in DuraTherm, Inc., which operated the largest facility in the United States for the treatment of refinery hazardous wastes. “My brother and I operated that company until 2008, when we sold it to retire early and refocus the priorities in our lives. In other words, we wanted to slow down

and live life a bit while we still could,” Barry quipped.

“During the course of building the business, a shared love of the outdoors led my father and I to purchase two tracts of land combining to 135 acres in an area of red clay hills near Luling that was known as the ‘Iron Mountains,’” Barry said. “The rolling iron-oxide hills were covered in pines, post oaks, native grasses, and had developed a thick yaupon understory. There were few deer around and our first efforts focused on cattle. We began acquiring additional acreage and quickly changed our focus to managing the wildlife.” In 2000, the Hogans high-fenced their ranch and not long afterward, began to intensively manage the property.

Since selling the business and subsequently retiring, Barry and Liz continue to split their time between Sugar Land and the ranch. Both agree that conveniences of the city are nice, the solitude of the country atmosphere is preferable. Enjoying retirement, Barry has redirected his attention to his passion for the outdoors at the ranch for the past 15 years. He has worked on projects too numerous to list, but some have included lodging, infrastructure, and wildlife management. During the course of management, he has conducted botanical inventories and added 42 plants to the Caldwell County plant database.

After its initial acquisition and following intensive management, deer hunting on the ranch has gone from nonexistent to spectacular. Eye-catching bucks are routinely observed and hunted on a sustainable basis. Throughout the years, Barry and Liz have hosted numerous hunts for family, friends, and guests. The ranch has become a special place of serene beauty to many visitors.

Countless newcomers to the sport of hunting have taken their first deer on the ranch. People from all walks of life have visited the ranch including doctors, surgeons, bankers, CPAs, engineers, home builders, construction and factory workers, taxidermists, game processors, and even Taekwondo instructors.

The Hogans are friends to many, including Texas Trophy Hunters, as they have hosted numerous hunts supporting

TTHA sponsored events. Barry explained his concerns and sharing his ranch in detail. “Our largest threat to hunting and wildlife preservation is the immersion of our children in modern entertainment and social media technologies. We need to get them to put the phones down and computers away and get outside to enjoy hunting, fishing, and the outdoors!”

Love of the outdoors led Barry and his wife Liz to become stewards of the land and conservationists in every sense of the word. Additionally, their willingness to share it with others is unprecedented. Presently, Barry and Liz continue to manage their diverse spread of Post Oak Savannah woodlands known as the Hogan Wilderness Retreat. Aside from fantastic hunting and fishing, visitors enjoy the opportunity to observe the many wonders of nature.

“The fantasies of my youth are now the realities of my adulthood and are due in part to our collective efforts to create a diverse wilderness experience out of the Iron Mountains understory,” Barry said. “It is our greatest joy to share our outdoor retreat, the Hogan Wilderness Retreat, to help nurture the spirits of our guests.”

Because of his lasting efforts to introduce friends and guests to the wonderful outdoors of Hogan’s Wilderness Retreat in the Iron Mountains of Caldwell County, and his devotion to the stewardship of the land, Texas Trophy Hunters is proud to honor Barry Hogan as a pioneer of our hunting heritage.

Do your part to preserve our hunting heritage. Share your passion with the next generation. Pass the torch.

Photos Courtesy of TTHA Member Lee Shetler

President Biden proclaimed January as National Mentoring Month, a nationwide observance honoring today’s mentors and encouraging communities to engage in mentoring activities to ensure positive outcomes for youth. “A rising number of adolescents are experiencing mental health challenges, including from bullying and social media harms,” President Biden said. “That is why, as part of my Unity Agenda I announced in my State of the Union address, my Administration is pairing children with mentors who can help them navigate these complexities, open up doors of opportunity, and give them the additional support they may need to excel in school and in their communities.”

The First Hunt Foundation continues to invest in youth mentoring nationwide. The FHF has the goal of being the largest boots on the ground, new hunter mentoring organization in the nation and is well on the way to reaching that goal. First Hunt Foundation currently has 840 volunteer mentors working across 41 states and growing. FHF will announce a new program focusing on bringing more diversity into the hunting ranks. To learn more about the organization’s mentoring efforts, go to firsthuntfoundation.org.

—courtesy FHF

Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Executive Director David Yoskowitz said he applauds 16 years of “tremendous” voluntary collaboration with private

landowners and industry to conserve lesser prairie-chicken habitat and reiterates the department’s opposition to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) listing the species. “This decision jeopardizes decades of voluntary conservation efforts, increases regulatory burden and does not assure recovery of the species,” Yoskowitz said.

USFWS published a final rule Nov. 25 listing the lesser prairie-chicken under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). Implemented in January, the decision will affect 14 counties in Texas, listing the bird as threatened in some and endangered in others. “Notwithstanding this very unfortunate decision, TPWD stands committed to working with private landowners and industry to conserve the lesser prairie-chicken and its habitat, just as we have for decades,” Yoskowitz said.

The new designation comprises a Northern Distinct Population Segment (DPS), where the bird will be listed

as threatened in seven counties in the northeast Texas Panhandle, and the Southern DPS, where the species will be listed as endangered in seven counties in the southwest Texas Panhandle. The listing under the ESA went into effect Jan. 24, 2023, and makes “take” of lesser prairie-chickens or their habitat a federal violation. Take means to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot, wound, kill, trap, capture or collect or to attempt to engage in any such conduct. Incidental take refers to takings that result from, but are not the purpose of, conducting an otherwise lawful activity.

Under the final USFWS ruling, a 4(d) rule for the Northern DPS provides for incidental take exemptions for routine agricultural activities on cultivated lands, prescribed grazing conducted under an approved plan and prescribed fire. Landowners in the northeast Texas Panhandle interested in receiving an approved prescribed grazing plan under the 4(d)

rule should contact a USFWS-certified prescribed grazing planner to initiate enrollment into that plan. A list of FAQs and certified planners will be continuously updated and available at www.fws. gov/lpc, and a list of FAQs is available on the USFWS Lesser Prairie-Chicken Listing FAQs website.

In 2006, TPWD entered a 20-year Candidate Conservation Agreement with Assurances (CCAA) with USFWS to work with private landowners to manage and improve lesser prairie-chicken habitat in exchange for assurances that no additional regulatory burden would be placed on participants if the species were listed. The 91 properties currently enrolled in the program, which cover 649,780 acres across 19 Texas Panhandle counties, are exempt from take and habitat management restrictions while they operate under a TPWD-approved wildlife management plan.

“The CCAA provides landowners the assurances that they can continue to manage their properties to meet their goals while also benefiting the lesser prairie-chicken,” said John Silovsky, TPWD director of wildlife. “We appreciate the tremendous collaboration with private landowners during the past 16 years and we want to continue those important partnerships for the benefit of the lesser prairie-chicken habitat.”

In 2013, TPWD along with the state wildlife agencies for Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma, developed the Lesser Prairie-Chicken Range-Wide Plan (RWP). The plan established population goals for four lesser prairie-chicken ecoregions and designated focal areas and connectivity zones to incentivize voluntary conservation for the species and its habitat.

Under the direction of WAFWA, the RWP also produced a CCAA for oil and gas companies to voluntarily mitigate for new development and operations across the species’ range. This CCAA provides funding to private landowners to improve or maintain lesser prairie-chicken habitat on their lands and provide a net conservation benefit to the species and regulatory certainty for industry.

Since then, USFWS has also approved

an Oil & Gas Habitat Conservation Plan (HCP) and Renewables HCP that provide additional opportunities for industry to mitigate for the incidental take of the species.

Landowners or industries interested in the Texas Lesser Prairie-Chicken CCAA, industry CCAA or HCP options should contact Brad Simpson, TPWD Panhandle Wildlife District Leader, 806-651-3012, brad.simpson@tpwd.texas.gov or Russell Martin, TPWD Panhandle Wildlife Diversity Biologist, 806-452-9616, russell. martin@tpwd.texas.gov.

—courtesy TPWD

The Texas Parks and Wildlife Department Inland Fisheries Division, local anglers, and the Bryan Texas Utilities Department (BTUD) collaborated with Major League Fishing (MLF) on a recent project to install new fish habitat in Lake Bryan.

MLF Fisheries Management Division, in partnership with Berkley Labs, spearheaded the initiative to improve catfish, crappie, largemouth bass and bluegill spawning survival, adult population density and catchability. TPWD’s Inland Fisheries Division deployed its brand-new habitat barge to aid in the installation of the new habitat structures, assembled by TPWD, MLF and BTUD staff along with local volunteers. The two-day project showcased how the agency, industry and anglers can work together to enhance Texas fisheries.

“We were excited when we were contacted by Steven Bardin (MLF Fisheries Management Biologist) about this project,” said Niki Ragan-Harbison, Fisheries Biologist for the College Station — Houston Inland Fisheries Division District. “BTUD has been a tremendous asset as well by not only allowing the project to take place, but also by providing their equipment, facilities, and manpower, as well as contributing to the habitat additions. Exciting things are happening at Lake Bryan, and we all look forward to seeing how the fishery responds in the coming years.”

The structures deployed included 14, 40-inch MossBack Fish Habitat Conservation Cubes, 12 Spawning Beds, 21 Trophy Tree XLs and 21 Safe Haven XLs. In addition, BTUD provided 33 concrete trash receptacle enclosures for use as catfish spawning habitat. Lowe’s of Bryan donated 100 cinder blocks for the MossBack structures and pea gravel to fill the spawning beds.

TPWD has downloadable GPS coordinates for the new fishing structures on the Lake Bryan fish habitat structures website. For more information visit the Inland Fisheries Division College Station-Houston District Facebook page and the MLF website. —courtesy TPWD

Safari Club International condemns the Canadian government’s latest sneak attack on hunters, which if implemented as intended, would qualify as the most extensive firearm ban in the country’s history. Liberal Member of Parliament (MP) Paul Chiang introduced two shady amendments (with designations G4 and G46) to the Liberal Party’s gun control legislation, Bill C-21. Although the bill was initially targeted at handgun control, both amendments would restrict thousands of long guns commonly used in hunting and sport shooting. Passage of the first amendment (G46) will add a 478-page list of specifically banned firearm models to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s already extreme list of 1,500 firearms immediately banned in 2020. These include thousands of additional models of hunting rifles and shotguns. MP Chiang’s second amendment (G4) expands the definition of prohibited firearms to include those “designed to accept a detachable cartridge magazine with a capacity greater than five cartridges of the type for which the firearm was originally designed.”

Bill C-21 was initially sold by Liberals as a way to target weapons most commonly used in crimes involving a firearm, so these amendments have no practical goal except to target law abiding

hunters. Members of Canada’s Conservative Party have said as much and have already clarified their opposition in the media, highlighting how these amendments are not a solution to improving public safety and would have harsh impacts. Conservative MP Raquel Dancho said the Liberal government is “going after Grandpa Joe’s hunting rifle instead of gangsters in Toronto.”

While this outrageous ban poses a clear threat to law-abiding gun owners and hunters in Canada, it’s also highly concerning for American hunters who will not be able to travel to Canada with their firearms or otherwise use many commonly owned hunting firearms once in Canada. This will disincentivize Americans from hunting in Canada, creating a devastating economic impact on the industry and communities that has contributed approximately $1.13 billion Canadian dollars to the country’s GDP this year alone.

Furthermore, the implementation and enforcement of the amendments remains very unclear, giving credence to arguments of Conservatives and the sporting community that this is nothing more than a way for emotionally driven political leaders to check a box on their gun control agenda, all at the expense of hunters. The ban’s projected cost has also been severely lowballed, contributing to its unrealistic and unfair elements.

“This cowardly attack on hunters and rural livelihoods flies in the face of repeated statements from Prime Minister Trudeau and members of the Liberal Party who insisted they weren’t coming after the hunters who play a critical role in wildlife conservation,” said SCI’s CEO W. Laird Hamberlin. “The motives of these political figures cannot be trusted, and sportsmen and women in Canada and across the world must stand firm against proposals like MP Paul Chiang’s knowing they have the full support of SCI members in Canada and across the world.”

SCI will continue its fight against repeated assaults on Canada’s hunting heritage and strongly urges Members of Parliament to strike down this radical proposal. —courtesy SCI

Three men orchestrated one of the largest poaching operations in Wyoming’s history that spanned four counties and resulted in more than 100 violations, officials announced in mid-December. After realizing law enforcement was on to their scheme, the men went to extremes to hide their violations, according to a Wyoming Game and Fish Department news release. The men bought Wyoming resident hunting licenses using a Wyoming address, but they lived in Alabama, Oklahoma and South Dakota, the release said.

In 2015, one of them asked for an interstate game tag to ship a deer head to Alabama for taxidermy work, officials said. It was a suspicious request considering the hunter had listed a Wyoming address when he purchased resident hunting licenses for years before then. The game warden in Gillette started unraveling “the case that would eventually identify dozens of wildlife violations in four different counties in Wyoming.” Investigators pieced together information from the hunter’s cellphone records and social media pages, which ended up implicating his acquaintance in Oklahoma and that man’s son in South Dakota, the release said.

For years, they had shared the same Gillette address on applications for resident hunting licenses and preference points, officials said. “Investigating and successfully prosecuting a case of this size and scope required years of effort by many individuals and agencies,” Game and Fish chief game warden Rick King said in a statement. “Dozens of people worked hard to make sure that even though some of these violations occurred a decade or more ago, they would not go unpunished.”

In 2017, law enforcement and wildlife officials searched the men’s homes in Alabama, South Dakota and Oklahoma and confiscated elk, deer, pronghorn and a bighorn sheep ram mount, the release said. They also uncovered violations of Alabama law associated with the man’s taxidermy shop and confiscated poached alligators and migratory birds, the release said.

Officials said they later learned he

had stashed more than a dozen wildlife mounts in a trailer over 60 miles away from his home. This included three bull moose and three bighorn sheep rams, the release said.

Across four Wyoming counties, the Alabama man was charged with 43 poaching violations dating to 2003, over $113,000 in fines and ordered to pay $87,000 in restitution. He spent more than a year in jail and was banned from hunting and fishing for life. The Oklahoma man faced many but not all of the same charges dating to 2003. Across three counties, he was charged with more than 35 poaching violations, $46,060 in fines and ordered to pay $36,550 in restitution. His jail sentence was 50 days, and his hunting and fishing privileges were revoked for life.

His son in South Dakota was charged with more than a dozen of wildlife violations dating to 2005. He was fined $12,045 and ordered to pay $8,035 in restitution. His hunting, fishing and trapping privileges were revoked for five years in Weston County and his hunting privileges revoked for another 15 in Campbell County, “beginning at the end of his five-year suspension from Weston County.” All three were charged with trespassing on private property to hunt.

The Alabama man surrendered multiple mounts, including four bull elk, one buck antelope, three buck mule deer and one gull, and dozens of poached animals including three bighorn sheep rams, three moose, seven elk, eight antelope, one mule deer and one walrus mask. The Oklahoma man gave up eight buck mule deer, two bull elk, a cow elk and a bobcat. The South Dakota man “forfeited a bighorn sheep ram shoulder mount, three buck antelope, eagle parts, elk antlers, elk meat and two buck mule deer.”

State statute requires the $171,230 in fines to go to public school funds in the counties where the violations took place. It also requires the $131,550 in restitution to go to a Wyoming Game and Fish Department account used to buy access easements to public and private land, the release says. And because 48 other states participate in the Wildlife Violator Compact, the men’s hunting and fishing licenses are revoked in all 49 states.

—courtesy Sacramento Bee

By Dr. James C. Kroll

By Dr. James C. Kroll

My hunting career transcends 59 years while my biologist career has included 53 years, making me one of the most blessed men on Earth. My “memory banks” are stuffed with countless experiences and joys of pursuing and studying whitetails. These are vivid memories. There is not a hunter alive who cannot tell you every detail about the first buck he or she shot.

I took my first buck near Hunt, Texas, in 1963 on a hunt with my biology teacher, Mr. Victor Rippy. I used a World War II surplus .30-06 open sight rifle, with an iron butt plate that promised to kick like a mule. Yet, I never felt the recoil that day, as I raised the rifle when the buck suddenly appeared among some sheep quietly grazing in a field. I just aimed and pulled the trigger, never giving a thought to the sheep until after the shot, but then I got worried.

Scanning the field, I saw no white bodies lying near the buck, so I breathed a sigh of relief and ran to the buck. I can tell you exactly what the weather was like, and the sights and sounds of woods on that December day, including my pounding heart.

Much has transpired since that day, and I have been fortunate enough to be part of the development of deer hunting and management in America. As a deer scientist, I contributed to the growing knowledge about deer biology and management, helping gather the “low hanging fruit” so abundant in those early days. Even then, although deer were the most popular game animal, we actually knew very little about their biology, much less deer management. It would take Al Brothers and Murphy Ray to open the door to actually managing these fantastic creatures in 1975, with their book, “Producing Trophy Whitetails.”

By the 1970s, interest in trophy hunting and deer management was snowballing. My friend, Jerry Johnston, made the first real advancement, with publication of The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters in 1975. In 1983, North American Whitetail magazine debuted. I have been blessed to contribute to both magazines since their inception.

It’s safe to say these two organizations and publications fueled the growing interest in trophy deer hunting and management. Each month, these magazines showed American hunters bucks

they only could imagine shooting. Big buck shows and extravaganzas cropped up across the country, including the Hunters Extravaganza and the Dixie Deer Classic.

My motivation in those days was to develop interest in actually managing deer on private lands by providing sound scientific information. Each issue of these magazines featured monster bucks taken in far away places like Texas, Mexico and Canada. But I wanted to show people you did not have to travel far to find good bucks. They could be produced right where you live, if you just applied a few simple management principles.

An entire industry developed around deer management, including food plots, minerals, feeds, and equipment such as the trail camera, which we were instrumental in development. Many of these products were just gimmicks, but the growing demand for new things out-raced education about the efficacy of products. Many hunters and landowners were searching for those magic bullets that provided a shortcut to success, and marketers were more than happy to feed that demand.

By the turn of the 21st century, deer management and hunting had become a mature industry, with a confusing, fragmented array of interest/user groups. Who would ever have thought bowhunters would war over the type of bow used? “Management mania” on private lands really scared professional biologists, who considered private management as a violation of the North American Wildlife Model. Deer hunting and management was quickly becoming a rich man’s sport. That young man who killed the buck near Hunt, Texas, in 1963 had saved up his money to pay the $50 lease fee to hunt on that ranch. The folks who had that lease were mostly relatives, and going to the lease was a memorable experience. We had Thanksgiving at the lease, dining on venison and wild turkey.

In 1999, Jerry Johnston, Gene Riser and I decided there was a need for a new organization in Texas that would represent all interests in deer management and hunting. We called it the Texas Deer Association. Our primary goal was to provide support to the “little man,” the folks who owned small parcels of land that had been passed down for generations. Farming and ranching on a small scale was dying, and in order to own property, you had to have a city job. The emerging developments in deer breeding provided an alternative source of income for these folks. At least, that was our theory. Through support from folks like Ken Bailey, we developed artificial breeding, something I now regret. Instead of helping out the little man, a huge industry made up of wealthy breeders took control. This further exacerbated resistance from state agencies to private management, especially when public perception had it marked as a rich man’s sport.

Today, many hunters suffer from what I call “antler fatigue.” A few years back, we had a replica of Milo Hansen’s world record typical in our booth at the Extravaganzas. I remember at shows in the 1980s, a 160-class buck would draw attention. But, you would be amazed how many people walked right by the world

The author was inundated by folks wanting help managing their relatively small properties for wildlife. These were people who had inherited their land or had worked all their lives to afford to buy a small piece of land. Landowners want to develop a place for their kids and grandkids, and they want to leave their land better than they found it.

record, without a comment. Outfitters were fighting the trend where prospective clients would not even consider any buck scoring less than 170.

In the 1960s, the goal in the Hill Country was to kill an eight-pointer. Because no one had ever heard of Boone and Crockett in South Texas, hunters on ranches set their sights on killing a 20-inch buck. My father-in-law and rancher, Bo Masters, when told by my wife that I had killed the fabled Boggy Slough Monster, sporting 9-inch bases and four drop tines, asked, “How wide was he?” Hunting was simple then.

With all this said, I had become pretty cynical over the last 10 years about the future of our beloved past time, until I opened my eyes to what was going on around me. I was being inundated by folks wanting help managing their relatively small properties for wildlife. These were people who had inherited their land or had worked all their lives to afford to buy a small piece of land. This included folks who had developed trust relationships or leases with larger landowners, and had been given the opportunity to manage land. In all cases, when asked about their goal, they replied, “We want to develop a place for our kids and grandkids, and we want to leave this land better than we found it.” What I had been seeking all along was right there under my nose and I did not even notice it!

This last decade has been one of the most exciting periods in my career. We now have landowners and lessees all over North America quietly developing their version of paradise for their families and friends. The Journal of the Texas Trophy Hunters has been a trailblazer from its beginning in providing what you, the reader and member want. At TTHA, we want to be leaders, not followers.

So, this column is the first of a threepart series, highlighting what folks are doing to enhance the real experiences associated with deer management and hunting. The second one will showcase a young family who do not own land, but have expanded on their three-generation relationship with a neighbor to assume the stewardship of an East Texas property. The third will highlight another family developing a relatively small property as a family heritage venture. These are not rich folks, just good people trying to leave a little piece of the earth better. I am excited to tell you about these folks.

By Horace Gore

By Horace Gore

American consumers are a strange bunch. Whether it’s vehicles, housing, guns or beer, the success goes to the one advertised best. Today, we have 75 million young consumers who are in a league of their own.

The key to what makes young folks tick is the magic of social media. They were born in a time of plenty and instant communication, which appears to give them a different look at the world. Rest assured, many Democratic presidential hopefuls will be courting young voters in 2024.

“Politics makes strange bedfellows” is a spinoff from Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” where a shipwrecked soul facing a monster cries out, “Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows.” If you look at the Democratic lineup, the truth in Shakespeare’s quote is quite evident.

But where does all of this fit with punching holes in paper targets? Or punching holes in hide and hair? I mentioned guns, because with today’s shooters and hunters, you can also lead them around as willing consumers with media hype. All you have to do is advertise a new gun caliber that’s said to be better than anything before, with a case capacity that saves money, a bullet that defies gravity, and a short shell for a short action that’s suitable for emu or elk. Just pick your bullet and carry a sharp knife.

I speak of the current trend toward the mild, but accurate 6.5 Creedmoor cartridge. The way it’s advertised, and the number of 6.5 Creedmoors sold or custom-made these days, would make you think it has some kind of kinetic magic—and that it can defy the laws of physics. That’s not true for both, but there’s something else, something that has gradually turned a lot of hunters and target shooters off for the last 60 years—the Magnum craze. Hunters are simply tired of being kicked around—no pun intended—for no good reason.

At least four characteristics in a cartridge draw the shooter to the cash register: accuracy, recoil, killing power, and ammo availability. Magnum killing power has been the big draw since 1958 when Winchester brought out the .264

Magnum, followed by Remington’s 7mm Magnum. Hunters jumped on the bandwagon, and have been on a Magnum craze that continues today. A few years before, Roy Weatherby had brought out his line of high-dollar Magnums, but they were out of the price range for most hunters. Then, Winchester and Remington brought out rifles priced right, and the Magnum craze shot up like a rocket.

For at least 40 years, hunters went belted Magnum, regardless of the hunt—whitetails at 100 yards to elk and pronghorn at long range—affluent hunters had to have a Magnum. Above all, they wanted velocity and killing power. Not to go unnoticed was the upswing in African safaris, where big Magnums were popular and often necessary.

A few years later, cartridge companies went short Magnum—same power and bullets—just a short, fat case without a belt suitable for short actions and lighter rifles. It was all in advertising, but it worked. Only one full-length belted Magnum still comes out of the gate today—the .300 Win. Mag., but it’s still winning races. However, today the general line of belted Magnum cartridges is waning.

The cartridge-popularity plot thickened after the turn of the century when folks at Hornady tinkered with a short case, a long neck, and a long 143-grain 6.5mm bullet. They dubbed the cartridge the 6.5 Creedmoor. Velocity was a mere 2,700 feet per second, but accuracy was superb.

Hornady thought of the cartridge as a long-range target load for short-action rifles. It fulfilled all expectations, but laid

around like a mangy dog for about 10 years. When short actions became popular in bolt rifles, and AR-type rifles became more popular—thanks, Obama—the 6.5 Creedmoor cartridge suddenly jumped to the top in popularity. Strangely enough, the Creedmoor craze seems to be following the Millennial age.

No surprise it’s one of the most accurate long-range target loads ever developed as a commercial cartridge. The big surprise in Texas was its popularity as a deer cartridge. Accuracy, yes; low recoil, yes; killing power at 2,700 fps with the 140-grain bullet, yes; ammo availability, yes. Then, you have to look at what’s actually needed to kill 90 percent of the 700,000 whitetails loaded into pickups each season in Texas.

Texas whitetails are commonly shot at close range from a comfortable blind, aided by a corn feeder where an accurate 140-grain bullet at 2,700 fps will consistently cause the demise of all deer. Enter the mild-mannered, pleasant-to-shoot, accurate 6.5 Creedmoor. Actually, most deer in Texas won’t know whether you’re shooting a 6.5, a .243, a .270 or .30-06. They will all succumb to the shot.

With mule deer and possibly elk, the medium-powered 6.5 Creedmoor will continue to do wonders when used with a tactical scope that will match the bullet and velocity. When shooting at game animals up to 400 yards with this setup, wind is the only problem. But, let’s face it—the 6.5 Creedmoor was designed for punching paper at long range, not punching hide, hair, or breaking bone at 300 to 400 yards.

Hunters who prefer the 6.5 bullets have some excellent choices not built for accuracy, but tried and proven on big game. The .264 diameter bullets weighing 120 to 140 grains have a high ballistic coefficient, making them superior for long-

range shooting—especially the sharp pointed spitzer 140-grain bullets. The definition of ballistic coefficient is a measure of a bullet’s ability to overcome air resistance in flight.

My choice of 6.5 caliber for hunting, using 140-grain bullets, would be more like the .264 Winchester or the 6.5-284 Norma. A third choice would be the 6.5x55 Swede. I have used both the .264 and 6.5x55 very successfully on Texas whitetails, and other game including Rocky Mountain mule deer and elk.

Hunting does not require the extreme accuracy the 6.5 Creedmoor will provide, but you need tolerable recoil and killing power, hence the long popularity of the .30-06 and the .270 Winchester on soft-skinned game like whitetails and pronghorns. I know hunters who regularly use .300 Win. Mags and .300 Weatherby Mags on Texas whitetails. I guess it follows the adage, “Shoot the cartridge that you can shoot well.” My daughter shoots a Winchester rifle and .243 100-grain bullets. She has taken 14 Texas whitetails with one-shot kills. Who’s to argue?

In general, the 6.5 Creedmoor is new to Texas hunting. A few of my friends use the 6.5 and swear by it. However, a long shot for most Texas hunters and their Creedmoors would be 150 yards, and more often, 75 yards at a whitetail deer eating corn. A better test for the Creedmoor would be mule deer in Wyoming at over 400 yards. The 6.5 Creedmoor will do it all, according to our field editor, Jason Shipman.

Regardless of the hype and advertising, hunters like the 6.5 Creedmoor because it’s accurate and has mild recoil. With the proper scope and bullet, it will easily kill a deer or pronghorn from here to yonder. But more so, they like it because it will put four holes the size of a quarter in a paper target at deer-killing distance. It’s pure confidence, Waldo!

Left: Here's Dr. James Kroll with a Browning X-Bolt boltaction rifle in Creedmoor 6.5. That's a 26-inch stainless-steel fluted barrel with 1-in-7 twist.

Below: This is the kind of accuracy that makes the 6.5 Creedmoor popular. Other factors that hunters like about the cartridge are soft recoil and good performance on deer at reasonable field-shooting distances.

Left: Here's Dr. James Kroll with a Browning X-Bolt boltaction rifle in Creedmoor 6.5. That's a 26-inch stainless-steel fluted barrel with 1-in-7 twist.

Below: This is the kind of accuracy that makes the 6.5 Creedmoor popular. Other factors that hunters like about the cartridge are soft recoil and good performance on deer at reasonable field-shooting distances.

At 18 years old, with a vast array of hunting behind her, Ella Hawk has experience beyond her youthful years. Ella began her hunting career at the tender age of three, going along with her hunting parents. Her first kill at age 8 was a whitetail deer with a .243 rifle. Shortly after she switched to a crossbow because she was too small to pull a compound bow.

“I enjoy the challenge of bowhunting.” Ella said. “My parents inspired me and my love for hunting has grown so much over the years.”

Her dad, Tony Hawk said, “It’s been pointed out by quite a few hunting buddies and ranch owners that Ella has more hunting experience than a lot of grown men. To me that says a lot!”

Tony owns an insulation company and is on Bowtech’s Pro Staff. Her mom, Cindy, a hairdresser, and Tony are both accomplished bowhunters. They were thrilled Ella wanted to follow their footsteps shortly after taking several animals with a rifle. Despite what’s going on outside of hunting, those moments together are the best days of their lives.

“Her mother is a natural at bowhunting, so Ella inherited her ability,” Tony said. “I’ve always sat with Ella hunting, and our time together is what I cherish. It’s created a bond that will last a lifetime.

In her pre-teen years, Ella requested hunting trips for birthdays and Christmas. Her parents gladly obliged. Draw-

ing on a mature whitetail at close range takes skill. Tony said, “I’ve watched this kid do it over and over, and it makes me so proud.”

Currently, Ella uses a Bowtech Eva Shockey compound bow and Easton FMJ arrows with G5 Striker broadheads. “I may eventually change if I start shooting bigger game,” she said.

Ella’s accomplishments and accolades are numerous, as this young lady has three times been named Trophy Game Records of the World (TGR) Youth Huntress of the Year. In 2019 she won TGR’s Crossbow Hunter of the Year, an adult division.

At age 10, she killed a 13-foot, 800-pound alligator on the Guadalupe River near Victoria, Texas, and set a new TGR crossbow alligator record. Her guide, Ryan Longer, said he had more confidence in her ability than most men he guided. This prompted Ella and her dad being featured on Fox and Friends.

Ella also holds TGR crossbow records for Transcaspian Urial, Rio Grande turkey, and South Texas whitetail, plus many top 10 animals of various species. Last year her Duval County buck with 25 points captured recognition as a TGR Youth Diamond Buck.

No stranger to big buck contests, including the TTHA Hunter Extravaganza Annual Deer Competition, she’s garnered awards. Ella has won various categories in the Muy Grande and Freer Deer Camp competitions. This season her 61⁄2 -year-old whitetail scored 2014⁄8 B&C at Muy Grande.

“I strive for the love and happiness that comes with hunting as a family. Getting that shot on the game you’re hunting wouldn’t be the same without celebrating with your favorite people.”

Ella added, “Feeling connected to nature is an amazing part of hunting.”

A couple years ago, an Oklahoma buck jumped her string, causing Ella’s arrow to hit the buck high. Ella was devastated, searching two days for the buck without success. A few days later it appeared on camera with a non-fatal wound, which made her feel better. In the Hawk family, no practice means no hunting, so Ella, Tony and Cindy are vigilant about practicing all year.

This beautiful young huntress envisions hunting forever. While she strives for a bigger buck or the next game species, things are always planned. Ella stated, “I can’t wait to pass the tradition and sport down to my children and family, to spend genuine time with them one day.”

Ella has a boyfriend named Carson but said, “I intimidate some of the boys at school with my skills and experience, while others aspire to know and do the things I’ve done already.”

Although she’s hunted mainly with her parents, Ella cites landowner Pete Guerra as a close friend, as well as ranch manager John Huber. They are two of the most important people in her life. “They’ve always made us feel welcome, like family. I couldn’t be more thankful for them.”

One of Ella’s most memorable and favorite hunts was an African safari family trip the summer of 2018. “I was able to take wildebeest, warthog, blesbok, and two impalas. We stayed with a warm, welcoming family. I can’t wait to go back!”

Ella also has a desire to hunt Alaska. “My dad has been several times, taking brown bear with a bow,” she said. “It’s the true wilderness. From what he tells me and photos he’s taken, it’s very beautiful. I’ve got my fingers crossed to go sometime!”

Ella’s undecided on what college to attend, but Texas State University is her top choice. “I want a career in property management while I also hope to continue hunting throughout college, and the rest of my life.”

This axis fell to Ella’s sharp shooting ability with a crossbow. She knows patience when hunting.

Luis and his grandfather were supposed to go hunting together, but his granddad took ill and unfortunately passed away. But before he died, Luis promised he would hunt for the big buck they had their eyes on, a buck nicknamed “Gulfstream.”

Iwill never forget the first time my granddad—Juan Martinez—and I visited Rancho Rio Escondido and laid eyes on a big beautiful Mexican whitetail by the nickname of “Gulfstream.” Together, we had browsed through many trail camera pictures and had seen a wide variety of different bucks. But this one stood out the most. I remember thinking to myself, “I can’t wait to bring him back once the season starts and gift him a hunt he will never forget.”

The day before we left, as we sat in the deer blind, we were speechless as we saw Gulfstream walking through the brush. We both sat in silence. We looked at one another and smiled, knowing very soon we would come back once the season started. Little did we know that the unexpected would happen.

As we returned to San Antonio, Texas, a couple of weeks later, Granddad had to be taken into heart surgery. The first thing he asked the doctors as he woke up from the anesthesia was, “When am I able to go hunting again?” The doctors explained his recovery process would be slow and he would not be able to go hunting until the next year. As I heard the news, I called my friend, Texas Harper, who’s the ranch owner, and asked him if we could have that deer until the next year, and he said yes.

A few months later in January, the unexpected happened. Granddad got COVID-19 and unfortunately passed away. The

last time I spoke with him, I told him not to worry. I would go back and hunt Gulfstream in his name.

The following year, Gulfstream grew even bigger, and my hunting buddies and I decided we would head to Rio Escondido on opening week of the 2021 hunting season. That first sit on the morning of the hunt, we saw many deer. It was easy to say buck fever was kicking in. I kept asking my friend Texas about this one buck at the feeder because I was ready to lay my gun on the window and take the shot. But he told me to be patient because it was only the first morning of the trip.

Throughout the remainder of the afternoon, we kept seeing many deer, but not Gulfstream. The following morning, we sat in the same deer blind from the previous morning, the same deer blind where we had seen Gulfstream the previous year. But around 7:45 a.m., we decided to switch up the game plan and jump into the side by side and rush over to another deer blind about a mile away. We quietly got into position in the blind and started seeing many deer coming and going to the feeder, but not Gulfstream.

At around 9 a.m. we decided it was time to head to the lodge for some coffee and breakfast. While we were climbing out of the deer stand, we heard something snort. We turned around and saw a monster buck walking out of the brush about 150

With a little help from his friend and guide, Texas Harper, Luis took the buck for his granddad.yards away. We climbed back into the deer stand and kept the windows closed to see if he would go to the feeder.

It took him about 10 minutes, and he finally did. He was an absolute beast. Texas was probably more excited than I was when he saw the deer in the open. We glassed him for several minutes, but the buck never took his eyes off us in the deer stand.

We finally were able to open the window to get a better view so I could stick my rifle out of it. Once I had put my rifle on him, he was at 200 yards standing broadside and staring right at me. I put my crosshairs on his shoulder and when I got ready to take the gun off safety, he decided he had enough and turned the other way and started walking back into the brush where he had come out. We grunted and he stopped for a split second, but I wasn’t able to get on him in time. Seconds later he was gone.

We went back to the lodge to have breakfast with the rest of the family. We began to share the stories about the deer we had seen and all the experiences we had just gone through. We were sitting by the fire in the living room and started to say to each other that we weren’t going to get lucky by just sitting inside. So, we decided to get to the deer blind a lot earlier than we had been. We took a 30-minute siesta and by 1 p.m. we were back at the deer stand waiting to get lucky. That afternoon seemed like an eternity. We didn’t see any activity until about 5:30 p.m. We saw a couple of does and some young deer. Nothing really exciting.

5:45 rolled around and it was getting dark fast. Texas said, “Let’s wait another 15 minutes. Let’s wait it out till the end.” And so we did.

Right after we made that decision, Texas picked up his binoculars, looked at me and said, “It’s Gulfstream.” It took him what seemed like 2 seconds to identify the buck and tell me to get my gun ready. He told me to wait for the buck because he was coming from the right, and headed towards the feeder. The buck had no idea that were even there.

Gulfstream finally made his way to the feeder, 150 yards away. By this time it was already getting even more dark, making it harder to identify the deer. Gulfstream was eating off the ground, facing away from me, and all I heard from Texas was, “Wait until he gets broadside.” Gulfstream stayed for what seemed an eternity in the same spot, which was only really 30 seconds.

He finally turned broadside and I got the green light from Texas. I gently applied pressure on the trigger then I saw a big blast from the end of the barrel. My brother Diego and Texas both began to scream and laugh out of joy. The deer had dropped in his tracks.

We were high fiving each other in the blind, but I wasn’t sure if the buck was truly the one Granddad was after. We got out of the deer stand and started our walk towards the deer. We finally approached him. The second I was able to lay my hands on Gulfstream, tears of joy started rolling down my cheeks. As I pointed and looked up to the sky, I said, “This one is for you, Granddad.”

Our inflationary times not only have an effect on daily living, but they also affect outdoor recreation such as hunting. Anybody who hunts the bigger game like whitetails, pronghorns, exotics, or maybe a Rocky Mountain mule deer or elk, knows it can cost as much as the pickup you’re driving, the guns you’re carrying and all the money in your pocket, just to go on a good hunt. The eight million Millennials balked at hunting and joining hunting organizations. This has influenced license sales and hunting throughout the state. Historically, inflation occurs when a government prints more money than goods and services are worth, or when demand is greater than supply. Money loses value as goods and services get more expensive. In the past, most countries that suffered society-killing inflation were European, along with some African nations, which printed more money than the economy could bear.

My Uncle Theo was in Germany at the close of World War II. I remember him telling me about looking for a place to sleep, when he opened a large trunk that looked like a quilt box. The trunk was full of paper money, so Theo slept on it. He said, “German money was so inflated that it took a wheelbarrow full to buy a loaf of bread.”

Some of us can remember when everyday living was 20 times less than it is today. People who made $50 a week now make $1,000. In 1950, the cheapest Ford car cost $1,800, and a deer lease in Gillespie County was $125 for a party of four— about $30 per hunter. About $200 would take you to Wyoming for an antelope hunt, and another $50 would get you a good

elk. We all now have much more money to buy these same things—it’s called inflationary spending—and it’s affecting how we hunt.

Hunting has become a specialized sport available to only a small percent of the population. Saturated deer habitats of 100 million acres are filled with 800,000 hunters, from 30 million Texans. If you break it down to the hunter-license buying ages, including both men and women, only 6% of Texans buy a hunting license, 4% hunt deer, and 2% hunt doves. Other game, including exotics, turkey, waterfowl, quail, pheasant, squirrel and varmints add a small percentage to the whole.

Hunting is a sport of supply and demand. There’s a limited amount of hunting, and it usually goes to the highest bidder. Two generations ago, about half of Texas hunting was free, via relatives, friends, or company leases. Now, with hunting values increasing each year, free hunts are scarce.

Texas hunters, per capita, dwindle every day. The cost of everything associated with hunting continues to increase, causing many Texans to look for other recreation. Looking ahead at 2050, over 90% of Texans will be urbanites with few places to hunt, regardless of the cost.

Today’s market shows each harvested deer in Texas is worth an average of $1,800, and by 2050, that value could double. The next generation may have to pay a summary cost of $200 or more for a limit of doves, and a duck hunt will cost more than a box seat Dallas Cowboys ticket. So, there may be a day when there are more golfers than hunters in Texas—a result of urbanization, inflation, and supply and demand.

The vibrant afternoon that held promise only a few hours before had morphed into a shadowy evening crammed no shortage of frustration, as well as no fish. The sloping sand flat littered with waving grass and oyster shells had produced

a number of good fish in the past, but on this coastal day, the only reds and specks that materialized were in my mind’s eye. As the kayak slowly rounded a bend in the sandy shore, I spied an older gentleman exiting the water only 50 yards from where

I’d launched. He had been fishing a deep cut that previously had given up fish and where an excess of artificial offerings had been sent on this day with no takers.

A bait bucket and floating fishing caddy trailed behind as he slowly creeped toward the bank, eventually using the butt of his rod as a cane to pry himself from the sticky mud and onto dry land. As the paddle sent me closer, the man took notice and gave a quick wave before shaking down his gear. Any thoughts of this gent sharing my angling futility quickly were thrown out when he lifted the hefty stringer of trout that had been hiding behind the caddy onto the tailgate of his pickup. This angler sheepishly paddled up to get the goods.

“At least somebody found them,” I casually offered.

Texas anglers have access to a prime location for rainbow trout fishing through a Texas Parks and Wildlife Department “no fee” public access lease on the Guadalupe River. Camp Huaco Springs, located between New Braunfels and Sattler, features a half-mile of bank access along alternating pools and riffles on the Guadalupe. Anglers can use the bank, which is gently sloped and rocky, or wade fish both upstream and downstream to take advantage of a low-water dam at the upper end of the property or a deep pool at the lower end. They can also launch non-motorized boats, canoes, kayaks or other floatable devices for the purpose of fishing.

The Canyon Reservoir Tailrace area features some of the best rainbow trout fishing in Texas, with regular stockings providing hefty fish in the cold-water area of the river.

More information: tpwd.texas.gov

“Yeah, I finally got some live shrimp from the bait shop,” the old man said. “I caught three sandies and five redfish, too, but they were too small.”

Chalking it up, the lesson was learned—again.

At its core, fishing is simple: Introduce a tempting offering complete with barb, your quarry takes it, and you reel them in. Somewhere along the way, all the tantalizing extras caught our fancy and made things more difficult than they have to be. Most die-hard bass anglers literally have boatloads of lures in a rainbow of colors and styles, some of which they never use. Many guys and gals who fit this description would be defined

act right and attack a dry fly. There was a time when the thought of a 6-inch brookie popping a yellow humpy trumped a 16-inch brown thumping a beaded nymph for me, too, but I soon came to my senses.

The key to fishing—especially this time of year—is to not make things harder than they have to be. With that in mind, the next few months are a great time to fish from or near the bank with live bait. Spring is a magical time for anglers looking to catch the biggest bass of their lives and though most lunkers are caught from a boat, there remains a good chance for someone angling from land to find big fish that have moved up to spawn. The same goes for crappie, which also move into the shallows to spawn as water temperatures slowly rise.

Boat docks and other structures near shore that may hold bass certainly also will have crappie near them this time of year. And there’s no better crappie bait than a live minnow. Our state record bass was caught on a minnow fished by an angler targeting crappie, so that certainly points to the versatility of using a live offering now.

Though largemouths and crappie are sought-after fish, they aren’t the only ones primed for natural offerings. White bass that have started to run up numerous rivers to spawn can be caught using minnows and other live bait choices and the ubiquitous catfish—flathead, channel and blue—can be found in some form in almost every lake and river in the state and has never been finicky about a meal.

as purists, the type of angler who would rather not catch fish than have to admit to using live or prepared bait to scoop them into a net.

Fly fishing also has its purists, those folks who can’t fathom dredging a nymph below the surface to catch a fish that won’t

The best part about using live bait is that it simply outfishes artificials, making it perfect for introducing a youngster or beginner to the pursuit. Wearing someone out with all-day casting and little to no results is a drag, and I certainly can attest to it.

Even if you don’t have a revved-up bass boat or some other craft, you still can catch fish if you adopt the simple strategy of trying live bait.

You can take it to the bank.

pening weekend of quail season, my son, nephew and I had slipped away to South Texas, hoping to fill the tags on some does along with a few bobwhites. It was early, barely first light, and I was in a treestand high up in live oak, busy watching a nice 10-point buck work his way almost directly underneath me. Suddenly, out of nowhere, another buck appeared at a feeder we had recently set up.

It was one of those foggy mornings, but even in the early light I could tell he was a big-bodied deer with heavy main beams. They were lighter in color than our typical mature bucks’ antlers and I was having a hard time discerning his overall rack. Between fog, feeder posts and tall grass, I eventually counted seven typical points on his right side, two of which looked like nubs or jagged teeth and four nice tines on his left side. He left as suddenly as he appeared but left me with a memorable impression of what I likened to teeth on a saw blade, so I quickly dubbed him “Saw Tooth.”

Luckily, I had snapped a few photos with my phone before he walked off. I sent the clearest pictures I had to the ranch biologist via text to get his opinion of the deer’s age. Based on a few factors such as his deep body, a block head and graying around the eyes and face, he estimated him to be 71/2 years old. As the days crept by and my next hunt slowly approached, I decided Saw Tooth would be my target buck this season, and my goal would be to get a shot at him with my bow.

On Nov. 15 I hosted a hunt for my father-in-law and his cousin who had traveled all the way from northern Tennessee to shoot a Texas buck for his 70th birthday. After putting him in a box blind where some shooter bucks had recently been seen, it wasn’t long before I heard the crack of a rifle echo through the river bottom. I knew his birthday gift had been delivered. He had taken a nice 51/2-year-old eightpoint management buck.

Being only 7:35 in the morning, I continued hunting in hope of another encounter with Saw Tooth. As the morning hunt progressed, the first deer I saw was an odd, dark antlered five-point. I considered drawing down on him when another 10-point wandered out from underneath me. He was a nice buck with chocolate brown antlers, but he needed another season or so to mature.

As he assessed the area and slowly stalked around in what seemed like a figure eight, I caught a glimpse of another deer in the brush right beneath me. It was Saw Tooth. As soon as I could see his light-colored rack, I noticed the two jagged nubs on his right side. Wow!

He looked even bigger and better seeing him up close. Nerves kicked in and my heart started to pound. Reminding myself to keep my head down through the shot and not to lift up to watch the arrow—something I had been guilty of before—I grabbed my bow and turned to position myself for a shot.

Saw Tooth worked steadily towards the feeder and presented a perfect broadside shot. My arrow stuck him, and he bolted off like a scalded dog. As he crashed through the brush, I noticed my arrow had barely penetrated his body and was sticking way out as he disappeared.

I decided to wait an hour before even getting out of the tree to look for blood. The suspense was agonizing, and within 20 minutes I decided to climb down and walk in the opposite direction towards the river to look for sheds

or anything that would get my mind off the buck. The treestand I was in is about 200 yards from the Aransas River on its south bank. All along the river, some of the thickest brush exists, mixed with massive trees, vines and all sorts of thorny brush, cactus, and ravines, making it very difficult to traverse.

As I walked along the river, I heard the crash of a large animal which flushed on the other side of the river. But I saw nothing. Was that my deer? No way, because this was in the opposite direction I saw him go. Finally, my allotted hour was up, and I crawled out from the dense river bottom to check for signs of blood near where I shot him.

Within 10 steps of the feeder, I found blood. Based upon the blood and other factors, I assumed I must have hit him in the shoulder. At that point I decided it would be best to come back later that afternoon, giving him plenty of time to expire.

Around 2 p.m. I returned with my two other hunters and picked up the thin blood trail. The terrain got too thick for the others to continue, but I searched on. I continued to track his blood trail which became spotty in places and ultimately lost it. After about an hour and a half I had made a semicircle down into the river bottom near where I had heard the animal flush, on the other side.

I decided to find a place to cross the river and see, if by chance, any blood lay near where that noise had come from. I found a shallow spot to cross and made it back to the game trail where I hoped I might find signs of my deer. Sure enough, I saw more blood signs and I was back on his trail. On the north bank of the river, the blood trail was even thicker.

I had to crawl on my hands and knees to get through some places to follow it. I lost the blood trail again and eventually

came to an area that forked where it looked like he could have chosen one of three different ways to vanish. One led left upriver, one went forward out of the river bottom towards the neighboring property and low fence, and one went to the right heading down stream.

My heart sank. I looked and looked and found no more deer signs at all. I phoned one of Texas’ most reputable dog tracking experts. At the end of our call, he talked me out of hiring him, saying he felt the chances of finding that deer were not good, and the deer probably wouldn’t die. It’s hard for anyone to imagine how down I felt following that call.

After a rough night of little to no sleep, I decided to have one more thorough search. I would go back to the fork and look in all three directions he might have gone. Maybe coyotes or vultures might lead me to him. I started looking upstream and found nothing.

When I searched out of the river bottom in the direction of the neighbor’s ranch, I noticed a couple vultures circling way down river. They weren’t sticking around, only diving down momentarily then flying off. I thought because that’s the only place I’d seen any sort of buzzards, I would look down stream at least as far as where they had been circling. Hunched over, in order to clear all the vines and low brush canopy, I gruelingly crawled and hiked up and down the opposite side of the river for nearly 21/2 hours.

I searched the river, the banks and brush everywhere and saw nothing. No signs of my deer, no more vultures, nothing. Zig zagging my search about 600 yards downstream through one thorn bush after another, just me and my bird dog, “Remi,” we still found nothing. Exhausted and with very a sore back, it was time to give up the search, find a place to cross the river and head back to my truck.

While walking back, I happened to glance upon a wide part of the river and noticed what appeared to be the hind end of an animal resembling a deer, floating just barely out of the water. It was on the far side where the river was deeper, and the bank was high with a straight drop to the water and

surrounded by dense foliage. As I stared at the tiny section of wet fur, I realized its hind legs were pointed away from me and it all appeared dark brown in color. Unsure what I was looking at, I took a picture and sent it to our ranch hand to see if he thought it looked like the rear end of a deer or a calf.

Suddenly, I noticed it rotated ever so slightly in the deeper water. A few minutes later, I could see some white on its hind quarters. It was a deer, but was it a doe, my buck, or another buck? There was only one way to find out.

I stripped down to my underwear and then Remi and I dove into the ice-cold water. The frigid water yanked my breath away. As we dog paddled across the river, my short breaths rapidly came and went, but seemed to regulate the closer we got to the submerged animal. Treading water with Remi by my side, I got my hand on its floating back hoof. I could see it was definitely a deer, but I still couldn’t see anything below the surface of the water. We started swimming back and I pulled the deer by its stiff back leg, when suddenly my kicking legs and bare feet rubbed against something smooth, slender and hard. It was my arrow and it was still sticking out of his side.

We swam to the bank where I’d laid all my clothes, and I popped up standing in about 2 feet of water and begun to turn the deer around, hoping to view its head. As its buoyant body flipped over, his whole body with all 11 points rose to the surface. “IT’S HIM, Remi”! No telling how many counties heard my shouts of joy.

I had found Saw Tooth. My arrow had landed in the vitals after all, but for some reason the expandable tip didn’t penetrate like it should have. Turtles and gars had begun dining on him, so I dragged him on land and caped out the head to haul it out and return to camp. Saw Tooth isn’t the biggest deer I’ve ever taken, but at 153 B&C he’s currently my best with a bow and without question my most memorable hunt.

A long distance view of Lynn’s buck floating in the river.

It was a cool, breezy November afternoon. So far, only one young five-point buck had passed our position. The sun was dipping low to the west and the temperature was dropping. Anticipation was building as my daughter, Emma, waited by my side. A flock of wild turkeys were seen in the area a few days earlier and we were shopping for a wild bird for the table.

We heard them before we saw them. A sound like a stampede coming from the creek. It was the fast feet of 30 wild turkeys. In the mob were 10 long-bearded gobblers.

Emma was ready with her 20-gauge. This was a well-rehearsed event, the taking of a gobbler to add a spice of the wild to the store-bought

bird already on the table for the family’s Thanksgiving feast. A tradition we do every year at the ranch. Emma’s aim was true, dropping a mature bird with a 9-inch beard. Fried turkey nuggets would soon be on a platter. Deer aren’t the only thing worth hunting in the fall.

That memorable afternoon took place on a Panhandle river bottom a few years ago. Since then, turkey numbers have taken a nosedive in North Texas and the Panhandle. Drought is mostly to blame. Jason Hardin, Wild Turkey Program Leader with TPWD, explained the status of Texas turkey numbers.

“A recent publication in the Journal of Wildlife Management pairing harvest estimates derived from TPWD banding efforts with TPWD’s Small Game Harvest survey estimated the statewide population of wild turkeys at 790,000 birds (2016-2020 average). Defining North Texas as the Rolling Plains and Cross Timbers I would estimate the current population in that landscape to be approximately 226,000 birds across those combined areas.

“The Rio Grande wild turkey annual population trends are heavily driven by cumulative rainfall with winter and spring rains providing the biggest driver in annual nesting effort, poult production and annual recruitment. Timely rain events and cooler spring and summer temperatures led to significant population growth from 2014-2016 in North Texas and across the Rio Grande range in Texas. However, across North Texas the population experienced a significant decline from 2017-2022 driven primarily by persistent drought conditions. Drought conditions going into the spring nesting season reduces the fitness of individual hens resulting in lowered fat reserves resulting in suppressed nesting effort.

“Other short-term impacts are reduced availability of both nesting and brooding cover, and reduced numbers of alternate prey sources (mice, rabbits, etc.) which puts nests and poults at greater risk of predation. Persistent droughts also lead to long term impacts when they result in the loss of traditional roost sites at the ranch scale. Long term impacts to the overall population density also means fewer hens entering the nesting season, which results in fewer nests. Under these circumstances, it may take several years for a population to recover.

“We need year one of good nesting—increase the number of hens available to nest in

year two. Next, we need year two of good nesting—then we get exponential population growth. Unfortunately, we have not stacked two good nesting seasons in a row since 2016.”

While numbers are down, it’s not all bad news. In late November 2022, I saw a flock of 19 turkeys on my favorite Panhandle creek. Seven were mature gobblers, two were jakes and 10 were hens. Friends hunting other riparian habitats at the top of Texas reported similar sightings. They are seeing turkeys while deer hunting, just not the large numbers from years past.

A conservative harvest is important to give that population as many adults as possible to help rebuild the flock for the future.

Texans have two distinct seasons to pursue wild turkeys, fall and spring. First, in many counties, legal hunting coincides with the opening day of archery season for deer in October. Check county listings where you hunt for exact season dates and bag limits. Fall hunting continues through the end of deer season in most counties that have stable numbers. In the fall, I would guess most turkeys taken are shot as a bonus while a deer hunter is waiting for his buck. Also in the fall, oftentimes mature gobblers travel in one flock and immature gobblers (jakes) and hens travel separately. Although it’s certainly possible to see the two sexes mingled together on a cold fall day.