Programme Notes

Thu 27 November • 20.15

conductor Lahav Shani

piano Martha Argerich

Johan Wagenaar (1862-1941)

Ouverture Cyrano de Bergerac, Op. 23 (1905)

Robert Schumann (1810–1856)

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op. 54 (1841/45)

• Allegro a ettuoso

• Intermezzo: Andantino grazioso

• Allegro vivace

intermission

Johannes Brahms (1833-1897)

Symphony No 2 in D major, Op. 73 (1877)

• Allegro non troppo

• Adagio non troppo

• Allegretto grazioso

• Allegro con spirito concert ends at around 22.30

Most recent performances by our orchestra:

Wagenaar Overture Cyrano de Bergerac: Jun 2025, conductor Lahav Shani (on tour) Schumann Piano Concerto: Feb 2018, piano Till Fellner, conductor Jukka-Pekka Saraste

Brahms Symphony No. 2: Jun 2020, conductor Lahav Shani

One hour before the start of the concert, Emanuel Overbeeke will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

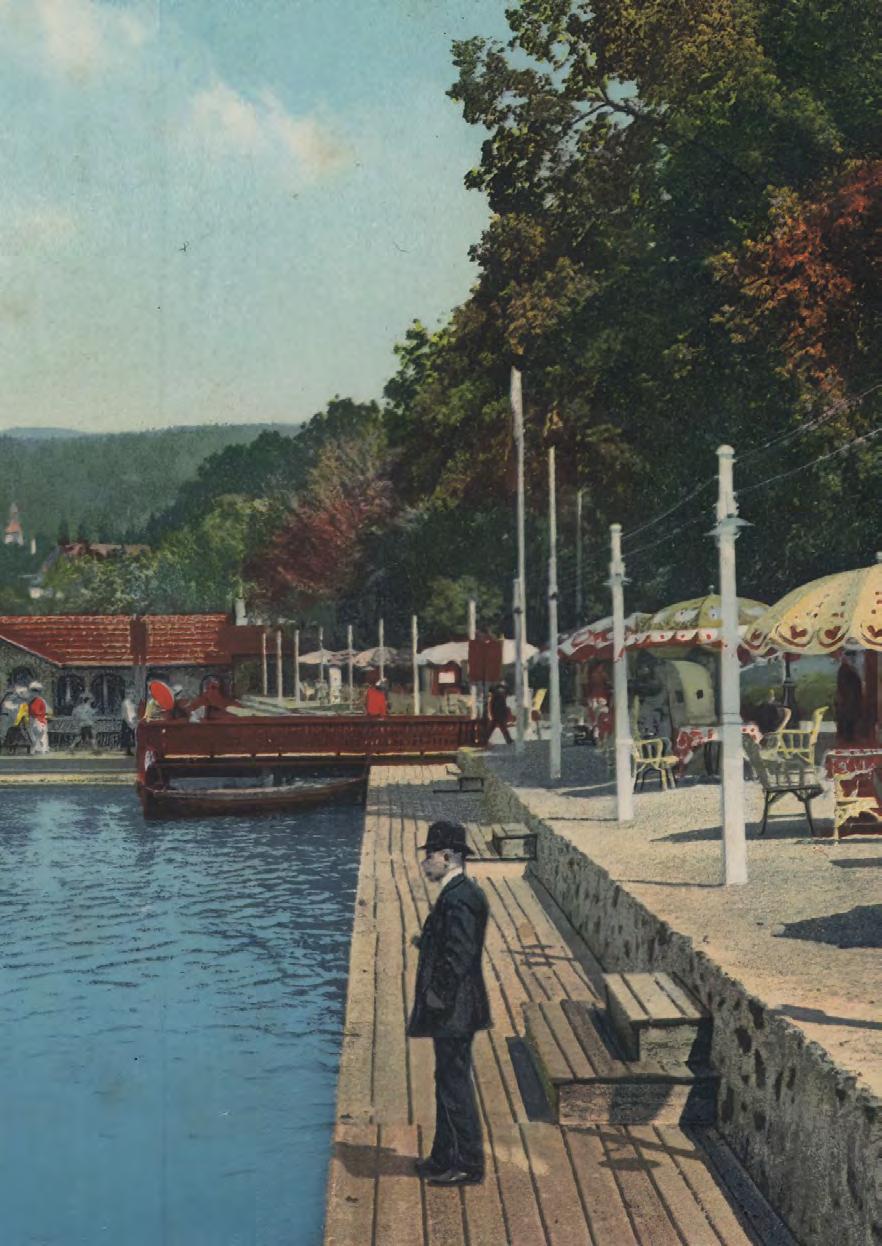

Cover: Photo Adrien Delforge (Unsplash) Pörtschach am Wörthersee, Brahms’s beloved holiday resort. Postcard (1911) by Leon Editions, Klagenfurt

The three composers from the Romantic period performed in this concert bring great happiness. We hear Wagenaar’s lyricism and heroism; the sunshine of Brahms; and Schumann’s yearning for love that transforms into joy.

In around 1900, Johan Wagenaar, organist of Utrecht’s cathedral and director of the Royal Conservatoire Te Hague, was one of the leading fgures of the music world in the Netherlands. Te fact that his name remains familiar is mostly due to his composition of brilliant concert overtures. Of these vibrantly orchestrated, eternally fresh works, Cyrano de Bergerac (1905) is one of the most captivating. At the top of the score, Wagenaar wrote, ‘Tis overture relates only to the principal character from Rostand’s comédie héroique and his characteristics’. Te frst theme we hear depicts Cyrano’s ‘Heroism’, followed by Wagenaar’s description of his ‘love, poetry’. Other personality traits are explored in the music, although the frst two musical themes have the upper hand. Wagenaar chooses not to delve into the plot of Rostand’s drama. Perhaps he assumed that listeners would know the story. Te soldier-poet Cyrano is secretly in love with Roxane, but he feels that love has little chance due to his disfguringly large nose. Christian, another soldier, also loves Roxane, but cannot fnd the words to express his love. Cyrano undertakes the role of ghostwriter; Roxane falls for the poetic love letters. By the time she learns the true identity of the author, it is too late: Cyrano dies.

A maelstrom of emotions characterise the music of Robert Schumann. Te composer was ofen pulled by competing inner voices. Modern psychology tends to diagnose him as manic depressive. But in fact it is hard now to get to the truth. In his earlier work Schumann ofen appears full of cheer. Tis is true of his Piano Concerto, composed for his wife, the pianist Clara Wieck. He was just 31; she was even ten years younger. He had been courting this beautiful young woman – a pianist of great promise - for years. But throughout these years her father thwarted any relationship between the two whenever he was able. But now, in 1841, they were married! ‘I don’t wish to write a virtuoso concerto. I have something diferent in mind’, explained Schumann, who wished to dedicate the piano and orchestra instead to more important, emotional causes. He poured out the love in his heart in this Piano Concerto, especially in the passionate Allegro afettuoso (‘with feeling’). Initially he had settled for this frst movement alone, to be published separately as a ‘Fantasy’. But four years later he added an Intermezzo and Finale to arrive at a threemovement concerto. If you were to study the original score of the Finale, you would notice something curious. One section of it

is written in a diferent hand: that of Clara. Schumann relied on her help in writing out some passages that he had already scored in a diferent key for this movement.

Originally Schumann had been urged by his publisher to expand his Fantasy into a threemovement work on the basis that a traditional Piano Concerto would sell better. In other words, a commercial concession. But what does that matter, when – at least to modern tastes - the more of Schumann we listen to, the better? But Schumann’s contemporaries clearly thought otherwise. At the concerto’s premiere in Vienna in 1847, conducted by Schumann with Clara at the piano, almost no one liked it. Its reception upset Clara, although curiously Schumann himself remained undeterred by the poor reviews: ‘Have faith,’ he told Clara. ‘In ten years’ time people will think completely diferently!’

A sunny postcard

‘You have never heard anything so worldweary,’ wrote Johannes Brahms to a friend on completion of his Second Symphony. ‘It is in F minor throughout’. To Clara Schumann, his most intimate confdante, he confrmed that his latest work had a ‘very elegiac’ character. In fact, Brahms tricked them both, because his Second Symphony is an undisguised evocation of a radiant summer, written in the glorious key of D major.

It is tempting to connect the relaxed atmosphere of Brahms’s Second Symphony with the background to its creation. Te 44-year-old composer was spending the summer of 1877 by Lake Wörthersee in modern-day Austria. Brahms was no stranger to melancholy, but in this idyllic setting he fourished and thoroughly enjoyed himself: ‘Lake Wörthersee is an untouched source,

melodies futter all around so one has to be careful not to step on them’. Te sun shone on his desk, diluting his black ink.

Rather than writing a virtuoso concerto, Schumann wished to dedicate the piano and orchestra instead to more important, emotional causes

But the origins of this work’s cheerful character probably reach deeper. Brahms’s First Symphony had been the result of twenty years of toil. He had been determined to write a symphony that could stand tall against the great Beethoven. At the première of the work it appeared that the mission had been accomplished. And now, he could begin work on his second with a sense of relief.

No movement of the symphony is in a minor key; there is not even any notable minor passage. Tere are no agonising introductions to fast tempo movements, as there are in his First Symphony. Brahms dispenses with all sudden mood swings and instead conjures up an unspoilt nineteenth-century undulating landscape. Rarely has his work sounded so carefree for such a long period. In the fnale the good mood expands into unalloyed joy, for which Brahms used a musical term rare for the Romantic period: ‘con spirito’, meaning ‘with spirit’. In that fnal movement there is scarcely pause for refection; the music is as exuberant as any fnal movement of Haydn, and as celebratory as any chorus from a Handel oratorio. Why Brahms could not express this feeling to Clara with honesty remains a mystery.

Stephen Westra

Born: Tel Aviv, Israel

Current position: chief conductor Rotterdam

Philharmonic Orchestra; music director Israel Philharmonic Orchestra; chief conductor designate Münchner Philharmoniker (from 2026)

Before: principal guest conductor Vienna Symphony Orchestra

Education: piano at the Buchmann-Mehta School of Music Tel Aviv; conducting and piano at the Academy of Music Hanns Eisler Berlin; mentor: Daniel Barenboim

Breakthrough: 2013, First Prize Gustav Mahler

International Conducting Competition in Bamberg

Subsequently: guest appearances Wiener Philharmoniker, Berliner Philharmoniker, Gewandhaus Orchester, Münchner

Philharmoniker, Symphonieorchester des Bayerischen Rundfunks, London Symphony Orchestra, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Philadelphia Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouworchestra

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2016

Born: Buenos Aires, Argentina

Education: with Friedrich Gulda in Austria; Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli, Stefan Askenase Awards: Geneva International Music Competition (1957); Ferruccio Busoni

International Piano Competition Bolzano (1957); Praemium Imperiale Award (2005), Kennedy Center Honor (2016)

Breakthrough: 1965, after winning the Fryderyk Chopin International Piano Competition

Warsaw

Subsequently: soloist with all major orchestras in the world

Chamber Music: with pianists Stephen Kovacevich, Alexandre Rabinovich, the late Nelson Freire and Nicolas Economou, violinist

Gidon Kremer, cellist Mischa Maisky

Festival: honorary president International Piano Academy Lake Como

Documentary: Martha Argerich – Evening Talk 2002

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 1969

Fri 28 November 2025 • 20.15

conductor Lahav Shani

violin Patricia Kopatchinskaja

Shostakovich Violin Concerto No. 1

Brahms Symphony No. 3 ‘Eroica’

Proms: Nutcracker & Company

Sat 13 December 2025 • 20.30

conductor Aziz Shokhakimov

violin Maria Milstein

Glinka Overture Ruslan and Ludmilla

Tchaikovsky The Nutcracker: Suite Tchaikovsky Serenade mélancolique

Khachaturian Masquerade: Suite

Music for Breakfast 2

Sun 14 December 2025 • 10.30

RDM Kantine musicians and programme: rpho.nl/en

Fri 19 December 2025 • 20.15

conductor Jan Willem de Vriend

oboe d’amore Karel Schoofs

Bach Sinfonia from Cantata No. 174

Bach Suite for Orchestra No. 3

Bach Concerto for Oboe d’Amore in A Mozart Adagio and Fugue

Mozart Symphony No. 35 ‘Ha ner’

Sat 20 December 2025 • 20.15

Sun 21 December 2025 • 14.15

conductor Eduardo Strausser

vocal ensemble King’s Singers Christmas Programme

Thu 8 January 2026 • 20.15

Sun 11 January 2026 • 14.15

conductor Giedrė Šlekytė

cello Truls Mørk

Dvořák Cello Concerto

Schubert Symphony No. 8

‘Unfinished’

Koldály Dances from Galanta

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, Concert Master

Vlad Stanculeasa,

Concert Master

Quirine Sche ers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Gustaw Bafeltowski

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Killian White

Paul Stavridis

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/

Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Adrián Martínez

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Martijn van Rijswijk

Timpani/ Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Harp Albane Baron