Negro Folk Symphony

Sun 16 March 2025 • 14.15

Negro Folk Symphony

Sun 16 March 2025 • 14.15

conductor Roderick Cox

piano Alexander Gavrylyuk

Richard Strauss (1864–1949)

Don Juan, op. 20 (1888–1889)

Symphonic poem for large orchestra after Nikolaus Lenau

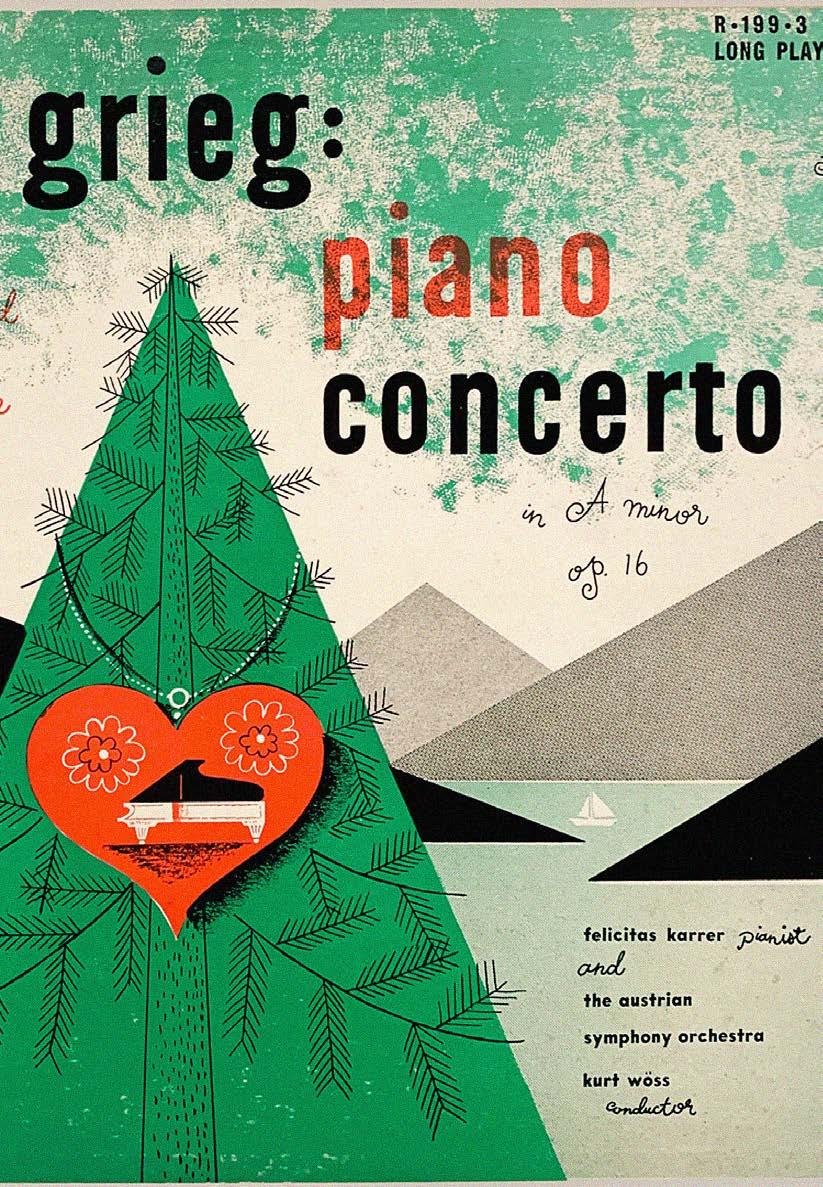

Edvard Grieg (1843–1907)

Piano Concerto in A minor, Op.16 (1868)

• Allegro molto moderato

• Adagio

• Allegro moderato molto e marcato –Quasi presto – Andante maestoso

intermission

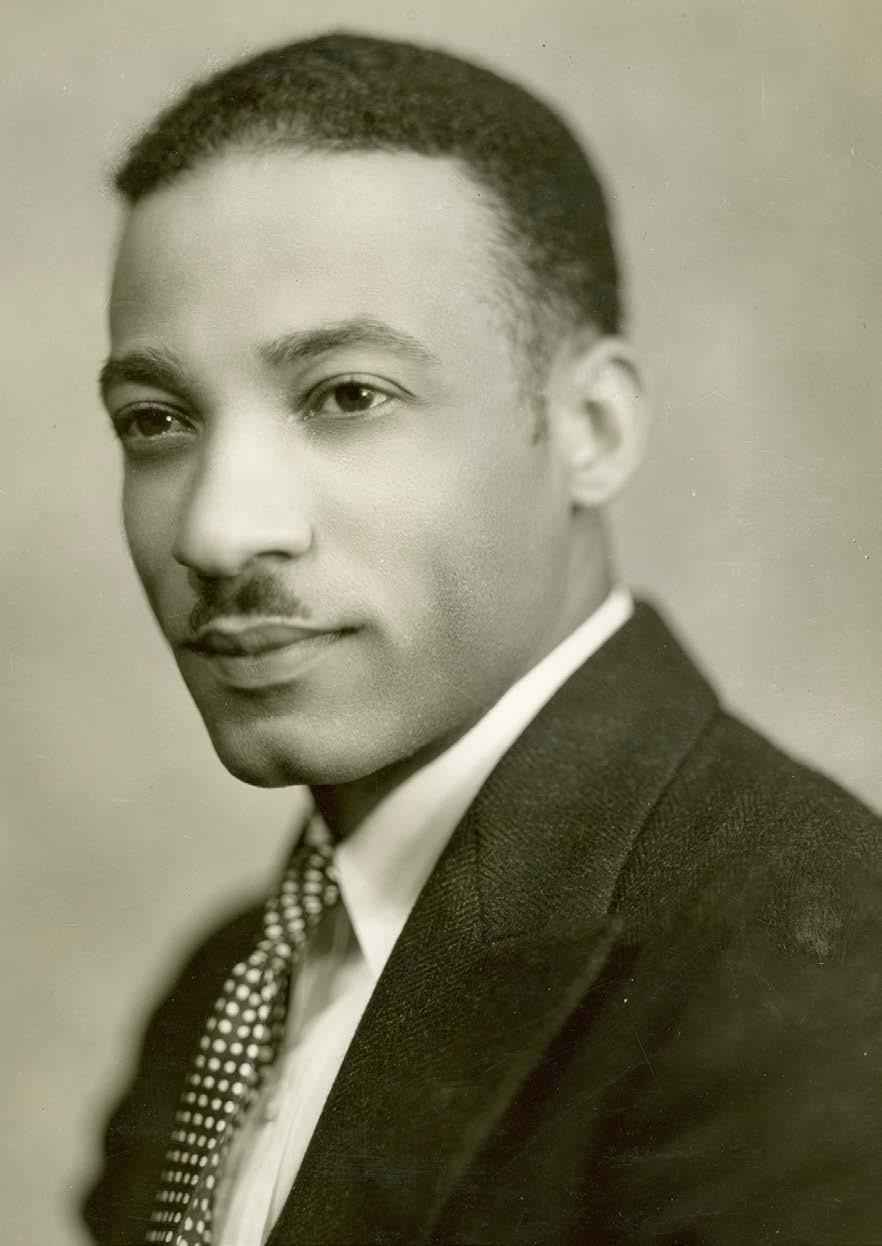

William L. Dawson (1899–1990)

Negro Folk Symphony (1934/1952)

Dutch Premiere

• The Bond of Africa

• Hope in the Night

• O, Le’ Me Shine, Shine Like a Morning Star!

Concert ends at around 16.15

Most recent performances by our orchestra:

Strauss Don Juan: Sep 2022, conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

Grieg Piano Concerto: Feb 2020, piano

Javier Perianes, conductor Krzysztof

Urbański

Dawson Negro Folk Symphony: first performance, Dutch Premiere

One hour before the start of the concert, Patrick van Deurzen will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

Cover: Photo Nsey Benajah (Unsplash)

Richard Strauss conquered the world with his brilliant instrumentations. Edvard Grieg won over his public with the folk-music influences in his work. William Dawson combines these two talents in his lavishly orchestrated Negro Folk Symphony, in which he follows a trail to his African roots.

At the age of 25, Richard Strauss published his first real symphonic poem, Don Juan, a work based on the play of the same name written in verse form by Nikolaus Lenau. The music depicts the life of a womanising nobleman in a series of narrative episodes. The introductory theme to the work introduces us to Don Juan himself, and weaves like a common thread through the entire work. Via various scenes of love and adventure, Strauss leads the hero to a masked ball. At the high point of the ball, the atmosphere changes. In the scene that follows, we find Don Juan in a churchyard by the grave of a nobleman he had once killed. The nobleman’s son suddenly appears and kills Don Juan in the inevitable duel that follows. In the quiet closing bars of the work, we hear Don Juan taking his last breaths. Such a quiet end signified the vibrant launch of Strauss’s career: full of bravado and seductive instrumentation, Don Juan established his name nationally and internationally.

At the same age as Richard Strauss – twenty-five - Edvard Grieg also enjoyed his international breakthrough. Not with a symphonic poem,

but a piano concerto – the only one he would ever compose. He drew inspiration not from world literature, but instead from the modest folk music of his native country of Norway. ‘Composers with the status of Bach or Beethoven built great churches and temples with their compositions’, Grieg would later clarify, ‘But it has always been my wish to build villages, places where people could feel happy and at ease. The music of my homeland has always been the model for this.’ In the first movement of his Piano Concerto that model may not yet be so clearly identifiable. The serene Adagio that follows already adopts a more recognisably Norwegian character. However, the final movement especially Grieg lets loose with his mother tongue. In the very first theme of this rondo-style movement we already hear the rhythm of the halling, Norway’s national folk dance. Later in the movement, Grieg imitates the sound of the Hardanger fiddle, the pre-eminent musical instrument of Norwegian folk music, with open fifths, bourdon tones and subtle glissandi. It is exactly these elements that give Grieg’s Piano Concerto such a unique sound – and which establish an affinity with the symphony of William Dawson.

William Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony is a masterpiece with a title that is now considered problematic, if not discomforting. However, in the 1930’s, the term negro still conveyed a feeling of pride when adopted by Black American artists. Born in the deep south of the USA in 1899, Dawson’s one and only

symphony honoured above all the negro spiritual music that gave light to his youth. These spirituals are unsung songs in Dawson’s symphony. They form a thread woven through the tight orchestral fabric of his work. ‘I want the listener to say: this can only have been composed by a negro’, said Dawson upon completion of the first version of the work in 1932. His symphony is ‘black’ in terms of its musical elements and ‘white’ in terms of its architecture. One can frequently hear a juba, an African rhythm that was kept alive on the American plantations, performed by singerdancers with the clapping of hands and hitting of their own bodies. Dawson has embedded such an element in a musical construct that would have been unthinkable without the examples of composers such as Dvořák, Franck and Beethoven. The work is imbued with the sounds of Dawson’s youth. Growing up in an environment in which a large part of the population lived in misery in the cotton fields, Dawson himself had the opportunity to study at a good ‘Black’ school, the Tuskegee Institute in Alabama. Dawson studied spiritual music there and concentrated on this musical tradition in his first compositions. Via Kansas City he found himself aged twenty-five within a typical ‘European-classical’ environment, the American Conservatory of Music in Chicago. With the bonus of attending concerts by the neighbouring Chicago Symphony Orchestra. There is a good chance that the lush orchestrations and ‘European’ harmonies of the Negro Folk Symphony find their origins in this period. The work begins with an enchanting horn solo, an original melody composed by Dawson himself. This leads into an older spiritual: Oh, M’ Littl’ Soul Gwine-a Shine. Tranquillity follows on from outbursts. Melodies have their counter-melodies. There is a striking, ecstatic change in atmosphere when the orchestra throws itself wildly into a juba, in which the effect of the clapping

hands is portrayed in all manner of orchestral combinations. In the second movement (‘Hope in the Night’) we hear a disconsolate trudge forward. A depiction, according to Dawson, of ‘250 years of captivity’. This, too, changes: Dawson depicts ‘children happily playing’. But the sense of hopelessness wins through – up to the final movement, when the spiritual O Le’ Me Shine Lik’ a Mornin’ Star offers illumination. And then what follows is a glittering anticipation of the future expressed in the spiritual Hallelujah, Lord I Been Down into the Sea. But what kind of future? Combining with the echoes of the preceding movements, musical themes swirl together within a raging orchestral whirlpool.

Listeners don’t need to be familiar with plantation life to appreciate Dawson’s work

Listeners don’t need to be familiar with plantation life to appreciate Dawson’s work. The work speaks for itself. Something that the conductor Leopold Stokowski well recognised when he and his Philadelphia Orchestra premiered the symphony to great acclaim in 1934. But after the ovations came silence. The sounds of the symphony became forgotten. Years later, Dawson took a journey through West Africa. The experience caused him to sharpen the rhythms of his symphony. Stokowski loved the results and recorded the final version for posterity. And then? Once more a silence. It is noteworthy that only in recent years Dawson’s Negro Folk Symphony has found its place in the repertoires of many American orchestras. Not, perhaps, thanks to its title. But perhaps instead due to its unique combination of musical energies.

Paul Janssen (Strauss en Grieg) and Roland de Beer (Dawson)

Roderick Cox • conductor

Born: Macon (GA), USA

Current position: chief conductor Opéra Orchestre National de Montpellier Occitanie Education: Shwob School of Music at Columbus State University, Northwestern University, summer courses conducting in Aspen and Interlochen Awards: Robert J. Harth Conducting Prize 2013

Breakthrough: Sir Georg Solti Conducting Award 2018

Subsequently: Philadelphia Orchestra, Boston Symphony, Orchestre de Paris, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Cincinnati Symphony, Cleveland Orchestra, Minnesota Orchestra, Detroit Symphony, Seattle Symphony, Philharmonia Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, BBC Symphony Orchestra, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Deutsches Symphonie-Orchester Berlin, Staatskapelle Dresden

Education programme: Roderick Cox Music Initiative, scholarship programme for young musicians from underrepresented communities

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2025

Born: Kharkiv, Ukraine

Education: first piano lessons at 7, further studies from age 13 with Victor Makarov at the Australian Institute of Music Awards: Winner Horowitz Competition Kyiv 1999, Winner Hamamatsu Piano Competition Japan 2000

Breakthrough: Golden Medal Arthur Rubinstein Piano Master Competition Tel Aviv 2005

Subsequently: solo appearances with the orchestras of New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, Seoul and Tokyo, Philharmonia Orchestra, City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra, Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra

Recitals: Musikverein Wenen, Tonhalle Zürich, Victoria Hall Geneva, Southbank Centre’s International Piano Series, Wigmore Hall, Concertgebouw Amsterdam, Suntory Hall, Tokyo Opera City Hall, Tokyo City Concert Hall

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2008

Fri 21 March 2025 • 20.15

conductor Yannick Nézet-Séguin

soprano Angel Blue

Strauss Vier letzte Lieder

Bruckner Symphony No. 3

Fri 28 March 2025 • 20.15

Sat 29 March 2025 • 20.15

conductor Joe Hisaishi

harp Emmanuel Ceysson

Hisaishi Adagio for Strings and two Harps

Hisaishi Harp Concerto

Ravel La valse

Hisaishi Spirited Away Suite

Thu 3 April 2025 • 20.15

Fri 4 April 2025 • 20.15

Sun 6 April 2025 • 14.15

conductor Lahav Shani

violin Hilary Hahn

Beethoven Symphony No. 2

Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 1

Mozart Symphony No. 39

Thu 17 April 2025 • 19.30

Fri 18 April 2025 • 19.30

Sat 19 April 2025 • 19.30

conductor Jonathan Cohen

soprano Lore Binon

countertenor Hugh Cutting

tenor (evangelist) Stuart Jackson

tenor (arias) Peter Gijsbertsen

bass (Christ) Neal Davies

bass (arias) Roderick Williams

chorus Laurens Collegium

Bach St-Matthew-Passion

Do you have a moment? You can help us by leaving a Google review. It will only take a minute: scan the QR code below and let us know what you think of our orchestra. Thank you!

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, concertmaster

Tjeerd Top, concertmaster

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Giulio Greci

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Killian White

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Robert Franenberg

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse

Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Adrián Martínez

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass Trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Hendrik-Jan Renes

Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Harp Albane Baron