Thu 5 June 2025 • 20.15 Fri 6 June 2025 • 20.15

Thu 5 June 2025 • 20.15 Fri 6 June 2025 • 20.15

conductor Tarmo Peltokoski

soprano Asmik Grigorian

bass Mika Kares

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975)

Symphony No. 14, Op. 135 (1969) for soprano, bass and chamber orchestra

• Adagio. De Profundis (Lorca/Tynyanova)

• Allegretto. Malagueña (Lorca/Geleskul)

• Allegro molto. Loreley (Apollinaire/Kudinov)

• Adagio. The Suicide (Apollinaire/Kudinov)

• Allegretto. On Watch (Apollinaire/Kudinov)

• Adagio. Madam, Look! (Apollinaire/Kudinov)

• Adagio. In the Santé Jail (Apollinaire/ Kudinov)

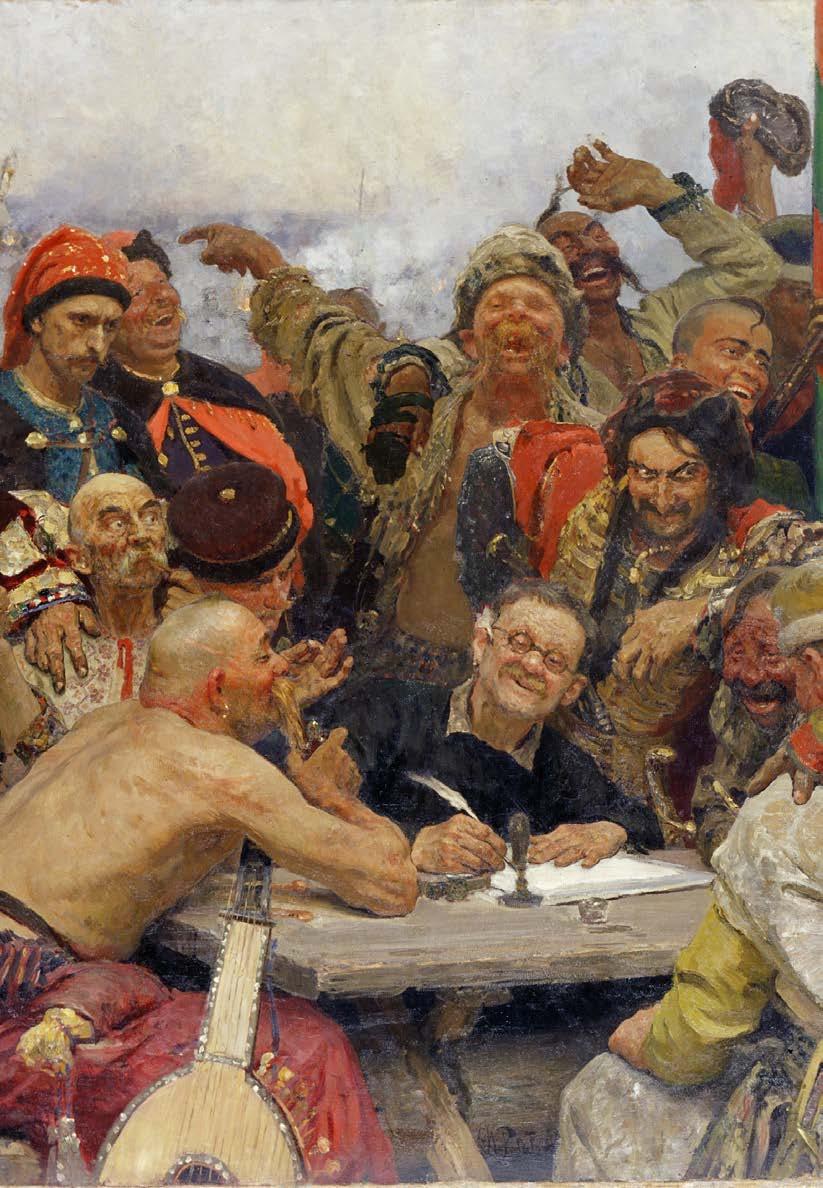

• Allegro. Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Sultan of Constantinople (Apollinaire/Kudinov)

• Andante. O Delvig, Delvig! (Küchelbecker)

• Largo. Death of the Poet (Rilke/Silman)

• Moderato. Conclusion (Rilke/Silman) intermission

Jean Sibelius (1865-1957)

Symphony No. 4 in A minor, Op. 63 (1911)

• Tempo molto moderato, quasi adagio

• Allegro molto vivace

• Il tempo largo

• Allegro

Concert ends at around 22.15

Most recent performances by our orchestra:

Shostakovich Symphony No. 14: Mar 2000, soprano Elisabeth Meyer-Topsøe, bass Robert Holl, conductor Claus-Peter Flor

Sibelius Symphony No. 4: May 2019, conductor JukkaPekka Saraste

One hour before the start of the concert, Ronald Ent will give an introduction (in Dutch) to the programme, admission €7,50. Tickets are available at the hall, payment by debit card. The introduction is free for Vrienden.

Cover: Photo Heather Zabriskie (Unsplash)

Blaník. Omslagillustratie door Antonín König voor de eerste uitgave van Smetana’s partituur (1894) Richard-Strauss-Institut

Lying in a Moscow hospital bed, fearing for the worst, Dmitri Shostakovich wrote a symphony about death. Similarly, Sibelius’s Symphony No. 4 echoes this fear for the end. Is this gaze into the abyss so bleak? Perhaps, but for Shostakovich there was also something especially purifying about it: ‘At the end, you rediscover how beautiful life is.’

Dmitri Shostakovich was a restless worker who never spent long on one composition. This was not just down to the pleasure he got from music, nor to his work ethic; it came also from the pressure that every Soviet artist felt from the authorities that were constantly peering over your shoulder. His Symphony No. 14 was completed in two months, in the relative quiet of the Moscow hospital where – not for the first time – he had been confined. He received no visitors; on the outside the city was in the midst of a flu epidemic. In his weakened condition, however, he was unable to keep thoughts of death at bay. Such thoughts spurred the driven composer to write a series of orchestral songs inspired by the elegies of various poets – a sort of oratorio without choir. After completion, he would always consider the work as one of his symphonies, albeit that it lacks the traditional symphonic form and the setting is sober. But the chilly soundscape of strings, percussion and celeste is impressively applied and fits perfectly with the feel conjured up by

the poems. And interspersing the apparently independent songs, Shostakovich creates a symphony-like cohesion through the skilful alternation of quiet and energetic passages so that the listener hears a living whole rather than a hotchpotch of pieces. And by permitting himself a few subtle changes to the texts of the original poems he was able to connect the various characters to each other.

An important impetus to this work was his admiration for Mussorgsky’s Songs and Dances of Death, a work for piano and solo voice that he had orchestrated seven years previously. It had always bothered him that his great predecessor had written just four songs about such a weighty subject; with this symphony he had risen to the challenge.

Shostakovich stayed closed to Mussorgsky’s melodic style of speech-song, with closely spaced notes and minimum of vocal embellishment. And, like Mussorgsky, he saw death here not as a bringer of peace or salvation: in all his songs people die too soon and mostly in violent ways. Such a perspective was naturally a reflection of his own traumatic experiences during Stalin’s reign of terror. But even sixteen years after Stalin’s death, Shostakovich avoided making a direct accusation against him. This symphony, he asserted at its first performance in 1969, was a homage to life and encouragement to get the most out of it, ‘because there is nothing else beyond life’. The songs describe soldiers and the nameless war dead (De Profundis,

On Watch ), the wafer-thin line between life and death (Malagueña, Loreley, The Suicide), languishing in captivity (In the Santé Jail) and the fate of ‘subversive’ artists (O Delvig! Delvig!, Death of the Poet). Shostakovich’s song Reply of the Zaporozhian Cossacks to the Sultan of Constantinople depicts an historical event close to home: the proud resistance of the Cossacks against the Sultan of Turkey in the 17th century, an event that mostly lives on in its colourful depiction on canvas by the Russian artist Ilya Repin. Shostakovich dedicated his symphony to his British colleague, Benjamin Britten – another interpreter of internal suffering, albeit of an entirely different order.

Jean Sibelius set Finnish nature and legend to very evocative music. However, he was very frugal with any autobiographical elements. Even in symphonic form – the ideal vehicle for personal confession since the romantic period – he gave very few glimpses of what was going on inside. However, his Fourth Symphony is an exception. This grim work depicts the dark clouds that hung over his life in around 1910. Serious health problems, financial difficulties, and a fear that his music was becoming outdated had driven him into a deep depression. With his first three symphonies, Sibelius had been able to draw an audience to his music. However, his fourth, dating from 1911, was not warmly received: the music seemed to have been dug out of the permafrost. In Helsinki, and throughout Europe and in America audiences did not know what to make of this bleakly cold work. On the one hand it is a romantic, heartfelt piece that expresses Sibelius’s fear of death; three years previously his excessive drinking and smoking habits had resulted in a throat tumour, from which he could scarcely believe he had been cured. On the other hand, it is a modern, uncompromising work that seems to explicitly

turn its back on the opulent sound of the romantic style. ‘This symphony dispenses with the circus’, he explained.

Sibelius’s drinking and smoking habits had resulted in a throat tumour, from which he could scarcely believe he had been cured

The work is indeed largely subdued, apart from the occasional musical outbursts. There are no tutti passages, and one hears instead the repeated change from one chamber-orchestra like group to another. The opening motif, that recurs in various manifestations, is the common thread that runs through the entire work. It is written in an indeterminate key – neither major nor minor – a destabilising force that characterises the entire symphony. The second and fourth movements are more lively, giving the impression of sudden vitality, but they fizzle out into a drifting pianissimo. In the last movement this has a definitely confrontational effect: just as the crisis seems to have been averted, the muttering of the lower strings brings the work to an abrupt, tragic end. Despite the reaction, Sibelius himself was particularly attached to this symphony. ‘I still think that there is not one single note I would add or take out’, he observed more than thirty years later. ‘My Fourth Symphony is an important part of who I am.’ He had previously expressed the wish for the slow movement to be played at his funeral. An event for which he would have to wait longer than anticipated: Sibelius lived to the grand old age of 91. He had long before then ceased composing, but he had every reason to boast: ‘I am still alive, and all the doctors who forbade me from smoking and drinking are dead.’

Michiel Cleij

Photo: Algirdas Bakas

Photo: Maik Schulze

Born: Vaasa, Finland

Current position: Music Director Latvia National Symphony Orchestra, Principal Guest Conductor Deutsche Kammerphilharmonie Bremen, Music Director Designate Orchestre National du Capitole de Toulouse and Hong Kong

Philharmonic Orchestra

Education: piano at Kuula College (Vaasa) and the Sibelius Academy (Helsinki), conducting with Jorma Panula, Sakari Oramo, Hannu Lintu and Jukka-Pekka Saraste

Guest appearances:Toronto Symphony Orchestra, RSO Berlin, Konzerthaus Orchester Berlin, SWR Symphonieorchester, Göteborgs Symfoniker, Los Angeles Philharmonic, a.o.

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2022

Born: Vilnius, Lithuania

Education: piano and choral conducting at the National Čiurlionis School of Art, voice at the Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre with her mother, the soprano Irena Milkevičiūtė

Breakthrough: 2014, debut with the Royal Swedish Opera in Puccini’s Madama Butterfly

Subsequently: opera at Salzburger Festspiele, Wiener Staatsoper, Bayerische Staatsoper, Deutsche Oper Berlin, Bayreuther Festspiele, Teatro alla Scala, Royal Opera House, Metropolitan Opera; concert appearances with Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Berliner Philharmoniker, Wiener Philharmoniker

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2025

Born: Laitila, Finland

Education: voice at the Sibelius Academy Helsinki with Roland Hermann

Breakthrough: 2015, debuts Opernhaus Zürich, Teatro Comunale di Bologna, Bayerische Staatsoper, Semperoper Dresden and Ruhrtriennale

Subsequently: opera at Sommerfestspiele Baden-Baden, Bayreuther Festspiele, Salzburger Festspiele, Dutch National Opera, Opéra National de Paris, Staatsoper Berlin, Bayerische Staatsoper, Wiener Staatsoper, Lyric Opera of Chicago; concert appearances with Gewandhausorchester Leipzig, Berliner Philharmoniker, London Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Symphony Orchestra

Debut Rotterdam Philharmonic: 2025

ICCR Finale: Opera

Wed 11 June 2025 • 10.00 (rehearsal) and 19.30 (concert) conductors Finalists ICCR soloists Singers International Vocal Competition Den Bosch

choir Laurens Symfonisch

Puccini highlights from various operas

ICCR Finale: Symphonic

Fri 13 June 2025 • 10.00 (rehearsal) and 19.30 (concert) conductors Finalists ICCR

Price Dances in the Canebrakes

Debussy La mer

Rachmaninoff Symphonic Dances

Music for Breakfast 5

Sun 15 June 2025 • 10.30

Rotterdam, RDM Kantine

Musicians and programme on rpho.nl

North Sea Jazz Festival

Fri 11 July 2025 • 16.30

Rotterdam, Ahoy RTM Stage conductor Clark Rundell

saxophone Dayna Stephens and Tineke Postma

piano Danilo Pérez

bass John Patitucci

drums Terri Lyne Carrington

The Symphonic Music of Wayne Shorter

Fri 12 September 2025 • 20.15

conductor Dalia Stasevska

soprano and nyckelharpa Aphrodite

Patoulidou

Meredith Nautilus

Sibelius Scene with Cranes

Berio Folk Songs

Patoulidou Improvisation

Sibelius Luonnotar

Respighi Pini di Roma

Chief Conductor

Lahav Shani

Honorary

Conductor

Yannick Nézet-Séguin

Principal Guest Conductor

Tarmo Peltokoski

First Violin

Marieke Blankestijn, concertmaster

Tjeerd Top, concertmaster

Quirine Scheffers

Hed Yaron Meyerson

Saskia Otto

Arno Bons

Rachel Browne

Maria Dingjan

Marie-José Schrijner

Noëmi Bodden

Petra Visser

Sophia Torrenga

Hadewijch Hofland

Annerien Stuker

Alexandra van Beveren

Marie Duquesnoy

Giulio Greci

Second Violin

Charlotte Potgieter

Frank de Groot

Laurens van Vliet

Elina Staphorsius

Jun Yi Dou

Bob Bruyn

Eefje Habraken

Maija Reinikainen

Babette van den Berg

Melanie Broers

Tobias Staub

Sarah Decamps

Viola

Anne Huser

Roman Spitzer

Galahad Samson

José Moura Nunes

Kerstin Bonk

Janine Baller

Francis Saunders

Veronika Lénártová

Rosalinde Kluck

León van den Berg

Olfje van der Klein

Jan Navarro

Cello

Emanuele Silvestri

Joanna Pachucka

Daniel Petrovitsch

Mario Rio

Eelco Beinema

Carla Schrijner

Pepijn Meeuws

Yi-Ting Fang

Killian White

Double Bass

Matthew Midgley

Ying Lai Green

Jonathan Focquaert

Arjen Leendertz

Ricardo Neto

Javier Clemen Martínez

Flute

Juliette Hurel

Joséphine Olech

Manon Gayet

Flute/Piccolo

Beatriz Baião

Oboe

Karel Schoofs

Anja van der Maten

Oboe/Cor Anglais

Ron Tijhuis

Clarinet

Julien Hervé

Bruno Bonansea

Alberto Sánchez García

Clarinet/ Bass Clarinet

Romke-Jan Wijmenga

Bassoon

Pieter Nuytten

Lola Descours

Marianne Prommel

Bassoon/ Contrabassoon

Hans Wisse

Horn

David Fernández Alonso

Felipe Freitas

Wendy Leliveld

Richard Speetjens

Laurens Otto

Pierre Buizer

Trumpet

Alex Elia

Adrián Martínez

Simon Wierenga

Jos Verspagen

Trombone

Pierre Volders

Alexander Verbeek

Remko de Jager

Bass Trombone

Rommert Groenhof

Tuba

Hendrik-Jan Renes

Percussion

Danny van de Wal

Ronald Ent

Martijn Boom

Harp

Albane Baron