PROGRAMME

conductor Tarmo Peltokoski

violin Daniel Lozakovich

Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky (1840-1893)

Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 35 (1878)

• Allegro moderato

• Canzonetta: Andante

• Finale: Allegro vivacissimo intermission

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Symphony No. 7 in C major, ‘Leningrad’ (1941)

• Allegretto

• Moderato (poco allegretto)

• Adagio

• Allegro non troppo

concert ends at around 22.45 / 16.15

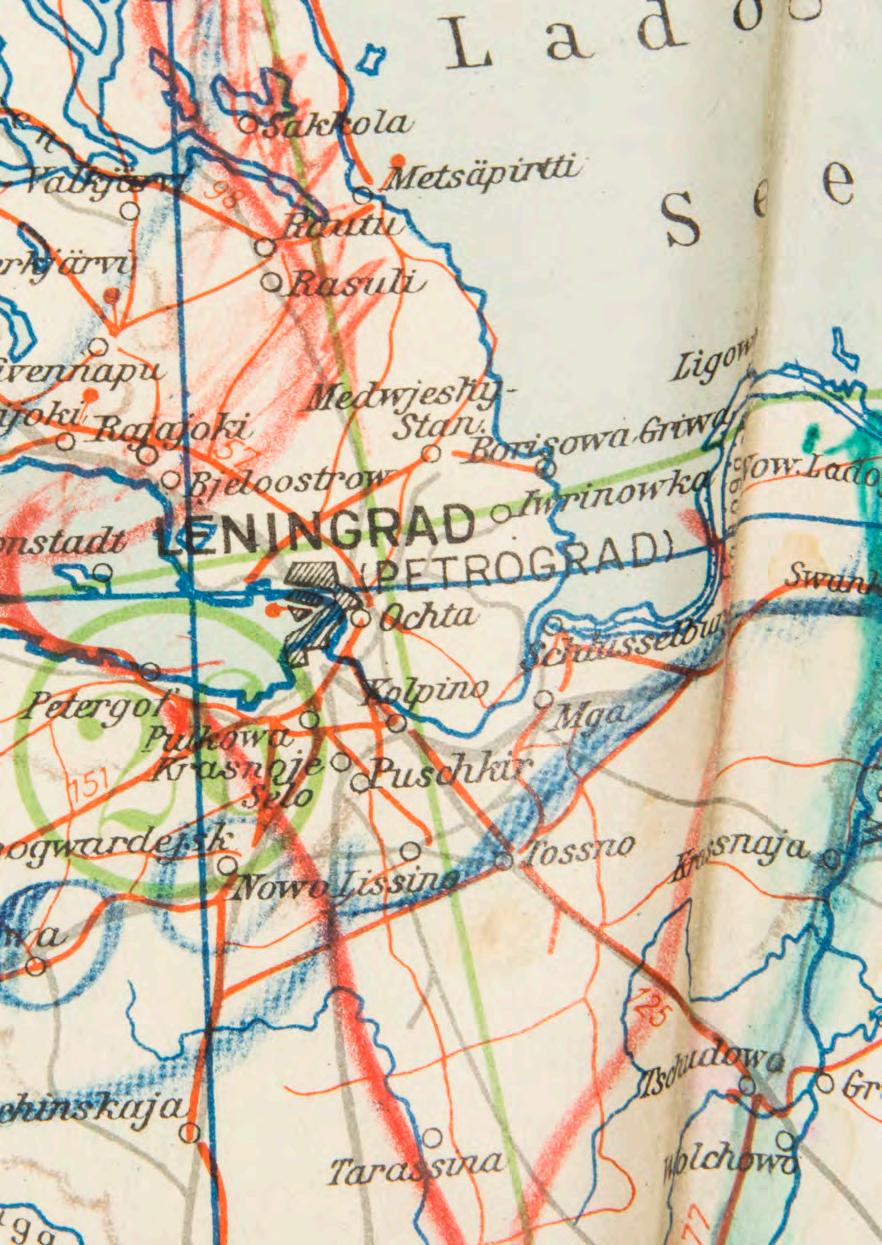

Cover: German Staff Map (1941) with marked positions around Leningrad. Photo fjm44.com

Nevski Prospekt in Leningrad during the siege. Photo Boris Kudoyarov (1942), coll. RIA Novosti archive

Most recent performances by our orchestra: Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto: Jun 2023, violin Akiko Suwanai, conductor Lahav Shani (on tour) Shostakovich Symphony No. 7: Apr 2013, conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin

One hour before the start of the concert, Ronald Ent will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

Crisis management

Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto was the product of a failed marriage. Shostakovich completed his Seventh Symphony during the gruelling siege of his home city of Leningrad. It is easy to view these two works as the chronicles of trials endured, but perhaps this perspective would be too simplistic.

New inspiration

Tchaikovsky is often depicted as a composer driven by intense emotions. Indeed, his body of work is coloured by his turbulent emotional life: musical clues as to his innate insecurity and frustration with his homosexual nature are unmistakable. But he was first and foremost a great craftsman whose search for self-expression was never at the expense of his craftsmanship. It is precisely for this reason that his Violin Concerto has earned the status of a timeless masterpiece. It was composed in 1878, shortly following the deepest crisis of his life; and yet, there is little evidence of that in the music.

A year previously, Tchaikovsky paid for his impulsive marriage to a student with a nervous breakdown, which sent him wandering around Europe for months. Yet there is no mourning in his Violin Concerto. Instead it embraces his huge talent for melody on which he could always rely. There were indeed some bright spots during this period of his life. Firstly, he was able to rely on rich widow Nadezjda von Meck for financial support. Secondly, he found inspiration in

his friendship with the fifteen-year younger violinist Iosif Kotek, who made a surprise visit to the composer during his stay by Lake Geneva. During this visit, Kotek played him the solo part of the brand new Symphonie espagnole by Édouard Lalo, a violin concerto that was causing a furore on the European concert platform. It immediately ignited a spark: Tchaikovsky was inspired by Kotek –and by Lalo’s ‘freshness, piquant rhythms and beautifully harmonised melodies’, as he wrote to Von Meck. Less than a month later, he had completed his own Violin Concerto.

Can music stink?

The sunny mood of this work is at odds with the tone of Tchaikovsky’s melancholy letters written over preceding months. It is as though all his bitterness over his failed marriage had suddenly vanished. Whilst it is true that the middle movement sobs with melancholy, passages like this are to be found in his earlier music too; wistfulness is a part of Tchaikovsky’s musical DNA. And it is precisely this Andante that expresses a warm Italian glow, picked up along with the many

folk tunes during Tchaikovsky’s wanderings through Southern Europe. Vitality returns in the final movement, thanks in part to the wholesale incorporation of Russian folk dances, a suggestion of the composer’s readiness for the journey home.

Taken as a whole, one could describe this concerto with precisely the same words with which Tchaikovsky had written about Lalo and his Symphonie espagnole: ‘He does not strive for depth, yet avoids the routine and experiments with form. He is more concerned

with musical beauty than in preserving traditions, as the Germans are wont to do.’

This Violin Concerto has since secured its place at the top of the violin repertoire, despite being roundly criticised at its first performance. The blunt opinion of Viennese critic Eduard Hanslick, in particular, was hard to shake off: ‘Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto fills us with chilling thought that there could be musical works that actually stink when listened to.’ Iosif Kotek, who had amply advised Tchaikovsky on the solo part,

Iosif Kotek and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky in 1877. Photo Studio Nikolay Borisov, Moscow

dared not include the work in his repertoire. This decision signalled the end of their friendship.

Cannon fodder

Little remained of Tchaikovsky’s romantic image of Russia when Dmitri Shostakovich composed his Seventh Symphony. The piece was largely composed in 1941, under horrendous circumstances. Germany was laying siege to Leningrad, whilst Stalin sent thousands of Russian troops to serve on the front as cannon fodder. However, the mobilisation was a lifesaver for Shostakovich: he was commissioned to maintain Russian morale by broadcasting music over the radio. He composed the first three movements with bullets almost literally flying past his ears. He completed the Finale once evacuated from the front line.

Shostakovich composed the first three movements with bullets almost literally flying past his ears

The work became one of Shostakovich’s most spectacular, but also most reviled symphonies. For the Russian people it became a moving symbol of resistance; for the authorities, ideal propaganda for the outside world. Once smuggled to the West on microfilm it also caused a stir, although not an entirely enthusiastic one. Various critics accused Shostakovich of sensationalism (‘the score to a cheap war film’, one of them wrote), whilst the swelling sound of the march in the first movement was derided as a pale imitation of Ravel’s Boléro. Their opinions left the composer indifferent. ‘This is how I experience war’, he retorted.

The fight against fascism

Viewed in this way, the Seventh Symphony delivers exactly what you would expect from war music. Shostakovich’s own explanation at the work’s premiere was also predictable: following the tumultuous opening is a second movement that is ‘a lyrical pause for breath, full of beautiful memories of times gone by’, whilst the third movement expresses a ‘joie de vivre and adoration of nature’. The final movement depicts ‘the ideal of a great future in which the enemy is defeated’. In its entirety, the work symbolised ‘our struggle against fascism.’

But here, as in many other of his symphonies, we can detect Shostakovich’s characteristic ambiguity. Decades later a number of his closest friends lifted just a corner of the veil: the composer had confided in them that this work was not only intended as a denunciation of the Nazis alone, but of any form of repression and terror – including the Stalin’s reign of terror over his own country. Furthermore, Shostakovich’s public declaration that the opening movement was a representation of Germany’s advancing army proved easy to debunk; it had already been written before the invasion of Russia. Shostakovich expert, Ian MacDonald, has unearthed compelling evidence in this regard. He has identified in the march theme a sequence of six falling notes that initially bear some resemblance to the controversial Deutschlandlied (‘Deutschland über alles’), but which, when this section reaches a climax in a dramatic key change, suddenly appears to quote the Fate Theme from Tchaikovsky’s Fifth Symphony. Shostakovich would surely have intended this to mean something. But what, exactly?

Michiel Cleij

Principal Guest Conductor

Born: Vaasa, Finland

Current position: Music Director Latvia

National Symphony Orchestra, Principal Guest Conductor Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie

Bremen, Music Director Designate Orchestre

National du Capitole de Toulouse, Music Director Designate Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra

Education: piano at Kuula College (Vaasa) and the Sibelius Academy (Helsinki), conducting with Jorma Panula, Sakari Oramo, Hannu Lintu and Jukka-Pekka Saraste

Breakthrough: 2022: positions in Bremen, Riga, Rotterdam, and Toulouse

Subsequently: debuts with Hong Kong Philharmonic, Toronto Symphony Orchestra, RSO Berlin, Konzerthaus Orchester Berlin, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, SWR Symphonieorchester, Göteborgs Symfoniker, Swedish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Orchestra dell’Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, Los Angeles Philharmonic

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2022

Born: Stockholm, Sweden

Education: : first violin lessons at the age of seven; violin studies at the Karlsruhe University of Music with Josef Rissin; mentored by Eduard Wulfson, Geneva

Breakthrough: 2016: winner Vladimir Spivakov International Violin Competition, contract with Deutsche Grammophon

Subsequently: solo-appearances with Chicago Symphony, Cleveland, Pittsburgh Symphony, Philadelphia, Boston Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, BBC Symphony at BBC Proms, City of Birmingham Symphony, Budapest Festival, Royal Stockholm Philharmonic, Seoul Philharmonic

Awards: Festival of Nations Young Artist of the Year 2017, Premio Batuta (Mexico), Excelentia Prize (Spain)

Instrument: ‘ex-Sancy’ 1713 Stradivari loaned by Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2025

Photo: Eduardus Lee

Tarmo Peltokoski •

Daniel Lozakovich • violin

Photo: Mezzo

Musicians Agenda

Fri 17 October 2025 • 20.15

Sun 19 October 2025 • 14.15

conductor Kazuki Yamada

piano Alexandre Kantorow

Takemitsu How Slow the Wind

Saint-Saëns Piano Concerto No. 5 ‘Egyptian’

Berlioz Symphonie fantastique

Music for Breakfast 1

Sun 26 October 2025 • 10.30

Dudok in het Park musicians and programme: rpho.nl/en

Thu 30 October 2025 • 20.15

Fri 31 October 2025 • 20.15

conductor Robin Ticciati

piano Yuja Wang

Haydn Chaos from The Creation

Ligeti Piano Concerto

Mahler Symphony No. 5

Harry Potter in Concert, part 1

Wed 12 November 2025 • 19.30

Thu 13 November 2025 • 19.30

Fri 14 November 2025 • 19.30

Sat 15 November 2025 • 19.30

Sun 16 November 2025 • 13.30

conductor Justin Freer

Williams Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone

Fri 21 November 2025 • 20.15

Sun 23 November 2025 • 14.15

conductor Bas Wiegers

piano Kirill Gerstein

Ivičević Black Moon Lilith

Adès Piano Concerto Stravinsky Petrushka

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, Concert Master

Vlad Stanculeasa, Concert Master

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Giulio Greci

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Gustaw Bafeltowski

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Killian White

Paul Stavridis

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/piccolo

Beatriz Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse

Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Adrián Martínez

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Martijn van Rijswijk

Timpani/ Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Harp

Albane Baron