11-14 June 2025

11-14 June 2025

Kindly supported by Eriadne & George Mackintosh, Claire & Anthony Tait, The Jones Family Charitable Trust and The Vaughan Williams Foundation.

Wednesday 11 June, 7.30pm Kames Village Hall

Thursday 12 June, 7.30pm Kilmelford Village Hall

Friday 13 June, 7.30pm Crianlarich Village Hall

Saturday 14 June, 7.30pm Gartmore Village Hall

with

with

MENDELSSOHN (arr CEBRIÁN) Scherzo from 'A Midsummer Night's Dream'

MOZART Divertimento in B-flat, K 270

CAPPERAULD Carmina Gadelica

Interval of 20 minutes

HUMMEL Octet

BEETHOVEN Duo for two flutes

FRANÇAIX Seven Dances from 'Les Malheurs de Sophie'

SCO Wind Soloists

SCO Flutes

Marta Gómez and André Cebrián

THANK YOU

Our Principal Conductor’s Circle are a special part of our musical family. Their commitment and generosity benefit us all – musicians, audiences and creative learning participants alike.

Annual Fund

James and Patricia Cook

Visiting Artists Fund

Colin and Sue Buchan

Harry and Carol Nimmo

Anne and Matthew Richards

International Touring Fund

Gavin and Kate Gemmell

Creative Learning Fund

Sabine and Brian Thomson

Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen

Donald and Louise MacDonald

Chorus Director Gregory Batsleer

Anne McFarlane

Principal Second Violin

Marcus Barcham Stevens

Jo and Alison Elliot

Second Violin Rachel Smith

J Douglas Home

Principal Viola Max Mandel

Ken Barker and Martha Vail Barker

Viola Brian Schiele

Christine Lessels

Viola Steve King

Sir Ewan and Lady Brown

Principal Cello Philip Higham

The Thomas Family

Sub-Principal Cello Su-a Lee

Ronald and Stella Bowie

American Development Fund

Erik Lars Hansen and Vanessa C L Chang

Productions Fund

Anne, Tom and Natalie Usher

Bill and Celia Carman

Anny and Bobby White

Scottish Touring Fund

Eriadne and George Mackintosh

Claire and Anthony Tait

Cello Donald Gillan

Professor Sue Lightman

Cello Eric de Wit

Jasmine Macquaker Charitable Fund

Principal Double Bass

Caroline Hahn and Richard Neville-Towle

Principal Flute André Cebrián

Claire and Mark Urquhart

Principal Oboe

The Hedley Gordon Wright Charitable Trust

Sub-Principal Oboe Katherine Bryer

Ulrike and Mark Wilson

Principal Clarinet Maximiliano Martín

Stuart and Alison Paul

Principal Bassoon Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Claire and Anthony Tait

Principal Timpani Louise Lewis Goodwin

Geoff and Mary Ball

“A crack musical team at the top of its game.”

HM The King

Patron

Donald MacDonald CBE

Life President

Joanna Baker CBE

Chair

Gavin Reid LVO

Chief Executive

Maxim Emelyanychev

Principal Conductor

Andrew Manze

Principal Guest Conductor

Joseph Swensen

Conductor Emeritus

Gregory Batsleer

Chorus Director

Jay Capperauld

Associate Composer

Information correct at the time of going to print

Flute

André Cebrián

Marta Gómez

Oboe

Katherine Bryer

Francesca Cox

Clarinet

Maximiliano Martín

William Stafford

Bassoon

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Alison Green

Horn

George Strivens

Jamie Shield

Cerys Ambrose-Evans

Principal Bassoon

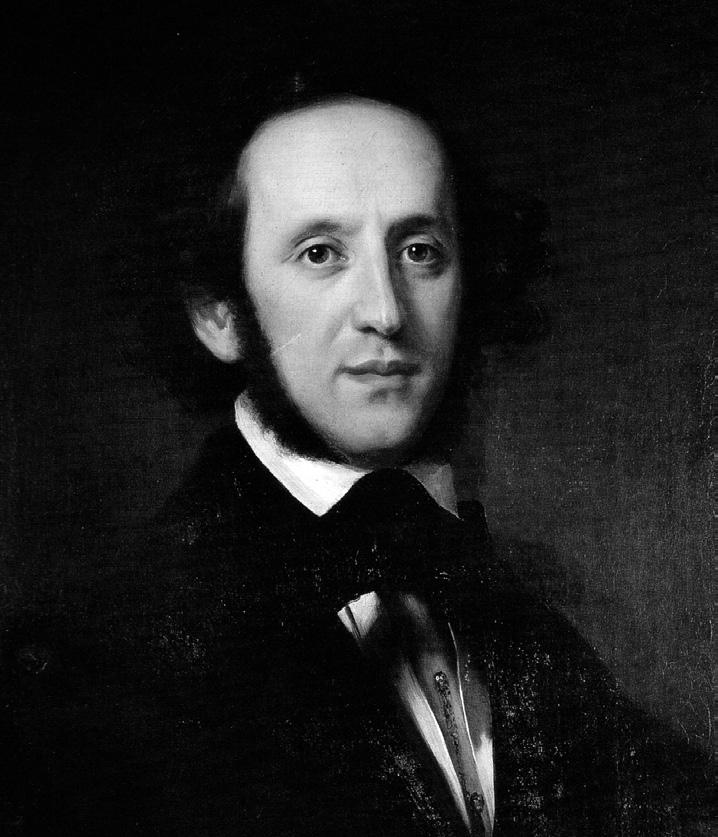

MENDELSSOHN (1809-1847)

Scherzo from 'A Midsummer Night’s

Dream' (1842-43) arr. Cebrián (2024)

Allegro vivace

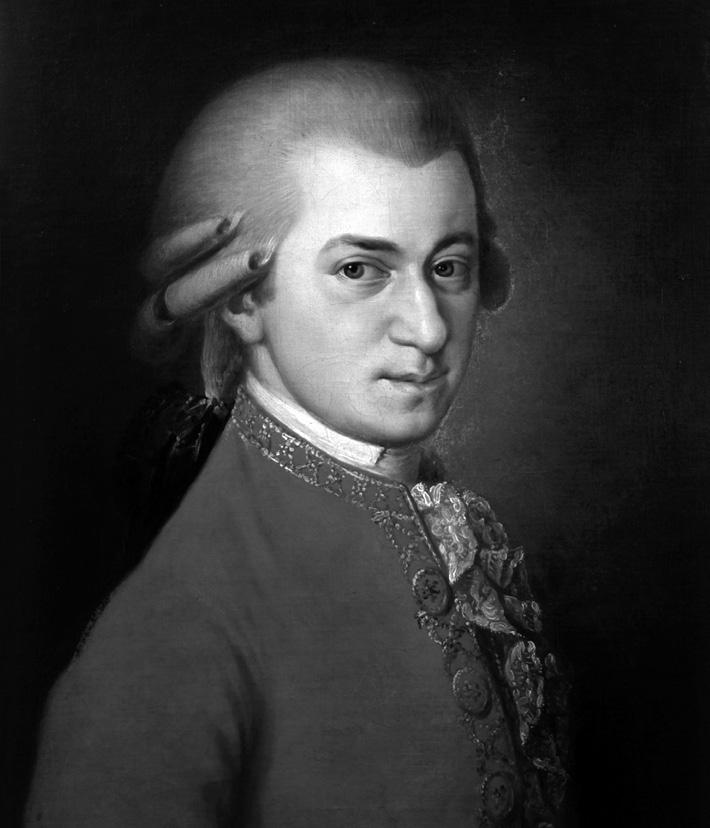

MOZART (1756-1791)

Divertimento in B-flat, K 270 (1777)

Allegro molto

Andantino

Menuetto

Presto

CAPPERAULD (b. 1989)

Carmina Gadelica (2025)

Incantations

Waterfall of Psalms

Waulking Songs

Laments

Fairy Songs

Commissioned by the Scottish Chamber Orchestra and generously supported by a grant from the Vaughan Williams Foundation

HUMMEL (1778-1837)

Octet-Partita in E-Flat Major (1803)

Allegro con spirito

Andante più tosto Allegretto

Vivace assai

BEETHOVEN (1770-1827)

Duo for two flutes, WoO 26 (1792)

Allegro

Minuet quasi Allegretto

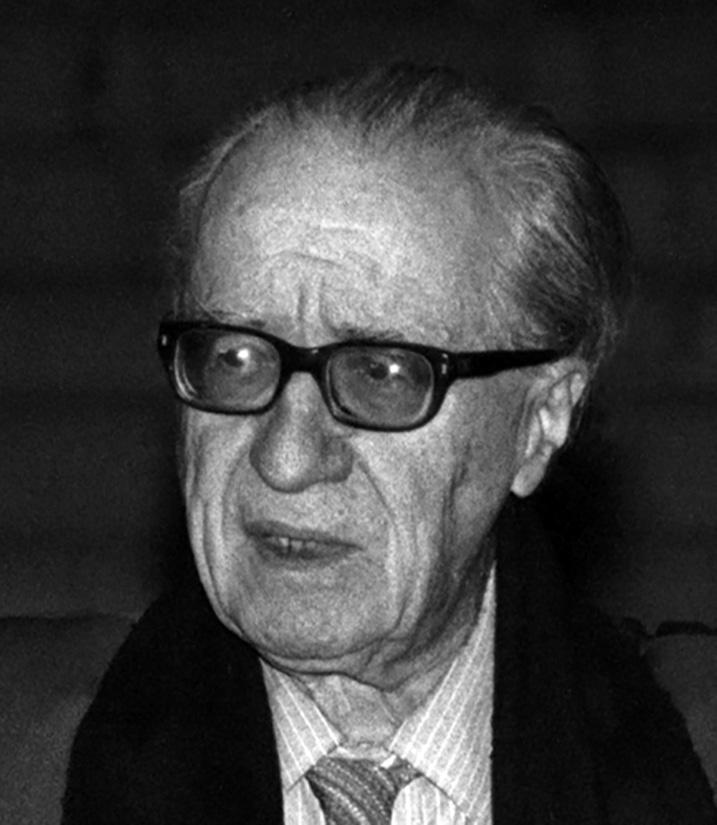

FRANÇAIX (1912-1997)

Seven Dances from 'Les Malheurs de Sophie' (1971)

Le jeu de la poupée

Funérailles de la poupée

La présentation des petits amis

Variation de Paul

Pas de deux entre Sophie et Paul

Le goûter

Danse des filets à papillons

The humble wind ensemble has an illustrious and long-standing history, and tonight’s concert samples key moments from across the centuries. The wind band – or Harmonie, to give it its proper name – was all the rage in central Europe during the second half of the 18th century, as nobles and wealthy landowners demanded light music from their house ensemble’s wind players for entertainment purposes. At its simplest, that might mean a few popular opera tunes as background music for dinner. At its most sophisticated, however, it led to elaborate rearrangements of symphonies or even whole operas, intended as serenades for banquets or garden parties, to charm and delight hunting expeditions, or even as ‘morning music’ to wake particularly esteemed guests.

Spring 1782 marked quite a turning point for the genre: the Austrian Emperor Joseph II ordered that an eight-piece wind ensemble assembled from his Vienna court orchestra (which would later become the Vienna Philharmonic) should provide his ‘table music’, comprising pairs of oboes, clarinets, horns and bassoons. It was a group that included some of the most illustrious players in Europe at the time, including one Anton Stadler, for whom Mozart would later write his Clarinet Quintet and Concerto.

If Joseph II set the trend, then many others across Europe followed, thereby hugely expanding the repertoire for wind groups –and also encouraging some unscrupulous money-making. Before any concept of copyright, arrangers might be expected to leap on the latest operatic hit and extract its big tunes for Harmonie versions, whether the original composer knew about

it or not. Mozart, for example, wrote from Vienna to his father in Salzburg that he planned to rearrange the whole of his opera Die Entführung aus dem Serail for wind ensemble before anyone else could get their hands on it. It was also Mozart who remembered being serenaded by a sextet of street wind musicians on his way home late one night – playing music that he himself had composed.

We’ll hear two pieces from the Harmonie’s heyday later in tonight’s concert. We begin, however, a little later, with the teenage Felix Mendelssohn in the 1820s. Born as he was into one of Europe’s elite cultural dynasties, it was no surprise that the young Mendelssohn would quickly discover – and grow to love – the plays of Shakespeare. Amid his childhood immersion in music, painting, literature and philosophy, he would also raid the family’s library and act out favourite scenes from Shakespeare with his sister Fanny. The Mendelssohns

The Mendelssohns acquired a new German translation of AMidsummerNight’sDream in 1826, and Felix devoured it –as well as immediately sensing its musical potential. The result was his AMidsummerNight’sDream Overture, written when he was just 17, and originally intended for the concert hall rather than the theatre.

acquired a new German translation of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in 1826, and Felix devoured it – as well as immediately sensing its musical potential. The result was his A Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, written when he was just 17, and originally intended for the concert hall rather than the theatre.

It was 17 years later, in 1843, that the now adult composer was requested to provide incidental music for a production of A Midsummer Night’s Dream in celebration of the birthday of King Friedrich-Wilhelm IV of Prussia. Incorporating his existing Overture into what was now a theatrical setting, Mendelssohn also set about reusing the musical themes he’d concocted as a teenager into the broader scope of an evening-long entertainment. Among the incidental music’s 14 separate numbers, tonight’s Scherzo introduces us to the world of the play’s fairies with appropriately lightfooted, mischievous music that scampers

through the piece from start to finish. Perhaps surprisingly, Mendelssohn sets his supernatural evocations in the darker, more wistful minor mode – maybe to suggest the beings’ unpredictable, unruly natures – although a more rustic-sounding tune in the brighter major enters later on.

Mendelssohn’s original makes great use of his orchestra’s wind instruments, especially its duo of flutes. Tonight’s arrangement –continuing those centuries-old Harmonie traditions – transfers the whole thing to winds, courtesy of SCO Principal Flute André Cebrián, who devised the reimagining.

Our earliest visit to the world of the Harmonie comes with tonight’s next piece, though slightly earlier than the ensemble’s heyday. Mozart wrote his Divertimento in B flat, K 270, a few years before his move to the bright lights and gold-paved streets of Vienna, while he was still a

jobbing musician at the court of the city of his birth, Salzburg. Not a lot is known about the Divertimento’s origins, but it was probably written as ‘Tafelmusik’ (literally ‘table music’, in other words for dinner accompaniment) for Salzburg’s PrinceArchbishop Hieronymus Colloredo, and its score is dated January 1777.

Mozart’s sextet of players – pairs of oboes, horns and bassoons – was a well-established ensemble. But what he did with his six musicians is anything but conventional. Perhaps predictably, he takes a sophisticated, innovative approach to his medium, scoring his material freely across the ensemble and making great play of the individual instruments’ distinctive personalities.

After a summons to attention (after all, Mozart wouldn’t want his diners to disregard the musicians entirely), the first movement opens with a perky theme in the

Mozart’s sextet of players – pairs of oboes, horns and bassoons – was a wellestablished ensemble. But what Mozart did with his six musicians is anything but conventional.

oboes, who follow it with a gentler second theme, moving through a brief but stormy central development section before the two themes return. His second movement is a stately, sonorous gavotte, followed by an elegant minuet dance with a more rustic, waltz-like Ländler as its central trio section. Mozart puts his players firmly through their paces in his sparkling, breathless finale, with witty writing that whizzes from instrument to instrument, and a treasured moment in the spotlight for the bassoons just before the end.

For tonight’s next piece, we step firmly into the present day (and possibly encounter some fairies from closer to home). Born in Ayrshire, Jay Capperauld is the Scottish Chamber Orchestra’s Associate Composer. He’s written widely for the SCO: his Bruckner’s Skull, reflecting on the possibly apocryphal tale of the earlier composer cradling the skulls of Beethoven and Schubert as they were moved between

© Euan Robertson

Viennese cemeteries, was premiered in February, while his theatrical work for children (and grown-ups) The Great Grumpy Gaboon recently entertained listeners across Scotland following its 2024 premiere. His Carmina Gadelica for ten wind players received its premiere performances earlier this year. Capperauld himself writes about the piece:

Carmina Gadelica is inspired by Alexander Carmichael’s 1800s collection of ancient Scottish folk poetry consisting of hymns, prayers, charms and incantations from the vanishing Western Isle cultures of Scotland. His compendium, titled Carmina Gadelica, which translates as ‘Song of the Gaels’, came into contention when its authenticity and authorship were questioned, leading to accusations that Carmichael may have fabricated and/or significantly altered its contents.

This new work for wind dectet explores

Carmina Gadelica is inspired by Alexander Carmichael’s 1800s collection of ancient Scottish folk poetry consisting of hymns, prayers, charms and incantations from the vanishing Western Isle cultures of Scotland.

the subject of authorship and cultural authenticity through various ‘Scottish’ melodies in a musical re-creation of Carmichael’s Carmina Gadelica. The piece is divided into five movements inspired by the collection’s various songs:

The first movement, ‘Incantations’, explores the various ritualistic charms and prayers of healing and harvest that reflect on the primal beliefs of bygone people. The second movement, ‘Waterfall of Psalms’, replicates the Gaelic tradition of psalm singing in which a precentor sings a musical line and the congregation attempts to follow this line while embellishing and improvising around it – this cascading and haunting effect becoming known as ‘waterfall music’. The third movement, ‘Waulking Songs’, presents a patchwork musical tapestry woven over a single steady beat, in reference to the thumping rhythm drummed out on tables by the hands of women who worked on cloth while they

sang songs to accompany their work. The musical material is put through its own processes which turn its metaphorical ‘cloth’ into a new product while the beatdriven song remains the same. The fourth movement, ‘Laments’, is inspired by the collection’s sorrowful songs of grief and the Gaelic tradition of ‘keening’ in which mourners cry or weep for the dead in song. The practice of keening was an integral part of funerals, with its characteristic melodious wailing, but the act has since died out with only a handful of recorded examples left as reference to its authentic style. The final movement, ‘Fairy Songs’, explores the collection’s folklore of fairies, which depicts the complex relationships between humans and these supernatural entities, who often appear to people as divine beings and other creatures to lead them in an impish dance to otherworldly realms.

Next, we travel back in time a couple of centuries to just a few years after Mozart

Johann Nepomuk Hummel might be a lesser-known figure to us today, but he was a hugely admired and influential musician in Vienna at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries.

was composing the Divertimento we heard earlier. Johann Nepomuk Hummel might be a lesser-known figure to us today, but he was a hugely admired and influential musician in Vienna at the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. He studied with Mozart, Salieri, Clementi and Haydn, and counted Beethoven and Schubert among his friends. Indeed, he’d been a fellow student of Beethoven’s among the pupils of Johann Georg Albrechtsberger, and had felt entirely overshadowed by the older composer’s fiery creativity, even as a young man. Their friendship endured, however, and Hummel later served as one of the pallbearers at Beethoven’s funeral in 1827.

As the Viennese public rushed to embrace the new-fangled emotion and unbridled creativity of Romantic composers such as Mendelssohn and Schumann, not to mention Liszt and Wagner, Hummel found his elegant, balanced, late Classical music rather overlooked. Which is a shame,

because there’s much to admire and enjoy in it, not least in his sunny, buoyant OctetPartita, whose score is dated 27 October 1803. After the military-style fanfares of its opening movement, its slow movement is charming and simple, while the horn calls of its dashing finale suggest we might be out at a hunt.

We turn to the composer who stole Hummel’s limelight for tonight’s next piece – and to a little-known work in his output. Beethoven wrote his Duo for two flutes in 1792, and it has the distinction of being one of the final works he composed while living in his birthplace of Bonn, before heading eastwards to the bright lights of Vienna in November that year. Indeed, the Duo was intended as something of a ‘souvenir’ for his friend Johann Martin Degenhart, a law student and accomplished flautist, so that Degenhart might cherish some fond memories of Beethoven once he’d left town. In that way, Beethoven never imagined

Beethoven never imagined the Duo for public consumption –indeed, it was only published after the composer’s death – although it provides a fascinating and surprisingly intimate glimpse into the composer’s early musical interests.

the Duo for public consumption – indeed, it was only published after the composer’s death – although it provides a fascinating and surprisingly intimate glimpse into the composer’s early musical interests. There are two contrasting movements: the sprightly, brisk opening Allegro con brio sets the two flautists chasing each other, and perpetually swapping roles between melody and accompaniment, while Beethoven closes with a graceful, tripping Minuet dance.

The concert closes, not in Germany, Austria or Scotland, but in France, another hotbed of wind music in the 19th and 20th centuries. It was in 1935 that Jean Françaix composed his ballet score Les malheurs de Sophie (‘Sophie’s Misfortunes’). Although Françaix was working a few years later than the Parisian mischief-making composers known as Les Six – in fact, he was only eight when that group received its nickname in 1920 – he shared much of

that group’s interest in clarity, objectivity, wit and sparkle. Indeed, he might just about have made it into their number: he was only six when he began composing, and went on to study with composition pedagogue extraordinaire Nadia Boulanger, who considered him one of her finest pupils. Françaix died as recently as 1997, and wrote prolifically during his long life (he described himself as ‘constantly composing’, barely finishing one piece before launching into the next). But he maintained a cheerful, neo-Classical, easyon-the-ear lightness throughout his output – which took in concertos, symphonies, operas and plenty more.

His 1935 ballet score was based on a very popular French children’s book from the 19th century by Sophie, Comtesse de Ségur (in fact, it’s probably a thinly disguised account her of own rather eventful early life). The book’s Sophie is a rather wayward – or, perhaps, simply curious – three-

Françaix was only six when he began composing, and went on to study with composition pedagogue extraordinaire Nadia Boulanger, who considered him one of her finest pupils.

year-old, who stuffs herself at afternoon tea, shaves off her own eyebrows, pulls apart her doll then holds a funeral for it, and cooks her mother’s pet fish – among numerous other hair-raising exploits. Françaix captures the sense of mischievous fun and child-like innocence in his witty, dashing score, seven dances from which he arranged for wind ensemble in 1971. Fanfares kick off its opening ‘Le jeu de la poupée’, while the subsequent ‘Funéraille de la poupée’ has the appropriately slow drag of a funeral cortege. Sophie’s older cousin Paul – frequently called upon to rescue her from her scrapes – makes an appearance in a strongly defined, muscular clarinet theme in a later movement, and the quick waltz of ‘Le goûter’ gets ever more manic as Sophie consumes more and more pastries and cakes. The gentle ‘Danse des filets à papillons’ brings the suite to an effervescent conclusion.

© David Kettle

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra includes a double-wind section of outstanding players who also appear as soloists with the Orchestra.

Inspired by the legacy of the great Mozartian conductors of the SCO including Sir Charles Mackerras, the players are known for their stylish and exuberant performances of repertoire ranging from the celebrated divertimenti and wind serenades of the 18th century to music of the present day.

The SCO Wind Soloists appear regularly in Scotland’s main cities and further afield, including the Highlands and Islands. They have also performed at Wigmore Hall, the Palace of Holyroodhouse in the presence of HRH the former Duke of Rothesay, and at the Aix-en-Provence Easter Festival. Since 2016 they have partnered annually with wind students of the Royal Conservatoire of Scotland in Side-by-Side rehearsals and concerts.

As an ensemble, the SCO Wind Soloists have recorded divertimenti and serenades by Mozart and Beethoven (Linn Records).

For full biography please visit sco.org.uk

The Scottish Chamber Orchestra (SCO) is one of Scotland’s five National Performing Companies and has been a galvanizing force in Scotland’s music scene since its inception in 1974. The SCO believes that access to world-class music is not a luxury but something that everyone should have the opportunity to participate in, helping individuals and communities everywhere to thrive. Funded by the Scottish Government, City of Edinburgh Council and a community of philanthropic supporters, the SCO has an international reputation for exceptional, idiomatic performances: from mainstream classical music to newly commissioned works, each year its wide-ranging programme of work is presented across the length and breadth of Scotland, overseas and increasingly online.

Equally at home on and off the concert stage, each one of the SCO’s highly talented and creative musicians and staff is passionate about transforming and enhancing lives through the power of music. The SCO’s Creative Learning programme engages people of all ages and backgrounds with a diverse range of projects, concerts, participatory workshops and resources. The SCO’s current five-year Residency in Edinburgh’s Craigmillar builds on the area’s extraordinary history of Community Arts, connecting the local community with a national cultural resource.

An exciting new chapter for the SCO began in September 2019 with the arrival of dynamic young conductor Maxim Emelyanychev as the Orchestra’s Principal Conductor. His tenure has recently been extended until 2028. The SCO and Emelyanychev released their first album together (Linn Records) in 2019 to widespread critical acclaim. Their second recording together, of Mendelssohn symphonies, was released in 2023, with Schubert Symphonies Nos 5 and 8 following in 2024.

The SCO also has long-standing associations with many eminent guest conductors and directors including Principal Guest Conductor Andrew Manze, Pekka Kuusisto, François Leleux, Nicola Benedetti, Isabelle van Keulen, Anthony Marwood, Richard Egarr, Mark Wigglesworth, Lorenza Borrani and Conductor Emeritus Joseph Swensen.

The Orchestra’s current Associate Composer is Jay Capperauld. The SCO enjoys close relationships with numerous leading composers and has commissioned around 200 new works, including pieces by Sir James MacMillan, Anna Clyne, Sally Beamish, Martin Suckling, Einojuhani Rautavaara, Karin Rehnqvist, Mark-Anthony Turnage, Nico Muhly and the late Peter Maxwell Davies.

SCO Wind Soloists in Concert

Wed 11 Jun Kames Village Hall

Thu 12 Jun Kilmelford Village Hall

Fri 13 Jun Crianlarich Village Hall

Sat 14 Jun Gartmore Village Hall

SCO Strings: Summer Serenade

Thu 12 Jun Brechin Cathedral

Fri 13 Jun Fochabers Public Institute

Sat 14 Jun Fortrose Academy Theatre

Schubert Symphony No.5

Thu 19 Jun Badenoch Centre, Kingussie

Fri 20 Jun Golspie High School

Sat 21 Jun Universal Hall, Findhorn

East Neuk Festival Opening Concert

Wed 25 Jun The Bowhouse, St Monans

Schubert & Mozart

Thu 26 Jun Stirling Castle

Fri 27 Jun Queen’s Hall, Dunoon

Sat 28 Jun Town Hall, Hawick

Summer Classics

Thu 17 Jul Town House, Hamilton

Fri 18 Jul Castle Douglas Town Hall

Sat 19 Jul Ayr Town Hall

Edinburgh International Festival

Sat 9 Aug Usher Hall, Edinburgh

Wed 13-Sat 16 Aug Edinburgh Playhouse

Rossini & Schubert

Wed 27 Aug Airdrie Town Hall

Thu 28 Aug Blair Castle, Blair Atholl

Fri 29 Aug Eden Court Theatre, Inverness

This summer, the Scottish Chamber Orchestra is bringing live music to 20 towns and villages across Scotland - from Golspie to Castle Douglas, Brechin to Kilmelford. Our Scottish Summer Tour celebrates the rich diversity of our musical heritage, featuring everything from timeless classics to a thrilling world premiere.

Your donation will help deepen our connections with local communities, showcase our exceptional musicians, and bring world-class performances to audiences who rarely have the opportunity to experience live orchestral music in their area.

For more information on how you can become a regular donor, please get in touch with Hannah on 0131 478 8364 or hannah.wilkinson@sco.org.uk