Summer Classics

17-19 July 2025

Summer Classics

The

is in association with

The Ayr concert is in association with

Kindly supported by Eriadne & George Mackintosh, Claire & Anthony Tait and The Jones Family Charitable Trust

Thursday 17 July, 7.30pm The Town House, Hamilton

Friday 18 July, 7.30pm Castle Douglas Town Hall

Saturday 19 July, 7.30pm Ayr Town Hall

HAYDN Symphony No 80 in D minor

CAPPERAULD Rewired Concerto (World Premiere)

Commissioned by Lewis Banks with generous support from Creative Scotland

Interval of 20 minutes

BEETHOVEN Symphony No 4 in B-flat

Jonathan Bloxham Conductor

Lewis Banks Saxophone

4 Royal Terrace, Edinburgh EH7 5AB

+44 (0)131 557 6800 | info@sco.org.uk | sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra is a charity registered in Scotland No. SC015039. Company registration No. SC075079.

Hamilton concert

© David Parker

Lewis Banks

Jonathan Bloxham

©Kaupo Kikkas

THANK YOU

PRINCIPAL CONDUCTOR'S CIRCLE

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

CHAIR SPONSORS

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Sub-Principal Cello Su-a Lee

Ronald and Stella Bowie

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Bill and Celia Carman

Anny and Bobby White

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Double Bass

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe

The Hedley Gordon Wright Charitable Trust

Sub-Principal Oboe Katherine Bryer

Ulrike and Mark Wilson

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

THANK YOU FUNDING PARTNERS

“A crack musical team at the top of its game.”

HM The King

Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE

Life President

Joanna Baker CBE

Chair

Gavin Reid LVO

Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev

Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze

Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen

Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld

Associate Composer

Our Musicians

YOUR ORCHESTRA TONIGHT

Information correct at the time of going to print

First Violin

Maia Cabeza

Tijmen Huisingh

Emma Baird

Kana Kawashima

Fiona Alexander

Amira Bedrush-McDonald

Wen Wang

Emily Ward

Second Violin

Bas Treub

Michelle Dierx

Stewart Webster

Abigail Young

Sian Holding

Catherine James

Viola

Max Mandel

Felix Tanner

Christine Anderson

Steve King

Cello

William Conway

Donald Gillan

Christoff Fourie

Kim Vaughan

Bass

Nikita Naumov

Jamie Kenny

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Oboe

Maria Victoria Muñoz

Zaragozá

Katherine Bryer

Clarinet

Cristina Mateo Saez

William Stafford

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Luis Eisen

Louise Lewis Goodwin Timpani / Percussion

Horn

Kenneth Henderson

Harry Johnstone

Trumpet

Peter Franks

Brian McGinley

Timpani/ Percussion

Louise Lewis Goodwin

© Ryan Buchanan

WHAT YOU ARE ABOUT TO HEAR

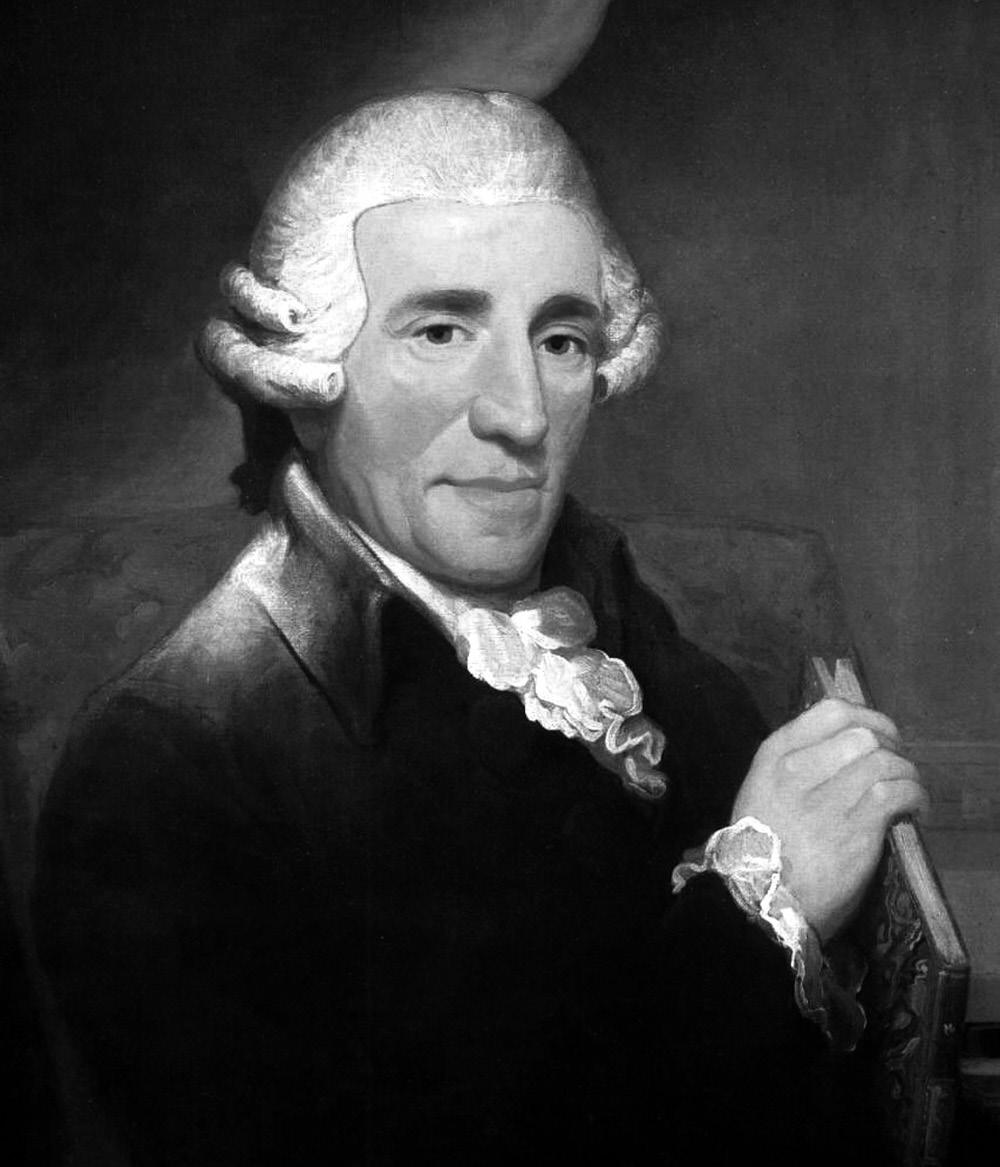

HAYDN (1732-1809)

Symphony No 80 in D minor (1784)

Allegro spiritoso

Adagio

Menuetto

Finale: Presto

CAPPERAULD (b. 1989)

Rewired (2025)

(World Premiere)

1. The Habit Loop

2. The Chill of Inertia

3. Spike Trains

4. The Healing Instinct

Commissioned by Lewis Banks with generous support from Creative Scotland

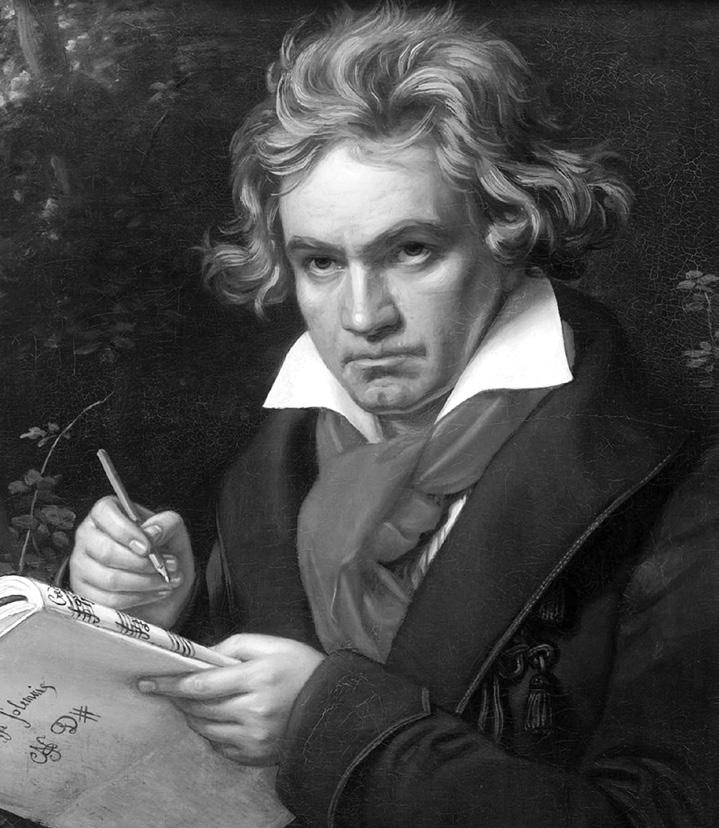

BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Symphony No 4 in B-flat, Op 60 (1806)

Adagio – Allegro vivace

Adagio

Scherzo: Allegro vivace

Allegro ma non troppo

When you stop to think about it, a symphony is a strange beast. Those more familiar with classical concerts might be used to the idea of what’s usually fairly abstract music, cast across several apparently different pieces (called ‘movements’ for reasons lost in the mists of time), all collected together to form the grander overall work. Those encountering a symphony for the first time, however, might wonder what all the fuss is about – and in addition, why that kind of piece is generally seen as the summation of a composer’s craft and skill. And yet the fact remains that almost any composer worth their salt (save those who took up more regular dwellings in the opera house) channelled their creativity into the often austere formality of the symphony –sometimes simply to entertain, or to provoke and inspire, or even as an expression of profound emotion.

We’ll hear two symphonies in tonight’s concert, both of which might somewhat confound expectations of their respective composers. In between comes an entirely different piece: a brand new concerto for soprano saxophone by SCO Associate Composer Jay Capperauld, written for his friend and musical colleague Lewis Banks, which peers deep inside the human mind and considers its remarkable abilities in selftransformation.

But let’s begin with Franz Joseph Haydn, who famously spent a large portion of his career –nearly three decades of it, in fact – employed by the fabulously wealthy Esterházy family in what’s now Austria and Hungary. His first post with them was as a 29-year-old in 1761, when he took the role of assistant Kapellmeister (roughly equivalent to Music Director) under Prince Paul Anton Esterházy. But he fully flourished as full Kapellmeister under the music-loving Prince Nikolaus,

spending much of his time at the family’s lavish and recently built Eszterháza Palace, dubbed the ‘Versailles of Hungary’, which boasted its own purpose-built concert hall and opera house.

Not that Haydn’s life in Eszterháza was one of luxury. In fact, he had little time to kick back and enjoy the sumptuous surroundings. As well as ensuring a steady flow of new compositions both for entertainment and more serious court occasions, he was responsible for directing performances, hiring and firing players, managing rehearsals, even keeping an eye on the court’s music library and instruments. And yet what Haydn achieved during his years with the Esterházy family was remarkable – not just in terms of his sheer output of symphonies, chamber music, operas, choral music and much more, but also in that he virtually established musical forms such as the symphony and string quartet, thereby setting the templates by which we know them today.

No 80, however, is a thoroughly distinctive, deeply idiosyncratic piece, one in which Haydn no doubt set out thoroughly to entertain Prince Nikolaus, but also to remind him of his remarkable skills and musical ambitions.

Haydn created his Symphony No 80 – this evening’s opening work – in the autumn of 1784 at Eszterháza, nominally as entertainment for his discerning employer. But viewing the Symphony simply as music to divert and amuse surely does it a disservice. The piece is a far more slippery, elusive creation, one that blends together stormy drama with knockabout comedy, to such an extent that you might consider it something of an aural illusion: is it a lighthearted piece with serious sections, or a serious-minded piece that happens to have its moments of humour?

It may be easy to dismiss Haydn (as many have done) as a composer capable of churning out symphonies at an alarming rate (he wrote no fewer than 106 of them during his lifetime, after all) but with little distinctiveness or drama. No 80, however, is a thoroughly distinctive, deeply idiosyncratic piece, one in which Haydn no doubt set out thoroughly to entertain Prince Nikolaus, but also to remind him of his remarkable

Franz Joseph Haydn

skills and musical ambitions. It’s perhaps no wonder that the composer chose No 80 – alongside Nos 79 and 81 – to send to publishers in Vienna, London and Paris, in an attempt to raise his international profile. It clearly worked: no less a figure than Mozart programmed No 80 in one of his own Viennese concerts in 1785.

So what’s all the fuss about? Just the Symphony’s first movement encapsulates the piece’s split personality and divided ambitions, as its decidedly tempestuous, even angry opening slowly gives way to a smiling, charming dance tune for flutes and violins against a pizzicato accompaniment. Smiles remain in the slower second movement, whose song-like theme for high violins quickly returns in a richer orchestration – though after a turn to the darker minor, the same music takes on a somewhat wistful mood towards the movement’s close.

The supposedly lighthearted dance music of the third movement in fact throws us back into the aggressive austerity of the Symphony’s very opening. Haydn closes, though, with more smiling wit – or perhaps that should be a mischievous grin. His finale’s main tune relies on almost undetectable syncopation – you’re never entirely sure if what you’re hearing is on or off the beat, which plays havoc with tapping your foot along to the music. No doubt it brought a smile to the face of Prince Nikolaus – although taken alongside the Symphony’s earlier drama and power, it surely demonstrated that his music director was capable of far more than mere entertainment.

Ayrshire-born Jay Capperauld has been the Scottish Chamber Orchestra’s Associate Composer since 2022, and he’s one of the most distinctive voices in current Scottish

music, combining a sense of immediacy in his wide-ranging works with an often uncompromising intellectual rigour. He’s written many works for the SCO, from the sparkling orchestral showpiece The Origin of Colour which launched the Orchestra’s 50th anniversary season in 2023, through to the theatrical storytelling work for families The Great Grumpy Gaboon, and the macabre Bruckner’s Skull, premiered in February and about to receive a repeat SCO performance later this month at the BBC Proms.

Capperauld wrote Rewired, his new concerto for soprano saxophone and chamber orchestra, for his regular collaborator, Glasgow-born saxophonist Lewis Banks. He writes about the piece:

Rewired takes its stimulus from the process of rewiring the primitive parts of the human brain after trauma and/or the development of negative emotional and physical habits that affect our most primal instincts. This concerto for soprano saxophone and orchestra focuses on the learnt, unlearnt and relearnt behaviours of the human brain, and explores the notion that, regardless of our individual circumstances and the loop of negativity in which we may find ourselves, the brain is infinitely malleable and capable of overcoming our primal fears, anxieties and obstacles to forge a positive future for ourselves.

The work is divided into four movements:

1. The Habit Loop

2. The Chill of Inertia

3. Spike Trains

4. The Healing Instinct

The first movement, ‘The Habit Loop’, explores the brain in turmoil from a multitude

© Euan Robertson

of different perspectives that show how the primal brain responds to external and internal stresses which develop into long-term effects – whether that be chronic pain conditions, negative rumination, anxiety, substance abuse, information overload, burnout or self-inflicted trauma. The cause of such emotional and physical responses can often be deep-rooted, subconscious and unknown, but the prominence of the resulting effects can overwhelm the individual to a point more traumatic than the initial trauma itself. In this movement, the saxophonist is caught in a loop of repetitive habits which manifests an expression of violence and mechanically unrelenting behaviour that attempts to mirror the habitual trauma felt by an individual in pain.

The second movement, ‘The Chill of Inertia’, explores the post-traumatic fear that negative thought-loops and cyclical rumination will continue, perhaps with accompanying chronic physical pain, without remedy. This emotional

Ayrshire-born Jay Capperauld has been the Scottish Chamber Orchestra’s Associate Composer since 2022, and he’s one of the most distinctive voices in current Scottish music, combining a sense of immediacy in his wide-ranging works with

an often uncompromising intellectual rigour.

plateau is common in the rewiring process as negative past experiences inform the present, which perceptively impacts the future in a negative way. Despite the immovability of inertia, at the core of this movement is an instinctual hope to change in the face of continual trauma.

The third movement, ‘Spike Trains’, refers to the graphs read by neuroscientists when studying the brain’s development of new neural connections – in this case, the forming of new behaviours that hint at the malleability of the brain and its capability to respond and react to positive stimulus and form new patterns of positive behaviour. The title also refers to the idea of literal trains and the journey individuals must take to heal and recover.

The final movement, ‘The Healing Instinct’, infers an innate ability of the body and mind to adapt and recover (insofar as it is possible) from trauma, and signifies the completion of

Jay Capperauld

the rewiring process. In an optimistic sense, this movement attempts to highlight the body and brain’s natural capacity to overcome its own self-imposed limitations and experiences by breaking the cycle of repetitive behavioural, physical and emotional trauma, and forging a free, natural and positive pathway for the future.

In essence, Rewired is an exploration of the neurological, physical and emotional effects of the modern world for our most basic instincts, as the saxophonist embodies the qualities of a learning brain that must interact with its rapidly changing orchestral environment. As the neural networks form, some musical ideas ferment and take hold while others fall by the wayside in a Darwinian struggle for prominence in the brain. Not all ideas are welcome, and some unwanted learnt behaviours develop, meaning the embodied saxophonist must learn, unlearn and relearn as the musical narrative unfolds in an uncertain and everchanging psychological search to find an internal balance, and ultimately forge a positive connection with life.

We return to the world of the symphony for tonight’s final piece, and to one of the form’s great titans. Ludwig van Beethoven effectively took the symphonic innovations of Haydn and transformed them into pioneering, deeply personal utterances that could convey profound emotion and compelling, sometimes audacious musical arguments – just think of the life-and-death struggles of the Fifth Symphony, or the epic grandeur and universal vision of the Ninth.

It might seem strange, then to describe a Beethoven symphony as neglected. There’s no denying, however, that his Fourth Symphony is probably his least

well known. That’s probably for the simple reason that it sits between his grander and more exuberant Third (the ‘Eroica’) and the heroic triumphalism of the Fifth. None other than composer Robert Schumann famously described the Fourth as ‘a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants’. But despite its sunny disposition and its modest, Haydn-esque proportions, we might be wrong if we simply consider it as a musical throwback between two pioneering masterpieces.

A lot of the Fourth Symphony’s lighthearted mood and humble proportions may come down to the circumstances of its commission. Beethoven spent the summer of 1806 away from the bustle of Vienna, at the Silesian country estate of his friend and patron Prince Karl Lichnowsky. The Prince invited the composer to visit a nearby friend – and, it turned out, Beethoven super-fan – Count Franz von Oppersdorff in Oberglogau (now Głogówek in Poland). So passionate about music was the Count that he not only kept his own private orchestra, but also insisted that every single person in his household learnt to play an instrument. And he demonstrated his enormous admiration for the visiting composer by asking him to write a new symphony for his private band, in return for a generous fee.

Given the flattery and the substantial sum involved, Beethoven was hardly likely to decline. He’d already started work on what would become his Fifth Symphony, but sensed that it wouldn’t suit Oppersdorff’s petite, Haydn-loving orchestra. Instead, he offered an entirely different piece, the Fourth Symphony – perhaps written expressly with Oppersdorff’s players in mind, though there’s substantial evidence to suggest that Beethoven had already composed the work,

and it was simply good luck that it chimed with the Count’s expectations.

Despite Beethoven giving Oppersdorff exclusive performance rights for six months, the Count graciously allowed the private premiere to take place in Vienna, at the city mansion of Prince Lobkowitz, another of the composer’s patrons, in March 1807. The public first heard the Fourth Symphony in April 1808 at Vienna’s Burgtheater, though it wasn’t much of a success, despite its relatively listener-friendly, conservative tone. Even fellow composer Carl Maria von Weber found it all a bit too radical and outlandish for his personal tastes, writing sarcastically that Beethoven, ‘above all things, throws rules to the winds, for they only hamper a genius’.

To modern ears, the Fourth might sound quite a bit more conservative, even backwardlooking, than the symphonies to either side of it. But that’s to disregard Beethoven’s

Ludwig van Beethoven effectively took the symphonic innovations of Haydn and transformed them into pioneering, deeply personal utterances that could convey profound emotion and compelling, sometimes audacious musical arguments

continuing innovations in terms of the music’s power, its tautness and ruthlessly rigorous structures. The first movement’s slow, brooding introduction manages to avoid the Symphony’s ‘home’ key of B-flat major for all of 42 bars, and when its main faster section bursts into life, it represents a wholesale change of mood. The slower second movement pulls a characteristically Beethovenian trick of contrasting a long, slowly unfolding melody against an accompaniment of almost military-style precision. The third movement – apparently a minuet dance, but really more of a sparkling scherzo – flickers constantly between light and darkness, with prominent woodwind writing in its central trio section. Beethoven closes with a dose of infectious jollity in his dashing finale – though spare a thought for the orchestra’s principal bassoonist, thrust unexpectedly into the spotlight alone towards the end of the movement.

© David Kettle

Ludwig van Beethoven

27-29 Aug, 7.30pm

Airdrie | Blair Atholl | Inverness

LEARN MORE

Jakob Lehmann conductor

Maximiliano Martín clarinet

Rossini & Schubert

Also including music by Spohr

Under 18s go FREE!

Book tickets at sco.org.uk/summertour

Tickets also available locally

JONATHAN BLOXHAM

British conductor Jonathan Bloxham was appointed Music Director of the Luzerner Theater in 2023, having debuted there in 2022 with Bluebeard’s Castle. After achieving great success last season with acclaimed new productions of La Bohème ("the opera highlight of the season", Luzerner Zeitung), I Capuleti e I Montecchi and Dido and Aeneas, in 24/25 Bloxham conducts Idomeneo, Fledermaus, Luisa Miller and Hansel and Gretel. Bloxham made his Glyndebourne Festival debut in 2021, conducting Luisa Miller with the London Philharmonic. In the same year he conducted Glyndebourne Touring Opera’s production of Don Pasquale, having performed Rigoletto with the orchestra in 2019.

After first debuting with the orchestra in 2020 this season Bloxham begins his tenure as Chief Conductor of the Nordwestdeutsche Philharmonie following in the footsteps of Andris Nelsons and Jonothan Heyward, and conducting concerts on two German tours as well as in their subscription season in Herford. In 2021 he recorded a CD of Strauss and Franck with the orchestra, described as "irresistible" by Musicweb International.

Guest highlights of the past couple of seasons have included London Philharmonic, NDR Elbphilharmonie, Tokyo Symphony, Salzburg Mozarteumorchester, Halle Orchestra, BBC Symphony, Belgian National, Residentie Orkest, Tonkuenstlerorchester Wien at the Grafenegg Festival, Bonn Beethovenorchester, Trondheim Symphony and Philharmonic Brass (musicians from Berlin and Vienna Philharmonic orchestras) – many of these on multiple occasions. This season he returns to the BBC Symphony to conduct Wagner and Charles Ives, conducts the BBC Philharmonic in an opera gala, and debuts at the Enescu Festival with the Romanian National Radio Orchestra.

For the past 16 years Bloxham has been Artistic Director of the Northern Chords Festival based in Newcastle-upon-Tyne, commissioning new works from young composers such as Jack Sheen and Freya Waley Cohen. He returned to the Festival in June 2025.

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

©Kaupo

Kikkas

Saxophone LEWIS BANKS

Lewis Banks is a Scottish saxophonist praised by The Herald for his ‘virtuosity and blinding characterisation’. No stranger to diverse and adventurous concert programming, Lewis is rapidly developing a reputation as an exciting soloist who thrives on traversing genre borders.

Winner of the Sussex Prize at the Royal Overseas League Music Competition, Lewis made his London recital debut at the Purcell Room in 2019 and regularly appears as a soloist across the UK, including recent performances on BBC Radio 3 and BBC Scotland.

Recent appearances as soloist include the music of John Williams with the RSNO, and the UK premieres of Courtney Bryan's 'Carmen Jazz Suite' in 2024 and ‘Inscriptions in Granite’ by Scottish composer Electra Perivolaris in 2023, both with the Glasgow Barons. Previously, he gave the UK premiere of the orchestral version of Santiago Baez’s L’Arlesienne Fantasy Concerto in 2020, and also appeared as concerto soloist with the Royal Scottish National Orchestra in 2016, performing Ibert’s Concertino da Camera.

Lewis is a frequent guest musician with ensembles such as The Royal Scottish National Orchestra, Ulster Orchestra, BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra, BBC Philharmonic, The Scottish Chamber Orchestra and Scottish Opera. He recently performed with the RSNO on their autumn residency (2023) in Austria, as well as their winter tour (2024) through the Netherlands and Germany.

Previously, Lewis studied at the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland where he won most performance prizes, was awarded the highest attainable recital marks in both his final degree recitals and graduated with the Principal’s Prize for Excellence in 2018.

Upcoming projects include a series of recital releases on Eleven Kinds Records. He is also co-director of a brand new saxophone summer school at the RCS in Glasgow and visiting saxophone lecturer at Aberdeen University.

© David Parker

SCOTTISH CHAMBER ORCHESTRA

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in 2023, with Schubert Symphonies Nos 5 and 8 following in 2024.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly and the late Peter Maxwell Davies.

SUPPORT THE SUMMER TOUR

This summer, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra is bringing live music to 20 towns and villages across Scotland - from Golspie to Castle Douglas, Brechin to Kilmelford. Our Scottish Summer Tour celebrates the rich diversity of our musical heritage, featuring everything from timeless classics to a thrilling world premiere.

Your donation will help deepen our connections with local communities, showcase our exceptional musicians, and bring world-class performances to audiences who rarely have the opportunity to experience live orchestral music in their area.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Hannah on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk

Su-a at the Kelpies in 2021