Magnetic Lens Changing System

Swiftlock Release Lever

Magnetic Lens Changing System

Swiftlock Release Lever

Magnetic Lens Changing System

Swiftlock Release Lever

Magnetic Lens Changing System

Swiftlock Release Lever

The British action sports and adventure writer travelled from his home in Trentino, Italy, to Switzerland to profile freeskier Kirsty Muir for us. “I’ve covered quite a few ski contests, including two winter Olympics, but I’ve never seen a crowd as big or as hyped as the one at Big Air Chur,” says Kennedy. “Kirsty’s ability to deal with that pressure was awe-inspiring.” Page 28

When Kirsty Muir (page 28) first set skis on an Aberdeen dry slope at the age of three, she had no idea it would shape the course of her life. But, as this month’s subjects prove, passions can lead you to surprising places. We caught up with Muir in Switzerland – where she was flexing the freeski prowess that has taken her around the world and onto this month’s cover of The Red Bulletin – to find out how the 18-year-old Scot sharpened her exceptional skills.

Also honed in Scotland, the rare two-wheeled talents of Danny MacAskill (page 58) have found a second home on the streets of San Francisco. The phenomenal trials rider has spent five years perfecting his latest film in the US city – we take a behind-the-scenes peek in this issue.

Published in The New York Times, Victory Journal and VICE, the Brooklyn-based journalist has documented offbeat topics including rural Colombian bullfighting, the world’s best checkers players and Cuban baseball. It made him ideal for our story on the Call of Duty community in Frisco. “There are interesting worlds hidden around us, even in mundane and unexpected places,” Swide says. Page 40

And from his bedroom in Liverpool to a high-stakes battle in Dallas, professional gamer Liam ‘Jukeyz’ James has been on his own improbable journey thanks to Call of Duty: Warzone. Jukeyz is one of the many players who has made the pilgrimage to low-latency mecca Frisco, Texas (page 40), in search of the ultimate gaming experience. Enjoy the issue.

Page 28

The iconic range returns.

8 Gallery: the tech, the teamwork and the training – preparation for the 37th America’s Cup starts here. Plus highlights from global photography contest Red Bull Illume, including BMX artistry in Philadelphia, creative skating in Mexico City, and climbing for comets in California

15 Greenback tracks: artist and producer Danger Mouse revisits four formative tunes

16 Form of remembrance: Holding the Flame – the AR statue that’s keeping social history alive

19 ‘Robot Tamer’ Madeline Gannon: making friends not overlords

20 Coast story: the Alaskan who’s drawing – and painting and filming – attention to the pollution crisis

The Greek tennis pro explains why mental strength is as vital in the game as a solid backhand 24

The US rapper/activist on sharing new queer narratives, and the long struggle to speak their truth 26

Seeing your high-school life played out on screen sounds a nightmare, but not for this Canadian pop twin 28

From Aberdeen dry slope to the ‘Glastonbury of snow sports’, the freeskiing teen is in the ascendency

Why are gamers flocking to Dallas? A love of 10-gallon hats and JR Ewing? Nope, it’s all about the ping 50

For this Finnish freediver, beneath the ice is a place where time stands still and records are broken 58

The bike ace talks us though his latest labour of love: a postcard from San Francisco, five years in the making

69 Top deck: sailing an Ocean Race yacht is mentally taxing, stomachchurning, claustrophobic and exhausting, but in the nautical world it’s hard to beat 74 Powder dressing: if you’re heading for the slopes, you need this gear 84 Vegetarians are weaklings? Tell that to this champion powerlifter

87 Ride high: the Wahoo Kickr Climb raises your indoor cycling game 88 Dune it right: how to nail new video game Dakar Desert Rally 90 Snow and steady: the highs and lows of being a ski patroller 92 Essential dates for your calendar 98 Outdoors wisdom from Semi-Rad

The life aquatic: Johanna Nordblad feels at home in the icy waters of the Arctic

An AC75 foiling monohull lifts out of the waters of the Mediterranean during a test run in October. This is BoatZero – the training yacht of Alinghi Red Bull Racing, a challenger for the 37th America’s Cup in 2024. The world’s longest continuously running sporting event (founded in 1851) and the pinnacle in yacht racing, the America’s Cup draws the best sailors and pushes the envelope in sail engineering. It’s also expensive – it can cost more than $100 million to take part – but Alinghi knows the deal, having won in 2003 and 2007. Now, the Swiss team is soaring back into the fray with a partner renowned for delivering in another bleeding-edge sport – F1 –and sailing under the banner of yacht club Société Nautique de Genève. It hasn’t been an easy ride – the boat capsized on its maiden sail just weeks earlier – but helmsman Arnaud Psarofaghis is confident they’ve got what it takes. “Since that training session the team has progressed at every level,” he says.

Photographer: Samo Vidic; redbullcontentpool.com

Photographer: Samo Vidic; redbullcontentpool.com

Maryland-born lensman Andrew Dixon had a clear aim with this shot of BMX ace Joshny Babu, which won him a semi-final place in the ‘Emerging by Black Diamond’ category of global photography contest Red Bull Illume. “My goal with this image was to merge two things I love most: shooting action and products,” Dixon says. “I wanted to completely over-engineer the image, which required a total of 10 strobes hoisted around the rider. It took tons of attempts because of the sheer amount of light that was being thrown at him, but at the end of the day we walked away with an awesome image.” adixonphoto.com; redbullillume.com

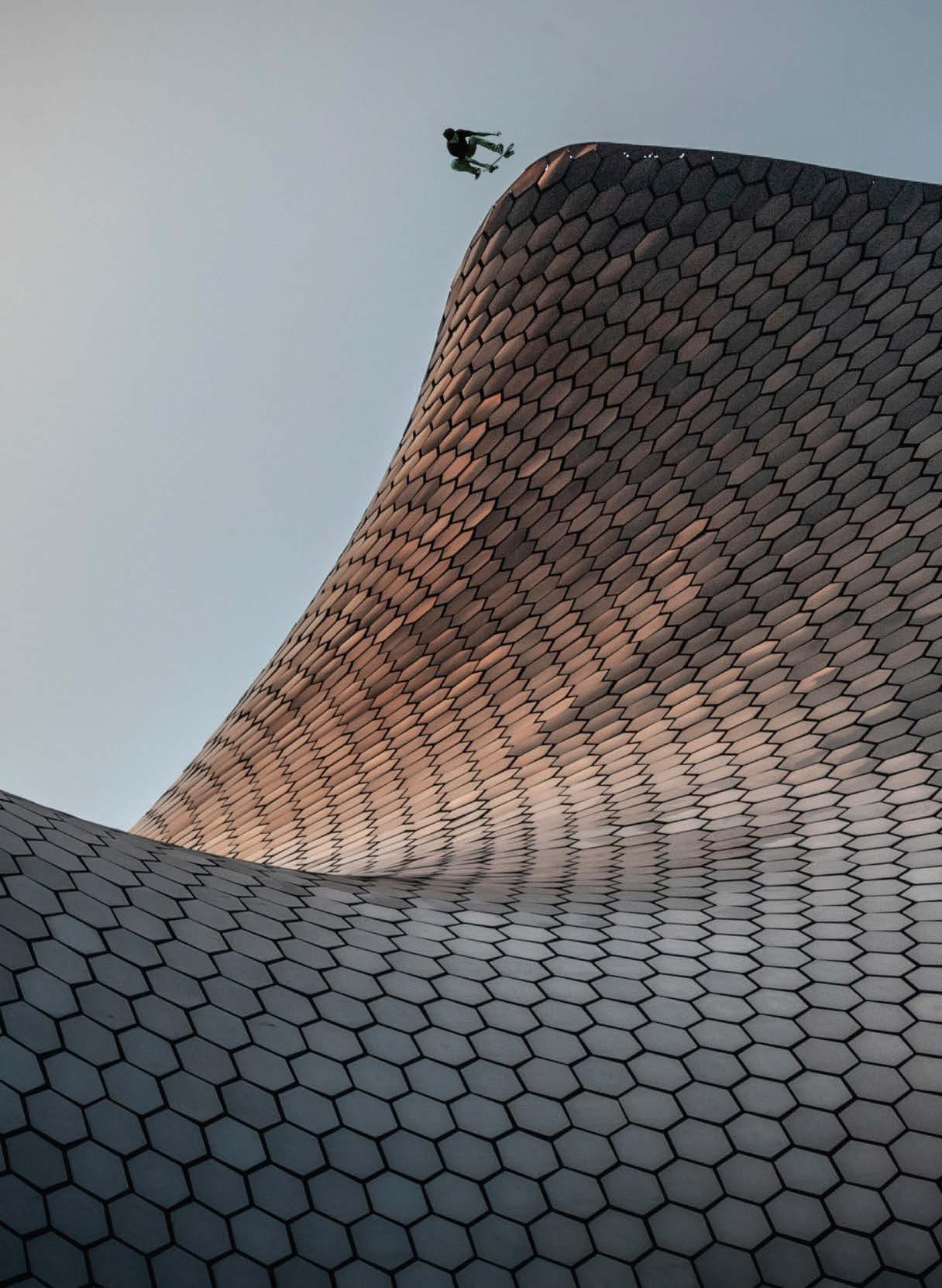

As a concert photographer, Luis Alejandro Arriaga Osorio has shot the likes of Muse and Billie Eilish, but his other speciality – action sports imagery –requires him to view the world through a different lens. Take this shot of skater Diego Alvarez – a finalist in Red Bull Illume’s ‘Creative by Skylum’ category. “This building is peculiar because of its shape, but all you have to do is turn your head to give it a new dimension,” says the snapper. “It became a colossal bowl with the architecture inbetween… In my mind I visualised it immediately.”

Instagram: @luisarriagaph; redbullillume.com

Forget AstroBranson and the MuskModule – the wonders of the cosmos can be seen without leaving Earth. Priscilla Mewborne proved this in downtime on a climbing shoot in Yosemite. “I was following the movements of the visible comet Neowise,” says the US photographer/aerialist, whose shot was a Red Bull Illume ‘Lifestyle by COOPH’ finalist. “It was expected to peak in the middle of my work week, but luckily a motivated group of fellow employees was keen to experience it, too.” Next day, it was back to work of a more terrestrial kind. Instagram: @lovealwayspriscilla; redbullillume.com

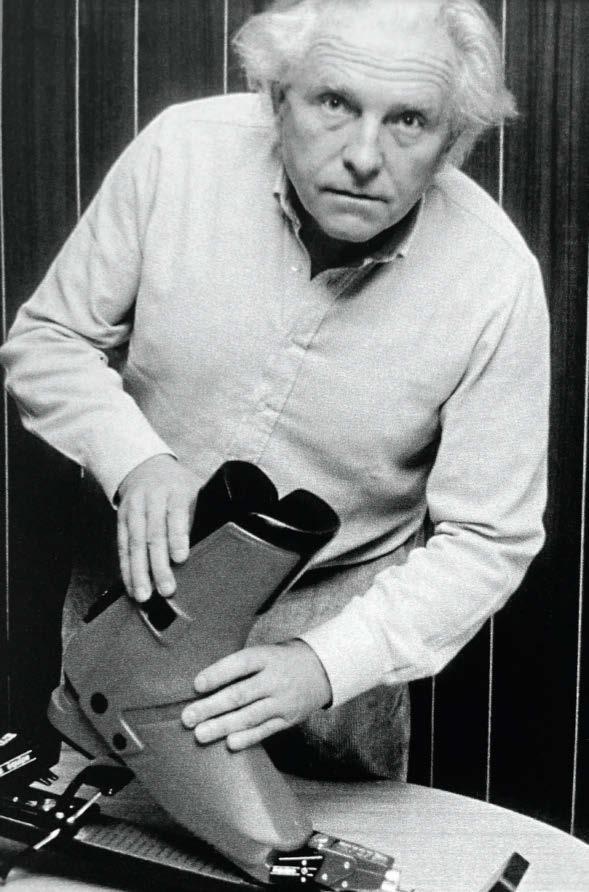

The artist/producer picks four songs that helped define his musical journey

Brian Burton, aka Danger Mouse, has produced tracks by some of music’s biggest names – Adele, Gorillaz and The Black Keys among them – but also has an impressive CV as an artist in his own right. His solo breakthrough was 2004’s The Grey Album, a mash-up of vocals from Jay-Z’s The Black Album and samples from The Beatles’ 1968 ‘White Album’, and as half of Gnarls Barkley he was responsible for the huge 2006 hit Crazy. To mark the release of Into the Blue, the third album by Broken Bells – his project with The Shins singer James Mercer (pictured, left, with Burton) – the 45-year-old picks four songs that left a mark on his life. brokenbells.com

Scan to hear our Playlist podcast with Danger Mouse on Spotify

From

“This is a beautiful song [by former Byrds member Clark] about how, in a way, you get closer to people who can hurt you; in order to not get hurt more, you get under their wing. Musically, the song is a mix of country and gospel. It’s very soulful and has this real melancholy, soulful element that comes in. It’s just one of my favourite songs ever. If you don’t know it, have a listen.”

“I remember being on tour in Europe with some project when I first heard Phantom Limb I loved it. James [Mercer, his Broken Bells bandmate] has a melodic sense that’s so unique; he’s one of those people who, almost like The Beach Boys, can make a song sound so pretty and upbeat but still inject that melancholy into it. I don’t know what the lyrics are about. I don’t even want to know, so I can just make the song my own.”

“This song [by Australian rock band The Church] is one of my favourites of all time. I kind of wish I was a teenager when it came out, but I wasn’t – I was only 11 at the time. I almost feel as if I was going through a heartbreak when I first heard it, though. [Laughs.] It makes me feel that melancholy and nostalgia of being young and getting your heart broken. I love that era of music so much – it’s a big influence on me.”

“This is an epic cover of Burt Bacharach’s Walk On By that defined a whole feel and sound for me when I was in college. It combined the soul music my parents used to play, the hiphop feel that influenced me in my youth, and the Pink Floydsounding kind of psychedelic prog stuff I loved at that time. And it’s 12 minutes long. I love the intent of that – it’s an artistic statement. This was definitely a big one for me.”

is a living role model, not just another dead, ‘great’ white man”. The person he chose was Marcia Rigg, the civilrights campaigner whose brother Sean died in police custody in Brixton in 2008.

But not only is its subject alive, the monument itself is far from a static lump of stone or marble. Created using augmented reality and 3D scanning technology, Holding the Flame is a virtual statue of Rigg that stands outside the police station where her brother died in Canterbury Square. Using the Aswarm XR app and their phone camera, passers-by can ‘trigger’ its appearance.

“People have to make that statue appear – you’re part of the act,” says McIntyre-Burnie. “Every time someone downloads it, they’re reigniting the flame. You can walk around it as if it’s really there, and hear Marcia’s voice speaking her story.”

The AR artwork challenging our understanding of what statues can be

In June 2020, as the UK emerged from lockdown and Black Lives Matter protests took place worldwide, the statue of slave trader Edward Colston was toppled from its plinth in Bristol, sparking a fiery debate about the role of statues in modern society. At the same time, Thor McIntyreBurnie and his public arts company Aswarm were looking for a way to mark the 40th anniversary of the 1981 Brixton uprisings in south London.

“Statues were tumbling down around us,” says the London-born artist and director, “and we’d had the death of George Floyd piped

into our living rooms. We’d had our public space taken away [by lockdown] and now, in a way, it was being given back to us. It was an interesting time to look at statues and public space, and who those things are serving,”

Working with the United Family & Friends Campaign, a London-based coalition set up by families affected by a death in custody – police, prison or psychiatric – Aswarm seized the opportunity “to diversify what the role of a statue can be… to break history from stone, keep it fluid and alive”. McIntyre-Burnie wanted to create a statue of someone “who could be questioned and

Bringing history to life: the Aswarm XR app is your gateway to viewing the statue

For McIntyre-Burnie, the year-long process of working with the Metropolitan Police and local authorities to create the statue was important: “As a father in a mixed-race relationship, bringing up a Black teenage boy in Brixton, I was touched by Marcia saying that growing up she never saw a statue that looked like her. I want my son to grow up in a city where there are statues that embody him or his mother. It’s also about venerating someone challenging the status quo.”

But what about the fact that an AR statue isn’t designed to exist for ever? “I think it’s OK,” says McIntyre-Burnie. “When you put something in a space for a while, you give people an idea of how that space can work. Then, by moving your piece, you’re sort of giving your space back to the public to do the next thing. Keeping that conversation alive makes it more powerful.”

Holding the Flame can be viewed in Canterbury Square, Brixton, until April 2023; aswarm.com

After having a baby during the pandemic, Madeline Gannon was conscious her daughter might be missing out on human interaction. So she turned to a different kind of companion – a robot named Ursa Major. Having constructed a swing for her daughter, Gannon built another so Ursa – a 1.3m-tall robotic arm originally created for light automation such as painting cars or sanding wood – could swing next to her. This might seem an unusual solution, but for Miami-based Gannon – known as ‘the Robot Tamer’ – robots are more than just machines. “These things might not be alive, but that doesn’t mean they can’t provide some level of comfort,” she says. “There’s this general fear about our relationship with technology, that we’re building our own obsolescence. I want to show that robots can enhance and augment our lives so they’re not just a source of anxiety.”

Originally an architect and now a researcher, artist and multidisciplinary designer, Gannon has become famous for blending art and science by programming robots with the autonomy to respond to their surroundings. Her work

has been exhibited at the Design Museum in London – her giant industrial robot, Mimus, could sense and interact with visitors – and she was commissioned to create Manus, a set of 10 robots programmed to behave like a pack of animals, for the 2018 World Economic Forum. “I give them the ability to see and understand the world around them, then I jump in the middle and interact with them like you would any other creature,” she says. “They just happen to be made of metal and motors instead of flesh and bones.”

Gannon’s first foray into working with robots after learning to program was a behemoth made by automation tech firm ABB for heavy industry. “The feeling and the risk of being face to face with this one-tonne beast of a machine is thrilling,” she says.

“I’ve been addicted to robots ever since.” Her most recent project at ETH Zurich university saw her ‘perform’ with 50 tonnes of industrial machinery usually used in car manufacture. “They do short repetitive tasks – it’s a very boring existence. So I make software that lets them improvise. I feed them agency until they start to surprise me, and that’s when I know I’ve found the right balance.”

Automatons can be our friends, says the US designer who has worked out how to tame even the biggest, most industrial machines

Right now, inspired by the FIFA World Cup, she’s teaching Ursa how to pass a football. “In the simulation, I can pass it a ball and it can hit it back,” Gannon says. “I can say if I want it on my head, shoulder, chest or leg. The next step will be to transfer the program to the physical robot, but Gannon has faith in Ursa: “The real challenge will be me hitting it back accurately!”

Ultimately, Gannon aims to show people what the future could look like if we learned to live alongside robots: “As an architect, I’m hypersensitive to how people move through space, and I’m giving these sensibilities to the robot. I’m not programming them, I’m convincing them. It doesn’t feel like I’m marching off into the future alone, because I have them with me to explore it.” atonaton.com

MADELINE GANNONIn the depths of the Alaskan winter, when temperatures fall to -20°C, artist Max Romey uses gin to mix his watercolours because water would freeze instantly on the page. “Painting in Alaska is not for the faint of heart,” he says. “But it’s a really cool conversation to have with the landscape.”

Romey’s home state is the largest in the US and also the most sparsely populated, with just 0.49 people per square kilometre. “It’s like Jurassic Park but with bears,” says the 28-year-old. “It feels like the last wild place on Earth.”

But in recent years Romey has seen this unspoilt environment engulfed by marine debris shredded on the harsh coastline. After years of travelling the world as a freelance filmmaker, he returned to Alaska for work and ended up

focusing on the pollution issue. “You almost have to be here to believe it,” he says. “You can’t walk the shoreline without crunching a plastic bottle. It’s ingrained in this landscape already, and it’s horrifying. It’s like finding worms in your cake.”

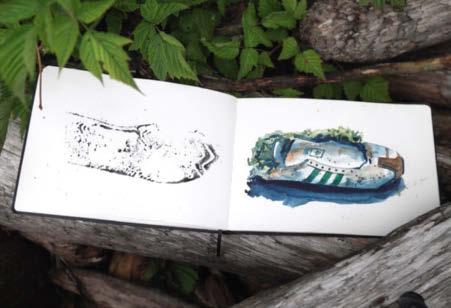

The extent of the problem was overwhelming, and Romey turned to art to help him communicate what he was witnessing. “I’m dyslexic and that’s been a big part of my life,” he says. “Reading and writing have been super-rough, but I can show you a picture and it just makes sense. Sketchbooks are wildly private, but as I’ve gone on I’ve realised they’re an amazing way to share my voice without words.”

Using his watercolours as a foundation, last year Romey made the short film If You Give a Beach a Bottle, his take on

the pollution crisis. “I’ve got a perspective here that not a lot do,” he says. “I want to light the spark that catches other people’s imagination. The issue of marine debris is enormous. It feels like an ultramarathon; you can’t win this thing quickly, but if you keep on moving forward you might get there eventually.”

The filmmaker hopes his next project will resonate even more with viewers as he tracks the hundreds of shoes that wash up on Alaska’s beaches. “It’s arguably the most eerie thing you’ll find out here. The shoes are this little bit of humanity because you know somebody was in them. And these things are still making footprints. Around 20.5 billion shoes get made each year, and there’s almost no way to recycle them.”

Romey doesn’t let himself off the hook, either. “I’ve had maybe about a hundred pairs of shoes in my life up until now,” he says. “The whole goal of this film is: will I find one of my own shoes out there? [The result] will be a mix of Wes Anderson and David Attenborough.” Watch a teaser for Max Romey’s new flm at maxromeyproductions.com

Drawing the line: (above) filmmaker Max Romey; (top) scenes from If You Give a Beach a Bottle MAX ROMEYMeet the Alaskan artist and filmmaker who’s using his talents to turn the tide of ocean pollution

think I’ve ever played at such high focus levels for so long. Everything felt like it made sense. It’s like a drug when you’re able to experience it –it brings you to another level. You’re not playing with your skill any more, you’re playing with your soul.

Can you find your flow whenever you want?

Words TARA BROCKWELL Photography ANTOINE TRUCHETGreek tennis ace Stefanos Tsitsipas first picked up a racket at the age of three, and now, at 24, he’s one of the sport’s most credible contenders. Last February the world number six celebrated his 200th tour-level win; two months later, in his adopted home of Monte-Carlo, he joined the select set of players who have successfully defended an ATP Masters 1000 title. Plus he has an Instagram account dedicated to his perfect hair (apparently the secret to his flowing locks is Greek oregano).

But, as January’s Australian Open looms, there’s no time for Tsitsipas to rest on his laurels. As a three-time semi-finalist in the tournament, the Greek is hungry for a win. And this, Tsitsipas tells The Red Bulletin, will all come down to mental magic.

the red bulletin: What’s your most significant mental strength? stefanos tsitsipas: Patience. I think this is something that this generation lacks. Especially with social media, they’re very impatient and want everything done right here, right now.

Have you always been a patient person, or is it a skill you’ve honed?

I was a pretty hyper kid, but I learned with time to become slowerpaced, to think about my intentions. It’s important to know when to let go, to reflect, and to appreciate the small things you’ve been able to contribute to what you’re trying to do, even if it’s [only] adding one per cent. Some people want big results

too soon. Of course, sometimes it’s difficult to manage that and be consistent in that kind of mindset, but in difficult moments I remind myself I’m here for the journey, not the destination.

How does patience improve your game on the court?

There were two times when I found myself in the same situation with the same opponent, but [it was] a different Stefanos each time. The first time I faced Rafael Nadal at the Australian Open in the semifinals [in 2019], I was really impatient. I remember thinking, “OK, I’m playing against one of the best. I really need to prove myself with big shots and go for it.” [He lost to Nadal in straight sets.] Two years later, I faced him again at the same tournament, this time in the quarter-finals. After going two sets down, I understood what I was doing wrong. I remember coming to an agreement with myself, saying, “OK, you’re going to become patient. You’re going to wait. You’re going to spend every single minute on the court enjoying the play and just make it a fun game.” It turned out to be one of the best comebacks in my career so far. [Tsitsipas fought back to take a surprise victory in five sets.]

How did that performance feel?

How can I describe it? It felt like I was in a cage and someone decided to unlock it. I suddenly felt free. Every decision I went for felt right. It’s what I like to call flow. I was able to reach that flow by decreasing my expectations. It was a pure fight. It was all mental. It was excruciating, physically and mentally – I don’t

I had this conversation with my mental trainer: how can we get into that flow state more often? The answer, surprisingly, is that you just have to let go. You can’t think you want to be in the flow state, or you’ll never reach it. It happens gradually, it builds up. It’s a climax you reach when you stop overthinking and just act, using more of your instinct.

How much of your game is mental as opposed to physical?

I haven’t lost many matches because of my physical condition; most have been because of the things going through my mind. Physically, many players are at the same level. I think [the difference] has to do a lot with mental preparation. You need food for your body to be physically fit, but also food for your brain to be mentally fit. Tennis is a very mental sport.

Do you have a mental goal?

To be the most positive guy on Earth, I guess. I have my days when I’m a little bit negative – I think we all do.

Can you always remain that positive as a competitor?

That’s a tricky question. Criticism is important – I like receiving it. When I was younger, I was very sensitive to it, but as I’ve got older I think it’s essential. It’s the only way you can achieve perfection. I mean, perfection doesn’t really exist, but you can get close. That also comes with your attitude to what you do. If you do it with love and care, if you wake up every morning and do the best things to succeed in what you do, with people who are chasing that same dream, anything is possible. With your mind, you can achieve everything you want in life. That’s where it all starts. It all starts with an idea.

Instagram: @stefanostsitsipas98

When the Greek tennis professional wanted to uncover the secret of winning, he discovered the answers were all inside his head

“In the flow, you’re not playing with your skill but your soul”

It’s impossible to pigeonhole Mykki Blanco. The non-binary performer (who uses the pronouns they/them) is a poet, performance artist, activist and musician who fuses a wide range of influences – including punk, grunge and trap – with rap to create unique, mould-breaking hip-hop tracks. The 36-year-old Californian, born Michael Quattlebaum Jr, has collaborated with everyone from Kanye West to Madonna, and their own DIY work ethic has played a large part in their success. But it has taken a decade of being in the spotlight for them to feel able to speak their truth through music.

the red bulletin: Your latest album is titled Stay Close to Music. What was the thinking behind that name?

mykki blanco: I didn’t start songwriting until I was 25. Now, to be able to write songs and be paid to have people listen and see you perform, that is a gift! What is life but a series of joys and struggles?

When I think about what’s happened in my life, when I was diagnosed with HIV [in 2011], when I had struggles with drugs or alcohol, when at the beginning of my career I faced a lot of taboos and a lot of homophobia and transphobia, and when I think of what it is to be a queer person of colour in this society… I went through all these various forms of intersectional oppression. I decided to call this

album Stay Close to Music as I found that, no matter what I’ve been going through, I wake up and I say, “No matter what’s going on, I’m gonna get up, have my coffee, maybe go for a quick run, and then I’m gonna write songs, and that’s my job.” That’s a gift.

You’ve worked with some of the world’s best-known music artists. But how did you get started?

I didn’t have a record label until recently, and [I never got a] mainstream push, so one of the things I had to do was play a lot of concerts. It’s the classic way of getting your name out there, like Sam Cooke and Elvis did. That’s how you build the fanbase. The birth of Tumblr and social media networks allowed me to grow my career, as people all over the world could say, “Hey, we want a Mykki Blanco show in Paris, in Sweden, in Cape Town, in São Paulo.” And I would go. I toured relentlessly. When I look back at the number of shows, it was psychotic! But we wouldn’t be sitting here now if I hadn’t done that.

After spending so much time on the road, where do you call home?

I don’t have a flat right now, but I was living for a bit in Portugal up until 2020, then I went to Paris, then I lived in LA for a few months, but I was still spending the majority of my time in Europe. I pretty much tend to live all over Europe; I’m not sure where my next country will be, but I connect more to the European lifestyle. Plus, there is something that happens when you’re in a place where you don’t speak the language: I get to be in my head, be more in

my imagination. Maybe I’m able to deal with myself when I’m not taking in this external stimuli [of conversation], and I think that influences my songwriting.

You’re well-known as a queer Black artist who has long played with drag and gender presentation, and your chosen pronouns are now they/them. How is your identity reflected in your music?

I have always tried to highlight queer narratives that I’ve lived but I don’t feel are promoted in the mainstream. In the mainstream media, we’re fed this palatable idea of what it is to be queer – this clean-cut, whitewashed idea; a queerness that plays by heterosexual rules. There are queer people who, in their authenticity, fit into that way of being, and that’s fine. But, for most of us, that’s not true to our lived experience. In my own trans journey, I was always a gender-nonconforming person. I was always a target, highly visible yet invisible at the same time. Yes, things have got way better, but still you’re a target.

How does it feel to put so much of yourself into the public realm?

[In the future] I will try to be more and more honest in my songwriting, because I’ve realised people don’t need to come to Mykki Blanco for just a feelgood dance song any more. I’m able to be multidimensional, and maybe people will value me more when I can give more sides of myself. That was not always so easy; it took years and a lot of different processes of songwriting: “Can I say this? Am I comfortable with this?” It’s taken me years to be comfortable with that kind of vulnerability. I was 25 when I wrote my first song, and now I’m 36 – it has taken 10 years for me to build these skills. If I’d started at the age of 15, maybe I would have been a more mature songwriter by 25, but I didn’t – that wasn’t my story, wasn’t my trajectory. Everything feels very organic. It feels like it’s happened right on time.

Mykki Blanco’s latest album, Stay Close to Music, is out now; mykkiblan.co

The American hip-hop artist and activist writes songs from a perspective rarely heard in mainstream music. But telling their truth didn’t come easy

“We’re fed this palatable idea of what it is to be queer”

The 42-year-old singer-songwriter on the strangeness of heading back to high school to see her life story turned into TV fiction

Words LOU BOYD Photography MICHELLE FAYETegan Quin is used to sharing her life with the public. The singersongwriter is one half of successful Canadian pop act Tegan and Sara, which she started with her identical twin sister in 1995, writing about small-town life in Calgary, Alberta. The duo won international success by the age of 15; they had a record deal before their 18th birthday.

From their very first song, Tegan Didn’t Go to School Today, Tegan and Sara’s songs have been intensely autobiographical, sharing their most private thoughts and feelings, so it made sense when, in 2019, they published a successful memoir of growing up in the ’90s. “It feels like you know everything about me, and that’s my job,” says Quin. “Because Sara and I have shared so much about what it was like to grow up together, people feel really close to us.”

Now, Quin is sharing her life once again in the Amazon Freevee TV series High School, a fictionalised coming-of-age comedy written in collaboration with actress/director Clea DuVall. The series, which stars real-life twins Seazynn and Railey Gilliland, follows a year of the Quin sisters’ adolescence as they discover music and explore their identities and sexuality (both Tegan and Sara have openly identified as queer since the start of their careers).

Here, Quin (pictured opposite, left, with Sara) speaks to The Red Bulletin about fictionalising her own life, the importance of centring queer narratives, and how she hopes the TV series will correct people’s assumptions of what it means to be a twin.

the red bulletin: Were you nervous about allowing your life story to be fictionalised? tegan quin: We clearly feel compelled to share stories about ourselves. I think the discomfort we sometimes feel in revealing our personal lives is worth it. There are so few stories like ours, so few queer stories that get told, especially when you really look at the intersection of being queer women and creatives and songwriters. We so rarely see stories about women being creatives. It felt important and worth the risk.

Was representing a queer female story one of the driving forces? Yeah. I love a lot of the queer TV coming out, but some of it – especially what’s aimed at adolescents and teens – feels a little neutered. I feel like this show is more real. It’s like a group of friends hanging out in the ’90s, figuring out who they are.

You went back to your old high school in Calgary to shoot the series. What was that like? Surreal. It was so weird to watch the monitors and to see our story play out in front of us. The biggest mindfuck, though, was thinking about what dirtbags we’d been at school. I don’t think anyone expected much of us, but now we’ve had a very successful career and we’re back in Calgary filming this show based on our lives.

You found Seazynn and Railey on TikTok. Were you nervous to cast sisters with no acting experience? I think people thought we were crazy for suggesting it. We saw the twins on the app, and it just felt right. They worked so hard with an

acting coach and trained in music, and they’ve amazed everyone with their performances.

Do you recognise yourselves in the characters they’ve created?

Sara and I were very verbose and hyperactive, quite extroverted and outgoing in high school. I feel like Railey and Seazynn’s performance shows more of our internal world. I see so much of how I felt on the inside, how I was privately struggling. Railey and Seazynn brought so much of themselves into their roles, and Clea [DuVall] and Laura [Kittrell, scriptwriter] put parts of themselves in there, too. Because of that, I never felt like I was watching myself. It was easy for me to disconnect and just watch it as a beautiful story about girlhood and adolescence.

The show confronts misconceptions not only of the teenage queer experience but also of what it means to be a twin. How have such assumptions affected you?

We’ve spent our entire career correcting myths and misconceptions about what it’s like to be twins. There’s the stupid stuff that people ask, like, “Can you read each other’s minds? Can you feel each other’s pain?” And there’s the fact that everybody thinks we’re best friends and we get along all the time.

What was it like to work with another set of identical twins? Meeting Railey and Seazynn was so good because I’d never been friends with other identical twins before. So much of what they said was just like me and Sara. They love each other, they do everything together, and yet they still struggle with that pull to be their own person. High School is a beautiful, nuanced portrait of what it’s like to be a twin, and I think it’ll resonate with people. You don’t have to be a twin to know what it’s like to feel lost in a crowd or next to those you’re closest to. Everyone knows what it’s like to feel overshadowed. High School is available to watch on Amazon Freevee (via Amazon Prime) now; teganandsara.com

“There are so few queer stories that get told”

At just 18, Scottish freeskier KIRSTY MUIR has the world of winter sports at her feetand not only because most of her professional life is spent in the air. Having started out far from top-rated resorts, the Olympian proves that hard graft, vision and a well-chosen soundtrack can take you to dizzying heights

Words TRISTAN KENNEDY Photography DAN CERMAK

Words TRISTAN KENNEDY Photography DAN CERMAK

Tall order: at 42m high, the jump at Big Air Chur is a challenge for any skier

t the top of a tower of scaffolding, 42m above the concrete of a Swiss car park, Kirsty Muir is getting ready to jump. Bouncing slightly from side to side, like a boxer preparing to throw a punch, she jerks her head back and to the left, practising to the last moment the movement she’s about to make in the air. Then, with her headphones blocking out the roar of thousands of expectant fans below, the pounding drums of The Pretender by Foo Fighters kick in. Without hesitation, Muir launches her skis down the narrow strip of snow sloping down from the 14-storey structure, gathers speed, and catapults herself into the sky.

AThis is big air, a discipline in which freestyle skiers such as Muir showcase their best tricks over a single, enormous jump. On a set-up this size, they can expect to hit the peak of their parabola 8m above the flat ‘table top’ of the jump – roughly the height of two double-decker buses – fly for a distance of around 20m (as long as two double-deckers back-toback) and reach speeds of up to 45kph.

The flight from the lip of the jump to the landing lasts two-and-a-half seconds. But with a skier as skilled as this 18-yearold, these instants seem to stretch as she unleashes the biggest trick in her arsenal: a double cork 1260. Spinning on two axes simultaneously, she completes

“Women’s skiing has progressed so much. The dream for me is to help push the sport along”

three-and-a-half full rotations and goes upside down twice before skiing down the landing – which at 38°, is as steep as most black pistes – backwards.

The physics of this feat are mindboggling. But it’s made all the more impressive by the fact that this artificial scaffold is far harder to ride than any normal ski-resort set-up. To create a ‘real snow’ jump like this in the middle of a town, the organisers of Big Air Chur – the first World Cup contest of the winter –use crystals of ice instead of snow. These last longer in the warm October weather, but they can freeze into ridges, making both take-offs and landings even trickier. Muir’s presence here, at the pinnacle of her sport, is almost as incongruous as the jump itself. Most of her fellow competitors, from Norway, Canada, Austria and France, have grown up riding actual snow on proper mountains. Muir is

from the UK, a nation not renowned for its winter-sports prowess, and grew up skiing on a dry slope in Scotland.

There’s no denying she deserves her place at the top table, however. Having landed her double cork 1260 – equalling the biggest trick landed by any female athlete all day–- she qualifies for the eight-woman final at Big Air Chur with ease. And the result is no fluke; Muir hasn’t finished outside the top 10 in a World Cup contest since the start of last season. In February, at the age of just 17, she finished fifth as big air made its

debut at the Winter Olympics in Beijing and, a week later, went toe-to-toe with the best in the world again in the Olympic slopestyle final, taking eighth. When the Games come to Italy in four years’ time, there’s every chance Muir will make history as the first British skier ever to win gold. But how did an unassuming teenager from Aberdeen become world-class?

“I started skiing pretty young,” says Muir over the phone a few days before the contest in Chur. “I was three, almost four, when my parents took me on the dry slope.” Her father Jim, who spoke to The Red Bulletin from Aberdeen where he works as a chemist on offshore oil rigs, and her mother Kim were both keen recreational skiers. “When the kids came along, we wanted to get them into skiing as soon as possible,” Jim says. The dry slope at Garthdee, near the family home, proved the perfect place to start.

Originally built in 1967 and known locally as Kaimhill Ski Slope, Adventure Aberdeen Snowsports Centre had fallen disrepair in the ’90s and eventually shut in 1996, with some of the land sold to Asda. But then, in 2004, the year Kirsty was born, it was reopened by the council. And crucially the slope was resurfaced not with Dendix – the scratchy, diamondpatterned matting that covers most of the UK’s ’60s-era slopes – but with a new material called Snowflex.

While neither feels much like real snow, Snowflex comes with a layer of padding underneath, which makes learning to jump, and falling over, significantly less painful. By the time Muir started skiing lessons, a surprisingly vibrant freestyle scene had developed at the slope. “I went to the Saturday kids’ club, where the majority was [normal skiing] technique,” she says. “But for the last 10 minutes of every session we got to go on the freestyle slope. The coaches could see how much I loved it straight away.”

nitially, skiing was just one of many activities that Muir and her siblings – older brother Jimmy and younger sister Fiona – tried out. But by the time one of her instructors, Andy Begg, encouraged her to join in his Wednesday freestyle sessions, she knew it was her favourite sport. “I had to choose whether to continue dance classes on Wednesday nights or start freestyle, and I was like, ‘I’m going skiing, I’m going skiing!’” Muir says. Her father recalls that “the dance teacher was really disappointed, because

“After the Winter Olympics, I really was buzzing”

Fever pitch: Big Air Chur attracts one of the biggest live audiences in skiing –12,000 attended the October 2022 event. Unfortunately, this time around, Muir missed out on a podium place

she was good at it”. But her parents were supportive. On weekends when the notoriously fickle Scottish weather played ball, the whole Muir family would wake up early to drive to the Highland resorts of Glenshee or The Lecht. “If there was snow, our car would always be the first in the car park,” says Jim. Muir, in her favourite pink ski outfit, her bright red plaits poking out from beneath her helmet, was always raring to go.

But the odds were still stacked against Muir becoming an elite winter-sports athlete. As vibrant as the local scene was, a dry slope next to an Asda car park is a far cry from the alpine resorts where most of her competitors learned to ski. Dry slopes, despite the name, must be sprayed with water constantly, quickly leaving skiers soaked through. On dark Aberdeen evenings, they’d do well to get two hours in before the cold and wet became too much.

Skiing in the Highlands, meanwhile, can be wonderful, but the weather is famously changeable. “When I coached Kirsty and the dry-slope crew in the mountains, I mainly taught them how to ski on heather, how to avoid rocks, and when to take hot-chocolate breaks because it was raining,” recalls Begg, laughing. On the bright side, Muir says, at least she learned to ski in all kinds of conditions: “The first time we went to the French Alps [as a family] we were the only ones on the hill, because of how windy it was. But we were still stoked to be out there, ’cos it was just like Scotland.”

Muir’s determination to make the most of the resources available to her has undoubtedly played a role in her success, say her coaches, but perhaps even more important is her methodical approach. She’s always had

an innate ability to appraise “the risk/ reward ratio,” according to Jamie Matthew, head freeski coach at GB Snowsport, the UK’s Olympic governing body, who first met Muir when she was 10. “It wasn’t so much that she had no fear, but she could rationalise stuff a lot better than other kids,” he says. “She understood the methodology of practice, and she got stuff that a lot of kids her age wouldn’t understand – even stuff that a lot of the more mature athletes wouldn’t necessarily get.”

Muir also had an impressive work ethic from a very young age, according to Joe Tyler, another coach who’s been instrumental in her development. Her father agrees. “She was just so dedicated, you could tell she loved it,” he says. “She was dedicated, she worked hard, and she was brave.” It’s perhaps this last trait that really set her apart. Given the choice, her coaches say, Muir would always hit the biggest jump, ignoring any evolutionary instinct of self-preservation to push herself further, higher, faster.

In 2018, at just 13 years old, she won all three freeski events – big air, slopestyle and half pipe – at the national championships, known as The BRITS, against a star-studded field of much older competitors. Two years later, when she was finally old enough to join GB Snowsport’s World Cup team, she made a splash straight away. “Her first World Cup was an inner-city big air in Italy that was hella sketchy,” says Matthew. “I remember speaking to Joe [Tyler] –he had to pull her back and say, ‘Look, I know you want to do your hardest trick, but that’s not a wise idea right now. Being here is enough.’”

For Muir, however, it wasn’t enough. “Even though the conditions were sketchy, the jump wasn’t great and the snow was absolute trash, she was like, ‘No, I want to do my hardest stuff,’” says Matthew. In the end, Tyler talked Muir down, and even with her easier trick she finished a credible 13th. “But that drive and determination…,” Matthew adds. “There were a million and one reasons for her to back down. She could have

“Music

“I don’t see any reason why she couldn’t win whatever she wants”

Henry Jackson, snow sports commentator

used any number of excuses, but she didn’t. It was the opposite. And that’s definitely not usual.”

Despite her laser focus on progression, in person Muir is about as far from a competition robot as you could find. At a café in Chur the day before the competition, she’s dressed in the grungeinspired uniform of today’s teens – huge baggy jeans, and a hoodie reaching halfway down her thighs – and beneath the Red Bull cap, pulled low over her auburn hair, there’s a ready smile.

This has, she says modestly in her soft Aberdeen accent, been quite a big year. In April, she turned 18. In July, she finished school, having taken two years to do her final exams because of all the time off for skiing. (She aced them, according to her dad, despite having to study on the road.) On snow, too, “last season was a season of firsts for me,” she says. There was her first Winter Olympics, of course, but she also earned invitations to the Dew Tour, The Nines, and the X Games –the most prestigious events in the freeski calendar, to which only a select few are given a golden ticket.

“After the Olympics, I really was buzzing,” she says. “I was very emotional and overwhelmed. And having seen the other girls sending some really insane tricks that haven’t been done lots in our sport… I was stoked to come fifth. The level of women’s skiing at the moment is so high. The progression has been really significant. That would be the dream for me – to help push the sport along. Hopefully this year I’ll get some new tricks down and we’ll see.”

As the professional milestones have racked up, Muir has grown in confidence personally, too. “I was definitely quite a quiet, shy person initially when I was on the circuit,” she says. “But I think in the last year I’ve become just a little bit more confident in myself. Not just my skiing, but in building friendships on the scene and stuff, being a part of the girls’ group.” These days, by all accounts, Muir is the life and soul of the party. “I still love dancing – I love doing the Worm,”

she laughs. Music has helped her on the slopes, too, calming the contest nerves as she lines up for a big jump. “[I started listening to tunes] in the last year and a half,” she says, “because I was very uptight in competitions, and I felt like music could help me relax more. Now, I listen to it all the time.”

The recent boost in Muir’s confidence has been obvious to her friends and coaches, too. “It’s like she almost needed the Olympics and a brand like Red Bull coming along to be able to square it away in her own head that, ‘Oh, I’m actually pretty good at this, I can do this,’” says Matthew.

Those who watch the sport closely now believe Muir can go all the way. “She got a fifth and an eighth at her first Olympics at 17,” says Henry Jackson, the TV commentator who has presented most of the biggest events in freestyle skiing and snowboarding for the past decade and has watched countless talented kids come through. “Next time she’ll be, what, 21 and physically a little stronger? I don’t see any reason why she couldn’t win whatever she wants.”

Back on the concrete in Chur, her eyes shining and adrenaline pumping, Muir is preparing to jump in the nighttime final. Watching this competition makes it easy to understand why athletes like her need strategies to help them focus and relax; this event – a mix of music and action sports –attracts one of the biggest live audiences in skiing. Competing here, you’re part athlete, part rock star. Over the course of the afternoon, a 12,000-strong crowd has gathered around the base of the jump and the Glastonbury-sized stage set-up to the left of it. Later in the evening, veteran US rapper Busta Rhymes will close proceedings with a hit-packed set, but the festival atmosphere has started early: Berlin-based rap trio KIZ are already whipping the audience into a frenzy as Muir and the skiers warm up. Huge circle pits form, with beanie-clad kids cannoning into each other every time the beat drops. Plastic cups of beer explode into the night sky as the MCs exhort the crowd to “jump, jump, jump”.

As excitable as the crowd is, there’s no doubt that the skiing – which starts with an audible blast of flame from pyro cannons built into the scaffold –is the main event. Local hero Mathilde Gremaud gets the biggest cheers, with

“Last season was a season of firsts for me”

have placed her among thefreeskiing elite

Swiss flags fluttering every time she drops in. But fans hold handwritten cardboard signs aloft for others, too. At the front, Lena Bianca from Corvatsch – a ski resort 80km south of Chur – is shouting herself hoarse for Muir. “I love her, she’s so amazing,” she says.

In the final, skiers are given three runs but must do two different tricks, and then the scores for their two best efforts are combined. Muir has spent the practice period concentrating on her second trick, an inverted 900° spin that involves skiing off the ramp backwards and is known as a switch bio 9. Frustratingly, it hasn’t felt perfect yet, she says. This means she hasn’t had time to try her double cork 1260 again since the morning’s session.

In the intervening hours, there’s been a dip in temperature, a few drops of rain have fallen and some lumps of ice have

hardened. Muir knows these small changes could make a big difference to her calculations of speed. It doesn’t help that, after she qualified, she fell attempting the double cork 1260 a second time – a mishap she blames on a musical mix-up. “For some reason, they took longer than normal to give the score to the girl ahead of me,” she says. This meant she mistimed pressing play on her headphones. “There’s about 10 seconds of quiet at the start of The Pretender, so I didn’t have the good part of the song, I didn’t feel good, and I rushed the take-off.”

It’s tempting to read into Muir’s choice of song for these crucial moments. The Pretender’s defiant chorus, which asks, “What if I say I will never surrender?”, could easily be taken as an affirmation of the determination that’s got her here, even in the face of such setbacks. In actual fact, she says, she’s picked it more

for the music than the lyrics; the driving drums and distorted guitars are exactly what Muir needs to get herself amped up as she enters the arena.

There’s something gladiatorial about the scene as Muir and her fellow skiers crowd into the narrow lift that carries them to the top of the scaffold, high above the hyped-up crowd. Bouncing on her skis, she rehearses that jerk of the head, drops in, and just fails to hold onto the backwards landing of the double cork 1260. Ahead of Muir’s second attempt, Matthew, standing with her at the top of the ramp, suggests she should try going bigger. She needs no encouragement. This time, she flies miles down the landing, only to go down harder. The sound of 12,000 people groaning in sympathy is audible as her skis fly off in different directions and she slides down the icy landing on her front.

Even though she has a third run, without two scores Muir won’t reach the podium at this contest. Worse still, the fall has left her hurt – she lifts her jacket to reveal where the artificial snow has scraped the skin off her stomach. Yet even though this last jump is meaningless from a competition point of view, there’s no question of her pulling out. As Alison Robb, the GB Snowsport physio, applies plasters to her wounds, Muir smiles. “It is what it is,” she says. Then she heads back into battle.

In the aftermath, Muir is welcomed with hugs from her fellow freeskiers. Everyone knows that at this level of competition the margins are minuscule. Had she landed her tricks, as she did earlier in the day, Muir would almost certainly be in the medals. What’s more important from her point of view, however, is the fact that she’s competing with these girls as friends and equals – not a pretender to the throne, but a queen in her own right. Behind her, in the crowd, Lena Bianca shouts, “Kirsty, I love you!”

She may have a lot still to do, but Kirsty Muir has nothing left to prove. Instagram: @kirski12

Giant steps: Muir makes the long and winding climb up the metal scaffold for one of her three runs at Big Air Chur

Giant steps: Muir makes the long and winding climb up the metal scaffold for one of her three runs at Big Air Chur

“The level of women’s skiing is so high right now”

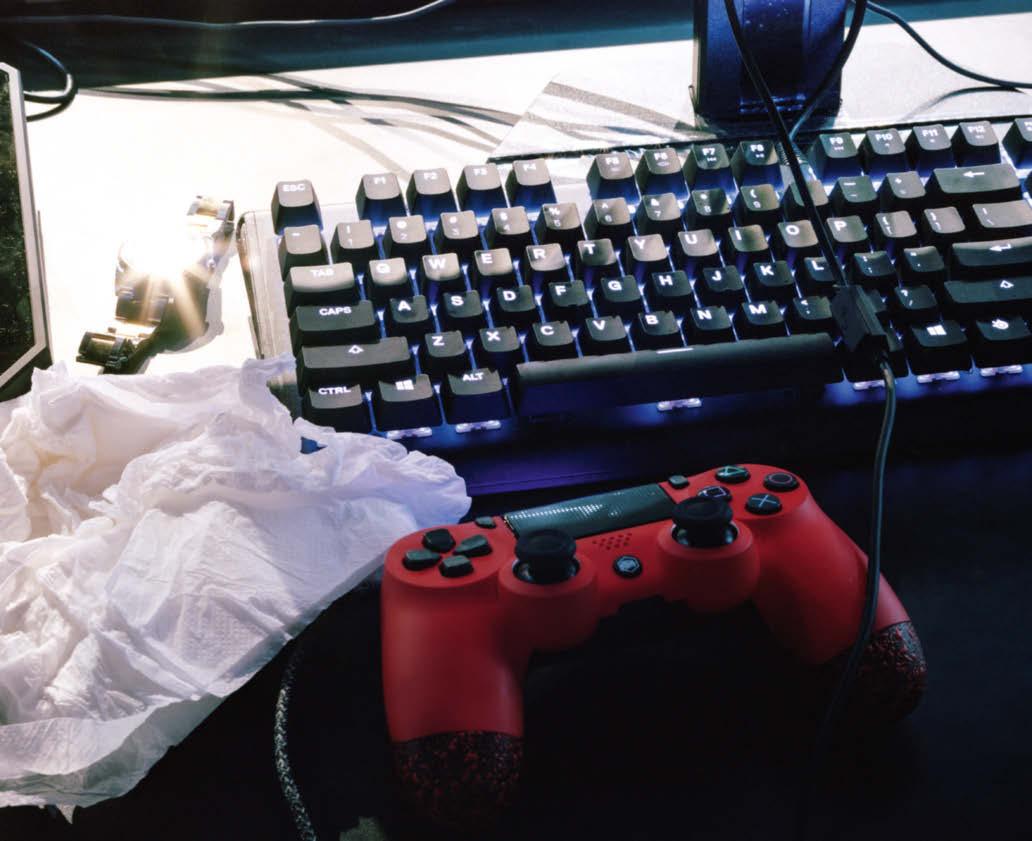

Light show: aHTracTXII plays in a $1,500 tournament from his bedroom in the Frisco apartment he shares with Flxnked

Light show: aHTracTXII plays in a $1,500 tournament from his bedroom in the Frisco apartment he shares with Flxnked

There is an invisible force all around us. It benefits almost all of us, but for an elite subculture of gamers it can bestow superpowers, immeasurable wealth and unparalleled freedom. And there’s one place where it exists in its purest, uncut form – Frisco is ground zero for the thing they call ping

“Anywhere else, the best ping you’ll get is 15 milliseconds. Here, it’s seven. It’s absurd”

Play to win: (opposite) a headset hangs on a monitor on the day of the wager match with Jukeyz at the Mavs Gaming Hub in Dallas – the monitor shows ‘0% packet loss’, which requires an extremely strong internet connection; (this page, from left) Almond and Tommey during the $6,000 wager match against Jukeyz and HisokaT42 at the Mavs Gaming Hub in Dallas

Frisco, Texas, is the last seven exits of the Dallas North Tollway. Around 50km from downtown Dallas, Frisco is where the line of suburban development – the office parks, bank towers, Whataburgers, and apartment complexes – begins to end, at least now. In between the new developments and construction sites are still bits and pieces of the old North Texas plains that have defined the region ever since the inland sea that once cut through North America receded into the gulf about 260 million years ago.

Around 1,200 years ago, the Caddo indigenous people moved west from the Mississippi River Valley and set up the first permanent settlements in this area, farming corn, squash and beans. Around 200 years ago, local cowboys built the first settlement of Frisco while driving cattle from ranches south of here up the Shawnee Trail and on to the markets in Kansas and Missouri, where they could make $30 to $50 per head. And since about 2020, young men from around the world have been quietly flocking to Frisco where, hidden away in mundane apartment complexes, they play Call of Duty: Warzone for up to 24 hours a day and earn incomes of up to $50,000 a month.

Call of Duty is a series of first-person shooter video games that began in 2003. In early 2020,

the series released Warzone, a free-to-download battle royale game in which up to 150 players compete against one another on a single enormous map, in teams of four, three, two, or individually, depending on the game type. Because the game was simple to play, free (its revenue model is based on microtransactions for special character and gun skins, and other unlockables) and entered the market just before a pandemic would trap millions of people in their living rooms for months, it quickly exploded in popularity and became the predominant first-person shooter game played around the world.

Flxnked and aHTracTXII live in a new apartment in a gated complex near the centre of Frisco. The apartment is clean and simply furnished: white walls, grey carpets, a stock image of a cityscape framed on the living-room wall, and a glass bowl of M&Ms on the kitchen countertop. From the back of a high-speed modem on the living-room floor, twin cables run into each bedroom where, next to neatly made beds, sit glowing computer set-ups optimised with dual monitors for simultaneous gaming, streaming, and communicating with fans.

Stretched out on the couch, aHTracTXII scrolls through local DoorDash [America’s Deliveroo]

options – Chick-Fil-A, Shake Shack, Raising Canes – before narrowing in on an order of Five Guys. Although it’s 5pm, he’s only been up for a couple of hours, making it somewhat unclear what meal this constitutes, but with a $1,500 online tournament starting in less than an hour, this might be his only chance to eat for the next five or six hours.

A soft-spoken and boyish 25-year-old from Chicago, aHTracTXII has been a professional gamer since he began making thousands of dollars a month in Call of Duty tournaments as a 13-year-old. However, until his move to Frisco a couple of months ago, he’d never lived away from home. “I’ve never had a real job. I just graduated high school and continued gaming,” he says. “I love it. It’s freedom – streaming whenever I want, eating whatever I want, doing my own thing and being on my own. Well, with him, I guess.”

Flxnked moved from Minnesota to Frisco in early 2022. He grew up playing hockey until a knee injury as a teenager shifted his focus towards Call of Duty In 2019, he received an esports scholarship to join the Call of Duty team at Davenport University in Grand Rapids, Michigan. However, when COVID struck, he dropped out of school and turned pro, hustling in the online community to gain access into the invitationonly tournaments that build the careers of elite players. “You’ll have months where you make zero dollars,” he says. “And then you’ll have months where you’ll make, like, $10-12,000 in one month.”

In a typical professional-level competition, two teams of two players each enter the game as one team of four. This way, they’re unable to kill each other, making the competition one in which each duo tries to rack up the most kills against the other players in the lobby. Therefore, unlike some esports

in which players compete on a Local Area Network or LAN – where computers are linked in close proximity – or at the very least in private sessions, Warzone pros are competing on the internet in public lobbies against regular people who often have no idea at all that there are pros alongside them playing for thousands of dollars. This aspect of Warzone competition is what makes it accessible and relatable to the masses of viewers who watch these matches on streams, but it’s also a system that leaves the potentially lucrative income of elite professionals at the mercy of internet speeds. It’s this emphasis on internet speed that sets Frisco apart for players like Flxnked.

“Anywhere else, the best ping you’ll usually get is like 15 [milliseconds],” he explains. “And here you get seven. You can even get lower sometimes. It’s absurd.”

For all of its invisible digital and wireless magic, the internet is essentially a vast physical network of servers, cables and modems that allow signals carrying information to travel between computers throughout the world. The speed by which information travels that network, either between devices or between servers and devices is referred to as ‘ping’ and is typically measured in milliseconds. There are essentially two major ways to shorten ping time. One is to improve the physical condition of the network itself so that information can move through it faster. For example, wireless internet is generally slower than connecting through physical cables, with fibre-optic cable networks being the absolute gold standard. But once speed is maximised through improving the hardware, the only other way of lowering ping time any further is by shortening the distance the information has to travel – setting up the computer as close as possible to the server.

Call of Duty’s servers are run by the game’s parent company, Activision Blizzard, and there are 29 dedicated Call of Duty servers around the world, with 12 in the US alone. While they’re located in various major metropolitan areas throughout the country – New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, Seattle, Atlanta etc – it’s known in the Call of Duty community that the Dallas servers, for whatever reason, provide the best ping times.

For the average internet user, latency or ping is often not very consequential – a slight delay in a video call or in live-streamed media. But for a gamer, every millisecond of delay in movement or reaction can have a tangible impact on the game. In Call of Duty, those milliseconds can be the deciding factor in landing a shot on an opponent before an opponent can fire a shot of their own. For the professional gamer who spends the majority of their waking hours playing wager games or online

“You’ll have months where you make zero dollars, then others it’ll be like $10-12,000”

industry: (below) a street sign for Internet Boulevard in Frisco

tournaments for thousands of dollars, this subtle advantage can mean the difference between never making it out of the stereotypical mother’s basement and living in a well-appointed Frisco apartment with a closet full of designer garments.

If Usain Bolt could guarantee a 30-millisecond advantage in every race simply by living in an apartment in Frisco, Texas, it’s fair to say that he very well might be renting the unit next door, with his own bowl of M&Ms on the counter.

Exit 14 of the Dallas North Tollway looks not so different from the 13 exits before it or the 25 after it. But past the Mattress Firm and Dick’s Sporting Goods, behind the Post Office, and before the Planet Fitness – in the middle of yet another perfectly manicured office park – a towering black monolith contains what could be the source of Frisco’s mystical essence. The name on the building reads ‘Inwood National Bank’, but public records list the address – 13760 Noel Road – as the Dallas-area home of Activision Publishing, Inc.

“If I were a betting man, I’d put money on that being where the servers are,” says Alex Gill, a gaming specialist for Red Bull who has spent the last four years in the Frisco esports scene. “If they’re not there, they’re in a private building nearby. We know they’re in the Dallas area, but everyone says Frisco. I don’t have a source for that; it could be that [Activision Blizzard] just told some people and it started a rumour. But it’s tribal knowledge.”

When he was growing up, Gill says, Dallas always had a seemingly magnetic pull for gamers. “Playing in the late ’90s, the companies that developed these earlier games didn’t have dedicated servers. The

way it worked was a player would set up a game, running it off of their computer as a server, or the developers would spin up [a session – enable an on-demand gaming server]. I remember Dallas was a place that a lot of them did spin up, because it’s centrally located in the US. Then, in the early 2000s, when online gaming started to ramp up, that’s when it happened.”

Whether it was gamers migrating to Frisco that brought the servers here, or the servers that drew the gamers, Gill says is a mystery. “It’s a chickenor-egg question. There were a few teams already located here – Complexity Gaming [founded in 2003] brag about being the oldest esports organisation that’s still in operation. They’re owned by the Dallas Cowboys. Team Envy, historically one of the biggest names in Call of Duty, was here. OpTic Gaming won top three esports brand globally for a couple of years in various rankings. I don’t know if the servers were already in Texas at the time, but they moved here from Chicago and it made this triumvirate of three of the larger older esports organisations. I haven’t talked to anyone at Activision Blizzard, but to me that would be the reason they’d want to build servers not only in Dallas but in Frisco. I don’t think it’s a coincidence.”

Then, in 2020, a global pandemic changed everything. “Servers became much more relevant,” says Gill. “Previously, [Activision Blizzard] did all their events in Columbus, Ohio. All the teams played on a private local server at the venue, where everything is even. But COVID threw a wrench in the system, because suddenly they had to do the pro leagues remotely. That brought ping back into the equation.” The 2020 Call of Duty League World Championship, the first time the championship was held online, was won by the Dallas Empire.

“There was a bit of drama early on, where these teams in Texas were winning and everyone was saying, ‘Oh, that’s just because the servers are in Dallas. You’re not really better than us.’ Then a weird thing happened: a bunch of the pro teams’ rosters all moved to Frisco. Their organisation operations stayed in LA, New York, wherever, but the rosters moved to apartments and houses in Frisco to be closer to the ping. I don’t think results changed that much, but that was a moment where the teams maybe recognised how important the ping was. When we really became a kind of a Call of Duty mecca for pro players.”

Today, however, the Inwood National Bank building isn’t giving up its secret. It’s the weekend and the office is closed. The sun is blazing, and the only person around is a guy across the street, quietly cleaning out his car.

“COVID threw a wrench in the system… Suddenly pro leagues had to be done remotely”

On a hot Saturday afternoon in the Deep Ellum section of Dallas, the city’s young, beautiful, and well-dressed pack the sidewalks outside the neighbourhood’s bars, restaurants and music venues as cars and motorcycles cruise the streets, creating a soundtrack that ranges from country to drill to Mexican corridos. A block from the main strip, in the air-conditioned calm of a converted industrial space that now houses the Dallas Mavericks Gaming Hub – a sleek esports venue funded by the city’s NBA franchise – Gill and a few staffers work quietly in the otherwise empty space to set up computers, monitors and an enormous projection screen for a Warzone match later that day. It will be between four of the top players in the world, who will be competing online in lobbies among the general public, for a wager of $6,000. As the staffers finish the set-up and run their first online test of the game, the computer reports a theoretically impossible ping of zero milliseconds.

The headliner for the day’s match is Jukeyz, a professional from Liverpool with more than $200,000 in career earnings from Warzone, which makes him one of only two Europe-based players on the game’s top 10 earnings list. Due to the effect of transatlantic distance on ping speeds, Europe-based players are at a significant disadvantage when playing a US-based game against US-based players on US-based servers. Jukeyz’ position on the earnings list despite this handicap speaks to both

Space to breathe: Jukeyz takes a puff on his asthma inhaler during a break in the $6,000 wager match against Almond and Tommey at the Mavs Gaming Hub in Dallas

Space to breathe: Jukeyz takes a puff on his asthma inhaler during a break in the $6,000 wager match against Almond and Tommey at the Mavs Gaming Hub in Dallas

his talent as well as the reason for his visit to North America, and Dallas in particular. While officially he was on a 12-day, three-city US tour to build his audience and grow his brand, a welcome bi-product of his time in the States was being able to play every day with better ping and win more money. And the centrepiece of his stop in Dallas was a match against two of the best players in the world – together, the best duo in the world – Frisco residents Almond and Tommey.

Another Minnesotan transplant to Frisco, Almond is a 23-year-old phenom who, according

to esportsearnings.com, earned more than $250,000 from Warzone in 2021 alone. Tommey, a 29-year-old from England who recently moved to Frisco as well, is currently the top earner of all time in Warzone, with listed winnings totalling more than $400,000.

Jukeyz’s playing partner is HisokaT42, a teenager from South San Francisco, California, who had been a junior college football player until he figured out he could make $50,000 a year playing Warzone His dad – whose equally imposing physique and youthful energy makes him seem almost like a big

War zone: (top) at Jukeyz’s playing station during a break in the wager match at the Mavs Gaming Hub in Dallas are his controller, a Rolex that he removes before a game, and a used tissue; (right) Jukeyz’s screen during the wager match –while the match has very few in person spectators, thousands of fans watch the livestream online; (opposite page, from front to back) Tommey, Almond, Jukeyz and HisokaT42 play in a two-on-two, best-of-five wager match for $6,000 at the Mavs Gaming Hub

brother – has come to support his son’s rising star with the same intensity as if this were the sideline of any major professional sport.

As they enter the Mavs Gaming Hub for the match, Tommey is wearing Balenciaga, while Almond carries a Gucci bag. HisokaT42 is draped in Burberry, and Jukeyz removes the Rolex from his wrist as he sits down in the gaming chair, takes a hit from his asthma inhaler, and the four men start the match.

In the best of five series, Almond and Tommey quickly take the first two games and thus gain control of the match, before Jukeyz and HisokaT42 manage to pick up a win in the third game and stay alive in the series. In the fourth game, HisokaT42 reaches what athletes in traditional sports would refer to as a flow state. In person, it looks like a man sitting frozen in a chair, staring unblinking into a screen, completely detached from the world around him. But on the screen, the seizure-inducing speed and agility with which his virtual avatar moves through the map, and the lightning quickness of his reflexes and reactions to every potential target or threat, are almost impossible to track.

“There are questions over how much ping really impacts the outcome of these matches,” comments Gill. “To a point, of course, it does matter, like if it’s really slow. But there’s a threshold where it doesn’t necessarily impact performance. If somebody has a 30 ping and another has a 10 ping, that’s 20 milliseconds advantage, but there’s another area being studied inside gaming and that’s human physical response time. There are players that have absolutely the fastest reaction time, but there are also players at the top that I might even have a faster reaction time than. However, they’re better because they’re actually able to predict the future – they’re inside the heads of their opponents.”

In a fast-paced, instinctual game like Warzone, the best players employ a technique called ‘prefiring’. “You literally start shooting before you even see an opponent, predicting where they’re going to be,” explains Gill. “The players entering that flow state are going to end up winning, no matter what. That being said, you still have that 20-50 millisecond advantage. I might not be able to feel it, but they can.”

HisokaT42 racks up 35 kills and evens the series as his dad’s celebration booms across the venue. Although he and Jukeyz lose the fifth game, and with it the $6,000 wager, the performance dominates the post-match conversation, exemplifying the mystical lure of Dallas for Warzone players. Eliminating every millisecond creates the potential for moments in which the distance between the

gamer and the game disappears, and every mental impulse is translated directly into virtual action.

For devotees of Call of Duty, there are other places in the world with Activision servers or high-speed internet. But there’s nowhere else like Frisco. Whether housed in an immaculate climate-controlled suite or a humble closet maintained by a lone IT guy, the ping is here. And while it might be nice to get a peek at these holy servers, the magic can’t be understood simply by looking at a couple of objects inside the Inwood National Bank building. It’s far more evident in the 25-year-olds from Chicago leaving home to spend all their waking hours in dimly lit suburban apartments, the 23-year-olds from Minnesota with closets full of Gucci and Balenciaga, and the Liverpudlian crossing the Atlantic to team up with a 19-year-old South San Franciscan just to experience this unadulterated gaming fix.

As the rest of their travelling party head-off for dinner and drinks, Jukeyz and HisokaT42 stay glued to their screens late into the night, savouring their last tastes of Dallas internet to win back their money in online wager games. Eventually, they’ll meet back up with the group at a nightclub in time for the VIP booth and bottle service.

There are Activision servers in other places, but for CoD fans there’s nowhere else like Frisco

Queen of the sea: Johanna Nordblad is a phenomenon in the world of ice diving

In March 2021, Finnish freediver JOHANNA NORDBLAD dived 103m beneath an ice sheet on just a single breath – further than anyone before. In this cold, dark, underwater world, it’s the 46-year-old’s lack of speed that’s become her greatest strength

Words KARIN CERNY Photography ELINA MANNINEN

Words KARIN CERNY Photography ELINA MANNINEN

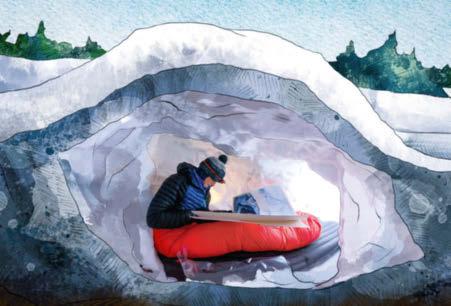

Ice diver Johanna Nordblad sits on a frozen lake in her swimwear. The ice hole in front of her reveals dark, threatening-looking water beneath a 60cm-thick rim of solid ice. The air is -7°C, the water about 2°C. It’s not easy to even imagine slipping slowly beneath the ice into this unknown environment, to dive the full length of a football feld with just the oxygen that’s in your lungs. But this is what the 46-year-old Finn did on this day in March 2021, setting a new world record in the process. No man or woman has ever dived further beneath the ice without an oxygen tank: 103m on a single breath. No fippers. No wetsuit.

Nordblad knew that diving into this hostile world for almost three minutes would push her to the very edge of what is humanly possible. It’s why the makers

of the Netfix documentary Hold Your Breath: The Ice Dive tailed the extreme diver for more than a year, capturing her self-doubt, training and willpower in twilight-blue images of a world of ice and snow.

“It’s eerie trying to set that type of record, because there is no background data to go on,” says Nordblad on a warm spring day a year later. The freelance graphic designer lives in Helsinki – close to the water, of course. “I took it to the absolute limit. From 80 metres on, it felt like my heart was only beating once an hour. The last few metres seemed to go on for days. I thought my heart was going to stop working.”

Nordblad laughs a deep, warm laugh, her eyes shining. There’s something of the Greenland shark about her, vital yet sedate. The sluggish giants of the Arctic

“I took it to the absolute limit”

New goals: ice diving was never part of Nordblad’s plan, but a mountain-biking accident in 2010 changed all that

Flipping cold: when the lakes in Finland freeze over, Nordblad starts diving, sometimes in a neoprene suit, but mostly without one

Ocean, which live three times longer than those from warmer waters, are part of a genus of sharks known as Somniosus – a Latin word meaning sleepy. In the cold, the metabolism runs on its lowest setting and everything slows down to an astonishing extent. It took time for Nordblad to get used to this life in slow motion, to the unsettling feeling of lethargy in both body and mind.

Ice diving is a paradoxical affair. You’re in a life-threatening situation, but you must remain calm and relaxed. The diving refex sets in underwater. The body knows it has to conserve oxygen and switches to survival mode: the heart rate drops – as low as an incredible 10 beats per minute in professional freedivers – and the blood retreats inwards so as just to supply the vital organs. A kind of trance sets in. It can quickly lead to a deadly blackout.

“The cold is so overwhelming,” Nordblad explains. “You feel so many different things at the same time. That’s why you have to be totally in the moment to decide, ‘Can I dive to the next hole?’” In this situation, of course, the wrong move could be fatal – there’s no room for hasty decisions. “I was always the slowest diver in competitions,” says Nordblad. But what was once a handicap is now a strength. “Being slow is my own way of dealing with this life-threatening challenge.”

Ice diving, Nordblad says, has taught her a lesson for life. It has made her calmer and more relaxed, but also more focused. Anyone venturing into this strange, dark world must be at one with themselves. A single wrong thought can cost valuable oxygen. “The secret to free diving is that there’s absolutely no room for fear,” says Nordblad. “For me, that’s also the beauty of it. I have to leave all my problems on land. My mind must be relaxed when I’m diving.” If something makes her nervous or is bothering her, Nordblad makes a date in her diary. “It gives me a kind of peace. On that date, I will try to solve the

problem. But for now I don’t have to think about it any more.”

Nordblad’s compulsion to be in the water began when she was a child. She spent every spare minute at the pool. Then, in 2000, she discovered freediving. Nordblad lay at the bottom of the pool and watched the people swimming above her. “They looked like animals,” she says. “Everything was so peaceful. I felt like I was at one with nature. I soon realised I was addicted to this feeling.”

In 2004, Nordblad broke the women’s world record in distance diving with fippers: 158m in six minutes, 39 seconds. She also coached the Finnish national men’s freediving team and competed at world championships in Serbia and

her home country. But in 2006 she found herself falling out of love with freediving. “Suddenly it wasn’t fun any more,” she says. “It had somehow become like a job. I no longer wanted to compete against others. I wanted to explore myself.” She looked for new, untried, untested ways of doing that.

“I started to train in my own way. I swam as slowly as I could for 20 minutes, to free up my head for new ideas.”

The cold wasn’t really part of her plan; Nordblad only fell in love with ice after an accident in 2010. She was downhill mountain-biking, but the track was slippery, and when her bike toppled over, her left foot got stuck in the pedal. She suffered severe damage to her leg.

Netflix and chill: Nordblad is the star of the documentary Hold Your Breath: The Ice Dive

The wound had to be kept open in hospital for ten days to avoid necrosis setting in. She was given morphine for the excruciating pain. While the bones eventually healed, the neural pathways didn’t want to play ball. Three years later, Nordblad was still waking up in the night, screaming in pain. “I thought I was going crazy,” she says. But then a doctor prescribed cold-water therapy. “I found it horrible at frst, sitting by the pool, putting my foot in the cold water. I had tears running down my face.” But two minutes later there was relief. The pain had disappeared. The cold helped Nordblad achieve inner peace and gave her a deep sense of satisfaction.